Title: Philosophy in Sport Made Science in Earnest

Author: John Ayrton Paris

Release date: November 30, 2014 [eBook #47499]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Elizabeth Oscanyan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Madam,

To whom can a work which professes to blend amusement with instruction, be dedicated with so much propriety, as to one, whose numerous writings have satisfactorily demonstrated the practicability and value of such a union;--to one, who has stripped Romance of her meretricious trappings, and converted her theatre into a temple worthy of Minerva? Justly has it been observed, that to the magic pens of Madame D’Arblay and yourself we are indebted for having the Novel restored to its consequence, and, therefore, to its usefulness; and I may be allowed to add, that your Harry and Lucy has shown how profitably, and agreeably, the machinery of fiction may be worked for the dissemination of truth.

That a life which has been so honourable to yourself, and so serviceable to the commonwealth, may be long extended, and deservedly enjoyed, is the fervent wish of

Tell me, gentle Reader, whether thou hast not heard of the box of Pandora, which was no sooner opened by the unhappy Epimetheus, than it gave flight to a troop of malevolent spirits, which have ever since tormented the human race.--Behold!--I here present you with a magic casket, containing a GENIUS alone capable of counteracting their direful spells. Thou mayest, perhaps, say that its aspect but ill accords with the richness of its promised treasure; so appeared the copper vessel found by the fisherman, as related in the Arabian tale; but, remember, that no sooner had he broken its mystic seal, than the imprisoned genius spread itself over the ocean and raised its giant limbs above the clouds. But this was an evil and treacherous spirit; mine is as benevolent as he is mighty, and seeks communion with our race for no other object than to render mortals virtuous and happy. To be plain, for you must already, my young friends, have unriddled my allegory, his name is Philosophy.

In your progress through life, be not so vain as to believe that you will escape the evils with which its path is beset. Arm yourselves, therefore, with the talisman that can, at once, deprive adversity of its sting, and prosperity of its dangers; for such, believe me, is the rare privilege of philosophy.

I must now take leave of you, for a short time, in order that I may address a few words to your parents and preceptors; but, as I have no plot to abridge your liberties, or lengthen your hours of study, you may listen to my address without alarm, and to my plan without suspicion. Imagine not, however, that I shall recommend the dismissal of the cane, or the whip; on the contrary, I shall insist upon them as necessary and indispensable instruments for the accomplishment of my design. But the method of applying them will be changed; with the one I shall construct the bow of the kite, with the other I shall spin the top.

The object of the present work is to inculcate that early love of science which can never be derived from the sterner productions. Youth is naturally addicted to amusement, and in this item his expenditure too often exceeds his allotted income. I have, therefore, taken the liberty to draw a draft upon Philosophy, with the full assurance that it will be gratefully repaid, with compound interest, ten years after date. But to be serious; those who superintend the education of youth should be apprised of the great importance of the first impressions. Rousseau has said, that the seeds of future vices or virtues are more frequently sown by the mother than the tutor; thereby intimating, that the characters of men are often determined by the earliest impressions; and, of so much moment did Quintillian regard this truth, that he recommends to us the example of Philip, who did not suffer any other than Aristotle to teach Alexander to read. In like manner those who do not commence their study of nature at an early season, will afterwards have many unnecessary obstacles to encounter. The difficulty of comprehending the principles of Natural Philosophy frequently arises from their being at variance with those false ideas which early associations have impressed upon the mind; the first years of study are, therefore, expended in unlearning, and in clearing away the weeds, which would never have taken root in a properly cultivated soil. Writers on practical education have repeatedly advocated the advantages of the plan I am so anxious to enforce; but, strange to say, it is only within a few years that any works have appeared at all calculated to afford the necessary assistance. In short, previous to the labours of Mrs. Marcet and Miss Edgeworth, the productions published for the purpose of juvenile instruction may be justly charged with the grossest errors; and must have proved as destructive to the mind of the young reader, as the book presented by the physician Douban is said to have been to the Grecian king, who, as the Arabian tale relates, imbibed fresh poison as he turned over each leaf, until he fell lifeless in the presence of his courtiers; or, to give another illustration, as mischievous as the magic volume of Michael Scott, which, as Dempster informs us, could not be opened without the danger of invoking some malignant fiend by the operation. How infinitely superior in execution and purpose are the juvenile works of the present century!--to borrow a metaphor from Coleridge, they may be truly said to resemble a collection of mirrors set in the same frame, each having its own focus of knowledge, yet all capable of converging to one point.

Allow me, friendly Reader, before I conclude my address, to say a few words upon the plan and execution of the work before you. It is not intended to supersede or clash with any of the elementary treatises to which I have alluded; indeed its plan is so peculiar, that I apprehend such a charge cannot be brought against it. The author originally composed it for the exclusive use of his children, and would certainly never have consigned it to the press, but at the earnest solicitations of those friends upon whose judgment he places the utmost reliance. Let this be received as an answer to those, who, believing that they can recognise the writer, may be induced to exclaim with Menedemus in Terence,--“Tantumne est ab re tuâ otii tibi aliena ut cures, eaque nihil quæ ad te attinent?” [1]

It is scarcely necessary to offer any apology for the conversational plan of instruction; the success of Mrs. Marcet’s dialogues has placed its value beyond dispute. It may, however, be observed, that this species of composition may be executed in two different ways, either as direct conversation, where none but the speakers appear, which is the method used by Plato; or as the recital of a conversation, where the author himself appears, and gives an account of what passed in discourse, which is the plan generally adopted by Cicero. The reader is aware, that Mrs. Marcet, in her “Conversations on Philosophy,” has adopted the former, while Miss Edgeworth, in her “Harry and Lucy,” has preferred the latter method. In composing the present work I have followed the plan of the last-mentioned authoress. Its advantages over the more direct conversational style appear to consist in allowing occasional remarks, which come more aptly from the author than from any of the characters engaged in the dialogue.

If scientific dialogues are less popular in our times than they were in ancient days, it must be attributed to the frigid and insipid manner in which they have too frequently been executed; if we except the mere external forms of conversation, and that one character is made to speak, and the other to answer, they are altogether the same as if the author himself spoke throughout the whole, instead of amusing with a varied style of conversation, and with a display of consistent and well-supported characters. The introduction of a person of humour, to enliven the discourse, is sanctioned by the highest authority. Cæsar is thus introduced by Cicero, and Cynthio by Addison. In the introduction of Mr. Twaddleton and Major Snapwell, I am well aware of the criticisms to which I am exposed; I have exercised my fancy with a freedom and latitude, for which, probably, there is not any precedent in a scientific work. I have even ventured so far to deviate from the beaten track as to skirmish upon the frontiers of the Novelist, and to bring off captive some of the artillery of Romance; but if, by so doing, I have enhanced the interest of my work, and furthered the accomplishment of its object, let me intreat that mere novelty may not be urged to its disparagement. The antiquarian Vicar, however, will, I trust, meet with cordial reception from the classical student. As to Ned Hopkins, although he may not bear a comparison with William Summers, the fool of Henry VIII.--or with Richard Tarlton, who “undumpished Queen Elizabeth at his pleasure;” or with Archibald Armstrong (vulgo Archee) Jester to Charles,--yet I will maintain, in spite of the Vicar’s censure, that he is a right merry fellow, and to the Major, and consequently to our history, a most important accessary.

If it be argued that several of my comic representations are calculated, like seasoning, to stimulate the palate of the novel-reader, rather than to nourish the minds of the younger class, for whom the work was written, I might, were I so disposed, plead common usage; for does not the director of a juvenile fête courteously introduce a few piquant dishes, for the entertainment of those elder personages who may attend in the character of a chaperone? You surely could not deny me the full benefit of such a precedent; and so, Gentle Reader, I bid thee--Farewell!

1.

Tom Seymour’s arrival from school--Description of Overton Lodge--The Horologe of Flora--A geological temple--A sketch of the person and character of the Reverend Peter Twaddleton--Mr. Seymour engages to furnish his son with any toy, the philosophy of which he is able to explain--Mr. Twaddleton’s arrival, and reception--His remonstrances against the diffusion of science amongst the village mechanics--A dialogue between Mr. Seymour and the Vicar, which some will dislike, many approve of, and all laugh at--The plan of teaching philosophy by the aid of toys developed and discussed--Mr. Twaddleton’s objections answered--He relents, and engages to furnish an antiquarian history of the various toys and sports

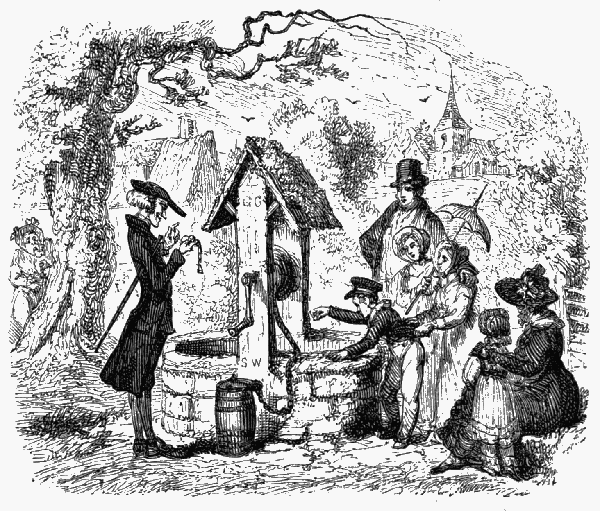

On gravitation--Weight--The velocity of falling bodies--At what altitude a body would lose its gravity--The Tower of Babel--The known velocity of sound affords the means of calculating distances--An excursion to Overton well--An experiment to ascertain its depth--A visit to the vicarage--The magic gallery--Return to the lodge

Motion--absolute and relative--Uniform, accelerated, and retarded velocity--The times of ascent and descent are equal--Vis inertiæ--Friction--Action and reaction are equal and in opposite directions--Momentum defined and explained--The three great laws of motion

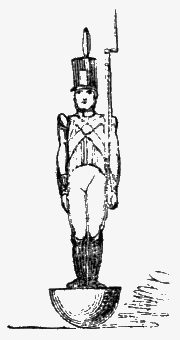

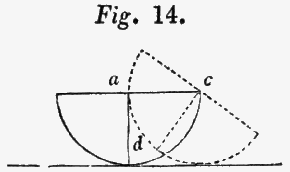

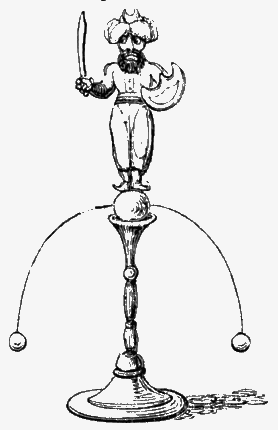

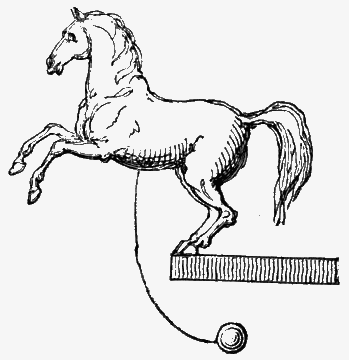

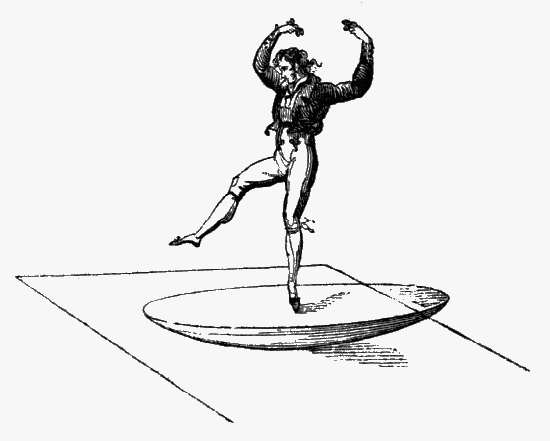

A sad accident turned to a good account--One example worth a hundred precepts--The centres of magnitude and gravity--The point of suspension--The line of direction--The stability of bodies, and upon what it depends--Method of finding the centre of gravity of a body--The art of the balancer explained and illustrated--Various balancing toys

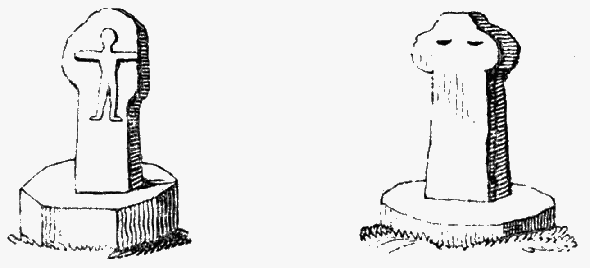

The Chinese tumblers, illustrating the joint effects of change in the centre of gravity of a body, and of momentum--Mr. Twaddleton’s arrival after a series of adventures--The dancing balls--The pea-shooter--A figure that dances on a fountain--The flying witch--Elasticity--Springs--The game of “Ricochet,” or duck and drake--The rebounding ball--Animals that leap by means of an elastic apparatus--A new species of puffing, by which the Vicar is made to change countenance

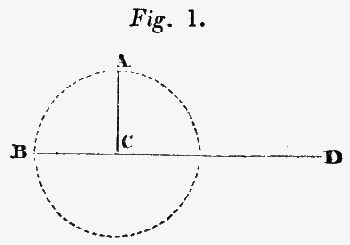

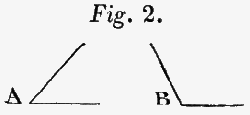

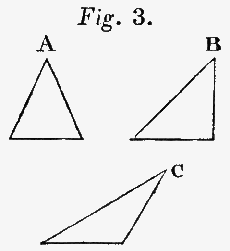

The arrival of Major Snapwell, and the bustle it occasioned--The Vicar’s interview with the stranger--A curious discussion--A word or two addressed to fox-hunters--Verbal corruptions--Some geometrical definitions--An enigma

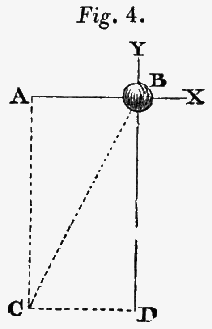

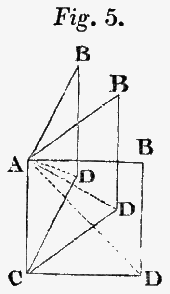

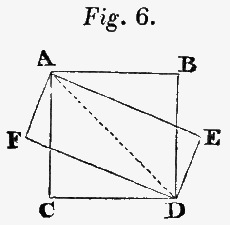

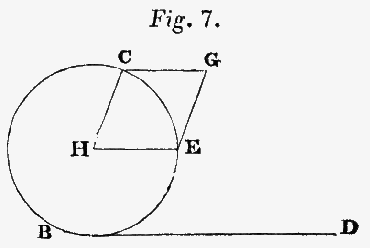

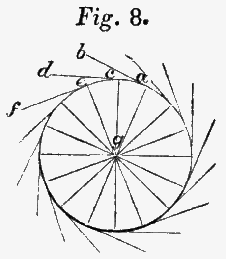

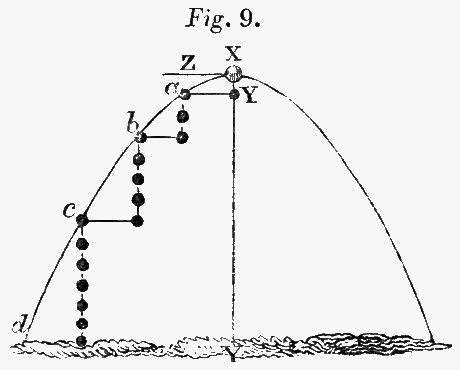

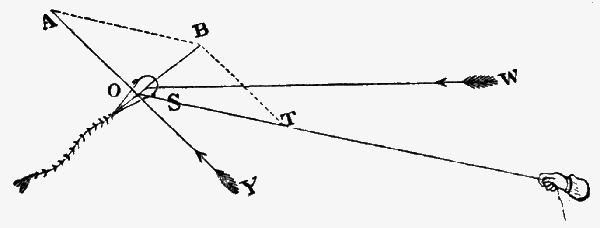

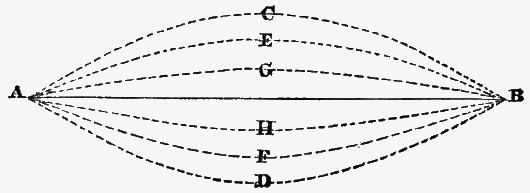

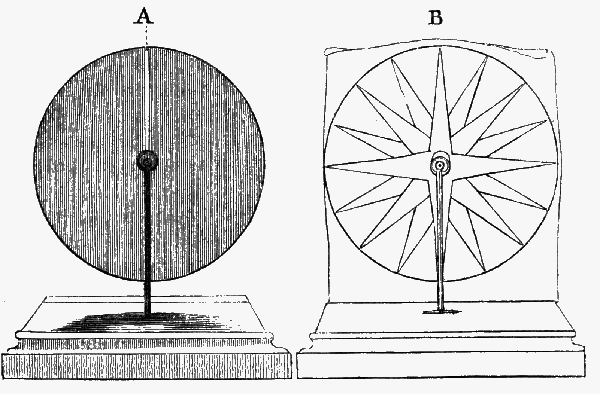

Compound forces--The composition and resolution of motion--Rotatory motion--The revolving watch-glass--The sling--The centrifugal and centripetal forces--Theory of projectiles--A geological conversation between Mr. Seymour and the Vicar

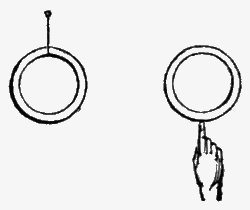

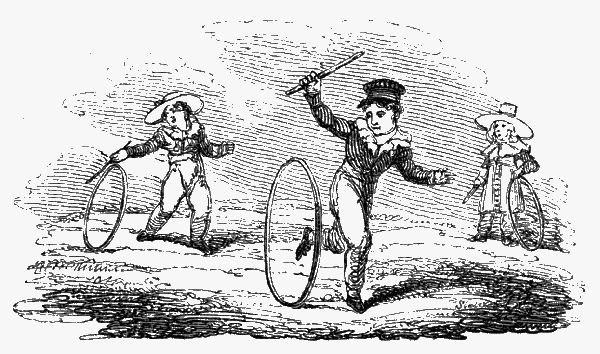

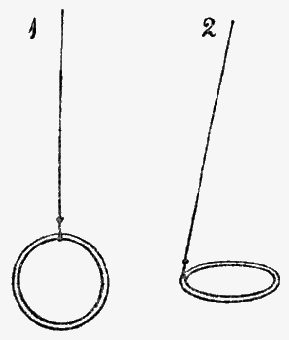

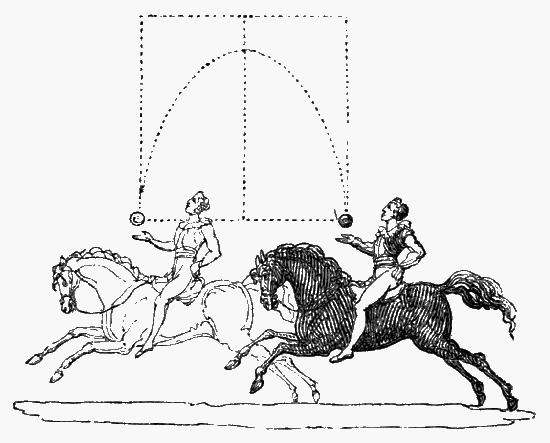

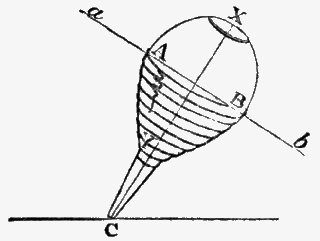

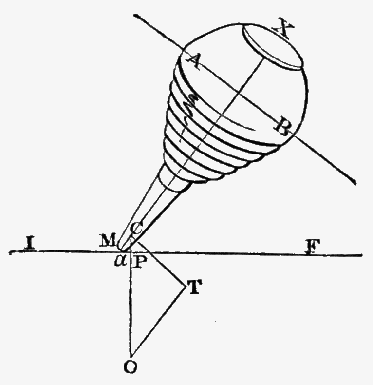

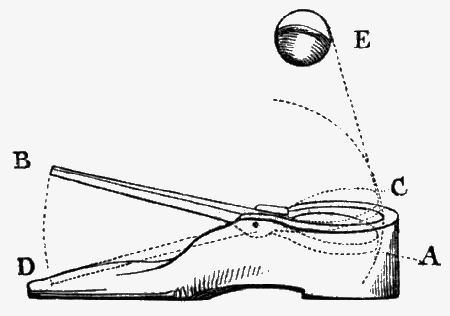

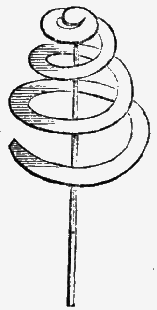

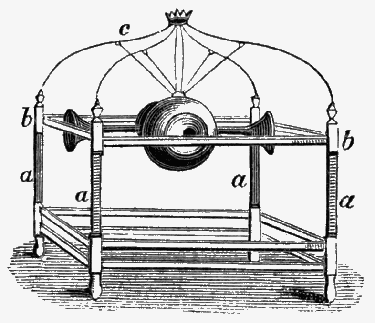

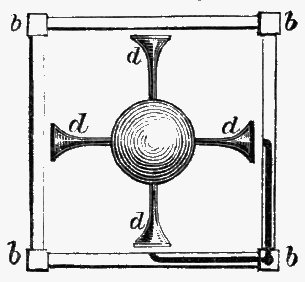

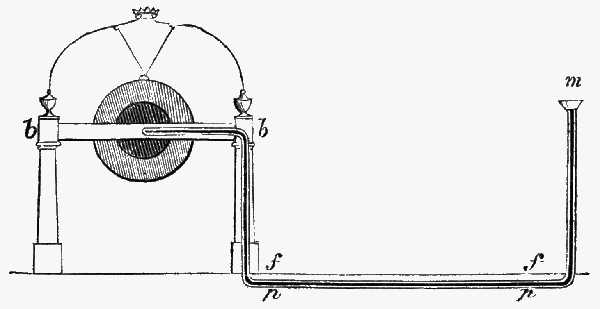

The subject of rotatory motion continued--A ball, by having a peculiar spinning motion imparted to it, may be made to stop short, or to retrograde, though it meets not with any apparent obstacle--The rectilinear path of a spherical body influenced by its rotatory motion--Bilboquet, or cup and ball--The joint forces which enable the balancer to throw up and catch his balls on the full gallop--The hoop--The centre of percussion--The whip and peg-top--Historical notices--The power by which the top is enabled to sustain its vertical position during the act of spinning--The sleeping of the top explained--The force which enables it to rise from an oblique into a vertical position--Its gyration

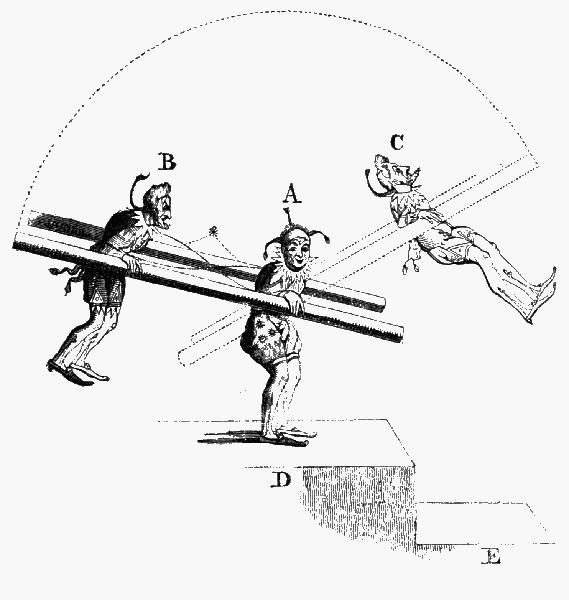

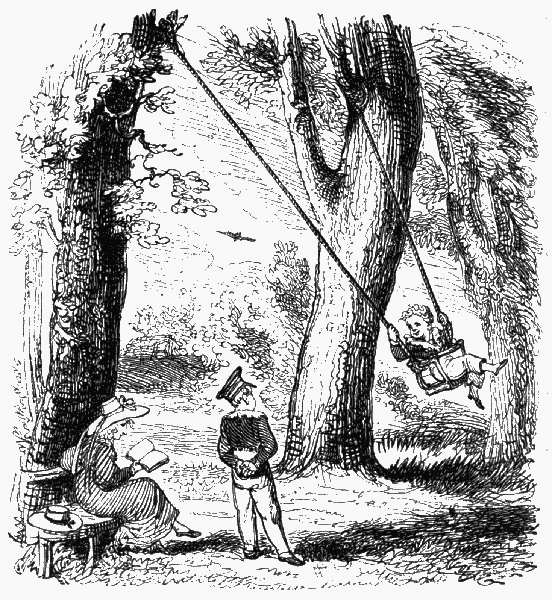

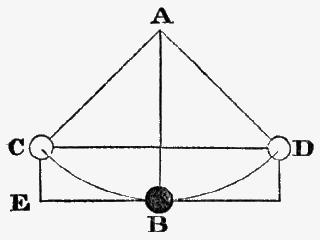

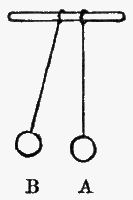

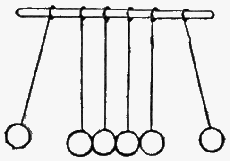

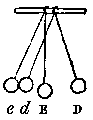

Trap and ball--Gifts from the Vicar--An antiquarian history of the ball--The see-saw--The mechanical powers--The swing--The doctrine of oscillation--Galileo’s discovery--The pendulum--An interesting letter--Mr. Seymour and the Vicar visit Major Snapwell

Marbles--Antiquity of the game--Method of manufacturing them--Ring-taw--Mr. Seymour, the Vicar, and Tom, enter the lists--The defeat of the two former combatants; the triumph of the latter--A philosophical explanation of the several movements--The subject of reflected motion illustrated--The Vicar’s apology, of which many grave personages will approve

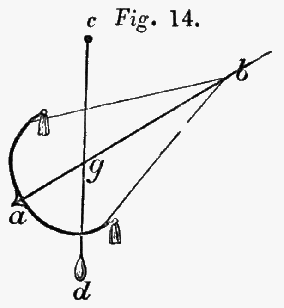

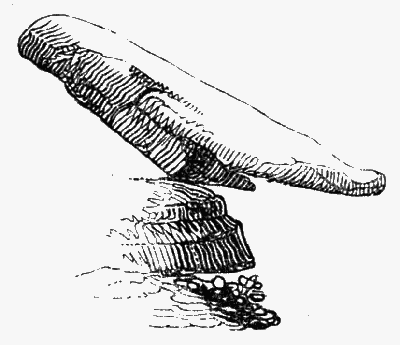

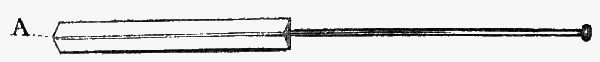

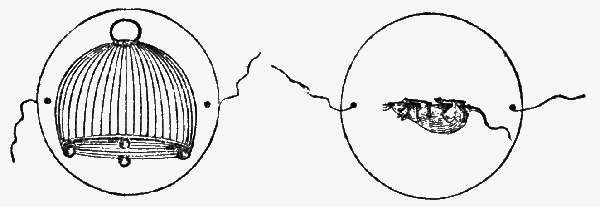

Mr. Seymour and his family visit the Major at Osterley Park--A controversy between the Vicar and the Major--The Sucker--Cohesive attraction--Pressure of the atmosphere--Meaning of the term suction--Certain animals attach themselves to rocks by a contrivance analogous to the sucker--The Limpet--The Walrus--Locomotive organs of the house-fly--A terrible accident--A scene in the village, in which Dr. Doseall figures as a principal performer--The Vicar’s sensible remonstrance--The density of the atmosphere at different altitudes--Inelasticity of water--Bottle-imps--The Barometer--The pop-gun--The air-gun--An antiquarian discussion, in which the Vicar and Major Snapwell greatly distinguish themselves

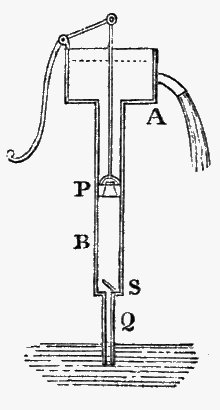

The soap-bubble--The squirt--The bellows; an explanation of their several parts--By whom the instrument was invented--The sucking and lifting, or common pump

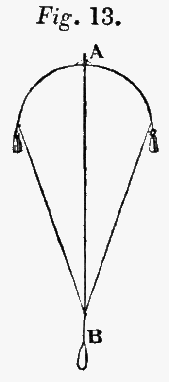

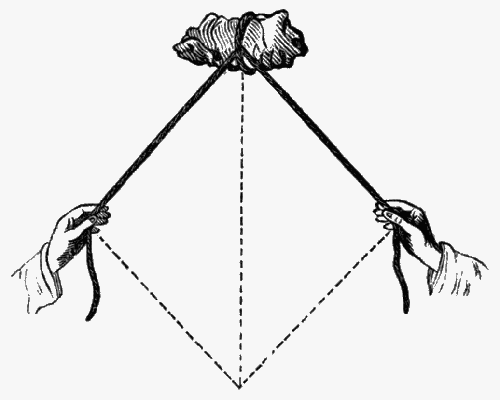

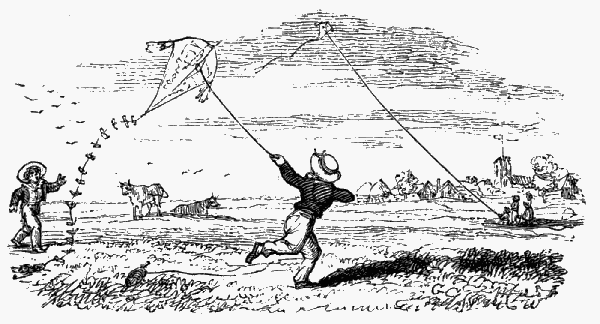

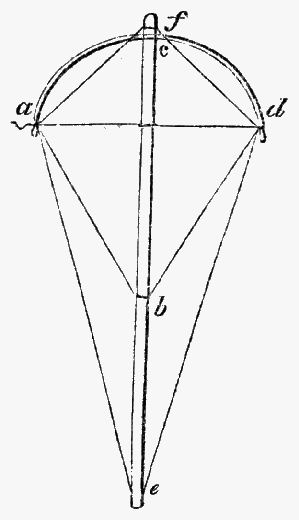

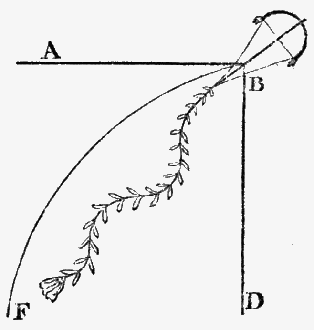

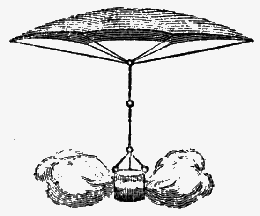

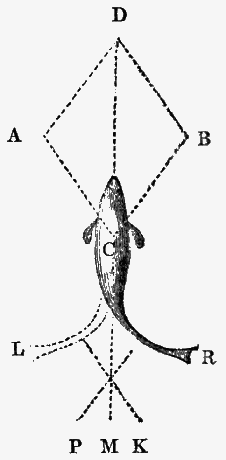

The kite--Its construction--The tail--An author’s meditations among the catacombs of Paternoster-row--Works in their winding sheets--How Mr. Seymour strung puns as he strung the kite’s tail--The Vicar’s dismay--The weather, with the hopes and fears which it alternately inspired--Kites constructed in various shapes--The figure usually adopted to be preferred--The flight of the kite--A philosophical disquisition upon the forces by which its ascent is accomplished--The tail--A discourse on the theory of flying--The structure and action of the wings of birds--A series of kites on one string--A kite carriage--The messenger--The causes and velocity of wind explained

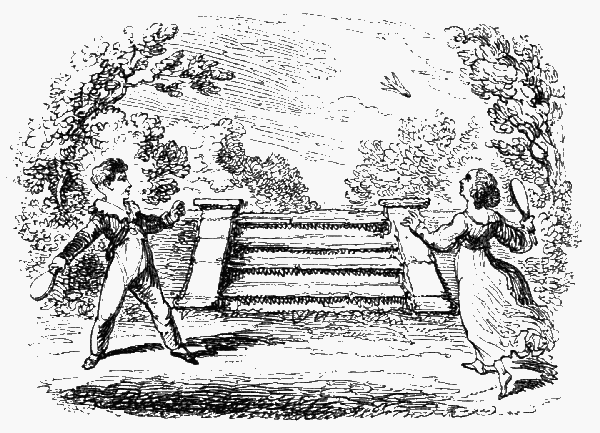

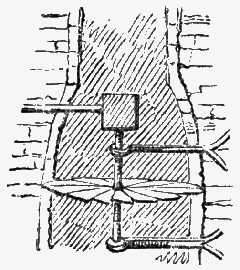

A short discourse--The shuttlecock--The solution of two problems connected with its flight--The windmill--The smoke-jack--A toy constructed on the same principle--The bow and arrow--Archery--The arrival of Isabella Villers

A curious dialogue between the Vicar and Miss Villers--An enigma--The riddles of Samson and Cleobulus--Sound--How propagated by aërial vibration--Music--A learned discussion touching the superior powers of ancient music--The magic of music, a game which the author believes is here described for the first time--Adventures by moonlight--Spirits of the valley

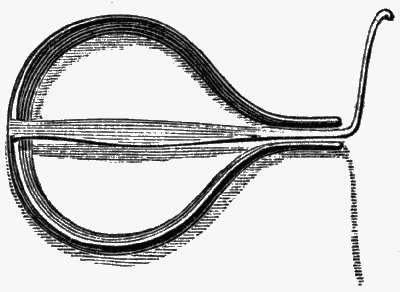

Origin of the crescent as the Turkish ensign--Apparitions dispelled by philosophy--Fairy rings--Musical instruments classed under three divisions--Mixed instruments--Theory of wind instruments--The Jew’s harp--The statue of Memnon--An interesting experiment--The flute--The whiz-gig, &c.--Echoes--The whispering gallery in the dome of St. Paul’s--The speaking trumpet--The invisible girl--Other acoustic amusements--Creaking shoes--Haunted rooms

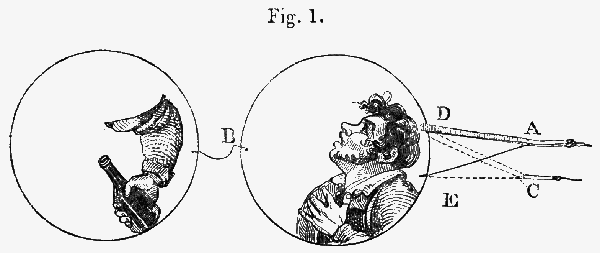

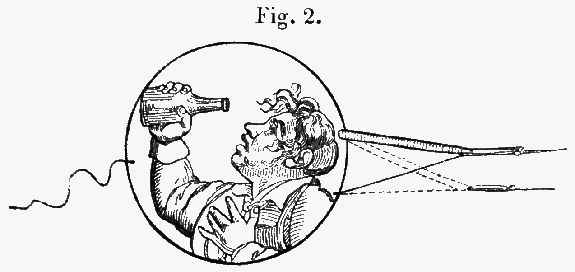

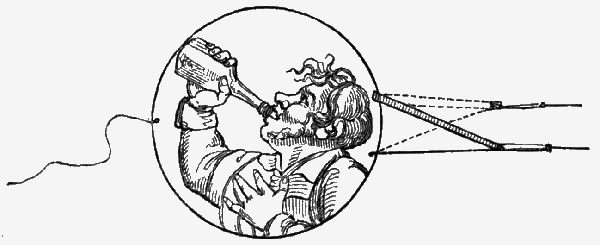

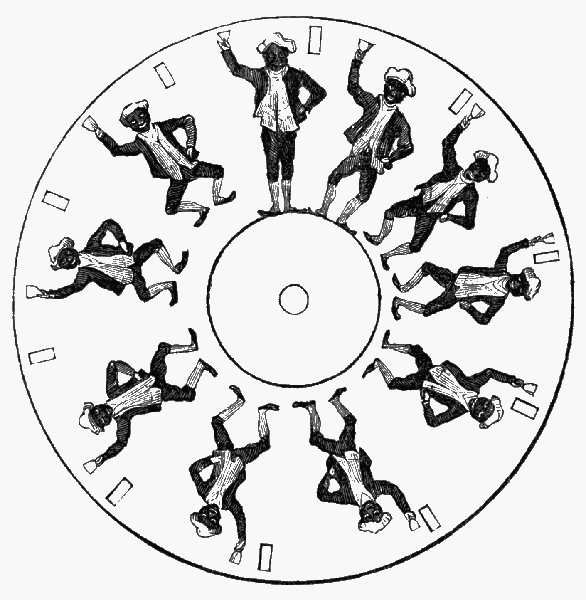

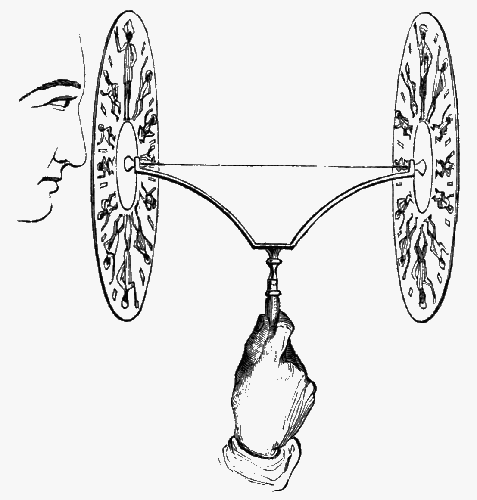

An interesting communication, from which the reader may learn that the most important events are not those which absorb the greatest portion of time in their recital--Major Snapwell communicates to Mr. Seymour and the Vicar, his determination to celebrate the marriage of his nephew by a fête at Osterley Park--An antiquarian discussion of grave importance--An interview with Ned Hopkins, during which the wit displayed both cunning and humour--The Thaumatrope--Its improved construction--Philosophy of its action--Another optical toy--The nature of optical spectra illustrated and explained--The spectral cross of Constantine

The Thaumatrope--A great improvement effected in its construction--Another toy upon the same optical principle

Preparations for the approaching fête--The procession of the bridal party to Osterley Park--The Major and his visitors superintend the arrangements in the meadow--The curious discussion which took place on that occasion--The origin of the swing--Merry-andrews--Trajetours, &c.--The dinner at the hall--The learned controversy which was maintained with respect to the game of Chess

The arrival of the populace at Osterley Park--The commencement of the festivities--Dancing on the tight and slack rope--Balancing--Conjuring--Optical illusions--Various games--Penthalum--The banquet--Grand display of fire-works--Conclusion

Tom Seymour’s arrival from school.--Description of Overton Lodge.--The Horologe of Flora.--A geological temple.--A sketch of the person and character of the Reverend Peter Twaddleton.--Mr. Seymour engages to furnish his son with any toy, the philosophy of which he is able to explain.--Mr. Twaddleton’s arrival and reception.--His remonstrances against the diffusion of science amongst the village mechanics.--A dialogue between Mr. Seymour and the vicar, which some will dislike, many approve of, and all laugh at.--The plan of teaching philosophy by the aid of toys developed and discussed.--Mr. Twaddleton’s objections answered.--He relents, and engages to furnish an antiquarian history of the various toys and sports.

The summer recess of Mr. Pearson’s school was not more anxiously anticipated by the scholars than it was by the numerous family of Seymour, who, at the commencement of the year, had parted from a beloved son and brother for the first time. As the season of relaxation approached, so did the inmates of Overton Lodge (for such was the name of Mr. Seymour’s seat) betray increasing impatience for its arrival. The three elder sisters, Louisa, Fanny, and Rosa, had been engaged for several days in arranging the little study which their brother Tom had usually occupied. His books were carefully replaced on their shelves, and bunches of roses and jasmines, which the affectionate girls had culled from the finest trees in the garden, were tastefully dispersed through the apartment; the festoons of blue ribbons, with which they were entwined, at once announced themselves as the work of graceful hands, impelled by light hearts; and every flower might be said to reflect from its glowing petals the smiles with which it had been collected and arranged. At length the happy day arrived; a post-chaise drew up to the front gate, and Tom was once again folded in the arms of his affectionate and delighted parents. The little group surrounded their beloved brother, and welcomed his return with all the warmth and artlessness of juvenile sincerity. “Well,” said Mr. Seymour, “if the improvement of your mind corresponds with that of your looks, I shall indeed have reason to congratulate myself upon the choice of your school. But have you brought me any letter from Mr. Pearson?” “I have,” replied Tom, who presented his father with a note from his master, in which he had commented, in high terms of commendation, not only upon Tom’s general conduct, but upon the rapid progress which he had made in his classical studies.

“My dearest boy,” exclaimed the delighted father, “I am more than repaid for the many anxious moments which I have passed on your account. I find that your conduct has given the highest satisfaction to your master; and that your good-nature, generosity, and, above all, your strict adherence to truth, have ensured the love and esteem of your school-fellows.” This gratifying report brought tears of joy into the eyes of Mrs. Seymour; Tom’s cheek glowed with the feeling of conscious merit; and the sisters interchanged looks of mutual satisfaction. Can there be an incentive to industry and virtuous conduct so powerful as the exhilarating smiles of approbation which the school-boy receives from an affectionate parent? Tom would not have exchanged his feelings for all the world, and he internally vowed that he would never deviate from a course that had been productive of so much happiness.

“But come,” exclaimed Mr. Seymour, “let us all retire into the library. I am sure that our dear fellow will be glad of some refreshment after his journey.”

We shall here leave the family circle to the undisturbed enjoyment of their domestic banquet, and invite the reader to accompany us in a stroll about the grounds of this beautiful and secluded retreat.

We are amongst those who believe that the habits and character of a family may be as easily discovered from the rural taste displayed in the grounds which surround their habitation, as by any examination of the prominences on their heads, or of the lineaments in their faces. How vividly is the decline of an ancient race depicted by the chilling desolation which reigns around the mansion, and by the rank weed which insolently triumphs over its fading splendour; and how equally expressive of the peaceful and contented industry of the thriving cottager, is the well cultivated patch which adjoins the humble dwelling, around whose rustic porch the luxuriant lilac clusters, or the aspiring woodbine twines its green tendrils and sweetly-scented blossoms! In like manner did the elegantly disposed grounds of Overton Lodge at once announce the classic taste and fostering presence of a refined and highly cultivated family.

The house, which was in the Ionic style of architecture, was situated on the declivity of a hill, so that the verdant lawn which was spread before its southern front, after retaining its level for a short distance, gently sloped to the vale beneath, and was terminated by a luxuriant shrubbery, over which the eye commanded a range of fair enclosure, beautified by an irregularly undulating surface, and interspersed with rich masses of wood. The uniformity of the lawn was broken by occasional clumps of flowering shrubs, so artfully selected and arranged, as to afford all the varied charms of contrast; while, here and there, a lofty elm flung its gigantic arms over the sward beneath, and cast a deep shade, which enabled the inhabitants of the Lodge to enjoy the air, even during the heat of a meridian sun. The shrubbery, which occupied a considerable portion of the valley, stretched for some distance up the western part of the hill; and, could Shenstone have wandered through its winding paths and deep recesses, his favourite Leasowes might have suffered from a comparison. Here were mingled shrubs of every varied dye; the elegant foliage of white and scarlet acacias was blended with the dark-green-leaved chestnut; and the stately branches of the oak were relieved by the gracefully pendulous boughs of the beech. At irregular intervals, the paths expanded into verdant glades, in each of which the bust of some departed poet or philosopher announced the genius to which they were severally consecrated. From a description of one or two of these sequestered spots, the reader will readily conceive the taste displayed in those upon which our limits will not allow us to dwell.

After winding, for some distance, through a path so closely interwoven with shrubs and trees, that scarcely a sunbeam could struggle through the foliage, a gleam of light burst through the gloom, and displayed a beautiful marble figure, which had been executed by a Roman artist, representing Flora in the act of being attired by Spring. It was placed in the centre of the expanse formed by the retiring trees, and at its base were flowering, at measured intervals, a variety of those plants to which Linnæus has given the name of Equinoctial flowers, since they open and close at certain and exact hours of the day, and thus by proper arrangement constitute the Horologe of Flora,(1)[2] or Nature’s time-piece. It had been constructed, under the direction of her mother, by Louisa Seymour. The hour of the day at which each plant opened, was represented by an appropriate figure of nicely trimmed box; and these, being arranged in a circle, not only fulfilled the duty, but exhibited the appearance of a dial.

2. These figures refer to the additional notes at the end of the work.

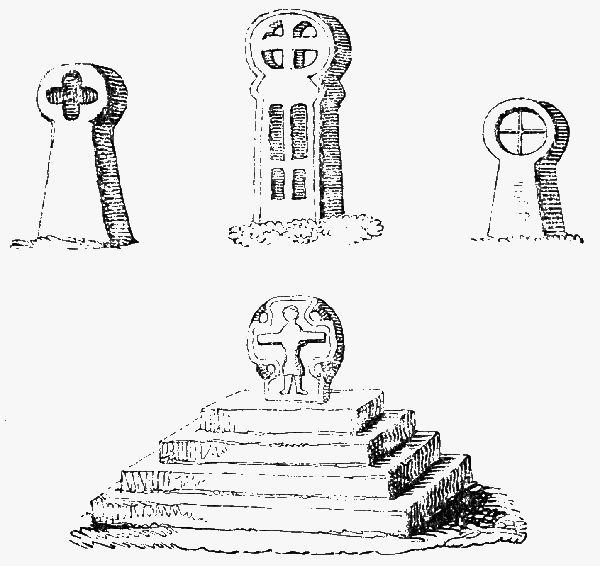

From this retreat several winding paths threaded their mazy way through the deep recesses of the wood; and the wanderer, quitting for a while the blaze of day, was refreshed by the subdued light which everywhere pervaded the avenue, except where the hand of taste had, here and there, turned aside the boughs, and opened a vista to bring the village spire into view, or to gladden the sight by a rich prospect of the distant landscape. After having descended for some way, the path, losing its inclined direction, proceeded on a level, and thus announced to the stranger his arrival at the bottom of the valley. What a rich display of woodland scenery was suddenly presented to his view! A rocky glen, in which large masses of sandstone were grouped with picturesque boldness, terminated the path, and formed an area wherein he might gaze on the mighty sylvan amphitheatre, which gradually rose to a towering height above him, and seemed to interpose an insuperable barrier between the solitude of this sequestered spot and the busy haunts of men; not a sound assailed the ear, save the murmur of the summer breeze, as it swept the trembling foliage, or the brawling of a small mountain stream, which gushed from the rock, and, like an angry chit, fretted and fumed as it encountered the obstacles that had been raised by its own impetuosity. This was the favourite retreat of Mr. Seymour, and he had dedicated it to the genius of geology; here had he erected a temple to the memory of Werner, and every pillar and ornament bore testimony to the refined taste of its architect. It consisted of a dome, constructed of innumerable shells and corallines, and surmounted by a marble figure of Atlas, bearing the globe on his shoulders, upon which the name of Werner was inscribed. The dome was supported by twelve pillars of so singular and beautiful a construction as to merit a particular description: the Corinthian capital of each was of Pentelican marble; the column consisted of a spiral of about six inches in breadth, which wound round a central shaft of not more than two inches in diameter; upon this spiral were placed specimens of various rocks, of such masses as to fill up the outline, and to present to the eye the appearance of a substantial and well-proportioned pillar. These specimens were arranged in an order corresponding with their acknowledged geological relations; thus, the Diluvial productions occupied the higher compartments; the Primitive strata, the lower ones; and the Secondary and Transition series found an intermediate place. The tessellated floor presented the different varieties of marble, so artfully interspersed as to afford a most harmonious combination; the Unicoloured, variegated, Madreporic, the Lumachella, Cipolino, and Breccia marbles, were each represented by a characteristic and well-defined specimen. The alcoved ceiling was studded with Rock Crystal, calcareous Stalactites, and beautiful Calcedonies. A group of figures in basso relievo adorned the wall which enclosed about a third part of the interior of the temple, and its subject gave evidence of the Wernerian devotion of Mr. Seymour; for it represented a contest between Pluto and Neptune, in which the watery god was seen in the act of wresting the burning torch from the hand of his adversary, in order to quench it in the ocean. Mr. Seymour had studied in the school of Freyburg, under the auspices of its celebrated professor; and, like all the pupils of Werner, he pertinaciously maintained the aqueous origin of our strata. But let us return to the happy party at the Lodge, whom the reader will remember we left at their repast. This having been concluded, and all those various subjects discussed, and questions answered, which the school-boy, who has ever felt the satisfaction of returning home for the holidays, will more easily conceive than we can describe, Tom enquired of his father, whether his old friend, Mr. Twaddleton, the Vicar of Overton, was well, and at the Parsonage. “He is quite well,” replied Mr. Seymour, “and so anxious to see you, that he has paid several visits, during the morning, to enquire whether you had arrived. Depend upon it, that many hours will not elapse before you see him.”

In that wish did Tom and the whole juvenile party heartily concur; for the vicar, notwithstanding his oddities, was the most affectionate creature in existence, and never was he more truly happy than when contributing to the innocent amusement of his little “playmates,” as he used to call Tom and his sisters.

It may be here necessary to present the reader with a short sketch of the character of a person, who will be hereafter found to perform a prominent part in the little drama of Overton Lodge.

The Rev. Peter Twaddleton, Master of Arts, and Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, for we must introduce him in due form, was about fifty-two years of age, twenty of which he had spent at Cambridge, as a resident Fellow of Jesus College. He had not possessed the vicarage of Overton above eight or nine years; and, although its value never exceeded a hundred and eighty pounds a year, so limited were his wants, and so frugal his habits, that he generally contrived to save a considerable sum out of his income, in order that he might devote it to purposes of charity and benevolence: his charity, however, was not merely of the hand, but of the heart; distress was unknown in his village; he fed the hungry, nursed the sick, and cheered the unfortunate; his long collegiate residence had imparted to his mind several peculiar traits, and a certain stiffness of address and quaintness of manner which at once distinguish the recluse from the man of the world; in short, as Shakspeare expresses it, “he was not hackneyed in the ways of men.” His face was certainly the very reverse to everything that could be considered “good-looking,” and yet, when he smiled, there was an animation that redeemed the irregularity of his angular features; so benevolent was the expression of his countenance, that it was impossible not to feel that sentiment of respect and admiration which the presence of a superior person is wont to inspire; but his superiority was rather that of the heart than of the head; not that we would insinuate any deficiency in intellect, but that his moral excellencies were so transcendent as to throw into the shade all those mental qualities which he possessed in common with the world. He entertained a singular aversion to the mathematics, a prejudice which we are inclined to refer to his disappointment in the senate-house; for, although he was known at Cambridge as one of those “pale beings in spectacles and cotton stockings,” commonly called “reading men,” yet, after all his exertions, he only succeeded in obtaining the “wooden spoon,” an honour which devolves upon the last of the “junior optimes.” Whether his failure arose from an exuberant or a deficient genius, or, to speak phrenologically, from an excess in his number of bumps, or a defect in his bump of numbers, we are really unable to state, never having had an opportunity of verifying our suspicions by a manual examination of his cranium; he was, however, well read in the classics, and so devoted to the works of Virgil that he never lost an opportunity of quoting his favourite poet; and it must be admitted, that, although these quotations so generally pervaded his conversation as to become irksome, they were sometimes apposite, and now and then even witty. But notwithstanding the delight which he experienced in a lusus verborum in a learned language, of such contradictory materials was he compossed, that his antipathy to an English pun was extravagant and ridiculous. This peculiarity has been attributed, but we speak merely from common report, to a disgust which he contracted for that species of spurious wit, during his frequent intercourse with the Johnians, a race of students who have, from time immemorial, been identified with the most profligate class of punsters; be this, however, as it may, we are inclined to believe that a person who resides much amongst those who are addicted to this vice, unless he quickly takes the infection, acquires a sort of constitutional insusceptibility, like nurses, who pass their lives in infected apartments with perfect safety and impunity. His favourite, and we might add his only pursuit, beyond the circle of his profession, was the study of antiquities; he was, as we have already stated, a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries; had collected a very tolerable series of ancient coins, and possessed sufficient critical acumen to distinguish between Attic ærugo, and the spurious verdure of the modern counterfeit. Often had he undertaken an expedition of a hundred miles to inspect the interior of an ancient barrow, or to examine the mouldering fragments of some newly-discovered monument; indeed, like the connoisseur in cheese, blue-mould and decay were the favourite objects of his taste, and the sure passports to his favour; for he despised all living testimony, but that of worms and maggots. A coin with the head of a living sovereign passed through his hands with as little resistance as water through a sieve, but he grasped the head of an Antonine or Otho with insatiable and relentless avarice. Mr. Twaddleton’s figure exceeded the middle stature, and was so extremely slender as to give him the air and appearance of a tall man. He was usually dressed in an old-fashioned suit of black cloth, consisting of a single-breasted coat, with a standing collar, and deep comprehensive cuffs, and a flapped waistcoat; but so awkwardly did these vestments conform with the contour of his person, that we might have supposed them the production of those Laputan tailors who wrought by mathematical principles, and held in sovereign contempt the illiterate fashioners who deemed it necessary to measure the forms of their customers; although it was whispered by certain censorious spinsters in the village that the aforesaid mathematical artists were better acquainted with the angles of the Seven Dials, than with the squares of the west end. They farther surmised that the vicar’s annual journey to London, which in truth was undertaken with no other objects than those of attending the anniversary of the Society of Antiquaries, on Saint George’s day, and of inspecting the cabinets of his old crony, the celebrated medallist of Tavistock-street, was for the laudable purpose of recruiting his wardrobe. If the aforesaid coat, with its straggling and disproportioned suburbs, possessed an amplitude of dimensions which ill accorded with the slender wants of his person, this misapplied liberality was more than compensated by the rigid economy exhibited in the nether part of his costume, which evidently had not been designed by a contemporary artisan; not so his shoes, which, for the accommodation of those unwelcome parasites, vulgarly called corns, were constructed in the form of a battledore, and displayed such an unbecoming quantity of leather, that, as Ned Hopkins, a subaltern wit of the village alehouse, observed, “however economical their parson might appear, he was undoubtedly supported in extravagance.” Nor did the natural association between tithes and “corn-bags” escape his observation, but was repeated with various other allusions of equal piquancy, to the no small annoyance of the reverend gentleman, and, as he declared, to the disparagement of his cloth.

After the social repast had been concluded, Tom proposed a ramble through the shrubbery. He was anxious to revisit the scene of his former sports; and Louisa readily met his wishes, for she was also desirous of showing him the botanical clock, which had been planned and completed since his absence. Mr. Seymour accompanied his children, and, as they walked across the lawn, Tom asked his father whether he remembered the promise he had made him on quitting home for school, that of furnishing him with some new amusements during the holidays.

“I perfectly remember,” said his father, “the promise to which you allude, and I hope that you equally well recollect the conditions with which it was coupled. When your mamma gave you a copy of Mrs. Marcet’s instructive Dialogues on Natural Philosophy, I told you that, after you had studied the principles which that work so admirably explains, you would have but little difficulty in understanding the philosophy of toys, or the manner in which each produced its amusing effects; and that, when the midsummer holidays commenced, I would successively supply you with a new amusement, whenever you could satisfactorily explain the principles of those you already possessed. Was not that our contract?”

“It was,” exclaimed Tom, with great eagerness, “and I am sure I shall win the prize, whenever you will try me, and I hope my mamma and sisters will be present.”

“Certainly,” replied Mr. Seymour, “and I trust that Louisa and Fanny, who are of an age to understand the subject, will not prove uninterested spectators. John, too, will profit by our scheme; for, as I shall necessarily require, for illustration, certain toys which can scarcely afford any amusement to a boy of your age and acquirements, it is but fair that they should be transferred into his hands; our little philosopher, Matthew, will also, I am sure, enter into the spirit of our pastimes with the greatest satisfaction.”

“Thank you! thank you! dear papa,” was simultaneously shouted by several voices, and the happy children looked forward to the morrow with that mixed sensation of impatience and delight which always attends juvenile anticipations.

On the following morning, the vicar was seen approaching, and Tom and his sisters immediately ran forward to greet him.

“My dear boy,” exclaimed the vicar, “I am truly rejoiced to see you;--when did you arrive from school?--How goes on Virgil?--Hey, my boy?--You must be delighted with the great Mantuan bard;--now confess, you little Trojan, can you eat a cheesecake without being reminded of the Harpy’s prophecy, and its fulfilment, as discovered by young Ascanius:--

“But, bless me, how amazingly you have grown! and how healthy you look!” Tom took advantage of this pause in the vicar’s address, which had hitherto flowed in so uninterrupted and rapid a stream as to preclude the possibility of any reply to his questions, to inform him that his father was on the lawn, and desirous of seeing him.

“Mr. Twaddleton,” exclaimed Mr. Seymour, “you are just in time to witness the commencement of a series of amusements, which I have proposed for Tom’s instruction during the holidays.”

“Amusement and instruction,” replied the vicar, “are not synonymous in my vocabulary; unless, indeed, they be applied to the glorious works of Virgil; but let me hear your scheme.”

“I have long thought,” said Mr. Seymour, “that all the first principles of natural philosophy might be easily taught, and beautifully illustrated, by the common toys which have been invented for the amusement of youth.”

“A fig for your philosophy,” was the unceremonious and chilling reply of the vicar. “What have boys,” continued he, “to do with philosophy? Let them learn their grammar, scan their hexameters, and construe Virgil; it is time enough to inflict upon them the torments of science after their names have been entered on the University boards.”

“I differ from you entirely, my worthy friend; the principles of natural philosophy cannot be too early inculcated, nor can they be too widely diffused. It is surely a great object to engage the prepossessions on the side of truth, and to direct the natural curiosity of youth to useful objects.”

“Hoity toity!” exclaimed the reverend gentleman, “such principles accord not with my creed; heresy, downright heresy; that a man of your excellent sense and intelligence can be so far deceived! But the world has run mad; and much do I grieve to find, that the seclusion of Overton Lodge has not secured its inmates from the infection. I came here, Mr. Seymour, to receive your sympathy, and to profit by your counsel, but, alas! alas! I have fallen into the camp of the enemy. ‘Medios delapsus in hostes,’ as Virgil has it.”

“You astonish me--what can have happened?” asked Mr. Seymour.

“There is Tom Plank, the carpenter,” said the vicar, “soliciting subscriptions for the establishment of a philosophical society. I understand that this mania--for by what other, or more charitable term can I express such conduct?--has seized this deluded man since his return from London, where he has been informed that all the ‘hewers of wood and drawers of water’ are about to associate themselves into societies for the promotion of science. Preposterous idea! as if a block of wood could not be split without a knowledge of the doctrine of percussion, nor a pail of water drawn from the well without an acquaintance with hydrostatics; but, as I am a Christian priest, I solemnly declare, that I grieve only for my flock, and raise my feeble voice for no other purpose than that of scaring the wolf from the fold: to be angry, as Pope says, would be to revenge the faults of others upon ourselves; but I am not angry, Mr. Seymour, I am vexed, sorely vexed.”

“Take it not thus to heart, my dear vicar,” replied his consoling friend; “‘Solve metus,’ as your poet has it. Science, I admit, is both the Pallas and Pandora of mankind; its abuse may certainly prove mischievous, but its sober and well-timed application cannot fail to increase the happiness of every class of mankind, as well as to advance and improve every branch of the mechanical arts; so thoroughly am I satisfied upon this point, that I shall subscribe to the proposed society with infinite satisfaction.”

“Mr. Seymour! Mr. Seymour! you know not what you do. Would you scatter the seeds of insubordination? manure the weeds of infidelity? fabricate a battering-ram to demolish our holy church? Such, indeed, must be the effect of your Utopian scheme, for truly may I exclaim with the immortal Maro--

“Come, come, my good friend, all this is declamation without argument.”

“Without argument! Many are the sad instances which I could adduce in proof of the evil effects which have already accrued from this abominable system. I am not in the habit, Sir, of dealing in empty assertion; already has the aforesaid Tom Plank ventured to question the classical knowledge of his spiritual pastor, and, as I understand, has openly avowed himself, at the sixpenny club, as my rival in antiquarian pursuits.”

“And why should he not?” said the mischievous Mr. Seymour; “I warrant you he already possesses many an old saw; ay, and of a very great age, too, if we may judge from the loss of its teeth.”

During this remonstrance, Mr. Twaddleton had been occupied in whirling round his steel watch-chain with inconceivable rapidity, and, after a short pause, he burst out into the following exclamation:--

“Worthy Sir! if you persist in asserting, that a man whose occupation is to plane deal, is prepared to dive into the sacred mysteries of antiquity, I shall next expect to hear that”--

“A truce, a truce,” cried Mr. Seymour, interrupting the vicar, “to all such hackneyed objections; and let us deal plainly with your planer of deals: you assert that the carpenter cannot speak grammatically, and yet he gains his livelihood by mending stiles; you complain of his presumption in argument, would it not be a desertion of his post to decline railing? and then, again, with respect to his antiquarian pretensions, compare them with your own; you rescue saws from the dust, he obtains dust from his saws.”

“What madness has seized my unfortunate friend?

as Virgil has it:--But let it pass, let it pass, Mr. Seymour; my profession has taught me to bear with humility and patience the contempt and revilings of my brethren; I forgive Tom Plank for his presumption, as in that case I alone am the sufferer; but I say to you, that envy, trouble, discontent, strife, and poverty, will be the fruits of the seeds you would scatter. I verily believe, that unless this ‘march of intellect,’ as it has been termed, is speedily checked, Overton, in less than twelve months, will become a deserted village; for there is scarcely a tradesman who is not already distracted by some visionary scheme of scientific improvement, that leads to the neglect of their occupations, and the dissipation of the honest earnings which their more prudent fathers had accumulated; ‘Meliora pii docuere parentes,’ as the poet has it. What think you of Sam Corkington, who proposes to erect an apparatus in the crater of Mount Vesuvius, in order to supply every city on the continent with heat and light; or of Billy Spooner, who is about to establish a dairy at Spitzbergen, that he may furnish all Europe with ice-cream from the milk of whales! ‘O, viveret Democritus!’”

The vicar was about to proceed with his lamentations, but the thread of his discourse was suddenly snapped asunder, and his ideas thrown into the wildest confusion, by the explosion of a most audacious pun, which in mercy to Mr. Seymour, as well as to our readers, we will not repeat.

“Mr. Seymour,” exclaimed the incensed vicar, “we will, if you please, terminate our discourse; I perceive that you are determined to meet my remonstrances with ridicule; when I had hoped to bring an argument incapable of refutation, Tum variæ illudunt pestes, as Virgil has it.”

“Pray, allow me to ask,” said Mr. Seymour, “whether my puns, or your quotations, best merit the title of pestes?”

“That you should compare the vile practice of punning with the elegant and refined habit of conveying our ideas by classic symbols, does indeed surprise and disturb me. Pope has said that words are the counters by which men represent their thoughts; the plebeian,” continued the vicar, “selects base metal for their construction, while the scholar forms them of gold and gems, dug from the richest mines of antiquity. But to what vile purpose does the punster prostitute such counters? Not for the interchange of ideas, but, like the juggler, to deceive and astonish by acts of legerdemain.”

“How fortunate is it that you had not lived in the reign of King James,” remarked Mr. Seymour; “for that singular monarch, as you may, perhaps, remember, made very few bishops who had not thus signalised themselves.”

“To poison our ears by quibbles and quirks did well become him who sought to deceive our senses and blind our reason--the patron of puns and the believer in witchcraft were suitably united,” replied the vicar.

“Well,” said Mr. Seymour, “as this is a subject upon which it is not likely that we should agree, I will pass to another, where I hope to be more successful; I trust I shall induce you to view with more complacency my project of teaching philosophy by the aid of toys and sports.”

“Mr. Seymour, the proposal of instructing children in the principles of natural philosophy, is really too visionary to require calm discussion; and can be equalled only in absurdity by the method you propose for carrying it into effect.”

“Come, come, my dear vicar, pray chain up your prejudices, and let your kind spirit loose for half an hour: let me beg that you will so far indulge me,” said Mr. Seymour, “as to listen patiently to the plan by which it is my intention to turn sport into science, or, in other words, toys into instruments of philosophical instruction.”

“And is it then possible,” said the vicar, in a tone of supplication, “that you can seriously entertain so wild, and, I might even add, so cruel a scheme? Would you pursue the luckless little urchin from the schoolroom into the very playground, with your unrelenting tyranny? a sanctuary which the most rigid pedagogue has hitherto held inviolable. Is the buoyant spirit so forcibly, though perhaps necessarily, repressed, during the hours of discipline, to have no interval for its free and uncontrolled expansion? Your science, methinks, Mr. Seymour, might have taught you a wiser lesson; for you must well know that the most elastic body will lose that property by being constantly kept in a state of tension.”

“A fine specimen of sophistry, upon my word,” cried Mr. Seymour, “which would, doubtless, raise every nursery-governess and doating grandmother in open rebellion against me: but let me add, that it ill becomes a man of liberal and enlarged ideas, to suffer his opinions to be the sport of mere words; for, that our present difference is an affair of words, and of words only, I will undertake to prove, to the satisfaction of any unprejudiced person. Play and work--amusement and instruction--toys and tasks--are invariably but most unjustifiably employed as words of contrast and opposition; an error which has arisen from the indistinct and very indefinite ideas which we attach to such words. If the degree of mental exertion be said to constitute the difference between play and work, I am quite sure that the definition would be violated in the first illustration; for let me ask, when do boys exert so much thought as in carrying into effect their holiday schemes? The distinction may, perhaps, be made to turn upon the irksome feelings which might be supposed to attend the drudgery of study, but this can never happen except from a vicious system of education that excludes the operations of thought; a school that locks in the body, but locks out the mind: depend upon it, Mr. Twaddleton, that the human mind, whether in youth or manhood, is ever gratified by the acquisition of information; every occupation soon cloys, unless it be seasoned by this stimulant. Is not the child idle and miserable in a nursery full of playthings, and to what expedient does he instinctively fly to relieve his ennui? Why, he breaks his toys to pieces, as Miss Edgeworth justly observes, not from the love of mischief, but from the hatred of idleness, or rather from an innate thirst after knowledge; and he becomes, as it were, an enterprising adventurer, and opens for himself a new source of pleasure and amusement, in exploring the mechanism of their several parts. Think you, then, Mr. Twaddleton, that any assistance which might be offered the boy, under such circumstances, would be received by him as a task? Certainly not. The acquisition of knowledge then, instead of detracting from, must heighten the amusement of toys; and if I have succeeded in convincing you of this truth, my object is accomplished.”

Thus did Mr. Seymour, like an able general, assail his adversary on his own ground; he drove him, as it were, into a corner, and by seizing the only pass through which he could make his escape, forced him to surrender at discretion.

“Why, truly,” replied the vicar, after a short pause, “I am ready to admit that there is much good sense in your observations; and, if the scientific instruction upon these occasions be not carried so far as to puzzle the boy, I am inclined to coincide with you.”

“Therein lies the whole secret,” said Mr. Seymour: “when an occupation agreeably interests the understanding, imagination, or passions of children, it is what is commonly understood by the term play or sport; whereas that which is not accompanied with such associations, and yet may be necessary for their future welfare, is, properly enough, designated as a task.”

“I like the distinction,” observed the vicar.

“Then may I hope that you will indulge me so far as to listen to the scheme by which it is my intention to turn ‘Sport into Science,’ or, in other words, Toys into instruments of Philosophical Instruction?”

The vicar nodded assent.

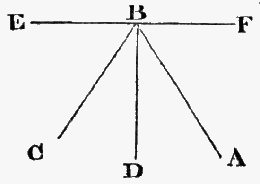

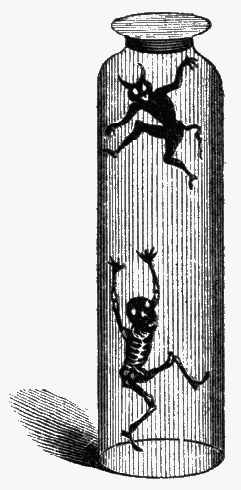

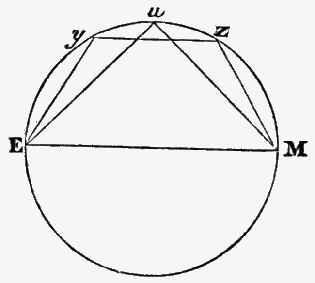

Mr. Seymour proceeded--“In the first place, I would give the boy some general notions with regard to the properties of matter, such as its gravitation, vis inertiæ, elasticity, &c. What apparatus can be required for such a purpose, beyond some of the more simple toys? Indeed, I will undertake to demonstrate the three grand laws of motion by a game at ball; while the composition and resolution of forces may be beautifully exemplified during a game of marbles, especially that of ‘ring-taw;’ but in order that you may more clearly comprehend the capability of my plan, allow me to enumerate the various philosophical principles which are involved in the operation of the several more popular toys and sports. We will commence with the ball; which will illustrate the nature and phenomena of elasticity, as it leaps from the ground;--of rotatory motion, while it runs along its surface;--of reflected motion, and of the angles of incidence and reflection, as it rebounds from the wall;--and of projectiles, as it is whirled through the air; at the same time the cricket-bat may serve to explain the centre of percussion. A game at marbles may be made subservient to the same purposes, and will farther assist us in conveying clear ideas upon the subject of the collision of elastic and non-elastic bodies, and of their velocities and direction after impact. The composition and resolution of forces may be explained at the same time. The nature of elastic springs will require no other apparatus for its elucidation than Jack in the box, and the numerous leaping-frogs and cats with which the nursery abounds. The leathern sucker will exemplify the nature of cohesion, and the effect of water in filling up those inequalities by which contiguous surfaces are deprived of their attractive power; it will, at the same time, demonstrate the nature of a vacuum, and the influence of atmospheric pressure. The squirt will afford a farther illustration of the same views, and will furnish a practical proof of the weight of the atmosphere in raising a column of water. The theory of the pump will necessarily follow. The great elasticity of air, and the opposite property of water, I shall be able to show by the amusing exhibition of the ‘Bottle Imps.’”

“Bottle Imps!--‘Acheronta movebis,’” muttered the vicar.

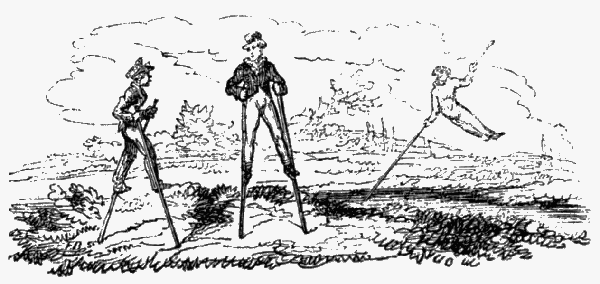

Mr. Seymour continued--“The various balancing toys will elucidate the nature of the centre of gravity, point of suspension, and line of direction: the seesaw, rocking-horse, and the operation of walking on stilts, will here come in aid of our explanations. The combined effects of momentum and a change in the centre of gravity of a body may be beautifully exemplified by the action of the Chinese Tumblers. The sling will demonstrate the existence and effect of centrifugal force; the top and tetotum will prove the power of vertiginous motion to support the axis of a body in an upright position. The trundling of the hoop will accomplish the same and other objects. The game of bilboquet, or cup and ball, will show the influence of rotatory motion in steadying the rectilinear path of a spherical body, whence the theory of the rifle-gun may be deduced. For conveying some elementary ideas of the doctrine of oscillation, there is the swing. The flight of the arrow will not only elucidate the principles of projectiles, but will explain the force of the air in producing rotatory motion by its impact on oblique surfaces: the revolution of the shuttlecock may be shown to depend upon the same resolution of forces. Then comes the kite, one of the most instructive and amusing of all the pastimes of youth,--the favourite toy of Newton in his boyish days:[4]--its ascent at once developes the theory of the composition and resolution of forces, and explains various subordinate principles, which I shall endeavour to describe when we arrive at the subject. The see-saw will unfold the general principle upon which the Mechanical Powers are founded; and the boy may thus be easily led to the theory of the lever, by being shown how readily he can balance the heavier weight of a man by riding on the longer arm of the plank. The theory of colours may be pointed out to him as he blows his soap-bubbles;[5] an amusement which will, at the same time, convince him that the air must exert a pressure equally in all directions. For explaining the theory of sound, there are the whistle, the humming-top, the whiz-gig, the pop-gun, the bull-roarer, and sundry other amusements well known in the play-ground; but it is not my intention, at present, to enumerate all the toys which may be rendered capable of affording philosophical instruction; I merely wish to convince you that my plan is not quite so chimerical as you were at first inclined to believe.”

“Upon my word,” said the vicar, “no squirrel ever hopped from branch to branch with more agility,--you are the very counterpart of Cornelius Scriblerus; but I must confess that your scheme is plausible, very plausible, and I shall no longer refuse to attend you in the progress of its execution.

as Virgil has it.”

Mr. Seymour, however, saw very plainly that, although the vicar thus withdrew his opposition, he was nevertheless very far from embarking in the cause with enthusiasm, and that, upon the principle already discussed, he would perform his part rather as a task than a pastime. Nor was the line which Mr. Twaddleton had quoted from the Æneid calculated to efface such an impression. It was true, that, like Anchises, he no longer refused to accompany him in his expedition; but, if the comparison were to run parallel, it was evident that he would have to carry him as a dead weight on his shoulders. This difficulty, however, was speedily surmounted by an expedient, with which the reader will become acquainted by the recital of what followed.

“I rejoice greatly,” said Mr. Seymour, “that we have at length succeeded in enlisting you into our service; without your able assistance, I fear that my instruction would be extremely imperfect; for you must know, my dear sir, that I am ambitious of making Tom an antiquary as well as a philosopher, and I look to you for a history of the several toys which I shall have occasion to introduce.”

This propitiatory sentence had its desired effect.

“Most cheerfully shall I comply with your wishes,” exclaimed the delighted vicar; “and I can assure you, sir, that, with regard to several of the more popular toys and pastimes, there is much very curious and interesting lore.”

Mr. Seymour had upon this occasion succeeded in opening the heart of the vicar, just as a skilful mechanic would pick a patent lock; who, instead of forcing it by direct violence, seeks to discover the secret spring to which all its various movements are subservient.

“To-morrow, then,” cried the vicar, in a voice of great exultation, “we will commence our career, from which I anticipate the highest satisfaction and advantage; in the mean time,” continued he, “I will refresh my memory upon certain points touching the antiquities of these said pastimes, or, as we used to say at college, get up the subject. I will also press into our service my friend and neighbour Jeremy Prybabel, whose etymological knowledge will greatly assist us in tracing the origin of many of the words used in our sports, which is frequently not very obvious.”

Mr. Seymour cast an intelligible glance at his wife, who was no less surprised at the sudden change in the vicar’s sentiments than she was pleased with the skill and address by which it had been accomplished.

3. “An engine’s raised to batter down our walls.”—Æn. ii. 46.

4. Sir Isaac Newton is said to have been much attached to Philosophical sports when a boy; he was the first to introduce paper kites at Grantham, where he was at school. He took pains to find out their proper proportions and figure, and the proper place for fixing the string to them. He made lanterns of paper crimpled, which he used to go to school by in winter mornings with a candle, and he tied them to the tail of his kites in a dark night, which at first frightened the country people exceedingly, who took his candles for comets.--Thomson’s Hist. of R.S.

5. The colours which glitter on a soap-bubble are the immediate consequence of a principle the most important from the variety of phenomena it explains, and the most beautiful from its simplicity and compendious neatness in the whole science of Optics.--Herschel’s Preliminary Discourses.

6. “I yield, my son, and no longer refuse to become your companion.”--Æn. ii. 704.

On Gravitation.--Weight.--The Velocity of Falling Bodies.--At what Altitude a Body would lose its Gravity.--The Tower of Babel.--The known Velocity of Sound affords the means of calculating Distances.--An Excursion to Overton Well.--An Experiment to ascertain its Depth.--A Visit to the Vicarage.--The Magic Gallery.--Return to the Lodge.

It was about two o’clock, when Mr. Twaddleton, in company with Mr. and Mrs. Seymour, joined the children on the lawn.

“Tom,” said his father, “are you prepared to commence the proposed examination?”

“Quite ready, papa.”

“Then you must first inform me,” said Mr. Seymour, taking the ball out of Rosa’s hand, “why this ball falls to the ground, as soon as I withdraw from it the support of my hand?”

“Because every heavy body that is not supported, must of course fall.”

“And every light one also, my dear; but that is no answer to my question; you merely assert the fact, without explaining the reason.”

“Oh! now I understand you; it is owing to the force of gravity; the earth attracts the ball, and the consequence is, that they both come in contact;--is not that right?”

“Certainly; but if the earth attract the ball, it is equally true that the ball must attract the earth; for you have, doubtless, learnt that bodies mutually attract each other; tell me, therefore, why the earth should not rise to meet the ball?”

“Because the earth is so much larger and heavier than the ball.”

“It is, doubtless, much larger, and since the force of attraction is in proportion to the mass, or quantity of matter, you cannot be surprised at not perceiving the earth rise to meet the ball, the attraction of the latter being so infinitely small, in comparison with that of the former, as to render its effect wholly nugatory; but with regard to the earth being heavier than the ball, what will you say when I tell you that it has no weight at all?”

“No weight at all!”

Tom begged that his father would explain to him how it could possibly be that the earth should not possess any weight.

“Weight, my dear boy, you will readily understand, can be nothing more than an effect arising out of the resisted attraction of a body for the earth: you have just stated, that all bodies have a tendency to fall, in consequence of the attraction of gravitation; but if they be supported, and prevented from approaching the earth, either by the hand, or any other appropriate means, their tendency will be felt, and is called weight.”

Tom understood this explanation, and observed, that “since attraction was always in proportion to the quantity of matter, so, of course, a larger body must be more powerfully attracted, or be heavier, than a smaller one.”

“Magnitude, or size, my dear, has nothing whatever to do with quantity of matter: will not a small piece of lead weigh more than a large piece of sponge? In the one case, the particles of matter may be supposed to be packed in a smaller compass; in the other, there must exist a greater number of pores or interstices.”

“I understand all you have said,” observed Louisa, “and yet I am unable to comprehend why the earth cannot be said to have any weight.”

“Cannot you discover,” answered Mr. Seymour, “that, since the earth has nothing to attract it, it cannot have any attraction to resist, and, consequently, according to the ordinary acceptation of the term, it cannot be correctly said to possess weight? although I confess that, when viewed in relation to the solar system, a question will arise upon this subject, since it is attracted by the sun.”

The children declared themselves satisfied with this explanation, and Mr. Seymour proceeded to put another question: “Since,” continued he, “you now understand the nature of that force by which bodies fall to the earth, can you tell me the degree of velocity with which they fall?”

Tom asserted that the weight of the body, or its quantity of matter, and its distance from the surface of the earth, must, in every case, determine that circumstance; but Mr. Seymour excited his surprise by saying, that it would not be influenced by either of those conditions; he informed them, for instance, that a cannon-ball, and a marble, would fall through the same number of feet in a given time, and that, whether the experiment were tried from the top of a house, or from the summit of Saint Paul’s, the same result would be obtained.

“I am quite sure,” exclaimed Tom, “that, in the Conversations on Natural Philosophy, it is positively stated, that attraction is always in proportion to the quantity of matter.”

“Yes,” observed Louisa, “and it is moreover asserted, that the attraction diminishes as the distances increase.”

Mr. Seymour said, that he perceived the error under which his children laboured, and that he would endeavour to remove it. “You cannot, my dears,” continued he, “divest your minds of that erroneous but natural feeling, that a body necessarily falls to the ground without the exertion of any force: whereas, the greater the quantity of matter, the greater must be the force exerted to bring it to the earth: for instance, a substance which weighs a hundred pounds will thus require just ten times more force than one which only weighs ten pounds; and hence it must follow, that both will come to the ground at the same moment; for, although, in the one case, there is ten times more matter, there is, at the same time, ten times more attraction to overcome its resistance; for you have already admitted that the force of attraction is always in proportion to the quantity of matter. Now let us only for an instant, for the sake merely of argument, suppose that attraction had been a force acting without any regard to quantity of matter, is it not evident that, in such a case, the body containing the largest quantity would be the slowest in falling to the earth?”

“I understand you, papa,” cried Tom: “if an empty waggon travelled four miles an hour, and were afterwards so loaded as to have its weight doubled, it could only travel at the rate of two miles in the same period, provided that in both cases the horses exerted the same strength.”

“Exactly,” said Mr. Seymour; “and to follow up your illustration, it is only necessary to state, that Nature, like a considerate master, always apportions the number of horses to the burthen that is to be moved, so that her loads, whatever may be their weight, always travel at the same rate; or, to express the fact in philosophical instead of figurative language, gravitation, or the force of the earth’s attraction, always increases as the quantity of matter, and, consequently, that heavy and light bodies, when dropped together from the same altitude, must come to the ground at the same instant of time.”

Louisa had listened with great attention to this explanation; and although she thoroughly understood the argument, yet it appeared to her at variance with so many facts with which she was acquainted, that she could not give implicit credence to it.

“I think,” papa, said the archly-smiling girl, “I could overturn this fine argument by a very simple experiment.”

“Indeed! Miss Sceptic: then pray proceed; and I think we shall find, that the more strenuously you oppose it, the more powerful it will become: but let us hear your objections.”

“I shall only,” replied she, “drop a shilling, and a piece of paper, from my bed-room window upon the lawn, and request that you will observe which of them reaches the ground first; if I am not much mistaken, you will find that the coin will strike the earth before the paper has performed half its journey.”

Tom appeared perplexed, and cast an enquiring look at his father.

“Come,” said Mr. Seymour, “I will perform this experiment myself, and endeavour to satisfy the doubts of our young sceptic; but I must first take the opportunity to observe, that I am never better pleased than when you attempt to raise difficulties in my way, and I hope you will always express them without reserve.”

“Here, then, is a penny piece; and here,” said Tom, “is a piece of paper.”

“Which,” continued Mr. Seymour, “we will cut into a corresponding shape and size.” This having been accomplished, he held the coin in one hand, and the paper disc in the other, and dropped them at the same instant.

“There! there!” cried Louisa, with an air of triumph; “the coin reached the ground long before the paper.”

“I allow,” said Mr. Seymour, “that there was a distinct interval in favour of the penny piece;” and he proceeded to explain the cause of it. He stated that the result was not contrary to the law of gravitation, since it arose from the interference of a foreign body, the air, to the resistance of which it was to be attributed; and he desired them to consider the particles of a falling body as being under the influence of two opposing forces,--gravity, and the air’s resistance. Louisa argued, that the air could only act on the surface of a body, and as this was equal in both cases (the size of the paper being exactly the same as that of the penny piece), she could not see why the resistance of the air should not also be equal in both cases.

“I admit,” said Mr. Seymour, “that the air can only act upon the surface of a falling body, and this is the very reason of the paper meeting with more resistance than the coin; for the latter, from its greater density, must contain many more particles than the paper, and upon which the air cannot possibly exert any action; whereas almost every particle of the paper may be said to be exposed to its resistance, the fall of the latter must therefore be more retarded than that of the former body.”

At this explanation Louisa’s doubts began to clear off, and they were ultimately dispelled on Mr. Seymour performing a modification of the above experiment in the following manner. He placed the disc of paper in close contact with the upper part of the coin, and, in this position, dropped them from his hand. They both reached the ground at the same instant.

“Are you now satisfied, my dear Louisa?” asked her father. “You perceive that, by placing the paper in contact with the coin, I skreened it from the action of the air, and the result is surely conclusive.”

“Many thanks to you, dear papa; I am perfectly satisfied, and shall feel less confident for the future.” Tom was delighted; for, as he said, he could now understand why John’s paper parachute descended so deliberately to the ground; he could also explain why feathers, and other light bodies, floated in the air. “Well then,” said Mr. Seymour, “having settled this knotty point, let us proceed to the other question, viz. ‘that a body will fall with the same velocity, during a given number of feet, from the ball of St. Paul’s as from the top of a house.’ You maintain, I believe, that, since the attraction of the earth for a body diminishes as its distance from it increases,[7] a substance at a great height ought to fall more slowly than one which is dropped from a less altitude.”

Neither Tom nor Louisa could think otherwise. Mr. Seymour told them that, in theory, they were perfectly correct, but that, since attraction acted from the centre, and not from the surface of the earth, the difference of its force could not be discovered at the small elevations to which they could have access: “for what,” said he, “can a few hundred feet be in comparison with four thousand miles, which is the distance from the centre to the surface of our globe?--You must therefore perceive that, in all ordinary calculations respecting the velocity of falling bodies, we may safely exclude such a consideration.”

“But suppose,” said Tom, “it were possible to make the experiment a thousand miles above the earth, would not the diminished effect of gravity be discovered in that case?”

“Undoubtedly,” replied his father, “indeed it would be sensible at a much less distance: for instance, if a lump of lead, weighing a thousand pounds, were carried up only four miles, it would be found to have lost two pounds of its weight.” (2)

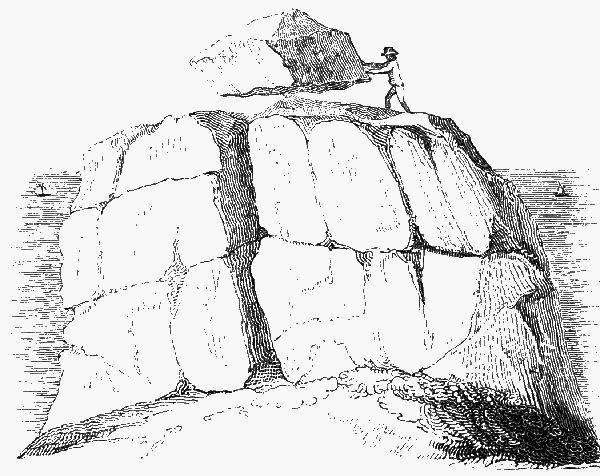

“This discussion,” observed Mr. Twaddleton, “reminds me of a problem that was once proposed at Cambridge, to find the elevation to which the Tower of Babel could have been raised, before the stones would have entirely lost their gravity.”

“Its solution,” said Mr. Seymour, “would require a consideration which Tom could not possibly understand at present, viz. the influence of the centrifugal force.”

“I am fully aware of it,” replied the vicar, “and in order to appreciate that influence, it would, of course, be necessary to take into account the latitude of the place; but, if my memory serves me, I think that under the latitude of 30°, which I believe is nearly that of the plains of Mesopotamia, the height would be somewhere about twenty-four thousand miles.”

Mr. Seymour now desired Tom to inform him, since all bodies fall with the same velocity, what that velocity might be.

“Sixteen feet in a second, papa;--I have just remembered that I had a dispute with a school-fellow upon that subject, and in which, thanks to Mrs. Marcet, I came off victorious, and won twelve marbles.”

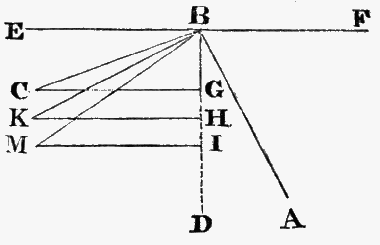

“Then let me tell you, my fine fellow, that unless your answer exclusively related to the first second of time, you did not win the marbles fairly; for, since the force of gravity is continually acting, so is the velocity of a falling body continually increasing, or it has what is termed an ‘accelerating velocity;’ it has accordingly been ascertained by accurate experiments, that a body descending from a considerable height falls sixteen feet, as you say, in the first second of time; but three times sixteen in the next; five times sixteen in the third; and seven times sixteen in the fourth; and so on, continually increasing according to the odd numbers 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, &c. so that you perceive,” continued Mr. Seymour, “by observing the number of seconds which a stone requires to descend from any height, we can discover the altitude, or depth, of the place in question.”

Louisa and Fanny, who had been attentively listening to their father’s explanation, interchanged a smile of satisfaction, and, pulling Tom towards them, whispered something which was inaudible to the rest of the party.

“Come, now,” exclaimed Mr. Seymour, “I perceive by your looks that you have something to ask of me: is Louisa sceptical again?”

“Oh dear no,” replied Tom; “Louisa merely observed, that we might now be able to find out the depth of the village well, about which we have all been very curious; for the gardener has told us that it is the deepest in the kingdom, and was dug more than a hundred years ago.”

Mr. Seymour did not believe that it was the deepest in the kingdom, although he knew that its depth was considerable; and he said that, if Mr. Twaddleton had no objection, they should walk to it, and make the proposed experiment.

“Objection! my dear Mr. Seymour, when do I ever object to afford pleasure to my little playmates, provided its indulgence be harmless? Let us proceed at once, and on our return I hope you will favour me with a visit at the vicarage; I have some antiquities which I am anxious to exhibit to yourself and Mrs. Seymour.” Tom and Rosa each took the vicar’s hand, and Mr. and Mrs. Seymour followed with Louisa and Fanny. The village well was about half a mile distant; the road to it led through a delightful shady lane, at the top of which stood the vicarage-house. Mr. and Mrs. Seymour and her daughters had lingered in their way to collect botanical specimens; and when they had come up to Tom and the vicar, they found them seated on the trunk of a newly-felled oak, in deep discourse.

“What interests you, Tom?” said Mr. Seymour, who perceived, by the enquiring and animated countenance of the boy, that his attention had been excited by some occurrence.

“I have been watching the woodman,” said Tom, “and have been surprised that the sound of his hatchet was not heard until some time after he had struck the tree.”

“And has not Mr. Twaddleton explained to you the reason of it?” asked Mr. Seymour.

“He has,” replied Tom, “and he tells me that it is owing to sound travelling so much more slowly than light.”

“You are quite right; and as we are upon an expedition for the purpose of measuring depths, it may not be amiss to inform you, that this fact furnishes another method of calculating distances.”

The party seated themselves upon the oak, and Mr. Seymour proceeded--“The stroke of the axe is seen at the moment the woodman makes it, on account of the immense velocity with which light travels;(3) but the noise of the blow will not reach the ear until some time has elapsed, the period varying, of course, in proportion to the distance, because sound moves only at the rate of 1142 feet in a second, or about 13 miles in a minute; so that you perceive, by observing the time that elapses between the fall of the hatchet and the sound produced by it, we can ascertain the distance of the object.”

Mr. Seymour fixed his eye attentively on the woodman, and, after a short pause, declared that he was about half a quarter of a mile distant.

“Why, how could you discover that?” cried Louisa; “you had not any watch in your hand.”