Title: Chats on Angling

Author: H. V. Hart-Davis

Release date: October 3, 2013 [eBook #43874]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Emmy and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

| A Woodland Stream | Frontispiece. | |

| Waiting for a Rise | Facing page | 5 |

| Bringing Him Down to the Net | " | 25 |

| The Sedge Hour | " | 35 |

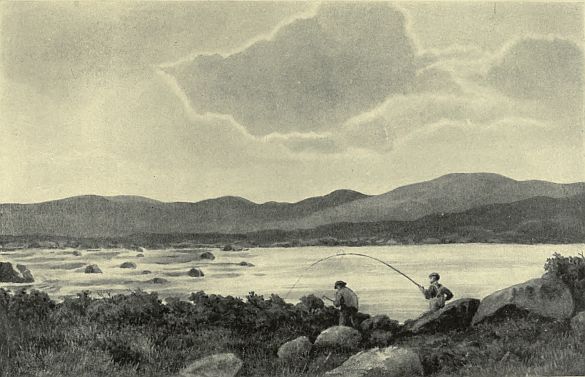

| A Dry Fly Day on Loch Ard | " | 47 |

| Luncheon | " | 61 |

| Nearing the End | " | 72 |

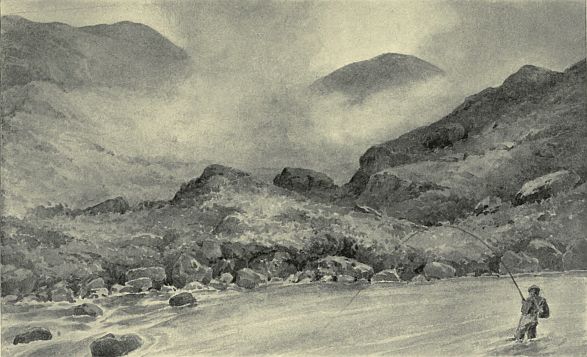

| Get the Gaff Ready | " | 79 |

| He Means Going Down | " | 88 |

| The Fall's Pool | " | 101 |

| Introductory | page | 1 |

CHAPTER I. |

||

| In Praise of the Dry Fly | " | 3 |

CHAPTER II. |

||

| Dry Fly Tackle and Equipment | " | 7 |

CHAPTER III. |

||

| Dry Fly Maxims | " | 13 |

CHAPTER IV. |

||

| Education of the South Country Trout | " | 23 |

CHAPTER V. |

||

| The May Fly | " | 27 |

CHAPTER VI. |

||

| The Evening Rise | " | 33 |

CHAPTER VII. |

||

| "Jack" | " | 37 |

CHAPTER VIII. |

||

| Weed Cutting | " | 40 |

CHAPTER IX. |

||

| [vi]The Angler and Ambidexterity | " | 43 |

CHAPTER X. |

||

| Loch Fishing | " | 46 |

CHAPTER XI. |

||

| Dapping for Trout | " | 53 |

CHAPTER XII. |

||

| Grayling Fishing | " | 57 |

CHAPTER XIII. |

||

| Notes on Rainbow Trout | " | 61 |

CHAPTER XIV. |

||

| Salmon Fishing | " | 66 |

CHAPTER XV. |

||

| A Trip to Ireland | " | 79 |

CHAPTER XVI. |

||

| Salmon and Flies | " | 86 |

CHAPTER XVII. |

||

| Salmon of the Awe | " | 91 |

CHAPTER XVIII. |

||

| Disappointing Days | " | 97 |

CHAPTER XIX. |

||

| Sea Trout Fishing and Its Chances | " | 106 |

L'Envoi |

" | 113 |

But to the outside world, to those who care nought for all we hold so dear, to those who would rank all fishermen as fools, and would classify them as Dr. Johnson was said to have done—to such these notes cannot appeal; they will regard them, not unnaturally perhaps, as yet one more addition, of a desultory kind, to an already overladen subject.

No form of sport has so enduring a charm to its votaries as angling. Its praises have been sung for centuries, from Dame Julia Berners to the present day. Once an angler, always an angler; years roll by only to increase the fervour of our devotion. It is a quiet, simple, unassuming kind of madness, without any of the excitement or the glamour of the race meeting or of the hunting field, and the love and the madness are incomprehensible and inexplicable to those who neither share them nor know them.

The quiet stroll by the stream or river bank, the constant communing with nature, the watching of bird and insect life, appeal with irresistible force and power to the angler. As the short winter days draw out, and[2] spring begins to assert her revivifying powers, the longing, intense as ever, comes over us, and we yearn for the river side. And the lessons that we learn from our love for it are not without value; patience and self-control come naturally to those who have the real angling instinct.

How widely spread this natural instinct is we may gather from observing the long lines of fishermen, each with his few feet of bank pegged out, engaged in some competition, and watching with intense interest for long hours the quiet float in front of him. Give him but a better chance of following up his instinct, and doubtless he would take with increased zeal to those higher branches of the sport that appeal more directly to most of us—the keenness is there, the opportunity alone is wanting.

Seeing that fishing and its charms have been so amply extolled and set forth by such able and various pens, from Father Walton, the merchant, prince of all writers on this subject, down to later days in continuous line, through such names as Kingsley (man of letters), or Sir Edward Grey (man of affairs)—writers whose works will live, and who can inspire in us the enthusiasm of sympathetic feeling—why, it may be asked, is it that we are not content, and that so many of us cannot refrain from publishing our impressions? There can be no answer to this query except it be as in my own case, the confession of a desire to record some of the experiences, gained through many years, in the hope that some crumb of information may be gleaned therefrom, and that the pleasure taken in recording them may find a responsive echo in some breast.

I would wish at once to disarm possible criticism by candidly admitting that this little work has no literary, or indeed any other pretensions. It is merely what it purports to be—a series of articles strung together, with the object that I have already described.

I would desire also to thank the proprietors of the Field for their permission to reprint such articles as have already appeared in that paper. My thanks are also due to my old friend Mr. W. Senior and to Mr. Sheringham for having been kind enough to glance through my MSS. and give me the benefit of their most valued criticism.

Wardley Hall, August, 1905.

From the latter are required in a special degree a quick and accurate eye, great delicacy and accuracy in the actual cast, and above all, a quiet, watchful disposition; he cannot whip the water on the chance of catching an unseen trout. His rôle is to scan the water, to watch the duns and ascertain their identity, to spot at once the dimple of a rising fish, and to differentiate between such a rise and the swirl made by a tailing fish. He will note the flow of the stream, and whether he will have to counteract the fateful drag. Having made up his mind, arranged his plan of action, and selected his fly, he will crawl up as near as may be desirable below his fish, taking care not to alarm in his approach any other that may lie between him and it; then, after one or two preliminary casts to regulate his distance, he will despatch his fly, to alight, as lightly as may be, some three or four inches above his fish. His field glasses will have told him, even if his natural eyesight could not, the quality of the fish he is trying for, and for good or evil his cast is made.

Perhaps he has under-estimated the distance, and if it be a bank fish he is attacking his fly may float down some twelve inches from the bank under which the fish is lying. In that case he will not withdraw it until it is well past the trout, but he may have noted that half-defined, but encouraging, movement which the trout made as the fly sailed past. His next cast is a better one, and, guided by the stream under the bank, the fly, jauntily cocking, an olive quill of the right size and shade, will pass over the trout's nose. A natural dun comes along abreast of his; will his poor imitation be taken in preference to the Simon pure? By the powers, it is! A confident upward tilt of the trout, a pink mouth opens, and the 000 hook is sucked in; one turn of the wrist, and he is hooked. Despite a mad dash up stream the bonnie two-pounder—in the lusty vigour of high condition—is soon controlled and steadied by the even strain of the ten-foot cane-built rod. Down stream now he rushes; he will soon exhaust himself at that game. Keep quietly below him, and keep the rod-point up. That was a narrow squeak! He nearly gained that weed-bank! Had he effected his purpose, nothing but hand-lining would have had the slightest chance of extricating him, but the rod strain being applied at the right moment and in the right direction, the gallant fish is turned back. That effort, happily counteracted, has beaten him; he soon begins to flop upon the[5] surface and show evident signs of surrendering. The landing net is quietly disengaged and half submerged in the stream below him—for if he sees it he will be nerved to fresh efforts—and his head being kept up, he is guided without fuss into its embrace. And after he is given his instant and humane quietus with one tap, rightly placed, of the "Priest," the pipe is lit, tackle is adjusted, and there is leisure to admire the beautiful proportions of a newly caught trout, the glorious colouring of his spots and golden belly. Something has been accomplished, something done. A fair stalk has been rewarded, and it is no chance success.

Those happy days when there is a good rise of fly, when the fish are in their stations, heads up, and lying near the top of the water, and the wind is not too contrary, should indeed be gratefully remembered. A short length of water will suffice for the dry fly man—a few hundred yards. For him there need be no restless rushing from place to place. Quiet watching and waiting, constant observation of what is going on in the river beneath him, these are his requirements.

But on the days when the rise is scant and short, and the trout seem to be all glued to the bottom, or when a strong down stream wind nearly baffles the angler, then his patience will be somewhat sorely tested; even under these discouraging conditions there are places in the river unswept by wind, most rivers having a serpentine course; on one of these our angler will take up his position, and his patience and perseverance will be rewarded. And if the trout be, as I have said, glued to the bed of the river, and there is no rise of fly to tempt them to the surface, he will wait patiently. It will not be always so; a change of temperature will come or some subtle atmospheric change about which we know so little, but which effects a wonderful change in the trout. They begin, as it were, at such changes to wake up from their lethargy, to come nearer to the surface and to re-assume their favourite positions—at the tail of yonder weed bank—or in the oily glide under the bank side. The first few flies of the hatch may be allowed to pass by them, apparently unheeded or unnoticed, but before long they settle down to feeding in a serious manner. Now is your opportunity, make the most of it; and if you keep well down and make no bungling cast, your creel will soon be somewhat weightier than it promised to be a short hour ago. Our friend the chalk stream trout will brook no bungling; he is easily put down and scared, and the delicate[6] accuracy needed in securing him forms the most potent of the many charms of this most beautiful of sports.

Should, as may often prove to be the case, the unpropitious conditions continue without improvement, our angler is not without resource. His surroundings are so entirely congenial; he lies on the fresh green meadow-grass, the hedgerows ablaze with blossom, the copses in their newly-donned green mantles, blue with the shimmering sheen of countless blue-bells, are full of rejoicing and of promise. The birds, instinct with their love-making and nesting operations, are full of life; all nature seems to be vigorous with new-born hope. The true angler can rejoice with them all, sharing their pleasure and delight, drinking in pure draughts of ozone, and adding, perchance, to his store of knowledge of insect and animal life. His field glasses, as he lies prone and sheltered, bring him within touch and range of many sights that otherwise would have passed unnoticed. That water vole coasting along the bank side, pausing incontinently to sit up and look around, those rabbits playing near the burrow mouth, the moorhens cruising round the flags and sedges, all afford interest and instruction. In the very grass on which he lies he will find ample scope for observation and amusement in his enforced leisure should he care to watch the teeming multitudes of insects that throng it, his ears meanwhile being solaced and refreshed by countless woodland songsters.

Built-up cane rods vary, of course, greatly in quality and durability. Cheap ones may be bought, and they will certainly turn out a dear purchase. It is best to buy one from the very best makers only, and eschew as worthless all cheap imitations. Having decided to purchase a built-up rod, we have to consider its length, etc. It is, I think, generally agreed that a length of from 9 ft. 6 in. to 10 ft. 6 in. is ample—the latter, in my opinion, for choice. Messrs. Hardy, of Alnwick and London, have devoted so much labour and attention to built-up rods as to deserve a somewhat pre-eminent position amongst the many successful firms that[8] make them. This firm produces many forms of rods suitable for dry fly work. Their "Perfection" rod is a very sweet weapon for the purpose, quick in its action, true as steel, has great power of recovery, and is light in the hand; but for choice I would pin my faith to one of their 10 ft. 6 in. "Pope" rods in two pieces. Such a one has been my constant companion for some seasons, and, though other makers may be able to turn out as good a rod, I feel convinced that none could turn out a better. The old attachments of the ferrules of former days have also gone by the board, and a bayonet joint has superseded them, to our great advantage. The upper ring on the point should be of the Bickerdyke pattern, the other rod rings of the ordinary snake pattern and made of German silver. The reel fittings should be of the "Universal" type, a conical socket taking one end of the reel base, the other end being secured by a loose ring. Personally, I do not care for a spear; I find them awkward at times, their only advantage being that your rod may be spiked when putting on a fly or when hand-lining a "weeded" fish. If one is desired, it should be carried inside the handle of the butt, the button screwing over it and holding it in its place.

I would not advocate a steel-centred rod, at any rate for a single-handed trout rod. The absolute union of metal and cane can never be secured, nor can the action of the two be precisely identical. Besides, how are you advantaged? The hexagonal form of the built-up rod is ideal for strength, and a rod without a steel centre can be made with perfect action, able to do all that may be required of it.

Reels also have undergone great improvements of late years. They are lighter, more easily cleaned, the check action is better regulated; a double check spring that allows the line to be reeled up quickly and easily, and at the same time offers a stronger resistance to an outward pull, is now almost universally employed. Aluminium, thin-brazed steel, have replaced brass and even ebonite. The air is admitted to the coils of line, and reeling up is rendered more rapid and effective. The "Moscrop" reel is excellent in many ways, and fulfils many of the chief requirements of modern reels, it has, moreover, a screw drag, which can be used to regulate the retarding action of the check. Messrs. Hardy produce an altogether admirable reel, which they have patented and call the "Perfect." Such a reel for an ordinary cane-built rod of the length we have chosen should be three[9] inches in diameter, and will carry forty yards of tapered line, with some backing, if thought necessary or desirable.

Avoid for choice patent aluminium American reels. I have one by me whilst writing. The check action is outside, and can be taken off at pleasure and the line allowed to run freely without hindrance. The perforated face of the drum which carries the handle is counter-balanced, so that it may be used as a Nottingham reel. But the main advantage claimed is that the rim, within which the drum revolves freely, is springy, and by pressing the thumb upon it the drum is at once arrested and its revolution stopped. Of course, by this means your line can be absolutely stopped at any moment should a fish make a determined rush into any obstacle, but at the expense of your fly and cast. I am told that experts with this reel cast with a free line, arresting the fly at the precise moment required by the thumb pressure, and thereby assisting themselves in judging the length of the cast, and that the check is never clicked into action until the fish is hooked. I have often tried it, and found that the inadvertent pressure of the thumb or wrist upon the rim has cost me several good fish. In fixing your reel, I would counsel its being so placed that the handle is on the left side of the rod. In playing the fish it will be necessary, therefore, to reverse your rod; the line will then run near the rod and avoid the friction against the rings, and the strain will be taken off your rod, or, rather, applied in a contrary direction to that which it so constantly receives when casting.

The line should be tapered, and should be of oil-dressed silk, such as is now supplied by all good tackle makers. The taper should be five or six yards in length, and when in use, in order to obviate the constant shortening process it receives from attaching it to your cast, I invariably whip a length of stoutish grilse gut to its end, to which I attach my cast. This upper length can always be renewed at pleasure. This plan I find better than a loop. The weight of the line is a most important point; it should be as heavy in its centre part beyond the taper as will bring out the best casting powers of your rod. The balance of the line to the rod is all important; a little trouble in selecting a suitable line will be amply repaid. Do not forget, after using it, to draw off many coils of line to dry before finally putting your reel away, and, as it is important that your[10] line should float well, do not forget to take some deer's fat with you with which to anoint it.

We next come to the cast. Two and a half yards of tapered gut are all that is necessary, tapered from stout to the finest undrawn procurable. I would discard drawn gut altogether, possibly because I am too clumsy to use it to my satisfaction. It is generally, however, easy to procure real undrawn gut of sufficient fineness from such firms as Ramsbottom, and a hank of such gut, in fifteen or sixteen-inch strands, should always be acquired when found. If kept out of the light, wrapped preferably in chamois leather, it will keep a long time. Take with you some dozen or so of such strands and a spare made-up cast in your damping box, and you will have all you will require in a day's fishing.

Your landing-net should be ample in circumference. The net itself deep and commodious; the ring should be solid, of bent wood, with a knuckle joint of gunmetal to attach it to the handle. The net should be of dressed cord, so that the fly will not become fixed in the knots. It is a great mistake to have too short a handle; you may have to reach far over sedges to get at your fish to land him. If you sling your landing-net on your left side, as is usually done, a long handle is very inconvenient in kneeling; therefore, use a telescope handle for choice. Wading trousers or stockings and brogues will complete your equipment, though, of course, some kind of basket or bag will be needed to enable you to carry your luncheon, your tackle, and your fish. All tackle makers will supply you with an ample assortment for choice in this matter. Possibly a waterproof bag with partitions and an outside net to place the fish in is the most convenient. Small linen bags in which to place the fish or linen cloths in which to wrap them are not out of place. One further article I should advise you to take with you, and that is a good pair of field glasses. They will multiply the pleasure of your stalk tenfold. With them you can search the water before you can spot effectively the most desirable fish, and ascertain more exactly what flies the fish are taking; whilst, if nothing is doing and the fish are lying like stones on the river bed or huddled away in the recesses of the weeds, you can amuse yourself with watching bird life and while away the time to your infinite pleasure.

Having fully equipped ourselves so far, we have now to consider our[11] flies. I take it that no one who fishes with the floating fly nowadays clings to the use of flies mounted upon gut. Eyed flies have no doubt replaced them for all time. The very drying of your fly is too severe upon the heads of gut-mounted flies. Eyed hooks have, however, had to fight their way to the front, so prejudiced are we all, and I can picture to myself now a prominent legislator, a great angler and the author of one of the best sporting books published of late, standing by me on Test side, on a meadow near Longparish, his cap literally covered with artificial flies attached to strands of gut—a most extraordinary sight. The fish were most unkind, taking greedily some kind of small black insect, or fisherman's curse. We had offered them every kind of midge fly or black gnat we could think of, with scant success. Our friend, in gazing for the twentieth time at his fly-bedecked cap, saw a group of black ants, on gut, amongst others. The first one put on not only procured a rise, but hooked the fish; one run, and he was gone, the fly remaining in his mouth. So with the next. In vain we soaked the gut; each fly met with the same result—it was at once taken and the fish was at once lost. The gut was absolutely rotten, and that pattern of ant was apparently the only medicine. Our friend fairly danced upon the bank in rage and disappointment. And it was all he could do to restrain himself from dancing on his rod and from using very unparliamentary language. I believe that even he is a convert to eyed flies now.

Whether the flies should have turned up or turned down eyes is a matter of controversy. Personally, I prefer the latter. In any case, the eye should not be too small, or much mental anguish will result. It is needless to say that they should be well tempered and with sound barbs. They should be tested in a piece of soft wood.

Have a reserve box of flies, made in compartments, so that you can replenish from time to time the little box you carry with you. This pocket box may be quite small. I like one three inches square and one inch deep, with rounded corners, and with bars of cork across it inside. It will carry all you need. My pliers I always attach to one of the buttons of my coat, as otherwise I am always misplacing them. Nothing beats Major Turle's Knot as an attachment of the gut collar to the fly.

If you should be fishing the evening rise at a time when it is difficult to thread the eye of a fly, even with the expenditure of many[12] matches, do not forget before you go out to mount some sedges or large red quills upon fairly stout gut points and put them in your cap. They will come in most usefully, and save a strain upon your temper.

The use of deodorised mineral oil for anointing your flies has been greatly decried of late. I can only say that it is a great assistance, especially on a pouring wet day, and I should be sorry to be without it. I do not like, however, the inconvenient bottle generally carried for this purpose. I use a common metal matchbox, in which I have placed a piece of spungeo-piline, on which I have poured a few drops of the oil. The hackles of the fly can be pressed against this, and so anointed with the greatest ease. Fish do not appear to mind the appearance of the oil that, of course, appears to float round your fly; and, as they do not mind and it enables you better to keep your fly floating and cocked under adverse conditions, why not use it?

As to the flies to be used, as I have said in another chapter, the fewer the better.

A few points may, however, be discussed with advantage. First, and foremost, do not be ambitious as to the length of line you can cast, or the amount of water you can cover. Be content, rather, to fish with just that length of line that you can control with ease and accuracy. In the actual act of casting never sway the body; keep the trunk rigidly still, never let your hand, in the backward cast, go beyond a vertical point above your shoulder; keeping the elbow near the side, get all the work you can out of the rod; it will do all that is required of it so long as you do not over-cast with it. Watch the expert angler;[14] how easily he works his twenty yards of line; there is an entire absence of all effort; it looks as easy as shelling peas. The beginner or duffer will invariably put too much effort into his cast; he will not allow time for the line to extend itself behind him; he will bring his hand so far back that the fly will be hung up in the grasses or bushes behind him, and the force of his forward cast will make the line cut the water like a knife, and the fly will be delivered in the midst of a series of curls of gut, presenting anything but an attractive appearance to the fish. The movement of the hand in an accomplished fisherman is singularly slight; I doubt if it ever traverses much more than twelve inches from the vertical position.

Rest content with the ordinary overhead cast until you are an absolute master of it. When this desirable result is accomplished, there are one or two casts well deserving of care and attention. One in particular you should seek to accomplish—viz., the cast into the teeth of an adverse wind. Recollect that, under those circumstances, you can usually approach much nearer to fish than when the wind is up stream or non-existent; therefore you can use a shorter line. The cast is called the "downward" cast, and is really very simple. The backward part is the same as in ordinary casting, but in the forward delivery the hand traverses a much greater angle, and at the finish the rod point is near to the water. At the moment of delivery the elbow is brought up level with the shoulder, the thumb is depressed, the knuckles being kept uppermost. The resultant effect is that the line cuts straight into the wind, and is little affected by it. In a foul wind flies cock and float more easily than in a down stream wind; so this, at any rate, is in your favour. Yet one more style of casting should be practised. I have found it invaluable when awkward trees have been overhanging my own bank. It is what is called by salmon anglers the "Spey Cast." Inasmuch as it avoids the necessity of bringing your line behind you, its value is self-evident. This is the method of the cast: Having got out as much line as you think you will need, get it out up stream of you, bring the fly quickly towards you out of the water, allow the fly just to kiss the water when it is just level with you, the curve of the line being down stream of you, then, with a similar kind of action to that advocated for the downward cast, your line will be sent[15] forward in a series of coils to the desired spot. It is always worth trying and may secure you a good fish, one perhaps that others have passed by as unapproachable, and which may thereby have acquired a confidence that may be misplaced. This form of casting is much easier in salmon fishing, as you are then fishing down stream, and the water extends and straightens your line for you. It is, however, quite easy of accomplishment, with a moderately short line, in up stream fishing.

Mr. Halford, in "Dry Fly Angling," p. 62, describes a cast which he terms the "Switch Cast," and it is one which, though difficult of acquisition, will accomplish the same object. He says, "It is accomplished by drawing the line towards you on the water, and throwing the fly with a kind of roll outwards on the water—in fact, a sort of downward cast; the possibility of making the cast depending upon the fly being in the water at the moment the rod point is brought down," &c. Personally, I should prefer the Spey cast, and inasmuch as most salmon fishermen know something of that peculiar cast, I would urge its occasional use in dry fly work, more especially having regard to the fact that fish in such positions have acquired a confidence through never having been angled for, and therefore there is greater chance of a somewhat bungling presentment of the dry fly being overlooked. To describe the Spey cast accurately so as to convey the desired instruction in such a way that all who run may read, is not by any means easy; but, as I have before said, it is probably familiar to many anglers from salmon fishing experiences.

One more thing deserves to be borne in mind: always imagine that the plane of the water is some foot or so higher than it really is—that is to say, cast as if the fish, and the water in which it lies, were a foot higher than in reality. The result will be that your collar will fall as lightly as gossamer. One of the most proficient manipulators of the rod and line I have ever seen can pitch a fly, cocked and floating, almost anywhere within reasonable limits, but his line invariably cuts the water from point to fly, straight and accurate enough may be, but like whip-cord. Consequently, he is not the successful angler that his qualifications entitle him to be. An ordinary fisherman casting a less straight, but lighter, line will frequently beat him in catching fish. Our friend would[16] beat most opponents in a casting tournament, but I would back many that I know against him in filling a creel.

Keep down out of sight, walk and crawl warily, and above all things avoid walking near the bank edge and unnecessarily scaring fish that others following you might otherwise have secured.

When trout are "bulging" (that is to say, as every angler knows, when they are taking the "nymphæ" just below the surface), it is almost hopeless to endeavour to secure them with a dry, floating fly. The fish are intent on another kind of game, and are best left severely alone.

Unfortunately, even experienced anglers are apt to be deceived by such a fish; the rise is often apparently that of a trout at a surface fly; a little careful observation will, however, convince you that such is not the case, for no floating flies are passing near him at the time of his rise. Don't waste another moment upon him, but try to find another in a more reasonable frame of mind. If all the fish on your stretch of water seem to be similarly occupied, and you are not willing to wait until they have decided to make a change of diet, then a gold ribbed hare's ear may, if fished wet, entice an odd fish, as it somewhat resembles a nympha.

It is, however, very chance work, as is that of endeavouring to secure a "tailing" fish with a down stream fly sunk below the surface, and jerked about in front of where his nose should be. No keen angler would call this serious fishing—it is a mere travesty of the real sport; but it may serve to pass the time, and perchance to wile a trout into your basket. The angler's patience will, however, be far more severely tried when fish are "smutting." What prophet is there who can tell us what we should do then? Those abominable "curses," so well named, appear to be able to baffle entirely the skill of the ablest of our entomologists, and the ability of our most capable of fly dressers. No lure has yet been discovered that can have any reasonable hope of imitating them. To watch a big trout slowly and majestically sail here and there on a still, hot day, barely dimpling the surface as he sucks down one after another of these little insignificant "curses," is quite enough to satisfy you as to the remoteness of your chance of deceiving him. Nothing that human hands could tie could simulate them. Place in the track of one of these fish the smallest gnat in your box, attached to the finest of undrawn gut, delivered with the lightest and truest cast[17] of which the human hand is capable and, as you watch the fish fade slowly down into the depths in disgust at the evident deception, you will realise the hopelessness of your endeavour.

It is an old accusation against fishermen that they are apt to overload themselves with multitudinous flies, of which perhaps they never try half; and in this accusation there is a good deal of truth. I recollect one occasion in particular, when five men sallied forth to fish, and on their return all more or less bewailed the shyness of the trout, and each declared that, though he had tried many changes of fly, he had only found one to succeed. Oddly enough, each man had pitched on a different fly: they were the Driffield dun, the pale olive, the hare's ear and yellow, the ginger quill, and the red quill. In each case the size was similar, viz., 000; but the fact is, that most men have a favourite fly to which they pin their faith, and to which they give ten chances for one to the others. There are occasions, of course, where one fly and only one will succeed.

I well remember one day, on the Tichbourne water on the Itchen, when that fine stretch of water was simply alive with olives, coming in droves and batches over the fish, and when it seemed hopeless for one's poor imitation to succeed, even when put correctly cocked in front of a batch, or behind a drove, or by itself. The trout were rising slowly and methodically, letting many flies pass scatheless, but now and then picking out one without moving an inch from their position. I tried vainly to discover the method of their madness, and at last realised that they were selecting from amongst the myriads of toothsome ephemeridæ floating over their heads a redder-looking fly. I could not wade, I could not manage to get one with my landing net, so I put on at hazard a small red quill, with no response; then a Hawker's yellow got a rise or two, and even deluded a brace of fish into my creel, and then the glorious rise was over. Next morning, when whirling back to town, I found myself in a carriage with four or five anglers who had been fishing the next beat, and the murder was out. One fortunate man had ascertained that they were taking the ginger quills, which were very sparsely scattered amongst the olives, and that information resulted in his taking nine brace of beautiful fish.

But as a rule, it is far more a question of the correct delivery of the fly than anything else, provided the size be right. For myself, I never leave a rising fish that I have not scared, unless I am convinced there is some objectionable and unavoidable drag; sooner or later you will get him, possibly with the same fly that has been over his head a dozen or so of times. We are all too ready to resort to a change of fly, and to leave a non-responsive fish in disgust, in the hope of finding an easier quarry. My advice is to stick to your fish unless, or until, he is scared. Possibly the most annoying fish is the one that drops slowly down, with his nose in close proximity to the fly, evidently uncertain as to whether or no it is the Simon Pure, until he gets perilously near to you. Even his scruples may be overcome if he gets back into position without being alarmed. One of the most successful anglers I ever knew on the upper Test, who owned a well-known stretch of water, was wont to sally forth with two rods put up, one of which he carried, while the other was carried by his keeper. On one was mounted a hare's ear, on the other a blue dun; and that these flies answered their purpose his records could testify.

A difficulty that presents itself to the chalk stream angler is the tendency of fish when hooked and when scared by seeing the angler to bury themselves in the heavy masses of weed. This has now been discounted by the modern method of hand lining—i.e., spiking the rod and taking a good deal of slack line off the reel, and then holding the line in the hand and using a gentle pressure on the fish in the direction contrary to that in which he went. He usually responds very readily, and the rod may then be resumed. Indeed, it is astonishing how fish can be led and coaxed under this influence—the fact being that, the upward play of the rod always tending to lift the fish out of his own element and so drown him, he naturally plays hard to avoid this; take the upward strain off him and he becomes another creature.

Yet another difficulty encountered by the dry fly fisherman is caused by fish coming short. What angler is there who has not experienced this annoyance, and how often, as Mr. Halford in his work on Dry Fly Fishing has noticed, does the angler find that after the first rush is over and the hook comes away there is a small scale firmly fixed on the barb, showing that the fish has been[19] foul-hooked? My observations on this class of rise would lead me to believe that the fish moved to the fly in the ordinary manner, but that something arose to excite his mistrust, and that he closed his mouth while the impetus of his rise broke the water, making the angler think that it was a real rise, so that he struck, and on his striking the hook took a light hold on the outside—a hold seldom effective, though most fishermen have landed fish hooked in such a way. I have generally found in such cases that a smaller hook has produced a more confident rise, and my experience would not lead me to endorse Mr. Halford's view that the use of a 000 hook handicaps the angler very heavily. It may do so with the heavy Houghton water fish, but I have not found it a severe handicap with the smaller trout—1 lb. to 2½ lb.—of the upper Test and similar waters.

A very keen and expert dry fly fisherman, the late Mr. Harry Maxwell, one of the best of friends and anglers, once showed me a method of taking fish lying with their tails against a wire fencing that crossed the Test at right-angles, the wire moreover being barbed. I was fishing in Hurstbourne Park, and he was accompanying me, as he often did, with his field-glass. Below the "cascade" a four or five-stranded barbed wire fence went straight across the water. Just above it, in mid-stream, in the stickle, a plump, transparent-looking Test fish of about 1½ lb. had taken up his position, and was boldly taking every dun within reach. My friend told me to catch him, and I said at once I did not know how to do it without getting hung up. He then explained his dodge, which may be carried out as follows:—Having waded in below the fish, take some loose coils of line off the reel in the left hand, then cast well above, and let the dry well-cocked fly float down to him. If he accepts it and comes down under the fence slack off the loose coils, get up to the fence as quickly as possible, pass the rod under and over, and then you are free to play the trout below you. If, on the other hand, he refuses the fly, do not attempt to recover the line in the usual manner or you will inevitably be hung up. Simply lower your rod point to the water, and then the quiet drag of the stream will bring your cast and fly slowly up and over the fence, even although the fly had floated a foot or two down-stream and under the wire. The action is so slow and even that there is no chance of being[20] entangled in the wires, and as a fish in such a position thinks he is in possession of a vantage-point, and is seldom fished for, he is generally a bold feeder. Having explained the method, my friend made me try the cast myself, and the first fly floating near enough to tempt the fish was taken boldly; the whole manœuvre succeeded, and I was able to land my trout below me. Since then I have frequently made use of my experience, and with invariable success. If any anglers who are not aware of this method care to try the experiment they will see how sweetly the line travels over the fence without the slightest risk of entanglement.

There is but little doubt that the fly that is kept going catches most fish. On a seemingly hopeless day an odd fish here and there can be picked up if really sought for; and on these days the rise, if any, is so inconstant and so short-lived that it may easily be missed. On such a day, on the wide shallows of the Longparish water of the Test, three of us were struggling with the adverse conditions of a lowish river, a bright sun, and a great lack of duns. We had agreed to meet at luncheon at about 1 p.m. in the hut on the river's bank. I had found a seat upon the upturned stump of a tree in mid-stream. There were fish all round me in the shallows, but all on the bottom, apparently asleep. I knew that if I left my place and waded ashore I should move them all. I was enjoying my pipe, and so sat on. The whistles and calls from the hut passed unheeded, for I had noticed that my friends the trout showed more signs of animation. An olive or two came down, and gradually the fish seemed to rise from the bottom and take up their positions. More calls from the shore. I shouted back to them not to wait, and at length they gave me up as a bad job.

Soon a fish on my left front took an obvious olive, a pale one, and I had a pale olive on my cast. Still I waited, and soon the first few olives were followed by quite a little procession. I then cast over my fish, and at the first offer he took it. I got him down below me, and soon netted him out, wading up again most carefully and slowly to my seat; and from that position, in about twenty minutes, got seven fish in succession, all taken with the same fly and from the same spot. They were none of them very big, it is true, but they were all over a pound in weight. By this time my friends had finished their luncheon, and came out of the hut just as I was netting my seventh fish. Hastily getting their rods, they were[21] just in time to get a fish apiece from the bankside, and the rise was over. Moreover, it was the only rise vouchsafed to us that morning or afternoon. So that the moral is that you can never tell when the psychological moment may arrive, and may easily miss it when it does come if you are lying on your back reading a novel, or with your eyes anywhere but on the water. One must lunch, no doubt, but it can generally be best enjoyed in the outer air, where you can watch the water and the fish whilst enjoying your luncheon and your rest. And on such inauspicious days do not relax your precautions in approaching the water, or from nonchalance or weariness allow yourself to cast carelessly. Your field glasses will often reveal to you a more likely fish—at the tail of the weed, maybe, or under the thorn bush on the opposite bank—and it may be worth while to float a fly over him and give him a trial. If he accepts the offer he is worth to you several got out under more favourable conditions.

When fish are really smutting, and the water is almost boiling with rises, the angler's patience is most sorely tried. Nothing seems to tempt them; the smallest gnats ever tied are far too big. Who will tell us what to do in such a case? In truth, I know not. All I can say is that they are in a peculiarly aggravating humour. How vexatious, too, are the tailing fish, boring their heads into the weeds and breaking the water with their broad tails—and their tails always look particularly broad at such times. I have at times caught them with a big alder, fished wet, and jerked past them when they have finished for the moment their diving operations, and their heads are up. It is chance work, and, if not productive of much use of the landing-net, will serve to pass the time and amuse you; for if you don't succeed in hooking many you will certainly get an occasional one to run at your fly, his back fin breaking the water and making as big a wave as if he were twice the size. In the quick water by the hatch holes on such a day you may find a rising fish, though when hooked he will probably prove unsizeable.

Never despair or give it up, unless you are one of the fortunate individuals who live by their water side, and who can therefore pick and choose. Where all days are yours it would be folly to persevere on really bad ones; but most of us are not so favourably situated, and we have to make the most of the odd chances we get. Therefore my counsel is to examine and watch the water, and be ever on the alert.

Where Sunday fishing is not permitted, the day of rest always seems to be the best angling day of the week, and you are tempted to be annoyed and objurgate Dame Fortune. Even then, if you are a wise man, you can turn such a day to your advantage by stalking up the water as carefully as if you were fishing, and by making mental notes that will very materially assist you on the following day. And if Sunday fishing is allowed, do not give umbrage to many of the parishioners going to church by making a parade of your waders and fishing rod. Either get to your water before church time or else wait till the church bells are over before you walk along the village street. Busy City men get scant leisure for sport, and may fairly be excused for utilising their week-end holiday to the full. Much latitude may be allowed to them in this respect, provided they are careful not to outrage the religious feelings of others. A walk along the river bank, enjoying and drinking in to the full the beauties of Nature and of God's creation, may be as productive of good to yourself as an indifferent sermon. It depends upon your temperament and the power that the beauties of Nature have over your mind. They can preach as eloquent a sermon as was ever delivered from the pulpit, and may produce in you a frame of mind that may be of real and lasting benefit to you. No man should be judged hastily by narrow-minded bigots, or be termed a Sabbath-breaker for so acting.

It is not given to everyone to command the sleight of hand of a master and to be able at will to pitch a fly, cocked and floating exactly right, whilst a bag of the line has been simultaneously sent up stream, so that for a short few moments whilst passing over the fateful spot the fly may float truly with the stream, out of the influence of the more rapid water between the fish and the fisherman. In streams where wading is allowed the fisherman has undoubtedly an advantage, as he can get more directly behind the fish, and so avoid the heavy current. But[24] wading is not always feasible in waters such as those of the lower Test, where the depth of the stream precludes it. Even then, skill and local knowledge will often overcome the difficulty, and a fish in such a position usually falls a ready victim to the fly that floats truly, as he has been lulled into a sense of false security by his previous experience that dangerous flies leave a trailing mark behind them. But what a revelation it is of the education that trout have received, and how capable they are of absorbing and profiting by it! It seems almost as if the constant catching and destruction of the freest rising fish must be having effect in leaving those only to propagate their species which are either past masters in cunning or which are more coarsely organised fish, that devote their time and energies to bottom feeding and avoid surface feeding, except, possibly, at night; the universally acknowledged fact that fish are far more difficult to catch than they formerly were may thus be explained. Certainly, nowadays, an angler would be somewhat out of it who tried to emulate the far-famed Colonel Hawker, of Long Parish, and to catch the wily trout in that beautiful stretch of the Test while fishing off a horse's back. Nor could any modern angler hope or expect to approach the baskets that were formerly creeled. So is it everywhere. On the beautiful Driffield Beck, in Yorkshire, a paradise for the dry-fly angler, the club limit of ten brace of sizeable fish in one day used to be constantly attained, and that, too, with the wet fly up or even down stream. Now, with split cane rods, the finest gut, and the deftest of floating duns, five or six brace is about the best basket obtainable by experienced and most skilful anglers.

The natural question that perplexes and worries chalk-stream anglers is whether this "advanced" education of brook and river trout is to go on increasing. If we can only hope to catch half the amount of fish our progenitors did, what are the prospects of the next generation? Shall we have to fall back on black bass or rainbow trout to secure a race of free-rising fish? Or does the fault lie in over-cutting of weeds and bad river farming? I am inclined to think it does. Riverside mills are in an almost hopeless position commercially. The miller requires a heavier head of water than formerly, and with a decaying industry it is hard to refuse him, the result being that to maintain his head of water the weeds are ruthlessly and unscientifically cut over vast stretches of water, shallows are bared, and the holts or refuges of trout are done away with,[25] and as a natural consequence trout become less confiding and far more easily alarmed. Modern agricultural drainage has, moreover, increased the difficulty by carrying off the water too rapidly. It behoves votaries of the gentle art to consider most carefully whether anything can be done to remedy the seriousness of the future outlook, and to disseminate the results of their inquiry; and if the Fly Fishers' Club, or some well-known leaders of repute, would take the matter up and tackle it seriously they would earn the blessings of the angling world.

It is considered to be undoubtedly a disadvantage in a club water to include one or two pre-eminently brilliant anglers, as it seems to breed a fear of their always being able to catch the easy fish, so that the more difficult ones only are left for the ordinary angler to attack. Not long ago I was invited to fish a certain well-known beat on the Itchen, but my host, in inviting me, said, "I don't know if it is much use, for So-and-So fishes our water, and has caught all the easy fish." This may be true in a sense, but favourite positions are always re-taken by other fish if the former occupant is killed. Just as a house in Grosvenor Square, or some well-known centre of fashion, will always secure a tenant, so a position where the trend of the current brings the flies quietly and steadily over a fish will never remain unoccupied. It is not so much the fish that is easy as his position, and therefore the ordinary duffer need never despond. One thing is certain—that the brilliant angler will never scare fish unnecessarily, and I would rather fish behind such an one than a so-called angler who, having successfully put his fish down by bad angling, proceeds to stand upright and possibly walk along the bankside close to the water's edge, scaring many a fish on his way up, utterly regardless of his brother anglers. Indeed, in this respect I think the etiquette of angling is hardly sufficiently considered in these modern days. Who is there that has not met, on club waters, the ardent and unsuccessful angler who wanders up and down, covering vast stretches of water, and effectually scaring many otherwise takeable fish, in the vain hope that he may find some purblind trout idiotic enough to take his proffered fly? I consider that unwritten etiquette demands that the utmost care should be taken by fishermen to do all in their power to prevent spoiling the sport of those who may be following. I can well recollect a day when the wind was foul, and there was one stretch of water sheltered on the windward side by a thick belt of[26] trees, and in this stretch were located many heavy fish. Working up to that water, I found an ardent ignoramus doing "sentry-go" up and down the stream, walking on the very edge of the water. I presume he thought that if he only persevered he would eventually find the "fool of the family," but the result—the inevitable result—was that the fish were scared throughout that whole length for the rest of that day, as that stretch was bare and sadly lacking in shelter.

In considering the merits and demerits of dry-fly fishing, one cannot be altogether blind to the fact that down-stream fishing must inevitably prick and therefore educate many more fish than the floating fly. This being so, it is still more inexplicable that in former days, in chalk-stream waters, our forerunners were able to account for far heavier baskets of trout than we are, despite the heavy restocking our streams now receive, to their great advantage; and we necessarily come back to the old point, what can we do to secure an adequacy of free-rising fish? Is our system of fishing the rise wrong? Or does the mischief lie more in our river, water, and weed management? And can we so improve these as to obtain the desired results? Angling is now so much sought after, chalk-stream and other similar waters command such high rents, that surely it is worth the while of those interested in the sport to initiate and carry through some exhaustive inquiry into the subject.

The main charm, however, lies in the fact that the advent of Ephemera Danica does bring up the big fish of the water in a way that no other fly food does or can. Hence its popularity, and in waters where the May fly is hatched in quantity, and there are heavy, big fish that as a rule find cannibalism pay better than duns, then the May fly has a real value. In other waters, however, were these big monsters taken out in order to secure a larger numerical stock of comparatively small but sizeable fish, I would have none of it; I would prefer to extend my angling season rather than take a large bulk of it condensed into one week of questionable pleasure.

Certainly, the May fly season comes at about the best time of the year to enjoy angling. A fine week about the commencement of June is most enjoyable on any river. All nature is at its best—leafy June, when sauntering by the riverside, even with scanty sport, is in itself a pleasure not to be despised.

Mr. Sidney Buxton, in his admirable "Fishing and Shooting," graphically describes a day in the Carnival time, when he grassed thirty fish from two pounds down, and of another when he creeled forty; but, good sportsman as he is, I rather fancy he would have enjoyed even more a day with half to a third of the basket when each fish had been stalked and picked out with a small fly. Not for a moment would I suggest or imply that equal care is not needed in casting with the May fly if you wish to fill your creel; but, all said and done, a bungling cast will often secure a good fish with that lure which would inevitably have put him down and scared him had he been feeding upon the ordinary flies. It is very noticeable nowadays how capricious the rise is. Indiscriminate weed cutting has almost entirely eradicated the May fly from some waters, and quite entirely on others—a boon to some minds, my own included, but a boon that bears sour fruit in other ways, for irregular and injudicious weed-cutting hits other fly food hard. It is curious, also, that in places where more judicious weed farming has been resorted to of late the May[29] fly has begun to return, patchily and scantily enough, but nevertheless in increasing quantities every year. I would fain leave them to hatch out upon the Kennet and the Colne and similar waters, and leave our bonnie streams alone, but here there is no choice; if they come, they come, and we must make the best of them.

A big rise of May fly is indeed a wonderful sight, the drakes flopping into your face, covering everything, seeming almost like a plague of locusts. Fat, luscious insects, enjoying to the full their brief spell of winged life, after having spent months in the larval state. See that one floating down-stream, airing and drying his wings, floating on his nymphal envelope. He is floating dangerously near that trout that has already annexed a goodly number of his fellows. Will he be taken too? No; he flutters off, clumsily enough, making for the shore, only to be swallowed by a hungry chaffinch. So his brief period of air life is over. And what a feast he and his congeners provide for the swallows, the finches, and other birds. Towards sunset, males and females of the green drake tribe float and flutter about in the air, make love and pair, then the female deposits her eggs on the water, and at last both fall on the river with outspread wings, forming what we call the spent gnat.

The trout take heavy toll of the nymphæ rising upwards before they reach the water surface, and will not then look at a floating imitation; and when the act of reproduction is completed they feed greedily upon the empty shucks and the spent gnats. Altogether, our friend the May fly seems to spend a hazardous and somewhat inglorious life. Could he but see himself in his larval state, I feel sure he would lose his self-respect. He is then no beauty, and to grovel and lie low in the mud at the bed of the river for, as some say, two years, cannot form a very exciting kind of life; whilst if he escapes in the imago state, countless enemies lie in wait for him, and his very love-making costs him his life.

The return of the May fly to a certain well-known chalk stream in Yorkshire seems to be an accomplished fact, though one not altogether to the satisfaction of the members of the club that fish its waters. This stream, known as the Driffield Beck, ranks high amongst kindred waters, the dry fly reigns supreme, the stream is as swift and even, the water as crystal clear, and the trout as fully educated as those of their brothers of the Itchen or Test. In former times the May fly hatched in countless[30] numbers on this stream, and the Carnival used in those days to be reserved strictly for the members of the club; but whether it were attributable to over-cutting of the weeds, or to some other cause, the May fly died away entirely from the stream, and for many a season not a fly was hatched. We members of the club—a very old one, by the way—rather congratulated ourselves on this change, as, instead of gorged fish who would not look at a dun for weeks after the May fly period, we were treated to an even rise at the small fly throughout all the angling months. But two seasons before we had noticed, to our surprise, the advent of a few May flies. I recollect impaling one upon a hook and drifting it down cunningly over a good 2½ lb. fish who had taken up his position under a thorn bush on my side of the river, and the scared bolt he made when it got to him and he had had a good look at it was a thing to remember. And, in fact, the few May flies which that year floated over fish in position made them all bolt as if they had been shot. Then in the next season there was a more considerable hatching of the fly, and in one spot in particular a few fish were taken with the green drake. The third year we arrived at the right time for the hatch, then a very local one on our stream; but in that particular part of the river there was a rise of May fly to satisfy the most gluttonous of those who love that form of angling. But the curious thing was the way in which the fish treated the fly. Every now and again the ½ lb. and ¾ lb. fish would take them boldly, and here and there a fish of that size would settle down to a regular feed, taking all within reach; but the heavier fish seemed to be thoroughly disinclined to take them. The bolder young ones now and again paid the penalty of their temerity, being consigned to the basket if fully 11 inches in length, or returned to the water if, as was too frequently the case, they were not sizeable. I do not pretend to any great experience of May fly fishing, though I have been a devoted dry-fly angler for many years; but I do not remember to have seen fish act so capriciously in my previous experiences. The birds, however—the warblers, chaffinches, &c.—were quite equal to the occasion, and took heavy toll of the ephemeridæ. I particularly noticed what I never remember to have seen before, i.e., a cock blackbird darting out of the bushes at intervals to secure a fluttering Ephemera Danica, and returning to his shelter to pick the luscious morsel to pieces at his leisure.

My luck was not considerable; the rise of dun was insignificant, the wind was simply abhorrent, and my baskets, naturally, were not as heavy as I could have wished. The water was in perfect order, the fish abundant, but sport indifferent. One day I went up one of the upper feeding streams, where I had often, poor performer though I may be, secured a really good basket of good fish. After rising and pricking more than a dozen fish, all of which rose short, and turning over and getting a short run out of a three-pounder which had permanently taken up his position above a bridge by a garden-side under some sedges in a difficult position—rendered more difficult by the violence of the wind—I had to content myself with a poor brace of 1¼ pounders, going home feeling regretfully that I had done that day a good deal in the way of educating fish!

The last day of my visit (June 10) I had somewhat of a more interesting experience. The wind was still high, though warmer, and, though no rain fell, there was a feeling that rain was not far off. The report that the May fly was up and in quantity had brought out a number of anglers, and when I got to the water-side, armed with a box of May flies given me by a prince among anglers, I found all the 'vantage spots (in the small extent of the water where the fly hatched in any quantity) duly occupied by an ardent angler ready for the fray. So I quietly gave that game up and retired to a small island between two branches of the river near the keeper's cottage. I had but a couple of hundred yards to fish, while the ground where I was standing was sedge covered elbow-high with charmingly and conveniently placed bushes here and there behind me, ready to hitch up any fly that, in the backward cast, should be driven by the wind into their embrace. The only chance was to keep up a kind of steeple cast, as the stream was a fair width across. The charm of the position, however, was that on the other side was a high bank with a plantation on it, which shed a welcome shade over the bank fish on that side. It was very difficult to locate a rise, but the stream was even and there was no drag. Nor was it an easy matter to land a fish, as the fringe of sedges was wide and thick, and the water deep; my landing-net was also over-short—a bad fault—and caused me to lose three good fish, one well over 2 lb. I spent nearly all the day on this place, and managed to hook every fish I saw rise, and that was not a great number,[32] the rise of dun being so small and the wind blowing them off the river almost as soon as they started on their swim down-stream. However, I managed to land five fish, all on a 000 gold-ribbed hare's ear, the best one 1 lb. 9 oz. and the smallest a little over a pound; but as they were all in the pink of condition, and each fish was a problem to get, I enjoyed the day far more than a more prolific one, when the duns might be sailing steadily, the fish all in position, and where catching them would be far more of a certainty, and where even a duffer could not have failed to score.

Perhaps I may have been somewhat unfortunate in my May fly experiences, and most anglers would be disinclined to agree with my faint appreciation of this insect and of the sport he assists to produce. Most of my friends speak of this form of angling in a totally different strain, therefore, presumably, I must be wrong in my view. To me, however, the May fly (as a means to an end) is of great value in tempting up the bigger cannibal fish, but as an adjunct to sport, I am inclined to consider him overrated.

Doubtless, in the hot days of July and August, when rivers appear, under sultry conditions, to be almost tenantless, when after, say, 3 p.m., you may watch for all you are worth without seeing a dimple or a rise, it is some consolation to go home for a little rest and an early meal, intending to avail yourself of the evening chances with a possible brace or so of fish to save, maybe, coming in clean. Eyes tired with the glare of the water are grateful for the rest, and with the proverbial hope rising freely in the angler's bosom, you mentally reckon up the big captures you are going to make in the short time afforded by the evening rise.

Refreshed in mind and body, you regain your favourite spot at 7 or 7.30 p.m., and the evening seems to promise well. It does not look as if those cruel mists would begin to rise at sundown; there is little or no wind; the hatch of fly throughout the day has been insignificant; surely there must be a good rise this evening, everything seems to foreshadow it. You take up your station and watch the water carefully, especially the one or two spots near the opposite bank that you know full well ought to be occupied by good fish. A few spinners hatch out and dance merrily about; the gnats hover purposely up and[34] down; an odd dun sails down ignored, as far as the fish are concerned, and at length, freeing himself from the water, gains the bank side. Surely that was a rising fish by the bank of rushes yonder? But the shadow of the rushes thrown by the lowered sun prevents you from locating him exactly. It was a floppy rise, probably caused by some small fish. Something must be done, for the time is short; so, letting out your line to the required length, you despatch your olive to sail down the bank of rushes. No response. Another trial provokes a rise, and you are fast in the fish; but, as anticipated, he proves to be a half-pounder, and, handling him gently, after having removed the fly, which was provokingly well fixed in his tongue, you carefully hold him in the water until he has regained his wind and recovered from his exhaustion. Whilst so engaged you hear a heavy splash to your right. Hastily glancing up, you cannot locate that rise either, but it is something that they are beginning. No sedges have appeared, so you retain your olive. A good quiet mid-stream boil above you attracts your attention. That fellow means business, anyhow. Your olive, however, though deftly offered, sails over his position unnoticed and despised. You change to a bigger fly, a 00 red quill; the light is still good. He refuses that equally, and whilst you are doubting whether to change or no, up he comes again. What is he taking? Some small fly, no doubt, but none that you can see. Try him with a hare's ear. You change, and whilst you are tying on the fly you hear a succession of floppy rises below you. You somewhat undecidedly give the trout one more chance, but half-heartedly, as you want to get down to those other fish—result, a bad cast, effectually putting down our friend.

The light is beginning to go, so you re-change to your bigger red quill and try your luck with those below you. Fly after fly, carefully placed, cocked and floating, produces but little result, one pounder succumbing. You see he is not a big one, and give him scant grace, meaning to get him into the net as soon as possible, and so bring him in half done. The net somewhat too hurriedly shown him produces an effort on his part, and he has weeded you. You spike your rod and try hand-lining; he does not seem to yield, and you are impatient, and resume your rod. Something must go; you have no time to lose. Suddenly with a wriggle he extricates himself from the weed, to your[35] infinite astonishment, and he is then soon brought to book. But many precious minutes have been wasted; the fly has got itself fixed in one of the knots in your landing net. Never mind, break it off; you must get to sterner business. So you take some few more minutes in threading the eye of a small, dark sedge fly, as the fish by now must be at work upon the larger flies. Flop! flop! on the opposite side, under the shadow of the reeds. See that your fly is dry and cocks well; keep out of sight—an absolute essential in evening fishing—and go for that uppermost fish. That was a good rise; was it at your fly? It is hard to see by the waning light. Evidently not. Try him again. This time he rises well, and you are fast in him; but you struck too heavily; he was a good fish, and you have left your fly in him, bad luck to it!

This time you have to make use of a match to enable you to thread the eye, but after some fumbling struggles you at last succeed. One more try. Pity you had not put on a somewhat stouter cast, but it is too late now. You must be a bit more gentle with them; a slight turn of the wrist is all you want. There is a good rise, just beyond mid-stream, and a good cast just four inches above the rise. You can see your fly, and also the neb of a good trout as he breaks the water to suck him in. Now gently does it! He is hooked, and goes careering up stream to the tune of the song of the reel. Steady him now; don't let him get into the rushes. The light is fast going, and you are inclined to hurry him. Better be cautious; his tail looked broad as he turned over that time; he is fat and in lusty condition, and has no intention of surrendering his life without a good struggle. Don't show him the net; that last run must have settled him; he flops on the surface; he is gently led into the mouth of the net, and is yours. Not so big as you fancied, by any means; might be 1½ lb.; you put him down as well over 2 lb. He is well hooked, and after taking the fly from his mouth you grip him well and give his head a good hard tap against the handle of your landing net; in so doing he slips from your grasp and nearly flops into the river. Hurriedly you put yourself between him and the water and get hold of him, making sure of him this time, and he goes into your bag. Is there still light for one more? Hardly, and it is no pleasure when you cannot see your fly.

You take up your rod again, and pass your hand down the line[36] and cast. Where is that fly? Caught up somewhere in your struggles with the trout. It is engagingly fixed in your coat, about the small of your back. So you lay your rod down again, take off your coat, and extricate your fly with your knife at the cost of some of the cloth of your coat. Pack up your things and trudge home somewhat annoyed with yourself and thinking of the opportunities you had lost, and determining next evening to have some points of gut attached to suitable flies in your cap, ready for the fray—no more threading eyes under such adverse conditions for you.

Next evening you repair to the place where you know the big trout lie and are sure to rise well. Fully equipped in every detail, and determined not to be induced to hurry, but to take things quietly and composedly, you reach your station. What is that in the meadow over there? A mist, by Jove! And soon the aforesaid mist begins to rise on the water, most effectually stopping all hope of sport; so reluctantly you leave the water side, a sadder and a wiser man, reflecting that the evening rise is by no means the certainty you had fondly hoped.

Of course it is not always so. I recollect one evening on the Test, when, after a hot day with scarce a semblance of a feeding fish, except tailers, there was a grand evening rise, and on a big red quill I got seven fish, almost from the same spot, in little over a quarter of an hour; but these days are too infrequent to alter my stated opinion that the evening rise is an overrated pleasure, and generally produces vexation of spirit.

If you do fish in the evening hours, recollect that you must be just as cautious in approaching fish as if it were broad daylight; that any sign of drag will as effectually put a fish down as in the earlier hours. Your fly must float and cock as jauntily as in the morning, but you lose the chief charm of fishing the floating fly, namely, that you cannot spot your fish in the water and watch their movements; you have to cast at a rise, or where you imagine a rise to have been. Use a small fly at first and then a little later change to a big red quill, or, if the sedge flies are out, to a small dark sedge. You can afford to have a point of stronger gut, for you will have often to play a fish pretty hard, and they don't appear to be so gut shy as the evening closes in. But as soon as you can no longer see your sedge fly on the water, reel up. Fishing in the dark is no true sport, and it is uncommonly near to poaching.

When I knew the water, some ten or twelve years ago, there were still a few of these goodly-proportioned fish remaining. They were well-known, and each one had his nickname. Thus one was known as "Jack"; he almost invariably lay in a narrow outlet to a culvert that led the surplus water from the pool above under the roadway into the pool below the bridge. For the greater portion of its length the water ran underground, emerging from the culvert some two or three yards from the river. The ground on either side at the end of the culvert was fully three feet above the water, the banks being nearly vertical, while the stream at the culvert's mouth was only about a foot wide. In this narrow gully or channel lay Jack, his nose being only a few inches from the masonry. Any unwary footfall speedily dislodged him from his little bay into the main stream, but by crawling up warily he could be seen and admired.

Many had tried to secure him by fair fishing, but though once or twice hooked he had so far got off scot free. Nor was his post an easy one to attack; the water was, of course, gin-clear, very narrow, and also very shallow. The slightest sign of gut—and he was off.

On a lovely summer morning—to be accurate, the 26th of June, 1893—my dear old friend Harry Maxwell and I had fished up from the bee-hive, past the cascade, and were nearing the bridge with rather more than average success, and had decided to eat our luncheon on the bankside, under the friendly shade of the bridge. It was, however, barely half-past twelve—too early, we agreed, for lunch—so Maxwell went up a little to fish the shallow above, and I elected to have a try for Jack, as I had reconnoitred and found him to be occupying his accustomed corner. As the river was rather low, and as bright as only a chalk stream can be, I decided to break through my general rule and put on two lengths of the finest drawn gut, feeling that in this instance any natural gut, however fine, would be out of the question.

I was careful to draw the gut through a bunch of weed, to diminish the glare; the Whitchurch dun was on the water, and its counterfeit had already secured us some fair fish, but for some reason or other I was impelled to select a small 000 pale watery dun, called the Driffield dun, for my lure. After carefully testing my line and cast I waded out into the heavy stream, opposite to and commanding the outlet of Jack's bay.

Knowing that there was little hope of dropping my fly at the desired spot without giving my friend a glimpse of the gut, after a preliminary cast or two, to make sure of my distance, I sent off my fly on its errand, intending to pitch it on the grass just above the culvert. The first cast, fortunately, went right, and by a gentle tap or two on the butt of my rod I dislodged the fly from the grass, and it fluttered down airily in front of Master Jack, the fine gut never having touched the water. No sooner had it done so than Jack had it. Fortunately I did not strike too hard, as one is so liable to do under such circumstances; just the requisite turn of the wrist and the small hook went home.

Before I had time to realise fully what had happened the fish had bolted from his holt into the main stream, a bag of unavoidable line behind him as he charged straight towards me. On regaining touch with him I found that the hook had still firm hold, and that Jack was[39] boring up for the bridge in the heavy water. Naturally, I had no idea of allowing him to thread his way up through the arch, as I could ill follow him there, so I had to keep up as steady and strong a strain as I dared. He soon had enough of that fun, and down he came at express speed past me, leaving me to get in my line by hand as best I could. By good luck, I was able to get the slack reeled up whilst Jack was careering about in the broader water below me. Hardly had I done so when, at the end of his run, he gave a grand leap, after the fashion of a sea trout; a dip of rod-point to his majesty saved a catastrophe, and I now began to try to reach terra firma. My friend, however, was not at all disposed to give me much time for such an operation, and just as I was trying to regain the bank—a sufficiently ticklish operation with a wild fish held only by the finest of drawn gut—he made a most determined rush for the big bed of flags below the bridge. Once let him attain that stronghold and I was fairly done; so I had once more to test my gut, and resolutely to determine that he should obey my will. Better be broke at once than lose him in that weed bed. Once more he gave way, and I was able to regain the bank. At that moment Maxwell turned up for luncheon, and the fish, now absolutely beaten, was successfully netted out. I found that in his mad rushes and gyrations he had managed to get two full turns of the gut round his gills. This no doubt accounted for his coming to bank so speedily. He weighed just over 3¼ lb.—no great monster after all, you may ejaculate, but he was about the most perfect specimen of a trout I have ever seen, and was in the pink of condition. He now graces my study in a glass case, the only specimen of a fish that I have ever set up. But there was some justification for this temporary mental aberration, and I often now look at him and recall his sporting end, and the difficult conditions under which I managed to capture him. He carries back my mind to the fond recollections of my old friend, now no more, one of the best and most unselfish of anglers, whose untimely loss has left a blank among his many friends that cannot be filled.

Those amongst us who have had the privilege of fishing in waters where the cutting of the weeds has been scientifically and wisely performed will have realised the difference this point alone can make to a fishery. All the details of weed and water-farming have been so exhaustively treated by Mr. Halford in his various works on "Dry fly fishing," that they need not be described here. No better mentor could be chosen.[41] But some of the chief points that ought to be had in mind may be touched upon. The chief desiderata, where there is an ample supply of weed, are, to put the matter very shortly, to cut in the deeper parts of the river lanes along both banks some ten feet wide, and in the shallower parts to cut bars or lanes across the water at right angles to the banks. At the same time lanes should, also, be cut parallel to the banks, to encourage the bank fish. Where weed is not in abundance recourse must be had to artificial shelters, or hides, under which the fish can obtain the shelter that they require. Stakes driven into the river bed soon attract a clinging mass of floating weed, the only drawback to their being used is that hooked fish may be lost through their bolting for and round them. Piles driven into the shallows afford a welcome rest to fish, and it will be found that a trout will nearly always take up his position behind them. Similarly, big stones placed in the shallows will have a beneficial effect.