Title: Popular British Ballads, Ancient and Modern, Vol. 2 (of 4)

Editor: R. Brimley Johnson

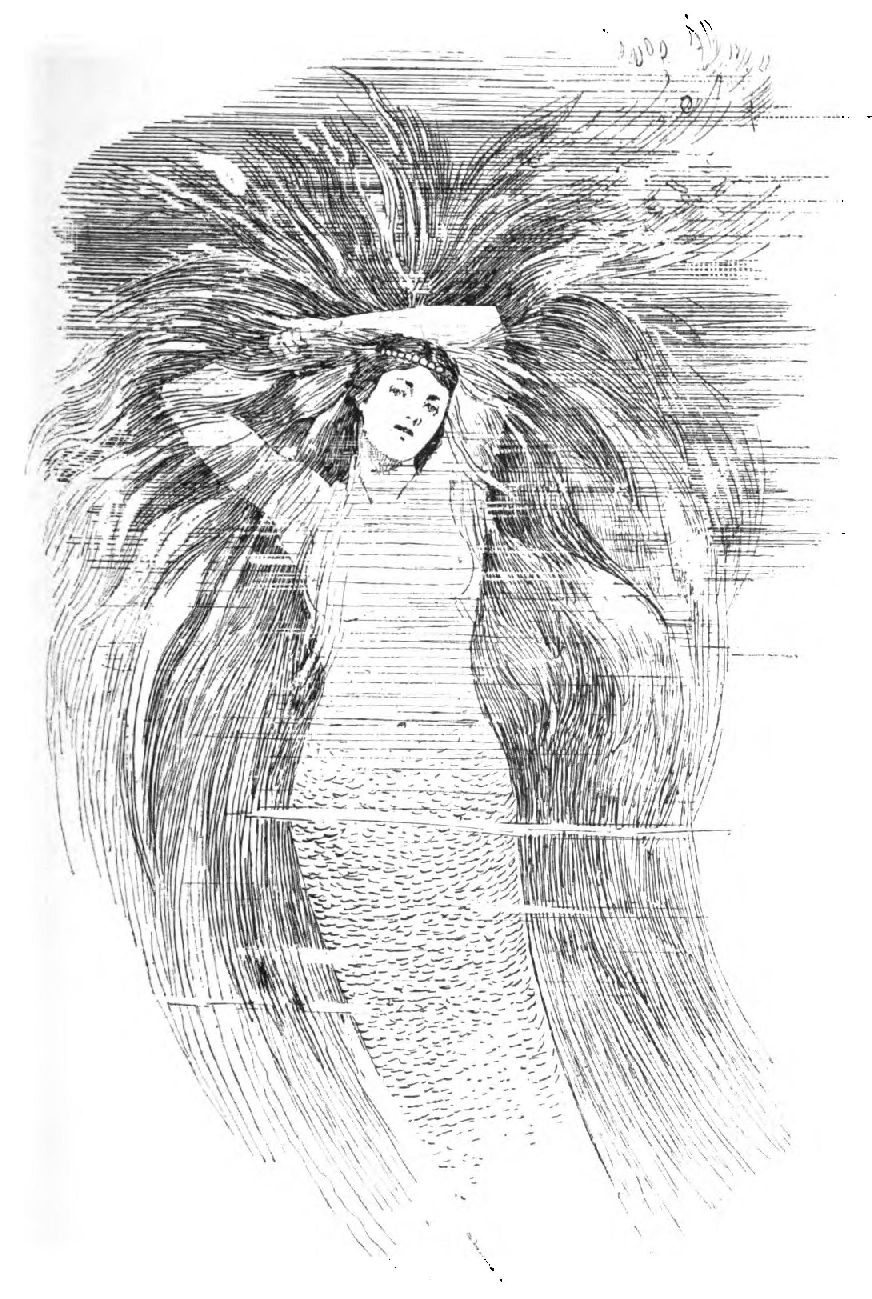

Illustrator: W. Cubitt Cooke

Release date: March 28, 2014 [eBook #45242]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger from page images generously

provided by Google Books

CONTENTS

THE LAMENT OF THE BORDER WIDOW

SIR ARTHUR AND CHARMING MOLLEE

THE BAILIFF'S DAUGHTER OF ISLINGTON

THE GAY LADY THAT WENT TO CHURCH

True Thomas lay o'er yon grassy bank;

And he beheld a lady gay;

A lady that was brisk and bold,

Come riding o'er the ferny brae.

Her shirt was o' the grass-green silk,

Her mantle o' the velvet fine;

At ilka tett of her horse's mane,

Hung fifty silver bells and nine.

True Thomas, he took off his hat,

And bowed him low down till his knee:

"All hail, thou mighty Queen of Heaven!

For your peer on earth I never did see."

"O no, O no, True Thomas," she says,

"That name does not belong to me;

I am but the Queen of fair Elfland,

And I am come here for to visit thee.

(tett, tuft.)

"Harp and carp, Thomas," she said;

"Harp and carp along wi' me;

And if ye dare to kiss my lips,

Sure of your body I will be."—

"Betide me weal, betide me woe,

That weird shall never daunton me."

Syne he has kissed her rosy lips,

All underneath the Eildon Tree.

"But ye maun go wi' me, now, Thomas;

True Thomas, ye maun go wi' me;

For ye maun serve me seven years,

Thro' weal or woe as may chance to be,"

(Harp and carp, chat.)

She turned about her milk-white steed;

And took true Thomas up behind:

And aye, whene'er her bridle rang,

The steed flew swifter than the wind.

For forty days and forty nights

He wade thro' red blude to the knee,

And he saw neither sun nor moon,

But heard the roaring of the sea.

O they rade on, and farther on;

Until they came to a garden green,

"Light down, light down, ye lady free,

Some of that fruit let me pull to thee."

"O no, O no, True Thomas." she says;

"That fruit maun not be touched by thee,

For a' the plagues that are in hell

Light on the fruit of this country.

"But I have a loaf here in my lap,

Likewise a bottle of claret wine,

And now ere we go farther on,

We'll rest a while and ye may dine."

When he had eaten and drunk his fill—

"Lay down your head upon my knee,"

The lady said, "ere we climb yon hill,

And I will shew you ferlies three.

"O see not ye yon narrow road,

So thick beset with thorns and briars?

That is the path of righteousness,

Though after it but few enquires.

"And see ye not that braid braid road,

That lies across that lily leven?

That is the path of wickedness,

Though some call it the road to heaven.

"And see not ye that bonny road,

That winds about the ferny brae?

That is the road to fair Elfiand,

Where you and I this night maun gae.

"But, Thomas, ye maun hold your tongue,

Whatever ye may hear or see;

For, gin ae word you should chance to speak,

Ye'll ne'er get back to your ain country."

(ferlies, marvels. leven, lawn.)

He has gotten a coat of the even cloth,

And a pair of shoes of velvet green;

And till seven years were gane and past,

True Thomas on earth was never seen.

O may she comes, and may she goes,

Down by yon gardens green,

And there she spied a gallant squire

As squire had ever been.

And may she comes, and may she goes,

Down by yon hollin tree,

And there she spied a brisk young squire,

And a brisk young squire was he.

"Give me your green mantle, fair maid,

Give me your maidenhead;

Gif ye winna gie me your green mantle,

Give me your maidenhead!

He has ta'en her by the milk-white hand,

And softly laid her down,

And when he's lifted her up again

Given her a silver kaim.

(even, fine.)

"Perhaps there may be bairns, kind sir,

Perhaps there may be nane;

But if you be a courtier,

You'll tell to me your name."

"I am nae courtier, fair maid,

But new come frae the sea;

I am nae courtier, fair maid,

But when I courteth thee.

"They call me Jack when I'm abroad,

Sometimes they call me John;

But when I'm in my father's bower

Jock Randal is my name."

"Ye lee, ye lee, ye bonny lad;

Sae loud's I hear ye lee!

For I'm Lord Randal's yae daughter,

He has nae mair nor me."

"Ye lee, ye lee, ye bonny may,

Sae loud's I hear ye lee!

For I'm Lord Randal's yae yae son,

Just now come o'er the sea."

She's putten her hand down by her spare,

And out she's ta en a knife,

And she has put'nt in her heart's bluid,

And ta'en away her life.

(spare, pocket.)

And hes ta en up his bonny sister,

With the big tear in his een,

And he has buried his bonny sister

Among the hollins green.

And syne hes hied him o'er the dale,

His father dear to see:

"Sing O and O for my bonny hind,

Beneath yon hollin tree!"

"What needs you care for your bonny hind?

For it you needna care;

There's aught score hinds in yonder park,

And five score hinds to spare.

"Four score of them are siller-shod,

Of those ye may get three;"

"But O and O for my bonny hind,

Beneath yon hollin tree!"

"What needs you care for your bonny hind?

For it you needna care;

Take you the best, give me the worst,

Since plenty is to spare."

"I carena for your hinds, my Lord,

I carena for your fee;

But O and O for my bonny hind,

Beneath the hollin tree!"

(aught, eight.)

"O were ye at your sisters bower,

Your sister fair to see,

Ye'll think na mair o' your bonny hind,

Beneath the hollin tree."

Lat never a man a wooing wend,

That lacketh thingés three;

A routh o' gold, an open heart,

And fu' o' courtesy.

As this was seen o' King Henry,

For he lay burd-alane;

And he has ta'en him to a haunted hunt's ha',

Was seven miles frae a town.

(routh, plenty. burd-alane, alone, without a burd or maiden.)

hunt's ha', hunting-lodge.

He's chas'd the dun deer thro' the wood,

And the roe down by the den,

Till the fattest buck in a' the herd

King Henry he has slain.

He's ta'en him to his hunting ha',

For to make bierly cheer;

When loud the wind was heard to sound,

And an earthquake rocked the floor.

And darkness covered a' the hall

Where they sat at their meat;

The gray dogs, youling, left their food

And crept to Henry's feet.

And louder howled the rising wind,

And burst the fastened door;

And in there came a grisly ghost,

Stood stamping on the floor.

Her head hit the roof-tree o' the house,

Her middle ye mot weel span;—

Each frightened huntsman fled the ha';

And left the king alone."

Her teeth was a' like tether stakes,

Her nose like club or mell;

And I ken naething she 'pear'd to be,

But the fiend that wons in hell.

(bierly, proper. mell, mallet. wons, dwells.)

"Some meat, some meat, ye King Henry;

Some meat ye gie to me."

"And what meats in this house, Lady?

That ye're nae welcome tae?"

"O ye's gae kill your berry-brown steed,

And serve him up to me."

O when he slew his berry-brown steed,

Wow but his heart was sair!

She ate him a' up, skin and bane,

Left naething but hide and hair.

"Mair meat, mair meat, ye King Henry,

Mair meat ye gie to me."

"And what meats in this house, Lady?

That yere nae welcome tae?"

"O ye do kill your good grey-hounds,

And ye bring them a to me."

O when he slew his good grey hounds,

Wow but his heart was sair!

She ate them a' up, ane by ane,

Left naething but hide and hair.

"Mair meat, mair meat, ye King Henry,

Mair meat ye bring to me."

"And what meat's in this house, Lady?

That I hae left to gie?"

"O ye do fell your gay gosshawks,

And ye bring them a' to me."

O when he felled his gay gosshawks,

Wow but his heart was sair!

She ate them a' up, bane by bane,

Left naething but feathers bare.

"Some drink, some drink, now, King Henry;

Some drink ye bring to me."

"O what drink's in this house, Lady,

That ye're nae welcome tae?"

"O ye sew up your horse's hide,

And bring in a drink to me."

And he's sewed up the bloody hide,

And put in a pipe o' wine;

She drank it a' up at ae draught,

Left na ae drap therein.

"A bed, a bed, now, King Henry,

A bed ye mak to me."

"And what's the bed i' this house, Lady,

That ye're nae welcome tae?"

"O ye maun pu' the green heather,

And mak a bed to me."

And pu'd has he the heather green,

And made to her a bed;

And up he's ta en his gay mantle,

And o'er it has he spread.

"Now swear, now swear, ye King Henry,

To take me for your bride,"

"O God forbid," says King Henry,

'"That ever the like betide;

That ever the fiend that wons in hell,

Should streak down by my side."

When day was come, and night was gane,

And the sun shone thro' the ha,

The fairest lady that ever was seen

Lay atween him and the wa'.

"O weel is me!" says King Henry;

"How lang'll this last wi' me?"

And out and spake that lady fair,—

"E en till the day you die.

"For I was witched to a ghastly shape,

All by my stepdame's skill,

Till I should meet wi' a curteous knight,

Would gie me a' my will."

(streak, stretch, lie.)

Willy's ta en him oer the faem,

Hes wooed a wife, and brought her hame;

Hes wooed her for her yellow hair,

But his mother wrought her mickle care;

And mickle dolour gar'd her dree,

For lighter she can never be;

But in her bower she sits wi' pain,

And Willy mourns oer her in vain.

And to his mother he has gane,

That vile rank witch, o' vilest kind!

He says—"My lady has a cup,

Wi' gowd and silver set about;

This goodly gift shall be your ain,

And let her be lighter o' her young bairn."—

(faem, sea. dree, suffer.)

"Of her young bairn she's ne'er be lighter,

Nor in her bower to shine the brighter:

But she shall die, and turn to clay,

And you shall wed another may."—

"Another may I'll never wed,

Another may I'll ne'er bring hame:"—

But, sighing, says that weary wight—

"I wish my life were at an end!"

"Yet do ye unto your mother again,

That vile rank witch, o' vilest kind!

And say, your lady has a steed,

The like o' him's no in the land o' Leed.

"For he is golden shod before,

And he is golden shod behind;

At ilka tett of that horse's mane,

There's a golden chess, and a bell to ring.

This goodly gift shall be your ain,

And let me be lighter o' my young bairn."—

"Of her young bairn she's ne'er be lighter,

Nor in her bower to shine the brighter;

But she shall die, and turn to clay,

And ye shall wed another may."—

"Another may I'll never wed,

Another may I'll ne'er bring hame:"—

(tett, tuft.)

Willy's Lady

But, sighing, said that weary wight—

"I wish my life were at an end!"—

"Yet do ye unto your mother again,

That vile rank witch, o' vilest kind!

And say your lady has a girdle,

It's of red gowd unto the middle;

"And aye, at every siller hem

Hang fifty siller bells and ten;

That goodly gift [shall] be her ain,

And let me be lighter o' my young bairn."—

"Of her young bairn she's ne'er be lighter,

Nor in her bower to shine the brighter;

For she shall die, and turn to clay,

And you shall wed another may."—

"Another may I'll never wed,

Another may I'll ne'er bring hame:"—

But, sighing, said that weary wight—

"I wish my days were at an end!"—

Then out and spake the Billy Blind,

(He spake aye in good time:)

"Ye do ye to the market-place,

And there ye buy a loaf of wax;

Ye shape it bairn and bairnly like,

And in it twa glassen een ye put;

"And bid her come to your boy's christening,

Then notice weel what she shall do;

And do you stand a little forbye,

And listen weel what she shall say."

[He did him to the market-place,

And there he bought a loaf o' wax;

He shaped it bairn and bairnly like,

And in twa glazen een he pat;

He did him till his mother then,

And bade her to his boy's christening;

And he did stand a little forbye,

And noticed well what she did say.

"O wha has loosed the nine witch knots,

That was amang that lady's locks?

And wha's ta'en out the kaims o' care,

That hang amang that lady's hair?

"And wha's ta'en down the bush o' woodbine,

That hung between her bower and mine?

And wha has kill'd the master kid,

That ran beneath that lady's bed?

And wha has loosed her left foot shee,

And letten that lady lighter be?"

O, Willy's loosed the nine witch knots,

That was amang that lady's locks;

And Willy's ta'en out the kaims o' care,

That hang amang that lady's hair;

(shee, shoe.)

The Dæmon Lover ss'

And Willy's ta'en down the bush o' woodbine,

Hung atween her bower and thine

And Willy has kill'd the master kid,

That ran beneath that lady's bed;

And Willy has loosed her left foot shee,

And letten his lady lighter be;

And now he's gotten a bonny young son,

And mickle grace be him upon.

O where have you been, my long, long love,

This long seven years and more?"—

"O I'm come to seek my former vows

Ye granted me before."—

"O hold your tongue of your former vows,

For they will breed sad strife;

O hold your tongue of your former vows,

For I am become a wife."

He turn'd him right and round about,

And the tear blinded his ee;

"I wad never hae trodden on Irish ground,

If it had not been for thee.

"I might hae had a king's daughter,

Far, far beyond the sea;

I might have had a king's daughter,

Had it not been for love o' thee."—

"If ye might have had a king's daughter,

Yoursel' ye had to blame;

Ye might have taken the king's daughter,

For ye kenned that I was nane."—

["O false are the vows of womankind,

But fair is their false bodie;

I never wad hae trodden on Irish ground,

Had it not been for love o' thee."—]

"If I was to leave my husband dear,

And my two babes also,

O what have you to take me to,

If with you I should go?"—

"I hae seven ships upon the sea,

The eighth brought me to land;

With four-and-twenty bold mariners,

And music on every hand."

She has taken up her two little babes,

Kiss'd them baith cheek and chin;

"O fair ye weel, my ain two babes,

For I'll never see you again."

She set her foot upon the ship,

No mariners could she behold;

But the sails were o' the taffety,

And the masts o' the beaten gold.

She had not sail'd a league, a league,

A league but barely three,

When dismal grew his countenance,

And drumlie grew his ee.

[The masts that were like the beaten gold,

Bent not on the heaving seas;

But the sails, that were o' the taffety,

Fill'd not in the east land-breeze.—]

They had not sailed a league, a league,

A league but barely three,

Until she espied his cloven foot,

And she wept right bitterly.

"O hold your tongue of your weeping," says he,

"Of your weeping now let me be;

I will show you how the lilies grow

On the banks of Italy."—

(drumlie, gloomy.)

"O what hills are yon, yon pleasant hills,

That the sun shines sweetly on?"—

"O yon are the hills of heaven," he said,

"Where you will never win."—

"O whaten a mountain is yon," she said,

"All so dreary wi' frost and snow?"—

"O yon is the mountain of hell," he cried,

"Where you and I will go."

[And aye when she turn'd her round about,

Aye taller he seem'd for to be;

Until that the tops o' that gallant ship

Nae taller were than he.

The clouds grew dark, and the wind grew loud,

And the levin fill'd her ee;

And waesome wail'd the snaw-white sprites

Upon the gurlie sea.]

He strack the tap-mast wi' his hand,

The fore-mast wi' his knee;

And he brake that gallant ship in twain,

And sank her in the sea.

(levin, lightning. gurlie, stormy.)

There lived a wife at Usher's Well,

And a wealthy wife was she,

She had three stout and stalwart sons,

And sent them o'er the sea.

They hadna been a week from her,

A week but barely ane,

When word came to the carline wife,

That her three sons were gane.

They hadna been a week from her,

A week but barely three,

When word came to the carline wife,

That her sons she'd never see.

"I wish the wind may never cease,

Nor fishes in the flood,

Till my three sons come hame to me.

In earthly flesh and blood."—

It fell about the Martinmas,

When nights are lang and mirk,

The carline wife's three sons came home,

And their hats were o' the birk.

It neither grew in syke nor ditch,

Nor yet in ony sheugh;

But at the gates o' Paradise,

That birk grew fair eneugh.

"Blow up the fire, my maidens!

Bring water from the well!

For a my house shall feast this night,

Since my three sons are well."—

And she has made to them a bed,

She's made it large and wide;

And she's ta'en heir mantle her about,

Sat down at the bed-side.

Up then crew the red red cock,

And up and crew the gray;

The eldest to the youngest said,

"'Tis time we were away."—

(syke, marsh, sheugh, furrow.)

The cock he hadna craw'd but once,

And clapp'd his wings at a',

When the youngest to the eldest said,

"Brother, we must awa'—

"The cock doth craw, the day doth daw,

The channerin' worm doth chide;

Gin we be missed out o' our place,

A sair pain we maun bide.

"Fare ye weel, my mother dear!

Fare weel to barn and byre!

And fare ye weel, the bonny lass,

That kindles my mothers fire."

(channerin', fretting.)

Clerk Saunders and may Margaret,

Walked ower yon gravelled green;

And sad and heavy was the love

I wot it fell this twa between.

"A bed, a bed," Clerk Saunders said,

"A bed, a bed for you and me!"—

"Fie na, fie na," the lady said,

"Until the day we married be;

"For in it will come my seven brothers,

And a their torches burning bright;

They'll say—' We hae but ae sister,

And here her lying wi' a knight! '"—

"Yell take the sword from my scabbard,

And lowly, lowly lift the gin;

And you may swear, and your oath to save,

Ye never let Clerk Saunders in.

"Yell take a napkin in your hand,

And yell tie up baith your een;

And you may swear, and your oath to save,

Ye saw na Sandy since late yestreen."

—"Ye'll take me in your armés twa,

Yell carry me ben into your bed,

And ye may swear, and your oath to save,

That in your bower-floor I ne'er tread."

She has ta en the sword frae his scabbard,

And lowly, lowly lifted the gin;

She was to swear, her oath to save,

She never let Clerk Saunders in.

She has ta'en a napkin in her hand,

And she tied up baith her een;

She was to swear, her oath to save,

She saw na him since late yestreen.

(gin, latch.)

She ta'en him in her armés twa

And carried him ben into her bed j

She was to swear her oath to save

He never on her bower-floor tread.

In and came her seven brothers,

And all their torches burning bright;

Says they, "We hae but ae sister,

And see there her lying wi' a knight!"

Out and speaks the first o' them,

"I wot that they hae been lovers dear!"

Out and speaks the next o' them,

"They hae been in love this many a year!"

Out and speaks the third o' them,

"It were great sin this twa to twain!"

Out and speaks the fourth of them,

"It were a sin to kill a sleeping man!"

Out and speaks the fifth of them,

"I wot they'll ne'er be twained by me";

Out and speaks the sixth of them,

"We'll tak our leave and gae our way."

Out and speaks the seventh o' them,

"Altho' there were no man but me;

I bear the brand I'll gar him dee."

Out he has ta'en a bright long brand,

And he has striped it through the straw,

And through and through Clerk Saunders' body

I wot he has gared cold iron gae.

(gar, make.)

Saunders he started, and Margaret she lept

Into his arms where she lay;

And well and wellsome was the night

I wot it was between those twa.

And they lay still and sleeped sound,

Until the day began to daw;

And kindly to him she did say,

"It is time, true love, you were awa'."

They lay still, and sleeped sound,

Until the sun began to sheen;

She looked atween her and the wa,

And dull and drowsy was his een.

She thought it had been a loathsome sweat,

I wot it had fallen these twa between;

But it was the blood of his fair body,

I wot his life-days were na lang.

O Saunders, I'll do for your sake

What other ladies would na thole;

When seven years is come and gone,

There's ne'er a shoe go on my sole.

O Saunders, I'll do for your sake

What other ladies would think mair;

When seven years is come and gone,

There's ne'er a comb go in my hair.

O Saunders, I'll do for your sake

What other ladies would think lack;

(thole, endure. lack, loss.)

When seven long years is come and gone,

I'll wear nought but dowie black.

The bells gaed clinking through the town,

To carry the dead corpse to the clay,

An sighing says her may Margaret,

I wot I bide a doleful day.

In and came her father dear,

Stout stepping on the floor.

"Hold your tongue, my daughter dear,

Let all your mourning a'be;

I'll carry the dead corpse to the clay,

And I'll came back and comfort thee."

"Comfort well your seven sons,

For comforted will I never be:

I ween 'twas neither lord nor loon

That was in bower last night wi' me."—

(dowie, sad.)

O where hae ye been a' day, Lord Donald, my son?

O where hae ye been a' day, my jolly young man?"

"I've been awa courtin':—mither, mak my bed sune,

For I'm sick at the heart, and I fain would lie doun."

"What wad ye hae for your supper, Lord Donald, my son?

What wad ye hae for your supper, my jolly young man?"

"I've gotten my supper:—mither, mak my bed sune,

For I'm sick at the heart, and I fain would lie doun."

"What did ye get for your supper, Lord Donald, my son?

What did ye get for your supper, my jolly young man?"

"A dish of sma' fishes:—mither, mak my bed sune,

For I'm sick at the heart, and I fain wad lie doun."

"Where gat ye the fishes, Lord Donald, my son?

Where gat ye the fishes, my jolly young man? ''

"In my fathers black ditches:—mither, mak my bed sune,

For I'm sick at the heart, and I fain would lie doun."

"What like were your fishes, Lord Donald, my son?

What like were your fishes, my jolly young man?"

"Black backs and speckl'd bellies:—mither, mak my bed sune,

For I'm sick at the heart, and I fain would lie doun."

"O I fear ye are poison'd, Lord Donald, my son!

O I fear ye are poison'd, my jolly young man!"

"O yes! I am poison'd:—mither, mak my bed sune,

For I'm sick at the heart, and I fain wad lie doun."

"What will ye leave to your father, Lord Donald, my son?

What will ye leave to your father, my jolly young man?"

"Baith my houses and land:—mither, mak my bed sune,

For I'm sick at the heart, and I fain wad lie doun."

"What will ye leave to your brither, Lord Donald, my son?

What will ye leave to your brither, my jolly young man?"

"My horse and the saddle:—mither, mak my bed sune,

For I'm sick at the heart, and I fain wad lie doun."

"What will ye leave to your sister, Lord Donald, my son?

What will ye leave to your sister, my jolly young man?"

"Baith my gold box and rings mither, mak my bed sune,

For I'm sick at the heart, and I fain wad lie doun."

"What will ye leave to your true-love, Lord Donald, my son?

What will ye leave to your true-love, my jolly young man?"

"The tow and the halter, for to hang on yon tree,

And lat her hang there for the poisoning o' me."

(tozu, rope.)

She sat down below a thorn,

Fine flowers in the valley;

And there she has her sweet babe born,

And the green leaves they grow rarely.

"Smile na sae sweet, my bonnie babe,

Fine flowers in the valley,

And ye smile sae sweet, ye'll smile me dead,"

And the green leaves they grow rarely.

She's ta'en out her little penknife,

Fine flowers in the valley,

And twinn'd the sweet babe o' its life,

And the green leaves they grow rarely.

She's howket a grave by the light o' the moon,

Fine flowers in the valley,

And there she's buried her sweet babe in,

And the green leaves they grow rarely.

As she was going to the church,

Fine flowers in the valley,

She saw a sweet babe in the porch,

And the green leaves they grow rarely.

"O sweet babe, and thou were mine,

Fine flowers in the valley,

I wad clead thee in the silk so fine,"

And the green leaves they grow rarely.

"O mother dear, when I was thine,

Fine flowers in the valley,

Ye did na prove to me sae kind,"

And the green leaves they grow rarely.

(howket, digged. clead, clad.)

O Lady, rock never your young son,

One hour longer for me;

For I have a sweetheart in Garlicks Wells,

I love thrice better than thee.

"The very soles of my love's feet

Is whiter than thy face:"

"But, nevertheless, now, Young Hunting,

Ye'll stay with me a' night?"

She has birled in him, Young Hunting,

The good ale and the beer;

Till he was as love-drunken

As any wild-wood steer.

She has birled in him, Young Hunting,

The good ale and the wine:

Till he was as love-drunken

As any wild-wood swine.

Up she has ta'en him, Young Hunting,

And she has had him to her bed.

And she has minded her of a little penknife,

That hangs low down by her gare,

(birled in, poured out drink for. gare, skirt.)

And she has gi'en him, Young Hunting,

A deep wound and a sair.

Out and spake the bonny bird

That flew abune her head;

"Lady! keep weel your green clothing

Frae that good lords blood."—

"O better I'll keep my green clothing

Frae that good lord's blood,

Nor thou can keep thy flattering tongue,

That flatters in thy head."

"Light down, light down, my bonny bird,

Light down upon my hand;

"O siller, O siller shall be thy hire,

An' goud shall be thy fee,

An' every month into the year

Thy cage shall changed be."

"I winna light down, I shanna light down,

I winna light on thy hand;

Full soon, soon wad ye do to me

As ye done to Young Hunting."

She has booted and spurred him, Young Hunting,

As he been ga'en to ride,

A hunting-horn about his neck

An' the sharp sword by his side.

And she has had him to yon water,

For a' man calls it Clyde.

The deepest pot intill it all

She has putten Young Hunting in;

A green turf upon his breast,

To hold that good lord down.

It fell once upon a day

The king was going to ride,

And he sent for him, Young Hunting,

To ride on his right side.

She has turned her right and round about,

She swear now by the corn,

"I saw na thy son, Young Hunting,

Since yesterday at morn."

She has turned her right and round about,

She swear now by the moon,

"I saw na thy son, Young Hunting,

Since yesterday at noon.

"It fears me sair in Clydes water,

That he is drown'd therein."—

O they hae sent for the kings duckers

To duck for Young Hunting.

They ducked in at the [tae] water-bank,

They ducked out at the other;

(pot, hole.)

"We'll duck nae mair for Young Hunting

Although he were our brother."

Out and spake the bonny bird

That flew abune their heads.

"O he's na drowned in Clyde's water,

'He is slain and put therein;

The lady that lives in yon castle

Slew him and put him in.

"Leave off your ducking on the day,

And duck upon the night;

Wherever that sackless knight lies slain,

The candles will shine bright."—

They left off their ducking on the day,

And duck'd upon the night;

And where that sackless knight lay slain,

The candles shone full bright.

The deepest pot intill it a',

They got Young Hunting in;

A green turf upon his breast,

To hold that gude lord down.

O they ha sent off men to the wood

To hew down both thorn and fern,

That they might get a great bonfire

To burn that lady in.

(sackless, guiltless.)

The Twa Corbies

"Put na the wite on me," she said,

"It was [my] may Catherine:"

When they had taen her, may Catherine,

In the bonfire set her in.

It wadna take upon her cheeks,

Nor take upon her chin;

Nor yet upon her yellow hair,

To heal the deadly sin.

Out they ta en her, may Catherine,

And they put that lady in;

O it took upon her cheek, her cheek,

An it took upon her chin;

An it took upon her fair body—

She burn'd like [holly-green].

As I was walking all alane,

I heard twa corbies making a mane;

The tane unto the t'other say,

"Where sall we gang and dine to-day?"—

(wite, blame,)

"In behint yon auld fail dyke,

I wot there lies a new-slain knight;

And naebody kens that he lies there,

But his hawk, his hound, and lady fair.

"His hound is to the hunting gane,

His hawk, to fetch the wild-fowl hame,

His lady's ta'en another mate,

So we may mak our dinner sweet.

"Ye'll sit on his white hals-bane,

And I'll pick out his bonny blue een:

Wi' ae lock o' his gowden hair,

We'll theek our nest when it grows bare.

"Mony a one for him makes mane,

But nane sail ken where he is gane:

O'er his white banes, when they are bare,

The wind sail blaw for evermair."—

Late at e'en, drinking the wine,

Or early in the morning,

They set a combat them between,

To fight it in the dawning.

(fail dyke, wall of sods. hals-bane, neck-bone. theek, thatch.)

"O stay at hame, my noble lord,

O stay at hame, my marrow!

My cruel brother will you betray

On the dowie houms of Yarrow.

"O fare ye weel, my lady gay!

O fare ye weel, my Sarah!

For I maun gae, though I ne'er return

Frae the dowie banks o' Yarrow."

She kiss'd his cheek, she kaim'd his hair,

As she had done before, O;

She belted on his noble brand,

And he's away to Yarrow.

O he's gane up yon high, high hill,

I wot he gaed wi' sorrow,

An' in a den spied nine arm'd men,

I' the dowie houms of Yarrow.

(marrow, mate. houms, marshes. dowie, gloomy.)

"O are ye come to drink the wine,

As ye hae doon before, oh?

Or are ye come to wield the brand,

On the bonny banks of Yarrow?"—

"I am no come to drink the wine,

As I hae doon before, oh,

But I am come to wield the brand,

On the dowie houms of Yarrow."

Four he hurt, and five he slew,

On the dowie houms of Yarrow,

Till that stubborn knight came him behind,

And ran his body thorough.

"Gae hame, gae hame, good-brother John,

And tell your sister Sarah,

To come and lift her noble lord;

Who's sleepin sound on Yarrow."—

"Yestreen I dream'd a dolefu' dream;

I kenn'd there wad be sorrow!

I dream'd I pu'd the heather green,

On the dowie banks o' Yarrow."

She gaed up yon high, high hill—

I wot she gaed wi' sorrow—

An' in a den spied nine dead men,

On the dowie houms of Yarrow.

She kissed his cheek, she kaim'd his hair,

As oft she did before, O;

She drank the red blood frae him ran,

On the dowie houms of Yarrow.

"O haud your tongue, my daughter dear!

For what needs a ' this sorrow;

I'll wed ye on a better lord,

Than him you lost on Yarrow."—

"O haud your tongue, my father dear!

And dinna grieve your Sarah;

A better lord was never born

Than him I lost on Yarrow.

"Take hame your ousen, take hame your kye,

For they hae bred our sorrow;

I wish that they had a' gane mad

When they came first to Yarrow."

Gude Lord Græme is to Carlisle gane,

Sir Robert Bewick there met he,

And arm in arm to the wine they did go,

And they drank till they were baith merry.

Gude Lord Græme has ta en up the cup,

"Sir Robert Bewick, and heres to thee!

And here's to our twa sons at hame!

For they like us best in our ain country."—

"O were your son a lad like mine,

And learn'd some books that he could read,

They might hae been twa brethren bold,

And they might hae bragged the Border side.

(bragged, defied.)

"But your son's a lad, and he is but bad,

And billy to my son he canna be;"

"[I] sent him to the schools, and he wadna learn;

[I] bought him books, and he wadna read;

But my blessing shall he never earn,

Till I see how his arm can defend his head."—

Gude Lord Græme has a reckoning call'd,

A reckoning then called he;

And he paid a crown, and it went roun',

It was all for the gude wine and free.

And he has to the stable gane,

Where there stood thirty steeds and three;

He's ta'en his ain horse amang them a',

And hame he rade sae manfully.

"Welcome, my auld father!" said Christie Graeme,

"But where sae lang frae hame were ye?"—

"It's I hae been at Carlisle town,

And a baffled man by thee I be.

"I hae been at Carlisle town,

Where Sir Robert Bewick he met me;

He says yere a lad, and ye are but bad,

And billy to his son ye canna be.

"I sent ye to the schools, and ye wadna learn;

I bought ye books, and ye wadna read;

Therefore my blessing ye shall never earn,

Till I see with Bewick thou save my head."

"Now, God forbid, my auld father,

That ever sic a thing should be!

Billy Bewick was my master, and I was his scholar,

And aye sae weel as he learned me."

"O hold thy tongue, thou limmer loon,

And of thy talking let me be!

If thou does na end me this quarrel soon,

There is my glove, I'll fight wi' thee."

Then Christie Græme he stooped low

Unto the ground, you shall understand;—

"O father, put on your glove again,

The wind has blown it from your hand?"

What's that thou says, thou limmer loon?

How dares thou stand to speak to me?

If thou do not end this quarrel soon,

There's my right hand thou shalt fight with me."—

Then Christie Graeme's to his chamber gane,

To consider weel what then should be;

Whether he should fight with his auld father,

Or with his billy Bewick, he.

(limmer, rascal.)

Græme and Bewick ss' 47

"If I should kill my billy dear,

God's blessing I shall never win;

But if I strike at my auld father,

I think 'twould be a mortal sin.

"But if I kill my billy dear,

It is God's will, so let it be;

But I make a vow, ere I gang frae hame,

That I shall be the next man's die."—

Then he's put on's back a gude auld jack,

And on his head a cap of steel,

And sword and buckler by his side;

O gin he did not become them weel!

We'll leave off talking of Christie Græme,

And talk of him again belive;

And we will talk of bonny Bewick,

Where he was teaching his scholars five.

When he had taught them well to fence,

And handle swords without any doubt,

He took his sword under his arm,

And he walk'd his father's close about.

He look'd atween him and the sun,

And a' to see what there might be,

Till he spied a man in armour bright,

Was riding that way most hastily.

(jacky coat of mail. belive, soon.)

"O wha is yon, that came this way,

Sae hastily that hither came?

I think it be my brother dear,

I think it be young Christie Græme.

"Yere welcome here, my billy dear,

And thrice ye're welcome unto me! "—

"But I'm wae to say, I've seen the day,

When I am come to fight wi' thee.

"My fathers gane to Carlisle town,

Wi' your father Bewick there met he:

He says I'm a lad, and I am but bad,

And a baffled man I trow I be.

"He sent me to schools, and I wadna learn;

He gae me books, and I wadna read;

Sae my father's blessing I'll never earn,

Till he see how my arm can guard my head."

"O God forbid, my billy dear,

That ever such a thing should be!

We'll take three men on either side,

And see if we can our fathers agree."

"O hold thy tongue, now, billy Bewick,

And of thy talking let me be!

But if thou'rt a man, as I'm sure thou art,

Come o'er the dyke, and fight wi' me."

"But I hae nae harness, billy, on my back,

As weel I see there is on thine."—

"But as little harness as is on thy back,

As little, billy, shall be on mine."—

Then he's thrown off his coat o' mail,

His cap of steel away flung he;

He stuck his spear into the ground,

And he tied his horse unto a tree.

Then Bewick has thrown off his cloak,

And's psalter-book frae's hand flung he;

He laid his hand upon the dyke,

And ower he lap most manfully.

O they hae fought for twa lang hours;

When twa lang hours were come and gane,

The sweat drapp'd fast frae off them baith,

But a drap of blude could not be seen.

Till Græme gae Bewick an awkward stroke,

Ane awkward stroke strucken sickerly;

He has hit him under the left breast,

And dead-wounded to the ground fell he.

"Rise up, rise up, now, billy dear,

Arise and speak three words to me!

Whether thou's gotten thy deadly wound,

Or if God and good leeching may succour thee?"

(sickerly, surely.)

"O horse, O horse, now, billy Græme,

And get thee far from hence with speed;

And get thee out of this country,

That none may know who has done the deed."—

"O I have slain thee, billy Bewick,

If this be true thou tellest to me;

But I made a vow, ere I came frae hame,

That aye the next man I wad be."

He has pitch'd his sword in a moodie-hill,

And he has leap'd twenty lang feet and three,

And on his ain sword's point he lap,

And dead upon the ground fell he.

'Twas then came up Sir Robert Bewick,

And his brave son alive saw he;

"Rise up, rise up, my son," he said,

"For I think ye hae gotten the victorie."

"O hold your tongue, my father dear,

Of your prideful talking let me be!

Ye might hae drunken your wine in peace,

And let me and my billy be.

"Gae dig a grave, baith wide and deep,

And a grave to hold baith him and me;

But lay Christie Græme on the sunny side,

For I'm sure he won the victorie."

(moodie-hill, mole-hill.)

"Alack! a wae!" auld Bewick cried,

"Alack! was I not much to blame?

I'm sure I've lost the liveliest lad

That e'er was born unto my name."

"Alack! a wae!" quo' gude Lord Græme,

"Im sure I hae lost the deeper lack!

I durst hae ridden the Border through,

Had Christie Græme been at my back.

"Had I been led through Liddesdale,

And thirty horsemen guarding me,

And Christie Græme been at my back,

Sae soon as he had set me free!

"I've lost my hopes, I've lost my joy,

I've lost the key but and the lock;

I durst hae ridden the world round,

Had Christie Græme been at my back."

My love he built me a bonny bower,

And clad it a wi' lily flower,

A brawer bower ye ne er did see

Than my true love he built for me.

(lack, loss.)

There came a man, by middle day,

He spied his sport, and went away;

And brought the King that very night,

Who brake my bower, and slew my knight.

He slew my knight, to me sae dear;

He slew my knight, and poin'd his gear;

My servants all for life did flee,

And left me in extremity.

I sew'd his sheet, making my mane;

I watch'd the corpse, myself alane;

I watch'd his body, night and day;

No living creature came that way.

I took his body on my back,

And whiles I gaed, and whiles I sat;

I digg'd a grave, and laid him in,

And happ'd him with the sod sae green.

But think na ye my heart was sair,

When I laid the mould on his yellow hair;

O think na ye my heart was wae,

When I turn'd about, away to gae?

Nae living man I'll love again,

Since that my lovely knight is slain;

Wi' ae lock of his yellow hair

I'll chain my heart for ever mair.

(poind, seized. happed, covered.)

It's narrow, narrow, make your bed,

And learn to lie your lane;

For I'm gaun o'er the sea, Fair Annie,

A braw bride to bring hame.

Wi' her I will get gowd and gear;

Wi' you I ne er got nane.

"But wha will bake my bridal bread,

Or brew my bridal ale?

And wha will welcome my brisk bride,

That I bring o er the dale?"—

"It's I will bake your bridal bread,

And brew your bridal ale;

And I will welcome your brisk bride,

That you bring oer the dale."—

"But she that welcomes my brisk bride

Maun gang like maiden fair;

She maun lace on her robe sae jimp,

And braid her yellow hair."—

"But how can I gang maiden-like,

When maiden I am nane?

Have I not born seven sons to thee,

And am with child again?"—

She's ta'en her young son in her arms,

Another in her hand;

And she's up to the highest tower,

To see him come to land.

"Come up, come up, my eldest son,

And look o'er yon sea-strand,

And see your father's new-come bride,

Before she come to land."—

"Come down, come down, my mother dear,

Come frae the castle wa'!

I fear, if langer ye stand there,

Ye'll let yoursel' down fa."—

(jimp, slim.)

And she gaed down, and farther down,

Her love's ship for to see;

And the topmast and the mainmast

Shone like the silver free.

And she's gane down, and farther down,

The bride's ship to behold;

And the topmast and the mainmast

They shone just like the gold.

She's ta'en her seven sons in her hand;

I wot she didna fail!

She met Lord Thomas and his bride,

As they came o'er the dale.

"You re welcome to your house, Lord Thomas,

You're welcome to your land;

You're welcome with your fair lady,

That you lead by the hand.

"You're welcome to your ha's, lady,

You're welcome to your bowers;

You're welcome to your hame, lady,

For a' that's here is yours."—

"I thank thee, Annie; I thank thee, Annie;

Sae dearly as I thank thee;

You're the likest to my sister Annie,

That ever I did see.

(free, precious.)

"There came a knight out o er the sea,

And steal'd my sister away;

The shame scoup in his company,

And land where er he gae!"—

She hang ae napkin at the door,

Another in the ha';

And a' to wipe the trickling tears,

Sae fast as they did fa'.

And aye she served the lang tables

With white bread and with wine;

And aye she drank the wan water,

To had her colour fine.

And aye she served the lang tables,

With white bread and with brown;

And ay she turned her round about,

Sae fast the tears fell down.

And hes ta en down the silk napkin,

Hung on a silver pin;

And aye he wipes the tear trickling

Adown her cheek and chin.

And aye he turn'd him round about,

And smiled amang his men,

Says—"Like ye best the old lady,

Or her that's new come hame?"—

(scaup, go. had, hold, keep.)

When bells were rung, and mass was sung,

And a' men bound to bed,

Lord Thomas and his new-come bride,

To their chamber they were gaed.

Annie made her bed a little for bye,

To hear what they might say;

"And ever alas!" fair Annie cried,

"That I should see this day!

"Gin my seven sons were seven young rats,

Running on the castle wa',

And I were a grey cat mysel',

I soon would worry them a'.

"Gin my seven sons were seven young hares,

Running o er yon lily lea,

And I were a greyhound mysel',

Soon worried they a' should be."—

And wae and sad fair Annie sat,

And dreary was her sang;

And ever, as she sobb'd and grat,

"Wae to the man that did the wrang!"—

"My gown is on," said the new-come bride,

"My shoes are on my feet,

And I will to fair Annies chamber,

And see what gars her greet.——

(forbye, on one side. grat, wept. gars, makes.)

"What ails ye, what ails ye, Fair Annie,

That ye make sic a moan?

Has your wine barrels cast the girds,

Or is your white bread gone?

"O wha was't was your father, Annie,

Or wha was't was your mother?

And had you ony sister, Annie,

Or had you ony brother?"—

"The Earl of Wemyss was my father,

The Countess of Wemyss my mother;

And a ' the folk about the house,

To me were sister and brother."—

"If the Earl of Wemyss was your father,

I wot sae was he mine;

And it shall not be for lack o' gowd,

That ye your love sall tyne.

"For I have seven ships o' mine ain,

A' loaded to the brim;

And I will gie them a' to thee,

Wi' four to thine eldest son.

But thanks to a the powers in heaven

That I gae maiden hame!"

(tyne, lose.)

O weel's me, my gay goss-hawk,

That he can speak and flee;

Hell carry a letter to my love,

Bring back another to me."

"O how can I your true love ken,

Or how can I her know?

When frae her mouth I ne er heard couth,

Nor wi' my eyes her saw."

"O weel sail ye my true love ken,

As soon as ye her see;

For, of a the flowers of fair England,

The fairest flower is she.

(heard, couth, could hear.)

"And even at my love's bower-door

There grows a bowing birk;

And sit ye doun and sing thereon

As she gangs to the kirk.

"And four-and-twenty ladies fair

Will wash and to the kirk,

But well shall ye my true-love ken,

For she wears goud on her skirt.

"And four-and-twenty gay ladies

Will to the mass repair;

But weel shall ye my true love ken,

For she wears goud on her hair."

And even at the lady's bower-door

There grows a bowing birk;

And [he] sat down and sang thereon

As she gaed to the kirk.

"O eat and drink, my Maries a',

The wine flows you among,

Till I gang to my shot-window,

And hear yon bonny bird's song.

"Sing on, sing on, my bonny bird,

The song ye sang [yestreen];

For I ken, by your sweet singing,

Ye're frae my true love sen."

(birk, birch. shot-windoiv, projecting window. sen, sent.)

O first he sang a merry song,

And then he sang a grave;

And then he pick'd his feathers gray,

To her the letter gave.

"Ha, there's a letter frae your love,

He says he sent you three;

He canna wait your love langer,

But for your sake he'll die.

"He bids you write a letter to him;

He says he's sent ye five;

He canna wait your love langer,

Tho' you're the fairest woman alive."

"Ye bid him bake his bridal bread,

And brew his bridal ale;

And I'll meet him in fair Scotland,

Lang, lang ere it be stale."

She's doen to her father dear,

Fa'en low down on her knee:

"A boon, a boon, my father dear,

I pray you, grant it me."

"Ask on, ask on, my daughter,

An granted it shall be;

Except ae squire in fair Scotland,

An him you shall never see."

"The only boon, my father dear,

That I do crave of thee,—

Is, gin I die in Southern lands,

In Scotland to bury me.

"And the first in kirk that ye come till,

Ye gar the bells be rung;

And the nextin kirk that ye come to,

Ye gar the mass be sung.

"And the thirdin kirk that ye come till,

You deal gold for my sake.

And the fourthin kirk that ye come till,

You tarry there till night."

She has doen her to her bigly bower

As fast as she could fare;

And she has ta'en a sleepy draught,

That she had mix'd wi' care.

(gar, make. bigly, big.)

The Gay Goss-Hawk ss' 63

She's laid her down upon her bed,

An soon she fa en asleep,

And soon o'er every tender limb

Cold death began to creep.

When night was flown, and day was come,

Nae ane that did her see

But thought she was a surely dead,

As ony lady could be.

Her father and her brothers dear

Gar'd make to her a bier;

The tae half was o' gude red gold,

The tither o' silver clear.

Her mither and her sisters fair

Gar'd work for her a sark;

The tae half was o' cambric fine

The tither o' needle wark.

An the first in kirk that they came till,

They gar'd the bells be rung;

The nextin kirk that they came till,

They gar'd the mass be sung.

The thirdin kirk that they came till,

They dealt gold for her sake,

An' the fourthin kirk that they came till,

Lo, there they met her make.

(make, mate.)

"Lay down, lay down the bigly bier,"

"Let me the dead look on:"

Wi' cherry cheeks and ruby lips

She lay and smiled on him.

"O ae shave of your bread, true love,

An' ae glass of your wine;

For I hae fasted for your sake

These fully days is nine.

"Gang hame, gang hame, my seven bold

brithers,

Gang hame and sound your horn!

And ye may boast in southern lands

Your sister's played you scorn."

O wha wad wish the wind to blaw,

Or the green leaves fa' therewith?

Or wha wad wish a lealer love

Than Brown Adam the Smith?

His hammer's o' the beaten gold,

His study's o' the steel,

(study, that which stands, i.e. the anvil (?))

His fingers white, are my delight,

He blows his bellows weel.

But they hae banish'd him, Brown Adam,

Frae father and frae mother;

And they hae banish'd him, Brown Adam,

Frae sister and frae brother.

And they hae banish'd Brown Adam,

Frae the flower o' a' his kin;

And he's bigged a bower i' the gude greenwood

Between his lady and him.

O it fell once upon a day,

Brown Adam he thought lang;

An' he would to the green-wood gang,

To hunt some venison.

He has ta'en his bow his arm o'er,

His bran' intill his han',

And he is to the gude green-wood

As fast as he could gang.

O he's shot up, and he's shot down,

The bird upon the briar;

And he sent it hame to his lady,

Bade her be of gude cheer.

O he's shot up, and he's shot down,

The bird upon the thorn;

And sent it hame to his lady,

Said he'd be hame the morn.

When he came to his lady's bower door

He stood a little forbye,

And there he heard a fu' fause knight

Tempting his gay lady.

For he's ta'en out a gay goud ring,

Had cost him many a poun',

"O grant me love for love, lady,

And this sal be thy own."—

"I lo'e Brown Adam weel," she says;

"I wot sae does he me;

An I wadna gie Brown Adam's love

For nae fause knight I see."—

Out has he ta'en a purse o' goud,

Was a' fu' to the string,

"O grant me but love for love, lady,

And a' this sail be thine."—

"I lo'e Brown Adam weel," she says;

"I wot sae does he me:

I wadna be your light leman,

For mair nor ye could gie."

Then out has he drawn his lang, lang bran',

And he's flash'd it in her een;

"Now grant me love for love, lady,

Or thro' ye this shall gang!"—

Oh, sighing, said that gay lady,

"Brown Adam tarries lang!"—

Then up it starts Brown Adam,

Says—"I'm just at your hand."—

He's gar'd him leave his bow, his bow,

He's gar'd him leave his brand,

He's gar'd him leave a better pledge—

Four fingers o' his right hand.

I will sing, if ye will hearken,

If ye will hearken unto me;

The king has ta'en a poor prisoner,

The wanton laird o' young Logie.

Young Logie's laid in Edinburgh chapel,

Carmichael's the keeper o' the key;

And May Margaret's lamenting sair,

A' for the love o' young Logie.

"Lament, lament na, May Margaret,

And of your weeping let me be;

For ye maun to the king himsel',

To seek the life o' young Logie."

May Margaret has kilted her green cleiding,

And she has curl'd back her yellow hair,—

"If I canna get young Logie's life,

Farewell to Scotland for evermair."

When she came before the king,

She kneelit lowly on her knee.

"O what's the matter, May Margaret?

And what needs a' this courtesy?"

"A boon, a boon, my noble liege,

A boon, a boon, I beg o' thee!

And the first boon that I come to crave

Is to grant me the life o' young Logie."

"Ona, O na, May Margaret,

Forsooth, and so it mauna be;

For a' the gowd o' fair Scotland

Shall not save the life o' young Logie."

But she has stown the king's redding kaim,

Likewise the queen her wedding knife;

And sent the tokens to Carmichael,

To cause young Logie get his life.

She sent him a purse o' the red gowd,

Another o' the white money;

' She sent him a pistol for each hand,

And bade him shoot when he gat free.

(stown, stolen. redding kaim, hair comb.)

When he came to the Tolbooth stair,

Then he let his volley flee;

It made the king in his chamber start,

Een in the bed where he might be.

"Gae out, gae out, my merrymen a,

And bid Carmichael come speak to me;

For I'll lay my life the pledge o' that,

That yon's the shot o' young Logie."

When Carmichael came before the king,

He fell low down upon his knee;

The very first word that the king spake

Was,—"Where's the laird of young Logie?"

Carmichael turn'd him round about,

(I wot the tear blinded his e'e,)—

"There came a token frae your grace

Has ta'en away the laird frae me."

"Hast thou play'd me that, Carmichael?

And hast thou play'd me that?" quoth he;

"The morn the Justice Court's to stand,

And Logie's place ye maun supply."

Carmichael's awa to Margaret's bower,

Even as fast as he may dri'e,—

"O if young Logie be within,

Tell him to come and speak with me!"

(drte, drive).

May Margaret turn'd her round about,

(I wot a loud laugh laughed she,)—

"The egg is chipp'd, the bird is flown,

Ye'll see nae mair of young Logie."

The tane is shipped at the pier of Leith,

The t'other at the Queen's Ferry;

And she's gotten a father to her bairn,

The wanton laird of young Logie.

Johnnie rose up in a May morning,

Call'd for water to wash his hands—

"Gar loose to me the gude gray dogs,

That are bound wi' iron bands."

When Johnnie's mother gat word o' that,

Her hands for dule she wrang—

"O Johnnie! for my benison,

To the greenwood dinna gang!

"Enough ye hae o' gude wheat bread,

And enough o' the blood-red wine;

And therefore, for nae venison, Johnnie,

I pray ye, stir frae hame."

But Johnnie's busk'd up his gude bent bow,

His arrows, ane by ane,

And he has gane to Durrisdeer,

To hunt the dun deer down.

As he came down by Merriemass,

And in by the benty line,

There has he espied a deer lying

Aneath a bush of ling.

Johnnie he shot, and the dun deer lap,

And he wounded her on the side;

But atween the water and the brae,

His hounds they laid her pride.

And Johnnie has bryttled the deer sae weel,

That he's had out her liver and lungs;

And wi' these he has feasted his bluidy hounds,

As if they had been earl's sons.

They eat sae much o' the venison,

And drank sae much o' the blude,

That Johnnie and a' his bluidy hounds

Fell asleep as they had been dead.

And by there came a silly auld carle,

An ill death mote he die!

For he's awa' to Hislinton,

Where the seven Foresters did lie.

(benty line, path covered with bent (?). bryttled, cut up. carle, churl.)

"What news, what news, ye gray-headed carle,

What news bring ye to me?"

"I bring nae news," said the gray-headed carle,

"Save what these eyes did see.

"As I came down by Merriemass,

And down among the scroggs,

The bonniest child that ever I saw

Lay sleeping amang his dogs.

"The shirt that was upon his back

Was o' the Holland fine;

The doublet which was over that

Was o' the Lincoln twine.

"The buttons that were on his sleeve

Were o' the goud sae gude;

The gude gray hounds he lay amang,

Their mouths were dyed wi' blude"

Then out and spak the First Forester

The head man ower them a'—

"If this be Johnnie o' Breadislee,

Nae nearer will we draw."

But up and spak the Sixth Forester,

(His sister's son was he,)

"If this be Johnnie o' Breadislee,

We soon shall gar him die."

(scroggs, stunted trees.)

The first flight of arrows the Foresters shot,

They wounded him on the knee;

And out and spak the Seventh Forester,

"The next will gar him die."

Johnnies set his back against an aik,

His foot against a stane;

And he has slain the Seven Foresters,

He has slain them a' but ane.

He has broke three ribs in that ane's side,

But and his collar bane;

He's laid him twa-fald ower his steed,

Bade him carry the tidings hame.

"O is there nae a bonny bird

Can sing as I can say,

Could flee away to my mother's bower,

And tell to fetch Johnnie away?"

The starling flew to his mother's window stane,

It whistled and it sang;

And aye the ower word o' the tune

Was—"Johnnie tarries lang!"

They made a rod o' the hazel bush,

Another o' the sloe-thorn tree,

And mony mony were the men

At fetching o'er Johnnie.

(aik, oak. the ower word, the refrain.)

Then out and spake his auld mother,

And fast her tears did fa'—

"Ye wad nae be warn'd, my son Johnnie,

Frae the hunting to bide awa'.

'' Aft hae I brought to Breadislee

The less gear and the mair,

But I ne'er brought to Breadislee

What grieved my heart sae sair.

"But wae betide that silly auld carle!

An ill death shall he die!

For the highest tree in Merriemas

Shall be his morning's fee."

Now Johnnie's gude bend bow is broke,

And his gude gray dogs are slain;

And his body lies dead in Durrisdeer,

And his hunting it is done.

O have ye na heard o' the fause Sakelde?

O have ye na heard of the keen Lord Scroope?

How they hae taen bould Kinmont Willy,

On Haribee to hang him up?

Had Willy had but twenty men,

But twenty men as stout as he,

Fause Sakelde had never the Kinmont ta'en,

Wi' eight score in his company.

They band his legs beneath the steed,

They tied his hands behind his' back;

They guarded him, five some on each side,

And they brought him ower the Liddel-rack.

They led him thro' the Liddel-rack,

And also thro' the Carlisle sands;

They brought him to Carlisle castle,

To be at my Lord Scroope's commands.

(band, bound.)

"My hands are tied, but my tongue is free,

And wha will dare this deed avow?

Or answer by the Border law?

Or answer to the bauld Buccleuch?"

"Now haud thy tongue, thou rank reiver!

There's never a Scot shall set thee free:

Before ye cross my castle yate,

I trow ye shall take farewell o' me."

"Fear na ye that, my lord," quo' Willy:

"By the faith o' my body, Lord Scroope," he said,

"I never yet lodged in a hostelry,

But I paid my lawing before I gaed."

Now word is gane to the bauld Keeper,

In Branksome Ha' where that he lay,

That Lord Scroope has ta'en the Kinmont Willy,

Between the hours of night and day.

He has ta'en the table wi' his hand,

He gar'd the red wine spring on high—

"Now Christ's curse on my head," he said,

"But avenged of Lord Scroope I'll be!

"O is my basnet a widow's curch?

Or my lance a wand of the willow-tree?

Or my arm a lady's lily hand,

That an English lord should lightly me!

(reiver, robber. yate, gate. lawing, reckoning. basnet, helmet. curch, kerchief.)

"And have they ta en him, Kinmont Willy,

Against the truce of Border tide,

And forgotten that the bauld Buccleuch

Is keeper there on the Scottish side?

"And have they e en ta en him, Kinmont Willy,

Withouten either dread or fear,

And forgotten that the bauld Buccleuch

Can back a steed, or shake a spear?

"O were there war between the lands,

As well I wot that there is none,

I would slight Carlisle castle high,

Though it were builded of marble stone.

"I would set that castle in a low,

And sloken it with English blood!

There's never a man in Cumberland,

Should ken where Carlisle castle stood.

"But since nae war's between the lands,

And there is peace, and peace should be;

I'll neither harm English lad or lass,

And yet the Kinmont freed shall be!"

He has call'd him forty Marchmen bauld,

I trow they were of his ain name,

Except Sir Gilbert Elliot, call'd

The Laird of Stobs, I mean the same.

(slight, i.e., make little of. sloken, slake.)

He has call'd him forty Marchmen bauld,

Were kinsmen to the bauld Buccleuch;

With spur on heel, and splent on spauld,

And gloves of green, and feathers blue.

There were five and five before them a',

Wi' hunting-horns and bugles bright:

And five and five came wi' Buccleuch,

Like warden's men, array'd for fight.

And five and five, like a mason-gang,

That carried the ladders lang and high;

And five and five, like broken men;

And so they reach'd the Woodhouselee.

And as we cross'd the Bateable Land,

When to the English side we held,

The first o' men that we met wi',

Wha should it be but fause Sakelde?

"Where be ye gaun, ye hunters keen?"

Quo' fause Sakelde; "come tell to me!"

"We go to hunt an English stag,

Has trespass'd on the Scots country."

"Where be ye gaun, ye marshal-men?"

Quo' fause Sakelde; "come tell me true!

"We go to catch a rank reiver,

Has broken faith wi' the bauld Buccleuch.'

(splent, armour. spauld, shoulder.)

"Where are ye gaun, ye mason lads,

Wi' a' your ladders lang and high?"

"We gang to herry a corbie's nest,

That wons not far frae Woodhouselee."

"Where be ye gaun, ye broken men?"

Quo' fause Sakelde; "Come tell to me!"

Now Dicky of Dry hope led that band,

And the never a word of lear had he.

"Why trespass ye on the English side?

Row-footed outlaws, stand!" quo' he;

Then never a word had Dicky to say,

Sae he thrust the lance through his fause body.

Then on we held for Carlisle toun,

And at Staneshaw-bank the Eden we cross'd;

The water was great and mickle of spate,

But the never a horse nor man we lost.

And when we reach'd the Staneshaw-bank,

The wind was rising loud and high;

And there the Laird gar'd leave our steeds,

For fear that they should stamp and neigh.

And when we left the Staneshaw-bank,

The wind began full loud to blaw;

But 'twas wind and weet, and fire and sleet,

When we came beneath the castle wa'.

(herry, harry. wons, dwells. lear, lying. row-footed, rough-footed.)

We crept on knees, and held our breath,

Till we placed the ladders against the wa';

And sae ready was Buccleuch himsel'

To mount the first before us a'.

He has taen the watchman by the throat,

He flung him down upon the lead—

"Had there not been peace between our lands,

Upon the other side thou hadst gaed!

"Now sound out, trumpets!" quo' Buccleuch;

"Let's waken Lord Scroope right merrily!"

Then loud the wardens trumpet blew—

O wha dare meddle wi' me?

Then speedily to wark we gaed,

And raised the slogan ane and a',

And cut a hole through a sheet of lead,

And so we wan to the castle ha'.

They thought King James and a' his men

Had won the house wi' bow and spear;

It was but twenty Scots and ten,

That put a thousand in sic a stear!

Wi' coulters, and wi' forehammers,

We gar'd the bars bang merrily,

Until we came to the inner prison,

Where Willy o' Kinmont he did lie.

(forehammers, sledge-hammers. stear, stir. slogan, war-cry.)

And when we came to the lower prison,

Where Willy o' Kinmont he did lie—

"O sleep ye, wake ye, Kinmont Willy,

Upon the morn that thou's to die?"

"O I sleep saft, and I wake aft,

It's lang since sleeping was fley'd frae me;

Gie my service back to my wife and bairns,

And a' gude fellows that speer for me."

Then Red Rowan has hente him up,

The starkest man in Teviotdale—

"Abide, abide now, Red Rowan,

Till of my Lord Scroope I take farewell.

"Farewell, farewell, my gude Lord Scroope!

My gude Lord Scroope, farewell!" he cried—

"I'll pay you for my lodging mail,

When first we meet on the Border side."

Then shoulder high, with shout and cry,

We bore him down the ladder lang:

At every stride Red Rowan made,

I wot the Kinmont's airns play'd clang.

"O mony a time," quo' Kinmont Willy,

"I have ridden horse baith wild and wood;

But a rougher beast than Red Rowan

I ween my legs have ne'er bestrode.

(hente, caught. fley'd, frightened. starkest, strongest. airns, irons.)

"And mony a time," quo' Kinmont Willy,

"I've prick'd a horse out ower the furs;

But since the day I back'd a steed,

I never wore sic cumbrous spurs."

We scarce had won the Staneshaw-bank,

When a' the Carlisle bells were rung,

And a thousand men on horse and foot

Came wi' the keen Lord Scroope along.

Buccleuch has turn'd to Eden Water,

Even where it flow'd frae bank to brim,

And he has plunged in wi' a' his band,

And safely swam them through the stream.

He turn'd him on the other side,

And at Lord Scroope his glove flung he—

"If ye like na my visit in merry England,

In fair Scotland come visit me!"

All sore astonish'd stood Lord Scroope,

He stood as still as rock of stane;

He scarcely dared to trew his eyes,

When through the water they had gane.

He is either himsel' a devil frae hell,

Or else his mother a witch maun be;

"I wadna hae ridden that wan water

For a' the gowd in Christianty."

(furs, furrows. trew, trust.)

Ye gie corn unto my horse,

An' meat unto my man;

For I will gae to my true love's gates

This night, that I can win."

"O stay at hame this ae night, Willy,

This ae bare night wi' me;

The best bed in a' my house

Shall be well made to thee."

"I carena for your beds, mither,

I carena a pin;

For I'll gae to my love's gates

This night, gin I can win."

4 Oh stay, my son Willy, this night,

This ae night wi' me;

The best hen in a' my roost

Shall be well made ready for thee."

"I carena for your hens, mither,

I carena a pin;

I shall gae to my love's gates

This night, gin I can win."

"Gin ye winna stay, my son Willy,

This ae bare night wi' me,

Gin Clyde's water's be deep and fu' o' flood,

My malison drown thee!"

He rade up yon high hill,

And down yon dowie den,

The roaring of Clyde's water

Wad hae fleyed ten thousand men.

"O spare me, Clyde's water,

O spare me as I gae!

Mak' me your wrack as I come back,

But spare me as I gae!"

He rade in, and farther in,

Till he came to the chin;

And he rade in, and farther in,

Till he came to dry land.

And when he came to his love's gates,

He tirled at the pin.

"Open your gates, Meggie,

Open your gates to me;

For my boots are fu' o' Clyde's water

And the rain rains ower my chin."

"I hae nae lovers thereout," she says,

"I hae nae love within;

My true-love is in my arms twa,

An' nane will I let in."

(den, hollow.)

"Open your gates, Meggie, this ae night,

Open your gates to me;

For Clydes water is fu' o' flood,

And my mother's malison 'll drown me."

"Ane o' my chambers is fu' o' corn,

An ane is fu' o' hay;

Another is fu' o' gentlemen;—

An' they winna move till day."

Out waked her may Meggie,

Out of her drowsy dream.

"I dreamed a dream sin the yestreen,

God read a' dreams to guid,

That my true love Willy

Was staring at my bed-feet."

"Lay still, lay still, my ae dochter,

An keep my back frae the call,

For it's na the space o' half an hour,

Sen he gaed frae your hall.''

An' hey Willy, and hoa, Willy,

Winna ye turn agen;

But aye the louder that she cried,

He rade against the win'.

He rade up yon high hill,

And doun yon dowie den;

The roaring that was in Clyde's water,

Wad ha fleyed ten thousand men.

(read explain. call, cold.)

He rade in, an' farther in,

Till he came to the chin;

An' he rade in, an' further in,

But never mair was seen.

There was na mair seen o' that guid lord,

But his hat frae his head;

There was na more seen of that lady,

But her comb and her snood.

There waders went up and doun,

Eddying Clyde's water;

Have done us wrang.

There were twa brethren in the north,

They went to the school together;

The one unto the other said

Will ye try a warsle afore?

They warsled up, they warsled down,

Till Sir John fell to the ground;

And there was a knife in Sir William's pouch,

Gi ed him a deadly wound.

(warsle, wrestle.)

"O brither dear, take me upon your back,

Carry me to yon burn clear,

And wash the blood from off my wound,

And it will bleed nae mair."

He's took him up upon his back,

Carried him to yon burn clear,

And wash'd the blood from off his wound,

But aye it bled the mair.

"Oh brither dear, take me on your back,

Carry me to yon kirk-yard,

And dig a grave baith wide and deep,

And lay my body there."

He's ta'en him up upon his back,

Carried him to yon kirkyard,

And dug a grave baith deep and wide,

And laid his body there.

"But what will I say to your father dear,

Gin he chance to say, Willy, where's John?"

"O say that he's to England gone,

To buy him a cask of wine."

"And what will I say to my mother dear,

Gin she chance to say, Willy, where's John?"

"Oh say that he's to England gone,

To buy her a new silk gown."

"And what will I say to my sister dear,

Gin she chance to say, Willy, where's John?"

"Oh say that he's to England gone,

To buy her a wedding ring."

"But what shall I say to her you love dear,

Gin she cry, why tarries my John?"

"Oh tell her I lie in Kirkland fair,

And home again will never come."

Down by yon garden green

Sae merrily as she gaes;

She has twa weel-made feet,

And she trips upon her taes.

She has twa weel-made feet;

Far better is her hand;

She's as jimp in the middle

As ony willow-wand.

"Gif ye will do my bidding,

At my bidding for to be,

It's I will make you lady

Of a the lands you see."

He spak a word in jest;

Her answer wasna good;

He threw a plate at her face,

Made it a' gush out o' blood.

She wasna frae her chamber

A step but barely three,

When up and at her right hand

There stood Man's Enemy.

"Gif ye will do my bidding,

At my bidding for to be;

I'll learn you a wile

Avenged for to be."

The Foul Thief knotted the tether;

She lifted his head on high;

The nourice drew the knot

That gar'd lord Waristoun die.

Then word is gane to Leith,

Also to Edinburgh town,

That the lady had kill'd the laird,

The laird o' Waristoun.

"Tak aff, tak aff my hood,

But lat my petticoat be;

Put my mantle o'er my head;

For the fire I daurna see.

"Now, a ye gentle maids,

Tak warning now by me,

And never marry ane

But wha pleases your e'e.

"For he married me for love,

But I married him for fee;

And sae brak out the feud

That gar'd my deary die."

In London city was Beichan born,

He longed strange countries for to see;

But he was ta en by a savage Moor,

Who handled him right cruelly;

For through his shoulder he put a bore;

And through the bore has putten a tree;

And he's gar'd him draw the carts of wine

Where horse and oxen had wont to be.

He's casten [him] in a dungeon deep,

Where he could neither hear nor see;

He's shut him up in a prison strong,

And he's handled him right cruelly.

O this Moor he had but ae daughter,

I wot her name was Susie Pye;

She doen her to the prison house,

And she's called young Beichan one word by.

"O have ye any lands, or rents,

Or cities in your own country,

Could free you out of prison strong,

And could maintain a lady free?"

"O London city is my own,

And other cities twa or three,

Could loose me out of prison strong,

And could maintain a lady free"

O she has brib'd her father's men

Wi' mickle gold and white money;

She's gotten the keys of the prison door

And she has set young Beichan free.

(bore, hole. tree, pole. free, noble.)

She's gi en him a loaf of good white bread,

But an' a flask of Spanish wine;

And she bad him mind on the lady's love

That sae kindly freed him out of pine.

"Go set your foot on good ship-board,

And haste ye back to your own country;

And before that seven years have an end,

Come back again, love, and marry me."

It was long ere seven years had an end,

She long'd full sore her love to see;

She's set her foot on good shipboard,

And turn'd her back on her own country.

She's sailed up, so has she doun,

Till she came to the other side;

She's landed at young Beichan's

gates,

An I hope this day she shall be his bride.

"Is this young Beichan's gates," says she,

"Or is that noble prince within?"

"He's up the stairs wi' his bonny bride,

An mony a lord and lady wi him."

(pinge, woe.0

"And has he ta'en a bonny bride?

An' has he clean forgotten me?"

An', sighin', said that gay lady,

"I wish I were in my own country."

But she's putten her han' in her pocket,

An' gien the porter guineas three;