Title: Road Scrapings: Coaches and Coaching

Author: M. E. Haworth

Release date: April 13, 2014 [eBook #45372]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Paul Clark and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note:

Every effort has been made to replicate this text as faithfully as possible. The errata listed at the end of the book have been fixed. Some minor corrections of puctuation have been made.

Larger versions of some of the illustrations may be seen by clicking on the illustration.

COACHES AND COACHING.

LONDON:

TINSLEY BROTHERS, 8, CATHERINE STREET, STRAND.

1882.

ROAD SCRAPINGS:

COACHES AND COACHING.

BY

CAPTAIN M. E. HAWORTH,

AUTHOR OF “THE SILVER GREYHOUND.”

London:

TINSLEY BROTHERS, 8, CATHERINE ST., STRAND.

1882.

[All rights reserved.]

In offering these pages to the public, my object has been confined to imparting such advice, in matters connected with coaching, as has been suggested by long experience; whilst, in order to dissipate as much as possible the “dryness” of being told “what to do” and “how to do it,” I have mingled the instruction with illustrative anecdotes and incidents, which may afford amusement to the general reader. If whilst my bars are “whistling” up the hill, and rattling down, I have been able to combine some useful hints with the amusement often to be discovered in what I have termed “Scrapings of the Road,” my desire will be amply gratified.

CHAPTER I. |

PAGE |

| The revival—Magazine magnificence—Death of coaching—Resurrection—Avoid powder—Does the post pull?—Summering hunters—The “Lawyer’s Daughter”—An unexpected guest | 1 |

CHAPTER II. |

|

| Young coachmen—Save your horses—The ribbons—The whip—A professional Jehu—An amateur—Paralysed fingers | 20 |

CHAPTER III. |

|

| Anecdotes: Coachmen (friends and enemies)—Roadside burial—Old John’s holiday—How the mail was robbed—Another method—A visit from a well-known character—A wild-beast attack—Carrier’s fear of the supernatural—Classical teams—Early practice with the pickaxe—Catechism capsized | 34 |

CHAPTER IV. |

|

| Opposition—A quick change—How to do it—Accident to the Yeovil mail—A gallop for our lives—Unconscious passengers—Western whips—Parliamentary obstruction | 51 |

CHAPTER V. |

|

| The “Warwick Crown Prince”—“Spicy Jack”—Poor old Lal!—“Go it, you cripples!”—A model horsekeeper—The coach dines here—Coroner’s inquest—The haunted glen—Lal’s funeral | 65[Pg viii] |

CHAPTER VI. |

|

| Commercial-room—The bagman’s tale—Yes—Strange company | 90 |

CHAPTER VII. |

|

| Draught horses—The old “fly-waggon”—Weight and pace—Sagacity of mules—Hanging on by a wheel—The Refuge—Hot fighting in the Alps—Suffocation—Over at last—Railway to Paris | 104 |

CHAPTER VIII. |

|

| Right as the mail—Proprietors and contractors—Guards and coachmen—A cold foot-bath—A lawyer nonsuited—Old Mac—The Spectre Squire—An unsolved mystery | 126 |

CHAPTER IX. |

|

| Public and private conveyances in Austria and Hungary—An English dragsman posed—The Vienna race-meeting—Gentleman “Jocks”—A moral exemplified | 145 |

CHAPTER X. |

|

| North-country fairs—An untrained foxhunter—Tempted again—Extraordinary memory of the horse—Satisfactory results from a Latch-key | 154 |

CHAPTER XI. |

|

| The Coach and Horses (sign of)—Beware of bog spirits—Tell that to the Marines—An early breakfast—Salmon poaching with lights—Am I the man? or, the day of judgment—Acquittal! | 168 |

CHAPTER XII. |

|

| Coaches in Ireland fifty years ago—Warm welcome—Still-hunting—Another blank day—Talent and temper—The Avoca coach | 182 |

CHAPTER XIII. |

|

| Virtue and vice—Sowing wild oats—They can all jump—Drive down Box Hill—A gig across country | 195 |

The revival—Magazine magnificence—Death of coaching—Resurrection—Avoid powder—Does the post pull?—Summering hunters—The “Lawyer’s Daughter”—An unexpected guest.

To their honour be it said, that there are noblemen and gentlemen in the land, who willingly devote time, energy, and money, to keep the dust flying from the wheels of the real old stage coach. The importance of driving well, and the pleasure derivable therefrom, are both enhanced by the[Pg 2] moral duty and responsibility involved in directing a public conveyance. The journey once advertised forms a contract which is most religiously observed, and the punctuality and precision noticeable in the coaches of the revival are among their most commendable features.

This is fortunate—since elderly critics may still be seen, grouped around the door of the White Horse Cellars, prepared to institute invidious comparisons, and difficult to be won over to believe in anything but “the old times,” when Sir Vincent Cotton and Brackenbury worked the “Brighton Age,” when Lord Edward Thynne piloted the “Portsmouth Rocket,” when “Gentleman Dean” waggoned the Bath mail, and a hundred minor celebrities glistened in the coaching sphere. Although the interval between these old coaching days and the revival was a long one, the connecting-link was never entirely broken. The “how to do it” has been[Pg 3] handed down by some of the most brilliant coachmen of the age, gentle and simple, who, although the obituary shows their ranks to have been grievously thinned, are still warm supporters of the revival, and who, by their example and practice, have restored in an amateur form a system of coaching which is quite equal (if not a little superior) to anything in the olden times. Where so many excel it would be invidious to particularise, but I have seen the “Oxford,” the “Portsmouth,” the “Guildford,” the “Brighton,” the “Windsor,” “St. Albans,” and “Box Hill,” as well as sundry other short coaches, leave the White Horse Cellars as perfectly appointed in every particular as anything the old coaching days could supply. Coaching in England had well-nigh died a natural death—ay, and, what is worse, been buried! Poor “Old Clarke” (supported by a noble duke, the staunchest patron of the road) fanned the[Pg 4] last expiring spark with the “Brighton Age,” until his health broke down and he succumbed. Another coach started against him on the opposite days by Kingston and Ewell, called the “Recherché” (a private venture), but it did not last even so long as the “Age.” Here was the interval! The end of everything.

In 1868 a coach was started to Brighton called the “Old Times,”[1] the property of a company composed of all the élite of the coaching talent of the day. It proved a great success, and became very popular; especially, it may be added, among its own shareholders, who, being all coachmen, in turn aspired to the box—those who could, as well as those who only fancied they could. The initiated will at once understand how fatal this was to the comfort of every fresh team which came under their lash.

At the end of the coaching season (October 30th, 1868) the stock was sold, and realised two-thirds more than had been invested in it. The goodwill and a large portion of the stock were purchased by Chandos Pole, who was afterwards joined by the Duke of Beaufort and “Cherry Angel,” and these gentlemen carried on the coach for three years.

The second coach started in the revival was one to Beckenham and Bromley, horsed and driven by Charles Hoare, who afterwards extended it to Tunbridge Wells. It was very well appointed, and justly popular. The ball once set rolling, coaching quickly became a mania. The railings of the White Horse Cellars were placarded with boards and handbills of all colours and dimensions: “A well-appointed four-horse coach will leave Hatchett’s Hotel on such and such days, for nearly every provincial town within fifty miles of London.”

From the 1st May to the 1st September the pavement opposite to the coach-office was crowded by all the “hossy” gentlemen of the period. Guards and professionals might be seen busy with the coach-ladders, arranging their passengers, especially attentive to those attired in muslin, who seemed to require as much coupling and pairing as pigeons in a dovecot. Knots of gentlemen discussed the merits of this or that wheeler or leader, till, reminded by the White Horse clock that time was up, they took a cursory glance at their way-bills, and, mounting their boxes, stole away to the accompaniment of “a yard of tin.”

A well-loaded coach with a level team properly handled, is an object which inspires even the passing crowd with a thrill of pleasurable approbation, if not a tiny atom of envy. Whyte Melville contended that a lady could never look so well as in a riding-habit[Pg 7] and properly mounted. Other authorities incline to the fact that the exhilarating effect produced by riding upon a drag, coupled with the opportunity of social conversation and repartee, enhances, if possible, the charms of female attractiveness. Be this as it may, when the end of a journey is reached, the universal regret of the lady passengers is, not that the coachman has driven too quickly, but that the journey is not twice as long as it is. Interesting as the animated scene in Piccadilly during the summer months may be to those who have a taste for the road, there is another treat in store for the coaching man, afforded by a meet of the drags at the Magazine during the London season on special days, of which notice is given. We do not stop to inquire if the coach was built in Oxford Street, Park Street, Piccadilly, or Long Acre; whether the harness was made by Merry or Gibson; whether the team had[Pg 8] cost a thousand guineas or two hundred pounds, but we say that the display of the whole stands unequalled and unrivalled by the rest of the world. This unbounded admiration and approval do not at all deteriorate from the merits of the well-appointed four-horse coaches leaving Piccadilly every morning (Sundays excepted), as there is as much difference between a stage-coach and a four-in-hand as there is between a mirror and a mopstick.

Horses for a road-coach should have sufficient breeding to insure that courage and endurance which enable them to travel with ease to themselves at the pace required, and if they are all of one class, or, as old Jack Peer used to say, “all of a mind,” the work is reduced to a minimum. Whereas, horses for the parade at the Magazine must stand sixteen hands; and, when bitted and beared up, should not see the ground they stand upon. They must[Pg 9] have action enough to kill them in a twelve-mile stage with a coach, even without a Shooter’s Hill in it.

I do not say this in any spirit of disparagement of the magnificent animals provided by the London dealers at the prices which such animals ought to command.

I may here remind my patient reader that unless the greatest care and vigilance is exercised in driving these Magazine teams, it is three to one in favour of one horse, one showy impetuous favourite, doing all the work, whilst the other three are running behind their collars, because they dare not face their bits. It’s a caution to a young coachman, and spoils all the pleasure of the drive. “He’s a good match in size, colour, and action, but he pulls me off the box; I’ve tried a tight curb and nose-band, a high port, a gag, all in vain! If I keep him and he must pull, let him pull the[Pg 10] coach instead of my fingers; run a side-rein through his own harness-terret to his partner’s tug.”

No amount of driving power or resin will prevent one “borer” from pulling the reins through your fingers. I hereby utterly condemn the use of anything of the sort. If your reins are new, they can be educated in the harness-room; but the rendering them sticky with composition entirely prevents the driver from exercising the “give and take” with the mouths of his team which is the key to good coachmanship. Let the back of the left hand be turned well down, the fingers erect; let the whip-hand act occasionally as a pedal does to a pianoforte, and, rely upon it, you are better without resin.

Whyte Melville, in his interesting work, “Riding Recollections,” recites an anecdote, which I may be forgiven for quoting, as it combines both theory and instruction.

“A celebrated Mr. Maxse, celebrated some fifteen years ago for a fineness of hand that enabled him to cross Leicestershire with fewer falls than any other sportsman of fifteen stone who rode equally straight, used to display much comical impatience with the insensibility of his servants to this useful quality. He was once seen explaining to his coachman, with a silk handkerchief passed round a post. ‘Pull at it,’ says the master. ‘Does it pull at you?’ ‘Yes, sir,’ answered the servant, grinning. ‘Slack it off then. Does it pull at you now?’ ‘No, sir.’ ‘Well then, you double-distilled fool, can’t you see that your horses are like that post? If you don’t pull at them, they won’t pull at you.’”

A team, if carelessly driven for a few journeys, will soon forget their good manners, and begin to lean and bore upon a coachman’s hands; and when the weight of one horse’s[Pg 12] head (if he declines to carry it himself) is considered and multiplied by four, it will readily be believed that a coachman driving fifty or sixty miles daily will make it his study to reduce his own labour by getting his horses to go pleasantly and cheerfully together.

There are, of course, instances which defy all the science which can be brought to bear. Horses do not come to a coach because they are found too virtuous for other employment, and the fact of their being engaged with a blank character, or, at most, “has been in harness,” does not inform the purchaser that they made firewood of the trap in their last situation.

I do not intend this remark to be defamatory of the whole of the horses working in the coaches of the revival. The average prices obtained at the sales at the end of the season prove the contrary. Many horses working in[Pg 13] the coaches of the present day have occupied very creditable places in the hunting-field, and, should they return thither, will be found none the worse for having been summered in a stage-coach.

Indeed, I am of opinion that this method of summering has considerable advantages over the system so often adopted, of first inflicting the greatest pain and punishment upon the animal by blistering all round, whether he requires it or not, and then sentencing him to five months’ solitary confinement in a melancholy box or very limited yard.

In the first case, a horse doing a comparatively short stage, provided he is carefully driven, is always amused. His muscles and sinews are kept in action without being distressed, his diet is generous and sufficient without being inflammatory, and, though last not least, he is a constant source of pleasurable satisfaction to his owner, as well[Pg 14] as a means of bringing him to the notice of many sporting admirers, who may materially help the average in the autumn sale.

There is no doubt that horses, as a rule, enjoy coaching work, and many become good disciples to a ten-mile stage which could not be persuaded to do a stroke of work of any other description.

There are many exceptions to this rule. I have found in my own experience that, when hurriedly getting together twenty or thirty horses for coaching purposes, I have been fascinated by symmetry, and perhaps by small figures, and have bought an unprofitable horse. A visit to St. Martin’s Lane, under such circumstances, once made me possessor of the very prettiest animal I almost ever saw—a red chestnut mare, a broad front, two full intelligent eyes, with a head which would have gone easily into a pint pot, ears well set on, a long lean neck, joining to such withers and shoulders as would have shamed a Derby[Pg 15] winner, legs and feet which defied unfavourable criticism. Here was a catch! And all this for eighteen guineas! Nothing said, nothing written; her face was her fortune, and I thought, mine too. She’s too good for the coach; she ought to ride, to carry a lady; appears a perfect lamb. I could not resist what appeared to me an opportunity which everybody except myself seemed to neglect; I bowed to the gentleman in the box, who immediately dropped his hammer, saying: “For you!”

I overheard some remarks from the spectators which did not confirm my satisfaction at having invested in an animal without any character. “She knows her way here by herself;” “She won’t have leather at any price,” whispered another coper; but, as all evil reports are resorted to by the craft on such occasions, I did not heed them.

I soon found out that my new purchase was[Pg 16] not precisely a lamb. To mount her was impossible. She reared, bucked, kicked, plunged, and finally threw herself down; so that part of the business I gave up. I then began to put harness upon her. To this she submitted cheerfully, and, when she had stood in it for two days, I gammoned her into her place in the break, when, having planted herself, she declined to move one inch. The schoolmaster (break-horse) exercised all the patience and encouragement which such equine instructors know so well how to administer. He started the load, pulling very gently. He pulled a little across her, he backed a few inches, then leaned suddenly from her. All this being to no purpose, he tried coercion, and dragged her on, upon which, turning the whites of her innocent eyes up, she made one plunge and flung herself down.

The schoolmaster looked at her reproachfully, but stood still as a mouse, in spite of[Pg 17] her whole weight being upon his pole-chain, till she was freed.

She was too handsome to fight about on the stones, so I determined to try another dodge; and, putting a pair of wheelers behind her, and giving her a good free partner, I put her before the bars (near-side lead). Here the cross of the lamb in her was predominant, she went away, showing all the gentleness without even the skipping.

I took her immediately into the crowded streets, a system I have always found most successful with those horses which require distraction, and her behaviour was perfect. I was so well satisfied, that without further trial I sent her down the road to make one of a team from Sutton to Reigate, where she worked steadily, and remained an excellent leader for one week, when it seemed as if a sudden inspiration reminded her that the monotony of[Pg 18] the work, as well as the bars of the coach, should be broken by some flight of fancy. She made one tremendous jump into the air, as high as a swallow ordinarily flies in fine weather—which evolution cost me “a bar,” and after a few consecutive buck-jumps went quietly away. She did not confine her romps, however, to this comparatively harmless frolic, but contrived to land from these wonderful jumps among groups of Her Majesty’s subjects where she was least expected.

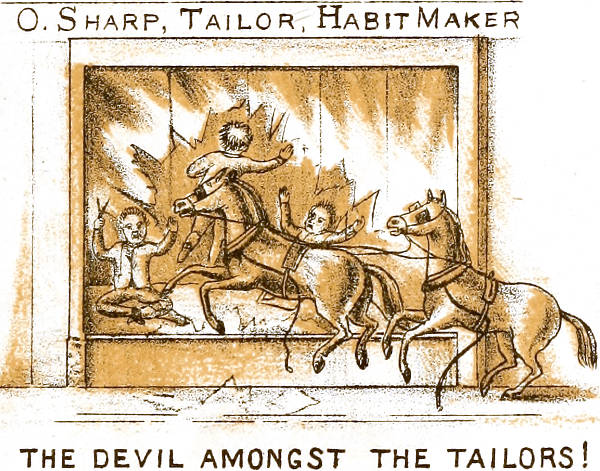

On one occasion I was coming away from a change at D——d, when, at the signal to go, she jumped from the middle of the road completely through the bay-window of a tailor’s shop, where several men were occupied on the board. At another time she was put to at S——n, where, the weather being oppressively hot, a party of yokels were regaling al fresco round a large table under the trees. Their[Pg 19] attention was naturally attracted to the coach during the change of horses, but little did they dream that in another minute one of the leaders would be on the table before them. So, however, it was. With one bound, scattering the pipes and pewters far and wide, she landed in the middle of the board.

I should have delighted in continuing my attempts to subdue the temper of this beautiful animal, especially as, once off, she made a superlatively good leader; but, where the public safety was jeopardised, I did not feel justified in further argument with the young lady, and therefore sold her to a stud company on the Continent.[2]

Young coachmen—Save your horses—The ribbons—The whip—A professional Jehu—An amateur—Paralysed fingers.

To a man who has a taste for driving, what can be more fascinating than to find himself upon the box of his own drag, with four three-parts-bred, well-matched horses before him, of which he is master? But how is this supreme pleasure to be arrived at? He may give fabulous prices for his horses, his coach and appointments may be faultless, all selected with great judgment, and still there will be moments when aching arms, paralysed fingers, and animals who seem determined to go “no how,” will compel him to[Pg 21] wish himself in any other position. In order to guard against this, I would enjoin a young beginner not to run away with the idea that because he has driven four horses without getting into trouble, or, as still more frequently occurs, because he can drive a tandem, he can be in any degree a match for a team of horses with spirit and mettle, unless he have first carefully mastered the rudiments of the ribbons. There are many self-taught men who are excellent coachmen, and who, from long habit and experience, may be as much at home, in cases of sudden difficulty, as some of the more educated; but they invariably lack a certain precautionary system which makes almost any team go well and comfortably, and reduces the chance of an accident to a minimum. There are, alas, very few preceptors of the old school, but why the present generation should not be as well able to instruct themselves as were the men of fifty years ago is to me an unexplained marvel.

It is quite true that when coaching was a most important business, and when the component parties—contractors, coachmen, horsekeepers, and horses—sprang into existence, apparently for the purpose of carrying it on, there was a professional caste about the whole affair which kept it distinct and separate from all others. A proprietor was a big man, and his importance was measured by the ground he covered. There was an emulative rivalry between these gentlemen, which reflected very healthily upon the style in which their coaches were done.

The contractor supplied such horses as the proprietor required to cover the ground at a given coaching price.

The coachman had to keep such time as was laid down by the rules of the coach, and this was a point upon which depended much of the merit of the man. A coachman who, from an[Pg 23] intimate knowledge of his ground, knew when to bustle and where to save his horses, was an invaluable acquisition to his employer. Horses themselves will sometimes suggest a little judicious springing, by which some of the most trying hills are more easily negotiated; but there is nothing better than to keep an even pace throughout the stage, jogging up all hills, easing them at the top, and coming steady off the crown of a descent. If circumstances should arise by which the time has been stolen from the horses, let me enjoin you, in the name of the whole equine race, not to attempt to make it up by showing your expertness with the whip up the hills; this is downright cruelty; and, in nine cases out of ten, the extra exertion and nervous efforts to respond are all made by one horse more sensitive than the rest of the team. It is better to wait for time than to race after it, the latter invariably resulting in one horse[Pg 24] being so much more baked than the others as to cause the knowing eyes around the White Horse Cellars to wink when you do arrive.

To make my reader comfortable with his team as quickly as possible, I would here offer a few hints, which I venture to think will be found valuable to all not too proud to learn.

Being, then, comfortably attired, taking care that no part of his clothing approaches to tightness, supplied with a good thick shoe and gaiter, an easy (very easy) dogskin glove, taking care that the fingers are not too long (he should always be provided with a pair of woollen gloves in case of wet weather), we may safely leave supplementary garments to his own taste.

Having looked round his horses—a proceeding which no coachman should neglect—he walks up to the flank of the off-wheeler and takes all his reins, which should have been doubled and tucked into the tug on the off[Pg 25]-side. Stepping back a pace, he separates his leading-reins, and pulls them through the terrets till he has gathered up the slack. He then slips his wheel-reins on either side of his right hand middle-finger, the near-side leading-rein over the forefinger, and the other over the wheel-rein between the fore and middle fingers of his right hand.

If he changes his whip it will be laid across the cruppers of the wheelers, and must be taken up, caught, and placed in the same hand with the reins, so as to leave the left free to seize the step of the front-boot, when, by stepping on the fore-wheel, and throwing the weight of his body well before it, the walk up on the bench will be comparatively easy and graceful. Having arrived there, still keeping the whip and reins in the right hand, he quickly settles his seat and apron, then shifting his reins to his left hand, in the same order which they occupied[Pg 26] in the right, he proceeds to shorten them till he just feels the mouths of his horses.

The beauty and grace of a driving-seat is to assume such a posture as does not admit of any constraint. Without freedom of the wrist and arm, the whip, instead of being a most interesting plaything, will be a constant source of annoyance and difficulty to a young coachman. “It won’t catch.” “Why not?” Always because he will not let the bow of the thong swing sufficiently away from him, but tries it with a stiff arm. When once the knack is acquired it will last a lifetime, and there is no instrument the proper handling of which gives such a finish and proficiency, as a well-poised “yew” or a properly-weighted “holly.” Often have I been obliged to give away old favourite “crops” because mine would “catch” and others would not.

A good coachman shows his proficiency as well by the manner of his getting up on the[Pg 27] bench as by the necessary preliminaries to make a comfortable start after he is seated. A lady, who must have been a close observer, once remarked to me that a certain gentleman, who was a mutual acquaintance, must be a very careful coachman, for, when riding upon the box-seat with him, he constantly asked her to hold the whip for him, while he went through a process of what appeared to her like “plaiting the reins.” There is a right way and a wrong way, and, at the risk of being a trifle wearisome, I venture to introduce a few hints for the benefit of such of my young readers as may desire to be guided in the acquirements of an art at once useful and agreeable, by tracing some of the oldest habits of the profession, and thus, in coaching parlance, picking up some of the “dodges of the road.”

Let us attempt to follow a professional “Jehu” over a stage or two of his ground.

His coach loaded and passengers placed, he[Pg 28] takes a careful look round to see that every part of his harness is in its place and properly adjusted, and, if reminded by seeing any particular horse that he had gone uncomfortably on his last journey, to endeavour to find out the cause and have it altered. I have known a horse, usually straight and pleasant in his work, all at once take to snatching the rein and run away wide of his partner, and this occasioned only by the winker-strap being too short, causing the winker to press against his frontal-bone, the apparently trifling irregularity causing so much pain as to drive him almost mad.

A wheeler sometimes takes to diving suddenly with his head, and almost snatching the rein out of the driver’s hand. This can only be prevented by putting a bearing-rein upon him; and though this has often been censured (on the road), it has as often been condoned at the end of the stage. His inspection made, he[Pg 29] mounts his box, according to the foregoing rules, and having given some parting instructions to his horsekeeper—“Send ‘Old Giles’ down o’ the off-side to-morrow, and rest the ‘Betsy Mare,’ etc. etc.”—the office to start is given; when the lightest feel of their mouths (wheelers having a little the most room) and a “klick” ought to be enough to start them.[3] Nothing is such “bad form” as to start with the whip; in dismissing which latter article I would caution young coachmen against the practice of carrying it in the socket. The moment when it may be required cannot be foreseen.

A well-organised team soon settles, and though for a mile or two they may appear to pull uncomfortably and not divide the work[Pg 30] evenly, this is often occasioned merely by freshness and impatience, when presently they will settle down and go like “oil.”

A young friend, who lived not one hundred miles from Queen’s Gate, once asked me to come and see a splendid team he had purchased. I was indeed struck by their appearance when they came to the door. All roans, sixteen-and-a-half hands, very well bred, decorated all over with crest and coronet. There was a small party for the drag, with, of course, some muslin on the box, and I took my place behind the driver. I very soon observed that, although they were very highly bitted, they were carrying too many guns for our coachman; and we had not proceeded far when I ventured to remark that he was going rather fast (at this moment three were cantering), and in reply my friend candidly declared “he could not hold them.” “Then pull them all up at once,” I said promptly,[Pg 31] “or they’ll be away with you.” Failing in this he accepted an offer of assistance, and, taking the reins, I, not without difficulty, stopped the runaways, and effected several alterations in their couplings, bittings, and harness.

I expected my friend would have resumed his post, but his hand was so paralysed that he could not grasp the reins. The explanation of this episode is twofold—firstly, the team was improperly put together; secondly, my friend discovered when we got to Richmond that he had been attempting to drive in a tight wrist-band, which, next to a tight glove, is of all things to be avoided. We had had unquestionably a narrow escape from what might have been a very serious accident. When four high-couraged horses, all very green and not properly strung together, get off “the balance” with a weak coachman, it is time to look out for a soft place. After I had made this team more[Pg 32] comfortable in their harness, and their mouths more easily reached by the coupling-reins, they became, in my hands, perfectly temperate and docile, and gave every promise of becoming a handy pleasant lot.

It is a dangerous thing for a young coachman to embark with a team without somebody with him who can relieve his paralysed fingers and wrists if occasion requires; and this danger is increased tenfold if the team is composed of high-mettled cattle unused to their work or their places. I have found it very useful to condition the muscles of the arm by dumb-belling or balancing a chair upon the middle-finger of the left hand with the arm extended.

I trust that the foregoing hints may not be received with disdain. How many men there are who, from mistaken self-sufficiency, go through a whole life in practising what must be very uncomfortable, merely because they have been[Pg 33] too proud to learn the A B C of the business. Without confidence—I may almost say without courage—no man can enjoy driving “a team.” He will be in a constant state of fret and in apprehension of all sorts of imaginary eventualities. The misgiving that they are either going too fast or not fast enough, not working straight, won’t stop the coach down hill, and a thousand other qualms, might all have been prevented by spending a few pounds at The Paxton.

Coachmen (friends and enemies)—Roadside burial—Old John’s holiday—How the mail was robbed—Another method—A visit from a well-known character—A wild-beast attack—Carrier’s fear of the supernatural—Classical teams—Early practice with the pickaxe—Catechism capsized.

In the time when the only method of telegraphing was through the arms and legs of a wooden semaphore, and the only means of public locomotion the public highroad, competition for public favour carried opposition to the highest pitch, and the pace acquired by some of the fast coaches was extraordinary. When ten or fifteen minutes could be scored over the arrival of the opposition—if the “Telegraph” could[Pg 35] get in four or five minutes before the “Eclipse”—it was a subject of anxious comment until this state of things was reversed. Notwithstanding this, no class of men lived on better terms with each other than stage-coachmen off the bench. They were a class of men peculiar to themselves. The very fact of the trust reposed in them invested them with a superiority. Many coachmen in those days were educated men and had occupied higher positions in life; but in cases where the taste existed, and the talent could be acquired, although the work was extremely hard—exposure to every change of weather, the unflagging strain upon the attention, the grave responsibility incurred by the charge of so many lives—there was something so fascinating in the work, that there were few instances of their relinquishing the ribbons except from physical incapacity. This love of the business followed them through life—and even after death—as exemplified by the following anecdote.

An old coachman, who had driven the Norwich mail for thirty years of his life, became at last superannuated, and retired to his native village and repose. But to the last day of his life he prepared himself at the accustomed hour to take his usual seat, being at great pains to adjust his shawl and pull on his driving-gloves, then, taking his coat upon his arm and his whip in his hand, he would shuffle down the little gravel path to the garden-gate, to await the passing of the mail. He died at the good old age of eighty-six years; but not before he had expressed his desire to be buried at the corner of the churchyard abutting upon the highroad, in order that “he might hear the coach go by.”

Another instance of the fascination of coach-driving is to be found in the case of “Old John,” who drove a pair-horse coach from Exeter to Teignmouth and back daily, a distance of forty miles, for a period of eighteen years, without[Pg 37] missing a single day. At last, being half-teazed, half-joked by his fellow-whips into taking a holiday, he reluctantly consented to do so. Being much at a loss how to spend “a happy day,” and enjoy his leisure to the full, he at length decided upon going to the coach-office and booking himself as a passenger on the opposition coach to Teignmouth and back. “Old John” (as he was called) never drove with lamps but once, and then he upset his coach. He always buckled his reins to the iron rail of the box before starting.

The guards of the old mails were always provided with spare gear in case of accidents, as well as a tool-chest; and—though last not least—an armoury consisting of one bell-mouthed blunderbuss—a formidable weapon, which, for an all-round shot would have been as effective as a mitrailleuse, both amongst friends and enemies—two large horse-pistols (ammunition to match), and a short dirky-looking sword.

There were many instances of the mails being robbed and plundered upon the road; but the success was more attributable to intrigue and stratagem than to personal daring and courage.

The plan was this. An impediment is placed in the road by lacing cords across the track. The mail comes to a stop; the horses are in confusion; the guard steps down to render assistance, when one of the highwaymen immediately jumps up and secures the arms, and probably the bags, which were carried under the feet of the guard. Any attempt at resistance on the part of the guard is met by threats with his own arms. The coachman being rendered powerless by the traces having been cut, in many instances (the day having been carefully selected as one of those on which the bankers’ parcel travelled) mail and cargo fell a rich and easy prey to the robbers.

Apart from the mails being selected by highwaymen as victims of plunder, they were frequently[Pg 39] used as co-operative vehicles in their iniquitous traffic.

On one occasion when the way-bill of the Dover mail bore the name of Miss ——, two inside places had been booked three weeks in advance. At the hour of leaving the coach-office, two trunks covered and sewn up in the whitest linen, two dressing-cases, two carpet-bags, besides the smaller articles, baskets, reticules, wrappers, etc., had been duly stowed in the inside. Presently the growl of a King Charles, thrusting his head out of a muff, proclaimed the advent of another occupant of the two vacant seats. A gentlemanly-looking man, with fine open features, and what was at once written down by the old ladies as a charitable expression, much wrapped up with shawls, etc., round his neck, stepped into the mail.

He caressed, admired, and noticed Bess. He helped to adjust shawls, and placed the windows entirely at the disposal of the ladies, though he[Pg 40] looked as though he might be suffocated at any moment.

The conversation was animated; the stranger entering freely into all the views and opinions of his fellow-travellers—politics, agriculture, history—endorsing every opinion which they might express. Both inwardly pronounced him a most charming companion, and blessed the stars which had introduced them to such society.

“You reside in the neighbourhood of Charlton, madam?”

“Yes; we have a lovely villa on the edge of Blackheath.”

“Blackheath! that is a favourite neighbourhood of mine. In fact I am going to Woolwich to join my regiment this evening, and I intend to get out at Blackheath to enjoy an evening stroll over the Heath.”

“Are you not afraid of being molested at night over Blackheath? Isn’t it very lonesome?”

“Sometimes it is lonesome, but I often meet very useful agreeable people in rambling over the Heath.”

Arrived at Blackheath, the two ladies descended, and, feeling that they had established a sufficient acquaintance with the polite gentleman who had been their fellow-traveller, they invited him to partake of a cup of tea at their residence before proceeding on his journey, which invitation he gratefully accepted.

As the evening wore on, a rubber of whist was proposed, the gentleman taking “dummy.”

After a short lapse of time, looking at his watch as by a sudden impulse, he observed that it was growing late, and he was afraid he was keeping them up.

“I shall now take my leave, deeply impressed by your kind hospitality; but before I make my bow I must trouble you for your watches, chains, money, and any small articles of jewellery which you may have in the house.”

The ladies looked aghast, hardly able to realise the situation. Their guest however remained inflexible, and having, with his own dexterous hands, cleared the tables of all articles sufficiently portable, was proceeding to ascend the stairs, when one of the ladies uttered a piercing scream. On this, he sternly assured them that silence was their only safety, whilst giving any alarm would be attended by instant death. Then, having possessed himself of all the money and valuables he could command, he left the house, telling the ladies with a smile, that they had conferred a most delightful and profitable evening on Mr. Richard Turpin.

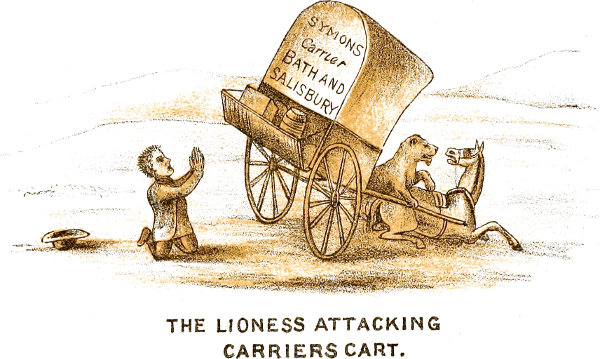

There are instances on record of attacks of other descriptions upon the royal mails. History records the strange adventure of the Salisbury mail, on its journey from London to Exeter in the year ——. Whilst passing the neighbourhood of Winterslow Hut, on Salisbury[Pg 43] Plain, the coachman’s attention was attracted to what he at first thought was a huge calf cantering alongside of his leaders. The team at once became very fretful, and evinced such fear that the driver had some difficulty in keeping them in the road. Suddenly the creature he had mistaken for a calf made a lightning spring on to the back of one of the leaders, and swinging round so as to catch it by the throat, clung like a leech to the paralysed and terrified animal. The guard displayed great presence of mind, and taking his firearms with him, ran forward and delivered a coup de grâce to the attacking monster, which proved to be a lioness escaped from a travelling menagerie. This was her second exploit of the kind. She had previously pounced upon a horse drawing a carrier’s cart, and killed, but not mutilated, the animal, the driver being far too much bewildered and alarmed to dream of resistance.

“A team well put together is half driven,” was an old and true adage, and of more certain application than many of the same character, as for example: “A bird well marked is half bagged.” Not a bit of it. The bird is awake, and, expecting to be flushed again, gets up much sooner than he is expected and flies awkwardly. “A bottle of physic well shaken is half taken.” I trust my readers have discovered this way of diminishing the dose.

In illustration of the first adage, I may mention that I had an innate love for driving, dating from so early a period as my keeping in my desk at school a well-matched team of cockchafers, until, finding them too slow for my work, I established in their place a very fashionable team of white mice, all bred on the premises. These when harnessed to a “Gradus” as a break were very safe and steady. With a Greek grammar or “Delectus” they could fly.

I inherited the love of driving from my father, who was a very good coachman; and in early days would frequently hang on a single leader to his carriage, making a “pickaxe” team, merely for the sake of initiating me in the manipulation of four reins. The promotion from donkies to ponies rather interrupted my practice; as, though we could always borrow mokes to make up a four-in-hand, it was not so easy to do so with ponies.

A real stage-coach passed our gates twice each day; and for the convenience of the contractor who horsed it, a stable was built upon my father’s premises. The incentive given to me by the desire to get my dismissal from my tutor in time to see the coach change horses conduced more to my classical acquirements than any other circumstance.

The regularity of coach work is one of its greatest merits, and operates more upon the[Pg 46] well-conditioning of the men, horses, and all concerned, than is usually supposed.

It is a pretty sight to see a team of coach horses at a roadside change prepared and turned round, each one listening anxiously for the horn which proclaims the arrival of the coach, and the commencement for them of a ten-mile stage, which may have to be done perhaps in fifty-two minutes, with a heavy load, woolly roads, and the wind behind.

This does not sound like attraction to create much pleasurable impatience; but such is the fascination of coaching work that all horses, except, of course, those underbred vulgar screws which can take delight in nothing, whatever their antecedents may have been, become so moulded into their work and places (for this is a most important feature in my text) that it perfects them for the work expected of them in every particular. Bad tempers are subdued and become amiable;[Pg 47] bad feeders become after a time so ravenous as to be able to entertain a “duck in their mess;” nervous fretful horses become bold and settled. Old Crab, who persistently refused to drink out of a bucket when he came here, or even to allow a stable bucket to be brought near him, has overcome all his scruples, and, to use the horsekeeper’s own words: “He wun’t wait for his turn, but when the bucket is ’ung on to the nose of the pump he’ll go and stick his old nose in it, and begin to neigh and ’oller like anything.”

A coach horse, although he has apparently few opportunities of employing his intelligence to his own advantage, whose life is spent in the stable, except when taken to the forge, or to the horsepond, will evince to his employers, in spite of this monotony, some habits and tastes which, if he is indulged in them, will nearly double his value. For instance, every coach horse has[Pg 48] a favourite place in a team, and will go well and do well in that place; and by careful watching it will soon become evident to the coachman and to the horsekeeper which is the place selected by his taste.

Regard to this is most important. The same animal which becomes a “lawyer,” because “he won’t do no more than we pay him for,” and is often forgotten at the near-side wheel, and is always coming back to you if put on the off-side, or, better still, before the bars, will be straight, steady, and cheerful in his work, with a mouth you might control with a thread.

This is when you have found out the place with which he is pleased and satisfied. Try him on the opposite side, and you will find him laying his whole weight upon the pole, his partner on your fingers.

“Everything in its place and a place for everything” was a maxim constantly preached by the[Pg 49] head-master of a certain public school, founded by one Sutton; and the proof of his theory was put to the test by a strange fancy he had taken. He was watching the evolutions of a small Carthusian army, under the command of a colour-sergeant of the Scots Guards, and observed that his first word of command was to “fall in” and “size.” This was quickly done, and the effect so much tickled the doctor, that, on the following Sunday morning, when his catechism class was arranged before him, he thought it would be well to impress a little of the military element into the arrangement of the boys; so he requested the young gentlemen to take their places according to their sizes. Of course they were very obtuse, and could not for the life of them understand his order. Even when he placed them with his own hands, there was a deal of shuffling and confusion to get back to their old places. The doctor, however, had his[Pg 50] way, and M or N, who was a short, thick, rosy-cheeked boy, was supplanted by a tall, overgrown, sickly-looking youth of double his stature, and so on according to height, the lowest being in the centre. No. 2 agreed to his “godfather” and “godmother” having given the name of M or N to No. 1; but he could not tell why No. 3, when asked what his sponsors then did for him, preserved an obstinate silence, and, when much pressed, said they were both dead! In fact, arranged as the class then was, if the doctor had asked the questions in High Dutch and expected the answers in Hebrew, he would have got as much information; whereas, if they had kept their own places there would not have been a word in the answers omitted.

Opposition—A quick change—How to do it—Accident to the Yeovil mail—A gallop for our lives—Unconscious passengers—Western whips—Parliamentary obstruction.

Although opposition was fierce, certain rules of etiquette and honour were most rigidly observed on the road, which rendered immunity from accidents much more general than would have been supposed. It was an understood thing that no coach should pass another actually in motion unless invited to do so by the coachman driving the leading coach at the time. The race became much more exciting in cases where there was a little diversity in the roads between two points in the destination.

The change in the fast coaches, where the horsekeeper and his mate knew their business, was effected in a minute and a half; and, like everything else connected with the fast coaches, required to be done strictly according to rule.

The man receiving the leader, near or off-side, seizes the rein behind the saddle or pad, and draws it out of the head-terret of the wheeler, then, doubling it several times, he passes of it through the terret, unhooks the coch-eyes the traces, and the leaders are free. Though still coupled they should be accustomed to walk aside a few paces, out of the way of the coach.

The horsekeeper at the heads of the wheelers should first double the rein through the terret, to prevent its being trodden upon and cut; then, by raising the end of the pole, unhook the pole-chain, which will admit of the horse standing[Pg 53] back in his work, and enable the traces to be easily lifted off the roller-bolts, the wheelers being uncoupled before he leaves their heads.

The fresh team, when brought out, should be placed behind the spot where the coach pulls up, so that they may walk straight up into their places without having to be turned round, which always entails delay. The fresh team being “in-spanned,” the coachman or guard (or both) assisting in running and buckling the reins, the business is complete.

However quickly the change may be effected, it behoves a coachman to look round before he takes his reins, as a very trifling omission may give rise to serious delay, if not dangerous trouble. I have known the most careful horsekeepers forget to couple the wheel-horses, which, especially in the dark, when it is more likely to happen, is an omission nothing but the greatest judgment and patience on the part of the coachman can[Pg 54] render harmless, since most coach-teams, more frequently than not, jump forward into their work, and are not so easily stopped.

It is in cases of this description that so many accidents are prevented, in the present day, by the use of that admirable invention the patent break. We are indebted to the French for this very useful appliance, and although many wheel-horses are spoiled by the too frequent use of it, the number of accidents and broken knees which are averted must be untold.

To pull up a heavily-loaded coach on a descent requires strength of arm, as well as power in the wheelers, to stop it; whereas, after having stopped the coach with a good strong break, the pulling up of the horses is comparatively easy. How different from the days when we had nothing but the old skid (or slipper) and chain, which was very little used except on the heavy coaches and over the most severe pitches,[Pg 55] on account of the loss of time occasioned by its adjustment and removal.

Accidents, however, are not always to be avoided by pulling-up, as I shall show by relating an incident which occurred to me many years ago in the West of England, in which nothing could have saved our limbs or necks but my having recourse to the opposite alternative, and keeping the team at the top of their speed for dear life.

I was indulging in my favourite pastime and driving the “Yeovil” mail. We were full inside, and there were two gentlemen besides the professional coachman, Jack Everett, outside. I had a little short-legged quick team, belonging to Mrs. Stevens, of the Halfmoon, from Crewkerne to Chard. They were accustomed to do this ground very fast, but would not stop an ounce down the hills.

The roads being hard and slippery, and,[Pg 56] having a load, I took the precaution to put on the shoe to come down Chard Hill. We were swinging along merrily when suddenly the skid chain, in jumping over a stone, parted. This catastrophe allowed the coach to slip uncomfortably and suddenly upon the shoulders and cruppers of the wheelers, and one of them, being a bit of a rogue, evinced his disapprobation by giving several sudden bolting lurches and throwing himself upon the pole.

In one of these evolutions more sudden and violent than the rest the pole snapped off in the futchells!

Here was a predicament! Half-way down one of the ugliest hills in England, with a resolute frightened team and a broken pole. Nothing for it but to put them along and keep them galloping. The broken pole bobbing and dancing along at the end of the chains helped me materially to do this. The leaders finding the bars at the[Pg 57] end of the whippletree all gone mad, took the hint and went off as hard as they could lay legs to the ground. My only care was to keep them straight, and the pace so good as to prevent the coach getting upon the lock, in which case we must have gone over.

It was a fearful moment, and never in all my coaching experience have I passed through such a crisis.

“Let ’em have it!” cries Jack Everett.

“Nothing but the pace can save us!” cries Fred North, the guard.

She rocked, they galloped, we shouted to encourage them. Fortunately they were very evenly matched in pace. If there had been one shirk it must have been fatal.

Providence protected us on this occasion, and I had the good fortune to keep the pace up till we got upon a level, and then gradually stopped her, and, by way of a finale, we had a rattling[Pg 58] good kicking match before we could get the wheelers away from the coach.

I have been in many coach accidents, some of which, I regret to say, have been much more serious in their results, but I always consider that our lives were in greater jeopardy for the four or five minutes after that pole snapped than during any other epoch of my life.

Rarely, if ever, has there been a similar accident upon a plain open road. Poles are often snapped by inexperienced coachmen getting upon the lock in attempting to turn without room, and trusting to the strength of the pole to drag the coach across the road.

Not a hundred yards from the place where I pulled up the mail stood the yard and premises of a working wheelwright, who improvised, in a marvellously short time, a temporary pole, and by attaching the main-bar to a chain leading from the foot-bed, and splicing it to the pole, we did[Pg 59] not lose three-quarters of an hour by the whole contretemps. Moreover, strange to say, until the wheelers began trying to write their names on the front-boot at the bottom of the hill, the four inside passengers were perfectly unconscious that there had been anything wrong! One of the party—a lady—remarked to me that “the mail travelled so delightfully fast that it appeared to have wings instead of wheels.”

When the iron monster had invaded England, and the investment of the principal towns was nearly complete, the last corner which remained to the coaches was the far West, where the business was carried on with great energy and spirit to the very last.

Exeter became the great centre. About seventy coaches left the city daily, Sundays excepted—the “Dorchester” and “London,” the “Falmouth,” “Plymouth,” “Bath,” “Launceston,” and “Truro” mails. The “London” mail (direct), commonly[Pg 60] called the “Quicksilver,” was said to be the fastest mail in England, performing the journey (one hundred and sixty-six miles) in twenty hours, except during fogs or heavy snow. This mail was driven out of London by Charles Ward (now the proprietor of the Paxton Yard, Knightsbridge), who left the White Horse Cellars (now the Bath Hotel), Piccadilly, at eight every evening, until Mr. Chaplin shifted his booking office to the Regent Circus.

The numerous coaches working between Exeter and the west coast were principally horsed by Cockrane, New London Inn; Pratt, Old London (now the Buda), and Stevens, Halfmoon Hotel.

The day and night travelling was kept up until fairly driven off by the common enemy.

During the two or three years before the railway was opened this part of England became the warm corner for coaching; and all the talent of the road, having been elbowed out of other[Pg 61] places, flocked to the West. Charles and Henry Ward, Tim Carter, Jack Everett, Bill Harbridge, Bill Williams, and Wood, not forgetting Jack Goodwin, the guard, who was one of the best key-buglers that ever rode behind a coach.

This incursion of talent aroused the energies of some of the Devonshire whips engaged at that time, M. Hervey, Sam Granville, Harry Gillard, Paul Collyns, William Skinner, etc.

There were four Johnsons, all first-class coachmen, sons of a tailor at Marlborough, who were working up to the last days of coaching. Anthony Deane—or Gentleman Deane, as he was commonly called—drove the only mail left after the opening of the rail to Plymouth—the “Cornish” mail to Launceston.

After she was taken off the road he did not long survive, but died at Okehampton. He was a fine coachman, a good nurse, and an admirable timekeeper.

The “Telegraph,” when first put on by Stevens of the Halfmoon, left Exeter at 6.30 A.M., breakfasted at Ilminster, dined at the Star at Andover, and reached Hyde Park Corner at 9.30 P.M., thus performing a journey of one hundred and sixty-six miles in fifteen hours, including stoppages. There was some encouragement to coaching in those days. A good mail was a real good property. The “Quicksilver” mail and the “Dorchester” mail, alone, paid the rent (twelve hundred pounds per annum) of the New London Inn. The profits of the former were a thousand pounds per annum; and those of the “Dorchester” two hundred pounds; the profits of the first-named being augmented by the fact of the booking office, both ways, being at Exeter. The mails from London on the second of each month were always a little behind time, being so heavily laden with the magazines and periodicals.

In spite of the tremendous pace at which the mails travelled, accidents were very rare. All coaches were heavily laden about Christmas time with parcels and presents. On one occasion, the “Defiance” from Exeter, with an unreasonable top-load, was overtaken by a dense fog, and the coachman (Beavis), getting off the road before he got to Ilminster, was upset and the driver killed upon the spot. An eminent friend and patron of the road, Mr. E. A. Sanders, took the matter in hand, and collected upwards of eight hundred pounds for the widow and children, with which, as the latter grew up, he started them all in life.

There were many fast coaches besides the ordinary six-insider, such as the “Balloon” and “Traveller,” from Pratt’s, New London, the “Defiance,” a fast coach, from the Clarence Hotel, Congleton, the “Favourite” (subscription), and several others.

In the year 1835, all the Exeter and London[Pg 64] coaches were stopped by heavy snow, at Mere, on the borders of Salisbury Plain. Amongst the passengers were the late Earl of Devon, the Bishop of Exeter, Mr. Charles Buller, and seven other members of Parliament, all on their way to attend the opening of the session. They were delayed a whole week.

As the London coaches were gradually knocked off by the advance of the rail, the competition upon other roads out of Exeter became more rife, and the opposition warmer.

The “Warwick Crown Prince”—“Spicy Jack”—Poor old Lal!—“Go it, you cripples!”—A model horsekeeper—The coach dines here—Coroner’s inquest—The haunted glen—Lal’s funeral.

The coach which I have selected by way of exemplifying my remarks was the “Warwick Crown Prince,” and, at the time I adopted it, was driven by Jack Everett, who was reckoned in his day to be as good a nurse, and to have fingers as fine, as anybody in the profession.

He took the coach from The Swan with Two Necks, in Ladd Lane, to Dunstable, and there split the work with young Johnson, who,[Pg 66] though sixty years of age, had three older brothers on the bench. “Spicy Jack” was the beau ideal of a sporting whip. He was always dressed to the letter, though his personal appearance had been very much marred by two coach accidents, in each of which he fractured a leg. The first one having been hurriedly set a little on the bow, he wished to have the other arranged as much like it as possible; the result being that they grew very much in the form of a horse-collar. These “crook’d legs,” as he called them, reduced his stature to about five feet three inches. He had a clean-shaved face, short black hair, sharp intelligent blue eyes, a very florid complexion, rather portly frame, clad in the taste of the period: A blue coat, buttons very widely apart over the region of the kidneys, looking as if they had taken their places to fight a duel, rather than belonging to the same coat. A[Pg 67] large kersey vest of a horsecloth pattern; a startling blue fogle and breast-pin; drab overalls, tightly fitted to the ankle and instep of a Wellington boot, strapped under the foot with a very narrow tan-coloured strap. The whole surmounted by a drab, napless hat, with rather a brim, producing a “slap-up” effect.

When at the local race-meetings, “Spicy Jack” dashed on to the course in a sporting yellow mail-phaeton, his whip perpendicular, his left hand holding the reins just opposite the third button of his waistcoat from the top. Driving a pair of “tits” which, though they had both chipped their knees against their front teeth, and one of them (a white one) worked in suspicious boots, produced such an impression upon the yokels that no one but “Spicy Jack” could come on to a racecourse in such form.[4]

All this appeared like “cheek,” but it was quite the reverse; for in spite of the familiarity which was universally extended to this “sporting whip,” he never forgot his place with a gentleman, and a more respectful man in his avocation did not exist.

“Well, Jack, what are we backing?” was the salutation of a noble lord who had given him a fiver to invest to the best of his judgment.

“Nothing, my lord; we are not in the robbery.”

“How’s that? we shall lose a race.”

“Well, you see, my lord, it was all squared and the plunder divided before I could get on.”

Nobody knew the ropes at Harpenden, Barnet, and St. Albans, when the platers ran to amuse the public, and the public “greased the ropes,” better than the waggoner of the “Crown Prince.”

This is a rest day and the “spare man” works. Let us take a full load away from Ladd Lane.[Pg 69] Ten and four with all their luggage; roof piled, boots chock full, besides a few candle-boxes in the cellar.[5] She groans and creaks her way through the city, carefully, yet boldly driven by our artist, and when she leaves her London team at the Hyde and emerges into an open road, she steals away at her natural pace, which, from the evenness of its character, is very hard to beat.

There was one coach, and only one, which could give these fast stage-coaches ten minutes and beat them over a twelve-mile stage!

It was before the legislature forbade the use of dogs as animals of draught, that there dwelt upon the Great North Road, sometimes in one place, sometimes in another, an old pauper who was born without legs, and, being of a sporting turn of mind, had contrived to get built for himself a small simple carriage, or waggon, very light, having[Pg 70] nothing but a board for the body, but fitted with springs, lamps, and all necessary appliances.

To this cart he harnessed four fox-hounds, though to perform his quickest time he preferred three abreast. He carried nothing, and lived upon the alms of the passengers by the coaches. His team were cleverly harnessed and well matched in size and pace. His speed was terrific, and as he shot by a coach going ten or twelve miles an hour, he would give a slight cheer of encouragement to his team; but this was done in no spirit of insolence or defiance, merely to urge the hounds to their pace. Arriving at the end of the stage, the passengers would find poor “Old Lal” hopping on his hands to the door of the hostelry, whilst his team, having walked out into the road, would throw themselves down to rest and recover their wind. For many years poor Old Lal continued his amateur competition with some of the fastest and best-appointed coaches on the road; his[Pg 71] favourite ground being upon the North Road, between the Peacock at Islington and the Sugarloaf at Dunstable. The latter place was his favourite haven of rest. He had selected it in consequence of a friendship he had formed with one Daniel Sleigh, a double-ground horsekeeper, and the only human being who was in any way enlightened as to the worldly affairs of this poor legless beggar.

Daniel Sleigh, as the sequel will prove, richly deserved the confidence so unreservedly placed in him—a confidence far exceeding the mutual sympathies of ordinary friendship; and Daniel Sleigh became Old Lal’s banker, sworn to secrecy.

Years went on, during which the glossy coats of Lal’s team on a bright December morning—to say nothing of their condition—would have humbled the pride of some of the crack kennel huntsmen of the shires. When asked how he fed his hounds, he was wont to say: “I never[Pg 72] feed them at all. They know all the hog-tubs down the road, and it is hard if they can’t satisfy themselves with somebody else’s leavings.” Where they slept was another affair; but it would seem that they went out foraging in couples, as Old Lal declared that there were always two on duty with the waggon.[6]

When the poor old man required the use of his hands, it was a matter of some difficulty to keep his perpendicular, his nether being shaped like the fag-end of a farthing rushlight; and he was constantly propped up against a wall to polish the brass fittings of his harness. In this particular his turnout did him infinite credit. Of course his most intimate, and indeed only friend, Dan Sleigh, supplied him with oil and rotten-stone when he quartered at Dunstable; and brass, when once cleaned and kept in daily use, does not require much elbow-grease. Lal’s[Pg 73] travelling attire was simplicity itself. His wardrobe consisted of nothing but waistcoats, and these garments, having no peg whereon to hang except the poor old man’s shoulders, he usually wore five or six, of various hues; the whole topped by a long scarlet livery waistcoat. These, with a spotted shawl round his neck, and an old velvet hunting-cap upon his head, completed his costume.

The seat of Lal’s waggon was like an inverted beehive. It would have puzzled a man with legs to be the companion of his daily journeys. These generally consisted of an eight-mile stage and back, or, more frequently, two consecutive stages of eight and ten miles.

An interval of several years elapsed, during which I did not visit the Great North Road. When at length I did so, I hastened to inquire for my old friends, many of whom I found had disappeared from the scene—coachmen changed,[Pg 74] retired, or dead; horsekeepers whom I had known from my boyhood, shifted, discharged, or dead.

Under any other circumstances than driving a coach rapidly through the air of a fine brisk autumnal morning, at the rate of eleven miles an hour, including stoppages, the answers to my inquiries would have been most depressing.

Dunstable was the extent of my work for that day, which afforded me the opportunity of working back on the following morning.

Arrived at The Sugarloaf, gradually slackening my pace and unbuckling my reins, I pulled up within an inch of the place whence I had so often watched every minute particular in the actions of the finished professionals.

D—— was the place at which the coach dined, and, being somewhat sharp set, I determined to dine with the coach, though I should have to spend the evening in one of the dullest provincial towns in England.

I had brought a full load down. The coaches dined in those days upon the fat of the land. Always one hot joint (if not two) awaited the arrival of the coach, and the twenty minutes allotted for the refreshment of the inward passenger were thoroughly utilised.

A boiled round of beef, a roast loin of pork, a roast aitchbone of beef, and a boiled hand of pork with peas-pudding and parsnips, a roast goose and a boiled leg of mutton, frequently composed a menu well calculated to amuse a hungry passenger for the short space allotted him.

The repast concluded and the coach reloaded, I watched her ascend the hill at a steady jog till she became a mere black spot in the road. I then directed my steps to the bottom of the long range of red-brick buildings used as coach-stables, where I found old Daniel Sleigh still busily engaged in what he called “Setting his ’osses fair.”

This implied the washing legs, drying flanks, and rubbing heads and ears of the team I had brought in half-an-hour ago. Although the old man looked after the “in-and-out” horses, he always designated the last arrival as “My ’osses,” and they consequently enjoyed the largest share of Dan’s attention: “Bill the Brewer,” “Betsy Mare,” “Old Giles,” and “The Doctor.”

Dan Sleigh was a specimen of the old-fashioned horsekeeper, a race which has now become obsolete. He had lived with Mrs. Nelson, who was one of the largest coach proprietors of the period, for thirty-nine years, always having charge of a double team. He rarely conversed with anybody but “his ’osses,” with whom, between the h—i—ss—e—s which accompanied every action of his life, he carried on a sotto voce conversation, asking questions as to what they did with them, at the other[Pg 77] end, and agreeing with himself as to the iniquitous system of taking them out of the coach and riding them into the horsepond, then leaving them to dry whilst Ben Ball—the other horsekeeper—went round to the tap to have half-a-pint of beer. O tempora! O mores!

Many of his old friends had fallen victims to this cruel treatment. A recent case had occurred in the death of old Blind Sal, who had worked over the same ground for thirteen years, and never required a hand put to her, either from the stable to the coach or from the coach to the stable. She caught a chill in the horsepond, and died of acute inflammation.

When I interrupted old Dan he was just “hissing” out his final touches, and beginning to sponge the dirt off his harness. He recognised me with a smile—a shilling smile—and the following dialogue ensued.

Daniel Sleigh was a man who, to use his own words, “kep’ ’isself to ’isself.” He never went to “no public ’ouses, nor yet no churches.” He had never altered his time of getting up or going to bed for forty years; and, except when he lay in the “horsepital” six weeks, through a kick from a young horse, he had never been beyond the smithy for eleven years. In any other grade of life he would have been a “recluse.”

His personal appearance was not engaging—high cheek-bones, small gray sunken eyes, a large mouth, and long wiry neck, with broad shoulders, a little curved by the anno domini; clothed always in one style, namely, a long plush vest, which might have been blue once; a pair of drab nethers, well veneered with blacking and harness paste; from which was suspended a pair of black leather leggings, meeting some thin ankle-jacks. This, with a no-coloured string, which had once been a necktie, and a catskin cap, completed[Pg 79] his attire. My attention had been attracted to an old hound—a fox-hound—reclining at full length on his side on the pathway leading to the stables, his slumbers broken by sudden jerks of his body and twitches of his limbs, accompanied by almost inaudible little screams; leading me to suppose that this poor old hound was reviewing in his slumbers some of the scenes of his early life, and dreaming of bygone November days when he had taken part in the pursuit of some good straight-necked fox in the Oakley or the Grafton country.

“What is that hound?” I asked. “He looks like one of poor Old Lal’s team.”

“Ah, that’s the last on ’em. They are all gone now but poor old Trojan, and he gets very weak and old.”

When I noticed him he slowly rose, and sauntered across the yard towards a large open coachhouse, used as a receptacle for hearses and[Pg 80] mourning-coaches. He did not respond to my advances, except by standing still and looking me in the face with the most wobegone expression possible, his deep brow almost concealing his red eyes. He was very poor, his long staring coat barely covering his protruding hips and ribs. There he stood, motionless, as if listening intently to the sad tale Daniel Sleigh was graphically relating.

“And what has become of poor Old Lal?” I asked.

“Oh, he’s left this two years or more.”

“Whither is he gone?”

“I don’t know as he’s gone anywheres; they took him up to the churchyard to be left till called for. You see, sir, he never ’ad no kins nor directors (executors), or anybody as cared whether they ever see him again or not. He was an honest man though a wagrant; which he never robbed nobody, nor ever had any parish relief.[Pg 81] What money he had I used to take care of for him; and when he went away he had a matter of sixteen pounds twelve and twopence, which I kep’ for him, only as he wanted now and again tenpence or a shilling to give a treat to his hounds.”

“Where did he die?”

“Ah, that’s what nobody knows nothing about. You see, sir, it was as this: He’d been on the road a-many years; but as he had no house in particular, nobody noticed when he came and when he went; when he laid here o’ nights, he used to sleep in the hay-house. The boys in the town would come down and harness up his team and set him fair for the day. He would go away with one of the up-coaches, and not be here again for a week (perhaps more). Well, there was one time, it was two years agone last March, I hadn’t seen nothing of Lal not for three weeks or a month; the weather was terrible rough, there was snow and hice; and the storm blowed down a-many[Pg 82] big trees, and them as stood used to ’oller and grunt up in the Pine Bottom, so that I’ve heerd folks say that the fir-trees a-rubbing theirselves against one another, made noises a nights like a pack of hounds howling; and people were afraid to go down the Pine Bottom for weeks, and are now, for a matter of that. For they do say as poor Old Lal drives down there very often in the winter nights. Well, one Sunday afternoon I had just four-o’clocked my ’osses, and was a-popping a sack over my shoulders to go down to my cottage; it was sleeting and raining, and piercing cold, when who should I meet but poor old Trojan. He come up, rubbed my hand with his nose, and seemed quite silly with pleasure at seeing me. Now, though I’ve known him on and off this five or six year, I never knew him do the like before. He had a part of his harness on, which set me a thinking that he had cut and run, and perhaps left Old Lal in trouble.

”You see, sir, what a quiet sullen dog he is. Always like that, never moves hisself quickly. Still, when he come to me that Sunday, he was quite different; he kep’ trotting along the road, and stopping a bit, then he’d look round, then come and lay hold of the sack and lead me along by it.

“The next day there was another of poor Old Lal’s team come to our place (Rocket), and he had part of his breast-collar fastened to him. They were both pretty nigh starved to death. Trojan he went on with these manœuvres, always trying to ’tice me down to the road leading to the Pine Bottom. Word was sent up and down the road by the guards and coachmen to inquire where Old Lal had been last seen. No tidings could be got, and strange tales got abroad. Some said the hounds had killed and eaten him! Some that he had been robbed and murdered! No tidings could be got. Still old Trojan seemed[Pg 84] always to point the same way, and would look pleased and excited if I would only go a little way down the road towards the Pine Bottom with him.

”Many men joined together and agreed to make a search, but nothing could be found in connection with the poor old man; so they gave it up. One morning after my coach had gone, I determined to follow old Trojan. The poor old dog was overjoyed, and led me right down to the Pine Bottom. I followed him pretty near a mile through the trees and that, until at last we come upon poor Old Lal’s waggon. There was his seat, there was part of the harness, and there lay, stone-dead, one of the hounds.

“No trace could be found of the poor old man, and folks were more puzzled than ever about his whereabouts.

”It seemed as though the waggon had got set fast between the trees, and Trojan and Rocket[Pg 85] had bitten themselves free, the third, a light-coloured one (a yellow one), had died.

“The finding of the waggon set all the country up to search for poor Old Lal, but it wasn’t for more’n a week after finding the waggon, that Trojan and Rocket pointed out by their action where to go and look for the poor old man. And he was found, but it was a long ways off from his waggon. There he lay, quite comfortable, by the side of a bank. The crowner said the hounds had given chase to something (maybe a fox crossed ’em) and clashed off the road, throw’d the poor old man off—perhaps stunned with the fall—and the hounds had persevered through the wood till the waggon got locked up in the trees. And there the poor things lay and would have died if they had not gnawed themselves out of their harness.”

“And what was the verdict?”

“Oh, there was no verdic’! They never found that.”

“There must have been some opinion given.”

“Jury said he was a pauper wagrant, that he had committed accidental death, and the crowner sentenced him to be buried in the parish in which he was last seen alive.”

“Had he any friends or relatives?”

“No; he said he never had any. He had no name, only Lal. Old Trojan has been with me ever since we followed a short square box up to the churchyard, containing the body of poor Old Lal, where we left it. There was nobody attended the funeral only we two. If the old dog ever wanders away for a day or two, he allers comes back more gloomier like than he looks now.”

The old hound had been standing in the same attitude, apparently a most attentive listener to this sad tale, and when I attempted a pat of sympathy he turned round and threaded his way through the crowd of mourning-coaches; and[Pg 87] Daniel Sleigh informed me that the wreck of poor Old Lal’s waggon had been stowed away at the back of this melancholy group. Upon this the old hound usually lay.

“And what about Rocket?”

“He was a younger and more ramblier dog. He never settled nowhere. The last I heerd of him, he had joined a pack of harriers (a trencher pack) at Luton. He was kinder master of them, frequently collecting the whole pack and going a-hunting with them by hisself. He was allers wonderful fond of sport. I mind one time when a lot of boys had bolted a hotter just above the mill, and was a-hunting him with all manner of dogs, Old Lal happened to come along with his waggon. The whole team bolted down to the water’s edge, and just at that moment the hotter gave them a view. The hue-gaze[7] was too much[Pg 88] for Rocket. He plunged in, taking with him the waggon and the other two hounds. Poor Old Lal bobbed up and down like a fishing-float, always keeping his head up, though before he could be poked out he was as nigh drownded as possible. And this is what makes me think Rocket was the instigator of the poor old man’s death. He must have caught a view of a fox, perhaps, or, at any rate, have crossed a line of scent, and bolted off the road and up through the wood, and after they had throwed the poor old man, continued the chase till the waggon got hung fast to a tree and tied them all up.”