Title: Special Days and Their Observance

Author: Anonymous

Release date: July 25, 2014 [eBook #46413]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Tom Cosmas and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

PROPERTY OF THE STATE OF NEW JERSEY

NOT TO BE TAKEN PERMANENTLY FROM THE SCHOOLROOM

STATE OF NEW JERSEY

DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION

TRENTON

Special Days

and their

Observance

September 1919

APPROVED BY

STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION

JUNE 1919

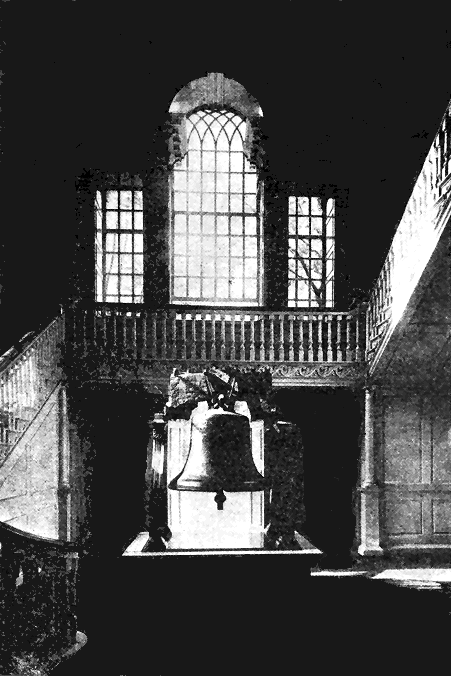

Liberty Bell

Liberty BellSTATE OF NEW JERSEY

DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION

TRENTON

Special Days

and their

Observance

September 1919

APPROVED BY

STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION

JUNE 1919

| PAGE | |

| Foreword | 7 |

| Acknowledgments | 9 |

| Opening Exercises | 11 |

| Morning Exercises, Jennie Haver | 13 |

| Morning Exercises, Florence L. Farber | 24 |

| Opening Exercises, Louis H. Burch | 27 |

| Columbus Day, J. Cayce Morrison | 33 |

| Thanksgiving Day, Roy L. Shaffer | 59 |

| Lincoln's Birthday, Charles A. Philhower | 69 |

| Washington's Birthday, Henry W. Foster | 89 |

| Arbor Day | 109 |

| Trees and Forests, Alfred Gaskill | 112 |

| Arbor Day observed by planting Hamilton Grove, Charles A. Philhower | 119 |

| Suggestions to Teachers, K. C. Davis | 121 |

| Value of our Forests, U. S. Bureau of Education | 123 |

| Memorial Day, George C. Baker | 125 |

| Flag Day, Hannah H. Chew | 141 |

| Bibliography, Katharine B. Rogers | 159 |

| PAGE | |

| Liberty Bell | Frontispiece |

| Columbus, "Admiral at the Helm" | 51 |

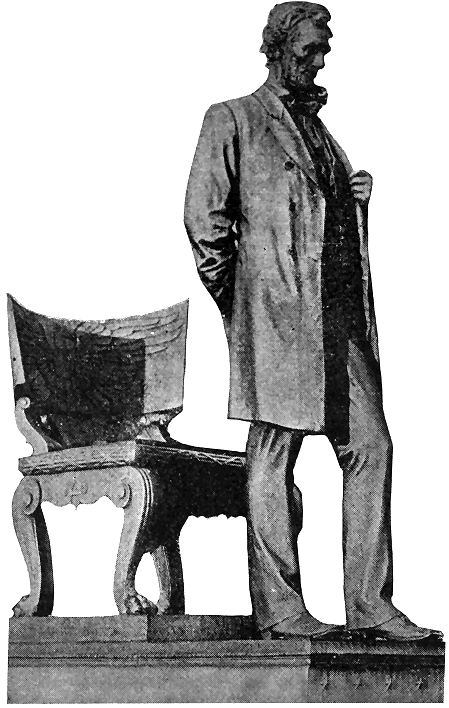

| Saint Gaudens' Lincoln | 73 |

| Gutzon Borglum's Lincoln | 85 |

| Stuart's Washington | 93 |

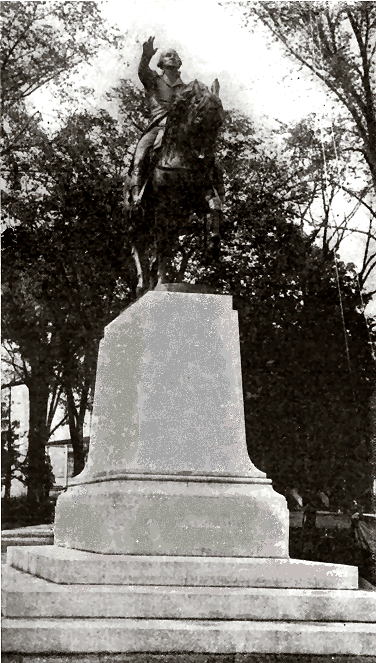

| Statue of Washington at West Point | 103 |

In the statutes of the state will be found the following:

The day in each year known as Arbor Day shall be suitably observed in the public schools. The Commissioner of Education shall from time to time prepare and issue to schools such circulars of information, advice and instruction with reference to the day as he may deem necessary.

For the purpose of encouraging the planting of shade and forest trees, the second Friday of April in each year is hereby designated as a day for the general observance of such purpose, and to be known as Arbor Day.

On said day appropriate exercises shall be introduced in all the schools of the State, and it shall be the duty of the several county and city superintendents to prepare a program of exercises for that day in all the schools under their respective jurisdiction.

In all public schools there shall be held on the last school day preceding the following holidays, namely, Lincoln's Birthday, Washington's Birthday, Decoration or Memorial Day and Thanksgiving Day, and on such other patriotic holidays as shall be established by law, appropriate exercises for the development of a higher spirit of patriotism.

It shall be the duty of the principals and teachers in the public schools of this State to make suitable arrangements for the celebration, by appropriate exercises among the pupils in said schools, on the fourteenth day of June, in each year, as the day of the adoption of the American flag by the Continental Congress.

The provisions of these statutes have been carried out in the schools of the state. They are believed in and supported heartily by the public opinion of the state.

In order that greater assistance may be rendered to teachers and school officers in preparing for these special days, this pamphlet on Special Days and their Observance has been prepared by the Department, chiefly through the efforts of Mr. Z. E. Scott, Assistant Commissioner in charge of Elementary Education.

The pamphlet also contains suggestions concerning the opening exercises of schools.

Mr. Scott has been assisted in this work by the following persons, the school officers having in turn been aided by their teachers. To all these grateful acknowledgment is hereby made.

George C. Baker, Supervising Principal, Moorestown

Louis H. Burch, Principal Bangs Avenue School, Asbury Park

Hannah Chew, Principal Culver School, Cumberland County

K. C. Davis, formerly of State Agricultural College, New Brunswick

Florence Farber, Helping Teacher, Sussex County

Henry W. Foster, Supervising Principal, South Orange

Alfred Gaskill, State Forester

Jennie Haver, Helping Teacher, Hunterdon County

J. Cayce Morrison, Supervising Principal, Leonia

Charles A. Philhower, Supervising Principal, Westfield

Katharine B. Rogers, Reference Librarian, State Library

Roy L. Shaffer, Supervisor of Practice, Newark State Normal School

It has been the aim of Mr. Scott and his associates to suggest exercises which would be appropriate for the observance of these several days, which would be of interest to pupils, and which at the same time would be of a character worthy of the dignity of the public schools of the state.

Calvin N. Kendall

Commissioner of Education

Grateful acknowledgment is hereby made to the following publishers and authors for permission to use copyrighted selections:

American Book Company, New York, for extract from Green's "Short History of the English People."

D. Appleton & Company, New York, for Bryant's "America" and extract from Edward S. Holden's "Our Country's Flag."

Henry Holcomb Bennett for "The Flag Goes By."

Bobbs-Merrill Company, Indianapolis, for "The Name of Old Glory," by James Whitcomb Riley.

Boosey & Company, New York, for "We'll keep Old Glory Flying," by Carleton S. Montanye.

Dr. Frank Crane for "After the Great Companions."

Thomas Y. Crowell Company, New York, for extract from "The Book of Holidays," by J. Walker McSpadden. Reprinted by permission of the publishers. Copyright 1917 by Thomas Y. Crowell Company.

Joseph Fulford Folsom for "The Unfinished Work."

Harper & Brothers, New York, for extract from "The Americanism of Washington," by Henry van Dyke.

Caroline Hazard for "The Western Land."

Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, for Bret Harte's "The Reveille" and extract from "Our National Ideals," by William Backus Gitteau.

Kindergarten Magazine Publishing Company, Manistee, Michigan, for nine selections, including two by Laura Rountree Smith and one by Mary R. Campbell.

Macmillan Company, New York, for extract from "The Making of an American," by Jacob A. Riis, and "On a Portrait of Columbus," by George Edward Woodberry, used by permission of and special arrangement with the publishers.

Moffat, Yard & Co., New York, for extract from "Memorial Day," by Robert Haven Schauffler.

New England Publishing Company, Boston, for "Columbus Day" and Walt Whitman's "Address to America." From "Journal of Education."

New York Evening Post for "America's Answer," by R. W. Lillard.

New York Herald for Mrs. Josephine Fabricant's "The Service Flag."

New York State Department of Education, Albany, for "The Boy Columbus" and an extract from speech of Chauncey M. Depew.

Theodore Presser Company, Philadelphia, for "Our Country's Flag," by Mrs. Florence L. Dresser.

G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, for "In Flanders Fields," by John McCrae.

Saturday Evening Post, Philadelphia, for "I Have a Son," by Emory Pottle.

Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, for extract from "With Americans of Past and Present Days," by J. J. Jusserand, copyright 1916; used by permission of the publishers.

C. W. Thompson & Company, Boston, for "The Unfurling of the Flag," by Clara Endicott Sears. Copyright; used by permission.

Horace Traubel, Camden, for "O Captain! My Captain!" by Walt Whitman.

P. F. Volland Company, Chicago, for "Your Flag and My Flag," by Wilbur D. Nesbit. Copyrighted 1916 by publishers.

Harr Wagner Publishing Company, San Francisco, for "Columbus," by Joaquin Miller.

Shakespeare

OPENING EXERCISES

JENNIE HAVER, HELPING TEACHER, HUNTERDON COUNTY

The morning exercise is a common meeting ground; it is the family altar of the school to which each brings his offerings—the fruits of his observations and studies, or the music, literature, and art that delight him; a place where all cooperate for the pleasure and well-being of the whole; where all contribute to and share the intellectual and spiritual life of the whole; where all bring their best and choicest experiences in the most effective form at their command.

This quotation from the Second Year Book of the Frances W. Parker School may well be an inspiration, a guide, and finally, a goal for us to use in preparation for the morning exercises.

The period given to the opening exercises may be made the most important period of the day. The pupils, whether they be in a one room rural school or a larger town school, need a more receptive attitude toward the work before them. A short time given to interesting, uplifting exercises will do much to control and lead the restless children, encourage the downhearted ones, inspire the indifferent, and give to teachers and pupils alike higher ideals for effective work and right living.

A part of the time given to opening exercises should be of a devotional nature—consisting of the reading of short selections from the Bible, without comment—and of prayer and singing. Very careful plans must be made for the devotional exercises if they are to function as they should. Too often the selection of song and Bible reading is made after the pupils are in their seats. A message that is truly inspiring is usually the result of considerable time spent in preparation. The thoughtful teacher will plan her opening exercises as carefully as any other part of her regular school work.

The morning exercise affords an opportunity to train pupils for leadership. Recently an interesting morning program of musical appreciation was carried out in a two room country school. When [14] the bell rang the twelve year old pupil leader went to the front of the room and placed a march record on the phonograph. After the pupils were seated she conducted the following program with a great deal of poise and self confidence:

America, by the School

Psalm XXIII

Bacarolle from "Tales of Hoffman" (phonograph)

Traumerei—Schumann (phonograph)

Spring Song—Mendelssohn (phonograph)

Flag salute, by the School

Following each record on the phonograph she asked for the name of the selection and the composer's name. It was surprising to see how familiar even the little ones were with the classical selections.

Some one has said that the only influence greater than that of a good book is personal contact with a great man or woman. Once in a while an interesting talk may be given by a visitor, but the morning exercise period should not be regarded as a lecture period. Occasionally it is well to have leaders of different occupations in the neighborhood give short, pertinent talks on their work.

All too often children are blind to the beauty, deaf to the music, and almost insensible to the wonder and mystery of the great world of nature. One day a little country girl found a large, silky, brown cocoon and carried it to school. She didn't know what it was: neither did her teacher. The cocoon was taken home and kept as an object of curiosity to be shown to the neighbors when they called. One warm spring morning a beautiful Cecropia moth, measuring six inches from tip to tip of wing, emerged from the cocoon. That girl will never forget her wonder and awe as she watched Nature stage one of her most beautiful miracles. Any teacher would find it an inspiration and a delight to bring such a charming bit of nature into her morning exercises. Every day Nature is unfolding just as wonderful stories. Our eyes must be open to see them.

The opening exercises, conducted as they should be, may be a source of inspiration and a means of training for moral and social behavior, for patriotism, for health, for vocational usefulness, for the right use of leisure—in other words, for useful, patriotic citizenship.

There is an abundance of material on every hand that can be used in morning exercises. Following are a few suggestions that may be of help.

SINGING

Profiting by the experience of French and English troops, instructors taught our sailors and soldiers to sing in unison. It has been found that singing does much to improve the morale of the company. Singing in the morning exercises does much to socialize the group and develop school spirit.

There is such a wealth of suitable songs for morning exercises that it seems hardly necessary to suggest many. The hymns selected should be inspiring and uplifting; the patriotic songs should be thoroughly learned and sung in an enthusiastic manner.

Patriotic Songs

America

Battle Hymn of the Republic

Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean

Dixie

Flag of the Free

God Speed the Right

Marching through Georgia

Marseillaise Hymn

Jerseyland

National Hymn

Old Glory

The American Hymn

The Battle Cry of Freedom

The Star Spangled Banner

Folk Songs

Annie Laurie

Auld Lang Syne

Flow Gently, Sweet Afton

Home, Sweet Home

Juanita

My Old Kentucky Home

Oft in the Stilly Night

Old Black Joe

Old Folks at Home

Robin Adair

Santa Lucia

The Blue Bells of Scotland

The Miller of Dee

Lullabies

Cradle Song

Lullaby and Good-night

Oh, Hush Thee, my Baby

Sweet and Low

Silent Night

Sacred

How Gentle God's Command

Holy, Holy, Holy

In Heavenly Love Abiding

Italian Hymn

Love Divine, All Love Excelling

Nearer, My God, to Thee

Oh, Worship the King

The King of Love

There's a Wideness in God's Mercy

Vesper Hymn

MUSICAL APPRECIATION

The introduction of the phonograph into the public school and the multitude of records which reproduce the great masterpieces now make it possible for every child to have an opportunity to hear and to be taught to appreciate good music. Frequently part of the morning exercise period should be devoted to an appreciation of good vocal and instrumental musical selections. In one rural school the pupils readily associate the name of the composition and composer with each of the following records, which they helped to purchase:

Anvil Chorus from "Il Trovatore"—Verdi

Barcarolle from "Tales of Hoffman"—Offenbach

Hearts and Flowers—Tobain

Humoresque—Dvorak

Intermezzo from "Cavalleria Rusticana"—Mascagni

Lo, Hear the Gentle Lark—Bishop

Melody in F—Rubinstein

Miserere from "Il Trovatore"—Verdi

Pilgrim's Chorus from "Tannhauser"—Wagner

Sextette from "Lucia di Lammermoor"—Donizetti

Spring Song—Mendelssohn

Traumerei—Schumann

Literature on musical appreciation will be mailed free to all teachers who request it from the educational departments of the phonograph manufacturers.

Teachers who are really interested in giving their pupils the best music will find that a number of their patrons are willing to lend records to the school for special exercises.

Following are suggestive musical programs:

A Morning with Beethoven

Bible Reading and Lord's Prayer

Minuet in G, No. 2 (phonograph)

"The Moonlight Sonata," Reading by pupil

The Moonlight Sonata (phonograph)

The Flag Salute, Pupils

A Morning with Mendelssohn

Hark! the Herald Angels Sing, Song by School

Bible Reading and Lord's Prayer

Spring Song (phonograph)

Oh, For the Wings of a Dove (phonograph)

The Flag Salute, School

Indian Songs

Bible Reading and Lord's Prayer

The Story of the Indians, Pupil

Navajo Indian Song (phonograph)

Medicine Song (phonograph)

Flag Salute, School

Negro Songs

Old Black Joe, School

Bible Reading and Prayer

Good News (phonograph)

Live a-Humble (phonograph)

The Flag Salute, School

(The records given are by the Tuskegee Institute Singers)

Irish Songs

Wearin' of the Green, School

Bible Reading and Prayer

Come Back to Erin (phonograph)

Macushla (phonograph)

The Flag Salute, School

Scotch Songs

My Laddie (phonograph)

Bible Reading and Prayer

Annie Laurie, School

My Ain Countrie (phonograph)

Flag Salute, School

LITERARY EXERCISES

To instil in the hearts of boys and girls a love for good literature is to give them a never ending source of happiness throughout life. Children can be interested in books by hearing stories read, by retelling them, and by reading them. The story of the author's life may add interest to the author's work. Much can be done in morning exercises to start children on the road to good reading. The more work children do themselves the more interested they will be. Following are suggestive literary programs:

Robert Louis Stevenson

Bible Reading by pupils—Philippians IV, 4-8

Stevenson's Prayer for a Day's Work, Recitation by pupil

Short story of Stevenson's life, Pupil

My Shadow, Pupil

The Land of Story Books, Pupil

God Speed the Right, Sung by School

The Flag Salute, School

Hans Christian Andersen

Psalm 100, Pupil

Lord's Prayer, School

A Poor Boy Who Became Famous, Retold by pupil

The Steadfast Tin Soldier, Retold by pupil

The Little Tin Soldier, Song by School

The Flag Salute, School

Henry W. Longfellow

The Arrow and the Song, Song by School

Bible Reading and Lord's Prayer

Scenes from Hiawatha, Dramatization by pupils

The Village Blacksmith, Recitation by pupil

DRAMATIC EXERCISES

When children are truly interested in reading, the natural outlet for the emotions aroused is dramatic action. Let different classes be responsible for dramatizing stories from their history or reading lessons and present the results in the morning exercises. The educative and socializing value to the class presenting the exercise is almost invaluable. Dramatizing the story makes an interesting incentive for a number of language lessons; rehearsing the play provides for much practice in oral expression; and producing the play before an audience gives valuable training in leadership, self confidence and poise.

ART APPRECIATION

We do not expect many of the school children to become artists, but all can learn to appreciate and tastefully select the beautiful in pictures, personal dress, home furnishing and decoration, and architecture. It has been truly said, "Though we travel the world over to find the beautiful, we must carry it with us or we find it not."

Frequently a few minutes of the morning exercises may be very profitably, spent in the study of the beautiful. Artistic material to use as illustrations for the talks is on every hand. Inexpensive reproductions of the world's great pictures; illustrations in magazines; [19] beautifully colored papers for color combinations in neckties, dress designing and hat trimming; magazine and catalog pictures of well designed furniture and home utensils can be easily obtained.

A suggestive list of morning talks is given below:

Famous Pictures

The First Step—Millet

Landscape with Windmill—Ruysdael

The Horse Fair—Bonheur

Sistine Madonna—Raphael

Morning—Corot

How Can We Get Good Pictures for Our Schoolroom

Color Harmony in Dress

Good Taste in Furniture

Home Decoration

Beautifying the School Ground

Washington, the City Beautiful

References

How to Enjoy Pictures—Emery

A Child's Guide to Pictures—Coffin

The Mentor

The School Arts Magazine

Ladies' Home Journal

The Perry Pictures

National Geographic Magazine

HEALTH TALKS FOR MORNING EXERCISES

Truly, "A people's health's a nation's wealth," and every encouragement should be given in school to further the doctrine of healthful living. The medical examiner, the school nurse, the pupils and the teachers, all may do their part to make the health talks practical and of much value to the school.

Suggestive Health Talks

Why we should exercise

Care of the Teeth

Care of the Eyes

Prevention of Colds

How to prevent Tuberculosis

Swat the Fly

How to destroy mosquitoes

Cleanliness

Safety First

Cigarette Smoking

Self Control and Good Manners

Emergencies

School Sanitation

References

Teaching of Hygiene and Safety Pamphlets of Health, from the National

Department of Health, Washington, D. C.

State Department of Health, Trenton, N. J.

Russell Sage Foundation, New York City

Health-Education League, Boston, Mass.

Farmer's Bulletins from U. S. Department of Agriculture

Modern Hygiene textbooks

Newspaper and Magazine Articles

NATURE TALKS

The study of the wonderful things of the world, their beautiful fitness for their existence and function, the remarkable progressive tendency of all organic life, and the unity that prevails in it create admiration in the beholder and tend to his spiritual uplifting.

Suggestive topics for morning exercises

How can we attract the birds?

How I Built A Bird House

Does it Pay the Farmer to Protect the Birds?

The Travel of Birds

The Life History of a Frog

The Life History of a Butterfly

How I made my Home Garden

How I raised an Acre of Corn

The Trees on our School Ground

THE LOCAL HISTORY OF THE COMMUNITY

A series of morning exercises may be devoted to the local history of a community. The material may be planned by the pupils with the assistance of some of the older people in the neighborhood. This idea was carried out very successfully in a small town and did much to interest the parents in the school. Many were willing to send family heirlooms to the classroom to use as illustrations for the talks. One charming old lady sent a written account of the history of her old home.

Following are some topics that might be developed:

Former Location of Indian Tribes in the Community

Evidences of Indian Occupation (old trails, implements, mounds, etc.)

The First White Settlers

Revolutionary Landmarks

Colonial Relics

Historic Homes in the Community

Famous People of the Community

A program for one morning might be conducted by the pupils as follows:

Proverbs 27:1-2, Pupil

Italian Hymn, School

Famous People of the Community

The Grandfather who fought in the Civil War, pupil

The Man who was Governor of the State, pupil

The Woman who was a Nurse in the World War, pupil

The Man who wrote a Book, pupil

The Soldier boy in France, pupil

America

THE USE OF PUPIL ORGANIZATION IN THE MORNING EXERCISES

Much interesting and instructive material can be secured for opening exercises by making use of members of recognized organizations for boys and girls. There are members of the Boy Scouts of America in almost every community. The Camp Fire Girls are getting to be almost as well known. Let each group prepare occasional programs for morning exercises.

Boy Scouts

Bible Reading and Lord's Prayer

The Origin and Growth of Scouting

The Three Classes of Scouts

The Scout Motto

The Scout Law

"America" and Flag Salute

Camp Fire Girls

Bible Reading and Lord's Prayer

The Seven Laws of the Order

The Wood Gatherer

The Fire Maker

The Torch Bearer

Song by School

The Flag Salute

PATRIOTIC EXERCISES

The patriotic note should be found in every morning exercise and some periods should be devoted entirely to patriotic selections. The national hymns should be learned from the first stanza to the last. It is hard to get the patriotic note in our singing when we do not know the words.

Suggestive Programs

America, School

Bible Reading and Lord's Prayer

Patrick Henry's Speech (phonograph)

Lincoln's Gettysburg Address (phonograph)

Flag Salute

Bible Reading and Prayer

Army Bugle Call No. 1 (phonograph)

The Junior Red Cross

Sewing for the Red Cross, A girl

Earning Money for the Red Cross, A boy

How the Work of the Junior Red Cross develops Patriotism

in a school, Pupil

Come, Thou Almighty King, School

"Patriotism consists not in waving a flag but in striving that our country shall be righteous as well as strong."—James Bryce

"One cannot always be a hero, but one can always be a man."—Goethe

"Go back to the simple life, be contented with simple food, simple pleasures, simple clothes. Work hard, play hard, pray hard. Work, eat, recreate and sleep. Do it all courageously. We have a victory to win."—Hoover

MEMORY GEMS

Madeline S. Bridges

Bailey

Louis E. Thayer

The day returns and brings us the petty round of irritating concerns and duties. Help us to play the man, help us to perform them with laughter and kind faces, let cheerfulness abound with industry. Give us to go blithely on our business all this day, bring us to our resting beds weary and content and undishonored, and grant us in the end the gift of sleep.

Robert Louis Stevenson

Maltbie D. Babcock

Jane Thompson

You cannot dream yourself into a character; you must hammer and forge yourself one.—James Anthony Froude

Wordsworth

Kindness is catching, and if you go around with a thoroughly developed case your neighbor will be sure to get it.

If you have faith, preach it; if you have doubts, bury them; if you have joy, share it; if you have sorrow, bear it. Find the bright side of things and help others to get sight of it also. This is the only and surest way to be cheerful and happy.

MORNING EXERCISES

FLORENCE L. FARBER, HELPING TEACHER, SUSSEX COUNTY

The short period known as the opening exercise period belongs to all the children of the school. This period should furnish especially favorable opportunities for the development of initiative on the part of pupils, group cooperation, development of the play spirit, interest in community life, interest in and love for our great men and women, and devotion to our Republic.

The first problem of the teacher, then, is to understand fully that she is to a great degree responsible for furnishing aims and purposes in this beginning period of the day, or rather in providing the situations through which these aims and purposes may develop. When she feels the importance of this period in the general scheme of the day's work she will plan for it as definitely and as carefully as she will any other part of her program. The working out of a detailed program is of secondary importance. The thing of first importance is that she become fully cognizant of the general aims and ideals which she hopes to achieve. With these firmly fixed in her mind she is ready then to cooperate with the pupils of her room in planning detailed programs.

The following projects are in keeping with the principles presented and have been found stimulating in one and two room schools:

Project 1. The teacher divides her children into groups on the basis of age and ability. For example, in a one room school a teacher might have two groups. Each group is to work out with the teacher a program which it is to give and for which it is responsible. This program may consist of a short story to be dramatized, the story to contain not more than two or three important scenes. The costuming, if any is needed, is to be done by pupils and teacher. Rehearsing is to be directed by the teacher. When the program is presented it should be as a new production to all the school except those who are engaged in presenting it. It is to be given, therefore, as a real play to a real audience. Each pupil should invite a member of the family or a friend.

The value of such work will soon be noticed in a better social spirit among the children. The dramatizations given may furnish the material for both oral and written language lessons. Dramatization itself will provide excellent practice in oral expression and also training [25] in initiative, leadership and cooperation. The story presented may furnish many funny settings which the pupils may enjoy with abandon. And what children do not need real merriment in school! Opportunity ought to be afforded all children of our public schools to enjoy a real laugh at least once each day.

Teachers need have no fear that the different groups will be over-critical or discourteous to one another. They will understand that they are being entertained and they will cooperate to make the play given worth while.

The following stories lend themselves very readily to dramatization.

First and Second Grades

The Three Billy Goats Gruff

Spry Mouse and Mr. Frog

The Three Bears

The Camel and The Jackal

The Tale of Peter Rabbit

Our First Flag

Third and Fourth Grades

The Sleeping Beauty

Snow White and Rose Red

Brother Fox's Tar Baby

How the Cave Man Made Fire

Scenes from Hiawatha

Early Settlers in New Jersey

Fifth and Sixth Grades

The Pied Piper of Hamelin

Joseph and His Brethren

Abou Ben Adhem

Paul Revere's Ride

Scenes from Life of Daniel Boone

Franklin's Arrival in Philadelphia

Scenes from Alfred the Great

The Battle of Hastings

How Cedric Became a Knight

Seventh and Eighth Grades

The Vision of Sir Launfal

Rip Van Winkle

The King of the Golden River

Scenes from Evangeline

Landing of the Pilgrims

Conquest of the Northwest Territory

The Man Without a Country

Project 2. A special problem in history or geography, for example, may be taken up, such as the life of the people in Japan, or the life of the people on a cattle ranch. In either case the class that presents the work as an opening exercise should be given opportunity to work out certain scenes which it wants to give. These scenes should be presented either by sand-table, by charts, by posters, by pictures from magazines, or by dramatization on the part of the children. Preparation of such work is decidedly worth while, and ought to be a regular part of the day's program. The important scenes should be rehearsed before the final presentation.

Project 3. Poster exhibit. This project could be arranged for all the children of a given school, in which case the best work would be selected and the children presenting it would discuss each poster in one or two minute talks. A still better way to handle the project would be to have the best posters from different schools. In this case at least one pupil from each school should be invited to present the posters from his school.

Project 4. War programs. A war opening exercise program could be worked out by the children of a given school. This could be done by having children collect war posters and war pictures made during the recent world war and arrange them in such a way that they tell a connected story. A group should be held responsible for presenting each story or part of a story. A sand-table should be provided if necessary.

An excellent war program could be provided by having the emphasis placed upon the various men who have led or are leading in our own national life. Pictures of these men should be secured and children called upon to tell what important work each man has done or is doing. This same device could be carried a step further and a special program arranged, centering around the pictures of the different men who led the allied forces. The older pupils of any school ought to be able to do this work.

An additional way by which our schools may help in the work of patriotism is to have an opening exercise by the children whose immediate relatives were at the front. Such a program ought to have for its purpose the idea of service to one's country.

Another helpful device would be to have at an appropriate time former soldiers come to the school and talk to the children concerning the meaning of the war.

The teacher who plans her opening exercise periods in keeping with the foregoing presentation will make these periods inspiring and helpful to herself and her children. She will be putting across the gospel of good cheer, and cooperation in the new kind of school which offers opportunities for participation in life's present day activities, not preparation for future activities.

OPENING EXERCISES

LOUIS H. BURCH, PRINCIPAL BANGS AVENUE SCHOOL, ASBURY PARK

Play is one of the first manifestations of the child in self expression. As the child grows older this play is made up in part of the imitation of the doings and sayings of the older persons and playmates with whom he is associated. The child reflects the life of his parents wherever it comes under his comprehension. The stick horse gives as much pleasure to the boy as the well trained saddle horse gives to the father.

When the child enters school much of the play element of his life is left behind, and teachers have often failed to use to advantage the experience and knowledge the child has in "living over" the actions and sayings of others. The ordinary child has observed the animals and birds around him and can imitate them. He can personify the tree, the flower, or the brook, and gain a clearer knowledge of the purpose and function of the thing personified by so doing. Under the proper direction of the teacher nearly all the common occurrences of life may be dramatized by the children in the ordinary schoolroom and with few so-called stage properties.

Older children are interested in the simple dramatizations of the little folks and should have opportunity to see them often, not alone to be entertained, but to be reminded of the simple and easy ways of "playing you are someone else." A grammar grade class may learn many things from watching a primary class dramatize "Three Bears," "Little Red Hen," or "Little Red Ridinghood."

The simple dramatization in the schoolroom furnish excellent material for general assemblies or morning exercises. Simple costumes and stage settings satisfy the children, and the setting of the stage or platform for the scene should, in most cases, be done before the children. Children who see the table set, the chairs placed, and the beds prepared for the "Three Bears" know how to get ready for their play when they are called upon to contribute their part for the assembly.

Children will bring material for their costumes and stage furnishings from home and should be encouraged to do so. Parents will come to see children take part in a program when nothing else would attract them to the school, and if the home is to be called upon to help the school there must be a closer relationship between parents and teacher.

In preparing dramatizations for elementary school pupils but few scenes should be chosen, and in those selected the language and action should be simple and within the capabilities of the children.

The following dramatizations were worked out by teachers and pupils of our building as class projects. They were presented in the opening exercises as worth-while classroom projects which would be entertaining and helpful to all pupils of the school, to teachers and to parents. In presenting these scenes the pupils secured excellent practice in oral English work, in dramatic action, and in community and group cooperation. The pupils and teachers who made up the audience enjoyed opening exercises in which there was purpose. All entered into the spirit of the play; all enjoyed the exercises without having to think why. The results have been better team work between teacher and pupils, better school spirit, more pupil participation in leadership activities.

The History of Cotton

Prepared by Bessie O'Hagen, Teacher of Fourth Grade, Bangs Avenue School, Asbury Park

Characters: Spirit of Cotton, Little Girl, Maiden from India, Maiden from Egypt, Maiden from America, Spirit of Eli Whitney.

Little Girl (coming into the room in bad humor). I hate this old cotton dress. I wish I had a silk one. I don't see why we have to use cotton anyway. We have to have cotton dresses, cotton sheets, cotton stockings, cotton everything. I just hate cotton! I'm not going out to play or anything. (Finally sits down.) I am so tired. I wish I had a silk dress. I hate this cotton dress. (Falls asleep.)

Spirit of Cotton (skipping into the room). Heigh ho! Ho heigh! Here am I, the Spirit of Cotton. I heard what you said, little girl. Did you ever see cotton grow?

Little Girl (frightened). Why, no.

Spirit of Cotton. How do you know whether it is interesting or not? I will tell you the story of my life. In the early spring the planter gets the ground ready for me. As soon as the frost is out of the ground, he plants me.

Little Girl. What happens then?

Spirit of Cotton. The good earth gives me food. The sun and rain make me grow, and soon—

Little Girl. How do you look?

Spirit of Cotton. My leaves are green like the maple. I have lovely blossoms. They are white the first day and pink the next.

Little Girl. I thought you said that you were a cotton plant.

Spirit of Cotton. So I did. My blossoms fall off, and then—

Little Girl. Is that all?

Spirit of Cotton. No, I have some friends who will tell you more about my life. (Goes out and returns leading a little girl by the hand.) This is my friend from India. (Goes out again.)

Little Girl. How did you get here?

Maiden from India. I heard the Spirit of Cotton calling and I obeyed.

Little Girl (pointing to a map of Asia which is pinned on Maiden from India). Is this your country?

Maiden from India. Yes, I have come to tell you something about cotton in my country. Cotton was first raised in my country. That was long, long, long ago.

Little Girl. A hundred years ago?

Maiden from India. We knew how to weave cotton thousands of years ago.

Little Girl. Did you know how to weave well?

Maiden from India. We made such fine dresses that you could draw a whole one through your ring.

Little Girl. I don't believe I could draw my dress through my ring.

Maiden from India. I know you couldn't.

Spirit of Cotton (outside). Heigh ho! Ho heigh!

Maiden from India. I must return. The Spirit of Cotton is calling. (Goes out.)

Spirit of Cotton (comes in, leading a little girl by the hand). This is my friend from Egypt. She has something to tell you too. (Goes out.)

Little Girl. Do you know about cotton?

Maiden from Egypt. Yes, we knew how to use cotton long before your country was even heard of.

Little Girl. Is this your country (pointing to a map)?

Maiden from Egypt. Yes.

Little Girl. Did your people like cotton dresses?

Maiden from Egypt. Yes; just think how warm those woolen ones were.

Little Girl. I guess every one who ever lived must have liked cotton.

Maiden from Egypt. All good children do now.

Spirit of Cotton (outside). Heigh ho! Ho heigh!

Maiden from Egypt. I must go. I hear the Spirit of Cotton calling.

Spirit of Cotton (bringing a little girl into the room). This is my friend from America. (Goes out again.)

Little Girl. I know you. We studied that map in school. You are from the United States. What did America have to do with cotton?

Maiden from America. When Columbus first landed on the Bahama Islands the natives came out to his ships in canoes, bringing cotton thread and yarn to trade.

Little Girl. That was in 1492, wasn't it?

Maiden from America. Yes, it was 427 years ago.

Little Girl. Why did you put all this cotton here (points to cotton pasted on different states)?

Maiden from America. They are the cotton states.

Little Girl. I know which ones they are—North Carolina, South Carolina, Louisiana, Arkansas and Texas. Did America do anything wonderful with cotton?

Maiden from America. Yes; we raise more cotton than any other place in the world. It is the best cotton too.

Little Girl. I am so glad of that. We won't let India and Egypt get ahead of us, will we?

Maiden from America. Of course not. All good little girls must help too.

Little Girl. I shall always like cotton after this.

Spirit of Cotton (outside). Heigh ho! Ho heigh!

Maiden from America. I hear the Spirit of Cotton calling; I must go. (Goes out.)

Spirit of Cotton (leading a boy into the room). This is my friend Eli Whitney. (Goes out.)

Eli Whitney. I am the Spirit of Eli Whitney. I was born in Massachusetts in 1765. One day when my father went to church, I took his watch to pieces and put it together again. Then I thought I would go to Yale College. When I finished Yale College I went to Georgia. I heard everyone there talking about cotton. They were trying to find out how to get the seeds out of it more easily. I invented the cotton gin.

Little Girl. What happened then?

Eli Whitney. One man could now clean fifty times as much cotton as he could before.

Spirit of Cotton (outside). Heigh ho! Ho heigh!

Eli Whitney. I hear the Spirit of Cotton calling; I must go. (Goes out.)

Little Girl (waking up). Where is the spirit of Cotton? Where is the Maiden from India? Where is the Spirit of Eli Whitney? It must have been a dream! I guess I got up on the wrong side of the bed this morning. I will always like cotton after this. I am going out to play now.

The Cat and His Servant

Prepared by Alice Lewis, Teacher of Second Grade, Bangs School, Asbury Park

Dramatized from story of same name

Characters: Farmer, Cat, Fox, Wolf, Bear, Rabbit, Cow, Sheep.

Materials used: Small branches of tree, box for house, cards with printed names of animals.

Scene: The Forest.

Enter the Farmer and the Cat

Farmer.—I have a cat. He is very wild so I will take him to the forest. (Puts cat in bag and takes him to tree.) I will leave him here. (Takes off bag and leaves the cat.)

Cat. I will build a house for myself and be the owner of this forest. (Brings in box and nails boards.) Now my house is done.

Enter the Fox

Fox. Good morning. What fine fur you have! What long whiskers you have! Who are you?

Cat. I am Ivan, the owner of this forest.

Fox. May I be your servant?

Cat. Yes; you may. Come into my house. (Both go in house.) I am hungry. Go out and get me something to eat.

Fox. I will go. (Goes into forest and meets Wolf.)

Wolf. Good morning.

Fox. Good morning.

Wolf. I have not seen you for a long time. Where are you living now?

Fox. I am living with Ivan. I am his servant.

Wolf. Who is Ivan?

Fox. He is the owner of this forest.

Wolf. May I come with you and see Ivan?

Fox. Yes; if you will promise to bring a sheep with you. If you do not Ivan will eat you.

Wolf. I will go and get one. (Leaves the fox and hunts for a sheep.)

Enter the Bear

Bear. Good morning, Mr. Fox.

Fox. Good morning, Mr. Bear.

Bear. I have not seen you for a long time. Where are you living?

Fox. I am living with Ivan. I am his servant.

Bear. Who is Ivan?

Fox. He is the owner of this forest.

Bear. May I go with you and see him?

Fox. Yes, but you must promise to bring a cow with you or Ivan will eat you.

Bear. I will go and get one. (Leaves the fox and hunts for a cow.)

The Fox returns to the house and enters

Cat. Did you bring me something to eat?

Fox. No; but I have sent for something and it will be here soon.

Cat. All right; we will wait.

Enter Wolf with a sheep and Bear with a cow

Bear. Good morning, Mr. Wolf. Where are you going?

Wolf. Good morning. I am going to see Ivan, the owner of this forest.

Bear. So am I. Let us go together.

Bear and Wolf walk to Cat's house and place sheep and cow near door

Wolf. You knock on the door.

Bear. No; you knock on the door. I am afraid.

Wolf. So am I. Shall we ask Mr. Rabbit to do it?

Bear. Yes; you ask him.

Wolf (calling to a rabbit who is passing). Hello, Mr. Rabbit; will you knock at the Cat's door for us?

Rabbit. Yes, I will. (Knocks.)

Bear and Wolf hide behind the trees and bushes

Cat (coming out of his house with the Fox and noticing the cow and sheep lying by the door). Look! here is what you got for my dinner. There is only enough for two bites.

Bear (to himself). How hungry he is. A cow would be enough to eat for four bears and he says it is only enough for two bites. What a terrible animal he is.

Cat (seeing Wolf behind the bushes). Look! there is a mouse. I must catch him and eat him. (Chases Wolf away.) I think I hear another mouse. (Sees Bear and tries to catch him but fails.) I am so tired that I cannot run at all. Let us sit by the door and eat our dinner. (Cat and Fox sit down and eat the sheep and cow.)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

See Bibliography at end of monograph.

October 12

Columbus, seeking the back door of Asia, found himself knocking at the front door of America.

James Russell Lowell

COLUMBUS DAY

J. CAYCE MORRISON, SUPERVISING PRINCIPAL, LEONIA

October 12, 1492! What a date in the world's history—the linking of the new world with the old—the dreams of a dreamer come true—the opening of the gates to a newer and better home for man—the promise of—America!

The story of Columbus is a story of romance, of patient perseverance, of high endeavor, of noble resolve—a story that grips and thrills. Every boy and every girl who feels the story wants to discover a new world; and out of that desire may well come the discovery of America—its aims, ideals, opportunities. The Columbus Day program is an opportunity to discover the new world into which we are emerging. Even childhood in the school may come to glimpse that which lies beyond and feel the exultation of the sailor who cried, "Land! Land!"

The materials of this program are largely suggestive. It is hoped that they may be of service in program making from kindergarten to high school.

The school program of most value is that which results from the creative genius of the children themselves. Let children live the life of Columbus in imagination and they will create their own program and express it in costume, tableaux, music, composition, acting, and dialog. The merit of the Columbus Day program will lie in its leading children, through their own expression, to a better understanding of their country, to a broader conception of patriotism.

SUBJECTS FOR COMPOSITION OR ORAL REPORTS

Marco Polo

A flat world

The new idea—sailing west to reach the east

The dangers of the western sea

The attempted mutiny (See Irving's "Life of Columbus")

The signs of land

Columbus in chains

San Salvador

October 12, 1492

The Columbian Exposition, 1892

The discovery of America, 1919

What Columbus would do today

A Little Program for Columbus Day

Recitation

(By three boys bearing the American flag, the Spanish flag, and a drum)

| 1st— | We are jolly little sailors; Join us as we come; We'll bear the flag of proud old Spain, And we will beat a drum! |

| 2d— | We are jolly little sailors, And we pause to say, We raise the bonny flag of Spain Upon Columbus Day. |

| 2d— | We are jolly little sailors; Raise the red, the white, the blue; Though we honor brave Columbus, To our own flag we are true. |

| All— | (Beat drum and wave flag) Salute the banners, one and all, O raise them once again; Salute the red, the white, the blue, Salute the flag of Spain! For countries old and countries new, We will wave the red, the white, the blue! |

Recitation

(By eight girls carrying banners that bear letters spelling "Columbus")

| C | Columbus sailed o'er waters blue, |

| O | On and on to countries new. |

| L | Long the ships sailed day and night, |

| U | Until at last land came in sight. |

| M | Many hearts were filled with fear, |

| B | But the land was drawing near. |

| U | Upon the ground they knelt at last |

| S | So their dangers all were past. |

| All | Wave the banners bright and gay, We meet to keep Columbus Day |

Crowning Columbus

(Recitation by four children. Picture of Columbus on easel. Children place on it evergreen and flower wreaths and flags)

| 1st— | Crown him with a wreath of evergreen, The very fairest ever seen— Our brave Columbus. |

| 2d— | Crown him with flowers fresh and fair; We'll place them by his picture there— Our brave Columbus. |

| 3d— | Crown him with the flag of Spain; Columbus day has come again— Our brave Columbus. |

| 4th— | Crown him with red, and white, and blue; Bring out the drum and banners too— Our brave Columbus. |

| All— | As we stand by his picture here, Columbus' name we all revere— Our brave Columbus. |

What We Can Do

(Recitation by two small boys, carrying flag)

| 1. | I wish I could do some great deed— Just find a world or two, So that the flag might wave for me As for Columbus true. It makes a small child very sad To think all great deeds done. What is then left for us to do? What's to be tried and won? |

| 2. | My father says—and he knows too, For he's a grown up man— That heroes leave some things for us To carry out their plan. He says that if we do our best, Just where we are, you see, We too shall serve our country's flag; True patriots we shall be. |

| Both. | We'll love our flag, we'll keep its pledge; We'll honor and obey; We'll love our fellow brothers all; And serve our land this way. |

Recitation

(By a very small child, carrying a flag)

Recitation

(By a very small child, carrying a flag)

Columbus Game

The children stand in a circle. They choose one to represent Columbus. The children all sing the song (given below). As they sing the fifth line Columbus points to three children, who become the Nina (baby), the Pinta, and the Santa Maria. These three children come inside the circle, and wave arms up and down as though sailing. The children now all repeat the song, marching round in the circle, waving arms up and down, and the children inside the circle skip round also.

The song is then repeated, children standing in a circle, and the three chosen as Nina, Pinta and Santa Maria choose three children to take their places by pointing at any three children in the circle.

Game may continue as long as desired or until all have had a chance to go inside the circle.[A]

[A] The story of Columbus may be dramatized in connection with this game.

Song

Laura Rountree Smith

My Little Ship

Song

Tune, Lightly Row

Laura Rountree Smith

Recitation for Very Little Boys

Play

(Ferdinand and Isabella on their thrones, chairs with a red drapery concealing them.)

Enter Columbus and followers, bowing low

Columbus

O most gracious majesties!

Ferdinand

(Bows his head and looks very wise. Columbus looks sadly around and sighs. Queen Isabella stretches forth her hand.)

Queen

Columbus and followers

All (except Columbus, who bows as he listens)

Headed by king and queen all march around and off

One returns

(Displays flag)

All except Columbus return and sing America

Mary R. Campbell

Recitation

(By three boys)

Discovery Day

The Flag of Spain

Tune—Long, Long Ago

Columbus

CLASS EXERCISE FOR COLUMBUS DAY

The foundation for these exercises should be laid in previous class recitations and specially prepared class compositions which relate developing incidents in the life of Columbus. Several periods used in the preparation of these oral and written exercises will be time well spent. Select the composition which portrays the life pictures most clearly and effectively; and as the writer reads his story, let other members of the class give tableaux or act scenes apropos. The children should be encouraged to initiate their own ideas and execute their own mental pictures in costume, arrangement, facial expression, etc.

The following are mentioned suggestively:

Acts portraying the life of Columbus

1. Columbus, the boy

Boy of nine to eleven years, seated, intently studying a geography,

or

Boy whittling a wooden toy ship.

2. Columbus, the man

Larger boy, posing as a dreamer, gazing at and studying the stars, or

Larger boy drawing maps, appearing wise and thoughtful.

(Let others stand aside, smiling and mockingly pointing.)

3. Columbus' appearance before King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella

King and Queen, dressed in royal style, on improvised throne; Columbus kneeling before them; the queen offering him her jewels.

4. On shipboard

Boys representing mutinous sailors, their faces depicting fear, anger, dejection—dressed sailor fashion.

Columbus displaying confidence, courage and patience—dressed in short full trousers, cape over his shoulders thrown back on one side. Let facial expressions and actions change to show land has been sighted.

5. The landing

Columbus planting the flag of Spain in the New World. Sailors (all with uncovered heads) kneeling. Indians (let the boys wear Indian suits) watching from the outskirts, one falling down in worship.

6. The return reception

King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella on throne, dressed as before, with guards on either side. Ladies-in-waiting, noblemen, etc., dressed in 15th century style, grouped about. Columbus enters (to music). All bow low except king and queen, who rise to meet him. Columbus kneels before them, kisses the queen's hand and rises.

Indians enter (with bow and arrow) and gaze in wonder about. One Indian plucks Columbus by sleeve and gruntingly interrogates him concerning some wonder in the room—a picture of the king and queen, decorated with Spanish flags. The king takes the hand of the Indian, places it in Columbus' hand and, covering them with his own left hand, raises the right to signify his blessing upon the newly found land.

Music gives the signal for the recessional. All fall into line and march out—guards, king, queen, Columbus, ladies, and courtiers. The Indians follow irregularly.

THE BOY COLUMBUS

COLUMBUS AND THE EGG

One day Columbus was at a dinner which a Spanish gentleman had given in his honor, and several persons were present who were jealous of the great Admiral's success. They were proud, conceited fellows, and they very soon began to try to make Columbus uncomfortable.

"You have discovered strange lands beyond the seas," they said, "but what of that? We do not see why there should be so much said about it. Anybody can sail across the ocean; and anybody can coast along the islands on the other side, just as you have done. It is the simplest thing in the world."

Columbus made no answer; but after a while he took an egg from a dish and said to the company:

"Who among you, gentlemen, can make this egg stand on end?"

One by one those at the table tried the experiment. When the egg had gone entirely around and none had succeeded, all said that it could not be done.

Then Columbus took the egg and struck its small end gently upon the table so as to break the shell a little. After that there was no trouble in making it stand upright.

"Gentlemen," said he, "what is easier than to do this which you said was impossible? It is the simplest thing in the world. Anybody can do it—after he has been shown how!"

COLUMBUS DAY

(Fitchburg, Massachusetts, Normal School)

This entertainment is simply an attempt to give a few of the most dramatic incidents in the life of Columbus as connected with his discovery of the New World. Other scenes could be readily added, although it would require some care to avoid an anti-climax.

A. In Spain at the Council of Salamanca

Before this scene is presented give a brief explanation and description of the early life of Columbus and his attempts to obtain aid.

Characters: Churchmen and counselors at the court of Spain (seven to ten) and Columbus.

Costumes: The churchmen are dressed in long black garments, except two, who have black capes with white underneath. Columbus wears a long, black garment or coat, which plainly shows the poverty of its owner.

Tableau I—Columbus before the Council at Salamanca

The characters are arranged somewhat as in a picture of this scene found in the Perry pictures. A picture of this scene is also found in[46] Lossing's History of the United States, volume I. Only the chief characters are shown in this tableau. Three churchmen or counselors are in center near Columbus; two at left, one pointing mockingly, or making fun of Columbus; two stand haughtily in the back, and there may also be two or three at right. Columbus has a partly open roll of parchment in one hand and is pointing with the other. One of the churchmen in the center has an open Bible in his hand, and another has a book which he is holding out to Columbus.

B. On Shipboard

Characters: Columbus, the mate, other sailors.

Costumes: Columbus, red cape; sailors, sweaters and sailor caps.

Tableau II—Nearing Land; Columbus and the Mate

The conversation in Joaquin Miller's "Columbus" takes place between Columbus and mate. The sailors are in the background, one holding a lantern. Between the different parts of his conversation with Columbus, the mate goes to consult with the sailors. The last stanza of the poem is given by some one from the wings. When the reader reaches the line, "A light! A light!" Columbus and the mate change their position. Columbus points and the mate raises his arm, peering forward. (Picture in "Leading Facts of American History," by Montgomery, revised edition. Also in "Stepping Stones of American History.")

C. In the new world

Characters: Columbus, three noblemen, eight sailors, six Indians.

Costumes: Columbus and the noblemen wear the Spanish costume of the fifteenth century (described later). Sailors wear sweaters and sailor caps made from blue, red or grey cambric. Indians wear Indian suits (nearly all boys have or may obtain them from any clothing store). They carry bows and arrows or tomahawks. The spears and swords for this and the following scene are made from wood, bronzed to look like silver. The tall cross is made of wood and stained with shellac. The banner of the expedition is white, with a green cross. Over the initials F and Y (Ferdinand and Ysabella) are two gilt crowns.

Tableau III—The landing of Columbus

The characters are posed from Vanderlyn's painting of the scene in the Capitol at Washington. Reproductions are found in many histories and among the Perry pictures. Columbus holds the banner of the expedition in one hand, and a drawn sword in the other. One of the men has a tall staff with the top in form of a cross; two others hold tall spears. The Indians are peering out at the white men from the sides of the stage; one of them is down on the stage with his head bowed on his hands, worshipping the strangers; the others seem to be full of fear and curiosity.

D. At Barcelona in Spain

Before this scene is presented a description of the reception of Columbus by the king and queen upon his return to Spain is given. This scene is more elaborate than any of the others.

Characters and costumes: Queen, red robe, purple figured front; collar and trimmings of ermine. She wears a crown. Ermine is made of cotton with little pieces of black cloth sewed on it, crown of cardboard covered with gilt paper. Dress cheesecloth with a front of silkoline.

King wears purple full, short trousers (trunks), purple doublet, purple cape and gilt crown. The trousers and cape are trimmed with ermine.

The two guards have black trousers (trunks) and red capes, collars, and knee pieces made from silver paper; they wear storm hats covered with silver paper, and carry spears.

The two ladies-in-waiting wear dresses fixed to resemble the dress of the period. They have high headpieces shaped like cornucopias, made from cardboard covered with gilt paper, and with long veils draped over them; this was one style of headpiece worn in the fifteenth century.

The eight churchmen, eight sailors and six Indians are dressed as in previous scenes.

The little page of Columbus is dressed in his own white suit.

Columbus wears grey and red clothing. The ten noblemen wear combinations of bright colors.

The general plan in regard to the dress of the Spanish nobility in the time of Columbus is to have the full, short trousers (trunks) made of one color and slashed with another; the upper garment or doublet made of figured silkoline; the cape of one color lined with another, worn turned back over one shoulder; pointed collars and cuffs of white glazed or silver paper; and soft felt hats with plumes. Each nobleman carries a sword.

The gold brought by the sailors may be made by gilding stones.

Tableau IV—Reception of Columbus by King and Queen

In center of stage is raised platform or throne with two or three steps leading up to it: this throne is covered with figured raw silk (yellow and brown). Chairs are placed on throne for king and queen.

The scene is an attempt to represent the reception of Columbus on his return to Spain after his first voyage. (See painting by Ricardo Balaca, the Spanish artist, of Columbus before Ferdinand and Isabella at Barcelona.)

A march may be played on the piano while the different characters in the tableau come on the stage and take their proper positions. First the two royal guards march to the throne, taking positions one on each side, so that the king and queen may pass between them in mounting the platform. They are followed by the king and queen, and then the ladies-in-waiting. The king and queen mount the platform and take seats; the ladies wait in front of the platform until the king and queen are seated, then they take positions on each side of the throne. The guards, after the king and queen are seated, take positions on the platform in the rear. [48] All these come as one group in the procession, with only a little space between them.

Next come the churchmen. One of them carries the tall cross. They take their places at the right of the queen.

The Indians come, shuffling across the stage to the extreme left of the king and queen. Of course they know nothing of keeping time to the music or paying homage to royalty.

The sailors march upon the stage, each bringing something from the New World—gold, a stuffed bird, or some product. Each in turn approaches the king and queen, kneels, and then places whatever he carries at the side of the platform, and takes his place on the left.

The noblemen, one by one, come in with great dignity, go to the front of the throne, kneel and salute with their swords. Then they go to the right of the stage.

Finally the music sounds a more triumphal note, announcing the approach of the hero of the occasion. Columbus is preceded by his page, carrying the banner of the expedition. The page kneels to the king and queen, then goes to the left, where he is to stand just back of the place reserved for Columbus.

As Columbus approaches the throne, the king and queen rise and come forward to do him honor. Columbus kneels, kisses the queen's hand, then rises and points out to the king and queen the treasures which his sailors have brought. He also brings forward one of the Indians. The king and queen regard everything with interest. After this, at a signal given on the piano, all kneel to give thanks for the discovery of the New World. The Te Deum Laudamus is chanted or the Doxology is sung.

This is the end of the reception.

This scene may be simplified, if desired, and given in the form of two tableaux. Columbus kneeling before the queen and king and Columbus telling his story may be given separately. There need not be as many characters in the scene. See the picture, "Reception of Columbus" (adapted from the picture by Ricardo Balaca) in "America's Story for American Children," by Mara L. Pratt.

It would be easy to give the substance of this entertainment in any schoolroom and without costumes. Even with these limitations the story of Columbus would become more real to the children in this way than it could be made by any description.

A good description of the reception of Columbus in Spain after his first voyage is given in the "Life of Columbus," by Washington Irving.

A description and picture of the banner of the expedition may be found in Lossing's "History of the United States," volume I.

Music that may be used: "Columbus Song," taken from "1492"; the "New Hail Columbia."

THE DISCOVERY OF AMERICA

It was on the morning of Friday, 12th of October, 1492, that Columbus first beheld the New World....

No sooner did he land than he threw himself upon his knees, kissed the earth, and returned thanks to God with tears of joy. His example was followed by the rest, whose hearts indeed overflowed with the same feelings of gratitude.

Columbus then rising drew his sword, displayed the royal standard, and ... took solemn possession in the name of the Castilian sovereigns, giving the island the name of San Salvador. Having complied with the requisite forms and ceremonies, he now called upon all present to take the oath of obedience to him, as admiral and viceroy, representing the persons of the sovereigns.

The feelings of the crew now burst forth in the most extravagant transports.... They thronged around the Admiral in their overflowing zeal. Some embraced him, others kissed his hands. Those who had been most mutinous and turbulent during the voyage, were now most devoted and enthusiastic. Some begged favors of him, as of a man who had already wealth and honors in his gift. Many abject spirits, who had outraged him by their insolence, now crouched as it were at his feet, begging pardon for all the trouble they had caused him, and offering for the future the blindest obedience to his commands.

Washington Irving

IMMORTAL MORN

Hezekiah Butterworth

All hail, Columbus, discoverer, dreamer, hero, and apostle! We here, of every race and country, recognize the horizon which bounded his vision, and the infinite scope of his genius. The voice of gratitude and praise for all the blessings which have been showered upon mankind by his adventure is limited to no language, but is uttered in every tongue. Neither marble nor brass can fitly form his statue. Continents are his monument, and unnumbered millions, past, present, and to come, who enjoy in their liberties and their happiness the fruits of his faith, will reverently guard and preserve, from century to century, his name and fame.

Chauncey Mitchell Depew

Little wonder that the whole world takes from the life of Columbus one of its best-beloved illustrations of the absolute power of faith. To a faithless world he made a proposal, and the world did not hear it. To that faithless world he made it again and again, and at last roused the world to ridicule it and to contradict it. To the same faithless world he still made it year after year; and at last the world said that, when it was ready, it would try if he were right; to which his only reply is that he is ready now, that the world must send him now on the expedition which shall show whether he is right or wrong. The world, tired of his importunity, consents, unwillingly enough, that he shall try the experiment. He tries it; he succeeds; and the world turns round and welcomes him with a welcome which it cannot give to a conqueror. In a moment the grandeur of his plans is admitted, their success is acknowledged, and his place is fixed as one of the great men of history.

Edward Everett Hale

Columbus

ColumbusThe fame of Columbus is not local or limited. It does not belong to any single country or people. It is the proud possession of the whole civilized world. In all the transactions of history there is no act which for vastness and performance can be compared with the discovery of the continent of America, "the like of which was never done by any man in ancient or in later times."

James Grant Wilson

With boldness unmatched, with faith in the teachings of science and of revelation immovable, with patience and perseverance that knew no weariness, with superior skill as a navigator unquestioned, and with a lofty courage unrivaled in the history of the race, Columbus sailed from Palos on the 3d of August, with three vessels, the largest (his flagship) of only ninety feet keel, and provided with four masts, eight anchors, and sixty-six seamen. Passing the Canaries and the blazing peak of Teneriffe, he pushed westward into the "sea of darkness," in defiance of the fierce dragons with which superstition had peopled it, and the prayers and threats of his mutinous seamen, and on the 12th of October landed on one of the Bahama Islands.

Benson J. Lossing

COLUMBUS[B]

[B] From complete works of Joaquin Miller, published by the Harr Wagner Publishing Company of San Francisco.

Joaquin Miller

George W. W. Houghton

With all the visionary fervor of his imagination, its fondest dreams fell short of the reality. He died in ignorance of the real grandeur of his discovery. Until his last breath, he entertained the idea that he had merely opened a new way to the old resorts of opulent commerce, and had discovered some of the wild regions of the East.... What visions of glory would have broke upon his mind, could he have known that he had indeed discovered a new continent, equal to the whole of the old world in magnitude, and separated by two vast oceans from all of the earth hitherto known by civilized man; and how would his magnanimous spirit have been consoled, amidst the chills of age and cares of penury, the neglect of a fickle public, and the injustice of an ungrateful king, could he have anticipated the splendid empires which were to spread over the beautiful world he had discovered, and the nations, and tongues, and languages, which were to fill its lands with his renown, and to revere and bless his name to the latest posterity!

Washington Irving

ON A PORTRAIT OF COLUMBUS

George Edward Woodberry

Of no use are the men who study to do exactly as was done before, who can never understand that today is a new day. There never was such a combination as this of ours, and the rules to meet it are not set down in any history. We want men of original perception and original action, who can open their eyes wider than to a nationality—namely, to considerations of benefit to the human race—can act in the interest of civilization; men of elastic, men of moral mind, who can live in the moment and take a step forward. Columbus was no backward-creeping crab, nor was Martin Luther, nor John Adams, nor Patrick Henry, nor Thomas Jefferson; and the Genius or Destiny of America is no log or sluggard, but a man incessantly advancing, as the shadow on the dial's face, or the heavenly body by whose light it is marked.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

ADDRESS TO AMERICA

(From a Commencement Poem, Dartmouth College. 1872)

Walt Whitman

AMERICA

William Cullen Bryant

THE WESTERN LAND

Caroline Hazard

OUR NATIONAL IDEALS[C]

[C] Used by permission of, and by special arrangement with, Houghton Mifflin Company, the authorized publishers.

Foremost among the ideals which have characterized our national life is the spirit of self-reliance. The very first chapter of our national history records the story of a man, who arose from among the toilers of his time, and whom eighteen years of disappointed hopes could not dismay. It tells how this man, holding out the promise of a new dominion, at last overcame the opposition of royal courtiers, and secured the tardy support[57] of reluctant rulers. And when, at Palos, Columbus flung to the breeze the sails of his frail craft, and ventured upon that unknown ocean from which, according to the belief of his age, there was no hope of return, he displayed the chief characteristic of the American people—the spirit of self-reliance.

What is this spirit? Emerson has expressed it in a sentence: "We will walk on our own feet; we will work with our own hands; we will speak our own minds." This was the spirit which animated that little group of colonists who preferred the unknown hardships of the new world to the certain tyranny of the old; who chose to break old ties, to brave the sea, to face the loneliness and perils of life in a strange land—a land of difficulties and dangers, but a land of liberty and opportunity....

In order that our country may continue this proud record of self-reliance, each one of us has a special obligation. Every citizen in his individual life should live up to the same ideal of self-reliance. The young citizen who relies on himself, who does honest work in school, never cheating or shirking, who is always, ready to do a little more than is actually required of him, who thinks for himself, acts rightly because he loves right actions—such a citizen is doing his part in helping to achieve our national ideal of self-reliance.

William Backus Guitteau

I believe in my country. I believe in it because it is made up of my fellow-men—and myself. I can't go back on either of us and be true to my creed. If it isn't the best country in the world it is partly because I am not the kind of a man that I should be.

Charles Stelzle

BIBLIOGRAPHY

See Bibliography at end of monograph.

Last Thursday in November

Ralph Waldo Emerson

THANKSGIVING DAY

ROY L. SHAFFER, STATE NORMAL SCHOOL, NEWARK

Among our national holidays Thanksgiving should be a red letter day. We need these days so that the modern tendency of reducing all days to the same mediocre level may be overcome. Such days, when contrasted with common school days, show a wonderful stimulation. Hence it is urged that the celebration of Thanksgiving take on the aspect of the play-festival. The play-festival will have a potent effect on the audience and the actors. The audience will be composed for the most part of the school body and on this body the festival program will have a unifying effect. For this reason it is further urged that an entire grade, or perhaps a group of grades, be employed to render the program. Such a rendition will be treated as a contribution from a part to the whole.

The festival to be effective must bind the entire school into one social group. The response of the audience will be complementary and the spirit and the pride of the school will give forth inspiration to the actor and the audience. The performer must make others feel what he knows, and thus his learning becomes intensified. The result is that the play-festival has two high values, the social and the educational.

The essential problem which arises, and which must be answered by every teacher, is, "What shall be done to provide a good program, and how shall it be done?" The answer will come from a careful survey of the needs, capacities, and make-up of each individual or group of pupils. The answer includes the utilization of the dramatic instinct, i. e., the play instinct, which finds expression through singing, speaking and dancing. The successful festival must be well organized, and this organization must be effected according to a suitable program. (1) The history of the day must be clearly brought to the attention of the pupils. (2) There should be a committee appointed to have supervision of the arranging of the festival. (3) A program full of content should-be arranged. (4) What constitutes the proper program for a Thanksgiving festival should have the careful thought of those in charge. The children should be actual factors in planning the program, as well as in presenting it.

In order that Thanksgiving Day may be celebrated in an appropriate[62] manner it is necessary that its history be fully comprehended by the entire school. Teachers of all grades should use the historic material that will meet the needs and capacities of their pupils. This material should be correlated with as much of the regular school work as may seem advisable. It is essential that the entire school fully appreciate the historic foundations of the day, so that they may comprehend the setting which has so much to do with this holiday. Furthermore, a full comprehension of the history as a background for this festival will stimulate the school audience, so that they will receive from the program those things which we believe they ought to receive from the celebration.

HISTORY

The following extracts relative to the history of Thanksgiving have been selected because they are exceptionally interesting; they show that traditionally the celebration of this holiday is truly American; they also give hints as to the wealth of material that may be woven into a program for the play-festival.

The first year of the Pilgrim settlement, in spite of that awful winter when nearly half of their number perished, had been comparatively successful. The Pilgrims had planted themselves well, and it is easy to understand why this fact should have appealed to the mind of their governor, William Bradford, as an especial reason for proclaiming a season of thanksgiving. The exact date is not certain, but from the records we learn that it was an open air feast. It is evident that it must have occurred in that lovely period of balmy, calm, cool air and soft sunshine which is called Indian Summer, and which may be considered to range between the latter week of October and the latter week of November. It came at the end of the year's harvest. In confirmation, let us quote from the writing of Edward Winslow, thrice governor of the Pilgrims:

"Our corn did prove well; and, God be praised, we had a good increase of Indian corn, and our barley indifferent good. Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling that so we might after a special manner rejoice together after we had gathered the fruit of our labors."