Title: Satan's Invisible World Displayed; or, Despairing Democracy

Author: W. T. Stead

Release date: December 21, 2013 [eBook #44476]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive.)

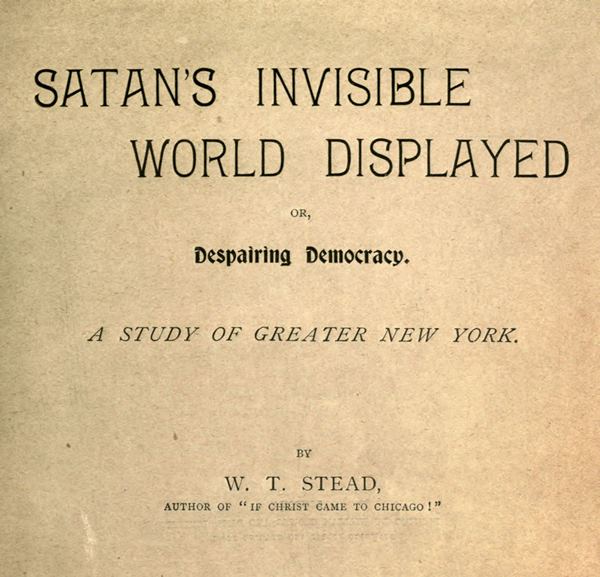

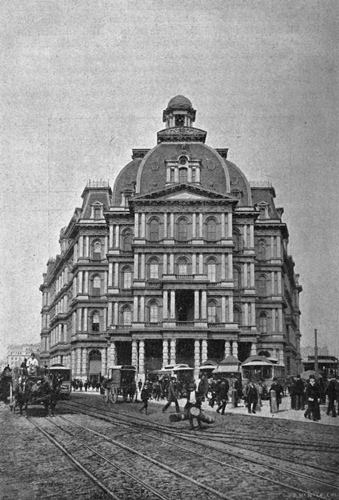

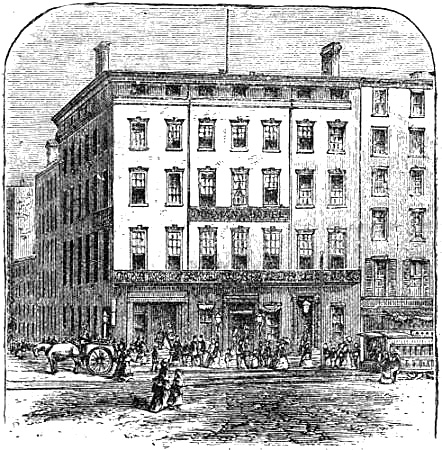

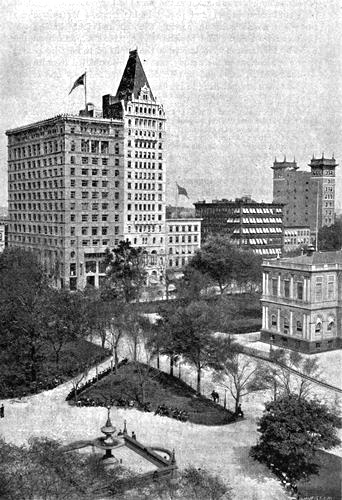

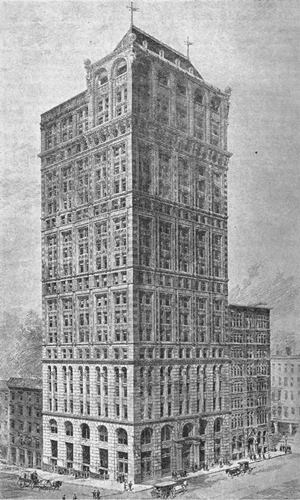

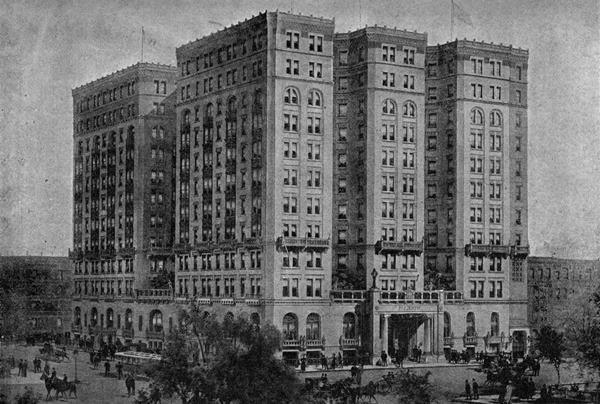

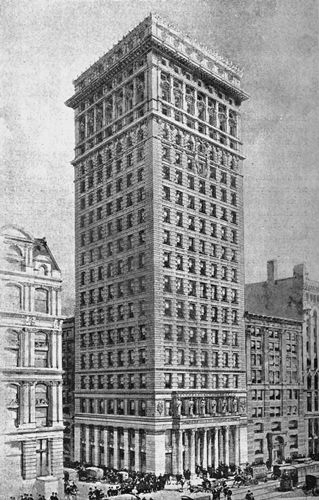

THE CITY HALL, NEW YORK.

SATAN’S INVISIBLE

WORLD DISPLAYED

OR,

Despairing Democracy.

A STUDY OF GREATER NEW YORK.

BY

W. T. STEAD,

AUTHOR OF “IF CHRIST CAME TO CHICAGO!”

“Inasmuch as no government can endure in which corrupt greed not only makes the laws but decides who shall construe them, many of our best citizens are beginning to despair of the Republic.”—Ex-Governor Altgeld, Labour Day, 1897.

The “Review of Reviews” Annual, 1898.

EDITORIAL OFFICES:

MOWBRAY HOUSE, NORFOLK STREET, LONDON, W.C.

PUBLISHING OFFICE:

125, FLEET STREET, LONDON, E.C.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED,

STAMFORD STREET AND CHARING CROSS.

For the past four years I have devoted the Annual of the Review of Reviews to a romance based upon the leading social or political event of the year. This year I intermit the publication of the Series of Contemporary History in Fiction in order to publish a study of the most interesting and significant of all the political and municipal problems of our time. To those who may object to the substitution of a companion volume to my Chicago book for their usual annual quantum of political romance, I reply, first, that “changes are lightsome” and a novelty is attractive, and, secondly, that nothing that the wildest imagination of the romance-writer could conceive exceeds in startling and sensational horror the grim outline of the facts which are set forth in this survey of that section of “Satan’s Invisible World” which was brought to light by the Lexow Committee.

The trite old saying that “Truth is stranger than Fiction” has seldom been better exemplified than in the story of the way in which the Second City in the World has been governed, unless it be in the consequences of the resulting despair. For if the revelations made before the Lexow Committee are almost incredible, the deliberate decision of the ablest and most public-spirited Americans that there is no way of escape save by the hamstrung Cæsarism of the Charter of Greater New York is still more marvellous as a confession of the shipwreck of faith. Sin, when it has conceived, bringeth forth Death, and the corruption that rotted the administration previous to 1894 has only brought forth its natural fruit in the adoption of a bastard Bonapartism of the Second Empire as the best government for the First City in the American Republic.

The election of the first Mayor for Greater New York, which is progressing while these pages are being written, gives a special actuality and interest to this study. But its permanent value does not depend upon the issue of the plébiscite which has decided who will sway the destinies of the Second City of the World at the eve and on the dawn of the Twentieth Century.

[Pg 6]It will, I hope, render available to the whole English-speaking world the gist and essence of the evidence taken before the Committee appointed by the Senate of the State of New York to inquire into the Police Department of the City. This Committee, presided over by Senator Lexow, held seventy sittings in the year 1894, and ultimately published the Report of their inquiry in five stout octavo volumes of 1100 pages each. All their proceedings were public, and the New York papers published ample reports from day to day. Outside New York nothing but brief telegrams or occasional letters informed the world of what was taking place, and the final Report was never published in the British or Colonial press. Yet the lesson of the state of things revealed by the Lexow Committee was one which every great city would do well to take to heart. What New York was, London, Glasgow, or Melbourne may—nay, will certainly—become, if the citizens lose interest in the good government of their city.

When I was in New York in September, I tried in vain to purchase a copy of the Lexow Report. As for exhuming the files of the daily papers, one might as well try to resurrect Cheops. Fortunately, just as I was stepping on board the Teutonic, the five bulky volumes were handed over to me as a loan. Dr. Shaw had at the last moment succeeded in borrowing the office copy of the Report from the Society for the Prevention of Crime. It was apparently the only available set in the whole city. I deemed it well therefore to master the voluminous evidence in order to construct a readable and authentic narrative which would make this great object-lesson accessible to the world.

W. T. STEAD.

Mowbray House,

Norfolk Street, London, W.C.

November, 1897.

| PAGE. | ||

| Frontispiece: The City Hall, New York | 2 | |

| Preface | 5 | |

| PART I.—THE GATEWAY OF THE NEW WORLD. | ||

| CHAPTER. | ||

| I. | Liberty Enlightening the World | 9 |

| II. | The Second City in the World | 17 |

| III. | St. Tammany and the Devil | 27 |

| IV. | The Lexow Searchlight | 43 |

| PART II.—“SATAN’S INVISIBLE WORLD.” | ||

| I. | The Police Bandits of New York | 57 |

| II. | The Powers and the Impotence of the Police | 61 |

| III. | Promotion by Pull and Promotion by Purchase | 67 |

| IV. | The Autobiography of a Police Captain | 79 |

| V. | “The Stranger within the Gates” | 87 |

| VI. | The Slaughter-Houses of the Police | 95 |

| VII. | King McNally and His Police | 107 |

| VIII. | The Pantata of the Policy Shop and Pool Room | 119 |

| IX. | Farmers-General of the Wages of Sin | 125 |

| X. | “All Sorts and Conditions of Men” | 135 |

| XI. | Belial on the Judgment Seat | 145 |

| XII. | The Worst Treason of all | 151 |

| PART III.—HAMSTRUNG CÆSARISM AS A REMEDY | ||

| I. | Despairing Democracy | 159 |

| II. | The Tsar-Mayor | 165 |

| III. | The Charter of Greater New York | 171 |

| IV. | Government by Newspaper | 179 |

| V. | Why not Try the Inquisition? | 189 |

| VI. | The Plebiscite for a Cæsar | 197 |

| VII. | The First Mayor of Greater New York | 211 |

| Appendix | 214 | |

| Index | 217 | |

THE JANITRESS OF THE LAND OF LIBERTY.

“SATAN’S INVISIBLE WORLD DISPLAYED”;

OR,

DESPAIRING DEMOCRACY.

The Gateway of the New World.

LIBERTY ENLIGHTENING THE WORLD.

The entrance to the harbour of New York is not unworthy its position as the gateway—the ever open gateway—of the New World.

And the colossal monument raised by the genius of Bartholdi at the threshold of the gateway is no inapt emblem of the sentiments with which millions have hailed the sight of the American continent.

The harbour, though guarded by great guns against hostile intruder, and infested by the myrmidons of the Customs, is nevertheless an appropriate antechamber of the Republic, from whose never-dying torch stream the rays of Liberty enlightening the world.

Over the great lagoon-like waters flit the white-winged yachts—the butterflies of the sea—dancing in the rays of the rising sun. On shore the luxuriant foliage of the trees betrays but here and there the hectic flush that portends the glories of the Indian summer. The islands, as emeralds in the setting of the sea, are a doubly welcome sight to eyes which for days past have seen nothing but the heaving billows of the broad Atlantic. Here and there, flecking with colour the sunlit scene, flutter the Stars and Stripes. Far away in the West, faintly audible in the distance, come the multitudinous sounds of the awakening seaport. The great Liner, which shuddered and throbbed for three thousand miles as it forged five hundred miles a day across the sea, is gliding smoothly and softly as a gondola towards the Venice of the Western World. Except when approaching the Golden Horn, no more beautiful scene greets the traveller on[Pg 10] approaching a great capital than that presented by the entrance to the harbour of New York. And right in the centre of the fair vision stands the Bartholdi monument, with its gigantic figure hailing the pilgrims from the Older World with the glad welcome of the New. What more appropriate janitress of the Land of Liberty?

The cynic may sneer that the analogy between the City of the Great Assassin and the City of the Boss extends further than the sea-gate to the city. But to the millions whose eyes have rested hungrily upon the nearing land such reflections are unknown. To them the New World, of which New York holds the keys, has ever been arrayed in the rainbow garment of Hope. New York, merely as the portal of the continent, had long been to them as a kind of New Jerusalem, let down from Heaven in mercy to hard-driven, hopeless men. From their earliest childhood they had heard of the great Commonwealth beyond the sea, where the blood-tax of the conscription was unknown, where all men were free and all men were equal, and where, in solid, unmistakable reality, the dreams of the poets were found embodied in a Constitution that was at once the envy and despair of the world:—

There’s freedom at thy gates and rest

For earth’s downtrodden and oppressed;

A shelter for the hunted head,

For the starved labourer toil and bread;

Power at thy bounds

Stops, and calls back his baffled hounds.

What wonder that the storm-tossed emigrant, as he first saw the city of New York glimmering through the haze, felt the magic charm with which the tribes of Israel first gazed upon the confines of the Promised Land.

To the great mass of the English, Scottish, and Irish people—as distinguished from the travelled and more or less cultured minority—the United States has for a hundred years been the land of their ideal, often dearer to them than their own. A very large section, possibly a majority, of our race has ever been more in sympathy with the people that was believed to have sprung from the loins of the men of the Mayflower than with the nation which recalled Charles the Second and still tolerates the ascendency of the Establishment and the dominance of the landed aristocracy. It is quite recently that this enthusiastic devotion to the American Commonwealth has been somewhat dashed in Great Britain. It still exists in full force across the Irish Channel. To the Irishman the United States is much more of a fatherland than the British Empire. We are, indeed, but a step-motherland to the Irishman, whereas in the United States he is not merely at home, but in most of the cities he is at the head of the household. But forty, thirty, and even twenty years ago it was practically the accepted creed of the English Radical that America led[Pg 11] the van, and whenever he was downcast and dispirited by the temporary triumph of the Tories, he found consolation in the reflection that in the great Republic beyond the Atlantic a new and vigorous race was carrying out his ideals, free from the hateful clog of the hidebound Conservatism of the Old Country. No one can read the speeches of Bright and Cobden without feeling that it was on the Hudson and the Mississippi they found their spiritual fatherland, and the generation that sat at their feet learned from them to regard America much as Walt Whitman painted it in his swinging dithyrambs in praise of “Liberty’s Nation.” We all more or less were brought up to exult in the belief that—

America is the continent of the Glories, and of the triumph of Freedom,

And of the Democracies, and of the fruits of Society, and of all that is begun.

Hence nothing more extravagant can be said in praise of New York Harbour than that even to those nurtured on such pabulum it is no unworthy approach to the sea-gate of a new and better world.

Nor is it only the outside of the harbour that is most impressive. The Hudson—that stately river compared with which the Rhine is but a muddy creek, and the Thames a sluggish rivulet—is not less worthy of its rôle as the throne of the great city. It is impossible to exaggerate the impression which the Hudson at night must produce on the peasant from the Carpathians or the labourer from Connemara. Even to those who have more travelled eyes, and are not unfamiliar with seagirt citadels, the spectacle is superb. Never shall I forget my first impression of the mighty river.

It seemed as if I had strayed to the entrance of faerie-land, or that, unawares, I had been transported to the sea-gate of some enchanted city. Midnight was near. In the sky overhead the stars gleamed, but they were faint and speck-like, for the moon was shining unveiled by cloud. But it was neither the lapping of the rippling water nor the silver sheen of the moonlight on the wave that gave the scene its fascination of wonder. These things are the universal poetry of Nature—the music of the waves and the magic of the moon. And there is no speech or language where their voice is not heard. But here there was something more. For on either side of the expanse of water rose high banks of irregular outline, from whose rugged shadows gleamed the lights as of a myriad eyes:—

Behold the enchanted towers of Carbonek,

A castle like a rock upon a rock,

With chasm-like portals open to the sea,

And steps that met the breaker.

Up and down either side, as far as you could see, until the dark outlines merged in the distant horizon, these innumerable eyes[Pg 12] looked out over the water. Sometimes they winked, and now and then one or another would close. It was as if each bank were guarded by some vast monster with a thousand times the eyes of him who watched the treasure of the Golden Fleece.

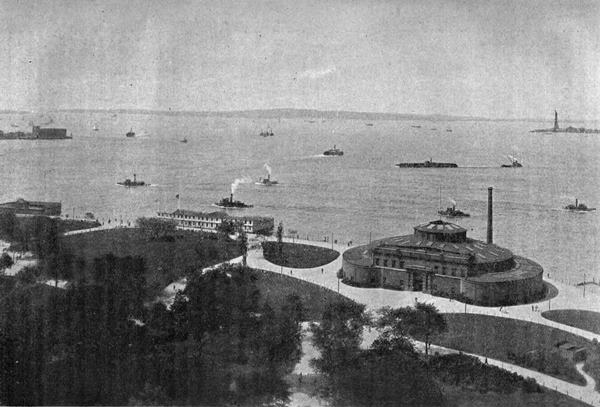

THE OCEAN GATE OF THE NEW WORLD.

A Misty Morning in New York.

[Pg 13]And behind the basilisk of the shore there rose, tier upon tier, the buildings of the city, in which dwelt millions and millions of the children of men. Palaces and temples, brightly outlined in light or towering dark against the luminous haze behind, pierced the sky-line. Amidst the vast confusion two lofty eminences stood out conspicuous, dominating the whole. One was a crown-like dome, poised in mid-air, shining resplendent with jewels of electric light; the other a lofty tower girdled with a blazing zone of fire. Stars of flame shone on its summit, while ever and anon a beam of white light, quick and piercing as a two-edged sword, flashed like the brand of an archangel over the shadowy city. And it was as it was written of old time, when our first parents, after being cast out of Eden, looked back and saw “a flaming sword turning every way to keep the way of the tree of life.” The sword was not of fire, but of pure white light. Above and below it made darkness visibly black, but revealed with startling distinctness everything on which it fell.

That was but the background, the framework of the picture. For the great scene was on the water. Never until at Spithead this midsummer, when six square miles of the Solent crowded with the warships of the world burst at a signal into a glittering wilderness of lights, had I ever seen anything to compare to the Hudson at midnight. In Paris on the night of the fête of the Republic in Exhibition year, when the Seine was crowded with steamers, all illuminated and decorated from stem to stern, there was something like this. But the Seine was but a skein of silk stretched across the city; the water was hidden by the craft. Here the whole expanse of waterway exceeded even that of the Neva at St. Petersburg; and, although full of life and colour and sound, was nowhere crowded.

Imagine a great arm of the sea across which, between the two shores, were swiftly, ceaselessly gliding like silent faerie shuttles in some enchanter’s loom huge floating palaces, radiant from end to end with innumerable lights. They moved with such strenuous rapidity that the waters foamed beneath their keel, and the anchored vessels seemed to fly past as we left them behind. No great galleon of Spain illuminated in honour of her patron saint ever shone more resplendent, and none ever moved with half the fierce, resistless rush of these monsters of the river. No sails had they or visible means of propulsion, they sped as if thought-impelled. Seldom had I seen anything more weirdly beautiful, or more calculated to impress the imagination.

[Pg 14]Now and then a smaller palace would float down the stream, reviving, I know not how, strange reminiscences of the great State barges in which the Rinaldos of mediæval romance would be rowed to some high festival in Armida’s garden. Two starry lights overhead, as at the masthead—though masts there were none—dimly revealed the contour below, where the light streaming from serried windows produced a curious effect, as if banks of illuminated oars were speeding the galley on her way. And then again, silent and slow, with but one light burning at her prow, a sombre melancholy scow would drift across the moonlit waters—like

the barge

Whereon the lily maid of Astolat

Lay smiling like a star on darkest night.

On sea and on shore it was one perpetual feast of lanterns. Mingled with the golden and silver rays of the electric lights there shone everywhere lamps of ruby and of amethyst and of emerald, glowing like jewels of intense colour, set in a tiara of diamonds and pearls.

And to add to the weirdness and mystery of the scene, ever and again there would rise from the waters a strange melodious murmur, increasing in intensity to a wail, which would continue a minute and then die away as it arose. It was like the plaintive lowing of sea-monsters for their lost or wandering calves. Otherwise all was still, save the lapping of the waves on the shore.

“And behold I saw,” said the seer of the Apocalypse, “as if it were a sea of glass mingled with fire. And lo——”

It was New York seen from a New Jersey ferry-boat on the Hudson, plying between 23rd Street and the Pennsylvania railway. Could there be a more sudden descent from the poetry of faerie-land to the vulgar prose of a work-a-day world? The light-crowned dome was the office of the World newspaper, the flashing beam from the tower the advertisement of a dry goods store from Chicago. Yet, nevertheless, the effect of the reality, as it may be seen every fine night, far exceeds my poor description. To those who have eyes to see it is one of the most wonderful and beautiful and suggestive of scenes.

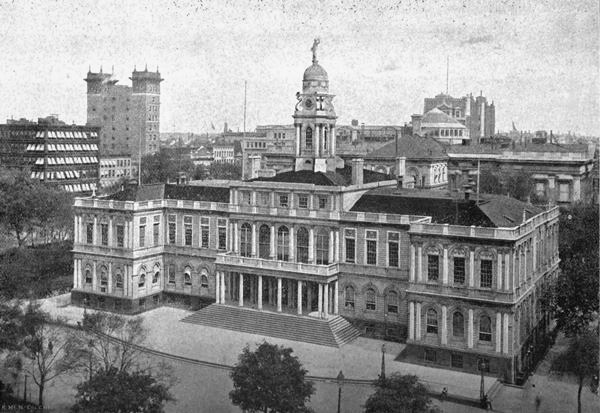

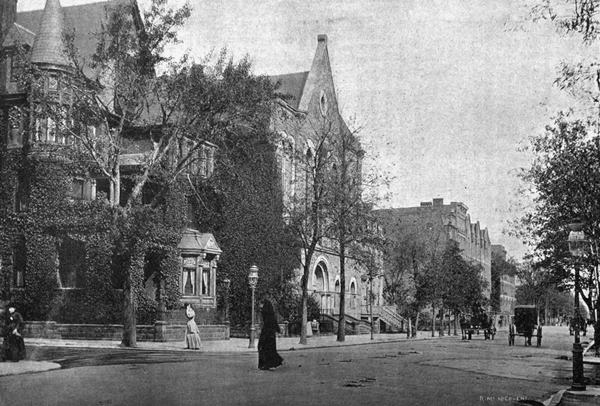

Such then is the outward and visible aspect of the Empire City, a city which from its situation is beautiful exceedingly, and which until quite recently was regarded as the joy of the whole earth, and which still does honour to the statue of such a martyr of Liberty as Nathan Hale. How it has come to pass that the mighty has fallen, and the city which was once a name at the sound of which men renewed their hope and faith in the progress of the world, has become a byword, a hissing and reproach, it will be the object of this volume to explain. It is a subject in which we of the Old World[Pg 15] have weighty reason to be interested. For we have suffered a severe blow and a grievous discouragement in the betrayal of the cause of Liberty in the very vestibule and entrance chamber of the Republic. For all round the world the shame of New York darkens the sombre shade which encompasses the oppressed and gladdens with evil joy the heart of the oppressor.

STATUE OF NATHAN HALE.

City Hall Park, New York.

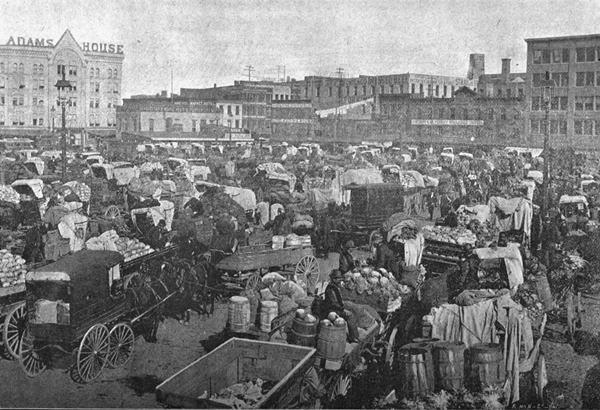

THE GRIDIRON STREETS OF THE NOISY CITY.

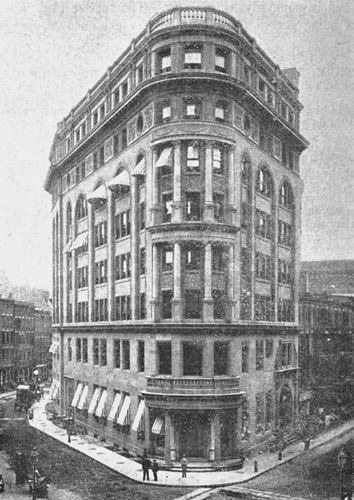

New York Post Office, Broadway.

THE SECOND CITY IN THE WORLD.

A pandemonium of type-writing machines—of gigantic type-writing machines driven by demons who never tire—in some vast hall of Eblis. The clank of the type, the swish of the machine, the quick nervous ring of the bell, all indefinitely multiplied and magnified, fill the vast space with a reverberating clangour. This clangour continuously increases until its very vibrations seem to become clotted and fill the air with a sound that can be felt in every pore. It is like the pressure of an atmosphere so dense you can almost cut it with a knife, an atmosphere that is never still, but perpetually frets, and moans, and snarls with feverish unrest.

How many machines there must be to crowd the air with this million times multiplied misery of click and clang—ring-ring—ring-ring—and clang and click, that never stops, but rises and falls, rhythmless and rude, like the waves of a choppy sea on a rocky beach! Now and again through the infernal hubbub there pierces a dreadful wail,

As it were, one voice in agony

Of lamentation, like a wind that shrills

All night in a waste land, where no one comes

Or hath come since the making of the world.

How hot the air is! a temperature of the antechamber of Tophet. As the perspiration bursts in great beads of moisture from your brow, you hear the faint hum of circling wings, faint at first, but ever growing shriller and more acute—hiss, zip—as the invisible fiend circles round his prostrate victim. Hiss, zip, nearer, louder than before, audible clearly even above the metallic storm of the type-writing machines. And as the mosquito settles on your ear, you awake with a start and suddenly realise where you are.

You are not in even the outermost circles of Dante’s “Inferno.” You are trying to sleep in the heart of Central New York, in the midst of all the thunder and the rush and the roar of her million-crowded streets, along which surges as a restless tide the turbid and foaming flood of city life. The bells of the tramcars continually sounding, the weariless trampling of the ironshod hoofs over granite roadway, the whirling rumble of the wheels, the roar of the trains which on the elevated railways radiate uproar from a kind of infernal firmament on high, all suffused and submerged in the murmurous[Pg 18] hum that rises unceasing from the hurrying footsteps in the crowded street, that inarticulate voice of New York—

Sad as the wail that from the populous earth

All day and night to high Olympus soars.

And that dreadful shriek is the farewell of an Ocean liner sounding a sonorous note with stentorian lungs as it quits the wharf.

There is nothing like it in London. Chicago, with all its bustle, has nothing to compare to this harsh metallic clangour of struggle and strife—although there the mournful death-tolling bell on the locomotives which thread the streets supplies a note of pathos and of awe that is missing in the racket and roar of New York.

One grows used to it in time, just as after a few days you become used to the thrust and swirl of the screw which drives the liner across the sea. The great ship vibrates in every nerve of steel, and the state-room throbs with the thud of the engines. So the great city pulses with strenuous power, and in the multitudinous uproar of its streets we hear the sound of the friction of the two-million manpower engine which has made even Lesser New York one of the greatest driving forces of the American Republic.

It is a dynamo of the first order. And like the dynamo it is instinct with magnetic power. All great cities are great magnets, and New York is the greatest—but one—in the world.

The figures of the portentous growth of cities in our epoch recall the familiar story in the “Arabian Nights Entertainments” of the vessel which, sailing too near the Loadstone Mountain, was whelmed into sudden destruction. For the attraction of the loadstone was such that all the iron nails in the vessel were drawn out of their fastenings, and the timbers that were once a ship became mere flotsam and jetsam on the water. It is a wild and romantic fable in the mouth of the Princess Scheherazade; but it is grim reality in the world to-day. For the great city is to the rural population exactly what the Arabian loadstone mountain was to the heedless sailor who came within the range of its fascination. All the iron in the rural ship of State is attracted to the mighty Babylon. The men with iron in their blood, the girls whose pulses leap and tingle with the eager flush of adventure and ambition, desert the village and the farm to crowd the roaring mart and glaring street. The country is denuded of its most vigorous children. The city engulfs into its insatiate maw all those the brightest, the bravest, and the best.

The process goes on at an ever accelerating ratio. As Mr. Godkin has well observed:—

Parks and gardens, cheap concerts, free museums and art galleries, cheap means of conveyance, model lodging-houses, rich charities, such as every city is now offering in abundance to all comers, are so many inducements to country poor to try their luck in the streets. They are the exact equivalents, as an invitation to the lazy and the pleasure-loving, of the Roman circus and free flour which we all[Pg 19] use in explanation of the decline and fall of the Empire. They are luxuries which seem to be within every man’s reach gratis, and they act with tremendous force on the rural imagination.—North American Review, June, 1890.

The percentage of urban to the total population of the United States, defining as urban all dwellers in cities of more than 8,000 population, was 3·35 in 1790. Forty years later it had doubled. But in 1860 it was 16·13, and in 1890, 29·12. But the growth of the cities which alone deserve the name of great has been still more phenomenal. In 1840—not sixty years ago—the ten greatest cities of America contained a total population of 711,652. To-day Brooklyn alone, which has been merged as a kind of suburb in Greater New York, has a population of a million, while the ten great cities, to be hereafter known as the Great Ten—New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Brooklyn, St. Louis, Boston, Baltimore, San Francisco, Cincinnati, and Cleveland—had in 1890 a population of 6,660,402, and will have in 1900 a population of eight millions. In fifty years the population of the United States did not quadruple itself, for it only expanded in round numbers from 17 millions to 62½ millions. But the great cities increased themselves nearly ten-fold in the same period, and to-day they contain 11 per cent. of the whole population of the Union. The latest estimate of the present population of the country gives the cities 25 millions out of the 72 million citizens of the United States.

If one-third of the inhabitants of the American Commonwealth dwell in cities, these urban centres possess even more than one-third of the wealth of the nation, and far more than one-third of its actual power. A writer in one of the recent American magazines points out that the wealth of the Great Ten in 1890 exceeded the wealth of the whole country, cities included, in 1850. The revenue of the same Great Ten amounted in 1890 to £25,000,000 per annum, a greater sum than was raised for State purposes in all the federated States and Territories. The annual Budget of New York and Brooklyn in 1890 dealt with ten millions sterling, a sum almost exactly equalling the Budget of the United States forty years ago.

It is now half a century since De Tocqueville wrote:—“I look upon the size of certain American cities, and especially upon the nature of their population, as a real danger which threatens the security of the Republic.” Since then this “real danger” has gone on increasing at an ever accelerating ratio. When De Tocqueville wrote, there were only three or four cities with a population over 100,000. To-day there are thirty. And most remarkable fact of all, the population of Greater New York is now equal in number to the total population of the United States at the time of the Declaration of Independence. Her 3,200,000 inhabitants exceed nearly four-fold the total number of the inhabitants in all the cities in the States at the time De Tocqueville visited America.[Pg 20] In the State of New York, sixty per cent, of the inhabitants live in cities; in Massachusetts, seventy per cent.

This tendency townwards, which is one of the most striking characteristics of the English-speaking race all round the world, is nowhere more conspicuous than in the United States; and New York, of all American cities, is that where this centripetal law is just now seen to be operating most powerfully. In the amalgamation by which the Greater New York has come into being we have the latest manifestation of the craving on the part of all modern men to come together in ever-increasing agglomerations of humanity. The fissiparous tendency so perceptible in politics is not visible in cities. There are numerous instances of two cities fusing into one; but no city having once achieved its unity splits it up. Amalgamation, not separation, is the order of the day. Where a river does not divide—as for instance, in the case of Gateshead, that “long, narrow, dirty lane leading into Newcastle-on-Tyne,” or in the case of Salford—the larger town invariably swallows up its minor neighbours, as a large raindrop on the window-pane attracts the smaller drops in its immediate vicinity. In the case of Greater New York, not even the dividing river has been able to prevent the law of gravitation doing its will.

The City of New York is indeed seated upon rivers, and if State boundaries had not stood in the way, there is little doubt that Jersey City would have shared the fate of Brooklyn and Long Island. But even without Jersey City, the new urban conglomerate will be the second city of the world in populousness and greater even than London in area.

The City of New York has an area of 39 square miles, while the area of Greater New York is over 300 square miles. Brooklyn contains 29 square miles, Staten Island comprises nearly 60 square miles, Westchester County annex has an area of about 20 square miles, and the Long Island townships included in the scheme have an aggregate extent of perhaps 170 miles.

At the first election for the Greater New York, held this year, no fewer than 567,000 citizens were registered as electors in this colossal constituency. The Greater New York charter divides the city into five boroughs. (1) Manhattan, consisting of the island of Manhattan, and the outlying islands naturally related to it. (2) The Bronx, including all that part of the present City of New York lying north of the Harlem, a territory which comprises two-thirds of the area of the present City of New York. (3) Brooklyn. (4) Queen’s, consisting of that portion of Queen’s County which is incorporated into the Greater New York. (5) Richmond; that is, Staten Island. The population of the City of New York which before the amalgamation was close on 2,000,000, is now swollen to 3,200,000, of whom nearly 2,000,000 live in tenement houses.

[Pg 21]The size of New York is by no means its most notable distinction. Chicago some day may, by right of its more central position, win the prize of being recognised as the real if not the political capital of the United States. But the position to which Chicago aspires has, for nearly a century, been held by New York. For New York is one of the few cities in the States which are not of yesterday. Of course, compared with London, which dates back to the Cæsars, New York is but a mushroom upstart. But as in the realm of the blind the one-eyed man is king, so in the New World a city which can count its history by centuries may be regarded as possessing quite a respectable antiquity.

To us in the Old World it is the window through which we look into America. Peter the Great built his capital on the Neva in order to have a window from which he could look into Europe. New York serves much the same purpose. It is through the window-pane of New York that the Old World sees what little it does see that is going on in the American Republic. All the newspaper correspondents of the European press without a single exception, so far as I know, cable from New York. Not a single British newspaper has a correspondent at Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, or[Pg 22] Washington. As for the suggestion of publishing telegrams from New Orleans or San Francisco, it would be more reasonable to expect to see despatches from Mars. This leads, no doubt, to much misconception. The New York window is by no means of transparent crystal. Those who consent to see the United States solely through their New York window-pane will often be egregiously misled. Nevertheless, the fact remains that New York is the only window through which the Old World peeps into the New.

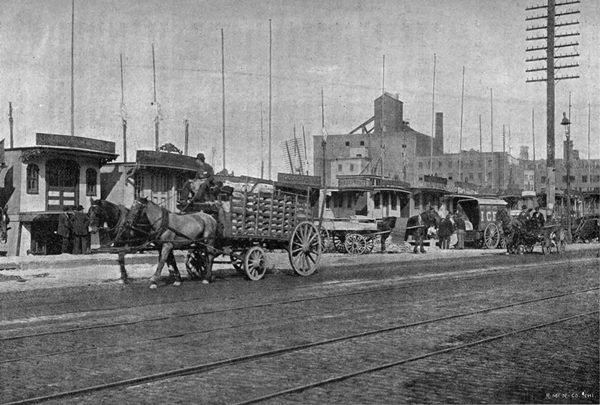

Nor is that the only special reason why New York is better known to us of the older branch of the race than any other part of the American Continent. New York is not more the only window than it is the only door of the New World. The Atlantic is furrowed by a thousand keels, but all the liners steer for New York. Steamers no doubt ply to Boston and to Philadelphia, but the great trade route—the only passenger route—lies past Sandy Hook. New York is the front gate of the Western hemisphere. Even Canada finds it more convenient to use the New York entrance than the ice-blocked mouth of the St. Lawrence. Hence, whatever else the Old World man may see or fail to see in the New World, the one place he is certain to see, the one place which he cannot avoid seeing, is the Queen of the Hudson.

And as New York is the first American city which every traveller sees, and the last which he leaves, so New York has attracted a greater number of European residents than any other city, with the doubtful exception of Chicago. In 1888, thirty-six per cent. of the citizens were either Irish or of Irish descent. The German element was in 1891 estimated at twenty-five per cent. In the City of New York the indigenous American only numbers twenty per cent.

But it is not its imported population which makes it so peculiarly European. Chicago is at least as cosmopolitan, but the city on Lake Michigan counts herself much more American than her sister on the Hudson. During the last Presidential Campaign New York was constantly singled out for attack by the Bryanite orators of the West and South as if it were a foreign and hostile colony encamped on American soil. Wall Street, the centre of the financial system of the United States, was as sound on the currency question as the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street, and the advocates of Free Silver confounded New York and London alike beneath their savage anathema. Community of interest begets community of ideas, and the Western men angrily declare that New York is no more a typical American city than London or Liverpool. This is an exaggeration, no doubt. But neighbourhood counts for something, and New York is a thousand miles nearer to London than to Chicago.

New York is only six days’ steaming from Europe. It is the centre from whence the mighty shuttles ply back and forth across[Pg 23] the Atlantic, weaving the ocean-sundered sections of our race into one. Of the threads, some end at Southampton and others at Liverpool. But they all start from New York.

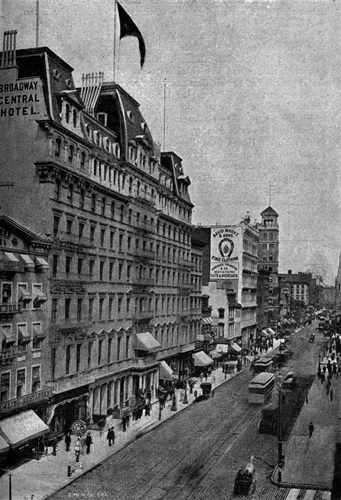

ONE OF THE WINDOW-PANES OF THE WINDOW OF THE NEW WORLD.

Printing-House Square, New York.

[Pg 24]There is another distinctive element about New York. It is the great literary producing-centre of the American people. Boston has long since been dethroned. No other city has even ventured to contest the primacy of New York. There is not a single magazine printed in America that has any circulation outside the United States which is not edited, printed, and published in New York. The advantages of a more central position enjoyed by Chicago are as nought compared with those which New York enjoys in other ways. When I proposed to publish the American Review of Reviews in Chicago, I was promptly silenced by the statement that with the exception of the Ladies’ Home Journal there was not a single periodical published outside New York which could claim to have achieved a success. New York, from the publishing point of view, is the hub of the American universe. Her magazines, admirably edited and marvellously illustrated, circulate in every nook and corner of the English-speaking world. The magazines of the other cities are virtually unknown outside the Republic, and often, it may be said, outside the city that gives them birth. New York, then, as the window and front door of the United States, with an unchallenged financial, commercial, shipping and literary ascendency, has the pull over all her rivals. To nine-tenths of mankind New York is America. All the rest of the country is but the pedestal upon which New York stands.

This pre-eminent position carries with it a grave responsibility. If the world at large judges the American Commonwealth by New York, then New York owes a double duty both to the American Commonwealth and to the world at large. Hence the extreme interest which the latest evolution in the civic development of New York naturally arouses. This Greater New York—what does it mean? How did it come into being? What were the issues at stake at the late Election? All these questions every one is asking. I propose to attempt to supply some answer.

It is a task of some difficulty and no little importance; for not merely is New York—rightly or wrongly—regarded as the most typical and best known American city, but the United States tends more and more to become not a federation of States and territories, but an association of huge cities. The Great Ten not merely include within their boundaries nearly eight million persons, or more than ten per cent. of the whole population; they do the thinking and the guiding and the managing of a very large proportion of the remaining nine-tenths. Draw a circle with a three-hundred-mile radius round the Great Ten, and you inclose an area which is practically dominated by the Ten and educated by their newspapers. The Newspaper Area[Pg 25] is a phrase not yet naturalised in geographies, but it is the most real and living area of all those into which the social organism is divided. For the newspaper collects its news every day, and sells its news every morning and evening, thereby creating a living, ever-renewed bond between the dwellers within the radius of its circulation infinitely superior to the nexus supplied by the tax-collector and the policeman. It is not difficult to define the length of the range within which a newspaper can create a constituency. It is rigidly limited by the distance from the printing-office in which a newspaper can be delivered before breakfast. After breakfast the influence of the newspaper dwindles every minute. Any one living so far off as not to be able to obtain his newspaper before dinner is practically outside the pale—unless, of course, he lives remote from any local centre of news distribution. In that case the range of influence is almost indefinite, as is shown to this day in the hold which the weekly New York Tribune exercises over farmers scattered everywhere between the Atlantic and the Rocky Mountains. But speaking generally, the range of the Newspaper Area is limited by breakfast-time.

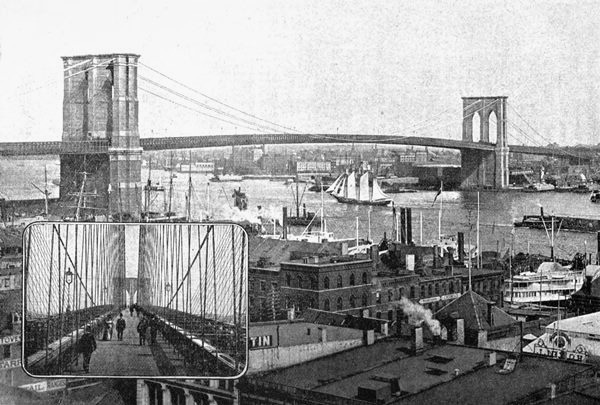

THE FRONT DOOR OF THE NEW WORLD.

[Pg 26]Greater New York has come into being in order to increase, not to diminish, the influence of New York in the Republic and in the world at large. This influence may be for evil. “Under the new charter,” says Mr. W. C. De Witt, Chairman of the Committee which drafted that document, “the City of New York at one bound becomes the mistress of the Western hemisphere and the second city of the world. It should be to its people what Athens was to the Greek, Rome to the Romans, Florence to the Florentine—an object of constant solicitude and of civic pride.”

The question whether they intend to obey the voice of their friendly mentor is one on which the future fortune of the American Commonwealth will largely depend. For, as Mr. J. C. Adams pointed out in a thoughtful article on “The Municipal Threat in National Politics,” which he contributed to the New England Magazine in July, 1891:—

The misgovernment of the cities is the prophecy of misgovernment of the nation; just as the paralysis of the great nerve-centres means the palsy of the whole body. There is graver danger to the republic in the failure of good government in our cities than arises from the moral corruption which accompanies that failure. The misgovernment of our cities means the break-down of one of the two fundamental principles upon which our political fabric rests. It is the failure of local self-government in a most vital part. It is as great a peril to the republic as the revolt against the Union. For the republic is organised upon two great political ideas, both essential to its existence. The first is the principle of federation, which is embodied in the Union; the second is the principle of local self-government, which places the business of the states and the towns in the hands of the people who live in them. Both of these are vital principles. The republic has survived the attempt to subvert one of them. It has just entered on its real struggle with a serious attack upon the other.

The fate, therefore, of the American Republic may be bound up with the fortunes of Greater New York.

ST. TAMMANY AND THE DEVIL.

Hitherto, the city government of New York has not been a credit to the Republic; otherwise I should not be publishing a survey of the way in which New York has been governed as “Satan’s Invisible World Displayed.” The title, of course, is an adaptation, not an invention. The original holder of the copyright was one Hopkins, of the seventeenth century, who, having had much experience in the discovery of witches, deemed himself an expert qualified to describe the inner history and secret mystery of the infernal regions under that picturesque title. I have adopted it as being on the whole the most appropriate description of the state of abysmal abomination into which the government of New York had sunk before the great revolt of 1894 broke the power of Tammany—for a season—and placed in office a Reform Government charged to cleanse the Augean stable. The old witchfinder had no story to tell so horrible or so incredible as that which I have drawn up from the sworn evidence of witnesses exposed to public cross-examination before a State Commission in the City of New York. In the reports of the infernal Sabbats, for attending which thousands of old women were burnt or hanged in the seventeenth century, there always figures in the background, as the central figure in the horrid drama, a form but half-revealed, concerning whose identity even the witchfinders speak with awe. The weird women, with their incantations and their broomsticks, their magic spells and their diabolical trysts, are but the slaves of the Demon, who, whether as their lover or their torturer, is ever their master, whose name they whisper with fear, and whose commands they obey with instant alacrity. For the Master of Ceremonies in the Infernal revels, the Lord of the Witches’ Sabbat, is none other than Satan himself, the incarnate principle of Evil, the Boss of Hell!

In the modern world, sceptical and superstitious, these tales of witches and warlocks seem childish nonsense, unworthy of the attention of grown-up men. But although the dramatis personæ have changed, and the mise-en-scène, the same phenomena reappear eternally. Here in the history of New York we have the whole infernal phantasmagoria once again, with heelers for witches, policemen as wizards, and secret sessions in Tammany Hall as the Witches’[Pg 28] Sabbat of the new era. And behind them all, always present but dimly seen—the omnipresent central force, whose name is muttered with awe, and whose mandate is obeyed with speed—is the same sombre figure whom his devotees regard with passionate worship, and whom his enemies dread even as they curse his name. And this modern Sathanas—this man who to every good Republican is the most authentic incarnation of the principle of Evil, the veritable archfiend of the political world—is the Boss of Tammany Hall.

Among the many legends which have clustered round the beginning of the great association which has played so conspicuous a part in the history of New York, there is one which appeals specially to the sense of humour. Tammany, according to tradition, was the name of a Delaware Indian who in ancient days belonged to a Redskin confederacy that inhabited the regions now known as New Jersey and Pennsylvania. His name has been variously spelled as Temane, Tamanend, Taminent, Tameny, and Tammany.

Curiously enough, by a kind of metamorphosis by no means without precedent among more historical saints, his name has been attached to a locality which he probably never visited, and with the inhabitants of which he and his people lived in hereditary feud. This was not, however, due to any of his conflicts with the Mohicans, who in those days pitched their wigwams on the island of Manhattan. He owes it to a battle which he fought with no less a personage than the great enemy of mankind. In the days when St. Tammany, passed his legendary existence, there were no white men on the American Continent; but although the Pale-Face was absent, the Black man was in full force, and one fine day St. Tammany was exposed to the fell onslaught of the foul fiend. At first, as is his wont, the bad spirit, with honeyed words, sought to be admitted to a share in the government of Tammany’s realm.

“Get thee behind me, Satan!” rendered in the choicest Delaware dialect, was the Saint’s response to the offers of the tempter. But as a more illustrious case attests, the Devil is not a person who will accept a first refusal. Changing his tactics, he brought upon St. Tammany and his Delawares many grievous afflictions of body and of estate, and while the good Chief’s limbs were sore and his heart was heavy, the cunning deceiver attempted to slink into the country unawares.

St. Tammany, however, although sick and sore, slept with one eye open, and the Devil was promptly ordered to “get out of that,” with an emphasis which left him no option but to obey. Again and again the Devil, renewing his attacks, tried his best to circumvent St. Tammany, but finding that all was in vain, he at last flung patience and strategy to the winds, and boldly attacked the great Sagamore in order to overwhelm him by his infernal might.

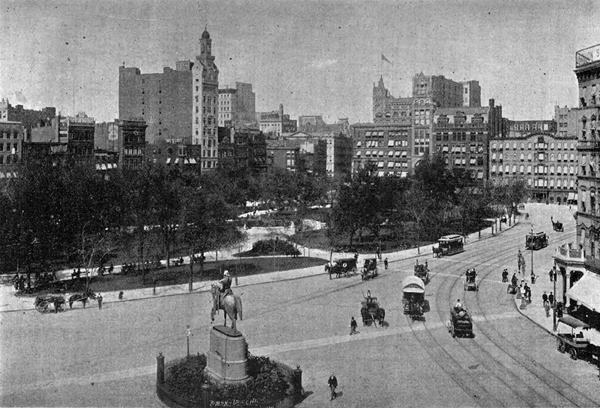

UNION SQUARE, NEW YORK, WITH THE WASHINGTON MONUMENT.

[Pg 30]Then, says the legend, ensued the most tremendous battle that has ever been waged between man and his great enemy. For many months the great fight went on, and as Tammany and the Devil wrestled to and fro in mortal combat, whole forests were broken down, and the ground was so effectually trampled under foot that it has remained prairie land to this day. At last, after the forests had been destroyed, and the country trodden flat, St. Tammany, catching his adversary unawares, tripped him up, and hurled him to the ground. It was in the nick of time, for Tammany was so exhausted with the prolonged struggle that when he drew his scalping-knife to make a final end of the Evil One, the fiend, to the eternal regret of all the children of men, succeeded in slipping from Tammany’s clutches. He escaped across the river to New York, where—so runs the legend, as it is recorded by a writer in Harper—“he was hospitably received by the natives, and has ever since continued to make his home.”

Such, in the quaint but suggestive narrative of the ancient myth, is the way in which the Devil first came to New York, where, as if in revenge for his defeat, he seems to have christened the political organisation which has been his headquarters after the name of Tammany.

The Tammany organisation did not in the beginning take its rise in New York. It first sprang into being in the ranks of the revolutionary army of Pennsylvania. Tammany, or Tamanend, as he was then called, was adopted by the Pennsylvanian troops under General Washington as their patron saint. There were two reasons for this. In the first place, it was Hobson’s choice, for St. Tammany was the only native American who had ever been canonised; and, in the second place, nothing seemed more appropriate to the revolutionary heroes than to adopt as their patron saint a brave who had “whipped the Devil.” St. Tammany, therefore, came to be adopted by the American army as a kind of counterpart to our own St. George. St. Tammany and the Devil seemed to be a good counterpoise to the legendary tale of St. George and the Dragon. The 12th of May was Tammany’s Saint’s Day, and was celebrated with wigwams, liberty poles, tomahawks, and all the regular paraphernalia of the Redskin. A soldier attired in Indian costume represented the great Sachem, “and, after delivering a talk full of eloquence for law and liberty and courage in battle to the members of the order, they danced with feathers in their caps and buck tails dangling on behind.” The practice spread from the Pennsylvania troops to the rest of the army, and so popular did Tammany become that May 12th bid fair to be much more a popular national festival than July 4th.

It was not until this century had begun that the Tammany Society was domiciled in New York. It was introduced there by an upholsterer of Irish descent, named William Mooney. He did[Pg 31] not take much stock in St. Tammany, but preferred to call his Society the Columbian Order, in honour of Columbus. The transactions of the Society dated from the discovery of America. Besides the European head, who was to be known as the Great Father, there were to be twelve Sachems, or counsellors—“Old Men” being the Indian signification of the word; a Sagamore, or master of ceremonies; a Wiskinkie, or doorkeeper of the sacred wigwam; and a Secretary.

The Society from its outset appears to have been political, but in its early days it combined charity with politics. In the second year of its existence it undertook the establishment of a Museum of Natural History, and got together the exhibits which formed the nucleus of Barnum’s famous museum. It was a social and convivial club, which met first in a hotel of Broadway, then in a public-house in Broad Street, and finally in the Pig-pen, a long room attached to a saloon kept by one Martling. In 1811 it erected a hall of its own. Its present address is “Tammany Hall, Fourteenth Street.”

There is no necessity to do more than glance at the curious beginnings of a society which is perhaps the most distinctively American of all the associations that have ever been founded in the New World. A writer of “The Story of Tammany,” which appeared in Harper’s Magazine many years ago, from which most of these facts are taken, says:—

The Tammany Society, or Columbian Order, is doubtless the oldest purely self-constituted political association in the world, and has certainly been by far the most influential. Beginning with the government, for it was organised within a fortnight of the inauguration of the first President, and at a spot within the sound of his voice as he spoke his first official words to his countrymen, it has not only continued down to the present time—through nearly three generations of men—but has controlled the choice of at least one President, fixed the character of several national as well as State administrations, given pseudonyms to half a dozen well-known organisations, and, in fact, has shaped the destiny of the country in several turning-points of its history.

Few suspect, much less comprehend, the extent of the influence this purely local association has exerted. To its agency more than any other is due the fact that for the last three-quarters of a century New York city has been the most potent political centre in the world, not even Paris excepted. Greater than a party, inasmuch as it has been the master of parties, it has seen political organisation after organisation, in whose conflicts it has fearlessly participated, arise, flourish, and go down, and yet has stood ready, with powers unimpaired, to engage in the struggles of the next crop of contestants. In this experience it has been solitary and peculiar. Imitators it has had in abundance, but not one of them has succeeded in catching that secret of political management which has endowed Tammany with its wonderful permanency.

What is that secret? It is unquestionably to be traced, in part, to the sagacity which Tammany’s leaders have at all times shown in forecasting the changes of political issues, or availing themselves of the opportunities afforded by current events as they have arisen. Tammany has not only furnished the most capable politicians the country has possessed, but has managed to ally itself with the shrewdest ones to be found outside of its own organisation. It has always shown a willingness to trade in the gifts at its command, and rarely indeed has it got the worst of a bargain.

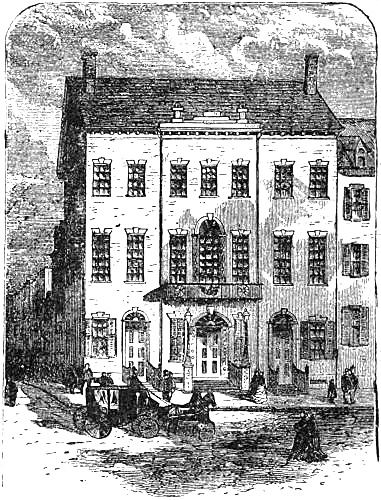

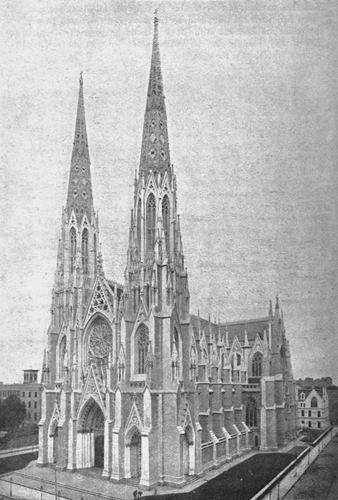

FIRST TAMMANY HALL, ERECTED 1811.

The writer in Harper, however, while attempting to explain the secret of Tammany, only raises a still more difficult question. How[Pg 32] is it that Tammany should have been able to discern the signs of the times better than its rivals? How is it that Tammany has been able to furnish the most capable politicians the country has ever possessed, and how is it that it has displayed so much wisdom? There is one explanation, which, no doubt, commends itself to many of those who have spent their life in fighting Tammany Hall. Tammany has little regard for the innocence of the dove, but it has always displayed the wisdom of the serpent. Considering the place where the Author of all Evil found refuge after his discomfiture by St. Tammany, a Republican may be pardoned for suggesting that the wisdom of Tammany is due to the wisdom of the Old Serpent. Certainly, many innocent persons have been accused of dalliance with the foul fiend on much worse primâ facie evidence than that which is furnished by the universal admission that Tammany, out of the most uncompromising materials, has succeeded in achieving exploits which antecedently would have been absolutely impossible. For Tammany, although preserving and maintaining from first to last a discipline which is the despair of all the other political machines in the country, has never been without fierce internecine fights. It has cast out leader after leader, and the ferocity of the feuds within Tammany has exceeded that of any of the combats which have been waged against the common enemy. Nevertheless,[Pg 33] notwithstanding all schisms, all reverses, all exposures, Tammany remains to this day the strongest, the best disciplined, and the most feared political organisation in the world.

TAMMANY HALL, OPENED 1860.

Mr. Croker, in the series of interviews which I reported in the October number of the Review of Reviews, argued with much force and plausibility that it was contrary to the law of human nature that an organisation could live and last so long if it were composed of Thugs and desperados, and that witness no doubt is true. Even so stout and stalwart an opponent of Tammany as Dr. Albert Shaw has frequently felt himself constrained to admit that the insane fashion in which New York has been governed rendered even the rule of Tammany preferable to the constitutional and legal chaos which was the only substitute. Dr. Shaw, speaking of the system under which New York has hitherto been governed, said:—

To know its ins and outs is not so much like knowing the parts and the workings of a finely adjusted machine as it is like knowing the obscure topography of the great Dismal Swamp considered as a place of refuge for criminals.

Again he wrote:—

In New York, the absurdly disjointed and hopelessly complex array of separate boards, functions, and administrative powers, first makes it impossible for the community to focalise responsibility anywhere in the formal mechanism of municipal government, and then makes it possible for an irresponsible self-centred political[Pg 34] and mercenary society like Tammany to gain for itself the real control, and thus to assume a domination that ought to be centred in some body or functionary directly accountable to the people. Government by a secret society like Tammany is better than the chaos of a disjointed government for which there can be no possible location of central responsibility.

It is not for me to dogmatise where experts, native to New York, hopelessly disagree. But viewed from the outside the secret of Tammany’s success seems to lie chiefly in the fact that Tammany has from the first been really a democratic organisation. No one was too poor, too wicked, or too ignorant to be treated by Tammany as a man and a brother if he would stand in with the machine and join the brotherhood.

This secret of Tammany—the open secret—was explained to me in Chicago by a saloon-keeper of more than dubious morals who had been a Tammany captain in New York. I saw him the night after Dr. Parkhurst had scored his first great success over the politicians of New York. The ex-Tammany Captain shook his head when I asked him what he thought of Dr. Parkhurst’s campaign. He had no use for Dr. Parkhurst. For a time, he thought, he might advertise himself, which was no doubt his object, but after that everything would go on as before. The one permanent institution in New York was Tammany.

I asked him to explain his secret. “Suppose,” said I, “that I am a newly arrived citizen in your precinct, and come to you and wish to join Tammany, what would be required of me?”

“Sir,” said he, “before anything would be required of you we would find out all about you. I would size you up myself, and then after I had formed my own judgment I would send two or three trusty men to find out all about you. Find out, for instance, whether you really meant to work and serve Tammany, or whether you were only getting in to find out all about it. If the inquiries were satisfactory then you would be admitted to the ranks of Tammany, and you would stand in with the rest.”

“What should I have to do?”

“Your first duty,” said he, “would be to vote the Tammany ticket whenever an election was on, and then to hustle around and make every other person whom you could get hold of vote the same ticket.”

“And what would I get for my trouble?” I asked.

“Nothing,” said he, “unless you needed it. I was twenty years captain and I never got anything for myself, but if you needed anything you would get whatever was going. It might be a job that would give you employment under the city, it might be a pull that you might have with the alderman in case you got into trouble, whatever it was you would be entitled to your share. If you get into trouble, Tammany will help you out. If you are out of a job Tammany will see that you have the first chance of whatever is[Pg 35] going. It is a great power, is Tammany. Whether it is with the police, or in the court, or in the City Hall, you will find Tammany men everywhere, and they all stick together. There is nothing sticks so tight as Tammany.”

Therein, no doubt, this worthy ex-captain revealed the great secret, of Tammany’s success. Tammany is a brotherhood. Tammany men stick together, and help each other.

The record of Tammany, however, hardly bears out the claim made for it by Mr. Croker as to the honesty and purity of its administration. From its very early days Tammany has had a bad record for dishonesty and utter lack of scruple. As early as 1837, two Tammany leaders, who had held the federal offices of Collector of the Port of New York, and of United States District Attorney for the Southern district of New York, skipped to Europe after embezzling, the one £250,000, the other £15,000. About twenty years later, another Tammany leader, who was appointed Postmaster for New York, advanced £50,000 of post-office money in order to carry Pennsylvania for Buchanan. These, however, were but bagatelles compared with the carnival of plunder which was established when Tweed was Tammany Boss.

It was not until about the middle of the century that Tammany laid the hand upon the agency which for nearly fifty years has been the sceptre of its power. A certain Southerner, rejoicing in the name of Rynders, who was a leading man in Tammany in the Forties, organised as a kind of affiliated institution the Empire Club, whose members were too disreputable even for Tammany. These men, largely composed of roughs and rowdies, who rejoiced in the expressive title of the Bowery Plug Uglies, were the first to lay their hand upon the immigrant and utilise him for the purpose of carrying elections. Mr. Edwards, writing in McClure’s Magazine, says:—

It was the Empire Club, indeed, which taught the political value of the newly-arrived foreigner. Its members approached the immigrants at the piers on the arrival of every steamship or packet; conducted them into congenial districts; found them employment in the city works, or perhaps helped them to set up in business as keepers of grog-shops.

“Politics in Louisiana,” General Grant is reported to have said on one occasion, “are Hell.” They seem to have been very much like hell in the days when the Plug Uglies with Rynders at their head ruled the roast at Tammany. Mr. Edwards tells a story which sheds a lurid ray of light on the man and manners of that time. Mr. Godwin, who preceded Mr. Godkin in the incessant warfare which the Evening Post has waged against Tammany, had given more than usual offence to Rynders. That worthy, therefore, decided to assassinate the editor as he was taking his lunch at the hotel. Mike Walsh, however, a plucky Irishman, interfered,[Pg 36] and enabled Godwin to make his escape. When the intended victim had gone out—

Rynders stepped up to Walsh and said: “What do you mean by interfering in this matter? It is none of your affair.”

“Well, Godwin did me a good turn once, and I don’t propose to see him stabbed in the back. You were going to do a sneaking thing; you were going to assassinate him, and any man who will do that is a coward.”

“No man ever called me a coward, Mike Walsh, and you can’t.”

“But I do, and I will prove that you are a coward. If you are not one, come upstairs with me now. We will lock ourselves into a room; I will take a knife and you take one; and the man who is alive after we have got through, will unlock the door and go out.”

Rynders accepted the challenge. They went to an upper room. Walsh locked the door, gave Rynders a large bowie-knife, took one himself, and said: “You stand in that corner, and I’ll stand in this. Then we will walk towards the centre of the room, and we won’t stop until one or the other of us is finished.”

Each took his corner. Then Walsh turned and approached the centre of the room. But Rynders did not stir. “Why don’t you come out?” said Walsh. Rynders, turning in his corner, faced his antagonist, and said: “Mike, you and I have always been friends; what is the use of our fighting now? If we get at it, we shall both be killed, and there is no good in that.” Walsh for a moment said not a word; but his lip curled, and he looked upon Rynders with an expression of utter contempt. Then he said: “I told you you were a coward, and now I prove it. Never speak to me again.”

Mike Walsh, the hero of this episode of the bowie-knife, is notable as having been the first man to publicly accuse Tammany of tampering with the ballot-box. He was not the last by any means; but Tammany seems to have begun well, for, says Mr. Edwards:—

Roscoe Conkling once said, chatting with a group of friends, that Governor Seward had told him that the Tammany frauds committed by the Empire Club in New York City in 1844 unquestionably gave Polk the meagre majority of five thousand which he obtained in New York State, and by which he was brought to the Presidency.

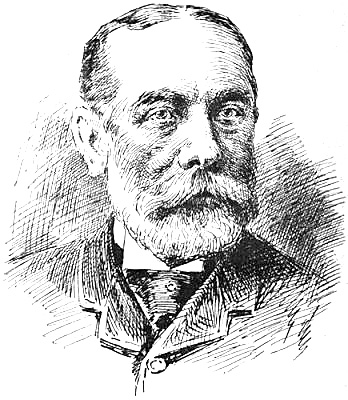

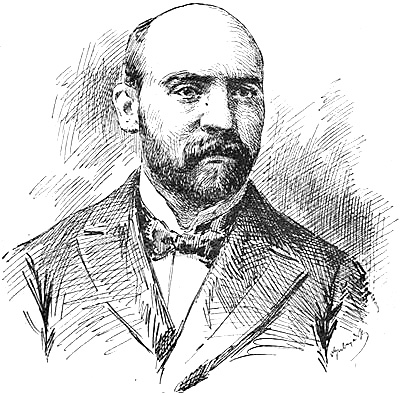

FERNANDO WOOD.

It is not surprising that with this beginning things went on from bad to worse until Mike Walsh, a few years before the War, publicly declared in a great Democratic meeting in the city:—

“I tell you now, and I say it boldly, that in this body politic of New York there is not political or personal honesty enough left to drive a nail into to hang a hat upon.”

[Pg 37]There is a fine picturesqueness about this phrase which enables it to stick like a burr to the memory. It was not, however, until the Irish emigration began in good earnest that Tammany found its vocation. Fernando Wood was first elected to the Mayoralty in 1854. Fernando Wood was a ward politician who first became known to the public by a prosecution in which it was proved that he had cheated his partner by altering the figures in accounts. He did not deny the charge, but pleaded statutory limitation. Having thus succeeded in avoiding gaol, he promptly ran for the Mayoralty, and was duly elected. With him came what Mr. Godkin calls “the organisation of New York politics on a criminal basis.” The exploits of Fernando Wood, however, were thrown entirely into the shade by the lurid splendour of his successor.

This was William M. Tweed, the famous “Boss” Tweed, who began his life as a journeyman, and ended it in Ludley Street Gaol, after having ruled New York for years, as if he were a Turkish Pasha. After serving apprenticeship as a Member of the New York Senate, Deputy Street Commissioner, and President of the Board of Supervisors, he gradually made his way upwards until he was recognised as Boss of Tammany. It was not, however, until the year 1868 that he succeeded in giving the public a true taste of his quality. Even hardened Tammany politicians were aghast at the colossal frauds which he practised at the polls—frauds not only unique in their dimensions, but in the exceeding variety and multiplicity of their methods. On January 1st, 1869, Tweed and his allies began to plunder the city in a fashion which might have made the mouth of a Roman proconsul water. His ally, Connolly, was made Comptroller, while Tweed himself found ample scope for his fraudulent genius in the posts of Deputy Street Commissioner and Supervisor. In the first year he issued fraudulent warrants for £750,000. The money was spent fast and furiously. Tweed was a fellow of infinite variety, and he seemed almost to revel in the diversity of methods by which he could plunder the public. One very ingenious and simple fraud was his securing an Act of the Legislature, making a little paper which he owned the official organ of the City Government. In that capacity he drew £200,000 a year from the rates and taxes, as compensation for printing the report of the proceedings of the Common Council. Mr. Edwards says:—

He established a printing company, whose main business was the printing of blank forms and vouchers, for which in one year two million eight hundred thousand dollars was charged. Another item was a stationer’s company, which furnished all the stationery used in the public institutions and departments, and this company alone received some three millions a year. On an order for six reams of cap paper, the same amount of letter paper, two reams of notepaper, two dozen pen-holders, four small ink-bottles, and a few other articles, all worth not more than fifty dollars, a bill of ten thousand dollars was rendered and paid.

The frauds upon which the conviction of Tweed was obtained consisted in the payment of enormously increased bills to mechanics, architects, furniture-makers,[Pg 38] and, in some instances, to unknown persons, for supplies and services. It was the expectation that an honest bill would be raised all the way from sixty to ninety per cent. In the first months of the ring’s stealing the increase was about sixty per cent. Some of the bills were increased by as much as ninety per cent., but the average increase was such as to make it possible to give sixty-seven per cent. to the ring, the confederates being allowed to keep thirty-three per cent.; and of that thirty-three per cent. probably at least one-half was a fraudulent increase.

After a time the outrageous nature of his stealings provoked a revolt in Tammany itself. It is to this which Mr. Croker looks back with such proud complacency as marking the advent of reformed Tammany. Tweed was beaten at the elections, and his opponents secured a majority on the Board of Aldermen. Thereupon the resourceful rascal promptly went down to Albany, bought up a sufficient number of Congressmen and senators to give him control of the Legislature, and so secured a new Charter for New York, which legislated his opponents out of office. By this Charter a board of audit was created which consisted of Tweed, Connolly and Mayor Hall. What followed is thus described by the Nation:—

The “Board” met once for but ten minutes, and turned the whole “auditing” business over to Tweed. This sounds like a joke, but is true. Tweed then went to work, and “audited” as hard as he could, Garvey and other scamps bringing in the raw material in the shape of “claims,” and he never stopped till he had “audited” about 6,000,000 dols. worth. Connolly’s part in the little game then came in, and that worthy citizen drew his warrants for the money, which that simple-minded “scholar and gentleman” the Mayor endorsed, without having the least idea what was going on. Tweed’s share of the plunder amounted to about 1,000,000 dols. in all. The Joint Committee, reporting on the condition of the city’s finances, declared that the discoverable stealings of three years are 19,000,000 dols., which is probably only half the real total.

Never was a more unblushing rascal, as Mr. Tilden said in his account of Tweed’s sovereignty. The Tammany Ring

controlled the State Legislature, the police, and every department or functionary of the law; several of the judges on the bench were its servile instruments, and issued decrees at its command; it secured the management of the election “machine,” and “ran” it at its own free will and pleasure; a large part of the press was absolutely at its disposal. In the course of three years it had paid to eleven newspapers the sum of 2,329,482 dols. (about £466,000) nominally for advertisements, most of which were never even published, or never seen. Not only the City government, but the lion’s share of the State government also had fallen into the hands of “Boss” Tweed and his confederates. Millions of dollars were stolen by the conspirators by means of “street openings,” “improvements,” new pavements, and other frauds. The Ring took from the public treasury a sum amounting to over £1,500,000 for furnishing and “repairing” a new Court-house. The charges for plastering alone came to about £366,000. For carpets, warrants were drawn for £120,000, although there were scarcely any carpets in the building. The floors were either bare, or covered with oil-cloth. Nearly £100,000 was alleged to have been paid for iron safes, and over £8,200 for “articles” not defined and never found. The total sum stolen was over £4,000,000.

WILLIAM M. TWEED.

Tweed’s brief but dazzling career—for he was indeed a hero clad in Hell-fire—is said by President Andrews to have cost the City of New York 160,000,000 dols. The fine levied by Germany on the City of Paris after the War of 1870-1 was only one-fourth that amount. Fraud may be more costly than War. The total direct[Pg 39] property loss occasioned by the great fire at Chicago in 1871, when three square miles of buildings were burned down, and 98,500 persons rendered homeless, was only 30,000,000 dols. above the plunder of Tweed and his gang. Thus Fraud can be almost as ruinous as Fire.

MR. TILDEN.

[Pg 40]Tweed was a fellow, if not of infinite jest like poor Yorick, at least of infinite insolent humour. In 1871 he boasted that he had amassed a fortune of 20,000,000 dols. Nor did he in the least scruple to avow the means by which he acquired it. President Andrews, of Brown University, in telling the history of the last quarter century, says, “He used gleefully to show his friends the safe where he kept money for bribing legislators, finding those of the Tammany-Republican stripe easiest game. Of the contractor who was decorating his country place at Greenwich he inquired, pointing to a statue, ‘Who the hell is that?’ ‘That is Mercury, the god of merchants and thieves,’ was the reply. ‘That’s bully,’ said Tweed; ‘put him over the front door.’”

Tweed was to the last popular with the masses of the people. Even when the whole town was ringing with proofs of his guilt, he stood as candidate for the Senate of New York State, and was elected. He had distributed in the poorer districts some £10,000 worth of coal and flour, and one of his champions brought down the house by declaring that “Tweed’s heart has always been in the right place, and, even if he is a thief, there is more blood in his little finger and more marrow in his big toe than the men who are abusing him have in their whole bodies.”

This man, with this excessive development of marrow in his big toe, was ultimately run down by Mr. Tilden and the Committee of Seventy. Connolly, the Comptroller, weakened and made terms with his opponents by appointing Mr. Green as Deputy-Comptroller. Mr. Green had little difficulty in laying hands upon all that was necessary in order to secure the prosecution and conviction of Tweed. Tweed’s two infamous judges were driven from the bench, and he himself was clapped into gaol. He made his escape, and sought refuge in Spain. He was, however, delivered up to the American[Pg 41] authorities, and reconducted to prison, where he died. To the last Tweed retained possession of much of his ill-gotten wealth. An offer which was made to surrender the residue of his millions in return for his liberty was rejected.

Tweed thought himself on the whole, an ill-used man. The judge who tried Tweed declared that he had perverted the “power with which he was clothed in a manner more infamous, more outrageous, than any instance of a like character which the history of the civilised world afforded.” But Tweed himself declared that he believed he had done right, and was willing to “submit himself to the just criticism of any and all honest men.” From this it would seem that Mr. Croker is not alone in his imperturbable consciousness of public rectitude. Tweed on one occasion admitted that he had perhaps erred, but he explained he was not to blame. The fault lay with human nature in the first place, and with the system under which New York was governed in the second. Therein, no doubt, he was right. “Human nature,” he said, “could not resist such temptations as were offered to men who were in power in New York, so long as the disposition of the offices of the city was at their command.”

The most outrageous thing that Tweed ever did was to pass a bill through the State Legislature at Albany, giving the judges unlimited power to punish summarily whatever they chose to consider to be contempt. By this law, which was fortunately vetoed by the Governor, every newspaper in New York would have been gagged as effectually as the press of Constantinople.

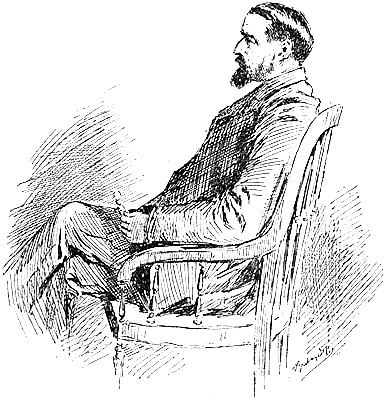

After Tweed fell, Tammany was reorganised under Honest John Kelly and Richard Croker. Mr. Godkin declares that Honest John Kelly was only honest in name. He says:—

John Kelly practised the great Greek maxim “not too much of anything,” simply made every candidate pay handsomely for his nomination, pocketed the money himself, and, whether he rendered any account of it or not, died in possession of a handsome fortune. His policy was the very safe one of making the city money go as far as possible among the workers by compelling every office-holder to divide his salary and perquisites with a number of other persons.

The same system had prevailed down to the year 1894, when Tammany, for the first time in many years, was driven from power. Just before the upset, the New York Evening Post published the records of the twenty-eight men who now or recently composed the Executive Committee of Tammany. It showed that they were all professional politicians, and that among them were one convicted murderer, three men who had been indicted for murder, felonious assault, and bribery, respectively, four professional gamblers, five ex-keepers of gambling houses, nine who either now or formerly sold liquor, three whose fathers did, three former pugilists, four former rowdies, and six members of the famous Tweed gang.[Pg 42] Seventeen of these held office, seven formerly did, and two were favoured contractors.

By these men New York was governed down to the year 1894. All the efforts of the reformers seemed in vain. Mr. Godkin reluctantly confessed:—

The power of the semi-criminal organisation known as Tammany Hall not only remains unshaken, but grows stronger from year to year. Every year its management descends, with perfect impunity, into the hands of a more and more degraded class.

But it is ever the darkest hour before the dawn. Although on the very eve of the November election of 1894 it was declared that “Mr. Croker held almost as despotic a sway over New York as an Oriental potentate over his kingdom,” one month after that statement had been made he was hurled from power by a great outburst of popular indignation. How that was brought about I will now proceed to tell.

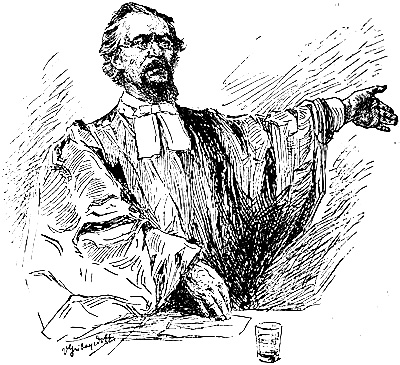

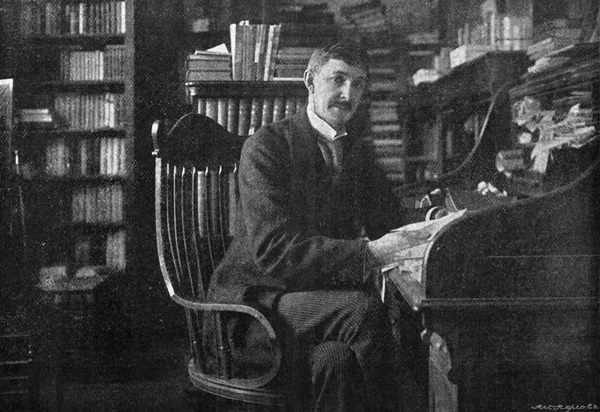

MR. E. L. GODKIN, EDITOR OF THE “EVENING POST,” NEW YORK.

The sworn foe of Tammany.

THE LEXOW SEARCHLIGHT.

Mr. Lowell good-humouredly chaffed John Bull when he declared that

He detests the same faults in himself he neglected,

When he sees them again in his child’s glass reflected,

and we only need to glance at current English criticisms upon American affairs to justify the poet’s remark. Especially is this the case with a vice which of all others is regarded as distinctively English. John Bull has plenty of faults, but of those which render him odious to his neighbours there is none which is quite so loathsome as his “unctuous rectitude.” That phrase, coined by Mr. Rhodes to express the contempt which he and every one who knew the facts felt on contemplating the hypocrisy and Pharisaism displayed in connection with the Jameson Raid, is likely to live long after Mr. Rhodes has vanished from this mortal scene. This tendency to Pharisaism and self-righteous complacency, which thanks God that it is not as other men are, is one of those vices which John Bull’s children seem to have inherited in full measure. We are pretty good at Pharisaism in the Old Country, but we are “not a circumstance,” to use the familiar slang, when we compare ourselves to some of the Pharisees reared across the Atlantic. This has nowhere been brought into such strong relief as when on the very eve of the exposure and discomfiture of Tammany their spokesmen took the stump and talked like very Pecksniffs concerning the immaculate purity of Tammany Hall.