Title: A History of Sumer and Akkad

Author: L. W. King

Release date: July 2, 2015 [eBook #49345]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Madeleine Fournier and Marc D'Hooghe (Images generously made available by the Hathi Trust.)

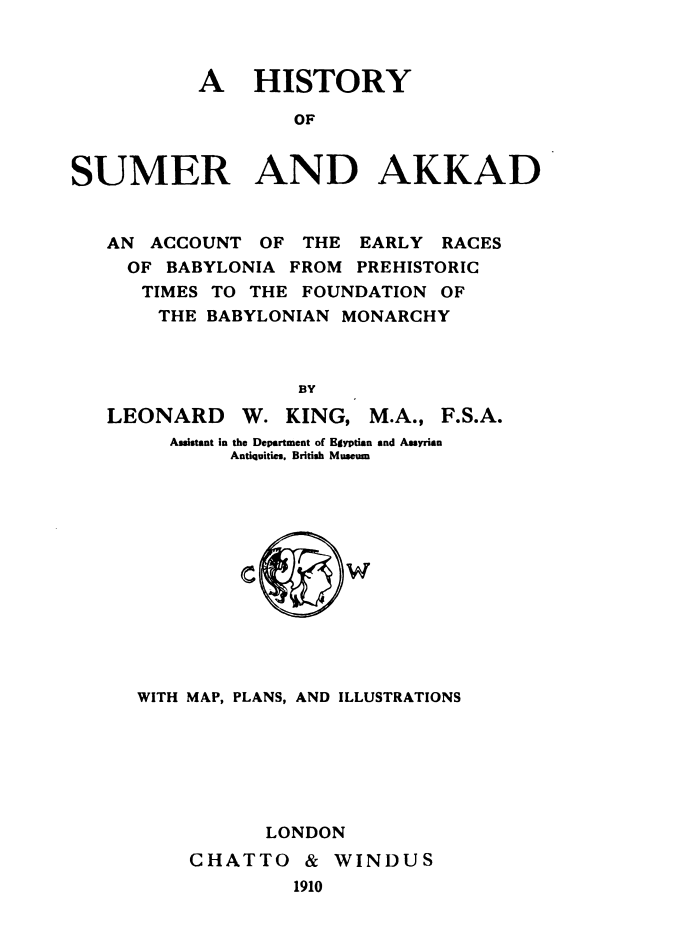

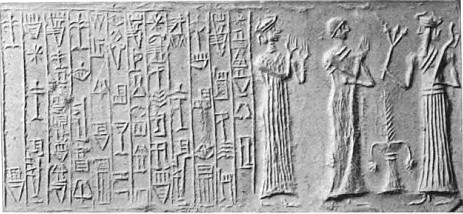

Stele of Narâm-Sin, king of Agade, representing the king and his allies in triumph over their enemies.—Photo, Mansell & Co.

The excavations carried out in Babylonia and Assyria during the last few years have added immensely to our knowledge of the early history of those countries, and have revolutionized many of the ideas current with regard to the age and character of Babylonian civilization. In the present volume, which deals with the history of Sumer and Akkad, an attempt is made to present this new material in a connected form, and to furnish the reader with the results obtained by recent discovery and research, so far as they affect the earliest historical periods. An account is here given of the dawn of civilization in Mesopotamia, and of the early city-states which were formed from time to time in the lands of Sumer and Akkad, the two great divisions into which Babylonia was at that period divided. The primitive sculpture and other archaeological remains, discovered upon early Babylonian sites, enable us to form a fairly complete picture of the races which in those remote ages inhabited the country. By their help it is possible to realize how the primitive conditions of life were gradually modified, and how from rude beginnings there was developed the comparatively advanced civilization, which was inherited by the later Babylonians and Assyrians and exerted a remarkable influence upon other races of the ancient world.

In the course of this history points are noted at which early contact with other lands took place, and it[Pg vi] has been found possible in the historic period to trace the paths by which Sumerian culture was carried beyond the limits of Babylonia. Even in prehistoric times it is probable that the great trade routes of the later epoch were already open to traffic, and cultural connections may well have taken place at a time when political contact cannot be historically proved. This fact must be borne in mind in any treatment of the early relations of Babylonia with Egypt. As a result of recent excavation and research it has been found necessary to modify the view that Egyptian culture in its earlier stages was strongly influenced by that of Babylonia. But certain parallels are too striking to be the result of coincidence, and, although the southern Sumerian sites have yielded traces of no prehistoric culture as early as that of the Neolithic and predynastic Egyptians, yet the Egyptian evidence suggests that some contact may have taken place between the prehistoric peoples of North Africa and Western Asia.

Far closer were the ties which connected Sumer with Elam, the great centre of civilization which lay upon her eastern border, and recent excavations in Persia have disclosed the extent to which each civilization was of independent development. It was only after the Semitic conquest that Sumerian culture had a marked effect on that of Elam, and Semitic influence persisted in the country even under Sumerian domination. It was also through the Semitic inhabitants of northern Babylonia that cultural elements from both Sumer and Elam passed beyond the Taurus, and, after being assimilated by the Hittites, reached the western and south-western coasts of Asia Minor. An attempt has therefore been made to estimate, in the light of recent discoveries, the manner in which Babylonian culture affected the early civilizations of Egypt, Asia, and the West. Whether through direct or indirect[Pg vii] channels, the cultural influence of Sumer and Akkad was felt in varying degrees throughout an area extending from Elam to the Aegean.

In view of the after effects of this early civilization, it is of importance to determine the region of the world from which the Sumerian race reached the Euphrates. Until recently it was only possible to form a theory on the subject from evidence furnished by the Sumerians themselves. But explorations in Turkestan, the results of which have now been fully published, enable us to conclude with some confidence that the original home of the Sumerian race is to be sought beyond the mountains to the east of the Babylonian plain. The excavations conducted at Anau near Askhabad by the second Pumpelly Expedition have revealed traces of prehistoric cultures in that region, which present some striking parallels to other early cultures west of the Iranian plateau. Moreover, the physiographical evidence collected by the first Pumpelly Expedition affords an adequate explanation of the racial unrest in Central Asia, which probably gave rise to the Sumerian immigration and to other subsequent migrations from the East.

It has long been suspected that a marked change in natural conditions must have taken place during historic times throughout considerable areas in Central Asia. The present comparatively arid condition of Mongolia, for example, is in striking contrast to what it must have been in the era preceding the Mongolian invasion of Western Asia in the thirteenth century, and travellers who have followed the route of Alexander's army, on its return from India through Afghanistan and Persia, have noted the difference in the character of the country at the present day. Evidence of a similar change in natural conditions has now been collected in Russian Turkestan, and the process is[Pg viii] also illustrated as a result of the explorations conducted by Dr. Stein, on behalf of the Indian Government, on the borders of the Taklamakan Desert and in the oases of Khotan. It is clear that all these districts, at different periods, were far better watered and more densely populated than they are to-day, and that changes in climatic conditions have reacted on the character of the country in such a way as to cause racial migrations. Moreover, there are indications that the general trend to aridity has not been uniform, and that cycles of greater aridity have been followed by periods when the country was capable of supporting a considerable population. These recent observations have an important bearing on the Sumerian problem, and they have therefore been treated in some detail in Appendix I.

The physical effects of such climatic changes would naturally be more marked in mid-continental regions than in districts nearer the coast, and the immigration of Semitic nomads into Syria and Northern Babylonia may possibly have been caused by similar periods of aridity in Central Arabia. However this may be, it is certain that the early Semites reached the Euphrates by way of the Syrian coast, and founded their first Babylonian settlements in Akkad. It is still undecided whether they or the Sumerians were in earliest occupation of Babylonia. The racial character of the Sumerian gods can best be explained on the supposition that the earliest cult-centres in the country were Semitic; but the absence of Semitic idiom from the earliest Sumerian inscriptions is equally valid evidence against the theory. The point will probably not be settled until excavations have been undertaken at such North Babylonian sites as El-Ohêmir and Tell Ibrâhîm.

That the Sumerians played the more important[Pg ix] part in originating and moulding Babylonian culture is certain. In government, law, literature and art the Semites merely borrowed from their Sumerian teachers, and, although in some respects they improved upon their models, in each case the original impulse came from the Sumerian race. Hammurabi's Code of Laws, for example, which had so marked an influence on the Mosaic legislation, is now proved to have been of Sumerian origin; and recent research has shown that the later religious and mythological literature of Babylonia and Assyria, by which that of the Hebrews was also so strongly affected, was largely derived from Sumerian sources.

The early history of Sumer and Akkad is dominated by the racial conflict between Semites and Sumerians, in the course of which the latter were gradually worsted. The foundation of the Babylonian monarchy marks the close of the political career of the Sumerians as a race, although, as we have seen, their cultural achievements long survived them in the later civilizations of Western Asia. The designs upon the cover of this volume may be taken as symbolizing the dual character of the early population of the country. The panel on the face of the cover represents two Semitic heroes, or mythological beings, watering the humped oxen or buffaloes of the Babylonian plain, and is taken from the seal of Ibni-Sharru, a scribe in the service of the early Akkadian king Shar-Gani-sharri. The panel on the back of the binding is from the Stele of the Vultures and portrays the army of Eannatum trampling on the dead bodies of its foes. The shaven faces of the Sumerian warriors are in striking contrast to the heavily bearded Semitic type upon the seal.

A word should, perhaps, be said on two further subjects—the early chronology and the rendering of Sumerian proper names. The general effect of recent[Pg x] research has been to reduce the very early dates, which were formerly in vogue. But there is a distinct danger of the reaction going too far, and it is necessary to mark clearly the points at which evidence gives place to conjecture. It must be admitted that all dates anterior to the foundation of the Babylonian monarchy are necessarily approximate, and while we are without definite points of contact between the earlier and later chronology of Babylonia, it is advisable, as far as possible, to think in periods. In the Chronological Table of early kings and rulers, which is printed as Appendix II., a scheme of chronology has been attempted; and the grounds upon which it is based are summarized in the third chapter, in which the age of the Sumerian civilization is discussed.

The transliteration of many of the Sumerian proper names is also provisional. This is largely due to the polyphonous character of the Sumerian signs; but there is also no doubt that the Sumerians themselves frequently employed an ideographic system of expression. The ancient name of the city, the site of which is marked by the mounds of Tello, is an instance in point. The name is written in Sumerian as Shirpurla, with the addition of the determinative for place, and it was formerly assumed that the name was pronounced as Shirpurla by the Sumerians. But there is little doubt that, though written in that way, it was actually pronounced as Lagash, even in the Sumerian period. Similarly the name of its near neighbour and ancient rival, now marked by the mounds of Jôkha, was until recently rendered as it is written, Gishkhu or Gishukh; but we now know from a bilingual list that the name was actually pronounced as Umma. The reader will readily understand that in the case of less famous cities, whose names have not yet been found in the later syllabaries and bilingual texts, the[Pg xi] phonetic readings may eventually have to be discarded. When the renderings adopted are definitely provisional, a note has been added to that effect.

I take this opportunity of thanking Dr. E. A. Wallis Budge for permission to publish photographs of objects illustrating the early history of Sumer and Akkad, which are preserved in the British Museum. My thanks are also due to Monsieur Ernest Leroux, of Paris, for kindly allowing me to make use of illustrations from works published by him, which have a bearing on the excavations at Tello and the development of Sumerian art; to Mr. Raphael Pumpelly and the Carnegie Institution of Washington, for permission to reproduce illustrations from the official records of the second Pumpelly Expedition; and to the editor of Nature for kindly allowing me to have clichés made from blocks originally prepared for an article on "Transcaspian Archaeology," which I contributed to that journal. With my colleague, Mr. H. R. Hall, I have discussed more than one of the problems connected with the early relations of Egypt and Babylonia; and Monsieur F. Thureau-Dangin, Conservateur-adjoint of the Museums of the Louvre, has readily furnished me with information concerning doubtful readings upon historical monuments, both in the Louvre itself, and in the Imperial Ottoman Museum during his recent visit to Constantinople. I should add that the plans and drawings in the volume are the work of Mr. P. C. Carr, who has spared no pains in his attempt to reproduce with accuracy the character of the originals.

L. W. KING.

INTRODUCTORY: THE LANDS OF SUMER AND AKKAD

Trend of recent archaeological research—The study of origins—The Neolithic period in the Aegean area, in the region of the Mediterranean, and in the Nile Valley—Scarcity of Neolithic remains in Babylonia due largely to character of the country—Problems raised by excavations in Persia and Russian Turkestan—Comparison of the earliest cultural remains in Egypt and Babylonia—The earliest known inhabitants of South Babylonian sites—The "Sumerian Controversy" and a shifting of the problem at issue—Early relations of Sumerians and Semites—The lands of Sumer and Akkad—Natural boundaries—Influence of geological structure—Effect of river deposits—Euphrates and the Persian Gulf—Comparison of Tigris and Euphrates—The Shatt en-Nîl and the Shatt el-Kâr—The early course of Euphrates and a tendency of the river to break away westward—Changes in the swamps—Distribution of population and the position of early cities—Rise and fall of the rivers and the regulation of the water—Boundary between Sumer and Akkad—Early names for Babylonia—"The Land" and its significance—Terminology—1

THE SITES OF EARLY CITIES AND THE RACIAL CHARACTER OF THEIR INHABITANTS

Characteristics of early Babylonian sites—The French excavations at Tello—The names Shirpurla and Lagash—Results of De Sarzec's work—German excavations at Surghul and El-Hibba—The so-called "fire-necropoles"—Jôkha and its ancient name—Other mounds in the region of the Shatt el-Kâr—Hammâm—Tell 'Îd—Systematic excavations at Fâra (Shuruppak)—Sumerian dwelling-houses and circular buildings of unknown use—Sarcophagus-graves and mat-burials—Differences in burial customs—Diggings at Abû Hatab (Kisurra)—Pot-burials—Partial examination of Bismâya (Adab)—Hêtime—Jidr—The fate of cities which escaped the Western Semites—American excavations at Nippur—British work at Warka (Erech), Senkera (Larsa), Tell Sifr, Tell Medîna, Mukayyar (Ur), Abû Shahrain (Eridu), and Tell Lahm—Our knowledge of North Babylonian sites—Excavations at Abû Habba (Sippar), and recent work at Babylon and Borsippa—The sites of Agade, Cutha, Kish and Opis—The French excavations at Susa—Sources of our information on the racial problem—Sumerian and Semitic types—Contrasts[Pg xiv] in treatment of the hair, physical features, and dress—Apparent inconsistencies—Evidence of the later and the earlier monuments—Evidence from the racial character of Sumerian gods—Professor Meyer's theory and the linguistic evidence—Present condition of the problem—The original home and racial affinity of the Sumerians—Path of the Semitic conquest—Origin of the Western Semites—The eastern limits of Semitic influence—16

THE AGE AND PRINCIPAL ACHIEVEMENTS OF SUMERIAN CIVILIZATION

Effect of recent research on older systems of chronology—Reduction of very early dates and articulation of historical periods—Danger of the reaction going too far and the necessity for noting where evidence gives place to conjecture—Chronology of the remoter ages and our sources of information—Classification of material—Bases of the later native lists and the chronological system of Berossus—Palaeography and systematic excavation—Relation of the early chronology to that of the later periods—Effect of recent archaeological and epigraphic evidence—The process of reckoning from below and the foundations on which we may build—Points upon which there is still a difference of opinion—Date for the foundation of the Babylonian Monarchy—Approximate character of all earlier dates and the need to think in periods—Probable dates for the Dynasties of Ur and Isin—Dates for the earlier epochs and for the first traces of Sumerian civilization—Pre-Babylonian invention of cuneiform writing—The origins of Sumerian culture to be traced to an age when it was not Sumerian—Relative interest attaching to many Sumerian achievements—Noteworthy character of the Sumerian arts of sculpture and engraving—The respective contributions of Sumerian and Semite—Methods of composition in Sumerian sculpture and attempts at an unconventional treatment—Perfection of detail in the best Sumerian work—Casting in metal and the question of copper or bronze—Solid and hollow castings and copper plating—Terra-cotta figurines—The arts of inlaying and engraving—The more fantastic side of Sumerian art—Growth of a naturalistic treatment in Sumerian design—Period of decadence—56

THE EARLIEST SETTLEMENTS IN SUMER; THE DAWN OF HISTORY AND THE RISE OF LAGASH

Origin of the great cities—Local cult-centres in the prehistoric period—The earliest Sumerian settlements—Development of the city-god and evolution of a pantheon—Lunar and solar cults—Gradual growth of a city illustrated by the early history of Nippur and its shrine—Buildings of the earliest Sumerian period at Tello—Store-houses and washing-places of a primitive agricultural community—The inhabitants of the country as portrayed in archaic sculpture—Earliest written records and the prehistoric system of land tenure—The first rulers of Shuruppak and their office—Kings and patesis of early city-states—The dawn of history in Lagash and the[Pg xv] suzerainty of Kish—Rivalry of Lagash and Umma and the Treaty of Mesilim—The rôle of the city-god and the theocratic feeling of the time—Early struggles of Kish for supremacy—Connotation of royal titles in the early Sumerian period—Ur-Ninâ the founder of a dynasty in Lagash—His reign and policy—His sons and household—The position of Sumerian women in social and official life—The status of Lagash under Akurgal—84

WARS OF THE CITY-STATES; EANNATUM AND THE STELE OF THE VULTURES

Condition of Sumer on the accession of Eannatum—Outbreak of war between Umma and Lagash—Raid of Ningirsu's territory and Eannatum's vision—The defeat of Ush, patesi of Umma, and the terms of peace imposed on his successor—The frontier-ditch and the stelæ of delimitation—Ratification of the treaty at the frontier-shrines—Oath-formulæ upon the Stele of the Vultures—Original form of the Stele and the fragments that have been recovered—Reconstitution of the scenes upon it—Ningirsu and his net—Eannatum in battle and on the march—Weapons of the Sumerians and their method of fighting in close phalanx—Shield-bearers and lance-bearers—Subsidiary use of the battle-axe—The royal arms and body-guard—The burial of the dead after battle—Order of Eannatum's conquests—Relations of Kish and Umma—The defeat of Kish, Opis and Mari, and Eannatum's suzerainty in the north—Date of his southern conquests and evidence of his authority in Sumer—His relations with Elam, and the other groups of his campaigns—Position of Lagash under Eannatum—His system of irrigation—Estimate of his reign—120

THE CLOSE OF UR-NINÂ'S DYNASTY, THE REFORMS OF URUKAGINA, AND THE FALL OF LAGASH

Cause of break in the direct succession at Lagash—Umma and Lagash in the reign of Enannatum I.—Urlumma's successful raid—His defeat by Entemena and the annexation of his city—Entemena's cone and its summary of historical events—Extent of Entemena's dominion—Sources for history of the period between Enannatum II. and Urukagina—The relative order of Enetarzi, Enlitarzi and Lugal-anda—Period of unrest in Lagash—Secular authority of the chief priests and weakening of the patesiate—Struggles for the succession—The sealings of Lugal-anda and his wife—Break in traditions inaugurated by Urukagina—Causes of an increase in officialdom and oppression—The privileges of the city-god usurped by the patesi and his palace—Tax-gatherers and inspectors "down to the sea"—Misappropriation of sacred lands and temple-property, and corruption of the priesthood—The reforms of Urukagina—Abolition of unnecessary posts and stamping out of abuses—Revision of burial fees—Penalties for theft and protection for the poorer classes—Abolition of diviner's fees and regulation of divorce—The laws of Urukagina and the Sumerian origin of Hammurabi's Code—Urukagina's relations to other cities—Effect of his reforms on the stability of the state—The fall of Lagash—157

EARLY RULERS OF SUMER AND KINGS OF KISH

Close of an epoch in Sumerian history—Increase in the power of Umma and transference of the capital to Erech—Extent of Lugal-zaggisi's empire, and his expedition to the Mediterranean coast—Period of Lugal-kigub-nidudu and Lugal-kisalsi—The dual kingdom of Erech and Ur—Eushagkushanna of Sumer and his struggle with Kish—Confederation of Kish and Opis—Enbi-Ishtar of Kish and a temporary check to Semitic expansion southwards—The later kingdom of Kish—Date of Urumush and extent of his empire—Economic conditions in Akkad as revealed by the Obelisk of Manishtusu—Period of Manishtusu's reign and his military expeditions—His statues from Susa—Elam and the earlier Semites—A period of transition—New light on the foundations of the Akkadian Empire—192

THE EMPIRE OF AKKAD AND ITS RELATION TO KISH

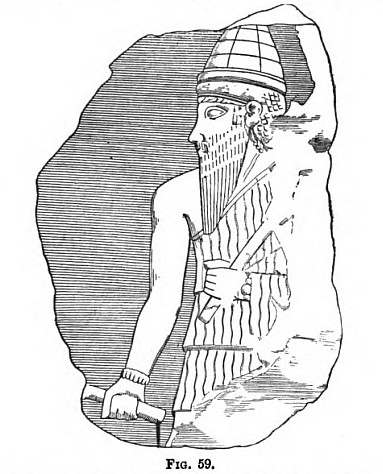

Sargon of Agade and his significance—Early recognition of his place in history—The later traditions of Sargon and the contemporary records of Shar-Gani-sharri's reign—Discovery at Susa of a monument of "Sharru-Gi, the King"—Probability that he was Manishtusu's father and the founder of the kingdom of Kish—Who, then, was Sargon?—Indications that only names and not facts have been confused in the tradition—The debt of Akkad to Kish in art and politics—Expansion of Semitic authority westward under Shar-Gani-sharri—The alleged conquest of Cyprus—Commercial intercourse at the period and the disappearance of the city-state—Evidence of a policy of deportation—The conquest of Narâm-Sin and the "Kingdom of the Four Quarters"—His Stele of Victory and his relations with Elam—Narâm-Sin at the upper reaches of the Tigris, and the history of the Pir Hussein Stele—Narâm-Sin's successors—Representations of Semitic battle-scenes—The Lagash Stele of Victory, probably commemorating the original conquest of Kish by Akkad—Independent Semitic principalities beyond the limits of Sumer and Akkad—The reason of Akkadian pre-eminence and the deification of Semitic kings—216

THE LATER RULERS OF LAGASH

Sumerian reaction tempered by Semitic influence—Length of the intervening period between the Sargonic era and that of Ur—Evidence from Lagash of a sequence of rulers in that city who bridge the gap—Archaeological and epigraphic data—Political condition of Sumer and the semi-independent position enjoyed by Lagash—Ur-Bau representative of the earlier patesis of this epoch—Increase in the authority of Lagash under Gudea—His conquest of Anshan—His relations with Syria, Arabia, and the Persian Gulf—His influence of a commercial rather than of a political character—Development in the art of building which marked the later Sumerian[Pg xvii] period—Evolution of the Babylonian brick and evidence of new architectural ideas—The rebuilding of E-ninnû and the elaborate character of Sumerian ritual—The art of Gudea's period—His reign the golden age of Lagash—Gudea's posthumous deification and his cult—The relations of his son, Ur-Ningirsu, to the Dynasty of Ur—252

THE DYNASTY OF UR AND THE KINGDOM OF SUMER AND AKKAD

The part taken by Ur against Semitic domination in an earlier age, and her subsequent history—Organization of her resources under Ur-Engur—His claim to have founded the kingdom of Sumer and Akkad—The subjugation of Akkad by Dungi and the Sumerian national revival—Contrast in Dungi's treatment of Babylon and Eridu—Further evidence of Sumerian reaction—The conquests of Dungi's earlier years and his acquisition of regions formerly held by Akkad—His adoption of the bow as a national weapon—His Elamite campaigns and the difficulty in retaining control of conquered provinces—His change of title and assumption of divine rank—Survival of Semitic influence in Elam under Sumerian domination—Character of Dungi's Elamite administration—His reforms in the official weight-standards and the system of time-reckoning—Continuation of Dungi's policy by his successors—The cult of the reigning monarch carried to extravagant lengths—Results of administrative centralization when accompanied by a complete delegation of authority by the king—Plurality of offices and provincial misgovernment the principal causes of a decline in the power of Ur—278

THE EARLIER RULERS OF ELAM, THE DYNASTY OF ISIN, AND THE RISE OF BABYLON

Continuity of the kingdom of Sumer and Akkad and the racial character of the kings of Isin—The Elamite invasion which put an end to the Dynasty of Ur—Native rulers of Elam represented by the dynasties of Khutran-tepti and Ebarti—Evidence that a change in titles did not reflect a revolution in the political condition of Elam—No period of Elamite control in Babylonia followed the fall of Ur—Sources for the history of the Dynasty of Isin—The family of Ishbi-Ura and the cause of a break in the succession—Rise of an independent kingdom in Larsa and Ur, and the possibility of a second Elamite invasion—The family of Ur-Ninib followed by a period of unrest in Isin—Relation of the Dynasty of Isin to that of Babylon—The suggested Amorite invasion in the time of Libit-Ishtar disproved—The capture of Isin in Sin-muballit's reign an episode in the war of Babylon with Larsa—The last kings of Isin and the foundation of the Babylonian Monarchy—Position of Babylon in the later historical periods, and the close of the independent political career of the Sumerians as a race—The survival of their cultural influence—303

THE CULTURAL INFLUENCE OF SUMER IN EGYPT, ASIA AND THE WEST

Relations of Sumer and Akkad with other lands—Cultural influences, carried by the great trade-routes, often independent of political contact—The prehistoric relationship of Sumerian culture to that of Egypt—Alleged traces of strong cultural influence—The hypothesis of a Semitic invasion of Upper Egypt in the light of more recent excavations—Character of the Neolithic and early dynastic cultures of Egypt, as deduced from a study of the early graves and their contents—Changes which may be traced to improvements in technical skill—Confirmation from a study of the skulls—Native origin of the Egyptian system of writing and absence of Babylonian influence—Misleading character of other cultural comparisons—Problem of the bulbous mace-head and the stone cylindrical seal—Prehistoric migrations of the cylinder—Semitic elements in Egyptian civilization—Syria a link in the historic period between the Euphrates and the Nile—Relations of Elam and Sumer—Evidence of early Semitic influence in Elamite culture and proof of its persistence—Elam prior to the Semitic conquest—The Proto-Elamite script of independent development—Its disappearance paralleled by that of the Hittite hieroglyphs—Character of the earlier strata of the mounds at Susa and presence of Neolithic remains—The prehistoric pottery of Susa and Mussian—Improbability of suggested connections between the cultures of Elam and of predynastic Egypt—More convincing parallels in Asia Minor and Russian Turkestan—Relation of the prehistoric peoples of Elam to the Elamites of history—The Neolithic settlement at Nineveh and the prehistoric cultures of Western Asia—Importance of Syria in the spread of Babylonian culture westward—The extent of early Babylonian influence in Cyprus, Crete, and the area of Aegean civilization—321

I. Recent Explorations in Turkestan in their Relation to the Sumerian Problem—351

II. A Chronological List of the Kings and Rulers of Sumer and Akkad—359

INDEX—363

LIST OF PLATES

I. Stele of Narâm-Sin, representing the king and his allies in triumph over their enemie — Frontispiece

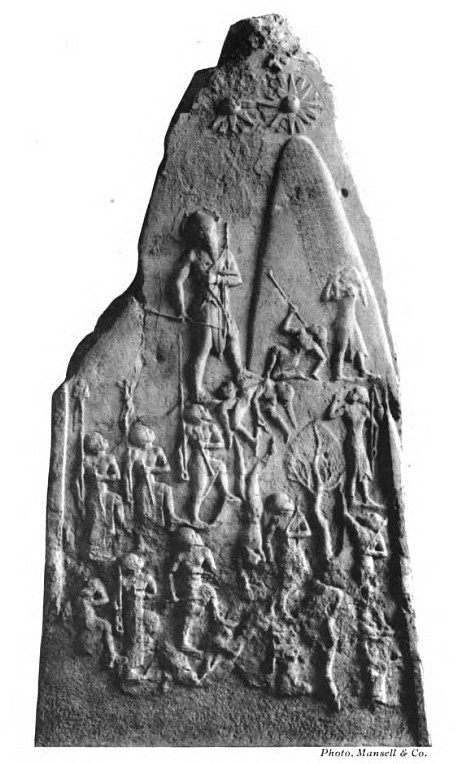

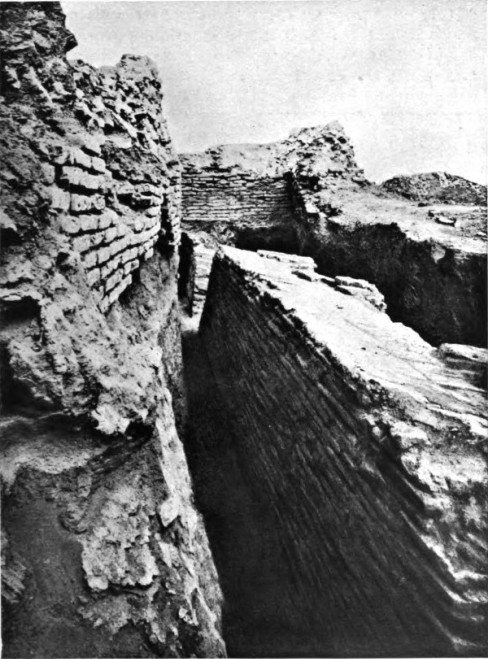

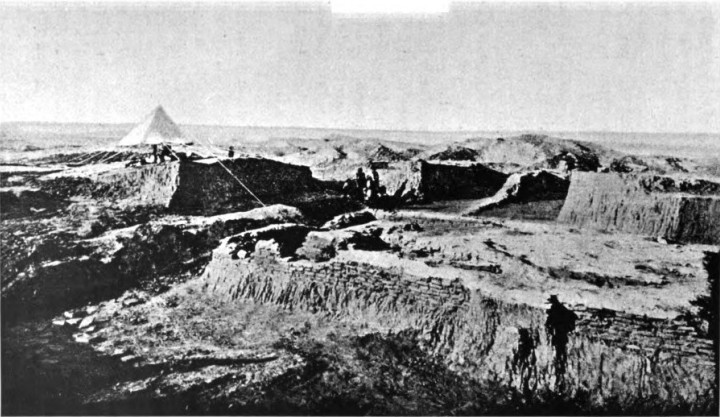

II. Doorway of a building at Tello erected by Gudea; on the left is a later building of the Seleucid Era 20

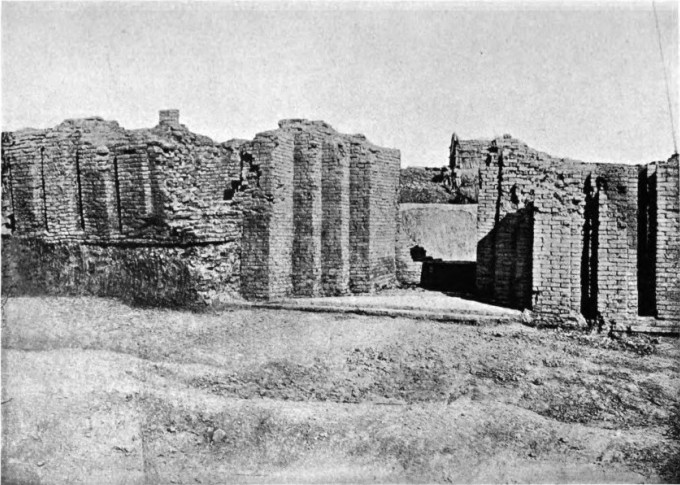

III. Outer face of a foundation-wall at Tello, built by Ur-Bau 26

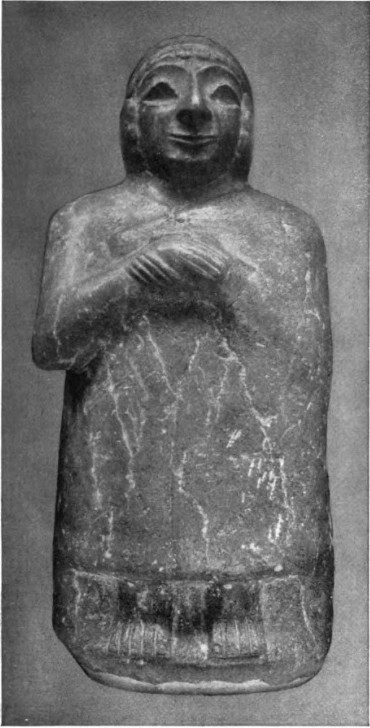

IV. Limestone figure of an early Sumerian patesi, or high official 40

V. Fragment of Sumerian sculpture representing scenes of worship 52

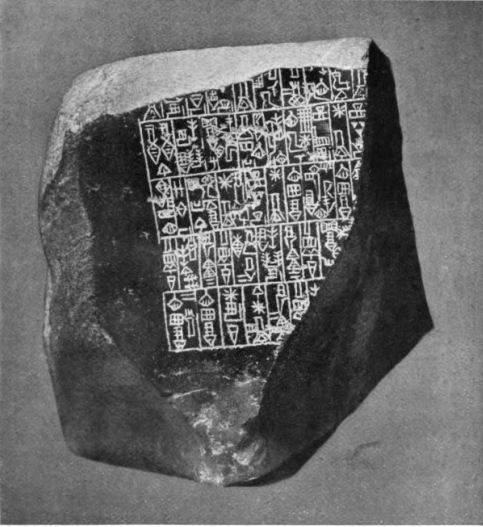

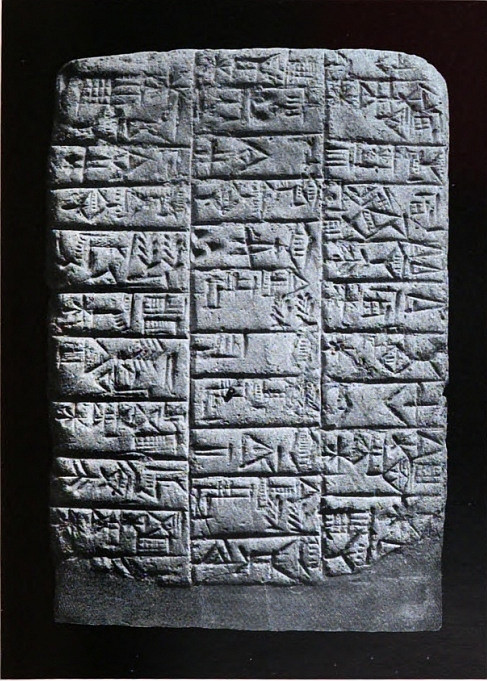

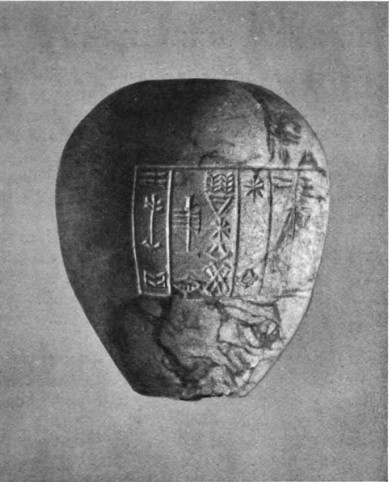

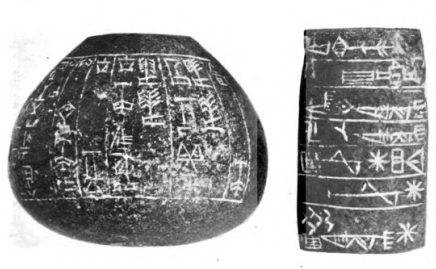

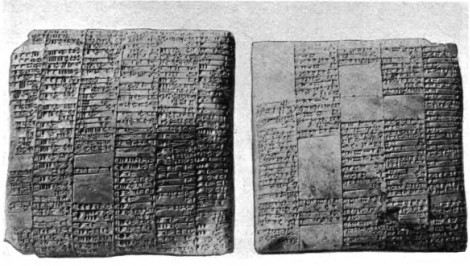

VI. The Blau monuments 62

VII. Diorite statue of Gudea, represented as the architect of the temple of Gatumdug 66

VIII. Clay relief stamped with the figure of a Babylonian hero, and fragment of limestone sculptured in relief; both objects illustrate the symbol of the spouting vase 72

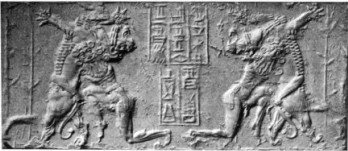

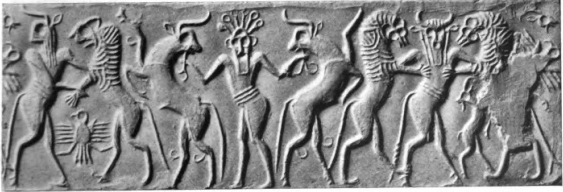

IX. Impressions of early cylinder-seals, engraved with scenes representing heroes and mythological beings in conflict with lions and bulls 76

X. South-eastern facade of a building at Tello, erected by Ur-Ninâ 90

XI. Limestone figures of early Sumerian rulers 102

XII. Plaques of Ur-Ninâ and of Dudu 111

XIII. Portion of these "Stele of the Vultures" sculptured with scenes representing Eannatum leading his troops in battle and on the march 124

XIV. The burial of the dead after battle 138

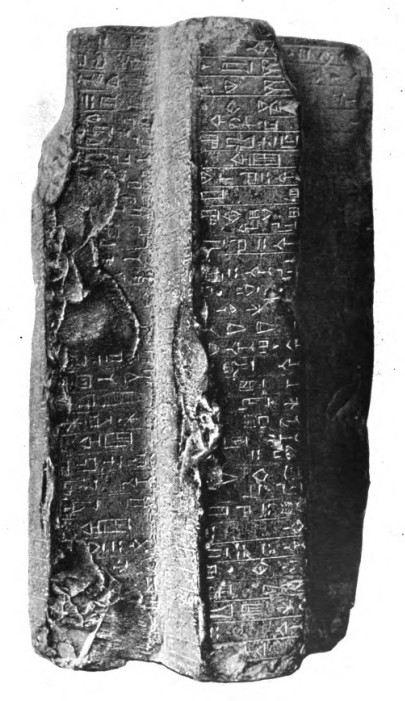

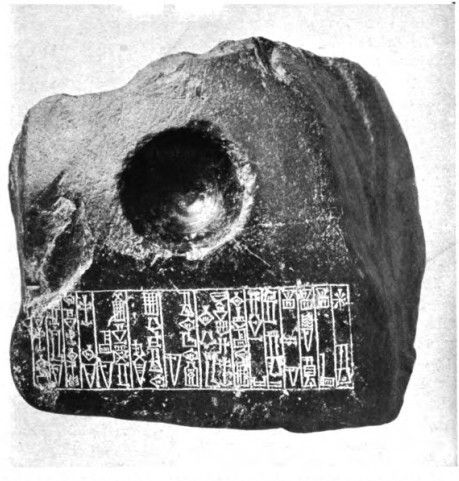

XV. Portion of a black basalt mortar bearing an inscription of Eannatum 146

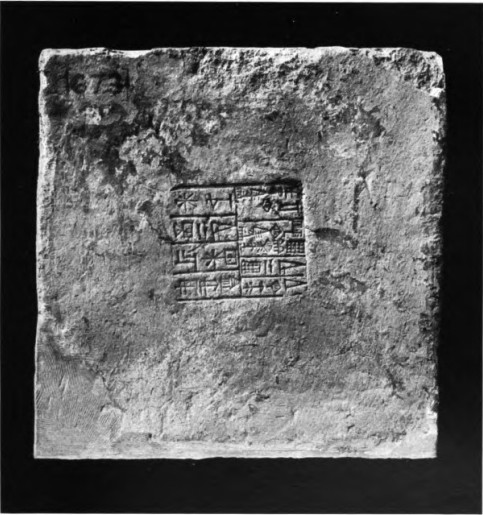

XVI. Brick of Eannatum, recording his genealogy and conquests and commemorating the sinking of a well in the temple of Ningirsu 154

XVII. Marble gate-socket, bearing an inscription of Entemena 162

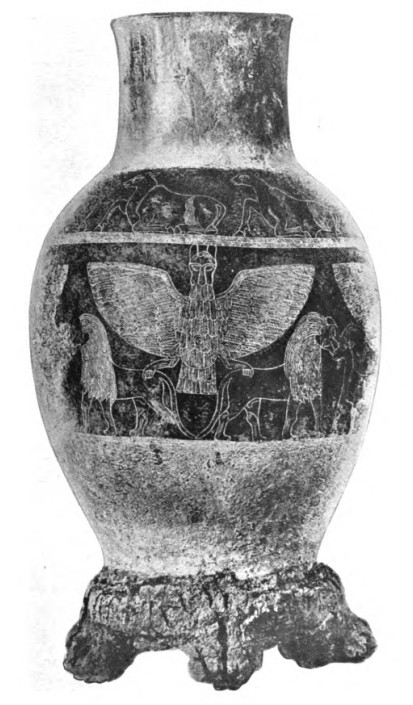

XVIII. Silver vase dedicated to the god Ningirsu by Entemena 168

XIX. Mace-heads and part of a diorite statuette dedicated to various deities 206

XX. Mace-head dedicated to the Sun-god by Shar-Gani-sharri, and other votive objects 218

XXI. Cruciform stone object inscribed with a votive text of an early Semitic king of Kish 224

XXII. Impressions of the cylinder-seals of Ubil-Ishtar, Khashkhamer, and Kilulla 247

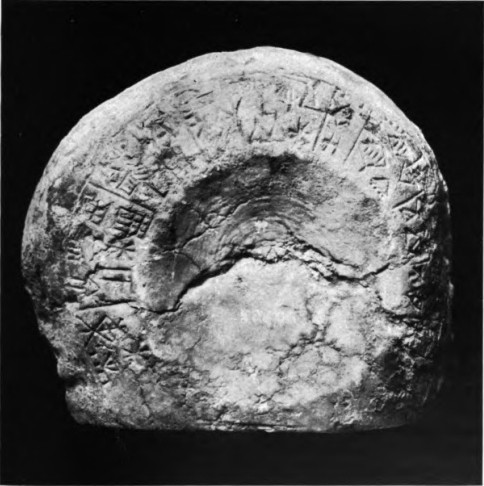

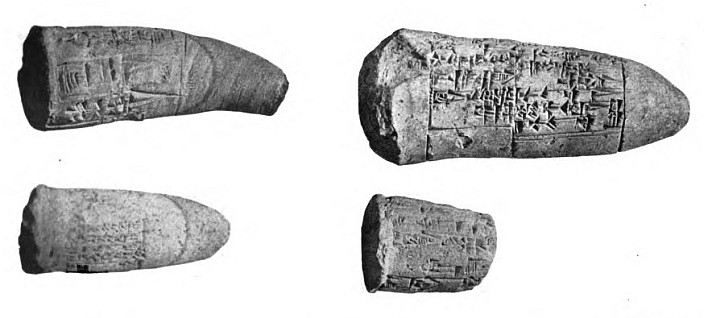

XXIII. Clay cones of Galu-Babbar and other rulers 259

XXIV. Brick pillar at Tello, of the time of Gudea 263

XXV. Seated figure of Gudea 268

XXVI. Votive cones and figures 273

XXVII. Gate-socket of Gudea, recording the restoration of the temple of the goddess Ninâ 274

XXVIII. Brick of Ur-Engur, King of Ur, recording the rebuilding of the temple of Ninni in Erech 280

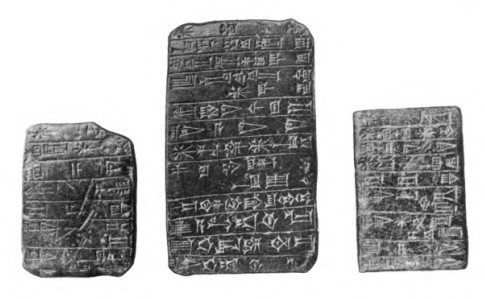

XXIX. Votive tablets of Dungi, King of Ur, and other rulers 288

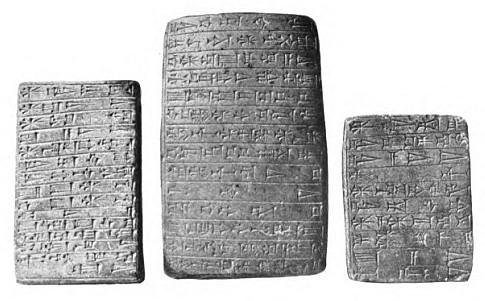

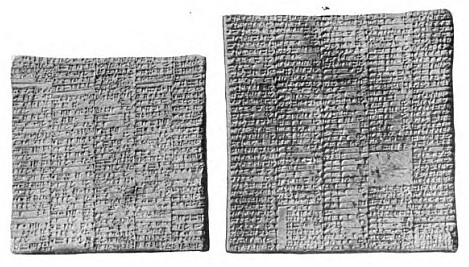

XXX. Clay tablets of temple-accounts, drawn up in Dungi's reign 292

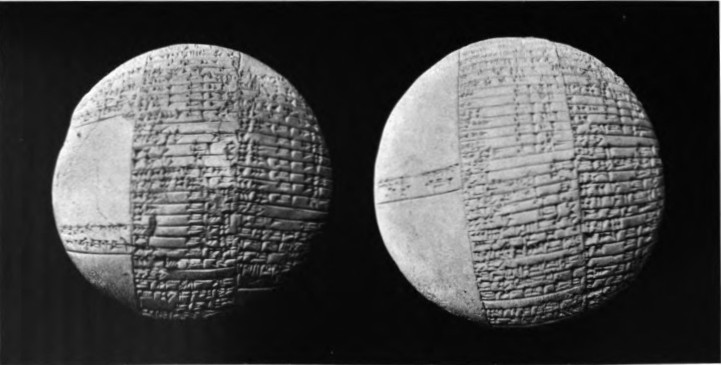

XXXI. Circular tablets of the reign of Bûr-Sin, King of Ur 298

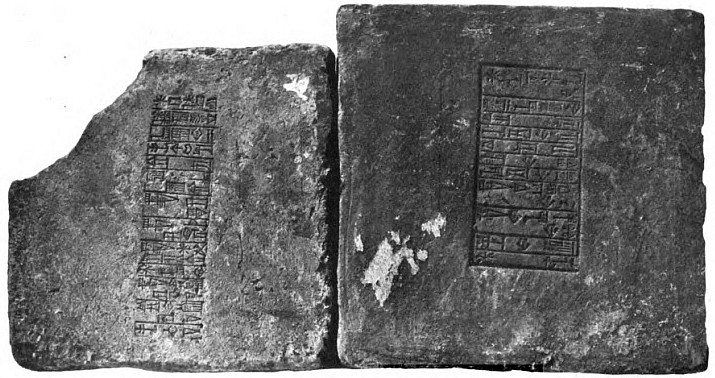

XXXII. Bricks of Bûr-Sin, King of Ur, and Ishme-Dagan, King of Isin 310

XXXIII. Specimens of clay cones bearing votive inscriptions 314

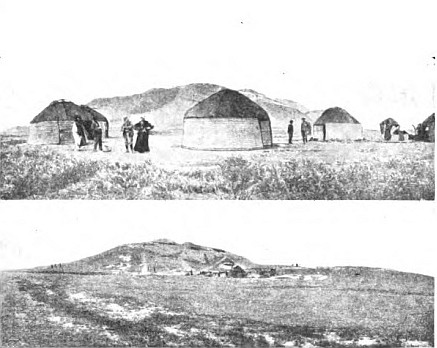

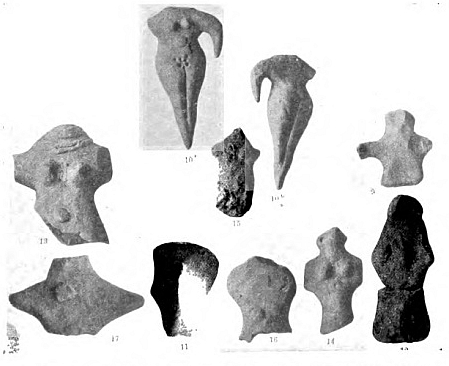

XXXIV. (i and ii) The North and South Kurgans at Anau in Russian Turkestan. (iii) Terra-cotta figurines of the copper age culture from the South Kurgan at Anau 352

ILLUSTRATIONS IN THE TEXT

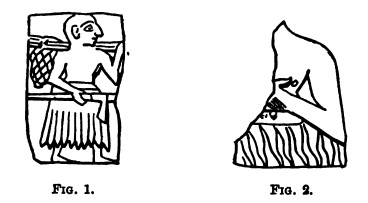

1-2. Figures of early Sumerians engraved upon fragments of shell. Earliest period: from Tello 41

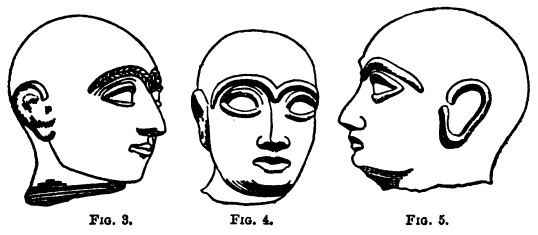

3-5. Later types of Sumerians, as exhibited by heads of male statuettes from Tello 42

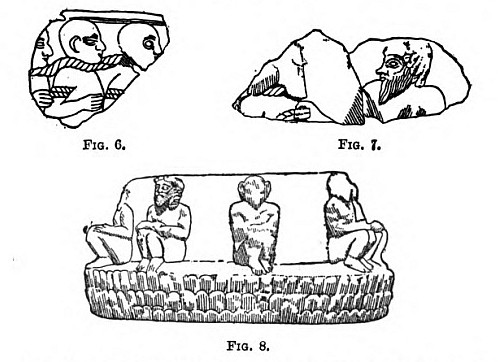

6-8. Examples of sculpture of the later period, representing different racial types 44

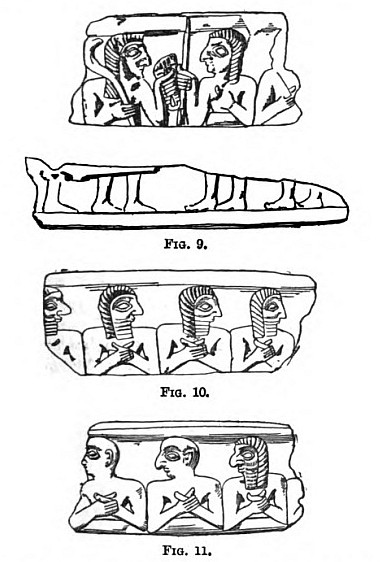

9-11. Fragments of a circular bas-relief of the earliest period, commemorating the meeting of two chieftains and their followers 45

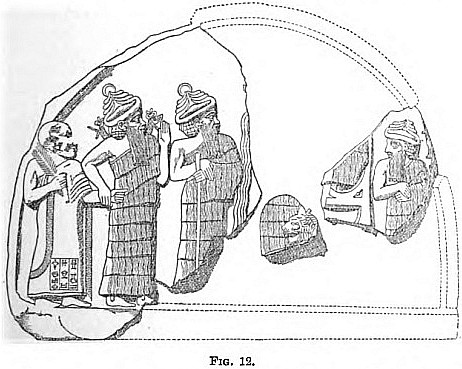

12. Limestone panel representing Gudea being led by Ningishzida and another deity into the presence of a seated god 47

13. Figure of the seated god on the cylinder-seal of Gudea 48

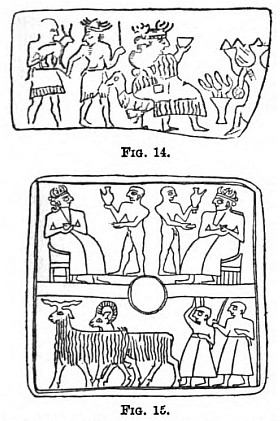

14-15. Examples of early Sumerian deities on votive tablets from Nippur 49

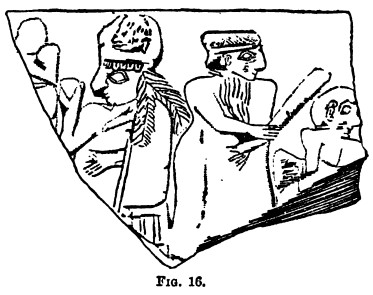

16. Fragment of an archaic relief from Tello, representing a god smiting a bound captive with a heavy club or mace 50

17-19. Earlier and later forms of divine headdresses 51

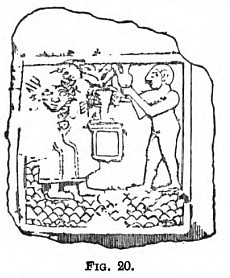

20. Perforated plaque engraved with a scene representing the pouring out of a libation before a goddess 68

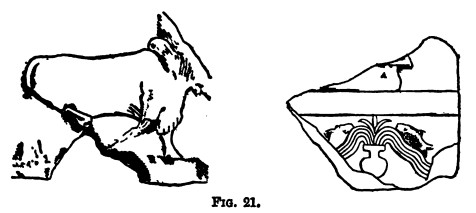

21. Fragments of sculpture belonging to the best period of Sumerian art 69

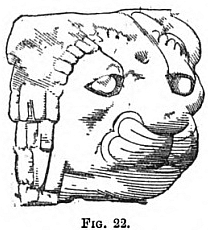

22. Limestone head of a lion from the corner of a basin in Ningirsu's temple 70

23. Upper part of a female statuette of diorite, of the period of Gudea or a little later 71

24. Limestone head of a female statuette belonging to the best period of Sumerian art 72

25. One of a series of copper female foundation-figures with supporting rings 74

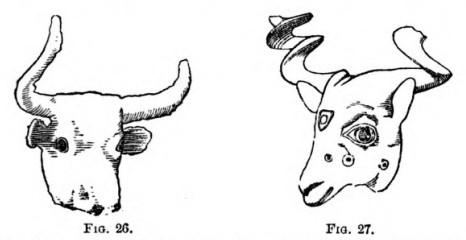

26-27. Heads of a bull and goat, cast in copper and inlaid with mother-of-pearl, lapis-lazuli, etc. 75

28. Stamped terra-cotta figure of a bearded god, wearing a horned headdress 75

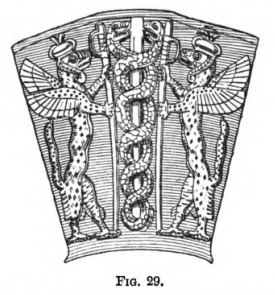

29. Scheme of decoration from a libation-vase of Gudea, made of dark green steatite and originally inlaid with shell 76

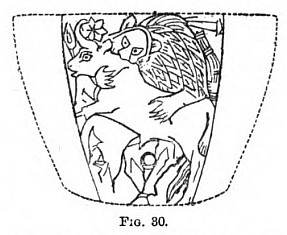

30. Convex panel of shell from the side of a cup, engraved with a scene representing a lion attacking a bull 79

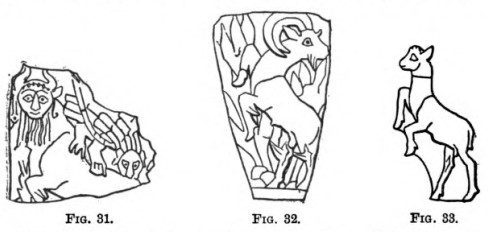

31-33. Fragments of shell engraved with animal forms, which illustrate the growth of a naturalistic treatment in Sumerian design 80

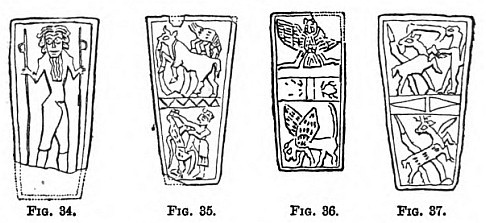

34-37. Panels of mother-of-pearl engraved with Sumerian designs, which were employed for inlaying the handles of daggers 82

38. Archaic plaque from Tello, engraved in low relief with a scene of adoration 94

39. Figure of Lupad, a high official of the city of Umma 96

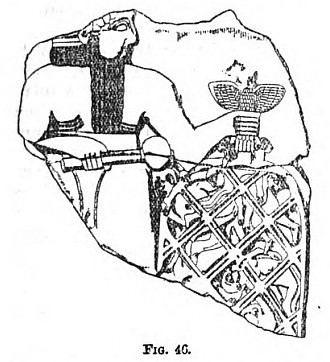

40. Statue of Esar, King of Adah 97

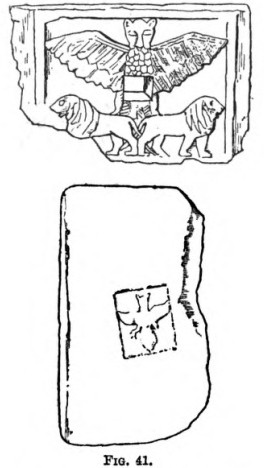

41. Emblems of Lagash and of the god Ningirsu 98

42. Mace-head dedicated to Ningirsu by Mesilim, King of Kish 99

43. Early Sumerian figure of a woman, showing the Sumerian dress and the method of doing the hair 112

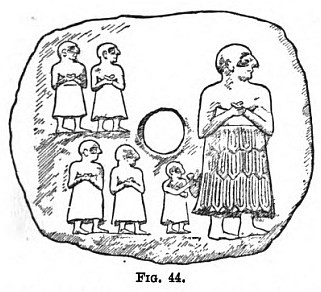

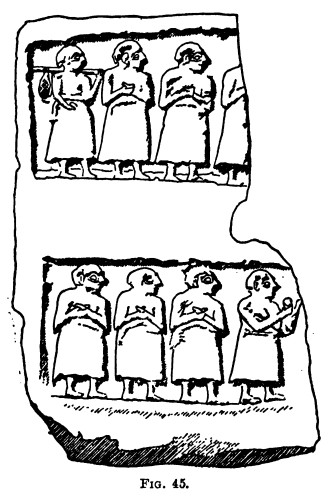

44. Plaque of Ur-Ninâ, King of Lagash 113

45. Portion of a plaque of Ur-Ninâ, sculptured with representations of his sons and the high officials of his court 114

46. Part of the Stele of the Vultures representing Ningirsu clubbing the enemies of Lagash in his net 131

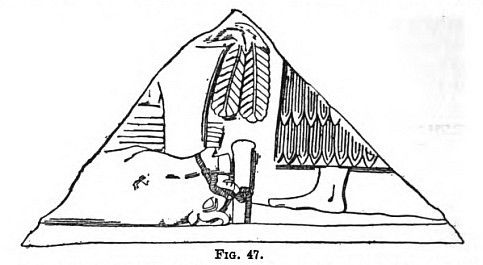

47. Part of the Stele of the Vultures sculptured with a sacrificial scene which took place at the burial of the dead after battle 140

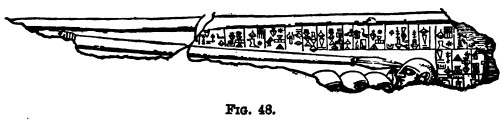

48. Part of the Stele of the Vultures representing Eannatum deciding the fate of prisoners taken in battle 141

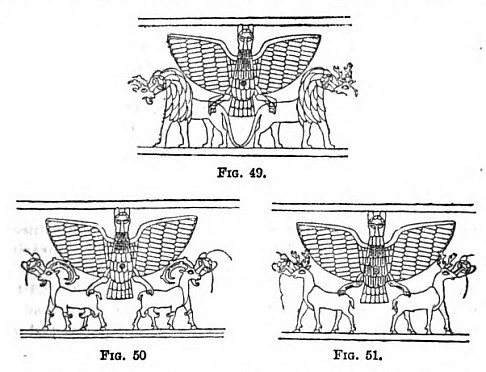

49-51. Details from the engravings upon Entemena's silver vase 167

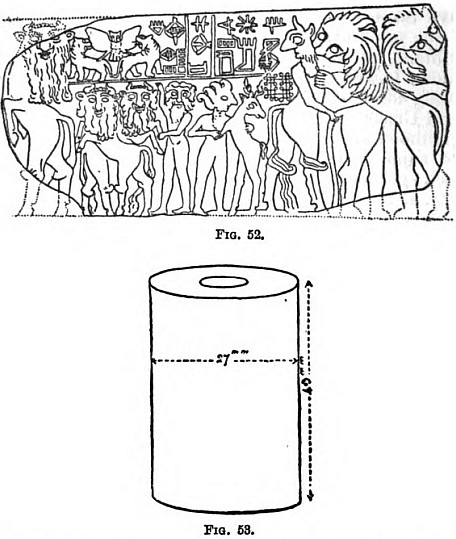

52-53. Seal-impression of Lugal-anda, patesi of Lagash, with reconstruction of the cylinder-seal 173

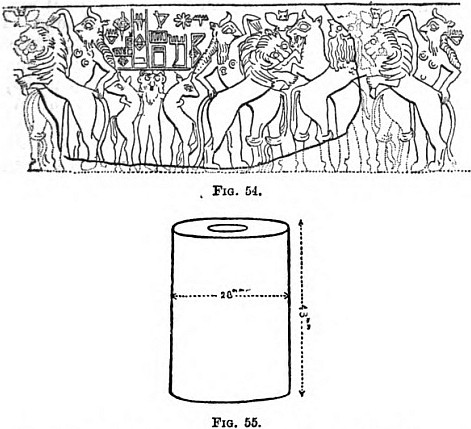

54-55. A second seal-impression of Lugal-anda, with reconstruction of the cylinder 175

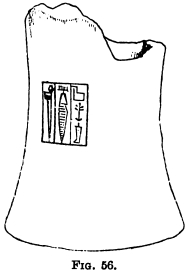

56. White marble vase engraved with the name and title of Urumush, King of Kish 204

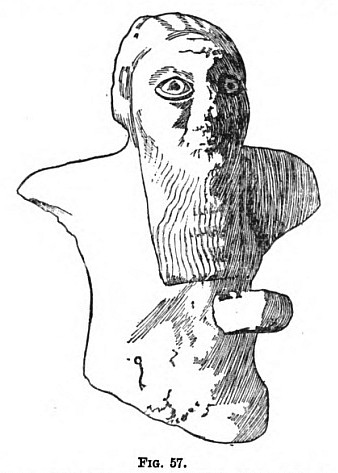

57. Alabaster statue of Manishtusu, King of Kish 214

58. Copper head of a colossal votive lance engraved with the name and title of an early king of Kish 229

59. Stele of Narâm-Sin, King of Akkad, from Pir Hussein 244

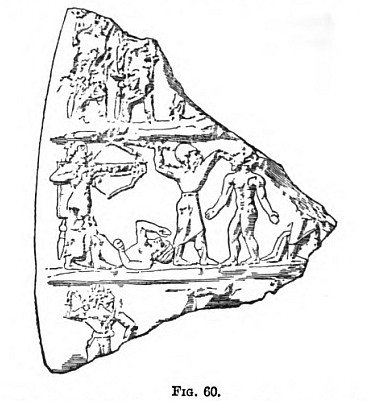

60. Portion of a Stele of Victory of a king of Akkad, sculptured in relief with battle-scenes; from Tello 248

61. Other face of Fig. 60 249

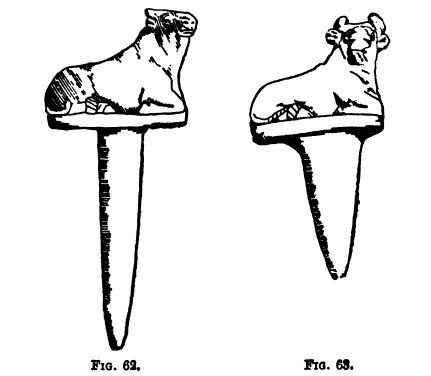

62-63. Copper figures of bulls surmounting cones, which were employed as votive offerings in the reigns of Gudea and Dungi 256

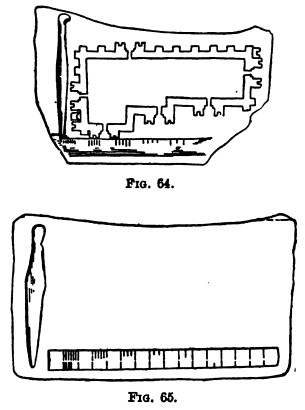

64-65. Tablets with architect's rule and stilus from the statues B and F of Gudea 265

66. Figure of a god seated upon a throne, who may probably be identified with Ningirsu 268

67. Mace-head of breccia from a mountain near the "Upper Sea" or Mediterranean, dedicated to Ningirsu by Gudea 271

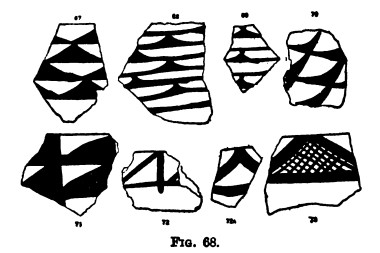

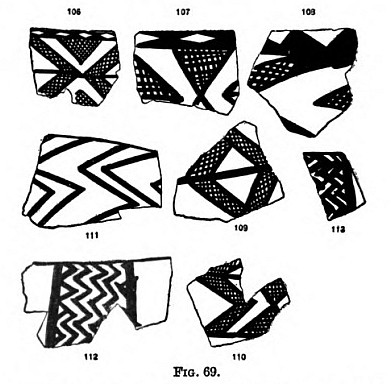

68. Designs on painted potsherds of the Neolithic period (Culture I.) from the North Kurgan at Anau 355

69. Designs on painted potsherds of the Aeneolithic period (Culture II.) from the North Kurgan at Anau 356

MAPS AND PLANS

I. Plan of Tello, after De Sarzec 19

II. Plan of Jôkha, after Andrae 22

III. Plan of Fâra, after Andrae and Noeldeke 25

IV. Plan of Abû Hatab, after Andrae and Noeldeke 29

V. Plan of Warka, after Loftus 33

VI. Plan of Muḳayyar, after Taylor 34

VII. Plan of Abû Shahrain, after Taylor 36

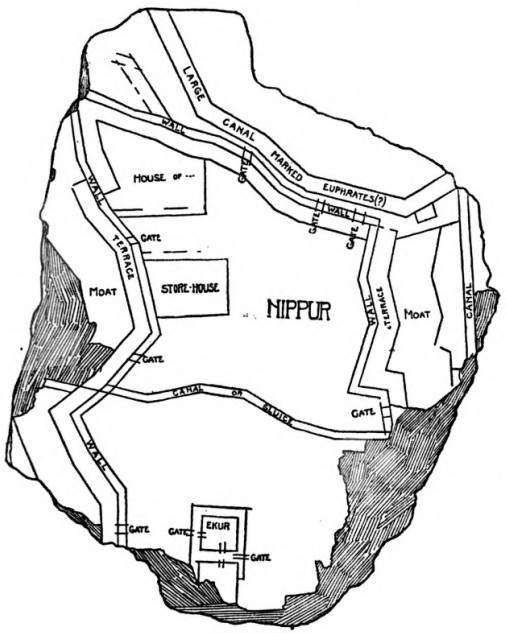

VIII. Early Babylonian plan of the temple of Enlil at Nippur and its enclosure; cf. Fisher, "Excavations at Nippur" I., pl. 1 87

IX. Plan of the Inner City at Nippur, after Fisher, "Excavations at Nippur," I., p. 10 88

X. Plan of the store-house of Ur-Ninâ, at Tello, after De Sarzec 92

XI. Plan of early building at Tello, after De Sarzec 93

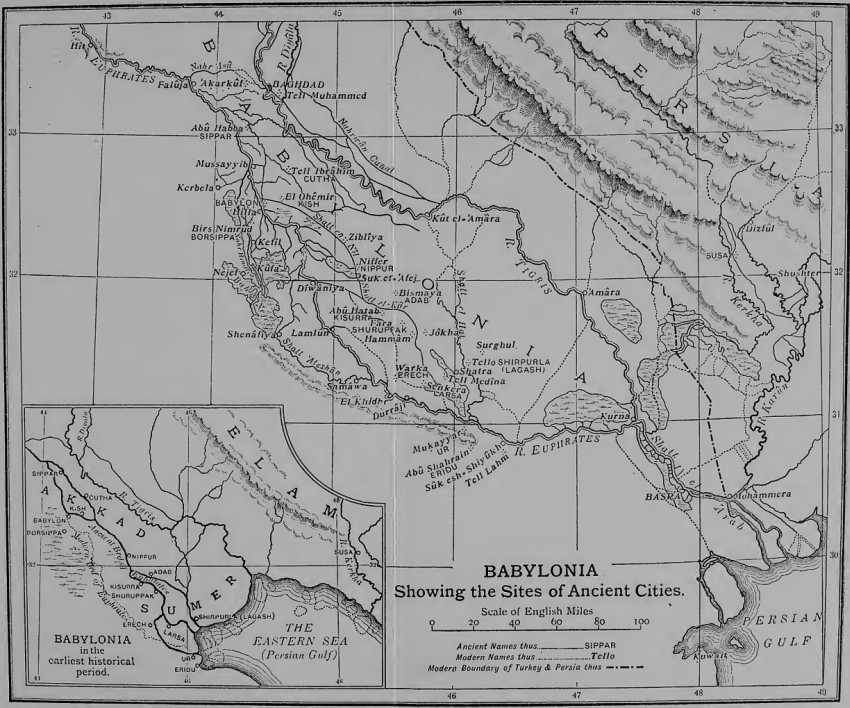

XII. Map of Babylonia, showing the sites of early cities. Inset: Map of Sumer and Akkad in the earliest historical period 380

The study of origins may undoubtedly be regarded as the most striking characteristic of recent archaeological research. There is a peculiar fascination in tracking any highly developed civilization to its source, and in watching its growth from the rude and tentative efforts of a primitive people to the more elaborate achievements of a later day. And it is owing to recent excavation that we are now in a position to elucidate the early history of the three principal civilizations of the ancient world. The origins of Greek civilization may now be traced beyond the Mycenean epoch, through the different stages of Aegean culture back into the Neolithic age. In Egypt, excavations have not only yielded remains of the early dynastic kings who lived before the pyramid-builders, but they have revealed the existence of Neolithic Egyptians dating from a period long anterior to the earliest written records that have been recovered. Finally, excavations in Babylonia have enabled us to trace the civilization of Assyria and Babylon back to an earlier and more primitive race, which in the remote past occupied the lower plains of the Tigris and Euphrates; while the more recent digging in Persia and Turkestan has thrown light upon other primitive inhabitants of Western Asia, and has raised problems with regard to their cultural connections with the West which were undreamed of a few years ago.

It will thus be noted that recent excavation and[Pg 2] research have furnished the archaeologist with material by means of which he may trace back the history of culture to the Neolithic period, both in the region of the Mediterranean and along the valley of the Nile. That the same achievement cannot be placed to the credit of the excavator of Babylonian sites is not entirely due to defects in the scope or method of his work, but may largely be traced to the character of the country in which the excavations have been carried out. Babylonia is an alluvial country, subject to constant inundation, and the remains and settlements of the Neolithic period were doubtless in many places swept away, and all trace of them destroyed by natural causes. With the advent of the Sumerians began the practice of building cities upon artificial mounds, which preserved the structure of the buildings against flood, and rendered them easier of defence against a foe. It is through excavation in these mounds that the earliest remains of the Sumerians have been recovered; but the still earlier traces of Neolithic times, which at some period may have existed on those very sites, must often have been removed by flood before the mounds were built. The Neolithic and pre-historic remains discovered during the French excavations in the graves of Mussian and at Susa, and by the Pumpelly expedition in the two Kurgans near Anau, do not find their equivalents in the mounds of Babylonia so far as these have yet been examined.

In this respect the climate and soil of Babylonia present a striking contrast to those of ancient Egypt. In the latter country the shallow graves of Neolithic man, covered by but a few inches of soil, have remained intact and undisturbed at the foot of the desert hills; while in the upper plateaus along the Nile valley the flints of Palaeolithic man have lain upon the surface of the sand from Palaeolithic times until the present day. But what has happened in so rainless a country as Egypt could never have taken place in Mesopotamia. It is true that a few palaeoliths have been found on the surface of the Syrian desert, but in the alluvial plains of Southern Chaldaea, as in the Egyptian Delta itself, few certain traces of prehistoric man have[Pg 3] been forthcoming. Even in the early mat-burials and sarcophagi at Fâra numerous copper objects[1] and some cylinder-seals have been found, while other cylinders, sealings, and even inscribed tablets, discovered in the same and neighbouring strata, prove that their owners were of the same race as the Sumerians of history, though probably of a rather earlier date.

Although the earliest Sumerian settlements in Southern Babylonia are to be set back in a comparatively remote period, the race by which they were founded appears at that time to have already attained to a high level of culture. We find them building houses for themselves and temples for their gods of burnt and unburnt brick. They are rich in sheep and cattle, and they have increased the natural fertility of their country by means of a regular system of canals and irrigation-channels. It is true that at this time their sculpture shared the rude character of their pottery, but their main achievement, the invention of a system of writing by means of lines and wedges, is in itself sufficient indication of their comparatively advanced state of civilization. Derived originally from picture-characters, the signs themselves, even in the earliest and most primitive inscriptions as yet recovered, have already lost to a great extent their pictorial character, while we find them employed not only as ideograms to express ideas, but also phonetically for syllables. The use of this complicated system of writing by the early Sumerians presupposes an extremely long period of previous development. This may well have taken place in their original home, before they entered the Babylonian plain. In any case, we must set back in the remote past the beginnings of this ancient people, and we may probably picture their first settlement in the neighbourhood of the Persian Gulf some centuries before the period to which we may assign the earliest of their remains that have actually come down to us.

In view of the important rôle played by this early race in the history and development of civilization in Western Asia, it is of interest to recall the fact that not[Pg 4] many years ago the very existence of the Sumerians was disputed by a large body of those who occupied themselves with the study of the history and languages of Babylonia. What was known as "the Sumerian controversy" engaged the attention of writers on these subjects, and divided them into two opposing schools. At that time not many actual remains of the Sumerians themselves had been recovered, and the arguments in favour of the existence of an early non-Semitic race in Babylonia were in the main drawn from a number of Sumerian texts and compositions which had been found in the palace of the Assyrian king, Ashur-banipal, at Nineveh. A considerable number of the tablets recovered from the royal library were inscribed with a series of compositions, written, it is true, in the cuneiform script, but not in the Semitic language of the Assyrians and Babylonians. To many of these compositions Assyrian translations had been added by the scribes who drew them up, and upon other tablets were found lists of the words employed in the compositions, together with their Assyrian equivalents. The late Sir Henry Rawlinson rightly concluded that these strange texts were written in the language of some race who had inhabited Babylonia before the Semites, while he explained the lists of words as early dictionaries compiled by the Assyrian scribes to help them in their studies of this ancient tongue. The early race he christened "the Akkadians," and although we now know that this name would more correctly describe the early Semitic immigrants who occupied Northern Babylonia, in all other respects his inference was justified. He correctly assigned the non-Semitic compositions that had been recovered to the early non-Semitic population of Babylonia, who are now known by the name of the Sumerians.

Sir Henry Rawlinson's view was shared by M. Oppert, Professor Schrader, Professor Sayce, and many others, and, in fact, it held the field until a theory was propounded by M. Halévy to the effect that Sumerian was not a language in the legitimate sense of the term. The contention of M. Halévy was that the Sumerian compositions were not written in the[Pg 5] language of an earlier race, but represented a cabalistic method of writing, invented and employed by the Babylonian priesthood. In his opinion the texts were Semitic compositions, though written according to a secret system or code, and they could only have been read by a priest who had the key and had studied the jealously guarded formulæ. On this hypothesis it followed that the Babylonians and Assyrians were never preceded by a non-Semitic race in Babylonia, and all Babylonian civilization was consequently to be traced to a Semitic origin. The attractions which such a view would have for those interested in ascribing so great an achievement to a Semitic source are obvious, and, in spite of its general improbability, M. Halévy won over many converts to his theory, among others Professor Delitzsch and a considerable number of the younger school of German critics.

It may be noted that the principal support for the theory was derived from an examination of the phonetic values of the Sumerian signs. Many of these, it was correctly pointed out, were obviously derived from Semitic equivalents, and M. Halévy and his followers forthwith inferred that the whole language was an artificial invention of the Babylonian priests. Why the priests should have taken the trouble to invent so complicated a method of writing was not clear, and no adequate reason could be assigned for such a course. On the contrary, it was shown that the subject-matter of the Sumerian compositions was not of a nature to justify or suggest the necessity of recording them by means of a secret method of writing. A study of the Sumerian texts with the help of the Assyrian translations made it obvious that they merely consisted of incantations, hymns, and prayers, precisely similar to other compositions written in the common tongue of the Babylonians and Assyrians, and thus capable of being read and understood by any scribe acquainted with the ordinary Assyrian or Babylonian character.

M. Halévy's theory appeared still less probable when applied to such of the early Sumerian texts as had been recovered at that time by Loftus and Taylor in Southern Babylonia. For these were shown to be[Pg 6] short building-inscriptions, votive texts, and foundation-records, and, as they were obviously intended to record and commemorate for future ages the events to which they referred, it was unlikely that they should have been drawn up in a cryptographic style of writing which would have been undecipherable without a key. Yet the fact that very few Sumerian documents of the early period had been found, while the great majority of the texts recovered were known only from tablets of the seventh century B.C., rendered it possible for the upholders of the pan-Semitic theory to make out a case. In fact, it was not until the renewal of excavations in Babylonia that fresh evidence was obtained which put an end to the Sumerian controversy, and settled the problem once for all in accordance with the view of Sir Henry Rawlinson and of the more conservative writers.[2]

That Babylonian civilization and culture originated with the Sumerians is no longer in dispute; the point upon which difference of opinion now centres concerns the period at which Sumerians and Semites first came into contact. But before we embark on the discussion of this problem, it will be well to give some account of the physical conditions of the lands which invited the immigration of these early races and formed the theatre of their subsequent history. The lands of Sumer and Akkad were situated in the lower valley of the Euphrates and the Tigris, and corresponded approximately to the country known by classical writers as Babylonia. On the west and south their boundaries are definitely marked by the Arabian desert and the Persian Gulf which, in the earliest period of Sumerian history, extended as far northward as the neighbourhood of the city of Eridu. On the east it is probable that the Tigris originally formed their natural boundary, but this was a direction in which expansion was possible, and their early conflicts with Elam were doubtless provoked by attempts to gain possession of the districts[Pg 7] to the east of the river. The frontier in this direction undoubtedly underwent many fluctuations under the rule of the early city-states, but in the later periods, apart from the conquest of Elam, the true area of Sumerian and Semitic authority may be regarded as extending to the lower slopes of the Elamite hills. In the north a political division appears to have corresponded then, as in later times, to the difference in geological structure. A line drawn from a point a little below Samarra on the Tigris before its junction with the Adhem to Hît on the Euphrates marks the division between the slightly elevated and undulating plain and the dead level of the alluvium, and this may be regarded as representing the true boundary of Akkad on the north. The area thus occupied by the two countries was of no very great extent, and it was even less than would appear from a modern map of the Tigris and Euphrates valley. For not only was the head of the Persian Gulf some hundred and twenty, or hundred and thirty, miles distant from the present coast-line, but the ancient course of the Euphrates below Babylon lay considerably to the east of its modern bed.

In general character the lands of Sumer and Akkad consist of a flat alluvial plain, and form a contrast to the northern half of the Tigris and Euphrates valley, known to the Greeks as Mesopotamia and Assyria. These latter regions, both in elevation and geological structure, resemble the Syro-Arabian desert, and it is only in the neighbourhood of the two great streams and their tributaries that cultivation can be carried out on any extensive scale. Here the country at a little distance from the rivers becomes a stony plain, serving only as pasture-land when covered with vegetation after the rains of winter and the early spring. In Sumer and Akkad, on the other hand, the rivers play a far more important part. The larger portion of the country itself is directly due to their action, having been formed by the deposit which they have carried down into the waters of the Gulf. Through this alluvial plain of their own formation the rivers take a winding course, constantly changing their direction[Pg 8] in consequence of the silting up of their beds and the falling in of the banks during the annual floods.

Of the two rivers the Tigris, owing to its higher and stronger banks, has undergone less change than the Euphrates. It is true that during the Middle Ages its present channel below Kût el-'Amâra was entirely disused, its waters flowing by the Shatt el-Hai into the Great Swamp which extended from Kûfa on the Euphrates to the neighbourhood of Kurna, covering an area fifty miles across and nearly two hundred miles in length.[3] But in the Sassanian period the Great Swamp, the formation of which was due to neglect of the system of irrigation under the early caliphs, did not exist, and the river followed its present channel.[4] It is thus probable that during the earlier periods of Babylonian history the main body of water passed this way into the Gulf, but the Shatt el-Hai may have represented a second and less important branch of the stream.[5]

The change in the course of the Euphrates has been far more marked, the position of its original bed being indicated by the mounds covering the sites of early cities, which extend through the country along the practically dry beds of the Shatt en-Nîl and the Shatt el-Kâr, considerably to the east of its present channel. The mounds of Abû Habba, Tell Ibrâhîm, El-Ohêmir and Niffer, marking the sites of the important cities[Pg 9] of Sippar, Cutha, Kish[6] and Nippur, all lie to the east of the river, the last two on the ancient bed of the Shatt en-Nîl. Similarly, the course of the Shatt el-Kâr, which formed an extension of the Shatt en-Nîl below Sûk el-'Afej passes the mounds of Abû Hatab (Kisurra), Fâra (Shuruppak) and Hammâm. Warka (Erech) stands on a further continuation of the Shatt en-Nîl,[7] while still more to the eastward are the mounds of Bismâya and Jôkha, representing the cities of Adab and Umma.[8] Senkera, the site of Larsa, also lies considerably to the east of the present stream, and the only city besides Babylon which now stands comparatively near the present bed of the Euphrates is Ur. The positions of the ancient cities would alone be sufficient proof that, since the early periods of Babylonian history, the Euphrates has considerably changed its course.

Abundant evidence that this was the case is furnished by the contemporary inscriptions that have been recovered. The very name of the Euphrates was expressed by an ideogram signifying "the River of Sippar," from which we may infer that Sippar originally stood upon its banks. A Babylonian contract of the period of the First Dynasty is dated in the year in which Samsu-iluna constructed the wall of Kish "on the bank of the Euphrates,"[9] proving that either the main stream from Sippar, or a branch from Babylon, flowed by El-Ohêmir. Still further south the river at Nippur, marked as at El-Ohêmir by the dry bed of the Shatt en-Nîl, is termed "the Euphrates of Nippur," or simply "the Euphrates" on contract-tablets found upon the site.[10] Moreover, the city of Shurippak or Shuruppak, the native town of Ut-napishtim, is described by him in the Gilgamesh epic as lying "on the bank of the Euphrates"; and Hammurabi, in one of his letters to Sin-idinnam, bids[Pg 10] him clear out the stream of the Euphrates "from Larsa as far as Ur."[11] These references in the early texts cover practically the whole course of the ancient bed of the Euphrates, and leave but a few points open to conjecture.

In the north it is clear that at an early period a second branch broke away from the Euphrates at a point about half-way between Sippar and the modern town of Falûja, and, after flowing along the present bed of the river as far as Babylon, rejoined the main stream of the Euphrates either at, or more probably below, the city of Kish. It was the extension of these western channels which afterwards drained the earlier bed, and we may conjecture that its waters were diverted back to the Euphrates at this early period by artificial means.[12] The tendency of the river was always to break away westward, and the latest branch of the stream, still further to the west, left the river above Babylon at Musayyib. The fact that Birs, the site of Borsippa, stands upon its upper course, suggests an early date for its origin, but it is quite possible that the first city on this site, in view of its proximity to Babylon, obtained its water-supply by means of a system of canals. However this may be, the present course of this most western branch is marked by the Nahr Hindîya, the Bahr Nejef, and the Shatt 'Ateshân, which rejoins the Euphrates after passing Samâwa. In the Middle Ages the Great Swamps started at Kûfa, and it is possible that even in earlier times, during periods of inundation, some of the surplus water from the river may have emptied itself into swamps or marshy land below Borsippa.

The exact course of the Euphrates south of Nippur during the earliest periods is still a matter for conjecture, and it is quite possible that its waters reached the Persian Gulf through two, if not three, mouths. It is certain that the main stream passed the cities of Kisurra, Shuruppak, and Erech, and eventually reached[Pg 11] the Gulf below Ur. Whether after leaving Erech it turned eastward to Larsa, and so southward to Ur, or whether it flowed from Erech direct to Ur, and Larsa lay upon another branch, is not yet settled, though the reference in Hammurabi's letter may be cited in favour of the former view. Another point of uncertainty concerns the relation of Adab and Umma to the stream. The mounds of Bismâya and Jôkha, which mark their sites, lie to the east, off the line of the Shatt el-Kâr, and it is quite possible that they were built upon an eastern branch of the river which may have joined the Shatt el-Hai above Lagash, and so have mingled with the waters of the Tigris before reaching the Gulf.[13]

In spite of these points of uncertainty, it will be noted that every city of Sumer and Akkad, the site of which has been referred to, was situated on the Euphrates or one of its branches, not upon the Tigris, and the only exception to this rule appears to have been Opis, the most northern city of Akkad. The preference for the Euphrates may be explained by the fact that the Tigris is swift and its banks are high, and it thus offers far less facilities for irrigation. The Euphrates with its lower banks tends during the time of high water to spread itself over the surrounding country, which doubtless suggested to the earliest inhabitants the project of regulating and utilizing the supply of water by means of reservoirs and canals. Another reason for the preference may be traced to the slower fall of the water in the Euphrates during the summer months. With the melting of the snow in the mountain ranges of the Taurus and Niphates during the early spring, the first flood-water is carried down by the swift stream of the Tigris, which generally begins to rise in March, and, after reaching its highest level in the early part of May, falls swiftly and returns to its summer level by the middle of June. The Euphrates, on the other hand, rises about a fortnight later, and continues at a high level for a much longer period.[Pg 12] Even in the middle of July there is a considerable body of water in the river, and it is not until September that its lowest level is reached. On both streams irrigation-machines were doubtless employed, as they are at the present day,[14] but in the Euphrates they were only necessary when the water in the river had fallen below the level of the canals.

Between the lands of Sumer and Akkad there was no natural division such as marks them off from the regions of Assyria and Mesopotamia in the north. While the north-eastern half of the country bore the name of Akkad, and the south-eastern portion at the head of the Persian Gulf was known as Sumer, the same alluvial plain stretches southward from one to the other without any change in its general character. Thus some difference of opinion has previously existed, as to the precise boundary which separated the two lands, and additional confusion has been introduced by the rather vague use of the name Akkad during the later Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian periods. Thus Ashur-bani-pal, when referring to the capture of Nanâ's statue by the Elamites, puts E-anna, the temple of Nanâ in Erech, among the temples of the land of Akkad, a statement which has led to the view that Akkad extended as far south as Erech.[15] But it has been pointed out that on similar evidence furnished by an Assyrian letter, it would be possible to regard Eridu, the most southern Sumerian city as in Akkad, not in Sumer.[16] The explanation is to be found in the fact that by the Assyrians, whose southern border marched with Akkad, the latter name was often used loosely for the whole of Babylonia. Such references should not therefore be employed for determining the original limits of the two countries, and it is necessary to rely only upon information supplied by texts of a period earlier than that in which the original distinction between the two names had become blurred.

From references to different cities in the early texts, it is possible to form from their context, a very fair idea of what the Sumerians themselves regarded as the limits[Pg 13] of their own land. For instance, from the Tello inscriptions there is no doubt that Lagash was in Sumer. Thus the god Ningirsu, when informing Gudea, patesi of Lagash, that prosperity shall follow the building of E-ninnû, promises that oil and wool shall be abundant in Sumer;[17] the temple itself, which was in Lagash, is recorded to have been built of bricks of Sumer;[18] and, after the building of the temple was finished, Gudea prays that the land may rest in security, and that Sumer may be at the head of the countries.[19] Again, Lugal-zaggisi, who styles himself King of the Land, i.e. the land of Sumer,[20] mentions among cities subject to him, Erech, Ur, Larsa, and Umma,[21] proving that they were regarded as Sumerian towns. The city of Kesh, whose goddess Ninkharsag is mentioned on the Stele of the Vultures, with the gods of Sumerian towns as guaranteeing a treaty between Lagash and Umma,[22] was probably in Sumer, and so, too, must have been Isin, which gave a line of rulers to Sumer and Akkad in succession to Ur; about Eridu in the extreme south there could be no two opinions. On the other hand, in addition to the city of Agade or Akkad, Sippar, Kish, Opis, Cutha, Babylon and Borsippa are certainly situated beyond the limits of Sumer and belong to the land of Akkad in the north. Between the two groups lay Nippur, rather nearer to the southern than to the northern cities, and occupying the unique position of a central shrine. There is little doubt that the town was originally regarded as within the limits of Sumer, but from its close association with any claimant to the hegemony, whether in Sumer or in Akkad, it acquired in course of time a certain intermediate position, on the boundary line, as it were, between the two countries.

Of the names Sumer and Akkad, it would seem that neither was in use in the earliest historical periods,[Pg 14] though the former was probably the older of the two. At a comparatively early date the southern district as a whole was referred to simply as "the Land,"[23] par excellence, and it is probable that the ideogram by which the name of Sumer was expressed, was originally used with a similar meaning.[24] The twin title, Sumer and Akkad, was first regularly employed as a designation for the whole country by the kings of Ur, who united the two halves of the land into a single empire, and called themselves kings of Sumer and Akkad. The earlier Semitic kings of Agade or Akkad[25] expressed the extent of their empire by claiming to rule "the four quarters (of the world)," while the still earlier king Lugal-zaggisi, in virtue of his authority in Sumer,[Pg 15] adopted the title "King of the Land." In the time of the early city-states, before the period of Eannatum, no general title for the whole of Sumer or of Akkad is met with in the inscriptions that have been recovered. Each city with its surrounding territory formed a compact state in itself, and fought with its neighbours for local power and precedence. At this time the names of the cities occur by themselves in the titles of their rulers, and it was only after several of them had been welded into a single state that the need was felt for a more general name or designation. Thus, to speak of Akkad, and even perhaps of Sumer, in the earliest period, is to be guilty of an anachronism, but it is a pardonable one. The names may be employed as convenient geographical terms, as, for instance, when referring to the country as a whole, we speak of Babylonia during all periods of its history.

[1] For a discussion of the conflicting evidence with regard to the occurrence of bronze at this period, see below, pp. 72 ff.

[2] The controversy has now an historical rather than a practical importance. Its earlier history is admirably summarized by Weissbach in "Die sumerische Frage," Leipzig, 1898; cf. also Fossey, "Manuel d'Assyriologie," tome I, (1904), pp. 269 ff. M. Halévy himself continues courageously to defend his position in the pages of the "Revue Sémitique," but his followers have deserted him.

[3] The origin of the Great Swamp, or Swamps, called by Arab geographers al-Baṭiḥa, or in the plural al-Baṭâyiḥ, is traced by Bilâdhuri to the reign of the Persian king Kubâdh I., towards the end of the fifth century B.C. Ibn Serapion applies the name in the singular to four great stretches of water (Hawrs), connected by channels through the reeds, which began at El-Kaṭr, near the junction of the Shatt el-Hai with the present bed of the Euphrates. But from this point as far northwards as Niffer and Kûfa the waters of the Euphrates lost themselves in reed-beds and marshes; cf. G. le Strange, "Journ. Roy. Asiat. Soc.," 1905, p. 297 f., and "Lands of the Eastern Caliphate," p. 26 f.

[4] According to Ibn Rusta (quoted by Le Strange, "Journ. Roy. Asiat. Soc.," 1905, p. 301), in Sassanian times, and before the bursting of the dykes which led to the formation of the swamps, the Tigris followed the same eastern channel in which it flows at the present time; this account is confirmed by Yâkût.

[5] See the map at the end of the volume. The original courses of the rivers in the small inset map of Babylonia during the earliest historical periods agree in the main with Fisher's reconstruction published in "Excavations at Nippur," Pt. I., p. 3, Fig. 2. For points on which uncertainty still exists, see below, p. 10 f.

[7] See the plan of Warka by Loftus, reproduced on p. 33. It will be noted that he marks the ancient bed of the Shatt en-Nîl as skirting the city on the east.

[9] Cf. Thureau-Dangin, "Orient. Lit.-Zeit.," 1909, col. 205 f.

[10] See Clay and Hilprecht, "Murashû Sons" (Artaxerxes I.), p. 76, and Clay, "Murashû Sons" (Darius II.), p. 70; cf. also Hommel, "Grundriss der Geographie und Geschichte des alten Orients," p. 264.

[11] Cf. King, "Letters of Hammurabi," III., p. 18 f.

[12] The Yusufiya Canal, running from Dîwânîya to the Shatt el-Kâr, was probably the result of a later effort to divert some of the water back to the old bed.

[13] Andrae visited and surveyed the districts around Fâra and Abû Hatab in December, 1902. In his map he marks traces of a channel, the Shatt el-Farakhna, which, leaving the main channel at Shêkh Bedr, heads in the direction of Bismâya (see "Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft," No. 16, pp. 16 ff.).

[14] Cf. King and Hall, "Egypt and Western Asia," pp. 292 ff.

[15] Cf. Delitzsch, "Wo lag das Paradies?" p. 200.

[16] Cf. Thureau-Dangin, "Journal asiatique," 1908, p. 131, n. 2.

[18] Ibid., Col. XXI., l. 25.

[19] Cyl. B, Col. XXII., l. 19 f.

[21] For this reading of the name of the city usually transcribed as Gishkhu or Gishukh, see below, p. 21, n. 3.

[23] The word kalam, "the Land," is first found in a royal title upon fragments of early vases from Nippur which a certain "king of the land" dedicated to Enlil in gratitude for his victories over Kish (see below, Chap. VII.). The word kur-kur, "countries" in such a phrase as lugal kur-kur-ge, "king of the countries," when applied to the god Enlil, designated the whole of the habitable world; in a more restricted sense it was used for foreign countries, especially in the inscriptions of Gudea, in contradistinction to the Land of Sumer (cf. Thureau-Dangin, "Zeits. für Assyr.," XVI., p. 354, n. 3).

[24] The ideogram Ki-en-gi, by which the name of Sumer, or more correctly Shumer, was expressed, already occurs in the texts of Eannatum, Lugal-zaggisi and Enshagkushanna (see Chaps. V. and VII.). It has generally been treated as an earlier proper name for the country, and read as Kengi or Kingi. But the occurrence of the word ki-en-gi-ra in a Sumerian hymn, where it is rendered in Semitic by mâtu, "land" (see Reisner, "Sum.-Bab. Hymnen," pl. 130 ff.), would seem to show that, like kalam, it was employed as a general designation for "the Land" (cf. Thureau-Dangin, "Die sumerischen und akkadischen Königsinschriften," p. 152, n.f.). The form ki-en-gi-ra is also met with in the inscriptions of Gudea (see Hommel, "Grundriss," p. 242, n. 4, and Thureau-Dangin, op. cit., pp. 100, 112, 140), and it has been suggested that the final syllable should be treated as a phonetic complement and the word rendered as shumer-ra (cf. Hrozný, "Ninib und Sumer," in the "Rev. Sémit.," July, 1908, Extrait, p. 15). According to this view the word shumer, with the original meaning of "land," was afterwards employed as a proper name for the country. The earliest occurrence of Shumerû, the Semitic form of the name, is in an early Semitic legend in the British Museum, which refers to "the spoil of the Sumerians" (see King, "Cun. Texts," Pt. V., pl. 1 f., and cf. Winckler, "Orient. Lit.-Zeit.," 1907, col. 346, Ungnad, op. cit., 1908, col. 67, and Hrozný, "Rev. Sémit.," 1908, p. 350).

[25] Akkad, or Akkadû, was the Semitic pronunciation of Agade, the older name of the town; a similar sharpening of sound occurs in Makkan, the Semitic pronunciation of Magan (cf. Ungnad, "Orient. Lit.-Zeit.," 1908, col. 62, n. 4). The employment of the name of Akkad for the whole of the northern half of the country probably dates from a period subsequent to the increase of the city's power under Shar-Gani-sharri and Narâm-Sin (see Chap. VIII.); on the employment of the name for the Semitic speech of the north, see below, p. 52. The origin of the name Ki-uri, or Ki-urra, employed in Sumerian as the equivalent of the name of Akkad, is obscure.

The excavations which have been conducted on the sites of early Babylonian cities since the middle of last century have furnished material for the reconstruction of their history, but during different periods and for different districts it varies considerably in value and amount. While little is known of the earlier settlements in Akkad, and the very sites of two of its most famous cities have not yet been identified, our knowledge of Sumerian history and topography is relatively more complete. Here the cities, as represented by the mounds of earth and débris which now cover them, fall naturally into two groups. The one consists of those cities which continued in existence during the later periods of Babylonian history. In their case the earliest Sumerian remains have been considerably disturbed by later builders, and are now buried deep beneath the accumulations of successive ages. Their excavation is consequently a task of considerable difficulty, and, even when the lowest strata are reached, the interpretation of the evidence is often doubtful. The other group comprises towns which were occupied mainly by the Sumerians, and, after being destroyed at an early date, were rarely, or never, reoccupied by the later inhabitants of the country. The mounds of this description, so far as they have been examined, have naturally yielded fuller information, and they may therefore be taken first in the following description of the early sites.

The greater part of our knowledge of early Sumerian history has been derived from the wonderfully successful[Pg 17] series of excavations carried out by the late M. de Sarzec at Tello,[1] between 1877 and 1900, and continued for some months in 1903 by Captain (now Commandant) Gaston Cros. These mounds mark the site of the city of Shirpurla or Lagash, and lie a few miles to the north-east of the modern village of Shatra, to the east of the Shatt el-Hai, and about an hour's ride from the present course of the stream. It is evident, however, that the city was built upon the stream, which at this point may originally have formed a branch of the Euphrates,[2] for there are traces of a dry channel upon its western side.

The name of the city is expressed by the signs shir-pur-la (-ki), which are rendered in a bilingual incantation-text as Lagash.[3] Hitherto it has been generally held that Shirpurla represented the Sumerian name of the city, which was known to the later Semitic inhabitants as Lagash, in much the same way as Akkad was the Semitic name for Agade, though in the latter case the original name was taken over. But the prolonged excavations carried out in the mounds of Tello have failed to bring to light any Babylonian remains later than the period of the kings of Larsa who were contemporaneous with the First Dynasty of Babylon. At that time the city appears to have been destroyed, and to have lain deserted and forgotten until it was once more inhabited in the second century B.C. Thus it is difficult to find a reason for a second name. We may therefore[Pg 18] assume that the place was called Lagash by the Sumerians, and that the signs which can be read as Shirpurla represent a traditional ideographic way of writing the name among the Sumerians themselves. There is no difficulty in supposing that the city's name and the way of writing it were preserved in Babylonian literature, although its site had been forgotten.

The group of mounds and hillocks which mark the site of the ancient city and its suburbs form a rough oval, running north and south, and measuring about two and a half miles long and one and a quarter broad. During the early spring the limits of the city are clearly visible, for its ruins stand out as a yellow spot in the midst of the light green vegetation which covers the surrounding plain. The grouping of the principal mounds may be seen in the accompanying plan, in which each contour-line represents an increase of one metre in height above the desert level. The three principal mounds in the centre of the oval, marked on the plan by the letters A, K, and V,[4] are those in which the most important discoveries have been made. The mound A, which rises steeply towards the north-west end of the oval, is known as the Palace Tell, since here was uncovered a great Parthian palace, erected immediately over a building of Gudea, whose bricks were partly reused and partly imitated. In consequence of this it was at first believed to be a palace of Gudea himself, an error that was corrected on the discovery that some of the later bricks bore the name of Hadadnadinakhe in Aramean and Greek characters, proving that the building belonged to the Seleucid era, and was probably not earlier than about 130 B.C. Coins were also found in the palace with Greek inscriptions of kings of the little independent province or kingdom of Kharakene, which was founded about 160 B.C. at the mouth of the Shatt el-'Arab. But worked into the[Pg 19] structure of this late palace were the remains of Gudea's building, which formed part of E-ninnû, the temple of the city-god of Lagash. Of Gudea's structure a gateway and part of a tower are the portions that are best preserved,[5] while under the south-east corner of the palace was a wall of the rather earlier ruler Ur-Bau.[6]

In the lower strata no other earlier remains were brought to light, and it is possible that the site of the temple was changed or enlarged at this period, and that in earlier times it stood nearer the mound K, where the oldest buildings in Tello have been found. Here was a storehouse of Ur-Ninâ,[7] a very early patesi of the city and the founder of its most powerful dynasty, and in its immediate neighbourhood were recovered the most important monuments and inscriptions of the earlier period. Beneath Ur-Ninâ's storehouse was a still earlier building,[8] and at the same deep level above the virgin soil were found some of the earliest examples of Sumerian sculpture that have yet been recovered. In the mound V, christened the "Tell of the Tablets," were large collections of temple-documents and tablets of accounts, the majority of them dating from the period of the Dynasty of Ur.

The monuments and inscriptions from Tello have furnished us with material for reconstructing the history of the city with but few gaps from the earliest age until the time when the Dynasty of Isin succeeded that of Ur in the rule of Sumer and Akkad. To the destruction of the city during the period of the First Dynasty of Babylon and its subsequent isolation we owe the wealth of early records and archaeological remains which have come down to us, for its soil has escaped disturbance at the hands of later builders except for a short interval in Hellenistic times. The fact that other cities in the neighbourhood, which shared a similar fate, have not yielded such striking results to the excavator, in itself bears testimony to the important position occupied by Lagash, not only as the seat of a long line of successful rulers, but as the most important centre of Sumerian culture and art.

DOORWAY OF A BUILDING AT TELLO ERECTED BY GUDEA, PATESI OF SHIRPURLA; ON THE LEFT IS PART OF A LATER BUILDING OF THE SELEUCID ERA. Déc. en Chald., pl. 53 (bis).

The mounds of Surghul and El-Hibba, lying to the north-east of Tello and about six miles from each other, which were excavated by Dr. Koldewey in 1887, are instances in point. Both mounds, and particularly the former, contain numerous early graves beneath houses [Pg 21]of unburnt brick, such as have subsequently been found at Fâra, and both cities were destroyed by fire probably at the time when Lagash was wiped out. From the quantities of ashes, and from the fact that some of the bodies appeared to have been partially burnt, Dr. Koldewey erroneously concluded that the mounds marked the sites of "fire-necropoles," where he imagined the early Babylonians burnt their dead, and the houses he regarded as tombs.[9] But in no period of Sumerian or Babylonian history was this practice in vogue. The dead were always buried, and any appearance of burning must have been produced during the destruction of the cities by fire. At El-Hibba remains were also visible of buildings constructed wholly or in part of kiln-baked bricks, which, coupled with the greater extent of its mounds, suggests that it was a more important Sumerian city than Surghul. This has been confirmed by the greater number of inscriptions which were found upon its site and have recently been published.[10] They include texts of the early patesis of Lagash, Eannatum and Enannatum I, and of the later patesi Gudea. A text of Gudea was also found at Surghul proving that both places were subject to Lagash, in whose territory they were probably always included during the periods of that city's power. That, apart from the graves, few objects of archaeological or artistic interest were recovered, may in part be traced to their proximity to Lagash, which as the seat of government naturally enjoyed an advantage in this respect over neighbouring towns.

During the course of her early history the most persistent rival of Lagash was the neighbouring city of Umma,[11] now identified with the mound of Jôkha, lying some distance to the north-west in the region between the Shatt el-Hai and the Shatt el-Kâr. Its[Pg 22] neighbourhood and part of the mound itself are covered with sand-dunes, which give the spot a very desolate appearance, but they are of recent formation, since between them can still be seen traces of former cultivation. The principal mound is in the form of a ridge over half a mile long, running W.S.W. to E.N.E. and rising at its highest point about fifteen metres above the plain. Two lower extensions of the principal mound stretch out to the east and south-east.