Title: Copper Coleson's Ghost

Author: Edward P. Hendrick

Illustrator: Harold James Cue

Release date: December 11, 2014 [eBook #47633]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Rod Crawford, Dave Morgan,

Special Collections of the University of Florida Library,

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

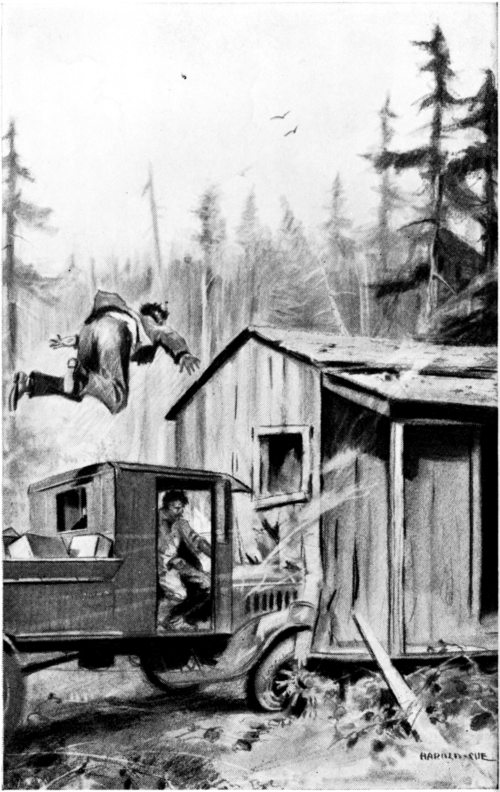

“A FIGURE CATAPULTED FROM THE REAR OF THE VEHICLE” (See page 295)

By

EDWARD P. HENDRICK

Author of

“THE CRUISE OF THE SALLY”

Illustrated by

HAROLD CUE

L. C. PAGE & COMPANY

BOSTON PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1930

By L. C. Page & Company

(INCORPORATED)

All rights reserved

Made in U. S. A.

First Impression, August, 1930

COMPOSED, PLATED AND PRINTED BY

C. H. SIMONDS COMPANY

BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, U. S. A.

BECAUSE THEIR ENCOURAGEMENT AND CRITICISM HAVE

BEEN HELPFUL TO ME DURING THE WRITING OF

THIS STORY, I AM DEDICATING IT TO MY BOYS

BOB AND JACK

In the rear of a white cottage, known to all residents of the town of Truesdell as “the Blake homestead,” stands a great apple tree, whose leafy boughs have afforded shade in summer and fruit in autumn to several generations of Blakes. At present, its hospitable branches have been converted into an out-of-door gymnasium by Ned Blake, great-grandson of old Josiah Blake, from whose half-eaten apple-core the tree sprang some seventy years ago. “Six feet, two inches in his socks and as wide as a door,” is how tradition describes old Josiah, and although Ned Blake at seventeen stands less than seventy inches in his sneakers and tips the scales at a trifle less than one hundred and fifty pounds, he has something of the supple strength and a goodly measure of the courage and grit that made old Josiah respected among the early settlers of Truesdell.

Clad in a sleeveless jersey, duck trousers and sneakers, Ned has just climbed a rope hand over hand to an upper limb from which he descends in a veritable cascade of cat-skinning, toe-holding, ape-like swings to drop on the turf beside his friend, Tommy Beals.

“Bully stuff!” applauded Tommy. “You sure can do the monkey tricks, Ned, but it makes me sweat just to watch ’em this weather,” and Tommy hitched his rotund form farther into the shade of the friendly tree.

“It would do you good to try some of them, Fatty,” laughed Ned. “Come on now. Here’s a simple one for a starter,” and catching a horizontal limb above his head, Ned proceeded to chin himself with first one hand, then with the other, and finished with a two-handed hoisting swing that left him seated upon the limb.

Tommy Beals wagged his head in a hopeless negative. “Nope, it can’t be done,” he sighed. “Whoever drew my plans must have been thinking about ballast instead of aviation, but if you ever want a good anchor for a tug-of-war team why just count on me.”

“All right, I’ll keep it in mind,” promised Ned, “but here’s something you can do for a little exercise,” he continued, dropping again to the ground. “I want to grind my camp axe a bit, if you’ll turn for me.”

“Sure, I’ll do it,” agreed Tommy good-naturedly and, fetching a soap box for a seat, he squatted beside a heavy grindstone that stood in the shade of the tree.

For perhaps ten minutes the sharp skurr of steel on stone sounded on the hot August air, then ceased abruptly as Ned lifted the axe from the whirling stone and tested its edge gingerly with his thumb. Tommy seized the opportunity to let go his hold of the crank-handle and wipe the beads of perspiration from his plump countenance.

“Gosh, it’s hot!” he panted. “Ain’t the old cleaver sharp yet, Ned?”

“It’s pretty good, except for a couple of nicks,” replied Ned, “but you needn’t turn any more, Fatty. Here comes Dave Wilbur and I’ll get him to spell you.”

“Yeah! I’ll sure admire to watch Weary Wilbur work,” grinned Beals, as a tall, lanky youth with hands deep in his pockets turned in at the gate and strolled leisurely across the lawn. “I’ll bet you the ice cream sodas, Ned, that Dave will find an alibi for any job—if he sees it coming,” continued Tommy, in a wheezy whisper.

“I’ll take that bet,” laughed Ned. “Hello, Dave,” he exclaimed, “you’re just in time to save Fatty’s life! Grab hold of that crank and turn a minute or so. I’ve got to grind a couple of nicks out of this axe.”

Dave Wilbur, affectionately known to his friends as “Weary,” glanced suspiciously at the axe in Ned Blake’s hands, then at the perspiring face of Tommy Beals whose grin was but partly concealed by his mopping handkerchief, and lastly at the heavy grindstone whose crank-handle projected so invitingly toward him. “Sure, I’ll turn for you,” he drawled. “Hop up, Fatty,” and as Beals surrendered the soap box, Dave seated himself with cool deliberation.

“Just a few turns will be enough, Dave,” were Ned’s reassuring words, as he pressed the axe upon the stone.

“Oh, that’ll be all right,” replied Wilbur. “One good turn deserves another, you know, but say, before I forget it, who’s your new neighbor?”

“Neighbor?” repeated Ned. “What neighbor?”

“Moving in next door,” explained Wilbur as he leaned back comfortably against the tree trunk and inserted a clean straw in the corner of his mouth.

Ned laid down the axe and stepped quickly to the fence which divided his back-yard from the property beyond. “I guess you’re right, Dave,” he remarked after a brief scrutiny. “There’s a big furniture van unloading, and the stuff is piled all over the sidewalk. There’s a young chap lugging it into the yard.”

“Yeah, I noticed him as I came along,” explained Wilbur. “I was just going to stop and give the young fellow a hand when I happened to think maybe you would want to be in on it—you and Fatty.”

“It’s mighty nice of you not to hog the job all by yourself, Dave,” laughed Ned, “but let’s see what’s going on,” and slipping his arms into the sleeves of a thin linen coat, he led the way toward the front of the house.

The furniture van had deposited its load and turned away toward the railroad station for a second installment. A slim, wiry lad about seventeen years of age was carrying the lighter articles into the house.

“Now’s your chance, Weary,” chuckled Tommy Beals. “Hop to it and rustle that piano up the front steps!”

“Here comes Dan Slade,” announced Ned. “I wonder just how much help he’ll offer.”

“Dan Slade could just about tote that piano all by himself, if he took the notion,” commented Beals, as he watched the youth who came swaggering toward them. “It seems to me he gets bigger and huskier every time I see him.”

“Yes. Bigger and huskier and meaner,” supplemented Wilbur. “It’ll be just like him to start razzing that chap. Let’s stroll over and listen in.”

Slade had stopped at the heap of furniture, and the three friends approaching from the opposite direction were concealed from view as they halted to hear his opening salutation.

“Hey, kid,” he began. “What’s the big idea blockin’ the sidewalk with all this junk? This is a public street.”

The new boy straightened from the box he was preparing to lift and turned toward the speaker a freckled countenance. He had a wide mouth with slightly upturned corners that gave an expression of good humor to his face. “Sorry,” he apologized good-naturedly, “I’ll have this stuff cleared away soon, but if you’re in a hurry, I’ll”—here he paused and regarded Slade’s great hulking figure with a suspicion of amusement in his blue eyes—“if you’re in a hurry I’ll try to carry you around it.”

The words, together with the grin that accompanied them, brought an ugly scowl to Slade’s face. “Don’t wise-crack me!” he growled. “I don’t have to be carried around this junk. I’m goin’ through it!” and lunging ahead he put his weight against a tall bureau, causing it to topple toward the glass doors of a sideboard directly beyond. The new boy sprang forward in time to prevent the smash and succeeded in restoring the bureau to its place. The good-humored expression of his face had changed to one of surprise, not unmixed with indignation.

“I’ll ask you not to knock over our stuff,” he began in a voice that seemed to tremble slightly in spite of his effort to control it.

“Ho! Ho!” jeered Slade, pleased by what he interpreted as an indication of fear. “Now who do you think is goin’ to stop me?”

The freckled face paled slightly, but the wide humorous mouth compressed itself to a thin line and the blue eyes grew steely. Stepping forward, the new boy placed himself squarely in front of his tormentor. “I’ll try to stop you,” he said quietly.

It is doubtful if Slade had intended to do more than merely amuse himself by bullying the weaker boy into a condition of pleading, but this unexpected show of resistance nettled him. Evidently the youngster had not been sufficiently impressed. At Slade’s feet lay a box containing articles of fireplace furniture. Stooping, he picked up a poker made from a square rod of heavy iron. He seized the implement by its ends and fixed his bold black eyes upon the freckled face opposite him.

“You’ll try to stop me, eh,” he sneered, “Why, I’d bend you like I bend this here poker!” and with a wrench of his powerful arms Slade changed the straight bar into a letter U. “It takes somebody who can do that to stop me,” he warned as he flung the distorted bar back into its box.

“That’s quite a stunt,” exclaimed a voice at his elbow. “Now can you straighten it again?”

Slade spun round to face Ned Blake, who had stepped into view closely followed by Tommy Beals and Dave Wilbur. A belligerent expression crossed Slade’s face as he eyed the group before him. “Who wants to know?” he sneered, doubling his big fists.

For a moment a fight seemed inevitable. Dave and Tommy felt the sudden tension and the new boy stiffened perceptibly; but to provoke a fight was not Ned Blake’s way of settling an argument and he answered without a trace of ill humor. “Why, I guess we’re all interested,” he said smilingly. “It takes some muscle to bend a bar like that, but they say it’s even harder to straighten it. Can you do it?”

Slade hesitated. Into his rather dull mind there crept a suspicion that perhaps he was being made the butt of some joke, and the thought brought an angry flush to his face. He would have welcomed an opportunity to try conclusions with this gray-eyed youth, who appeared so irritatingly cool and unafraid and yet offered no reasonable grounds for offense. Slade looked him up and down for a minute. “Sure I can straighten it—if I want to,” he growled.

“I’m wondering,” laughed Ned.

Stung to action as much by the tone as by the look of doubt in the smiling gray eyes, Slade snatched up the poker. “I’ll show you,” he gritted as he put forth his strength upon it.

To his surprise the U-shaped poker resisted stubbornly. It was an awkward shape to handle, and in addition the attempted straightening brought into play a very different set of muscles from those required to bend it. Pausing for a new hold, Slade strained upon the bar till the sweat streamed down his face and his breath came in wheezy gasps. Slowly the ends of the poker yielded to his power until the bar had assumed the general shape of a crude letter W, much elongated. With a grunt of disgust, Slade flung it upon the ground.

“It’s crookeder than ever,” grinned Tommy Beals with an audible chuckle.

Slade made no reply, but his hard breathing was as much the result of rage as of physical effort. Ned Blake picked up the bar and balanced it lightly in his hand.

“Bending a bar is much like mischief,” he remarked. “It’s easier to do than to undo.” As he spoke, Ned shifted his grip close to one end of the bar and that portion of the crooked iron straightened slowly in his grasp. It was done with seeming ease, but a close observer would have detected evidence of a tremendous effort in the whitening of the knuckles and the quiver of the muscles in chest and neck. The other crooked end yielded in much the same manner, and the poker had again assumed the shape of a letter U or horseshoe.

Ned paused and drew his knuckles across his eyes, into which the sweat of effort had rolled. Stooping, he dried his hands in the powdery dust of the gutter and grasped the bar, not as Slade had done, but close upon each side of the crook. With elbows pressed against his sides he inhaled to the full capacity of his lungs, bringing into play at the same moment every ounce of power in his wrists and forearms. Slowly the stubborn metal yielded until, after another quick shifting of grip, Ned’s extended thumbs came together in a straight line where the crook of the U had been.

“Here you are,” he said as he handed the bar to its owner, who had watched with no little surprise and uncertainty the little by-play enacted before his eyes. “And by the way,” continued the speaker, “my name is Blake—Ned Blake—next door, you know.”

The new boy’s freckles vanished in the flood of color that flushed his cheeks, as still keeping a wary eye upon Slade he reached forward to grip the friendly hand extended toward him. “Somers is my name—Dick Somers.” And as he spoke, the humorous expression again lighted his face.

“You seem to be obstructing traffic,” laughed Ned. “We’ll give you a hand with this stuff. Tommy Beals, here, is a great worker and as for Dave Wilbur—why, he’s absolutely pining for a job.”

For a moment Slade listened with ill-concealed disgust to this conversation, then realizing how completely the mastery of the situation had been wrested from him, he swung round on his heel and slouched away.

“Is he a neighbor?” asked Somers with a jerk of his thumb in the direction of the departing Slade.

“No, thank heaven, he’s not,” replied Beals. “His name is Dan Slade—Slugger Slade they call him where he lives up in the town of Bedford. He’s got a reputation as a great bully, but I don’t know just how far he’d really go.”

“‘A barking dog seldom bites,’” drawled Wilbur, “but just the same, Somers, you showed a lot of spunk standing up to him the way you did. My guess is that you’re the right sort.”

“I don’t mind admitting I was plumb scared half to death when I saw him bend that poker,” grinned Somers, “but that wasn’t anything compared with straightening it,” he continued with a look of genuine admiration at Ned Blake.

“Both stunts are mostly trick stuff,” declared the latter, “but let’s get busy with this furniture, before somebody else gets sore about the sidewalk being blocked.”

Four pairs of hands made short work of the pile, and by the time the van had arrived from the freight house with its second load, the walk was cleared and the boys were helping Mrs. Somers arrange the articles indoors.

“This is awfully kind of you boys!” exclaimed Dick’s mother gratefully when the job was finished. “I wish I could offer you something cold to drink after your hard, hot work, but I haven’t a bit of ice in the house.”

“Don’t you worry about us, Mrs. Somers,” laughed Ned. “We’ve just invited Dick to go down to the corner and join us in an ice cream soda. It’s Fatty Beals’ treat.”

“Sure,” agreed Beals, “you win all right, Ned,” and then with a grinning glance at the perspiring countenance of Dave Wilbur he continued, “You win—but I’ll say it’s been worth the price.”

If Tommy Beals found the open-air gymnasium impracticable, the same was not true of Dick Somers, whose slim, wiry body took most kindly to the various hanging rings and flying trapezes that adorned the limbs of the old apple tree. Only in such stunts as depended upon sheer muscular strength could Ned Blake greatly excel this new friend, who had accepted with enthusiasm the invitation to make himself at home in the Blake back-yard.

“Let’s go for a swim,” suggested Tommy from the soap box, where he sat fanning himself with his hat and watching the two young acrobats do their stuff.

“That’s a good idea, Fatty,” agreed Ned. “Where’ll we go?”

“Oh, most anywhere,” wheezed Tommy. “It’s ninety right here in the shade!” and he glared reproachfully at a rusty thermometer, which was nailed to the tree trunk.

“Let’s get Dave Wilbur to run us out to Coleson’s in his flivver,” suggested Ned. “I’ll go in and phone him.”

“Where’s Coleson’s—and what is it?” asked Dick, when Ned had returned with the information that Wilbur would be over in a few minutes.

“It’s an old copper mine on the shore of the lake about ten miles out from town,” explained Ned. “It used to be just a third-rate farm where Eli Coleson lived and grubbed a scanty living out of his few acres. The story is that one day he started to dig a well in his back-yard and down about ten feet he came upon a vein of almost pure copper ore. They say he quit farming that very minute and went to mining copper. For awhile he made money hand over fist, but, like lots of people who strike it rich, Eli Coleson couldn’t stand prosperity.”

“Here comes Dave,” interrupted Tommy Beals, as a battered car came into sight around the corner. “He’s brought Charlie Rogers with him. Hey there, Red!” he shouted to a boy on the front seat, who by reason of his fiery locks had been given that expressive nickname. “Who asked you to the party?”

“Nobody asked me, Fatty. I just horned in,” grinned Rogers. “I figured that if four of us sat on the front seat there’d be room for you in back.”

“Tell me some more about this Eli Coleson,” urged Dick, when the seating arrangements had been settled and the car was again in motion.

“Well,” resumed Ned, “the old man just naturally lost his head when he saw the dollars rolling in so fast. The first thing he did was to rip down his old farmhouse, which job he accomplished with a couple of sticks of dynamite, and right on the old foundation he began a great house of brick and stone.”

“Yes, and if he’d ever finished it, he’d have had one of the swell places of the state,” declared Rogers.

“There’s no doubt of that,” agreed Ned. “Every dollar old Eli got for his copper he spent on the house. The vein of ore was only about ten feet wide and extended toward the lake. They followed it out under the lake bottom as far as they dared; then they started digging in the other direction and tunneled back under the cellar of the house, but soon afterward the vein petered out and so did Eli’s fortune. The workmen had just got the roof on the new house when they had to stop. Eli was broke.”

“What became of him?” asked Dick.

“Oh, he’s still hanging around out there, living in one of the partly finished rooms and pecking away with pick and shovel trying to get a few more dollars out of the mine,” explained Ned. “Maybe we’ll see him. He’s got a long white beard streaked with green stains from copper ore he’s always handling. Copper Coleson, they call him.”

“I hear he’s got a fellow named Latrobe working for him,” remarked Beals. “I never saw him, but they say he’s an ugly guy.”

“Ugly is right,” declared Rogers. “Since Latrobe’s been out there, nobody’s allowed to go down into the mine, but I guess he won’t object if we take a swim off the beach.”

Eight miles from town the car turned sharply from the main highway to follow a narrow road which wound through a desolate stretch of scrubby woodland for some three miles and emerged upon the shore of Lake Erie. Here on a slight elevation dotted with thickets of scrub oak and birch stood the unfinished mansion known locally as Copper Coleson’s Folly.

“It surely started out to be a grand place,” exclaimed Dick, as he gazed up at the tall brick front with its rows of windows, in none of which glass had ever been placed.

“We’ll leave the car out here in the road,” decided Wilbur. “We can walk around the house and get down to the beach without bothering anybody.”

Beyond the house the land sloped to the water’s edge, ending in a sandy shore which afforded fine bathing, and here the boys disported themselves for an hour, swimming and diving in the cool water.

“I’d like to get a look at this copper mine,” remarked Dick. “I never saw a mine or anything like one—except an old limestone quarry, and that was only a big hole in the ground.”

“There isn’t a whole lot to see in this mine,” replied Ned; “just a vertical shaft about fifteen feet deep, which is nothing more than the old well Coleson was digging when he struck the copper ore. It’s right behind the house. We can go up there and look down it, if you want to, but it’s hardly worth the trouble.”

Getting into their clothes the boys followed a footpath up the slope and crossed a sandy stretch to the rear of the house. Nobody appeared to oppose their progress, and in a moment they were grouped about the mouth of the shaft staring down into the blackness below.

“The tunnel runs both ways from the bottom of this shaft,” explained Ned. “One end is right under the house but the other is some distance out under the lake-bottom—I don’t know just how far it extends, although I’ve been down through it several times. Probably Coleson is down there now with his pick and shovel. He fills a dump car with ore, hauls it to the bottom of the shaft and hoists it with this rigging,” and Ned indicated a rusty windlass which stood at the edge of the pit.

“Some job turning that crank,” murmured Dave Wilbur, as he eyed the dilapidated mechanism.

“Yeah, it would be a lot wors’n turning a grindstone,” chuckled Tommy Beals. “By the way, Weary, when are you going to finish that job on Ned’s axe?”

“D’j’ever hear about the man who ‘always had an axe to grind’?” drawled Wilbur.

“What does Coleson do with the ore after he gets it to the surface?” asked Dick, who was still staring down into the mine.

“He loads it onto a truck and runs it up to the smelter at Cleveland,” explained Rogers. “There’s only about one load a week, because it’s mighty slow work knocking chunks off the walls of the tunnel, and they don’t dare fire a blast for fear of bringing down the roof of the mine and the lake with it. There’s no money in this kind of mining, and I don’t see how Coleson makes enough to keep him from starving.”

“You’re right!” exclaimed Tommy Beals, with an expression of genuine concern on his plump features. “And speaking of starvation reminds me that—”

“That you’ve been dieting for almost four hours and are about to pass out of the picture,” laughed Ned. “All right, boys,” he continued, “if Dick has seen enough, let’s save Fatty’s life right now by heading back for home and supper.”

Dave Wilbur was washing the flivver—or, to be entirely accurate, Dave was playing the hose on the car while Tommy Beals and Charlie Rogers wielded sponge and rag in an effort to remove mud and road oil. The job was nearly completed when Ned Blake and Dick Somers vaulted the back fence and joined the group.

“Heard the news?” cried Ned and Dick in a breath. “Coleson’s mine has caved in!”

“When? How?” came the excited chorus.

“It must have happened soon after we were out there,” replied Ned. “This fellow Latrobe, who worked for Coleson, had been away for a few days, so he says, and when he got back yesterday he couldn’t find the old man. According to the story Latrobe told, when he reached town about an hour ago, he lowered himself down the shaft and followed the tunnel till he came to the water. The roof had fallen in somewhere out beyond the shoreline and the lower end of the mine is full of water.”

“Did he find—” began Tommy Beals in an awestruck tone.

Ned shook his head. “No, they say he didn’t find any sign of Coleson. They’re out at the mine searching for him now. The theory is that he got discouraged with pick-and-shovel work and fired a blast to bring down a big bunch of copper ore. What he brought down was the roof of the tunnel and the lake with it. Some think he was blown to bits and buried in some crevice where he’ll never be found.”

For the next few days, gossip of Copper Coleson and his mine was the principal topic of conversation in the town of Truesdell. The wildest rumors were in circulation. Somebody stated that Coleson had been seen across the lake in Canada. Others declared that he was hiding somewhere about the premises. Still another story was whispered to the effect that Latrobe knew more of the matter than he had told. He was said to have bought a quantity of blasting powder a short time before, and it was hinted that he might have fired the blast for reasons of his own.

A diver made a search of the flooded mine but found no trace of Coleson. The diver reported a considerable amount of loose copper ore at the lower end of the tunnel, and it was determined to bring this to the surface. A floating dredge was brought and anchored above the point where the bottom of the lake had caved in.

“Look at her scoop it up!” yelped Tommy Beals, who, with most of the younger population of Truesdell, was watching operations from the shore. “Why, every bucketful is more than poor, old Copper Coleson took out in a week!”

“Yes, and when they clean up in one place, they’ll pull the dredge in shore a few feet and start over again,” asserted Ned. “All they have to do is keep the dredge in line with that tall stake on the beach and that white mark on the chimney of Coleson’s house and they know they’re right plumb over the hole. I heard the foreman explain it. He says the hole is about fifty feet long.”

“Look! The diver’s going down again!” exclaimed Dick Somers.

“That’s not the regular diver,” declared Rogers, “that’s Latrobe. He says that he and Coleson were partners and he claims a share of this ore they’re taking out. I guess that’s why he’s keeping such a close watch on the job.”

“Well, I’ll say I admire Latrobe’s nerve,” remarked Beals. “I wouldn’t go down and explore that tunnel for a million times what he or anybody else will ever get out of it!”

A murmur of agreement followed this declaration as the boys watched while the diving helmet was fitted over the man’s head. In a moment he had been lowered from the forward end of the dredge and he sank from view amid a burst of silvery bubbles that shot upward from the air valve in the top of the helmet.

For several days the work of dredging went on, until the diver reported that there was no more copper ore remaining in the caved-in part of the tunnel. This was confirmed by Latrobe, who made a final examination for his own satisfaction. There was some talk of firing another blast to bring down more of the tunnel’s roof, but as fully half the stuff recovered by the dredge had proved upon examination to be worthless sand and rock, the project was abandoned.

“Who’s going to own the Coleson place now?” asked Dick when it was reported that the dredge had been taken back to Cleveland.

“The town will take the house and sell it for taxes—if anybody is foolish enough to buy it,” announced Dave Wilbur. “They’ve locked it up and put shutters over every window to keep folks out.”

“Yes, and they took the windlass away and sealed up the mouth of the shaft with big stone slabs set in cement to keep people from falling down the hole and breaking their necks,” added Ned. “I guess that’s about the finish of both Copper Coleson and his mine.”

This seemed to be the general verdict. During the following weeks a few people drove out to the deserted house, drawn to the spot by a morbid curiosity; but as there was really nothing to be seen, these visits soon ceased and the place was abandoned to desolation and decay. Summer passed and autumn’s falling leaves collected upon the broad porch and banked themselves at the angles of the wide cornices. Later came the eddying snow, sifting through crevices in the rattling window-shutters to melt and trickle down the inner walls in little streams of staining moisture. Storm-driven owls sought temporary shelter in the gables and sent their ghostly screams echoing through the night. Dubious rumors began to circulate regarding the house. A negro, returning after dark from a duck-hunting foray along the lake-shore, made a frightened report of strange, dancing lights and uncanny sounds in and about the building. Most people scoffed at these stories, but such as were more credulous or more imaginative made them the basis for a revival of gossip to the effect that old Copper Coleson still lurked in the neighborhood. Others of superstitious mind derived a kind of blood-curdling satisfaction in the belief that the house and the sealed-up mine were haunted by the ghost of Copper Coleson.

The winter, which dealt so severely with the great melancholy house standing lonely on the shore of Lake Erie, was proving a very cheerful season for the lads of Truesdell. Dick Somers, by reason of his natural aptitude for making friends, had quickly found a place in high school activities. A certain proficiency with the tenor-banjo had won him membership in a jazzy school orchestra, in which organization were some of his closest friends, including Ned Blake, Jim Tapley, Wat Sanford, Dave Wilbur and, jazziest of all, Charlie Rogers, who, in the words of Tommy Beals, “sure did wail a mean saxophone.”

Cold weather had set in much earlier than usual, and before school had closed for the Christmas holidays, the lake was frozen for a width of two miles along its southern shore. Skates were hastily resurrected from dusty attic nooks and exciting games of hockey were of daily occurrence. As the strip of ice increased in width, a few ice-boats made their appearance, skimming along shore like great white gulls.

“When are you going to get out the old Frost King, Ned?” asked Tommy Beals, as he leaned on his hockey stick to watch the speeding boats.

“We’ll have her out the minute the ice gets strong enough,” declared Ned, “but you know she weighs a lot more than any of those boats you’re looking at.”

“Have you got an ice-boat, Ned?” asked Dick, eagerly.

“I’ll say he has,” boasted Tommy, “about the fastest one on the lake, too. We keep it stored in my barn. Come on, Ned,” he continued coaxingly, “it’s getting colder every minute and by tomorrow the ice will be six inches thick, easy. Let’s get the boat out so’s to be ready.”

“All right, Fatty,” replied Ned, “get some of the crowd to help and we’ll start now.”

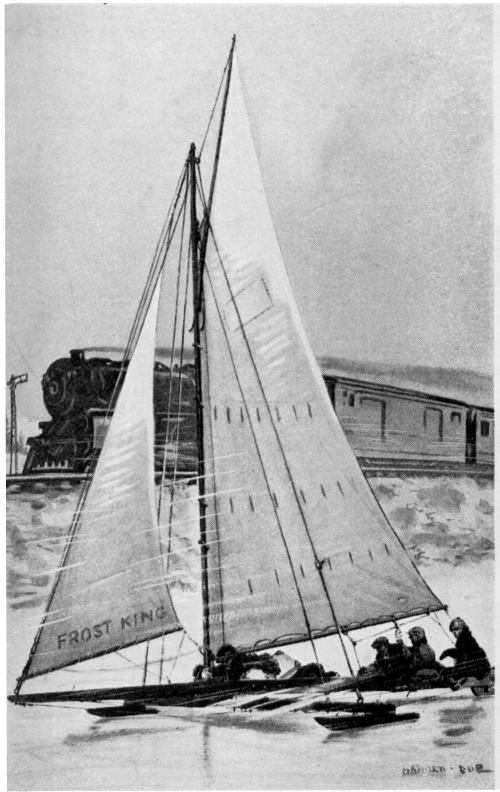

As most of my readers know, an ice-yacht is built of two timbers or heavy planks arranged in the form of a big letter T. A steel-shod shoe, not unlike a big wooden skate or sled-runner, is bolted firmly to each end of the cross-plank; while a similar shoe, equipped with an iron post and tiller, supports the stern and acts as a rudder. The Frost King was a powerful boat, carrying a huge main-sail and also a big jib which was rigged on a long bowsprit that projected far forward.

All the remainder of the day and until noon of the next, the boys were hard at work hauling the boat from her storage in the Beals barn and getting her ready for the ice. Charlie Rogers, Jim Tapley and Wat Sanford had responded to Tommy’s call for assistance, and Dave Wilbur got around in time to help in hoisting the heavy mast and setting up the wire rigging that held it in place.

“Gee, fellows!” chattered Dick Somers, as he threshed his arms to restore the circulation in fingers benumbed by his rather clumsy attempts at handling the frozen rigging. “I guess a Hottentot knows more about an ice-boat than I do! I can’t make head nor tail of this tangle of rope!”

In spite of inexperience, however, Dick did his level best, disentangling the stiffened ropes and pulling and hauling on hoist or clew-line with unfailing good nature. Over all, Ned Blake kept a watchful eye, setting up and testing each bolt and stay, mindful of his responsibility for the safety of both boat and crew. At last all was ready and with a steady breeze filling her sails, the Frost King shot out from the shelter of the docks and went careening along shore at a speed that few of her competitors could equal.

“Zowie!” gasped Dick as the boat at length rounded into the wind and stopped. “This thing must have been going a mile a minute!”

“Easily that much,” laughed Ned. “She’ll do better than that in a stiff breeze.”

At almost any time during the week of Christmas vacation, the Frost King might have been seen skimming swiftly over the ice with as many boys on board as she could carry. To Dick Somers, this novel sport was a source of never-ending delight, and seldom did the ice-boat leave port without including him among her crew.

One afternoon as Ned, Tommy, and Dick stepped from the boat after an exciting spin, they saw a man emerge from the shelter of a lumber pile on the dock and come toward them. He was muffled in a heavy fur coat, and a cap of the same material, pulled low upon his forehead, effectively concealed his features. In one gloved hand he carried a big valise, which, from the way he handled it, was evidently of considerable weight.

“I want to get to Cleveland as quick as I can,” announced the stranger in a voice which was muffled to a harsh growl by the thickness of his fur collar.

“There’s a train leaving in half an hour,” replied Ned, with a glance at his watch. “The station is only a few steps beyond the dock.”

The stranger shook his head. “That’s a slow local,” he said impatiently. “It’s the Detroit express I want, but it doesn’t stop here and they won’t flag it for me. I’ll give you ten dollars if you’ll run me up to Cleveland, so I can board it there.”

“It’s all of fifty miles to Cleveland and it’s four o’clock now,” objected Tommy Beals.

The man shot a quick glance back toward the station where the engine of the despised local was blowing off steam in a tempest of sound. “Yes, it’s fifty miles,” he growled. “I’ll pay you twenty-five dollars, if you get me there ahead of the express.”

“Can we do it?” asked Dick, a bit doubtfully. “How about it, Ned?”

“We might,” replied Ned, and then added with native caution, “but I’d want to see the money before we start.”

With an impatient grunt, the stranger plunged a hand beneath his coat and brought forth a roll of paper money, from which he selected two bills.

“Here’s fifteen dollars!” he exclaimed. “I’ll pay you the other ten if you land me at Cleveland station ahead of the express.”

With a nod of agreement Ned pocketed the money, and at his command the ice-boat was swung around till her long bowsprit pointed westward. The passenger took his place forward, where he lay flat, grasping the foot of the mast. The big valise he handled with care, holding it tightly in the crook of his free arm.

“There goes the express!” cried Dick as, with a shriek of its whistle, the big locomotive tore past Truesdell station with unabated speed and roared away down the line, dragging a long line of swaying coaches in its wake.

Rather slowly at first, the Frost King nosed its way out from the partial shelter of the docks and headed out upon the frozen lake. She was half a mile from shore before the full force of the wind struck her and then, with a sharp crunch of her keen runners, the big craft shot forward in pursuit of the already vanished express.

For the first few miles the ice was almost perfectly smooth, and to Dick’s excited senses it seemed as if the boat were actually flying through space, so steady was her bullet-like speed. Soon he caught sight of the train far ahead. It disappeared behind a wooded point, and when a few minutes later it had reappeared, they were running almost abreast of the rear coach. Car by car the flying ice-boat overhauled the fast express, till it ran neck and neck with the locomotive and a moment later had poked its long bowsprit into a clear lead. A flutter of white from the window of the cab told that the engine crew also watched the race with keen interest.

“We’ve got ’em licked!” screamed Dick as he waved back frantically; but at that instant Ned shoved the tiller hard down. The Frost King slewed into the wind with her canvas slatting furiously and came to a quick stop.

“What the blazes!” yelped Dick, bouncing up from his place and staring about him in astonishment. “What’s the idea?”

The passenger likewise straightened up and demanded the reason for the sudden stop.

“There’s a big crack ahead,” explained Ned briefly, and leaping from the boat, he ran forward to investigate.

Large bodies of water, such as Lake Erie, do not freeze with uniform smoothness as do small ponds. At intervals over their frozen surfaces great cracks form, which the varying winds cause to open and close with a force sufficient to tilt the ice along their borders at a sharp angle. It was one of these open cracks dead ahead that had caught Ned’s watchful eye.

“‘WE’VE GOT ‘EM LICKED!’ SCREAMED DICK”

“It’s ten feet wide if it’s an inch,” grumbled Tommy, as he stood at the edge of the lane of black water that stretched far to right and left of their course. “Can you jump it, Ned?”

“Not with the load we’re carrying,” was the decided answer. “We’ll have to look for a better place.”

Hurrying back to the boat, they skirted the crack for a mile, coming at last to a spot where a great cake of ice on the near side of the opening lay tilted at an angle that afforded a good take-off for the jump.

“Here’s the only possible chance I can see to make it,” observed Ned, after a quick survey of the situation. Then addressing the stranger he rapidly stated the case. “This crack right where we are is almost six feet wide,” he explained. “There’s a fair chance that we can jump it, but I’ll admit it’s none too easy a stunt. Do you want to risk it?”

“Sure,” growled the man in the fur coat. “Go ahead.”

Without another word, Ned tacked quickly to starboard, swung in a wide circle and headed directly for the crack, driving the Frost King to the very limit of her speed.

“Here we go!” yelled Tommy. “Hold everything!” And at that instant the big boat struck the tilted ice-cake, fairly leaped into the air, and a second later landed with a splintering crash on the farther side of the crack.

“Zowie!” yelped Dick. “That loosened every tooth in my head!”

“We’re lucky it didn’t take the mast out of her,” answered Ned. “Now keep a sharp lookout ahead. I’m going to drive her.”

For the next twenty miles the Frost King tore along at a speed that almost forced the breath from the bodies of her crew. The wind was increasing in strength, and in some of the sharper gusts it would lift the windward shoe clear off the ice, dropping it again with a jolt that caused the mast to sway and buckle dangerously.

“It’s up to you to stop that, Fatty,” shouted Ned and, obedient to orders, Tommy Beals crept out along the cross-plank till his ample weight reposed at the extreme outer end, where he held tightly to the wire shrouds.

With this extra ballast to windward, the boat held to the ice much better and showed a considerable increase in speed, such that very soon Dick pointed to a white plume of steam which showed against the dark stretch of woodland far ahead.

“She’s blowing for some crossing,” shouted Ned, above the whistle of the wind. “We’re picking up on her but she’s got a big lead.”

The early winter twilight soon closed down, making it difficult to distinguish objects a hundred yards ahead. The green and red lights of a railroad switch-tower swept past, and a moment later Dick sighted the rear lights of the train. At the same moment a second plume of steam appeared and the faint scream of a distant whistle reached their ears. Foot by foot the lead was cut down till once again the Frost King ran neck and neck with the big locomotive. A bobbing red lantern saluted them from the window of the cab and then, as the express slackened in the outlying suburbs of the city, the ice-boat shot ahead and in a few minutes was rounding the breakwater that protects Cleveland’s waterfront.

“Here we are!” announced Ned, as he brought the boat into the wind. “We’ve beat the express by five minutes.”

The man in the fur coat rose stiffly from his place beside the mast. “All right,” he replied gruffly. “Here’s your money,” and peeling a ten-dollar bill from his roll, he handed it to Ned and hurried away across the ice, holding the heavy valise beneath his arm.

For a long minute after the stranger had departed, Ned Blake stood staring after him, a puzzled frown wrinkling his forehead.

“Humph!” grunted Dick, who also was gazing after the hurrying figure. “He must have been in an awful rush, if he’d pay twenty-five dollars just to get here ahead of the express. What do you make of it, Ned?”

Dick had to repeat his question before Ned roused himself to reply; but now the conversation was interrupted by the plaintive voice of Tommy Beals, who had dragged himself from the end of the cross-plank and was stamping the blood back into his aching feet.

“Gosh, I’m about froze to death!” he wailed. “Froze and starved! What’s the program, Ned?”

Ned cast a quick look at the fast-gathering shadows, which already lay in a black smudge along the shore of the lake. “We’d better not try to get home tonight,” he decided. “I’ve no mind to chance jumping that crack after dark. There’s a hotel close by the station where we can get a good dinner and a bed. We’ve got the cash to pay for both.”

“Yeah, that’s the idea!” exclaimed Tommy fervently. “A steak smothered in onions and French fried spuds! What?”

“How about the boat?” asked Dick.

“We’ll furl the sails and push her in against the dock,” replied Ned. “We can unship the tiller and hide it so that nobody will be tempted to run off with her.”

This was quickly done and the boys turned their steps toward the Union Station, the lights of which gleamed a scant hundred yards ahead. The express had thundered into the station while they were taking care of the boat, and now, as they crossed the tracks, her rear lights were blinking in the distance as she picked her way through the switch-yards westward bound.

“There goes our twenty-five-dollar passenger,” remarked Dick, with a characteristic jerk of his thumb toward the departing train. “He had plenty of time to catch her, I guess.”

“I can’t get it out of my mind that I’ve seen that man somewhere before today,” began Ned. “I couldn’t see his face clearly, he was so muffled up, and yet there was something about him that seemed familiar—the way he stood—or walked—or something.”

The hotel was just across the street from the station, and here the boys registered after bargaining for a room containing three beds.

“And now for that steak and onions,” gloated Tommy Beals as he headed for the grill room closely followed by Dick.

“I’ll be with you in a jiffy,” Ned called after them as he paused at a telephone booth. “I’ll just shoot a word to the folks that we’re O.K. and will be home in the a.m.”

It took Ned several minutes to complete his call, and then, as he was about to step from the booth, he halted suddenly at the sound of a voice in the telephone compartment next to his own. There was a familiar note to the harsh growl. As Ned paused in surprise, the words came clearly to his ears.

“Sure, I made it on time and Miller was there, too. Where was you?” Silence a moment; then the voice continued. “Local nothing! I told you I’d be in on the express—stop or no stop. As a matter of fact I got there ahead of time—never mind how. Now listen.”

For a moment the heavy voice rumbled on but in a lower tone so that no word reached Ned’s ears; then the door of the booth was jerked open and its occupant crossed the hotel lobby with a rapid stride. He was joined by a tall, red-faced man and the two disappeared through the door leading to the street. For the second time within half an hour, Ned Blake found himself staring after a short, thick-set figure in a fur coat. There was no doubt of it. The growling voice in the telephone booth had been that of his mysterious passenger on the Frost King. Hurrying to the grill room, Ned acquainted his companions with what he had learned.

“Then that yarn about wanting to catch the Detroit express was all bunk!” exclaimed Dick.

“Evidently,” agreed Ned. “But also it’s sure that he had some important date that coincided with the arrival of the train. That red-faced man ‘Miller’ showed up on time but somebody else missed out. I wonder what the game is.”

“We should worry about him or his business,” was Tommy’s cheerful comment as he eyed with huge satisfaction the nicely browned steak, which at the moment was being placed before him on the table. “Right now I’m for enjoying this feed that he’s paying for. Afterwards, I’ll wonder—if you insist,” and Tommy helped himself lavishly to the savory fried onions that accompanied the steak.

Long exposure to the biting wind had induced appetites which required a deal of satisfying, but at length even Tommy’s splendid yearnings had been appeased and he sank back in his chair, the picture of well-fed contentment. Hardly had the boys left the dining-room, when drowsiness came upon them as the natural reaction to long hours in the open air supplemented by a heavy meal.

“Can’t keep my eyes open,” mumbled Dick after a prodigious yawn. “Me for little old bed-o, even if it is only seven-thirty.”

The idea was accepted unanimously and the boys lost no time in seeking their room and making ready for bed. But now the puzzling question regarding their unknown passenger recurred to Ned with redoubled force. Before his mind’s eye there passed countless faces and figures of men he had known or seen. He was groping painfully in an effort to place one thick-set figure in a fur coat.

“What’s the matter, Ned? Do you see a ghost?” grinned Dick at his friend who sat on the edge of the bed, shoe in hand, staring blankly at the opposite wall.

“Not unless ghosts wear fur coats,” muttered Ned, flinging the shoe under the bed. “Hang it all! I’m sure I’ve seen that fellow—or at least somebody a whole lot like him. I wish I could remember when or where!”

“While you’re wishing you might as well wish for that roll he packed,” chuckled Tommy. “Gosh! I’ll bet there was half a thousand dollars in it—and that fur coat!” Here Tommy rolled up his eyes enviously.

“One thing I am sure of,” continued Ned, “whoever he is, he probably does at least a part of his business in Canada. That last bill he gave me was Canadian money. I noticed it when I paid the dinner charge. Luckily, they accept Canadian money here.”

“What do you suppose he had in that suitcase he was so fussy about?” queried Dick. “It was darned heavy—from the way he handled it.”

“That’s another question I’d like answered,” admitted Ned, “also, what was he doing in Truesdell, when all the time he was so anxious to get to Cleveland that he was willing to risk his neck on the Frost King, just to save half an hour or so?”

“Heigh, ho! I’ll give it up,” yawned Tommy and, with a sigh of unalloyed satisfaction, the plump youth rolled over luxuriously and buried his face in the pillow.

Dick was only seconds behind Tommy in his plunge into the depths of sleep; but long after his companions were sunk in blissful oblivion, Ned lay racking his brain in what proved to be a futile effort to find some reasonable solution of the puzzle. Weariness at last closed his eyes, but through his troubled dreams there persisted these tantalizing, half-formed questions, always on the point of being answered but ever eluding his grasp.

The sharp rattle of icy particles on the window awakened Dick Somers next morning. Springing out of bed, he roused his companions and they stared out at a world rapidly whitening under a driving storm of snow.

“This will never do!” cried Ned. “We’ve got to get a move on or we’ll be snowed in down here!”

After a quick breakfast of bacon, eggs, rolls and coffee, the boys hastened down to the lake. The snow was, as yet, only about two inches deep, but it was whipping out of the north with a power that warned of much more to come. Sails were quickly hoisted and the Frost King shot away, homeward bound.

Holding close enough to the shore so that its dim outline served as a guide, Ned kept his bearings; and although slowed somewhat by the fast gathering snow, the ice-boat made fair speed. Constant wind pressure had closed the shoreward end of the big crack and a cautious crossing was made without difficulty. Through a six-inch depth of snow, the Frost King plowed to a stop beside the dock at Truesdell, where the crews of other boats were busily engaged in removing the canvas from their craft.

“That’s what we’ve got to do right now,” declared Ned. “This storm feels like a genuine blizzard that will probably put an end to ice-boating for the rest of the winter.”

As rapidly as possible the sails were removed, the stiffened canvas folded up and stored in a safe place and the boat itself hauled as far up on shore as possible, pending the time when the boys would return her to her former place of storage.

“Well, we’ve had a bully time and a swell feed and have fifteen simoleons to divvy up among the crew of the Frost King,” chortled Tommy Beals as they trudged homeward. “I’ll say that’s good enough for anybody.”

“Yes, it’s O.K.,” agreed Ned, “but I’m going to keep my eye out for that fellow in the fur coat, and the next time I get a look at him, I’ll try to find out who he is or whom he reminds me of.”

As it transpired, however, many months were to pass and many strange happenings were to take place before Ned Blake again found himself face to face with the mysterious stranger.

It had been a great winter for the lads of Truesdell. Although the big blizzard put an end to ice-boating, it provided instead snow-shoeing, ski-running, and many other delightful winter sports. Plenty of hard study interspersed with recreation made the winter months pass rapidly, and when the last shrunken snow-drift had sunk to a muddy grave and the balmy south winds were drying soggy fields and muddy lanes as if by magic, the boys turned from winter sports to the enthusiastic consideration of baseball possibilities.

“We’ve got a swell chance to cop the championship pennant in the Lake Shore League,” declared Charlie Rogers to a group which had gathered in a sunny nook behind the school building. “Believe me! We’ll wipe the earth with Bedford this year!”

“Where do you get that stuff, Red?” demanded Abner Jones, a sallow youth whose prominent knee and elbow joints had won for him the nickname “Bony.” “I hear Slugger Slade is going to play third for Bedford. He’s an old-timer and knows every trick in the bag; and can he hit? Oh, boy!”

“Slade is tricky all right,” agreed Rogers. “He’s tricky and dirty, too, if he gets a chance, but when it comes to hitting, why we’ve got a couple of pitchers who may fool him.”

“Forget it!” scoffed Jones. “Slade will make a monkey of any pitcher we’ve got—even Ned Blake.”

“Here comes Ned right now,” interposed Wat Sanford. “Let’s hear what he has to say about it.”

“What’s all the row?” asked Ned, as he came down the steps swinging a strapful of books.

“Bony, the crape-hanger, says we can’t beat Bedford with Slade playing for ’em, and I say we’ll wipe ’em off’n the map,” explained Rogers. “How about it, Ned?”

“Both wrong—as usual,” laughed Ned, clapping a strong hand on the disputants and pushing his broad shoulders between them. “Now here’s how I see it,” he continued. “Slade is a wicked hitter and a tough man in the field. He’ll be a big help to Bedford, but he can’t play the whole game. Keep that in mind, Bony. On the other hand, Red, remember that plenty of teams are world-beaters before the season starts. We’ve got some good material, but it will take a lot of hard work to make a winning nine out of it. That’s what it’s up to us to do. I’ve just posted a notice for the squad to show up for practice this afternoon. The field is drying fast and I want every man on the job.”

“All except the pitchers, I suppose,” yawned Dave Wilbur. “I’ll be around the first of next week and work on the batting practice.”

“You’ll be right on the job at two p.m. this afternoon, Dave,” replied Ned, firmly. “I’m depending on you to set a good example to the new men.”

“Do you hear that, Weary?” gibed Tommy Beals. “You’re expected to set the old alarm for one forty-five p.m. and be made an example of.”

“That’s the idea, Fatty,” laughed Ned. “Anybody going my way?”

“I am, if you don’t walk too darned fast,” replied Beals.

Dick Somers also rose to his feet and joined the two as they shouldered their way out of the group and strode down the street.

“Bony Jones is an awful knocker,” remarked Tommy, when they were out of hearing.

“He’s that all right,” agreed Ned, “and yet for the good of the team right now, I’d rather they’d hear Bony’s knocking than Red’s boasting. Over-confidence at the start of the season is a mighty bad thing, and as captain of the team, it’s up to me to kill it if I can.”

“What’s the real dope on this fellow Slade?” asked Dick. “I don’t have any very pleasant recollections of him myself, but how about his playing?”

“I’ve seen him in a couple of games,” replied Ned. “He’s a good third baseman and a small edition of Babe Ruth when it comes to hitting.”

“How about these stories of his spiking men on bases and other dirty work?” persisted Dick.

“I don’t know,” answered Ned with a shrug of his shoulders. “I won’t condemn a man till I actually see him do something of the kind myself. I’m more worried right now about how good our fellows are going to be than how bad somebody else is. By the way, Dick,” he continued, “how much ball have you played?”

“Oh, not a whole lot,” answered Dick, modestly. “We had a pretty fair team where I used to live. They let me chase around out in right field.”

“Well, I want you and Fatty to be on hand this afternoon,” declared Ned. “We’re going to need every man who shows any class.”

Promptly at two o’clock the Truesdell squad assembled on the muddy field and began the season with an easy workout. Dick Somers quickly demonstrated a remarkable throwing arm, both for distance and accuracy, while his quickness of foot promised to make him a valuable fielder and base-runner. The development of hitting ability was Captain Blake’s most difficult problem, and upon this first day and for many days thereafter he kept the weak hitters swinging at pitched balls till their shoulders ached.

“D’j’ever hear about ‘the straw that broke the camel’s back’?” grumbled Dave Wilbur as he left the pitcher’s box after a particularly long session of batting practice. “Ned’s an awful glutton for work. He’s making me wear out my wing throwing balls past these dubs, who couldn’t hit a balloon with a bass viol!”

“Don’t kid yourself, Weary,” gibed Rogers. “Ned is figuring on giving you some much-needed practice in hurling. We’re just standing up there so’s you can learn to locate the plate.”

“Aw say, use your bean,” grinned Dave. “I can put ’em over the old pan with my eyes shut!”

The first regular game of the schedule was won by Truesdell but the victory proved costly. Charlie Rogers, sliding home with the winning run, sprained his ankle and was pronounced out of the game for the rest of the season.

“There goes the best fielder in the Lake Shore League,” wailed Tommy Beals, as he watched Rogers hobble from the field. “A few more unlucky breaks like that will make hard going for us!”

This pessimism seemed well founded, for a few days afterward, Ned Blake dropped into Somers’ home with another gloomy bit of news. “Tinker Owen flunked math. yesterday,” he announced, shortly. “That wipes him out of the picture, unless old Simmons will relent—and you know how much chance there is of that.”

“Not a look-in,” agreed Dick, picking up his banjo from the couch and plunking a few chords in a doleful minor key.

“It leaves us only nine real players anyhow you figure it,” continued Ned, who was checking off the names from a slip of paper. “You’ll have to play center field in Red’s place, Dick, and we’ll try out Fatty Beals in Tinker’s position behind the bat. Dave and I will have to alternate pitch and right field.”

“It’s pretty tough on Weary Wilbur, making him pitch every other game and play right field between times,” grinned Dick. “He’ll crab plenty when he hears the news!”

“I’m not worrying about Dave,” was Ned’s reply. “Of course he’ll crab a bit and probably he’ll spring one of his everlasting proverbs on us, but he’ll come through in his own lazy fashion. It’s a shame we haven’t got a few more good subs, but we’ll manage somehow.”

Truesdell High struggled through the next three games with its changed line-up, winning each by a narrow margin but improving steadily in the matter of speed and smoothness. Bedford Academy, although heavily scored against, likewise kept a clean slate showing six victories. It was freely predicted by the followers of baseball that this year’s annual game between the two great rivals would be “for blood.”

A special train brought a wild crowd of Bedford supporters down to Truesdell for the big game. Rooters for the local team jammed the bleachers and watched the preliminary practice with critical eyes.

“I can’t see Fatty Beals as catcher,” grumbled Bony Jones. “He might do all right for a backstop, but he can’t throw down to second to save his life! I could do better myself.”

“Why didn’t you think to mention that the first of the season?” demanded Charlie Rogers, whose hair was only a shade redder than his temper when one of his friends was assailed. “It’s a crime to keep your talents hidden that way, Bony!”

“Fatty’s all right,” declared Wat Sanford, “and anyhow, Ned Blake’s going to pitch, and there won’t be a Bedford man get to first—take it from me!”

The Truesdell players were soon called in and Bedford took the diamond for ten minutes fast work, handling infield hits and throwing around the bases.

“Look at Slugger Slade over on third!” exclaimed Jim Tapley. “This is his first year with Bedford, but I hear he’s a semi-pro. He looks more like a football fullback than a third sacker!”

“He’ll try football stuff, if he gets a chance,” asserted Rogers. “I’m hoping the umpire keeps his eye peeled for crooked work. Here’s our team,” he continued, hoisting himself up on his one sound foot with the help of a cane. “Come on, boys. Let’s give ’em a cheer!”

The long yell rolled forth from half a thousand throats. “Oh well! Oh well! Oh WELL! Truesdell! Truesdell! TRUESDELL.” To which the Bedford rooters responded with their snappy “B-E-D-F-O-R-D!”

The visiting team was first at bat and three men went out in quick succession, not a man reaching first.

“What did I tell you!” chortled Wat Sanford. “You should worry about the heavy hitters, Bony!”

Truesdell’s efforts at bat were, however, little better than Bedford’s. The first man up drew a base on balls but perished on an attempt to steal second; the next fouled out and Ned’s long fly was captured by Bedford’s left-fielder.

Slugger Slade came to bat in the first half of the second inning and smashed to right field a wicked line-drive, which Dave Wilbur gathered in with his usual lazy grace.

“Atta boy, Weary!” screamed Jim Tapley. “You tell ’em!”

“What do you think now about Slade’s hitting?” demanded Jones. “That drive of his would have gone for a homer sure, if it had got past Dave!”

“Horsefeathers!” snorted Charlie Rogers.

What looked like a break for Truesdell came in their half of the fourth. Dick Somers bunted safely and went down to second on the first pitch, running like a scared rabbit and scoring the first stolen base of the game. Tommy Beals hit a grounder to right field, which was returned to first base before the plump, short-legged youth was half-way there. Dick raced round to third on the play and Truesdell’s chances for a run were excellent. Ned Blake ran out to the third-base coaching line.

“Great work, Dick,” he chattered. “Only one gone! Take a big lead. I’ll watch ’em for you!”

Slugger Slade, the third baseman, threw him a sour look. “Keep back of that coaching line, you!” he snarled.

Dave Wilbur was up, and as the bleachers yelled lustily for a hit, he lifted a high sky-scraper to center field. Dick clung to the bag till he saw the ball settle in the fielder’s glove; then dashed for home. Ordinarily it would have been an easy steal for a runner of Dick’s speed, but he had faltered noticeably in his start and the throw-in to the plate beat him by a narrow margin for the third out.

“I want to enter a protest on that decision!” cried Dick to the umpire, as the Bedford players trooped in from the field.

“What’s the matter?” demanded the official. “The catcher had the ball on you half a yard from the plate!”

“I know that, but I’m claiming interference by the third baseman,” yelped Dick, wrathfully. “He held me by the belt just long enough to spoil my start!”

“That’s right, I saw him do it!” asserted Ned, who had run in to add his protest to that of Dick.

“What’s all the crabbin’ about?” growled Slade, swaggering up to the group. “You was out by a mile!”

“I’m not crabbing,” declared Dick. “I’m just calling the umpire’s attention to some of your dirty playing!”

“Who says I play dirty ball?” demanded Slade, doubling up his big fists menacingly.

“I do, for one!” Ned spoke quietly, but his gray eyes were blazing. “I saw you hook your fingers under Dick’s belt when you stood behind him on the bag!”

“You mean you think that’s what you saw,” sneered Slade. “The umpire says he’s out and that settles it!”

There seemed no chance for further argument, and Dick walked out to center field in a savage humor, which was somewhat appeased when Ned, a moment later, struck the slugger out with three fast ones. The next Bedford man was out at first, and a long fly to Dick ended the inning.

Ned Blake was up in Truesdell’s half and brought the crowd to its feet with a screaming three-bagger.

“Wow! That’s cracking ’em out!” yelled Wat Sanford. “It’s a crime we didn’t have a couple of men on bases when Ned got hold of that one!”

“There’s nobody gone, any kind of a hit will mean a run now!” cried Charlie Rogers.

The next Truesdell batter swung at two bad balls, but lifted the third for a high fly to right field. Slugger Slade’s heavy breathing sounded in Ned Blake’s ear as he crouched on third base, all set for the dash for home. With quick fingers he loosened his belt-buckle and as the fielder’s hands closed upon the fly ball, Ned sprang from the bag; stopped short in his tracks; and yelled lustily for the umpire. Every eye turned in his direction and saw Slade standing stupidly on third base with Ned Blake’s belt dangling from his hand. The Slugger had been caught in his own trap.

A chorus of boos and jeers changed to cheers as the umpire motioned Ned home; a penalty which Slade had earned for his team by interfering with a base-runner.

“Oh, boy! What a stunt!” shrieked Jim Tapley. “Slade met his match that time!”

The wild yells and jeers seemed to rattle the Bedford team for the moment. Slade, purple with rage, let an easy grounder roll between his legs, and before the inning was over, two more Truesdell runs came across, making the score three to nothing.

In their half of the next inning, two Bedford batters were easy outs, but the third drove a savage liner straight for the pitcher’s box. Ned knocked it down and managed to get the ball to first for the third out. The effort proved costly, however, for he came in with the blood streaming from his pitching hand, two fingers of which were badly torn.

“You’ll have to finish the game, Dave,” announced Ned, and the lanky southpaw at once began warming up.

Ned’s injured fingers were hastily taped and he took Wilbur’s place in right field.

“Oh, I’d give a million dollars to be out there now!” groaned Charlie Rogers, as he shifted his lame ankle to a more comfortable position.

Dave Wilbur had scant time to warm up before he faced the leaders of Bedford’s batting order. He was found for four hits and two runs scored. The score was now Truesdell three—Bedford two, and thus it stood when the latter came to bat in the first half of the ninth.

“Holy cat!” wailed Jim Tapley, as the first man up whaled out a two-bagger. “A couple more like that and we’re sunk!”

The second batter hit to shortstop and reached first on a fumble. Bedford now had men on first and second, with none out.

“For the luv o’ Mike, hold ’em, Dave!” screamed Wat Sanford.

Tommy Beals threw off his mask and ran half-way to the pitcher’s box to confer with Wilbur. Yells and jeers from the Bedford stand greeted this evidence of worry on the part of Truesdell’s battery, but it took more than mere noise to rattle Dave Wilbur. Strolling lazily back to the box, he fanned the next two men, and the Bedford yells subsided for the moment. The next batter, however, sent a pop-fly just out of the shortstop’s reach, and Bedford had the bases loaded with two out. Slugger Slade was up, and as he swaggered to the plate, the Bedford yells again rent the air.

“Come on now, Slugger! Knock the cover off’n it! Put it out of the lot!”

“One strike!”

The umpire’s shrill voice cut through the babel of yells from the Bedford stand. Slade glared round at the official and muttered something in protest. Dave Wilbur took his time in the wind-up and delivered the ball in his customary effortless style.

“Strrrike two!”

A yell of delight from the Truesdell rooters greeted this decision. Slade rubbed his hands in the dirt and gripped his bat till his big knuckles were white. Dave Wilbur had fooled him with two slow out-drops and the crowd fell strangely silent as the lanky youth began his third wind-up. Dave put everything he had into the pitch—a high, lightning-fast ball over the inside corner of the plate.

The sharp crack of the Slugger’s bat brought the Bedford crowd to its feet with a roar, while the silent Truesdell bleachers watched with sinking hearts as the horse-hide sphere sailed high and far between right and center fields.

Ned Blake and Dick Somers were playing deep, and at the crack of the bat both started on the instant. The ball curved away from Ned and a bit toward Dick who was running as he had never run before. For a moment it seemed to the watchers that the two racing fielders would crash together. Suddenly they saw Dick make a desperate leap into the air with upstretched arm. The ball struck the tip of his glove, and bouncing high to one side, fell into Ned’s extended hands for the final out.

Truesdell had won, and with the sort of finish that comes once in a lifetime. With a roar, the Truesdell rooters swept across the diamond, and hoisting Ned Blake and Dick Somers high above the surging crowd, bore them in triumph from the field.

Slugger Slade stared after the retreating crowd and a savage scowl darkened his face. Into his mind there flamed a great hatred of these jubilant lads who had beaten him so unaccountably. Deep within him arose the sullen wish that he might somehow even matters with them. It was a wish that would later bear much fruit.

The school year had ended in a fashion to delight the heart of every loyal son of Truesdell, and the day following graduation found a group of the boys lounging in Dave Wilbur’s yard, a convenient meeting-place by reason of its central location.

“Are you going to play ball this summer, Ned?” asked Jim Tapley. “I hear they’re looking for a pitcher on the North Shore Stars. You could make the team easy, and there’s seventy-five a month in it plus expenses.”

Ned Blake shook his head. “Nothing doing, Jim,” he said regretfully. “I’ll admit the money would mean a lot to me, for, as you all know, I’m trying to scrape together enough to enter college in the fall. But if I get there, I want to play ball and this professional stuff would bar me.”

“What I’d like to do is go to England on a cattle steamer,” declared Charlie Rogers. “All you have to do is rustle hay and water for the steers.”

“Yeah, that’s all, Red,” drawled Dave Wilbur, “and they only eat about four tons a day and drink—well, they’d drink a river dry, and you sleep down somewhere on top of the keel and eat whatever the cook happens to throw you—unless you’re too blamed sea-sick to eat anything.”

“Well, even that would be better than hanging round this dead dump all summer,” retorted Rogers, with some spirit.

“Dan Slade has got a job over across the lake in Canada,” announced Wat Sanford. “I saw him at the station yesterday when the train came through from Bedford. He was bragging that he was going to pull down a hundred a month, but he didn’t say what the job was.”

“Some crooked work probably,” remarked Tommy Beals. “Now what I’d like would be a good job bell-hopping at some swell summer hotel. A fellow can make all kinds of dough on tips.”

“Sure, you’d look cute in a coat with no tail to it and a million little brass buttons sewed all over the front!” laughed Dick Somers. “What you really need, Fatty, is a job as soda-fountain expert, where you can get enough sugar and cream to keep your weight up to the notch.”

There was a general laugh at this in which Tommy joined good-naturedly.

“I guess what we’re all looking for is a chance to make some money this summer,” suggested Ned. “What Red says about this being a dead dump is true of every town, until somebody starts something. It’s up to us to show signs of life. I don’t believe any of us would be content to loaf till next September.”

“Speak for yourself, Ned,” yawned Dave Wilbur, who, stretched at full length on his back, was lazily trying to balance a straw on the tip of his long nose. “I’m enjoying myself fine right here—and besides you want to remember that ‘a rolling stone gathers no moss.’”

“Bony Jones got a job down at the Pavilion dance hall,” remarked Tapley. “His old man has something to do with the place and they took Bony on as assistant. Pretty soft, I’ll say.”

“I was hoping to get a chance down there with the jazz orchestra,” lamented Rogers, “but I hear they’ve brought two saxophone players up from Cleveland, which lets me out.”

“Tough luck, Red,” sympathized Tommy. “You and Wat ought to find a chance somewhere to do a turn with sax and traps; the Pavilion isn’t the only place.”

“What’s the matter with our running some dances of our own?” asked Ned. “The Pavilion is usually over-crowded and we ought to get some of the business.”

“Who do you mean by we?” inquired Wat Sanford.

“Well, there’s you with the traps and Red with the sax—as Fatty has just suggested,” began Ned. “Dick is pretty fair on the banjo and Jim can play the piano with the best of ’em. Dave can do his stuff on the clarinet—if he’s not too exhausted—and I would make a bluff with the trumpet. Fatty could take tickets and act as a general utility man. That makes seven, all we need for a start.”

“That’s about half of the high school orchestra,” remarked Dick. “I guess with a little practice we might get by as far as music is concerned, but where would we run the dances?”

Several possibilities were suggested, only to be turned down as impracticable for one reason or another.

“What we want is a place just out of town which auto parties can reach handily,” declared Jim Tapley, who was taking a lively interest in the scheme. “We could serve refreshments and make something that way.”

“There’s one place we might do something with,” began Ned, a bit doubtfully. “I’m thinking of the Coleson house,” he continued. “Of course it’s a good ten miles out and quite a distance off the main road.”

“Yes, and that’s not the whole story either,” objected Rogers. “The house was going to wrack and ruin even while Coleson lived in it, and lying shut up so long can’t have improved it a whole lot.”

“Guess it’s in bad shape all right,” agreed Tommy Beals. “Haunted, too—if you can believe all you hear about it. There’s talk of some mighty queer things going on out there.”

“What kind of things?” asked Wat Sanford, quickly.

“Can’t say exactly,” admitted Beals. “Some folks claim to have seen and heard things that couldn’t be explained. Last fall a darky went past the house after dark and was scared pretty near dippy.”

“That’s the bunk,” drawled Dave Wilbur. “D’j’ever see a darky that wasn’t nuts on ghosts?”

“What do you say we take a run out there anyhow?” suggested Rogers. “It’s a swell day for a ride and we can go swimming; the water’s elegant; I was in yesterday!”

“Bully idea, Red,” applauded Tapley. “Come on, Weary! Crank up the old flivver!” he cried, as he stirred up the recumbent Wilbur with his toe.

Thus appealed to, Dave arose lazily to back the little car out of the garage, and piling in, the boys settled themselves as best they could upon its lumpy cushions.

“What do you reckon we’ll find out there, Ned?” asked Wat Sanford a bit anxiously, when the flivver after sundry protesting coughs and sputters, had finally gotten under way.

“Oh, dirt and lonesomeness, mostly,” laughed Ned. “They’re the usual furniture of a deserted house—especially if it’s supposed to be haunted.”

Lonesomeness seemed, in truth, to pervade the very air and to settle like a pall upon the spirits of the boys, as the flivver coughed its way up the weed-grown drive and came to a halt before the tall, gloomy, brick front.

Charlie Rogers sprang out, and mounting the weatherbeaten steps leading to the broad porch, rattled the great iron knob of the massive front door. “It’s locked, all right,” he reported, “and these window-shutters seem pretty solid.”

Further investigation proved this to be true of all the openings of the lower story, but at the rear of the house one window-shutter of the story above had broken from its fastenings and swung creakingly in the breeze.

“If we only had a ladder—” began Wat Sanford.

“That’s not necessary,” interrupted Ned. “The question is who’s got the nerve to go through that window and find his way down to open one of these lower shutters?”

“I’ll do it,” volunteered Dick. “That is, I will if I can reach that window-sill; it’s about fifteen feet up.”

“We’ll put you there,” promised Ned, and he locked arms with Dave Wilbur. The two braced themselves close to the wall of the house. Tapley and Rogers mounted to their shoulders and Dick, climbing nimbly to the top of this human pyramid, grasped the window ledge above and drew himself upon it. In a moment he was inside, and pausing only long enough to accustom his eyes to the gloom of the interior, he picked his way down the unfinished stairs and unhooked a shutter that opened upon the front porch. By this means the other boys entered, but paused in awe of the deathly stillness of the place.

“Gee! It’s like a tomb!” shivered Sanford, and struggling with a window-fastening, he threw open another shutter at the westerly end, admitting a flood of sunlight which revealed an apartment nearly thirty feet square, partly paneled with oak and floored with the same material.

Opposite the entrance, a stairway had been completed up to its first broad landing, but the remainder of the flight was still in a rough, unfinished condition. Through a wide, arched doorway could be seen another large room, evidently designed for a dining-hall but entirely unfinished except for the floor, which, as in the case of the first apartment, was of quartered oak.

“What’s down below?” asked Wat, as he peered through a rectangular opening into the blackness beneath. “Ugh! It looks spooky!”

“There’s nothing down there except a big cellar,” replied Ned, reassuringly. “This hole was left for the cellar stairs to be built in, but they were never even begun.”

Further investigation of the interior showed the oaken paneling to be warped and cracked by dampness and long neglect, but the floors, beneath their thick covering of dust, were in fairly good condition.

“It’s the floor that we’re most interested in for our proposition,” declared Dick. “I believe that a few days of hard work with scrapers would make these two rooms fit for dancing. We could put the music on that stair-landing and leave this whole lower space free and clear.”

“Do you think we could get a crowd to come way out here?” asked Tommy Beals doubtfully. “It’s a lonesome dump even in the daytime, and at night it is mighty easy to believe these yarns about its being haunted.”

“Why not make that the big attraction!” exclaimed Ned with sudden inspiration. “Everybody is looking for thrills nowadays. We might be able to give ’em a brand new one.”

A chorus of approval greeted this suggestion.

“Bully stuff, Ned!” cried Charlie Rogers. “Great idea! And if there don’t happen to be any honest-to-goodness ghosts on the job, we can manufacture a few just to keep up the interest.”

“What do you think it would cost to fix up the old shebang?” asked Wilbur, who, despite his rather affected laziness, was beginning to take an interest in the scheme.

“Oh, not a whole lot,” replied Ned, glancing about with an appraising eye. “As Dick says, the floor is our chief consideration, and if we do the work on it ourselves, the only expense will be for scrapers and sandpaper. We can string bunting and flags to cover the breaks in the walls and ceiling. We’ll have to lay a floor over that stair-opening, or somebody will manage to tumble through into the cellar, but I guess we can find enough lumber around here to do the job.”

“How about lights?” inquired Sanford. “There isn’t an electric line within five miles.”

“We’ll use candles,” decided Ned. “A dim light will be just what we want for ghost stunts anyhow, and candles won’t cost much if we buy ’em in wholesale lots.”

“Shall we figure on refreshments?” asked Rogers.

“Sure thing!” asserted Dick. “The Pavilion sells ice cream and soft drinks; we can do the same and serve the stuff from the butler’s pantry. That will be just the job for Fatty!”

“Nothing doing!” objected Beals in an injured tone. “I draw the line on handing out grub for other folks to eat, but I’ll manage the refreshment business and get our darky, Sam, to serve the stuff. Sam used to work in a restaurant and can do the trick in style.”

“All right, then,” announced Ned, who had, by common consent, assumed leadership, “let’s get organized into working shape. There are seven of us, and if we chip in two dollars each, it will put fourteen dollars into the treasury for immediate expenses.”

This was agreed to and Tommy Beals was elected treasurer.