LIFE OF NAPOLEON

Pocket Edition

VOL. I.

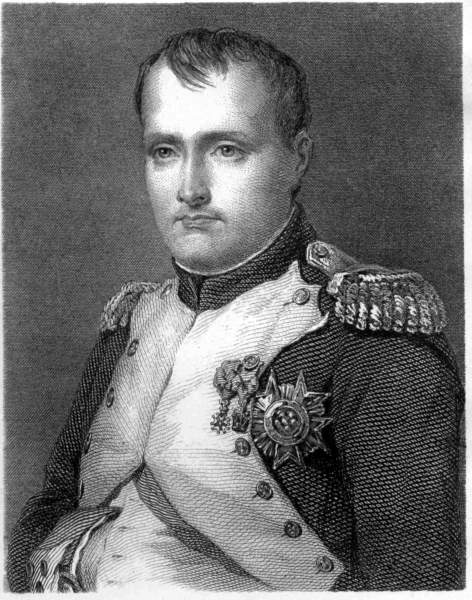

NAPOLEON BONAPARTE

1802

Title: Life of Napoleon Bonaparte, Volume I.

Author: Walter Scott

Release date: May 2, 2015 [eBook #48837]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Susan Skinner and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Pocket Edition

VOL. I.

NAPOLEON BONAPARTE

1802

LIFE OF

NAPOLEON BONAPARTE

By SIR WALTER SCOTT, BART.

VOL. 1.

Napoleons Logement Qua Cont

EDINBURGH; A. & C. BLACK.

1876{iii}

The extent and purpose of this Work, have, in the course of its progress, gradually but essentially changed from what the Author originally proposed. It was at first intended merely as a brief and popular abstract of the life of the most wonderful man, and the most extraordinary events, of the last thirty years; in short, to emulate the concise yet most interesting history of the great British Admiral, by the Poet-Laureate of Britain.[1] The Author was partly induced to undertake the task, by having formerly drawn up for a periodical work—"The Edinburgh Annual Register"—the history of the two great campaigns of 1814 and 1815; and three volumes were the compass assigned to the proposed work. An introductory volume, giving a general account of the Rise and Progress of the French Revolution, was thought necessary; and the single volume, on a theme of such extent, soon swelled into two.

As the Author composed under an anonymous title, he could neither seek nor expect information from those who had been actively engaged in the changeful scenes which he was attempting to record; nor was his object more ambitious than that of compressing and arranging such information as the ordinary authorities afforded. Circumstances, however, unconnected with the undertaking, induced him to lay aside an incognito, any farther attempt to preserve which must have been considered as affectation; and since his having done so, he has been favoured with access to some valuable materials, most of which have now, for the first time, seen the light. For these he refers to the Appendix at the close of the Work, where the reader will find several articles of novelty and interest. Though not at liberty, in every case, to mention the quarter from which his information has been derived, the Author has been careful not to rely upon any which did not come from sufficient authority. He has neither grubbed for anecdotes in the libels and private scandal of the {iv}time, nor has he solicited information from individuals who could not be impartial witnesses in the facts to which they gave evidence. Yet the various public documents and private information which he has received, have much enlarged his stock of materials, and increased the whole work to more than twice the size originally intended.

On the execution of his task, it becomes the Author to be silent. He is aware it must exhibit many faults; but he claims credit for having brought to the undertaking a mind disposed to do his subject as impartial justice as his judgment could supply. He will be found no enemy to the person of Napoleon. The term of hostility is ended when the battle has been won, and the foe exists no longer. His splendid personal qualities—his great military actions and political services to France—will not, it is hoped, be found depreciated in the narrative. Unhappily, the Author's task involved a duty of another kind, the discharge of which is due to France, to Britain, to Europe, and to the world. If the general system of Napoleon has rested upon force or fraud, it is neither the greatness of his talents, nor the success of his undertakings, that ought to stifle the voice or dazzle the eyes of him who adventures to be his historian. The reasons, however, are carefully summed up where the Author has presumed to express a favourable or unfavourable opinion of the distinguished person of whom these volumes treat; so that each reader may judge of their validity for himself.

The name, by an original error of the press, which proceeded too far before it was discovered, has been printed with a u,—Buonaparte instead of Bonaparte. Both spellings were indifferently adopted in the family; but Napoleon always used the last,[2] and had an unquestionable right to choose the orthography which he preferred.

Edinburgh, 7th June, 1827.

Sir Walter Scott left two interleaved copies of his Life of Napoleon, in both of which his executors have found various corrections of the text, and additional notes. They were directed by his testament to take care, that, in case a new edition of the work were called for, the annotations of it might be completed in the fashion here adopted, dates and other marginal elucidations regularly introduced, and the text itself, wherever there appeared any redundancy of statement, abridged. With these instructions, except the last, the Editor has now endeavoured to comply.[3]

"Walter Scott," says Goëthe, "passed his childhood among the stirring scenes of the American War, and was a youth of seventeen or eighteen when the French Revolution broke out. Now well advanced in the fifties, having all along been favourably placed for observation, he proposes to lay before us his views and recollections of the important events through which he has lived. The richest, the easiest, the most celebrated narrator of the century, undertakes to write the history of his own time.

"What expectations the announcement of such a work must have excited in me, will be understood by any one who remembers that I, twenty years older than Scott, conversed with Paoli in the twentieth year of my age, and with Napoleon himself in the sixtieth.

"Through that long series of years, coming more or less into contact with the great doings of the world, I failed not to think seriously on what was passing around me, and, after my own fashion, to connect so many extraordinary mutations into something like arrangement and interdependence.

"What could now be more delightful to me than leisurely and calmly to sit down and listen to the discourse of such a man, while clearly, truly, and with all the skill of a great artist, he recalls to me the incidents on which through life I have meditated, and the influence of which is still daily in operation?"—Goëthe's Posthumous Works, vol. vi., p. 253.

Lucani, Pharsalia, Lib. I.[4]

VIEW OF THE FRENCH REVOLUTION.

PAGE

Chap. I.—Review of the state of Europe after the Peace of Versailles—England—France—Spain—Prussia—Imprudent

Innovations of the Emperor

Joseph—Disturbances in his Dominions—Russia—France—Her ancient

System of Monarchy—how organised—Causes of its Decay—Decay of

the Nobility as a body—The new Nobles—The Country Nobles—The

Nobles of the highest Order—The Church—The higher Orders of the

Clergy—The lower Orders—The Commons—Their increase in Power

and Importance—Their Claims opposed to those of the Privileged

Classes, 1

Chap. II.—State of France continued—State of Public Opinion—Men of Letters encouraged by the Great—Disadvantages attending this Patronage—Licentious tendency of the French Literature—Their Irreligious and Infidel Opinions—Free Opinions on Politics permitted to be expressed in an abstract and speculative, but not in a practical Form—Disadvantages arising from the Suppression of Free Discussion—Anglomania—Share of France in the American War—Disposition of the Troops who returned from America, 22

Chap. III.—Proximate Cause of the Revolution—Deranged State of the Finances—Reforms in the Royal Household—System of Turgot and Necker—Necker's Exposition of the State of the Public Revenue—The Red-Book—Necker displaced—Succeeded by Calonne—General State of the Revenue—Assembly of the Notables—Calonne dismissed—Archbishop of Sens Administrator of the Finances—The King's Contest with the Parliament—Bed of Justice—Resistance of the Parliament and general Disorder in the Kingdom—Vacillating Policy of the Minister—Royal Sitting—Scheme of forming a Cour Plénière—It proves ineffectual—Archbishop of Sens retires, and is succeeded by Necker—He resolves to convoke the States-General—Second Assembly of Notables previous to Convocation of the States—Questions as to the Numbers of which the Tiers Etat should consist, and the Mode in which the Estates {viii}should deliberate, 39

Chap. IV.—Meeting of the States-General—Predominant Influence of the Tiers Etat—Property not represented sufficiently in that Body—General character of the Members—Disposition of the Estate of the Nobles—And of the Clergy—Plan of forming the Three Estates into two Houses—Its advantages—It fails—The Clergy unite with the Tiers Etat, which assumes the title of the National Assembly—They assume the task of Legislation, and declare all former Fiscal Regulations illegal—They assert their determination to continue their Sessions—Royal Sitting—Terminates in the Triumph of the Assembly—Parties in that Body—Mounier—Constitutionalists—Republicans—Jacobins—Orleans, 58

Chap. V.—Plan of the Democrats to bring the King and Assembly to Paris—Banquet of the Garde du Corps—Riot at Paris—A formidable Mob of Women assemble to march to Versailles—The National Guard refuse to act against the Insurgents, and demand also to be led to Versailles—The Female Mob arrive—Their behaviour to the Assembly—To the King—Alarming Disorders at Night—La Fayette arrives with the National Guard—Mob force the Palace—Murder the Body Guards—The Queen's safety endangered—Fayette's arrival with his Force restores Order—Royal Family obliged to go to reside at Paris—The Procession—This Step agreeable to the Views of the Constitutionalists, Republicans, and Anarchists—Duke of Orleans sent to England, 88

Chap. VI.—La Fayette resolves to enforce order—A Baker is murdered by the Rabble—One of his Murderers executed—Decree imposing Martial Law—Introduction of the Doctrines of Equality—They are in their exaggerated sense inconsistent with Human Nature and the progress of Society—The Assembly abolish titles of Nobility, Armorial bearings, and phrases of Courtesy—Reasoning on these Innovations—Disorder of Finance—Necker becomes unpopular—Seizure of Church lands—Issue of Assignats—Necker leaves France in unpopularity—New Religious Institution—Oath imposed on the Clergy—Resisted by the greater part of the Order—General View of the operations of the Constituent Assembly—Enthusiasm of the People for their new Privileges—Limited Privileges of the Crown—King is obliged to dissemble—His Negotiations with Mirabeau—With Bouillé—Attack on the Palace—Prevented by Fayette—Royalists expelled from the Tuileries—Escape of Louis—He is captured at Varennes—Brought back to Paris—Riot in the Champ de Mars—Louis accepts the Constitution, 102

Chap. VII.—Legislative Assembly—Its Composition—Constitutionalists—Girondists or Brissotins—Jacobins—Views and Sentiments of Foreign Nations—England—Views of the Tories and Whigs—Anacharsis Clootz—Austria—Prussia—Russia—Sweden—Emigration of the French Princes and Clergy—Increasing Unpopularity of Louis from this Cause—Death of the Emperor Leopold, and its Effects—France declares War—Views and Interests of the different Parties in France at this Period—Decree against Monsieur—Louis interposes his Veto—Decree against the Priests who should refuse the Constitutional Oath—Louis again interposes his Veto—Consequences of these Refusals—Fall of De Lessart—Ministers now chosen from the Brissotins—All Parties favourable to {ix}War, 128

Chap. VIII.—Defeats of the French on the Frontier—Decay of Constitutionalists—They form the Club of Feuillans, and are dispersed by the Jacobins—The Ministry—Dumouriez—Breach of confidence betwixt the King and his Ministers—Dissolution of the King's Constitutional Guard—Extravagant measures of the Jacobins—Alarms of the Girondists—Departmental Army proposed—King puts his Veto on the decree, against Dumouriez's representations—Decree against the recusant Priests—King refuses it—Letter of the Ministers to the King—He dismisses Roland, Clavière, and Servan—Dumouriez, Duranton, and Lacoste, appointed in their stead—King ratifies the decree concerning the Departmental Army—Dumouriez resigns, and departs for the Frontiers—New Ministers named from the Constitutionalists—Insurrection of 20th June—Armed Mob intrude into the Assembly—Thence into the Tuileries—La Fayette repairs to Paris—Remonstrates in favour of the King—But is compelled to return to the Frontiers—Marseillois appear in Paris—Duke of Brunswick's manifesto, 152

Chap. IX.—The Day of the Tenth of August—Tocsin sounded early in the Morning—Swiss Guards, and relics of the Royal Party, repair to the Tuileries—Mandat assassinated—Dejection of Louis, and energy of the Queen—King's Ministers appear at the Bar of the Assembly, stating the peril of the Royal Family, and requesting a Deputation might be sent to the Palace—Assembly pass to the Order of the Day—Louis and his Family repair to the Assembly—Conflict at the Tuileries—Swiss ordered to repair to the King's Person—and are many of them shot and dispersed on their way to the Assembly—At the close of the Day almost all of them are massacred—Royal Family spend the Night in the Convent of the Feuillans, 172

Chap. X.—La Fayette compelled to Escape from France—Is made Prisoner by the Prussians, with three Companions—Reflections—The Triumvirate, Danton, Robespierre, and Marat—Revolutionary Tribunal appointed—Stupor of the Legislative Assembly—Longwy, Stenay, and Verdun, taken by the Prussians—Mob of Paris enraged—Great Massacre of Prisoners in Paris, commencing on the 2d, and ending 6th September—Apathy of the Assembly during and after these Events—Review of its Causes, 182

Chap. XI.—Election of Representatives for the National Convention—Jacobins are very active—Right hand Party—Left hand side—Neutral Members—The Girondists are in possession of the ostensible Power—They denounce the Jacobin Chiefs, but in an irregular and feeble manner—Marat, Robespierre, and Danton, supported by the Commune and Populace of Paris—France declared a Republic—Duke of Brunswick's Campaign—Neglects the French Emigrants—Is tardy in his Operations—Occupies the poorest part of Champagne—His Army becomes sickly—Prospects of a Battle—Dumouriez's Army recruited with Carmagnoles—The Duke resolves to Retreat—Thoughts on the consequences of that measure—The retreat disastrous—The Emigrants disbanded in a great measure—Reflections on their Fate—The Prince of Condé's Army, 199

Chap. XII.—Jacobins determine upon the Execution of Louis—Progress {x}and Reasons of the King's Unpopularity—Girondists taken by surprise, by a proposal for the Abolition of Royalty made by the Jacobins—Proposal carried—Thoughts on the New System of Government—Compared with that of Rome, Greece, America, and other Republican States—Enthusiasm throughout France at the Change—Follies it gave birth to—And Crimes—Monuments of Art destroyed—Madame Roland interposes to save the Life of the King—Barrère—Girondists move for a Departmental Legion—Carried—Revoked—and Girondists defeated—The Authority of the Community of Paris paramount even over the Convention—Documents of the Iron-Chest—Parallel betwixt Charles I. and Louis XVI.—Motion by Pétion, that the King should be Tried before the Convention, 208

Chap. XIII.—The Trial of Louis—Indecision of the Girondists, and its Effects—The Royal Family insulted by the Agents of the Community—The King deprived of his Son's society—The King brought to Trial before the Convention—His First Examination—Carried back to Prison amidst Insult and Abuse—Tumult in the Assembly—The King deprived of Intercourse with his Family—Malesherbes appointed as Counsel to defend the King—and De Seze—Louis again brought before the Convention—Opening Speech of De Seze—King remanded to the Temple—Stormy Debate—Eloquent attack of Vergniaud on the Jacobins—Sentence of Death pronounced against the King—General Sympathy for his Fate—Dumouriez arrives in Paris—Vainly tries to avert the King's Fate—Louis XVI. beheaded on 21st January, 1793—Marie Antoinette on the 16th October thereafter—The Princess Elizabeth in May 1794—The Dauphin perishes, by cruelty, June 8th, 1795—The Princess Royal exchanged for La Fayette, 19th December, 1795, 236

Chap. XIV.—Dumouriez—His displeasure at the Treatment of the Flemish Provinces by the Convention—His projects in consequence—Gains the ill-will of his Army—and is forced to fly to the Austrian Camp—Lives many years in retreat, and finally dies in England—Struggles betwixt the Girondists and Jacobins—Robespierre impeaches the Leaders of the Girondists, and is denounced by them—Decree of Accusation against Marat—Commission of Twelve—Marat acquitted—Terror of the Girondists—Jacobins prepare to attack the Palais Royal, but are repulsed—Repair to the Convention, who recall the Commission of Twelve—Louvet and other Girondist Leaders Fly from Paris—Convention go forth in procession to expostulate with the People—Forced back to their Hall, and compelled to Decree the Accusation of Thirty of their Body—Girondists finally ruined—and their principal Leaders perish—Close of their History, 258

Chap. XV.—Views of Parties in Britain relative to the Revolution—Affiliated Societies—Counterpoised by Aristocratic Associations—Aristocratic Party eager for War with France—The French proclaim the Navigation of the Scheldt—British Ambassador recalled from Paris, and French Envoy no longer accredited in London—France declares War against England—British Army sent to Holland, under the Duke of York—State of the Army—View of the Military Positions of France—in Flanders—on the Rhine—in Piedmont—Savoy—on the Pyrenees—State of the War in La Vendée—Description of the Country—Le Bocage—Le {xi}Louroux—Close Union betwixt the Nobles and Peasantry—Both strongly attached to Royalty, and abhorrent of the Revolution—The Priests—The Religion of the Vendéans outraged by the Convention—A general Insurrection takes place in 1793—Military Organisation and Habits of the Vendéans—Division in the British Cabinet on the Mode of conducting the War—Pitt—Wyndham—Reasoning upon the subject—Vendéans defeated—They defeat, in their turn, the French Troops at Laval—But are ultimately destroyed and dispersed—Unfortunate Expedition to Quiberon—La Charette defeated and executed, and the War of La Vendée finally terminated—Unsuccessful Resistance of Bourdeaux, Marseilles, and Lyons, to the Convention—Siege of Lyons—Its Surrender and dreadful Punishment—Siege of Toulon, 274

Chap. XVI.—Views of the British Cabinet regarding the French Revolution—Extraordinary Situation of France—Explanation of the Anomaly which it exhibited—System of Terror—Committee of Public Safety—Of Public Security—David the Painter—Law against Suspected Persons—Revolutionary Tribunal—Effects of the Emigration of the Princes and Nobles—Causes of the Passiveness of the French People under the Tyranny of the Jacobins—Singular Address of the Committee of Public Safety—General Reflections, 307

Chap. XVII.—Marat, Danton, Robespierre—Marat poniarded—Danton and Robespierre become Rivals—Commune of Paris—their gross Irreligion—Gobel—Goddess of Reason—Marriage reduced to a Civil Contract—Views of Danton—and of Robespierre—Principal Leaders of the Commune arrested—and Nineteen of them executed—Danton arrested by the influence of Robespierre—and, along with Camille Desmoulins, Westermann, and La Croix, taken before the Revolutionary Tribunal, condemned, and executed—Decree issued, on the motion of Robespierre, acknowledging a Supreme Being—Cécilée Regnault—Gradual Change in the Public Mind—Robespierre becomes unpopular—Makes every effort to retrieve his power—Stormy Debate in the Convention—Collot D'Herbois, Tallien, &c., expelled from the Jacobin Club at the instigation of Robespierre—Robespierre denounced in the Convention on the 9th Thermidor, (27th July, 1794,) and, after furious struggles, arrested, along with his brother, Couthon, and Saint Just—Henriot, Commandant of the National Guard, arrested—Terrorists take refuge in the Hotel de Ville—Attempt their own lives—Robespierre wounds himself—but lives, along with most of the others, long enough to be carried to the Guillotine, and executed—His character—Struggles that followed his Fate—Final Destruction of the Jacobinical System—and return of Tranquillity—Singular colour given to Society in Paris—Ball of the Victims, 321

Chap. XVIII.—Retrospective View of the External Relations of France—Her great Military Successes—Whence they arose—Effect of the Compulsory Levies—Military Genius and Character of the French—French Generals—New Mode of Training the Troops—Light Troops—Successive Attacks in Column—Attachment of the Soldiers to the Revolution—Also of the Generals—Carnot—Effect of the French principles preached to the Countries invaded by their Arms—Close of the Revolution with the fall of Robespierre—Reflections upon what was to succeed, 364

VIEW OF THE FRENCH REVOLUTION.

Review of the state of Europe after the Peace of Versailles—England—France—Spain—Prussia—Imprudent Innovations of the Emperor Joseph—Disturbances in his Dominions—Russia—France—Her ancient System of Monarchy—how organized—Causes of its Decay—Decay of the Nobility as a body—The new Nobles—The Country Nobles—The Nobles of the highest Order—The Church—The higher Orders of the Clergy—The lower Orders—The Commons—Their increase in Power and Importance—Their Claims opposed to those of the Privileged Classes.

When we look back on past events, however important, it is difficult to recall the precise sensations with which we viewed them in their progress, and to recollect the fears, hopes, doubts, and difficulties, for which Time and the course of Fortune have formed a termination, so different probably from that which we had anticipated. When the rush of the inundation was before our eyes, and in our ears, we were scarce able to remember the state of things before its rage commenced, and when, subsequently, the deluge has subsided within the natural limits of the stream, it is still more difficult to recollect with precision the terrors it inspired when at its height. That which is present possesses such power over our senses and our imagination, that it requires no common effort to recall those sensations which expired with preceding events. Yet, to do this is the peculiar province of history, which will be written and read in vain, unless it can connect with its details an accurate idea of the impression which these produced on men's minds while they were yet in their transit. It is with this view that we attempt to resume the history of France and of Europe, at the conclusion of the American war—a period now only remembered by the more advanced part of the present generation.{2}

The peace concluded at Versailles in 1783, was reasonably supposed to augur a long repose to Europe. The high and emulous tone assumed in former times by the rival nations, had been lowered and tamed by recent circumstances. England, under the guidance of a weak, at least a most unlucky administration,[5] had purchased peace at the expense of her North American Empire, and the resignation of supremacy over her colonies; a loss great in itself, but exaggerated in the eyes of the nation, by the rending asunder of the ties of common descent, and exclusive commercial intercourse, and by a sense of the wars waged, and expenses encountered for the protection and advancement of the fair empire which England found herself obliged to surrender. The lustre of the British arms, so brilliant at the Peace of Fontainbleau, had been tarnished, if not extinguished. In spite of the gallant defence of Gibraltar, the general result of the war on land had been unfavourable to her military reputation; and notwithstanding the opportune and splendid victories of Rodney, the coasts of Britain had been insulted, and her fleets compelled to retire into port, while those of her combined enemies rode masters of the channel.[6] The spirit of the country also had been lowered, by the unequal contest which had been sustained, and by the sense that her naval superiority was an object of invidious hatred to united Europe. This had been lately made manifest, by the armed alliance of the northern nations, which, though termed a neutrality, was, in fact, a league made to abate the pretensions of England to maritime supremacy. There are to be added to these disheartening and depressing circumstances, the decay of commerce during the long course of hostilities, with the want of credit and depression of the price of land, which are the usual consequences of a transition from war to peace, ere capital has regained its natural channel. All these things being considered, it appeared the manifest interest of England to husband her exhausted resources, and recruit her diminished wealth, by cultivating peace and tranquillity for a long course of time. William Pitt, never more distinguished than in his financial operations, was engaged in new modelling the revenue of the country, and adding to the return of the taxes, while he diminished their pressure. It could scarcely be supposed that any object of national ambition would have been permitted to disturb him in a task so necessary.

Neither had France, the natural rival of England, come off from the contest in such circumstances of triumph and advantage, as{3} were likely to encourage her to a speedy renewal of the struggle. It is true, she had seen and contributed to the humiliation of her ancient enemy, but she had paid dearly for the gratification of her revenge, as nations and individuals are wont to do. Her finances, tampered with by successive sets of ministers, who looked no farther than to temporary expedients for carrying on the necessary expenses of government, now presented an alarming prospect; and it seemed as if the wildest and most enterprising ministers would hardly have dared, in their most sanguine moments, to have recommended either war itself, or any measures of which war might be the consequence.

Spain was in a like state of exhaustion. She had been hurried into the alliance against England, partly by the consequences of the family alliance betwixt her Bourbons and those of France, but still more by the eager and engrossing desire to possess herself once more of Gibraltar. The Castilian pride, long galled by beholding this important fortress in the hands of heretics and foreigners, highly applauded the war, which gave a chance of its recovery, and seconded, with all the power of the kingdom, the gigantic efforts made for that purpose. All these immense preparations, with the most formidable means of attack ever used on such an occasion, had totally failed, and the kingdom of Spain remained at once stunned and mortified by the failure, and broken down by the expenses of so huge an undertaking. An attack upon Algiers, in 1784-5, tended to exhaust the remains of her military ardour. Spain, therefore, relapsed into inactivity and repose, dispirited by the miscarriage of her favourite scheme, and possessing neither the means nor the audacity necessary to meditate its speedy renewal.

Neither were the sovereigns of the late belligerent powers of that ambitious and active character which was likely to drag the kingdoms which they swayed into the renewal of hostilities. The classic eye of the historian Gibbon saw Arcadius and Honorius, the weakest and most indolent of the Roman Emperors, slumbering upon the thrones of the House of Bourbon;[7] and the just and{4} loyal character of George III. precluded any effort on his part to undermine the peace which he signed unwillingly, or to attempt the resumption of those rights which he had formally, though reluctantly, surrendered. His expression to the ambassador of the United States,[8] was a trait of character never to be omitted or forgotten:—"I have been the last man in my dominions to accede to this peace, which separates America from my kingdoms—I will be the first man, now it is made, to resist any attempt to infringe it."

The acute historian whom we have already quoted seems to have apprehended, in the character and ambition of the northern potentates, those causes of disturbance which were not to be found in the western part of the European republic. But Catherine, the Semiramis of the north, had her views of extensive dominion chiefly turned towards her eastern and southern frontier, and the finances of her immense, but comparatively poor and unpeopled empire, were burdened with the expenses of a luxurious court, requiring at once to be gratified with the splendour of Asia and the refinements of Europe. The strength of her empire also, though immense, was unwieldy, and the empire had not been uniformly fortunate in its wars with the more prompt, though less numerous armies of the King of Prussia, her neighbour. Thus Russia, no less than other powers in Europe, appeared more desirous of reposing her gigantic strength, than of adventuring upon new and hazardous conquests. Even her views upon Turkey, which circumstances seemed to render more flattering than ever, she was contented to resign, in 1784, when only half accomplished; a pledge, not only that her thoughts were sincerely bent upon peace, but that she felt the necessity of resisting even the most tempting opportunities for resuming the course of victory which she had, four years before, pursued so successfully.

Frederick of Prussia himself, who had been so long, by dint of genius and talent, the animating soul of the political intrigues in Europe, had run too many risks, in the course of his adventurous and eventful reign, to be desirous of encountering new hazards in the extremity of life. His empire, extended as it was from the shores of the Baltic to the frontiers of Holland, consisted of various detached portions, which it required the aid of time to consolidate into a single kingdom. And, accustomed to study the signs of the times, it could not have escaped Frederick, that sentiments and feelings were afloat, connected with, and fostered by, the spirit of unlimited investigation, which he himself had termed philosophy, such as might soon call upon the sovereigns to arm in a common cause, and ought to prevent them, in the meanwhile, from wasting their strength in mutual struggles, and giving advantage to a common enemy.

If such anticipations occupied and agitated the last years of{5} Frederick's life, they had not the same effect upon the Emperor Joseph II., who, without the same clear-eyed precision of judgment, endeavoured to tread in the steps of the King of Prussia, as a reformer, and as a conqueror. It would be unjust to deny to this prince the praise of considerable talents, and inclination to employ them for the good of the country which he ruled. But it frequently happens, that the talents, and even the virtues of sovereigns, exercised without respect to time and circumstances, become the misfortune of their government. It is particularly the lot of princes, endowed with such personal advantages, to be confident in their own abilities, and, unless educated in the severe school of adversity, to prefer favourites, who assent to and repeat their opinions, to independent counsellors, whose experience might correct their own hasty conclusions. And thus, although the personal merits of Joseph II. were in every respect acknowledged, his talents in a great measure recognised, and his patriotic intentions scarcely disputable, it fell to his lot, during the period we treat of, to excite more apprehension and discontent among his subjects, than if he had been a prince content to rule by a minister, and wear out an indolent life in the forms and pleasures of a court. Accordingly, the Emperor, in many of his schemes of reform, too hastily adopted, or at least too incautiously and peremptorily executed, had the misfortune to introduce fearful commotions among the people, whose situation he meant to ameliorate, while in his external relations he rendered Austria the quarter from which a breach of European peace was most to be apprehended. It seemed, indeed, as if the Emperor had contrived to reconcile his philosophical professions with the exercise of the most selfish policy towards the United Provinces, both in opening the Scheldt, and in dismantling the barrier towns, which had been placed in their hands as a defence against the power of France. By the first of these measures the Emperor gained nothing but the paltry sum of money for which he sold his pretensions,[9] and the shame of having shown himself ungrateful for the important services which the United Provinces had rendered to his ancestors. But the dismantling of the Dutch barrier was subsequently attended by circumstances alike calamitous to Austria, and to the whole continent of Europe.

In another respect, the reforms carried through by Joseph II. tended to prepare the public mind for future innovations, made with a ruder hand, and upon a much larger scale.[10] The suppression of the religious orders, and the appropriation of their revenues{6} to the general purposes of government, had in it something to flatter the feelings of those of the Reformed religion; but, in a moral point of view, the seizing upon the property of any private individual, or public body, is an invasion of the most sacred principles of public justice, and such spoliation cannot be vindicated by urgent circumstances of state-necessity, or any plausible pretext of state-advantage whatsoever, since no necessity can vindicate what is in itself unjust, and no public advantage can compensate a breach of public faith.[11] Joseph was also the first Catholic sovereign who broke through the solemn degree of reverence attached by that religion to the person of the Sovereign Pontiff. The Pope's fruitless and humiliating visit to Vienna furnished the shadow of a precedent for the conduct of Napoleon to Pius VII.[12]

Another and yet less justifiable cause of innovation, placed in peril, and left in doubt and discontent, some of the fairest provinces of the Austrian dominions, and those which the wisest of their princes had governed with peculiar tenderness and moderation. The Austrian Netherlands had been in a literal sense dismantled and left open to the first invader, by the demolition of the barrier fortresses; and it seems to have been the systematic purpose of the Emperor to eradicate and destroy that love and regard for their prince and his government, which in time of need proves the most effectual moral substitute for moats and ramparts. The history of the house of Burgundy bore witness on every page to the love of the Flemings for liberty, and the jealousy with which they have, from the earliest ages, watched the privileges they had obtained from their princes. Yet in that country, and amongst these people, Joseph carried on his measures of innovation with a hand so unsparing, as if he meant to bring the question of liberty or arbitrary power to a very brief and military decision betwixt him and his subjects.

His alterations were not in Flanders, as elsewhere, confined to the ecclesiastical state alone, although such innovations were peculiarly offensive to a people rigidly Catholic, but were extended through the most important parts of the civil government.{7} Changes in the courts of justice were threatened—the great seal, which had hitherto remained with the chancellor of the States, was transferred to the Imperial minister—a Council of State, composed of commissioners nominated by the Emperor, was appointed to discharge the duties hitherto intrusted to a standing committee of the States of Brabant—their universities were altered and new-modelled—and their magistrates subjected to arbitrary arrests and sent to Vienna, instead of being tried in their own country and by their own laws. The Flemish people beheld these innovations with the sentiments natural to freemen, and not a little stimulated certainly by the scenes which had lately passed in North America, where, under circumstances of far less provocation, a large empire had emancipated itself from the mother country. The States remonstrated loudly, and refused submission to the decrees which encroached on their constitutional liberties, and at length arrayed a military force in support of their patriotic opposition.

Joseph, who at the same time he thus wantonly provoked the States and people of Flanders, had been seduced by Russia to join her ambitious plan upon Turkey, bent apparently before the storm he had excited, and for a time yielded to accommodation with his subjects of Flanders, renounced the most obnoxious of his new measures, and confirmed the privileges of the nation, at what was called the Joyous Entry.[13] But this spirit of conciliation was only assumed for the purpose of deception; for so soon as he had assembled in Flanders what was deemed a sufficient armed force to sustain his despotic purposes, the Emperor threw off the mask, and, by the most violent acts of military force, endeavoured to overthrow the constitution he had agreed to observe, and to enforce the arbitrary measures which he had pretended to abandon. For a brief period of two years, Flanders remained in a state of suppressed, but deeply-founded and wide-extended discontent, watching for a moment favourable to freedom and to vengeance. It proved an ample store-house of combustibles, prompt to catch fire, as the flame now arising in France began to expand itself; nor can it be doubted, that the condition of the Flemish provinces, whether considered in a military or in a political light, was one of the principal causes of the subsequent success of the French Republican arms. Joseph himself, broken-hearted and dispirited, died in the very beginning of the troubles he had wantonly provoked.[14] Desirous of fame as a legislator and a warrior, and certainly born with talents to acquire it, he left his arms dishonoured by the successes of the despised Turks, and his{8} fair dominions of the Netherlands and of Hungary upon the very eve of insurrection. A lampoon, written upon the hospital for lunatics at Vienna, might be said to be no unjust epitaph for a monarch, one so hopeful and so beloved—"Josephus, ubique Secundus, hic Primus."

These Flemish disturbances might be regarded as symptoms of the new opinions which were tacitly gaining ground in Europe, and which preceded the grand explosion, as slight shocks of an earthquake usually announce the approach of its general convulsion. The like may be said of the short-lived Dutch revolution of 1787, in which the ancient faction of Louvestein, under the encouragement of France, for a time completely triumphed over that of the Stadtholder, deposed him from his hereditary command of Captain-General of the Army of the States, and reduced, or endeavoured to reduce, the confederation of the United States to a pure democracy. This was also a strong sign of the times; for, although totally opposite to the inclination of the majority of the States-General, of the equestrian body, of the landed proprietors, nay, of the very populace, most of whom were from habit and principle attached to the House of Orange, the burghers of the large towns drove on the work of revolution with such warmth of zeal and promptitude of action, as showed a great part of the middling classes to be deeply tinctured with the desire of gaining further liberty, and a larger share in the legislation and administration of the country, than pertained to them under the old oligarchical constitution.

The revolutionary government, in the Dutch provinces, did not, however, conduct their affairs with prudence. Without waiting to organize their own force, or weaken that of the enemy—without obtaining the necessary countenance and protection of France, or co-operating with the malecontents in the Austrian Netherlands, they gave, by arresting the Princess of Orange, (sister of the King of Prussia,) an opportunity of foreign interference, of which that prince failed not to avail himself. His armies, commanded by the Duke of Brunswick, poured into the United Provinces, and with little difficulty possessed themselves of Utrecht, Amsterdam, and the other cities which constituted the strength of the Louvestein or republican faction. The King then replaced the House of Orange in all its power, privileges, and functions. The conduct of the Dutch republicans during their brief hour of authority had been neither so moderate nor so popular as to make their sudden and almost unresisting fall a matter of general regret. On the contrary, it was considered as a probable pledge of the continuance of peace in Europe, especially as France, busied with her own affairs, declined interference in those of the United States.

The intrigues of Russia had, in accomplishment of the ambitious schemes of Catherine, lighted up war with Sweden, as well as with Turkey; but in both cases hostilities were commenced{9} upon the old plan of fighting one or two battles, and wresting a fortress of a province from a neighbouring state; and it seems likely, that the intervention of France and England, equally interested in preserving the balance of power, might have ended these troubles, but for the progress of that great and hitherto unheard-of course of events, which prepared, carried on, and matured, the French Revolution.

It is necessary, for the execution of our plan, that we should review this period of history, the most important, perhaps, during its currency, and in its consequences, which the annals of mankind afford; and although the very title is sufficient to awaken in most bosoms either horror or admiration, yet, neither insensible of the blessings of national liberty, nor of those which flow from the protection of just laws, and a moderate but firm executive government, we may perhaps be enabled to trace its events with the candour of one, who, looking back on past scenes, feels divested of the keen and angry spirit with which, in common with his contemporaries, he may have judged them while they were yet in progress.

We have shortly reviewed the state of Europe in general, which we have seen to be either pacific or disturbed by troubles of no long duration; but it was in France that a thousand circumstances, some arising out of the general history of the world, some peculiar to that country herself, mingled, like the ingredients in the witches' cauldron, to produce in succession many a formidable but passing apparition, until concluded by the stern Vision of absolute and military power, as those in the drama are introduced by that of the Armed Head.[15]

The first and most effective cause of the Revolution, was the change which had taken place in the feelings of the French towards their government, and the monarch who was its head. The devoted loyalty of the people to their king had been for several ages the most marked characteristic of the nation; it was their honour in their own eyes, and matter of contempt and ridicule in those of the English, because it seemed in its excess to swallow up all ideas of patriotism. That very excess of loyalty, however, was founded not on a servile, but upon a generous principle. France is ambitious, fond of military glory, and willingly identifies herself with the fame acquired by her soldiers. Down to the reign of Louis XV., the French monarch was, in the eyes of his subjects, a general, and the whole people an army. An army must be under severe discipline, and a general must possess absolute power; but the soldier feels no degradation from the restraint which is necessary to his profession, and without which he cannot be led to conquest.

Every true Frenchman, therefore, submitted, without scruple{10} to that abridgement of personal liberty which appeared necessary to render the monarch great, and France victorious. The King, according to this system, was regarded less as an individual than as the representative of the concentrated honour of the kingdom; and in this sentiment, however extravagant and Quixotic, there mingled much that was generous, patriotic, and disinterested. The same feeling was awakened after all the changes of the Revolution, by the wonderful successes of the Individual of whom the future volumes are to treat, and who transferred, in many instances to his own person, by deeds almost exceeding credibility, the species of devoted attachment with which France formerly regarded the ancient line of her kings.

The nobility shared with the king in the advantages which this predilection spread around him. If the monarch was regarded as the chief ornament of the community, they were the minor gems by whose lustre that of the crown was relieved or adorned. If he was the supreme general of the state, they were the officers attached to his person, and necessary to the execution of his commands, each in his degree bound to advance the honour and glory of the common country. When such sentiments were at their height, there could be no murmuring against the peculiar privileges of the nobility, any more than against the almost absolute authority of the monarch. Each had that rank in the state which was regarded as his birth-right, and for one of the lower orders to repine that he enjoyed not the immunities peculiar to the noblesse, would have been as unavailing, and as foolish, as to lament that he was not born to an independent estate. Thus, the Frenchman, contented, though with an illusion, laughed, danced, and indulged all the gaiety of his national character, in circumstances under which his insular neighbours would have thought the slightest token of patience dishonourable and degrading. The distress or privation which the French plebeian suffered in his own person, was made up to him in imagination by his interest in the national glory.

Was a citizen of Paris postponed in rank to the lowest military officer, he consoled himself by reading the victories of the French arms in the Gazette; and was he unduly and unequally taxed to support the expense of the crown, still the public feasts which were given, and the palaces which were built, were to him a source of compensation. He looked on at the Carousal, he admired the splendour of Versailles, and enjoyed a reflected share of their splendour, in recollecting that they displayed the magnificence of his country. This state of things, however illusory, seemed, while the illusion lasted, to realize the wish of those legislators, who have endeavoured to form a general fund of national happiness, from which each individual is to draw his personal share of enjoyment. If the monarch enjoyed the display of his own grace and agility, while he hunted, or rode at the ring, the spectators had their share of pleasure in witnessing it:{11} if Louis had the satisfaction of beholding the splendid piles of Versailles and the Louvre arise at his command, the subject admired them when raised, and his real portion of pleasure was not, perhaps, inferior to that of the founder. The people were like men inconveniently placed in a crowded theatre, who think little of the personal inconveniences they are subjected to by the heat and pressure, while their mind is engrossed by the splendours of the representation. In short, not only the political opinions of Frenchmen but their actual feelings, were, in the earlier days of the eighteenth century, expressed in the motto which they chose for their national palace—"Earth hath no nation like the French—no Nation a City like Paris, or a King like Louis."

The French enjoyed this assumed superiority with the less chance of being undeceived, that they listened not to any voice from other lands, which pointed out the deficiencies in the frame of government under which they lived, or which hinted the superior privileges enjoyed by the subjects of a more free state. The intense love of our own country, and admiration of its constitution, is usually accompanied with a contempt or dislike of foreign states, and their modes of government. The French, in the reign of Louis XIV., enamoured of their own institutions, regarded those of other nations as unworthy of their consideration; and if they paused for a moment to gaze on the complicated constitution of their great rival, it was soon dismissed as a subject totally unintelligible, with some expression of pity, perhaps, for the poor sovereign who had the ill luck to preside over a government embarrassed by so many restraints and limitations.[16] Yet, into whatever political errors the French people were led by the excess of their loyalty, it would be unjust to brand them as a nation of a mean and slavish spirit. Servitude infers dishonour, and dishonour to a Frenchman is the last of evils. Burke more justly regarded them as a people misled to their disadvantage, by high and romantic ideas of honour and fidelity, and who, actuated by a principle of public spirit in their submission to their monarch, worshipped, in his person, the Fortune of France their common country.

During the reign of Louis XIV., every thing tended to support the sentiment which connected the national honour with the wars and undertakings of the king. His success, in the earlier years of his reign, was splendid, and he might be regarded for many years, as the dictator of Europe. During this period, the universal opinion of his talents, together with his successes abroad, and his magnificence at home, fostered the idea that the Grand Monarque was in himself the tutelar deity, and only representative, of the great nation whose powers he wielded. Sorrow and desolation came on his latter years; but be it said to the honour{12} of the French people, that the devoted allegiance they had paid to Louis in prosperity, was not withdrawn when fortune seemed to have turned her back upon her original favourite. France poured her youth forth as readily, if not so gaily, to repair the defeats of her monarch's old age, as she had previously yielded them to secure and extend the victories of his early reign. Louis had perfectly succeeded in establishing the crown as the sole pivot upon which public affairs turned, and in attaching to his person, as the representative of France, all the importance which in other countries is given to the great body of the nation.

Nor had the spirit of the French monarchy, in surrounding itself with all the dignity of absolute power, failed to secure the support of those auxiliaries which have the most extended influence upon the public mind, by engaging at once religion and literature in defence of its authority. The Gallican Church, more dependent upon the monarch, and less so upon the Pope, than is usual in Catholic countries, gave to the power of the crown all the mysterious and supernatural terrors annexed to an origin in divine right, and directed against those who encroached on the limits of the royal prerogative, or even ventured to scrutinize too minutely the foundation of its authority, the penalties annexed to a breach of the divine law. Louis XIV. repaid this important service by a constant, and even scrupulous attention to observances prescribed by the Church, which strengthened, in the eyes of the public, the alliance so strictly formed betwixt the altar and the throne. Those who look to the private morals of the monarch may indeed form some doubt of the sincerity of his religious professions, considering how little they influenced his practice; and yet, when we reflect upon the frequent inconsistencies of mankind in this particular, we may hesitate to charge with hypocrisy a conduct, which was dictated perhaps as much by conscience as by political convenience. Even judging more severely, it must be allowed that hypocrisy, though so different from religion, indicates its existence, as smoke points out that of pure fire. Hypocrisy cannot exist unless religion be to a certain extent held in esteem, because no one would be at the trouble to assume a mask which was not respectable, and so far compliance with the external forms of religion is a tribute paid to the doctrines which it teaches. The hypocrite assumes a virtue if he has it not, and the example of his conduct may be salutary to others, though his pretensions to piety are wickedness to Him, who trieth the heart and reins.

On the other hand, the Academy formed by the wily Richelieu served to unite the literature of France into one focus, under the immediate patronage of the crown, to whose bounty its professors were taught to look even for the very means of subsistence. The greater nobles caught this ardour of patronage from the sovereign, and as the latter pensioned and supported the principal literary characters of his reign, the former granted shelter and support to{13} others of the same rank, who were lodged at their hotels, fed at their tables, and were admitted to their society upon terms somewhat less degrading than those which were granted to artists and musicians, and who gave to the Great, knowledge or amusement in exchange for the hospitality they received. Men in a situation so subordinate, could only at first accommodate their compositions to the taste and interest of their protectors. They heightened by adulation and flattery the claims of the king and the nobles upon the community; and the nation, indifferent at that time to all literature which was not of native growth, felt their respect for their own government enhanced and extended by the works of those men of genius who flourished under its protection.

Such was the system of French monarchy, and such it remained, in outward show at least, until the peace of Fontainbleau. But its foundation had been gradually undermined; public opinion had undergone a silent but almost a total change, and it might be compared to some ancient tower swayed from its base by the lapse of time, and waiting the first blast of a hurricane, or shock of an earthquake, to be prostrated in the dust. How the lapse of half a century, or little more, could have produced a change so total, must next be considered; and this can only be done by viewing separately the various changes which the lapse of years had produced on the various orders of the state.

First, then, it is to be observed, that in these latter times the wasting effects of luxury and vanity had totally ruined the greater part of the French nobility, a word which, in respect of that country, comprehended what is called in Britain the nobility and gentry, or natural aristocracy of the kingdom. This body, during the reign of Louis XIV., though far even then from supporting the part which their fathers had acted in history, yet existed, as it were, through their remembrances, and disguised their dependence upon the throne by the outward show of fortune, as well as by the consequence attached to hereditary right. They were one step nearer the days, not then totally forgotten, when the nobles of France, with their retainers, actually formed the army of the kingdom; and they still presented, to the imagination at least, the descendants of a body of chivalrous heroes, ready to tread in the path of their ancestors, should the times ever render necessary the calling forth the Ban, or Arrière-Ban—the feudal array of the Gallic chivalry. But this delusion had passed away; the defence of states was intrusted in France, as in other countries, to the exertions of a standing army; and, in the latter part of the eighteenth century, the nobles of France presented a melancholy contrast to their predecessors.

The number of the order was of itself sufficient to diminish its consequence. It had been imprudently increased by new creations. There were in the kingdom about eighty thousand families enjoying the privileges of nobility; and the order was divided{14} into different classes, which looked on each other with mutual jealousy and contempt.

The first general distinction was betwixt the Ancient, and Modern, or new noblesse. The former were nobles of old creation, whose ancestors had obtained their rank from real or supposed services rendered to the nation in her councils or her battles. The new nobles had found an easier access to the same elevation, by the purchase of territories, or of offices, or of letters of nobility, any of which easy modes invested the owners with titles and rank, often held by men whose wealth had been accumulated in mean and sordid occupations, or by farmers-general, and financiers, whom the people considered as acquiring their fortunes at the expense of the state. These numerous additions to the privileged body of nobles accorded ill with its original composition, and introduced schism and disunion into the body itself. The descendants of the ancient chivalry of France looked with scorn upon the new men, who, rising perhaps from the very lees of the people, claimed from superior wealth a share in the privileges of the aristocracy.

Again, secondly, there was, amongst the ancient nobles themselves, but too ample room for division between the upper and wealthier class of nobility, who had fortunes adequate to maintain their rank, and the much more numerous body, whose poverty rendered them pensioners upon the state for the means of supporting their dignity. Of about one thousand houses, of which the ancient noblesse is computed to have consisted, there were not above two or three hundred families who had retained the means of maintaining their rank without the assistance of the crown. Their claims to monopolize commissions in the army, and situations in the government, together with their exemption from taxes, were their sole resources; resources burdensome to the state, and odious to the people, without being in the same degree beneficial to those who enjoyed them. Even in military service, which was considered as their birth-right, the nobility of the second class were seldom permitted to rise above a certain limited rank. Long service might exalt one of them to the grade of lieutenant-colonel, or the government of some small town, but all the better rewards of a life spent in the army were reserved for nobles of the highest order. It followed as a matter of course, that amidst so many of this privileged body who languished in poverty, and could not rise from it by the ordinary paths of industry, some must have had recourse to loose and dishonourable practices; and that gambling-houses and places of debauchery should have been frequented and patronised by individuals, whose ancient descent, titles, and emblems of nobility, did not save them from the suspicion of very dishonourable conduct, the disgrace of which affected the character of the whole body.

There must be noticed a third classification of the order, into the Haute Noblesse, or men of the highest rank, most of whom{15} spent their lives at court, and in discharge of the great offices of the crown and state, and the Noblesse Campagnarde, who continued to reside upon their patrimonial estates in the provinces.

The noblesse of the latter class had fallen gradually into a state of general contempt, which was deeply to be regretted. They were ridiculed and scorned by the courtiers, who despised the rusticity of their manners, and by the nobles of newer creation, who, conscious of their own wealth, contemned the poverty of these ancient but decayed families. The "bold peasant" himself not more a kingdom's pride than is the plain country gentleman, who, living on his own means, and amongst his own people, becomes the natural protector and referee of the farmer and the peasant, and, in case of need, either the firmest assertor of their rights and his own against the aggressions of the crown, or the independent and undaunted defender of the crown's rights, against the innovations of political fanaticism. In La Vendée alone, the nobles had united their interest and their fortune with those of the peasants who cultivated their estates, and there alone were they found in their proper and honourable character of proprietors residing on their own domains, and discharging the duties which are inalienably attached to the owner of landed property. And—mark-worthy circumstance!—in La Vendée alone was any stand made in behalf of the ancient proprietors, constitution, or religion of France; for there alone the nobles and the cultivators of the soil held towards each other their natural and proper relations of patron and client, faithful dependents, and generous and affectionate superiors.[17] In the other provinces of France, the nobility, speaking generally, possessed neither power nor influence among the peasantry, while the population around them was guided and influenced by men belonging to the Church, to the law, or to business; classes which were in general better educated, better informed, and possessed of more talent and knowledge of the world than the poor Noblesse Campagnarde, who seemed as much limited, caged, and imprisoned, within the restraints of their rank, as if they had been shut up within the dungeons of their ruinous chateaux; and who had only their titles and dusty parchments to oppose to the real superiority of wealth and information so generally to be found in the class which they affected to despise. Hence, Ségur describes the country gentlemen of his younger days as punctilious, ignorant, and quarrelsome, shunned by the better-informed of the middle classes, idle and dissipated, and wasting their leisure hours in coffee-houses, theatres, and billiard-rooms.[18]

The more wealthy families, and the high noblesse, as they were called, saw this degradation of the inferior part of their order without pity, or rather with pleasure. These last had risen as{16} much above their natural duties, as the rural nobility had sunk beneath them. They had too well followed the course which Richelieu had contrived to recommend to their fathers, and instead of acting as the natural chiefs and leaders of the nobility and gentry of the provinces, they were continually engaged in intriguing for charges round the king's person, for posts in the administration, for additional titles and decorations—for all and every thing which could make the successful courtier, and distinguish him from the independent noble. Their education and habits also were totally unfavourable to grave or serious thought and exertion. If the trumpet had sounded, it would have found a ready echo in their bosoms; but light literature at best, and much more frequently silly and frivolous amusements, a constant pursuit of pleasure, and a perpetual succession of intrigues, either of love or petty politics, made their character, in time of peace, approach in insignificance to that of the women of the court, whom it was the business of their lives to captivate and amuse.[19] There were noble exceptions, but in general the order, in every thing but military courage, had assumed a trivial and effeminate character, from which patriotic sacrifices, or masculine wisdom, were scarcely to be expected.

While the first nobles of France were engaged in these frivolous pursuits, their procureurs, bailiffs, stewards, intendants, or by whatever name their agents and managers were designated, enjoyed the real influence which their constituents rejected as beneath them, rose into a degree of authority and credit, which eclipsed recollection of the distant and regardless proprietor, and formed a rank in the state not very different from that of the middle-men in Ireland. These agents were necessarily of plebeian birth, and their profession required that they should be familiar with the details of public business, which they administered in the name of their seigneurs. Many of this condition gained power and wealth in the course of the Revolution, thus succeeding, like an able and intelligent vizier, to the power which was forfeited by the idle and voluptuous sultan. Of the high noblesse it might with truth be said, that they still formed the grace of the court of France, though they had ceased to be its defence. They were accomplished, brave, full of honour, and in many instances endowed with talent. But the communication was broken off betwixt them and the subordinate orders, over whom, in just degree, they ought to have possessed a natural influence. The chain of gradual and insensible connexion was rusted by time, in almost all its dependencies; forcibly distorted, and contemptuously wrenched asunder, in many. The noble had neglected and flung from him the most precious jewel in his{17} coronet—the love and respect of the country-gentleman, the farmer, and the peasant, an advantage so natural to his condition in a well-constituted society, and founded upon principles so estimable, that he who contemns or destroys it, is guilty of little less than high treason, both to his own rank, and to the community in general. Such a change, however, had taken place in France, so that the noblesse might be compared to a court-sword, the hilt carved, ornamented, and gilded, such as might grace a day of parade, but the blade gone, or composed of the most worthless materials.

It only remains to be mentioned, that there subsisted, besides all the distinctions we have noticed, an essential difference in political opinions among the noblesse themselves, considered as a body. There were many of the order, who, looking to the exigencies of the kingdom, were patriotically disposed to sacrifice their own exclusive privileges, in order to afford a chance of its regeneration. These of course were disposed to favour an alteration or reform in the original constitution of France; but besides these enlightened individuals, the nobility had the misfortune to include many disappointed and desperate men, ungratified by any of the advantages which their rank made them capable of receiving, and whose advantages of birth and education only rendered them more deeply dangerous, or more daringly profligate. A plebeian, dishonoured by his vices, or depressed by the poverty which is their consequence, sinks easily into the insignificance from which wealth or character alone raised him; but the noble often retains the means, as well as the desire, to avenge himself on society, for an expulsion which he feels not the less because he is conscious of deserving it. Such were the debauched Roman youth, among whom were found Cataline, and associates equal in talents and in depravity to their leader; and such was the celebrated Mirabeau, who, almost expelled from his own class, as an irreclaimable profligate, entered the arena of the Revolution as a first-rate reformer, and a popular advocate of the lower orders.

The state of the Church, that second pillar of the throne, was scarce more solid than that of the nobility. Generally speaking, it might be said, that, for a long time, the higher orders of the clergy had ceased to take a vital concern in their profession, or to exercise its functions in a manner which interested the feelings and affections of men.

The Catholic Church had grown old, and unfortunately did not possess the means of renovating her doctrines, or improving her constitution, so as to keep pace with the enlargement of the human understanding. The lofty claims to infallibility which she had set up and maintained during the middle ages, claims which she could neither renounce nor modify, now threatened, in more enlightened times, like battlements too heavy for the foundation, to be the means of ruining the edifice they were designed to defend. Vestigia nulla retrorsum, continued to be the motto of the Church{18} of Rome. She could explain nothing, soften nothing, renounce nothing, consistently with her assertion of impeccability. The whole trash which had been accumulated for ages of darkness and ignorance, whether consisting of extravagant pretensions, incredible assertions, absurd doctrines which confounded the understanding, or puerile ceremonies which revolted the taste, were alike incapable of being explained away or abandoned. It would certainly have been—humanly speaking—advantageous, alike for the Church of Rome, and for Christianity in general, that the former had possessed the means of relinquishing her extravagant claims, modifying her more obnoxious doctrines, and retrenching her superstitious ceremonial, as increasing knowledge showed the injustice of the one, and the absurdity of the other. But this power she dared not assume; and hence, perhaps, the great schism which divides the Christian world, which might otherwise never have existed, or at least not in its present extended and embittered state. But, in all events, the Church of Rome, retaining the spiritual empire over so large and fair a portion of the Christian world, would not have been reduced to the alternative of either defending propositions, which, in the eyes of all enlightened men, are altogether untenable, or of beholding the most essential and vital doctrines of Christianity confounded with them, and the whole system exposed to the scorn of the infidel. The more enlightened and better informed part of the French nation had fallen very generally into the latter extreme.

Infidelity, in attacking the absurd claims and extravagant doctrines of the Church of Rome, had artfully availed herself of those abuses, as if they had been really a part of the Christian religion; and they whose credulity could not digest the grossest articles of the Papist creed, thought themselves entitled to conclude, in general, against religion itself, from the abuses engrafted upon it by ignorance and priestcraft. The same circumstances which favoured the assault, tended to weaken the defence. Embarrassed by the necessity of defending the mass of human inventions with which their Church had obscured and deformed Christianity, the Catholic clergy were not the best advocates even in the best of causes; and though there were many brilliant exceptions, yet it must be owned that a great part of the higher orders of the priesthood gave themselves little trouble about maintaining the doctrines, or extending the influence of the Church, considering it only in the light of an asylum, where, under the condition of certain renunciations, they enjoyed, in indolent tranquillity, a state of ease and luxury. Those who thought on the subject more deeply, were contented quietly to repose the safety of the Church upon the restrictions on the press, which prevented the possibility of free discussion. The usual effect followed; and many who, if manly and open debate upon theological subjects had been allowed, would doubtless have been enabled to winnow the wheat from the chaff, were, in the state of{19} darkness to which they were reduced, led to reject Christianity itself, along with the corruptions of the Romish Church, and to become absolute infidels instead of reformed Christians.

The long and violent dispute also betwixt the Jesuits and the Jansenists, had for many years tended to lessen the general consideration for the Church at large, and especially for the higher orders of the clergy. In that quarrel, much had taken place that was disgraceful. The mask of religion has been often used to cover more savage and extensive persecutions, but at no time did the spirit of intrigue, of personal malice, of slander, and circumvention, appear more disgustingly from under the sacred disguise; and in the eyes of the thoughtless and the vulgar, the general cause of religion suffered in proportion.

The number of the clergy who were thus indifferent to doctrine or duty was greatly increased, since the promotion to the great benefices had ceased to be distributed with regard to the morals, piety, talents, and erudition of the candidates, but was bestowed among the younger branches of the noblesse, upon men who were at little pains to reconcile the looseness of their former habits and opinions with the sanctity of their new profession, and who, embracing the Church solely as a means of maintenance, were little calculated by their lives or learning to extend its consideration. Among other vile innovations of the celebrated regent, Duke of Orleans, he set the most barefaced example of such dishonourable preferment, and had increased in proportion the contempt entertained for the hierarchy, even in its highest dignities,—since how was it possible to respect the purple itself, after it had covered the shoulders of the infamous Dubois?[20]

It might have been expected, and it was doubtless in a great measure the case, that the respect paid to the characters and efficient utility of the curates, upon whom, generally speaking, the charge of souls actually devolved, might have made up for the want of consideration withheld from the higher orders of the Church. There can be no doubt that this respectable body of churchmen possessed great and deserved influence over their parishioners; but then they were themselves languishing under poverty and neglect, and, as human beings, cannot be supposed to have viewed with indifference their superiors enjoying wealth{20} and ease, while in some cases they dishonoured the robe they wore, and in others disowned the doctrines they were appointed to teach. Alive to feelings so natural, and mingling with the middling classes, of which they formed a most respectable portion, they must necessarily have become embued with their principles and opinions, and a very obvious train of reasoning would extend the consequences to their own condition. If the state was encumbered rather than benefited by the privileges of the higher order, was not the Church in the same condition? And if secular rank was to be thrown open as a general object of ambition to the able and the worthy, ought not the dignities of the Church to be rendered more accessible to those, who, in humility and truth, discharged the toilsome duties of its inferior offices, and who might therefore claim, in due degree of succession, to attain higher preferment? There can be no injustice in ascribing to this body sentiments, which might have been no less just regarding the Church than advantageous to themselves; and, accordingly, it was not long before this body of churchmen showed distinctly, that their political views were the same with those of the Third Estate, to which they solemnly united themselves, strengthening thereby greatly the first revolutionary movements. But their conduct, when they beheld the whole system of their religion aimed at, should acquit the French clergy of the charge of self-interest, since no body, considered as such, ever showed itself more willing to encounter persecution, and submit to privation for conscience' sake.

While the Noblesse and the Church, considered as branches of the state, were thus divided amongst themselves, and fallen into discredit with the nation at large; while they were envied for their ancient immunities without being any longer feared for their power; while they were ridiculed at once and hated for the assumption of a superiority which their personal qualities did not always vindicate, the lowest order, the Commons, or, as they were at that time termed, the Third Estate, had gradually acquired an extent and importance unknown to the feudal ages, in which originated the ancient division of the estates of the kingdom. The Third Estate no longer, as in the days of Henry IV., consisted merely of the burghers and petty traders in the small towns of a feudal kingdom, bred up almost as the vassals of the nobles and clergy, by whose expenditure they acquired their living. Commerce and colonies had introduced wealth, from sources to which the nobles and the churchmen had no access. Not only a very great proportion of the disposable capital was in the hands of the Third Estate, who thus formed the bulk of the moneyed interest of France, but a large share of the landed property was also in their possession.

There was, moreover, the influence which many plebeians possessed, as creditors, over those needy nobles whom they had supplied with money, while another portion of the same class rose{21} into wealth and consideration, at the expense of the more opulent patricians who were ruining themselves. Paris had increased to a tremendous extent, and her citizens had risen to a corresponding degree of consideration; and while they profited by the luxury and dissipation, both of the court and courtiers, had become rich in proportion as the government and privileged classes grew poor. Those citizens who were thus enriched, endeavoured, by bestowing on their families all the advantages of good education, to counterbalance their inferiority of birth, and to qualify their children to support their part in the scenes, to which their altered fortunes, and the prospects of the country, appeared to call them. In short, it is not too much to say, that the middling classes acquired the advantages of wealth, consequence, and effective power, in a proportion more than equal to that in which the nobility had lost these attributes. Thus, the Third Estate seemed to increase in extent, number, and strength, like a waxing inundation, threatening with every increasing wave to overwhelm the ancient and decayed barriers of exclusions and immunities, behind which the privileged ranks still fortified themselves.

It was not in the nature of man, that the bold, the talented, the ambitious, of a rank which felt its own power and consequence, should be long contented to remain acquiescent in political regulations, which depressed them in the state of society beneath men to whom they felt themselves equal in all respects, excepting the factitious circumstances of birth, or of Church orders. It was no less impossible that they should long continue satisfied with the feudal dogmas, which exempted the noblesse from taxes, because they served the nation with their sword, and the clergy, because they propitiated Heaven in its favour with their prayers. The maxim, however true in the feudal ages when it originated, had become an extravagant legal fiction in the eighteenth century, when all the world knew that both the noble soldier and the priest were paid for the services they no longer rendered to the state, while the roturier had both valour and learning to fight his own battles and perform his own devotions; and when, in fact, it was their arms which combated, and their learning which enlightened the state, rather than those of the privileged orders.[21]

Thus, a body, opulent and important, and carrying along with their claims the sympathy of the whole people, were arranged in formidable array against the privileges of the nobles and clergy, and bound to further the approaching changes by the strongest of human ties, emulation and self-interest.

The point was stated with unusual frankness by Emeri, a distinguished member of the National Assembly, and a man of honour and talent. In the course of a confidential communication with the celebrated Marquis de Bouillé, the latter had avowed his{22} principles of royalty, and his detestation of the new constitution, to which he said he only rendered obedience, because the King had sworn to maintain it. "You are right, being yourself a nobleman," replied Emeri, with equal candour; "and had I been born noble, such would have been my principles; but I, a plebeian Avocat, must naturally desire a revolution, and cherish that constitution which has called me, and those of my rank, out of a state of degradation."[22]