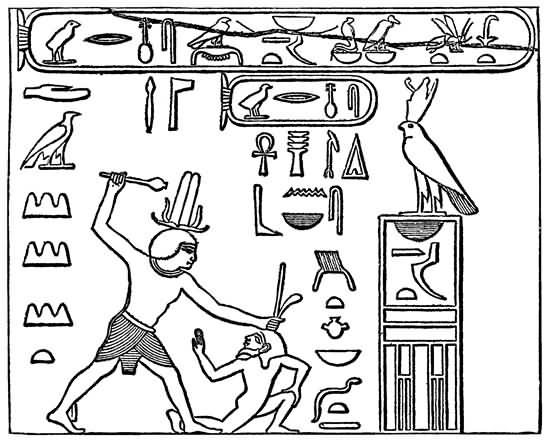

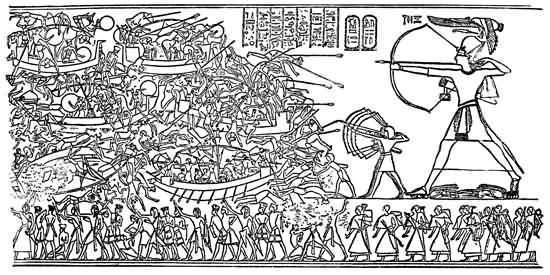

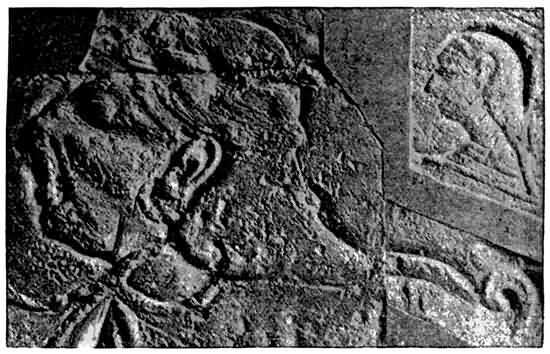

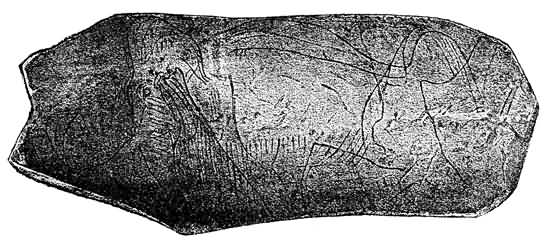

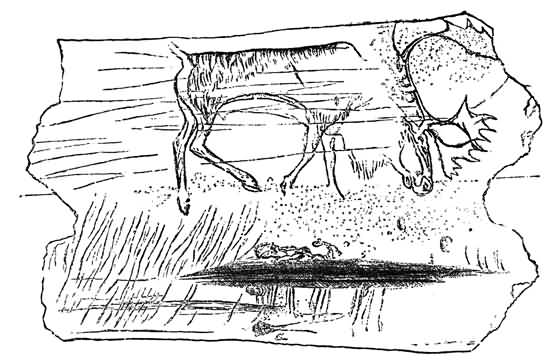

TABLET OF SNEFURA AT WADY MAGERAH.

(The oldest inscription in the world, probably 6000 years old. The king conquering an Arabian or Asiatic enemy.)

Title: Human Origins

Author: S. Laing

Release date: July 23, 2014 [eBook #46379]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Marilynda Fraser-Cunliffe, Mary Akers and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive)

HUMAN ORIGINS

HUMAN ORIGINS.

Published July 1892, 1500 copies.

Reprinted August 1892, 1500 copies.

Reprinted September 1892, 2000 copies.

BY

S. LAING

AUTHOR OF

"PROBLEMS OF THE FUTURE," "MODERN SCIENCE AND MODERN THOUGHT,"

"A MODERN ZOROASTRIAN," ETC.

With Illustrations

FIFTH THOUSAND

CHAPMAN AND HALL: Ld.

1892

[All rights reserved]

Richard Clay & Sons, Limited,

London & Bungay.

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | 1 |

| PART I.—Evidence from History. | |

| CHAPTER I. EGYPT. |

|

| Historical Standard of Time—Short Date inconsistent with Evolution—Laws of Historical Evidence—History begins with Authentic Records—Records of Egypt oldest—Manetho's Lists—Confirmed by Hieroglyphics—Origin of Writing—The Alphabet—Phonetic Writing—Clue to Hieroglyphics—The Rosetta Stone—Champollion—Principles of Hieroglyphic Writing—Language Coptic—Can be read with certainty—Confirmed by Monuments—Manetho's Date for Menes 5004 b.c.—Old, Middle, and New Empires—Old Empire, Menes, to end of Sixth Dynasty—Break between Old and Middle Empires—Works of Twelfth Dynasty—Fayoum—Thirteenth and Fourteenth Dynasties—Hyksos Conquests—Duration of Hyksos Rule—Their Expulsion and Foundation of New Empire—Conquests in Asia of Seventeenth and Eighteenth Dynasties—Wars with Hittites and Assyrians—Persian and Greek Dynasties—Summary of Evidence for Date of Menes—Period prior to Menes—Horsheshu—Sphynx—Stone Age—Neolithic and Palæolithic Remains—Horner, Haynes, and Pitt-Rivers | 5 |

| CHAPTER II. CHALDÆA. |

|

| Chronology—Berosus—His Dates mythical—Dates in Genesis—Synchronisms with Egypt and Assyria—Monuments—Cuneiform Inscriptions—How deciphered—Behistan Inscription—Grotefend and Rawlinson—Layard—Library of Koyunjik—How vi preserved—Accadian Translations and Grammars—Historical Dates—Elamite Conquest—Commencement of Modern History—Ur-Ea and Dungi—Nabonidus—Sargon I., 3800 b.c.—Ur of the Chaldees—Sharrukin's Cylinder—His Library—His Son Naram-Sin—Semites and Accadians—Accadians and Chinese—Period before Sargon I.—Patesi—De Sarzec's find at Sirgalla—Gud-Ea, 4000 to 4500 b.c.—Advance of Delta—Astronomical Records—Chaldæa and Egypt give similar results—-Historic Period 6000 or 7000 years—and no trace of a beginning | 42 |

| CHAPTER III. OTHER HISTORICAL RECORDS. |

|

| China—Oldest existing Civilization—but Records much later than those of Egypt and Chaldæa—Language and Traditions Accadian—Communication how effected. | |

| Elam—Very Early Civilization—Susa, an old City in First Chaldæan Records—Conquered Chaldæa in 2280 b.c.—Conquered by Assyrians 645 b.c.—Statue of Nana—Cyrus an Elamite King—His Cylinder—Teaches Untrustworthiness of Legendary History. | |

| Phœnicia—Great Influence on Western Civilization—but Date comparatively late—Traditions of Origin—First distinct Mention in Egyptian Monuments 1600 b.c.—Great Movements of Maritime Nations—Invasions of Egypt by Sea and Land, under Menepthah, 1330 b.c., and Ramses III., 1250 b.c.—Lists of Nations—Show Advanced Civilization and Intercourse—but nothing beyond 2000 or 2500 b.c. | |

| Hittites—Great Empire in Asia Minor and Syria—Turanian Race—Origin Cappadocia—Great Wars with Egypt—Battle of Kadesh—Treaty with Ramses II.—Power rapidly declined—but only finally destroyed 717 b.c. by Sargon II.—Capital Carchemish—Great Commercial Emporium—Hittite Hieroglyphic Inscriptions and Monuments—Only recently and partially deciphered—Results. | |

| Arabia—Recent Discoveries—Inscriptions—Sabæa—Minæans—Thirty-two Kings known—Ancient Commerce and Trade-routes—Incense and Spices—Literature—Old Traditions—Oannes—Punt—Seat of Semites—Arabian Alphabet—Older than Phœnician—Bearing on Old Testament Histories. | |

| Troy and Mycenæ—Dr. Schliemann's Excavations—Hissarlik—Buried Fortifications, Palaces, and Treasures of Ancient Troy—Mycenæ and Tiryns—Proof of Civilization and Commerce—Tombs—Absence of Inscriptions and Religious Symbols—Date of Mycenæan Civilization—School of Art—Pictures on Vases—Type of Race | 66 |

| CHAPTER IV. ANCIENT RELIGIONS.vii |

|

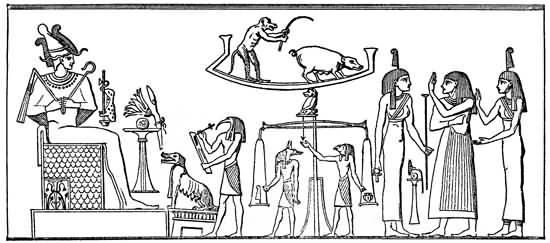

| Egypt—Book of the Dead—Its Morality—Metaphysical Character—Origins of Religions—Ghosts—Animism—Astronomy and Astrology—Morality—Pantheism and Polytheism—Egyptian Ideas of Future Life and Judgment—Egyptian Genesis—Divine Emanations—Plurality of Gods and Animal Worship—Sun Worship and Solar Myths—Knowledge of Astronomy—Orientation of Pyramids—Theory of Future Life—the Ka—the Soul—Confession of Faith before Osiris. | |

| Chaldæan Religion—Oldest Form Accadian—Shamanism—Growth of Philosophical Religion—Astronomy and Astrology—Accadian Trinities—Anu, Mull-il, Ea—Twelve great Gods—Bel-Ishtar—Merodach—Assur—Pantheism—Wordsworth—Magic and Omens—Penitential Psalms—Conclusions from | 105 |

| CHAPTER V. ANCIENT SCIENCE AND ART. |

|

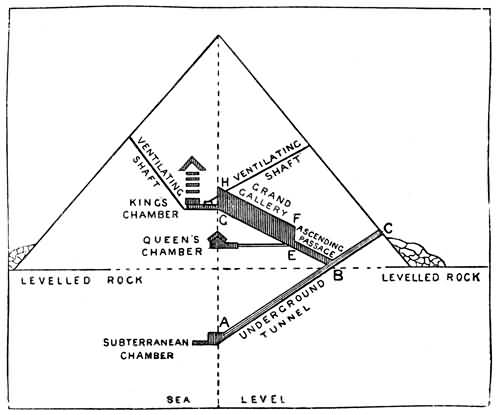

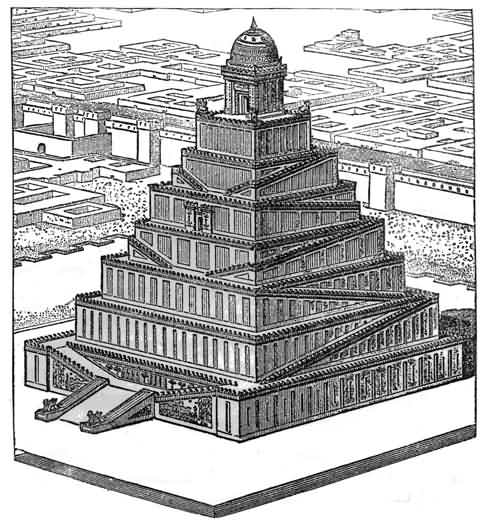

| Evidence of Antiquity—Pyramids and Temples—Arithmetic—Decimal and Duodecimal Scales—Astronomy—Geometry reached in Egypt at earliest Dates—Great Pyramid—Piazzi Smyth and Pyramid-Religion—Pyramids formerly Royal Tombs, but built on Scientific Plans—Exact Orientation on Meridian—Centre in 30° N. Latitude—Tunnel points to Pole—Possible use as an Observatory—Procter—Probably Astrological—Planetary Influences—Signs of the Zodiac—Mathematical Coincidences of Great Pyramid—Chaldæan Astronomy—Ziggurats—Tower of Babel—Different Orientation from Egyptian Pyramids—Astronomical Treatise from Library of Sargon I., 3800 b.c.—Eclipses and Phases of Venus—Measures of Time from Old Chaldæan—Moon and Sun—Found among so many distant Races—Implies Commerce and Intercourse—Art and Industry—Embankment of Menes—Sphynx—Industrial Arts—Fine Arts—Sculpture and Painting—The Oldest Art the best—Chaldæan Art—De Sarzec's Find at Sirgalla—Statues and Works of Art—Imply long use of Bronze—Whence came the Copper and Tin—Phœnician and Etruscan Commerce—Bronze known 200 years earlier—Same Alloy everywhere—Possible Sources of Supply—Age of Copper—Names of Copper and Tin—Domestic Animals—Horse—Ox and Ass—Agriculture—All proves Extreme Antiquity | 134 |

| viiiCHAPTER VI. PREHISTORIC TRADITIONS. |

|

| Short Duration of Tradition—No Recollection of Stone Age—Celts taken for Thunderbolts—Stone Age in Egypt—Palæolithic Implements—Earliest Egyptian Traditions—Extinct Animals forgotten—Their Bones attributed to Giants—Chinese and American Traditions—Traditions of Origin of Man—Philosophical Myths—Cruder Myths from Stones, Trees, and Animals—Totems—Recent Events soon forgotten—Autochthonous Nations—Wide Diffusion of Prehistoric Myths—The Deluge—Importance of, as Test of Inspiration—More Definite than Legend of Creation—What the Account of the Deluge in Genesis really says—Date—Extent—Duration—All Life destroyed except Pairs preserved in the Ark—Such a Deluge impossible—Contradicted by Physical Science—By Geology—By Zoology—By Ethnology—By History—How Deluge Myths arise—Local Floods—Sea Shells on Mountains—Solar Myths—Deluge of Hasisadra—Noah's Deluge copied from it—Revised in a Monotheistic Sense at a comparatively Late Period—Conclusion—Rational View of Inspiration | 178 |

| CHAPTER VII. THE HISTORICAL ELEMENT IN THE OLD TESTAMENT. |

|

| Moral and Religious distinct from Historical Inspiration—Myth and Allegory—The Higher Criticism—All Ancient History unconfirmed by Monuments untrustworthy—Cyrus—Old Testament and Monuments—Jerusalem—Tablet of Tell-el-Amarna—Flinders Petrie's Exploration of Pre-Hebrew Cities—Ramses and Pi-thom—First certain Synchronism Rehoboam—Composite Structure of Old Testament—Elohist and Jehovist—Priests' Code—Canon Driver—Results—Book of Chronicles—Methods of Jewish Historians—Post-Exilic References—Tradition of Esdras—Nehemiah and Ezra—Foundation of Modern Judaism—Different from Pre-Exilic—Discovery of Book of the Law under Josiah—Deuteronomy—Earliest Sacred Writings—Conclusions—Aristocratic and Prophetic Schools—Triumph of Pietism with Exile—Both compiled partly from Old Materials—Crudeness and Barbarism of Parts—Pre-Abrahamic Period clearly mythical—Derived from Chaldæa—Abraham—Unhistoric Character—His Age—Lot's Wife—His double ix Adventure with Sarah—Abraham to Moses—Sojourn in Egypt—Discordant Chronology—Josephus' Quotation from Manetho—Small Traces of Egyptian Influence—Future Life—Legend of Joseph—Moses—Osarsiph—Life of Moses full of Fabulous Legends—His Birth—Plagues of Egypt—The Exodus—Colenso—Contradictions and Impossibilities—Immoralities—Massacres—Joshua and the Judges—Barbarisms and Absurdities—Only safe Conclusion no History before the Monarchy—David and Solomon—Comparatively Modern Date | 209 |

| PART II.—Evidence from Science. | |

| CHAPTER VIII. GEOLOGY AND PALÆONTOLOGY. |

|

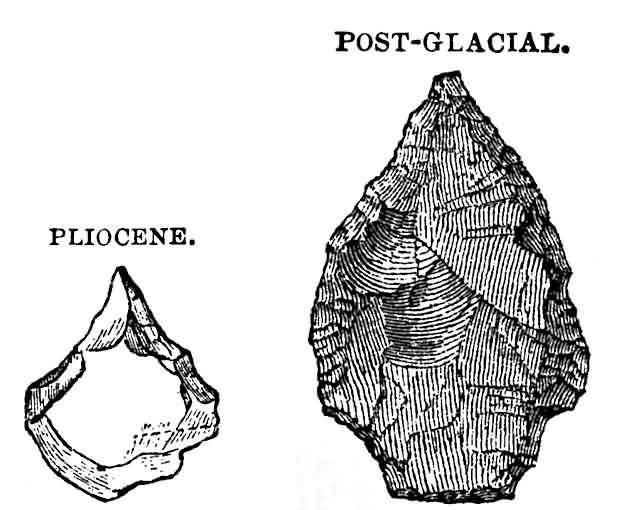

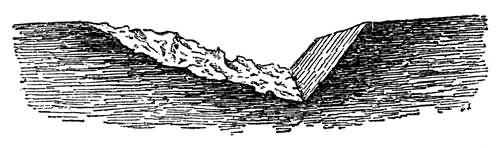

| Proved by Contemporary Monuments—As in History—Summary of Historical Evidence—Geological Evidence of Human Periods—Neolithic Period—Palæolithic or Quaternary—Tertiary—Secondary and Older Periods—The Recent or Post-Glacial Period—Lake-Villages—Bronze Age—Kitchen-Middens—Scandinavian Peat-mosses—Neolithic Remains comparatively Modern—Definition of Post-Glacial Period—Its Duration—Mellard Read's Estimate—Submerged Forests—Changes in Physical Geography—Huxley—Objections from America—Niagara—Quaternary Period—Immense Antiquity—Presence of Man throughout—First Glacial Period—Scandinavian and Laurentian Ice-caps—Immense Extent—Mass of Débris—Elevation and Depression—In Britain—Inter-Glacial and Second Glacial Periods—Antiquity measured by Changes of Land—Lyell's Estimate—Glacial Débris and Loess—Recent Erosion—Bournemouth—Evans—Prestwich—Wealden Ridge and Southern Drift—Contain Human Implements—Evidence from New World—California | 260 |

| CHAPTER IX. THE GLACIAL PERIOD AND CROLL'S THEORY. |

|

| Causes of Glacial Periods—Actual Conditions of existing Glacial Regions—High Land in High Latitudes—Cold alone insufficient—Large Evaporation required—Formation of Glaciers—They flow like Rivers—Icebergs—Greenland and x Antarctic Circle—Geographical and Cosmic Causes—Cooling of Earth and Sun, Cold Spaces in Space, and Change in Earth's Axis, reviewed and rejected—Precession alone insufficient—Unless with High Eccentricity—Geographical Causes, Elevation of Land—Aërial and Oceanic Currents—Gulf Stream and Trade Winds—Evidence for greater Elevation of Land in America, Europe, and Asia—Depression—Warmer Tertiary Climates—Alps and Himalayas—Wallace's Island Life—Lyell—Croll's Theory—Sir R. Ball—Former Glacial Periods—Correspondence with Croll's Theory—Length of the different Phases—Summary—Croll's Theory a Secondary Cause—Conclusions as to Man's Antiquity | 293 |

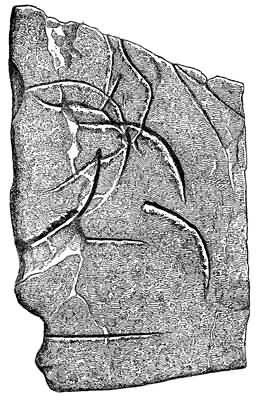

| CHAPTER X. QUATERNARY MAN. |

|

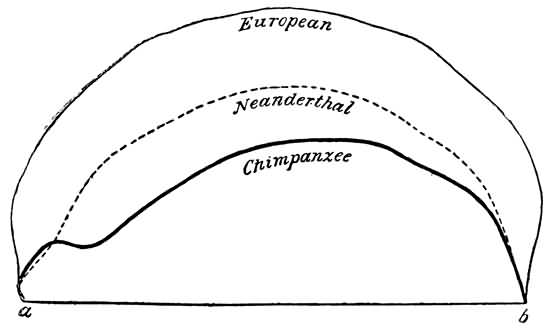

| No longer doubted—Men not only existed, but in numbers and widely spread—Palæolithic Implements of similar Type found everywhere—Progress shown—Tests of Antiquity—Position of Strata—Fauna—Oldest Types—Mixed Northern and Southern Species—Reindeer Period—Correspondence of Human Remains with these Three Periods—Advance of Civilization—Clothing and Barbed Arrows—Drawing and Sculpture—Passage into Neolithic and Recent Periods—Corresponding Progress of Physical Man—Distinct Races—How tested—Tests applied to Historical, Neolithic, and Palæolithic Man—Long Heads and Broad Heads—Aryan Controversy—Primitive European Types—Canon Taylor—Huxley—Preservation of Human Remains depends mainly on Burials—About forty Skulls and Skeletons known from Quaternary Times—Summary of Results—Quatrefages and Hamy—Races of Canstadt—Cro-Magnon—Furfooz—Truchere—Skeletons of Neanderthal and Spy—Canstadt Type oldest—Cro-Magnon Type next—Skeleton of Cro-Magnon—Broad-headed and Short Race resembling Lapps—American Type—No Evidence from Asia, Africa, India, Polynesia, and Australia—Negroes, Negrillos, and Negritos—Summary of Results | 317 |

| CHAPTER XI. TERTIARY MAN. |

|

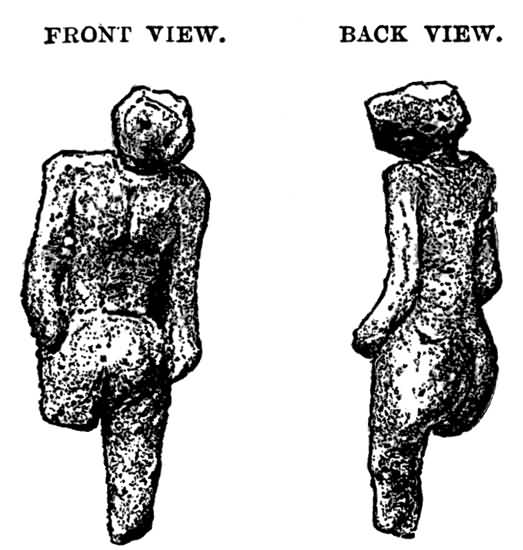

| Definition of Periods—Passage from Pliocene to Quaternary—Scarcity of Human Remains in Tertiary—Denudation—Evidence from Caves wanting—Tertiary Man a necessary inference from widespread existence of Quaternary Man—Both xi equally inconsistent with Genesis—Was the first great Glaciation Pliocene or Quaternary?—Section of Perrier—Confirms Croll's Theory—Elephas Meridionalis—Mammoth—St. Prest—Cut Bones—Instances of Tertiary Man—Halitherium—Balæonotus—Puy-Courny—Thenay—Evidence for—Proofs of Human Agency—Latest Conclusions—Gaudry's Theory—Dryopithecus—Type of Tertiary Man—Skeleton of Castelnedolo—Shows no approach to the Missing Link—Contrary to Theory of Evolution—Must be sought in the Eocene—Evidence from the New World—Glacial Period in America—Palæolithic Implements—Quaternary Man—Similar to Europe—California—Conditions different—Auriferous Gravels—Volcanic Eruptions—Enormous Denudation—Great Antiquity—Flora and Fauna—Point to Tertiary Age—Discovery of Human Remains—Table Mountain—Latest Finds—Calaveras Skull—Summary of Evidence—Other Evidence—Tuolumne—Brazil—Buenos Ayres—Nampa Images—Take us farther from First Origins and the Missing Link—If Darwin's Theory applies to Man, must go back to the Eocene | 343 |

| CHAPTER XII. RACES OF MANKIND. |

|

| Monogeny or Polygeny—Darwin—Existing Races—Colour—Hair—Skulls and Brains—Dolichocephali and Brachycephali—Jaws and Teeth—Stature—Other Tests—Isaac Taylor—Prehistoric Types in Europe—Huxley's Classification—Language no Test of Race—Egyptian Monuments—Human and Animal Races unchanged for 6000 years—Neolithic Races—Palæolithic—Different Races of Man as far back as we can trace—Types of Canstadt, Cro-Magnon, and Furfooz—Oldest Races Dolichocephalic—Skulls of Neanderthal and Spy—Simian Characters—Objections—Evidence confined to Europe—American Man—Calaveras Skull—Tertiary Man—Skull of Castelnedolo—Leaves Monogeny or Polygeny an open Question—Arguments on each side—Old Arguments from the Bible and Philology exploded—What Darwinian Theory requires—Animal Types traced up to the Eocene—Secondary Origins—Dog and Horse—Fertility of Races—Question of Hybridity—Application to Man—Difference of Constitutions—Negro and White—Bearing on Question of Migration—Apes and Monkeys—Question of Original Locality of Man—Asiatic Theory—Eur-African—American—Arctic—None based on sufficient Evidence—Mere Speculations—Conclusion—Summary of Evidence as to Human Origins | 391 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

HUMAN ORIGINS.

The reception which has been given to my former works leads me to believe that they have had a certain educational value for those who, without being specialists, wish to keep themselves abreast of the culture of the day, and to understand the leading results and pending problems of Modern Science. Of these results the most interesting are those which bear upon the origin and evolution of the human race. In my former works I have treated of these mainly from the point of view of geology and palæontology, and have hardly touched on the province which lies nearest to us, that of history and of prehistoric traditions. In this province, however, a revolution has been effected by the discoveries of the present century, which is no less important than that made by geological research and by the doctrine of Evolution.

Down to the middle of the nineteenth century, and to a considerable extent down to the present day, the Hebrew Bible was held to be the sole and sufficient authority as to the early history of the human race. 2 It was believed, with a certainty which made doubt impious, that the first man Adam was created in or about the year 4004 b.c., or not quite 6000 years ago; and that all human and other life was destroyed by a universal Deluge, 1656 years later, with the exception of Noah and his wife, their sons and their wives, and pairs of all living creatures, by whom the earth was repeopled from the mountain-peak of Ararat as a centre.

The latest conclusions of modern science show that uninterrupted historical records, confirmed by contemporary monuments, carry history back at least 1000 years before the supposed Creation of Man, and 2500 years before the date of the Deluge, and show then no trace of a commencement; but populous cities, celebrated temples, great engineering works, and a high state of the arts and of civilization, already existing. This is of the highest interest, both as bearing on the dogma of the Divine inspiration of the historical and scientific, as distinguished from the moral and religious, portions of the Bible, and on the still more important question of the true theory of Man's origin and relations to the Universe. The so-called conflict between Religion and Science is at bottom one between two conflicting theories of the Universe—the first that it is the creation of a personal God who constantly interferes by miracles to correct His original work; the second, that whether the First Cause be a personal God or something inscrutable to human faculties, the work was originally so perfect that the whole succession of subsequent events has followed by Evolution acting by invariable laws. The former is the theory of orthodox believers, the latter that of men of science, and of liberal theologians who, 3 like Bishop Temple, find that the theory of "original impress" is more in accordance with the idea of an Omnipotent and Omniscient Creator, to whom "a thousand years are as a day," than the traditional theory of a Creator constantly interfering to supplement and amend His original Creation by supernatural interferences.

It is evidently important for all who desire to arrive at truth, and to keep abreast of the culture of the day, to have some clear conception of what historical and geological records really teach, and what sort of a standard or measuring-rod they supply in attempting to carry back our researches into the depths of prehistoric and of geological time.

I have therefore in this work begun with the historic period, as giving us a solid foundation and standard of time, by which to gauge the vastly longer periods which lie behind, and ascended from this by successive steps through the Neolithic and Palæolithic ages, and the Quaternary and Tertiary periods, so far as the most recent discoveries throw any light on the mysterious question of "Human Origins."

If I have succeeded in stimulating some minds, especially those of my younger readers, and of the working-classes who are striving after culture, to feel an interest in these subjects, and to pursue them further, my object will have been attained. They have been to me the solace of a long life, the delight of many quiet days, and the soother of many troubled ones, and I should be glad to think that I had been the means, however humble, of introducing to others what I have found such a source of enjoyment, and enlisting, if it 4 were only a few, in the service of that "divine Philosophy," in which I have ever found, as Wordsworth did in Nature,

Historical Standard of Time—Short Date inconsistent with Evolution—Laws of Historical Evidence—History begins with Authentic Records—Records of Egypt oldest—Manetho's Lists—Confirmed by Hieroglyphics—Origin of Writing—The Alphabet—Phonetic Writing—Clue to Hieroglyphics—The Rosetta Stone—Champollion—Principles of Hieroglyphic Writing—Language Coptic—Can be read with certainty—Confirmed by Monuments—Manetho's Date for Menes 5004 b.c.—Old, Middle, and New Empires—Old Empire, Menes, to end of Sixth Dynasty—Break between Old and Middle Empires—Works of Twelfth Dynasty—Fayoum—Thirteenth and Fourteenth Dynasties—Hyksos Conquests—Duration of Hyksos Rule—Their Expulsion and Foundation of New Empire—Conquests in Asia of Seventeenth and Eighteenth Dynasties—Wars with Hittites and Assyrians—Persian and Greek Dynasties—Summary of Evidence for Date of Menes—Period prior to Menes—Horsheshu—Sphynx—Stone Age—Neolithic and Palæolithic Remains—Horner, Haynes, and Pitt-Rivers.

In measuring the dimensions of space we have to start from some fixed standard, such as the foot or yard, taken originally from the experience of our ordinary senses and capable of accurate verification. From this we arrive by successive inductions at the size of the earth, the distance of the sun, moon, and planets, and finally at the parallax of the fixed stars. So in speculations as to the origin and evolution of the human race, history affords the standard from which we start, through the successive 6 stages of prehistoric, neolithic, and palæolithic man, until we pass into the wider ranges of geological time.

Any error in the original standard becomes magnified indefinitely, whether in space or time, as we extend our researches backwards into remoter regions.

Thus whether the authentic records of history extend only for some 4500 years backwards from the present time to the scriptural date of Noah's flood, as was universally assumed to be the case until quite recently; or whether Egyptian and Chaldæan records carry us back for 7000 years, and show us then a dense population, powerful empires, large cities, and generally a highly advanced civilization already existing, makes a wonderful difference in the standpoint from which we view the course of human evolution.

To begin with, a short date necessitates supernatural interferences. It is quite impossible that if man and all animal life were created only about 4000 years b.c., and were then all destroyed save the few pairs saved in Noah's ark, and made a fresh start from a single centre some 1500 years later, there can be any truth in Darwin's theory of evolution. We know for a certainty from the concurrent testimony of all history, and from Egyptian monuments, that the different races of men and animals were in existence 5000 years ago as they are at the present day; and that no fresh creations or marked changes of type have taken place during that period. If then all these types, and all the different races and nations of men, sprung up in the interval of less than 1000 years, which is the longest that can by any possibility be allowed between the Biblical date of the Deluge and the clash of the mighty monarchies of Assyria and Egypt in Palestine, the date of which is 7 proved both by the Bible and by profane historians, it is obviously impossible that such a state of things could have been brought about by natural causes.

But if authentic historical records carry us back not for 3000 or 4000, but for 6000 or 7000 years, and then show no trace of a beginning, the case is altered, and we may assume an almost unlimited duration of time, through historical, prehistoric, neolithic, and palæolithic ages, during which evolution may have operated. It is of the first importance therefore to inquire what these records really teach in the light of modern research, and what is the evidence for the longer dates which are now generally accepted.

Furnished with such a measuring-rod it becomes easier to attempt to bring into some sort of co-ordination the vast mass of facts which have been accumulated in recent years as to prehistoric, neolithic, and palæolithic man; and the glimpses of light respecting the origin, antiquity, and early history of the human race, which have come in from other sciences such as astronomy, geology, zoology, and philology.

To do this exhaustively would be an encyclopædic task which I do not pretend to accomplish, but I am not without hope that the following chapters, connected as they are by the one leading idea of tracing human origins backward to their source, may assist inquiry, and create an interest in this most interesting of all questions, especially among the young who are striving after knowledge, and the millions who, not having the time and opportunity for reading technical works, feel a desire to keep themselves abreast of modern thought and of the advanced culture of the close of the nineteenth century.

8 Before examining these records in detail it is well to begin with the general laws upon which historical evidence is based. History begins with writings. All experience shows that what may be transmitted by memory and word of mouth, consists mainly of hymns and portions of ritual, such as the Vedas of the Hindoos; and to a certain extent of heroic poems and ballads in which the historical element is so overlaid by mythology and poetry, that it is impossible to discriminate between fact and fancy. Thus the legend of Hercules is evidently in the main a solar myth, and his twelve labours are related to the signs of the zodiac, but it is possible that there may have been a real Hercules, the actual or eponymic ancestor of the tribe of Heraclides. So, at a later period, the descent of the Romans from the pious Æneas, and of the Britons from another Trojan hero Brute, are obviously fabulous; and at a still more recent date, our own Arthurian legends are evidently a mediæval romance, though it is possible that there may have been a chief of that name of the Christianized Romano-Britons, who opposed a gallant resistance to the flood of Saxon invasion.

But to make real history we require something very different; concurrent and uninterrupted testimony of known historians; absence of impossible and obviously fabulous dates and events; and, above all, contemporary records, written or engraved on tombs, temples, and monuments, or preserved in papyri or clay cylinders.

Another remark is, that these authentic records of early history only begin to appear when civilization is so far advanced as to have established powerful dynasties and priestly organizations. The history of a nation is at first the history of its kings, and its records are 9 enumerations of their genealogies, successive reigns, foundation or repair of temples, great industrial works, and warlike exploits. These are made and preserved by special castes of priestly colleges and learned scribes, and they are to a great extent precise in date and accurate in fact. Before the establishment of such historical dynasties we have nothing but legends and traditions, which are vague and mythical, the mythological element rapidly predominating as we go backwards in time, until we soon arrive at reigns of gods, and lives of thousands of years. But as we approach the period of historical dynasties the mythological element diminishes, and we pass from gods reigning 10,000 years, and patriarchs living to 900, to later patriarchs living 150 or 200 years, and finally to mortal men, living, and kings reigning, to natural ages.

In fact, with the first appearance of authentic records the supernatural disappears, and the average duration of lives, reigns, and dynasties, and the general course of events, are much the same as at present, and fully confirm, the statement of the Egyptian priests to Herodotus, that during the long succession of ages of the 345 high priests of Heliopolis, whose statues they showed him in the great temple of the sun, there had been no change in the length of human life or in the course of nature, and each one of the 345 had been a piromis, or mortal man, the son of a piromis. The first question is how far back these authentic historical records can be traced, and Egypt affords the first answer.

The first step in the inquiry as to Egyptian antiquity is afforded by the history of Manetho. Ptolemy Philadelphus, whose reign began 284 b.c., was an enlightened king. He founded the great Alexandrian library, and 10 was specially curious in collecting everything which bore on the early history of his own and other countries. With this view he had the Greek translation, known as the Septuagint, made of the sacred books of the Hebrews, and he commissioned Manetho to compile a history of Egypt from the earliest times, from the most authentic temple records and other sources of information. Manetho was eminently qualified for such a task, being a learned and judicious man, and a priest of Sebennytus, one of the oldest and most famous temples.

The history of Manetho is unfortunately lost, being probably the greatest loss the world has sustained by the burning of the Alexandrian library, but fragments of it have been preserved in the works of Josephus, Eusebius, Julius Africanus and Syncellus, of whom Eusebius and Africanus profess to give Manetho's lists and dates of dynasties and kings from the first King Menes down to the conquest of Alexander the Great in 332 b.c. With the curious want of critical faculty of almost all the Christian fathers, these extracts, though professing to be quotations from the same book, contain many inconsistencies, and in several instances they have obviously been tampered with, especially by Eusebius, in order to bring their chronology more in accordance with that of the Old Testament. But enough remains to show that Manetho's lists comprised thirty-one dynasties, and about 370 kings, whose successive reigns extended over a period of about 5500 years, from the accession of Menes to the conquest of Egypt by Alexander the Great in 332 b.c., making the date of the first historical king who united Upper and Lower Egypt, about 5800 b.c. There may be some doubt as to the precise dates, for the lists, of Manetho have obviously been tampered 11 with to some extent by the Christian fathers who quoted them, but there can be no doubt that his original work assigned an antiquity to Menes of over 5500 b.c.

The only other historical information as to the history of Ancient Egypt was gleaned from references to it in the extant works of Josephus and of Greek authors, especially Homer, Herodotus, and Diodorus Siculus. Josephus, in his Antiquity of the Jews, quotes passages from Manetho, but they only extend to the period of the Hyksos invasion, the Captivity of the Jews, and the Exodus, which are all comparatively recent events in Manetho's annals. Homer's account of hundred-gated Thebes does not carry us back beyond the echo which had reached Ionian Greece of the splendours of the nineteenth dynasty. Herodotus visited Egypt about 450 b.c., and wrote a description of it from what he saw and heard on the spot. It contains a good deal of valuable information, for he was a shrewd observer. But he was credulous, and not very critical in distinguishing between fact and fable, and it is evident that his sources of information were often not much better than vague popular traditions, or the tales told by guides, and even the more authentic information is so disconnected and mixed with fable, that it can hardly be accepted as material for history. As far as it goes, however, it tends to confirm Manetho, as, for instance, in giving the names correctly of the kings who built the three great pyramids, and in saying that he saw the statues of 342 successive high priests of the great Temple of Heliopolis, which correspond very well with Manetho's lists of 370 kings.

Diodorus gives us very much the same narratives as those of Herodotus; and, on the whole, we had to fall 12 back on Manetho as the only authority for anything like precise dates and connected history.

Manetho's dates, however, were so inconsistent with preconceived ideas based on the chronology of the Bible, that they were universally thought to be fabulous. They were believed either to represent the exaggerations of Egyptian priests desirous of magnifying the antiquity of their country, or, if historical, to give in succession the names of a number of kings and dynasties who had really reigned simultaneously in different provinces. So stood the question until the discovery of reading hieroglyphics enabled us to test the accuracy of Manetho's lists by the light of contemporary monuments and manuscripts. This discovery is of such supreme importance that it may be well to begin at the beginning, and lay a solid foundation by showing how it was made, and the demonstration on which it rests.

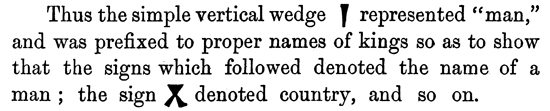

Reading presupposes writing, as writing presupposes speech. Ideas are conveyed from one mind to another in speech through the ear, in writing through the eye. The origin of the latter method is doubtless to be found in picture-writing. The palæolithic savage who drew a mammoth with the point of a flint on a piece of ivory, was attempting to write, in his rude way, a record of some memorable chase. And the accounts of the old Empires of Mexico and Peru at the time of the Spanish Conquest, show that a considerable amount of civilization can be attained and information conveyed by this primitive method. But for the purpose of historical record more is required. It is essential to have a system of signs and symbols which shall be generally understood, and by which knowledge shall be handed 13 down unchanged to successive generations. All experience shows that before knowledge is thus fixed and recorded, anything that may be transmitted by memory and word of mouth, fades off almost immediately into myth, and leaves no certain record of time, place, and circumstance. A few religious hymns and prayers like those of the Vedas, a few heroic ballads like those of Homer, a few genealogies like those of Agamemnon or Abraham, may be thus preserved, but nothing definite or accurate in the way of fact and date. History, therefore, begins with writing, and writing begins with the invention of fixed signs to represent words. A system of writing is possible, like the Chinese, in which each separate word has its own separate sign, but this is extremely cumbrous, and quite unintelligible to those who have not got a living key to explain the meaning of each symbol. It is calculated that an educated Chinese has to learn by heart the meaning of some 15,000 separate signs before he can read and write correctly. We have a trace of this ideographic system in our own language, as where arbitrary signs such as 1, 2, 3, represent not the sounds of one, two, and three, but the ideas conveyed by them. But for all practical purposes, intelligible writing has to be phonetic, that is, representing spoken words, not by the ideas they convey, but by the sounds of which they are composed. In other words there must be an Alphabet.

The alphabet is the first lesson of childhood, and it seems such a simple thing that we are apt to forget that it is one of the most important and original inventions of the human intellect. Some prehistoric genius, musing on the meaning of spoken words, has seen that they might all be analyzed into a few simple sounds. To 14 make this more easily intelligible, I will suppose the illustrations to be taken from our own language. "Dog" and "dig" express very different ideas; but a little reflection will show that the primary sounds made by the tongue, teeth, and palate, viz. 'd' and 'g,' are the same in each, and that they differ only by a slight variation in the soft breathing or vowel, which connects them and renders them vocal. The next step would be to see that such words as "good" or "God," consisted of the same root-sounds, only transposed and connected with a slight vowel difference. Pursuing the analysis, it would finally be discovered that the many thousand words of spoken language could all be resolved into a very small number of radical sounds, each of which might be represented and suggested to the mind through the eye instead of the ear by some conventional sign or symbol. Here is the alphabet, and here the art of writing.

This great achievement of the human intellect appears to have been made in prehistoric times; and where not obviously imported from a foreign source, as in the Phœnician alphabet from the Egyptian and the Greek from the Phœnician, it is attributed to some god, that is, to an unknown antiquity.

Thus in Egypt, Thoth the Second, known to the Greeks as Hermes Trismegistus, a fabulous demi-god of the period succeeding the reign of the great gods, is said to have invented the alphabet and the art of writing. The analysis of primary sounds varies a little in different times and countries in order to suit peculiarities in the pronunciation of different races and convenience in writing; but about sixteen primitive sounds, which is the number of the letters of the first 15 alphabet brought by Cadmus to Greece, are always its basis. In our own alphabet it is easy to see that it is not formed on strictly scientific principles, some of the letters being redundant. Thus the soft sound of 'c' is expressed by 's,' and the hard sound by 'k'; and 'x' is an abbreviation of three other letters, 'eks.' Some letters also express sounds which run so closely into one another that in some alphabets they are not distinguished, as 'f' and 'v,' 'd' and 't', 'l' and 'r'; while some races have guttural and other sounds, such as 'kh' and 'sj,' which occur so frequently as to require separate signs, while they baffle the vocal organs of other races, and in some cases syllables which frequently occur, instead of being spelt out alphabetically, are represented by single signs. But these are mere details, the question substantially is this—if a collection of unknown signs is phonetic, and we can get any clue to its alphabet, it can be read; if not it must remain a sealed book.

To apply this to hieroglyphics; it had been long known that the monuments of ancient Egypt were carved with mysterious figures, representing commonly birds, animals, and other natural objects, but all clue to their meaning had been lost. It seemed more natural to suppose that they were ideographic; that a lion for instance represented a real lion, or some quality associated with him, such as fierceness, valour, and kingly aspect, rather than that his picture stood simply for our letter 'l.' The long-desired clue was afforded by the famous Rosetta stone. This is a mutilated block of black basalt, which was discovered in 1799 by an engineer officer of the French expedition, in digging the foundations of a fort near Rosetta. It was captured, with 16 other trophies, by the British army, when the French were driven out of Egypt, and is now lodged at the British Museum. It bears on it three inscriptions, one in hieroglyphics, the second in the demotic Egyptian character employed for popular use, and the third in Greek. The Greek can of course be read, and it is an inscription commemorating the coronation of Ptolemy Epiphanes and his Queen Arsinoe, in the year 196 b.c. It was an obvious conjecture that the two Egyptian inscriptions were to the same effect, and that the Greek was a literal translation of this. To turn this conjecture, however, into a demonstration, a great deal of ingenuity and patient research were required. The principle upon which all interpretation of unknown signs rests may be most easily understood by taking an illustration from our own language. The first step in the problem is to know whether these unknown signs are ideographic or phonetic. Thus if we have two groups of signs, one of which we have reason to know stands for "Ptolemy" and the other for "Cleopatra," if they are phonetic, the first sign in Ptolemy will correspond with the fifth in Cleopatra; the second with the seventh, the third with the fourth, the fourth with the second, and the fifth with the third; and we shall have established five letters of the unknown alphabet, 'p, t, o, l,' and 'e.' Other names will give other letters, as if we know "Arsinoe," its comparison with "Cleopatra" will give 'a' and 'r,' and confirm the former induction as to 'o' and 'e.'

And it will be extremely probable that the two last signs in Ptolemy represent 'm' and 'y'; the first in Cleopatra 'c'; and the third, fourth, and fifth in Arsinoe, 's, i,' and 'n.' Suppose now that we find in an inscription on an ancient temple at Thebes, a name which 17 begins with our known sign for 'r,' followed by our known 'a,' then by our conjectural 'm,' then by the sign which we find third in Arsinoe, or 's,' then by our known 'e,' and ending with a repetition of 's,' we have no difficulty in reading "Ramses," and identifying it with one of the kings of that name mentioned by Manetho as reigning at Thebes. The identification of letters was facilitated by the custom of inclosing the names of kings in what is called a cartouche or oval.

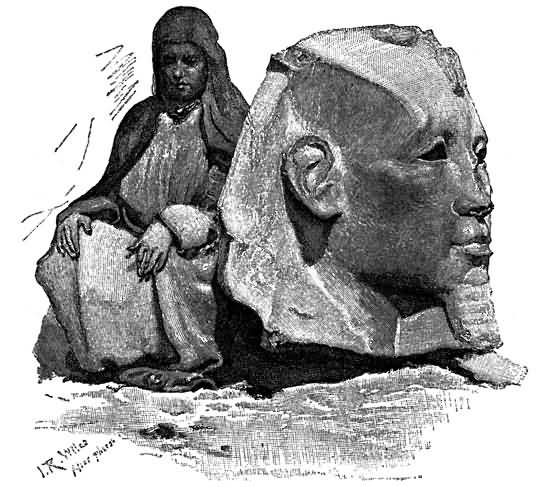

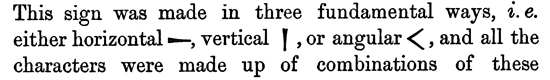

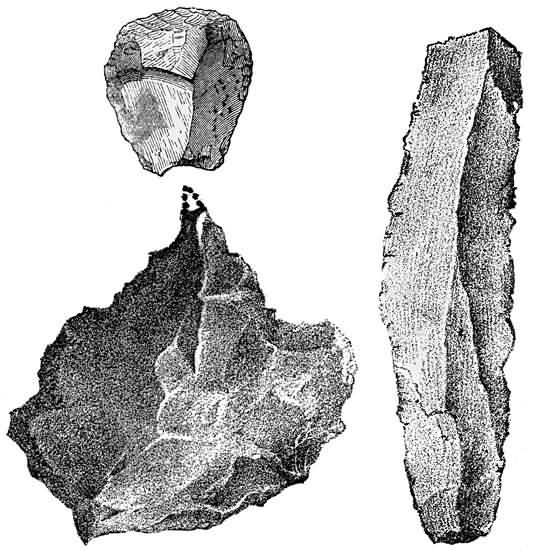

TABLET OF SNEFURA AT WADY MAGERAH.

(The oldest inscription in the world, probably 6000 years old. The king conquering an Arabian or Asiatic enemy.)

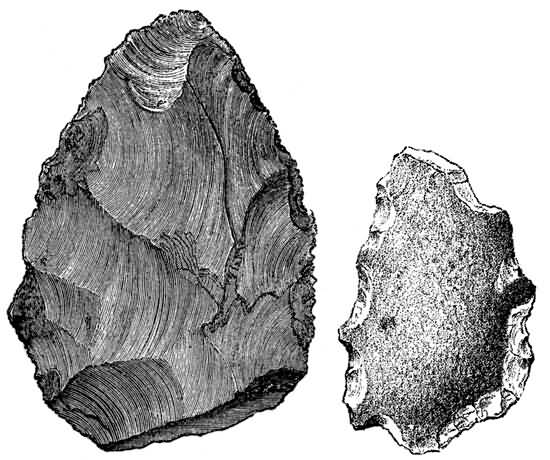

This name reads "Snefura," which is the name of the king of the third dynasty who reigned about 4000 b.c., or before the building of the Great Pyramids, which inscription is the earliest contemporary one of an Egyptian king as yet discovered. It was found at the copper mines of Wady Magerah, in the peninsula of 18 Sinai, and represents the victory of the king over an Arabian or Asiatic enemy.

The first step towards the decipherment of the hieroglyphics on the Rosetta stone was made in 1819 by Dr. Young, who was one of the most ingenious and original thinkers of the nineteenth century, and is also famous as the first discoverer of the undulatory theory of light. But in both cases he merely indicated the right path and laid down the correct principles. The development of his theories was reserved for two Frenchmen; Fresnel in the case of Light, and Champollion in that of Hieroglyphics. The task was one which required immense patience and ingenuity, for the hieroglyphic alphabet turned out to be one of great complexity. Not only were many of the signs not phonetic, but ideographic or determinative; and some of them standing for syllables and not letters; but the letters themselves were not represented, as in modern languages, each by a single sign or at most by two signs, as A and a, but by several different signs. The Egyptian alphabet was in fact constructed very much as young children often learn theirs, by—

with this difference, that several objects, whose names begin with A and other letters, might be used to represent them. Thus some of the hieroglyphic letters had as many as twenty-five different signs or homophones. It is as if we could write for 'a,' the picture either of an apple, or of an ass, archer, arrow, anchor, or any word beginning with 'a.'

However, Champollion with infinite difficulty, and 19 aided by the constant discovery of fresh inscriptions, solved the problem, and succeeded in producing a complete alphabet of hieroglyphics comprising all the various signs, thus enabling us to translate every hieroglyphic sign into its corresponding sound or spoken word.

The next question was, what did these words mean, and could they be recognized in any known language? The answer to this was easy; the Egyptians spoke Egyptic, or as it is abbreviated Coptic, a modern form of which is almost a living language, and is preserved in translations of the Bible still in use and studied by the aid of Coptic dictionaries and grammars. This enabled Champollion to construct a hieroglyphic dictionary and grammar, which have been so completed by the labours of subsequent Egyptologists, that it is not too much to say that any inscription or manuscript in hieroglyphics can be read with nearly as much certainty as if it had been written in Greek or in Hebrew.

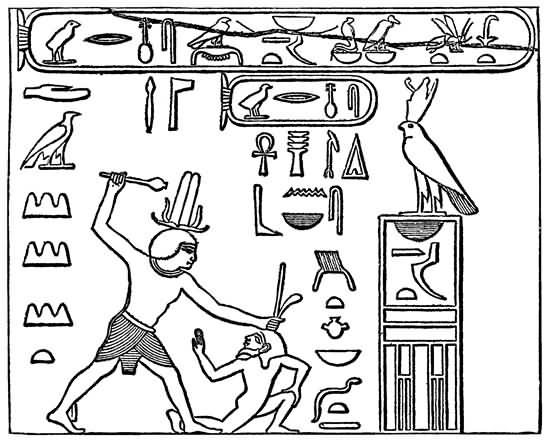

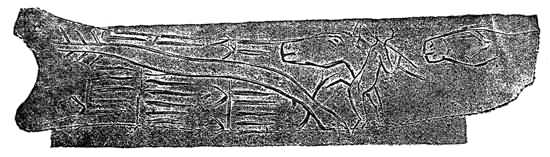

SPECIMEN OF HIEROGLYPHIC ALPHABET. (From Champollion's Egypt.)

The above illustrations from English characters are only given as the simplest way of conveying to the minds of those who have had no previous acquaintance with the subject, an idea of the nature of the process and force of the evidence, upon which the decipherment of hieroglyphic inscriptions is based. In reality the 20 process was far from being so simple. Though many of the hieroglyphics are phonetics, like our letters of the alphabet, they are not all so, and many of them are purely ideographic, as when we write 1, 2, 3, for one, two, and three. All writing has begun with picture-writing, and each character was originally a likeness of the object which it was wished to represent. The next stage was to use the character not only for the material object, but as a symbol for some abstract idea associated with it. Thus the picture of a lion might stand either for an actual lion, or for fierceness, courage, majesty, or other attribute of the king of animals. In this way it became possible to convey meanings to the mind through the eye, but it involved both an enormous number of characters, and the use of homophones, i.e. of single characters standing for a number of separate ideas. To obviate this, what are called "determinatives" were invented, i.e. special signs affixed to characters or groups of characters to determine the sense in which they were to be taken. For instance, the picture of a star (*) affixed to a group of hieroglyphics may be used to denote that they represent the name of a god, or some divine or heavenly attribute; and the picture of rippling water ~~~~~~~~ to show that the group means something connected with water, as a sea or river. Beyond this the Chinese have hardly gone, and it is reckoned that it requires some 1358 separate characters, or conventionalized pictures, taken in distinct groups, to be able to read and write correctly the 40,000 words in the Chinese language. Even for the ordinary purposes of life a Chinaman instead of committing to memory twenty-six letters of the alphabet, like an English child, has to learn by heart some 6000 or 7000 21 groups of characters often distinguished only by slight dots and dashes. Such a system is cumbrous in the extreme, and involves spending many of the best years of life in acquiring the first rudiments of knowledge. Indeed it is only possible when not only writing but speech has been arrested at the first stage of its development, and a nation speaks a language of monosyllables. In the case of Egypt and other ancient nations the standpoint of writing went further, and the symbolic pictures came to represent phonograms, i.e. sounds or spoken words instead of ideas or objects; and these again were further analyzed into syllabaries, or the component articulate sounds which make up words; and these finally into their ultimate elements of a few simple sounds, or letters of an alphabet, the various combinations of which will express all the complex sounds or words of a spoken language.

Now in the hieroglyphic writing of ancient Egypt, along with those pure phonetics or letters of an alphabet, are found numerous survivals of the older systems from which they sprung, and Champollion, who first attempted the task of forming a hieroglyphic dictionary and grammar, had to contend with all the difficulties of ideograms, polyphones, determinatives, and other obstacles.

Those who wish to pursue this interesting subject further will do well to read Dr. Isaac Taylor's book on the Alphabet, and Sayce on the Science of Writing; but for my present purpose it is sufficient to establish the scientific certainty of the process by which hieroglyphic texts are read. With this key a vast mass of constantly accumulating evidence has been brought to light, illustrating not only the chronology and history of 22 ancient Egypt, but also its social and political condition, its literature and religion, science and art. The first question naturally was how far the monuments confirmed or disproved the lists of Manetho. Manetho was a learned priest of a celebrated temple, who must have had access to all the temple and royal records and other literature of Egypt, and who must have been also conversant with foreign literature, to have been selected as the best man to write a complete history of his native country for the royal library in Greek. Manetho's lists of the reigns of dynasties and kings when summed up show a date of 5867 b.c. for the foundation of the united Egyptian Empire by Menes, a date which is of course absolutely inconsistent with those given by Genesis, not only for the Deluge, but for the original Creation.

It is evident that the monuments alone could confirm or contradict these lists, and give a solid basis for Egyptian chronology and history. This has now been done to such an extent that it may fairly be said that Manetho has been confirmed, and it is fully established, as a fact acquired by science, that nearly all his kings and dynasties are proved by monuments to have existed, and that successively and not simultaneously, so that the margin of uncertainty as to the date of Menes is reduced to one of a few hundred years on one side or other of 5000 b.c.

Mariette, who is the best and latest authority, and who has done so much to discover monuments of the earlier dynasties, concludes, as the result of a careful revision of Manetho's lists, and of the authentic records from temples, tombs, and papyri, that 5004 b.c. is the most probable date for the accession of Menes, and this 23 date is generally adopted by modern Egyptologists. Some make it rather longer, as Boeck 5702 b.c., and Unger 5613 b.c.; while others make it a little shorter, as Maspero 4500 b.c., and Brugsch[1] 4455; but it is to be observed that the date has always lengthened with the progress of discovery. Thus the earlier Egyptologists such as Wilkinson, Birch, and Poole assigned a date not exceeding 3000 b.c. for the accession of Menes; twenty years later Bunsen and Lepsius gave respectively 3623 and 3892 b.c.; and since the latest discoveries, no competent scholar assigns a lower date than 4500 b.c., while some go up to 5702 b.c., and that most generally accepted is 5004 b.c. It is safe to conclude, therefore, that about 5000 b.c., or very nearly 7000 years before the present time, may be taken provisionally as the date of the commencement of authentic Egyptian history, and that if this date be corrected by future discoveries it is more likely to be increased than diminished.

This immensely long period of Egyptian history is divided into three stages—the Old, the Middle, and the New Empires. The Old Empire began with Menes, and lasted without interruption for about 1500 years, under six dynasties of kings, who ruled over the whole of Egypt. It was a period of peace, prosperity, and progress, during which the pyramids, the greatest of all human works, were built, literature flourished, and the industrial and fine arts attained a high degree of perfection.

At the very commencement of this period we find 24 the first King Menes carrying out a great work of hydraulic engineering, by which the course of the Nile was diverted, and a site obtained on its western banks for the new capital of Memphis. His immediate successor is said to have written a celebrated treatise on Medicine, and the extremely life-like portrait-statues and wooden statuettes, which were never equalled in any subsequent stage of Egyptian art, date back to the fourth dynasty.

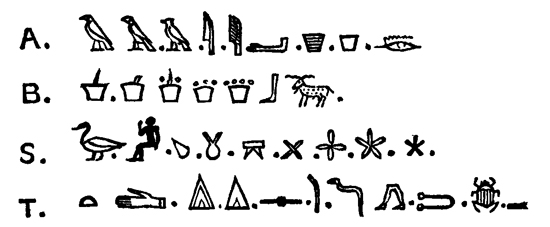

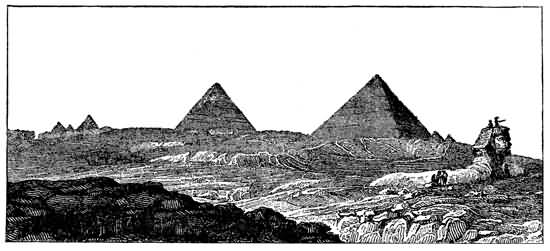

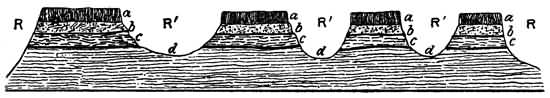

PYRAMIDS OF GIZEH AND SPHYNX. (From Champollion's Egypt.)

It is singular that this extremely ancient period is the one of which, although the oldest, we know most, for the monuments, the papyri, and especially the tombs in the great cemeteries of Sakkarah and Ghizeh, give us the fullest details of the political and social life of Egypt during the fourth, fifth, and sixth dynasties, with sufficient information as to the three first dynasties to check and confirm the lists of Manetho. We really know the life of Memphis 6000 years ago better than we do that of London under the Saxon kings, or of Paris under the descendants of Clovis.

The sixth dynasty was succeeded by a period which 25 seems to have been one of civil war and anarchy, during which there was a complete cessation of monuments; or, if they existed, they have not yet been discovered. The probable duration of this eclipse of Egyptian records is somewhat uncertain, as we cannot be sure, in the absence of monuments, that the four dynasties of short reigns assigned to the interval between the sixth and the eleventh dynasties by Manetho, and the numerous names of unknown kings on the tablets, were successive sovereigns who reigned over united Egypt, or local chiefs who got possession of power in different parts of the Empire. All we can see is that the supremacy of Memphis declined, and that its last great dynasty was replaced, either in whole or in part, by a rebellion in Upper Egypt which introduced two dynasties whose seat was at Heracleopolis on the Middle Nile, In any case the duration of this period must have been very long, for the eclipse was very complete, and when we once more find ourselves in the presence of records in the eleventh dynasty, the seat of empire is established at Thebes, and the state of the arts, religion, and civilization are different and much ruder than they were at the close of the great Memphite Empire with the sixth dynasty. Mariette says, "When Egypt, with the eleventh dynasty, awoke from its long sleep, the ancient traditions were forgotten. The proper names of the kings and ancient nobility, the titles of the high functionaries, the style of the hieroglyphic writing, and even the religion, all seemed new. The monuments are rude, primitive, and sometimes even barbarous, and to see them one would be inclined to think that Egypt under the eleventh dynasty was beginning again the period of infancy 26 which it had already passed through 1500 years earlier under the third." The tomb of one of these kings of the eleventh dynasty, Entef I., is remarkable as showing on a funeral pillar the sportsman-king surrounded by his four favourite dogs, whose names are given, and which are of different breeds, from a large greyhound to a small turnspit.

However, the chronology of this eleventh dynasty is well attested, its kings are known, and under them Upper and Lower Egypt were once more consolidated into a single state, forming what is known as the Middle Empire. Under the twelfth dynasty, which succeeded it, this Empire bloomed rapidly into one of the greatest and most glorious periods of Egyptian history. The dynasty only lasted for 213 years, under seven kings, whose names were all either Amenemes or Osirtasen; but during their reigns the frontiers of Egypt were extended far to the south, Nubia was incorporated with the Empire, and Egyptian influence extended over the whole Soudan, and perhaps nearly to the equator on the one hand, and over Southern Syria on the other. But the dynasty was still more famous for the arts of peace.

One of the greatest works of hydraulic engineering which the world has seen was carried out by Amenemes III., who took advantage of a depression in the desert limestone near the basin of Fayoum, to form a large artificial lake connected with the Nile by canals, tunnelled through rocky ridges and provided with sluices, so as to admit the water when the river rose too high, and let it out when it fell too low, and thus regulate the inundation of a great part of Middle and Lower Egypt, independently of the seasons. Connected with 27 this Lake Mœris was the famous Labyrinth, which Herodotus pronounced to be a greater wonder than even the great Pyramid. It was a vast square building erected on a small plateau on the east side of the lake, constructed of blocks of granite which must have been brought from Syene, with a façade of white limestone; and containing in the interior a vast number of small square chambers and vaults—Herodotus says 3000—each roofed with a single large slab of stone, and connected by narrow passages, so intricate that a stranger entering without a clue would be infallibly lost. The object seems to have been to provide a safe repository for statues of gods and kings and other precious objects. In the centre was a court containing twelve hypostyle chapels, six facing the south and six the north, and at the north angle of the square was a pyramid of brick faced with stone forming the tomb of Amenemes III.

In addition to this colossal work, the kings of this dynasty built and restored many of the most famous temples and erected statues and obelisks, among the latter the one now standing at Heliopolis. It was also an age of great literary activity, and the biographies of many of the priests, nobles, and high officers, inscribed on their tombs and recorded in papyri, give us the most minute knowledge of the history and social life of this remote period.

The prosperity of Egypt during the Middle Empire was continued under the thirteenth dynasty of sixty Theban kings, to whom Manetho assigns the period of 453 years. Less is known of this period than of the great twelfth dynasty which preceded it, but a sufficient number of monuments have been preserved to confirm the general accuracy of Manetho's statements. A 28 colossal statue of the twenty-fourth or twenty-fifth king, Sevckhotef VI., found on the island of Argo near Dongola, shows that the frontier fixed by the conquests of Amenemes at Semneh, had not only been maintained, but extended nearly fifty leagues to the south into the heart of Ethiopia; and another statue found at Tanis shows that the rule of this dynasty was firmly established in Lower Egypt. But the scarcity of the monuments, and the inferior execution of the works of art, show that this long dynasty was one of gradual decline, and the rise of the next or fourteenth dynasty at Xois, transferring the seat of power from Thebes to the Delta, points to civil wars and revolutions.

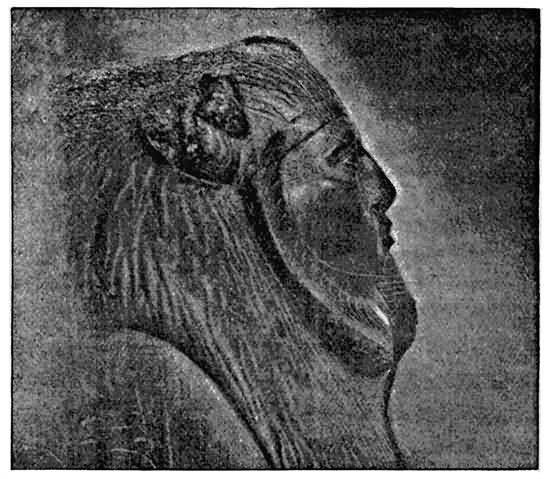

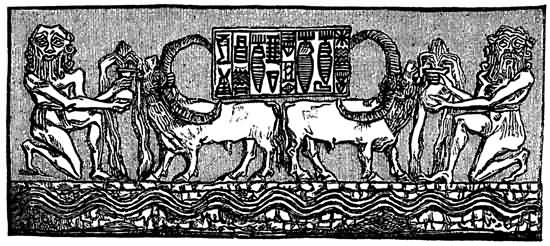

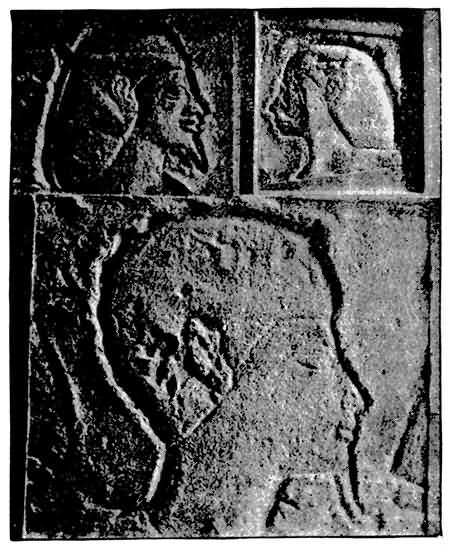

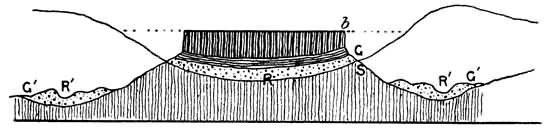

FELLAH WOMAN AND HEAD OF SECOND HYKSOS STATUE. (From photograph by Naville in Harper's Magazine.)

HYKSOS SPHYNX. (From photograph by Naville in Harper's Magazine.)

Manetho assigns seventy-five kings and 484 years to the fourteenth dynasty, and it is to this period that a good deal of uncertainty attaches, for there are no monuments, and nothing to confirm Manetho's lists, except a number of unknown names of kings of the dynasty enumerated among the royal ancestors in the Papyrus of Turin. If Manetho's figures are correct, the period must have been one of anarchy and civil war, for the average duration of each reign is less than six and a half years, while that of the twelfth and other well-known historical dynasties exceeds thirty years. The same remark applies to the thirteenth dynasty, the reigns of whose sixty kings average only seven and a half years each, and it is probable that the end of this dynasty and the whole of the fourteenth was a period of anarchy, during which so-called kings rose and fell in rapid succession, as in the case of our own dynasties of Lancaster and York, and the annals are so confused that the dates are unreliable. What is certain is that the great Middle Empire sank rapidly into a state of 29 anarchy and impotence, which prepared the way for a great catastrophe. This catastrophe came in the form of an invasion of foreigners, who, about the year 2000 b.c., broke through the eastern frontier of the Delta, and apparently without much resistance, conquered the whole of Lower Egypt up to Memphis, and reduced the princes of the Upper Provinces to a state of vassalage. the princes of the Upper Provinces to a state of vassalage. There is considerable doubt who these invaders were, who were known as Hyksos or Shepherd Kings. They consisted probably, mainly of nomad tribes of Canaanites, Arabians, and other Semitic races, but the Turanian Hittites seem to have been associated with them, and the leaders to have been Turanian, judging from the portrait-statues of two of the later kings of the Hyksos 30 dynasty which have been recently discovered by Naville at Bubastis, and which are unmistakably Turanian and even Chinese in type. Our information as to this Hyksos conquest is derived mainly from fragments of Manetho quoted by Josephus, and from traditions repeated by Herodotus, and is very vague and imperfect. But this much seems certain, that at first the Hyksos acted as savage barbarians, burning cities, demolishing temples, and massacring part of the population and reducing the rest to slavery. But, as in the parallel case of the Tartar conquest of China, as time went on they adopted the superior civilization of their subjects, and the later kings were transformed into genuine Pharaohs, differing but little from those of the old national dynasties. This is conclusively proved by the 31 discoveries recently made at Tanis and Bubastis, which have revealed important monuments of this dynasty. At Tanis an avenue of sphynxes was discovered, copied evidently from those at Thebes and from the Great Sphynx at Gizeh, with lion bodies and human heads, the latter with a different head-dress from the Egyptian, and a different type of feature. At Bubastis two colossal statues of Hyksos kings, with their heads broken off, but one of them nearly perfect, were unexpectedly discovered by Naville in 1887, and it was proved that they had stood on each side of the entrance to an addition made by those kings to the ancient and celebrated temple of the Egyptian goddess Bast, thus proving that the Hyksos had adopted not only the civilization but also the religion of the Egyptian nation. There are but few inscriptions known of the Hyksos dynasty, for their cartouches have generally been effaced, and those of later kings chiselled over them; but enough remains to show that they were in the hieroglyphic character, and the names of two or three of their kings can still be deciphered, among which are two Apepis, the second probably the last of the dynasty. It was probably under one of these Hyksos kings that Joseph came to Egypt, and the tribes of Israel settled on its eastern frontier. The duration of the Hyksos rule is thus left in some uncertainty. Manetho, if correctly quoted by Josephus, says they ruled over Egypt for 511 years, though his lists only show one dynasty of 259 years, and then the Theban dynasty, who reigned over Upper Egypt for 260 years contemporaneously with Hyksos kings in Lower Egypt. We regain, however, firm historical ground with the rise of the eighteenth Theban dynasty of native Egyptian kings, 32 who finally expelled the Hyksos, after a long war, and founded what is known as the New Empire. The date of this event is fixed by the best authorities at about 1750 b.c., and from this time downwards we have an uninterrupted succession of undoubted historical records, confirmed by contemporary monuments and by the annals of other nations, down to the Christian era. The reaction which followed the expulsion of the Hyksos led to campaigns in Asia on a great scale, in which Egypt came into collision with powerful nations, and for a long time was the dominant power in Western Asia, extending its conquests from the Persian Gulf to the Black Sea and Mediterranean, and receiving tribute from Babylon and Nineveh. Then followed wars, waged on more equal terms, with the Hittites, who had founded a great empire in Asia Minor and Syria; and as their power declined and that of Assyria rose, with the long series of warlike Assyrian monarchs, who gradually obtained the ascendency, and not only stripped Egypt of its foreign conquests, but on more than one occasion invaded its territory and captured its principal cities. It is during this period that we find the first of the certain synchronisms between Egyptian history and the Old Testament, beginning with the capture of Jerusalem by Shishak in the reign of Rehoboam, and ending with the captivity of the Jews and temporary conquest of Egypt by Nebuchadnezzar. Then came the Persian conquest by Cambyses and alternate periods of national independence and of Persian rule, until the conquest of Alexander and the establishment of the dynasty of the Ptolemies, which lasted until the reign of Cleopatra, and ended finally by the annexation of Egypt as a province of the Roman Empire.

33 The history of this long period is extremely interesting, as showing what may be called the commencement of the modern era of great wars, and of the rise and fall of civilized empires; but for the present purpose I only refer to it as helping to establish the chronological standard which I am in search of as a measuring-rod to gauge the duration of historical time. We may sum up the conclusions derived from Manetho's lists and the monuments as follows:—

Manetho's lists, as they have come down to us, show a date of 5867 years b.c. for the accession of Menes. Of this period, we may say that we know 1750 years for the New Empire and the period of the Persians and the Ptolemies, from contemporary monuments and records, with such certainty that any possible error cannot exceed fifty or one hundred years. The Hyksos period is less certain, but there is no sufficient reason for doubting that it may have lasted for about 511 years. Manetho could have had no object in overstating the duration of the rule of hated foreigners, and a long time must have elapsed before the rude invaders could have so completely adopted the civilization of the subject race. The dates of the Middle Empire, to which Manetho assigns 1241 years, are more uncertain, and we can only check them by monuments for the eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth dynasties. The length of the fourteenth Xoite dynasty seems to be exaggerated, and the later obscure Theban dynasties may have been contemporary with the rule of the Hyksos in Lower Egypt. Of the 2105 years assigned to the Ancient Empire, the first 1645 from Menes to the end of the sixth dynasty are well authenticated by monuments and inscriptions, and the 460 for the seventh, 34 eighth, ninth, and tenth are obscure, though a considerable time must have elapsed for such a complete eclipse of the monuments and arts as appears to have occurred between the nourishing period of the sixth dynasty and the revival of the Middle Empire under the eleventh. We may say, therefore, that we have about 4000 years of undoubted history between the accession of Menes and the Christian era, and 1600 more years for which we have only the authority of Manetho's lists, and the names of unknown kings in genealogical records, with a few scattered monuments, and to which it is difficult to assign specific dates. This may enable us to appreciate the nature of the evidence upon which Mariette and so many of the best and oldest authorities base their estimates in assigning a date of about 5000 b.c. for the accession of Menes.

The glimpses of light into the prehistoric stages of Egyptian civilization prior to Menes are few and far between. We are told that before the consolidation of the Empire by Menes, Egypt was divided into a number of separate nomes or provinces, each gathered about its own independent city and temple, and ruled by the Horsheshu or servants of Horus, who were apparently the chief priests of the respective temples, combining with the character of priest that of king, or local ruler. Parts of the Todtenbuch or Sacred Book of the Dead certainly date from this period, and the great Temple of the Sun at Heliopolis had been founded, for we are told that certain prehistoric Heliopolitan hymns formed the basis of the sacred books of a later age. At Edfu the later temple occupies the site of a very ancient structure, traditionally said to date back to the mythic reign of the gods, and to have been built 35 according to a plan designed by Nuhotef the son of Pthah. At Denderah an inscription found by Mariette in one of the crypts of the great temple, expressly identifies the earliest sanctuary built upon the spot with the time of the Horsheshu. It reads, "There was found the great fundamental ordinance of Denderah, written upon goatskin in ancient writing of the time of the Horsheshu. It was found in the inside of a brick wall during the reign of King Pepi (i.e. Pepi-Merira of the sixth dynasty). The name of Chufu, the king of the fourth dynasty, who built the great pyramid, was found by Naville in a restoration of part of the famous temple of Bubastis, and its foundation doubtless dates back to the same prehistoric period.

But the most important prehistoric monuments are those connected with the great Sphynx. An inscription of Chufu (Cheops) preserved in the museum of Boulak, says that a temple adjoining the Sphynx was discovered by chance in his reign, which had been buried under the sand of the desert, and forgotten for many generations. This temple was uncovered by Mariette, and found to be constructed of enormous blocks of granite of Syene and of alabaster, supported by square pillars, each of a single block of stone, without any mouldings or ornaments, and no trace of hieroglyphics. It is, in fact, a sort of transition from the rude dolmen to scientific architecture. But the masonry, and still more the transport of such enormous blocks from Syene to the plateau of the desert at Gizeh, show a great advance already attained in the resources of the country and the state of the industrial arts. The Sphynx itself probably dates from the same period, for it is mentioned on the same inscription as being much older than the great 36 Pyramids, and requiring repairs in the time of Chufu. It is a gigantic work consisting of a natural rock sculptured into the form of a lion's body, to which a human head has been added, built up of huge blocks of hewn stone. It is directed accurately towards the east so as to face the rising sun at the equinox, and was an image of Hormachen, the Sun of the Lower World, which traverses the abode of the dead. In addition to the direct evidence for its prehistoric antiquity, it is certain that if such a monument had been erected by any of the historical kings, it would have been inscribed with hieroglyphics, and the fact recorded in Manetho's lists and contemporary records, whereas all tradition of its origin seems to have been lost in the night of ages.

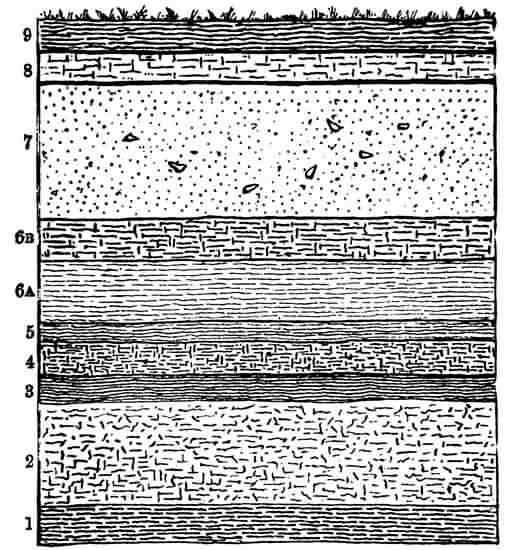

Although there are no monuments of the Stone Age in Egypt like those of the Swiss lake villages and Danish kitchen-middens, to enable us to trace in detail the progress of arts and civilization from rude commencements through the neolithic and prehistoric ages, yet there is abundant evidence to show that the same stages had been traversed in the valley of the Nile long prior to the time of Menes. Borings have been made on various occasions and at various localities through the alluvial deposits of the Nile valley, from which fragments of pottery have been brought up from depths which show a high antiquity. Horner sunk ninety-six shafts in four rows at intervals of eight miles, across the valley of the Nile, at right angles to the river near Memphis, and brought up pottery from various depths, which, at the known rate of deposit of the Nile mud of about three inches per century, indicate an antiquity of at least 11,000 years. In another boring a copper knife was brought up from a depth of twenty-four feet, and 37 pottery, from sixty feet below the surface. This is specially interesting, as making it probable that here, as in many other countries, an age of copper preceded that of bronze, while a depth of sixty feet at the normal rate of deposit would imply an antiquity of 26,000 years. Borings, however, are not very conclusive, as it is always open to contend that they may have been made at spots where, owing to some local circumstances, the deposit was much more rapid than the average.

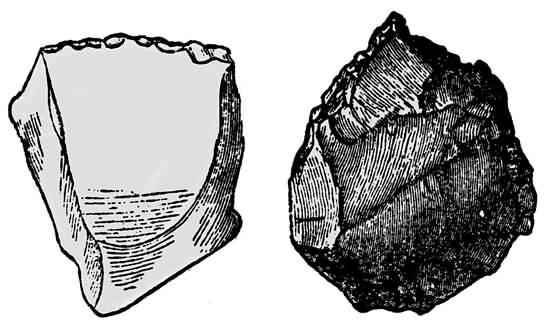

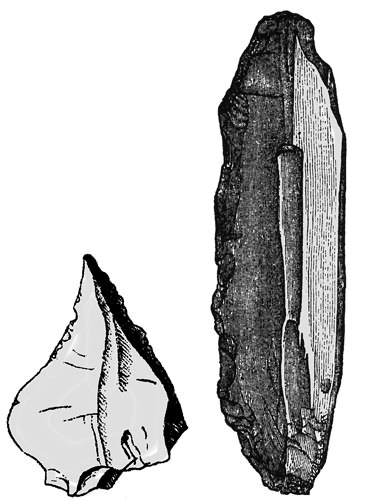

These objections, however, cannot apply to the evidence which has been afforded by the discovery of flint implements, both of the neolithic and palæolithic type, in many localities and by various skilled observers. Professor Haynes found, a few miles east of Cairo, not only a number of flint implements of the types usual in Europe, but an actual workshop or manufactory where they had been made, showing that they had not been imported, but produced in the country in the course of its native development. He also found multitudes of worked flints of the ordinary neolithic and palæolithic types scattered on the hills near Thebes. Lenormant and Hamy saw the same workshop and remains of the stone period, and various other finds have been reported by other observers. Finally, General Pitt-Rivers and Professor Haynes found well-developed palæolithic implements of the. St. Acheul type, not only on the surface and in superficial deposits, but from six and a half to ten feet deep in hard stratified gravel at Djebel-Assas, near Thebes, in a terrace on the side of one of the ravines falling from the Libyan desert into the Nile valley, which was certainly deposited in early quaternary ages by a torrent pouring down from a plateau where, under existing geographical and climatic conditions, 38 rain seldom or never falls. These relics, as Mr. Campbell says, who was associated with General Pitt-Rivers in the discovery, are "beyond calculation older than the oldest Egyptian temples and tombs," and they certainly go far to prove that the high civilization of Egypt at the earliest dawn of history or tradition had been a plant of extremely slow growth from a state of provincial savagery.

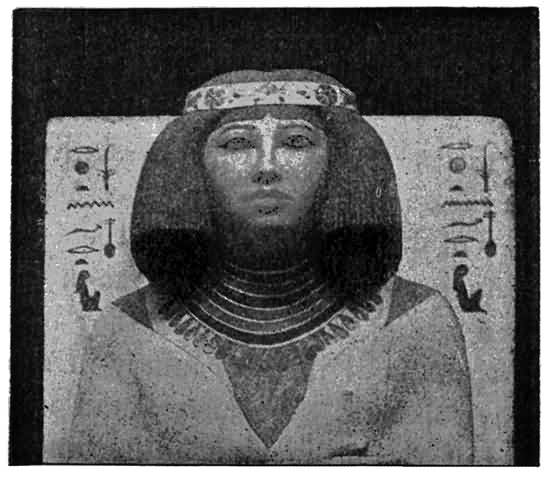

STATUE OF PRINCE RAHOTEP'S WIFE. (Refined type.)

(Gizeh Museum.—Discovered in 1870 in a tomb near Meydoon.—According to the chronological table of Mariette, it is 5800 years old.—From a photograph by Sebah, Cairo.)

It is remarkable that all the traditions of the Egyptians represent them as being autochthonous. There is no legend of any immigration, no Oannes who comes out of the sea and teaches the arts of civilization. On the contrary, Thoth and Osiris are native Egyptian gods or kings, who reigned long ago in Egyptian cities. There are no legends of an inferior race who were exterminated or driven up the Nile; though it would seem from the portraits on early monuments that there were two types 39 in the very early ages one coarse and approximating to the African, the other a refined and aristocratic type, more resembling that of the highest Asiatic or Arabian races.

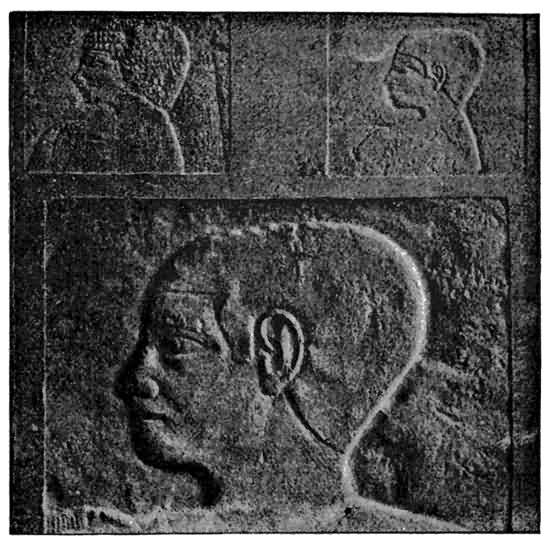

KHUFU-ANKH AND HIS SERVANTS—EARLY EGYPTIANS. (Coarse type.)

It has been conjectured that this latter race may have come from Punt, that is, from Southern Arabia, and the opposite African coast of Soumali land, where there are races of a high, civilization at a very early period. This conjecture is based on the fact that Punt is constantly referred to in the Egyptian monuments as a divine or sacred land, while other surrounding nations are loaded with opprobrious epithets. Also the earliest traditions refer the origin of Egyptian civilization not to Lower Egypt, where the Isthmus of Suez affords a land route from Asia, nor to Upper Egypt, as if it had 40 descended the Nile from Africa, but to Abydos and This in Middle Egypt, where the gods were feigned to have reigned, which are comparatively close to Coptos, the port on the Red Sea by which intercourse was most easily kept up between the valley of the Nile and the land of Punt.

This conjecture, however, is very vague, and when we come to positive facts we find that the language and system of writing, when we first meet with them, are fully formed and apparently of native growth, not derived from any Semitic, Aryan, or Turanian speech of any historical nation. It is certainly an agglutinative language originally, but far advanced beyond the simpler forms of that mode of speech as spoken by Mongolians. It shows some distant affinities with Semitic, or rather with what may have been a proto-Semitic, before it had been fully formed, and is perhaps nearer to what may have been the primitive language of the Libyans of North Africa. But there is nothing in the language from which we can infer origin, and the pictures from which hieroglyphics are derived are those of animals and objects proper to the Nile valley, and not like those of the Accadians and Chinese, such as point to a prehistoric nomad existence on elevated plains. The only positive fact tending to confirm the existence of two races in Egypt, one rude and aboriginal, the other of high type, is the difference of type shown by the early portraits and the discovery by Mr. Flinders Petrie, in the very old cemetery of Meydoon, of two distinct modes of interment, one of the ordinary mummy extended at full length, the other in a crouching attitude as is common in neolithic graves.

For any further inquiries as to the origin and 41 antiquity of Egyptian civilization, we have to fall back on the state of religion, science, literature, and art, which we find prevailing in the earliest records which have come down to us, and which I will proceed to examine in subsequent chapters. But before doing so, I will endeavour to exhaust the field of positive history, and inquire how far the annals of other ancient nations contradict or confirm the date of about 5000 years b.c., which has been shown to be approximately that of the accession of Menes.

Chronology—Berosus—His Dates mythical—Dates in Genesis—Synchronisms with Egypt and Assyria—Monuments—Cuneiform Inscriptions—How deciphered—Behistan Inscription—Grotefend and Rawlinson—Layard—Library of Koyunjik—How preserved—Accadian Translations and Grammars—Historical Dates—Elamite Conquest—Commencement of Modern History—Ur-Ea and Dungi—Nabonidus—Sargon I., 3800 b.c.—Ur of the Chaldees—Sharrukin's Cylinder—His Library—His son Naram-Sin—Semites and Accadians—Accadians and Chinese—Period before Sargon I.—Patesi—De Sarzec's find at Sirgalla—Gud-Ea, 4000 to 4500 b.c.—Advance of Delta—Astronomical Records—Chaldæa and Egypt give similar results—Historic Period 6000 or 7000 years—and no trace of a beginning.

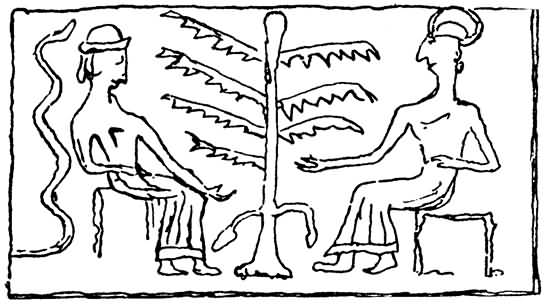

Chaldæan chronology has within the last few years been brought into the domain of history, and carried back to a date almost, if not quite, as remote as that of Egypt. And this has been effected by a process identical in the two cases, the decipherment of an unknown language in inscriptions on ancient monuments. Until this discovery the little that was known of the early history of Chaldæa was derived almost entirely from two sources: the Bible, and the fragments quoted by later writers from the lost work of Berosus. Berosus was a learned priest of Babylon, who lived about 300 b.c., shortly after the conquest of Alexander, and wrote in Greek a history of the country from the most ancient times, compiled from the annals preserved in the 43 temples, and from the oldest traditions. He began with a Cosmogony, fragments of which only are preserved, from which little could be inferred, except that it bore some general resemblance to that of Genesis, until the complete Chaldæan Cosmogony was deciphered by Mr. George Smith from tablets in the British Museum. Then followed a mythical period of the reigns of ten gods or demi-gods, reigning for 432,000 years, in the middle of which period the divine fish-man, Ea-Han or Oannes, was said to have come up out of the Persian Gulf, and taught mankind letters, sciences, laws, and all the arts of civilization; 259,000 years after Oannes, under Xisuthros (the Greek translation of Hasisastra), the last of the ten kings, a Deluge is said to have occurred; which is described in terms so similar to the narrative of Noah's deluge in Genesis, as to leave no doubt that they are different versions of the same legend.