Title: Strange Teas, Dinners, Weddings and Fetes

Author: Various

Release date: January 28, 2014 [eBook #44779]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Emmy, Dianna Adair and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

| Page. | ||

| I. | My Tea to Mehemet Ali and Fareedie | 9 |

| II. | A Japanese Dinner | 21 |

| III. | A Roman Christmas | 31 |

| IV. | Sylvester-Abend | 42 |

| V. | A Coptic Wedding | 51 |

| VI. | In the Bois de Boulogne | 57 |

| VII. | An Arab Dinner-Party | 66 |

| VIII. | A Birthday Party in the West Indies | 79 |

| IX. | A Siamese Hair-Cutting | 91 |

| X. | Old English Harvest Customs | 96 |

| XI. | Easter at Jerusalem | 109 |

| XII. | The Moqui Snake-Dance | 115 |

The Pasha rode a fine bay horse and was dressed in European costume, excepting that he wore a turban instead of a hat. He was short and stout, well bronzed by the sun, and had that air of command which so much distinguishes a soldier[10] if he possesses it. He seemed to be about fifty years of age, although I have heard he was much older.

Just here I shall tell you that I never saw a tall and slender Turk, though I have seen many handsome ones. They all seemed to show in their features and frame their Tartar origin.

Damascus is the capital of the Pashalic, and Midhat went there to live in the palace of the Governors, which is near the famous Mosque of the Sultan Selim. Damascus is about ninety miles from Beirût, and the road that connects the two cities is an excellent one. It was built by the French after the terrible massacres in the Lebanon Mountains in 1860.

We soon heard the new Pasha was very much disliked in Damascus. He tried to reform several abuses in the administration of affairs, and gave great offence to all classes of the people; so he brought his family with him and came to live in Beirût.

The Turks are Orthodox Mohammedans, you know, and are polygamists. In his youth Midhat[11] married a lady, who was remarkable for her goodness, and he esteemed her very much. But this lady had a great sorrow, for no little children were hers. After awhile she asked Midhat to marry a lady she knew, and he did so.

These ladies were very fond of one another; the elder was the adviser and counselor of her husband, interested in politics and business; the other was very industrious, made beautiful fancy-work and embroidery, and was always busy with her needle, so neither became a horrible scold, nor a lazy, fat animal, as almost all Mohammedan women become because they are so idle and have nothing to think about.

I knew the two dear little children of the second wife. The boy, Mehemet Ali, was seven years old, and the little girl, Fareedie, was five. I became acquainted with them in this way.

Midhat wished the children to be well educated, and he engaged an English lady, named Mrs. Smith, to be their governess, with the distinct understanding that she was never in any way to mention any of the doctrines of our Christian religion[12] to them. This was a hard thing for her to promise, but she did so and assumed the charge of the children. They slept in a room opening from hers and she watched over them night and day with loving care. I knew Mrs. Smith very well, and through her knew the children and their mother.

The little ones could speak French very well (French is the favorite language of all Orientals), but not any English.

I seem to be a long time in reaching my story, but I had to tell you all this, else how would you have known who Mehemet Ali and Fareedie were, or how extraordinary it was for the children of a Turkish Pasha to go anywhere to tea?

I invited them to take luncheon with me, but Mrs. Smith said that would interfere with their morning lessons, so the invitation was changed, and I asked them to come to tea.

It was a beautiful November afternoon (November in Syria is warm and is the perfection of weather), and I sent a carriage for them at half-past three o'clock. They soon came, no one with them but Mrs. Smith.

Mehemet Ali wore a light gray suit made like an American boy's, only his trousers were long and he had a red tarboosh on his head. He had worn a hat, but this gave offence to the Turks and was one of the charges made against his father by the people of Damascus, so it had been discarded.

Fareedie wore a dark blue velvet frock with a frill of lace around the neck, and on her feet were little red Turkish slippers. She was very beautiful, eager and quick—nay, passionate in all her feelings—and from the time she entered my house until she left it in a quiver of excitement. When she came in, she kissed me on the cheek and gave me some white jasmine blossoms strung like beads upon a fine wire, something little Syrian children are very fond of. Her first astonishment was the long mirror in my wardrobe; she never had seen one before, and when she caught sight of herself in it, she cried breathlessly: "Oh! très jolie! très jolie!" and turned herself in every direction to see the effect, then ran to me and gave me another kiss and called me, "chère Madame."

She darted hither and thither, looking at every[14] thing and chattering; but Mehemet Ali was very grave, although his little beady black eyes were looking at everything also, and showed the interest he felt but wished to conceal.

Now Fareedie was on the balcony looking down on the fountain below and some shrubs covered with wonderful large blue flowers (like morning-glories, only ever so much larger)—"trees of flowers," she called the shrubs; then she spied a little rocking-chair, something that was a wonderful curiosity to her, and, when told that she might sit in it, she rocked back and forth furiously, till I really feared she would break her pretty little neck.

I said to Mrs. Smith, "This will never do; I will take her on my lap and show her pictures."

"Yes," said she, "that will be a great treat, for she has never seen any."

"It is not possible!" I exclaimed.

"Indeed it is. You forget the Mohammedans do not allow pictures anywhere in their houses, and the little books I have to teach the children from are French ones without illustrations."

By this time I had gotten a book of Natural History, and, taking the little girl on my knees, I said I would show her something. I opened the book at random, and I shall never forget the look upon Fareedie's face, nor the quiver that ran through her little body, when she saw the picture and screamed out, "Tigre! Tigre!"

At this Ali ran to us and the two turned over the pages hurriedly, mentioning the names of each animal they knew, with a delight I cannot describe to you.

Then Ali said, "Perhaps, Madame, it may be you have a picture of an engine of a ship—is it so?"

(This sentence of Ali's I have translated for fear it would be hard for you, if I gave it in French. You remember he did not know English.)

"Now what shall I do!" I thought, "for I don't know anything about engines, and I don't know where to find any pictures of them;" but the black eyes helped in the search, and before I could think where to look the boy seized upon a copy of the Scientific American, and there, fortunately, were several[16] pictures of engines and boilers. He did not move for a long time afterward, except to say, "It is a regret that I do not know the English to read." He sat as still as a statue, perfectly absorbed, even pale, so intense were his feelings.

Soon Prexea, my slender Syrian maid, came in and announced that tea was served. Prexea was a Greek in religion and hated the Turks, so she was not in a good humor, as I knew very well by the way she opened the door.

Fareedie ran into the dining-room, but Ali evidently did not wish to lay down his paper, till Mrs. Smith gently told him he must; then he obeyed.

"A table! Chairs! How droll! How droll!" cried Fareedie.

And now a great difficulty presented itself. They had never sat at a table, and I had no high chairs for them. They always sat on the floor, on a rug, to eat, and had a low Arabic table put in front of each of them. Their tables are about eighteen inches high, made of olive wood inlaid with mother-of-pearl and silver, perhaps all silver. As to dishes, the children seldom had even a bowl.

Arabic bread is very peculiar. It is baked in thin flat cakes, about the size of a dinner plate, and does not look in the least like bread, more like leather. The children usually had one of these cakes for the dish, and all that they were to have to eat would be put on it, then another cake would be given to them which they would break in pieces, using them as spoons, and last of all, eating spoons and dish, too.

So you can imagine how surprised they were when they saw my table. But what about chairs for them? A brilliant idea struck me. I ran to the bookcase and got two dictionaries, which I put on the chairs they were to occupy, and with Ali on Webster's and Fareedie on Worcester's, we began our meal.

Ali had been very serious during these proceedings and, as soon as we were seated, he pointed to my sideboard and the silver on it, and said impressively, "Très magnifique!"

The knives and forks were too much for them. They sawed away with the one and speared the food with the other so ineffectively, that we told[18] them they might eat with their fingers, which they did very nicely.

I had tea and coffee, sandwiches, cold chicken, blackberry jam, and other sweets and cake. The sandwiches were of eggs, not ham, of course; for it would have been an insult to their parents to have let them taste pork, which is held in great abhorrence by all Mohammedans. Why, many of them will not wear European shoes, for fear the bristles of swine may have been used in sewing them.

Both children asked for coffee "à la Frank," as they called it. They had never seen it with cream in it, nor served in anything but a tiny Oriental cup. I gave it to them in our own coffee cups, with plenty of cream in, and they stirred it with their spoons and said it was "very grand."

Fareedie was a little sloppy, I must confess, but otherwise they behaved very politely.

But the questions they asked! Fareedie was an animated interrogation point, I thought; and after tea Ali lost his impassiveness, and went round the house examining everything with curiosity, especially[19] anything that could be moved, or had casters on it.

At last the visit was over. My tall "cawass" came in and announced the carriage was at the door to take them home. With many promises to come again, they went away, kissing me lovingly, Ali with the coveted Scientific American under his arm, and Fareedie with a cup and saucer her little heart had longed for.

But they never did come, and I never saw them anywhere again. For, Wasif Effendi, the Secretary of the Pasha, hated Mrs. Smith, and by some underhand means contrived to have her dismissed. Then Midhat was transferred to Smyrna, and my little friends left Beirût, never to return, I fear. Perhaps you know the Pasha was ordered to Constantinople and tried for the murder of the Sultan Abdul Aziz. It was proved that he had been an accomplice, and he was exiled for life, to a place called Jeddah.

And there on the shores of the terrible Red Sea, near Mecca, and far from all civilizing and good influences, my dear little friends are forced to live.[20] Their father is dead, but his family are still at Jeddah.

You would be surprised to know how often I think of them, and how sad it makes me. Their future is full of peril. I wonder if they ever think of me!

We took off our shoes at the door, and those who had not been sufficiently provident to bring with them a pair of wool slippers, entered in their stocking feet.

We were at once greeted by our host and hostess. Japanese ladies do not often act the hostess at a dinner-party, but usually remain in the background. Our friend, however, having travelled considerably in America and Europe, was advanced in his ideas, and gave his wife a wife's place.

Several beautiful Japanese girls were in waiting[22] who at once conducted us to a spacious dining-room on the second floor.

Going out on the long piazza adjoining, we saw in the distance the bay with its calm blue waters and white-winged boats; and to the right Mount Fuji, her peerless head losing itself in ambient clouds; while at our feet lay a bewildering maze of dwelling houses, shops, and temples.

The floor of the porch was polished smooth as marble, and the patterns in the lattice work were graceful combinations of maple leaves.

As we re-entered the dining-room our first impression was that of a vast empty apartment. The only visible signs of preparation for our coming were the cushions upon which we were to sit, and the hibachi or fire bowls, over which we were to toast our fingers. We sat down upon the mats, trying hard to fold our limbs under us à la Japanese, but our attempts were for the most part very awkward.

Then came some introductions. Our host had invited two friends to meet us, Mr. and Mrs. Suyita. Mr. Suyita, being a Japanese of the old school and very ceremonious, bowed low, so low[23] that his honorable nose quite kissed the floor; and remembering that when we are in Turkey we must do as the Turkeys do, we endeavored to salute him in the same formal manner.

At length recovering our equilibrium we resumed our old position on the mats, tried to look comfortable, and began to study the details of our surroundings. The cushions upon which we sat were covered with beautiful dark-blue crêpe relieved here and there by branches of maple leaves, the rich October coloring making a striking but exquisite contrast with the more sombre background. The mats were marvellously fine, and so clean that one might suppose our party the first that had ever assembled there.

At one end of the room just above the toko-noma, or raised platform on which all the ornaments of the room are placed, was a kakemono, or picture scroll, the work of a celebrated painter named Isanenobu, and very old. On this platform stood a large vase of brown wicker work so wondrously fine that at a little distance it appeared like an elegant bronze. In this vase were branches of[24] flowering plum and cherry arranged as only Japanese know how to arrange flowers. The ceilings were panels of cryptomeria, and without either paint or varnish, were beautiful enough for a prince's palace.

This immense room was divided by sliding doors into three apartments. The doors were covered with paper. Here, too, was the prevailing pattern, for over the rich brown background of the paper were maple-leaf designs in gold and silver, and above the doors were paintings of maple branches with foliage of scarlet, maroon, and every shade of green. On the opposite side of the room was another raised platform. Here also were two large vases, and in them branches of flowering shrubs, some of which were covered with lichens. A bronze ornament of rare workmanship stood between, for which many a seeker of curiosities would give hundreds of dollars.

Soon beautiful serving-maids entered and placed in front of us trays on which were tea and sweetmeats. In Japan the dessert comes first. The trays were ornamented with carvings of maple[25] leaves, the tea-cups were painted in the same design, and the cakes themselves were in the shape of maple leaves, with tints as glowing, and shading almost as delicate as though painted by the early frosts of autumn. We ate some of the cakes and put some in our pockets to carry home. It is etiquette in Japan to take away a little of the confectionery, and paper is often provided by the hostess in which to wrap it. The native guests put their packages in their sleeves, but our sleeves were not sufficiently capacious to be utilized in this way. I have been told that at a foreign dinner given to General Grant in Japan, some of the most dignified officials, in obedience to this custom, put bread and cake, and even butter and jelly, into their sleeves to take home.

After our first course came a long interval during which we played games and amused ourselves in various ways. At the end of this time dinner was announced. Once more we took our places on the cushions and silently waited, wondering what would happen next. Soon the charming waiters again appeared and placed on the floor in[26] front of each visitor a beautiful gold lacquer tray, on which were a covered bowl of fish soup, and a tiny cup of sake. Sake is a light wine distilled from rice, and is of about the strength of table sherry. A paper bag containing a pair of chopsticks also rested upon the tray; and taking the chopsticks out, we uncovered our soup and began to look around to see how our Japanese friends were eating theirs. We shyly watched them for a moment. It looked easy; we were sure we could do it, and confidently attempted to take up some of the floating morsels of fish; but no sooner did we touch them, than they coyly floated off to the other side of the bowl. We tried again, and again we failed; and once again, but with no better success. At last our perseverance was partially rewarded, and with a veni-vidi-vici air we conveyed a few solid fragments to our mouths, drank a little of the soup, and then covering our bowl, as we saw others do, we waited for something else to happen.

In the meantime large china vessels of hot water had been brought in and our host kindly showed us their use. Emptying his sake cup, he rinsed[27] it in the hot water, and then re-filling it with wine, presented it to a friend who emptied his cup, rinsed and re-filled it in the same way, and gave it in exchange for the one he received.

The next course consisted of fish, cakes made of chestnuts, and yams; the third, of raw fish with a very pungent sauce; the fourth, of another kind of fish and ginger root. After this we were favored with music on the ningenkin. This is a harp-like instrument giving forth a low weird sound, utterly unlike anything I have ever heard called music. The fifth course consisted of fish, ginger root, and "nori," a kind of seaweed.

After this we had more music, this time on the koto. The koto is also something like a harp in appearance. The performer always wears curious ivory thimble-like arrangements on the tips of her fingers, and to my uneducated ear, the so-called music is merely a noise which any one could make. We were next favored with singing. This, too, was low and plaintive, bearing about the same resemblance to the singing of a European that the cornstalk fiddle of a country schoolboy bears to[28] the rich mellow tones of a choice violin. This same singing, however, is regarded as a great accomplishment in Japan. The singer on this occasion was a rare type of Japanese beauty, fair as a lily, with hands and feet so delicate and shapely that she was almost an object of envy. Her coiffure, like the coiffures of all Japanese women, was fearfully and wonderfully made. Her dress was of the richest crêpe, quite long and very narrow, opening in front to display a gorgeous petticoat, and with square flowing sleeves that reached almost to the floor. Her obi, or girdle, was brocade stiff with elegance, and probably cost more than all the rest of the costume. The mysteries of the voluminous knot in which it was tied at the back I will not pretend to unravel. Her face and neck were powdered to ghostly whiteness, and her lips painted a bright coral; altogether she looked just like a picture, not like a real woman at all.

After this came another course consisting of fowl and fish stewed together in some incomprehensible way. There was also an entree of pickled fish. The eighth course consisted of fish and[29] a vegetable similar to asparagus; the ninth of rice and pickled daikon. Rice is the staple dish, and, according to Japanese custom, is served last. The daikon is a vegetable somewhat resembling a radish. It grows to an enormous size. Indeed it is a common saying among vegetable-growers that one daikon grown in the province of Owari, takes two men to carry it, and that two Satsuma turnips make a load for a pony. This sounds somewhat incredible, and yet it is stated for a fact that a daikon was not long ago presented to the emperor which measured over six feet in girth. These monster turnips are generally sound to the core; and to the Japanese they are an exceedingly delicate and palatable aliment; with us the odor of them alone is sufficient to condemn them.

Last of all came tea which was served in the rice bowls without washing them. The dinner lasted four hours; and when at the close we attempted to rise from the mats, our limbs were so stiff from sitting so long in this uncomfortable position that we could hardly move.

We put on our shoes soon after, and were then[30] conducted round the grounds. In the same enclosure was a summer rest-house for the Mikado. We looked inside for the shōji, or sliding doors, were all open, and we could see the whole length of the house. Here, as in all Japanese houses, the mats were the only furniture. They were beautifully fine, and the rooms though empty were attractive.

After walking about for a little while we went through a long calisthenic exercise of bows, and with warmest thanks to our kind host and hostess, stowed ourselves away in jinrikishas, and rode off to our homes.

This of course is not a description of an ordinary dinner in Japan. Indeed it was a very extraordinary one given in honor of a party of Americans about to return to the United States. The common people dine with very little formality. Bread, beef, milk and butter are unknown to them. They live principally on rice, fish, and vegetables, served in very simple fashion; and they eat so rapidly that dyspepsia is even more common in Japan than in America.

In the morning, about half-past ten, I went to a church on the Capitol Hill, called Church of the Altar of Heaven. This hill is high and there are one hundred and twenty-four steps leading to the door of the church. It was a dull gray day, and the rain was pouring down so hard that there were little pools and streams all over the old stone steps. But many people were going up. There were men from the country in blue coats and short[32] trousers, and women with bodices and square white head-dresses, who carried the largest umbrellas you have ever seen, blue or green, or purple with bright borders around them. And there were children, more than you could count, some with the country people, others with their nurses, and many who were very ragged, all by themselves. At the top of the steps men were selling pious pictures and did not seem to mind the rain in the least. Over the doors were red hangings in honor of Christmas.

Inside were more people. At the far end service was going on and the monks, to whom the church belongs, were chanting, and there was a great crowd around the altar. But near the door by which I came in, and in a side aisle was a still larger crowd, and it was here that all the little ones had gathered together. They were waiting in front of a chapel, the doors of which were closed tight. For they knew that behind them was the Manger which every year the monks put up in their church. Right by the chapel was a big statue of a Pope, larger than life, and some[33] eager boys had climbed up on it and were standing at its knee. And some who had arrived very late were perched on another statue like it on the other side, and even in the baptismal font and on tombstones at the foot of the church. Women and men were holding up their babies, all done up in queer tight bandages, that they too might see. And all were excited and looking impatiently down the long aisle. Presently, as I waited with the children, there came from the side door a procession. First came men in gray robes, holding lighted tapers, then monks in brown with ropes around their waists, and last three priests who carried a statue of the Infant which is almost as old as the church itself. When they reached the chapel the doors were thrown open, and they took this statue in and placed it at the foot of those of the Virgin and St. Joseph.

I wish you could have been there to look in as I did. It was all so bright and sunny and green. It seemed like a bit of summer come back. In front was the Holy Family with great baskets of real oranges and many bright green things at[34] their feet. And above them, in the clouds, were troops of angels playing on harps and mandolins, and in the distance you could see the shepherds and their sheep, and then palm trees, and a town with many houses. It was so pretty that a little whisper of wonder went through all the crowd, while many of the boys and girls near me shouted aloud for joy.

So soon as the procession was over, every eye was turned from the chapel to a small platform on the other side of the church. It had been raised right by an old column which, long before this church was built, must have stood in some temple of Pagan Rome. Out on the platform stepped a little bit of a girl, as fresh and as young as the column was old and gray. She was all in white, and she made a pretty courtesy to the people, and then when she saw so many faces turned towards her, she tried to run away. But her mother, who was standing below, would not let her, but whispered a few words in her ear, and the little thing came back and began to give us all a fine sermon about the Christ-child. Such funny little gestures[35] as she made! Just like a puppet, and, every now and then, she looked away from us and down into her mother's face, as if the sermon were all for her. But her voice was very sweet, and by and by she went down on her knees and raised her hands to Heaven and said a prayer as solemnly as if she really had been a young preacher. But after that, with another courtesy, she jumped down from her pulpit platform as fast as ever she could.

And this is the way Roman children celebrate Christmas. On Christmas Day, and for a week afterwards, for one hour every afternoon, they preach their sermons, and all the people in the city and the country around, the young and the old, the grave and the gay, come to hear them.

I made a second visit to the church two or three days later. The rain had stopped and the sky was bright and blue, and the sun was shining right on the steps, for it was about three in the afternoon. And such a sight you have never seen! From top to bottom people were going and coming, many in the gayest of gay colors. And on each side were pedlers selling toys. "Everything[36] here for a cent!" they were calling. And others were selling books, through which an old priest was looking, and oranges with the fresh green leaves still on their stems, and beans, which the Romans love better than almost anything else, and pious pictures and candy. Ragged urchins, who had spent their pennies, had cleared a space in one corner and were sending off toy trains of cars. Climbing up in front of me, two by two, were about twenty little boys, all studying to be priests and dressed in the long black gowns and broad-brimmed hats which priests in Italy wear. To one side was a fine lady in slippers with such high heels that she had to rest every few minutes on her way up. On the other were three old monks with long gray beards and sandals on their bare feet. And at the church door there was such pushing in and out that it took me about five minutes to get inside.

Here I found a greater crowd even than on

Christmas. There were ever so many peasants,

the men's hair standing straight up on end, something

like Slovenly Peter's only much shorter, and[37]

[38]

[39]

the women, clasping their bundles of babies in

their arms. And close to them were finely dressed

little girls and boys with their nurses. If you once

saw a Roman nurse, you would never forget her,

for she wears a very gay-colored dress, all open at

the neck, around which are strings of coral. And

on her head is a ruching of ribbon, tied at the back

with a bow and long ends, and through her hair is

a long silver pin, and in her ears, large ear-rings.

And there were many priests and monks and even

soldiers, and the boys had climbed up again on

the statues, and one youngster had put a baby he

was taking care of right in the Pope's lap.

The lights were burning in the Manger, but the people were standing around the platform, for the preaching had begun. Before I left I heard about ten little boys and girls make their speeches. One or two of the girls were quite grown up, that is to say they were perhaps ten or twelve years old. And they spoke very prettily and did not seem in the least bit afraid. Some wore fine clothes and had on hats and coats, and even carried muffs. But others had shabby dresses, and their heads[40] were covered with scraps of black veils. First came a young miss, whose words tumbled out of her mouth, she was so ready with them, and who made very fine gestures, just as if she had been acting in a theatre. And next came a funny little round-faced child, who could hardly talk because she was cutting her teeth and had none left in the front of her mouth, and who clutched her dress with both hands, and never once clasped them or raised them to Heaven, or pointed them to the Manger, as I am sure she had been taught to do. But she was so frightened I was glad for her sake when her turn was over. Two little sisters, with hats as big as the halos around the saints' heads in the pictures, recited a short dialogue, and all through it they held each other's hands tight for comfort, even when they knelt side by side and said a prayer for all of us who were listening. And after that a little bit of a tot said her little piece, and she shrugged her shoulders until they reached her pretty little ears, and she smiled so sweetly all the time, that when she had finished every one was smiling with her, and some even laughed outright.[41] But while they were still laughing a boy, such a wee thing, even smaller than the little smiler, dressed in a sailor suit and with close-cropped yellow head, toddled out. He stood still a moment and looked at us. Then he opened his mouth very wide, but not a word could he get out. His poor little face grew so red, and he looked as if he were about to cry. And the next moment he had rushed off and into his mother's arms. But indeed the big boy who took his place was almost as badly scared, and half the time he thrust his hands deep into his pockets, and you could see it was hard work for him to jerk them out to make a few gestures.

They were all pretty little sermons and prayers, and I think they must have done the people good. When I went out from the cool gray church on to the steps again, the sun shone right into my eyes and half blinded me, and perhaps it was that which made me sneeze twice. A small bareheaded girl ran out from the crowd when she heard me, and cried "Salute!" which is the Italian way of saying "God bless you." And I thought it a very fitting Amen to the sermons.

It so happened a few years ago that I was spending the holidays in one of the pleasantest homes in one of the most beautiful towns of South Germany, and there I learned how this festival was kept.

The first of January being in that country St. Sylvester's Day, it is New Year's Eve which is celebrated as Sylvester Eve, or Abend.

"You will come into the drawing-room, after coffee, and see the Christmas-tree plundered," the Doctor's wife had said to me, smiling, at dinner; and all the children had clapped their hands and[43] shouted, "Oh yes! the Christmas-tree plundered, huzza!"

There were more children around the Frau Doctor's table than you could easily count. Indeed, there were more than the long table could accommodate, and three or four had to be seated at the round "Cat's table" in the bow window. There were the two fair-haired little daughters of the house, their tall, twelve-year-old brother, two little Russian boys, three Americans, and another German, who boasts of being the godson of the Crown Prince; all these were studying under the direction of Monsieur P—— the French tutor. Besides, there were half a dozen older boys, who had come from all parts of the globe, England, Cuba, Chili, and where not, to study with the Herr Doctor himself, who is a learned German Professor. And since to-day was holiday—there was little Hugo, pet and baby, standing upon his mother's knee, clapping his hands and shouting with all his might "Me too! plunder Christmas-tree!"

"Why do you call it Sylvester Evening?" I asked the Frau Doctor.

"Because it is Sylvester evening; that is, to-day is dedicated to St. Sylvester, in the Romish Calendar. He was bishop of Rome in the time of the Emperor Constantine, I believe. But there is no connection between the saint's day and the tree-plundering. Still we always do it on Sylvester evening, and so, I think, do most people because it is a convenient time, as every one is sitting up to watch for the birth of the New Year. In some families, however, the tree is kept until Twelfth Night, and in yet others it is plundered the third or fourth day after Christmas."

"Is there any story about St. Sylvester?" asked Nicholas, the bright little Russian, always on the lookout for stories.

"More than one; but I have only time to tell you one which I think the prettiest. You are not to believe it, however.

"When the Emperor Constantine who had been a heathen, was converted to Christianity, some Jewish Rabbis came, to try to make him a Jew. St. Sylvester was teaching the Emperor about Christ, and the Rabbis tried to prove that what[45] he said was false; but they could not. At this, they were angry, and they brought a fierce wild bull, and told Sylvester to whisper his god's name in its ear, and he should see that it would fall down dead. Sylvester whispered, and the beast did fall dead. Then the Rabbis were very triumphant. Even the emperor began to believe that they must be right. But Sylvester told them that he had uttered the name of Satan, not of Christ, in the bull's ear, for Christ gave life, not destroyed it. Then he asked the Rabbis to restore the creature to life, and when they could not, Sylvester whispered the name of Christ, and the bull rose up, alive, and as mild and gentle as it had before been fierce and wild. Then everybody present believed in Christ and Sylvester baptized them all."

The Christmas-tree, which all the week had stood untouched, to be admired and re-admired, was once more lighted up when we went into the drawing-room in the early twilight after four o'clock coffee. All the children were assembled, from the oldest to the youngest, and gazing in silent admiration; little Hugo, with hands clasped[46] in ecstasy, being the foremost of the group. As you probably know, the Christmas presents had not been upon the tree itself, but upon tables around it. It was the decorations of the tree, candy and fruit, and fantastic cakes, very beautiful, which had remained, and which we were now to treat as "plunder."

When Frau Doctor had produced more pairs of scissors than I had supposed could be found at one time in a single house be it ever so orderly and had armed the family therewith, the cutting and snipping began in good earnest. It was a pretty picture: the brilliantly-lighted tree with its countless, sweet, rich decorations, and the eager children intent on their "plundering;" the little ones jumping up to reach the threads from which hung the prizes, and the elder boys climbing upon chairs to get at those which were upon the topmost boughs.

Frau Doctor received all the rifled treasures, as they were rapidly brought to her, heaping them upon a great tray, while Monsieur P. beamed delight through his green spectacles and wide mouth,[47] and Herr Doctor, in the background, amused himself with the droll exclamations, in all sorts of bad German, with which the foreign boys gave utterance to their delight.

When the last ornament was cut off and laid upon the heaped-up tray, and the last candle had burned out, we adjourned to supper.

When that meal was over and the cloth brushed, the tray was brought on, and with it two packs of cards. Now came some exciting moments. All watched as Frau Doctor laid a sweetmeat toy upon each card of one pack, and then dealt the remaining pack around among us. When all were provided, she held up the card nearest her, for us all to see, displaying at the same time, the prize which belonged to it. Then came an eager search in everybody's hand, and great was the delight when little Hugo produced a card exactly like the one which his mamma held up, and received the great gingerbread heart, or "lebkuchen" which happened to belong to that card; for in little Hugo's estimation lebkuchen was the choicest of dainties. Another card and another, with their[48] respective sweetmeats, were quickly turned, the children becoming more eager as one after another received a prize. Again and again the cards were dealt, for the tray of delicious and funny things seemed inexhaustible. The game grew more and more merry as it went on. What cheers greeted the discomfited Monsieur P. as a tiny sugar doll, in bridal array, fell to his lot! what huzzas resounded when Herr Doctor threatened to preserve his long cane of sugar-candy, as a rod to chastise unruly boys withal!

When the last card had been turned, and every place showed a mighty heap of dainties, the tea-kettle was brought on, and Frau Doctor brewed some hot lemonade as a substitute for the "punch" which is thought quite essential at every German merrymaking. In this we drank each other's healths merrily, the boys jumping up to run around the table and clink glasses, and all shouting "lebe hoch!" at the top of their lungs after each name. Then we drank greetings to all who, in whatever land, should think of us this night. This toast was not so noisy as the others had been, and the[49] unusual quiet gave us time to reckon up the many places in which our absent relatives were. From Russia to Australia they were scattered, through nearly every country on the map.

At last, with Frau Doctor's name on our lips, and many clinkings and wavings of glasses, and shouts of "Frau Doctor, lebe ho-o-o-ch!" the party broke up. The little ones went to bed, the older boys and the "grown-ups" into the parlor to "watch for the New Year," a ceremony which may by no means be omitted. What with games and music and eating of nuts and apples the evening was a short and merry one; but when the clock pointed to a quarter before midnight, silence fell upon us.

Suddenly, the peals rang out from all the church towers; cannons were fired and rockets sent up from the market place; we rushed to throw the windows wide open to let the New Year in. Then we turned and shook hands all around and wished "Happy New Year;" then again to the windows. Out of doors all was astir; the bells still pealing, rockets blazing, people in the streets shouting to[50] one another. The opposite houses were all lighted up, and through the open windows we could see all their inmates shaking hands and kissing one another.

But it was too cold to stand long at an open window. The New Year was already nipping fingers and noses as his way of making friendly overtures; merry Sylvester-Abend was gone and so we bade each other and the Old Year good-night.

But now she was to be married—this baby girl. Her future husband had never seen her face; for, according to the custom of the people, the parents had made all the arrangements, and the contract usual in such ceremonies had been drawn up by the fathers and mothers and signed in the presence of a priest without a word or suggestion from the parties most concerned in the transaction. The intended bridegroom was a young clerk in the employ[52] of an English friend, a handsome, intelligent boy, but with little experience of life. We had heard the wedding was to be a grand affair, and were glad to accept an invitation to this Egyptian ceremony.

On the night of the marriage, the bridal procession, or zeffeh as it is called, looked as if wrapped in flames as it came slowly up the narrow street in the midst of hundreds of colored torches. A band was playing Arab tunes and women were ringing out the zaghareet—wedding laugh of joy—which is a kind of trill made with the tongue and throat. The entire way was lit with expensive fireworks of brilliant variety, and all the street wraps worn were of gorgeous colors.

Our little friend marched in this slow procession, her features concealed, as usual; that is, she was wrapped in a cashmere shawl, not covered by a canopy, as in Arab weddings, although in many respects the Coptic ceremony is similar to that of the Moslems.

She wore a white silk gown embroidered with gold, and over this a long flowing robe of lace,[53] while masses of diamonds fastened the white face-veil to her turban.

Just before her walked two little boys carrying censers the smoke of which must have poured directly into her face as she walked slowly on enveloped in her cashmere wrappings.

On either side and a little in advance of the bride were the male relatives and friends, while behind her, continually trilling the zaghareet, followed the female friends; and along the whole procession two boys ran back and forth, bearing silver flasks of pomegranate form filled with perfume which they jetted in the faces of the guests in a most delicious spray.

The house of the bridegroom's father where the marriage was to take place, is situated in a narrow street off the Mooski, and as we reached the entrance we were met by black slaves who handed us each a lighted taper. Then a sheep was killed on the door-stone—a custom, I believe, observed only in Cairo, and some of the larger cities of Egypt. The bride, glittering with her diamonds and gorgeous costume, was carried over it and[54] then the whole procession walking over the blood—the body having been removed—all of us bearing our lights—went in to the marriage, and the door was shut. Does it not remind you of the Parable of the Ten Virgins of old?

We were conducted to a room, very lofty and spacious. A low divan reached around it and constituted its sole furniture, excepting the table on which was spread the marriage supper.

At this supper I witnessed a custom which reminded me of an old Roman story. A slave brought in two sugar globes on separate dishes. When these were placed upon the table, one of the guests was invited to open them. Immediately upon one having been broken, out flew a lovely white dove, its neck encircled with tiny bells which rang merrily as it flew about. The other dove did not at first fly, when liberated from its sugar cage; but one of the guests lifted it up until it fluttered away like the other. If either of the doves should not fly, these superstitious people would draw from it an evil omen.

Many Arab dishes were set before us, among[55] them boned fowl stuffed with raisins, pistachio, nuts, bread and parsley; sweets and melons following. But as an Arab eats with remarkable rapidity, one course was hardly brought before another took its place.

We were soon ready to accompany our host to the room where the marriage ceremony was to be performed, into which we were ushered in the midst of Arab music, sounding cymbals, smoking-incense, the zaghareet, and the unintelligible mutterings of many priests.

The bridegroom, clad in an immense white silk cloak embroidered with silk and gold, sat waiting in one of two palatial-looking chairs. In the midst of a perfect storm of music and confusion a door opened, and the bride, her face still veiled, entered and took the chair beside the bridegroom.

There were four priests to officiate in this novel marriage, three of whom were blind; these muttered Coptic prayers and filled the air with incense, while the priest whose eyes were perfect tied the nuptial knot by binding the waiting couple to each other with several yards of tape, knocking their[56] heads together, and at last placing his hands in benediction on their foreheads and giving them a final blessing.

This concluded the ceremony.

We were glad to escape from the close room into the pure out-of-door air. We drove away under the clear, star-lit heavens, through the narrow streets with their tall houses and projecting balconies, out into the Mooski, the Broadway of Cairo, now silent and deserted; on into the wide, new streets, and so home; but it was nearly morning before I fell asleep, for the tumultuous music and trillings and mutterings of that strange ceremony rang in my ears and filled my thoughts with as strange reveries as if I had eaten hasheesh.

The greater part of our time was spent in Paris and as we lived near the Bois de Boulogne we were taken there every day by our bonne and allowed to play to our hearts' content. Some of you have probably been in this beautiful park and walked through its broad avenues and its hundreds of shady little alleys.

You may have followed as we did some of the merry little streams to find out where they would lead you, or better than all you may have joined in the play of some of the French children and discovered games new and strange to you. All[58] this became very familiar to us and I often think of the good times we had there, when all the days were like fête days, and of the pretty games we used to play there with the charming French children.

French children think "the more the merrier;" so when a game is proposed the first thing they do is to look about and see if there are not other children near by whom they can ask to join them. This is done as much for the sake of showing politeness as to increase numbers, and as it is the custom, the mammas or the nurses of the invited children never refuse to let them take part in the fun.

Hide-and-seek or "cache-cache," blind-man's-buff or "Colin Maillard," tag, marbles, all these we also played; but there were other games I have never seen in this country.

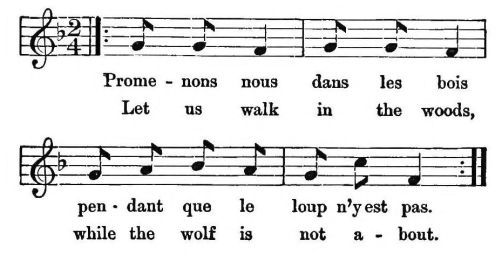

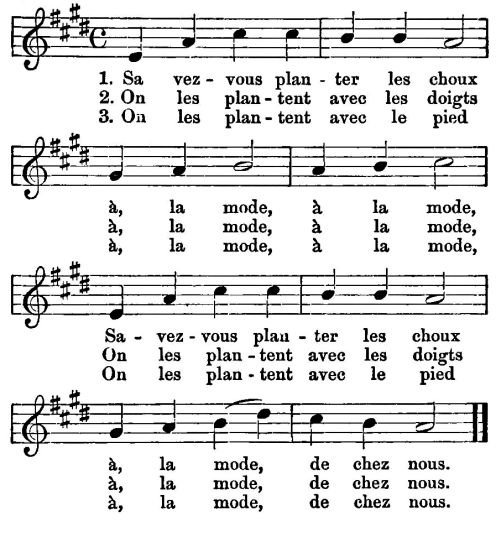

One of which we never tired was "Le Loup—the Wolf." A boy was usually chosen for the wolf, and while he withdrew a short distance the others sauntered about among the trees, leisurely singing this little song:

Then they call "Loup, viens-tu?—Wolf, are you coming?" "Non, je me lève—No, I'm getting up," replies the Wolf. Then they sing again and call, "Loup, viens-tu?" "Non, je m'habille—No, I'm dressing." This goes on for some time, the wolf prolonging the agony as much as possible, and stopping to get his hat, his cane, or cigar, but finally making a rush with, "Je viens—I'm coming!" he dives into the crowd, scattering the children in every direction and making general havoc. The one who happens to be captured is the "wolf" the next time.

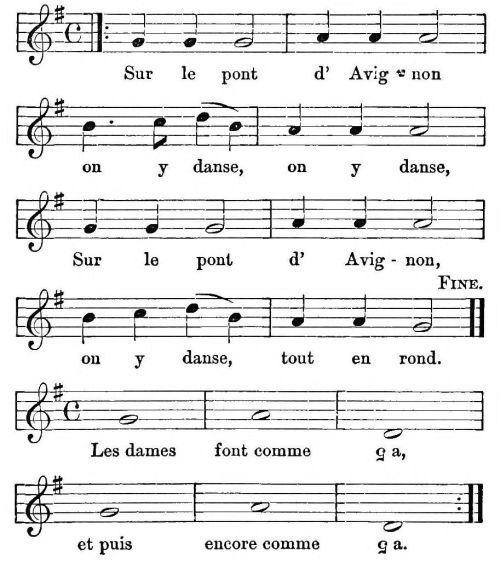

Another game more limited to little girls, was, "Sur le Pont d'Avignon." We formed a ring and danced around singing:

"On the bridge of Avignon the people dance in a ring, the ladies do this way" (courtesying).

The next time it is "Les blanchiseuses font comme ça—the washerwoman, etc.," suiting the action to words; then "Les couturières font comme ça—the dressmakers do this way." Every trade or occupation[61] was gone through with in like manner with the greatest earnestness.

Here is another of the same character:

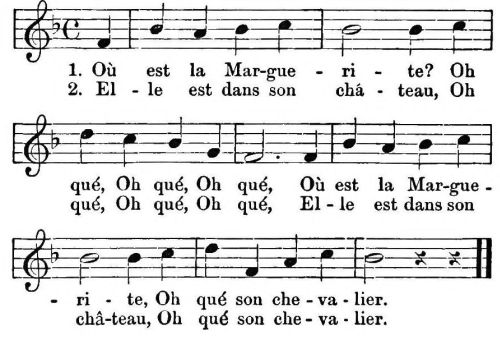

But the prettiest of these singing games was "La Marguerite." To play this a circle was formed around La Marguerite, who was supposed to be a beautiful princess waiting to be rescued from her[62] imprisonment. Two knights seeking her walked round the ring singing:

The skipping-rope and the hoop are, or were then, much more used there then here; and to skip the rope gracefully, or guide a hoop dexterously, was an accomplishment.

Whoever was agile enough to pass the rope under the feet twice while giving one skip was looked upon with admiration. New developments[63] constantly took place with the skipping-rope or "corde à sauter," and all sorts of evolutions were gone through with, many of which were pretty and graceful.

Lively games were usually played in some wide open space near the Porte Maillot, one of the entrances to the Bois, as there was always sure to be a great number of both grown people and children thereabout. But there were retired nooks where our little band sometimes gathered and made merry. One favorite retreat was a pine grove; "Les Sapins" we called it.

Here the little girls liked best to play dolls, or make a dinette with their goûter of a tablet of chocolate and some bread which forms the regulation lunch of most French children. Sometimes we amused ourselves in gathering the resinous matter which oozed from the pines, sticking to the bark, and from it we made little plasters and doll medicines.

"La Mousse" was the name of another haunt; this was a mossy bank which on one side sloped gently down to one of the main avenues and on the[64] other descended abruptly into a ravine called La Fosse. It was a great place for the boys and such a turning of somersets and racings down the steep sides of the Fosse as there were!

A favorite occupation was the making of gardens; and then there was a hunt for the prettiest mosses, the tiniest, brightest pebbles and the most tree-like twigs. Then a place was marked out on the side of the smooth sandy path and usually near a bench where would be sitting our bonnes or whoever was taking care of us. Paths were traced and bordered with the pebbles; smooth lawns made of the velvety moss, and small branches stuck in for trees; while miniature flower-beds were made and filled with the smallest flowers to be found.

These gardens were often very pretty and much ingenuity could be displayed in laying them out. We sometimes made them in some secluded spot hoping to find them again the next day; but we never did, for Paris is the neatest city in the world and the Bois de Boulogne receives its share of cleaning and garnishing every day in the year.

There is nothing "snubby" or ungracious about[65] French children, and I remember how many a time we helped poor peasant children pick up stray bits of wood to make their fagots, or invited them to share our fun.

One day we saw a crowd of these children carrying baskets filled with acacia-blossoms which they said were to be made into fritters!

We found that a large acacia-tree, laden with the snowy fragrant clusters, had been cut down and the people were plucking as much of the booty as they could carry away with them. We followed their example and that evening we had the addition of some delicious fritters to our dinner. The grape-like clusters had been dipped into a light batter, fried and sprinkled with sugar; truly they made a dish fit for a king.

Happy hours were those spent in the dear old Bois de Boulogne and if any of you girls and boys who read this ever go there, may you have as happy ones!

But there is an ennui that comes of watching the slow shifting scenes of the banks while the dahabeeah drifts onward with the Nile's current—an ennui that the heat of an Egyptian April day rather heightens than lessens, wherefore I determined to go ashore for a ramble. Our destination for the evening was the small village, El Wasta, some few miles further to the north; so telling my friends that I would rejoin them there, and taking with me my boon companion in all such enterprises, a pretty-faced Syrian boy named Gomah, whose knowledge of a dozen French words and about half that number of English made him a serviceable interpreter with the Arabs, I rowed to the western shore. We chose for a landing-place one of those desert offshoots, and consequently had much tiring exercise trudging through the soft sand till the borders of the neighboring fields were reached. Here and there we passed a solitary palm or dwarfed cluster of sont-trees, and occasionally our steps would lead us by some dry-mud hollow, startling the repose of some white ibis, or the meditations of the ubiquitous gray-headed crow.

We had wandered thus by a long circuit inland when, emerging again on the river, we sighted a small village half-hidden amongst its tall palms, and too insignificant on the map of the world to bear the dignity of a name. Between us and its small cluster of huts was a field of tall clover, by the borders of which were playing about some young goats too intent on their gamboling to notice how closely they were being watched by the keen eyes of an eagle perched on a mound amongst the fodder. This bird I endeavored to stalk by performing the somewhat tiring feat of crawling through the tall clover with my gun under me, and, successfully getting within range, brought him toppling down from his high pinnacle. The subsequent results, however, were very unexpected. No sooner had I risen to my feet than all the village dogs set on me, and commenced howling in most atrocious unison, with the decided intention of resisting my unbidden presence in their domains. Happily these were soon silenced by a native woman passing at the moment, whose authority they were in nowise anxious to resent. One old[70] yellow cur, however, dissatisfied perhaps with the peaceful turn things had taken, climbed one of the mud huts and from that stronghold of safety gave vent to most persistent growls.

Several of the men and boys now issued forth from the narrow lanes of the village, and, after the formalities of salutation had been interchanged, commenced examining my gun. They seemed greatly pleased with its appearance, but flatly refused to believe in its powers until convinced by actual experiment.

While we were thus chatting the shaykh of the village had joined us unperceived and now coming forward, with many salutations asked me to visit his house. This I readily assented to as well from a desire to talk with this gray-bearded old lion in his den, as from the necessities of Eastern courtesy.

So escorted by some of the Arabs carrying their long staves of wood or "nebuts," we passed on down the tortuous alleys of this animated dust-heap, by tumbling hut, and dusty square, by the village pond—half-dried with the summer heat, and from the margin of which two or three palms reared[71] their feathered heads, until the party came to a standstill before a mud-hut, somewhat larger, perhaps, than its surrounding neighbors, but not a whit less simple or ruinous.

Mud-built, with a low door and two small windows, it had little to boast of grandeur, except a coat of whitewash which sadly needed renewing. Like its fellows it was crowned with many white and gray jars sunk into the muddy composition of the building, wherein a multitude of pigeons found habitation; while every nook and corner round about these earthen pigeon-homes was fitted with branches of sont or other wood to serve as perches for them. Over the doorway was let into the mud of the lintel the customary broken saucer to guard against and absorb the harmful intentions of those possessed of the "evil-eye," and having duly gazed thereon we were bidden to enter this unpretentious "home" of the village shaykh.

The bright glare of the sun streaming in through the empty doorway lent a sort of twilight to the interior of the hut sufficient to distinguish objects clearly by. It was a large room—that is large[72] as things-Egyptian go—roofed with split palm logs intertwined with their leaves, and its floor, like the walls, bare mud save for the kind carpeting of sand which some windy day had carried thither. On two sides of the room a couple of earthen "divans" faced each other, and in the far corner was a large kulleh in which the grain provisions of the family were doubtless stored, but other furniture there was none. In the wall opposite the entrance, the dark shadow of another doorway showed in contrast against the brown surroundings, but whether it led into the intricacies of the shaykh's domestic household, or out into some village lane, was wrapped in the secrecy of its own gloom.

In the centre of this square swallow's nest sort of habitation the shaykh, myself, Gomah and some half-dozen elders of the village had seated ourselves on the floor in a circle, and the inevitable cigarettes and coffee were handed round. Over these we discussed, more or less satisfactorily considering the extremely limited linguistic powers possessed by myself, Gomah and the company, various topics[73] until the dinner hour of our aged host arrived.

I had hoped to have escaped this ordeal, but the laws of courtesy forbade any retreat. Moreover I had some ambition to witness the ordinary dinner of an Arab household, and this taking "potluck" with a shaykh was a chance too excellent to be missed. The arrangements were admirably simple, and charmingly well fitted to the general convenience. In the centre of our circle an Arab boy first placed a three-legged-stool affair on which he proceeded to balance a large circular tray, big enough to hold dinner for twice the number of guests present. In the middle of this improvised table he next placed an enormous bowl of boiled beans—a veritable vegetable Goliath, steaming and of decidedly savory odor—which he then surrounded with sundry small saucers containing butter, sour milk, cream, carraway seeds, and an infinitude of a peculiar kind of brown bread, which is happily only to be found in the land of Pharaohs and Ptolemies. By the side of each person was placed a small kulleh of water, and now the feast was ready.

Though I had attended at something of the same sort before in Egypt I did not feel quite confident of the modus operandi to be followed here. Believing that possibly local customs might differ I concluded the wiser course would be to await events and see how my neighbors managed, so that I might adopt their method as my own. But alas! Arab politeness was too rigid to allow me to carry out my desire, and from the general delay it was evident that I was expected to lead off the revels.

Accordingly putting a bold face on my doubts I broke off a piece of the bread, dipped it first into the cream (for the excellent reason that that particular saucer was nearest) then into the milk and anything that came handy and—purposely forgetting that awful mountain of beans—tried to look happy while I overcame the difficulties of the unsavory morsel. Apparently my attempts at guessing the method in vogue were not wholly unsuccessful, or the manners of my fellow guests were too good to allow me to think otherwise, and with this debût away all started at eating.

And how they did eat! To judge by the appetites[75] being displayed around me, there had not been any food distributed in the village for many a long day. Into that fast diminishing mound of beans hands were plunging each moment, bread was being broken and dipped into all the smaller saucers seemingly indiscriminately, and water ever carried to the well-nigh choked lips.

In the midst of all this I saw, with much expectant horror, the shaykh arrange on a small piece of bread a choice (to him) assortment of beans, butter, cream, and all the strange ingredients of the meal. Too well I knew what that mistaken courtesy boded for me, and as its maker leant invitingly forward, I had perforce to allow the old dusky rascal to pop the undesirable morsel with all its hideous unpalatableness into my mouth. When I had duly recovered the effects of this moment, the tragedy had, of course, to be re-enacted on my own part. Calling into play therefore all my lost memories of how to feed a young blackbird, I concocted the counterpart of his admixture, and "catching his eye," I—well, reciprocated the compliment.

This incident seemed to end the first part of the entertainment and the despoiled fragments were now taken away to be replaced by a central pile of bread, adorned with similar small saucers, as before, containing milk in various stages of sourness, cream, carraway seeds, and honey. Here again was I expected to give the sign for beginning, and so taking a fragment of bread I dipped it bodily with all the contempt that comes of familiarity into the milk first, which loosened its already very flabby consistency and then into the honey in which it promptly broke off and stuck. This unlucky essay of mine proved too much for the mirthfulness of some of the party, but one burly neighbor, with a gentleness most foreign to his fierce aspect, undertook to show me how to overcome the difficulty. It was very simple and my fault was merely the ordinary one of reversing the order of things. First dipping the bread into the honey my kind instructor then dipped it into the milk and conveyed the result to his spacious mouth. Thus enlightened I did likewise and achieved success, and all set to work again at the edibles before them.

But this course was much less violent than the last, and soon disposed of. When it was over the boy, who had heretofore filled the part of food-bearer, came around to each guest in turn and poured over their hands water from a pitcher which he carried, holding a bowl underneath meanwhile, and presenting a cloth to each after such ablution. A not unnecessary service, for the absence of knives and forks at dinner may have the advantage of economy, and revert for authority to the primitive days of Eden, but when carried out it is fraught with much that is compromising to the fingers. Moreover Egyptian honey is no less sticky than that of other lands.

The dinner was now wound up with coffee and cigarettes—not the least pleasing part to me—and a hubbub of chatting. But as the evening shadows were already creeping amongst the palms outside, and El Wasta—my harbor of refuge for the night—was yet some distance off, I begged my kind host's permission to continue my way. His Arab courtesy, however, was not to be hindered even here, and he insisted upon accompanying[78] me to the confines of his village fields, where with many pretty excuses for his years and duties he at last consented to bid me farewell.

He left me to the care of "two of his young men," as he called them, charging them to take me safely to El Wasta, the palms of which we could see far down the river standing out against the evening sky.

Of the many pleasant mental photographs which I have of travel, that simple dinner with my kind shaykh of the unknown village holds a prominent tablet to itself. I had asked him for his ancient and time-worn tobacco-pouch when bidding farewell, that I might have the excuse of giving him mine in exchange, which at least had the advantage to an Eastern eye of plenty of color and bright metal. A fellow traveller whose wanderings have since led him by my steps of that day, tells me he found the old shaykh still owning that poor gift of mine, and that he keeps strange talismans and Koranic-script in its recesses as an infallible preventive against the dangers of ophthalmia, and to guard against his pigeon homes blowing down.

It belonged to Denmark, and was inhabited by people of almost every nation, for the city was a busy trading place and famous sea-port.

This variety of nationalities is an advantage, or a disadvantage, just as you choose to think. To us children it was the most delightful thing in the world—why, we saw a Malay sailor once; but an English novelist, who wrote many books, visited our island, and said in a contemptuous way that it was "a Dano-Hispano-Yankee Doodle-niggery place." This was in the book he published about the West Indies and the Spanish Main. We children never forgave that remark.

An American refers incidentally to our old home in a beautiful story, called A Man Without a Country. How the tears rolled down our cheeks as we read that Philip Nolan had been there in the harbor—perhaps just inside Prince Rupert's Rocks!

I wonder if you have read that story? To us it was almost sacred, so strong was our love of country, and we believed every word to be true. The first piece of poetry Tom wished to learn was "Breathes there a man with soul so dead." But Tom was too small to learn anything but Mother Goose at the time he had his Birthday Party. He was a chubby little fellow, whose third anniversary was near at hand, and he was so clamorous for a party—he scarcely knew what a party was, but he wanted it all the more for that reason—that his parents laughingly gave way to him.

We did not keep house as people do in this country; in fact the house itself differed greatly from such as you see.

The climate was warm all the year round, and there were no chimneys where no fires were needed.[81] There were no glass windows, excepting on the east side. At all other windows we had only jalousie blinds, with heavy wooden shutters outside to be closed when a hurricane was feared. The wonderful Trade Winds blew from the East, and sometimes brought showers; for this reason, we had glass on that side. The floors were of North Carolina pine, one of the few woods insects will not eat into and destroy. It is a pretty cream yellow, that looked well between the rugs scattered over it. Balconies and wide verandas were on all sides of the house.

As to servants, they were all colored and we had to have a great many, for each would only take charge of one branch of service, and usually must have a deputy or assistant to help. For instance, Sophie, the cook, had a woman to clean fish, slice beans, and do such work for her, as well as attend to the fires. There was no stove in the kitchen. A kind of counter, three feet wide and about as high, built of brick, was on two sides of the room; this had holes in the top here and there. The cooking was done over these holes filled with charcoal; so instead of one fire to cook dinner, Sophie had a[82] soup fire, a fish fire, a potato fire, and so forth. A small brick oven baked the few things she cooked that way.

Tom's nurse, or Nana, as all West India nurses were called, was a tall negress, very dignified and imposing in her manners, and so good we loved her dearly. She always wore a black alpaca gown, a white apron covering the whole front of it, a white handkerchief crossed over her bosom, and one tied over her hair. Her long gold ear-rings were her only ornaments. These rings were very interesting, because Nana often announced to us that she had lost a friend and was wearing "deep mourning." This meant that she had covered her ear-rings with black silk neatly sewed on. They were mournful-looking objects then, I assure you.

I cannot describe all the servants, odd as they were, nor give you any idea of their way of talking—Creole, Danish, and broken English—but I must mention our butler, or "houseman," Christian Utendahl, the most important member of the household in his own opinion.

As soon as the party was decided on, Christian[83] and Nana were called in to be consulted. Then it was discovered what a tiresome undertaking a child's party might be. All children under the care of Nanas must have those Nanas specially invited, and a particular kind of punch must be made for them; then champagne must be provided for the little ones to drink toasts.

"Oh, this will never do. I cannot think of such a thing," said mamma.

"I must advise you so to do, Madame," answered Christian. "Nana's punch is lemonade wid leetle bit claret in it; and when you see de glasses I'll permide fer de champagne you'll see fer you'sef dey can't hole a timmle full. Fer de credit of de family, Madame, fer fear folks'll say 'Americains don't know how to behave,' I must adwise you."

The last sentence was a powerful argument, and the solemn negro used it with effect.

Here Nana interposed, saying, "My lady, how you expec my leetle man to know how to conduct hes-sef less we begin wid his manners jes now?" Then she added that she could not appear without a new gown, apron and head-handkerchief, and the[84] apron ought to have Mexicain drawn-work a finger "deep at de bottom of it to be credi-tabble."

Next, Nana said the birthday cake must be made by Dandy and covered with as many "sugar babies" as there were guests.

These babies were pure sugar figures on straws and were stuck into the cake through the icing.

"The 'Kranse Kage' and the 'Krone Kage' can be made at home by Ellen and Sophie, Miss Lind and Mrs. Harrigen," said Christian.

"Is a 'Kranse Kage' absolutely necessary?" asked mamma. "It will keep the women pounding almonds a whole day and it is very unwholesome."

"Of course it is necessary," said both advisers together, and "it would bring de chile bad luck to have it made out of de house," said Nana.

"Then we will have it and dispense with the 'Krone Kage.'"

"Not have a 'Krone Kage'! Oh, we must have dat out of compliment to de King, Madame."

Here mamma gave up in despair and let the rulers of the household have their way without further resistance.

Christian delivered the invitations to the party in his most formal manner. The Hingleberg boys, Emile Haagensen, Alma Pretorius, Ingeborg Hjerm, Nita Gomez, Achille Anduze, and several other boys and girls accepted promptly.

During the next few days there was so much excitement in the household, so much disagreement between Christian and Nana, and Tom was so vociferous, mamma said nothing would ever induce her to give a party for children again.

In Tom's good moments you would be sure to see him standing with his hands behind him, while Nana trained him in what he should say and do. "Sissy," he whispered to me, "Nana says if I ain't very, very dood she'll gie me a fatoi before evelly body."

(We never knew what this mysterious punishment was, and now we think it must be Creole for something that never happens. We were often threatened with it and as often escaped it.)

At last the day came, and Tom was to be allowed to haul up the flag that morning. (We always kept the American flag floating over our[86] house.) When the Danish soldiers fired the sunrise cannon from the fort, Tom pulled on the ropes with all his strength, his dear little face as red as it could be, and when the flag reached the top of the tall staff he gave a long sigh of satisfaction.

We were not to see the parlors till just before the guests were to come, about twelve o'clock. When we did go in we screamed with delight. The rooms were filled with flowers. The pillars were hidden by long ferns and the Mexican vine which has long wreaths of tiny pink flowers, such as you may have seen in the dress caps of babies. Tall vases of pink and white oleander filled the alcove, and everywhere were white carnations, jasmine, frangipanni, and doodle-doo blossoms. All this had been done by the servants as a surprise.

In the middle of the room was the table. The gorgeous birthday cake, bristling with knights, ladies, angels and all kinds of figures, was in the centre, and the Kranse Kage and Krone Kage were at either end of it; in the former a small silk American flag, in the latter a Danish one, were placed; between them were all sorts of good things,[87] just such as you have at your parties. At each plate was the queerest wee glass imaginable.

Tom received many presents. One of them, a gun with a bayonet, gave almost too much bliss. He sat and hugged it, evidently thinking it was "the party."

Christian, dressed in white, met every one at the street gate. To the guests he said, "Mr. and Mrs. Alger presents deir complements and are glad to see you;" and to the Nanas he said politely, "How you so far dis mawning?"

To get to our house, one had to mount three or four steps from the street, then there was a high iron fence and gate. On each side of this were the only trees I ever disliked. We called them the "Boiled Huckleberry Pudding" trees. They had large poisonous-looking leaves, and bore pale lumpish fruit about as large as a quart measure, with small black seeds here and there through them. There were no other trees like them on the island and we had a tradition that they came from Otaheite and would kill any one instantly who tasted the fruit. There were beautiful trees[88] and flowers on this terrace and on all; then came a wall covered with vines, and fifteen stone steps leading to another terrace and another wall. In this second wall, near the pepper-tree, was the home of our two monkeys Jack and Jill. On the third terrace was the house.

Tom received his friends nicely, Nana standing just behind him dressed in her new gown and beautiful apron. We could see she was very anxious lest he should disgrace her before the other Nanas. Often we heard her whisper "Say howdy wid de odder hand, My Heart," or "Mind what I tole you, Son." She escorted the Nanas to the court, where the bowl of punch was standing, and they drank Tom's health with many good wishes.

As soon as all the children had arrived they were seated at table, each Nana standing behind her charge. Daintily and prettily the little ones ate, and when Christian passed the cake around the "sugar babies" were drawn out with much ceremony. Then the other large cakes were cut and served and Christian put a drop of champagne in each little glass. As soon as this was done, quick[89] as thought Carl Hingleberg stood up and said:

"Lienge leve Kongen!"

Would you believe it? Every little tot lifted his or her glass and drank this solemnly. Christian filled the glasses again and we saw Bebé Anduze was being nudged and pushed by her Nana; at last she put her finger in her mouth and hung her head but said very sweetly, "I wiss Tom Alger have many nice birfdays and be a dood boy!"

How we all laughed! And how surprised we were when Tom bowed and said, "Tak," but he spoiled it all by pounding on the table and shouting "Hurrah for Grant!"

When all had done, Nana lifted Tom down from his chair and turned him to the right. Each child he took by the hand and said, "Velbekomme;" and the answer given to him was "Fak for mad." Then Tom scampered off, and came back with his gun and singing with all his might "Den tapre land soldat;" and where he did not know the Danish words, he sang "Good Night, my brudder Ben!" which Nana proudly explained "he composed hes-sef." All the children joined in the chorus and[90] were pleased at his singing something they all knew.

Now came the great event of the day. We went down to the wharf, where papa had boats ready to take us off to the American man-of-war in the harbor. We were kindly taken all over it and Tom was allowed to fire off a large cannon. This consoled him for the loss of his bayonet, which fell overboard on our way to the ship, by mamma's special request.

We had a delightful afternoon, and, when we returned home, Tom shook hands with all and said,

Note.—Kranse Kage, Wreath Cake; Krone Kage, Crown Cake; Tak, Thanks; Den tapre land soldat, The brave land soldier; Velbekomme, Welcome; Fak for mad, Thanks for bread, or the food; Lienge leve Kongen, Long live the King; Farvel Kom igjen, Farewell, come again.

The cutting of this top-knot, as it is called, is an occasion of great ceremony. All the friends and relatives are invited to attend, and the festivities continue three days. On the third day the hair is cut by a priest, and a lock is preserved in the family. The cutting of the top-knot is equivalent to our coming of age, though the children are generally between eleven and fourteen, and sometimes even younger than that.

The hair-cutting of the King's eldest daughter,[92] Princess Civili, was a most magnificent affair. We went to the palace at ten in the morning for the purpose of seeing the procession. After passing through the outer and inner courts which were thronged with people of almost every Eastern nationality, we were shown into a building reserved for Europeans. Soon we heard the band playing the National Anthem, and then, preceded by the royal body-guard, His Majesty appeared and took his seat near the private entrance to the Temple. Then the procession commenced to file past us. It was headed by a number of men with hatchets, and attired in odd-looking garments. Some of these men wore horrible masks and wigs of long, tangled hair. They looked much like apes, and represented wild men. Next followed two rows of "angels" as they are called, these being men dressed in long loose robes of thin white muslin bordered with gold-embroidered bands. On their heads were tall conical hats of white and gold. These "angels" carried a cord which was attached to the Princess' chair. Between these two rows of angels walked a dozen men in loose red jackets,[93] and short red trousers, with flat caps to match. They held in their hands long reed instruments on which they blew, making a shrill, strange sound.

This was the signal of the approach of the Princess who soon appeared, carried in a high chair, and surrounded by nobles and relatives. She sat as immovable as an image, and looked neither to the right nor the left. With a little more expression, she would have been a very pretty child.

Behind Her Royal Highness' chair were her favorite slaves carrying all the beautiful presents that had been given her.

Apropos of presents, here is a short account of one of them. The United States ship Ashuelot was at that time anchored in the river Chow Phya Miniam, on which river Bangkok is situated. There is a custom in Siam of giving a present in return for one received, though the present given in return is always one of less value. The paymaster of the Ashuelot, hearing of this custom, presented Her Royal Highness with a diamond ring, and received in return a handsome gold betel-box of native workmanship. The captain of the[94] Ashuelot who was much annoyed that a subordinate should receive so handsome a gift while he himself received nothing, had the paymaster court-martialed on the ground that an officer in the United States employ had no right to receive a gift from a foreign nation.

But to return to the procession. Following the slaves, came a number of little Siamese girls dressed in white, and wearing a profusion of jewelry. After them, came girls from the provinces all decked in their gayest attire; then two rows of little Chinese girls with painted cheeks and lips, and having artificial flowers in their hair. Closely following came rows upon rows of native women (slaves of the Princess) who walked sedately on with their bright fluttering scarves of red, yellow and green, their hands folded as if in prayer.

Then came a great many little native boys; after these, Chinese boys, and, finally the procession was ended by a company of Hindoostani children followed by a detachment of men servants.

The next two days the procession was exactly the same, except that on the third day the "angels"[95] and the little Siamese girls wore pink robes instead of white.