Title: The Reason Why

Author: Robert Kemp Philp

Release date: December 23, 2014 [eBook #47748]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Christian Boissonnas and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

A CAREFUL

COLLECTION OF MANY HUNDREDS OF REASONS FOR THINGS

WHICH, THOUGH GENERALLY BELIEVED, ARE

IMPERFECTLY UNDERSTOOD.

A BOOK OF CONDENSED SCIENTIFIC KNOWLEDGE FOR THE MILLION.

By THE AUTHOR OF "INQUIRE WITHIN."

This collection of useful information on "Common Things" is put in the interesting form of "Why and Because," and comprehends a familiar explanation of many subjects which occupy a large space in the philosophy of Nature, relating to air, animals, atmosphere, caloric, chemistry, ventilation, materia medica, meteorology, acoustics, electricity, light, zoölogy, etc.

NEW YORK:

DICK & FITZGERALD, PUBLISHERS,

No. 18 ANN STREET.

We are all children of one Father, whose Works it should be our delight to study. As the intelligent child, standing by his parent's knee, asks explanations alike of the most simple phenomena, and of the most profound problems; so should man, turning to his Creator, continually ask for knowledge. Not because the profession of letters has, in these days, become a fashion, and that the man of general proficiency can best work out his success in worldly pursuits; but because knowledge is a treasure which gladdens the heart, dignifies the mind, and ennobles the soul.

The occupation of the mind, by the pursuit of knowledge, is of itself a good, since it diverts from evil, and by elevating and refining the mind, and strengthening the judgment, it fortifies us for the hour of temptation, and surrounds us with barriers which the powers of sin cannot successfully assail.

It is not contended that the mere acquisition of knowledge will either ensure a good moral nature, or convey religious truth. But both religion and morals will find in the diffusion of knowledge a ground work upon which their loftier temples may discover an acceptable foundation.

The man who comprehends the order of Nature, and the immutability of Divine law, must of necessity bring himself in some degree into accordance with that order, and under submission to the law: hence the tendency of knowledge will always be found to harmonise the fragment with the mass, and to subvert the evil to the good.

The troubles of the world have arisen from the want of knowledge, not from the possession of it. And in proportion as man becomes an intelligent and reflective being, he will be a better creature in all the relations of life. If these benefits, vast and incalculable as they are, be the real tendency and result of knowledge, why is ignorance allowed to remain, and why is the world still distracted by error?

It is because the moral and intellectual qualities of man are, like all creations and gifts of God, the subjects of development, whose law is progression.

We can aid human improvement, but we cannot unduly hasten it. Whenever man has sprung too rapidly to a conclusion, he has alighted upon error, and has had to retrace his steps.

The greatest philosophers have been those who have clung to the demonstrative sciences, and have held that a simple truth well ascertained, is greater than the grandest theory founded upon questionable premises. Newton made more scientific revelations to mankind than any other philosopher; and his discoveries have borne the searching test of time, because he snatched at nothing, leaped over no chasm to establish a favourite dogma; but, by the slowest steps, and by regarding the merest trifles, as well as the highest phenomena, he learnt to read Nature correctly. He discovered that her atoms were letters, her blades of grass were words, her phenomena were sentences, and her complete volume a grand poem, teaching on every page the wisdom and the power of an Almighty Creator.

When he observed an apple fall to the ground, he asked the "Reason Why;" and in answer to that enquiry, there came one of the grandest discoveries that has ever been recorded upon the book of science. With that discovery a flood of light burst upon the human mind, illustrating in a far higher degree than had ever previously been conceived, the vastness of Almighty Power.

Why should not each of us enquire the "Reason Why" regarding everything that we observe? Why should we mentally [Pg v] grope about, when we may see our way? When addressed in a foreign tongue, we hear a number of articulated sounds, to which we can attach no meaning; they convey nothing to the mind, make no impression upon the in-dwelling soul. When those sounds are interpreted to us, in a language that we can understand, they impart impressions of joy, hope, surprise, or sorrow, because the words convey to us a meaning. In like manner, if we fail to understand Nature, its beauties, its teachings are lost. Everything speaks to us, but we do not understand the voices. They come murmuring from the brook, trilling from the bird, or pealing from the thunder; but though they reach the ear of the body, they do not impress the listening spirit.

Every flower, every ray of light, every drop of dew, each flake of snow, the curling smoke, the lowering cloud, the bright sun, the pale moon, the twinkling stars, speak to us in eloquent language of the great Hand that made them. But millions lose the grand lesson which Nature teaches, because they can attach no meaning to what they see or hear.

"The Reason Why" is offered as an interpreter of many of Nature's utterances. Great care has been taken that these interpretations may be consistent with the latest knowledge, obtained from the highest sources. If the author finds that his work if accepted for the good of those who seek not only to know, but to understand, he will make it his constant care to read the Book of Nature, and to add to the pages of this volume whatever interpretations the progress of enquiry and discovery may demand and supply.

☞ The numbers refer to the Questions. The Index Lessons do not correspond with the Chapters, but are designed to bring together in their alphabetical connection, all the Questions and Answers upon each particular subject included in the work.

"God looked down from heaven upon the children of men, to see if there were any that did understand that did see God."—Psalm liii.

1. Why should we seek knowledge?

Because it assists us to comprehend the goodness and power of God.

And it gives us power over the circumstances and associations by which we are surrounded: the proper exercise of this power will greatly promote our happiness.

2. Why does the possession of knowledge enable us to exercise power over surrounding circumstances?

Knowledge enables us to understand that, in order to live healthily, we require to breathe fresh and pure air. It also tells us that animal and vegetable substances, undergoing decay, poison the air, though we may not be able to see, or to smell, or otherwise discover the existence of such poison. Knowing this, we become careful to remove from our presence all such matters as would tend to corrupt the atmosphere. This is only one of the countless instances in which knowledge gives us power over surrounding circumstances.

3. Name some other instances in which knowledge gives us power.

Knowledge of Geography and of Navigation enables the mariner to guide his ship across the trackless deep, and to reach the sought-for port, though he had never before been on its shores.

Knowledge of Chemistry enables us to separate or to combine the various substances found in nature. Thus we obtain useful and [Pg 28] precious metals from what at first appeared to be useless stones; transparent glass from pebbles, through which no light could pass; soap from oily substances; and gas from solid bodies.

"Give instruction to a wise man, and he will be yet wiser; teach a just man, and he will increase in learning."—Proverbs ix.

Knowledge of Medicine enables the physician to overcome the ravages of disease, and to save suffering patients from sinking prematurely to the grave.

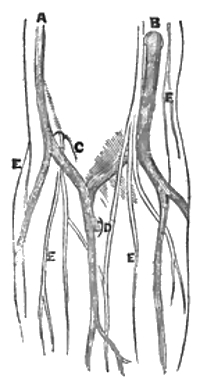

Knowledge of Anatomy and of Surgery enables the surgeon to bind up dangerous fractures and wounds, and to remove, even from the internal parts of bodies, ulcers and diseased formations that would otherwise be fatal to life.

Knowledge of Mechanics enables man to increase his power by the construction of machines. The steam-ship crossing the ocean in opposition to wind and tide, the railway locomotive travelling at 60 miles an hour, and the steam-hammer beating blocks of iron into useful shapes, are evidences of the power which man acquires through a knowledge of mechanics.

Knowledge of Electricity enables man to stand in comparative safety amid the awful war of the elements. Lightning, the offspring of electricity, has a tendency to strike upon lofty objects by which it may be attracted. By its mighty powers churches or houses may be instantly levelled with the dust. But man, knowing that electricity is strongly attracted by particular substances, raises over lofty buildings rods of steel communicating with bars that descend into the ground. The lightning, rushing with indescribable force toward the steeple, is attracted by the bar of steel, and conducted harmlessly to the earth. Man may thus be said to take even lightning by the hand, and to divert its destroying force by the aid of Knowledge. And in countless other instances "Knowledge is Power."

Because the air contains oxygen, which is necessary to life.

5. Why is oxygen necessary to life?

Because it combines with the carbon of the blood, and forms carbonic acid gas.

"Be not as the horse, or as the mule, which have no understanding: whose mouth must be held with the bit and bridle."—Psalm xxxii.

6. Why is this combination necessary?

Because we are so created that the substances of our bodies are constantly undergoing change, and this resolving of solid matter into a gaseous form, is the plan appointed by our Creator to remove the matter called carbon from our systems.

7. Why do our bodies feel warm?

Because, in the union of oxygen and carbon, heat is developed.

8. What is this union of oxygen and carbon called?

It is called combustion, which, in chemistry, means the decomposition of substances, and the formation of new combinations, accompanied by heat; and sometimes by light, as well as heat.

9. What is formed by the union of oxygen and carbon?

Carbonic acid gas.

10. What becomes of this carbonic acid gas?

It is sent out of our bodies by the compressure of the lungs, and mingles with the air that surrounds us.

11. Is this carbonic acid gas heavier or lighter than the air?

Pure carbonic acid gas is the heaviest of all the gases. That which is sent out of the lungs is not pure, because the whole of the air taken into the lungs at the previous inspiration has not been deprived of its oxygen, and the nitrogen is returned. Therefore the breath sent out of the lungs may be said to consist of air, with a large proportion of carbonic acid gas.

12. What is the composition of air in its natural state?

It consists of oxygen, nitrogen, and carbonic acid gas, in the proportions of oxygen 20 volumes, nitrogen 79 volumes, and carbonic acid gas 1 volume. It also contains a slight trace of watery vapour.

13. What is the state of the air after it has once been breathed?

It has parted with about one-sixth of its oxygen, and taken up an equivalent of carbonic acid. And were the same air to be breathed [Pg 30] six times successively, it would have parted with all its oxygen, and could no longer sustain life.

"A prudent man forseeth the evil, and hideth himself; but the simple pass on, and are punished."—Proverbs xxvii.

14. Is the impure air sent out of the lungs lighter or heavier than common air?

At first, being rarefied by warmth, it is lighter. But, if undisturbed, it would become heavier as it cooled, and would descend.

15. Why is it proper to have beds raised about two feet from the ground?

Because at night, the bed-room being closed, the breath of the sleeper impregnates the air of the room with carbonic acid gas, which, descending, lies in its greatest density near to the floor.

16. What are the chief sources of carbonic acid gas?

The vegetable kingdom (as will be hereafter explained), the combustion of substances composed chiefly of carbon, the breathing of animals, and the decomposition of carbonic compounds.

17. Is breathing a kind of combustion?

It is. In the breathing of animals, the burning of coals, or of wood, or candles, &c., similar changes occur. The oxygen of the air combines with the carbon of the substance said to be burnt, and forms carbonic acid gas, which unfits the air for the purposes of either breathing or of burning, until it has been renewed by admixture with the air.

It is one of the elementary bodies, and is very abundant throughout nature. It abounds mostly in vegetable substances, but is also contained in animal bodies, and in minerals. The form in which it is most familiar to us is that of charcoal, which is carbon almost pure.

19. What is meant by an elementary body?

An elementary body is one of those substances in which chemistry is unable to discover more than one constituent. For instance, the chemist finds that water is composed of oxygen and hydrogen. Water is therefore a compound body. But carbon consists of carbon only, and therefore it is called a simple, or elementary body.

"Where no wood is, there the fire goeth out: so where there is no tale-bearer, the strife ceaseth."—Proverbs xxvi.

20. Why is it dangerous to burn charcoal in rooms?

Because, being composed of carbon that is nearly pure, its combustion gives off a large amount of carbonic acid gas.

21. What is the effect of carbonic acid gas upon the human system?

It induces drowsiness and stupor, which, if not relieved by ventilation, would speedily cause death.

22. What is the reason that people feel drowsy in crowded rooms?

Because the large amount of carbonic acid gas given off with the breaths of the people, makes the air poisonous and oppressive.

23. What other causes of drowsiness are there?

The candles, gas, or fires that may be burning in the rooms where people are assembled. Three candles produce as much carbonic acid gas as one human being; and it is probable that one gas-light produces as much carbonic acid gas as two persons.

24. Have people ever been poisoned by their own breaths?

In the reign of George the Second, the Rajah of Bengal took some English prisoners in Calcutta, and put 146 of them into a place which was called the "Black Hole." This place was only 18 feet square by 16 feet high, and ventilation was provided for only by two small grated windows. One hundred and twenty-three of the prisoners died in the night, and most of the survivors were afterwards carried off by putrid fevers. Many other instances have occurred, but this one is the most remarkable.

Oxygen is one of the most widely diffused of the elementary substances. It is a gaseous body.

"Stand in awe and sin not: commune with your own heart upon your bed and be still"—Psalm iv.

26. Why do persons who are walking, or riding upon horseback feel warmer than when they are sitting still?

Because as they breathe more rapidly, the combustion of the carbon in the blood is increased by the oxygen inhaled, and greater heat is developed.

27. Why does the fire burn more brightly when blown by a bellows?

Because it receives, with every current of air, a fresh supply of oxygen, which unites with the carbon and hydrogen of the coals, causing more rapid combustion and increased heat.

28. Why does not the oxygen of the air sometimes take fire?

Because oxygen, by itself, is incombustible. The wick of a candle, which retains the slightest spark, being immersed in oxygen, will instantly burst into a brilliant flame; and even a piece of iron wire made red-hot, and dipped in oxygen, will burn rapidly and brilliantly. Oxygen, though non-combustible of itself, is the most powerful supporter of combustion.

29. Why do we know that oxygen will not burn of itself?

Because when we immerse a burning substance into a jar of oxygen, it immediately burns with intense brilliancy; but directly it is withdrawn from the oxygen, the intensity of the flame diminishes, and the oxygen which remains is unaffected.

30. Why do we know that oxygen is necessary to our existence?

Because animals placed in any kind of gas, or in any combination of gases, where oxygen does not exist, die in a very short time.

It is found in the air, mixed with nitrogen; in water combined with hydrogen; in the tissues of vegetables and animals; in our blood; and in various compounds called, from the presence of oxygen, oxides.

32. Why is the oxygen of the air mixed so largely with nitrogen?

Because oxygen in any greater proportion than that in which it is found in the atmosphere, would be too exciting to the animal [Pg 33] system. Animals placed in pure oxygen die in great agony from fever and excitement, amounting to madness.

"As vinegar is to the teeth, and as smoke to the eyes, so is the sluggard to him that sent him."—Proverbs x.

Nitrogen is an elementary body in the form of gas.

It is chiefly found in the air, of which it constitutes 79 out of 100 volumes. It may be mixed with oxygen in various proportions; but in the atmosphere it is uniformly diffused. It is found in most animal matter, except fat and bone. It is not a constituent of the vegetable acids, but it is found in most of the vegetable alkalies.

Acids are a numerous class of chemical bodies. They are generally sour. Usually (though there are exceptions) they have a great affinity for water, and are easily soluble therein; they unite readily with most alkalies, and with the various oxides. All acids are compounds of two or more substances. Acids are found in all the kingdoms of nature.

Alkalies are a numerous class of substances that have a great affinity for, and readily combine with, acids, forming salts. They exercise peculiar influence upon vegetable colours, turning blues green, and yellows reddish brown. But they will restore the colours of vegetable blues which have been reddened by acids; and, on the other hand, the acids restore vegetable colours that have been altered by the alkalies. Alkalies are found in all the kingdoms of nature.

37. Could animals live in nitrogen?

No; they would immediately die. But a mixture of oxygen and nitrogen, in equal volumes, constitutes nitrous oxide, which gives a pleasurable excitement to those who inhale it, causing them to be merry, almost to insanity; it has, therefore, been called laughing gas.

38. Why does nitrous oxide produce this effect?

Because it introduces into the body more oxygen than can be consumed. It, therefore, deranges the nervous system, and being [Pg 34] a powerful stimulant, gives an unnatural activity to the nervous centres and the brain.

"Lord, make me know mine end, and the measure of my days, that I may know how frail I am."—Psalm xxxix.

39. In what proportions are the atmospheric gases found in the blood?

The mean quantity of the gases contained in the human blood has been found to be equal to 1-10th of its whole volume. In venous blood, the average quantity of carbonic acid is about 1-18th, that of oxygen about 1-85th, and that of nitrogen about 1-100th of the volume of the blood. In arterial blood their quantities have been found to be carbonic acid about 1-14th, oxygen about 1-38th, and nitrogen about 1-72nd.

40. Then is nitrogen taken into the blood from the air?

Such a supposition is highly improbable. It is probably derived from nitrogenised food, just as carbonic acid is derived from carbonised food.

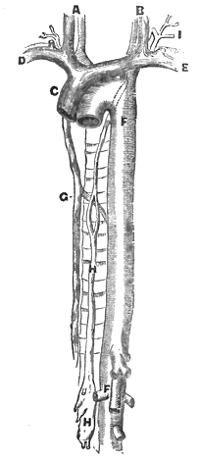

Venous blood is that which is returning through the veins of the body from the organs to which it has been circulated.

Arterial blood is that which is flowing from the heart through the arteries to nourish the parts where those arteries are distributed.

43. What is the difference between venous and arterial blood?

Venous blood contains more carbonic acid, and less oxygen and nitrogen than arterial blood.

It will not burn, nor will it support combustion.

45. What is the difference between "burning" and "supporting combustion?"

Oxygen gas will not burn of itself, but it aids the decomposition by fire of bodies that are combustible. It is therefore called a supporter of combustion. But hydrogen gas, though it burns of itself [Pg 35] will extinguish a flame immersed in it. It is therefore said to be a body which will burn, but will not support combustion.

"As coals are to burning coals, and wood to fire; so is a contentious man to kindle strife."—Proverbs xxvi.

46. What becomes of the nitrogen that is inhaled with the air?

It is thrown off with the breath, mixed with carbonic acid gas, and flies away to be renewed by a fresh supply of oxygen.

47. Where does nitrogen find a fresh supply of oxygen?

In the atmosphere. Nitrogen is said to possess a remarkable tendency to mix with oxygen, without having a positive chemical affinity for it. That is to say, neither the oxygen nor the nitrogen undergoes any change by the union, except that of admixture. The oxygen and the nitrogen still possess their own peculiar properties. Oxygen and nitrogen are found in nearly the same proportions in all climates, and at all altitudes.

48. In combustion does any other result take place besides the union of oxygen and carbon forming carbonic acid gas?

Yes. Usually hydrogen is present, which in burning unites with oxygen, and forms water.

Hydrogen is an elementary gas, and is the lightest of all known bodies.

50. Will hydrogen support animal life?

It will not. It proves speedily fatal to animals.

51. Will hydrogen support combustion?

Although it will burn, yielding a feeble bluish light, it will, if pure, extinguish a flame that may be immersed in it. Hydrogen will therefore burn, but will not support combustion.

52. Why will hydrogen explode, if it will not support combustion?

When hydrogen explodes it is always in combination with oxygen, [Pg 36] or with the common air, which contains oxygen. Two measures of hydrogen and one of oxygen form a most explosive compound.

"As smoke is driven away, so drive them away: as wax melteth before the fire, so let the wicked perish at the presence of God."—Psalm xlvi.

53. Why does hydrogen explode, when mixed with oxygen, upon being brought in contact with fire?

Because of its strong affinity for oxygen, with which, upon the application of heat, it unites to form water.

54. Where does hydrogen chiefly exist?

In the form of water, where it exists in combination with oxygen. Eleven parts of hydrogen, and eighty-nine of oxygen, form water.

55. Is hydrogen found elsewhere?

It is never found but in a state of combination; united with oxygen, it exists in water; with nitrogen, in ammonia; with chlorine, in hydro-chloric acid; with fluorine, in hydro-fluoric acid; and in numerous other combinations.

56. Is the gas used to illuminate our streets, hydrogen gas?

It is; but it is combined with carbon, derived from the coals from which it is made. It is therefore called carburetted hydrogen, which means hydrogen with carbon.

57. How is hydrogen gas obtained from coals?

It is driven out of the coals by heat, in closed vessels, which prevent its union with oxygen.

58. What becomes of the water which is formed by the burning of hydrogen in oxygen?

It passes into the air in the form of watery vapour. Frequently it condenses, and may be seen upon the walls and windows of rooms where many lights or fires are burning. Sometimes, also, portions of it become condensed in the globes of the glasses that are suspended over the jets of gas. A large volume of these gases forms only a very small volume of water.

59. What becomes of the carbonic acid gas which is produced by combustion?

It is diffused in the air, which should be removed by adequate ventilation.

"I will both lay me down in peace and sleep: for thou, Lord, only, makest me dwell in safety."—Psalm iv.

60. What proportion of carbonic acid gas is dangerous to life?

Any proportion over the natural one of 1 per cent. may be regarded as injurious. But toxicologists state that five per cent. of carbonic acid gas in the atmosphere is dangerous to life.

Persons who study the nature and effects of poisons and their antidotes.

62. Which kind of combustible used for lighting tends most to vitiate the air?

Assuming all the lights to be of the same intensity, the degree in which the substances burnt would vitiate the atmosphere may be gathered from the number of minutes each would take to exhaust a given quantity of air. This has been found to be: rape oil, 71 minutes; olive oil, 72; Russian tallow, 75; town tallow, 76; sperm oil, 76; stearic acid, 77; wax candles, 79; spermaceti candles, 83; common coal gas, 98; canal coal gas, 152. Thus it is shown that rape oil is most destructive of the atmosphere, and that coal gas is the least destructive.

63. Is an escape of hydrogen gas from a gas-pipe dangerous to life?

It is dangerous, first, by inhalation. There are no less than six deaths upon record of persons who were killed by sleeping in rooms near to which there was a leakage of gas.

It is dangerous, secondly, by explosion.

In 1848, an explosion of gas occurred in Albany-street, Regent's-park, London. The gas accumulated in a shop for a very short time only. It had been escaping from a crack in the meter for about one hour and twenty minutes. The area of the room was about 1,620 cubic feet. When the gas exploded, it blew out the entire front of the premises, carried two persons through a window into an adjoining yard, and forced another person on to the pavement on the opposite side of the street, where she was killed. The effect of the explosion was felt for more than a quarter of a mile on each side of the house, and most of the windows in the neighbourhood were shattered. The iron railings over the area of the house directly opposite were snapped asunder; and a part of the roof, and the back windows of another house, were carried to a distance of from 200 to 300 yards. The pavement was torn up for a considerable [Pg 38] length, and the damage done to 103 houses was afterwards reported to amount to £20,000. Other serious explosions have taken place. The explosions of "coal damp," which frequently occur in mines, are of a similar character.

"O Lord, our Lord, how excellent is thy name in all the earth! who hast set thy glory above the heavens."—Psalm viii.

64. What proportion of hydrogen gas with atmospheric air will explode?

According to the researches of Sir Humphrey Davy, seven or eight parts of air, to one of gas, produce the greatest explosive effect; while larger proportions of gas are less dangerous. A mixture of equal parts of gas and air will burn, but it will not explode. The same is the case with a mixture of two of air, or three of air, and one of gas; but four of air and one of gas begin to be explosive, and the explosive tendency increases up to seven or eight of air and one of gas, after which the increased proportion of gas diminishes the force of the explosion.

65. What is the best method of preventing the explosion of gas?

Observe the rule, never to approach a supposed leakage with a light. Fortunately the gas, which threatens our lives, warns us of the danger by its pungent smell. The first thing to be done is to open windows and doors, and to ventilate the apartment. Then turn the gas off at the main, and wait a short time until the accumulated gas has been dispersed.

66. Does hydrogen gas rise or fall when it escapes?

Being twelve times lighter than common air it rises, and therefore it would be better for ventilation to open the window at the top than at the bottom. But all gases exhibit a strong tendency to diffuse themselves, and therefore they do not rise or fall in the degree that might be anticipated.

67. What proportion of hydrogen in the air is dangerous to life, if inhaled?

One-fiftieth part has been found to have a serious effect upon animals. The effects it produces upon the human system are those of depression, headache, sickness, and general prostration of the vital powers. It is therefore advisable to observe precautions in the use of gas.

"From the place of his habitation he looketh upon all the inhabitants of the earth."—Psalm xxxiii.

68. What proportion of gas in the air may be recognised by the smell?

By persons of acute powers of smelling it may be recognised when there is one part of gas in five hundred parts of atmospheric air; but it becomes very perceptible when it forms one part in a hundred and fifty. Warning is, therefore, given to us long before the point of danger arrives.

69. What other sources of hydrogen are there in our dwellings?

It arises from the decomposition of animal and vegetable substances, containing sulphur and hydrogen. These give off a gas called sulphuretted hydrogen, from which the fætid effluviam of drains and water-closets chiefly arise. We should, therefore, take every precaution to secure effective drainage, and to keep drain-traps in proper order.

70. May the use of gas for purposes of illumination be considered highly dangerous?

Not if it is intelligently managed. The appliances for the regulation of gas are so very simple and perfect, that accidents seldom arise except from neglect. In England 6,000,000 tons of coal are usually consumed in the manufacture of gas, producing 60,000,000,000 cubic feet of gas. And yet accidents are of very uncommon occurrence.

Heat is a principle in nature which, like light and electricity, is best understood by its effects. We popularly call that heat, which raises the temperature of bodies submitted to its influence.

Caloric is another term for heat. It is advisable, however, to use the term caloric when speaking of the cause of heat, and of heat as the effect of the presence of caloric.

"While the earth remaineth, seed-time and harvest, and cold and heat, and summer and winter, and day and night, shall not cease."—Gen. viii.

73. What is the source of caloric?

The sun is its chief source. But caloric, in some degree, exists in every known substance.

74. What are the effects of caloric?

Heat which, in proportion to its intensity, acts variously upon all bodies, causing expansion, fusion, evaporation, decomposition, &c.

75. Why is caloric called a repulsive agent?

Because its chief effects are to expand, fuse, evaporate, or decompose the substances upon which it acts.

76. What is an attractive agent, in contradistinction to a repulsive agent?

Chemical attraction, or affinity, is an attractive agent—as when bodies seek of their own natures to unite and form some new body.

77. When is a body said to be hot?

When it holds so much caloric that it diffuses heat to surrounding objects.

78. When is a body said to be cold?

When it holds less caloric than surrounding objects, and absorbs heat from them.

79. How may caloric be excited to develop heat?

By any means which cause agitation, or produce an active change in the condition of bodies. Thus friction, percussion, sudden condensation or expansion, chemical combination, and electrical discharges, all develope heat.

80. Why do "burning glasses" appear to set fire to combustible substances?

Because they gather into one point, or focus, several rays of caloric as they are travelling from the sun, and the accumulation of caloric developes that intensity of heat which constitutes fire.

In optics, it is the point or centre at which, or around which, divergent rays are brought into the closest possible union.

"Yet man is born to trouble, as the sparks fly upward.—I would seek unto God, and unto God would I commit my cause."—Job v.

It is a violent chemical action attending the combustion of the ingredients of fuel with the oxygen of the air.

83. What are the properties of fire?

It imparts heat, which has the effect of expanding both fluids and solids.

It cannot exist without the presence of combustible materials.

It has a tendency to diffuse itself in every direction.

It cannot exist without oxygen or atmospheric air.

84. What elements take part in the maintenance of a fire?

Hydrogen, carbon, and oxygen. Hydrogen and carbon exist in the fuel, and oxygen is supplied by the air.

85. How does the combustion of a fire begin?

A match made of phosphorous and sulphur (highly inflammable substances) is drawn over a piece of sand-paper; the friction of the match induces the presence of caloric, which developes heat, and ignites the match, the burning of which is sustained by the oxygen of the air. The flame is then applied to paper or wood, and the heat of the flame is sufficient to drive out hydrogen gas, which unites with the oxygen of the air, and burns, imparting greater heat to the carbon of the coals, which assumes the form of carbonic acid gas by union with oxygen, and in a little while all the conditions of combustion are established.

86. What are the properties of heat?

It may exist without fire or light.

It is not sensible to vision.

It makes an impression upon our feelings.

It acts powerfully upon all bodies.

It has no weight.

It attends, or is connected with, all the operations of nature.

It radiates from all bodies in straight lines, and in all directions.

It strikes most powerfully in direct lines.

Its rays may be collected into a focus, just as the rays of the sun.

It may be reflected from a polished surface.

It is more easily conducted by some substances than by others.

"For my days are consumed like smoke, and my bones are burned as an hearth."—Psalm cii.

Animal heat is derived from the slow combustion of carbon in the blood of animals with the oxygen of the air which the animals breathe.

Latent heat (or more properly latent caloric) is that which exists, in some degree, in all bodies, though it may be imperceptible to the senses.

89. Is there latent caloric in ice, snow, water, marble, &c?

Yes; there is some amount of caloric in all substances.

A blacksmith may hammer a small piece of iron until it becomes red hot. With this he may light a match, and kindle the fire of his forge. The iron has become more dense by the hammering, and it cannot again be heated to the same degree by similar means, until it has been exposed in fire, to a red heat. Is it not possible that, by hammering, the particles of iron have been driven closer together, and the latent heat driven out? No further hammering will force the atoms nearer, and therefore no further heat can be developed. But when the iron has again absorbed caloric, by being plunged in a fire, it is again charged with latent heat. Indians produce sparks by rubbing together two pieces of wood. Two pieces of ice may be rubbed together until sufficient warmth is developed to melt them both. The axles of railway carriages frequently become red hot from friction.

Yes; whenever oxygen combines with carbon to form carbonic acid gas, an extrication of heat takes place, however minute the amount. Such a combination occurs much more extensively during the germination of seeds and the impregnation of flowers, than at any other time. In the germination of barley heaped in rooms, previous to being converted into malt, it is well known that a considerable amount of heat is developed.

91. Has any investigation of this subject ever been carefully made?

Yes. Lamarck, Senebier, and De Candolle, found the flowers of the Arum Maculatum, between three and seven o'clock in the afternoon, as much as 7 deg. Reaum. warmer than the external air. Schultz found a difference of 4 deg. to 5 deg. between the heat of the spathe of the Canadian pinnatifolium and the surrounding [Pg 43] air, at six to seven o'clock p.m. Other observations have established differences of as much as 30 deg. between the temperature of the spathe of the Arum cordifolium, and that of the surrounding atmosphere.

"And there are diversities of operations, but it is the same God which worketh in all."—Corinthians xii.

92. Have plants sometimes a temperature lower than that of the surrounding air?

Yes. It has not only been found that under particular circumstances the heat of certain parts of plants is elevated to a very remarkable degree, but that, under nearly all circumstances, they have a temperature different from that of the external air, being warmer in winter, and cooler in summer.

93. How many kinds of combustion are there?

There are three, viz., slow oxydation, when little or no light is evolved; a more rapid combination, when the heat is so great as to become luminous; and a still more energetic action, when it bursts into flame.

94. Why does phosphorous look luminous?

Because it is undergoing slow combustion.

95. Why do decayed wood, and putrifying fish, look luminous?

Because they are undergoing slow combustion. In these cases the heat and light evolved are at no one time very considerable. But the total amount of heat, and probably of light, generated through the lengthy period of this slow oxydation, amounts to exactly the same as would be evolved during the most rapid combustion of the same substances.

It is gaseous matter burning at a very high temperature.

97. Why, when we put fresh coals upon a fire, do we hear the gas escaping from the coals without taking fire?

Because, the fire being slow, the temperature is not high enough to ignite the gas.

"I will praise thee, O Lord, with my whole heart; I will show forth thy marvellous work."—Psalm ix.

98. What is the gas which escapes from the coals?

Carburetted hydrogen.

99. Why, if we light a piece of paper, and lay it where the gas is escaping from the coals, will it burst into flame?

Because the lighted paper gives a heat sufficient to ignite the gas; and because also hydrogen requires the contact of flame to ignite it.

100. Why, when the coals have become heated, will the hydrogen burst into flame?

Because the carbon of the coals, and the oxygen of the air, have begun to combine, and have greatly increased the heat, and have produced a rapid combustion, so nearly allied to flame, that it ignites the hydrogen.

101. What temperature is required to produce flame?

That depends upon the nature of the combustible you desire to burn. Finely divided phosphorous and phosphorated hydrogen will take fire at a temperature of 60 deg. or 70 deg.; solid phosphorous at 140 deg.; sulphur at 500 deg.; hydrogen and carbonic oxide at 1,000 deg. (red heat); coal gas, ether, turpentine, alcohol, tallow, and wood, at about 2,000 deg. (incipient white heat). When once inflamed they will continue to burn, and will maintain a very high temperature.

Smoke consists of small particles of carbon of hydrogen gas, and other volatile matters, which are driven off by heat and carried up the chimney.

103. Is it not a waste of fuel to allow this matter to escape?

It is, as it might all be burnt up by better management.

104. How may the waste be avoided?

By putting on only a little coals at a time, so that the heat of the fire shall be sufficient to consume these volatile matters as they escape.

"And the strong shall be as tow, and the maker of it as a spark, and they shall both burn together, and none shall quench them."—Isaiah i.

105. Why is there so little smoke when the fire is red?

Because the hydrogen and the volatile parts of the coal have already been driven off and consumed, and the combustion that continues is principally caused by the carbon of the coals, and the oxygen of the air.

106. Will carbon, burnt in oxygen, produce flame and smoke?

It burns brightly, but it produces neither flame nor smoke.

107. Why do not charcoal and coke fires give flame?

Because the hydrogen has been driven off by the processes by which charcoal and coke are made.

108. What is a conductor of heat?

A conductor of heat is any substance through which heat is readily transmitted.

109. What is a non-conductor of heat?

A non-conductor is any substance through which heat will not pass readily.

110. Name a few good conductors.

Gold, silver, copper, platinum, iron, zinc, tin, stone, and all dense solid bodies.

111. Name a few non-conductors.

Fur, wool, down, wood, cotton, paper, and all substances of a spongy or porous texture.

112. How is heat transmitted from one body to another?

By Conduction, Radiation, Reflection, Absorption and Convection.

113. What is the Conduction of heat?

It is the communication of heat from one body to another by contact. If I lay a penny piece upon the hob, it becomes hot by conduction.

114. What is the Radiation of heat?

The transmission of heat by a series of rays. If I hold my hand [Pg 46] before the fire, the rays of heat fall upon it, and my hand receives the heat through radiation.

"Sing praises to the Lord, which dwelleth in Zion, declare among the people his doings."—Psalm ix.

115. What is the Reflection of heat?

The reflection of heat is the throwing back of its rays towards the direction whence they came. In a Dutch oven the rays of heat pass from the fire to the oven, and are reflected back again by the bright surface of the tin. There is, therefore, considerable economy of heat in ovens, and other cooking utensils constructed upon this plan.

116. What is the Absorption of heat?

The absorption of heat is the taking of it up by the body to which it is transmitted or conducted. Heat was conveyed to my hand by radiation, and taken up by my hand by absorption.

117. What is the Convection of heat?

The convection of heat is the transmission of it through a body or a number of bodies, or particles of bodies, by those substances which first received it; as when hot water rises from the bottom of a kettle and imparts heat to the cold water lying above it.

118. Why does not a piece of wood which is turning at one end, feel hot at the other end?

Because wood is a bad conductor of heat.

119. Why is wood a bad conductor of heat?

Because the arrangement of the particles of which it is composed does not favour the transmission of caloric.

120. Why do some articles of clothing feel cold, and others warm?

Because some are bad conductors of heat, and do not draw off much of the warmth of our bodies; while others are better conductors, and take up a larger portion of our warmth.

"The fining pot is for silver, and the furnace for gold: but the Lord trieth the hearts."—Proverbs xvii.

121. Which feels the warmer, the conductor or non-conductor?

The non-conductor, as it does not readily absorb the warmth of our bodies.

122. What substances are the best conductors of heat?

Gold, silver, copper, and most substances of close and hard formation, &c.

123. What substances are the worst conductors of heat?

Fur, eider down, feathers, raw silk, wood, lamp-black, cotton, soot, charcoal, &c.

124. Why has the toasting-fork a wooden handle?

Because wood is not so good a conductor as metal, therefore the wood prevents the heat from being transmitted by conduction to our hands.

125. Why has the coffee-pot a wooden handle?

Because the metal of the coffee-pot would otherwise conduct the heat to the hand; but wood, being a bad conductor, prevents it.

126. Why does hot water in a metal jug feel hotter than in an earthenware one?

Because metal, being a good conductor, readily delivers heat to the hand; but earthenware, being an indifferent conductor, parts with the heat slowly.

127. How can we ascertain that wood prevents the conduction of heat to the hand?

By passing the top of the finger along the wooden handle of the coffee-pot, until it reaches the point where the wood meets the metal. The wooden handle will be found to be cool, but the metal will feel very hot.

128. Of what use are kettle-holders?

Being made of bad conductors, such as wood, paper, or woollen cloth, they will not readily conduct the heat from the kettle to the hand.

"Wisdom is the principal thing; therefore get wisdom: and with all thy getting get understanding."—Proverbs iv.

129. Will a kettle-holder, being a bad conductor, sometimes conduct heat to the hand?

Yes. But so slowly that the hand will not feel the inconvenience of too much heat.

130. Why does hot metal feel hotter than heated wool, though they may both be of the same degree of temperature?

Because metal gives out heat more rapidly than wool, by which it is made more perceptible to our feelings.

131. Which would become cold first—the metal or the wool?

The wool, because, although the metal conducts heat more rapidly, to a substance in contact with it, it does not radiate heat as well as a black and rough substance.

132. Why do iron articles feel intensely cold in winter?

Because iron is one of the best conductors, and draws off heat from the hand very rapidly.

133. What is the cause of the sensation called cold?

When we feel cold, heat is being drawn off from our bodies.

134. What is the cause of the sensation called heat?

When we feel hot, our bodies are absorbing heat from external causes.

The condition here implied is that of health, and of ordinary circumstances. A person in a condition of fever, suffering from intense heat arising from a diseased state of the blood, could not be said to be absorbing heat. Nor could such a description apply to a person who, by a very rapid walk, has raised the temperature of his body considerably above its natural state, by the internal combustion which has already been described. A person feeling hot in bed, from excessive clothes, feels hot from the development of heat internally, which is not conducted away with sufficient rapidity to maintain the natural temperature of the body.

135. If a person, sitting before a fire-place, without a fire, were to set one foot upon a rug, and the other upon the stone hearth, which would feel the colder?

The foot on the stone, because stone is a good conductor, and would conduct the warmth of the foot away from it.

"The earth is the Lord's, and the fulness thereof; the world, and they that dwell therein."—Psalm xxiv.

136. What does the hearth-stone do with the heat that it receives?

It delivers it to the surrounding air, and to any other bodies with which it may be in contact—and as it parts with heat, it takes up more from any body hotter than itself.

137. When there is no fire in a room, what is the relative temperature of the various things in the room?

They are all of the same temperature.

138. If all the articles in the room are of the same temperature, why do some feel colder than others?

Because they differ in their relative powers of conduction. Those that are the best conductors feel coldest, as they convey away the heat of the hand most rapidly.

If you lay your hand upon the woollen table cover, or upon the sleeve of your coat or mantle, it will feel neither warm nor cold, under ordinary circumstances. But if you raise your hand from the table cover, or coat, and lay it on the marble mantel piece, the mantel-piece will feel cold. If now you return your hand from the mantel-piece to the table cover or coat, a sensation of warmth will become distinctly perceptible. This will afford a good conception of the relative powers of conduction of wool and marble.

139. How long does a substance feel cold or hot to the touch?

Until it has brought the part touching it to the same temperature as itself.

140. When do substances feel neither hot nor cold?

When they are of the same temperature as our bodies.

141. Why, under these circumstances, do they feel neither hot nor cold?

Because they neither take heat from, nor supply it to, the body.

142. Which would feel the warmer, when the fire was lighted, the hearth-rug or the hearth-stone?

The hearth-stone, because it is a good conductor, and would not only receive heat readily, but would part with it as freely (thereby [Pg 50] making its heat perceptible). But the hearth-rug, being a bad conductor, would part with its heat very slowly, and it would therefore be less perceptible.

"Fire and hail; snow and vapour; stormy wind fulfilling his word."—Psalm cxlviii.

143. Would the hearth-stone feel hotter than the hearth-rug though both were of the same temperature?

It would feel hotter than the hearth-rug, because it would part with its heat so rapidly that it would be the more perceptible.

144. But if the hearth-stone and the hearth-rug were both colder than the hand, which would feel the colder of the two?

Then the hearth-stone would feel the colder, because, being a good conductor, it would take heat from the hand more freely than the hearth-rug, which is a bad conductor.

145. Why would the hearth-stone feel comparatively hotter in the one case, and colder in the other?

Because, being a good conductor, it would conduct heat rapidly to the hand when hot, and take heat rapidly from the hand when cold.

146. Which are the better conductors of heat, fluids or solids?

Generally speaking, solids, especially those of them that are dense in their substance.

147. Why are dense substances the best conductors of heat?

Because the heat more readily travels from particle to particle until it pervades the mass.

148. Why are fluids bad conductors of heat?

Because of the want of density in their bodies; and because a portion of the imbibed heat always passes off from fluids by evaporation.

"He casteth forth his ice like morsels: who can stand before his word,"—Psalm cxlvii.

149. Why are woollen fabrics bad conductors of heat?

Because there is a considerable amount of air occupying the spaces of the texture.

150. Is air a good or a bad conductor?

Air is a bad conductor, and it chiefly transmits heat, as water does, by convection.

151. Is water a good or a bad conductor?

Water is an indifferent conductor, but it is a better conductor than air.

152. Why, when we place our hands in water, which may be of the same temperature as the air, does the water feel some degrees colder?

Because water, being a better conductor than air, takes up the warmth of the hand more rapidly.

153. Why, when we take our hands out of water do they feel warmer?

Because the air does not abstract the heat of the hand so rapidly as the water did, and the change in the degree of rapidity with which the heat is abstracted produces a sensation of increased warmth.

154. Why do we see blocks of ice wrapped in thick flannel in summer time?

Because the flannel, being a non-conductor, prevents the external heat from dissolving the ice.

Flannel wrapped around a warm body keeps in its heat; and wrapped around a cold body, prevents heat from passing into it.

155. How do we know that air is not a good conductor of heat?

Because, in still air, heat would travel to a given point much more rapidly, and in greater intensity, through even an indifferent solid conductor, than it would through the air.

156. How do we know that water is not a good conductor of heat?

Because in a deep vessel containing ice, and with heat applied at the top, some portion of the water may be made to boil before the ice, which lies a little under the surface, is melted.

"As snow in summer, and as rain in harvest; so honour is not seemly for a fool."—Prov. xxvi.

157. Why would you apply the heat at the top, in this experiment?

Because in heating water it expands and rises. The boiling of water is caused by the heated water ascending from the bottom, and the colder water descending to occupy its place. If the heat were not applied at the top, it would be distributed quickly by convection, but not by conduction.

158. Why are bottles of hot water, used as feet-warmers, wrapped in flannel?

Because the flannel, being a bad conductor, allows the heat to pass only gently from the bottle, and preserves the warmth for a much longer time.

159. Why are hot rolls sent out by the bakers, wrapped up in flannel?

Because the flannel, being a bad conductor, does not carry off rapidly the heat of the rolls.

160. Why is it said that snow keeps the earth warm?

Because snow is a bad conductor, and prevents the frosty air from depriving the earth of its warmth.

161. Why are snow huts which the Esquimaux build found to be warm?

Because snow, being a bad conductor, keeps in the internal heat of the dwelling, and prevents the cold outer air from taking away its warmth.

162. Why is snow, being composed of congealed water (and water being a better conductor than air), so good a non-conductor?

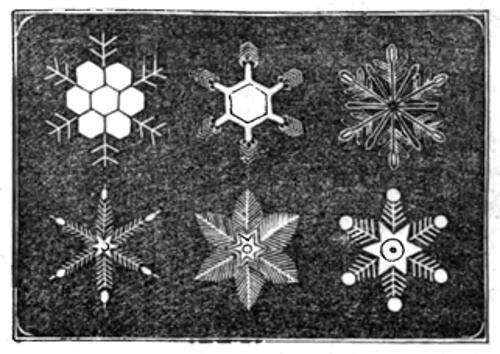

Because in the process of congealation it is frozen into crystalline forms, which, being collected into a mass, form a woolly body, thus [Pg 53] proving the truthfulness of the Bible simile, which says, God "giveth snow like wool."

"He giveth snow like wool: he scattereth the hoar frost like ashes."—Psalm cxlvii.

163. Why does it frequently feel warmer after a frost has set in?

Because, in the act of congealation a great deal of heat is given out, and taken up by the air, and thus the severity of the cold is in some degree moderated.

164. Why is it frequently colder when a thaw takes place?

Because, in the process of thawing, a certain amount of heat is withdrawn from the air, and enters the thawed ice.

165. What benefit results from these provisions of Nature?

They moderate both the severity of frosts, and the rapidity of thaws, which, in changeable climates, would be seriously detrimental to life, and to vegetation.

166. Why are furs and woollens worn in the winter?

Because, being non-conductors, they prevent the warmth of the body from being taken up by the cold air.

167. Why are the skins of animals usually covered with fur, hair, wool, or feathers?

Because their coverings, being non-conductors of heat, preserve the warmth of the bodies of the animals.

"He sendeth out his word, and melteth them: he causeth his wind to blow, and the waters to flow."—Psalm cxlvii.

168. How is the greater warmth of animals provided for in the winter?

It is observed that, as winter approaches, there comes a short woolly or downy growth, which, adding to the non-conducting property of their coats, confines their animal warmth.

In small birds during winter, let the external colour of the feathers be what it may, there will be found a kind of black down next their bodies. Black is the warmest colour, and the purpose here is to keep in the heat, arising from the respiration of the animal.

169. How is warmth provided for in animals that have no such coats?

They are furnished with a layer of fat, which lies underneath the skin. Fat consists chiefly of carbon, and is a non-conductor.

170. Why are summer breezes said to be cool?

Because, as they pass over the heated surface of the body, they bear away a part of its heat.

171. Why is a still summer air said to be sultry?

Because, being heated by the sun's rays, and being a bad conductor, it does not relieve the body by carrying off its heat.

172. Why does fanning the face make it feel cooler?

Because, by inducing currents of air to pass over the face, a part of the excessive heat is taken up and carried away.

173. Why does perspiration cool the body?

Because it takes up a part of the heat, and, evaporating, carries it into the air.

174. Why does blowing upon hot tea cool it?

Because it directs currents of air over the surface of the tea, and these currents take up a part of the heat and bear it away.

175. Why does air in motion feel cooler than air that is still?

Because each wave of air carries away a certain portion of heat [Pg 55] and being followed by another portion of air, a further amount of heat is borne away.

"Though I walk in the valley of the shadow of death I will fear no evil, for thou art with me."—Psalm xxiii.

176. Is the atmosphere ever as hot as the human body?

Not in this country. On the hottest day it is 10 or 12 deg. cooler than the temperature of our bodies.

177. What is the highest degree of artificial heat which man has been known to bear?

A man may be surrounded with air raised to the temperature of 300 deg. (the boiling point being 212), and yet not have the heat of his body raised more than two or three degrees above its natural temperature of from 97 deg. to 100 deg.

178. Why may man endure this degree of heat for a short time without injury?

Because the skin, and the vessels of fat that lie underneath it, are bad conductors of heat.

And because perspiration passing from the skin and evaporating, would bear the heat away as fast as it was received.

Because, also, the vital principle (life) exercises a mysterious influence in the preservation of living bodies from physical influences.

179. Is the air ever hot enough, in any part of the world, to destroy life?

Yes. The hot winds of the Arabian deserts, which are called simooms, scatter death and desolation in their track, withering trees and shrubs, and burying them under waves of hot sand. When camels see the approach of a simoom they rush to the nearest tree or bush, or to some projecting rock, where they place their heads in an opposite direction to that from which the wind blows, and endeavour to escape its terrible violence. The traveller throws himself on the ground on the lee side of the camel, and screens his head from the fiery blast within the folds of his robe. But frequently both man and beast fall a prey to the terrible simoom.

180. Why are these hot winds so terrible in their effects?

Because, being in motion, they search their way to every part of [Pg 56] the body, and passing over it leave some portion of their heat behind, which is again followed by additional heat from every fresh blast of wind.

"The fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge: but fools despise wisdom and instruction."—Proverbs i.

The radiation of heat is a motion of the particles, in a series of rays, diverging in every direction from a heated body.

182. What is this phenomena of Radiation understood to arise from?

From a strongly repulsive power, possessed by particles of heat, by which they are excited to recede from each other with great velocity.

183. What is the greatest source of Radiation?

The sun, which sends forth rays of both light and heat in all directions.

184. When does a body radiate heat?

When it is surrounded by a medium which is a bad conductor.

185. When we stand before a fire, does the heat reach us by conduction or by radiation?

By radiation.

186. What becomes of the heat that is radiated from one body to another?

It is either absorbed by those bodies, or transmitted through them and passed to other bodies by conduction, or diffused by convection, or returned by reflection.

187. How do we know that heat is diffused by radiation?

If we set a metal plate (or any other body, though metal is best for the experiment) before the fire, rays of heat will fall upon it. If we turn the plate at a slight angle, and place another [Pg 57] object in a line with it, we shall find that the plate will reflect the rays it has received by radiation, on to the object so placed; but if we place an object between the fire and the plate, we shall find that the rays of heat will be intercepted, and that the latter can no longer reflect heat.

"The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom: a good understanding have all they that do his commandments."—Psalm cxi.

188. Does the agitation of the air interfere with the direction of rays of heat?

It has been found that the agitation of the air does not affect the direction of rays of heat.

189. Why, then, if a current of air passes through a space across which heat is radiating, does the air become warmer?

Because it takes up some portion of the heat, but it does not alter the direction of the rays.

This is clearly illustrated by reference to rays of light which are seen under many circumstances. But they are never bent, moved, nor in any way affected by the wind.

190. Why will not a current of air disturb the rays of heat, just as it would a spider's web, or threads of silk?

Because heat is an imponderable agent, that is, something which cannot be acted upon by the ordinary physical agencies. It has no weight, presents no substantial body, and is, in these latter respects, similar to light and electricity.

191. What other sources of radiation of heat are there besides the sun and the fire?

The earth, and all minor bodies, are, in some degree, radiators of heat.

192. What substances are the best radiators?

All rough and dark coloured substances and surfaces are the best radiators of heat.

193. What substances are the worst radiators of heat?

All smooth, bright, and light coloured surfaces are bad radiators of heat.

Dr. Stark, of Edinburgh, has proved, by a series of experiments, the influence which the colours of bodies have upon the velocity of radiation. He surrounded [Pg 58] the bulb of a thermometer successively with equal weights of black, red, and white wool, and placed it in a glass tube, which was heated to the temperature of 180 deg. by immersion in hot water. The tube was then cooled down to 50 deg. by immersion in cold water; the black cooled in 21 minutes, the red in 26 minutes, and the white in 27 minutes.

"Say unto wisdom, Thou art my sister; and call understanding thy kinswoman."—Proverbs vii.

194. If you wished to keep water hot for a long time, should you put it into a bright metal jug, or into a dark earthenware one?

You should put it into a bright metal jug, because, being a bad radiator, it would not part readily with the heat of the water.

195. Why would not the dark earthenware jug keep the water hot as long as the bright metal one?

Because the particles of earthenware being rough, and of dark colour, they radiate heat freely, and the water would thereby be quickly cooled.

196. But if (as stated in the Lessons upon Conduction) metal is a better conductor of heat than stone or earthenware, why does not the metal jug conduct away the heat of the water sooner than the earthenware jug?

It would do so, if it were in contact with another conductor; but, being surrounded by air, which is a bad conductor, the heat must pass off by radiation, and as bright metal surfaces are bad radiators, the metal jug would retain the heat of the water longer than the earthenware one.

197. Supposing a red-hot cannon ball to be suspended by a chain from the ceiling of a room, how would its heat escape?

Almost entirely by radiation. But if you were to rest upon the ball a cold bar of iron, a part of the heat would be drawn off by conduction. Warm air would rise from around the ball, and, moving upwards, would distribute some of the heat by convection. [Pg 59] And some of its rays, falling upon a mirror, or any other bright surface, might be diffused by reflection.

"I will teach you by the hand of God; that which is with the Almighty will I not conceal."—Job xxvii.

198. Do some substances absorb heat?

Yes; those substances which are the best radiators are also the best absorbers of heat.

199. Why does scratching a bright metal surface increase its power of radiation?

Because every irregularity of the surface acts as a point of radiation, or an outlet by which the heat escapes.

200. Why does a bright metal tea-pot produce better tea than a brown or black earthenware one?

Because bright metal radiates but little heat, therefore the water is kept hot much longer, and the strength of the tea is extracted by the heat.

201. But if the earthenware tea-pot were set by the fire, why would it then make the best tea?

Because the dark earthenware tea-pot is a good absorber of heat, and the heat it would absorb from the fire would more than counterbalance the loss by radiation.

202. How would the bright metal tea-pot answer if set upon the hob by the fire?

The bright metal tea-pot would probably absorb less heat than it would radiate. Therefore it would not answer so well, being set upon the hob, as the earthenware tea-pot.

203. Why should dish covers be plain in form, and have bright surfaces?

Because, being bright and smooth, they will not allow heat to escape by radiation.

204. Why should the bottoms and back parts of kettles and saucepans be allowed to remain black?

Because a thin coating of soot acts as a good absorber of heat, and overcomes the non-absorbing quality of the bright surface.

"And the foolish said unto the wise, Give us of your oil, for our lamps are gone out."

205. But why should soot be prevented from accumulating in flakes at the bottom and sides of kettles and saucepans?

Because, although soot is a good absorber of heat, it is a very bad conductor; an accumulation of it, therefore, would cause a waste of fuel, by retarding the effects of heat.

206. Why should the lids and fronts of kettles and saucepans be kept bright?

Because bright metal will not radiate heat; therefore, the heat which is taken up readily through the absorbing and conducting power of the bottom of the vessel, is kept in and economised by the non-radiating property of the bright top and front.

207. Does cold radiate as well as heat?

It was once thought that cold radiated as well as heat. But a mass of ice can only be said to radiate cold, by its radiating heat in less abundance than that which is emitted from other bodies surrounding it. It is, therefore, incorrect to speak of the radiation of cold.

208. Why, if you hold a piece of looking-glass at an angle towards the sum, will light fall upon an object opposite to the looking-glass?

Because the rays of the sun are reflected by the looking-glass.

209. Why, when we stand before a mirror, do we see our features therein?

Because the rays of light that fall upon us are reflected upon the bright surface of the mirror.

210. Why, if a plate of bright metal were held sideways before a fire, would heat fall upon an object opposite to the plate?

Because rays of heat may be reflected in the same manner as the rays of light.

"But the wise answered saying, Not so; lest there be not enough for us and you: but go ye rather to them that sell, and buy for yourselves."—Matt. xxv.

211. Why would not the same effect arise if the plate were of a black or dark substance?

Because black and dark substances are not good reflectors of heat.

212. What are the best reflectors of heat?

Smooth, light-coloured, and highly polished surfaces, especially those of metal.

213. Why does meat become cooked more thoroughly and quickly when a tin screen is placed before the fire?

Because the bright tin reflects the rays of heat back again to the meat.

214. Why is reflected heat less intense than the primary heat?

Because it is impossible to collect all the rays, and also because a portion of the caloric, imparting heat to the rays, is absorbed by the air, and by the various other bodies with which the rays come in contact.

215. Can heat be reflected in any great degree of intensity?

Yes; to such a degree that inflammable matters may be ignited by it. If a cannon ball be made red hot, and then be placed in an iron stand between two bright reflectors, inflammable materials, placed in a proper position to catch the reflected rays, will ignite from the heat.

There is a curious and an exceptional fact with reference to reflected heat, for which we confess that we are unable to give "The Reason Why." It is found that snow, which lies near the trunks of trees or the base of upright stones, melts before that which is at a distance from them, though the sun may shine equally upon both. If a blackened card is placed upon ice or snow under the sun's rays, the frozen body underneath it will be thawed before that which surrounds it. But if we reflect the sun's rays from a metal surface, the result is directly contrary—the exposed snow is the first to melt, leaving the card standing as upon a pyramid. Snow melts under heat which is reflected from the trees or stones while it withstands the effect of the direct solar rays. In passing through a cemetery this winter (1857), when the snow lay deep, we [Pg 62] were struck with the circumstance that the snow in front of the head-stones facing the sun was completely dissolved, and, in nearly every instance, the space on which the snow had melted assumed a coffin-like shape. This forced itself so much upon our attention that we remained some time to endeavour to analyse the phenomena; and it was not until we remembered the curious effect of reflected heat that we could account for it. It is obvious that the rays falling from the upper part of the head-stone on to the foot of the grave would be less powerful than those that radiated from the centre of the stone to the centre of the grave. Hence it was that the heat dissolved at the foot of the grave only a narrow piece of snow, which widened towards the centre, and narrowed again as it approached the foot of the head-stone, where the lines of radiation would naturally decrease. Such a phenomena would prove sufficient to raise superstition in untutored minds.

"The light of the righteous rejoiceth, but the lamp of the wicked shall be put out."—Proverbs xiii.

216. Are good reflectors of heat also good absorbers?

No; for reflectors at once send back the heat which they receive, while absorbers retain it. It is obvious, therefore, that reflectors cannot be good absorbers.

217. How do fire-screens contribute to keep rooms cool?

Because they turn away from the persons in the room rays of heat which would otherwise make the warmth excessive.

218. Why are white and light articles of clothing cool?

Because they reflect the rays of heat.

White, as a colour, is also a bad absorber and conductor.

219. Why is the air often found excessively hot in chalk districts?

Because the soil reflects upon objects near to it the heat of the solar rays.

220. How does the heat of the sun's rays ultimately become diffused?

It is first absorbed by the earth. Generally speaking, the earth absorbs heat by day, and radiates it by night. In this way an equilibrium of temperature is maintained, which we should not otherwise have the advantage of.

221. Does not the air derive its heat directly from the sun's rays?

Only partially. It is estimated that the air absorbs only one-third of the caloric of the sun's rays—that is to say, that a ray of [Pg 63] solar heat, entering our atmosphere at its most attenuated limit (a height supposed to be about fifty miles), would, in passing through the atmosphere to the earth, part with only one-third of its calorific element.

"As for the earth, out of it cometh bread; and under it is turned up as it were fire."—Job xxviii.

222. What becomes of the remaining two-thirds of the solar heat?

They are absorbed chiefly by the earth, the great medium of calorific absorption; but some portions are taken up by living things, both animal and vegetable. When the rays of heat strike upon the earth's surface, they are passed from particle to particle into the interior of the earth's crust. Other portions are distributed through the air and water by convection, and a third portion is thrown back into space by radiation. These latter phenomena will be duly explained as we proceed.

223. How do we know that heat is absorbed, and conducted into the internal earth?

It is found that there is a given depth beneath the surface of the globe at which an equal temperature prevails. The depth increases as we travel south or north from the equator, and corresponds with the shape of the earth's surface, sinking under the valleys, and rising under the hills.

224. Why may we not understand that this internal heat of the earth arises, as has been supposed by many philosophers, from internal combustion?

Because recent investigations have thrown considerable and satisfactory light upon the subject. It has been ascertained that the internal temperature of the earth increases to a certain depth, one degree in every fifty feet. But that below that depth the temperature begins to decline, and continues to do so with every increase of depth.

Yes. They both absorb and radiate heat, under varying circumstances. The majestic tree, the meek flower, the unpretending grass, all perform a part in the grand alchemy of nature.

"Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin."

When we gaze upon a rose it is not its beauty alone that should impress us: every moment of that flower's life is devoted to the fulfilment of its part in the grand scheme of the universe. It decomposes the rays of solar light, and sends the red rays only to our eyes. It absorbs or radiates heat, according to the temperature of the ærial mantle that wraps alike the flower and the man. It distills the gaseous vapours, and restores to man the vital air on which he lives. It takes into its own substance, and incorporates with its own frame, the carbon and the hydrogen of which man has no immediate need. It drinks the dew-drop or the rain-drop, and gives forth its sweet odour as a thanksgiving. And when it dies, it preaches eloquently to beauty, pointing to the end that is to come!

226. How do we know that plants operate upon the solar and atmospheric heat?

A delicate thermometer, placed among the leaves and petals of flowers, will at once establish the fact, not only that flowers and plants have a temperature differing from that of the external air, but that the temperature varies in different plants according to the hypothetical, or supposed requirements, of their existences and conditions.

227. What is the chief cause of variation in the temperature of flowers?

It is generally supposed that their temperature is affected by their colours.

228. Why is it supposed that the colour of a flower influences its temperature?

Because it is found by experiment that the colours of bodies bear an important relation to their properties respecting heat, and hold some analogy to the relation of colours to light.

If when the ground is covered with snow, pieces of woollen cloth, of equal size and thickness, and differing only in colour, are laid upon the surface of the snow, near to each other, it will be found that the relation of colour to temperature will be as follows:—In a few hours the black cloth will have dissolved so much of the snow beneath it, as to sink deep below the surface; the blue will have proved nearly as warm as the black; the brown will have dissolved less of the snow; the red less than the brown; and the white the least, or none at all. Similar experiments may be tried with reference to the condensation of dew, &c. And it will be uniformly found that the colour of a body materially affects its powers of absorption and of radiation.

"And yet I say unto you, that even Solomon, in all his glory, was not arrayed like one of these."—Matt. vi.

229. Why do we know that these effects are not the result of light?

Because they would occur, in just the same order, in the absence of light.

230. Why are dark coloured dresses usually worn in winter, and light in summer?

Because black absorbs heat, and therefore becomes warm; while light colours do not absorb heat in the same degree, and therefore they remain cool.

231. Why do iron articles, even when near fire, usually feel cool?

Because they are bad absorbers, and do not take up heat freely, unless they are in contact with a hot body.

232. How is heat diffused through the atmosphere?

By convection. The warmth radiating from the surface of the earth warms the air in contact with it; the air expands, and becoming lighter, flies upwards, bearing with it the caloric which it holds, and diffusing it in its course.

233. How do the waters of the ocean become heated?

Chiefly by convection. Nearly all the heat which the sun sheds upon the ocean is borne away from its surface by evaporation, or is radiated back into the atmosphere. But the ocean gathers its heat by convection from the earth. It girdles the shores of tropical lands where, being warmed to a high degree of temperature, it sets across the Atlantic from the Gulf of Mexico, and exercises an important influence upon the temperature of our latitude.

234. What is the cause of winds?

Currents of air, and winds, are the result of convection. The air, heated by the high temperature of the tropics, ascends, while the colder air of the temperate and the frigid zones blows towards the equator to supply its place.

"Give unto the Lord the glory due unto his name; worship the Lord in the beauty of holiness."—Psalm xxix.

235. What is the cause of sea breezes?

Sea breezes are also the result of convection. The land, under the heat of the day's sunshine, becomes of a high temperature, and the expanded air on its surface flies away towards the ocean. As the sun goes down, the earth cools again, and the air flies back to find its equilibrium.