TRANSCRIBER’S NOTES:

—Obvious print and punctuation errors were corrected.

—The transcriber of this project created the book cover image using the front cover of the original book. The image is placed in the public domain.

THE TALK OF THE TOWN

VOL. I.

Miss Margaret lifted her eyes from her plate with a smile of welcome.

THE TALK OF THE TOWN

BY

JAMES PAYN

AUTHOR OF ‘BY PROXY’ ETC. ETC.

IN TWO VOLUMES

VOL. I.

SECOND EDITION

LONDON

SMITH, ELDER, & CO., 15 WATERLOO PLACE

1885

[All rights reserved]

CONTENTS

OF

THE FIRST VOLUME.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | AUNT MARGARET | 1 |

| II. | OUT IN THE COLD | 11 |

| III. | A RECITATION | 28 |

| IV. | A REAL ENTHUSIAST | 47 |

| V. | THE OLD SETTLE | 66 |

| VI. | AN AUDACIOUS CRITICISM | 87 |

| VII. | A COLLECTOR’S GRATITUDE | 101 |

| VIII. | HOW TO GET RID OF A COMPANY | 120 |

| IX. | AN UNWELCOME VISITOR | 144 |

| X. | TWO POETS | 158 |

| XI. | THE LOVE-LOCK | 171 |

| XII. | A DELICATE TASK | 183 |

| XIII. | THE PROFESSION OF FAITH | 196 |

| XIV. | THE EXAMINERS | 218 |

| XV. | AT VAUXHALL | 230 |

| XVI. | A BOMBSHELL | 246 |

| XVII. | THE MARE’S NEST | 259 |

| XVIII. | ‘WHATEVER HAPPENS, I SHALL LOVE YOU, WILLIE’ | 271 |

ILLUSTRATIONS TO VOL. 1.

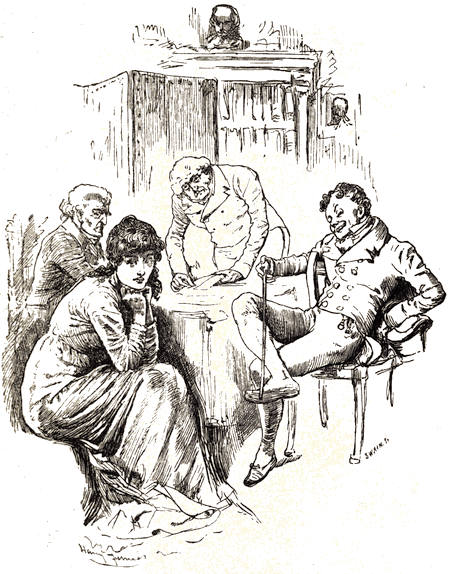

| MISS MARGARET LIFTED HER EYES FROM HER PLATE WITH A SMILE OF WELCOME | Frontispiece | |

| ‘SCIENCE!’ INTERRUPTED THE ANTIQUARY, VEHEMENTLY, ‘THAT IS THE ARGUMENT OF THE ATHEIST AGAINST THE SCRIPTURES.’ | to face p. | 98 |

| THE DILETTANTI | ” | 134 |

| ‘MAGGIE, MAGGIE, HERE IS A PRESENT FOR YOU.’ | ” | 174 |

| THE PROFESSION OF FAITH | ” | 206 |

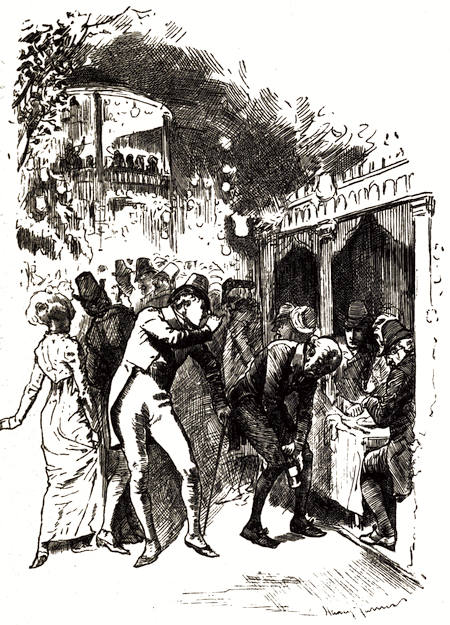

| VAUXHALL GARDENS | ” | 236 |

| A VERY CHEERLESS PROCEEDING | ” | 262 |

THE TALK OF THE TOWN.

CHAPTER I.

AUNT MARGARET.

WHEN I was a very young man nothing used to surprise me more than the existence of a very old one—one of those patriarchs who, instead of linking the generations ‘each with each,’ include two or three in their protracted span; a habit which runs in families, as in the case[2] of the old gentleman of our own time whose grandsire (once or twice ‘removed,’ it is true, but not nearly so often as ‘by rights’ he should have been) gathered the arrows upon Flodden Field. Such persons seemed to me little inferior in interest to ghosts (whom indeed in appearance they greatly resembled), and I was wont to listen to their experiences of the past with the same rapt attention, (unalloyed by the alarm), that I should have paid to a denizen of another world. There are, it seems to me, very few old persons about now, absolutely none (there used to be plenty) three or four times my age; and this, perhaps, renders the memory (for she did die at last) of my great-aunt Margaret a thing so rare and precious to me.

She was born, as we, her young relatives, were wont to say, ‘ages and ages ago,’ but as a matter of fact just one age ago; that is to say, if she had been alive but a few years back, she would have been exactly one hundred years old. Think of it, my young friends who are about to be so good, in your turn, as to give her story your attention—think of it having[3] been possible that you yourselves should have met this very personage in the flesh (though the poor dear had but little of it)—you perhaps in your goat carriage, upon the King’s Parade, Brighton, and she in her wheeled chair—the two extremities (on wheels) of human life!

To things you have read of as history, matters as dead and gone to you, if not quite so old, as the Peloponnesian war, she was a living witness. She was alive, for example, though not of an age to ‘take notice’ of the circumstances, when the independence of America was acknowledged by the mother country, and when England was beginning to solace herself for that disruption by the acquisition of India. If Aunt Margaret did not know as much about Hyder Ali as became a contemporary, with matters nearer home, such as the loss of the ‘Royal George,’ ‘with all her crew (or nearly so) complete,’ she was very conversant. ‘I saw it,’ she was used to say, ‘with my own eyes;’ and it was only by the strictest cross-examination that you could get her to confess that she was but a child in arms when that[4] catastrophe took place. As to politics, indeed, though we were at war with everybody in those times, the absence of special correspondents, telegraphs, and even newspapers, made public matters of much more limited interest than it is nowadays easy to imagine. Aunt Margaret, at all events, cared almost nothing about them, with the exception of the doings of the pressgang—an institution of which she always spoke with the liveliest horror. On some one, however, chancing to say in her hearing (and by way of corroboration of her views) that it was marvellous how men who had been so infamously treated should have been got to fight under the national flag, she let fly at him like the broadside of a seventy-gun frigate, and gave him to understand that the sailors of those days had never had their equals. On that, as on all other subjects, she exercised the right of criticism upon the institutions of her time to an unlimited extent, but if they were attacked by others she became their defender.

Her chief concern, however, was with social[5] matters, when speaking of which she seemed entirely to forget the age in which she was living: it was as though some ancestress, in hoop and farthingale, had stepped down from her picture and read us a page of the diary she had written overnight. She seemed hardly like one of ourselves at all, though it was obvious enough that she was of the female gender, from the prominence she gave to the topic of costumes. She confessed that she preferred the hair ‘undressed’—a phrase which misled her more youthful hearers, who imagined her to be praising a dissolute luxuriance of love-locks, which was very far from her intention; on the other hand, she lamented the disuse of black satin breeches, which she ascribed to the general decay of limb among the male sex. There was nothing like your top-boots and hessians, she would say, for morning wear, but in the evening, every man that had a leg was, in her opinion, bound to show it.

I have reason to believe that my aunt Margaret was the last person who ever journeyed from London to Brighton in a post-chaise—a[6] mode of travel, she was wont to remark, justly eulogised by the wisest and best of men and Londoners. If he had been spared to see a railway locomotive, she expressed herself as confident that he would have considered it the direct offspring of the devil; and that conjectural opinion of the great lexicographer she herself shared to her dying day. Like him, she was a Londoner, and took an immense interest, not municipal of course, but social, in the affairs of the great city. ‘My dear,’ she often used to say reprovingly, when speaking of some event of which I was obliged to confess I had never so much as heard, ‘it was the topic of every tongue.’

Although she had never been the theme of London gossip herself, she had been very closely connected with one who had been; and to those who were intimate with her he was the constant subject of her discourse. Her thoughts dwelt more with him, I am sure, than with all the other personages together with whom she had been acquainted during her earthly pilgrimage; and yet she always thought[7] of him in his adolescence, as a very young man.

‘He was just your age, my dear,’ she was wont to say to me, ‘when he became the “Talk of the Town.”’

Perhaps this circumstance gave him an additional interest in my eyes; but certainly her account of this one famous personage was more interesting to me than everything else which Aunt Margaret had to tell me. It has dwelt in my mind for many a year, and when this is the case with any story, I have generally found that I have been able to interest others in its recital. In this particular case, however, my way is not so plain as usual. The story is not my story, nor even Aunt Margaret’s; in its more important details it is common property. On the other hand, not even the oldest inhabitant has any remembrance of it. The hearts that were once wounded to the quick by the occurrences which I am about to describe can be no more pained by any allusion to them; they have long been dust. No relative, to my knowledge, is now living of the unfortunate[8] young man whose memory—execrated by the crowd—was kept so green and fresh (watered by her tears) by one living soul for nearly eighty years. Why should I not tell his ‘pitiful story?’

A second question, however, presents itself at the outset concerning him. Shall I give or conceal his name? I here frankly confess that in its broad details the tale has no novelty to recommend it: it is not only true, but it has been told. The bald, bare facts have been put before the public by the youth himself nearly a hundred years since. There is the rub. To a few ‘persons of culture,’ as the phrase goes nowadays, the main incident of his career will be familiar; though, however cultured, it is unlikely they will know how it affected my great-aunt Margaret; but to tens of thousands (including, I’ll be bound, the upper ten) it will be utterly unknown.

Now I have noticed that there is nothing your well-informed person so much delights in as to make other people aware of his being so. Indeed, the chief use of information in his eyes[9] is not so much to raise oneself above the crowd (though a sense of elevation is agreeable), as to have the privilege of imparting it to others with a noble air of superiority and self-importance. I will therefore call my hero by such a name as will at once be recognised by the learned, whom I shall thus render my intermediaries—exponents of the transparent secret to those who are in blissful ignorance of it. I will call him William Henry Erin.

I must add in justice to myself that the story was not told me in confidence.

How could it be so when at the very beginning of our intimacy the narrator had already almost reached the extreme limit of human life, while I had but just left school? It was the similarity of age on my part with that of the person she had in her mind which no doubt, in part at least, caused her to make me the repository of her long-buried sorrow. She judged, and rightly judged, that for that reason I was more likely to sympathise with it. Indeed, whenever she spoke of it I forgot her age; as in the case of the pictured[10] grandmamma so felicitously described by Mr. Locker, I used to think of her at such times—

As she looked at seventeen

As a bride.

Her rounded form was lean,

And her silk was bombazine,

Well I wot.

With her needles she would sit,

And for hours would she knit,

Would she not?

Ah, perishable clay!

Her charms had dropped away,

One by one.

Yet when she spoke of the lover of her youth, there seemed nothing incongruous in her so doing. I forgot the Long Ago in which her tale was placed; her talk, indeed, on those occasions being of those human feelings which are independent of any epoch, took little or no colour from the past; it seemed to me a story of to-day, and as such I now relate it.

CHAPTER II.

OUT IN THE COLD.

A few years ago it would have been almost impossible for modern readers to imagine what a coach journey used to be in the good old times; but, thanks to certain gilded youths, more fortunate than persons of a higher intellectual type who have striven in vain to—

Revive old usages thoroughly worn out,

The souls of them fumed forth, the hearts of them torn out,

it is not now so difficult. Any one who has gone by one of our ‘summer coaches’ for a short trip out of town can picture the ‘Rockets’ and ‘Highflyers’ in which our ancestors took their journeys at the end of the last century. Those old mail-coaches were, in fact, their very counterparts; for the ‘basket[12]’ had already made way for ‘the hind seat;’ only, instead of our aristocratic driver, there was a professional ‘whip,’ who in fair weather came out in scarlet like the guard, though in wet and winter-time he was wrapped in heavy drab, as though a butterfly should become a grub again. The roads were good, the milestones in a much better condition than they are at present, and the inns at which the passengers stopped for refreshments greatly superior to their successors, or rather to their few ghastly survivors, all room and no company, which still haunt the roadside. The highwaymen, too, were still extant, which gave an opportunity to young gentlemen of spirit to assure young female fellow-passengers of their being under safe escort, if not of displaying their own courage. Still, after eight hours in a stage-coach, most ‘insides’ felt that they had had enough of it, and were glad enough to stretch their legs when the chance offered.

This feeling was experienced by two out of the three passengers in the London coach ‘Tantivy,’ which on a certain afternoon in May,[13] at the end of the last century, drew up at the ‘White Hart’ in the town of Banbury: it was their last ‘stopping stage’ before they arrived at their destination—Stratford-on-Avon; and they wished (at least two of them did) that they had reached it already.

Mr. Samuel Erin, the senior and head of the little party, was a man of about sixty years of age, but looked somewhat older. He still wore the attire which had been usual in his youth, but was now pronounced old-fashioned: a powdered wig of moderate dimensions; a plain braided frock coat, with waistcoat to match, almost as long; a hat turned up before and behind, and looking like a cross between a cocked hat and the head-gear of a modern archdeacon; knee-breeches, and buckled shoes. Upon his forehead—their ordinary resting-place when he was not engaged in his profession (that of a draughtsman), or poring over some musty volume—reposed, on a bed of wrinkles, a pair of gold spectacles. His eyes, which, without being very keen, were intelligent enough, appeared smaller than they[14] really were, from a habit he had of puckering their lids, engendered by the more delicate work of his calling, and also by frequent examination of old MSS. and rare editions, of which he was a connoisseur.

As he left the coach with slow, inelastic step, he was followed by his friend Frank Dennis. This gentleman was a much younger man, but he too, though not so retrograde in attire as his senior, paid little attention to the prevailing fashion. He wore, indeed, his own hair, but closely cut; a pepper-and-salt coat and waistcoat, and a neckcloth, that looked like a towel, tied carelessly under his chin. Though not in his first youth, he was still a young man, with frank and comely features; but an expression habitually thoughtful, and a somewhat slow delivery of what he had to say, made him appear of maturer years than belonged to him. He was an architect by profession, but had some private means; his tastes were somewhat similar to those of his friend and neighbour Erin, and he could better afford to indulge them. His present expedition was no business[15] of his own, but undertaken, as he professed, that he might enjoy the other’s society for a week or two in the country. It so happened, however, that Mr. Erin was bringing his niece, Miss Margaret Slade, with him; and, to judge by the tenderness of Mr. Dennis’s glance when it rested on her, it is probable that the prospect of her companionship had had some attraction for him.

Last of the three, she tripped out of the coach, declining, with a pretty toss of her head, the assistance the younger man would have rendered her in alighting. She could trip and toss her head like any fairy. No tower of hair ‘like a porter’s knot set upon end’ had she; her dress, though to modern eyes very short-waisted, was not, as an annalist of her time has described it, ‘drawn exceeding close over stays drawn still closer;’ her movements were light and free. Her lustrous brown hair fell in natural waves from under a beaver hat turned up on the left side, and ornamented with one grey feather. A grey silk spencer indicated, under pretence of concealing—for it was[16] summer weather, and she could not have worn it for warmth—the graces of her form. Her eyes were bright and eager, and her pretty lips murmured a sigh of relief, as she touched ground, at her release from durance.

‘How I wish this was Stratford-on-Avon’! cried she naïvely.

‘That would be wishing that Shakespeare had been born at Banbury,’ said her uncle, in a tone of reproof.

‘Banbury is it?’ she said; ‘then this is where the lady lived who went about with rings on her fingers and bells on her toes, and therefore had music wherever she goes—I mean went.’

Mr. Dennis smiled, and murmured very slowly that other young ladies brought music with them without the instruments of which she spoke, or indeed any instruments; they had only to open their mouths.

‘I am hungry,’ observed Miss Margaret, without any reference to that remark about opening her mouth at all—in fact, she studiously ignored it.

Mr. Dennis sighed.

He was that minority of one who would rather have remained in the coach—that is, if Miss Margaret had done likewise; he would not in the least have objected to Mr. Samuel Erin getting out. A circumstance over which he had no control, the fact of his having been born half a century too early, prevented his being acquainted with the poem in which Mr. Thomas Moore describes the pleasure he felt in travelling in a stage-coach with a fair companion; but he had experienced it all the same. He was not displeased that there was another stage to come yet.

If he was satisfied, however, with the opportunities that had been afforded to him of making himself agreeable to Miss Margaret on the road, he must have been a man thankful for small mercies. She had given him very little encouragement. His attempts to engage her in conversation had been anything but successful. When a young lady wishes to be tender, we know that the mere offer to open or shut a coach window for her may lead to[18] volumes of small-talk, but nothing had come of his little politenesses beyond the bare acknowledgment of them. Even that, however, was something. An ‘I thank you, sir,’ from the pretty lips of Margaret Slade was to Mr. Frank Dennis more than the acceptance of plan, elevation, and section of any proposed town-hall from a municipal council. It is strange how much harder is the heart of the female than the male under certain circumstances. If a young lady obviously endeavours to make herself agreeable to a young gentleman, he never repulses her, or at least I have never known an instance of it. ‘But suppose,’ I hear some fair one inquire, ‘he should be engaged to be married to some one else?’ ‘Madam,’ I reply to that imaginary questioner, ‘it would not make one halfpennyworth of difference. If the other young woman was not there, you would never guess from his behaviour that she was in existence.’

It must not, however, be concluded from this observation that Miss Margaret Slade was in love with anybody else. She was but[19] seventeen at most; an age at which among well-conducted young persons no such idea enters the head, nor indeed, in her case, as one would think, had there been any opportunity for its entrance. She had been brought up in the country in seclusion, and only a few months ago, upon the death of Mrs. Erin, had been sent for by her uncle to keep house for him. His establishment in Norfolk Street, Strand, was a very simple one, and the company he entertained numbered none of these who, in the language of the day, were called ‘the votaries of Cupid.’ No young beaux ever so much as crossed the threshold. Mr. Erin’s visitors were all grave elderly gentlemen, more interested in a binding than in a petticoat, and preferring some old-world volume to a maiden in her spring-time. There was indeed, ‘though,’ as the song says, ‘it is hardly worth while to put that in,’ a son of Mr. Erin’s, of her own age, who dwelt in his father’s house. But the young man was out all day engaged in his professional avocation—that of a conveyancer’s clerk; and even when he returned at eve,[20] mixed but little with the family. It seemed to Margaret that his father did not treat him very kindly.

There had been only one mention of him in the long coach journey from town. Mr. Dennis, addressing himself as usual to Margaret, when a chance offered of interrupting Mr. Erin’s interminable talk upon antiquarian subjects, had inquired after her cousin William Henry; and she had replied, with the least rose tint of a blush, that he had gone, she believed, on some business of his employer to Bristol. A statement which her uncle had corroborated, adding drily, ‘The boy has asked to have his holiday with us now instead of later in the year, so I have told him to come on to Stratford; he may be useful to me in collecting information upon Shakespearean matters.’

The remark scarcely breathed the spirit of a doating parent, but then that was not Mr. Erin’s way.

‘Your son has made a good choice of locality,’ said Mr. Dennis, in his rather ponderous manner. ‘It is not every young fellow[21] who would choose Stratford-on-Avon to disport himself in, in preference to Tunbridge Wells, for instance; his taste for antiquities is certainly most remarkable. He will prove a chip of the old block, I’ll warrant,’ he added, with a side-long smile at Margaret. Margaret did not return his smile, though she did not frown as her uncle did. The fact was, though neither Margaret nor Mr. Dennis had the faintest idea of it, the latter could hardly have paid the old gentleman a more objectionable compliment.

‘I do not think,’ he replied coldly, after an unpleasant pause, ‘that William Henry cares much about Shakespeare; but he has probably asked for his holiday thus early, in hopes that, by hook or by crook, he may get another one later on.’

To this there was no reply from either quarter. Mr. Dennis, though a good-natured fellow enough, did not feel called upon to defend William Henry’s want of Shakespearean feeling against his parent, while Miss Margaret not only closed her mouth, but shut her eyes. If she slept, to judge by the expression of her[22] face she had pleasant dreams; but it is possible she was only pretending to sleep, in order to chew the cud of some sweet thought at greater leisure. She disagreed with her uncle about the motive that was bringing William Henry to Stratford, but was quite content to accept the fact—of which she had previously been ignorant—without debate. She herself did not, I fear, care so much about Shakespeare as it behoved Mr. Samuel Erin’s niece to do; but from henceforth she looked forward with greater pleasure than she had done to this visit to his birthplace. Hungry as she had professed herself to be, she would no doubt have done justice to the ample, if somewhat solid, viands that were set before the coach passengers, and on which her uncle exercised his knife and fork like a man who knows he will be charged the same whether he eats much or little, but for an unlooked-for circumstance.

Hardly had the meal commenced when the cheerful note of the horn announced the approach of a coach from some other quarter, the tenants of which presently crowded into[23] the common dining-room. Among them was a young gentleman who, without a glance at beef or pasty, at once made up to our party of three.

His first salutation, contrary to the laws of etiquette, was made to Mr. Erin.

‘Hollo!’ said that gentleman, unwillingly relinquishing his knife and holding out two fingers to the new-comer, ‘what brings you here, sir?’

‘The Banbury coach, sir. I came across country from Bristol in the hopes of catching you at this stage, which I have fortunately succeeded in doing.’

‘Humph! it seems to me you must have come miles out of the way; however, since you are here, you had better set-to on the victuals and save your supper at Stratford.’

Mr. Dennis shook hands with the young man cordially enough, and recommended the meat pie.

Miss Margaret just lifted her eyes from her plate and gave him a smile of welcome, but at the same time she moved a little towards the[24] top of the table, so as to leave a space for him on the other side of her, an invitation which he lost no time in accepting.

A scornful poet, whose appetite was considerably jaded, has expressed his disgust at seeing women eat; but women, I have noticed, take great pleasure in seeing men, for whom they have any regard, relish a hearty meal. The new-comer ate as only a young gentleman who has travelled for hours on a coach-top can eat, and Margaret so enjoyed the spectacle that she neglected her own opportunities in that way, to watch him. ‘The ardour with which you attack that veal, Willie,’ she whispered slily, ‘reminds me of the Prodigal Son after his diet of husks.’

‘Did you think the manner in which my arrival was welcomed in other respects, Maggie,’ he inquired bitterly, ‘carried out the parable?’

‘Never mind; you are out for your holiday, remember, and must only think of enjoying yourself.’

‘Well, I hope you are glad to see me, at all events.’

‘Well, of course I am; it’s a very unexpected pleasure.’

‘Is it? I should have thought you might have guessed that I should have managed to join you somehow.’

‘I have not your genius for plots and strategies, Willie; it is so great that it sometimes a little alarms me,’ she answered gravely.

‘The weak must take up such weapons as lay to their hand,’ he replied drily.

This conversation, carried on as it was in a low tone, was drowned by the clatter of knives and forks; before the latter had ceased the notes of the horn were once more heard, the signal for the resumption of their journey.

The party rose at once, Mr. Erin leading the way. He took no notice of his son as he pushed by him, but the neglect was more than compensated for by the attention of the female members of the company.

William Henry was a very comely young fellow; his complexion dark, but not swarthy; his eyes keen and bright; a profusion of black curling hair was tied by a ribbon under his hat,[26] which gave him a somewhat feminine appearance, though it was not unusual so to wear it; his attire, though neat, was far from foppish—a dark blue coat with a short light waistcoat; a neckcloth by no means so large as was worn by many young persons in his station of life; and nankeen breeches.

If it is difficult for us to suppose such a costume becoming, it was easy for those who were accustomed to it to think so. His figure, it was observed, as he walked rapidly to overtake his father, was especially good.

‘I have made inquiries, Mr. Erin,’ he said respectfully, as the old man placed his foot on the step, ‘and find there is plenty of room in the coach.’

‘You mean on the coach,’ was the dry reply; ‘surely a young man like you—leaving out of question the ridiculous extravagance of such a proceeding—would never wish to be an inside passenger on an afternoon like this.’ And with a puff, half of displeasure, half of exhaustion, caused by the effort of the ascent, the antiquary sank into his seat.

‘Do you not ride with us?’ inquired Mr. Dennis good-naturedly, as he came up to the door with Margaret upon his arm.

The young man’s cheeks flushed with anger.

‘You do not know William Henry,’ said the girl, interposing with a smile; ‘he does not care for the nest when he can sit upon the bough.’

‘It is pleasanter outside—for some things—no doubt,’ assented Mr. Dennis as he assisted her into the coach. She cast a sympathising glance over her shoulder at William Henry, as he swung himself up to the hind seat, and he returned it with a grateful look. She had saved him from a humiliation.

It was a warm evening, as his father had observed, but in one sense he had been turned out into the cold, and he felt it bitterly.

CHAPTER III.

A RECITATION.

There is one spot, and only one, in all England, which can in any general sense be called hallowed—sacred to the memory of departed man. Priests and kings have done their best for other places, with small effect; here and there, as in Westminster Abbey, an attempt has been made to make sacred soil by collecting together the bones of our greatest men—warriors, authors, divines, statesmen; but these various elements do not kindly mix: the devotion we would pay to our own particular idol is chilled perhaps by the neighbourhood of those with whom we feel no especial sympathy. In all cathedrals, too, there is a certain religious feeling, artificial as the light which finds its way through the ‘prophets blazoned on its panes;’ it is difficult[29] in them to feel enthusiasm. In other places, again, exposed to the free air of heaven, association is weakened by external influences. I, at least, only know of one place where Nature, as it were, effaces herself, and becomes the setting and framework to the epitaph of a dead man. It is Stratford-on-Avon.

There, save once a year, when Shakespeare’s birthday is commemorated, fashion brings but few persons to simulate admiration. It is not as at some great funeral, where curiosity or official position or other extraneous motive brings men together to do honour to the departed; they come like humble friends, to pay tribute to one whom they not only admire, but revere, to this little Warwickshire town. It is too remote from the places where men congregate to entice the thoughtless crowd; nor has it any attractions save its associations with that marvellous mind, of which the crowd has but a vague and cold conception. It is, to my poor thinking, a very comfortable sign of the advance of human intelligence that, year after year, in hundreds and in thousands, but not in crowds—for[30] they arrive alone, or in twos or threes together—there come, from the uttermost parts of our island, and even from the ends of the earth, more and more pilgrims to this simple shrine.

In the days of which I write, Stratford, of course, had far fewer visitors than at present; but those it did have were certainly not inferior in enthusiasm. Indeed, it was a time when Shakespeare, if not more read than now, was certainly more talked about and thought about. His plays were much oftener acted. The theatre occupied a more intellectual position in society. Kemble and his majestic sister, Mrs. Siddons, trod the boards; quotations from Shakespeare were as common in the mouths of clerks and counter-jumpers as are now the most taking rhymes from a favourite burlesque; even the paterfamilias who did not ‘hold by’ stage plays made an exception in honour of the Bard of Avon. In literary circles an incessant war was waging concerning him; pamphlet after pamphlet—attack and rejoinder—was published almost every week by[31] this or that partisan of a phrase, or discoverer of a new reading. Mr. Samuel Erin was in the fore-front of this contest, and, as a rule, a stickler for the text. He opposed the advocates for change in the same terms which Dr. Johnson used to reformers in politics. The devil, he was wont to say, was the first commentator. The famous Shakespearean critic Malone was the object of his special aversion, which was most cordially reciprocated, and often had they transfixed one another with pens dipped in gall.

It was curious, since the object of Mr. Erin’s adoration has taken such pains to instil gentleness and feeling among his fellow-creatures, that his disciple should have harboured the sentiments he sometimes expressed; and yet it is hardly to be wondered at when one remembers that the advocates of Christianity itself have fallen into the same error, and from the same cause. Mr. Samuel Erin was not only a devotee, but a fanatic.

As the coach crossed the river, near their journey’s end, Mr. Dennis broke a long silence[32] by a reference to the beauty of the scenery, which his friend had come professionally to illustrate.

‘Here is a pretty bit of river for your pencil, Mr. Erin.’

‘Hush! hush!’ rejoined that gentleman reprovingly; ‘it is the Avon. We are on the threshold of his very birthplace.’

It was on the tip of Mr. Dennis’s tongue, who had been thinking of nothing but Margaret for the last half-hour, to inquire, ‘Whose birthplace?’—which would have lost him the other’s friendship for ever. Fortunately he recollected himself (and Shakespeare) just in time, and in some trepidation at his narrow escape, which his friend took for reverential awe, murmured some more suitable reply.

William Henry, on the other hand, was not so fortunate. At the instigation of the guard (who had a commission from the innkeeper on the guests he brought him), he leant down from the coach-top to inquire which house Mr. Erin meant to patronise, suggesting that the[33] party should put up at the ‘Stratford Arms,’ as being the best accommodation.

‘You fool!’ roared the old gentleman; ‘we put up at the “Falcon,” of course. The idea,’ he continued indignantly, ‘of our going elsewhere, when the opportunity is afforded us of residing under the very roof which once sheltered our immortal bard!’

‘Shakespeare did not live in an inn, did he, uncle?’ inquired Margaret demurely. She knew perfectly well that he had not done so, but was unwilling to let this outburst against her cousin pass by without some kind of protest.

‘Well, no,’ admitted Mr. Erin; ‘but he lived just opposite to it, and, it is supposed—indeed, it may be reasonably concluded—that he patronised it for his—ahem—convivial entertainments.’

‘I suppose there is some foundation for the story of the “Topers” and the “Sippers,”’ observed Dennis, ‘and for the bard being found under the crab-tree vino et somno.’

‘There may be, there may be,’ returned the[34] other indifferently; ‘but as for Shakespeare being beaten, even in a contest of potations, that is entirely out of the question. It was not in the nature of the man. If he ran, he would run quickest; if he jumped, he would jump the highest; and if he drank, he would undoubtedly have drunk deeper than anybody else.’

The Falcon Inn had no great extent of accommodation—it was perhaps too full of ‘association’ for it—but Margaret had a neat chamber enough; and, since it looked on the Guild Chapel and Grammar School where Shakespeare had been educated, and on the walls which surrounded the spot where he had spent his latter days, the niece of her uncle could hardly have anything to complain of. The young men had an attic apiece. As to what sort of a room was assigned to Mr. Samuel Erin, he could not have told you himself, for he took no notice of it. His head was always out of the window. It was his first sight of the shrine of his idol, and the very air seemed to be laden with incense from it.

To think that that long, low tenement yonder, with the projecting front, was the very house in which Shakespeare had ‘crept unwillingly to school,’ that his young feet had helped to wear those very stones away, and that that ancient archway had echoed his very tones, sent a thrill of awe through him such as could only be compared with that felt by some mediæval beholder of ‘a bit of the true cross.’ But, in that case, faith—and a good deal of it—had been essential to conviction; whereas in this the facts were indisputable. Behind yonder walls, too, stood the house to which, full of honour though not of years, he had retired to spend that leisure in old age which he had desiderated more than most men.

The aim of all is but to crown the life

With honour, wealth, and ease in waning age,

were the words Mr. Erin repeated to himself with mystic devotion, as a peasant mutters a Latin prayer. He had no poetic gifts himself, nor was he even a critic in a high sense; but[36] his long application to Shakespearean literature had given him some reflected light. What he understood of it he understood thoroughly; what was too high for his moderate, though by no means dwarfish intelligence, to grasp, or what through intermediate perversion was unintelligible, he not only took on trust, but accepted as reverentially as did those who were wont to consult her, the utterances of the Sibyl. In literature we have few such fanatics as Samuel Erin now; but in art he has many modern parallels—men who, having once convinced themselves that a painting is by Rubens or Titian, will see in it a hundred merits where there are not half a dozen, and even discover beauties in its spots and blemishes.

While the head of the little party was thus in the seventh heaven of happiness above-stairs, the junior members of it had assembled together in the common sitting-room; the landlady had inquired what refreshments they would please to have, and tea had been ordered rather with a view of putting a stop to her importunities than because, after that[37] ample meal at Banbury, they stood in need of any food.

‘If your uncle were here, Maggie,’ said William Henry, not perhaps without some remembrance of the snubbing he had just received from the old gentleman, and from which he was still smarting, ‘he would be ordering “sherrie sack,” or “cakes and ale.”’

Margaret glanced at him reprovingly, but said nothing. She regretted that he took such little pains to bridge the breach that evidently existed between his father and himself, and always discouraged his pert sallies. William Henry hung his head: if he did not find sympathy with his cousin, he could, he thought, find it nowhere.

Frank Dennis, however, came to his rescue. He either did not look upon the penniless, friendless lad as a real rival, or he was very magnanimous.

‘And how did you enjoy your trip to Bristol?’ he inquired. ‘St. Mary’s Redcliffe is a fine church, is it not?’

‘Yes, indeed; I paid a visit to the turret,[38] where the papers were stored to which Chatterton had access, and from which he drew the Rowley poems.’

‘How interesting!’ exclaimed Margaret; it was plain by her tone that she wanted to make amends to the young fellow. ‘Are any of his people still at Bristol?’

‘Oh yes, his sister lives there, a Mrs. Newton. I had a great deal of talk with her. She told me how angry he was with her on one occasion when she cut up some old deeds and other things he had brought home with him, and which she had thought valueless, to make into thread-papers; he collected them together, thread-papers and all, and carried them into his own room.’

‘Considering the use the poor young fellow made of them,’ observed Dennis gravely, ‘she had better have burnt them.’

‘Still, they did give him a certain spurious immortality,’ put in Margaret pitifully. ‘The other was out of his reach.’

‘Surely, my dear Miss Slade, you cannot mean that?’ remonstrated Dennis gently.

‘At all events, everybody was very hard upon him just because they were taken in,’ argued Margaret. ‘If he had acknowledged what they admired so much to have been his own, they would have seen nothing in it to admire. I think Horace Walpole behaved like a brute.’

‘That is very true,’ admitted Dennis. ‘Still, the lad was a forger.’

‘People are not starved to death, as he was, even for forging,’ rejoined Margaret. ‘His own people, too, did not care about him. He had no friends, poor fellow.’

Dennis listened to her with pleasure—though he thought her too lenient—because she took the side of the oppressed. William Henry was even more grateful, because he secretly compared his own position with that of Chatterton—for he too had written poems which nobody thought much of—and guessed that Margaret had his own case in her eye.

‘Amongst other things that Mrs. Newton told me,’ continued William Henry, ‘was that her brother was very reserved and fond of seclusion. On one occasion he was most[40] severely chastised for having absented himself for half a day from home. He did not shed a tear, but only observed that it was hard indeed to be whipped for reading.’

‘It was certainly most unfortunate,’ admitted Dennis, ‘that the boy was amongst persons who did not understand him.’

‘And who, though they were his own flesh and blood, treated him with contempt and cruelty,’ added Margaret, with indignation. ‘Did this sister of his never give him credit for possessing talent even?’

‘She thought him odd as a child, it seems,’ answered William Henry. ‘He preferred to be taught his letters from an old black-letter Bible rather than from any book of modern type. He seems to have had a natural leaning for the line that he took in life.’

‘In other words, you think he was born with a turn for forgery,’ observed Dennis drily. ‘That is not a very high compliment to him, nor indeed to Providence either.’

‘But how else could he have become celebrated?’ argued the young man impatiently.

‘Is it necessary then, my lad, to become celebrated?’ inquired Dennis, smiling.

‘I don’t say necessary, but it must be very nice.’

‘The same thing may be said of most of our vices,’ answered the other reprovingly. Frank Dennis often spoke the words of wisdom, but spoke them cut and dried, like proverbs from a copy-book. He was an excellent fellow, but not quite human enough for ordinary use. Margaret would have liked him better, perhaps, if he had been a trifle worse. The pedagogic tone in which he had spoken to her cousin, and his use of the words ‘my lad,’ which, as she argued to herself (quite wrongly), he must know were very offensive to him, irritated her a little. She felt that William Henry had been schooled enough, and wanted encouragement.

‘Did you get any inspiration from the turret of St. Mary Redcliffe?’ she inquired.

‘Well, yes.’ he answered, blushing, and a blush very well became his handsome face; ‘I did perpetrate—— ‘

‘Some mischief, I’ll warrant,’ exclaimed a[42] harsh, disdainful voice. It was that of Mr. Samuel Erin, who had entered the room unobserved. ‘And what was it you perpetrated, sir?’

William Henry looked abashed and annoyed. Margaret, though she stood in no little fear of her uncle, could hardly restrain her indignation. Frank Dennis as usual interposed with the oil can.

‘Your son has perhaps only written a poem, Mr. Erin, which in so young a man can hardly be considered a crime.’

‘I don’t know that, if the poem—as it probably was—was a bad one. If he has committed it’—here the old gentleman’s face softened, as under the influence of the infrequent and home-made joke the grimmest face will do—‘he has doubtless committed it to memory. Come, sir, let us have it.’

Now as, of all the pleasant moments which mitigate this painful life, there are none more charming than those passed in the recital of a poem of our own composition to (one pair of) loving ears, so there are none more embarrassing[43] than those which are occupied in doing the same thing before an unsympathetic audience. Imagine poor Shelley condemned to recite his ‘Skylark’ or Keats his ‘Nightingale’ to a vestry meeting! That would indeed be bad enough; but if the bard himself is conscious that he has no skylark nor nightingale, but only a tomtit or yellowhammer, to let fly for their edification, how much more terrible must be his position! Poor William Henry was in even worse case, for one of his audience, as he well knew, was not only not en rapport with him, but antagonistic, a hostile critic. I once beheld a shivering schoolboy compelled to make an extempore ode to the moon to a circle of his fellow-students armed with towels knotted at the end, to flick him with if his muse should be considered unsatisfactory. Except that he was not in his night-shirt, as my young friend was, poor William Henry’s position was almost as bad, and yet he dared not refuse to obey the paternal mandate.

‘There are only a very few verses, sir,’ he stammered.

‘The fewer the better,’ said Mr. Erin. He meant it for an encouragement, no doubt, a sort of ‘so far the Court is with you,’ but it had not an encouraging effect upon his son. It seemed to him that he had just swallowed a pint of vinegar.

‘Leave off those damnable faces and begin,’ exclaimed Mr. Erin. It was only a quotation from his favourite bard, and not an inappropriate one, but it did not sound kind.

‘It is brutal,’ murmured Margaret under her breath, and at the same time she cast a glance of ineffable pity at the victim. It was like a ray of sunshine upon a chill day, at sight of which the bird bursts into song.

‘The lines are on Chatterton,’ he began by way of prelude:—

Comfort and joys for ever fled,

He ne’er will warble more;

Ah me! the sweetest youth is dead

That e’er tuned reed before.

The hand of misery laid him low,

E’en hope forsook his brain;

Relentless man contemned his woe,

To him he sighed in vain.

Oppressed with want, in wild despair he cried,

‘No more I’ll live!’ swallowed the draught, and died.

Mr. Samuel Erin looked as if he had swallowed a draught; one of those recommended to persons suffering from the effects of poison.

‘Shade of Shakespeare!’ he cried, ‘do you call that a poem?’

William Henry murmured something in mitigation about its being an acrostic. The old gentleman’s sense of hearing was not acute, and led him to imagine he was being reproached for his surliness. He turned as red as a turkey-cock.

Margaret also flushed to her forehead; she too had misunderstood what her cousin had said, and the more easily because the words she thought he had used (a cross stick) were so appropriate. But how could he, could he, be so foolish as thus to give reins to his temper!

Lastly, Frank Dennis became a brilliant scarlet. He was half suffocated with suppressed laughter. Still, true to his mission of peacemaker, he contrived to splutter out that when a poem was an acrostic, such perfection was not to be looked for as when the muse was unfettered.

‘Oh, that’s it, is it?’ said Mr. Erin grimly. ‘I’ve heard of young men wasting their time, and, what is worse, the time of their employers, in many ways; but that they should take to writing acrostics seems to me the ne plus ultra of human folly. Bah! give me a dish of tea.’

CHAPTER IV.

A REAL ENTHUSIAST.

I am afraid it is rather taken for granted by parents in general, as regards any behaviour they may adopt towards their offspring, that religion is always upon their own side. And yet there is a very noteworthy text about ‘provoking our children to wrath,’ which it is a mistake to ignore. Wise and reverend signors may well have learnt by experience to take trifling annoyances with equanimity; but the amour propre of the young is a tender shoot, and very sensitive to rough handling.

The most sensitive plant of all is the lad with a turn for literature; and, as a rule, parents have the least patience with him. When the turn is not a mere taste, but a natural gift, this does not much matter; no true flame was ever[48] put out by the breath of contempt: but when it halts midway the youth has a bad time of it. He shivers at every sneer, without the means of giving it the lie. ‘Like a dart it strikes to his liver,’ because his armour, unlike that of true genius, is not arrow-proof. He knows that he is not the fool that his folk take him for, but he has an uneasy consciousness that they are partly right; that his powers are not equal to his pretensions. This was the case with William Henry Erin.

He had a turn for literature, and, if an uncommon facility for writing indifferent verses is any proof of it, even for poetry; and he found nobody to admit it, not even Margaret. ‘It is very good, Willie, for a first attempt,’ was the fatal eulogium she once passed upon the most cherished of his poetical productions; and his father, as we have seen, made no scruple of ridiculing his literary efforts. If the boy’s predilection for such matters had interfered with his professional duties, it might have been excusable enough; but the conveyancers to whom William Henry was articled were quite[49] satisfied with him. He was very careful and diligent, and though he had come to years of indiscretion, far from dissipated. If he loitered on his way to his employers’ chambers in the[50] New Inn, it was to turn over the leaves of some old poem on a book-stall, rather than to gaze on the young woman who might be behind it. Still, not being perfection, it was natural that he should feel resentment at his father’s harshness, and at the slights to which his muse was exposed at his unsympathising hands. He had never had any one to sympathise with his poetical aspirations except his friend Reginald Talbot, a fellow-clerk of his own age, who was also devoted to the Muses; and Talbot’s praise had its drawbacks. First, he did not think it worth much; and secondly, it could not be obtained without reciprocity; and it went against William Henry’s conscience to praise Talbot’s poems.

‘Well,’ thought the young man, as he looked out of his attic window, which commanded a distant view of Stratford Church, ‘there lies a man who was as little appreciated at my age as I am; and yet he made some noise in the world. He, too, some say, was a scrivener’s clerk. He, too, was called Will—which is at least an interesting coincidence. He, too, fell[51] in love at my age.’ Here his reflections ended with a sigh, for the parallel extended no further. Shakespeare had not only wooed, but—with a little too much ease, indeed—had won; whereas Margaret Slade was far out of his reach. He had a shrewd suspicion that Mr. Erin intended her to marry Dennis, and had brought him down with him to Stratford ‘to throw the young people together,’ as he would doubtless express it. Young people, indeed! why, Frank Dennis was old enough—well, scarcely, to be her father, unless he had been unusually precocious, but certainly to know better. ‘Crabbed age’—the man was thirty if he was a day—‘and youth cannot live together.’ It was a most monstrous proposition! On the other hand, what could he, poor William Henry, do? If he could persuade Maggie to run away with him to-morrow, they must literally run, for he had hardly money enough, after that Bristol trip, to pay the first pike out of Stratford, and far less a post-chaise.

As he thought of his unacknowledged merits, and of the many obstacles to his union,[52] he grew bitter against the whole scheme of creation. If poetic impulse could have projected him fifty years forward, he would doubtless have exclaimed, with the bard of Bon Gaultier,—

Cussed be the clerk and the parson,

Cussed be the whole concern!

but not having that vent for his feelings, he only loosened his neckcloth a bit and looked moody. Poor fellow! he had but two wishes in the world—to marry Margaret, and to get into print; and both these desires, just because he had no money, were denied him.

At that very time, Margaret at her window was thinking of him. She was not—she was certain she was not, the idea was quite ridiculous—in love with him; but, thanks to his father’s conduct, she felt that pity for him which is akin to love. And he was certainly very handsome, and very fond of her. He had been foolish to come down to Stratford when it was clear her uncle didn’t want him; but it was ‘very nice of him,’ too, and since he was there and upon his holiday—his one holiday in the year, poor fellow—it was[53] cruel to snub him! Frank Dennis didn’t snub him, that she would say for Frank: he was a kind, honest fellow, though rather old-fashioned, and just a trifle heavy in hand. She wished William Henry would talk like him when addressing his father; though when addressing her, she confessed to herself that she preferred William Henry’s way. It was really distressing to see her uncle and his son together; they mixed no better than oil and vinegar. She was well pleased to remember that Mr. Jervis, the Stratford poet, was coming that morning to breakfast with them, since his presence would prevent anything unseemly; moreover, he would probably take her uncle and Frank Dennis away with him to investigate antiquities, which would leave William Henry and herself to themselves.

John Jervis was but a carpenter in a small way of business, but he was much respected in the town, and had made himself a name beyond it, on account of the interest he took in all Shakespearean matters. The gentry in the neighbourhood spoke of him as ‘a civil and inoffensive creature,’ but he was ‘corresponded[54] with’ by men of letters and learning in London. His position would have been better than it was had he not been so foolish as to publish a volume of poems—to be paid by subscription. This had subjected him to something much worse than criticism—to patronage. Every one who had advanced a few shillings for the appearance of that unfortunate volume became in a sense his master, and some of them exacted interest for their investment in advice, remonstrance, and dictation. It was a foolish thing of John Jervis to set up his trade—not carpentering, but the other—in Stratford-on-Avon. In Paisley there are, I have heard say, at this present moment fifty poets, all complaining that the world which will give them a monument after their death, in the meantime permits them to starve; but Paisley is a place which is scarcely poetic to begin with, whereas to be a local poet in Stratford was like setting up a shed for small coal in Newcastle. The good man had become quite aware of this by this time; he was very dissatisfied with his published productions (it is a common case; what[55] we have in our desk seems as superior to what lies on our table as that which moves in our brain is to what lies in our desk). He would have given as much to suppress his little volume as William Henry would have given to get his own broadcast over an admiring land. And yet there was no question of comparison between them as respected merit. John Jervis was, within certain narrow limits, a true poet: what he saw he noted, what he noted he felt; so far he followed his great master. He even emitted a modest light of his own, which was not reflected: he was not a star, but he was a glow-worm. Most of us are but worms without the glow.

Every one who came to Stratford at that time for Shakespeare’s sake—and no one came for any other reason—was recommended to apply to John Jervis for information. On receiving any summons of this nature he put aside his carpenter’s tools, took off his apron, and donned his Sabbath garb. A carpenter in his Sunday clothes in these days is a sad sight; he represents one branch of his business only,[56] that of the undertaker: but in the times of which we write it was not so. Wigs were not yet gone out of fashion in Warwickshire, but John Jervis could not afford what was called the ‘Citizen’s Sunday Buckle’ or ‘Bob Major,’ because it had three tiers of curls. He had too much good taste to use the ‘Minor Bob’ or Hair Cap, short in the neck to show the stock buckle, and stroked away from the face so as to seem (like Tristram Shandy) as though the wearer had been skating against the wind. He wore his own grey hair and a modest grey suit, in which, however, none but a flippant young fellow like Master William Henry Erin could have likened him to a master baker. His face was homely but pleasant, and had a certain dignity; his manner retiring but not reticent. It was his business to answer questions, but he did not volunteer information. He had, indeed, a secret contempt for the majority of his clients; they had more appetite for the Shakespearean husks, the few dry details that could be picked up concerning their Idol, than for the corn—what manner of man he had been in[57] spirit, or how the scenery about his home had affected his writings. Jervis found Mr. Erin to be no better than his other visitors: hungry for facts, greedy for particulars, and combative. He talked of the Confession of Faith found in the roof of the house in Henley Street, and rubbed his hands, notwithstanding that his enemy had since retracted his belief in it, over Malone’s credulity.

‘“An unworthy member of the Holy Catholic religion,” indeed! It is monstrous, incredible.’

‘That phrase had reference to the father, however,’ observed Jervis.

‘True, but that was the art of the forger, himself of the old faith, no doubt. He wished to make our Shakespeare a born Papist. Now, that he was a good Protestant is indubitable. “I’d beat him like a dog,” says Sir Andrew. “What! for being a Puritan?” returns Sir Toby. What irony! You are of my opinion, I hope, Mr. Jervis?’

‘I have scarcely formed an opinion upon the matter,’ was the modest reply. ‘Shakespeare[58] was Catholic in one sense, but I agree with you that he was not one to be much comforted by the “holy sacrifice of the mass,” as the so-called Confession put it.’

‘I should think not, indeed. He was not partial to priests. “When thou liest howling,”’ quoted Mr. Erin triumphantly.

‘Still, being a stage-player, I doubt if he was partial to the Puritans. No; such things moved him neither way; religious controversies he looked upon as on other quarrels, as “valour misbegot.” If he could not see into the future, he saw five hundred years ahead of his contemporaries, who were burning Francis Kett for heresy at Norwich.’

Mr. Erin was not certain whether Kett was a Protestant or a Catholic (on which depended his view of the circumstance), so he only shook his head.

‘You mean, Mr. Jervis,’ said Margaret timidly, ‘that in Shakespeare’s eyes there were no heretics?’

The man in grey looked at his gentle inquirer and bowed his head assentingly. ‘None,[59] as I think, young lady, save those who disbelieved in good.’

‘That is not established,’ said Mr. Erin argumentatively.

‘I am afraid your uncle thinks me a heretic,’ said Mr. Jervis, smiling. Then, perceiving that Margaret looked interested, he told her of the marvellous boy—name unknown, but whose fame still survived—who had been Shakespeare’s contemporary at Stratford. How, so the legend ran, he had been thought his equal in genius, and his future greatness been prophesied with the same confidence, but who had died in youth, a mute, inglorious Shakespeare.

‘I often picture to myself,’ said the old man dreamily, ‘the friendship of those two boys.’

‘Do you think they went out poaching together?’ inquired William Henry demurely. He was not without humour, and was also perhaps a little jealous of the attention Margaret paid their visitor.

‘Poaching!’ exclaimed Mr. Erin angrily, ‘how gross and contemptible are your ideas, sir!’

‘Still,’ interposed Dennis, his sense of justice[60] aiding his wish to stand between Mr. Erin’s wrath and its object—Margaret’s cousin—‘Shakespeare did transgress in that way. It is not likely that he strained at a hare if he swallowed a deer.’

‘No doubt he poached,’ admitted Jervis gravely. ‘He was very human, and did all things that became a boy. But I was thinking rather of the companionship of the two boys than their pursuits. Their talk was not of hares nor of rabbits. How one would like to know their boyish confidences! what were their ambitions, their aspirations, their views of life; which one was about to leave, and in which the other was to fill so large a space in the thoughts of man—for ever. It was in this little town they lived and talked together; learnt their lessons from one book perhaps, in yonder school, each without a thought of the other’s immortality, albeit of such different kinds.’

The solemnity of the speaker’s manner, and the genuineness of feeling which his tone displayed, had no little effect upon his audience,[61] but on each in a different way. Margaret’s mind was stirred to its depths by this simple dream-picture, and seeing her so the two young men felt a touch of sympathy with it.

‘Is there any sure foundation to go upon as to this playmate of Shakespeare’s?’ inquired Mr. Erin, note-book in hand—‘any record, any document?’

The visitor shook his head. ‘Nothing, but wherever, in the country round, Shakespeare’s youth is alluded to, this story of his friend is told. It is a local legend, that is all; but it seems to me to have life in it. The world outside knows nothing of it. It interests itself in Shakespeare only, and but little in his belongings; but with us, breathing the air he breathed, walking on the same ground he trod, things are different; we still fancy him amongst us, and not alone. There is Hamnet, too; we still speak of Hamnet.’

It was fortunate for William Henry that he repressed the observation that rose to his lips. He was about to say, ‘You don’t mean Hamlet, do you?’

The same idea I am afraid occurred to Mr. Dennis, but for even a briefer space; he felt that there must be some mistake somewhere; but also that he himself might be making it.

‘Buried here, August the 11th, 1596,’ observed Mr. Erin, as though he was reading from the register itself.

‘Just so,’ continued Jervis, ‘only a little over two hundred years ago. He was eleven years old, too young to understand the greatness of him who begat him, yet old enough to have an inkling of it. Once a year or so, as it is believed, his father came home to Stratford fresh from the companionship of the great London wits and poets—Jonson, Beaumont, Fletcher, Camden, and Selden. What meetings must those have been with his only son; the boy whom he fondly hoped, but hoped in vain, would inherit the proceeds of his fame! I wonder how his mother used to speak of her husband to her children? Did she excuse to them his long absence, his dwelling afar off, or[63] did she inveigh against it? Did she recognise the splendour of his genius, or did she only love him? Or did she not love him?’

‘Let us hope she was not unworthy of him,’ said Mr. Erin, his enthusiasm, stirred by the other’s eloquence, rising on a stronger wing than usual.

‘As a wife she was sorely tried,’ murmured Mr. Jervis. ‘I love to think of her less than of Hamnet, so lowly born in one sense, and in the other of such illustrious parentage. The news of his father’s growing fame must have reached the boy, and the contrast could not fail to have struck him. Then to have seen that father bending over his little bed, to have kissed that noble face, and felt himself in his embrace; to have known that he was the child whom Shakespeare’s soul loved best in all the world, what a sensation, what an experience!’

‘Some mementoes of the immortal bard are, I hope, still to be purchased?’ observed Mr. Erin curtly. He had engaged Mr. Jervis’s[64] services for practical purposes, and began to resent this waste of time—which was money—upon sentimental hypothesis. Shakespeare’s wife was a topic one could sympathise with; there was documentary evidence in existence concerning her, but over little Hamnet’s grave there was not even a tombstone.

‘Mementoes? Yes, there is mulberry-wood enough to last some time,’ said Mr. Jervis slily; ‘you shall have your pick of them.’

‘But no MSS.?’

‘Not that I know of. There has been a report, however, of late, that Mr. Williams, of Clopton House, has found some that were removed from New Place at the time of the fire.’

‘Great heavens!’ exclaimed Mr. Erin, with much excitement, ‘what, from New Place, Shakespeare’s own home? Let us go at once; all other things can wait.—William Henry, come along with us, and bring your little book.—You can stay here with Maggie, Dennis, till I come back.’

If he could have dispensed with the[65] presence of John Jervis himself, he would have been glad to do so; for what is true of a feast is also true of treasure-trove, ‘the fewer (the finders) the better the fare.’

CHAPTER V.

THE OLD SETTLE.

WILLIAM HENRY, far from sharing his father’s enthusiasm at any time, was on this occasion less than ever inclined to applaud it. If Clopton House should be found full of Shakespearean MSS., it would not afford him half the pleasure[67] he would have derived from a tête-à-tête with his cousin Margaret; a treat which, it seemed, was to be thrown away upon Frank Dennis. Why didn’t Mr. Erin select him to take notes for him from the musty documents? A question the folly of which only a high state of irritation could excuse. He knew perfectly well that his own dexterity and promptness in copying had caused himself to be chosen for the undesirable task, and that knowledge irritated him the more. It was only when he could be of some material use to him, as in the present instance, that his father took the least account of him. If he could bring himself to steal one of those precious documents, was his bitter reflection, and secrete it as some wretched slave secretes a diamond in the mines of Golconda, then, perhaps, and then only, he might be permitted to marry Margaret. For a bit of parchment with Shakespeare’s name upon it, most certainly for a whole play in his handwriting, Mr. Samuel Erin, it was probable, would have bartered fifty nieces, and thrown his own soul into the bargain. Our young friend, however, was quite[68] aware of what a poet of a later date would have told him, that ‘an angry fancy’ is a poor ware to go to market with; so, with as good a grace as he could, he put on his hat and accompanied Mr. Erin and his cicerone to Clopton House, which was but a few yards down the street.

It was a good-sized mansion of great antiquity, but had fallen into disrepair and even decay. Its present tenant, Mr. Williams, was a farmer in apparently far from prosperous circumstances. Half of the many chambers were in total darkness, the windows having been bricked up to save the window tax, and the handsome old-world furniture was everywhere becoming a prey to the moth and the worm. As a matter of fact, however, these were not evidences of poverty. Mr. Williams had enough and to spare of worldly goods, only of some of them he did not think so much as other people of more cultivated taste would have done. A Warwickshire farmer of to-day would have considered many things as valuable in Clopton House which their unappreciative proprietor had relegated to the cock-loft. It was to that[69] apartment, indeed, that Mr. Erin was led as soon as the nature of his inquiries—which he had stated generally, and to avoid suspicion of his actual object, to be concerning antiquities—was understood. The room was filled with mouldering household goods of remote antiquity, chiefly of the time of Henry VII., in whose reign the proprietor of the house, Sir Hugh Clopton, had been Lord Mayor of London. Among other things, for example, there was an emblazoned representation on vellum of Elizabeth, Henry’s wife, as she lay in state in the chapel of the Tower, where she died in child-birth.

‘You may have that if you like,’ said Mr. Williams to his visitor carelessly. He was a fat, coarse man, but very good-natured. ‘For, being on vellum, it is no use to light the fire with.’

‘You don’t mean to say you light your fire with anything I see here?’ gasped Mr. Erin.

‘Well, no, there’s nothing much left of that sort of rubbish; we made a clean sweep of it all about a fortnight since.’

‘There were no old MSS., I hope?’

‘MSS.! Heaps on ’em. They came from New Place at the time of the fire, you see, though Heaven knows why any one should have thought them worth saving. They were all piled in that little room yonder, and as I wanted a place for some young partridges as I am bringing up, I burnt the whole lot of ‘em.’

‘You looked at them first, of course, to make sure that there was nothing of consequence?’

‘Well, of course I did. I hope Dick Williams ain’t such a fool as to burn law documents. No, they were mostly poetry and that kind of stuff.’

‘But did you make certain about the handwriting? Else, my good sir, it might have been that of Shakespeare himself.’

‘Shakespeare! Well, what of him? Why, there was bundles and bundles with his name wrote upon them. It was in this very fireplace I made a regular bonfire of them.’

There was a solitary chair in the little chamber, set apart for the partridges, into[71] which Mr. Samuel Erin dropped, as though he had been a partridge himself, shot by a sportsman.

‘You—made—a—bonfire—of—Shakespeare’s—poems!’ he said, ejaculating the words very slowly and dejectedly, like minute guns. ‘May Heaven have mercy upon your miserable soul!’

‘I say,’ cried Mr. Williams, turning very red, ‘what the deuce do you mean by talking to me as if I was left for execution? What have I done? I’ve robbed nobody.’

‘You have robbed everybody—the whole world!’ exclaimed Mr. Erin excitedly. ‘In burning those papers you burnt the most precious things on earth. A bonfire, you call it! Nero, who fiddled while Rome was burning, was guiltless compared to you. You are a disgrace to humanity. Shakespeare had you in his eye, sir, when he spoke of “a marble-hearted fiend.”’

Mr. Samuel Erin had his favourite bard by heart, and was consequently in no want of ‘base comparisons,’ but he stopped a moment[72] for want of breath. Annoyance and indignation had had the same effect upon Mr. Williams. He had never been ‘bully-ragged’ in his own house for ‘nothing’—except by his wife—before. Purple and speechless, he regarded his antagonist with protruding eyes, a human Etna on the verge of eruption.

Mr. John Jervis knew his man. Up to this point he had taken no part in the controversy; but he now seized Mr. Erin by the arm, and led him rapidly downstairs. Their last few steps were accomplished with dangerous velocity, for a flying body struck both of them violently on the back. This was William Henry, who, unable to escape the wild rush of the bull, had described a parabola in the air.

‘If there’s law in England, you shall smart for this,’ roared the infuriated animal over the banisters.

‘Perhaps I ought to have told you that Mr. Williams was of a hasty disposition,’ observed Mr. Jervis apologetically, when they found themselves in the street.

‘Hasty!’ exclaimed Mr. Erin, whose mind was much too occupied with sacrilege to concern himself with assault; ‘a more thoughtless and precipitate idiot never breathed. The idea of his having burnt those precious papers! I suppose, after what has happened, it would be useless to inquire just now whether any scrap of them has escaped the flames; otherwise my son can go back—— ‘

‘I am sure that wouldn’t do,’ interposed Mr. Jervis confidently.

William Henry breathed a sigh of relief. The impressions of Stratford-on-Avon seemed to him indelible; they had left on him such ‘local colouring’ as time itself, he felt, could hardly remove. Fortunately for his amour propre, not a word was said by his father of their reception at Clopton House. His whole mind was monopolised by the literary disappointment. The inconvenience that had happened to his son did not weigh with him a feather.

The whole party now proceeded to Mr. Jervis’s establishment, where the remains of[74] the famous mulberry tree were kept in stock. Mr. Erin was haunted by the notion that some Shakespearean fanatic might step in and buy the whole of it before he could secure some mementoes, whereas the birthplace in Henley Street could ‘wait;’ an idea at which, for the life of him, the proprietor of the sacred timber could not restrain a dry smile. It was the general opinion that enough tobacco stoppers, busts, and wafer seals had already been sold to account for a whole grove of mulberry trees. Mr. Erin was very energetic with his new acquaintance on the road, about precautions against fire (insurance against it was out of the question, of course), but when he had possessed himself of what he wanted, and the matter was again referred to as they came away, it was noticeable that he had not another word to say upon the side of prudence.

‘He declaimed against Mr. Williams’ rashness,’ whispered William Henry to Margaret; ‘but my belief is that he would now set fire to that timber yard without a scruple in order to render his purchases unique.’

Maggie held up her finger reprovingly, but her laughing eyes belied the gesture.

Both these young people, indeed, had far too keen a sense of fun to be enthusiasts.

To Mr. Hart the butcher (who at that time occupied the house in Henley Street), as an indirect descendant of the immortal bard, through his sister, Mr. Erin paid a deference that was almost servile. He examined his lineaments, in the hopes of detecting a likeness to the Chandos portrait, with a particularity that much abashed the object of his scrutiny, and even tried to get him to accompany him to the church, that he might compare his features with those of the bust of the bard in the chancel.

But it was in the presence of the bust itself that Mr. Erin exhibited himself in the most characteristic fashion. Standing on what was to him more hallowed ground than any blessed by priests, and within a few feet of the ashes of his idol, he was nevertheless unable to restrain his indignation against the commentator Malone, through whose influence the coloured bust had[76] recently been painted white. Instead of bursting into Shakespearean quotation, as it was his wont to do on much less provocation, he repeated with malicious gusto the epigram to which the act of vandalism in question had given birth:—

Stranger, to whom this monument is shown,

Invoke the poet’s curses on Malone,

Whose meddling zeal his barbarous taste displays,

And daubed his tombstone as he marred his plays.

His rage, indeed, so rose at the spectacle, that for the present he protested that he found himself unable to pursue his investigations within the sacred edifice, and proposed that the party should start forthwith to visit Anne Hathaway’s cottage at Shottery.

There was at present no more need for Mr. Jervis’s services, so that gentleman was left behind. Mr. Erin and Frank Dennis led the way by the footpath across the fields that had been pointed out to them, and William Henry and Margaret followed. It was a lovely afternoon; the trees and grass, upon which a slight shower had recently fallen, emitted a fragrance[77] inexpressibly fresh. All was quiet save for the song of the birds, who were giving thanks for the sunshine.

‘How different this is from Norfolk Street!’ murmured Margaret.

‘It is the same to me,’ answered her companion in a low tone, ‘because all that makes life dear to me is where you are. When you are not there, Margaret, I have no home.’

‘You should not talk of your home in that way,’ returned she reprovingly.

‘Yet you know it is the truth, Margaret; that there is no happiness for me under Mr. Erin’s roof, and that my very presence there is unwelcome to him.’

‘I wish you would not call your father Mr. Erin,’ she exclaimed reproachfully.

‘Did you not know, then, that he was not my father?’

‘What?’ In her extreme surprise she spoke in so loud a key that it attracted the attention of the pair before them. Mr. Erin looked back with a smile. ‘Shakespeare must[78] have taken this walk a thousand times, Maggie,’ he observed.

She nodded and made some suitable reply, but for the moment she was thinking of things nearer home. She now remembered that she had heard something to the disadvantage of Mr. Erin’s deceased wife, one of those unpleasant remarks concerning some one connected with her which a modest girl hears by accident, and endeavours to forget. Until Mr. Erin had become a widower Margaret had never been permitted by her mother to visit Norfolk Street. Mrs. Erin had been a widow—a Mrs. Irwyn—but she had not become Mr. Erin’s wife at first, because her husband had been alive. It was probable, then, that what William Henry had said was true; he was Mrs. Erin’s son, but not Mr. Erin’s, though he passed as such. This was doubtless the reason why her uncle and he were on such distant terms with one another, and why he never called him father. On the other hand, it was no reason why her uncle should be so harsh with the young man, and treat him with such scant consideration. Some[79] women would have despised the lad for the misfortune of his birth, but Margaret was incapable of an injustice; her knowledge of his unhappy position served to draw him closer to her than before.

By the blush that, in spite of her efforts to repress it, spread over her face, William Henry understood that she gave credit to his statement, and by the tones of her voice he felt that it had done him no injury in her eyes. It was a matter, however, which, though necessary to be made plain, could not be discussed.

‘What your uncle says is very true, Maggie,’ he quietly remarked. ‘This must have been Shakespeare’s favourite walk, for love never goes by the high road when it can take the footpath. The smell of that bean-field, the odour of the hay of that very meadow, may have come to his nostrils as it comes to ours. His heart as he drew nigh to yonder village must have beat as mine beats, because he knew his love was near him.’

‘There is the cottage,’ cried Mr. Erin excitedly, pointing in front of him, and addressing[80] his niece. ‘Is it not picturesque, with its old timbers and its mossy roof?’

‘It will make an excellent illustration for your book,’ observed Frank Dennis the practical.

‘It has been illustrated already pretty often,’ returned the other drily, ‘or we should not recognise it so easily.’

‘Let us hope it’s the right one,’ muttered William Henry, ‘for it will be poor I who will have to suffer for it if it is not.’

Fortunately, however, there was no mistake. They stepped across the little brook, and stood in the garden with its well and its old-world flowers. Before them was the orchard ‘for whispering lovers made,’ and on the right the low vine-clad cottage with the settle, or courting-seat, at its door.

Here Shakespeare came to win and woo his wife; whatever doubt may be thrown on his connection with any other dwelling, that much is certain. On the threshold of the cottage Mr. Erin took off his hat, not from courtesy, for he was not overburdened with politeness,[81] but from the same reverence with which he had doffed it at the church. He entered without noticing whether he was followed by the others or not. A descendant of Anne Hathaway’s, though not of her name, received him; fit priest for such a shrine. That he had not read a line of Shakespeare in no way detracted from his sacred character. Frank Dennis, himself not a little moved, went in likewise. As Margaret was following him, William Henry gently laid his hand upon her wrist and led her to the settle, which was very ancient and worm-eaten.

‘Sit here a moment, Maggie; this is the very seat, as Mr. Jervis tells me, on which Shakespeare sat with her who became his wife. Here, on some summer afternoon like this, perhaps, he told her of his love.’

Margaret trembled, but sat down.

‘It is amazing to think of it,’ she said; ‘he must have looked on those same trees, and on this very well.’