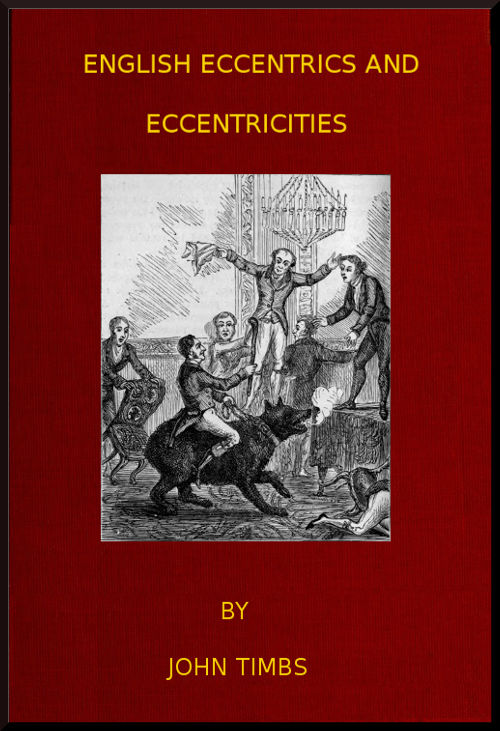

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain. The illustration is of Squire Mytton on his bear. (Page 48)

Title: English Eccentrics and Eccentricities

Author: John Timbs

Release date: November 12, 2015 [eBook #50439]

Most recently updated: October 22, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Whitehead, Chris Curnow and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain. The illustration is of Squire Mytton on his bear. (Page 48)

The Earl of Bridgewater and his dogs.

GENTLE READER, a few words before we introduce you to our Eccentrics. They may be odd company: yet how often do we find eccentricity in the minds of persons of good understanding. Their sayings and doings, it is true, may not rank as high among the delicacies of intellectual epicures as the Strasburg pies among the dishes described in the Almanach des Gourmands; but they possess attractions in proportion to the degree in which "man favours wonders." Swift has remarked, that "a little grain of the romance is no ill ingredient to preserve and exalt the dignity of human nature, without which it is apt to degenerate into everything that is sordid, vicious, and low." Into the latter extremes Eccentricity is occasionally apt to run, somewhat like certain fermenting liquors which cannot be checked in their acidifying courses.

Into such headlong excesses our Eccentrics rarely stray; and one of our objects in sketching their ways, is to show that with oddity of character may co-exist much goodness of heart; and your strange fellow, though, according to the lexicographer, he be outlandish, odd, queer, and eccentric, may possess claims[vi] to our notice which the man who is ever studying the fitness of things would not so readily present.

Many books of character have been published which have recorded the acts, sayings, and fortunes of Eccentrics. The instances in the present Work are, for the most part, drawn from our own time, so as to present points of novelty which could not so reasonably be expected in portraits of older date. They are motley-minded and grotesque in many instances; and from their rare accidents may be gathered many a lesson of thrift, as well as many a scene of humour to laugh at; while some realize the well-remembered couplet or the near alliance of wits to madness.

A glance at the Table of Contents and the Index to this volume will, it is hoped, convey a fair idea of the number and variety of characters and incidents to be found in this gallery of English Eccentrics.

It should be added, that in the preparation of this Work, the Author has availed himself of the most trustworthy materials for the staple of his narratives, which, in certain cases, he has preferred giving ipsissimis verbis of his authorities to "re-writing" them, as it is termed; a process which rarely adds to the veracity of story-telling, but, on the other hand, often gives a colour to the incidents which the original narrator never intended to convey. The object has been to render the book truthful as well as entertaining.

John Timbs.

| Gilray and his Caricatures | 330 |

| William Blake, Painter and Poet | 339 |

| Nollekens, the Sculptor | 350 |

"Vathek" Beckford.

THE histories of the Beckfords, father and son, present several points of eccentricity, although in very[2] different spheres. William Beckford, the father, was famed for his great wealth, which chiefly consisted of large estates in Jamaica; and the estate of Fonthill, near Hindon, Wilts. He was Alderman of Billingsgate Ward, London, and a violent political partisan with whom the great Lord Chatham maintained a correspondence to keep alive his influence in the City. When Beckford opposed Sir Francis Delaval to contest the borough of Shaftesbury, the latter said—

Art thou the man whom men famed Beckford call?

To which Beckford replied—

Art thou the much more famous Delaval?

Alderman Beckford died on the 21st of June, 1770, in his second mayoralty, within a month after his famous exhibition at Court, when, after presenting a City Address to George III., and having received his Majesty's answer, he was said to have made the reply which may be read on his monument in Guildhall, but which he never uttered. The day before Beckford died, Chatham forced himself into the house in Soho Square (now the House of Charity), and got away all the letters he had written to the demagogue Alderman. His house at Fonthill, with pictures and furniture to a great value, was burnt down in 1755. The Alderman was then in London, and on being informed of the catastrophe, he took out his pocket-book and began to write, and on being asked what he was doing, he coolly replied, 'Only calculating the expense of rebuilding it. Oh! I have an odd fifty thousand pounds in a drawer, I will build it up again; it won't be above a thousand pounds each to my different children.' The house was rebuilt.

The Alderman had several natural sons, to each of whom he left a legacy of 5,000l.; but the bulk of his[3] property went to his son by his wife, who was then a boy ten years old, and is said to have thus come into a million of ready money, and a revenue exceeding 100,000l. Three years later, Lord Chatham, who was his godfather, thus describes him to his own son William Pitt—"Little Beckford is just as much compounded of the elements of air and fire as he was. A due proportion of terrestrial solidity will I trust come and make him perfect." The promise which his liveliness and precocity had given, was fulfilled by a jeu-d'esprit, written by him in his seventeenth year. This was a small work published in 1780, entitled Biographical Memoirs of Extraordinary Painters, and originated as follows. The old mansion at Fonthill contained a fine collection of paintings, which the housekeeper was directed to show to applicants; but she often told descriptions of the painters and the pictures, which were very ludicrous. Young Beckford, therefore, to methodize and assist the housekeeper's memory, wrote their lives, which she received from her youthful master as matters-of-fact. Thus, after descanting on Gerard Douw, she would add the particulars of that artist's patience and industry in expending four or five hours in painting a broomstick. There were other extravagancies which she believed; a few copies of the book were printed to confirm her belief; hence the book is very rare. Beckford, in after-life, spoke of it as his Blunderbussiana. It was, in fact, a satire upon certain living artists, and the common slang of connoisseurship.

Young Mr. Beckford had been educated at home: he was quick and lively, and had literary tastes; he had a great passion for genealogy and heraldry, and studied Oriental literature. He had visited Paris, and mixed in the society of that capital, in 1778, when he met Voltaire, who gave him his blessing. He had fine taste for music, and had been taught to play the pianoforte by Mozart.

Mr. Beckford travelled and resided abroad until his[4] twenty-second year, when he wrote in French Vathek,[1] a work of startling beauty. More than fifty years afterwards he told Mr. Cyrus Redding that he wrote Vathek at one sitting. "It took me," he said, "three days and two nights of hard labour. I never took off my clothes the whole time. This severe application made me very ill.... Old Fonthill had a very ample loud echoing hall—one of the largest in the kingdom. Numerous doors led from it into different parts of the house through dim, winding passages. It was from that I introduced the Hall—the idea of the Hall of Eblis being generated by my own. My imagination magnified and coloured it with the Eastern character. All the females in Vathek were portraits of those in the domestic establishment of old Fonthill, their fancied good or ill qualities being exaggerated to suit my purpose." An English translation of the work afterwards appeared, the author of which Beckford said he never knew; he thought it tolerably well done.

At twenty-four, Mr. Beckford married the Lady Margaret Gordon, daughter of Charles, fourth Earl of Aboyne, but the lady died in three years. In 1784 he was returned to Parliament for Wells; in 1790 he sat for Hindon; but in 1794 he accepted the Chiltern Hundreds, and again went abroad. He now fixed himself in Portugal, where he purchased an estate near Cintra, and built the sumptuous mansion, the decoration and desolation of which some years afterwards Lord Byron described in the first canto of his Childe Harold, in the stanza beginning—

Many years after, Mr. Beckford published his Travels, one volume of which was An Excursion to the Monasteries of Alcobaça and Batalha. Of the kitchen of the magnificent Alcobaça, he gives the following glowing picture:—"Through the centre of the immense and groined hall, not less than sixty feet in diameter, ran a brisk rivulet of the clearest water, flowing through pierced wooden reservoirs, containing every sort and size of the finest river-fish. On one side, loads of game and venison were heaped up; on the other, vegetables and fruit in endless variety. Beyond a long line of stoves extended a row of ovens, and close to them hillocks of wheaten flour whiter than snow, rocks of sugar, jars of the purest oil, and pastry in vast abundance, which a numerous tribe of lay-brothers and their attendants were rolling out and puffing up into a hundred different shapes, singing all the while as blithely as larks in a cornfield!" The banquet is described as including "exquisite sausages, potted lampreys, strange messes from the Brazils, and others still more strange from China (viz. birds'-nests and sharks'-fins) dressed after the latest mode of Macao, by a Chinese lay-brother. Confectionery and fruits were out of the question here; they awaited the party in an adjoining still more sumptuous and spacious saloon, to which they retired from the effluvia of viands and sauces." On another[6] occasion, by aid of Mr. Beckford's cook, the party sat down to "one of the most delicious banquets ever vouchased a mortal on this side of Mahomet's paradise. The macédoine was perfection, the ortolans and quails lumps of celestial fatness, the sautés and bechamels beyond praise; and a certain truffle-cream was so exquisite, that the Lord Abbot piously gave thanks for it."

Mr. Beckford returned to England in 1795, and occupied himself with the embellishment of his house at Fonthill. Meanwhile, he had studied Ecclesiastical Architecture, which induced him to commence building the third house at Fonthill, considering the second too near a piece of water. In 1801, the superb furniture was sold by auction; when the furniture of the Turkish room, which had cost 4,000l., realized only 740 guineas. Next year there was a sale in London of the proprietor's pictures. In 1807 the mansion was mostly taken down, when the materials were sold for 10,000l.; one wing was left standing, which was subsequently sold to Mr. Morrison, M.P., who added to it, and adapted it for a country seat.

These proceedings were, however, only preliminary to the commencement of a much more magnificent collection of books, pictures, curiosities, rarities, bijouterie, and other products of art and ingenuity, to be placed in the new "Fonthill Abbey," built in a showy monastic style. Mr. Beckford shrouded his architectural proceedings in the profoundest mystery: he was haughty and reserved; and because some of his neighbours followed game into his grounds, he had a wall twelve feet high and seven miles long built round his home estate, in order to shut out the world. This was guarded by projecting railings on the top, in the manner of chevaux-de-frise. Large and strong double gates were provided in this wall, at the different roads of entrance, and at these gates were stationed persons who had strict orders not to admit a stranger.

The building of the Abbey was a sort of romance. A[7] vast number of mechanics and labourers were employed to advance the works with rapidity, and a new hamlet was built to accommodate the workmen. All round was activity and energy, whilst the growing edifice, as the scaffolding and walls were raised above the surrounding trees, excited the curiosity of the passing tourist, as well as the villagers. It appears that Mr. Beckford pursued the objects of his wishes, whatever they were, not coolly and considerately like most other men, but with all the enthusiasm of passion. No sooner did he decide upon any point than he had it carried into immediate execution, whatever might be the cost. After the building was commenced, he was so impatient to get it furnished, that he kept regular relays of men at work night and day, including Sundays, supplying them liberally with ale and spirits while they were at work; and when anything was completed which gave him particular pleasure, adding an extra 5l. or 10l. to be spent in drink. The first tower, the height of which from the ground was 400 feet, was built of wood, in order to see its effect; this was then taken down, and the same form put up in wood covered with cement. This fell down, and the tower was built a third time on the same foundation with brick and stone. The foundation of the tower was originally that of a small summer-house, to which Mr. Beckford was making additions, when the idea of the Abbey occurred to him; and this idea he was so impatient to realize, that he would not wait to remove the summer-house to make a proper foundation for the tower, but carried it up on the walls already standing, and this with the worst description of materials and workmanship, while it was mostly built by men in a state of intoxication.

To raise the public surprise and afford new scope for speculation, a novel scene was presented in the works in the winter of 1800, when in November and December nearly 500 men were employed day and night to expedite the works, by torch and lamp-light, in time for the reception of[8] Lord Nelson and Sir William and Lady Hamilton, who were entertained here by Mr. Beckford with extraordinary magnificence, on December 20, 1800. On one occasion, while the tower was building, an elevated part of it caught fire and was destroyed; the sight was sublime, and was enjoyed by Mr. Beckford. This was soon rebuilt. At one period, every cart and waggon in the district were pressed into the service; at another, the works at St. George's Chapel, Windsor, were abandoned that 400 men might be employed night and day on Fonthill Abbey. These men relieved each other by regular watches, and during the longest and darkest nights of winter it was a strange sight to see the tower rising under their hands, the trowel and the torch being associated for that purpose. This Mr. Beckford was fond of contemplating. He is represented as surveying from an eminence the works thus expedited, the busy bevy of the masons, the dancing lights and their strange effects upon the wood and architecture below, and feasting his sense with this display of almost superhuman exertion.

Upon one memorable occasion Mr. Beckford was willing to run the risk of spoiling a good dinner, in order to show that nothing possible to man was impossible to him. He had sworn by his beloved St. Anthony, that he would have his Christmas dinner cooked in the new Abbey kitchen. The time was short, the work was severe, for much remained to be done. Still, Beckford had said it, and it must be done. So every exertion that money could command was brought to bear. The apartment, indeed, was finished by the Christmas morning, but the bricks had not time to settle readily into their places, the beams were not thoroughly secured, the mortar, which was to keep the walls together, had not dried. However, Beckford had invoked the blessed St. Anthony, and he would not depart from it. The fire was lit, the splendid repast was cooked, the servants were carrying the dishes through the long passages into the[9] dining-room, when the kitchen itself fell in with a loud crash; but it was not a misfortune of any consequence; no person was injured, the master had kept his word, and he had money enough to build another kitchen.

Mr. Loudon, in 1835, collected at Fonthill some curious evidence in confirmation of his idea that Mr. Beckford's enjoyments consisted of a succession of violent impulses. Thus, when he wished a new walk to be cut in the woods, or work of any kind to be done, he used to say nothing about it in the way of preparation, but merely give orders, perhaps late in the afternoon, that it should be cleared out and in a perfect state by the following morning at the time he came out to take his ride, and the whole strength of the village was then put upon the work, and employed during the night and next day, when Mr. Beckford came to inspect what was done; if he was pleased with it he used to give a 5l. or 10l. note to the men who had been employed, to drink, besides, of course, paying their wages, which were always liberal. His charities were performed in the same capricious manner. Suddenly he would order a hundred pairs of blankets to be purchased and given away; or all the firs to be cut out of an extensive plantation, and all the poor who chose to take them away were permitted to do so, provided it were done in one night. He was also known to suddenly order all the waggons and carts that could be procured to be sent off for coal to be distributed among the poor.

Mr. Beckford seldom rode out beyond his gates, but when he did he was generally asked for charity by the poor people. Sometimes he used to throw a one-pound note or a guinea to them; or he would turn round and give the supplicants a severe horse-whipping. When the last was the case, soon after he had ridden away, he generally sent back a guinea or two to the persons whom he had whipped. In his mode of life at Fonthill he had many singularities: though he never had any society, yet his table was laid every day in the most splendid style. He was known to[10] give orders for a dinner for twelve persons and to sit down alone to it, attended by twelve servants in full dress; yet he would eat only of one dish, and send the rest away. There were no bells at Fonthill, with the exception of one room, occupied occasionally by Mr. Beckford's daughter, the Duchess of Hamilton. The servants used to wait by turns in the ante-rooms to the apartments which Mr. Beckford occupied; they were very small and low in the ceiling. He led almost the life of a hermit within the walls of the Fonthill estate; here he could luxuriate within his sumptuous home, or ride for miles on his lawns, and through forest and mountain woods,—amid dressed parterres of the pleasure-garden, or the wild scenery of nature. This garden, the vast woods, and a wild lake, abounded with game, and the choristers of the forest, which were not only left undisturbed by the gun, but were fed and encouraged by the lord of the soil and his long retinue of servants. A widower, and without any family at home, Mr. Beckford resided at the Abbey for more than twenty years, ever active, and constantly occupied in reading, music, and the converse of a choice circle of friends, or in directing workmen in the erection of the Abbey, which had been in progress since the year 1798.

About the year 1822 his restless spirit required a change; besides which his fortunes received a shock from which they never recovered. He now purchased two houses in Lansdown Crescent, Bath, with a large tract of land adjoining, and removed thither. The property at Fonthill was then placed at the disposal of Mr. Christie, who prepared a catalogue for the sale of the estate, the Abbey, and its gorgeous contents. The place was made an exhibition of in the summer of 1822: the price of admission was one guinea for each person, and 7,200 tickets were sold: thousands flocked to Fonthill; but at the close of the summer, instead of a sale on the premises, the whole was bought in one lot by Mr. Farquhar, it was understood, for the sum of 350,000l.[11] Mr. Beckford's outlay upon the property had been, according to his own account, about 273,000l., scattered over sixteen or eighteen years. The reason he assigned for disposing of the property was the reduction of his income by a decree of the Court of Chancery, which had deprived him of two of his Jamaica estates. "You may imagine their importance," he added, "when I tell you that there were 1,500 slaves upon them."

Mr. Farquhar, the purchaser of the property, was an old miser who had amassed an immense fortune in India. By the advice of Mr. Phillips, the auctioneer, of Bond Street, in the following year another exhibition was made of Fonthill and its treasures, to which articles were added, and the whole sold as genuine property; the tickets of admission were half-a-guinea each, the price of the catalogues 12s., and the sale lasted thirty-seven days.

In December, 1825, the tower at Fonthill, which had been hastily built and not long finished, fell with a tremendous crash, destroying the hall, the octagon, and other parts of the buildings. Mr. Farquhar, with his nephew's family, had taken the precaution of removing to the northern wing: the tower was above 260 feet high.

Mr. Loudon, when at Fonthill in 1835, collected some interesting particulars of this catastrophe. He describes the manner in which the tower fell as somewhat remarkable. It had given indications of insecurity for some time; the warning was taken, and the more valuable parts of the windows and other articles were removed.

Mr. Farquhar, however, who then resided in one angle of the building, and who was in a very infirm state of health, could not be brought to believe there was any danger. He was wheeled out in his chair on the front lawn about half an hour before the tower fell; and though he had seen the cracks and the deviation of the centre from the perpendicular, he treated the idea of its coming down as ridiculous. He was carried back to his room, and the tower fell almost[12] immediately. From the manner in which it fell, from the lightness of the materials of which it was constructed, neither Mr. Farquhar, nor the servants who were in the kitchen preparing dinner, knew that it had fallen, though the immense collection of dust which rose into the atmosphere had assembled almost all the inhabitants of the village, and had given the alarm even as far as Wardour Castle. Only one man (who died in 1833) saw the tower fall; it first sank perpendicularly and slowly, and then burst and spread over the roofs of the adjoining wings on every side. The cloud of dust was enormous, so as completely to darken the air for a considerable distance around for several minutes. Such was the concussion in the interior of the building, that one man was forced along a passage as if he had been in an air-gun to the distance of 30 feet, among dust so thick as to be felt. Another person, on the outside, was, in like manner, carried to some distance; fortunately, no one was seriously injured. With all this, it is almost incredible that neither Mr. Farquhar, nor the servants in the kitchen, should have heard the tower fall, or known that it had fallen, till they saw through the window the people of the village who had assembled to see the ruins. Mr. Farquhar, it is said, could scarcely be convinced that the tower was down, and when he was so he said he was glad of it, for that now the house was not too large for him to live in. Mr. Beckford, when told at Bath by his servant that the tower had fallen, merely observed, that it had made an obeisance to Mr. Farquhar which it had never done to him.

One of the last things which Mr. Beckford did, after having sold Fonthill, and ordered horses to be put to his carriage to leave the place for ever, was to mount his pony, ride round with his gardener, to give directions for various alterations and improvements which he wished to have executed. On returning to the house, his carriage being ready, he stepped into it, and never afterwards visited[13] Fonthill. Though Mr. Beckford had spent immense sums of money there, it is said, on good authority, 1,600,000l., it did not appear that he had at all raised the character of the working classes: the effect was directly the reverse; the men were sunk, past recovery, in habits of drunkenness; and when Mr. Loudon visited Fonthill, there were only two or three of the village labourers alive who had been employed in the Abbey works.

We now follow Mr. Beckford to Bath, where he was storing his twin houses with some of the choicest articles from his old libraries and cabinets; was forming and creating new gardens, with hot-houses and conservatories, on the steep and rocky slope of Lansdown. On its summit he built a lofty tower, which commands a vast extent of prospect. A street intervened between the two houses, but they were soon united by a flying gallery. One of these houses was fitted up for Mr. Beckford's residence, and here he lived luxuriously; the splendour and state of Fonthill being followed here on a smaller scale. In his wine-cellars he had a portion of the nineteen pipes of the fine Malmsey Madeira, which his father, Alderman Beckford, had bought. The merchant who imported them offered them to Queen Charlotte, who could only purchase one, as the price was so great; the Fonthill Crœsus, however, purchased the remainder of the cargo.

The new proprietor of Fonthill was a very different man from Mr. Beckford. Born in Aberdeen, Mr. John Farquhar, like many of his countrymen, started in early life to seek his fortune in India. The interest of some relatives procured him a cadetship in the service of the East India Company, on the Bombay establishment; there the young Scotsman had the certainty of slowly but steadily rising in position, and should health be left to him, of enjoying a reputable and independent competency. He, however, received a dangerous wound in the leg, which first caused a painful and constant lameness, and soon after led to general derangement[14] of his health, and even danger to life itself. He now obtained leave to remove to Bengal, partly in hopes of a more salubrious climate, but chiefly in search of that medical talent which was likely to be most abundant at the chief seat of Government. Settled in Bengal, he obtained the advice of the best physicians. He also studied chemistry and medicine; and it was before long generally said that the sickly cadet who was so attached to chemical experiments, was well fitted to be sent into the interior of the country, where was a large manufactory of gunpowder established by the Government, but which was unsuccessful. The shrewd Scotsman took charge of the mill, henceforth the powder was faultless; and shortly after Farquhar became the sole contractor for the Government. The Governor-General, Warren Hastings, reposed much confidence in Farquhar; and this, added to his own indefatigable vigour of mind, soon laid the foundation of a fortune, which was rapidly increased by his penurious habits.

It was the time when war and distresses in Europe kept the funds so low, that fifty-five was a common price for the Three per cents. Accordingly, as Farquhar's money accumulated, he sent large remittances to his bankers, Messrs. Hoare, of Fleet Street, for investment in the above tempting securities. When he had thus amassed half a million, he determined to return to his native country, and he bade adieu to the East where he had found the wealth he coveted. Landing at Gravesend, he took his seat upon the outside of the coach, and in due time found himself in London. Weather-beaten, and covered with dust, he made his way to his bankers, and there, stepping up to one of the clerks, expressed a wish to see Mr. Hoare himself. But his rough appearance and common make of the clothes about his sunburnt limbs, suggested to the clerk that he must be some unlucky petitioner for charity; and he was left to wait in the cash-office until Mr. Hoare happened to pass through. The latter was some time before he could understand who Mr.[15] Farquhar was. His Indian customer, indeed, he knew well by name, but he had none of that hauteur which was then common with the successful Anglo-Indians. At length, however, Mr. Hoare was satisfied as to the identity of his wealthy visitor, who then asked him for 25l., and saluting him, retired.

On first arriving in England, Mr. Farquhar took up his abode with a relative of some rank, who mixed a good deal in London society, and who proposed to introduce to his circle Mr. Farquhar, by giving a grand ball in honour of his successful return from India. This relative had tolerated Mr. Farquhar's fancies as regarded his every-day attire; but his fashionable mind was horrified when the day of the coming ball was only a week off, and there was, nevertheless, no sign of his intending to provide himself with a new suit of clothes for the gay occasion. He ventured accordingly to hint to him the propriety of doing so; when Mr. Farquhar made a short reply, packed up his clothes, and in a few minutes was driven from the door in a hackney-coach, not even taking leave of his too-critical host.

He then settled in Upper Baker Street, where his windows were ever remarkable for requiring a servant's care, and his whole house notable for its dingy and dirty appearance; at which we cannot wonder when we learn that his sole attendant was an old woman, and that from even her intrusive care his own apartment was strictly kept free. Yet in charitable deeds Mr. Farquhar was munificent to a princely extent, and often, when he had left his comfortless home with a crust of bread in his pocket to save the expenditure of a penny at an oyster shop, it was to give away in the course of the day hundreds of pounds to aid the distressed, and to cure and care for those who suffered from biting poverty, hunger, and want. But in his personal expenditure he was extremely parsimonious; and whilst he resided in Baker Street, he expended on himself and his household but 200l. a year out of the 30,000l. or 40,000l.[16] which his many sources of income must have yielded him.[2]

Such was the man who succeeded the luxurious Beckford at Fonthill! He, however, sold the property about 1825, and died in the following year. The immense fortune he had struggled to make, and to increase which he had lived a solitary and comfortless life, he made no disposal of by will; the law distributed it among his next-of-kin, and those he favoured and those he neglected inherited equal portions. Three nephews and four nieces became entitled to 100,000l. each. Fonthill Abbey had been taken down, merely enough of its ruins being left to show where it had stood. Mr. Farquhar possessed Fonthill for so short a time, and it was demolished so soon after he had parted with it, and so many years before Mr. Beckford followed him to the grave, that the latter lived to know that its last proprietor was comparatively forgotten, and the strange glories of the fantastic pile will be connected by the public voice with no name but that of its eccentric architect.

On settling at Bath, Mr. Beckford was frequently seen on horseback in the streets with his groom, and appeared as the plain unostentatious country gentleman: he was no longer the wealthy lord of Fonthill; still his appearance always excited the gaze and speculation of idlers and gossips. A dwarf, an Italian named Piero, was occasionally seen on a pony with the groom, and strange conjectures were hazarded on the history of this human phenomenon. The fact is, Mr. Beckford had taken charge of him in Italy, when he was deserted by his parents and was homeless and friendless; and he was brought to England by a humane patron, who supported him through life.

In 1844, Mr. Cyrus Redding, when at Bath, had several interviews and conversations with Mr. Beckford, whose mind was then vigorous: his spirits were good, and he displayed his wonted activity of body nearly to the last. In his seventy-sixth year he said that he had never felt a moment's ennui in his life. He was the most accomplished man of his time: his reading was very extensive; he used to say that he could easily read and understand an octavo volume during his breakfast. Besides the classical languages of antiquity, he spoke four modern European tongues, and wrote three of them with great elegance. He read Russian and Arabic. We have said that he was taught music by Mozart, to whom he was so much attached, that when the great composer settled in Vienna, Mr. Beckford made a visit to that capital "that he might once more see his old master."

Mr. Redding tells us that Mr. Beckford's custom, "in fine weather, was to rise early, ride to the tower or about the grounds, walk back and breakfast, and then read until a little before noon, generally making pencil notes in the margin of every book, transact business with his steward; afterwards, until two o'clock, continue to read and write, and then ride out two or three hours." Mr. Beckford was never idle. When planning or building, he passed the larger part of the day where the work was proceeding. He sometimes expressed contempt by a sarcastic sneer, peculiar to himself. Few could utter more cutting things than the author of Vathek, the delivery with a caustic expression of countenance that made them tell with double effect. Mr. Redding once ventured to remark, "It must have cost you much pain to quit Fonthill." "Not so much as you might think. I can bend to fortune. I have philosophy enough not to cry like a child about a play-thing." Mr. Britton, who had seen much of Mr. Beckford, tells us that the remarks and opinions in the novels of Cecil a Coxcomb and Cecil a Peer, mostly written by Mrs. Gore when on a visit to[18] Mr. Beckford at Bath, afford the nearest approach he had seen in print to the language, the ideas, the peculiar sentiments of the author of Vathek.

Mr. Beckford continued to reside in Bath (except his annual visits to the metropolis, when he lived in Park Lane and in Gloucester Place[3]) for about twenty years, and died there on May 2, 1844, in the eighty-fourth year of his age. His intention was to make the ground attached to the Lansdown tower the place of his sepulchre, and he had prepared and placed on the spot a granite sarcophagus, inscribed with a passage from Vathek; but the ecclesiastical authorities refused to consecrate the ground, the body was embalmed and placed in the sarcophagus in the cemetery of Lyncomb, to the south of Bath. It was afterwards removed to Lansdown, when the ground was consecrated.

The author of Vathek was unquestionably a man of genius and rare accomplishments. "But his abilities were overpowered and his character tainted by the possession of wealth so enormous. At every stage his money was like a millstone round his neck. He had taste and knowledge; but the selfishness of wealth tempted him to let these gifts of the mind run to seed in the gratification of extravagant freaks. He really enjoyed travelling and scenery, but he felt it incumbent on him, as a millionnaire, to take a French cook with him wherever he went;[4] and he found that the Spanish grandees and ecclesiastical dignitaries who welcomed him so cordially valued him as the man whose cook could make such wonderful omelettes. From the day when[19] Chatham's proxy stood for him at the font till the day when he was laid in his pink granite sarcophagus, he was the victim of riches. Had he had only 5,000l. a year, and been sent to Eton, he might have been one of the foremost men of his time, and have been as useful in his generation as, under his unhappy circumstances, he was useless."[5] It may be added, that he was worse: for he so threw about his money at Fonthill as to corrupt and demoralise the simple country people.

Against this judgment must, however, be placed Mr. Beckford's own declaration, that he never felt a single moment of ennui.

Mr. Beckford left two daughters, the eldest of whom, Susan Euphemia, was married to the Marquis of Clydesdale in 1810, and became Duchess of Hamilton. The tomb at Lansdown, with its polished granite, emblazoned shields, and bronzed and gilt embellishments, was not long cared for; since in 1850, it presented in its neglected state a lamentable object. Vathek will be remembered. Byron, a good judge of such a subject, has pronounced that "for correctness of costume, beauty of description, and power of imagination," it far surpasses all other European imitations of the Eastern style of fiction.

The speech on the pedestal of Beckford's statue, and referred to at p. 2 ante, is the one which the Alderman is said to have addressed to his Majesty on the 23rd of May, 1770, with reference to the King's reply to the Remonstrance address which Beckford had presented:—"That he should have been wanting to the public as well as to himself if he had not expressed his dissatisfaction at the late address."[20] Horace Walpole thus notes the affair: "The City carried a new remonstrance, garnished with my lord's own ingredients, but much less hot than the former. The country, however, was put to some confusion by my Lord Mayor, who, contrary to all form and precedent, tacked a volunteer speech to the 'Remonstrance.' It was wondrous loyal and respectful, but, being an innovation, much discomposed the solemnity. It is always usual to furnish a copy of what is said to the King, that he may be prepared with his answer. In this case, he was reduced to tuck up his train, jump from the throne, and take sanctuary in his closet, or answer extempore, which is not part of the Royal trade; or sit silent, and have nothing to reply. This last was the event, and a position awkward enough in conscience."—Walpole to Sir Horace Mann, May 24, 1770.

Now, at the end of the Alderman's speech, in his copy of the City addresses, Mr. Isaac Reed has inserted the following note:—"It is a curious fact, but a true one, that Beckford did not utter one syllable of this speech (on the monument). It was penned by John Horne Tooke, and by his art put on the records of the City and on Beckford's statue, as he told me, Mr. Braithwaite, Mr. Sayer, &c., at the Athenæum Club.—Isaac Reed." There can be little doubt that the worthy commentator and his friends were imposed upon. In the Chatham Correspondence, volume iii., p. 460, a letter from Sheriff Townsend to the Earl expressly states that with the exception of the words "and necessary" being left out before the word "revolution," the Lord Mayor's speech in the Public Advertiser of the preceding day is verbatim. (The one delivered to the King.)—Wright—Note to Walpole.

Gifford says (Ben Jonson, VI. 481) that Beckford never uttered before the King one syllable of the speech upon his monument; and Gifford's statement is fully confirmed both by Isaac Reed (as above) and by Maltby, the friend of Roger and Horne Tooke. Beckford made a "remonstrance[21] speech" to the King; but the speech on Beckford's monument is the after speech written for Beckford by Horne Tooke.—See Mitford, Gray, and Mason's Correspondence, pp. 438, 439.—Cuningham's Note to Walpole, v. 239.

Such is the historic worth of this strange piece of monumental bombast, upon which Pennant made this appropriate comment:—

The things themselves are neither scarce nor rare,

The wonder's how the devil they got there.

Mr. John Farquhar over the ruins of Fonthill.

Beau Brummel. (From a miniature.)

This celebrated leader of fashion in the times of the Regency—George Bryan Brummel—was born June 7, 1778. His grandfather was a pastrycook in Bury Street, St. James's, who, by letting off a large portion of his house, became a moneyed man. While Brummel's father was yet a boy, Mr. Jenkinson came to lodge there, and this led to the lad being employed in a Government office, when his lodger and patron had attained to eminence; he was subsequently private secretary to Lord Liverpool, and at his death, left the Beau little less than 30,000l. Brummel was sent to Eton, and thence to Oxford, and at sixteen he was gazetted to a cornetcy in the 10th Hussars, at that time commanded by the Prince of Wales, to whom he had been presented on the Terrace at Windsor, when the Beau was a boy at Eton. He[23] became an associate of the Prince, then two-and-thirty, but who, according to Mr. Thomas Raikes, disdained not to take lessons in dress from Brummel at his lodgings. Thither would the future King of nations wend his way, where, absorbed in the mysteries of the toilet, he would remain till so late an hour that he sometimes sent his horses away, and insisted on Brummel giving him a quiet dinner, which generally ended in a deep potation.

Brummel's assurance was one of his earliest characteristics. A great law lord, who lived in Russell Square, one evening gave a ball, at which J., one of the beauties of the time, was present. Numerous were the applications made to dance with her; but being as proud as she was beautiful, she refused them all, till the young Hussar made his appearance; and he having proffered to hand her out, she at once acquiesced, greatly to the wrath of the disappointed candidates. In one of the pauses of the dance, he happened to find himself close to an acquaintance, when he exclaimed, "Ha! you here? Do, my good fellow, tell me who that ugly man is leaning against the chimney-piece." "Why, surely you must know him," replied the other, "'tis the master of the house." "No, indeed," said the Cornet, coolly; "how should I? I never was invited."

Captain Jesse, the biographer of Brummel, has drawn his portrait at about this time. "His face was rather long and complexion fair; his whiskers inclined to sandy, and hair light brown. His features were neither plain nor handsome; but his head was well shaped, the forehead being unusually high; showing, according to phrenological development, more of the mental than the animal passions—the bump of self-esteem was very prominent. His countenance indicated that he possessed considerable intelligence, and his mouth betrayed a strong disposition to indulge in sarcastic humour: this was predominant in every feature, the nose excepted, the natural regularity of which, though it had been broken by a fall from his charger, preserved his features from[24] degenerating into comicality. His eyebrows were equally expressive with his mouth; and while the latter was giving utterance to something very good-humoured or polite, the former, and the eyes themselves, which were grey and full of oddity, could assume an expression that made the sincerity of his words very doubtful. His voice was very pleasing."

Brummel was one of the first who revived and improved the taste for dress, and his great innovation was effected upon neckcloths; they were then worn without stiffening of any kind, and bagged out in front, rucking up to the chin in a roll: to remedy this obvious awkwardness and inconvenience, he used to have his slightly starched; and a reasoning mind must allow that there is not much to object to in this reform. He did not, however, like the dandies, test their fitness for use by trying if he could raise three parts of their length by one corner without their bending; yet, it appears that if the cravat was not properly tied at the first effort, or inspiring impulse, it was always rejected. His valet was coming down stairs one day with a quantity of tumbled neckcloths under his arm, and, being interrogated on the subject, solemnly replied, "Oh, they are our failures." Practice like this, of course, made Brummel perfect; and his tie soon became a model that was imitated but never equalled. The method by which this most important result was attained, was thus told to Captain Jesse:—"The collar, which was always fixed to his shirt, was so large that, before being folded down, it completely hid his head and face; and the white neckcloth was at least a foot in height. The first coup d'archet was made with the shirt-collar, which he folded down to its proper size; and Brummel, then standing before the glass, with his chin poked up to the ceiling, by the gentle and gradual declension of the lower jaw, creased the cravat to reasonable dimensions, the form of each succeeding crease being perfected with the shirt which he had just discarded."

"Brummel's morning dress was similar to that of every other gentleman. Hessians and pantaloons, or top-boots and buckskins, with a blue coat and a light or buff-coloured waistcoat, of course fitting to admiration on the best figure in England. His dress of an evening was a blue coat and white waistcoat, black pantaloons, which buttoned tight to the ankle, striped stockings, and opera-hat; in fact he was always carefully dressed, but never the slave of fashion.

"Brummel's tailors were Schweitzer and Davidson in Cork Street; Weston; and a German of the name of Meyer, who lived in Conduit Street. The trousers which opened at the bottom of the leg, and were closed by buttons and loops, were invented either by Meyer or Brummel. The Beau, at any rate, was the first who wore them, and they immediately became quite the fashion and continued so for some years."

Brummel was addicted to practical jokes, one of which may be related. The victim was an old French emigrant, whom he had met on a visit to Woburn or Chatsworth, and into whose hair-pouch he managed to introduce some finely-powdered sugar. Next morning the poor Marquis, quite unconscious of his head being so well-sweetened, joined the breakfast-table as usual; but scarcely had he made his bow and plunged his knife into the Perigord pie before him, than the flies began to desert the walls and windows to settle upon his head. The weather was exceedingly hot; the flies of course numerous, and even the honeycomb and marmalade upon the table seemed to have lost all attraction for them. The Marquis relinquished his knife and fork to drive off the enemy with his handkerchief. But scarcely had he attempted to renew his acquaintance with the Perigord pie, than back the whole swarm came, more teazingly than ever. Not a wing was missing. More of the company who were not in the secret, could not help wondering at this phenomenon, as the buzzing grew louder and louder every moment. Matters grew still worse when the sugar, melting,[26] poured down the Frenchman's brow and face in thick streams; for his tormentors then changed their ground of action, and having thus found a more vulnerable part, nearly drove him mad with their stings. Unable to bear it any longer, he clasped his head with both hands, and rushed out of the room in a cloud of powder, followed by his persevering tormentors, and the laughter of the company.

Brummel was the autocrat of the world in which he moved. It has been said that Madame de Staël was in awe of him, and considered her having failed to please him as her greatest misfortune; while the Prince of Wales having neglected to call upon her, she placed only as a secondary cause of lamentation. The great French authoress, however, was not without reason in her regrets; to offend or not to please Brummel was to lose caste in the fashionable world, to be exposed to the most cutting sarcasm and the most poignant ridicule.

Captain Jesse thus tells the story of Brummel's cutting quarrel with the Prince of Wales. Lord Alvanley, Brummel, Henry Pierrepoint, and Sir Harry Mildmay, gave at the Hanover Square Rooms a fête, which was called the Dandies' Ball. Alvanley was a friend of the Duke of York; Harry Mildmay, young, and had never been introduced to the Prince Regent; Pierrepoint knew him slightly, and Brummel was at daggers drawn with his Royal Highness. No invitation was, however, sent to the Prince, but the ball excited much interest and expectation, and to the surprise of the Amphitryons, a communication was received from his Royal Highness intimating his wish to be present. Nothing, therefore, was left but to send him an invitation, which was done in due form, and in the name of the four spirited givers of the ball; the next question was how were they to receive the guest, and which, after some discussion, was arranged thus:—When the approach of the Prince was announced, each of the four gentlemen took in due form a candle in his hand. Pierrepoint, as knowing the Prince, stood nearest[27] the door with his wax-light; and Mildmay, as being young and void of offence, opposite. Alvanley, with Brummel opposite, stood immediately behind the other two. The Prince at length arrived, and, as was expected, spoke civilly and with recognition to Pierrepoint, and then turned and spoke a few words to Mildmay; advancing, he addressed several sentences to Alvanley; and then turned towards Brummel, looked at him, but as if he did not know who he was, or why he was there, and without bestowing on him the slightest recognition. It was then, at the very instant he[28] passed on, that Brummel, seizing with infinite fun and readiness the notion that they were unknown to each other, said aloud for the purpose of being heard, "Alvanley, who's your fat friend?" Those who were in front, and saw the Prince's face, say that he was cut to the quick by the aptness of the remark.

Lord Alvanley. A pillar of White's.

Mr. Grantley Berkeley (in his Life and Recollections) relates the story less circumstantially:—"There is a well-known anecdote I am able to correct, given to me by a medical friend of mine, who had it from the late Henry Pierrepoint, brother to the late Lord Manners:—'We of the Dandy Club issued invitations to a ball from which Brummel had influence enough to get the Prince excluded. Some one told the Prince this, upon which his Royal Highness wrote to say he intended to have the pleasure of being at our ball. A number of us lined the entrance-passage to receive the Prince, who, as he passed along, turned from side to side to shake hands with each of us; but when he came to Brummel, he passed him without the smallest notice, and turned to shake hands with the man opposite to Brummel. As the Prince turned from that man—I forget who it was—Brummel leaned forward across the passage, and said, in a loud voice, 'Who is your fat friend?' We were all dismayed; but in those days Brummel could do no wrong."

The following story was supplied to Captain Jesse by a correspondent. The Beau, it appears, had a great penchant for snuff-boxes:—"Brummel had a collection chosen with singular sagacity and good taste; and one of them had been seen and admired by the Prince, who said, 'Brummel, this box must be mine: go to Gray's and order any box you like in lieu of it.' Brummel begged that it might be one with his Royal Highness' miniature; and the Prince, pleased and flattered at the suggestion, gave his assent to the request. Accordingly, the box was ordered, and Brummel took great pains with the pattern and form, as well as with the miniature and diamonds round it. When some progress[29] had been made, the portrait was shown to the Prince; who was charmed with it, suggested slight improvements and alterations, and took the liveliest interest in the work as it proceeded. All in fact was on the point of being concluded when the scene at Claremont took place; [where this writer describes the quarrel as originating, through the Prince preventing Brummel from joining a party, on the plea of Mrs. Fitzherbert disliking him.] A day or two after this, Brummel thought he might as well go to Gray's and inquire about the box; he did so, and was told that special directions had been sent by the Prince of Wales that the box was not to be delivered: it never was, nor was the one returned for which it was to have been an equivalent. It was this, I believe, more than anything besides, which induced Brummel to bear himself with such unbending hostility towards the Prince of Wales. He felt that he had treated him unworthily, and from this moment he indulged himself by saying the bitterest things. When pressed by poverty, however, and, as I suppose, broken in spirit, he at a later period recalled the Prince's attention to the subject of the snuff-box. Colonel Cooke (who was at Eton called 'Cricketer Cooke,' afterwards known as 'Kangaroo Cooke'), when passing through Calais, saw Brummel, who told him the story, and requested that he would inform the Prince Regent that the promised box had never been given, and that he was now constrained to recall the circumstance to his recollection. The Regent's reply was: 'Well, Master Kang, as for the box it is all nonsense; but I suppose the poor devil wants a hundred guineas, and he shall have them;' and it was in this ungracious manner that the money was sent, received, and acknowledged. I have heard Brummel speak of the affair of the snuff-box, but I never heard him say that he received the hundred guineas."

Brummel, late in life, stood to his Whig colours. His evening dress consisted of a blue coat, with velvet collar and the consular button; a buff waistcoat, black trousers and[30] boots. His white neckcloth was unexceptionable. The only articles of jewellery about him were a plain ring and a massive chain of Venetian ducat-gold, which served as a guard to his watch, and was evidently as much for use as ornament, only two links of it were to be seen; those passed from the buttons of his waistcoat to the pocket; the chain was peculiar, and was of the same pattern as those suspended in terrorem outside the principal entrance to Newgate. The ring was dug out on the Field of the Cloth of Gold by a labourer, who sold it to Brummel when he was at Calais. An opera-hat, and gloves which were held in his hand, completed an attire that being remarkably quiet, could never have attracted attention on any other person. His mise was peculiar only for its extreme neatness, and wholly at variance with an opinion very prevalent among those who were not personally acquainted with him, that he owed his reputation to his tailor, or to an exaggerated style of dress.

Brummel, however, maintained his supremacy in the world of fashion for years after the Prince had cut him. "But though even royal disfavour could not seriously lower him, he managed in the end to do that which no one else could do, he ruined himself; the gaming table, in the long run, deprived him of all his fortune. Then came bills to supply the deficiencies of the hour, and with that the consummation which they never fail to bring about when necessity has recourse to them. A quarrel ensuing with the friends joined in one of these acceptances, and who accused him of taking the lion's share, he was obliged to quit England and take up his abode at Calais. It has been said, ludicrously enough, that Brummel and Bonaparte fell together. The Moscow of the former, according to his own account, was a crooked sixpence, to the possession of which his good fortune was attached, but which he unfortunately lost.

"But, if he had lost his magical sixpence, he had not yet exhausted all his friends, from some of whom he was continually receiving even large sums of money, so much in one instance as a thousand pounds. He was thus enabled[31] to furnish his lodgings according to his usual refined habits, and living much retired, he set seriously to work in acquiring the French language, and succeeded.

"His resources now decreased. Some friends were lost to him by death, others, perhaps, grew weary of relieving him. A visit of George IV. held out to him a momentary gleam of hope. But the king came to Calais, and did not send for him, or in any way notice him. Still he was not wholly bereft of friends, but continued from time to time to receive remittances from England; and at length, by the intervention of the Duke of Wellington with King William, Brummel was appointed English Consul in the capital of Lower Normandy. By this time he was deeply involved in debt, and when he had settled at Caen, the large deductions made from his income to discharge the arrears of debt incurred at Calais left him an insufficiency for a man of his habits. He became as deeply involved at Caen as he had before been at Calais. Next, upon his own showing of its uselessness, the consulate at Caen was abolished, and he was left penniless. He obtained funds from England. But he had more than one attack of paralysis. He was flung into prison at Caen by his French creditors, and confined in a wretched, filthy den, with felons for his companions. He was enabled by aid from England to leave his prison, after more than two months' confinement. Sickness, loss of memory, absolute imbecility, and finally, inability to distinguish bread from meat, or wine from coffee, now came with their attendant ills. His friends obtained him admission into the hospital of the Bon Sauveur, and he was placed in a comfortable room, that had once been occupied by the celebrated Bourrienne. Here he died on the evening of the 30th of March, 1840."[6]

The different stages of mental decay through which this unfortunate man passed, before he became hopelessly imbecile, it is painful to read of. One of his most singular[32] eccentricities was, on certain nights some strange fancy would seize him that it was necessary he should give a party, and he accordingly invited many of the distinguished persons with whom he had been intimate in former days, though some of them were already dead. On these gala evenings he desired his attendant to arrange his apartment, set out a whist table, and light the bougies (he burnt only tallow at the time), and at eight o'clock this man, to whom he had already given his instructions, opened wide the door of his sitting-room, and announced the "Duchess of Devonshire." At the sound of her grace's well-remembered name, the Beau, instantly rising from his chair, would advance towards the door, and greet the cold air from the staircase as if it had been the beautiful Georgiana herself. If the dust of that fair creature could have stood reanimate in all her loveliness before him, she would not have thought his bow less graceful than it had been thirty-five years before; for, despite poor Brummel's mean habiliments and uncleanly person, the supposed visitor was received with all his former courtly ease of manner, and the earnestness that the pleasure of such an honour might be supposed to excite. "Ah! my dear Duchess," faltered the Beau, "how rejoiced am I to see you; so very amiable of you at this short notice! Pray bury yourself in this arm-chair: do you know it was a gift to me from the Duchess of York, who was a very kind friend of mine; but, poor thing, you know she is no more." Here the eyes of the old man would fill with the tears of idiocy, and, sinking into the fauteuil himself, he would sit for some time looking vacantly at the fire, until Lord Alvanley, Worcester, or any other old friend he chose to name, was announced, when he again rose to receive them and went through a similar pantomime. At ten his attendant announced the carriages, and this farce was at an end.

Brummel's sayings are not brilliant in point. They doubtless owed their success to the inimitable impudence with which they were uttered. We have thrown together a few of his many repartees.

Dining at a gentleman's house in Hampshire, where the champagne was very far from being good, he waited for a pause in the conversation, and then condemned it by raising his glass, and saying loud enough to be heard by every one at the table, "John, give me some more of that cider."

"Brummel, you were not here yesterday," said one of his club friends; "where did you dine?" "Dine! why with a person of the name of R——s. I believe he wishes me to notice him, hence the dinner; but, to give him his due, he desired that I would make up the party myself, so I asked Alvanley, Mills, Pierrepoint, and a few others; and I assure you the affair turned out quite unique; there was every delicacy in or out of season; the sillery was perfect, and not a wish remained ungratified; but, my dear fellow, conceive my astonishment when I tell you that Mr. R——s had the assurance to sit down and dine with us."

An acquaintance having, in a morning call, bored him dreadfully about some tour he made in the north of England, inquired with great pertinacity of his impatient listener which of the lakes he preferred? When Brummel, quite tired of the man's tedious raptures, turned his head imploringly towards his valet, who was arranging something in the room, and said, "Robinson?" "Sir." "Which of the lakes do I admire?" "Windermere, sir," replied that distinguished individual. "Ah, yes; Windermere," repeated Brummel; "so it is—Windermere."

Having been asked by a sympathising friend how he happened to get such a severe cold, his reply was, "Why, do you know, I left my carriage yesterday evening, on my way to town from the Pavilion, and the infidel of a landlord put me into a room with a damp stranger."

On being asked by one of his acquaintance, during a very unseasonable summer, if he had ever seen such an one, he replied, "Yes; last winter."

Having fancied himself invited to some one's country seat, and being given to understand, after one night's[34] lodging, that he was in error, he told an unconscious friend in town, who asked him what sort of place it was, "that it was an exceedingly good house for stopping one night in."

On the night that he quitted London, the Beau was seen as usual at the opera, but he left early, and, without returning to his lodgings, stepped into a chaise which had been procured for him by a noble friend, and met his own carriage a short distance from town. Travelling all night as fast as four post-horses and liberal donations could enable him, the morning dawned on him at Dover, and immediately on his arrival there he hired a small vessel, put his carriage on board, and was landed in a few hours on the other side. By this time the West-end had awoke and missed him, particularly his tradesmen.

It was while promenading one day on the pier, and not long before he left Calais, that an old associate of his, who had just arrived by the packet from England, met him unexpectedly in the street, and, cordially shaking hands with him, said, "My dear Brummel, I am so glad to to see you, for we had heard in England that you were dead; the report, I assure you, was in very general circulation when I left." "Mere stock-jobbing, my good fellow—mere stock-jobbing," was the Beau's reply.

We have said that Brummel's grandfather was a pastrycook. His aunt is said to have been the widow of a grandson of Brawn, the celebrated cook who kept 'The Rummer,' in Queen Street, and who had himself kept 'The Rummer' public-house, at the Old Mews Gate, at Charing Cross. Brummel spoke with a relish worthy a descendant of 'The Rummer,' of the savoury pies of his aunt Brawn, who then resided at Kilburn. Henry Carey, in the Dissertation on Dumpling, assumes Braun, or Braund, as he calls him, to have been the direct descendant in the male line of his imaginary Brawnd, knighted by King John for his unrivalled skill in making dumplings, and who subsequently resided, as he tells us, "at the ancient manor of Brands, alias Braunds, near Kilburn, in Middlesex." Curious the[35] accident that found Brummel's "Aunt Brawn" a resident at Kilburn, a century after the Dissertation on Dumpling was written.

Beau Brummel at Calais.

Sir Lumley Skeffington in a "Jean de Brie."

This accomplished gentleman was the son of Sir William Skeffington, a much respected Baronet of Bilsdon, in Leicestershire, where he enjoyed considerable estates and great provincial esteem. He was born in 1778, and was educated at Soho School, and at Newcome's, at Hackney. At the latter he distinguished himself in the dramatic performances for which the school was long celebrated. Dr.[37] Benjamin Hoadley, author of The Suspicious Husband, and his brother, Dr. John Hoadley, were both educated here, and shone in their amateur performances; at the representation of 1764, there were upwards of "one hundred gentlemen's coaches." Young Skeffington excelled in Hamlet, as he afterwards shone in "the glass of fashion." His hereditary prospects afforded him a ready introduction to the fashionable world, and during upwards of twenty years he was considered as a leader of ton, and one of the most finished gentlemen in England. He was a person of considerable taste in literature: he wrote The Word of Honour, a comedy, and the dialogue and songs of a highly finished melodrama, founded on the legend of The Sleeping Beauty. In 1818 he lost his father, who having embarrassed his estates, his son, as an act of filial duty to rescue a parent from distress, consented to the cutting off the entail, by which he deprived himself of that substantial provision without which the life of a gentleman is a life of misery.

Sir Lumley was the dandy of the olden time, and a kinder, better-hearted man never existed. He was of the most polished manners; nor had his long intercourse with fashionable society at all affected that simplicity of character for which he was remarkable. He was a true dandy, and much more than that, he was a perfect gentleman. In 1827, a contributor to the New Monthly Magazine wrote: "I remember, long, long since, entering Covent Garden Theatre, when I observed a person holding the door to let me pass; deeming him to be one of the box-keepers, I was about to nod my thanks, when I found, to my surprise, that it was Skeffington who had thus good-naturedly honoured a stranger by his attention. We with some difficulty obtained seats in a box, and I was indebted to accident for one of the most agreeable evenings I remember to have passed.

"I remember visiting the Opera when late dinners were the rage, and the hour of refection was carried far into the[38] night. I was again placed near the fugleman of fashion, for to his movements were all eyes directed, and his sanction determined the accuracy of all conduct. He bowed from box to box, until recognizing one of his friends in the lower tier, 'Temple,' he exclaimed, drawling out his weary words, 'at—what—hour—do—you—dine—to-day?' It had gone half-past eleven when he spoke.

"I saw him once enter St. James's Church, having at the door taken a ponderous red morocco prayer-book from his servant; but although prominently placed in the centre aisle, the pew-opener never offered him a seat; and stranger still, none of his many friends beckoned him to a place. Others in his rank of life might have been disconcerted at the position in which he was placed; but Skeffington was too much of a gentleman to be in any way disturbed; so he seated himself upon the bench between two aged female paupers, and most reverently did he go through the service, sharing with the ladies his book, the print of which was more favourable to their devotions than their own diminutive liturgies."

Sir Lumley Skeffington continued to the last to take especial interest in the theatre and its artists, notwithstanding his own reduced fortunes. He was a worshipper of female beauty, his adoration being poured forth in ardent verse. Thus, in the spring 1829, he inscribed to Miss Foote the following ballad:

Again, on the termination of the engagement of Miss Foote, at Drury Lane Theatre, in May, 1826, Sir Lumley addressed her in the following impromptu:

Sir Lumley, through the ingratitude and treachery of

Friends found in sunshine, to be lost in storm,

became involved in difficulties and endless litigation, and his latter years were clouded with sorrow; still his buoyant spirits never altogether left him, although "the observed of all observers" passed his latter years in compulsory residence in a quarter of the great town ignored by the Sybarites of St. James's.

When Madame Vestris established a theatre of her own, Sir Lumley thus sang, in the columns of The Times:—

Sir Lumley, who had long been unheard of in fashionable circles, died in London in 1850 or 1851.

Skiffy at the Birthday Ball.

Robert Coates, the Amateur of Fashion, as Romeo.

This celebrated leader of fashion, who rejoiced in the sobriquets of "Romeo" and "Diamond," obtained the[42] former from his love of amateur acting, and the latter from his great wealth obtained from the West Indies. He was likewise noted by his splendid curricle, the body of which was in the form of a cockleshell, bearing the cock-bird as his crest; and the harness of the horses was mounted with metal figures of the same bird, with which got associated the motto of "Whilst we live, we'll crow."

By his amateur performances he shared with young Betty (Roscius) the admiration of the town. A writer in the New Monthly Magazine, 1827, pleasantly describes one of these performances:—"Never shall I forget his representation of Lothario (some sixty years since), at the Haymarket Theatre, for his own pleasure, as he accurately termed it; and certainly the then rising fame of Liston was greatly endangered by his Barbadoes rival. Never had Garrick or Kemble in their best times so largely excited the public attention and curiosity. The very remotest nooks of the galleries were filled by fashion; while in a stage-box sat the performer's notorious friend, the Baron Ferdinand Geramb.

"Coates's lean Quixotic form being duly clothed in velvets and in silks, and his bonnet highly fraught with diamonds (whence his appellation), his entrance on the stage was greeted by so general a crowing (in allusion to the large cocks, which as his crest adorned his harness), that the angry and affronted Lothario drew his sword upon the audience, and actually challenged the rude and boisterous tenants of the galleries, seriatim or en masse, to combat on the stage. Solemn silence, as the consequence of mock fear, immediately succeeded. The great actor, after the overture had ceased, amused himself for some time with the Baron ere he condescended to indulge the wishes of an anxiously expectant audience.

"At length he commenced: his appeals to the heart were made by the application of the left hand so disproportionately lower down than 'the seat of life' has been supposed[43] to be placed; his contracted pronunciation of the word 'breach,' and other new readings and actings, kept the house in a right joyous humour, until the climax of all mirth was attained by the dying scene of

that gallant, gay Lothario:

but who shall describe the grotesque agonies of the dark seducer, his platted hair escaping from the comb that held it, and the dark crineous cordage that flapped upon his shoulders in the convulsions of his dying moments, and the cries of the people for medical aid to accomplish his eternal exit? Then, when in his last throes his coronet fell, it was miraculous to see the defunct arise, and after he had spread a nice handkerchief on the stage, and there deposited his head-dress, free from impurity, philosophically resume his dead condition; but it was not yet over, for the exigent audience, not content 'that when the men were dead, why there an end,' insisted on a repetition of the awful scene, which the highly flattered corpse executed three several times, to the gratification of the cruel and torment-loving assembly."

Coates was destined to be tantalized by the celebrated fête given at Carlton House, in 1821, in honour of the Bourbons. Having no opportunity of learning in the West Indies the propriety of being presented at Court ere he could be upon a more intimate footing with the Prince Regent, he was less astonished than delighted at the reception of an invitation on that occasion to Carlton House. What was the fame acquired by his cockleshell curricle; his theatrical reputation; all the applause attending the perfection of histrionic art; the flatteries of Billy Finch, a sort of kidnapper of juvenile actors and actresses of the O.P. and P.S., in Russell Court; the sanction of a Petersham; the intimacy of a Barry More; even the polite endurance of a Skeffington to this! To be classed with the proud, the noble, and the great! It seemed a natural query whether[44] the Bourbon's name were not a pretext for his own introduction to Royalty, under circumstances of unprecedented splendour and magnificence. It must have been so. What cogitations respecting dress, and air, and port, and bearing! What torturing of the confounded lanky locks, to make them but revolve ever so little! Then the rich cut velvet,—the diamond buttons,—ay, every one was composed of brilliants. The night arrived—but for Coates's mortification. Theodore Hook had contrived to imitate one of the Chamberlain's tickets, and to produce a facsimile, commanding the presence of Coates; he then put on a scarlet uniform, and delivered the card himself. On the night of the fête, June 19th, Hook stationed himself by the screen at Carlton House, and saw Romeo arrive and enter the palace; he passed in without question, but the forgery was detected by the Private Secretary, and Coates had to retrace his steps to the street, and his carriage being driven off, to get home to Craven Street in a hackney-coach. When the Prince was informed of what had occurred, he signified his regret at the course the Secretary had taken; he was sent by his Royal Highness to apologize in person, and invite Coates to come and look at the state rooms; and Romeo went.

Mr. Coates, who by his cockleshell curricle had acquired some of his celebrity, lost his life by a vehicular accident: he died February 23, 1848, from being run over in one of the London streets. He was in his seventy-sixth year.

Abraham Newland, who was nearly sixty years in the service of the Bank of England, and whose name became a synonym for a bank-note, was one of a family of twenty-five children, and was born in Southwark in 1730. At the age of eighteen he entered the Bank service as junior clerk. He was very fond of music, which led him into much[45] dissipation. Still, he was very attentive to business, and in 1782 he was appointed chief cashier, with a suite of rooms for residence in the Bank, and for five-and-twenty years he never once slept out of the building. The pleasantest version of his importance is contained in the famous song in the Whims of the Day, published in 1800:—

In 1807, he retired from the office of chief cashier, after declining a pension. He had hitherto been accustomed, after the business at the Bank in his department had closed, and he had dined moderately, to order his carriage and drive to Highbury, where he drank tea at a small cottage. Many who lived in that neighbourhood long recollected Newland's daily walk—hail, rain, or sunshine—along Highbury Place. It was said that he regretted his retirement from the Bank; but he used to say that not for 20,000l. a year would he return. He then removed to No. 38, Highbury Place. His health and strength declined, it is said, through the distress of mind brought upon him by the forgeries of Robert Aslett, a clerk in the Bank, whom Newland had treated as his own son. It was well known that Abraham had accumulated a large fortune; legacy-hunters came about him, and an acquaintance sent him a ham as a present; but Newland despised the mercenary motive, and next time he saw the donor he said, "I have received a ham from you; I thank you for it," said he, but raising his finger in a significant manner, added, "I tell you it won't do, it won't do."

Newland had no extravagant expectations that the world would be drowned in sorrow when it should be his turn to leave it; and he wrote this ludicrous epitaph on himself shortly before his death:—

His physician, in one of his latest visits, found him reading the newspaper, when the doctor expressing his surprise, Newland replied, smiling, "I am only looking in the paper in order to see what I am reading to the world I am going to." He died November 21, 1807, without any apparent pain of body or anxiety of mind, and his remains were deposited in the church of St. Saviour, Southwark.

Newland's property amounted to 200,000l., besides a thousand a year landed estates. It must not be supposed that this was saved from his salary. During the whole of his career, the loans for the war proved very prolific. A certain amount of them was always reserved for the cashier's office (one Parliamentary Report names 100,000l.), and as they generally came out at a premium, the profits were great. The family of the Goldsmids, then the leaders of the Stock Exchange, contracted for many of these loans, and to each of them he left 500l. to purchase a mourning ring. Newland's large funds, it is said, were also occasionally lent to the Goldsmids to assist their various speculations.

Squire Mytton on his bear.

The extravagant fellows of a family, says Sir Bernard Burke, Ulster, have done more to overturn ancient houses than all the other causes put together; and no case could[49] be more in point to establish the fact than the history of John Mytton, descended from the Myttons of Halston, who represented, in the days of the Plantagenets, the borough of Shrewsbury in Parliament, and filled the office of High Sheriff of Shropshire at a very remote period. So far back as 1480, Thomas Mytton, when holding that appointment, was the fortunate captor of Stafford, Duke of Buckingham, whom he conducted to Salisbury for trial and decapitation; and in requital Richard III. bestowed on "his trusty and well-beloved squire, Thomas Mytton," the Duke's forfeited castle and lordship of Cawes. Halston, to which the Myttons transferred their seat from their more ancient residence of Cawes Castle and Habberley, is called in ancient deeds "Holystone," and was in early times a preceptory of Knights Templars. The Abbey, taken down about one hundred and sixty years ago, was erected near where the present mansion stands. In the good old times of Halston, before reckless waste had dismantled its halls and levelled its ancestral woods, the oak was seen here in its full majesty of form; and it is related that one particular tree, coeval with many centuries of the family's greatness, was cut down by the spendthrift squire in the year 1826, and contained ten tons of timber.

In the great civil war, Mytton of Halston was one of the few Shropshire gentlemen who joined the Parliamentary standard. From this gallant and upright Parliamentarian, the fifth in descent was John Mytton, the eccentric, wasteful, dissipated, open-hearted, open-handed Squire of Halston, in whose day and by whose wanton extravagance and folly, a time-honoured family and a noble estate, the inheritance of five hundred years, was recklessly destroyed.