Title: Through the Yukon Gold Diggings: A Narrative of Personal Travel

Author: Josiah Edward Spurr

Release date: October 25, 2013 [eBook #44038]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Moti Ben-Ari and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive).

BY

JOSIAH EDWARD SPURR

Geologist, United States Geological Survey

BOSTON

EASTERN PUBLISHING COMPANY

1900

As a geologist of the United States Geological Survey, I had the good fortune to be placed in charge of the first expedition sent by that department into the interior of Alaska. The gold diggings of the Yukon region were not then known to the world in general, yet to those interested in mining their renown had come in a vague way, and the special problem with which I was charged was their investigation. The results of my studies were embodied in a report entitled: "Geology of the Yukon Gold District," published by the Government.

It was during my travels through the mining regions that the Klondike discovery, which subsequently turned so many heads throughout all of the civilized nations, was made. General conditions of mining, travelling and prospecting are much the same to-day as they were at that time, except in the limited districts into which the flood of miners has poured. My travels in Alaska have been extensive since the journey of which this work is a record, and I have noted the same[4] scenes that are herein described, in many other parts of the vast untravelled Territory. It will take two or three decades or more, to make alterations in this region and change the condition throughout.

In recording, therefore, the scenes and hardships encountered in this northern country, I describe the experiences of one who to-day knocks about the Yukon region, the Copper River region, the Cook Inlet region, the Koyukuk, or the Nome District. My aim has been throughout, to set down what I saw and encountered as fully and simply as possible, and I have endeavored to keep myself from sacrificing accuracy to picturesqueness. That my duties led me to see more than would the ordinary traveller, I trust the following pages will bear witness.

Let the reader, therefore, when he finds tedious or unpleasant passages, remember that they record tedious or unpleasant incidents that one who travels this vast region cannot escape, as will be found should any of those who peruse these pages go through the Yukon Gold Diggings.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | The Trip to Dyea | 9 |

| II. | Over the Chilkoot Pass | 35 |

| III. | The Lakes and the Yukon to Forty Mile | 65 |

| IV. | The Forty Mile Diggings | 109 |

| V. | The American Creek Diggings | 156 |

| VI. | The Birch Creek Diggings | 161 |

| VII. | The Mynook Creek Diggings | 207 |

| VIII. | The Lower Yukon | 229 |

| IX. | St. Michael's and San Francisco | 264 |

| PAGE | |

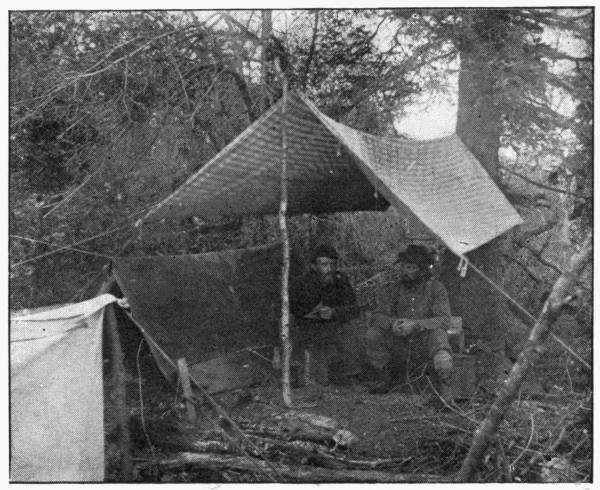

| "We of the Flannel Shirt and the Unblacked Boot" | Frontispiece |

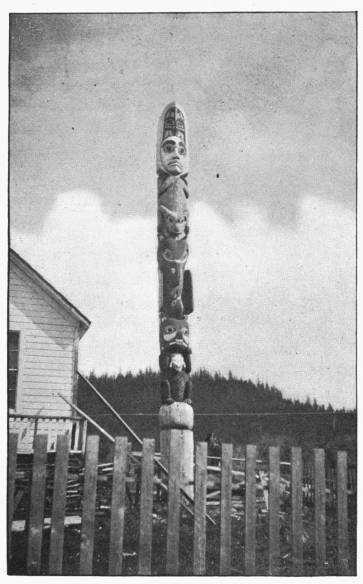

| An Alaskan Genealogical Tree | 12 |

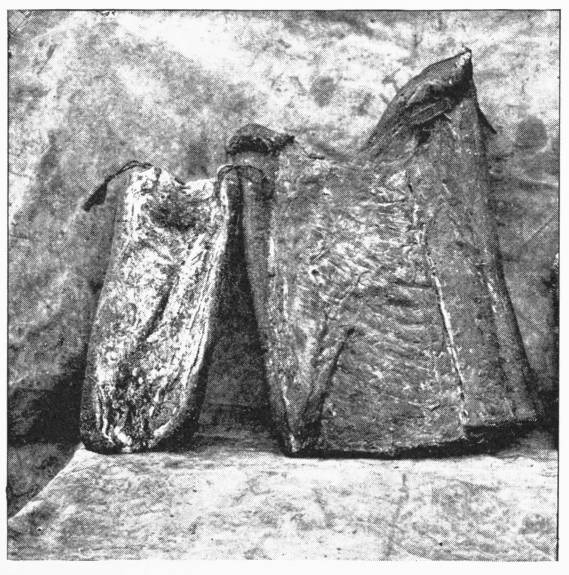

| Bacon, Lord of Alaska | 21 |

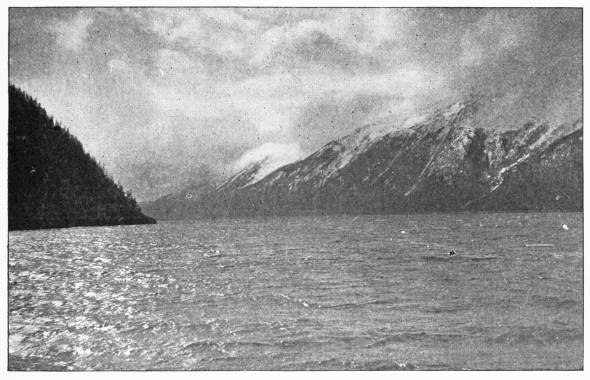

| Lynn Canal | 31 |

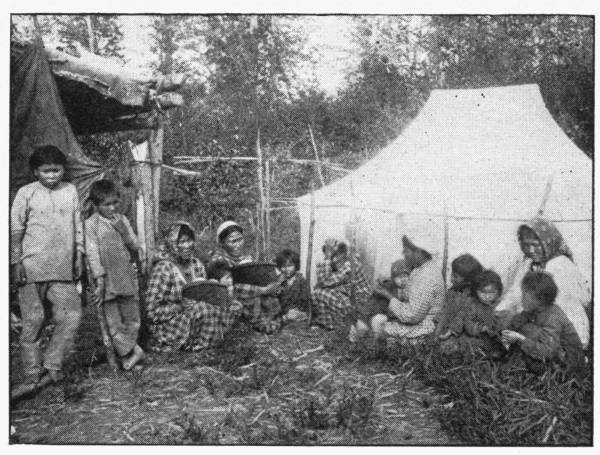

| Alaskan Women and Children | 40 |

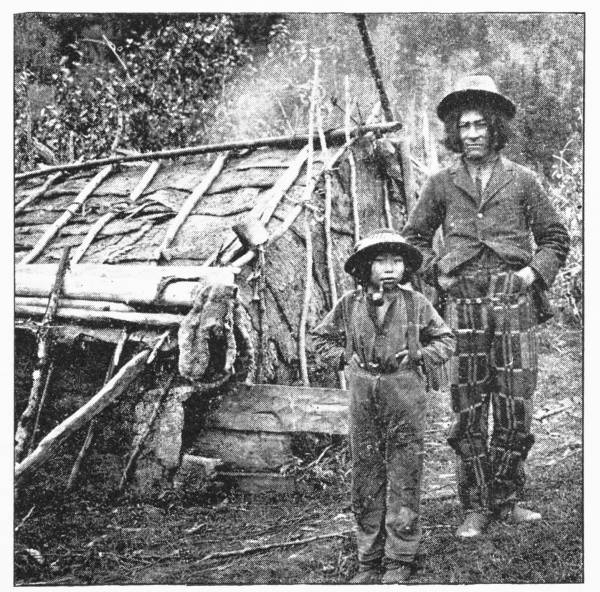

| Alaskan Indians and House | 63 |

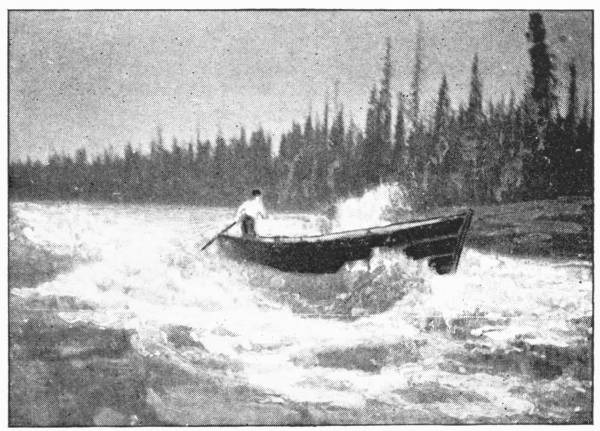

| Shooting the White Horse Rapids | 93 |

| Talking it Over | 98 |

| Alaska Humpback Salmon, Male and Female | 107 |

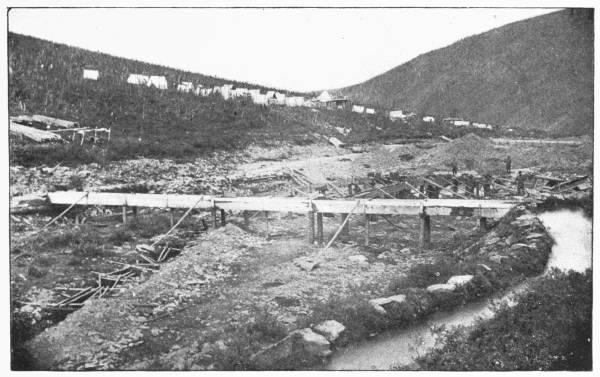

| Washing Gravel in Sluice-Boxes | 131 |

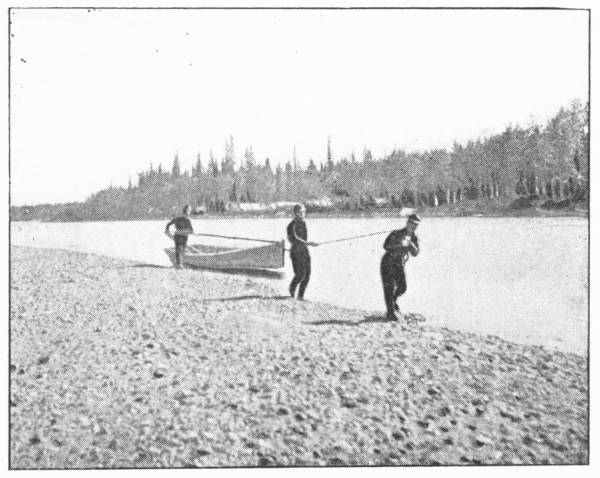

| "Tracking" a Boat Upstream | 137 |

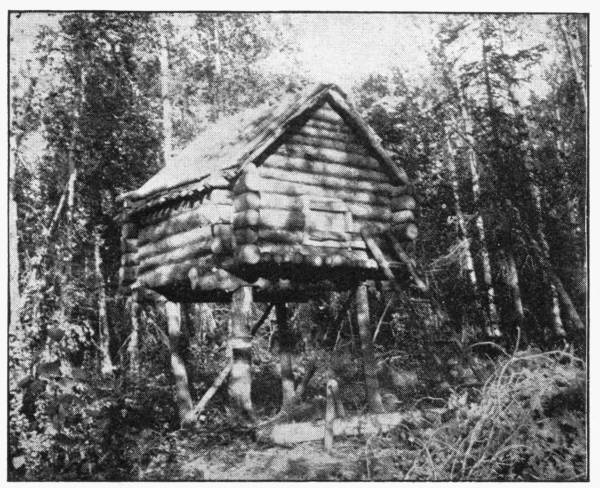

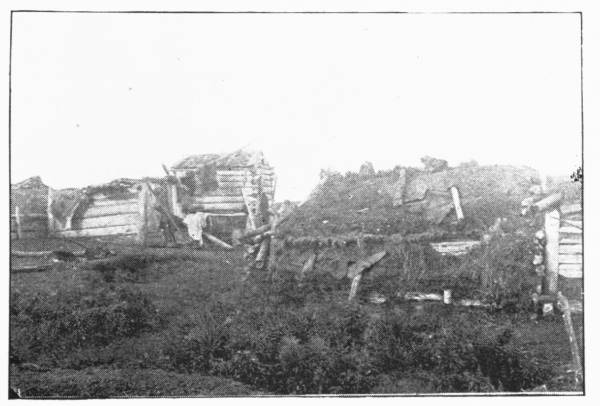

| A "Cache" | 140 |

| Native Dogs | 153 |

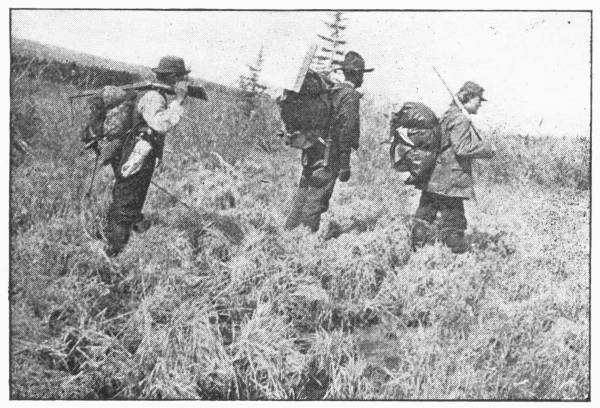

| On the Tramp Again | 165 |

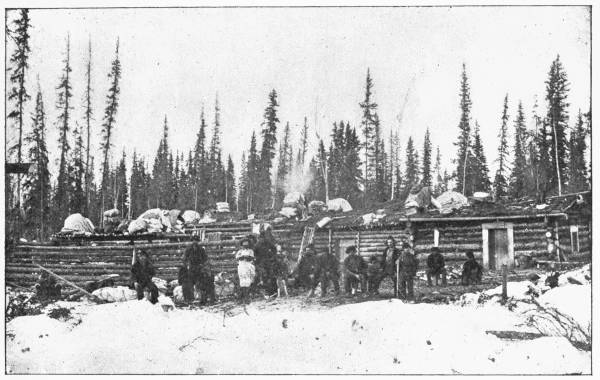

| Hog'em Junction Road-House | 171 |

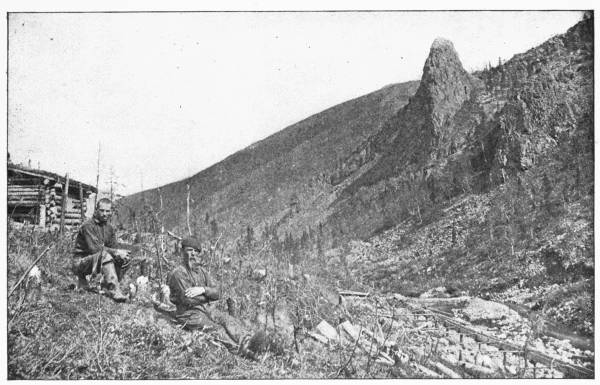

| On Hog'em Gulch | 177 |

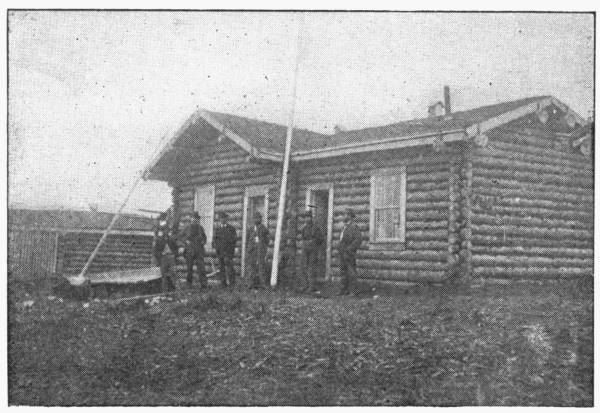

| Custom House at Circle City | 190 |

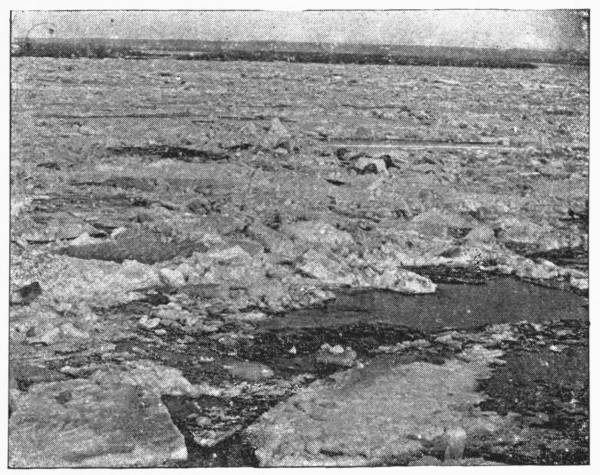

| The Break-up of the Ice on the Yukon | 213 |

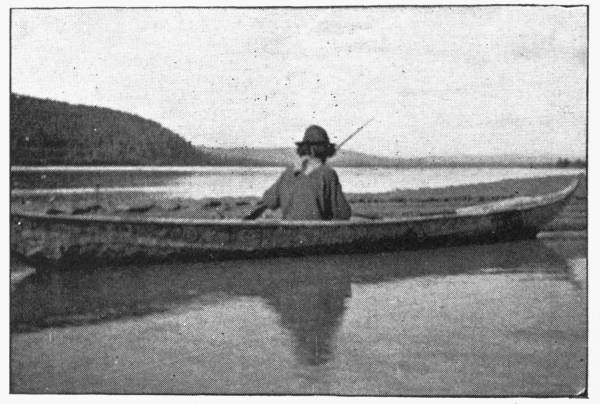

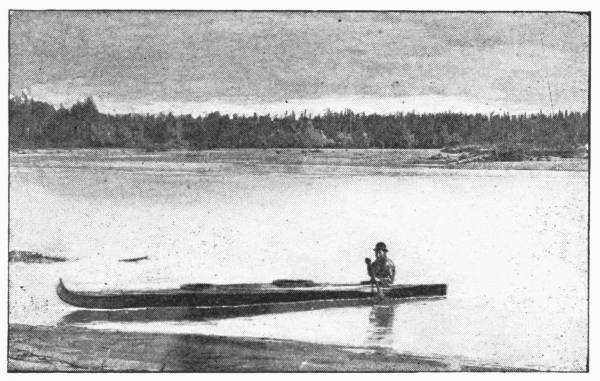

| A Yukon Canoe | 230 |

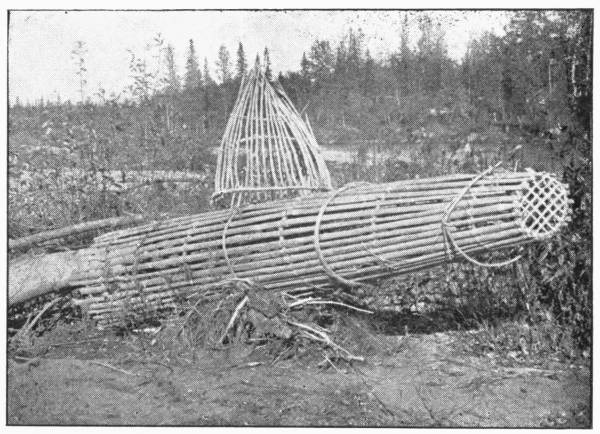

| Indian Fish-traps | 231 |

| In a Tent Beneath Spruce Trees | 239 |

| Three-hatch Skin Boat, or Bidarka | 261 |

| Eskimo Houses at St. Michael's | 265 |

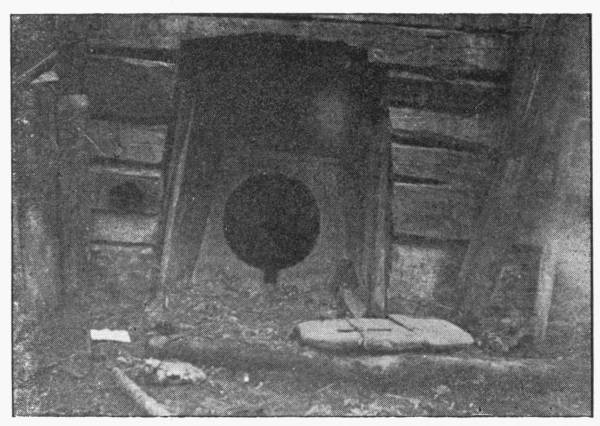

| A Native Doorway | 266 |

| The Captured Whale | 271 |

The author wishes to express his indebtedness to Messrs. A. H. Brooks, F. C. Schrader, A. Beverly Smith, and the United States Geological Survey, for the use of photographs.

It was in 1896, before the Klondike boom. We were seated at the table of an excursion steamer, which plied from Seattle northward among the thousand wonderful mountain islands of the Inland Passage. It was a journey replete with brilliant spectacles, through many picturesque fjords from whose unfathomable depths the bare steep cliffs rise to dizzy heights, while over them tumble in disorderly loveliness cataracts pure as snow, leaping from cliff to cliff in very wildness, like embodiments of the untamed spirits of nature.

We had just passed Queen Charlotte Sound,[10] where the swells from the open sea roll in during rough weather, and many passengers were appearing at the table with the pale face and defiant look which mark the unfortunate who has newly committed the crime of seasickness. It only enhanced the former stiffness, which we of the flannel shirt and the unblacked boot had striven in vain to break—for these were people who were gathered from the corners of the earth, and each individual, or each tiny group, seemed to have some invisible negative attraction for all the rest, like the little molecules which, scientists imagine, repel their neighbors to the very verge of explosion. They were all sight-seers of experience, come, some to do Alaska, some to rest from mysterious labors, some—but who shall fathom at a glance an apparently dull lot of apparent snobs? At any rate, one would have thought the everlasting hills would have shrunk back and the stolid glaciers blushed with vexation at the patronizing way with which they were treated in general. It was depressing—even European tourists' wordy enthusiasm over a mud puddle or a dunghill would have been preferable.

There are along this route all the benefits of a sea trip—the air, the rest—with none of its disadvantages. So steep are the shores that the steamer may often lie alongside of them when she stops and run her gang-plank out on the rocks. These stops show the traveller the little human life there is in this vast and desolate country. There are villages of the native tribes, with dwellings built in imitation of the common American fashion, in front of which rise great totem poles, carved and painted, representing grinning and grotesque animal-like, or human-like, or dragon-like figures, one piled on top of the other up to the very top of the column. A sort of ancestral tree, these are said to be,—only to be understood with a knowledge of the sign symbolism of these people—telling of their tribe and lineage, of their great-grandfather the bear, and their great-grandmother the wolf or such strange things.

The people themselves, with their heavy faces and their imitation of the European dress—for the tourist and the prospector have brought prosperity and the thin veneer of civilization to these southernmost tribes of Alaska—with their flaming neckerchief or head-kerchief of red and yellow silk that the silk-worm had no part in making, but only the cunning Yankee weaver, paddle out in boats dug from the great evergreen trees that cover the hills so thickly, and bring articles made of sealskin, or skilfully woven baskets made out of the fibres of spruce roots, to sell to the passengers. Or the steamer may stop at a little hamlet of white pioneers, where there is fishing for halibut, with perhaps some mining for gold on a small scale; then the practical men of the party, who have hitherto been bored, can inquire whether the industry pays, and contemplate in their suddenly awakened fancies the possibilities of a halibut syndicate, or another Treadwell gold mine. So the artist gets his colors and forms, the business man sees wonderful possibilities in this shockingly unrailroaded wilderness, the tired may rest body and mind in the perfect peace and freedom from the human element, old ladies may sleep and young ones may flirt meantimes.

All this would seem to prove that the passengers were neither professional nor business men, nor young nor old ladies—part of which appeared[14] to me manifestly, and the rest probably untrue; or else that they were all enthusiastic and interested in the dumb British-American way, which sets down as vulgar any betrayal of one's self to one's neighbors.

Some one at the table wearily and warily inquired when we should get to the Muir glacier, on which point we of the flannel-shirted brotherhood were informed; and incidentally we remarked that we intended to leave the festivities before that time, in Juneau.

"Oh my!" said the sad-faced, middle-aged lady with circles about her eyes. "Stay in Juneau! How dreadful! Are you going as missionaries, or," here she wrestled for an idea, "or are you simply going."

"We are going to the Yukon," we answered, "from Juneau. You may have heard of the gold fields of the Yukon country." And strange and sweet to say, at this later day, no one had heard of the gold fields—that was before they had become the rage and the fashion.

But the whole table warmed with interest—they were as lively busybodies as other people and we were the first solution to the problems[15] which they had been putting to themselves concerning each other since the beginning of the trip. There was a fire of small questions.

"How interesting!" said an elderly young lady, who sat opposite. "I suppose you will have all kinds of experiences, just roughing it; and will you take your food with you on—er—wagons—or will you depend on the farmhouses along the way? Only," she added hastily, detecting a certain gleam in the eye of her vis-a-vis, "I didn't think there were many farmhouses."

"They will ride horses, Jane," said the bluff old gentleman who was evidently her father, so authoritatively that I dared not dispute him—"everybody does in that country." Then, as some glanced out at the precipitous mountain-side and dense timber, he added, "Of course, not here. In the interior it is flat, like our plains, and one rides on little horses,—I think they call them kayaks—I have read it," he said, looking at me fiercely. Then, as we were silent, he continued, more condescendingly, "I have roughed it myself, when I was young. We used to go hunting every fall in Pennsylvania, when I was a boy, and once two of us went off together and were[16] gone a week, just riding over the roughest country roads and into the mountains on horseback. If our coffee had not run out we would have stayed longer."

"But isn't it dreadfully cold up there?" said the sweet brown-eyed girl, with a look in her eyes that wakened in our hearts the first momentary rebellion against our exile. "And the wild animals! You will suffer so."

"I used to know an explorer," said the business man with the green necktie, who had been dragged to the shrine of Nature by his wife. He had brought along an entire copy of the New York Screamer, and buried himself all day long in its parti-colored mysteries. "He told me many things that might be useful to you, if I could remember them. About spearing whales—for food, you know—you will have to do a lot of that. I wish I could have you meet him sometime; he could tell you much more than I can. Somebody said there was gold up there. Was it you? Well don't get frozen up and drift across the Pole, like Nansen, just to get where the gold is. But I suppose the nuggets——"

"Let's go on deck, Jane," said the old gentleman;—then[17] to us, politely but firmly, "I have been much interested in your account, and shall be glad to hear more later." We had not said anything yet.

We disembarked at Juneau. We had watched the shore for nearly the whole trip without perceiving a rift in the mountains through which it looked feasible to pass, and at Juneau the outlook or uplook was no better. Those who have been to Juneau (and they are now many) know how slight and almost insecure is its foothold; how it is situated on an irregular hilly area which looks like a great landslide from the mountains towering above, whose sides are so sheer that the wagon road which winds up the gulch into Silver Bow basin is for some distance in the nature of a bridge, resting on wooden supports and hugging close to the steep rock wall. The excursionists tarried a little here, buying furs at extortionate prices from the natives, fancy baskets, and little ornaments which are said to be made in Connecticut.

In the hotel the proprietor arrived at our business in the shortest possible time, by the method of direct questioning. He was from Colorado, I[18] judged—all the men I have known that look like him come from Colorado. There was also a heavily bearded man dressed in ill-fitting store-clothes, and with a necktie which had the strangest air of being ill at ease, who was lounging near by, smoking and spitting on the floor contemplatively.

"Here, Pete," said the proprietor, "I want you to meet these gentlemen." He pronounced the last word with such a peculiar intonation that one felt sure he used it as synonymous with "tenderfeet" or "paperlegs" or other terms by which Alaskans designate greenhorns.

I had rather had him call me "this feller." "He says he's goin' over the Pass, an' maybe you can help each other." Pete smiled genially and crushed my hand, looking me full in the eye the while, doubtless to see how I stood the ordeal. "Pete's an old timer," continued the hotel-man, "one of the Yukon pioneers. Been over that Pass—how many times, Pete, three times, ain't it?"

"Dis makes dirt time," answered Pete, with a most unique dialect, which nevertheless was Scandinavian. "Virst time, me an' Frank Densmore,[19] Whisky Bill an' de odder boys. Dat was summer som we washed on Stewart River, on'y us—fetched out britty peek sack dat year—eh?" He had a curious way of retaining the Scandinavian relative pronoun som in his English, instead of who or that.

"You bet, Pete," answered the other, "you painted the town; done your duty by us."

"Ja," said Pete, "blewed it in; mostly in 'Frisco. Was king dat winter till dust was all been spent. Saw tings dat was goot; saw udder tings was too bad, efen for Alaskan miner. One time enough. I tink dese cities kind of bad fer people. So I get out. Sez I,—'I jes' got time to get to Lake Bennett by time ice breaks,' so I light out." He smiled happily as he said this, as a man might talk of going home, then continued, "Den secon' dime I get a glaim Forty Mile, Miller Greek,—dat's really Sixty Mile, but feller gits dere f'm Forty Mile. Had a pardner, but he went down to Birch Greek, den I work my glaim alone."

He put his hand down in his trousers pocket and brought up a large flat angular piece of gold, two inches long; it had particles of quartz[20] scattered through, and was in places rusty with iron, but was mostly smooth and showed the wearing it must have had in his pocket. He shoved the yellow lump into my hand. "Dat nugget was de biggest in my glaim dat I found; anoder feller he washed over tailin's f'm my glaim efter, an' he got bigger nuggets, he says, but I tinks he's dam liar. Anyhow, I get little sack an' I went down 'Frisco, an' I blewed it in again. Now I go back once more."

We talked awhile and finally agreed to make the trip to Forty Mile together, since we were all bound to this place, and Pete, unlike most miners and prospectors, had no "pardner." We were soon engaged in making the rounds of the shops, laying in our supplies—beans, bacon, dried fruit, flour, sugar, cheese, and, most precious of all, a bucket of strawberry jam. We made up our minds to revel in jam just as long as we were able, even if we ended up on plain flour three times a day. For a drink we took tea, which is almost universally used in Alaska, instead of coffee, since a certain weight of it will last as long as many times the same weight of coffee: moreover, there is some quality in this[21] beverage which makes it particularly adapted to the vigorous climate and conditions of this northern country. Men who have never used tea acquire a fondness for it in Alaska, and will drink vast quantities, especially in the winter. The Russians, themselves the greatest tea-drinkers of all European nations, long ago introduced "Tschai" to the Alaskan natives; and throughout[22] the country they will beg for it from every white man they meet, or will travel hundreds of miles and barter their furs to obtain it.

Concerning the amount of supplies it is necessary to take on a trip like ours, it may be remarked that three pounds of solid food to each man per day, is liberal. As to the proportion, no constant estimate can be made, men's appetites varying with the nature of the articles in the rations and their temporary tastes. On this occasion Pete picked out the supplies, laying in what he judged to be enough of each article: but it appeared afterwards that a man may be an experienced pioneer, and yet never have solved the problem of reasonably accurate rations, for some articles were soon exhausted on our trip, while others lasted throughout the summer, after which we were obliged to bequeath the remainder to the natives. Camp kettles, and frying-pans, of course, were in the outfit, as well as axes, boat-building tools, whip-saw, draw-shave, chisels, hammers, nails, screws, oakum and pitch. It was our plan to build a boat on the lakes which are the source of the Yukon, felling the spruce trees, and then with a whip-saw slicing off[23] boards, which when put together would carry us down the river to the gold diggings.

For our personal use we had a single small tent, A-shaped, but with half of one of the large slanting sides cut out, so that it could be elevated like a curtain, and, being secured at the corners by poles or tied by ropes to trees, made an additional shelter, while it opened up the interior of the tent to the fresh air or the warmth of the camp-fire outside. Blankets for sleeping, and rubber blankets to lay next to the ground to keep out the wet; the best mosquito-netting or "bobinet" of hexagonal mesh, and stout gauntleted cavalry gloves, as protection against the mosquitoes. For personal attire, anything. Dress on the frontier, above all in Alaska, is always varied, picturesque, and unconventional. Flannel or woollen shirts, of course, are universal; and for foot gear the heavy laced boot is the best.

As usual, we were led by the prospective terrors of cold water in the lakes and streams to invest in rubber boots reaching to the hip, which, however, did not prove of such use as anticipated. We had brought with us canvas bags[24] designed for packing, or carrying loads on the back, of a model long used in the Lake Superior woods. They were provided with suitable straps for the shoulders, and a broad one for the top of the head, so that the toiler, bending over, might support a large part of the load by the aid of his rigid neck. These we utilized also as receptacles for our clothes and other personal articles.

Other men were in Juneau also, bound for the Yukon,—not like the hordes that the Klondike brought up later from the States, many of whom turned back before even crossing the passes, but small parties of determined men. We ran upon them here and there. In the hotel we sat down at the table with a self-contained man with a suggestion of recklessness or carelessness in his face, and soon found that he was bound over the same route as ourselves, on a newspaper mission. Danlon, as we may call him, had brought his manservant with him, like the Englishman he was. He was a great traveller, and full of interesting anecdotes of Afghanistan, or Borneo, or some other of the earth's corners. He had engaged to go with him a friend of Pete's, another pioneer, Cooper by name, short, blonde and[25] powerfully built. Between us, we arranged for a tug to take us the hundred miles of water which still lay between us and Dyea, where the land journey begins; after which transaction, we sat down to eat our last dinner in civilization. How tearfully, almost, we remarked that this was the last plum-pudding we should have for many a moon!

We sailed, or rather steamed away, from Juneau in the evening. Our tug had been designed for freight, and had not been altered in the slightest degree for the accommodation of passengers. Her floor space, too, was limited, so that while ten or twelve men might have made themselves very comfortable, the fifty or sixty who finally appeared on board found hard work to dispose of themselves in any fashion. She had been originally engaged for our two parties, but new passengers continually applied, who, from the nature of things, could hardly be refused. So the motley crowd of strangers huddled together, the engines began clanking, and the lights of Juneau soon dropped out of sight, as we steamed up Lynn Canal under the shadow of the giant mountains.

Our fellow-passengers were mostly prospectors; nearly all newcomers, as we could see by the light of the lantern which hung up in the bare apartment where we were. They had their luggage and outfit with them, which they piled up and sat or slept on, to make sure they would not lose it. There were men with grey beards and strapping boys with down on their chins; white handed men and those whose huge horny palms showed a life of toil; all strange, uneasy, and quiet at first, but soon they began to talk confidentially, as men will whom chance throws together in strange places.

There was a Catholic priest bound to his mission among the Eskimos on the lower Yukon,—calm, patient, sweet-tempered, and cheerful of speech; and near him was a noted Alaskan pioneer and trader, bound on some wild trip or other alone. There was another Alaskan—one of those who settle down and take native women as mates and are therefore somewhat scornfully called "squaw-men"; he had been to Juneau as the countryman visits the metropolis, and had brought back with him abundant evidence of the worthlessness of the no-liquor laws of Alaska, in[27] the shape of a lordly drunk, and the material for many more, in a large demijohn, which he guarded carefully. The conversation among this crowd was of the directest sort, as it is always on the frontier.

"Where are you goin', pardner? Prospectin', I reckon?"

Then inquiries as to what each could tell the other concerning the conditions of the land we were to explore, mostly unknown to all: and straightway Pete and Cooper were constituted authorities, by virtue of their previous experience, and were listened to with great deference by the rest. The night was not calm, and the little craft swashed monotonously into the waves. One by one the travellers lay down on the bare dusty floor and slept; and so limited was the room that the last found it difficult to find a place.

Glancing around to find a vacant nook I was struck with the picturesqueness of the scene. Under the lantern the last talkers—the Catholic priest in a red sweater, smoking a bent pipe, the professional traveller and book-maker, and another Englishman with smooth face and oily[28] manners,—were discussing matters with as much reserve and decorum as they would in a drawing-room. Around them lay stretched out, over the floor, under the table, and even on it, motley-clad men, breathing heavily or staring with wide fixed eyes overhead. The pioneer had gone to sleep lying on his back and was snoring at intervals, but by a physical feat hard to understand, retained his quid of tobacco, which he chewed languidly through it all. The only space I could find was in a narrow passageway leading to the pilot-house. Here I coiled myself, hugging closely to the wall, but it was dark and throughout the night I was awakened by heavy boots accidentally placed on my body or head; yet I was too sleepy to hear the apologies and straightway slept again.

It was natural, under the circumstances, that all should be early risers, and we were ravenously hungry for the breakfast which was tardily prepared. The only table was covered with oilcloth, and was calculated for four, but about eight managed to crowd around it: yet with all possible haste the last had breakfast about noon. We sat down where a momentary opening was[29] offered at the third or fourth sitting. A moment later a couple of prospectors appeared who apparently had counted on places, and the hungry stomach of one of them prompted some very audible mutterings to the effect that all men were born free and equal, and he was as good as any one. The priest immediately got up, and with sincere kindness offered his seat, which so overcame the man with shame that he politely refused and retired; but the rest of us insisted on crowding together and making room for him. And for the remainder of the trip a more punctiliously polite individual than this same prospector could not be found.

After each round of eaters, the tin plates and cups and the dingy black knives and forks were seized by a busy dishwasher, who performed a rapid hocus-pocus over them, in which a tiny dishpan filled with hot water that came finally to have the appearance and consistency of a hodge-podge, played an important part; then they were skillfully shyed on to the table again. I looked at my plate. Swimming in the shallow film of dish-water, were flakes of beans, shreds of corned-beef and streaks of apple-sauce, which[30] took me back in fancy to all the different tables that had eaten before: the boat was swaying heavily and I gulped down my stomach before I passed the plate to the dishwasher and suggested wiping. He was a very young man, remarkably dashing, like the hero of a dime novel. He was especially proficient in profanity and kept up a running fire of insults on the cook. He took the plate and eyed me scornfully, witheringly.

"Seems to me some tenderfeet is mighty pertickler," said he, with a very evident personal application, then swabbed out the plate with a towel, the sight of which made me turn and stare at the spruce-clad mountain-sides, in a desperate effort to elevate my mind and my stomach above trifles.

"This is no place for a white man," said a prospector who had been staring out of the door all day. "Good enough for bears and—and—Siwash, maybe." Most, I think shared more or less openly his depression, for the shores of Lynn Canal are no more attractive to the adventurer than the rest of the bleak Alaskan mountain coast.

It was a chilly, drizzling day. The clouds ordinarily hid the tops of the great steep mountains, so that these looked as if they might be walls that reached clear up to the heavens, or, when they broke away, exposed lofty snowy peaks, magnificent and gigantic in the mist. We caught glimpses of wrinkled glaciers, crawling down the valleys like huge jointed living things, in whose fronts the pure blue ice showed faintly and coldly. Here and there waterfalls appeared, leaping hundreds of feet from crag to crag, and all along was the rugged brown shore, with the surf lashing the cliffs, and no place where even a boat might land. All men, whether they clearly perceive it or not, find in the phenomena of Nature some figurative meanings, and are depressed or elevated by them.

We anchored in the lee of a bare rounded mountain that night, it being too rough to attempt landing, and the next morning were off Dyea, where we were to go ashore. The surf was still heavy, but the captain ventured out in a small boat to get the scow in which passengers and goods were generally conveyed to the shore; for the water was shallow, and the steamer had to keep a mile or so from the land. In the surf the boat[33] capsized, and we could see the captain bobbing up and down in the breakers, now on top, now under his boat, in the icy water. The dishwasher, who evidently knew the course of action in all such emergencies from dime-novel precedents, yelled out "Man the lifeboat!" The captain had taken the only boat there was. The entire crew, it may be mentioned, consisted, besides the dishwasher and the captain, of the sailor, who was also the cook. The duty of manning the lifeboat—had there been one—would thus apparently have devolved on the sailor, but he grew pale and swore that he did not know how to row and that he had just come from driving a milk-wagon in San Francisco. A party of prospectors became engaged in a heated discussion as to whether, if there had been a boat on board, it would not have been foolish to venture out in it, even for the sake of trying to rescue the captain; some urging the claims of heroism, and others loudly proclaiming that they would not risk their lives in any such d——d foolish way as that.

However, all this was only the froth and excitement of the moment. The captain hauled his[34] boat out of the breakers, skillfully launched it again, and came on board, shivering but calm, a strapping, reckless Cape Breton Scotch-Canadian. In due course of time afterwards the scow was also got out, and we transferred our outfits to it and sat on top of them, while we were slowly propelled ashore by long oars.

At this time there was only one building at Dyea—a log house used as a store for trading with the natives, and known by the name of Healy's Post. (Two years afterwards, on returning to the place, I found a mushroom, sawed-board town of several thousand people; but that was after the Klondike boom.) We pitched our tents near the shore that night, spreading our blankets on the ground.

In the morning all were bustling around, following out their separate plans for getting over the Pass as soon as possible. Of the different notches in the mountain wall by which one may cross the coast range and arrive at the head waters of the Yukon, the Chilkoot, which is reached from Dyea, was at that time the only one practicable. It was known that Jack Dalton, a pioneer trader of the country, was wont to go over the Chilkat Pass, a little further south,[36] while Schwatka, Hayes, and Russell, in an expedition of which few people ever heard, had crossed by the way of the Taku River and the Taku Pass to the Hootalinqua or Teslin River, which is one of the important streams that unite to make up the upper Yukon. But the White Pass, which afterwards became the most popular, and which lies just east of the Chilkoot, was at that time entirely unused, being a rough long trail that required clearing to make it serviceable.

The Chilkoot, though the highest and steepest of the passes, was yet the shortest and the most free from obstructions; it had been, before the advent of the white adventurer in Alaska, the avenue of travel for the handful of half-starved interior natives who were wont to come down occasionally to the coast, for the purpose of trading. The coast Indians are, as they always have been, a more numerous, more prosperous, stronger and more quarrelsome class, for the sea yielded them, directly and indirectly, a varied and bountiful subsistence. The particular tribe who occupied the Dyea region,—the Chilkoots—were accustomed to stand guard over the Pass[37] and to exact tribute from all the interior natives who came in; and when the first white men appeared, the natives tried in the same way to hinder them from crossing and so destroying their monopoly of petty traffic. For a short time this really prevented individuals and small parties from exploring, but in 1878 a party of nineteen prospectors, under the leadership of Edmund Bean, was organized, and to overcome the hostility of the Chilkoots, a sort of military "demonstration" was arranged by the officers in charge at Sitka. The little gunboat stationed there proceeded to Dyea, and, anchoring, fired a few blank shots from her heaviest (or loudest) guns; afterwards the officer in charge went on shore, and made a sort of unwritten treaty or agreement with the thoroughly frightened natives, by which the prospectors, and all others who came after, were allowed to proceed unmolested.

The fame of that "war-canoe" spread from Indian to Indian throughout the length and breadth of the vast territory of Alaska. One can hear it from the natives in many places a thousand miles from where the incident occurred,[38] and each time the story is so changed and disguised, that it might be taken for a myth by an enthusiastic mythologist, and carefully preserved, with all its vagaries, and very likely proved to be an allegory of the seasons, or the travels of the sun, moon, and stars. In proportion as the story reached more and more remote regions, the statements of the proportions of the canoe became more and more exaggerated, and the thunder of the guns more terrible, and the number of warriors on board increased faster than Jacob's flock. The gunboat was the butt for many good-natured jokes from navy officers, on account of her small dimensions and frail construction. Yet the natives a little way into the interior will tell you of the wonderful snow-white war-canoe, half a mile long, armed with guns a hundred yards or so in length; and by the time one gets in the neighborhood of the Arctic Circle, he will hear of the "great ship" (the native will perhaps point to some mountain eight or ten miles away) "as long as from here to the mountain"; how she vomited out smoke, fire and ashes like a volcano, and at the same time exploded her guns and killed many people, and[39] how she ran forwards and backwards, with the wind or against it, at a terrific speed,—a formidable monster, truly!

At the time of our trip (in 1896) the immigration into the Yukon gold country had gone on, in a small way, for some years; several mining districts were well developed, and the natives had settled down into the habit of helping the white man, for a substantial remuneration. These natives were all camped or housed close to the shore. They were odd and interesting at first sight. The men were of fair size, strong, stolid, and sullen-looking; clothed in cheap civilized garb in this summer season,—it was in the early part of June—in overalls and jumpers, with now and then a woollen Guernsey jacket, and with straw hats on their heads. The women were neither beautiful nor attractive. Many of them had covered their faces with a mixture of soot and grease, which stuck well. Other women had their chins tattooed in stripes with the indelible ink of the cuttlefish—sometimes one, sometimes three, sometimes five or six stripes. This custom I found afterwards among the women of many tribes and peoples in different[40] parts of Alaska, and it seems, in some regions at least, to be a mark of aristocracy, indicating the wealth of the parents at the time the girl-child was born. All the natives were living in tents or rude wooden huts, in the most primitive fashion, cooking by a smouldering fire outside, and sleeping packed close together, wrapped in skins and dirty blankets.

It had been the custom of the miners to engage these natives to carry their outfits for them, from Dyea, and some of the men who had come with[41] us, immediately hired packers for the whole trip to Lake Lindeman, paying them, I think, eleven cents a pound for everything carried. The storekeeper, however, had been constructing a foot trail for about half the distance and had bought a few pack-horses, and we engaged these to transport our outfit as far as possible, trusting to Indians for the rest. We had brought with us from Juneau, on a last sudden idea, a lot of lumber with which to build our boat when we should get to Lake Lindeman, and here the transportation of this lumber became a great problem. To pack it on the horses was an impossibility, and the Indians refused absolutely to take the boards unless they were cut in two, which would destroy much of their value, and even if this were done, demanded an enormous price for the carrying; therefore it was concluded to leave them behind, and trust to good luck in the future.

In one way or another, everybody was furnished with some kind of transportation, and the whole visible population of Dyea, permanent or transient, began moving up the valley. Some of the natives put their loads in wooden dugout canoes, which they paddled, or pushed with poles, six[42] or seven miles up the small stream which goes by the name of the Dyea River; others took their packs on their backs, and led the way along the trail. Not stronger, perhaps, than white men, the Chilkoots showed themselves remarkably patient and enduring, carrying heavy loads rapidly long distances without resting. Not only the men, but the women and children, made pack-animals of themselves. I remember a slight boy of thirteen or so, who could not have weighed over eighty pounds, carrying a load of one hundred. The dog belonging to the same family, a medium-sized animal, waddled along with a load of about forty pounds; he seemed to be imbued with the same spirit as the rest, and although the load nearly dragged him to the ground, he was patient and persevering.

The trail was a tiresome one, being mostly through loose sand and gravel alongside the stream: several times we had to wade across. As we went up, the valley became narrower, and we had views of the glacier above us, which reached long slender fingers down the little valleys from the great ice-mass on the mountain. It was evident that the glacier had once filled the[43] entire valley. As soon as we were up a little we were obliged to clamber over the piled-up boulders in the strips of moraine which the ice had left; in places the rows were so regular that they had the appearance of stone walls.

We were seized with fatigue and a terrible hunger. "You haven't a sandwich about your clothes, have you?" I asked of some prospectors whom I overtook resting in the lee of a cliff. Here the stream becomes so rough and rapid that the natives can work their canoes no further, and so the place has been somewhat pompously named on some maps the "Head of Navigation," by which most people infer that a gunboat may steam up this far.

"No, by ——, pardner," was the answer, "if we had, we'd a' eaten it ourselves before now."

Crossing the stream for the last time, on the trunk of a fallen tree, which swayed alarmingly, the trail led up steeply among the bare rocks of the hillside. All the pedestrian groups had separated into singles by this time, every one going his "ain gait" according to his own ideas and strength, and in no mood for conversation. I overtook a young Irishman, who had started out[44] with a pack of about seventy-five pounds; he was resting, and quite downcast with fatigue and hunger.

Just where we stopped some one had left a load of canned corn and tomatoes. We eyed them hungrily, and gravely discussed our rights to helping ourselves. We did not know the owners and could not find them—certainly they were none of those that had come with us. We could not take them and leave money, for although the natives respected "caches" of provisions, we could not expect them to do the same with money. "Again," said the Irishman, "the feller what lift them here may be dipinding on every blissed can of swate corn for some little schayme of his, while we have plenty grub of our own, if we can on'y get our flippers on it."

At this period, all through Alaska, provisions and other property was regarded with utmost respect. Old miners and prospectors have told me that they have left provisions exposed in a "cache" for a year, and on returning after having been hundreds of miles away, have found them untouched, although nearly starving natives had passed them almost daily all winter. In the[45] mining camps the same custom prevailed. Locks were unknown on the doors. When a white man arrived at the hut of an absent prospector, he helped himself, taking enough provisions from the "cache" to keep him out of want, till he could make the next stage of his journey, and wrote on paper or on the wooden door, "I have taken twenty pounds of flour, ten pounds of bacon, five pounds of beans, and a little tea," signed his name, and departed. It was not a bill, but an acknowledgment; and to have left without making the acknowledgment constituted a theft, in the eyes of the miner population. This condition of primitive honesty did not last, however. Later, with the Klondike boom, came the ordinary light-fingeredness of civilization, and a state of affairs unique and instructive passed away.

We arrived finally at the end of the horse-trail, a spot named Sheep Camp by an early party of prospectors who killed some mountain sheep here. Steep, rocky and snowy mountains overhang the valley, with a vast glacier not far up; and here, since our visit, have occurred a number of fatal disasters, from snowslides and[46] landslides. Pete had arrived before us: he had set up a Yukon camp stove of sheet iron, had kindled fire therein and was engaged in the preparation of slapjacks and fried bacon, a sight that affected us so that we had to go and sit back to, and out of reach of the smell, till Pete yelled out in vile Chinook "Muk-a-muk altay! Bean on the table!" There were no beans and no table, of course, but that was Pete's facetious way of putting it.

Further than Sheep Camp the horse-trail was quite too rocky and steep for the animals; so we tried to engage Indians to take our freight for the remaining part of the distance across the Pass. Up to the time of our arrival, the regular price for packing from Dyea to Lake Lindeman had been eleven cents a pound. For the transportation by horses over the first half of the distance—thirteen miles—we had paid five cents a pound, and we had expected to pay the Indians six cents for the remainder of the trip. In the first place, however, it was difficult to gather the Indians together, for they were off in bands in different parts of the neighboring country, on expeditions of their own; and when they arrived[47] in Sheep Camp, with a bluster and a racket, they were so set up by the number of men that were waiting for their help that they took it into their heads to be in no hurry about working. Finally they sent a spokesman who, with an insolence rather natural than assumed for the occasion, demanded nine cents per pound instead of six, for packing to Lake Lindeman. It was a genuine strike—the revolt of organized labor against helpless capital.

Being in a hurry to get ahead and fulfill our mission, we should doubtless have yielded; but there were many parties camped here besides ourselves—namely, all those who had been our fellow-sufferers on board the Scrambler—and a general consultation being held among the gold-hunters, it was decided that the proposed increase of pay for labor would prove ruinous to their business. A committee representing these gentlemen waited on us and begged us not to yield to the strikers, in the carelessness of our hearts and our plethoric pocket-books, but to consider that in doing so they—the prospectors—must follow suit, the precedent being once established; whereas they were poor[48] men, and could not afford the extra price. To this view of the case we agreed, considering ourselves as a part of the Sheep Camp community, rather than as an individual party; and the English traveller (who was likewise suspected of being overburdened with funds, and therefore likely to be careless with them) was also waited upon and persuaded to resist the demands. So everybody camped and waited, and was obstinate, for several days: not only the white men, but the Siwash.

By way of digression it may be mentioned that the word Siwash is indiscriminately applied by the white men to all the Alaskan natives, to whatever race—and there are many—they belong. The word therefore has no definite meaning, but corresponds roughly to the popular name of "nigger" for all very dark-skinned races, or "Dago" for Spaniards, Portuguese, Italians, Greeks, Turks, Armenians, and a host of other black-haired, olive-skinned nations. The name has been said to be a corruption of the French word "sauvage,"—savage,—and this seems very likely.

Like the corresponding epithets cited, the word[49] Siwash has a certain familiar, facetious, and contemptuous value, and this may have been the idea which prompted its use just now, when speaking of the natives as strikers and opponents. At any rate, they took the situation in a careless, matter-of-fact way; cooked, ate, slept, borrowed our kettles, begged our tea and stole our sugar with utmost cheerfulness, and were apparently contented and happy. We white men likewise tried to conceal our restlessness, and chatted in each others' tents, admired the scenery, or went rambling up the steep mountain-sides in search of experiences, exercise, and rocks. Some of us clambered over the huge boulders, each as big as a New England cottage, which had been brought here by glacial action, then up over the steep cliffs, wrenched and crumbling from the crushing of the same mighty force, supporting ourselves,—when the rocks gave way beneath our feet and went rattling down the cliff,—by the tough saplings that had taken root in the crevices, and grew out horizontally, or even inclined downwards, bent by continuous snowslides. So we reached the base of the glacier, where a sheer wall of clear blue ice rose to a height which we[50] estimated at three or four hundred feet, back of which stretched a great uneven white ice field, as far as the eye could see, clear up till the view was lost in the mists of the upper mountains; an ice field seamed with great yawning crevasses, where the blue of the ice gleamed as streaks on the dead white.

One morning we heard a yell from the Siwash, and soon they came running over the little knoll which separated our camp from theirs, and began grabbing the articles that belonged to some of the miners. We were at a loss to know the meaning of what seemed at first to be a very unceremonious proceeding, but when we saw the miners, with many shamefaced glances at us, help the natives in the distribution of the material, we realized that these men had forsaken us and their resolutions; so greedy were they to reach the land of gold that they had gone to the natives and agreed to pay them the demanded rates on condition that they should have all the packers themselves, leaving none to us. We let these men and their natives go in peace, without even a reproach: less than a week afterwards we had the deep satisfaction of passing them on the[51] trail, and even in lending them a hand in a series of little difficulties for which, in their haste, they had come unprepared. The veteran miner in Alaska is a splendid, open-hearted, generous fellow; the newcomer, or "chicharko," is a thing to be avoided.

After this we had to wait till the natives had got back from carrying the miners' supplies, and then we agreed, with what grace we could, to pay the price that the others had. The Indians were quite a horde, capable of carrying in one trip all the supplies belonging to our party and that of the English traveller. Since they were paid by the pound they vied in taking enormous loads; the largest carried was 161 pounds, but all the men's packs ranged from 125 to 150 pounds. Women and half-grown boys carried packs of 100 pounds. It was a "Stick" or interior Indian, named at the mission Tom, but originally possessed of a fearful and unpronounceable name, who carried the largest load. He was barely tolerated and was somewhat badgered by the Chilkoots, hence he fled much to the society of the whites, and would squat near for hours, always smiling horribly when[52] looked at; he claimed to be a chief among his own wretched people, and spent all his spare time in blackening his face, reserving rings around the eyes which he smeared with red ochre—having done which, he grinned ghastly approval of himself!

Pete started over the Pass in advance of the party, to procure for us if possible a boat at Lake Lindeman.

"Dis is dirt time I gross Pass," said Pete. "Virst dime I dake leedle pack—den I vos blayed out; nex' dime I dake leedle roll of clo'es—den I vos blayed out too, py chimney: dis dime I dake notting—den I vill be blayed out too!"

The natives, after much shouting and confusion and wrangling, made up their packs about noon, and started out, we following; just before getting to snow-line they stopped in a place where a chaotic mass of boulders form a trifling shelter, grateful to wild beasts or wild men like these. Here they deposited their loads, and with exasperating indifference composed themselves to sleep. We tried to persuade them to go on, but to no avail, and we discovered afterwards, as often happened to us in our dealing[53] with the natives, that they were right. It was June, and yet the snow lay deep on all the upper parts of the Pass; and in the long, warm days it became soft and mushy, making travel very difficult, especially with heavy packs. As soon as the sun went down behind the hills, however, the air became cool, and a hard crust formed, so that walking was much better.

We left the natives and followed a trail which led among the boulders and then higher up the mountain, where many moccasined feet had left a deep path through the icy snow. We tramped onward, sometimes on hard ice, sometimes through soft snow, strung out in Indian file, saying nothing, saving our breath for our lungs; at times the crust rang hollow to our tread, and beneath us we could hear torrents raging. It was about eight o'clock at night when we started, and the sun in the narrow valley had already gone down behind the high glaciers on the mountain-tops, even at this latitude and in the month of June; so the long northern twilight which is Alaska's substitute for night in the summer months soon began to settle down upon us. At the same time the moisture from[54] the snow which all day long had been lying in the sun, began cooling into mists, changeful and of different thicknesses; and in the dim light gave to everything a weird and unnatural aspect.

Even our fellow-travellers were distorted and magnified, now lengthwise, now sidewise, so that those above us were powerful-limbed giants, striding up the hill, while those behind us were flattened and broadened, and seemed straddling along as grotesquely as spiders. When we drew near and looked at each other we were inclined to laugh, but there was something in the pale-blue, ghastly color of the faces that made us stop, half-frightened. At twelve o'clock it was so dark that we could hardly follow the trail; then we saw a fire gleaming like a will-o'-the-wisp somewhere above us, and clambering up the steep rock which stuck out of the snow and overhung the trail, we saw a couple of figures crouching over a tiny blaze of twigs and smoking roots. It was a native and his "klutchman" or squaw; he turned out to be deaf-and-dumb, but made signs to us,—as we squatted ourselves around the fire,—that the night was dark, the trail dangerous, and that it would be[55] better to wait till it grew a little lighter. So we kept ourselves warm for a half-hour or more by our exertions in tearing up roots for a fire: the fire itself being nothing more than a smoky, flary pile of wet fagots, hardly enough to warm our numbed fingers by. Then a dim figure came toiling up to us. It was one of our packers, and he explained in broken, profane, and obscene English, of which he was very proud, (the foundation of his knowledge had been laid in the mission, and the trimmings, which were profuse and with the same idea many times repeated, like an art pattern, had been picked up from straggling whites) that the trail was good now. So we very gladly took up our march again.

Two of us soon got ahead of the guide and all the rest of our party, following the beaten track in the snow; after a while the ascent became very steep, as the last sheer declivity of the Pass was reached, and we began to suspect that we had strayed from the right path, for although here was a track, we could find no footprints on it, but only grooves as if from things which had slid down. Yet we decided not to go back, for we did not know how far we had strayed from the path,[56] and the climbing was not so easy that we were anxious to do it twice. So we kept on upward, and the ascent soon became so steep that we were obliged to stop and kick footholds in the crust at every step.

It was twilight again, but still foggy, and we could see neither up nor down, only what appeared to be a vast chasm beneath us, wherein great indistinct shapes were slowly shifting—an impression infinitely more grand and appalling than the reality. At any rate, it made us very careful in every step, for we had no mind that a misplaced foot should send us sliding down the grooves we were following. At last we gained the top, found here again the trail we had lost, and waited for the rest. Around us, sticking out of the snow, were rocks, which appeared distorted and moving. It was the mists which moved past them, giving a deceptive effect. My companion suddenly exclaimed, "There's a bear!" On looking, my imagination gave the shape the same semblance, but on going towards it, it resolved itself very reluctantly into a rock, as if ashamed of its failure to "bluff." Most grown-up people, as well as children, I fancy, are more or less[57] afraid of the dark—where the uncertain evidence of the eyes can be shaped by the imagination into unnatural things. Goethe must once have felt something like what Faust expressed when he stood at night in one of the rugged Hartz districts:

Presently the rest of the party came up from quite a different direction and with them a whole troop of packers. The main trail, from which we had strayed, was much longer, but not so steep; while the one we had followed was simply the mark of the articles which the packers were accustomed to send down from the summit to save carrying, while they themselves took the more circuitous route.

On the interior side of the summit is a small lake with steep sides, which the miners have named Crater Lake, fancying from the shape that it had been formed by volcanic action; it has no such origin however, but occupies what is[58] known as a glacial cirque or amphitheatre—a deep hollow carved out of the dioritic mountain mass by the powerful wearing action of a valley glacier. This lake was still frozen and we crossed on the ice, then followed down the valley of the stream which flowed from it and led into another small lake. There are several of these small bodies of water and connecting streams before one reaches Lake Lindeman, which is several miles long, and is the uppermost water of the Yukon which is navigable for boats. Our path was devious, following the packers, but always along this valley. We crossed and recrossed the streams over frail and reverberant arches, half ice, half snow, which, already broken away in places, showed foaming torrents beneath. As we descended in elevation, the ice on the little lakes became more and more rotten and the snow changed to slush, through which we waded knee deep for miles, sometimes putting a foot through the ice into the water beneath.

We were all very tired by this time and were separated from one another by long distances, each silent, and travelling on his nerve. The Indian packers, too, in spite of their long experience,[59] were tired and out of temper; but the most pitiful sight of all was to see the women, especially the old ones, bending under crushing loads, dragging themselves by sheer effort at every step, groaning and stopping occasionally, but again driven forward by the men to whom they belonged. One could not interfere; it was a family matter; and as among white people, the woman would have resented the interference as much as the man.

Finally we came to a lake where the water was almost entirely open and were obliged to skirt along its rocky shores to where we found a brawling and rocky stream entering it, cutting us off. After a moment of vain glancing up and down in search of a ford, we took to the water bravely, floundering among the boulders on the stream's bottom, and supporting ourselves somewhat with sticks. Afterwards we found a trail which led away from the lake high over the rocky hillside, where the rocks had been smoothed and laid bare by ancient glaciers, now vanished. Here we found the remnants of a camp, left by some one who had recently gone before us; we inspected the corned beef cans lying about[60] rather hungrily, thinking that something might have been left over. Our only lunch since leaving Sheep Camp had been a small piece of chocolate and a biscuit. The biscuit possessed certain almost miraculous qualities, to which I ascribe our success in completing the trip and in arriving first among the travellers at Lake Lindeman. I myself was the concocter of this biscuit, but it was done in a moment of inspiration, and since I have forgotten certain mystic details, it probably could never be gotten together again. It was the first and last time that I have made biscuit in my life, and I did it simply for the purpose of instruction to the others, who were shockingly ignorant of such practical matters.

We had brought a reflector with us for baking,—a metal arrangement which is set up in front of a camp-fire, and, from polished metallic surfaces, reflects the heat up and down, on to a pan of biscuit or bread, which is slid into the middle. These utensils as used in the Lake Superior region, that home of good wood-craft, are made of sheet iron, tinned; but thinking to get a lighter article, I had one constructed out of aluminum. This first and last trial with our[61] aluminum reflector at Sheep Camp showed us that one of the peculiar properties of this metal is that it reflects heat but very little, but transmits it, almost as readily as glass does light. So when I had arrived at the first stage of my demonstration and had the reflector braced up in front of the fire, I found that the dough remained obstinately dough, while the heat passed through the reflector and radiated itself around about Sheep Camp. Still I persisted, and after several hours of stewing in front of the fire, most of the water was evaporated from the dough, leaving a compact rubbery grey BISCUIT, as I termed it. I offered it for lunch and I ate one myself; no one else did, but I was rewarded by feeling a fullness all through the tramp, while the others were empty and famished. I also was sure that it gave me enormous strength and endurance; while some of the rest were unkind enough to suggest that the same high courage which led me up to the biscuit's mouth, figuratively speaking, kept me plugging away on the Lake Lindeman trail.

We reached Lake Lindeman at about nine o'clock in the morning, and found Pete and[62] Cooper already there. It was raining drearily and they had made themselves a shelter of poles and boughs under which they were lying contentedly enough, waiting until the packers should bring the tents. In a very short time after we had arrived all the natives were at hand, and setting down their packs demanded money. They could not be induced to accept bills, because they could not tell the denomination of them, and would as soon take a soap advertisement as a hundred-dollar note; they dislike gold, because they get so small a quantity of it in comparison with silver.

Like the Indians of the United States, the Alaskans formerly used wampum largely as a medium of exchange—small, straight, horn-shaped, rather rare shells, which were strung on thongs—but when the trading companies began shipping porcelain wampum into the country the natives soon learned the trick and stopped the use of it. I have in my possession specimens of this porcelain wampum, which I got from the agent of one of the large trading companies on the Yukon. Silver is now the favorite currency, whether or not on the basis of sound political[63] economy; and each particular section has often a preference for some special coin, such as a quarter, ("two bits," as it is called in the language of the west coast) a half-dollar or a dollar. Where the natives have had to deal only with quarters, you cannot buy anything for half-dollars, except for nearly double the price you would pay in quarters; while dimes, however large the quantity, would probably be refused entirely.

The Chilkoots, however, on account of their residence on the coast and consequent contact with the whites, had become more liberal in their views as regarded denomination of silver, but drew the line at bimetalism, and had no faith whatsoever in the United States as the fulfiller of promises to redeem greenbacks in silver coin. So there was some trouble in paying them satisfactorily; and after they were paid they came back, begging for a little flour, a little tea, etc., and keeping up the process with unwearied ardor till the supply was definitely shut off. The toughness of these people is well shown by the fact that when they had rested an hour and had cooked themselves a little food and drunk a little tea, they departed over the trail again for Sheep Camp, although they had made the same journey as the white men, who were all exhausted, and had, in addition, carried loads of as high as 160 pounds over the whole of the rough trail of thirteen miles. When affairs were settled we pitched our tents, rolled into our blankets, and for the next twenty hours slept.

Upon reaching Lake Lindeman, we found a number of other parties encamped,—men who had come over the trail before us, and had been delaying a short time, for different reasons. From one of these parties Pete had been lucky enough to buy a boat already built, so that we did not have to wait and build one ourselves—a job that would have consumed a couple of weeks. The boat was after the dory pattern, but sharp at both ends, made of spruce, lap-streaked and unpainted, with the seams calked and pitched; about eighteen feet long, and uncovered. During the trip later we decided that it ought to be christened, and so we mixed some soot and bacon-grease for paint, applied it hot to the raw, porous wood, and inscribed in shaky letters the words "Skookum Pete," as a compliment to our pilot. Skookum is a Chinook word signifying strength, courage, and other excellent[66] qualities necessary for a native, a frontiersman, or any other dweller in the wilderness—qualities which were conspicuous in Pete. Pete was overcome with shame on reading the legend, however, and straightway erased his name, so that she was simply the Skookum. And skookum she proved herself, in the two thousand miles we afterwards travelled, even though she sprung a leak occasionally or became obstinate when being urged up over a rapid.

It may be observed that the Chinook, to which this word belongs, is not a language, but a jargon, composed of words from many native American and also from many European tongues. It sprung up as a sort of universal language, which was used by the traders of the Hudson Bay Company in their intercourse with the natives, and is consequently widely known, but is poor in vocabulary and expression.

There were several boats ready to start, craft of all models and grades of workmanship, variously illustrating the efforts of the cowboy, the clerk, or the lawyer, at ship-carpentry. Several of us got off together in the morning, our boat carrying four, and the English traveller's boat[67] the same number, for he had taken into his party the priest whom we had met on the Scrambler.

This gentleman, with a number of miners and a newspaper reporter, had been unlucky enough to fall into the trap of a certain transportation company, which had a very prettily furnished office in Seattle. This office was the big end of the company. As one went north towards the region where the company was supposed to be doing its transportation, it shrunk till nothing was left but a swindle. They promised for a certain sum of money to transport supplies and outfits over the Pass, and to have the entire expedition in charge of an experienced man, who would relieve one of all worry and bother; and after transportation across the Pass, to put their passengers on the COMPANY'S steamers, which would carry them to the gold fields. Even at Juneau the "experienced man" who was to take the party through, and who was a high officer of the company, kept up the ridiculous pretences and succeeded in obtaining a number of passengers for the trip. When these men learned later, however, that the guide had never yet been further than Juneau; that he had no means[68] of transporting freight over the Pass; that the steamers existed only in fancy; and finally, when opportunity to hire help offered, that the leader had no funds, so that they were obliged to do all the work themselves, in order to move along: when they learned all this they were naturally a disgusted set of men, but having now given away their money, most of them decided to stick together till the diggings were reached. The priest, however, who was in a hurry, became nervous when he saw different parties leaving the rapid and elegant transportation company in the rear, and effected a separation.

When we left Sheep Camp, the manager was trying to cajole his passengers into carrying their own packs to the summit, even going so far as to take little loads himself—"just for exercise," as he airily informed us. He was an Englishman, of aristocratic tendencies, with an awe-inspiring acquaintance with titles. "You know Lord Dudson Dudley, of course," he would begin, fixing one with his eye as if to hypnotize; "his sister, you remember, made such a row by her flirtation with Sir Jekson Jekby.—Never heard of them?—Humph!"[69] And then with a look which seemed to say "What kind of a blarsted Philistine is this?" he would retreat to his own camp-fire.

We sailed down Lake Lindeman with a fair brisk wind, using our tent-fly braced against a pole, for a sail. The distance is only four or five miles, so that the lower end of the lake was reached in an hour. A mountain sheep was sighted on the hillside above us, soon after starting, and a long-range shot with the rifle was tried at it, but the animal bounded away.

At the lower end of this first of the Yukon navigable lakes there is a stream, full of little falls and rapids, which connects with Lake Bennett, a much larger body of water. According to Pete, the boat could not run these rapids, so we began the task of "lining" her down. With a long pole shod with iron, especially brought along for such work, Pete stood in the bow or stern, as the emergency called for, planting the pole on the rocks which stuck out of the water and so shoving and steering the boat through an open narrow channel, while we three held a long line and scrambled along the bank or waded in the shallow water. We had put on long rubber boots[70] reaching to the hip and strapped to our belts, so at first our wading was not uncomfortable. On account of the roar of the water we could not hear Pete's orders, but could see his signals to "haul in," or "let her go ahead." On one difficult little place he manœuvered quite a while, getting stuck on a rock, signalling us to pull back, and then trying again. Finally he struck the right channel, and motioned energetically to us to go ahead. We spurted forward, waddling clumsily, and the foremost man stepped suddenly into a groove where the water was above his waist. Ugh! It was icy, but he floundered through, half swimming, half wading, dragging his great water-filled boots behind him like iron weights; and the rest followed. We felt quite triumphant and heroic when we emerged, deeming this something of a trial: we did not know that the time would come when it would be the ordinary thing all day long, and would become so monotonous that all feelings of novelty would be lost in a general neutral tint of bad temper and rheumatism.

On reaching shallow water the weight of the water-filled rubber boots was so great that we could no longer navigate among the slippery[71] rocks, so we took turns going-ashore and emptying them. There was a smooth round rock with steep sides, glaring in the sun; on this we stretched ourselves head down, so that the water ran out of our boots and trickled in cold little streams down our backs; then we returned to our work.

Before undertaking to line the Skookum through the rapids we had taken out a large part of the load and put it on shore, in order to lighten the boat, and also to save our "grub" in case our boat was capsized. The next task was to carry this over the half-mile portage. Packing is about the hardest and most disliked work that a pioneer has to do, and yet every one that travels hard and well in Alaska and similar rough countries must do it ad nauseam. In such remote and unfinished parts of the world transportation comes back to the original and simple phase,—carrying on one's back. The railroad and the steamboat are for civilization, the wheeled vehicle for the inhabited land where there are roads, the camel for the desert, the horse for the plains and where trails have been cut, but for a large part of Alaska Nature's only highways are the rivers,[72] and when the water will not carry the burdens the explorer must.

In a properly-constructed pack-sack, the weight is carried partly by the shoulders but mainly by the neck, the back being bent and the neck stretched forward till the load rests upon the back and is kept from slipping by the head strap, which is nearly in line with the rigid neck. An astonishing amount can be carried in this way with practice,—for half a mile or so, very nearly one's own weight. Getting up and down with such a load is a work of art, which spoils the temper and wrenches the muscles of the beginner. Having got into the strap he finds himself pinned to the ground in spite of his backbone-breaking efforts to rise, so he must learn to so sit down in the beginning that he can tilt the load forward on his back, get on his hands and knees and then elevate himself to the necessary standing-stooping posture; or he must lie down flat and roll over on his face, getting his load fairly between his shoulders, and then work himself up to his hands and knees as before. Sometimes, if the load is heavy, the help of another must be had to get an upright position, and then the packer goes[73] trudging off, red and sweating and with bulging veins.

By the time we had carried our outfits over the portage, we were ready for supper, and after that for a sleep. We pitched no tent—we were too tired, and the blue sky and the still shining sun looked very friendly—so we rolled in our blankets and slumbered.

There were other craft than ours at Lake Bennett,—belonging to parties who had come over before us, and who had not yet started. The most astonishing thing was a small portable sawmill, which had been pulled across the Chilkoot Pass in the winter, over the snow and ice; and the limited means of communication in this country are well shown by the fact that no news of any such mill was to be had anywhere along the route. Men went over the Chilkoot Pass into the interior, but rarely any came back that way.

Among the gold hunters was a solitary Dutchman, a pathetic, desperate, mild-mannered sort of an adventurer, who had built himself a boat like a wood-box in model and construction, square, lop-sided, and leaky; but he started[74] bravely down Lake Bennett, paddling, with a rag of a square-sail braced against a pole. We pitied, admired, and laughed at him, but many were the doubts expressed as to whether he could reach the diggings in his cockle-shell. Then there was a large scow, also frailly built; this contained several tons of outfit, and a party of seven or eight men and one woman. They were the parasites of the mining camp, all ready, with smuggled whisky and faro games—Wein, Weib, und Gesang—to relieve the miners of some of their gold-dust: and I am told that the manager of the expedition brought out $100,000 two years later.

We all got away, one after the other. There was a stiff fair wind blowing down the lake, which soon increased to a gale, and the waves became very rough. The lake is narrow and fjord-like, walled in by high mountains which often rise directly from the shores. Lakes like this all through Alaska are naturally subject to frequent and violent gales, since the deep mountain valleys form a kind of chimney, up and down which the currents of air rush to the frosty snowy mountains from the warmer lowlands,[75] or in the opposite direction. The further we went the harder the wind blew, and the rougher became the water, so that when about half-way down we made a landing to escape a heavy squall. After dinner, it seemed from our snug little cove that the wind had abated, and we put out again. On getting well away from the sheltering shore we found it rougher than ever; but while we were at dinner we had seen the scow go past, its square bow nearly buried in foaming water, and had seen it apparently run ashore on the opposite side of the lake, some miles further down. Once out, therefore, we steered for the place where the scow had been beached, for the purpose of giving aid if any were necessary. On the run over we shipped water repeatedly over both bow and stern, and sometimes were in imminent danger of swamping, but by skillful managing we gained the shelter of a little nook about half a mile from the open beach where the scow was lying, and landed. We then walked along the shore to the scow, and found its passengers all right, they having beached voluntarily, on account of the roughness of the water.

However, we had had enough navigation for one day, so we did not venture out again. Presently another little boat came scudding down the lake through the white, frothy water, and shot in alongside the Skookum. It was a party of miners—the young Irishman whom I had overtaken on the trail to Sheep Camp, and his three "pardners."

It was not an ideal spot where we all camped, being simply a steep rocky slope at the foot of cliffs. When the time came to sleep we had difficulty in finding places smooth enough to lie down comfortably, but finally all were scattered around here and there in various places of concealment among the rocks. I had cleared a space close under a big boulder, of exactly my length and breadth (which does not imply any great labor), and with my head muffled in the blankets, was beginning to doze, when I heard stealthy footsteps creeping toward me. As I lay, these sounds were muffled and magnified in the marvellous quiet of the Alaskan night (although the sun was still shining), so that I could not judge of the size and the distance of the animal. Soon it got quite close to me, and I could[77] hear it scratching at something; then it seemed to be investigating my matches, knife and compass. Finally, wide-awake, and somewhat startled, I sat up suddenly and threw my blanket from my face, and looked for the marauding animal. I found him—in the shape of a saucy little grey mouse, that stared at me in amazement for a moment, and then scampered into his hole under the boulder. As I had no desire to have the impudent little fellow lunching on me while I slept, I plugged the hole with stones before I lay down again. Some of the same animals came to visit Schrader in his bedchamber, and nibbled his ears so that they were sore for some time.[1]

As the gale continued all the next day without abatement, we profited by the enforced delay to climb the high mountain which rose precipitously above us. And apropos of this climb, it is remarkable what difference one finds in the appearance of a bit of country when simply surveyed from a single point and when actually travelled over. Especially is this true in mountains. Broad slopes which appear to be perfectly easy to traverse are in reality cut up by narrow and deep canyons, almost impossible to cross; what seems to be a trifling bench of rock, half a mile up the mountain, grows into a perpendicular cliff a hundred feet high before one reaches it; and pretty grey streaks become gulches filled with great angular rock fragments, so loosely laid one over the other that at each careful step one is in fear of starting a mighty avalanche, and of being buried under rock enough to build a city.

Owing to difficulties like these it was near supper-time when we gained the top of the main mountain range. As far as the eye could see in all directions, there rose a wilderness of barren peaks, covered with snow; while in one direction lay a desolate, lifeless table-land, shut in by high mountains. Below and near us lay gulches and canyons of magnificent depth, and the blue waters of one of the arms of Lake Bennett appeared, just lately free from ice. Above, rose a still higher peak, steep, difficult of access, and covered with snow; this the lateness of the hour prevented us from attempting to climb.

Next day and the next the wind was as high as ever; but the waiting finally became too tedious, and we started out, the four miners having preceded us by a half an hour. Once out of the shelter of the projecting point, we found the gale very strong and the chop disagreeable. We squared off and ran before the wind for the opposite side of the lake, driving ahead at a good rate under our little rag of a sail. Although the boat was balanced as evenly as possible, every minute or two we would take in water, sometimes over the bow, sometimes in the stern, sometimes amidships. I have in my mind a very vivid picture of that scene: Wiborg in the stern, steering intently and carefully; Goodrich and Schrader forward, sheets in hand, attending to the sail; and myself stretched flat on my face, in order not to make the boat top-heavy, and bailing out the water with a frying-pan. On nearing the lower shore we noticed that the boat containing the miners had run into the breakers, and presently one of the men came running along the beach, signaling to us. Fearing that they were in trouble, we made shift to land, although it was no easy matter on this exposed[80] shore; and we then learned that they had kept too near the beach, had drifted into the breakers and had been swamped, but had all safely landed. Three of our party went to give assistance in hauling their boat out of the water, while I remained behind to fry the bacon for dinner.

After dinner we concluded to wait again before attempting the next stage; so we picked out soft places in the sand and slumbered. When we awoke we found the lake perfectly smooth and calm, and lost no time in getting under way. On this day we depended for our motive power solely on our oars, and we found the results so satisfactory that we kept up the practice hundreds of miles.