Bach

Title: Sebastian Bach

Author: Reginald Lane Poole

Release date: June 23, 2014 [eBook #46076]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Turgut Dincer, Henry Flower and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Bach

Edited by Francis Hueffer

By REGINALD LANE POOLE, M.A.

BALLIOL COLLEGE, OXFORD

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF LEIPZIG

LONDON

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON & COMPANY

Limited

St. Dunstan’s House

Fetter Lane, Fleet Street, E.C.

| Uniform with this Volume, price 3s. each. THE GREAT MUSICIANS A SERIES OF BIOGRAPHIES EDITED BY FRANCIS HUEFFER. |

|

| WAGNER. WEBER. SCHUBERT. ROSSINI. PURCELL. HAYDN. MOZART. |

HANDEL. MENDELSSOHN. SCHUMANN. BERLIOZ. BEETHOVEN. CHERUBINI. |

| ENGLISH CHURCH COMPOSERS. | |

No one will expect a life of Bach to be amusing, but it will be my own fault if the present Essay does not offer an interest of a high and varied character. If it labours under a disadvantage, as the first biography of the master written in this country, on the other hand it is only now that, thanks to the devotion of Professor Spitta, we can congratulate ourselves on the possession of absolutely all the attainable facts. Hitherto, three translations or abridgements of German works have appeared in England; and the first is one of those books which, however incomplete, can never really be superseded. It is a translation of the “Life” of J. N. Forkel, published at Leipzig in 1802, and in London in 1820. Forkel was not only pre-eminent among the learned musicians of the end of the last century, but also the friend and scholar of Bach’s sons Friedemann and Emanuel. He presents us, therefore, with more than a masterly criticism of Bach’s science, knowing, it should seem, little beyond the organ and clavichord works: he is full of anecdotes and reminiscences of the master, all the more valuable, because told with a naïveté and freshness that stamp them at once as genuine and uncoloured.

The translation of Forkel was followed after a long interval by a volume based partly upon it, partly upon a sketch written by Hilgenfeldt as a centenary memorial in 1850. Though presumably edited by the late Mr. Rimbault, whose initials are appended to the preface, the abstract is so unfaithful and illiterate as to be practically without value. The third biography to which I have alluded is of a different character; it is a plain and conscientious abridgement of the work of C. H. Bitter, now minister of finance in Berlin, and only to be laid aside in view of the more complete materials which have been made accessible to us by Professor Spitta, and in the later publications of the Bach-Gesellschaft.

Dr. Spitta’s “Johann Sebastian Bach,” published at Leipzig in two volumes in 1873 and 1880, represents the many years’ study of a professed musician. For all the facts of Bach’s life, and all the obtainable data relative to his works, it is a final and exhaustive treasure-house. Nothing can be more scientific and workmanlike than the method with which he has exhumed and collected every detail from every source that might possibly bear upon his subject, and nothing more admirable than the warm enthusiasm which lights up his work. Practically he has left hardly anything for further research, nothing certainly that could be made use of in a short sketch like the present. When, however, I state that my facts are mainly due to him, I do not wish to imply his responsibility for a single word not covered by this admission. In criticism I give exclusively the results of an independent study of Bach’s works, which I have pursued for a number of years. Nor am I sure that Dr. Spitta would invariably approve of my arrangement of his facts, and especially of the extent to which I have drawn from the personal narrative of Forkel. In many respects, a small book demands a different treatment from a large one, and I have not restricted my freedom of choice in a sketch that can never by possibility enter into competition with Dr. Spitta’s work. My best wishes for it are that it may serve the modest aim of preparing a worthy reception for his English translation which is shortly to appear.

It would be affectation to conceal the great help in the composition of this volume which I have had from my wife, not merely in the selection of material, but even more in the judgment and taste with which she has controlled my writing.

R. L. Poole.

Leipzig, 21st March, 1882.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

| Bach’s Ancestry | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. 1685-1708. |

|

| His Youth and Apprenticeship—in an orchestra at Weimar—and as organist at Arnstadt and Muehlhausen:—Marriage | 14 |

| Early Compositions chiefly for Organ and Clavichord | 21-42 |

| CHAPTER III. 1708-1717. |

|

| Organist and Concertmeister at Weimar | 29 |

| The Organ Works | 37-42 |

| CHAPTER IV. 1717-1723. |

|

| Capellmeister at Coethen: Second Marriage | 43 |

| The Works for Clavichord, Chamber, and Orchestra | 51-56 |

| CHAPTER V. 1723-1730. |

|

| Cantor at Leipzig: the Music of Bach’s Household | 58 |

| CHAPTER VI. 1730-1734. |

|

| Bach’s Work at Leipzig | 73 |

| The Secular Cantatas | 75-80 |

| The Church Cantatas and Oratorios | 80-86 |

| The Motets | 86-87 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| The Passion Music and the High Mass | 88 |

| CHAPTER VIII. 1734-1750. |

|

| Bach’s later years at Leipzig: his Death | 103 |

| The Great Collections of Fugues | 111-116 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Characteristic of Bach: Estimation in England | 118 |

| Pedigree of Musicians in the Family of Bach | 128 |

| Chronological List of Church Cantatas | 131 |

SEBASTIAN BACH.

It is never without interest to seek out the beginnings of genius in a great man’s forefathers. The mere tracking of pedigrees has an attraction for more than will willingly confess to what is reputed mainly an innocent weakness of old age. The pursuit, however, gains in dignity when it is not only the kinship but also the intellectual growth of the family, not only the blood but also the soul, with which we have to do. In no family, perhaps, is it of greater moment than in that of Sebastian Bach, wherein his special tastes and powers all have their prophecy and preparation in a tradition where everything is musical.

From the first years of the sixteenth century—so soon, in other words, as the arising of a national religion has revealed to us the life of the German people—we have already traces of Bachs scattered among the valleys of Thuringia. There are Bachs near Arnstadt, in Erfurt, and Gotha, and Wechmar, places hereafter to be remembered in the musicalPg 2 vocations of their descendants. The ancestor of Sebastian appears, a little later, as a baker of Wechmar. This Veit Bach († 1619), named from Saint Vitus, the patron of the church there, is related to have passed some years in Hungary, and to have gone back to his home when the rigour of dominant Jesuitism made living in Hungary hard and perilous. We may here note the sole basis for the common story that the family of Bach was of Hungarian descent. Veit sold his goods and set up as a baker, and then as a miller, in his native village. He had—so Sebastian tells the tale—his chief delight in a little cithara (Cythringen), which he would take with him into his mill and play thereon while the corn was grinding. They must have sounded merrily together! Howbeit, so he learnt the sense of time; and in this wise music first came into his house. But music had already a professor among the Bachs, and it was to Caspar Bach, the town piper of Gotha, that Veit entrusted his son Hans.

Hans Bach, player and carpet-weaver, whose portrait was taken with a fiddle and a brave beard1 and ornamented with a fool’s cap, returned from his apprenticeship in his double craft, to settle at Wechmar, where he lived until 1626, when the plague killed him, with many of his kinsfolk, in middle life. His was a blithe personality, in great request in all Pg 3the places round, as much, it seems, for his hearty goodfellowship as for the help he gave the town musicians wherever he went. To three of his large family, which included apparently three Hanses and certainly two Heinrichs, he handed down, with a part of his open generous nature, that musical inheritance which in their hands grew into an artistic possession rich with the promise of greater fruit. It is worth while to stay a moment at this point to observe how deep roots music had struck into the family of Bach. For it seems that Hans had a brother whose three sons shewed sufficient excellence for the Count of Schwarzburg-Arnstadt to send them into Italy that they might complete their artistic training. Another son became the ancestor of a continuous succession of musicians, the last of whom, fourth of his line holding office in the ducal court of Meiningen, died organist there in 1846. Among this branch Johann Christian, distinguished as Clavier-Bach, a music-master at Halle, deserves commemoration from his friendship with Wilhelm Friedemann, the son of Sebastian, if only to illustrate the bond which held together the most remotely connected members of the family.

The household at Wechmar was broken up at the death of Hans, and the three brothers, Johann, Christoph, and Heinrich, separated to form new homes in other parts of Thuringia. But the intercourse of themselves and of their children was never in the least relaxed. They married into the same families, helped one another in sickness or poverty; the younger members were apprenticed to their elderPg 4 kinsfolk and often succeeded to their posts when they died; and the yearly gatherings of the entire family held their ground for a century. The closeness of this attachment merits insisting upon especially, when we consider the troubled times on which the family was thrown at its first dispersion. For the thirty years’ war in its wearisome progress makes the outward history of Germany, in the second quarter of the seventeenth century, little more than a record of battles and sieges, with scant breathing-spaces of peace, not long enough for the towns to recover from exhausting occupations of foreign troops. In this age of continued misery the foundations of German society seemed to be gradually undermined. A struggle, which added to the confusion of civil war the passion of religious hatred, threatened to dissolve the natural bonds of the family and of the race. Men sank into a blind and listless state, abandoning themselves to any vice or excess that seemed to deaden the thought of the morrow. It was therefore amid every circumstance of adversity that the Bach family grew to its full stature; and it is the more noteworthy that the latest, most learned, and most laborious biographer of Sebastian is unable to furnish a single evidence, in the entire records of his kindred, of the least deflection from the straitest paths of virtue.2

Johann Bach, the eldest of Hans’s family with whom we have to do, was apprenticed to the town piper of Pg 5Suhl, whose daughter he afterwards married, and whose son he came in time to welcome as a pupil and a kinsman in his house. He became organist at Schweinfurt, and ultimately director of the town musicians at Erfurt. It was a hard time, this of war, for musicians; but they had their meed of glory—and profit—when any peace festivities came. And Johann Bach seems to have made himself indispensable, like his father, in all the musical affairs of the place. He began, in fact, a line of musicians so indissolubly bound up with the life of the town, that more than a century later, when all the house was extinct, the town musicians of Erfurt still retained the generic title of "the Bachs." Adding to the duties of town musician those of organist to the Dominican church, he becomes a prominent forerunner in the two paths in which the genius of his family was to reach its climax. His home, also, lying equally accessible to Arnstadt and Eisenach, remained for long the centre of the greater family of the Bachs in general. It was in Johann that his youngest brother, Heinrich, found a guardian, when he was left an orphan in his twelfth year. Heinrich was not only the greatest musician of his generation, but also specially his father’s son in that kindliness and merry temper which made him as much the delight of his family as he had been of his father in his boyish days. He played in the Erfurt band until he gained the post for which nature and training had fitted him, as organist at Arnstadt, a post which he retained with increasing honour and distinction for above half a century. Of his organ works littlePg 6 remains, but we have the accordant testimony of his contemporaries to place him among the greatest organists of his time. An equal agreement acknowledges his genial lovable nature, in all its freshness and childlike gaiety, which it was beyond the power of adversity to embitter or to corrupt.

Johann and Heinrich married sisters. Both had to pass through their times of misfortune, and Heinrich’s first years of marriage were also years of great poverty. The pittance allowed him by the town of Arnstadt was irregularly paid, or not paid at all, in consequence of the immense drain upon the resources of Germany made by the continued—it seemed, the endless—war. Heinrich had to sue as a beggar to the Count of Schwarzburg. But no trouble made either of the brothers waver in their warm-hearted generosity to their kin or in their earnestness in their calling. They lived in the honourable esteem of the Thuringian towns wherein they dwelt, and left behind them a new generation to carry on and to exalt their fathers’ art and name. Each left two sons; and, by a curiously repeated custom, each of these pairs of brothers married sisters. Renown first came to the younger branch, and the skill and learning with which the sons of Heinrich were informed remains a monument of their father’s powers, as distinct and certain as if he were still known to us as a composer. Johann Christoph and Johann Michael are an astonishing phenomenon in this mid-time of national depression. Their writing has a freshness and vigour which seems to carry us back to the beginning of the seventeenthPg 7 century, when the spirit of Germany was strong and creative, or forward to the age following, when the people had again recovered its strength. Of the greater achievements of the latter time the work of Johann Christoph and Michael appears as a prelude. In the pedigree of Sebastian Bach they fade to a comparative obscurity; viewed by themselves they are luminaries of signal brilliance. Johann Christoph was more than a complete master of the musical science of his day; he was also one of the first who ventured to deviate from the rigid rules of the early contrapuntists, to make them freer, more flexible, and more significant. He is a link between ancient and modern music, blending the old church modes with the modern tonality of major and minor. Besides this, he marks an important step in the growth of dramatic music. His Michaelmas piece, The Fight with the Dragon, follows in the track of those Germans who had invented the idea of setting to music scenes from Biblical history, Schuetz and Hammerschmidt; but it goes far beyond them in command of the orchestral body, and in the genius of dramatic utterance. The sacred drama is, in his hands, clearly on the road which leads to the perfected oratorio of Handel or the no less perfected Passion music of Sebastian Bach. But the permanent interest of Johann Christoph Bach lies, even more than in his historical significance, in the beauty of his melodies and the expressiveness3 with Pg 8which he wrought them. It was Sebastian, his cousin in the next generation, who first knew how to appreciate his great predecessor. Contemporaries, however, were attracted rather by Johann Michael. But, excellent musician as he was, and gifted with a fine artistic sense, Michael failed specially in that power of expression which signalized his brother. The motets by which he is best known are deficient in symmetry. The ideas they contain are irregularly worked, and appeal to us by isolated beauties rather than by the unity of their spirit. The performance lags behind the conception. Of the instrumental works of the two brothers, works principally for the organ, and also for clavichord, there is not space to speak here. It is enough to have indicated in bare outline their general position. Their external history need only so far detain us as to notice that the elder was organist at Eisenach, the younger at Gehren near Arnstadt, and that Michael’s daughter became the wife of her cousin Sebastian.

The musical faculty grew to ripeness more rapidly in the family of Heinrich Bach than in those of either of his brothers. Johann’s sons were of course musicians, but composition first appeared in a grandson, Johann Bernhard, a man of wide capacity. He was cembalist in the Duke of Saxe-Eisenach’s band, and of such distinction as an organist, that he was chosen to succeed to the post of his illustrious cousin, Johann Christoph, at the latter’s death. He holds an honourable rank as a composer, having written orchestral suites as well as the proper productions of his office, organ-chorales.Pg 9 The latter follow somewhat directly in the steps of the famous organist of Erfurt—afterwards of Nuernberg—Johann Pachelbel, whose influence is indeed paramount over all the Bachs of his time. The orchestral works, however, have overtures which are described as equal in power and energy to some of those to Handel’s operas and as only surpassed in genius and richness by Sebastian’s own. They have the peculiar interest of existing mostly in the autograph of the latter, who transcribed and esteemed them at the period of his greatest maturity when he was cantor at Leipzig.

Leaving the rest of the musician-posterity of Johann and Heinrich Bach—and hardly a place in Thuringia or even Saxony but claimed some of them whether as organists or cantors, or in the minor arts of town piper or fiddler—we return to the brother who stands between them in age, and who is the grandfather of Sebastian. Christoph Bach, who was born at Wechmar in 1613, is the most secular of the sons of Hans. He was simply and solely a player, first in the service—menial as well as musical—of the Duke of Saxe-Weimar; then at Prettin in Saxony, where he took to him a wife; and thirdly, when he was near thirty, in the Company of Musicians in the more familiar town of Erfurt. His last years were spent in the band of the court and town of Arnstadt, where he died at the age of forty-eight, on the 14th September, 1661, his widow following him on the 8th of the next month.

Georg Christoph, his eldest son, of whom a concerted piece of church music was long preserved in the family, retreated in middle life from the immediate circle ofPg 10 the Bachs; he became cantor at Schweinfurt, and founded the Franconian branch of the continually expanding house. Next to him came two sons, twins, Johann Ambrosius and Johann Christoph, born on the 22nd of February, 1645. The coincidence of their birth was, in their case, accompanied by an almost unique identity of physical nature, character, and taste. The brothers were so alike that their own wives could not tell them apart: both adopted the family profession, and both the same instrument, the viol. Their strange psychological affinity subjected the one with the other to the same illnesses; and the elder survived the younger by little more than a year. Johann Christoph is the subject of one of the few detailed narratives which we encounter in the history of the Bachs before Sebastian; and this, if it does not seriously damage his reputation, equally does not credit him with the prudence that is characteristic of his kin. It appears that an indiscreet though innocent friendship with one of the Arnstadt maidens, accompanied, most rashly, with an exchange of rings, brought upon the young fiddler a prosecution at the hands of his would-be mother-in-law. The consistory, it is presumed, urged amends by the marriage of the parties; but Bach was firm—this is a family trait—and appealed to the higher consistory at Weimar, from which at length he obtained release from his difficulty. An experience of this sort made him hesitate before he finally decided to take a wife; and, after his marriage, misfortune—not of his own making—followed him for some years more. His place in the Arnstadt band was harassed by thePg 11 jealous persecution of the principal town musician. The Bachs of Erfurt and Arnstadt combined in a memorial in his favour, but nothing came of it. In the end the Count dismissed the entire band for indolence and disunion. Christoph, in his poverty, still helped his uncle Heinrich in the Sunday music of his church; but this brought no subsistence to his household. He was fain to go to Gehren, if he might but do some service with quiet music, whereby to support himself and his family in their need. The death of the Count at last brought them rescue, for his successor restored Bach to the posts of court musician and town piper. From this time, 1682, the musician lived in peace; but his death eleven years later left a legacy of new troubles to his widow and her five children, the eldest just ten years of age. They had a long time of poverty and sickness to struggle with, though the boy, Johann Ernst, did his best to gain a living for them in the family craft. But he was a poor musician, and fortune kept him waiting. Ultimately he got the organistship at Arnstadt vacated by Sebastian, who, himself ill-provided and on the point of marriage, left Ernst the arrears of his salary and ended his kinsman’s days of trouble.

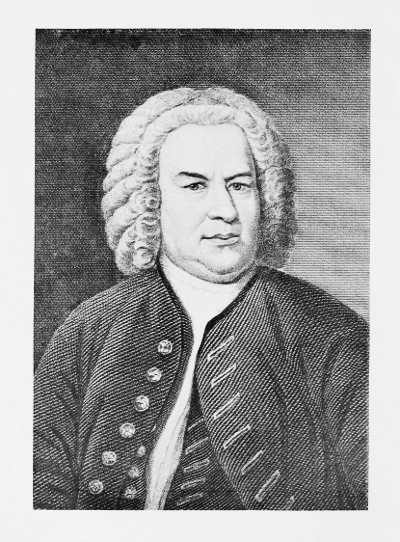

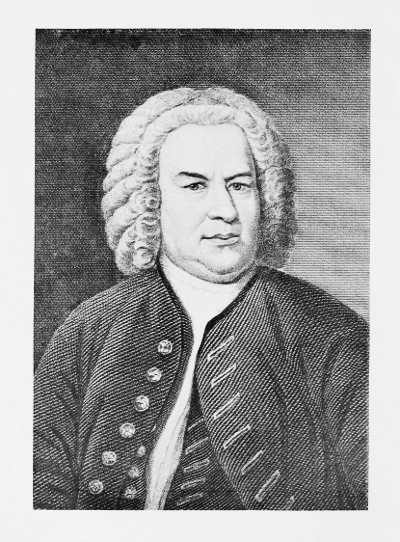

Johann Ambrosius, the brother of the unlucky Christoph, has a meagre record. He was attached to the town band of Erfurt, afterwards of Eisenach; and married twice. His first wife, Elisabeth, daughter of Valentin Laemmerhirt, a furrier of Erfurt, gave him eight children, of whom six were sons. Three of these only grew to man’s estate; the youngest is the subjectPg 12 of the present study. Ambrosius’ second marriage was followed in two months by his death, in January, 1695. Of his character we have but one solitary notice, when a funeral sermon on a weak-minded sister gave occasion to the preacher to mark the contrast with her two brothers: whom we see to be men of a good understanding, endowed with art and skill, who are well seen and heard in churches and schools, and in the common life of the town, in such wise that the work praiseth the Master. A portrait of Ambrosius, which looks down upon the precious reliques of his son in the Berlin library, is notable not only for its likeness to Sebastian but also for the simplicity of its manner. There he is, not sprucely dressed out for the occasion in wig and powder, but in plain working clothes, with brown hair and moustache. There is a certain pride in this disdain of outward decoration.

Before closing the recital of the genealogy of the Bachs, a word of notice is claimed by the Companies of Players that existed in Germany in their time, and with which they necessarily stood in close relation. The regulations of these fellowships are in some cases preserved, and are interesting memorials of the pious care which their framers took to guard against the abuses to which the musician’s craft was peculiarly exposed, to inflict the sternest penalties on profligate or irreligious conduct, and to exclude the singing or accompanying of any but virtuous music. It does not appear, however, that any of the Bachs belonged to such a company. Many of them held a better worldly position, most were better educated than the commonPg 13 town player. It is a plausible inference that their number alone served to constitute them an informal guild by themselves, of which the name was that of their family, and the only regulation that which sprang from the generosity of their nature and the close ties which knit the kin together in a common pride and emulation in their common art. Emanuel Bach, Sebastian’s son, has left us a genial picture of how the kinsmen would gather all together, at Erfurt, or Eisenach, or Arnstadt, once in the year, and there make merry. First they sang a chorale; and, this duty ended, soon turned to a medley of secular songs. The climax was reached in the quodlibet, when all joined in a sort of comic chorus. The music consisted of any scrap, no matter whether sacred or profane, that occurred to any of the assembled company. It was an improvised catch. Each man in turn gave his own part or refrain, all different and all in harmony. The words were as incongruous as the music, and every one added his own quip or jest to the general jollity. Such was the homely festival that held its place in the family life of the Bachs as late as the middle years of Sebastian’s career.

Johann Sebastian Bach was born at Eisenach on the 21st March, 1685.4 The Thuringian town had been a home of the Bachs ever since the two sons of Johann Bach had found their wives there. Two of the family, and no less men than Johann Christoph and Johann Bernhard, had successively filled the post of organist in the town church. The death of his parents, however, before he had completed his tenth year removed Sebastian from the surroundings that seemed so fitted for the training of his genius. Already he was his father’s apt pupil on the violin, and the music which was the daily occupation of the house was not lost upon the eager ears of the child. He passed from Eisenach into the care of his brother Johann Christoph, his elder by fourteen years, who was organist in the little town of Ohrdruf; and it was here, in one of the Pg 15most beautiful of the valleys of Thuringia, that the rest of his boyhood was passed. The impression of this country of soft hills and warm wooded valleys became a part of Sebastian’s nature and still lives in his music. The least attentive listener cannot mistake the inclination to a pastoral treatment which is continually appearing not in the professed Pastorales, as in the Christmas Oratorio, merely, but throughout the compass of Bach’s works; still more striking is his vein of idyllic melody, peculiarly obvious in the fine gold into which he transmuted the baser metal of the Italian aria, to illuminate his church cantatas.

At Ohrdruf Bach lived until he was fifteen, learning the clavichord from his brother, who was a pupil of Pachelbel, and apparently exciting his jealousy by the facility of his progress. A story of him tells us that he once coveted a book containing compositions by several of the great German masters, Froberger, Bruhns, Pachelbel, and Buxtehude; but the obtuseness of the elder brother forbade his venturing into studies too high for him. So the boy went every moonlit night to the cupboard in which it was shut away, and, thrusting his hand into the lattice, rolled up the volume and stealthily made his copy of it. However, when the deed was discovered, this labour of half a year was taken from him and not restored until after his brother’s death.

If Bach’s musical discipline at home left much for him to find out by himself, his education at the Ohrdruf Lyceum proceeded fairly enough and in music excellently. He learned Latin and the Greek TestaPg 16ment, with a little arithmetic and rhetoric. Of these subjects indeed Latin only had any pretence to thoroughness, and, although its range of reading did not extend beyond Cicero and Cornelius Nepos, it included a good deal of composition both in prose and verse. Very different was the musical instruction of the Ohrdruf school, which qualified the boys to furnish all the choral music of the church, besides singing motets and concerts at weddings and funerals.

Five years of this routine, and Bach left Ohrdruf. There was little more to be learned from his brother, who, with a family of his own, was no doubt glad to be rid of his charge. Accordingly he travelled, with a comrade of the school, to Lueneburg, and the lads together joined the choir of the Michaëlisschule. It seems that Thuringian boys were in special request for their musical training, as well as for the remarkable quality of their voices; and Bach’s proficiency on the violin and clavichord, added to his fine treble, placed him at once in the select Matin choir.

Lueneburg at this time enjoyed a wide repute throughout North and Middle Germany for the goodness of its musical training. There were two schools belonging to the churches of S. Michael and S. John, and the rivalry was so keen between the scholars that, when in winter time they perambulated the town—like the rude manner of our waits—it was necessary to mark out the road which each should take to avoid an unseemly wrangle. This custom of itinerant choirs, however bad for the singers’ voices, was of service in quickening the popular sympathy with music; andPg 17 the rivalry itself was useful in stimulating the ardour of the colleges. The principal work of the school of S. Michael’s was to prepare the music for the choral services of its church, two on Sundays, with motets and anthems, and, above all, high services with orchestra on the eighteen feast-days of the Lutheran kalendar. These formed the business of Bach’s life for three years. Some employment in playing or in the training of the choir must have occupied him after his voice changed, for he continued to take his commons at the free board until 1703.

All this time his general education was carried on much after the Ohrdruf pattern, with a rather wider circle of Latin authors, the Greek Testament, divinity, and logic. Higher than this the course did not go; and Bach had not the means, if he had the wish, to engage private teaching there, or to proceed to one of the universities. We shall see hereafter that he obtained an exemption from the classical work of the Thomasschule at Leipzig. At Lueneburg poverty conspired with his natural impulse to keep him closely to the profession as well as to the study of music. It was the period of his apprenticeship in the three branches in which he was afterwards to achieve a supreme excellence. At the Michaëlisschule he gained an intimate knowledge of the capacities of choral singing; he worked at the organ; and he became acquainted with the lighter instrumental music lately brought to Germany from France.

The organ claimed his chief and unremitting labour, and more than once did he journey to Hamburg toPg 18 attend the performances of Reincke, the father of North German organists. Old Reincke, as he is affectionately known—he lived well into his hundredth year and died in 1722—was a pupil of Sweelinck and one of the channels by which the learning and method of the great Amsterdam organist was diffused through the entire length of Northern Germany. From the dexterous and graceful toccatas which still attest Reincke’s powers Bach probably derived little; the principal reward of his Hamburg visits was the insight he acquired into the scope of organ composition, a lesson which he so worked out as to receive (according to a well-known story) the honourable testimony of the master himself. I thought, said Reincke, when, just before the old man’s death, Bach elaborated before him the chorale An Wasserflüssen Babylons in the true organ style, I thought that this art was dead, but now I see that it lives in you.

Bach stood in a closer connexion with a pupil of Reincke, Georg Boehm, organist at S. John’s Church, Lueneburg, and also a distinguished composer. In chamber-music as well as in the organ Bach learned much from him, but more in the manner of instrumental treatment and in the theory of composition, than by any direct influence on his writings. At this time also he made acquaintance with French music at Celle, where it had been naturalised forty years since and was now in its prime at the court of Duke Georg Wilhelm and his Huguenot consort Eléonore d’Esmiers.

A further training in instrumental music was afforded by the post which Bach held for some months after leaving Lueneburg, in 1703, in the band of Prince Johann Ernst at Weimar. But he could not long be content with the limited scope of a court violinist; and a chance visit to Arnstadt, where his grand-uncle Heinrich had founded a tradition of organ playing, but, dying eleven years before, had left no worthy successor, offered to Bach the opportunity of following out his special bent. An organ had recently been built in the new church of the town, but the burghers had not yet succeeded in finding a musician who satisfied their notion of the importance of the post. The man they had engaged they watched so jealously that he was not even trusted with the keys of his loft: one of them was deputed to receive them back from him as soon as playing was over. It is significant of the skill which Bach had already won, that he no sooner tried the organ—it does not appear, as a candidate—than the consistory welcomed in this lad of eighteen the musical heir of their honoured town organist, dismissed the incapable Boerner, and forcibly installed Bach at a triple salary augmented out of the municipal chest. On the 14th August, 1703, he took the solemn pledge of diligence and faithfulness and all that appertaineth to an honourable servant and organist before God and the worshipful Corporation.

The brilliancy of Bach’s reception at Arnstadt was transient. The New Church was a sort of chapel-of-ease to the principal church of the town; and BachPg 20 was only entrusted with the training of a small, partly voluntary, choir. His duties accordingly engrossed but a couple of hours on three days of the week, and the townspeople were well satisfied if he did not fall short in them. In this languid atmosphere he found no incitement to convince the town, by his performances, how far his hopes and ambitions exceeded those of the ordinary organist. He seems in time to have been content with a bare fulfilment of his duties, or hardly that, and to have concentrated himself in his private studies. After two years the respite of a month’s leave enabled him to visit Luebeck, the home of the illustrious organist Buxtehude; and hither a long walk of fifty leagues brought him in November, 1705.

As Reincke was a Dutchman, so Dietrich Buxtehude, who did as much, on his own lines, to establish the North German school of organists, was a Dane. He had settled in Luebeck in 1660, and the enthusiasm with which his art was attended was such that his influence remained in the town until the present century. One of the causes of his popularity was the custom which he innovated of having concerts, with a full orchestra of uncommon strength, in his church. A deeper reason was his consummate command over the organ and the important advances he made in composition.

Buxtehude stands apart from the organ composers of the rest of Germany, in the greater technical elaboration of his works. In spirit he has a single point of alliance with the organists of SouthernPg 21 Germany, in his want of sympathy with, his estrangement from, the chorale, in which the music of Middle Germany had its life. The melodic richness which this training in popular music developed in Pachelbel and Johann Christoph Bach was lacking in Buxtehude. His strength lay in pure instrumental music and was displayed specially in fugue-writing, to the development of which he contributed much, both in the combination of several themes in a fugue and in the extended function he assigned to the pedal. The form is conceived with breadth and freedom, the voices are melodiously worked together, and the harmonies are unusual in their originality, often so unusual as to seem merely discordant, harsh, restless. For if the works of Buxtehude strike one first by the massiveness, they strike no less by their inequality, their strange, erratic transitions from a sombre, often tempestuous, mood to one of tenderness and pathos.

It was at the feet of this rugged genius that Bach sat for three months; and the impress left upon his mind was distinct and durable. His fastidious censorship in later years allowed very little of his Arnstadt work to survive. A single church cantata comes down to us in the shape to which a careful revision at Leipzig reduced it5; but several instrumental works let us see how far he had advanced in composition, and two organ fugues,6 at least, how much he needed the Pg 22education of these months at Luebeck to complete the studies hitherto influenced by the school of Pachelbel. The subjects in them are ingeniously constructed, but the entire compositions are deficient in relief and coherence. They shew the earnest spirit in which he worked, but also that this earnestness acted as a weight upon the freedom and brightness of the result. Outwardly he retires under the established musical forms of his time, but even now his individuality forces itself into view. An instance of his technical immaturity is afforded by his treatment of the pedal, which, according to the universal custom except in Northern Germany, Bach used merely occasionally, limiting it to the production of sustained notes or at the most of slow progressions.7 Buxtehude, on the other hand, changed it from a capricious accessory into a real support to the manuals and often entrusted it with a brilliant solo part. In this important element of organ composition, his Luebeck visit opened a new road to Bach and a road which he was not slow to follow.8

The clavichord works that occupied his leisure at Arnstadt seem, to judge from the few specimens that Pg 23have come down to us,9 to have been chiefly of that sort of free fugue, sometimes with a humorous design, to which it was the custom to give the name of capriccio. In one of them, a sonata (No. 216, p. 12), a fugue of the most melodious conception is followed by a capriccio founded on the cackle of a hen; Thema all’ Imitatio Gallina Cucca is the macaronic title. Another (No. 208, p. 30) portrays the feelings and the circumstances attending the departure of his brother—sopra la lontananza del suo fratello dilettissimo—Johann Jakob, who went as hautboy-player in the Swedish guard of Charles XII. We have the sad gathering of the family, and their recitals of the perils that may befall the traveller in a strange land. They seek in vain to stay him, and, finding him resolute, join in a general lamento—a fine composition, by the way, written upon two ground-basses, and tenderly pathetic—ere they take leave. When the slow fare-*well is ended, the postilion makes his appearance, and the sorrow of the departure is exchanged for the lively bustle of the road, the picture ending gaily with the post-horn deftly worked into a fugue.10 This curiously Pg 24elementary form of what it is the fashion to call programme-music may appear to have been suggested by the fantastic compositions of Couperin and others, which Bach heard at Celle. But, in this regard at least, the old German Froberger was another Couperin. He is recorded to have written a suite depicting the Journey of the Count of Thurn and the Peril that came to him on the Rhine, plainly delivered before eye and ear. Probably, however, Bach’s immediate reference is to a work that had recently been published by a musician whom in after-life he was to succeed as cantor at Leipzig. Johann Kuhnau’s Biblische Historien are scenes from the history of the children of Israel presented in a series of sonatas for the clavichord. To judge by their contents it is likely that Bach took the idea of this capriccio from them, but it is significant of his insight into the unsatisfying nature of the peculiar style, that he never returned to it, unless indeed we admit a kindred basis in the rare examples of the imitation of outward emotion, which appear in his Passion music.

When Bach returned home from Luebeck, in February, 1706, his month’s holiday having expanded into three, he not unnaturally encountered the displeasure of the authorities. Summoned before the consistory, he excused himself on the ground that he had been to Luebeck with the intent to perfect himself in certain matters touching his art, and, having provided a substitute for the time, he was under no misgivings as to the discharge of his duties at Arnstadt. But heavier charges lay behind. He was to be rebukedPg 25 (to quote the pedantry of the official record) for that he hath heretofore made sundry perplexing variations and imported divers strange harmonies, in such wise that the congregation was thereby confounded. In the future, continues the Minute, when he will introduce a tonus peregrinus, he is to sustain the same and not to fall incontinent upon another, or even, as he hath been wont, to play a tonus contrarius. A witness added that the organist Bach hath at the first played too tediously; howbeit, on notice received from the superintendent, he hath straightway fallen into the other extreme and made the music too short. Evidently he had brought things into a bad way, for the next charge is, that he refused to train the choir. Bach retorted by demanding a conductor. He was allowed time to consider whether he would comply with the order of the Board or leave them to appoint some one to fill his place. Under the circumstances it shows a surprisingly gentle temper in the consistory, possibly a just appreciation of their organist’s great, however capricious, excellence, that they waited near nine months before they repeated, with some severity, the demand for an explanation. Bach agreed to furnish one; but the document has unfortunately not been preserved. It is evident, however, from the indifference with which he treated the consistory, as well as from his unwillingness to fulfil the conditions of his post, that he had already decided to resign it on the first opportunity.

The opportunity was not long coming: before the end of the year the organist’s place at S. Blasius’ Church, Muehlhausen, fell vacant. A succession ofPg 26 distinguished musicians and the various eminence of the last holder of the post, Johann Georg Ahle—perhaps also the fame of the poet’s crown with which the Emperor had decorated him—made the office an exceptionally coveted one. Among the various candidates, however, it was adjudged apparently without debate to Bach, who was even requested to make his own terms as to the salary he should receive. He modestly stipulated the same sum as he had been allowed at Arnstadt—it was indeed considerably in excess of Ahle’s salary—together with the accustomed dues of corn, wood, and fish, to be delivered without charge at his door. He asked also for a cart to bring his goods to his new house.11 These trifling details are oddly characteristic of the man, and remind us of a letter he wrote long after to a relative, thanking him for a cask of wine, but quoting the expense of carriage, and begging that the costly present might not be repeated. Just at present he had a special reason for thrift. He left Arnstadt by the end of June, 1707; in the following October, the 17th, he was married at a village near Arnstadt, to his cousin Maria Barbara, daughter of the great Gehren organist, Pg 27Johann Michael Bach. A single year after his appointment he accepted the more ambitious post of organist in the Ducal Chapel at Weimar.

His short stay at Muehlhausen had been pleasant and useful to him. He entered upon his work, which was purely that of organist, with ardour, and—in contrast with his lax performance of his duties at Arnstadt—even took a share in the training of the choir, although there was a cantor as well. The only drawback was that the pastor of his church was a strenuous pietist, one of those puritans who found, not a spiritual gain, but a worldly intrusion upon the sacredness of divine worship, in those church cantatas which it was Bach’s work to create anew. The organist held to a close friendship with his pastor’s hot antagonist at the Church of S. Mary, and seems to have gone into the neighbouring villages whenever he wished to produce music upon which he could not venture in his own church. This can hardly have been, however, the principal reason of his leaving Muehlhausen so quickly as he did. The charges of married life made his stipend barely a maintenance, even without a family. He had had enough of the subordination of a town organist. But most of all he must have been stimulated by the renown of the music at Weimar, with which he had become acquainted in an inferior capacity four years before, and the wide field it promised for the cultivation of his art in all its departments. On the 25th June, 1708, he respectfully submitted his resignation to the consistory. Their answer, requesting that his departure should not hinder his continuingPg 28 to supervise the repair of the church organ with which they had entrusted him, is evidence of the good terms on which they separated.

For the next fifteen years Bach stands in a circle of greater honour, removed from the small troubles of a town official. His return to a burgher’s life in 1723—and at Leipzig he was never free from the harass of the wiseacres of his consistory—may surprise us, unless we conclude that the experience of his intervening years had taught him that if the delights of life came more liberally in the atmosphere of a court, a great town was after all the place for him who would live laborious days.

Passing from Muehlhausen to Weimar was to Bach as the step from school to a university. The nine years of his life there produced works in which almost any other musician might glory as the perfect consummation of his powers; but when we range them beside the performance of Bach’s middle life, we see that all this time was still a period of preparation. Wonderful indeed is this strenuous preparation, carried on with increasing earnestness to his thirty-second year; this prelude to a life-long study—the index of the faithful artist—which was never relaxed until sight and strength forsook him. And no less wonderful is the growth of his genius—when we look back upon his earlier performances—revealed in rapid stages from the beginning of his sojourn at Weimar. But it was not only the years that had come upon him, but also the opportunity they brought with them, that make this change so marked an epoch in his life. Little as we know of the court of Weimar, there are some facts about its condition at this time which let us see that its intellectual atmosphere could not have been without its excitement and inspiration to Bach.

The Duke, Wilhelm Ernst, was a man of naturallyPg 30 grave and religious character. It is told of him that at eight years old he preached a sermon before his parents and their company; and in later life his chief pleasure and occupation lay in building churches, organizing religious schemes, and founding schools. In the troubles of an unhappy marriage and the approach of a childless age, his serious temper deepened into austerity. But, if always averse from gaiety or the least approach to the wonted dissipations of a court, he was a good friend to arts and letters; and the forty-five years of his rule began the tradition of culture which led up to the historical era in the annals of Weimar a century later. He founded the library, had a collection of coins, and—what is more to our purpose—took a strong and pious delight in hearing and fostering the music in the castle chapel.

The strict and sombre discipline which the Duke imposed upon his homely court—it went to bed, we are told, at eight in winter, and only an hour later in summer—was relieved by the brighter influence of his brother, Johann Ernst, the prince with whom Bach had taken service as a violinist in 1703. He died in 1707, but his son, also Johann Ernst, inherited his father’s taste for the chamber-music of France and Italy, and showed himself in his short life a composer of promise. The boy liked to be surrounded by musicians, to take lessons from them, and hear his favourite music. At the present time there was a brilliant circle at Weimar, and in this the prominent figures were the town organist Walther, known for his Musical Dictionary, and Bach. A famous story connects the two. Bach, we are told, had boasted ofPg 31 his ability to play anything at first sight, and Walther determined to baffle him. He asked him to breakfast, and, knowing Bach’s habits, laid among the music upon the clavichord a piece of simple and innocent appearance. While the meal was making ready the host leaves the room. Bach comes upon the piece, tries it and halts, begins again, and breaks down. Then he leaves the instrument in exasperation, shouting to his friend, No, one cannot play everything off: the thing is impossible.

Of the routine of Bach’s life at Weimar we can only gather the outline. He held the double post of organist and musicus in the court. The latter function involved in Bach’s case either taking a fiddle in the orchestra—a band of sixteen performers all attired in a grotesque uniform of Hungarian heyducks—or accompanying from the basso continuo on the harpsichord (cembalo). When after some years he was appointed concertmeister he of course took the place of first violin. He was now required to supply a certain number of church compositions; and the age of the capellmeister often added to his duties the task of conducting. The series of church cantatas written at this time—among which the magnificent one, Ich hatte viel Bekümmerniss, stands preëminent—are sufficient evidence of the energy with which he applied himself to his additional duties. If we ask how he lived in his household—and no man lived more than Bach in the life of his home—we are answered by a blank. We have not even a clue as to the manner of woman his wife was. Six of her seven children were born at Weimar, and two, twins, died there inPg 32 1713. The names of the sponsors to them show the varied popularity Bach had gained among the different ranks with whom he was thrown. Pages in waiting and a Muehlhausen clergyman appear beside Bach’s kinsfolk or his professional comrades—Telemann is among them—or the humbler associates of his early life at Ohrdruf or Arnstadt. His continually increased salary—it never indeed exceeded some thirty pounds, added to the usual perquisites paid in kind—is one of the many signs of his being valued. More significant is the request he was in as an organist throughout Saxony, and even in a wider circle. He was always being invited to try or inspect organs, to play at different courts and attend musical celebrations, till it came to be a yearly practice with him to break the busy monotony of his Weimar life by a holiday spent in answer to these various calls. Some accounts that remain of these journeys are the more interesting since they are the only record, outside his compositions, of these years.

In 1713 he was at Halle, and so much attracted by the quality of a new organ then building as to offer himself for the organistship. The consistory eagerly accepted him, and Bach composed a cantata on the spot, and brought it out as a testimonial. The documents of office quickly followed him back to Weimar for signature. But Bach was dissatisfied with the terms, possibly the Duke had persuaded him to stay at the castle; in any case, he wrote a courteous letter asking for some changes in the conditions of the post. The church authorities were indignant, refused to alterPg 33 a word in the agreement, and hinted, quite falsely, that Bach had merely played with them in order to get an increase of pay at Weimar. Bach wound up the correspondence by a vigorous and dignified defence of his action; and it is pleasant to know that peace was tacitly re-established by Bach’s accepting a flattering invitation to play upon that same organ on its completion in 1716.

Another autumn journey of Bach took him to Cassel (1714), where he played a pedal solo on the organ, a feat of miraculous agility, which few, one relates, could equal with their hands. The hereditary prince, who was present, took a precious ring from his finger and expressed by the oriental gift his admiration of the performance.12 Other years Bach went to Leipzig, perhaps to Meiningen, and his excursions from Weimar end with the celebrated visit to Dresden. Just before this, in 1716, Mattheson, one of the most influential musical critics of his day, had asked for his biography, and wrote of him as the renowned organist; in the following year his mere name vanquished a redoubtable harpsichord-player, Marchand, who had never before been confronted by an equal. The Frenchman was so popular at the Dresden court that some friends of Bach in the orchestra there seem to have induced the German master to stand forward in defence of his national music. It is certain that a challenge was sent to Marchand, and that a large company awaited the contest of the pianists in the Pg 34house of one of the royal ministers. Bach was there, but not Marchand. After long expectation, a messenger at last was sent to his lodging, only to bring back the news that he had left Dresden by express post that morning. No defeat could be more decisive, especially when we remember that Bach’s fame had hitherto rested upon his consummate powers as an organist. It may be added that he was so far from being prejudiced by his personal relations with Marchand that he always valued the gracefulness and exuberant variety of the French composer; and Adlung, who tells the story, says that he only once was able to appreciate his music, and that was when Bach played it to him. Success never affected Bach’s judgment: his generosity was always without vanity.

In leaving Weimar in 1717, Bach ceased for ever to be by calling an organist, though the instrument remained always his chief delight, and once at least he was tempted again to resume it as a profession. As a performer he seems to have grown every year in mature strength. In 1720, when he visited Hamburg, his performance at S. Katharine’s Church was attended by the aged organist, Reincke, and an assemblage of many of the principal men of the city. How he impressed Reincke has already been related, and no doubt it was partly the enthusiasm with which he was greeted that made him view Hamburg as a congenial home for him. An organistship was vacant at one of the other churches there, and Bach directly offered himself for the place. He had to leave before the trial of the candidates took place, but was so eager for the apPg 35pointment that he wrote from Coethen to repeat his willingness to accept it. The post as it turned out, was given to the man who paid the highest premium, and Mattheson was not the only man in Hamburg who expressed indignation at the well-to-do tradesman’s son, who could prelude better with dollars than with fingers, being preferred to the great virtuoso whose mastery excited the admiration of every one. Neumeister, who was chief preacher of the church, took occasion to remark in a sermon just after, that he was sure enough that if one of the angels who sang at Bethlehem were to come down from heaven and play divinely and desire to be organist of S. James’s, nevertheless if he had no money he might as well fly back again straight.

There are constant and innumerable proofs, besides the few we have noticed, of the impression Bach made as an organist: not the least striking among these is a note by Gesner, with whom Bach was closely connected in later years at Leipzig, illustrating a musical passage in Quintilian. After describing in vigorous rhetoric the almost superhuman powers of his friend, he adds, Though none can surpass me in my support of the ancients I opine that many Orpheuses and twenty Arions are comprehended singly in my Bach and any, if such there be, like to him.13 The characteristics which gave Bach his quite unique position as an organist are partly those of an extraordinary originality in the application of the mechanical resources of the instrument. How minutely he knew its structure is shewn by the frequency with which he was chosen, almost from boyhood, to pronounce upon the necessity and the Pg 36detail of repair in organs, and to judge the success of the result. His arrangement of stops before he played was so singular as to make connoisseurs absolutely incredulous of the possibility of so producing harmonious combinations, but when he began the doubt was changed into amazement at the swiftness, the precision, and the power of his movements both of feet and hands. If, however, a by-stander expressed astonishment, he would silence him with quiet modesty. There is nothing to wonder at in that, he would say: you have only to touch the right key at the right time and the instrument plays itself. As a rule he gave the pedal a real part of its own, often of incredible difficulty; and by this means he left his hands free to develop the theme in the broadest manner, and to apply the stops, each as it appeared most appropriate and characteristic, with wonderful insight and ingenuity. He liked also to use the pedal to announce a tenor part whenever (as was the case at Weimar) he could find a four-foot register. Of difficulties he seemed unconscious, and this was equally true when he was elaborating a simple bass or a chorale, or improvising a fugue, as when he was playing from a written score. Indeed Forkel, who knew Bach’s sons, relates that “his unpremeditated voluntaries on the organ, where nothing was lost in writing down, are said to have been still more devout, solemn, dignified, and sublime,” than those which stand in record of his supreme command of the instrument. Forkel instances Bach and the son to whom his gifts were transmitted in a special measure, Wilhelm Friedemann, as solitary examples of consummate skill equallyPg 37 on clavichord and organ. “Both,” he says, “were elegant performers on the clavichord; but when they came to the organ, no trace of the harpsichord-player was to be perceived. Melody, harmony, motion, &c., all was different, that is, all was adapted to the nature of the instrument and its destination. When I heard Will. Friedemann on the harpsichord, all was delicate, elegant, and agreeable. When I heard him on the organ, I was seized with reverential awe. There, all was pretty; here, all was grand and solemn. The same was the case with John Sebastian, but both in a much higher degree of perfection. William Friedemann was here too but a child to his father, and most frankly concurred in this opinion.”14

I have already taken occasion to trace the studies by which Bach prepared himself to become the greatest organ composer as well as the greatest organist of all time. At the present break in his life it will be convenient to give a summary account of his total production in this department,15 though it must be little more than an enumeration of the works that survive; since organ music least of all lends itself to any but a scientific analysis, such as would be altogether out of place here. My references are to the compositions contained in the Fifth Series of Peters’ collected edition of Bach’s instrumental works.16

Bach’s organ works divide themselves into three great branches, the first of which is connected most closely with his religious office. It is well known that the German chorale since the days of Luther has always held its regular place in the service of the church. This form of melody, however much more beautiful, is essentially the same with what we in England used to sing as psalm tunes, at a time when one metrical version of the Psalter was employed and the modern hymn with its new words and heterogeneous structure had not yet made its voice heard. In Germany words and music were alike familiar to every one; they formed in fact the nucleus of Lutheran worship both in church and at home. We shall see hereafter how Bach collected two hundred and forty chorales for use in his household; and there are hardly any of his church cantatas which do not contain at least one. In church, whenever a chorale was announced, every one present could be trusted to sustain the melody, and it was allowed to the organist to vary the harmonies almost to any extent he pleased without fear of confusing the people.17 In this way it came to be a recognised part of the organist’s function, at least in Middle Germany, to adorn the simple grandeur or pathos of the chorale by means of preludes, interludes, and variations, generally improvised at the moment; and this treatment of chorales was so popular, through the influence of Johann Christoph and Michael Bach, Pachelbel, and a number of leading organists just before Sebastian Pg 39Bach’s time, that it became extended so as to form the basis of independent instrumental compositions, for use at other intervals in the church service. It was a custom of which Bach was peculiarly fond, giving him, as it did, a firm groundwork, with high associations, upon which his fancy could build with the utmost freedom. And though he wrote down but a minute part of what he composed, we possess in print no less than a hundred and thirty elaborations of chorales (parts 5-7), besides twenty-eight of which the genuineness is disputed (suppl. 9-36). They range from short and slight preludes to works of the most intricate brilliancy, abounding in all the science as well as in all the melodious art of which Bach was master. Those to whom the organ chorales are inaccessible may learn their spirit by unravelling the harmonies he has used in the fivefold setting of one chorale in the S. Matthew Passion or from other no less remarkable instances in that according to S. John, to quote only from works which are best known in England. The inexhaustible invention which is pressed into the brief compass of these verses, is in the organ-chorales distributed over a long composition; but the extension is never for the purpose of display, and the fundamental motive insistently maintains itself throughout.

In opposition to these the second branch of Bach’s organ works stands remote from the church. It was not choice only but also the determined bent of musical taste at Weimar that directed his study again to the instrumental music of Italy; and the influence for the present lay strongly upon his organ music as well asPg 40 upon the rest of his compositions. Three of Vivaldi’s violin-concertos with a movement of a fourth (part 8, 1-4) he arranged for his instrument; he wrote fugues on themes by Legrenzi and Corelli18 (4. 6, 8), and a fugue and canzone (8. 6; 4. 10) recalling the manner of the great Roman organist, Frescobaldi, whose Fiori Musicali, published in 1635, he possessed.

But it would be a great mistake to imagine that Bach was at this time engrossed by the Italian masters. On the contrary Weimar was the place where he wrote the bulk of his organ works of the third branch, the preludes, fantasias, toccatas, and fugues, in which his strong religious sense united with his power of musical creation to build up masterpieces of a perfection never approached either before or since. The list of his works of this period is as follows:—

1. Three Preludes, in A minor, C, and G (4. 13; 8. 8, 11):

2. Three Fugues, in G minor, C, and G minor (4. 7; 8. 10, 12):

3. Fifteen Preludes and Fugues in A, F minor, C minor, G minor, E minor, C, G, and D; besides a collection of eight shorter ones (2. 3, 5, 6; 3. 5, 10; 4. 2, 3; 8. 5. i-viii.):

4. Three Toccatas and Fugues, in F, C, and D minor (3. 2, 8; 4. 4):

5. Two Fantasias and Fugues both in C minor (3. 6; 4. 12): to which must be added three single works, namely a Fantasia in C (8. 9); a Pastorale in F (1. 3); Pg 41 and the superb Passacaglio in C minor, well known to all organists worthy of the name (1. 2).

For the years succeeding those he spent at Weimar, Bach has left us, with one grand exception, no certain record on the organ; we shall see hereafter that he was otherwise occupied. But there is hardly a doubt that he took advantage of the exceptional opportunity offered by his Hamburg visit in 1720, to produce his famous Fantasia and Fugue in G minor (2. 4). It does not surprise us to find that the Fugue, which English musicians have personified as the Giant, left an abiding impression among the listeners.19 As we possess it, it has undergone a rigorous revision, to which, in common with the major part of his younger works, Bach afterwards submitted it when at Leipzig.

Accordingly the short series which he is believed to have composed in later years does not represent more than a fraction of his activity in this direction; since revising in his case usually meant re-writing, certainly re-thinking. The compositions which are presumed to date originally from the year 1723 onwards, consist of seven Preludes and Fugues, in C, G, A minor, E minor, B minor, E flat, and D minor,20 (2. 1, 2, 8, 9, 10; 3. 1, 4), and a Toccata and Fugue in D minor, known as the Doric toccata (3. 3); together with six Sonatas written Pg 42to exercise the growing skill of Bach’s eldest boy, Wilhelm Friedemann (1. 1).21

It is impossible to characterise in a few words the works which gave Bach his chief renown among contemporaries, and the familiarity of many of the greatest of them renders such an attempt unnecessary. It may suffice to direct attention to the majestic motion of the august Passacaglio, as contrasted with the idyllic grace of the Pastorale which follows it in the printed edition, and which remains lamentably a fragment;—to the broad directness of the Fugue in C (2. 1), the daring invention of the longest of the fugues, that in E minor (2. 9), which proceeds almost entirely by chromatic intervals, the irresistible charm of the G minor, or the marvellously varied solemnity of the E flat, naturalised in England as the S. Ann Fugue. It is as an organ composer that Bach stands, as a colossus, absolutely unapproached and unapproachable.

The reasons which determined Bach to leave Weimar are not quite clear. He was in fact one of those quick-tempered men whom a small irritation might kindle to a resolve of disproportionate gravity. In the present case he had a real grievance in the appointment of a son as successor to the old capellmeister, whose work Bach had done for a long time and the reversion of whose office he might reasonably have counted upon. Leopold, the reigning prince of Anhalt-Coethen was no stranger at Weimar. A family alliance connected the two courts, and it is likely that he had heard Bach there. In any case Bach was known to him by report, and in 1717 was invited to take the post of capellmeister at Coethen.

The six years that Bach spent in the service of this prince make a kind of pause or breathing-space in his life. It is not that he was idle during this period: his work was different. He had, as it were, stepped aside from the road upon which he had journeyed all the years of his manhood, to follow a by-lane where he might loiter if it pleased him. And if this short abandonment of his peculiar art, dedicated to the service of the church, in favour of the writing of suites for strings or clavichord, hardly needs apology, it remains rePg 44markable that Bach consented to take a position in which church music or even organ-playing had no place. In no one of the three churches in Coethen had he any control; perhaps he was not sorry in the present case, since two of them, with the bulk of the population, belonged to (his special aversion) the reformed or Calvinistic sect.22 The Castle Church could boast but an indifferent organ and was unprovided with a choir; so that even had Bach wished to overstep the limitations of his duty, there were no opportunities, but rather discouragement, in Coethen for him to return to his old work.

He was designated Capellmeister and Director of his Highness’s Chamber Music, but in the peculiar situation of the Coethen court the title imperfectly describes the nature of his post. Leopold was a young bachelor who gave to music the loving worship he had not yet consecrated to a woman. He cultivated his art with an eager enthusiasm, sang a full bass, and was no mean performer on violin, viola-da-gamba, and clavichord. He welcomed Bach as a brother in the craft, and not only employed him to compose for his varied requirements, but took him into his familiar fellowship,23 played with him, sang with him, insisted on his company whenever, as was his habit, he journeyed abroad.

Before this he had learned some knowledge of the world, had travelled in England and Italy, and made acquaintance with the music of Rome and Venice. For the future we find him and Bach making repeated visits to Karlsbad and other distant places, and the obedient capellmeister sometimes perhaps a little ennuyé, if we may credit a story which relates that on one of these journeys he consoled himself for the lack of all musical instruments by striking off the greater part of the Wohltemperirte Clavier. The incongruous performance recalls the tale of the famous printer, Henry Estiennes, that he divided the New Testament into verses, the verses which we still retain, on a ride from Paris to Lyons.

In spite of the widened experience, it was in truth a narrowing life to Bach. He was not one of a musical group as at Weimar; there is no record of his having any friends in the place. If he had the pleasantness of the grateful appreciation of the Prince, he had no public to sustain his ambition. His days were divided between his house and the music-room of the castle; and he only came into contact with the musical society outside by the custom which he still maintained of employing his holiday in the autumn to visit towns where he was known, where he was invited to try organs and exhibit his skill, or to produce occasional cantatas. Once he went to Leipzig to prove the new organ at the University Church, another time, as has been already mentioned, to Hamburg. Once again he travelled to Halle in the hope of making Handel’s acquaintance, but just missed him.

A visit with Prince Leopold to Karlsbad in 1720,Pg 46 was sadly memorable to Bach. For while he was on his way home and no news could reach him, his wife suddenly fell sick and died. He arrived only to learn that she was already buried. How deep a grief this was to the family—the mother was but thirty-five—we know from the recollection of it which the second son, Philipp Emanuel, then a child of six, bore more than thirty years later. His tender, flexible nature reflected hers closely, as his elder brother Friedemann’s robust vigour did that of his father. And the fact that the two most striking figures, as also the most musical, among Bach’s twenty children sprang from this marriage may be taken in evidence of the near sympathy subsisting between the parents. Else we know nothing of Maria Barbara, and one is apt to depreciate her by comparison with the more gifted woman whom Bach chose for his second wife.

His care was now mainly for the children, four of his seven alone surviving their infancy. The eldest was a daughter, Katharina Dorothea, whom we shall hereafter meet again as helping with her voice in the family concerts; then came three sons, the two already mentioned, and Johann Gottfried Bernhard.24 It was Wilhelm Friedemann, now a lad of ten, who claimed his father’s most anxious attention; and never was a charge fulfilled with greater love and willingness. In later life Bach’s relation to him was one of intimate friendship; already the promise of his musical skill aroused the keenest hopes of his father. He showed Pg 47afterwards that he had all the characteristics of Sebastian accentuated: stolid independence was carried into wilful obstinacy, hotness of temper into a confirmed irascibility, morose when not violent. At present he was only the hopeful eldest son, for whose sake Bach developed a complete scheme of musical training, beginning with a Clavier-Büchlein of easy pieces, as early as January, 1720. There is an air of tenderness for the small fingers he loved, and longed to educate, in the ladder of difficulties he so carefully constructed, and in the little preface, in nomine Jesu. This was followed by Inventions in two and three parts, designed to cultivate an equable strength and free motion in all the fingers. The title was apparently chosen to indicate that beyond this he sought to teach in these pieces the elements of musical taste, invention in the scholastic sense being a compound of just disposition of the members and appropriate expression.25 The third stage in the course of instruction was constituted by the preludes and fugues of the Wohltemperirte Clavier, in which technical execution is combined with beauty of form and expression, each in its finest development. One of the points on which Bach insisted was that the practice of the clavichord should from the outset go hand in hand with composition. He assumed that no one should learn to play who could not think musically, as he expressed it; and he never allowed a pupil to compose at the instrument. He would not, he said, have him to be a piano-hussar, a taunt that might well be taken to heart by some of our modern composers. A Pg 48parallel system of training for the organ was also primarily intended for Friedemann; and both alike shew the clearness and penetration with which Bach understood the functions of a teacher.

In after-years the rector of his school at Leipzig, between whom and Bach there was no love lost, said of him that he was a bad teacher and could not keep order in class. The latter is likely enough, and the former may not be without foundation in the particular case. A man of Bach’s extreme sensibility would certainly appear at his worst in the irritating surroundings of a rude schoolroom. That he could teach, however, and teach better than any man of his time, is proved by the string of distinguished names that appear among his scholars and by the unbroken succession of pupils whom he had in his house from his marriage almost to his death, the applicants increasing in his later days until he was continually forced to turn them back. To his chosen pupils he was kind and genial, and full of encouragement. You have five as good fingers on each hand as I have, was his answer to complaints of difficulty. He never set himself up as a model to which others could not attain: I was obliged, he would say, to be industrious; whoever is equally industrious will succeed as well. From these glimpses of his bearing we may readily conceive the love and enthusiastic reverence which he aroused in his pupils, and as for his irritability, the common failing of great artists, experience shews that at least it does not make a man a bad teacher in private, however much it may militate against his success in a school.

Bach did not remain long a widower. The tradition of his ancestors contained no law requiring a year of mourning; indeed his father married again in seven months. Sebastian was more patient, waited nearly a year and a half, and chose wisely. His new wife, Anna Magdalena Wuelken, held a position as singer at the Coethen court; her father was trumpeter in that of the Duke of Saxe-Weissenfels. She was twenty-one, fifteen years younger than her husband.

The marriage, which took place on the third of December, 1721, was entirely happy. Anna Magdalena proved herself no mere hausfrau, but a real companion to Bach in all his tastes, a helper in work and a sharer in all his pleasures. She had a fine soprano voice, for which her husband delighted to arrange songs and recitatives. Often she copied them out for herself, and besides this her clear well-formed hand, closely resembling Bach’s, occurs constantly in the collections of his manuscripts. On his side he helped her to master the clavichord. Two Clavier-Büchleins, written for her, exist in his autograph, and to judge by their handsome bindings and the inscriptions in them, were intended as gifts to her, one just after their marriage, in 1722, the other in 1725. She used and added to them afterwards as a sort of album. They contain a great part of what we now know as the French suites, with a variety of preludes, arrangements of airs from his cantatas, &c., and also a set of rules for thorough-bass. It is plain that if the one was an indulgent teacher, the other was a ready and diligent pupil.

The beginning of Bach’s new happiness was soon attended with an unexpected drawback. Prince Leopold married a week after his capellmeister, and from this time forth his interest in music declined. His wife, so unlike Bach’s, cared nothing for music the concerts were still attended, but no longer listened to, and Bach’s work became more and more irksome to him. He had no outside public to take the place of the now indifferent court. He continued, however, for a year, until the death of Kuhnau, the learned and original cantor of the Thomasschule at Leipzig, offered to him an opportunity of returning to that work in the service of the church for which he must have longed all these years. He left Coethen in the summer of 1723, having first composed two church cantatas, as evidence of his fitness for the post. It is probable that, in the hope of the election taking place before Easter, he wrote the S. John Passion Music to grace his arrival, as though to prove that the divorce from sacred music which he had supported for so long a time had made his fertility and creative force only the more abundant. But the delay of the Leipzig authorities postponed the production of this masterpiece. By a coincidence the Princess of Coethen, the determining course of Bach’s removal, died just before he left. Perhaps for the moment he regretted the step he had taken: to us that step is the most fortunate act in his life and the herald of his greatest triumphs.

As we considered the Weimar time as representative of Bach’s career as an organist, so Coethen is the scenePg 51 of his most extensive production for the clavichord, for the chamber, and for the orchestra. We may therefore here enumerate the compositions that belong to these classes, reserving for the present the great collections of fugues contained in the Wohltemperirte Clavier, of which the second half falls under a later date when the first was alone entirely rearranged and partly rewritten, and the Kunst der Fuge which was the achievement of Bach’s last years.

The clavichord works admit of a double classification. On the one hand we have independent compositions, of which the idea is mostly derived from the organ-style; on the other stand the suites, or sets of pieces in dance-measures, which are moulded upon Italian models. Both alike are adapted by Bach to the clavichord in such a manner that they are completely naturalised in their new-found country. To the former class belong the following works arranged in conformity with Dr. Spitta’s critical results; the numbers refer to Peters’ cheap edition:—

A. Weimar Period.

1. Four Fantasias, in D, A minor, G minor, and B minor (211, p. 28; 215, pp. 3, 30; 216, p. 9):26