Title: The Lost Mine of the Amazon: A Hal Keen Mystery Story

Author: Percy Keese Fitzhugh

Illustrator: Bert Salg

Release date: September 17, 2015 [eBook #49989]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Rick Morris and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

A HAL KEEN MYSTERY STORY

By

HUGH LLOYD

Author of

The Copperhead Trail Mystery

The Hermit of Gordon’s Creek

The Doom of Stark House, Etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY

BERT SALG

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS : : NEW YORK

Copyright, 1933, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP, Inc.

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the United States of America

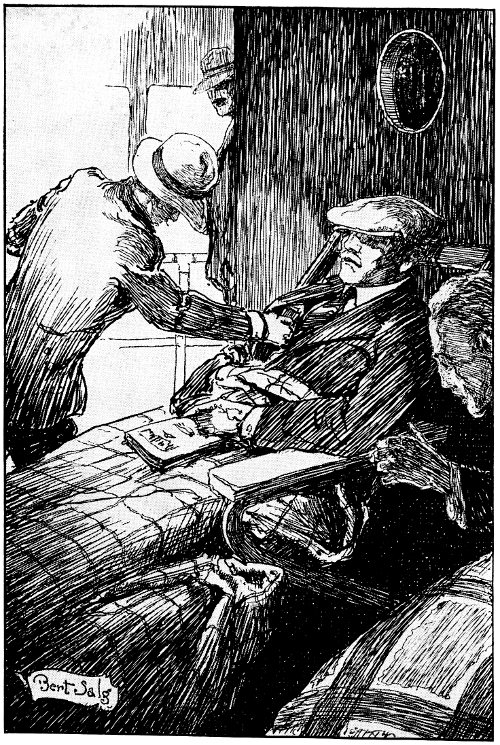

Hal lay rigid in his deck chair and watched from under half-closed lids. The dapper little man came toward them soundlessly and approached Denis Keen’s chair with all the slinking agility of a cat. Suddenly his hand darted down toward the sleeping man’s pocket.

SUDDENLY THE MAN’S HAND DARTED DOWN TOWARD THE SLEEPING MAN’S POCKET.

Hal leaped up in a flash, grasping the little man’s pudgy wrist.

“What’s the idea, huh? Whose pocket do you think....”

Denis Keen awakened with a start.

“Hal—Señor Goncalves!” he interposed. “Why, what’s the fuss, eh?”

“Fuss enough,” said Hal angrily. “The fine Señor Goncalves has turned pickpocket I guess. I saw him reaching down to your pocket and....”

“But you are mistaken,” protested the dapper Brazilian. His voice, aggrieved and sullen, suddenly resumed its usual purr. “See, gentlemen?” he said with a note of triumph.

Hal and his uncle followed the man’s fluttering hand and saw that he was pointing toward a magazine thrust down between the canvas covering and the woodwork of Denis Keen’s deck chair.

“I came to get that—to have something to read,” purred the Señor. He turned to Hal with that same triumphant manner. “Being short of chairs, I have shared this one with your uncle. This afternoon I have sat in it and read the magazine. I leave it there at dinner and now I come to get it—so?”

“Which is all true,” said Denis Keen, getting to his feet. “I’m terribly sorry that my nephew put such a construction on your actions, Señor Goncalves—terribly sorry. But he didn’t know about our sharing chairs and that accounts for it.”

Hal’s smile was all contrition. He shrugged his broad shoulders and gave the Brazilian a firm, hearty handclasp.

“My error, Goncalves. You see, I don’t know the arrangements on this scow yet. I’ve been knocking around below decks ever since we left Para—talking to the crew and all that sort of thing. It’s my first experience in Amazon, South America.” He laughed. “I just came up a little while ago and after snooping around found Unk asleep in that chair so I just flopped into the vacant one next. Then you came along—well, I’m sorry.”

Señor Goncalves moved off into the shadows of the upper deck, smiling and content. The small echo of his purring goodnight lingered on the breeze, bespeaking the good will with which he parted from his new-found American friends.

Hal and his uncle had again settled themselves in the deck chairs and for a long time after the Brazilian had gone they sat in silence. The boat ploughed on through the softly swishing Amazon and there was no other sound save the throbbing of the engines below.

“Well, Hal, ‘all’s well that ends well,’ eh?” said Denis Keen, stifling a yawn. “I’m mighty glad that our dapper Señor took our apologies and parted in a friendly spirit. It goes to prove how necessary it is for you to curb that reckless reasoning of yours.”

Hal shifted his lanky legs and ran his fingers through a mass of curly red hair. His freckled face was unusually grave as he turned to his uncle.

“Gosh, you didn’t fall for that, did you?” he asked with not a little surprise.

“Why not—you were in the wrong! As I said before—your recklessness, Hal....”

“Unk, that wasn’t recklessness; that was just plain cautiousness. If you had seen the way he came sliding and slinking toward you in the darkness, you wouldn’t be so touched by the little tussle I gave him. People don’t sneak around looking for mislaid magazines—they stamp around and yell like the dickens. I know I do. Besides, he made no attempt to take the magazine; his browned and nicely manicured hand shot straight for your inner coat pocket and I don’t mean maybe.”

“Hal, you’re unjust—you’re....”

“Now, Unk,” Hal interposed. “I’m not that bad, honest. I know what I saw, and believe me I’d rather think that he didn’t want to go for your inner pocket. But he did! If he was so bent on getting the magazine and if his feelings were ruffled to the point that he made out they were, how is it he went off without it!”

“What?”

“Why, the magazine. There it is alongside of you, right where it was all along.”

“So it is, Hal.” Denis Keen thrust his long fingers down between the canvas and the woodwork and brought forth the disputed magazine. He studied it for a moment, shaking his long, slim head.

“Well, do you still think it doesn’t look mighty funny, Unk?” Hal asked in smiling triumph.

“Hal, my dear boy, there’s an element of doubt in everything—most everything. You’ll learn that quickly enough if you follow in my footsteps. And as for this particular incident—well, you must realize that Señor Goncalves suffered insult at your hands. You admitted yourself his feelings were ruffled. Well then, is it not perfectly plausible that he could have forgotten the magazine because of his great stress? I dare say that anyone would forget the object of his visit in the face of that unjust accusation. Señor Goncalves was thinking only of his wounded pride when he bid us goodnight.”

“Maybe,” said Hal with a contemptuous sniff, “and maybe not. Anyway, I’ve got to hand it to you, Unk, for thinking the best of that little Brazil-nut. You want to see things for yourself, huh? Well, I’ve got a hunch you’ll see all you want of that bird.”

“What could he possibly know or want?”

“Listen, Unk,” Hal answered, lowering his voice instinctively, “the Brazilian Government must have a few leaks in it the same as any other government. They invited the U. S. to send you down here to coöperate with them in hunting down the why and wherefore of this smuggling firearms business, didn’t they? Well, what’s to stop a few outsiders from finding out where and when you’re traveling?”

“Good logic, Hal,” Denis Keen smiled. “You think there must be informers in the government here giving out a tip or two to the rebel men, eh? In other words, you think that perhaps our dapper Señor Carlo Goncalves is a rebel spy, eh?”

“Righto, Unk, old scout. And I think that Brazil-nut was trying to pick your pocket—I do! Listen, Unk, have you any papers you wouldn’t care about losing right now, huh?”

“One, and it’s my letter of introduction from Rio to the interventor (he’s a sort of Governor, I believe) of Manaos. It’s a polite and lengthy document, in code of course, asking his help in securing a suitable retinue for our journey into the interior after that scamp Renan.”

“Renan!” Hal breathed admiringly. “Gosh, Unk, that fellow’s name just makes me want to meet him even if he is being hunted by two countries for smuggling ammunition to Brazilian rebels.”

“He’s merely wanted in connection with the smuggling, Hal. Naturally he takes no actual part in it. He merely exercises his gracious personality in forcing unscrupulous American munitions manufacturers to enter into his illegal plans. Renan is a soldier of fortune from what I can understand. No one seems to know whether he’s English or American—it is certain that he’s either one or the other. But everyone is agreed that he’s a man of mystery.”

It was then that they became aware of a figure moving in the shadows aft. Hal jumped from his chair and was after it in a flash. However, the figure eluded him, and though he searched the deck and near saloon for a full five minutes he returned without a clue.

“Not a soul anywhere, Unk,” he announced breathlessly, “I circled the whole blame deck too. Didn’t even run into a sailor. Funny. Were we talking very loud that time?”

“Not above a whisper. Hardly that. I dare say one would have had to come right up to our chairs to catch a word. Regardless of your hunches, Hal, I never take chances in talking—not anywhere.”

“I know—I just thought maybe ... say, Unk, is the Brazil-nut’s cabin the fourth one from ours?”

“I believe so. Why?”

“Just that there wasn’t a light or anything. But then, maybe he went to bed.”

“Even a Brazilian like Señor Goncalves has to go to bed, you know.”

Hal smiled good-naturedly at the playful thrust and shook back an errant lock of hair from his forehead.

“Even so, Unk, my impression of him is that he goes to bed when other people don’t. Don’t ask me why I think it. I couldn’t tell you. That bird is a riddle to me.”

“And you’re going to solve him yourself, I suppose?”

“Me?” asked Hal. He laughed. “I’d like to, but, who knows?”

Who, indeed!

As they undressed for bed they heard the throb of the engines cease and, after the captain gave some orders in blatant Portuguese, the boat slowed down and stopped. An obliging steward informed Hal that they were anchoring at the entrance to the Narrows, waiting for daybreak before they dared pass through its tiny channels.

“Then that means we’ll have a nice, quiet night to sleep,” said Denis Keen, stifling a yawn. “Those engines are the noisiest things in Christendom.”

Hal undressed with alacrity and said nothing until after he had crawled into his bunk.

“You feel all right about everything, huh, Unk?” he asked thoughtfully. “That is—I mean you don’t think that these revolutionary fellows would have any reason to get after you, huh?”

Denis Keen laid his shoes aside carefully and then got into the bunk above his nephew.

“My mind’s at peace with all the world,” he chuckled. “I’m not interested in the revolutionary fellows—I’m interested in trailing down Renan to find out how, when and where he gets in communication with American munitions men. That’s my job, Hal. It’s the American munitions men that the U. S. government will eventually handle satisfactorily, and I’ve got to find who they are. As for Renan—if he’s a U. S. citizen and we can get him on U. S. territory—well, so much the better. But if not, Brazil has reason enough to hold him, and if I can help them to do it, I will. Of course, in sifting things down to a common denominator, the Brazilian rebels wouldn’t have any reason to think kindly of me. My presence in their country is a warning that their munitions supply will shortly be cut off.”

“Then the Brazil-nut—if he is a spy, would have reason enough to want to find out what you know, huh?”

“If he is a spy, he would. If he could decipher my letter he would find out that the Brazilian Government has reason to believe that Renan is in a jungle spot many miles back from the Rio Yauapery. It is in a section still inhabited by wild tribes. But Renan wouldn’t worry about a little thing like that. If he’s visiting General Jao Ceara, commanding the rebel forces, then the savage element is twofold. From all accounts, Ceara’s got a wild lot of men—half-castes for the most part—he’s one himself.”

“Man, and we’ve got to go to a place like that!”

“Maybe not. If I know these half-castes as well as I think I do, they can be bribed into giving me a little information. In that way I can find out when and where the next munitions shipment is due and lo, to trace the rest of the story, both before and after, will be comparatively easy.”

“I hope so, Unk. Gosh, there’s promise of thrills, though, huh?”

“Some. We’ve been promised adequate military protection. We’re to work out of Manaos. Now I’ve told you all I know, Hal, so put your mind at rest for the night. My precious code letter is safe in my pajama pocket. Go to sleep. I can hardly talk, I’m so drowsy.”

Hal stretched out and, after pounding his pillow into a mound, lay down. He could catch a glimpse of the deck rail through the tiny window and watched the shadows playing upon it from the mooring lights, fore and aft.

A deep, languorous silence enveloped the clumsy boat, and now and again Hal caught a whiff of the damp, warm jungle in the faint breeze that blew about his curly head. It gave him pause, that smell of jungle, and in his mind he went many times over every detail of what his uncle had told him concerning Renan, that colorful man of mystery who was even then hidden away in a savage stronghold.

The thought of it was fascinating to an adventurous young man like Hal and he felt doubly glad that he had given up the prospect of a mild summer in the north woods for this strange and hazardous journey on the Amazon. He closed his eyes to try and visualize it more clearly and was soon fast asleep.

His dreams were vivid, fantastic things in which he did much breathless chasing through trackless jungle after hundreds of bayonets. That the bayonets were animate, breathing things did not seem to surprise him in the least. Neither did he feel any consternation that this vast army of firearms should suddenly resolve itself into one human being who quickly overpowered him and stood guard over his supine body.

Ever so gradually his subconscious being was aroused to an awareness that another presence was standing over him and looking down upon his sleeping countenance. Startled by this realization, Hal became suddenly alert. He felt a little chilled to lie there trying to feign sleep while he thought out what move he should make first.

Suddenly, however, he knew that this alien presence was no longer beside him. He heard not a sound until the door creaked and in a second he was on his feet shouting after the fleeing intruder.

A sailor came running and at Hal’s orders he continued the chase while the excited young man hurried back into the cabin to get his shoes. Denis Keen was by that time thoroughly aroused and on his feet.

Hal explained the situation in a few words while he pulled on his shoes.

“I guess I surprised him, Unk—just in time,” he said breathlessly.

“Just in time to see him get away,” said Denis Keen significantly. “My pajama pocket....”

“You mean, Unk....”

“That my letter has been stolen.”

Before Hal had recovered from his astonishment, there burst into the cabin, the sailor, who was leading a cringing, ratlike little man. Behind them came the captain, wringing his hands excitedly and talking in vociferous Portuguese.

“Many pardons, Señors!” said he, bowing apologetically. “This half-caste, Pizella—he come up from steerage to rob you—yes?”

“I’ve been robbed of something important,” Denis Keen answered and explained in Spanish the importance of his letter.

The captain was irate with the half-caste, Pizella, and with the aid of the sailor proceeded to search him most thoroughly. But this availed them nothing.

“Nothing?” Hal asked. He glanced at the sailor. “You sure this is the bird I told you to beat it after?”

“Most certain, Señor,” the sailor assured him. “I caught him half-way down the stairway.”

“Hmph,” said Denis Keen, “question him, then.”

A few more minutes ensued in which the captain and the sailor took turns at arguing with the man in an unintelligible patois. But nothing came of this either, for the half-caste protested that he was entirely innocent.

“Then what can we do?” the captain beseeched Denis Keen. “We find nothing stolen on Pizella, the young Señor Hal does not know sure that it was he in the cabin—he admits it very truly when he asks the sailor was he sure.”

“That is very true, Captain,” said Denis Keen. “My nephew could not swear to it that this man was the intruder, can you, Hal?”

Hal could not. A fair-sized group of upper deck passengers had gathered about their cabin door listening to the singular conversation. At the head of them stood Señor Carlo Goncalves in a state of partial dishabille and listening attentively.

When Denis Keen had dismissed the wretched Pizella because of lack of evidence, the dapper Brazilian came forward twisting his little waxed moustache and smiling.

“Perhaps you have lost not so very much—yes?” he asked sympathetically.

“Perhaps not,” Denis Keen smiled. “Just a letter, Señor.”

Señor Goncalves looked astonished, then comprehending.

“Ah, but the letter is important—no?”

“Yes,” Denis Keen smiled, “it is important. You know nothing about this man Pizella?”

“Nothing except he is half-caste and that speaks much, Señor,” said Goncalves genially. “They do quite funny things, these half-castes.”

“Such as espionage?” Denis Keen asked quietly, yet forcefully.

Hal watched the dapper Brazilian narrowly, but caught not one betraying movement. The man’s swarthy face showed only a sincere concern that these aliens should be distressed in his beloved country.

“The half-castes they are all rebels perhaps,” said the man at length. “But that they should bother the Señors—ah, it is deplorable. For why should the half-caste Pizella....”

“Perhaps he had reason to believe I had something to do with your government,” interposed Denis Keen. “I have—as a friendly neighbor. But my letter—it was one of introduction to the interventor at Manaos. With his aid I am to get together a party suitable to my purpose. I am interested in anthropology, Señor, just a dilettante, of course, and my nephew, Hal, inherits the curse.”

Señor Goncalves laughed with great gusto and twisted his tiny moustache until each end resembled sharp pin points.

“Ah, but that is interesting, Señor,” said he genially. “But as for your letter—ah, it is nothing, for I myself know the interventor—I can take you to him.”

“That is indeed kind, Señor,” said Denis Keen relaxing. “Very kind.”

“Ah, it is nothing, Señors, quite nothing. I should be delighted to help my neighbor Americanos on their interesting journey into the Unknown. And now shall we enjoy the rest of the journey to Manaos—no?”

“Yes,” Denis Keen chuckled. “We shall indeed.”

Hal smiled wryly—he was still smiling when the Señor had bowed himself out of their cabin to dress for breakfast. Denis Keen observed him carefully.

“You seem to be laughing up your sleeve, as usual, Hal.”

“I am, Unk. It’s a case of the noise is ended but the suspicion lingers on.”

“You’re just hopeless, Hal. I watched the man closely—so did you. Besides, he is acquainted with the interventor and that serves my purpose. I shall have no further use for the Señor, once I get an audience with the interventor. He’ll know no more about us than he does now.”

“Well, that gives him a pretty wide margin, Unk. Wasn’t it telling him a lot just to say you missed that letter?”

“Not at all. Most Americans on such expeditions as it is believed we contemplate secure letters of introduction along their itinerary. The dapper chap is just a former prosperous man forced by circumstances to go trading into the interior for rubber as his only means of livelihood. He’s a jolly chap, you must admit, and with an inherent sense of hospitality. And as for any continued suspicion of him, Hal, you saw with your own eyes that he was in pajamas and dressing gown, while you are sure that the man who ran from this cabin was fully dressed.”

“Yes, that’s true, Unk. Oh, I guess I’m just a bug on hunches. I’ll try and forget it, because I do admit the Brazil-nut’s a friendly little guy—yes, he isn’t half bad for a shipmate. But I would like to know about that letter.”

“Who wouldn’t? It’s futile to wonder, though. I’m convinced that the little Pizella isn’t what he looks. I think he took the letter all right, but my idea is that he’s either hidden it or thrown it into the river before the sailor caught him at the foot of the stairs. But our chances for holding him were nil when you couldn’t identify him.”

“How could I in the dark and when he ran so fast, too?” Hal protested. “I couldn’t say it honestly even if I felt I was right.”

“Of course. But put it out of your mind. The captain has promised to have Pizella watched closely for the rest of the voyage. Now let’s hurry and dress so we can get breakfast over with. The Señor promised me yesterday afternoon that he’d escort me below this morning. He’s going to explain in his inimitable way two or three quite interesting looking half-castes that I happened to spot down in the steerage yesterday. He seems to have a knack for worming historical facts out of people. He did that with a Colombian sailor who was stationed up forward.”

“Well, look out he doesn’t worm any historical facts out of you.”

They laughed over this together and finished dressing. Breakfast followed, and when they strolled out on deck to meet the dapper Brazilian, the steamer was chugging her way through the Narrows.

They spent an interesting hour down in the steerage with the vivacious Brazilian, then lingered at the deck rail there to view the surrounding forest which all but brushed the ship on either side. At times it seemed as if the jungle had closed in and was trying to choke them, and that they were writhing out of its clutches, struggling ahead with heroic effort.

Hal felt stifled at the scene and said so. Señor Goncalves was at once all concern. They would return to the upper deck immediately he said and proceeded to lead the way, when the half-caste, Pizella, shuffled into sight. Instinctively they stopped, waiting for him to pass.

He glanced at them all in his shiftless, sullen way—first at Denis Keen and then at Hal. Suddenly his dark little eyes rested on the Brazilian, then quickly dropped. In a moment, he had disappeared around the other side of the deck.

Not a word passed among them concerning the wretched-looking creature and Hal followed the others to the upper deck in silence. He was thinking, however, and greatly troubled. Try as he would, he could not repress that small questioning voice within.

Was there any significance in the glance that passed between the half-caste and Goncalves?

By nightfall they had wormed their way out of the Narrows and came at last to the main stream of the Amazon River. Hal had his first glimpse of it shortly after evening coffee when he strolled out on deck alone. His uncle preferred reading a long-neglected book in the cabin until bedtime.

Hal stood with his elbows resting on the polished rail and placidly puffed a cigarette. The setting sun in all its glory was imprisoned behind a mass of feathery clouds and reflected in the dark yellow water surging under the steamer’s bow.

The day had been a pleasant one and Hal had been untroubled by the morning’s haunting doubts. Señor Goncalves was proving to be more and more a thoroughly good fellow and pleasant shipmate. There was nothing to worry about and, had it not been for the singular disappearance of his uncle’s letter, all would be well.

But he tried not to let that disturb his placidity, and fixed his dreamy glance on the dense, low-lying forest stretching along the river bank in an unbroken wall of trees. Being at the end of the rainy season, the jungle seemed more than ever impenetrable because of the water covering the roots and creeping far up the trunks of the trees.

A monkey swung high in the bough of a distant tree, a few macaws and parrots hovered near by seeking a perch for the night. Then the fleecy clouds faded into the deep turquoise heavens and the shadows of night stole out from the jungle and crept on over the surging Amazon.

The formidable shriek of a jaguar floated down on the breeze, leaving a curious metallic echo in its wake. When that had died away Hal was conscious of a melancholy solitude enveloping the steamer. Not a soul but himself occupied that end of the deck; everyone else seemed to be in the saloon, playing cards and smoking.

He yawned sleepily and sought the seclusion of a deck chair that stood back in the shadow of a funnel. He would have a smoke or two, then go in and join his uncle with a book.

He had no sooner settled himself, however, than he heard the soft swish of a footstep coming up the stair. It struck him at once as not being that of a seaman’s sturdy, honest tread. It sounded too cautious and secretive, and though he was curious as to who it might be, he was too lazy to stir in his comfortable chair and find out. But when the footstep sounded on the last step and pattered upon the deck in a soft, shiftless tread, Hal was suddenly aroused.

He leaned forward in the chair and got a flashing glimpse of Pizella’s face as he disappeared around the bow toward port side.

Hal was on his feet and stole cautiously after him. He was certain that the man hadn’t seen him, yet, when he got around on the deck, the fellow was almost aft. It was then that he turned for a moment and, after looking back, darted about to the other side again.

Hal chased him in earnest then, leaping along in great strides until he came back to where he had started. Pizella was not to be seen, however, neither down the stairway nor anywhere about the upper deck, which the irate young man circled again.

After a futile search, Hal strolled past the saloon. Señor Goncalves was one of the many passengers in there making merry and contributing his share to the sprightly entertainment. In point of fact, the dapper Brazilian was the proverbial “life of the party” and his soft, purring voice preceded several outbursts of laughter.

Hal went on and he had no sooner got out of earshot of the merrymakers when he heard a door close up forward. Even as he looked, he recognized Pizella’s small figure going toward the stairway. He knew it was the half-caste; that time he could have sworn to it, yet....

“He swore up and down that he wasn’t near this deck,” Hal declared vehemently, when he got back to his uncle’s cabin ten minutes later. “No one in the steerage saw him come up or come down. I was the only one who saw him slinking around up here—I know it was him this time, Unk! But the sailors below thought I was seeing things I guess, for when I got down there, friend Pizella had his shoes and trousers off and was stretched out in his bunk as nice as you please.”

“Strange, strange,” murmured Denis Keen, putting his book down on the night table beside his elbow.

“Sure it is. The way I figured it, he must have started peeling off on his way down. Undressing on the wing, huh?”

“It would seem so, Hal. Your very earnestness convinces me that it was no mere hunch you acted upon this time. The fellow is up to something—that’s a certainty. But he wasn’t anywhere near this cabin. I heard not a sound.”

“And the Brazil-nut was strutting his stuff in the saloon, so he’s out of the picture.”

“Well, that’s something to feel comfortable about.” Denis Keen laughed. “Surely you didn’t think....”

“Unk, when there’s sneaking business going around like this that you can’t explain or even lay one’s finger on, why, one is likely to suspect everybody. Anyway, I guess they’ll keep closer watch on him just to get rid of me.”

“No doubt they’re beginning to suspect that you have some reason for picking on Pizella. Either that or they’ll think you’re suffering from a Pizella complex. But in any case, Hal, I think it won’t do a bit of harm to have the man watched in Manaos.”

They forgot about Pizella for the rest of the voyage, however, mainly because Pizella did not again appear above decks. Hal quickly forgot his hasty suspicions and was lost in the charm of the country on either side of the river. The landscape changed two days after they entered the Amazon, and in place of the low-lying swamps, a series of hills, the Serra Jutahy, rose to their right.

After leaving the hills behind, they caught a brief glimpse of two settlements, larger and more important than most of those they had seen. The captain pointed out the first of these, Santarem, which lay near the junction of the Amazon and Tapajos, the latter an important southern tributary.

“Santarem,” the captain obligingly explained, “should interest the Señors.”

“Why?” Hal asked immediately.

“It is full of the romance of a lost cause,” said the captain. “After the Civil War in your great United States, a number of the slave-owning aristocracy, who refused to admit defeat and bow their heads to Yankee rule, came and settled in this far-away corner of the Amazon.”

“A tremendous venture,” said Denis Keen. “I dare say their task was too much for them.”

“For some, Señor. Some of them returned to your fair country broken in body and spirit, but others held on. Only a very few of the older generation live, but there are the sons and grandsons and great-grandsons to carry on—yes? A few of these families—they have scattered up this stream—down that stream. One of them that is perhaps interesting more than the others is the Pemberton family. Everyone familiar with the Amazon has heard their sad story. It began when Marcellus Pemberton, the first, settled in Santarem along with several other old families from Virginia.”

“Marcellus Pemberton, eh?” said Denis Keen. “That certainly smacks of Old Virginia.”

“He was a very bitter man, the first Marcellus Pemberton. A very young man when he went to fight against the North, he fled from his home after the War rather than bow to Yankee rule. He settled in Santarem with other Virginia families, took a wife from one of them, and had many children. All died but his youngest son—even his wife got the fever and died. Marcellus and his youngest son left the settlement then and went to live a little way up the Rio Pallida Mors. And so it is with that son that the story centers, even though he married an American señorita from Santarem.”

“And they had a son, huh?” Hal asked interested.

“Yes, Señor Hal. But of him I know little—the grandson. It is as I said Old Marcellus’ son who is interest—yes? Ten years ago he disappeared mysteriously. His wife died heartbroken a little later and left behind the girl Felice, a fair flower in the jungle wilderness, and the grandson who must now be twenty-five. Felice, like the good girl she is, stays with her grandfather who is now getting very old.”

“And I suppose they’re as poor as the dickens, huh?” Hal queried. “They’re starving to death I bet, and yet I suppose they’re keeping up the old tradition. Pride, and all that. They ought to know the war is forgotten. Peace and good will ought to be their motto and bring them back to the U. S.”

“Too true, Señor Hal,” the captain agreed, “but they do not stay for that, I do not think. They stay because of an uncertainty and that is the sad part of the story. I did not tell you how the Señor Marcellus, Junior, died ten years ago.”

“Ah, I thought this wouldn’t end without Hal getting the pièce de résistance out of the story,” Denis Keen chuckled.

“Well, I notice you’re listening intently yourself,” said Hal good-naturedly. “Go on, Captain.”

“To be sure,” said the captain amiably. “It takes but a moment to tell you that Señor Marcellus was looking for gold up the Rio Pallida Mors (Pale Death)—most people call it Dead River, Señors. One day he started out prepared for his long journey to his lode and he stopped a moment to tell his wife to promise him that, if some day he did not come back, they would not rest until they found his body. He had what you call a presentiment—no? But his wife she promised and the children promised, also his father. So he went and as he feared he did not return.”

“And they never found him?”

“No, Señor Hal. Neither did they find where his lode had gone. To this day they have found neither him nor the mine. And so they look always for his body. The Indians they say he has come back from death in the form of a jaguar and every moonlight night he shrieks along the banks of the river, crying for his children or his father to come and find his body in the rushing waters of Pallida Mors.”

“A tragic story, Captain,” said Denis Keen. “They must be an unhappy group up there, being reminded of their father’s sad ending every time there’s a moon.”

“Something spooky about him being reincarnated in jaguar form, huh? Gosh, they don’t believe that part of it, this Pemberton family, do they, Captain?” Hal asked.

“Ah, no. They cannot even believe he is really dead, Señors—they say they won’t believe it till they find his body. And so they wait and the jaguar shrieks on moonlight nights. But Santarem is long in the distance, Señors—the story is ended.”

“Not for the Pembertons, I guess,” said Hal sympathetically. “Gosh blame it, I’d like to help those poor people find that man so’s they could get away and live like civilized people.”

“I think,” said his uncle, after the captain had left them quite alone, “that you have enough on your hands right now. What with your worries about Pizella, my future worries about tracing these munitions to Renan, I think we have sufficient for two human minds.”

“Aw, we could tackle this Pemberton business afterward, couldn’t we, Unk? Even if we just stopped to pay them a friendly visit. Gol darn it, I should think they’d be tickled silly to talk to a couple of sympathetic Americans after living in the wilderness and surrounded by savages all their....”

“I take it this Pallida Mors will have you for a visit, come sunshine or storm, eh, Hal?”

“And how! A nice little surprise visit to the Pembertons,” Hal mused delightedly.

Destiny thought differently about it evidently, for Hal was the one to be surprised, not the Pembertons.

They departed from the main stream and proceeded up the black waters of the Rio Negro just after sunrise. Manaos, with its modern buildings, crowded streets and electric lights, was indeed a “city lost in the jungle,” for a half mile beyond the city limits, the jungle, primeval and inviolable, lay like a vast green canvas under the sparkling sunlight.

“No one in the city knows what is in that forest twenty miles away,” Señor Goncalves informed Hal and his uncle as they drew into the wharf. “Manaos does not care to know, Señors, for she prefers to be a little New York and forget the naked savages that roam the forests.”

“Believe me, I wouldn’t forget the naked savages if I was a Manaosan,” said Hal earnestly. “I’d take hikes into the jungle and see what was doing.”

“That is understood, Hal,” laughed his uncle. “But there are few Manaosans, if any, that are cursed with your snoopiness. Life apparently means much to them and they are far too wise to risk that precious gift just to find out what the wild, naked savage is doing in his own jungle. You don’t mean to tell me that you are adding the suburbs of Manaos to your already overcrowded itinerary!”

“Listen, Unk, I’m going to see all there is to see and you can’t blame me. Gol darn it, this is my first trip to Brazil and the Amazon, and I’ve only got a few months to see it in. Boy, it’s the chance of a lifetime maybe, so why miss anything?”

The dapper Brazilian twisted his trim little moustache and laughed.

“Ah, Señor Hal he has the right idea, Señor Keen,” he said. “He goes in for—what you call it—sport? Ah, but that is well. So I shall show him places—no? There are the movies to go to—even you shall see this afternoon a fine aviation field where is a great friend of mine, José Rodriguez. He is what you Americans call the Ace—yes?”

“Gosh,” Hal said, “I’d think it was immense to meet a Brazilian Ace. Think he’d like to take us up for a spin around?”

“Ah, that is just what I was going to suggest, Señor Hal. He is very kind, José. Perhaps you would like him to take you for the spin over the Manaos jungle, eh?”

“Great—immense!” Hal enthused. “You do think of things, Goncalves—I’ll say that for you! So we start this afternoon, huh?”

“To be sure, Señor Hal.”

It was something to look forward to and Hal did all of that while the amiable Señor escorted his uncle to Manaos’ best hotel. The trials of registering and selecting comfortable rooms always bored him and he preferred returning to the hostelry when all those formalities were over with.

Consequently, Hal strolled through the busy little city after having breakfast at a quaint coffee house. Up one street and down another, he ambled along with a grace that attracted attention wherever he went. Clad in white polo shirt, immaculate flannels and sport shoes, his splendid, towering physique and crown of red-gold hair stood out in bold relief against the short, dark-skinned Manaosans. More than one dusky damosel arrayed in New York’s latest fashion allowed herself a second glance at him in passing.

But Hal was invulnerable where the Manaos maidens were concerned. His weakness was adventure. Also, during the first part of his stroll he was too interested in watching the thousands of Amazonian vultures which hovered overhead. Garden after garden was crowded with strange birds: egrets with their delicate feathers, duckbills, curious snipe with claws in the bend of their wings, and parrots shrieking in an alien tongue as he passed.

Once he stopped to observe a blustering jaribu, or Amazonian heron, who was trying to lord it over two gorgeously plumed egrets. Suddenly he was aware of a shadow behind him, and when he turned he saw Pizella not ten feet distant. Hal swung completely about and faced the half-caste.

“You’re not,” he said calmly, “following me, are you?”

Pizella was inscrutable. He did not even slacken his shambling pace and as he caught up with Hal his shifty eyes were expressionless and seemed not to see his questioner. In point of fact, he even made so bold as to attempt to pass right by.

But Hal would have none of it. He leaned down from his great height and closed his large, slim hand tightly over the man’s scruff.

“I was talking to you, Pizella,” he said quietly. “Maybe you can’t understand my language, but, by heck, you can understand what my hand means.”

Pizella’s face never changed. He glanced up at Hal in that same expressionless manner as if he neither heard nor understood. To make matters worse a crowd began to gather and in a couple of seconds there was such a pushing, babbling and confusion that the half-caste got away.

Hal pushed through the throng after him but was destined to disappointment. Pizella was nowhere in sight. Gardens to the right of him, gardens to the left of him—the man might have escaped through any number of them. In any event, he was not to be found.

After searching for almost two hours, Hal turned back to the hotel, thoughtful and troubled.

“It’s got to look downright serious, Unk,” Hal said, after entering their rooms in the hotel. “It’s not just a coincidence, my meeting him like that, or he wouldn’t have pulled away when he saw his chance. Why wasn’t he reported to the police?”

“The captain promised me he would attend to it, Hal. Apparently he didn’t. I myself saw Pizella not fifteen minutes ago.”

“How—where?”

“Señor Goncalves has a room on the next floor,” Denis Keen explained. “I had occasion to think that perhaps I could get him to give me that letter to His Excellency, the interventor, this afternoon and I went up. Just as I got to the Señor’s room, whom was he showing out the door but Pizella.”

“Unk! You....”

“Wait a minute before you come to conclusions. I did. Goncalves acted annoyed more than surprised—I would even go so far as to say that he was somewhat agitated.”

“With you coming unexpectedly?”

“He directed a flow of abuse at the departing Pizella’s head. Told him not to show his nose around there again and words to that effect. Then, with his usual cheeriness and perfect hospitality, he invited me in and told me that Pizella had the brass to seek him out and ask him for a job as guide on his expedition. So that explained it.”

“What do you think about it, Unk?”

“Everything,” Denis Keen chuckled, and rose to fleck some ashes from his cigarette. “Perhaps that poor devil has really been seeking a job as guide right along. Perhaps that is why he did all that sneaking around the boat—one can’t get much out of him. He seems hopelessly ignorant and yet there’s always that sullen look and shifty eye to consider.... Oh, well, he’s either one thing or the other—an ignorant half-caste or an exceedingly clever half-caste. I’d like to know which.”

A knock sounded at the door and at their summons a boy entered with a note. Hal took it.

“From the Brazil-nut,” he said after the boy had gone. “Very informal. He says: ‘Will the Señors excuse me from accompanying them to the field at two o’clock this afternoon? Business will detain me, but I beg of the Señors to not disappoint my very good friend, José Rodriguez, as he has made arrangements and has set aside time to take you up for the spin—yes? A car will come for you at two, Señors.... Regretfully....’ He’s signed his name with a flourish, Unk. Well, it’s up to us to put in our appearance alone. I....”

“Then you’ll put in your appearance alone, Hal. I have no intention of going. I’ve got a more serious matter to attend to. Besides, I’m not keen about airplaning in any country—much less this. I’d be just as pleased if you didn’t go either.”

“Aw, Unk, you’d think I was some kid. Why, I can handle controls now like nobody’s business. Besides, this Rodriguez is an Ace! Do you suppose anything’s likely to happen just because we’re in Brazil? Gosh....”

“Oh, I know, Hal. It’s absurd, I suppose, for me to object to your going, but I guess you’re wishing some of that accursed hunch business on me. Something’s making me feel this way.” He laughed uneasily. “Perhaps I’m just a little upset about other matters. Still, promise me you’ll be careful—I could never face your mother if anything happened to you while you were with me.”

“Unk, you’re the limit! You’d think I had never set foot in a cockpit before! Why, Mother’s been up in the air with me. She says I’m a world beater and she’s going to let me try for my pilot’s license next year. Why, she came up with me twice when Bellair was down on a visit to teach me. Gosh....”

“All right, Hal,” said Denis Keen, pacing up and down the room. “You’re old enough to know what you’re doing, I suppose. This Bellair—he’s one of the famous brothers, eh? Oh, I know they’re considered expert airmen. Glad to hear they’ve taught you what you know. Guess they could give you some fair pointers as to what to do in a tight place, eh?”

“And how!” Hal exclaimed with a wry smile. “They don’t teach anything else but. They’re stunters on a large scale, and if you can’t learn about planes from them, you’ll never learn. But why all these questions about what I learned from the Bellairs, huh? Are you really afraid I might get into a tight place with an expert like this Rodriguez is supposed to be?”

“Well, strangers, you know, Hal ... methods are varied among airmen, aren’t they? Oh, I know you’re laughing up your sleeve. Now’s your chance to poke fun at me about hunches, eh? Well, I won’t give in to it, then. You go ahead. We’ll have luncheon, then I’ll ride with you in the car that Señor Goncalves has so generously sent for. The mansion of His Excellency, the interventor, is half-way toward the field, I’ve been given to understand.”

“You going there this afternoon, Unk? Why, I thought Goncalves was going to write that letter and fix it for you to go there tomorrow?”

“No, he changed all that when I saw him in his room just a while ago. He told me he had already telephoned the interventor, explaining my want of guides and an interpreter, and His Excellency, being terribly busy with the affairs of State, requested Señor Goncalves to arrange those matters himself.”

“In other words, the interventor doesn’t want to be bothered with you, huh, Unk? He wants the Brazil-nut to do the work.”

“So the dapper Señor told me in his inimitable way. But the fly in the ointment is this—Goncalves doesn’t know that it is the duty of the interventor to see me, neither does he know that it is of paramount importance for me to see His Excellency regarding Renan and Ceara before I leave Manaos. His Excellency apparently didn’t understand who the American Señor was whom Goncalves was trying to tell him about. They assured me when I left Rio that the interventor here would be notified of my coming. So I’m going this afternoon and no one is to be enlightened as to my whereabouts—no one! Understand, Hal?”

“Cross my heart and hope to die,” Hal laughed. “Go to it, Unk.”

“Most assuredly I will. I’ve got to see His Excellency about getting Federal aid. Do you know, Hal, I had the feeling when I was talking with Goncalves in his room that he wasn’t any too anxious for me to see the interventor! His attitude ... I don’t know ... perhaps, I imagined that too. Come on, let’s wash up and get down to luncheon before I hatch up some more hunches to worry about.”

“Unk,” Hal laughed, “you’re a chip off the young block and I don’t mean maybe.”

Hal got out of the car at the edge of San Gabriel aviation field and looked about. Leveled from the surrounding jungle, it was situated at the extreme end of the city and here and there over its smooth-looking surface were divers planes, some throbbing under the impetus of running engines and some still, with their spread wings catching the reflection of the afternoon sun.

Three good-sized hangars dotted the right side of the field and Hal caught a glimpse of mechanics busy within. Several groups of men stood about chattering, while here and there some nondescript individual loitered about with that solitary air that at once proclaimed him as being one of that universal brotherhood of hoboes.

One, whose features were distinctly Anglo-Saxon, despite the ravages which the South American climate had made upon his once fair skin, strolled over to Hal’s side the moment he espied him. He was hatless and his blond hair had been burned by countless Brazilian suns until it was a kind of burnt straw color. And his clothes, though worn and thin, gave mute testimony of the wearer having seen a far happier and more prosperous era than the present one.

Hal caught the look of racial hunger on his face and warmed toward him immediately.

“Hello, fellow,” said he with a warmth in his deep voice. “My name’s Keen—Hal Keen.”

A light shone from the stranger’s gray eyes.

“Carmichael’s mine, Keen,” he said pleasantly. “Rene Carmichael. Awfully glad to speak the English language with a fellow being.”

“But Americans aren’t speaking the English language, Carmichael,” Hal laughed with a twinkle in his deep blue eyes. “Nevertheless, as long as you can understand me, that’s all that counts, huh?”

“It’s music to my ears, Keen,” answered Carmichael gravely. “It’s deucedly odd how one will criticize Americans when one is safe at home, but just get away in this corner of nowhere and see the smiling face and broad shoulders of a Yankee pop up out of this dark-skinned crowd! I tell you, Keen, it makes a chap like myself almost want to fall on your shoulder and weep.” His weather-beaten face crinkled up in a smile, as he looked up at Hal. “You don’t carry a stepladder around with you so I can do that, eh?” he asked whimsically.

“Nope,” Hal laughed. “Notwithstanding my height, I couldn’t conceal it.” He glanced at Carmichael sympathetically. “Funny what you just said about Americans—I’ve thought that way about Englishmen too and yet as soon as I laid eyes on you, I felt just like you say you do. Kindred spirits and all that sort of thing, huh? Anyway, I guess the real trouble, the reason for all our prejudices is that we dislike everything we don’t know and, consequently, can’t understand, huh?”

“And now that you’ve met a regular Englishman—what is it, love at first sight?” His eyes danced with merriment.

“You’re aces high, Carmichael. I’m tickled pink we’ve run into each other, that’s a fact. My uncle and I were supposed to look for a Brazilian named Rodriguez out here who is dated to take us for a spin. Unk couldn’t come, so here am I alone. How would you like to take his place? I’d feel better if you came along—someone who can understand me.”

The fellow studied Hal closely for a moment, then nodded.

“I’ll come, but I shouldn’t really. I’m due to sail for Moura at four. I’ve got a toothbrush and one or two other necessities of life back at the hotel which I have to get.”

“Then you’re not a ho ...” Hal just caught himself in time. “Honestly, I’m sorry, awfully....”

“Save the effort, Keen. I love to be thought a hobo. As a matter of fact I am—in a sense. I’m very poor really, but I don’t have to wear my clothes as long as I’ve worn this suit. It’s just that it suits my—ah, purpose.” He laughed and his voice was musically resonant. “Literally, though, I’m not a hobo. I really do something for a living, and a hard enough living it is, old chap.”

“I believe it,” said Hal earnestly. He studied the fellow a moment, taking note of the buoyant broad shoulders and tall slender figure. For he was really quite tall, when one did not consider Hal’s towering height.

“You’re deucedly odd for what I’ve heard about Americans, Keen,” said Carmichael. “You’re straightforward and honest, and not a bit snoopy. Seem to take me at my face value and all that. No questions—nothing.”

“Why not?” Hal countered. “It wouldn’t be my business, Carmichael. But somebody’s given you a devil of an opinion of Americans! I know there are some pretty poor specimens that go shouting around in Europe, but there’s lots of the other kind too, and lots that stay at home. Well, I guess I’m the kind you haven’t heard about, huh? I’m snoopy in some things, though—don’t think I’m not.”

“Aren’t we all?” Carmichael returned. “It’s the way of life and people, I suppose. But there’re some kinds that get on a chap’s nerves. Yours is the kind that doesn’t. That’s why I want to tell you not to take seriously what I gave you to understand about my being from the continent. I’ve lived all my life in Brazil—perhaps that’s why I like to play for five minutes or so that I’m really a native of some other country. I was educated in an English school in Rio and for eight happy years I fooled myself that I was a citizen of some Anglo-Saxon country. No doubt that sounds deucedly odd coming from a chap born here. But I shall never assimilate Latin ways if I live to a ripe old age in this desolate corner of the world.” He laughed bitterly. “I can only hope then that I shall be allowed the company of Anglo-Saxons in the spirit world, eh, Keen?”

“If you wish to live among Anglo-Saxons as much as that, Carmichael, I should think you’d get your wish before you die.” He looked across the field and saw a short, helmeted figure coming toward them. “Don Rodriguez, I bet. He’s smiling, so that must be he. He’s smiling with recognition as if he’s been given a pretty accurate description of me.”

“And a description one could never forget,” said Carmichael. “You must tell me more about yourself, Keen—that is if you care to. If all Americans are like you, then I want to meet heaps of them.”

“Well, I’m glad I’ve done so much for my country,” Hal laughed. “And I’ll tell you all you want to hear. Wait until we get up in the air—we’ll have a little shouting party, huh?”

“Righto.”

The helmeted figure came straight to Hal with outstretched hand and black, smiling eyes.

“Señor Hal Keen—tall like a mountain and red at the top,” he said in broken English, and laughed. Then he turned to Rene. “And this is the Señor uncle—no?”

“Yes,” answered Carmichael with a swift chuckle, “his Dutch uncle.” And in an undertone to Hal, he said: “Do I look as old as that?”

“It depends on how old looking you think an uncle ought to look,” Hal grinned. “My unk seems like a kid to me yet. He’s not forty.”

“And I’m not thirty,” said Carmichael with a poignancy in his voice that did not escape Hal. But he was all laughter the next second and he added: “At that I can still be your Dutch uncle, eh? Your Uncle Rene?”

“I’ll tell the world you can! You are!” Hal turned then to the still-smiling Rodriguez. “When do we hop off in your bus?”

“Ah, to be sure,” said the aviator. “The plane, you mean, eh? She is there—see?” he said, pointing to a small, single-motor cabin plane. “Now shall we take a fly over the jungle, you and the Señor uncle?”

“Sure,” they answered unanimously. And as they followed at the aviator’s heels, Rene whispered: “I kind of like this, being your Dutch uncle. And as long as he thinks so....”

“Why bother to explain, huh?” Hal returned in the spirit of the thing. “There’s not that much difference between a real uncle and a Dutch uncle anyway.”

But Hal was to learn that there was a difference as far as Rodriguez was concerned.

When they got to the plane, Rodriguez proceeded on into his cockpit, motioning his passengers to make themselves comfortable in the tiny cabin. After a moment they were off.

They bumped across the field, then rose into the air, hesitated a moment as if they were going to fly straight for the jungle, then soared high into the blue. Hal nodded with satisfaction, after a half hour had elapsed.

“Some beautiful country,” he shouted at Carmichael. “Like a big painted canvas.”

“You wouldn’t think so if you got lost in it,” Rene shouted back. “This fellow’s taking us for quite a long hop, eh?”

Hal nodded and looked out of the tiny window down upon the endless sea of jungle over which they were passing. The plane roared on through the glistening blue and for a time neither of the young men spoke. Yet they were both aware of a peculiar sound coming from the motor. It was not missing, yet each revolution seemed more labored than the one preceding it.

Rene looked at Hal questioningly.

“I’ve traveled in these things plenty, but I don’t know a thing about them. But I can tell the thing isn’t running perfectly.”

“It isn’t,” Hal roared across to his newly found friend. “We’re going to have trouble in a sec and I don’t mean maybe. If I could talk to Rodriguez I could find out, but his English is painful and my Portuguese hasn’t even begun.”

“If that’s the difficulty, Hal,” said Rene unconsciously using the name with all the affection of an old acquaintance, “why, I can help you out that way. I can speak Rodriguez,” he added with a conscious chuckle.

“Gosh, that’s fine,” said Hal. “Come on, we’ll pile up there and you ask him.”

The Brazilian seemed surprised to see his two passengers appear in the narrow, low doorway of his cockpit. In point of fact, Hal sensed that he was even startled. The smile that he gave them looked twisted and forced.

Carmichael questioned him in Portuguese, an undertaking which seemed interminable to Hal. Meanwhile, the engine sounded worse and after another second it began to miss. They were in for trouble. Rodriguez’ gloomy face augured the worst.

Hal noticed then with something of a start that he was wearing a chute. Neither he nor Carmichael had been asked to wear one and he wondered why. It puzzled him greatly.

“Ask him what’s the idea?” Hal queried, drawing Carmichael’s attention to the pilot’s chute. “Do we look like orphans? We’re his guests.”

Carmichael stared at the chute, then grabbed Rodriguez roughly by the shoulder and a flow of Portuguese ensued. Suddenly he turned back to Hal, his weather-beaten face a little drawn.

“Of all absurd excuses, Keen—he says he didn’t think to ask us if we wanted one. This is the only one on this plane—the one he’s safely wearing. He also says the bus is doomed—comforting news. We’re no less than two hundred miles from Manaos already and there isn’t a deuced place for him to land in this jungle.”

“Then if he thinks we’re doomed, why the devil doesn’t he turn back!” Hal said impatiently. “What’s the idea of continuing north? Besides there might be a place we can find if he’s got the nerve to fly low enough to see. There’s a chance that we’ll pancake and get a bit banged up, of course, but it’s better than letting a bus crack up right under our noses without us making any attempt to prevent it! If you ask me—he’s yellow!”

“I’m thinking so too, Keen.” Carmichael frowned. “You seem to know more about planes than this chap—at least you use your head in a pinch. What do you think the chances are if we landed as you suggest. It’s dense jungle right below.”

“If we could find a bit of a clearing we could take it easy and let her go nose first. One thing, I guess it’s all swamp down there, huh? Well, that’s a help—it makes a softer berth. But to answer your question—if we can find a clearing large enough, there’s a darn good chance for us skinning through whole.”

“But little chance of us getting out,” said Carmichael thoughtfully. “I can answer that, for I know the jungle. One of us ought to bail out in that chute right away and take a chance that this east wind blows him near enough to a settlement so that help could be had. It’s necessary for one of us to go, Keen. Otherwise we’ll all be lost. As long as Rodriguez is wearing the chute....”

“No,” said Hal decisively, “we’ll flip a coin. Heads goes with the chute, tails stays. It’ll be between you and me, then between Napoleon there and yourself. O. K.?”

“Suits me. Here goes—I’ll spin,” said Carmichael, taking a Brazilian coin out of his pocket and flipping it in the air. “Yours first, Keen,” he called as the coin came down on his palm.

It was tails. Carmichael’s flip brought heads and with the next turn the pilot lost too. Hal lost no time in ripping the chute from him and adjusting it on Carmichael.

“Good luck to you, fellow,” he said. “I’ll try to find a spot as near here as possible. Have you got our position.”

Carmichael nodded gravely. Rodriguez uttered a little squeal, the color went from his face and in a second the plane began to wobble. Hal pulled him from behind the wheel and himself righted the ship.

“I’ll keep hold of her now,” he assured Carmichael who stood anxiously in the low doorway of the cockpit. “Our brave Ace isn’t fit to steer a baby carriage. He hasn’t morale enough to keep himself going, much less a ship. All right, now, I’m giving you enough altitude to let you clear us nicely. Can’t keep it up more than a couple of minutes though. Listen to her missing! Bail out now, Rene,” he added, using the latter’s Christian name unconsciously. “See you later.”

“Sooner than that, Hal,” Carmichael smiled wistfully. “Promise me you’ll be careful.”

“Doggone right I will! Scoot now!”

Hal knew he was going, knew he was gone. There was that about Carmichael, he felt, that one immediately missed—that effulgent something which seemed to radiate from his slim person. Now that light had gone with him and there was no sound but the unsteady throb of the motor. Rodriguez was huddled over in the corner of the cockpit shivering, with his eyes fixed fearfully over the illimitable roof of the jungle.

Hal, however, had ceased to consider his presence at all. Moreover, there wasn’t time. Every precious second he used in circling lower and lower over the glistening green jungle and trying to remember word for word the valuable advice that the famous brothers Bellair had given him as to what could be done in a pinch.

He had cut down a thousand feet, then two thousand, and then he could pick out the colorful birds flying from tree to tree. A few hundred feet more and he could see them quite plainly. After that he dared to let her dive a little and coming out on an even keel he saw something between the dense foliage that made his heart thump.

It was a clearing.

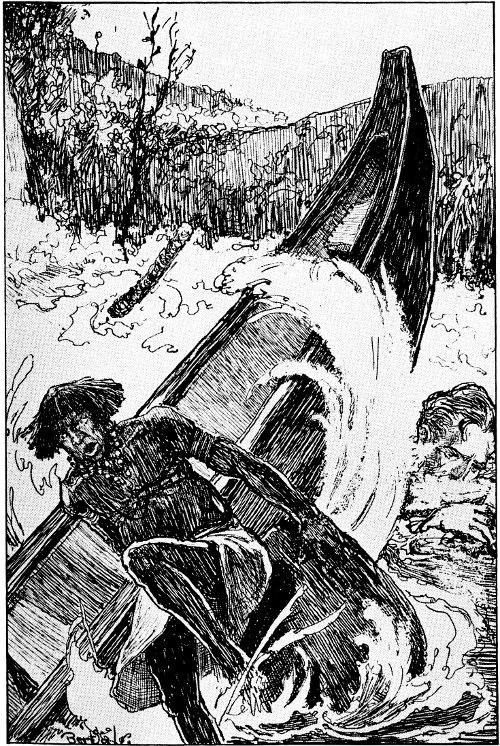

Hal shut down the motor after that, let the plane circle once more under its own momentum, then pointed her nose straight down toward the clearing.

Within a flash he had slid from behind the wheel, reached over in the corner and dragged Rodriguez by the collar, pulling him into the cabin with a swift jerk. That accomplished, he flung himself down to the floor, head down, and called to the cowardly pilot to do the same.

Hal tried to keep his mind a blank during the ensuing seconds. Rodriguez’ shrieks of fear, the tearing, ripping sounds of the fabric, and the shattering of glass did not make him move a muscle. And when he did stir it was by force, for the plane thrust her nose into the swampy ground with such an impact that he was thrown the length of the cabin floor.

There was another terrific vibration, another shattering of glass and, before the plane settled her nose in the mud, Hal and the pilot were whisked summarily against the cockpit door. Then all was still.

Hal straightened up as best he could. His head felt bruised and when he looked at his hands they were covered with blood. Aghast, he saw that it came from Rodriguez, who was lying quite still beside him in a pool of blood. An ugly gash had severed the fellow’s dark throat—his lips were gray.

Hal tumbled about in getting out his handkerchief from his back pocket, for the tail of the ship was in mid-air, and he was all confused. But he managed to bandage the pilot’s throat temporarily and set about rubbing his wrists. At that juncture an ominous smell floated by with the jungle breeze.

“Ship’s caught afire, all right,” he muttered, as a small spiral of blue smoke floated past the shattered window at his elbow.

Hal was out of it in a moment, jumping down into the soggy ground and pulling the unconscious Rodriguez after him. A rumble sounded through the plane and the next second it was enveloped in high, shooting flames.

Hal stumbled and tripped, sinking into mire over his ankles. But he managed to drag Rodriguez’ heavy, inert body along, dodging and trampling down bushes, creepers, and clinging vines that grew in the little spaces between the tree trunks.

HAL MANAGED TO DRAG RODRIGUEZ’ HEAVY, INERT BODY ALONG.

After what seemed an endless journey to him, he came at last to a sort of eminence, a tiny area of higher ground that showed evidences of having been a former human habitation. The jungle, however, was beginning to reclaim it, for the whole space was covered with a substantial growth.

Hal looked about thoughtfully, but seeing that it was the only suitable spot in sight, he lay Rodriguez down carefully. After that he hunted around them for a few sticks of wood and started a fire to keep away the mosquitoes.

That done, he set about trying to revive the pilot and after a trying five minutes saw his eyelids flicker, then open.

“It’s I, Rodriguez! Keen! We’re here—safe! How you feeling?”

The fellow seemed to understand perfectly, for he nodded and a look of hope came into the black eyes that were so filled with fear not fifteen minutes before. Hal noted that his lips, however, were an ashen gray.

“You saved the plane—yes?” Rodriguez muttered weakly.

“Nope,” Hal answered, shaking his head vigorously. “It’s up in smoke—fire. We should worry though, huh? We’re saved, anyhow.”

Rodriguez smiled feebly and lifted his head, looking around, interested. Suddenly he put his hand to his bandaged throat and a terrified expression filled his eyes.

“Is it danger—no?” he asked Hal.

“No,” Hal lied. “You’ve just got a bad cut, Rodriguez. You’ve lost a lot of blood. Just lie still and take it easy. I’ll get some more wood to keep these pesky mosquitoes away.”

“The glass she cut me—no?” He seemed to be obsessed by his wound.

“I’ll say she did. That’s why I wanted you to lie face down as I did. I knew we were in for something.”

“I feel weak like baby.”

“I’m sorry, old fellow,” said Hal sincerely. “I’m sorry we couldn’t let you take the chute and escape all this, but it wouldn’t have been sporting. Understand?”

The pilot nodded weakly. He even smiled.

“I was not frightened for death so much, Señor Hal. More I was frightened for myself—my sins.”

Hal frowned until his freckled brow wrinkled into one deep channel between his bright blue eyes. Then a light of understanding spread over his fair face and he smiled.

“Oh, you mean your religion, huh, Rodriguez?” he asked. “You mean you were afraid of your sins in case you did die, huh?”

Rodriguez made the sign of the cross and his dark-skinned hands fell limply to his sides.

“Yes, yes, Señor. My sins were many—too many to die a peaceful death, Señor. I would have to tell you....” He closed his eyes and seemed to doze off.

Hal shrugged his shoulders and got up. He could hear the burning plane snapping and cracking against its steel frame. Its acrid fumes carried on the breeze even to where he stood and hung heavily on the air in a blue haze.

A monkey scolded sharply from a near-by tree and instinctively Hal picked up a piece of dead limb and swung it at him.

“Can’t you see there’s a sick boy here who needs sleep!” he stage whispered to the animal above them.

The monkey stared down with an almost sad expression on its little old face. Then after he scolded some more he swung along to the opposite branch and was soon swallowed up in the dense foliage.

Hal continued to gather more wood after that, looking at his patient at five-minute intervals. But Rodriguez slept on, despite the fact that a fresh bandage had been adjusted—the pilot’s own handkerchief.

It was almost dark in the dense forest before Hal stopped. His pile of wood had become quite high—enough to do them for the long night, he thought, as he sat down on it to have a smoke.

A parrot screeched somewhere in the distance, the jungle teemed with life and sound, and yet it seemed to Hal he had never sat in such oppressive silence before. Suddenly, to his great delight, Rodriguez awakened and, noting the glow of their campfire, smiled.

“Ah, it is comfort, the fire,” he sighed. “You know the jungle—no?”

“Yes,” Hal answered with a cheerful smile. “I’ve been in Panama—yes. I know the jungle.”

“Ah,” the pilot sighed weakly and closed his eyes again.

Hal glanced at him quickly and a fear asserted itself. Rodriguez’ throat was still bleeding profusely—the fellow’s face had a ghastly look in the firelight.

Did it mean death?

The black vault of heaven with its twinkling stars could be seen in narrow strips through the entangled tops of closely growing trees. Hal looked up at it longingly from time to time and wondered if a searching party did come flying overhead, whether or not they would be able to penetrate the dense screen and see them.

Their campfire, though piled so high, seemed pitifully inadequate for such a purpose, and he experienced a sinking sensation in his stomach when he thought how much less it could be seen in the daylight. Too, Carmichael might not be any better off than they. Parachutes very often failed one. Perhaps it would have been better if they had all stuck and taken their chances together. Rodriguez was in such a bad way.... Hal had long ago given up trying to stop the bleeding. But he felt so hopeless about it, so helpless. There seemed nothing for him to do but sit and wait.

He leaned over to the woodpile from time to time, replenishing the blaze. Sometimes Rodriguez would sigh, then sink into a deeper sleep than before. Hal was always hoping that the sleep was doing him good, but it occurred to him after a time that the pilot’s strength was slowly ebbing and that it wasn’t slumber, but a torpor which held him in its grip.

His heart went out to the young man and he completely forgave him his cowardice. Certainly Rodriguez was getting the worst of it. Perhaps it was true that he had feared the consequences of his sins more than his actual departure from life. Hal shrugged his shoulders at the thought—the Latin temperament was indeed strange.

For a little while after that, Hal began to think of food and water. He had had neither since luncheon and, for a healthy young man with his appetite, that was a fearful length of time to go without nourishment. But that too seemed an after consideration in the face of the present pall that hung over that strange little jungle camp.

Hal reached out and taking Rodriguez’ hand felt of his pulse. He knew little about such things, yet enough to realize that the pilot’s pulse beats were anything but normal. At times he could barely distinguish any pulsation at all. Moreover, the fellow’s hand felt cold and clammy in his own.

When he went to relinquish his hold, Rodriguez showed some resistance. He held feebly to Hal’s warm, strong hand and smiled.

“I feel not so cold, Señor,” he explained hesitantly. “It’s....” he seemed too weak to say more.

“You mean it makes you feel better and warmer for me to hold on to your hands?” Hal asked him solicitously.

Rodriguez nodded.

“All right, fellow. Here, give me the other one—I’ll rub them, huh? We’ll have a little holding hands party.” Hal chuckled, trying not to see the questioning, poignant look in the pilot’s eyes.

He went to sleep again this way, but Hal kept hold of both his hands, pressing them with his own at intervals. It gave him a peculiar sensation, this maternal gesture on his part, and if he had not felt so utterly sad about Rodriguez’ condition he would have been abashed at his display of tenderness.

The long hours crept by—a glimpse of full moon showed in a single silver moonbeam through the trees. From the depths beyond the clearing came the mournful sound of living things unseen. The weird plaint of the sloth came drifting down the breeze, tree frogs and crickets clacked and hummed with a monotony that was utterly depressing, and once the air shook with a thunderous concussion from some falling tree.

Hal started but it did not seem to bother the airman. He merely moved in his torpor and muttered unintelligibly. After five minutes of this he spoke aloud, feebly yet clearly.

“It was for the Cause, Señor ... the Cause. Señor Goncalves he too did it for the Cause. But ah, how it troubles me, Señor....”

“What troubles you, Rodriguez?” Hal asked, pressing gently down on his hand. “What are you talking about, fellow?”

The airman seemed not to hear, however, but went on muttering, sometimes aloud, sometimes not. Hal came to the conclusion that he was in a sort of delirium and realized that he ought to have water for the suffering fellow. Suddenly he began talking again:

“Señor Goncalves he came to me and asked would I take the Señors, uncle and nephew, up for the Cause ... for the Cause. I was to wear the chute—I was to escape, Señor ... escape, eh?” He laughed feebly, bitterly. “Ah, but I am punished ... punished. It is I who don’t escape, eh? I who would see two innocent Señors die for the Cause ... now....”

There sounded then through that dark, breathless atmosphere a call steeped in wretchedness and black despair—the wail of that lonely owl, known to bushmen as “the mother of the moon.” Hal had heard many times when lost in the jungle of Panama what portent was in that cry, and he was thinking of it then when Rodriguez raised his head with effort.

“Ah, Señor Hal!” he cried in a terrified whisper. “’Tis ‘the mother of the moon’ and evil to me, for I have heard it. Ah, Señor....”

“Lie back, old fellow,” Hal soothed him. “Now there, calm down! I’ve heard about Old Wise Eyes too, but you don’t think I believe it, do you? Back in the good old U. S. we’d call that hokum pure and simple. Nothing to it. It’s just an old owl hooting his blooming head off because he hasn’t the brains to do anything else. In other words he’s yelling whoopee in Portuguese or Brazilian or whatever you spiggotty down here. I bet you haven’t understood a word of what I said? No? Well, I don’t blame you exactly.”

“I have not much time, Señor. I am weak ... the owl she....”

“Now for the love of Pete, Rodriguez, forget it!” Hal said, scolding him gently. “It tires you too much to talk about such hokum. Lie still and if you can only hold out perhaps Señor Carmichael will get help to us soon. He may have got a break and landed near some settlement.”

“Señor ... Carmichael?” asked the airman faintly.

“Sure,” Hal answered smiling, “that’s the fellow who went out in the chute—the fellow who came up with us. His name’s Carmichael. Oh say, I almost forgot, Rodriguez—of course you wouldn’t understand—Carmichael and I were only fooling you about him being my uncle. My real uncle couldn’t come—he backed out at the last minute. I met Carmichael at the field just before you came along. Understand?”

Rodriguez did understand—only too well. His ghastly face looked more ghastly than ever. He pressed desperately on Hal’s warm hand and sighed. Suddenly he released his own right hand and from forehead to breast devoutly made the sign of the cross.

“Señor Hal,” he gasped, “I am dying ... there is something I must tell....”

“Aw, Rodriguez, you’re just feeling kind of low down, that’s all,” Hal soothed him. “In the morning you’ll be shipshape, you’ll see. Things are just sort of looking black to you.”

“I am dying, Señor Hal!” Rodriguez repeated. “You must listen or I shall not die peacefully!”

“Aw, all right, old top. If it eases you to tell me something, go ahead. But you’ll be as fit as a top in the morning. From what I know of Brazil-nuts, they’re pretty darn hard to crack,” Hal added facetiously.

The ghost of a smile flickered about Rodriguez’ ashen lips but soon he was grave again.

“I am for the Cause,” he said faintly; “I pledged my life, my honor for the Cause if need be, Señor.”

“You don’t mean the rebels?” Hal asked, taking a moment to replenish the fire.

“Ah, you call it that, Señor. To us it is the Cause. We want freedom—political.”

“That’s what all you birds say. But go on, Rodriguez.”

“Señor Goncalves he is a comrade of mine, Señor—a comrade in the Cause. And Señor Pizella....”

“Aha, we’re getting somewhere,” Hal interposed, taking a sudden interest. “Pizella, huh, Rodriguez?”

“Yes, Señor. He was given command to follow your Señor uncle, for you were suspect to what you call—thwart?... yes, thwart General Ceara’s plans. The General he expect big munition shipment and your Señor uncle he was suspect to perhaps prevent the guns from coming. So Pizella he was told to find out if Señor Keen had letter and what it say about what he was going to do.”

“And it was Pizella who took that letter from my uncle when we were sleeping, huh?”

“Yes, Señor Hal. And that night when passengers are in saloon, Pizella he takes letter to Señor Goncalves’ cabin and leaves it there for him to decipher. They work together—no, Señor?”

“I hope to tell you they do,” Hal said thoughtfully. “Just as I suspected from the beginning, but Unk wouldn’t listen to anything about Goncalves. Yet he must have suspected something this afternoon ... but go on, Rodriguez.”

“Señor Goncalves he find out from letter that your Señor uncle is on trail of Ceara’s munition shipment—no? That Señor Goncalves is ordered by Ceara not to let happen. He must do anything, everything to prevent—yes? Señor Goncalves thinks one way—to invite your Señor uncle up in plane with me—the plane she is crippled over the jungle and what happens—no?”

“Yes,” Hal answered grimly. “I see. It was all a hoax—a plot, huh? Only I was the fly in the ointment. To get Unk to fly, you people had to get me interested, but it fell out anyway. Unk has probably found out everything from the interventor by now—I wouldn’t doubt but that they’re even suspecting foul play with me already. But Goncalves, they’ll get him....”

“Ah, if they can, Señor. But the Señor he was gone after noon today. He is now with the General Ceara and they are traveling toward a safe hiding place in the jungle.” Rodriguez gasped at this juncture and lay still a long time because of his extremely weakened condition.

Hal looked at him, sympathizing, yet doubting. Suddenly he leaned over the Brazilian.

“But why are you telling me all this, Rodriguez? Isn’t it against your famous Cause?”

“Ah, but yes,” answered the airman in such a whisper that Hal had to listen intently. “But when one is dying ... one’s sins against one’s brother man.... Señor Hal, my religion prompts this. My soul she would never rest unless I asked your forgiveness.”

“Rodriguez, old scout, I still insist you’re not going to die, but if it makes you get stronger, I’ll tell you that I have nothing in my heart toward you but good will. What have you done to me? Oh, I know I could have been cracked up plenty, but the thing is, I’m not.”

“Not yet, not yet. But you are two hundred miles perhaps from white man, Señor. It is fever and jungle—no water, savage Indians before you get out. Señor Hal, you will die and I am the cause. I send you to it and it makes me afraid to die.”

“Bosh, old egg,” Hal said with a cheerfulness that he did not quite feel. “I’m a lean horse for a long race and, as I told you, I’ve been lost in the jungle before. Of course not quite as serious as this—I didn’t have a lot of bloodthirsty Indians to take into account. Still, I can handle that when I come to it. Where there’s a will, huh? But say, let’s not talk of gloomy things—tell me how you managed to get that plane crippled just at the crucial moment?”

“A powder, Señor, like sand,” he gasped. “She was poured into the oil—enough to make her grind up the engine in the hour—no?”

“I’ll say it would. Clever trick. A gritty substance, huh? Enough to completely disrupt the machinery. Well, it did all right. And how! And you were supposed to try and save yourself as best you could with the chute, huh? Well, I’m sorry now we didn’t let you do it. You wouldn’t be feeling so rotten now. Carmichael’s the kind that can skim through things, I’m certain. I can’t believe he won’t get out.”

“It is my punishment, Señor, my religion she slaps back for thinking too much of the Cause and not enough of human life ... your life!”

“As I told you before, Rodriguez, forget about me. I’m not holding it against you. I’m alive and kicking so far, and if I don’t keep it up, well, then I’m not as good a guy as I thought I was. I’ve got brains and the Indians haven’t. Fever and water and ... well, I haven’t got them yet, but if I do, I’ll pull through.”

“And if not, Señor Hal, would you curse José Rodriguez?” asked the airman pathetically. “Would you curse me if the Indians....”