Title: Jack Sheppard: A Romance, Vol. 1 (of 3)

Author: William Harrison Ainsworth

Illustrator: George Cruikshank

Release date: December 26, 2013 [eBook #44521]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger

“Upon my word, friend,” said I, “you have almost made me long to try what a robber I should make.” “There is a great art in it, if you did,” quoth he. “Ah! but,” said I, “there's a great deal in being hanged.” Life and Actions of Guzman d'Alfarache.

CONTENTS

EPOCH THE FIRST, 1703, JONATHAN WILD

CHAPTER I. THE WIDOW AND HER CHILD.

CHAPTER III. THE MASTER OF THE MINT.

CHAPTER IV. THE ROOF AND THE WINDOW.

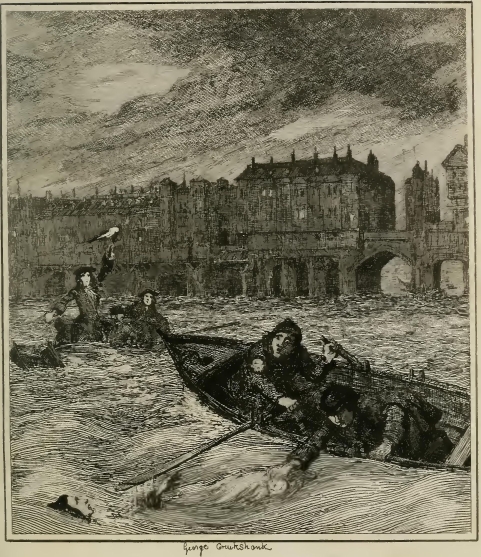

CHAPTER VII. OLD LONDON BRIDGE.

EPOCH THE SECOND, 1715, THAMES DARRELL

CHAPTER I. THE IDLE APPRENTICE.

CHAPTER IV. MR. KNEEBONE AND HIS FRIENDS.

CHAPTER VI. THE FIRST STEP TOWARDS THE LADDER.

CHAPTER VII. BROTHER AND SISTER.

CHAPTER VIII. MICHING MALLECHO.

CHAPTER IX. CONSEQUENCES OF THE THEFT.

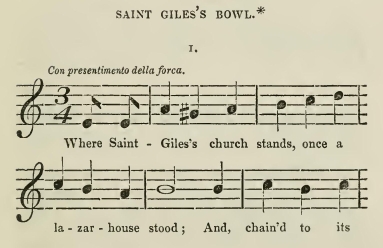

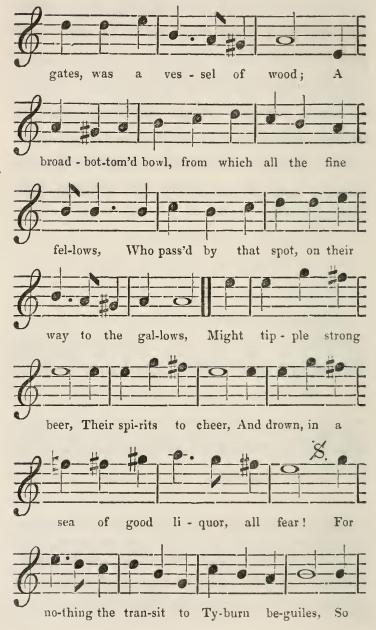

CHAPTER XII. SAINT GILES'S ROUND-HOUSE.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Mr. Wood offers to adopt little Jack Sheppard

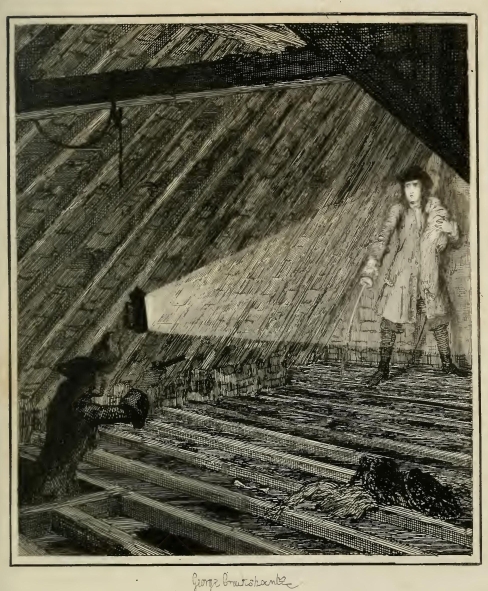

Jonathan Wild discovers Darrell in the Loft

“May I be cursed if ever I try to be honest again”

Jack Sheppard exhibits a vindictive character

Jack Sheppard accuses Thames Darrell of Theft

On the night of Friday, the 26th of November, 1703, and at the hour of eleven, the door of a miserable habitation, situated in an obscure quarter of the Borough of Southwark, known as the Old Mint, was opened; and a man, with a lantern in his hand, appeared at the threshold. This person, whose age might be about forty, was attired in a brown double-breasted frieze coat, with very wide skirts, and a very narrow collar; a light drugget waistcoat, with pockets reaching to the knees; black plush breeches; grey worsted hose; and shoes with round toes, wooden heels, and high quarters, fastened by small silver buckles. He wore a three-cornered hat, a sandy-coloured scratch wig, and had a thick woollen wrapper folded round his throat. His clothes had evidently seen some service, and were plentifully begrimed with the dust of the workshop. Still he had a decent look, and decidedly the air of one well-to-do in the world. In stature, he was short and stumpy; in person, corpulent; and in countenance, sleek, snub-nosed, and demure.

Immediately behind this individual, came a pale, poverty-stricken woman, whose forlorn aspect contrasted strongly with his plump and comfortable physiognomy. She was dressed in a tattered black stuff gown, discoloured by various stains, and intended, it would seem, from the remnants of rusty crape with which it was here and there tricked out, to represent the garb of widowhood, and held in her arms a sleeping infant, swathed in the folds of a linsey-woolsey shawl.

Notwithstanding her emaciation, her features still retained something of a pleasing expression, and might have been termed beautiful, had it not been for that repulsive freshness of lip denoting the habitual dram-drinker; a freshness in her case rendered the more shocking from the almost livid hue of the rest of her complexion. She could not be more than twenty; and though want and other suffering had done the work of time, had wasted her frame, and robbed her cheek of its bloom and roundness, they had not extinguished the lustre of her eyes, nor thinned her raven hair. Checking an ominous cough, that, ever and anon, convulsed her lungs, the poor woman addressed a few parting words to her companion, who lingered at the doorway as if he had something on his mind, which he did not very well know how to communicate.

“Well, good night, Mr. Wood,” said she, in the deep, hoarse accents of consumption; “and may God Almighty bless and reward you for your kindness! You were always the best of masters to my poor husband; and now you've proved the best of friends to his widow and orphan boy.”

“Poh! poh! say no more about it,” rejoined the man hastily. “I've done no more than my duty, Mrs. Sheppard, and neither deserve nor desire your thanks. 'Whoso giveth to the poor lendeth to the Lord;' that's my comfort. And such slight relief as I can afford should have been offered earlier, if I'd known where you'd taken refuge after your unfortunate husband's—”

“Execution, you would say, Sir,” added Mrs. Sheppard, with a deep sigh, perceiving that her benefactor hesitated to pronounce the word. “You show more consideration to the feelings of a hempen widow, than there is any need to show. I'm used to insult as I am to misfortune, and am grown callous to both; but I'm not used to compassion, and know not how to take it. My heart would speak if it could, for it is very full. There was a time, long, long ago, when the tears would have rushed to my eyes unbidden at the bare mention of generosity like yours, Mr. Wood; but they never come now. I have never wept since that day.”

“And I trust you will never have occasion to weep again, my poor soul,” replied Wood, setting down his lantern, and brushing a few drops from his eyes, “unless it be tears of joy. Pshaw!” added he, making an effort to subdue his emotion, “I can't leave you in this way. I must stay a minute longer, if only to see you smile.”

So saying, he re-entered the house, closed the door, and, followed by the widow, proceeded to the fire-place, where a handful of chips, apparently just lighted, crackled within the rusty grate.

The room in which this interview took place had a sordid and miserable look. Rotten, and covered with a thick coat of dirt, the boards of the floor presented a very insecure footing; the bare walls were scored all over with grotesque designs, the chief of which represented the punishment of Nebuchadnezzar. The rest were hieroglyphic characters, executed in red chalk and charcoal. The ceiling had, in many places, given way; the laths had been removed; and, where any plaster remained, it was either mapped and blistered with damps, or festooned with dusty cobwebs. Over an old crazy bedstead was thrown a squalid, patchwork counterpane; and upon the counterpane lay a black hood and scarf, a pair of bodice of the cumbrous form in vogue at the beginning of the last century, and some other articles of female attire. On a small shelf near the foot of the bed stood a couple of empty phials, a cracked ewer and basin, a brown jug without a handle, a small tin coffee-pot without a spout, a saucer of rouge, a fragment of looking-glass, and a flask, labelled “Rosa Solis.” Broken pipes littered the floor, if that can be said to be littered, which, in the first instance, was a mass of squalor and filth.

Over the chimney-piece was pasted a handbill, purporting to be “The last Dying Speech and Confession of TOM SHEPPARD, the Notorious Housebreaker, who suffered at Tyburn on the 25th of February, 1703.” This placard was adorned with a rude wood-cut, representing the unhappy malefactor at the place of execution. On one side of the handbill a print of the reigning sovereign, Anne, had been pinned over the portrait of William the Third, whose aquiline nose, keen eyes, and luxuriant wig, were just visible above the diadem of the queen. On the other a wretched engraving of the Chevalier de Saint George, or, as he was styled in the label attached to the portrait, James the Third, raised a suspicion that the inmate of the house was not altogether free from some tincture of Jacobitism.

Beneath these prints, a cluster of hobnails, driven into the wall, formed certain letters, which, if properly deciphered, produced the words, “Paul Groves, cobler;” and under the name, traced in charcoal, appeared the following record of the poor fellow's fate, “Hung himsel' in this rum for luv off licker;” accompanied by a graphic sketch of the unhappy suicide dangling from a beam. A farthing candle, stuck in a bottle neck, shed its feeble light upon the table, which, owing to the provident kindness of Mr. Wood, was much better furnished with eatables than might have been expected, and boasted a loaf, a knuckle of ham, a meat-pie, and a flask of wine.

“You've but a sorry lodging, Mrs. Sheppard,” said Wood, glancing round the chamber, as he expanded his palms before the scanty flame.

“It's wretched enough, indeed, Sir,” rejoined the widow; “but, poor as it is, it's better than the cold stones and open streets.”

“Of course—of course,” returned Wood, hastily; “anything's better than that. But take a drop of wine,” urged he, filling a drinking-horn and presenting it to her; “it's choice canary, and'll do you good. And now, come and sit by me, my dear, and let's have a little quiet chat together. When things are at the worst, they'll mend. Take my word for it, your troubles are over.”

“I hope they are, Sir,” answered Mrs. Sheppard, with a faint smile and a doubtful shake of the head, as Wood drew her to a seat beside him, “for I've had my full share of misery. But I don't look for peace on this side the grave.”

“Nonsense!” cried Wood; “while there's life there's hope. Never be down-hearted. Besides,” added he, opening the shawl in which the infant was wrapped, and throwing the light of the candle full upon its sickly, but placid features, “it's sinful to repine while you've a child like this to comfort you. Lord help him! he's the very image of his father. Like carpenter, like chips.”

“That likeness is the chief cause of my misery,” replied the widow, shuddering. “Were it not for that, he would indeed be a blessing and a comfort to me. He never cries nor frets, as children generally do, but lies at my bosom, or on my knee, as quiet and as gentle as you see him now. But, when I look upon his innocent face, and see how like he is to his father,—when I think of that father's shameful ending, and recollect how free from guilt he once was,—at such times, Mr. Wood, despair will come over me; and, dear as this babe is to me, far dearer than my own wretched life, which I would lay down for him any minute, I have prayed to Heaven to remove him, rather than he should grow up to be a man, and be exposed to his father's temptations—rather than he should live as wickedly and die as disgracefully as his father. And, when I have seen him pining away before my eyes, getting thinner and thinner every day, I have sometimes thought my prayers were heard.”

“Marriage and hanging go by destiny,” observed Wood, after a pause; “but I trust your child is reserved for a better fate than either, Mrs. Sheppard.”

The latter part of this speech was delivered with so much significance of manner, that a bystander might have inferred that Mr. Wood was not particularly fortunate in his own matrimonial connections.

“Goodness only knows what he's reserved for,” rejoined the widow in a desponding tone; “but if Mynheer Van Galgebrok, whom I met last night at the Cross Shovels, spoke the truth, little Jack will never die in his bed.”

“Save us!” exclaimed Wood. “And who is this Van Gal—Gal—what's his outlandish name?”

“Van Galgebrok,” replied the widow. “He's the famous Dutch conjuror who foretold King William's accident and death, last February but one, a month before either event happened, and gave out that another prince over the water would soon enjoy his own again; for which he was committed to Newgate, and whipped at the cart's tail. He went by another name then,—Rykhart Scherprechter I think he called himself. His fellow-prisoners nicknamed him the gallows-provider, from a habit he had of picking out all those who were destined to the gibbet. He was never known to err, and was as much dreaded as the jail-fever in consequence. He singled out my poor husband from a crowd of other felons; and you know how right he was in that case, Sir.”

“Ay, marry,” replied Wood, with a look that seemed to say that he did not think it required any surprising skill in the art of divination to predict the doom of the individual in question; but whatever opinion he might entertain, he contented himself with inquiring into the grounds of the conjuror's evil augury respecting the infant. “What did the old fellow judge from, eh, Joan?” asked he.

“From a black mole under the child's right ear, shaped like a coffin, which is a bad sign; and a deep line just above the middle of the left thumb, meeting round about in the form of a noose, which is a worse,” replied Mrs. Sheppard. “To be sure, it's not surprising the poor little thing should be so marked; for, when I lay in the women-felons' ward in Newgate, where he first saw the light, or at least such light as ever finds entrance into that gloomy place, I had nothing, whether sleeping or waking, but halters, and gibbets, and coffins, and such like horrible visions, for ever dancing round me! And then, you know, Sir—but, perhaps, you don't know that little Jack was born, a month before his time, on the very day his poor father suffered.”

“Lord bless us!” ejaculated Wood, “how shocking! No, I did not know that.”

“You may see the marks on the child yourself, if you choose, Sir,” urged the widow.

“See the devil!—not I,” cried Wood impatiently. “I didn't think you'd been so easily fooled, Joan.”

“Fooled or not,” returned Mrs. Sheppard mysteriously, “old Van told me one thing which has come true already.”

“What's that?” asked Wood with some curiosity.

“He said, by way of comfort, I suppose, after the fright he gave me at first, that the child would find a friend within twenty-four hours, who would stand by him through life.”

“A friend is not so soon gained as lost,” replied Wood; “but how has the prediction been fulfilled, Joan, eh?”

“I thought you would have guessed, Sir,” replied the widow, timidly. “I'm sure little Jack has but one friend beside myself, in the world, and that's more than I would have ventured to say for him yesterday. However, I've not told you all; for old Van did say something about the child saving his new-found friend's life at the time of meeting; but how that's to happen, I'm sure I can't guess.”

“Nor any one else in his senses,” rejoined Wood, with a laugh. “It's not very likely that a babby of nine months old will save my life, if I'm to be his friend, as you seem to say, Mrs. Sheppard. But I've not promised to stand by him yet; nor will I, unless he turns out an honest lad,—mind that. Of all crafts,—and it was the only craft his poor father, who, to do him justice, was one of the best workmen that ever handled a saw or drove a nail, could never understand,—of all crafts, I say, to be an honest man is the master-craft. As long as your son observes that precept I'll befriend him, but no longer.”

“I don't desire it, Sir,” replied Mrs. Sheppard, meekly.

“There's an old proverb,” continued Wood, rising and walking towards the fire, “which says,—'Put another man's child in your bosom, and he'll creep out at your elbow.' But I don't value that, because I think it applies to one who marries a widow with encumbrances; and that's not my case, you know.”

“Well, Sir,” gasped Mrs. Sheppard.

“Well, my dear, I've a proposal to make in regard to this babby of yours, which may, or may not, be agreeable. All I can say is, it's well meant; and I may add, I'd have made it five minutes ago, if you'd given me the opportunity.”

“Pray come to the point, Sir,” said Mrs. Sheppard, somewhat alarmed by this preamble.

“I am coming to the point, Joan. The more haste, the worse speed—better the feet slip than the tongue. However, to cut a long matter short, my proposal's this:—I've taken a fancy to your bantling, and, as I've no son of my own, if it meets with your concurrence and that of Mrs. Wood, (for I never do anything without consulting my better half,) I'll take the boy, educate him, and bring him up to my own business of a carpenter.”

The poor widow hung her head, and pressed her child closer to her breast.

“Well, Joan,” said the benevolent mechanic, after he had looked at her steadfastly for a few moments, “what say you?—silence gives consent, eh?”

Mrs. Sheppard made an effort to speak, but her voice was choked by emotion.

“Shall I take the babby home with me!” persisted Wood, in a tone between jest and earnest.

“I cannot part with him,” replied the widow, bursting into tears; “indeed, indeed, I cannot.”

“So I've found out the way to move her,” thought the carpenter; “those tears will do her some good, at all events. Not part with him!” added he aloud. “Why you wouldn't stand in the way of his good fortune surely? I'll be a second father to him, I tell you. Remember what the conjuror said.”

“I do remember it, Sir,” replied Mrs. Sheppard, “and am most grateful for your offer. But I dare not accept it.”

“Dare not!” echoed the carpenter; “I don't understand you, Joan.”

“I mean to say, Sir,” answered Mrs. Sheppard in a troubled voice, “that if I lost my child, I should lose all I have left in the world. I have neither father, mother, brother, sister, nor husband—I have only him.”

“If I ask you to part with him, my good woman, it's to better his condition, I suppose, ain't it?” rejoined Wood angrily; for, though he had no serious intention of carrying his proposal into effect, he was rather offended at having it declined. “It's not an offer,” continued he, “that I'm likely to make, or you're likely to receive every day in the year.”

And muttering some remarks, which we do not care to repeat, reflecting upon the consistency of the sex, he was preparing once more to depart, when Mrs. Sheppard stopped him.

“Give me till to-morrow,” implored she, “and if I can bring myself to part with him, you shall have him without another word.”

“Take time to consider of it,” replied Wood sulkily, “there's no hurry.”

“Don't be angry with me, Sir,” cried the widow, sobbing bitterly, “pray don't. I know I am undeserving of your bounty; but if I were to tell you what hardships I have undergone—to what frightful extremities I have been reduced—and to what infamy I have submitted, to earn a scanty subsistence for this child's sake,—if you could feel what it is to stand alone in the world as I do, bereft of all who have ever loved me, and shunned by all who have ever known me, except the worthless and the wretched,—if you knew (and Heaven grant you may be spared the knowledge!) how much affliction sharpens love, and how much more dear to me my child has become for every sacrifice I have made for him,—if you were told all this, you would, I am sure, pity rather than reproach me, because I cannot at once consent to a separation, which I feel would break my heart. But give me till to-morrow—only till to-morrow—I may be able to part with him then.”

The worthy carpenter was now far more angry with himself than he had previously been with Mrs. Sheppard; and, as soon as he could command his feelings, which were considerably excited by the mention of her distresses, he squeezed her hand warmly, bestowed a hearty execration upon his own inhumanity, and swore he would neither separate her from her child, nor suffer any one else to separate them.

“Plague on't!” added he: “I never meant to take your babby from you. But I'd a mind to try whether you really loved him as much as you pretended. I was to blame to carry the matter so far. However, confession of a fault makes half amends for it. A time may come when this little chap will need my aid, and, depend upon it, he shall never want a friend in Owen Wood.”

As he said this, the carpenter patted the cheek of the little object of his benevolent professions, and, in so doing, unintentionally aroused him from his slumbers. Opening a pair of large black eyes, the child fixed them for an instant upon Wood, and then, alarmed by the light, uttered a low and melancholy cry, which, however, was speedily stilled by the caresses of his mother, towards whom he extended his tiny arms, as if imploring protection.

“I don't think he would leave me, even if I could part with him,” observed Mrs. Sheppard, smiling through her tears.

“I don't think he would,” acquiesced the carpenter. “No friend like the mother, for the babby knows no other.”

“And that's true,” rejoined Mrs. Sheppard; “for if I had not been a mother, I would not have survived the day on which I became a widow.”

“You mustn't think of that, Mrs. Sheppard,” said Wood in a soothing tone.

“I can't help thinking of it, Sir,” answered the widow. “I can never get poor Tom's last look out of my head, as he stood in the Stone-Hall at Newgate, after his irons had been knocked off, unless I manage to stupify myself somehow. The dismal tolling of St. Sepulchre's bell is for ever ringing in my ears—oh!”

“If that's the case,” observed Wood, “I'm surprised you should like to have such a frightful picture constantly in view as that over the chimney-piece.”

“I'd good reasons for placing it there, Sir; but don't question me about them now, or you'll drive me mad,” returned Mrs. Sheppard wildly.

“Well, well, we'll say no more about it,” replied Wood; “and, by way of changing the subject, let me advise you on no account to fly to strong waters for consolation, Joan. One nail drives out another, it's true; but the worst nail you can employ is a coffin-nail. Gin Lane's the nearest road to the churchyard.”

“It may be; but if it shortens the distance and lightens the journey, I care not,” retorted the widow, who seemed by this reproach to be roused into sudden eloquence. “To those who, like me, have never been able to get out of the dark and dreary paths of life, the grave is indeed a refuge, and the sooner they reach it the better. The spirit I drink may be poison,—it may kill me,—perhaps it is killing me:—but so would hunger, cold, misery,—so would my own thoughts. I should have gone mad without it. Gin is the poor man's friend,—his sole set-off against the rich man's luxury. It comforts him when he is most forlorn. It may be treacherous, it may lay up a store of future woe; but it insures present happiness, and that is sufficient. When I have traversed the streets a houseless wanderer, driven with curses from every door where I have solicited alms, and with blows from every gateway where I have sought shelter,—when I have crept into some deserted building, and stretched my wearied limbs upon a bulk, in the vain hope of repose,—or, worse than all, when, frenzied with want, I have yielded to horrible temptation, and earned a meal in the only way I could earn one,—when I have felt, at times like these, my heart sink within me, I have drank of this drink, and have at once forgotten my cares, my poverty, my guilt. Old thoughts, old feelings, old faces, and old scenes have returned to me, and I have fancied myself happy,—as happy as I am now.” And she burst into a wild hysterical laugh.

“Poor creature!” ejaculated Wood. “Do you call this frantic glee happiness?”

“It's all the happiness I have known for years,” returned the widow, becoming suddenly calm, “and it's short-lived enough, as you perceive. I tell you what, Mr. Wood,” added she in a hollow voice, and with a ghastly look, “gin may bring ruin; but as long as poverty, vice, and ill-usage exist, it will be drunk.”

“God forbid!” exclaimed Wood, fervently; and, as if afraid of prolonging the interview, he added, with some precipitation, “But I must be going: I've stayed here too long already. You shall hear from me to-morrow.”

“Stay!” said Mrs. Sheppard, again arresting his departure. “I've just recollected that my husband left a key with me, which he charged me to give you when I could find an opportunity.”

“A key!” exclaimed Wood eagerly. “I lost a very valuable one some time ago. What's it like, Joan?”

“It's a small key, with curiously-fashioned wards.”

“It's mine, I'll be sworn,” rejoined Wood. “Well, who'd have thought of finding it in this unexpected way!”

“Don't be too sure till you see it,” said the widow. “Shall I fetch it for you, Sir?”

“By all means.”

“I must trouble you to hold the child, then, for a minute, while I run up to the garret, where I've hidden it for safety,” said Mrs. Sheppard. “I think I may trust him with you, Sir,” added she, taking up the candle.

“Don't leave him, if you're at all fearful, my dear,” replied Wood, receiving the little burthen with a laugh. “Poor thing!” muttered he, as the widow departed on her errand, “she's seen better days and better circumstances than she'll ever see again, I'm sure. Strange, I could never learn her history. Tom Sheppard was always a close file, and would never tell whom he married. Of this I'm certain, however, she was much too good for him, and was never meant to be a journeyman carpenter's wife, still less what is she now. Her heart's in the right place, at all events; and, since that's the case, the rest may perhaps come round,—that is, if she gets through her present illness. A dry cough's the trumpeter of death. If that's true, she's not long for this world. As to this little fellow, in spite of the Dutchman, who, in my opinion, is more of a Jacobite than a conjurer, and more of a knave than either, he shall never mount a horse foaled by an acorn, if I can help it.”

The course of the carpenter's meditations was here interrupted by a loud note of lamentation from the child, who, disturbed by the transfer, and not receiving the gentle solace to which he was ordinarily accustomed, raised his voice to the utmost, and exerted his feeble strength to escape. For a few moments Mr. Wood dandled his little charge to and fro, after the most approved nursery fashion, essaying at the same time the soothing influence of an infantine melody proper to the occasion; but, failing in his design, he soon lost all patience, and being, as we have before hinted, rather irritable, though extremely well-meaning, he lifted the unhappy bantling in the air, and shook him with so much good will, that he had well-nigh silenced him most effectually. A brief calm succeeded. But with returning breath came returning vociferations; and the carpenter, with a faint hope of lessening the clamour by change of scene, took up his lantern, opened the door, and walked out.

Mrs. Sheppard's habitation terminated a row of old ruinous buildings, called Wheeler's Rents; a dirty thoroughfare, part street, and part lane, running from Mint Street, through a variety of turnings, and along the brink of a deep kennel, skirted by a number of petty and neglected gardens in the direction of Saint George's Fields. The neighbouring houses were tenanted by the lowest order of insolvent traders, thieves, mendicants, and other worthless and nefarious characters, who fled thither to escape from their creditors, or to avoid the punishment due to their different offenses; for we may observe that the Old Mint, although it had been divested of some of its privileges as a sanctuary by a recent statute passed in the reign of William the Third, still presented a safe asylum to the debtor, and even continued to do so until the middle of the reign of George the First, when the crying nature of the evil called loudly for a remedy, and another and more sweeping enactment entirely took away its immunities. In consequence of the encouragement thus offered to dishonesty, and the security afforded to crime, this quarter of the Borough of Southwark was accounted (at the period of our narrative) the grand receptacle of the superfluous villainy of the metropolis. Infested by every description of vagabond and miscreant, it was, perhaps, a few degrees worse than the rookery near Saint Giles's and the desperate neighbourhood of Saffron Hill in our own time. And yet, on the very site of the sordid tenements and squalid courts we have mentioned, where the felon openly made his dwelling, and the fraudulent debtor laughed the object of his knavery to scorn—on this spot, not two centuries ago, stood the princely residence of Charles Brandon, the chivalrous Duke of Suffolk, whose stout heart was a well of honour, and whose memory breathes of loyalty and valour. Suffolk House, as Brandon's palace was denominated, was subsequently converted into a mint by his royal brother-in-law, Henry the Eighth; and, after its demolition, and the removal of the place of coinage to the Tower, the name was still continued to the district in which it had been situated.

Old and dilapidated, the widow's domicile looked the very picture of desolation and misery. Nothing more forlorn could be conceived. The roof was partially untiled; the chimneys were tottering; the side-walls bulged, and were supported by a piece of timber propped against the opposite house; the glass in most of the windows was broken, and its place supplied with paper; while, in some cases, the very frames of the windows had been destroyed, and the apertures were left free to the airs of heaven. On the groundfloor the shutters were closed, or, to speak more correctly, altogether nailed up, and presented a very singular appearance, being patched all over with the soles of old shoes, rusty hobnails, and bits of iron hoops, the ingenious device of the former occupant of the apartment, Paul Groves, the cobbler, to whom we have before alluded.

It was owing to the untimely end of this poor fellow that Mrs. Sheppard was enabled to take possession of the premises. In a fit of despondency, superinduced by drunkenness, he made away with himself; and when the body was discovered, after a lapse of some months, such was the impression produced by the spectacle—such the alarm occasioned by the crazy state of the building, and, above all, by the terror inspired by strange and unearthly noises heard during the night, which were, of course, attributed to the spirit of the suicide, that the place speedily enjoyed the reputation of being haunted, and was, consequently, entirely abandoned. In this state Mrs. Sheppard found it; and, as no one opposed her, she at once took up her abode there; nor was she long in discovering that the dreaded sounds proceeded from the nocturnal gambols of a legion of rats.

A narrow entry, formed by two low walls, communicated with the main thoroughfare; and in this passage, under the cover of a penthouse, stood Wood, with his little burthen, to whom we shall now return.

As Mrs. Sheppard did not make her appearance quite so soon as he expected, the carpenter became a little fidgetty, and, having succeeded in tranquillizing the child, he thought proper to walk so far down the entry as would enable him to reconnoitre the upper windows of the house. A light was visible in the garret, feebly struggling through the damp atmosphere, for the night was raw and overcast. This light did not remain stationary, but could be seen at one moment glimmering through the rents in the roof, and at another shining through the cracks in the wall, or the broken panes of the casement. Wood was unable to discover the figure of the widow, but he recognised her dry, hacking cough, and was about to call her down, if she could not find the key, as he imagined must be the case, when a loud noise was heard, as though a chest, or some weighty substance, had fallen upon the floor.

Before Wood had time to inquire into the cause of this sound, his attention was diverted by a man, who rushed past the entry with the swiftness of desperation. This individual apparently met with some impediment to his further progress; for he had not proceeded many steps when he turned suddenly about, and darted up the passage in which Wood stood.

Uttering a few inarticulate ejaculations,—for he was completely out of breath,—the fugitive placed a bundle in the arms of the carpenter, and, regardless of the consternation he excited in the breast of that personage, who was almost stupified with astonishment, he began to divest himself of a heavy horseman's cloak, which he threw over Wood's shoulder, and, drawing his sword, seemed to listen intently for the approach of his pursuers.

The appearance of the new-comer was extremely prepossessing; and, after his trepidation had a little subsided, Wood began to regard him with some degree of interest. Evidently in the flower of his age, he was scarcely less remarkable for symmetry of person than for comeliness of feature; and, though his attire was plain and unpretending, it was such as could be worn only by one belonging to the higher ranks of society. His figure was tall and commanding, and the expression of his countenance (though somewhat disturbed by his recent exertion) was resolute and stern.

At this juncture, a cry burst from the child, who, nearly smothered by the weight imposed upon him, only recovered the use of his lungs as Wood altered the position of the bundle. The stranger turned his head at the sound.

“By Heaven!” cried he in a tone of surprise, “you have an infant there?”

“To be sure I have,” replied Wood, angrily; for, finding that the intentions of the stranger were pacific, so far as he was concerned, he thought he might safely venture on a slight display of spirit. “It's very well you haven't crushed the poor little thing to death with this confounded clothes'-bag. But some people have no consideration.”

“That child may be the means of saving me,” muttered the stranger, as if struck by a new idea: “I shall gain time by the expedient. Do you live here?”

“Not exactly,” answered the carpenter.

“No matter. The door is open, so it is needless to ask leave to enter. Ha!” exclaimed the stranger, as shouts and other vociferations resounded at no great distance along the thoroughfare, “not a moment is to be lost. Give me that precious charge,” he added, snatching the bundle from Wood. “If I escape, I will reward you. Your name?”

“Owen Wood,” replied the carpenter; “I've no reason to be ashamed of it. And now, a fair exchange, Sir. Yours?”

The stranger hesitated. The shouts drew nearer, and lights were seen flashing ruddily against the sides and gables of the neighbouring houses.

“My name is Darrell,” said the fugitive hastily. “But, if you are discovered, answer no questions, as you value your life. Wrap yourself in my cloak, and keep it. Remember! not a word!”

So saying, he huddled the mantle over Wood's shoulders, dashed the lantern to the ground, and extinguished the light. A moment afterwards, the door was closed and bolted, and the carpenter found himself alone.

“Mercy on us!” cried he, as a thrill of apprehension ran through his frame. “The Dutchman was right, after all.”

This exclamation had scarcely escaped him, when the discharge of a pistol was heard, and a bullet whizzed past his ears.

“I have him!” cried a voice in triumph.

A man, then, rushed up the entry, and, seizing the unlucky carpenter by the collar, presented a drawn sword to his throat. This person was speedily followed by half a dozen others, some of whom carried flambeaux.

“Mur—der!” roared Wood, struggling to free himself from his assailant, by whom he was half strangled.

“Damnation!” exclaimed one of the leaders of the party in a furious tone, snatching a torch from an attendant, and throwing its light full upon the face of the carpenter; “this is not the villain, Sir Cecil.”

“So I find, Rowland,” replied the other, in accents of deep disappointment, and at the same time relinquishing his grasp. “I could have sworn I saw him enter this passage. And how comes his cloak on this knave's shoulders?”

“It is his cloak, of a surety,” returned Rowland “Harkye, sirrah,” continued he, haughtily interrogating Wood; “where is the person from whom you received this mantle?”

“Throttling a man isn't the way to make him answer questions,” replied the carpenter, doggedly. “You'll get nothing out of me, I can promise you, unless you show a little more civility.”

“We waste time with this fellow,” interposed Sir Cecil, “and may lose the object of our quest, who, beyond doubt, has taken refuge in this building. Let us search it.”

Just then, the infant began to sob piteously.

“Hist!” cried Rowland, arresting his comrade. “Do you hear that! We are not wholly at fault. The dog-fox cannot be far off, since the cub is found.”

With these words, he tore the mantle from Wood's back, and, perceiving the child, endeavoured to seize it. In this attempt he was, however, foiled by the agility of the carpenter, who managed to retreat to the door, against which he placed his back, kicking the boards vigorously with his heel.

“Joan! Joan!” vociferated he, “open the door, for God's sake, or I shall be murdered, and so will your babby! Open the door quickly, I say.”

“Knock him on the head,” thundered Sir Cecil, “or we shall have the watch upon us.”

“No fear of that,” rejoined Rowland: “such vermin never dare to show themselves in this privileged district. All we have to apprehend is a rescue.”

The hint was not lost upon Wood. He tried to raise an outcry, but his throat was again forcibly griped by Rowland.

“Another such attempt,” said the latter, “and you are a dead man. Yield up the babe, and I pledge my word you shall remain unmolested.”

“I will yield it to no one but its mother,” answered Wood.

“'Sdeath! do you trifle with me, sirrah?” cried Rowland fiercely. “Give me the child, or—”

As he spoke the door was thrown open, and Mrs. Sheppard staggered forward. She looked paler than ever; but her countenance, though bewildered, did not exhibit the alarm which might naturally have been anticipated from the strange and perplexing scene presented to her view.

“Take it,” cried Wood, holding the infant towards her; “take it, and fly.”

Mrs. Sheppard put out her arms mechanically. But before the child could be committed to her care, it was wrested from the carpenter by Rowland.

“These people are all in league with him,” cried the latter. “But don't wait for me, Sir Cecil. Enter the house with your men. I'll dispose of the brat.”

This injunction was instantly obeyed. The knight and his followers crossed the threshold, leaving one of the torch-bearers behind them.

“Davies,” said Rowland, delivering the babe, with a meaning look, to his attendant.

“I understand, Sir,” replied Davies, drawing a little aside. And, setting down the link, he proceeded deliberately to untie his cravat.

“My God! will you see your child strangled before your eyes, and not so much as scream for help?” said Wood, staring at the widow with a look of surprise and horror. “Woman, your wits are fled!”

And so it seemed; for all the answer she could make was to murmur distractedly, “I can't find the key.”

“Devil take the key!” ejaculated Wood. “They're about to murder your child—your child, I tell you! Do you comprehend what I say, Joan?”

“I've hurt my head,” replied Mrs. Sheppard, pressing her hand to her temples.

And then, for the first time, Wood noticed a small stream of blood coursing slowly down her cheek.

At this moment, Davies, who had completed his preparations, extinguished the torch.

“It's all over,” groaned Wood, “and perhaps it's as well her senses are gone. However, I'll make a last effort to save the poor little creature, if it costs me my life.”

And, with this generous resolve, he shouted at the top of his voice, “Arrest! arrest! help! help!” seconding the words with a shrill and peculiar cry, well known at the time to the inhabitants of the quarter in which it was uttered.

In reply to this summons a horn was instantly blown at the corner of the street.

“Arrest!” vociferated Wood. “Mint! Mint!”

“Death and hell!” cried Rowland, making a furious pass at the carpenter, who fortunately avoided the thrust in the darkness; “will nothing silence you?”

“Help!” ejaculated Wood, renewing his cries. “Arrest!”

“Jigger closed!” shouted a hoarse voice in reply. “All's bowman, my covey. Fear nothing. We'll be upon the ban-dogs before they can shake their trotters!”

And the alarm was sounded more loudly than ever.

Another horn now resounded from the further extremity of the thoroughfare; this was answered by a third; and presently a fourth, and more remote blast, took up the note of alarm. The whole neighbourhood was disturbed. A garrison called to arms at dead of night on the sudden approach of the enemy, could not have been more expeditiously, or effectually aroused. Rattles were sprung; lanterns lighted, and hoisted at the end of poles; windows thrown open; doors unbarred; and, as if by magic, the street was instantaneously filled with a crowd of persons of both sexes, armed with such weapons as came most readily to hand, and dressed in such garments as could be most easily slipped on. Hurrying in the direction of the supposed arrest, they encouraged each other with shouts, and threatened the offending parties with their vengeance.

Regardless as the gentry of the Mint usually were (for, indeed, they had become habituated from their frequent occurrence to such scenes,) of any outrages committed in their streets; deaf, as they had been, to the recent scuffle before Mrs. Sheppard's door, they were always sufficiently on the alert to maintain their privileges, and to assist each other against the attacks of their common enemy—the sheriff's officer. It was only by the adoption of such a course (especially since the late act of suppression, to which we have alluded,) that the inviolability of the asylum could be preserved. Incursions were often made upon its territories by the functionaries of the law; sometimes attended with success, but more frequently with discomfiture; and it rarely happened, unless by stratagem or bribery, that (in the language of the gentlemen of the short staff) an important caption could be effected. In order to guard against accidents or surprises, watchmen, or scouts, (as they were styled,) were stationed at the three main outlets of the sanctuary ready to give the signal in the manner just described: bars were erected, which, in case of emergency; could be immediately stretched across the streets: doors were attached to the alleys; and were never opened without due precautions; gates were affixed to the courts, wickets to the gates, and bolts to the wickets. The back windows of the houses (where any such existed) were strongly barricaded, and kept constantly shut; and the fortress was, furthermore, defended by high walls and deep ditches in those quarters where it appeared most exposed. There was also a Maze, (the name is still retained in the district,) into which the debtor could run, and through the intricacies of which it was impossible for an officer to follow him, without a clue. Whoever chose to incur the risk of so doing might enter the Mint at any hour; but no one was suffered to depart without giving a satisfactory account of himself, or producing a pass from the Master. In short, every contrivance that ingenuity could devise was resorted to by this horde of reprobates to secure themselves from danger or molestation. Whitefriars had lost its privileges; Salisbury Court and the Savoy no longer offered places of refuge to the debtor; and it was, therefore, doubly requisite that the Island of Bermuda (as the Mint was termed by its occupants) should uphold its rights, as long as it was able to do so.

Mr. Wood, meantime, had not remained idle. Aware that not a moment was to be lost, if he meant to render any effectual assistance to the child, he ceased shouting, and defending himself in the best way he could from the attacks of Rowland, by whom he was closely pressed, forced his way, in spite of all opposition, to Davies, and dealt him a blow on the head with such good will that, had it not been for the intervention of the wall, the ruffian must have been prostrated. Before he could recover from the stunning effects of the blow, Wood possessed himself of the child: and, untying the noose which had been slipped round its throat, had the satisfaction of hearing it cry lustily.

At this juncture, Sir Cecil and his followers appeared at the threshold.

“He has escaped!” exclaimed the knight; “we have searched every corner of the house without finding a trace of him.”

“Back!” cried Rowland. “Don't you hear those shouts? Yon fellow's clamour has brought the whole horde of jail-birds and cut-throats that infest this place about our ears. We shall be torn in pieces if we are discovered. Davies!” he added, calling to the attendant, who was menacing Wood with a severe retaliation, “don't heed him; but, if you value a whole skin, come into the house, and bring that woman with you. She may afford us some necessary information.”

Davies reluctantly complied. And, dragging Mrs. Sheppard, who made no resistance, along with him, entered the house, the door of which was instantly shut and barricaded.

A moment afterwards, the street was illumined by a blaze of torchlight, and a tumultuous uproar, mixed with the clashing of weapons, and the braying of horns, announced the arrival of the first detachment of Minters.

Mr. Wood rushed instantly to meet them.

“Hurrah!” shouted he, waving his hat triumphantly over his head. “Saved!”

“Ay, ay, it's all bob, my covey! You're safe enough, that's certain!” responded the Minters, baying, yelping, leaping, and howling around him like a pack of hounds when the huntsman is beating cover; “but, where are the lurchers?”

“Who?” asked Wood.

“The traps!” responded a bystander.

“The shoulder-clappers!” added a lady, who, in her anxiety to join the party, had unintentionally substituted her husband's nether habiliments for her own petticoats.

“The ban-dogs!” thundered a tall man, whose stature and former avocations had procured him the nickname of “The long drover of the Borough market.”

“Where are they?”

“Ay, where are they?” chorussed the mob, flourishing their various weapons, and flashing their torches in the air; “we'll starve 'em out.”

Mr. Wood trembled. He felt he had raised a storm which it would be very difficult, if not impossible, to allay. He knew not what to say, or what to do; and his confusion was increased by the threatening gestures and furious looks of the ruffians in his immediate vicinity.

“I don't understand you, gentlemen,” stammered he, at length.

“What does he say?” roared the long drover.

“He says he don't understand flash,” replied the lady in gentleman's attire.

“Cease your confounded clutter!” said a young man, whose swarthy visage, seen in the torchlight, struck Wood as being that of a Mulatto. “You frighten the cull out of his senses. It's plain he don't understand our lingo; as, how should he? Take pattern by me;” and as he said this he strode up to the carpenter, and, slapping him on the shoulder, propounded the following questions, accompanying each interrogation with a formidable contortion of countenance. “Curse you! Where are the bailiffs? Rot you! have you lost your tongue? Devil seize you! you could bawl loud enough a moment ago!”

“Silence, Blueskin!” interposed an authoritative voice, immediately behind the ruffian. “Let me have a word with the cull!”

“Ay! ay!” cried several of the bystanders, “let Jonathan kimbaw the cove. He's got the gift of the gab.”

The crowd accordingly drew aside, and the individual, in whose behalf the movement had been made immediately stepped forward. He was a young man of about two-and-twenty, who, without having anything remarkable either in dress or appearance, was yet a noticeable person, if only for the indescribable expression of cunning pervading his countenance. His eyes were small and grey; as far apart and as sly-looking as those of a fox. A physiognomist, indeed, would have likened him to that crafty animal, and it must be owned the general formation of his features favoured such a comparison. The nose was long and sharp, the chin pointed, the forehead broad and flat, and connected, without any intervening hollow, with the eyelid; the teeth when displayed, seemed to reach from ear to ear. Then his beard was of a reddish hue, and his complexion warm and sanguine. Those who had seen him slumbering, averred that he slept with his eyes open. But this might be merely a figurative mode of describing his customary vigilance. Certain it was, that the slightest sound aroused him. This astute personage was somewhat under the middle size, but fairly proportioned, inclining rather to strength than symmetry, and abounding more in muscle than in flesh.

It would seem, from the attention which he evidently bestowed upon the hidden and complex machinery of the grand system of villany at work around him, that his chief object in taking up his quarters in the Mint, must have been to obtain some private information respecting the habits and practices of its inhabitants, to be turned to account hereafter.

Advancing towards Wood, Jonathan fixed his keen gray eyes upon him, and demanded, in a stern tone whether the persons who had taken refuge in the adjoining house, were bailiffs.

“Not that I know of,” replied the carpenter, who had in some degree recovered his confidence.

“Then I presume you've not been arrested?”

“I have not,” answered Wood firmly.

“I guessed as much. Perhaps you'll next inform us why you have occasioned this disturbance.”

“Because this child's life was threatened by the persons you have mentioned,” rejoined Wood.

“An excellent reason, i' faith!” exclaimed Blueskin, with a roar of surprise and indignation, which was echoed by the whole assemblage. “And so we're to be summoned from our beds and snug firesides, because a kid happens to squall, eh? By the soul of my grandmother, but this is too good!”

“Do you intend to claim the privileges of the Mint?” said Jonathan, calmly pursuing his interrogations amid the uproar. “Is your person in danger?”

“Not from my creditors,” replied Wood, significantly.

“Will he post the cole? Will he come down with the dues? Ask him that?” cried Blueskin.

“You hear,” pursued Jonathan; “my friend desires to know if you are willing to pay your footing as a member of the ancient and respectable fraternity of debtors?”

“I owe no man a farthing, and my name shall never appear in any such rascally list,” replied Wood angrily. “I don't see why I should be obliged to pay for doing my duty. I tell you this child would have been strangled. The noose was at its throat when I called for help. I knew it was in vain to cry 'murder!' in the Mint, so I had recourse to stratagem.”

“Well, Sir, I must say you deserve some credit for your ingenuity, at all events,” replied Jonathan, repressing a smile; “but, before you put out your foot so far, it would have been quite as prudent to consider how you were to draw it back again. For my own part, I don't see in what way it is to be accomplished, except by the payment of our customary fees. Do not imagine you can at one moment avail yourself of our excellent regulations (with which you seem sufficiently well acquainted), and the next break them with impunity. If you assume the character of a debtor for your own convenience, you must be content to maintain it for ours. If you have not been arrested, we have been disturbed; and it is but just and reasonable you should pay for occasioning such disturbance. By your own showing you are in easy circumstances,—for it is only natural to presume that a man who owes nothing must be in a condition to pay liberally,—and you cannot therefore feel the loss of such a trifle as ten guineas.”

However illogical and inconclusive these arguments might appear to Mr. Wood, and however he might dissent from the latter proposition, he did not deem it expedient to make any reply; and the orator proceeded with his harangue amid the general applause of the assemblage.

“I am perhaps exceeding my authority in demanding so slight a sum,” continued Jonathan, modestly, “and the Master of the Mint may not be disposed to let you off so lightly. He will be here in a moment or so, and you will then learn his determination. In the mean time, let me advise you as a friend not to irritate him by a refusal, which would be as useless as vexatious. He has a very summary mode of dealing with refractory persons, I assure you. My best endeavours shall be used to bring you off, on the easy terms I have mentioned.”

“Do you call ten guineas easy terms?” cried Wood, with a look of dismay. “Why, I should expect to purchase the entire freehold of the Mint for less money.”

“Many a man has been glad to pay double the amount to get his head from under the Mint pump,” observed Blueskin, gruffly.

“Let the gentleman take his own course,” said Jonathan, mildly. “I should be sorry to persuade him to do anything his calmer judgment might disapprove.”

“Exactly my sentiments,” rejoined Blueskin. “I wouldn't force him for the world: but if he don't tip the stivers, may I be cursed if he don't get a taste of the aqua pompaginis. Let's have a look at the kinchen that ought to have been throttled,” added he, snatching the child from Wood. “My stars! here's a pretty lullaby-cheat to make a fuss about—ho! ho!”

“Deal with me as you think proper, gentlemen,” exclaimed Wood; “but, for mercy's sake don't harm the child! Let it be taken to its mother.”

“And who is its mother?” asked Jonathan, in an eager whisper. “Tell me frankly, and speak under your breath. Your own safety—the child's safety—depends upon your candour.”

While Mr. Wood underwent this examination, Blueskin felt a small and trembling hand placed upon his own, and, turning at the summons, beheld a young female, whose features were partially concealed by a loo, or half mask, standing beside him. Coarse as were the ruffian's notions of feminine beauty, he could not be insensible to the surpassing loveliness of the fair creature, who had thus solicited his attention. Her figure was, in some measure, hidden by a large scarf, and a deep hood drawn over the head contributed to her disguise; still it was evident, from her lofty bearing, that she had nothing in common, except an interest in their proceedings, with the crew by whom she was surrounded.

Whence she came,—who she was,—and what she wanted,—were questions which naturally suggested themselves to Blueskin, and he was about to seek for some explanation, when his curiosity was checked by a gesture of silence from the lady.

“Hush!” said she, in a low, but agitated voice; “would you earn this purse?”

“I've no objection,” replied Blueskin, in a tone intended to be gentle, but which sounded like the murmuring whine of a playful bear. “How much is there in it!”

“It contains gold,” replied the lady; “but I will add this ring.”

“What am I to do to earn it?” asked Blueskin, with a disgusting leer,—“cut a throat—or throw myself at your feet—eh, my dear?”

“Give me that child,” returned the lady, with difficulty overcoming the loathing inspired by the ruffian's familiarity.

“Oh! I see!” replied Blueskin, winking significantly, “Come nearer, or they'll observe us. Don't be afraid—I won't hurt you. I'm always agreeable to the women, bless their kind hearts! Now! slip the purse into my hand. Bravo!—the best cly-faker of 'em all couldn't have done it better. And now for the fawney—the ring I mean. I'm no great judge of these articles, Ma'am; but I trust to your honour not to palm off paste upon me.”

“It is a diamond,” said the lady, in an agony of distress,—“the child!”

“A diamond! Here, take the kid,” cried Blueskin, slipping the infant adroitly under her scarf. “And so this is a diamond,” added he, contemplating the brilliant from the hollow of his hand: “it does sparkle almost as brightly as your ogles. By the by, my dear, I forgot to ask your name—perhaps you'll oblige me with it now? Hell and the devil!—gone!”

He looked around in vain. The lady had disappeared.

Jonathan, meanwhile, having ascertained the parentage of the child from Wood, proceeded to question him in an under tone, as to the probable motives of the attempt upon its life; and, though he failed in obtaining any information on this point, he had little difficulty in eliciting such particulars of the mysterious transaction as have already been recounted. When the carpenter concluded his recital, Jonathan was for a moment lost in reflection.

“Devilish strange!” thought he, chuckling to himself; “queer business! Capital trick of the cull in the cloak to make another person's brat stand the brunt for his own—capital! ha! ha! Won't do, though. He must be a sly fox to get out of the Mint without my knowledge. I've a shrewd guess where he's taken refuge; but I'll ferret him out. These bloods will pay well for his capture; if not, he'll pay well to get out of their hands; so I'm safe either way—ha! ha! Blueskin,” he added aloud, and motioning that worthy, “follow me.”

Upon which, he set off in the direction of the entry. His progress, however, was checked by loud acclamations, announcing the arrival of the Master of the Mint and his train.

Baptist Kettleby (for so was the Master named) was a “goodly portly man, and a corpulent,” whose fair round paunch bespoke the affection he entertained for good liquor and good living. He had a quick, shrewd, merry eye, and a look in which duplicity was agreeably veiled by good humour. It was easy to discover that he was a knave, but equally easy to perceive that he was a pleasant fellow; a combination of qualities by no means of rare occurrence. So far as regards his attire, Baptist was not seen to advantage. No great lover of state or state costume at any time, he was generally, towards the close of an evening, completely in dishabille, and in this condition he now presented himself to his subjects. His shirt was unfastened, his vest unbuttoned, his hose ungartered; his feet were stuck into a pair of pantoufles, his arms into a greasy flannel dressing-gown, his head into a thrum-cap, the cap into a tie-periwig, and the wig into a gold-edged hat. A white apron was tied round his waist, and into the apron was thrust a short thick truncheon, which looked very much like a rolling-pin.

The Master of the Mint was accompanied by another gentleman almost as portly as himself, and quite as deliberate in his movements. The costume of this personage was somewhat singular, and might have passed for a masquerading habit, had not the imperturbable gravity of his demeanour forbidden any such supposition. It consisted of a close jerkin of brown frieze, ornamented with a triple row of brass buttons; loose Dutch slops, made very wide in the seat and very tight at the knees; red stockings with black clocks, and a fur cap. The owner of this dress had a broad weather-beaten face, small twinkling eyes, and a bushy, grizzled beard. Though he walked by the side of the governor, he seldom exchanged a word with him, but appeared wholly absorbed in the contemplations inspired by a broadbowled Dutch pipe.

Behind the illustrious personages just described marched a troop of stalwart fellows, with white badges in their hats, quarterstaves, oaken cudgels, and links in their hands. These were the Master's body-guard.

Advancing towards the Master, and claiming an audience, which was instantly granted, Jonathan, without much circumlocution, related the sum of the strange story he had just learnt from Wood, omitting nothing except a few trifling particulars, which he thought it politic to keep back; and, with this view, he said not a word of there being any probability of capturing the fugitive, but, on the contrary, roundly asserted that his informant had witnessed that person's escape.

The Master listened, with becoming attention, to the narrative, and, at its conclusion, shook his head gravely, applied his thumb to the side of his nose, and, twirling his fingers significantly, winked at his phlegmatic companion. The gentleman appealed to shook his head in reply, coughed as only a Dutchman can cough, and raising his hand from the bowl of his pipe, went through precisely the same mysterious ceremonial as the Master.

Putting his own construction upon this mute interchange of opinions, Jonathan ventured to observe, that it certainly was a very perplexing case, but that he thought something might be made of it, and, if left to him, he would undertake to manage the matter to the Master's entire satisfaction.

“Ja, ja, Muntmeester,” said the Dutchman, removing the pipe from his mouth, and speaking in a deep and guttural voice, “leave the affair to Johannes. He'll settle it bravely. And let ush go back to our brandewyn, and hollandsche genever. Dese ere not schouts, as you faind, but jonkers on a vrolyk; and if dey'd chanshed to keel de vrow Sheppard's pet lamb, dey'd have done her a servish, by shaving it from dat unpleasant complaint, de hempen fever, with which its laatter days are threatened, and of which its poor vader died. Myn Got! hanging runs in some families, Muntmeester. It's hereditary, like de jigt, vat you call it—gout—haw! haw!”

“If the child is destined to the gibbet, Van Galgebrok,” replied the Master, joining in the laugh, “it'll never be choked by a footman's cravat, that's certain; but, in regard to going back empty-handed,” continued he, altering his tone, and assuming a dignified air, “it's quite out of the question. With Baptist Kettleby, to engage in a matter is to go through with it. Besides, this is an affair which no one but myself can settle. Common offences may be decided upon by deputy; but outrages perpetrated by men of rank, as these appear to be, must be judged by the Master of the Mint in person. These are the decrees of the Island of Bermuda, and I will never suffer its excellent laws to be violated. Gentlemen of the Mint,” added he, pointing with his truncheon towards Mrs. Sheppard's house, “forward!”

“Hurrah!” shouted the mob, and the whole phalanx was put in motion in that direction. At the same moment a martial flourish, proceeding from cow's horns, tin canisters filled with stones, bladders and cat-gut, with other sprightly, instruments, was struck up, and, enlivened by this harmonious accompaniment, the troop reached its destination in the best possible spirits for an encounter.

“Let us in,” said the Master, rapping his truncheon authoritatively against the boards, “or we'll force an entrance.”

But as no answer was returned to the summons, though it was again, and more peremptorily, repeated, Baptist seized a mallet from a bystander and burst open the door. Followed by Van Galgebrok and others of his retinue, he then rushed into the room, where Rowland, Sir Cecil, and their attendants, stood with drawn swords prepared to receive them.

“Beat down their blades,” cried the Master; “no bloodshed.”

“Beat out their brains, you mean,” rejoined Blueskin with a tremendous imprecation; “no half measures now, Master.”

“Hadn't you better hold a moment's parley with the gentlemen before proceeding to extremities?” suggested Jonathan.

“Agreed,” responded the Master. “Surely,” he added, staring at Rowland, “either I'm greatly mistaken, or it is—”

“You are not mistaken, Baptist,” returned Rowland with a gesture of silence; “it is your old friend. I'm glad to recognise you.”

“And I'm glad your worship's recognition doesn't come too late,” observed the Master. “But why didn't you make yourself known at once?”

“I'd forgotten the office you hold in the Mint, Baptist,” replied Rowland. “But clear the room of this rabble, if you have sufficient authority over them. I would speak with you.”

“There's but one way of clearing it, your worship,” said the Master, archly.

“I understand,” replied Rowland. “Give them what you please. I'll repay you.”

“It's all right, pals,” cried Baptist, in a loud tone; “the gentlemen and I have settled matters. No more scuffling.”

“What's the meaning of all this?” demanded Sir Cecil. “How have you contrived to still these troubled waters?”

“I've chanced upon an old ally in the Master of the Mint,” answered Rowland. “We may trust him,” he added in a whisper; “he is a staunch friend of the good cause.”

“Blueskin, clear the room,” cried the Master; “these gentlemen would be private. They've paid for their lodging. Where's Jonathan?”

Inquiries were instantly made after that individual, but he was nowhere to be found.

“Strange!” observed the Master; “I thought he'd been at my elbow all this time. But it don't much matter—though he's a devilish shrewd fellow, and might have helped me out of a difficulty, had any occurred. Hark ye, Blueskin,” continued he, addressing that personage, who, in obedience to his commands, had, with great promptitude, driven out the rabble, and again secured the door, “a word in your ear. What female entered the house with us?”

“Blood and thunder!” exclaimed Blueskin, afraid, if he admitted having seen the lady, of being compelled to divide the plunder he had obtained from her among his companions, “how should I know? D'ye suppose I'm always thinking of the petticoats? I observed no female; but if any one did join the assault, it must have been either Amazonian Kate, or Fighting Moll.”

“The woman I mean did not join the assault,” rejoined the Master, “but rather seemed to shun observation; and, from the hasty glimpse I caught of her, she appeared to have a child in her arms.”

“Then, most probably, it was the widow Sheppard,” answered Blueskin, sulkily.

“Right,” said the Master, “I didn't think of her. And now I've another job for you.”

“Propose it,” returned Blueskin, inclining his head.

“Square accounts with the rascal who got up the sham arrest; and, if he don't tip the cole without more ado, give him a taste of the pump, that's all.”

“He shall go through the whole course,” replied Blueskin, with a ferocious grin, “unless he comes down to the last grig. We'll lather him with mud, shave him with a rusty razor, and drench him with aqua pompaginis. Master, your humble servant.—Gentlemen, your most obsequious trout.”

Having effected his object, which was to get rid of Blueskin, Baptist turned to Rowland and Sir Cecil, who had watched his proceedings with much impatience, and remarked, “Now, gentlemen, the coast's clear; we've nothing to interrupt us. I'm entirely at your service.”

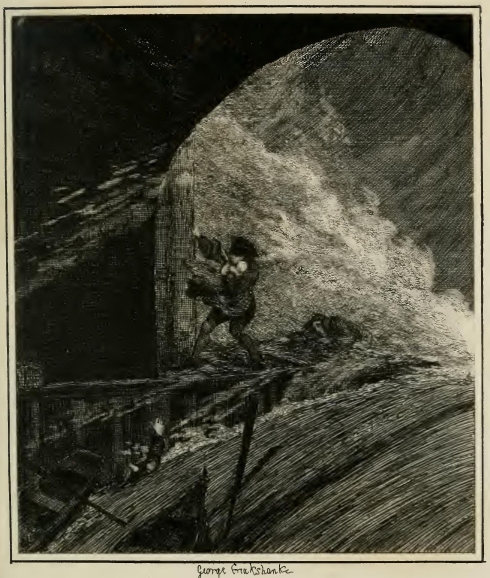

Leaving them to pursue their conference, we shall follow the footsteps of Jonathan, who, as the Master surmised, and, as we have intimated, had unquestionably entered the house. But at the beginning of the affray, when he thought every one was too much occupied with his own concerns to remark his absence, he slipped out of the room, not for the purpose of avoiding the engagement (for cowardice was not one of his failings), but because he had another object in view. Creeping stealthily up stairs, unmasking a dark lantern, and glancing into each room as he passed, he was startled in one of them by the appearance of Mrs. Sheppard, who seemed to be crouching upon the floor. Satisfied, however, that she did not notice him, Jonathan glided away as noiselessly as he came, and ascended another short flight of stairs leading to the garret. As he crossed this chamber, his foot struck against something on the floor, which nearly threw him down, and stooping to examine the object, he found it was a key. “Never throw away a chance,” thought Jonathan. “Who knows but this key may open a golden lock one of these days?” And, picking it up, he thrust it into his pocket.

Arrived beneath an aperture in the broken roof, he was preparing to pass through it, when he observed a little heap of tiles upon the floor, which appeared to have been recently dislodged. “He has passed this way,” cried Jonathan, exultingly; “I have him safe enough.” He then closed the lantern, mounted without much difficulty upon the roof, and proceeded cautiously along the tiles.

The night was now profoundly dark. Jonathan had to feel his way. A single false step might have precipitated him into the street; or, if he had trodden upon an unsound part of the roof, he must have fallen through it. He had nothing to guide him; for though the torches were blazing ruddily below, their gleam fell only on the side of the building. The venturous climber gazed for a moment at the assemblage beneath, to ascertain that he was not discovered; and, having satisfied himself in this particular, he stepped out more boldly. On gaining a stack of chimneys at the back of the house, he came to a pause, and again unmasked his lantern. Nothing, however, could be discerned, except the crumbling brickwork. “Confusion!” ejaculated Jonathan: “can he have escaped? No. The walls are too high, and the windows too stoutly barricaded in this quarter, to admit such a supposition. He can't be far off. I shall find him yet. Ah! I have it,” he added, after a moment's deliberation; “he's there, I'll be sworn.” And, once more enveloping himself in darkness, he pursued his course.

He had now reached the adjoining house, and, scaling the roof, approached another building, which seemed to be, at least, one story loftier than its neighbours. Apparently, Jonathan was well acquainted with the premises; for, feeling about in the dark, he speedily discovered a ladder, up the steps of which he hurried. Drawing a pistol, and unclosing his lantern with the quickness of thought, he then burst through an open trap-door into a small loft.

The light fell upon the fugitive, who stood before him in an attitude of defence, with the child in his arms.

“Aha!” exclaimed Jonathan, acting upon the information he had obtained from Wood; “I have found you at last. Your servant, Mr. Darrell.”

“Who are you!” demanded the fugitive, sternly.

“A friend,” replied Jonathan, uncocking the pistol, and placing it in his pocket.

“How do I know you are a friend?” asked Darrell.

“What should I do here alone if I were an enemy? But, come, don't let us waste time in bandying words, when we might employ it so much more profitably. Your life, and that of your child, are in my power. What will you give me to save you from your pursuers?”

“Can you do so?” asked the other, doubtfully.

“I can, and will. Now, the reward?”

“I have but an ill-furnished purse. But if I escape, my gratitude—”

“Pshaw!” interrupted Jonathan, scornfully. “Your gratitude will vanish with your danger. Pay fools with promises. I must have something in hand.”

“You shall have all I have about me,” replied Darrell.

“Well—well,” grumbled Jonathan, “I suppose I must be content. An ill-lined purse is a poor recompense for the risk I have run. However, come along. I needn't tell you to tread carefully. You know the danger of this breakneck road as well as I do. The light would betray us.” So saying, he closed the lantern.

“Harkye, Sir,” rejoined Darrell; “one word before I move. I know not who you are; and, as I cannot discern your face, I may be doing you an injustice. But there is something in your voice that makes me distrust you. If you attempt to play the traitor, you will do so at the hazard of your life.”

“I have already hazarded my life in this attempt to save you,” returned Jonathan boldly, and with apparent frankness; “this ought to be sufficient answer to your doubts. Your pursuers are below. What was to hinder me, if I had been so inclined, from directing them to your retreat?”

“Enough,” replied Darrell. “Lead on!”

Followed by Darrell, Jonathan retraced his dangerous path. As he approached the gable of Mrs. Sheppard's house, loud yells and vociferations reached his ears; and, looking downwards, he perceived a great stir amid the mob. The cause of this uproar was soon manifest. Blueskin and the Minters were dragging Wood to the pump. The unfortunate carpenter struggled violently, but ineffectually. His hat was placed upon one pole, his wig on another. His shouts for help were answered by roars of mockery and laughter. He continued alternately to be tossed in the air, or rolled in the kennel until he was borne out of sight. The spectacle seemed to afford as much amusement to Jonathan as to the actors engaged in it. He could not contain his satisfaction, but chuckled, and rubbed his hands with delight.

“By Heaven!” cried Darrell, “it is the poor fellow whom I placed in such jeopardy a short time ago. I am the cause of his ill-usage.”

“To be sure you are,” replied Jonathan, laughing. “But, what of that? It'll be a lesson to him in future, and will show him the folly of doing a good-natured action!”

But perceiving that his companion did not relish his pleasantry and fearing that his sympathy for the carpenter's situation might betray him into some act of imprudence, Jonathan, without further remark, and by way of putting an end to the discussion, let himself drop through the roof. His example was followed by Darrell. But, though the latter was somewhat embarrassed by his burthen, he peremptorily declined Jonathan's offer of assistance. Both, however, having safely landed, they cautiously crossed the room, and passed down the first flight of steps in silence. At this moment, a door was opened below; lights gleamed on the walls; and the figures of Rowland and Sir Cecil were distinguished at the foot of the stairs.

Darrell stopped, and drew his sword.

“You have betrayed me,” said he, in a deep whisper, to his companion; “but you shall reap the reward of your treachery.”

“Be still!” returned Jonathan, in the same under tone, and with great self-possession: “I can yet save you. And see!” he added, as the figures drew back, and the lights disappeared; “it's a false alarm. They have retired. However, not a moment is to be lost. Give me your hand.”

He then hurried Darrell down another short flight of steps, and entered a small chamber at the back of the house. Closing the door, Jonathan next produced his lantern, and, hastening towards the window, undrew a bolt by which it was fastened. A stout wooden shutter, opening inwardly, being removed, disclosed a grating of iron bars. This obstacle, which appeared to preclude the possibility of egress in that quarter, was speedily got rid of. Withdrawing another bolt, and unhooking a chain suspended from the top of the casement, Jonathan pushed the iron framework outwards. The bars dropped noiselessly and slowly down, till the chain tightened at the staple.

“You are free,” said he, “that grating forms a ladder, by which you may descend in safety. I learned the trick of the place from one Paul Groves, who used to live here, and who contrived the machine. He used to call it his fire-escape—ha! ha! I've often used the ladder for my own convenience, but I never expected to turn it to such good account. And now, Sir, have I kept faith with you?”

“You have,” replied Darrell. “Here is my purse; and I trust you will let me know to whom I am indebted for this important service.”

“It matters not who I am,” replied Jonathan, taking the money. “As I said before, I have little reliance upon professions of gratitude.”

“I know not how it is,” sighed Darrell, “but I feel an unaccountable misgiving at quitting this place. Something tells me I am rushing on greater danger.”

“You know best,” replied Jonathan, sneeringly; “but if I were in your place I would take the chance of a future and uncertain risk to avoid a present and certain peril.”

“You are right,” replied Darrell; “the weakness is past. Which is the nearest way to the river?”

“Why, it's an awkward road to direct you,” returned Jonathan. “But if you turn to the right when you reach the ground, and keep close to the Mint wall, you'll speedily arrive at White Cross Street; White Cross Street, if you turn again to the right, will bring you into Queen Street; Queen Street, bearing to the left, will conduct you to Deadman's Place; and Deadman's Place to the water-side, not fifty yards from Saint Saviour's stairs, where you're sure to get a boat.”

“The very point I aim at,” said Darrell as he passed through the outlet.

“Stay!” said Jonathan, aiding his descent; “you had better take my lantern. It may be useful to you. Perhaps you'll give me in return some token, by which I may remind you of this occurrence, in case we meet again. Your glove will suffice.”

“There it is;” replied the other, tossing him the glove. “Are you sure these bars touch the ground?”

“They come within a yard of it,” answered Jonathan.

“Safe!” shouted Darrell, as he effected a secure landing. “Good night!”

“So,” muttered Jonathan, “having started the hare, I'll now unleash the hounds.”

With this praiseworthy determination, he was hastening down stairs, with the utmost rapidity, when he encountered a female, whom he took, in the darkness, to be Mrs. Sheppard. The person caught hold of his arm, and, in spite of his efforts to disengage himself, detained him.

“Where is he?” asked she, in an agitated whisper. “I heard his voice; but I saw them on the stairs, and durst not approach him, for fear of giving the alarm.”

“If you mean the fugitive, Darrell, he has escaped through the back window,” replied Jonathan.

“Thank Heaven!” she gasped.

“Well, you women are forgiving creatures, I must say,” observed Jonathan, sarcastically. “You thank Heaven for the escape of the man who did his best to get your child's neck twisted.”

“What do you mean?” asked the female, in astonishment.

“I mean what I say,” replied Jonathan. “Perhaps you don't know that this Darrell so contrived matters, that your child should be mistaken for his own; by which means it had a narrow escape from a tight cravat, I can assure you. However, the scheme answered well enough, for Darrell has got off with his own brat.”

“Then this is not my child?” exclaimed she, with increased astonishment.

“If you have a child there, it certainly is not,” answered Jonathan, a little surprised; “for I left your brat in the charge of Blueskin, who is still among the crowd in the street, unless, as is not unlikely, he's gone to see your other friend disciplined at the pump.”

“Merciful providence!” exclaimed the female. “Whose child can this be?”

“How the devil should I know!” replied Jonathan gruffly. “I suppose it didn't drop through the ceiling, did it? Are you quite sure it's flesh and blood?” asked he, playfully pinching its arm till it cried out with pain.

“My child! my child!” exclaimed Mrs. Sheppard, rushing from the adjoining room. “Where is it?”

“Are you the mother of this child?” inquired the person who had first spoken, addressing Mrs. Sheppard.

“I am—I am!” cried the widow, snatching the babe, and pressing it to her breast with rapturous delight “God be thanked, I have found it!”

“We have both good reason to be grateful,” added the lady, with great emotion.

“'Sblood!” cried Jonathan, who had listened to the foregoing conversation with angry wonder, “I've been nicely done here. Fool that I was to part with my lantern! But I'll soon set myself straight. What ho! lights! lights!”

And, shouting as he went, he flung himself down stairs.