Title: Lord Tedric

Author: E. E. Smith

Illustrator: Lawrence Sterne Stevens

Release date: July 16, 2015 [eBook #49462]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Time is the strangest of all mysteries. Relatively unimportant events, almost unnoticed as they occur, may, in hundreds of years, result in Ultimate Catastrophe. On Time Track Number One, that was the immutable result. But on Time Track Number Two there was one little event that could be used to avert it—the presence of a naked woman in public. So, Skandos One removed the clothing from the Lady Rhoann and after one look, Lord Tedric did the rest!

Skandos One (The Skandos of Time Track Number One, numbered for reasons which will become clear) showed, by means of the chronoviagraph, that civilization would destroy itself in one hundred eighty-seven years. To prevent this catastrophe he went back to the key point in time and sought out the key figure—one Tedric, a Lomarrian ironmaster who had lived and died a commoner; unable, ever, to do anything about his fanatical detestation of human sacrifice.

Skandos One taught Tedric how to make one batch of super-steel; watched him forge armor and arms from that highly anachronistic alloy. He watched him do things that Tedric of Time Track One had never done.

Time, then, did fork. Time Track One was probably no longer in existence. He must have been saved by his "traction" on the reality of Time Track Two. He'd snap back up to his own time and see what the situation was. If he found his assistant Furmin alone in the laboratory, the extremists would have been proved wrong. If not....

Furmin was not alone. Instead, Skandos Two and Furmin Two were at work on a tri-di of Tedric's life: so like, and yet so wildly unlike, the one upon which Skandos One and Furmin One had labored so long!

Shaken and undecided, Skandos One held his machine at the very verge of invisibility and watched and listened.

"But it's so maddeningly incomplete!" Skandos Two snorted. "When it goes into such fine detail on almost everything else, why can't we get how he stumbled onto one lot, and never any other, of high-alloy steel—chrome-nickel-vanadium-molybdenum-tungsten steel—Mortensen's super-steel, to be specific—which wasn't rediscovered for thousands of years?"

"Why, it was revealed to him by his personal god Llosir—don't you remember?" Furmin snickered.

"Poppycock!"

"To us, yes; but not to them. Hence, no detail, and you know why we can't go back and check."

"Of course. We simply don't know enough about time ... but I would so like to study this Lord of the Marches at first hand! Nowhere else in all reachable time does any other one entity occupy such a uniquely key position!"

"So would I, chief. If we knew just a little more I'd say go. In the meantime, let's run that tri-di again, to see if we've overlooked any little thing!"

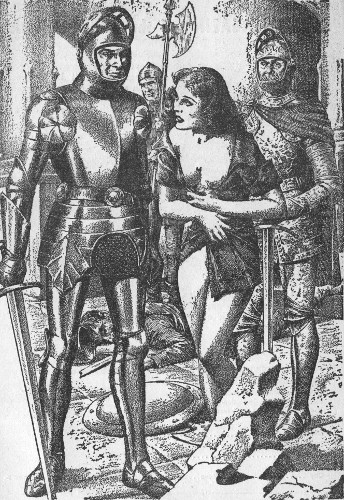

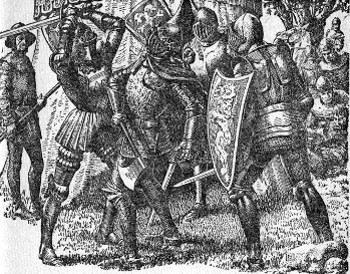

In the three-dimensional, full-color projection Armsmaster Lord Tedric destroyed the principal images of the monstrous god Sarpedion and killed Sarpedion's priests. He rescued Lady Rhoann, King Phagon's eldest daughter, from the sacrificial altar. The king made him Lord of the Marches, the Highest of the High.

"This part I like." Furmin pressed a stud; the projector stopped. A blood-smeared armored giant and a blood-smeared naked woman stood, arms around each other, beside a blood-smeared altar of green stone. "Talk about being STACKED! If I hadn't checked the data myself I'd swear you went overboard there, chief."

"Exact likenesses—life size," Skandos Two grunted. "Tedric: six-four, two-thirty, muscled just like that. Rhoann: six feet and half an inch, one-ninety. The only time she ever appeared in the raw in public, I guess, but she didn't turn a hair."

"What a couple!" Furmin stared enviously. "We don't have people like that any more."

"Fortunately, no. He could split a full-armored man in two with a sword; she could strangle a tiger bare-handed. So what? All the brains of the whole damned tribe, boiled down into one, wouldn't equip a half-wit."

"Oh, I wouldn't say that," Furmin objected. "Phagon was a smooth, shrewd operator."

"In a way—sometimes—but committing suicide by wearing gold armor instead of high-alloy steel doesn't show much brain-power."

"I'm not sure I'll buy that, either. There were terrific pressures ... but say Phagon had worn steel, that day at Middlemarch Castle, and lived ten or fifteen years longer? My guess is that Tedric would have changed the map of the world. He wasn't stupid, you know; just bull-headed, and Phagon could handle him. He would have pounded a lot of sense into his skull, if he had lived."

"However, he didn't live," Skandos returned dryly, "and so every decision Tedric ever made was wrong. But to get back to the point, did you see anything new?"

"Not a thing."

"Neither did I. So go and see how eight twelve is doing."

For Time Test Number Eight Hundred Eleven had failed; and there was little ground for hope that Number Eight Hundred Twelve would be any more productive.

And the lurking Skandos One who had been studying intensively every aspect of the situation, began to act. It was crystal clear that Time Track Two could hold only one Skandos. One of them would have to vanish—completely, immediately, and permanently. Although in no sense a killer, by instinct or training, only one course of action was possible if his own life—and, as a matter of fact, all civilization—were to be conserved. Wherefore he synchronized, and shot his unsuspecting double neatly through the head. The living Skandos changed places with the dead. A timer buzzed briefly. The time-machine disappeared; completely out of synchronization with any continuum that a world's keenest brain and an ultra-fast calculator could compute.

This would of course make another fork in time, but that fact did not bother Skandos One at all—now. As for Tedric; since the big, dumb lug couldn't be made to believe that he, Skandos One, was other than a god, he'd be a god—in spades!

He'd build an image of flesh-like plastic exactly like the copper statue Tedric had made, and go back and announce himself publicly as the god Llosir. He'd come back—along Time-Track Three, of course—and do away with Skandos Three. There might have to be another interference, too, to get Tedric started along the right time-track. He could tell better after seeing what Time-Track Three looked like. If so, it would necessitate the displacement of Skandos Four.

So what? He had never had any qualms; and, now that he had done it once, he had no doubt whatever as to his ability to do it twice more.

Of the three standing beside Sarpedion's grisly altar, King Phagon was the first to become conscious of the fact that something should be done about his daughter's nudity.

"Flasnir, your cloak!" he ordered sharply; and the Lady Rhoann, unclamping her arms from around Tedric's armored neck and disengaging his steel-clad arm from around her waist, covered herself with the proffered garment. Partially covered, that is; for, since the cloak had come only to mid-thigh on the courtier and since she was a good seven inches taller than he, the coverage might have seemed, to a prudish eye, something less than adequate.

"Chamberlain Schillan—Captain Sciro," the king went on briskly. "Haul me this carrion to the river and dump it in—put men to cleaning this place—'tis not seemly so."

The designated officers began to bawl orders, and Tedric turned to the girl, who was still just about as close to him as she could get; awe, wonder, and relieved shock still plain on her expressive face.

"One thing, Lady Rhoann, I understand not. You seem to know me; act as though I were an old, tried friend. 'Tis vast honor, but how? You of course I know; have known and honored since you were a child; but me, a commoner, you know not. Nor, if you did, couldst know who it was neath all this iron?"

"Art wrong, Lord Tedric—nay, not 'Lord' Tedric; henceforth you and I are Tedric and Rhoann merely—I have known you long and well; would recognize you anywhere. The few of the old, true blood stand out head and shoulders above the throng, and you stand out, even among them. Who else could it have been? Who else hath the strength of arm and soul, the inner and the outer courage? No coward I, Tedric, nor ever called so, but on that altar my very bones turned jelly. I could not have swung weapon against Sarpedion. I tremble yet at the bare thought of what you did; I know not how you could have done it."

"You feared the god, Lady Rhoann, as do so many. I hated him."

"'Tis not enough of explanation. And 'Rhoann' merely, Tedric, remember?"

"Rhoann ... Thanks, my lady. 'Tis an honor more real than your father's patent of nobility ... but 'tis not fitting. I feel as much a commoner...."

"Commoner? Bah! I ignored that word once, Tedric, but not twice. You are, and deservedly, the Highest of the High. My father the king has known for long what you are; he should have ennobled you long since. Thank Sarp ... thank all the gods he had the wit to put it off no longer! 'Tis blood that tells, not empty titles. The Throne can make and unmake nobility at will, but no power whatever can make true-bloods out of mongrels, nor create real manhood where none exists!"

Tedric did not know what to say in answer to that passionate outburst, so he changed the subject; effectively, if not deftly. "In speaking of the Marches to your father the king, you mentioned the Sages. What said they?"

"At another time, perhaps." Lady Rhoann was fast recovering her wonted cool poise. "'Tis far too long to go into while I stand here half naked, filthy, and stinking. Let us on with the business in hand; which, for me, is a hot bath and clean clothing."

Rhoann strolled away as unconcernedly as though she were wearing full court regalia, and Tedric turned to the king.

"Thinkst the Lady Trycie is nearby, sire?"

"If I know the jade at all, she is," Phagon snorted. "And not only near. She's seen everything and heard everything; knows more about everything than either of us, or both of us together. Why? Thinkst she'd make a good priestess?"

"The best. Much more so, methinks, than the Lady Rhoann. Younger. More ... umm ... more priestess-like, say?"

"Perhaps." Phagon was very evidently skeptical, but looked around the temple, anyway. "Trycie!" he yelled.

"Yes, father?" a soft voice answered—right behind them!

The king's second daughter was very like his first in size and shape, but her eyes were a cerulean blue and her hair, as long and as thick as Rhoann's own, had the color of ripe wheat.

"Aye, daughter. Wouldst like to be Priestess of Llosir?"

"Oh, yes!" she squealed; but sobered quickly. "On second thought ... perhaps not ... no. If sobeit sacrifice is done I intend to marry, some day, and have six or eight children. But ... perhaps ... could I take it now, and resign later, think you?"

"'Twould not be necessary, sire and Lady Trycie," Tedric put in, while Phagon was still thinking the matter over. "Llosir is not at all like Sarpedion. Llosir wants abundance and fertility and happiness, not poverty and sterility and misery. Llosir's priestess marries as she pleases and has as many children as she wants."

"Your priestess I, then, sirs! I go to have cloth-of-gold robes made at once!" The last words came floating back over her shoulder as Trycie raced away.

"Lord Tedric, sir." Unobserved, Sciro had been waiting for a chance to speak to his superior officer.

"Yes, captain?"

"'Tis the men ... the cleaning ... They ... We, I mean ..." Sciro of Old Lomarr would not pass the buck. "The bodies—the priests, you know, and so on—were easy enough; and we did manage to handle most of the pieces of the god. But the ... the heart, and so on, you know ... we know not where you want them taken ... and besides, we fear ... wilt stand by and ward, Lord Tedric, while I pick them up?"

"'Tis my business, Captain Sciro; mine alone. I crave pardon for not attending to it sooner. Hast a bag?"

"Yea." The highly relieved officer held out a duffle-bag of fine, soft leather.

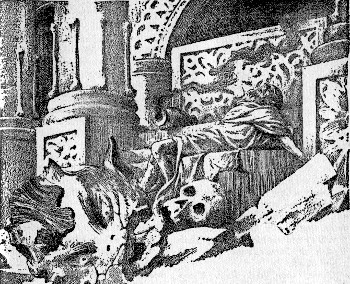

Tedric took it, strode across to the place where Sarpedion's image had stood, and—not without a few qualms of his own, now that the frenzy of battle had evaporated—picked up Sarpedion's heart, liver, and brain and deposited them, neither too carefully nor too carelessly, in the sack. Then, swinging the burden up over his shoulder—

"I go to fetch the others," he explained to his king. "Then we hold sacrifice to end all human sacrifice."

"Hold, Tedric!" Phagon ordered. "One thing—or two or three, methinks. 'Tis not seemly to conduct a thing so; lacking order and organization and plan. Where dost propose to hold such an affair? Not in your ironworks, surely?"

"Certainly not, sire." Tedric halted, almost in midstride. He hadn't got around yet to thinking about the operation as a whole, but he began to do so then. "And certainly not on this temple or Sarpedion's own. Lord Llosir is clean: all our temples are foul in every stone and timber...." He paused. Then, suddenly: "I have it, sire—the amphitheater!"

"The amphitheater? 'Tis well. 'Tis of little enough use, and a shrine will not interfere with what little use it has."

"Wilt give orders to build...?"

"The Lord of the Marches issues his own orders. Hola, Schillan, to me!" the monarch shouted, and the Chamberlain of the Realm came on the run. "Lord Tedric speaks with my voice."

"I hear, sire. Lord Tedric, I listen."

"Have built, at speed, midway along the front of the amphitheater, on the very edge of the cliff, a table of clean, new-quarried stone; ten feet square and three feet high. On it mount Lord Llosir so firmly that he will stand upright forever against whatever may come of wind or storm."

The chamberlain hurried away. So did Tedric, with his bag of spoils. First to his shop, where his armor was removed and where he scratched himself vigorously and delightfully as it came off. Thence to the Temple of Sarpedion, where he collected the other, somewhat-lesser-hallowed trio of the Great One's vital organs. Then, and belatedly, to home and to bed.

A little later, while the new-made Lord of the Marches was sleeping soundly, the king's messengers rode furiously abroad, spreading the word that ten days hence, at the fourth period after noon, in Lompoar's Amphitheater, Great Sarpedion would be sacrificed to Llosir, Lomarr's new and Ultra-powerful god.

The city of Lompoar, Lomarr's capital, lying on the south bank of the Lotar some fifty miles inland from the delta, nestled against the rugged breast of the Coast Range. Just outside the town's limit and some hundreds of feet above its principal streets there was a gigantic half-bowl, carved out of the solid rock by an eddy of some bye-gone age.

This was the Amphitheater, and on the very lip of the stupendous cliff descending vertically to the river so far below, Llosir stood proudly on his platform of smooth, clean granite.

"'Tis not enough like a god, methinks." King Phagon, dressed now in cloth-of-gold, eyed the gleaming copper statue very dubiously. "'Tis too much like a man, by far."

"'Tis exactly as I saw him, sire," Tedric replied, firmly. Nor was he, consciously, lying: by this time he believed the lie himself. "Llosir is a man-god, remember, not a beast-god, and 'tis better so. But the time I set is here. With your permission, sire, I begin."

Both men looked around the great bowl. Near by, but not too near, stood the priestess and half a dozen white-clad fifteen-year-old girls; one of whom carried a beaten-gold pitcher full of perfumed oil, another a flaring open lamp wrought of the same material. Slightly to one side were Rhoann—looking, if the truth must be told, as though she did not particularly enjoy her present position on the side-lines—her mother the queen, the rest of the royal family, and ranks of courtiers. And finally, much farther back, at a very respectful distance from their strange new god, arranged in dozens of more or less concentric, roughly hemispherical rows, stood everybody who had had time to get there. More were arriving constantly, of course, but the flood had become a trickle; the narrow way, worming upward from the city along the cliffs stark side, was almost bare of traffic.

"Begin, Lord Tedric," said the king.

Tedric bent over, heaved the heavy iron pan containing the offerings up onto the platform, and turned. "The oil, Priestess Lady Trycie, and the flame."

The acolyte handed the pitcher to Trycie, who handed it to Tedric, who poured its contents over the twin hearts, twin livers, and twin brains. Then the lamp; and as the yard-high flames leaped upward the armored pseudo-priest stepped backward and raised his eyes boldly to the impassive face of the image of his god. Then he spoke—not softly, but in parade-ground tones audible to everyone present.

"Take, Lord Llosir, all the strength and all the power and all the force that Sarpedion ever had. Use them, we beg, for good and not for ill."

He picked up the blazing pan and strode toward the lip of the precipice; high-mounting, smoky flames curling backward around his armored figure. "And now, in token of Sarpedion's utter and complete extinction, I consign these, the last vestiges of his being, to the rushing depths of oblivion." He hurled the pan and its fiercely flaming contents out over the terrific brink.

This act, according to Tedric's plan, was to end the program—but it didn't. Long before the fiery mass struck water his attention was seized by a long, low-pitched, moaning gasp from a multitude of throats; a sound the like of which he had never before even imagined.

He whirled—and saw, shimmering in a cage-like structure of shimmering bars, a form of seeming flesh so exactly like the copper image in every detail of shape that it might well have come from the same mold!

"Lord Llosir—in the flesh!" Tedric exclaimed, and went to one knee.

So did the king and his family, and a few of the bravest of the courtiers. Most of the latter, however, and the girl acolytes and the thronging thousands of spectators, threw themselves flat on the hard ground. They threw themselves flat, but they did not look away or close their eyes or cover their faces with their hands. On the contrary, each one stared with all the power of his optic nerves.

The god's mouth opened, his lips moved; and, although no one could hear any sound, everyone felt words resounding throughout the deepest recesses of his being.

"I have taken all the strength, all the power, all the force, all of everything that made Sarpedion what he was," the god began. In part his pseudo-voice was the resonant clang of a brazen bell; in part the diapason harmonies of an impossibly vast organ. "I will use them for good, not for ill. I am glad, Tedric, that you did not defile my hearth—for this is a hearth, remember, and in no sense an altar—in making this, the first and the only sacrifice ever to be made to me. You, Trycie, are the first of my priestesses?"

The girl, shaking visibly, gulped three times before she could speak. "Yea, my—my—Lord Llosir," she managed finally. "Th—that is—if—if I please you, Lord Sir."

"You please me, Trycie of Lomarr. Nor will your duties be onerous; being only to see to it that your maidens keep my hearth clean and my statue bright."

"To you, my Lord—Llo—Llosir, sir, all thanks. Wilt keep...." Trycie raised her downcast eyes and stopped short in mid-sentence; her mouth dropping ludicrously open and her eyes becoming two round O's of astonishment. The air above the yawning abyss was as empty as it had ever been; the flesh-and-blood god had disappeared as instantaneously as he had come!

Tedric's heavy voice silenced the murmured wave of excitement sweeping the bowl.

"That is all!" he bellowed. "I did not expect the Lord Llosir to appear in the flesh at this time; I know not when or ever he will deign to appear to us again. But this I know—whether or not he ever so deigns, or when, you all know now that our great Lord Llosir lives. Is it not so?"

"'Tis so! Long live Lord Llosir!" Tumultuous yelling filled the amphitheater.

"'Tis well. In leaving this holy place all will file between me and the shrine. First our king, then the Lady Priestess Trycie and her maids, then the Family, then the Court, then the rest. All men as they pass will raise sword-arms in salute, all women will bow heads. Will be naught of offerings or of tribute or of fractions; Lord Llosir is a god, not a huckstering, thieving, murdering trickster. King Phagon, sire, wilt lead?"

Unhelmed now, Tedric stood rigidly at attention before the image of his god. The king did not march straight past him, but stopped short. Taking off his ornate head-piece and lifting his right arm high, he said:

"To you, Lord Llosir, my sincere thanks for what hast done for me, for my family, and for my nation. While 'tis not seemly that Lomarr's king should beg, I ask that you abandon us not."

Then Trycie and her girls. "We engage, Lord Sir," the Lady Priestess said, at a whispered word from Tedric, "to keep your hearth scrupulously clean; your statue shining bright."

Then the queen, followed by the Lady Rhoann—who, although she bowed her head meekly enough, was shooting envious glances at her sister, so far ahead and so evidently the cynosure of so many eyes.

The rest of the Family—the Court—the thronging spectators—and, last of all, Tedric himself. Helmet tucked under left arm, he raised his brawny right arm high, executed a stiff "left face," and march proudly at the rear of the long procession.

And as the people made their way down the steep and rugged path, as they debouched through the city of Lompoar, as they traversed the highways and byways back to the towns and townlets and farms from which they had come, it was very evident that Llosir had established himself as no other god had ever been established throughout the long history of that world.

Great Llosir had appeared in person. Everyone there had seen him with his own eyes. Everyone there had heard his voice; a voice of a quality impossible for any mortal being, human or otherwise, to produce; a voice heard, not with the ears, which would have been ordinary enough, but by virtue of some hitherto completely unknown and still completely unknowable inner sense or ability evocable only by the god. Everyone there had heard—sensed—him address the Lord Armsmaster and the Lady Priestess by name.

Other gods had appeared personally in the past ... or had they, really? Nobody had ever seen any of them except their own priests ... the priests who performed the sacrifices and who fattened on the fractions.... Llosir, now, wanted neither sacrifices nor fractions; and, powerful although he was, had appeared to and had spoken to everyone alike, of however high or low degree, throughout the whole huge amphitheater.

Everyone! Not to the priestess only; not only to those of the Old Blood; not only to citizens or natives of Lomarr; but to everyone—down to mercenaries, chance visitors, and such!

Long live Lord Llosir, our new and plenipotent god!

King Phagon and Tedric were standing at a table in the throne-room of the palace-castle, studying a map. It was crudely drawn and sketchy, this map, and full of blank areas and gross errors; but this was not an age of fine cartography.

"Tark, first, is still my thought, sire," Tedric insisted, stubbornly. "'Tis closer, our lines shorter, a victory there would hearten all our people. Too, 'twould be unexpected. Lomarr has never attacked Tark, whereas your royal sire and his sire before him each tried to loose Sarlon's grip and, in failing, but increased the already heavy payments of tribute. Too, in case of something short of victory, hast only the one pass and the Great Gorge of the Lotar to hold 'gainst reprisal. 'Tis true such course would leave the Marches unheld, but no more so than they have been for four years or more."

"Nay. Think, man!" Phagon snorted, testily. "'Twould fail. Four parts of our army are of Tark—thinkst not their first act would be to turn against us and make common cause with their brethren? Too, we lack strength, they outnumber us two to one. Nay. Sarlon first. Then, perhaps, Tark; but not before then."

"But Sarlon outnumbers us too, sire, especially if you count those barbarian devils of the Devossian steppes. Since Taggad of Sarlon lets them cross his lands to raid the Marches—for a fraction of the loot, no doubt—'tis certain they'll help him against us. Also, sire, your father and your grandfather both died under Sarlonian axes."

"True, but neither of them was a strategist. I am; I have studied this matter for many years. They did the obvious; I shall not. Nor shall Sarlon pay tribute merely; Sarlon must and shall become a province of my kingdom!"

So argument raged, until Phagon got up onto his royal high horse and declared it his royal will that the thing was to be done his way and no other. Whereupon, of course, Tedric submitted with the best grace he could muster and set about the task of helping get the army ready to roll toward the Marches, some three and a half hundreds of miles to the north.

Tedric fumed. Tedric fretted. Tedric swore sulphurously in Lomarrian, Tarkian, Sarlonian, Devossian, and all the other languages he knew. All his noise and fury were, however, of very little avail in speeding up what was an intrinsically slow process.

Between times of cursing and urging and driving, Tedric was wont to prowl the castle and its environs. So doing, one day, he came upon King Phagon and the Lady Rhoann practicing at archery. Lifting his arm in salute to his sovereign and bowing his head politely to the lady, he made to pass on.

"Hola, Tedric!" Rhoann called. "Wouldst speed a flight with us?"

Tedric glanced at the target. Rhoann was beating her father unmercifully—her purple-shafted arrows were all in or near the gold, while his golden ones were scattered far and wide—and she had been twitting him unmercifully about his poor marksmanship. Phagon was in no merry mood; this was very evidently no competition for any outsider—least of all Lomarr's top-ranking armsmaster—to enter.

"Crave pardon, my lady, but other matters press...."

"Your evasions are so transparent, my lord; why not tell the truth?" Rhoann did not exactly sneer at the man's obvious embarrassment, but it was very clear that she, too, was in a vicious temper. "Mindst not beating me but never the Throne? And any armsmaster who threwest not arrows by hand at this range to beat both of us should be stripped of badge?"

Tedric, quite fatuously, leaped at the bait. "Wouldst permit, sire?"

"No!" the king roared. "By my head, by the Throne, by Llosir's liver and heart and brain and guts—NO! 'Twould cost the head of any save you to insult me so—shoot, sir, and shoot your best!" extending his own bow and a full quiver of arrows.

Tedric did not want to use the royal weapon, but at the girl's quick, imperative gesture he smothered his incipient protest and accepted it.

"One sighting shot, sire?" he asked, and drew the heavy bow. Nothing whatever could have forced him to put an arrow nearer the gold than the farthest of the king's; to avoid doing so—without transparently missing the target completely—would take skill, since one golden arrow stood a bare three inches from the edge of the target.

His first arrow grazed the edge of the butt and was an inch low; his second plunged into the padding exactly half way between the king's wildest arrow and the target's rim. Then, so rapidly that it seemed as though there must be at least two arrows in the air at once, arrow crashed on arrow; wood snapping as iron head struck feathered shaft. At end, the rent in the fabric through which all those arrows had torn their way could have been covered by half of one of Rhoann's hands.

"I lose, sire," Tedric said, stiffly, returning bow and empty quiver. "My score is zero."

Phagon, knowing himself in the wrong but unable to bring himself to apologize, did what he considered the next-best thing. "I used to shoot like that," he complained. "Knowst how lost I my skill, Tedric? 'Tis not my age, surely?"

"'Tis not my place to say, sire." Then, with more loyalty than sense—"And I split to the teeth any who dare so insult the Throne."

"What!" the monarch roared. "By my...."

"Hold, father!" Rhoann snapped. "A king you—act it!"

Hard blue eyes glared steadily into unyielding eyes of green. Neither the thoroughly angry king nor the equally angry princess would give an inch. She broke the short, bitter silence.

"Say naught, Tedric—he is much too fain to boil in oil or flay alive any who tell him unpleasantnesses, however true. But me, father, you boil not, nor flay, nor seek to punish otherwise, or I split this kingdom asunder like a melon. 'Tis time—yea, long past time—that someone told you the unadorned truth. Hence, my rascally but well-loved parent, here 'tis. Hast lolled too long on too many too soft cushions, hast emptied too many pots and tankards and flagons, hast bedded too many wenches, to be of much use in armor or with any style of weapon in the passes of the High Umpasseurs."

The flabbergasted and rapidly-deflating king tried to think of some answer to this devastating blast, but couldn't. He appealed to Tedric. "Wouldst have said such? Surely not!"

"Not I, sire!" Tedric assured him, quite truthfully. "And even if true, 'tis a thing to remedy itself. Before we reach the Marches wilt regain arm and eye."

"Perhaps," the girl put in, her tone still distinctly on the acid side. "If he matches you, Tedric, in lolling and wining and wenching, yes. Otherwise, no. How much wine do you drink, each day?"

"One cup, usually—sometimes—at supper."

"On the march? Think carefully, friend."

"Nay—I meant in town. In the field, none, of course."

"Seest, father?"

"What thinkst me, vixen, a spineless cuddlepet? From this minute 'til return here I match your paragon youngblade loll for loll, cup for cup, wench for wench. Is it what you've been niggling at me to say?"

"Aye, father and king, exactly—for as you say, you do." She hugged him so fervently as almost to lift him off the ground, kissed him twice, and hurried away.

"A thing I would like to talk to you about, sire," Tedric said quickly, before the king could bring up any of the matters just past. "Armor. There was enough of the god-metal to equip three men fully, and headnecks for their horses. You, sire, and me, and Sciro of your Guard. Break precedent, sire, I beg, and wear me this armor of proof instead of the gold; for what we face promises to be worse than anything you or I have yet seen."

"I fear me 'tis true, but 'tis impossible, nonetheless. Lomarr's king wears gold. He fights in gold; at need he dies in gold."

And that was, Tedric knew, very definitely that. It was senseless, it was idiotic, but it was absolutely true. No king of Lomarr could possibly break that particular precedent. To appear in that spectacularly conspicuous fashion, one flashing golden figure in a sea of dull iron-gray, was part of the king's job. The fact that his father and his grandfather and so on for six generations back had died in golden armor could not sway him, any more than it could have swayed Tedric himself in similar case. But there might be a way out.

"But need it be solid gold, sire? Wouldst not an overlay of gold suffice?"

"Yea, Lord Tedric, and 'twould be a welcome thing indeed. I yearn not, nor did my father nor his father, to pit gold 'gainst hard-swung axe; e'en less to hide behind ten ranks of iron while others fight. But simply 'tis not possible. If the gold be thick enough for the rivets to hold, 'tis too heavy to lift. If thin enough to be possible of wearing, the gold flies off in sheets at first blow and the fraud is revealed. Hast ideas? I listen."

"I know not, sire...." Tedric thought for minutes. "I have seen gold hammered into thin sheets ... but not thin enough ... but it might be possible to hammer it thin enough to be overlaid on the god-metal with pitch or gum. Wouldst wear it so, sire?"

"Aye, my Tedric, and gladly: just so the overlay comes not off by handsbreadths under blow of sword or axe."

"Handsbreadths? Nay. Scratches and mars, of course, easily to be overlaid again ere next day's dawn. But handsbreadths? Nay, sire."

"In that case, try; and may Great Llosir guide your hand."

Tedric went forthwith to the castle and got a chunk of raw, massy gold. He took it to his shop and tried to work it into the thin, smooth film he could visualize so clearly.

And tried—and tried—and tried.

And failed—and failed—and failed.

He was still trying—and still failing—three weeks later. Time was running short; the hours that had formerly dragged like days now flew like minutes. His crew had done their futile best to help; Bendon, his foreman, was still standing by. The king was looking on and offering advice. So were Rhoann and Trycie. Sciro and Schillan and other more or less notable persons were also trying to be of use.

Tedric, strained and tense, was pounding carefully at a sheet of his latest production. It was a pitiful thing—lumpy in spots, ragged and rough, with holes where hammer had met anvil through its substance. The smith's left hand twitched at precisely the wrong instant, just as the hammer struck. The flimsy sheet fell into three ragged pieces.

Completely frustrated, Tedric leaped backward, swore fulminantly, and hurled the hammer with all his strength toward the nearest wall. And in that instant there appeared, in the now familiar cage-like structure of shimmering, interlaced bars, the form of flesh that was Llosir the god. High in the air directly over the forge the apparition hung, motionless and silent, and stared.

Everyone except Tedric gave homage to the god, but he merely switched from the viciously corrosive Devossian words he had been using to more parliamentary Lomarrian.

"Is it possible, Lord Sir, for any human being to do anything with this foul, slimy, salvy, perverse, treacherous, and generally-bedamned stuff?"

"It is. Definitely. Not only possible, but fairly easy and fairly simple, if the proper tools, apparatus, and techniques are employed," Llosir's bell-toned-organ pseudo-voice replied. "Ordinarily, in your lifetime, you would come to know nothing of gold leaf—although really thin gold leaf is not required here—nor of gold-beater's skins and membranes and how to use them, nor of the adhesives to be employed and the techniques of employing them. The necessary tools and materials are, or can very shortly be made, available to you; you can now absorb quite readily the required information and knowledge.

"For this business of beating out gold leaf, your hammer and anvil are both completely wrong. Listen carefully and remember. For the first, preliminary thinning down, you take ..."[A]

Lomarr's army set out at dawn. First the wide-ranging scouts: lean, hard, fine-trained runners, stripped to clouts and moccasins and carrying only a light bow and a few arrows apiece. Then the hunters. They, too, scattered widely and went practically naked: but bore the hundred-pound bows and the savagely-tearing arrows of their trade.

Then the Heavy Horse, comparatively few in number, but of the old blood all, led by Tedric and Sciro and surrounding glittering Phagon and his standard-bearers. It took a lot of horse to carry a full-armored knight of the Old Blood, but the horse-farmers of the Middle Marches bred for size and strength and stamina.

Next came century after century of light horse—mounted swordsmen and spearmen and javelineers—followed by even more numerous centuries of foot-slogging infantry.

Last of all came the big-wheeled, creaking wagons: loaded, not only with the usual supplies and equipment of war, but also with thousands of loaves of bread—hard, flat, heavy loaves made from ling, the corn-like grain which was the staple cereal of the region.

"Bread, sire?" Tedric had asked, wonderingly, when Phagon had first broached the idea. Men on the march lived on meat—a straight, unrelieved diet of meat for weeks and months on end—and all too frequently not enough of that to maintain weight and strength. They expected nothing else; an occasional fist-sized chunk of bread was sheerest luxury. "Bread! A whole loaf each man a day?"

"Aye," Phagon had chuckled in reply. "All farmsmen along the way will have ready my fraction of ling, and Schillan will at need buy more. To each man a loaf each day, and all the meat he can eat. 'Tis why we go up the Midvale, where farmsmen all breed savage dogs to guard their fields 'gainst hordes of game. Such feeding will be noised abroad. Canst think of a better device to lure Taggad's ill-fed mercenaries to our standards?"

Tedric couldn't.

There is no need to dwell in detail upon the army's long, slow march. Leaving the city of Lompoar, it moved up the Lotar River, through the spectacularly scenic gorge of the Coast Range, and into the Middle Valley; that incredibly lush and fertile region which, lying between the Low Umpasseurs on the east and the Coast Range on the west, comprised roughly a third of Lomarr's area. Into and through the straggling hamlet of Bonoy, lying at the junction of the Midvale River with the Lotar. Then straight north, through the timberlands and meadows of the Midvale's west bank.

Game was, as Phagon had said, incredibly plentiful; out-numbering by literally thousands to one both domestic animals and men. Buffalo-like lippita, moose-like rolatoes, pig-like accides—the largest and among the tastiest of Lomarr's game animals—were so abundant that one good hunter could kill in half an hour enough to feed a century for a day. Hence most of the hunters' time was spent in their traveling dryers, preserving meat against a coming day of need.

On, up the bluely placid Lake Midvale, a full day's march long and half that in width. Past the Chain Lakes, strung on the river like beads on a string. Past Lake Ardo, and on toward Lake Middlemarch and the Middlemarch Castle which was to be Tedric's official residence henceforth.

As the main body passed the head of the lake, a couple of scouts brought in a runner bursting with news.

"Thank Sarpedion, sire, I had not to run to Lompoar to reach you!" he cried, dropping to his knees. "Middlemarch Castle is besieged! Hurlo of the Marches is slain!" and he went on to tell a story of onslaught and slaughter.

"And the raiders worn iron," Phagon remarked, when the tale was done. "Sarlonian iron, no doubt?"

"Aye, sire, but how couldst ..."

"No matter. Take him to the rear. Feed him."

"You expected this raid, sire," Tedric said, rather than asked, after scouts and runner had disappeared.

"Aye. 'Twas no raid, but the first skirmish of a war. No fool, Taggad of Sarlon; nor Issian of Devoss, barbarian though he is. They knew what loomed, and struck first. The only surprise was Hurlo's death ... he had my direct orders not to do battle 'gainst any force, however slight-seeming, but to withdraw forthwith into the castle, which was to be kept stocked to withstand a siege of months ... this keeps me from boiling him in oil for stupidity, incompetence, and disloyalty."

Phagon frowned in thought, then went on: "Were there forces that appeared not...? Surely not—Taggad would not split his forces at all seriously: 'tis but to annoy me ... or perhaps they are mostly barbarians despite the Sarlonian iron ... to harry and flee is no doubt their aim, but for Lomarr's good not one of them should escape. Knowst the Upper Midvale, Tedric, above the lake?"

"But little, sire; a few miles only. I was there but once."

"'Tis enough. Take half the Royal Guard and a century of bowmen. Cross the Midvale at the ford three miles above us here. Go up and around the lake. The Upper Midvale is fordable almost anywhere at this season, so stay far enough away from the lake that none see you. Cross it, swing in a wide circle toward the peninsula on which sits Middlemarch Castle, and in three days...?"

"Three days will be ample, sire."

"Three days from tomorrow's dawn, exactly as the top rim of the sun clears the meadow, make your charge out of the covering forest, with your archers spread to pick off all who seek to flee. I will be on this side of the peninsula; between us they'll be ground like ling. None shall get away!"

Phagon's assumptions, however, were slightly in error. When Tedric's riders charged, at the crack of the indicated dawn, they did not tear through a motley horde of half-armored, half-trained barbarians. Instead, they struck two full centuries of Sarlon's heaviest armor! And Phagon the King fared worse. At first sight of that brilliant golden armor a solid column of armored knights formed as though by magic and charged it at full gallop!

Phagon fought, of course; fought as his breed had always fought. At first on horse, with his terrible sword, under the trenchant edge of which knight after knight died. His horse dropped, slaughtered; his sword was knocked away; but, afoot, the war-axe chained to his steel belt by links of super-steel was still his. He swung and swung and swung again; again and again; and with each swing an enemy ceased to live; but sheer weight of metal was too much. Finally, still swinging his murderous weapon, Phagon of Lomarr went flat on the ground.

At the first assault on their king, Tedric with his sword and Sciro with his hammer had gone starkly berserk. Sciro was nearer, but Tedric was faster and stronger and had the better horse.

"Dreegor!" he yelled, thumping his steed's sides with his armored legs and rising high in his stirrups. Nostrils flaring, the mighty beast raged forward and Tedric struck as he had never struck before. Eight times that terrific blade came down, and eight men and eight horses died. Then, suddenly—Tedric never did know how it happened, since Dreegor was later found uninjured—he found himself afoot. No place for sword, this, but made to order for axe. Hence, driving forward as resistlessly as though a phalanx of iron were behind him, he hewed his way toward his sovereign.

Thus he was near at hand when Phagon went down. So was doughty Sciro; and by the time the Sarlonians had learned that sword nor axe nor hammer could cut or smash that gold-seeming armor fury personified was upon them. Tedric straddled his king's head, Sciro his feet; and, back to back, two of Lomarr's mightiest armsmasters wove circular webs of flying steel through which it was sheerest suicide to attempt to pass. Thus battle raged until the last armored foeman was down.

"Art hurt, sire?" Tedric asked anxiously as he and Sciro lifted Phagon to his feet.

"Nay, my masters-at-arms," the monarch gasped, still panting for breath. "Bruised merely, and somewhat winded." He opened his visor to let more air in; then, as he regained control, he shook off the supporting hands and stood erect under his own power. "I fear me, Tedric, that you and that vixen daughter of mine were in some sense right. Methinks I may be—Oh, the veriest trifle!—out of condition. But the battle is almost over. Did any escape?"

None had.

"'Tis well. Tedric, I know not how to honor...."

"Honor me no farther, sire, I beg. Hast honored me already far more than I deserved, or ever will.... Or, at least, at the moment ... there may be later, perhaps ... that is, a thing ..." he fell silent.

"A thing?" Phagon grinned broadly. "I know not whether Rhoann will be overly pleased at being called so, but 'twill be borne in mind nonetheless. Now you, Sciro; Lord Sciro now and henceforth, and all your line. Lord of what I will not now say; but when we have taken Sarlo you and all others shall know."

"My thanks, sire, and my obeisance," said Sciro.

"Schillan, with me to my pavilion. I am weary and sore, and would fain rest."

As the two Lords of the Realm, so lately commoners, strode away to do what had to be done:

"Neither of us feels any nobler than ever, I know," Sciro said, "but in one way 'tis well—very well indeed."

"The Lady Trycie, eh? The wind does set so, then, as I thought."

"Aye. For long and long. It wondered me often, your choice of the Lady Rhoann over her. Howbeit, 'twill be a wondrous thing to be your brother-in-law as well as in arms."

Tedric grinned companionably, but before he could reply they had to separate and go to work.

The king did not rest long; the heralds called Tedric in before half his job was done.

"What thinkst you, Tedric, should be next?" Phagon asked.

"First punish Devoss, sire!" Tedric snarled. "Back-track them—storm High Pass if defended—raze half the steppes with sword and torch—drive them the full length of their country and into Northern Sound!"

"Interesting, my impetuous youngblade, but not at all practical," Phagon countered. "Hast considered the matter of time—the avalanches of rocks doubtless set up and ready to sweep those narrow paths—what Taggad would be doing while we cavort through the wastelands?"

Tedric deflated almost instantaneously. "Nay, sire," he admitted sheepishly. "I thought not of any such."

"'Tis the trouble with you—you know not how to think." Phagon was deadly serious now. "'Tis a hard thing to learn; impossible for many; but learn it you must if you end not as Hurlo ended. Also, take heed: disobey my orders but once, as Hurlo did, and you hang in chains from the highest battlement of your own Castle Middlemarch until your bones rot apart and drop into the lake."

His monarch's vicious threat—or rather, promise—left Tedric completely unmoved. "'Tis what I would deserve, sire, or less; but no fear of that. Stupid I may be, but disloyal? Nay, sire. Your word always has been and always will be my law."

"Not stupid, Tedric, but lacking in judgment, which is not as bad; since the condition is, if you care enough to make it so, remediable. You must care enough, Tedric. You must learn, and quickly; for much more than your own life is at hazard."

The younger man stared questioningly and the king went on: "My life, the lives of my family, and the future of all Lomarr," he said quietly.

"In that case, sire, wilt learn, and quickly," Tedric declared; and, as days and weeks went by, he did.

"ALL previous attempts on the city of Sarlo were made in what seemed to be the only feasible way—crossing the Tegula at Lower Ford, going down its north bank through the gorge to the West Branch, and down that to the Sarlo." Phagon was lecturing from a large map, using a sharp stick as pointer; Tedric, Sciro, Schillan, and two or three other high-ranking officers were watching and listening. "The West Branch flows into Sarlo only forty miles above Sarlo Bay. The city of Sarlo is here, on the north bank of the Sarlo River, right on the Bay, and is five-sixths surrounded by water. The Sarlo River is wide and deep, uncrossable against any real opposition. Thus, Sarlonian strategy has always been not to make any strong stand anywhere along the West Branch, but to fight delaying actions merely—making their real stand on the north bank of the Sarlo, only a few miles from Sarlo City itself. The Sarlo River, gentlemen, is well called 'Sarlo's Shield.' It has never been crossed."

"How do you expect to cross it, then, sire?" Schillan asked.

"Strictly speaking, we cross it not, but float down it. We cross the Tegula at Upper Ford, not Lower...."

"Upper Ford, sire? Above the terrible gorge of the Low Umpasseurs?"

"Yea. That gorge, undefended, is passable. 'Tis rugged, but passage can be made. Once through the gorge our way to the Lake of the Spiders, from which springs the Middle Branch of the Sarlo, is clear and open."

"But 'tis held, sire, that Middle Valley is impassable for troops," a grizzled captain protested.

"We traverse it, nonetheless. On rafts, at six or seven miles an hour, faster by far than any army can march. But 'tis enough of explanation. Lord Sciro, attend!"

"I listen, sire."

"At earliest dawn take two centuries of axemen and one century of bowmen, with the wagonload of wood-workers' supplies about which some of you have wondered. Strike straight north at forced march. Cross the Tegula. Straight north again, to the Lake of the Spiders and the head of the Middle Branch. Build rafts, large enough and of sufficient number to bear our whole force; strong enough to stand rough usage. The rafts should be done, or nearly, by the time we get there."

"I hear, sire, and I obey."

Tedric, almost stunned by the novelty and audacity of this, the first amphibian operation in the history of his world, was dubious but willing. And as the map of that operation spread itself in his mind, he grew enthusiastic.

"We attack then, not from the south but from the north-east!"

"Aye, and on solid ground, not across deep water. But to bed, gentlemen—tomorrow the clarions sound before dawn!"

Dawn came. Sciro and his force struck out. The main army marched away, up the north bank of the Upper Midvale, which for thirty or forty miles flowed almost directly from the north-east. There, however, it circled sharply to flow from the south-east and the Lomarrians left it, continuing their march across undulating foothills straight for Upper Ford. From the south, the approach to this ford, lying just above (east of) the Low Umpasseur Mountains, at the point where the Middle Marches mounted a stiff but not abrupt gradient to become the Upper Marches, was not too difficult. Nor was the entrapment of most of the Sarlonians and barbarians on watch. The stream, while only knee-deep for the most part, was wide, fast, and rough; the bottom was made up in toto of rounded, mossy, extremely slippery rocks. There were enough men and horses and lines, however, so that the crossing was made without loss.

Then, turning three-quarters of a circle, the cavalcade made slow way back down the river, along its north bank, toward the forbidding gorge of the Low Umpasseurs.

The north bank was different, vastly different, from the south one. Mountains of bare rock, incredible thousands of feet higher than the plateau forming the south bank, towered at the rushing torrent's very edge. What passed for a road was narrow, steep, full of hair-pin turns, and fearfully rugged. But this, too, was passed—by dint of what labor and stress it is not necessary to dwell upon—and as the army debouched out onto the sparsely-wooded, gullied and eroded terrain of the high barren valley and began to make camp for the night. Tedric became deeply concerned. Sciro's small force would have left no obvious or lasting traces of its passing; but such blatant disfigurements as these....

He glanced at the king, then stared back at the broad, trampled, deep-rutted way the army had come. "South of the river our tracks do not matter," he said, flatly. "In the gorge they exist not. But those traces, sire, matter greatly and are not to be covered or concealed."

"Tedric, I approve of you—you begin to think!" Much to the young man's surprise, Phagon smiled broadly. "How wouldst handle the thing, if decision yours?"

"A couple of fives of bowmen to camp here or nearby, sire," Tedric replied promptly, "to put arrows through any who come to spy."

"'Tis a sound idea, but not enough by half. Here I leave you; and a full century each of our best scouts and hunters. See to it, my lord captain, that none sees this our trail from here to the Lake of the Spiders; or, having seen it, lives to tell of the seeing."

Tedric, after selecting his sharp-shooters and watching them melt invisibly into the landscape, went down the valley about a mile and hid himself carefully in a cave. These men knew the business in hand a lot better than he did, and he would not interfere. What he was for was to take command in an emergency; if the operation were a complete success he would have nothing whatever to do!

He was still in the cave, days later, when word came that the launching had begun. Rounding up his guerillas, he led them at a fast pace to the Lake of the Spiders, around it, and to the place where the Lomarrian army had been encamped. Four fifty-man rafts were waiting, and Tedric noticed with surprise that a sort of house had been built on the one lying farthest down-stream. This luxury, he learned, was for him and his squire Rahlion and their horses and armor!

The Middle Branch was wide and swift; and to Tedric and his bowmen, landlubbers all, it was terrifyingly rough and boisterous and full of rocks. Tedric, however, did not stay a landlubber long. He was not the type to sit in idleness when there was something physical to do, something new to learn. And learning to be a riverman was so much easier than learning to be King Phagon's idea of a strategist!

Thus, stripped to clout and moccasins, Tedric reveled in pitting his strength and speed at steering-oar or pole against the raft's mass and the river's whim.

"A good man, him," the boss boatman remarked to one of his mates. Then, later, to Tedric himself: "'Tis shame, lord, that you got to work at this lord business. Wouldst make a damn good riverman in time."

"My thanks, sir, and 'twould be more fun, but King Phagon knows best. But this 'Bend' you talk of—what is it?"

"'Tis where this Middle Branch turns a square angle 'gainst solid rock to flow west into the Sarlo; the roughest, wickedest bit of water anybody ever tried to run a raft over. Canst try it with me if you like."

"'Twould please me greatly to try."

Well short of the Bend, each raft was snubbed to the shore and unloaded. When the first one was bare, the boss riverman and a score of his best men stepped aboard. So did Tedric.

"What folly this?" Phagon yelled. "Tedric, ashore!"

"Canst swim, Lord Tedric?" the boss asked.

"Like an eel," Tedric admitted modestly, and the riverman turned to the king.

"'Twill save you rafts, sire, if he works with us. He's quick as a cat and strong as a bull, and knows more of white water already than half my men."

"In that case ..." Phagon waved his hand and the first raft took off.

Many of the rafts were lost, of course; and Tedric had to swim in icy water more than once, but he loved every exhausting, exciting second of the time. Nor were the broken logs of the wrecked rafts allowed to drift down the river as tell-tales. Each bit was hauled carefully ashore.

Below the Bend, the Middle Branch was wide and deep, hence the reloaded rafts had smooth sailing; and the Sarlo itself was of course wider and deeper still. In fact, it would have been easily navigable by an 80,000-ton modern liner. The only care now was to avoid discovery—which matter was attended to by several centuries of far-ranging scouts and by scores of rivermen in commandeered boats.

Moyla's Landing, the predetermined point of debarkation, was a scant fifteen miles from the city of Sarlo. It was scarcely a hamlet, but even so any one of its few inhabitants could have given the alarm. Hence it was surrounded by an advance force of bowmen and spearmen, and before those soldiers set out Phagon voiced the orders he was to repeat so often during the following hectic days.

"NO BURNING AND NO WANTON KILLING! None must know we come, but nonetheless Sarlon is to be a province of Lomarr my kingdom and I will not have its people or its substance destroyed! To that end I swear by my royal head, by the Throne, by Great Llosir's heart and brain and liver, that any man of whatever rank who slays or burns without my express permission will be flayed alive and then boiled in oil!"

Hence the taking of Moyla's Landing was very quiet, and its people were held under close guard. All that day and all the following night the army rested. Phagon was pretty sure that Taggad knew nothing of the invasion as yet; but it would be idle to hope to get much closer without being discovered. Every mile gained, however, would be worth a century of men. Therefore, long before dawn, the supremely ready Lomarrian forces rolled over the screening bluff and marched steadily toward Sarlo. Not fast, note; thirteen miles is a long haul when there is to be a full-scale battle at the end of it.

Plodding slowly along on mighty Dreegor at the king's right, Tedric roused himself from a brown study and, gathering his forces visibly, spoke: "Knowst I love the Lady Rhoann, sire?"

"Aye. No secret that, nor has been since the fall of Sarpedion."

"Hast permission, then, to ask her to be my wife, once back in Lompoar?"

"Mayst ask her sooner than that, if you like. Wilt be here tomorrow—with the Family, the Court, and an image of Great Llosir—for the Triumph."

Tedric's mouth dropped open. "But sire," he managed finally, "how couldst be that sure of success? The armies are too evenly matched."

"In seeming only. They have no body of horse or foot able to stand against my Royal Guard; they have nothing to cope with you and Sciro and your armor and weapons. Therefore I have been and am certain of Lomarr's success. Well-planned and well-executed ventures do not fail. This has been long in the planning, but only your discovery of the god-metal made it possible of execution." Then, as Tedric glanced involuntarily at his gold-plated armor: "Yea, the overlay made it possible for me to live—although I may die this day, being the center of attack and being weaker and of lesser endurance that I thought—but my life matters not beside the good of Lomarr. A king's life is of import only to himself, to his Family, and to a few—wouldst be surprised to learn how very few—real friends."

"Your life matters to me, sire—and to Sciro!"

"Aye, Tedric my almost-son, that I know. Art in the forefront of those few I spoke of. And take this not too seriously, for I expect fully to live. But in case I die, remember this: kings come and kings go; but as long as it holds the loyalty of such as you and Sciro and your kind, the Throne of Lomarr endures!"

Taggad of Sarlon was not taken completely by surprise. However, he had little enough warning, and so violent and hasty was his mobilization that the Sarlonians were little if any fresher than the Lomarrians when they met, a couple of miles outside the city's limit.

There is no need to describe in detail the arrangement of the centuries and the legions, nor to dwell at length upon the bloodiness and savagery of the conflict as a whole nor to pick out individual deeds of derring-do, of heroism, or of cowardice. Of prime interest here is the climactic charge of Lomarr's heavy horse—the Royal Guard—that ended it.

There was little enough of finesse in that terrific charge, led by glittering Phagon and his two alloy-clad lords. The best their Middlemarch horses could do in the way of speed was a lumbering canter, but their tremendous masses—a Middlemarch warhorse was not considered worth saving unless he weighed at least one long ton—added to the weight of man and armor each bore, gave them momentum starkly irresistible. Into and through the ranks of Sarlonian armor the knights of Lomarr's Old Blood crashed; each rising in his stirrups and swinging down with all his might, with sword or axe or hammer, upon whatever luckless wight was nearest at hand.

Then, re-forming, a backward smash; then another drive forward. But men were being unhorsed; horses were being hamstrung or killed; of a sudden king Phagon himself went down. Unhorsed, but not out—his god-metal axe, scarcely stoppable by iron, was taking heavy toll.

As at signal, every mounted Guardsman left his saddle as one; and every Guardsman who could move drove toward the flashing golden figure of his king.

"Where now, sire?" Tedric yelled, above the clang of iron.

"Taggad's pavilion, of course—where else?" Phagon yelled back.

"Guardsmen, to me!" Tedric roared. "Make wedge, as you did at Sarpedion's Temple!" and the knights who could not hear him were made by signs to understand what was required. "To that purple tent we ram Phagon our King. Elbows in, sire. Short thrusts only, and never mind your legs. Now, men—DRIVE!"

With three giants in impregnable armor at point—Tedric and Sciro were so close beside and behind the king as almost to be one with him—that flying wedge simply could not be stopped. In little over a minute it reached the pavilion and its terribly surprised owner. Golden tigers seemed to leap and creep as the lustrous silk of the tent rippled in the breeze; magnificent golden tigers adorned the Sarlonian's purple-enameled armor.

"Yield, Taggad of Sarlon, or die!" Phagon shouted.

"If I yield, Oh Phagon of Lomarr, what...." Taggad began a conciliatory speech, but even while speaking he whirled a long and heavy sword out from behind him, leaped, and struck—so fast that neither Phagon nor either of his lords had time to move; so viciously hard that had Lomarr's monarch been wearing anything but super-steel he would have joined his fathers then and there. As it was, however, the fierce-driven heavy blade twisted, bent double, and broke.

Phagon's counter-stroke was automatic. His axe, swung with all his strength and speed, crashed to the helve through iron and bone and brain; and, as soon as the heralds with their clarions could spread the news that Phagon had killed Taggad in hand to hand combat, all fighting ceased.

"Captain Sciro, kneel!" With the flat of his sword Phagon struck the steel-clad back a ringing blow. "Rise, Lord Sciro of Sarlon!"

"So be it," Skandos One murmured gently, and took up the life and the work of Skandos Four.

Ultimate catastrophe was five hundred twenty-nine years away.

[A] See Encyclopedia Britannica (plug). E.E.S.

Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from Universe Science Fiction March 1954. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.