Title: True Stories of the Great War, Volume 4 (of 6)

Editor: Francis Trevelyan Miller

Release date: July 7, 2015 [eBook #49391]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brian Coe, Moti Ben-Ari, missing pages from

HathiTrust Digital Library and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by University

of California libraries)

TRUE STORIES OF THE GREAT WAR

TALES OF ADVENTURE—HEROIC DEEDS—EXPLOITS

TOLD BY THE SOLDIERS, OFFICERS, NURSES,

DIPLOMATS, EYE WITNESSES

Collected in Six Volumes

From Official and Authoritative Sources

(See Introductory to Volume I)

VOLUME IV

Editor-in-Chief

FRANCIS TREVELYAN MILLER (Litt. D., LL.D.)

Editor of The Search-Light Library

1917

REVIEW OF REVIEWS COMPANY

NEW YORK

The following stories have been selected for VOLUME IV by the Board of Editors, according to the plan outlined in "Introductory" to Volume I for collecting from all sources the "Best Stories of the War." This group includes personal experiences of Soldiers at the front, Submarine Officers, Aviators, Prisoners, Ambulance Drivers, Red Cross Nurses, Priests, Spies, and American Eye-Witnesses. They have been collected from twenty-eight of the most authentic sources in Europe and America and include 134 adventures and episodes. Full credit is given in every instance to the original source.

| "WHEN THE PRUSSIANS CAME TO POLAND"—A TRAGEDY | 1 |

| EXPERIENCES OF AN AMERICAN WOMAN DURING THE | |

| GERMAN INVASION | |

| Told by Madame Laura de Gozdawa Turczynowicz | |

| (Permission of G. P. Putnam's Sons) | |

| MY EXPERIENCES WITH SPIES IN THE GREAT WAR | 16 |

| VISITING WITH SPIES IN AMERICA, NORWAY, SWEDEN, | |

| DENMARK AND GERMANY | |

| Told by Bernhart Paul Hoist | |

| (Permission of Hoist Publishing Company, Boone, Iowa) | |

| "THE ADVENTURE OF THE U-202"—THE KAISER'S ARMADA | 40 |

| HUNTING THE SEAS ON A GERMAN SUBMARINE | |

| Told by Baron Spiegel Von Und Zu Peckelsheim, Captain Lieutenant | |

| Commander of the U-202 | |

| (Permission of The Century Company) | |

| "PASSED BY THE CENSOR"—TRUE STORIES FROM THE | |

| FIELDS OF BATTLE | 55 |

| EXPERIENCES OF AN AMERICAN NEWSPAPER MAN IN | |

| FRANCE | |

| Told by Wythe Williams, Correspondent of the "New York | |

| Times" | |

| (Permission of E. P. Dutton and Company) | |

| "PRIESTS IN THE FIRING LINE"—THE CROSS AND CRUCIFIX | 72 |

| A REVEREND FATHER IN THE FRENCH ARMY | |

| Told by Réné Gaell | |

| (Permission of Longmans, Green and Company) | |

| STORIES OF AN AMERICAN WOMAN—SEEN WITH HER OWN | |

| EYES | 84 |

| "JOURNAL OF SMALL THINGS" | |

| Told by Helen Mackay | |

| (Permission of Duffield and Company) | |

| "PRISONER OF WAR"—SOLDIER'S TALES OF THE ARMY | 94 |

| FROM THE BATTLEFIELD TO THE CAMP | |

| Told by André Ward | |

| (Permission of J. B. Lippincott Company) | |

| WAR SCENES I SHALL NEVER FORGET | 100 |

| Told by Carita Spencer | |

| (Permission of Carita Spencer, of New York) | |

| "WAR LETTERS FROM FRANCE"—THE HEARTS OF HEROES | 123 |

| COLLECTED FROM THE SOLDIERS | |

| Told by A. De Lapradelle and Frederic R. Coudert | |

| (Permission of A. Appleton and Company) | |

| A NURSE AT THE WAR—THE WOMAN AT THE FRONT | 129 |

| AN ENGLISHWOMAN IN THE F.A.N.Y. CORPS IN FRANCE | |

| AND BELGIUM | |

| Told by Grace MacDougall | |

| (Permission of Robert M. McBride and Company) | |

| "FROM DARTMOUTH TO THE DARDANELLES"—A MIDSHIPMAN'S | |

| LOG | 140 |

| Told by a Dartmouth Student (Name Suppressed) | |

| (Permission of E. P. Dutton and Company) | |

| HORRORS OF TRENCH FIGHTING—WITH THE CANADIAN | |

| HEROES | 148 |

| REMARKABLE EXPERIENCES OF AN AMERICAN SOLDIER | |

| Told by Roméo Houle | |

| (Permission of Current History) | |

| THE FLIGHT FROM CAPTIVITY ON "THE THIRD ATTEMPT" | 174 |

| HOW I ESCAPED FROM GERMANY | |

| Told by Corporal John Southern and set down by A. E. Littler | |

| (Permission of Wide World, of London) | |

| CLIMBING THE SNOW-CAPPED ALPIAN PEAKS WITH THE | |

| ITALIANS | 191 |

| "BATTLING WHERE MEN NEVER BATTLED BEFORE" | |

| Told by Whitney Warren | |

| (Permission of New York Sun) | |

| AT SEA IN A TYPHOON ON A UNITED STATES ARMY TRANSPORT | 203 |

| STORY OF A VOYAGE IN THE CHINA SEA | |

| Told by (Name Suppressed), a United States Army Officer | |

| A BOY HERO OF THE MIDI—THE LAD FROM MONACO | 214 |

| Translated from the Diary of Eugene Escloupié by Frederik Lees | |

| (Permission of Wide World) | |

| KNIGHTS OF THE AIR—FRENCHMEN WHO DEFY DEATH | 232 |

| TALES OF VALOR IN BATTLES OF THE CLOUDS | |

| Told by the Fliers Themselves | |

| (Permission of Literary Digest) | |

| FOUR AMERICAN PRISONERS ABOARD THE YARROWDALE | 243 |

| ADVENTURES WITH THE GERMAN RAIDER "MOEWE" | |

| Told by Dr. Orville E. McKim | |

| (Permission of New York World) | |

| HUMORS OF THE EAST AFRICAN CAMPAIGN | 254 |

| Told by "A. E. M. M." | |

| (Permission of Wide World) | |

| STORIES OF HEROIC WOMEN IN THE GREAT WAR | 264 |

| TALES OF FEMININE DEEDS OF DARING | |

| (Permission of New York American) | |

| HOW WE STOLE THE TUG-BOAT | 283 |

| THE STORY OF A SENSATIONAL ESCAPE FROM THE | |

| GERMANS | |

| Told by Sergeant "Maurice Prost" | |

| (Permission of Wide World) | |

| THE RUSSIAN SUN—ON THE TRAIL OF THE COSSACKS | 293 |

| "WE ARE THE DON COSSACKS—WE DO NOT SURRENDER!" | |

| Told by Herr Roda Roda | |

| (Permission of New York Tribune) | |

| A BOMBING EXPEDITION WITH THE BRITISH AIR SERVICE | 301 |

| DARING ADVENTURES OF THE ROYAL FLIERS | |

| Told by First Lieutenant J. Errol D. Boyd | |

| (Permission of New York World) | |

| HINDENBURG'S DEATH TRAP | 310 |

| STORY FROM LIPS OF A YOUNG COSSACK | |

| Told by Lady Glover | |

| (Permission of Wide World) | |

| ON THE GREAT WHITE HOSPITAL TRAIN—GOING HOME | |

| TO DIE | 321 |

| AN AMERICAN GIRL WITH A RED CROSS TRAIN | |

| Told by Jane Anderson | |

| (Permission of New York Tribune) | |

| MY EXPERIENCES IN THE GREATEST NAVAL BATTLE IN | |

| THE WAR | 334 |

| WHAT HAPPENED WHEN THE "BLUECHER" WENT DOWN | |

| Told by a Survivor | |

| (Permission of New York American) | |

| "TODGER" JONES, V. C. | 342 |

| THE MAN WHO CAPTURED A HUNDRED GERMANS | |

| SINGLE-HANDED | |

| Told by Himself, set down by A. E. Littler | |

| (Permission of Wide World) | |

| AN OFFICER'S STORY | 357 |

| Retold by V. Ropshin | |

| (Permission of Current History) |

"THE GLAD HAND"

An American Sailor in London Meets a Friend in the Canadian Army

THE STARS AND STRIPES PASSES THROUGH LONDON TOWN

The Parade of the First American Contingent Past Cheering Multitudes of Londoners

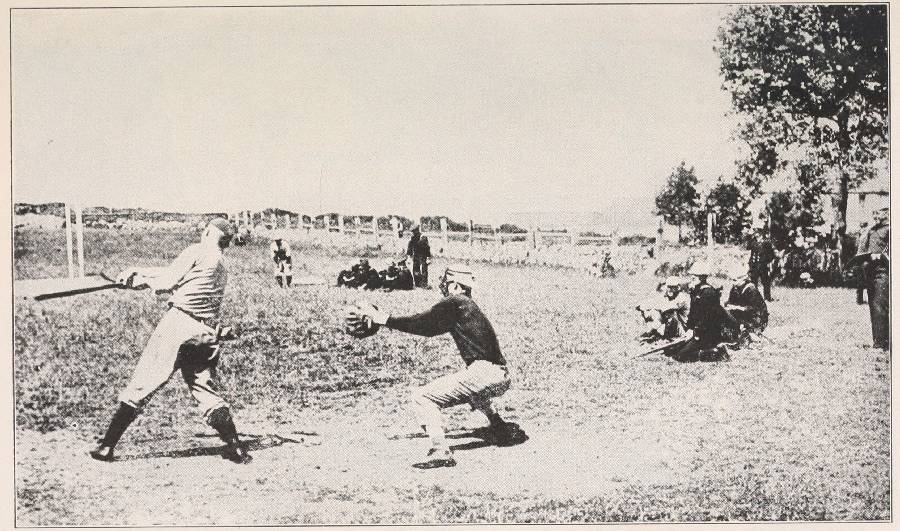

A LONG WAY FROM THE POLO GROUNDS

The Germans Complain That the English Don't Take War With Proper Seriousness: They Actually Play Football Between "Shock" Attacks. The American

is Just as Bad: These Members of Admiral Sims' Destroyer Squadron Must Have Their Baseball in England as at Home.

SEEING THEMSELVES IN THE HOME PAPER

American Nurses Who Have Just Found Pictures of Themselves

Experiences of an American Woman During the German Invasion

Told by Madame Laura de Gozdawa Turczynowicz

This is the story of an American woman, the wife of a Polish noble, who was caught in her home by the floodtide of the German invasion of the ancient kingdom of Poland. It is a straightforward narrative, terribly real, of her experiences in the heart of the eastern war-zone, of her struggle with the extreme conditions, of her Red Cross work, of her fight for the lives of her children and herself against the dread Typhus, and at last, of her release and journey through Germany and Holland to this country; and it is offered to the public as typical of the experiences of hundreds of other cultured Polish women. How truly she was in line of the German advance may be appreciated from the fact that iron-handed von Hindenberg for some days made his headquarters under her roof. A few of her hundreds of interesting experiences are told below by permission of her publishers, G. P. Putnam's Sons: Copyright 1916.

[1] I—STORY OF THE POLISH NOBLES

Very near the borderline between Russia and Germany lies Suwalki. It was a delightful, old-fashioned spot full of homes, and with many estates in the neighborhood. As one says in Polish, there were there very many of the "intelligence," meaning the noble class. People who were proud of the heirlooms, the old and valuable furniture, the beautiful pictures and books contained in their homes.

Into this old-world peace, came war, and of the homes and people, there is left only destruction and hopeless gray misery. How well I remember, and with what astonishment I think upon all that was before war was declared.

My children were crying from the discomfort of being awakened so early, and had raised their voices in protest at the general state of disorder.

These three were Wanda, six years, and Stanislaw and Wladislaw, twin boys, five years! I think they were also protesting that no one was paying the slightest attention to them, and that was a state of affairs to which they were not used!...

II—THE FALL OF KING ALCOHOL

I think it was about a week after the first news when the Ukase of the Czar was published—that all spirits were to be destroyed, and the use of alcohol forbidden. What excitement prevailed over this announcement in a country where at dinner one must reckon at least one bottle of wodka for each guest! Such strong stuff was it that the only time I ever tried it I thought my last moment had come! The day before the official destruction was to take place we went to get alcohol for the hospital—both the pure, and the colored for burning in lamps, etc. There were tremendous crowds about, all struggling to get a last bottle to drink, already drunken—without shame, and horrid! I thought then what a wonderful thing the Czar had done for humanity. How brave it was deliberately to destroy a tremendous source of income[3] in order to help his people! We were forced to have police protection to bring the bottles home. Such bottles! Each one holding twelve quarts!

The next day we saw the destruction of the "Monopol." The chief of police ordered all spirits carried to the top of a hill in the outskirts of Suwalki—then with much ceremony the bottles were smashed, letting the fiery stuff flow in streams! What cries there were from the people—the peasants threw themselves down on the ground, lapped the wodka with their tongues, and when they could swallow no more they rolled over and over in it! After a while my husband thought it better to leave; even in an automobile there was little safety among such mad creatures. We were very glad when "King Alcohol" had been vanquished, and we shuddered to think what would have been if such an orgy had taken place without police to quell it!

About nine o'clock a peasant came to tell me the Germans were coming! Some one had seen them. I made the four soldiers eat, and gave them food and cigarettes to carry with them. They were ill men. After a mutual blessing they went back to await their fate.

Suddenly hearing an uproar, I saw some of the bad elements of the town looting, searching for food, knocking each other down, screaming—a horrid sight! The Jews who were always so meek, had now more self-assertion, strutting about, stretching up until they looked inches taller. It was hard work to tear myself away from the balcony. I, too, seemed unable to control myself, running from the balcony to the child and from the child to the balcony.

At eleven the streets again grew quiet, the time was near, and I saw the first pikel-haube come around the corner, rifle cocked—on the lookout for snipers!

III—STORY OF THE "OLD WOMAN SPY"

The first one was soon followed by his comrades. Then an officer, who rounded the corner, coming to a stop directly before our windows. An old Jewess stepped out and saying, "Guten Tag," handed him a packet of papers, and gave various directions with much gesticulation. A spy at our very door! A woman I had seen many times! Busy with Wladek I saw no more for a while when a cry from the two other children made me rush to the window. They were coming into our court. The soldiers! And in a moment rushed into the room where we were, in spite of the signs tacked up on all doors "Tyfus." Seeing me in the Red Cross uniform they held back a moment. One bolder than his comrades laughed, saying, "She is trying to deceive us," and came toward me with a threatening gesture. Then with all my fear, God gave me strength to defy them. In German, which fortunately I speak very well, I asked what they wanted.

"Food and quarters."

"You cannot stop here. There is typhus."

"Show us the ill ones."

Opening the door to my own bedroom where the child lay, talking, moving the little hands incessantly, I saw that the nurse from the excess of fright had crawled under the bed. The soldier yanked her out, saying he would not hurt her, chucked her under the chin, and called her a "pretty animal!" Poor Stephinia, she could hardly stand! I, in my anxiety, pushed the soldier from the room, to find the others already making themselves at home.

"You cannot stop here. Go away! I am not afraid of you; I am an American. If you do any harm to us the world shall hear of it!"

They had been drinking, and the very fact that I defied them made an impression.

"Go out on the road. I will send food to you."

They went. One of them, giving me a look of sympathy, said:

"You have my sympathy, Madame."

That gave me courage, and shutting the door I went back to my boy. Always the same; I should not have left his side for an instant.

IV—INVASION OF AN AMERICAN WOMAN'S HOME

The town by now was in an uproar, every one seemed screaming together. As I looked from the window, my hand touched the prayer-book lying on the table.

"Lord, give me a word, a promise, to keep me steadfast and sane!" The book opened at the 55th Psalm—"As for me I will call upon God, and the Lord shall save me." Even in the stress of the moment reading to the end of the chapter—"Cast thy burden on the Lord." A conviction came to me then that God would keep us all safe!

Soon I had to wake to the fact that the house was being looted. Jacob, his wife, and daughter ran into the room. The soldiers had been knocking them about, taking all the food they could lay their hands upon. It was pandemonium let loose! An under-officer came to make a levy on my food for the army going through to Augustowo. He, with his men, looked into every hole and corner, but did not think to look inside the couches, which were full of things! To see your provisions carried off by the enemy is not a pleasant sensation. I asked the under-officer if it were possible the town was to be looted and burned.

"Looted—yes—to revenge East Prussia! Burned, not yet,—not unless we go!"

These first men had a black cover drawn over their caps and afterwards I heard they were from the artillery. Always the worst! Just at this time there was a great tramping of horses right in the rooms under us—where the hospital had been arranged—a thundering knock on the door, and a captain with his staff walked in. A tremendously big man, he seemed to fill the place!

"Guten Tag."

"Guten Tag, meine Schwester—Hier habe ich quartier."

"Are you not afraid of typhus?"

"Nonsense—we are all inocculated. Is there really typhus?"

"Have you a doctor, Captain? Let him decide!"

A very fat boy just from the university was presented to me; so young, twenty-three and inexperienced, to have such a responsibility. Examining Wladek he decided it was dysentery, and tore down my notices!

As there was no appeal, I tried to be amiable. The Herr Kapitain was not so bad; he cleared the house out, and at least only orderlies came through; but for us was left only the bedroom. Children, servants, all packed together with the typhus patient. The captain was courteous enough, but said I would have to feed staff and men. That day seemed endless. With every moment came fresh troops, and I was glad the Herr Kapitain was in my apartments. At least there would be no looting. The rest of the house was full to overflowing with soldiers. Naturally they blamed the horrible disorder there on to the Russians. A telephone was soon in operation, and we were headquarters. All sorts of wires there were, and a rod sticking out of the roof.[7] We were forbidden to go near that part of the house.

Every few minutes some one came to ask me to help them; the poor people, they thought I could make the soldiers give up pig or horse or chickens. At six the captain told me he wished supper in half an hour. The cook seemed on the verge of losing her reason with some one continually making a raid on the kitchen, but she managed to get ready by seven. There were eight officers at the table—and they demanded wine.

"I have no wine."

"The old Jewess told us you brought home two bottles of wine when the Russians left."

"That was given me for my children."

"The children have no typhus, the doctor says, so they do not need wine—bring it to us."

So I gave up my precious bottles. The forage-wagons of the Germans had not come; they had no food with them and no wines, but the town fed them to the last mouthful. They turned in at half-past ten, leaving an atmosphere you could cut. It was so thick with tobacco smoke! Once more I could be without interruption with my children, for I had to serve the officers, pour their tea, etc.; it seemed as if one could not live through another such day. My boy was unconscious,—talking—talking—talking—all night long—no rest for me!...

V—NIGHT OF TERROR—SACKED BY GERMANS

The night wore away. The child grew terribly weak about four o'clock, and it seemed as if he were going and were held only by sheer force of my desire. If he could only sleep! Stas slept restlessly. Little Wanda was sorry for her mother, constantly waking to ask why Mammy did not lie down.

When six o'clock came the Captain thundered in, demanding breakfast, and hoping I had slept well.

Arousing those poor people lying about on the floor, I freshened my own costume, trying to look as formal as possible. There was no bread. The Captain, informed of this, brought a loaf. They finished my butter, and drank an enormous amount of coffee. As I served them the cook came to tell me a lot of people were waiting, begging me to intercede for them. An old man rushed in after her, threw himself on the floor, kissing my hands and knees, weepingly telling how the soldiers had held him, had taken his two young daughters, had looted the hut, even to his money buried in the earth of the floor. They had then gone, taking the girls with them. The poor father crawled around the table, kissing the officers' hands. They laughed uproariously when one gave him a push which sent him sprawling over the floor.

The Captain, seeing my look of disgust (I learned to conceal my feelings better afterwards), asked me, "Whatever was the trouble—why he howled so!"

After I told him what had happened the Captain looked black and silent for a moment; then said he could do nothing. The girls now belonged to the soldiers, and I even saw he was sorry. One of the others, however, laughed, saying the father was foolish to have stopped about when he was not wanted. That was my introduction to Prussian Schrecklichkeit.

The other people waiting had mostly been turned out of doors while the soldiers slept in their beds, or were asking help to get back a pig or a horse, or else they were injured. I told them to go away and be glad they had their lives, that just now there was no help, but I would do all that lay in my power.

We heard the sound of battle all that day over Augustowo[9] way. It seemed already like a friend, our only connection with the world. Another day of miserable anxiety, the boy always worse, and the trouble of providing food for all those men. I knew that a friendly seeming attitude on my part was our salvation. The Captain under all his gruffness had a kind heart, but even in that short time I had learned what the German system means. Their idea is so to frighten people that all semblance of humanity is stamped out! Every time something awful happened they said there was East Prussia to pay for.

It was about dinner-time ... the officers were just about to sit down when my cook rushed in crying out that two soldiers came into the kitchen—while one held her (I am sure he bore the marks of her nails!) the other ran off with a ham and the potatoes ready for the table.

The officers were furious, and went out to find the culprits. They were found, and a part of the ham and potatoes also. Both got a terrible lashing, enough to take all the manhood out of them.

When this was told me as their supper was served, I asked why the men had been punished. They all had license to do as they pleased. Many dinners had been taken from the stoves that day in Suwalki. "But not where die Herrn Offiziere are!" There was the whole story. We did not exist—therefore no one could be punished for what they might do to harm us!

During that supper, it seemed as if all the officers in Suwalki came to say good-evening. I would hardly get one samovar emptied and go to the children than they would ask for another, at the same time expressing sorrow for my trouble, and saying the officers wished to meet the American lady,—and I dared not refuse! It[10] was possible to avoid giving my hand in greeting because of the sick child. How miserable to be so torn asunder! To be kept there with those men when my baby needed me every minute, but what was there to do? C'est la Guerre, as all the Germans remarked in exceedingly bad French. One of the officers who came was evidently a very great personage. They paid him such deferential respect. He looked just like an Englishman. I told him so and he said his mother was an English woman—seemingly taking great pleasure in my remark, going on, however, to say the stain could only be washed from his blood by the shedding of much English blood! I shivered to hear the awful things he said; about having fought since the beginning of the war on the west front where he had many to his account; how, when the affair with the Russians was settled, and a peace made, he was going to England to call on his cousins, with not less than a hundred lives to the credit of his good sabre! It made me ill to hear him talk. In their power, one loses the vision of freedom or right; they filled the horizon; it is very difficult not to lose courage and hope. I did ask if there were no one else to take into consideration.

"Who?"

"Just God!"

"God stands on the side of the German weapons!"

VI—CAROUSAL OF SOLDIERS IN HOUSE OF THE SICK

That night was worse than the first, the forage-wagons had come! The drinking began. After I had served many samovars of tea, if you could call it so, half a cup of rum and a little tea, in and out, in and out from the children to the table, the officer whose mother's blood he wished to wash away, had sufficient decency to say I was[11] tired and should be left undisturbedly with the children. That second night was as the first, only Stas also began to rave, talking in that curious dragging, almost lilting, tone,—one who has heard does not forget that dread sign!

Going from one little bed to the other, placing compresses, wetting the lips so cruelly dry, changing the sheets,—while in the next room those men caroused! It was only God's mercy kept me sane. Afraid to put on a dressing-gown, I remained as I was.

About five o'clock there was a great rushing about. Fresh troops were ordered to Augustowo. Many from our house were leaving. The staff remained, but my acquaintance of the night before was off. He came at that hour to wish me good-bye, showing me the picture of his wife and little daughter, telling me how "brilliantly" the child was going through the teething process! A gallant figure he was, mounted on a beautiful horse, as I looked out of the window, thinking sadly what those new troops meant.

That morning a Jew came to tell me he had some bread. By paying him well he gave me quite a quantity. Our supplies were getting low. The officers' mess had come, which served them with meat—but there was still much for me to provide, and it was only the third day!

The house was much quieter that morning, so that the sound of the little voices carried into the sitting-room. Every once in awhile Stas would shriek horribly, frightening me even more; but as a rule, during the day, they lay, constantly moving hands and head, talking incessantly, not recognizing me, and not sleeping. I should have given them milk, but there was none,—the only thing I had was tea or coffee—both rapidly disappearing.

The weather was very bad, snowing, the icy kind,[12] which hurts one's face; it seemed to fit in with the other misery.

The officers were gay at dinner. They told me that day about the amiable project to surround Great Britain with submarines, that no atom of food might reach her shores. How in a few days the blockade was to begin, every ship was to be torpedoed! England through starvation was to be brought to her knees, the Germans were to be the lords of the universe, etc., etc. What a picture was drawn for me! Hard to keep one's balance and think the other side would also have a word to say in such a matter, not sitting idly by while the Germans put the world into their idea of order!

Shortly after dinner they all went away, leaving only the orderlies, to watch things. The two belonging to the Captain were very unpleasant. I could not bear them about, especially Max. Fritz was brutal and stupid—Max was cruel and not stupid! About my usual work, and trying to amuse Wanda girl, we all suddenly stopped still, breathless at sounds from the street! Wanda cried out:

"Oh, Mammy, our soldiers have come back—I hear their voices."

VII—STORY OF THE RETURN OF THE RUSSIANS

Yes, they had come back,—but how! The street was full of them, thousands, driven along like dogs, taunted, beaten, if they fell down, kicked until they either got up or lay forever still; hungry, exhausted by the long retreat and the terrible battle. I could have screamed aloud at what was enacted before my eyes, but there was my poor little girlie to quiet; she cried so bitterly. I told her she should carry bread to the Russians. My cook brought[13] the bread cut up in chunks. I told her to go down to the mounting block with Wanda, thinking surely a little delicate child would be respected, and the surest means of getting the bread into the prisoners' hands. It seemed to me if I could not help some of those men I should go mad.

Leaving the nurse with my sons, I went to the balcony, seeing many familiar faces in the company of misery. When Wanda and the cook reached the block, there was a wild rush for the bread; trembling hands reached out, only to be beaten down. One German took a piece from my little girl's hands, broke off little bits, throwing them into the air to see those starving men snatch at them and then hunt in the mud. Finally one Christian among them gave the cook assistance; the bread was getting to the men, only we had so little.

Then something so terrible happened that while I live it can never be blotted from my memory. Wanda—my little tender, sensitive child, had a chunk of bread in her hand, in the act of reaching it to a prisoner, when Max, the Captain's orderly came up. Taking the bread from her hand he threw it in the mud, stamping on it! The poor hungry prisoner with a whimpering cry, stooped down, wildly searching, when Max raised his foot, and kicked him violently in the mouth! Wanda screamed: "Don't hurt Wanda's soldier!" The blood spurted all over her!

Rushing downstairs I gathered my poor little girlie into my arms, her whole little body quivering with sobs, and faced the brute, which had done the deed.

"What religion are you, Max?"

"Roman Catholic."

"Then I hope the Mother of God will not pray for you when you die, for you have offended one of God's little ones."

The soldier with bleeding mouth was lying on the side of the road; my cook tried to help him, but was roughly driven away.

Carrying Wanda upstairs, trying to still her; heartbroken myself, what could I tell the little creature? Suddenly she asked:

"Mammy—why does God sleep?"

"God is not asleep, darling——"

"Then Wanda don't love God when He lets the soldiers be hurt and kicked!"

"God sees all and loves all—but the bad man gets into the hearts of some of His children——"

Difficult it was to do anything when I came back into that room where my little sons lay raving, not to just sit down and nurse my girlie, six years old, to have seen such sights! While attending the boys, another scream from Wanda took me to the window. No wonder she screamed! The captured guns were being brought into the town with the Russians hitched to them, driven with blows through the icy slush of the streets, while the horses were led along beside them! Wanda cried so hysterically, that she had to have bromide; the child was ill. Surely there was nothing worse to come?

The Captain, hearing the sounds and wanting his supper, came into the room.

"Go away, Captain, if you are a man, and leave me alone with my babies."

"What is the trouble? Is the little girl ill also?"

"Have you seen what is happening with the Russian soldiers, taken prisoners?"

"Yes, I have seen."

I told him what his orderly, Max, had done. He slowly, gravely answered:

"Yes, that is bad."

"Where are all those prisoners?"

"In the churches."

Then he said, "Do not show so much sympathy—it will only do you harm and help no one. A great man will be quartered here to-morrow. Do not let him see you like this; some day when the children are well you will wish to get away from here."

"But the Russians will have retaken Suwalki long before that day, and my husband will be here."

"Never, and never, not while there is a German soldier! Now, be brave and smile, and I will help you as lays in my power."

But that evening I was not "begged" (?) to serve tea! What a night it was. My boys were so ill, and I could not pray that God save them for me. I dare not! God knows, I had come to a stone wall. It was not even possible to feel that somewhere my husband was alive. We were cut off from the living.

(Madame Turczynowicz, in her tales, "When the Prussians Came to Poland," vividly describes "The Aeroplane Visits," "The Flight to Warsaw," "Off to Galicia," "Back to Suwalki," and how she secured her release and freedom, which finally brought her to America.)

[1] All numerals throughout this volume relate to the stories herein—not to chapters in the original books.

Visiting with Spies in America, Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Germany

Told by Bernhart Paul Holst, an American

This is the remarkable recital of the adventures of an American who decided to penetrate the war-ridden countries. Armed with passports and credentials, with letters of introduction by United States Senators, and knowledge of secret grips and passwords, he made a journey which brought him into contact with the gigantic spy system of Europe. The author, who is one of the best known educators of the Middle West, has given his experiences permanent historical record in his book: "My Experiences with Spies in the European War." With his permission selections have been woven into the narrative herein presented. Copyright 1916, Holst Publishing Company, Boone, Iowa.

[2] I—STORY OF THE START OF A LONG JOURNEY

Manifold were the motives that induced me to leave my home in Boone, a thriving town in Iowa, and undertake a trip to Europe while the sparks were flying from the fire of many battlefields. I had no desire to expose myself to the carnage of war, or to witness the destruction of men as they fought for the principles which their country espoused, but rather to pursue in peaceful manner investigations....

My 40-horse-power automobile did good service in the drive of seven blocks on the rainy evening of September nineteenth, 1915, when I began my trip to the turbulent scenes of Europe, where the great war, which, since its beginning in the Balkan states, had been spread as a cloud of evil over the largest part of the continent.

I confess even now that to me the liabilities of a venture into Europe at this hazardous time seemed to become magnified, especially as thoughts of the fate of the Lusitania, the Arabic and other ships passed through my mind, but such illusions, as I choose to call them now, quickly passed away and I soon felt fully assured of utmost safety even in the war zone.

In my possession I had an official passport to enable me to conduct my work of study and research in Norway, Denmark, Sweden and Switzerland, issued by authority of the United States Government, which, in order to become valid in the belligerent countries, required the visa of a consular officer of each of the countries which were at war and which I necessarily must enter to conduct my investigations. With this document in regular form, I felt that my security was absolute, so long as I traveled on a ship of a neutral country, such as steamship Frederick VIII, which carried the flag of Denmark. These conditions well guarded, I left home and friends with pleasant anticipations of an interesting trip across the Atlantic.

As I was about to board the Pullman car, I noticed one of the leading suffragettes of the community among those who had gathered on the platform. She was coming toward me with the winsome smile that only a veteran in the battalion of a suffragette campaign can wear, and I felt rather pleased than disappointed to have her among those who were to wish me a pleasant journey and a safe return.

"Put a few bullets into the kaiser for me while you are in Europe" were the words with which this apostle of equal rights greeted me as I felt her hand taking mine. "Well," said I earnestly, "I am an American and am going to Europe to study, to explore, not to fight. If it were possible, and, if the life of the kaiser were at stake, I would put forth an effort to save it as quickly as I would, to the extent of my ability, protect the life of the king of England or the President of the United States. I believe it to be the duty of an American, when he is abroad, to so conduct himself that he will be a credit and honor to his country. This duty compels me to preserve absolute neutrality in relation to the belligerent nations instead of—" At this point she began speaking and I cannot recall all she said, but her parting words, which she intended to be friendly, were these: "If that is the way you feel about it, if you are not going to help overthrow the kaiser, I do not care what happens to you."

Having dispatched general business matters, my final object in Chicago was to have my passport visaed so as to admit me to the warring countries of Europe. However, this was merely a matter of form, as the personal letters which I carried from Senator Cummins, Congressman Woods, Governor Clarke, Senator Kenyon, Professor Bell and many other men prominent in politics and in education were sufficient to make the introduction ample and effective.

II—MYSTERIOUS STRANGERS ON THE PULLMAN TRAIN

The train was speeding swiftly when breakfast was announced in the diner.... My eyes surveyed the passengers with more than ordinary interest, not that I was[19] looking for a familiar face, but because I was attracted by the appearance of several gentlemen who gave the impression that they were not Americans.... It was my conclusion that the faces in which I was interested included those of one Englishman, one German and two Frenchmen. They seemed to avoid conversation with each other, both here and later in the Pullman cars, and I began to think of them as secret agents who were operating in connection with the business end of the war in Europe.

At the first call for lunch I again made my way to the diner and noticed that the gentleman whom I had suspected of being an Englishman was seated at a small table by himself. This appeared to be my opportunity to study him more closely and I took the seat left unoccupied at the same table, facing him squarely, and began a conversation about the weather and other topics which usually are uppermost in the semi-vacant mind. My first effort secured the information that he had boarded the train at Niagara Falls and was ticketed for New York, where he had very important business not entirely of a personal nature. His conversation was guarded and considerate, while mine began to appear evasive; at least this is my estimate of the diplomacy we were practising.

Several years before I had been told by a court-joker, of which there are many in Europe, that the name of Hanson is borne by one-third of the people of Denmark and that the remainder of the populace in that country is largely of the Holst, Peters and Larsen families. Now, under these circumstances, if I would gain the confidence of this fellow traveler, I could not reveal my real identity, but, instead, must choose one or more of the methods of concealment which are so common in detective work.

"I take you to be an Englishman, or at least an English subject," said I, after a pause.

He smiled knowingly and answered affirmatively, saying, "Your guess is correct in both particulars."

"Well," I continued, "I was born English, that is, I hail from the Australian state of Victoria, near the city of Hamilton, where my father settled on land nearly seventy years ago."

"Oh, indeed," said he, "then you must know much of Ballarat and Melbourne and Geelong, where I have been often."

After this our conversation was easy and covered a wide range of topics. Luckily we did not occupy seats in the same Pullman car, hence we agreed to meet at Albany and take dinner together on the run from that city to New York. I indicate that it was fortunate that we did not occupy seats in the same car, and I found it so, because it gave me an opportunity to plan a line of conversation for the evening ride.

III—THE "SIGN OF SILENCE"—THE SPY'S PASSPORT

At Albany all passengers for New York were required to change cars and it was necessary to wait a brief time to make connections. On the platform I met my new acquaintance, who had made himself known to me as John Fenwick of Adelaide, Australia, and here he was in earnest conversation with two young men. These he introduced to me as George Fenton and James Barton, the former a stout man with blue eyes and auburn hair and the latter a tall individual with keen, dark eyes and slightly gray hair.

In greeting them I took the right hand in mine and pressed the last joint of the small finger between my[21] thumb and second finger of my right hand. Then I opened the back cover of my watch and inside of it exposed the Sign of Silence, saying, "This is the safe side." They answered, each for himself, "I notice."

Having made the impression that I had knowledge of this order of secret agents and their manner of identification, I won their confidence. This way of winning them to trust me I had learned in Chicago several weeks before, where I met a number of large buyers of horses, who confided in me because I knew much of the horse market and the shipment of horses from Iowa.

Although Mr. Fenwick and his companions looked upon me as one of their class of people, I was far from it and entered upon a study of this line of operations as an interesting adjunct of the great war in Europe and Asia.

The trio of spies, as I choose to call them now, hailed with satisfaction the intelligence that I had been in Iowa, where I had made observations of the purchase and shipment of horses for the Allies, especially England and France. These shipments included several thousand animals.

This information was correct, as I had seen many carloads of horses unloaded for feeding at Boone, Valley Junction and other railway divisions in the Mississippi valley, later to be reloaded and forwarded to points east and eventually to Europe. I had also seen many horses that had been bought in the vicinity of Boone for the entente Allies and had examined them in the yards before shipment.

The western farming and ranching country, especially the Mississippi Valley, was covered by agents buying draft and army horses. Hundreds of posters were scattered throughout the stock-raising districts, among mule and horse raisers, and many newspapers carried display advertising in their columns.

They secured the impression that I was on my way to Europe for the purpose of looking more closely into the stock market in Denmark, where Germany had purchased quite heavily at the beginning of the war. As all this caused them to speak more freely, I evaded a discussion of my mission to Denmark, but told them I was ticketed for Copenhagen and that I expected to make the Hotel Central, on Raadhuspladsen, my headquarters. This induced them to have even greater confidence in me than before, as strangers usually give the mailing address at general delivery in the post-office, instead of divulging their place of abode.

IV—AROUND THE TABLE WITH THE SECRET AGENTS

Soon after the train left Albany, I joined the trio in the dining car and, fortunately, we secured a table by ourselves. This was to be the farewell dinner of four who had widely diverging routes and vastly different purposes before them. Mr. Fenwick was to sail to Liverpool, Mr. Fenton and Mr. Barton were en route to the South and West, and I, as stated in a former chapter, was bound for Copenhagen. How wonderful it would be if we could meet two months later to compare the experiences and achievements of each traveler with that of the others!

The effect of my feint was that I was invited to meet with them at Hotel Belmont in New York, where they had planned a consultation. This invitation I accepted and agreed to be there as soon as possible after I would reach the city, not later than eight o'clock.

After a short visit in the lobby of the hotel, we repaired for a light luncheon to a café in the vicinity, where a private dining room had been reserved for us and to[23] which refreshments, including cigars and several bottles of champagne, had been brought. It was not long until we got down to "merriment and business," as Mr. Fenwick called the proceedings.

Unfortunate in good fellowship is he who attends such a meeting, if he has not learned to smoke and to imbibe the nectar of Bacchus, but this was my plight in the council which had assembled to promote or influence the labors of Mars. However, I was excused good-naturedly on the ground that, as I was to sail on the morrow, such indulgence would unsettle me as a sailor.

Between jokes and drinks, both of which came fast, but of which the latter came the faster, the discussion turned almost entirely to the project of starving Germany and her allies into submission.

"Well," said Mr. Barton, after emptying a fair-sized glass of champagne and blowing a cloud of tobacco smoke across the room, "I think the best dope is to keep the Yankees thinking the Germans are about to invade New York with an army of a million men, supported by a fleet of fifty superdreadnaughts. This will keep them discussing what they call 'preparedness for defense' while England is destroying neutral trade between America and Europe."

Having made what he considered a capital speech, Mr. Fenwick blinked his eyes and lilted in an unusually cheerful tone the rag-time he had hummed several times before:

The trio laughed merrily and smacked their lips as[24] they sipped the champagne drawn from a bottle with a long, slender neck. Mr. Fenton held his glass near his chin and smiled approvingly, shouting, "That is the spirit of genuine liberality."

To me his smile appeared bland and harmless, but the impression he made, as he moved the glass up and down, was sinister and betrayed covert evil and danger. I began to feel uneasy and uncertain of the situation. This was the first experience of the kind I had ever witnessed.

Instead of studying me and my motives and purposes, these men became anxious to tell me of their experiences in the past and what they had set out to accomplish in the future. Instead of being a plastic organism in their hands, to be formed into shape and used to accomplish their desires as they had intended, they were divulging to me what I wanted to know of them in particular and the work of secret agents in general.

The school in which I had suddenly become a student was interesting beyond my power to describe. They howled and roared like raving beasts that are seeking to devour each other. My eyes and ears were open every moment, permitting nothing to escape, while I said only sufficient to keep the trio busy in their eagerness to surpass each other in relating the smart stories with which detectives are familiar. In this manner I easily accomplished my purpose, that is, I learned much of the work and methods of secret agents in America and received the information which enabled me to find their compatriots in Europe.

At this juncture I also learned that Mr. Fenwick was ultimately to locate in Holland, where he was to join other secret service men in keeping a close watch of the movements of goods imported with the consent of Great Britain from North and South America. He was to ascertain whether any of these goods were finding their[25] way into Germany, and, if so, in what quantity and under what conditions.

By this time we had finished our luncheon.

I was ready to leave the table and planned to do so as gracefully as possible. All I still wanted was some information about the confederates of Mr. Fenwick in Denmark. This was not difficult to obtain.

These spies, or secret service men as they called themselves, had the impression that I was in the same line of work as Mr. Fenwick, except that I was to operate in Denmark. For this reason they gave me much information about commercial affairs which were not open for publication and supplied me with addresses of people in Denmark in whom I could confide. The session came to a close at about ten o'clock, after which I hurried to the place of my residence near the Battery, where I had engaged quarters.

V—STORY OF A SEA VOYAGE FROM NEW YORK TO CHRISTIANA

Before leaving New York I mailed several letters and many American newspapers to the Danish capital, addressing them in care of Hoved Post Kontor, Kopenhagen, Denmark. The letters had been given to me by Mr. Fenwick for identification among some people he knew and they later proved of much value to me in conducting my study of the work of spies and its effect upon commerce and the trend of the war. My purpose in mailing the letters and newspapers was to evade the possibility of losing them in case of detention and seizure of the ship before reaching the capital of Denmark, which was not entirely out of the range of probability.

The ocean-liner Frederick VIII was throbbing under the pressure of superheated steam when I arrived at the[26] docks in Hoboken, shortly before two o'clock in the afternoon of September twenty-second. Everything was ready for her to put to sea in the long route across the northern part of the Atlantic.

At the table to which the chief steward assigned me were one Danish officer of the steamship and seven passengers. The latter included one English, one German, two Belgian and three American citizens. The general conversation was in German, and this was pleasing to me, as it gave me an opportunity to cultivate the use of the Teutonic tongue with much effect.

Among the passengers was Mr. Niels Petersen, who had been in Canada and had taken pictures at the principal seaports, such as St. John, Halifax, Quebec and Montreal. His photographs included views of harbors, bridges, railway terminals, stretches of highways and prominent buildings. He had been tracked to New York, where he was detected by British spies, and a telegram to Kirkwall by way of London demanded his arrest on the charge that he was guilty of espionage.

This party declared his innocence and claimed to be a Dane. He admitted having the photographs, but said they were taken for his personal study and for no other purpose. On the seventh day at Kirkwall he was taken from the ship as a spy and removed in a small boat. At the time of his arrest he was singing a patriotic song of Denmark, verses of which he continued singing as he was removed, and while taken away he waved his hand in farewell to the steamship that had carried him into the hands of his accusers. This was the last seen of him by the passengers; it is said he was taken to a detention camp and later imprisoned.

At Christiana British trade spies were numerous at the railway stations and in the vicinity of the docks. I saw them at restaurants and in the lobbies of the leading[27] hotels, especially at the Grand, the Scandinavie, and the Continental. It was not difficult to identify myself by using the Sign of Silence, which I had employed successfully at Albany, when the two companions of Mr. Fenwick were introduced to me. My knowledge of the purchase of horses, grain, cotton and meat by the allies in America interested them.

These spies were studying the register at the leading hotels so they might know the class of strangers who were in the city, whether German, Russian, French, etc., and the effect which the propaganda of these or any of them had upon public thought in Norway.

VI—WITH THE SPIES IN SWEDEN

From Christiana I went to Trondhjem and later to Hell, both seaports on fjords with deep harbors. At both these places I found spies of the allies on the same mission as those at Christiana, but in addition also agents friendly to Russia who were counteracting the rising feeling against the czar and his alleged desire to annex northern Sweden and Norway, to secure an outlet through an open port on the Atlantic.

On my second day at Trondhjem, shortly after leaving the Grand Hotel, I met Mr. Solomon Lankelinsky, a Hebrew merchant, from whom I learned much of the Russian agents who were working to influence sentiment. In fact I had met many Jews and all with whom I came in contact expressed themselves anti-Russian.

At this time the campaign at the Dardanelles was in full swing, which the czar expected would be forced by the British and French, after which Constantinople would be captured and the whole region annexed to Russia to connect her commercially with the Mediterranean. Several secret agents of Russia I met here and at Hell[28] made this solution in the near East the theme of conversation and promulgated discussion by publishing articles regarding it in the newspapers. It appeared singular that these secret agents, although acting for Russia, conversed almost entirely in the German language, which tongue is spoken extensively in Warsaw and many large cities of Russia.

In the Swedish capital, the city of Stockholm, the secret service men likewise were abundant. They were active in the lobbies of the Grand, the Continental and the Central hotels. I met them in the city and in the suburbs, everywhere busy as bees. Here the work of spies was not so much concerned with commerce as with the study and direction of public sentiment, for which purpose they wrote for newspapers both in Sweden and in their own countries.

This was before the movement for conscription had made much progress in England, and the British were endeavoring in vain to induce men to join the army. One of the English secret agents showed me a poster that was being used to enlist the support of the women, thinking they would lend a hand to induce their husbands, sons or sweethearts to go to war.

VII—STORY OF A RUSSIAN MADAM ON SECRET SERVICE

On the eighteenth of October I ticketed for Malmö by way of Nörrkoping, taking the train from the central station. The seat opposite mine in the well-cushioned compartment was occupied by a lady of middle age. She kept her suit case near her seat as if she feared it might become lost.

Little was said at the beginning of the trip. She took observations through the window of the compartment,[29] especially of the outlying districts of the city, a part of which is known as Gamle Stockholm, and seemed interested in the fields, gardens and forests.

I busied myself reading in a guide of Sweden. At length we began a conversation. She tried to convey the idea that she spoke no language but Swedish, but I soon discovered her accent to be that of a Slav and that she was able to converse freely in German.

Pointing my finger at her, I said, "You are a Russian spy and the evidence is in your suit case."

To me it seemed that her face displayed all the colors of the rainbow. She threw up her hands excitedly, moving them up and down like a country pedlar.

"Sir," she said at length, "you surprise me, you offend my loyalty. Why accuse me for no other reason than that I am a Russian?"

"Calm yourself, madam," I replied. "Although I am an American, I know of your work and have you noted in a list of people who are practicing espionage. However, you need not fear me in the least. I am neutral and am interested in you only as a matter of general information."

Then I showed her my American passport and many letters of identification, in which manner she was led to confide in me. My guess had proven a correct one.

She gave her name as Miss Michailowitsch and showed me some letters to bear out her statement. The work she was doing consisted of coöperating with others in watching Finland, where the men of military age had become restive and many were emigrating. It was her special business to observe these people and, if possible, learn who and how many were joining the German army in Poland and on the Dvinsk River.

I left the train at Nörrkoping while Miss Michailowitsch went on to Malmö. At the time of leaving the[30] train, I advised her to change her occupation, if she valued her life. This admonition elicited a bland smile.

VIII—SPIES OF DENMARK—COPENHAGEN THE MECCA OF SPIES

The steamer ran into port at Havnegade, which is the landing place for the vessels crossing the Sound, and I made haste to Hotel Central, on Raadhuspladsen. At this hotel and at general postal delivery I expected mail from America and from secret agents I had met at New York and at various places in Europe. The mailman was liberal and gave me many letters and packages, small and large, which reminded me of an American mail order house. Had I been in a country at war, where strangers were carefully watched, I would have been under no mild suspicion.

The first evening, after a hasty meal, I made a trip to the leading hotels, including the Bristol, the Cosmopolite, the Dagmar, the Palads, the Monopol and the Grand Hotel National. By this initial but rapid tour it was possible to locate the places where strangers gather and to feel the pulse of commerce and public sentiment. My first impression was right: "Copenhagen is at present the Babel of travel and the Mecca of European secret service work."

When I was about to retire for the night, while on my way back to the hotel, I met a man who wanted to sell me a lead pencil. I purchased, but at the same time studied the expression of his face, which seemed to tell a story of a different life than that of the street vendor. He limped while stepping on his right foot and carried a rather elegant looking cane.

On Raadhuspladsen I met several men who were taking pictures for travelers. They were agreeable looking[31] fellows and I engaged them to take several views of me, including one of the monument known as Death and Sorrow which is a fine bronze piece near the Hellig Aand Church. It was not long until I made the discovery that these men were spies. Indeed, I found spies disguised as street vendors, newspaper sellers, bootblacks, interpreters, guides and as workers in many other common callings. At the Bristol Hotel I met several spies to whom Mr. Fenwick had referred me while I was in New York. They gave spice to my leisure moments and stimulated interest in the war.

After I had been in Copenhagen several days, late in the afternoon, I decided to go to the docks and shipping yards to take observations of the freight which was moving through the city. Here I discovered a man making notations of cars which were either loading or unloading. These cars were from the continent and were marked from different places, such as Bromberg, Dresden, Munich, Bautzen and other cities of Germany.

Here was the clue that Denmark was trading extensively with the Central Powers. This spy was listing the cars and steamships engaged in this trade; he was taking the names of the ships and cars and making a record of the commodities in which trading was done. After observing his work for some time, I made my presence known and found him to be the street vendor from whom I had purchased a lead pencil on my first evening in the city, but he was now posing as a railroad official and held his cane before him as he walked rapidly away.

It did not require much time for the street vendor, who pretended to be lame as he leaned upon his cane, to dent the crown of his hat and assume the more important attitude of a railway and steamboat inspector. He may have deceived others a long time, but I was on his[32] trail and discovered his smart delusion much sooner than he expected.

Several times I invited a number of the spies that I met at the Bristol Hotel to accompany me to entertainments, including a certain John Denton, a friend of Mr. Fenwick, who went with me to the Scala Theater, where a comic opera known as Polsk Blod was presented. This gentleman entertained much and came in contact with many prominent Danes.

I gave him the letter written by Mr. Fenwick at New York, but not before I made a copy of it, thinking this precaution would serve my purpose to an advantage elsewhere. Later, when I returned to New York, I secured stationery and had duplicate copies written on letterheads of Hotel Belmont.

IX—THROUGH CORDONS OF SPIES TO BERLIN

After some time of interesting visits and conversations, I left Copenhagen to go partly by train and partly by steamer to Berlin, making the trip to Germany by way of Warnemünde. This is the port on the Baltic Sea through which the German capital and the interior of Europe may be reached most conveniently.

I had not been in Germany many days until I learned from personal observation that some travelers I met professed friendship for Germany and in spite of their professions were false and dangerous enemies. To me it seemed, in view of this fact, that the authorities leaned rather on the side of leniency than on the side of severity. In all public places was the notice:

The translation is as follows: Soldiers, careful in conversations; danger of spies!

That there was an invasion of spies and secret service men, mostly representing England and France, I learned soon after I reached the large cities of Germany. They were disguised in various ways, as laborers, students and professional and business men.

I had been in Berlin more than three weeks, had consulted with the American ambassador, Hon. James W. Gerard; with Mr. James O'Donnell Bennett and Mr. Robert J. Thompson, American newspaper reporters; with members of the German parliament, and many officials in civic and military positions, including Herr Gottlieb von Jagow, the German secretary of foreign affairs, before I obtained privileges to visit prison camps, border fortifications and fields in the east where action had destroyed cities and devastated the country.

After I had traveled to inspect the points which I wanted to visit, I began to plan to learn from first hand experience the strange and horrible action and destruction in war. It was my purpose to meet those who had fought at the front and had been in the thick of the fight at noted engagements. In this manner I obtained information by personal inspection and at the same time saw safely by proxy what would otherwise be dangerous and impossible.

X—"THE SPY I MET IN WARSAW"

The shortest trip from Berlin to Warsaw is by way of Bromberg and Thorn, but I chose the route going through Breslau-Oppeln-Czestochowa, the last mentioned town being in Russia, which takes the traveler through Skierniewice and enters Warsaw from the south-west. In returning, I chose the route Skierniewice-Alexandrowa,[34] which, in Germany, is the line Thorn-Bromberg-Schneidemühle-Berlin.

This route permits the traveler to see much of the farming districts in eastern Germany and a large part of Poland, which, by the way, is no mean ambition in the time of war. Here as nowhere else is exemplified the great faith the Germans had in the soil as a mainstay of success. They had gone into partnership with nature to work out their salvation.

My entrance into the Polish capital was without formality. I went at once to Hotel Rom, where I left my hand baggage, and then reported at the police station. The fact that I had announced myself as a literary writer (Schriftsteller) seemed to entitle me to more than ordinary courtesies.

In the afternoon of my first day in the city, while near the main building of the university, I met a young man who was walking leisurely. He was holding a cane and was resting his chin upon his right hand.

Not long afterward, in an angular street near by, I saw a person who reminded me of the young man I had met shortly before. His pants seemed to be made of the same kind of woolen goods, but his hat and coat appeared different.

The following day I met the same person and took the liberty to speak to him. In the course of time I learned that he was a secret service man and had been detailed to watch a number of strangers who were sojourning in the city. Those who were under surveillance, I learned soon after, included me as well as several guests at Hotel Rom.

This young man had a coat with two sides suitable for outside wear. When one was exposed, he looked like a student, and in the other he had the appearance of a newspaper seller. He was one of many secret service[35] men in civilian clothes who were doing police duty and detective work.

XI—STORY OF THE DAINTY SPY AT BERLIN

When I returned to Berlin from the east, I engaged quarters at Pension Stern, a pleasant place on Unter den Linden. The outlook from the front window enabled me to see all that famous thoroughfare, from the statue of Frederick the Great to the Brandenburger Tor. The panorama included the vacant French embassy, the Cafe Victoria, the main building of the University of Berlin and the Dom Kirche in the distance.

I had returned to the capital city to visit the museums, art galleries and palaces of Berlin as well as the suburbs of Spandau, Charlottenburg and Potsdam. It was my purpose to study life at the capital as well as to see the military side of the war in the German metropolis, including the great prison camp at Döberitz.

At the reading rooms of the Chicago Daily News, on Unter den Linden, I found many American and English periodicals and went there frequently to peruse them. Several times I met at this place a dainty lady who spoke German like a Bavarian and English with the (ze) accent of a Parisian. This lady I learned to know as Miss Julia Bross and I put her on my list of possible spies.

She accepted pleasantly my invitation to take dinner at Cafe Victoria, where she drank coffee and smoked a cigarette while I labored over a cup of tea as a final course in a long list of eatables. Her home was in Denmark, which was evidenced by numerous letters which she carried, and she was in the city to teach French and study German.

The story of the dainty dame was well planned, but[36] I doubted her. She was a spy and was on dangerous footing. With apologies to Bret Harte, I wrote in my diary:

The city was full of soldiers,—at churches, in theaters, at restaurants, on the streets, in short, everywhere were soldiers. Life was no departure from the usual. The shops were full of goods and everybody was doing business in the even tenor of his way. The sound of martial music, the marching of soldiers and the flutter of many German, Bulgarian, Turkish and Austria-Hungarian flags in public places were the only reminders that war was in progress.

On a train of the Stadtbahn (city railway) I went to Döberitz, where I made a complete tour of the military camp, including the prison yards, the military drill grounds and the field of aviation. The clear sky was dotted with many flying machines, including taubes, biplanes and Zeppelins, making the district buzz with their rapid-working machinery.

Toward evening I wended my way from the prison yards to the depot, about a half mile, walking slowly over the sandy tract. When I arrived at the station I was surprised to find that Miss Bross was among the passengers who were waiting to return to the city.

Miss Bross had reached the place by a different train than the one by which I came. She had been busy in the sunlight, she said, enjoying the open sky and the warm, autumnal breezes.

To me her mission to Döberitz appeared very different. It seemed that she had no interest in the prison camp,[37] that to her the sanitation and employment of prisoners was a blank book, but everything I mentioned about the drill of soldiers and the maneuvers of flying machines aroused her interest. To the one she was blind and to the others she was wide awake and far-seeing. The difference in her feeling on these topics deepened my suspicion that she was practicing a clever game of espionage.

I had taken a seat beside her on a bench in the railway station and began to study her face. She was alert and cunning, but her attitude was vague and evasive.

When the express train rolled into the station, I was ready to board it without delay. The evening was pleasant and the train moved rapidly toward the metropolis. Miss Bross alighted at Potsdamer Platz, while I went as far as Friedrich Strasse.

Several times I met Miss Bross at the reading rooms of the Chicago Daily News, where she observed the news columns and editorials of the German-American newspapers with special interest. Near the last of November she told me she had decided to go home to Denmark on the third of December. By this time I had purchased passage to New York and left for Copenhagen the same morning.

After luncheon on the railway diner, Miss Bross seemed worried about the examination at Warnemünde, where German officers inspected the baggage and person of the passengers. This examination, owing to much espionage, had been greatly intensified.

"What do you think of the case of Miss Edith Cavell?" she asked, "I mean the nurse who was executed as a spy in Belgium by the Germans."

"This case," I answered, "is an unusual one. Miss Cavell had the utmost confidence of the German officers, who granted her extraordinary privileges as a nurse, while she busied herself most of the time organizing a[38] band of spies to operate against the German army in France."

"Yes, that is true; but she was a woman who had done some good and her life should have been spared. At least they think so in France and England where funds are being raised to build monuments to her memory."

XII—THE "SCRAP OF PAPER"—A DEATH WARRANT

The train was entering the station at Warnemünde. Miss Bross seemed nervous. She handed me a small scrap of paper, saying, "If I am on the train after we leave Warnemünde, hand it back to me; otherwise do what you like with it."

It was currently reported that all the passengers when entering or leaving a country at war, in Germany as well as in France and England, would be required to remove all their clothes and undergo a thorough examination. This proved to be the case in this instance, except where travelers could make an unusually good showing of neutrality and fairness, under which condition I passed the scrutinizing officers to my utmost satisfaction.

When the steamship was crossing the Baltic Sea, I looked in vain among the passengers for Miss Bross, who, according to subsequent reports, was retained as a spy. The examining officer, a German lady, had found a plat of the military grounds at Spandau pasted to the sole of her bare foot. I never saw her again.

This gave me the liberty to do as I pleased with the scrap of paper Miss Bross handed to me on the train. On examination I found it embodied a somewhat faulty plat of the military camp at Döberitz.

It occurred to me immediately that I had assumed a dangerous and unnecessary risk in permitting her to place[39] it in my custody. Had I known the contents of this innocent looking scrap of paper, it would have been utterly impossible to have induced me to even touch it. However, the matter ended without injury to me, and I was extremely glad that I was sailing on the Baltic Sea, instead of being at the inspection rooms at Warnemünde with the scrap of paper in my pocket.

(The author continues his interesting narrative with an illuminating description of the methods of spying and many other phases of his journeys.—Editor.)

[2] All numerals relate to stories told herein—not to chapters in the book.

Hunting the Seas on a German Submarine

By Baron Spiegel Von Und Zu Peckelsheim, Captain Lieutenant Commander of the U-202

This is a thrilling day by day story of the daring, hunting raid of a German submarine, told by the officer in charge. He tells how the undersea boat is maneuvered; how the English and French attempt to guard the channel against the enemy's deadly U-boats. He reveals the emotions of the officers and crew of the little 202 in the presence of what seemed death the next moment, and tells of their marvellous achievements in the midst of their sinister tasks. This is one of the most astounding personal narratives that the War has yielded. These selections are taken from the German Commander's logbook with the permission of the publishers, The Century Company, copyright 1917, published by arrangement with the New York World.

[3] I—STORY OF THE SUBMARINE CAPTAIN

What peculiar sensations filled me. We were at war—the most insane war ever fought! And now I am a commander on a U-boat!

I said to myself:

"You submarine, you undersea boat, you faithful U-202, which has obediently and faithfully carried me thousands of miles and will still carry me many thousand miles! I am a commander of a submarine which scatters death and destruction in the ranks of the enemy, which carries death and hell fire in its bosom, and which rushes through the water like a thoroughbred. What am I searching for in the cold, dark night? Do I think about honor and success? Why does my eye stare so steadily into the dark? Am I thinking about death and the innumerable mines which are floating away off there in the dark, am I thinking about enemy scouts which are seeking me?

"No! It is nerves and foolish sentiments born of foolish spirits. I am not thinking about that. Leave me alone and don't bother me. I am the master. It is the duty of my nerves to obey. Can you hear the melodious song from below, you weakling nerves? Are you so dull and faint-hearted that it does not echo within you? Do you not know the stimulating power which the thin metal voice below can inspire within you?

"This song brings greetings to you from a distance of twelve hundred miles and through twelve hundred miles it comes to you. Ahead we must look; we must force our eyes to pierce the darkness on all sides."

The spy-glass flew to the eye. There is a flash in the west. A light!

"Hey, there! Hey! There is something over there——"

"That is no ordinary light. What about it?"

II—NIGHT ON THE OCEAN—ON DECK OF A SUBMARINE

Lieutenant Petersen was looking through his night glasses at the light.

"I believe he is signaling," he said excitedly. "The light flashes continually to and fro. I hope it is not a scout ship trying to speak with some one."

Hardly had the lieutenant uttered these words when[42] we all three jumped as if electrified, because certainly in our immediate neighborhood flashed before us several quick lights giving signals, which undoubtedly came from the ship second in line, which was signaling to our first friend.

"Great God! An enemy ship! Not more than three hundred meters ahead!" I exclaimed to myself.

"Hard a starboard! Both engines at highest speed ahead! To the diving stations!"

In a subdued voice, I called my commands down the tower.

The phonograph in the crew-room stopped abruptly. A hasty, eager running was discernible through the entire boat as each one hurried to his post.

The boat immediately obeyed the rudder and was flying to starboard. Between the two hostile ships there was a continuous exchange of signals.

"God be praised it is so dark!" I exclaimed with a deep breath as soon as the first danger had passed.

"And to think that the fellow had to betray his presence by his chattering signals just as we were about to run right into his arms," was the answer. "This time we can truly say that the good God, Himself, had charge of the rudder."

The engineer appeared on the stairway which leads from the "Centrale" up to the conning tower.

"May I go to the engine-room, Herr Captain-Lieutenant?"

It was not permissible for him to leave his diving station, the "Centrale," which is situated in the center of the boat, without special permission.

"Yes, Herr Engineer, go ahead down and fire up hard!" I replied.

The thumping of the heavy oil-motors became stronger, swelled higher and higher, and, at last, became a long[43] drawn out roar, and entirely drowned the sound of the occasional jolts which always were distinctly discernible when going at slower speed. One truly felt how the boat exerted its strength to the utmost and did everything within its power.

We had put ourselves on another course which put the anxiously signaling Britishers obliquely aport of our stern, and rushed with the highest speed for about ten minutes until their lights became smaller and weaker. We then turned point by point into our former course, and thus slipped by in a large half circle around the hostile ships.

"Just as a cat around a bowl of hot oatmeal," said Lieutenant Petersen.

"No, my dear friend," I said laughingly, "it does not entirely coincide. The cat always comes back, but the oatmeal is too hot for us in this case. Or do you think that I intend to circle around those two rascals for hours?"

"Preferably not, Herr Captain-Lieutenant. It could end badly!"

"Both engines in highest speed forward, let the crew leave the diving stations, place the guards!" I ordered.[4]

It was three minutes after six o'clock, and within about half an hour the sun would rise, but the sea and the sky still floated together in the colorless drab of early dawn and permitted one only to imagine, not see, that partition wall, the horizon.

Unceasingly our binoculars pierced the gray dusk of daybreak. Suddenly a shiver went through my body when—only a second immovable and in intense suspense—a dark shadow within range of the spy-glass made me jump. The shadow grew and became larger, like a giant on the horizon—one mast; one, two, three, four funnels—a destroyer.

A quick command—I leap down into the tower. The water rushes into the diving tanks. The conning tower covers slam tight behind me—and the agony which follows tries our patience, while we count seconds with watches in hand until the tanks are filled, and the boat slips below the sea.

Never in my life did a second seem so long to me. The destroyer, which is not more than two thousand meters distant from us, has, of course, seen us, and is speeding for us as fast as her forty thousand horse power can drive her. From the guns mounted on her bow flash one shot after another aimed to destroy us.

Good God! If he only does not hit! Just one little hit, and we are lost! Already the water splashes on the outside of the conning tower up to the glass windows through which I see the dark ghost, streaking straight for us. It is terrifying to hear the shells bursting all around us in the water. It sounds like a triphammer against a steel plate, and closer and closer come the metallic crashes. The rascal is getting our range.

There—the fifth shot—the entire boat trembles—then the deceitful daylight disappears from the conning-tower window. The boat obeys the diving rudder and submerges into the sea.

A reddish-yellow light shines all around us; the indicator of the manometer, which measures our depth, points to eight meters, nine meters, ten meters, twelve meters. Saved!

III—HOW IT FEELS TO PLUNGE BENEATH THE SEAS

What a happy, unexplainable sensation to know that you are hiding deep in the infinite ocean! The heart, which had stopped beating during these long seconds because it had no time to beat, again begins its pounding.

Our boat sinks deeper and deeper. It obeys, as does a faithful horse, the slightest pressure of a rider's knees, which, in this case, are the diving rudders placed in the bow and the stern. The manometer now shows twenty-four meters, twenty-six meters. I had given orders we should go down to thirty meters.

Above us we still hear the roaring and crackling in the water, as if it were in an impotent rage. I turn and smile at the mate who is standing with me in the conning tower—a happy, carefree smile. I point upwards with my thumb.

"Do you hear it? Do you hear it?"

It is an unnecessary question, of course, because he hears it as plainly as I do, and all the others aboard hear it, too. But the question can still be explained because of the tremendous strain on our nerves which has to express itself even in such a simple question.