CROSSING THE KOMATI RIVER.

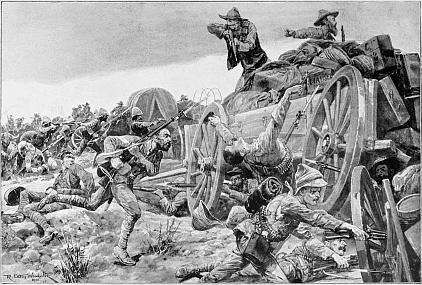

CROSSING THE KOMATI RIVER.Drawing by Donald E. M’Cracken.

Title: South Africa and the Transvaal War, Vol. 7 (of 8)

Author: Louis Creswicke

Release date: October 16, 2014 [eBook #47132]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brownfox and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

South Africa

and the

Transvaal War

BY

LOUIS CRESWICKE

AUTHOR OF “ROXANE,” ETC.

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS

VOL. VII.—THE GUERILLA WAR. FROM FEBRUARY 1901 TO THE CONCLUSION OF HOSTILITIES. THE DEVELOPMENT OF PEACE NEGOTIATIONS FROM FEBRUARY 23, 1901, TO MAY 31, 1902

MANCHESTER: KENNETH MACLENNAN

75 PICCADILLY

Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson & Co.

At the Ballantyne Press

| PAGE | |

| CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE | viii |

| COMPOSITION AND STRENGTH OF COLUMNS | xiv |

| THE SITUATION—FEBRUARY 1901 | 1 |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Continuation of the De Wet Chase, 1st to 10th March—Across the Orange River | 7 |

| Lyttelton’s Sweeping Movement—10th to 20th March—Thabanchu Line | 9 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Cape Colony—Pursuit of Raiders—March and April—Chasing Kruitzinger | 14 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The Operations of General French in the Eastern Transvaal, from 27th January to 16th April 1901 | 19 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| In the Western Transvaal—January to May | 31 |

| April, Orange River Colony—Operations of General Bruce-Hamilton and General Rundle | 40 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Combined Movement for the Clearance of the Northern Transvaal—March and April | 43 |

| Lieutenant-General Sir Bindon Blood’s Operations North of the Line Middelburg—Belfast—Lydenburg | 45 |

| Colonel Grenfell at Pietersburg | 48 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| General Elliot’s Operations from Kroonstad | 50 |

| General Elliot’s Operations—Second Phase | 52 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| General Bruce-Hamilton’s Operations, Orange River Colony (South) | 55 |

| Major-General C. Knox, Orange River Colony (Centre)—May and June | 57 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Lord Methuen, Transvaal (South-West)—May and June | 59 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Operations between the Delagoa and Natal Lines—May and June | 66 |

| Brigadier-General Plumer in the Eastern Transvaal | 68 |

| Major-General Beatson’s Operations | 70 |

| Lieutenant-General Sir Bindon Blood, Eastern Transvaal | 71 |

| Activities around Standerton and Heidelberg | 73 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Lieutenant-Colonel Grenfell’s Operations, Transvaal, N. | 75 |

| Situation and Skirmishes in Cape Colony—May and June | 77 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| Orange River Colony, S.—Major-Generals Bruce-Hamilton and C. Knox—July | 82 |

| Orange River Colony, N.—Major-General Elliot | 84 |

| Orange River Colony, E.—Lieutenant-General Sir L. Rundle | 90 |

| Orange River Colony, N.—Colonel Rimington—Brigadier-General Bullock—Brigadier-General Spens | 92 |

| Transvaal, S.W.—Operations of General Fetherstonhaugh—Clearing the Magaliesberg—July | 93 |

| Transvaal, E.—Lieutenant-General Sir Bindon Blood | 94 |

| Standerton-Heidelberg—Lieutenant-Colonel Colville | 97 |

| Cape Colony—July | 98 |

| The Situation—August | 100 |

| [Pg iv]CHAPTER XII | |

| Orange River Colony—August | 105 |

| Orange River Colony, S.—Brigadier-General Plumer | 107 |

| Orange River Colony, E.—Major-General Elliot—August | 107 |

| Sweeping the Kroonstad District—Brigadier-General Spens | 109 |

| Operations near Honing Spruit and the Losberg—Lieutenant-Colonel Garratt | 110 |

| Scouring the Magaliesberg—Colonels Allenby and Kekewich | 112 |

| Transvaal, S.W. | 114 |

| The Pietersburg Line—Lieut.-Colonel Grenfell | 116 |

| The Transvaal (North-East)—General Blood’s Operations | 116 |

| Lieutenant-Colonel Colville’s Operations | 120 |

| Natal—Lieutenant-General Sir H. Hildyard | 121 |

| Cape Colony—Lieutenant-General Sir J. French | 122 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| Natal and the Eastern Transvaal—September 1901 | 127 |

| Transvaal (West) | 131 |

| Operations on the Vaal | 133 |

| Operations in the Orange River Colony, N. | 133 |

| Major-General Elliot—Orange River Colony, E. | 133 |

| Events in Cape Colony | 136 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| Progress in October 1901 | 140 |

| Transvaal (East) | 140 |

| Transvaal (West) | 144 |

| October in the Orange River Colony | 145 |

| Operations in Cape Colony | 146 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| The Close of 1901—Progress in November and December | 149 |

| Transvaal (East) | 149 |

| Transvaal (West) | 150 |

| Orange River Colony | 151 |

| The Swazi Border | 153 |

| November and December | 153 |

| Transvaal (East)—December | 154 |

| In the Northern Transvaal | 157 |

| Transvaal (West) | 158 |

| Orange River Colony | 158 |

| Cape Colony | 162 |

| The Situation—January 1902 | 163 |

| The Loyalists of the Cape Colony | 171 |

| The Soldiers’ Christian Association | 176 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| The New Year—January 1902 | 178 |

| Transvaal (East) | 178 |

| Transvaal (North) | 179 |

| Transvaal (West) | 180 |

| Orange River Colony | 180 |

| A Big Trap for De Wet | 181 |

| Cape Colony | 183 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| The Events of February and March 1902 | 184 |

| Transvaal (East) | 184 |

| Transvaal (West) | 185 |

| Orange River Colony—Majuba Day | 189 |

| The Cape Colony | 190 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| The Close of Hostilities—March, April, and May 1902 | 192 |

| Transvaal (East) | 192 |

| Finishing Clearance of the Orange River Colony | 193 |

| Transvaal (West)—March | 194 |

| Cape Colony—March | 196 |

| The Situation—April and May | 199 |

| APPENDIX—THE PEACE NEGOTIATIONS. Commenced March 12, 1902; Concluded May 31, 1902 | 201 |

| OFFICIAL CORRESPONDENCE AFTER THE BATTLE OF COLENSO, December 15, 1899 | 210 |

| RECIPIENTS OF THE VICTORIA CROSS | 212 |

| 1. COLOURED PLATES | |

| PAGE | |

| Crossing the Komati River | Frontispiece |

| Cecil J. Rhodes at Groote Schuur | 32 |

| An Army Doctor at Work in the Firing Line | 64 |

| Delagoa Bay | 100 |

| Church Square, Pretoria | 104 |

| Bullock Waggon Crossing a Drift on the Umbelosi River, Swaziland | 120 |

| De Wet’s Attempt to Cross the Railway | 160 |

| A Dutch Village near Edenburg | 176 |

| 2. FULL-PAGE PLATES | |

| Defending a Train Derailed by the Boers | 24 |

| Charge of the Bushmen and New Zealanders on the Boer Guns during the Attack on Babington’s Convoy near Klerksdorp | 36 |

| Defeat of a Night Attempt to Cross the Railway | 44 |

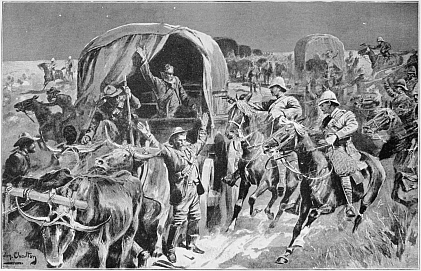

| The Capture of De Wet’s Convoy at Reitz | 52 |

| The Engagement at Vlakfontein | 60 |

| The Mishap to the Victorians at Wilmansrust | 72 |

| Boers caught in the Act of Cutting the Telegraph Wires | 96 |

| Night Attack on a Boer Convoy by Mounted Infantry under Colonel Williams | 112 |

| The Defence of Fort Itala | 128 |

| The Gallant Bugler of Fort Itala | 132 |

| The Fight at Bakenlaagte | 140 |

| Mishap to the Scots Greys at Klippan | 184 |

| Lord Methuen Rallying his Broken Forces at Tweebosch | 186 |

| Brilliant Defence by New Zealanders at Holspruit | 188 |

| The Train Conveying the Remains of Mr. Rhodes saluted by the Blockhouse Guards | 196 |

| Surrendered Boers at Belfast anxious to Join the National Scouts | 206 |

| 3. FULL-PAGE PORTRAITS | |

| Major-General Charles Knox | 8 |

| Major-General Sir H. H. Settle | 16 |

| Brigadier-General the Earl of Erroll | 68 |

| Major-General Bruce-Hamilton | 80 |

| Major-General Walter Kitchener | 88 |

| Lieut.-General Sir Bindon Blood | 148 |

| Major-General Arthur Paget | 152 |

| Major-General Babington | 168 |

| 4. MAPS AND ENGRAVINGS IN THE TEXT | |

| Map—De Wet’s Rush in Cape Colony | 4 |

| Map—De Wet’s Escape from the Enveloping Cordon | 6 |

| Map—Operations in South-East of Orange River Colony | 10 |

| Map—Reorganisation of Troops in Orange River Colony | 12 |

| Map of Operations in Eastern Transvaal | 20 |

| Map—Position of Forces around Ermelo | 23 |

| Colonel Benson | 36 |

| Map of Combined Movement to clear Northern Transvaal | 47 |

| Colonel de Lisle | 53 |

| A Typical Blockhouse | 56 |

| Map of Operations between Delagoa Bay and Natal Lines | 67 |

| Colonel Colenbrander | 76 |

| General Elliot’s Sweep South of the Vaal | 89 |

| Concentration Camp at Norval’s Pont | 99 |

| General Elliot | 110 |

| Lieut.-Colonel Gorringe | 123 |

| Colonel Bethune and His Brigade Staff | 134 |

| Map of Eastern Portion of Cape Colony | 147 |

| Colonel Pilcher | 151 |

| General Beatson | 156 |

| Map of the Blockhouse System | 163 |

| Map of Western Portion of Cape Colony | 172 |

| Colonel Crewe | 191 |

| Colonel H. T. Lukin | 193 |

| Colonel Douglas Haig | 193 |

JANUARY 1901.

1.—“Call to arms” at Cape Town. General Charles Knox and others continued the pursuit of De Wet.

2.—Arrival of Lord Roberts at Osborne. He is created by the Queen an Earl.

30.—De Wet breaks through the Bloemfontein-Ladybrand line going south.

FEBRUARY 1901.

1.—General French continued to operate against Botha in the Eastern Transvaal.

6.—The War Office decided to reinforce Lord Kitchener by 30,000 mounted troops beyond those already landed in Cape Colony. “Call to arms” at Cape Town.

9.—“Call to arms” at Cape Town.

10.—“Call to arms” at Cape Town.

22.—Extraordinary proclamation signed by Steyn and De Wet published.

23.—Accounts of Boer atrocities published. “Call to arms” at Cape Town.

Severe defeat of De Wet by General Plumer, who captured two guns, fifty prisoners, and all De Wet’s ammunition. De Wet’s attempt to invade Cape Colony completely failed.

General French gained several victories over Botha in Eastern Transvaal, with capture of guns, ammunition, and waggons.

28.—Further great captures from the Boers by General French, and heavy Boer losses.

MARCH 1901.

2.—De Wet was forced over the Orange River with the loss of his guns and convoy.

Sir Alfred Milner proceeded north from Cape Town to take up the duties of the Governor of the Transvaal and Orange River Colonies.

26.—Victory by General Babington over Delarey at Ventersdorp. Nine Boer guns captured.

APRIL 1901.

6.—General French, in his sweeping operations in the Eastern Transvaal, captured all the enemy’s guns in that district.

8.—Colonel Plumer captured Pietersburg, the terminus of the railway running due north from Pretoria.

10.—Civil administration resumed in the Transvaal.

15.—Smuts’ commando defeated near Klerksdorp. Two guns captured.

18.—Sir A. Milner obtained leave of absence on account of the state of his health.

19.—Generals Plumer and Walter Kitchener co-operated with General French in clearing the Eastern Transvaal and Lydenburg district.

30.—General Blood discovered documents and banknotes of Transvaal Government at Roosenekal, from which place Mr. Schalk Burger fled.

MAY 1901.

8.—Municipal Government started in Johannesburg.

24.—Sir A. Milner arrived in London and had a peerage conferred upon him by the King.

JUNE 1901.

1.—Severe engagement between General Dixon and Delarey at Vlakfontein, in the Magaliesberg. Enemy repulsed with heavy loss. Our casualties also heavy.

6.—De Wet severely defeated near Reitz by General Elliot, who made large captures.

9.—Lieut.-General Sir John French assumed command of the troops in Cape Colony.

12.—General Beatson surprised near Middelburg (Transvaal). Loss of two pom-poms.

JULY 1901.

5.—In reply to Botha’s inquiries about ending the war, Kruger telegraphed to Botha to continue fighting.

6.—A train wrecked on the Pretoria-Pietersburg line.[Pg vii]

15.—Capture of the so-called “Orange Free State Government” at Reitz. Important Boer papers seized. Steyn alone of the members of his “Government” escaped—in his shirt.

16.—Important success by General French in Cape Colony.

19.—Publication of Lord Kitchener’s despatch embodying contents of important documents seized at Reitz.

Death of Mrs. Kruger.

AUGUST 1901.

2.—More murders by Boers officially announced. One of the murdered men was an Imperial Yeoman.

8.—Commandant de Villiers and two Field Cornets surrendered at Warmbaths.

10.—Lord Kitchener by proclamation called upon the Boer leaders to surrender on or before the 15th of September.

13.—Lord Kitchener reported the largest return of Boer losses yet sustained in a week. More than 800 prisoners, 700 waggons, and 33,000 cattle.

27.—Lord Kitchener received letters from Steyn and De Wet protesting against his proclamation.

28.—Lord Milner arrived at the Cape from England.

SEPTEMBER 1901.

2.—Another case of train-wrecking on the Pretoria-Pietersburg railway.

7.—Lotter and his entire commando captured in Cape Colony.

20.—Reverse to Major Gough near Utrecht.

Severe fighting in Cape Colony.

21.—Reverse at Vlakfontein, near Sanna’s Post. Two guns lost. (Afterwards recovered.)

23.—The camp of Lovat’s Scouts rushed by Kruitzinger near Herschel.

Koch’s commando captured near Edenburg.

The Carolina commando captured by Colonel Benson.

26.—Ten Boer leaders banished under Lord Kitchener’s proclamation.

Attacks on Fort Itala and Fort Prospect. Boers repulsed with very heavy losses at both places.

The attempt of Botha and De Wet to invade Natal foiled.

29.—Proclamation issued in Pretoria providing for the sale of the properties of Boers still in the field, in accordance with Lord Kitchener’s proclamation.

30.—Great attack by Delarey and Kemp on Colonel Kekewich’s camp near Magato Nek, in the Magaliesberg. Boers repulsed. Severe losses on both sides. The Scottish Horse especially distinguished themselves and sustained severe loss.

OCTOBER 1901.

6.—General Walter Kitchener and General Bruce-Hamilton engaged Botha’s forces in the south-east of the Transvaal. Botha escaped to the north.

9.—Martial law extended to the whole of Cape Colony.

11.—Commandant Lotter sentenced to death. Death sentence on five members of his commando was commuted to penal servitude for life.

13.—Lieut.-Colonel Hon. J. Byng attacked laager at Jackfontein and captured eighteen prisoners.

15.—Major Damant took prisoner Adjutant Theron. Colonel de Lisle surprised laager at Wilge River and captured fifteen prisoners.

16.—Colonel Rawlinson returned to Standerton with twenty prisoners and many prizes.

21.—Colonel Lukin surprised Vander Venter’s laager near New Bethesda.

22.—Colonel Benson captured laager at Klippoortje.

23.—Gallant attack on laager in Pongola Bosch.

24.—Colonel von Donop’s brilliant defeat of 1000 Boers at Kleenfontein.

25.—Botha’s farm surrounded at Schimmelhoek. His papers captured.

26.—Colonel Benson repulsed attack on hi class="hangindent"s rearguard on the Steenkool Spruit.

27.—Colonel Williams’ force occupied the Witnek Pass and routed a strong body of Boers from the position.

30.—Attack on Colonel Benson’s force[Pg viii] at Bakenlaagte. Colonel Benson and Colonel Guinness killed.

Colonel Kekewich captured a laager at Beestekraal.

NOVEMBER 1901.

2.—Patrol under Captain Walker captured twenty-one prisoners near Wolvekop.

7.—Attack on Piquetberg repulsed by garrison under Major Wilson and Town Guard.

General B. Hamilton commenced operations against Botha in the Eastern Transvaal.

8.—Major Wiggin (26th Mounted Infantry) surrounded laager near Mahamba. Fourteen prisoners secured.

9.—Line blown up at Myburg Siding by Fouché.

11.—Major Pack Beresford and detachment of South African Constabulary captured laager at Doornhoek.

13.—Squadron Imperial Yeomanry detached from Hickie’s force surprised and surrounded. Rescued by reinforcements.

14.—Rearguard of Colonel Byng’s column attacked near Heilbron by 400 of the enemy under De Wet. Boers repulsed. British loss considerable.

16.—Further captures by Major Wiggin within Swaziland border.

18.—Lieutenant Welshman with patrol of West Yorkshire Regiment surprised party of Boers and captured eight prisoners.

20.—Engagement with Buys near Villiersdorp. Major Fisher killed. Buys captured by Colonel Rimington.

Captain Elliot successfully engaged Boers in Griqualand. Captain Elliot killed. Three officers wounded.

24.—General Dartnell, with Highland Light Infantry, engaged Boers near Harrismith. Captured twelve and killed two.

Offer of Canadian Government to raise 600 more troops for service in South Africa accepted.

25.—General Dartnell’s force surprised Boers near Bethlehem and took twelve prisoners.

26.—Lord Basing engaged Joubert in Orange River Colony. Joubert wounded and captured.

Major Pack Beresford attacked convoy near Paardeberg.

27.—Imperial Light Horse under Colonel Mackenzie took twenty-four prisoners, &c.

Attack on Colonel Rimington’s rearguard by De Wet repulsed. Many prisoners taken.

28.—Van Rensburg and thirteen burghers captured by Colonel Lowry Cole in Wepener district.

DECEMBER 1901.

1.—General Elliot reached Kroonstad with 15 prisoners, 114 waggons, 89 carts, 2470 cattle, and 1280 horses.

3.—Colonel Colenbrander broke up Badenhorst’s commando, and took fifteen prisoners and all the waggons.

4.—Laager surprised at Oshoek (twenty miles from Ermelo) by Spens’ and Rawlinson’s columns. Ninety-three prisoners taken.

7.—Colonel C. Mackenzie, in night march towards Watervaal (Eastern Transvaal), took sixteen prisoners.

Colonel Holland surprised Brand’s laager and took six Boers.

11.—Badenhorst and twenty-two burghers secured by Colonels Colenbrander and Dawkins, near Zandriverspoort.

13.—Brilliant surprise of Boers by General B. Hamilton at Witkraus. Laager broken up. One of Benson’s guns recovered.

15.—Secretary of State for War congratulated General Bruce-Hamilton on his brilliant achievements.

16.—Haasbroek killed in encounter with Colonel Barker’s men in the Doornberg.

Capture of Kruitzinger by Colonel Dorans’ and Lord Charles Bentinck’s columns.

18.—Colonel Steele, with South African Constabulary, captured thirty-six Boers in the region of the Magaliesberg.

Four hours’ fighting between De Wet and General Dartnell. Boers driven off.

Lord Methuen reported capture of thirty-two Boers.

19.—Colonel Allenby captured thirty-two of the enemy near Heidelberg.

20.—Colonel Damant attacked by 800 Boers. Two officers killed, three wounded. Boers repulsed.

21.—Capture of Smuts’ convoy, near Bothwell, by Colonel Mackenzie.

22.—Seven hundred Cape raiders attacked columns of Colonels Wyndham and Crabbe. Were driven off with loss of five killed and twenty wounded.

23.—Successful attack on Grobelaar’s laager by General B. Hamilton.

24.—Colonel Du Moulin surprised laager near Jagersfontein. Captured two Field-Cornets and twenty other Boers.

25.—Colonel Firman’s camp at Tweefontein rushed by huge force under De Wet.

28.—Successful engagement near Burghersdorp by Colonel Price. Field-Cornet Jan Venter killed.

JANUARY 1902.

3.—Capture of General Erasmus by General Bruce-Hamilton.

10.—Surprise of laager near Ermelo by Colonel Wing and capture of forty-two prisoners.

12.—More captures by General B. Hamilton.

13.—Fight for a convoy by De Villiers. Gallant charge of Munster Fusiliers.

16.—Capture of laager and twenty-four prisoners by Lord Methuen.

18.—Execution of Scheepers on various charges of murder at Graaff Reinet.

Night expedition to Witbank. General Hamilton secured more prisoners.

21.—Colonels Park and Urmston engaged party of Boers under Muller and Trichardt, occasioning stampede of Boer Government from Houtenbek.

24.—Important captures by General Plumer’s troops. Thirty burghers secured by Colonel Fry, West Yorkshire Regiment.

Attack on Pietersburg repulsed. Volunteer Town Guard distinguished itself.

25.—Capture of Viljoen near Kruger’s Post by detachment of Royal Irish under Major Orr.

26.—Successful engagement on the Modder by Major Driscoll’s column.

Huge laager at Nelspan dispersed by General Bruce-Hamilton’s force.

27.—Colonel Du Moulin killed in a night attack on his camp. Enemy repulsed by Major Gilbert (Sussex Regiment).

30.—Colonel Rawlinson’s troops after tremendous march surprised Manie Botha’s laager and made valuable captures.

31.—Capture of convoy at Groothoop by Colonel Rimington.

FEBRUARY 1902.

2.—De Wet’s commando gallantly charged by New Zealanders, Queensland Imperial Bushmen, and South African Light Horse. Enormous captures.

4.—Capture and destruction of British convoy by Boers in Cape Colony. Major Crofton killed.

5.—Surprise and capture of Commandant S. Alberts’ laager by Scottish Horse under Major Leader.

6.—Major Vallancey dispersed Beyers’ commando. Gigantic movement to entrap De Wet started.

7.—De Wet, by brilliant manœuvre, ruptured the British cordon and escaped.

8.—Big capture from Potgieter’s laager by Colonel von Donop’s force.

13.—Bouvers’ laager in Cape Colony rushed by Colonel Kavanagh’s men.

18.—Capture of Judge Hugo in Cape Colony. Boers cut off and surrounded a portion of squadron of Scots Greys south-east of Springs.

20.—Two laagers surprised by Colonel Park’s troops; 164 prisoners taken.

21.—Capture of laager at Buffelskloof by Colonel E. Williams’ column.

24.—Some East Griqualand rebels surrendered to Colonel Stanford.

25.—Determined attack on Colonel von Donop’s convoy by Delarey and Kemp. Waggons lost. Escort, which made gallant defence, overpowered. Five British officers and fifty-three men killed; six officers and 123 men wounded; others taken prisoners.

26.—Jacob’s laager captured by Colonel Driscoll.

27.—Anniversary of Majuba. Combined operations for driving Boers against Harrismith-Van Reenan’s[Pg x] blockhouse line. Manie Botha killed; 600 Boers killed, wounded, or prisoners. Splendid defence by New Zealanders under Major Bauchop and New South Wales Mounted Infantry under Colonel Cox.

28.—Capture of Boers near Steynsdorp by Captain Holgate (Steinacker’s Horse).

MARCH 1902.

6.—Colonel Ross (Canadian Scouts) made valuable captures in a cave near Tafel Kop.

7.—Successful attack by Delarey on Lord Methuen’s force at Tweebosch. Lord Methuen seriously wounded and taken prisoner.

11.—Close of big drive in Orange River Colony; 127 Boers taken. Commandant Celliers wounded.

12.—Many prisoners captured by Colonel Ternan and Colonel Pilcher.

13.—Little garrison of fifty men at Fort Edward surrounded by Beyers’ commando.

15.—Attack on laager near Vryheid by General Bruce-Hamilton. General Cherry Emmett captured.

16.—Rebels at Sliphock captured by Captain Bowker.

17.—Some of Bezuidenhout commando captured in Cape Colony by Colonel Baillie.

18.—Lieutenant Williams, a notorious train-wrecker, captured by National Scouts.

21.—Colonel Harrison sent out from Pietersburg small force under Colonel Denny to relief of Fort Edward. Advance opposed by Boers.

23.—Arrival at Pretoria of so-called Acting Transvaal Government to discuss the terms of peace.

26.—Death of Cecil John Rhodes.

28.—Colonel Colenbrander from Krugersdorp moved to Pietersburg and from thence accomplished relief of Fort Edward.

29.—Total defeat of Beyers and dispersal of investing commando.

30.—Serious railway accident at Barberton.

31.—Delarey defeated in engagement with Colonels Keir and Cookson. R.H.A. Rifles, Canadian Rifles, and 28th Mounted Infantry distinguished themselves.

APRIL 1902.

1.—Laager surprised by 2nd Dragoon Guards near Springs. Four officers wounded.

3.—State funeral of the late Mr. Rhodes at Cape Town.

4.—Ookief invested by Commandant Smuts.

8.—Successful attack on Beyers’ laager near Pietersburg by Colonels Colenbrander and Murray.

9.—Conference between Transvaal and Orange Free State leaders at Klerksdorp in regard to negotiations for peace.

10.—Burial of Cecil John Rhodes in the Matoppos.

“They left him alone in his glory.”

11.—Meeting of Boer representatives at Klerksdorp in relation to Peace movement. Colonel Kekewich defeated Boers in Western Transvaal and captured two guns and a pom-pom.

12.—Laager at Schweizerreneke surprised by Colonel Rochfort. Fifty-five prisoners taken.

MAY 1902.

1.—Relief of Ookiep by British troops under Colonels Cooper and Caldwell.

2.—Lieutenant Murray (District Mounted troops) killed at Tweefontein by Boers in kharki.

6.—Pieter de Wet sentenced by Treason Court to pay a fine of £1000 or undergo two years’ imprisonment.

9.—Patrol attacked by Boers near Middelburg, Cape Colony. Captain Hinks killed.

15.—Members of the late Governments met together to discuss Peace proposals.

17.—Surrender of Hinton, the notorious train-wrecker.

20.—Delegates of late Governments arrived at Pretoria to arrange terms of surrender.

27.—Malan mortally wounded and captured by Jansenville District Mounted Horse (under Major Collett), and Lovat’s Scouts.

30.—Peace Agreement signed.

Composition and Strength of Columns Engaged in Major-General Bruce-Hamilton’s Operations in Southern Orange River Colony.[1]

Lieut.-Colonel du Moulin’s Column.

Colonel Rochfort’s Column.

Lieut.-Colonel Byng’s Column.

Lieut.-Colonel W. H. Williams’ Column.

Colonel Monro’s Column. (Afterwards in Cape Colony.)

Lieut.-Colonel A. Murray’s Column. (Afterwards in Cape Colony.)

Lieut.-Colonel White’s Column. 28/6/01. (Since broken up.)

Colonel Henry’s Column.

Kimberley Column.

Columns Engaged in Major-General Charles Knox’s Operations in Central Orange River Colony.

Colonel Pilcher’s Column.

Major Pine Coffin’s Column.

Lieut.-Colonel Thorneycroft’s Column.

Colonel Henry’s Column.

Kimberley Column.

Columns Engaged in Major-General Elliot’s Operations in Northern Orange River Colony.

Brigadier-General Broadwood’s Column.

Colonel Bethune’s Column.

Lieut.-Colonel Colville’s Column.

Colonel Rimington’s Column.

Lieut.-Colonel De Lisle’s Column.

Colonel E. C. Knox’s Column.

Lieut.-Colonel Western’s Column.

Columns Engaged in Lieut.-Colonel Western’s Operations on the Vaal River.

Brigadier-General G. Hamilton’s Column.

Lieut.-Colonel Western’s Column.

Colonel Allenby’s Column.

Colonel Henry’s Column.[Pg xiii]

Columns Engaged in Clearing the East of the Orange River Colony.

Major-General B. Campbell’s Column.

Colonel Harley’s Column.

Columns Engaged in Operations in the South-West Transvaal.

Lieut.-General Lord Methuen’s Column.

Major-General Babington’s Column.

Colonel Sir H. Rawlinson’s Column.

Lieut.-Colonel Hickie’s Column.

Brigadier-General Dixon’s Column.

Lieut.-Colonel E. C. Williams’ Column.

Brigadier-General G. Hamilton’s Column.

Colonel Allenby’s Column.

General Barton’s Column.

Major G. Williams’ Column.

Columns Engaged in Operations between the Delagoa and Natal Lines.

Brigadier-General Plumer’s Column.

Lieut.-Colonel Grey’s (afterwards Lieut.-Colonel Garratt’s) Column.

Major-General W. Kitchener’s Column.

Brigadier-General Bullock’s Column.

Lieut.-Colonel Pulteney’s Column.

Colonel Rimington’s Column.

Colonel Allenby’s Column.

Colonel E. C. Knox’s Column.

Columns Engaged in Brigadier-General Plumer’s Operations in South-Eastern Transvaal.

Brigadier-General Plumer’s Column.

Colonel E. C. Knox’s Column.

Colonel Rimington’s Column.[Pg xv]

Major-General Beatson’s Operations.

Major-General Beatson’s Column.

Columns Engaged in Lieut.-General Sir Bindon Blood’s Operations in the Eastern Transvaal.

Major-General Babington’s Column.

Lieut.-Colonel Benson’s (R.A.) Column.

Brigadier-General Spens’ Column.

Colonel Campbell’s Column.

Colonel Park’s Column.

Lieut.-Colonel Douglas’ Column.

Major-General W. Kitchener’s Column.

Lieut.-Colonel Pulteney’s Column.

Major-General Beatson’s Column.

Lieut.-Colonel Colville’s Column.

Colonel Garratt’s Column.

Columns Engaged in Operations on the Pietersburg Line.

Major McMicking’s Column.

Lieut.-Colonel Wilson’s Column.

Lieut.-Colonel Grenfell’s Column.

Operations in the Standerton-Heidelberg District.

Lieut.-Colonel Colville’s Column.

Lieut.-Colonel Grey’s Column.[Pg xvi]

Columns Engaged in Operations in Cape Colony.

Colonel Doran’s Column. (Late Lieut.-Colonel Henniker’s.)

Lieut.-Colonel Crabbe’s Column.

Lieut.-Colonel Gorringe’s Column.

Lieut.-Colonel Crewe’s Column.

Captain Lund’s Column.

Lieut.-Colonel Scobell’s Column.

Lieut.-Colonel Wyndham’s Column.

Lieut.-Colonel Hon. A. D. Murray’s Column.

Colonel Monro’s Column.

Note.—Where two figures appear, the first refers to effective men, the second to effective horses.

Force Employed at Vlakfontein (584) on May 29th.

(a) Left (afterwards rear), under Major Chance, R.A.

(b) Centre, under Brigade-General Dixon.

(c) Right, under Lieut.-Colonel Duff.

Major-General Beatson’s Column (on 12th June).

Of which the following were detached to Wilmansrust (22) under Major Morris, R.F.A.:—

[1] This table represents the columns as they were disposed at Midsummer 1901.

SOUTH AFRICA AND THE TRANSVAAL WAR

PEACE

The reign of His Majesty King Edward VII. began in clouds! There was no denying that the last half-year had been one of retrogression. In June 1900, from the Orange River southwards, there had been comparative quietude. The southern and eastern half of the Orange River Colony had become fairly settled, while even in some districts of the Transvaal—towards the south-western area especially—the inhabitants gave indications of a willingness to accept British rule, and of a desire to return to their agricultural and peaceful avocations. But with the end of the year came a deplorable change. The enemy, broken up into a large number of desultory gangs, commenced raiding and wrecking, consequently the British forces, in order to cope with and pursue these vagrant bands, had to be broken up to correspond. The area of hostility and destruction grew larger daily and the difficulty of fighting more extreme. The lack of supplies now drove the Boers, who lived entirely on the country through which they passed, to spend their time in looting, in pouncing on the farms and small villages, and in seizing everything they might need. Stores, clothing, horses, cattle, all were grabbed at the point of the rifle, if not, as in some cases, delivered up on demand. To frustrate the tactics of the enemy, the British forces were compelled to denude the country of every movable thing, and to place whatever could be conveyed there in refuge camps which were established at points along the railway lines. But in this operation great loss was entailed, owing to the difficulty of finding sufficient grass for the number of collected animals, and of keeping them alive en route.

The loss of crops and stock became a still more serious matter than even the destruction of farm buildings—a measure which had almost entirely been abandoned. Having regard to the inexpensive[Pg 2] character of these structures, this measure, to quote Sir Alfred Milner, was a “comparatively small item” in the total damage caused by the war to the agricultural community. But, he said, the wanton and malicious injury done to the headgear, stamps, and other apparatus of some of the outlying mines by Boer raiders was a form of destruction for which there was no excuse. It was a vandalism unjustified by the requirements of military operations and outside the scope of civilised warfare. Directly or indirectly, all South Africa, including the agricultural population, owes its prosperity to the mines, and, of course, especially to the mines of the Transvaal. To money made in mining it is indebted for such progress, even in agriculture, as it has recently made, and the same source will have to be relied upon for the recuperation of agriculture after the ravages of war. The damage done to the mines Lord Milner estimated was not large “relatively to the vast total amount of the fixed capital sunk in them. The mining area,” he said, “is excessively difficult to guard against purely predatory attacks having no military purpose, because it is, so to speak, ‘all length and no breadth’—one long thin line, stretching across the country from east to west for many miles. Still, garrisoned as Johannesburg now is, it was only possible successfully to attack a few points in it. Of the raids previously made, and they have been fairly numerous, only one has resulted in any serious damage. In that instance the injury done to the single mine attacked amounted to £200,000, and it is estimated that the mine is put out of working for two years. This mine is only one out of a hundred, and is not by any means one of the most important. These facts may afford some indication of the ruin which might have been inflicted, not only on the Transvaal and all South Africa, but on many European interests, if that general destruction of mine works which was contemplated just before our occupation of Johannesburg had been carried out. However serious in some respects may have been the military consequences of our rapid advance to Johannesburg, South Africa owes more than is commonly recognised to that brilliant dash forward, by which the vast mining apparatus, the foundation of all her wealth, was saved from the ruin threatening it.”

The events of the last six months promised to involve a more vast amount of repair and a longer period of recuperation, especially for agriculture, than would have been anticipated at the commencement of hostilities. Still, having regard to the fact that both the Rand and Kimberley were virtually undamaged, and that the main engines of prosperity, when once set going again, would not take very long to get into working order, the economic consequences of the war, though grave, did not appear by any means appalling. The country population it was admitted would need a good deal of help, first to[Pg 3] preserve it from starvation, and then, probably, to supply it with a certain amount of capital to make a fresh start. And the great industry of the country would require some little time before it would be able to render any assistance. But, in a young country with great recuperative powers, many years would not elapse before the economic ravages of the war would be effaced.

Still, the moral effect of the recrudescence of the war was lamentable. Everywhere after the occupation of Pretoria the inhabitants had seemed resigned to the state of affairs—the feeling in the colony had been one of acquiescent relief. The rebellious element was glad of the opportunity to settle down. Had these people been shut off from communication with the enemy they would have maintained their calm, and engaged themselves with their former peaceful pursuits. As it was, while the great advance to Pretoria, and subsequently to Delagoa Bay, demanded the presence of the British troops in the north, the country was left open to raiders, who daily grew more audacious as the small successes of their guerilla leaders appeared to give promise of a turn of fortune’s wheel.

And now came the real tug of war. These raiders, both on the brink of the Orange Colony and the Southern Transvaal, kept the peaceable inhabitants of the colony in an unenviable quandary. These, and many others, on taking the oath of neutrality, instead of being made prisoners of war, had been permitted to return to their farms. But under pressure from their old comrades, they now wavered between the obligations of their oath and the calls of friendship—and many of them fell. Men who had been exceptionally well treated were again in arms, sometimes justifying their break of faith by the poor apology that they had not been “preserved from the temptation to commit it.” Naturally, on the return of the troops to again quell a rising in the south, their conduct was not marked by the same leniency which had characterised the original conquest. Still, these parole breakers were not punished with the severity which might have been meted out to them in the same circumstances by other nations. Though we were by the rules of war entitled to shoot men who had broken their parole, we had not availed ourselves of the right.

We remained as humane as the exigence of discipline would permit. Efforts were made to check the general demoralisation by establishing refuge camps for the peaceable along the railway lines, but these camps were mainly tenanted by the women and children of burghers who still determined to flout us.

Lord Milner, in speaking of the situation in the new territories and the Cape Colony, described it as possibly “the most puzzling that we have had to confront since the beginning of the war.” On the one hand there was the outcry for greater severity and for a[Pg 4] stricter administration of martial law. On the other hand, there was the expression of the fear that strict measures would only exasperate the people. He himself was in favour of reasonable strictness as the proper attitude in the presence of a grave national danger, and he further affirmed that exceptional regulations for a time of invasion, the necessity of which every man of sense could understand, if clearly explained and firmly adhered to, were not only not incompatible with, but actually conducive to, the avoidance of injustice and cruelty. He went on to say:—

“I am satisfied by experience that the majority of those Dutch inhabitants of the Colony who sympathise with the Republics, however little they may be able to resist giving active expression to that sympathy when the enemy actually appear amongst them, do not desire to see their own districts invaded or to find themselves personally placed in the awkward dilemma of choosing between high treason and an unfriendly attitude to the men of their own race from beyond the border. There are extremists who would like[Pg 5] to see the whole of the Cape Colony overrun. But the bulk of the farmers, especially the substantial ones, are not of this mind. They submit readily enough even to stringent regulations having for their object the prevention of the spread of invasion. And not a few of them are, perhaps, secretly glad that the prohibition of seditious speaking and writing, of political meetings, and of the free movement of political firebrands through the country, enables them to keep quiet, without actually themselves taking a strong line against the propaganda, and, to do them justice, they behave reasonably well under the pass and other regulations necessary for that purpose, as long as care is taken not to make these regulations too irksome to them in the conduct of their business, or in their daily lives.”

He suggested that the fact that there had been an invasion at all was no doubt due to the weakness of some of the Dutch colonists in tolerating, or supporting, the violent propaganda, which could not but lead the enemy to believe that they had only to come into the Colony in order to meet with general active support. But this had been a miscalculation on the part of the enemy, though a very pardonable one. They knew the vehemence of the agitation in their favour as shown by the speeches in Parliament, the series of public meetings culminating in the Worcester Congress, the writings of the Dutch press, the very general wearing of the Republican colours, the singing of the Volkslied, and so forth, and they regarded these demonstrations as meaning more than they actually did. Three things were forgotten. Firstly, that a great proportion of the Afrikanders in the Colony who really meant business, had slipped away and joined the Republican ranks long ago. Secondly, that the abortive rebellion of a year ago had left the people of the border districts disinclined to repeat the experiment of a revolt. Thirdly, that owing to the precautionary measures of the Government the amount of arms and ammunition in the hands of the country population throughout the greater part of the Colony is not now anything like as large as it usually was, and far smaller than it was at the onset of the war.

In regard to the “call to arms” that took place on the 1st of January, and the vehement response it had met, Lord Milner stated that it had always been admitted, by their friends and foes alike, that the bulk of the Afrikander population would never take up arms on the side of the British Government in this quarrel, even for local defence. The appeal therefore had been virtually directed to the British population, mostly townspeople, and to a small, but no doubt very strong and courageous, minority of the Afrikanders who have always been loyalists. These classes had been already immensely drawn on by the Cape Police, the regular Volunteer Corps, and the numerous Irregular Mounted Corps[Pg 6] which had been called into existence because of the war. There must have been 12,000 Cape colonists under arms before the recent appeal, and as things were going, as many more promised to answer that appeal—a truly remarkable achievement under a purely voluntary system.

Position of Troops after the Engagement of 23rd February. De Wet’s

Escape from the Enveloping Cordon, 28th February 1901

Position of Troops after the Engagement of 23rd February. De Wet’s

Escape from the Enveloping Cordon, 28th February 1901

How gloriously the system worked throughout the year 1901 has yet to be seen, for peace was still a great way off. All yearned for it, all were fairly sick of carnage and ruin and sacrifice, but, nevertheless, it was agreed that to endure and fight to the bitter end were preferable to an ignoble compromise, which must inevitably bring about a recurrence of the terrible scourge in the future. All were determined that South Africa should become one country under one flag, and that the British; and this once accomplished, they would be ready to bury racial animosities for ever. But, in order to bring about that happy, that inevitable end, all decided that a vigorous prosecution of the war, at whatever cost, was an imperative duty.

CONTINUATION OF THE DE WET CHASE, 1st to 10th MARCH—ACROSS THE ORANGE RIVER

On the last day of February, as we know, De Wet and Steyn, with a bedraggled, hungry commando of some fifteen hundred Boers, precipitately crossed the Orange River at Lilliefontein, near Colesberg Bridge. They were seen by some few men of Nesbitt’s Horse under Sergeant-Major Surworth, and promptly fired upon as men and horses strove to battle with the current. This unlooked for attack caused considerable dismay, so much so, that many Cape carts and some clothing were left on the south bank, while several fugitives were seen to be galloping off in Garden of Eden attire. Many Boers were left in the neighbourhood of the Zeekoe River, and of these some thirty-three were captured by Captain Dallimore and sixteen Victorian Rifles.

The retirement becoming known to General Lyttelton, who was directing the operations, the pursuing columns were ordered to converge on Philippolis. General Plumer, Colonels Haig and Thorneycroft, entering Orange River by Norval’s Pont, operated from Springfontein to the river, while General C. Knox and Colonel Bethune at Orange River Bridge mounted guard there, and threatened such marauders as might retire in their direction. On the arrival of General Plumer at Philippolis, on the 3rd, he discovered that De Wet was fleeing to Fauresmith, and Hertzog, with 500 men, was making for Luckhoff. He therefore, with almost inexhaustible energy, instantly pursued the great raider, and after a rearguard action on the 4th at Zuurfontein, reached Fauresmith on the 5th, only to find the bird flown viâ the Petrusburg Road. On and on then went the troops, past Petrusburg—De Wet ever twenty-four hours ahead—till they reached Abraham Kraal Drift on the Modder River. By this time (the 7th) the Boer flock had dispersed over the enormous track of country with which they are so intimate, and De Wet himself vanished, as usual, into “thin air.” The 8th was spent in recuperation, replenishing stores, and gaining information. On the following two days the northerly march was continued in search of De Wet, who was reported to have crossed the line (on the night of the 8th) on the[Pg 8] way to Senekal. But, as the redoubtable one trekked at the rate of some five miles a day more than the best column, General Plumer gave him up as lost, and marched to Brandfort, and thence proceeded under orders to Winburg. The chase had been far from stimulating, for heavy rain had fallen, causing much inconvenience to man and beast, and hindering transport operations. The veldt, however, soon assumed a rich green garb, which rendered all the English horses independent of the Commissariat Department.

Meanwhile Colonel Haig, in conjunction, had moved to Philippolis on the 4th, only to learn that General Plumer was on the track of De Wet. He therefore turned his attention to Hertzog, caught him on the 5th at Grootfontein, ten miles north-west of Philippolis, engaged him and forced him westward. He then waited orders at Springfontein lest a more speedy movement by rail might be directed.

Colonel Bethune, in his position near Orange River Bridge, spent this time in fighting and dispersing large bodies of raiders, passing at length viâ Petrusburg, on the 6th, to the line Abraham’s Kraal, Roodewal, on the 8th. Here he halted. An empty convoy returning from him to Bloemfontein was attacked by the Boers, but the escort tackled the enemy, and, with the assistance of the Prince of Wales’ Light Horse, put them to flight.

General C. Knox’s columns (Colonels Pilcher and Crewe, moving by way of Kalabas Bridge and Koffyfontein respectively), advanced at the same time, reaching Bloemfontein on the 10th and 11th, the astute Pilcher having captured a Boer laager by the way. He had three killed, eleven wounded, three missing, and his captures included twenty-four prisoners, 1500 horses, and some cattle.

Colonel Crewe engaged in a smart tussle with Brand’s commando at Olivenberg (south-west of Petrusburg), and reached his destination plus five prisoners, twenty-one waggons and carts with teams complete, and 2000 horses.

During March, Major Goold-Adams, the Deputy-Administrator of the Orange River Colony, in whom the burghers placed much confidence, bent his mind to the organisation of the civil administration of the colony. Mr. Conrad Linder, an ex-official of the late Government, was provisionally appointed registrar. A scheme of education, based on the Canadian principle, was drawn up, and the organisation of the civil police taken in hand. The Imperial authorities were engaged in a scheme for restocking the country after the war by establishing stock depots on the Government farms in both the Transvaal and Orange River.

The enemy, under the direction of Fourie, in many small gangs of from two to four hundred, still hovered in the region between the Orange River and the Thabanchu-Ladybrand line. With the object of sweeping them up, General Lyttelton organised a combined northward movement which began on the 10th of March. General Bruce-Hamilton’s columns, under Lieutenant-Colonels Monro, Maxwell, and White pushed up from Aliwal North, Colonel Hickman and Lieutenant-Colonel Thorneycroft moved out from Bethulie and Springfontein respectively, prolonging the line on the left to the railway, while Colonel Haig’s troops advanced from Edenburg. Later on, as the columns swept upwards, Colonel Bethune’s Brigade took its place in the scheme, filling the gap between Leeuw Kop and Boesman’s Kop, with its right flank resting on the Kaffir River. While these were marching up, the line of posts from Bloemfontein viâ Thabanchu to the Basutoland border was temporarily reinforced by Colonel Harley, who, with some 200 mounted men, two guns, and a battalion, had been detached from the portion of General Rundle’s force which was holding Ficksburg. The road still further north, near Houtnek, was watched by Colonel Pilcher to guard against hostile movement in that region. The combined advance, though there was little fighting, was decidedly successful. Heavy stocks of grain were found, and such as could not be accommodated in the British waggons were destroyed. Though, as usual, the Boers were dispersed in driblets and most of the farms were deserted and the property abandoned, some of their number got caught in the meshes of the military net. Colonel Pilcher’s men succeeded in securing some thirty-three Boers and about 3000 horses, and the total haul of the columns on reaching the Thabanchu line on the 20th amounted to 70 prisoners, 4300 horses, and many trek oxen. After this date General Bruce-Hamilton’s force and that of Colonel Hickman disposed themselves between Wepener and Dewetsdorp, while Colonel Haig was ordered to keep his eye on rambling raiders from Cape Colony, in the region of the Caledon. Colonel Bethune’s Brigade, marching north viâ Winburg and Ventersburg, soon swelled the mounted force of some 7000 men, being organised at Kroonstad (under the command of General Elliot), and Colonel Thorneycroft, now under orders of General C. Knox, took up a position at Brandfort. This place at that time was somewhat harassed by meandering marauders, who were in the habit of taking up a nightly post on a hill near by. These were[Pg 10] surprised by the mounted infantry and burgher police, and their number considerably thinned.

From all points the clearance of the Colony was pursued with vigour. On the 24th Colonel White, in the Thabanchu region, surprised parties of Boers, capturing six waggons, thirty-four horses, and some cattle, and on the 25th some smart work was done by a detachment of Lancers, Yeomanry, and Rimington’s Guides, who drove off and dispersed various portions of Fourie’s commando without loss to themselves. At this time Fourie, Joubert, Pretorius, and Coetzee had been all hanging about the neighbourhood of Dewetsdorp, and on the 25th and 26th some spirited encounters took place between them and Captain Damant, who, with some of Rimington’s Scouts, engaged in many perilous excursions. On the 27th General Bruce-Hamilton, with Hickman’s column and Rimington’s Scouts,[Pg 11] moved out with a view to clearing off the snipers that fringed the surrounding hills. The Scouts and the Lancaster Mounted Infantry routed the Boers from one position after another, chasing them for miles as far as Blesbokfontein, where they dispersed. Meanwhile on the left, near Byersberg, our troops had discovered the Boer laager, whereupon Rimington’s Scouts rode round the position, driving the enemy, who scampered from their concealment in the ridges, in a south-westerly direction. Owing to the exhaustion of the horses the pursuit could not be continued, but the troops returned to camp with a goodly show of horses, cattle, and Cape carts as a prize for their endurance.

Concurrently with the activities in the south-east of the Orange River Colony, in the region of Winburg and Heilbron, good work had been going forward. Colonel Williams and Major Pine Coffin, working in combination, had cleared the Doornberg, a supply depot, which, owing to De Wet’s absence, was but weakly guarded. All stock was removed, and during the operations General P. Botha and seven Boers were killed and many were taken prisoners. Colonel Williams and the combined forces, reinforced by Major Massy’s column from Edenburg, now took up a position near the Vet and Zand Rivers, in order to catch De Wet should he break northward. But as this leader was now in hiding, “taking a breather” for fresh nimbleness in future, it was found unnecessary to wait there, and the column moved on towards Heilbron. Here, accompanied by a detachment from the garrison under Major Weston, Colonel Williams continued his work of clearance, fighting betimes, and capturing grain, forage, foodstuffs, and ammunition in great quantities. Colonel Williams then moved to the north of Heilbron, performing the same task of clearance between the Wilge River and the main line of rail. This occupation took him well into April, of which month more anon.

During the middle of March Lord Kitchener engaged himself with the rearrangement of the mobile columns in the Orange River Colony, dividing the place into four military districts. Each district was placed under the control of a General Officer, whose duty it was to deal with any encroachments of the enemy, to prevent the concentration of commandos, and to clear the country of horses and cattle, and any supplies which might stimulate the marauders to new exertion. The southern district, bounded on the south by the Orange River, on the north by the line Petrusburg-Ladybrand, on the west by the Kimberley Railway, on the east by Basutoland, was entrusted to General Lyttelton, his force including the columns of General Bruce-Hamilton and Colonels Hickman and Haig.[Pg 12]

The central district, bounded on the south by General Lyttelton’s command, on the north by the Bultfontein-Winburg-Ficksburg line, extending to Boshof, was assigned to General C. Knox, with whom were the columns of Colonels Pilcher and Thorneycroft.

The northern district, including part of Orange River Colony north of General C. Knox’s command, bounded on the east by the Frankfort-Reitz-Bethlehem line, was allotted to General Elliot, whose troops consisted of Colonel Bethune’s Cavalry Brigade, Colonel de Lisle’s Column (withdrawn from Cape Colony), and General Broadwood’s Brigade, composed of 7th Dragoon Guards, three battalions Imperial Yeomanry, and six guns.

The eastern district, as before, remained in charge of General Rundle, who, with the original 8th Division and some Mounted Infantry and Yeomanry, protected the line Frankfort-Reitz-Bethlehem-Ficksburg.

By the end of March recruiting for General Baden-Powell’s Police ceased. The work of training, clothing, mounting, and equipping was carried on with all speed, and the recruits who[Pg 13] arrived from England promptly displayed their grit and their zeal by withstanding the assaults of the Boers, who invariably attacked such districts as they fancied were in charge of the “raw” element. The new-comers were no fledgelings, however, for the members of the Constabulary were mostly gentlemen or farmers of a high class, selected with a view to making good colonists.

CAPE COLONY—PURSUIT OF RAIDERS—MARCH AND APRIL—CHASING KRUITZINGER

While the pursuit of De Wet was going forward, our troops under General Settle, and subsequently under Colonel Douglas Haig (Colonels Henniker, Gorringe, Grenfell, Scobell, and Crewe), worked unceasingly against the Boer raiders who were making themselves obstreperous in various parts of the Colony. Pearston was occupied by seven hundred of the enemy with two guns, who captured sixty rifles and 15,000 rounds of ammunition, in spite of the gallant defence of the tiny garrison. The invaders, a part of Kruitzinger’s commando, were promptly swept away by Colonel Gorringe, who reoccupied the place on the 5th, and caused the fugitives to be pursued. Accordingly the commando broke into three parties and fled eastward over the railway.

About the same time one hundred raiders, under Scheepers, made a desperate attack upon the village of Aberdeen—an attack which happily failed owing to the smartness of the garrison. This consisted of a portion of the 4th Derbyshire Militia, Town Guard, and twenty men of the 9th Lancers, under Colonel Priestly. The Boers, however, succeeded in penetrating into the town, and releasing some of their compatriots who were in gaol. They further tried to loot the stores, but were not given the opportunity, so promptly did the Town Guard send them to the right-about. Colonel Parsons arrived on the scene in the afternoon, followed, the next day, by Colonel Scobell and some Colonials, and soon, though not without sharp fighting, the kopjes surrounding the place were purged of the raiders. The sharpshooters of the Imperial Yeomanry under Major Warden were untiring in the energy of their pursuit of the enemy from hill to hill, and the detachment of the 6th Dragoons under Captain Anstice helped in the discomfiture of the foe. These escaped by means of the thick bush and dongas, which afforded them timely cover.

It was now necessary to prevent Scheepers and his Boers from entering Murraysburg. To circumvent him, Colonel Scobell—commanding a force of Cape Mounted Rifles, Cape Police, Diamond Fields Horse, and Brabant’s Horse, with some guns—marched hot foot at the rate of fifty-nine miles in less than twenty-five hours.[Pg 15] Meanwhile Captain Colenbrander, commanding the Fighting Scouts, moved promptly from Richmond towards Murraysburg, located Scheepers’ hordes in an adjacent village, and attacked them. The enemy were repulsed with the loss of five of their number, while the British party had no casualties.

Kruitzinger’s commando, continuing its depredations, seized Carlisle Bridge with a view to pressing towards Grahamstown, but the activity of Colonels De Lisle and Gorringe frustrated all effort to get to the sea. The invaders gave a vast amount of trouble, however, burning farms and securing horses, and several encounters took place. In one of these, a few miles from Adelaide, Captain Rennie and some of the Bedford detachment of the Colonial Defence Corps gave an excellent account of themselves. The Boers lost one man killed, one taken prisoner, and three wounded, together with six horses.

The raiders were routed from Maraisburg, which was reoccupied by the British on the 8th; but in the interval the magistrate had had a somewhat uncomfortable experience, having been imprisoned in his own house. The enemy reaped a certain reward of their exertions in the form of some horses, saddles, and a revolver. They afterwards broke into small gangs, and were hunted by Colonel Donald’s column.

The 15th found Colonels Scobell and Colenbrander’s columns still in pursuit of Scheepers, who, having caused some commotion by burning the house of a British scout named Meredith, was now hiding in the mountains around Graf Reinet. Colonel Gorringe at the same time was dodging about the neighbourhood of Kruitzinger (who had abandoned the hope of going south, and was now making for Blinkwater) and keeping him perpetually on the move. Space does not admit of a detailed account of these continuous activities, but in an engagement on the 15th some smart work was done by Captain Stewart, assisted by Gunner Sawyer (5th Field Battery). While the guns were being hauled up a precipitous slope, and most of the gunners were dismounted, they were assailed by a furious fire from the ambushed foe. With admirable presence of mind, Sawyer took in the situation, and, with the assistance of Captain Stewart, unlimbered one of the guns and gave the Boers a quid pro quo. This considerably damped their ardour, and afforded time for the rest of the guns to come into action. The position was finally stormed by the Albany defence force under Captain Currie. In the engagement nine Boers were killed and nine wounded. On the 17th, after a sharp action, the Boers, abandoning seventy excellent horses and saddles, besides losing some forty of their number, were driven across Elands River. Kruitzinger got across the Elands River in safety, but, while turning an angle of the main[Pg 16] road towards Tarkastad, on the morning of the 18th, he came suddenly in collision with Colonel de Lisle, who, by night, was marching—a memorable march in a terrific storm!—from Magermansberg to Tarkastad. The British force, as surprised at the sudden encounter as that of the Boers, promptly sprang to action, and succeeded in shelling the rearguard, while the Mounted Infantry started off in pursuit. From ridge to ridge went hunted and hunters, the Irish Yeomanry, under Captain Moore, with Mounted Infantry, under Colonel Knight, doing splendid work; but at last the wily quarry, through some of the troops having lost direction, succeeded in getting away through the loophole of Elands Poort. Kruitzinger, still maintaining a north-easterly direction, was next traced across the railway at Hemming Station on the 21st. Scheepers, Fouché, and Malan, who had growing forces, and had been beaten, with the loss of nine killed and seven wounded, by Major Mullins on the 15th, were proceeding east from Marais Siding. Other detached parties gave trouble elsewhere. Some, on the 16th, attacked at Yeefontein, near Steymburg, a patrol of Prince Alfred’s Guards under Major Court, but left behind them two killed, three wounded, and three prisoners, while the Guards lost one killed and two seriously wounded. Fighting was taking place in various other places daily. On the 20th and 21st Colonel Scobell’s force, increased by Colonel Grenfell’s, skirmished in the region north of Jansenville with excellent effect. Kitchener’s Fighting Scouts, under Captain Colenbrander, Major Mullins, and Colonel Gorringe converged from their various positions, while the main body made for Blaankrantz. On the 20th, by 9 A.M., a hammer-and-tongs engagement had begun, Captain Doune’s two guns being met by a blizzard from the foe in the surrounding ridges. The assailants were, however, rapidly silenced and forced to retire, the British party taking up the vacated position, and “speeding the parting guest” with a salvo from pom-poms, rifles, and field-guns. But the enemy could not be entirely netted, for in ones and twos they squeezed through the bushes and made their escape. Four, however, were left on the veldt, and four were taken prisoners, while about one hundred sound horses came in handy at a time when they were much in demand. The British force lost three killed and four wounded.

Kruitzinger at this time was being gradually pressed towards the Orange River (which was known to be unfordable) by Colonel de Lisle’s column, which formed part of a cordon, composed of the columns of Colonels Gorringe, Herbert, and Major Crewe on one side, and Colonels Crabbe, Codrington, and Henniker on the other. Nearly all the commandos which had invaded the Colony were retracing their sorry steps after the failure of their expedition.[Pg 17] The fact that they had been able to keep the field so long was attributed to the persistent way in which they avoided fighting, and their mode of hugging the sheltering kopjes and bushes, and never emerging from those beneficent harbours of refuge. According to good authority, the raiders succeeded in gaining certain recruits among the Colonial Dutch, but not nearly so many as they had expected. They were amply supplied with food from the sympathetic rural population, however, and received on all sides timely information of the movements of the pursuing columns, which enabled them to double like hares at the very moment when the pursuers seemed about to pounce on them.

Train-wrecking continued, and of necessity the running of night trains had to be suspended. Some of the raiders began to drive over the less known drifts of the Orange and disappear, while certain rebels contrived to hide themselves in the mountain fastnesses so as to escape both the Boer bands and the British pursuit. On the 30th of March a skirmish took place between some of Henniker’s troops (Victorian Bushmen) and a large force of Boers, during which the Colonials again showed their tenacity and grit. An advanced party of four only, under a splendid fellow, Sergeant Sandford, were set upon by the foe in the vicinity of Zuurberg. The enemy succeeded in wounding a Bushman, who fell beneath his dead horse, and was there pinned. His companions, under a perpetual sleet from the marauders’ Mausers, with great coolness engaged in the immensely difficult task of moving the dead animal and drawing out their comrade from his perilous position. They then managed to mount the rescued man on Sergeant Sandford’s horse and all got away in safety. Reinforcements arriving now frightened off the Boers, who had lost four of their number.

On the whole, things were progressing wonderfully. At the headquarters of General Baden-Powell’s Constabulary at Modderfontein 2000 more recruits were now expected to join the 1000 already on duty there. Australian and Canadian drafts were to follow. The clerical staff of the Rand Mines’ Corporation was about to proceed from the Cape to Johannesburg, a sure sign of approaching settlement. A warning to colonists was soon published stating that acts of rebellion committed after April 12 would not be tried under the Special Tribunals Act of last session, but by the old common law, the penalties under which include capital punishment or any term of imprisonment or fine which an ordinary court may impose.

On the 6th of April a post, ten miles north of Aberdeen, consisting of one hundred men of the 5th Lancers, thirty-two Imperial Yeomanry under Captain Bretherton, and Brabant’s Horse,[Pg 18] was assailed by a horde of 400 Boers. After fighting vigorously from dawn till 11 A.M. the force was overpowered. Twenty-five of the number only escaped—one was killed and six were wounded.

On the 11th, Colonel Byng surprised a laager near Smithfield, captured thirteen tatterdemalions, who were not loth to rest, and some horses and stores.

Colonel Haig, on the 12th, reached Rosmead and took command of all the columns operating in the midlands, and he soon began the hunting of Scheepers’ and Malan’s commandos with his flying columns. According to Reuter’s correspondent, the Boer forces in the midlands at this date comprised Scheepers, with 180 men, in the Sneeuwberg; Malan, with forty men, reported to be breaking northward; Swanepoel, with sixty men, near New Bethseda; and Fouché, with a force estimated variously at several hundreds, in the Zuurberg.

On the 14th of April Colonel Gorringe returned to Pretoria after three months’ of exceptionally hard work and incessant trekking over some of the worst country in South Africa. His Colonial column had done on an average a daily trek of some thirty-one and a half miles. On one occasion, when rushing to the succour of Pearston[2] when it was overpowered by raiders, these hardy troopers, with guns and equipments, covered seventy-four miles in forty hours, crossing the frowning heights of Coelzeeberg by a bridle path.

General MacDonald now proceeded to England in order to take up command of an important post on the Afghan frontier, and General Fitzroy Hart succeeded him in command of the 3rd Brigade. Sir Alfred Milner made preparations to go home on leave.

On the 24th the Dordrecht Volunteer Guard and Wodehouse’s Yeomanry gave an excellent account of themselves. They were attacking raiders for the most part of the day, and sent the Dutchmen to the right-about, capturing their horses and forcing them to make good their escape on Shanks’ pony.

On the 29th Major Du Moulin’s column, accompanied by Lovat’s Scouts under Major Murray, arrived at Aliwal North from Orange River Colony, bringing with it 30 prisoners, 60,000 sheep, 6000 head of cattle, 100 waggons, 800 refugees, and 300 horses.

[2] See page 8.

THE OPERATIONS OF GENERAL FRENCH IN THE EASTERN TRANSVAAL, FROM 27th JANUARY to 16th APRIL 1901

It may be remembered that at the close of 1900 the Boer chiefs, De Wet and Botha, had invented a concerted scheme of some magnitude. They had arranged that Hertzog should enter Cape Colony and proceed to Lambert’s Bay to meet a ship which was said to be bringing from Europe mercenaries, guns, and ammunition. De Wet was to follow south viâ De Aar, join hands with Hertzog, and together, with renewed munitions of war and a tail of rebels at their heels, attack Cape Town. General Botha at the same time was to keep the British occupied in the Eastern Transvaal and prevent them drawing off troops to the south, and, so soon as the plans of De Wet and Hertzog were being carried out, he was to enter Natal with a picked force of 5000 mounted men and make for Durban.

Having seen how the parent scheme, the invasion of the Cape Colony, was frustrated, it is necessary to turn to scheme two, and follow General French in the remarkable operations which defeated Botha’s designs. A considerable concentration of Boers, under the Commandants Louis Botha, Smuts, Spruyt, and Christian Botha, had taken place in Ermelo, Carolina, and Bethel, which districts constituted depôts for the supply of the enemy’s forces. The Commander-in-chief therefore decided to sweep the country between the Delagoa and Natal Railway lines, from Johannesburg to the Swazi and Zulu frontiers, and to clear it of supplies and families. With this object in view, on the 28th of January the following columns were concentrated from the meridian of Springs: Major-General Paget, Brigadier Alderson, Colonel E. Knox (18th Hussars), Lieutenant-Colonel Allenby (6th Dragoons), Lieutenant-Colonel Pulteney (Scots Guards), and Brigadier-General Dartnell (Commandant of Volunteers, Natal).

The troops—the southern columns under the command of Lieutenant-General Sir John French—were to form a north and south line between the railway, and thus drive the enemy before them to Ermelo. They were commanded from north to south in the order shown above. While this line was advancing, Lieutenant-Colonel Campbell and Lieutenant-Colonel Spens, moving a march south from Middelburg and Wonderfontein, were to act as side[Pg 20] stops, while Major-General Smith-Dorrien, with a force 3000 strong, was to advance from Belfast viâ Carolina to Lake Chrissie, for the purpose of preventing the Boers from breaking north-east. A weak column, under Lieutenant-Colonel Colville (Rifle Brigade), was to work south of Colonel Dartnell to cover the movement of supplies, first from Greylingstad to the north, and then from Standerton to Ermelo.

Eventually, owing to the movements of De Wet, General Paget was recalled from this sphere of action, and his place was taken by Colonel Campbell. General Alderson’s and Knox’s lines of advance were slightly diverted to the north, and the line between them was filled by Lieutenant-Colonel Pulteney, who originally was to have been held in reserve.

The first two marches took the western troops to a line north[Pg 21] of Greylingstad to Vangatfontein, in the valley of the Wilge River, where there was a two days’ halt till the 31st. The march was not without excitement, for Beyers was found to be ensconced in a strong and extended position stretching north and south, and covering the approach to the valley of the Wilge River. Bushman’s Kop, fourteen miles east of Springs, was strongly held, and the advanced troops of Knox and Allenby were assailed with fierce artillery from the surrounding heights. But when Allenby’s mounted men had wheeled round the south of the position, the Boers thought it high time to retreat, leaving behind them two dead. This was on the 29th. Two days were spent in receiving supplies from Greylingstad and sending the emptied waggons full of Boer families to the rail and clearing the country of supplies.

The Boers, holding a chain of sloping hills some twenty-three miles west of Bethal, were again encountered on the 1st of February. While Colonel Rimington (commanding Colonel Pulteney’s mounted troops) worked round the north of the position, Colonel Allenby and the rest of Pulteney’s troops held them in front. But the wily Dutchmen, now rapidly becoming demoralised, instantly they found their flank threatened, were off to the east before they could be cut off. The commanders on the right had also met with slight opposition.

The operations of the 2nd of February much resembled those of the previous day, for some 2000 Boers, who had planted themselves about ten miles west of Bethal, ceased their opposition to Colonel Allenby, when they found Pulteney’s cavalry sweeping round to their north, and they made such haste to depart that they left behind them an English 15-pounder gun, with damaged breech. The village of Bethal was reached by General French on the 4th, all Boers, save a few women and children, having fled. The troops were now hurriedly pushing forward with a view to surrounding Ermelo. Their position was as follows: Allenby on the south-east; Dartnell on the south and south-west; Pulteney on the west; Knox on the north-west; Anderson and Campbell on the north; and Smith-Dorrien on the north-east and east. The enemy, seeing security at this place thus threatened, split into two factions. Louis Botha, with a following of some 3000 men, scurried to the north toward Komati without impediment, in the form of families and stock, while the rest, protecting their waggons, retreated toward Piet Retief. Botha, while scurrying as aforesaid, discovered on the 5th that Smith-Dorrien’s force, about 3000 strong (with a big convoy for his own, Campbell’s, and Alderson’s columns), had reached Bothwell, north of Lake Chrissie. Here was a fine chance! and the Boer leader speedily availed[Pg 22] himself of it. He determined to attack the British column before the troops of Campbell and Alderson, moving from the west, could get in touch with it. Accordingly, dividing his force into three, and rising betimes, in the thick mists of daybreak, on the 6th, he delivered a vigorous semicircular attack upon the camp. This was successfully repulsed.

The Boers lost heavily, General Spruyt and several field-cornets being among the slain. The British had one officer and twenty-three men killed, three officers and fifty-two men wounded. Some 300 horses were killed or stampeded during the surprise. The Boers, owing to the heavy fog of the morning, got away to the north. At the moment Botha was making his attack on the camp, the officer bearing orders from General French for General Smith-Dorrien, after an exciting and hazardous ride, reached Bothwell. Owing to the fight these orders—to move on the 6th to a position E.N.E. of Ermelo—could then not be executed. General Smith-Dorrien therefore remained at Bothwell.

Meanwhile, in the south, fighting went forward. Colonel Allenby, who had been rapidly pushing east, came on the enemy’s rearguard, which was occupying a ridge south of Ermelo. With infantry and artillery, and supported by Dartnell’s Brigade, he engaged them, holding them on the west while the mounted troops endeavoured to wheel round the southern flank and surround them. But the Boers, who had had a long start, nimbly made good their escape over the Vaal at Witpunt before Allenby’s troops could possibly reach that point, and consequently the brilliant attempt to cut off their retreat proved a failure. Ermelo was occupied on the 6th, and thus the first phase of the operations was accomplished.

It was now necessary to sweep the country from Ermelo to the Swazi frontier, which movement occupied from the 9th to the 16th of February. To this end the flanks were immediately opened out again, and the line Bothwell-Ermelo-Amersfoort taken. From this line the force wheeled half-right, the left flank (rationed on reduced scale up to the 20th) beginning to extend east towards Swaziland on the 9th.

The whole force was now so ordered as to form a complete cordon for the purpose of hemming in the enemy and their belongings in the south-eastern corner of the Transvaal. The troops were here to converge on Amsterdam and Piet Retief from north and south-west, and, with the escort to the convoy from Utrecht, were to form a line from Utrecht and the Natal frontier to the Swazi frontier north of Piet Retief. On the 9th General Smith-Dorrien, moving east-north-east, encountered the Boers, and Colonel Mackenzie and his gallant men, with the assistance of[Pg 23] the 2nd Imperial Light Horse, succeeded in capturing a convoy and putting twenty-one Boers hors de combat by a brilliant charge.

Affairs were somewhat hampered by lack of supplies, but at last (on the 10th) a convoy from Standerton having come in, the right wing (Dartnell and Allenby) were provided for. On the following day General French moved on, while Colville’s emptied waggons started back with a pathetic load of Boer families and prisoners and British sick.

On the 12th, the Boers offered some opposition to the advancing troops of Pulteney and Allenby, and near Klipfontein they, for a wonder, made a stand, and gave Colonel Rimington and the Inniskilling Dragoons an opportunity for smart work. A dashing charge, magnificently led, cleared the ground, and five dead Boers and some wounded were left to tell the tale of the encounter.

On the 13th Dartnell, who had taken up a position at Amersfoort, moved from thence steadily in line with the whole force, which proceeded with insignificant opposition to clear away stock and destroy supplies.[Pg 24]