BIRDS.

ILLUSTRATED BY COLOR

PHOTOGRAPHY.

| Vol. III. |

APRIL, 1898. |

No. 4. |

AVIARIES.

A N admirer of birds recently said to

us: "Much is said of the brilliant specimens which you have presented in your magazine, but I

confess that they have not been the most attractive to me. Many birds of no special beauty of

plumage seem to me far more interesting than those which have little more than bright colors and a

pretty song to recommend them to the observer." He did not particularize, but a little reflection

will readily account for the justness of his opinion. Many plain birds have characteristics which

indicate considerable intelligence, and may be watched and studied with continued and increasing

interest. To get sufficiently near to them in their native haunts for this purpose is seldom

practicable, hence the limited knowledge of individual naturalists, who are often mere

generalizers, and the necessity of the accumulated knowledge of many patient students. In an

aviary of sufficient size, in which there is little or no interference with the natural habits of

the birds, a vast number of interesting facts may be obtained, and the birds themselves suffer no

harm, but are rather protected from it. Such an aviary is that of Mr. J. W. Sefton, of San Diego,

California. In a recent letter Mrs. Sefton pleasantly writes of it for the benefit of readers of

Birds. She says:

N admirer of birds recently said to

us: "Much is said of the brilliant specimens which you have presented in your magazine, but I

confess that they have not been the most attractive to me. Many birds of no special beauty of

plumage seem to me far more interesting than those which have little more than bright colors and a

pretty song to recommend them to the observer." He did not particularize, but a little reflection

will readily account for the justness of his opinion. Many plain birds have characteristics which

indicate considerable intelligence, and may be watched and studied with continued and increasing

interest. To get sufficiently near to them in their native haunts for this purpose is seldom

practicable, hence the limited knowledge of individual naturalists, who are often mere

generalizers, and the necessity of the accumulated knowledge of many patient students. In an

aviary of sufficient size, in which there is little or no interference with the natural habits of

the birds, a vast number of interesting facts may be obtained, and the birds themselves suffer no

harm, but are rather protected from it. Such an aviary is that of Mr. J. W. Sefton, of San Diego,

California. In a recent letter Mrs. Sefton pleasantly writes of it for the benefit of readers of

Birds. She says:

"My aviary is out in the grounds of our home. It is built almost entirely of wire, protected

only on the north and west by an open shed, under which the birds sleep, build their nests and

gather during the rains which we occasionally have throughout the winter months. The building is

forty feet long, twenty feet wide, and at the center of the arch is seventeen feet high. Running

water trickles over rocks, affording the birds the opportunity of bathing as they desire. There

are forty-seven varieties of birds and about four hundred specimens. The varieties include a great

many whose pictures have appeared in Birds: Quail, Partridge, Doves,

Skylarks, Starlings, Bobolinks, Robins, Blackbirds, Buntings, Grosbeaks, Blue Mountain Lory,

Cockateel, Rosellas, Grass Parrakeet, Java Sparrows, Canaries, Nonpariels, Nightingales, Cardinals

of North and South America, and a large number of rare foreign Finches, indeed nearly every

country of the world has a representative in the aviary.

"We have hollow trees in which the birds of the Parrot family set up housekeeping. They lay

their eggs on the bottom of the hole, make no pretention of building a nest, and sit three weeks.

The young birds are nearly as large as the parents, and are fully feathered and colored when they

crawl out of the home nest. We have been very successful, raising two broods of Cockateel and one

of Rosellas last season. They lay from four to six round white eggs. We have a number of Bob White

and California Quail. Last season one pair of Bob Whites decided to go to housekeeping in some

brush in a corner, and the hen laid twenty-three eggs, while another pair made their nest in the

opposite corner and the hen laid nine eggs. After sitting two weeks the hen with the nine eggs

abandoned her nest, when the male {122}took her place

upon the eggs, only leaving them for food and water, and finally brought out six babies, two days

after the other hen hatched twenty-three little ones. For six days the six followed the lone cock

around the aviary, when three of them left him and went over to the others. A few days later

another little fellow abandoned him and took up with a California Quail hen. The next day the poor

fellow was alone, every chick having deserted him. The last little one remained with his adopted

mother over two weeks, but at last he too went with the crowd. These birds seemed just as happy as

though they were unconfined to the limits of an aviary.

"We have had this aviary over two years and have raised a large number of birds. All are

healthy and happy, although they are out in the open both day and night all the year round. Many

persons, observant of the happiness and security of our family of birds, have brought us their

pets for safe-keeping, being unwilling, after seeing the freedom which our birds enjoy, to keep

them longer confined in small cages.

"Around the fountain are calla lillies, flags, and other growing plants, small trees are

scattered about, and the merry whistles and sweet songs testify to the perfect contentment of this

happy family."

Yes, these birds are happy in such confinement. They are actually deprived of nothing

but the opportunity to migrate. They have abundance of food, are protected from predatory animals,

Hawks, conscienceless hunters, small boys, and nature herself, who destroys more of them than all

other instrumentalities combined. Under the snow lie the bodies of hundreds of frozen birds

whenever the winter has seemed unkind. A walk in the park, just after the thaw in early March,

revealed to us the remorselessness of winter. They have no defense against the icy blast of a

severe season. And yet, how many escape its ruthlessness. On the first day of March we saw a

white-breasted Sparrow standing on the crust of snow by the roadside. When we came up close to it

it flew a few yards and alighted. As we again approached, thinking to catch it, and extending our

hand for the purpose, it flew farther away, on apparently feeble wing. It was in need of food. The

whole earth seemed covered with snow, and where food might be found was the problem the poor

Sparrow was no doubt considering.

Yes, the birds are happy when nature is bountiful. And they are none the less happy when man

provides for them with humane tenderness. For two years we devoted a large room—which we

never thought of calling an aviary—to the exclusive use of a beautiful pair of Hartz

mountain Canaries. In that short time they increased to the number of more than three dozen. All

were healthy; many of them sang with ecstacy, especially when the sun shone brightly; in the

warmth of the sun they would lie with wings raised and seem to fairly revel in it; they would

bathe once every day, sometimes twice, and, like the English Sparrows and the barnyard fowl, they

would wallow in dry sand provided for them; they would recognize a call note and become attentive

to its meaning, take a seed from the hand or the lips, derive infinite pleasure from any vegetable

food of which they had long been deprived; if a Sparrow Hawk, which they seemed to see instantly,

appeared at a great height they hastily took refuge in the darkest corner of the room, venturing

to the windows only after all danger seemed past; at the first glimmering of dawn they twittered,

preened, and sang a prodigious welcome to the morn, and as the evening shades began to appear they

became as silent as midnight and put their little heads away under their delicate yellow

wings.

Charles C. Marble.

{123}

FOREIGN SONG BIRDS IN

OREGON.

I N 1889 and 1892 the German Song Bird

Society of Oregon introduced there 400 pairs of the following species of German song birds,

to-wit: Song Thrushes, Black Thrushes, Skylarks, Woodlarks, Goldfinches, Chaffinches, Ziskins,

Greenfinches, Bullfinches, Grossbeaks, Black Starlings, Robin Redbreasts, Linnets, Singing Quails,

Goldhammers, Linnets, Forest Finches, and the plain and black headed Nightingales. The funds for

defraying the cost of importation and other incidental expenses, and for the keeping of the birds

through the winter, were subscribed by the citizens of Portland and other localities in Oregon. To

import the first lot cost about $1,400. After the birds were received they were placed on

exhibition at the Exposition building for some days, and about $400 was realized, which was

applied toward the expense. Subsequently all the birds, with the exception of the Sky and Wood

Larks, were liberated near the City Park. The latter birds were turned loose about the fields in

the Willamette Valley.

N 1889 and 1892 the German Song Bird

Society of Oregon introduced there 400 pairs of the following species of German song birds,

to-wit: Song Thrushes, Black Thrushes, Skylarks, Woodlarks, Goldfinches, Chaffinches, Ziskins,

Greenfinches, Bullfinches, Grossbeaks, Black Starlings, Robin Redbreasts, Linnets, Singing Quails,

Goldhammers, Linnets, Forest Finches, and the plain and black headed Nightingales. The funds for

defraying the cost of importation and other incidental expenses, and for the keeping of the birds

through the winter, were subscribed by the citizens of Portland and other localities in Oregon. To

import the first lot cost about $1,400. After the birds were received they were placed on

exhibition at the Exposition building for some days, and about $400 was realized, which was

applied toward the expense. Subsequently all the birds, with the exception of the Sky and Wood

Larks, were liberated near the City Park. The latter birds were turned loose about the fields in

the Willamette Valley.

When the second invoice of birds arrived it was late in the season, and Mr. Frank Dekum caused

a very large aviary to be built near his residence where all the sweet little strangers were

safely housed and cared for during the winter. The birds were all liberated early in April. Up to

that time (Spring of 1893) the total cost of importing the birds amounted to $2,100.

Since these birds were given their liberty the most encouraging results have followed. It is

generally believed that the two varieties of Nightingales have become extinct, as few survived the

long trip and none have since been seen. All the other varieties have multiplied with great

rapidity. This is true especially of the Skylarks. These birds rear from two to four broods every

season. Hundreds of them are seen in the fields and meadows in and about East Portland, and their

sweet songs are a source of delight to every one. About Rooster Rock, twenty-five miles east of

Portland on the Columbia, great numbers are to be seen. In fact the whole Willamette Valley from

Portland to Roseburg is full of them, probably not as plentiful as the Ring-neck Pheasant but

plentiful enough for all practical purposes. In and about the city these sweet little songsters

are in considerable abundance. A number of the Black Starling make their homes about the high

school building. The Woodlarks are also in evidence to a pleasing extent.

There is a special State law in force for the protection of these imported birds.

They are all friends of the farmer, especially of the orchardists. They are the tireless and

unremitting enemy of every species of bug and worm infesting vegetables, crops, fruit,

etc.—S. H. Greene, in Forest and Stream.

{124}

BIRD SONGS OF MEMORY.

Oh, surpassing all expression by the rhythmic use of words,

Are the memories that gather of the singing of the birds;

When as a child I listened to the Whipporwill at dark,

And with the dawn awakened to the music of the lark.

Then what a chorus wonderful when morning had begun!

The very leaves it seemed to me were singing to the sun,

And calling on the world asleep to waken and behold

The king in glory coming forth along his path of gold.

The crimson-fronted Linnet sang above the river's edge;

The Finches from the evergreens, the Thrushes in the hedge;

Each one as if a dozen songs were chorused in his own,

And all the world were listening to him and him alone.

In gladness sang the Bobolink upon ascending wing,

With cheering voice the bird of blue, the pioneer of spring;

The Oriole upon the elm with martial note and clear,

While Martins twittered gaily by the cottage window near.

Among the orchard trees were heard the Robin and the Wren,

And the army of the Blackbirds along the marshy fen;

The songsters in the meadow, and the Quail upon the wheat,

And the Warbler's minor music, made the symphony complete.

Beyond the towering chimneyd walls that daily meet my eyes

I hold a vision beautiful, beneath the summer skies;

Within the city's grim confines, above the roaring street,

The happy birds of memory are singing clear and sweet.

—Garrett Newkirk.

{126}

|

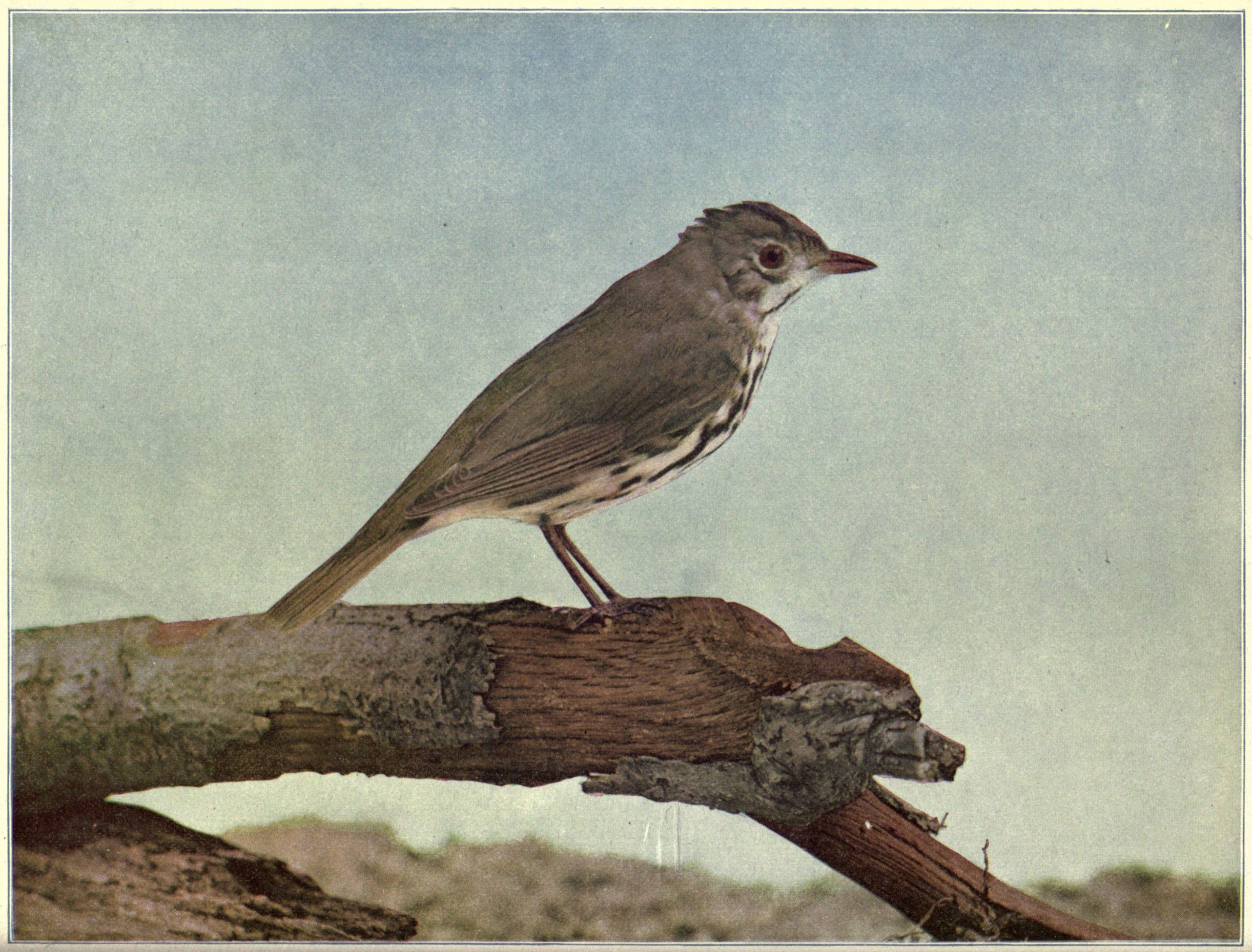

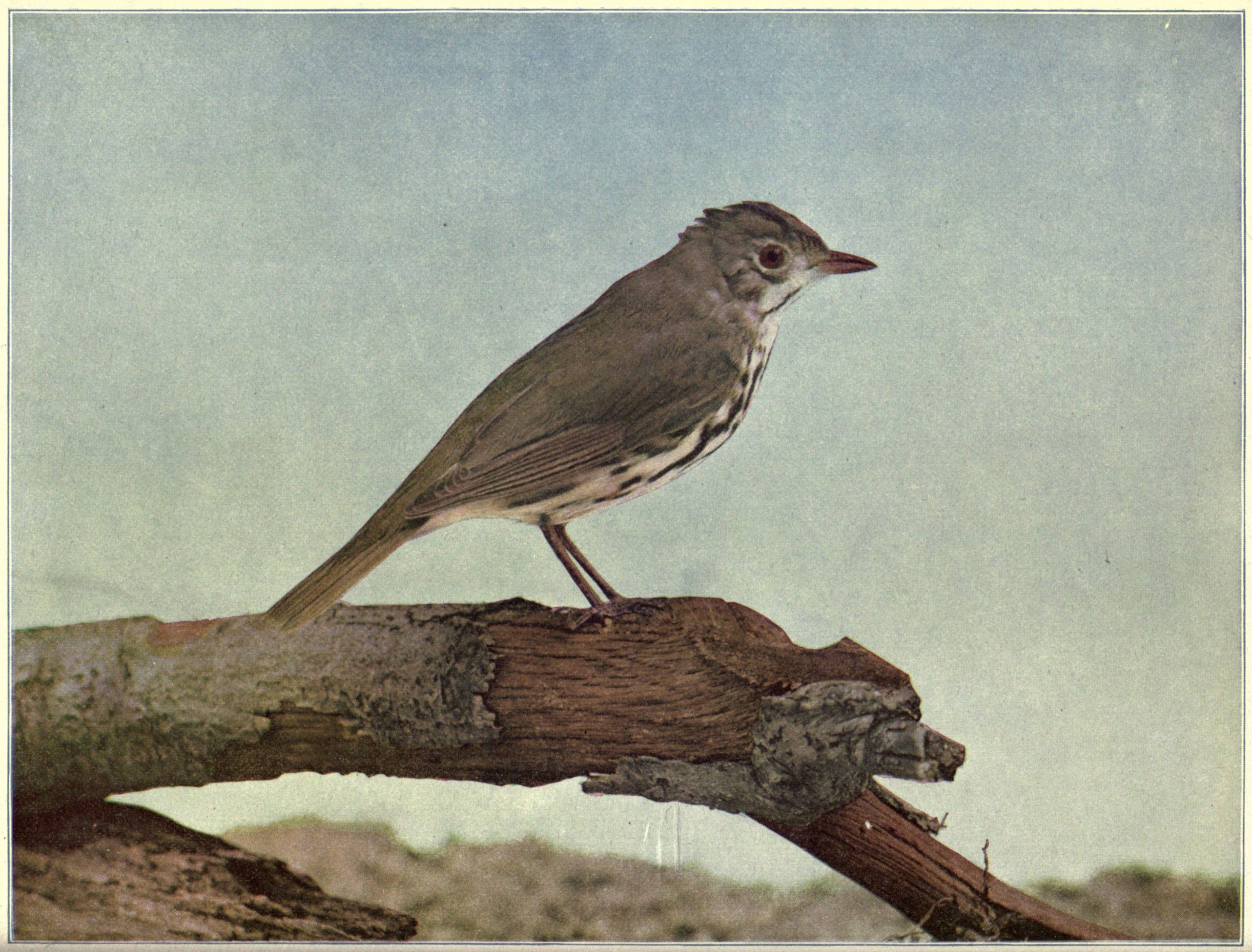

| From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences. |

OVEN BIRD.

4⁄5 Life-size. |

Copyright by Nature Study

Pub. Co., 1898. Chicago. |

{127}

THE OVENBIRD.

N OW and then an observer has the

somewhat rare pleasure of seeing this Warbler (a trifle smaller than the English Sparrow) as he

scratches away, fowl fashion, for his food. He has more than one name, and is generally known as

the Golden-crowned Thrush, which name, it seems to us, is an appropriate one, for by any one

acquainted with the Thrush family he would at once be recognized as of the genus. He has still

other names, as the Teacher, Wood Wagtail, and Golden-crowned Accentor.

OW and then an observer has the

somewhat rare pleasure of seeing this Warbler (a trifle smaller than the English Sparrow) as he

scratches away, fowl fashion, for his food. He has more than one name, and is generally known as

the Golden-crowned Thrush, which name, it seems to us, is an appropriate one, for by any one

acquainted with the Thrush family he would at once be recognized as of the genus. He has still

other names, as the Teacher, Wood Wagtail, and Golden-crowned Accentor.

This warbler is found nearly all over the United States, hence all the American readers of

Birds should be able to make its personal acquaintance.

Mr. Ridgway, in "Birds of Illinois," a book which should be especially valued by the citizens

of that state, has given so delightful an account of the habits of the Golden-crown, that we may

be forgiven for using a part of it. He declares that it is one of the most generally distributed

and numerous birds of eastern North America, that it is almost certain to be found in any piece of

woodland, if not too wet, and its frequently repeated song, which, in his opinion, is not musical,

or otherwise particularly attractive, but very sharp, clear, and emphatic, is often, especially

during noonday in midsummer, the only bird note to be heard.

You will generally see the Ovenbird upon the ground walking gracefully over the dead leaves, or

upon an old log, making occasional halts, during which its body is tilted daintily up and down.

Its ordinary note, a rather faint but sharp chip, is prolonged into a chatter when one is

chased by another. The usual song is very clear and penetrating, but not musical, and is well

expressed by Burroughs as sounding like the words Teacher, teacher, teacher, teacher,

teacher! the accent on the first syllable, and each word uttered with increased force. Mr.

Burroughs adds, however, that it has a far rarer song, which it reserves for some nymph whom it

meets in the air. Mounting by easy flights to the top of the tallest tree, it launches into the

air with a sort of suspended, hovering flight, and bursts into a perfect ecstacy of song, rivaling

the Gold Finch's in vivacity and the Linnet's in melody. Thus do observers differ. To many, no

doubt, it is one of the least disagreeable of noises. Col. Goss is a very enthusiastic admirer of

the song of this Warbler. Hear him: "Reader, if you wish to hear this birds' love song in its

fullest power, visit the deep woods in the early summer, as the shades of night deepen and most of

the diurnal birds have retired, for it is then its lively, resonant voice falls upon the air

unbroken, save by the silvery flute-like song of the Wood Thrush; and if your heart does not

thrill with pleasure, it is dead to harmonious sounds." What more has been said in prose of the

song of the English Nightingale?

The nests of the Golden Crown are placed on the ground, usually in a depression

among leaves, and hidden in a low bush, log, or overhanging roots; when in an open space roofed

over, a dome-shaped structure made of leaves, strippings from plants and grasses, with entrance on

the side. The eggs are from three to six, white or creamy white, glossy, spotted as a rule rather

sparingly over the surface. In shape it is like a Dutch oven, hence the name of the bird.

{128}

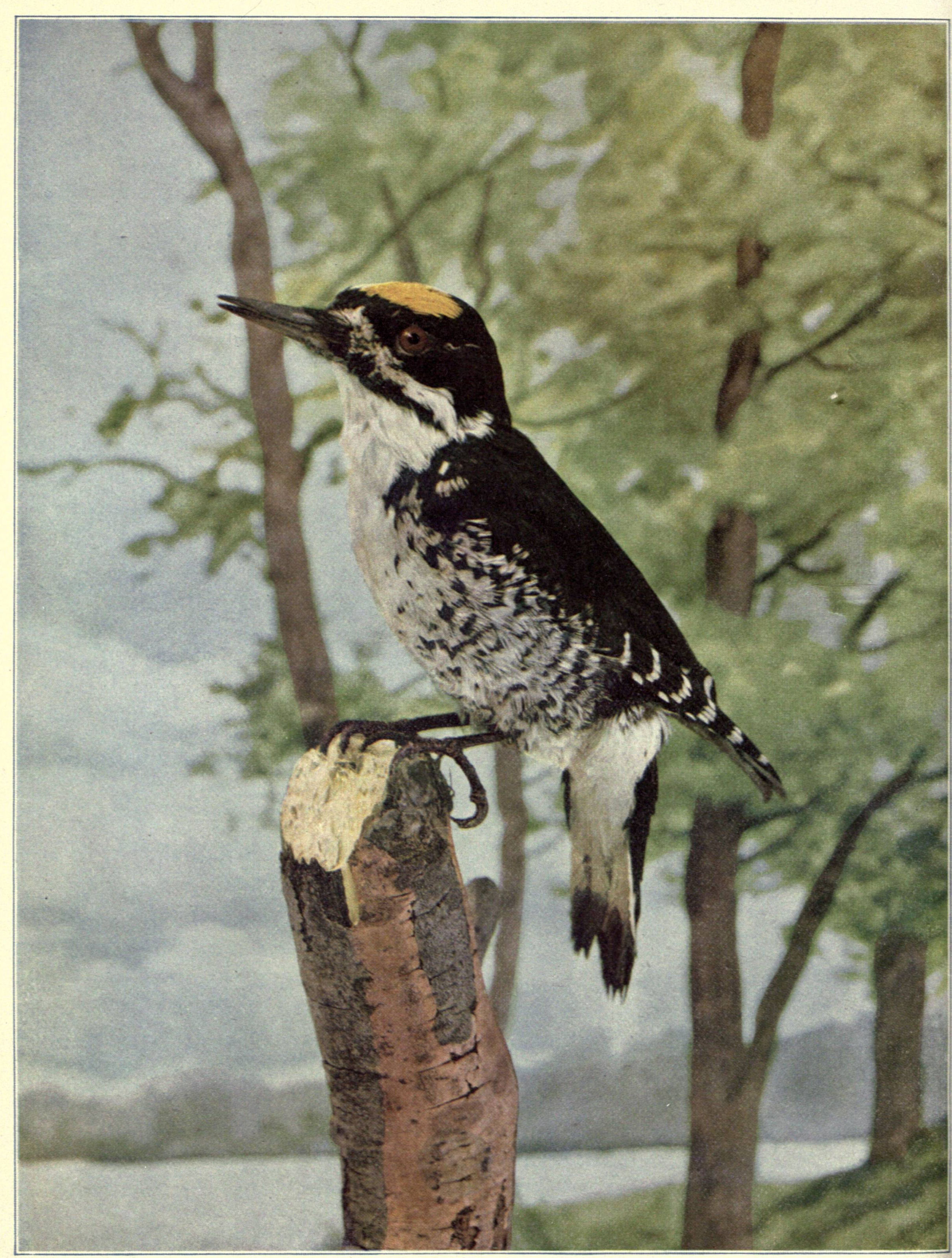

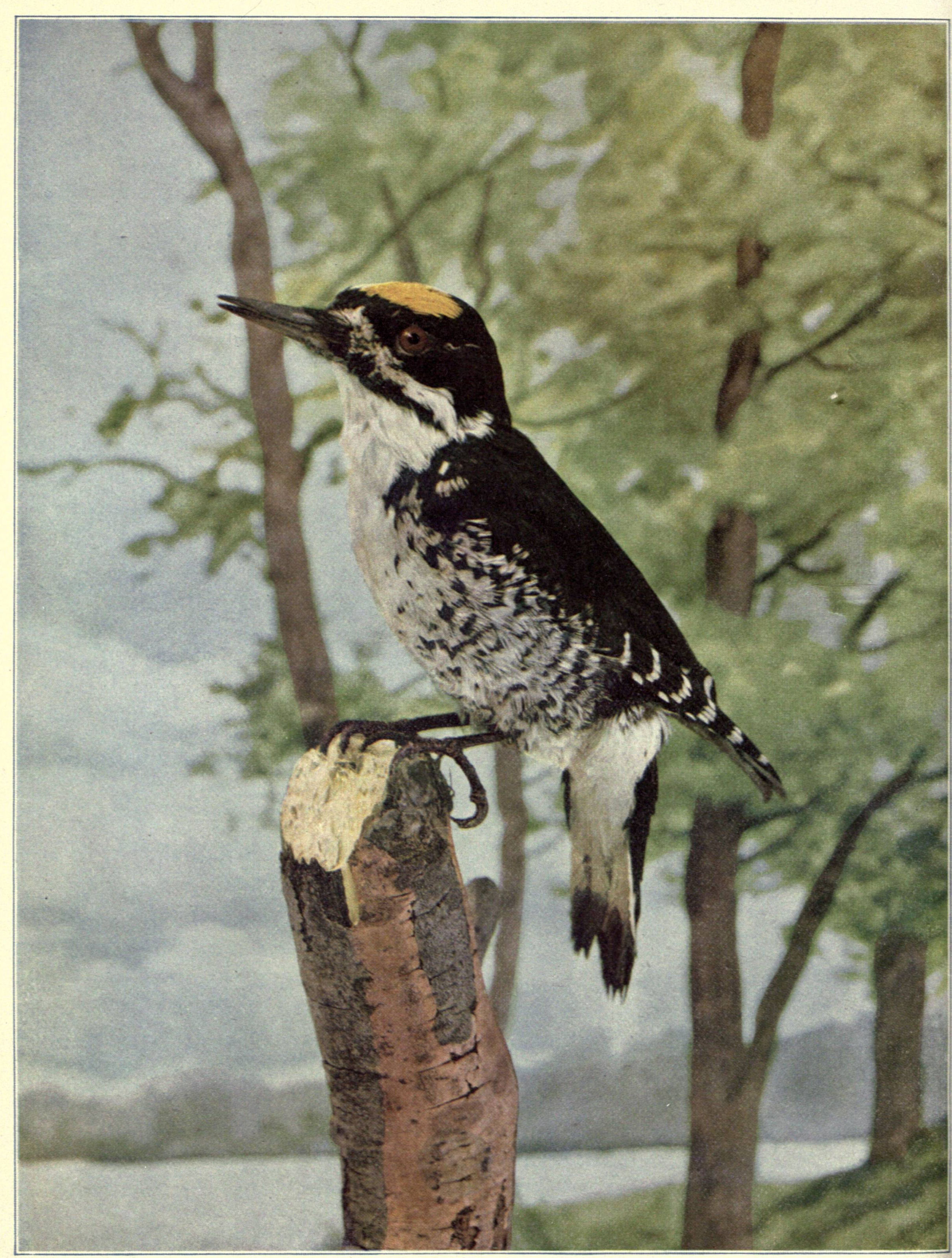

ARCTIC THREE-TOED

WOODPECKER.

Well, here I am, one of those "three-toed fellows," as the Red-bellied Woodpecker called me in

the February number of Birds. It is remarkable how impolite some folks can

be, and how anxious they are to talk about their neighbors.

I don't deny I have only three toes, but why he should crow over the fact of having four

mystifies me. I can run up a tree, zig-zag fashion, just as fast as he can, and play hide-and-seek

around the trunk and among the branches, too. Another toe wouldn't do me a bit of good. In fact it

would be in my way; a superfluity, so to speak.

In the eyes of those people who like red caps, and red clothes, I may not be as handsome as

some other Woodpeckers whose pictures you have seen, but to my eye, the black coat I wear, and the

white vest, and square, saffron-yellow cap are just as handsome. The Ivory-billed Woodpeckers, who

sent their pictures to Birds in the March number, were funny looking

creatures, I think, though they were dressed in such gay colors. The feathers sticking out

at the back of the heads made them look very comical, just like a boy who had forgotten to comb

his hair. Still they were spoken of as "magnificent" birds. Dear, dear, there is no accounting for

tastes.

Can I beat the drum with my bill, as the four-toed Woodpeckers do? Of course I can. Some time

if you little folks are in a school building in the northern part of the United States, near a

pine woods among the mountains, a building with a nice tin water-pipe descending from the roof,

you may hear me give such a rattling roll on the pipe that any sleepy scholar, or teacher, for

that matter, will wake right up. Woodpeckers are not always drumming for worms, let me tell you.

Once in awhile we think a little music would be very agreeable, so with our chisel-like bills for

drum-sticks we pound away on anything which we think will make a nice noise.

{130}

|

| From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences. |

AMERICAN THREE-TOED WOODPECKER.

⅝ Life-size. |

Copyright by Nature Study

Pub. Co., 1898. Chicago. |

{131}

THE ARCTIC THREE-TOED

WOODPECKER.

A GENERAL similarity of appearance is

seen in the members of this family of useful birds, and yet the dissimilarity in plumage is so

marked in each species that identification is easy from a picture once seen in Birds. This Woodpecker is a resident of the north and is rarely, if ever, seen

south of the Great Lakes, although it is recorded that a specimen was seen on a telegraph pole in

Chicago a few years ago.

GENERAL similarity of appearance is

seen in the members of this family of useful birds, and yet the dissimilarity in plumage is so

marked in each species that identification is easy from a picture once seen in Birds. This Woodpecker is a resident of the north and is rarely, if ever, seen

south of the Great Lakes, although it is recorded that a specimen was seen on a telegraph pole in

Chicago a few years ago.

The Black-backed Three-toed Woodpecker—the common name of the Arctic—has an

extended distribution from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and from the northern boundary of the

United States northward to the Arctic regions. Its favorite haunts are pine woods of mountainous

country. In some portions of northern New England it is a rare summer resident. Audubon says that

it occurs in northern Massachusetts, and in all portions of Maine covered by tall trees, where it

resides. It has been found as far south as northern New York, and it is said to be a not uncommon

resident in those parts of Lewis county, New York, which pertain to the Canadian fauna; for it is

found both in the Adirondack region and in the coniferous forests in the Tug Hill range. In the

vicinity of Lake Tahoe and the summits of the Sierra Nevada it is quite numerous in September at

and above six thousand feet. It is common in the mountains of Oregon and is a rare winter visitant

to the extreme northern portion of Illinois.

Observation of the habits of this Woodpecker is necessarily limited, as the bird is not often

seen within the regions where it might be studied. Enough is known on the subject, however, to

enable us to say that they are similar to those of the Woodpeckers of the states. They excavate

their holes in the dead young pine trees at a height from the ground of five or six feet, in this

respect differing from their cousins, who make their nests at a much greater height. In the nests

are deposited from four to six pure ivory-white eggs.

We suggest that the reader, if he has not already done so, read the biographies and study the

pictures of the representatives of this family that have appeared in this magazine. To us they are

interesting and instructive beyond comparison, with the majority of other feathered factors in

creation, and present an exceedingly attractive study to those who delight in natural history.

They are not singing birds, and therefore do not "furnish forth music to enraptured ears," but

their agreeable call and love notes, their tenor drum-beats, their fearless presence near the

habitations of man, winter and summer, their usefulness to man in the destruction of insect pests,

their comparative harmlessness (for they cannot be denied subsistence), all prove that they should

be ever welcome companions of him who was given dominion over the beasts of the field and the

birds of the air.

In city parks where there are many trees, bushes, and thick shrubbery, a good many birds may be

seen and heard near the middle of March. Today, the 22nd of the month, in a morning stroll, we saw

and heard the Song Sparrow, a Blue Bird, a Robin, and two Bluejays, and would, no doubt, have been

gratified with the presence of other early migrants, had the weather been more propitious. The sun

was obscured by clouds, a raw north wind was blowing, and rain, with threatened snow flurries,

awakened the protective instinct of the songsters and kept them concealed. But now, these April

mornings, if you incline to early rising, you may hear quite a concert, and one worth

attending.

—C. C. M.

{132}

IRISH BIRD

SUPERSTITIONS.

T HE HEDGEWARBLER, known more popularly

as the "Irish Nightingale," is the object of a most tender superstition. By day it is a roystering

fellow enough, almost as impish as our American Mocking Bird, in its emulative attempts to

demonstrate its ability to outsing the original songs of any feathered melodist that ventures near

its haunts among the reeds by the murmuring streams. But when it sings at night, and particularly

at the exact hour of midnight, its plaintive and tender notes are no less than the voices of babes

that thus return from the spirit land to soothe their poor, heart-aching mothers for the great

loss of their darlings. The hapless little Hedge Sparrow has great trouble in raising any young at

all, as its beautiful bluish-green eggs when strung above the hob are in certain localities

regarded as a potent charm against divers witch spells, especially those which gain an entrance to

the cabin through the wide chimney. On the contrary, the grayish-white and brown-mottled eggs of

the Wag-tail are never molested, as the grotesque motion of the tail of this tiny attendant of the

herds has gained for it the uncanny reputation and name of the Devil's bird.

HE HEDGEWARBLER, known more popularly

as the "Irish Nightingale," is the object of a most tender superstition. By day it is a roystering

fellow enough, almost as impish as our American Mocking Bird, in its emulative attempts to

demonstrate its ability to outsing the original songs of any feathered melodist that ventures near

its haunts among the reeds by the murmuring streams. But when it sings at night, and particularly

at the exact hour of midnight, its plaintive and tender notes are no less than the voices of babes

that thus return from the spirit land to soothe their poor, heart-aching mothers for the great

loss of their darlings. The hapless little Hedge Sparrow has great trouble in raising any young at

all, as its beautiful bluish-green eggs when strung above the hob are in certain localities

regarded as a potent charm against divers witch spells, especially those which gain an entrance to

the cabin through the wide chimney. On the contrary, the grayish-white and brown-mottled eggs of

the Wag-tail are never molested, as the grotesque motion of the tail of this tiny attendant of the

herds has gained for it the uncanny reputation and name of the Devil's bird.

THE STARLING, THE MAGPIE, AND THE CROW.

When the Starling does not follow the grazing cattle some witch charm has been put

upon them. The Magpie, as with the ancient Greeks, is the repository of the soul of an evil-minded

and gossiping woman. A round-tower or castle ruin unfrequented by Jackdaws is certainly haunted.

The "curse of the crows" is quite as malevolent as the "curse of Cromwell." When a "Praheen Cark"

or Hen Crow is found in the solitudes of mountain glens, away from human habitations, it assuredly

possesses the wandering soul of an impenitent sinner. If a Raven hover near a herd of cattle or

sheep, a withering blight has already been set upon the animals, hence the song of the bard Benean

regarding the rights of the kings of Cashel 1,400 years ago that a certain tributary province

should present the king yearly "a thousand goodly cows, not the cows of Ravens." The Waxwing, the

beautiful Incendiara avis of Pliny, whose breeding haunts have never yet been discovered by

man, are the torches of the Bean-sidhe, or Banshees. When the Cuckoo utters her first note

in the spring, if you chance to hear it, you will find under your right foot a white hair; and if

you keep this about your person, the first name you thereafter hear will be that of your future

husband or wife.

FOUR MOURNFUL SUPERSTITIONS.

Four other birds provide extremely mournful and pathetic superstitions. The Linnet pours forth

the most melancholy song of all Irish birds, and I have seen honest-hearted peasants affected by

it to tears. On inquiry I found the secret cause to be the belief that its notes voiced the

plaints of some unhappy soul in the spirit land. The changeless and interminable chant of the

Yellow Bunting is the subject of a very singular superstition. Its notes, begun each afternoon at

the precise hour of 3, are regarded as summons to prayer for souls not yet relieved from

purgatorial penance. A variety of Finch has notes which resemble what is called the "Bride-groom's

song" of unutterable dolor for a lost bride—a legend of superstition easily traceable to the

German Hartz mountain peasantry; while in the solemn intensity of the Bittern's sad and plaintive

boom, still a universally received token of spirit-warning, can be recognized the origin of the

mournful cries of the wailing Banshee.

{134}

|

| From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences. |

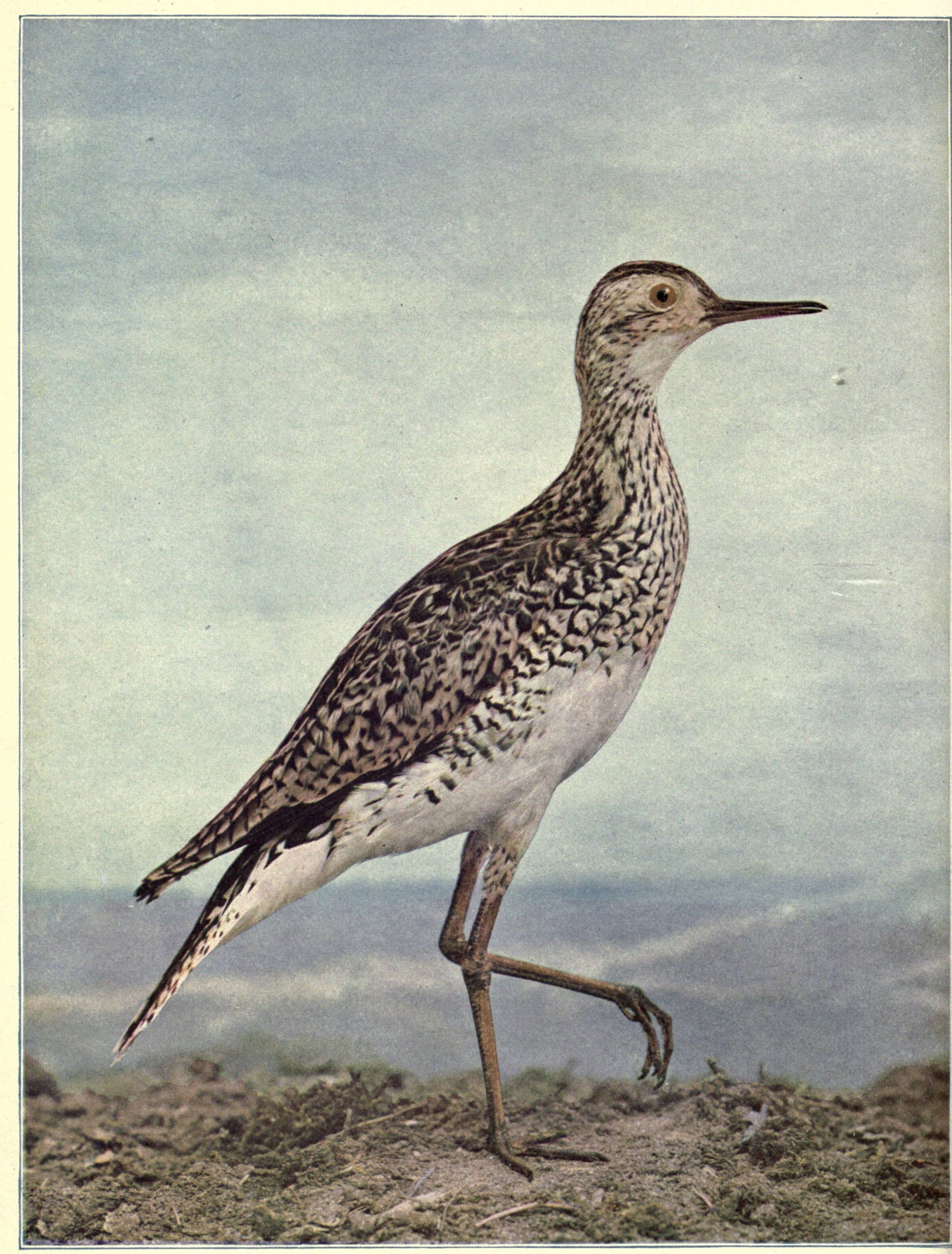

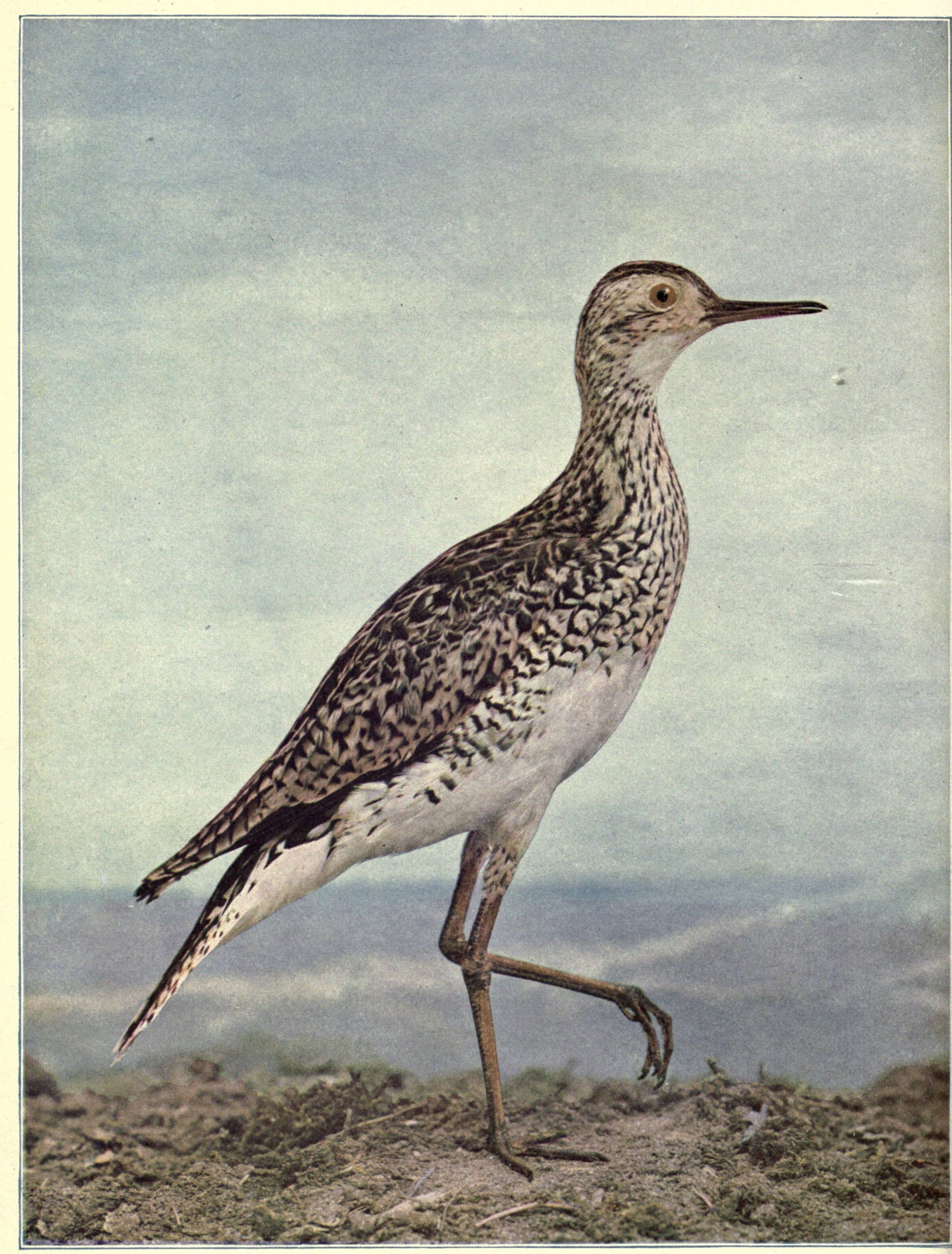

BARTRAMIAN SANDPIPER.

⅔ Life-size. |

Copyright by Nature Study

Pub. Co., 1898. Chicago. |

{135}

THE BARTRAMIAN

SANDPIPER.

T HIS pretty shore bird, known as

Bartram's Tattler, is found in more or less abundance all over the United States, but is rarely

seen west of the Rocky Mountains. It usually breeds from the middle districts—Ohio, Indiana,

Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, and the Dakotas northward, into the fur country, and in Alaska. It is

very numerous in the prairies of the interior, and is also common eastward. It has a variety of

names, being called Field Plover, Upland Plover, Grass Plover, Prairie Pigeon, and Prairie Snipe.

It is one of the most familiar birds on the dry, open prairies of Manitoba, where it is known as

the "Quaily," from its soft, mellow note. The bird is less aquatic than most of the other

Sandpipers, of which there are about twenty-five species, and is seldom seen along the banks of

streams, its favorite resorts being old pastures, upland, stubble fields, and meadows, where its

nest may be found in a rather deep depression in the ground, with a few grass blades for lining.

The eggs are of a pale clay or buff, thickly spotted with umber and yellowish-brown; usually four

in number.

HIS pretty shore bird, known as

Bartram's Tattler, is found in more or less abundance all over the United States, but is rarely

seen west of the Rocky Mountains. It usually breeds from the middle districts—Ohio, Indiana,

Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, and the Dakotas northward, into the fur country, and in Alaska. It is

very numerous in the prairies of the interior, and is also common eastward. It has a variety of

names, being called Field Plover, Upland Plover, Grass Plover, Prairie Pigeon, and Prairie Snipe.

It is one of the most familiar birds on the dry, open prairies of Manitoba, where it is known as

the "Quaily," from its soft, mellow note. The bird is less aquatic than most of the other

Sandpipers, of which there are about twenty-five species, and is seldom seen along the banks of

streams, its favorite resorts being old pastures, upland, stubble fields, and meadows, where its

nest may be found in a rather deep depression in the ground, with a few grass blades for lining.

The eggs are of a pale clay or buff, thickly spotted with umber and yellowish-brown; usually four

in number.

The Sandpiper frequently alights on trees or fences, like the Meadow Lark. This

species is far more abundant on the plains of the Missouri river region than in any other section

of our country. It is found on the high dry plains anywhere, and when fat, as it generally is,

from the abundance of its favorite food, the grasshopper, is one of the most delicious

imaginable.

Marshall Saunders tells us that in Scotland seven thousand children were carefully trained in

kindness to each other and to dumb animals.

It is claimed that not one of these in after years was ever tried for any criminal

offense in any court. How does that argue for humane education? Is not this heart training of our

boys and girls one which ought to claim the deepest sympathy and most ready support from us when

we think of what it means to our future civilization? "A brutalized child," says this

great-hearted woman, "is a lost child." And surely in permitting any act of cruelty on the

part of our children, we brutalize them, and as teachers and parents are responsible for the

result of our neglect in failing to teach them the golden rule of kindness to all of God's

creatures. It is said that out of two thousand criminals examined recently in American prisons,

only twelve admitted that they had been kind to animals during youth. What strength does that fact

contain as an argument for humane education?

{136}

THE NIGHTINGALE.

You have heard so much about the Nightingale that I am sure you will be glad to see my picture.

I am not an American bird; I live in England, and am considered the greatest of all bird

vocalists.

At midnight, when the woods are still and everybody ought to be asleep, I sing my best. Some

people keep awake on purpose to hear me. One gentleman, a poet, wept because my voice sounded so

melancholy. He thought I leaned my breast up against a thorn and poured forth my melody in

anguish. Another wondered what music must be provided for the angels in heaven, when such music as

mine was given to men on earth.

All that sounds very pretty, but between you and me, I'd sing another tune if a thorn should

pierce my breast.

Indeed, I am such a little bird that a big thorn would be the death of me. No, indeed, I am

always very happy when I sing. My mate wouldn't notice me at all if I didn't pour out my feelings

in song, both day and night. That is the only way I have to tell her that I love her, and to ask

her if she loves me. When she says "yes," then we go to housekeeping, build a nest and bring up a

family of little Nightingales. As soon as the birdies come out of their shell I literally change

my tune.

In place of the lovely music which everybody admires, I utter only a croak, expressive of my

alarm and anxiety. Nobody knows the trouble of bringing up a family better than I do. Sometimes my

nest, which is placed on or near the ground, is destroyed with all the little Nightingales in it;

then I recover my voice and go to singing again, the same old song: "I love you, I love you. Do

you love me?"

Toward the end of summer we leave England and return to our winter home, way off in the

interior of Africa. About the middle of April we get back to England again, the gentlemen

Nightingales arriving several days before the lady-birds.

{138}

|

| From coll. Mr F. Kaempfer. |

NIGHTINGALE.

4⁄5 Life-size. |

Copyright by Nature Study

Pub. Co., 1898. Chicago. |

{139}

THE NIGHTINGALE.

N O doubt those who never hear the song

of the Nightingale are denied a special privilege. Keats' exquisite verses give some notion of it,

and William Drummond, another English poet, has sung sweetly of the bird best known to fame.

"Singer of the night" is the literal translation of its scientific name, although during some

weeks after its return from its winter quarters in the interior of Africa it exercises its

remarkable vocal powers at all hours of the day and night. According to Newton, it is justly

celebrated beyond all others by European writers for the power of song. The song itself is

indiscribable, though numerous attempts, from the time of Aristophanes to the present, have been

made to express in syllables the sound of its many notes; and its effects on those who hear it is

described as being almost as varied as are its tones. To some they suggest melancholy; and many

poets, referring to the bird in the feminine gender, which cannot sing at all, have described it

as "leaning its breast against a thorn and pouring forth its melody in anguish." Only the male

bird sings. The poetical adoption of the female as the singer, however, is accepted as

impregnable, as is the position of Jenny Lind as the "Swedish Nightingale." Newton says there is

no reason to suppose that the cause and intent of the Nightingales' song, unsurpassed though it

be, differ in any respect from those of other birds' songs; that sadness is the least impelling

sentiment that can be properly assigned for his apparently melancholy music. It may in fact be an

expression of joy such as we fancy we interpret in the songs of many other birds. The poem,

however, which we print on another page, written by an old English poet, best represents our own

idea of the Nightingale's matchless improvisation, as some call it. It may be that it is always

the same song, yet those who have often listened to it assert that it is never precisely the same,

that additional notes are introduced and the song at times extended.

O doubt those who never hear the song

of the Nightingale are denied a special privilege. Keats' exquisite verses give some notion of it,

and William Drummond, another English poet, has sung sweetly of the bird best known to fame.

"Singer of the night" is the literal translation of its scientific name, although during some

weeks after its return from its winter quarters in the interior of Africa it exercises its

remarkable vocal powers at all hours of the day and night. According to Newton, it is justly

celebrated beyond all others by European writers for the power of song. The song itself is

indiscribable, though numerous attempts, from the time of Aristophanes to the present, have been

made to express in syllables the sound of its many notes; and its effects on those who hear it is

described as being almost as varied as are its tones. To some they suggest melancholy; and many

poets, referring to the bird in the feminine gender, which cannot sing at all, have described it

as "leaning its breast against a thorn and pouring forth its melody in anguish." Only the male

bird sings. The poetical adoption of the female as the singer, however, is accepted as

impregnable, as is the position of Jenny Lind as the "Swedish Nightingale." Newton says there is

no reason to suppose that the cause and intent of the Nightingales' song, unsurpassed though it

be, differ in any respect from those of other birds' songs; that sadness is the least impelling

sentiment that can be properly assigned for his apparently melancholy music. It may in fact be an

expression of joy such as we fancy we interpret in the songs of many other birds. The poem,

however, which we print on another page, written by an old English poet, best represents our own

idea of the Nightingale's matchless improvisation, as some call it. It may be that it is always

the same song, yet those who have often listened to it assert that it is never precisely the same,

that additional notes are introduced and the song at times extended.

The Nightingale is usually regarded as an English bird, and it is abundant in many parts of the

midland, eastern, and western counties of England, and the woods, coppices, and gardens ring with

its thrilling song. It is also found, however, in large numbers in Spain and Portugal and occurs

in Austria, upper Hungary, Persia, Arabia, and Africa, where it is supposed to spend its

winters.

The markings of the male and female are so nearly the same as to render the sexes almost

indistinguishable.

They cannot endure captivity, nine-tenths of those caught dying within a month. Occasionally a

pair have lived, where they were brought up by hand, and have seemed contented, singing the song

of sadness or of joy.

The nest of the Nightingale is of a rather uncommon kind, being placed on or near the ground,

the outworks consisting of a great number of dead leaves ingeniously put together. It has a deep,

cup-like hollow, neatly lined with fibrous roots, but the whole is so loosely constructed that a

very slight touch disturbs its beautiful arrangement. There are laid from four to six eggs of a

deep olive color.

Towards the end of summer the Nightingale disappears from England, and as but little has been

observed of its habits in its winter retreats, which are assumed to be in the interior of Africa,

little is known concerning them.

It must be a wonderful song indeed that could inspire the muse of great poets as

has that of the Nightingale.

{140}

THE BIRDS OF

PARADISE.

T HE far-distant islands of the Malayan

Archipelago, situated in the South Pacific Ocean, the country of the bird-winged butterflies,

princes of their tribe, the "Orang Utan," or great man-like ape, and peopled by Papuans and

Malays—islands whose shores are bathed perpetually by a warm sea, and whose surfaces are

covered with a most luxuriant tropical vegetation—these are the home of a group of birds

that rank as the radiant gems of the feathered race. None can excel the nuptial dress of the

males, either in the vividness of their changeable and rich plumage or the many strangely modified

and developed ornaments of feather which adorn them.

HE far-distant islands of the Malayan

Archipelago, situated in the South Pacific Ocean, the country of the bird-winged butterflies,

princes of their tribe, the "Orang Utan," or great man-like ape, and peopled by Papuans and

Malays—islands whose shores are bathed perpetually by a warm sea, and whose surfaces are

covered with a most luxuriant tropical vegetation—these are the home of a group of birds

that rank as the radiant gems of the feathered race. None can excel the nuptial dress of the

males, either in the vividness of their changeable and rich plumage or the many strangely modified

and developed ornaments of feather which adorn them.

The history of these birds is very interesting. Before the year 1598 the Malay traders called

them "Manuk dewata," or God's birds, while the Portuguese, finding they had no wings or feet,

called them Passaros de sol, or birds of the sun.

When the earliest European voyagers reached the Moluccas in search of cloves and nutmegs, which

were then rare and precious spices, they were presented with dried skins of Birds so strange and

beautiful as to excite the admiration even of these wealth-seeking rovers. John Van Linschoten in

1598 calls them "Avis Paradiseus, or Paradise birds," which name has been applied to them down to

the present day. Van Linschoten tells us "that no one has seen these birds alive, for they live in

the air, always turning towards the sun, and never alighting on the earth till they die." More

than a hundred years later, Funnel, who accompanied Dampier and wrote of the voyage, saw specimens

at Amboyna, and was told that they came to Banda to eat nutmegs, which intoxicated them and made

them fall down senseless, when they were killed by ants.

In 1760 Linnaeus named the largest species Paradisea apoda (the footless Paradise bird). At

that time no perfect specimen had been seen in Europe, and it was many years afterward when it was

discovered that the feet had been cut off and buried at the foot of the tree from which they were

killed by the superstitious natives as a propitiation to the gods. Wallace, who was the first

scientific observer, writer, and collector of these birds, and who spent eight years on the

islands studying their natural history, speaks of the males of the great Birds of Paradise

assembling together to dance on huge trees in the forest, which have wide-spreading branches and

large but scattered leaves, giving a clear space for the birds to play and exhibit their plumes.

From twelve to twenty individuals make up one of these parties. They raise up their wings, stretch

out their necks and elevate their exquisite plumes, keeping them in a continual vibration. Between

whiles they fly across from branch to branch in great excitement, so that the whole tree is filled

with waving plumes in every variety of attitude and motion. The natives take advantage of this

habit and climb up and build a blind or hiding place in a tree that has been frequented by the

birds for dancing. In the top of this blind is a small opening, and before day-light, a native

with his bow and arrow, conceals himself, and when the birds assemble he deftly shoots them with

his blunt-pointed arrows.

The great demand for the plumage of Birds of Paradise for decorative purposes is

causing their destruction at a rapid rate, and this caprice of a passing fashion will soon place

one of the most beautiful denizens of our earth in the same category as the great Auk and

Dodo.—Cincinnati Commercial-Gazette.

{141}

TO A NIGHTINGALE.

As it fell upon a day,

In the merry month of May,

Sitting in a pleasant shade,

Which a grove of myrtles made;

Beasts did leap, and birds did sing,

Trees did grow, and plants did spring;

Everything did banish moan,

Save the nightingale alone.

She, poor bird, as all forlorn,

Leaned her breast up—till a thorn;

And there sung the dolefull'st ditty,

That to hear it was great pity.

Fie, fie, fie, now would she cry;

Teru, teru, by and by;

That, to hear her so complain,

Scarce I could from tears refrain;

For her griefs, so lively shewn,

Made me think upon mine own.

Ah!—thought I—thou mourn'st in vain;

None takes pity on thy pain:

Senseless trees, they cannot hear thee;

Ruthless bears, they will not cheer thee;

King Pandion, he is dead;

All thy friends are lapped in lead;

All thy fellow-birds do sing,

Careless of thy sorrowing!

—Richard Barnfield.

Old English Poet.

{142}

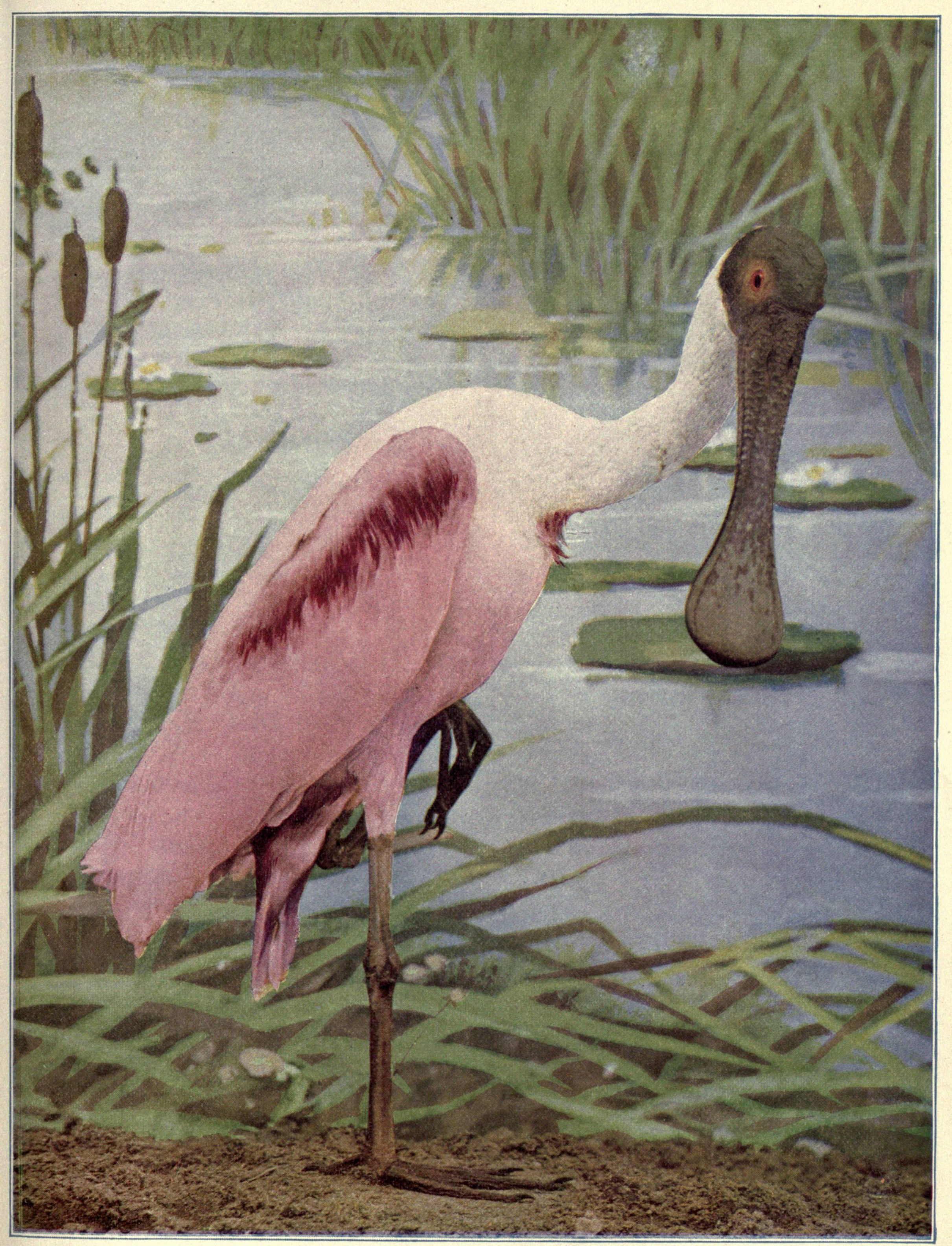

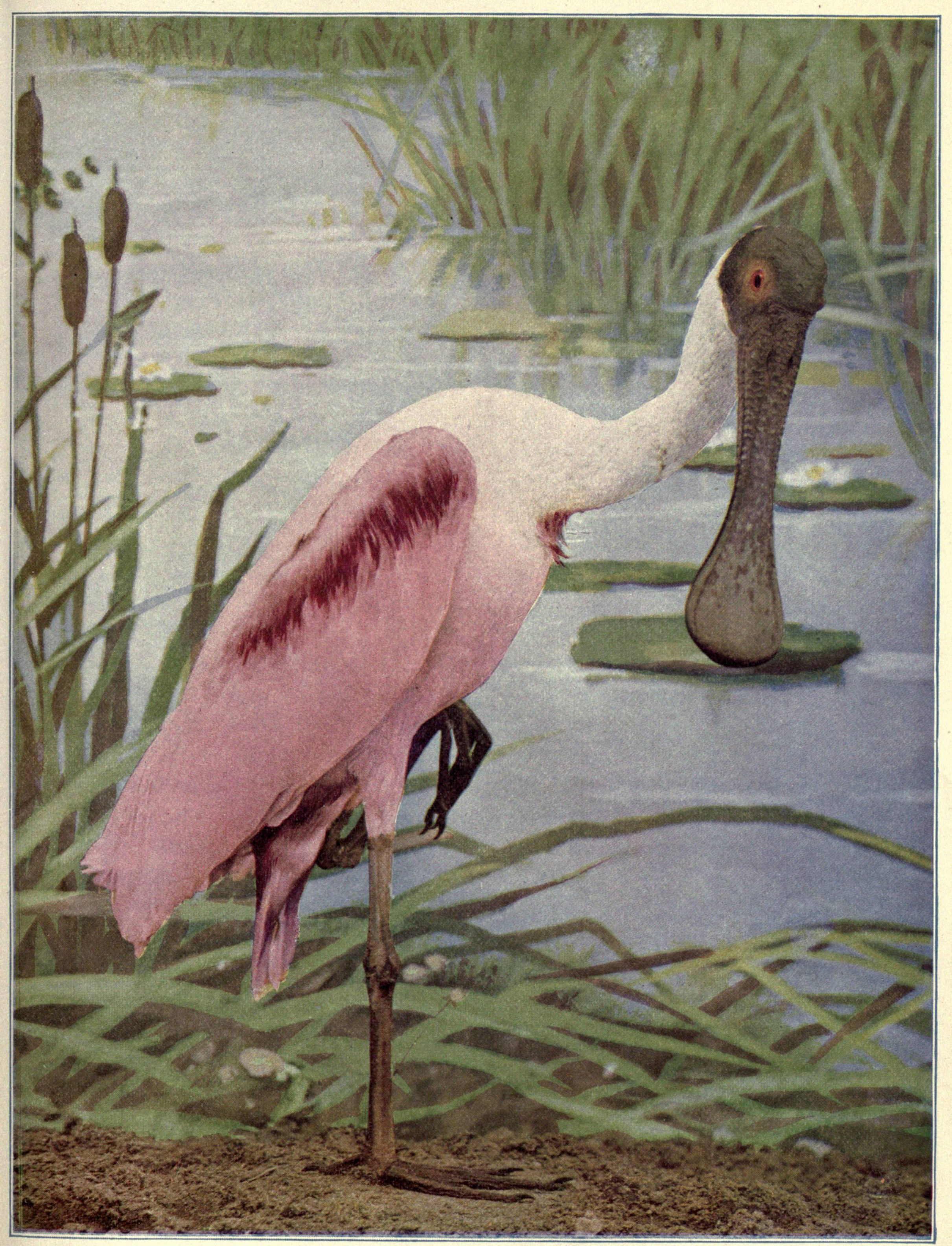

THE ROSEATE

SPOONBILL.

S PECIMENS of this bird when seen for

the first time always excite wonder and admiration. The beautiful plumage, the strange figure, and

the curiously shaped bill at once attract attention. Formerly this Spoonbill was found as far west

as Illinois and specimens were occasionally met with about ponds in the Mississippi Bottoms, below

St. Louis. Its habitat is the whole of tropical and subtropical America, north regularly to the

Gulf coast of the United States.

PECIMENS of this bird when seen for

the first time always excite wonder and admiration. The beautiful plumage, the strange figure, and

the curiously shaped bill at once attract attention. Formerly this Spoonbill was found as far west

as Illinois and specimens were occasionally met with about ponds in the Mississippi Bottoms, below

St. Louis. Its habitat is the whole of tropical and subtropical America, north regularly to the

Gulf coast of the United States.

Audubon observed that the Roseate Spoonbill is to be met with along the marshy or muddy borders

of estuaries, the mouths of rivers, on sea islands, or keys partially overgrown with bushes, and

still more abundantly along the shores of the salt-water bayous, so common within a mile or two of

the shore. There it can reside and breed, with almost complete security, in the midst of an

abundance of food. It is said to be gregarious at all seasons, and that seldom less than half a

dozen may be seen together, unless they have been dispersed by a tempest. At the approach of the

breeding season these small flocks come together, forming immense collections, and resort to their

former nesting places, to which they almost invariably return. The birds moult late in May, and

during this time the young of the previous year conceal themselves among the mangroves, there

spending the day, returning at night to their feeding grounds, but keeping apart from the old

birds, which last have passed through their spring moult early in March. The Spoonbill is said

occasionally to rise suddenly on the wing, and ascend gradually in a spiral manner, to a great

height. It flies with its neck stretched forward to its full length, its legs and feet extended

behind. It moves with easy flappings, until just as it is about to alight, when it sails over the

spot with expanded wing and comes gradually to the ground.

Usually the Spoonbill is found in the company of Herons, whose vigilance apprises it of any

danger. Like those birds, it is nocturnal, its principal feeding time being from near sunset until

daylight. In procuring its food it wades into the water, immerses its immense bill in the soft

mud, with the head, and even the whole neck, beneath the surface, moving its partially opened

mouth to and fro, munching the small fry—insects or shell-fish—before it swallows

them. Where many are together, one usually acts as a sentinel. The Spoonbill can alight on a tree

and walk on the large branches with much facility.

The nests of these birds are platforms of sticks, built close to the trunks of trees, from

eight to eighteen feet from the ground. Three or four eggs are usually laid. The young, when able

to fly, are grayish white. In their second year they are unadorned with the curling feathers on

the breast, but in the third spring they are perfect.

Formerly very abandant, these attractive creatures have greatly diminished by the constant

persecution of the plume hunters.

{143}

|

| From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences. |

ROSEATE SPOONBILL.

⅓ Life-size. |

Copyright by Nature Study

Pub. Co., 1898. Chicago. |

{145}

THE ROSEATE

SPOONBILL.

If my nose and legs were not so long, and my mouth such a queer shape, I would be handsome,

wouldn't I? But my feathers are fine, everybody admits that—especially the ladies.

"How lovely," they all exclaim, when they see one of us Spoonbills. "Such a delicate, delicate

pink!" and off they go to the milliners and order a hat trimmed with our pretty plumes.

That is the reason so few of us spoonbills are to be found in certain localities now-a-days,

Florida especially. Fashion has put most of us to death. Shame, isn't it, when there are silk, and

ribbon, and flowers in the world? Talk to your mothers and sisters, boys, and plead with them to

let the birds alone.

We inhabit the warmer parts of the world; South and Central America, Mexico, and the Gulf

regions of the United States. We frequent the shores, both on the sea coast and in the interior;

marshy, muddy ground is our delight.

When I feel like eating something nice, out I wade into the water, run my long bill, head and

neck, too, sometimes, into the soft mud, move my bill to and fro, and such a lot of small fry as I

do gather—insects and shell fish—which I munch and munch before I swallow.

I am called a "wader" for doing this. My legs are not any too long, you observe, for such work.

I am very thankful at such times that I don't wear stockings or knickerbockers.

We are friendly with Herons and like to have one or two of them accompany us. They are very

vigilant fellows, we find, and make good sentinels, warning us when danger approaches.

Fly? Oh, yes, of course we do. With our neck stretched forward and our legs and feet extended

behind, up we go gradually in a spiral manner to a great height.

In some countries, they say, our beaks are scraped very thin, polished, and used as a spoon,

sometimes set in silver. I wonder if that is the reason we are called Spoonbills?

The Spoonbills are sociable birds; five or six of us generally go about in company,

and when it comes time for us to raise families of little Spoonbills, we start for our nesting

place in great flocks; the same place where our nests were built the year before.

{146}

DICKCISSEL.

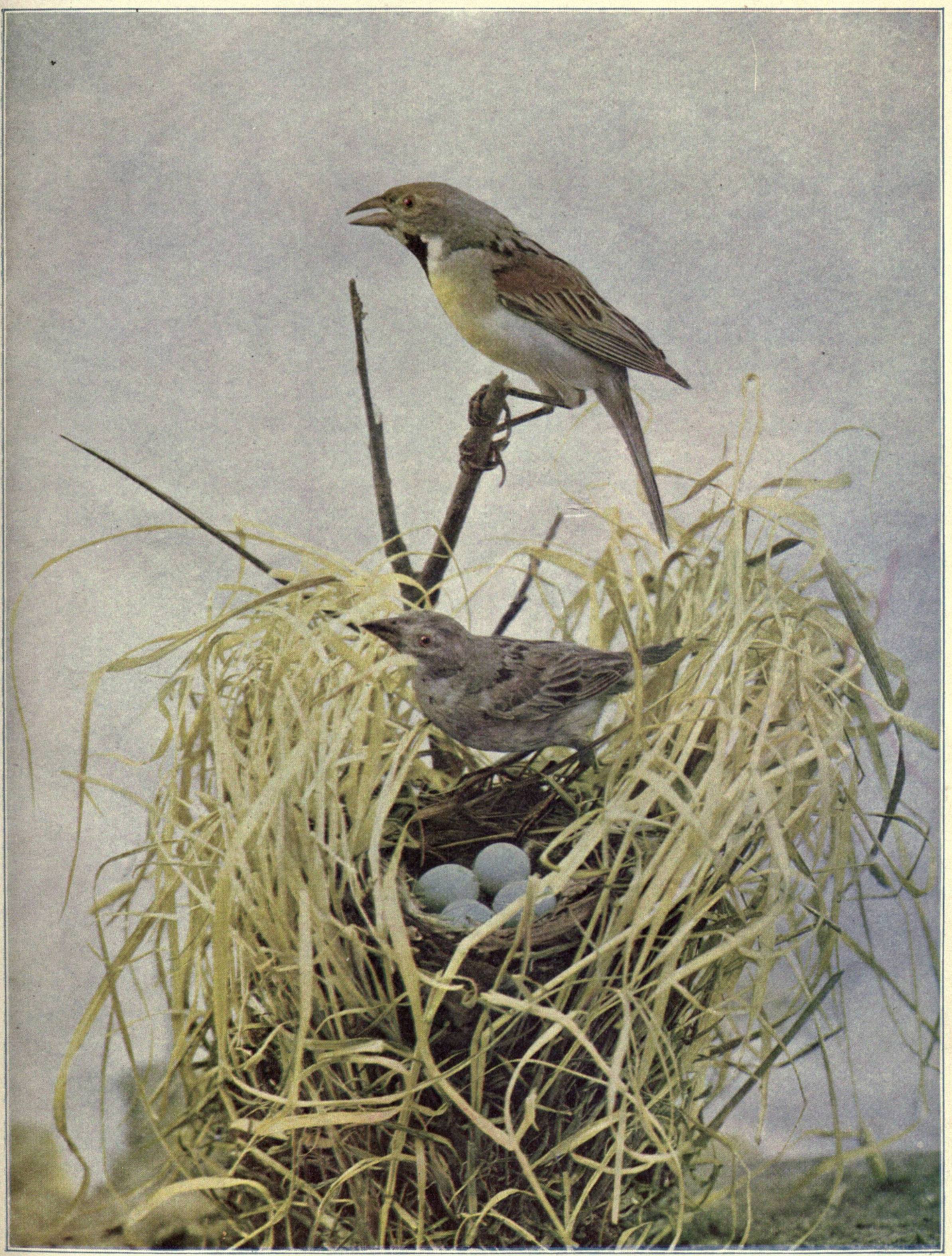

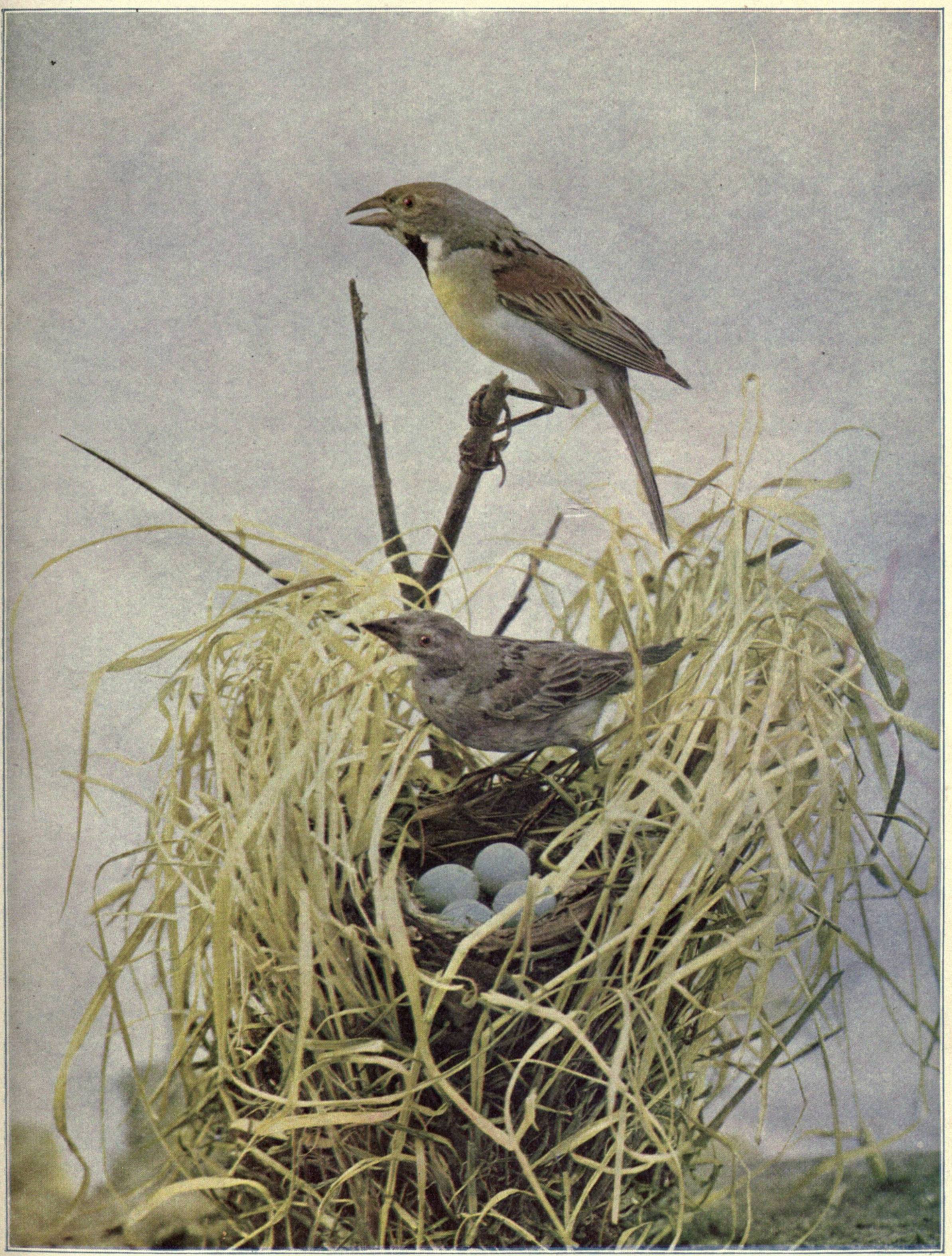

M R. P. M. SILLOWAY, in his charming

sketches, "Some Common Birds," writes: "The Cardinal frequently whistles the most gaily while

seated in the summit of the bush which shelters his mate on her nest. It is thus with Dickcissel,

for though his ditties are not always eloquent to us, he is brave in proclaiming his happiness

near the fountain of his inspiration. While his gentle mistress patiently attends to her household

in some low bush or tussock near the hedge, Dick flutters from perch to perch in the immediate

vicinity and voices his love and devotion. Once I flushed a female from a nest in the top of an

elm bush along a railroad while Dick was proclaiming his name from the top of a hedge within

twenty feet of the site. Even while she was chirping anxiously about the spot, apprehending that

her home might be harried by ruthless visitors, he was brave and hopeful, and tried to sustain her

anxious mind by ringing forth his cheerful exclamations."

R. P. M. SILLOWAY, in his charming

sketches, "Some Common Birds," writes: "The Cardinal frequently whistles the most gaily while

seated in the summit of the bush which shelters his mate on her nest. It is thus with Dickcissel,

for though his ditties are not always eloquent to us, he is brave in proclaiming his happiness

near the fountain of his inspiration. While his gentle mistress patiently attends to her household

in some low bush or tussock near the hedge, Dick flutters from perch to perch in the immediate

vicinity and voices his love and devotion. Once I flushed a female from a nest in the top of an

elm bush along a railroad while Dick was proclaiming his name from the top of a hedge within

twenty feet of the site. Even while she was chirping anxiously about the spot, apprehending that

her home might be harried by ruthless visitors, he was brave and hopeful, and tried to sustain her

anxious mind by ringing forth his cheerful exclamations."

Dick has a variety of names, the Black-throated Bunting, Little Field Lark, and "Judas-bird."

In general appearance it looks like the European House Sparrow, averaging a trifle larger.

The favorite resorts of this Bunting are pastures with a sparse growth of stunted bushes and

clover fields. In these places, its unmusical, monotonous song may be heard thoughout the day

during the breeding season. Its song is uttered from a tall weed, stump, or fence-stake, and is a

very pleasing ditty, says Davie, when its sound is heard coming far over grain fields and meadows,

in the blaze of the noon-day sun, when all is hushed and most other birds have retired to shadier

places.

As a rule, the Dickcissels do not begin to prepare for housekeeping before the first of June,

but in advanced seasons the nests are made and the eggs deposited before the end of May. The nest

is built on the ground, in trees and in bushes, in tall grass, or in clover fields. The materials

are leaves, grasses, rootlets, corn husks, and weed stems; the lining is of fine grasses, and

often horse hair. It is a compact structure. Second nests are sometimes built in July or August.

The eggs number four or five, almost exactly like those of the Bluebird.

The summer home of Dickcissel is eastern United States, extending northward to southern New

England and Ontario, and the states bordering the great lakes. He ranges westward to the edge of

the great plains, frequently to southeastern United States on the migration. His winter home is in

tropical regions, extending as far south as northern South America. He is commonly regarded as a

Lark, but is really a Finch.

In the transactions of the Illinois Horticultural Society, Prof. S. A. Forbes

reports that his investigations show that sixty-eight per cent. of the food of the Dickcissels

renders them beneficial to horticulture, seven per cent. injurious, and twenty-five per cent.

neutral, thus leaving a large balance in their favor.

THOUGHTS.

Who knows the joy a flower knows

When it blows sweetly?

Who knows the joy a bird knows

When it goes fleetly?

Bird's wing and flower stem—

Break them, who would?

Bird's wing and flower stem—

Make them, who could?

—Harper's Weekly.

{147}

|

| From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences. |

DICKCISSEL.

⅔ Life-size. |

Copyright by Nature Study

Pub. Co., 1898. Chicago. |

{149}

THE DICKCISSEL.

You little folks, I'm afraid, who live or visit in the country every summer, will not recognize

me when I am introduced to you by the above name. You called me the Little Field Lark, or Little

Meadow Lark, while all the time, perched somewhere on a fence-stake, or tall weed-stump, I was

telling you as plain as I could what my name really is.

"See, see," I said, "Dick, Dick—Cissel, Cissel."

To tell you the truth I don't belong to the Lark family at all. Simply because I wear a yellow

vest and a black bow at my throat as they do doesn't make me a Lark. You can't judge birds,

anymore than people, by their clothes. No, I belong to the Finch, or Bunting family, and they who

call me the Black-throated Bunting are not far from right.

I am one of the birds that go south in winter. About the first of April I get back from the

tropics and really I find some relief in seeing the hedges bare, and the trees just putting on

their summer dress. In truth I don't care much for buds and blossoms, as I only frequent the trees

that border the meadows and cornfields. Clover fields have a great attraction for me, as well as

the unbroken prairie.

I sing most of the time because I am so happy. To be sure it is about the same tune, "See,

see,—Dick, Dick—Cissel, Cissel," but as it is about myself I sing I never grow

tired of it. Some people do, however, and wish I would stop some time during the day. Even in the

hottest noonday you will see me perched on a fence-stake or a tall weed-stalk singing my little

song, while my mate is attending to her nest tucked away somewhere in a clump of weeds, or bush,

very near the ground.

There, I am sorry I told you that. You may be a bad boy, or a young collector, and

will search this summer for my nest, and carry it and all the pretty eggs away. Think how

sorrowful my mate would be, and I, no longer happy, would cease to sing, "See, See,—Dick,

Dick, Cissel, Cissel."

{150}

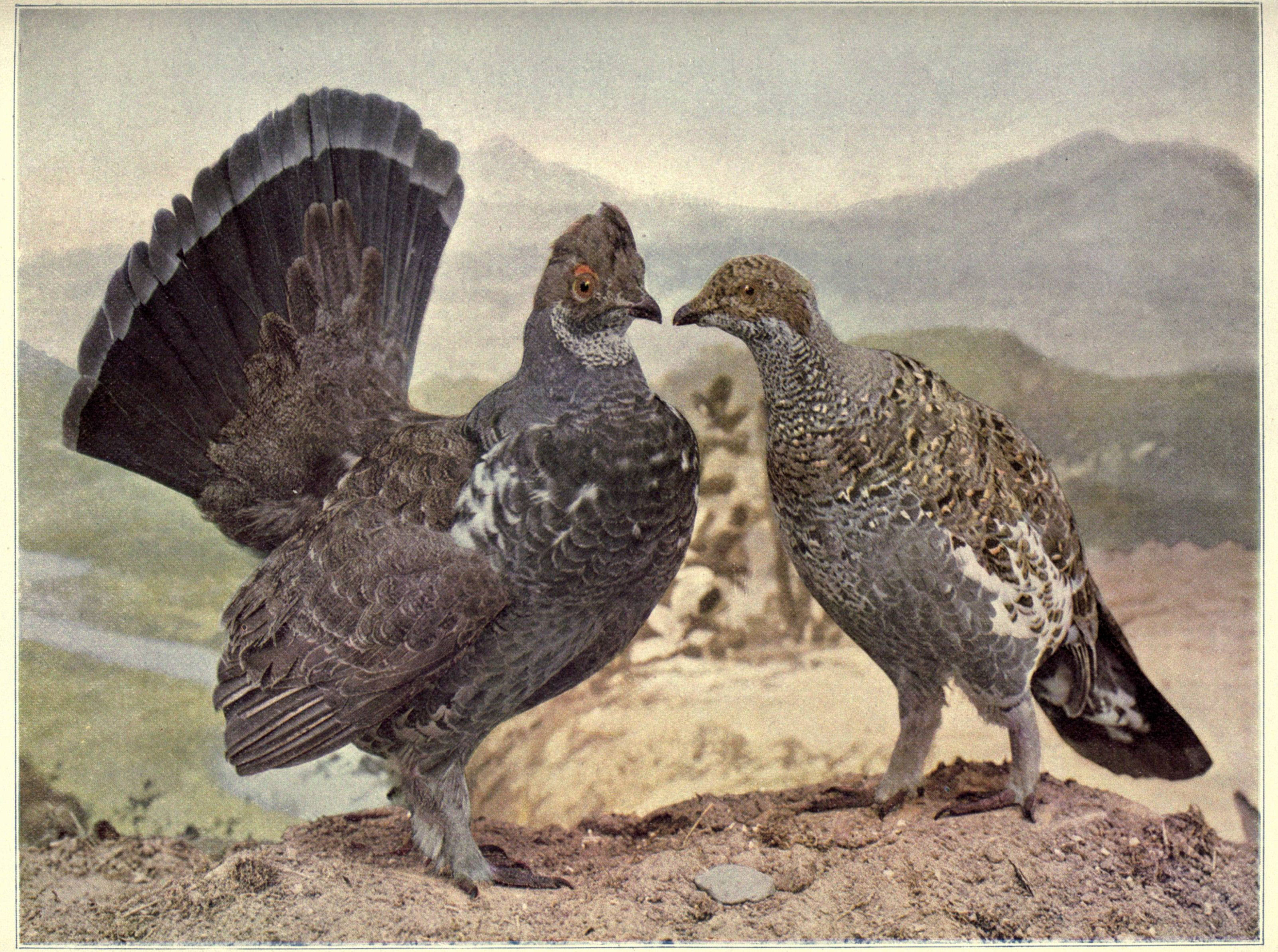

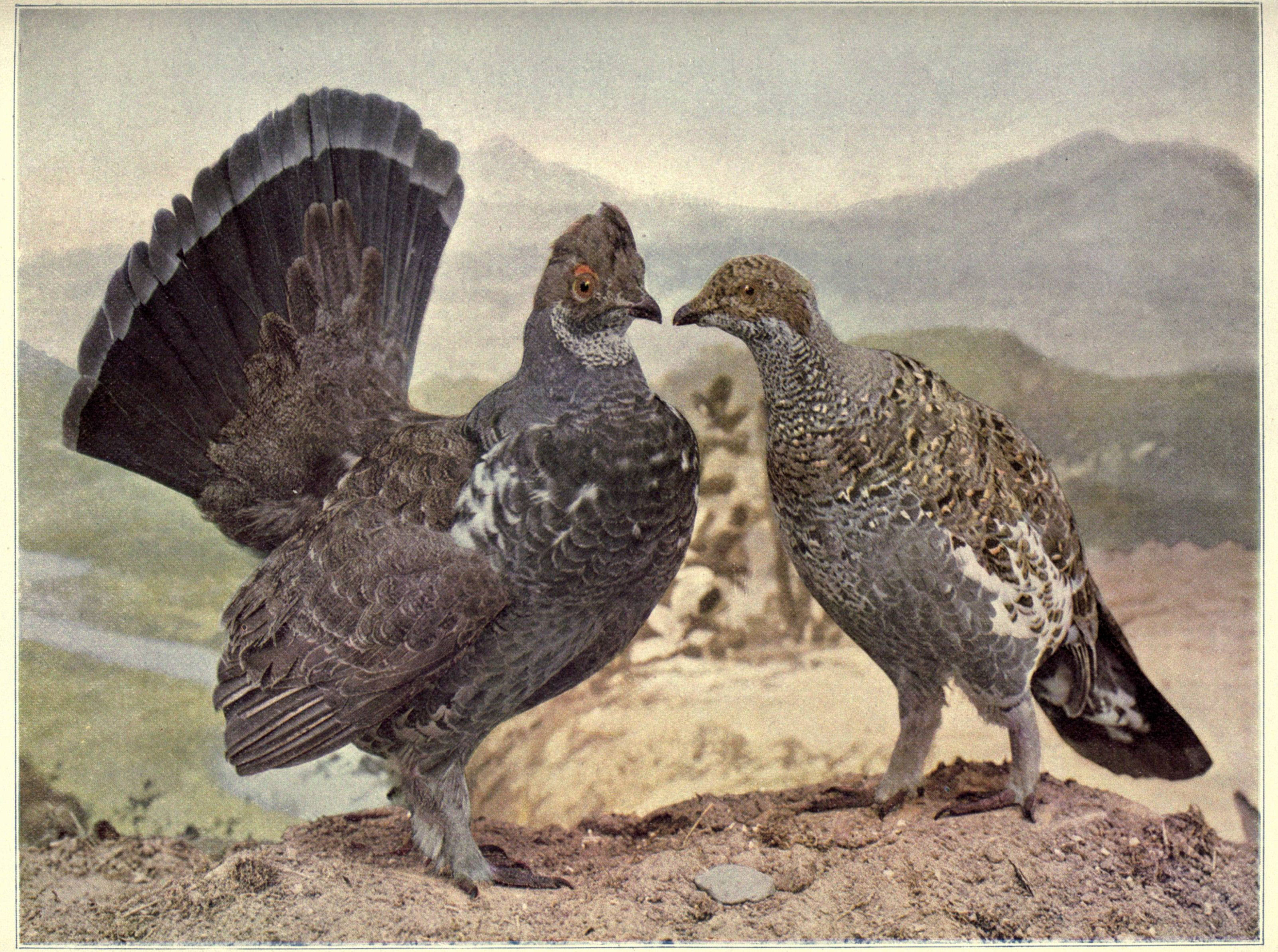

THE DUSKY GROUSE.

U NDER various names, as Blue Grouse,

Grey Grouse, Mountain Grouse, Pine Grouse, and Fool-hen, this species, which is one of the finest

birds of its family, is geographically distributed chiefly throughout the wooded and especially

the evergreen regions of the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific and northward into British America. In

the mountains of Colorado Grouse is found on the border of timber line, according to Davie,

throughout the year, going above in the fall for its principal food—grasshoppers. In summer

its flesh is said to be excellent, but when frost has cut short its diet of insects and berries it

feeds on spruce needles and its flesh acquires a strong flavor. Its food and habits are similar to

those of the Ruffed Grouse. Its food consists of insects and the berries and seeds of the pine

cone, the leaves of the pines, and the buds of trees. It has also the same habits of budding in

the trees during deep snows. In the Blue Grouse, however, this habit of remaining and feeding in

the trees is more decided and constant, and in winter they will fly from tree to tree, and often

are plenty in the pines, when not a track can be found in the snow. It takes keen and practiced

eyes to find them in the thick branches of the pines. They do not squat and lie closely on a limb

like a quail, but stand up, perfectly still, and would readily be taken for a knot or a broken

limb. If they move at all it is to take flight, and with a sudden whir they are away, and must be

looked for in in another tree top.

NDER various names, as Blue Grouse,

Grey Grouse, Mountain Grouse, Pine Grouse, and Fool-hen, this species, which is one of the finest

birds of its family, is geographically distributed chiefly throughout the wooded and especially

the evergreen regions of the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific and northward into British America. In

the mountains of Colorado Grouse is found on the border of timber line, according to Davie,

throughout the year, going above in the fall for its principal food—grasshoppers. In summer

its flesh is said to be excellent, but when frost has cut short its diet of insects and berries it

feeds on spruce needles and its flesh acquires a strong flavor. Its food and habits are similar to

those of the Ruffed Grouse. Its food consists of insects and the berries and seeds of the pine

cone, the leaves of the pines, and the buds of trees. It has also the same habits of budding in

the trees during deep snows. In the Blue Grouse, however, this habit of remaining and feeding in

the trees is more decided and constant, and in winter they will fly from tree to tree, and often

are plenty in the pines, when not a track can be found in the snow. It takes keen and practiced

eyes to find them in the thick branches of the pines. They do not squat and lie closely on a limb

like a quail, but stand up, perfectly still, and would readily be taken for a knot or a broken

limb. If they move at all it is to take flight, and with a sudden whir they are away, and must be

looked for in in another tree top.

Hallock says that in common with the Ruffed Grouse (see Birds, Vol. I,

p. 220), the packs have a habit of scattering in winter, two or three, or even a single bird,

being often found with no others in the vicinity, their habit of feeding in the trees tending to

separate them.

The size of the Dusky Grouse is nearly twice that of the Ruffed Grouse, a full-grown bird

weighing from three to four pounds. The feathers are very thick, and it seems fitly dressed to

endure the vigor of its habitat, which is in the Rocky Mountains and Sierra Nevada country only,

and in the pine forests from five to ten thousand feet above the level of the sea. The latter

height is generally about the snow line in these regions. Although the weather in the mountains is

often mild and pleasant in winter, and especially healthy and agreeable from the dryness and

purity of the atmosphere, yet the cold is sometimes intense.

Some years ago Mr. Hallock advised that the acclimation of this beautiful bird be tested in the

pine forests of the east. Though too wild and shy, he said, to be domesticated, there is no reason

why it might not live and thrive in any pine lands where the Ruffed Grouse is found. Since the

mountain passes are becoming threaded with railroads, and miners, herders, and other settlers are

scattering through the country, it will be far easier than it has been to secure and transport

live birds or their eggs, and it is to be hoped the experiment will be tried.

This Grouse nests on the ground, often under shelter, of a hollow log or projecting rock, with

merely a few pine needles scratched together. From eight to fifteen eggs are laid, of buff or

cream color, marked all over with round spots of umber-brown.

{151}

|

| From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences. |

DUSKY GROUSE.

⅓ Life-size. |

Copyright by Nature Study

Pub. Co., 1898. Chicago. |

{153}

APPLE BLOSSOM TIME.

The time of apple blooms has come again,

And drowsy winds are laden with perfume;

In village street, in grove and sheltered glen

The happy warblers set the air atune.

Each swaying motion of the bud-sweet trees

Scatters pale, fragrant petals everywhere;

Reveals the tempting nectar cups to bees

That gild their thighs with pollen. Here and there

The cunning spoilers roam, and dream and sip

The honey-dew from chalices of gold;

The brimming cups are drained from lip to lip

Till, cloyed with sweets, the tiny gauze wings fold.

Above the vine-wreathed porch the old trees bend,

Shaking their beauty down like drifted snow:

And as we gaze, the lovely blossoms send

Fair visions of the days of long ago.

Yes, apple blossom time has come again,

But still the breezes waft the perfumes old,

And everywhere in wood, and field, and glen

The same old life appears in lovelier mold.

—Nora A. Piper.

{154}

LET US ALL PROTECT THE EGGS OF

THE BIRDS.

E LIZABETH NUNEMACHER, in Our Animal

Friends, writes thus of her observation of birds. Would that her suggestions for their

protection might be heeded.

LIZABETH NUNEMACHER, in Our Animal

Friends, writes thus of her observation of birds. Would that her suggestions for their

protection might be heeded.

"Said that artist in literature, Thomas Wentworth Higginson: 'I think that, if required, on

pain of death to name instantly the most perfect thing in the universe, I would risk my fate on a

bird's egg; ... it is as if a pearl opened and an angel sang.' But far from his beautiful thought

was the empty shell, the mere shell of the collector. How can he be a bird lover who, after

rifling some carefully tended nest, pierces the two ends of one of these exquisite crusts of

winged melody, and murderously blows one more atom of wings and song into nothingness? The

inanimate shell, however lovely in color, what is it? It is not an egg; an egg comprehends the

contents, the life within. Aside from the worthlessness of such a possession, each egg purloined

means we know not what depth of grief to the parent, and a lost bird life; a vacuum where song

should be.

People who love birds and the study of them prefer half an hour's personal experience with a

single bird to a whole cabinet of "specimens." Yet a scientist recently confessed that he had

slain something like four hundred and seventy-five Redstarts, thus exterminating the entire

species from a considable range of country, to verify the fact of a slight variation in color. One

would infinitely prefer to see one Redstart in the joy of life to all that scientific lore could

impart regarding the entire family of Redstarts by such wholesale butchery, which nothing can

excuse.

We hear complaints of the scarcity of Bluebirds from year to year. I have watched, at intervals

since early April, the nest of a single pair of Bluebirds in an old apple tree. On April 29th

there were four young birds in the nest. On May 4th they had flown; an addition was made to the

dwelling, and one egg of a second brood was deposited. On May 31st the nest again held four young

Bluebirds. June 15th saw this second quartette leave the apple tree for the outer world, and

thinking surely that the little mother had done, I appropriated the nest; but on June 25th I found

a second nest built, and one white egg, promising a third brood. From the four laid this time,

either a collector or a Bluejay deducted one, and on July 14th the rest were just out of the

shell. This instance of the industry of one pair of Bluebirds proves that their scarcity is no

fault of theirs. I may add that the gentle mother suffered my frequent visits and my meddling with

her nursery affairs without any show of anger or excitement, uttering only soft murmurs, which

indicated a certain anxiety. May not the eleven young Bluebirds mean a hundred next season, and is

not the possessor of the missing egg guilty of a dozen small lives?"

We have observed that the enthusiasm of boys for collecting eggs is frequently inspired by

licensed "collectors," who are known in a community to possess many rare and valuable specimens.

Too many nests are despoiled for so-called scientific purposes, and a limit should be set to the

number of eggs that may be taken by any one for either private or public institutions. Let us

influence the boys to "love the wood-rose, and leave it on its stalk."

{155}

|

| From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences. |

EGGS

|

Copyright by Nature Study

Pub. Co., 1898. Chicago. |

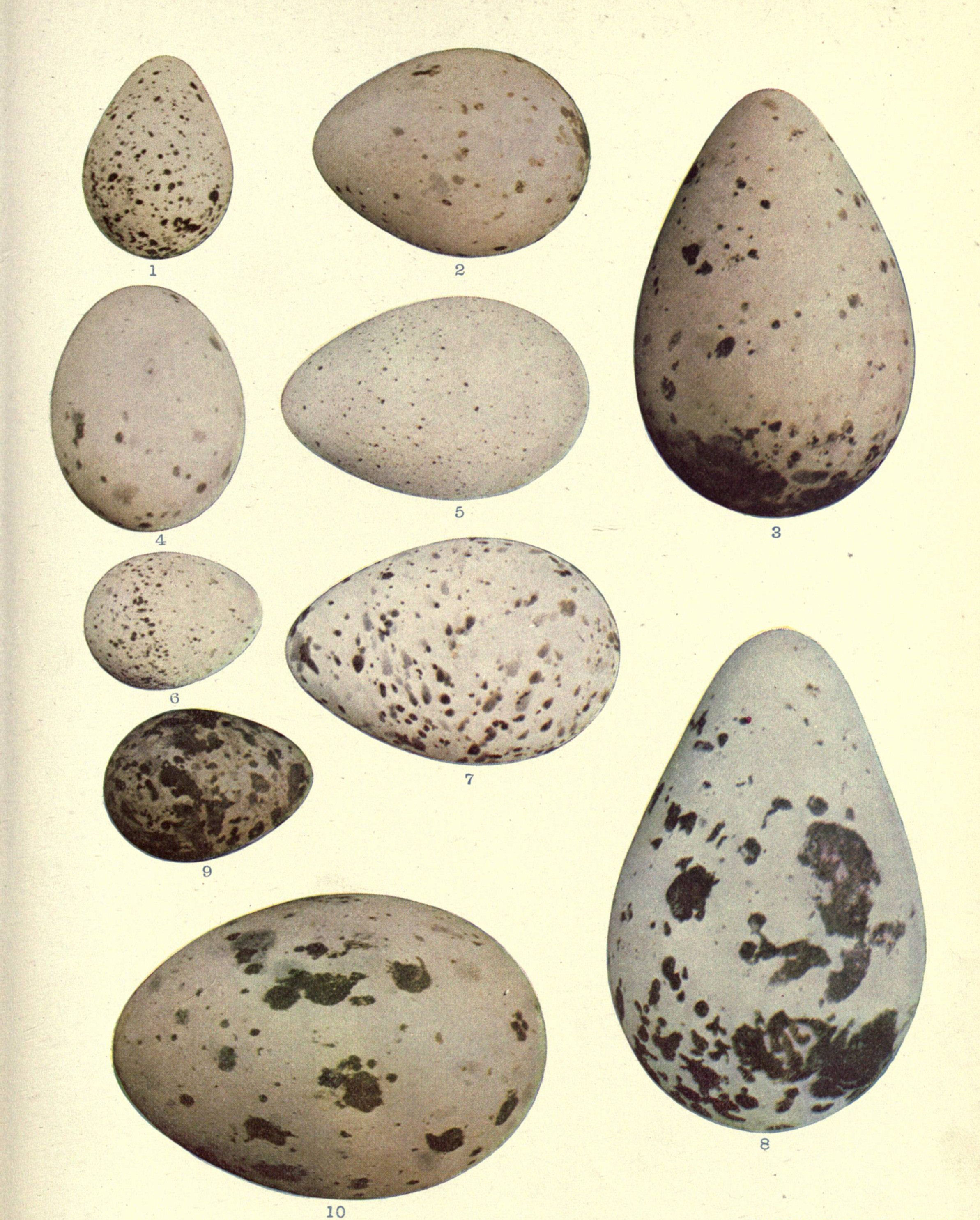

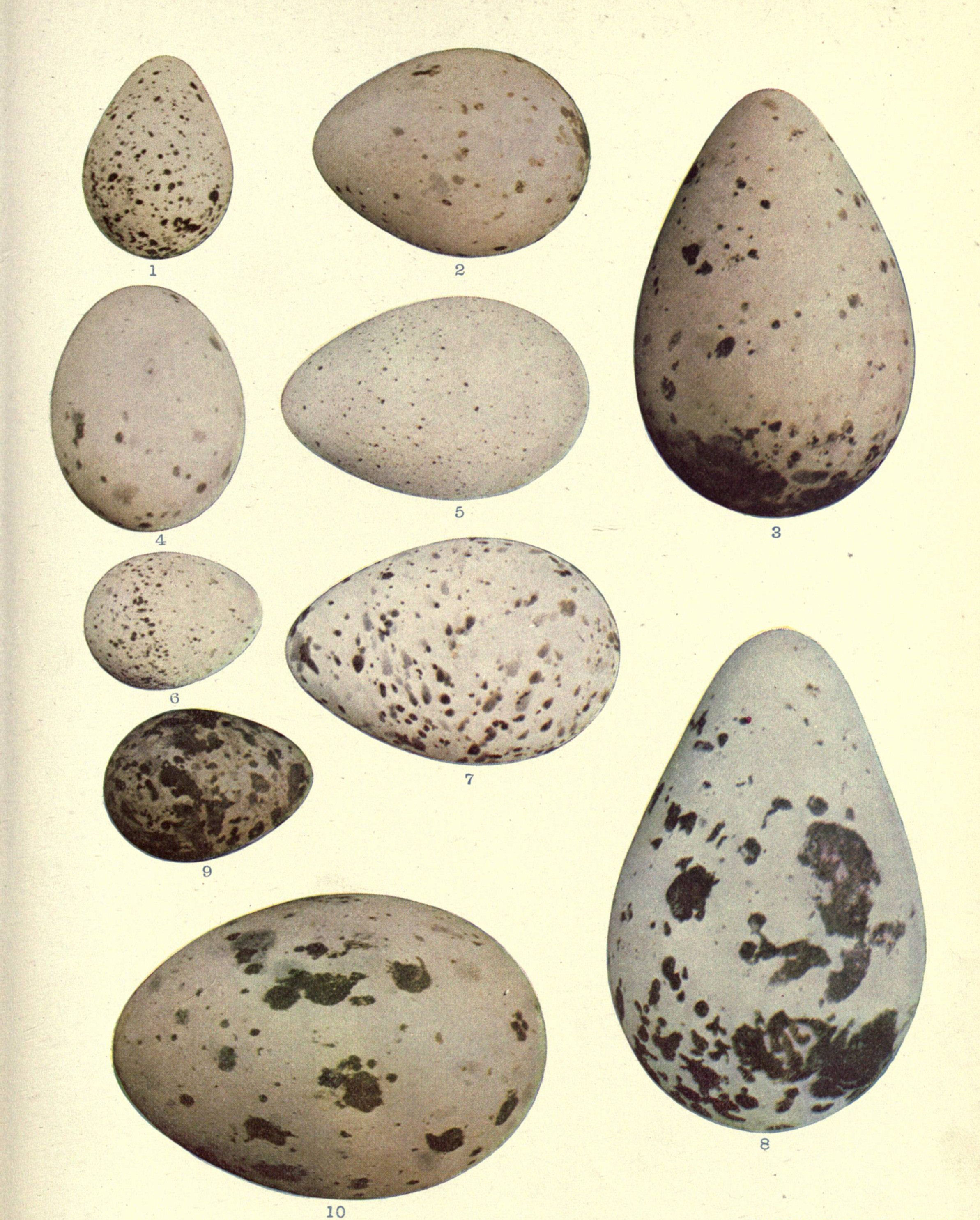

1. Spotted Sandpiper.

2. Bartramian Sandpiper.

3. Marbled Godwit.

4. King Rail.

5. American Coot.

6. Least Tern.

7. Sooty Tern.

8. Common Murre.

9. Black Tern.

10. Herring Gull.

{157}

THE NEW TENANTS.

By Elanora Kinsley Marble.

Mrs. Wren, in a very contented frame of mind, sat upon her nest, waiting with an ever growing

appetite for that delicious spider or nice fat canker worm which her mate had promised to fetch

her from the orchard.

"How happy I am," she mused, "and how thankful I ought to be for so loving a mate and such a

dear, little cozy home. Why, keeping house and raising a family is just no trouble at all.

Indeed—" but here Mrs. Wren's thoughts were broken in upon by the arrival of Mrs. John, who

announced, as she perched upon the rim of the tin-pot and looked disdainfully around, that she had

but a very few minutes to stay.

"So this is the cozy nest your husband is so fond of talking about," she said, her bill in the

air. "My, my, whatever possessed you, my dear, to begin housekeeping in such humble quarters.

Everything in this world depends upon appearances; the sooner you find that out, Jenny, the

better. From the very first I was determined to begin at the top. The highest pole in the

neighborhood, or none, I said to Mr. John when he was looking for a site on which to build our

house; and to do him justice Mr. Wren never thought of anything lower himself. A tin-pot, indeed,

under a porch. Dear, dear!" and Mrs. John's bill turned up, and the corners of her mouth turned

down in a very haughty and disdainful manner.

"I—didn't—know, I'm—sure," faltered poor little Mrs. Jenny, her feathers

drooping at once. "I—thought our little house, or flat, was very nice and comfortable. It is

in an excellent neighborhood, and our landlord's family is—"

"Oh, bother your landlord's family," interrupted Mrs. John impolitely. "All your neighbors are

tired and sick of hearing Mr. Wren talk about his landlord's family. The way he repeats their

sayings and doings is nauseating, and as for naming your brood after them, why—" Mrs. John

shrugged her wings and laughed scornfully.

Mrs. Wren's head feathers rose at once, but experience had taught her the folly of quarreling

with her aunt, so she turned the subject by inquiring solicitously after her ladyship's

health.

"Oh, its only fair, fair to middlin'," returned Mrs. John, poking her bill about the edge of

the nest as though examining its lining. "I told Mr. John this morning that I would be but a

shadow of myself after fourteen days brooding, if he was like the other gentlemen Wrens in the

neighborhood. Catch me sitting the day {158}through listening to him singing or showing off for my benefit. No,

indeed! He is on the nest now, keeping the eggs warm, and I told him not to dare leave it till my

return."

Mrs. Jenny said nothing, but she thought what her dear papa would have done under like

circumstances.

"All work and no play," continued Mrs. John, "makes dull women as well as dull boys. That was

what my mama said when she found out papa meant her to do all the work while he did the playing

and singing. Dear, dear, how many times I have seen her box his ears and drive him onto the nest

while she went out visiting," and at the very recollection Mrs. John flirted her tail over her

back and laughed loudly.

"How many eggs are you sitting upon this season, Aunt?" inquired Mrs. Jenny, timidly.

"Eight. Last year I hatched out nine; as pretty a brood as you would want to see. If I had

time, Jenny, I'd tell you all about it. How many eggs are under you?"

"Six," meekly said Jenny, who had heard about that brood scores of times, "we thought—we

thought—"

"Well?" impatiently, "you thought what?"

"That six would be about as many as we could well take care of. I am sure it will keep us both

busy finding worms and insects for even that number of mouths."

"I should think it would" chuckled Mrs. John, nodding her head wisely, "but—" examining a

feather which she had drawn out of the nest with her bill, "what is this? A chicken

feather, as I live; a big, coarse, chicken feather. And straw too, instead of hay. Ah! little did

I think a niece of mine would ever furnish her house in such a shabby manner," and Mrs. John,

whose nest was lined with horse-hair, and the downiest geese feathers which her mate could

procure, very nearly turned green with shame and mortification.

Mrs. Jenny's head-feathers were bristling up again when she gladly espied Mr. Wren flying

homeward with a fine wriggling worm in his bill.

"Ah, here comes your hubby," remarked Mrs. John, "he's been to market, I see. Well, ta, ta,

dear. Run over soon to see us," and off Mrs. John flew to discuss Mrs. Jenny's housekeeping

arrangements with one of her neighbors.

Mr. Wren's songs and antics failed, to draw a smile from his mate the remainder of that day.

Upon her nest she sat and brooded, not only her eggs, but over the criticisms and taunts of Mrs.

John. Straw, chicken-feathers, and old tin pots occupied her thoughts to the exclusion of

everything else, and it was not without a feeling of shame she recalled her morning's happiness

and spirit of sweet content. The western sky was still blushing under the fiery gaze of the sun,

when Mrs. Jenny fell into a doze and dreamed that she, the very next day, repaid Mrs. John Wren's

call. The wind was blowing a hurricane and the pole on which Mrs. John's fine house stood, shook

and shivered till Mrs. Jenny looked every minute for pole and nest and eggs to go crashing to the

ground.

"My home," thought she, trembling with fear, "though humble, is built {159}upon a sure foundation. Love makes her home there, too. Dear little

tin-pot! Chicken feathers or straw, what does it matter?" and home Mrs. Jenny hastened, very

thankful in her dream for the protecting walls, and overhanging porch, as well as the feeling of

security afforded by her sympathetic human neighbors.

The fourteen days in truth did seem very long to Mrs. Wren, but cheered by her mate's love

songs and an occasional outing—all her persuasions could not induce Mr. Wren to brood the

eggs in her absence—it wasn't a man's work, he said—the time at length passed, and the

day came when a tiny yellow beak thrust itself through the shell, and in a few hours, to the

parents delight, a little baby Wren was born.

Mr. Wren was so overcome with joy that off he flew to the nearest tree, and with drooping tail

and wings shaking at his side, announced, in a gush of song, to the entire neighborhood the fact

that he was a papa.

"A pa-pa, is it?" exclaimed Bridget, attracted by the bird's manner to approach the nest. "From

watchin' these little crathers it do same I'm afther understandin' bird talk and bird-ways most

like the misthress herself," and with one big red finger she gently pushed the angry Mrs. Wren

aside and took a peep at the new born bird.

"Howly mither!" said she, retreating in deep disgust, "ov all the skinny, ugly little bastes!

Shure and its all head and no tail, with niver a feather to kiver its nakedness. It's shamed I'd

be, Mr. Wren, to father an ugly crather loike that, so I would," and Bridget, who had an idea that

young birds came into the world prepared at once to fly, shook her head sadly, and went into the

house to inform the family of the event.

One by one the children peeped into the nest and all agreed with Bridget that it was indeed a

very ugly little birdling which lay there.

"Wish I could take it out, mama," said Dorothy, "and put some of my doll's clothes on it. It is

such a shivery looking little thing."

"Ugh!" exclaimed Walter, "what are those big balls covered with skin on each side of its head;

and when will it look like a bird, mama?"

"Those balls are its eyes," she laughingly replied, "which will open in about five days. The

third day you will perceive a slate-colored down or fuzz upon its head. On the fourth its wing

feathers will begin to show. On the seventh the fuzz will become red-brown feathers on its back

and white upon its breast. The ninth day it will fly a little way, and on the twelfth will leave

its nest for good."

"An' its a foine scholard ye's are, to be shure, mum," said Bridget in open-mouthed admiration.

"Whoiver 'ud hev thought a mite ov a crather loike that 'ud be afther makin' so interesthing a

study. Foreninst next spring, God willin," she added, "its meself, Bridget O'Flaherty, as will be

one ov them same."