(p. 334)

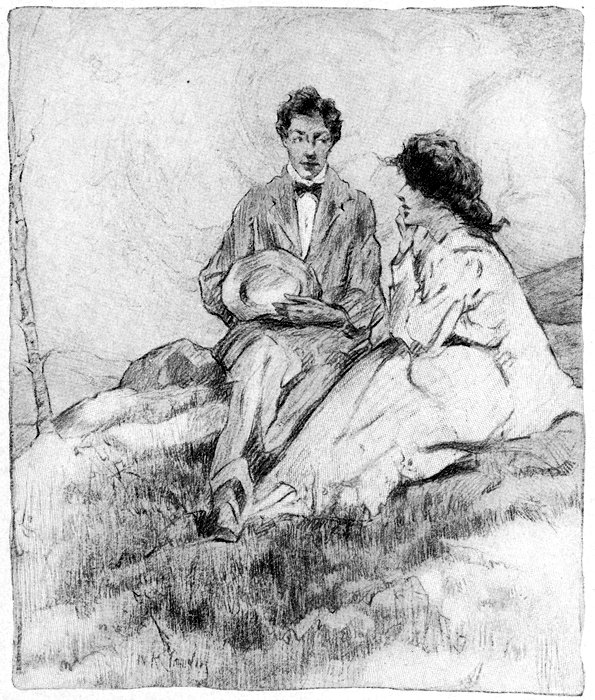

"IT'S BEAUTIFUL UP HERE, ISN'T IT, KATY?"

Title: Katy Gaumer

Author: Elsie Singmaster

Release date: March 16, 2015 [eBook #48501]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Ernest Schaal, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

By Elsie Singmaster

KATY GAUMER. Illustrated.

GETTYSBURG. Illustrated.

WHEN SARAH WENT TO SCHOOL. Illustrated.

WHEN SARAH SAVED THE DAY. Illustrated.

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

Boston and New York

(p. 334)

"IT'S BEAUTIFUL UP HERE, ISN'T IT, KATY?"

![KATY GAUMER BY ELSIE SINGMASTER [Illustration] BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY The Riverside Press Cambridge 1915 KATY GAUMER BY ELSIE SINGMASTER [Illustration] BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY The Riverside Press Cambridge 1915](images/titlepage.jpg)

COPYRIGHT, 1910, BY THE CENTURY COMPANY

COPYRIGHT, 1915, BY ELSIE SINGMASTER LEWARS

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Published February 1915

Note.—The first two chapters were published as a short story under the title of "The Belsnickel" in the Century Magazine for January, 1911.

KATY GAUMER

Every Wednesday evening in winter Katy Gaumer went to the Millerstown post-office for her grandfather's "Welt Bote," the German paper which circulated among the Pennsylvania Germans of Millerstown. By six o'clock she and Grandfather Gaumer and Grandmother Gaumer had had supper; by half past six she had finished drying the dishes; by half past seven she had learned her lessons for the next day; and then, a scarlet shawl wrapped about her, a scarlet "nubia" on her head, scarlet mittens on her hands, Katy set forth into Millerstown's safe darkness.

Sometimes—oh, the thrill that closed her throat and ran up and down her spine and set her heart to throbbing and her eyes to dancing at sound of that closed door!—sometimes it rained and she pushed her way out into the storm as a viking might have pushed his boat from the shore into an unfriendly sea; sometimes it snowed and she lifted her hot face so that she might feel the light, cold flakes against her cheek; sometimes deep drifts lay already on the ground and she flung herself upon them or into them; [pg 2] sometimes she danced back to say a second good-bye so that she might enjoy her freedom once more; sometimes she stole round under the tall pine trees and knocked ponderously at the door, knowing perfectly well that her grandmother and grandfather would only smile at each other and not stir.

Sometimes she crossed the yard in snow to her knees to rap against the kitchen window of Bevy Schnepp, who kept house for Great-Uncle Gaumer, the squire. Bevy's real name was Maria Snyder, but Katy had renamed her for one of the mythical characters of whom Millerstown held foolish discourse, and the village had adopted the title. Bevy was little and thin and a powerful worker. She was cross with almost every one in the world, even with Katy whom she adored and spoiled. There was a tradition in Millerstown that she was once about to be married, but that at the ceremony her spirit rebelled. When the preacher asked her whether she would obey, she cried out aloud, "By my soul, no!" and the match was thereupon broken off. Bevy adorned her speech with many proverbs, and she had an abiding faith in pow-wowing, and also in spooks, hexahemeron cats, and similar mysterious creatures. She had named the squire's dog "Whiskey" so that he could not be bewitched. She would as soon have thrown her cabbage plants away as to have planted them in any other planetary sign than that of the Virgin. She belonged, strangely enough, to a newly established religious sect in Millerstown, that of the [pg 3] Improved New Mennonites, who had no relation to the long-established worthy followers of Menno Simons in other parts of the Pennsylvania German section. It is difficult to understand how Bevy reconciled her belief in the orthodox if sensational preaching of the Reverend Mr. Hill with her use of such superstitious rhymes as

to which she had recourse when trouble threatened.

Sometimes Katy untied "Whiskey" and they scampered wildly, crazily away together. Katy did everything in the same unthinking, impetuous way. Both she and Whiskey were young, both were irresponsible, both were petted, indulged, and entirely care-free. Katy was the orphan child of her grandparents' Benjamin; it was not strange that they could deny her nothing. Of her mother and father she had no recollection; to her grandparents she owed anything she might now be or might become.

To-night there was no snow upon the ground. The stars shone crisply; in the west the young moon was declining; though it was December, the season seemed more like autumn than like winter. Millerstown lay still and lovely under its leafless trees; not in the quiet of perpetual drowsiness,—Millerstown was stirring enough by day!—but in repose after the day's labor and excitement. To the east of the [pg 4] village the mountain rose somberly; to the south the pike climbed a hill toward the church and the school-house; to the west and north lay the wide fields. To the north might be seen the dim bulk of the blast furnace with the great starlike light of the bleeder flame.

"I wonder what it looks like now from the top of the mountain," soliloquized Katy. "I would like to climb once in the dark night to the Sheep Stable. I wonder if it is any one in all Millerstown brave enough to go along in the dark. I wonder what the church looks like inside without any light. I wonder—"

Awed by the quiet, Katy stood still under the pine trees at the gate. She heard Whiskey whine to be let loose; she heard Bevy open the door of the squire's kitchen.

"Katy, Katy Gaumer! Come here once, Katy Gaumer!"

Katy did not answer. Bevy had probably a cake for her or some molasses candy; she could just as well put it in the putlock hole in the wall of grandfather's house. A putlock hole is an aperture left by the removal of a scaffolding. It is supposed to be filled in, but either the builder of the old stone house had overlooked one of the openings, or the stone placed there had fallen out. It now made a fine hiding-place for Katy's treasures.

Katy had at this moment no time to give to Bevy. Her heart throbbed, her hands clutched the gate. [pg 5] She did not know why she was always so thrilled and excited when she was out alone at night.

"It is like Bethlehem," she whispered to herself, as she looked down the street, then up at the sky. "The shepherds might be watching or the kings might come."

Katy opened the gate.

"I love Millerstown," she declared. "I love Millerstown. I love everybody and everything in Millerstown."

The post-office was next to the store and on the same street as Grandfather Gaumer's. There are only three streets in the village, Main Street and Locust and Church, and all the houses are built out to the pavement in the Pennsylvania German fashion, so that the little settlement does not cover much ground. Perhaps that was why Katy, leaving Main Street and starting forth on Locust, came so soon to the end of her spasm of affection. There did not seem to be enough of the village to warrant any such fervent outpouring. At any rate, Katy's mood changed.

"I am tired of Millerstown," she declared with equal fervor. "It is dumb. It is quiet. Nothing ever happens in this place."

The residents of Locust Street were especially dull to Katy's thinking. Dumb Coonie Schnable lived here and dumb Ellie Schindler, and Essie Hill, whom she hated. Essie was the daughter of the pastor of the Improved New Mennonites, of whom Bevy [pg 6] Schnepp was one. The preacher himself was tall and angular and rather blank of countenance, but Essie was small and pretty and pink and smooth of speech and by no means "dumb." Once, being a follower of her father's religious practices, Essie had risen in school and had prayed for forgiveness for Katy's outrageous impudence to the teacher, and had thereupon become his favorite forever. That Essie could really be what she seemed, that she could like to hear her father shout about the Millerstown sinners, that she could admire the silly, short-back sailor hat adorned with a Bible verse, which was the head-covering of the older female members of the Improved New Mennonite Church—this Katy could not, would not believe. Essie was a hypocrite.

Sometimes the Improved New Mennonites might be heard singing or praying hysterically. Katy had often watched them through the window, in company with Ollie Kuhns and Billy Knerr and one or two other naughty boys and girls, and had sometimes helped a little with the hysterical shrieking. To-night the little frame building was dark, and here, as down on Main Street, there was not a sound.

At the end of Locust Street, Katy went through a lane to Church Street, and there again she stood perfectly still, her eyes gleaming, her ears listening, listening, listening. On the mountain road above her, she could see dimly a little white house, which seemed to hug the hillside and to hold itself aloof from Millerstown. Here lived old Koehler, who was [pg 7] not really very old, but who was crazy and who was supposed to have stolen the beautiful silver communion service of Katy's church. The children used to shout wildly at him, "Bring it back! Bring it back!" and sometimes he ran after them. One sign of his lunacy was his constant praying in all sorts of queer places and at queer times that the communion service might be returned, when all he needed for the answering of his prayer was to seek the service where he had hidden it and to put it back in its place. The Millerstown children never carried their mocking to his house, since they believed that he was able to set upon them the swarms of bees that lived in hives in his little garden, among which he went without fear. They said among themselves—at least the romantic girls said—that he did not give his son, poor, handsome Alvin, enough to eat.

Suddenly Katy's heart beat with a new thrill. There was no instinct within her which was not awake or wakening. Her cheeks flushed, her scarlet mittens clasped each other. She liked handsome Alvin because she liked him—no better reason was given or required in Katy's feminine soul.

"I think Alvin is grand," exclaimed Katy to herself. "I am sorry for him. I think he is grand."

There was a sound, and Katy started. Suppose Alvin should come upon her suddenly! She went on a few steps, then once more she stopped to listen. Once more Millerstown was quiet, again she looked and listened.

[pg 8] Back in the shadows across the street stood a large, fine house, the home of John Hartman, Millerstown's richest man. There were in that house fine carpets and beautiful furniture. But in spite of their possessions the Hartmans were not a happy family. Mrs. Hartman was handsome and she had beautiful clothes and a sealskin coat to wear to church, but she was disturbed if leaves drifted down on the grass in her yard or if the coming of visitors made it necessary to let the sunlight in on her thick carpets. Her only child, David, was sullen and stupid and cross. Remembering the delightful bass singing of one Wenner in the church choir, Katy had run away from home when a mere baby to visit the church on a week day and from there John Hartman had driven her home. Her grandmother to whom she had fled had insisted that he had not been angry, but that he had only sent her back sternly and properly where she belonged. But the impression was not quite persuaded away. Katy used to pretend in some of her wild races that she was fleeing from John Hartman.

Suddenly there was another sound. Some Millerstonian had opened a window or had closed a shutter and Katy took to her heels. It amused her to pretend once more that she was running away from John Hartman. In a moment she had opened the door of the village store and had flashed in.

Round the stove sat four men, old and middle-aged; to the other three, Caleb Stemmel was holding forth dismally, his voice low, dreary as his mind, his [pg 9] mind dull as the dim room. Upon them Katy flashed in her scarlet attire, her thin legs in their black stockings completing her resemblance to a very gorgeous tanager or grosbeak. Katy had recovered from all her thrills; she was now pure mischief and impertinence.

"Nothing," complained Caleb Stemmel, "nothing is any more like it was when I was young."

"No, it is much better," commented the scarlet tanager.

"We took always trouble." Caleb paid no heed to the impertinent interruption. "We had Christmas entertainments that were entertainments—speeches and cakes and apples and a Belsnickel. But these children and these teachers, they are too lazy and too good-for-nothing."

Katy had no love for her teacher; she, too, considered him good-for-nothing; but she had less love for Caleb Stemmel.

"We are going to have a Christmas entertainment that will flax [beat] any of yours, Caleb Stemmel," she boasted.

"Yes, you will get up and say a few Dutch pieces and then you will go home."

"Well, everything was Dutch when you were young. You ought to like that!"

"Things should now be English," insisted Caleb. "But you are too lazy, all of you, from the teacher down. You will be pretty much ashamed of yourselves this year, that I can tell you."

[pg 10] Katy was already halfway to the door, her black legs flying. She would waste no words on Caleb Stemmel. But now she turned and went back. Katy was curious.

"Why this year?"

"Because," teased Caleb.

"That is a dumb answer! Why because?"

"Because it is some one coming."

"Who?"

"A visitor." Caleb pronounced it "wisitor."

"Pooh! What do I care for a 'wisitor'?" mocked Katy.

"This is one that you care for!"

"Who is it?"

"Don't you wish you knew?"

Katy stamped her foot.

"If you don't tell, I'll throw you with snow when the snow comes," she threatened. Katy had respect for age in general, but not for Caleb Stemmel.

Caleb did not answer until he saw that Danny Koser was about to tell.

"It is a governor coming," he announced impressively.

Katy drew a step closer, her face aglow. No eyes of tanager or grosbeak could have shone blacker against brilliant plumage.

"Do you mean"—faltered Katy—"do you mean that my Uncle Daniel is coming home once, my Uncle Daniel Gaumer?"

"The squire was here and he told us." Danny [pg 11] Koser was no longer to be restrained. "Then he went to your gran'pop. He got a letter, the squire did. What do you think of that now?"

"And what," jeered Caleb Stemmel,—"what will the governor think of Dutch Millerstown and the Dutch entertainment and Dutch Katy; what—"

Once more had Katy reached the door at the other end of the long room. She had a habit of forecasting her own actions; already she could see herself pounding at the teacher's door, then racing home to her grandfather's, her heart throbbing, throbbing, her whole being in the glow of excitement which she loved, and of which she never had enough.

Suddenly she stopped, her hand on the latch. She had a secret, the whole Millerstown school had a secret, but now it must be told. Every father and mother in Millerstown would have to know if the great project, really her great project, were to succeed. Since the news would have to come out, it might as well be announced at once.

"We are going to have an English entertainment, Caleb Stemmel," she cried. "It is planned this long time already; we have been practicing for a month, Caleb Stemmel. We will have you in it; we will have you say, 'A wery wenimous wiper jumped out of a winegar wat'; that will be fine for you, Caleb. Aha! Caleb!"

Outside Katy paused and stretched forth her arms. There was still not a soul in sight, there was still not a sound; she looked up the street and down [pg 12] and could see the last house at each end. Then Katy started to run. Ten minutes ago she had been only little Katy Gaumer, with lessons learned for the morrow and bedtime near, hating the quiet village, a good deal bored with life; now she was Katy Gaumer, the grandniece of one of the great men of the world.

"I wonder what he will look like," said Katy. "I want to do something. I want to be something. I want to make speeches. I want to be rich and learned. I want to do everything. If he would only help me, I might be something."

There was no one at hand to tell her that she was a vain child; no one to remind her that she was only one of twenty-odd grandnieces and nephews and that the governor of a Western State was after all not such an important person, since there were many still higher offices in the land. No Millerstonian would have so discounted Daniel Gaumer, who had made his own way and had achieved greater success than any of his Millerstown contemporaries. To Katy he was far more wonderful than the President of the United States. If she could do well at the entertainment—she, of course, had the longest and most important piece, and she had also drilled the other children—if it only turned out well, and if some one only said to the governor that success was due to her efforts, he might persuade her grandfather to send her away to school; he might—

But this was not the time to dream. With a fresh [pg 13] gasp for breath, Katy ran on and hurled herself against the teacher's door, or rather against the door of Sarah Ann Mohr, in whose house the teacher boarded. In an instant she was in the kitchen where Sarah Ann and the teacher sat together.

Sarah Ann was large and ponderous and good-natured. She was now reading the paper and hemming a gingham apron by turns. Sarah Ann loved to read. Her favorite matter was the inside page of the Millerstown "Star," which always offered varied and interesting items of general news. Sarah Ann was far less interested in the accounts of Millerstown's births and deaths and marriages than she was in the startling events of the world outside. Sarah Ann's taste inclined to the shocking and morbid. This evening she had read many times about a man who had committed suicide by sitting on a box of dynamite and lighting the fuse, and about a man whose head was gradually becoming like that of a lion. When she observed that the next item dealt with the remarkable invention of a young woman who baked glass in her husband's pies, Sarah Ann laid down the paper to compose her mind with a little sewing.

The teacher, who was small and slender and somewhat near-sighted, was going painstakingly over a bundle of civil service examination questions. He was only in Millerstown for a little while, acting as a substitute and waiting for something to turn up. He was a Pennsylvania German, but he would as [pg 14] soon have been called a Turk. He had changed his name from Schreiner to Carpenter and the very sound of his native tongue was hateful to him. He did not like Katy Gaumer; he did not like any young, active, springing things.

Now he listened to Katy in astonishment. Katy flung herself upon Sarah Ann.

"Booh! Don't look so scared. I will not eat you, Sarah Ann! And I am no spook! I am only in a hurry. Teacher, I have told the people about the English entertainment. It is out. I had to tell, because the children must know their pieces better. Ollie Kuhns, he won't learn his until his pop thrashes him a couple of times, and Jimmie Weygandt's mom will have to make him learn with a stick, and then he will not know it anyhow, perhaps, and they won't leave us have the Sunday School organ to practice beforehand for the singing unless they know why it is, and everybody must practice all the time from now on. You see, I had to tell."

The teacher looked at her dumbly. So did Sarah Ann.

"But why?" asked they together.

"Why?" repeated Katy, impatiently, as though they might have divined the wonderful reason. "Why, because my Uncle Daniel is coming. Isn't that enough?"

Sarah Ann laid down her apron.

"Bei meiner Seel'!" said she solemnly.

The teacher laid down his papers.

[pg 15] "The governor?" said he. He had heard of Governor Gaumer. He thought of the appointments in a governor's power; he foresaw at once escape from the teaching which he hated; he blessed Katy because she had proposed an English entertainment. He blessed her inspired suggestion of parental whippings for Ollie and Jimmie. "Sit down once, Katy, sit down."

It gave Katy another thrill of joy to be thus solicited by her enemy. But now she could not stop.

"I must go first home and see my folks. Then I will come back."

At the squire's gate, Bevy Schnepp awaited her.

"Ach, come once in a little, Katy!"

"I cannot!"

"Just a little! I have something for you." Bevy put out a futile arm. People were forever trying to catch Katy.

"No," laughed Katy. "I'll put a hex on you, Bevy! I'll bewitch you, Bevy!"

Katy was gone, through her grandfather's gate, down the brick walk under the pine trees to the kitchen where sat grandfather and grandmother and the squire. Seeing them together, the two old men with their broad shoulders and their handsome heads and the old woman with her kindly face, a stranger would have known at once where Katy got her active, erect figure and her curly hair and her dark eyes. All three were handsome; all three cultivated as far as their opportunities would allow; [pg 16] all three would have been distinguished in a broader circle than Millerstown could offer. But here circumstances had placed them and had kept them. Even the squire, whose desk was frequently littered with time-tables, and who planned constantly journeys to the uttermost parts of the earth, had scarcely ever been away from Millerstown.

Upon these three Katy rushed like a whirlwind.

"Is it true?" she demanded breathlessly in the Pennsylvania German which the older folk loved, but which was falling into disuse among the young.

"Is what true?" asked grandfather and the squire together. They liked to tease Katy, everybody liked to tease Katy.

"That my uncle the governor is coming?"

"Yes," said Grandfather Gaumer. "Your uncle the governor is coming."

On the afternoon of the entertainment there was an air of excitement, both within and without the schoolroom. Outside the clouds hung low; the winter wheat in the Weygandt fields seemed to have yielded up some of its brilliant green; there was no color on the mountain-side which had been warm brown and purple in the morning sunshine. A snowstorm was brewing, the first of the season, and Millerstown rejoiced, believing that a green Christmas makes a fat graveyard. But in spite of the threatening storm nearly all Millerstown moved toward the schoolhouse.

The schoolroom was almost unrecognizable. The walls were naturally a dingy brown, except where the blackboards made them still duller; the desks were far apart; the distance from the last row, where the ill-behaved liked to sit, to the teacher's desk, to which they made frequent trips for punishment, seemed on ordinary days interminable.

This afternoon, however, there was neither dullness nor extra space. The walls were hidden by masses of crowfoot and pine, brought from the mountain; the blackboards had vanished behind festoons of red flags and bunting. Into one quarter of the [pg 18] room the children were so closely crowded that one would have said they could never extricate themselves; into the other three quarters had squeezed and pressed their admiring relatives and friends.

Grandfather and Grandmother Gaumer were here, the latter with a large and mysterious basket, which she helped Katy to hide in the attic, the former laughing with his famous brother. The governor had come on the afternoon train, and Katy had scarcely dared to look at him. He was tall,—she could see that without looking,—and he had a deep, rich voice and a laugh which made one smile to hear it. "Mommy Bets" Eckert was here, a generation older than the Gaumer men, and dear, fat Sarah Ann Mohr, who would not have missed a Christmas entertainment for anything you could offer her. There were half a dozen babies who cooed and crowed by turns, and at them cross Caleb Stemmel frowned—Caleb was forever frowning; and there was Bevy Schnepp, moving about like a restless grasshopper, her bright, bead-like eyes on her beloved Katy.

"She is a fine platform speaker, Katy is," boasted Bevy to those nearest her. "She will beat them all."

Alvin Koehler, tall, slender, good-looking even to the eyes of older persons than Katy Gaumer, was an usher; his presence was made clear to Katy rather by a delicious thrill than by visual evidence. It went without saying that his crazy father had not come to the entertainment, though none of his small businesses of bricklaying, gardening, or bee culture [pg 19] need have kept him away. When Koehler was not at work, he spent no time attending entertainments; he sat at his door or window, watching the mountain road, and scolding and praying by turns.

Upon the last seat crouched David Hartman, sullen, frowning, as ever. The school entertainment was not worth the attention of so important a person as his father, and his mother could not have been persuaded to leave the constant toil with which she kept spotless her great, beautiful house.

Millerstown's young bachelor doctor had come, and he, too, watched Katy as she flew about in her scarlet dress. The doctor was a Gaumer on his mother's side, and from her had inherited the Gaumer good looks and the Gaumer brains. Katy's Uncle Edwin and her Aunt Sally had brought their little Adam, a beautiful, blond little boy, who had his piece to say on this great occasion. Uncle Edwin was a Gaumer without the Gaumer brains, but he had all the Gaumer kindness of heart. Of these two kinsfolk, Uncle Edwin and fat, placid Aunt Sally, Katy did not have a very high opinion. Smooth, pretty little Essie Hill had not come; her pious soul considered entertainments wicked.

But Katy gave no thought to Essie or to her absence; her mind was full of herself and of the great visitor and of Alvin Koehler. For Katy the play had begun. The governor was here; he looked kind and friendly; perhaps he would help her to carry out some of her great plans for the future. Since his [pg 20] coming had been announced, Katy had seen herself in a score of rôles. She would be a great teacher, she would be a fine lady, she would be a missionary to a place which she called "Africay." No position seemed beyond Katy's attainment in her present mood.

Katy knew her part as well as she knew her own name. It was called "Annie and Willie's Prayer." It was long and hard for a tongue, which, for all its making fun of other people, could not itself say th and v with ease. But Katy would not fail, nor would her little cousin Adam, still sitting close between his father and mother, whom she had taught to lisp through "Hang up the Baby's Stocking." If only Ollie Kuhns knew the "Psalm of Life," and Jimmie Weygandt, "There is a Reaper whose Name is Death," as well! When they began to practice, Ollie always said, "Wives of great men," and Jimmie always talked about "deas" for "death." But those faults had been diligently trained out of them. All the children had known their parts this morning; they had known them so well that Katy's elaborate test could not produce a single blunder, but would they know them now? Their faces grew whiter and whiter; the very pine branches seemed to quiver with nervousness; the teacher—Mr. Carpenter, indeed!—tried in vain to recall the English speech which he had written out and memorized. As he sat waiting for the time to open the entertainment, he frantically reminded himself that the prospect of [pg 21] examinations had always terrified him, but that he invariably recovered his wits with the first question.

Once he caught Katy Gaumer's eye and tried to smile. But Katy did not respond. Katy looked at him sternly, as though she were the teacher and he the pupil. She saw plainly enough what ailed him, and prickles of fright went up and down her backbone. His speech was to open the entertainment; if he failed, everybody would fail. Katy had seen panic sweep along the ranks of would-be orators in the Millerstown school before this. She had seen Jimmie Weygandt turn green and tremble like a leaf; she had heard Ellie Schindler cry. If the teacher would only let her begin the entertainment, she would not fail!

But the teacher did not call on Katy. No such simple way out of his difficulty occurred to his paralyzed brain. The Millerstonians expected the fine English entertainment to begin; the stillness in the room grew deathlike; the moments passed, and Mr. Carpenter sat helpless.

Then, suddenly, Mr. Carpenter jumped to his feet, gasping with relief. He knew what he would do! He would say nothing at all himself; he would call upon the stranger. It was perfectly true that precedent put a visitor's speech at the end of an entertainment, rather than at the beginning, but the teacher cared not a rap for precedent. The stranger should speak now, and thus set an example to the children. Hearing his easy th's and v's, they would [pg 22] have less trouble with their English. Color returned to the teacher's cheeks; only Katy Gaumer realized how terrified he had been. So elated was he that he introduced the speaker without stumbling.

"It is somebody here that we do not have often with us at such a time," announced Mr. Carpenter. "It is a governor here; he will make us a speech."

The governor rose, smiling, and Millerstown, smiling, also, craned its neck to see. Then Millerstown prepared itself to hear. What it heard, it could scarcely believe.

The governor had spoken for at least two minutes before his hearers realized anything but a sharp shock of surprise. The children looked and listened, and gradually their mouths opened; the fathers and mothers heard, and at once elbows sought neighboring sides in astonished nudges. Bevy Schnepp actually exclaimed aloud; Mr. Carpenter flushed a brilliant, apoplectic red. Only Katy Gaumer sat un-moved, being too much astonished to stir. She had looked at the stranger with awe; she regarded him now with incredulous amazement.

The governor had been away from Millerstown for thirty years; he was a graduate of a university; he had honorary degrees; the teacher had warned the children to look as though they understood him whether they understood him or not.

"If he asks you any English questions and you do not know what he means, I will prompt you a [pg 23] little," the teacher had promised. "You need only to look once a little at me."

But the distinguished stranger asked no difficult English questions; the distinguished stranger did not even speak English; he spoke his own native, unenlightened Pennsylvania German!

It came out so naturally, he seemed so like any other Millerstonian standing there, that they could hardly believe that he was distinguished and still less that he was a stranger. He said that he had not been in that schoolroom for thirty years, and that if any one had asked him its dimensions, he would have answered that it would be hard to throw a ball from one corner to the other. And now from where he stood he could almost touch its sides!

He remembered Caleb Stemmel and called him by name, and asked whether he had any little boys and girls there to speak pieces, at which everybody laughed. Caleb Stemmel was too selfish ever to have cared for anybody but himself.

Still talking as though he were sitting behind the stove in the store with Caleb and Danny Koser and the rest, the governor said suddenly an astonishing, an incredible, an appalling thing. Mr. Carpenter, already a good deal disgusted by the speaker's lack of taste, did not realize at first the purport of his statement, nor did the fathers and mothers, listening entranced. But Katy Gaumer heard! He said that he had come a thousand miles to hear a Pennsylvania German Christmas entertainment!

[pg 24] He said that it was necessary, of course, for every child to learn English, that it was the language of his fatherland; but that at Christmas time they should remember that they had an older fatherland, and that no nation felt the Christmas spirit like the Germans. It was a time when everybody should be grateful for his German blood, and should practice his German speech. He said that a man with two languages was twice a man. He had been looking forward to this entertainment for weeks; he had told his friends about it, and had made them curious and envious; he had thought about it on the long journey; he knew that there was one place where he could hear "Stille Nacht." He almost dared to hope that this entertainment would have a Belsnickel. If old men could be granted their dearest wish, they would be young again. This entertainment, he said, was going to make him young for one afternoon.

The great man sat down, and at once the little man arose. Mr. Carpenter did not pause as though he were frightened, he was no longer panic-stricken; he was, instead, furious, furious with himself for having called on Daniel Gaumer first, furious with Daniel Gaumer for thus upsetting his teaching. He said to himself that he did not care whether the children failed or not. He announced "Annie and Willie's Prayer."

It seemed for a moment as though Katy herself would fail. She stared into the teacher's eyes, and [pg 25] the teacher thought that she was crying. He could not have prompted her if his life had depended upon it. He glanced at the programme in his hand to see who was to follow Katy.

But Katy had begun. Katy's tears were those of emotion, not those of fright. She wore a red dress, her best, which was even redder than her everyday apparel; her eyes were bright, her cheeks flushed, she moved lightly; she felt as though all the world were listening, and as though—if her swelling heart did not choke her before she began—as though she might thrill the world. She knew how the stranger felt; this was one of the moments when she, too, loved Millerstown, and her native tongue and her own people. The governor had come back; this was his home; should he find it an alien place? No, Katy Gaumer would keep it home for him!

Katy bowed to the audience, she bowed to the teacher, she bowed to the stranger—she had effective, stagey ways; then she began. To the staring children, to the astonished fathers and mothers, to the delighted stranger, she recited a new piece. They had heard it all their lives, they could have recited it in concert. It was not "Annie and Willie's Prayer"; it was not even a Christmas piece; but it was as appropriate to the occasion as either. It was "Das alt Schulhaus an der Krick," and the translation compared with the original as the original Christmas entertainment compared with Katy Gaumer's.

Katy was perfectly self-possessed throughout; it must be confessed that praised and petted Katy was often surer of herself than a child should be. There were thirty-one stanzas in her recitation; there was time to look at each one in her audience. At the fathers and mothers she did not look at all; at Ollie Kuhns and Jimmie Weygandt and little Sarah Knerr, however, she looked hard and long. She was still staring at Ollie when she reached her desk, staring so hard that she scarcely heard the applause which the stranger led. She did not sit down gracefully, but hung halfway out of her seat, bracing herself with her arm round little Adam and still gazing at Ollie Kuhns. She had ceased to be an actor; she was now stage-manager.

The teacher failed to announce Ollie's speech, but no one noticed the omission. Ollie rose, grinning. This was a beautiful joke to him. He knew what Katy meant; he was always quick to understand. Katy was not the only bright child in Millerstown. He knew a piece entitled "Der Belsnickel," a description of the masked, fur-clad creature, the St. Nicholas with a pelt, who in Daniel Gaumer's day had brought cakes for good children and switches for the "nixnutzige." Ollie had terrified [pg 27] his schoolmates a hundred times with his representation of "Bosco, the Wild Man, Eats 'em Alive"; it would be a simple thing to make the audience see a fearful Belsnickel.

And little Sarah Knerr, did she not know "Das Krischkindel," which told of the divine Christmas spirit? She had learned it last year for a Sunday School entertainment; now, directed by Katy, she rose and repeated it with exquisite and gentle painstaking. When Sarah had finished, Katy went to the Sunday School organ, borrowed for the occasion, on which she had taught herself to play. There was, of course, only one thing to be sung, and that was "Stille Nacht." The children sang and their fathers and mothers sang, and the stranger led them all with his strong voice.

Only Katy Gaumer, fixing one after the other of the remaining performers with her eye, sang no more after the tune was started. There was Coonie Schnable; she said to herself that he would fail in whatever he tried to say. It would make little difference whether Coonie's few unintelligible words were English or German. Coonie had always been the clown of the entertainments of the Millerstown school; he would be of this one, also.

But Coonie did not fail. Ellie Schindler recited a German description of "The County Fair" without a break; then Coonie Schnable rose. He had once "helped" successfully in a dialogue. For those who know no Pennsylvania German it must suffice [pg 28] that the dialogue was a translation of a scene in "Hamlet." For the benefit of those who are more fortunate, a translation is appended. Coonie recited all the parts, and also the names of the speakers.

Ghost: Pity mich net, aber geb mir now dei' Ohre,

For ich will dir amohl eppas sawga.

Hamlet: Schwets rous, for ich will es now aw hera.

Ghost: Und wann du heresht, don nemhst aw satisfaction.

Hamlet: Well was is's? Rous mit!

Ghost: Ich bin dei'm Dawdy sei' Schpook!

To the children Coonie's least word and slightest motion were convulsing; now they shrieked with glee, and their fathers and mothers with them. The stranger seemed to discover still deeper springs of mirth; he laughed until he cried.

Only Katy, stealing out, was not there to see the end. Nor was she at hand to speed little Adam, who was to close the entertainment with "Hang up the Baby's Stocking." But little Adam had had his whispered instructions. He knew no German recitation—this was his first essay at speech-making—but he knew a German Bible verse which his Grandmother Gaumer had taught him, "Ehre sei Gott in der Höhe, und Friede auf Erden, und Den Menschen ein Wohlgefallen." (Glory to God in the Highest and on earth, peace, good will toward men.) He looked like a Christmas spirit as he said it, with his flaxen hair and his blue eyes, as the stranger might have looked sixty years ago. Daniel Gaumer started [pg 29] the applause, and as little Adam passed him, lifted him to his knee.

It is not like the Millerstonians to have any entertainment without refreshments, and for this entertainment refreshments had been provided. Grandmother Gaumer's basket was filled to the brim with cookies, ginger-cakes, sand-tarts, flapjacks, in all forms of bird and beast and fish, and these Katy went to the attic to fetch. She ran up the steps; she had other and more exciting plans than the mere distribution of the treat.

In the attic, by the window, sullen, withdrawn as usual, sat David Hartman.

"You must get out of here," ordered Katy in her lordly way. "I have something to do here, and you must go quickly. You ought to be ashamed to sit here alone. You are always ugly. Perhaps"—this both of them knew was flippant nonsense—"perhaps you have been after my cakes!"

David made no answer; he only looked at her from under his frowning brows, then shambled down the steps and out the door into the cold, gray afternoon. Let him take his sullenness and meanness away! Then Katy's bright eyes began to search the room.

In another moment, down in the schoolroom, little Adam cried out and hid his face against the stranger's breast; then another child screamed in excited rapture. The Belsnickel had come! It was covered with the dust of the schoolhouse attic; it [pg 30] was not of the traditional huge size—it was, indeed, less than five feet tall; but it wore a furry coat—the distinguished stranger leaped to his feet, saying that it was not possible that that old pelt still survived!—it opened its mouth "like scissors," as Ollie Kuhns's piece had said. It had not the traditional bag, but it had a basket, Grandmother Gaumer's, and the traditional cakes were there. It climbed upon a desk, its black-stockinged legs and red dress showing through the rents of the old, ragged coat, and the children surrounded it, laughing, begging, screaming with delight.

The stranger stood and looked at Katy. He did not yet realize how large a part she had had in the entertainment, though about that a proud grandfather would soon inform him; he saw the Gaumer eyes and the Gaumer bright face, and he remembered with sharp pain the eyes of a little sister gone fifty years ago.

"Who is that child?" he asked.

Katy's grandfather called her to him, and she came slowly, slipping like a crimson butterfly from the old coat, which the other children seized upon with joy. She heard the governor's question and her grandfather's answer.

"It is my Abner's only child."

Then Katy's eyes met the stranger's bright gaze. She halted in the middle of the room, as though she did not know exactly what she was doing. Their praise embarrassed her, her foolish anger at David [pg 31] Hartman hurt her, her head swam. Even her joy seemed to smother her. This great man had hated Millerstown, as she hated Millerstown, sometimes, or he would not have gone away; he had loved it as she did, or he would not have come back to laugh and weep with his old friends. Perhaps he, too, had wanted everything and had not known how to get it; perhaps he, too, had wanted to fly and had not known where to find wings! A consciousness of his friendliness, of his kinship, seized upon her. He would understand her, help her! And like the child she was, Katy ran to him. Indeed, he understood even now, for stooping to kiss her, he hid her foolish tears from Millerstown.

On ordinary Christmas days, when only the squire and the doctor and Uncle Edwin and Aunt Sally and little Adam and Bevy Schnepp dined at Grandfather Gaumer's, Grandmother Gaumer and Bevy prepared a fairly elaborate feast. There was always a turkey, a twenty-five pounder with potato filling, there were all procurable vegetables, there were always cakes and pies and preserves and jellies without number. One gave one's self up with cheerful helplessness to indigestion, one resigned one's self to next day's headache—that is, if one were not a Gaumer. No Gaumer ever had headache.

It cannot be claimed for Katy that she was of much assistance to her elders on this Christmas Day, tall girl though she was. Grandfather Gaumer and the governor started soon after breakfast to pay calls in the village and her thoughts were with them. How glad every one would be to see the governor; how they would press cakes and candy upon him; how he would joke with them; how they would treasure what he said! What a wonderful thing it was to be famous and to have every one admire you!

"I would keep the chair he sat in," said Katy. "I would put it away and keep it."

[pg 33] Presently Katy saw Katy Gaumer coming back to her native Millerstown, covered with honors, of what sort Katy did not exactly know, and going about on Christmas morning to see the Millerstown Christmas trees and to receive the homage of a delighted community.

Meanwhile, Katy tripped over her own feet and sent a dish flying from the kitchen table, and started to fill the teakettle from the milk-pitcher. Finally, to Bevy Schnepp's disgust, Katy spilled the salt. Bevy was as much one of the party as the governor. She moved swiftly about, her little face twisted into a knot, profoundly conscious of the importance of her position as assistant to the chief cook on this great day, her shrill voice now breathing forth commands, now recounting strange tales. Grandmother Gaumer, to whose kitchen Bevy was a thrice daily visitor, had long ago accustomed herself not to listen to the flow of speech, and had thereby probably saved her own reason.

"You fetch me hurry a few coals, Katy. Now don't load yourself down so you cannot walk! 'The more haste the less speed!' Adam, you take your feet to yourself or they will get stepped on for sure. Gran'mom, your pies! You better get them out or they burn to nothing! Go in where the Putz is, Adam, then you are not all the time under the folks' feet. Sally Edwin, you peel a few more potatoes for me, will you, Sally, for the mashed potatoes? Mashed potatoes go down like nothing. Ach, I had [pg 34] the worst time with my supper yesterday! The chicken wouldn't get, and the governor was there. I tell you, the Old Rip was in it! But I carried the pan three times round the house and then it done fine for me. Katy, if you take another piece of celery, I'll teach you the meaning. To eat my nice celery that I cleaned for dinner! And the hard, yet! If you want celery, fetch some for yourself and clean it and eat it. I'd be ashamed, Katy, a big girl like you! You want to be so high gelernt, you think you are a platform speaker, yet you would eat celery out of the plate. Look out, the salt, Katy! Well, Katy! Would you spill the salt, yet! Do you want to put a hex on everything? I—"

"Bevy!" Katie exploded with alarm.

"What is it?" cried Bevy.

"Your mouth is open!"

"I—I—" Bevy gurgled, then gasped. Bevy was not slow on the uptake. "I opened it, I opened it a-purpose to tell you what I think of you. I—"

But Katy, hearing an opening door, had gone, dancing into the sitting-room, where, on great days like this, the feast was spread. The room was larger than the kitchen; in the center stood the long table, and in one corner was the Christmas tree with the elaborate "Putz," a garden in which miniature sheep and cows walked through forests and swans swam on glass lakelets. Before the "Putz," entranced, sat fat Adam; near by, beside the shiny "double-burner," the governor and his brothers [pg 35] and young Dr. Benner were establishing themselves. The governor had still a hundred questions to ask.

Katy perched herself on the arm of her grandfather's chair, saying to herself that Bevy might call forever now and she would not answer. The odor of roasting turkey filled the house, intoxicating the souls of hungry men, but it was not half so potent as this breath of power, this atmosphere of the great world of affairs, which surrounded Great-Uncle Gaumer. Katy's heart thumped as she listened; the great, vague plans which she had made in the night seemed at one moment possible of execution, at the next absolutely mad. Her face flushed and her skin pricked as she thought of making known her desires; her heart seemed to sink far below its proper resting-place. She listened to the governor with round, excited eyes, now praying for courage, now yielding to despair.

The governor's questions did not refer to the great world,—it seemed as though the world had become of no account to him,—but to Millerstown, the Millerstown of his youth, of apple-butter matches, of raffles, of battalions, of the passing through of troops to the war, of the rough preachers of a stirring age. He remembered many things which his brothers had forgotten; they and the younger folk listened entranced. As for Bevy, moving about on tiptoe, so as not to miss a word,—it was a marvel that she was able to finish the dinner.

[pg 36] "He traveled on horseback," said the governor. "He had nothing to his name in all the world but his horse and his old saddlebags, and he visited the people whether they wanted him or not. At our house he was always welcome,—he stayed once a whole winter,—and on Sundays he used to give it to us in church, I can tell you! Everything he'd yell out that would come into his mind. One Sunday he yelled at me, 'There you stand in the choir, and you couldn't get a pig's bristle between your teeth. Sing out, Daniel!'

"But he could preach powerfully! He made the people listen! There was no sleeping in the church when he was in the pulpit. If the young people did not pay attention, he called right out, 'John, behave! Susy, look at me!'"

"We have such a preacher here," said Uncle Edwin in his slow way. "He is a Improved New Mennonite. He—"

"They wear hats with Scripture on them, and they sing, 'If you love your mother, keep her in the sky,'" interrupted Katy.

"'Meet her in the sky,'" corrected Grandmother Gaumer. "That has some sense to it."

"He won't read the words as they are written in the Bible," went on Uncle Edwin, apparently not minding the interruption. He shared with the rest of Katy's kin their foolish opinion of Katy. "He says the words that are printed fine don't belong there, they are put in. It is like riding on a bad road, [pg 37] his reading. It goes bump, bump. It sounds very funny."

"He preaches on queer texts," said Katy. "He preached on 'She Fell in Love with her Mother-in-Law.'"

"Now, Katy!" admonished Grandmother Gaumer.

Bevy Schnepp had endured as much as she could of insult to the denomination to which she belonged and to the preacher under whom she sat.

"Your Lutheran preachers have 'kein Saft und kein Kraft, kein Salz und kein Peffer' [no sap and no strength, no salt and no pepper]," she quoted. "They are me too leppish [insipid]. You must give these things a spiritual meaning. It meant Naomi and Ruth."

The governor smiled his approval at Bevy. "Right you are, Bevy!" Then he began to ask questions about his former acquaintances.

"What has come over John Hartman?"

"While he is so cross, you mean?" said Grandfather Gaumer. "I don't know what has come over him. It is a strange thing. He is so long queer that we forget he was ever any other way."

"Was he ugly this morning?" asked Grandmother Gaumer.

"He didn't ask us to come in and she didn't come to the door at all."

Bevy Schnepp, entering with laden hands, made sharp comment.

[pg 38] "She is afraid her things will get spoiled if the sun or the moon or the cold air strikes them. She is crazy for cleanness. She will get yet like fat Abby. Fat Abby once washed her hands fifteen times before breakfast, and if he (her husband) touched the coffee-pot even to push it back with his finger if it was boiling over, then she would make fresh."

"And do the Koehlers still live on the mountain?"

"There are only two Koehlers left," answered the squire, "William and his boy." The squire shook his head solemnly. "It is a queer thing about the Koehlers, too. The others were honest and right in their minds, but William, he is none of these things."

"Not honest!" said the governor.

"About fifteen years ago he did some bricklaying at the church and he had the key of the communion cupboard. The solid service was there and while he was working it disappeared."

"Disappeared!" repeated the governor. "You mean he took it? What could he do with it?"

"I don't know. Nobody knows. He goes about muttering and praying over it. They say his boy hardly gets enough to eat. I can't understand it."

"He!" Bevy now had the great turkey platter in her arms; its weight and her desire to express herself made her gasp. "He! He looks at a penny till it is a twenty-dollar gold-piece. And you ought to see his boy! He is for all the world like a girl. 'Like father, like son!' He'll do something, too, yet."

[pg 39] Katy slid from the arm of her grandfather's chair, her cheeks aflame.

"You have to look at pennies when you are poor," she protested. "You can't throw money round when you don't have it!"

Bevy slid the platter gently to its place on the table, then she faced about.

"Now, listen once!" cried she with admiration. "You can't throw money round when you don't have it, can't you? What do you know about it, you little chicken?"

Katy's face flushed a deeper crimson. If looks could have slain, Bevy would have dropped. Young Dr. Benner turned and looked at Katy suddenly and curiously. She would have gone on expostulating had not Grandmother Gaumer risen and the other Gaumers with her, all moving with one accord toward the feast. There was time only for a secret and threatening gesture toward Bevy, then Katy bent her head with the rest.

"'The eyes of all wait upon Thee,'" said Grandfather Gaumer in German. "'Thou givest them their meat in due season.'"

Heartily the Gaumers began upon the Christmas feast, the feast beside which the ordinary Christmas dinner was so poor and simple a thing. Here was the turkey, done to a turn, here were all possible vegetables, all possible pies and cakes and preserves. To these Grandmother Gaumer had added a few common side-dishes, so that her brother-in-law [pg 40] might not return to the West without a taste, at least, of all the staple foods of his childhood. There was a slice of home-raised, home-cured ham; there was a piece of smoked sausage; there was a dish of Sauerkraut and a dish of "Schnitz und Knöpf,"—these last because the governor had mentioned them yesterday in his speech. It was well that the squire lived next door and that Bevy had her own stove to use as well as Grandmother Gaumer's.

Bevy occupied the chair nearest the kitchen door. There are few class distinctions in Millerstown, though one is not expected to leave the station in life in which he was born. It was proper for Bevy to occupy the position of maid and for little Katy to go to school. If Katy had undertaken to live out, or Bevy to become learned, Millerstown would have disapproved of both of them. When each remained in her place, they were equal.

The governor tasted all the dishes serenely, and Grandmother Gaumer apologized from beginning to end, as is polite in Millerstown. The turkey might have been heavier—if he had, he would certainly have perished long before Grandfather's axe was sharpened for him! The pie might have been flakier, the sausage might have been smoked a bit longer—it would have been sinful to add a breath of smoke to what was already perfect.

"And then it wouldn't have been ready for to-day!" said the governor.

"But we might have begun earlier." Grandmother [pg 41] Gaumer would not yield her point. "If we had butchered two days earlier, it would have been better."

When human power could do no more, when Bevy had no more breath for urgings, such as, "Ach, eat it up once, so it gets away!" or "Ach, finish it; it stood round long enough already!" the Gaumers pushed back their chairs and talked with mellower wit and softer hearts of old times, of father and mother and grandparents, and of the little sister who had died.

"She was just thirteen," said Governor Gaumer. "She was the liveliest little girl! I often think if she had lived, she would have made of herself something different from the other people in Millerstown. But now she would have been an old woman, think of that!" The governor held out his hand and Katy came across to him, her eyes filled with tears. Katy was always easily moved. "Didn't she look like this one?"

"Yes," agreed Grandfather Gaumer. "That I always said."

The governor laid both his hands on Katy's shoulders.

"And what"—said he,—"what are you going to do in this world, Miss Katy?"

Katy looked up at him with a deep, deep breath. She had thought that yesterday held a great moment, but here was a much greater one. She clasped her hands, she gasped again, she looked the governor [pg 42] straight in the face. Here was her opportunity, the opportunity which she had begun to think would never come.

"Ach," said Katy with a deep sigh, "when I am through the Millerstown school, I should like to go to a big school and learn everything!"

The governor smiled upon her.

"Everything, Katy!"

"Yes," sighed Katy.

"Listen to her once!" cried Bevy Schnepp with pride.

"Can't you learn enough here?"

"I am already in the next to the highest class," explained Katy. "And our teacher, he is not a very good one. He wants to be English and a teacher ought to be English, but he is werry Germaner than the scholars. He said to us in school, 'We are to have nothing but English here, do you versteh?' That is exactly the way he said it to us. He says lots of words that are not English. I want to be English. I—"

"Just listen now!" cried Bevy again, her hands piled high with dishes.

"I want to be well educated," finished Katy with glowing cheeks.

"And what would you do when you were educated?" asked the governor.

"I would leave Millerstown," said Katy.

"Why?" asked the governor.

"It would be no use having an education in Millerstown," [pg 43] answered Katy with conviction. "You have no idea how slow Millerstown is."

"And where did you think you would go?"

"Perhaps to Phildel'phy," answered Katy. "Perhaps I would be a missionary to Africay."

Strange sounds issued from the throats of Katy's kin.

"You are sure you could do nothing in Millerstown with an education?" asked the governor.

"It is nothing to do here," explained Katy. "You can walk round Millerstown a whole evening and you don't hear anything and you don't see anything."

"Would she like murders?" demanded Bevy Schnepp.

"You go in the store and Caleb Stemmel and Danny Koser are too dumb and lazy even to read the paper, and Sarah Ann Mohr is hemming and everybody else is sleeping. The married people sit round and don't say anything, and—"

"Do you want them to fight?" Bevy was not discouraged by being ignored.

"You think it would be better to be a missionary?" said the governor.

"It would be better to be anything," declared Katy fervently. "I cannot stand Millerstown!" Katy clasped her hands and looked into the face of her distinguished relative. "Oh, please, please make them send me away to a big school! I prayed for it!" added Katy.

[pg 44] Over Katy's head the eyes of her elders met. The older folk thought of the little girl who might have been something different, the squire remembered the journeys he had planned in his youth and the years he had waited to take them.

But to Katy's chagrin and bitter disappointment, no one said another word about an education. Grandmother Gaumer suggested that Katy might help Aunt Sally and Bevy with the dishes. Afterwards, Katy was called upon to say her piece once more. When little Adam followed with his Bible verse and was given equal praise, Katy's poor heart, sinking lower and lower, reached the most depressed position which it is possible for a heart to assume. Her cause was lost.

Then the governor prepared to start on his long journey to the West. There he had grown sons and daughters and little grandchildren whom these Eastern cousins might never see. He kissed Grandmother Gaumer and his niece Sally and little Adam and Katy, and shook hands with Bevy Schnepp, then he returned and kissed Grandmother Gaumer once more. There was something solemn in his farewell; at sight of Grandmother Gaumer's face Katy was keenly conscious once more of her own despair. From the window she watched the three old men go down the street, the famous man who had gone away from Millerstown and the two who had stayed. It seemed to Katy that the two were less noble because of the obscurity of their lives.

[pg 45] "Why did gran'pop stay here always?" she asked when she and her grandmother were alone. "Why did uncle go away?"

"Gran'pop was the oldest, and he and the squire had to stay here. Uncle had the chance to go."

"But—" Katy crossed to her grandmother's side. Everything was still in the warm, pine-scented room. "But, grandmother, why do you cry?"

"I am not crying," said grandmother brightly.

"But you look—you look as if"—Katy struggled for words in which to express her thoughts—"as if everything were finished!"

Grandmother sighed gently. "I am an old woman, Katy, and your uncle is an old man. We may never see each other again."

"Oh, dear! oh, dear!" cried Katy. "This is a very sad Christmas!"

It was not the sadness of parting which made Katy cry. It was unthinkable that anything should change for her. Everything would be the same, always—alas, that it should be so! She, Katy Gaumer, with all her smartness in school, and all her ability to plan and manage entertainments, would stay here in this spot until she died. Grandmother Gaumer, reproaching herself, comforted her for that which was not a grief at all.

"We will be here a long time yet. And you are to go away to school, and—"

Katy sprang to her feet.

[pg 46] "Who says it, gran'mom? Who says I dare go to school?"

"Your gran'pop said it, and your uncles said it when you were out with Bevy. You are to study here till you are through with the highest class, then you are to go away. Your uncle will find a school: he will send us catalogues and he will give us advice."

Katy clasped her hands.

"I do not deserve it!"

"You said you prayed for it," reminded Grandmother Gaumer.

"But I prayed without faith," confessed Katy. "I did not believe for one little minute it would ever come true in this world!"

"Well," said Grandmother Gaumer, "it is coming true."

Here for once was bliss without alloy, here was a rapture without reaction. Christmas entertainments, at which one did well, ended; there was no outlook from them, and it was the same with perfect recitations in school. But this was different. One had the moment's complete joy, one had also something much better.

"I must study," planned Katy. "I must learn. I must make"—alas, that one's joy should be another's bitter trial!—"I must make that teacher learn me everything he knows!"

It was dusk when Grandfather Gaumer came home.

[pg 47] "I told Katy," said Grandmother Gaumer.

"Daniel gave me two hundred dollars to put in the bank in Katy's name," announced Grandfather Gaumer solemnly. "It shall be spent for books and to start Katy. He and the squire and I will see her through."

Katy flung herself upon her grandfather.

"I will learn everything," she promised. "I will make you proud of me. Like it says in the Sunday School book, 'I will bring home my sheaves.' And now," said Katy, "I am going to run out to the schoolhouse and back."

In an instant she was gone, scarlet shawl about her, slamming the door. Perhaps the two old people sitting together were not sorry to have her away for a while. The day with its memories and its parting had been hard, and the mere youthfulness of youth is sometimes difficult for age to bear.

"Her legs fly like the arms of a windmill," said Grandfather Gaumer.

Then they sat silently together.

Already Katy was halfway out to the schoolhouse. The threatened snow had fallen and the sky had cleared at sunset. There was still a faint, rosy glow in the west, a glow which was presently dimmed by the brighter light which spread over the landscape as the cinder ladle at the furnace turned out its fiery charge upon the cinder bank. When that flame faded, the stars were shining brightly; Katy stood in the road before the schoolhouse and looked up [pg 48] at them and then round about her. The schoolhouse, glorified by her recent triumph, was further sanctified by her great hopes. Beside it on the hillside stood the little church, where she had been confirmed and had had her first communion, where during the long German sermons she had dreamed many dreams, and where she had been thrilled by solemn watch-night services. Millerstown was not without power to impress itself even upon one who hated it.

Now Katy raced down the hill. But she was not ready to go into the house. She shrieked into Bevy Schnepp's kitchen window; she almost upset Caleb Stemmel as he plodded to his place behind the stove in the store, wishing that there were no Christmases; she ran once more to the end of Locust Street and across to Church Street and looked through the thick trees at the Hartman house. David had surely some handsome Christmas gifts from his parents. Then, straining her eyes, she gazed up at the little white house on the mountain-side. There was not much Christmas there, that was certain, but Alvin was there, handsome, adorable. Alvin would pay heed to her if she was going away, the one person in Millerstown to be educated!

Then Katy stretched out her arms.

"Oh, dear Millerstown!" cried Katy. "Oh, dear, dumb Millerstown, I am going away from you!"

At Grandfather Gaumer's house, where the governor dined; at the Weygandt farm where there was another great family dinner; at the Kuhnses, where Ollie still swelled proudly over yesterday's oratorical triumph; at Sarah Ann Mohr's, where ten indigent guests filled themselves full of fat duck,—indeed, one might say at every house in Millerstown, there was feasting. The very air smelled of roasting and boiling and frying, and the birds passing overhead stopped and settled hopefully on trees and roofs.

But in the house of William Koehler, just above Millerstown on the mountain road, there was no turkey or goose done to a turn, there were no pies, there was no fine-cake. Here was no mother or grandmother to make preserves or to compound mincemeat in preparation for this day of days. What mother there had been was seldom thought of in the little house.

Here the day passed like any other day, except that it was duller and less tolerable. There was no school for Alvin and no work for his father, and they had to spend the long hours together. Alvin did not like school, but to-day he would cheerfully have gone [pg 50] before daylight and have remained until dark. His father did not like holidays; they removed the goal, for which he worked and of which he thought night and day, a little farther away from him. He would have preferred to work every day, even on Sundays.

William was a mason by trade, but when there was no mason work for him, he was willing to turn his hand to anything which would bring him a little money. Another mason had recently established himself in the village, urged, it was supposed, by those who were unwilling to admit Koehler to their houses for the occasional bits of plastering which had to be done. There was no question that Koehler was very queer. Not only was he likely to kneel down at any moment and begin to pray, but he did other singular things. He had once worked until two o'clock in the afternoon without his dinner, because his watch had stopped and he had not sense enough to know it. It was not strange that thrifty Millerstown agreed that he was not a safe person to have about.

Between him and his son there was little sympathy; there was, indeed, seldom speech. Alvin was bitterly ashamed of his father, of his miserly ways, of his shabby clothes, and above all, of his insane habit of praying. William prayed incoherently about the communion service which he was supposed to have stolen—at least, that was what seemed to be the burden of his petition. Whether he prayed for grace to return it, or for forgiveness for having taken it, Millerstown did not know, so confused was his [pg 51] speech. Alvin's position was a hard one. He was humiliated by the taunts of the Millerstown boys; he hated the poverty of his life; he was certain that never had human being been so miserable.

Early on Christmas morning the two had had their breakfast together in the kitchen of the little white house where they lived, and there Alvin had made an astonishing request. Alvin was fond of fine clothes; there was a certain red tie in the village store at which he had looked longingly for days. Alvin was given to picturing himself, as Katy Gaumer pictured herself, in conspicuous and important positions in the eyes of men. Alvin's coveted distinction, however, was of fine apparel, and not of superior education. He liked to be clean and tidy; he disliked rough play and rough work which disarranged his clothes and soiled his hands.

"Ach, pop," he begged, "give me a Christmas present!" His eyes filled with tears, he had been cruelly disappointed because he had found no way to get the tie in time for the Christmas entertainment. "Everybody has a Christmas present!"

"A Christmas present!" repeated William Koehler, his quick, darting eyes shining with amazement. His were not mean features; he had the mouth of a generous man, and his eyes were full and round. But between his brows lay a deep depression, as though experience had moulded his forehead into a shape for which nature had not intended it. If it had not been for that deep wrinkle, one would have [pg 52] said that he was a gentle, kindly, humorous soul. "A Christmas present!" said he again.

Without making any further answer, he rose and went out the kitchen door and down the board walk toward the chicken house. He repeated the monstrous request again and again, like a person of simple mind.

"A Christmas present! He asks me for a Christmas present!"

When he reached the chicken house, he stood still, leaning against the fence. The chickens clustered about him with crowings and squawkings, some flying to his shoulders. Birds and beasts and insects loved and trusted poor William if human beings did not. It was possible for him to go about among his bees and handle them as he would without fear of stings.

Now he paid no heed to the flapping, eager fowl, except to thrust them away from him. He stood leaning against the fence and looking down upon the gray landscape. It was not yet quite daylight and the morning was cloudy. The depression in his forehead deepened; he was looking fixedly at one spot, John Hartman's house, as though he had never seen it before, or as though he meant to fix it in his mind forever.

The Hartman house was always there. He had seen it a thousand times, would see it a thousand times more. On moonlight nights, its wide roofs glittered, on dark nights a gleaming lamp set on a [pg 53] post before the door fixed it in place. In winter its light and its great bulk, in summer its girdle of trees, distinguished it from all the other houses in Millerstown. William Koehler could see it from every foot of his little house and garden. It was before his eyes when he worked among his plants, which seemed to love him also, and when he sat for a few minutes on his porch, and when he tended his bees or fed his chickens.

Beyond the Hartman house he did not look. There the country spread out in a wide, cultivated, varicolored plain, with the mountains bounding it far away. To the right of the village was the little cemetery where his wife lay buried, and near it the Lutheran church to which they had both belonged, but he glanced at neither. Sometimes he could see John Hartman helping his wife from the carriage when they returned from church, or stamping the snow from his feet before he stepped into his buggy in the stable yard. Often, at this sight, when there was no one within hearing, William waved his arms and shouted, as though nothing but a wild sound could express his emotion. He was not entirely free from the superstitions in which Bevy and many other Millerstonians believed, superstitions long since seared upon the souls of a persecuted generation in the fatherland. He recited the strange verse, supposed to ward away evil,—

[pg 54] and he carried about with him a little spray of five-finger grass as a charm.

When John Hartman drove along the mountain road, his broad shoulders almost filling his buggy, William had more than once shouted an insane accusation at him. This Millerstown did not know. Koehler never spoke thus unless they were alone, and Hartman told no one of the encounter. One is not likely to tell the world that he has been accused of stealing, even though the accuser is himself known to be a madman and a thief. But John Hartman came presently to avoid the mountain road.

After a while William roused himself and fed his chickens and looked once more at the house of John Hartman. There was smoke rising from the chimney, and tears came into William's eyes, as though the smoke had drifted across the fields and had blinded him. Suddenly he struck the sharp paling a blow with his hard hand and spoke aloud, not with his usual faltering and mumbling tongue, but clearly and straightforwardly. William had found a help and a defense.

"I will tell him!" cried he. "This day I will tell my son, Alvin!"

All the long, snowy Christmas morning, Alvin sat about the house. He did not read because he had no books, and besides, he did not care much for books. Alvin was a very handsome boy, but he did not have much mind. He did not sing or whistle on this Christmas morning because he was not cheerful; he did [pg 55] not whittle because whittling would have wasted both knife and stick, and his father would have reproved him. He did not walk out because he was not an active boy like David Hartman, and he did not visit because he was not liked in Millerstown. He did not take a boy's part in the games; he was afraid to swim and dive; he whined when he was hurt.

He looked out the window toward the Hartman house with a vague envy of David, who had so much while he had so little. He watched his father's parsimonious preparation of the simple meal—how Grandmother Gaumer and Bevy Schnepp would have exclaimed at a Christmas dinner of butcher's ham!

"Oh, the poor souls!" Grandmother Gaumer would have cried. "I might easily have invited them to us to eat!"

"Where does the money go, then?" Bevy would have demanded. "He surely earns enough to have anyhow a chicken on Christmas! Where does he put his money? No sugar in the coffee! Just potatoes fried in ham fat for vegetables!"

All the long afternoon, also, Alvin sat about the house. He did not think again of the Hartmans; he did not think of Katy Gaumer, who thought so frequently of him; he thought of the red tie and wished that he had money to buy it.

All the long afternoon his father huddled close to the other side of the stove and muttered to himself as though he were preparing whatever he meant [pg 56] to tell Alvin. It must be either a very puzzling or a very long story, or one which required careful rehearsing. When the sun, setting in a clear sky, had touched the top of a mountain far across the plain, he began to speak suddenly, as though he had given to himself the departure of day for a signal. He did not make an elaborate account of the strange events he had to relate; on the contrary, he could hardly have omitted a word and have had his meaning clear. He said little of Alvin's mother; he drew no deductions; he simply told the story.

"Alvin!" cried he, sharply.

Alvin looked up. His head had sunk on his breast; he was at this moment half asleep. He was startled not alone by the tone of his father's voice, but by his father's straightened shoulders, by his piercing glance.

"I am going to tell you something!"

Alvin looked at his father a little eagerly. Perhaps his father was going to give him a present, after all. It would take only a quarter to buy the red tie. But it was a very different announcement which William had to make. He began with an alarming statement.

"After school closes you are to work at the furnace. I let you do nothing too long already, Alvin!"

"At the furnace!" Alvin's astonishment and alarm made him cry out. He hated the sight of Oliver Kuhns and Billy Knerr when they came home all grimy and black.

[pg 57] "I will tell you something," said his father again. "Listen good, Alvin!"

Alvin needed no such command to make him hearken. Alvin had not much will, but he was determining with all his power that he would never, never work in the furnace. He did not observe how his father's cheeks had paled above his black beard, and how steadily he kept his eyes upon his son. The story William had to tell was not that of a man whose mind was gone.

"You know the church?" said William.

"Of course."

"I mean the Lutheran church where I used to go, where my pop went."

"Yes."

"You go in at the front of the church, but the pulpit is at the other end. There were once long ago two windows, one on each side of the pulpit. They went almost down to the floor. From there the sun shone in the people's eyes. You can't remember that, Alvin. That was before your time."

Alvin sat still, sullenly. This conversation was, after all, only of a piece with his father's strange mutterings; it had to do with no red necktie.

"But now the Sunday School is there and those windows are gone this long time. One is a door into the Sunday School, the other is a wall. I built that wall, Alvin."

William paused as though for some comment, but Alvin said nothing.

[pg 58] "I was sitting where I am sitting now one evening and she [his wife] was sitting where you are sitting and you were running round, and the preacher climbed the hill to us and he came in and he said to me, 'William,' he said, 'it is decided that the big window is to be walled up. When can you do it?' That was the way he said it, Alvin. I said to him, 'I can do it to-morrow. I had other work for the afternoon at Zion Church, but I can put it off.' She could have told you that that was just what he said and what I said. I was in the congregation and there was at that time no other mason but me in Millerstown. It was to be made all smooth, so that nobody could ever tell there was a window there. Then the preacher, he said to me,—she could tell you that, too, if she were here,—he said, 'Come in the morning and I will give you the key of the communion cupboard,' the little cupboard in the wall, Alvin. There the communion set was kept. It was silver, real silver, all shiny." William's hands began to tremble and he moistened his dry lips. William spoke of objects which were to him manifestly holy. His son bent his head now, not idly and indifferently, but stubbornly. He remembered the names which the boys had shouted at his father; with all his soul he recoiled from hearing his father's confession. "There was a silver pitcher, so high, and a silver plate and a silver cup on a stem like a goblet. The preacher put it away there and he locked the door always.

[pg 59] "But he gave me the key and I went to my work. I thought once I would have to open the door and I stuck the key in the lock. It was a funny key.