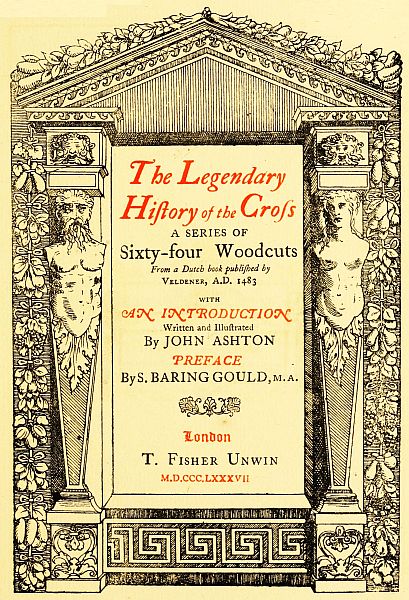

Title: The Legendary History of the Cross

Illustrator: active 1473-1486 Johann Veldener

Author of introduction, etc.: S. Baring-Gould

Contributor: William Caxton

de Voragine Jacobus

Editor: John Ashton

Release date: September 7, 2014 [eBook #46800]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

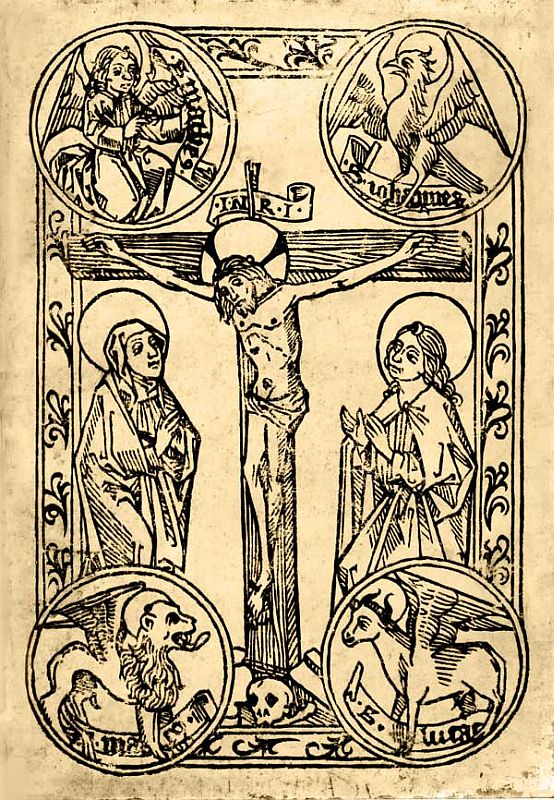

A SERIES OF

Sixty-four Woodcuts

From a Dutch book published by

Veldener, A.D. 1483

WITH

AN INTRODUCTION

Written and Illustrated

By JOHN ASHTON

PREFACE

By S. BARING GOULD, m.a.

London

T. Fisher Unwin

M.D.CCC.LXXXVII

THE origin of the mediæval romance of the Cross is hard to discover. It was very popular. It occurs in a good number of authors, and is depicted in a good many churches in stained glass.

I may perhaps be allowed here to repeat what I have said in my article on the Legend of the Cross, in “Myths of the Middle Ages:”—

“In the churches of the city of Troyes alone it appears in the windows of four: S. Martin-ès-Vignes, S. Pantaléon, S. Madeleine, and S. Nizier. It is frescoed along the walls of the choir of S. Croce at Florence, by the hand of Agnolo Gaddi. Pietro della Francesca also dedicated his pencil to the history of the Cross in a series of frescoes in the chapel of the Bacci, in the church of S. Francesco at Arezzo. It occurs as a predella painting among the specimens[ii] of early art at the Accademia delle Belle Arti at Venice, and is the subject of a picture by Beham, in the Munich Gallery. The Legend is told in full in the ‘Vita Christi,’ printed at Troyes in 1517; in the ‘Legenda Aurea’ of Jacques de Voragine; in a French MS. of the thirteenth century, in the British Museum. Gervase of Tilbury relates a portion of it in his ‘Otia Imperalia,’ quoting Peter Comestor; it appears in the ‘Speculum Historiale’ of Gottfried of Viterbo, in the ‘Chronicon Engelhusii,’ and elsewhere.”

In the very curious Creation window of S. Neot’s Church, Cornwall, Seth is represented putting three pips of the Tree of Life into the mouth and nostrils of dead Adam, as he buries him.

Of the popularity of the story of the Cross there can be no doubt, but its origin is involved in obscurity. It is generally possible to track most of the religious and popular folk tales and romances of the Middle Ages to their origin, which is frequently Oriental, but it is not easy to do so with the Legend of the Cross. It would rather seem that it was made up by some romancer out of all kinds of pre-existing material, with no other object than to write a religious novel for pious readers, to displace the sensuous novels which were much in vogue.

We know that this was largely done after the third century, and a number of martyr legends, such as those of S. Apollinaris Syncletica, SS. Cyprian and Justina, the story of Duke Procopius, S. Euphrosyne, SS. Zosimus and Mary, SS. Theophanes and Pansemne, and many others were composed with this object. The earliest of all is undoubtedly the Clementine Recognitions, which dates from a remotely early period, and carries us into the heart of Petrine Christianity, and in which many a covert attack is made on S. Paul and his teaching. On the other hand, we know that an Asiatic priest, as Tertullian tells us, wrote a romance on “Paul and Thecla, out of love to Paul.” S. Jerome says that a Pauline zealot, when convicted before his bishop of having written the romance, tried to exculpate himself by saying that he had done it out of admiration for S. Paul, but the Bishop would not accept the excuse, and deprived him. Unfortunately this romance has not come down to us, though we have another on S. Paul and his relations to Thecla, who is said to have accompanied him on his apostolic rambles, disguised in male attire.

The Greek romance literature was not wholesome reading for Christians. Some of the writers of these tales became Christian bishops, and probably devoted[iv] their facile pens to more edifying subjects than the difficulties of parted lovers.

Heliodorus, who wrote “Theagenes and Charicheia,” is said to have become Bishop of Tricca, in Thessaly. Socrates, in the fifth century, in speaking of clerical celibacy, mentions the severity of the rule imposed on his clergy by this Heliodorus, “under whose name there are love-books extant, called Ethiopica, which he composed in his youth.”

Achilles Tatius, author of the “Loves of Clitophon and Leucippe,” is said also to have become a bishop. So also Eustathius of Thessalonica, author of the “Lives of Hysemene and Hysmenias,” but this is more than doubtful.

Three things conduced to the production of a Christian romance literature in the early ages of the Church:—(1) The necessity under which the Church lay of supplying a want in human nature; (2) The need there was for producing some light wholesome literature to supply the place of the popular love-romances then largely read and circulated; (3) The fact that some bishops and converts were experienced novel writers, and therefore ready to lend their hands to some better purpose than amusing the leisure and flattering the passions of the idle and young.

Much the same conditions existed in the Middle Ages. There was an influx of sensuous literature from the East, through the Arabs of Spain and Sicily; Oriental tales easily took Western garb, in which the caliphs became kings of Christendom, and the fakirs and imauns were converted into monks and Catholic priests. To counteract these stories, collections of which may be found in Le Grand d’Aussi and Von der Hagen, and in Boccaccio, the Gesta Romanorum was drawn up, a collection of moral tales, many of them of similar Oriental parentage. But beside these short stories, or novels, were long romances, some heroic, and founded on early national traditions and ballads. To these belong the Niebelungen Lied and Noth, the Gudrun, the Heldenbuch, the cycles of Karlovingian and of Arthurian romance.

As it happens, we have two authors in the Middle Ages, living much about the same time, one intensely heathen in all his conceptions, the other as entirely Christian, each dealing with subjects from the same cycle, and the one writing in avowed opposition to the tendency of the other’s book. I allude to Wolfram of Eschenbach and Gottfried of Strassburg. The latter wrote the Tristram, the former the Parzival. In Gottfried, the moral sense seems to be absolutely[vi] dead; there is no perception of the sacredness of truth, of chastity, of honour, none of religion. Wolfram is his exact converse. Wolfram gives us the history of the Grail, but he did not invent the myth of the Grail, he derived it from pre-existing material. The Grail myth is almost certainly heathen in its origin, but it has been entirely Christianised. The holy basin is that in which the Blood of Christ is preserved, and only the pure of heart can see it; but the Grail was really the great cauldron of Nature, the basin of Ceridwen, the earth goddess of the Kelts, or, among Teutonic nations, the sacrificial cauldron of Odin, in which was brewed the spirit of poesy, of the blood of Mimer. The remembrance of the mysterious vessel remained after Kelt and Teuton had become Christian, and the poets and romancists gave it a new spell of life by christening it. It was much the same with the story of the Cross. In the Teutonic North, tree worship was widely spread; the tree was sacred to Odin, who himself, according to the mysterious Havamal, hung nine nights wounded, as a sacrifice to himself, a voluntary sacrifice, in “the wind-rocked tree.”

That tree was Yggdrasill, the world tree, whose roots extended to hell, and whose branches spread to heaven.

Northern mythology is full of allusion to this tree, but we have, unfortunately, little of the history of it preserved to us; we know of it only through allusions. The Christmas tree is its representative; it has been taken up out of paganism, and rooted in Christian soil, where it flourishes to the annual delight of thousands of children.

Now the mediæval romancists laid hold of this tree, as they laid hold of the Grail basin, and used it for Christian purposes. The Grail cup became the chalice of the Blood of Christ, and the Tree of Odin became the Cross of Calvary. They worked into the romance all kinds of material gathered from floating folk-tale of heathen ancestry, and they pieced in with it every scrap of allusion to a tree they could find in Scripture. It is built up of fragments taken from all kinds of old structures, put together with some skill, and built into a goodly romance; but the tracing of every stone to its original quarry has not been done by anyone as yet. The Grail myth has had many students and interpreters, but not the Cross myth. That remains to be examined, and it will doubtless prove a study rewarding the labour of investigation.

S. BARING-GOULD.

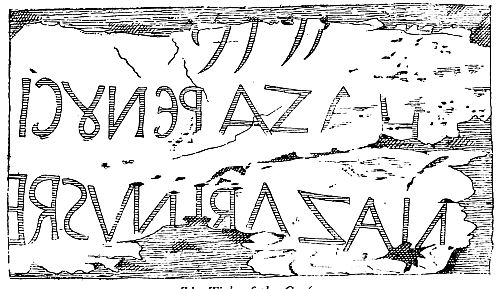

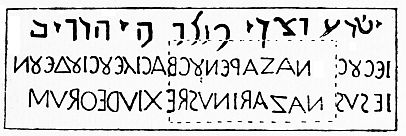

THE Cross on which our Lord and Saviour suffered, would, naturally, if properly authenticated, be an object of the deepest veneration to all Christian men, be their creed, or shade of opinion what it might; but, for over 300 years it could not be found, and it was reserved for the Empress Helena in her old age (for she was 79 years old) to discover its place of concealment.1 That this Invention, or finding of the Cross was believed in, at the time, there can be no manner of doubt, for it is alluded to by[x] St. Cyril, Patriarch of Jerusalem (A.D. 350 to 386), and by St. Ambrose. Rufinus of Aquila, a friend of St. Jerome, in his Ecclesiastical History, gives an account of its finding, in the following words: “About the same time, Helena, the mother of Constantine, a woman of incomparable faith, whose sincere piety was equalled by her rare munificence, warned by celestial visions, went to Jerusalem, and inquired of the inhabitants where was the place where the Divine Body had been affixed and hung on a gibbet. This place was difficult to find, for the persecutors of old had raised a statue to Venus,2 in order that the Christians who might wish to adore Christ in that place, should appear to address their homage to the goddess; and thus it was little frequented, and almost forgotten. After clearing away the profane objects which defiled it, and the rubbish that was there heaped up, she found three crosses placed in confusion. But the joy[xi] which this discovery caused her was tempered by the impossibility of distinguishing to whom each of them had belonged. There, also, was found the title written by Pilate in Greek, Latin, and Hebrew characters; but still there was nothing to indicate sufficiently clearly the Cross of our Lord. This uncertainty of man was settled by the testimony of heaven.” And then follows the story of the dead woman being raised to life.

Not only did Rufinus write thus, but Socrates, Theodoret, and Sozomen, all of whom lived within a century after the Invention, tell the same story, so that it must have been of current belief.

The punishment of the Cross was a very ordinary one, and of far wider extent than many are aware. It was common among the Scythians, the Greeks, the Carthaginians, the Germans, and the Romans, who, however, principally applied it to their slaves, and rarely crucified[xii] free men, unless they were robbers or assassins.

Alexander the Great, after taking the city of Tyre, caused two thousand inhabitants to be crucified.

Flavius Josephus relates, in his Antiquities of the Jews, that Alexander, the King of the Jews, on the capture of the town of Betoma, ordered eight hundred of the inhabitants to suffer the death of the Cross, and their wives and children to be massacred before their eyes, whilst they were still alive.

Augustus, after the Sicilian War, crucified six thousand slaves who had not been claimed by their masters.

Tiberius crucified the priests of Isis, and destroyed their temple.

Titus, during the siege of Jerusalem, crucified all those unfortunates who, to the number of five or six hundred daily, fled from the city to escape the famine; and so numerous were these executions, that crosses were wanting,[xiii] and the land all about seemed like a hideous forest.

These instances are sufficient to show that death by crucifixion was a common punishment; but, singularly enough, the shape of the Cross has never been satisfactorily settled; practically, the question lies between the Crux capitata, or immissa, which is the ordinary form of the Latin Cross, and the Crux ansata, or commissa, frequently called the Tau Cross, from the Greek letter T. The Tau-shaped Cross is, undoubtedly, to be met with most frequently in the older representations; and the more ancient authorities, such as Tertullian, St. Jerome, St. Paulinus, Sozomen, and Rufinus, are of opinion that this was the shape of the Cross. After the fifteenth century, our Lord is rarely depicted on the Crux commissa, it being reserved for the two thieves.

M. Adolphe Napoleon Didron, in his Iconographie Chretienne, gives a few illustrations of the antiquity of the[xiv] Tau Cross: “The Cross is our crucified Lord in person; ‘Where the Cross is, there is the martyr,’ says St. Paulinus. Consequently it works miracles, as does Jesus Himself: and the list of wonders operated by its power is in truth immense. By the simple sign of the Cross traced upon the forehead or the breast, men have been delivered from the most imminent danger. It has constantly put demons to flight, protected the virginity of women, and the faith of believers; it has restored men to life, or health, inspired them with hope or resignation.

“Such is the virtue of the Cross, that a mere allusion to that sacred sign, made even in the Old Testament, and long before the existence of the Cross, saved the youthful Isaac from death, redeemed from destruction an entire people whose houses were marked by that symbol, healed the envenomed bites of those who looked at the serpent raised in the form of a Tau upon a pole. It called back the[xv] soul into the dead body of the son of that poor widow who had given bread to the prophet.

“A beautiful painted window, belonging to the thirteenth century, in the Cathedral of Bourges, has a representation of Isaac bearing on his shoulders the wood that was to be used in his sacrifice, arranged in the form of a Cross; the Hebrews, too, marked the lintel of their dwellings with the blood of the Paschal lamb, in the form of a Tau or Cross without a summit. The widow of Sarepta picked up and held crosswise two pieces of wood, with which she intended to bake her bread. These figures, to which others also may be added, serve to exalt the triumph of the Cross, and seem to flow from a grand central picture which forms their source, and exhibits Jesus expiring on the Cross. It is from that real Cross indeed, bearing the Saviour, that these subjects from the Old Testament derive all their virtue.”

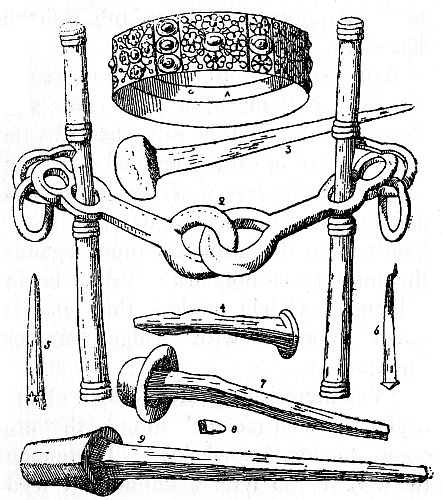

The wood of which it was made is as unsettled as its shape. The Venerable Bede says that our Lord’s Cross was made of four kinds of wood: the inscription of box, the upright beam of cypress, the transverse of cedar, and the lower part of pine. John Cantacuméne avers that only three woods were employed: the upright, cedar; the transverse, pine; and the head in cypress. Others say that the upright was cypress, the transverse in palm, and the head in olive; or cedar, cypress, and olive. Most authorities seem to concur that it was made of several woods, but there is a legend that it was made from the aspen tree, whose leaves still tremble at the awful use the tree was put to; whilst that veritable traveller, Sir John Maundeville, says: “And also in Iherusalem toward the Weast is a fayre church where the tree grew of the which the Crosse was made.” Lipsius says that it was made of but one wood, and that was oak; but M. Rohault de Fleury (to[xvii] whose wonderful and comprehensive work, Mémoire sur les Instruments de la Passion de notre Sauveur Jesus Christ, I am deeply indebted, says, “M. Decaisne, member of the Institut, and M. Pietro Savi, professor at the University of Pisa, have shewn me by the microscope that the pieces in the Church of the Holy Cross of Jerusalem at Rome, in the Cathedral at Pisa, in the Duomo at Florence, and in Notre Dame at Paris, were of pine.” And he adds, in a footnote, “Independently of the experiments which M. Savi kindly made in my presence, he wrote me the results of other observations, which tended to confirm.”

Starting with the Invention of the Holy Cross, the loving, but fervid, imaginations of the faithful soon wove round it a covering of imagery, as we have just seen in the case of the several woods of the Cross, and the sacred tree became the subject of a legend (for so it always was only meant to be), which[xviii] was incorporated in the Legenda Aurea Sanctorum, or Golden Legend of the Saints, of Jacobus de Voragine, a collection of legends connected with the services of the Church. This book was exceedingly popular, and, when Caxton set up his printing-press at Westminster, he produced a translation, the history of which he quaintly tells us in a preface.[A]

As this Golden Legend is the standard authority on the subject, and as it will[xix] much assist the intelligent appreciation of the wood-blocks, I reproduce it, premising that I have used throughout the first edition, 20 Nov., 1483:—

3 But alle the dayes of adam lyvynge

here in erthe amounte to the somme of

![]() [B] yere / And in thende of his lyf[xx]

[B] yere / And in thende of his lyf[xx]

[xxi]

whan he shold dye / it is said but of none

auctoryte / that he sente Seth his sone in

to paradys for to fetch the oyle of mercy

/ where he receyuyde certayn graynes of

the fruyt of the tree of mercy by an

angel / And whan he come agayn / he

fonde his fader adam yet alyve and told

hym what he had don. And thenne[xxii]

Adam lawhed4 first / and then deyed /

and thenne he leyed the greynes or

kernellis under his faders tonge and

buryed hym / in the vale of ebron / and

out of his mouth grewe thre trees of the

thre graynes / of which the crosse that

our lord suffred his passion on / was made

by vertue of which he gate5 very mercy

and was brought out of darknes in to

veray light of heven / to the whiche he

brynge us that lyveth and regneth god

world with oute ende.

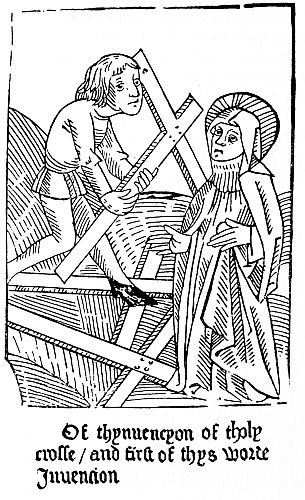

THE6 Invencion[C] of the holy crosse is said bycause that this day the holy crosse was founden / for to fore7 it was founden of seth in paradyse terestre / lyke as hit shal be sayd here after / and also it was founden of salamon in the mounte of lybane and of the quene of saba / in the temple of salamon / And of the[xxiii] Iewes in the water of pyscyne[D] / And on thys day it was founden of Helayne in the mounte of Calvarye/.

THE holy crosse was founden two

hondred yere after the resurrexyon

of our lord / It is redde in the gospel of

nychodemus[E] / that whan adam wexyd

seck / Seth hys sone wente to the gate of

paradyse terestre, for to gete the oyle of[xxiv]

mercy for to enoynte wythal hys faders

body / Thenne apperyd to hym saynt

mychel thaungel and sayd to hym /

travayle not the in vayne / for thys oyle

/ for thou mayst not have it till fyve

thousand and fyve hondred yere been

passed / how be it that fro Adam unto

the passyon of our lord were but fyve

![]() and

and ![]() yere / In another place

it is redde that the aungel broughte hym

a braunche / and commaunded hym to

plante it in the mounte of lybanye Yet[xxv]

fynde we in another place / that he gafe

to hym of the tree that Adam ete of /

And sayd to hym that whan that bare

fruyte he should be guarisshed8 and alle

hoole9 /. whan seth came ageyn he founde

his fader deed / and planted this tree

upon his grave / And it endured there

un to the tyme of Salomon / and bycause

he sawe that it was fayre, he dyd10 doo

hewe it doun / and sette it in his hows

named saltus / and whan the quene of

saba came to vysyte Salamon / She worshypped

this tre bycause she sayd the

savyour of alle the world shold be hanged

there on / by whome the royame11 of the

Iewes that be defaced and seace.12 Salomon

for this cause made hit to be taken up /

& dolven13 depe in the grounde. Now it

happed after that they of Ierusalem (dyd

do make a grete pytte for a pyscyne14 /

where at the mynysters of the temple

sholde wesshe theyre bestys / that they

shold sacrefyse / and there founde thys

tre / and thys pyscyne had suche vertue,[xxvi]

that the aungels descended and mevyd

the water / and the first seke man that

descendyd in to the water after the

mevyng / was made hole of what somever

sekenesse he was seek of. And whan

the tyme approched of the passyon of

our lord / thys tree aroos out of the

water and floted above the water / And

of this pyece of tymbre made the Iewes

the crosse of our lord / Thenne after

this hystorye / the crosse by which we

been saved / came of the tree by whiche

we were dampned. And the water of

that pyscyne had not his vertue onely of

the aungel / but of the tre/. With this

tre wherof the crosse was maad / there

was a tree that went over thwarte / on

whiche the armes of our lord were

nayled/. And another pyece above which

was the table / wherin the tytle was

wryten / and another pyece wherein the

sokette or mortys was maad that the

body of the crosse stood in soo that

there were foure manere of trees / That[xxvii]

is of palme of cypres / of cedre and of

olyve. So eche of thyse foure pyeces was

of one of those trees/. This blessed

crosse was put in the erthe and hyd by

the space of on hondred yere and more /

But the moder of themperour which

was named helayne[F] which founde it in thys

manere / For Constantyn came wyth a

grete multytude of barbaryns nygh unto

the ryver of the dunoe / whyche wold

have goon over for to have destroyed alle

the contree / And whan constantyn had[xxviii]

assembled his hoost / He went and sette

them ageynst that other partye / But as

sone as he began to passe the ryver / he

was moche aferde / by cause he shold

on the morne have batayle / and in the

nyght as he slepte in his bedde / an

aungel awoke hym / and shewed to hym

the sygne of the crosse in heven / and

sayd to hym / Beholde on hye on heven/.

Thanne sawe he the crosse made of

ryght clere lyght / & was wryten there

upon wyth lettres of golde / In this

sygne thou shalte over come the batayle/[xxix]

Thenne was he alle comforted of thys

vysion / And on the morne / he put

in his banere the Crosse15 / and made it

to be borne tofore hym and his hoost /

And after smote in the hoost of his

enemyes / and slewe and chaced grete

plente / After thys he dyd doo16 calle the

bysshoppes of the ydolles / and demaunded

them to what god the sygne of the crosse

apperteyned. And whan they coude not

answere / some cristen men that were

there tolde to hym the mysterye of the

crosse / and enformed hym in the faythe

of the trynyte / Thenne anone he bylevyd

parfytly (in) god / and dyd do baptyse

hym / and after, it happed that constantyn

his sone remembred the vyctorye of

his fader / Sente to helayn his modre[xxx]

for to fynde the holy crosse / Thenne

helayne wente in to Iherusalem / and

dyd doo assemble all the wyse men of

the contre / and whan they were assembled

/ they wold fayn knowe wherfore

they were called / Thenne one Iudas

sayd to them / I wote17 wel that she wyl

knowe of us where the crosse of Ihesu

criste was leyed / but beware you al

that none of you tell hyr / for I wote

wel then shall our lawe be destroyed /

For zacheus my olde18 fader sayde to

symon my fader / And my fader sayde

to me at his dethe / be wel ware / that

for no tormente that ye may suffre / telle

not where the crosse of Ihesu criste was

leyde / for after that hit shal be founden

/ the Iewes shal reygne no mour / But

the cristen men that worshypped the

crosse shal then reygne / And verayly

this Ihesus was the sone of god.

yere / In another place

it is redde that the aungel broughte hym

a braunche / and commaunded hym to

plante it in the mounte of lybanye Yet[xxv]

fynde we in another place / that he gafe

to hym of the tree that Adam ete of /

And sayd to hym that whan that bare

fruyte he should be guarisshed8 and alle

hoole9 /. whan seth came ageyn he founde

his fader deed / and planted this tree

upon his grave / And it endured there

un to the tyme of Salomon / and bycause

he sawe that it was fayre, he dyd10 doo

hewe it doun / and sette it in his hows

named saltus / and whan the quene of

saba came to vysyte Salamon / She worshypped

this tre bycause she sayd the

savyour of alle the world shold be hanged

there on / by whome the royame11 of the

Iewes that be defaced and seace.12 Salomon

for this cause made hit to be taken up /

& dolven13 depe in the grounde. Now it

happed after that they of Ierusalem (dyd

do make a grete pytte for a pyscyne14 /

where at the mynysters of the temple

sholde wesshe theyre bestys / that they

shold sacrefyse / and there founde thys

tre / and thys pyscyne had suche vertue,[xxvi]

that the aungels descended and mevyd

the water / and the first seke man that

descendyd in to the water after the

mevyng / was made hole of what somever

sekenesse he was seek of. And whan

the tyme approched of the passyon of

our lord / thys tree aroos out of the

water and floted above the water / And

of this pyece of tymbre made the Iewes

the crosse of our lord / Thenne after

this hystorye / the crosse by which we

been saved / came of the tree by whiche

we were dampned. And the water of

that pyscyne had not his vertue onely of

the aungel / but of the tre/. With this

tre wherof the crosse was maad / there

was a tree that went over thwarte / on

whiche the armes of our lord were

nayled/. And another pyece above which

was the table / wherin the tytle was

wryten / and another pyece wherein the

sokette or mortys was maad that the

body of the crosse stood in soo that

there were foure manere of trees / That[xxvii]

is of palme of cypres / of cedre and of

olyve. So eche of thyse foure pyeces was

of one of those trees/. This blessed

crosse was put in the erthe and hyd by

the space of on hondred yere and more /

But the moder of themperour which

was named helayne[F] which founde it in thys

manere / For Constantyn came wyth a

grete multytude of barbaryns nygh unto

the ryver of the dunoe / whyche wold

have goon over for to have destroyed alle

the contree / And whan constantyn had[xxviii]

assembled his hoost / He went and sette

them ageynst that other partye / But as

sone as he began to passe the ryver / he

was moche aferde / by cause he shold

on the morne have batayle / and in the

nyght as he slepte in his bedde / an

aungel awoke hym / and shewed to hym

the sygne of the crosse in heven / and

sayd to hym / Beholde on hye on heven/.

Thanne sawe he the crosse made of

ryght clere lyght / & was wryten there

upon wyth lettres of golde / In this

sygne thou shalte over come the batayle/[xxix]

Thenne was he alle comforted of thys

vysion / And on the morne / he put

in his banere the Crosse15 / and made it

to be borne tofore hym and his hoost /

And after smote in the hoost of his

enemyes / and slewe and chaced grete

plente / After thys he dyd doo16 calle the

bysshoppes of the ydolles / and demaunded

them to what god the sygne of the crosse

apperteyned. And whan they coude not

answere / some cristen men that were

there tolde to hym the mysterye of the

crosse / and enformed hym in the faythe

of the trynyte / Thenne anone he bylevyd

parfytly (in) god / and dyd do baptyse

hym / and after, it happed that constantyn

his sone remembred the vyctorye of

his fader / Sente to helayn his modre[xxx]

for to fynde the holy crosse / Thenne

helayne wente in to Iherusalem / and

dyd doo assemble all the wyse men of

the contre / and whan they were assembled

/ they wold fayn knowe wherfore

they were called / Thenne one Iudas

sayd to them / I wote17 wel that she wyl

knowe of us where the crosse of Ihesu

criste was leyed / but beware you al

that none of you tell hyr / for I wote

wel then shall our lawe be destroyed /

For zacheus my olde18 fader sayde to

symon my fader / And my fader sayde

to me at his dethe / be wel ware / that

for no tormente that ye may suffre / telle

not where the crosse of Ihesu criste was

leyde / for after that hit shal be founden

/ the Iewes shal reygne no mour / But

the cristen men that worshypped the

crosse shal then reygne / And verayly

this Ihesus was the sone of god.

Then demaunded I my fader / wherfore had they hanged hym on the crosse sythe it was knowen that he was the sone[xxxi] of god / thenne he sayd to me fayre sone I never accorded thereto / But gayn said it alwaye / But the Pharisees dyd it bycause he repreyvd theyr vyces / but he aroos on the thyrd day / and his dysciples seeing / he ascended in to heven / Thenne by cause that Stephen thy broder belevyd in him / the Iewes stoned hym to dethe.

Then when Iudas had sayd theyse wordes to his selawes / they answerd we never herde of suche thynges / never the lesse kepe the wel if the quene demaunde the therof / that thou say no thynge to hyr / Whan the quene had called them / and demaunded them the place where our lord Ihesu criste had been crucefyed/ they wold never tell her nor ensygne19 her /. Then commaunded she to brenne20 them alle/. But then they doubted and were aferde / & delyvered Iudas to hyr and sayd / lady thys man is the sone of a prophete and of a juste man / and knoweth right wel the lawe / & can[xxxii] telle to you al thynge that ye shal demaunde hym/.

Thenne the quene lete al the other goo, and reteyned Iudas without moo21/. Thenne she shewed to hym his life & dethe & bade hym chese whyche he wold. Shewe to me sayd she the place named golgota where our lord was crucefyed / by cause and to the end that we may fynde the crosse/. Thenne sayd Iudas, it is two hondred yere passed & more / & I was not thenne yet borne. Thenne sayd to hym the lady / by him that was crucyfyed / I shal make the perisse for hungre/ yf thou telle not to me the trouthe.

Thenne made she hym to be caste into a drye pytte / and there tormented hym by hungre / and evyl reste / whan he had been seuen dayes in that pytte / thenne sayd he yf I myght be drawen out / he shold say the trouthe / Thenne he was drawen out / and whan he came to the place / anone the erthe moevyd[xxxiii] and a fume of grete swettnesse was felte in suche wyse that Iudas smote his hondes togyder for ioye / and sayd / in trouthe Ihesu criste thou art the savyour of the worlde.

It was so that adryan the Emperour

had doo make in the same place where

the crosse laye a temple of a goddesse by

cause that all they that come in that

place shold adoure that goddesse/. But

the quene did doo destroy the temple /

Thenne Iudas made hym redy and began

to dygge / and whan he came to ![]() paas22 depe / he fonde three crosses and

broughte them to the quene / And

bycause he knewe not whiche was the

crosse of our lord / he leyed them in the

myddel of the cyte / and abode the

demonstraunce of god / and aboute the

houre of none / there was the corps of

a yonge man brought to be buryed /

Iudas reteyned the byere / and layed

upon hit one of the crosses / and after

the second / and whan he leyed on hit[xxxiv]

the third / anone the body that was dede

came ageyn to lyf/.

paas22 depe / he fonde three crosses and

broughte them to the quene / And

bycause he knewe not whiche was the

crosse of our lord / he leyed them in the

myddel of the cyte / and abode the

demonstraunce of god / and aboute the

houre of none / there was the corps of

a yonge man brought to be buryed /

Iudas reteyned the byere / and layed

upon hit one of the crosses / and after

the second / and whan he leyed on hit[xxxiv]

the third / anone the body that was dede

came ageyn to lyf/.

Thenne cryed the devyll in the eyre Iudas what hast thou doon / thou hast doon the contrarye that thother Iudas dyd/. For by hym I have wonne many sowles / and by the I shal lose many / by hym I reygned on the peple / And by the I have lost my royame / never the lesse I shal yelde to the this bountee/. For I shal send one that shal punysshe the / and that was accomplysshed by Iulian the apostata / which tormented hym afterward whan he was bysshop of Iherusalem / and whan Iudas herde hym he cursed the devyl and sayd to hym / Ihesu cryste dampne the in fyre pardurable23/. After this Iudas was baptyzed and was named quyryache[G]/. And after was made bysshop of Iherusalem/. Whan helayn had the crosse of Ihesu criste / and saw she had not the nayles / Thenne he dyd[xxxv] dygge in therthe so longe / that he founde them shynyng as golde/. thenne bare he them to the quene / and anone as she sawe them she worshypped them wyth grete reverence/.

Thenne gafe saynt helayn a part of the crosse to hir sone / And that other parte she lefte in Iherusalem closyd in golde / sylver and precious stones/.

And hyr sone bare the nayles to themperour / And the emperour dyd do sette them in hys brydel and in hys helme whan he wente to batayle/. This referreth Eusebe whiche was bysshop of Cezayr24/ how be it that other say otherwyse/. Now it happed that Iulyan the appostate dyd doo25 slee quyriache that was bysshop of Iherusalem / by cause he had founde the crosse / for he hated hit soo mooche / that where somever he founde the crosse / he dyd hit to be destroyed / For whan he wente in batayle ageynste them of perse / he sente and commaunded quyriache to make sacrefyse[xxxvi] to thydolles / and whan he wold not doo hit / he dyd do smyte of his right honde / and sayd wyth this honde hast thou wryten many letters / by whyche thou repellyd moche folke fro doynge sacrefyse to our goddes/.

Quyriache sayd thou wood hounde26 thou hist doon to me grete prouffyte / For thou hast cut of the hande / wyth whiche I have many tymes wreton to the synagoges that they shold not byleve in Ihesu criste / and now sythe27 I am cristen / thou hast taken from me that whiche noyed me / thenne dyd Iulyan do melte leed, and caste it in his mowthe / and after dyd doo brynge a bedde of yron / and made quyriache to be layed and stratched theron / and after leyed under brennyng cooles / and threwe therein grece and salte / for to torment hym the more / and whan quyriache moved not / Iulyan themperour said to hym / outher thou shalt sacrefyse (to) our goddes / or thou shalt say at the[xxxvii] leste thou art not cristen/. And whan he sawe he wolde not do never neyther / he dyd doo make a depe pytte ful of serpentes and venemous bestys / and caste hym therein / & whan he entred / anone the serpentes were al deed/. Thenne Iulyan put hym in a cawdron ful of boylyng oyle / and whan he shold entre in to hit / he blessyd it & sayd / Fayre lord torne thys bane28 to baptysm of marterdom / Thenne was Iulyan moche angry / and commaunded that he should be ryven thorough his herte with a swerde / and in this manere he fynysshed his lyff.

The vertue of the crosse is declared to us by many miracles / For it happed on a tyme that one enchantour had dysceyved a notarye / and brought hym to a place / where he had assembled a grete companye of devylles / and promysed to hym to have muche rychesse / and whan he came there / he saw one persone blacke syttynge on a grete chayer / And[xxxviii] all aboute hym al ful of horyble people and blacke whiche had speres and swerdes / Thenne demaunded thys grete devyll of the enchantour / who was that clerke / thenchantour sayd to hym / Syr he is oures / thenne sayd the devyl to hym yf thou wylte worshyp me and be my servaunte / and denye Ihesu cryste / thou shalt sytte on my right syde / The clerke anone blessyd hym wyth the sygne of the crosse / and sayd that he was the servaunte of Ihesu criste / his savyour / And anone as he had made the crosse / that grete multitude of devylles vanysshed aweye. It happed that this notarye after this on a tyme entryd with hys lord in the chyrche of saynt sophye / & knelyd doun on his knees to fore the ymage of the crucyfyxe / the which crucifyxe as it semed loked moche openly and sharpelye on hym/. Thenne his lord made hym to go aparte on another syde / and alleweye the crucifixe torned his eyen toward hym/. Thenne he made hym[xxxix] goo on the lefte syde / and yet the crucifixe loked on hym / Thenne was the lord moche admerveyled / and charged hym & commaunded hym that he shold telle hym wherof he had so deserved that the crucifyxe so behelde and loked on hym / Thenne sayde the notarye that he coude not remembre hym of no good thynge that he had doon / saufe that one tyme he wold not renye nor forsake the crucifixe tofore the devyl/.

Thenne late us so blesse us with the sygne of the blessyd crosse that we may therby be kepte fro the power of our ghoostly and dedely enemye the devyl / and by the glorious passyon that our saveour Ihesu cryst suffred on the crosse after this lyf we may come to his everlastyng blysse amen/.

Thus endeth thynvencion of the holy crosse.

Exaltation of the holy Crosse29 is sayd / bycause that on this daye the hooly crosse & faythe were gretely enhaunced/. And it is to be understonden that tofore the passion of our lord Ihesu cryste / the tree of the crosse was a tree of fylthe / For the crosses were made of vyle trees, & of trees without fruyte / For al that was planted on the Mount of Calvarye bare no fruyt. It was a fowle place / for hit was the place of torment of thevys / It was derke / for it was in a derke place and without any beaute / It was the tree of deth / for men were put there to dethe / It was also the tree of stenche / for it was planted amonge the caroynes30 / & after the passyon the Crosse was moche enhaunced / For the Vylte31 was transported into preciousyte / Of the whiche the blessyd saynt Andrewe sayth / O precious holy Crosse god save the / his bareynes was torned into fruyte / as it is sayd in the Cantyques / I shall ascende up in to a palme tree / et cetera / His[xlii] ignobylyte or unworthynes was tourned into sublymyte and heyght / The Crosse that was tormente of thevys is now born in the front of themperours / his derkenes is torned into lyght and clerenesse/ wherof Chrysostom sayth the Crosse and the Woundes shall be more shynyng than the rayes of the Sonne at the jugement / his deth is converted into perdurabylyte of lyf / whereof it is sayd in the preface / that fro hens the lyf resourded32 / and the stenche is torned into swetenes / canticorum /. This exaltacion of the hooly crosse is solempnysed and halowed solempnly of the Chirche / For the faythe is in hit moche enhaunced /.

For the yere of oure lord five honderd

& ![]() / our lord suffred his people moche

to be tormentyd by the cruelte of the

paynyms / And Cosdroe33 Kynge of the

Perceens subdued to his empyre all the

Royaumes of the world / And he cam

into Iherusalem and was aferd and a

dred of the sepulcre of our lord &[xliii]

retorned / but he bare with hym the parte

of the hooly Crosse / that saynte Helene

had left ther. And then he wold be

worshiped of alle the peple / as a god /

& dyd do make a tour of gold and of

sylver wherein precious stones shone /

and made therein the ymages of the

sonne and of the mone and of the sterres

/ and made that by subtyle conduytes

water to be hydde / and to come doune

in the maner of rayne / And in the laste

stage he made horses to draw charyotes

round aboute lyke as they had mevyd

the toure / and made it to seme as

it had thondred / and delyvered his

Royaume to his sone. And thus this

cursyd man abode in this Temple / and

dyd doo sette the crosse of our lord by

hym and commaunded that he shold be

callyd god of alle the peple / And as it is

redde in libro de mitrali[H] officio the said

Cosdroe resydent in his trone as a fader /[xliv]

sette the tree of the Crosse on his ryght

syde in stede of the sonne / and a cock

in the lyft syde in stede of the hooly

ghoost / & commaunded / that he shold

be called fader /. And then Heracle[I]

themperour assembled a grete hoost /

and cam for to fyght wyth the sonne of

Cosdroe by the ryver of danubie / &

thenne hit pleasyd to eyther prynce /

that eche of them shold fyght one

ageynste that other upon the brydge /

& he that shold vaynquysshe & overcome

his adversarye sholde be prynce of

thempyre withoute hurtyng eyther of

bothe hostes / & so hit was ordeyned &

sworn / & that who somever shold helpe

his prynce shold have forthwith his

legges & armes cut of / & to be plonged

/ & cast in to the Ryver.

/ our lord suffred his people moche

to be tormentyd by the cruelte of the

paynyms / And Cosdroe33 Kynge of the

Perceens subdued to his empyre all the

Royaumes of the world / And he cam

into Iherusalem and was aferd and a

dred of the sepulcre of our lord &[xliii]

retorned / but he bare with hym the parte

of the hooly Crosse / that saynte Helene

had left ther. And then he wold be

worshiped of alle the peple / as a god /

& dyd do make a tour of gold and of

sylver wherein precious stones shone /

and made therein the ymages of the

sonne and of the mone and of the sterres

/ and made that by subtyle conduytes

water to be hydde / and to come doune

in the maner of rayne / And in the laste

stage he made horses to draw charyotes

round aboute lyke as they had mevyd

the toure / and made it to seme as

it had thondred / and delyvered his

Royaume to his sone. And thus this

cursyd man abode in this Temple / and

dyd doo sette the crosse of our lord by

hym and commaunded that he shold be

callyd god of alle the peple / And as it is

redde in libro de mitrali[H] officio the said

Cosdroe resydent in his trone as a fader /[xliv]

sette the tree of the Crosse on his ryght

syde in stede of the sonne / and a cock

in the lyft syde in stede of the hooly

ghoost / & commaunded / that he shold

be called fader /. And then Heracle[I]

themperour assembled a grete hoost /

and cam for to fyght wyth the sonne of

Cosdroe by the ryver of danubie / &

thenne hit pleasyd to eyther prynce /

that eche of them shold fyght one

ageynste that other upon the brydge /

& he that shold vaynquysshe & overcome

his adversarye sholde be prynce of

thempyre withoute hurtyng eyther of

bothe hostes / & so hit was ordeyned &

sworn / & that who somever shold helpe

his prynce shold have forthwith his

legges & armes cut of / & to be plonged

/ & cast in to the Ryver.

And then Heracle commaunded hym

all to god and to the hooly crosse wyth

all the devocion that he myght. And[xlv]

thenne they fought longe / And at the

last our lord gaf the vyctory to Heracle

and subdued hym to his empyre / The

hoost that was contrary / and alle the

peple of Cosdroe obeyed them to the

Crysten faythe / and receyved the hooly

baptysme / And Cosdroe knew not the

end of the batayll / For he was adoured

and worshiped of alle the peple as a god

/ so that no man durst say nay to him /

And thenne Heracle came to hym / and

fonde hym syttinge in his syege34 of

golde / and sayd to hym / For as moche

as after the manere thou hast honoured

the Tree of the Crosse / yf thou wyld

receyve baptym and the faythe of Ihesu

Cryst / I shal gete it to the / and yet shalt

thow holde thy crowne and Royamme

with lytel hostages / And I shall lete the

have thy lyf / and yf thou wylt not / I

shall flee the wyth my swerde / and

shalle smyte of thyne heed / and whanne

he wold not accorde therto / he did anon

do smyte of his hede / and commaunded[xlvi]

that he shold be buryed / by cause he

had be(en) a Kynge /. And he fonde

with hym one his sone of the age of ten

yere / whome he dyd doo baptyse and

lyft hym fro the fonte / and left to hym

the Royaume of his fader / and then he

dyd doo breke that Toure / And gaf the

sylver to them of his hooste / and gaf

the gold and precious stones for to repayre

the chirches that the tyraunt had

destroyed / and tooke the hoole crosse /

and brought it ageyne to Ierusalem / and

as he descended from the mount of

Olyvete / and wold have entryd by the

gate by whiche our savyour wente to his

passyon on horsbacke adourned as a Kynge

/ sodenly the stones of the gates descended

/ and ioyned them togyder in

the gate like a wall & all the peple was

abashed35 / and thenne the Aungel of

oure lord appyeryd upon the gate holdyng

the signe of the signe (sic) of the

Crosse in his honde / and sayd / Whanne

the Kynge of heven went to his passion[xlvii]

by this gate / he was not arayed like a

Kynge / ne on horsbake / but cam

humbly upon an asse / in shewynge

thexample of humylite which he left to

them that honoure hym. And when

this was sayd / he departed and vanysshed

aweye / Thenne th’emperour took of his

hosen and shone36 himself in wepynge /

and despollyed hymselfe of alle his clothes

in to his sherte / and tooke the crosse of

oure lord / and bare it moche humbly

into the gate / and anone the hardnes of

the stones felte the celestyalle commaundement

/ and remeved anone / and opened

and gaf entree unto them that entred /

Thenne the sweete odour that was felt

that day whanne the hooly Crosse was

taken fro the Toure of Cosdroe / and

was brought ageyne to Iherusalem fro so

ferre countre / and so grete space of

londe retourned in to Iherusalem in that

moment / and replenysshed it with al

swetnes / Thenne the ryght devoute

Kyng beganne to saye the praysynges of[xlviii]

the Crosse in this wyse / O Crux splendydior

/ et cetera / O Crosse more

shynynge than alle the Sterres / honoured

of the world / right holy / and moche

amyable to alle men / whiche only were

worthy to bere the raunson of the world

Swete tree / Swete nayles / Swete yron /

Swete spere berynge the swete burthens

/ Save thou this present company / that

is this daye assembled in thy lawe and

praysynges /. And thus was the precious

tree of the Crosse re establysshed in

his place / and the auncient myracles

renewed /. For a dede man was reysed

to lyf / and foure men taken with the

palsey were cured and heled / ![]() lepres

were made clene / and fyften blynde

receyved theyr syghte ageyn / Devylles

were put out of men / and moche peple

/ and many / were delyvered of dyverse

sekenes and maladyes /. Thenne themperour

dyd doo repayre the Chirches /

and gaf to them grete geftes / And after

retorned home to his Empyre / And hit[xlix]

is said in the Cronycles that this was

done otherwise / For they say that

whanne Cosdroe hadde taken many

Royammes / he took Iherusalem / and

Zacharye the patriarke / and bare aweye

the tree of the Crosse / And as Heracle

wold make pees with hym / the Kyng

Cosdroe swore a grete othe / that he wold

never make pees with Crysten men and

Romayns / yf they denyed not hym that

was crucyfyed / and adoured the sonne /.

And thenne Heracle / whiche was armed

wythe faythe / brought his hooste ageynst

hym / and destroyed and wasted the

Persyens with many batayles that he

made to them / and made Cosdroe to

flee unto the Cyte of thelyfonte /. And

atte the laste Cosdroe hadde the flyxe in

his bely / And wolde therefore crowne

his sone Kynge / which was named

Mendasa /. And whenne Syroys his

oldest sone herde thereof he made alyance

with Heracle / And pursewed his fader

with his noble peple / and set hym in[l]

bondes / And susteyned him with breede

of trybulacion / and with water of

anguysshe / And atte last he made to

shote arowes at him bycause he wold not

bileve in god & so deyde / & after this

thynge he sente to Heracle the patriarke

the tree of the Crosse and all the prysoners

/ And Heracle bare into Iherusalem

the precious tree of the Crosse /.

And thus it is redde in many Cronycles

also/. Sybyle sayth thus of the tre of the

Crosse / that the blessyd tree of the

Crosse was thre tymes with the paynyms

/ as it is sayd in thystorie trypertyte O

thryse blessyd tree on whiche god was

stratched / This peradventure is sayd for

the lyf of Nature / of grace / and of

glorye / which cam of the crosse /. At

Constantynople a Iewe entyred in to the

chirche of seynt sophye / and consydered

that he was there allone / and sawe an

ymage of Ihesu cryste / and tooke his

swerde and smote thymage in the throte

/ and anone the bloode guysshed oute /[li]

and sprange in the face and on the hide

of the Iewe / And he thenne was aferd

and took thymage / and cast it into a

pytte / and anone fledde awey /. And it

happed that a Crysten man mett hym /

and sawe hym al blody / and sayd to

hym / fro whens comest thou / thou

hast slayne soume man / And he sayd I

have not / the crysten man sayd Veryly

thou has commysed somme homycyde /

for thou art all besprongen37 with the

blood. And the Jewe said / Veryly the

god of Crysten men is grete and the

faythe of hym is ferme and approved in

all thynges / I have smyten no man /

but I have smyten thymage of Ihesu

Cryste / and anone yssued blood of his

throte /. And thenne the Jewe brought

the Crysten man to the pytte / and then

they drewe oute that hooly ymage /.

And yet is sene on this daye the wounde

in the throte of thymage / And the Iewe

anone bycam a good Crysten man, &

was baptysed / In Syre in the cyte of[lii]

baruth there was a cristen man / which

had hyred an hous for a yere / & he had

set thymage of the crucifixe by his bedde

to whiche he made dayly his prayers and

said his devocions / & at the yeres ende

he remeved and tooke another hous / &

forgate & lefte thymage behynde hym /

and it happed that a Iewe hyred that

same hows / & on a daye he had another

Iewe one of his neyghbours to dyne / &

as they were at mete it happed hym that

was boden38 in lookyng on the walle to

espye this ymage whiche was fyxed to

the walle and beganne to grenne at it

for despyte / and ageynst hym that bad

hym / & also thretned & menaced hym

bycause he durst kepe in his hous

thymage of Ihesu of nazareth / & that

other Iewe sware as moche as he myght /

that he had never sene it / ne knewe

not that it was there / & thenne the

Iewe fayned as he had been peasyd39. /

& after went strayt to the prynce of the

Iewes / & accused that Iewe of that[liii]

whiche he hadde sene in his hous /

thenne the Iewes assembleden & cam to

the hous of hym / & sawe thymage of

Ihesu Cryst / and they took that Iewe

and bete hym / & did to hym many

iniuryes / & caste hym out half dede of

their synagoge / & anone they defowled

thymage with their feet / & renewed in

it all the tormentes of the passion of oure

lorde / & and when they perced his syde

with the spere / blood and water yssued

haboundauntly / in so moche that they

fylled a vessel / whiche they set therunder

/ And thenne the Iewes were

abasshhed & bare this blood in to theyr

synagoge & and alle the seke men and

malades that were enoynted therwyth /

were anone guarysshed & made hool /

& thenne the Iewes told & recounted al

this thynge by ordre to the bishop of

the countre / & alle they with one wyll

receyved baptysm in the faythe of Ihesu

Cryst / & the bisshop putt the blood in

ampulles40 of Crystalle & of glas for to[liv]

be kepte / & thenne he called / the

Crysten man that had lefte it in the hows

/ & enquyred of hym / who had made

so fayr an ymage / & he said that Nychodemus

had made it / And when he

deyde / he lefte it to gamalyel / And

Gamalyel to Zachee and Zachee to

Iaques / and Iaques to Symon / and

hadde ben thus in Ierusalem unto the

destruction of the Cyte / and fro thennes

hit was borne in to the Royamme of

Agryppe of Crysten men / and fro

thennes hit was brought ageyne into my

countreye / & it was left to me by my

parentes by rightful herytage / & this

was done in ye yere of our lord seven

honderd and fifty / and thenne alle the

Iewes halowed41 their synagogues in to

chirches and therof cometh the custoume

that Chirches ben hallowed / For tofore

that tyme the aultres were but halowed

only / and for this myracle the chirche

hath ordeyned / that the fyfte Kalendar

of december / or as it is redde in another[lv]

place / the fyfthe ydus of Novembre

shold be the memorye of the passyon of

oure lord / wherfor at Rome the chirche

is halowed in thonoure of our savyour

whereas is kepte an ampulla with the

same blood / And there a solempne feste

is kepte and done / and there is proved

the ryght grete vertue of the crosse unto

the paynyms and to the mysbylevyd men

in alle thynges /.

lepres

were made clene / and fyften blynde

receyved theyr syghte ageyn / Devylles

were put out of men / and moche peple

/ and many / were delyvered of dyverse

sekenes and maladyes /. Thenne themperour

dyd doo repayre the Chirches /

and gaf to them grete geftes / And after

retorned home to his Empyre / And hit[xlix]

is said in the Cronycles that this was

done otherwise / For they say that

whanne Cosdroe hadde taken many

Royammes / he took Iherusalem / and

Zacharye the patriarke / and bare aweye

the tree of the Crosse / And as Heracle

wold make pees with hym / the Kyng

Cosdroe swore a grete othe / that he wold

never make pees with Crysten men and

Romayns / yf they denyed not hym that

was crucyfyed / and adoured the sonne /.

And thenne Heracle / whiche was armed

wythe faythe / brought his hooste ageynst

hym / and destroyed and wasted the

Persyens with many batayles that he

made to them / and made Cosdroe to

flee unto the Cyte of thelyfonte /. And

atte the laste Cosdroe hadde the flyxe in

his bely / And wolde therefore crowne

his sone Kynge / which was named

Mendasa /. And whenne Syroys his

oldest sone herde thereof he made alyance

with Heracle / And pursewed his fader

with his noble peple / and set hym in[l]

bondes / And susteyned him with breede

of trybulacion / and with water of

anguysshe / And atte last he made to

shote arowes at him bycause he wold not

bileve in god & so deyde / & after this

thynge he sente to Heracle the patriarke

the tree of the Crosse and all the prysoners

/ And Heracle bare into Iherusalem

the precious tree of the Crosse /.

And thus it is redde in many Cronycles

also/. Sybyle sayth thus of the tre of the

Crosse / that the blessyd tree of the

Crosse was thre tymes with the paynyms

/ as it is sayd in thystorie trypertyte O

thryse blessyd tree on whiche god was

stratched / This peradventure is sayd for

the lyf of Nature / of grace / and of

glorye / which cam of the crosse /. At

Constantynople a Iewe entyred in to the

chirche of seynt sophye / and consydered

that he was there allone / and sawe an

ymage of Ihesu cryste / and tooke his

swerde and smote thymage in the throte

/ and anone the bloode guysshed oute /[li]

and sprange in the face and on the hide

of the Iewe / And he thenne was aferd

and took thymage / and cast it into a

pytte / and anone fledde awey /. And it

happed that a Crysten man mett hym /

and sawe hym al blody / and sayd to

hym / fro whens comest thou / thou

hast slayne soume man / And he sayd I

have not / the crysten man sayd Veryly

thou has commysed somme homycyde /

for thou art all besprongen37 with the

blood. And the Jewe said / Veryly the

god of Crysten men is grete and the

faythe of hym is ferme and approved in

all thynges / I have smyten no man /

but I have smyten thymage of Ihesu

Cryste / and anone yssued blood of his

throte /. And thenne the Jewe brought

the Crysten man to the pytte / and then

they drewe oute that hooly ymage /.

And yet is sene on this daye the wounde

in the throte of thymage / And the Iewe

anone bycam a good Crysten man, &

was baptysed / In Syre in the cyte of[lii]

baruth there was a cristen man / which

had hyred an hous for a yere / & he had

set thymage of the crucifixe by his bedde

to whiche he made dayly his prayers and

said his devocions / & at the yeres ende

he remeved and tooke another hous / &

forgate & lefte thymage behynde hym /

and it happed that a Iewe hyred that

same hows / & on a daye he had another

Iewe one of his neyghbours to dyne / &

as they were at mete it happed hym that

was boden38 in lookyng on the walle to

espye this ymage whiche was fyxed to

the walle and beganne to grenne at it

for despyte / and ageynst hym that bad

hym / & also thretned & menaced hym

bycause he durst kepe in his hous

thymage of Ihesu of nazareth / & that

other Iewe sware as moche as he myght /

that he had never sene it / ne knewe

not that it was there / & thenne the

Iewe fayned as he had been peasyd39. /

& after went strayt to the prynce of the

Iewes / & accused that Iewe of that[liii]

whiche he hadde sene in his hous /

thenne the Iewes assembleden & cam to

the hous of hym / & sawe thymage of

Ihesu Cryst / and they took that Iewe

and bete hym / & did to hym many

iniuryes / & caste hym out half dede of

their synagoge / & anone they defowled

thymage with their feet / & renewed in

it all the tormentes of the passion of oure

lorde / & and when they perced his syde

with the spere / blood and water yssued

haboundauntly / in so moche that they

fylled a vessel / whiche they set therunder

/ And thenne the Iewes were

abasshhed & bare this blood in to theyr

synagoge & and alle the seke men and

malades that were enoynted therwyth /

were anone guarysshed & made hool /

& thenne the Iewes told & recounted al

this thynge by ordre to the bishop of

the countre / & alle they with one wyll

receyved baptysm in the faythe of Ihesu

Cryst / & the bisshop putt the blood in

ampulles40 of Crystalle & of glas for to[liv]

be kepte / & thenne he called / the

Crysten man that had lefte it in the hows

/ & enquyred of hym / who had made

so fayr an ymage / & he said that Nychodemus

had made it / And when he

deyde / he lefte it to gamalyel / And

Gamalyel to Zachee and Zachee to

Iaques / and Iaques to Symon / and

hadde ben thus in Ierusalem unto the

destruction of the Cyte / and fro thennes

hit was borne in to the Royamme of

Agryppe of Crysten men / and fro

thennes hit was brought ageyne into my

countreye / & it was left to me by my

parentes by rightful herytage / & this

was done in ye yere of our lord seven

honderd and fifty / and thenne alle the

Iewes halowed41 their synagogues in to

chirches and therof cometh the custoume

that Chirches ben hallowed / For tofore

that tyme the aultres were but halowed

only / and for this myracle the chirche

hath ordeyned / that the fyfte Kalendar

of december / or as it is redde in another[lv]

place / the fyfthe ydus of Novembre

shold be the memorye of the passyon of

oure lord / wherfor at Rome the chirche

is halowed in thonoure of our savyour

whereas is kepte an ampulla with the

same blood / And there a solempne feste

is kepte and done / and there is proved

the ryght grete vertue of the crosse unto

the paynyms and to the mysbylevyd men

in alle thynges /.

And saynt Gregory recordeth in the

thirdde booke of his dyalogues / that

whanne andrewe Bisshop of the Cyte of

Fundane suffred an holy noune to dwelle

with him / the fende42 thenemy beganne

temprynte in his herte the beaulte of her

/ in such wise / that he thought in hys

bedde wycked and cursyd thynges / and

on a daye a Iewe cam to Rome / and

whanne he sawe / that the day fayled /

and myghte fynde no lodgynge / he

wente that nyght / and abode in the

Temple of appolyn /. And bycause he

doubted of the sacrylege of the place /[lvi]

how be hit / that he hadde no faythe in

the Crosse / yet he markyd and garnysshed

hym wyth the signe of the

Crosse / then at mydnyght whan he

awoke / he sawe a companye of evylle

sprytes / whiche went to fore one / like

as he hadde somme auctoryte puysiance43

above thother by subiection / and thenne

he sawe hym sytte in the myddes among

the others / and beganne to enquyre the

causes and dedes of everyche44 of these

evylle sprytes / whyche obeyed hym /

and he wold knowe / what evylle

everyche had doo / But Gregory passyth

the maner of this vysyon / bycause of

shortnes / But we fynde semblable in the

lyf of faders / That as a man entryd in a

Temple of thydolles / he sawe the devylle

syttynge / and all his meyny45 aboute

hym. And one of these wycked / sprytes

cam / and adouryd hym / and he demaunded

of hym / Fro whens comest

thow / and he sayd / I have ben in such

a provynce / and have moeved grete[lvii]

warres / and made many trybulacions

and have shedde moche blood / and am

come to telle it to the / and Sathan sayd

to hym / in what tyme hath thow done

this / and he sayd in thyrtty dayes and

Sathan sayd / why hast thow be soo

longe there aboutes / and sayd to them

that stode by hym / goo ye and bete hym

/ and all to lasshe hym / Thenne cam

the second and worsshiped hym / & sayde

Syre I have ben in the see / and have

moeved grete wyndes and tormentes /

& drowned many shippes / & slayn many

men / and Sathan sayde how longe hast

thow ben aboute thys / & he sayd ![]() dayes / & Sathan sayd hast thou done no

more in this tyme / & commanded that

he shold be beten / and the third cam /

& said / I have ben in a Cyte & have

mevyd stryves and debate in a weddynge

/ and have shed moche blood / & have

slayne the hosbond / & am come to telle

the / & sathan sayd / in what time hast

thou done this / & he said in ten dayes /[lviii]

& he sayd hast thou done no more in

that time / & commanded them that

were aboute hym to bete hym also /

Thenne cam the fourth & sayd / I have

ben in the wylderness fourty yere / and

have laboured aboute a monke / &

unnethe at the laste I have throwen &

made hym falle in the synne of the

flesshe / & when satan herd that / he

aroos fro his sete / & kyssed hym / &

tooke hys crowne of his hede / & set it

on his hede / & made hym to sytte with

hym / & sayde / thou hast done a grete

thynge / & hast laboured more / than

all thother / and this may be the maner

of the vysyon / that saynt gregorye leveth

/ whan eche had sayd / one sterte up in

the myddle of them alle / & seyd he

hadde mevid Andrewe ageynste the

name / & had mevyd the fourth part of

his fleshe agenst her in temptacion / &

therto / yt yesterday he drough46 so moche

his mynde on her / that in the hour of

evensonge he gaf to her in Iapping47 a[lix]

busse48 / & seid pleynly yt she must here

it that he wold synne with her / thenne

the mayster commanded hym that he

shold perform yt he had begonne / &

for to make hym to synne he shold have

a syngular Vyctory and reward among

alle the other /. And thenne commaunded

he that they shold goo loke who that

was that laye in the Temple / And they

wente / & loked / And anone they were

ware / that he was marked with the

signe of the crosse / And they levynge

aferd escaped / and sayd / veryly this is

an empty vessel / alas / alas / he is

marked /. And with49 thus wys alle the

company of the wykked sprytes vanysshed

awaye / And thenne the Iewe al

amoevyd cam to the bisshop / and told

to hym all by ordere what was happend /

And whan the bisshoppe herd this / he

wept strongly / and made to voyde all

the wymmen oute of his hows / And

thenne he baptysed the Iewe.

dayes / & Sathan sayd hast thou done no

more in this tyme / & commanded that

he shold be beten / and the third cam /

& said / I have ben in a Cyte & have

mevyd stryves and debate in a weddynge

/ and have shed moche blood / & have

slayne the hosbond / & am come to telle

the / & sathan sayd / in what time hast

thou done this / & he said in ten dayes /[lviii]

& he sayd hast thou done no more in

that time / & commanded them that

were aboute hym to bete hym also /

Thenne cam the fourth & sayd / I have

ben in the wylderness fourty yere / and

have laboured aboute a monke / &

unnethe at the laste I have throwen &

made hym falle in the synne of the

flesshe / & when satan herd that / he

aroos fro his sete / & kyssed hym / &

tooke hys crowne of his hede / & set it

on his hede / & made hym to sytte with

hym / & sayde / thou hast done a grete

thynge / & hast laboured more / than

all thother / and this may be the maner

of the vysyon / that saynt gregorye leveth

/ whan eche had sayd / one sterte up in

the myddle of them alle / & seyd he

hadde mevid Andrewe ageynste the

name / & had mevyd the fourth part of

his fleshe agenst her in temptacion / &

therto / yt yesterday he drough46 so moche

his mynde on her / that in the hour of

evensonge he gaf to her in Iapping47 a[lix]

busse48 / & seid pleynly yt she must here

it that he wold synne with her / thenne

the mayster commanded hym that he

shold perform yt he had begonne / &

for to make hym to synne he shold have

a syngular Vyctory and reward among

alle the other /. And thenne commaunded

he that they shold goo loke who that

was that laye in the Temple / And they

wente / & loked / And anone they were

ware / that he was marked with the

signe of the crosse / And they levynge

aferd escaped / and sayd / veryly this is

an empty vessel / alas / alas / he is

marked /. And with49 thus wys alle the

company of the wykked sprytes vanysshed

awaye / And thenne the Iewe al

amoevyd cam to the bisshop / and told

to hym all by ordere what was happend /

And whan the bisshoppe herd this / he

wept strongly / and made to voyde all

the wymmen oute of his hows / And

thenne he baptysed the Iewe.

Seynt Gregory reherceth in his[lx] dyalogues that a nonne entryd into a gardyne / and sawe a letuse / and coveyted that / and forgate to make the signe of the Crosse / and bote50 it glotonously / And anone fylle doune and was ravysshed of a devylle / And ther cam to her saint Equycyon[J] / And the devylle beganne to crye and to saye / What have I doo / I satte uppon a lettuse / and she cam / and bote me / and anone the devylle yssued oute by the commaundement of the holy man of god /. It is redde in thystorye Scolastyke / that the paynyms had peynted on a walle the armes of Serapis / And Theodosyen dide doo putt them oute / and made to be paynted in the same place the signe of the Crosse / And when the paynims & priestes of thydolles sawe that / anone they dyde them to be baptysed / sayenge / that it was gyven them to understonde of their olders /[lxi] that those armes shold endure tyll / that suche a signe were made then / in whiche were lyf / And they have a lettre / of whiche they use / yt they calle holy / & had a forme that they said it exposed and signyfyed lyf perdurable.

Thus endeth the exaltacion of the holy Crosse.

Having read these extracts from the Golden Legend, we shall be able to understand the accompanying illustrations, which represent some frescos of the fifteenth century, which formerly adorned the walls of the / Chapel of the Gild of the Holy Cross, at Stratford-upon-Avon; which stands close by New Place, Shakespeare’s house. These frescos, alas! no longer exist, for, in 1804, the Chapel underwent considerable repair, during which, under the whitewash, were discovered traces of paint, and these, being scraped, a series illustrating the legend of the Cross was found in the chancel,[lxii] which was built in 1450. In other parts of the Chapel were found representations of the Ressurection, and the day of Judgment, St. George and the Dragon, and the death of St. Thomas a Becket, besides others.

Luckily, a gentleman from London, a Mr. Fisher, was then staying at Stratford-on-Avon, and he drew, and painted them—afterwards, in 1807, publishing them—and it is from his sketches that these illustrations are taken. The barbarians of Stratford hacked the plaster on which the Holy Cross series was painted to bits, and whitewashed all the other paintings. It is presumed they still exist, for, when the Chapel was thoroughly restored in 1835, traces of the other pictures were visible under the whitewash.

These pictures of the Invention, and Exaltation, of the Holy Cross are especially interesting, not only on account of their age and artistic merit, but from the fact that they are of English work,[lxiii] and show the English idea of treating the subject. I have reproduced them all but two; one, the fight on the bridge over the Danube between Heraclius and the son of Chosroes, and the other representing Heraclius smiting off Chosroes’ head.

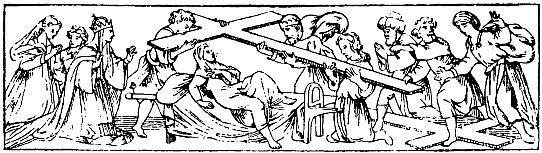

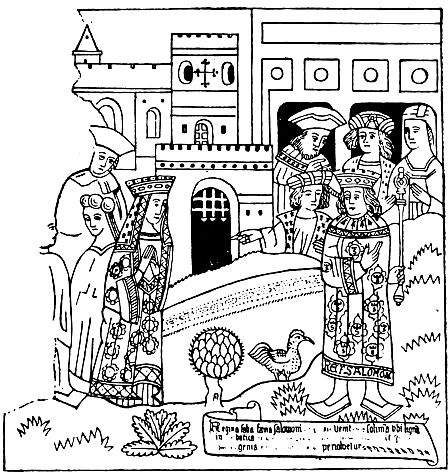

Plate A represents the visit of the Queen of Sheba to Solomon. Her name was Balkis, and, in her legendary history, it is reported that Solomon, having heard of her riches and power, sent her a peremptory message to submit herself to his rule. She, dreading war with so potent a sovereign, sent an embassy to try and find out whether Solomon was as wise as he was represented to be. With this object she dressed five hundred boys as girls, and a like number of girls as boys, and, among other presents, sent a pearl, a diamond cut through in zigzags, and a crystal box; and she should be able to judge of his wisdom and power, if he could tell the boys from the girls, pierce the pearl, thread the diamond, and fill the goblet with water that came neither from the earth nor the sky.

Needless to say, Solomon passed through the ordeal triumphantly. He ordered silver basins to be brought, so that the[lxvi] ambassadors’ suite might wash their hands after their long journey, and the boys were easily distinguished from the girls, for they dipped their hands only in the water, whilst the girls tucked up their sleeves and washed their arms as well as their hands. Then he opened the box containing the pearl, diamond, and goblet, and, taking out the pearl, he applied his magic stone, Samur, or Schamir, which a raven had brought him, and which had the power of cleaving anything, and lo! the pearl was pierced; then he examined the diamond, which was so pierced that no thread could be passed through it; so he took a worm, and having placed a piece of silk in its mouth, it wriggled through, and the diamond was threaded. The next task was to fill the goblet, which he gave to a negro slave, and bade him mount a wild horse and gallop it till it streamed with sweat, and then to fill the goblet with it, thus fulfilling the imposed conditions. He[lxvii] then gave back these presents to the ambassadors, who speedily returned to Queen Balkis. She at once saw that it would be useless to oppose the powerful will of Solomon, and immediately set out on her journey to that monarch.

It is here that her connection with the holy Cross comes in, for its wood, which Solomon had cut down in order to incorporate it into his Temple, and which had the inconvenient property of fitting in nowhere, being either too long or too short for any purpose, was in consequence thrown aside, and ultimately was used as a foot-bridge across a brook. Across this plank the Queen had to pass, but she, recognising its holy virtue, refused to walk across it, preferring to wade the brook, which, having done, she expounded its value to Solomon, and prophesied that out of it should be made the Cross on which Jesus should suffer.

She afterwards became one of Solomon’s

wives, and bore him a son, and then[lxviii]

[lxix]

returned to her own land, and from this

son are descended the kings of Abyssynia.

The legend on the label is, as far as is legible, Regina Saba fama Salomonis (adduct) a venit (Iero)soluma ubi lignum in . . . abatica . . . it . . . genis . . . persolvetur.

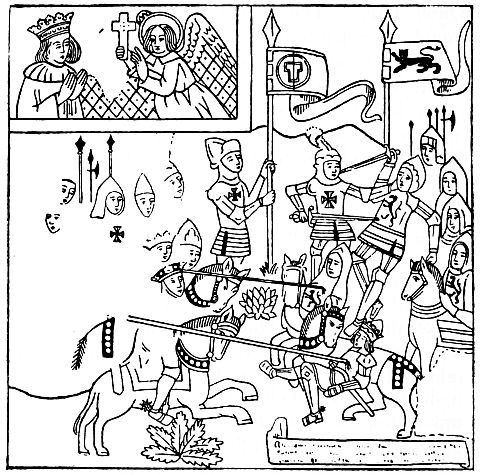

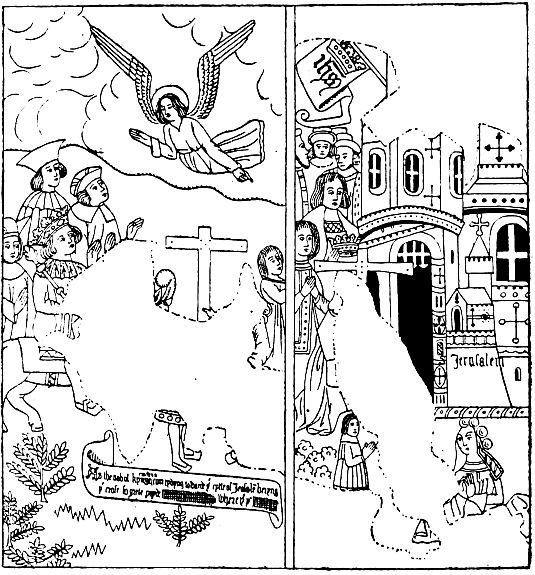

Plate B is, virtually, two; one showing the angel appearing to Constantine when, early in the fourth century, he was advancing towards Rome against Maxentius; but the legend of the miraculous inscription which appeared in the sky, “In hoc signo vinces,” does not appear. The other, and larger portion, represents his victory over Maxentius, and he is represented as spearing and killing that monarch; but this is not historically correct, for, after his defeat, as Maxentius fled towards Rome, essaying to cross the Tiber over a rotten bridge, it gave way, and he was drowned. It is noticeable that the Christian flag bears the Tau Cross.

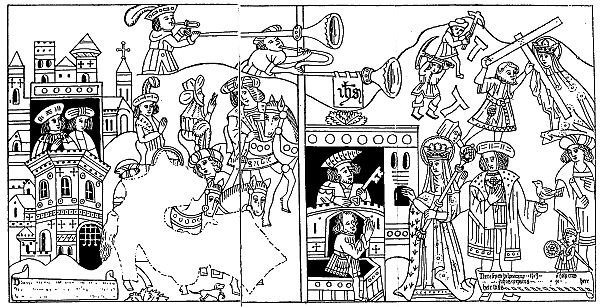

The Plates C and D run into each other, although they portray different subjects, C being the departure of St. Helena for Jerusalem on her quest of the holy Cross. The label in this fresco is utterly illegible.

Plate D shows Judas (called Julius in the label) Cyryacus (the Quyryache of the Golden Legend) being released, after having been forced, through imprisonment and starvation, into confessing where the holy Cross lay buried. In the upper part St. Helena is receiving the holy Cross, whilst labourers are uncovering the Tau Crosses of the two thieves.

The legend is mutilated, but enough remains to make its meaning clear: “Here Seynte helyne examy(neth) the I(ews for) ye Holy cros . . . . Iulius cyryacus (saith that he knew w)here hete was.”

The legend in Plate E is nearly perfect, and accurately describes the painting, “Hyt was proved evidently by myrakel which was ye very cros that oure Savyour suffyred . . . . In resynge a made from deth to lyfe.”

Here all the Crosses are of the Tau type, and the scene is laid in a forest, where an old labourer, and a bill-man, and the deer nibbling the trees, give a rural aspect, instead of in the City of Jerusalem, as saith the Golden Legend.

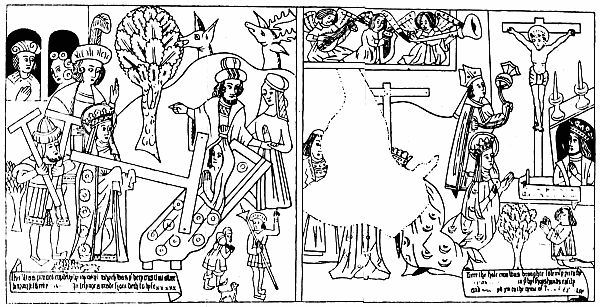

Plate F evidently consists of two separate paintings—one, where St. Helena is reverently carrying the Cross into Jerusalem, whilst the angels in heaven are discoursing celestial music; and the other, its reception either in Jerusalem or Byzantium, whither St. Helena sent a portion as a present to her son. And this latter seems the more probable, if we imagine the King, who, with St. Helena, is adoring the Crucifix, to be the emperor Constantine, a fact which might have been settled had the label been legible.

The legend at the bottom is unfortunately

mutilated, but that evidently

relates to that portion of the Cross which

remained at Jerusalem, because it speaks[lxxii]

[lxxiii]

of Chosroes: “Here the hole cros

was broughte solemly yn to the

. . . in ye bysshops hands easily

and (remaynyd) un to the tyme of

(King Codsd)roe.

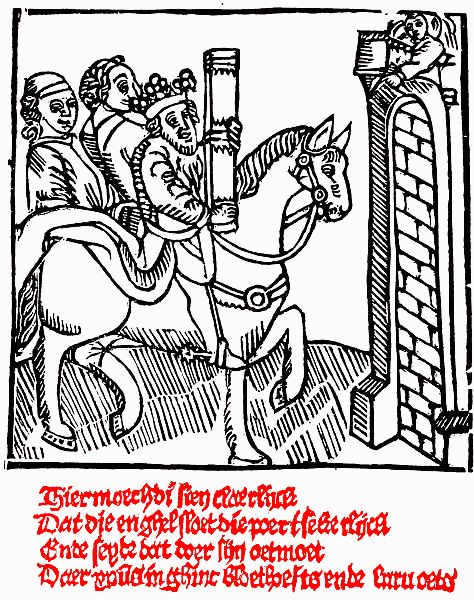

Plates G and H represent the story told in the Golden Legend, of Heraclius bearing the Cross into Jerusalem, how the gate miraculously closed, and an angel appeared in the heavens and reproved Heraclius for riding in state on the very spot where Jesus had gone in all meekness, and lowliness, to His passion. The legend is erased in parts, the unmutilated portion reading, “As the nobul kynge eraclyus com rydyng towarde ye cytte of Ierusalem beryng ye crosse so grete pryde . . . where ye . . . .”