Title: Birds and Nature, Vol. 10 No. 3 [October 1901]

Author: Various

Editor: William Kerr Higley

Release date: September 15, 2015 [eBook #49982]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Stephen Hutcheson, Joseph Cooper

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

BIRDS AND NATURE. | ||

| ILLUSTRATED BY COLOR PHOTOGRAPHY. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vol. X. | OCTOBER, 1901. | No. 3 |

The month of carnival of all the year,

When Nature lets the wild earth go its way,

And spend whole seasons on a single day.

The spring-time holds her white and purple dear;

October, lavish, flaunts them far and near;

The summer charily her reds doth lay

Like jewels on her costliest array;

October, scornful, burns them on a bier.

The winter hoards his pearls of frost in sign

Of kingdom: whiter pearls than winter knew,

Or Empress wore, in Egypt’s ancient line,

October, feasting ’neath her dome of blue,

Drinks at a single draught, slow filtered through

Sunshiny air, as in a tingling wine!

—Helen Hunt Jackson.

October comes, a woodman old,

Fenced with tough leather from the cold;

Round swings his sturdy axe, and lo!

A fir-branch falls at every blow.

—Walter Thornbury.

The Yellow-bellied Flycatcher with the kingbird, the phoebe and the wood pewee belongs to a family of birds peculiar to America—the family Tyrannidæ or the family of tyrants. No better name could be applied to these birds when we take into consideration the enormous number of insects, of all descriptions, that they capture and devour and their method of doing it. They resemble the hawks in some respects. They are at home only where there are trees, on the outer branches of which they can perch and await a passing insect, and when one appears they “launch forth into the air; there is a sharp, suggestive click of the broad bill and, completing their aerial circle, they return to their perch and are again en garde.”

In the tropics, the land of luxuriant vegetable growth, where the number and kinds of insects seem almost innumerable, the larger number of the three hundred and fifty known species are found. In the United States we are favored with the visits, during the warmer months, of but thirty-five species of these interesting and useful birds.

As we would naturally expect of birds of prey, whether hunters of insects or of higher animal life, these birds are not usually social, even with their own kind. They are also practically songless, a characteristic which seems perfectly fitted to the habits of the Flycatchers. Some of the species have sweet-voiced calls. This is the case with the wood pewee, of which Trowbridge has so beautifully written in the following verse:

“Long-drawn and clear its closes were—

As if the hand of Music through

The sombre robe of Silence drew

A thread of golden gossamer;

So pure a flute the fairy blew.

Like beggared princes of the wood,

In silver rags the birches stood;

The hemlocks, lordly counselors,

Were dumb; the sturdy servitors,

In beechen jackets patched and gray,

Seemed waiting spellbound all the day

That low, entrancing note to hear—

‘Pe-wee! pe-wee! peer!’”

The Flycatchers are fitted both in the structure of their bills and in the colors of their plumage for the kind of life that they live. The bills are broad and flat, permitting an extensive gape. They live in trees and are usually plainly colored, either a grayish or greenish olive, being not so easily seen by the insects as if more brightly arrayed. This characteristic is known as deceptive coloration.

The Yellow-bellied Flycatcher has its summer home in eastern North America, breeding from Massachusetts northward to Labrador. In the United States it frequents only the forests of the northern portion and the mountain regions. In the winter it passes southward into Mexico and Central America. Like all the Flycatchers of North America, the very nature of its food necessitates extensive migrations.

Its generic name is very suggestive. It is Empidonax, from two Greek words, meaning mosquito and a prince—Mosquito Prince!

Major Bendire says: “In the Adirondack mountains, where I have met with it, it was observed only in primitive mixed and rather open woods, where the ground was thickly strewn with decaying, moss-covered logs and boles, and almost constantly shaded from the rays of the sun. The most gloomy looking places, fairly reeking with moisture, where nearly every inch of ground is covered with a luxuriant carpet of spagnum moss, into which one sinks several inches at every step, regions swarming with mosquitoes and black flies, are the localities that seem to constitute their favorite summer haunts.” Surely the name Empidonax is most appropriate.

YELLOW-BELLIED FLYCATCHER.

(Empidonax flaviventris).

About Life-size.

FROM COL. CHI. ACAD. SCIENCES.

The nest is usually constructed on upturned roots near the ground, or on the ground deeply imbedded in the long mosses. A nest belonging to the National Museum is thus described: “The primary foundation of the nest was a layer of brown rootlets; upon this rested the bulk of the structure, consisting of moss matted together with fine broken weed stalks and other fragmentary material. The inner nest could be removed entire from the outer wall, and was composed of a loosely woven but, from its thickness, somewhat dense fabric of fine materials, consisting mainly of the bleached stems of some slender sedge and the black and shining rootlets of ferns, closely resembling horsehair. Between the two sections of the structure and appearing only when they were separated, was a scant layer of the glossy orange pedicels of a moss not a fragment of which was elsewhere visible. The walls of the internal nest were about one-half an inch in thickness and had doubtless been accomplished with a view of protection from dampness.” The nests are sometimes made of dried grasses interwoven with various mosses and lined with moss and fine black wire-like roots. Again, the birds seem to have an eye for color and will face the outside of the nest with fresh and bright green moss. In every way the nest seems a large house for so small a bird.

To study this Flycatcher “one must seek the northern evergreen forests, where, far from human habitations, its mournful notes blend with the murmur of some icy brook tumbling over mossy stones or gushing beneath the still mossier decayed logs that threaten to bar the way. Where all is green and dark and cool, in some glen overarched by crowding spruces and firs, birches and maples, there it is we find him and in the beds of damp moss he skillfully conceals his nest.”

When dews begin to chill

The blossom throngs,

And soft the brooklets trill

Their slumber-songs,

We dusky Whippoorwills

In conquest hold the hills.

When, thro’ the midnight dells,

Wild star-beams glow,

Like wan-eyed sentinels,

We dreamward go,

And hear sung sweetly o’er

The songs we stilled before.

When waketh dawn, we flee

The slumber-main,

And bid the songsters be

With us again

To sing in praise of light

Above the buried night.

But O, when sunrise gleams,

We vanish fast,

And woo again in dreams

The starlit past,

Till, lo! at twilight gray,

We wail the dirge of day!

—Frank English.

“What wondrous power from heaven upon thee wrought?

What prisoned Ariel within thee broods?”

—Celia Thaxter.

“Thou singest as if the God of Wine

Had helped thee to a valentine;

A song in mockery and despite

Of shades and dews and silent night,

And steady bliss and all the loves

Now sleeping in these peaceful groves.”

—Wordsworth.

Like a bee with its honey, when the Ruby-crown has unloaded his vocal sweetness, there is comparatively little left of him, and, ebullient with an energy that would otherwise rend him, his incredible vocal achievement is the safety valve that has so far preserved his atoms in their Avian semblance.

Dr. Coues says that his lower larynx, the sound-producing organ, is not much bigger than a good-sized pin’s head, and the muscles that move it are almost microscopic shreds of flesh. “If the strength of the human voice were in the same proportion to the size of the larynx, we could converse with ease at a distance of a mile or more.”

“The Kinglet’s exquisite vocalization,” he continues, “defies description; we can only speak in general terms of the power, purity and volume of the notes, their faultless modulation and long continuance. Many doubtless, have listened to this music without suspecting that the author was the diminutive Ruby-crown, with whose commonplace utterance, the slender, wiry ‘tsip,’ they were already familiar. This delightful role, of musician, is chiefly executed during the mating season, and the brief period of exaltation which precedes it. It is consequently seldom heard in regions where the bird does not rear its young, except when the little performer breaks forth in song on nearing its summer resorts.”

When Rev. J. H. Langille heard his first Regulus calendula, he said, “The song came from out of a thick clump of thorns, and was so loud and spirited that I was led to expect a bird at least as large as a thrush. Chee-oo, chee-oo, chee-oo, choo, choo, tseet, tseet, te-tseet, te-tseet, te-tseet, etc., may represent this wonderful melody, the first notes being strongly palatal and somewhat aspirated, the latter slender and sibilant and more rapidly uttered; the first part being also so full and animated as to make one think of the water-thrush, or the winter wren; while the last part sounded like a succeedant song from a slender-voiced warbler. Could all this come from the throat of this tiny, four-inch Sylvia? I was obliged to believe my own eyes, for I saw the bird many times in the act of singing. The melody was such as to mark the day on which I heard it.”

H. D. Minot says, “In autumn and winter their only note is a feeble lisp. In spring, besides occasionally uttering an indescribable querulous sound, and a harsh, ‘grating’ note, which belongs exclusively to that season, the Ruby-crowned wrens sing extremely well and louder than such small birds seem capable of singing. Their song begins with 103 a few clear whistles, followed by a short, very sweet, and complicated warble, and ending with notes like the syllables tu-we-we, tu-we-we, tu-we-we. These latter are often repeated separately, as if the birds had no time for a prelude, or are sometimes prefaced by merely a few rather shrill notes with a rising inflection.”

Messrs. Baird, Brewer and Ridgway say that “The song of this bird is by far the most remarkable of its specific peculiarities,” and Mr. Chapman declares, “Taking the small size of the bird into consideration, the Ruby-crown’s song is one of the most marvellous vocal performances among birds; being not only surpassingly sweet, varied and sustained, but possessed of sufficient volume to be heard at a distance of two hundred yards. Fortunately he sings both on the spring and fall migrations.”

Mrs. Wright describes the call-note as “Thin and metallic, like a vibrating wire,” and quotes Mr. Nehrling, who speaks of the “Power, purity and volume of the notes, their faultless modulation and long continuance.”

Mr. Robert Ridgway wrote that this little king of song was one of our very smallest birds he also “ranks among the sweetest singers of the country. It is wonderfully powerful for one so small, but it is remarkable for its softness and sweet expression more than for other qualities. It consists of an inexpressibly delicate and musical warble, astonishingly protracted at times, and most beautifully varied by softly rising and falling cadences, and the most tender whistlings imaginable.”

Mr. Ridgway quotes from Dr. Brewer: “The notes are clear, resonant and high, and constitute a prolonged series, varying from the lowest tones to the highest, and terminating with the latter. It may be heard at quite a distance, and in some respects bears more resemblance to the song of the English skylark than to that of the canary, to which Mr. Audubon compares it.” Mr. Ridgway continues: “We have never heard the skylark sing, but there is certainly no resemblance between the notes of the Ruby-crowned Kinglet and those of the canary, the latter being as inferior in tenderness and softness as they excel in loudness.”

Mr. Audubon had stated: “When I tell you that its song is fully as sonorous as that of the canary-bird, and much richer, I do not come up to the truth, for it is not only as powerful and clear, but much more varied and pleasing to the ear.”

While the frequent sacrifice of the adult regulus and regina through their reckless absorption in their own affairs and obliviousness to the presence of enemies, lends color to the statement that “The spirits of the martyrs will be lodged in the crops of green birds,” yet by virtue of a talent other than vocal, they compel few of the human family to echo the remorseful lament of John Halifax, Gentleman,

“I took the wren’s nest,

Bird, forgive me!”

For but few of the most ardent seekers have succeeded in locating the habitation of the fairy kinglet, and the unsuccessful majority perforce exclaim with Wordsworth,

“Oh, blessed bird! The earth we pace

Again appears to be

An unsubstantial, fairy place,

That is fit home for thee!”

Juliette A. Owen.

Heap high the farmer’s wintry hoard!

Heap high the golden corn!

No richer gift has autumn poured

From out her lavish horn!

Let other lands, exulting, glean

The apple from the pine,

The orange from its glossy green,

The cluster from the vine;

We better love the hardy gift

Our ragged vales bestow,

To cheer us when the storm shall drift

Our harvest-fields with snow.

Through vales of grass and meads of flowers,

Our ploughs their furrows made,

While on the hills the sun and showers

Of changeful April played.

We dropped the seed o’er hill and plain,

Beneath the sun of May,

And frightened from our sprouting grain

The robber crows away.

All through the long, bright days of June,

Its leaves grew green and fair,

And waved in hot midsummer’s noon

Its soft and yellow hair.

And now, with Autumn’s moonlit eves,

Its harvest time has come,

We pluck away the frosted leaves,

And bear the treasure home.

Then, richer than the fabled gift

Apollo showered of old,

Fair hands the broken grain shall sift,

And knead its meal of gold.

Let vapid idlers loll in silk,

Around their costly board;

Give us the bowl of samp and milk,

By homespun beauty poured!

Where’er the wide old kitchen hearth

Sends up its smoky curls,

Who will not thank the kindly earth,

And bless our farmer girls?

Then shame on all the proud and vain,

Whose folly laughs to scorn

The blessing of our hardy grain,

Our wealth of golden corn!

Let earth withhold her goodly root,

Let mildew blight the rye,

Give to the worm the orchard’s fruit,

The wheat-field to the fly;

But let the good old crop adorn

The hills our fathers trod;

Still let us, for his golden corn,

Send up our thanks to God!

—John Greenleaf Whittier.

OLIVE-SIDED FLYCATCHER.

(Contopus borealis).

About Life-size.

FROM COL. CHI. ACAD. SCIENCES.

The Olive-sided Flycatcher is a North American bird breeding in the coniferous forests of our Northern States, northward into Canada and in mountainous regions. It winters in Central and South America.

Like all Flycatchers, their food consists almost exclusively of winged insects, such as beetles, butterflies, moths and the numerous gadflies which abound in the places frequented by these birds. A dead limb or the decayed top of some tall tree giving a good outlook close to the nesting site, is usually selected for a perch, from which excursions are made in different directions after passing insects, which are often chased for quite a distance. This Flycatcher usually arrives on its breeding grounds about the middle of May, and its far-reaching call notes can then be heard almost constantly in the early morning hours and again in the Four Birds & Nature Tues—Hammond evening. Unless close to the bird, this note sounds much like that of the wood pewee, which utters a note of only two syllables, like “pee-wee,” while that of the Olive-sided Flycatcher really consists of three, like “hip-pin-whee.” The first part is uttered short and quick, while the latter two are so accented and drawn out, that at a distance the call sounds as if likewise composed of only two notes, but this is not the case. Their alarm note sounds like “puip-puip-puip,” several times repeated, or “puill-puill-puill;” this is usually given only when the nest is approached, and occasionally a purring sound is also uttered.

Tall evergreen trees, such as pines, hemlocks, spruces, firs and cedars, situated near the edge of an opening or clearing in the forest, not too far from water and commanding a good outlook, or on a bluff along a stream, a hillside, the shore of a lake or pond, are usually selected as nesting sites by this species, and the nest is generally saddled well out on one of the limbs, where it is difficult to see and still more difficult to get at. Only on rare occasions will this species nest in a deciduous tree.

While it appears tolerant enough toward other species, it will not allow any of its own kind to nest in close proximity to its chosen home, to which it returns from year to year. Each pair seems to claim a certain range, which is rarely less than half a mile in extent, and is usually located along some stream, near the shore of a lake, or by some little pond; generally coniferous forests are preferred, but mixed ones answer their purpose almost equally well as long as they border on a body of water or a beaver meadow and have a few clumps of hemlock or spruce trees scattered through them which will furnish suitable nesting sites and lookout perches.

While on a collecting trip a nest of this species was observed in a spruce tree and about forty-five feet from the ground. The birds betrayed the location of the nest by their excited actions and incessant scolding. They were very bold, flying close around the climber’s head, snapping their bills at him, and uttering angry notes of defiance rather than of distress, something like “puy-pip-pip.” They could not possibly have been more pugnacious.

The nest was a well-built structure. It was outwardly composed of fine, wiry roots and small twigs, mixed with green moss and lined with fine roots and moss. It was securely fixed among a mass of fine twigs growing out at that point of the limb.

As a rule the nests are placed at a considerable height from the ground, usually from forty to sixty feet, though occasionally one is found that is not more than twenty feet.

In spite of their pugnacious and quarrelsome habits these birds are so attached to the localities they have selected for their homes that they will usually lay a second set of eggs in the same nest from which their first set has been taken—Adapted from Charles Bendire’s Life Histories of North American Birds.

Over in Farmer Goodman’s timber there was a great stir. Everybody was busy. All summer the trees had been planning a picnic reception to be given to the Month brothers and sisters when the hot weather had passed.

When it became noised around the whole neighborhood was delighted with the thought. Everyone wanted to do what little he could to help things along. Several dignified old owls, who had holes in the trees, promptly offered to chaperone the party. The cat-tails along the brook just at the edge of the timber promised to wear their prettiest head-dresses if they would be allowed to wait on the door. The golden rod, purple asters and other flowers along the road and the ferns, wahoo, sumac and their companions agreed to outdo themselves in the effort to furnish beautiful, tasty decorations.

The refreshments would cost nothing. The spring at the foot of the hill offered to supply clear cool drinks for all, free of charge. They had an abundance of wild grapes, wild cherries, pawpaws, red haws, hazel, hickory and other nuts.

Prof. Wind was engaged to have his band there to furnish music for the dancing.

As it was hoped to make this a long-to-be-remembered event, all summer was spent in planning and preparation. Many were the happy hours passed by the trees in discussing the styles and colors in which they were to be decked. Whenever the band was practicing its new pieces for the occasion the little leaves would dance and skip for joy.

The names of Mr. January Month and all his brothers and sisters, February, March, April, May, June, July, August, September, October, November, December were written on a sheet of paper. The list was handed to a gay little squirrel, with a handsome tail and pretty stripes down his back. He was then given instructions and sent to do the inviting. A funny little hop-toad wished to go along. The squirrel said that he would be pleased to have company, but he scampered around from place to place as though he were going for a doctor for a dying child. As the little hop-toad could not keep up, he came home crying.

Fancy the disappointment when the squirrel brought back word that pretty Miss October Month was the only one who had accepted the kind invitation. All said that they would be delighted to be there, that they knew that it would be a very happy, jolly affair; but each month claimed that having his own work to do without help he is kept so busy that he has no time for roving and sport. After the trees and their friends had so kindly made such great arrangements for their entertainment and honor, the narrow-minded months were not grateful nor polite enough to even try to manage their work so that they could get off for a day. Perhaps they had forgotten that there is such a thing as fun and rest. Poor Months! No wonder they die so early!

Every plan for a brilliant event had been made. Bright, amiable October came. The day was sunny and warm, but not hot. Everyone did his part according to agreement. The common yellow butterflies, some caterpillars and other insects who had been in no hurry to disappear, were there. Although many of the birds had left for their southern trip, there were a number of catbirds, hermit thrushes, brown thrushes, phoebes, song sparrows and others who furnished rare solos and grand choruses between dances. The cowbirds and yellow-bellied sapsuckers who do not sing wished to do something, too. The cowbirds offered to keep the flies and other insects off of the 109 victuals, and the sapsuckers agreed to give tapping signals from their high places in the tall trees whenever a change of program was to be announced.

A mischievous blue jay made a slight disturbance by trying to steal some of the dinner before the table was set. When Mrs. Chipmunk tried to drive him off, he showed fight, but in less than a minute such a crowd had gathered to see what was the matter that he took flight in great shame.

Everybody seemed to have fallen in love with Miss October. The affair was such a success and the very air was filled with such good will and jollity, that all begged and coaxed her to remain for a visit.

They had no trouble in arranging amusements for every day. Grandaddy long legs danced several jigs. The crickets and the grasshoppers got up a baseball game. When the baby show came off, Mrs. Quail took the prize for the prettiest baby under a year. Mother Pig who had heard of it and had broken out of Farmer Goodman’s pasture in order to bring the plumpest of her litter, carried back the prize for the fattest baby. Mrs. English Sparrow reported the largest number of broods raised. The locusts and the katydids took part in a cake walk.

A great fat young grasshopper and a young robin entered a hopping race. As they came out even there was trouble and prospects of hard feelings. Three butterflies who were acting as judges decided to award the prize to the grasshopper because he was smaller. This decision did not suit the robin. In a fit of impatience he ended the matter by swallowing the grasshopper—legs and all.

During the moonshiny nights Mr. Man-in-the-Moon took great pains to furnish excellent light. On other nights the fireflies showed their brightest lanterns.

Sometimes at night, white-robed Jack Frost would come and play kissing games with the leaves who would then get happier, more radiant faces. But he would box and wrestle with the nuts until their shells would crack open. Then when they came to play tag or puss-wants-a-corner with the leaves, as the little West Wind brothers frequently did, they, in their rough sport, would knock the nuts out of their cosy shells upon the ground, so that the children could pick them up. Merry times were these!

In this way the sports were carried on for thirty-one days and nights. By that time everyone, even Miss October herself, was tired out. The fine dresses of the trees being the worse for wear, dropped, leaf by leaf, and some of the trees were left nearly naked. The grasshoppers, butterflies and caterpillars who could no longer keep their eyes open had dropped into their winter’s sleep.

Except the meadow-larks, red winged blackbirds, robins, blue jays, bluebirds and a few others the feathered tribes had been obliged to leave. Some fox sparrows on their way to the south had stopped for a few days; but they said that they could not stay until the festivities were over.

Finally her mother, Mrs. Year, telegraphed to Miss October, who did not know when her welcome was worn out, bidding her to make her adieux and start home instantly. Being exhausted from sleepless days and nights she was glad to leave.

After her departure, in the timber everything became quiet and still, but the trees hoped that sometime in the future they might have another picnic as delightful and jolly, and all felt satisfied and voted the reception a perfect success.

Loveday Almira Nelson.

“I like to see them feasting on the seed stalks above the crust, and hear their chorus of merry tinkling notes, like sparkling frost crystals turned to music.” —Chapman.

One who loves birds cannot fail to be attracted by the sparrows and especially by the Tree Sparrow, whose pert form is the subject of our picture. This little bird comes to us in the Eastern United States in September or October and remains throughout the winter. It is at this time common or even abundant as far to the westward as the great plains, and is rare farther west. It is a winter bird and breeds in the colder latitudes north of the United States, where it builds its home of grasses, shreds of bark and small roots interlaced with hair, not high up in trees, as its name might indicate, but upon or near the ground.

Gentle and of a retiring disposition, they prefer the cultivated fields, the meadows, the woods with their borders of shrubs or the trees of the orchard. Such is their confidence, however, that they will even visit the dooryards and prettily pick up the scattered crumbs or grain.

While tramping through a meadow in the early winter and before the snow has disappeared or the frost has hardened and changed the surface of the earth, the tramper may frequently disturb numbers of the sparrows. Flying from the dried grass they will seem to come out of the ground. Speaking of such an incident, Mr. Keyser says: “This unexpected behavior led me to investigate, and I soon found that in many places there were cozy apartments hollowed out under the long thick tufts of grass, with neat entrances at one side like the door of an Eskimo hut. These hollows gave ample evidence of having been occupied by the birds, so there could be no doubt about their being bird bed-rooms.”

These little birds seem almost a part of one’s animal family, and a companion in those regions where the snow covers the ground a part of the year. They chirp and often sing quite gaily in the spring. They may often be seen when the thermometer indicates a temperature below zero and the snow is a foot or more in depth. Seemingly all that is required to satisfy them is a plenty of weeds from which they may gather the seeds. They are driven southerly only by a lack of a suitable food supply. Often they may be found resting under clumps of tall grass or vines on which the snow has gathered, forming a sort of roof over the snug retreat. “Whether rendered careless by the cold or through a natural heedlessness, they are very tame at such times; they sit unconcernedly on the twigs, it may be but a few feet distant, chirping cheerfully, with the plumage all loosened and puffy, making very pretty roly-poly looking objects.”

A very pretty sight, and one that may frequently be seen, is a flock of Tree Sparrows around some tall weed. Some of the birds will be actively gathering seeds from the branches of the weed, while others will stand upon the ground or snow and pick up those seeds that are dropped or shaken off by their relatives above. While thus feeding there seems to be a constant conversation. If we could but translate this sweet-voiced chirping perhaps we should find that they are expressing to each other the pleasure that the repast is giving them.

TREE SPARROW.

(Spizella monticola).

About Life-size.

FROM COL. CHI. ACAD. SCIENCES.

Their song is sweet and pleasing. They are not constant songsters, but seem to be moved by some unseen spirit, for a flock will suddenly burst out in a melody of song that is entrancing. He who has been favored with such a concert is indeed fortunate. Their whole being seems to be brought into action in the production of this song, which is “somewhat crude and labored in technique, but the tones are very sweet indeed, not soft and low but quite loud and clear. Quite often the song opens with one or two long syllables and ends with a merry little trill having a delightfully human intonation. There is, indeed, something innocent and child-like about the voices of these sparrows.”

The Tree Sparrow is often called the Winter Chippy and is confounded with the chipping sparrow, which it resembles. It is a larger bird and carries a mark of identification by which it may be easily known. There is on the grayish white breast a small black spot. Moreover, the Tree Sparrow arrives in its winter range about the time that the chippy retires to the Gulf States and Mexico.

“Wee, wee, weet, tweet, tweet, tweet!”

What a clatter, what a chatter

In the village street.

“Chee, chee, cheep, cheep, chee, chee, chee!”

What a rustling, what a hustling

In the maple tree.

“Twit, twit, flit, flit, get away, quit!”

How they gabble, how they scrabble

As to rest they flit.

“Peep, peep, tweet, tweet, wee, wee, wee!”

How they hurry, how they scurry,

Noisy as can be.

“Tr’r, tr’r, sh, sh, do be still,

You’re no wood thrush, wish you could hush,

You know you can’t trill.”

“Tr’r, tr’r, r’r, r’r, yip, peep, peep,

You’re another, I’ll tell mother,

I was most asleep.”

“Tr’r, sh, chee, chee, peep, yip, yip!”

See them swinging, gaily clinging

To the branch’s tip.

“Tr’r, sh, cheep, peep, tee, hee, hee!”

Hear them titter, hear them twitter,

Full of energy.

* * * * * *

Sudden silence falls,

Not a peep is heard;

To its neighbor calls

Not one little bird,

Silent too the trees

Calm their secret keeping;

Gently sighs the breeze;

Sparrows all are sleeping.

—Adene Williams.

We all know some of the members of the Sparrow family, little gray and brown birds, striped above and lighter underneath. They belong to the Finch family, which is the largest of all the bird families. One-seventh of all the birds belong to this family. Just think how many uncles and cousins and aunts the little sparrows have! They are birds of the ground, not birds of the trees, like the vireos. They only choose high perches when they wish to rest or sing. We see them hunting for food in the grassy meadows, or fresh-plowed field, or in the dusty road. They usually make their nests in low bushes or on the ground and, as a rule, they fly only short distances, and do not skim around just for the fun of it, like the swallows.

There are over forty different kinds of sparrows in our country.

The English sparrows are found all over the world. They stay with us all the year round. We ought to be friendly with them as we have such a good chance to become acquainted. They certainly intend to be friendly with us for they scarcely fly away at our approach. Mother Sparrow is a hard worker, raising four broods every year. Just think how many children and grand-children one sparrow can have! English sparrows are called quarrelsome birds, and I believe it is true that they have driven away many of the pretty bluebirds, but we sometimes think they are quarreling when they are not. Have you ever noticed a crowd of sparrows following one bird? I used to think that they were all quarreling with that one bird; but no, they follow her because they admire and like her. Some people scold a great deal about the harm that the sparrows do to the fruit and grain. But think of the many insects that these birds eat in one year! I believe they do more good than harm, don’t you?

The chipping sparrow often builds its nest in tall trees. This is the only sparrow I know of, which builds its nest up high. This bird is smaller than the English sparrow. It has a reddish-brown back and crown. Did you ever hear its funny little song? It sounds like the buzzing of a locust. It can call, chip! chip! too.

The field sparrow is about the same size as the chipping sparrow and its head and back are of the same color. As can be guessed from its name, it is fond of fields and meadows. The field sparrow sings very sweetly.

Then there is the fox sparrow, which is not only the largest of the sparrows, but the finest singer. It comes about as early as the bluebird. We often hear its sweet song in March. It is called the fox sparrow, not because it is sly like the fox, but on account of its color which is reddish like the fox’s fur.

The grasshopper sparrow is smaller than the English sparrow. It has a cry which sounds like a grasshopper in the grass.

The song sparrow is one of the commonest of our birds, staying with us nearly all the year. The name indicates to us that it has a sweet voice. It begins to sing almost as early as the robin and will sing every hour in the day and seems never to tire of singing. The song sparrow is about the same size as the English sparrow.

Then there are the savanna sparrow and the seaside sparrow which are fond of marshes, near the sea; and the white-crowned. This and the white-throated sparrows are both fine singers and handsome birds. They are larger than the English sparrow. The vesper sparrow has a fine voice, singing late in the afternoon and evening. It is as fond of the meadows as the field sparrow. The two birds are often taken for each other, but if the vesper sparrow is watched when it flies, it will be seen that it has white tail quills which the field sparrow does not possess. Both are about the same size.

The winter chippy or tree sparrow is a 115 winter bird, in the United States appearing in the fall and flying away early in the spring. Its name would indicate that it was fond of trees, but this is not the case, as it is usually seen on the ground and even makes its nest there.

There are many other members of the sparrow family, but this is enough for to-day. I hope that you will watch them and try to become acquainted with all.

Narcisia Lewis.

Many people suppose that the instinct of birds and animals is never wrong, but this is a mistake. I have often seen the wild geese fly north over the western prairies only to come squawking back in a few days, to linger with us, if not going farther south, until the sun warmed up the northland and they dared another flight.

Once my brother witnessed a most amusing case of mistaken judgment among birds. He had opened a store in a northern town, and during the month of March was much discouraged by the continued cold weather.

“O! but spring’s here!” exclaimed his partner gleefully one bleak day. “See those sparrows building a nest in our eaves? That’s a sure sign!” From that day on the two young men took great interest in the new home going up under—or rather over—their very eyes. Each new bit of rag or straw woven in was noted, and they even strewed cotton about in handy places for the birds to use as “carpeting in the mansion.”

But the weather did not improve, in spite of the sparrow’s prophecy; instead of that, a sleet set in one night, and morning saw a most wintry-looking earth. When the young men went down to open up the store for business, they heard loud, really angry, chirping coming from the eaves. Mr. and Mrs. Sparrow were discussing something with energy, and when at last a decision was reached they both swooped down upon their almost finished nest and tore it all to pieces. Not one twig or rag or straw was left in place. When the destruction was complete they gave a loud chirp of satisfaction and flew off together, never to return.

They had simply made a mistake in their calendar.

Lee McCrae.

I stood by my study window after dark. An electric light a few blocks distant, cast shadows of the small limbs of a tree upon the window-pane. Those shadows were in constant motion because of the wind blowing through the trees. Through the dancing shadows I saw the brilliant light against the darkness of the western sky. My breath condensed into moisture on the cold glass, and through that moisture the electric light shone in the center of a brilliantly-colored circle, composed of myriads of pencils of light, radiating from the dazzling central point. As the moisture evaporated the pencils became fewer and coarser, bright lines and fragments of lines, rather than pencils. A few breaths on the glass, more moisture condensed and again the pencils were in myriads. I enjoyed the small but brilliant view in the same spirit in which I enjoy the starry heavens on a grand mountain outlook.

As I looked I thought of many things. I thought of my own mind with its wondrous thinking machinery; I thought of my eyes and of their marvelous mechanism by which the brain received so much thought-producing material; I thought of the burning furnace within my body that sent out heated air laden with the invisible vapor of water; I thought of the laws of heat and cold by which that vapor was instantly condensed and became visible when it came in contact with the cold glass; I thought of the transparent glass and of all the changes it had passed through since it was a mineral in the primeval rocks; I thought of the tree with its naked branches whose fibers were being toughened by constant wrestling with the wind; I thought of the leaves that in a few weeks would cover those twigs and conceal from me the electric light; I thought of the invisible air with its strange elements and properties, and of the laws of meteorology that produced the wind; I thought of the electric wire and of the distant copper mines from which it came; I thought of the mysterious force that we call electricity, of the coal, the engine, the machinery, that produce it, and of the light that it produces; I thought of the mysterious thing that we call light and of the laws of light that gave me those penciled rays; I thought of the things that were made for “glory and for beauty” as well as for practical utility; and I thought of God.

And so, according to such knowledge as I had of psychology, of physiology, of physics, of meteorology, of botany, of mineralogy, of chemistry, of optics, of electricity, of esthetics, and of natural theology, were my thoughts manifold, rich, suggestive, correlated, inspiring, spiritual even, in their last analysis.

That which to many would be a thing of no interest, a commonplace sight not worth a second glance, was to me full of beauty, tinged with glory, spiritually helpful, and an occasion for praising and worshiping God.

Roselle Theodore Cross.

BLACK-THROATED GREEN WARBLER.

(Dendroica virens).

Life-size.

FROM COL. CHI. ACAD. SCIENCES.

One of the interesting nature studies is an investigation of the groups of insect-eating birds in reference to their food and the methods employed in obtaining it. Some insects are useful to man, but by far the larger number are a detriment to his interests in one way or another.

The swallows and swifts are almost constantly on the wing, dexterously catching any insects that come in their way. They are day birds and at night are replaced by the nighthawks that feed upon the night flying insects. Next are the flycatchers that dart “from ambush at passing prey, and with a suggestive click of the bill, return to their post.” The beautiful little hummingbird, ever active on the wing, quickly sees and picks from leaf or flower insects that would escape the attention of other birds. The woodpeckers and allied birds examine the tree trunks and carefully listen for the insect that may be boring through the wood within. The vireos, like the good housekeeper, examine the “nooks and corners to see that no skulker escapes.” The robin and its sister thrushes and the numerous sparrows attend to the surface of the earth, and aquatic birds extensively destroy those insects whose development takes place either in or on the water.

Not the least among the birds that assist man in his warfare upon insect pests are our beautiful and active warblers that frequent the foliage of tree and shrubs patiently gathering their insect food.

One of these is the Black-throated Green Warbler of our illustration. If we desire to examine its habits, except during the period of migration, we must visit the forests of cone bearing trees in the northern woods of the eastern United States, in the Allegheny mountains and from these points northward to Hudson Bay. It is almost useless to seek this bird in other places. Here, high up in the cedars, pines and hemlock in cozy retreats far out on the branches it builds its nest. “The foundation of the structure is of fine shreds of bark, fine dry twigs of the hemlock, bits of fine grass, weeds and dried rootlets, intermixed with moss and lined with rootlets, fine grass, some feathers and horse hair.” The nests are usually bulky and loosely constructed. These rollicksome Warblers have a peculiar song which is very characteristic and not easily forgotten. The descriptions of this song are almost as numerous as are the observers. One has given this rendering: “Hear me Saint Ther-e-sa.” Another has very aptly described it as sounding like, “Wee-wee-su-see,” the syllables “uttered slowly and well drawn out; that before the last in a lower tone than the two former, and the last syllable noticeably on the upward slide; the whole being a sort of insect tone, altogether peculiar, and by no means unpleasing.”

The song of the Black-throated Green Warbler is so unlike that of the other warblers that it becomes an important characteristic of the species. Mr. Chapman says, “There is a quality about it like the droning of bees; it seems to voice the restfulness of a midsummer day.”

Those who wish to observe this bird and cannot go to its nesting retreats, in the evergreen forests, must seek in any wooded land during its migrations to and from the tropics, where it finds an abundance of food during the rigors of our northern winters.

A few days ago I was watching the curious actions of a sparrow on the sidewalk in a rather quiet part of town. On either side of the street were lofty brick and stone buildings, with the usual multiplicity of little niches and cavities in and about the projecting cornices and ornamental architecture. These sheltered and inviting ledges had been utilized from year to year by divers smaller tribes of the feathered folk as nest-building sites, and the little bird which had attracted my attention had already laid the foundation timbers of its prospective house in a cosy niche of the cornice almost directly over my head where I was standing.

It was plainly evident that the sprightly creature was seeking sticks of proper length and strength to barricade a broad hiatus in the front part of the cavity it had chosen for its future home.

This opening was angular in form with the vertex at the bottom and its sides separating outwards towards the top, where there was a span of perhaps four or five inches.

As I stood with my elbow resting against the low paling the confiding sparrow hopped to within a yard or two of my feet in searching for tiny twigs that had fallen from the overhanging shrubbery.

It picked up a great many pieces and as quickly dropped them. Then it would stand perfectly still for a few minutes intently scanning the limited landscape as if in a brown study as to what move it should next make.

Finally it set vigorously to work picking up bits of material from an inch or two to six inches in length. Instead of flying away with a load it dropped them in a little heap nearly if not quite parallel to each other. Then poking its beak into the pile and throwing the sticks hither and thither it settled down to practical business by seizing a stick of medium length and flying away with its burden dangling in the air. Of course, I watched the little architect and saw her mount straight up to the chosen ledge and deposit the twig exactly crosswise of the gaping notch. This operation she repeated several times, always throwing the sticks about as if intent upon selecting a piece of special dimensions. No human carpenter with measuring rule in his hand could have been more expert.

In a moment the truth flashed into my mind and I realized that I was verily the human pupil of a little bird made famous by honored mention in Holy Writ.

Why, the cunning worker had foreseen to the ridicule of my own confessed stupidity that in order to effectually bar the exposed side of the chamber it must of necessity select girders of successively increasing length and size. Thus, as I fancied it reasoned, a short stick would not span the top of the dangerous gap; while, on the other hand, a long stick could not be used at the bottom because it would strike smack against the side walls before it could be placed in position low enough. So all this clearly explained why the bird should exercise such studied care in selecting the large “timbers.”

A few days afterwards I visited the scene of operations again, and by using an opera glass found that the nest was very nearly if not quite finished. The menacing gap in the ledge no longer existed; for there was a solid bulkhead in its stead composed of longitudinal sticks tied and stiffened by interwoven bits of dry grass and such shreds of various waste material as only bird intelligence knows where to find.

More interested now than ever, I took pains to climb into the attic of the three story building where from a narrow 121 gable window I could look obliquely down into the pretty nest now neatly lined with tiny feathers and thistle down. So much, then, for the sparrows and their house building. I say sparrows now, for during my later observations I had seen both Mr. and Mrs. Sparrow diligently working together.

But to advert now to our alleged “libel” on the birds, I have only to say that it is very convenient for great men and ponderous books to tell us that the lower animals perform their actions by means of a tendency called “instinct;” and thus divest themselves of all further responsibility in the matter. Confronted by this obscure declaration we are led as pupils in natural history to ask, “What is instinct?” The following definitions of this much-abused term are, perhaps, the best to be found in the English language:

“Instinct is a propensity prior to experience and independent of instruction.”—William Paley.

“Instinct is a blind tendency to some mode of action, independent of any consideration on the part of the agent, of the end to which the action leads.”—Richard Whately.

“Instinct is an agent which performs blindly and ignorantly a work of intelligence and knowledge.”—Sir William Hamilton.

Now such names as Paley, Whately and Hamilton stand high upon the roll of honor in the sparkling literature of our language; and yet the words of these great scholars are but as sounding brass and a tinkling cymbal when they undertake to tell us what is the real import and inwardness of that occult and wonderful faculty in the mental essence of animals which scientists by force of circumstances have agreed to call “instinct.”

“Aha!” my little sparrow would say, could she speak our language, “we perform our actions neither blindly nor ignorantly, as your famous Mr. Hamilton learnedly remarks; but God has taught us to both reason and work according to existing circumstances, from cause to effect; nay, even as your great logicians would have it, a priori. And although five of our little bodies were sold in the markets of Jerusalem for two farthings, not one of us ever fell to the ground without our Father’s notice!”

There, that is about the kind of sermon our little bird would preach to the utter discomfiture of human wisdom, which, after all, is but “foolishness with God.”

Verily, and in conclusion, we declare that it is a libel upon the birds to say that they build their nests guided only by that nameless tendency signified by the common acceptation of the term “instinct.”

The humblest creature God has made

Fulfills some noble, wise design;

And, dowered rich with reason’s aid,

It boasts a lineage divine.

L. P. Veneen.

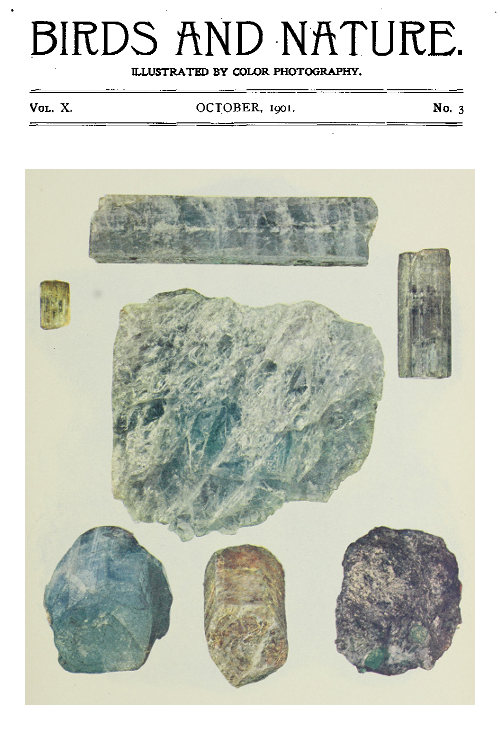

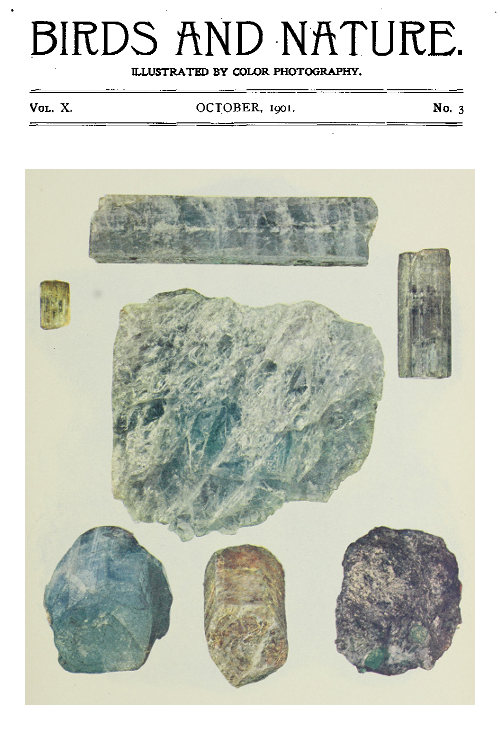

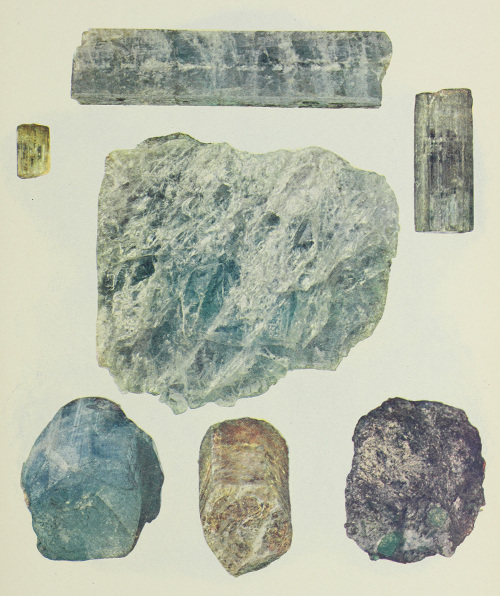

This mineral species includes a number of varieties which are highly valued as gems. These are, besides Beryl itself, the gems emerald, aquamarine and golden beryl. Chrysoberyl, it may be noted, is not a variety of Beryl, but a distinct species.

While these gems all differ in color, they are the same mineral and are practically identical in composition, hardness and other properties. In composition they are a silicate of aluminum and glucinum, the percentage being, for normal beryl, 67 per cent of silica, 19 per cent of alumina and 14 per cent of glucina.

The beautiful green color of the emerald is probably due to a small quantity of chromium which it usually contains, though some authorities believe organic matter to be the coloring ingredient. To what substance the other varieties of the species owe their color is not known.

In hardness the varieties of Beryl differ little from quartz, the hardness being 7.5 to 8 in the scale of which quartz is 7. They are somewhat inferior therefore to such gems as topaz, sapphire and ruby in wearing qualities, although hard enough for ordinary purposes.

The specific gravity of Beryl is also about like that of quartz, ranging from 2.63 to 2.80; the specific gravity of quartz being 2.65. The varieties of Beryl are therefore relatively light as compared with other gems.

Beryl crystallizes in the hexagonal system. It usually occurs as six-sided prisms, commonly terminated by a single flat plane, but sometimes by numerous small planes giving a rounded effect and occasionally by pyramidal planes which cause the prism to taper to a sharp point.

The crystals sometimes grow to enormous size, exceeding those of any other known mineral. Thus, one found in Grafton, New Hampshire, was four and one-quarter feet in length and weighed two thousand nine hundred pounds. Another in the same locality is estimated to weigh two and one-half tons. In the museum of the Boston Society of Natural History and in the United States National Museum are exhibited single crystals also of great size. That in Boston is three and one-half feet long by three feet wide and weighs several tons. That in the National Museum weighs over six hundred pounds.

None of these crystals are of a high degree of purity or transparency, but the crystal planes at least of the prisms are well developed.

Beryl crystals have no marked cleavage except a slight one parallel with the base. Where broken, the surface shows what is called conchoidal fracture, i. e. it exhibits little rounded concavities and convexities resembling a shell in shape.

The mineral is quite brittle. Some emeralds even have the annoying habit of breaking of their own accord soon after removal from the mine. This can be prevented by warming them gradually before exposing them to the heat of the sun or other sudden heat.

Beryl and its varieties, like tourmaline, are dichroic, i. e. the stones exhibit different colors when viewed in different directions. This dichroism can sometimes be observed by the naked eye, but often not without the aid of the instrument known as the dichroscope. When seen it furnishes a positive means of distinguishing a true stone from any glass imitations.

The varieties of Beryl have none of the brilliancy of the diamond and therefore depend wholly on their body colors and their lustre for their beauty and attractiveness. Fortunately they exhibit these qualities as well by artificial light as by daylight.

BERYL.

Ordinary Beryl is a mineral of comparatively common occurrence, being often found in granitic and metamorphic rocks.

That of common occurrence is usually too clouded and fractured to be of use for gem cutting. There are many localities, however, where Beryls of gem quality occur.

The finest emeralds in the world come from Muso, a locality in the United States of Colombia, seventy-five miles N. N. W. of Bogota. It is a wild and inaccessible region and the mining of the gems is a precarious occupation. The emeralds occur according to Bauer in a dark, bituminous limestone which is shown by fossils to be of Cretaceous age. As emeralds in other localities occur only in eruptive or metamorphic rocks, it seems probable that the Muso emeralds have washed in from an older formation. The emerald bearing beds are horizontal, overlying red sandstone and clay slate. Calcite, quartz, pyrite and the rare mineral parisite are other minerals found associated with the emerald. The manner of working these emerald mines is thus described by Streeter:

“The mine is now worked by a company, who pay an annual rent for it to the government, and employ one hundred and twenty workmen. It has the form of a tunnel of about one hundred yards deep, with very inclined walls. On the summit of the mountains, and quite near to the mouth of the mine, are large lakes, whose waters are shut off by means of water-gates, which can be easily shifted when the laborers require water. When the waters are freed they rush with great rapidity down the walls of the mine, and on reaching the bottom of it they are conducted by means of an underground canal through the mountain into a basin. To obtain the emeralds the workmen begin by cutting steps on the inclined walls of the mine, in order to make firm resting places for their feet. The overseer places the men at certain distances from each other to cut out wide steps with the help of pickaxes. The loosened stones fall by their own weight to the bottom of the mine. When this begins to fill, a sign is given to let the waters loose, which rush down with great vehemence, carrying the fragments of rock with them through the mountain into the basin. This operation is repeated until the horizontal beds are exposed in which the emeralds are found.”

The next most prominent locality whence gem emeralds are obtained is that in Siberia on the river Tokovoya, forty-five miles east of Ekaterinburg. The emeralds here found are often larger than any yet obtained in South America, but they are not of so good quality. They occur in mica schist (see colored plate), and often associated with the mineral phenacite, chrysoberyl, rutile, etc.

Other localities whence emeralds are obtained are Upper Egypt (the source of those known to the ancients), the Heubachthal in Austria, and Alexander county, North Carolina, in our own country. The latter locality is no longer worked, but it has afforded a number of fine crystals.

Aquamarines and transparent Beryls are found in Siberia, India, Brazil, and in many localities in the United States. Dana describes an aquamarine from Brazil which approaches in size, and also in form, the head of a calf. It weighs two hundred and twenty-five ounces troy, is transparent and without a flaw. In the Field Columbian Museum is to be seen a beautiful cut aquamarine from Siberia more than two inches in diameter and weighing three hundred and thirty-one carats. Here is also the finest specimen of blue Beryl ever cut in the United States. It was found in Stoneham, Me., is rich sea green color in one direction and sea blue in another. It weighs one hundred and thirty-three carats. Numerous other Maine localities have furnished gem Beryls. Golden Beryls are found in Maine, Connecticut, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and other United States localities, as well as in Siberia and Ceylon. From them are obtained gems of rich golden color resembling topaz.

Beryl of a pale rose color is sometimes found, and when of good quality is cut for gem purposes, but it is of too rare occurrence to be important.

Emeralds seem to have been known and prized from the earliest times. They are mentioned in the Bible in several places, the earliest mention being in Exodus, where they are described as one of the stones making up the ephod of the high priest.

Their use in Egypt dates back to an unrecorded past and they frequently appear in the ornaments found upon mummies. Readers of Roman history will remember that the Emperor Nero used an emerald constantly as an eye glass.

The Incas, Aztecs and other highly civilized peoples of South America were found using these gems profusely for purposes of adornment and for votive offerings when first visited by the Spaniards. It was partly the desire to secure these gems which led Cortez and his followers, early in the sixteenth century, to undertake the conquest of Peru. Some of the emeralds wrested from the Incas by Cortez and brought to Spain are said to have been marvels of the lapidary’s art. One was carved into the form of a rose, another that of a fish with golden eyes, and another that of a bell with a pearl for a clapper.

During the years following Cortez’ conquest large quantities of emeralds were brought to Europe, and they became much more popular and widely distributed than previously. Joseph D’Acosta, a traveler of the period, says the ship in which he returned from America to Spain carried two chests, each of which contained one hundred pounds’ weight of fine emeralds.

From what locality the Peruvians themselves obtained these gems is not known, unless it was the Colombian locality at Muso, already described. The Spaniards were led to these mines in 1558. They continued the working of them, and there has been practically no interruption in their operation since that time.

The ancients had many superstitions regarding the emerald, one being that it had a power to cure diseases of the eye. Another was that it would reveal the inconstancy of lovers by changing color.

“It is a gem that hath the power to show

If plighted lovers keep their troth or no.

If faithful, it is like the leaves of Spring;

If faithless, like those leaves when withering.”

So writes one poet.

Again, they believed the emerald would blind the eyes of the serpent:

“Blinded like serpents when they gaze

Upon the emerald’s virgin blaze.”

—Moore.

Of these traditions, perhaps the only one held in any esteem at the present time is that which associates the emerald with the month of June, making it the talismanic gem or “birth stone” of persons born in that month.

The largest and most beautiful emerald known to be in existence at the present time is one owned by the Duke of Devonshire. This is an uncut six-sided crystal about two inches long and of the same diameter. It is of perfect color, almost flawless and quite transparent.

Like all other gems, the value of emeralds varies much according to their perfection. Those of the best grade are worth at least one hundred dollars a carat. The color should be a dark velvety green, those of lighter shades being much less valuable. Owing to the extreme brittleness of the mineral, emeralds usually contain flaws, so that “an emerald without a flaw” has passed into a proverb to indicate a thing almost unattainable.

Aquamarine and other varieties of Beryl seem not to have been as highly esteemed as emerald by the ancients, although Beryl is mentioned in the Bible, and early writers describe gems evidently belonging to the species. They were probably less well known to the ancients, as nearly all the localities from which aquamarines and Beryls are now obtained are of comparatively modern discovery. They are gems in every way as worthy as the emerald, however, and will doubtless become more popular as their qualities are better known.

Oliver Cummings Farrington.

“A pleasing land of drowsy-head it was,

Of dreams that wave before the half-shut eye.”

“New birds, new flowers, new pleasures,” I murmur as my vision widens upon the, to me, new world of Arizona. A new delight indeed, notwithstanding the often impressed fact that the old footpath-ways of Ohio are, after many years, still but half discovered countries. But ’tis human, this desire for novelty, and I am not at all in advance of my fellow kindred in arriving at that stage of blessed content which we see expressed upon every side of us in the lives of the lesser (?) creatures who abide without unrest until compelled by the necessities of necessity to “move on.” But I echo Richard Jefferies: “a fresh flower, a fresh path-way, a fresh delight,” and am so far content; and, truly, coming from the east of living greens, ’tis a new kingdom of somber mountains and sandy desert at which I have arrived. To an imaginative person it is a land filled with the echoes of a distant past, even now but half heard and in my mind the golden glow of a day that is dead enfolds the silent hills, a silence of grandeur, not of nature which is here alive and keen to the fullest extent. With many other naturalists, I agree that if one desires to learn the secrets of the field and forest, one must go about singly and alone. There is something strange about it too, while one person alone is allowed to see many of the inner movements of wild life, when two or three are gathered together, they seem to intimidate the wood folk to an unlimited extent.

But bird life in this far away territory, notwithstanding Dr. Charles Abbott’s experience to the contrary, seems to me to be much more companionable and less timid than in the more thickly populated east, and also, bird curiosity is more noticeable than in those states where generations of experience has obviated all desire for any close scrutiny or investigation of that queer biped without feathers. One has only to sit silent and quiet for a few moments to have his ornithological interest aroused by numerous visitors, who, with impatient “chips” and “twits” question his presence among them. While Gila county makes up her quota of song birds in quantity, she lacks something in decorative quality, at least so far as coloring of plumage is concerned. There is no question but what the very arid atmosphere of this section is not without its marked effect upon feather coloring, and on account of this dullness of plumage, I was at first unable to classify numbers of birds who were perfectly familiar to me in Ohio. Birds like the blue jay lose much of the metallic gorgeousness of their plumage and are under a veil as it were, showing a dull, bluish gray. The blackbirds also are decidedly rusty in appearance, hardly holding their own with the great glossy ravens (Corvus principalis) who have so adapted themselves to civilization as to have become almost a necessity as purveyors of edible refuse and debris which accumulates in such abundance about the abodes of mankind, who are supposedly the most hygienic and cleanly of all creatures, but whose abiding places ‘au natural’ present an unsightly spectacle in comparison with the nests of birds, but of course it is because our requirements are so much greater, and education has developed a love of “accumulations” among us, herein must lie all blame. But we “progress” or so we have determined.

However, I never see these dignified crows of stately motion moving about without remembering Virgil’s:

“The crow with clamorous cries the shower demands,

And single stalks along the desert sands.”

But in Arizona his demand for showers is vain, for the absence of the “rain maker” is her greatest deficit.

To return to the atmospheric or arid effect upon color, I fail to understand why the bleaching process is so observable in feathers, yet the most brilliant and tropical coloring predominates in the flora. Does the plant world absorb all of the richest coloring matter of the sunlight, or do they possess an antidote to the alkaline properties of the air? Is atmospheric 128 moisture that is not obtainable necessary in feather coloring? Some of the plants here are sufficient unto themselves, brewing their own sustenance as it were, as I have seen the Bisnaga, sometimes called “Well of the Desert” in which a deep hole had been cut, produce in a short time at least a cup full of watery liquid, which is very invigorating to the thirsty traveler, and growing, too, in a sand as dry as powder, there not having been a drop of rain near it in months, if not years, and dew an unknown quantity. This liquor seems necessary for the full fruition of the rich, yellow flower, so carefully guarded by immense fish-hook spines or barbs that is such efficient protection to this species of cacti. As effectual is this protection as is the venomous reputation of that much maligned saurian, the Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum), which is not one-half so bad as his looks would imply, but he is formidable in appearance when he puffs forth his breath like a miniature steam engine and at the same time emits a greenish saliva from his mouth, which is to say the least a forbidding performance, but I really believe him to be comparatively harmless, for after considerable acquaintance with his habits, I have only learned of one person being bitten by this reptile, and that was a man who was drunk and insisted upon tickling the Gila monster on the mouth and was bitten for his pains. The reptile had to be killed before its teeth could be unlocked. As an antidote an attempt was made to fill the man with whisky, but as he was already full but little could be accomplished in that line; when he got sober he was all right save that his hand was somewhat paralyzed.

There is a marked gregariousness among the song birds of Arizona or else the present abundance of all species gives one that impression, for the numbers are almost countless, though human depredators are fast depopulating the songsters for the sake of their own pleasure or bird plumage for profit. While women anathematize men for their inordinate desire to kill something, they take an equivocal stand as critics, yet wearing a hat adorned with one or more dead bodies of birds. It is truly the old question of mote and beam re-enacted.

I do not remember of meeting with but one bird which I have been entirely unable to classify or even learn its common name if it has one. It darts in and out of a thorn bush after the manner of a thresher or cat bird, and about equals them in size; is of a dull canary yellow in color save for a rich red cap slightly tufted and worn jauntily on top of his head. I have never heard any note from him save a startled chip, and have been unable to learn anything about him from the various bird histories.

Dr. Abbott has remarked on the lack of vocal powers among the birds of Arizona, and says:

“I listened hour after hour to these cheerful birds, fancying there was melody in their attempts at song, and wondering why, when their lines had been cast in such forbidding places, the gift of sweet song had not been vouchsafed them. Does the extremely dry atmosphere have to do with it? Not a sound that I heard had that fulness of tone common to the allied utterances at home. At the limit of my longest stroll I heard a mountain mocking bird, as it is misnamed in the books, and his was a disappointed song. It was the twanging of a harp of a single string, and that a loose one.”

This absence of note richness is a feature that I have not observed, and never have I heard a more musical chorus from bird throats as one after another of the many sorts and conditions awoke at sunrise. Many a time have I listened while camping on a lone mountaintop, where our only canopy was the pine-fretted blue heavens, and heard the rich burst of song in which not a note lacked flavor; mocking birds, thrushes, orioles, wrens, finches, vireos, grosbeaks, robins (and their distinguishable note is likely to make one homesick) thrashers, blue birds, tanagers, etc., all filling in the score, as each was awakened and filled in the line of song, to say nothing of whip-poor-wills, owls and other night singers who have had “their day.” I feel sure if Dr. Abbott had given a little more time to the study of bird song in this territory he would have had no cause to complain of or discredit the vocal powers of these western songsters.

AFRICAN LION.

(Felis leo).

The African Lion, familiar to the general public as the sulky tenant of a barred cage, ranges with freer strides throughout the length and breadth of Africa, and even extends through Persia into the northwestern part of India. Fossil remains show that at one time Felis leo inhabited the southern part of Europe as well, but the king of beasts was evidently considered good sport by primitive man, and he became extinct in Europe except where, in the Roman amphitheatres, and in many a meaner cage since, he has roared for the edification of the populace.

The literature of all nations is full of allusions to the Lion; to his bravery, his grandeur and his strength. The old Assyrian kings carved pictures of themselves in bas relief hurling javelins into crouching Lions, and many a sportsman is to-day beating the thorn-thickets and trailing over the sandy plains of Africa with the same unreasoning enthusiasm, yet hoping, perhaps, in a vague way to hand down his name along with the Assyrian kings by writing a book. It is the Lion’s misfortune as well as his glory that he is king of beasts.

The Lion differs from the other Felidæ in the great strength and massive proportions of his head and shoulders, and more especially in the arrangement and growth of the hair on the body. Where, in other cats, the hair lies flat and close along the skin, the Lion is so clothed only on his yellowish-brown body. The hair of the top of the head and of the neck to the shoulders stands erect or bristles forward, forming the beautiful and characteristic mane of the adult male and suggesting in a way not otherwise possible the massive strength of the great paws, one blow from which will fell an ox or crush the skull of a man without an effort. In most Lions the mane is of a darker color than the remainder of the body, being often almost black. The elbows, tip of tail and the under parts of the body are also clothed with this long, bristly hair, but it is found only on males above three years of age. The females have smaller heads and shoulders and are of a uniform color.

In many minor ways the Lion is specially adapted for his predatory life. Every tooth in his head is sharp pointed or sharp edged. The great canine teeth are set far apart in his square jaws and locked together like a vice. The molars are transformed from grinders into incisors, yet are so strong that they will crack heavy bones. The papillæ on the tongue are so developed that they resemble long, horny spines curved backwards, giving the tongue the appearance of a coarse rasp. With this rough tongue the Lion can lick the meat from bones as easily as a house cat eats butter, and should a friendly Lion lick his keeper’s hand the flesh would be torn and the blood flow. The claws are very large and sharp, and are so nicely sheathed in the soft cushions of his feet that the Lion neither blunts nor wears them down. Yet when he strikes with tense paws every claw is like a hook and a dagger to tear and cut.

In seeking his prey the Lion lies in wait by springs and water holes and leaps upon his victims from the ambush of some bush or rock as yellow as his own tawny hide; or, failing in this, he sneaks up the wind and through the thickets and reeds of a watercourse or swamp and quickly leaps upon a surprised antelope or zebra or savage buffalo, crushing it to the ground by his great weight, while he strikes and tears it with paws and teeth. In cultivated districts the Lion prowls about the fields and villages, seizing cattle and sheep, and often, when he is old and lazy, rushes into some camp or hut at night and carries off a man. In many parts of Africa the natives build great 132 corrals of thorns about their camps to keep the Lions away, and should one be heard in the night they light fires and wave torches until the dawn.

Under ordinary circumstances the Lion attends to his own hunting, and when seen in the daytime retreats to some denser cover where he will not be disturbed. This is often cited as an evidence of cowardice, but is such a common characteristic of big game and of animals, and even men of undoubted courage, that it should not be held against him. There is no animal in the world which can consistently hunt for trouble and survive, and so long as the Lion can keep his stomach filled and his sleep undisturbed he is probably content to waive the title of king of beasts.

Lion hunting has been held a royal sport in all times, with the result that the Lion has been exterminated in many parts of its natural habitat and forced back into the wilder parts of desert and plain. Unlike the tiger, the Lion is rarely found in forests, and is unable to climb trees. He is ordinarily stalked in the daytime, when, with stomach full, he sleeps among rocks and bushes, or shot from stands as he approaches some water hole or carcass by night. The literature of African exploration and travel abounds with accounts of Lions killed by men and men killed by Lions. In these days of zinc balls and repeating rifles it is generally the Lion that is killed. To the thorough-paced English sportsman like Sir Samuel Baker or Gordon Cumming the Lion hunt is recreation merely, and with their ten-bore rifles and British phlegm they are in no more danger than if they were chasing foxes through the dales of England.

The family life of the Lion is very interesting and human. So far as is known, a single male and female remain together year after year, irrespective of the pairing season, the Lion feeding and caring for his Lioness and cubs and educating the young in the duties of life. For two or three years the cubs follow their parents, so that Lions are often found in small troops. Cases have been reported where they have joined for a preconcerted hunt, and the Lioness often goes up the wind to startle game and drive it towards her ambushed mate, following after for a share of the prey. Hon. W. H. Drummond, in “The Large Game and Natural History of South and Southeast Africa,” gives the following account of the feast after the victim had been slain: “The Lion had by this time quite killed the beautiful animal, but instead of proceeding to eat it, he got up and roared vigorously until there was an answer, and in a few minutes a Lioness, accompanied by four whelps, came trotting up from the same direction as the zebra, which no doubt she had been to drive towards her husband. They formed a fine picture as they all stood round the carcass, the whelps tearing it and biting it, but unable to get through the tough skin. Then the Lion lay down, and the Lioness, driving her offspring before her, did the same, four or five yards off, upon which he got up and, commencing to eat, had soon finished a hind leg, retiring a few yards on one side as soon as he had done so. The Lioness came up next and tore the carcass to shreds, bolting huge mouthfuls, but not objecting to the whelps eating as much as they could find. There was a good deal of snarling and quarreling among these young Lions, and occasionally a standup fight for a minute, but their mother did not take any notice of them except to give them a smart blow with her paw if they got in her way. There was now little left of the zebra but a few bones, and the whole Lion family walked quietly away, the Lioness leading, and the Lion often turning his head to see that they were not followed, bringing up the rear.”

Dane Coolidge.

’Twas a holiday joy when I was a boy,

To follow the brook a-trouting,

’Twas gold of pleasure without alloy,

To trudge away through the livelong day—

Not a bite to eat, or a word to say,

And never a failing or doubting.

Then home at night in a curious plight—

Heavy and tired and hungry quite—

With a string of the “speckles” hung out of sight,

And a chorus of boyish shouting.

Only a line of the commonest twine,

Only a pole of alder;

None of your beautiful things that shine—

Tackle so nice and so high in price

That a trout would laugh to be taken twice.

And sing like a Swedish scalder

For a jump at a sign of a thing so fine,

And scorn rough implements such as mine;

Only a line of the commonest twine—

Only a pole of alder!

Wet to the skin in our raiment thin—

Never a word of complaining,

Never too late in the day to begin;

Dropping a hook in the beautiful brook

Till day was taking his farewell look

No matter how hard it was raining!

Ah! few, indeed, would fail to succeed

In the angling of life—if they’d only heed

The trout-boy’s patience, whatever impede,

And his joy, both in seeking and gaining.

—Belle A. Hitchcock.