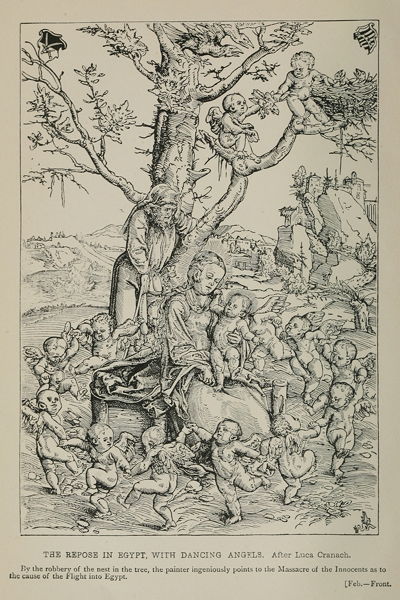

THE REPOSE IN EGYPT, WITH DANCING ANGELS. After Luca Cranach.

By the robbery of the nest in the tree, the painter ingeniously points to the Massacre of the Innocents as to the cause of the Flight into Egypt.

Feb.-Front.

Title: The Lives of the Saints, Volume 02 (of 16): February

Author: S. Baring-Gould

Release date: May 7, 2014 [eBook #45604]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Bergquist, Chris Pinfield and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber's Note:

Apparent typographical errors have been corrected. The use of hyphens is not always consistent.

Illustrations on separate plates have been incorporated in the text. Their locations, in the List of Illustrations, have been modified accordingly.

THE

Lives of the Saints

REV. S. BARING-GOULD

SIXTEEN VOLUMES

VOLUME THE SECOND

THE REPOSE IN EGYPT, WITH DANCING ANGELS. After Luca Cranach.

By the robbery of the nest in the tree, the painter ingeniously points to the Massacre of the Innocents as to the cause of the Flight into Egypt.

Feb.-Front.

BY THE

REV. S.

BARING-GOULD, M.A.

New Edition in 16 Volumes

Revised with Introduction and Additional Lives of

English Martyrs, Cornish and Welsh Saints,

and a full Index to the Entire Work

ILLUSTRATED BY OVER 400 ENGRAVINGS

VOLUME THE SECOND

February

LONDON

JOHN C. NIMMO

14 KING

WILLIAM STREET, STRAND

MDCCCXCVII

Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson & Co

At the Ballantyne Press

| A | ||

| PAGE | ||

| S. | Abraham | 298 |

| " | Adalbald | 41 |

| " | Adelheid | 140 |

| " | Adeloga | 42 |

| " | Æmilian | 212 |

| " | Agatha | 136 |

| " | Aldetrudis | 413 |

| " | Alexander | 433 |

| " | Alnoth | 448 |

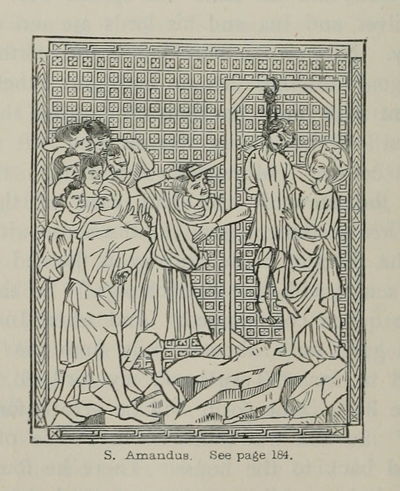

| " | Amandus | 182 |

| SS. | Ananias and comp. | 412 |

| S. | Andrew Corsini | 105 |

| " | Angilbert | 337 |

| " | Ansbert | 246 |

| " | Anskar | 56 |

| " | Apollonia | 231 |

| " | Aristion | 366 |

| " | Athracta | 236 |

| " | Augulus | 190 |

| " | Auxentius | 299 |

| " | Auxibius | 339 |

| " | Aventine of Chateaudun | 86 |

| " | Aventine of Troyes | 84 |

| " | Avitus | 138 |

| B | ||

| S. | Baldomer | 447 |

| " | Baradatus | 368 |

| " | Barbatus | 342 |

| " | Belina | 344 |

| " | Benedict of Aniane | 284 |

| " | Berach | 307 |

| " | Berlinda | 50 |

| " | Bertulf | 139 |

| " | Besas | 442 |

| " | Blaise | 47 |

| " | Boniface, Lausanne | 343 |

| " | Bridget | 14 |

| " | Bruno | 304 |

| C | ||

| S. | Cæsarius | 412 |

| " | Castor | 289 |

| " | Catharine de Ricci | 295 |

| " | Ceadmon | 272 |

| " | Celerina | 46 |

| SS. | Celerinus and comp. | 46 |

| " | Charalampius and comp. | 248 |

| S. | Chronion | 442 |

| " | Chrysolius | 189 |

| " | Clara of Rimini | 256 |

| SS. | Claudius and comp. | 329 |

| " | Constantia and comp. | 330 |

| S. | Cornelius of Rome. | 314 |

| " | Cornelius the Cent. | 38 |

| " | Cuthman | 220 |

| D | ||

| S. | Damian | 376 |

| " | Darlugdach | 22 |

| SS. | Dionysius and others | 212 |

| S. | Dionysius (Augsburg) | 432 |

| " | Dorothy | 176 |

| " | Dositheus | 378 |

| E | ||

| S. | Earcongotha | 382 |

| " | Eleutherius | 350 |

| " | Elfleda | 214 |

| SS. | Elias and others | 314 |

| S. | Ephraem, Syrian | 7 |

| " | Ermenilda | 292 |

| " | Ethelbert | 406 |

| " | Ethelwold | 283 |

| " | Eubulus | 449 |

| " | Eucher | 355 |

| " | Eulalia | 276 |

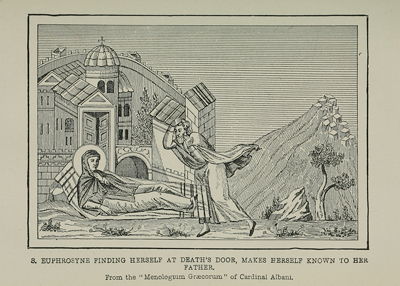

| " | Euphrosyne | 264 |

| " | Eusebius | 306 |

| F | ||

| SS. | Faustinus and Jovita | 305 |

| S. | Finan | 325 |

| " | Fintan | 324 |

| " | Flavian | 331 |

| " | Fortchern | 321 |

| " | Fortunatus | 47 |

| " | Fulcran | 294 |

| SS. | Fusca and Maura | 286 |

| G | ||

| S. | Gabinius | 340 |

| " | Gelasius, Boy | 83 |

| " | Gelasius, Actor at Heliopolis | 443 |

| " | George of Amastris | 363 |

| " | Georgia | 306 |

| SS. | German and Randoald | 361 |

| S. | Gilbert | 99 |

| " | Gregory II. (Pope) | 293 |

| H | ||

| S. | Hadelin | 49 |

| " | Honestus | 313 |

| " | Honorina | 444 |

| " | Hrabanus Maurus | 91 |

| I | ||

| S. | Ignatius, Antioch | 1 |

| " | Ignatius, Africa | 46 |

| " | Ina | 186 |

| " | Indract and comp. | 140 |

| " | Isaias | 314 |

| " | Isidore | 84 |

| J | ||

| S. | Jeremias | 314 |

| " | Joan of Valois | 109 |

| " | John de Britto | 112 |

| " | John of the Grate | 26 |

| " | John of Matha | 226 |

| " | John William | 255 |

| " | Jonas the Gardener | 263 |

| " | Joseph of Leonissa | 111 |

| " | Jovita | 305 |

| " | Julian of Cæsarea | 320 |

| " | Julian in Africa | 395 |

| " | Julian, Alexandria | 442 |

| " | Juliana | 316 |

| " | Juventius | 211 |

| L | ||

| S. | Laurence, Cant. | 39 |

| " | Laurence, the Illuminator | 49 |

| " | Laurentinus | 46 |

| " | Lazarus, B. Milan | 264 |

| " | Lazarus, Constantinople | 386 |

| " | Leander | 445 |

| " | Licinius | 292 |

| " | Limnæus | 367 |

| SS. | Loman and Fortchern | 321 |

| S. | Lucius | 395 |

| M | ||

| SS. | Mael and others | 178 |

| S. | Mansuetus | 341 |

| " | Margaret of Cortona | 371 |

| " | Mariamne | 318 |

| " | Martha | 373 |

| " | Martian | 289 |

| Martyrs at Alexandria | 449 | |

| "in Arabia | 367 | |

| "of Japan | 141 | |

| "of Ebbecksdorf | 45 | |

| S. | Matthias, Ap. | 393 |

| " | Maura | 286 |

| SS. | Maurice and comp. | 358 |

| S. | Maximian | 369 |

| " | Maximus | 329 |

| " | Mary, B. V., Purification of | 34 |

| " | Melchu | 178 |

| " | Meldan | 193 |

| " | Meletius | 278 |

| " | Mengold | 220 |

| " | Milburgh | 382 |

| " | Mildred | 354 |

| " | Modan | 91 |

| " | Modomnoc | 291 |

| SS. | Montanus and comp. | 395 |

| " | Moses and others | 192 |

| S. | Moses of Syria | 376 |

| " | Mun | 178 |

| N | ||

| S. | Nestor | 430 |

| " | Nicephorus | 233 |

| " | Nicolas | 92 |

| " | Nithard | 56 |

| SS. | Nymphas and Eubulus | 449 |

| O | ||

| S. | Odran | 341 |

| " | Olcan | 349 |

| " | Onesimus | 312 |

| " | Oswald, York | 455 |

| P | ||

| S. | Papias | 366 |

| " | Parthenius | 191 |

| " | Paula | 348 |

| " | Paul of Verdun | 213 |

| " | Pepin | 360 |

| " | Peter Cambian | 45 |

| " | Peter Damiani | 387 |

| " | Peter's Chair at Antioch | 365 |

| SS. | Phileas and others | 80 |

| S. | Photinus | 358 |

| SS. | Pionius and comp. | 5 |

| S. | Polychronius, B. M. | 319 |

| " | Polychronius, H. | 376 |

| " | Polyeuctus | 287 |

| " | Porphyrius | 434 |

| " | Prætextatus | 402 |

| " | Priamianus | 376 |

| " | Proterius | 451 |

| Purification of B. V. Mary | 34 | |

| R | ||

| S. | Randoald | 361 |

| " | Raymond of Fitero | 29 |

| " | Rembert | 98 |

| " | Richard | 194 |

| " | Rioch | 178 |

| " | Robert of Arbrissel | 426 |

| " | Romanus | 452 |

| " | Romuald | 194 |

| S | ||

| S. | Sabine | 241 |

| " | Saturninus | 259 |

| " | Scholastica | 250 |

| " | Sebastian | 212 |

| " | Serenus | 374 |

| " | Sergius | 402 |

| " | Severus (Avranches) | 23 |

| " | Severus (Ravenna) | 12 |

| " | Severus (Valeria) | 306 |

| " | Sigebert | 24 |

| " | Sigfried | 310 |

| " | Simeon | 328 |

| " | Soteris | 248 |

| " | Stephen of Grandmont | 224 |

| " | Sura | 252 |

| " | Susanna | 246 |

| " | Symphorian | 451 |

| T | ||

| S. | Tanco | 317 |

| " | Taraghta | 236 |

| " | Tarasius | 416 |

| " | Teilo | 238 |

| SS. | Thalassius and Limnæus | 367 |

| S. | Thalelæus | 444 |

| " | Theodora, Empress | 275 |

| " | Theodore of Apamea | 358 |

| " | Theodore of Heraclea | 190 |

| SS. | Theodulus and Julian | 320 |

| S. | Theophilus, Penitent | 88 |

| " | Tresan | 192 |

| SS. | Tyrannio and comp. | 346 |

| V | ||

| S. | Valentine | 296 |

| " | Vedast | 179 |

| " | Verdiana | 31 |

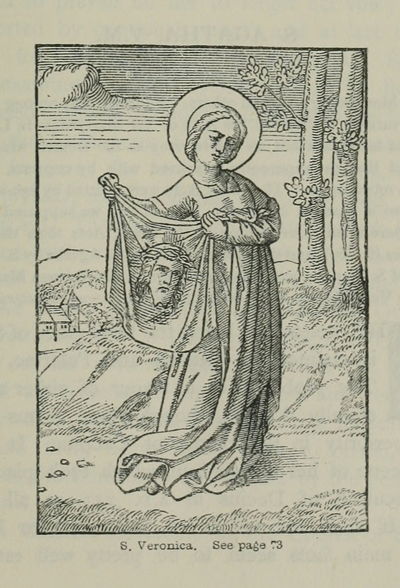

| " | Veronica | 73 |

| " | Victor | 410 |

| SS. | Victor and Susanna | 246 |

| " | Victorinus and comp. in Egypt | 410 |

| S. | Vitalina | 359 |

| W | ||

| S. | Walburga | 414 |

| " | Walfrid | 309 |

| " | Werburga | 52 |

| " | William of Maleval | 253 |

| " | Wulfric | 356 |

| Z | ||

| S. | Zabdas | 341 |

| " | Zacharias (Jerusalem) | 359 |

| SS. | Zebinus and others | 376 |

| S. | Zeno | 249 |

| The Repose in Egypt, with Dancing Angels | Frontispiece |

| After Luca Cranach. | |

| PAGE | |

| Martyrdom of S. Ignatius | 3 |

| From the "Menologium Græcorum." | |

| S. Ephraem | 9 |

| After Cahier. | |

| S. Bridget | 17 |

| After Cahier. | |

| Tomb of Joshua | 33 |

| The Greek Menology. | |

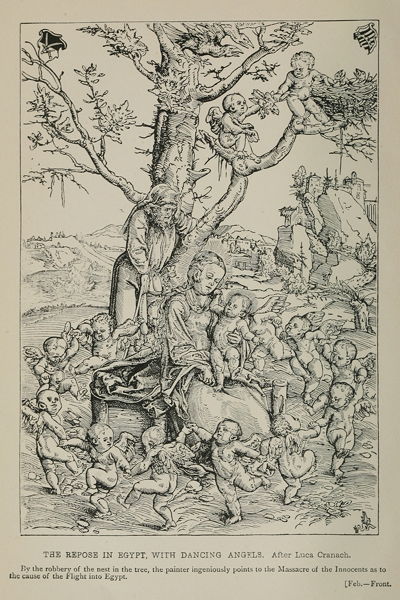

| Purification of S. Mary the Virgin | 35 |

| From the Great Vienna Missal. | |

| The Flight into Egypt | 37 |

| After Fra Angelico. | |

| S. Blaise | 49 |

| From Cahier. | |

| S. Werburga | 53 |

| From Cahier. | |

| S. Gilbert, Prior of Sempringham | 105 |

| From a Drawing by A. Welby Pugin. | |

| S. Veronica (see p. 73) | 135 |

| SS. Agnes, Cecilia, and Dorothy | 176 |

| After Angelica de Fiesole. | |

| S. Amandus (see p. 184) | 188 |

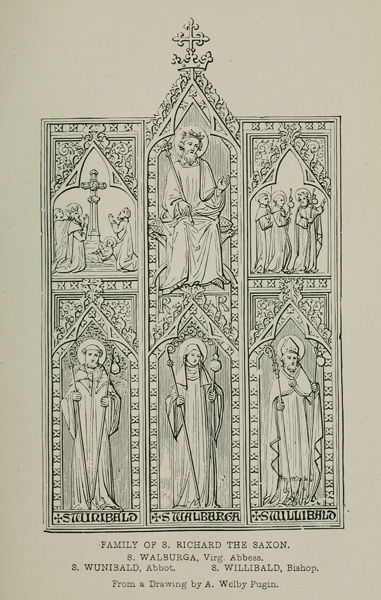

| S. Richard the Saxon and his Sons | 194 |

| From Cahier. | |

| Family of S. Richard the Saxon | 194 |

| From a Drawing by A. Welby Pugin. | |

| A Learned Doctor and Church Historian | 210 |

| An Enthusiastic Collector of Saintly Legends | 230 |

| S. Euphrosyne, finding herself at Death's Door, makes herself known to her Father |

271 |

| From the "Menologium Græcorum" of Cardinal Albani. | |

| The Papermaker | 285 |

| An Early Reliquary | 318 |

| S. Agatha (see p. 136) | 338 |

| The Printer | 357 |

| S. Margaret Cortona | 370 |

| From Cahier. | |

| The Bookbinder | 372 |

| S. Milburgh | 385 |

| After Cahier. | |

| Beheading of S. Matthias | 395 |

| From Cahier. | |

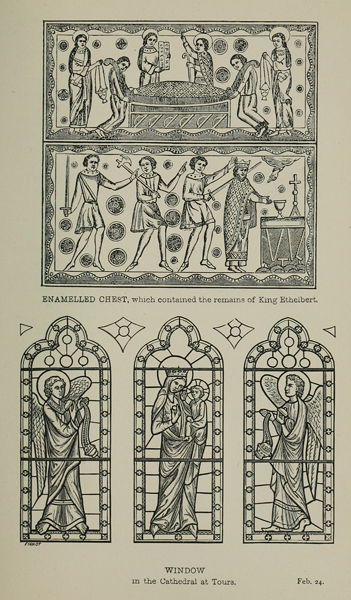

| Enamelled Chest which contained the Remains of King Ethelbert |

409 |

| Window in the Cathedral at Tours (Virgin with Angels) |

409 |

| S. Walburga | 415 |

| From Cahier. | |

[S. Ignatius is commemorated variously, on June 10th, Oct. 8th, Nov. 24th, Dec. 14th or 19th; but by the Roman Martyrology his festival is fixed for Feb. 1st. In the Bruges and Treves Martyrologies, his commemoration was placed on Jan. 31st, so as not to interfere with that of S. Bridget on this day. The authorities for his life and passion are his own genuine Epistles, the Acts of his martyrdom, Eusebius, and S. Chrysostom's Homily on S. Ignatius.]

SAINT IGNATIUS was a convert and disciple of S. John the Evangelist. He was appointed by S. Peter to succeed Evodius in the see of Antioch, and he continued in his bishopric full forty years. He received the name of Theophorus, or one who carries God with him. In his Acts, Trajan is said to have asked {2} him why he had the surname of God-bearing, and he answered, because he bore Christ in his heart.[1]

Socrates, in his "Ecclesiastical History," says, "We must make some allusion to the origin of the custom in the Church of singing hymns antiphonally. Ignatius, third bishop of Antioch in Syria from the apostle Peter, who also had conversed familiarly with the apostles themselves, saw a vision of angels, hymning in alternate chants the Holy Trinity; after which he introduced this mode of singing into the Antiochian Church, whence it was transmitted by tradition to all the other churches."[2]

It seems probable that Evodius vacated the see of Antioch about the year 70. There are traditions that represent Evodius to have been martyred; and Josephus speaks of a disturbance in Antioch about that period, which was the cause of many Jews being put to death.[3] There is a difficulty in supposing S. Peter to have appointed Ignatius bishop of Antioch, if he did not succeed Evodius till the year 70. But it is probable, that later writers have confounded the appointment of Ignatius to the see of Antioch, with his consecration to the episcopal office; and it is highly probable that he received this from the hands of the Prince of the Apostles.

The date of the martyrdom of Ignatius can be fixed with tolerable certainty as occurring in the year 107. The Acts expressly state that Trajan was then at Antioch, and that Sura and Senecio were consuls: two events, which will be found to meet only in the year 107.

Trajan made his entry into Antioch in January; his first concern was to examine into the state of religion there, and {3} the Christians were denounced to him as bringers-in of strange gods. Ignatius was brought before him, and boldly confessed Christ to be God. "Dost thou mean Him who was crucified?" asked the emperor, scornfully. Ignatius answered, "The very same, Who by His death overcame sin, and enabled those who bear Him in their hearts to trample under foot all the power of the devils."

Then Trajan ordered him to be taken to Rome, and exposed to wild beasts in the amphitheatre. It was generally a distinction reserved for Roman citizens, that if they had committed an offence in the provinces, they were sent for punishment to the capital. This, however, does not appear to have been the reason in the case of Ignatius. The punishment to which he was condemned was generally reserved for culprits of the lowest condition; and the Christians were perhaps viewed in this light by the heathen. Ecclesiastical history has scarcely preserved a more interesting and affecting narrative, than that of the journey of Ignatius from Antioch to Rome. In tracing the procession of the martyr to his final triumph, we forget that we are reading of a prisoner who was dragged to his death in chains. He was committed to a guard of ten soldiers, who appear to have treated him with severity; and, after taking ship at Seleucia, they landed for a time at Smyrna. He had here the gratification of meeting with Polycarp, who was bishop of that see, and who, like himself, had enjoyed a personal acquaintance with S. John. His arrival also excited a sensation through the whole of Asia Minor. Onesimus, bishop of Ephesus; Polybius, bishop of Tralles; and Demas, bishop of Magnesia, came from their respective cities, with a deputation of their clergy, to visit the venerable martyr. Ignatius took the opportunity of writing from Smyrna to the Churches over which these bishops presided; and his epistles to the Ephesians, Trallians, and Magnesians, are still extant. {4} Hearing also of some Ephesians, who were going to Rome, and who were likely to arrive there more expeditiously than himself, he addressed a letter to the Church in that city. His principal object in writing was to prevent any attempt which the Roman Christians might have made to procure a reprieve from the death which was awaiting him. He expresses himself not only willing, but anxious, to meet the wild beasts in the amphitheatre; and there never, perhaps, was a more perfect pattern of resignation than that which we find in this letter.

From Smyrna he proceeded to Troas, where he was met by some of the neighbouring bishops, and the bishop of Philadelphia became the bearer of a letter which he wrote to the Christians in that city. He also wrote from the same place to the Church of Smyrna; and the personal regard which he had for Polycarp, the bishop of that see, will explain why he also wrote to him, and made it his dying request that he would attend to the Church of Antioch. These seven epistles, which were written by Ignatius from Smyrna and Troas, are still extant.

It appears that Ignatius had intended to write letters to some other Churches, from Troas; but his guards were impatient to proceed, and once more setting sail, they followed the course which S. Paul had taken upon his first journey into Greece, and landed at Neapolis. Hurrying through Macedonia, he embarked once more on the western coast of Epirus, and crossing the Adriatic, arrived at Rome. There was now an exhibition of games, which lasted some days; and it seems to have been intended that the death of Ignatius should form part of the spectacle. The voyage had been hurried on this account; and on the last day of the games, which was the 19th December, the holy martyr was led into the amphitheatre, and his death seems to have been the work of a moment. In his letter to the Roman Church, he had {5} prayed that the wild beasts might despatch him speedily, and not refuse to touch him, as had sometimes been the case. His prayer was heard; and the Christians of Rome, who had thought themselves blessed to have even seen the apostolic bishop of Antioch among them, had now to pick up a few of the larger and harder bones, which was all that the wild beasts had spared. These were carried to Antioch, and it is evidence of the great reverence at that early age shown to the relics of the saints, that the same honours were paid to the sacred relics as had been paid to the holy martyr himself, when he touched at the different cities. The friends of Ignatius speak of his remains as "an invaluable treasure;" and as such they were deposited near one of the gates in the suburbs of Antioch.

The relics of S. Ignatius were retranslated to Rome, and are dispersed among several of the churches of the city. The head, however, is in the possession of the Jesuits of Prague.

[Roman and many ancient Martyrologies on this day. The Greeks on March 11th; the Martyrology attributed to S. Jerome, on March 12th. Authorities:—The genuine Acts of these martyrs, and the brief account in Eusebius, lib. iv. c. 15.]

In the persecution of Decius, S. Pionius, a priest of Smyrna, was apprehended; together with Sabina, Macedonia, Asclepiades, and Linus a priest, whilst they were celebrating the festival of S. Polycarp, on February 23. Pionius having fasted on the vigil, was forewarned of his coming passion in a vision. On the morning, which was the Sabbath, or Saturday, they took holy bread (the Eulogies) and water, and {6} were then surprised and taken by Polemon, the chief priest of the idol temple in Smyrna, and his satellites. Polemon in vain urged them to conform to the imperial edicts, and sacrifice to the gods; but they set their faces as flint against his solicitations, and were led into the forum, where Pionius took the opportunity of haranguing the crowds who hurried up to be present at their trial.

The Smyrnian Church was then suffering the shame of having seen its bishop, Eudæmon, apostatize, and his example had been followed by many timorous Christians.

The interrogatory was conducted by Polemon, and is dryly recorded by the notary who wrote the acts:—The Idol priest said, "Pionius! sacrifice." But he answered, "I am a Christian." "Whom," said Polemon, "dost thou worship?" "The Almighty God," answered Pionius, "who made heaven and earth, and all things in heaven and earth, and us men; who giveth to all men liberally, as they need; whom we know through His Word, Christ." Polemon said, "Sacrifice then, only to the Emperor." Pionius said, "I cannot sacrifice to any man. I am a Christian."

Then—the notary writing all down—Polemon asked, "What is thy name?" He answered, "Pionius." Polemon said, "Thou art a Christian?" He answered, "Certainly I am." "To what Church dost thou belong?" asked Polemon. "I belong to the Catholic Church," answered Pionius. "There is none other with Christ."

Then he went to Sabina, and put to her the same questions, which she answered almost in the same words. Next he turned to Asclepiades, and asked, "What is thy name?" "Asclepiades." "Art thou a Christian?" "I am." Then said Polemon, "Whom dost thou worship?" Asclepiades answered, "I worship Jesus Christ." "What!" asked Polemon, "Is that another God?" "No," answered Asclepiades, "He is the same God of whom the others spake."

{7} After this the martyrs were taken to prison, followed by a crowd jeering and insulting them. On the morrow they were led forth again to trial, and the idol priest endeavoured to force them to enter the temple, and by violence to compel them to sacrifice. Pionius tore from his head the sacrificial garlands that the priest had placed upon him. Polemon, unable to bend the holy martyrs to submission, delivered them over to Quintilian, the pro-consul, on his arrival at Smyrna, and he sentenced Pionius to be hung on a rack, and his body to be torn with hooks of iron, and afterwards to be nailed to a post, and burnt alive. Metrodorus, a Marcionite priest, underwent the same punishment with him.

[Roman and all Latin Martyrologies, except that of Bede, which gives July 9th. Commemorated by the Greeks on Jan. 28th. His death took place in summer or autumn. Authorities:—His own narration to his monks of his conversion, his confession and testament; also the oration upon him by S. Gregory Nyssen; an account of him in the Life of S. Basil, attributed to S. Amphilochius, Sozomen, etc.]

Saint Ephraem was the son of poor parents of Nisibis, who had confessed Christ before the persecutors, under Diocletian or his successors. In his narrative of his conversion, S. Ephraem laments some of the faults of his youth. "When I was a boy," says he, "I was rather wild. One day my parents sent me out of the town, and I found a cow that was in calf feeding in the road leading to the wood. This cow belonged to very poor people. I took up stones, and began pelting the cow, and driving it before me into the wood, and I drove the beast on till in the evening, it fell down {8} dead, and during the night wild beasts ate it. On my way back I met the poor man who owned it, and he asked me, 'My son, have you been driving away my cow?' Then I not only denied, but heaped abuse and insult upon him." Some few days after he was sent out of the town by his parents again, and he wandered in the wood, idling with some shepherds, till night fell. Then, as it was too late to return, he remained the night with the shepherds. That night the fold was broken into, and some of the sheep were carried off. Then the shepherds, thinking the boy had been in league with the robbers, dragged him before the magistrate, and he was cast into prison, where he found two men in chains, charged, one with homicide, the other with adultery, though they protested their innocence. In a dream an angel appeared to Ephraem, and asked him why he was there. The boy began at once to declare himself guiltless. "Yes," said the angel, "guiltless thou art of the crime imputed to you, but hast thou forgotten the poor man's cow? Listen to the conversation of the men who are with thee, and thou wilt learn that none suffer without cause."

In the morning, the two men began to speak, and one said, "The other day, as I was going over a bridge, I saw two fellows quarrelling, and one flung the other over into the water; and I did not put forth my hand to save him, as I might have done, and so he was drowned."

Presently the other man said, "I am not guilty of this adultery of which I am charged, but nevertheless I have done a very wicked thing. Two brothers and a sister were left an inheritance by their father, and the two young men wished to deprive their sister of what was her due, and they bribed me to give false evidence whereby the will was upset, and the property divided between them, to the exclusion of the poor girl."

After an imprisonment of forty days, Ephraem was {9} brought before the magistrate along with his fellow prisoners. He says, that when he saw the two men stripped, and stretched on the rack, "An awful terror came over me, and I trembled, thinking I was sure to be subjected to the same treatment as they. Therefore I cried, and shivered, and my heart altogether failed me. Then the people and the apparitors began to laugh at my tears and fright, and asked me what I was crying for? 'You ought to have considered this before, boy! but now tears are of no avail. You shall soon have a taste of the rack too, never doubt it.' Then, at these words, my soul melted clean away."

However, he was spared this time, and the innocence of his companions having been proved, they were set free. Ephraem was taken back to prison, where he spent forty more days; and whilst he was there, the two men who had defrauded their sister of her inheritance, and the man who had flung his adversary into the river, were caught and chained in the dungeon with him. These men and Ephraem were brought forth to trial together, and the men were sentenced, after they had been racked, and had confessed their crime, to lose their right hands. Ephraem, in another paroxysm of fear, made a vow that he would become a monk, if God would spare him the suffering of the rack. To his extreme terror the magistrate ordered him to be stripped, and the question to be applied. Then Ephraem stood naked and trembling beside the rack, when fortunately the servant came up to the magistrate to tell him that dinner was ready. "Very well," said the magistrate, "then I will examine this boy another day." And he ordered him back to prison. On his next appearance, the magistrate, thinking Ephraem had been punished enough, dismissed him, and he ran off instantly to the mountains, to an old hermit, and asked him to make of him a monk.[4]

{10} He was eighteen years old when he was baptized, and immediately after he had received the Sacrament of Regeneration, he began to discipline his body and soul with great severity. He lay on the bare ground, often fasted whole days, and spent a considerable part of the night in prayer. He exercised the handicraft of a sail-maker. He was naturally a very passionate man, but he learned so completely to subdue his temper, that the opposite virtue of meekness became conspicuous, so that he received the title of the "Peaceable man of God." Sozomen relates that once, after Ephraem had fasted several days, the brother, who was bringing him a mess of pottage, let the dish fall and broke it, and strewed the food upon the floor. The saint seeing his confusion, said cheerfully, "Never mind, if the supper won't come to me, I will go to the supper." Then, sitting down on the ground by the broken dish, he picked up the pottage as well as he could.

"He devoted his life to monastic philosophy," says Sozomen; "and although he had received no education, he became, contrary to all expectation, so proficient in the learning and language of the Syrians, that he comprehended with ease the most abstruse problems of philosophy. His style of writing was so full of glowing oratory and sublimity of thought, that he surpassed all the writers of Greece. The productions of Ephraem were translated into Greek during his life, and translations are even now being made, and yet they preserve much of their original force, so that his works are not less admired in Greek than in Syriac. Basil, who was subsequently bishop of the metropolis of Cappadocia, was a great admirer of Ephraem, and was astonished at his condition. The opinion of Basil, who was the most learned and eloquent man of his age, is a stronger testimony I {11} think, to the merit of Ephraem, than anything that could be indicted in his praise."[5]

S. Gregory Nyssen gives the following testimony to the eloquence of S. Ephraem: "Who that is proud would not become the humblest of men, reading his discourse on Humility? Who would not be inflamed with a divine fire, reading his treatise on Charity? Who would not wish to be chaste in heart and soul, by reading the praises he has lavished on Virginity? Who would not be frightened by hearing his discourse on the Last Judgment, wherein he has depicted it so vividly, that nothing can be added thereto? God gave him so profound a wisdom, that, though he had a wonderful facility of speech, yet he could not find expression for the multitude of thoughts which poured from his mind." At Edessa, S. Ephraem was ordained deacon; it has been asserted that he afterwards received the priesthood from the hands of S. Basil, but this is contradicted by most ancient writers, who affirm that he died a deacon. He was elected bishop of one town, but hearing it, he comported himself so strangely, that the people and clergy, supposing him to have lost his mind, chose another in his place; and he maintained the same appearance of derangement till the other candidate was consecrated. The city of Edessa having been severely visited by famine, he quitted the solitary cell in which he dwelt, and entering the city, rebuked the rich for permitting the poor to die around them, instead of imparting to them of their superfluities; and he represented to them that the wealth which they were treasuring up so carefully would turn to their own condemnation, and to the ruin of their souls, which were of more value than all the wealth of earth. The rich men replied, "We are not intent on hoarding our wealth, but we know of no one whom we may trust to {12} distribute our goods with equity." "Then," said Ephraem, "entrust me with that office."

As soon as he had received their money, he fitted up three hundred beds in the public galleries, and there tended those who were suffering from the effects of the famine. On the cessation of the scarcity, he returned to his cell; and after the lapse of a few days expired.

S. Ephraem was a valiant champion of the orthodox faith. Finding that the Syrians were fond of singing the heretical hymns of Bardasanes, he composed a great number of orthodox poems which he set to the same tunes, and by introducing these, gradually displaced those which were obnoxious. One instance of his zeal against heresy is curious, though hardly to be commended. The heretic Apollinarius had composed two reference books of quotations from Scripture, and arguments he intended to use in favour of his doctrines, at a public conference with a Catholic, and these books he lent to a lady. Ephraem borrowed the books, and glued the pages together, and then returned them. Apollinarius, nothing doubting, took his volumes to the discussion, but when he tried to use them, found the pages fast, and retired from the conference in confusion.

[S. Severus, B. M., of Ravenna, is commemorated on Jan. 1; S. Severus, B. C., of Ravenna, on Feb. 1st. Authorities:—Three ancient lives, with which agree the accounts in the Martyrologies.]

S. Severus was a poor weaver in Ravenna. Upon the see becoming vacant, the cathedral was filled with electors to choose a new bishop. Severus said to his wife Vincentia, "I will visit the minster and see what is going on." "You {13} had much better remain at home, and not show yourself in your working clothes among the nobles and well-dressed citizens," said she. "Wife! what harm is there in my going?" "You have work to do here, for your daughter and me, instead of gadding about, sight seeing." And when Severus persisted in desiring to go, "Very well," said Vincentia, "go, and may you come back with a good box on your ear." And when she saw that he was bent on going, she said, mocking, "Go then, and get elected bishop."

So he went, and entering the cathedral, stood behind the doors, as he was ashamed of his common dress covered with flocks of wool. Then when the Holy Spirit had been invoked to direct the choice of the people, suddenly there appeared in the cathedral a beautiful white dove, fluttering at the ear of the poor spinner. And he beat it off, but the bird returned, and rested on his head. Then the people regarded this as a heavenly sign, and he was unanimously chosen to be their bishop. Now Vincentia was at home, and one came running, and told her that her husband was elected bishop of Ravenna. Then she laughed, and would not believe it, but when the news was repeated, she said, "This is likely enough, that a man who tosses a shuttle should make a suitable prelate!" But when she was convinced, by the story being confirmed by other witnesses, her amazement rendered her speechless.

After his consecration, Severus lived with her as with a sister, till she died, and was followed shortly after by her daughter, Innocentia. Then he laid them both in a tomb, in the church, which had been prepared for himself. And after many years he knew that he was to die. So he sang High Mass before all the people, and when the service was over, he bade all the congregation depart, save only one server. And when they were gone, he bade the boy close the doors of the cathedral. Then the bishop went, vested {14} in his pontifical robes, to the sepulchre of his wife and daughter, and he and the boy raised the stone, and Severus stood, and looking towards the bodies of his wife and daughter, he said, "My dear ones, with whom I lived in love so long, make room for me, for this is my grave, and in death we shall not be divided." Having said this, he descended into the grave, and laid himself down between his wife and daughter, and crossed his hands on his breast, and looked up to heaven and prayed, and then closing his eyes, gave one sigh, and fell asleep. The relics were translated to Mayence, in 836, and Oct. 22nd is observed as the feast of this translation. In art, Severus is represented as a bishop with a shuttle at his side.

[S. Bridget, or Bride as she is called in England, is the Patroness of Ireland, and was famous throughout northern Europe. Leslie says, "She is held in so great honour by Picts, Britons, Angles, and Irish, that more churches are dedicated to God in her memory, than to any other of the saints;" and Hector Boece says, that she was regarded by Scots, Picts, and Irish as only second to the B. Virgin Mary. Unfortunately, little authentic is known of her. The lives extant are for the most part of late composition, and are collected from oral traditions of various value. One life is attributed, however, to Bishop Ultan Mac Concubar, d. circ. 662; another, a metrical one, is by the monk Chilian, circ. 740; another by one Cogitosus, is of uncertain date; another is by Laurence, prior of Durham, d. 1154; and there is another, considered ancient, by an anonymous author.]

Ireland was, of old, called the Isle of Saints, because of the great number of holy ones of both sexes who flourished there in former ages; or, who, coming thence, propagated the faith amongst other nations. Of this great number of saints the three most eminent, and who have therefore been {15} honoured as the special patrons of the island, were S. Patrick their apostle, S. Columba, who converted the Picts, and S. Bridget, the virgin of Kildare, whose festival is marked in all the Martyrologies on the 1st day of February.

This holy virgin was born about the middle of the fifth century, in the village of Fochard, in the diocese of Armagh. Her father was a nobleman, called Dubtach, descended from Eschaid, the brother of King Constantine of the Hundred Battles, as he is surnamed by the Irish historians. The legend of her origin is as follows, but it is not to be relied upon, as it is not given by Ultan, Cogitosus, or Chilian of Inis-Keltra.[6] Dubtach had a young and beautiful slave-girl, whom he dearly loved, and she became pregnant by him, whereat his wife, in great jealousy and rage, gave him no peace till he had sold her to a bard, but Dubtach, though he sold the slave-girl, stipulated with the purchaser that the child should not go with the mother, but should be returned to him when he claimed it.

Now one day, the king and queen visited the bard to ask an augury as to the child they expected shortly, and to be advised as to the place where the queen should be confined. Then the bard said, "Happy is the child that is born neither in the house nor out of the house!" Now it fell out that Brotseach, the slave-girl, was shortly after returning to the house with a pitcher of fresh warm milk from the cow, when she was seized with labour, and sank down on the threshold, and was delivered neither in the house nor out of the house, and the pitcher of warm sweet milk, falling, was poured over the little child.

When Bridget grew up, her father reclaimed her, and treated her with the same tenderness that he showed to his legitimate children. She had a most compassionate heart, {16} and gave to every beggar what he asked, whether it were hers or not. This rather annoyed her father, who took her one day with him to the king's court, and leaving her outside, in the chariot, went within to the king, and asked his majesty to buy his daughter, as she was too expensive for him to keep, owing to her excessive charity. The king asked to see the girl, and they went together to the door. In the meantime, a beggar had approached Bridget, and unable to resist his importunities, she had given him the only thing she could find, her father's sword, which was a present that had been made him by the king. When Dubtach discovered this, he burst forth into angry abuse, and the king asked, "Why didst thou give away the royal sword, child?" "If beggars assailed me," answered Bridget calmly, "and asked for my king and my father, I would give them both away also." "Ah!" said the king, "I cannot buy a girl who holds us so cheap."

Her great beauty caused her to be sought in marriage by a young noble of the neighbourhood, but as she had already consecrated herself by vow to Jesus, the Spouse of virgins, she would not hear of this match. To rid herself of the importunity of her suitor, she prayed to God, that He would render her so deformed that no one might regard her. Her prayer was heard, and a distemper fell on one of her eyes, by which she lost that eye, and became so disagreeable to the sight, that no one thought of giving her any further molestation.[7] Thus she easily gained her father's consent that she should consecrate her virginity to God, and become a nun. She took with her three other virgins of that country, and bidding farewell to her friends, went in 469 to the holy bishop Maccail, then at Usny hill, Westmeath; who gave the sacred veil to her and her companions, and received {17} their profession of perpetual virginity. S. Bridget was then only fourteen years old, as some authors assert. The Almighty was pleased on this occasion to declare how acceptable this sacrifice was, by restoring to Bridget the use of her eye, and her former beauty, and, what is still more remarkable, and is particularly celebrated, as well in the Roman, as in other ancient Martyrologies, was, that when the holy virgin, bowing her head, kissed the dry wood of the feet of the altar, it immediately grew green, in token of her purity and sanctity. The story is told of her, that when she was a little child, playing at holy things, she got a smooth slab of stone which she tried to set up as a little altar; then a beautiful angel joined in her play, and made wooden legs to the altar, and bored four holes in the stone, into which the legs might be driven, so as to make it stand.

S. Bridget having consecrated herself to God, built a cell for her abode, under a goodly oak, thence called Kil-dare or the Cell of the Oak; and this foundation grew into a large community, for a great number of virgins resorted to her, attracted by her sanctity, and put themselves under her direction. And so great was the reputation of her virtues, and the place of her abode was so renowned and frequented on her account, that the many buildings erected in the neighbourhood during her lifetime formed a large town, which was soon made the seat of a bishop, and in process of time, the metropolitan see of the whole province.

What the rule embraced by S. Bridget was, is not known, but it appears from her history, that the habit which she received at her profession from S. Maccail was white. Afterwards, she herself gave a rule to her nuns; so that she is justly numbered among the founders of religious Orders. This rule was followed for a long time by the greatest part of the monasteries of sacred virgins in Ireland; all acknowledging our Saint as their mother and mistress, and {18} the monastery of Kildare as the headquarters of their Order. Moreover, Cogitosus informs us, in his prologue to her life, that not only did she rule nuns, but also a large community of men, who lived in a separate monastery. This obliged the Saint to call to her aid out of his solitude, the holy bishop S. Conlaeth, to be the director and father to her monks; and at the same time to be the bishop of the city. The church of Kildare, to suit the requirements of the double monastery and the laity, was divided by partitions into three parts, Cogitosus says, one for the monks, one for the nuns, and the third for the lay people.

As S. Bridget was obliged to go long journeys, the bishop ordained her coachman priest, and the story is told that one day as she and a favourite nun sat in the chariot, the coachman preached to them the Word of God, turning his head over his shoulder. Then said the abbess, "Turn round, that we may hear better, and throw down the reins." So he cast the reins over the front of the chariot, and addressed his discourse to them with his back to the horses. Then one of the horses slipped its neck from the yoke, and ran free; and so engrossed were Bridget and her companion in the sermon of the priestly charioteer, that they did not observe that the horse was loose, and the carriage running all on one side. On another occasion she was being driven over a common near the Liffey, when they came to a long hedge, for a man had enclosed a portion of the common. Then the man shouted to them to go round, and Bridget bade her charioteer so do. But he, thinking that they had a right of way across the newly made field, drove straight at the hedge; then the proprietor of the field ran forward, and the horses started, and the jolt of the chariot threw S. Bridget and the coachman out of the vehicle, and severely bruised them both. Then the abbess, picking herself up said, "Better to have gone round; short cuts bring broken bones."

{19} Once a family came to Kildare, leaving their house and cattle unguarded, that they might attend a festival in the church, and receive advice from S. Bridget. Whilst they were absent, some thieves stole their cows, and drove them away.

They had to pass the Liffey, which was much swollen, consequently the thieves stripped, and tied their clothes to the horns of the cattle, intending to drive the cows into the river, and swim after them. But the cows ran away, carrying off with them the clothes of the robbers attached to their horns, and they did not stop till they reached the gates of the convent of S. Bridget, the nude thieves racing after them. The holy abbess restored to them their garments, and severely reprimanded them for their attempted robbery.

Other strange miracles are attributed to her, of which it is impossible to relate a tithe. She is said, after a shower of rain, to have come hastily into a chamber, and cast her wet cloak over a sunbeam, mistaking it, in her hurry, for a beam of wood. And the cloak remained there, and the ray of sun did not move, till late at night one of her maidens ran to her, to tell her that the sunbeam waited its release, so she hasted, and removed her cloak, and the ray retired after the long departed sun.

Once a rustic, seeing a wolf run about in proximity to the palace, killed it; not knowing that it was the tame creature of the king; and he brought the dead beast to the king, expecting a reward. Then the prince in anger ordered the man to be cast into prison and executed. Now when Bridget heard this, her spirit was stirred within her, and mounting her chariot, she drove to the court, to intercede for the life of the poor countryman. And on the way, there came a wolf over the bog racing towards her, and it leaped into the chariot, and allowed her to caress it. {20} Then, when she reached the palace, she went before the king, with the wolf at her side, and said, "Sire! I have brought thee a better wolf than that thou hast lost, spare therefore the life of the poor man who unwittingly slew thy beast." Then the king accepted her present with great joy, and ordered the prisoner to be released.

One evening she sat with sister Dara, a holy nun, who was blind, as the sun went down; and they talked of the love of Jesus Christ, and the joys of Paradise. Now their hearts were so full, that the night fled away whilst they spoke together, and neither knew that so many hours had sped. Then the sun came up from behind Wicklow mountains, and the pure white light made the face of earth bright and gay. Then Bridget sighed, when she saw how lovely were earth and sky, and knew that Dara's eyes were closed to all this beauty. So she bowed her head and prayed, and extended her hand and signed the dark orbs of the gentle sister. Then the darkness passed away from them, and Dara saw the golden ball in the east, and all the trees and flowers glittering with dew in the morning light. She looked a little while, and then, turning to the abbess, said, "Close my eyes again, dear mother, for when the world is so visible to the eyes, God is seen less clearly to the soul." So Bridget prayed once more, and Dara's eyes grew dark again.

A madman, who troubled all the neighbourhood, came one day across the path of the holy abbess. Bridget arrested him, and said, "Preach to me the Word of God, and go thy way." Then he stood still and said, "O Bridget, I obey thee. Love God, and all will love thee. Honour God, and all will honour thee. Fear God, and all will fear thee." Then with a howl he ran away. Was there ever a better sermon preached in fewer words.

A very remarkable prophesy of the heresies and false {21} doctrines of later years must not be omitted. One day Bridget fell asleep whilst a sermon was being preached by S. Patrick, and when the sermon was over, she awoke. Then the preacher asked her, "O Bridget, why didst thou sleep, when the Word of Christ was spoken?" She fell on her knees and asked pardon, saying, "Spare me, spare me, my father, for I have had a dream." Then said Patrick, "Relate thy vision to me." And Bridget said, "Thy hand-maiden saw, and behold the land was ploughed far and wide, and sowers went forth in white raiment, and sowed good seed. And it sprang up a white and goodly harvest. Then came other ploughers in black, and sowers in black, and they hacked, and tore up, and destroyed that beauteous harvest, and strewed tares far and wide. And after that, I looked, and behold, the island was full of sheep and swine, and dogs and wolves, striving with one another and rending one another." Then said S. Patrick, "Alas, my daughter! in the latter days will come false teachers having false doctrine; who shall lead away many, and the good harvest which has sprung up from the Gospel seed we have sown will be trodden under foot; and there shall be controversies in the faith between the faithful and the bringers-in of strange doctrine."

Now when the time of her departure drew nigh, Bridget called to her a dear pupil, named Darlugdach and foretold the day on which she should die. Then Darlugdach wept bitterly, and besought her mother to suffer her to die with her. But the blessed Bridget said, "Nay, my daughter, thou shalt live a whole year after my departure; and then shalt thou follow me." And so it came to pass. Having received the sacred viaticum from the hands of S. Nennidh, the bishop, the holy abbess exchanged her mortal life for a happy immortality, on February 1st, 525.[8] Her body was {22} interred in the church of Kildare; where her nuns for some ages, to honour her memory, kept a fire always burning; from which that convent was called the House of Fire, till Henry of London, Archbishop of Dublin, to take away all occasion of superstition, in 1220, ordered it to be extinguished.

The body of the Saint was afterwards translated to Down-Patrick, where it was found in a triple vault, together with the bodies of S. Patrick and S. Columba, in the year 1185. These bodies were, with great solemnity, translated the following year by the Pope's legate, accompanied by fifteen bishops, in presence of an immense number of the clergy, nobility, and people, to a more honourable place of the cathedral of Down; where they were kept, with due honour, till the time of Henry VIII., when the monument was destroyed by Leonard, Lord Grey, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. S. Bridget's head was saved by some of the clergy, who carried it to Neustadt, in Austria; and from thence, in 1587, it was taken to the church of the Jesuits at Lisbon, to whom the Emperor Rudolf II. gave it.

In art, S. Bridget is usually represented with her perpetual flame as a symbol; sometimes with a column of fire, said to have been seen above her head when she took the veil.

[Authorities:—The lives of S. Bridget.]

Amongst the nuns of S. Bridget's monastery of Kildare, there was one named Darlugdach. When young, she followed S. Bridget, and being very dear to her, slept with the abbess.

Darlugdach, not guarding her eyes with sufficient strictness, {23} saw, and fell in love with a man, who also became enamoured of her, and their ardent glances revealed their mutual passion. A plan was formed that she should elope with him, on a certain night; and she laid herself in the bosom of the sleeping abbess with beating heart, troubled by a conflict between duty and passion. At last she rose, and in an agony of uncertainty, cast herself on her knees, and besought God to give her strength to master her love, and then, in the vehemence of her resolve, she thrust her naked feet into the red coals that glowed on the hearth, and held them there till the pain had conquered the passion. After that, she softly stole into bed again, and crept into the bosom of her holy mother. When morning broke, Bridget rose, and looked at the blistered and scorched soles, and touching them, said gently, "I slept not, dear child, but was awake, and saw thy struggle, and now, because thou hast fought valiantly, and hast conquered, the flame of lust shall no more hurt thee." And she healed her feet.

Darlugdach, as has been related in the life of S. Bridget, besought her spiritual mother to let her die with her, but S. Bridget promised that she should follow on the anniversary of her departure, after the expiration of a year. And so it was.

[French Martyrologies. Authority:—A life by an anonymous author of uncertain date, but apparently trustworthy.]

S. Severus was the child of very poor Christian parents, who hired him to a nobleman named Corbecan, a heathen, who employed him in tending his herd of mares. The boy loved to pasture the horses in the neighbourhood of a little {24} church dedicated to S. Martin, on the excuse that the herbage there was richer than elsewhere, but really out of love for the House of God. Unable to bear the sight of the misery of the poor, during a cold winter, the boy gave them the clothes off his back, and returned one day through the snow to his master's castle, stripped of everything save his breeches. Corbecan, in a rage, drove him out of the house, and forbade him to shelter in it that night. The lad went to the horses, and crouched among them, taking warmth from their breath. His gentleness and piety, in the end, produced such an impression on Corbecan, that he placed himself under instruction in the faith, and was baptized, he and his whole house. Severus afterwards retired into a solitary place, and lived as an hermit, till a number of disciples gathering round him, he was ordained priest. Against his will he was dragged from his beloved retreat to be consecrated bishop of Avranches. He ruled that see for several years with great zeal and discretion, till the burden became intolerable, and he besought the people to elect a successor. Then he laid down his staff, and retired once more to his forest cell, where he became the master of the blessed Giles. The day of his death is uncertain. His body was translated to the cathedral of Rouen.

In art he is represented with the mares of his master.

[French Martyrology. Authorities:—His life by Sigebert of Gemblours, d. 1112, and mention by Gregory of Tours, and Flodoard.]

This royal saint was the son of Dagobert I., King of France. The father for a long time refused to have his son baptized, but at length by the advice of S. Ouen and {25} S. Eligius, then laymen in his court, he recalled S. Amand, bishop of Maestricht, whom he had banished for reproving his vices, and bade him baptize his son Sigebert. The young prince's education was entrusted to Pepin, mayor of the palace, who carried his charge into Aquitain, to his estates. But at the age of three, Sigebert was invested by his father with the kingdom of Austrasia, or Eastern France, including Provence, Switzerland, Bavaria, Swabia, Thuringia, Franconia, the Rhenish Palatinate, Alsace, Trèves, Lorraine, Champagne, Upper Picardy, and Auvergne.

Dagobert died in 638, and was succeeded by Clovis II., in the kingdom of Western France. Pepin of Landen, was mayor of the palace to Sigebert, and strove to train the young king in godliness and Christian virtues. By his justice and temperance, S. Sigebert rendered himself in his youth greatly beloved and respected by his subjects.

Pepin dying in 640, the king appointed Grimoald, mayor of the palace, in his father's room. The Thuringians revolting, Sigebert reduced them to their duty; and this is the only war in which he was engaged. His munificence in founding churches and monasteries, his justice in ruling, and the private virtues of his spotless life, made him to be regarded as a model of a saintly king. After a reign of eighteen years from the date of his father's death, he died at the age of twenty-five, and was buried in the abbey of S. Martin, near Metz, which he had built. His body was found incorrupt in 1063, and in 1170 it was enshrined in a silver case. When Charles V. laid siege to Metz, Francis of Lorraine, Duke of Guise, demolished all the monasteries and other buildings in the suburbs which could give harbour to the enemy, amongst others that of S. Martin. The relics of the saintly king were then removed to the collegiate church of Our Lady, at Nancy, where they repose in a magnificent shrine.

[His festival is observed as a double by the Church of S. Malo, in Brittany. His name is inserted in Saussaye's supplement to the Gallican Martyrology. Authorities:—The letters of S. Bernard and Nicolas of Clairvaux.]

The illustrious prelate S. John, commonly called "Of the Grate," because of an iron grating which surrounded his sepulchre, was a Breton, the son of parents in a middle class of life. He was born about the year 1098; and from an early age gave indications of piety. In the schools to which he was sent, in a short time he made rapid progress. Peter, abbot of Celle, speaking of him, calls him "the holy bishop, faithful servant of God, a man of courage, loving poverty, a brilliant light, dissipating the densest darkness." His life, as a bishop, was spent in a series of lawsuits with the monks of Marmoutiers. His episcopal seat was at Aleth on the main land, but he desired to transfer it to the island of Aaron, now called S. Malo, on account of the peril to which Aleth was exposed through pirates, and the intestine wars which devastated Brittany. He claimed the island as belonging to the episcopal property of Aleth, but was opposed by the monks of Marmoutiers, who claimed the Church of S. Malo. The case was referred to the Pope, who ordered a commission of French bishops to try the case, and they decided against John. He considered that his cause had been prejudged by them, and visited Rome to carry his appeal in person to the Pope. But Lucius II. would not listen to him, and he was condemned to lose his see. He then retired under the protection of S. Bernard, to Clairvaux, till, on the decease of Lucius II., a monk of Clairvaux was elevated to the papal throne, under the title of Eugenius III. John {27} at once appealed again, and was heard; a fresh commission was appointed, and he was restored to all his rights, and the monks of Marmoutiers were obliged to cede the Church of S. Malo to the bishop. John obtained decisions conformable to that of Eugenius III., from his successors, Anastasius IV. and Adrian IV. That the claim of John was reasonable appears certain. Only three years before he made it, the inhabitants of Aleth had been obliged to take refuge in the island of Aaron to escape the ravages of the Normans, who had already twice pillaged and burnt the city; and it is certain that several of the predecessors of John of the Grate had borne the title of bishop of S. Malo, as well as of Aleth.

During his reign a strange heresy broke out. Eon de l'Etoile, a fanatic, took to himself the title of "Judge of the quick and dead," and armed with a forked stick, shared with God the empire of the universe. When he turned upwards the two prongs of his stick, he gave to the Almighty the government of two-thirds of the world, and when he turned the prongs downwards, he assumed them as his own. This poor visionary was followed by a number of peasants who pillaged churches, and committed all sorts of disorders. They were condemned, in 1148, by the Council of Rheims, and were reduced to submission by the temporal power. John exerted himself, by persuasion and instruction, to disabuse of their heresy such of the fanatics as over-ran his diocese, and succeeded in converting many of his wandering sheep.

He died in the odour of sanctity on Feb. 1st, 1163, and was buried on the Gospel side of the altar in the Church of S. Malo. His reputation for virtue was so well established, that almost immediately he received popular reverence as a Saint. Numerous miracles augmented the devotion of the people. In 1517, one of his successors, Denis Brigonnet, {28} ambassador of the king to Rome, obtained from Pope Leo X. permission for him to be commemorated in a solemn office, as a confessor bishop. This was the year in which began the schism of Luther.

On the 15th October, 1784, Mgr. Antoine-Joseph des Laurents, last bishop of S. Malo but one, examined the relics of the blessed one. He found the bones of S. John enveloped in his pontifical vestments, his pastoral staff at his side, and ring on his finger. During the Revolution the relics of the Saint were ordered to be cast into the sea, but the order was countermanded, and the sexton was required to bury them on the common fosse in the cemetery. The grave-digger, whose name was Jean Coquelin, being a good Catholic, disobeyed the order so far as to lay the bones apart in a portion of the new cemetery as yet occupied by no other bodies. In November, 1799, he announced the secret to M. Manet, a priest who had remained through the Reign of Terror, in S. Malo; and this venerable ecclesiastic assisted by another priest and some religious, verified the relics. A sealed box received the precious deposit, and it was restored to its ancient shrine on 7th March, 1823. Unfortunately the loss of a document which supplied one necessary link in the chain of evidence authenticating the relics was missing, consequently they could not be exposed to the veneration of the faithful. By a strange accident this document was recovered later; whereupon the bishop wrote to Rome to state the proofs which were now complete. The necessary sanction having been received, the sacred relics were enshrined on the 16th November, 1839, with great ceremony; and are now preserved in the Church of S. Malo.

In French, S. John is called S. Jean de la Grille; in Latin, S. Joannes de Craticula.

[Cistercian Breviary. Authority:—Radez, Chronic de las ordines y Cavall. de Santiago, Calatrava, y Alcantara.]

In the year a.d. 714, the Moors, having conquered King Roderick, took possession of Andalusia, and fortified the city of Oreto, to which they gave the name of Calatrava; of which they remained masters for nearly four hundred years, till Alfonso the Warlike took possession of it, in the year 1147, and gave it to the Templars, to guard against the irruption of the infidels. But they held it for only eight years. The forces which the Moors assembled to recover Calatrava so discouraged them, that they gave up the city into the hands of Don Sancho, who had succeeded to the kingdom of Castille, on the death of Alfonso, and withdrew from it. This prince announced to his court that if any nobleman would undertake the defence of the place, he should have and hold it, in perpetuity, as his own property. But no one offered; the host of the Moors which had so alarmed the Templars, caused equal dismay in the minds of the nobles at court. A monk of the order of Citeaux alone had courage to undertake the defence of the town. This was Don Didacus Velasquez, monk of the abbey of Our Lady of Fitero, in the kingdom of Navarre. He had borne arms before he assumed the white habit of Citeaux, and was well known to King Sancho, and this perhaps was the reason why his abbot, Don Raymond, had taken him with him on a visit to the king, about some matter concerning his monastery, at this very time. He entreated the abbot to allow him to ask permission of Sancho to undertake the defence of Calatrava. Raymond, at first, rejected the proposal, but at length, gained by the {30} zeal and confidence of Didacus, he boldly asked the city of the prince. He was regarded as mad, but Sancho was prevailed upon by the evident assurance of the two monks to give the town of Calatrava to the Cistercian Order, and especially to the abbey of Fitero, on condition that the monks held it against the infidels. This was in 1158.

The abbot Raymond and his companion Velasquez then proposed to the king to found a military Order of Calatrava, and after having obtained his consent, they communicated their design to the bishop of Toledo, who not only approved it, but gave them a large sum of money for the fortification of the town, and accorded indulgences to all such as should take arms in its defence, or contribute arms or money for the purpose. Several persons joined the two monks, and in a short while an army was raised, at the head of which they entered Calatrava, and took possession of it. The walls were repaired and completed with such expedition and strength, that the Moors abandoned their purpose of attacking it, and withdrew.

The abbot Raymond, having nothing further to fear from the infidels, applied himself to organise the new military Order, which took its name from this town. The general chapter of Citeaux prescribed the manner of life and habit of these warrior monks, but historians are not agreed as to the colour or shape of the original habit.

As the territory of Calatrava was almost devoid of inhabitants, the abbot Raymond returned to Fitero, where he left only the aged and infirm monks, bringing all who were active and young to Calatrava, together with a great number of cattle, and twenty thousand peasants, that he might settle them in the newly acquired territory. He governed the order six years, and died at Cirvelos, in the year 1163. After his death, the knights of Calatrava, although they were novices of Citeaux into whose hands he had put arms, {31} refused to be governed by an abbot, and to have monks among them. They elected as their Grand Master one of their number, Don Garcias; and the monks, who had chosen their new abbot, Don Rudolf, retired with him to Cirvelos, where they began an action against the knights, to eject them, that they might recover possession of Calatrava, which the king had given to their order, and especially to their house of Fitero. But a reconciliation was effected, probably through fear of the Moors, and the knights ceded to them a house at S. Petro de Gurniel, in the diocese of Osma, with all its dependencies, and there they built a monastery, leaving Calatrava in the hands of the knights.

In the year 1540, the knights were allowed to marry, and took only the vows of poverty, obedience, and conjugal fidelity; since the year 1652, they have added a fourth; to defend and maintain the Immaculate Conception of the blessed Virgin.

[Roman and Benedictine Martyrology, those of Menardus, Ferrarius, &c. Authority:—An old contemporary life, falsely attributed to Atto, B. of Pistoria.]

Verdiana was the child of poor, though well-born parents; and her knowledge of the sufferings of the poor from her own experience in early years made her ever full of pity for those in need. At twelve years old she was noted for her beautiful and modest countenance, and humble deportment. A wealthy relation, a count, took her into his house, and made her wait upon his wife. Her strict probity and scrupulous discharge of her duties so gained the confidence of her master and mistress, that they entrusted to her the entire management of their house. {32} One day that there was a famine raging in the diocese of Florence, and the poor were in extreme distress, the girl saw some miserable wretches dying from exhaustion at the door. Her master had a vessel of beans, and she hastily emptied the box, and fed the starving wretches with them. This would have been an act of questionable morality, were it not for the extremity of the case, when, to save life, an act is justified which would have been unjust were there no such an imperious necessity. Her master had, in the meantime, sold the beans, and he shortly after returned with the money. He went to the vessel, to send it to the purchaser, but found it empty. "Then," says the contemporary writer, "he began to shout and storm against the servants, and make such a to-do as to cause great scandal in the house and among the neighbours. Now when all the house was turned topsy-turvy about these beans, and was in an uproar, the lord's hand-maiden, with great confidence, betook herself to prayer, and spent the night in supplication. And on the morrow, the vessel was found full of beans as before. Then the master was called, and she bade him abstain for the future from such violence, for Christ who had received the beans had returned them."

By the kindness of the Count, her relative, she was enabled to make a pilgrimage to S. James, of Compostella, in company with a pious lady. On her return, she resolved to adopt the life of a recluse, and after long preparation, and a visit to Rome, where she spent three years, she obtained the desire of her heart, and received the veil from the hands of a canon of the Church of Castel Fiorentino, her native place, and bearing the Cross, preceded and followed by all the clergy and people, she was conducted to her cell, and, having been admitted into it, the door was walled up. In this cell she spent many years, conversing with those who visited her, and receiving her food through a window, {33} through which, also, the priest communicated her. Two large snakes crept in at this window, one day, and thenceforth took up their abode with her. She received these fellow-comrades with great repugnance, but overcame it, and fed them from her own store of provisions. They would glide forth when no one was near, but never failed to return for the night, and when she took her meals. On one occasion they were injured by some peasants who pursued them with sticks and stones. Verdiana healed them, nevertheless the rustics attacked them again, killed one, and drove the other away, so that it never returned to the cell of the recluse.

When the holy woman felt that the hour of her release approached, she made her last confession and received the Blessed Sacrament through her window, and then closing it opened her psalter, and began to recite the penitential psalms. Next morning the people finding the window closed, and receiving no answer to their taps, broke into the cell, and found her dead, kneeling with eyes and hands upraised to heaven, and the psalter before her open at the psalm Miserere mihi, "Have mercy upon me, O God! after Thy great goodness; and according to the multitude of Thy mercies, do away mine offences."

[1] Vincent of Beauvais, and other late writers, say that the name of God was found after his death written in gold letters on his heart; but this is only one instance of the way in which legends have been coined to explain titles, the spiritual significance of which was not considered sufficiently wondrous for the vulgar.

[2] Lib. vi. c. 8.

[3] De Bel. Jud. vii. 3.

[4] As S. Ephraem related the incident several times to his monks, and they wrote it down from what he had related, there exist several versions of the story slightly differing from one another.

[5] Hist. Eccl. lib. iii. c. 16.

[6] Moreover it contradicts the positive statements of more reliable authors, that Bridget was the legitimate daughter of Brotseach, the wife of Dubtach.

[7] But this legend is given very differently in another Life, and Cogitosus and the first and fourth Lives do not say anything about it.

[8] As near as can be ascertained; see Lanigan, Eccl. Hist. of Ireland, vol. 1, p. 455.

The Purification of S. Mary.

THE PURIFICATION is a double feast, partly in memory of the B. Virgin's purification, this being the fortieth day after the birth of her Son, which she observed according to the Law (Leviticus xii. 4), though there was no need for such a ceremony, she having contracted no defilement through her childbearing. Partly also in memory of Our Lord's presentation in the temple, which the Gospel for the day commemorates.

The Old Law commanded, that a woman having conceived by a man, if she brought forth a male child, should remain forty days retired in her house, as unclean; at the end of which she should go to the temple to be purified, and offer a lamb and a turtle dove; but, if she were poor, a pair of turtle doves or pigeons, desiring the priest to pray to God for her. This law the Blessed Virgin accomplished (Luke ii. 12) with the exercise of admirable virtues; especially did she exhibit her obedience, although she knew {35} that she was not obliged to keep the law, yet, inasmuch as her Son had consented to be circumcised, though He needed it not, so did she stoop to fulfil the law, lest she should offend others. She also exhibited her humility, in being willing to be treated as one unclean, and as one that stood in need of being purified, as if she had not been immaculate. Among the Greeks, the festival goes by the name of Hypapante, which denotes the meeting of our Lord by Symeon and Anna, in the temple; in commemoration of which occurrence it was first made a festival in the Church by the emperor Justinian I., a.d. 542. The emperor is said to have instituted it on occasion of an earthquake, which destroyed half the city of Pompeiopolis, and of other calamities. It was considered in the Greek Church as one of the feasts belonging to her Lord (Despotikaì Heortaì). The name of the Purification was given to it in the 9th century by the Roman pontiffs. In the Greek Church the prelude of this festival, which retains its first name, Hypapante, is "My soul doth magnify the Lord, for He hath regarded the lowliness of his hand-maiden;" and a festival of Symeon and Anna is observed on the following day.

In the Western Church it has usually been called "Candlemas Day," from the custom of lighting up churches with tapers and lamps in remembrance of our Saviour having been this day declared by Symeon to be "a light to lighten the Gentiles." Processions were used with a similar object, of which S. Bernard gives the following description:—"We go in procession, two by two, carrying candles in our hands, which are lighted not at a common fire, but a fire first blessed in the church by a bishop. They that go out first return last; and in the way we sing, 'Great is the glory of the Lord.' We go two by two in commendation of charity and a social life; for so our Saviour sent out his disciples. We carry light in our hands: first, to signify {36} that our light should shine before men; secondly, this we do on this day, especially, in memory of the Wise Virgins (of whom this blessed Virgin is the chief) that went to meet their Lord with their lamps lit and burning. And from this usage and the many lights set up in the church this day, it is called Candelaria, or Candlemas. Because our works should be all done in the holy fire of charity, therefore the candles are lit with holy fire. They that go out first return last, to teach humility, 'in humility preferring one another.' Because God loveth a cheerful giver, therefore we sing in the way. The procession itself is to teach us that we should not stand idle in the way of life, but proceed from virtue to virtue, not looking back to that which is behind, but reaching forward to that which is before."

The Purification is a common subject of representation in Christian art, both Eastern and Western. From the evident unsuitableness of the mystery of the Circumcision to actual representation, it is not usually depicted in works of art, and the Presentation in the Temple has been generally selected, with better taste, for this purpose. The prophecy of Symeon, "Yea, a sword shall pierce through Thine own soul also," made to the blessed Virgin, is the first of her seven sorrows.

The Christian rite of "The Churching of Women" is a perpetuation of the ancient ceremony required by the Mosaic Law. How long a particular office has been used in the Christian Church, for the thanksgiving and benediction of woman after child-birth, it would be difficult to say; but it is probably most ancient, since we find that all the Western rituals, and those of the patriarchate of Constantinople, contain such an office. The Greeks appoint three prayers for the mother on the first day of the child's birth. On the eighth day, the nurse brings the child to church, and prayer is made for him before the entrance to the nave. On the {37} fortieth day, the mother and the future sponsor at the child's baptism bring the child. After an introductory service of the usual kind, the mother, holding the child, bows her head; the priest crosses the child, and touching his head, says, "Let us pray unto the Lord; O Lord God Almighty, the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who didst create by Thy word all creatures, rational and irrational, who didst bring into being all things out of nothing; we beseech and entreat Thee, purify from all sin and pollution this Thy handmaid, whom by Thy will, Thou hast preserved and permitted to enter into Thy holy Church; that she may be deemed worthy to partake, without condemnation, of Thy holy mysteries." (If the child has not survived, the prayer ends here; if it be alive, the priest continues), "And bless the child born of her. Increase, sanctify, direct, teach, guide him; for Thou hast brought him to the birth and hast shown him the light of this world; that so he may be deemed worthy of the mental light at the time that Thou hast ordained, and be numbered among Thy holy flock: through Thy only begotten Son, with whom Thou art blessed, together with Thy all-holy, good, life-giving Spirit, now, always, and for ever and ever."

Other prayers referring to the mother of the child follow. Allusion is made to the presentation of Christ, in the Temple. The child is taken in the priest's arms to various parts of the church as an introduction to the sanctuary. A boy is taken to the altar; a girl only to the central door of the screen. There is a separate form in case of miscarriage.

[Roman and other Western Martyrologies. Commemorated by the Greeks on Sept. 13th. Authorities:—The Acts of the Holy Apostles, c. 10, the notices in the Martyrologies, and allusions in the Epistles of S. Jerome. The Acts given by Metaphrastes are not deserving of much attention.]

Cornelius, the centurion, was officer of the Italian band at Cæsarea. He was a devout proselyte, who feared God, with all his household, and gave much alms to the poor and prayed often and earnestly to God. He saw in a vision an angel, who told him that his prayers and alms had come up for a memorial before God, and that he was now to hear the words of Salvation, and to be instructed in the fulness of divine truth. He was to send to Joppa, to the house of one Simon, a tanner, for S. Peter, the prince of the Apostles, who would instruct and baptize him.

This he accordingly did, and S. Peter, hastening to Cæsarea, baptized him and all his house. And the Holy Ghost fell upon them.

Cornelius was afterwards, by S. Peter, ordained bishop of Cæsarea, where he strove mightily to advance the kingdom of Christ, and witnessed a good confession before the chief magistrate. He died at a ripe old age, and was buried secretly in a tomb belonging to a friend, a Christian of wealth. And, it is said, that a bramble grew over the spot and laced the entrance over with its thorny arms, so that none could enter in till S. Silvanus, bishop of Philippopolis, in Thrace, in the beginning of the 5th century, hacked away the bramble, and discovered, and translated the sacred relics.

[Roman and other Western Martyrologies. Authorities:—Bede, Hist. Eccl. lib. ii. c. 4, 6, 7. Malmesbury lib. de Gest. Pontif. Angl.]