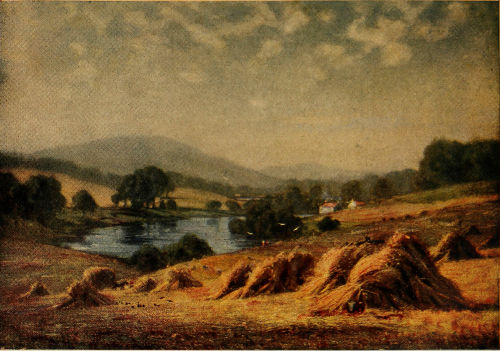

THE MOUNTAIN MEADOWS, BAVARIAN TYROL

From original painting by the late John MacWhirter, R. A.

Title: On Old-World Highways

Author: Thos. D. Murphy

Release date: May 2, 2014 [eBook #45567]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Sonya Schermann, Greg Bergquist and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

THE MOUNTAIN MEADOWS, BAVARIAN TYROL

From original painting by the late John MacWhirter, R. A.

I know that of making books of travel there is no limit—they come from the press in a never-ending stream; but no one can say that any one of these is superfluous if it finds appreciative readers, even though they be but few.

My chief excuse for the present volume is the success of my previous books of motor travel, which have run through several fair-sized editions. I have had many warmly appreciative letters concerning these from native Englishmen and the books were commended by the Royal Automobile Club Journal as accurate and readable. So I take it that my point of view from the wheel of a motor car interests some people, and I shall feel justified in writing such books so long as this is the case.

I know that in some instances I have had to deal with hackneyed subjects; but I have striven for a different viewpoint and I hope I have contributed something worth while in describing even well-known places. On the other hand, I know that I have discovered many delightful nooks and corners in Britain that even the guide-books have overlooked.

Besides, I am sure that books of travel have ample justification in the fact that travel itself is one of the greatest of educators and civilizers. It teaches us that we are not the only people—that wisdom shall not die with us alone. It shows us that in some things other people may do better than we are doing and it may enable us to avoid mistakes that others make. In short, it widens our horizon and tones down our self-conceit—or it should do all of this if we keep ears and eyes open when abroad.

I make no apology for the fact that the greater bulk of the present volume deals with the Motherland, even if its title does not so indicate. Her romantic charm is as limitless as the sea that encircles her. Even now, after our long journeyings in every corner of the Island, I would not undertake to say to what extent we might still carry our exploration in historic and picturesque Britain. Should one delight in ivy-covered castles, rambling old manors, ruined abbeys, romantic country-seats, haunted houses, great cathedrals and storied churches past numbering, I know not where the limit may be. But I do know that the little party upon whose experiences this book is founded is still far from being satisfied after nearly twenty thousand miles of motoring in the Kingdom, and if I fail to make plain why we still think of the highways and byways of Britain with an undiminished longing, the fault is mine rather than that of my subject.

In this book, as in my previous ones, the illustrations play a principal part. The color plates are from originals by distinguished artists and the photographs have been carefully selected and perfectly reproduced. The maps will also be of assistance in following the text. I hope that these valuable adjuncts may make amends for the many literary shortcomings of my text.

THOMAS D. MURPHY

Red Oak, Iowa, January 1, 1914.

| CONTENTS | ||

| Page | ||

| I | BOULOGNE TO ROUEN | 1 |

| II | THE CHATEAU DISTRICT | 29 |

| III | ORLEANS TO THE GERMAN BORDER | 45 |

| IV | COLMAR TO OBERAMMERGAU | 59 |

| V | BAVARIA AND THE RHINE | 77 |

| VI | THE CAPTAIN’S STORY | 104 |

| VII | A FLIGHT THROUGH THE NORTH | 125 |

| VIII | THE MOTHERLAND ONCE MORE | 145 |

| IX | OLD WHITBY | 157 |

| X | SCOTT COUNTRY AND HEART OF HIGHLANDS | 173 |

| XI | IN SUTHERLAND AND CAITHNESS | 191 |

| XII | DOWN THE GREAT GLEN | 210 |

| XIII | ALONG THE WEST COAST | 224 |

| XIV | ODD CORNERS OF LAKELAND | 246 |

| XV | WE DISCOVER DENBIGH | 262 |

| XVI | CONWAY | 279 |

| XVII | THE HARDY COUNTRY AND BERRY POMEROY | 298 |

| XVIII | POLPERRO AND THE SOUTH CORNISH COAST | 320 |

| XIX | LAND’S END TO LONDON | 336 |

| XX | THE ENGLISH AND THEIR INSTITUTIONS | 355 |

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS | |

| COLOR PLATES | |

| Page | |

| THE MOUNTAIN MEADOWS, BAVARIAN TYROL | Frontispiece |

| SUNSET IN TOURAINE | 1 |

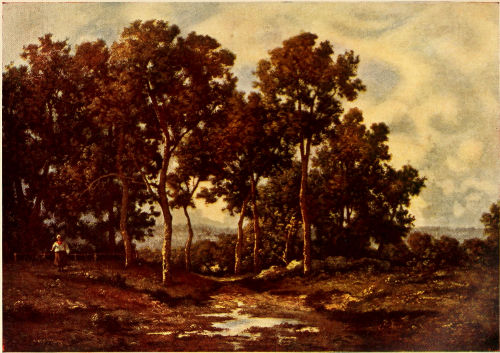

| WOODS IN BRITTANY | 26 |

| PIER LANE, WHITBY | 164 |

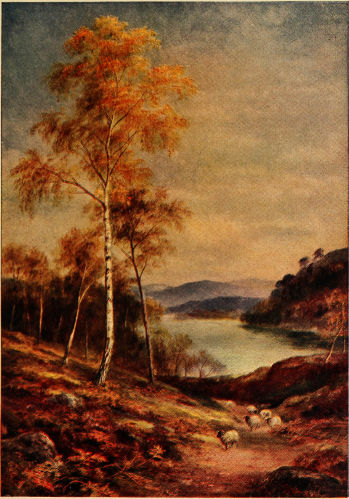

| HARVEST TIME, STRATHTAY | 180 |

| A HIGHLAND LOCH | 188 |

| ACKERGILL HARBOUR, CAITHNESS | 204 |

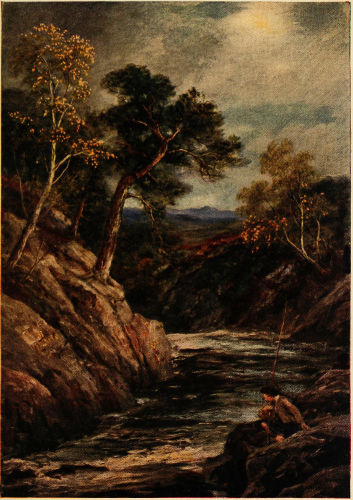

| GLEN AFFRICK, NEAR INVERNESS | 208 |

| THE GREAT GLEN, SUNSET | 210 |

| “THE COTTER’S SATURDAY NIGHT” | 236 |

| THE FALLEN GIANT—A HIGHLAND STUDY | 240 |

| CONWAY CASTLE, NORTH WALES | 280 |

| “THE NEW ARRIVAL” | 282 |

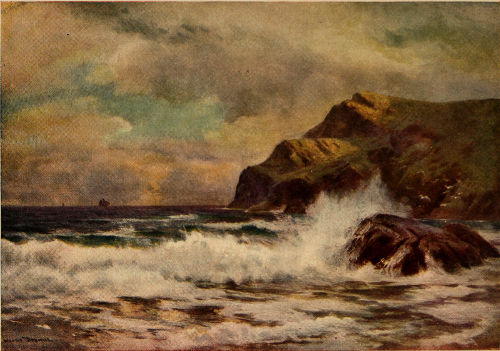

| KYNANCE COVE, CORNWALL | 334 |

| SUNSET NEAR LAND’S END, CORNWALL | 336 |

| “A DISTANT VIEW OF THE TOWERS OF WINDSOR” | 355 |

| DUOGRAVURES | |

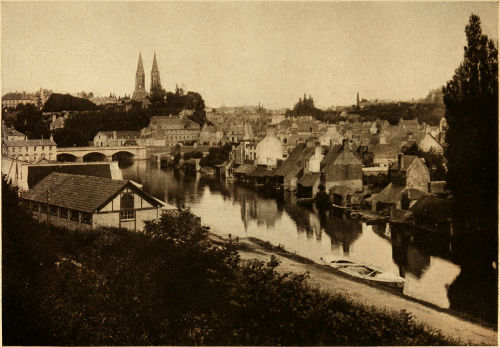

| ST. LO FROM THE RIVER | 18 |

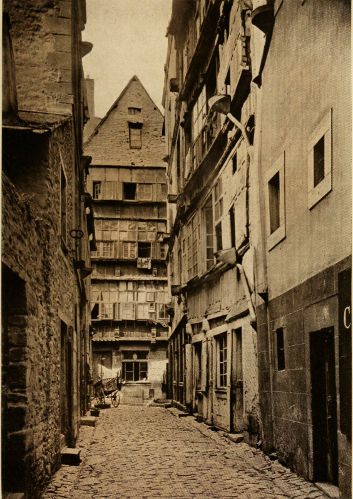

| A STREET IN ST. MALO | 24 |

| CHENONCEAUX—THE ORIENTAL FRONT | 32 |

| AMBOISE FROM ACROSS THE LOIRE | 34 |

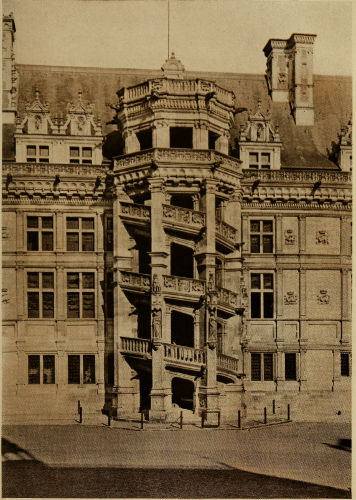

| GRAND STAIRWAY OF FRANCIS I. AT BLOIS | 36 |

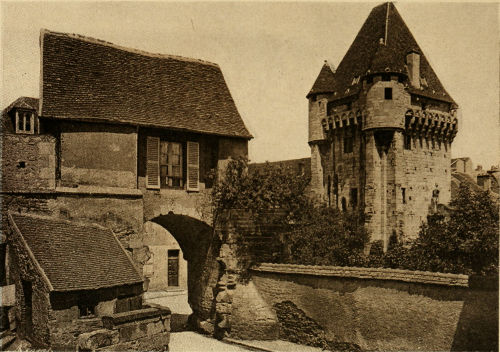

| PORT DU CROUX—A MEDIEVAL WATCHTOWER AT NEVERS | 46 |

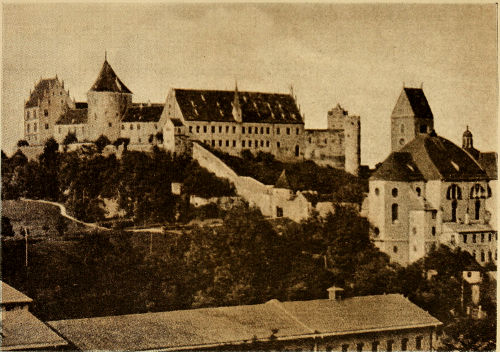

| CASTLE AT FUSSEN | 66 |

| OBERAMMERGAU | 70 |

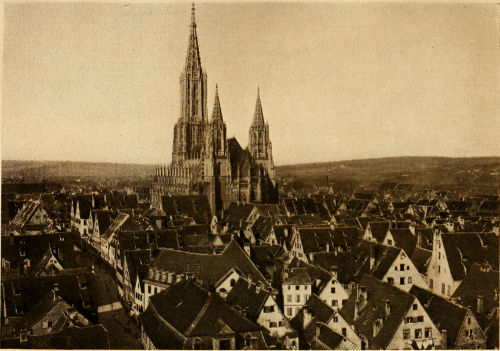

| ULM AND THE CATHEDRAL | 82 |

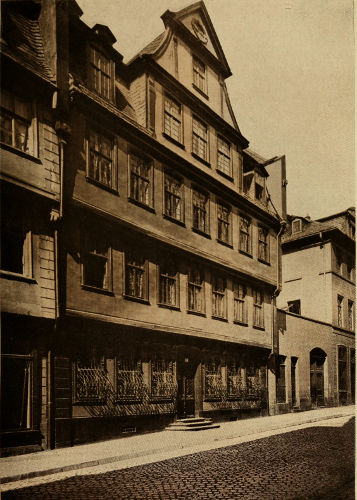

| GOETHE’S HOUSE—FRANKFORT | 86 |

| BINGEN ON THE RHINE | 88 |

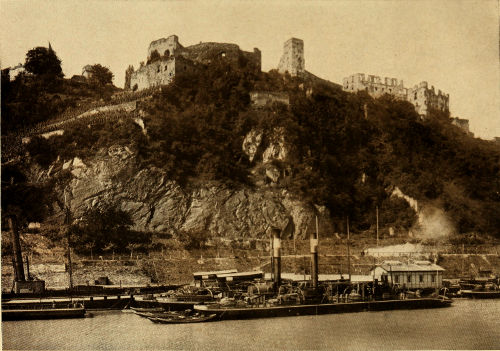

| CASTLE RHEINSTEIN | 90 |

| EHRENFELS ON THE RHINE | 92 |

| RUINS OF CASTLE RHEINFELS | 94 |

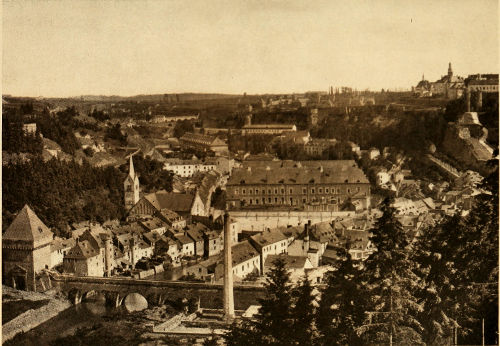

| LUXEMBURG—GENERAL VIEW | 102 |

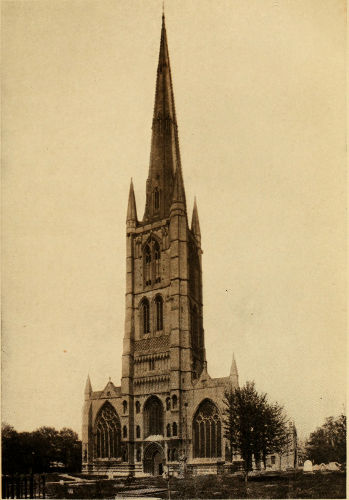

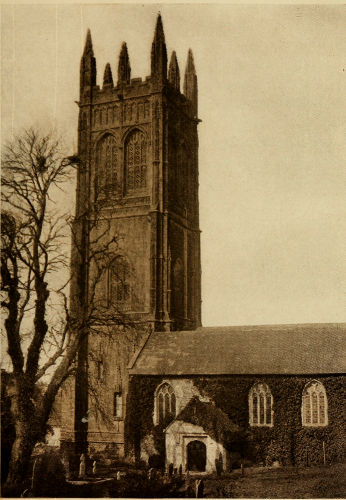

| ST. WULFRAM’S CHURCH—GRANTHAM | 150 |

| OLD PEEL TOWER AT DARNICK, NEAR ABBOTSFORD | 178 |

| HOTEL, JOHN O’GROATS | 200 |

| URQUHART CASTLE, LOCH NESS | 214 |

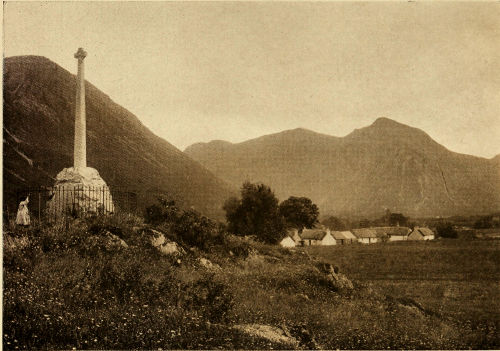

| THE MACDONALD MONUMENT, GLENCOE | 220 |

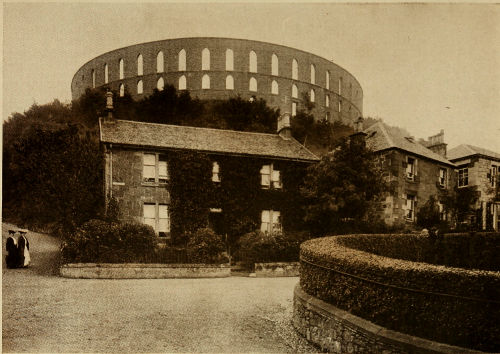

| “McCAIG’S FOLLY,” OBAN | 224 |

| GLENLUCE ABBEY | 242 |

| SWEETHEART ABBEY | 244 |

| WORDSWORTH’S BIRTHPLACE—COCKERMOUTH | 250 |

| CALDER ABBEY, CUMBERLAND | 252 |

| KENDAL CASTLE | 258 |

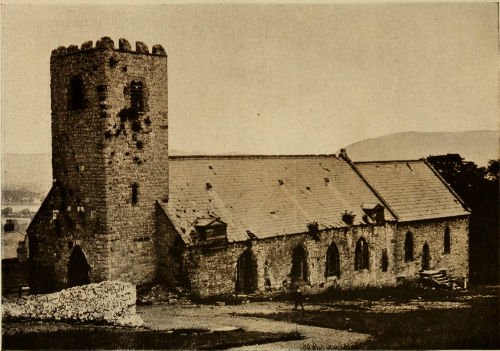

| KENDAL PARISH CHURCH | 260 |

| DENBIGH CASTLE—THE ENTRANCE AND KEEP | 266 |

| ST. HILARY’S CHURCH, DENBIGH | 272 |

| GATE TOWERS RHUDDLAN CASTLE, NORTH WALES | 276 |

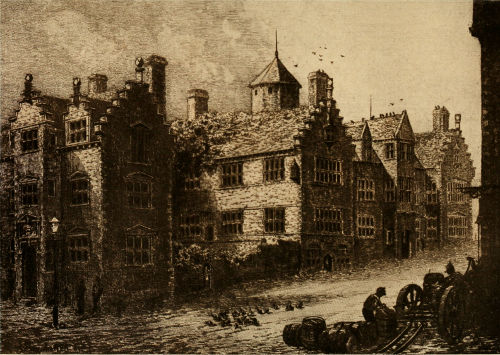

| PLAS MAWR, CONWAY, HOME OF ROYAL CAMBRIAN ACADEMY | 284 |

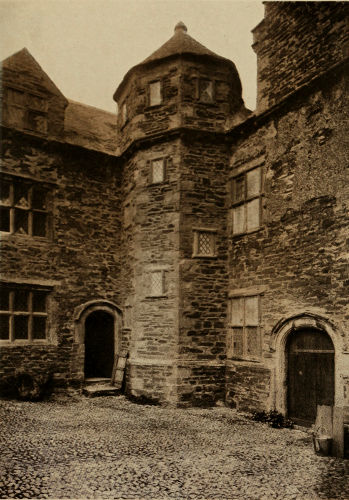

| INNER COURT, PLAS MAWR, CONWAY | 286 |

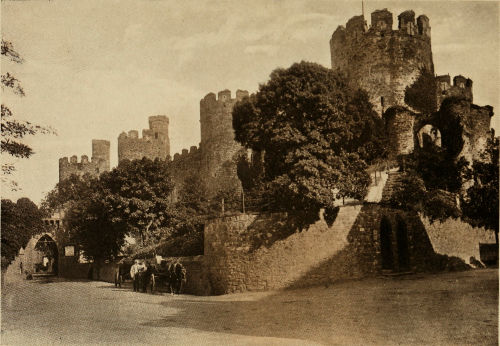

| CONWAY CASTLE—THE OUTER WALL | 292 |

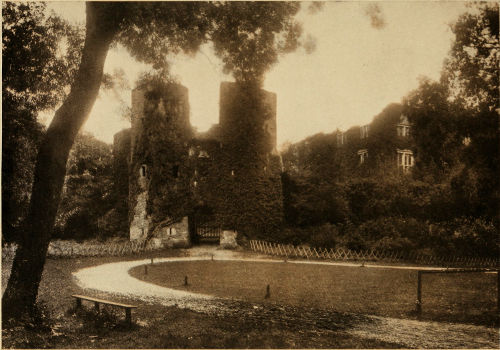

| BERRY POMEROY CASTLE, ENTRANCE TOWERS | 312 |

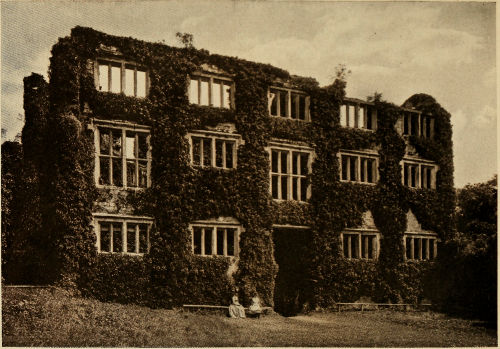

| BERRY POMEROY CASTLE—WALL OF INNER COURT | 316 |

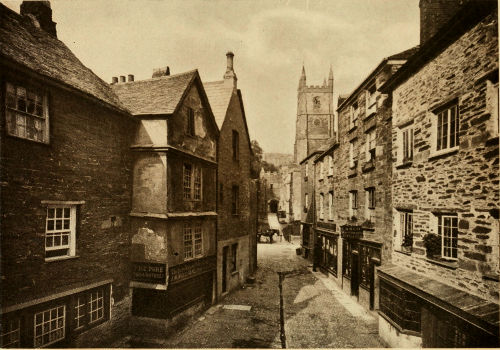

| A STREET IN EAST LOOE—CORNWALL | 322 |

| POLPERRO, CORNWALL—LOOKING TOWARD THE SEA | 324 |

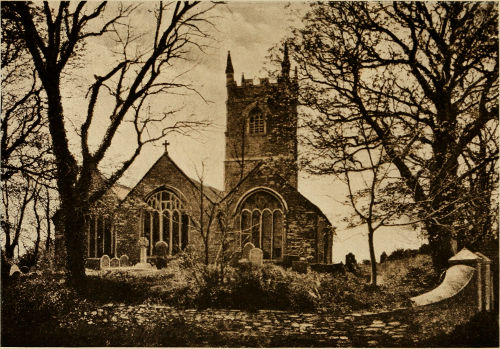

| LANSALLOS CHURCH, POLPERRO | 326 |

| A STREET IN FOWEY—CORNWALL | 330 |

| PROBUS CHURCH TOWER, CORNWALL | 332 |

| MAPS | |

| FRANCE AND GERMANY | 380 |

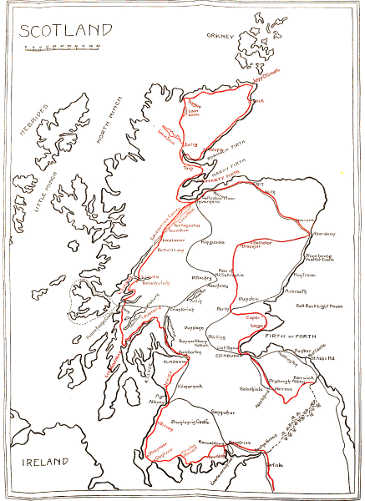

| SCOTLAND | 388 |

| ENGLAND AND WALES | 388 |

SUNSET IN TOURAINE

From original painting by Leon Richet

Our three summer pilgrimages in Britain have left few unexplored corners in the tight little island—we are thinking of new worlds to conquer. Beyond the narrow channel the green hills of France offer the nearest and most attractive field. Certainly it is the most accessible of foreign countries for the motorist in England and every year increasing numbers of English-speaking tourists are seen in the neighboring republic. The service of the Royal Automobile Club, with its usual enterprise and thoroughness, leaves little to be desired in arranging the details of a trip and supplies complete information as to route. An associate membership was accorded me on behalf of the Automobile Club of America, whose card I presented and which serves an American many useful ends in European motordom. Mr. Maroney, the genial touring secretary, at once interested himself in our proposed tour. He undertook to outline 2 a route, to arrange for transportation of our car across the Channel, to provide for duties and licenses and, lastly, to secure a courier-guide familiar with the countries we proposed to invade and proficient in the French and German languages. The necessary guide-books and road-maps are carried in stock by the club and the only charge made is for these. Our proposed route was traced on the map, a typewritten list of towns and distances was made and a day or two later I was advised that a guide had been engaged. Mr Maroney expressed regret that the young men who serve the club regularly in this capacity were already employed, but he had investigated the man secured for us and found him competent and reliable.

“Still,” said Mr. Maroney with characteristic British caution, “we would feel better satisfied with one of our own men on the job; but it is the best we can do for you under the circumstances.”

We learned that our guide was a young Englishman of good family, at present in somewhat straitened circumstances, which made him willing to accept any position for which his talents might fit him. He had previously piloted motor parties through France and Italy and spoke four languages with perfect fluency. He had done a lot of knocking about, having recently been in a shipwreck off 3 the coast of South America and having held a captain’s commission in the South African War. We therefore called him “the Captain,” and I may as well adopt that designation in referring to him in these pages, since his real name would interest no one. He was able to drive the car and declared willingness to do a chauffeur’s part in caring for it. The only doubt expressed by Mr. Maroney was that the Captain might “forget his place”—that of a servant—and before long consider himself a member of our party, and with characteristic frankness the touring secretary cautioned our guide in my presence against any such presumption.

It is a fine May afternoon when we drive from London to Folkestone to be on hand in time to attend to the formalities for crossing the Channel on the following day. Police traps, we are warned, abound along the road and we proceed quite soberly, taking some four hours for the seventy-five miles including the slow work of getting out of London. The Royal Pavilion Hotel on low ground near the docks is strictly first-class and its rates prove more moderate than we found at its competitors on the cliff.

Our car is left at the dock, arrangements for its transport having been made beforehand by the Royal Automobile Club; but we saunter down in 4 the morning to see it loaded. We need not worry about this, for it goes “at the company’s risk,” a provision which costs us ten shillings extra. It is pushed upon a large platform and a steam crane soon swings it high in the air preparatory to depositing it on the steamer deck.

“She’s an airship now,” said an old salt as the car reached its highest point. “We did fetch over a sure-enough airship last week—belonged to that fellow Paulhan and he’s a decentish chap, too; you’d never think he was a Frenchman!”—which would seem to indicate that the entente cordiale had not entirely cleared away prejudice from the mind of our sailor-friend.

Our crossing was as comfortable as any Channel crossing could be—which in our case is not saying much, for that green, rushing streak of salt water, the English Channel, always gives us a squeamish feeling, no matter how “smooth” it may be. We are only too glad to get on terra firma in Boulogne and to see our car almost immediately swung to the dock.

I had read in a recently published book by a motor tourist of the dreadful ordeal he underwent in securing his license to drive; a stern official sat beside him and put him through all his paces to ascertain if he was competent to pilot a car in 5 France. I was expecting to be compelled to give a similar exhibit, when the Captain came out of the station with driving licenses for both himself and me and announced that we would be ready to proceed as soon as he attached a pair of very indistinct number plates.

“But the examination ‘pour competence,’” I said.

“O,” he replied, “I just explained to his nobs that we were in a great hurry and couldn’t wait for an examination—and a five-franc piece did the rest.” A piece of diplomacy which no doubt left the honest official feeling happier than if I had given him a joy-ride over the cobbles of Boulogne.

Filling our tank with “essence,” which we learn, after translating some jargon concerning “litres” and “francs,” will cost about thirty-five cents per gallon—we strike out on the road to Montreuil. It proves a typical French highway and our first impressions are confirmed later on. The road is broad, with perfect contour and easy grades, running straight away for miles—or should I say kilometers?—and showing every evidence of engineering skill and careful construction. But it is old-fashioned macadam without any binding material. The motor car has torn up the surface and scattered it in loose dust which rises in clouds from our wheels or has been 6 swept away by the wind, leaving the roadbed bare but rough and jagged—a perfect grindstone on rubber tires. The same description applies to nearly all the roads we traversed in France, and no doubt the vast preponderance of them are still in the same state or worse. A movement for re-surfacing the main highways is now in progress and in a few years France will again be at the front, though at this time she is far behind England in the matter of modern automobile roads. The long straight stretches and the absence of police traps in the country make fast time possible—if one is willing to pay the tire bill. Thirty miles an hour is an easy jog and though we left Boulogne after three, we find we have covered one hundred and ten miles at nightfall, including a stop for luncheon. At Montreuil we strike the first and only serious grade, a long, steep hill up which winds the cobble-paved main street of the town—our first experience with the cobble pavement of the provincial towns, of which more anon.

A few miles beyond Montreuil the Captain steers us into a narrow byroad which leads into the quaint little fisher town of Berck-sur-Mer and, indeed, the much-abused “quaint” is not misapplied here. The old buildings straggle along the single street, quite devoid of any touch of the picturesque and thronged 7 by people of all degrees. We see many queer four-wheeled vehicles—not much larger than toy wagons—drawn by ponies and donkeys, the drivers lying at full length on their backs, staring at the sky or asleep, their motive power wandering along at its own sweet will. It is indeed ridiculous to see full-grown men riding in such a primitive fashion, but the sight is not unusual. We meet a troop of prawn fishers coming in from the sea—as miserable specimens of humanity as we ever beheld—ragged, bedraggled, bare-headed and bare-footed creatures; many old women among them, prancing along like animated rag-bags.

Swinging back into the main highway, we soon reach Abbeville, whose roughly paved streets wind between bare, unattractive buildings. In places malodorous streams run along the streets—practically open sewers, if the smell is any indication. Abbeville affords an example of the terrible cobblestone pavement that we found in nearly all French cities of the second class. The round, uneven stones—in the States we call them “niggerheads”—have probably lain undisturbed for centuries. Besides the natural roughness of such a pavement, there are numerous chuck-holes. No matter how slowly we drive, we bounce and jump over these stones, which strike the tires with sledge-hammer force, sending 8 a series of shivers throughout the car. It is no wonder that such pavements and the grindstone roads often limit the life of tires to a few hundred miles.

Out of Abbeville we “hit up” pretty strongly, for it is nearly dark and we plan to reach Rouen for the night. The straight fine road offers temptation to speed, under the circumstances, and our odometer does not vary much from forty miles—when we are suddenly treated to a surprise that makes us more cautious about speeding on French roads at dusk. In a little hollow we strike a ditch six inches deep by two or three feet in width—a “canivau,” as they designate it in France—with a terrific jolt which almost threatens the car with destruction. The frame strikes the axles with fearful force; it seems impossible that nothing should be broken. A careful search fails to reveal any apparent damage, though a fractured axle-rod a short time later is undoubtedly a result of the violent blow. It seems strange that an important main road should have such a dangerous defect, though we find many similar cases later; but as we travel no more after dusk, and generally at much more moderate speed, we have no further mishap of the kind. We light our lamps and proceed at a more sober pace to Neufchatel, where we decide to stop for the night 9 at the rather unattractive-looking Lion d’Or. We have reason to congratulate ourselves, for the wayside inn is really preferable to the Angleterre at Rouen and the rates are scarcely half so much. It is a rambling old house, partly surrounding a stable-yard court where the motor is stored for the night. The regular meal time is past, but a plain supper is prepared for us. We are tired enough not to be too critical of our accommodations and the rooms and beds are clean and fairly comfortable. We have breakfast at a long table where the guests all sit together and the fare, while plain, is good.

There is nothing of interest in Neufchatel, though its cheese has given it a world-wide fame. It is a market town of four or five thousand people, depending largely on the prosperous country surrounding it.

We are early away for Rouen and in course of an hour we come in sight of the cathedral spire, the highest in all France, rising nearly five hundred feet and overtopping Salisbury, the loftiest in England, by almost one hundred feet. At the Captain’s recommendation we seek the Hotel Angleterre—which means the Hotel England—a bid, no doubt, for the patronage of the numerous English-speaking tourists who visit the city. There is a deal of dickering before we get settled, for the rates are 10 unreasonably high; but after considerable parley a bargain is made. We enter the diminutive “lift,” which holds two persons by a little crowding, but after the first trip we use the stairway to save time.

One could not “do” Rouen in the guide-book sense in less than a week—but such is not the object of our present tour. If one brings a motor to France he can hardly afford to let it stand idle to spend several days in any city. We shall see what we can of Rouen in a day and take the road again in the morning.

Our first thought is of Jeanne d’Arc and her martyrdom in the old city and our second of the cathedral, in some respects one of the most remarkable in Europe. It is but a stone’s throw from our hotel and is consequently our first attraction. The facade is imposing despite its incongruous architectural details and has a world of intricate carving and sculpture, partly concealed by scaffolding, for the church is being restored. The towers flanking the facade are unfinished, both lacking the tall Gothic spire originally planned and, indeed, necessary to give a harmonious effect to the whole. A spire of open iron-work nearly five hundred feet in height replaces the original wooden structure burned by lightning in 1822 and is severely criticised as being 11 out of keeping with the elaborate stone building which it surmounts.

Once inside we are overwhelmed by a sense of vastness—the great church is nearly five hundred feet in length, while the transept is a third as wide. The arches of the nave seem almost lost in the dim, softly toned light that streams in from the richly colored windows, some of which date from the twelfth century. If the exterior is incongruous, the interior is indeed a symphony in stone, despite a few jarring notes in the decorations of some of the private chapels. There are many beautiful monuments, mainly to French church dignitaries whom we never heard of and care little about, but the battered gigantic limestone effigy discovered in 1838 is full of fascinating interest, for it represents Richard the Lion-Hearted—the Richard of “Ivanhoe”—whose heart, enclosed in a triple casket of lead, wood and silver, is buried beneath. The figure is nearly seven feet in length and we wonder if this is a true representation of the stature of our childhood’s hero, who,

12 For Richard’s body was interred at Fontevraud, near Orleans, with other members of English royalty. Henry II. is also buried in Rouen Cathedral—all indicative that there was a day when English kings regarded Normandy as their home!

Another memorial which interests us is dedicated to LaSalle, the great explorer, who was born in Rouen. He was buried, as every schoolboy knows, in the great river which he discovered, but his memory is cherished by his native city as the man who gave the empire of Louisiana to France.

Rouen has at least two other churches of first magnitude—St. Ouen and St. Maclou—but we shall have to content ourselves with a cursory glance at their magnificence. The former is declared to be “one of the most beautiful Gothic churches in existence, surpassing the cathedral both in extent and excellence of style.” Such is the pronouncement of that final authority on such matters, Herr Baedeker!

But, after all, is not Rouen best known to the world because of its connection with the strange figure of Jeanne d’Arc? Indeed, her career savors of myth and legend—not the sober fact of history—and it is hard to conceive of the scene that took place around the fatal spot in the Vieux-Marche, now marked with a large stone bearing the inscription, 13 “Jeanne d’Arc, 30 Mar. 1431.” Here a tender young woman whose only crime was an implicit belief that she was divinely inspired, was burned at the stake by order of a reverend bishop who, surrounded by his satellites, approvingly looked on the dreadful scene. And these men were not painted savages, but high dignitaries of Christendom. Much of old Rouen stands to-day as it stood then, but what a vast change has been wrought in humankind! Only a single ruinous tower remains of the castle where the Maid was confined. While imprisoned here she was intimidated by being shown the instruments of torture; but she withstood the callous brutality of her persecutors with fortitude and heroism that baffled them, though it only enraged them the more.

We acknowledge the hopelessness of getting any adequate idea of a city of such antiquity and importance in a day and the Captain says we may as well quit trying. He suggests that we take the tram for Bonsecours, situated on the steep hill towering high over the town from the right bank of the river. Here is a modern Catholic cemetery with many handsome tombs and monuments and, in the center, a recently erected memorial to Joan of Arc. This consists of three little temples in the Renaissance style, the central chapel enclosing a 14 marble statue of the Maid. There is a modern church near by whose interior—a solid mass of bright green, red and gold—is the most gorgeous we have seen. The specialty of this church is “votive tablets”—the walls are covered with little marble placards telling what some particular saint has done for the donor in response to a vow. A round charge, the Captain says, is made for each tablet, so that the income of Bonsecours Church must be a good one.

But one will not visit Bonsecours to see the church or the memorial, though both are interesting in their way, but for the unmatched view of the city and the Seine Valley, which good authorities pronounce one of the finest panoramas in Europe. From the memorial the whole city lies spread out like a map—so far beneath that the five-hundred-foot spire of Notre Dame is below the level of our vision. The city, with its splendid spires rising amidst the wilderness of streets and house-roofs, fills the valley near at hand and the broad, shining folds of the Seine, with its old bridges and wooded shores, lends a glorious variety to the scene. The view up and down the river is quite unobstructed, covering a beautiful and prosperous valley bounded on either side by the verdant hills of Normandy. This view alone well repays a visit to Bonsecours, whether one’s stay in Rouen be short or long.

15 In leaving Rouen we cross the Seine and follow the fine straight road which runs through Pont Audemer to Honfleur on the coast. This was not our prearranged route, but the Captain apparently gravitates toward the sea whenever possible, and he is responsible for the diversion. From Honfleur we follow the narrow road along the coast—its sharp turns, devious windings, short steep hills and the hedgerows which border it in places recalling the byways of Devon and Cornwall. We again come out on the shore at Trouville-sur-Mer, a watering place with an array of imposing hotels. It is not yet the “season” and many of the hotels are closed, but the Belvue, one of the largest, is doing business and we have an elaborate luncheon here which costs more than we like to pay.

Out of Trouville our road still pursues the coast, running through a series of resorts and fishing villages until it swings inland for Caen—a quaint, irregular old place which, next to Rouen, declares Baedeker, is the most interesting city in Normandy. We are sorry that many of its show-places are closed to us, for it is Sunday and the churches are not open to tourist inspection. In St. Stephen’s we might have seen the tomb of William the Conqueror, though his remains no longer rest beneath it, having been disinterred and scattered by the Huguenots in 16 1562. Caen has two other great churches—St. Peter’s and Trinity, which we can view only from the outside.

It is Pentecost Sunday and the streets are thronged with young girls in white who have taken part in confirmation services; we have seen others at many places during the day. It is about the only thing to remind us that it is Sunday, for the shops are open, work is going on in the fields, and road-making is in progress; we note little suspension of week-day activities. The peasants whom we see by the roadside and in the little villages are generally very dirty but seem happy and content. The farm houses are usually unattractive, often with filthy surroundings—muck-heaps in front of the doors—not unlike what we saw in some parts of Ireland.

The road from Caen to Bayeux runs as straight as an arrow’s flight, broad, level and bordered—as most main roads are in France—by rows of stately trees. We give the motor full rein and the green sunny fields flit joyously past us. What a relief to “open her up” without thought of a policeman behind every bush! Is it any wonder that the oft-trapped Englishman considers France a motorist’s paradise?

The spires of Bayeux Cathedral soon rise before us 17 and we must content ourselves with the exterior of this magnificent church. Not so with the museum which contains the Bayeux Tapestry, for the lady member of our party is determined to see this famous piece of needlework, willy nilly. The custodian is finally located and we are admitted to view the relic. It is a strip of linen cloth eighteen inches wide and two hundred thirty feet long, embroidered in colored thread with scenes representing the Conquest of England by William of Normandy. It is claimed that the work was done by Queen Matilda and her maidens, though this is disputed by some authorities; but its importance as a contemporary representation of historic events of the time of William I. far outweighs its artistic significance.

The main road from Bayeux to St. Lo is one of the most glorious highways in France. It runs through an almost unbroken forest of giant trees for a good part of the distance—a little more than twenty miles—and the sunset sky gleaming through the stately trunks relieves the otherwise somber effect.

By happy accident we reach St. Lo at nightfall and turn into the courtyard of the Hotel de Univers, a comfortable-looking old house invitingly close to the roadside. I say by happy accident, for we never planned to stop at St. Lo and but 18 for chance might have remained in ignorance of one of the most charming little cathedral towns in France. Indeed, we feel that St. Lo is ours by right of discovery, for we find but scant mention of it in the guide-books. After an excellent though unpretentious dinner, we sally forth from our inn to view our surroundings in the deepening twilight. The town is situated on the margin of a still little river which wonderfully reflects the ancient vine-covered houses that climb the sharply sloping hillside. The huge bulk of the cathedral looms mysteriously over the town and its soaring twin spires are sharply outlined against the dim moonlit sky. The towers are not exact duplicates, as they appear from a distance, but both exhibit the same general characteristics of Gothic style. The whole scene is one of enchanting beauty; the dull glow of the river, the houses massed on the hillside, with lighted windows gleaming here and there and and crowning all the vast sentinellike form of the cathedral—a scene that would lose half its charm if viewed by the flaunting light of day. And we secretly resolve that we shall have no such disenchantment; we shall steal quietly out of St. Lo in the early morning with never a backward glance. We do not, therefore, see the interior of the church, which has several features of peculiar interest, and 19 we may be pardoned for adopting the description of an English writer:

“Notre Dame de Saint-Lo has a very unusual and original plan, widening towards the east and adding another aisle to the north and south ambulatories. On the north side is its chief curiosity, an out-door pulpit, built at the end of the fifteenth century and probably used by Huguenot preachers, to whom a sermon was a sermon, whether preached under a vaulted roof or the open sky. What strikes one most about the interior of the church is its want of light. The nave is absolutely unlighted, having neither tri-forium nor clerestory, and the aisles have only one tier of large windows, whose glass is old and very fine, though in most cases pieced together; the nave piers are massive, with a cluster of three shafts; those of the choir are quite simple, and have one noticeable feature, the absence of capitals, the vault mouldings dying away into the pier.”

ST. LO FROM THE RIVER

We shall remember our hotel as the best type of the small-town French inn—a simple, old-fashioned house where we had attentive service and a studied effort to please was made by all connected with the place. And not the least of its merits are its moderate charges—less than half we paid at many of the larger places, often for less satisfactory accommodations.

20 Twenty miles westward from St. Lo we come to Coutances, which boasts of a cathedral church of the first magnitude and one of the oldest in Normandy, dating almost in entirety from the thirteenth century. Leaving the main highway a little beyond Coutances, we follow the narrow byroad running about a mile from the coast through Granville, a well-known seaside resort, to Avranches. This road is scarcely more than a winding lane with many sharp little hills, hedge-bordered in places and often overarched by trees—a little like the roads of Southern England, a type not very common in France. South of Granville it closely follows the shore for a few miles, then swings inland for a mile or two, affording only occasional glimpses of the sea. Avranches, from its commanding site on a lofty hill, soon breaks into view, and the Captain suggests luncheon at the Grand Hotel de France et de Londres, which he says is famous in this section. Besides, it is well worth while to ascend the hill for the panorama of St. Michel’s Bay, with its cathedral-crowned islet, which may be seen to the best advantage from the town. It is a stiff, winding climb to the summit, but we reach the cobble-paved, vine-embowered court of the hotel just in time for dinner. I suppose the “Londres” was added to the name of the inn with a view of 21 catching the English-speaking trade, which is considerable in Avranches, since the town is the stopping-place of many tourists who visit Mont St. Michel. From the courtyard we are ushered into the dining-room where, after the fashion of country inns in France, a single long table serves all the guests. At the head sits the proprietor, a suave, gray-bearded gentleman who graciously does the courtesies of the table. The meal is quite an elaborate one and there is plenty of old port wine for the bibulously inclined. I might say here that this inclusion of wines without extra charge is a common but not universal practice with the French country inns; generally these liquors are of the cheapest quality, little better than vinegar, and one trial will make the average tourist a teetotaler unless he wishes to order a better grade as an “extra.” After the meal our host comes out to wish us “bon voyage” as we depart and we are at a loss to understand his intention when he picks up a small ladder and begins climbing up the wall. We see, however, that a rose-vine bearing a few beautiful blossoms clings to the stones above a window. The old gentleman cuts some of the choicest flowers and presents them, with a gracious bow, to the lady of our party.

The new causeway makes Mont St. Michel easily 22 accessible to motorists and affords a splendid view as one approaches the towered and pinnacled rock and the little town that climbs its steep sides. Formerly the tide covered the rough road that led to the mount, much the same as it still covers the approach to the Cornish St. Michael; but the new grade is above high-tide level and the abbey may be reached at any time of the day. It is a wearisome climb to the summit—for the car cannot enter the narrow streets of the town—and for some time we wait the pleasure of the guide, who, being a government official, does not permit himself to be unduly hurried. He speaks only French and but for the Captain’s services we should know little of his story. To our half-serious remark that a lift would save visitors some hard work he replies with a shrug,

“A lift in Mont St. Michel? It wouldn’t be Mont St. Michel any longer!”—a hint of how carefully the atmosphere of mediaevalism is preserved here.

The abbey as it stands to-day is largely the result of an extensive restoration begun by the government in 1863. This accounts for the surprisingly perfect condition of much of the building, and it also confirms the wisdom of the undertaking by which a great service has been rendered to architecture. 23 Previous to the restoration the abbey was used as a prison, but it is now chiefly a show-place, though services are regularly conducted in the chapel. Especially noteworthy are the cloisters, a thirteenth-century reproduction, with two hundred and twenty columns of polished granite embedded in the wall and ranged in double arcades, the graceful vaults decorated with exquisite carving and a beautiful frieze. The most notable apartment is the Hall of the Chevaliers, likewise a thirteenth-century replica. The vaulting of solid stone is supported by a triple row of massive columns running the full length of nearly one hundred feet—like ranks of giant tree trunks. There is a beautiful chapel and dungeons and crypts galore, the names of which we made no attempt to remember. Likewise we gave little attention to the historic episodes of the mount, which are not of great importance. The interest of the tourist centers in the remarkably striking effect of the great group of Gothic buildings crowning the rock and in the artistic beauty of the architectural details. Many wonderful views of the sea and of the hills and towns around the bay may be seen to splendid advantage from the terraces and battlements. There are a number of pleasant little tea gardens where one may order light refreshments and in the meanwhile enjoy a most inspiring view of the 24 sea and distant landscape. The little town at the foot of the rock is a quaint old-world place with a single street but a few feet wide. The small population subsists on tourist trade—restaurants and souvenir shops making up the village. Little is doing to-day, as we are in advance of the liveliest season. The greatest number of visitors come on Sunday—a gala day at Mont St. Michel in summer.

A rough, stony road takes us to St. Malo and adds considerable wearisome tire trouble to an already strenuous day. We are glad to stop at the Hotel de Univers, even though it is not prepossessing from without.

A STREET IN ST. MALO

St. Malo’s antiquity and quaintness are its stock in trade, and these, together with its position on a peninsula, with the sea on every hand, make it one of the most popular resorts in France. Steamers from Southampton bring numbers of English visitors—we find no interpreter needed at the hotel. The town is encircled by walls, the greater part recently restored. They are none the less picturesque and the mighty towers at the entrance gateways savor strongly indeed of mediaevalism. In the older part of the town the streets are so narrow and crooked as to exclude motors, the widest not exceeding twenty feet, and there are seldom walks on either side. The houses bordering them show every evidence of 25 age—St. Malo is best described by the often overworked term, “old-world.” The huge church—formerly a cathedral—is so hedged in by buildings that it is impossible to get a good view of the exterior or to take a satisfactory photograph. As a result of such crowding it is poorly lighted inside, though it really has an impressive interior. A walk round the walls or ramparts of St. Malo affords a wonderful view of the sea and surrounding country and also many interesting glimpses of queer nooks and corners in the town itself. The bay is finest at full tide, which rises here to the astonishing height of forty-nine feet above low water. There are numerous fortified islands and it is possible to reach some of these on foot when the tide is out. St. Malo was besieged many times during the endless wars between England and France, but owing to its remarkable fortifications was never taken.

There is more rough, badly worn road between St. Malo and Rennes, though in the main it is broad and level. Its effect on tires is indeed disheartening—we have run less than a thousand miles since landing and new envelopes are showing signs of dissolution. Part of the game, no doubt, but it is hard to be cheerful losers in such a game, to say the least.

Rennes, we find, has other claims to fame than 26 the Dreyfus trial, which is the first distinction that comes to mind. Its public museum and galleries contain one of the best provincial collections in France, and there is an imposing modern cathedral. We have an excellent lunch at the Grand Hotel, though it is a dingy-looking place that would hardly invite a lengthy stop if appearances should be considered. It is not Baedeker’s number one and there is doubtless a better hotel in Rennes.

The road which we follow in leaving the town is the best we have yet traversed in France; it is broad, straight and newly surfaced, and the thirty or more miles to Chateaubriant are rapidly covered. Here we find an ancient town of a few thousand people, and an enormous old castle partly in ruins, a fit match for Conway or Harlech in Britain. Its square-topped, crenelated towers and long embrasured battlements are quite different from the pointed Gothic style of the usual French chateau.

Beyond Chateaubriant the road runs broad and straight for miles through a beautiful and prosperous country. Evidently the land is immensely fertile and tilled with the thoroughness that characterizes French agriculture. The small village is the only discordant note. We pass through several all alike, bare, dirty and uninteresting, quite different from the trim, flower-decked beauty of the English village. 27 And they grow steadily more repulsive as we progress farther inland until, as we near the German border—but the subject is not pleasant enough to anticipate!

WOODS IN BRITTANY

From original painting by Leon Richet

Angers is a cathedral town of eighty thousand people on the River Maine, two or three miles above its confluence with the Loire. It is of ancient origin, but the French passion for making everything new (according to an English critic) has swept away most of its old-time landmarks save the castle and cathedral. The former was one of the most extensive mediaeval fortresses in all France and is still imposing, despite the fact that several of its original seventeen towers have been razed and its great moat filled up. It is now more massive than picturesque. “It has no beauty, no grace, no detail, nothing to charm or detain you; it is simply very old and very big and it takes its place in your recollections as a perfect specimen of a superannuated feudal stronghold.” The huge bastions, girded with iron bands, and the high perpendicular walls springing out of the dark waters of the moat must have made the castle impregnable against any method of assault before the days of artillery. The castle is easily the most distinctive feature of Angers and the one every visitor should see, though I must confess we failed to visit it. We should also have seen 28 the cathedral and museum, but museums consume time and time is the first consideration on a motor tour.

Our Hotel, the Grand, though old, is cleanly and pleasant, with high ceilings and broad corridors which have immense full-length mirrors at every turn. The prices for all this magnificence are quite moderate—largely due, no doubt, to the Captain’s prearrangement with the manager. The service, however, is a little slack, especially at the table.

At Angers we are in the edge of the Chateau District, and as my chapter has already run to considerable length, I shall avail myself of this logical stopping place. The story of the French chateaus has filled many a good-sized volume and may well occupy a separate chapter in this rather hurried record.

For more than two hundred miles after leaving Angers we follow a road that may justly be described as one of the most unique and picturesque in France. It seldom takes us out of sight of the shining Loire and most of the way it runs on an embankment directly overlooking the river, affording a panoramic view of the fertile valley which stretches to green hills on either side. The embankment is primarily to confine the waters during freshets, but its broad level top makes an excellent roadbed, which is generally in good condition. A few miles out of Angers we get our first view of the Loire, a majestic river three or four hundred yards in width and in full flow at the present time. Occasional islets add to the beauty of the scene and the landscape on either hand is studded with splendid trees. It is an opulent-looking country and we pass miles of green fields interspersed at times with unbroken stretches of forest. There are several towns and villages on both sides of the river and they are cleaner and better in 30 appearance than those we passed yesterday. Near Tours the country becomes more broken and the hillsides are covered with endless vineyards. In places the clifflike hills rise close to the roadside and these are honeycombed with caves; some are occupied as dwellings by the peasants, but the greater number serve as storage cellars for wine, which is produced in large quantities in this vicinity. These modern “cliff-dwellers” are not so poor as their homes would indicate; there are many well-to-do peasants among them. In fact, the very poor are scarce in rural France; the universal habits of industry and economy have spread prosperity among all classes of people; rough attire and squalid surroundings are seldom indicative of real poverty, as in England. Everybody is engaged in some useful occupation—old women may be seen herding a cow, donkey or geese by the roadside and knitting industriously the while.

Tours is one of the most beautiful of the older French provincial cities. We have a fine view of the town from across the Loire as we approach, for it lies on the south side of the river. It is a famous tourist center—perhaps the first objective, after Paris, of the majority of Americans and English, and it has several pretentious hotels. We choose the newest, the Metropole, which proves 31 very satisfactory. Here the Captain’s wiles fail to reduce the first-named tariff, for the hotel is full, and we can only guess what the charge might have been if not agreed upon in advance. In defense of his bargaining the Captain tells a story of a previous trip he made with an American party in Italy. English was spoken at a hotel where one of the party asked the rates and the proprietor, assuming that his prospective guests did not understand the language of the country, had a little by-talk with a henchman as to charges and remarked that the tourists, being Americans, would probably stand three or four times the regular rates, which the inn-keeper proceeded to ask. He was greatly chagrinned when the Captain repeated the substance of the conversation he had heard and told the would-be robber that the party would seek accommodations elsewhere.

I will let this little digression take the place of descriptive remarks concerning Tours, which has probably been written about more than any other city in France excepting Paris. The cathedral everyone will see; it is especially noteworthy for the facade, which is the best and most ornate example of the so-called Flamboyant style in existence. The great Renaissance towers are comparatively 32 modern and to our mind lack the grace and fitness of the pointed Gothic style.

The country about Tours has more to attract the tourist than the city itself, for within a few miles are the famous chateaus which have been exploited by literary travelers of all degrees. But it has lost none of its charm on that account and perhaps every writer has presented to some extent a different viewpoint of its beauty and romance. Touraine is quite unlike any other part of France; its vistas of grayish-green levels, diversified with slim shimmering poplars and flashes of its broad lazy rivers, are quite unique and characteristic. And when such a landscape is dotted with an array of splendid historic palaces such as Blois, Amboise, Chinon, Chaumont and Chenonceaux, it assuredly reaches the height of romantic interest. All of these, it is true, are not within the exact political limits of Touraine, but all are within easy reach of Tours.

We make Chenonceaux our objective for the afternoon. It lies a little more than twenty miles east of Tours and the road follows the course of the Cher almost the whole distance. The palace stands directly above the river, supported on massive arches which rest on piles in the bed of the stream. A narrow drawbridge at either end cuts the entrances from the shore, though these bridges 33 were never intended as a means of defense. Chenonceaux was in no sense a military fortress—its memories are of love and jealousy and not of war or assassination. It was built early in the sixteenth century by a receiver of taxes to King Francis, but so much of the public funds went into the work that its projector died in disgrace and his son atoned as best he could by turning the chateau over to the king.

CHENONCEAUX—THE ORIENTAL FRONT

And here, in the heart of old France, we come upon another memory of Mary Stuart, for here, with Francis II., she spent her honeymoon—if, indeed, we may style her short loveless marriage a honeymoon—coming direct from Amboise, where she had unwillingly witnessed the awful scenes of the massacre of the Huguenots. What must have been the reveries of the girl-queen at Chenonceaux! In a foreign land, surrounded by a wicked, intriguing court, with scenes of bloodshed and death on every hand and wedded to a hopeless imbecile, foredoomed to early death—surely even the strange beauty of the river palace could not have driven these terrible ghosts from her mind.

Chenonceaux has many memories of love and intrigue, for here in 1546 Francis I. and his mistress, the famous Diane of Poitiers, gave a great hunting party; but the heir-apparent, Prince Henry, 34 soon gained the affections of the fair Diane and on his accession to the throne presented her with the chateau, to which she had taken a great fancy. She it was who built the bridgelike hall connecting the castle with the south bank of the river and she otherwise improved the palace and grounds; but on the death of the king, twelve years later, the queen—the terrible Catherine de Medici—compelled Diane to give up Chenonceaux and to betake herself to the older and less attractive Chaumont. The chateau escaped serious injury during the fiery period of the Revolution, but the insurrectionists compelled the then owner, Madame Dupin, to surrender her securities, furniture, priceless paintings and objects of art—the collection of nearly three centuries—and all were destroyed in a bonfire.

Chenonceaux is now the property of a wealthy Cuban who has spent a fortune in its restoration and improving the grounds, which accounts for the trim, new appearance of the place. The great avenue leading from the public entrance passes through formal gardens brilliant with flowers and beautified with rare shrubbery and majestic trees. It is a pleasant and romantic place and the considerateness of the owner in opening it to visitors for a trifling fee deserves commendation.

AMBOISE FROM ACROSS THE LOIRE

35 Quite different are the memories of Amboise, the vast, acropolislike pile which towers over the Loire some dozen miles beyond Tours and which we reach early the next day after a delightful run along the broad river. We have kept to the north bank and cross the river into the little village, from which a steep ascent leads to the chateau. The present structure is largely the result of modern restoration, the huge round tower being about all that remains of the ancient castle. This contains a circular inclined plane, up which Emperor Charles V. of the Holy Roman Empire rode on horseback when he visited Francis I. in 1539, and it is possible for a medium-sized automobile to make the ascent to-day.

Amboise is chiefly remembered for the awful deeds of Catherine de Medici, who from the balcony overlooking the town watched the massacre, which she personally directed, of twelve hundred Huguenots. With her were the young king, Francis II., and his bride, Mary Stuart, who were compelled to witness the series of horrible executions which were carried out in the presence of the court. The leaders were hung from the iron balconies and others were murdered in the courtyard. They met their fate with stern religious enthusiasm, singing, it is recorded, 36 until death silenced their voices. The direct cause of the massacre was the discovery of a plot on the part of the Huguenot leaders to abduct the young king in order to get him from under the evil influence of his mother.

The chateau contains a tomb that alone should make it the shrine of innumerable pilgrims, for here is buried that many-sided genius, Leonardo da Vinci, who died in Amboise in 1519 and whom many authorities regard as the most remarkable man the human race has yet produced.

But enough of horrors and tombs; we go out on the balcony, where the old tigress stood in that far-off day, and contemplate the enchanting scene that lies beneath us. Out beyond the blue river a wide peaceful plain stretches to the purple hills in the far distance; just below are the gray roofs of the town and there are glorious vistas up and down the broad stream. This is the memory we should prefer to carry away with us, rather than that of the murderous deeds of Catherine de Medici!

On arriving at Blois, twenty miles farther down the river road, thoughts of belated luncheon first engage our minds and the Hotel de Angleterre sounds good, looks good, and proves good, indeed. Its dining-room is a glass-enclosed balcony overhanging the river, which adds a picturesque view 37 to a very excellent meal. The chateau, a vast quadrangular pile surrounding a great court, is but a short distance from the hotel. Only the historic apartments are shown—quite enough, since several hours would be required to make a complete round of the enormous edifice. The castle has passed into the hands of the government and is being carefully restored. It is planned to make it a great museum of art and history and several rooms already contain an important collection. The palace was built at different periods, from the thirteenth to the seventeenth centuries, and was originally a nobleman’s home, but later a residence of the kings of France.

GRAND STAIRWAY OF FRANCIS I. AT BLOIS

Inside the court our attention is attracted by the elaborate decorations and carvings of the walls. On one side is a long open gallery supported by richly wrought columns; but most marvelous is the great winding stairway projecting from the wall and open on the inner side. Every inch of this structure—its balconies, its pillars and its huge central column—is wrought over with beautiful images and strange devices, among which the salamander of Francis I. is most noticeable. When we have admired the details of the court to our satisfaction, the guide conducts us through a labyrinth of gorgeously decorated rooms with many magnificent fireplaces 38 and mantels but otherwise quite unfurnished. The apartments of the crafty and cruel Catherine de Medici are especially noteworthy, one of them—her study—having no fewer than one hundred and fifty carved panels which conceal secret crypts and hiding-places. These range from small boxes—evidently for jewels or papers—to a closet large enough for one to hide in.

The overshadowing tragic event of Blois—there were a host of minor ones—was the assassination of the Duke of Guise in 1588. Henry III., a weak and vacillating king, was completely dominated by this powerful nobleman, whose fanatical religious zeal led him to establish a league to restore the supremacy of the Catholic religion. The king was forced to proclaim the duke lieutenant-general of the kingdom and to pledge himself to extirpate the heretics; but despite his outward compliance Henry was resolved on vengeance. According to the ideas of the times an objectionable courtier could best be removed by assassination and this the king determined upon. He piously ordered two court priests to pray for the success of his plan and summoned the duke to his presence. Guise was standing before the fire in the great dining-room and though he doubtless suspected his royal master’s kind intentions toward him, walked into the next 39 room, where nine of the king’s henchmen awaited him. They offered no immediate violence, but followed him into the corridor, where they at once drew swords and fell upon him. Even against such odds the duke, who was a powerful man, made a strong resistance and though repeatedly stabbed, fought his way to the king’s room, where he fell at the foot of the royal bed. Henry, when assured that his enemy was really dead, came trembling out of the adjoining room and kicking the corpse, exclaimed, “How big he is; bigger dead than alive!” The next morning the duke’s brother, the Cardinal of Lorraine, was also murdered in the castle as he was hastening to obey a summons from the king.

There is little suggestion of such horrors in the polished floors and gilded walls that surround us today as we hear the Captain translate the gruesome details from the guide’s voluble sentences. We listen only perfunctorily; it all seems unreasonable and unreal as the sun, breaking from the clouds that have prevailed much of the day, floods the great apartments with light. We have not followed this tale of blood and treachery closely; it is only another reminder that cruelty and inhumanity were very common a few centuries ago.

There is a minor cathedral in Blois, but the most interesting church is St. Nicholas, formerly a part 40 of the abbey and dating from 1138. Its handsome facade with twin towers is the product of recent restoration. There are also many quaint timbered houses in Blois, dating from the fifteenth century and later, but we pay little attention to them. I hardly know why our enthusiasm for old French houses is so limited, considering how eagerly we sought such bits of antiquity in England.

We pursue the river road the rest of the day, though in places it swings several miles from the Loire—or does the Loire swing from the road, which seems arrow-straight everywhere?—and cuts across some lovely rural country. Fields of grain, just beginning to ripen, predominate and there are also green meadows and patches of carmine clover. Crimson poppies and blue cornflowers gleam among the wheat, lending a touch of brilliant color to the billowy fields.

The village of Beaugency, which we passed about midway between Tours and Orleans, is one that will arrest the attention of the casual passerby. It is more reminiscent of the castellated small town of England than one often finds in France. It is overshadowed by a huge Norman keep with sheltered, ivy-grown parapets, the sole remaining portion of an eleventh-century castle. The remainder of the present castle was built as a stronghold 41 against the English, only to be taken by them shortly after its completion. The invaders, however, were driven out by the French army under Joan of Arc in 1429. The bridge at Beaugency is the oldest on the Loire, having spanned the river since the thirteenth century. The town has stood several sieges and was the scene of terrible excesses in the religious wars of the sixteenth century, the abbey having been burned by the Protestants in 1567.

Towards evening we again come to the river bank and ere long the towers of Orleans break on our view. Despite its great antiquity the city appears quite modern, for it has been so rebuilt that but few of its ancient landmarks remain. Even the cathedral is a modern restoration—almost in toto—and there is scarcely a complete building in the town antedating 1500. The main streets are broad and well-paved and electric trams run on many of them. Our hotel, the Grand Aignan, is rather old-fashioned and somewhat dingy, but it is clean and comfortable and its rates are not exorbitant. There is a modern and more fashionable hotel in the city, but we have learned that second-class inns in cities of medium size are often good and much easier on one’s purse.

Our first thought, when we begin our after-dinner ramble, is that Orleans should change its 42 name to Jeanne d’Arcville. I know of no other instance where a city of seventy thousand people is so completely dominated by a single name. The statues, the streets, the galleries, museums, churches and shops—all remind one of the immortal Maid who made her first triumphal entry into Orleans in 1429, when the city was hard pressed by the English besiegers. Every postcard and souvenir urged upon the visitor has something to do with the patron saint of the town and, after a little, one falls in with the spirit of the place, rejoicing that the memories of Orleans are only of success and triumph and forgetting Rouen’s dark chapter of defeat and death.

In the morning we first go to the cathedral—an ornate and imposing church, though one that the critics have dealt with rather roughly. It faces the wide Rue Jeanne d’Arc—again Orleans’ charmed name—and it seems to us that the whole vast structure might well be styled a memorial to the immortal Maid of France. The facade is remarkable for its Late-Gothic towers, nearly three hundred feet high, while between them to the rear rises the central spire, some fifty feet higher. There are three great portals beneath massive arches, rising perhaps one-fourth the height of the towers, and above each of these is an immense rose window. 43 Perhaps the design as a whole is not according to the best architectural tenets, but the cathedral seems grand to such unsophisticated critics as ourselves. Being a rather late restoration, it does not show the wear and tear of the ages, like so many of its ancient rivals, and perhaps loses a little charm on this account. The vast vaultlike interior is quite free from obstructions to one’s vision and is lighted by windows of beautifully toned modern glass. These depict scenes in the life of Joan of Arc, beginning with the appearance of her heavenly monitors and ending with her martyrdom at the stake. The designing is of remarkably high order and the color toning is much more effective than one often finds in modern glass. There are a number of paintings and images, many of them referring to the career of the now venerated Maid. The usual gaudy chapels and altars of French cathedrals are in evidence, though none are especially interesting.

Orleans has several other churches and all pay some tribute to the heroine of the town. A small part of St. Peter’s dates from the ninth century, one of the few relics of antiquity to be found in Orleans. The Hotel de Ville, built about 1530, has a beautiful marble figure of Joan in the court, and an equestrian statue of the Maid is in the Grand Salon of the building, representing her horse in the 44 act of trampling a mortally wounded Englishman. Both of these statues are the work of Princess Marie of Orleans—a scion of the old royal family of France. The Hotel de Ville also recalls a memory of Mary Stuart; here in 1560 her boy-husband, Francis II., expired in the arms of his wife, and her career was soon transferred from the French court to its no less troubled and cruel contemporary in Scotland. The town possesses an unusually good museum, which includes a large historical collection, and the gallery contains a number of paintings and sculptures of real merit. Of course one will wish to see the house where the patron saint of the town lodged, and this may be found at No. 37 Rue de Tabour. There is also on the same street the Musee Jeanne d’Arc, which contains a number of relics and paintings relating to the heroine and her times.

But for all the worship of Joan of Arc in Orleans, she was not a native of the place and actually spent only a short time within the walls of the old city. The Maid was born in the little village of Domremy in Lorraine, some two hundred miles eastward, where her humble birthplace may still be seen and which we hope to visit when we make our next incursion into France.

We have no more delightful run in France than our easy jaunt from Orleans to Nevers. We still follow the Loire Valley, though the road only occasionally brings us in sight of the somewhat diminished river. The distance is but ninety-six miles over the most perfect of roads and we proceed leisurely, often pausing to admire the landscapes—beautiful beyond any ability of mine to adequately describe. The roadside resembles a well-kept lawn; it is bordered by endless rows of majestic trees and on either hand are fertile fields which show every evidence of the careful work of the farmer. The silken sheen of bearded wheat and rye is dotted with crimson poppies and starred with pale-blue cornflowers. At times the poppies have gained the mastery and burn like a spot of flame amidst the emerald-green of the fields. Patches of dark-red clover lend another color variation, and here and there are dashes of bright yellow or gleaming white of buttercups and daisies. With such surroundings and on such a clear, exhilarating 46 day our preconceived ideals of the beauty of Summer France suffer no disenchantment.

Cosne is an old river town now rather dominated by manufactories and here Pope Pius VII. sojourned when he came to France upon the neighborly invitation of Napoleon I. He stopped at the Hotel du Cerf, but we try the Moderne for luncheon, which proves unusually good.

About three o’clock we reach Nevers and a sudden thunder shower determines us to stop for the night at the Hotel de France. Outside it is quite unpretending, though queer ornamental panels between the windows and a roof of moss-green tiles redeem it somewhat from the commonplace. We have no reason to repent our decision, for the rambling old inn is scrupulously clean and the service has the personal touch that indicates the watchful eye of a managing proprietor. We are somewhat surprised to see a white-clad chef very much in evidence about the hotel and even taking a lively interest in guests who have suffered a break-down and are wrestling with their car in the stable-yard garage. We learn that this chef is the proprietor, and his wife, an English woman, is the manageress. The combination is an effective one; English-speaking guests are made very much at 47 home and the excellence of the meals is sufficient proof of the competence of the proprietor-chef.

PORT DU CROUX—A MEDIEVAL WATCHTOWER AT NEVERS

Nevers has a cathedral dating in part from the twelfth century, though the elaborate tower with its host of sculptured prophets, apostles and saints was built some three hundred years later. The most notable relic of mediaevalism in the town is the queer old Port du Croux, a fourteenth-century watch-tower which one time formed part of the fortifications. It is a noble example of mediaeval defense—a tall gateway tower with long lancet openings and two pointed turrets flanking the steep, tile-covered roof. The ducal palace and the Hotel de Ville are also interesting old-time structures, though neither is of great historic importance. The history of Nevers is in sharp contrast with the checkered career of its neighbor, Orleans, being quite uneventful and prosaic. It is a quiet place to-day, its chief industry being the potteries, which have been in existence some centuries.

The next day, thirty miles on the road to Autun, we experience our first break-down in eighteen thousand miles of motoring in Europe—that is, a break-down that means we must abandon the car for the time. Near the little village of Tamnay-Chatillon an axle-rod breaks and a new one must be made before we can proceed. Our objective 48 point, Dijon, is the nearest place where we will be likely to find facilities for repair and we resolve to go thither by train. We have been so delayed that train-time is past and we shall have to pass the night at the village inn. It is extremely annoying at the time, though in retrospect we are glad of our experience with at least one very small country road-house in France. The inn people spare no effort to make us as comfortable as possible and we have had many worse meals in good-sized cities than is served to us this evening. Our beds, though apparently clean, are not very restful, but we are too weary to be excessively critical. The next morning, leaving the crippled car in the stable-yard, we take the train for Dijon. The Captain carries the broken axle-rod as a pattern and soon after our arrival a workman is shaping a new one from a steel bar. And in this connection I might remark that we found the average French mechanic quick and intelligent, with almost an intuitive understanding of a piece of machinery. Our job proves slower than we anticipated; the work can be done by only one man at a time and it is not completed before midnight of the following day.

In the meanwhile we have established ourselves at the Grand Hotel de la Cloche, a pretentious—and, as it proves, a very expensive stopping-place. 49 We have large, well-furnished rooms which afford an outlook upon a small park fronting the hotel. Our enforced leisure allows us considerably more time to look about Dijon than we have been giving to such towns and we endeavor to make the most of it. The town is one of the military centers of France, being defended by no fewer than eight detached forts, and we see numerous companies of soldiers on the streets.

The museum, we are assured, is the greatest “object of interest” in the city and, indeed, it comes up to the claims made for it. The municipal art gallery contains possibly the best provincial collection of paintings in France—an endless array of pictures of priceless value, representing the greatest names of French art. There is also a splendid showing of sculpture, occupying five separate rooms. The marble tombs of Philip the Brave and John the Fearless, old-time dukes of Burgundy, are wonderful creations. They were originally in the Church of Chartreuse, destroyed in 1793, when the tombs were removed to the cathedral in a somewhat damaged condition. They were later placed in the museum and restored as nearly as possible to their original state. Both have a multitude of marble statuettes, every one a distinct artistic study—some representing mourners for the deceased—and 50 each little face has some peculiar and characteristic expression of grief. The strong contrast of white and black marbles is relieved by judicious gilding and, altogether, we count these the most elaborate and artistic mediaeval tombs we have seen, if we except the Percy monument at Beverly in England. The museum also has an important archaeological collection, including a number of historical relics found in the vicinity, for the city dates back to Roman times. The showing of coins, gems, vases, ivory, cabinets and jewelry would do credit to any metropolitan museum. And all this in a town of but seventy-five thousand people—which shows how far the French municipalities have advanced in such matters. Dijon is no exception in this regard, though other cities of the class may not quite equal this collection, which I have described in merest outline.

Dijon has several churches of the first order, though none of them has any notable distinguishing feature. The Cathedral of St. Benigne is the oldest, dating in its present form from about 1280, though there are portions which go back still farther. It was originally built as an abbey church, but the remainder of the abbatial buildings have disappeared. St. Michael’s Church is some four hundred years later than the cathedral, and has, according 51 to the guide-books, a Renaissance facade, though it seems to us to be better described as a Moorish adaptation of the Gothic style. At any rate, it is an inartistic and unattractive structure and illustrates the poor results often attained in too great an effort after the unusual. Notre Dame is about the same date as the cathedral, though it has been so extensively restored as to have quite a new appearance. Its most remarkable feature is its queer statuettes—nearly a hundred little figures contorted into endless expressions and attitudes—which serve as gargoyles. The churches of Dijon are not particularly noteworthy for their interiors and none has especially good windows. Our extended sojourn in the city enables us to visit a number of shops, for which we have heretofore found little time. These are well-stocked and attractive and quite in keeping with a city of the size of Dijon. According to Herr Baedeker, the town is famous “for wine and corn, and its mustard and gingerbread enjoy a wide reputation.”

The Captain and myself take an early train for Tamnay-Chatillon and have the satisfaction of finding the new axle-rod a perfect fit. We enjoy the open car and the fine road more than ever after our enforced experience with the railway train. The country between Tamnay and Dijon 52 is rolling and the road often winds up or down a great hill for two or three miles at a stretch, always with even and well-engineered gradients that insure an easy climb or a long exhilarating coast. There are many glorious panoramas from the hill-crests—wide reaches of hill and valley, with groves and vineyards and red-tiled villages nestling in wooded vales or lying on the sunny slopes. Most of the towns remain unknown to us by name, but the Captain points out Chateau Chinon clinging to a rather steep hillside and overshadowed by the vast ruined castle which once defended it. A portion of the old wall with three watch-towers still stands—the whole effect being very grim and ancient. Near the town of Pommard the hills are literally “vine-clad,”—vineyards everywhere running up to the very edge of the town.

The Hotel St. Louis et de la Poste at Autun does not present a very attractive exterior, but it proves a pleasant surprise and we are hungry enough to do justice to an excellent luncheon, having breakfasted in Dijon at five o’clock. Autun has an unusual cathedral—“a curious building of the transition period”—some parts of which go back as far as the tenth century. The beautiful Gothic spire—the first object to greet our eyes when approaching the town—was built about 1470. Portions 53 of the old fortifications still remain. St. Andrew’s Gate, partly a restoration, is an imposing portal pierced by four archways and forms one of the main entrances. There is also the usual museum and Hotel de Ville to be found in all enterprising provincial towns of France.

Beyond Autun the character of the country changes again; we come into a less prosperous section, intersected by stone fences which cut the rocky hillsides into small irregular fields. We pass an occasional bare-looking village and one or two ruined chateaus and we remark on the scarcity of ruins in France, so far as we have seen it, as compared with England. A more fertile and thriving country surrounds Dijon, which we reach in the late afternoon.

We have had quite enough of Dijon, but we shall remain until morning; an early start should carry us well toward the German frontier before night. We find some terribly rough roads to Gray and Vesoul—macadam which has begun to disintegrate. The country grows quite hilly and while, in the words of the old hymn, “every prospect pleases,” we are indeed tempted to add that “only man is vile.” For the filthiness of some of the villages and people can only be designated as unspeakable; if I should describe in plain language 54 the conditions we behold, my book might be excluded from the mails! The houses of these miserable little hamlets stretch in single file along both sides of the broad highway. In one end of the house lives the family and in the other the domestic animals—pigs, cows and donkeys. Along the road on each side the muck-piles are almost continuous and reach to the windows of the cottages. Recent rains have flooded the streets with seepage, which covers the road to a depth of two or three inches, and the odors may be imagined—if one feels adequate to such a task. The muck is drained into pools and cisterns from which huge wooden or iron pumps tower above the street. By means of these the malodorous liquid is elevated into wagon-tanks to be hauled away to the fields. And this work is usually done by the women! In fact, women are accorded equal privileges with a vengeance in this part of rural France—they outnumber the men in the fields and no occupation appears too heavy or degraded for them to engage in. We see many of the older ones herding domestic animals—or even geese and ducks—by the roadside. Sometimes it is only a single animal—a cow, donkey, goat or pig—that engages the old crone, who is usually knitting as well. The pigs, no doubt because of 55 their headstrong proclivities, are usually confined by a cord held by their keepers, and with one of these we have an amusing adventure. The pig becomes unruly, heading straight for our car, and only a vigorous application of the brakes prevents disaster to the obstreperous brute. But the guardian of his hogship—who has been hauled around pretty roughly while hanging to the cord—is in a towering rage and screams no end of scathing language at us. “You, too, are pigs,” is one of her compliments which the Captain translates, and he says it is just as well to let some of her remarks stand in the original!

As we approach Remiremont, where we propose to stop for the night, we enter the great range of hills which form the boundary between France and Germany and which afford many fine vistas. Endless pine forests clothe the hillsides and deep narrow valleys slope away from the road which winds upward along the edges of the hills. Remiremont is a pleasant old frontier town lying along the Moselle River at the base of a fortified hill two thousand feet in height. It is cleaner than the average French town of ten thousand and clear streams of mountain water run alongside many of its streets. The Hotel du Cheval de Bronze seems a solid, comfortable old inn and we turn into 56 the courtyard for our nightly stop. The courtyard immediately adjoins the hotel apartments on the rear and is not entirely free from objectionable odors—our only complaint against the Cheval de Bronze. Our rooms front on the street, the noise being decidedly preferable to the assortment of smells in the rear. The town has nothing to detain one, and is rather unattractive, despite its pleasing appearance from a distance. On the main street near our hotel are the arcades, which have a considerable resemblance to the famous rows of Chester.

We are awakened early in the morning by the tramp of a large company of soldiers along the street, for Remiremont, being so near the frontier, is heavily garrisoned. These French soldiers we have seen everywhere, in the towns and on the roads, enough of them to remind us that the country is really a vast military camp. They are rather undersized, as a rule, and their attire is often slouchy and worse for wear. Their bearing seems to us anything but soldierly as they shuffle along the streets. Perhaps we remember this the more because of the contrast we see in Germany a little later. A good authority, however, tells us that the French army is in a fine state of preparedness 57 and would give a good account of itself if called into action.

We are early away from Remiremont on a fine road winding among the pine-clad hills. Some sixteen miles out of the town we find a splendid hotel at Gerardmer on a beautiful little lake of the same name in the Vosges Forest, where we should no doubt have had quite different service from the Cheval de Bronze. We have no regrets, however, since Remiremont is worth seeing as a typical small frontier town. At Gerardmer we begin the long climb over the mountain pass which crosses the German border; there are several miles of the ascent and in some places the grades are steep enough to seriously heat the motor. We stop many times on the way and there is a clear little stream by the roadside from which we replenish the water in the heated engine. The air grows cooler and more bracing as we ascend and though it is a fine June day, we see banks of snow along the road. On either side are great pine trees, through which we catch occasional glimpses of wooded hills and verdant valleys lying far beneath us. Despite the cool air, flowers bloom along the road and the ascent, though rather strenuous, is a delightful one.