The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

[Pg i]

MICHELIN ILLUSTRATED GUIDES

TO THE BATTLEFIELDS (1914-1918)

THE

YSER

AND

THE BELGIAN COAST

An illustrated

history

and guide

- MICHELIN & Cie, CLERMONT-FERRAND, FRANCE.

- MICHELIN TYRE Co., Ltd., 81, Fulham Road, LONDON, S. W. 3.

- MICHELIN TIRE Co., MILLTOWN, N. J., U. S. A.

Michelin gives all profits from the sales of the present guides to the "Repopulation française" (Alliance Nationale)

10, Rue Vivienne.—PARIS.

[Pg ii]

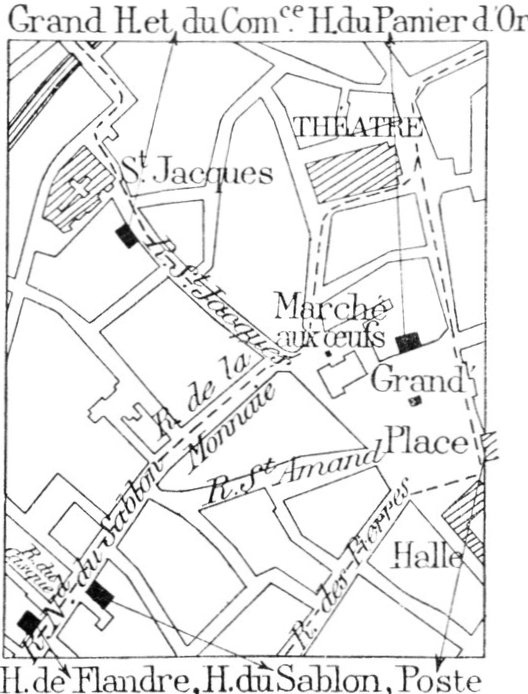

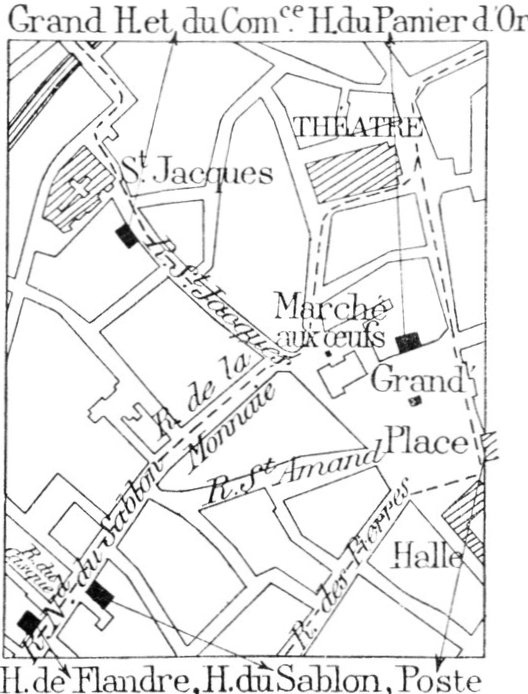

HOTELS

BRUGES

- Hôtel de Flandre, 38, rue Nord-du-Sablon. Tel. 19.

- Grand Hôtel et du Commerce, 39, rue Saint-Jacques. Tel. 114.

- Hôtel du Sablon, 21, rue Nord-du-Sablon.

- Hôtel du Panier d'Or, Grand'Place.

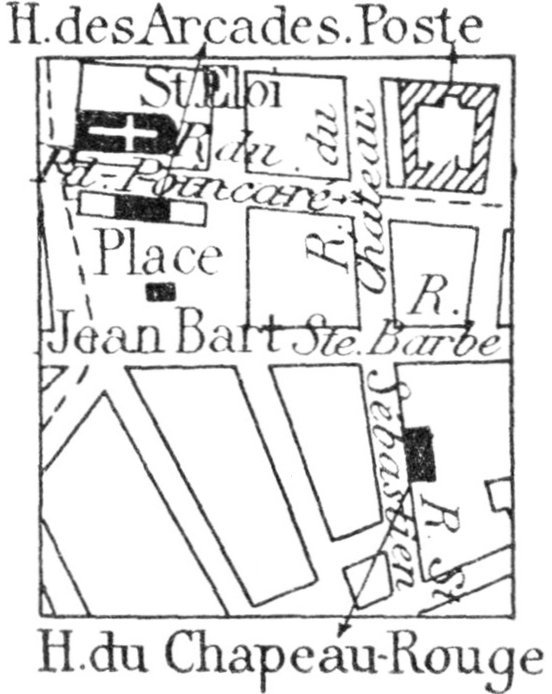

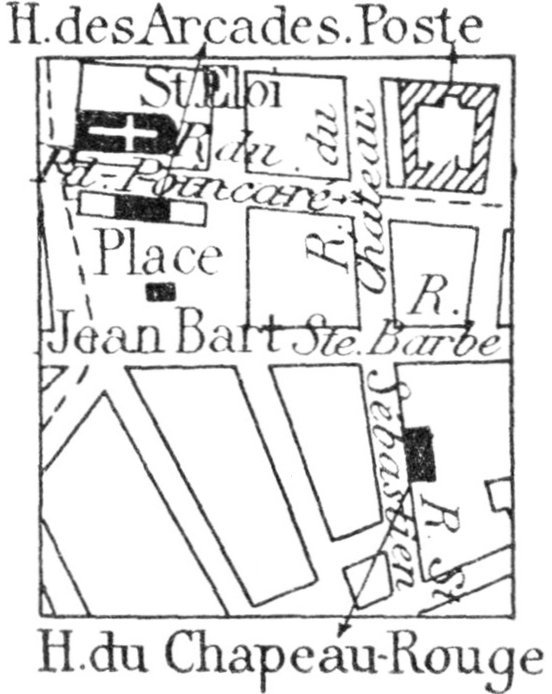

DUNKIRK

- Hôtel des Arcades, 37, place Jean-Bart,

Arcades. Tel. 1·89.

Arcades. Tel. 1·89.

- Hôtel du Chapeau-Rouge, de Flandre,

et Grand-Hôtel réunis, 5. rue Saint-Sébastien,

Tel. 2·15.

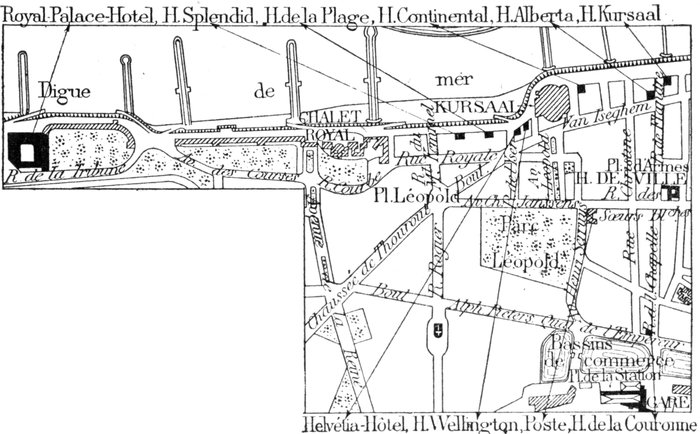

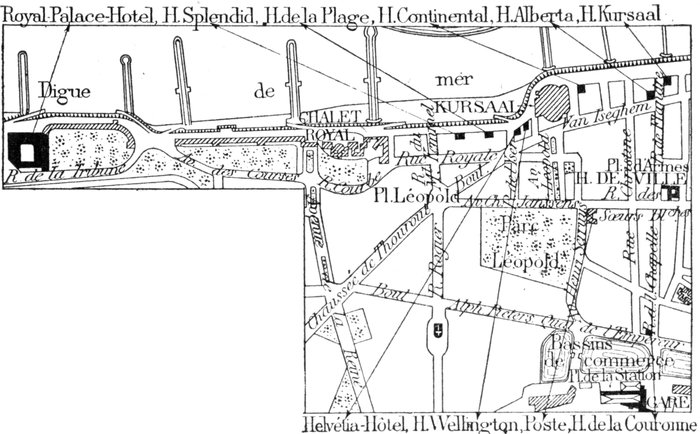

OSTEND

-

Royal Palace-Hôtel, Digue de Mer,

Tel. 173, 435 et 271.

- Hôtel Continental, Digue de Mer,

63, & rue de l'Yser. Tel. 154.

- Splendid-Hôtel, 67, rue Royale &

Digue de Mer. Tel. 13.

- Hôtel de la Plage, 65, Digue de

Mer & r. Royale. Tel. 152 et 593.

- Hôtel Kursaal et Beau-Site, 40, Digue

de Mer. Tel. 121.

- Hôtel de la Couronne, 17, quai de

l'Empereur. Tel. 43.

- Rouget's Hôtel Beau-Séjour, 110-112,

boul. Van Iseghem. Tel. 504.

- Helvétia-Hôtel, 62, Digue de Mer.

Tel. 200.

- Hôtel Wellington, 60, Digue de Mer

- Hôtel Alberta 31, Rampe de Flandre.

POPERINGHE.—Skindles-Hôtel, 43, rue de l'Hôpital. Tel. 24.

ZEEBRUGGE.—Zeebrugge-Palace. Tel. 6, Heyst.

[Pg iii]

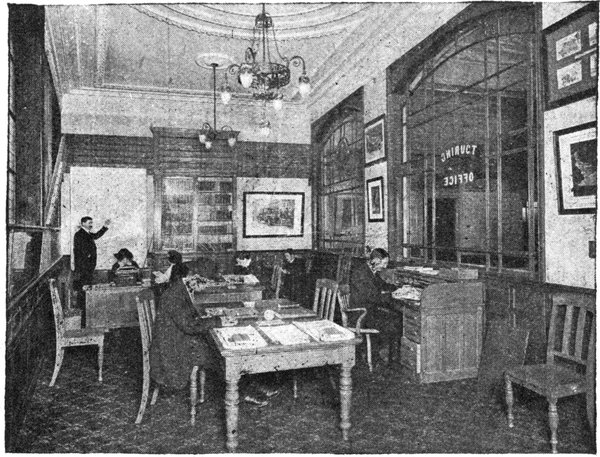

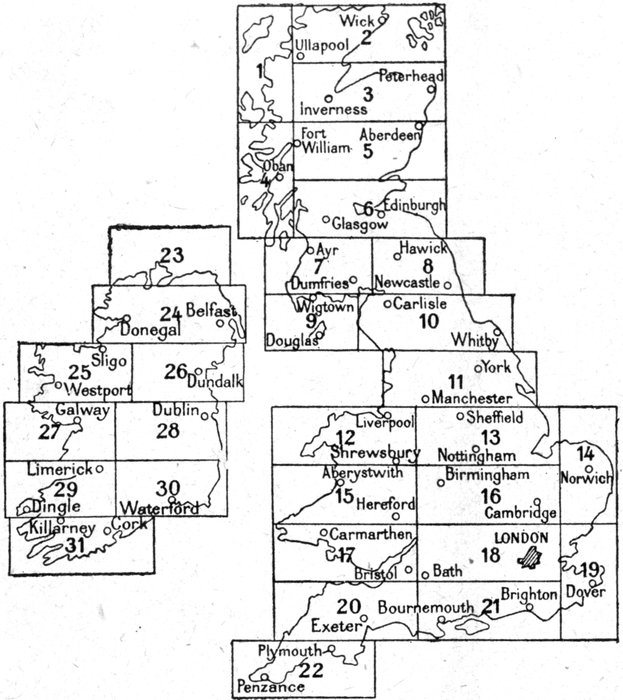

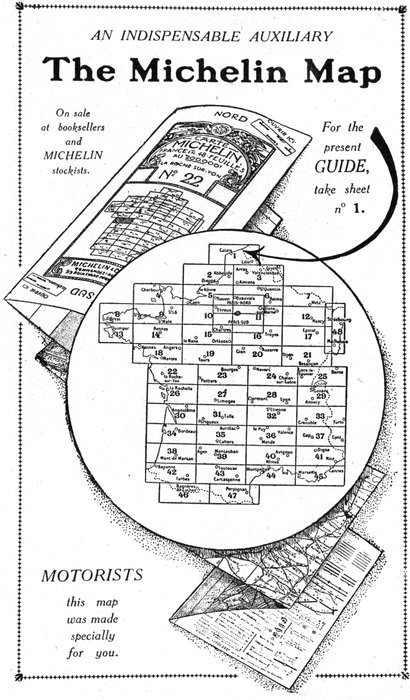

AN INDISPENSABLE AUXILIARY

The Michelin Map

On sale

at booksellers

and

MICHELIN

stockists.

For the

present

GUIDE

take sheet

no 1.

MOTORISTS

this map

was made

specially

for you.

[Pg iv]

The "Michelin Wheel"

BEST of all detachable wheels

because the least complicated

Smart

It embellishes even the finest coachwork.

Simple

It is detachable at the hub and fixed by six

bolts only.

Strong

The only wheel which held out on all fronts

during the War.

Practical

Can be replaced in 3 minutes by anybody

and cleaned still quicker.

It prolongs the life of tyres by cooling them.

AND THE CHEAPEST

[Pg 1]

IN MEMORY

OF THE MICHELIN WORKMEN AND EMPLOYEES WHO DIED GLORIOUSLY

FOR THEIR COUNTRY

THE

YSER

AND THE

BELGIAN COAST

Ce n'est qu'un bout de sol dans l'infini du monde...

Ce n'est qu'un bout de sol étroit,

Mais qui renferme encore et sa reine et son roi,

Et l'amour condensé d'un peuple qui les aime...

Dixmude et ses remparts. Nieuport et ses canaux,

Et Furnes, avec sa tour pareille à un flambeau.

Vivent encore ou sont défunts sous la mitraille.

Émile Verhaeren.

Compiled and published by:

MICHELIN ET CIE

Clermont-Ferrand (France)

All rights of translation, adaptation or reproduction (in part or whole) reserved in all countries.

CONTENTS

[Pg 2]

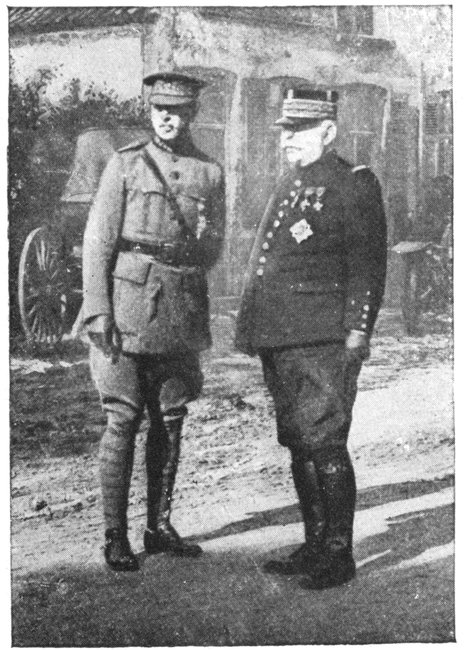

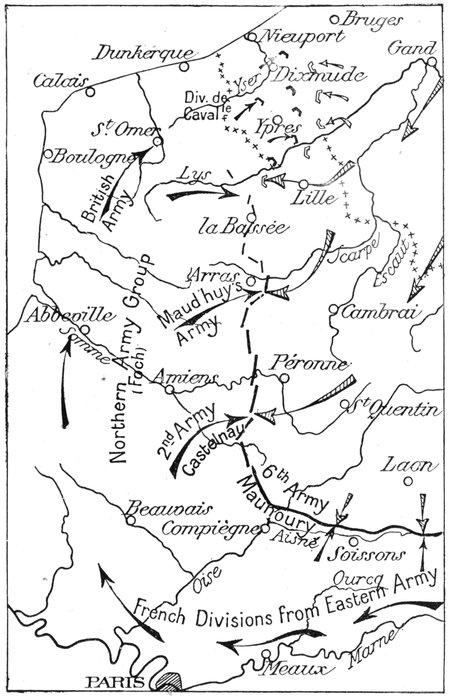

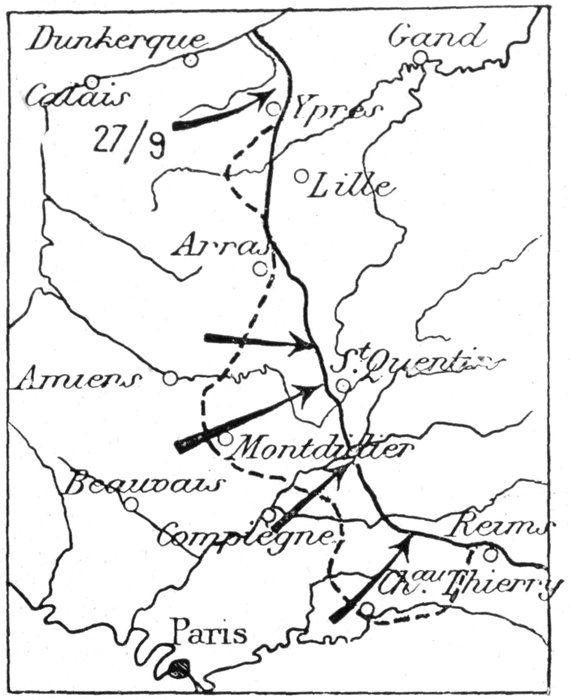

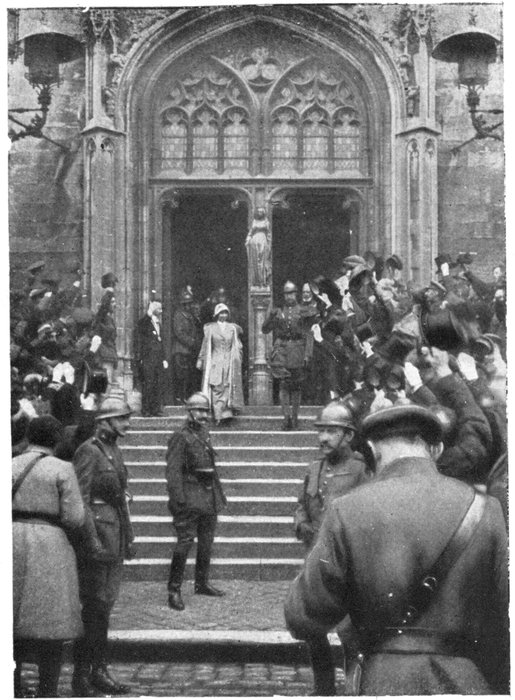

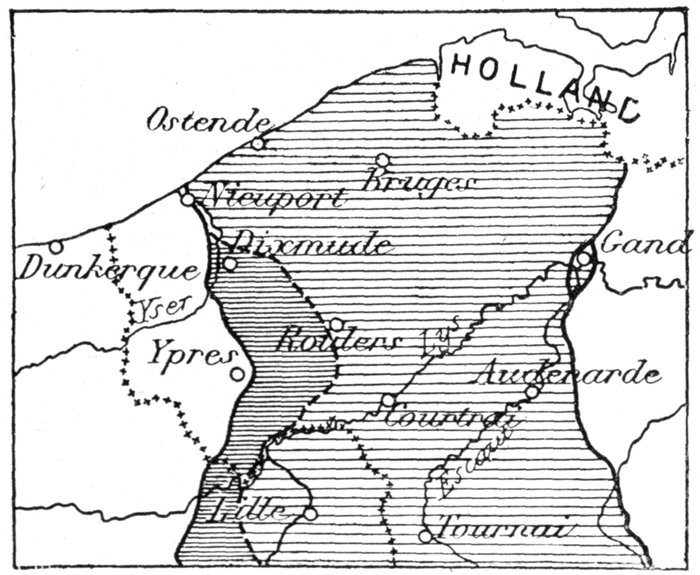

The Race to the Sea.

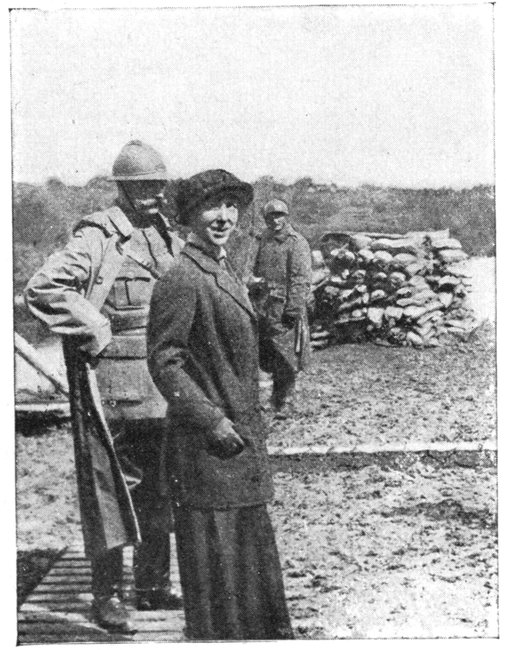

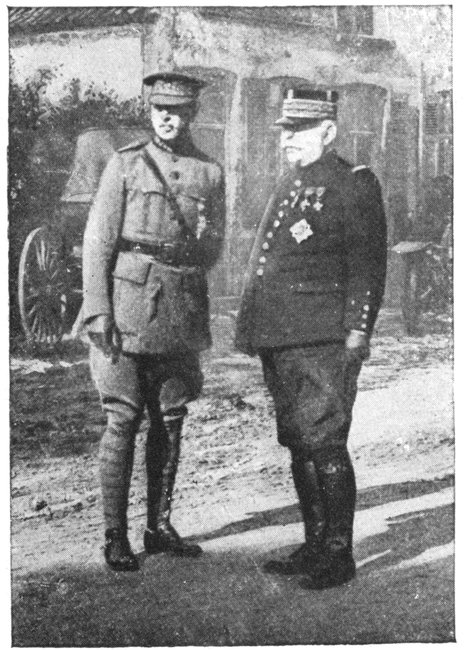

King Albert and General Joffre.

In September 1914, after the Battle of the Marne and the German retreat,

the centre and right of the French Armies quickly became fixed in front of

the lines which the enemy had prepared in the rear, and were then fortifying.

While the Allies' right, abutting

on the Swiss frontier, was protected

against any turning movement

on the part of the enemy, their left

(the 6th Army) was exposed.

The French 6th Army (General

Maunoury) held the right bank of

the Oise, north of Compiègne (See

map p. 3). The Germans attacked it

in force and attempted their favourite

turning movement.

General Joffre parried the manœuvre,

and while strengthening the 6th

Army, formed a mobile corps on his

left wing, strong enough to withstand

the enemy's outflanking movement.

The 2nd Army, consisting of corps

brought up from the east, was formed

and placed under the command of

General de Castelnau. Preceded and

protected by divisions of cavalry, it

gradually extended its front to the

south of Arras.

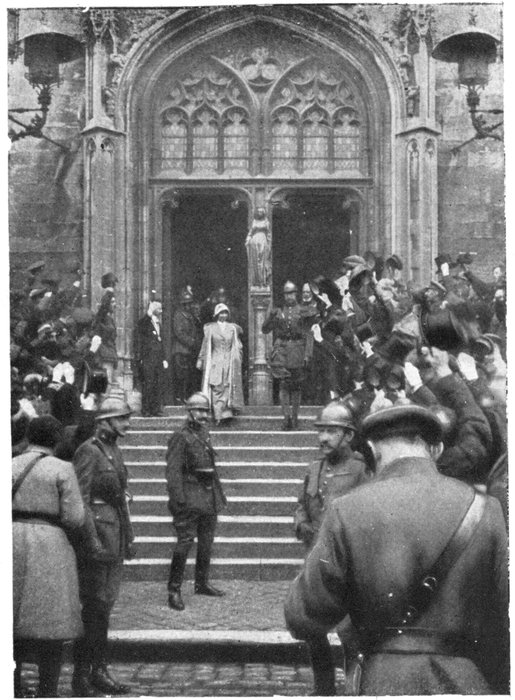

Queen Elizabeth in the Belgian

Lines, on the Yser

The Germans carried out a similar

movement, and the opposing armies,

in their attempt to outflank each

other, gradually prolonged their

front northwards and approached

the sea.

Against the German right wing,

which steadily extended itself northwards,

General de Maud'huy's Army

deployed from the Somme to La

Bassée, and gave battle in front of

Arras.

The Germans attacked furiously

and attempted both to crush the

Allied front and continue their

turning movement. Six Army Corps

and two Cavalry Corps were thrown

against General de Maud'huy's Army

but the latter, reinforced, held its

ground.

The command of the Northern

Army Group was entrusted to General

Foch.

The new chief promptly co-ordinated

the dispositions, in view of a

general action.

[Pg 3]

The northward movement of the armies became more pronounced. The

cavalry divisions of the Corps commanded by Generals de Mitry and

Conneau advanced towards the Plains of Flanders.

Simultaneously, the British Army was relieved on the Aisne, and drew

nearer to their threatened coast bases, in the region of Saint-Omer.

By October 19, they were completely installed in their new positions from

La Bassée to Ypres, thus prolonging northwards the Army of General de

Maud'huy. Between the British left and the North Sea Coast, there still

remained a gap, crossed from west to east by the roads leading to the

Channel Ports. It was this gap which the Belgian Army, after its escape

from Antwerp, was destined to stop.

[Pg 4]

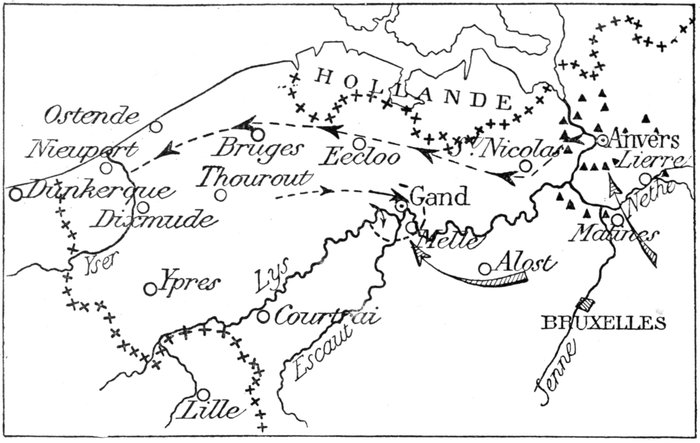

The fall of Antwerp and the Belgian retreat.

To capture Antwerp, the Germans adopted their usual tactics. Concentrating

their powerful siege artillery—which had previously destroyed the

forts of Liége, Namur and Maubeuge—in the sector south of the Nethe, they

effected a breach in the outer line of forts, and having crossed the Nethe,

with a loss of nearly 50,000 men, they attacked the inner line of forts, so as

to be able to bombard and reduce the town.

After consultation with the French General Staff, it was decided to abandon

the town, in order to save the Belgian Army.

Leaving a small number of troops in the forts, with orders to mask the

evacuation of the town, the Belgian Army, after destroying everything

likely to be of use to the enemy, crossed the Escaut by night, together with

the British forces, which, as early as September, had been despatched

to help in defending the city. These troops withdrew westward, via

St. Nicolas and Ecloo. On October 9, Antwerp capitulated.

To protect the flank of the columns retreating towards Bruges, the French

Marine Brigade, a detachment of Belgian Cavalry and volunteers, and the

British 7th Division took up positions in front of the eastern outskirts

of Ghent.

On October 4, Admiral Ronarc'h who had meanwhile concentrated his

brigade in the entrenched camp of Paris, received orders to transfer his

quarters to Dunkirk. Leaving St. Denis on the 7th, accompanied by his

staff, and closely followed by the Brigade, he reached Dunkirk in the evening,

proceeding thence to Antwerp. On the evening of the 8th, they were met

at the railway station of Ghent by General Pau with orders to defend that

town.

The Marines took up positions east of Ghent, and to the north and

south of Melle. Belgian volunteers occupied the bend in the Escaut. These

troops were supported by a group of Belgian artillery belonging to the

4th Mixed Brigade.

The Germans violently attacked in greatly superior numbers along the

Alost-Ghent road, but for forty-eight hours the Marines carried out their

mission of flank-guard. On receiving orders to retreat, the Franco-Belgian

detachment, covered by units of the British 7th Division, re-crossed the

Escaut and fell back towards the Yser, via Thourout, where the Belgian

Army was arriving, closely followed by detachments of German cavalry.

[Pg 5]

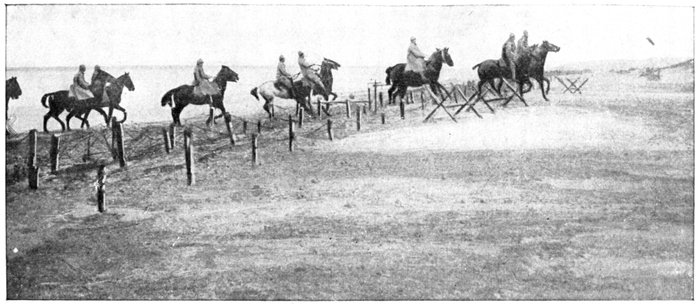

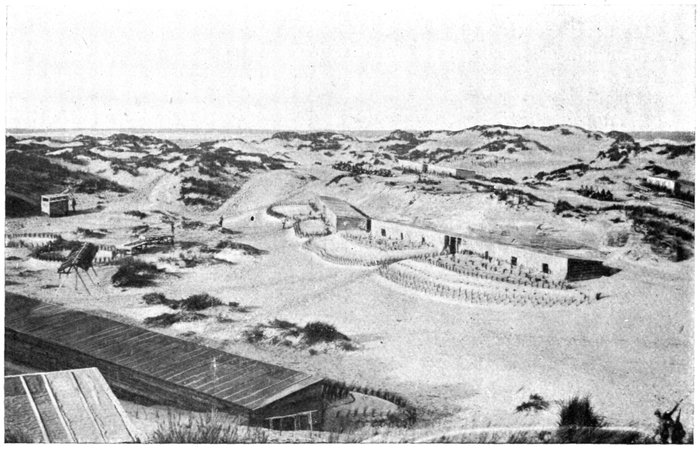

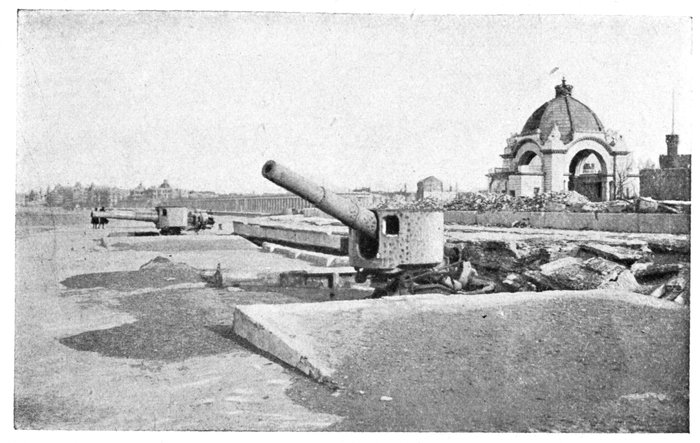

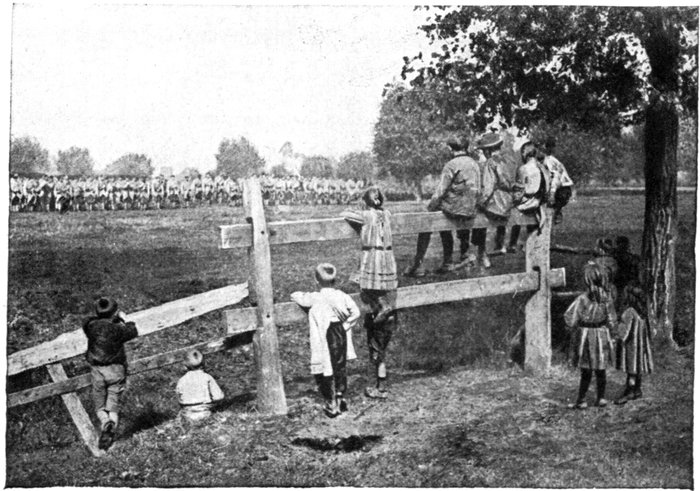

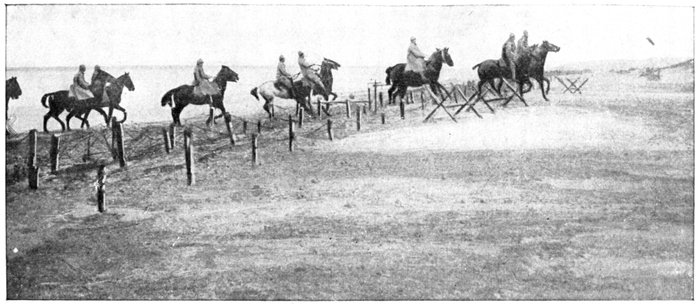

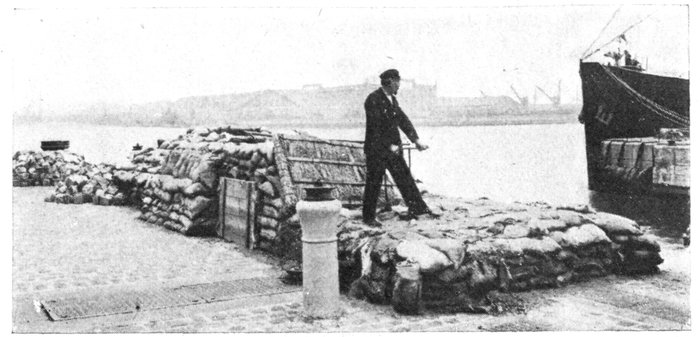

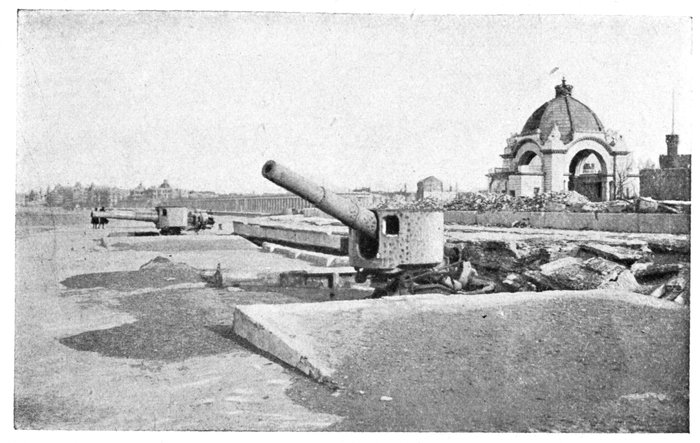

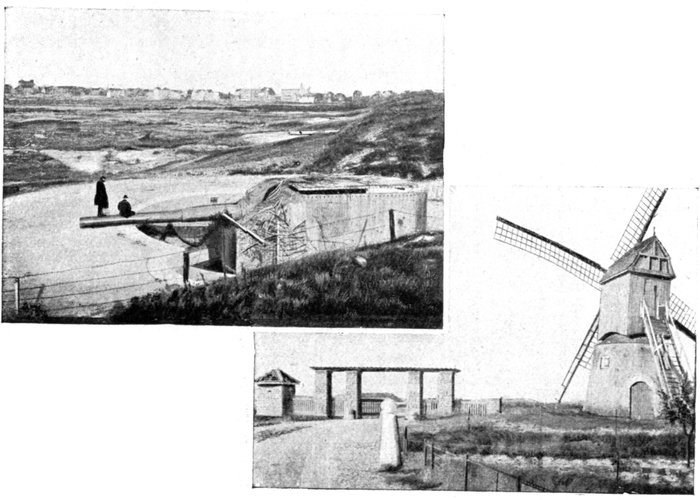

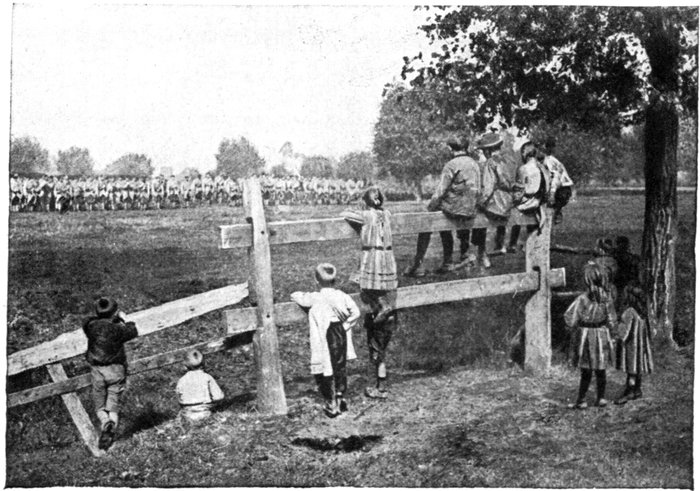

Cavalry on the beach at Malo-les-bains.

(Note the barbed-wire entanglements.)

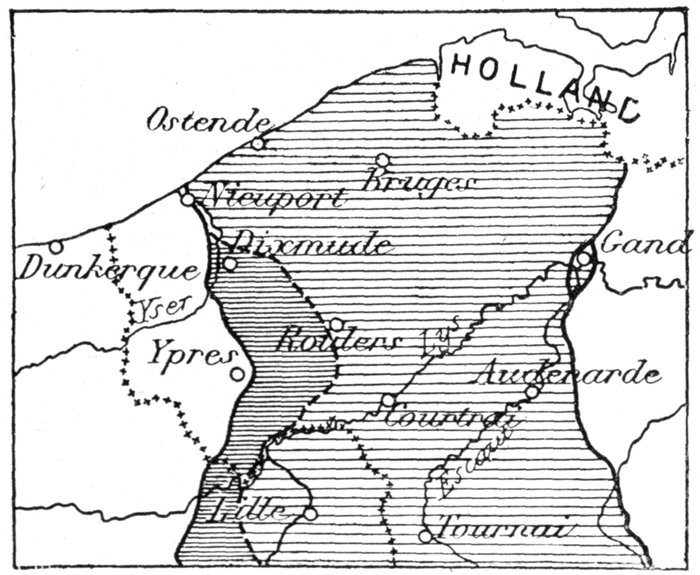

The Battlefield.

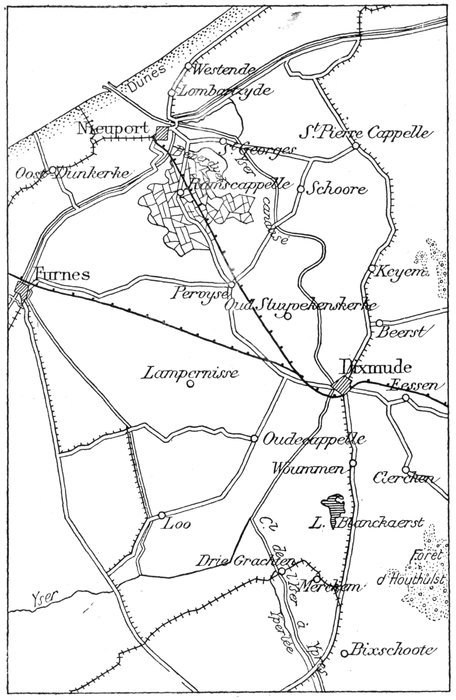

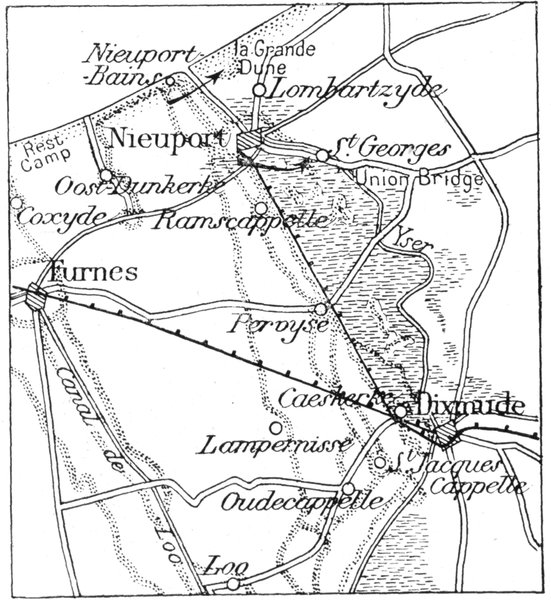

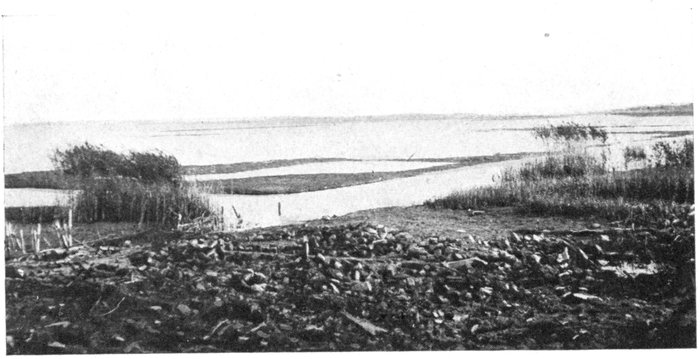

The last strip of unconquered Belgian territory, on which the German thrust

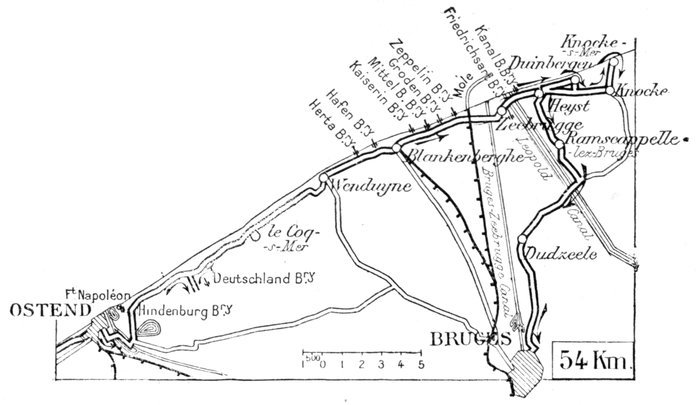

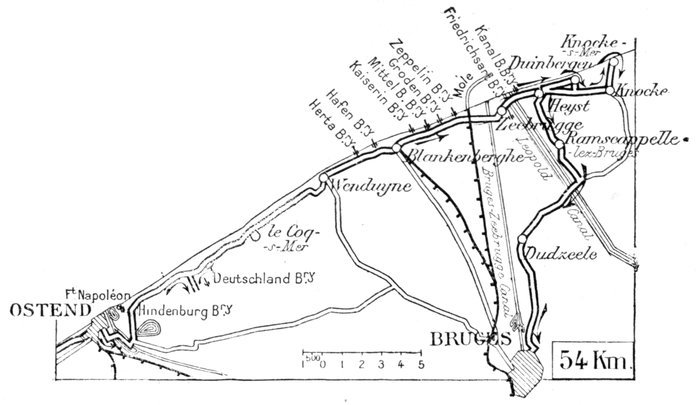

was destined to be broken, forms part of Maritime Flanders (See map, p. 6).

This vast plain was formerly a sea-gulf, and as late as the 11th century, was

often raided by the "drakkers" of the Scandinavian pirates. In the Middle-Ages,

the gulf gradually filled up with sand. This vast polder is almost

entirely below sea-level at high tide, and is each day invaded by the waves.

Water is everywhere: in the air, on the ground, under the ground.

It is the land of dampness, the kingdom of water. It rains three days out of four.

The north-west winds, breaking off the tops of the stunted trees, making

them bend as if with age, carry heavy clouds of cold rain formed in the open sea.

As soon as the rain ceases to fall, thick white mists rise from the ground, giving

a ghost-like appearance to men and things alike. (Le Goffic's, "Dixmude").

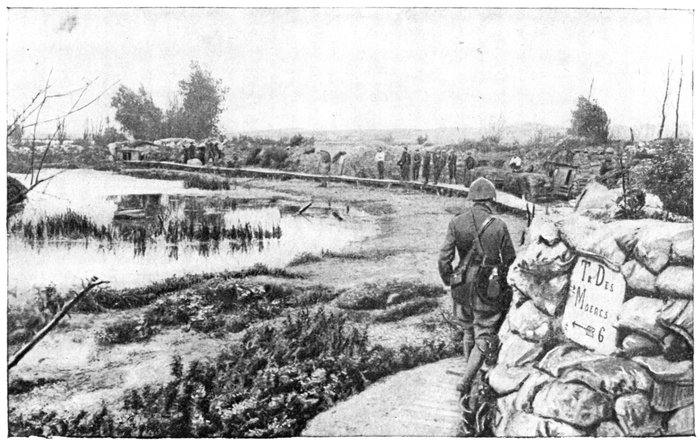

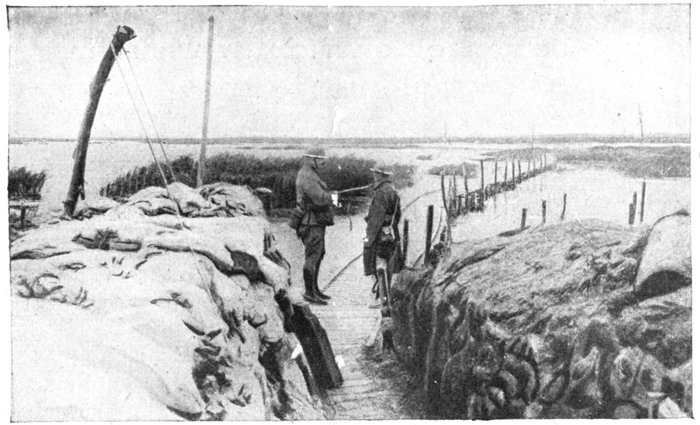

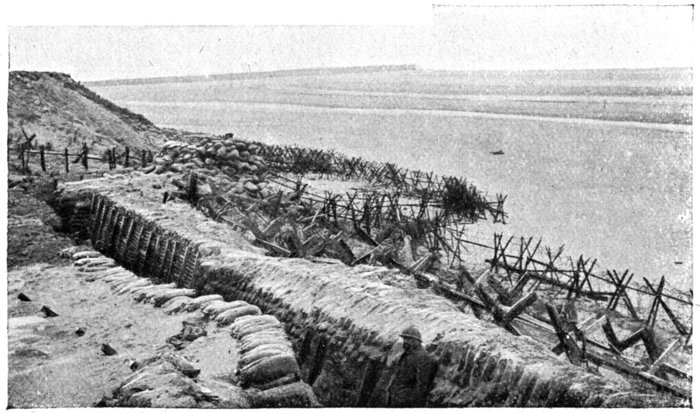

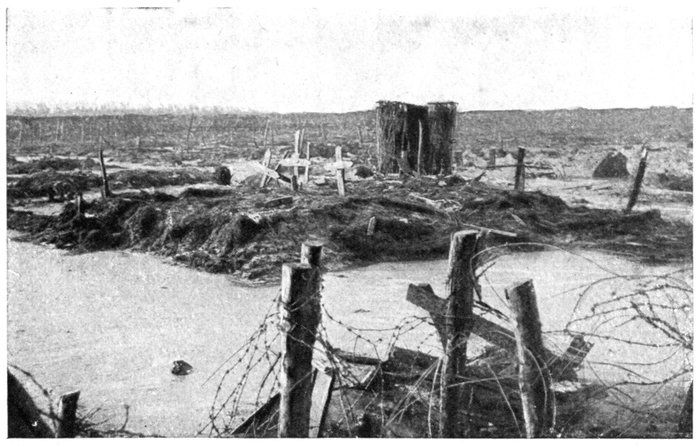

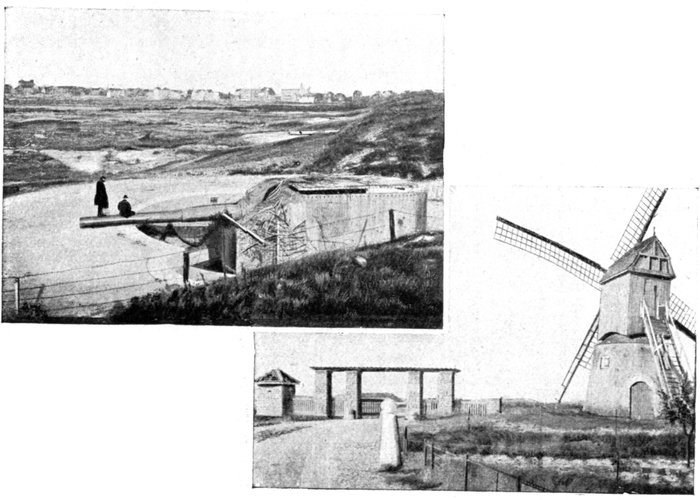

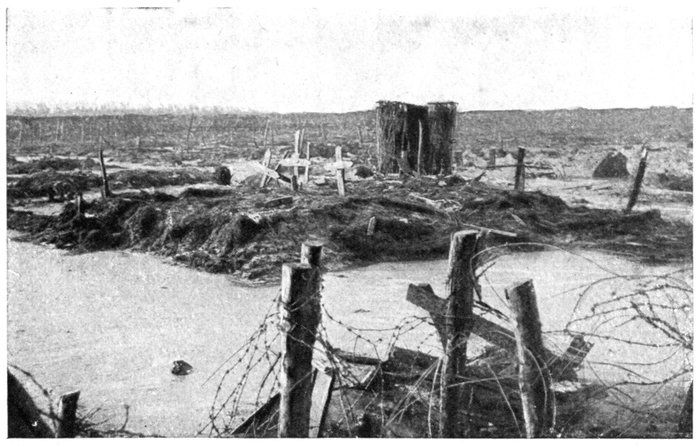

Line of Defence near Noordschote.

[Pg 6]

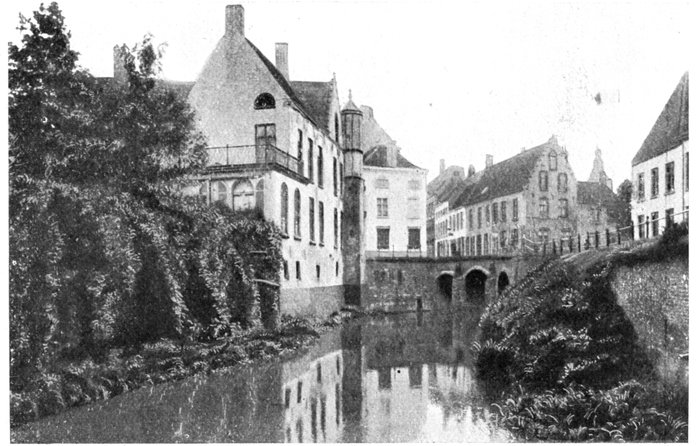

Water, which oozes up out of the soil, giving a blister-like appearance to

the soft clay covering, is found at a depth of less than three feet.

This water was carefully drained off, under the control of the Belgian State,

by associations of farmers and land-owners ("gardes wateringues"). Countless

ditches and canals ("watergands") skirting the willow hedges and

intersecting the entire plain, carried away this surplus water.

All the canals and ditches communicate with numerous water-courses,

e.g. the Yperlée, Kemmelbeck, Berteartaart, Vliet and many other nameless

ones, which run between embankments into the Yser.

[Pg 7]

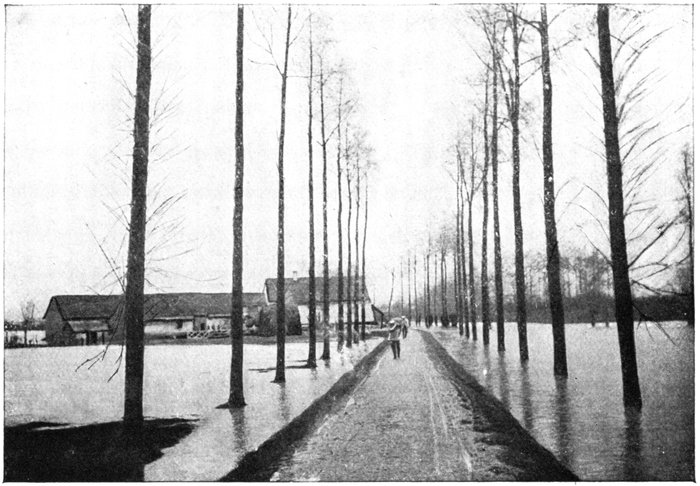

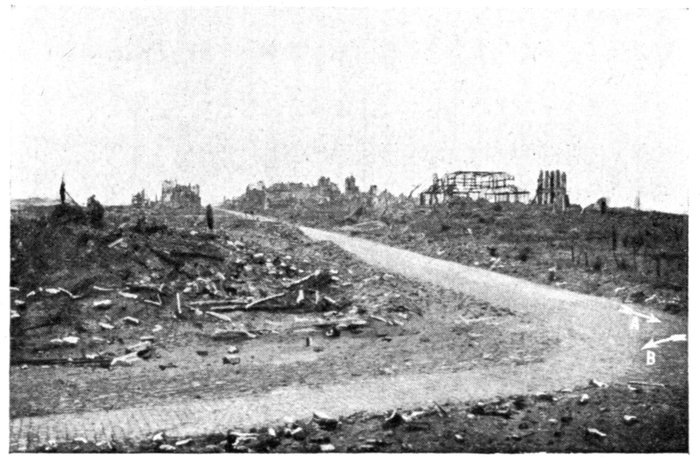

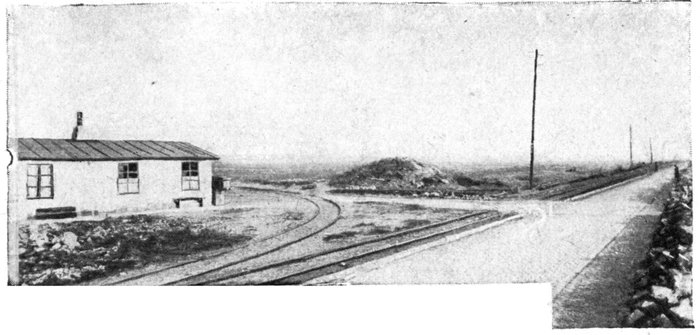

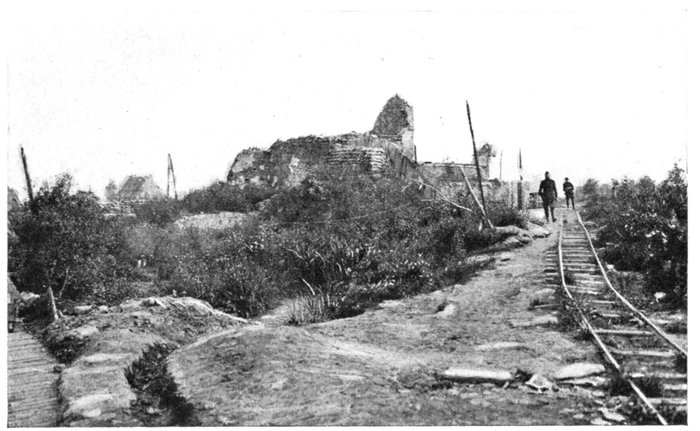

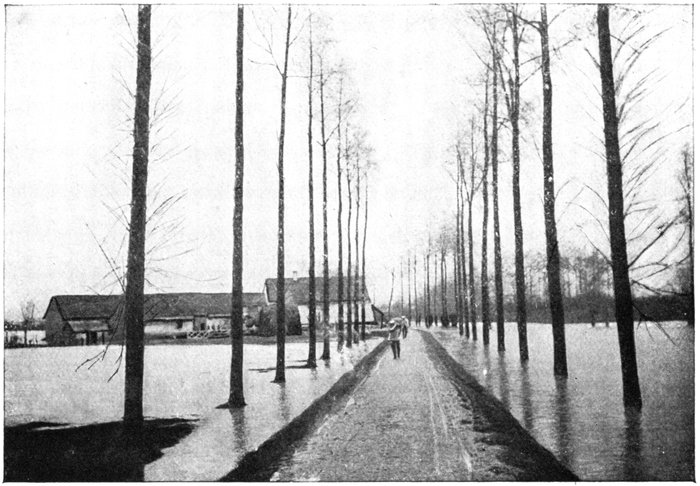

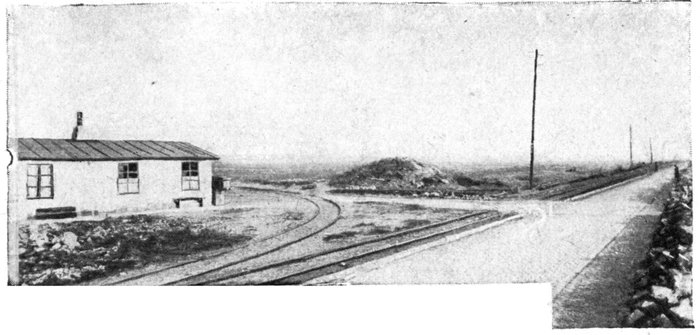

The road from Furnes to Ypres, near Westvleteren, in December 1915.

(See page 127.)

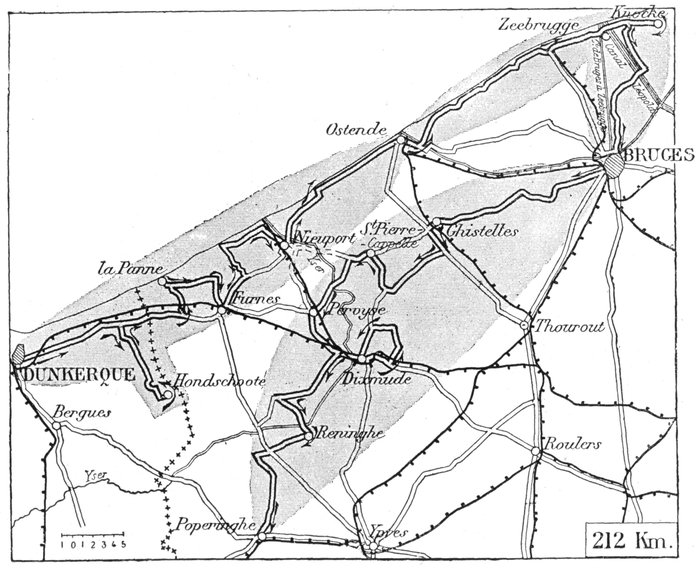

The Yser, a small coastal river, having its source in French Flanders

empties itself into the sea between two jetties. Its shallow bed, dredged

along the greater part of its course, describes a wide semi-circle. At its

mouth, at Nieuport, the Yser and the canals which likewise end there, are

closed by a series of locks, which shut out the sea at high tide and prevent

it from invading the plain through the streams and canals.

The few roads and the Nieuport-Dixmude railway run along embankments

seven to ten feet high.

Formerly, flocks of sheep and herds of cattle, tended by grey-coated

shepherds, grazed in this plain. Immense fields of beet and turnips

alternated with the meadows. Hedges, willows, clusters of bending poplars,

and the roofs of the low farmsteads built on little hillocks, broke the monotony

of the landscape. Here, where peace and prosperity reigned, the

inundations and war have left a vast expanse of reeds, in which the roads,

ruined farmhouses and a few broken trees stand out dismally.

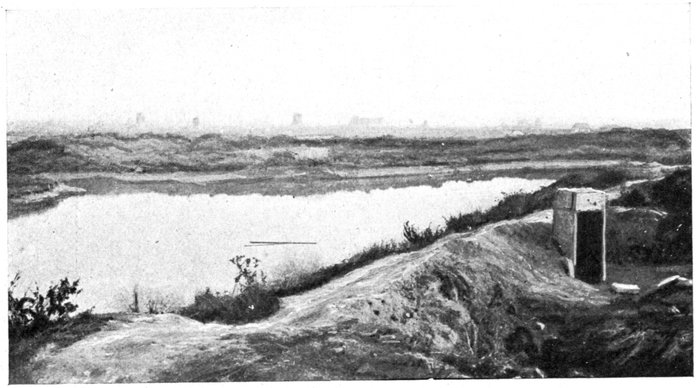

The plain is bounded on the west by a line of wind-formed sand dunes

planted with oyats. These dunes extend along the straight unbroken coast.

To the east of Dixmude rises a series of heights, which, marking the beginning

of the solid ground, are continued further east by the long unbroken

crest of Clerken.

South of this crest stretches the Forest of Houthulst, now entirely devastated

by shellfire.

The spongy nature of the soil makes it impossible to excavate to any

depth, nor was there any high ground to mask the defence-works and

batteries of artillery.

Two great embankments: that of the Yser, arc-shaped, and that of the

Nieuport-Dixmude railway, connecting up to the two ends of the former,

were the framework of the defence lines. However, the dominating element:

water, provided the defenders with a supreme and irresistible arm.

[Pg 8]

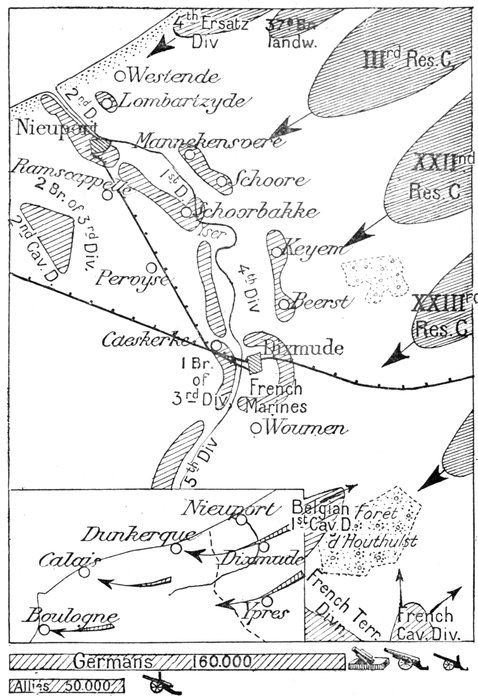

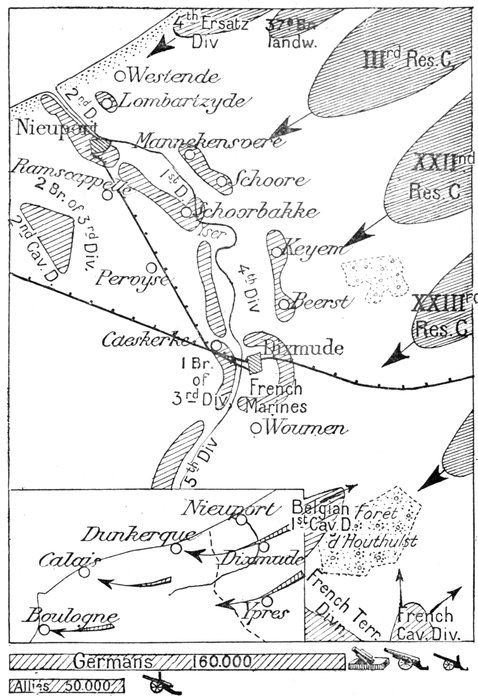

The Opposing Forces.

The right wing of the German IVth Army, under the command of the Prince

of Württemberg, marched via Bruges towards Dunkirk. This newly formed

army was partly composed of young men belonging to the German aristocracy,

volunteers and former students, worked up to frenzied patriotism by

the German victories.

These admirably equipped troops were supported by at least 500 guns of

all calibres, to which was soon added the heavy siege artillery that had just

crushed the forts of Antwerp.

This mass of 160,000 men, drunk with the furor teutonicus, pursued its

victorious march on the Channel ports, certain of crushing the small Belgian

Army which had again escaped them at Antwerp, but which this time was

to be annihilated.

Without losing a single gun during their stirring retreat, the Belgian

Army reached the Yser line. In its death-grapple with the invader, it

had been seriously reduced by more than two months of hard fighting.

Minus the greater part of its officers, and reduced to 43,000 rifles, 300 75's

and 23 6in. howitzers, its reserves of munitions were barely sufficient to deliver

another battle. There was no hope of new supplies, as the army was deprived

of its arsenals.

The men, with their torn and muddy uniforms, seemed to have reached

the limits of physical endurance, and to be incapable of further prolonged

effort.

It was then that King Albert issued his stirring Order of the Day:

Soldiers,

For two months and more you have been fighting for the most just of causes:

your homes and national independence.

You have held the enemy's armies, sustained three sieges, executed several

sorties, and successfully carried out a long retreat through a narrow defile.

So far, you have been alone in this tremendous struggle. Now you are at

the side of the valiant French and British Armies.

It is your duty to uphold the reputation of our arms with that spirit of tenacity

and bravery of which you have given so many proofs. Our national honour is

at stake.

Soldiers,

Look on the future with confidence, and fight with courage.

In whatever positions I place you, look ahead, and consider as a traitor to the

Motherland whoever speaks of retreat, without the formal order having been

given.

The time has come for us, with the aid of our powerful allies, to drive the

enemy from our dear country, which they invaded in contempt of their word and

of the sacred rights of a free people.

(Signed) Albert.

The supreme battle was about to begin. To hold the enemy's thrust

against Dunkirk and Calais, the Belgian Army, supported by the Allies, once

again resolutely placed itself across his path and barred the way.

From the sea to Zuydschoote (8 km. North of Ypres), the Belgian Army

was at first obliged, with the help of only 6,000 French Marines, to hold a

twenty-two mile front.

[Pg 9]

The unequal strength of the opposing forces seemed to warrant

the enemy's expectations of crushing in the Allied front and breaking through to

the Channel ports.

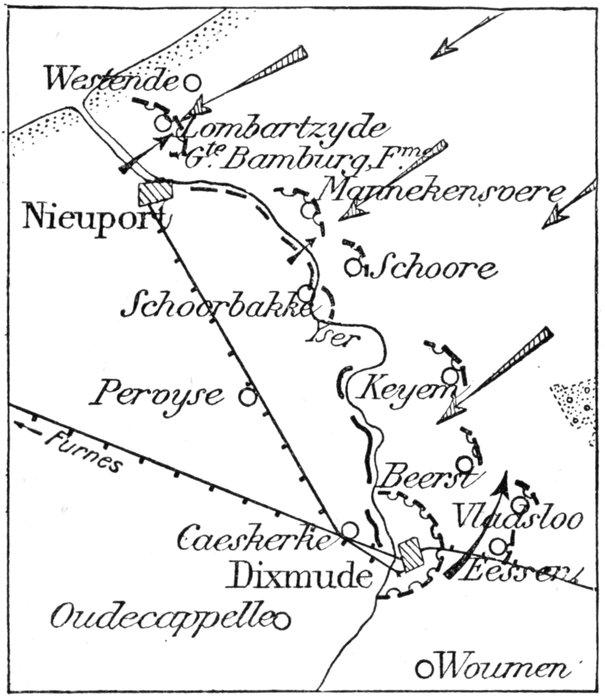

To defend this wide front, the whole Army was deployed. From the coast

to Dixmude, the 2nd, 1st and 4th Divisions were echeloned, with units

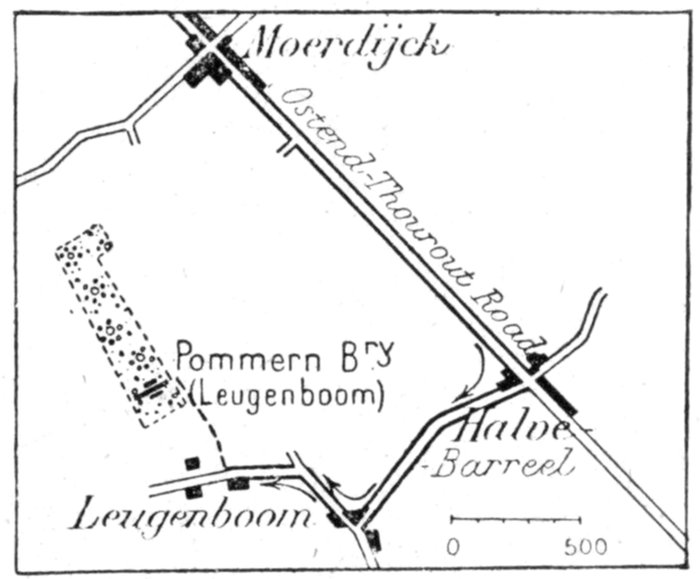

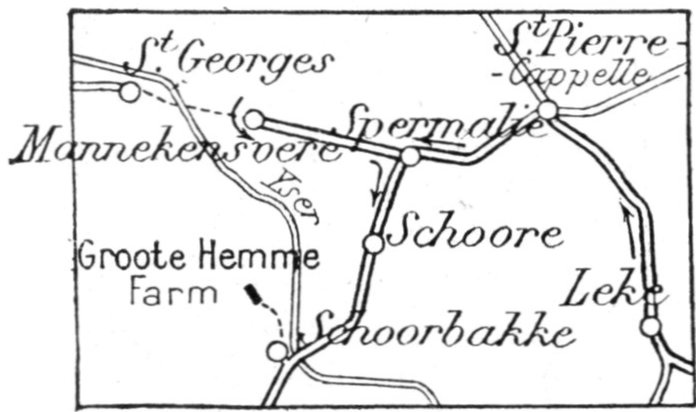

beyond the Yser holding the advance-posts of Lombartzyde, Mannekensvere,

Schoore, Keyem, Beerst and the two bridgeheads of Nieuport and Schoorbakke.

The bridgehead of Dixmude was held by the brigade of French Marines and

a brigade of the Belgian 3rd Division. South of Dixmude, the 5th Division,

in positions along the canalised portion of the Yperlée, occupied the region of

Boesinghe in liaison, on the right, with divisions of Brittany Territorials.

The 1st Division of Belgian cavalry operated near the woods of Houthulst

and Roulers, with French Cavalry divisions of General de Mitry's 2nd Corps,

thus protecting the Belgian right.

There remained in reserve only two Brigades of the 3rd Division and

2nd Cavalry Division to the south-west of Nieuport.

[Pg 10]

THE BATTLE OF THE YSER.

The fighting in the advance-positions.

The Franco-Belgian troops had hardly taken up their defensive positions

when, on October 15, the guns began to roar in the direction of Dixmude.

On October 16 and 17, strong German reconnoitering parties, supported by

field artillery, came into contact with the Allies' positions.

On the 18th, the enemy hurriedly attempted to crush the defenders,

before reinforcements arrived. After a violent bombardment, a powerful

attack was launched against the Mannekensvere-Schoore-Keyem-Beerst

line, held by units of the Belgian 2nd, 1st and 4th Divisions.

Assault after assault was beaten off, but finally, after very heavy losses,

fresh enemy masses carried Mannekensvere and Keyem, where they were

held by the volley fire of the Belgian 75's. The defenders of Mannekensvere

withdrew behind the Yser, while those of Keyem (units of the 1st Division)

held their ground on the

right bank of the river. The

same night a spirited counter-attack

gave them back

their lost positions.

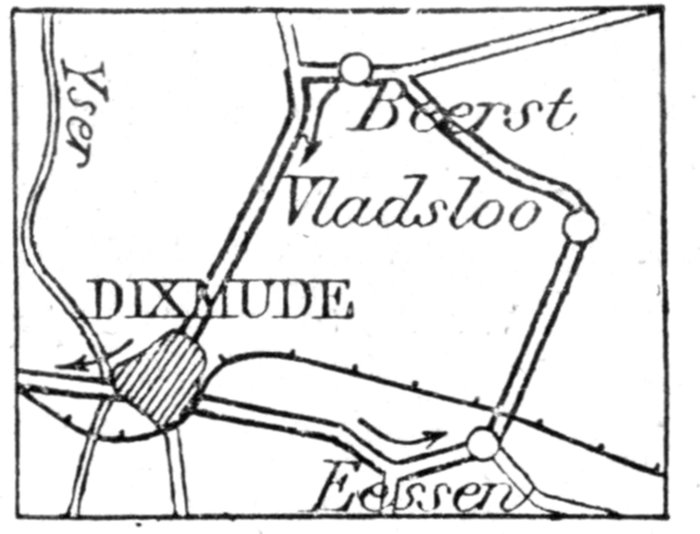

On the 19th, the attacks

doubled in fury, the enemy's

main effort being made

against the two wings.

Nieuport and the advanced

lines of Lombartzyde

were violently bombarded.

The Belgian 2nd Division

stood firm, and beat off

three German assaults.

On the right wing, the

Germans, driven out of

Keyem on the previous day,

attacked this village again

and also Beerst, further

south. Under a terrific

artillery fire, the defenders

gave way.

However, the Belgian 5th

Division and the French

Marines debouching from Dixmude, captured Vladsloo and Beerst, in spite

of considerable losses. With their left threatened, the enemy's efforts before

Keyem weakened.

This brilliant counter-offensive was held by a new menace. Strong

enemy columns were signalled to the south-east, debouching from Roulers

and marching on Dixmude.

The 5th Division and the Marines fell back upon their original positions

before Dixmude, their retreat bringing about the fall of Beerst and Keyem,

whose defenders withdrew beyond the Yser.

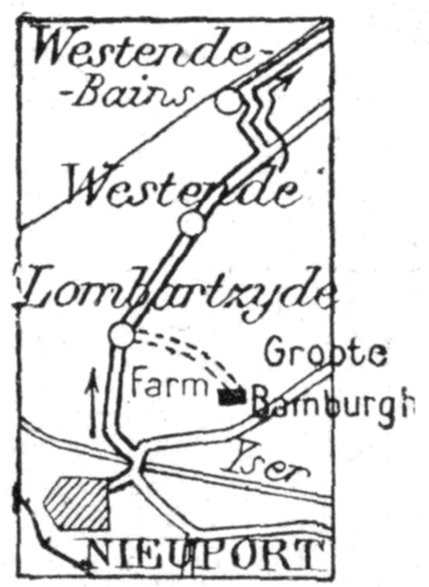

On the 20th the Germans threw themselves against the advanced positions

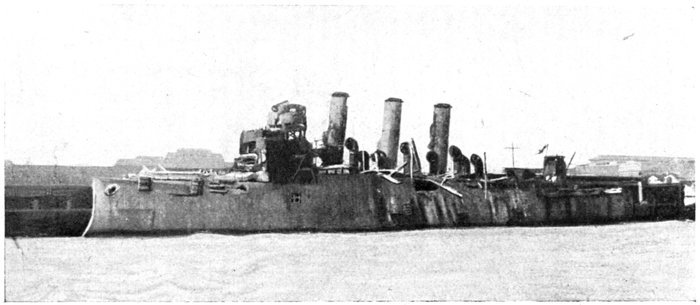

of Lombartzyde. The defenders were supported by the artillery of the

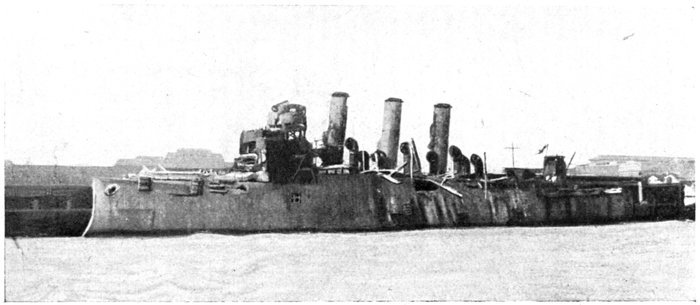

British monitors, whose guns swept the coastline. To the south-east of

Lombartzyde, Groote-Bamburg Farm was first lost, then reoccupied after

a spirited counter-attack.

The Germans redoubled their costly efforts, and succeeded in getting a

footing in Lombartzyde in the evening, but were unable to debouch.

[Pg 11]

Only after five days of sanguinary fighting, were the enemy able to reach

the Allies' main line of defences, formed by the Yser and the two bridgeheads

of Nieuport and Dixmude.

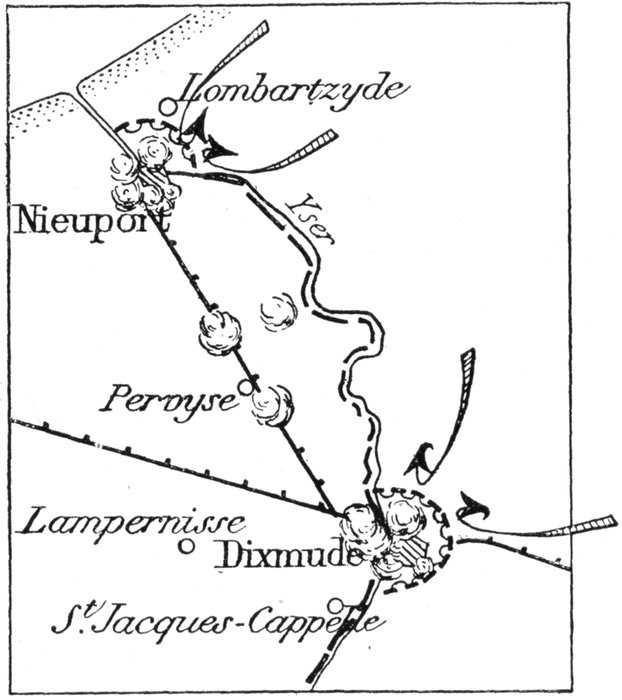

The Battle on the Main Line of Defence.

The situation was none the less critical, and the battle waxed more and

more furious. The Yser front was continuously deluged with shells. The

Belgian batteries of 75's were unable to engage the German heavy guns.

None of the villages could be held; Nieuport and Dixmude were in flames.

Supported by the Brigade of French Marines, the remains of the six Belgian

Divisions still defended, single-handed, the twelve-mile front between

St. Jacques-Cappelle and the sea. They were reinforced by the 6th Division

near Lampernisse and Pervyse, thus strengthening the centre.

Against these depleted, exhausted and ill-revictualled troops, crushed

beneath a continuous bombardment,

the Germans brought

up heavy reinforcements from

Roulers.

The Attack on Dixmude

and Nieuport.

Nieuport and Dixmude formed

the bastions of the Allied

defences, and their capture

meant the falling of the Yser

and the railway lines into the

enemy's hands.

The brunt of the German

attack was directed against

Dixmude.

The French Marine Brigade

and the mixed brigade of the

Belgian 3rd I. D. under the

command of Admiral Ronarc'h,

were deployed in a semi-circle,

about 500 yards from the

outskirts of Dixmude, resting

on the Yser. A second line was established along the canalised river.

On October 20, after an artillery preparation which lasted all the morning,

the enemy made an unsuccessful attack on Dixmude. A fresh attack the

same night was likewise repulsed. Meanwhile the town continued to burn.

On the 21st, at dawn, the bombardment redoubled in violence. The

Germans attacked again, only to be mown down and repulsed.

In the afternoon, new enemy reinforcements delivered converging attacks

of great violence, combining them with a furious thrust against the Schoorbakke

Pass, situated half-way between Dixmude and Nieuport. At both

points the German rush was broken.

In exasperation, the enemy threw fresh battalions into the battle. This

time the blow was aimed directly at the town itself and the canal to the

south, but the defence remained unshaken. Simultaneously, the Germans

were threatening the entire front, and in particular, the bridgehead of

Nieuport. This town suffered the same fate as Dixmude.

Still the Yser remained impassable. Both Dixmude and Nieuport held

out, and the end of the day registered a fresh enemy check.

[Pg 12]

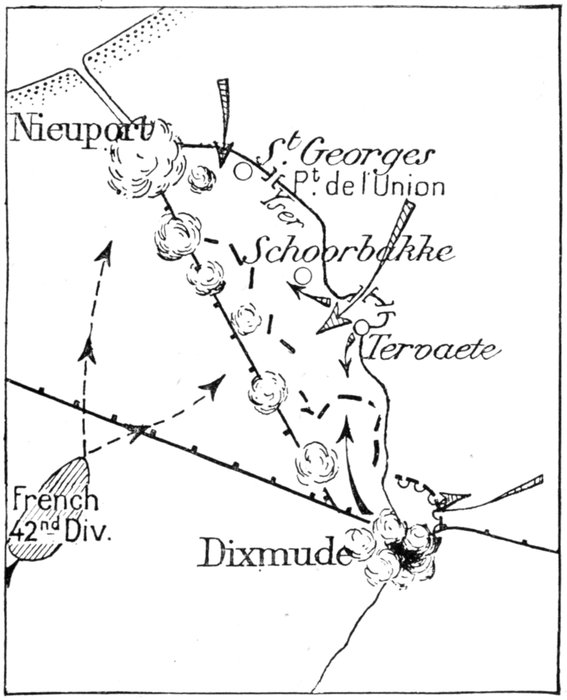

The Breach in the Centre of the Line.

After their failure before Nieuport and Dixmude, the enemy made a

surprise attack against the centre, on the night of the 21st.

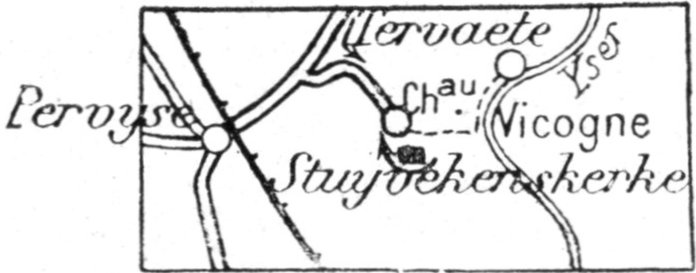

Between Nieuport and Dixmude, the easterly loop in the Yser at Tervaete

facilitated flank, enfilade and rear firing, and was consequently a weak

point in the defences.

Under cover of darkness, the enemy threw a bridge over the river, near

Tervaete, and effected a crossing. The situation was critical, as if the

front were pierced, the two centres of resistance, Nieuport and Dixmude,

which until then had proved impregnable, would be taken in the rear.

In a supreme effort, units of the Belgian 1st Division counter-attacked

furiously, and in spite of terrible losses, held the enemy. Reinforcements of

Grenadiers and Carabiniers succeeded, in a further attack, in driving back

the Germans across the river, and in reoccupying their positions. However,

on the night of the 22nd, the enemy recaptured Tervaete, but the Belgians

remained masters of the line

between the two ends of the

loop.

On the 23rd, the situation

was still very critical. To fill

the gaps in the fighting line

and to "hold out to the last, in

spite of all", in accordance with

the orders of the Belgian General

Headquarters, the last reserves

were thrown into the

battle.

Fortunately, the first French

reinforcements,—the famous

"Grossetti" (42nd) Division

which General Foch, at Fère-Champenoise,

in the centre of

the battle-line at the Marne,

had thrown against the flank of

the German columns, thereby

turning the scales at the psychological

moment (See the Michelin

Guide: The Marshes of

St. Gond—part 2 of The First

Battle of the Marne),—arrived at this juncture.

The first units to arrive relieved the exhausted Belgians before Nieuport.

Meanwhile, the bombardment of the town and bridgehead had reached an

incredible degree of violence.

In the centre, the situation was still more serious, the exhausted remnants

of the Belgian 1st and 4th Divisions having reached the limit of endurance.

The enemy threw ten battalions with machine-guns and artillery into the

loop at Tervaete. The bridgehead of Schoorbakke, attacked from the rear

was captured.

On the 24th, the 83rd Brigade of Grossetti's Division was moved to the

centre, to oppose the German thrust, at the time when the enemy had just

carried the Union Bridge.

Encouraged by the advantage which they had just secured, the Germans

renewed their efforts against Dixmude, where their left wing was being held

in check.

They had already gained a footing on the left bank of the Yser, north of

the town, and were threatening to outflank it from the west.

[Pg 13]

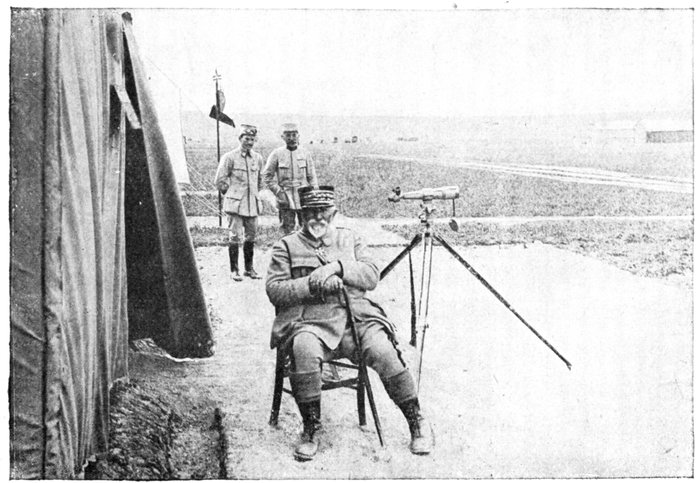

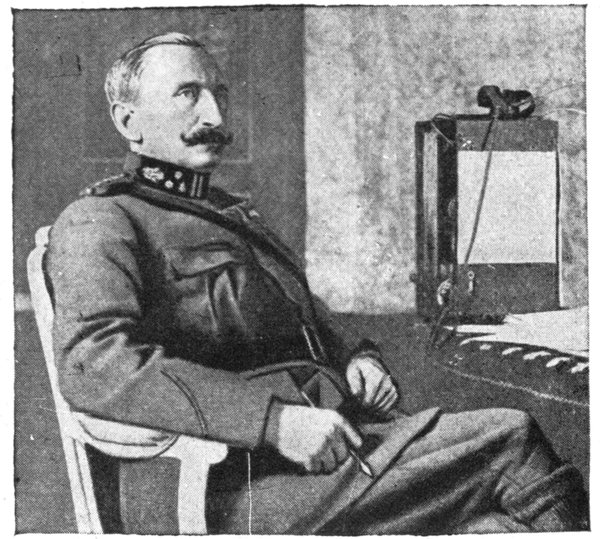

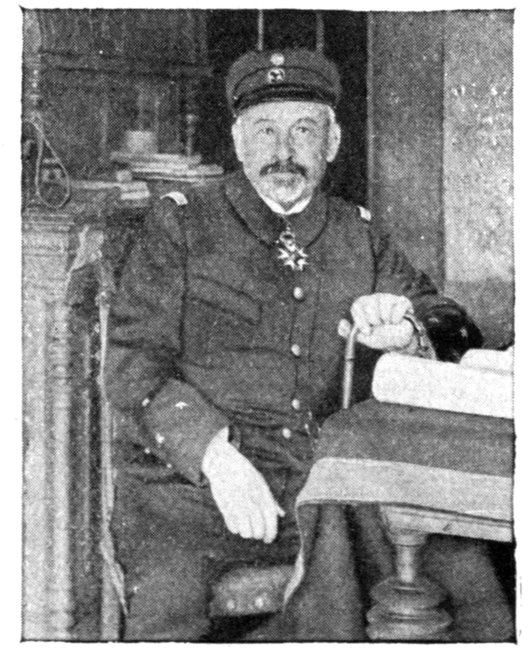

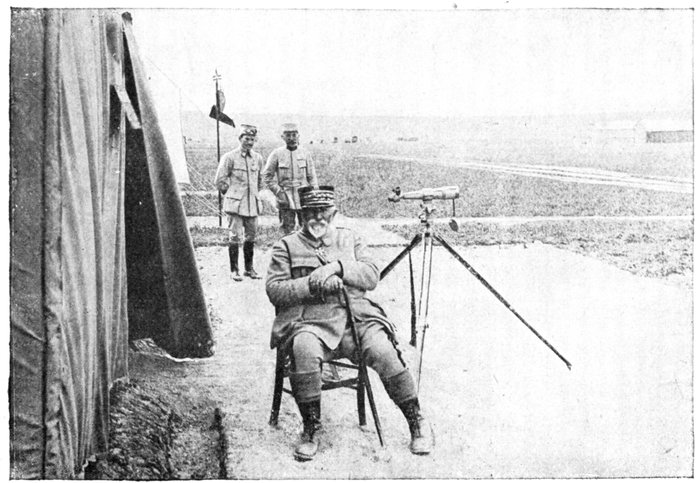

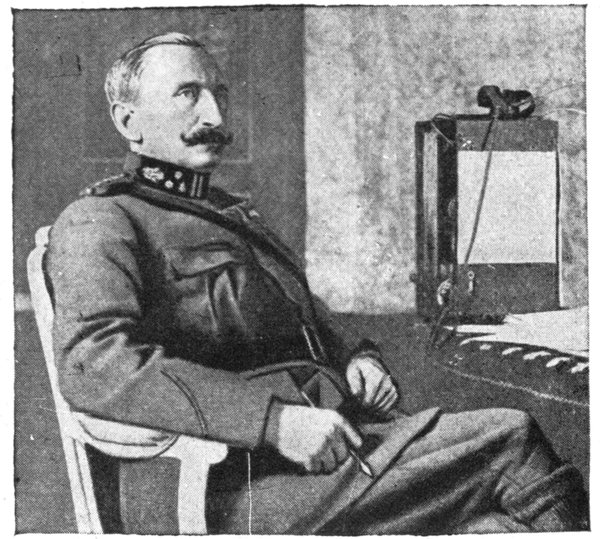

General Grossetti, commanding the 42nd Division.

A supreme effort was made against the bridgehead, no less than fifteen

assaults being delivered on the 24th.

The fierceness and horror of the struggle were indescribable, the men

grappling with one another in pitch darkness.

However, the German furor spent itself against the heroism of the

Belgian Infantry and French Marines who, for more than a week, remained

in the breach day and night.

Dixmude remained inviolate.

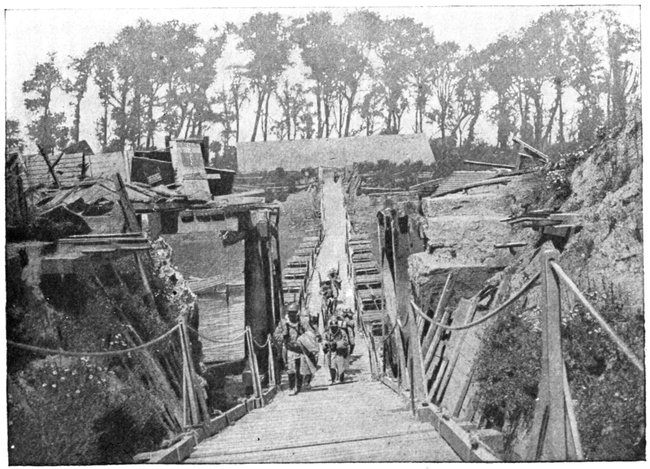

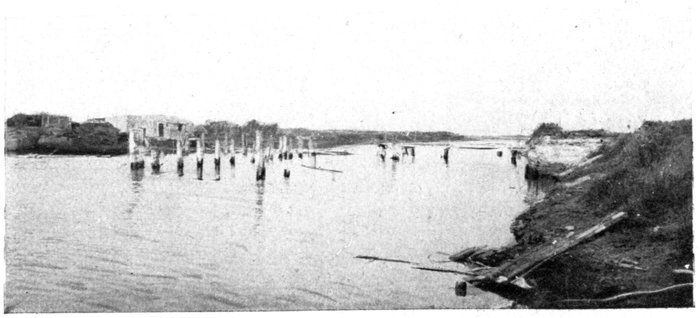

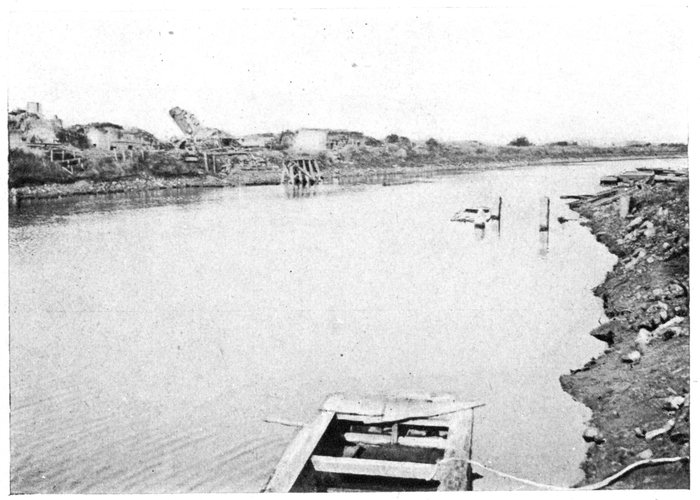

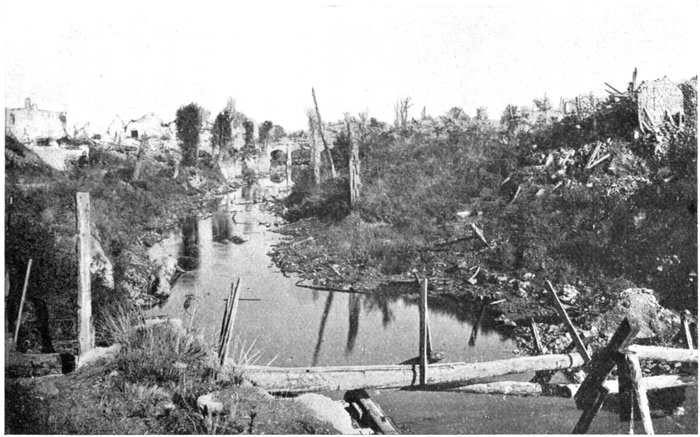

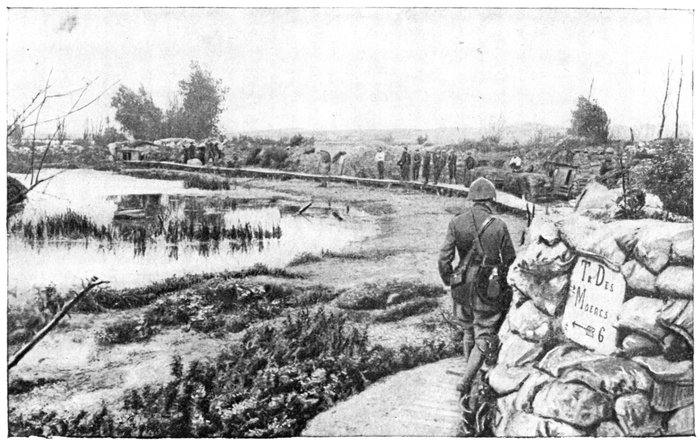

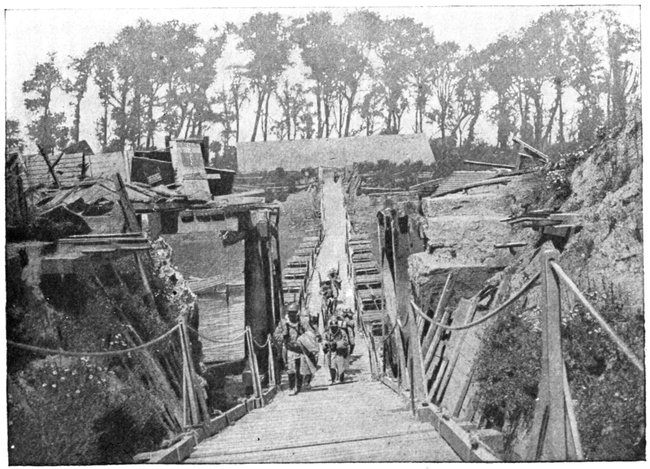

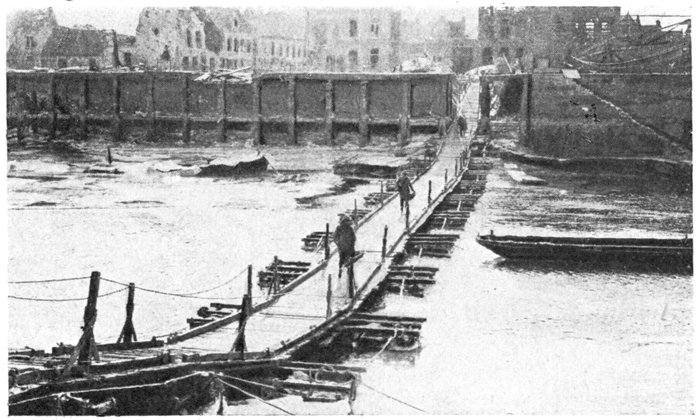

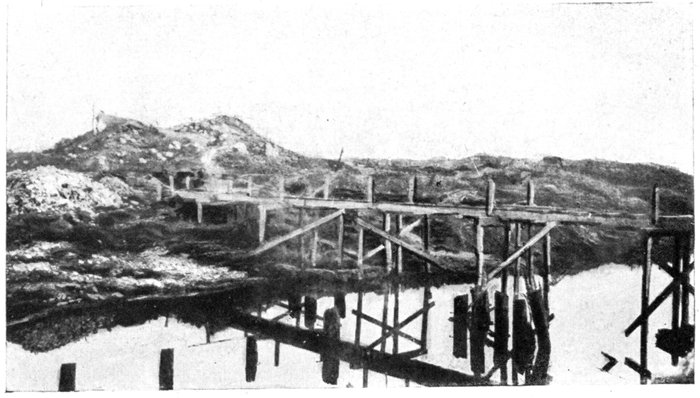

Pontoon Bridge across the Yser.

[Pg 14]

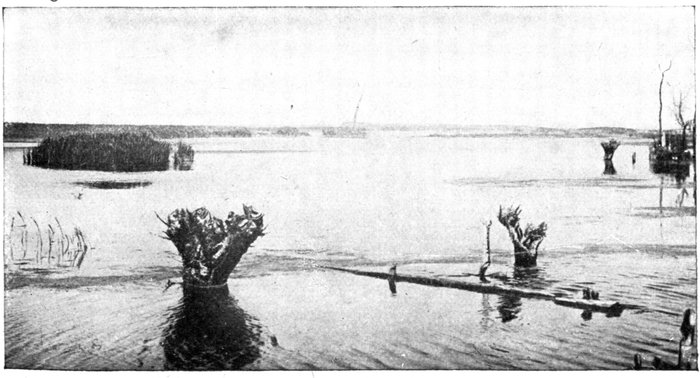

The Inundations.

October 25 brought a pause in the German thrust, the enemy being visibly

exhausted.

But the Belgian Army also was exhausted; many of their 75's were out of

action through intensive firing; scarcely a hundred shells per gun remained.

Would they be able to hold out against another desperate assault?

The General Staff were considering a retreat on Dunkirk—which would

have spelt disaster—when, informed of this by telephone, Foch hurried to the

G. H. Q. where he arrived during a sitting of the War Council. In despair,

the last dispositions for the retreat were being discussed, when in his simple

unaffected way, Foch indicated a line of resistance and suggested inundating

the country. "Inundation formerly saved Holland, and may well save Belgium.

The men will hold out as best they can until the country is under water". (Commandant

Grasset's, "Foch").

To Staff-Captain Nuyten, assisted

by Charles Louis Kogge, a

"wateringue" guard of long experience

and thoroughly acquainted

with the working of the system of

canals and locks, was entrusted the

task of carrying out the plan.

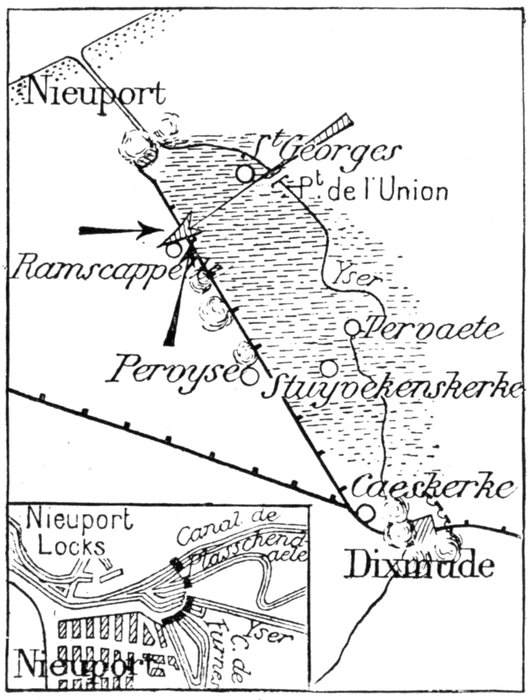

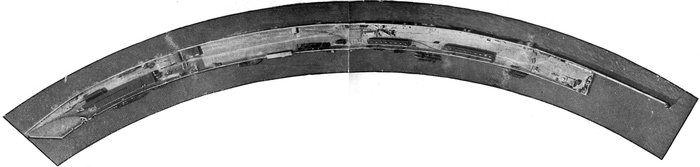

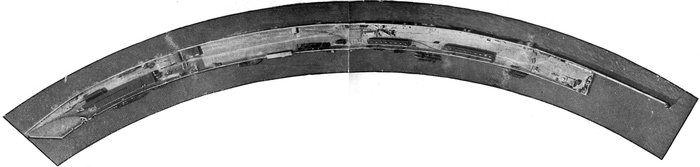

The plain between Dixmude and

Nieuport, being level with the sea,

is protected at Nieuport against

high water by a system of locks

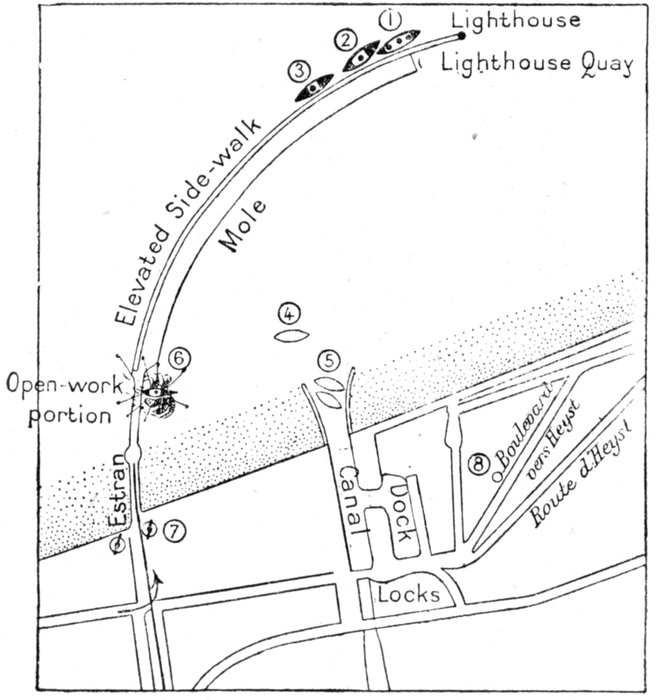

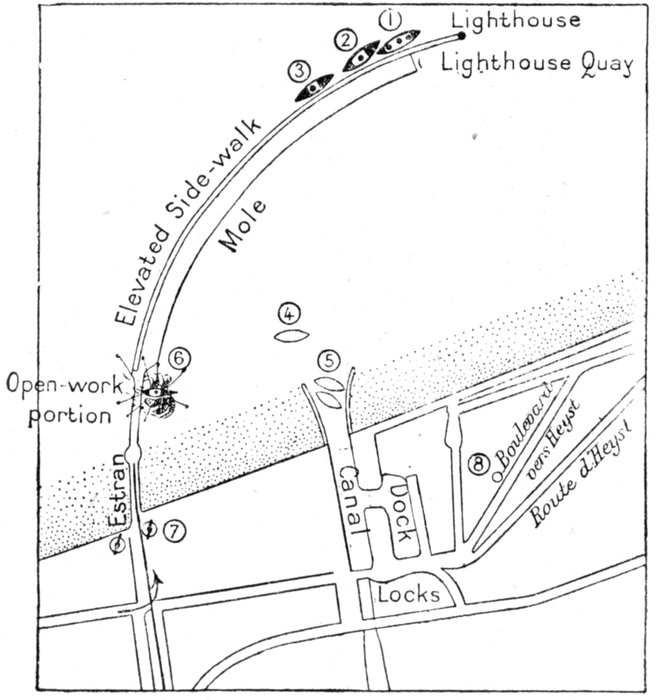

(sketch opposite). The canals and the

Yser are dammed by embankments.

The railway itself runs along a wide

straight dike three to six feet in

height.

Under bombardment, Belgian

Engineers transformed this railway

embankment into a water-tight

dike, by stopping up all the openings

through which the roads

passed and then made wide breaches

in the embankments of the

drainage-canals, so as to allow the water to spread. The whole plain,

between Nieuport and Dixmude was thus transformed into a vast basin

closed on the Belgian side by the railway embankment, the latter being at the

same time organized as a line of resistance.

Certain locks were secretly opened at high-tide, through which the sea

gradually and imperceptibly invaded the basin.

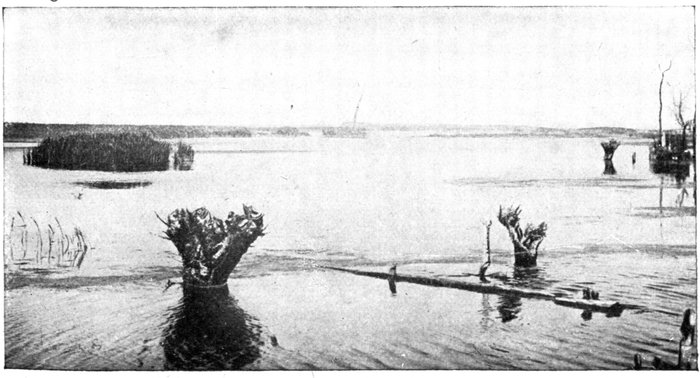

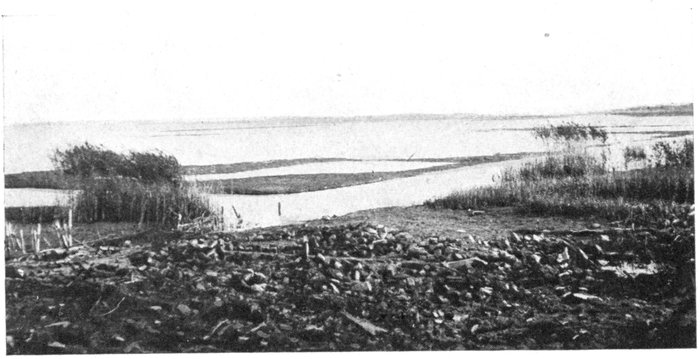

While the sea was thus preparing to play its all important rôle, a fresh

enemy attack forced the Franco-Belgian troops, on the 26th, to withdraw

behind the railway. Orders were given to hold the latter at all cost.

Nieuport and Dixmude were still holding out. At Dixmude, two battalions

of Senegalese relieved the most exhausted units of the defenders.

Behind the railway, units of the 42nd Division and a few battalions of

Territorials supported the desperate efforts of the Belgians.

On the 26th and 27th, while the bombardment continued, the water

began, little by little, to invade the trenches of the enemy, who, however,

did not yet realise the position.

On the 28th, the water began to rise and, on the 29th, spread southwards.

An extremely violent bombardment on the 29th preceded the German[Pg 15]

attacks of the 30th, against the railway. Thanks to their minenwerfer, the

Germans gained a footing on the railway, and advanced as far as the villages

of Ramscappelle and Pervyse. It was a critical moment, the main line

of resistance being pierced.

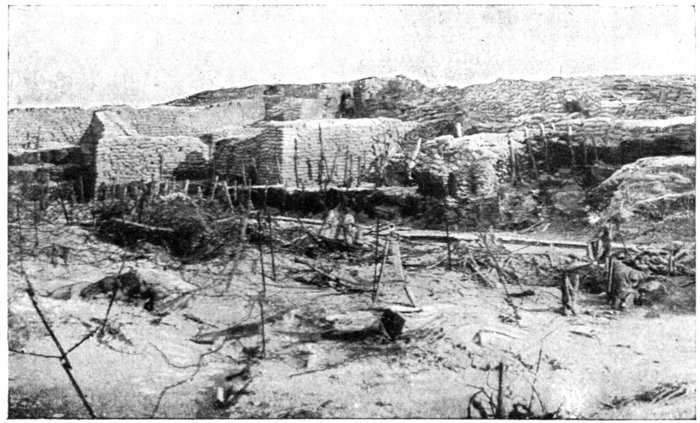

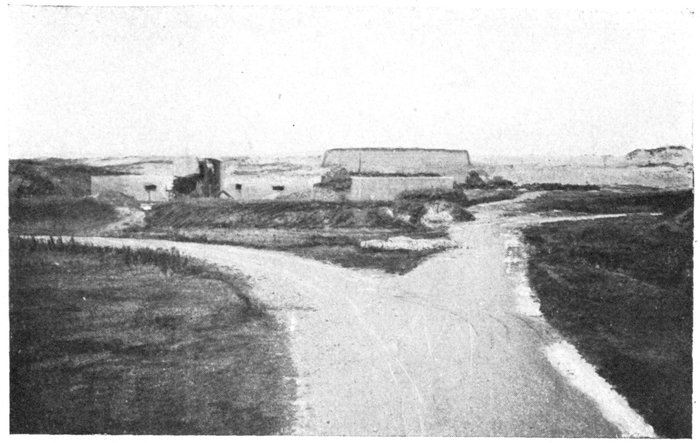

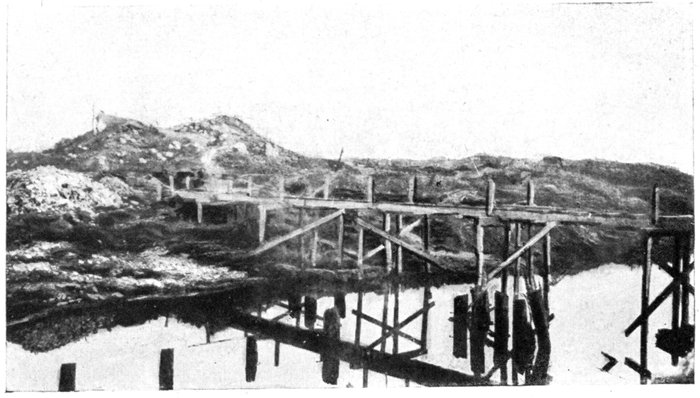

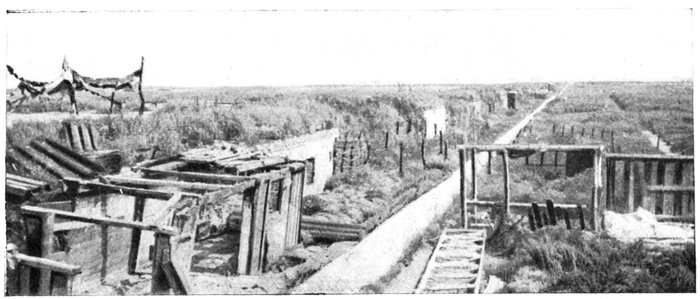

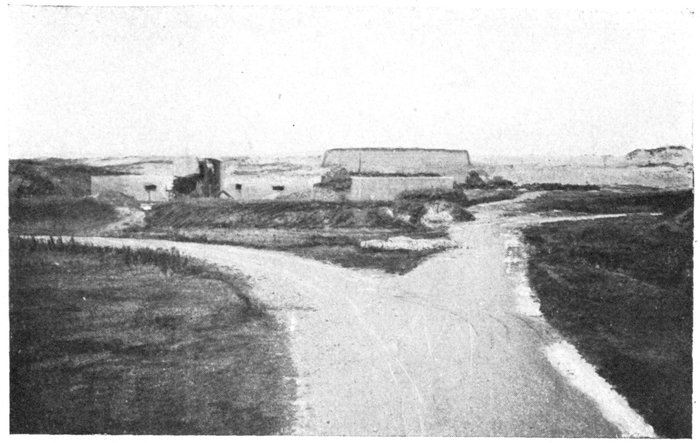

Fortified Embankment at Ramscappelle.

The defenders pulled themselves together for a last effort, and after a violent

concentration of artillery fire, counter-attacked.

On the 31st, at nightfall, the 42nd Division and Belgian units—remnants

of battalions belonging to the 6th, 7th and 14th line regiments—charged

furiously with the bayonet, to the sound of the bugles. The enemy was

thrown into disorder, Ramscappelle recaptured, and the line re-established.

Imperceptibly but relentlessly the floods invaded the enemy's entrenchments,

turning their retreat into a rout; their dead, wounded, heavy guns,

arms and munitions were swallowed up in the huge swamp. The Battle

of the Yser was over.

The Belgian Army, whose original mission was to hold out for forty-eight

hours, had, with the help of 6,000 French Marines, fought first single-handed,

and then with the support of a single French Division, continued the struggle

until October 31, thus fighting for fifteen days without interruption.

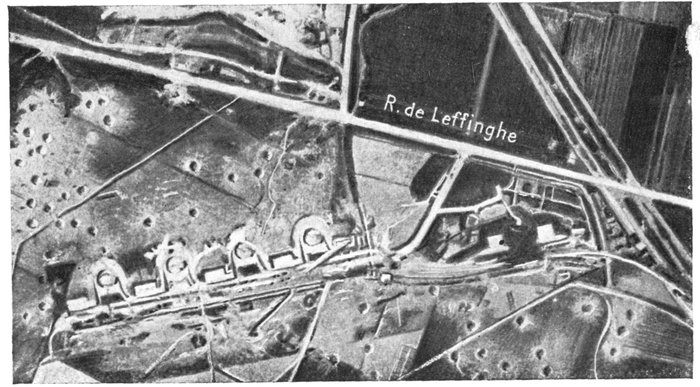

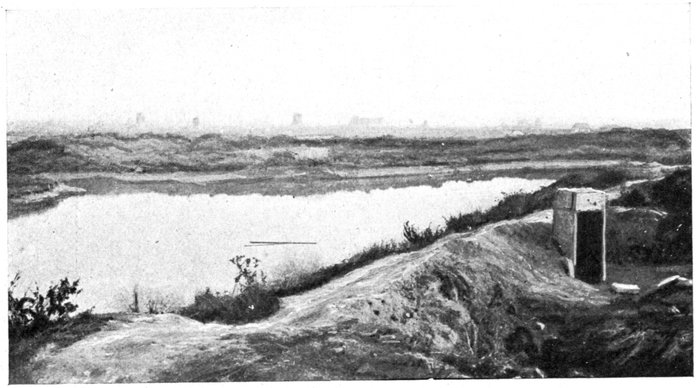

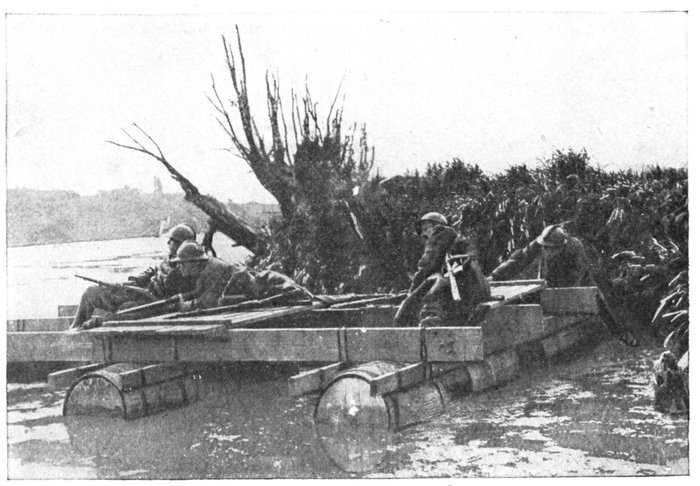

The Allies' Supreme Resource: The Inundations.

[Pg 16]

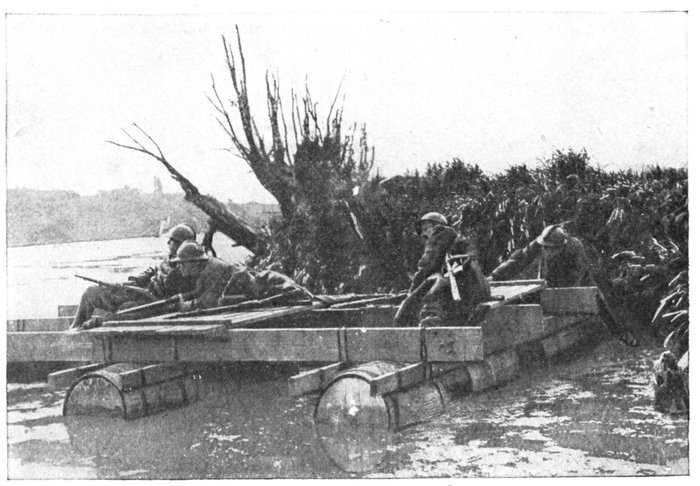

Belgian

Patrols

on

rafts.

Throughout these 360 hours of deadly strife, the entire Belgian forces had

been in the thick of the battle, without respite. Crouching in their shallow half-formed

trenches, or in the muddy ditches, with no shelters, ill-fed, and fully

exposed to the inclement weather, the men nevertheless stood firm. In their tattered

muddy uniforms, they scarcely looked human. The number of wounded

during the last thirteen days was more than 9,000, that of the killed and missing

over 11,000. The numbers of sick and exhausted ran into hundreds. The

units were reduced to skeletons. The losses in officers were particularly heavy;

in one regiment only six were left.

Thanks to the sacrifices stoically borne, the Belgian Army barred the way to

Dunkirk and Calais; the Allies' left wing was not turned, and the enemy failed

to reach the coast, from which they expected to threaten England in her very vitals.

For the Germans, the battle ended in total and bloody defeat. For Belgium

the name "Yser", which their gallant king caused to be embroidered on the

flags of his heroic regiments, is that of glorious victory. (Comm. Willy Breton).

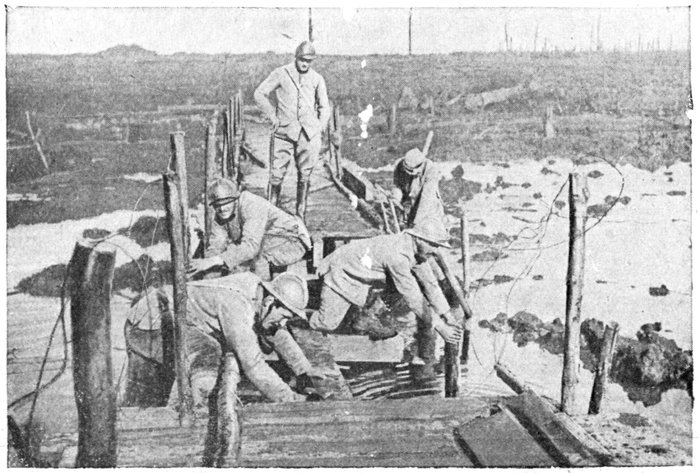

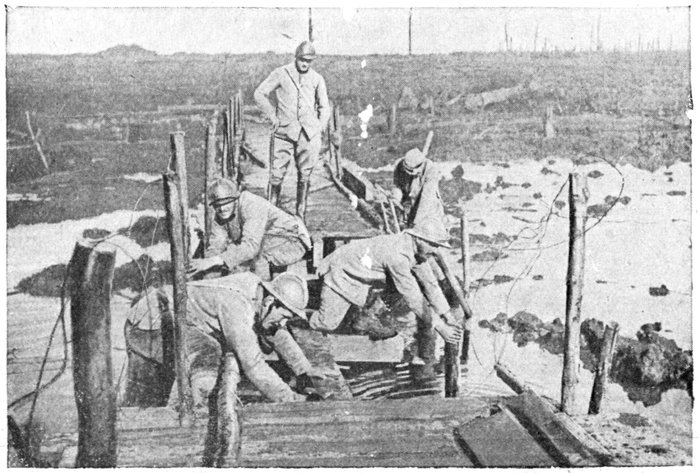

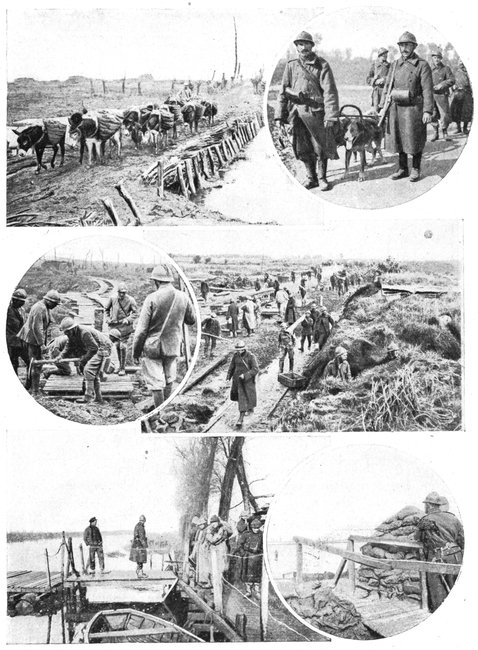

Building

a

temporary

bridge.

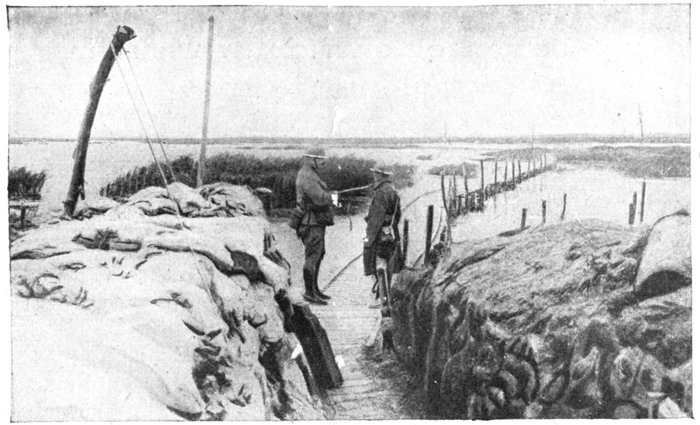

[Pg 17]

Temporary

Bridges

across the

inundated

Plain.

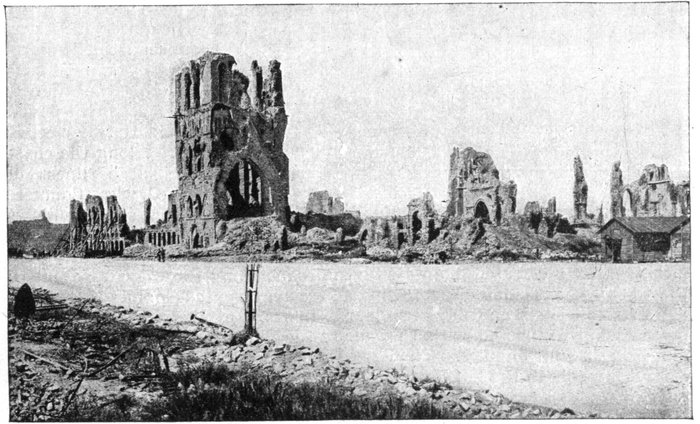

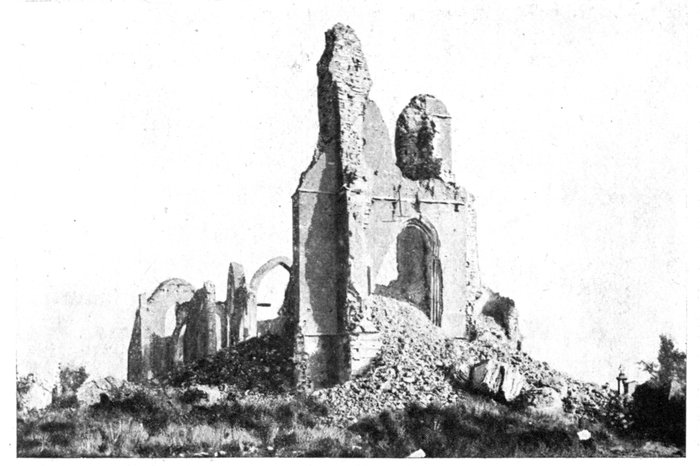

The fall of Dixmude.

The useless sacrifices on the Yser did not turn the Germans from their

plans for taking Calais.

They now attempted to pierce the Allied front in the neighbouring sector,

between Dixmude and Ypres, where the 87th Territorials, 42nd Division,

(withdrawn from the Yser front), and the 9th Corps strengthened the defences.

On November 9, the bombardment grew more violent. On the 10th,

from Dixmude to Bixschoote, along the whole of the canalised Yser and

the Yser-Ypres canal, huge masses of enemy troops attacked in deep column

formation.

After prolonged sanguinary street fighting, in which the French Marine

Brigade again distinguished itself, Dixmude succumbed. The Germans

were, however, unable to cross the Yser, and the respective front lines

became fixed on the canal embankments. The battle spread eastwards,

around the salient of Ypres (See the Michelin Guide: "Ypres and the Battles

of Ypres".)

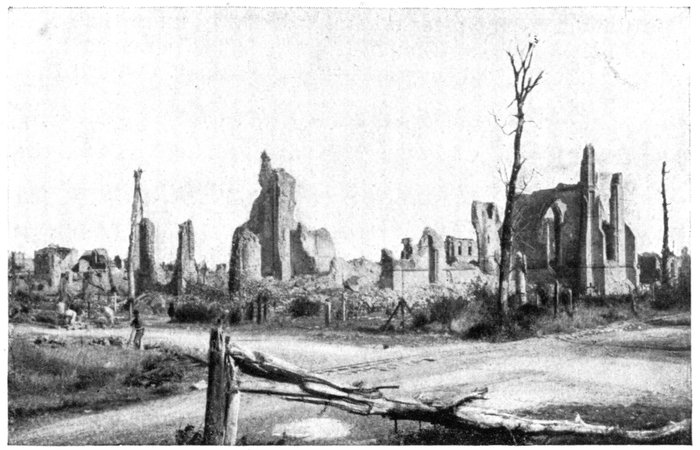

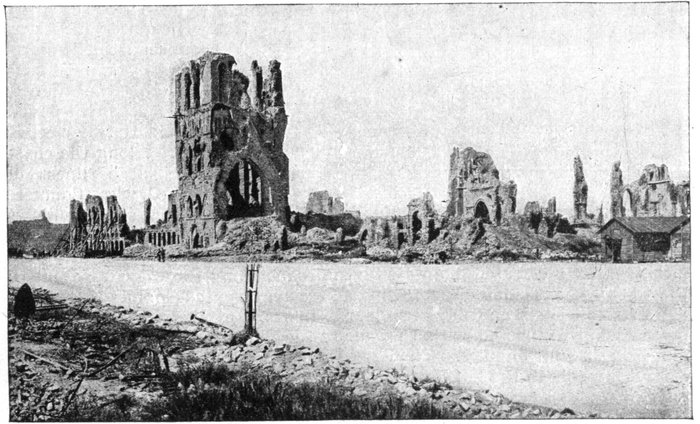

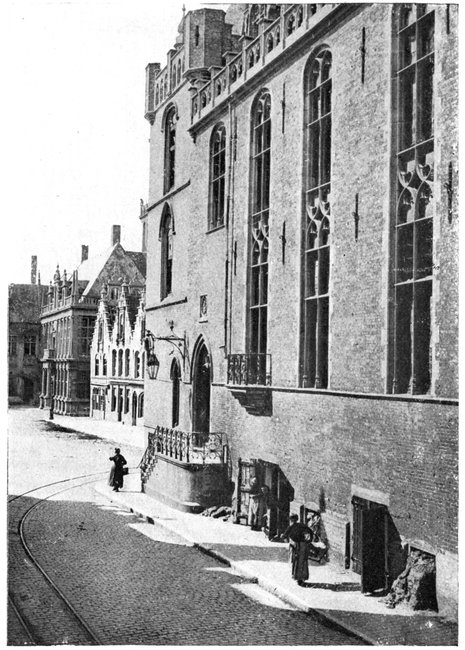

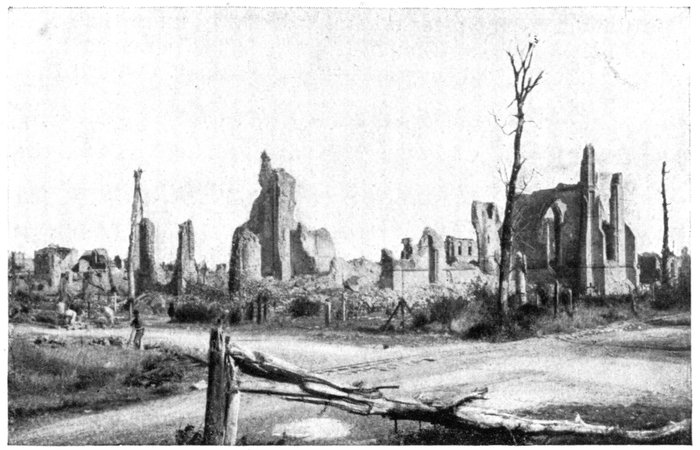

The Cloth Hall at Ypres, in 1919.

See the Michelin Guide: "Ypres, and the Battles of Ypres".

[Pg 18]

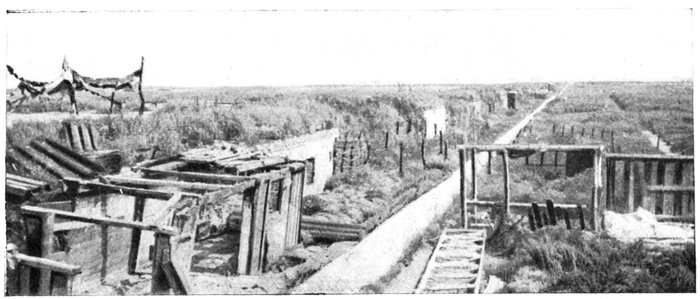

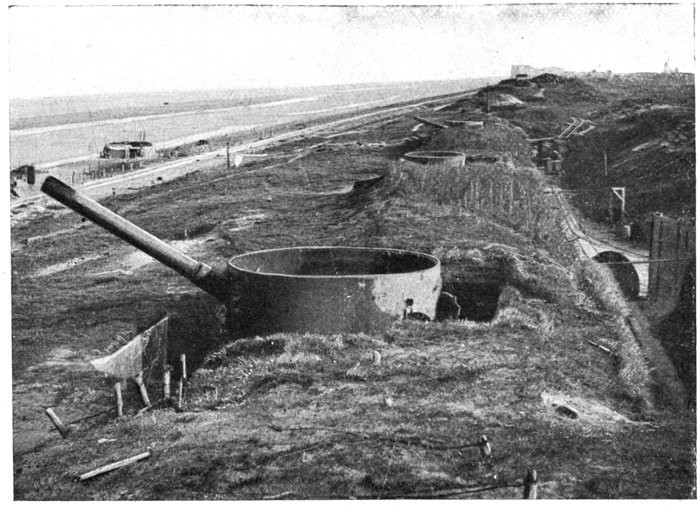

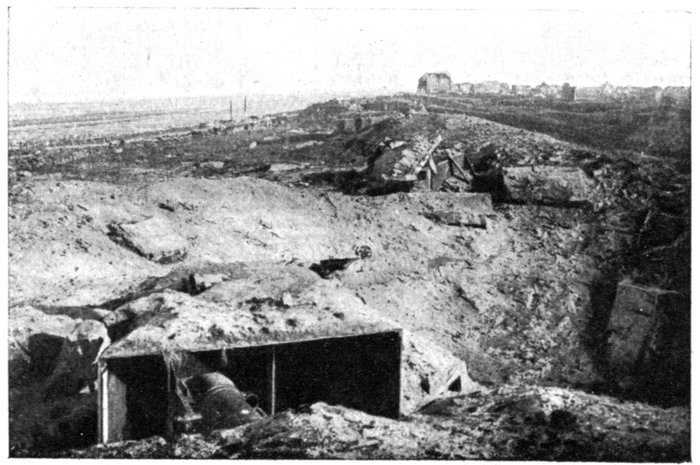

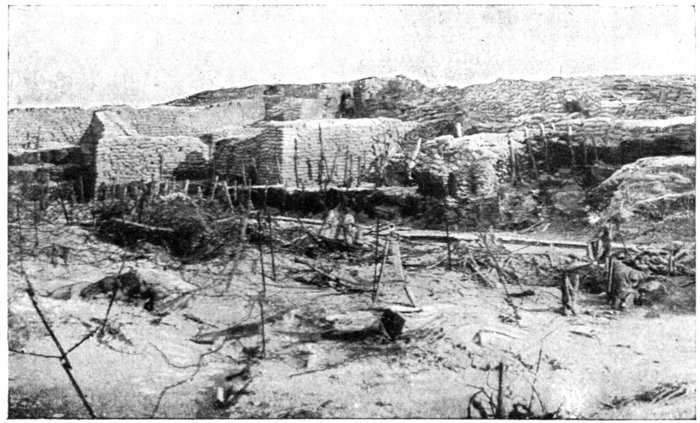

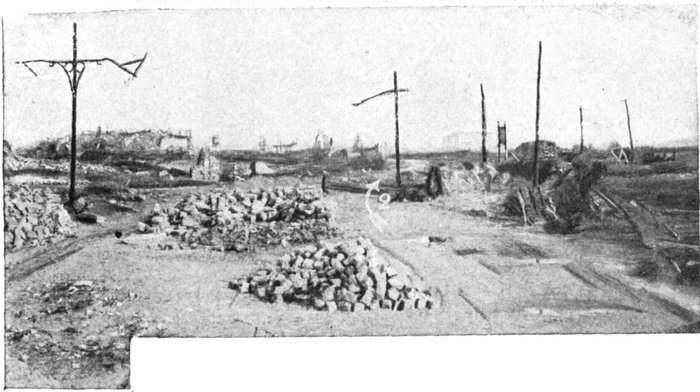

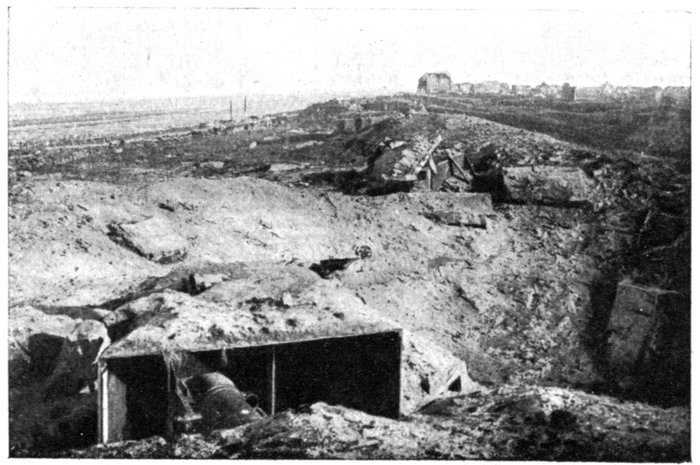

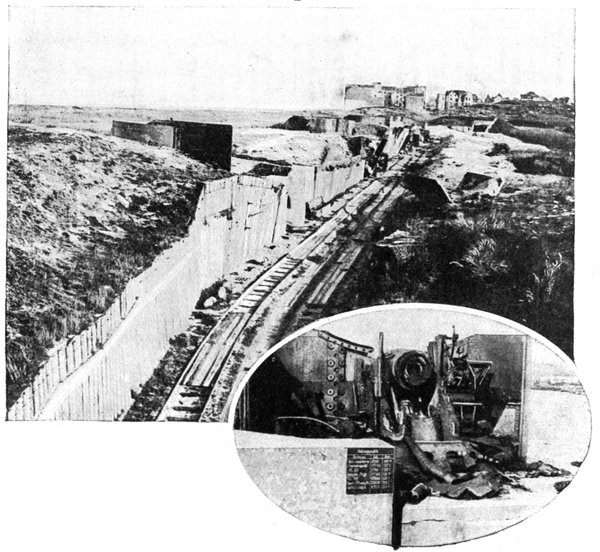

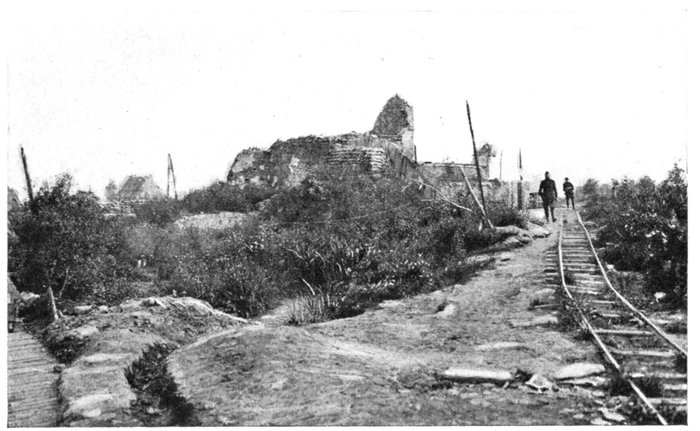

THE PERIOD OF STATIONARY WARFARE.

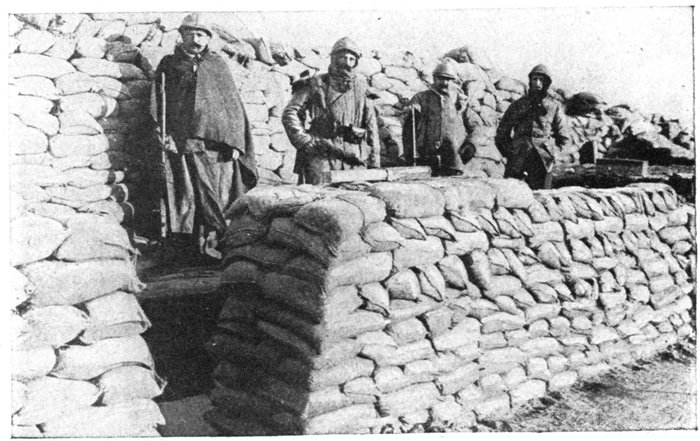

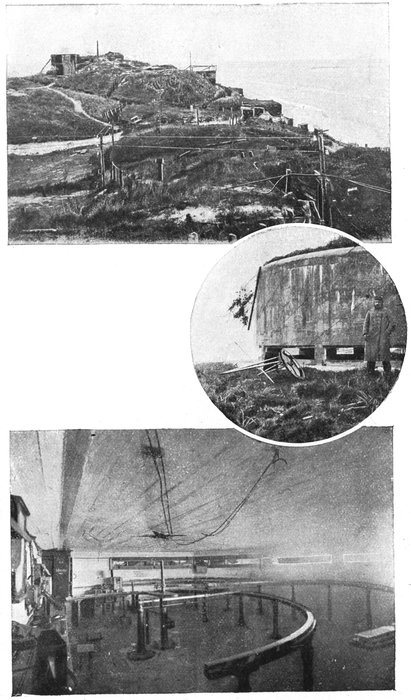

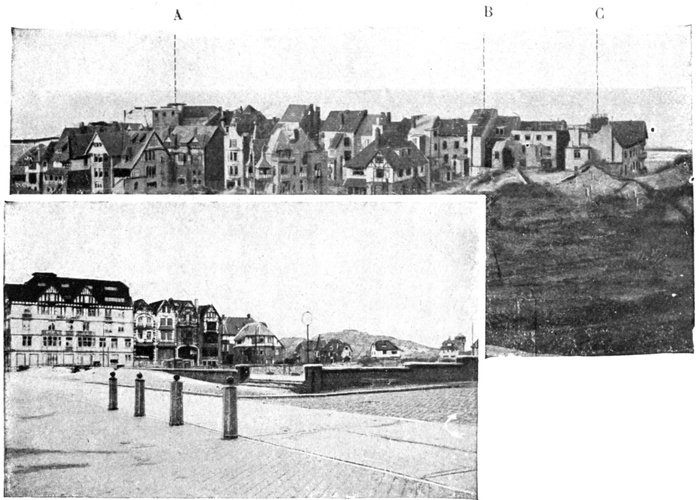

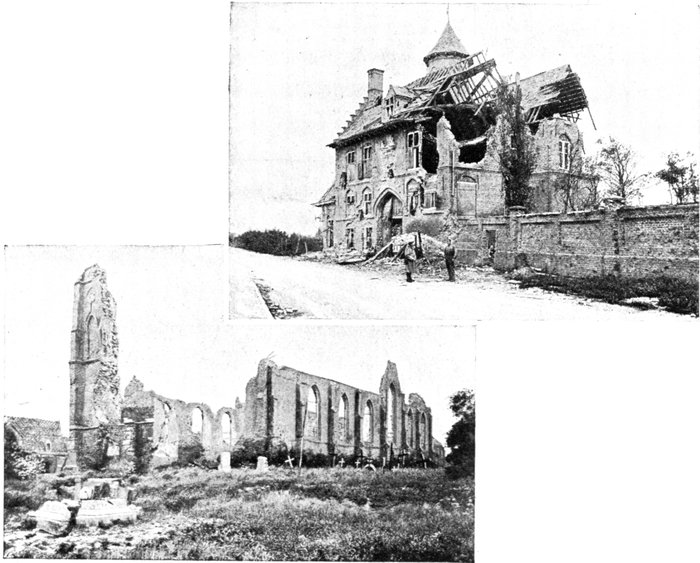

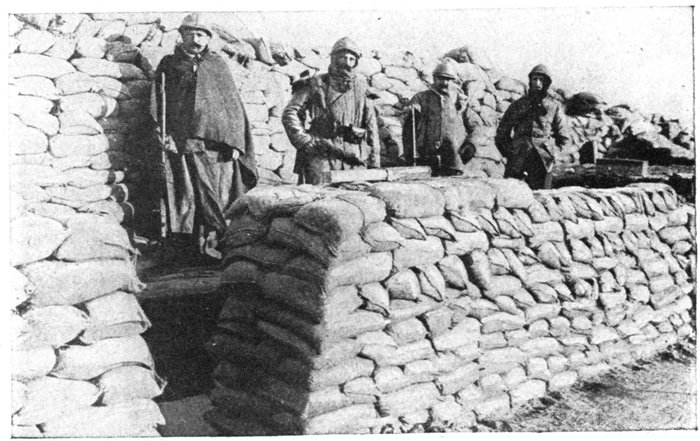

Photos, pp. 19-21.

The front-line became fixed in the partially inundated maritime plain of

Flanders, in the oozy soil of which it was impossible to make any trenches.

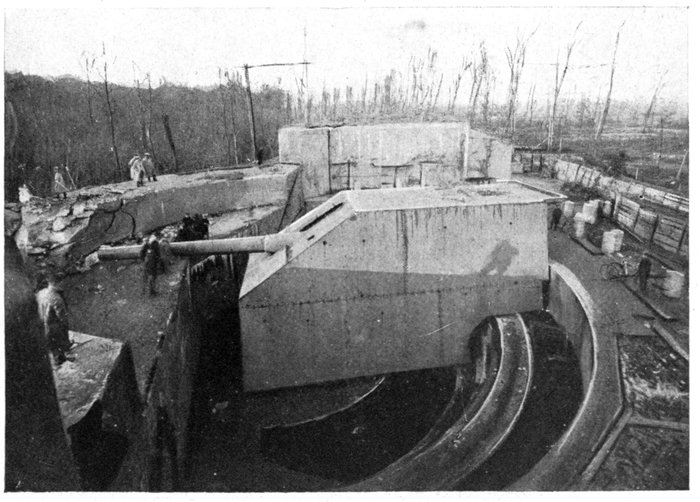

The defence-works, boyaux, and battery emplacements consequently took

the form of superstructures, strengthened with piled-up sacks of earth

(photos, pp. 19-21).

Being above the ground, these defences were easily marked down by

the German gunners and levelled with each bombardment. Thus the fruit

of weeks of hard work was wiped out again and again.

The ground, soaked with the frequent rains and churned up by the shells,

quickly became a vast quagmire which swallowed up everything.

During the first winter, all the heavy materials used in the construction

of the shelters, etc., as well as the food and munitions had to be carried

by the men,—combatants,

stretcher-bearers

and fatigue

parties alike wading

knee-deep in the slime.

Little by little, the

situation improved.

Narrow-gauge railways

were laid down to

bring up supplies and

munitions to the front

lines. Stronger and

more comfortable shelters

were built, together

with casemates and

concrete observation-posts

right up to the

front lines.

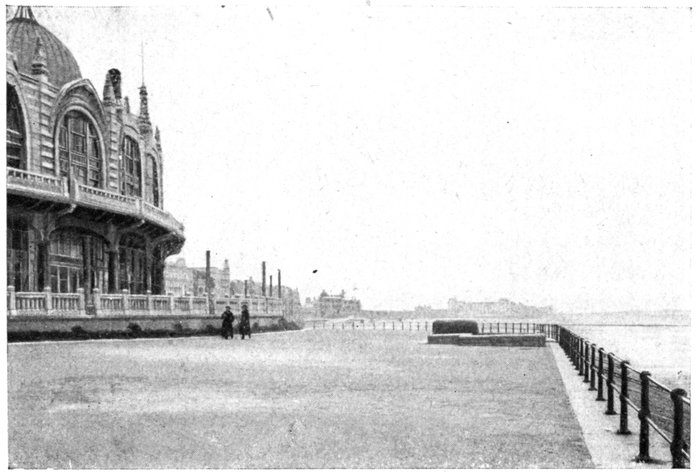

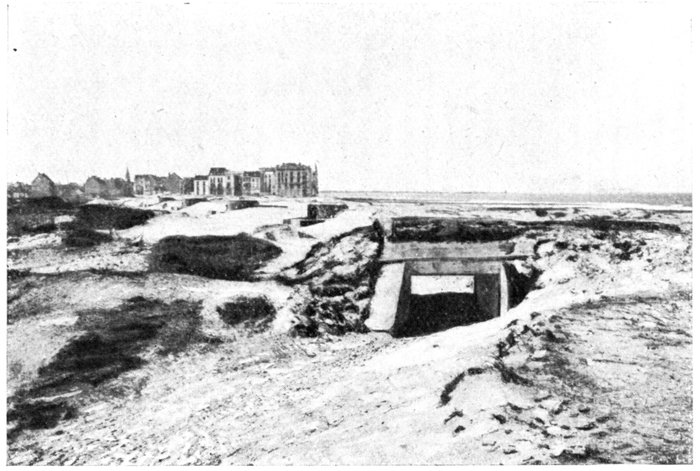

Nieuport-Ville was

connected to Nieuport-Bains

by two tunnels

through the dunes,

propped, brick-paved

and lighted by electricity.

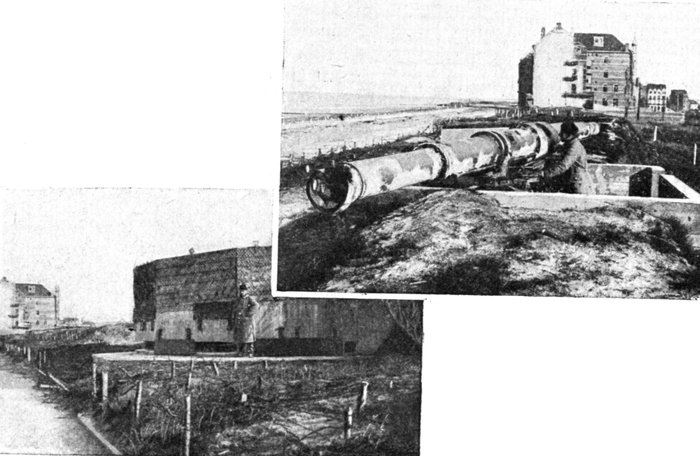

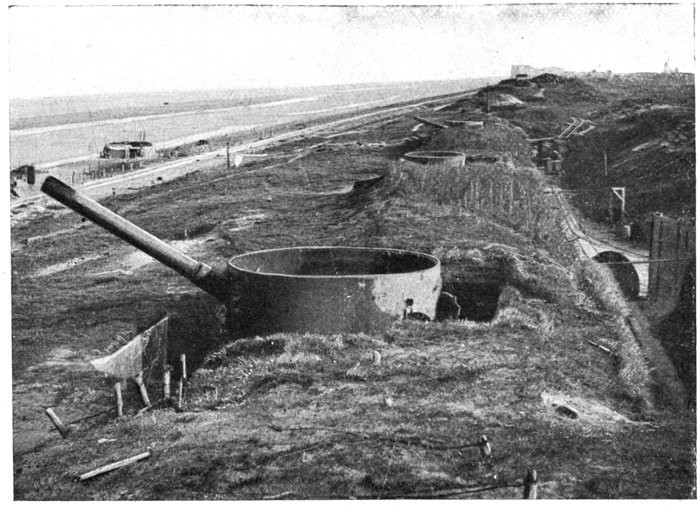

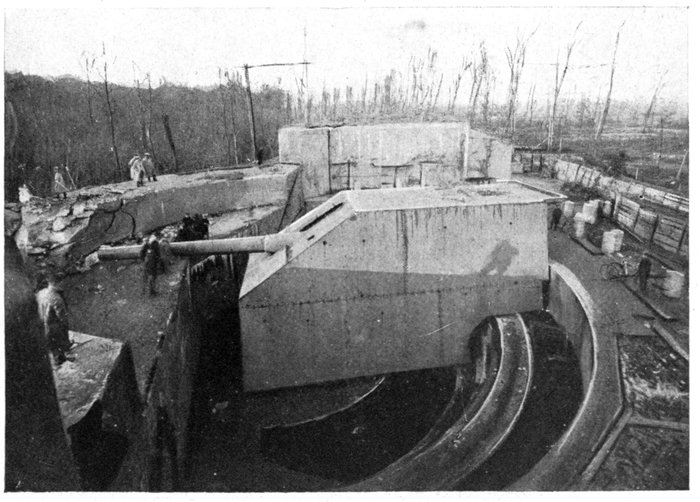

Along the coast

were deep lines of

barbed wire. Concrete

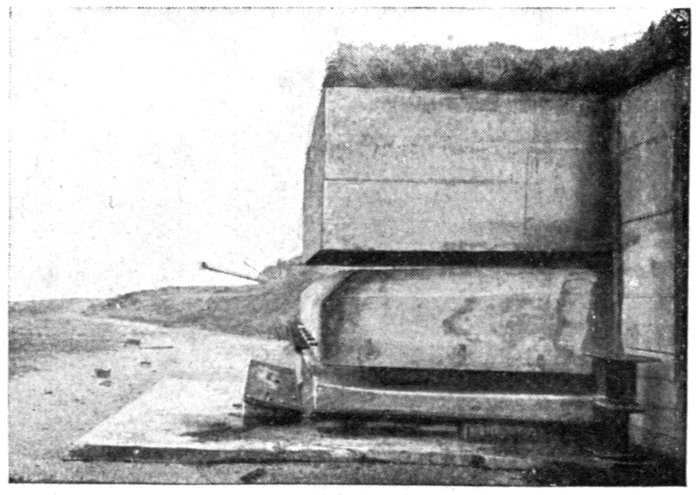

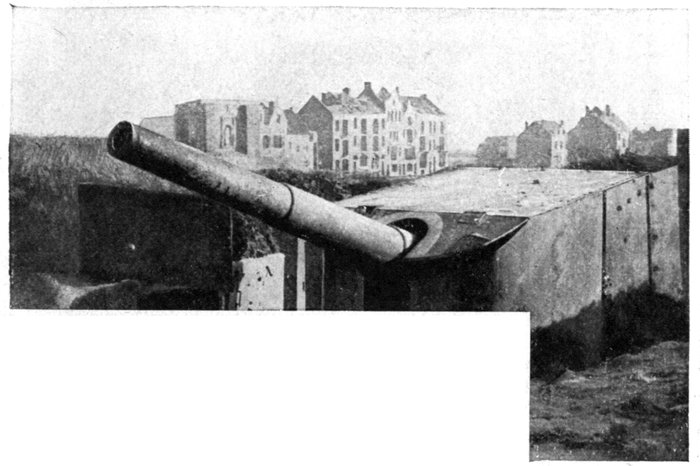

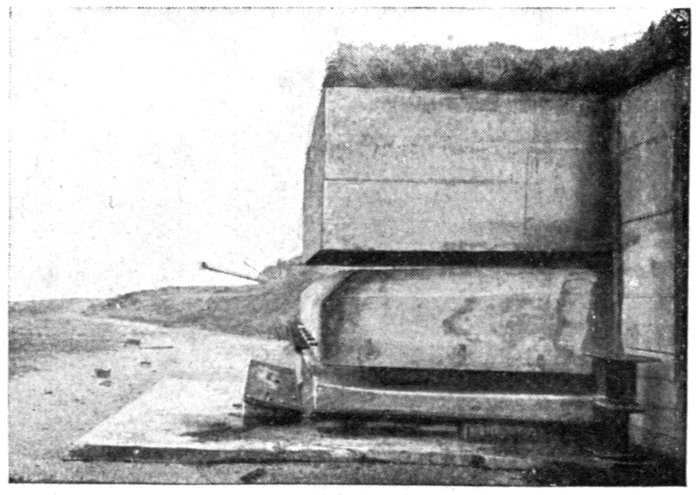

cupolas sheltered naval guns. Further south, in the dunes, stretched lines

of carefully camouflaged huts, parks, stores and rest camps. In places,

along the Yser, the inundations did not give absolute protection. Isolated

farms built on elevated points and the roads along the dikes rose out of

the water, like so many islets. These fiercely disputed points formed a

line of small posts and advance guards in front of the main line of resistance,

being connected with that along the railway embankment by long

foot-bridges built on piles. The line of resistance followed the railway, then

curved inwards to the left bank of the Yser, finally passing in front of the

town.

This line was strengthened by two other lines which took in Ramscappelle,

Pervyse, Lampernisse and St. Jacques-Cappelle. A second system of defence-works

ran in front of and behind Loo Canal.

[Pg 19]

General Gillain.

Chief of the General Staff of the Belgian

Army.

The sector of the inundated

plain was held throughout by the

Belgian Army. That of the dunes

and Nieuport was held in 1914-1915

by the French Tirailleurs,

Zouaves, and dismounted cavalry,

grouped under the command of

General de Mitry, and the brigade

of Marines; in 1916, by a division

of the 36th Corps (General Hély

d'Oissel); in 1917, by regiments

of the British 4th Army (General

Rawlinson) which attacked along

the coast in co-operation with British

warships.

Finally, the Belgian Army, completely

reformed and newly equipped,

took over the entire sector of

the Yser, and extended its lines

as far as the outskirts of Ypres.

The enemy front was held by

the German Marine Corps and Landwehr units.

For four years, the whole sector in front of the Yser Plain remained relatively

quiet, with occasional daring raids or short bombardments.

Before Dixmude and Nieuport, the operations were more active. The

"Boyau de la Mort", in front of Dixmude, cost the Belgians some losses, the

trench, which ran alongside the Yser, being enfiladed. The enemy's rifle

fire came mostly from the Flour Mill (photo, p. 124), a large concrete building

on the banks of the Yser, which it was difficult to destroy with the heavy

artillery, on account of its proximity to the Belgian lines (about thirty yards

away).

The liveliest part of the sector was that in front of Nieuport.

In 1914-1915, the troops under General de Mitry, and later the French

Marines, succeeded in clearing the town, by capturing the great dune north

of St. Georges and various redoubts on the east.

In 1917, the Germans attacked units of the British 4th Army, which

was then taking up its positions, and recaptured the dunes as far as the Yser

Channel.

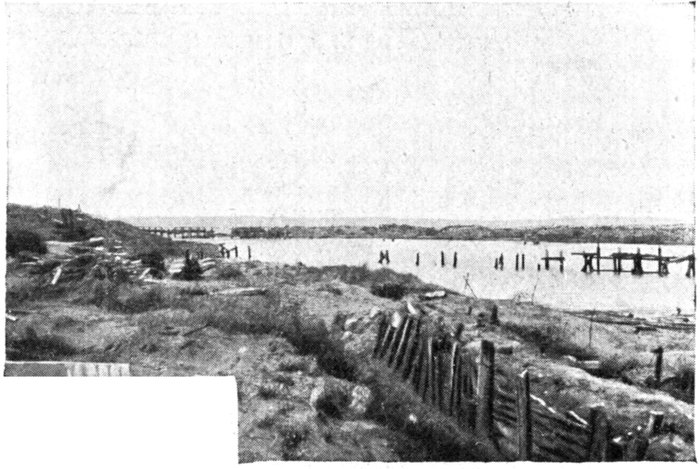

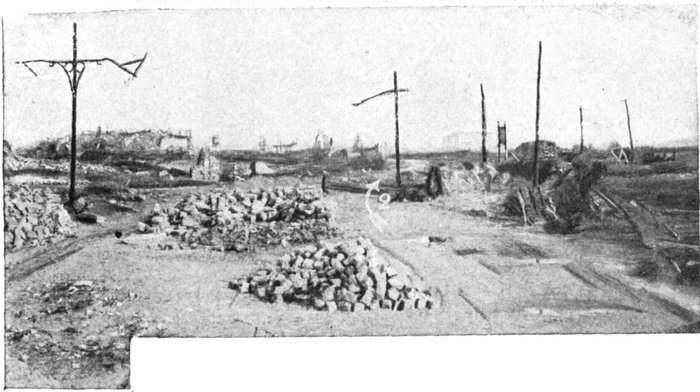

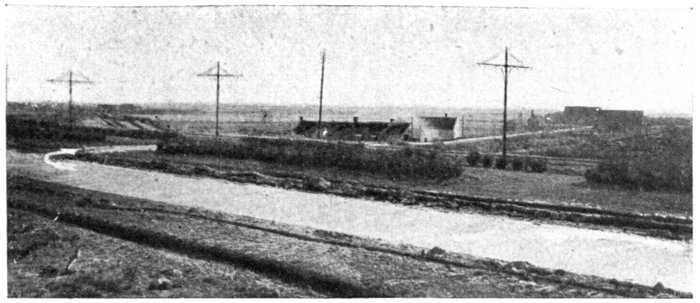

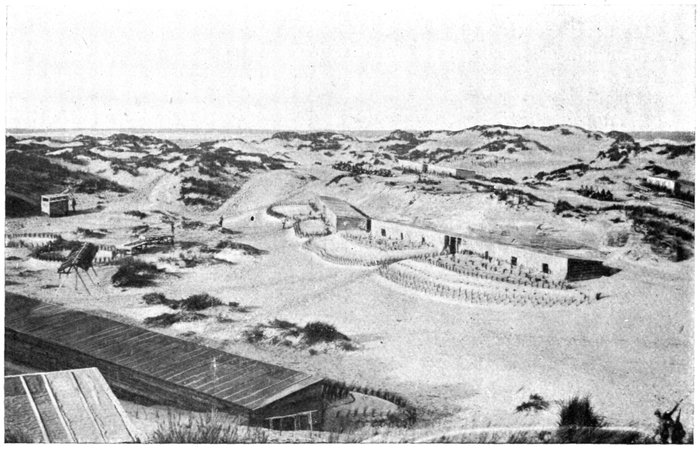

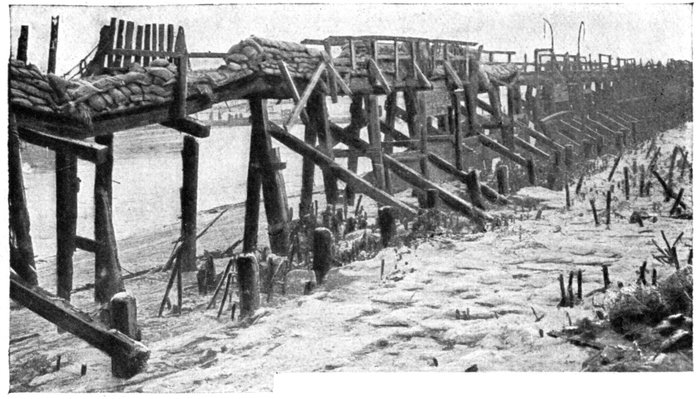

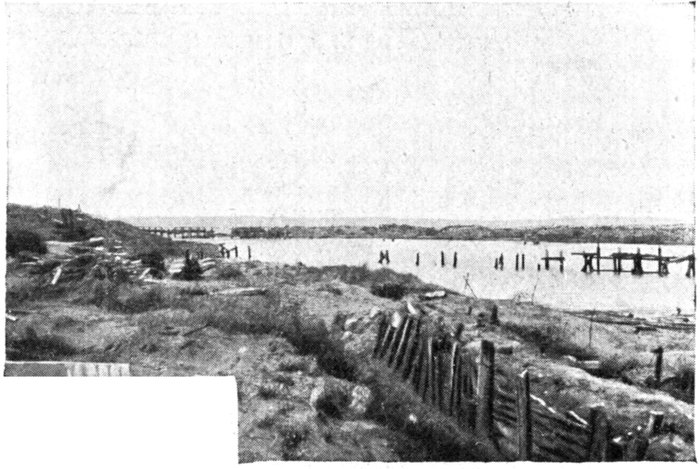

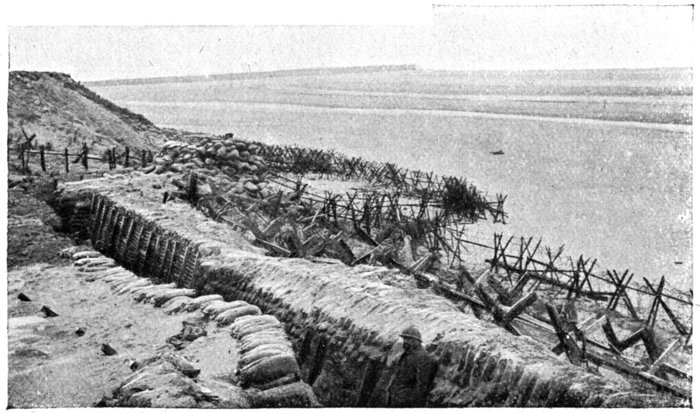

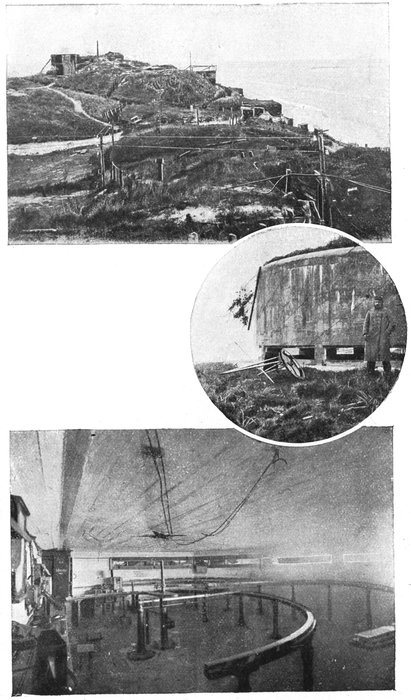

Line of

Defence

between

Nieuport

and

Lombartzyde

(held by the

Territorials.)

[Pg 20]

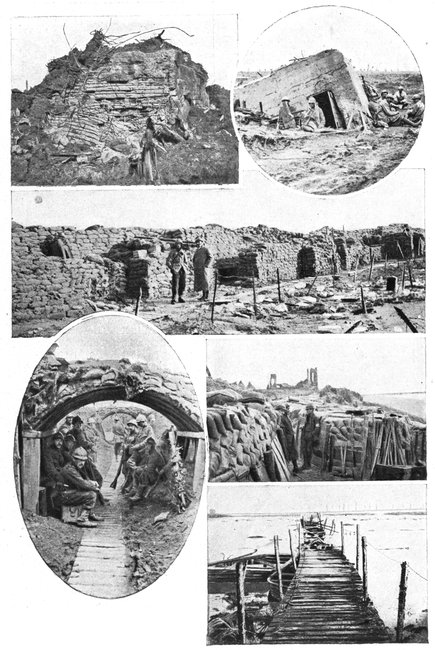

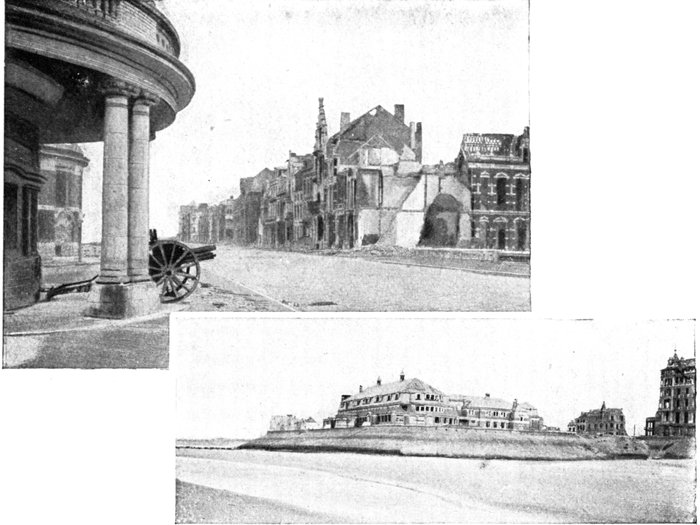

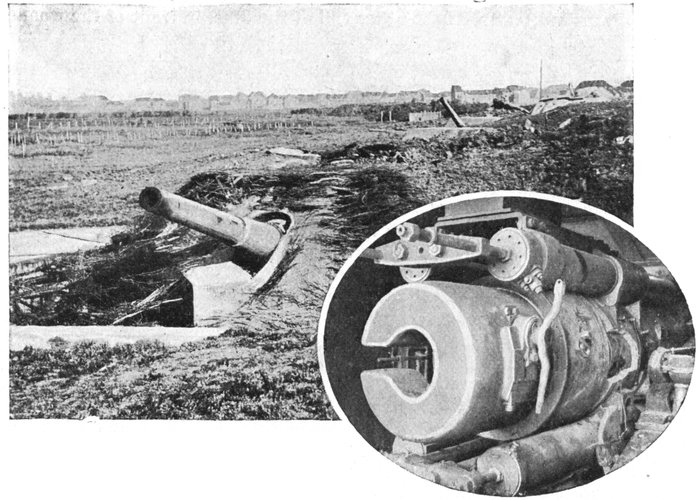

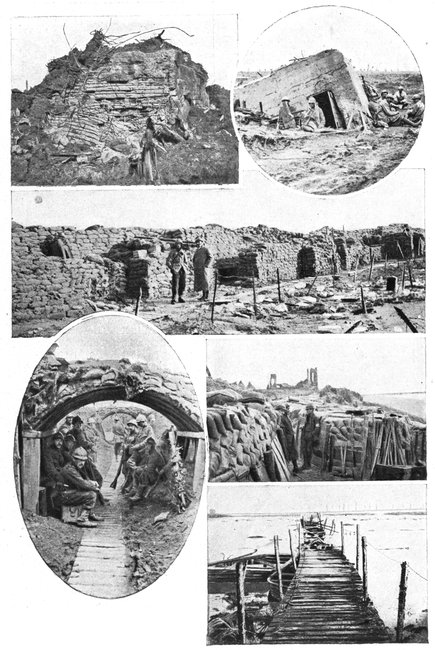

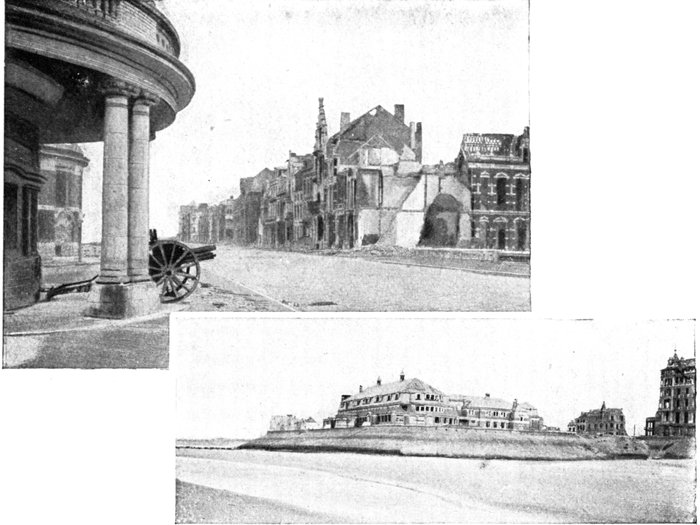

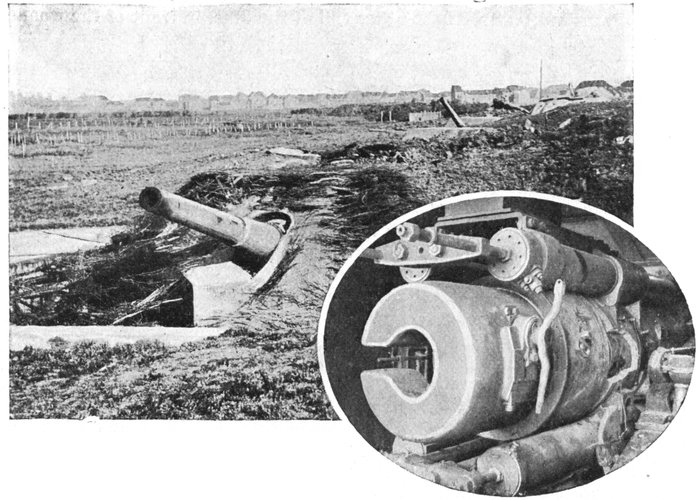

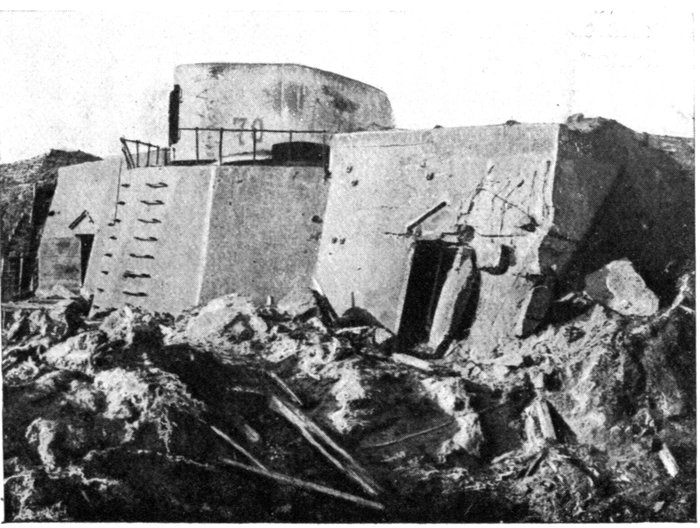

At top of page: Two German Blockhouses

wrecked by shellfire. Underneath: Line of Defence

before Lombartzyde.

On the left (inset): Belgian trench along the Yser, with splinter-proof

Shelters. On the right (upper): Advance boyau on the coast, near the

Grande Dune. On the right (lower): German Temporary Bridge partly

captured during a raid, with chevaux-de-frise separating the

Allied and enemy lines.

[Pg 21]

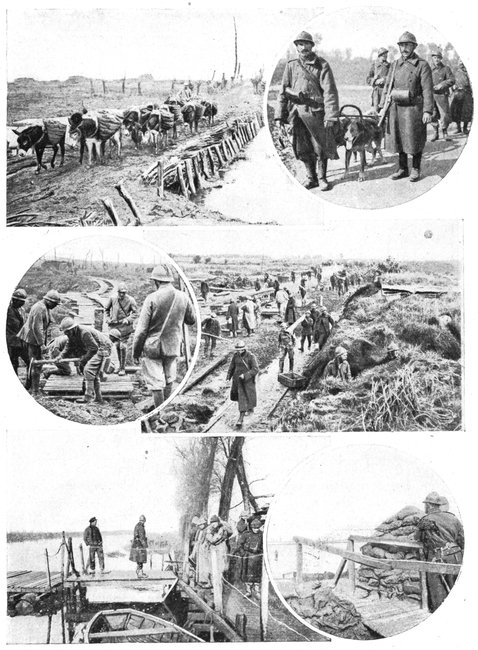

At top of page: Donkeys bringing up supplies.—Machine-gun Dog Teams.

In the middle: Building road on piles.—Making a log road.

At bottom of page: Isolated Post surrounded by water, and raft used

for revictualling same.—Front-line Post before the inundated plain.

[Pg 22]

THE VICTORY OFFENSIVE.

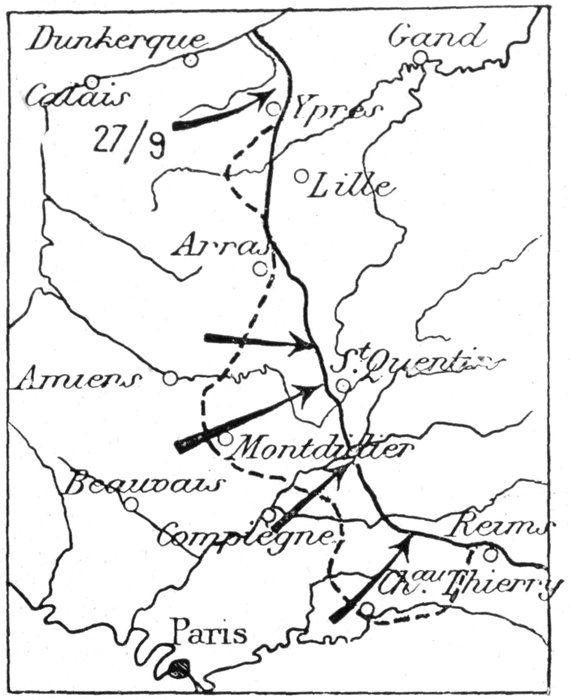

The general situation, when the

offensive in Flanders was launched.

In 1918, after the fiasco of the enemy's Spring offensives, the initiative

passed into the hands of the Allies. The latter, victorious on the Marne,

Vesle, Aisne and before Compiègne, continued to press the enemy without

respite. The battle spread northwards. On September 28, the "Liberty"

Offensive in Flanders began. The group of armies operating in Flanders

under the command of King Albert

with General Degoutte as Major-General,

comprised the valiant Belgian

Army, the British 2nd Army,

and the French 6th Army.

On the 28th the first two enemy

positions, north and east of the

Ypres Salient, were captured. On

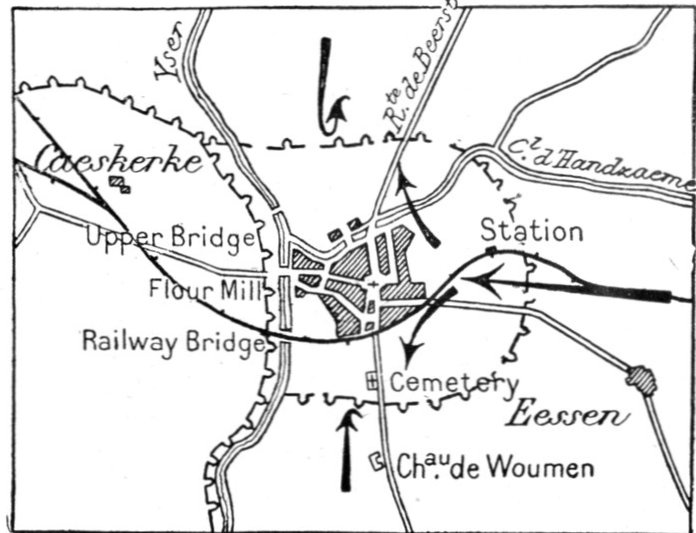

the 29th, the Belgian 4th Division

following up this success and pivoting

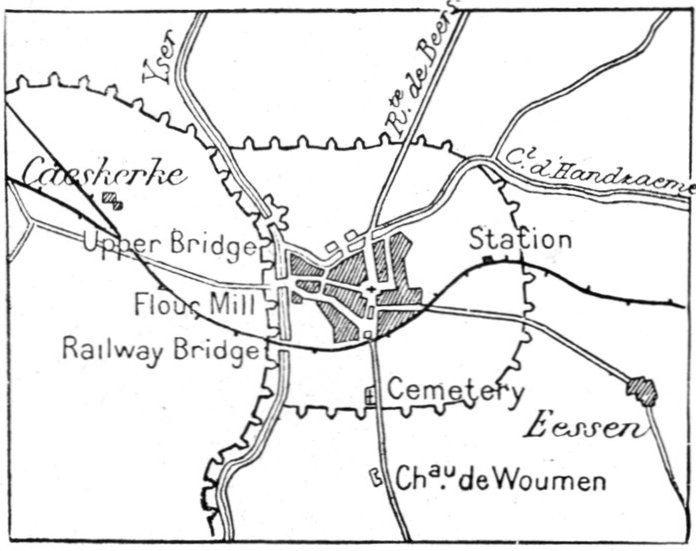

east of Dixmude, captured

Eessen to the north and occupied

the banks of the Handzaeme Canal

(See p. 120). Dixmude, outflanked

on the north, fell.

All the heights of Flanders were

now in the Allies' hands. In danger

of being cut off, the Germans

began to prepare their withdrawal

from the Belgian Coast on September

28.

After an interruption of several

days, owing to bad weather, the

offensive was continued on October

14.

On October 15, Belgian divisions

holding the inundated front, from Dixmude to Nieuport, crossed the

Yser in pursuit of the enemy, who hurriedly retreated to the north-east.

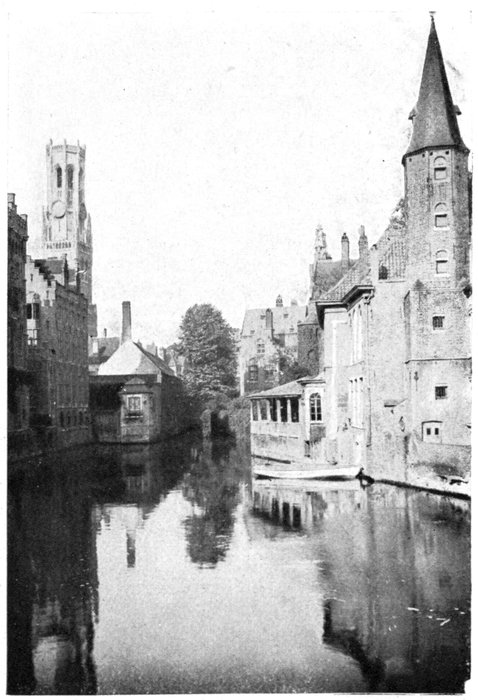

The Two Stages in the Flanders Offensive.

On October 17, the Belgian infantry reached Ostend, while their cavalry,

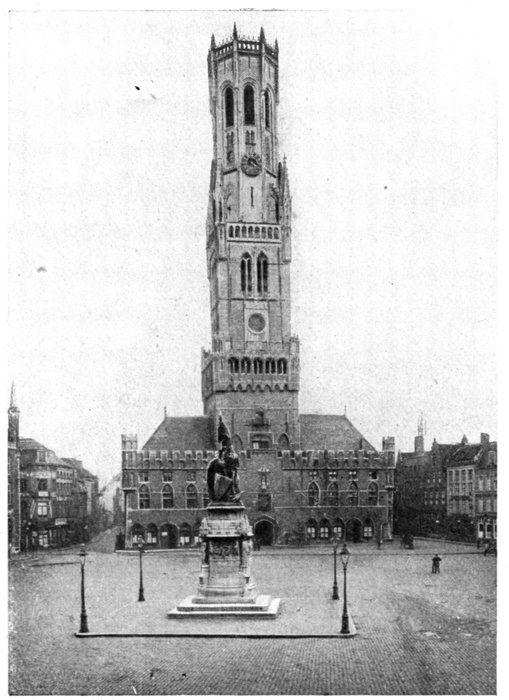

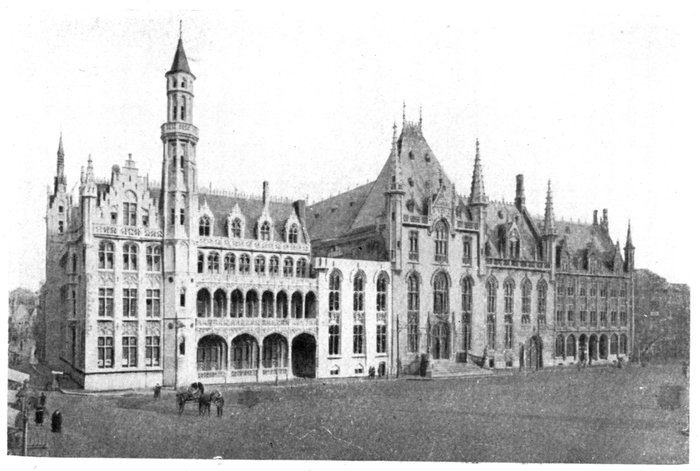

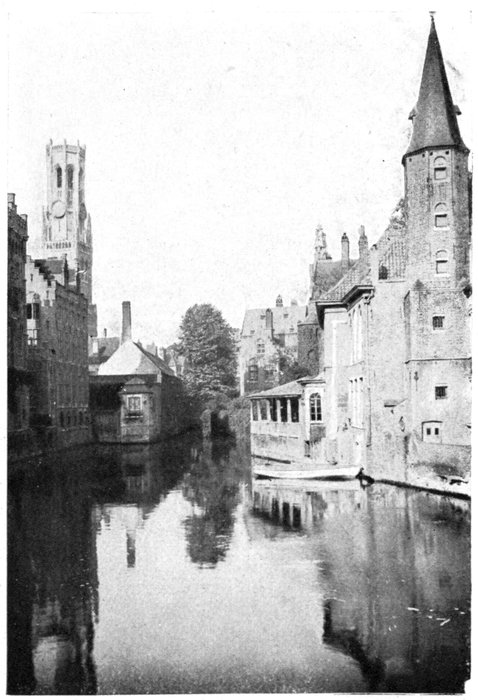

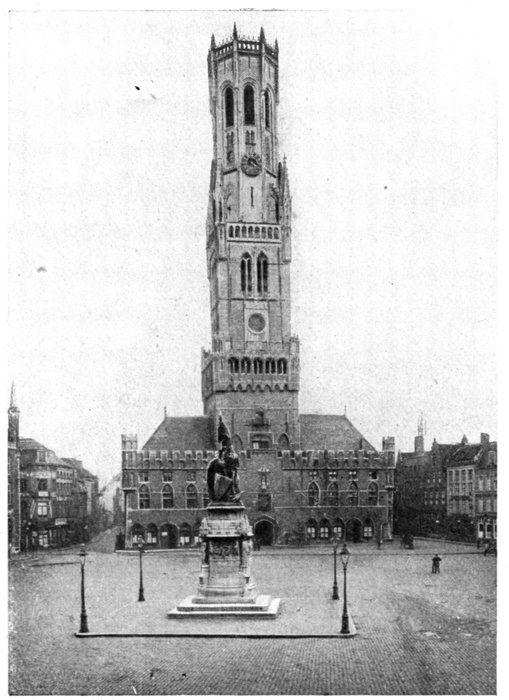

before the gates of Bruges, heard the belfry chimes joyfully announce the

precipitate departure of the last of the enemy troops. The Allies' advance

had been so rapid that the

Germans had not time to

set fire to the city. On

the coast, the port of Zeebrugge,

together with

huge quantities of stores,

fell into the hands of

the Belgians.

The whole of the maritime

Plain of Flanders

was thus liberated. The

exhausted, demoralised

enemy were in full retreat.

On November 11,

beyond Ghent, the Armistice

saved them from

the utter rout into which

their defeat was fast degenerating.

[Pg 23]

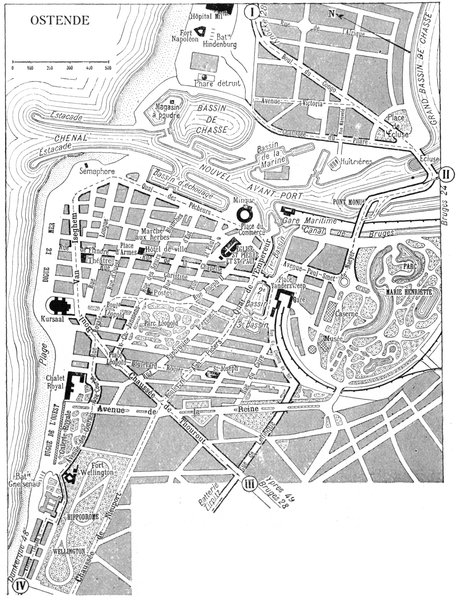

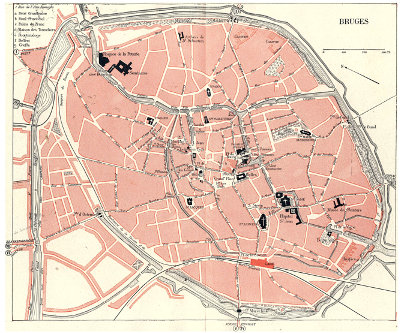

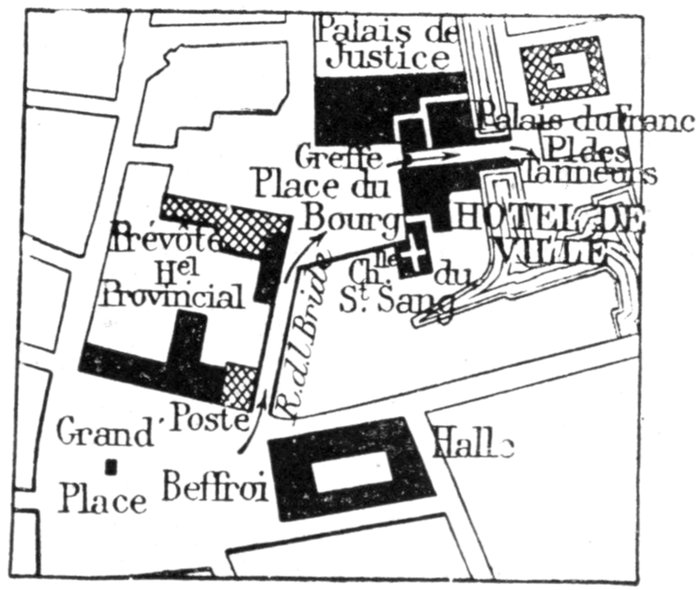

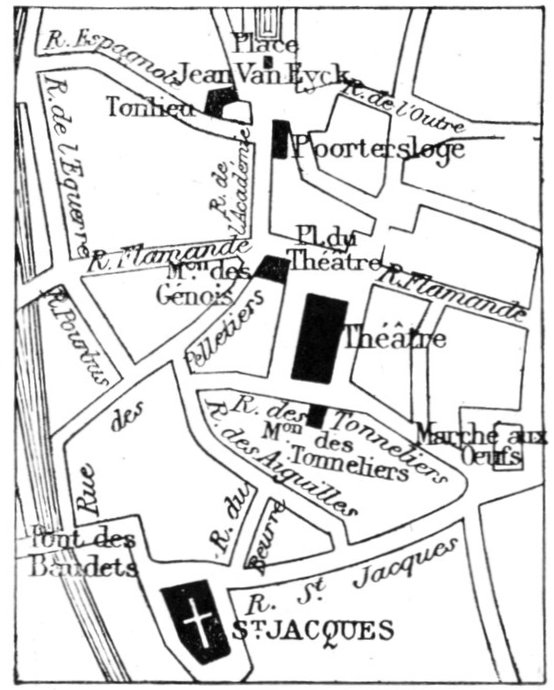

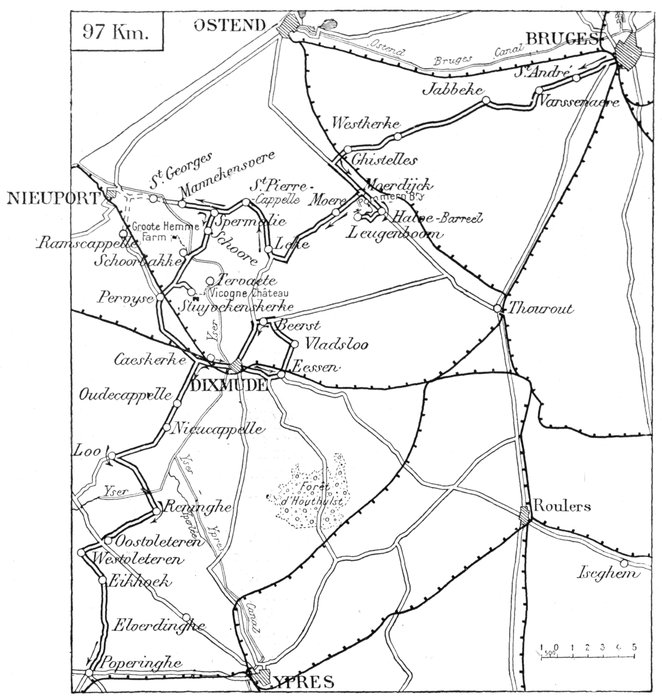

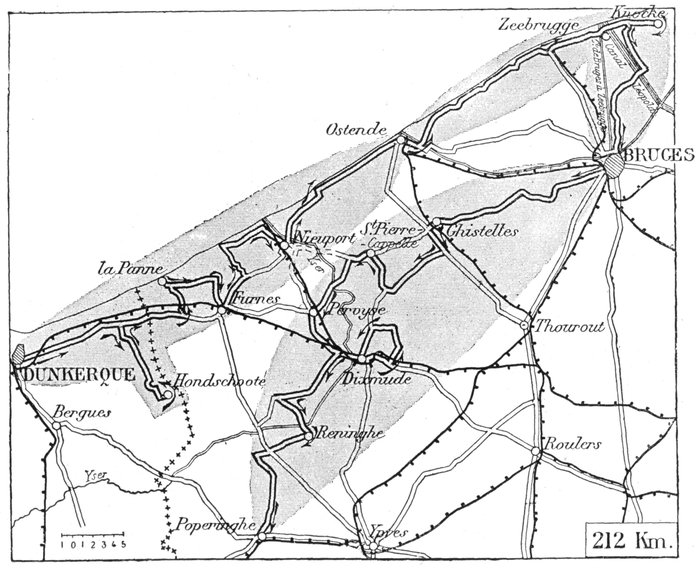

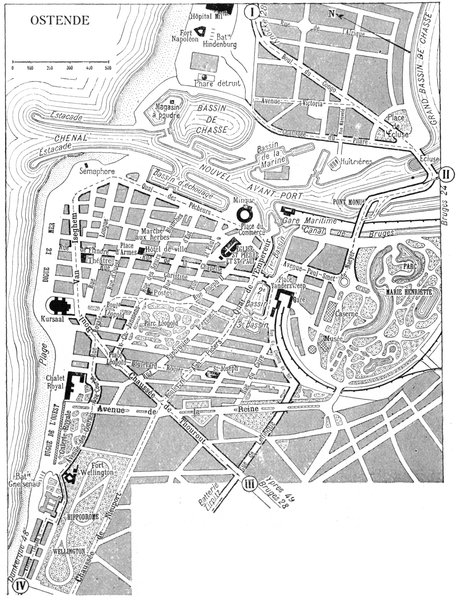

The Itinerary starts from Dunkirk and is divided into four days.

- First day:

- Dunkirk, Nieuport, Ostend (pp. 24-66.)

- Second day:

- Ostend, Zeebrugge, Bruges (pp. 67-85.)

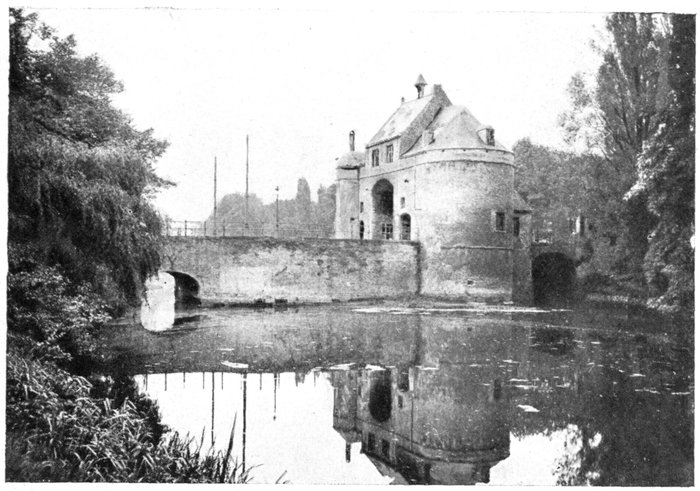

- Third day:

- Bruges (pp. 86-111.)

- Fourth day:

- Bruges, Dixmude, Poperinghe (pp. 112-127.)

Poperinghe is the nearest touring centre to Ypres. For the itineraries

between Ypres and Lille, see the Michelin Guide: "Ypres, and the Battles

of Ypres".

[Pg 24]

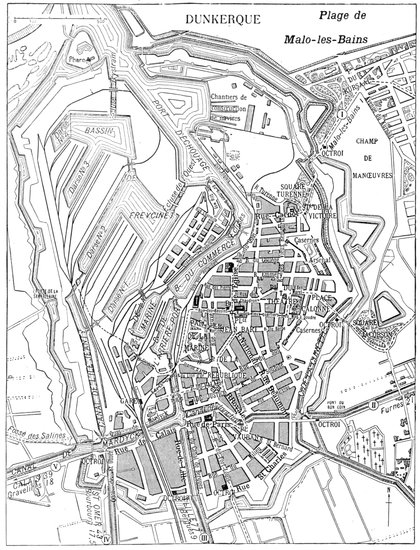

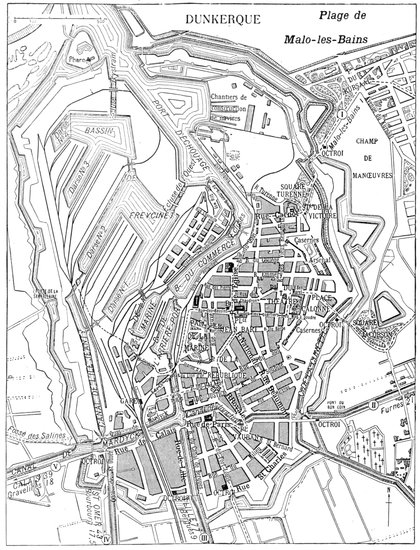

PLAN OF DUNKIRK.

- A. Church of St-Éloi.

- B. Belfry.

- D. Church of John-the-Baptist.

- E. Chapel of Notre-Dame des Dunes.

- F. Church of St-Martin.

- H. Hôtel-de-Ville.

- T. Theatre.

[Pg 25]

Origin and Chief Historical Events.

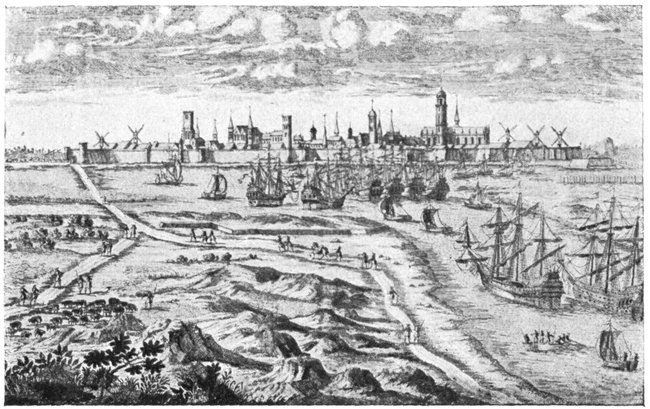

The first mention in history of Dunkirk goes back to the 10th century.

As early as the 12th century, it proved to be an "Apple of Discord" between

the kings of France and the counts of Flanders. Few towns have had such

a stirring history. Ten times besieged, it was taken by Condé in 1646.

Recaptured at a later period by the Spaniards, it was given back to the

French by Turenne, after the battle of the Dunes (1658). Louis XIV ceded

it to his ally Cromwell, but redeemed it from Charles II of England in 1662.

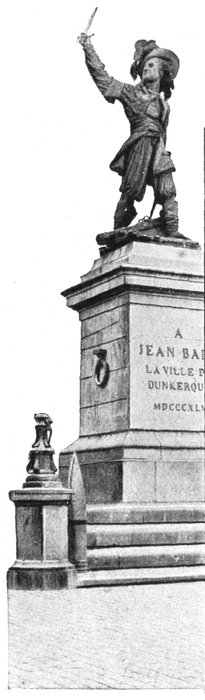

The Dunkirkian corsairs—most famous among whom was Jean-Bart (1651-1702)—inflicted

such losses on the English, that the Treaties of Utrecht and

Paris (1713 and 1763) provided for the destruction of the port. In 1793, the

town was besieged for the last time. By holding out for three weeks against

40,000 men under the Duke of York, it enabled General Houchard to reach

Hondschoote, where the English were decisively defeated. This feat of

arms was commemorated by the device: "Dunkirk deserved well of the

country, 1793", which was inscribed on the city's coat-of-arms.

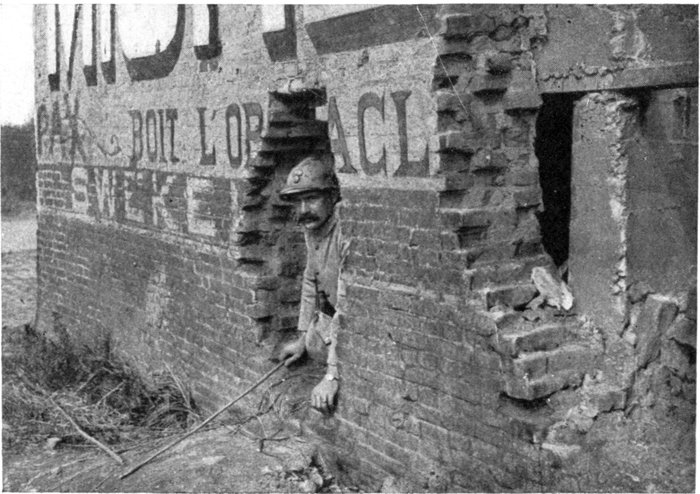

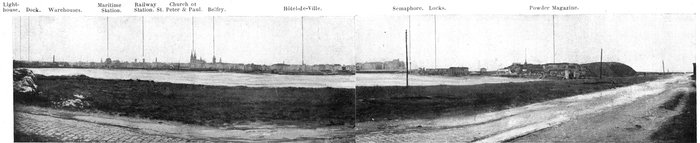

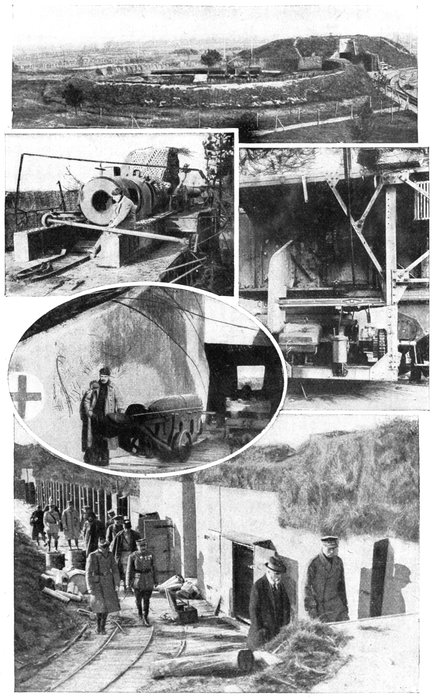

During the Great War of 1914-1918, Dunkirk was an extremely important

revictualling centre for the Allied troops. It also played a great part in

helping to keep the mastery of the North Sea, and as such, was constantly

bombarded by the enemy. It was to reach Dunkirk and Calais, that the

Germans made their furious thrusts at Ypres and on the Yser. Of all the

towns not directly in the front-line, Dunkirk was probably the one which

suffered most. It was bombarded once by Zeppelins, seventy-seven times

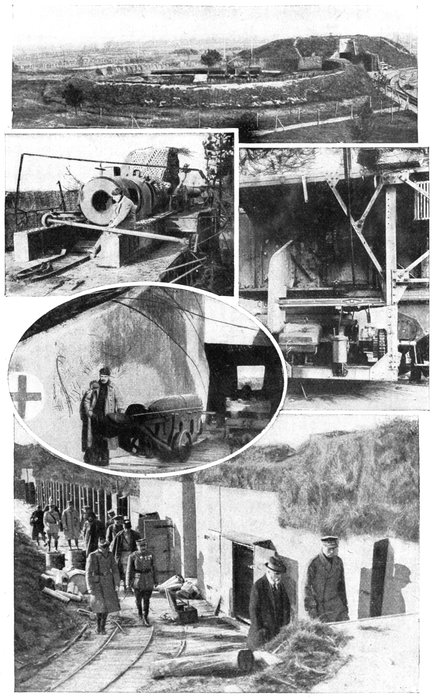

by aeroplanes and four times by warships. Lastly, a 15in. naval gun posted

twenty-three miles away, shelled the town at regular intervals from April

1915 onwards. In all, more than eight thousand shells fell in the town,

killing five hundred people and wounding over one thousand others. In

spite of all, the town maintained considerable activity throughout the war.

The damaged and destroyed buildings were rapidly cleared away or repaired.

Under bombardment, the shipbuilding-yards turned out three vessels of[Pg 26]

19,000 tons. Munitions of war were also manufactured in very large quantities.

The following citation in the Army Order of October 17, 1917, which

is to be incorporated in the city's coat-of-arms, was well deserved:

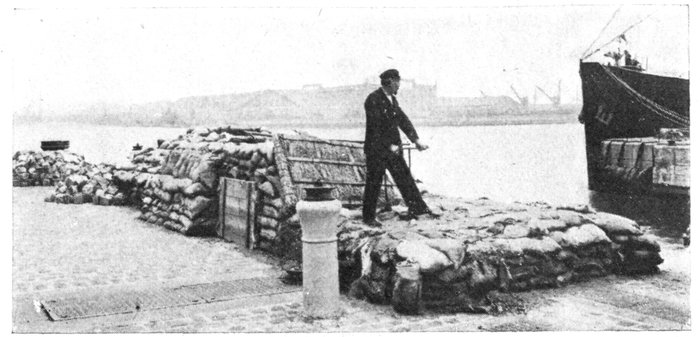

Quai de la Citadelle struck by a 15in. shell.

Subjected for three years to violent and frequent bombardments, Dunkirk was

able, thanks to the admirable coolness and courage of her inhabitants, to maintain

and develop its economic life in the interests of National Defence, thereby

rendering invaluable service to the Army and Country. This heroic city is an

example to the whole nation.

The Croix de la Légion d'Honneur was conferred on Dunkirk by President

Poincaré on August 11, 1919.

Building a bomb-proof shelter in front of the Station.

[Pg 27]

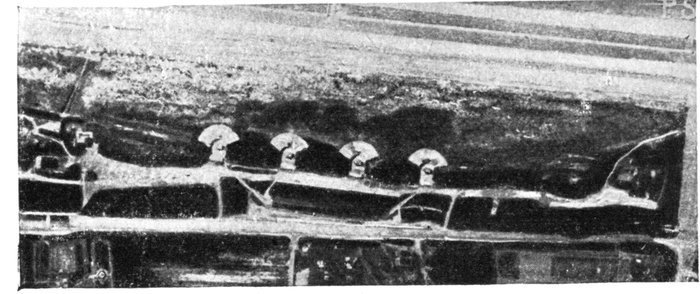

Protecting the mechanism of the Locks from the Shells.

A Visit to Dunkirk.

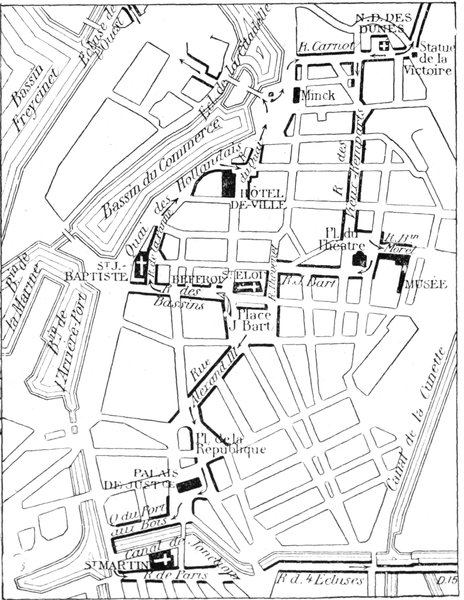

Follow the arrows along the streets indicated by thick lines in the plan below.

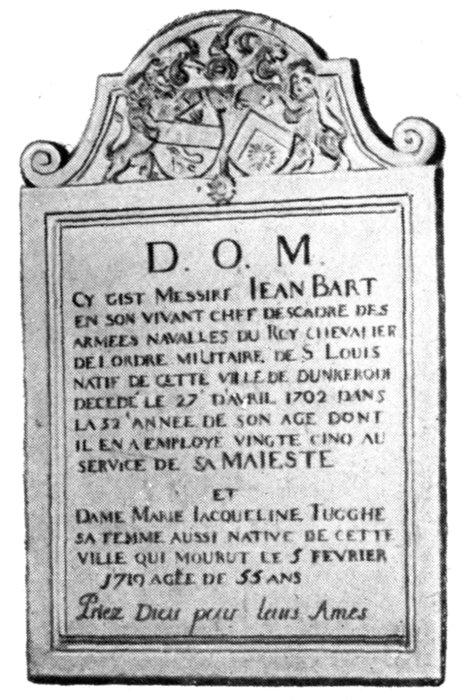

Starting-point: Place Jean-Bart in the middle of

which is a statue of Jean-Bart (1844) (photo below).

[Pg 28]

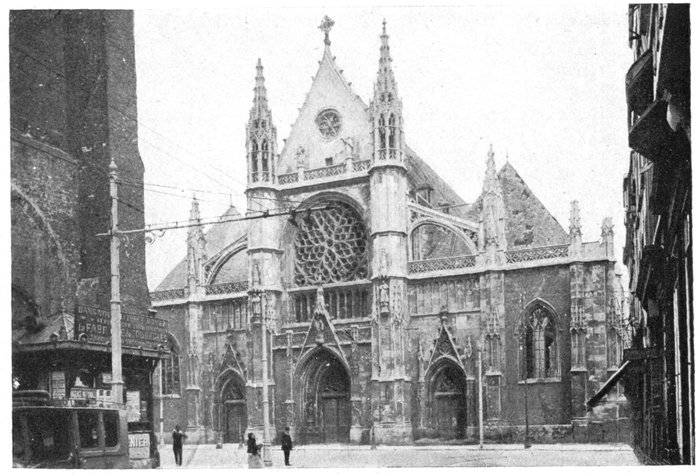

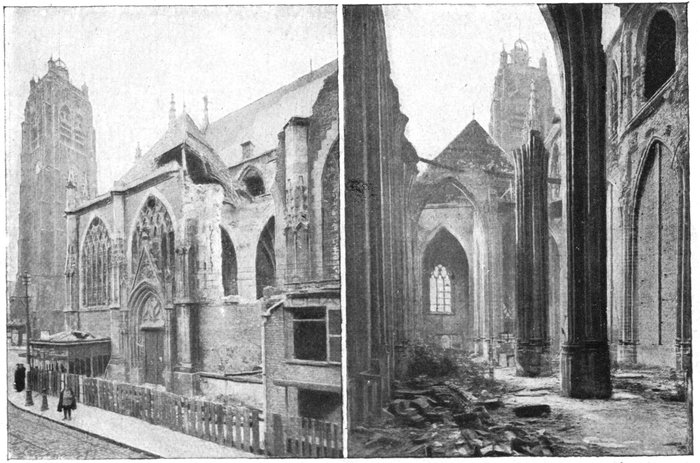

Take Rue de l'Eglise (Rue Clemenceau) in which, immediately to the right,

stands the Church of St. Éloi with the Belfry opposite.

Built in the 16th century, St. Éloi Church contains a nave flanked by

four side-aisles. The first bays, nearest the façade, having being pulled

down, the belfry—an old watch-tower, which formerly abutted on the

church—is now separated from it by the width of the street. The façade was

rebuilt in 1890. In the interior are a fine XVIIIth century pulpit, some old

paintings, and the tomb of Jean-Bart (left aisle) (photo, p. 29). The right

aisle was torn open by the shells (photo below).

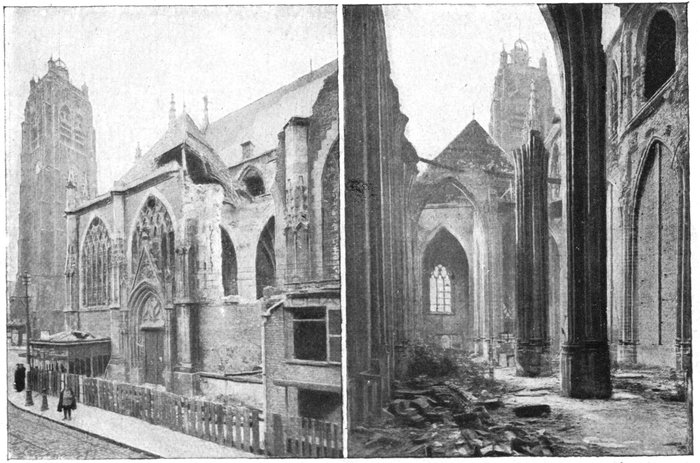

The Belfry, and ruined side aisle of St. Éloi Church.

Exterior. Interior.

[Pg 29]

The Belfry, a large square tower of brick,

190 feet high, was built in 1440. It contains

a peal of bells. From the top, there is a very

fine view.

The entrance is on the rear side of the tower.

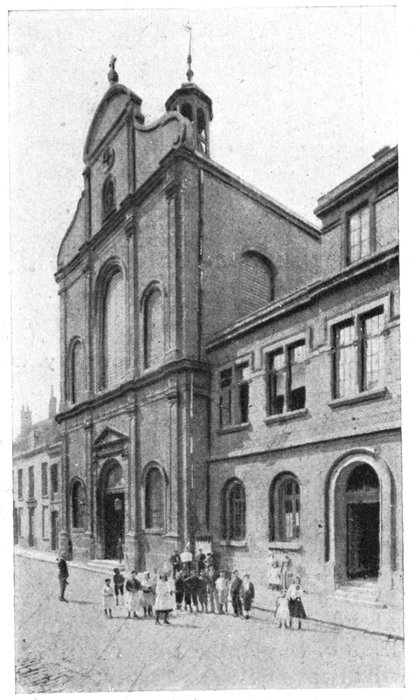

Take Rue des Bassins, opposite the church,

and turn to the right along Rue de La Panne, in

which stands the Church of John-the-Baptist.

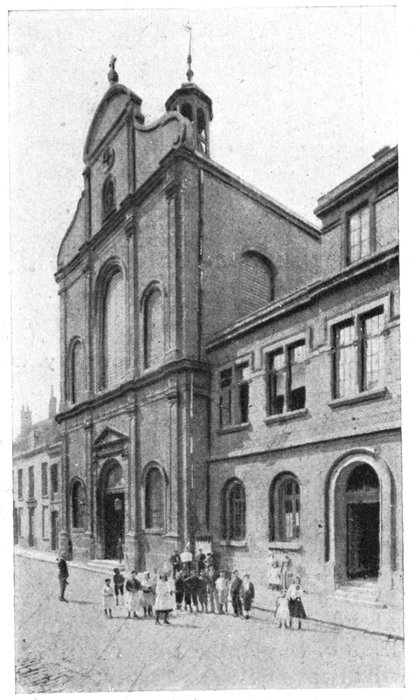

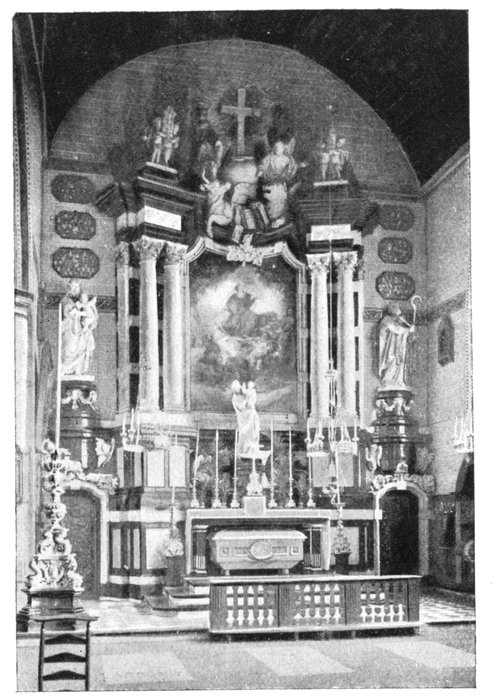

Church of John-the-Baptist.

This 18th

century

church

contains

some fine

paintings.

On the altar:

The Consecration of Dunkirk to

the Virgin (Elias); in the chancel,

The Death of Mary the Egyptian (G.

de Crayer); The Holy Family (Erasme

Quellin); The Holy Family (Le

Guide); Jesus crowned with thorns

(Van Dyck). In the nave: Paintings

by Elias and de Janssens. On the

northern side of the church are the

cloister and modern chapel of St. Philomène

(shrine).

Keep along Rue de la Panne; follow

Quai des Hollandais, and turn to the

right into Place d'Armes, in which

stands the Hôtel-de-Ville.

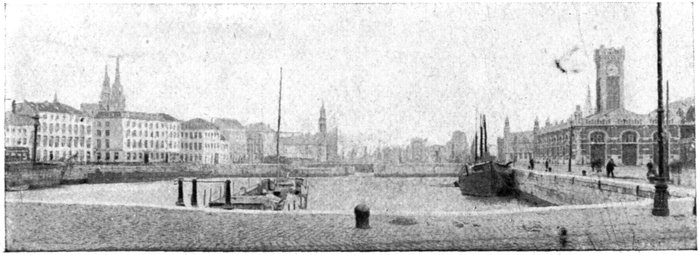

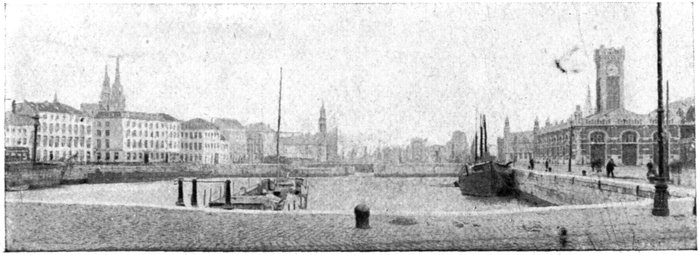

Quai des Hollandais and the Hôtel-de-Ville.

The Hôtel-de-Ville was rebuilt in

1896-1901 of brick and stone (architect,

L. Cordonnier). On the first

floor are statues of illustrious Dunkirkians.

Just below the roof

there is an equestrian statue of

Louis XIV. The tower is 250

feet high.

[Pg 30]

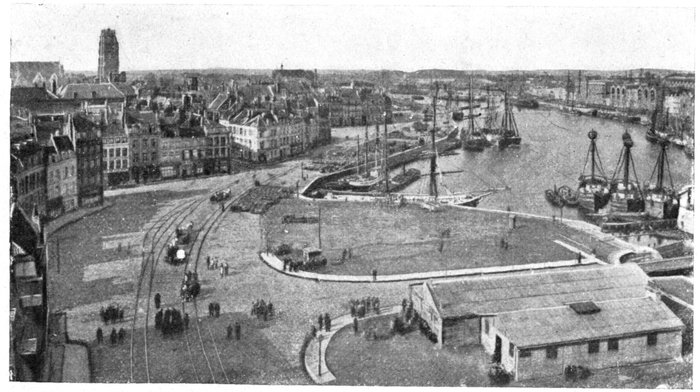

Fishing-boat Dock. In the background: Hôtel-de-Ville and Belfry.

Take Rue du Quai, on the left, to the large square in front of the port, in

which is the Fish-Market (Mynk). (See sketch-map, p. 27.)

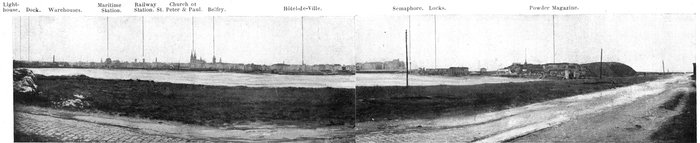

The port of Dunkirk.

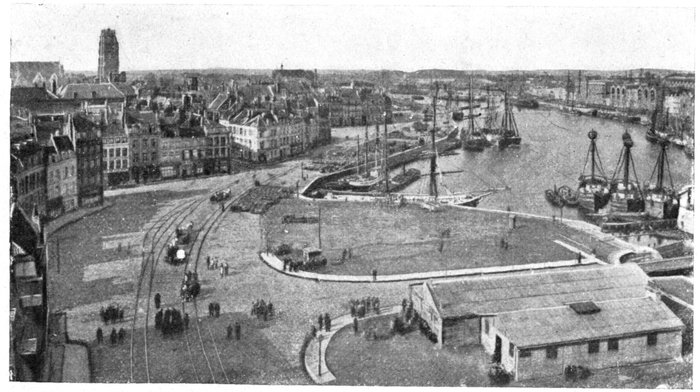

General View of Dunkirk and the Docks.

One of the busiest fishing and coast-trading ports in France, Dunkirk is

especially important by reason of its import trade. The raw materials

required for the industries of Northern France are discharged there, whilst

iron ore, oil and metals are exported. Since the beginning of the 19th century

Dunkirk has steadily grown and the fortifications have twice had to be

extended (1861-1906). The ruined industries of the North and the competition

of the Rhine may retard this growth, but the port's natural situation

will always ensure a fine future for it. In 1920, the docks covered an area of

about 100 acres, whilst the total length of the wharves was about six miles.

[Pg 31]

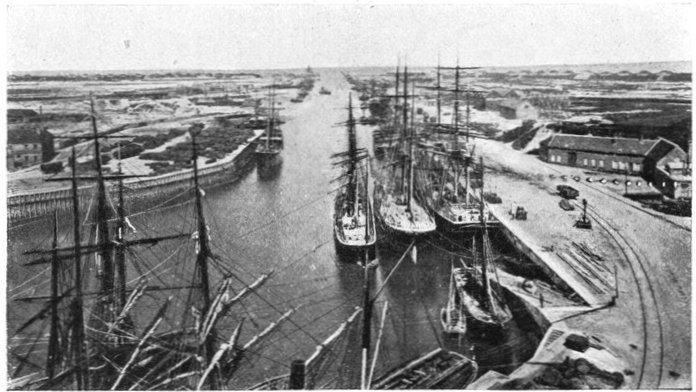

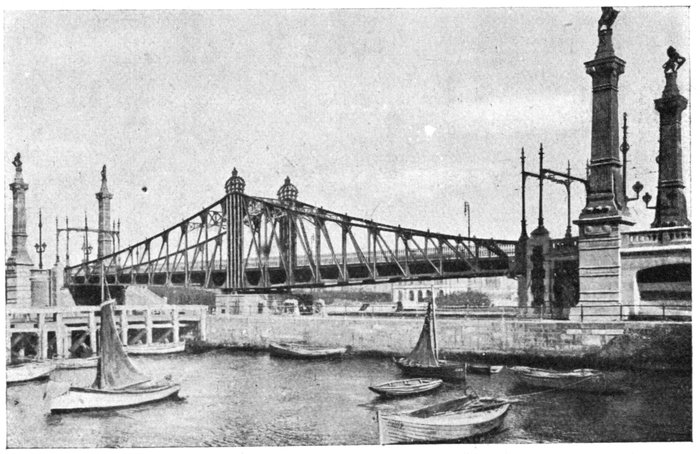

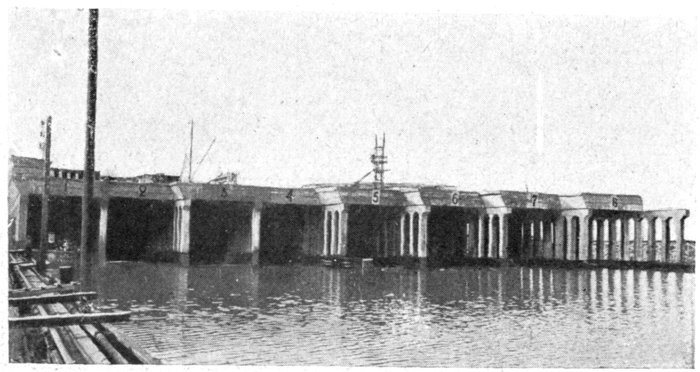

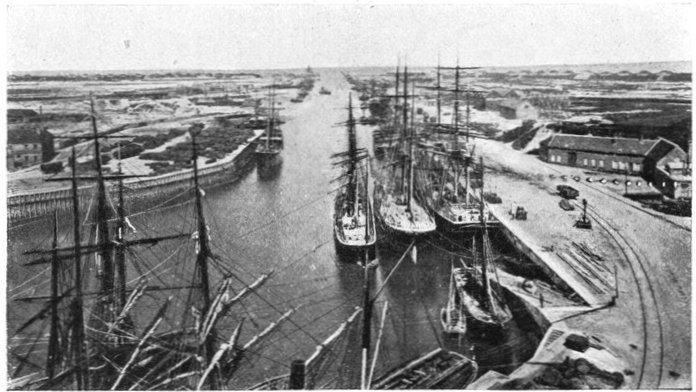

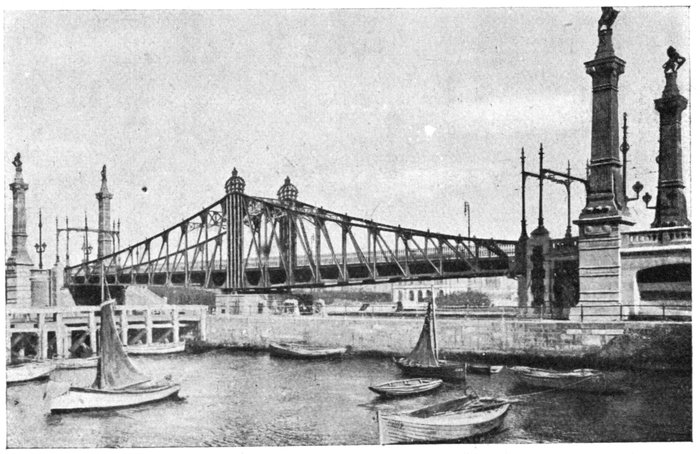

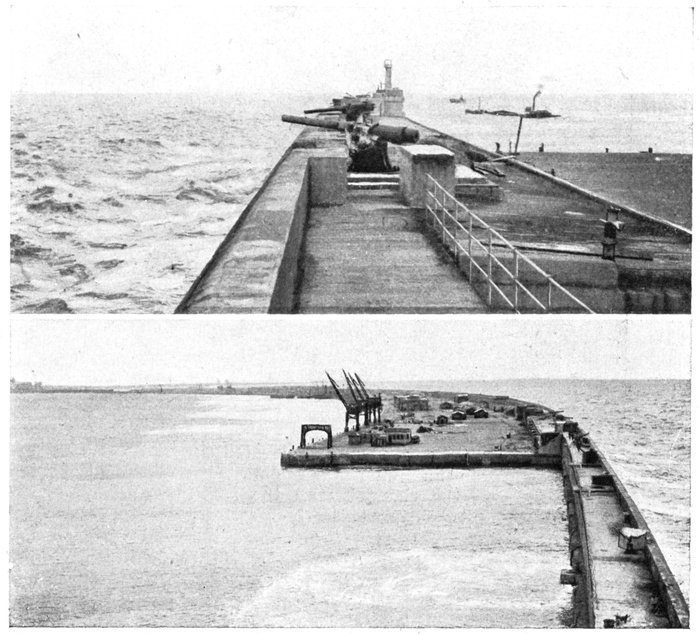

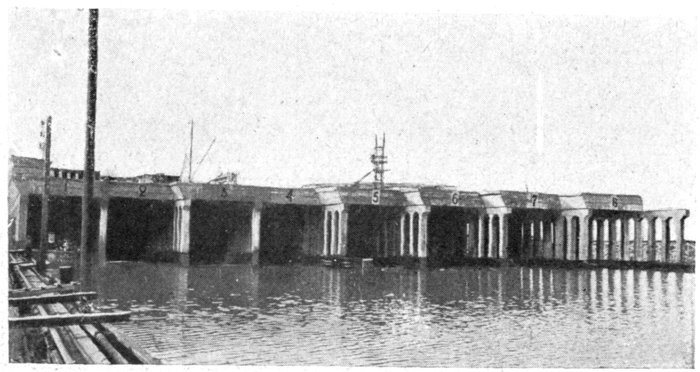

The port consists of a series of parallel docks, i.e., the extended rear port,

the naval dock, the commerce dock, and wet-docks 1, 2, 3, 4, connected

by the Freycinet dock. All these docks lie at right-angles to the great

water-line formed by the grounding port and outer harbour, into which the

channel debouches. Dunkirk also possesses extensive naval stocks provided

with five large dry docks and a launching dock fifteen acres in extent (See

plan, p. 24.)

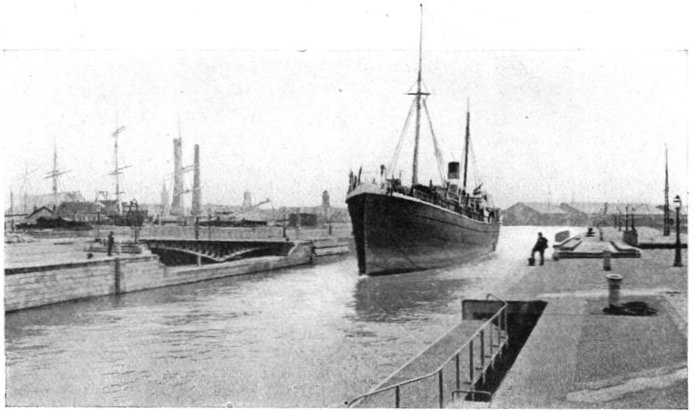

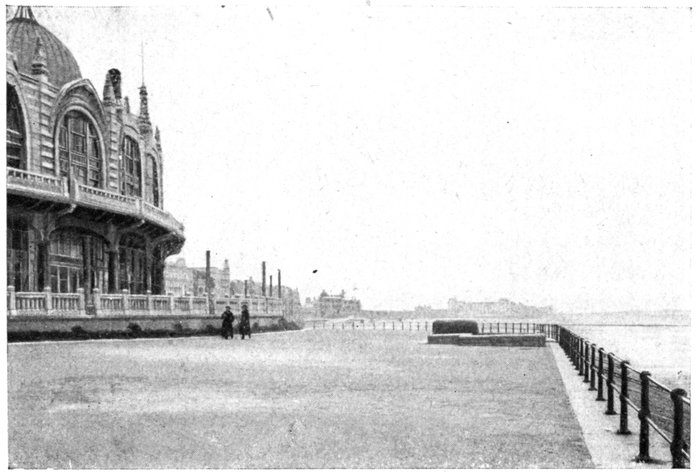

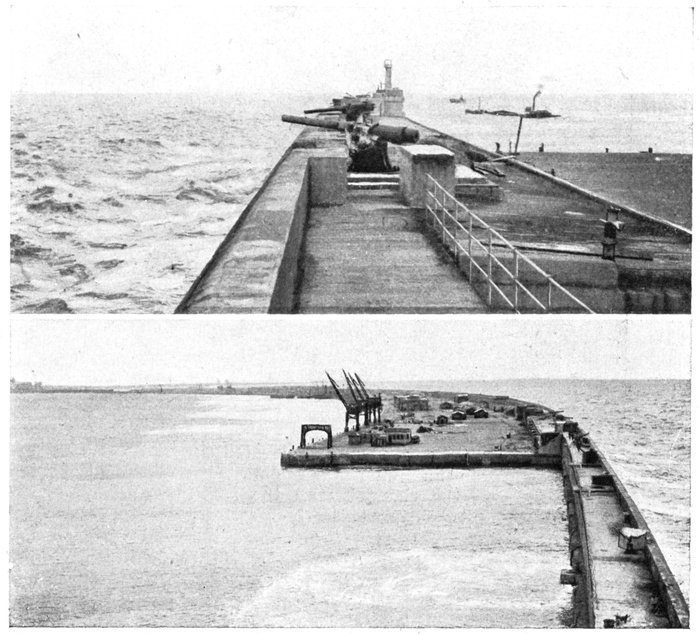

The Outer Port of Dunkirk and the Channel.

To visit the port, cross the bridges over Citadelle Lock and Western Lock;

turn to the right along the quay, passing behind the wet-docks and skirting

the graving-docks. On the right, on the other side of the grounding port,

the naval dock-yards come into view. Cross the bridge of Trystram Lock,

which connects up Freycinet Dock with the channel, then turn immediately

to the right and cross the small bridge opposite the lighthouse, leaving the latter

on the left. Skirt the channel (about 230 yards long and 27 yards wide), as

far as the two booms which terminate it. There are several observation-posts

and armoured concrete machine-gun shelters near the lighthouse.

[Pg 32]

Return to the square in front of the port and

follow the quay, on the left, as far as Rue Carnot

on the right, which leads to the Chapel of Notre-Dame-des-Dunes.

(See itinerary, p. 27).

This chapel is a favourite pilgrimage. The

fisherwomen of Dunkirk made it the headquarters

of their Sisterhood.

A little further on stands the Statue of Victory

commemorating the siege of 1793. This monument

is the work of Ed. Lormier (1893) and was

erected on the site of the old ramparts.

Follow the tram-lines to Malo-les-Bains,

Dunkirk's beach.

Return to Rue Carnot and take Rue des Vieux-Remparts

on the left to Place du Theatre, where

turn to the left into Rue Benjamin-Morel, in

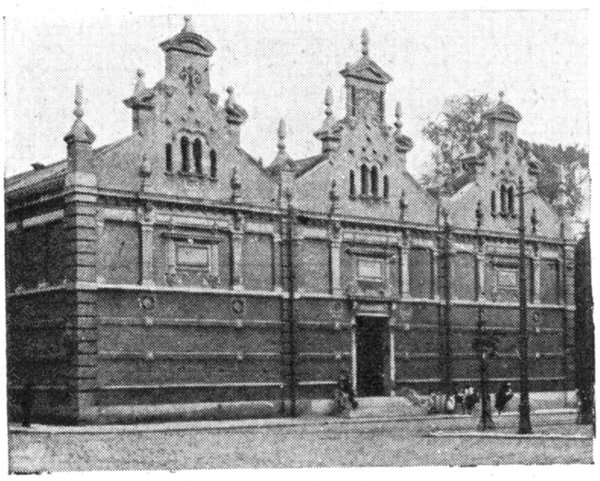

which stands The Museum (photo below.)

Take Rue Jean-Bart on the right, behind the theatre, then Rue Thévenet on

the left, leading back to Place Jean-Bart.

Cross the latter diagonally to Rue Alexandre

III (see Itinerary, p. 27) which leads

to Place de la République. Here stands

the monument erected to the memory of

the Dunkirkians who fell fighting for their

country. (L. Morice, 1906.)

Cross Place de la République, then

Place du Palais-de-Justice, turn to the

right along Quai du Port au Bois then cross

the bridge on the left (see Itinerary, p. 27).

Take Rue de Paris on the left, in which

stands St. Martin's Church. This modern

church, primitive Gothic in style, is

flanked by two towers with spires.

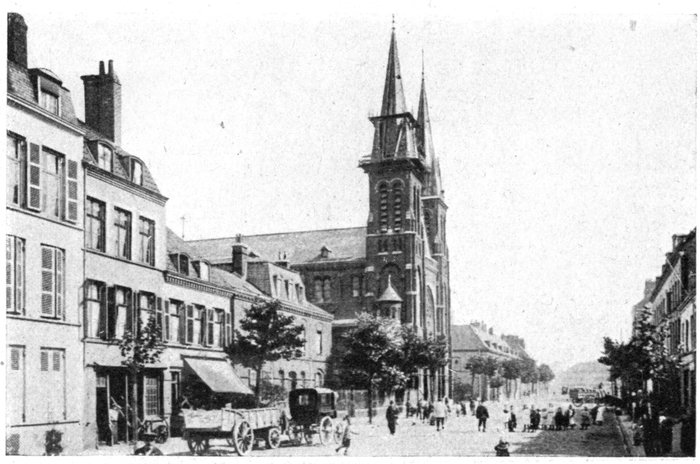

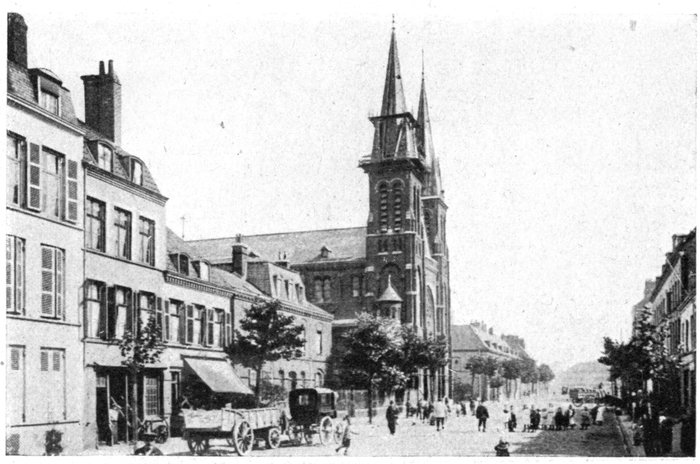

Church of St. Martin and Rue de Paris.

The tourist leaves Dunkirk by Rue de Paris and Rue des 4-Ecluses, which

prolongs it, to follow the itinerary of the first day.

[Pg 33]

A VISIT TO THE YSER BATTLEFIELD

AND THE BELGIAN COAST.

First Day:

DUNKIRK, NIEUPORT

AND OSTEND.

Lunch at Nieuport.

Leave Dunkirk by Rue de Paris, continued by Rue des 4-Ecluses, cross

the Canal de la Cunette (see lower half of itinerary, p. 27, and text, p. 32), and

take the Furnes road (D. 15) which follows the right bank of the Dunkirk-Furnes

Canal.

At Rosendael (2½ kms. on the other side of the canal) stood the Civilian

Hospital of Dunkirk, which was shelled several times during the war.

On the left, 3 kms. further on, is Dunes Fort.

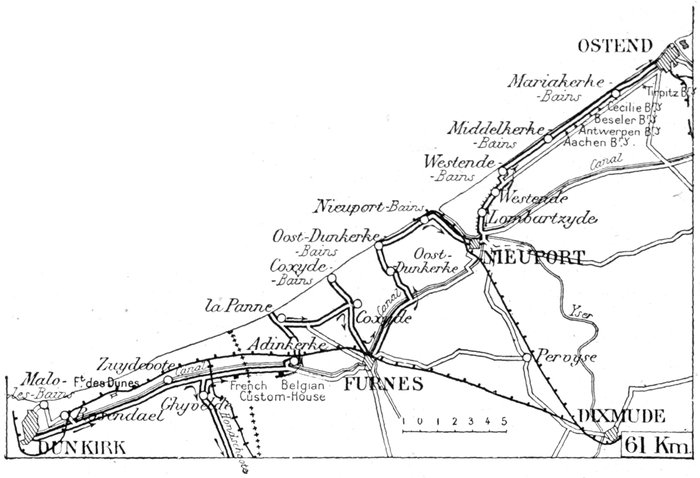

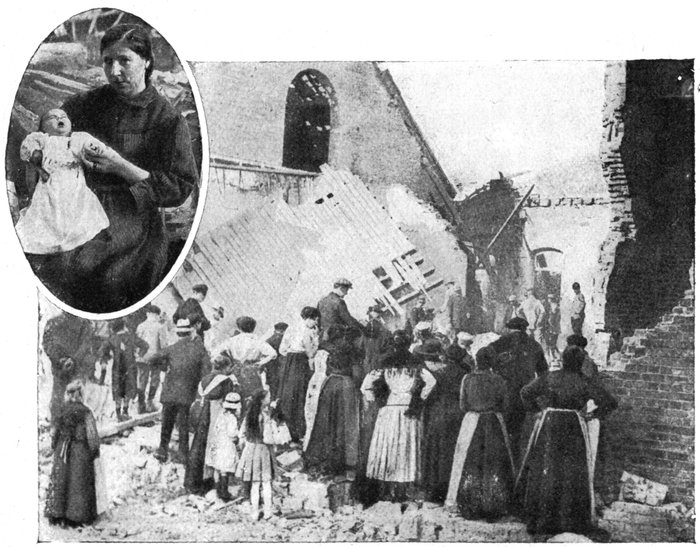

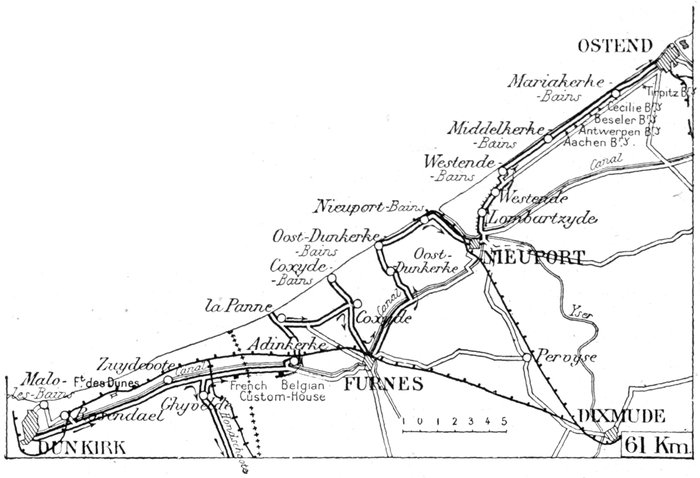

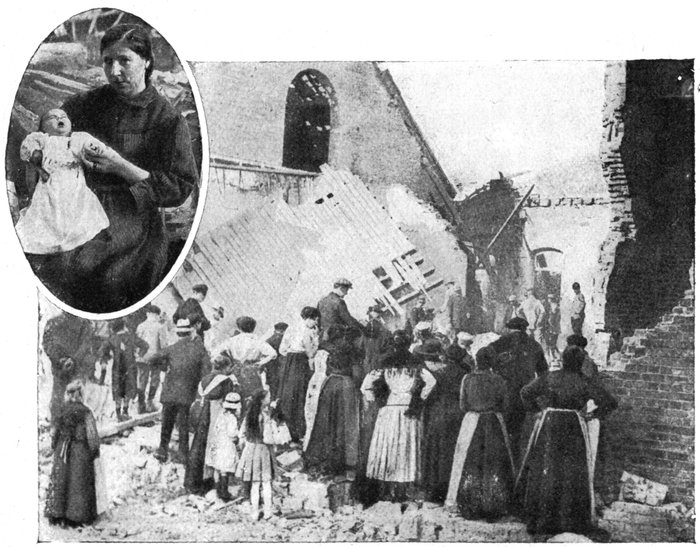

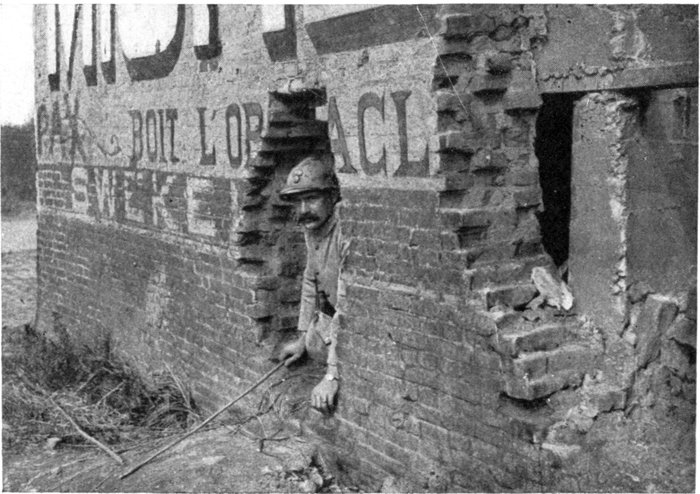

Hospital at Rosendael bombed by a German aeroplane.

The baby in the medallion had one of its hands cut off by a splinter.

[Pg 34]

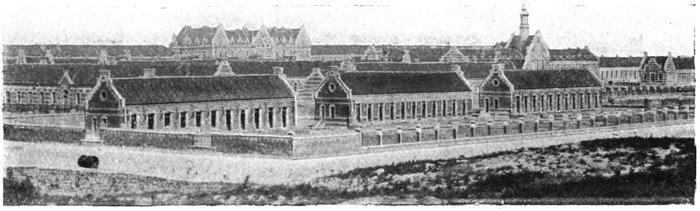

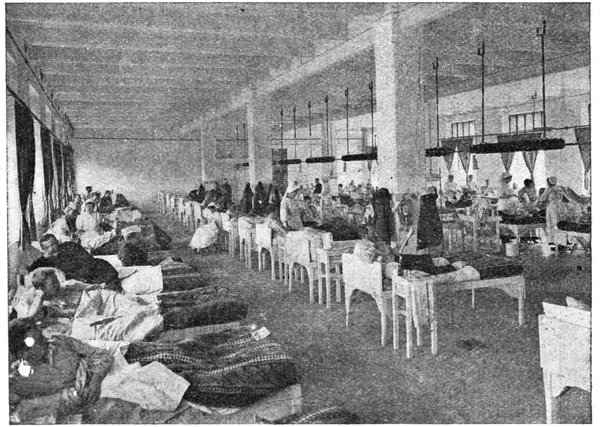

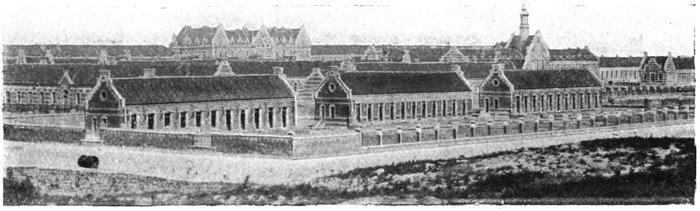

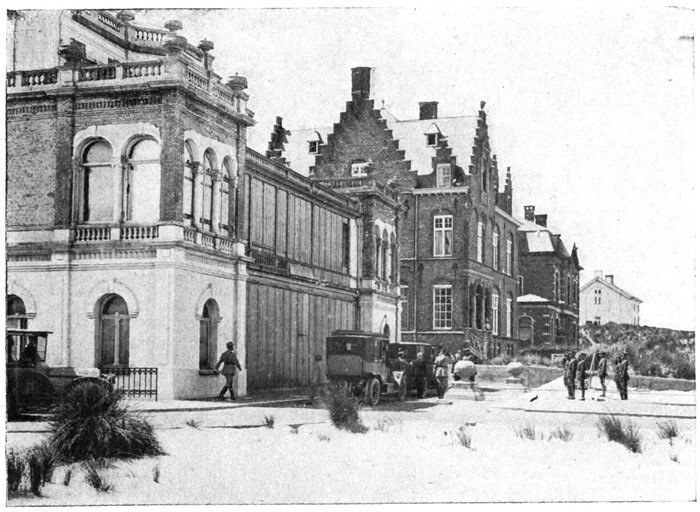

Sanatorium at Zuydcoote. (Cliché LL.)

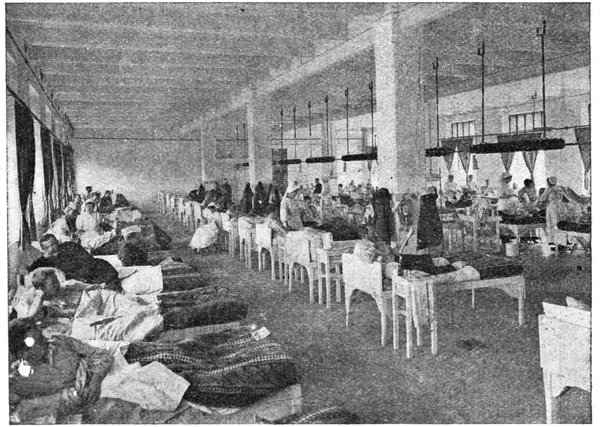

At the first cross-roads (9 kms. from Dunkirk), the tourist may take the left-hand

road to Zuydcoote, to see the great Sanatorium for children, on the

coast, founded by M. Van Covenberghe. Converted into a military hospital,

it rendered invaluable service during the War (photo above).

To visit, go through Zuydcoote, turn to the left, beyond the level-crossing,

then to the right 200 yards further on.

Return to D. 15, and follow same on the left.

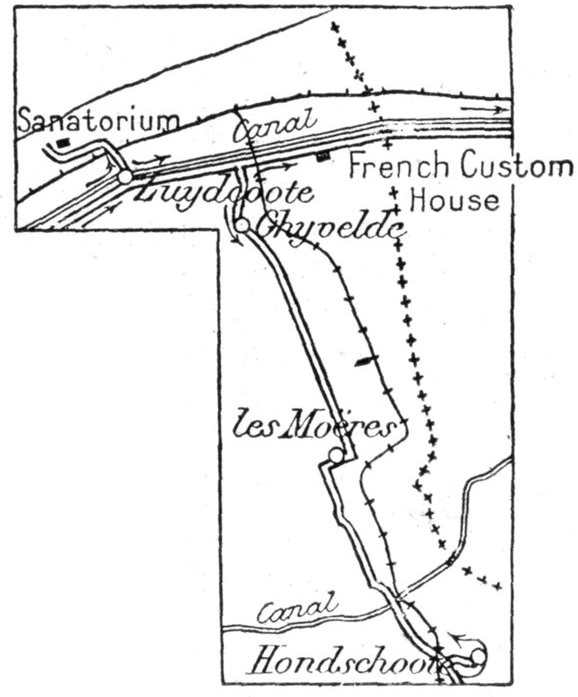

At the first cross-roads (2 kms.) take G. C. 4

on the right to Hondschoote (12 kms.)

Pass through Ghyvelde, then at Les

Moeres turn to the right, and on leaving,

to the left.

Beyond the level-crossing, Hondschoote is

reached. Take Rue de la Prévôlé on the left, which leads

to the Grand' Place.

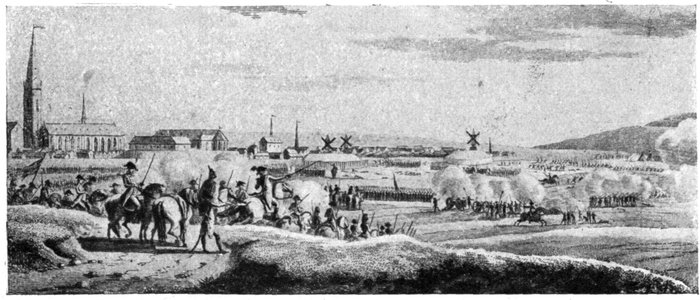

Hondschoote is a small town of ancient origin,

whose population has greatly decreased since the

16th century. It was there that, on September

8, 1793 the French, under Houchard, defeated and

drove back the English who were besieging Dunkirk

(engraving below).

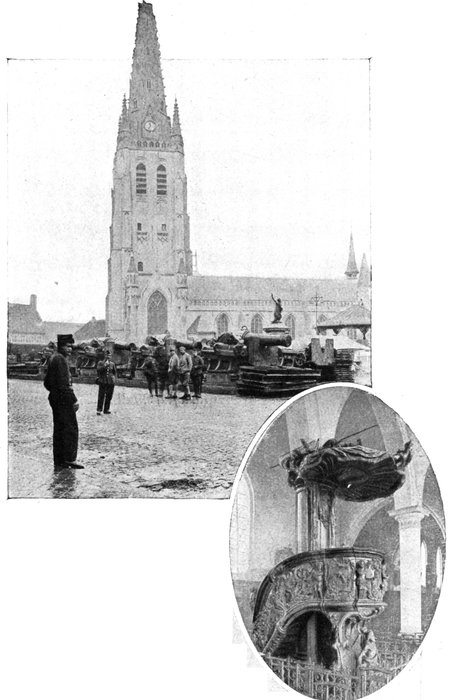

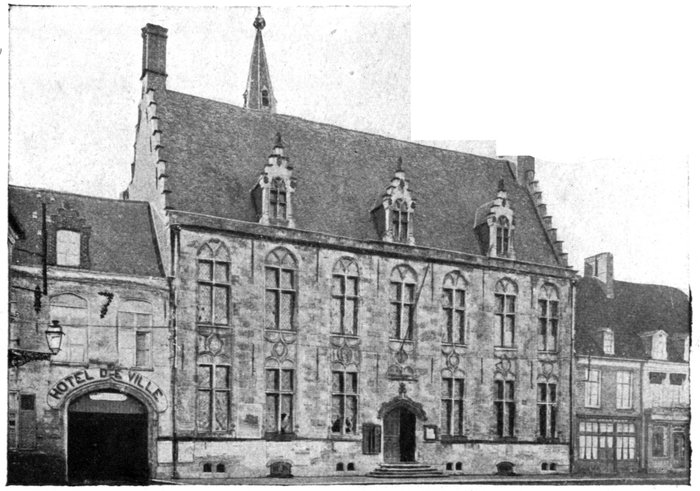

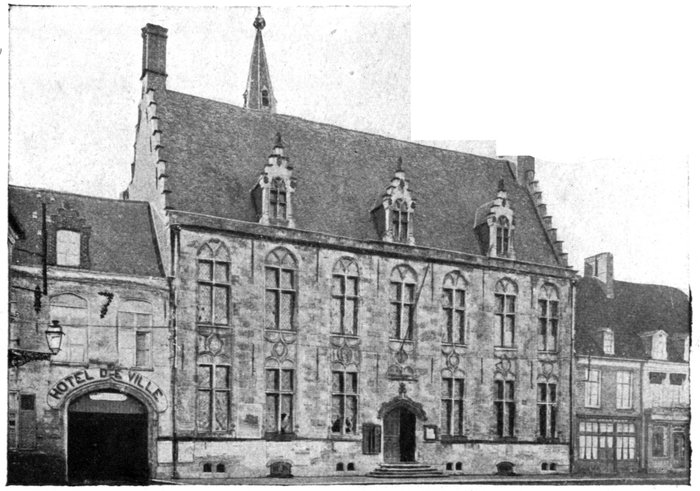

On the right of the Square (photos, p. 35) is the 17th

century Renaissance Hôtel-de-Ville, while in the centre

stands the early 16th century church, in which are

a fine pulpit and organ loft (1755). Near by is a monument (Darcq) commemorating

the victory of 1793.

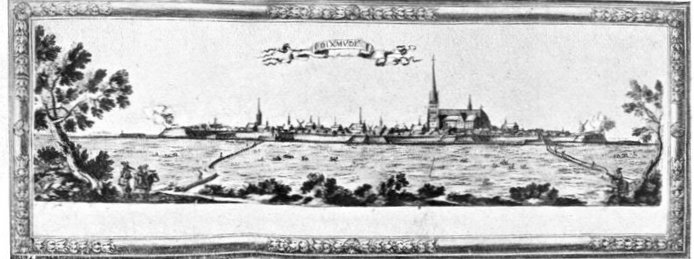

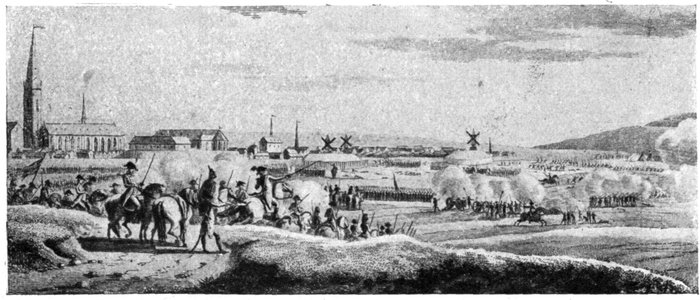

The Victory at Hondschoote. (21 Fructidor, Year 1.)

[Pg 35]

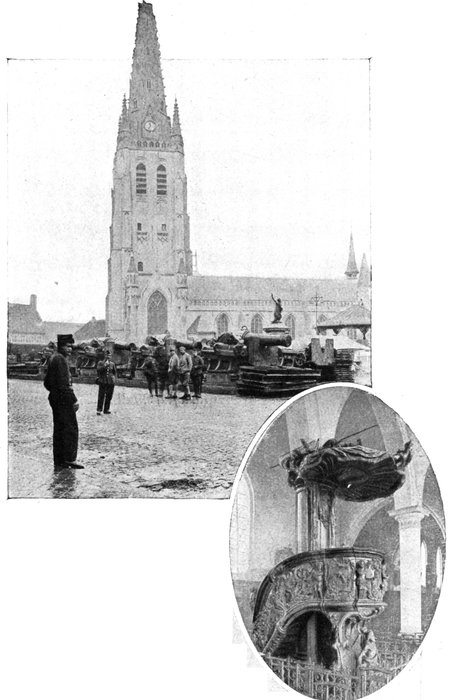

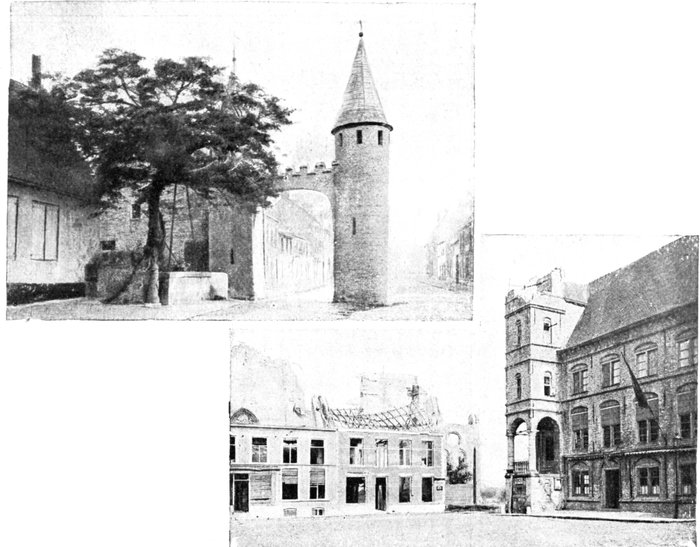

Hondschoote.

Hondschoote Church.

In front: 9in. Mortars.

In the medallion:

The Pulpit.

Hondschoote. The Hôtel-de-Ville.

[Pg 36]

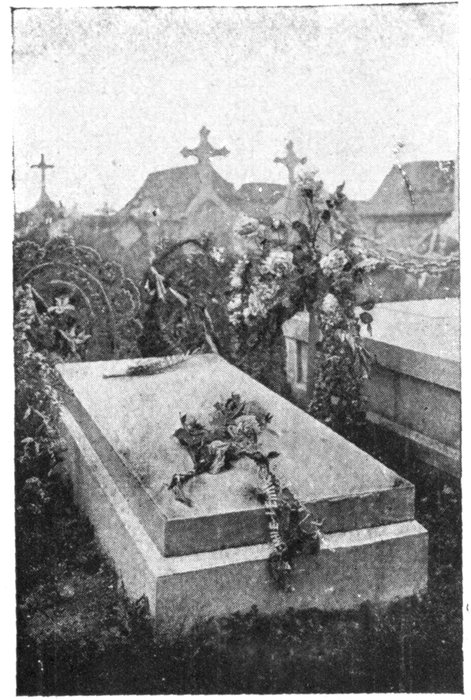

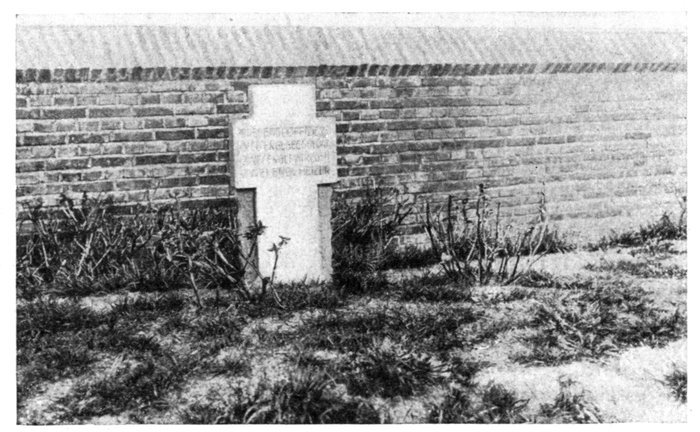

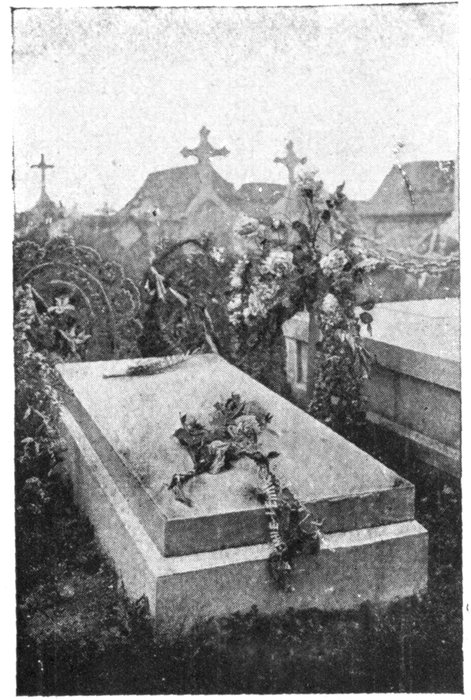

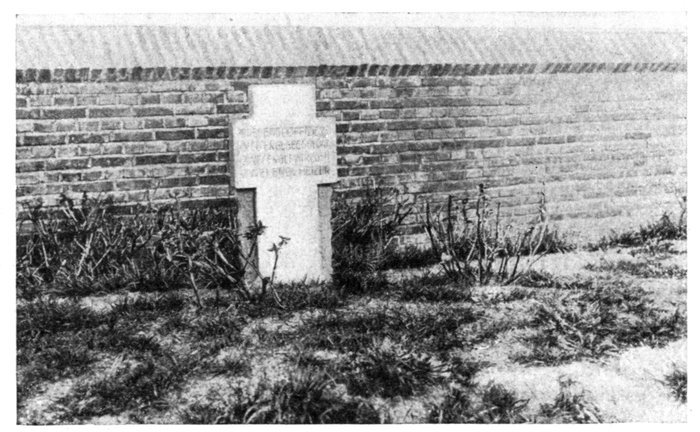

Verhaeren's Tomb at

Adinkerke (1918).

Return to D. 15 and follow same to the

right; cross the railway (l.c.); 2 kms. further

on is the French Custom-House. The

Belgian Custom-House

is 3 kms.

further on, near

Adinkerque.

Cross the canal

and enter

Adinkerke.

Take the street

on the left which

skirts the churchyard.

Behind

the church is

a large Franco-Belgian

cemetery, containing the

grave of the Belgian poet Verhaeren.

After the Armistice, his remains were

transferred to his native town.

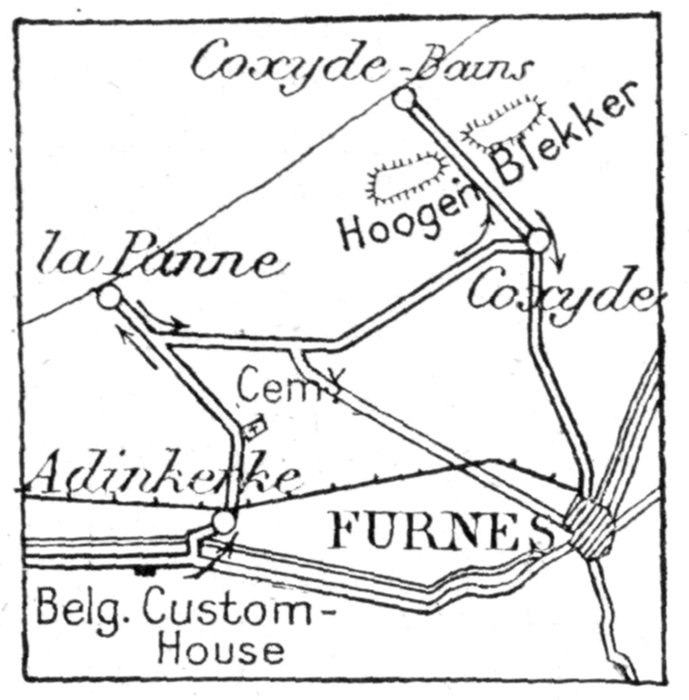

Keep straight on along the La Panne road;

600 yards beyond the Dunkirk-Furnes

railway, a small foot-path on the right leads

to a military cemetery. La Panne is

next reached (3 kms.). This small seaside

resort was one of the least modern places on the coast. Follow Avenue

de la Mer as far as the dike, to the left of which are three villas which were

occupied during the war by King Albert and his staff.

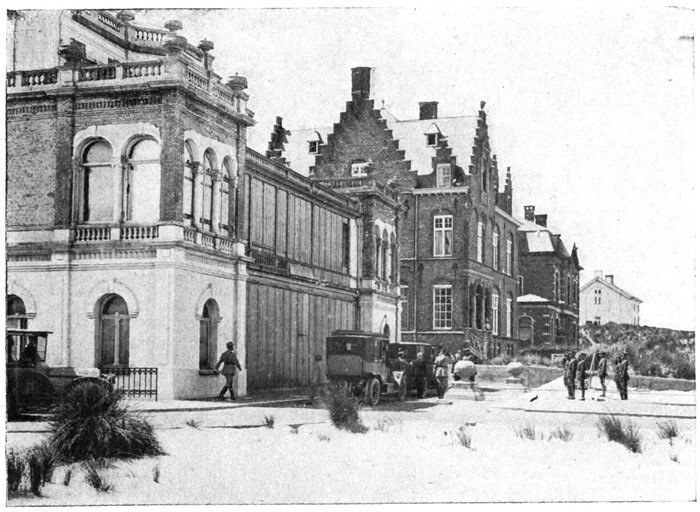

Reception of President Poincaré by King Albert at the Royal Villa,

La Panne, January 22, 1917.

[Pg 37]

Villa of the French

Mission at La Panne

(October 1916.)

Return along Avenue de la Mer to the first street

on the left, in which is the Hôpital de l'Océan.

0 km. 800 further on, on the left, take the street

which runs alongside the local railway. At the

first fork, take the left-hand road to Coxyde (5 kms.

from La Panne.) Wire entanglements and shelters

in the Dunes may be seen all along the road.

There is a military cemetery on the left, O km. 500

before reaching Coxyde.

Coxyde, like most of the towns on the coast,

is divided into the town proper, situated behind

the Dunes, and the Baths on the coast.

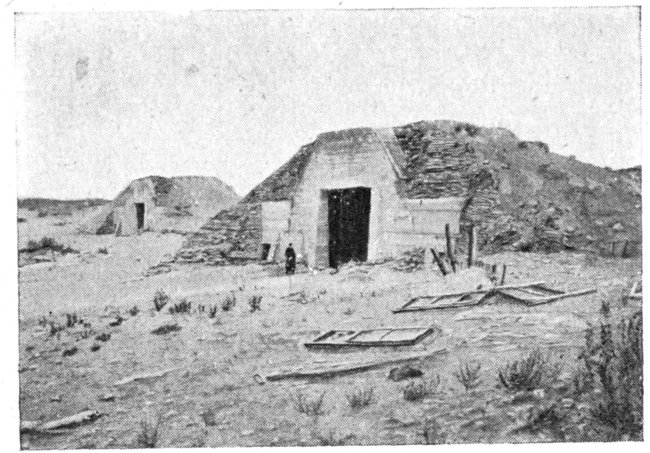

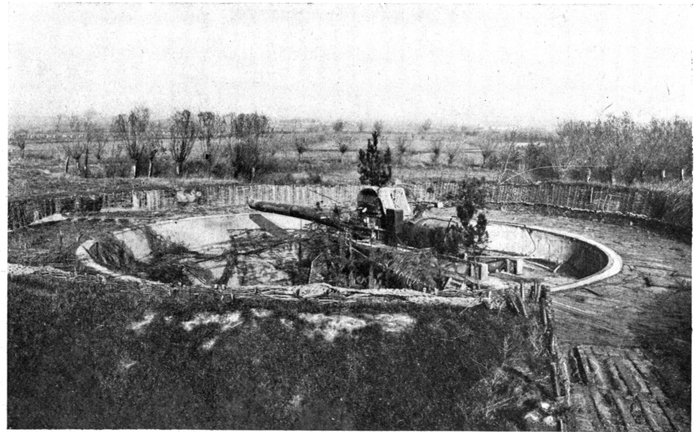

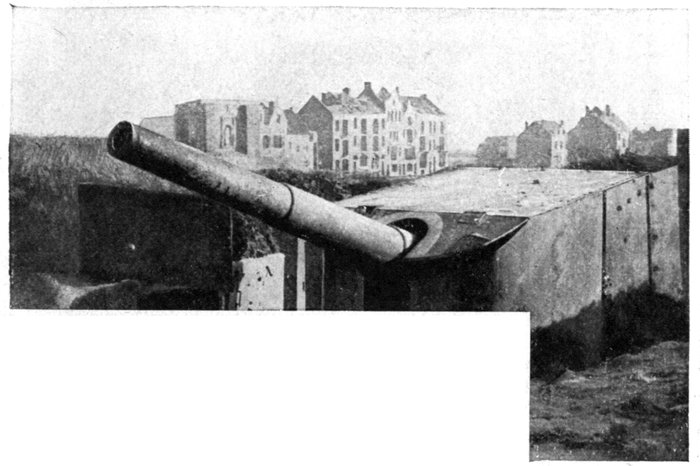

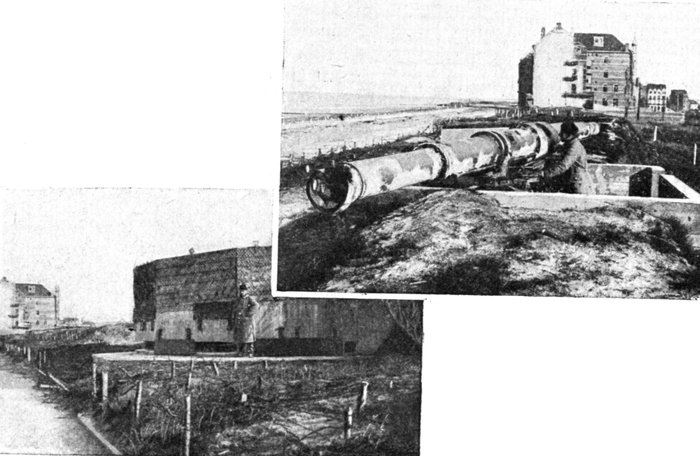

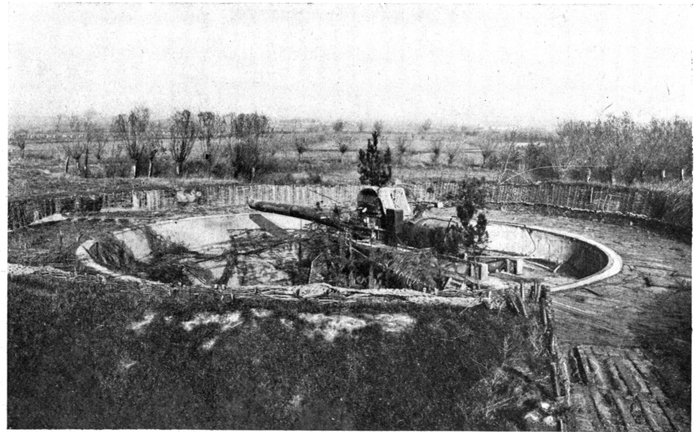

Concrete Gun Shelter,

100 yards east of Coxyde-Bains.

Turn to the left on entering the village. The road

crosses the Dunes, which are highest at Hoogen-Blekker

(105 feet). Vestiges of trenches, wire

entanglements, shelters and gun emplacements

are to be seen on every hand.

In the Dunes, on the right, is

an emplacement for naval guns

(Photo opposite). Between this

position and the sea is the camp

known as that of Adjutant Lefèvre

(Photo below).

The tourist may go as far as

Coxyde-Bains (2 kms.) Return

to and cross through Coxyde, keeping

straight on to Furnes (3½

kms.)

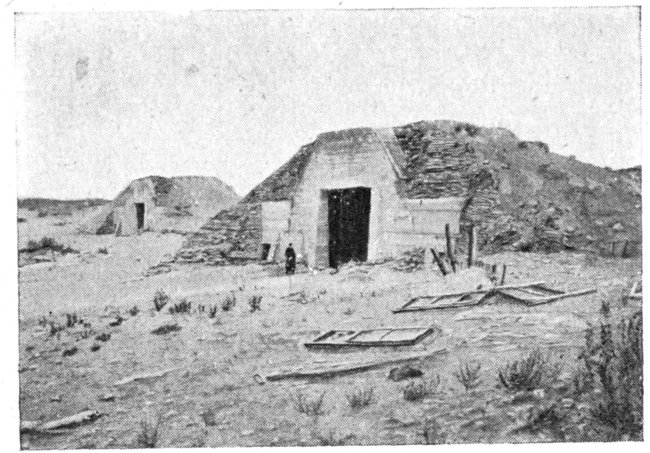

The Camp of Adjutant Lefèvre at Coxyde-Bains.

[Pg 38]

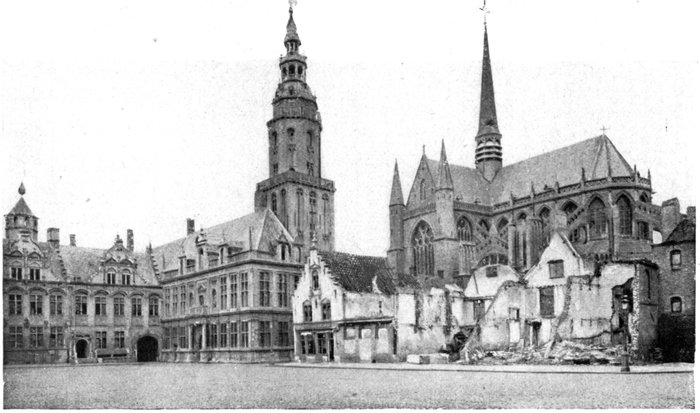

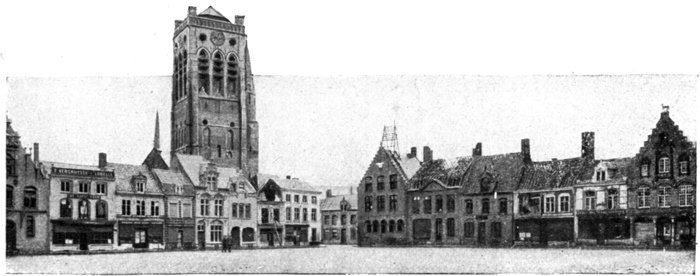

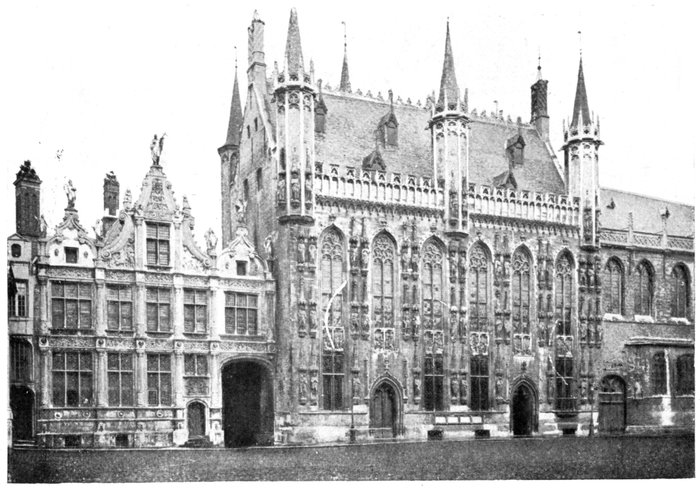

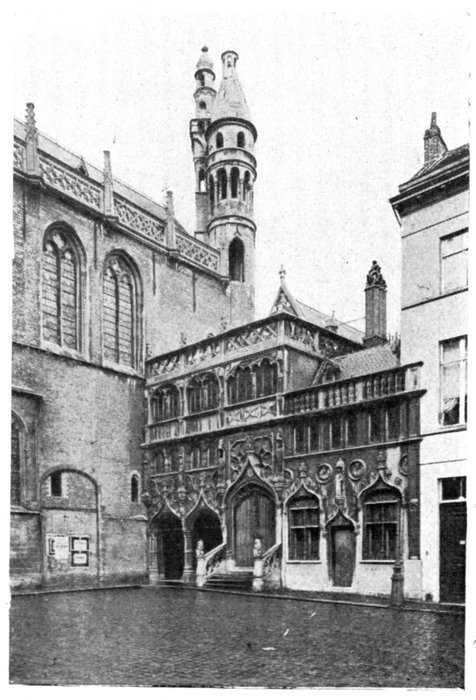

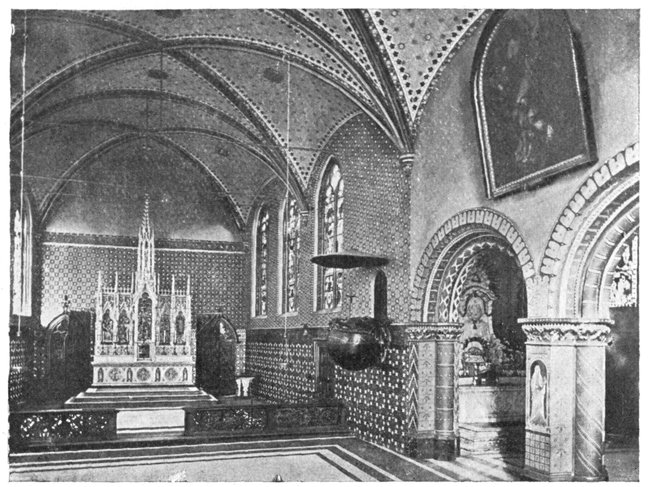

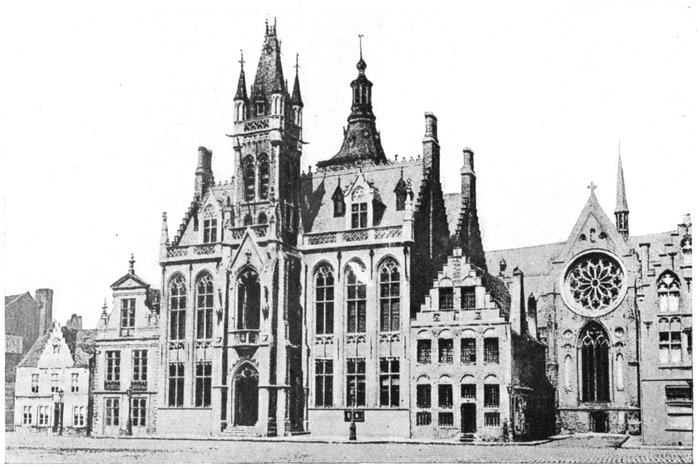

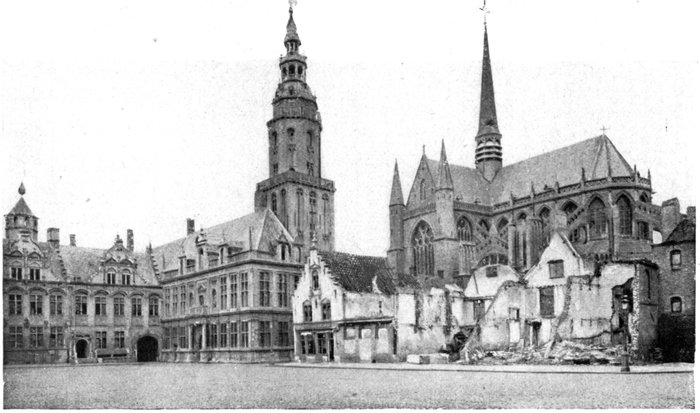

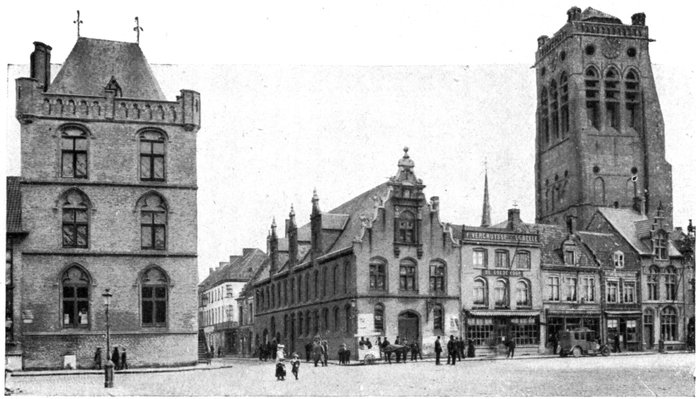

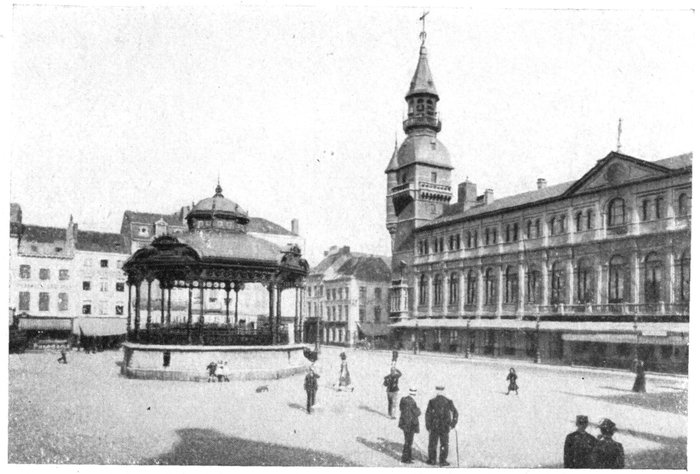

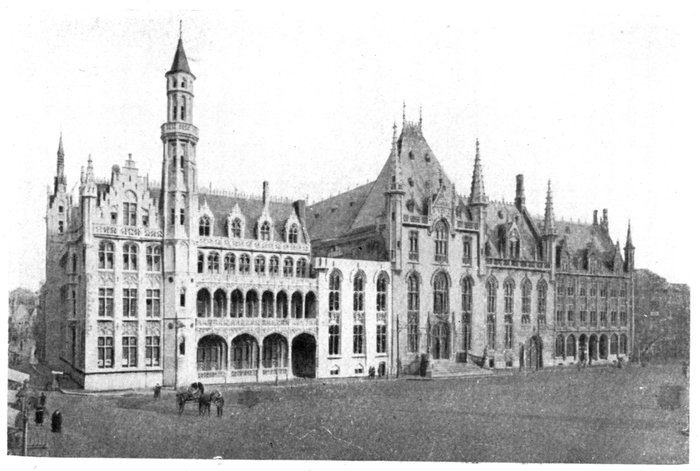

Hôtel-de-Ville, Palais-de-Justice, Belfry, Church of St-Walburge.

The Grand'Place, Furnes.

FURNES

Furnes (Veurne) is a small town of about 6,000 inhabitants. Of ancient

origin, it was the chief town of the "Veurne Ambacht" castellany, in the

Middle-Ages. By the Treaty of 1715, the Dutch were empowered to place

a garrison there, as a barrier against France.

During the War, Furnes became, after Antwerp and Ostend, the General

Head-Quarters of the Belgian Army for a few months (1914-1915),

the same being subsequently transferred to La Panne. More fortunate

than Dixmude and Nieuport, practically all its public buildings and monuments

escaped uninjured, although parts of the town were seriously damaged

by the bombardments.

On January 28, 1920, President Poincaré, in the presence of King Albert,

fastened the French Croix de Guerre to the town's arms, with the following

citation:

"During four trying years, in spite of incessant bombardments by aeroplanes

and long-range guns, always set a fine example of unshakeable faith in the

final Victory".

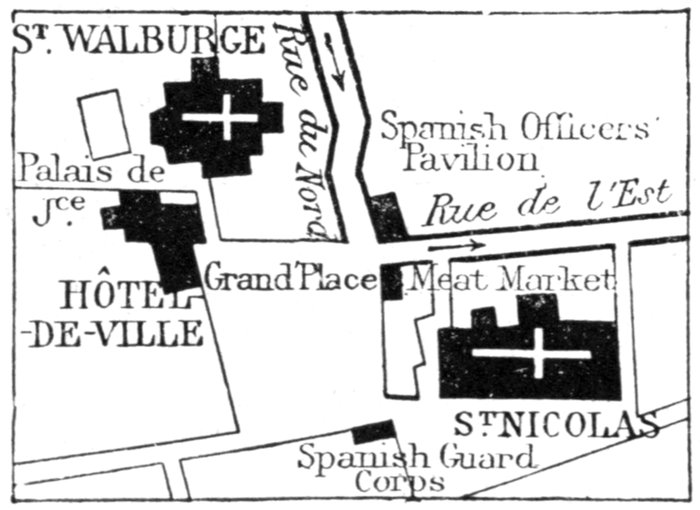

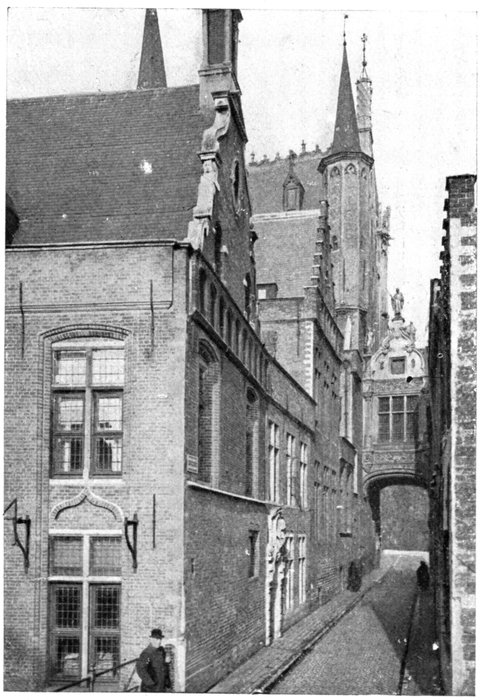

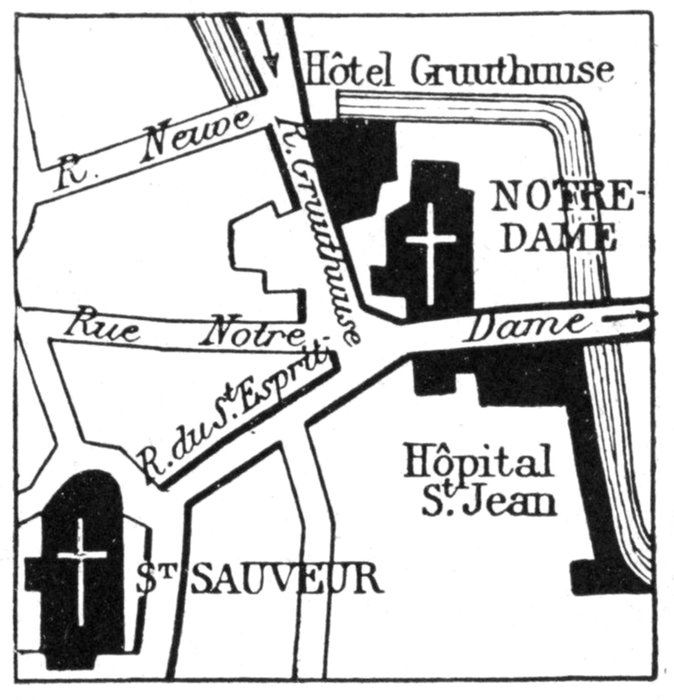

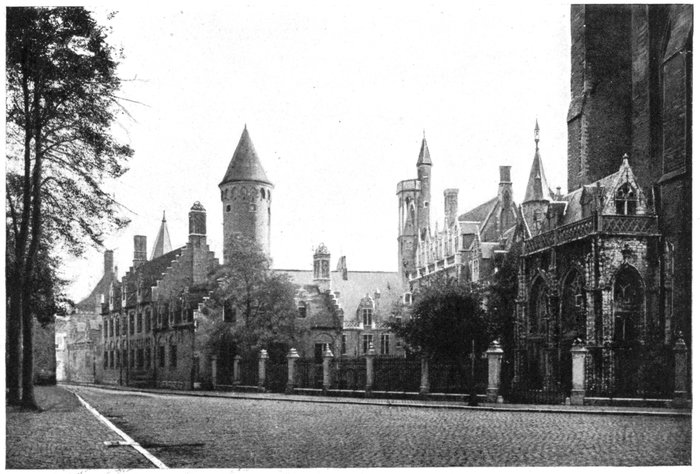

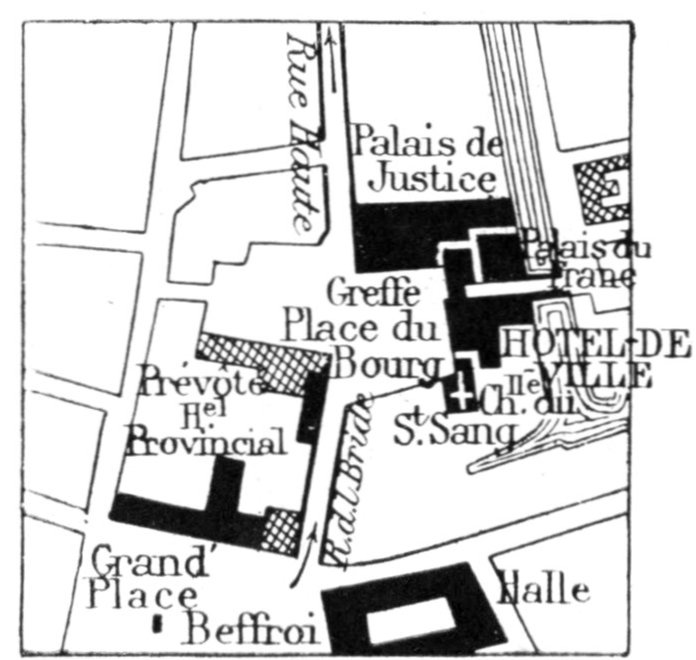

Tourists arrive by Rue du Nord which opens out into the Grand' Place,

the ancient ornamental paving of which is very fine. Around the square

are grouped the principal buildings.

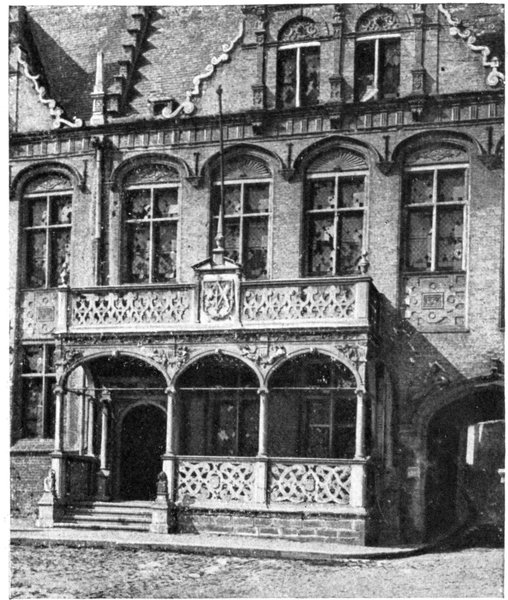

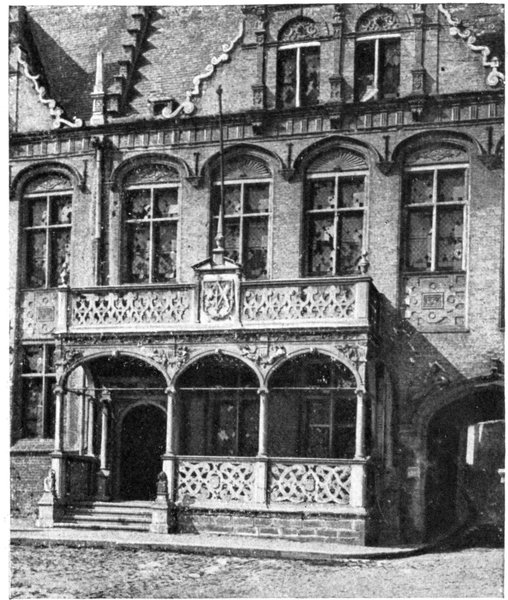

The Hôtel-de-Ville is on the right.

Renaissance in style, it was erected

in 1596-1612, from the plans of Lieven

Lukas. The façade has two gables,

one of which was preceded by a graceful

loggia which was removed during

the war (Photo, p. 40). The high

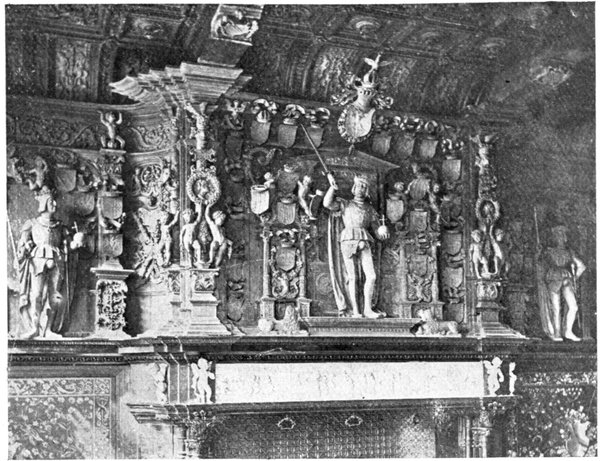

belfry dates from 1628. On the ground-floor

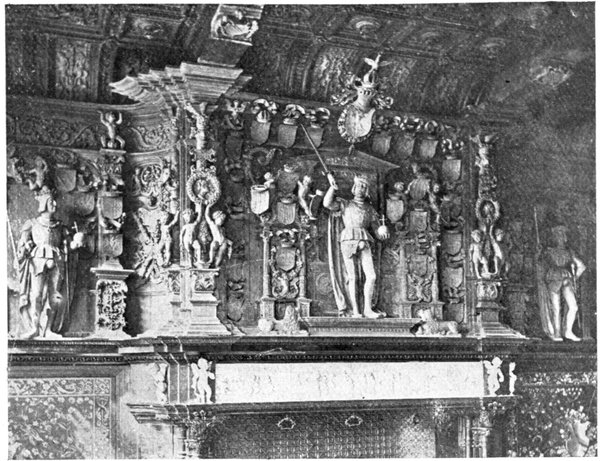

see: the Council Chamber, with

Spanish leather hangings: the College

Chamber, with Utrecht velvet hangings;

the Marriage Hall, with a [Pg 39]still-life

painting attributed to Snyders (on the mantelpiece). The Great Hall on

the first floor, with Spanish leather hangings, contains several royal portraits.

Spanish Officers' Pavilion. Rue de l'Est. Meat Market. St-Nicolas' Tower.

The Grand'Place, Furnes.

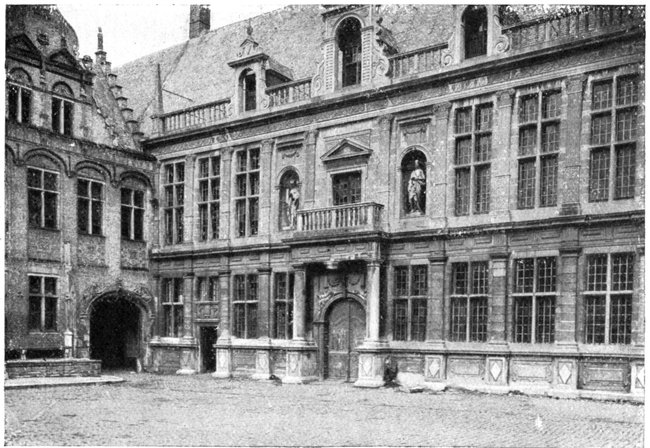

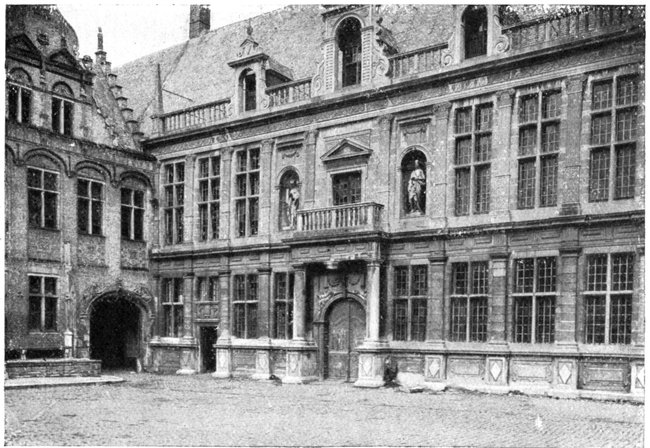

Near by is the Palais-de-Justice, formerly the ancient castellany,

built in 1612-1628 from the plans of Sylvain Boulin. Behind the Palais-de-Justice

is the Belfry. The interior, restored in 1894, comprises several

finely decorated rooms: the Waiting-Hall, the Justice Chamber (17th

century), and the old Inquisition Chamber (on the first floor). The Chapel

contains some fine vaulting and a carved wooden gallery. A number of

bronze tablets recording judgments are kept there.

A narrow street between the Palais-de-Justice and a block of old houses

with ruined gables, of which only mutilated fragments of the façades remain,

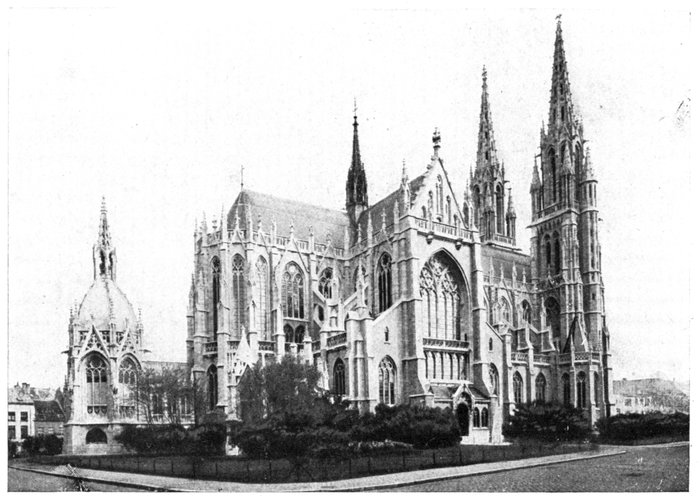

leads to the Church of St. Walburge.

Of very ancient origin, its reconstruction was begun in the 14th century.

The choir was completed in the 15th century. The nave is 14th century.

The church contains magnificent stalls (early 17th century), wood-work,

doors, and pulpit, also a Descent from the Cross attributed to Pourbus. In

the sacristy there is a 15th century shrine. The stalls, organ and altars

were removed to a place of safety during the war. Much of the stained-glass

was destroyed.

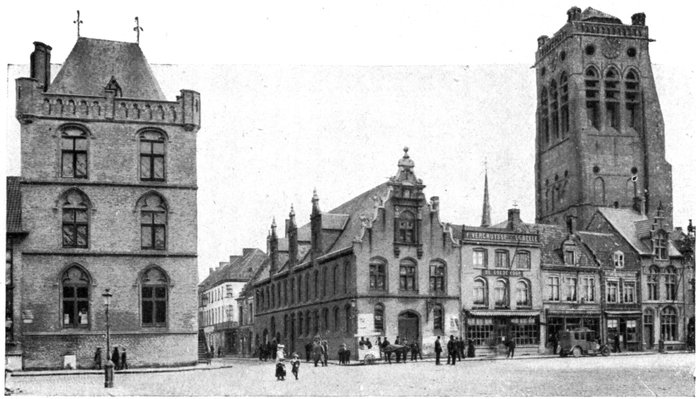

St. Nicolas' Tower. Spanish Guard House.

The Grand'Place, Furnes.

Furnes. The loggia of the Hôtel-de-Ville.

(Sept. 4, 1917.)

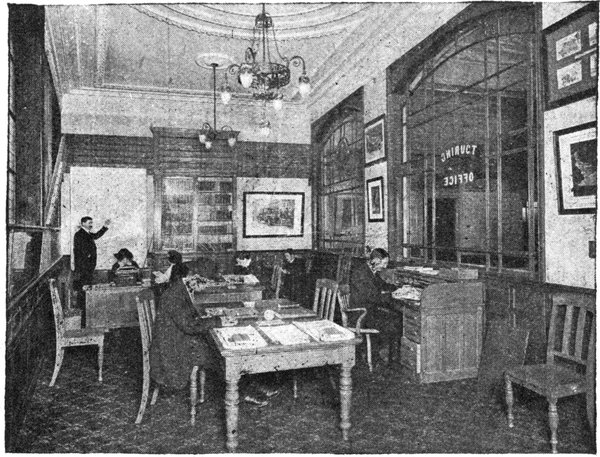

At the corner of the Grand' Place and the Rue de l'Est stands

the Pavilion of the Spanish Officers, built by the Spaniards

in the 16th century as a barracks. Restored at[Pg 40]

a later date, it now

serves as the Town

Library and Archives

(Photos, pp. 39

and 41).

Opposite is the old

Meat Market, now

a theatre, with its

fine early 17th century

façade.

Furnes. The Palais-de-Justice (Ancient Castellany).

On the left, the Hôtel-de-Ville whose "loggia" (photo above) was taken down (1918).

At the end of the

square, facing the Rue

du Nord, is the

Old Spanish Guard

House, an arcaded

building of early 17th

century construction.

The lateral façade

overlooks the

Place du Marché-aux-Pommes,

in

which stands St.

Nicolas' Church.

Begun in the 14th

century, building was

continued in the

15th, and completed

in the 16th centuries.

The church,[Pg 41]

which has a high, unfinished tower suffered little during the war, although

some of the stained-glass was broken.

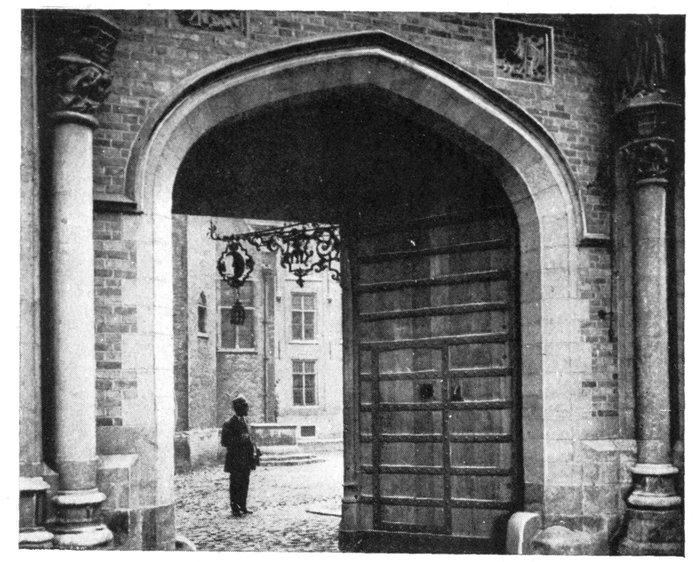

The door of the Spanish Officers' Pavilion (Sept. 4, 1917).

In the background: The Palais-de-Justice and Hôtel-de-Ville (photos, p. 40.)

In the foreground: Rue de l'Est, by which tourists leave Furnes.

Furnes possesses a number of curious old houses, the most noteworthy

of which are the Noble Rose Hostelry, 11, Rue du Nord, near the Grand'Place,

and the Pomme d'Or Hostelry in the Grand'Place.

Victor Hugo lived in one of them in August 1837. The "Pomme d'Or"

was used as a residence by the Spanish Officers (16th-17th centuries).

Rebuilt in the 16th century, the "Noble Rose" was restored shortly before

the War; it is now partly destroyed.

Every year, since the 12th century, a famous penitential procession took

place at Furnes on the last Sunday in July, when the "Sodalité Brotherhood"

performed the "Passion Play" in Flemish.

[Pg 42]

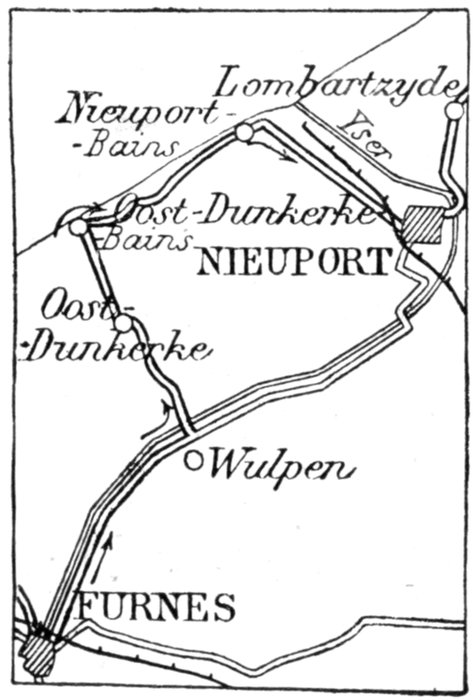

From Furnes to Nieuport.

Leave Furnes by the Rue

de l'Est, and immediately

after crossing the canal,

take the Nieuport road, on

the left. At Wulpen (5

kms.), cross the canal to

go to Oost-Dunkirk (2

kms.) Numerous shelters,

trenches, and wire entanglements

are to be

seen along the road.

After crossing the railway

(l.c.) turn to the left

into Oost-Dunkirk. Like

Coxyde, Oost-Dunkirk

comprises the town proper—situated

behind the dunes, on a road which, via Coxyde, linked up

Furnes with Nieuport—and the baths, 2 kms. further north, on the coast.

Both places served as billeting quarters for the French Marines in 1915.

The immense camps of wooden huts were occupied

later by the Zouaves.

The town was practically destroyed by the

bombardments; most of the houses are in ruins,

but the church is still standing.

To visit the Baths (2 kms.) take the road on the

right, beyond the church, noticing the numerous

shelters in the dunes. Coming back from the dike,

take the first road on the left to Nieuport-Bains

(4 kms.) The road crosses a region covered with

defence-works, trenches and wire entanglements,

alternating with shelters and battery positions.

The battle zone began there. All vestiges of life

and vegetation have disappeared.

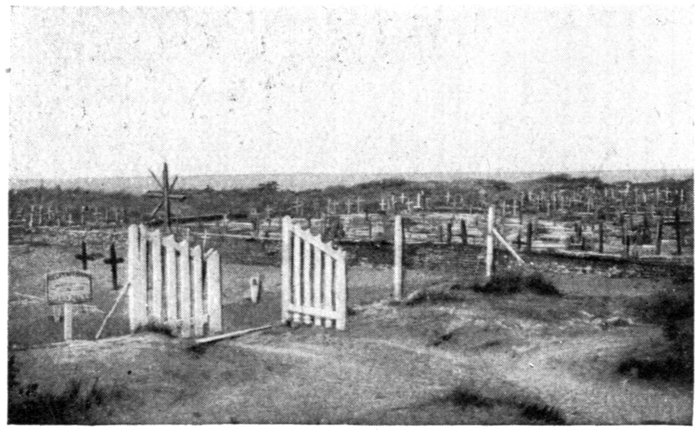

Before reaching Nieuport-Bains, a Franco-British

cemetery [Pg 43](photo below) is seen on the left, and

a little further on, the ruins of the church, with a cemetery in front.

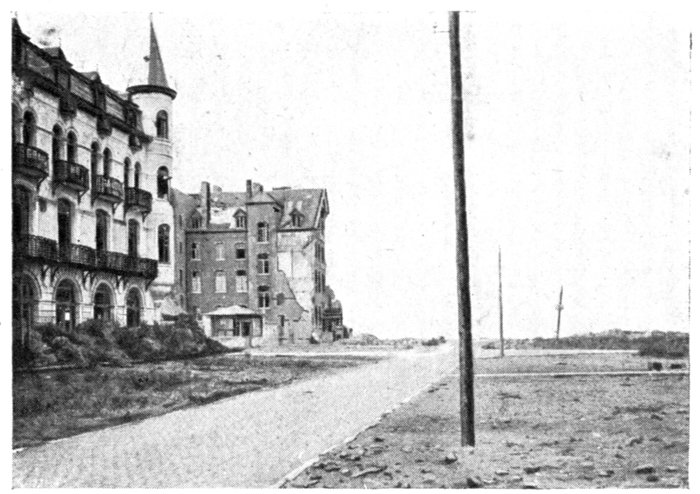

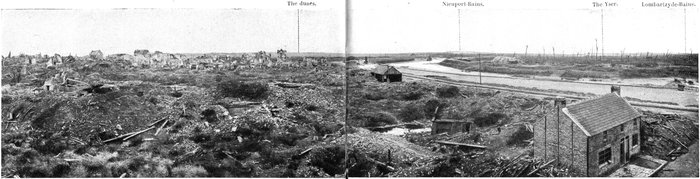

Nieuport-Bains, a small watering-place situated 3 kms. from Nieuport

and 17 kms. from Ostend, was perhaps the prettiest of the Belgian seaside

places. There the dunes rise in places to a height of 100 feet.

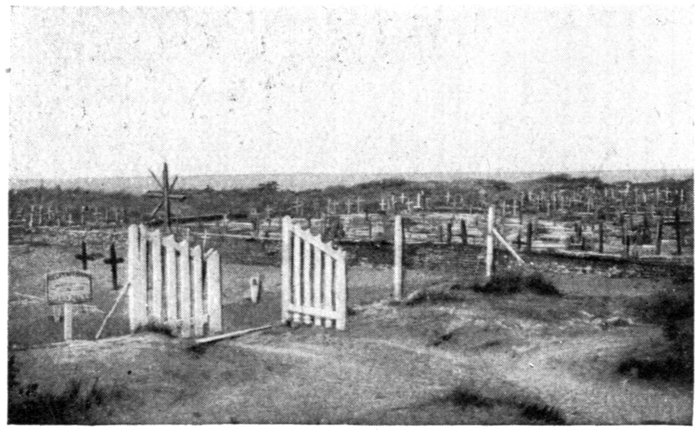

Cemetery at the entrance to Nieuport-Bains.

As witness the trenches

and boyaux which run

through the ruins of its

pretty villas and fine hotels,

Nieuport-Bains stood

in the front line.

At the end of the dike

the road turns to the right

in the direction of Nieuport-Ville.

From here the

tourist crosses the dunes

parallelly to the sea.

Traversing the zone which

formed the first line during

the stabilisation

period, the mouth of the

Yser, protected by two wooden piers about three-quarters of a mile long

and covered with sacks of earth, is reached. The Grande Dune, which

General de Mitry attacked in January 1915, is on the right bank of the

estuary, opposite Nieuport-Bains. The polders of Lombartzyde are somewhat

to the south-west (See p. 53).

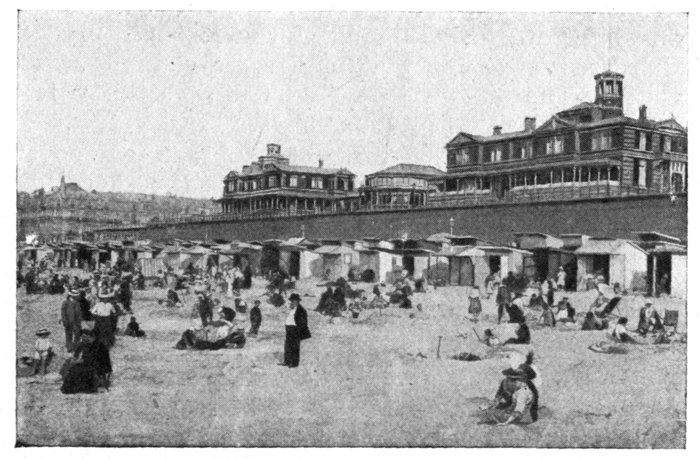

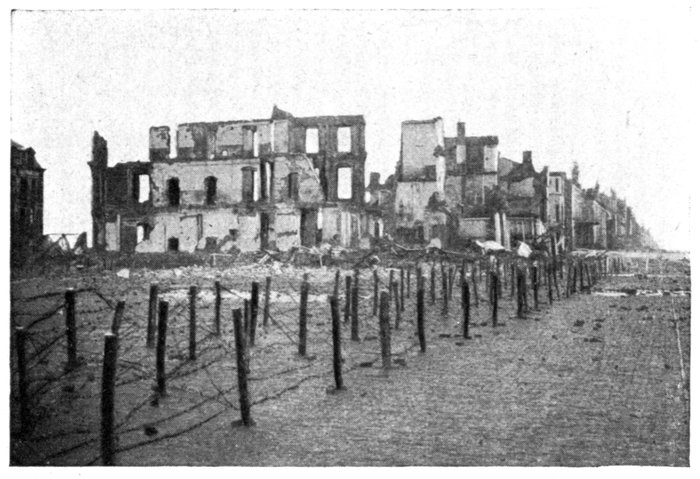

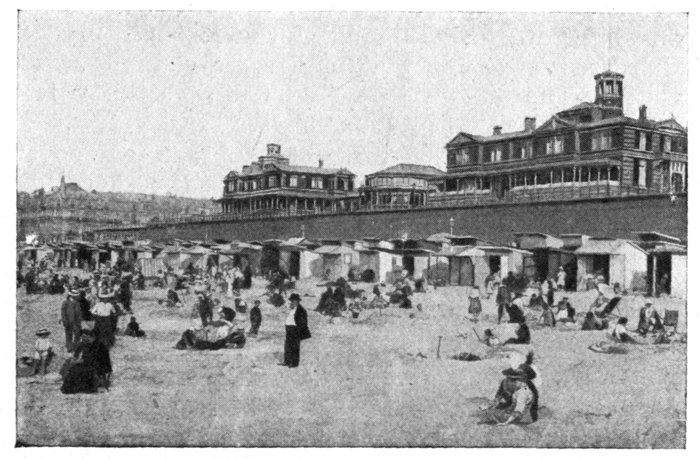

The Hotels on the sea-front at Nieuport-Bains.

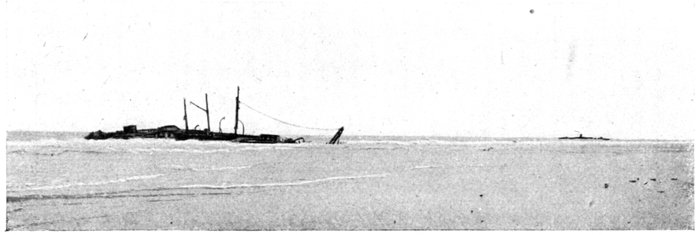

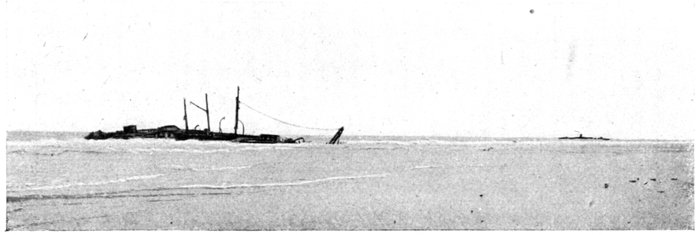

Broken fragments of walls mark the site of the station on the dune. In

front are a derelict engine and train, which have been there since 1914.

Near by is the entrance to the covered trench which connected Nieuport-Ville

with Nieuport-Bains; same may be visited.

Return to the car and take the road to the left towards Nieuport-Ville (photo

below).

Proceed to Nieuport (3 kms.) by the road (very rough) running parallel to

the estuary of the Yser, past several shelters and artillery positions. After

crossing the bridge over a small canal, the tourist comes out on the wharves of

Nieuport. Once an important fishing port, little remains today of its

former prosperity. A few fishing boats still give some little activity to the

place.

Road leading to the mouth of the Yser.

At the end of the dike, leave the car and go on foot, in the direction of arrow A,

along the path leading to the mouth of the river (photos, p. 44). Return to the car

and take the road to the left (arrow B.) to Nieuport-Ville.

[Pg 44]

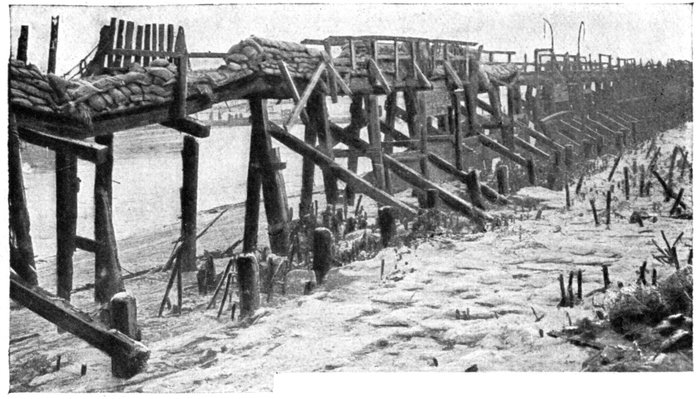

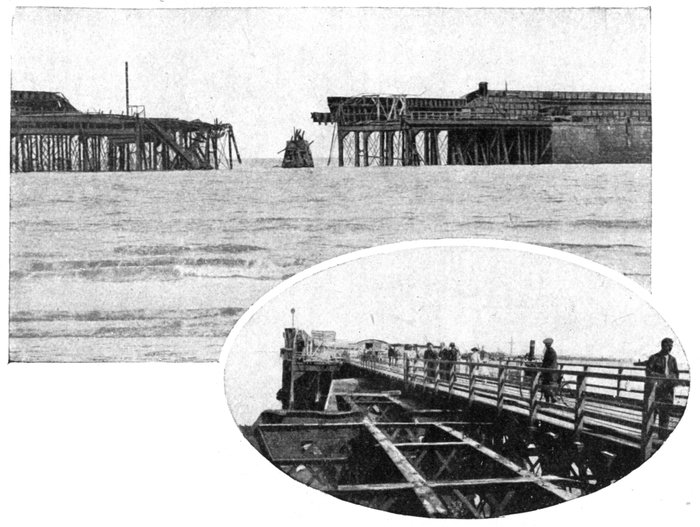

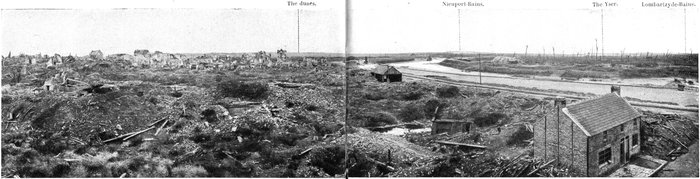

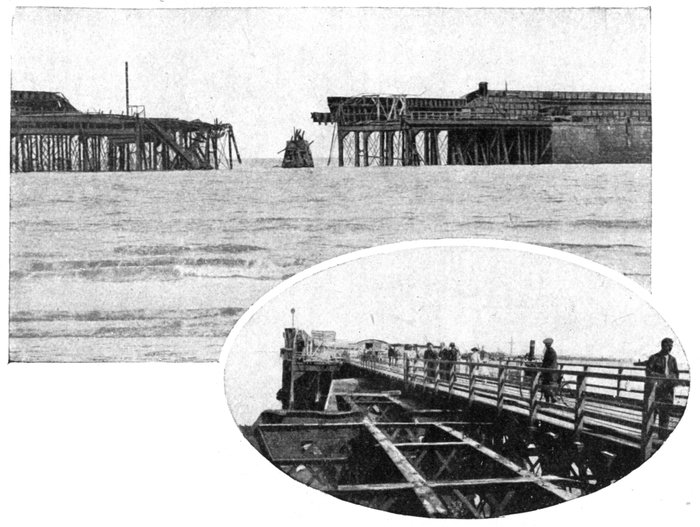

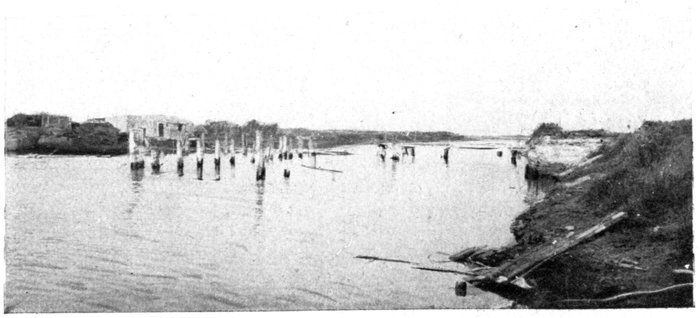

Wooden Pier at the

mouth of the Yser.

On the right:

View, looking towards

the sea.

On the left:

View looking towards

Nieuport.

In the foreground: Concrete

Shelter and destroyed

Wooden Pier.

Below:

French Trench along the Beach,

to the left of the river mouth. In

the background: Nieuport Pier.

[Pg 45]

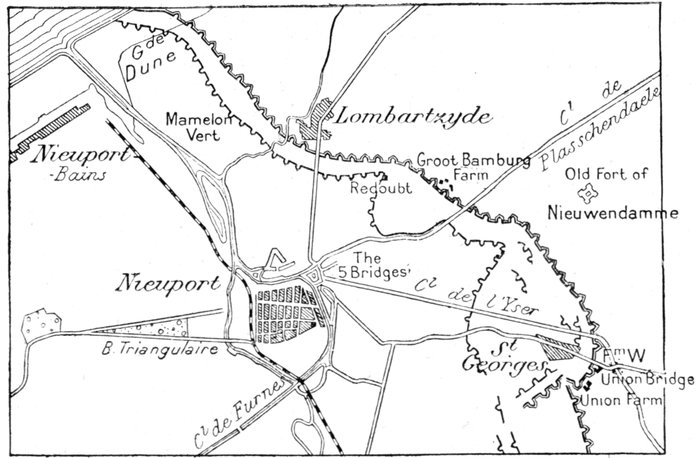

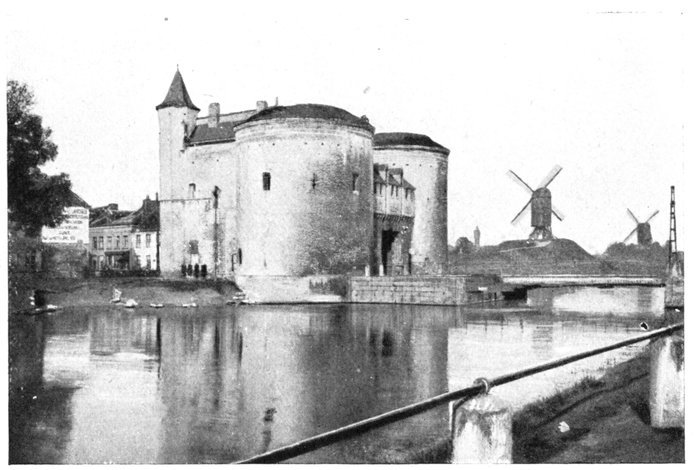

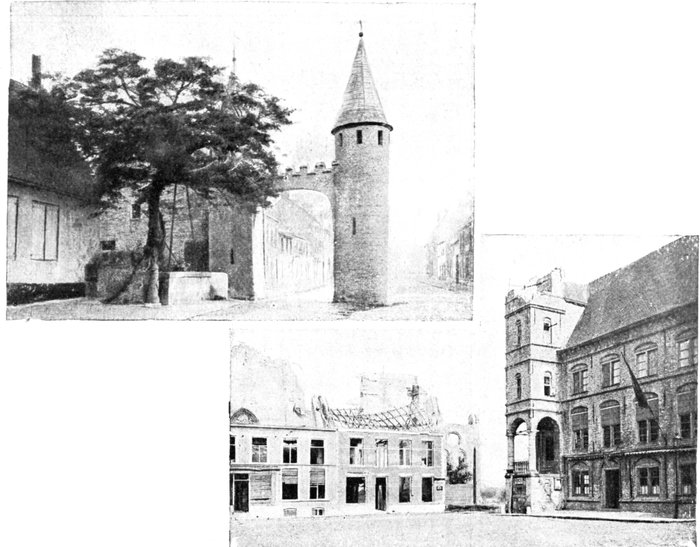

The small town of Nieuport is of very ancient origin. As early as the

9th century its site was occupied by a castle built by the Counts of Flanders

to defend the coast against the Normans. The burgh, first known as Santhoven,

took the name of Nieuport (Neoportus) after the inhabitants of Lombaertzyde

had migrated there. Situated on the Yser, the town served as

a port for Ypres, and was an important business centre. It was besieged

by the English in 1383 and by the French in 1489.

After a long period of stagnation, the enclosing walls were pulled down

in 1860. However, with laudable respect for the past, the Municipality

saw to it that the charming old-world aspect of the place was carefully

preserved, by severely controlling the plans of all new constructions, and

by prohibiting the use of materials not in harmony with the buildings

already existent.

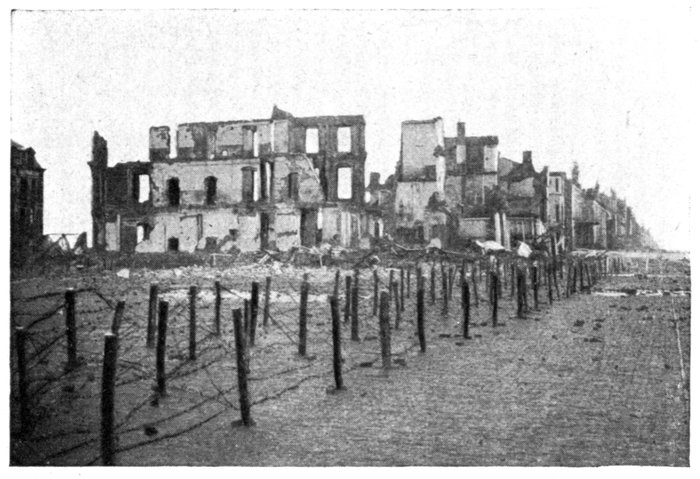

Nieuport, of which nothing remains but a few scattered ruins, was the

scene of desperate fighting.

With Dixmude, it was one of the two main centres in the Yser defences,

these two towns being, in fact, the bastions of the line of resistance.

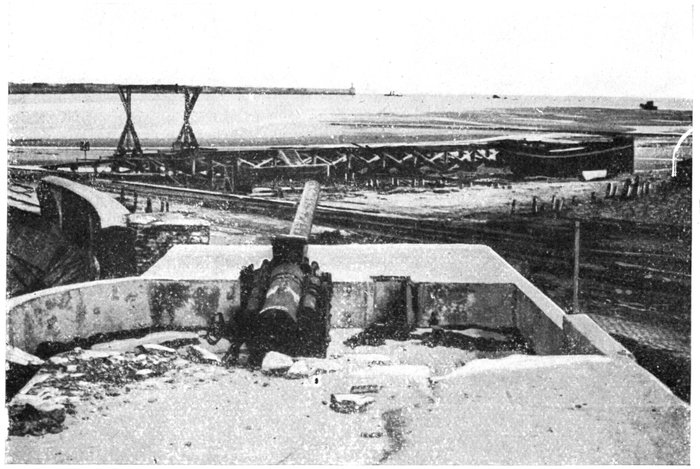

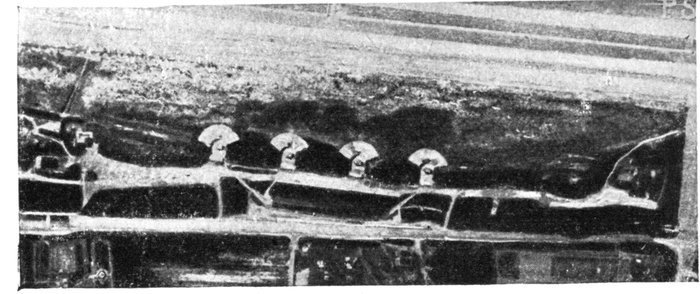

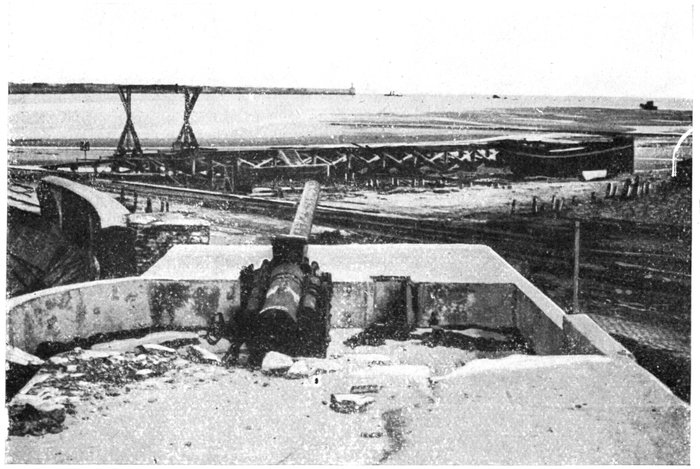

Amongst other things, Nieuport possessed an elaborate system of lock-gates

and sluices, by means of which the water in the canals throughout

maritime Flanders was regulated.

It was easier to defend than Dixmude. The canals and water-courses

which united in its port, separated the town from the enemy. It

could, moreover, be more effectively protected by the guns of the Allied Fleet.

In October 1914, the Belgian 2nd Division held the outlying defences at

Lombartzyde and Mannekensvere (east of St. Georges).

On October 19, it was attacked by the German 4th Reserve Division.

Three consecutive attacks against Lombartzyde having failed, the enemy

began to shell Nieuport with their heavy artillery.

Renewing their attacks, the enemy captured Lombartzyde, but were

unable to debouch. Crushed by the bombardment, Nieuport fell into

ruins.

From October 18 to 25, in spite of the heavy bombardment, the Belgian

7th Infantry Regiment held the banks of the Yser, to the east, in front of

St. Georges, near the Union Bridge, which the Germans, debouching from

Mannekensvere, tried in vain to carry. The Belgian batteries, often without[Pg 46]

cover, stubbornly supported the defenders. On several occasions, guns

were hauled up on the river bank into the infantry lines, whence their direct

hits smashed the farmhouses and German machine-guns concealed in them.

Panorama of the ruins of Nieuport, seen from King Albert's Hôtel.

The enemy crossed the Yser at Schoorbakke, outflanking St. Georges

from the south, which had to be evacuated.

Instantly, batteries of the Belgian 5th Brigade, brought up by hand,

opened a rapid fire at short range with high explosive shells upon St. Georges

and the approaches to the canal, where the enemy were concentrating.

Mowed down where they stood, the assailants vainly attempted

to debouch from the village, where piles of their dead lay among the ruins.[Pg 47]

The 14th Line Regiment, which had meanwhile relieved the 7th, was able

to withdraw in good order.

At nightfall, the batteries were gradually withdrawn behind the railway

whence they helped first to hold, then to force back the German attack

upon Ramscappelle.

The defenders being now exhausted, and the enemy's attack gathering

strength, the Belgian General Staff gave orders to flood the area between the

Yser and the railway embankment. The road to Calais, via Nieuport, was

thus definitely barred to the invaders.

The Germans revenged themselves by bombarding Nieuport, attempting

at the same time to slip along the dunes of Lombartzyde, towards the town,

in order to seize the locks. Before the unflinching resistance of the defenders

supported by the fire of the British and French monitors, the attack broke

down.

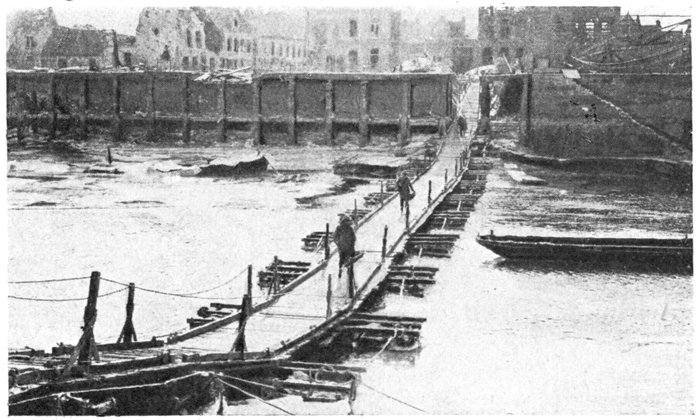

Temporary Foot-bridge across the Yser at Nieuport.

[Pg 48]

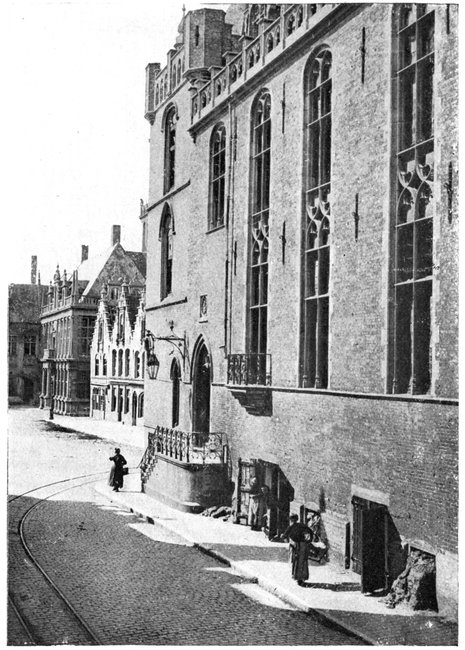

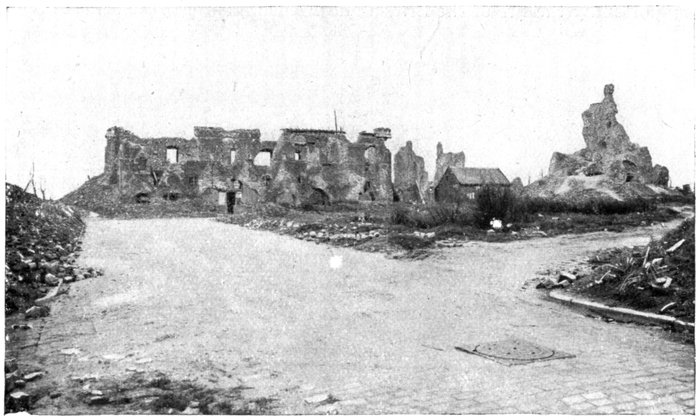

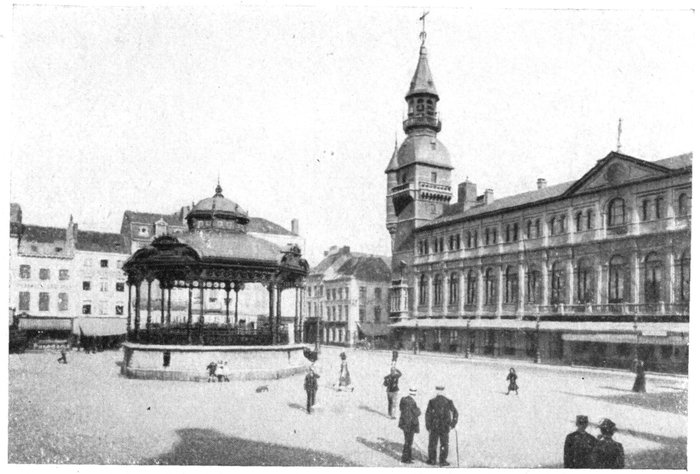

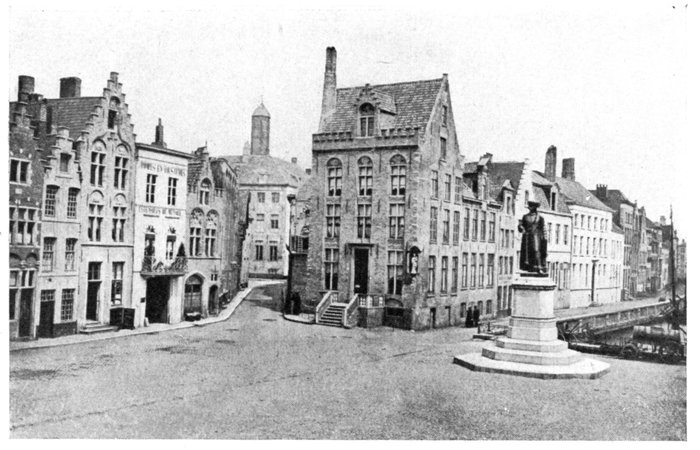

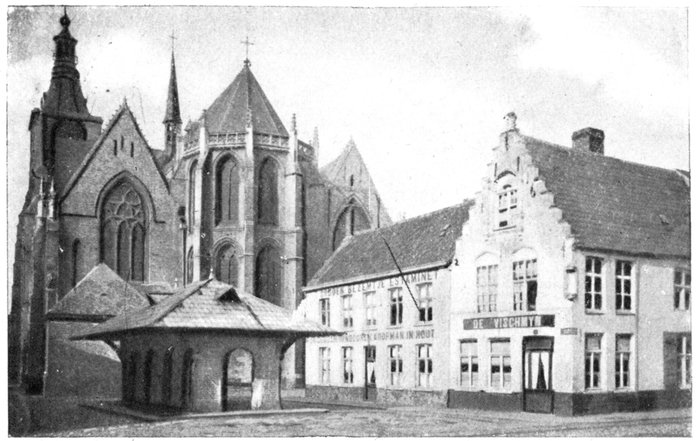

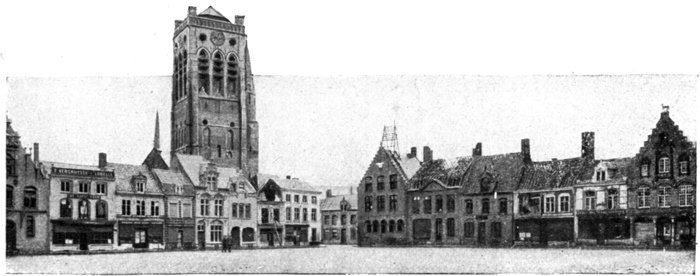

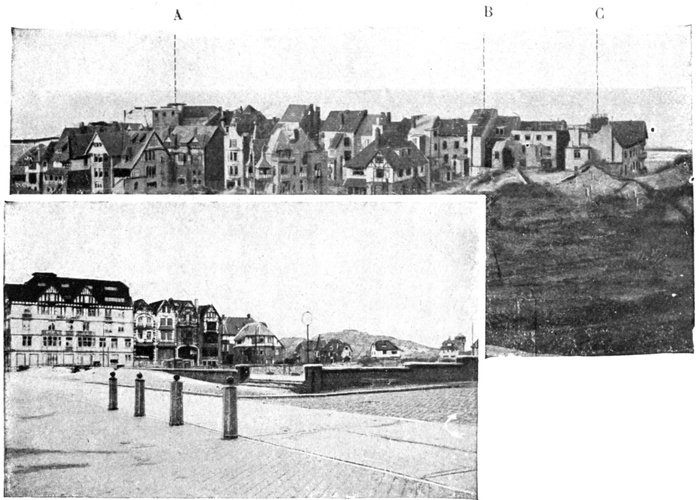

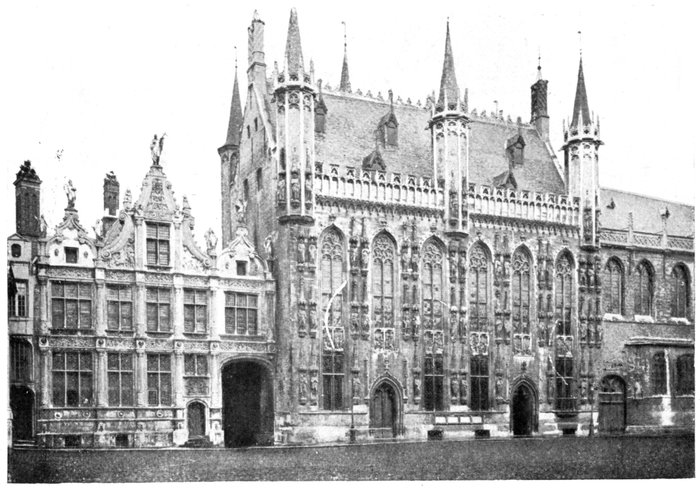

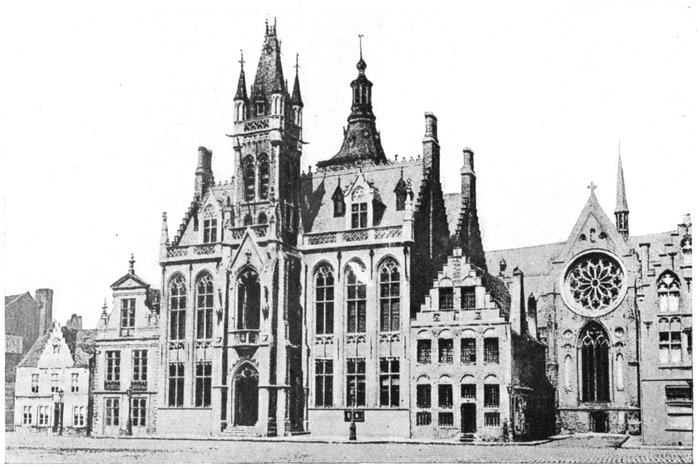

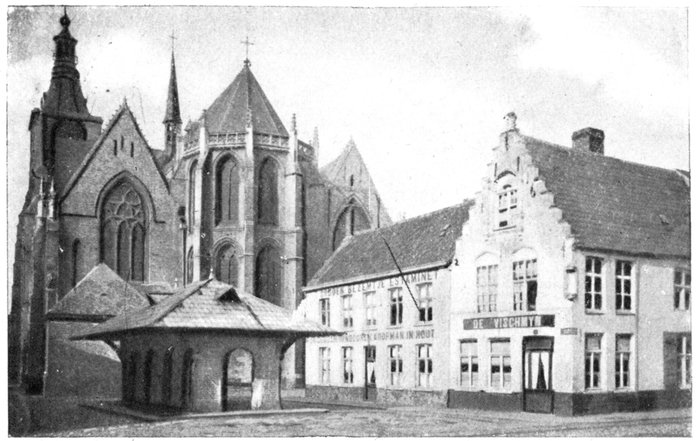

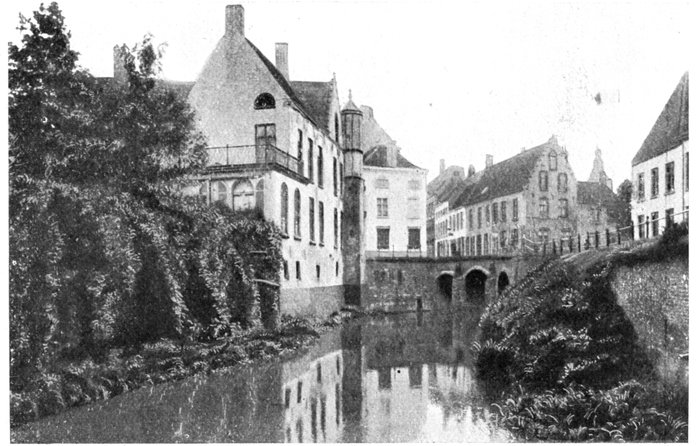

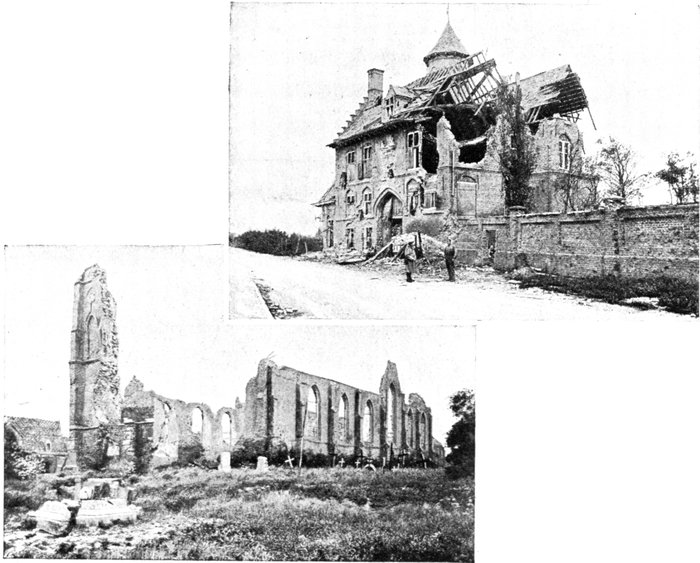

Nieuport, the Grand'Place and the Markets, before the War.

(Photo Nels.)

At the beginning of November Lombartzyde, in the northern sector, was

the scene of uninterrupted fighting, with alternating advances and retreats.

In December a powerful offensive, having for its objective the capture of

the German defences along the Belgian sea-coast, was begun, with General

de Mitry in command of the Nieuport forces.

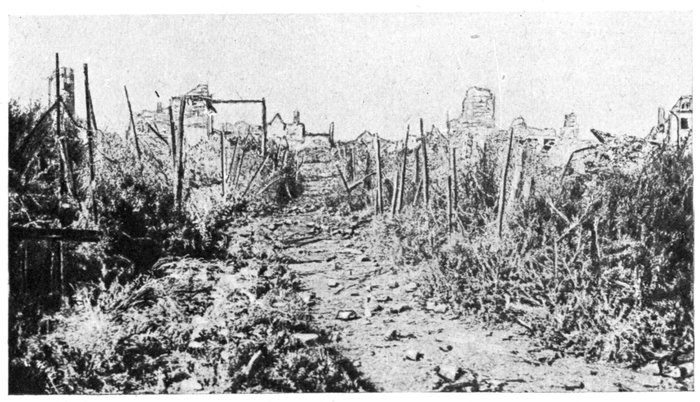

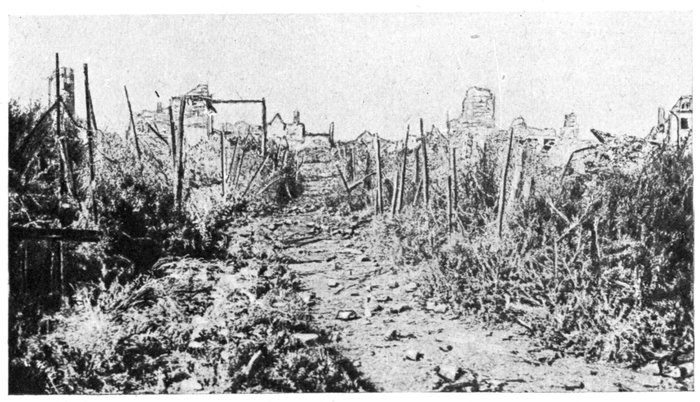

Ruins of the Grand'Place in 1919. (See photo above.)

On December 16, the French carried the western outskirts of Lombartzyde

in a single rush, and reached the first houses of St. Georges. The

enemy, however, resisted desperately, and progress was slow. By the end[Pg 49]

of the month, the Moroccan Brigade succeeded, with great difficulty, in

reaching the Grande Dune. On January 7, the 4th Regiment of Zouaves

scaled the Mamelon Vert. A few days later the French Marines, who

had been relieved in the Steenstraate sector, by Tirailleurs and dismounted

cavalry units of the 2nd Corps, attacked the Grande Dune and Lombartzyde.

After extremely desperate fighting, entailing heavy losses, the Grande Dune

was captured.

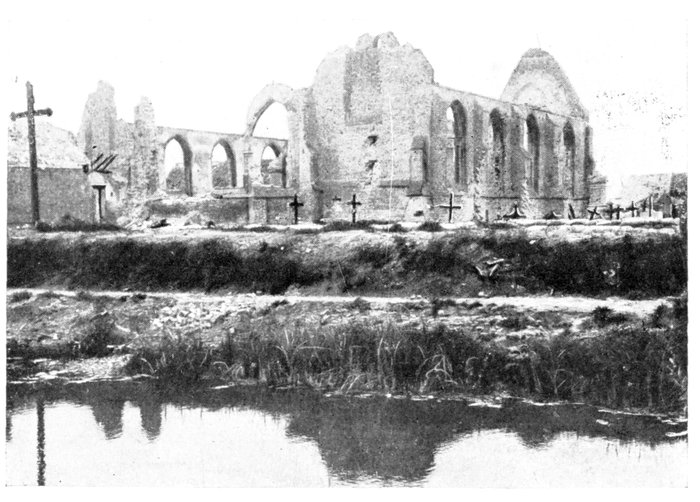

Nieuport.

The ruined

church.

The attack was stayed, and the French clung to the thin strip of land on the

right bank of the Yser.

The bombardment of Nieuport increased in violence. Each morning, the

huge 16½in. shells wrecked the houses and public buildings, and crushed in

the cellars where the defenders had taken shelter. One after another, the

12th century Church, the Abbey on the Dunes, the "Halles" with their

graceful belfry, and the massive Templars' Tower crashed to the ground.

Meanwhile, the battle continued to rage all around the town.

On May 9, a German attack from Lombartzyde to St. Georges was

broken, and on the following day the French marines carried "W" and

Union Farms, with fine dash, and destroyed the enemy's blockhouses.

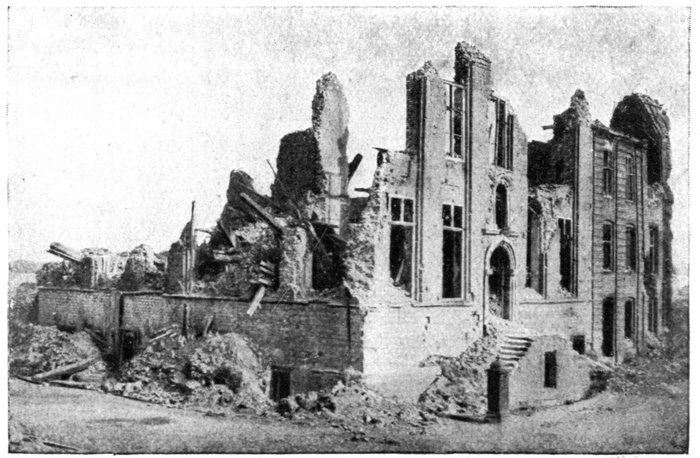

Nieuport.

Ruins of the

Hôtel-de-Ville.

[Pg 50]

In 1916 (January 24), after a bombardment of more than 20,000 shells,

the Germans attempted to debouch from their positions near the mouth of

the Yser. Repulsed with heavy loss, they once more deluged the unhappy

town with shells.

In 1917, the British prepared their great Spring and Summer offensives,

extending from east of Arras to the region of Ypres, and relieved their French

comrades in the sector stretching from St. Georges to the sea.

They had hardly taken up their positions, when the Germans attacked

(July 10). Thrown back into their trenches before Lombartzyde, the

enemy renewed their attacks with increased violence, and forced back the

British in the direction of Nieuport. The latter managed, however, to keep

a bridgehead at the exit from the town.

Meanwhile, in the Dunes sector, two British Battalions, in spite of their

gallant resistance, were forced back upon the river. Of these, only four

officers and seventy men escaped, by swimming across during the night.

The Germans on the right bank of the river occupied the Dunes.

The pressure on Nieuport increased, but the Yser remained impassable.

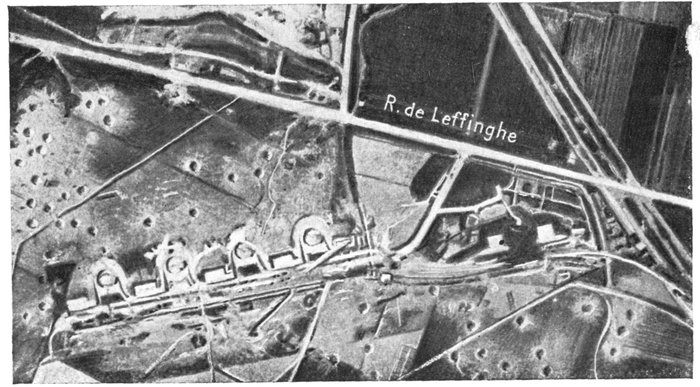

In 1918 (September 28), the great liberating offensive, under the command

of King Albert, was launched in the plains, to the east of Dixmude, and

Ypres. On October 16, the Belgian 5th Division, east of Nieuport, charged

from the famous islets in front of the Yser. The enemy, badly shaken,

retreated, closely followed by the Belgians, who harried their rear-guards

and completely swept the coast to a point beyond Ostend.

Nieuport, terribly ravaged by four years of the fiercest fighting at its very

gates, was at last delivered.

On January 25, 1920, in the presence of King Albert and the Burgomaster,

President Poincaré conferred the Croix de Guerre with the following mention

on the indomitable city:

"Martyred City, involved in all the vicissitudes

of a desperate struggle lasting four years,

Nieuport maintained intact her faith in the

future, in spite of all her trials.

Her ruins bear witness to the heroism of

her defenders and to the bravery of her inhabitants."

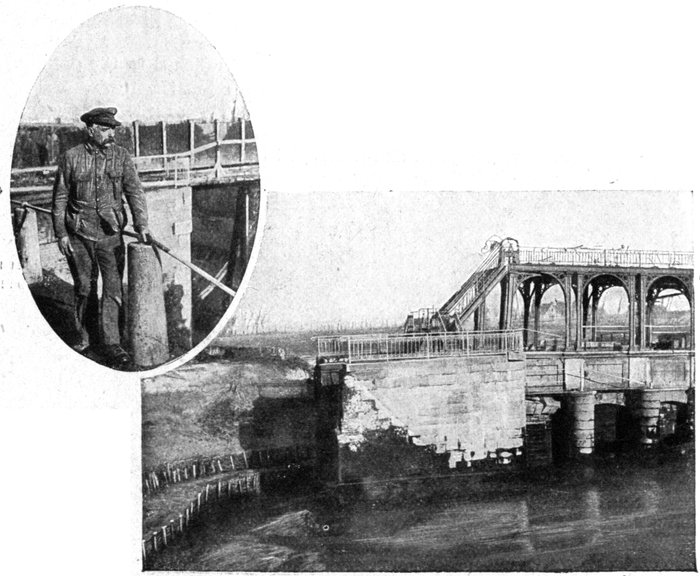

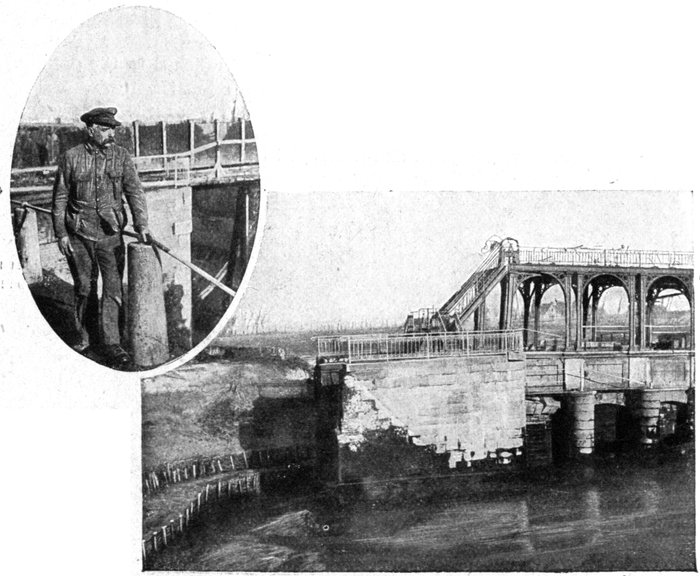

Nieuport.

Furnes Canal

Lock (Nov. 11, 1915)

Inset: Lock-Keeper

Geraert, who flooded

the Plain

(See p. 51.)

[Pg 51]

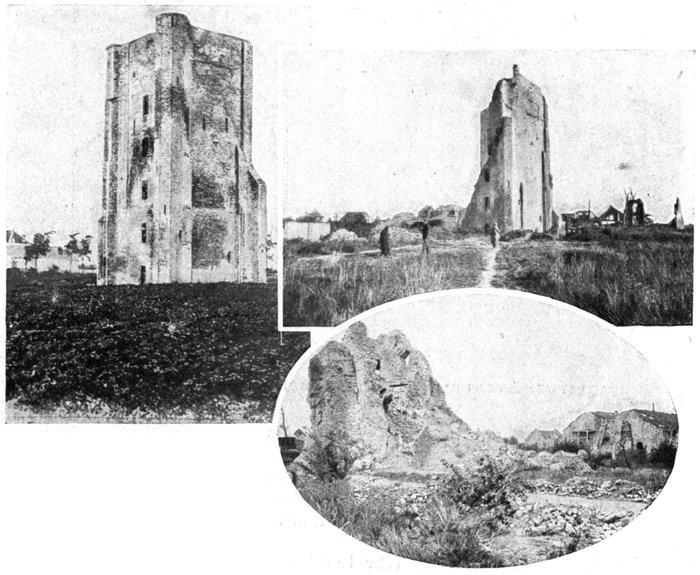

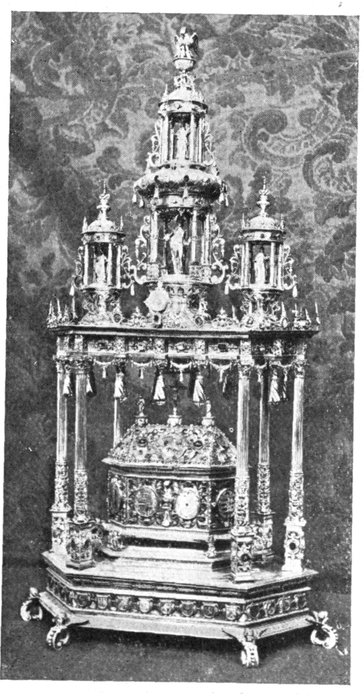

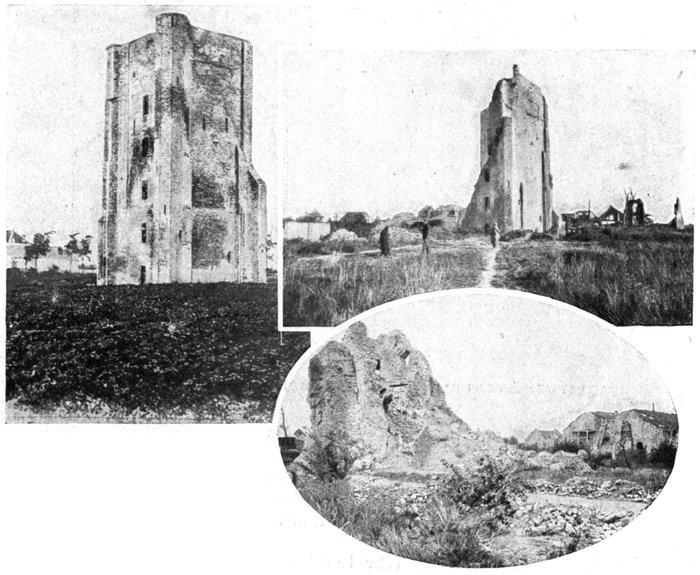

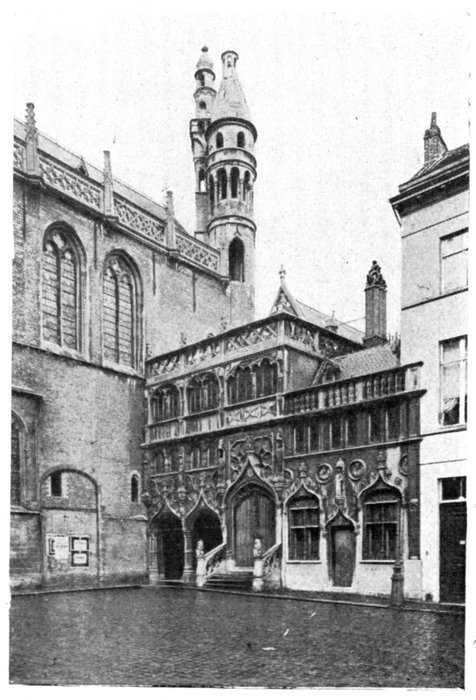

The Templars' Tower.

Before the War, in November

1915, and in 1919.

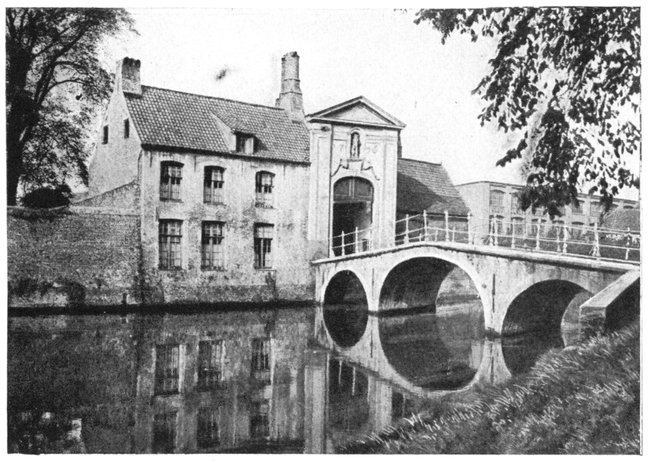

On reaching the wharves, take the first street on the right, then the second on

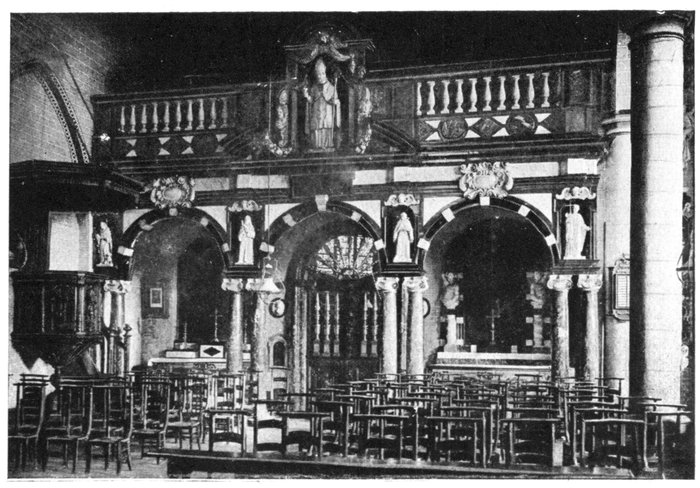

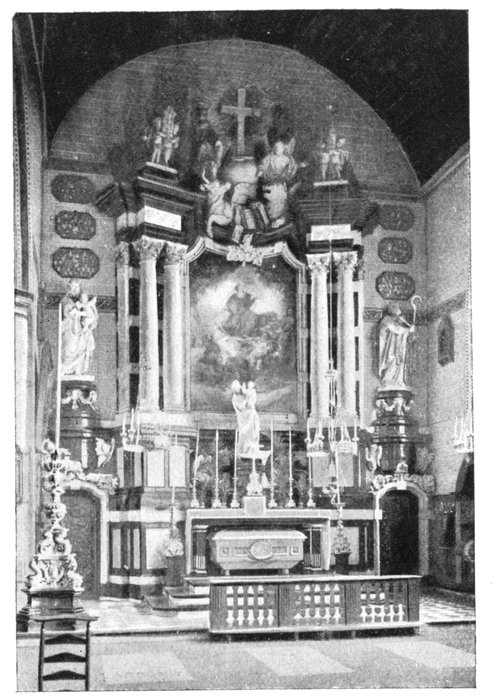

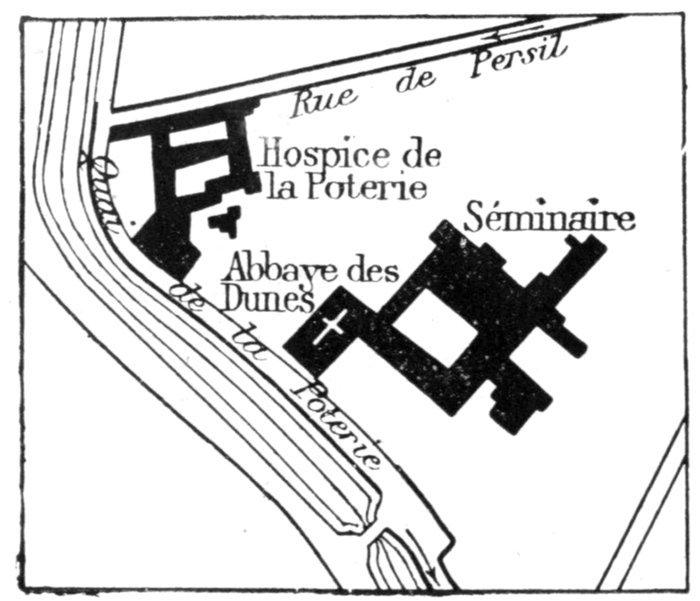

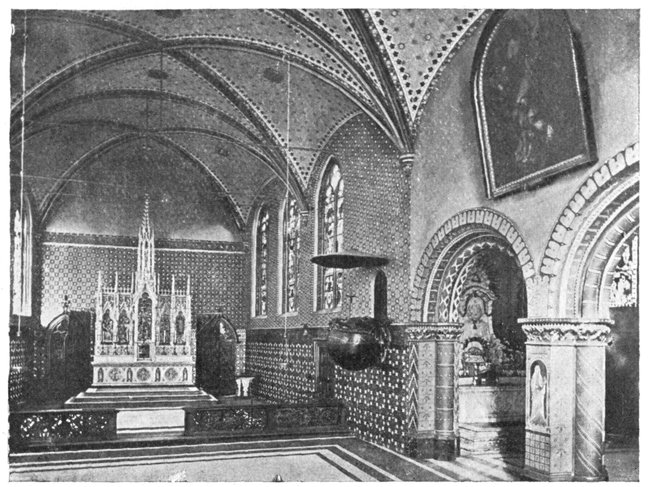

the left, to the Grand'Place, in which the Collegiate Church of Notre-Dame

used to stand.

Consecrated in 1163, this Gothic edifice had retained portions of the original

12th century church. The northern doorway was 15th century, and

the main entrance 16th century. The tower was somewhat massive. In

the interior, a 15th century rood-loft, the high altar (1630), the 17th century

stalls (by Desmet), a 15th century pulpit, an ancient tabernacle (by Jean

Aert of Bruges-1733), and several old tombs, were noteworthy.

Nothing remains of the church but broken fragments of walls and the

ruined belfry. In the surrounding graveyard, among the broken tombstones,

Belgian and French soldiers lie buried. Their graves were often

devastated by the shells.

In the same square stood the 14th-15th century Cloth-Hall, whose belfry

was restored in recent times. Only a portion of the façade remains.

At the end of the Square, opposite the Markets, take Rue du Marché, then

the first street on the right (Rue Longue). At the corner of these two streets is

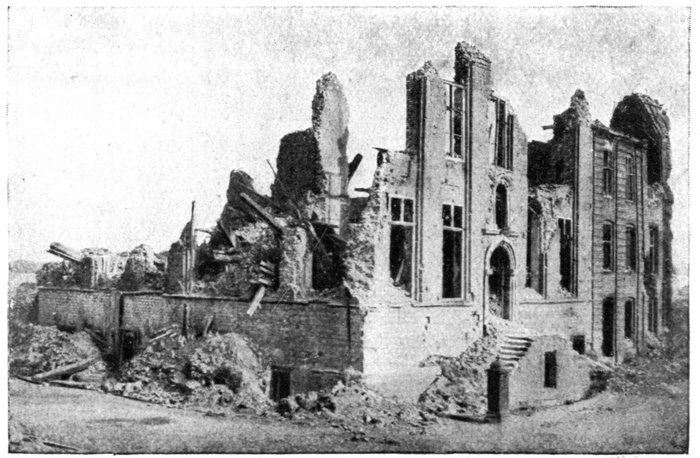

the Hôtel-de-Ville (in ruins) which used to contain portraits of the kings

of Spain and the arch-dukes.

Continue to the end of Rue Longue, where, on the right, are the ruins of

the Templars' Tower. The square donjon is all that remains of a commandery

which formerly belonged to the Templars, and which was destroyed

during the siege of 1383. Behind, are vestiges of the ancient city

ramparts.

Return to the port by the first (very wide) street on the right, which leads to

the Ostend Road Bridge across the Yser. To the right of the bridge are the

Nieuport locks which served, during the War, to inundate the surrounding

country, being opened at high water and closed at low water (see photo, p. 50).

[Pg 52]

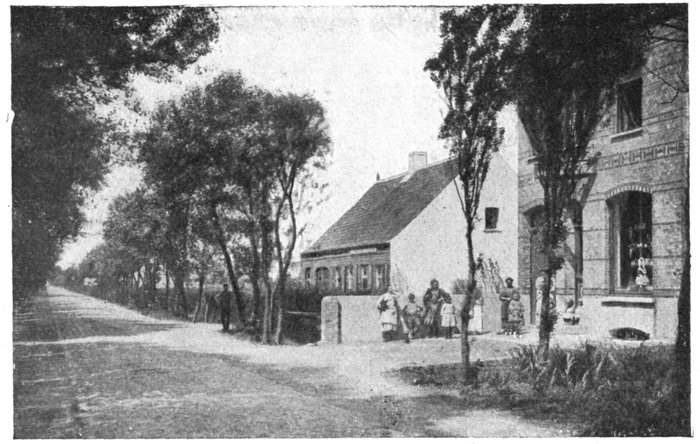

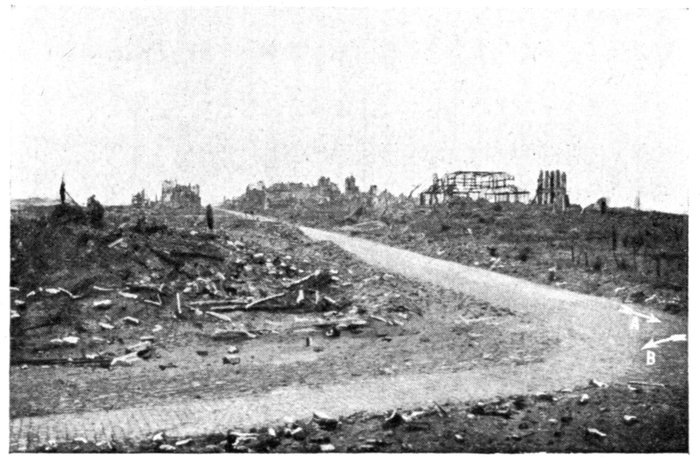

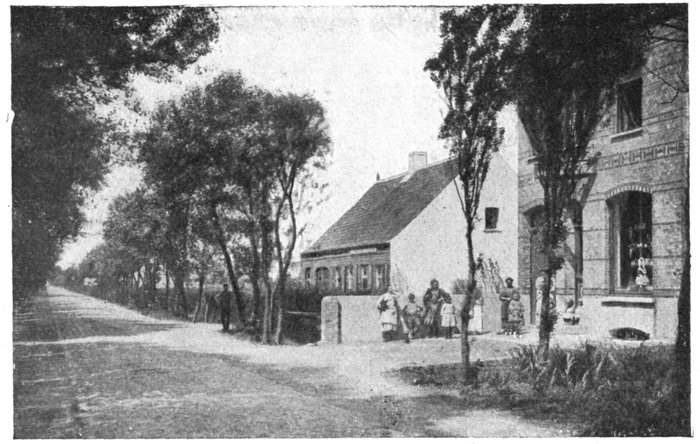

Lombartzyde. Avenue de la Reine, before the War (Photo Nels.)

From Nieuport to Ostend.

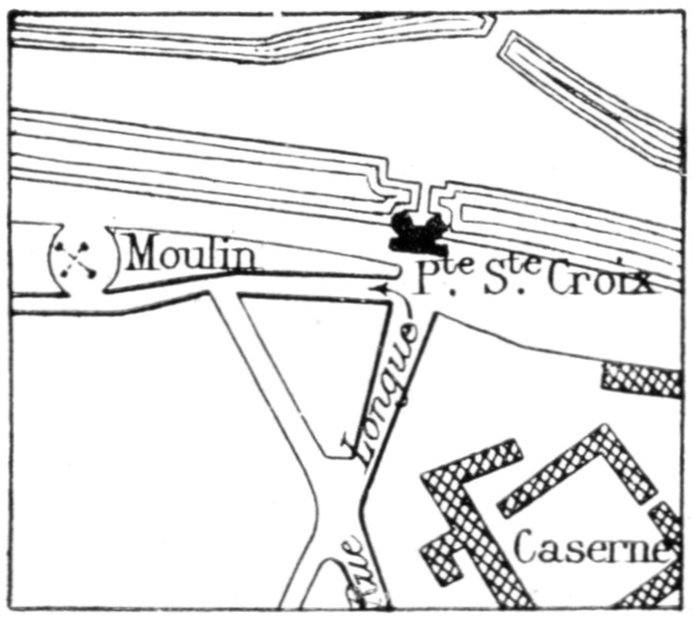

1½ kms. further on, the tourist reaches the site on which Lombartzyde used

to stand (2 kms.); the scarcely visible ruins are now overrun with grass

and weeds. A few huts and a wooden church have recently

been built.

Lombartzyde (the Lombards' Corner) owed its name and

prosperity to the merchants and bankers, many of them

Lombards, who settled there in the Middle-Ages. The town

was, however, soon deserted in favour of Nieuport. Its

large plain church, of no particular interest, contained a

statue of the Virgin, much venerated by the fisher-people, who

often visited it in the summer-time. Lombartzyde, formerly

a sea-port, was later cut off from the sea by the Dunes,

and Lombartzyde-Bains—the seaside portion of the town—grew

up there. The steam-trams running between Nieuport and Ostend

may be taken to reach it.

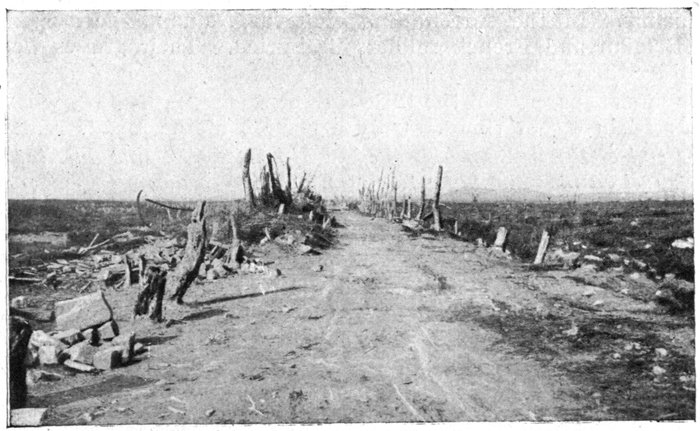

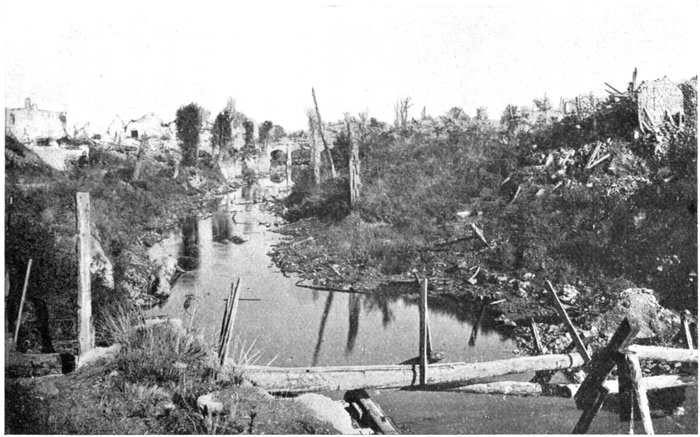

Lombartzyde. Avenue de la Reine, in 1919. (See photo above.)

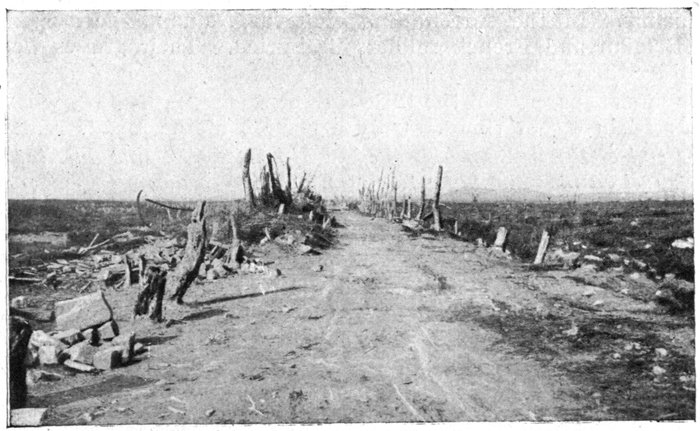

[Pg 53]

Lombartzyde. Graves and trenches on the site of the Church

(entirely razed).

Situated about 1 km. in front of Nieuport, on the right bank, Lombartzyde

was occupied on September 15, 1914, by the advanced posts of the

Belgian 2nd Division.

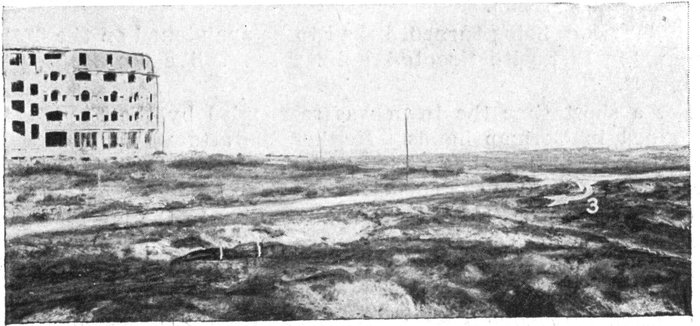

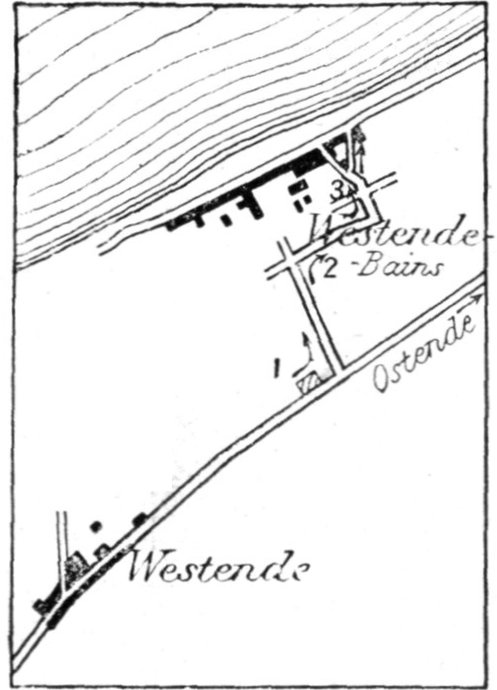

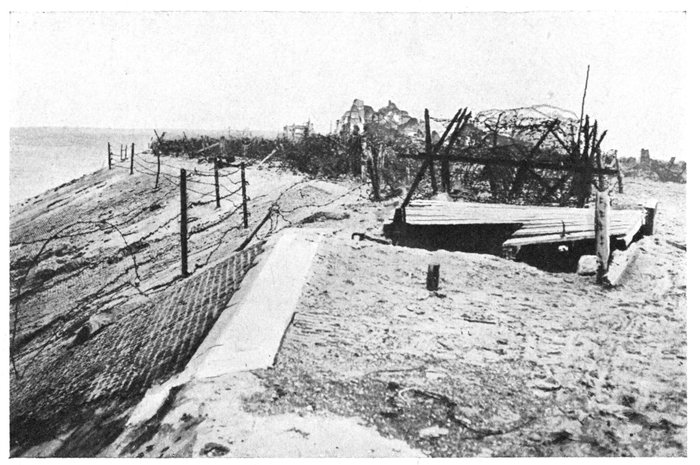

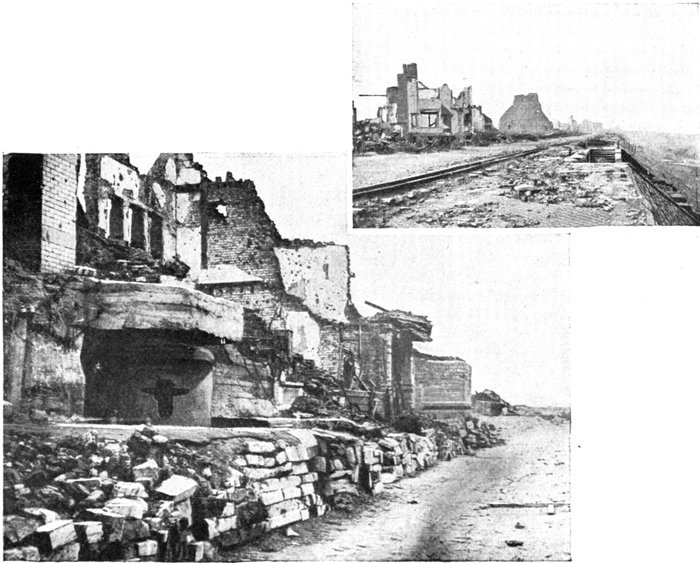

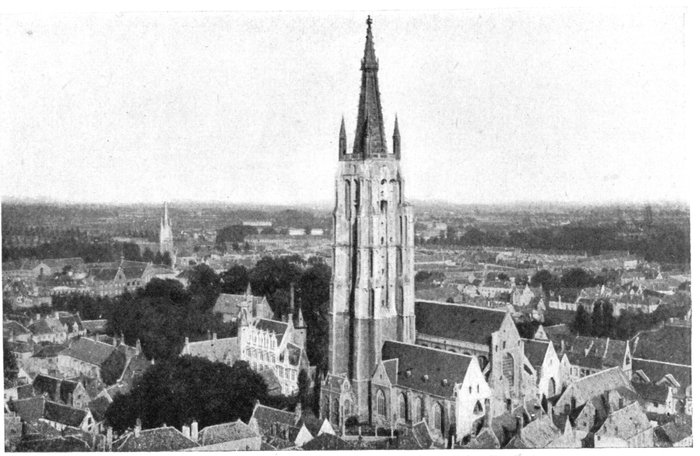

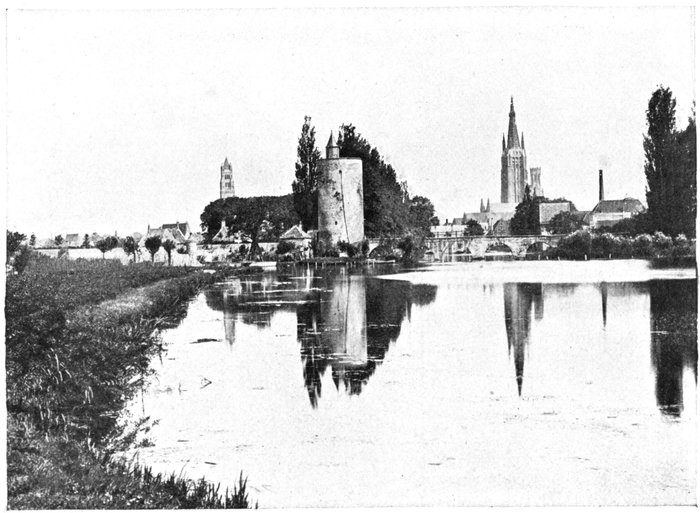

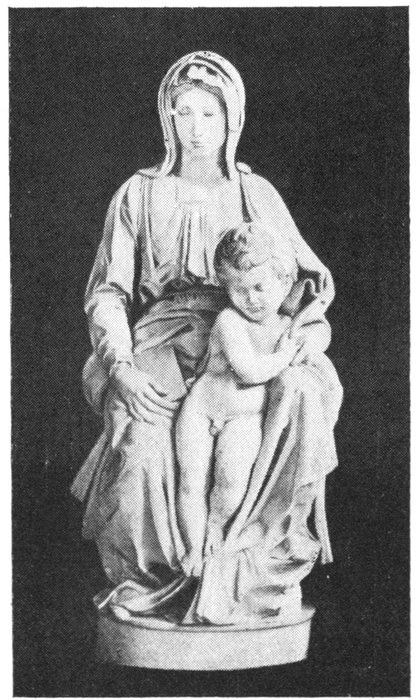

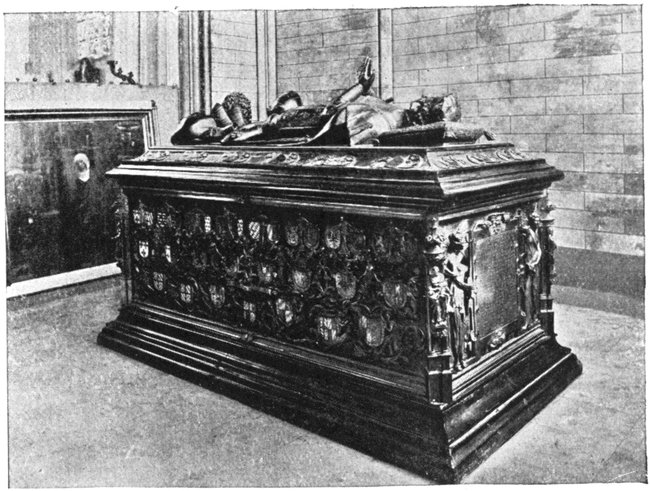

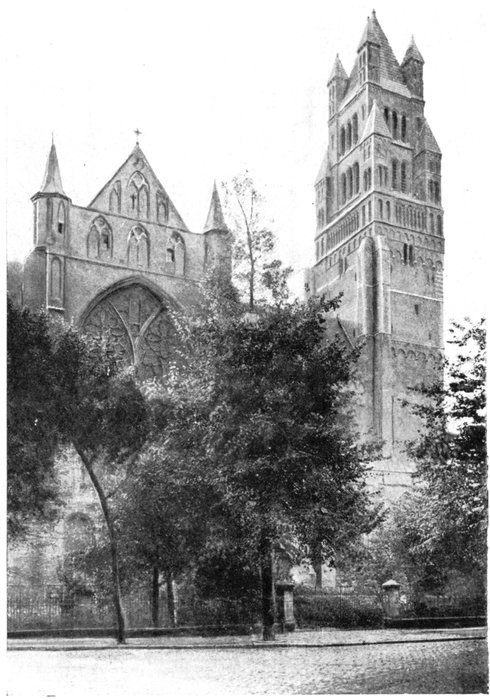

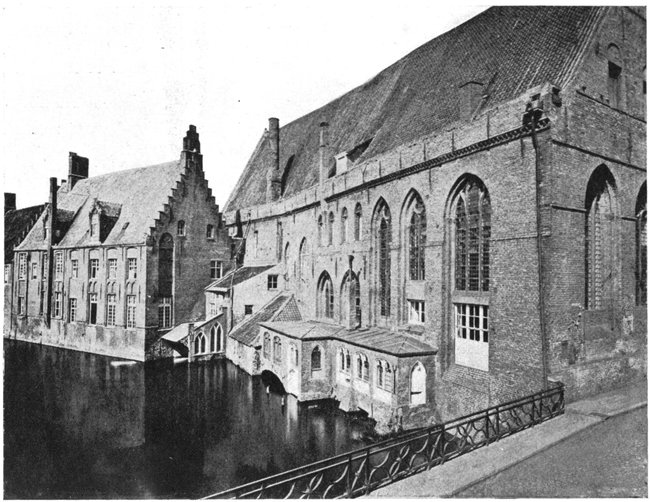

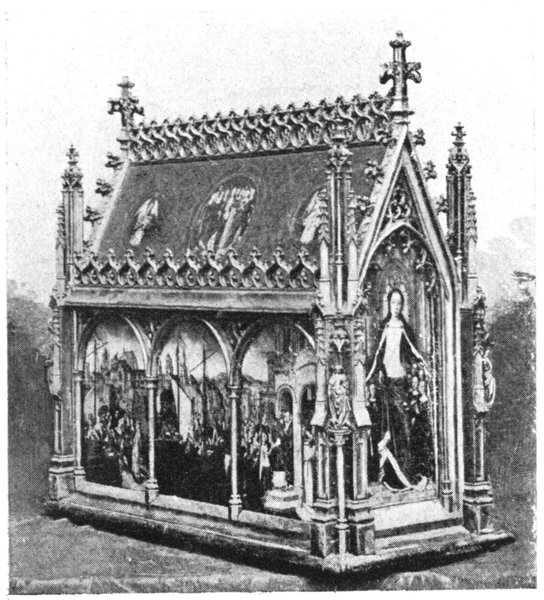

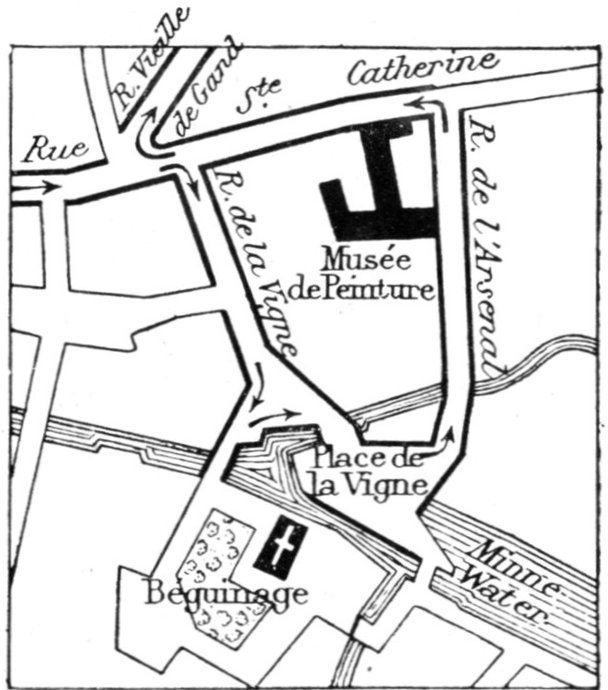

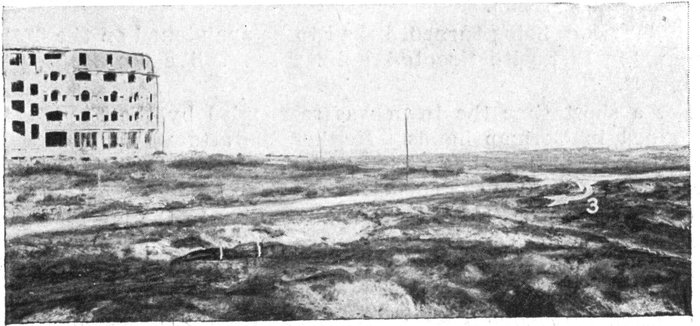

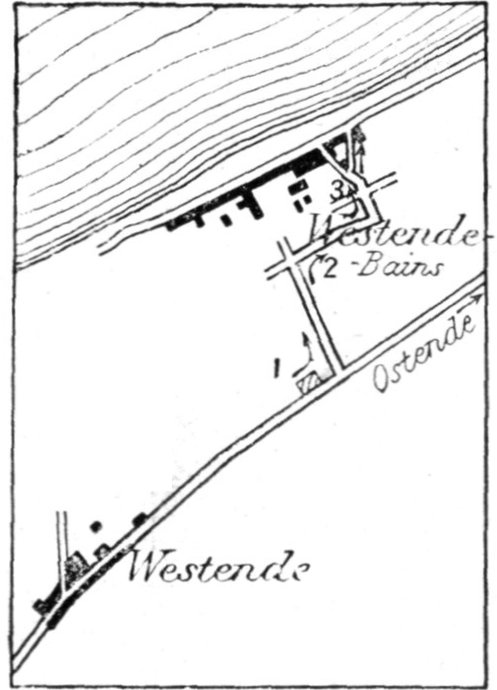

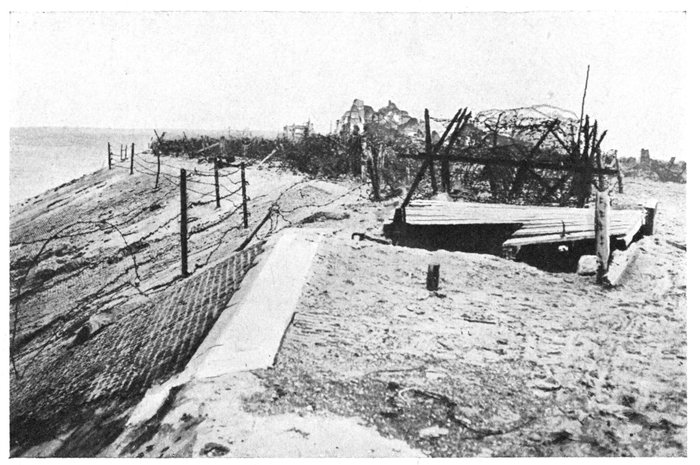

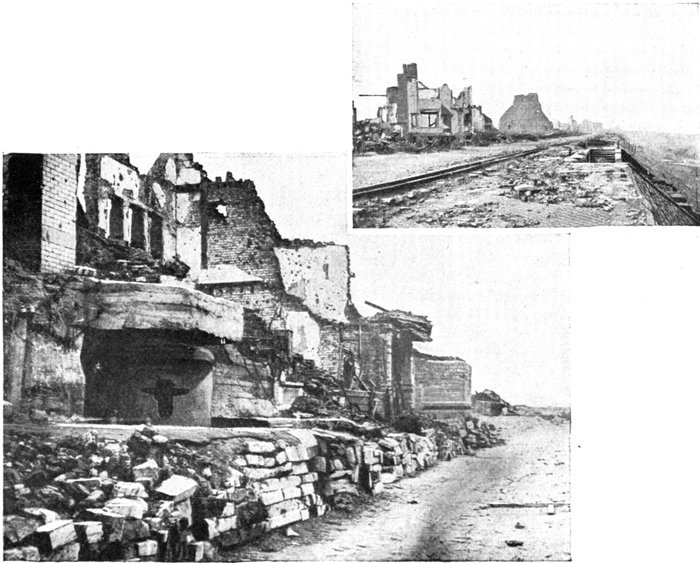

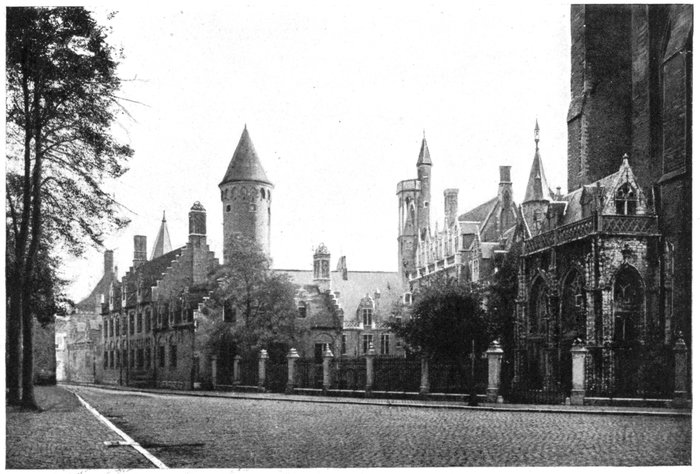

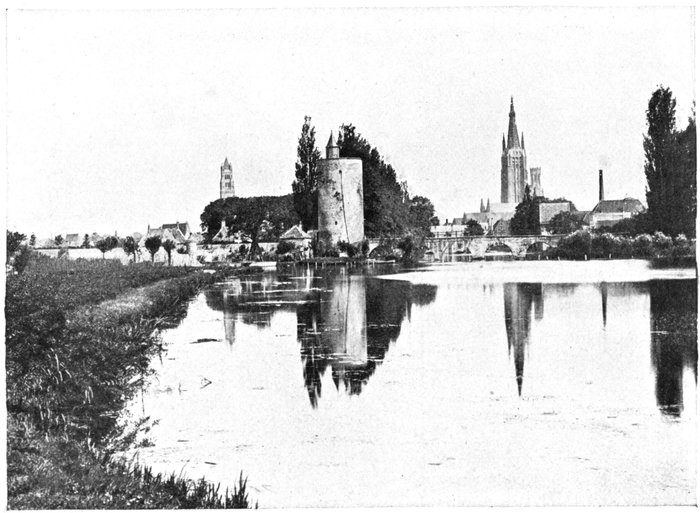

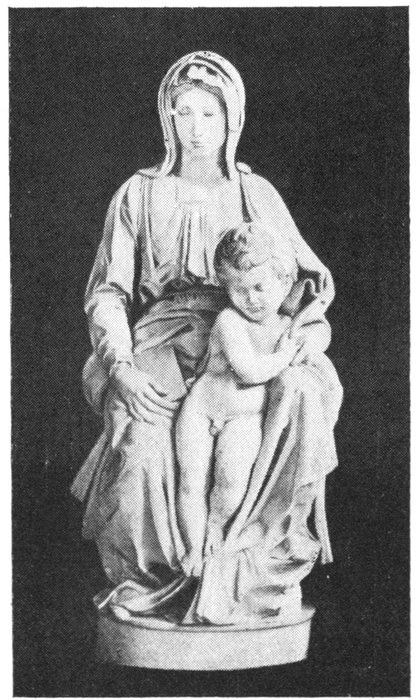

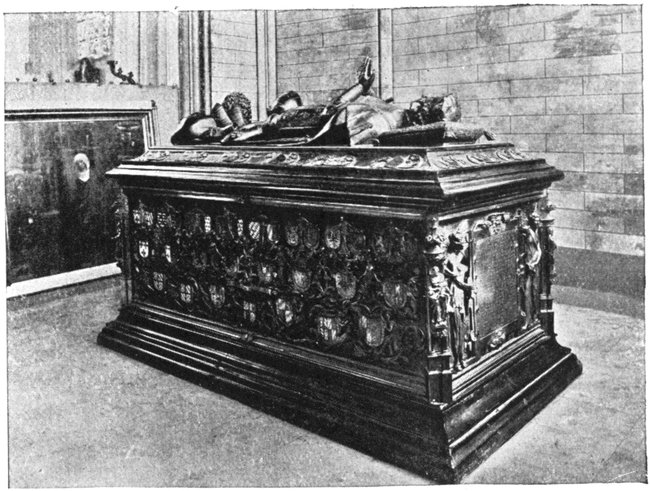

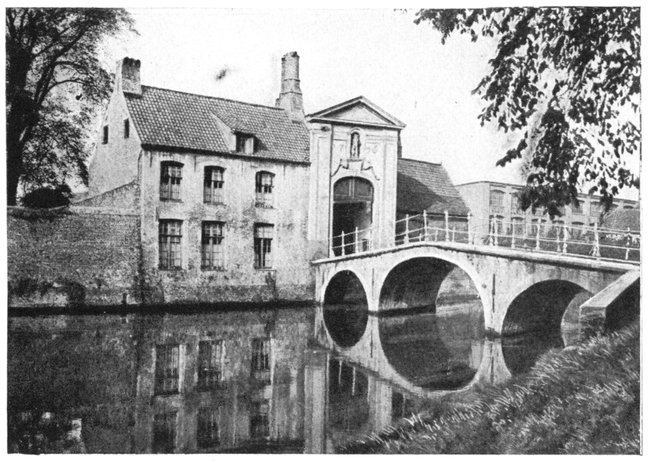

In danger of being turned, it had to be abandoned on the 20th, at about