Title: The Mentor: Guynemer, The Wingèd Sword of France, Vol. 6, Num. 18, Serial No. 166, November 1, 1918

Author: Howard W. Cook

Release date: July 16, 2015 [eBook #49455]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

LEARN ONE THING

EVERY DAY

NOVEMBER 1 1918

SERIAL NO. 166

THE

MENTOR

GUYNEMER

THE WINGÈD SWORD

OF FRANCE

By HOWARD W. COOK

DEPARTMENT OF

BIOGRAPHY

VOLUME 6

NUMBER 18

TWENTY CENTS A COPY

By Commandant Brocard, of the “Stork Squadron”

For more than two years all of us have seen him cleaving the heavens above our heads, the heavens lighted up by shining sun or darkened by lowering tempests, bearing upon his poor wings a part of our dreams, of our faith in success, of all that our hearts held of confidence and hope.

“Guynemer was a powerful idea in a frail body, and I lived near him with the secret sorrow of knowing that some day the idea would slay the container.

“Poor boy! All the children of France, who wrote to him daily, to whom he was the marvelous ideal, vibrated with all his emotions, lived through his joys and suffered his dangers. He will remain to them the living model hero, greatest in all history. They love him as they have learned to love the purest glories of our country.

“Guynemer was great enough to have done that which he did without seeking recompense save in the silent consciousness of having done his full duty.”

THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

Established for the Development of a Popular Interest in Art, Literature, Science, History, Nature and Travel

THE MENTOR IS PUBLISHED TWICE A MONTH

BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC., AT 114-116 EAST 16TH STREET, NEW YORK. N.Y. SUBSCRIPTION, FOUR DOLLARS A YEAR. FOREIGN POSTAGE 75 CENTS EXTRA. CANADIAN POSTAGE 50 CENTS EXTRA. SINGLE COPIES TWENTY CENTS. PRESIDENT, THOMAS H. BECK; VICE-PRESIDENT, WALTER P. TEN EYCK; SECRETARY, W. D. MOFFAT; TREASURER, J. S. CAMPBELL; ASSISTANT TREASURER AND ASSISTANT SECRETARY, H. A. CROWE.

NOVEMBER 1st, 1918.VOLUME 6NUMBER 18

Entered as second-class matter, March 10, 1918, at the postoffice at New York, N. Y., under the act of March 3, 1879. Copyright, 1918, by The Mentor Association, Inc.

THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, Inc., 114-116 East 16th Street, New York, N. Y.

Statement of the ownership, management, circulation, etc., required by the Act of Congress of August 24, 1912, of The Mentor, published semi-monthly at New York, N. Y., for October 1, 1918. State of New York, County of New York. Before me, a Notary Public, in and for the State and county aforesaid, personally appeared Thomas H. Beck, who having been duly sworn according to law, deposes and says that he is the Publisher of the Mentor, and that the following is, to the best of his knowledge and belief, a true statement of the ownership, management, etc., of the aforesaid publication for the date shown in the above caption, required by the Act of August 24, 1912, embodied in section 443, Postal Laws and Regulations, to wit: (1) That the names and addresses of the publisher, editor, managing editor and business manager are: Publisher, Thomas H. Beck, 52 East 19th Street, New York; Editor, W. D. Moffat, 114-116 East 16th Street, New York; Managing Editor, W. D. Moffat, 114-116 East 16th St., New York; Business Manager, Thomas H. Beck, 52 East 19th Street, New York. (2) That the owners are: Mentor Association, Inc., 114-116 East 16th St., New York; Thomas H. Beck, W. P. Ten Eyck, J. F. Knapp, J. S. Campbell, 52 East 19th Street, New York; W. D. Moffat, 114-116 East 16th St., New York; American Lithographic Company; 52 East 19th Street, New York. Stockholders of American Lithographic Co. owning 1 per cent. or more of that Corporation. J. P. Knapp, Louis Ettlinger, C. K. Mills, 52 East 19th Street, New York; Chas. Eddy, Westfield, N. J.; M. C. Herczog, 28 West 10th Street, New York; William T. Harris, 37th Street, Philadelphia, Pa.; Mrs. M. E. Heppenheimer, 51 East 58th Street, New York; Emilie Schumacher, Executrix for Luise E. Schumacher and Walter L. Schumacher, Mount Vernon, N. Y.; Samuel Untermyer, 120 Broadway, New York. (3) That the known bondholders, mortgagees, and other security holders owning or holding 1 per cent. or more of total amount of bonds, mortgages, or other securities, are: None. (4) That the two paragraphs next above, giving the names of the owners, stockholders, and security holders, if any, contain not only the list of stockholders and security holders as they appear upon the books of the Company, but also, in cases where the stockholder or security holder appears upon the books of the Company as trustee or in any other fiduciary relation, the name of the person or corporation for whom such trustee is acting, is given; also that the said two paragraphs contain statements embracing affiant’s full knowledge and belief as to the circumstances and conditions under which stockholders and security holders who do not appear upon the books of the Company as trustees, hold stock and securities in a capacity other than that of a bona fide owner; and this affiant has no reason to believe that any other person, association, or corporation has any interest direct or indirect in the said stock, bonds, or other securities than as so stated by him. Thomas H. Beck, Publisher. Sworn to and subscribed before me this twenty-fourth day of September, 1918. J. S. Campbell, Notary Public, Queens County. Certificate filed in New York County. My commission expires March 30, 1919.

THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, Inc., 114-116 East 16th St., New York, N.Y.

GEORGES GUYNEMER, WHEN HE BEGAN HIS FLIGHTS

ONE

Not only modern, but ancient French records glorify the name of Guynemer. In the time of Roland and Charlemagne, there was a Guinemer that performed noble deeds. An eleventh-century history of the Crusades extols the name of a Guinemer of Boulogne. The Treaty of Guérande, which terminated in 1365 a war of succession in Brittany, bore the signature of Geoffroy Guinemer among thirty knightly signers. In 1464 the old and honorable name was first spelled with a y by Yvon Guynemer, a man of arms in the service of his country.

Bernard Guynemer, great grandfather of Georges, was an instructor in jurisprudence in Paris during the Revolution, and was later made president of the Tribunal of Mayence. A son, Auguste, who lived to be ninety-three, left to posterity a remarkable collection of memoirs of the Revolution, the Empire, and the Restoration. One of his brothers, an officer in Napoleon’s army, was killed at the siege of Vilna in 1812; another, a naval officer, died of wounds received at Trafalgar. A fourth brother named Achille became the grandfather of Georges, and it was his exploits, among all the tales of his forbears, that the youthful grandson loved best to read about. One venturous anecdote of the child Achille became part of family history, and in its revelation of mature purpose and utter poise under confounding circumstances recalls instances of the boyhood of the future Ace of Aces. When the small Achille arrived one morning at his school in Paris he found it closed. The mistress, he was told, had been taken away, summoned before the Revolutionary Tribunal. When he inquired where this Tribunal was, he was laughingly informed, and straightway he set out to find it. When the eight-year-old appeared in the court room alone, he was received by assembly and judges with amazement, then with raillery, but, in no wise disconcerted, he continued up the imposing aisle to the place where the mighty Robespierre sat. Humorously, Robespierre met his request that his teacher be allowed to return to her classes by remarking that the child’s need of her could not be great, as doubtless she had taught him little in the past. In his desire to refute the injustice, the boy begged permission to recite his lessons for the day. When he had finished, Robespierre impulsively took him in his arms and embraced him. Then he gave into his charge the school mistress, and permitted them both to depart.

Seven years later, Achille Guynemer was a volunteer in the army that invaded Spain. In 1812, he was taken prisoner; later he escaped, and in 1813, at the age of twenty-one, he was decorated with the Cross of the Legion of Honor. His grandson, who strongly resembled his early portraits, received the same honor when he was a few months younger.

Of the four sons of the president of the Tribunal of Mayence, only one, Achille, had descendants. The son of the latter was Paul Guynemer, a French army officer and military historian, and his only son was Georges, the young chieftain of the sky.

Even as a very little boy, Georges carried his head with pride and set his ambitions high. Adored by his mother and sisters, he was a constant object of solicitude because of ill health. When he was of school age he received instruction from the governess of his sisters. Very young he showed evidences of those qualities of honor, truth and bravery that earned him in later years all the honors France could bestow. Very young he fell under the spell of Joan of Arc, she who was wounded in Compiègne, the home of his boyhood, and he clamored for stories of her and of others of his country’s warriors.

An indifferent pupil in the grammar-school at Compiègne, he was placed in Stanislas Military College, his father’s Alma Mater. A group photograph of the students represents Georges as a boy of twelve, pale, thin, with dark, wilful eyes lighted by smouldering fires of dream and ambition. As a student he was quick and intelligent, but he was mischievous and headstrong under discipline. In play he preferred warlike games, and invariably chose parts that gave him opportunities to attack, which he did with agility and vigor, often to the discomfiture of older opponents. One of his teachers wrote a sketch of his school-boyhood that betrays many outstanding traits of the Guynemer of the future. In playground battles he had no desire to command; he liked above all to fight, and to fight alone. He attacked the strongest, without consideration for any advantage they might have of weight, height or numbers. Even as a boy, he excelled by adroitness, suppleness of maneuver, and will-to-win.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 6, No. 18. SERIAL No. 166

COPYRIGHT, 1918. BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

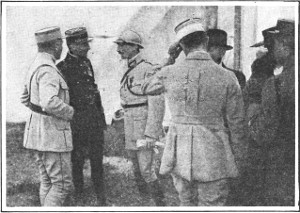

GUYNEMER AND HIS FAITHFUL GUNNER, GUERDER

TWO

Though hampered by illness and enforced vacations, Guynemer graduated from Stanislas College in his fifteenth year with honors. In the autumn he re-entered the school for a further course of study. His leisure hours were passed installing miniature telephones, and experimenting with paper airplane models. His ability for invention and mechanics was marked. All the sciences held interest for him, but he had special liking for chemistry and mathematics. He was fond of reading, but his choice of books fell solely on those that dealt with war, chivalry and adventure.

One of young Guynemer’s intimates was Jean Krebs, whose father was a pioneer in the development of aerostatics and aviation. He was then director of the great Panhard automobile works, and on Sundays the two youths spent hours studying motor parts. With their fellow students at the college they were often taken to visit technical establishments after school. Georges was always to be found beside the one that explained the operations of the machinery. When they were permitted to attend automobile and airplane exhibitions, his delight was boundless. Keen, excited, agitated, he passed from one exhibit to another, commenting, interrogating, and incidentally filling his pockets with catalogues and pamphlets about the different makes of cars and planes. While still at school he fashioned a small airplane, which he launched with glee over the heads of his companions.

At that time (1910), the eyes of Europe were on the sky. Blériot had crossed the Channel; Paulhan had soared to a record height of over four thousand feet. It was the ambition of all French youth to fly. With Guynemer the desire was an obsession. From the aerodrome near Compiègne he secretly made his first flight, crouched behind an obliging pilot, cramped and uncomfortable, but ecstatically happy. So determined was he to follow the profession of the air that pleasures of world travel, enjoyed for months in the fond companionship of his mother and sisters, served in no way to distract him from his purpose. “What career shall you adopt?” his father inquired, when they returned. And Georges answered, as if it were the most natural thing in the world, “I shall be an aviator.” His parent protested that aviation was not a career, but a sport. The boy was obstinate. He confessed that his life was already dedicated to this passion. That on the morning he had first seen a birdman fly above the college of Stanislas, he had been possessed by a sensation he could not explain. “I felt an emotion so deep it seemed sacred,” he told his father. “I knew then that I must ask you to let me become an aviator.”

Refused admission to the École Polytechnique because the professors believed him too frail to finish the courses, he was taken with his family to Biarritz on the coast of France, and there rumors came to them of the war, in the month of July, 1914. War was declared August second. The following day Georges presented himself for medical examination at Bayonne,—was rejected, and when he tried still other times, was rejected again. Finally his persistence, his devotion to France, his resolve to serve her in the way he felt he could be of the most value, won him the reward of acceptance in the training school at Pau.

In January, 1915, Guynemer received his first lessons as a student-aviator, after having studied two months as a mechanic. On February first, according to his own narrative, his apprenticeship as a pilot took on aerial character. “I drove a ‘taxi,’ and then the following week I mounted an airplane, going in straight lines, turning and gliding, and on March tenth I made two flights lasting twenty minutes in daylight. At last I had found my wings. I passed the examination the next day.”

Once, Guynemer barely escaped being scratched from the list of military aviators at the school of Avord, because a head pilot complained that he was imprudent in making flights that were too difficult for one of his experience, and because he persisted in flying when the weather was unfavorable.

When he had flown for six months, he was sent one day on a photographing mission. The enemy discovered him. A rain of shells fell on his plane. Keeping on amid the deluge, Guynemer made not a single turn to escape the attacks. For an hour he went straight toward his objective until his observer gave the signal to return. Even then the pilot continued to drive on toward the guns that were trying to beat him down, and, handing his personal photographic apparatus to his companion, asked him to take some pictures of the mortar attacking the airplane. From that day, no one in the squadron doubted the future of this youth, “this eagle of the birdmen, this young Frenchman with the face of a woman and the heart of a lion.”

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 6, No. 18. SERIAL No. 166

COPYRIGHT, 1918. BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

COPYRIGHT BY UNDERWOOD & UNDERWOOD

GUYNEMER AT THE WHEEL

THREE

Fernand Forest, a countryman of Guynemer’s invented, thirty years ago, an explosion motor whose operations formed the basis of many subsequent experiments in petrol engines. And it was a Frenchman, Clement Ader, who was the first to fly with a motor-driven flying machine. For a time Ader experimented under the patronage of the French Ministry of War, but he was eventually deprived of Governmental sanction and assistance because he was deemed visionary, and his inventions impractical. However, the machine in which he made several flights in the year 1897, the “Avion,” was later one of the treasured exhibits of the first Aeronautical Salon, and was placed beside the airplanes of Wilbur Wright, Delagrange and Blériot “as convincing proof that to France belonged the honor of making the first flying machine.” It is related that when Ader first found himself leaving the ground for a test flight, “he was so taken by surprise that he nearly lost his senses.”

Charles C. Turner, author of “Marvels of Aviation,” narrates the early adventures of Alberto Santos-Dumont, the rich young Brazilian who arrived in Paris in 1898 for the purpose of having a navigable balloon made there. Already the name Zeppelin had received passing notice in French and English newspapers, but most people refused to believe reports of his inventions, and those of Santos-Dumont, concluding that they were both mad. Santos-Dumont, “the man who initiated the modern airship movement in France and made the first officially observed airplane flight in Europe,” flew around the Eiffel Tower and over the roofs and treetops of startled Paris in his small spherical balloons, propelled by gasoline motor, and in 1902 made flights over the Mediterranean. In Paris he built the first airship station ever constructed. In 1903, his maneuvers above the French army review of July fourteenth led to negotiations with the French Minister of War, to whom the young Brazilian made the offer “to put his aerial fleet at the disposition of France in case of hostilities with any country except the two Americas.” He explained, “It is in France that I have met with all my encouragement; in France and with French material I made all my experiments. I excepted the two Americas because I am an American.”

Santos-Dumont, who had astounded the world by the success of his airship experiments, was also the pioneer aviator in France, when he became convinced of the practicality of the heavier-than-air machine. When Delagrange, Blériot and the Wright brothers leapt into fame, Santos-Dumont continued quietly to study and contrive, and in 1909 he brought out the “Demoiselle,” a small airplane on whose design he claimed no patent rights, offering it to the world as a gift of his invention.

Between the years 1907 and 1910 many unknown inventors and mechanics won renown through their aerial accomplishments. Outbursts of fervor greeted every fresh success in air endeavor. On wings the patriotism of France soared to heights of exaltation. Lethargy gave way to enthusiasm. Voisin, Blériot, Delagrange, Latham, Paulhan, Védrines became national heroes. If a popular aviator flew a winning race, crowds attended his steps and surrounded his hotel. If one was injured, a sympathetic assembly gathered outside the hospital where he lay, and extras were issued by the daily journals as to his condition. Annual airplane meets and exhibitions had the patronage of the French Government. Experts were constantly occupied in making mechanical improvements in the motor, steering gear and wings of the wondrous new machines that had intrigued the imagination, the very soul of awakened France.

Though France owes a debt to American inventors, always generously acknowledged, French aviators quickly attained supremacy on the continent. When the war came, the country was already dotted with aerodromes and airplane factories, and hundreds of trained aviators and mechanicians were ready to take the air for their beloved France.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 6, No. 18. SERIAL No. 166

COPYRIGHT, 1918. BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

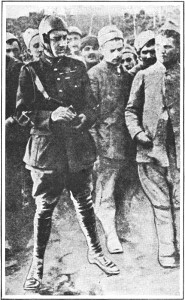

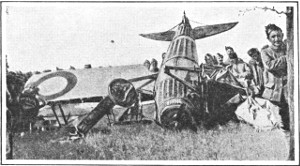

GUYNEMER BROUGHT DOWN BY A BOCHE, BUT WITHIN FRENCH LINES

FOUR

At the time of Guynemer’s death he was commander of the Flying Storks, a squadron of high-record fighting aviators whose feats have for over three years been the sensation of the Allied front. The original membership comprised ten pilots, some of whom had already attained national renown. Approximately fifty warriors that have carried its emblem down the highways of the air have been killed, wounded, or reported missing. Three squadron chiefs, Captain Auger, Lieutenant Peretti and Captain Guynemer, have fallen in aerial battles; three other chiefs have been gravely wounded—Commandant Brocard, Captain Heurteaux and Lieutenant Duellin. The prowess of The Storks may be gauged by the statement that fourteen members of this famous escadrille, (only one of ten score flying organizations attached to the French army), brought down a third of all the German planes destroyed before January, 1918, or two hundred in less than three years. This is the official count. Many more enemy planes met defeat from their guns, but without the required number of official witnesses.

“Les Cicognes” (The Storks) were organized in April, 1915, by Commandant Brocard, now retired from active fighting. The first machine adopted by the corps was the Nieuport-3, on whose side was painted a stork with spread wings. In 1917, Spad models supplanted the Nieuports in the service of The Storks.

The official records of a dozen Aces of the squadron are given: Captain Guynemer, 53 enemy planes downed; Lieutenant René Dormé, 24; Captain Alfred Heurteaux, 21; Lieutenant Duellin, 19; Captain Armand Pinsard, 16; Lieutenant Jean Caput, 15; Lieutenant Tarascon, 11; Lieutenant Mathieu de la Tour, 11; Captain Albert Auger, 7; Lieutenant Gond, 6; Lieutenant Borzecky, 5; Adjutant Herrison, 5.

Captain Heurteaux, chief of the corps from December, 1916, until he was wounded in September of the following year, rivaled the marksmanship of Guynemer when he downed a hostile plane with a single bullet. Heurteaux, in the words of an appreciative chronicler of The Storks, “used to amuse himself in the midst of battle by politely bowing and waving ironic greetings to his encircling enemies. This open contempt for them increased their hatred, he explained, and tempted them to shake their fists at him in reply, thus often exposing them in their blind fury to his superior adroitness in maneuvering and attack.”

A grave young pilot named René Dormé became so skilful in handling his machine that the superb Guynemer regarded his ability as greater than that of any of his fellows. Dormé was also a remarkable shot. In four months he was victor over twenty-six enemy planes, fifteen of which were officially witnessed as they fell. The end of René Dormé is veiled in mystery. Following a fierce combat high in the clouds on May 25, 1917, he pursued his opponents above German territory. Later, observation balloons reported that a French airplane had come to earth across the enemy lines and had been consumed by fire, which indicated to their practised vision that the pilot had been able to set his plane ablaze before it was seized by German captors. Though the enemy subsequently announced Dormé’s death, the report, for certain suspicious reasons, has been given little credence. “Second only to the crushing loss of Guynemer, France’s idol,” has his passing been mourned by fellow aviators and by the nation. As a discriminating observer of The Storks has stated, “While both were lads of excessive modesty, Guynemer’s air tactics were far more spectacular than those of Dormé, Guynemer was perhaps the better marksman of the two, but Dormé, he conceded, was the better pilot. Dormé’s dodging maneuvers were celebrated throughout France.”

It was on the day of Dormé’s disappearance that Guynemer achieved the Magic Quadruple, besides defeating two more planes that fell far within the German lines. Guynemer the avenger! Guynemer the miraculous knight of the air! Less than four months later he fell as Dormé fell, on hated enemy soil. And, in turn, his death was avenged by the famous French Ace, René Fonck of Escadrille Nieuport-103, who within two weeks slew the Hun airman that had brought to earth the Wingèd Sword of France.

“He was our friend and our master, our pride and our protection. His loss is the most cruel of all those, so numerous, alas, that have emblazoned our ranks. Nevertheless, our courage has not been beaten down with him. Our victorious revenge will be hard and inexorable.” These are the words of Lieutenant Raymond, Guynemer’s successor as Commandant of The Flying Storks.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 6, No. 18. SERIAL No. 166

COPYRIGHT, 1918. BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

GUYNEMER AFTER A BOCHE VICTORY

Translated from the French

FIVE

The public as a rule has a false idea of hunting and the hunters. They very easily imagine that we are ’way up there at our ease, directing events, and that the nearer we are to heaven the more we are invested with Divine Power. I cannot express in words the enervation that I feel sometimes while listening to the inept remarks addressed to me in the form of compliments, and which I am compelled to accept with a smile, which is almost a bite. I want to shout out to the speaker: “But, my poor fellow, you ought not to speak about this subject, for you know nothing whatever about it. You do not understand the first word of it all, and you can hardly believe how little your eulogies please me, under the circumstances.”

But if I answered in this way, no one would think of honoring my sincerity, or my desire to spread sane ideas—rather all would declare that I was a rude fellow, pretentious and a swaggerer, or something worse.

This is the reason that I listen, remain dumb, and let the enervation gnaw at me. Some tell me: “It is better to leave to hunting that mysterious atmosphere which serves as an aureole to the Ace. If the layman were to become competent to judge, he would possibly no longer hold the same admiration for the hunters.” You will admit that this suggestion is not very flattering to us. In fine, according to this suggestion, we are interesting to them only because they know nothing about our work.

They say of me: “Guynemer is a lucky dog.”

Certainly, I am a lucky dog, for I have added up forty-nine (this was written before the grand total was made) victories and am still alive, and I might have been killed during my first fight. If we talk this way, every person alive today is lucky; for he might have died yesterday.

But I might astonish some persons considerably if I answered: “It’s a good thing that I was a lucky dog, for I have been brought down by the enemy on seven different occasions.”

I know that they will rejoin that this was really luck, for I managed to escape death. But, was it luck that day, when, carried along by the great speed of my Nieuport, I rushed right past a Boche, giving him a chance to puncture an arm and wound me in the jaw? Was that luck, my fall of 3,000 meters after a shell had passed through a wing of the machine? And how many episodes there are of a similar character! Certainly, I do not wish to pretend that the question of chance, which I call Providence, does not intervene in war. But between that and the assurance that every act is guided by a manifestation of a good star—there is a world of difference. And if I dispute this opinion so sharply, as far as it concerns me, it is not, certes, because I am annoyed, but, on the contrary, because I believe that it is rendering a poor service to say that we succeed in any human activity through luck.

Yet if we will only eliminate this factor we shall recognize the fact that neither that unfortunate Dormé nor I are instances of the effect of chance upon the career of airplane-hunters. He was surnamed “Invulnerable” because he almost always came back from his cruises without a scratch. We were almost astounded if his airplane bore the mark of a single bullet. With me, on the contrary, I had the special faculty of coming back with missiles all over my machine.

Why was there this difference? We had almost the same methods of attack. We proceeded along uniform principles, approaching the enemy to point-blank distance. What then? The reason is plain: Dormé was better at maneuvering than I. He called upon his skill to help him at the moment of attack, and when he judged that he was not sure of success, he went into a spin and broke away from the duel. I, on the contrary, used the normal method of flying, never having recourse to acrobatics, unless it was the last means to be employed. I stayed close to my adversary, as if I were possessed. When I held him, I would not let him go. These two systems have their advantages and their defects, which should not astonish you, for perfection is not of this world.

I can draw but one conclusion from these two methods of fighting, and it is of capital importance.

It is that hunting in the air must be done according to the temperament and character of each individual hunter. If it show itself as individual prowess, all the better. This must be cried out aloud, for many young men come to the squadron with false ideas and arrested wills, planning to bring down Boches in the style of Dormé or Heurteaux. It is deplorable. Nothing is to be expected of the man who relies upon his memory in attacking an airplane. He may recall the way that some Ace acted under similar circumstances. He may attain a measure of success, but he will never be a real scout.

He who has in him the quality of a champion is the pilot who has recourse to his own initiative, to his own judgment, to his own personal equation.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 6, No. 18. SERIAL No. 166

COPYRIGHT, 1918. BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

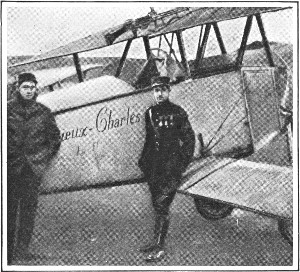

GUYNEMER, THE ACE OF ACES

Translated from the French

SIX

“How difficult it is to find a little black point through a rift in the clouds, which, found again soon afterwards in the field of blue, is about to wrap itself in a mist of white smoke, and seems to be celebrating in its own honor, but is only Death’s messenger. That is Guynemer, far up there, or some other of ‘The Storks’ under attack by German shrapnel. This war, beyond the range of vision, in the tragic infinity of space, watched by all the world!

“He who was able to place himself in the first rank of that band of messengers from the earth to the heights, in response to the wingèd beings that the heavens sent us long ago, fully merits to live among us as a symbol of one of the greatest efforts of the human will.

“There, all alone, in the very highest, in the imperturbable calm of absolute self-possession, waiting for nothing but a succession of unerring motions gauged by correctness of eyesight and promptness of bold decisions, on the edge of a bottomless abyss ready to swallow everything, without the supreme aid of a look or the hand of a friend—is that not something far above all the historic beauty of the greatest sacrifices for the noblest causes—something as it were of a miraculous concentration of superhumanity? To face every day the sublime adventure, in the sun, in the wind, in the rain, to pursue the enemy and seize upon the decisive moment that will place him at the mercy of the cannonading, beneath the fugitive angle which is offered suddenly, and will never occur again, to begin, and begin again, every day, and to always come back victorious. Thus lived Guynemer, now borne away in a great apotheosis, amid the acclamations of his companions in glory.

“Guynemer, born to civil life like so many of his companions, when William II of Germany decided that the hour had come for France to demonstrate what she had preserved of that nobility of blood in which her history had been moulded—Guynemer, without a word, resolved to lift his France to the highest! And upon that day when his destiny was achieved, all of us bear witness that he acted upon his resolution.

“One day, it was granted me to clasp that hand in which not a quiver revealed the control of the supreme power of nerves and courage. Eyes of lovable youth! A gentle smile of timidity! Simple, quiet replies, gestures disguising the consciousness of great hours incessantly lived over! In the greatest heart lies the purest simplicity.”

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 6, No. 18. SERIAL No. 166

COPYRIGHT, 1918. BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

By HOWARD W. COOK

Entered as second-class matter March 10, 1913, at the postoffice at New York, N.Y., under the act of March 3, 1879. Copyright, 1918, by The Mentor Association, Inc.

MENTOR GRAVURES

GUYNEMER WHEN HE BEGAN HIS FLIGHTS

GUYNEMER AND HIS FAITHFUL GUNNER, GUERDER

GUYNEMER AT THE WHEEL

MENTOR GRAVURES

GUYNEMER BROUGHT DOWN BY THE BOCHE

GUYNEMER AND A BOCHE VICTORY

GUYNEMER, THE ACE OF ACES

By courtesy of the Century Co. From the drawing by Madame J.C. Breslau.

GEORGES GUYNEMER

NOTE—The following article is based on Guynemer’s own records and the account of his exploits published by his close friend and authorized reporter, Jacques Mortane.

GUYNEMER WHEN SIX YEARS OLD

When the history of the World War is finally written, one of the names conspicuous in its pages will be that of Georges (jorje) Guynemer (gee-ne-mare). The name of Guynemer has become synonymous with brave deeds and symbolical of the great spiritual glory that belongs to France. Guynemer has been called “The Ace of Aces” and “The Wingèd Sword of France”; but these names express only in part the characteristics of a world-famous hero whose life, as Clemenceau (klem’-ahng-so) so aptly terms it, “even though short, was a sufficiently beautiful adventure.” Guynemer’s part in the World War is over. His own active chapter is done, but his spirit lives on in the hearts of every allied airman.

Guynemer, born in December, 1894, was the son of a retired officer. As a boy he was agile and ambitious in sports, though of slender build and somewhat delicate. He was especially fond of mechanical toys and miniature airplanes, and even in the early school days, when flying was looked upon more as a sport than an actual military factor, Georges declared to his father his ambition to become an aviator.

GUYNEMER AT TEN YEARS OF AGE

And then came the war. The youth, who because of physical weakness was refused admission to the army no less than five times, was finally accepted at the age of twenty, on November 23, 1914. Then began a career that in a few short years was destined to make the name of Georges Guynemer immortal.

In describing his first meeting with the Boche (bosh) on July 19, 1915, to his friend, Jacques Mortane, Guynemer said:

“I was on a two-seated ‘Parasol’ with Guerder, my mechanic, as passenger. I had promised myself for some time to undertake a pursuit in my airplane, but I had always been ordered on reconnaissances or photographic missions, and that kind of work did not suit me at all. It is always set aside for the newcomers in the squadrons, and I wanted to show that grit was not the exclusive possession of the older men.”

A Boche had been sighted at Coeuvres (koev-r), and Guynemer took flight with Guerder and was soon in pursuit of the enemy. As the Boche’s plane was faster there was no possibility of catching him. Nevertheless, the joy of finding a first adversary made Guynemer eager to attempt anything. From a great distance he fired at his opponent—possibly without any hope of hitting him, but steadily nevertheless. He pursued him as far as the Coucy aerodrome, where he saw him alight. This displeased Guynemer greatly. He had gone out to “get” a Boche and had to go back empty-handed.

“There we were,” he said, “with these sad thoughts, when suddenly another black point appeared on the horizon. As we came nearer, the point became larger and was soon plain, as a Boche. He was moving towards the French lines, thinking only of what he might find ahead. He did not dream that on his track were two young fellows determined not to return to the squadron without performing their task, two young fellows who believed that to return to headquarters without a Boche would mean derision.

“It was not until Soissons (swahs-sohng) was reached that we came up with him, and there the combat took place. During the space of ten minutes everybody in the city watched the fantastic duel over their heads. I kept about fifteen meters from my Boche—below, back of and to the left of him, and, notwithstanding all his twistings, I managed not to lose touch with him. Guerder fired 115 shots, but could not fire precisely, as his gun jammed continually. On the other hand, in the course of the fight my companion was hit by one bullet in the hand and another ‘combed’ his hair. He answered with his rifle, shooting well. We began to ask ourselves how this duel was going to end, but at the 115th shot fired by Guerder I saw the pilot fall to the bottom of his car, while the ‘look-out’ raised his arms in a gesture of despair, and the plane did a nose spin, and plunged down into the abyss in flames. He fell between the trenches. I hastened to land not far away.

“At last I was able to live my dream! I, who had so long desired to join in the fighting, had managed to gain a victory. What shall I say about the reception given me by the troops on the ground—ovations, congratulations, all under the vengeful cannon of the enemy. I have beaten down other Boches since that time, but when I think over my aerial duels my recollections always fly back to that first one.”

Official recognition came to Guynemer the next day when the Military Medal was awarded him for being “a pilot full of spirit and boldness.”

In considering Guynemer’s personal accounts of his various flights, it is evident that the Ace, while not inspired by the same craving for combat that Major Bishop acknowledges, was a hero of unusually high-pitched nerves, inspired with dreams of battle, and whose quests for the Boche were insatiable.

Guynemer talked much concerning his “will.” It was his will to get into service in spite of his five rejections and being compelled to enter as a mechanic. He would scorn an observer’s work and become a hunter. He would make his score larger and larger. He would fly regardless of climatic conditions or his own health, going up even when convalescing from injuries. And it was this will which doubtless made him the terror of his enemies and the glory of France.

Among the first duties assumed by an airman when he is learning the mastery of his machine is that of reconnoitering. But Guynemer, fast becoming specialized in pursuit, soon stopped all reconnoitering and found himself assigned to a single-seated airplane. It was on February 3, 1916, that in the course of a single flight he succeeded in getting his first official “double.”

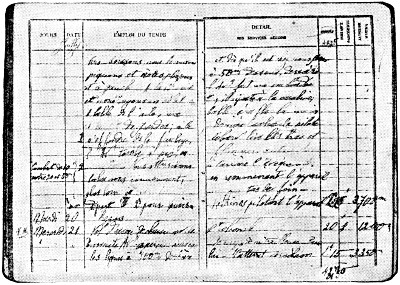

A PAGE FROM GUYNEMER’S NOTE BOOK OF FLIGHT

Showing record of his first victory, July 19, 1915

He was making his usual round in the Roy section just before noon, and was about to end his flight, when he saw an airplane in the distance. “The game was coming to me,” he said. All he had to do was not to let it escape. Guynemer gave chase and soon caught up with it. The enemy did not seem to wish to avoid the fight. Possibly he had not seen Guynemer at all. Being faster than he, Guynemer got behind him, opening fire at 100 meters,[A] and, as he fired at rapid intervals, his cartridges were soon exhausted. At that instant a cloud of smoke, which increased rapidly, made a sinister tail to the Boche, who dived, severely wounded. He fell, however, within his own lines, and Guynemer could not follow him to earth. It was certainly one enemy less, but Guynemer’s total record was not improved.

[A] A meter is a little more than a yard in length—exactly stated, 39.37 inches.

Fortune, however, favored him. “I was coming back,” he said, “thinking over the methods of fighting, considering how I had attacked, asking myself whether I would not have done better to approach from some other direction, when at almost 11.30 I found another hunting plane. Yes, I had made a mistake just now, when I opened fire from so far away—I should have waited. At 100 meters we cannot be sure of the aim. My method, which up to this time always consisted in attacking almost point-blank, seemed to me much better. It is more risky, but everything lies in maneuvering so as to remain in the dead angle of fire. Certainly it is rather difficult, but nevertheless it can be mastered with skill.

“While going over these things to myself I had come near enough to the Boche without running any great danger. At 20 meters I fired. Almost at once my adversary tumbled in a tail-spin. I dived after him, continuing to fire my weapon. I plainly saw him fall in his lines. That was all right, no doubt about him. I had my fifth! I was really in luck, for less than ten minutes later another plane, sharing the same lot, spun downward with the same grace, taking fire as it fell through the clouds.

“The second day afterwards, before Frise, in a new tête-à-tête with a hunting Boche, I leaped forward, caught up with him, got in back of him, a little below to avoid his fire, and at 15 meters fired 45 cartridges. He swayed sadly, in the shock of death, which I was beginning to be able to diagnose, then fell like a stone, taking fire on the way. He must have been burned up between Assevillers and Herbecourt. Although he was really my seventh Boche, he alone gained me the honor of a special mention.”

GUYNEMER BEING DECORATED WITH THE ROSETTE OF THE LEGION OF HONOR

Guynemer (in dark uniform) has just received the Rosette

Guynemer’s fifth citation rewarded him for this exploit, and declared him a hunting pilot with audacity and energy for any adventure.

According to Guynemer’s own testimony, one of the most difficult things an airman of the Allies has to do is to compel the Boche to accept a duel, not that the latter lacks courage, but rather that he prefers not to run the risk of being brought down. As a result of forcing engagements, Guynemer seldom returned from a flight without a wound of some sort or other. On several occasions his garments were drilled with holes, his clothing more than once taking on the appearance of a sieve. This was the youth who in less than eight months from the downing of his fifth Boche had been awarded seven palms for his war cross.

Like Nungesser, Dormé (dor-may) and Triboulet (trib-oo-lay), Guynemer would not rest when he had left the hospital convalescent from some of his more serious wounds, and it is by signs like these that we find the souls of great heroes who know nothing about “vacations,” even for their health, so long as others are fighting. Guynemer was not strong and should have rested after his stay in the hospital. His parents begged him to rest, so Guynemer compromised by agreeing to establish himself near his family at Compiègne (kom-pee-ane), where at the same time he could serve France. Not far from his paternal home, at Vauciennes (vo-see-enn), his Baby Nieuport rested in a hangar, ready to carry him into those great open spaces to search for the enemy whenever the atmosphere permitted.

GUYNEMER READY FOR FLIGHT

One of the hero’s sisters was entrusted with the task of studying the atmosphere at dawn each day to see if it were “Boche weather.” And as soon as it was light enough, slyly, like a boy planning mischief against the orders of his elders, the Second Lieutenant Ace came down from his room and mounted his Nieuport for a prospective fray.

He was convinced that no one in the house suspected his escapades except his sister. How little he understood the hearts of a father and mother! Father Guynemer has told of the anxieties, the worries lived through during that convalescence. The boy had gone. Would he come back? Would some hateful enemy appear on the way and prevent his return to the bosom of his family? The minutes of anxiety were as long as centuries. As for the loving Mother Guynemer, she did not dare show her son that she was undeceived by his stratagems, nor did she wish him to see her when she watched him fly away. Through the blinds, with tear-dimmed eyes, she watched him depart in the service of his country. When she saw her boy draw far away, she returned to her household duties—but not until Georges’ machine had become a tiny speck.

GUYNEMER AND MACHINE AFTER 3,000-METER TUMBLE

Here is one of the most moving pages in the hero’s life—this feigned ignorance on the part of the parents, the plotting of brother and sister. Guynemer, face to face with his family, pretended that he would run no danger. He insisted on his own prudence. Nothing serious could happen to him, because he avoided all risks. But as soon as he began to turn the conversation upon the subject which was all his life, the comforting words which he had spoken were at once contradicted by the many adventures and varied anecdotes which he recalled. No peril had been too great for him. He played with danger, and looked for it.

Guynemer hated the word “luck,” perhaps because he was accused of having so much of it, and when his Spad was struck by a shell 3,000 meters from the earth, the airman falling the entire distance, he repudiated the suggestion that his was a lucky star!

This phenomenal escape took place on September 23, 1916, Guynemer having just finished an exploit humorously set down by his friend Mortane as follows: “Put an egg in boiling water when the Ace of Aces begins a battle; you wait until he has downed three Boches, you take out the egg, and it is done to a turn. What a triumph for the restaurant menus!”

While contemplating the immensity of the azure heavens at an altitude of 3,000 meters above the earth, Guynemer suddenly felt a shell strike one of the wings of his airplane with all its force. The left wing was torn to shreds, the canvas sent floating in the wind, as the airman and his machine began a descent.

GUYNEMER FACE TO FACE WITH A DEFEATED BOCHE

“My apparatus fell,” said Guynemer, “broke apart, crumpled up in the abyss, unable to bear me any longer. I really felt the call of death and I seemed to be hastening towards it. It seemed that there was nothing to prevent my crashing to the earth. A tail-spin, terrible, fearful, began at 3,000 meters and continued to 1,600 meters.

“I felt as if I were indeed lost, and all that I asked of Providence was that I should not fall in enemy territory. Never that! They would have been too happy. Can you think of me buried with my victims? But I was powerless to exert my will, my airplane refused to obey.

“At 1,600 meters I tried anyway. The wind had driven me almost over our lines. I was already half-happy. Now I dreamed of being interred with sympathetic comrades following my body. That was not a fine dream, but at least it was better than the other.

“I had no longer to fear the pointed helmets. But, nevertheless, I felt all that death might be, and it was not a pleasant thought. The fall continued. The steering gear would not respond to my tugging. Nothing worked. I tried it to the right, to the left, pulling, pushing, but got no result. The comet did not slow a bit, I was drawn invincibly towards the earth where I was about to be crushed.

“There it was! One last brutal effort, but in vain. I closed my eyes, I saw the earth, I was plunging towards it at 180 kilometers[A] an hour, like a plummet. A terrible crashing, a great noise, I looked around. There was nothing left of my Spad.

“How did it happen that I was still alive? I asked myself, but I felt that it was so, and that was enough. However, I think that it was the straps which held me in my seat that had saved me. Without them I would have been thrown forward or would have broken some bones. On the contrary, they were dug deep into my shoulders, a silent proof, doubtless, that I should give them full consideration. Had it not been for them I would certainly have been killed.”

[A] A kilometer is a thousand meters, or 3,280 feet, 10 inches.

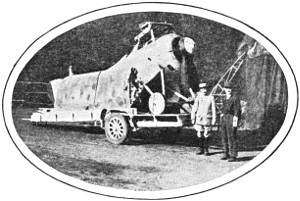

GUYNEMER’S FAVORITE AIRPLANE, VIEUX CHARLES (OLD CHARLES), ON EXHIBITION IN PARIS

Infantrymen hurried to the spot to pick up the pieces. Finding Guynemer not only alive, but unhurt except for a bruised knee, they conducted him home in triumph, singing the “Marseillaise” at the top of their voices.

Guynemer went to view the remains of the Boche that he had brought down first. The pilot had on his body a card, almost burned up, on which a feminine hand had written these words: “I hope that you will bring back many victories.”

GUYNEMER WITH THE MILITARY MEDAL AND “LEGION OF HONOR”

The Magic Quadruple,—the successive defeat of four airplanes, was Guynemer’s achievement, one of which was downed in one minute, on May 25, 1917, according to the following schedule:

1st airplane, 8.30, 2nd airplane, 8.31, 3rd airplane, 12.01, 4th airplane, 6.30.

THE DEBRIS OF THREE AIRPLANES BROUGHT DOWN BY GUYNEMER IN ONE DAY

Four airplanes beaten down on one day by the same aviator was a record. On February 26, 1916, Navarre secured his first “double.” Nungesser, on the Somme, destroyed a balloon and two airplanes on a single morning. But by his quadruple victory Guynemer exceeded these two earlier records and the one established by himself in the Lorraine when he brought down three airplanes in one day. On the morning of May 25th Guynemer saw three enemy airplanes flying in concert toward French lines. He pounced upon them, and they took to flight. He attacked one of them, maneuvering to get him in the line of fire, then fired, and after the first shots the enemy machine dived and fell in flames.

Meanwhile the danger for the single-seated machine was surprise from the rear. While he was attacking in front, it was necessary for Guynemer to watch the rear. Guynemer turned, and saw a second adversary coming full at him, trying to reach him. But he had fired already from above downward, and hit him with an explosive bullet. Like the first, this airplane took fire. The victories of Guynemer were lightning-like, requiring only a few seconds of fighting.

GUYNEMER BROUGHT DOWN BY A SHELL FROM A HEIGHT OF OVER 9,000 FEET

His only injury was a bruised knee

Towards noon an audacious German airplane flew over the aviation field. French squadrons have taught the enemy respect for their lines and the unfortunate fellow who ventures above them seldom returns home. It was something of a mystery how this one had broken through the barrage. But to ascend to the sky after him and to reach him, no matter how speedy the machine, required several minutes, time enough for the enemy to flee, his mission accomplished. All of the machines had come down except the one driven by Guynemer.

Guynemer came upon his adversary like a whirlwind. He fired. Only one shot from his machine-gun was heard. The airplane fell, the propeller revolving at full speed, and dug itself into the earth. Guynemer had killed the pilot with a bullet in the head.

That evening Guynemer went out for the third time. It was about seven o’clock, over the gardens of Guignicourt (geen-ye-koor), that a fourth machine, beaten down by him, fell in flames.

And as the young conqueror came down at sunset, he executed all kinds of fancy figures in the air to announce his victory to his comrades,—all the turns, and twists and loopings of which he was so great a master.

LAST PAGE OF GUYNEMER’S FLIGHT-BOOK

Recording his final departure

But some facts must be added as a sequence to the official announcements. The first airplane brought down was a two-seater, one of whose wings was broken in descent; it fell into the trees near Corbeny. The second, another two-seater, fell on fire near Juvincourt. The third was also brought down afire near Courlandon. Finally, the fourth, also set on fire, dropped between Condé-sur-Suippes (sweep) and Guignicourt. Add to this that, on that same day, Guynemer had collaborated with Captain Auger (the slain Ace) in putting to flight a group of six single-seaters.

It was the quadruple that brought Captain Guynemer the Rosette of the Legion of Honor with this commendation:

“An élite officer, a fighting pilot as skillful as audacious. He has rendered glowing service to the country, both by the number of his victories and the daily example he has set of burning ardor and even greater mastery increasing from day to day. Unconscious of danger, on account of his sureness of method and precision of maneuvers, he has become the most redoubtable of all to the enemy. On May 25, 1917, he accomplished one of his most brilliant exploits, beating down two enemy airplanes in one minute, and gaining two more victories on the same day. By all of his exploits he has contributed towards exalting the courage and enthusiasm of those who, from the trenches, were the witnesses of his triumphs. He has brought down forty-five airplanes, received twenty citations and been seriously wounded twice.”

One of the most conspicuous virtues of Guynemer was his extreme modesty. He wore his crosses and medals not from love of show, declaring that while it was sweet to know one was celebrated, that glory was accompanied by many drawbacks.

“You no longer belong to yourself,” said Guynemer, “you belong to everybody. To be well known is to see around you all the time a number of persons who never cared for you before but have suddenly assumed a pseudo-friendship for you. All at once they find out that you are a charming conversationalist, an infinitely fine soul, and more of the same kind of gush. Their object is to go out with you, and to take you to see their people. And when they look at you they imagine that you admire them. Such is the misfortune of renown! You no longer know where sincerity begins, whether they are pleasant to you out of friendship or vanity. We are apt to become unjust to those who do not deserve it, and confide in others who deserve it still less.”

ON THE EVE OF HIS DEATH, SEPTEMBER 10, 1917

Guynemer—on the further side of the airplane—was obliged to land at a Belgian aerodrome for repairs

It was on August 20, 1917, that Guynemer, piloting “Old Charles,” achieved his last official triumph,—a German plane, which crashed to earth at Poperinghe, Belgium. A few days after this Guynemer took command of the Stork Squadron. Thus the difficult task of guiding the administrative work of The Storks fell upon the shoulders of this young soldier. With these new duties he might have abstained from flying. But this would not have been like Guynemer. He flew from five to six hours each day. On September 11th, notwithstanding the bad weather, Guynemer started upon a cruise with Second Lieutenant Verduraz. After furrowing space for a long time without success, for atmospheric conditions kept the Boches on the earth, the two pilots at last saw a two-seater which appeared to be lost in the clouds. The hero darted forward, attacked, but his gun missed fire. He maneuvered for position again without even trying to dodge the answering fire, so sure was he of himself in dealing with this Boche. A single two-seater was but a trivial thing to him.

Second Lieutenant Bozon Verduraz had gone towards other fights with the conviction that his comrade would, without a doubt, come out of the duel victorious; but he found nothing there when he returned. Guynemer, the hero of dreams, had vanished in mystery.

And here above Poelcapelle the career of this most brilliant pilot of the air was terminated, after he had added up 755 hours of airplane flight!

The censor forbade the announcement of Guynemer’s disappearance, but the news was passed from mouth to mouth. Guynemer? Every one deemed him invulnerable—no one believed that he could be killed.

But many days afterward came the news from a German source. The Ace of Aces had been beaten down near the cemetery of Flemish Poelcapelle. Two soldiers had been present at the place of the catastrophe. One wing of the Spad had been broken. The pilot lay there, killed, with a bullet in his head, and one leg broken. On him was found his commission, which made it possible to identify the body.

The district in which Guynemer had ended his career in a burst of glory was being hammered by the English artillery. Attacks followed. The Allies looked for his grave in the cemetery of Poelcapelle when they took it. But they never succeeded in finding it. It was learned later that, on account of the incessant danger, the Germans had not been able to remove the remains to inter them. The soul of Guynemer in the Great Beyond had the supreme satisfaction of knowing that the body was not defiled by his enemy.

Lieutenant Weisemann, the German airman who had brought Guynemer’s career to a close, survived his success but a few days.

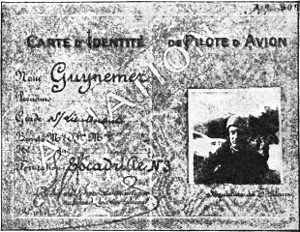

GUYNEMER’S PILOT CARD, REPRODUCED IN “DIE WOCHE” (THE WEEK) OF BERLIN, AFTER HIS DEATH

GUYNEMER, THE ACE OF ACES. A Record of His Achievements.

By His Friend, Jacques Mortane

EPIC OF THE AIR

Article in The Living Age, June 8, 1918

GEORGES GUYNEMER, KNIGHT OF THE AIR.

A Biography, Translated from the French of Henry Bordeaux.

GEORGES GUYNEMER, ACE OF ACES

Literary Digest, October 13, 1917

⁂ Information concerning the above books may be had on application to the Editor of The Mentor.

A year has passed since Guynemer gave his life for France, and his story is now history. During the year other skymen have made great records: some of them may accomplish supreme achievements in the future. But there is a certain halo of romance about the young Sir Galahad of the Sky that distinguishes him and gives him a place of his own.

Moreover, there are special considerations to be taken into account in reckoning up Guynemer’s achievements. While other airmen of the World War have been credited officially with a greater number of victories, it is a recognized fact among Parisian journalists and Guynemer’s own associates among “The Storks,” that Guynemer was victor over perhaps twice as many Boche planes as the fifty-three accredited him by the French Militaire. The French system of accounting downed airplanes has been extremely exacting. The French insist that the aviator must send his victim to destruction in sight of two official observers. In Guynemer’s case this rigorous method of checking up official records was strongly emphasized because of his world-astonishing prowess. When Guynemer’s friends protested, he only smiled—and downed more Boches.

English and German officials, have been more lenient in giving official credit to their airmen. A German scores if he simply sends a bullet through his adversary’s motor, compelling descent. Germany, with her idolatry of all things German-done, accredits Captain Baron von Richthofen with something more than a hundred victories. Major William A. Bishop of the English flying forces, according to his own story recently published, downed seventy-two enemy planes in confirmed victories during the year 1917. The rigid system of official accounting by the French is shown in the case of Lieutenant Nungesser, the second French Ace cited for the Legion of Honor. Also in the officially accredited victories of Lieutenant René Fonck, recognized as the greatest French air fighter since Captain Guynemer, Fonck is credited with bringing down more than sixty enemy airplanes—six of them in one day in the course of two patrols.

While Georges Guynemer received nearly every honor that the French Government had in its power to bestow for the services rendered his country, the fifty-three airplanes he officially destroyed meant more in the period between 1915 and 1917 than the downing of many more planes thereafter; for it was Guynemer who led French warfare in the air from defeat to victory, and who was supremely successful despite the mechanical shortcomings of the airplanes that were in use when he entered the service.

The story of Guynemer and his wondrous exploits forms one of the great dramatic chapters of the World War, and it will go down the years as a record of poetic heroism to be read for the inspiration of future generations of youth. There are many brilliant airmen. Guynemer was more than that; he was a dedicated soul.

W. D. Moffat

Editor

That classic mausoleum for famous Frenchmen in Paris, the following inscription has been set up to perpetuate the memory of Guynemer:

“Captain Guynemer, commander of Squadron No. 3, died on the field of honor September 11, 1917. A hero of legendary power, he fell in the wide heaven of glory, after three years of hard fighting. He will long remain the purest symbol of the qualities of the race: indomitable in tenacity, enthusiastic in energy, sublime in courage. Animated with inextinguishable faith in victory, he bequeathes to the French soldier the imperishable remembrance which will exalt the spirit of sacrifice and the most noble emulation.”

MARY SIEGRIST.

By permission of the New York Times.

THE MENTOR

It gives us great pleasure to advise our friends that the sixth volume of The Mentor Library is now ready for distribution. It contains issues one hundred twenty-one to one hundred forty-four inclusive, and is, in every particular, uniform with the volumes previously issued.

One of the great advantages of owning The Mentor Library is that it grows in value from year to year—giving an endless supply of instructive and wonderfully illustrated material that would be impossible to obtain elsewhere. It constitutes one of the most valuable educational sets that you could possibly own, and, each year, the set is enlarged by one volume at a very small additional cost.

The beautiful numbers of the unique Mentor Library will never be out of date, as every issue of The Mentor is devoted to an important subject of enduring interest. The concise form in which scores of subjects are covered makes it of the greatest practical value to the business man, to the active woman who appreciates the importance of being well informed, and to children, who will find it of great direct value in their school work. You will want Volume Number Six, which will complete The Mentor Library to date. That you may receive it you need only send the coupon or postcard without money.

The volume will be forwarded to you, all charges paid. You can remit $1.25 upon receipt of bill, and $1.00 a month for only six months; or a discount of 5% is allowed if payment in full is made within ten days from date of bill. If you are now paying for the Bound Volumes we will ship this volume to you and add the amount to your account. We urge you to act at once.

The Mentor Association.

114-116 East 16th St., New York.

Gentlemen:

I am anxious to have the new volume of The Mentor Library. Please send it to me all charges paid, and I will send you $1.25 upon receipt of bill and $1.00 per month for six months—$7.25 in all.

Very truly yours,

Name.............................................

Street...........................................

Town..................... State..................

A discount of 5% is allowed if payment in full is made within 10 days from date of bill.

THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, 114-116 East 16th St., New York City

MAKE THE SPARE

MOMENT COUNT