INDIAN CURRENCY AND FINANCE

MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited

LONDON · BOMBAY · CALCUTTA

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK · BOSTON · CHICAGO

DALLAS · SAN FRANCISCO

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

INDIAN CURRENCY

AND FINANCE

BY

JOHN MAYNARD KEYNES

FELLOW OF KING’S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE

MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED

ST. MARTIN’S STREET, LONDON

1913

COPYRIGHT

PREFACE

When all but the last of the following chapters were already in type, I was offered a seat on the Royal Commission (1913) on Indian Finance and Currency. If my book had been less far advanced, I should, of course, have delayed publication until the Commission had reported, and my opinions had been more fully formed by the discussions of the Commission and by the evidence placed before it. In the circumstances, however, I have decided to publish immediately what I had already written, without the addition of certain other chapters which had been projected. The book, as it now stands, is wholly prior in date to the labours of the Commission.

J. M. KEYNES.

King’s College, Cambridge,

12th May 1913.

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER I | |

| PAGE | |

| The Present Position of the Rupee | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| The Gold–Exchange Standard | 15 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Paper Currency | 37 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| The Present Position of Gold in India and Proposals for a Gold Currency | 63 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Council Bills and Remittance | 102 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| The Secretary of State’s Reserves and the Cash Balances | 124[viii] |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Indian Banking | 195 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| The Indian Rate of Discount | 240 |

| INDEX | 261 |

| ———————— | |

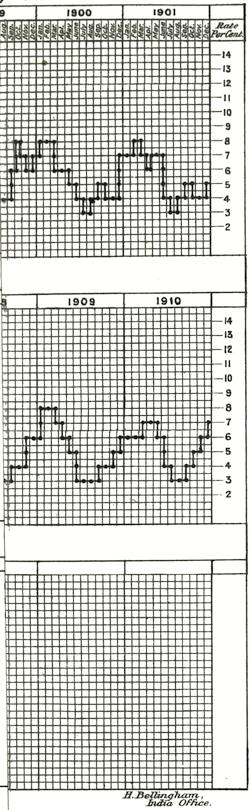

| Chart Showing the Rate of Discount at the Presidency Bank of Bengal | Face page 240 |

CHAPTER I

THE PRESENT POSITION OF THE RUPEE

1. On the broad historical facts relating to Indian currency, I do not intend to spend time. It is sufficiently well known that until 1893 the currency of India was on the basis of silver freely minted, the gold value of the rupee fluctuating with the gold value of silver bullion. By the depreciation in the gold value of silver, extending over a long period of years, trade was inconvenienced, and Public Finance, by reason of the large payments which the Government must make in sterling, gravely disturbed; until in 1893, after the breakdown of negotiations for bimetallism, the Indian Mints were closed to the free mintage of silver, and the value of the rupee divorced from the value of the metal contained in it. By withholding new issues of currency, the Government had succeeded by 1899 in raising the gold value of the rupee to 1s. 4d., at which figure it has remained without sensible variation ever since.

2. There can be no doubt that at first the Government of India did not fully understand the nature of[2] the new system; and that several minor mistakes were made at its inception. But few are now found who dispute on broad general grounds the wisdom of the change from a silver to a gold standard.

Time has muffled the outcries of the silver interests, and time has also dealt satisfactorily with what were originally the principal grounds of criticism, namely,—

(1) that the new system was unstable,

(2) that a depreciating currency is advantageous to a country’s foreign trade.

3. The second of these complaints was urged with great persistency in 1893. The depreciating rupee acted, it was said, as a bounty to exporters; and the introduction of a gold standard, so it was argued, would greatly injure the export trade in tea, corn, and manufactured cotton. It was plainly pointed out by theorists at the time (a) that the advantage to exporters was largely at the expense of other members of the community and could not profit the country as a whole, and (b) that it could only be temporary.

The recent spell of rising prices in India has shown clearly in how many ways a depreciating currency damages large sections of the community, although it may temporarily benefit other sections. In fact, some recent complaints against the existing currency policy have been occasioned by the tendency of prices to rise; whereas it is plain that the great change of 1893 must have tended to make them fall,[3] and that rupee prices would, in all probability, be higher than they now are, if the change had not been effected.

With regard to the temporary nature of the effect on exporters, experience has decisively supported theory. The nature of this experience was admirably summed up by Mr. J. B. Brunyate in the Legislative Council (February 25, 1910), speaking in reply to the similar line of argument brought forward by the Bombay mill–owning interests in connexion with the imposition in 1910 of a duty on silver.[1]

4. The criticisms of 1893, therefore, are no longer heard, and the Currency Problems with which we are now confronted are new. The evolution of the Indian currency system since 1899 has been rapid, though silent. There have been few public pronouncements of policy on the part of Government, and the legislative changes have been inconsiderable. Yet a system has been developed, which was contemplated neither by those who effected nor by those who opposed the closing of the Mints in 1893, and which was not favoured either by the Government or by the Fowler Committee in 1899, although something like it was suggested at that time. It is not possible to point to any one date at which the currency policy now in force was deliberately adopted.

The fact that the Government of India have drifted into a system and have never set it forth plainly is partly responsible for a widespread misunderstanding of its true character. But this economy of explanation, from which the system has suffered in the past, does[5] not make it any the worse intrinsically. The prophecy made before the Committee of 1898 by Mr. A. M. Lindsay, in proposing a scheme closely similar in principle to that which was eventually adopted, has been largely fulfilled. “This change,” he said, “will pass unnoticed, except by the intelligent few, and it is satisfactory to find that by this almost imperceptible process the Indian currency will be placed on a footing which Ricardo and other great authorities have advocated as the best of all currency systems, viz., one in which the currency media used in the internal circulation are confined to notes and cheap token coins, which are made to act precisely as if they were bits of gold by being made convertible into gold for foreign payment purposes.”

5. In 1893 four possible bases of currency seemed to hold the field: debased and depreciating currencies usually of paper; silver; bimetallism; and gold. It was not to be supposed that the Government of India intended to adopt the first; the second they were avowedly upsetting; the third they had attempted, and had failed, to obtain by negotiation. It seemed to follow that their ultimate objective must be the last—namely, a currency of gold. The Committee of 1892 did not commit themselves; but the system which their recommendations established was generally supposed to be transitional and a first step towards the introduction of gold. The Committee of 1898 explicitly declared themselves to be[6] in favour of the eventual establishment of a gold currency.

This goal, if it was their goal, the Government of India have never attained. The rupee is still the principal medium of exchange and is of unlimited legal tender. There is no legal enactment compelling any authority to redeem rupees with gold. The fact that since 1899 the gold value of the rupee has only fluctuated within narrow limits is solely due to administrative measures which the Government are under no compulsion to undertake. What, then, is the present position of the rupee?

6. The main features of the Indian system as now established are as follows:—

(1) The rupee is unlimited legal tender and, so far as the law provides, inconvertible.

(2) The sovereign is unlimited legal tender at £1 to 15 rupees, and is convertible at this rate, so long as a Notification issued in 1893 is not withdrawn, i.e., the Government can be required to give 15 rupees in exchange for £1.

(3) As a matter of administrative practice, the Government is, as a rule, willing to give sovereigns for rupees at this rate; but the practice is sometimes suspended and large quantities of gold cannot always be obtained in India by tendering rupees.

(4) As a matter of administrative practice, the Government will sell in Calcutta, in return for rupees tendered there, bills payable in London in sterling[7] at a rate not more unfavourable than 1s. 329/32d. per rupee.

The fourth of these provisions is the vital one for supporting the sterling value of the rupee; and, although the Government have given no binding undertaking to maintain it, a failure to do so might fairly be held to involve an utter breakdown of their system.

Thus the second provision prevents the sterling value of the rupee from rising above 1s. 4d. by more than the cost of remitting sovereigns to India, and the fourth provision prevents it from falling below 1s. 329/32d. This means in practice that the extreme limits of variation of the sterling value of the rupee are 1s. 4⅛d. and 1s. 329/32.

7. The important characteristics of the Indian system are so much a matter of notification and administrative practice that it is impossible to point to single Acts which have made the system what it is. But the following list of dates may be useful for purposes of reference:—

1892. Herschell Committee on Indian Currency.

1893. Act closing the Indian mints to the coinage of silver on private account. Notifications by Government fixing the rate, at which rupees or notes would be supplied in exchange for the tender of gold, at the equivalent of 1s. 4d. the rupee.

1898. Fowler Committee on Indian Currency. Exchange value of rupee touched 1s. 4d.

1899. Act declaring the British sovereign legal tender at 1s. 4d. to the rupee.

1899–1903. Negotiations for coinage of sovereigns in India (dropt indefinitely Feb. 6, 1903).

1900. Gold Standard Reserve instituted out of profits of coinage.

1904. Secretary of State’s notification of his willingness to sell Council Bills on India at 1s. 4⅛d. the rupee without limit.

1905. Act authorising the establishment of the Currency Chest of “earmarked” gold at the Bank of England as part of the Currency Reserve against notes,[2] and the investment of a stated part of the Currency Reserve in sterling securities.

1906. The Notification withdrawn which had directed the issue of rupees against the tender of gold (as distinguished from British gold coin).

1907. Rupee branch of the Gold Standard Reserve instituted.

1908. Sterling drafts sold in Calcutta on London at 1s. 329/32d. the rupee, and cashed out of funds from the Gold Standard Reserve.

1910. Act rendering Currency notes of Rs. 10 and 50 universal legal tender,[3] and directing the issue of notes in exchange for British gold coins.

1913. Royal Commission on Indian Finance and Currency.

8. In § 6 I have stated the practical effect of these successive measures. But the legal position is so complicated and peculiar, that it will be worth while to state it quite precisely. Previous to 1893 the Government were bound by the Coinage Act of 1870 to issue rupees, weight for weight, in exchange for silver bullion. There was also in force a Notification of the Governor–General in Council, dating from 1868,[9] by which sovereigns were received at Government Treasuries as the equivalent of ten rupees and four annas. This Notification, which had superseded a Notification of 1864 fixing the exchange at ten rupees, had long been inoperative (as the gold exchange value of ten rupees four annas had fallen much below a sovereign). The Act of 1893 was merely a repealing Act, necessary in order to do away with those provisions of the Act of 1870 which provided for the free mintage of silver into rupees. At the same time (1893) the Notification of 1868 was superseded by a new Notification fixing fifteen rupees as the rate at which sovereigns would be accepted at Government Treasuries; and a Notification was issued under the Paper Currency Act of 1882, directing the issue of currency notes in exchange for gold at the Rs. 15 to £1 ratio. The direct issue of rupees against the tender of gold also has been regulated by a series of Notifications, of which the first was published in 1893, up to 1906 rupees being issued against either gold coin or gold bullion; and since 1906 against sovereigns and half–sovereigns only. Apart from Notifications, an Act of 1899 declared British sovereigns legal tender at the Rs. 15 to £1 ratio, an indirect effect of which was to make it possible for Government, so far as Acts are concerned, to redeem notes in gold coin and refuse silver. And lastly, the Paper Currency Act of 1910 bound the Government to issue notes against the tender of British gold coin.

The convertibility of the sovereign into rupees at the Rs. 15 to £1 ratio is not laid down, therefore, in any Act whatever. It depends on Notifications withdrawable by the Executive at will. Further, the management of the Gold Standard Reserve is governed neither by Act nor by Notification, but by administrative practice solely; and the sale of Council Bills on India and of sterling drafts on London is regulated by announcements changeable at administrative discretion from time to time.

All this emphasises the gradual nature of the system’s growth, and the transitional character of existing legislation. As matters now are, there is something to be said for a new Act, which, while leaving administrative discretion free where there is still good ground for this, might consolidate and clarify the position.

9. As a result of these various measures, the rupee remains the local currency in India, but the Government take precautions for ensuring its convertibility into international currency at an approximately stable rate. The stability of the Indian system depends upon their keeping sufficient reserves of coined rupees to enable them at all times to exchange international currency for local currency; and sufficient liquid resources in sterling to enable them to change back the local currency into international currency, whenever they are required to do so. The special features of the system, although, as we shall[11] see later, these features are not in fact by any means peculiar to India, are: first, that the actual medium of exchange is a local currency distinct from the international currency; second, that the Government is more ready to redeem the local currency (rupees) in bills payable in international currency (gold) at a foreign centre (London) than to redeem it outright locally; and third, that the Government, having taken on itself the responsibility for providing local currency in exchange for international currency and for changing back local currency into international currency when required, must keep two kinds of reserves, one for each of these purposes.

I will deal with these characteristics in successive chapters. It is convenient to begin with the second of them and at the outset to discuss in a general way the system of currency, of which the Indian is the most salient example, known to students as the Gold–Exchange Standard. Then we will take the first of them in Chapters III. and IV. on Paper Currency and on the Present Position of Gold in India and Proposals for a Gold Currency; and the third in Chapter VI. on the Secretary of State’s Reserves.

10. But before we pass to these several features of the Indian system, it will be worth while to emphasise two respects in which this system is not peculiar. In the first place a system, in which the rupee is maintained at 1s. 4d. by regulation, does not affect[12] the level of prices differently from the way in which it would be affected by a system in which the rupee was a gold coin worth 1s. 4d., except in a very indirect and unimportant way to be explained in a moment. So long as the rupee is worth 1s. 4d. in gold, no merchant or manufacturer considers of what material it is made when he fixes the price of his product. The indirect effect on prices, due to the rupee’s being silver, is similar to the effect of the use of any medium of exchange, such as cheques or notes, which economises the use of gold. If the use of gold is economised in any country, gold throughout the world is less valuable—gold prices, that is to say, are higher. But as this effect is shared by the whole world, the effect on prices in any country of economies in the use of gold made by that country is likely to be relatively slight. In short, a policy which led to a greater use of gold in India would tend, by increasing the demand for gold in the world’s markets, somewhat to lower the level of world prices as measured in gold; but it would not cause any alteration worth considering in the relative rates of exchange of Indian and non–Indian commodities.

In the second place, although it is true that the maintenance of the rupee at or near 1s. 4d. is due to regulation, it is not true, when once 1s. 4d. rather than some other gold value has been determined, that the volume of currency in circulation depends in the least upon the policy of the Government or the caprice[13] of an official.[4] This part of the system is as perfectly automatic as in any other country. The Government has put itself under an obligation to supply rupees whenever sovereigns are tendered, and it often permits or encourages the tender of sovereigns in London as well as in India; but it has no power or opportunity of forcing rupees into circulation otherwise. In two matters only does the Government use a discretionary power. First, in order that it may always be possible to fulfil this obligation, it is necessary to keep a certain reserve of coined rupees, just as some authority in this country—in point of fact the Bank of England—must keep some reserve of token silver and coined sovereigns and not hold in its vaults too large a proportion of uncoined or foreign gold. The magnitude of this reserve is within the discretion of the Indian Government. To a certain extent they must anticipate probable demands on the output of the Mint. But if they miscalculate and mint more than they need, the new rupees must lie in the Government’s own chests until they are wanted, and the date at which they emerge into circulation it is beyond the power of the Government to determine. In the second[14] place, the Government can postpone for a short time a demand for rupees by refusing to supply them in return for sovereigns tendered in London and by insisting upon the sovereigns being sent to Calcutta. Sometimes they do this, but very often it is worth their while, for reasons to be explained in detail later on, to accept the tender of sovereigns in London. In either of these cases the permanent effect of their action one way or the other on the volume of circulation is inconsiderable. The kind of difference it makes is comparable to the difference which would be made if it lay within the discretion of a government to charge or not, as it saw fit, a small brassage not much greater than the cost of coining.[5]

CHAPTER II

THE GOLD–EXCHANGE STANDARD

1. If we are to see the Indian system in its proper perspective, it is necessary to digress for a space to a discussion of currency evolution in general.

My purpose is, first, to show that the British system is peculiar and is not suited to other conditions; second, that the conventional idea of “sound” currency is chiefly derived from certain superficial aspects of the British system; third, that a somewhat different type of system has been developed in most other countries; and fourth, that in essentials the system which has been evolved in India conforms to this foreign type. I shall be concerned throughout this chapter with the general characteristics of currency systems, not with the details of their working.

2. The history of currency, so far as it is relevant to our present purpose, virtually begins with the nineteenth century. During the second quarter of this century England was alone in possessing an orthodox “sound” currency on a gold basis. Gold was the sole standard of value; it circulated freely[16] from hand to hand; and it was freely available for export. Up to 1844 bank notes showed a tendency to become a formidable rival to gold as the actual medium of exchange. But the Bank Act of that year set itself to hamper this tendency and to encourage the use of gold as the medium of exchange as well as the standard of value. This Act was completely successful in stopping attempts to economise gold by the use of notes. But the Bank Act did nothing to hinder the use of cheques, and the very remarkable development of this medium of exchange during the next fifty years led in this country, without any important development in the use of notes or tokens, to a monetary organisation more perfectly adapted for the economy of gold than any which exists elsewhere. In this matter of the use of cheques Great Britain has been followed by the rest of the English–speaking world—Canada, Australia, South Africa, and the United States of America. But in other countries currency evolution has been, chiefly, along different lines.

3. In the early days of banking of the modern type in England, gold was not infrequently required to meet runs on banks by their depositors, who were always liable in difficult times to fall into a state of panic lest they should be unable to withdraw their deposits in case of real need. With the growth of the stability of banking, and especially with the growth of confidence in this stability amongst[17] depositors, these occasions have become more and more infrequent, and many years have now passed since there has been any run of dangerous proportions on English banks. Gold reserves, therefore, in Great Britain are no longer held primarily with a view to emergencies of this kind. The uses of gold coin in Great Britain are now three—as the medium of exchange for certain kinds of out–of–pocket expenditure, such as that on railway travelling, for which custom requires cash payment; for the payment of wages; and to meet a drain of specie abroad.

Fluctuations in the demand for gold in the first two uses are of secondary importance, and can usually be predicted with a good deal of accuracy,—at holiday seasons, at the turn of the quarter, at the end of the week, at harvest. Fluctuations in the demand in the third use are of greater magnitude and, apart from the regular autumn drain, not so easily foreseen. Our gold reserve policy is mainly dictated, therefore, by considerations arising out of the possible demand for export.

To guard against a possible drain of gold abroad, a complicated mechanism has been developed which in the details of its working is peculiar to this country. A drain of gold can only come about if foreigners choose to turn into gold claims, which they have against us for immediate payment, and we have no counterbalancing claims against them for equally immediate payment. The drain can only be stopped[18] if we can rapidly bring to bear our counterbalancing claims. When we come to consider how this can best be done, it is to be noticed that the position of a country which is preponderantly a creditor in the international short–loan market is quite different from that of a country which is preponderantly a debtor. In the former case, which is that of Great Britain, it is a question of reducing the amount lent; in the latter case it is a question of increasing the amount borrowed. A machinery which is adapted for action of the first kind may be ill suited for action of the second. Partly as a consequence of this, partly as a consequence of the peculiar organisation of the London Money Market, the “bank rate” policy for regulating the outflow of gold has been admirably successful in this country, and yet cannot stand elsewhere unaided by other devices. It is not necessary for the purposes of this survey to consider precisely how changes in the bank rate affect the balance of immediate indebtedness. It will be sufficient to say that it tends to hamper the brokers, who act as middlemen between the British short–loan fund and the foreign demand for accommodation (chiefly materialised in the offer of bills for discount), and to cause them to enter into a less volume of new business than that of the short loans formerly contracted and now falling due, thus bringing to bear the necessary counterbalancing claims against foreign countries.

4. The essential characteristics of the British[19] monetary system are, therefore, the use of cheques as the principal medium of exchange, and the use of the bank rate for regulating the balance of immediate foreign indebtedness (and hence the flow, by import and export, of gold).

5. The development of foreign monetary systems into their present shapes began in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. At that time London was at the height of her financial supremacy, and her monetary arrangements had stood the test of time and experience. Foreign systems, therefore, were greatly influenced at their inception by what were regarded as the fundamental tenets of the British system. But foreign observers seem to have been more impressed by the fact that the Englishman had sovereigns in his pocket than by the fact that he had a cheque–book in his desk; and took more notice of the “efficacy” of the bank rate and of the deliberations of the Court of Directors on Thursdays, than of the peculiar organisation of the brokers and the London Money Market, and of Great Britain’s position as a creditor nation. They were thus led to imitate the form rather than the substance. When they introduced the gold standard, they set up gold currencies as well; and in several cases an official bank rate was established on the British model. Germany led the way in 1871–73. Even now apologists of the Reichsbank will sometimes speak as if its bank rate were efficacious by itself in the same manner as the[20] Bank of England’s. But, in fact, the German system, though ostensibly modelled in part upon the British system, has become, by force of circumstances, essentially different.

It is not necessary for this survey to consider individual systems in any detail. But, confining ourselves to European countries, whether we consider, for example, France, Austria–Hungary, Russia, Italy, Sweden, or Holland, while most of these countries have a gold currency and an official Bank Rate, in none of them is gold the principal medium of exchange, and in none of them is the bank rate their only habitual support against an outward drain of gold.

6. With the use of substitutes for gold I will deal in Chapter IV. in treating of the proper position of gold in the Indian system. But what props are commonly brought to the support of an “ineffective” Bank Rate in countries other than Great Britain? Roughly speaking, there are three. A very large gold reserve may be maintained, so that a substantial drain on it may be faced with equanimity; free payments in gold may be partially suspended; or foreign credits and bills may be kept which can be drawn upon when necessary. The Central Banks of most European countries depend (in varying degrees) upon all three.

The Bank of France uses the first two,[6] and her[21] holdings of foreign bills are not, at normal times, important.[7] Her bank rate is not fixed primarily with a view to foreign conditions, and a change in it is usually intended to affect home affairs (though these may of course depend and react on foreign affairs).

Germany is in a state of transition, and her present position is avowedly unsatisfactory. The theory of her arrangements seems to be that she depends on her bank rate after the British model; but in practice her bank rate is not easily rendered effective, and must usually be reinforced by much unseen pressure by the Reichsbank on the other elements of the money market. Her gold reserve is not large enough for the first expedient to be used lightly. Free payment in gold is sometimes, in effect, partially suspended,[8] though covertly and with[22] shame. To an increasing extent the Reichsbank depends on variations in her holding of foreign bills and credits. A few years ago such holdings were of small importance. The table given below shows with what rapidity the part taken by foreign bills and credits in the finance of the Reichsbank has been growing. The authorities of the Reichsbank have now learnt that their position in the international short loan market is not one which permits them to fix the bank rate and then idly to await the course of events.

Reichsbank’s Holdings of Foreign Bills (excluding Credits).

| Average for Year. |

Maximum. | Minimum. | |

| 1895 | £120,000 | £152,000 | £100,000 |

| 1900 | 1,270,000 | 3,540,000 | 160,000 |

| 1905 | 1,580,000 | 2,490,000 | 970,000 |

| 1906 | 2,060,000 | 2,990,000 | 830,000 |

| 1907 | 2,223,000 | 3,000,000 | 1,130,000 |

| 1908 | 3,544,000 | 6,366,000 | 977,800 |

| 1909 | 5,362,000 | 7,978,000 | 2,824,800 |

| 1910a | 7,032,000 | 8,855,000 | 4,893,300 |

(a): Since 1910 these figures have not been stated in the Reichsbank’s annual reports.

Reichsbank’s Holdings of Foreign Bills and Credits with Foreign Correspondents on last Day of each Year.

| 31st Dec. | Bills. | Credits. | Total. |

| 1906 | £3,209,000 | £993,000 | £4,202,000 |

| 1907 | 1,289,000 | 503,000 | 1,792,000 |

| 1908 | 6,457,000 | 1,234,000 | 7,691,000 |

| 1909 | 6,000,000 | 3,369,000 | 9,369,000 |

| 1910 | 8,114,000 | 4,205,000 | 12,309,000 |

| 1911 | 7,114,000 | 1,439,000 | 8,553,000 |

| 1912 | ... | ... | ... |

7. If we pass from France, whose position as a creditor country is not altogether unlike Great Britain’s, and from Germany, which is at any rate able to do a good deal towards righting the balance of immediate indebtedness by the sale of securities having an international market, to other countries of less financial strength, we find the dependence of their Central Banks on holdings of foreign bills and on foreign credits, their willingness to permit a premium on gold, and the inadequacy of their bank rates taken by themselves, to be increasingly marked. I will first mention very briefly one or two salient facts, and will then consider their underlying meaning, always with an ultimate view to their bearing on the affairs of India.

8. To illustrate how rare a thing in Europe a perfect and automatic gold standard is, let us take the most recent occasion of stringency—November 1912. The Balkan War was at this time at an acute stage, but the European situation was only moderately anxious. Compared with the crisis at the end of 1907, the financial position was one of comparative calm. Yet in the course of that month there was a premium on gold of about ¾ per cent in France, Germany, Russia, Austria–Hungary,[9] and Belgium. So high a premium as this is as effective in retaining gold as a very considerable addition to the bank rate.[24] If, for example, the premium did not last more than three months, it would add to the profits of a temporary deposit of funds for that period as much as an addition of 3 per cent to the discount rate; or, to put it the other way round, there would need to be an additional profit of 3 per cent elsewhere if it were to be worth while to send funds abroad.

9. The growing importance of foreign bills in the portfolios of the Reichsbank has been shown above. The importance of foreign bills and credits in the policy of the Austro–Hungarian Bank is of longer standing and is better known. They always form an important part of its reserves, and the part first utilised in times of stringency.[10] It was supposed that in the third quarter of 1911 the Bank placed not less than £4,000,000 worth of gold bills at the disposal of the Austro–Hungarian market in order to support exchange. Amongst European countries, Russia now keeps the largest aggregate of funds in foreign bills and in balances abroad—amounting in November 1912 to £26,630,000.[11] Account being taken of their total resources, however, the banks of the three Scandinavian countries, Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, hold the[25] highest proportion in the form of balances abroad—amounting in November 1912, for the three countries in the aggregate, to about £7,000,000. These are enough examples for my purpose.

10. What is the underlying significance of this growing tendency on the part of European State Banks to hold a part of their reserves in foreign bills or foreign credits? We saw above that the bank–rate policy of the Bank of England is successful because by indirect means it causes the Money Market to reduce its short–period loans to foreign countries, and thus to turn the balance of immediate indebtedness in our favour. This indirect policy is less feasible in countries where the Money Market is already a borrower rather than a lender in the international market. In such countries a rise in the bank–rate cannot be relied on to produce the desired effect with due rapidity. A direct policy on the part of the Central Bank, therefore, must be employed. If the Money Market is not a lender in the international market, the Bank itself must be at pains to become to some extent one. The Bank of England lends to middlemen who, by holding bills or otherwise, lend abroad. A rise in the bank rate is equivalent to putting pressure on these middlemen to diminish their commitments. In countries where the Money Market is neither so highly developed nor, in relation to foreign countries, so self–supporting, the Central Bank, if it is to be secure, must take the matter[26] in hand itself and, by itself entering the international money market as a lender at short notice, place itself in funds, at foreign centres, which can be rapidly withdrawn when they are required. The only alternative would be the holding of a much larger reserve of gold, the expense of which would be nearly intolerable. The new method combines safety with economy. Just as individuals have learnt that it is cheaper and not less safe to keep their ultimate reserves on deposit at their bankers than to keep them at home in cash, so the second stage of monetary evolution is now entered on, and nations are learning that some part of the cash reserves of their banks (we cannot go further than this at present) may be properly kept on deposit in the international money market. This is not the expedient of second–rate or impoverished countries; it is the expedient of all those who have not attained a high degree of financial supremacy—of all those, in fact, who are not themselves international bankers.

11. In the forty years, therefore, during which the world has been coming on to a gold standard (without, however, giving up for that reason its local currencies of notes or token silver), two devices—apart from the bullion reserve itself and the bank rate—have been evolved for protecting the local currencies. The first is to permit a small variation in the ratio of exchange between the local currency and gold, amounting perhaps to an occasional premium[27] of ¾ per cent on the latter; this may help to tide over a stringency which is seasonal or of short duration without raising to a dangerous level the rate of discount on purely local transactions. The second is for the Government or Central Bank to hold resources available abroad, which can be used for maintaining the gold parity of the local currency, when there is the need for it.

12. We are now more nearly in a position to come back to the currency of India herself, and to see it in its proper relation to those of other countries. At one end of the scale we have Great Britain and France—creditor nations in the short–loan market.[12] In an intermediate position comes Germany—a creditor in relation to many of her neighbours, but apt to be a debtor in relation to France, Great Britain, and the United States. Next come such countries as Russia and Austria–Hungary—rich and powerful, with immense reserves of gold, but debtor nations, dependent in the short–loan market on their neighbours. From the currencies of these it is an easy step to those of the great trading nations of Asia—India, Japan, and the Dutch East Indies.

13. I say that from the currencies of such countries as Russia and Austria–Hungary to those which have[28] explicitly and in name a Gold–Exchange Standard[13] it is an easy step. The Gold–Exchange Standard is simply a more regularised form of the same system as theirs. In their essential characteristics and in the monetary logic which underlies them the currencies of India and Austria–Hungary (to take these as our examples) are not really different. In India we know the extreme limits of fluctuation in the exchange value of the rupee; we know the precise volume of reserves which the Government holds in gold and in credits abroad; and we know at what moment the Government will step in and utilise these resources for the support of the rupee. In Austria–Hungary the system is less automatic, and the Bank is allowed a wide discretion. In detail, of course, there are a number of differences. India keeps a somewhat higher proportion of her reserves in foreign credits, and keeps some part of these credits in a less liquid form. She also keeps a portion of her gold reserve in London—a practice made possible by the fact that for India London is not strictly a foreign centre. On the other hand, India is probably more willing than the Bank of Austria–Hungary to supply gold on demand. If we are to judge from the experience of[29] recent years, India inclines to use her gold reserves, Austria–Hungary her foreign credits, first. But in the essentials of the Gold–Exchange Standard—the use of a local currency mainly not of gold, some degree of unwillingness to supply gold locally in exchange for the local currency, but a high degree of willingness to sell foreign exchange for payment in local currency at a certain maximum rate, and to use foreign credits in order to do this—the two countries agree.

14. To say that the Gold–Exchange Standard merely carries somewhat further the currency arrangements which several European countries have evolved during the last quarter of a century is not, of course, to justify it. But if we see that the Gold–Exchange Standard is not, in the currency world of to–day, anomalous, and that it is in the main stream of currency evolution, we shall have a wider experience, on which to draw, in criticising it, and may be in a better position to judge of its details wisely. Much nonsense is talked about a gold standard’s properly carrying a gold currency with it. If we mean by a gold currency a state of affairs in which gold is the principal or even, in the aggregate, a very important medium of exchange, no country in the world has such a thing.[14] Gold is an international, but not a local currency. The currency problem of each country is to ensure that they shall run no risk of being[30] unable to put their hands on international currency when they need it, and to waste as small a proportion of their resources on holdings of actual gold as is compatible with this. The proper solution for each country must be governed by the nature of its position in the international money market and of its relations to the chief financial centres, and by those national customs in matters of currency which it may be unwise to disturb. It is as an attempt to solve this problem that the Gold–Exchange Standard ought to be judged.

15. We have been concerned so far with transitional systems of currency. I will conclude this chapter with a brief history in outline of the Gold–Exchange Standard itself. It will then be time to pass from high generalities to the actual details of the Indian system.

The Gold–Exchange Standard arises out of the discovery that, so long as gold is available for payments of international indebtedness at an approximately constant rate in terms of the national currency, it is a matter of comparative indifference whether it actually forms the national currency.

The Gold–Exchange Standard may be said to exist when gold does not circulate in a country to an appreciable extent, when the local currency is not necessarily redeemable in gold, but when the Government or Central Bank makes arrangements for the provision of foreign remittances in gold at a fixed[31] maximum rate in terms of the local currency, the reserves necessary to provide these remittances being kept to a considerable extent abroad.

A system closely resembling the Gold–Exchange Standard was actually employed during the second half of the eighteenth century for regulating the exchange between London and Edinburgh. Its theoretical advantages were first set forth by Ricardo at the time of the Bullionist Controversy. He laid it down that a currency is in its most perfect state when it consists of a cheap material, but having an equal value with the gold it professes to represent; and he suggested that convertibility for the purposes of the foreign exchanges should be ensured by the tendering on demand of gold bars (not coin) in exchange for notes,—so that gold might be available for purposes of export only, and would be prevented from entering into the internal circulation of the country. In an article contributed to the Contemporary Review of 1887, Dr. Marshall again brought these advantages to the notice of practical men.

16. The first crude attempt in recent times at establishing a standard of this type was made by Holland. The free coinage of silver was suspended in 1877. But the currency continued to consist mainly of silver and paper. It has been maintained since that date at a constant value in terms of gold by the Bank’s regularly providing gold when it is required for export and by its using its authority at the same[32] time for restricting so far as possible the use of gold at home. To make this policy possible, the Bank of Holland has kept a reserve, of a moderate and economical amount, partly in gold, partly in foreign bills.[15] During the long period for which this policy has been pursued, it has been severely tried more than once, but has stood the test successfully.

It must be noticed, however, that although Holland has kept gold and foreign bills as a means of obtaining a credit abroad at any moment, she has not kept a standing credit in any foreign financial centre. The method of keeping a token currency at a fixed par with gold by means of credit abroad was first adopted by Count Witte for Russia in the transitional period from inconvertible paper to a gold standard;—in the autumn of 1892 the Department of Finance offered to buy exchange on Berlin at 2·18 marks and to sell at 2·20. In the same year (1892) the Austro–Hungarian system, referred to above, was established. As in India their exchange policy was evolved gradually. The present arrangements, which date[33] from 1896, were made possible by the strong preference of the public for notes over gold and by the provision of the law which permitted the holding of foreign bills as cover for the note issue. This exchange policy is the easier, because the Austro–Hungarian Bank is by far the largest dealer in exchange in Vienna;—just as the policy of the Government of India is facilitated by the commanding influence which the system of Council Bills gives it over the exchange market.

17. But although India was not the first country to lead the way to a Gold–Exchange Standard, she was the first to adopt it in a complete form. When in 1893, on the recommendation of the Herschell Committee, following upon the agitation of the Indian Currency Association, the Mints were closed to the free coinage of silver, it was believed that the cessation of coinage and the refusal of the Secretary of State to sell his bills below 1s. 4d. would suffice to establish this ratio of exchange. The Government had not then the experience which we have now; we now know that such measures are not by themselves sufficient, except under the influence of favouring circumstances. As a matter of fact the circumstances were, at first, unfavourable. Exchange fell considerably below 1s. 4d., and the Secretary of State had to sell his bills for what he could get. If there had been, at the existing level of prices, a rapidly expanding demand for currency at the time when the[34] Mints were closed, the measures actually taken might very well have proved immediately successful. But the demand did not expand, and the very large issue of currency immediately before and just after the closure of the Mints proved sufficient to satisfy the demand for several years to come;—just as a demand for new currency on an abnormally high scale from 1903 to 1907, accompanied by high rates of discount, was followed in 1908 by a complete cessation of demand and a period of comparatively low rates of discount. Favourable circumstances, however, came at last, and by January 1898 exchange was stable at 1s. 4d. The Fowler Committee, then appointed, recommended a gold currency as the ultimate objective. It is since that time that the Government of India have adopted, or drifted into, their present system.

18. The Gold–Exchange Standard in the form in which it has been adopted in India is justly known as the Lindsay scheme. It was proposed and advocated from the earliest discussions, when the Indian currency problem first became prominent, by Mr. A. M. Lindsay, Deputy–Secretary of the Bank of Bengal, who always maintained that “they must adopt my scheme despite themselves.” His first proposals were made in 1876 and 1878. They were repeated in 1885 and again in 1892, when he published a pamphlet entitled Ricardo’s Exchange Remedy. Finally, he explained his views in detail to the Committee of 1898.

Lindsay’s scheme was severely criticised both by Government officials and leading financiers. Lord Farrer described it as “far too clever for the ordinary English mind with its ineradicable prejudice for an immediately tangible gold backing to all currencies.” Lord Rothschild, Sir John Lubbock (Lord Avebury), Sir Samuel Montagu (the late Lord Swaythling) all gave evidence before the Committee that any system without a visible gold currency would be looked on with distrust. Mr. Alfred de Rothschild went so far as to say that “in fact a gold standard without a gold currency seemed to him an utter impossibility.” Financiers of this type will not admit the feasibility of anything until it has been demonstrated to them by practical experience. It follows, therefore, that they will seldom give their support to what is new.

19. Since the Indian system has been perfected and its provisions generally known, it has been widely imitated both in Asia and elsewhere. In 1903 the Government of the United States introduced a system avowedly based on it into the Philippines. Since that time it has been established, under the influence of the same Government, in Mexico and Panama. The Government of Siam have adopted it. The French have introduced it in Indo–China. Our own Colonial Office have introduced it in the Straits Settlements and are about to introduce it into the West African Colonies. Something similar has existed in Java under Dutch influences for many years. The[36] Japanese system is virtually the same in practice. In China, as is well known, currency reform has not yet been carried through. The Gold–Exchange Standard is the only possible means of bringing China on to a gold basis, and the alternative policy (the policy of our own Foreign Office) is to be content at first with a standard, as well as a currency, of silver. A powerful body of opinion, led by the United States, favours the immediate introduction of a gold standard on the Indian model.

It may fairly be said, therefore, that in the ten years the Gold–Exchange Standard has become the prevailing monetary system of Asia. I have tried to show that it is also closely related to the prevailing tendencies in Europe. Speaking as a theorist, I believe that it contains one essential element—the use of a cheap local currency artificially maintained at par with the international currency or standard of value (whatever that may ultimately turn out to be)—in the ideal currency of the future. But it is now time to turn to details.

CHAPTER III

PAPER CURRENCY

1. The chief characteristics of the Indian system of currency have been roughly sketched in the first chapter. I will now proceed to a description of the system of note issue.

2. In existing conditions the rupee, being a token coin, is virtually a note printed on silver. The custom and convenience of the people justify this, so far as concerns payment in small sums. But in itself it is extravagant. When rupees are issued, the Government, instead of being able to place to reserve the whole nominal value of the coin, is able to retain only the difference between the nominal value and the cost of the silver.[16] For large payments, therefore, it is important to encourage the use of notes to the utmost extent possible,—from the point of view of economy, because by these means the Government may obtain a large part of the reserves necessary for[38] the support of a Gold–Exchange Standard, and also because only thus will it be possible to introduce a proper degree of elasticity in the seasonal supply of currency.

3. By Acts of 1839–43 the Presidency Banks of Bengal, Bombay, and Madras were authorised to issue notes payable on demand; but the use of the notes was practically limited to the three Presidency towns.[17] These Acts were repealed in 1861, when the present Government Paper Currency was first instituted. Since that time no banks have been allowed to issue notes in India.

Proposals for a Government Paper Currency were instituted in 1859 by Mr. James Wilson on his going out to India as the first Financial Member.[18] Mr. Wilson died before his scheme could be carried into effect, and the Act setting up the Paper Currency scheme, which became law in 1861, differed in some important respects from his original proposals.[19] The system was eventually set up under the influence of the very rigid ideas as to the proper regulation of note issue prevailing, as a result of the controversies which had culminated in the British Bank Act of 1844, amongst English economists of that time. According to these ideas, the proper principles of note issue[39] were two—first, that the function of note issue should be entirely dissociated from that of banking; and second, that “the amount of notes issued on Government securities should be maintained at a fixed sum, within the limit of the smallest amount which experience has proved to be necessary for the monetary transactions of the country, and that any further amount of notes should be issued on coin or bullion.”[20] These principles were orthodox and all others “unsound.” “The sound principle for regulating the issue of a Paper Circulation,” wrote the Secretary of State, “is that which was enforced on the Bank of England by the Act of 1844.” In England, of course, bankers immediately set themselves to recover the economy and elasticity, which the Act of 1844 banished from the English system, by other means; and with the development of the cheque system to its present state of perfection they have magnificently succeeded. In foreign countries all kinds of new principles have been tried for the regulation of note issue, and some of them have been very successful. In India the creed of 1861 is still repeated; but by unforeseen chance the words have changed their meanings, and have permitted the old system to acquire through inadvertence a certain degree of usefulness. The coin, in which the greater part of the reserve had to[40] be held, was, of course, the rupee. In 1861 this was a freely minted coin worth no more than its bullion value. When the rupee became an artificially valued token, rupees tacitly remained the legitimate form of the reserve (although after a time sovereigns were added as an optional alternative). Thus the authorities are free, if they like, to hold the whole of the Currency Reserve in rupee–tokens, and this reserve has become, therefore (as we shall see below), an important part of the mechanism by which the supply of silver rupees to the currency is duly regulated. While, however, the note issue has managed to evolve an important function for itself, I think the time has come when the usefulness of the Currency Reserve may be much increased by a deliberate consideration of the place it might fill in the organism of the Indian Money Market. I return to this later in the chapter. In the meantime I pass to a description of the Paper Currency as it now is—insisting, however, that when we come to consider how it may be improved, the circumstances of its origin be not forgotten.

4. For the first forty years of their existence the Government notes, though always of growing importance, took a very minor place in the currency system of the country. This was partly due to an arrangement, now in gradual course of abolition, by which for the purposes of paper currency India has been divided up in effect into several separate countries. These[41] ‘circles,’ as they are called, now seven[21] in number, correspond roughly to the principal provinces of India, the offices of issue being as follows:—

| Calcutta | for | Bengal, Eastern Bengal, and Assam. |

| Cawnpore | ” | the United Provinces. |

| Lahore | ” | the Punjab and North–West Frontier Province. |

| Madras | ” | the Madras Presidency and Coorg. |

| Bombay | ” | Bombay and the Central Provinces. |

| Karachi | ” | Sind. |

| Rangoon | ” | Burma. |

The currency notes[22] are in the form of promissory notes of the Government of India payable to the bearer on demand, and are of the denominations Rs. 5, 10, 50, 100, 500, 1000, and 10,000. Thus the lowest note is of the face value of 6s. 8d. They are issued without limit from any Paper Currency office in exchange for rupees or British gold coin, or (on the requisition of the Comptroller–General) for gold bullion.[23]

5. Up to 1910 the following arrangements were in force.

Every note was legal tender in its own circle. Payment of dues to the Government could be made in the currency notes of any circle; and railway companies could, if they accepted notes of any circle[42] in payment of fares and freight, recover the value of them from the Government.

But, until recently, no notes were legal tender outside their own circle, and were payable only at the offices of issue of the town from which they were originally issued.

Beyond this the law imposed no obligation to pay. For the accommodation of the public, however, notes of other circles could be cashed at any Paper Currency office to such extent as the convenience of each office might permit. In ordinary circumstances every Government treasury, of which there are about 250, has cashed or exchanged notes if it could do so without inconvenience; and when this could not be done conveniently for large sums, small sums have generally been exchanged for travellers.

6. It is easy to understand the reasons for these restrictions. India is an enormously large country, over which the conditions of trade lead coins to ebb and flow within each year. At the beginning of the busy season when the autumn crops are harvested, rupees flow in great volume from the Presidency towns up country; in early spring they are carried to Burma for the rice crop; and so on—slowly finding their way back again to the Presidency towns during the summer. If the Government had made its notes encashable at a great variety of centres, it would have been taking on itself the expense and responsibility of carrying out these movements of[43] coin at different seasons of the year. When a country is habituated to the use of notes for making payments, they can be very usefully employed for purposes of remittance also. But a note–issuing authority puts itself in a difficulty if it provides facilities for remittance before a general habit has grown up of using notes for other purposes. If, on the other hand, the notes had been made universal legal tender, but only encashable at Presidency towns, there would undoubtedly have been a premium on coin at certain times of the year. And this would have greatly hindered the growth of the notes’ popularity.

The Government, therefore, did what it could to make the notes useful and popular for purposes other than those of remittance; and it facilitated remittance so far as the proceeds of taxation, accumulating in its treasuries, permitted it to do this without expense. But it shrank from taking upon itself further responsibility. Its practice may be compared with that of the branches of the Reichsbank.

On the other hand, the objections to a policy, which divided the country up for the purposes of paper currency, are also plain. The limitation of the areas of legal tender and of the offices where the notes were encashable on demand greatly restricted the popularity of the notes. It might well have seemed worth while to popularise them, even at the expense of temporary loss. As soon as the public had become[44] satisfied that the notes could be turned into coin readily and without question, their desire to cash them would probably have been greatly diminished. It is not certain that Government would have lost in the long–run if it had undertaken the responsibility and expense of regulating the flow of coin to the districts where it might be wanted at the different seasons of the year.

7. After the establishment of the Gold–Exchange Standard the importance of enlarging the functions of the note issue became apparent; and since 1900 the question of increasing the availability of the notes has been constantly to the front. In 1900 the Government issued a circular asking for opinions on certain proposals, including one for “universalising” the notes or making them legal tender in all circles. Some authorities thought that notes of small denominations (Rs. 5 and Rs. 10) might be safely universalised, without risk (on account of the trouble involved) of their being used for remittance on a large scale. It is on these lines that the use of the notes has been developed. In 1903 five–rupee notes were universalised except in Burma—that is to say, five–rupee notes of any circle were legal tender and encashable at any office of issue outside Burma; and in 1909 the Burmese limitation was removed.

In 1910 a great step forward was taken, and the law on the subject was consolidated by a new Act. Notes of Rs. 10 and Rs. 50 were universalised; and[45] power was taken to universalise notes of higher denominations by executive order. In pursuance of this authority notes of Rs. 100 were universalised in 1911. “At the same time the receipt of notes of the higher denominations in circles other than the circle of issue, in payment of Government dues and in payments to railways, post and telegraph offices, was stopped by executive orders”; and “with a view to minimise any tendency to make use of the new universal notes for remittance purposes, it was decided concurrently with the new Act to offer facilities to bankers and merchants to make trade remittances between the currency centres by means of telegraphic orders granted by Government at a reduced rate of premium.”[24] In the following year the Comptroller of Paper Currency reported that no difficulty whatever was experienced as the result of universalising the Rs. 10 and Rs. 50 notes; and the inconveniences, the fear of which had retarded the development of the note system for many years, were not realised.

8. The effect of these successive changes has been to make the old system of circles virtually inoperative. With notes of Rs. 100 universal legal tender it is difficult to see what can prevent the public from using them for purposes of remittance if they should wish to do so. The “circles” can no longer serve any useful purpose, and it would help to make clear[46] in the public mind the nature of the Indian note issue if they were to be abolished in name as well as in effect.

9. There must have been many occasions under the old system, on which ignorant persons suffered inconvenience through having notes of foreign circles passed off on them; and a long time may pass before distrust of the notes, as things not readily convertible, bred out of the memories of these occasions, entirely disappears. But, in combination with other circumstances, the universalising of the notes has had already a striking effect on the volume of their circulation, as is shown in the figures given below. It should be explained that by gross circulation (in the Government Statistics) is meant the value of all notes that have been issued and not yet paid off; that the net circulation is this sum less the value of notes held by Government in its own treasuries; and that the active circulation is the net reduced by the value of notes held by the Presidency banks at their head offices.[25] For some purposes the active circulation is the most important. But it is the reserve of rupees held against the gross circulation which is the best indication of the surplus volume of coined silver available, if necessary, for the purposes of circulation. The following table gives for various years the[47] average of the circulation on the last day of each month:—

| (In lakhs of rupees.) | (In £ million at 1s. 4d. the rupee throughout.) |

||||

| Gross. | Net. | Active. | Gross. | Active. | |

| 1892–1893 | 2710 | 2333 | 1953 | 18 | 13 |

| 1893–1894 | 2829 | 2083 | 1785 | 19 | 12 |

| 1899–1900 | 2796 | 2367 | 2127 | 18½ | 14 |

| 1900–1901 | 2888 | 2473 | 2205 | 19½ | 14½ |

| 1902–1903 | 3374 | 2735 | 2349 | 22½ | 15½ |

| 1904–1905 | 3920 | 3276 | 2811 | 26 | 18½ |

| 1906–1907 | 4514 | 3949 | 3393 | 30 | 22½ |

| 1908–1909 | 4452 | 3902 | 3310 | 29½ | 22 |

| 1909–1910 | 4966 | 4535 | 3721 | 33 | 25 |

| 1910–1911 | 5435 | 4648 | 3875 | 36 | 26 |

| 1911–1912 | 5737 | 4949 | 4189 | 38 | 28 |

The following table gives in £ million the gross circulation of currency notes on March 31 of each year:—

| £ million. | £ million. | |||

| 1900 | 19 | │ | 1909 | 30½ |

| 1902 | 21 | │ | 1910 | 36½ |

| 1904 | 25½ | │ | 1911 | 36½ |

| 1906 | 30 | │ | 1912 | 41 |

| 1908 | 31½ | │ | 1913 | 46 |

The following table gives the average monthly gross circulation in £ million (at 1s. 4d. the rupee throughout):—

| £ million. | ||||

| Five years ending | 1880–1881 | ——— | 8 | ½ |

| ”———”— | 1885–1886 | 9 | ½ | |

| ”———”— | 1890–1891 | 11 | ½ | |

| ”———”— | 1895–1896 | 19 | ||

| ”———”— | 1900–1901 | 17 | ½ | |

| ”———”— | 1905–1906 | 24 | ||

| ”———”— | 1910–1911 | 32 | ||

| The year | 1911–1912 | 38 | ||

10. The rules governing the reserves which must be held against currency notes are very simple. A certain fixed maximum, the amount of which is determined from time to time by law, may be held invested, chiefly in Government of India rupee securities. Up to 1890 the invested portion of the reserve amounted to 600 lakhs (Rs. 600,00,000). This was increased to 700 lakhs in 1891, to 800 lakhs in 1892, to 1000 lakhs in 1897; to 1200 lakhs, of which 200 lakhs might be in English Government securities, in 1905; and to 1400 lakhs (£9,333,000), of which 400 lakhs (£2,666,000) might be in English securities, in 1911. The interest thus accruing on the invested portion of the reserve, less the expenses of the Paper Currency Department, is credited to the general revenues of the Government under the head “Profits of Note Circulation.” This interest now amounts to £300,000 annually.

Up to 1898 the whole of the rest was held in silver coin in India. Under the Gold Note Act of 1898 the Government of India obtained authority to hold any part of the metallic portion of the reserve in gold coin. An Act of 1900 gave authority to hold part of this gold in London; but this power was only intended to be used for purposes of temporary convenience, and, although some gold was held in London in 1899 and 1900, this was not part of a permanent policy. An Act of 1905, however, gave full power to the Government to hold the metallic[49] portion of the reserve, or any part of it, at its free discretion, either in London or in India, or partly in both places, and also in gold coin or bullion, or in rupees or silver bullion, subject only to the exception that all coined rupees should be kept in India and not in London. The actual figures, showing where the gold reserve has been held at certain dates, are given below.

Gold in Paper Currency Reserve (£ Million).

| March 31. | In India. | In London. | Total. | |||

| 1897 | nil | – | nil | – | nil | – |

| 1898 | ¼ | nil | ¼ | |||

| 1899 | 2 | nil | 2 | |||

| 1900 | 7 | ½ | 1 | ½ | 9 | |

| 1901 | 6 | nil | 6 | |||

| 1902 | 7 | nil | 7 | |||

| 1903 | 10 | nil | 10 | |||

| 1904 | 11 | nil | 11 | |||

| 1905 | 10 | ½ | nil | 10 | ½ | |

| 1906 | 4 | 7 | 11 | |||

| 1907 | 3 | ½ | 7 | 10 | ½ | |

| 1908 | 2 | ½ | 3 | ½ | 6 | |

| 1909 | nil | 1 | ½ | 1 | ½ | |

| 1910 | 6 | 2 | ½ | 8 | ½ | |

| 1911 | 6 | 5 | 11 | |||

| 1912 | 15 | ½ | 5 | ½ | 21 | |

| 1913 | 19 | ½ | 6 | 25 | ½ | |

Distribution of Reserve, March 31, 1913.

| Rupees | £11,000,000 |

| Gold in India | 19,500,000 |

| Gold in London | 6,000,000 |

| Securities | 9,500,000 |

| ————— | |

| £46,000,000 | |

| ═══════ | |

11. Gold was originally accumulated in the reserve in India through the automatic working of the rule by which rupees could be obtained in exchange for sovereigns. After exchange touched par in 1898, we see from the above table that gold began to flow in. When in 1900 the accumulations reached £5,000,000, attempts were made, in accordance with the recommendations of the Fowler Committee, to force it into circulation.[26] After the comparative failure of this attempt, and the passing of the Act of 1905, as described above, the Paper Currency Chest in England was instituted, and by 1906 about two–thirds of the gold which had been accumulated up to that time was transferred to this fund. This stock is kept at the Bank of England, but is not included in the Bank of England’s own reserve. Gold which is thus transferred is said to be “ear–marked.” The fund is under the absolute control of the Secretary of State for India in Council, and transferences to it are, so far as the accounts of the Bank of England are concerned, reckoned as exports. Policy as to how much of the gold should be kept in London and how much in India has fluctuated from time to time. I shall discuss it in Chapter VI.

12. These are the chief relevant facts of law. Important considerations of policy do not lie so plainly on the surface. Since 1899 the circulation of notes has more than doubled, but the invested[51] portion of the reserve has been increased by only 40 per cent. As the note issue has become more firmly established and more widely used, a growing and not a diminishing proportion of the reserves has been kept in liquid form. This is due to a deliberate change of policy, and to the use of the liquid part of the reserve for a new purpose. The bullion reserve is no longer held solely with the object of securing the ability to meet the obligation to cash notes in legal tender (rupees or gold) on demand. It is now utilised for holding gold by means of which the Secretary of State can support exchange in times of depression and maintain at par the gold value of the rupee. For the sake of this object the Government are content to forego the extra profit which might be gained by increasing the investments, and have steadily increased instead (as shown in the table on p. 49) the gold portion of the reserve. The Paper Currency Reserve is thus used to provide the gold which is the first line of defence of the currency system as a whole, and hence can hardly be distinguished from the resources of the Gold Standard Reserve proper.

It is not profitable to discuss the reserve policy of the Paper Currency under existing conditions in isolation from the other reserves which the Government now hold. The whole problem of the reserves, regarded as a current practical question, is dealt with in Chapter VI. In this chapter I wish to look at the matter from a broad standpoint, with[52] an eye to the proper policy in a future, possibly remote.

13. The present policy was designed in its main outlines at a time when notes formed an insignificant part of the country’s currency, and when the system of circles still greatly restricted their usefulness. The notes were at first, and were intended to be, little more than silver certificates. The rules governing the Reserve were framed (see § 3) at a time which, to the modern student of currency, is almost prehistoric, under the influence of the Bank of England’s system of note issue and of the British Bank Act,—an Act which had the effect of destroying the importance of notes as a form of currency in England, and which it has been found impossible, in spite of some attempts, to imitate in the note–using countries of Europe. As has been urged in Chapter II., England is in matters of currency the worst possible model for India; for in no country are the conditions so wholly different. A good deal of experience with regard to note issues has now been accumulated elsewhere which ought some day to prove useful to India if her English rulers can sufficiently free themselves from their English traditions and preconceptions. Let me first give a short account of the nature of the seasonal demand for money in India; and then discuss the salient respects in which her system of note issue differs from those of typical note–using countries.

14. In contrast to what happens in the case of most note systems, the gross circulation in India diminishes instead of increasing during the busy seasons of autumn and spring. This is due to the fact that the Government Treasuries, the Presidency Banks, and possibly other banks and large merchants, use the notes as a convenient method of avoiding the custody of large quantities of silver during the slack season when rupees are not wanted.[27] That is to say, they deposit their surplus rupees during the summer in the Currency Reserve, holding their own reserves in the form of notes; and when the drain of rupees begins up country for moving the crops these notes have to be cashed. Thus in the dull season currency is largely in the hands of a class of persons and institutions which finds it most convenient to hold it in the form of notes, and in the busy season it is dissipated through the country and is, temporarily, in the hands of smaller men—cultivators who have sold their crops, small moneylenders and others, who habitually deal in small sums for which the rupee is the most convenient unit, or who do not yet understand the use of notes and still prefer, therefore, to be paid in actual coin.

15. Notes themselves, however, are used also, and to an increasing extent, for moving crops; and,[54] although the gross circulation falls during the busy season for the reasons just given, the active circulation (i.e., excluding the holdings of the Government Treasuries and the Presidency Banks) does, as we should expect, increase at this time of year. When, therefore, we are considering what proportion of liquid reserves ought to be maintained, or what part the note issue plays in supplying the much needed element of elasticity in the busy season, it is of the active rather than of the gross circulation that we must take account. The figures are given below in lakhs of rupees:—

| Months of Minimum and Maximum active circulation. |

1906–1907. | 1907–1908.(a) | 1908–1909. | 1909–1910. | 1910–1911. | 1911–1912. | ||||||

| 1. | 2. | 1. | 2. | 1. | 2. | 1. | 2. | 1. | 2. | 1. | 2. | |

| Min.— | ||||||||||||

| June | 31,15 | 14,41 | 35,04 | 13,01 | 31,13 | 14,12 | 34,19 | 15,10 | 36,58 | 20,37 | 38,44 | 19,78 |

| July | 32,43 | 12,87 | 34,34 | 15,89 | 31,58 | 16,52 | 34,31 | 17,22 | 36,56 | 22,60 | 39,15 | 21,14 |

| August | 32,11 | 13,59 | 34,30 | 17,47 | 31,90 | 12,71 | 35,49 | 16,25 | 36,86 | 21,20 | 40,99 | 18,70 |

| Max.— | ||||||||||||

| January | 35,54 | 9,11 | 33,20 | 8,62 | 33,67 | 8,54 | 41,47 | 10,37 | 39,67 | 11,45 | 44,14 | 10,56 |

| Feb | 36,07 | 9,42 | 33,28 | 9,38 | 34,36 | 9,50 | 41,42 | 9,12 | 40,95 | 12,57 | 44,58 | 12,61 |

| March | 36,45 | 10,50 | 32,61 | 14,28 | 34,95 | 10,54 | 39,98 | 14,43 | 40,17 | 14,82 | 44,61 | 16,75 |

Columns(1): Active circulation. Columns(2): Holdings of Treasuries and Presidency

Banks, i.e., excess of gross over active circulation.

(a) An abnormal year.

We see, therefore, that, while the notes held by the Presidency Banks and the Treasury fall in the busy season by 700 to 1000 lakhs below their highest figure in the slack season, the active circulation increases in the busy season over its lowest figure in the slack season by about 400 lakhs (in the latest year for which we have figures, 1911–1912, by more than[55] 600 lakhs). Of course this is not a very high proportion of the total increase in the volume of currency which is required in the busy season. But it is an amount well worth considering, and these figures put the note issue in a more favourable light as a source of currency in the busy season than is usually realised. The relative importance of notes and rupees[28] in supplying the seasonal needs of trade is well shown in the following table:—

Net Absorption (in Lakhs of Rupees) of Currency into Circulation (+) or Return of Currency from Circulation (–).(a)

| Year. | April to June. | July to Sept. | Oct. to Dec. | Jan. to March. | Whole Year. | |||||||||||||||

| Rupees. | Notes. | Rupees. | Notes. | Rupees. | Notes. | Rupees. | Notes. | Rupees. | Notes. | |||||||||||

| 1905–1906 | – | 116 | + | 83 | + | 339 | + | 58 | + | 1139 | + | 175 | + | 88 | + | 101 | + | 1450 | + | 417 |

| 1906–1907 | – | 24 | – | 148 | + | 600 | + | 220 | + | 1068 | + | 310 | + | 156 | 0 | + | 1800 | + | 382 | |

| 1907–1908 | + | 182 | – | 141 | + | 145 | + | 29 | + | 735 | – | 126 | – | 670 | – | 146 | + | 392 | – | 384 |

| 1908–1909 | – | 798 | – | 148 | – | 718 | + | 198 | + | 339 | + | 112 | – | 311 | + | 72 | – | 1488 | + | 234 |

| 1909–1910 | + | 47 | – | 76 | – | 58 | + | 286 | + | 1065 | + | 130 | + | 268 | + | 163 | + | 1322 | + | 503 |

| 1910–1911 | – | 287 | – | 340 | – | 100 | + | 147 | + | 722 | + | 144 | – | 1 | + | 68 | + | 334 | + | 19 |

| 1911–1912 | – | 130 | – | 173 | + | 220 | + | 262 | + | 499 | + | 356 | + | 565 | – | 1 | + | 1154 | + | 444 |

(a) In this table rupees (but not notes) in the Presidency Banks are treated as being in circulation. It would be a troublesome piece of work to exclude them, and would make, I think, very little difference to the result. The main variable element in the reserves of the Presidency Banks is the notes, and these are duly allowed for in the above table.

The above table is exceedingly instructive. It shows that the notes supply an increasingly important proportion of the seasonal demand for additional currency. It shows also that the demand for notes from one year to another has been of a steadier character than the demand for rupees. In the period[56] of depression from the winter of 1907 until the autumn of 1908 the active rupee circulation was much harder hit than the active note circulation; for in the six months January to June 1908 the rupee circulation fell by 1468 lakhs, while the active note circulation fell by 294 lakhs, and for the nine months January to September 1908 the former fell by 2186 lakhs, while the latter fell by only 96 lakhs.[29]

16. Let me now turn to three salient characteristics, all closely connected with one another, and chiefly distinguishing the Indian system of paper currency from those of most note–using countries.

In the first place, the function of note–issue is wholly dissociated in India from the function of banking. To discount bills is one of the functions of banks. Where there are Central Banks with the right of note issue, they are usually able, subject to various restrictions, to increase their note issue at certain seasons of the year in order to discount more bills.

In the second place, as there is no Central Bank in India, there is no Government Banker. It is true that the Government keep some funds (rather more than £2,000,000, as a rule) at the three Presidency Banks. But the bulk of their floating resources is held either in London or in cash in their own Treasuries in India. Thus, as in the United States, the Government maintains an independent Treasury system. This[57] means, just as it does in the United States, that, at certain seasons of the year when taxes are flowing in fastest, funds may sometimes be withdrawn from the money market. The difficulty and inconvenience to which this system has given rise in the United States are well known to those who are acquainted with the recent financial history of that country. The ill effects of it are to a certain extent counteracted, in the case of India, by a transference of these funds to London and a release of the accumulating currency in India through the sale of Council Bills. But this is not a perfect solution.