Title: Reptiles and Birds

Author: Louis Figuier

Editor: Parker Gillmore

Illustrator: A. Mesnel

Alphonse Marie de Neuville

Edouard Riou

Release date: June 3, 2014 [eBook #45873]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Wayne Hammond and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

i ii

iv

REPTILES AND BIRDS.

A POPULAR ACCOUNT OF THEIR VARIOUS ORDERS,

WITH A DESCRIPTION OF

THE HABITS AND ECONOMY OF THE MOST INTERESTING.

By LOUIS FIGUIER,

AUTHOR OF "THE WORLD BEFORE THE DELUGE," "THE VEGETABLE WORLD,"

"THE INSECT WORLD," ETC. ETC.

ILLUSTRATED WITH 307 WOODCUTS.

BY MM. A. MESNEL, A. DE NEUVILLE, AND E. RIOU.

Edited and Adapted by

PARKER GILLMORE

("UBIQUE").

NEW YORK: D. APPLETON AND CO.

1870.

v

LONDON:

PRINTED BY VIRTUE AND CO.,

CITY ROAD.

vi

In presenting to the public this English version of Louis Figuier's interesting work on Reptiles and Birds, I beg to state that where alterations and additions have been made, my object has been that the style and matter should be suited to the present state of general knowledge, and that all classes should be able to obtain useful information and amusement from the pages which I have now the honour and pleasure of presenting to them.

On commencing my undertaking I was not aware of the immensity of the labour to be done, and fear that I must have relinquished my arduous task but for the kind encouragement of Frank Buckland, Esq., Inspector of Salmon Fisheries, and Henry Lee, Esq., F.L.S., F.G.S., &c., to both of whom I take this opportunity of returning my sincere thanks.

December, 1869. vii

CONTENTS. |

|

|---|---|

| REPTILES. | |

| PAGE | |

| Introductory Chapter | 1 |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| AMPHIBIA, OR BATRACHIANS. | |

| Structural Distinctions | 8 |

| Intelligence | 13 |

| Characteristics | 15 |

| Historical Antiquity | 18 |

| Distribution | 19 |

| Frogs | 19 |

| Habits of Life | 21 |

| Development of Young | 22 |

| Green | 23 |

| Common | 23 |

| Green Tree | 24 |

| Toads | 25 |

| Natterjack | 26 |

| Surinam | 28 |

| Land Salamander | 31 |

| Spotted | 32 |

| Black | 33 |

| Aquatic Salamanders | 33 |

| Crested | 34 |

| Gigantic | 34 |

| Transformations and Reproduction | 35 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| OPHIDIAN REPTILES, OR TRUE SNAKES. | |

| Snakes | 38 |

| Burrowing | 42 |

| Ground | 43 |

| Tree | 43 |

| Fresh-water | 43 |

| Sea | 43 |

| Innocuous | 46 |

| Blind | 46 |

| Shield-tail | 47 |

| Black | 49 |

| Rat | 49 |

| Ringed | 49 |

| Green and Yellow | 52 |

| Viperine | 52 |

| Desert | 53 |

| Whip | 54 |

| Blunt-heads | 56 |

| Boas | 56 |

| Diamond | 59 |

| Carpet | 59 |

| Rock | 61 |

| Natal Rock | 61 |

| Guinea Rock | 61 |

| Royal Rock | 61 |

| Aboma | 62 |

| Anaconda | 65 |

| Cobra | 70 |

| Asp | 75 |

| Bungarus | 76 |

| Pit Vipers | 78 |

| Fer-de-lance | 79 |

| Jararaca | 80 |

| Trimeresurus | 80 |

| Rattle | 82 |

| Copperhead | 82 |

| Tic-polonga | 88 |

| Puff Adders | 89 |

| Common Adder | 92viii |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| THE ORDER OF LIZARDS—SAURIANS. | |

| Lizards, Distribution and Division | 99 |

| Grey | 109 |

| Green | 110 |

| Ocellated | 110 |

| Ameivas | 112 |

| Iguanas | 117 |

| Basilisk | 127 |

| Anoles | 129 |

| Flying | 132 |

| Gecko | 134 |

| Chameleons | 136 |

| Crocodiles | 141 |

| Jacares | 145 |

| Alligators | 145 |

| Caiman | 147 |

| True | 149 |

| Gavials | 153 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| CHELONIANS, OR SHIELDED REPTILES. | |

| Formation | 155 |

| Distribution and Classification | 157 |

| Tortoises | 158 |

| Land | 158 |

| Margined | 159 |

| Moorish | 159 |

| Greek | 160 |

| Elephantine | 160 |

| Genus Pyxis | 161 |

| Ditto Kinixys | 161 |

| Homopodes | 161 |

| Elodians, or Marsh Tortoises: | |

| Mud | 162 |

| Emydes | 163 |

| Pleuroderes | 164 |

| Potamians, or River Tortoises: | |

| Trionyx | 164 |

| Thalassians, or Sea Tortoises: | |

| Green | 177 |

| Hawk's-bill | 177 |

| Loggerhead | 178 |

| Leather-back | 178 |

| BIRDS. | |

| INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER. | |

| Anatomy | 181 |

| Plumage | 184 |

| Beaks | 189 |

| Digestive Organs | 191 |

| Powers of Sight | 193 |

| Vocal Organs | 195 |

| Nests | 197 |

| Reproduction | 201 |

| Longevity | 203 |

| Utility | 205 |

| Classification | 207 |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| THE NATATORES, OR SWIMMING BIRDS. | |

| Divers | 212 |

| Great Northern | 213 |

| Imbrine | 216 |

| Arctic | 216 |

| Black-throated | 216 |

| Red-throated | 217 |

| Penguins | 218 |

| Manchots | 219 |

| Grebes | 221 |

| Castanean | 222 |

| Crested | 223 |

| Guillemots | 224ix |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| DUCKS, GEESE, SWANS, AND PELICANS. | |

| Mallard | 232 |

| Golden-eyed Garrot | 242 |

| Poachard | 243 |

| Shoveller | 244 |

| Shieldrake | 246 |

| Eider Duck | 247 |

| Common Teal | 250 |

| Velvet Duck | 253 |

| Scoter, Black | 253 |

| Great-billed | 258 |

| Goosander | 259 |

| Smew | 260 |

| Goose | 261 |

| Wild | 262 |

| Bean | 266 |

| Domestic | 266 |

| Bernicle | 269 |

| White-fronted Bernicle | 269 |

| Swan | 270 |

| Whooping | 273 |

| Black | 277 |

| Frigate Bird | 277 |

| Tropic Bird | 279 |

| Darter | 281 |

| Gannet | 283 |

| Cormorant | 285 |

| Shag | 289 |

| Pelicans | 291 |

| White | 294 |

| Crested | 295 |

| Brown | 296 |

| Spectacled | 297 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| THE LARIDÆ. | |

| Tern | 299 |

| Little | 301 |

| Noddy | 302 |

| Silver-winged | 302 |

| Arctic | 302 |

| Whiskered | 303 |

| Gull-billed | 303 |

| Roseate | 303 |

| Sandwich | 303 |

| Caspian | 303 |

| Scissors-bills | 303 |

| Black | 304 |

| Gulls | 304 |

| Large White-winged | 306 |

| Great Black-backed | 306 |

| Herring | 306 |

| Sea Mews | 304 |

| White, or Senator | 307 |

| Brown-masked | 307 |

| Laughing | 307 |

| Grey | 308 |

| Skua | 308 |

| Parasite | 309 |

| Richardson's | 309 |

| Pomerine | 309 |

| Common | 310 |

| Petrels | 310 |

| Giant | 311 |

| Chequered | 311 |

| Fulmar | 311 |

| Stormy | 311 |

| Blue | 312 |

| Puffins | 312 |

| Grey | 312 |

| English | 312 |

| Brown | 312 |

| Albatross | 312 |

| Common | 314 |

| Black-browed | 314 |

| Brown | 314 |

| Yellow and Black-beaked | 314 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| GRALLATORES, OR WADING BIRDS. | |

| Palmidactyles: | |

| Flamingo | 317 |

| Avocet | 320 |

| Stilt Bird | 321 |

| Macrodactyles: | |

| Water Hens | 322 |

| Common | 323 |

| Purple, or Sultana Fowl | 324 |

| Rails | 325 |

| Coots | 326 |

| Bald | 328 |

| Crested | 328 |

| Blue | 328 |

| Glareola | 328 |

| Jacana | 328 |

| Kamichi | 330 |

| Horned | 332 |

| Faithful | 332x |

| Longirostres: | |

| Sandpipers | 332 |

| Brown | 334 |

| Greenshank | 334 |

| Redshank | 334 |

| Pond | 334 |

| Wood | 334 |

| Green | 334 |

| Common | 334 |

| Turnstone | 334 |

| Ruff | 336 |

| Knot | 338 |

| Sanderlings | 339 |

| Woodcock | 339 |

| Snipe | 343 |

| Common | 344 |

| Great | 345 |

| Jack | 345 |

| Wilson's | 345 |

| Godwit | 345 |

| Curlew | 346 |

| Ibis | 348 |

| Sacred | 348 |

| Green | 351 |

| Scarlet | 351 |

| Cultrirostres: | |

| Spoonbills | 352 |

| White | 352 |

| Rose-coloured | 352 |

| Storks | 353 |

| White | 353 |

| Black | 357 |

| Argala | 357 |

| Jabiru | 359 |

| Ombrette | 359 |

| Bec-ouvert | 359 |

| Drome | 359 |

| Tantalus | 360 |

| Boatbill | 360 |

| Herons | 361 |

| Common | 362 |

| Purple | 364 |

| White | 364 |

| Bitterns | 366 |

| Crane | 366 |

| Ash-coloured | 366 |

| Demoiselle | 371 |

| Crested | 371 |

| Hooping | 371 |

| Caurale | 373 |

| Pressirostres: | |

| Cariama | 373 |

| Oyster-catchers | 373 |

| Runners | 376 |

| Lapwings | 376 |

| Plovers | 378 |

| Great Land | 379 |

| Doterel | 379 |

| Ringed | 379 |

| Kentish | 380 |

| Golden | 380 |

| Pluvian | 381 |

| Bustard | 381 |

| Great | 381 |

| Brevipennæ: | |

| Ostrich | 383 |

| Rhea | 390 |

| Cassowary | 392 |

| Emu | 393 |

| Apteryx | 395 |

| Extinct Brevipennæ: | |

| Dodo | 397 |

| Epiornis | 397 |

| Dinornis | 397 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| GALLINACEOUS BIRDS. | |

| Habits, origin, &c. | 399 |

| Tetraonidæ: | |

| Capercailzie | 401 |

| Grouse, Black | 402 |

| Pinnated | 402 |

| Ruffed | 403 |

| Cock of the Plains | 402 |

| Gelinotte | 403 |

| Ptarmigans | 404 |

| Common | 404 |

| Red Grouse | 405 |

| Perdicides: | |

| Gangas | 405 |

| Pin-tailed Sand Grouse | 406 |

| Heteroclites | 406 |

| Quails | 406 |

| Partridges | 410 |

| Grey | 415 |

| Partridges, Red-legged | 417 |

| Gambra | 417 |

| Colin, Virginian | 417 |

| Californian | 418 |

| Solitary | 419 |

| Francolins | 419 |

| Chinese | 419 |

| European | 420 |

| African and Indian | 420 |

| Coturnix | 420 |

| Turnix tachydroma | 420 |

| Tinamides | 420 |

| Chionidæ | 421 |

| Megapodidæ | 421 |

| Phasianidæ: | |

| Pheasants | 422 |

| Common | 422 |

| Golden | 425xi |

| Silver | 425 |

| Ring-necked | 427 |

| Reeves's | 427 |

| Lady Amherst's | 427 |

| Argus | 427 |

| Gallus | 427 |

| Common | 427 |

| Bankiva | 429 |

| Jungle-fowl | 429 |

| Bronzed | 429 |

| Fork-tailed | 429 |

| Kulm | 429 |

| Negro | 429 |

| Tragopans | 435 |

| Pintados | 435 |

| Turkeys | 437 |

| Wild | 437 |

| Domestic | 440 |

| Ocellated | 441 |

| Peacocks | 441 |

| Domestic | 442 |

| Wild | 444 |

| Polyplectrons | 444 |

| Impeyan Pheasants | 444 |

| Alectors | 444 |

| Hocco, or Curassow | 444 |

| Pauxis | 446 |

| Penelopes, or Guans | 446 |

| Hoazins | 446 |

| Columbidæ: | |

| Colombi-Gallines | 447 |

| Pigeons (Colombes) | 448 |

| Ring or Wood | 450 |

| Wild Rock | 450 |

| Common Domestic | 450 |

| Pouter | 451 |

| Roman | 451 |

| Swift | 452 |

| Carrier | 452 |

| Tumbler | 452 |

| Wheeling | 452 |

| Nun | 452 |

| Fan-tailed | 452 |

| Turtle Dove | 453 |

| Ring Dove | 453 |

| Passenger | 453 |

| Columbars | 456 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| SCANSORES, OR CLIMBERS. | |

| Parrots | 457 |

| Macaw | 464 |

| Parrakeets | 465 |

| Tabuan | 465 |

| Parrot, Grey | 466 |

| Green | 466 |

| Cockatoos | 466 |

| Toucans | 467 |

| Proper | 468 |

| Aracaris | 469 |

| Cuckoo | 469 |

| Grey | 469 |

| Indicators | 472 |

| Anis | 473 |

| Barbets | 474 |

| Trogons | 475 |

| Resplendent | 476 |

| Mexican | 476 |

| Woodpeckers | 476 |

| Wry-necks | 479 |

| Jacamars | 480 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| PASSERINES. | |

| Syndactyles: | |

| Hornbills | 482 |

| Rhinoceros | 483 |

| Fly-catchers | 483 |

| King-fishers | 484 |

| Ceyx Meninting | 486 |

| Bee-eaters | 486 |

| Common | 488 |

| Momots | 487 |

| Tenuirostres: | |

| Hoopoes | 488 |

| Epimachus | 490 |

| Promerops | 490 |

| Colibri | 491 |

| Proper | 491 |

| Humming-birds | 491 |

| Creepers | 495 |

| Picumnus | 496 |

| Furnarius | 496 |

| Sucriers | 497 |

| Soui-mangas | 497 |

| Nuthatches | 498 |

| Conirostres: | |

| Birds of Paradise | 499 |

| Great Emerald | 500 |

| King Bird | 500 |

| Superb | 500 |

| Sifilets | 501 |

| Crows | 502 |

| Raven | 502 |

| Carrion | 502 |

| Royston | 502xii |

| Rook | 502 |

| Jackdaw | 502 |

| Magpies | 507 |

| Common | 508 |

| Brazilian | 509 |

| Chinese | 509 |

| Jays | 509 |

| Nut-cracker | 510 |

| Rollers | 511 |

| Starlings | 512 |

| Common | 513 |

| Sardinian | 513 |

| Baltimore Oriole | 514 |

| Beef-eater | 514 |

| Crossbill | 515 |

| Grosbeak | 516 |

| Bullfinch | 517 |

| Siskin | 517 |

| House Sparrow | 518 |

| Goldfinch | 519 |

| Linnets | 519 |

| Chaffinch | 520 |

| Canary | 521 |

| Widow Bird | 523 |

| Java Sparrow | 523 |

| Weaver Birds | 523 |

| Republican | 524 |

| Buntings | 524 |

| Reed | 525 |

| Cirl | 526 |

| Ortolan | 526 |

| Snow | 527 |

| Tits | 527 |

| Great | 528 |

| Long-tailed | 528 |

| Larks | 529 |

| Crested Lark | 531 |

| Fissirostres: | |

| Swallow | 531 |

| Salangane | 537 |

| Goatsuckers | 538 |

| Night-jar | 540 |

| Guacharos | 541 |

| Dentirostres: | |

| Manakins | 542 |

| Cock of the Rock | 542 |

| Warblers | 542 |

| Nightingale | 543 |

| Sedge Warbler | 545 |

| Night Warbler | 545 |

| La Fauvette Couturière | 546 |

| Garden | 547 |

| Robin | 547 |

| Wrens | 547 |

| Golden-crestet | 548 |

| European | 548 |

| Wood | 548 |

| Stone Chat | 549 |

| Wagtails | 550 |

| Pied | 551 |

| Quaketail | 551 |

| Pipits | 552 |

| Lyretail | 552 |

| Orioles | 553 |

| Golden | 553 |

| Mion | 554 |

| Honey-sucker | 555 |

| Ouzel, Rose-coloured | 555 |

| Water | 556 |

| Solitary Thrush | 556 |

| Blackbird, Common | 557 |

| Ringed | 559 |

| Solitary | 559 |

| Thrush, Polyglot | 559 |

| Song | 560 |

| Redwing | 561 |

| Tanagers | 561 |

| Drongos | 562 |

| Cotingas | 563 |

| Caterpillar-eater | 563 |

| Chatterers | 564 |

| Fly-catchers | 565 |

| Tyrants | 567 |

| Cephalopterus ornatus | 567 |

| Shrikes | 568 |

| Vangas | 571 |

| Cassicus | 571 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| RAPTORES, OR BIRDS OF PREY. | |

| Nocturnal: | |

| Horned Owls | 576 |

| Great | 576 |

| Virginian | 579 |

| Short-eared | 579 |

| Ketupu | 581 |

| Scops | 581 |

| Hornless Owls | 583 |

| Sparrow | 583 |

| Small Sparrow | 584 |

| Pampas Sparrow | 584 |

| Burrowing | 585 |

| Tawny | 585 |

| Barn | 585 |

| Canada | 588 |

| Hawk | 589 |

| White | 589 |

| Caparacoch | 590 |

| Harfang | 590xiii |

| Lapland | 591 |

| Ural | 591 |

| Diurnal: | |

| Eagles | 592 |

| Royal | 602 |

| Imperial | 602 |

| Bonelli's | 602 |

| Tawny | 602 |

| Booted | 602 |

| Reinwardt's | 602 |

| Vulturine | 602 |

| Sea Eagles | 602 |

| European | 603 |

| American | 604 |

| Marine | 604 |

| Piscivorous | 604 |

| Caffir | 604 |

| Mace's | 604 |

| Pondicherry | 604 |

| Indian | 604 |

| Osprey | 605 |

| Huppart | 606 |

| Falco urubitinga | 606 |

| Harpy | 606 |

| White-bellied Eagle | 607 |

| Falcons | 608 |

| Gyrfalcons | 608 |

| White | 609 |

| Iceland | 609 |

| Norway | 609 |

| Falcons | 610 |

| Lanier | 610 |

| Sultan | 610 |

| Peregrine | 610 |

| Hobby | 613 |

| Merlin | 613 |

| Kestrel | 613 |

| Bengal | 613 |

| Goshawk | 622 |

| Sparrow-hawks | 623 |

| Common | 623 |

| Dwarf | 623 |

| Chanting Falcon | 624 |

| Kites | 624 |

| Common | 624 |

| Black | 625 |

| Parasite | 625 |

| American | 625 |

| Buzzard | 626 |

| Common | 627 |

| Honey | 627 |

| Rough-legged | 627 |

| Harriers | 627 |

| Hen | 628 |

| Moor | 628 |

| Frog-eating | 628 |

| Pale-chested | 629 |

| Jardine's | 629 |

| Ash-coloured | 629 |

| Caracaras | 629 |

| Brazilian | 629 |

| Chimango | 629 |

| Long-winged | 629 |

| Chimachima | 629 |

| Funebris | 631 |

| Vultures | 631 |

| Griffons | 632 |

| Bearded | 632 |

| Sarcoramphi | 634 |

| Condor | 634 |

| King Vulture | 638 |

| Cathartes | 639 |

| Urubu | 639 |

| Turkey Buzzard | 641 |

| Common Vulture | 641 |

| Percnopterus | 641 |

| Vulture, Pondicherry | 642 |

| Kolbe's | 642 |

| Yellow | 642 |

| Sociable | 645 |

| Chinese | 646 |

| Oricou | 646 |

| Serpent-eaters | 646 |

| Secretary Bird | 646 |

xiv

xv

Phasianus cristatus indicus, in page 448, should be attributed to Brisson, not Latham.

The synonym for Ring Pigeon, in page 448, should be Columba palumbus.

Woodcut 182 represents the Stock Dove, erroneously named Wood Pigeons in page 450. xvi 1

REPTILES AND BIRDS.

There is little apparent resemblance between the elegant feathered warbler which makes the woods re-echo to its cheerful song, and the crawling reptile which is apt to inspire feelings of disgust when the more potent sensation of terror is absent—between the familiar Swallow, which builds its house of clay under the eaves of your roof, or the warbler whose nest, with its young progeny, carefully watched by the father of the brood in the silent watches of the night, is now threatened by the Serpent which has glided so silently into the bush, its huge mouth already open to swallow the whole family, while the despairing and fascinated parents have nothing but their slender bills to oppose to their formidable foe. "Placed side by side," says Professor Huxley, "a Humming-bird and a Tortoise, or an Ostrich and a Crocodile, offer the strongest contrast; and a Stork seems to have little but its animality in common with the Snake which it swallows." Nevertheless, unlike as they are in outward appearance, there is sufficient resemblance in their internal economy to bring them together in most attempts at a classification of the Animal Kingdom. The air-bladder which exists between the digestive canal and kidneys in some fishes, becomes vascular with the form and cellular structure of lungs in reptiles; the heart has two auricles, the ventricle in most is imperfectly divided, and more or less of the venous blood is mixed with the arterial which circulates over the body; but retaining their gills and being therefore transitional in structure, they are also cold-blooded. In 2 birds, the lungs are spongy, the cavity of the air-bags becoming obliterated by the multiplication of vascular cellules; the heart is four-chambered, transmitting venous blood to the lungs, and pure arterial blood to the body; the temperature is raised and maintained at 90° to 100° Fahr.

Thus Reptiles, like Birds, breathe the common air by means of their lungs, but respiration is much less active. "Although," remarks Professor Owen, "the heart of Birds resembles in some particulars that of Reptiles, the four cavities are as distinct as in the Mammalia, but they are relatively stronger, their valvular mechanism is more perfect, and the contractions of this organ are more forcible and frequent in birds, in accordance with their more extended respiration and their more energetic muscular action." It is true, as Professor Huxley informs us, that the pinion of a bird, which corresponds with the human hand or the fore paw of a reptile, has three points representing three fingers: no reptile has so few.1 The breast-bone of a bird is converted into membrane-bone: no such conversion takes place in reptiles. The sacrum is formed by a number of caudal and dorsal vertebræ. In reptiles the organ is constituted by one or two sacral vertebræ.

In other respects the two classes present many obvious differences, but these are more superficial than would be suspected at first glance. And Professor Huxley believes that, structurally, "reptiles and birds do really agree much more closely than birds with mammals, or reptiles with amphibians."

While most existing birds differ thus widely from existing reptiles, the cursorial or struthious genera, comprising the Ostrich, Nandou, Emu, Cassowary, Apteryx, and the recently extinct Dinornis of New Zealand, come nearer to the reptiles in structure than any others. All of these birds are remarkable for the shortness of their wings, the absence of a crest or keel upon the breast-bone, and some peculiarities of the skull, which render them more peculiarly reptilian. But the gap between reptiles and birds is only slightly narrowed by their existence, and is somewhat unsatisfactory to those who advocate the development theory, which asserts that all animals have proceeded, by gradual modification, from a common stock. 3

Traces had been discovered in the Mesozoic formations of certain Ornitholites, which were too imperfect to determine the affinities of the bird. But the calcareous mud of the ancient sea-bottom, which has hardened into the famous lithographic slate of Solenhofen, revealed to Hermann von Meyer, in 1861, first the impression of a feather, and, in the same year, the independent discovery of the skeleton of the bird itself, which Von Meyer had named Archæopteryx lithographicus. This relic of a far-distant age now adorns the British Museum.

The skull of the Archæopteryx is almost lost, but the leg, the foot, the pelvis, the shoulder-girdle, and the feathers, as far as their structure can be made out, are completely those of existing birds. On the other hand, the tail is very long. Two digits of the manus have curved claws, and, to all appearance, the metacarpal bones are quite free and disunited, exhibiting, according to Professor Huxley, closer approximation to the reptilian structure than any existing bird. Mr. Evans has even detected that the mandibles were provided with a few slender teeth.

On the other hand, the same writer points out certain peculiarities in the single reptile found also among the Solenhofen slates, which has been described and named Compsognathus longipes by the 4 late Andreas Wagner. This reptile he declares "to be a still nearer approximation to the missing link between reptiles and birds," thus narrowing the gap between the two classes.

While we think it proper to point to these structural resemblances of one class of the animal creation to others very different in their external appearance, it is necessary to guard ourselves and our readers from adopting the inferences sometimes deduced from them; that "these infinitely diversified forms are merely the final terms in an immense series of changes which have been brought about in the course of immeasurable time, by the operation of causes more or less similar to those which are at work at the present day." Domestication and other causes have no doubt produced changes in the form of many animals; but none from which this inference can be drawn, except in the imagination of ingenious men who strain the facts to support a preconceived hypothesis. In spite of the innumerable forms which the pigeon assumes by cross-breeding and domestication, it still remains a pigeon; the dog is still a dog, and so with other animals. Nor does it seem to us to be necessary, or calculated to advance our knowledge in natural history, to form theories which can only disturb our existing systems without supplying a better. Systems are necessary for the purpose of arrangement and identification; but it should never be forgotten that all classifications are artificial—a framework or cabinet, into the partitions of which many facts may be stowed away, carefully docketed for future use. "Theories," says Le Vaillant, "are more easily made and more brilliant probably than observations; but it is by observation alone that science can be enriched." A bountiful Creator appears to have adopted one general plan in the organization of all the vertebrate creation; and, in order to facilitate their study, naturalists have divided them into classes, orders, and genera, formed on the differences which exist in the structure of their vital functions. The advantages of this are obvious, but it does not involve the necessity of fathoming what is unfathomable, of explaining what is to man inexplicable in the works of God.2

5

In previous volumes of this series3 we have endeavoured to give the reader some general notions of the form, life, and manners of the branches of the animal kingdom known as Zoophytes, Mollusca, Articulata, and Pisces. We now continue the superior sub-kingdom (to which the fishes also belong) of the Vertebrated Animals, so called from the osseous skeleton which encircles their bodies, in which the vertebral column, surmounted by the cranium, its appendage, forms the principal part.

The presence of a solid frame in this series of animals admits of their attaining a size which is denied to any of the others. The skeleton being organized in such a manner as to give remarkable vigour and precision to all their movements.

In the vertebrated animals the nervous system is also more developed. There is, consequently, a more exquisite sensibility in them than in the classes whose history we have hitherto discussed. They possess five senses, more or less fully developed, a heart, a circulation, and their blood is red.

We have now to deal with a class advanced above that of fishes, that of Reptilia, which is divided as follows:—

Animals having ribs or processes, or short, slight, and free vertebræ, forming a series of separate centrums, deeply cupped at both ends, one of which is converted by ossification in the mature animal into a ball, which may be the front one, as in the Surinam Toad, Pipa, or the hind ones in the Frogs and Toads, Rana. The skin is nude, limbs digitate, gills embryonal,—permanent in some, in most lost in metamorphosis,—to be succeeded by pulmonary respiration,—or both; a heart with one ventricle and two auricles. They consist of:—

| I. Ophiomorpha. | |

|---|---|

| Cæciliadæ or Ophiosomæ. | |

| II. Icthyomorpha. | |

| Proteidæ or Sirens, Proteus, Newts, and Salamanders.6 | |

| III. Theriomorpha. | |

| Aglosa | Pipa or Surinam Toads. |

| Ranidæ | Frogs. |

| Hylidæ | Tree Frogs. |

| Bufonidæ | Toads. |

Distinguished by the double shield in which their bodies are enclosed, whether they are terrestrial, fresh-water, or marine.

| The Turtles, Chelonia, have the limbs natatory. | ||

| Mud Turtles, Trionyx, | } limbs amphibious. | |

| Terrapens, Emys, | ||

| Tortoises, Testudo, limbs terrestrial. | ||

Having a single transverse process on each side, single-headed ribs, two external nostrils, eyes with movable lids; body covered with horny, sometimes bony, scales.

Lacerta—the Monitors, Crocodiles, Lizards; having ambulatory limbs.

Anguis—Ophisaurus, Bimanus, Chalcides, Seps; limbs abortive; no sacrum.

Having numerous vertebræ with single-headed hollow ribs, no visible limbs, eyelids covered by an immovable transparent lid; body covered by horny scales. It includes:—

| Viperinæ—the Vipers and Crotalidæ. |

| Colubrinæ—the Colubers, Hydridæ, and Boidæ. |

Teeth in a single row, implanted in distinct sockets; body depressed, elongated, protected on the back by solid shield; tail longer than the trunk, compressed laterally, and furnished with crests above. The several families are:—

| Crocodilidæ—the Gavials, Mecistops, Crocodiles. |

| Alligatoridæ—Jacares, Alligators, Caiman.4 |

7

Those geographers who divide the world into land and sea overlook in their nomenclature the extensive geographical areas which belong permanently to neither section—namely, the vast marshy regions on the margins of lakes, rivers, and ponds, which are alternately deluged with the overflow of the adjacent waters, and parched and withering under the exhalations of a summer heat; regions which could only be inhabited by beings capable of living on land or in water; beings having both gills through which they may breathe in water, and lungs through which they may respire the common air. The first order of reptiles possesses this character, and hence its name of Amphibia, from αμφιβιος, having a double life.

The transition from fishes to reptiles is described by Professor Owen, with that wonderful power of condensation which he possesses, in the following terms:—"All vertebrates during more or less of their developmental life-period float in a liquid of similar specific gravity to themselves. A large proportion, constituting the lowest organised and first developed forms of this province, exist and breathe in water, and are called fishes. Of these a few retain the primitive vermiform condition, and develop no limbs; in the rest they are 'fins' of simple form, moving by one joint upon the body, rarely adapted for any other function than the impulse or guidance of the body through the water. The shape of the body is usually adapted for moving with least resistance through the liquid medium. The surface of the body is either smooth and lubricous or it is smoothly covered with overlapping scales; it is rarely defended by bony plates, or roughened by tubercles. 8 Still more rarely it is armed with spines." Passing over the general economy of fishes we come to the heart. "The heart," he tells us, "consists of one auricle receiving the venous blood, and one ventricle propelling it to the gills or organs submitting that blood in a state of minute subdivisions to the action of aërated water. From the gills the aërated blood is carried over the entire body by vessels, the circulation being aided by the contraction of the surrounding muscles."

The functions of gills are described by the Professor with great minuteness. "The main purpose of the gills of fishes," he says, "being to expose the venous blood in this state of minute subdivision to streams of water, the branchial arteries rapidly divide and sub-divide until they resolve themselves into microscopic capillaries, constituting a network in one plane or layer, supported by an elastic plate, covered by a tesselated and non-ciliated epithelium. This covering and the tunics of the capillaries are so thin as to allow chemical interchange and decomposition to take place between the carbonated blood and the oxygenated water. The requisite extent of the respiratory field of capillaries is gained by various modes of multiplying the surface within a limited space." "Each pair of processes," he adds, "has its flat side turned towards contiguous pairs, and the two processes of each pair stand edgeway to each other, being commonly united for a greater or less extent from their base; hence Cuvier describes each pair as a single bifurcated plate, or 'feuillet.'"

The modification which takes place in the respiratory and other organs in Reptilia, is described in a few words. "Many fishes have a bladder of air between the digestive canal and the kidneys, which in some communicate with an air-duct and the gullet; but its office is chiefly hydrostatic. When on the rise of structure this air-bladder begins to assume the vascular and pharyngeal relations with the form and cellular structure of lungs, the limbs acquire the character of feet: at first thread-like and many jointed, as in the Lepidosiren; then bifurcate, or two-fingered, with the elbow and wrist joints of land animals, as in Amphiuma; next, three-fingered, as in Proteus, or four-fingered, but reduced to the pectoral pair, as in Siren."

In all reptiles the blood is conveyed from the ventricular part 9 of the heart, really or apparently, by a single trunk. In Lepidosiren the veins from the lung-like air-bladders traverse the auricle which opens directly into the ventricle. In some the vein dilates before communicating with the ventricle into a small auricle, which is not outwardly distinct from the much larger auricle receiving the veins of the body. In Proteus the auricular system is incomplete. In Amphiuma the auricle is smaller and less fringed than in the Sirens, the ventricle being connected to the pericardium by the apex as well as the artery. This forms a half spiral turn at its origin, and dilates into a broader and shorter bulb than in the Sirens.

"The pulmonic auricle," continues the learned Professor, "thus augments in size with the more exclusive share taken by the lungs in respiration; but the auricular part of the heart shows hardly any outward sign of its diversion in the Batrachians. It is small and smooth, and situated on the left, and in advance of the ventricle in Newts and Salamanders. In Frogs and Toads the auricle is applied to the base of the ventricle, and to the back and side of the aorta and its bulb."

In the lower members of the order, the single artery from the ventricle sends, as in fishes, the whole of the blood primarily to the branchial organs, during life, and in all Batrachians at the earlier aquatic periods of existence. In the Newt three pairs of external gills are developed at first as simple filaments, each with its capillary loop, but speedily expanding, lengthening, and branching into lateral processes, with corresponding looplets; those blood-channels intercommunicating by a capillary network. The gill is covered by ciliated scales, which change into non-ciliated cuticle shortly before the gills are absorbed. In the Proteus anguinus, three parts only of branchial and vascular arches are developed, corresponding with the number of external gills. In Siren lacertina the gills are in three pairs of branchial arches, the first and fourth fixed, the second and third free, increasing in size according to their condition.

The Amphibia, then, have all, at some stage of their existence, both gills and lungs co-existent: respiring by means of branchiæ or gills while in the water, and by lungs on emerging into the open air. 10

All these creatures seem to have been well known to the ancients. The monuments of the Egyptians abound in representations of Frogs, Toads, Tortoises, and Serpents. Aristotle was well acquainted with their form, structure, and habits, even to their reproduction. Pliny's description presents his usual amount of error and exaggeration. Darkness envelops their history during the middle ages, from which it gradually emerges in the early part of the sixteenth century, when Belon and Rondiletius in France, Salviani in Italy, and Conrad Gesner in Switzerland, devoted themselves to the study of Natural History with great success. In the latter part of the same century Aldrovandi appeared. During fifty years he was engaged in collecting objects and making drawings, which were published after his death, in 1640, edited by Professor Ambrossini, of Bologna, the Reptiles forming two volumes. In these volumes, twenty-two chapters are occupied by the Serpents. But the first arrangement which can be called systematic was that produced by John Ray. This system was based upon the mode of respiration, the volume of the eggs, and their colour.

Numerous systems have since appeared in France, Germany, and England; but we shall best consult our readers' interest by briefly describing the classification adopted by Professor Owen, the learned Principal of the British Museum, in his great work on the Vertebrata.

The two great classes Batrachians and Reptiles, include a number of animals which are neither clothed with hair, like the Mammalia, covered with feathers like the birds, nor furnished with swimming fins like fishes. The essential character of reptiles is, that they are either entirely or partially covered with scales. Some of them—for instance, Serpents—move along the ground with a gliding motion, produced by the simple contact and adhesion of the ventral scales with the ground. Others, such as the Tortoises, the Crocodiles, and the Lizards, move by means of their feet; but these, again, are so short, that the animals almost appear to crawl on the ground—however swiftly, in some instances. The locomotive organs in Serpents are the vertebral column, with its muscles, and the stiff epidermal scutes crossing the under surface of the body. "A Serpent may, however, be 11 seen to progress," says Professor Owen, "without any inflection, gliding slowly and with a ghost-like movement in a straight line, and if the observer have the nerve to lay his hand flat in the reptile's course, he will feel, as the body glides over the palm, the surface pressed as it were by the edges of a close-set series of paper knives, successively falling flat after each application." Others of the class, such as the Tortoises, Crocodiles, and Lizards, move by the help of feet, which are generally small and feeble—in a few species being limited to the pectoral region, while in most both pairs are present. In some, as in various Lizards, the limbs acquire considerable strength.

There is one genus of small Lizards, known as the Dragons, Draco, whose movements present an exception to the general rule. Besides their four feet, these animals are furnished with a delicate membranous parachute, formed by a prolongation of the skin on the flanks and sustained by the long slender ribs, which permits of their dropping from a considerable height upon their prey.

Batrachians, again, differ from most other Reptilia by being naked: moreover, most of them undergo certain metamorphoses; in the first stage of their existence they lead a purely aquatic life, and breathe by means of gills, after the manner of fishes. Young Frogs, Toads, and Salamanders, which are then called tadpoles, have, in short, no resemblance whatever to their parents in the first stage of their existence. They are little creatures with slender, elongated bodies, destitute of feet and fins, but with large heads, which may be seen swimming about in great numbers in stagnant ponds, where they live and breathe after the manner of fishes. By degrees, however, they are transformed: their limbs and air-breathing lungs are gradually developed, then they slowly disappear, and a day arrives when they find themselves conveniently organized for another kind of existence; they burst from their humid retreat, and betake themselves to dry land. "The tadpole meanwhile being subject to a series of changes in every system of organs concerned in the daily needs of the coming aërial and terrestrial existence, still passes more or less time in water, and supplements the early attempt at respiration by pullulating loops and looplets of capillaries from the branchial vessels." (Owen.) 12

Nevertheless, they do not altogether forget their native element; thanks to their webbed feet, they can still traverse the waters which sheltered their infancy; and when alarmed by any unusual noise, they rush into the water as a place of safety, where they swim about in apparent enjoyment. In some of them, as Proteus and the amphibious Sirens, where the limbs are confined to the pectoral region, swimming seems to be the state most natural to them. They are truly amphibious, and they owe this double existence to the persistence of their gills; for in these perennibranchiate Batrachians, arteries are developed from the last pair of branchial arches which convey blood to the lungs: while, in those having external deciduous gills, the office being discharged, they lose their ciliate and vascular structure and disappear altogether. The skull in Reptiles generally consists of the same parts as in the Mammalia, though the proportions are different. The skull is flat, and the cerebral cavity, small as it is, is not filled with brain. The vertebral column commences at the posterior part of the head, two condyles occupying each side of the vertebral hole (Fig. 2). The anterior limbs are mostly shorter than the posterior, as might be expected of animals whose progression is effected by leaps. Ribs there are none. The sternum is highly developed, and a large portion of it is cartilaginous; it moves in its mesial portions the two clavicles and two coracoid bones, which fit on to the scapula, the whole making a sort of hand which supports the anterior extremities, and an elongated disk which supports the throat, and assists in deglutition and respiration. The bone of the arm (humerus) is single, and long in proportion to the fore arm. In the Frogs (Rana), the ilic bone is much elongated, and is articulated in a movable manner on the sacrum, so that the two heads of the thigh bones seem to be in contact. The femur, or thigh, is much lengthened and slightly curved, and the bones of the leg so soldered together as to form a single much elongated bone.

The respiration of Reptiles and some of the Batrachians, like that of Birds and Mammals, is aërial and pulmonary, but it is much less active. Batrachians have, in addition, a very considerable cutaneous respiration. Some of them, such as Toads, absorb more oxygen through the skin than by the lungs. Their circulation is 13 imperfect, the structure of the heart only presenting one ventricle; the blood, returning after a partial regeneration in the lungs, mingles with that which is not yet revivified: this mixed fluid is launched out into the economic system of the animal. Thus Reptiles and Batrachians are said to be cold-blooded animals, more especially the former, in which the respiratory organs, which are a constant source of interior heat, are only exercised very feebly. Owing to this low temperature of their bodies, reptiles affect warm climates, where the sun exercises its power with an intensity unknown in temperate regions; hence it is that they abound in the warm latitudes of Asia, Africa, and America, whilst comparatively few are found in Europe. This is also the cause of their becoming torpid during the winter of our latitudes: not having sufficient heat in themselves to produce reaction against the external cold, they fall asleep for many months, awakening only when the temperature permits of their activity. Serpents, Lizards, Tortoises, Frogs, are all subjected to this law of their being. Some hybernate upon the earth, under heaps of stones, or in holes; others in mud at the bottom of ponds. The senses are very slightly developed in these animals; those of touch, taste, and smell, are very imperfect; that of hearing, though less obtuse, leaves much to be desired; but sight in them is very suitably exercised by the large eyes, with contractile eye-balls, which enables certain reptiles—such, for instance, as the Geckos, to distinguish objects in the dark. Most Reptiles and Batrachians are almost devoid of voice: Serpents, 14 however, utter a sharp hissing noise, some species of Crocodiles howl energetically, the Geckos are particularly noisy, and Frogs have a well-known croak. In Reptiles and Batrachians the brain is small, a peculiarity which explains their slight intelligence and the almost entire impossibility of teaching them anything. They can, it is true, be tamed; but although they seem to know individuals, they do not seem to be susceptible of affection: the slight compass of their brain renders them very insensible, and this insensibility to pain enables them to support mutilations which would prove immediately fatal to most other animals. For instance, the Common Lizard frequently breaks its tail in its abrupt movements. Does this disturb him? Not at all! This curtailment of his being does not seem to affect him; he awaits patiently for the return of the organ, which complaisant nature renews as often as it becomes necessary. In the Crocodiles and Monitor Lizards, however, a mutilated part is not renewed, and the renovated tails of other Lizards do not develop bone. In some instances, the eyes may be put out with impunity, or part of the head may be cut off; these organs will be replaced or made whole in a certain time without the animal having ceased to perform any of the functions which are still permitted to him in his mutilated state. A Tortoise will continue to live and walk for six months after it is deprived of its brain, and a Salamander has been seen in a very satisfactory state although its head was, so to speak, isolated from the trunk by a ligature tied tightly close round the neck. There is another curious peculiarity in the history of Reptiles and Batrachians: each year as they awake from their state of torpor, they slough their old covering, and thus each year renew their youth; so far as the skin is concerned, it is certain that they retain their youth a very long time. Their growth is slow, and continues almost through the whole duration of their existence; they are, moreover, endowed with remarkable longevity. This is not very astonishing, if we consider that (at least in our latitudes) they remain torpid for several months yearly; thus using up less of the materials of life than most animals, they ought, consequently, to attain a more advanced age. The activity of organization in Reptiles and Batrachians is so slight that their stomachs feel less of the exigencies of hunger; hence they rarely take nourishment; they digest 15 their food with equal deliberation. With the exception of the Land Tortoises, whose regimen is herbivorous, most reptiles feed on living prey. Some, such as Lizards, Frogs, and Toads, prey on worms, insects, small terrestrial or aquatic Molluscs; others, such as Ophidians and Crocodiles, attack Birds, and even Mammalia. Large Serpents, owing to the distensibility of their œsophagus, swallow animals much larger than themselves. The Boa-constrictor darts upon the Deer, binds him in its snaky coils, breaks his bones, and little by little swallows him entirely.

Reptiles, whether Batrachians, Ophidians, or Chelonians, are mostly oviparous, sometimes ovo-viviparous, and some of them are very prolific. The eggs of some are covered with a calcareous envelope, as in the Turtle. Sometimes they are soft, and analogous to the spawn of fish, as in the Batrachians. They do not hatch their eggs by sitting upon them, but bury them in the sand, and take no further care of them, trusting to the heat of the sun, which hatches them in due course. To this the Pythons form a partial exception. Batrachians content themselves with diffusing their spawn or eggs in the marshy waters or ponds, or they bear them on their backs until the time of hatching approaches. On leaving the egg the young Tortoises have to provide immediately for their own wants, for the parents are not present to bring them their nourishment or to defend them against their enemies. This parental protection, so manifest among the superior animals, does not exist in oviparous species; that is, in those whose eggs are not hatched in the body of the mother. The young are, so to speak, produced in a living state, and fully prepared for the battle of life. The loves of these animals present none of that character of mutual affection and tender sympathy which distinguishes the Mammalia and Birds.5 When they have ensured the perpetuity of their species, they separate, and betake themselves again to their solitary existence.

Some reptiles attain dimensions truly extraordinary, which render them at times very formidable. Turtles are met with which weigh as much as sixteen hundred pounds, and the carapace 16 of one of these measured as much as six feet in length. The size of an ordinary Crocodile is from eight to nine feet, but they have been seen twenty-four and even thirty feet long, with a mouth opening from six to eight feet wide.

In Chelonians the surface of the skull is continuous without movable articulations. The head is oval in the Land Tortoises, the interval between the eyes large and convex, the opening of the nostrils large, the orbits round. The general distinguishing characteristic of Tortoises is the external position of the bones of the thorax, at once enveloping with a cuirass or buckler the muscular portion of the frame, and protecting the pelvis and shoulder bones. The ribs are inserted by means of sutures into these plates, and united with each other. A three-branched shoulder and cylindrical shoulder-blade are characteristic of the Tortoises. 17

In tropical regions enormous Serpents are found, which are as bulky as a man's thigh, and are said to be not less than forty feet in length. Roman annals mention one forty feet long, which Regulus encountered in Africa during the Punic wars, and which is fabulously said to have arrested the march of his army. These gigantic reptiles are not, however, the enemies which man has most cause to fear; their very size draws attention to them in such a manner that it is easy to avoid them. It is quite otherwise with Vipers twenty or thirty inches long; they glide after their prey without being seen, strike it cruelly with their fangs, leaving in the wound a venom which produces death with startling rapidity. Doubtless this fatal power was the origin of the worship which was rendered to certain reptiles by barbarous nations of old, and these animals are indeed still venerated by many savage races. The whole class of Reptiles are, for the most part, calculated to inspire feelings of disgust, and such has been the sentiment in all ages. Few people can suppress a movement of fright at the sight of an ordinary Snake, Lizard, or Frog, notwithstanding that they are most inoffensive animals. Several causes concur to this aversion. In the first place the low temperature of their bodies, contact with which communicates an involuntary shudder in the person who tries to touch one of them; then the moisture which exudes from the skins of Frogs, Toads, and Salamanders; their fixed and strong gaze, again, impresses one painfully in thinking of them; the odour which some of them exhale is so disgusting, that it alone sometimes causes fainting; add to this the fear of a real or often exaggerated danger, and we shall have the secret of the sort of instinctive horror which is felt by many people at the sight of most reptiles. Nevertheless, the injurious species are exceptional amongst reptiles, and there are not any amongst the Batrachians, for it is altogether a mistake to take for venom the fluid which the toad discharges.6 It is true that these animals are repulsive in appearance, we can nevertheless recognise their services in the economy of nature. Inhabitants of slimy mud and 18 impure swamps, they make incessant war upon the worms and insects which abound in those localities. In their turn they find implacable enemies in the birds of the marshes, which check their prodigious multiplication. In this manner equilibrium is maintained.

Some of the animals which now occupy our attention render more direct service to man by the part which they fulfil at his table. Frogs are eaten in the south of France, Italy, and many other countries; and in some parts of the south of France, Adders are eaten under the name of Hedge-eels. We know the favour in which Turtles are held in England, where turtle-soup is considered a dish only fit for merchant princes. In some countries Iguanas, Crocodiles, and even Serpents are eaten. Viper-broth, which was known to Hippocrates, is discontinued as an article of food.

As we have already remarked, the peculiar nature of their organization leads Reptiles and Batrachians to seek the warmer regions of the earth. It is in those regions that they attain the enormous dimensions which distinguish certain Serpents; there, too, they secrete their most subtle poisons, and display the most lively colours—which, if less rich than those of Birds and Fishes, are not less startling in effect. Many Serpents and Lizards glitter with radiant metallic reflections, and some of them present extremely varied combinations of colour. Chameleons are found in the same localities, but in the Old World only; these and some other Lizards are remarkable for changing their colour, a phenomenon which is also seen among the Frogs, but in a smaller degree.

Reptiles and Batrachians were numerous in the early ages of our globe. It was then that those monstrous Saurians lived, whose dimensions even are startling to our imagination. The forms of the Reptiles and Batrachians of the early ages of the earth were much more numerous, their dimensions much greater, and their means of existence more varied than those of the present time. Our existent Reptiles are very degenerate descendants of those of the great geological periods, unless we except the Crocodiles and the gigantic Boas and Pythons. Whilst the Reptiles of former ages disported their gigantic masses, and spread terror amongst other living creatures, alike by their formidable armature and their prodigious numbers, they are now 19 reduced to a much lower number of species. There are now but little more than 1,500 species of Reptiles and Batrachians described, and only 100 of those belong to Europe.7

Animals which compose this class have long been confounded with reptiles, from which they differ in one fundamental peculiarity in their organization. At their birth they respire by means of gills, and consequently resemble fishes. In a physiological point of view, at a certain time in their lives, these animals are fishes in form as well as in their habits and organization. As age progresses, they undergo permanent metamorphosis—they acquire lungs, and thenceforth an aërial respiration. It is, then, easy to understand that these animals hold a doubtful rank, as they have long done, amongst Reptiles, which are animals with an aërial respiration; they ought to form a separate class of Vertebrates.8

Batrachians establish a transitional link between Fishes and Reptiles—they are, as it were, a bond of union between those two groups of animals. In the adult state Batrachians are cold-blooded animals with incomplete circulation, inactive respiration, and the skin is bare. In the introductory section to this chapter we have given the general characteristics which belong to them. The Frogs—Tree Frogs, Toads, Surinam Toads, Salamanders, and Newts—are the representatives of the principal families of Batrachians of which we propose giving the history.

The Frogs, Rana, have been irreparably injured by their resemblance to the Toads. This circumstance has given rise to an unfavourable prejudice against these innocent little Batrachians. Had the Toad not existed, the Frog would appear to us as an animal of a curious form, and would interest us by the phenomena of transformation which it undergoes in the different epochs of its development. We should see in it a useful inoffensive animal of slender form, with delicate and supple limbs, arrayed in that 20 green colour which is so pleasant to the eye, and which mingles so harmoniously with the carpeting of our fields.

The body of the Edible Frog, Rana esculenta (Fig. 4), sometimes attains from six to eight inches in length, from the extremity of the muzzle to the end of the hind feet. The muzzle terminates in a point; the eyes are large, brilliant, and surrounded with a circle of gold colour. The mouth is large; the body, which is contracted behind, presents a tubercular and rugged back. It is of a more or less decided green colour on the upper, and whitish on the under parts. These two colours, which harmonize well, are relieved by three yellow lines, which extend the whole length of the back, and by scattered black marbling. It is, therefore, much to be regretted that prejudice should cause some at least of us to turn away from this pretty little hopping animal, when met with in the country; with its slight dimensions, quick movements, and graceful attitudes. For 21 ourselves, we cannot see the banks of our streams embellished by the colours and animated with the gambols of these little animals without pleasure. Why should we not follow with our eyes their movements in our ponds, where they enliven the solitude without disturbing its tranquillity. Frogs often leave the water, not only to seek their nourishment, but to warm themselves in the sun. When they repose thus, with the head lifted up, the body raised in front and supported upon the hind feet, the attitude is more that of an animal of higher organization than that of a mean and humble Batrachian. Frogs feed on larvæ, aquatic insects, worms, and small mollusks. They choose their prey from living and moving creatures; for they set a watch, and when they perceive it, they spring on it with great vivacity. A large Indian species (R. tigrina) has been seen to prey occasionally upon young Sparrows. Far from being dumb, like many oviparous quadrupeds, Frogs have the gift of voice. The females only make a peculiar low growl, produced by the air which vibrates in the interior of two vocal pouches placed on the sides of the neck; but the cry of the male is sonorous, and heard at a great distance: it is a croak which the Greek poet, Aristophanes, endeavoured to imitate by the inharmonic consonants, brekekurkoax, coax! It is principally during rain, or in the evenings and mornings of hot days, that Frogs utter their confused sounds. Their chanting in monotonous chorus makes this sad melody very tiresome. Under the feudal system, during the "good old times" of the middle ages, which some people would like to bring back again, the country seats of many of the nobility and country squires were surrounded by ditches half full of water, all inhabited by a population of croaking Frogs. Vassals and villains were ordered to beat the water in these ditches morning and evening in order to keep off the Frogs which troubled the sleep of the lords and masters of the houses. Independent of the resounding and prolonged cries of which we have spoken, at certain times the male Frog calls the female in a dull voice, so plaintive that the Romans described it by the words "ololo," or "ololygo." "Truly," says Lacépède, "the accent of love is always mingled with some sweetness."

When autumn arrives Frogs cease from their habitual voracity, 22 and no longer eat. To protect themselves from the cold, they bury themselves deeply in the mud: troops of them joining together in the same place. Thus hidden, they pass the winter in a state of torpor; sometimes the cold freezes their bodies without killing them. This state of torpor gives way in the first days of spring. During the month of March, Frogs begin to awake and to move themselves; this is their breeding season. Their race is so prolific that a female can produce from six to twelve hundred eggs annually. These eggs are globular, and are in form a glutinous and transparent spheroid, at the centre of which is a little blackish globule; the eggs float, and form like chaplets on the surface of the water.

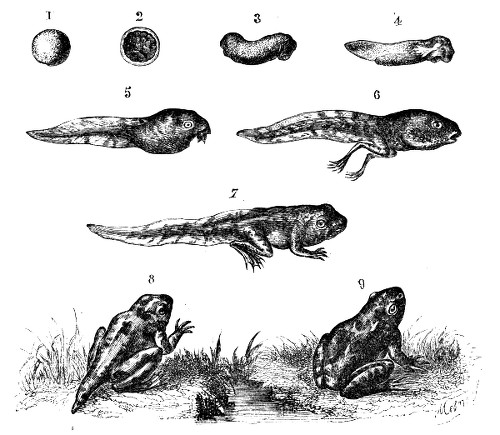

Fig. 5.—Development of the Tadpole.

1. Egg of the Frog. 2. The Egg fecundated, and surrounded by its visicule. 3. First state of the Tadpole. 4. Appearance of the breathing gills. 5. Their development. 6. Formation of the hind feet. 7. Formation of the fore feet, and decay of the gills. 8. Development of the lungs, and reduction of the tail. 9. The perfect Frog.

All who have observed the small ponds and ditches in the country at this season, will have seen these light and elegant 23 crafts swimming on the surface of the water. After a few days, more or less according to the temperature, the little black spot which is the embryo of the egg, and which has developed itself in the interior of the glairy mass which envelops it, disengages itself and shoots forth into the water: this is the tadpole of the Frog.

The body of the tadpole is oval in shape, and terminates in a long flat tail, which forms a true fin; on each side of the neck are two large gills, in shape like a plume of feathers; the tadpole has no legs. These gills soon begin to wither, without aquatic respiration ceasing, however; for, besides these, the tadpole possesses interior gills like fishes. Soon after, the legs begin to show themselves, the hind legs appearing first; they acquire a considerable length before the fore feet begin to show themselves. These develop themselves under the skin, which they presently pierce through. When the legs have appeared, the tail begins to fade, and, little by little, withers away, until in the perfect animal it entirely disappears. About the same time the lungs become developed, and assume their functions. In Fig. 5 may be traced the successive phases of its transformation from the egg to the tadpole, till we finally reach the perfect Batrachian. Through these admirable modifications we see the Fish, little by little, become a Batrachian. In order to follow this strange metamorphosis, it suffices to gather some Frog's eggs, and to place them with some aquatic herbs in an aquarium, or in a globe with Gold and Silver Fish; it there constitutes a most interesting spectacle, and we advise our readers to give themselves this instructive and easy lesson in natural history.

At present, there exist two species of Frog in Europe: the Green or Edible Frog, and the Common Frog. The Green Frog is that which we have described, and of which we have given a representation in Fig. 4. They are found in running streams and stagnant waters. It is this species to which La Fontaine alludes in one of his fables. Common Frogs are smaller than the preceding: they inhabit damp places in fields and vineyards, and only return to the water to breed or to winter.

The flesh of the Edible Frog is very tender, white, and delicate. As an article of food, it is lightly esteemed by some, but undeservedly 24 so. Prepared in the same manner, Green Frogs closely resemble very young fowls in taste. In almost all parts of France Frogs are disdained as articles of food; it is only in the south that a taste for them is openly avowed, and there Frogs are sought for and brought to market. Therefore, I never could comprehend how the notion popular in England, when it is wished to express contempt for Frenchmen, should be to call them Frog-eaters. It is a reproach which might be addressed to Provençals and Languedocians like the author of this work, but not at all to the majority of Frenchmen.

The Green Tree Frog is easily distinguished by having little plates under its toes. These organs are a species of sucker, by means of which the animal is enabled, like the house-fly, to cling strongly to any surface, however smooth and polished it may be. The smoothest branch, even the lower surface of a leaf, forms a sufficient hold and support to these delicate organs.

The upper part of the body is of a beautiful green, the lower part, where little tuberculi are visible, is white. A yellow line, lightly bordered with violet, extends on each side of the head and back, from the muzzle to the hind legs. A similar line runs from the jaw to the front legs. The head is short, the mouth round, and the eyes raised. Much smaller than the ordinary Frog, 25 they are far more graceful. During the summer they live upon the leaves of trees in damp woods, and pass the winter at the bottom of some pond, which they do not leave till the month of May, after having deposited their eggs. They feed on small insects, worms, and mollusks; and in order to catch them, they will remain in the same place an entire day. During the glare of the sun, they remain hidden amongst the leaves; but when twilight approaches, they move about and climb up the trees. We must repeat of these Green Tree Frogs what we have already said of Frogs. Get rid of all prejudice towards their kind, and then you will examine with pleasure their lively colours, which harmonize so well with the green leaves; remark their tricks and ambuscades; follow them in their little hunting excursions; see them suspended upside down upon the leaves in a manner which appears marvellous to those who are not aware of the organs which have been given to enable them to attach themselves to the smoothest bodies: and it will give as much pleasure as can be derived from the consideration of the plumage, habits, and flight of birds. The croak of the Green Tree Frogs is like that of other Frogs, although less sharp and sometimes stronger in the males; it can be pretty well translated by the syllables caraccarac, pronounced from the throat. This cry is principally heard in the morning and evening; then, when one Frog begins to utter its croak, all the others imitate it. In the quiet night the voice of a troop of these little Batrachians sometimes reaches to an enormous distance.

Toads, Bufo, are squat and disagreeable in shape: it is difficult to comprehend why nature, which has bestowed elegance and a kind of grace upon Frogs and Tree Frogs, has stamped the Toad with so repulsive a form. These much despised beings occupy a large place in the order of nature: they are distributed with profusion, but one cannot say exactly to what end; their movements are heavy and sluggish. In colour they are usually of a livid grey, spotted with brown and yellow, and disfigured by a number of pustules or warts. A thick and hard skin covers a flat back; its large belly always appears to be swollen; the head a little broader than the rest of its body; the mouth and the eyes are large and prominent. It lives chiefly at the bottom of ditches, especially those 26 where stagnant and corrupt water has lain a long time. It is found in dung heaps, caves, and in dark and damp parts of woods. One has often been disagreeably surprised on raising some great stone to discover a Toad cowering against the earth, frightful to see, but timorous, seeking to avoid the notice of strangers. It is in these different obscure and sometimes fœtid places of refuge that the Toad shuts itself up during the day; going out in the evening, when our common species moves by slight hops; whilst another, the Natterjack Toad, Bufo calamita, only crawls, though somewhat fastly. When seized, it voids into the hand a quantity of limpid water imbibed through the pores of its skin; but if more irritated, a milky and venemous humour issues from the glands of its back.

One peculiarity of its structure offers a defence from outward attacks. Its very extensible skin adheres feebly to the muscles, and at the will of the animal a large quantity of air enters between this integument and the flesh, which distends the body, and fills the vacant space with an elastic bed of gas, by means of which it is less sensible to blows. Toads feed upon insects, worms, and small mollusks. In fine evenings, at certain seasons especially, they may be heard uttering a plaintive monotonous sound. They assemble in ponds, or even in simple puddles of water, where they 27 breed and deposit their eggs. When hatched, the young Toads go through the same metamorphosis as do the tadpoles of the Frogs.

Their simple lives, though very inactive, are nevertheless very enduring; they respire little, are susceptible of hibernation, and can remain for a considerable time shut up in a very confined place.

It is proper, however, to caution the reader against believing all that has been written about the longevity of Toads. Neither must implicit faith be given to the discovery of the living animal (Fig. 7) in the centre of stones. "That Toads, Frogs, and Newts, occasionally issue from stones broken in a quarry or in sinking wells, and even from coal-strata at the bottom of a mine," is true enough; but, as Dr. Buckland observes, "the evidence is never perfect to show that these Amphibians were entirely enclosed in a solid rock; no examination is made until the creature is discovered by the breaking of the mass in which it was contained, and then it is too late to ascertain whether there was any hole or crevice by which it might have entered." These considerations led Dr. Buckland to undertake certain experiments to test the fact. He caused blocks of coarse oölitic limestone and sandstone to be prepared with cells of various sizes, in which he enclosed Toads of different ages. The small Toads enclosed in the sandstone were found to die at the end of thirteen months; the same fate befell the larger ones during the second year: they were watched through the glass covers of their cells, and were never seen in a state of torpor, but at each successive examination they had become more meagre, until at last they were found dead. This was probably too severe a test for the poor creatures, the glass cover implying a degree of hardness and dryness not natural to half amphibious Toads. Moreover, it is certain that both Toads and Frogs possess a singular facility for concealing themselves in the smallest crevices of the earth, or in the smallest anfractuosities of stones placed in dark places.

This animal, so repulsive in form, has been furnished by nature with a most efficient defensive armature; namely, an acrid secretion which will be described farther on. It is a bad leaper, an obscure and solitary creature, which shuns the sight of man, as if it comprehended the blot it is on the fair face of creation. It is, nevertheless, susceptible of education, and 28 has occasionally been tamed; but these occasions have been rare. Pennant, the zoologist, relates some curious details respecting a poor Toad, which took refuge under the staircase of a house. It was accustomed to come every evening into a dining-room near to the place of its retreat. When it saw the light it allowed itself to be placed on a table, where they gave it worms, wood-lice, and various insects. As no attempt was made to injure it, there were no signs of irritation when it was touched, and it soon became, from its gentleness (the gentleness of a Toad!), the object of general curiosity; even ladies stopped to see this strange animal. The poor Batrachian lived thus for six and thirty years; and it would probably have lived much longer had not a Crow, tamed, and, like it, a guest in the house, attacked him at the entrance of his hole, and put out one of his eyes. From that time he languished, and died at the end of a year.

Nearly allied to the Toads, Bufo, the Surinam Toad, Pipa, holds its place. Its physiognomy is at once hideous and peculiarly 29 odd: the head is flat and triangular, a very short neck separates it from the trunk, which is itself depressed and flattened. Its eyes are extremely small, of an olive, more or less bright, dashed with small reddish spots. It has no tongue. There is only one species of Pipa, viz. the American Pipa (Fig. 8), which inhabits Guiana and several provinces of Brazil. The most remarkable feature in this Batrachian is its manner of reproduction. It is oviparous, and when the female has laid her eggs, the male takes them, and piles upon the back of his companion these, his hopes of posterity. The female, bearing the fertilized eggs upon her back, reaches the marshes, and there immerses herself; but the skin of the back which supports the eggs soon becomes inflamed, erysipelatous inflammation follows, causing an irritation, produced by the presence of eggs, which are then absorbed into the skin, and disappear in the integument until hatched.

The young Pipa Toads are rapidly developed in these dorsal cells, but they are extricated at a less advanced stage than almost any other vertebrate animal. After extrication, the tadpole grows rapidly, and the chief change of form is witnessed in the gills. As to the mother Batrachian, it is only after she has got rid of her progeny that she abandons her aquatic residence.9

The Batrachians differ essentially from all other orders of Reptilia. They have no ribs; their skin is naked, being without scales. The young, or tadpoles, when first hatched, breathe by means of gills, being at this stage quite unlike their parents. These gills, or branchiæ, disappear in the tailless Batrachians, as the Frogs and Toads, in which the tail disappears, are called. In the tadpoles the mouth is destitute of a tongue, this organ only making its appearance when the fore limbs are evolved. The habits also change. The tadpole no longer feeds on decomposing substances, and cannot live long immersed in water. The branchiæ disappear one after the other, by absorption, giving place to pulmonary vessels. The principal vascular arches are converted into the pulmonary artery, and the blood is diverted from the largest of the branchiæ to the lungs. 30 In the meantime the respiratory cavity is formed, the communicating duct advances with the elongation of the œsophagus, and at the point of communication the larynx is ultimately developed. The lungs themselves extend as simple elongated sacs, slightly reticulated on the inner surface backwards into the abdominal cavity. These receptacles being formed, air passes into and expands the cavity, and respiration is commenced, the fore limbs are liberated from the branchial chambers, and the first transformation is accomplished.

The alleged venemous character of the Common Toad has been altogether rejected by many naturalists; but Dr. Davy found that venemous matter was really contained in follicles in the true skin, and chiefly about the head and shoulders, but also distributed generally over the body, and on the extremities in considerable quantities. Dr. Davy found it extremely acrid, but innocuous when introduced into the circulation. A chicken inoculated with it was unaffected, and Dr. Davy conjectures that this acrid liquid is the animal's defence against carnivorous Mammalia. A dog when urged to attack one will drop it from its mouth in a manner which leaves no doubt that it had felt the effects of the secretion.

In opposition to these opinions the story of a lad in France is told, who had thrust his slightly wounded hand into a hole, intending to seize a Lizard which he had seen enter. In place of the Lizard he brought out a large Toad. While holding the animal, it discharged a milky yellowish white fluid which introduced itself into the wound in his hand, and this poison occasioned his death; but then it is not stated that the boy was previously healthy.

Warm and temperate regions with abundant moisture are the localities favourable to all the Batrachians. Extreme cold, as well as dry heat, and all sudden changes are alike unfavourable to them. In temperate climates, where the winters are severe, they bury themselves under the earth, or in the mud at the bottom of pools and ponds, and there pass the season without air or food, till returning spring calls them forth.

The species of this family are very numerous. MM. Duméril and Bibron state that the Frogs, Rana, number fifty-one species; the Tree Frogs, Hyla, sixty-four; and the Toads, Bufo, thirty-five. 31 They are found in all parts of the world, the smallest portion being found in Europe, and the largest in America. Oceania is chiefly supplied with the Tree Frogs. There are several curious forms in Australia, and one species only is known to inhabit New Zealand. The enormous fossil Labyrinthodon, of a remote geological era, is believed to have been nearly related to these comparatively very diminutive Batrachians.10

Sometimes called Urodeles, from ουρα, "tail," δηλος, "manifest." The constant external character which distinguishes these Amphibians in a general manner is the presence of a tail during the whole stage of their existence. Nevertheless they are subject to the metamorphoses to which all the Amphibians submit. "The division, therefore, of reptiles," says Professor Rymer Jones, "into such as undergo metamorphoses and such as do not, is by no means philosophical although convenient to the zoologist, for all reptiles undergo a metamorphosis although not to the same extent. In the one the change from the aquatic to the air-breathing animal is never fully accomplished; in the tailed Amphibian the change is accomplished after the embryo has escaped from the ovum."

Salamanders have had the honour of appearing prominently in fabulous narrative. The Greeks believed that they could live in fire, and this error obtained credence so long, that even now it has not been entirely dissipated. Many people are simple enough to believe from the Greek tradition that these innocent animals are incombustible. The love of the marvellous, fostered and excited by ignorant appeals to superstition, has gone even further than this; it has been asserted that the most violent fire becomes extinguished when a Salamander is thrown into it. In the middle ages this notion was held by most people, and it would have been dangerous to gainsay it. Salamanders were necessary animals in the conjurations of sorcerers and witches; accordingly painters among their symbolical emblems represented Salamanders as capable of 32 resisting the most violent action of live coal. It was found necessary, however, that physicians and philosophers should take the trouble to prove by experiment the absurdity of these tales.

The skull of the Land or Spotted Salamander, Salamandra maculosa, is well described by Cuvier as being nearly cylindrical, wider in front so as to form the semi-circular face, and also behind for the crucial branches, containing the internal ears. The cranium of the aquatic Salamander differs from the terrestrial in having the entire head more oblong, and they differ also among themselves.