SWEET HAY-MAKERS

Title: A book of the west. Volume 1, Devon

being an introduction to Devon and Cornwall

Author: S. Baring-Gould

Release date: March 8, 2015 [eBook #48439]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Julia Neufeld and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

LIFE OF NAPOLEON BONAPARTE

THE TRAGEDY OF THE CÆSARS

THE DESERT OF SOUTHERN FRANCE

STRANGE SURVIVALS

SONGS OF THE WEST

A GARLAND OF COUNTRY SONG

OLD COUNTRY LIFE

YORKSHIRE ODDITIES

FREAKS OF FANATICISM

A BOOK OF FAIRY TALES

OLD ENGLISH FAIRY TALES

A BOOK OF NURSERY SONGS

AN OLD ENGLISH HOME

THE VICAR OF MORWENSTOW

THE CROCK OF GOLD

A

BOOK OF THE WEST

BEING AN INTRODUCTION

TO DEVON AND CORNWALL

BY S. BARING-GOULD

VOL. I.

DEVON

WITH THIRTY-FIVE ILLUSTRATIONS

METHUEN & CO.

36 ESSEX STREET, W.C.

LONDON

1899

In this "Book of the West" I have not sought to say all that might be said relative to Devon and Cornwall; nor have I attempted to make of it a guide-book. I have rather endeavoured to convey to the visitor to our western peninsula a general idea of what is interesting, and what ought to attract his attention. The book is not intended to supersede guide-books, but to prepare the mind to use these latter with discretion.

In dealing with the history of the counties and of the towns, it would have swelled the volumes unduly to have gone systematically through their story from the beginning to the present; it would, moreover, have made the book heavy reading, as well as heavy to carry. I have chosen, therefore, to pick out some incident, or some biography connected with the several towns described, and have limited myself thereto.

My object then must not be misunderstood, and my book harshly judged accordingly. There are[vi] ten thousand omissions, but I venture to think a good many things have been admitted which will not be found in guide-books, but which it is well for the visitor to know, if he has a quick intelligence and eyes open to observe.

In the Cornish volume I have given rather fully the stories of the saints who have impressed their names indelibly on the land. It has seemed to me absurd to travel in Cornwall and have these names in the mouth, and let them remain nuda nomina.

They have a history, and that is intimately associated with the beginnings of that of Cornwall. But their history has not been studied, and in books concerning Cornwall most of the statements about them are wholly false.

I have not entered into any critical discussion concerning moot points. I have left that for my "Catalogue of the Cornish Saints" that is being issued in the Journal of the Royal Institution of Cornwall.

There are places that might have been described more fully, others that have been passed over without notice. This has been due to no disregard for them on my part, but to a dread of making the volumes too bulky and cumbrous.

Finally, I owe a debt of gratitude to many kind[vii] friends who have assisted me with their local knowledge, as Mrs. Troup, of Offwell House, Honiton; the Rev. J. B. Hughes, for some time Head Master of Blundell's School, Tiverton, and now Vicar of Staverton; Mr. R. Burnard, of Huckaby House, Dartmoor, and Hillsborough, Plymouth, my alter ego in all that concerns Dartmoor; Mr. J. D. Enys, whose knowledge of things Cornish is encyclopædic; Messrs. Amery, of Druid, Ashburton; Mr. J. D. Prickman, of Okehampton; and many others.

S. BARING-GOULD

Lew Trenchard House, Devon

June, 1899

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Western Folk | 1 |

| II. | Villages and Churches | 30 |

| III. | Honiton | 43 |

| IV. | A Landslip | 60 |

| V. | Exeter | 68 |

| VI. | Crediton | 79 |

| VII. | Tiverton | 101 |

| VIII. | Barnstaple | 122 |

| IX. | Bideford | 134 |

| X. | Dartmoor and its Antiquities | 155 |

| XI. | Dartmoor: Its Tenants | 176 |

| XII. | Okehampton | 208 |

| XIII. | Moreton Hampstead | 225 |

| XIV. | Ashburton | 248 |

| XV. | Tavistock | 266 |

| XVI. | Torquay | 289 |

| XVII. | Totnes | 310 |

| XVIII. | Dartmouth | 323 |

| XIX. | Kingsbridge | 337 |

| XX. | Plymouth | 352 |

| Sweet Hay-makers | Frontispiece | |

From a photograph by Mr. Chenhall, Tavistock. | ||

| Clovelly Fishermen | To face page | 16 |

From a photograph by the Rev. F. Partridge. | ||

| Sheepstor | " | 30 |

From a painting by A. B. Collier, Esq. | ||

| Holne Pulpit and Screen | " | 38 |

From a photograph by J. Amery, Esq. | ||

| Honiton Lace | " | 51 |

From specimens kindly lent by Miss Herbert, Exeter, and Mrs. Fowler, Honiton. Photographed by the Rev. F. Partridge. | ||

| High Street, Exeter | " | 68 |

From a photograph by the Rev. F. Partridge. | ||

| A Cob Cottage, Sheepwash | " | 80 |

From a photograph by the Rev. F. Partridge. | ||

| East Window, Crediton Church, before "Restoration" | " | 82 |

From a sketch by F. Bligh Bond, Esq. | ||

| Tiverton | " | 101 |

From a photograph by Mr. Mudford, Tiverton. | ||

| Queen Anne's Walk, Barnstaple | " | 122 |

From a photograph by the Rev. F. Partridge. | ||

| Chapel Rock, Ilfracombe | " | 128 |

From a photograph by Wellington and Ward, Elstree. | ||

| Hartland Smithy | " | 134 |

From a photograph by the Rev. F. Partridge. | ||

| Clovelly | " | 151 |

From a photograph by the Rev. F. Partridge. | ||

| Staple Tor | " | 155 |

From a photograph by James Shortridge, Esq. | ||

| Rippon Tor Logan Stone | " | 160 |

From a photograph by J. Amery, Esq. | ||

| [xii]Broadun Pounds | " | 165 |

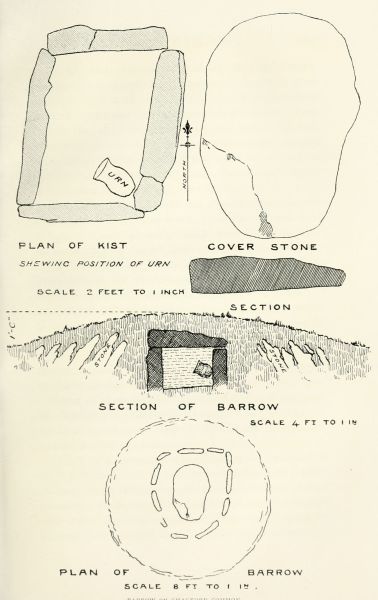

| Barrow on Chagford Common | " | 166 |

Drawn by R. H. Worth, Esq. | ||

| Lakehead Kistvaen | " | 168 |

From a photograph by R. Burnard, Esq. | ||

| Urn from Kistvaen | " | 172 |

Drawn by R. H. Worth, Esq. | ||

| Vixen Tor | " | 176 |

From a painting by A. B. Collier, Esq. | ||

| Lower Tarr | " | 182 |

From a photograph by J. Amery, Esq. | ||

| Tavy Cleave | " | 197 |

From a painting by A. B. Collier, Esq. | ||

| Taw Marsh | " | 208 |

From a painting by A. B. Collier, Esq. | ||

| Yes Tor | " | 212 |

From a painting by A. B. Collier, Esq. | ||

| The Calculating Boy | " | 232 |

From a miniature in the possession of Miss Bidder. | ||

| Grimspound | " | 239 |

From a plan by R. H. Worth, Esq. | ||

| J. Dunning, Lord Ashburton | " | 252 |

From a painting by Sir J. Reynolds. | ||

| Old Oak Carving, Ashburton | " | 258 |

From a photograph by J. Amery, Esq. | ||

| Brent Tor | " | 266 |

From a painting by A. B. Collier, Esq. | ||

| On the Dart | " | 310 |

From a photograph by the Rev. F. Partridge. | ||

| Dartmouth Castle | " | 323 |

From a photograph by the Rev. F. Partridge. | ||

| Grammar School, Plympton | " | 354 |

From a drawing by F. Bligh Bond, Esq. | ||

| In Plympton | " | 354 |

From a drawing by F. Bligh Bond, Esq. | ||

| Sutton Pool | " | 358 |

From a photograph by the Rev. F. Partridge. | ||

| Alms-houses, S. Germans | " | 366 |

From a drawing by F. Bligh Bond, Esq. |

Ethnology of the Western Folk—The earliest men—The Ivernian race—The arrival of the Britons—Mixture of races in Ireland—The Attacottic revolt—The Dumnonii—The Scottic invasion of Dumnonia—The story of the Slave of the Haft—Athelstan drives the Britons across the Tamar—Growth of towns—The yeomen represent the Saxon element—The peasantry the earlier races—The Devonshire dialect—Courtesy—Use of Christian names—Love of funerals—Good looks among the girls—Dislike of "Foreigners"—The Cornish people—Mr. Havelock Ellis on them—The types—A Cornish girl—Religion—The unpardonable sin—Folk-music—Difference between that of Devon and Cornwall and that of Somersetshire.

It is commonly supposed that the bulk of the Devonshire people are Saxons, and that the Cornish are almost pure Celts.

In my opinion neither supposition is correct.

Let us see who were the primitive occupants of the Dumnonian peninsula. In the first place there were the men who left their rude flint tools in the Brixham and Kent's caverns, the same people who have deposited such vast accumulations in the lime and chalk caves and shelters of the Vézère and Dordogne. Their[2] remains are not so abundant with us as there, because our conditions are not as favourable for their preservation; and yet in the Drift we do find an enormous number of their tools, though not in situ, with their hearths, as in France; yet sufficient to show that either they were very numerous, or what is more probable, that the time during which they existed was long.

This people did not melt off the face of the earth like snow. They remained on it.

We know that they were tall, that they had gentle faces—the structure of their skulls shows this; and from the sketches they have left of themselves, we conclude that they had straight hair, and from their skeletons we learn that they were tall.

M. Massenat, the most experienced hunter after their remains, was sitting talking with me one evening at Brives about their relics. He had just received a volume of the transactions of the Smithsonian Institute that contained photographs of Esquimaux implements. He indicated one, and asked me to translate to him the passage relative to its use. "Wonderful!" said he. "I have found this tool repeatedly in our rock-shelters, and have never known its purport. It is a remarkable fact, that to understand our reindeer hunters of the Vézère we must question the Esquimaux of the Polar region. I firmly hold that they were the same race."

A gentle, intelligent, artistic, unwarlike people got pressed into corners by more energetic, military, and aggressive races. And, accustomed to the reindeer, some doubtless migrated North with their favourite[3] beasts, and in a severer climate became somewhat stunted.

It is possible—I do not say that it is more than possible—that the dark men and women found about Land's End, tall and handsome, found also in the Western Isles of Scotland and in West Ireland, may be the last relics of this infusion of blood.

But next to this doubtful element comes one of which no doubt at all exists. The whole of England, as of France, and as of Spain, was at one time held by a dusky, short-built race, which is variously called Iberian, Ivernian, and Silurian, of which the Basque is the representative so far as that he still speaks a very corrupted form of the original tongue. In France successive waves of Gaul, Visigoth, and Frank have swept over the land and have dominated it. But the fair hair and blue eyes and the clear skin of the conquering races have been submerged by the rising and overflow of the dusky blood of the original population. The Berber, the Kabyle are of the same race; dress one of them in a blue blouse, and put a peaked cap on his head, and he would pass for a French peasant.

The Welsh have everywhere adopted the Cymric tongue, they hug themselves in the belief that they are pure descendants of the ancient Britons, but in fact they are rather Silurians than Celts. Their build, their coloration, are not Celtic. In the fifth century Cambria was invaded from Strathclyde by the sons of Cunedda; fair-haired, white-skinned Britons, they conquered the North and penetrated a certain way South; but the South was already occupied by a[4] body of invading Irish. When pressed by the Saxons, then the retreating Britons poured into Wales; but the substratum of the population was alien in tongue and in blood and in religion.

It was the same in Dumnonia—Devon and Cornwall. It was occupied at some unknown time, perhaps four centuries before Christ, by the Britons, who became lords and masters, but the original people did not disappear, they became their "hewers of wood and drawers of water."

Then came the great scourge of the Saxon invasion. Devon remained as a place of refuge for the Britons who fled before the weapons of these barbarians, till happily the Saxons accepted Christianity, when their methods became less ferocious. They did not exterminate the subject people. But what had more to do with the mitigation of their cruelty than their Christianity, was that they had ceased to be mere wandering hordes, and had become colonists. As such they needed serfs. They were not themselves experienced agriculturalists, and they suffered the original population to remain in the land-the dusky Ivernians as serfs, and the freemen, the conquered Britons, were turned into tenant farmers.

This is precisely what took place in Ireland. The conquering Gadhaels or Milesians, always spoken of as golden-haired, tall and white-skinned, had subdued the former races, the Firbolgs and others, and had welded them into one people whom they called the Aithech Tuatha, i.e. the Rentpaying Tribes; the Classic writers rendered this Attacotti.

In the first two centuries of our era there ensued[5] an incessant struggle between the tenant farmers and the lords; the former rose in at least two great revolutions, which shows that they had by no means been exterminated, and whole bodies of them, rather than be crushed into submission and ground down by hard rents, left Ireland, some as mercenaries, others, perhaps, to fall on the coasts of Wales, Devon, and Brittany, and effect settlements there.

When brought into complete subjugation in Ireland, the Gadhelic chiefs planted their duns throughout the country in such a manner as to form chains, by which they could communicate with one another at the least token of a revival of discontent; and they distributed the subject tribes throughout the island in such a manner as to keep them under supervision, and to break up their clans. As Professor Sullivan very truly says, "The Irish tenants of to-day are composed of the descendants of Firbolgs and other British and Belgic races; Milesians, ... Gauls, Norwegians, Anglo-Saxons, Anglo-Normans, and English, each successive dominant race having driven part at least of its predecessors in power into the rent-paying and labouring ranks beneath them, or gradually falling into them themselves, to be there absorbed. This is a fact which should be remembered by those who theorise over the qualities of the 'pure Celts,' whoever they may be."[1]

The Dumnonii, whose city or fortress was at Exeter, were an important people. They occupied[6] the whole of the peninsula from the river Parret to Land's End. East of the Tamar was Dyfnaint, the Deep Vales; west of it Corneu, the horn of Britain.

The Dumnonii are thought to have invaded and occupied this territory about four centuries before the Christian era. The language of the previous dusky race was agglutinative, like that of the Tartars and Basques, that is to say, they did not inflect their substantives. Although there has been a vast influx of other blood, with fair hair and white complexions, the earlier type may still be found in both Devon and Cornwall.

Then came the Roman invasion; this affected our Dumnonian peninsula very slightly; Cornwall hardly at all. When that came to an end, a large portion of Britain had fallen under the sway of the Picts, Saxons, and Scots. By Scots are meant the Irish, who after their invasion of Alba gave the present name to Scotland. But it must be distinctly understood that the only Scots known in the first ten or eleven centuries, to writers on British affairs, were Irish.

In alliance with the Picts and Saxons, Niall of the Nine Hostages poured down on Britain and exacted tribute from the conquered people. In 388 he carried his arms further and plundered Brittany. In 396 the Irish supremacy was resisted by Stilicho, and for a while shaken; it was reimposed in 400. In 405, Niall invaded Gaul, and was assassinated there on the shores of the English Channel.

In 406 Stilicho a second time endeavoured to repel the Hiberno-Pictic allies, but, unable to do much by[7] force of arms, entered into terms with them, for Gildas speaks of the Romans as making confederates of Irish. Doubtless Stilicho surrendered to them their hold over and the tribute from the western part of Britain. And now I must tell a funny story connected with the introduction of lap-dogs into Ireland. It comes to us on the authority of Cormac, king-bishop of Cashel, who died in 903, and who wrote a glossary of old Irish words becoming obsolete even in his day.

"The slave of the Haft," says he, "was the name of the first lap-dog that was known in Erin. Cairbre Musc was the man who first brought it there out of Britain. At that time the power of the Gadhaels (Scots or Irish) was great over the Britons; they had divided Albion among them into farms, and each of them had a neighbour and friend among the people." Then he goes on to say how that they established fortresses through the land, and founded one at Glastonbury. "One of those divisions of land is Dun Map Lethan, in the country of the Britons of Cornwall." This lasted to A.D. 380.

Now Cairbre was wont to pass to and fro between Britain and Ireland.

At this time lap-dogs were great rarities, and were highly prized. None had hitherto reached Ireland. And Cairbre was desirous of introducing one there when he went to visit his friends. But the possessors of lap-dogs would on no account part with their treasures.

Now it happened that Cairbre had a valuable knife, with the handle gold-inlaid. One night he[8] rubbed the haft over with bacon fat, and placed it before the kennel of the lap-dog belonging to a friend. The dog gnawed at the handle and sadly disfigured it.

Next morning Cairbre made a great outcry over his precious knife, and showed his British host how that the dog had disfigured it. The Briton apologised, but Cairbre promptly replied, "My good friend, are you aware of the law that 'the transgressor is forfeit for his transgression?' Accordingly I put in a legal claim to the dog." Thus he became its owner, and gave it the name of Mogh-Eimh, or the Slave of the Haft.

The dog was a bitch, and was with young when Cairbre carried her over to Ireland. The news that the wonderful little beast had arrived spread far and wide, and the king of Munster and the chief king, Cormac Mac Airt (227-266) both laid claim to it; the only way in which Cairbre could satisfy them was to give each a pup when his lap-dog had littered. So general was the amazement over the smallness and the beauty of the original dog, that some verses were made on it, which have been preserved to this day.

It was probably during the Irish domination that a large portion of North Devon and East Cornwall was colonised from the Emerald Isle.

But to return to the Saxon conquest. When[9] Athelstan drove the Britons out of Exeter and made the Tamar their limit, it is not to be supposed that he devastated and depopulated Devon; what he did was to destroy the tribal organisation throughout Devon, banish the princes and subjugate the people to Saxon rule.

The Saxon colonists planted themselves in "Stokes" mostly in the valleys. The Celts had never been anything of a town-building people; they had lived scattered over the land in their treffs and boths, and only the retainers of a chieftain had dwelt around his dun.

But with the Saxons, the fact that they lived as a few surrounded by an alien population that in no way loved them, obliged them to huddle together in their "Stokes." Thus towns sprang into existence, and bear Saxon names.

It is probable that the yeomen of the land at the present day represent the Saxon; and most assuredly in the great body of the agricultural labourers, the miners, and artisans, we have mainly a mixture of British and Ivernian blood.

Throughout the Middle Ages, and indeed till this present century, there can have been no easy, if possible, passage out of the labouring community into that of the yeoman class—hardly into that of tenant farmer; whereas the yeomen and the tradesmen, wool merchants and the like, were incessantly feeding the class of armigeres, squires; and their descendants supplied the nobility with accretions.

There is, perhaps, in the east of Devon a preponderating element of Saxon, but I have observed[10] in the Seaton and Axminster district so much of the dark hair and eye, that I believe there is less than is supposed, and that there is a very large understratum of the earlier Silurian. Perhaps in North Devon there may be more of the Saxon. West of Okehampton there is really not much difference between the Devonian and the Cornishman, but of this more presently.

It is remarkable that the Devonshire dialect prevails in Cornwall above a diagonal line drawn from Padstow to Saltash, on the Tamar; west of this and below it the dialect is different. This is probably due to the Cornish tongue having been abandoned in the west and south long subsequent to its disappearance in the north-east. But this line also marks the limits of an Irish-Gwentian occupation.

The dialect is fast dying out, but the intonation of the voice will remain long after peculiar words have ceased to be employed.

The "z" has a sound found nowhere else, due to the manner in which the tongue is turned up to the palate for the production of the sound; "ou" and "oo" in such words as "you" and "moon" is precisely that of the French u in "lune."

Gender is entirely disregarded; a cow is a "he," who runs dry, and of a cock it is said "her crows in the morn." But then the male rooster is never a cock, but a stag.

The late Mr. Arnold, inspector of schools, was much troubled about the dialect when he came into the county. One day, when examining the school[11] at Kelly, he found the children whom he was questioning very inattentive.

"What is the matter with you?" he asked testily.

"Plaaze, zur, us be a veared of the apple-drayne."

In fact, a wasp was playing in and out among their heavily oiled locks.

"Apple-drayne!" exclaimed Mr. Arnold. "Good gracious! You children do not seem to know the names of common objects. What is that bird yonder seated on the wall?" And he pointed out of the window at a cock.

"Plaaze, zur, her's a stag."

"I thought as much. You do not know the difference between a biped and a quadruped."

I was present one day at the examination of a National School by H.M. Inspector.

"Children," said he, "what form is that?"

"A dodecahedron."

"And that?"

"An isosceles triangle."

"And what is the highest peak in Africa?"

"Kilima Ndjaro."

"Its height?"

"Twenty thousand feet."

"And what are the rivers that drain Siberia?"

"The Obi, the Yenesei, and the Lena."

Now in going to the school I had plucked a little bunch of speedwell, and I said to the inspector, "Would you mind inquiring of the children the name of this plant?"

"What is this plant?" he demanded.

Not a child knew.

"What is the river that flows through your valley?"

Not a child knew.

"What is the name of the highest peak of Dartmoor you see yonder?"

Not a child knew.

And this is the rubbish in place of education that at great cost is given to our children.

Education they do not get; stuffing they do.

They acquire a number of new words, which they do not understand and which they persistently mispronounce.

"Aw my! isn't it hot? The prepositions be runin' all hover me."

"Ay! yü'm no schollard! I be breakin' out wi' presbeterians."

The "oo" when followed by an "r" has the sound "o" converted into "oa"; thus "door" becomes "doar."

"Eau" takes the sound of the modified German "ü"; thus "beauty" is pronounced "büty."

"Fe" and "g" take "y" to prolong and emphasise them; thus "fever" becomes "feyver," and "meat" is pronounced "mayte."

"F" is frequently converted into "v"; "old father" is "ole vayther." But on the other hand "v" is often changed to "f," as "view" into "fü."

The vowel "a" is always pronounced long; "landed" is "lānded," "plant" is "plānt." "H" is frequently changed into "y"; "heat" is spoken of as "yett," "Heathfield" becomes "Yaffel," and "hall" is "yall."

"I" is interjected to give greater force, and "e" is sounded as "a"; "flesh" is pronounced "flaish."[13] "S" is pronounced "z," as in examples already given. "O" has an "ou" sound in certain positions, as "going," which is rendered "gou-en." "S" in the third person singular of a verb is "th," as "he grows," "a grawth," "she does" is "her düth."

Here is a form of the future perfect: "I shall 'ave a-bin an' gone vur tü dü it."

There is a decided tendency to soften harsh syllabic conjunctions. Thus Blackbrook is Blackabrook, and Matford is Mattaford; this is the Celtic interjected y and ty.

This is hardly a place for giving a list of peculiar words; they may be found in Mrs. Hewett's book, referred to at the end of this chapter, and collected by the committee on Devonshire provincialisms in the Transactions of the Devonshire Association.

As a specimen of the dialect I will give a couple of verses of a popular folk song.

The Devonian and Cornishman will be found by the visitor to be courteous and hospitable. There is no roughness of manner where unspoiled by periodic influx of strangers; he is kindly, tender-hearted, and somewhat suspicious. There is a lack of firmness of purpose such as characterises the Scotchman; and a lively imagination may explain a slackness in adhesion to the truth. He is prone to see things as he would like them to be rather than as they are. On the road passers-by always salute and have a bit of a yarn, even though personally unacquainted; and to go by in the dark without a greeting is a serious default in good manners. A very marked trait especially noticeable in the Cornish is their independence. Far more intimately than the inhabitants of any other part of England, they are democrats. This they share with the Welsh; and, like the Welsh, though politically they are Radicals, are inherently the most conservative of people.

It is a peculiarity among them to address one another by the Christian name, or to speak of a man by the Christian name along with the surname, should there be need to distinguish him from another. The term "Mr." is rarely employed. A gentleman is "Squire So-and-so," but not a mister; and the trade is often prefixed to the name, as Millard Horn, or Pass'n John, or Cap'n Zackie.

There is no form of enjoyment more relished by a West Country man or woman than a "buryin'." Business occupations are cast aside when there is to be a funeral. The pomp and circumstance of woe[15] exercise an extraordinary fascination on the Western mind, and that which concerns the moribund person at the last is not how to prepare the soul for the great change, but how to contrive to have a "proper grand buryin'." "Get away, you rascal!" was the address of an irate urchin to another, "if you gie' me more o' your saāce you shan't come to my buryin'." "Us 'as enjoyed ourselves bravely," says a mourner, wiping the crumbs from his beard and the whiskey-drops from his lips; and no greater satisfaction could be given to the mourners than this announcement.

On the other hand a wedding wakes comparatively little interest; the parents rarely attend.

The looks of Devonshire and Cornish lasses are proverbial. This is not due to complexion alone, which is cream and roses, but to the well-proportioned limbs, the litheness of form, uprightness of carriage, and to the good moulding of the features. The mouth and chin are always well shaped, and the nose is straight; in shape the faces are a long oval.

I am not sure that West Country women ever forget that they were once comely. An old woman of seventy-five was brought forward to be photographed by an amateur: no words of address could induce her to speak till the operation was completed; then she put her finger into her mouth: "You wouldn't ha' me took wi' my cheeks falled in? I just stuffed the Western Marnin' News into my mouth to fill'n out."

Although both in Devon and Cornwall there is great independence and a total absence of that[16] servility of manner which one meets with in other parts of England, it would be a vast mistake to suppose that a West Country man is disrespectful to those who are his superiors—if he has reason to recognise their superiority; but he does not like a "foreigner," especially one from the North Country. He does not relish his manner, and this causes misunderstanding and mutual dislike. He is pleased to have as his pass'n, as his squire, as a resident in his neighbourhood, a man whom he knows all about, as to who were his father and his grandfather, as also whence he hails. A clergyman who comes from a town, or from any other part of England, has to learn to understand the people before they will at all take to him. "I have been here five years," said a rector one day to me, a man transferred from far, "and I don't understand the people yet, and until I understand them I am quite certain to be miscomprehended by them."

The West Country man must be met and addressed as an equal. He resents the slightest token of approach de haut en bas, but he never presumes; he is always respectful and knows his place; he values himself, and demands, and quite rightly, that you shall show that you value him.

The other day a bicyclist was spinning down the road to Moreton Hampstead. Not knowing quite where he was, and night approaching, he drew up where he saw an old farmer leaning on a gate.

"I say, you Johnnie, where am I? I want a bed."

"You'm fourteen miles from Wonford Asylum," was the quiet response, "and fourteen from Newton[17] Work'us, and fourteen from Princetown Prison, and I reckon you could find quarters in any o' they—and suitable."

With regard to the Cornish people, I can but reiterate what has already been said relative to the Western folk generally. What differences exist in character are not due to difference of race, but to that of occupation. The bulk of Cornishmen in the middle and west have been associated with mines and with the sea, and this is calculated to give to the character a greater independence, and also to confer a subtle colour, different in kind to that which is produced by agricultural labour. If you take a Yorkshireman from one side of the Calder or Aire, where factory life is prevalent, and one from the other side, where he works in the fields, you will find as great, if not a greater, difference than you will between a Devonshire and a Cornish man. Compare the sailors and miners on one side of the Tamar with those on the other, and you will find no difference at all.

There will always be more independence in miners who travel about the world, who are now in Brazil, then in the African diamond-fields, next at home, than in the agricultural labourer, who never goes further than the nearest market town. The mind is more expanded in the one than in the other; but in race all may be one, though differing in ideas, manners, views, speech.

I venture now to quote freely from an article on Cornishmen that is written by an outsider, and which appeared in a review.

"The dweller in Cornwall comes in time to perceive the constant recurrence of various types of man. Of these, two at least are well marked, very common, and probably of great antiquity and significance. The man of the first type is slender, lithe, graceful, usually rather short; the face is smooth and delicately outlined, without bony prominences, the eyebrows finely pencilled. The character is, on the whole, charming, volatile, vivacious, but not always reliable, and while quick-witted, rarely capable of notable achievement or strenuous endeavour. It is distinctly a feminine type. The other type is large and solid, often with much crispy hair on the face and shaggy eyebrows. The arches over the eyes are well marked and the jaws massive; the bones generally are developed in these persons, though they would scarcely be described as raw-boned; in its extreme form a face of this type has a rugged prognathous character which seems to belong to a lower race."

Usually the profile is fine, with straight noses; and a well-formed mouth, with oval, rather long face is general, the chin and mouth being small. I do not recall at any time meeting with the "rummagy" faces, with no defined shape, and ill-formed noses that one encounters in Scotland.

There is a want of the strength and force such as is encountered in the North; but on the other hand there is remarkable refinement of feature.

I had at one time some masons and workmen engaged upon a structure just in front of my dining-room windows, and a friend from Yorkshire was visiting me. The men working for me were perhaps fine specimens, but nothing really extraordinary for the country. One, a tall, fair-haired, blue-eyed mason, my friend at once designated Lohengrin; and he was[19] the typical knight of the swan—I suspect a pure Celt. Another was not so tall, lithe, dark, and handsome. "King Arthur" was what my friend called him.

The writer, Mr. Havelock Ellis, whom I have already quoted, continues:—

"The women are solid and vigorous in appearance, with fully-developed breasts and hips, in marked contrast with the first type, but resembling women in Central and Western France. Indeed, the people of this type generally recall a certain French type, grave, self-possessed, deliberate in movement, capable and reliable in character. I mention these two types because they seem to me to represent the two oldest races of Cornwall, or, indeed, of England. The first corresponds to the British neolithic man, who held sway in England before the so-called Celts arrived, and who probably belonged to the so-called Iberian race; in pictures of Spanish women of the best period, indeed, and in some parts of modern Spain, we may still see the same type. The second corresponds to the more powerful, and as his remains show, the more cultured and æsthetic Celt, who came from France and Belgium.... When these types of individual are combined, the results are often very attractive. We then meet with what is practically a third type: large, dignified, handsome people, distinguished from the Anglo-Saxon not only by their prominent noses and well-formed chins, but also by their unaffected grace and refinement of manner. In many a little out-of-the-world Cornish farm I have met with the men of this type, and admired the distinction of their appearance and bearing, their natural instinctive courtesy, their kindly hospitality. It was surely of such men that Queen Elizabeth thought when she asserted that all Cornishmen are courtiers.

"I do not wish to insist too strongly on these types which[20] blend into one another, and may even be found in the same family. The Anglo-Saxon stranger, who has yet had no time to distinguish them, and who comes, let us say, from a typically English county like Lancashire, still finds much that is unfamiliar in the people he meets. They strike him as rather a dark race, lithe in movement, and their hands and feet are small. Their hair has a tendency to curl, and their complexions, even those of the men, are often incomparable. The last character is due to the extremely moist climate of Cornwall, swept on both sides by the sea-laden Atlantic. More than by this, however, the stranger accustomed to the heavy, awkward ways of the Anglo-Saxon clodhopper will be struck by the bright, independent intelligence and faculty of speech which he finds here. No disguise can cover the rusticity of the English rustic; on Cornish roads one may often meet a carman whose clear-cut face, bushy moustache, and general bearing might easily add distinction to Pall Mall."

There are parts of Devon and of Cornwall where the dark type prevails. "A black grained man" is descriptive of one belonging to the Veryan district, and dark hair and eyes, and singular beauty are found about the Newlyn and St. Ives districts. The darkest type has been thrust into corners. In a fold of Broadbury Down in Devon, in the village of Germansweek, the type is mainly dark; in that of North Lew, in another lap of the same down, it is light. It has been noticed that a large patch of the dusky race has remained in Bedfordshire.

The existence of the dark eyes and hair and fine profiles has been attempted to be explained by the fable that a Spanish vessel was wrecked now here, now there, from the Armada, and that the sailors[21] remained and married the Cornish women. I believe that this is purely a fable. The same attempt at solution of the existence of the same type in Ireland and in Scotland has been made, because people would not understand that there could be any other explanation of the phenomenon.

I have been much struck in South Wales, on a market day, when observing the people, to see how like they were in build, and colour, and manner, and features to those one might encounter at a fair in Tavistock, Launceston, or Bodmin.

I positively must again quote Mr. Havelock Ellis on the Cornish woman, partly because his description is so charmingly put, but also because it is so incontestably true.

"The special characters of the race are often vividly shown in its women. I am not aware that they have ever played a large part in the world, whether in life or art. But they are memorable enough for their own qualities. Many years ago, as a student in a large London hospital, I had under my care a young girl who came from labour of the lowest and least skilled order. Yet there was an instinctive grace and charm in all her ways and speech which distinguished her utterly from the rough women of her class. I was puzzled then over that delightful anomaly. In after years, recalling her name and her appearance, I knew that she was Cornish, and I am puzzled no longer. I have since seen the same ways, the same soft, winning speech equally unimpaired by hard work and rude living. The Cornish woman possesses an adroitness and self-possession, a modulated readiness of speech, far removed from the awkward heartiness of the Anglo-Saxon woman, the emotional inexpressiveness of the Lancashire lass whose eyes wander[22] around as she seeks for words, perhaps completing her unfinished sentence by a snap of the fingers. The Cornish woman—at all events while she is young and not submerged by the drudgery of life—exhibits a certain delightful volubility and effervescence. In this respect she has some affinity with the bewitching and distracting heroines of Thomas Hardy's novels, doubtless because the Wessex folk of the South Coast are akin to the Cornish. The Cornish girl is inconsistent without hypocrisy; she is not ashamed of work, but she is very fond of jaunts, and on such occasions she dresses herself, it would be rash to say with more zeal than the Anglo-Saxon maiden, but usually with more success. She is an assiduous chapel-goer, equally assiduous in flirtations when chapel is over. The pretty Sunday-school teacher and leader of the local Band of Hope cheerfully confesses as she drinks off the glass of claret you offer her that she is but a poor teetotaller. The Cornish woman will sometimes have a baby before she is legally married; it is only an old custom of the county, though less deeply rooted than the corresponding custom in Wales."[2]

The Cornish are, like the Welsh, intensely religious, but according to their idea religion is emotionalism and has hardly enough to do with morality.

"So Mr. So-and-So is dead," in reference to a local preacher. "I fear he led a very loose life."

"Ah! perhaps so, but he was a sweet Christian."

Here is something illustrative at once of West Country religion and dialect. I quote from an amusing paper on the "Recollections of a Parish Worker" in the Cornish Magazine (1898):—

"'How do you like the vicar?' I asked. 'Oh, he's a lovely man,' she answered, 'and a 'ansome praicher—and[23] such a voice! But did 'ee hear how he lost un to-day? Iss, I thought he would have failed all to-wance, an' that wad have bin a gashly job. But I prayed for un an' the Lord guv it back to un again, twice as loud, an' dedn't 'ee holler! But 'ee dedn't convart me. I convarted meself. Iss a ded. I was a poor wisht bad woman. Never went to a place of worship. Not for thirty years a hadn't a bin. One day theer came word that my brother Willum was hurted to the mine. So I up an' went to un an' theer he was, all scat abroad an' laid out in scritches. He was in a purty stank, sure 'nuff. But all my trouble was his poor sowl. I felt I must get he convarted before he passed. I went where he was to, an' I shut home the door, an' I hollered an' I rassled an' I prayed to him, an' he nivver spoke. I got no mouth spaich out of him at awl, but I screeched and screeched an' prayed until I convarted myself! An' then I be to go to church. Iss, we awl have to come to it, first an' last, though I used to say for christenings an' marryin's an' berrin's we must go to church, but for praichin' an' ennytheng for tha nex' wurld give me the chapel; still, I waanted to go to church an' laive everybody knaw I wur proper chaanged. So I pitched to put up my Senday go-to-mittun bonnet, an' I went. An' when I got theer aw! my blessed life 'twas Harvest Thanksgivin', an' when I saw the flowers an' the fruit an' the vegetables an' the cotton wool I was haived up on end!' And heaved up on the right end she was."

The table of Commandments is with the Cornish not precisely that of Moses. It skips, or treats very lightly, the seventh, but it comprises others not found in Scripture: "Thou shalt not drink any alcohol," and "Thou shalt not dance."

On Old Christmas Day, in my neighbourhood, a great temperance meeting was held. A noted[24] speaker on teetotalism was present and harangued. A temperance address is never relished without some horrible example held up to scorn. Well, here it was. "At a certain place called ——, last year, as Christmas drew on, the Guardians met to decide what fare should be afforded to the paupers for Christmas Day. Hitherto it had been customary for them to be given for their dinner a glass of ale—a glass of ale. I repeat it—at public cost—a glass of ale apiece. On that occasion the Guardians unanimously agreed that the paupers should have cocoa, and not ale. Then up stood the Rector—the Rector, I repeat—and in a loud and angry voice declared: 'Gentlemen, if you will not give them their drop of ale, I will.' And he—he, a minister of the gospel or considering himself as such."—(A shudder and a groan.) "I tell you more—I tell you something infinitely worse—he sent up to the work-house a dozen of his old crusted port." (Cries of "Shame! shame!" and hisses.)

That, if you please, was the unpardonable sin.

If we are to look anywhere for local characteristics in the music of the people in any particular part of England, we may surely expect to find them in the western counties of Somerset, Devon, and Cornwall. These three counties have hitherto been out of the beaten track; they are more encompassed by the sea than others, and lead only to the Land's End.

And as a matter of fact, a large proportion of the melodies that have been collected from the peasantry in this region seem to have kept their habitation, and so to be unknown elsewhere.

I take it for granted that they are, as a rule, home productions. The origin of folk-song has been much debated, and it need not be gone into now. But it would be vain to search for local characteristics in anything that has not a local origin.

In folk-song, then, we may expect to see reflected the characteristics of the race from which it has sprung, and, as in the counties of Devon and Cornwall on one side and Somersetshire on the other, we are brought into contact with two, at least, races—the British and the Saxon—we do find two types of melody very distinct. Of course, as with their dialects, so with their melodies, the distinctions are sometimes marked, and sometimes merged in each other. The Devonshire melodies have some affinity with those of Ireland, whilst the Somersetshire tunes exhibit a stubborn individuality—a roughness, indeed, which is all their own.

Taking first the Devonshire songs, I think one cannot fail to be struck with the exceeding grace and innate refinement which distinguish them. These qualities are not always perceptible in the performance of the songs by the untutored singers; nor do the words convey, as a rule, any such impressions, but evident enough when you come to adjust to their proper form the music which you have succeeded in jotting down. It surprises you. You are not prepared for anything like original melody, or for anything gentle or tender. But the Devonshire songs are so. Their thought is idyllic. Through shady groves melodious with song, the somewhat indolent lover of Nature wanders forth[26] without any apparent object save that of "breathing the air," and (it must be added) of keeping an open eye for nymphs, one of whom seldom fails to be seeking the same seclusion. Mutual advances ensue; no explanations are needed; constancy is neither vowed nor required. The casual lovers meet and part, and no sequel is appended to the artless tale.

Sentiment is the staple of Devonshire folk-song; it is a trifle unwholesome, but it is unmistakably graceful and charming. Take such songs as "By chance it was," "The Forsaken Maiden," "The Gosshawk," "Golden Furze;" surely there is a gush of genuine melody and the spirit of poetry in such tunes.

In some respects the folk-song of Devonshire is rather disappointing. There is no commemoration, no appreciation, of her heroes. The salt sea-breeze does not seem to reach inland, save to whisper in a wailing tone of "The Drowned Lover," or the hapless "Cabin Boy." Sea-songs may be in her ports, but they were not born there.

Nor are the joys of the chase proclaimed with such robustness as elsewhere, any more than are the pleasures and excitements of the flowing bowl. This may be attributed to the same refinement of character of which I have spoken.

A pastoral and peace-loving community will not be expected to develop any special sense of humour. Devonshire is by no means deficient in it, but it is of a quiet sort, a sly humour something allied to what the Scotch call "pawky," of which "Widicombe[27] Fair" is as good an example as can be had. Of what may be called the religious element, save in Christmas and Easter carols, I have never discovered any trace.

The Rev. H. Fleetwood Sheppard, who has spent ten years in collecting the melodies of Devon and Cornwall, says of them, "I have found them delightful, full of charm and melody. I never weary of them. They are essentially poetical, but they are also essentially the songs of sentiment, and their one pervading, almost unvarying theme is—The Eternal Feminine."

When we pass into Somersetshire the folk-music assumes quite a different character. The tenderness, the refinement have vanished. Judging from their songs, we might expect to find the Somersetshire folk bold, frank, noisy, independent, self-assertive; and this view would be quite in keeping with their traditional character. In Shakespeare's time bandogs and bull baiting were the special delight of the country gentry,[3] and Fuller describes the natives of Taunton Dean as "rude, rich, and conceited." If one turn to the music, "Richard of Taunton Dean," or "Jan's Courtship," "George Riddler's Oven," and the like, are in entire keeping with the character of the people as thus depicted. There is vigour and go in their songs, but no sweetness; ruggedness, no smoothness at all; and it is precisely this latter quality that marks the Cornish and Devonshire airs.

Take such a tune as that to which the well-known hunting song of Devon, "Arscott of Tetcott," is[28] wedded. The air is a couple of centuries older than the words, for the Arscott whom the song records died in 1788, though we can only trace the tune back to D'Urfey at the end of the seventeenth century. The music is impetuous, turbulent, excited, it might be the chasing the red deer on Exmoor; the hunt goes by with a rush like a whirlwind to a semi-barbarous melody, which resembles nothing so much as that of the spectral chase in Der Freischütz.

But Somersetshire song can be tender at times, though not quite with the bewitching grace of Devonia. There is a charming air which found its way from the West up to London some sixty years ago, the original words of which are lost, but the tune became immensely popular under the title of "All round my hat," a vulgar ditty sung by all little vulgar boys in the streets. The tune is well worth preserving. It is old, and there is a kind of wail about it which is touching.

But who were the composers of these folk-airs? In the old desks in west galleries of churches remain here and there piles of MS. music: anthems, and, above all, carols, the composition of local musicians unknown beyond their immediate neighbourhood, and now unknown even by name.

A few years ago I was shown such a pile from Lifton Church. I saw another great library, as I may call it, that was preserved in the rack in the ceiling of a cottage at Sheepstor, the property of an old fiddler, now dead. I saw a third in Holne parish. I have seen stray heaps elsewhere.[29] Mr. Heath, of Redruth, published two collections from Cornwall and one from Devon, the latter from the Lifton store in part, to which I had directed his attention. I cannot doubt that some of the popular tunes that are found circulating among our old singers—or to be more exact, were found—were the composition of these ancient village musicians. Alas! the American organ and the strident harmonium came in and routed out the venerable representatives of a musical past; and the music-hall piece is now driving away all the sound old traditional melody, and the last of the ancient conservators of folk-song makes his bow, and says:—

Note.—For the history of Devon: Worth (R. N.), History of Devonshire. London, 1886. For Devonshire dialect: Hewett(S.), The Peasant Speech of Devon. E. Stock. London, 1892. For Devonshire folk-music: Songs of the West. Methuen. London, 1895. (3rd ed.) A Garland of Country Song. Methuen. London, 1895.

For most of what has been said above on the folk-songs of Devon I am indebted to the Rev. H. Fleetwood Sheppard, who has made it his special study.

Devonshire villages not so picturesque as those of Sussex and Kent—Cob and stone—Slate—Thatch and whitewash—Churches mostly in the Perpendicular style—Characteristics of that style—Foliage in stone—Somerset towers—Cornish peculiarities of pinnacles—Waggon-headed roofs—Beer and Hatherleigh stone—Polyphant—Treatment of granite—Wood-work in Devon churches—Screens—How they have been treated by incumbents—Pulpits—Bench-ends—Norman fonts—Village crosses—How the Perpendicular style maintained itself in the West—Old mansions—Trees in Devon—Flora—The village revel.

A Devonshire village does not contrast favourably with those in Essex, Kent, Sussex, and other parts of England, where brick or timber and plaster are the materials used, and where the roofs are tiled.

But of cottages in the county there are two kinds. The first, always charming, is of cob, clay, thatched. Such cottages are found throughout North Devon, and wherever the red sandstone prevails. They are low, with an upper storey, the windows to which are small, and the brown thatch is lifted above these peepers like a heavy, sleepy brow in a very picturesque manner. But near Dartmoor stone is employed, and an old, imperishable granite house is delightful when thatched. But thatch has given way[31] everywhere to slate, and when the roof is slated a great charm is gone. There is slate and slate. The soft, silvery grey slate that is used in South Devon is pleasing, and when a house is slated down its face against the driving rains, and the slates are worked into patterns and are small, they are vastly pretty. But architects are paid a percentage on the outlay, and it is to their profit to use material from a distance; they insist on Welsh or Delabole slate, and nothing can be uglier than the pink of the former and the chill grey of the other—like the tint of an overcast sky in a March wind.

I once invited an architect to design a residence on a somewhat large scale. He did so, and laid down that Delabole slate should be employed with bands of Welsh slate of the colour of beetroot. "But," said I, "we have slate on the estate. It costs me nothing but the raising and carting."

"I dislike the colour," said he. "If you employ an architect, you must take the architect's opinion."

I was silenced. The same day, in the afternoon, this architect and I were walking in a lane. I exclaimed suddenly, "Oh, what an effect of colour! Do look at those crimson dock-leaves!"

"Let me see if I can find them," said the architect. "I am colour-blind, and do not know red from green."

It was an incautious admission. He had forgotten about the slates, and so gave himself away.

The real objection, of course, was that my own slates would cost me nothing. But also of course he did not give me that reason.

Where the slate rocks are found, grauwacke and schist, there the cottages are very ugly—could not well be uglier—and new cottages and houses that are erected are, as a rule, eyesores.

However, we have in Devon some very pretty villages and clusters of cottages, and the little group of roofs of thatch and glistening whitewashed walls about the old church, the whole backed by limes and beech and elm, and set in a green combe, is all that can be desired for quiet beauty; although, individually, each cottage may not be a subject for the pencil, nor the church itself pre-eminently picturesque.

The churches of Devonshire belong mainly to the Perpendicular style; that is to say, they were nearly all rebuilt between the end of the fourteenth and the sixteenth centuries.

Of this style, this is what Mr. Parker says: "The name is derived from the arrangement of the tracery, which consists of perpendicular lines, and forms one of its most striking features. At its first appearance the general effect was usually bold and good; the mouldings, though not equal to the best of the Decorated style, were well defined; the enrichments effective and ample without exuberance, and the details delicate without extravagant minuteness. Subsequently it underwent a gradual debasement: the arches became depressed; the mouldings impoverished; the ornaments crowded, and often coarsely executed; and the subordinate features confused from the smallness and complexity of their parts. A leading characteristic of the style, and one which prevails throughout its continuance, is the square[33] arrangement of the mouldings over the heads of doorways, creating a spandrel on each side above the arch, which is usually ornamented with tracery, foliage, or a shield. The jambs of doorways are generally moulded, frequently with one or more small shafts."

The style is one that did not allow of much variety in window tracery. The object of the adoption of upright panels of glass was to allow of stained figures in glass of angels filling the lights, as there had been a difficulty found in suitably filling the tracery of the heads of the windows with subjects when these heads were occupied by geometrical figures composed of circles and arcs intersecting.

In the west window of Exeter Cathedral may be seen a capital example of "Decorated" tracery, and in the east window one in the "Perpendicular" style.

Skill in glass staining and painting had become advanced, and the windows were made much larger than before, so as to admit of the introduction of more stained glass.

Pointed arches struck from two centres had succeeded round arches struck from a single centre, and now the arches were made four-centred.

Foliage in carving had, under Early English treatment, been represented as just bursting, the leaves uncurling with the breath of spring. In the Decorated style the foliage is in full summer expansion, generally wreathed round a capital. Superb examples of Decorated foliage may be seen in the corbels in the choir at Exeter. In Perpendicular architecture the leaves are crisped and wrinkled with frost.

In Devonshire the earlier towers had spires. When the great wave of church building came over the land, after the conclusion of the Wars of the Roses, then no more spires were erected, but towers with buttresses, and battlemented and pinnacled square heads. In the country there are no towers that come up to the splendid examples in Somersetshire; but that of Chittlehampton is the nearest approach to one of these.

In the Somerset towers the buttresses are frequently surmounted by open-work pinnacles or small lanterns of elaborate tabernacle work, and the parapets or battlements are of open tracery; but in Devon these latter are plain with bold coping, and the pinnacles are well developed and solid, and not overloaded with ornament. Bishop's Nympton, South Molton, and Chittlehampton towers are locally described as "Length," "Strength," and "Beauty."

A fine effect is produced when the turret by which the top of the tower is reached is planted in the midst of one side, usually the north; and it is carried up above the tower roof. There are many examples. I need name but Totnes and Ashburton.

A curious effect is produced among the Cornish towers, and those near the Tamar on the Devon side, of the pinnacles being cut so as to curve outwards and not to be upright. The effect is not pleasant, and the purpose is not easily discoverable; but it was possibly done as being thought by this means to offer less resistance to the wind.

The roofs are usually "waggon-headed." The open timber roof, so elaborated in Norfolk, is not common. A magnificent example is, however, to be seen in Wear Gifford Hall. But cradle roofs do exist, and in a good many cases the waggon roofs are but ceiled cradle roofs. A good plain example of a cradle roof is in the chancel of Ipplepen, and a very rich one at Beaford.

The mouldings of the timbers are often much enriched. A fine example is Pancras Week. The portion of the roof over the rood-screen is frequently very much more elaborately ornamented than the rest. An example is King's Nympton, where, however, before the restoration, it was even more gorgeous than at present. The waggon roof presents immense advantages over the open timber roof; it is warmer; it is better for sound; it is not, like the other, a makeshift. It carries the eye up without the harsh and unpleasant break from the walling to the barn-like timber structure overhead.

Wherever white Beer stone or rosy Hatherleigh stone could be had, that was easily cut, there delicate moulding and tracery work was possible; but in some parts of the county a suitable stone was lacking. In the neighbourhood of Tavistock the doorways and windows were cut out of Roborough stone, a volcanic tufa, full of pores, and so coarse that nothing refined could be attempted with it. Near Launceston, however, were the Polyphant quarries, the stone also volcanic, but close-grained and of a delicate, beautiful grey tone. This was employed for pillars and window tracery. The fine Decorated[36] columns of Bratton Clovelly Church, of a soft grey colour, are of this stone. The run of the stone was, however, limited, and was thought to be exhausted. It was not till the Perpendicular style came in that an attempt was made to employ granite. The experiment led to curious results. The tendency of the style is to flimsiness, especially in the mouldings; but the obduracy of the material would not allow of delicate treatment, and the Perpendicular mouldings, especially noticeable in doorways, are often singularly bold and effective. A tour de force was effected at Launceston Church, which is elaborately carved throughout in granite, and in Probus tower, in Cornwall. For beauty in granite work Widecombe-in-the-Moor tower cannot be surpassed; there the tower is noble and the church to which it belongs is mean. In using Ham Hill stone or Beer stone, that was extracted in blocks, the pillars, the jambs of doors and windows were made of several pieces laid in courses and cut to fit one another. But when the architects of Perpendicular times had to deal with granite there was no need for this; they made their pillars and jambs in single solid blocks. A modern architect, bred to Caen stone or Bath oolite, sends down a design for a church or house to be erected near Dartmoor, or in Cornwall, and treats the granite as though it came out of the quarry in small blocks; and the result is absurd. An instance of this blundering in treatment is the new east window of Lanreath Church, Cornwall, designed by such a "master in Israel" as Mr. Bodley. The porch doorway is in six stones, one for each base, one for each[37] jamb, and two form the arch. The old windows are treated in a similar fashion—each jamb is a single stone. But Mr. Bodley has built up his new window of little pieces of granite one foot deep. The effect is bad. Unhappily, local architects are as blind to local characteristics as London architects are ignorant of them. So also, when these gentry attempt to design hood mouldings, or indeed any mouldings, for execution in granite, they cannot do it—the result is grotesque, mean, and paltry: they think in Caen stone and Bath, and to design in granite a man's mind must be made up in granite.

In Cornwall there are some good building materials capable of ornamental treatment, more delicate than can be employed in granite. Such are the Pentewan and Catacleuse stones. The latter is gloomy in colour, but was used for the finest work, as the noble tomb of Prior Vivian, in Bodmin Church.

As stone was an intractable material, the Devonshire men who desired to decorate their churches directed their energies to oak carving, and filled them with very finely sculptured bench-ends and screens of the most elaborate and gorgeous description.

So rich and elaborate are these latter, that when a church has to be restored the incumbent trembles at the prospect of the renovation of his screen, and this has led to many of them being turned out and destroyed. South Brent screen was thus wantonly ejected and allowed to rot. Bridestowe was even worse treated: the tracery was cut in half and turned upside down, and plastered against deal boarding—to form a dwarf screen.

"What will my screen cost if it be restored?" asked a rector of Mr. Harry Hems.

"About four hundred pounds."

"Four hundred pounds! Bless me! I think I had best have it removed."

"Very well, sir, be prepared for the consequences. Your name will go down to posterity dyed in infamy and yourself steeped in obloquy."

"You don't mean to say so?"

"Fact, sir, I assure you."

That preserved the screen.

Then, again, some faddists have a prejudice against them. This has caused the destruction of those in Davidstow and West Alvington. Others, however, have known how to value what is the great treasure in their churches entrusted to their custody, and they have preserved and restored them. Such are Staverton, Dartmouth, Totnes, Harberton, Wolborough. That there must have been in the sixteenth century a school of quite first-class carvers cannot be doubted, in face of such incomparable work as is seen in the pulpit and screen of Kenton. But if there was good work by masters there was also some poor stuff, formal and without individual character—such as the screens at Kenn and Laneast.

The pulpits are also occasionally very rich and of the same date as the screens. There are noble examples of stone pulpits elaborately carved at South Molton, Bovey Tracey, Chittlehampton, and Harberton, and others even finer in wood, as Holne, Kenton, Ipplepen, Torbrian.

Among churches which have fine bench-ends may[39] be noted Braunton, Lapford, Colebrook, Horwood, Broadwood Widger (dated 1529), North Lew (also dated), Plymtree, Lew Trenchard, Peyhembury.

Several early fonts remain of Norman style, and even in some cases perhaps earlier. The finest Norman fonts are Stoke Canon, Alphington, S. Mary Steps (Exeter), Hartland, and Bere Ferrers. In the west, about the Tamar, one particular pattern of Norman font was reproduced repeatedly; and it is found in several churches. There are a number of village crosses remaining, a very fine one at South Zeal; also at Meavy, Mary Tavy, Staverton, Sampford Spiney, Holne, Hele, and some extremely rude on Dartmoor.

There was a churchyard cross at Manaton. The Rev. C. Carwithen, who was rector, found that the people carried a coffin thrice round it, the way of the sun, at a funeral; although he preached against the usage as superstitious, they persisted in doing so. One night he broke up the cross, and removed and concealed the fragments. It is a pity that the cross did not fall on and break his stupid head.

It is interesting to observe how late the Perpendicular style maintained itself in the West. At Plymouth is Charles Church, erected after the Restoration, of late Gothic character. So also are there aisles to churches, erected after the Reformation, of debased style, but nevertheless distinctly a degeneration of the Perpendicular.

In domestic architecture this is even more noticeable. Granite-mullioned windows and four-centred doorways under square hoods, with shields and flowers[40] in the spandrels, continued in use till the beginning of the eighteenth century.

A very large number of old mansions, belonging to the squirearchy of Elizabethan days, remain. The Devonshire gentry were very numerous, and not extraordinarily wealthy. They built with cob, and with oak windows, or else in stone with granite mullions, but neither material allowed of great splendour. A house in granite cost about three times as much as one of a like size in brick.

The mansions are too numerous to be mentioned. One who is desirous of seeing old houses should provide himself with an inch to the mile Ordnance Survey map, and visit such houses as are inserted thereon in Old English characters. Unhappily, although this serves as a guide in Cornwall, the county of Devon has been treated in a slovenly manner, and in my own immediate neighbourhood, although such a fine example existed as Sydenham House, it remained unnoticed; and the only two mansions indicated in Old English were a couple of ruins, uninhabited, that have since disappeared. Where the one-inch fails recourse must be had to the six-inch map.

Devonshire villages and parks cannot show such magnificent trees as the Midlands and Eastern counties. The elm grows to a considerable size on the red land, but the elm is much exposed to be blown over in a gale, especially when it has attained a great size. Oak abounds, but never such oak as may be seen in Suffolk. The fact is that when the tap-root of an oak tree touches rock the tree makes no progress, and as the rock lies near the surface almost throughout[41] the county, an oak tree does not have the chance there that it does in the Eastern counties, where it may burrow for a mile in depth without touching stone.

Moreover, situated as the county is between two seas, it is windblown, and the trees are disposed to bend away from the prevailing south-westerly and westerly gales. But if trees do not attain the size they do elsewhere, they are very numerous, and the county is well wooded. Its rocks and its lanes are the homes of the most beautiful ferns that grow with luxuriance, and in winter the moors are tinted rainbow colours with the mosses. The flora is varied with the soil. What thrives on the red land perishes on the cold clay; the harebell, which loves the limestone, will not live on the granite, and does not affect the schist.

The botanist may consult Miss Helen Saunders' "Botanical Notes" in the Transactions of the Devonshire Association; Miss Chaunters' Ferny Combes; and the appendix to Mr. Rowe's Dartmoor.

The village revel was till twenty years ago a great institution, and a happy though not harmless one. But it has died out, and it is now sometimes difficult to ascertain, and then only from old people, the days of the revel in the several villages. In some parishes, however, the clergy have endeavoured to give a better tone to the old revel, which was discredited by drunkenness and riot, and their efforts have not been unsuccessful. The clubs march to church on that day, and a service is given to them.

One of the most curious revels was that at Kingsteignton, where a ram was hunted, killed, roasted, and eaten. The parson there once asked[42] a lad in Sunday School, "How many Commandments are there?" "Three, sir," was the prompt reply; "Easter, Whitsuntide, and the Revel."

Another, where a sheep was devoured after having been roasted whole, was at Holne. At Morchard, the standing dish at farmhouses on Revel day was a "pestle pie," which consisted of a raised paste, kept in oval shape by means of iron hoops during the process of baking, being too large to be made in a dish. It contained all kinds of meat: a ham, a tongue, whole poultry and whole game, which had been previously cooked and well seasoned.

The revel, held on the réveil or wake of the saint of the parish, was a relic of one of the earliest institutions of the Celts. It was anciently always held in the cemetery, and was attended by funeral rites in commemoration of the dead. This was followed by a fair, and by a deliberative assembly of the clan, or subdivision of a clan, of which the cemetery was the tribal centre. It was the dying request of an old Celtic queen that her husband would institute a fair above her grave.

One long street—The debatable ground—Derivation of the name—Configuration of the East Devon border—Axminster—The Battle of Brunnaburgh—S. Margaret's Hospital—Old camps—S. Michael's Church—Colyton—Little Chokebone—Sir George Yonge—Honiton lace—Pillow-lace—Modern design—Ring in the Mere—Dunkeswell.

"This town," said Sir William Pole in 1630, "is near three-quarters of a mile in length, lying East and West, and in the midst there is one other street towards the South." The description applies to-day, except only that the town has stretched itself during two hundred and eighty years to one mile in place of three-quarters. A quarter of a mile in about three centuries, which shows that Honiton is not a place that stands still.

It is, in fact, a collection of country cottages that have run to the roadside to see the coaches from London go by, and to offer the passengers entertainment.

The coach-road occupies mainly the line of the British highway, the Ikenild Street, a road that furnished the chief means of access to the West, as the vast marshes of the Parret made an approach to the peninsula from the North difficult and dangerous.

And the manner in which every prominent height has been fortified shows that the whole eastern boundary of the county has been a debated and fiercely contested land, into which invaders thrust themselves, but from which they were hurled back.

Honiton is on the Otter (y dwr, W. the Water) a name that we find farther west in the Attery, that flows into the Tamar. Honiton does not derive from "honey," flowing with milk and honey though the land may be, but from the Celtic hen (old), softened in a way general in the West into hena before a hard consonant.

We have the same appellative in Hennacott, Honeychurch, and Honeydykes, also in Hembury, properly Henbury, and in Hemyock. Perhaps the old West Welsh name for the place was Dunhen, or Hennadun, which the Saxons altered into Hennatun or Honeyton.

The singular configuration of the eastern confines of Devon and Dorset has been ingeniously explained. Till 1832 the two parishes of Stockland and Dalwood belonged to the county of Dorset, although surrounded entirely by Devon. In 710 a great battle was fought by Ina, King of the West Saxons, against Geraint, King of the Dumnonii, the West Welsh, on the Black Down Hills, when Geraint was defeated and fled. Then Ina built Taunton, and made it a border fortress to keep the Britons in check. Simultaneously, there can be little doubt, the men of Dorset took advantage of the situation, made an inroad and secured a large slice of territory, possibly up to the Otter.

Ina was succeeded by inert princes, or such as had their hands engaged elsewhere, and the Devonians thrust themselves forward, retook Taunton, and advanced their borders to where they had been before 710.

It has been supposed that on this occasion they were unable to dispossess the Dorset men from their well-fortified positions at Stockland and Dalwood, but swept round them and captured the two camps of Membury and Musbury. The possession of these fortresses would thrust back the Dorset frontier for some miles to the east of the Axe. So matters would remain for a considerable period, such as allowed the boundaries to become settled; and when the final subjugation of Devon took place, this tract to the east of the Axe remained as part of the lands of the Defnas, while the Dorsaetas retained the islet which they had so long and so successfully defended. It was not till eleven hundred and twenty years had elapsed that the Devon folk could recover these points.[4]

Axminster was the scene of a great battle in the reign of Athelstan, in which five kings and seven earls fell. The minster, as a monastic colony, had been in existence before that, but Athelstan now endowed a college there for six priests to pray for the souls of those who fell in the battle.

Now, what battle can that have been? In the register of Newnham Abbey is a statement made in the reign of Edward III., that the battle took place[46] "at Munt S. Calyxt en Devansyr," and that it ended at Colecroft under Axminster. S. Calyxt is now Coaxdon.

The only great battle that answers to the description was that of Brunanburgh, fought in 937.

It was fought between Athelstan and the Ethelings, Edmund, Elwin and Ethelwin, on one side, and Anlaf the Dane, from Ireland, united with Constantine, the Scottish king, on the other. It is this latter point which has made modern historians suppose that the conflict took place somewhere in the North.

But, on the other hand, there are grave reasons for placing it at Axminster.

First, we know of no other battle that answers the description. Then, during the night before it, the Bishop of Sherborne arrived at the head of a contingent. The two younger Ethelings who fell were transported to Malmesbury to be buried; clearly because it was the nearest great monastery. And it seems most improbable that Athelstan should have endowed Axminster that prayers might there be offered for those who fell in the battle, if Brunanburgh were in Northumberland. The difficulty about Constantine may thus be solved. Constantine had been expelled his kingdom by Athelstan, and had taken refuge in Ireland. He had, indeed, been restored, but when he resolved on revolt, he may have gone to Dublin to Anlaf, and have concerted with him an attack on the South, where the assistance of the Britons in Devon and Cornwall might be reckoned on, whilst the North British would rise, and the Welsh descend from their mountains.

The story of the battle is this, as given by William of Malmesbury.

The Danes from Dublin, together with Constantine and a party of Scots (Irish), came by sea, and fell upon England. Athelstan and his brother marched against them. Just before the battle Anlaf, desirous of knowing the disposition of the English forces, entered the camp in the garb of a gleeman, harp in hand. He sang and played before Athelstan and the rest, and they did not recognise him. As they were pleased with his song, they gave him a largess of gold. He took the money, but as he left the camp, he put it under the earth, as it did not behove a king to receive hire. This was observed by a soldier, who at once went to Athelstan and informed him of it. The king said angrily, "Why did you not at once arrest him and deliver him into my hands?" "My lord king," answered the man, "I was formerly with Anlaf, and I took oath of fidelity to him. Had I broken that, would you have trusted me? Take my advice, O king, and shift your quarters."

This was good advice, and Athelstan acted on it, but scarcely had he shifted his quarters than Werstan, Bishop of Sherborne, arrived, and he took up the ground vacated by the king.

During the night Anlaf made an attack and broke through the stockade, and directed his course towards the king's tent. There he fell on and killed the bishop, and massacred the Sherborne contingent. The tumult roused the king, and the fight became general, and raged till day. Great numbers fell on[48] both sides, but in the end Anlaf was defeated, and fled to his ships. The only trace of the name Brunanburgh is in Brinnacombe, under the height whereon traditionally the fight raged; and Membury may be the place where the king was fortified. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle calls the place Brumby: B and M are permutable letters.

Honiton has not many relics of antiquity about it. Repeated fires have destroyed the old houses; the High Street still retains its runnel, confined within a conduit, with square dipping-places at frequent intervals. The street runs straight down hill to the bridge and across the Giseage, and up again on the road towards Exeter. The town is completely surrounded by toll-gates; the tolls collected do not go to pay for the maintenance of the roads, but to defray a debt incurred by removing buildings, including the ancient shambles, from the middle of the street early in the century. This accounts for the street being particularly wide.

The Dolphin, the principal inn, is supposed to still possess some portion of the ancient building once belonging to the Courtenays, whose cognisance is the inn sign.

S. Margaret's Hospital is one of the points of interest, and is picturesquely pretty. It was intended as a leper hospital, but is now used as almshouses. It was built and endowed by Dr. Thomas Chard, the last abbot of Ford.