The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Hermit Doctor of Gaya: A Love Story of Modern India

Title: The Hermit Doctor of Gaya: A Love Story of Modern India

Creator: I. A. R. Wylie

Illustrator: W. J. Shettsline

Release date: July 30, 2015 [eBook #49555]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

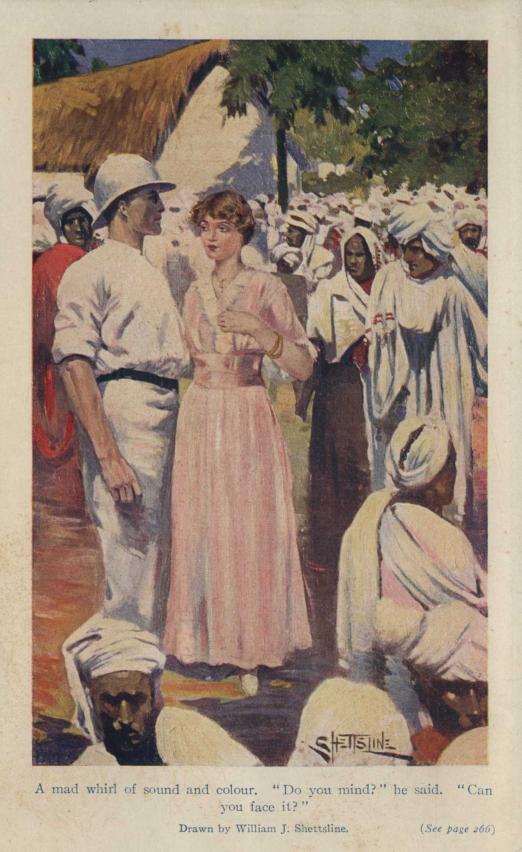

"Can you face it?"

Drawn by William J. Shettsline. (See page 266.)

The Hermit Doctor of Gaya

A Love Story of Modern India

By

I. A. R. Wylie

Author of "The Native Born," etc.

"This kiss to the whole world"

Beethoven's Ninth Symphony

G. P. Putnam's Sons

New York and London

The Knickerbocker Press

1916

COPYRIGHT, 1916

BY

I. A. R. WYLIE

The Knickerbocker Press, New York

CONTENTS

BOOK I

CHAPTER

I.—The Story of Kurnavati

II.—Tristram the Hermit

III.—Tristram Becomes Father-Confessor

IV.—The Interlopers

V.—A Vision of the Backwater

VI.—Broken Sanctuary

VII.—Anne Boucicault Explains

VIII.—The Two Listeners

IX.—Lalloo, the Money-Lender

X.—An Encounter

XI.—Inferno

XII.—In which Fortune Pleases to Jest

XIII.—Crossed Swords

XIV.—Tristram Chooses his Road

XV.—The Weavers

XVI.—A Meredith to the Rescue

XVII.—Mrs. Smithers Does Accounts

XVIII.—The Feast of Siva

BOOK II

I.—Mrs. Compton Stands Firm

II.—A Home-Coming

III.—Mrs. Boucicault Calls the Tune

IV.—Anne Makes a Discovery

V.—Crisis

VI.—"Of your Blood"

VII.—The Price Paid

VIII.—Return

IX.—For the Last Time

X.—Anne Chooses

XI.—Freedom

XII.—The Meeting of the Ways

XIII.—To Gaya!

XIV.—Resurrection

XV.—The Snake-God

XVI.—Towards Morning

BOOK I

CHAPTER I

THE STORY OF KURNAVATI

"Thus it came about that, for her child's sake, the Rani Kurnavati saved herself from the burning pyre and called together the flower of the Rajputs to defend Chitore and their king from the sword of Bahadur Shah."

The speaker's voice had not lifted from its brooding quiet. But now the quiet had become a living thing repressed, a passion disciplined, an echo dimmed with its passage from the by-gone years, but vibrant and splendid still with the clash of chivalrous steel.

The village story-teller gazed into the firelight and was silent. Swift, soft-footed shadows veiled the lower half of his face, but his eyes smouldered and burnt up as they followed their visions among the flames. He was young. His lithe, scantily-clad body was bent forward and his slender arms were clasped loosely about his knees. Compared with him, the broken circle of listeners seemed half living. They sat quite still, their skins shining darkly like polished bronze, their eyes blinking at the firelight. Only the headman of the village moved, stroking his fierce grey beard with a shrivelled hand.

"Those were the great days!" he muttered. "The great days!"

The silence lingered. The Englishman, whose long, white-clad body linked the circle, shifted his position. He lay stretched out with a lazy, unconscious grace, his head supported on his arm, his eyes lifted to the overhanging branches of the peepul tree, whose long, pointed leaves fretted the outskirts of the light and sheltered the solemn, battered effigy of the village god like the dome of a temple. A suddenly awakened night-breeze stirred them to a mysterious murmur. They rustled tremulously and secretly together, and the clear cold fire of a star burnt amidst their shifting shadows. Beyond and beneath their whispering there were other sounds. A night-owl hooted, a herd of excited, lithe-limbed monkeys scrambled noisily in the darkness overhead, chattered a moment, and were mischievously still. From the distance came the long, hungry wail of a pariah dog, hunting amidst the village garbage. These discords dropped into the night's silence, breaking its placid surface into widening circles and died away. The peepul leaves shivered and sank for an instant into grave meditation on their late communings, and through the deepened quiet there poured the distant, monotonous song of running water. It was a song based on one deep organ note, the primæval note of creation, and never changed. It rose up out of the earth and filled the darkness and mingled with the silence, so that they became one. The listeners heard it and did not know they heard it. It was the background on which the night sounds of living things painted themselves in vivid colours.

The Englishman turned his face to the firelight.

"Go on, Ayeshi," he said, with drowsy content. "You can't leave the beautiful Rani in mid-air like that, you know. Go on."

"Yes, Sahib." The young man pushed back the short black curls from his neck and resumed his old attitude of watchfulness on the flames. But his voice sounded louder, clearer:

"Thereafter, Sahib, the need of Chitore grew desperate. In vain, the bravest of her nobles sallied forth—the armies of Bahadur Shah swept over them as the tempest sweeps over the ripe corn, and hour by hour the ring about the city tightened till the very gates shivered beneath the enemy's blows. It was then the Rani bethought her of a custom of her people. With her own hands she made a bracelet of silver thread bound with tinsel and gay with seven coloured tassels, and, choosing a trusty servant, sent him forth out of Chitore to seek Humayun, the Great Moghul, whose conquering sword even then swept Bengal like a flail. By a miracle, the messenger escaped and came before Humayun and laid the bracelet in his hands, saying:

"'This is the gift of Kurnavati, Rani of Chitore.'

"And Humayun looked at the messenger and asked:

"'And if Humayun accept the gift of the Rani Kurnavati, what then?'

"'Then shall Humayim be her bracelet-bound brother, and she shall be his dear and virtuous sister.'

"And Humayun looked at the gift and asked:

"'And if I become bracelet-bound brother to the Rani Kurnavati, what then?'

"'Then will the Rani of Chitore call upon her dear and reverend brother, according to the bond, to succour her from the cruel vengeance of Bahadur Shah.'

"And because the heart of Humayun loved all chivalrous and noble deeds better than conquest and rich spoils, he took the bracelet and bound it about his wrist, saying: 'Behold, according to the custom, Humayun accepts the bond, and from henceforth the Rani Kurnavati is his dear and virtuous sister, and his sword shall not rest in its scabbard till she is free from the threat of her oppressors.' And he set forth with all his horsemen and rode night and day till the walls of Chitore were in sight."

"Well——?" The story-teller had ceased speaking and the Englishman rolled over, clipping his square chin in his big hands. "Go on, Ayeshi."

"He came too late." The metal had gone from the boy's voice, and the firelight awoke no answering gleam in his watching eyes.

"The Rani Kurnavati and three thousand of her women had sought honour on the funeral pyre. The grey smoke from their ashes greeted Humayun as he passed through the battered gates. The walls of Chitore lay in ruins and without them slept their defenders, clad in saffron bridal robes, their faces lifted to the sun, their broken swords red with the death of their enemies. And Humayun, seeing them, wept."

Ayeshi's voice trailed off into silence. The headman nodded to himself, showing his white teeth.

"Those were the great days," he muttered, "when men died fighting and the women followed their husbands to the——" He coughed and glanced at the Englishman.

"But ours are the days of the Sahib," he added, with great piety, "full of wisdom and peace."

"Just so." The Sahib rose to his feet, stretching himself. "And, talking of wives, Buddhoos, if thou dost not give that luckless female of thine the medicine I ordered, instead of offering it up to the village devil, I will mix thee such a compound as will make thy particular hereafter seem Paradise by comparison. Moreover, I will complain to the Burra Sahib and thou wilt be most certainly degraded and become the mock of Lalloo, thy dear and loving brother-in-law. Moreover, if I again find thirty of thy needy brethren herded together in thy cow-stall, I will assuredly dose thy whole family. Hast thou understood?"

The headman salaamed solemnly.

"The Dakktar Sahib's wishes are law," he declared fervently.

"I should like to think so. And now, Ayeshi, it is time. We have ten miles to go before morning. Give me my medicine-chest. I see that Buddhoos has a longing eye on it. Come, Wickie!"

The last order was in English, and a small, curious shape uncurled itself from the shadows at the base of the tree and trotted into the firelight. The most that could be said of it with any truth was, that it had been intended for a dog. Many generations back there had been an Aberdeen in the family, and since then the peculiarities of that particular strain had been modified to an amazing degree by a series of mésalliances. In fact, all that remained of the Aberdeen were a pair of bandy legs and a wistful, pseudo-innocent eye. Nevertheless, it was evidently an object of veneration. The village elders made way for it, regarding it with gloomy apprehension as it leisurely stretched itself, yawned, and then, with the dignity which goes with conscious yet modest superiority, proceeded to follow the massive white figure of its master into the darkness.

The headman salaamed again deeply and possibly thankfully.

"A safe journey and return, Sahib!" he called.

The Sahib's answer came back cheerily through the stillness. He looked back for an instant at the patch of firelight and the sharply cut silhouettes of moving figures, and then strode on, keeping well to the middle of the dusty roadway, his footsteps ringing out above the soft accompaniment of Ayeshi's patter and the fussy tap-tap of Wickie's unwieldy paws. He whistled cheerfully. So long as the sleeping, odoriferous mud-huts of the village bound them in on either hand, he clung tenaciously to his disjointed scrap of melody, but, as they came out at last into the open country, he broke off, sighing, and stood still, his arms outstretched, breathing in the freedom and untainted air with a thirsty, passionate gratitude.

There was no moon. The luminous haze which poured out over the limitless space before them was a mysterious thing, born of itself without source, without body. Its pallid, greenish clarity stretched in a ghostly sea between the earth and the black, beacon-studded sky, distorting and magnifying, as still water distorts and magnifies the rocks and tangled seaweed at its bed. It lapped soundlessly against the cliff of rising jungle land to the right, and beneath its quiet surface the shadow of the village temple floated like a sunken island, its slender sikhara alone rising up into the darkness, a finger of warning and admonition. It was very still. The voice of the invisible, swift-flowing river had indeed grown louder, but it was a sound outside this world of shadows and phantoms. It beat against the protecting wall of dreams, unheeded yet ominous and threatening in its implacable reality.

The two men crossed the path which encircled the village and made their way over the uneven ground towards the temple. As they drew nearer, the light seemed to recede, leaving the great roofless manderpam a shapeless ruin, whilst the sikhara faded into the black background of the jungle. The Dakktar Sahib whistled softly; a horse whinnied in answer, and the amazing Wickie bounded forward as though recognizing an old acquaintance. The Sahib laughed under his breath.

"We know each other, Wickie, Arabella and I," he said. "A wonderful animal that, Ayeshi."

"Truly, a noble creature, Sahib," Ayeshi answered very gravely.

A minute later they reached the carved gateway of the temple where two horses had been casually tethered. They stood deep in shadow, but the strange, unreal light which covered the plain filled the manderpam with its broken avenue of pillars, and threw into sharp relief the carved gateway and the figure seated cross-legged and motionless beneath the arch. Both men seemed to have expected the apparition. Ayeshi knelt down before it and placed a bowl of milk, which he had been carefully carrying, within reach of the long, lifeless-looking arms.

"For the God thou servest, O Holy One," he said, and for a moment knelt there with his forehead pressed to the ground.

The old mendicant seemed neither to have heard nor seen. He was almost naked. The bones started out of the shrivelled flesh, and the long, matted grey hair hung about his shoulders and mingled with the dishevelled beard, so that he seemed scarcely human, scarcely living. Only for an instant his eyes, half hidden beneath the wild disorder, flashed over the kneeling figure, and then closed, shutting the last vestige of life behind blank lids.

The Dakktar Sahib bent down and placed a coin in the upturned palms.

"That also is for thy God, Vahana," he said, with grave respect. Receiving no answer, he turned away and untethered his horse, a quadruped which even the solemn shadow could not dignify. It must have stood over seventeen hands high and its shape was comically suggestive of a child's drawing—six none too steady lines representing legs, back, and neck. The Dakktar Sahib whispered to it tenderly and reassuringly: "Only ten miles, Arabella, on my word of honour, only ten miles. And you shall have all tomorrow. I know it's rotten bad luck, but then I have got to stick it, too—it's our confounded, glorious duty to stick it, Arabella, and you wouldn't leave me in the lurch, would you, old girl?" Then came the crunch of sugar and the sound of Arabella's affectionate nozzling in the region of coat pockets. The Dakktar swung himself on to her lengthy back. "Now, then, Ayeshi; now then, Wickie!"

The three strange companions trotted out of the shadow, threading their way through the long, coarse grass in the direction of the river; but once the Englishman turned in his saddle and looked back. By some atmospheric freak, the temple seemed to have drawn all the green phosphorescent haze into its ruined self and hung like a great, dimly lit lamp against the wall of jungle. The Dakktar Sahib lingered a moment.

"They must have dreamed wonderfully in those old days," he said, wistfully. "To have built that—think of it, Ayeshi! To have given one's soul an abiding expression to wake the souls of other men thousands of years hence—to bring a lump into the throat of some human being long after one's bones have crumbled to dust. Well—well——"

He broke off with a sigh. "And you believe that tonight the Snake God will drink your milk, Ayeshi?"

"He or his many brethren, Sahib. He lies coiled about the branches of the highest tree in the jungle and on every branch of the forest another such as he keeps guard over his rest."

"No man has ever seen him, Ayeshi?"

"No man dares set foot within the jungle, Sahib, save Vahana, and he is a Sadhu, a holy man. He has sat before the temple for a hundred years, and none have seen him eat or heard him speak."

"You believe that, Ayeshi?"

The boy hesitated a moment, then answered gravely:

"Yes, Sahib. My people have believed it."

"Your people? Well—that's a good reason—one of our pet reasons for our pet beliefs, if you did but know it, Ayeshi. There's not such a gulf between East and West, after all." He rode on in silence, and then turned his head a little as though trying to distinguish his companion's features through the darkness. "Who are your people, Ayeshi—your father, your mother, your brothers? You have never spoken of them. Are they dead?"

"I do not know, Sahib. I have never known father or mother or brethren."

The Dakktar Sahib nodded to himself.

"You are not like the other villagers," he said. "One feels it—one doesn't talk in the same way to you. Tell me, Ayeshi, have you no ambitions?"

"None but to serve you, Sahib."

The Englishman threw back his head and laughed.

"Well, that's a poor sort of ambition. Why, I might get knocked on the head any time—typhoid, cholera, enteric—I'm cheek by jowl with the lot of them half the days of my life. And then where would you be, Ayeshi?"

"I should follow you, Sahib."

"That sounds almost biblical. And what for, eh?"

"Because of this, Sahib——" Suddenly and passionately, he discarded the English language which he used with ease and plunged into his own vernacular. "Behold, Sahib, there is the snake-bite on my arm, the wound which the Sahib cleansed with his own lips. Is that a thing to be forgotten? A life belongs to him who saves it."

"Pooh, nonsense!" The Englishman leant over his saddle. "For the Lord's sake, Wickie, keep away from Arabella's hoofs! Are you a dog or an idiot? Ayeshi, you don't understand. That sort of thing's my job—there, now, you've nearly run us into the river with your silly chatter——"

They drew rein abruptly. It was now close on the dawn, and the darkness had become intensified. The stars seemed colder and dimmer. Where they stood, their horses snuffing nervously at the unknown, they could hear the steady hurrying of the water at their feet, but they could see nothing. The Englishman patted the neck of his steed with a comforting hand. "In a year or two, there will be a bridge across," he said. "Then Mother Ganges won't have such terrors for us."

"Mother Ganges demands toll of those who curb her," Ayeshi answered solemnly.

"You mean, that no bridge could be built here?"

"I mean, Sahib, that the price will be a heavy one."

The Dakktar Sahib made no answer. Suddenly he laughed, not as though amused, but with a vague embarrassment.

"That was a fine story you told us tonight, Ayeshi. I don't know what there was about it—something that made one tingle from head to foot. I've been thinking of it on and off all the time. Those were days when men did mad, splendid things—bad too—worse than anything we do, but also finer. Sometimes one wishes—but it's no good wishing. The Rani Kurnavati and her bracelet are gone forever."

"Humayun also is dead," Ayeshi said, in his grave way.

"You mean——? Yes, that's true, too, I suppose. But oh Lord"—he lifted himself in his saddle with a movement of joyous, fiery vitality—"though I'm no Great Moghul, worse luck, still, if a woman sent me her bracelet and she were being murdered on the top of Mount Ararat, I'd——"

"The Sahib would come in time," Ayeshi interposed gently and significantly.

The Englishman dropped back in his saddle.

"Well, anyhow, Arabella, Wickie, and I would have a good shot at it," he said, gaily. He turned his horse's head eastwards and touched her gently to a trot. "But it's no good bragging. No one's going to make either of us bracelet brother. That's not for the like of us. And meanwhile, we've got eight miles to go and the dawn will be on us in an hour. I wish we'd got the seven-league boots handy. But you don't know the story of the seven-league boots, do you, Ayeshi? I'll tell it you as we go along. A story for a story, eh?"

"Yes, Sahib."

They trotted off along the bank of the river, Arabella slightly in advance, Wickie skirmishing skilfully on either hand, the Dakktar Sahib's voice mingling with the song of the waters as he told the story of the seven-league boots.

Behind them the temple had sunk into profound shadow.

Vahana, the mendicant, still sat beneath the archway. He took the bowl of milk and drained it thirstily. The coin he spat on with a venomous hatred and sent spinning into the darkness.

CHAPTER II

TRISTRAM THE HERMIT

"Of course, all that one can do is to hope," Mrs. Compton said, ruffling up her dark, curly hair with a distracted hand. "I don't know who it was talked about hope springing eternal in the something-something, but he must have lived in Gaya. If we hadn't hope and pegs in this withered desert——"

"My dear," her husband interposed, "in the first place, Gaya isn't a desert. It's the Garden of India. In the second place, no lady talks about pegs—certainly not in the tone of devout thankfulness which you have used. Pegs is—are masculine. They uphold us in our strenuous hours, of which you women appear to know nothing; they soothe our overwrought nerves and prepare the way for a liverish old age in Cheltenham. Praise be to Allah!"

Mrs. Compton sighed and surveyed the curtain which she had been artistically draping. Her manner, like her whole wiry, restless personality, expressed a good-tempered irascibility.

"Anyhow, they keep you human and grant us luckless females a lucid interval in which we can call our souls our own. What you men would be like if you didn't have your drinks and your tubs and all your other multitudinous creature comforts—well, it doesn't stand thinking about. Archie, do you like the curtain tied up with a bow or—oh, of course, it's no use asking you, you materialistic lump." She turned from the long, lean figure sprawling on the wicker chair by the verandah window and appealed to the second member of her audience.

"Mr. Meredith, you're a clergyman, you ought to have a soul. Do you like bows or don't you?"

Meredith looked up with a faint smile on his grave face.

"I like bows, Mrs. Compton. I hope it's a good sign of my artistic and spiritual development?"

"Yes, it is. I like bows myself. Oh, dear——" She stopped suddenly. "But supposing she's a horror! Supposing she paints and smothers herself in diamonds, and gets hilarious at dinner, and has a shrill voice! Goodness knows, I don't boast about our morals, but we're immoral in our own conventional way, so that it becomes almost respectable, and anything else would shock us frightfully. You know, I think we're running an awful risk."

Captain Compton guffawed cheerfully, and the smile still lingered in Owen Meredith's pleasant eyes.

"I shouldn't worry, my dear lady," he recommended. "After all, some of them are the last thing in respectability. It belongs to their profession. They're bound to be physically perfect, and physical perfection goes with morality. Besides, I understand that there can be genius in that sort of thing, and that she's a genius."

"Well, genius doesn't go with respectability, anyhow," Mary Compton retorted. "A professional dancer and a guest of the Rajah's! What can one hope for?"

Meredith compressed his lips and passed his hand over his black hair with a movement that somehow or other revealed the Anglican. A look of what might have been habitual anxiety settled on his square, blunt features, and he found no answer.

Captain Compton got up, stretching himself.

"The Rajah's the best guarantee we could have," he said lazily. "He's a harmless type of the little degenerate princeling who apes the European and lives in a holy terror of doing the wrong thing. He wouldn't set Gaya by the ears for untold gold. I know just what's happened. He saw Mlle. Fersen dance and he sent her a bouquet—very respectfully—and gave a supper-party in her honour—also very respectable—and assured her of a warm, respectable welcome in Gaya should she ever visit India. Well, she's come—as why shouldn't she?—and he's trying to do the handsome and the respectable at the same time. You don't suppose old Armstrong would have written about her if everything wasn't quite all right." He pulled out his cigarette case and looked round helplessly for the matches. "My dear, you will find that she is not only a perfect lady, but that our ways will shock her into fits, and that we shall have to live up to her."

Mrs. Compton gave him the matches with the air of a nurse tending a peculiarly incapable child.

"You disappoint me horribly," she said, and went out on the verandah. A minute later she called the two men after her and pointed an indignant finger in the direction of the highway. "Look at that, Archie! How do you suppose anybody's going to respect us with that sort of thing running about! It's positively unpatriotic. It's a blow at the very foundations of the Empire——!"

"Why, it's the old Hermit," Compton interrupted, soothingly. "Don't worry about him. If there were a few more hermits—Bless the man! what's he doing? Ahoy, Tristram, ahoy there!"

In answer to the shouted welcome, the little procession which had aroused Mrs. Compton's ire turned in at the compound gates. The Dakktar Sahib came first. He wore a duck suit with leggings, and carried his pith helmet in both hands as though it were a bowl full of priceless liquid. In its place, a loud bandanna handkerchief offered a slight protection to his head and neck. Behind him, at her untrammelled leisure; came Arabella, her reins trailing, her nose almost on the ground, her legs obviously wavering under the burden of her protruding ribs. Behind her again, in a cloud of sulky dust, waddled Wickie, forlorn and spiritless. The three halted at the steps of the verandah, and the Dakktar Sahib sat down on the first step without ceremony.

"I'm done," he said.

Mrs. Compton almost snorted at him.

"I should think so! What on earth were you walking for, you impossible person? What is the use of having a horse—if you call that object a horse—if you don't ride?"

"Arabella's dead beat," he explained simply. He put his pith helmet between his knees and stared down into its depths as though something hidden there interested him. "I know she's no beauty," he went on earnestly. "But she's an awful brick. Never done me or any one a bad turn in her lire. Can't say that of myself. And just because I paid fourteen quid for her, I don't see why I should put upon her. I suppose we three couldn't have a drink, could we?"

Compton shook his head. He came and sat down on the step beside the big, travel-stained figure and looked cooler and more immaculate by contrast.

"Afraid not. If you weren't so delightfully absent-minded, Hermit, you would know perfectly well that we're not at home. Don't you recognize the old dâk-bungalow when you see it?"

Tristram turned and looked about him rather blankly. At that moment Mrs. Compton, who was feeling unjustifiably irritable, thought he was quite the ugliest man she had ever set eyes on.

"No—to tell you the truth, I was too dead to notice. I just tottered in. What's happened? The old place looks as though it had had its face washed. Who are you expecting?"

"Ever heard of Sigrid Fersen?"

Tristram returned rather suddenly to the contemplation of the mysterious contents of his helmet.

"Yes—on my last leave home. I saw her dance the night before I sailed."

"Well, she's coming here—world tour or something. The Rajah invited her to Gaya, and Armstrong gave us a hint to do the hospitable. Mary is all on the qui vive, hoping she'll do the high kick at a Vice-Regal function or something."

Tristram made no answer, and his silence was at once irritating and final. He seemed scarcely to have heard. Mrs. Compton, watching his profile with dark, exasperated eyes, suddenly softened.

"You do look fagged!" she exclaimed impulsively. "Has it been a bad time, Hermit?"

He looked up at her.

"Pretty bad. I haven't seen a white face for two months or slept in the same quarters for two nights running. There's any amount of trouble brewing out there in the villages. It's the drought—and the poor beggars can't get the hang of our notions. Anything might develop. I'm going back to Heerut tonight. I came along only to get fresh medical supplies. I left Ayeshi at the last village. He's a gem."

Meredith, who had been standing by the verandah railings, drew himself up, his swarthy face was brightened by his eyes, which were alight with a grave, sincere fervour.

"Yes, Ayeshi's unusual," he said. "He's different from the rest. I've often noticed him. I wish we could get hold of him, Tristram."

"Get hold of him?"

"Give him a chance. You know what I mean. It's that type of man we want. He ought to be encouraged to go ahead."

"Ayeshi's all right," Tristram remarked slowly. "He's happy. And he's a sort of poet, you know. I'd leave him alone, if I were you."

Meredith laughed good-temperedly.

"It's not my business to leave people alone," he said.

There was a silence which unaccountably threatened to become strained. Mrs. Compton, wearied by her struggles with refractory curtains, drew a chair up to the steps of the verandah and sat down, ruffling her husband's sleek hair with an absent-minded affection. He bore the affliction patiently, his lazy blue eyes intent on the approach of a neat, slow-going dog-cart which had turned the bend of the high-road.

"It's the Boucicaults' turn-out," he said. "And little Anne driving herself, too, by Jove! I wonder what she wants round here?"

"Whatever it is, she must want it pretty badly," his wife remarked. "She hates driving—if the truth were told, I believe that pony terrifies her out of her life. Poor little soul!"

"No nerve," Compton agreed. "Broken long ago."

Meanwhile, with a lightness and agility that was unexpected in a man of his short, heavy build, Owen Meredith had swung himself over the verandah rails and walked down to meet the new-comer. The trio on the steps watched him in silence. Then Compton chuckled rather mirthlessly. "She'd make a first-rate parson's wife," he said. "If only——" then he broke off and became suddenly business-like and astonishingly keen. "Tristram—stop fidgeting with that damned helmet of yours. I know you're dog-tired, old chap, but I want you to go round to the Boucicaults before you return to the wilds."

Tristram looked up. The tiredness had gone out of his face.

"Anything wrong—I mean, worse than usual?"

Compton threw his half-finished cigarette at Wickie.

"You don't know what it's been like these last two months. The man's mad, Tristram, or he's possessed of the devil. The whole regiment is suffering from c.b. and extra drill and stopped leave—for nothing—nothing. I oughtn't to talk about it, I suppose, but something's got to be done. The men are getting nervy and out of hand, and no wonder. There are moments when I feel ready to lash out myself."

"Can't something be done? Can't you get rid of him?"

Compton laughed shortly.

"You know what happens to men who complain of their superior officers. Besides, he's so devilishly efficient, and everything he does is done in cold blood. It's drink, of course, but it doesn't make him lose his head. It makes him deadly, hideously quiet. And it's not only the regiment, Tristram—there's his wife. We hardly ever see her—and when we do—well, they say——"

Mrs. Compton clenched her small brown fist and thumped her husband's shoulder in a burst of indignation.

"They say he beats her," she said between clenched teeth.

Tristram got up as though he had been stung.

"That's—that's damnable!" he stuttered.

"That's just the word," Mrs. Compton acknowledged gratefully. She looked up at him and admitted to herself that, after all, he pleased her profoundly. At that moment he was not ugly in her eyes. In one way, she recognized him to be magnificent. She knew no other man with such shoulders or who carried his height and strength with so natural a grace. But now even his face pleased her, red-bearded and unlovely though it was. In her quick, Celtic way, she imagined a sculptor who, in an inspired mood, had modelled a masterpiece, incomplete, rough-hewn, yet vigorous with life and significance. She liked his blue eyes, which usually looked out on the world with a whimsical simplicity and now flared up, dangerously bright. "Positively," said Mrs. Compton, "there are moments when I love you, Hermit."

Archibald Compton grimaced and pulled himself to his feet.

"Anyhow, after that brazen-faced declaration you might help us," he said. "You're a doctor. It's your business to interfere. Couldn't you drop a hint at headquarters—suggest long leave or something? Do—there's a good fellow——"

Tristram had no opportunity to reply, for Anne Boucicault her companion were now within earshot. Meredith walked at the wheel of her cart and was talking gaily, his face lifted to hers, and, freed for the moment from its habitual expression of fervid purpose, was almost boyish. She smiled down at him, and then, glancing up at the group at the verandah, the smile faded and she jerked the reins of her pony so that the animal came to an abrupt stand-still.

"Major Tristram!" she exclaimed. "Why, I didn't know you were back—I thought——" She broke off, flushing to the brows. Her incoherency and that quick change of colour added to her rather touching sweetness. She was not pretty. Neither the dainty white frock nor the shady hat could help her to more than youth. But her youth was vivid and gracious. There was something, too, in her expression, in the look of the brown eyes, that had all the appeal, the wistfulness of an anxious, frightened child. There was nothing mature about her save her mouth, which was firm, even obstinate.

Major Tristram came to her and gave her his big hand.

"I'm back for only a few hours," he explained, "and then my victims have me again. But it's good to catch a glimpse of anything so fresh as yourself. Isn't the sun ever going to wither you like other mortals?"

The smile dawned shyly about the corners of her lips.

"I don't know. I keep out of it as much as possible. I don't like it. I only came out this afternoon because——" She hesitated and then added rather breathlessly: "I knew Mrs. Compton was here—and I'm anxious about mother."

Mary Compton laid an impulsive brown hand on the white one which held the reins in its frail, ineffectual fingers.

"Well, here we all are, anyhow," she said, "and just dying to be useful. What's the trouble, dear?"

"Mother is ill," Anne Boucicault answered, with the same curious hesitancy. "I was frightened. Major Tristram, if only you could come——"

He did not wait for her to finish her appeal. He scrambled up on to the seat beside her, and took the reins from her hands.

"You look after Arabella and Wickie, Compton," he said, "and hand me up my helmet. No—not like that—for goodness' sake, be careful, man! Thanks, that's better."

"And I hope you're going to wear it," Mrs. Compton remarked, with asperity. "I suppose you don't want to arrive with a sunstroke or give Mrs. Boucicault a fit with that awful handkerchief?"

Tristram shook his head.

"Sorry, can't be done. It's occupied already. A patient of mine." He put his battered headgear between his knees and poked gingerly about the depths, producing, finally, amidst a confusion of straw and grass, a tiny bulbul. The little creature fluttered desperately, and then, as though there were something miraculous in the man's hand, lay still, a soft, bright-eyed ball of colour, and stared around it with an audacious contentment.

"Its wing's hurt," Tristram explained. "Wickie bit it. In point of fact, Wickie and I aren't on speaking terms as a result. It's a subject we shall never agree upon." He soothed the little creature's ruffled plumage with a tender forefinger, and held it out for Anne Boucicault's inspection. She peered at it curiously and rather coldly.

"It's very sweet," she said, "but wouldn't it be kinder to put it out of its misery?"

"Rather not. Besides"—his eyes twinkled in Meredith's direction—"it's not my business to put people out of their misery. And I'd rather keep this little chap alive than some men I know of. He's one of creation's top-notes. He's a poem all to himself. He wants to live and he's a right to live, and he's going to. His wing'll mend. I've mended dozens. It's an instinct—mending. I've got a baby cheetah with a broken paw at my diggins——"

Compton laughed hilariously at his wife's grim disapproval.

"I don't believe you could drown a kitten," she said.

"Why on earth should I want to drown a kitten?" He put his protégé tenderly back in its impromptu nest. "I brought two tabbies from England, and there are a lot more now. The whole village looks after them. They believe they're a specially imported sort of devil, and take every opportunity to propitiate them with edible offerings. It's great!"

Mrs. Compton looked helpless.

"You beware of that man, Anne," she said. "He's probably got a dyspeptic rattlesnake in one of his pockets. As to you, Tristram Tristram, I warn you that sooner or later you will get into serious trouble. You're a sentimentalist. There—go along. And, meanwhile, I'll let Arabella eat the grass tidy, and that so-called dog shall have a bone. Good luck to you!"

"I'm awfully obliged," he said solemnly. "Not a chicken bone, please. They stick in his throat."

"If I followed my conscience, I should give him poison," Mrs. Compton retorted, with her brows knitted over laughing eyes.

She had, however, no opportunity to carry out her threat. As the dog-cart turned out of the compound gates the disgruntled Wickie, who had been lying afar off, panting and disgraced, picked himself up, and, uttering a hoarse wail of indignation and despair, took to his bandy legs and rolled after the disappearing vehicle in a miniature storm of dust.

CHAPTER III

TRISTRAM BECOMES FATHER-CONFESSOR

So long as the gleaming, unsheltered roadway lasted, Tristram remained silent. His eyes were swollen with fatigue, and the sun blinded him. Through a silver shimmer of heat, he could see the undulating plain, yellow with the harvest, and his knowledge saw beyond that to the river and the rising jungle land, and the scattered hapless villages where his enemy awaited him. Cool and beautiful, Gaya lay above them, circling the hillside, the white walls of the bungalows sparkling amidst the dark green of the trees like the gems of a diadem. Tristram and his companion watched it thirstily. As they trotted at last into an avenue of flowering Mohwa trees, he drew rein and glanced down at the girl beside him. She was sitting very straight as though in defiance of the heat, her hands folded in front of her, her lips sternly composed. The youthful tears were not far off, yet, through a transient break in the future, he saw her as she would be years hence. And somehow the vision amused and touched him. It was as though the phenomenon reversed itself, and a stern-featured, middle-aged woman had grown young before his eyes.

"You mustn't worry," he said gently. "I don't suppose it's anything serious. Tell me about it. I don't want to worry her with questions."

"It won't worry her." He saw how her hands trembled as she clasped them and unclasped them. "She wants to talk—it's terrible—that's why I was so anxious—I had to find some one who would listen—and—and soothe her. I really came for Mr. Meredith. She doesn't like him, I'm afraid, poor mother, but that's because she doesn't understand. He's so awfully good."

"He's a fine fellow," Tristram agreed.

"And I thought he might help her," she went on, earnestly,—"might give her strength. Trouble overwhelms her. She resents it. And she has nothing to fall back on—nothing to console her."

Tristram did not answer immediately. They were going uphill, and he gave the pony his head, letting him manage the ascent after his own fashion.

"It takes a lot to console a man when his machinery's out of order," he said at last. "And one somehow does resent it. And then, I must say, if I had the toothache, I shouldn't want Mr. Meredith."

She gave a little nervous, unamused laugh.

"You know quite well what I mean, Major Tristram."

"Yes, I do. And I'm wondering if, after all, Meredith isn't the man you want. He and I both concentrate on humanity, but we do it from different points of view. I'm the man who looks after the house and sees that it's hygienic and watertight and all that. Meredith puts in the furniture and the electric fittings and keeps them polished."

He glanced whimsically at her puzzled face. "I mean just that the soul isn't my business," he added.

She raised eager, trusting eyes to his.

"I think it is, Major Tristram, I'm sure it is."

"Well, to tell you the truth, I think so too. I believe that the soul is the body and the body is the soul, and that one can't be healthy or unhealthy without affecting the other. But that's heresy, isn't it?"

A waxen, beautiful blossom from an overhanging mango-tree fell into her lap. Mechanically she picked it up and tore it with her restless fingers.

"It's not what we are taught to believe," she answered.

"No. You see, I'm a Pagan, Miss Boucicault. It's hereditary. My old mother—she's nearly eighty—she still totters up on to the mountain tops to say her prayers. As for me—" he gave a contented chuckle—"you hear that little chap chirping inside my helmet? Well, he's my consolation for every ache and sorrow I ever had—he and his like, and the trees and the stars and the flowers—even that mango blossom you're tearing up. To me they're just so many parts of God."

"Oh!——" She looked at the tattered flower in her lap and brushed it aside as though it suddenly frightened her. "I don't think that can be right. I'm sure you're not a Pagan, anyhow, Major. You couldn't be—and do the things you do."

They came out of the belt of shadow into the broad sunlight, and the blinding change covered his silence. A company of native infantry came up from a cross-road and swung past them amidst a cloud of slow-rising dust. The officers saluted Tristram. For an instant they seemed to throw off their weary dejection and to become almost gay. But the men did not lift their eyes. Their beards were white with dust and their faces set and sullen. They passed on, the beat of their feet sounding muffled and heavy on the palpitating quiet.

"They look pretty bad," Tristram commented.

"I'm frightened of them," she returned quickly. "Some of them mutinied last week, and father was nearly shot. I wake up every night and fancy I hear them firing on us."

"They belong to a regiment that stuck to us through thick and thin in 1857," he answered. "It's not like them to turn against us."

Her lips tightened.

"You can't trust any of them," she said.

By this time they had reached the first large bungalow of the European quarter. It was at once a sombre, pretentious building, evidently newly done up, and as they passed, a man on horseback turned out of the compound. Seeing Anne Boucicault, he saluted at once with a faintly exaggerated courtesy. The exaggeration matched the ultra-smartness of his English riding-clothes and the un-English flashiness of his good looks. Anne Boucicault returned the salutation stiffly, not meeting his direct glance, which passed on with an unveiled curiosity to Tristram. The latter urged the pony to a smarter trot as though something had irritated him.

"That's a stranger, anyhow," he said. "Two months brings changes even to Gaya. I thought that place was deserted and haunted for all time."

"Mr. Barclay has it now," she answered. "He came six weeks ago. I believe he trades with the native weavers or something. He's very rich."

"He doesn't look like an Englishman."

"He's not—not really. An Eurasian. His mother was a native, and his father——" She broke off. "He makes it a sort of half mystery. He just hints at things—I don't believe he knows himself. Anyhow, we hate him and try to avoid him. It's awfully awkward."

"I seemed to know his face," Tristram said, half to himself. He heard her sigh, and the sigh roused him from his tired search after an elusive memory. "He doesn't bother you, does he?" he asked.

She shook her head, but he saw her lips tremble with a new agitation.

"Not exactly—only it's all going to be so different. We were like a big family, weren't we, Major Tristram—all friends, all of the same set, and now this man has come, and then—you've heard, haven't you—about this woman, this dancer——"

"Mlle. Fersen, you mean?"

"That's what she calls herself." There was a chilly displeasure in her tone, which made her seem suddenly much older. "What does she want here? Why does she come? She can't have anything in common with us. She may even be a foreigner—vulgar and horrid——"

"I don't think she's like that," he interposed.

She flashed round on him.

"You know her, then?"

"I've seen her—just once," he answered, slowly.

"Is she——" She seemed to struggle with the question. "Is she very beautiful, Major Tristram?"

"No—I think not—not at all."

"That's worse then." And then quickly, passionately: "Oh, I wish she wasn't coming! I don't know why the very thought of her frightens me. It's as though I knew she was going to bring trouble—a sort of presentiment——"

"You're tired and anxious," he interrupted, and smiled down at her. "Nothing will happen—or perhaps I'm sanguine because I shan't be there to witness the upheaval."

"You're going into camp again?"

"Tonight."

"For long?"

"Until I've got things straight."

He happened to see her hands, and how they were tightly interlocked as though she were holding herself back. But her voice was quiet enough.

"Will you go on like that always, Major Tristram?"

"Until they push me on to the rubbish heap," he answered lightly.

"It must be very, very lonely."

He plunged his hand into his side-pocket and drew out a big bundle of letters. His blue eyes twinkled.

"You'd better not waste sympathy on me, Miss Boucicault. Look at these. I picked them up at the station—two by every mail. What do you think of that? And all from one woman!"

"A woman?" she echoed, stupidly.

"My old mother." He laughed with a boyish satisfaction. "We're the greatest pals on earth, she and I. A man couldn't be lonely with her in the background. We've got each other to live for."

"But she's in England. How she must miss you!"

He put the letters slowly back in his pocket.

"Yes. It's like a chronic pain. It hurts, but it weaves itself into the pattern of one's life. My mother's like that. My father was out here too, and they were often separated. She accepts it as inevitable."

"But you—your loneliness must be worse, out there in the wilderness."

"It's not a wilderness, it's peopled with all kinds of things—all kinds of"—— He caught himself up. "And I have friends in all the villages, and my animals and my work."

"I know your work is wonderful—the noblest work in the world." She spoke with a grave, youthful wisdom. "But the loneliness must remain all the same, Major Tristram."

He was silent for a moment, and then shook himself as though freeing himself from a burden.

"It can't be helped," he said. "No one can share it with me."

"Many people would be proud and glad to share it," she answered. She held her head high, and there was a fervent simplicity in her low voice which raised the impulsive words above suspicion. He turned to her with warm eyes.

"Thank you," he said. "I don't think it's true, and I shan't ever put it to the test—but it's good hearing."

He turned the pony neatly into the gates of the Boucicaults' bungalow and drove up the shady avenue to the porch. A syce ran out to meet them and caught the reins, and a minute later Anne Boucicault had been lifted gently to the ground. "And we've chattered so much," Tristram remarked shamefacedly, "that I don't even know your mother's symptoms."

She made no answer, indeed did not seem to have heard him. She had lost all her vigour, all her faintly self-opinionated eagerness. As they stood together in the entrance hall she seemed just cowed and broken, a white, frightened little ghost.

"My mother's in here," she said, scarcely above a whisper. She held the door open for him, and he went past her into a room so carefully darkened that for a moment he hesitated blindly on the threshold. Then a sound guided him. It was the sound of some one crying. Not passionately, not desperately, but with a terrible monotony. Then one salient feature detached itself from the shadows—a wicker chair drawn up by the curtained window, and beside it, huddled together, with her face buried in her arms, the figure of a woman. She wore some loose, dark-coloured garment, and was so small and still that she would have seemed scarcely living, but for the jerking sobs. Tristram checked the girl's anxious movement and went forward alone. He knelt down by the piteous heap and put his hand on her arm, and remained thus for a full minute. He did not speak to her, and she seemed unconscious of his presence. The sobbing went on unbrokenly. Then he picked her up quietly and effortlessly, and placed her in the chair, dexterously slipping a silk cushion behind her head.

"Mrs. Boucicault!" She did not answer. Her eyes were closed. Her small, white face under the mop of fair hair, fast turning grey, was puckered like a child's. Her little hands gripped the arms of her chair. From her place near the door, Anne watched with a frightened wonder. "Mrs. Boucicault!" Tristram repeated quietly. Her eyes opened then. They were tearless and very bright. She stared straight ahead, her under-lip between her white teeth, and began to rock herself backwards and forwards. She was still sobbing. Tristram knelt again and took one of her hands and held it between his own. She looked down then—first at her hand, as though it puzzled her, and then at him. Suddenly, violently, she freed herself and tore open the heavily embroidered kimono. Her shoulders were bare. On the right shoulder was a black swollen stain bigger than a man's hand.

"Look!" she said.

Anne Boucicault caught her breath with a vague, vicarious shame. She saw that Tristram had moved very slightly. His square jaws looked ugly against the dim light of the window.

"Get hot water and bandages," he commanded. "Linen will do—and ointment—anything greasy." As she slipped from the room he drew the kimono gently over the poor lacerated shoulder. "You've had a nasty accident, Mrs. Boucicault," he said, levelly.

"It was no accident." Her sobs had stopped. Her voice sounded like the rasp of steel against steel. "He did it—my husband. It's not the first time, Major Tristram. It won't be the last. He'll kill me—and he'll kill her." She nodded towards the door. The words poured from her as though released from a long restraint, but she was coldly, violently coherent. "Yes—he'll kill her—slowly, by inches. He'll break her. She'll go under fast. She's not like me—I'm wiry—she's hard, but she'll snap. For all her prayers and her church and her God, she'll go under." Something contemptuous and angry crept into her face. "Anne's cowed already. And it's not only us. His men—they tried to shoot him. Did you hear?"

He nodded.

"Yes."

Her eyes blazed.

"Oh, I wish to God they'd done it!" she burst out, from between clenched teeth. "Oh, why didn't they? He's goaded them enough. One of these days they'll murder us all for his sake. He's a devil. He's made life a hell. He likes to make suffering. He likes to see us wince. Oh, if he were only dead!" Suddenly the tense mask of hatred broke up into piteous lines of helpless misery. Two great tears rolled unheeded down her white cheeks. "Anne talked about bearing our cross, and prayer, and God's will," she went on chokingly. "But I want to be happy, Major Tristram, I want to be happy."

"You have an absolute right to happiness," he answered. "You've got to be happy, Mrs. Boucicault. I'm going to see to it."

She dropped back wearily among her cushions. Her grey eyes, now pale and faded-looking, rested on his face with a childish questioning.

"You talk as though—as though you could."

"Well, I can do something—I promise you. Close your eyes."

She closed them at once, and he took his handkerchief and brushed the tears from her cheeks. Then he resumed his kneeling position, her hand in his, soothing it much as he had soothed the frightened, broken-winged bird. Once she sighed deeply, as if released from some stifling weight, and thereafter her breathing sounded quiet and regular. By the time Anne Boucicault returned, her mother had dropped into a heavy sleep.

Major Tristram got up noiselessly, and motioned the girl to follow him. His movements were curiously light and noiseless, and brought no shadow of change on the sleeper's face.

"It's better that she should sleep," he said quietly. "I shall come in again tonight before I leave. I doubt if she wakes before then."

They went out together. On the mat the ubiquitous Wickie lay extended in a state of dusty misery. He rolled over as Tristram appeared, displaying much humility and a blood-stained paw. Tristram picked him up and hugged him. "You're not a dog—you're an ass, Wickie," he declared. "And I'll wager you consider yourself a martyr into the bargain, you assassin of innocent bulbuls. What do you suppose I'm going to do with you—carry you, I suppose?" He turned a wry, laughing face to his companion.

"Well, I'll be off now, anyhow," he said. "You'll see me tonight. Good-bye till then—and don't worry her or yourself."

She took his extended hand.

"Thank you. I thought it would be so terrible—for any one to know how things are with us. I haven't minded you a bit."

"I'm awfully glad."

He took up his impromptu bird's-nest from its place of safety in an empty fern-pot. The contents chirped defiance and terror, and Tristram looked up smiling. He saw then that Anne Boucicault's eyes were fixed on something beyond him, and that they were wide and stupid-looking with dread. He turned. A man stood in the sunlit verandah. Against the golden background he bulked huge and threatening, his features and whatever expression they bore blotted out by shadow. The switch which he carried beat an irritable tattoo against his riding-boots.

Tristram nodded a greeting.

"Good evening, Colonel."

"Good evening, Major." He bowed satirically and crossed the threshold. "This is a pleasant surprise. I understood you were out camping."

"I have been for the last two months. I am off again tonight."

"Then my daughter and I are indeed fortunate to catch this glimpse of you." He came farther into the shade, half turning to fling his helmet and whip on to a table. The light fell on his profile, revealing the livid skin, the brutal line of the jaw. "To what are we indebted, Major?"

"I came professionally," Tristram answered.

"On Anne's behalf, I suppose?"

"No, for Mrs. Boucicault." He scrutinized the elder man deliberately. "Perhaps I could do something for you, Colonel. You're not looking well. You ought to take a year's leave."

Colonel Boucicault allowed a moment to elapse before he answered. He had the tensely vicious look of a hard drinker who is never drunk, and whose jangling nerves are always writhing under restraint. Finally, he seemed to take a stronger hold over himself. He laughed out, shortly.

"Thanks, I'm very well. I'll last the regiment another year or two—to its infinite satisfaction, no doubt. As to Mrs. Boucicault, your visit was kind but unnecessary. There's nothing wrong in that quarter but feminine hysteria."

"I don't think so," Tristram returned. He had coloured slowly to the roots of his ruddy hair, but his voice was even quieter. "I take a serious view of the case. I have ordered Mrs. Boucicault an immediate return to England."

There was another break. The two men eyed each other squarely.

"That is an absurd proposition which I cannot sanction," Boucicault said in the same tone of violent self-restraint.

"I'm afraid you'll have to, Colonel."

The antagonism, whose note had sounded even in their greeting of each other, now rang out clearly. Boucicault's big hands twitched at his sides.

"Surely, Major, that is scarcely fitting language——" he began.

"I don't care a damn for what's fitting," Tristram broke in. "Mrs. Boucicault's going to England with Anne. If she doesn't, I'll have you hounded out of the army even if I get hounded out myself in the doing of it. That's my bargain."

"By God, Major——" Boucicault took a step nearer.

By reason of his heavy build, he seemed to tower over the younger man. His eyes were bloodshot in their inflamed rims; his whole body quivered. "You'd better get out of here," he stammered thickly. "And take my advice—keep clear of this place—keep out of my way."

"Thanks." Tristram tucked Wickie more securely under one arm. "I'll be round this evening," he added.

He ignored the threatening gesture, and went leisurely down the steps and along the drive. At the gates he stopped, drawing his breath with a quick, deep relief.

Across the roadway, the stems of the trees stood out black and straight as the pillars of a great temple, whose red-gold lamp had been lowered from the dome and now sank swiftly into an extinguishing pool of shadow. A breeze rustled coolly overhead, brushing away the sweet, heavy incense of many flowers and bringing the first warning of nightfall. A belated finch fluttered amidst the dense foliage, and then all was still again.

Tristram remained motionless, apparently plunged in his own thoughts, for he started when a hand touched his arm and turned almost angrily. Anne Boucicault stood beside him. She was breathless, her lips were parted, and the wind had blown the dark, curly hair from her white forehead, adding impulse and eagerness to her staid girlishness.

"I had to come," she panted, "to—to thank you. And then—you mustn't keep your promise. You mustn't come—it isn't safe——"

He shook his head. His eyes, after the first glance, had gone back to the fading light.

"I shouldn't hurt your father," he said, gravely.

"But you——!" she exclaimed. "No one knows what he might do to you."

"I don't think that matters," he returned, still in the same rather absent tone. "Anyway, if he's mad, he's not a fool. You mustn't worry."

She lingered. Her hand rested tremblingly on his arm.

"And I want to thank you, Major Tristram. You've helped poor mother—and I was so proud. No one's ever faced him like that. I wish——" She faltered. "If we could only do something for you——"

He was silent for a moment, then, as though her words only reached him gradually, he turned with a quick smile.

"You can. Take Wickie in as a boarder, will you? He's lame, and my hands are full already. I couldn't take him with me. Ayeshi could fetch him in a week or two. Would you mind?"

"I'd love to have him." She took the unwieldy, protesting mongrel, and held him rather clumsily in her arms. "And your little bird?" she asked.

"No, he'll want special medical treatment. Thanks awfully, all the same." He bent and patted Wickie's black snout with an apologetic gentleness. "Don't fret your heart out, old chap. It's your own fault—and Ayeshi shall come for you, upon my honour he shall."

"I'll take care of him," Anne said.

"I know you will."

"Good-bye, Major Tristram." The sunlight was in her eyes, and they were very bright. The colour in her cheeks deepened. "And God bless you," she added, timidly but very seriously.

He smiled down at her.

"And you and Wickie and everybody," he said. "I'm sure He does."

He strode off, and at the bend of the road turned and waved.

But long after he had disappeared, she stood there gazing into the dusk, the unhappy Wickie pressed tightly against her breast.

CHAPTER IV

THE INTERLOPERS

Rajah Rasaldû was wonderfully, if not impressively, European. He wore a frock-coat and grey trousers, English in intention, French in execution. They were almost too perfect. The native, brightly hued turban, an unwilling concession, as he admitted, to local prejudice, came as a rather startling finale, though it suited him better than his Europeanism. He was a short, unmuscular little man, built in circles rather than in straight lines, and a determined course of Parisian good-living had added seriously to a natural tendency to embonpoint. His manner, even in sitting still, was restless and fussy. He had, in fact, neither the inscrutable dignity of the native nor the self-assured ease of the race he aped.

"When I look at you, Mademoiselle," he was saying, earnestly, "I forget that I am in this dreadful country, and I imagine myself back to London. I see myself in the darkened box, and you in all the brightness. I hear the music and the roar of applause. I feel at home—almost happy." He stared down at his round, soft hands as though he were rather pleased with their severe lack of adornment, and sighed. The woman he addressed did not look at him. She was watching the little groups of white-clad figures dotted about the garden, with her head turned slightly away from him. Next her, Mary Compton and the Judge's wife were talking with the lazy earnestness engendered by tea and the cool shade of a flowering mango.

"But this is your country," Sigrid Fersen said. "You are surely happiest here."

He shrugged his shoulders.

"I was born here. The Government has put me in a position of trust, and it is my duty to be at my post from time to time. But my heart is with you—with the West and Western civilization. And of all that, Mademoiselle, you are the personification."

She laughed a little, as though secretly amused.

"Tell me your impressions of Paris, Rajah," she said.

He told her. From time to time his brown, dissipated eyes shot irritable glances at the figure seated immediately behind his hostess. It was perhaps a somewhat startling figure, and though Gaya approved of companions and chaperons, and had indeed heaved a sigh of relief over Mrs. Smithers's existence, it had none the less been considerably startled by her personality. She was well past middle age, and, in spite of the considerable heat, was dressed severely in black grenadine, and wore a mob-cap on a remarkably fine head of white hair, which she occasionally patted with a nervous hand. If it is true all human beings bear a resemblance to some animal, then Mrs. Smithers might easily have been associated with a bull-dog of exceedingly determined character. Her face was settled in wrinkles of challenging tenacity, but she never moved and never changed her expression. She sat there, bolt upright, and only her roving eyes betrayed the fact that she was alive. They expressed also the bitterest and most annihilating disapproval of everything existent.

Mrs. Compton accepted her third cup of tea from an engagingly youthful subaltern and went on talking.

"Of course he's mad," she was saying. "He hates Tristram worse than any one living, which is saying a lot. They had an awful row over Mrs. Boucicault just before Tristram went away, and now Boucicault is taking his turn. He refuses to forward Tristram's appeal for help—says the whole thing's a scare, and that Tristram is simply fussing for his own glorification. But it isn't true. Ayeshi came to my husband last night and told him. It's cholera—oh, my dear Susan, don't jump like that! Heerut's fifteen miles away, and we've the river between us, and Gaya's healthy when everything else is riddled. Besides, Tristram has got the thing in hand. He hasn't slept for four days. Ayeshi said he didn't look human. Some of the natives went crazy with fright and got out of hand. But Tristram managed them—single-handed, my dear, and with not so much as a revolver. Ayeshi talked about him as though he were the tenth Avatar, or whatever they call it. Of course, he'll do that sort of thing once too often. C'est magnifique, mais ce n'est pas la guerre. But I love that man. I tell Archie once a day at least, and he's getting quite tired about it——"

"Of whom are you talking, Mrs. Compton?"

Mrs. Compton started, and the Rajah, who had been expatiating on French genius as revealed in the Bal du Moulin Rouge, went on for a minute, carried forward by his own momentum. Then he stopped and dropped into a silence, which would have been sulky in any one less anxious to appear civilized. As for Mrs. Compton, the question had come with such self-assured, if quiet authority, that she felt certain that, as a woman on her own ground, she ought to take offence. In fact, all Gaya, as represented in the old dâk-bungalow's garden, was in much the same position. Without performing the high kick at the club dinner or otherwise living up to the conventional reputation of her class, the newcomer had sailed serenely across all their unwritten laws, and not only had Gaya not been outraged, but it had been secretly delighted. And it was ashamed of itself for being delighted. Mrs. Compton was ashamed of herself—ashamed that she, the untamable spirit of the station who had insulted Colonel Boucicault to his face should sit there and meet this woman with a smile of propitiating amiability.

"Major Tristram," she said. "He belongs to the Medical Service. You haven't met him yet, and I don't suppose any of us will see him for some time. He's fighting the cholera in one of the native villages."

Sigrid Fersen nodded thoughtfully. Then she got up.

"I heard you say just now that you were interested in old china," she said, abruptly. "I have a piece in the drawing-room which I should like you to see. Will you come?"

"I should be delighted——"

"Your guests, Mademoiselle," Rasaldû murmured. But his protest passed unheeded, and Mrs. Compton got up and left the Judge's wife without a word of apology. Mrs. Smithers had risen with equal promptitude and brought up the rear.

They crossed the garden to the bungalow, and the little parties grouped lazily in the vicinity of the tea-tables became silent, and remained silent until Sigrid Fersen had disappeared. Then they went on talking. Very few of them realized that they had ever stopped, much less that they had been staring with the naïve directness of children. They certainly made no comment. Only Jim Radcliffe, the newly joined subaltern, who had the inexhaustible restlessness of a fox-terrier puppy, became quiet to the point of thoughtfulness.

"By Jove, did you see her walk?" he said to Mrs. Brabazone. But the latter made no reply, being in a state of dudgeon and not inclined to appreciation.

Meantime, Mary Compton had become aware of a profound and very mysterious change in her own psychology. As she crossed the threshold of the darkened drawing-room she perceived that every earnest, painstaking effort of hers to make the place habitable and presentable had suffered a ruthless upheaval. The hours of patient questioning which she had spent on the to-be or not-to-be of the curtain bows had been so many hours wasted. Yet her fiery Celtic susceptibilities remained unruffled. She admitted at once that the changes were improvements,—small but effective strokes of genius. Moreover, various new items had been introduced—a piano procured from heaven alone knew where, a few rich embroideries, a vase or two, and a pale-tinted Persian rug. She was busy cataloguing these items, when her quick eyes encountered Mrs. Smithers. Mrs. Smithers had seated herself promptly on the chair nearest the door, and assumed her former attitude of unbending severity and disapproval. Her appearance somehow made a further reduction in Mrs. Compton's forces of self-assurance, and when her hostess, who had been busy with the contents of a carved chest, came back to her, she was overpowered by an unusual sense of almost fatuous helplessness. Whatever this small woman meant to do, she would do. And therewith the fate of Gaya seemed sealed.

"There—you recognize it, of course."

Mrs. Compton forgot Gaya and her own lost prestige. In the ten years of her married life, there was one passion for which she and the easy-going, hard-working Archie had scraped and saved. It was a passion which was one day to find a fitting background in some English home, a place created almost daily afresh in their minds but always with the abiding features of spacious lawns and an orchard and stables, and within doors oak cupboards guarding the treasures of the hard years. But with all their savings and searchings, they had never possessed anything like this.

"It's Sèvres—of course—how beautiful! I'm almost afraid to touch it."

"Don't be. It's yours."

"Mine!" Mary Compton gasped—whether audibly or not, she did not know. She felt that there was fresh cause for offence coming and that she had no adequate forces with which to meet it. "But, of course not——"

"I bought it for you."

Mrs. Compton nearly regained her usual briskness.

"That's nonsense. We haven't known each other a week. And you must have bought that in Europe."

"Yes—I did, years ago. But I bought it for you, all the same. I bought it for some one who would look at it and touch it as you did. And besides, I want you to have something of mine—I am selfish enough to wish to be remembered by those who have been kind to me—as you have been. It was the Rajah's invitation which brought me to Gaya, but only a woman could have welcomed me. Any one in my position makes enemies automatically, and without you I should have had to face a whole army of prejudices. But you paved the way—you made it possible to invite all these people without offending them—and this in spite of the fact that you thought you were probably introducing a firebrand." She laughed in her curious, reflective way. "And then it was your hands prepared this beautiful home for me," she added.

Mrs. Compton crimsoned and swallowed the delicate morsel of brazen flattery with a ridiculous pleasure. She made a last effort, however, to retire to her first position of friendly reserve.

"Of course, we did what we could," she said. "Gaya is rather proud of its hospitality. We wanted you to take back a good impression, Mademoiselle——"

A quick gesture interrupted her.

"I'm not 'mademoiselle.' I'm English. My mother was a Swede, and I took her maiden name because—there never has been a great English dancer, and in England what hasn't been can't be. It's just one of the Rajah's foibles to give everything a Gallic touch. But I'm just Miss Fersen—or Sigrid if you like."

The Celtic temperament works both ways. The only certain feature is its uncertainty. Mrs. Compton abandoned her offensive-defensive and with great dexterity managed to cling to the Sèvres vase and kiss the giver on both cheeks without disaster.

"I'd like it to be Sigrid," she said warmly. "And my name's Mary—and I'm going to take the Sèvres because I want it badly, and because I like you and I shan't mind feeling horribly grateful. And I hope you'll make me your master of ceremonies, and our bungalow your headquarters. You will, won't you?"

She thrilled under the touch of the cool, small hand on hers.

"Yes, I promise you. It's what I wanted. I shall need a friend. A great many people will hate me—men and women. I have seen it in the eyes of one woman already. And, besides that I want to get to know real human beings. All my life I have lived for and in the one thing. People have been shadows to me. Now I need them. But they must be real—good, honest flesh and blood. Not puppets." She sat down on the big divan drawn up against the wall and patted the seat beside her. "Tell me about this Major Tristram," she said.

And Mrs. Compton, whose rules of etiquette were Gaya's social law, sat down and for half an hour talked about Major Tristram, whilst Sigrid Fersen's guests wandered unshepherded about her garden.

At the end of the half-hour Mrs. Compton found her husband near the gates, disconsolate and alone, guarding the rather shabby little turn-out which they called a dog-cart. He was in uniform, and had evidently been at some pains to escape notice.

"You said six o'clock and it's half-past," he commented, gloomily. "I shall be confoundedly late. What on earth have you been doing? And what's that you've got under your arm?"

She chuckled to herself.

"Can't you recognize Sèvres when you see it?"

"By George—what a piece!" His eyes opened with a hungry appreciation. Then he shook his head at her. "My dear girl, put it back! I knew we should come to this sooner or later—all collectors do. Put it back before it's missed. Think of the scandal. And a newcomer, too!"

She broke into a half-pleased, half-ashamed laugh and wrapped the precious trophy in the protecting folds of a rug.

"She gave it me—yes, she did. And she calls me Mary, and I call her Sigrid, and we've kissed each other, and I've given her the run of our bungalow." She climbed up into the driver's seat and took the reins. "You know how I hate those sort of sudden familiarities, Archie. But I've no explanation. Have you?"

"Not one."

"She isn't beautiful. I'm better-looking myself."

"A dozen times, old girl."

She smiled down upon him with a rather absent-minded graciousness.

"I believe she's got electric wires instead of nerves and sinews," she said reflectively. "I felt them in her hand. It was like putting one's fingers into a steel glove covered with velvet. What bosh I'm talking. I believe I'm hypnotized. I shall go round and look up poor Anne and restore my self-respect. Mr. Meredith told me she looked as though she was breaking her heart over something. Of course, it's that brute! Why aren't you men plucky enough to shoot him——?"

"My dear girl——"

His wife cut short his protest by turning her pony out of the gates and up the broad avenue which led from the outlying dâk-bungalow to Gaya proper. The steep hill, her new possession, and various rather confused speculations accounted for the fact that her pony promptly dropped to a walk and was allowed to proceed in a leisurely fashion, which culminated in an abrupt halt. Mrs. Compton awoke then. She felt vaguely annoyed with herself, and her annoyance changed to something like consternation when she perceived that the stoppage was not attributable either to the pony's disinclination or her own day-dreaming. A man stood at the animal's head and now came up to the step, his long, brown hand lifted to his topee in greeting.

"I called to you, Mrs. Compton," he said, "but you didn't hear me, and I took the liberty of stopping you. I hope I'm forgiven."

She stared down at him. Her confusion of warm disjointed musings chilled instantly to her usual trenchant matter-of-factness.

"If you wanted to speak to me, Mr. Barclay——" she began.

"I know—I might have called formally. But I ran the risk either of being refused or landing into a crowd of people. I wanted to see you alone." He waited a moment. His hand rested firmly on the side of the cart, and she could not have driven on without going over him. She saw also the dogged set of his dark face and waited with an angry resignation. "You've just come from Mademoiselle Fersen's At Home, haven't you?" he asked.

"Yes."

"I used to know her," he said, "that is to say, I was introduced at some big reception in England. She wouldn't remember me. That was in my undergrad days. I was at Balliol, you know."

Mrs. Compton's fine lips twitched satirically. She was not feeling charitable, and this man was offering her his credentials in a way that incited derision. He must have seen her expression, for his brown eyes, with their blue-tinted whites, never left her face. "I want you to do me a favour," he burst out. "I want you to introduce me again, Mrs. Compton."

Her smile faded. She was thoroughly angry, but some other less definable emotion confused her indignation to the point of ineffectuality.

"I'm sorry, Mr. Barclay, but I really haven't the right or the power to introduce any one to Miss Fersen without her permission."

"I know that—at least, your friends and acquaintances would be introduced naturally——" He broke off. The nostrils of his fine, aquiline nose distended, his whole face, handsome in line and profoundly brooding in its fundamental expression, was tense and strained-looking. He seemed like a man doggedly setting himself to a hated task. "May I be straightforward with you, Mrs. Compton?"

"Of course. Why not?"

"I know you are anxious to drive on—over me even," he said, with a flash from a smothered bitterness. "But you are the only person I feel I can speak to, and I mayn't get you alone again. Look here, Mrs. Compton, I'm an Englishman. My father was English—I was educated at an English University—I hold an English degree. I've got any amount of money. It seems to me I've got the right to demand—well, decent civility. So far—I've been here two months—I've been out of things. Of course, I don't belong to the military lot, and I haven't a government appointment—but it seems to me-out here in an alien country—we English ought to hold together——" He was choking and breaking over his words like a man breathless with running, the fatal mincing accent betraying itself in his gathering excitement, and instinctively Mrs. Compton looked away from him. He was trembling, and somehow the sight filled her with an odd pity almost stronger than her repugnance.

"What do you want me to do, Mr. Barclay?" she asked.

"After all—it's not much. If your husband would put me up for the Polo Club—I'm a good player, and I've got some of the finest ponies in India. Gaya could beat any team you like with my ponies. Your husband's popular—he could easily do it—if he wanted to——"

"I couldn't ask him," she interrupted hurriedly. "It's not my business. I hate backstair influence with husbands." She took refuge in a cowardly compromise. "You ought to speak to Captain Compton yourself."

He laughed shortly.

"That means you won't," he broke out suddenly and violently. "It's the touch of the tar brush that's worrying you, isn't it? Yet you don't mind kowtowing to a full-blooded native. You'll have that dissipated degenerate Rasaldû at all your feasts, though he's not even accepted by his own people. His grandfather was a village cow-herd, and the Government set his people up in the place of the hereditary heirs because they were likely to be more tractable. You know all that, and yet you'd lick his boots, whilst I, with your own blood in my veins——" He caught himself up, smoothing his working features with a desperate effort. "Look here, Mrs. Compton, I want to do the right thing. I want to serve my country loyally. But I've got to have a country—I've got to belong somewhere. Otherwise——"

She tightened the reins, moving her pony's head round so that she could go forward without driving over him.

"I'm sorry," she said, coldly. "I have no prejudices myself, but I also have no right to interfere with the prejudices of other people. You must make your own way. Please let me pass——"