Title: The Houseboat Book: The Log of a Cruise from Chicago to New Orleans

Author: W. F. Waugh

Release date: January 13, 2014 [eBook #44656]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Martin Pettit and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

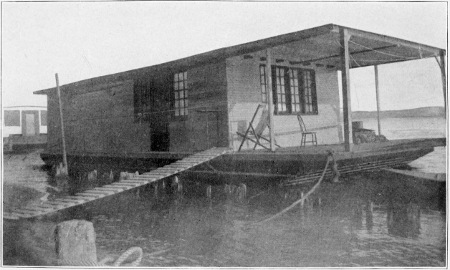

THE HELEN W. OF CHICAGO.

The Log of a Cruise from

Chicago to New Orleans

BY

WILLIAM F. WAUGH

THE CLINIC PUBLISHING COMPANY

CHICAGO

1904

Copyright, 1904,

By William F. Waugh.

PRESS OF

THE CLINIC PUBLISHING CO.

CHICAGO.

| PAGE | ||

| I. | Prelude | 5 |

| II. | Gathering Information | 9 |

| III. | Preparations | 13 |

| IV. | The First Shipwreck | 23 |

| V. | The Canal | 27 |

| VI. | The Illinois River | 40 |

| VII. | Building the Boat | 46 |

| VIII. | The Lower Illinois | 55 |

| IX. | Towing | 68 |

| X. | St. Louis | 77 |

| XI. | The Mississippi | 81 |

| XII. | Cairo and the Ohio | 90 |

| XIII. | Duck Shooting | 103 |

| XIV. | Snagged in Tennessee Chute | 109 |

| XV. | Mooring | 116 |

| XVI. | A Levee Camp | 118 |

| XVII. | Vicksburg | 128 |

| XVIII. | River Pirates | 133 |

| XIX. | The Atchafalaya | 136 |

| XX. | Melville. Deer Hunting | 141 |

| XXI. | Baton Rouge. The Panther | 150 |

| XXII. | The Bobcat | 163 |

| XXIII. | Ascending the Atchafalaya | 167 |

| XXIV. | Ducking at Catahoula Lake | 173 |

| XXV. | Some Louisiana Folks | 185 |

| XXVI. | From Winter to Summer in a Day | 192 |

| XXVII. | Voyage Ended | 196 |

| XXVIII. | Dangers and Delights | 199 |

| XXIX. | Results | 205 |

PRELUDE.

Once upon a time there was a doctor who, after many years spent in that pursuit concluded to reform. But strong is the influence of evil associates, and those who had abetted him in his old ways still endeavored to lead him therein.

One day his good angel whispered in his ear the magic words, "House boat;" and straightway there arose in his mental vision the picture of a broad river, the boat lazily floating, children fishing, wife's cheery call to view bits of scenery too lovely for solitary enjoyment, and a long year of blissful seclusion where no tale of woe could penetrate, no printer's devil cry for copy. Incidentally the tired eyes could rest, and the long stretches of uninterrupted time be transmuted into creative work; with no banging telephone or boring visitor to scatter the faculties into hopeless desuetude. Sandwich with hours[Pg 6] busy with those recuperative implements, the rod and gun, the adventures and explorations incident to the trip, and here was a scheme to make the heart of a city-tired man leap.

So he went to the friend whose kindly appreciation had put a monetary value upon the emanations from his brain, and suggested that now was the time for the besom of reform to get in its work, and by discharging him to clear the way for new and improved editorial talent. But the friend received the suggestion with contumely, threatening to do the editor bodily harm if he so much as mentioned or even contemplated any attempt to escape. The scheme was perforce postponed for a year, and in the meantime attempts were made to gather useful information upon the subject.

The plan seemed simple enough—to leave Chicago by the Drainage Canal, float down to the Illinois River, then down it to the Mississippi, by it to New Orleans, then to strike off through the bayous or canals into the watery wastes southwest, and spend there the time until the approach of the Carnival called us back to the southern metropolis. By starting about [Pg 7]September 1st we could accompany the ducks on their southern journey, and have plenty of time to dawdle along, stopping wherever it seemed good to us.

So we went to work to gather information. The great bookstores were ransacked for books descriptive of houseboat trips down the Mississippi. There were none. Then we asked for charts of the Illinois and Mississippi. There were none of the former in existence; of the latter the Government was said to have published charts of the river from St. Louis to the Gulf; and these were ordered, though they were somewhat old, and the river changes constantly. Then a search was made for books on American houseboats and trips made upon them; books giving some rational information as to what such things are, how they are procured, furnished, managed, what is to be had and what avoided; but without avail. Even logs of canoe trips on the great river, and accounts of recent steamer trips, are singularly scarce. People insisted on forcing upon our notice Bangs' "Houseboat on the Styx," despite our reiterated asseverations that we did not care to travel over that route just now.[Pg 8] Black's "Strange Adventures of a Houseboat" is principally remarkable for the practical information it does not give.

Scarcely a juvenile was to be found treating of the subjects; nor have the novelists paid any attention to the rivers for a third of a century. Books of travel on the great system of inland American waters are similarly rare.

It has finally come home to us that this is a virgin field; that the great American people reside in the valley of the greatest river in the world, and pay no attention to it; write nothing of it, know nothing, and we fear care nothing. And while many persons utilize houseboats, and many more would do so if they knew what they are, and how much pleasure is to be derived therefrom, no one has seen fit to print a book that would make some amends to an intending purchaser for his lack of experience. Possibly the experiences detailed in the following pages may in some degree fulfill this need, and aid some one to avoid the mistakes we made.

GATHERING INFORMATION.

From magazine articles we gathered that a new boat would cost about $1,000. We were assured, however, that we could buy an old one that would answer all needs for about $100. We were told that if the boat measures 15 tons or more our rapidly-becoming-paternal government requires the services of a licensed pilot. All steamers are required to have licensed engineers, though the requirements for an owner's license are not very rigid. Gasoline boats as yet do not come under any laws, though there is talk of legislation upon them, and there may be, by the time this book reaches its readers.

Houseboats usually have no direct power, but are gently propelled by long sweeps. If the boat is small this is all right; but as large a boat as ours would require about four strong men to hold her steady in dangerous places. It takes a much smaller investment if power is excluded; and if the boat goes only down stream, with[Pg 10] force enough to manage her in currents and blows it is cheaper to hire towage when requisite. But if possible have power, and enough. Many boats we saw in the Mississippi are fitted with stern wheels and gasoline engines, and these have great advantages. In cold weather the engineer is protected, and can run in and get warm, while if in a towing boat he may suffer. The expense is less, as there is the hull of the towboat to buy when separate. The motion communicated to the cabin by an attached engine is soon forgotten. You should not calculate in selling either cabin, engine or towboat when ready to leave for the north, as prices in the south are uncertain; and if you have not invested in power you lose that much less if you desert your outfit.

Between steam and gasoline as power there is much to be said. With steam you require a license, it is dirty, more dangerous, takes time to get up steam, and care to keep it up. But you can always pick up wood along shore, though an engine of any size burns up a whole lot, and it takes so much time to collect, cut and saw the wood, and to dry it, that if you are paying a crew their time makes it costly. Low down the[Pg 11] river, in times of low water, coal is to be gathered from the sand bars; but this cannot be counted upon as a regular supply. But you can always get fuel for a wood-burning engine, and if you contemplate trips beyond civilization it may be impossible to obtain gasoline.

Gasoline boats are cleaner, safer, always ready to start by turning a few buttons, and cheaper, if you have to buy your fuel. If you are going beyond the reach of ordinary supplies you may run out, and then your power is useless; but in such cases you must use foresight and lay in a supply enough for emergencies.

Both varieties of engines are liable to get out of order, and require that there shall be someone in charge who understands their mechanism and can find and remedy the difficulty. Our own preference in Mississippi navigation is unquestionably for the gasoline. If we go to the West Indies or the Amazon we will employ steam. Were we contemplating a prolonged life on a boat, or a trading trip, we would have the power attached to the cabin boat; and the saved cost of the hull of a towboat would buy a small gasoline cutter—perhaps $150—which could be used as a[Pg 12] tender. But when you get power, get enough. It saves more in tow bills than the cost of the engine; and if it is advisable to bring the outfit back to the north full power saves a great loss. Quod est demonstrandum in the course of this narrative.

PREPARATIONS.

Our search for a second-hand houseboat was not very productive. At Chicago the choice lay between three, and of these we naturally chose the worst. It was the old Jackson Park boat, that after long service had finally become so completely watersoaked that she sank at her moorings; but this we learned later. In fact, as in many instances, our foresight was far inferior to our hindsight—and that is why we are giving our experiences exactly as they occurred, so that readers may avoid our mistakes.

This houseboat was purchased for $200, the vendor warranting her as sound and safe, in every way fit and suitable for the trip contemplated. He even said she had been through the canal as far as the Illinois river, so there was no danger but that she could pass the locks. The cabin measured 24 x 14.3 x 7 feet; and there was a six-foot open deck in front, three feet behind, and two feet on either side, making her width 18 feet 3 inches. One end of the cabin was [Pg 14]partitioned off, making two staterooms and a kitchen, each 7 feet in depth. The rest formed one large room. It was well lighted, with 14 windows; and had doors in each side and two at the front opening into the kitchen and one stateroom. The roof was formed of two thicknesses of wood and over this a canvas cover, thickly painted.

The staterooms were fitted with wire mattress frames, arranged to be folded against the sides when not in use for beds. In the large room we placed an iron double bed and two single ones, shielded from view by a curtain. There was a stove capable of burning any sort of fuel; two bookcases, dining table, work table, dresser, chairs, sewing machine, sewing table, etc. We had a canvas awning made with stanchions to go on the top, but this we never used, finding it pleasanter to sit on the front deck.

Among the equipment were the following: A canoe with oars and paddle, 50-lb. anchor, 75 feet ¾-inch rope, 75 feet 1-inch rope, 100 feet ½-inch rope, boat pump, dinner horn, 6 life preservers, 2 boathooks, 2 hammocks, 4 cots, Puritan water still, small tripoli filter, a tube of chemical powder fire extinguisher, large and[Pg 15] small axes, hatchet, brace and bits, saws, sawbuck, tool-box well furnished, soldering set, repair kit, paper napkins, mattresses, bedding, towels, and a liberal supply of old clothes, over and under. We had an Edison Home phonograph and about 50 records; and this was a useful addition. But many articles we took were only in the way, and we shall not mention them.

We had a full supply of fishing material, frog spears, minnow seine, minnow trap, railroad lantern, tubular searchlight with bull's-eye reflector, electric flashlight with extra batteries, twine, trotline, revolver and cartridges, 50-gauge Spencer for big game, and as a second gun, with 150 cartridges; 32-H. P. S. Marlin rifle, with 400 cartridges; Winchester 12-gauge pump, with 2,000 shells; Browning automatic shotgun; folding decoys, 4 shell bags, McMillan shell extractor, U. S. Gov't rifle cleaner, Marlin gun grease, grass suit, shooting clothes heavy and light, hip boots, leggings, sweaters, chamois vest, mosquito hats, two cameras with supplies, including developers, compass (pocket), copper wire, whetstone, can opener and corkscrew, coffee pot to screw to wall, matches in waterproof[Pg 16] box, a Lehman footwarmer and two Japanese muff stoves, with fuel. For the kitchen we got a gasoline stove with an oven. There was a good kerosene lamp, giving sufficient light to allow all hands to read about the table; also three lamps with brackets for the small rooms.

In preparing our lists of supplies we derived great assistance from Buzzacott's "Complete Camper's Manual." It was a mistake to buy so many shot-gun shells. All along the river we found it easy to get 12-gauge shells, better than those we had.

The boy rejoiced in a 20-gauge single barrel. We had so much trouble in getting ammunition for it that we purchased a reloading outfit and materials at Antoine's. This little gun was very useful, especially when we wanted little birds.

A full supply of medicines went along, mainly in alkaloidal granules, which economize space and give extra efficiency and many other advantages. A pocket surgical case, a few of the instruments most likely to be needed, surgical dressings, quinidine (which is the best preventive of malaria among the cinchona derivatives), insect powder, sulphur for fumigation, potassium[Pg 17] permanganate for the water, petrolatum, absorbent cotton, a magnifying glass to facilitate removal of splinters, extra glasses for those wearing them; and a little whisky, which was, I believe, never opened on the entire trip.

The boy was presented with a shell belt; and a week before starting we found he was sleeping with the belt on, filled with loaded shells. Say, tired and listless brethren, don't you envy him? Wouldn't you like to enjoy the anticipation of such a pleasure that much?

Among the things that were useful we may add a game and shell carrier, a Marble axe with sheath, and a Val de Weese hunter's knife. After serving their time these made acceptable presents to some kindly folk who had done much to make our stay at Melville pleasant.

We fitted out our table and kitchen from the cast offs of our home, taking things we would not miss were we to leave them with the boat when through with her. It matters little that you will find the most complete lists wanting in important particulars, for ample opportunity is given to add necessaries at the first town. But the Missis insisted on taking a full supply of[Pg 18] provisions, and we were very glad she did. Buzzacott gives a list of necessaries for a party of five men camping five days. It seems liberal, when added to the produce of rod and gun.

20 lbs. self-raising flour.

6 lbs. fresh biscuit.

6 lbs. corn meal.

6 lbs. navy beans.

3 lbs. rice.

5 lbs. salt pork.

5 lbs. bacon.

10 lbs. ham.

15 lbs. potatoes.

6 lbs. onions.

3 lbs. can butter.

3 lbs. dried fruits.

½ gallon vinegar pickles.

½ gallon preserves.

1 qt. syrup.

1 box pepper.

1 box mustard.

6 lbs. coffee.

6 lbs. sugar.

½ lb. tea.

[Pg 19]½ lb. baking powder.

4 cans milk and cream.

1 sack salt.

6 boxes matches (tin case).

1 lb. soap.

1 lb. corn starch.

1 lb. candles.

1 jar cheese.

1 box ginger.

1 box allspice.

1 lb. currants.

1 lb. raisins.

6 boxes sardines.

1 screwtop flask.

Fresh bread, meat, sausage, eggs for first days.

The wife laid in her stock of provisions, costing about sixty dollars and including the articles we use generally.

Among the books we found that seemed likely to provide some useful information are:

Trapper Jim—Sandys.

Last of the Flatboats—Eggleston.

Houseboat series—Castlemon.

Bonaventure—Cable.

Down the Mississippi—Ellis.

Down the Great River—Glazier.

Four Months in a Sneak Box—Bishop.

The Wild-Fowlers—Bradford.

The Mississippi—Greene.

The Gulf and Inland Waters—Mahan.

The Blockade and the Cruisers—Soley.

The History of Our Navy—Spears.

In the Louisiana Lowlands—Mather.

Hitting and Missing with the Shotgun—Hammond.

Among the Waterfowl—Job.

Up the North Branch—Farrar.

Botanist and Florist—Wood.

The Mushroom Book—Marshall.

Wild Sports in the South—Whitehead.

Cooper's Novels.

Catalog from Montgomery Ward's mail order house.

And a good supply of other novels, besides the children's schoolbooks.

By writing to the U. S. port office at St. Louis we secured a list of the lights on the Western rivers, a bit antique, but quite useful. From Rand & McNally we also obtained a chart of the[Pg 21] Mississippi River from St. Louis to the Gulf, which was invaluable. The Desplaines had a lot of separate charts obtained from the St. Louis port officers, which were larger and easier to decipher.

The question of motive power was one on which we received so much and such contradictory advice that we were bewildered. It seemed preferable to have the power in a tender, so that if we were moored anywhere and wished to send for mail, supplies or aid, the tender could be so dispatched without having to tow the heavy cabin boat. So we purchased a small gasoline boat with a two-horse-power engine. At the last moment, however, Jim persuaded us to exchange it for a larger one, a 20-footer, with three-horse-power Fay & Bowen engine. In getting a small boat see that it is a "water cooler," as an air-cooler will run a few minutes and stop, as the piston swells. Also see that she is fitted with reversing gear. Not all boats are. This was a fine sea boat, the engine very fast, and she was well worth the $365 paid for her.

The crew of the "Helen W. of Chicago," consisted of the Doctor, the Missis, the Boy (aged[Pg 22] 11), Miss Miggles (aged 10), Millie the house-keeper, Jim and J. J. We should have had two dogs, little and big; and next time they go in as an essential part of the crew.

We carried far too many things, especially clothes. The most comfortable proved to be flannel shirt or sweater, blue cloth cap, tennis shoes, knickerbockers, long wool stockings, and a cheap canvas hunting suit that would bear dirt and wet. Knicks attract too much attention outside the city. One good suit will do for visiting in the cities.

THE FIRST SHIPWRECK.

Our first experience in shipwrecks came early. We were all ready to start; the home had been rented, furniture disposed of, the outfit ordered, and the boat lay ready for occupancy, fresh and clean in new paint—when we discovered that we had to go through the old canal—the Illinois and Michigan—to La Salle, instead of the drainage ditch, on which we were aware that Chicago had spent many millions more than drainage demanded, with the ulterior object of making a deep waterway between the great city and the Gulf! Here was an anxious thought—would the old canal admit our boat? We visited headquarters, but naturally no one there knew anything about so essential a matter. We went down to the first lock at Bridgeport, and the lockmaster telephoned to Lockport, but the Chief Engineer was out and no one else knew the width of the locks. But finally we met an old seafarer who carried in his pocket a list of all the locks of all[Pg 24] the canals in the U. S., including Canada; and from him we got the decisive information that the narrowest lock admitted boats with a maximum width of 17 feet. Ours measured 18 feet 3 inches!

After prolonged consultation it was determined that the only way out was to cut off enough of the side to admit her. So the purveyor, who had guaranteed the boat as fit in every way for the trip, began to cut, first building an inner wall or side with two-by-fours. Getting this up to a convenient height he concluded to try for leaks, and slid the scow back into the water with the side half up. It was just an inch too low; and when he rose next morning the scow reposed peacefully on the bottom of the river, the water having, in the night, come in at the low side. The following week was consumed in endeavors to raise the boat and get the water out. Meanwhile we were camping out in an empty house, eating off the kitchen table, sleeping anywhere, and putting in spare time hurrying the very deliberate boatmen.

Just then we received from the Sanitary District folks the belated information that the locks[Pg 25] are 18 feet wide, and 110 feet long, and that the height of the boat from the water line must not exceed 17 feet to enable it to pass under bridges.

For nearly a week various means of raising the craft were tried, without success. Finally the wind shifted during the night, and in the morning we found the upper margin of the hull out of water. The pumps were put in operation and by noon the boat was free from water. It was found to be reasonably watertight, despite the straining by jacks, levers, windlasses, and other means employed to raise first one corner and then another, the breaking of ropes and planks by which the corners had been violently dropped, etc. But the absence of flotation, as evidenced by the difficulty of raising an unloaded boat, wholly constructed of wood, should have opened our eyes to her character.

The side was rapidly completed, the furniture and stores brought aboard, and the boats started down the canal, while the Doctor and Missis went to Joliet to meet the outfit and avoid the odors of the drainage. The men ran all night and reached Lock No. 5, at Joliet, about 5 p. m., Wednesday, Sept. 30, 1903. This was altogether unnecessary,[Pg 26] and we might as well have come down on the boat. Meanwhile we found a shelter in a little bakery near the Joliet bridge, where the kindly folk took care of the little invalid while we watched for the arrival of the boats.

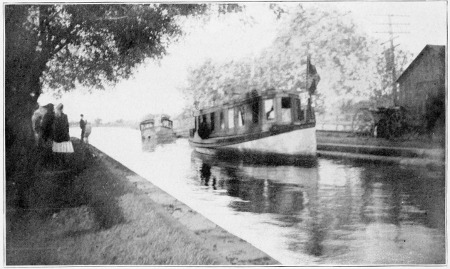

THE OLD CANAL.

THE CANAL.

That night was our first on board. We found the boat piled high with the "necessaries" deemed imperative by the Missis. Days were spent in the arrangement of these, and in heaving overboard articles whose value was more than counterbalanced by the space they occupied. Hooks were inserted, trunks unpacked, curtains hung, and it is safe to say that our first week was thus occupied. The single beds were taken down and the children put to sleep on cots consisting of strips of canvas with eye-holes at the corners. These were fastened to stout hooks, screwed into the walls. Difficulty supervened in finding a place to fasten the outer ends, and we had to run ropes across the cabin, to our great annoyance when rising during the night. Otherwise these are the best of cots, as they can be taken down and rolled away during the day.

The delight of those days, drifting lazily down the old canal, the lovely vistas with long rows of[Pg 28] elms along the deserted towpath, the quiet farms. Sometimes it was showery, at others shiny, but we scarcely noticed the difference. It is surely a lazy man's paradise. There is no current in the canal, and the launch could only drag the heavy scow along at about a mile and a half an hour; while but little wind sufficed to seriously retard all progress. Even with our reduced width it was all we could do to squeeze through the locks, which are smaller toward the bottom. At No. 5 we only got through after repeated trials, when the lock-keeper opened the upper gates and let in a flood of water, after the lower had been opened, and the boat worked down as close as possible to the lower gate. And here let us say a word as to the uniform courtesy we received from these canal officials; something we were scarcely prepared to expect after our experience with the minor official of the city. Without an exception we found the canal officials at their posts, ready to do their duty in a courteous, obliging manner.

Friday, Oct. 2, we reached Lock 8 just at dusk, passing down as a string of three canal boats passed up for Chicago, laden with corn. We[Pg 29] are surprised at the number of boats engaged in this traffic; as we had thought the canal obsolete, judging from the caricatures in the daily papers. Coal was passing down and corn and wood up. During this day 12 laden boats went by us.

Saturday, Oct. 3.—Head winds blew the boat about, to the distraction of the crew. We tried towing, with a line along the towpath, and the boat banged against the bank constantly. But the weather was lovely and clear, everyone happy and the interior economy getting in order. It was well the wise little Missis insisted on bringing a full supply of provisions, for we have not passed a town or a store since leaving Joliet, and we would have fared poorly but for her forethought. We stopped at a farm, where we secured some milk for which we, with difficulty, persuaded the farmer to accept a nickel—for a gallon. He said milk was not so precious as in the city. But at Lock 8 the keeper's wife was alive to her opportunities and charged us city prices.

We were well pleased with our crew. Jim is a guide from Swan Lake, aged 24; fisher, hunter,[Pg 30] trapper and boatman all his life. J. J. is a baseball player and athlete about the same age. Both volunteered for the trip, for the pleasure of it. They asked to go for nothing, but we do not care to make such an arrangement, which never works well and leads to disagreements and desertions when the novelty has worn off; so we paid them wages. During the months they were with us we never asked them to do a thing they did not willingly do, nor was there ever a complaint of them in the score of behavior, lack of respect for the ladies, language before the children, or any of those things that might have led to unpleasantness had they not been gentlemen by instinct and training. They are built of muscle and steel springs, never shirk work, have good, healthy appetites and are always ready to meet any of the various requirements of the trip. Everything comes handy to them. They put the boat in shape, run the engine, do carpentry and any other trade that is needed. It was hard to guide the unwieldy boat so they designed a rudder, went to town for material, hunted up a blacksmith and showed him what they wanted, and put the rudder together and hung it in good shape. It has[Pg 31] a tiller up on the roof, whence the steersman can see ahead.

We secured some food at Morris, with difficulty. By noon the rudder was hung and we were off for Seneca, the boy happy in charge of the tiller. We wish we were a word painter, to describe the beauty of the scenery along the canal. The water has lost all reminiscence of Chicago's drainage. At 3 p. m. we stopped at a farm and obtained milk, eggs and chickens, with half a bushel of apples for good measure. The boat excites much interest among the farmers. At Morris we had our first call upon the drugs, the boys finding a friend whose horse had a suppurating wound. Dressed it with antiseptics and left a supply. We each took two grains of quinine, to ward off possible malaria. Millie suffered serious discomfort, her whole body breaking out, with itching and flushing, lasting some hours. And this was about the only time we took quinine during the trip, except when wet, to prevent a cold. We never saw anything like malaria.

After tea we had a delightful run by moonlight, stopping several miles from Seneca. It is[Pg 32] a good rule to stop before coming to a town, as the loafers do not get sight of the boat until it comes in next morning.

On Monday we ran into Seneca, and stopped for supplies. We always needed something, ample as we thought our outfit. It is always ice, milk, eggs, butter, or fruit. Here it is gasoline, on which we depend for our motive power.

It is useless to look for the picturesque in the Illinois farmer. He speaks the language of the schools, with the accent of culture, and wears his hair and whiskers in modern style. Probably he hears more lectures, sees more operatic and histrionic stars, reads more books and gets more out of his newspapers than does the city man. In fact, there is no country now; the whole State is merely a series of suburbs.

During the afternoon we reached Marseilles, where we tied up for the night. We obtained a gallon of milk here, and a can of gasoline. A neighboring well supplied artesian water, which tasted too much of sulphur for palates accustomed to Chicago water. In fact, we now hear that there is no such water as that of the great lake metropolis.

Tuesday, Oct. 6, we left Marseilles with a favoring breeze. Our craft sails best with the wind about two points abaft the beam. When it shifts to two points forward we are driven against the shore. We had hard work to reach the viaduct over the Fox river. At 2 p. m. we reached Ottawa, and there replenished our gasoline barrel. Hinc illae lachrymae. At Seneca and Marseilles we had been able to obtain only five gallons each, and that of the grade used for stoves. We also learned that we might have saved three dollars in lock fees, as below La Salle the water is so high that the dams are out of sight and steamers pass over them. The registry and lock fees from Chicago to St. Louis are $6.88.

We had now passed ten locks with safety, but the captain of the Lulu tells us the next is the worst of all.

It is evident that our boat is not fit for this expedition, and we must take the first opportunity to exchange her for one with a larger and stronger scow, to cope with the dangers of the great river. The scow should stand well up from the water so that the waves will not come over[Pg 34] the deck. Every morning and night there is over a barrel of water to be pumped out, but that might be remedied by calking.

Near Marseilles we passed a number of houseboats, and hear that many are being prepared for the trip to St. Louis next summer. Berths along the river front there are now being secured.

Among our useful supplies is a portable rubber folding bath tub. It works well now, but I am doubtful as to its wearing qualities. The water-still is all right when we have a wood or coal fire going, but when run by a gasoline stove it distils nearly as much water as it burns gasoline.

Wednesday.—We came in sight of the lock below Ottawa about 5 p. m. last night, and tied up. All night the wind blew hard and rattled the stores on the roof. Rain comes is around the stovepipe, in spite of cement. This morning it is still raining but the wind has fallen. A rain-coat comes in handy. We must add oilskins to our outfit. A little fire goes well these damp mornings, taking off the chill and drying out the cabin. Fuel is the cheapest thing yet. We pick[Pg 35] up a few sticks every day, enough for the morning fire, and could load the boat with wood, if worth while. And there is no better exercise for the chest than sawing wood. We keep a small pile behind the stove to have it dry.

The gasoline launch is a jewel—exactly what we need; and works in a way to win the respect of all. The boys got wire rope for steering, as the hemp stretched; but the wire soon wore through.

Thirty cents a pound for creamery butter at Ottawa. We must rely on the farms.

Whence come the flies? The ceiling is black with them. We talk of fumigating with sulphur. The cabin is screened, but whenever the door is opened they come streaming in. The little wire fly-killer is a prime necessity. It is a wire broom six inches long and as wide, with a handle; and gets the fly every time. Burning insect powder gets rid of mosquitoes, but has no effect on flies.

A string of canal boats passed up this morning, the first we have seen since leaving Seneca. The traffic seems to be much lighter in the lower part of the canal.

The canal official at Ottawa seems to be something of a joker. A dog boarded our craft there and this man informed us it had no owner, so we allowed the animal to accompany us. But further down the line the dog's owner telephoned dire threats after us, and we sent him back from La Salle.

After lunch we tackled Lock No. 11, and a terror it was. The walls were so dilapidated that care had to be exercised to keep the edges of the scow and roof from catching. Then the roof caught on the left front and the bottom on the right rear, and it was only at the fourth trial, when we had worked the boat as far forward as possible, that we managed to scrape through. The wind was still very brisk and dead ahead, so we tied up just below the lock. A steam launch, the Lorain, passed through bound down. She filled the lock with smoke, and we realized how much gasoline excels steam in cleanliness. A foraging expedition secured a quart of milk and four dozen eggs, with the promise of spring chickens when their supper afforded a chance to catch them.

Thursday, Oct. 8, 1903.—All night we were held by the fierce wind against which we were powerless. The squeeze in the lock increased the leakage and this morning it took quite a lot of pumping to free the hull of water. After breakfast we set out, and found Lock 12 much better than its predecessor. All afternoon the wind continued dead ahead, and the towing rope and poles were required to make even slight headway. Then we passed under a low bridge, and the stovepipe fell down. If we do not reach a town we will be cold tonight. Two small launches passed us, going to La Salle, where there is some sort of function on.

The children's lessons go on daily; with the girl because she is a girl and therefore tractable, with the boy because he can not get out till they are learned.

Friday, Oct. 9.—We lay in the canal all day yesterday, the folks fishing for catfish. Our foraging was unsuccessful, the nearest house containing a delegation of Chicago boys—17 of them—sent out by a West Side church, who took all the milk of the place. The boy fell in the[Pg 38] canal and was promptly rescued by J. J., who is an expert swimmer. His mother was excited, but not frightened. After tea, as the wind had fallen, we used the launch for two hours to get through the most of the "wide water," so as to have the protection of the high banks next day. The lights of a large town—electric—are visible below. Very little water that evening, not a fourth what we pumped in the morning.

On Friday morning the water is smooth and we hope to make La Salle today.

And then the gasoline engine stopped!

It had done good service so far, but there was a defect in it: a cup for holding lubricating oil that had a hole in it. Curious for a new engine, and some of the crew were unkind enough to suggest that the seller had taken off the new cup and put on a broken one from his old boat. All day we worked with it, till at lunch time it consented to go; and then our old enemy, the west wind, came up, but less violent than before, so that we made several miles before the engine again quit. We were well through the wide water, and tied up in a lovely spot, where someone had been picnicking during the morning. The[Pg 39] boys towed the launch to Utica with the canoe, while we secured some milk at a Swede's near by, and a jar of honey from another house.

Saturday, Oct. 10, 1903.—At 7 p. m. the boys returned with a little steam launch they had hired for six dollars to tow us the eight miles to La Salle. Lock No. 13 was true to its hoodoo, and gave us some trouble. About midnight we tied up just above Lock 14, which looks dubious this morning. We missed some fine scenery during the night, but are tired of the canal and glad to be near its end. A Street Fair is going on here, and the streets are full of booths. Jim says J. J. will throw a few balls at the "nigger babies," and then write home how he "missed the children!" These things indicate that he is enjoying his meals.

Not much water today in the hold. Temp. 39 at 7 a. m.

THE ILLINOIS RIVER.

Monday, Oct. 12, 1903.—We passed Locks 14 and 15 without difficulty and moored in the basin with a number of other houseboats. We find them very polite and obliging, ready to give any information and assistance in their power. All hands took in the Street Fair, and aided in replenishing our constantly wasting stores. The boy drove a thriving trade in minnows which he captured with the seine. In the afternoon Dr. Abbott came down, to our great pleasure. A man from the shop came and tinkered with the gasoline engine a few hours' worth, to no purpose. Several others volunteered advice which did not pan out.

Sunday we lay quiet, until near noon, when the engineer of the government boat Fox most kindly pointed out the trouble, which was, as to be expected, a very simple one—the sparker was so arranged that the single explosion caught the piston at the wrong angle and there was no [Pg 41]second explosion following. Then all hands went for a ride down into the Illinois river. Dr. Abbott got off at 8:15 and the boys took a run up to Tiskilwa—for what reason we do not hear, but have our suspicions. We still recollect the days when we would travel at night over a five-mile road, lined with farms, each fully and over-provided with the meanest of dogs—so we ask no questions.

This morning the temperature is 48, foggy; all up for an early start.

One undesirable acquisition we made here was a numerous colony of mice, which must have boarded us from a boat that lay alongside. The animals did much damage, ruining a new dress and disturbing us at night with their scampering. Nor did we finally get rid of them until the boat sank—which is not a method to be recommended. Fumigation with sulphur, if liberally done, is about the best remedy for any living pests.

Tuesday, Oct. 13, finds us still tied up below La Salle. The fortune-teller kindly towed us to the mouth of the canal, where we spent the day trying to persuade the engine to work. After an[Pg 42] expert from the shops here had put in the day over it, he announced that the fault lay with the gasoline bought at Ottawa. In truth our troubles date from that gasoline, and we hope he may be right. The engine he pronounces in perfect order. Nothing here to do, and the little Missis has a cold and is getting impatient to be going. So far we have met none but friendly and honest folks along the canal, all anxious to be neighborly and do what they can to aid us. All hands are discouraged with the delay and trouble with the engine—all, that is, except one old man, who has been buffeted about the world enough to realize that some share of bad luck must enter every human life, and who rather welcomes what comes because it might have been so much worse. Come to think of it, we usually expect from Fate a whole lot more than we deserve. What are we that we should look for an uninterrupted career of prosperity? Is it natural? Is it the usual lot of man? What are we that we should expect our own lot to be such an exceptional career of good fortune? Think of our deserts, and what some men suffer, and humbly thank the good Lord that we are let off so easily.

If that is not good philosophy we can answer for its helping us a whole lot to bear what ills come our way.

We got off early and began our first day's floating. It was quite pleasant, much more so than lying idle. The Fox came along and rocked us a bit, but not unpleasantly. We tied up below the bridge at Spring Valley, and the boys went up to town, where they succeeded in getting five gallons of gasoline, grade 88. After lunch we pumped out the old stuff and put in the new and the little engine started off as if there had never been a disagreement. At 4 p. m. we are still going beautifully, passed Marquette, and all happy. But if the man who sold us low-grade gasoline at Ottawa, for high, were in reach he might hear something he would not like.

At night we tied up a mile above Hennepin, where we obtained some milk and a few eggs at a farm house.

Wednesday, Oct. 14, 1903.—Yesterday we passed the opening of the Hennepin canal, that monument of official corruption, which after the expenditure of fifty millions is not yet ready for[Pg 44] use—the locks not even built. Compare with the work done on the Drainage Canal, and we conclude Chicago is not so very bad. At Hennepin this morning we secured three gallons of gasoline at 74, the best available; also fresh beef, for which we are all hungry. Left at 9 a. m. for Henry.

During the preceding night the Fred Swain passed down and bumped us against the rocky shore harder than at any time previously. Next morning there was less water in the hull than ever before, so it seems to have tightened her seams. We ran into the creek above Henry and moored at the landing of the Swan River Club, where Jim's father resides. Here we lay for several weeks, for reasons that will appear. Millie kindly varied the monotony and added to the general gaiety by tumbling into the creek; but as the water was only about three feet deep no serious danger resulted. The boys usually disappeared at bedtime and talked mysteriously of Tiskilwa next morning, and appeared sleepy. We examined several boats that were for sale, but did not find any that suited us. We wished to feel perfectly safe, no matter what we might [Pg 45]encounter on the great river. Some one has been trying to scare the boys with tales of the whirlpools to be encountered there; and of the waves that will wash over the deck. These we afterward found to be unfounded. No whirlpool we saw would endanger anything larger than a canoe, and our two-strake gunwales were high enough for any waves on the river.

We found few ducks; not enough to repay one for the trouble of going out after them. Until we left Henry we caught a few fish, but not enough to satisfy our needs.

BUILDING THE BOAT.

November 1, 1903.—We had settled that the scow was not strong enough for the river voyage, and she kindly confirmed this view by quietly sinking as she was moored in the creek. There was no accident—the timbers separated from decay. We were awaked by the sound of water running as if poured from a very large pitcher; jumped up, ran to the stern of the boat, and saw that the rudder, which was usually six inches above water, was then below it. We awoke the family and hastily removed the articles in the outer end of the boat to the end resting on shore, and summoned the boys. It was just getting towards dawn. By the time this was done the lower end of the cabin floor was covered with water. Had this happened while we were in the river the consequences would have been serious.

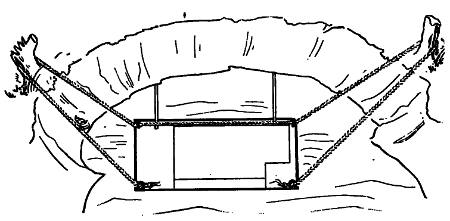

Jim's father, Frank Wood, went to Peoria and selected materials for the new scow. The sides[Pg 47] are technically termed gunwales—"gunnels"—and should be of solid three-inch plank. But we found it might take six months to get three-inch plank forty feet long, so we had to splice. He got eight plank, 22 to 24 feet long. Two of these were spliced in the center for the lower strake, and one long one placed in the center above, with half a length at each end. This prevented both splices coming together. The plank were sawed in a Z shape. Holes were then bored through both plank at intervals of four feet, and half-inch iron braces driven through and screwed firmly together. The ends were then sawn for the sloping projections.

Through the middle, from end to end, was set a six-by-six timber, and on each side midway between this and the gunwales ran a three-by-six. Then the two-inch plank were nailed firmly to the gunwales and intermediate braces, each with twenty-three 60- and 40-penny nails. We find a strong prejudice against wire nails, these fishers and boatbuilders preferring the old-fashioned square nails when they can get them. They say the wire is more apt to rust; but this may be simply the conservatism that always meets an [Pg 48]innovation. The cheapness of the wire is an item.

The plank were placed as closely together as possible. Here a difficulty arose, as they were warped, so that when one end was laid close, the other was an inch from its fellow. But this did not bother our men. They put a triangular block up to the refractory end, nailed it firmly to the beam underneath, and drove wedges between till the crooked plank was forced as nearly straight as possible—or as prudent, for too great a strain would be followed by warping.

When all the planks were nailed on, two coats of tar and rosin were applied, and next day the boat was turned over. It was brought down till one side was in two feet of water, then the upper side was hoisted by blocks and tackles applied on upright timbers, till nearly upright, when the men pushed it over with big poles. She had first been braced carefully with an eight-by-eight across the middle, and by a number of other timbers. The eight-by-eight was broken and the middle of the boat forced up six inches by the shock, requiring the services of a jack to press it down to its place.

What fine workers these men are, and how[Pg 49] silently they work, keeping at the big spikes hour after hour, driving every one with thought and care, and yet wasting no time. What use they make of a few simple mechanical aids—the lever, the wheel and screw, the jack, buck, etc.; and they constantly use the square before sawing. Americans, every one of them; and not a drop of beer or whisky seen about the work, from first to last.

The seams in the gunwales were caulked with hemp and payed with white lead, before the boat was turned. Then they went over the inside and wherever a trickle of water appeared they stuffed in cotton.

The scow is 40 feet long and 16 feet wide. Over the gunwales were laid four-by-fours, 18 feet long, and spiked down. Then supports were placed under these and toenailed to the three inner braces, and to the four-by-fours. A two-foot projection was made at each end, making the floor 44 feet long. The flooring is of Georgia pine, tongued and grooved.

The lumber cost, including freight from Peoria to Henry, about $100; the work about fifty more. There were over 100 pounds of nails used,[Pg 50] 50 pounds of white lead in filling cracks, and several hundred pounds of tar on the bottom.

The gunwales are of Oregon fir, straight and knotless. It would not add to the strength to have them of oak, as they are amply able to withstand any strain that can possibly be put on them in navigating even the greatest of rivers. Oak would, however, add largely to the weight, and if we were pounding upon a snag this would add to the danger. As it was, we many times had this experience, and felt the comfort of knowing that a sound, well-braced, nailed and in every way secure hull was under us. The planking was of white pine, the four-by-fours on which the deck rested of Georgia pine. The cabin was of light wood, Oregon fir. When completed the hull formed a strong box, secure against any damage that could befall her. We cannot now conjure up any accident that could have injured her so as to endanger her crew. Were we to build another boat she should be like this one, but if larger we would have water-tight compartments stretching across her, so that even if a plank were to be torn off the bottom she would still be safe. And we would go down to Henry[Pg 51] to have "Abe" De Haas and "Frank" Wood and "Jack" Hurt build her.

Some leakage continued for some weeks, till the seams had swelled completely shut, and she did not leak a drop during the whole of the cruise.

During this time we continued to live in the cabin, the deck sloping so that it was difficult to walk without support. When the cabin was being moved we availed ourselves of Mrs. Wood's courtesy and slept in her house one night. After the cabin had been moved off we took the old scow apart, and a terrible scene of rottenness was revealed. The men who saw it, fishermen and boatbuilders, said it was a case for the grand jury, that any man should send a family of women and little children afloat on such a boat. There was no sign of an accident. The water had receded, leaving the shore end of the scow resting on the mud. This let down the stern a little. The new side was constructed of two-by-fours laid on their sides, one above the other, and to the ends were nailed the plank forming the bow and stern. Of these the wood was so rotten that[Pg 52] the long sixty-penny spikes pulled out, leaving a triangular opening, the broad end up. As the stern of the boat sank the water ran in through a wider orifice and filled up the hull more and more rapidly. The danger lay in the absolute lack of flotation. New wood would have kept her afloat even when the hull was full of water, but her timbers were so completely watersoaked that the stout ropes broke in the attempt to raise her, even though with no load.

Through the favor of Providence this occurred while we were moored in a shallow creek. Had it happened while in the deep river nothing could have saved us from drowning. As it was, we lost a good deal of canned goods and jelly, soap, flour, and other stores. But the most serious harm was that we were delayed by the necessity of building a new boat, so that we were caught in the November storms, and the exposure brought back the invalid's asthma; so that the main object of the trip was practically lost. We are thus particular to specify the nature of the trouble, as the vendor of the boat has claimed that the accident was due to the inexperience of our crew. That this was a mistake must be [Pg 53]evident to even an inexperienced sailor, who reads this account.

The old house on the sunken scow was cut loose and moved over onto the new one, and securely nailed down. An addition 8 feet square was added at the back for a storeroom, and the roof extended to the ends of the scow at both ends. This gives us a porch 11 by 18 feet in front, and one 10 by 8 behind. These are roofed with beaded siding and covered with the canvas we got for an awning, which we have decided we do not need. This is to be heavily painted as soon as we have time.

The entire cost of the new boat, the additional room and roofs, labor and materials, was about $250; the old boat cost $200, but the cabin that we moved onto the new hull could not have been built and painted for that, so that there was no money loss on the purchase. The launch, with its engine, cost $365, so that the entire outfit stood us at $830, including $15 for a fine gunning skiff Jim got at Henry. The furniture is not included, as we took little but cast-offs; nor the outfit of fishing and sporting goods.

We must stop here to say a word as to the[Pg 54] good people at Henry. Frank Wood and his family opened their house to us and furnished us milk and other supplies, for which we could not induce them to accept pay. Members of the Swan Lake Club placed at our disposal the conveniences of their club house. During the time our boat was building our goods lay out under a tree with no protection, not even a dog, and not a thing was touched. These fishermen surely are of a race to be perpetuated. Mr. Grazier also allowed us to use his ferryboat while endeavoring to raise the sunken boat and to store goods, and Mrs. Hurt offered to accommodate part of our family on her houseboat while our cabin was being moved to the new scow.

THE LOWER ILLINOIS.

Saturday, Oct. 31, we bade adieu to the kind friends at Swan Lake, who had done so much to make us comfortable, and pulled down to Henry, passing the locks. Here we tied up till Sunday afternoon, the engine still giving trouble, and then set off. We passed Lacon pontoon bridge and town about 5 p. m., and three miles below tied up for the night. Next morning, the engine proving still refractory, we floated down to the Chillicothe bridge, which was sighted about 11 a. m. This day was rainy and the new unpainted roof let in the water freely.

We waited at Chillicothe for the Fred Swain to pass, and then swung down to the bank below town, where we tied up. A farm house stood near the bank, and as we tied up a woman came out and in a loud voice called to some one to lock the chicken-house, and rattled a chain, suggestively; from which we infer that houseboat people have not the best reputation. We played[Pg 56] the phonograph that evening, and the household gathered on shore to listen; so that we trust they slept somewhat securely. In the morning we bought some of the chickens we had had no chance to steal, and found the folks quite willing to deal with us. We had to wait for the Swain, as it was quite foggy and without the launch we could not have gotten out of her way.

We drifted slowly down past Sand Point and The Circle lights, and tied up to a fallen tree, opposite the little village of Spring Bay. The boys were out of tobacco and had to row in for it. About 9 p. m. I heard shouts and then shots, and went out, to find a thick fog. They had lost their direction and it was only after some time and considerable shouting that they came near enough to see the lantern. We heard that the previous night the man who lights the channel lamps was out all night in the fog.

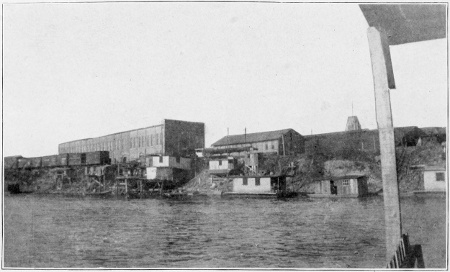

HOUSEBOAT TOWN, PEORIA.

Again we had to wait for the Swain to pass, and then floated down past Blue Creek Point. Here we saw a houseboat tied up, which a fisherman told us belonged to a wealthy old bachelor who lived there from choice. The current was slow as the river was wide, so about 2 p. m. we[Pg 57] took a line from the good canal boat City of Henry, which for three dollars agreed to tow us to Peoria. This was faster traveling, but not a bit nice. However, it was necessary to get the engine in order, so we put up with it. We tied up above the upper bridge, with a nasty row of jagged piles between us and the shore. About 5 a. m. a northeast gale sprang up and washed us against the piles, to our great danger. Our boys arranged a two-by-four, nailing it against the side, so that the end stuck into the sand and fended us off the piles, and our gangway plank served the same purpose at the other end. This is a most important matter, as the snags might loosen a plank from the bottom.

Friday, Nov. 6, 1903.—At last we seem to have found a real expert on gasoline engines. Instead of guessing that "mebbe" this or "mebbe" that was the matter, he went at it and soon found the difficulty. In a short time the boat was circling 'round the lake at a most enticing rate. We laid in a new store of groceries and at 9 a. m. today set out. By lunch time we had passed Pekin, and are now heading for the locks at Cop[Pg 58]peras Creek, the engine going beautifully and the weather bright and cool. About Peoria we saw great numbers of houseboats, many in the water, but the aged members had climbed out upon the banks and perched among a wonderful array of shanties. One house seemed to be roosting among the branches of several large trees. Many were seen along the river below, some quite pretty, but none we fancied as well as our own.

Friday, Nov. 8, 1903.—We were held back by head winds and stopped before we reached the lock. Saturday we had good weather and little wind, and reached Copperas Creek just after lunch. There were three feet of water on the dam, and even the Bald Eagle, the largest steamer here, runs over it; but as we had paid for the lock we went through it. The lock-keeper took it out of us, though, by charging 15 cents for two quarts of milk, the highest price paid yet.

We got off this morning at 8:15, and although a heavy head wind prevails are making good time. Many loons are passing south, in large flights, and some ducks. The marshes on either side seem to be well supplied, but are club[Pg 59] grounds, we are told. It is much warmer than yesterday, the south wind blowing strongly. We moored with the anchor out at the outer corner, up the river, and the line and gangway plank on shore, allowing about ten feet from boat to shore; and when the Eva Alma and the Ebaugh passed us there was no bumping against the shore. Evidently that is the way to moor, though in the great river we must give more space and more cable to the anchor.

At 10 a. m. we passed Liverpool, a hamlet of 150 inhabitants, half of whom must reside in houseboats. Some of these were quite large and well built.

We reached Havana about 4 p. m. Sunday, and as the south wind had become too fierce for our power we tied up below the bridge, at a fisherman's shanty. Monday morning it looked like rain, and the wind blew harder than ever, so we lay by and the boys finished putting on the tar paper roofing. When the wind is strong enough to blow the boat up stream against the current, the launch will be unable to make head against it. A couple live in an old freight car by us, and[Pg 60] their home is worth seeing. The sand bluff is dug out for a chicken cave and pig-pen, and beautiful chrysanthemums are growing in boxes and pans, placed so as to retain the earth that would otherwise wash away. Fruit trees are also planted, and the woman tells me that the whole place is filled with flowering plants, now covered with sand for the winter. We notice two dracaenas.

Tuesday, Nov. 10, 1903.—The storm lasted all day yesterday, pinioning us relentlessly to the beach. By 5 p. m. it let up, but we concluded to remain at our moorings till morning. This morning we got off at 7 a. m., and passed the Devil's Elbow lights before lunch. We did not tie up then, but threw out our anchor, which is less trouble and in every way better, as there is less danger of the snags that beset the shore. The air is rather cool for sitting outside but we spend much time there. The river is narrowing. Each little creek has a houseboat, or several, generally drawn up out of the water and out of reach of the ice. We saw a woman at one of the shabbiest shanty boats washing[Pg 61] clothes. She stooped down and swung the garment to and fro in the water a few moments and then hung it up to dry.

The shores are thickly dotted with little flags and squares of muslin, put up by the surveyors who are marking out the channel for the proposed deep waterway. These were few in the upper river. Every shallow is appropriated by some fisherman's nets, and at intervals a cleared space with sheds or fish boxes shows how important are the fisheries of this river.

There is a great deal of dispute along shore over the fishing rights. The submerging of thousands of acres of good land has greatly extended the limits of what is legally navigable water. The fishermen claim the right to set their nets wherever a skiff or a sawlog can float; but the owners think that since they bought the land from the Government and paid for it, and have paid taxes for forty years, they have something more of rights than any outsider. If not, what did they buy? The right to set nets, they claim, would give the right to plant crops if the water receded. Eventually the courts will have to decide it; but if these lands are thrown open[Pg 62] to the public, the Drainage Board will have a heavy bill of damages. For it seems clear that it is the canal which has raised the level of the water.

Meanwhile the fishing is not profitable. The fish have so wide a range that netting does not result in much of a catch. But if this rise proves only temporary, there will be good fishing when the water subsides.

The boy does not get enough exercise, and his constant movement is almost choreic; so we sent him out to cut firewood, which is good for his soul. The girl amuses herself all day long with some little dolls, but is ever ready to aid when there is a task within her strength. She is possessed with a laughing demon, and has been in a constant state of cachinnation the whole trip. At table some sternness is requisite to keep the fun within due bounds. All hands mess together—we are a democratic crowd. Saturday John W. Gates' palatial yacht, the Roxana, passed down while we were at lunch. We saw a cook on deck; and two persons, wrapped up well, reclined behind the smokestack.[Pg 63]

Nov. 11, 1903.—After a run of 22 miles—our best yet—we tied up at the Sangamon Chute, just below the mouth of that river. The day had been very pleasant. During the night our old friend the South Wind returned, but we were well moored and rode easily. The launch bumped a little, so the doctor rose and moved it, setting the fenders, also. Rain, thunder and lightning came, but secure in our floating home we were content. Today the wind has pinioned us to the shore, though the sun is shining and the wind not specially cold. The boys cut wood for the stove and then went after ducks, returning at noon with a pair of mallards. The new roof is tight, the stove draws well, and we ought to be happy, as all are well. But we should be far to the south, out of reach of this weather. We can see the whitecaps in the river at the bend below, but an island protects us from the full sweep of wind and wave.

Regular trade-wind weather, sun shining, wind blowing steadily, great bulks of white cloud floating overhead, and just too cold to permit enjoyable exposure when not exercising.[Pg 64]

Friday, Nov. 13, 1903.—This thing grows monotonous. Yesterday we set out and got to Browning, a mile, when the wind blew us ashore against a ferry boat that was moored there, and just then the engine refused to work. We remained there all day. The wind was pitiless, driving us against the boat till we feared the cable would break. We got the anchor into the skiff and carried it out to windward as far as the cable reached, and then drew in till there were five feet between the ferryboat and ours. In half an hour the anchor, firmly embedded in tenacious clay, had dragged us back to the boat and we had again to draw in cable by bracing against the ferry.

At 2 p. m. the wind had subsided, and after working with the engine till 4 we got off, and drew down a mile beyond the turn, where we would be sheltered. We moored with the anchor out up stream, and a cable fast ashore at the other end, lying with broadside up stream to the current, and a fender out to the shore. This fender is made of two two-by-fours set on edge and cross pieces let in near each end. The boat end is tied to the side and the shore end rams[Pg 65] down into the mud. While at dinner the Bald Eagle came up, but we hardly noticed her wash. Moored thus, far enough out to avoid snags, we are safe and comfortable. But if too close in shore there may be a submerged snag that when the boat is lifted on a wave and let down upon it punches a hole in the bottom or loosens a plank.

The night was quiet. We had our first duck supper, the boys getting a brace and a hunter at the fish house giving us two more. They had hundreds of them, four men having had good shooting on the Sangamon. This morning it is cool and cloudy, the wind aft and light, and the boys are coaxing the engine. If we can get a tow we will take it, as there is some danger we may be frozen in if we delay much longer.

Saturday, Nov. 14, 1903.—Despite the hoodoo of yesterday, Friday the 13th, we got safely to Beardstown before lunch, in a drizzle of rain that turned to a light snow. Temperature all day about 35. After lunch we started down and passed La Grange about 4:30 p. m. Probably this was a town in the days when the river was[Pg 66] the great highway, but stranded when the railways replaced the waterways. There is a very large frame building at the landing, evidently once a tavern, and what looks like an old street, with no houses on it now. The tavern is propped up to keep it from falling down. No postoffice. We tied up about a mile above the La Grange lock, so that we may be ready to go through at 8 a. m. We hear that the locks are only opened to small fry like gasolines at 8 a. m. and 4 p. m., and it behooves us to be there at one of those hours. Just why a distinction should be made between steamers and gasolines is for officialdom to tell.

Twice yesterday the launch propeller fouled the towrope, once requiring the knife to relieve it. This accident is apt to occur and needs constant attention to prevent. We arranged two poles to hold up the ropes, and this did well. It is good to have a few poles, boards and various bits of timber aboard for emergencies. Heavy frost last night, but the sun is coming up clear and bright, and not a breath of wind. We look for a great run today if we manage the lock[Pg 67] without delay. The quail are whistling all around us, but we are in a hurry. The Bald Eagle passed down last evening, running quite near us and sending in big waves, but thanks to our mooring, we were comfortable and had no bumping. The water does no harm; it is the shore and the snags we fear.

We were told that we would find the lockmen at La Grange grouty and indisposed to open the locks except at the hours named above; but this proved a mistake. They showed us the unvarying courtesy we have received from all canal officials since starting. They opened the gate without waiting for us. They said that in the summer, picnic parties gave them so much unnecessary trouble that they had to establish the rule quoted, but at present there was no need for it. The day is decidedly cool and a heavy fog drifting in from the south.

At Meredosia at 11 a. m., where Dr. Neville kindly assisted us to get a check cashed. Found a youngster there who "knew gasoline engines," and by his help the difficulty was found and remedied. Laid in supplies and set out for Naples. Weather cool, but fog lifted, though the sun refused to be tempted out.

TOWING.

Monday, Nov. 16, 1903.—The engine bucked yesterday, for a change, so we 'phoned to Meredosia and secured the services of the Celine, a gasoline launch of five-horse-power. She started at once, but arriving in sight of Naples she also stopped and lay two hours before she condescended to resume. About 3 p. m. we got under way, the Celine pushing, with a V of two-by-fours for her nose and a strong rope reaching from her stern to each after corner of the scow. Then our own engine awoke, and ran all day, as if she never knew what a tantrum was. We made Florence, a town of 100 people, and tied up for the night. An old "doctor" had a boat with a ten-horse-power gasoline tied up next us. He travels up and down the river selling medicines. As these small towns could scarcely support a doctor, there is possibly an opening for a real physician, who would thus supply a number of them. Telephonic [Pg 69]communication is so free along the river that he could cover a large territory—at least better than no doctor at all.

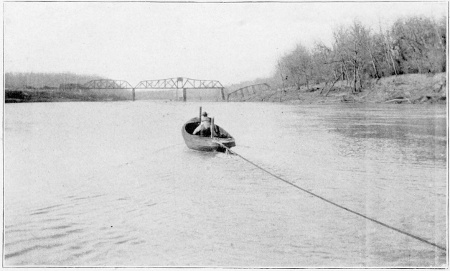

LAUNCH TOWING.

During the night it blew hard, and rain, thunder and lightning made us feel sorry for the poor folk who were exposed to such dangers on shore. This morning we got off about 7:15, with a dull, lowering sky, fog, but a wind dead astern and a strong current, so that we are in hopes of a record run. So far our best has been 22 miles in one day.

The right bank shows a series of pretty high bluffs, the stratified rock showing through. Ferries grow numerous. A good deal of timber is at the riverside awaiting shipment—a good deal, that is, for Illinois—and remarkably large logs at that. It seems to go to Meredosia. The boy and his father had made a gangway plank, and a limber affair it was; so the boys are taking it to pieces and setting the two-by-fours up on edge, which gives more strength. There is a right and a wrong way of doing most things, and we invariably choose the wrong till shown better.

Bought some pecans at Meredosia—$3.00 a[Pg 70] bushel. It ought to pay to raise them at that price, which is rather low than high. The river is said to be lined with the trees, and one woman says she and her two daughters made $150 gathering them this season. Hickory nuts cost 80 cents to $1.20, the latter for big coarse nuts we would not gather in the East.

Tuesday, Nov. 17, 1903.—Kampsville, Ill. Yesterday Mr. Hauser brought us this far with the gasoline launch Celine, and then quit—too cold. Cost $12 for the tow. By the time we got here the northeast wind was blowing so fierce and cold that we tied up. The town seems very lively for so small a place, having a number of stores. They charged us 25 cents a gallon for stove gasoline, but only 8 cents a pound for very fair roasting beef. We were moored on a lee shore, with our port bow to land, lines from both ends to stakes on shore, and the gangway plank roped to the port corner side and staked down firmly; the anchor out from the starboard stern, so as to present that side to the wind and current. She swung easily without bumping, but the plank complained all night. We scarcely felt[Pg 71] the waves from the Bald Eagle when she came in, but the wind raised not only whitecaps but breakers and we rocked some. It grew so cold that there was a draft through the unlined sides of the boat that kept our heads cold. Fire was kept up all night and yet we were cold.

We now see as never before how much harm was done by the old boat, that compelled us to remain so long in this northern latitude and get the November storms. But for this we would have been well below Memphis, and escaped these gales.

We got new batteries here, but this morning all the gasolines are frozen up, and we lay at our moorings, unable to move. They wanted $20 to tow us 29 miles to Grafton, but have come down to $15 this morning. We will accept if they can get up power, though it is steep—$5.00 being about the usual price for a day's excursion in summer. All hands are stuffing caulking around the windows and trying to keep in some of the heat. Sun shining, but the northeast wind still blows whitecaps, with little if any sign of letting up. The launch that proposes to tow us is busy thawing out her frozen pump. We have put the[Pg 72] canoe and skiff on the front "porch," so as to have less difficulty steering.

The little Puritan still sits on the stove in the cabin, and easily furnishes two gallons of water a day when sitting on top of the stove lid. Four times we have turned on the water and forgotten it till it ran over. We might arrange it to let a drop fall into the still just as fast as it evaporates, if the rate were uniform, but on a wood stove this is impossible. Last night it burned dry and some solder melted out of the nozzle, but not enough to make it leak. It did not hurt the still, but such things must be guarded against.

The weather is warmer, sun shining brightly, but we must wait for our tow. The boys are getting tired of the monotony, especially Jim, who likes action. We have the first and only cold of the trip, contracted the cold night when our heads were chilled.

This afternoon Jim and the boy went one way for pecans and squirrels, and the three women another for pecans alone. This is the pecan country, the river being lined with the trees for many miles. In the cabin-boat alongside, the old proprietor is still trying to get his engine to[Pg 73] work, while both his men are drunk. And he never did get them and the engine in shape, but lost the job. He did not know how to run his own engine, which is unpardonable in anyone who lives in such a boat or makes long trips in it.

Thursday, Nov. 19, 1903.—Another tedious day of waiting. Cold and bright; but the cold kept us in. After dark Capt. Fluent arrived with his yacht, the Rosalie, 21-horse-power gasoline; and at 9 a. m. we got under way. Passed the last of the locks at 9:15, and made about five miles an hour down the river. Passed Hardin, the last of the Illinois river towns. Many ducks in the river, more than we had previously seen. Clear and cold; temperature at 8 a. m. 19; at 2 p. m., 60. About 3:25 p. m. we swung into the Mississippi. The water was smooth and did not seem terrible to us—in fact we had passed through so many "wides" in the Illinois that we were not much impressed. But we are not saying anything derogatory to the river god, for we do not want him to give us a sample of his powers. We are unpretentious passers by, no Aeneases or other distinguished bummers, but[Pg 74] just a set of little river tramps not worth his godship's notice.

Grafton is a straggling town built well back from the river, and looking as if ready to take to the bluffs at the first warning. The Missouri shore is edged with willows and lies low. We notice that our pilot steers by the lights, making for one till close, and then turning towards the next, keeping just to the right or left, as the Government list directs: Probably our craft, drawing so little water, might go almost anywhere, but the channel is probably clear of snags and other obstructions and it is better to take no chances. It was after 6 when we moored in Alton. Day's run, 45 miles in nine hours. We picked up enough ducks on the way down for to-night's dinner—two mallards and two teal.

Friday, Nov. 20, 1903.—Cold this morning, enough to make us wish we were much farther south. Capt. Fluent has quite a plant here—a ferry boat, many small boats for hire, etc. In the night a steamer jolted us a little, but nothing to matter. Even in the channel the launch ran over a sunken log yesterday. We note a [Pg 75]gasoline launch alongside that has one of the towing cleats and a board pulled off, and hear it was in pulling her off a sand bar; so there is evidently wisdom in keeping in the channel, even if we only draw eight inches.

A friend called last evening. Waiting at the depot he saw our lights and recognized the two side windows with the door between. It was good to see a familiar face.

We are now free from the danger of ice blockade. The current at the mouth of the Illinois is so slow that ice forming above may be banked up there, and from this cause Fluent was held six weeks once—the blocking occurring in November. But the great river is not liable to this trouble. Still we will push south fast. This morning we had a visit from a bright young reporter from an Alton paper, who wrote up some notes of our trip. The first brother quill we had met, so we gave him a welcome.

At 9 a. m. we set out for St. Louis, Mrs. Fluent and children accompanying her husband. The most curious houseboat we have yet seen lay on shore near our mooring place. It was a small raft sustained on barrels, with a cabin about six[Pg 76] feet by twelve. A stovepipe through the roof showed that it was inhabited. Reminded us of the flimsy structures on which the South American Indians entrust themselves to the ocean.

The Reynard and her tender are following us, to get the benefit of Fluent's pilotage. A head wind and some sea caused disagreeable pounding against the front overhang, which alarmed the inexperienced and made us glad it was no wider. But what will it do when the waves are really high?

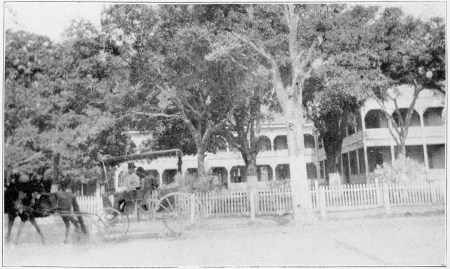

"BLUFF." THE DESPLAINES.

ST. LOUIS.

St. Louis, Nov. 26, 1903.—We moored at the private landing belonging to Mr. Gardner, whose handsome yacht, the Annie Russell, came in on the following day. This was a great comfort, affording a sense of security, which the reputation of the levee made important. A reporter from the Globe-Democrat paid us a visit, and a notice of the boat and crew brought swarms of visitors. We were deluged with invitations so numerous that we were compelled to decline all, that no offense might be given. But Dr. Lanphear and his wife were not to be put off, so they drove down to take us for a drive through the Fair grounds, with their huge, inchoate buildings; and then brought to the boat materials for a dinner which they served and cooked there. It is needless to add that we had a jolly time.

Many applications were made for berths on the boat, which also we had to decline. One distinguished professor of national repute offered to[Pg 78] clean guns and boots if he were taken along. Despite the bad reputation of the levee we saw absolutely nothing to annoy us. We heard of the cruelty of the negroes to animals but scarcely saw a negro here. It is said that they catch rats on the steamers and let them out in a circle of negro drivers, who with their blacksnake whips tear the animal to pieces at the first blow.

We visited the market and had bon marche there, and at Luyties' large grocery. Meat is cheap here, steak being from 10 to 12 cents a pound.

Foreman turned up with the Bella, and tried to get an interview; but we refused to see him, the memory of the perils to which he had exposed a family of helpless women and children, as well as the delay that exposed us to the November gales, rendering any further acquaintance undesirable.

Frank Taylor, the engineer of the Desplaines, was recommended to us by his employer, Mr. Wilcox, of Joliet, as the best gasoline expert in America; and he has been at work on our engine since we reached St. Louis. It is a new make to him, and he finds it obscure. We have[Pg 79] had so much trouble with it, and the season is so far advanced, that we arranged with the Desplaines, whose owner very kindly agreed to tow us to Memphis. This is done to get the invalid below the frost line as quickly as possible. The Desplaines is selling powder fire extinguishers along the river; and we are to stop wherever they think there is a chance for some business.

At St. Louis we threw away our stove, which was a relic of Foreman, and no good; and bought for $8.00 a small wood-burning range. It works well and we can do about all our cooking on it, except frying. As we can pick up all the wood we wish along the river, this is more economic than the gasoline stove, which has burned 70 gallons of fuel since leaving Chicago.

We stopped for Thanksgiving dinner above Crystal City, and the Desplaines crowd dined with us—Woodruff, Allen, Clements, Taylor and Jake. A nice crowd, and we enjoyed their company. Also the turkey, goose, mince pie, macaroni, potatoes, onions, celery, cranberries, pickles, nuts, raisins, nut-candy, oranges and coffee. The current of the river is swifter than at any[Pg 80] place before met, and carries us along fast. The Desplaines is a steamer and works well.

We made about 50 miles today and tied up on the Illinois side, just above a big two-story Government boat, which was apparently engaged in protecting the banks from washing. Great piles of stone were being dumped along the shore and timber frames laid down. It was quite cold. The shore was lined with driftwood and young uprooted willows, and we laid in a supply of small firewood—enough to last a week.

Friday morning, Nov. 27.—Temperature 20; clear and cold, with a south wind blowing, which makes the waves bump the boat some, the wind opposing the swift current. Got off about 7:45, heading for Chester, where the Desplaines expects to stop for letters.

THE MISSISSIPPI.