DANDY OF THE TIME OF CHARLES I.

(From a Broadside, dated 1646.)

Title: Cassell's History of England, Vol. 2 (of 8)

Author: Anonymous

Release date: December 17, 2015 [eBook #50710]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Chris Curnow, Jane Robins, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/cassellshistoryo02londuoft |

FROM THE WARS OF THE ROSES

TO THE GREAT REBELLION

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS,

INCLUDING COLOURED

AND REMBRANDT PLATES

VOL. II

THE KING'S EDITION

CASSELL AND COMPANY, LIMITED

LONDON, NEW YORK, TORONTO AND MELBOURNE

MCMIX

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

WARS OF THE ROSES. PAGE

Cade's Rebellion—York comes over from Ireland—His Claims and the Unpopularity of the Reigning Line—His First Appearance in Arms—Birth of the Prince of Wales—York made Protector—Recovery of the King—Battle of St. Albans—York's second Protectorate—Brief Reconciliation of Parties—Battle of Blore Heath—Flight of the Yorkists—Battle of Northampton—York Claims the Crown—The Lords Attempt a Compromise—Death of York at Wakefield—Second Battle of St. Albans—The Young Duke of York Marches on London—His Triumphant Entry 1

REIGN OF EDWARD IV.

The Battle of Towton—Edward's Coronation—Henry escapes to Scotland—The Queen seeks aid in France—Battle of Hexham—Henry made Prisoner—Confined in the Tower—Edward marries Lady Elizabeth Grey—Advancement of her Relations—Attacks on the Family of the Nevilles—Warwick negotiates with France—Marriage of Margaret, the King's Sister, to the Duke of Burgundy—Marriage of the Duke of Clarence with a Daughter of Warwick—Battle of Banbury—Rupture between the King and his Brother—Rebellion of Clarence and Warwick—Clarence and Warwick flee to France—Warwick proposes to restore Henry VI.—Marries Edward, Prince of Wales, to his Daughter, Lady Ann Neville—Edward IV.'s reckless Dissipation—Warwick and Clarence invade England—Edward expelled—His return to England—Battle of Barnet—Battle of Tewkesbury, and ruin of the Lancastrian Cause—Rivalry of Clarence and Gloucester—Edward's Futile Intervention in Foreign Politics—Becomes a Pensioner of France—Death of Clarence—Expedition to Scotland—Death and Character of the King 17

EDWARD V. AND RICHARD III.

Edward V. proclaimed—The Two Parties of the Queen and of Gloucester—Struggle in the Council—Gloucester's Plans—The Earl Rivers and his Friends imprisoned—Gloucester secures the King and conducts him to London—Indignities to the young King—Execution of Lord Hastings—A Base Sermon at St. Paul's Cross—Gloucester pronounces the two young Princes illegitimate—The Farce at the Guildhall—Gloucester seizes the Crown—Richard crowned in London and again at York—Buckingham revolts against him—Murder of the two Princes—Henry of Richmond—Failure of Buckingham's Rising—Buckingham beheaded—Richards title confirmed by Parliament—Queen Dowager and her Daughters quit the Sanctuary—Death of Richard's Son and Heir—Proposes to Marry his Niece, Elizabeth of York—Richmond lands at Milford Haven—His Progress—The Troubles of Richard—The Battle of Bosworth—The Fallen Tyrant—End of the Wars of the Roses 46

PROGRESS OF THE NATION IN THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY.

The Study of Latin and Greek—Invention of Printing—Caxton—New Schools and Colleges—Architecture, Military, Ecclesiastical, and Domestic—Sculpture, Painting, and Gilding—The Art of War—Commerce and Shipping—Coinage 64

REIGN OF HENRY VII.

Henry's Defective Title—Imprisonment of the Earl of Warwick—The King's Title to the Throne—His Marriage—Love Rising—Lambert Simnel—Henry's prompt Action—Failure of the Rebellion—The Queen's Coronation—The Act of [vi]Maintenance—Henry's Ingratitude to the Duke of Brittany—Discontent in England—Expedition to France and its Results—Henry's Second Invasion—Treaty of Étaples—Perkin Warbeck—His Adventures in Ireland, France, and Burgundy—Henry's Measures—Descent on Kent—Warbeck in Scotland—Invasion of England—The Cornish Rising—Warbeck quits Scotland—He lands in Cornwall—Failure of the Rebellion—Imprisonment of Warbeck and his subsequent Execution—European Affairs—Marriages of Henry's Daughter and Son—Betrothal of Catherine and Prince Henry—Henry's Matrimonial Schemes—Royal Exactions—A Lucky Capture—Henry proposes for Joanna—His Death 76

REIGN OF HENRY VIII.

The King's Accession—State of Europe—Henry and Julius II.—Treaty between England and Spain—Henry is duped by Ferdinand—New Combinations—Execution of Suffolk—Invasion of France—Battle of Spurs—Invasion of England by the Scots—Flodden Field—Death of James of Scotland—Louis breaks up the Holy League—Peace with France—Marriage and Death of Louis XII.—Rise of Wolsey—Affairs in Scotland—Francis I. in Italy—Death of Maximilian— Henry a Candidate for the Empire—Election of Charles—Field of the Cloth of Gold—Wolsey's Diplomacy—Failure of his Candidature for the Papacy—The Emperor in London 102

REIGN OF HENRY VIII. (continued).

The War with France—The Earl of Surrey Invades that Country—Sir Thomas More elected Speaker—Henry and Parliament—Revolt of the Duke of Bourbon—Pope Adrian VI. dies—Clement VII. elected—Francis I. taken Prisoner at the Battle of Pavia—Growing Unpopularity of Wolsey—Change of Feeling at the English Court—Treaty with France—Francis I. regains his liberty—Italian League, including France and England, established against the Emperor—Fall of the Duke of Bourbon at the Siege of Rome—Sacking of Rome, and Capture of the Pope—Appearance of Luther—Henry writes against the German Reformer—Henry receives from the Pope the style and Designation of "Defender of the Faith"—Anne Boleyn—Henry applies to the Pope for a Divorce from the Queen—The Pope's Dilemma—War declared against Spain—Cardinal Campeggio arrives in England to decide the Legality of Henry's Marriage with Catherine—Trial of the Queen—Henry's Discontent with Wolsey—Fall of Wolsey—His Banishment from Court and Death—Cranmer's advice regarding the Divorce—Cromwell cuts the Gordian Knot—Dismay of the Clergy—The King declared Head of the Church in England—The King's Marriage with Anne Boleyn—Cranmer made Archbishop—The Pope Reverses the Divorce—Separation of England from Rome 130

REIGN OF HENRY VIII. (continued).

The Maid of Kent and Her Accomplices—Act of Supremacy and Consequent Persecutions—The "Bloody Statute"—Deaths of Fisher and More—Suppression of the Smaller Monasteries—Trial and Death of Anne Boleyn—Henry Marries Jane Seymour—Divisions in the Church—The Pilgrimage of Grace—Birth of Prince Edward—Death of Queen Jane—Suppression of the Larger Monasteries—The Six Articles—Judicial Murders—Persecution of Cardinal Pole—Cromwell's Marriage Scheme—Its Failure and his Fall 158

REIGN OF HENRY VIII. (concluded).

Divorce of Anne of Cleves—Catherine Howard's Marriage and Death—Fresh Persecutions—Welsh Affairs—The Irish Insurrection and its Suppression—Scottish Affairs—Catholic Opposition to Henry—Outbreak of War—Battle of Solway Moss—French and English Parties in Scotland—Escape of Beaton—Triumph of the French Party—Treaty between England and Germany—Henry's Sixth Marriage—Campaign in France—Expedition against Scotland—Capture of Edinburgh—Fresh Attempt on England—Cardinal Beaton and Wishart—Death of the Cardinal—Struggle between the two Parties in England—Death of Henry 183

REIGN OF EDWARD VI.

Accession of Edward VI.—Hertford's Intrigues—He becomes Duke of Somerset and Lord Protector—War with Scotland—Battle of Pinkie—Reversal of Henry's Policy—Religious Reforms—Ambition of Lord Seymour of Sudeley—He[vii] marries Catherine Parr—His Arrest and Death—Popular Discontents—Rebellion in Devonshire and Cornwall—Ket's Rebellion in Norfolk—Warwick Suppresses it—Opposition to Somerset—His Rapacity—Fall of Somerset—Disgraceful Peace with France—Persecution of Romanists—Somerset's Efforts to regain Power—His Trial and Execution—New Treason Law—Northumberland's Schemes for Changing the Succession—Death of Edward 204

REIGN OF MARY.

Proclamation of Lady Jane Grey—Mary's Resistance—Northumberland's Failure—Mary is Proclaimed—The Advice of Charles V.—Execution of Northumberland—Restoration of the Roman Church—Proposed Marriage with Philip of Spain—Consequent Risings throughout England—Wyatt's Rebellion—Execution of Lady Jane Grey—Imprisonment of Elizabeth—Marriage of Philip and Mary—England Accepts the Papal Absolution—Persecuting Statutes Re-enacted—Martyrdom of Rogers, Hooper, and Taylor—Di Castro's Sermon—Sickness of Mary—Trials of Ridley, Latimer, and Cranmer—Martyrdom of Ridley and Latimer—Confession and Death of Cranmer—Departure of Philip—The Dudley Conspiracy—Return of Philip—War with France—Battle of St. Quentin—Loss of Calais—Death of Mary 221

REIGN OF ELIZABETH.

Accession of Elizabeth—Sir William Cecil—The Coronation—Opening of Parliament—Ecclesiastical Legislation—Consecration of Parker—Elizabeth and Philip—Treaty of Cateau-Cambresis—Affairs in Scotland—The First Covenant—Attitude of Mary of Guise—Riot at Perth—Outbreak of Hostilities—The Lords of the Congregation apply to England—Elizabeth hesitates—Siege of Leith—Treaty of Edinburgh—Return of Mary to Scotland—Murray's Influence over her—Beginning of the Religious Wars in France—Elizabeth sends Help to the Huguenots—Peace of Amboise—English Disaster at Havre—Peace with France—The Earl of Leicester—Project of his Marriage with Mary—Lord Darnley—Murder of Rizzio—Birth of Mary's Son—Murder of Darnley—Mary and Bothwell—Carberry Hill—Mary in Lochleven—Abdicates in favour of her Infant Son—Mary's Escape from Lochleven—Defeated at Langside—Her Escape into England 246

REIGN OF ELIZABETH (continued).

Elizabeth Determines to Imprison Mary—The Conference at York—It is Moved to London—The Casket Letters—Mary is sent Southwards—Remonstrances of the European Sovereigns—Affairs in the Netherlands—Alva is sent Thither—Elizabeth Aids the Insurgents—Proposed Marriage between Mary and Norfolk—The Plot is Discovered—Rising in the North—Its Suppression—Death of the Regent Murray—Its Consequences in Scotland—Religious Persecutions—Execution of Norfolk—Massacre of St. Bartholomew—Siege of Edinburgh Castle—War in France—Splendid Defence of La Rochelle—Death of Charles IX.—Religious War in the Netherlands—Rule of Don John—The Anjou Marriage—Deaths of Anjou and of William the Silent 274

REIGN OF ELIZABETH (continued).

Affairs of Ireland: Shane O'Neil's Rebellion—Plantation of Ulster—Spanish Descent on Ireland—Desmond's Rebellion—Religious Conformity—Campian and Parsons—The Anabaptists—Affairs of Scotland—Death of Morton—Success of the Catholics in Scotland—The Raid of Ruthven—Elizabeth's Position—Throgmorton's Plot—Association to Protect Elizabeth—Mary removed to Tutbury—Support of the Protestant Cause on the Continent—Leicester in the Netherlands—Babington's Plot—Trial of Mary—Her Condemnation—Hesitation of Elizabeth—Execution of Mary 295

REIGN OF ELIZABETH (concluded).

State of Europe on the Death of Mary—Preparations of Philip of Spain—Exploits of English Sailors—Drake Singes the King of Spain's Beard—Preparations against the Armada—Loyalty of the Roman Catholics—Arrival of the Armada[viii] in the Channel—Its Disastrous Course and Complete Destruction—Elizabeth at Tilbury—Death of Leicester—Persecution of the Puritans and Catholics—Renewed Expeditions against Spain—Accession of Henry of Navarre to the French Throne—He is helped by Elizabeth—Essex takes Cadiz—His Quarrels with the Cecils—His Second Expedition and Rupture with the Queen—Troubles in Ireland—Essex appointed Lord-Deputy—His Failure—The Essex Rising—Execution of Essex—Mountjoy in Ireland—The Debate on Monopolies—Victory of Mountjoy—Weakness of Elizabeth—Her last Illness and Death 313

THE PROGRESS OF THE NATION IN THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY.

The Tudors and the Nation—The Church—Population and Wealth—Royal Prerogative—Legislation of Henry VIII.—The Star Chamber—Beneficial Legislation—Treason Laws—Legislation of Edward and Mary—Elizabeth's Policy—Religion and the Church—Sketch of Ecclesiastical History under the Tudors—Literature, Science, and Art—Greatness of the Period—Foundation of Colleges and Schools—Revival of Learning—Its Temporary Decay—Prose Writers of the Period—The Poets—Scottish Bards—Music—Architecture—Painting and Sculpture—Furniture and Decorations—Arms and Armour—Costumes, Coins, and Coinage—Ships, Commerce, Colonies, and Manufactures—Manners and Customs—Condition of the People 342

REIGN OF JAMES I.

The Stuart Dynasty—Hopes and Fears caused by the Accession of James—The King enters England—His Progress to London—Lavish Creation of Peers and Knights—The Royal Entrance into the Metropolis—The Coronation—Popularity of Queen Anne—Ravages of the Plague—The King Receives Foreign Embassies—Rivalry of the Diplomatists of France and Spain—Discontent of Raleigh, Northumberland, and Cobham—Conspiracies against James—"The Main" and "The Bye"—Trials of the Conspirators—The Sentences—Conference with Puritans—Parliament of 1604—Persecution of Catholics and Puritans—Gunpowder Plot—Admission of Fresh Members—Delays and Devices—The Letter to Lord Mounteagle—Discovery of the Plot—Flight of the Conspirators—Their Capture and Execution—New Penal Code—James's Correspondence with Bellarmine—Cecil's attempts to get Money—Project of Union between England and Scotland—The King's Collisions with Parliament—Insurrection of the Levellers—Royal Extravagance and Impecuniosity—Fresh Disputes with Parliament and Assertions of the Prerogative—Death of Cecil—Story of Arabella Stuart—Death of Prince Henry 404

REIGN OF JAMES I (concluded).

Reign of Favourites—Robert Carr—His Marriage—Death of Overbury—Venality at Court—The Addled Parliament—George Villiers—Fall of Somerset—Disgrace of Coke—Bacon becomes Lord Chancellor—Position of England Abroad—The Scottish Church—Introduction of Episcopacy—Andrew Melville—Visit of James to Scotland—The Book of Sports—Persecution of the Irish Catholics—Examination into Titles—Rebellion of the Chiefs—Plantation of Ulster—Fresh Confiscations—Quarrel between Bacon and Coke—Prosperity of Buckingham—Raleigh's Last Voyage—His Execution—Beginning of the Thirty Years' War—Indecision of James—Despatch of Troops to the Palatinate—Parliament of 1621—Impeachment of Bacon—His Fall—Floyd's Case—James's Proceedings during the Recess—Dissolution of Parliament—Reasons for the Spanish Match—Charles and Buckingham go to Spain—The Match is Broken Off—Punishment of Bristol—Popularity of Buckingham—Change of Foreign Policy—Marriage of Charles and Henrietta Maria—Death of James 448

REIGN OF CHARLES I.

Accession of Charles—His Marriage—Meeting of Parliament—Loan of Ships to Richelieu—Dissolution of Parliament—Failure of the Spanish Expedition—Persecution of the Catholics—The Second Parliament—It appoints three Committees—Impeachment of Buckingham—Parliament dissolved to save him—Illegal Government—High Church Doctrines—Rupture with France—Disastrous Expedition to Rhé—The Third Parliament—The Petition of Right—Resistance and Final Surrender of Charles—Parliament Prorogued—Assassination of Buckingham—Fall of La [ix]Rochelle—Parliament Reassembles and is Dissolved—Imprisonment of Offending Members—Government without Parliament—Peace with France and Spain—Gustavus Adolphus in Germany—Despotic Proceedings of Charles and Laud 508

Reign of Charles I (continued).

Visit of Charles to Scotland—Laud and the Papal See—His Ecclesiastical Measures—Punishment of Prynne, Bastwick, and Burton—Disgrace of Williams—Ship-money—Resistance of John Hampden—Wentworth in the North—Recall of Falkland from Ireland—Wentworth's Measures—Inquiry into Titles—Prelacy Riots in Edinburgh—Jenny Geddes's Stool—The Tables—Renewal of the Covenant—Charles makes Concessions—The General Assembly—Preparations for War—Charles at York—Leslie at Dunse Hill—A Conference held—Treaty of Berwick—Arrest of Loudon—Insult from the Dutch—Wentworth in England—The Short Parliament—Riots in London—Preparations of the Scots—Mutiny in the English Army—Invasion of England—Treaty of Ripon—Meeting of the Long Parliament—Impeachment of Strafford—His Trial—He is abandoned by Charles—His Execution—The King's Visit to Scotland 550

DANDY OF THE TIME OF CHARLES I.

(From a Broadside, dated 1646.)

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| Dandy of the Time of Charles I. | IX |

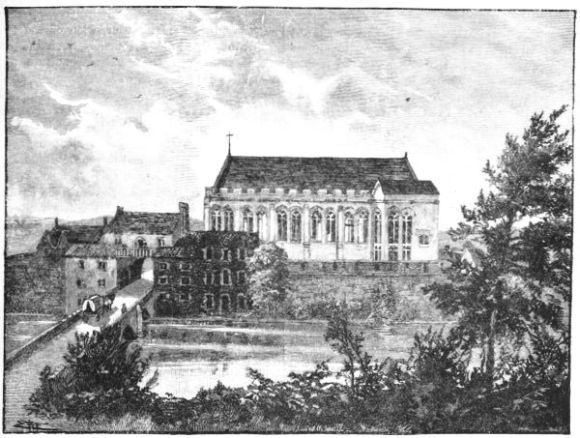

| Eltham Palace, from the North-east | 1 |

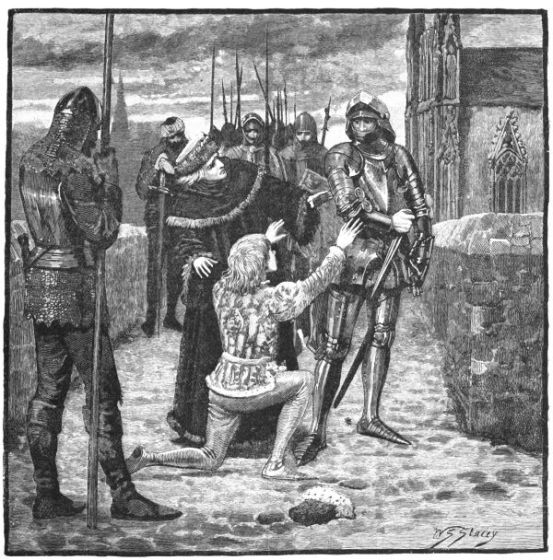

| The Duke of York Challenged to Mortal Combat | 5 |

| View in Lübeck: The Church of St. Ægidius | 9 |

| Clifford's Tower: York Castle | 12 |

| Rutland beseeching Clifford to spare his Life | 13 |

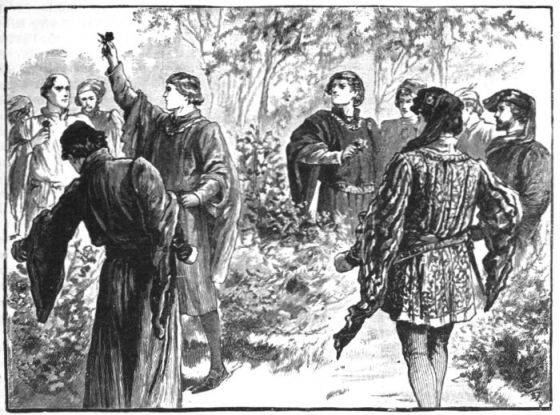

| The Quarrel in the Temple Gardens | 17 |

| Edward IV. | 20 |

| Dunstanburgh Castle | 21 |

| Great Seal of Edward IV. | 25 |

| Gold Rose Noble of Edward IV. | 28 |

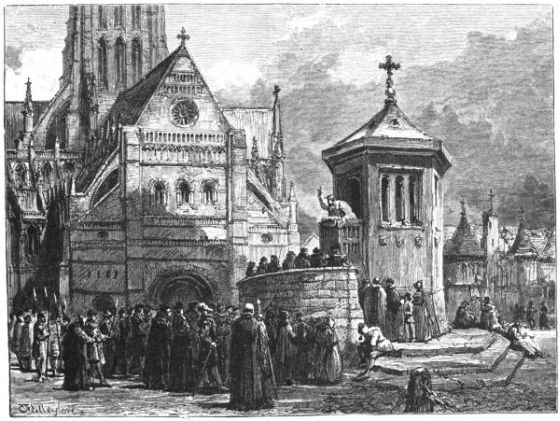

| Preaching at St. Paul's Cross | 29 |

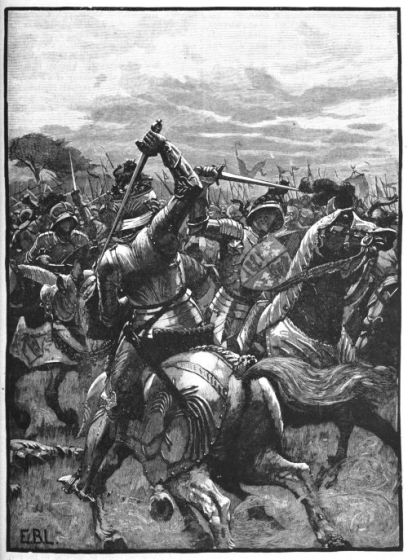

| Battle of Barnet: Death of the King-maker | 33 |

| Burial of King Henry | 37 |

| Louis XI. and the Herald | 41 |

| St. Andrews, from the Pier | 45 |

| Great Seal of Edward V. | 48 |

| Edward V. | 49 |

| The Tower of London: Bloody and Wakefield Towers | 52 |

| Great Seal of Richard III. | 53 |

| The Princes in the Tower | 56 |

| Richard III. | 57 |

| Richard III. at the Battle of Bosworth | 61 |

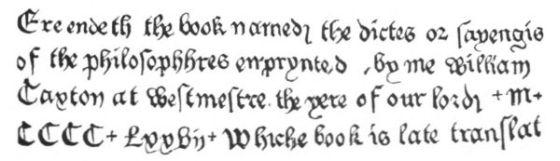

| Facsimile of Caxton's Printing in the "Dictes and Sayings of Philosophers," (1477) | 65 |

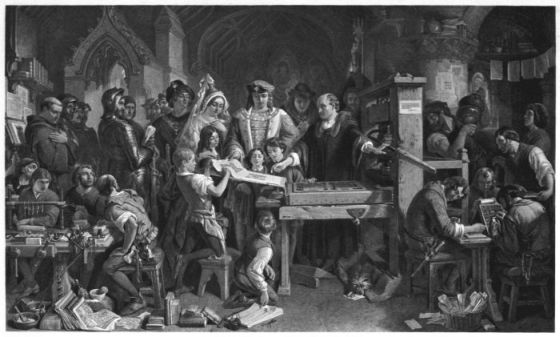

| Earl Rivers Presenting Caxton to Edward IV. | 65 |

| The Quadrangle, Eton College | 68 |

| Interior of King's College Chapel, Cambridge | 69 |

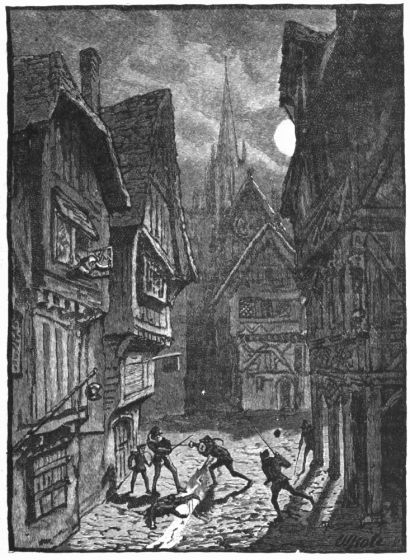

| Street in London in the Fifteenth Century | 73 |

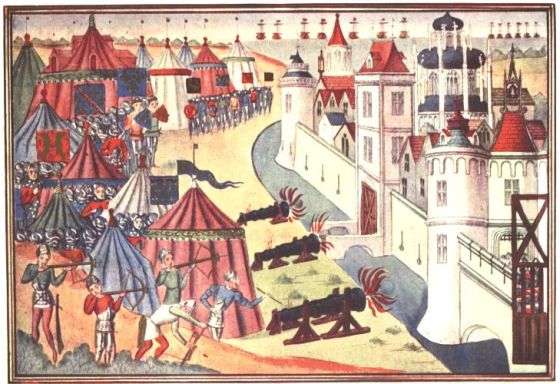

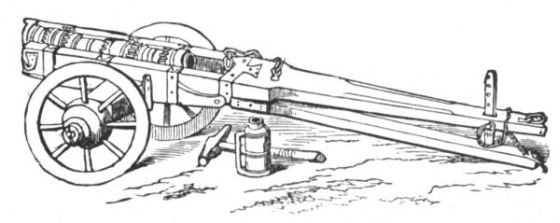

| Cannon of the End of the Fifteenth Century | 75 |

| Great Seal of Henry VII. | 77 |

| Henry VII. | 80 |

| The Last Stand of Schwarz and his Germans | 81 |

| Penny of Henry VII. Angel of Henry VII. Noble of Henry VII. Sovereign of Henry VII. | 85 |

| Stirling Castle | 89 |

| St. Michael's Mount, Cornwall | 92 |

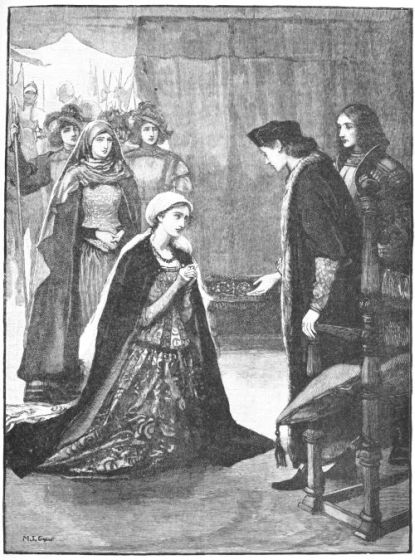

| Lady Catherine Gordon before Henry VII. | 93 |

| The Byward Tower, Tower of London | 97 |

| King Henry's Departure from Henningham Castle | 100 |

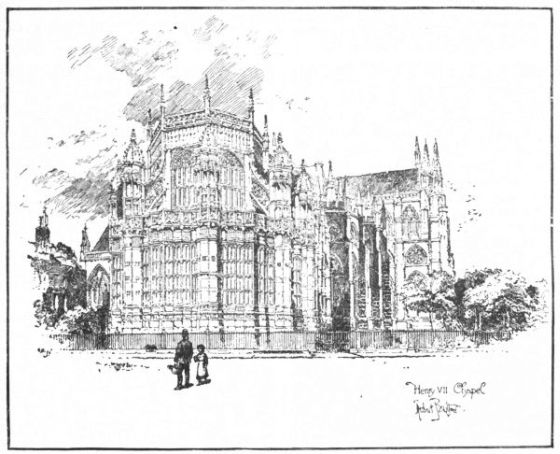

| Henry VII.'s Chapel, Westminster Abbey | 101 |

| Great Seal of Henry VIII. | 105 |

| Meeting of Henry and the Emperor Maximilian | 108 |

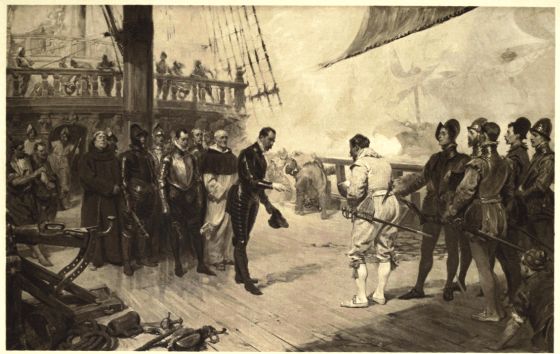

| Henry and the captured French Officers | 109 |

| Edinburgh after Flodden | 113 |

| Archbishop Warham | 117 |

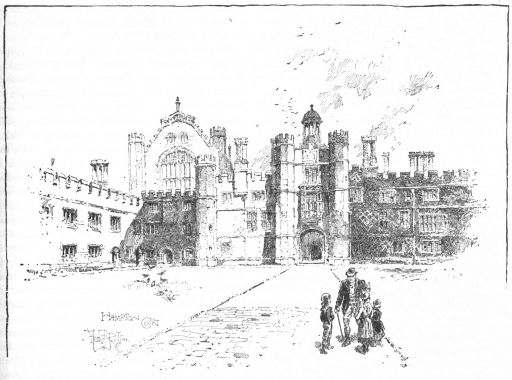

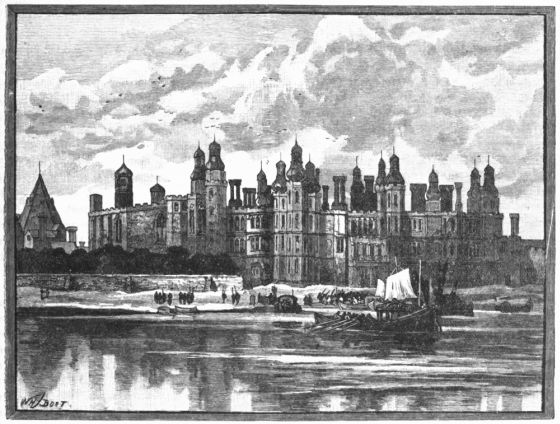

| Hampton Court Palace | 121 |

| Henry VIII. | 125 |

| Great Ship of Henry VIII. | 129 |

| Stirling, from the Abbey Craig | 132 |

| Cardinal Wolsey | 133 |

| Silver Groat of Henry VIII. Gold Crown of Henry VIII. George Noble of Henry VIII. | 136 |

| Pound Sovereign of Henry VIII. Double Sovereign of Henry VIII. | 137 |

| Surrender of Francis on the Battle-field of Pavia | 141 |

| Martin Luther | 145 |

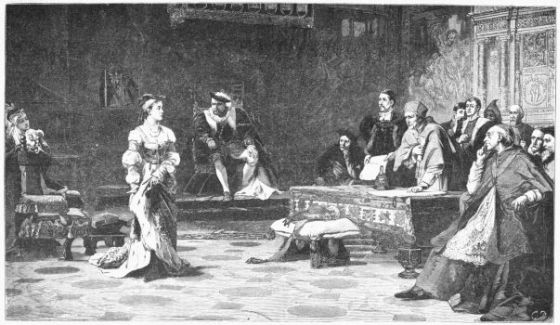

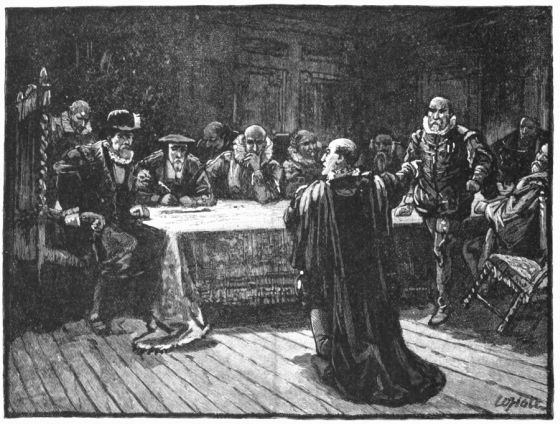

| The Trial of Queen Catherine | 149 |

| The Dismissal of Wolsey | 153 |

| The Tower of London: Sketch in the Gardens | 157 |

| Sir Thomas More | 160 |

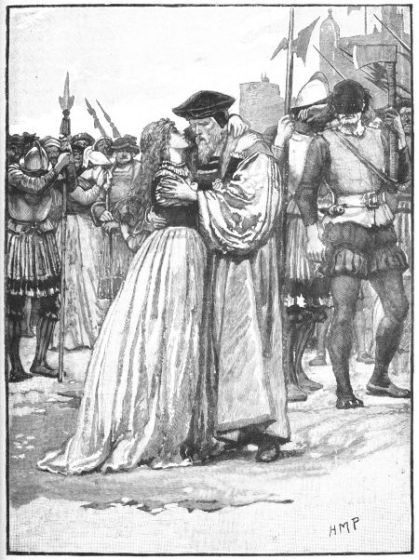

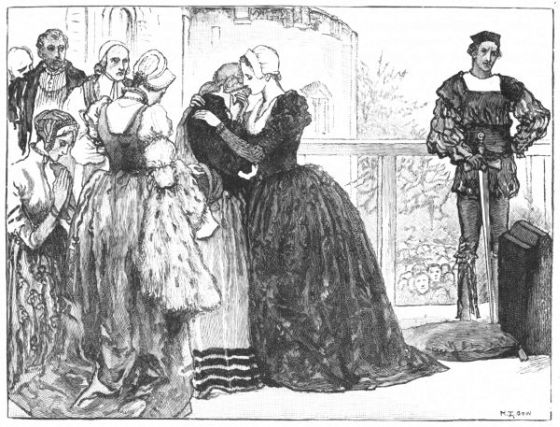

| The Parting of Sir Thomas More and his Daughter | 161 |

| Anne Boleyn | 165 |

| Anne Boleyn's Last Farewell of her Ladies | 168 |

| St. Peter's Chapel, Tower Green, London, where Anne Boleyn was Buried | 169 |

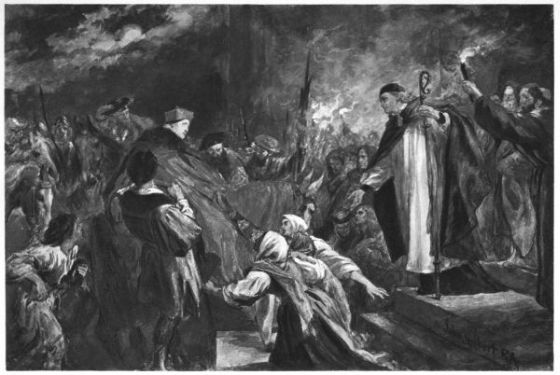

| The Pilgrimage of Grace | 173 |

| Gateway of Kirkham Priory | 176 |

| Beauchamp Tower, and Place of Execution within the Tower of London | 177 |

| Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex | 181 |

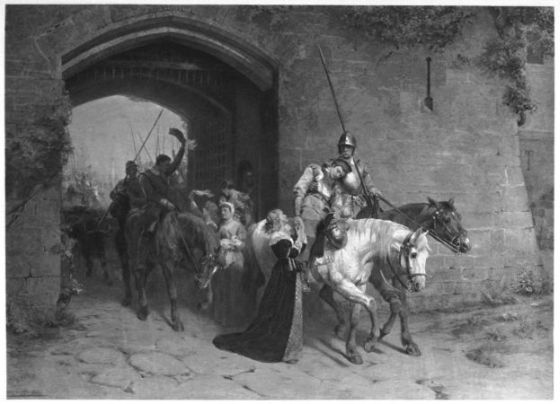

| Catherine Howard being conveyed to the Tower | 185 |

| Capture of the Fitzgeralds | 188 |

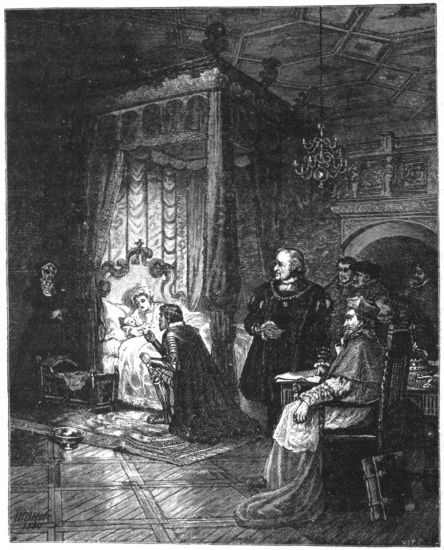

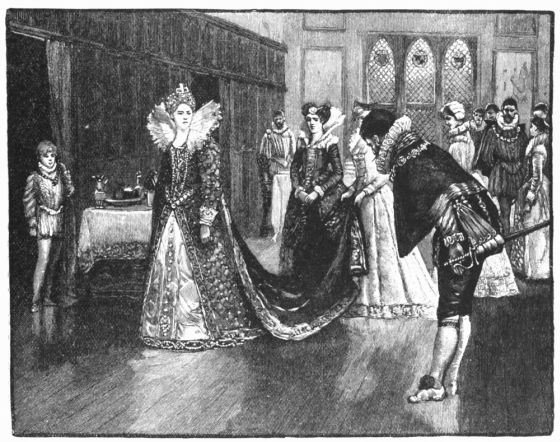

| The First Levee of Mary Queen of Scots | 192 |

| View in St. Andrews: North Street | 193 |

| Francis I. | 197 |

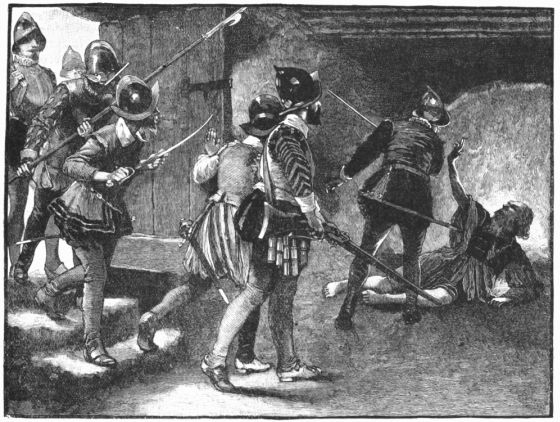

| The Assassination of Cardinal Beaton | 201 |

| Edward VI. | 205 |

| Great Seal of Edward VI. | 209 |

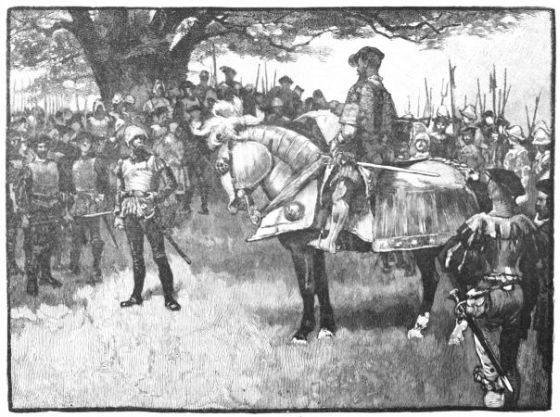

| The Royal Herald in Ket's Camp | 212 |

| Old Somerset House, London | 213 |

| The Duke of Somerset | 217 |

| Silver Crown of Edward VI. | 219 |

| Sixpence of Edward VI. Shilling of Edward VI. Pound Sovereign of Edward VI. Triple Sovereign of Edward VI. | 220 |

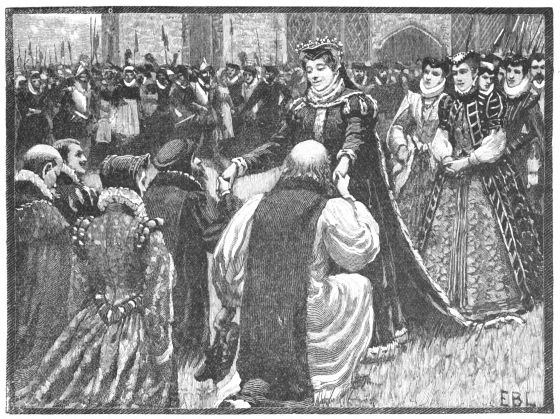

| Queen Mary and the State Prisoners in the Tower | 221 |

| Great Seal of Philip and Mary | 224 |

| View from the Constable's Garden, Tower of London | 225 |

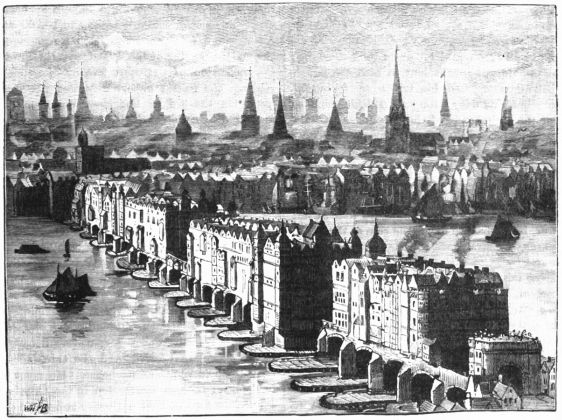

| Old London Bridge, with Nonsuch Palace | 229 |

| Lady Jane Grey on her way to the Scaffold | 233 |

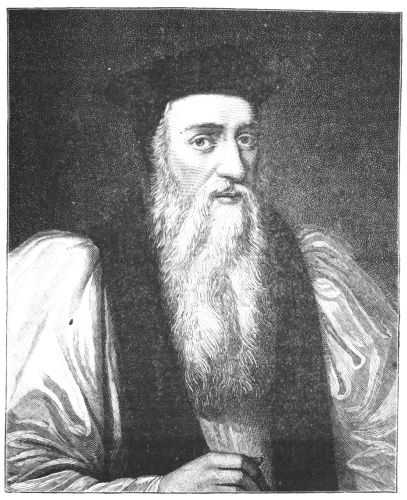

| Archbishop Cranmer | 237 |

| The Place of Martyrdom, Old Smithfield | 240 |

| Mary I. | 241 |

| The Hôtel de Ville and Old Lighthouse, Calais | 244 |

| Shilling of Philip and Mary. Real of Mary I. | 245 |

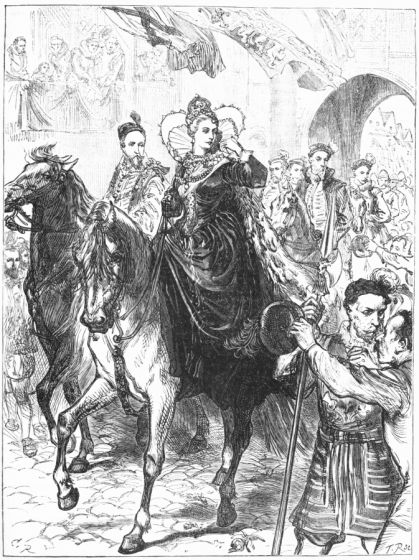

| Elizabeth's Public Entry into London | 249 |

| Elizabeth | 252 |

| Autograph of Elizabeth | 253 |

| Mar's Work, Stirling | 257 |

| Great Seal of Elizabeth | 260 |

| Mary, Queen of Scots | 261 |

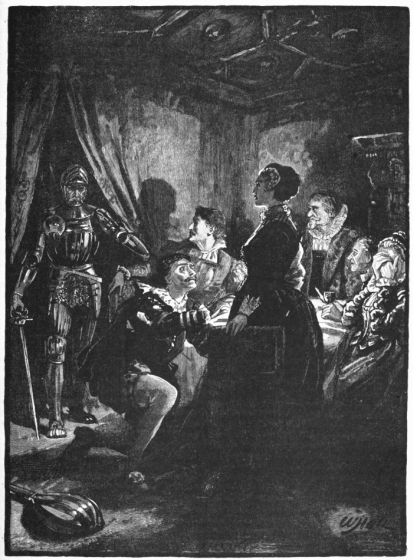

| The Murder of Rizzio | 265 |

| Holyrood Palace, Edinburgh | 269 |

| Mary Signing the Deed of Abdication in Lochleven Castle | 273 |

| Lord Burleigh | 276 |

| Farthing of Elizabeth. Halfpenny of Elizabeth. Penny of Elizabeth. Twopence of Elizabeth. Half-crown of Elizabeth. Half-sovereign of Elizabeth | 277 |

| The Duke of Norfolk's Interview with Elizabeth | 281 |

| The Regent Murray | 284 |

| High Street, Linlithgow | 285 |

| Kenilworth Castle | 289 |

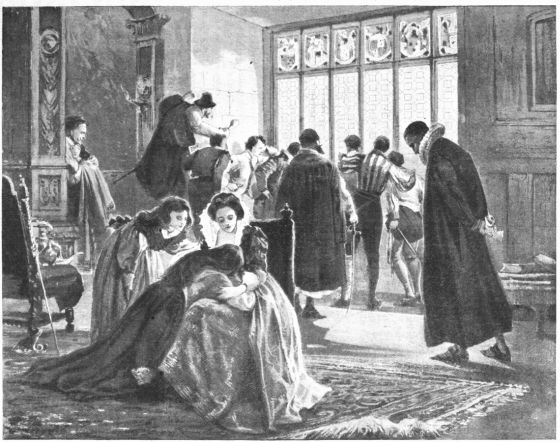

| The House of the English Ambassador during the Massacre of St. Bartholomew | 293 |

| Murder of the Earl of Desmond | 297 |

| The Earl of Arran accusing Morton of the Murder of Darnley | 300[xi] |

| Dumbarton Rock, with view of Castle | 301 |

| The Earl of Leicester | 305 |

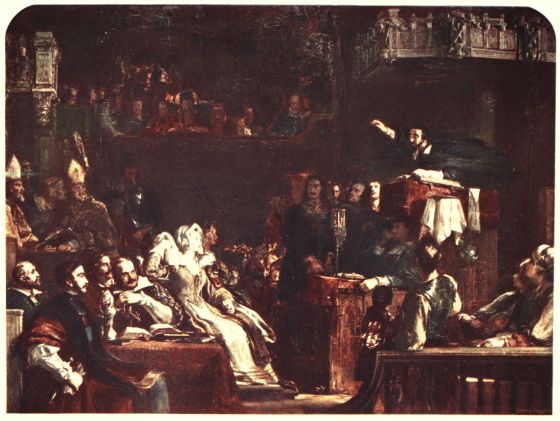

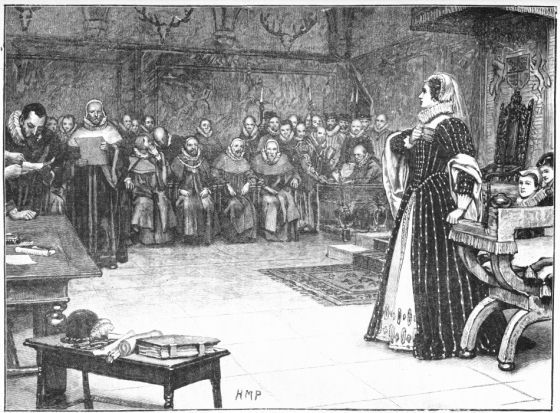

| Trial of Mary Queen of Scots in Fotheringay Castle | 309 |

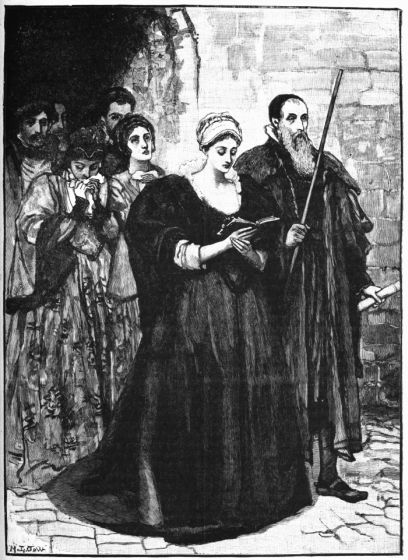

| Mary Queen of Scots receiving Intimation of her Doom | 312 |

| Sir Francis Drake | 317 |

| The Hoe, Plymouth | 320 |

| The Armada in Sight | 321 |

| Philip II. | 325 |

| Beauchamp Tower, Warders' Houses, and Yeoman Gaolers' Lodgings: Tower of London | 329 |

| The Quarrel between Elizabeth and the Earl of Essex | 332 |

| The Earl of Essex | 333 |

| Lord Grey and his Followers Attacking the Earl of Southampton | 337 |

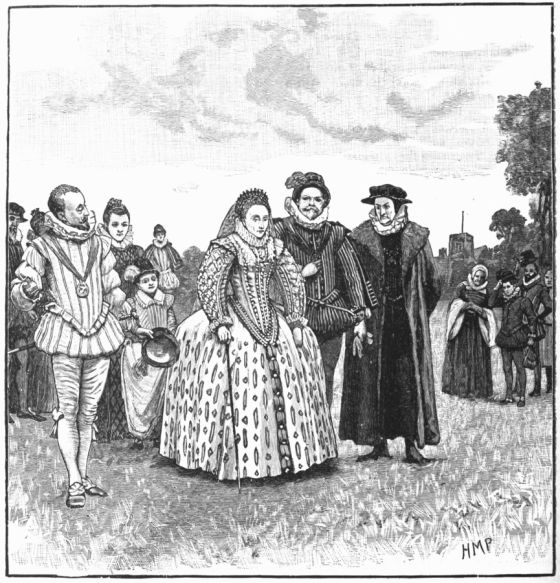

| Elizabeth's Promenade on Richmond Green | 340 |

| Richmond Palace | 341 |

| Town and Country Folk of Elizabeth's Reign | 345 |

| State Trial in Westminster Hall in the Time of Elizabeth | 349 |

| John Knox | 353 |

| Reduced Facsimile of the Title-page of the Great Bible, also called Cromwell's Bible | 357 |

| Christ's Hospital, London | 361 |

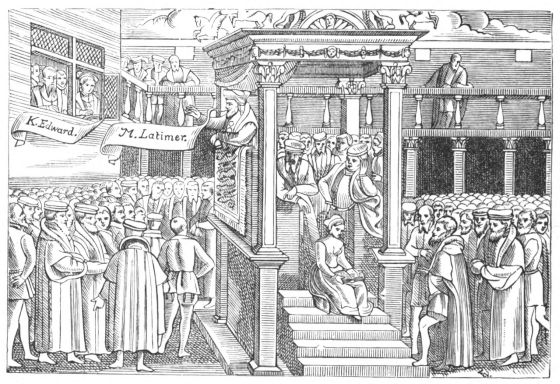

| Latimer Preaching before Edward VI. | 364 |

| Roger Ascham's Visit to Lady Jane Grey | 365 |

| Edmund Spenser | 369 |

| The House at Stratford-on-Avon in which Shakespeare was Born | 373 |

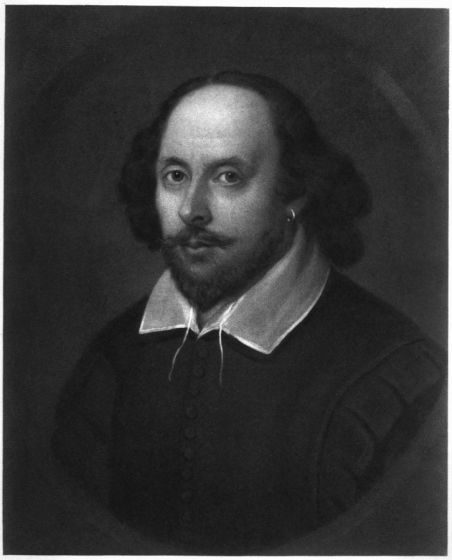

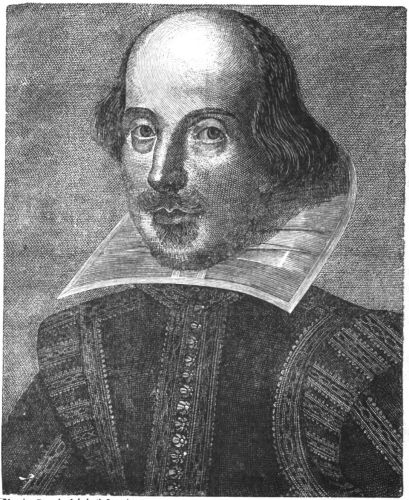

| Shakespeare | 376 |

| The Acting of one of Shakespeare's Plays in the Time of Queen Elizabeth | 377 |

| Queen Elizabeth's Cither and Music-book | 379 |

| Holland House, Kensington | 380 |

| The Great Court of Kirby Hall, Northamptonshire | 381 |

| Entrance from the Courtyard of Burleigh House, Stamford | 383 |

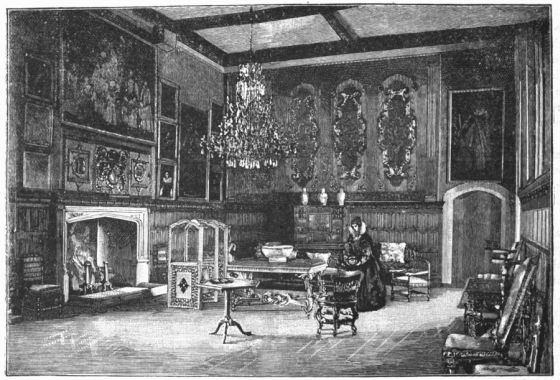

| Elizabeth's Drawing-room, Penshurst Place | 384 |

| Soldiers of the Tudor Period | 385 |

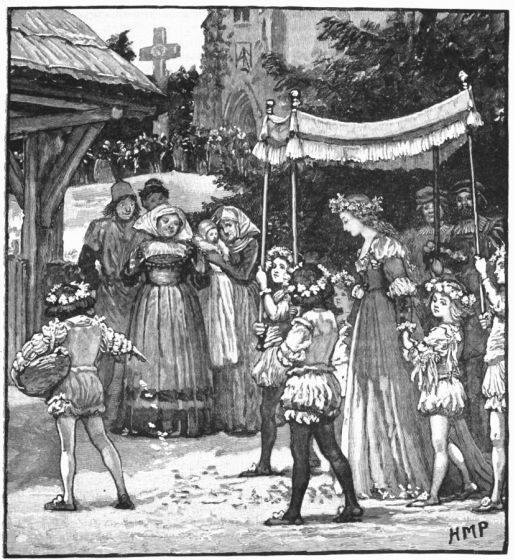

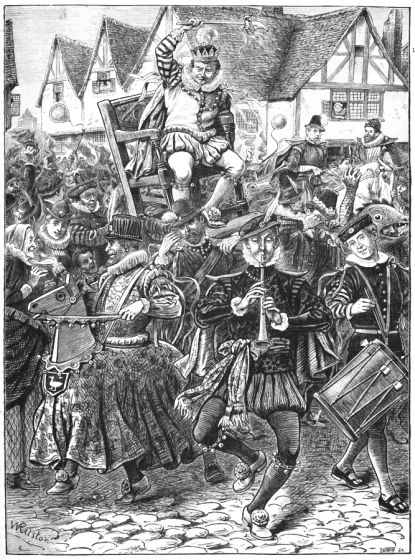

| The Wedding of Jack of Newbury: The Bride's Procession | 389 |

| Ships of Elizabeth's Time | 393 |

| The First Royal Exchange, London (Founded by Sir Thomas Gresham) | 396 |

| Sir Thomas Gresham | 397 |

| The Frolic of My Lord of Misrule | 401 |

| Punishment of the Stocks | 403 |

| James I. | 405 |

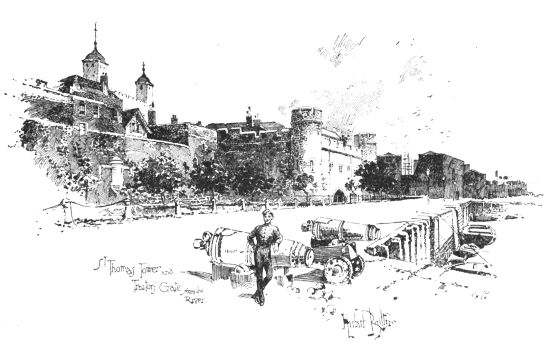

| St. Thomas's Tower and Traitor's Gate, Tower of London | 409 |

| Sir Walter Raleigh | 412 |

| The Dissenting Divines Presenting their Petition to James | 413 |

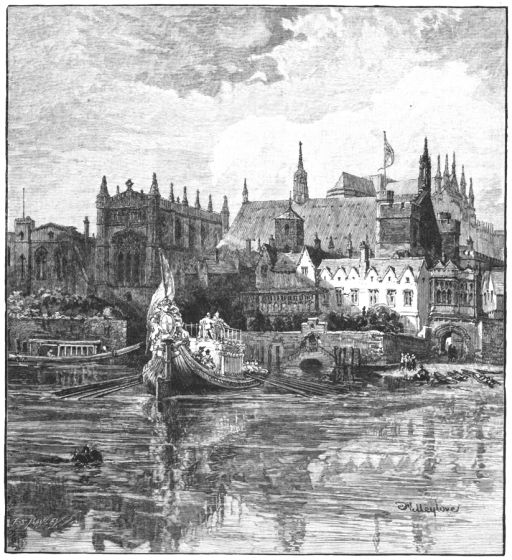

| The Old Palace, Westminster, in the time of Charles I. | 417 |

| Great Seal of James I. | 420 |

| Guy Fawkes's Cellar under Parliament House | 421 |

| Lord Monteagle and the Warning Letter about the Gunpowder Plot | 425 |

| Arrest of Guy Fawkes | 428 |

| Pound Sovereign of James I. Unit or Laurel of James I. (Gold). Spur Rial of James I. (Gold). Thistle Crown of James I. (Gold) | 432 |

| Sir Robert Cecil, afterwards Earl of Salisbury | 433 |

| Shilling of James I. Crown of James I. | 436 |

| James and his Courtiers setting out for the Hunt | 437 |

| The Star Chamber | 441 |

| Flight of the Lady Arabella Stuart | 444 |

| Notre Dame, Caudebec | 445 |

| Sir Francis Bacon (Viscount St. Albans) | 449 |

| The Banqueting House, Whitehall | 452 |

| Greenwich Palace in the time of James I. | 456 |

| Sir Edward Coke | 457 |

| Andrew Melville before the Scottish Privy Council | 461 |

| Keeping Sunday, according to King James's Book of Sports | 465 |

| Parliament House, Dublin, in the Seventeenth Century | 469 |

| Sir Francis Bacon waiting an Audience of Buckingham | 472 |

| Arrest of Sir Walter Raleigh | 476 |

| Sir Walter Raleigh before the Judges | 477 |

| The Franzensring, Vienna | 481 |

| Interview between Bacon and the Deputation from the Lords | 484 |

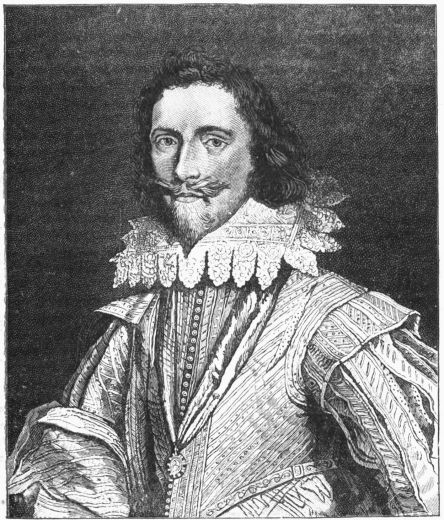

| George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham | 485 |

| The Fleet Prison | 489 |

| Public Reception of Prince Charles in Madrid | 493 |

| Prince Charles's Farewell of the Infanta | 497 |

| The Royal Palace, Madrid | 500 |

| The Ladies of the French Court and the Portrait of Prince Charles | 504 |

| Henrietta Maria | 505 |

| Great Seal of Charles I. | 509 |

| Charles welcoming his Queen to England | 512 |

| Charles I. | 513 |

| Reception of Viscount Wimbledon at Plymouth | 516 |

| York House (The Duke of Buckingham's Mansion) | 517 |

| Trial of Buckingham | 521 |

| Interior of the Banqueting House, Whitehall | 525 |

| Sir John Eliot | 529 |

| Assassination of the Duke of Buckingham | 533 |

| Tyburn in the time of Charles I. | 537 |

| Three Pound Piece of Charles I. Broad of Charles I. Briot Shilling of Charles I. | 540 |

| John Selden | 541 |

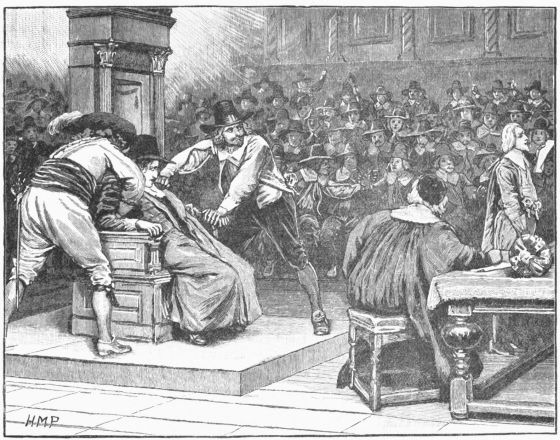

| Scene in the House of Commons: The Speaker Coerced | 545 |

| Interior of Old St. Paul's | 549 |

| Dunblane | 552 |

| Archbishop Laud | 553 |

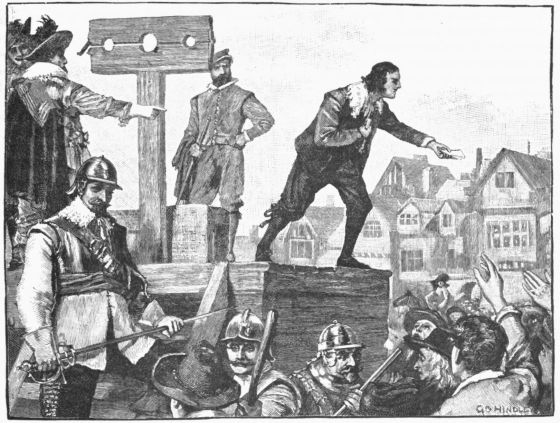

| John Lilburne on the Pillory | 557 |

| The Birmingham Tower, Dublin Castle | 561 |

| Sir Thomas Wentworth (Earl of Strafford) | 564 |

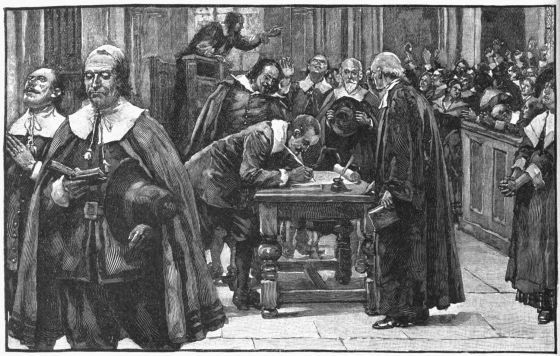

| The People Signing the Covenant in St. Giles's Church, Edinburgh | 568 |

| St. Giles's Church, Edinburgh, in the 17th Century | 569 |

| The Old College, Glasgow, in the 17th Century | 573 |

| Charles and the Scottish Commissioners | 577 |

| John Hampden | 581 |

| Guildhall, London, in the time of Charles I. | 585 |

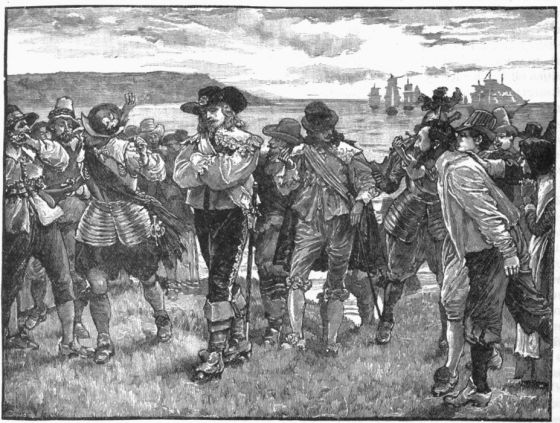

| Advance of the Covenanters across the Border into England | 589 |

| John Pym | 592 |

| Arrest of the Earl of Strafford | 593 |

| Westminster Hall and Palace Yard in the time of Charles I. | 597 |

| Charles Signing the Commission of Assent to Strafford's Attainder | 601 |

| The Old Parliament House, Edinburgh | 604 |

| The Marquis of Montrose | 605 |

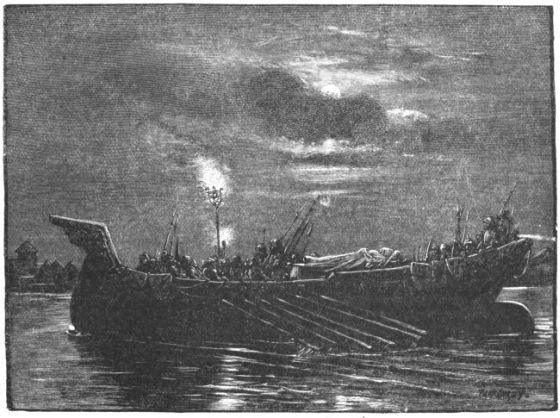

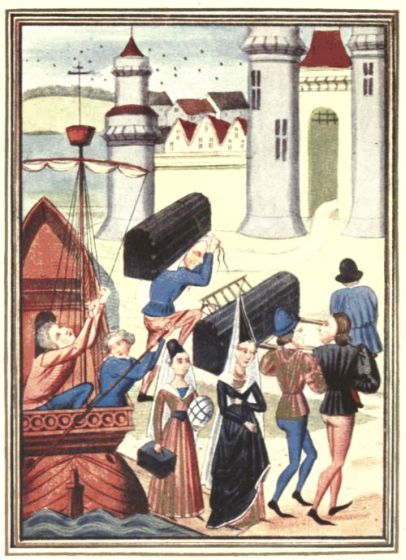

| Departure of English and French from Genoa in 1390 to Chastise the | ||

| Barbary Corsairs. (From the Froissart MS. in the British Museum) | Frontispiece | |

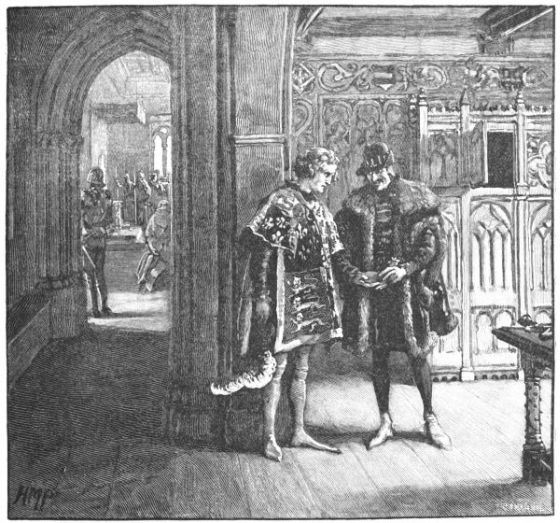

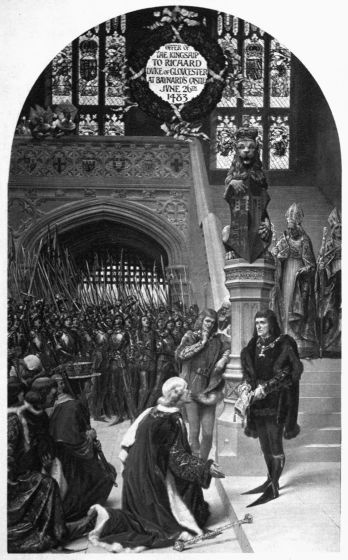

| The Crown of England being Offered to Richard, Duke of Gloucester, at | ||

| Baynard's Castle, in 1483. (By Sigismund Goetze) | To face p. | 50 |

| Caxton Showing the First Specimen of his Printing to King Edward IV., | ||

| at the Almonry, Westminster. (By Daniel Maclise, R.A.) | " | 64 |

| The Grand Assault upon the Town of Africa by the English and French. | ||

| (From the Froissart MS. in the British Museum) | " | 72 |

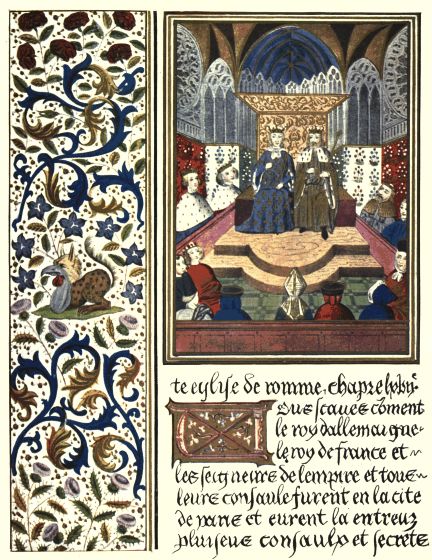

| Froissart Presenting his Book of Love Poems to Richard II., in 1395.—The | ||

| Landing of the Lady de Coucy at Boulogne. (From the Froissart MS. in | ||

| the British Museum) | " | 74 |

| Cardinal Wolsey Going in Procession to Westminster Hall. (By Sir John | ||

| Gilbert, R.A., P.R.W.S.) | " | 118 |

| Cardinal Wolsey at Leicester Abbey. (By Sir John Gilbert, R.A., P.R.W.S.) | " | 154 |

| Sweethearts and Wives. (Moss-troopers Returning from a Foray.) | ||

| (By S. E. Waller) | " | 190 |

| Lady Jane Grey's Reluctance to Accept the Crown of England. | ||

| (By C. R. Leslie, R.A.) | " | 222 |

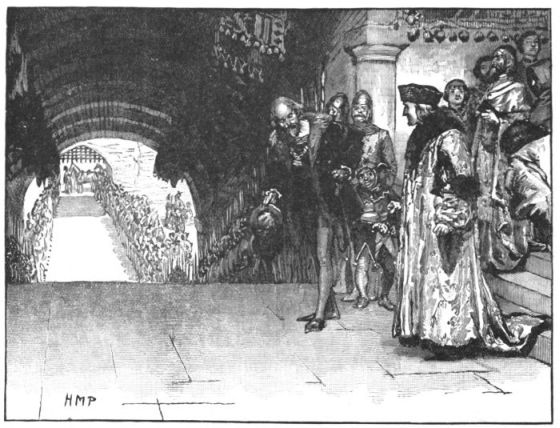

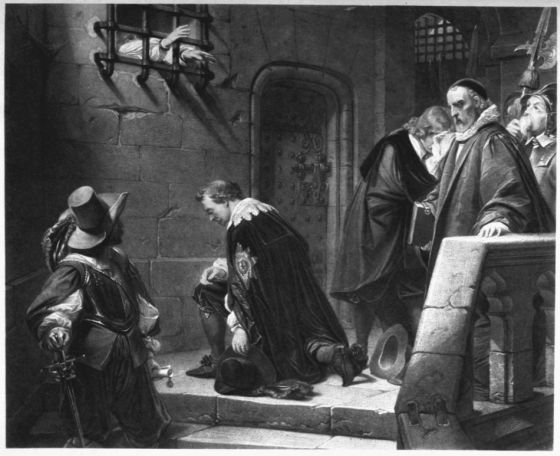

| Cranmer at Traitors' Gate. (By F. Goodall, R.A.) | " | 226 |

| Queen Elizabeth. (By F. Zucchero) | " | 246 |

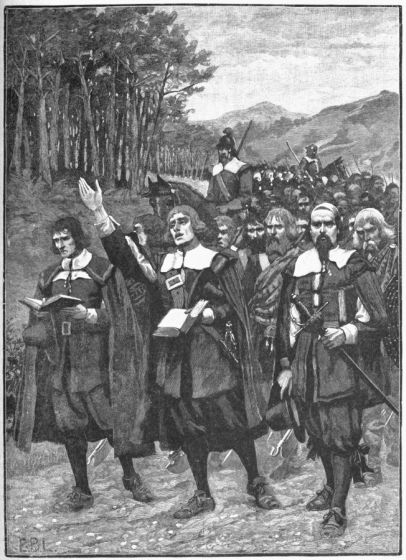

| The Preaching of John Knox before the Lords of the Congregation, | ||

| 10th June, 1559. (By Sir David Wilkie, R.A.) | " | 256 |

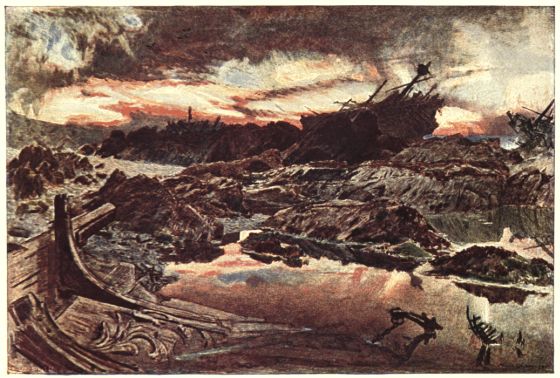

| The Invincible Armada. (By Albert Goodwin, R.W.S.) | " | 312 |

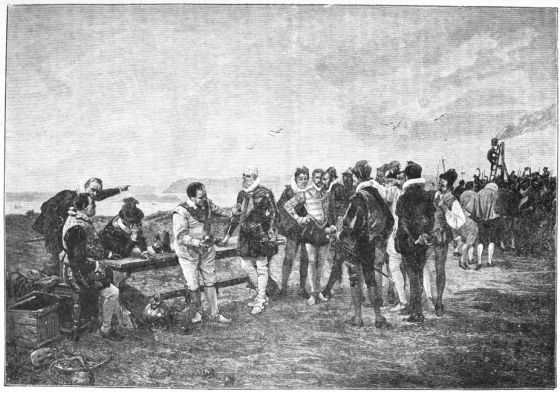

| "The Surrender": An Incident of the Spanish Armada. (By Seymour | ||

| Lucas, R.A.) | " | 322 |

| A Story of the Spanish Main. (By Seymour Lucas, R.A.) | " | 338 |

| William Shakespeare. (From the Painting known as the Chandos Portrait, and | ||

| attributed to Richard Burbage, in the National Portrait Gallery) | " | 374 |

| Map of the World at the End of the Sixteenth Century, showing the | ||

| Discoveries of British and other Explorers | " | 394 |

| The Departure of the "Mayflower." (By A. W. Bayes) | " | 474 |

| Illuminated Page, with Bordering. (From the Froissart MS. in the British Museum) | " | 512 |

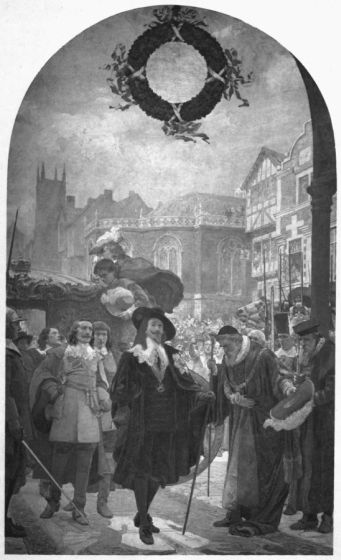

| Visit of Charles I. to the Guildhall. (By Solomon J. Solomon, R.A.) | " | 582 |

| Strafford Going to Execution. (By Paul Delaroche) | " | 604 |

From the Froissart MS. in the British Museum. Reproduced by André & Sleigh, Ld., Buskey, Herts.

DEPARTURE OF ENGLISH AND FRENCH FROM GENOA IN 1390 TO CHASTISE THE BARBARY CORSAIRS.

THE PERSONAGE IN THE PLACE OF HONOUR IN THE ROWING-BOAT IS BELIEVED TO BE THE DUKE OF BOURBON. THE VESSEL IN THE CENTRE CONTAINS SEVERAL FRENCH KNIGHTS: IN THAT ON THE LEFT IS HENRY DE BEAUFORT (A NATURAL SON OF THE DUKE OF LANCASTER), WITH ENGLISH KNIGHTS AND SQUIRES.

ELTHAM PALACE, FROM THE NORTH-EAST. (After an Engraving published in 1735.)

THE WARS OF THE ROSES.

Cade's Rebellion—York comes over from Ireland—His Claims and the Unpopularity of the Reigning Line—His First Appearance in Arms—Birth of the Prince of Wales—York made Protector—Recovery of the King—Battle of St. Albans—York's second Protectorate—Brief Reconciliation of Parties—Battle of Blore Heath—Flight of the Yorkists—Battle of Northampton—York Claims the Crown—The Lords Attempt a Compromise—Death of York at Wakefield—Second Battle of St. Albans—The Young Duke of York Marches on London—His Triumphant Entry.

Henry the Sixth and his queen were plunged into grief and consternation at the extraordinary death of Suffolk in 1450. They saw that a powerful party was engaged in thus defeating their attempt to rescue Suffolk from his enemies by a slight term of exile; and they strongly suspected that the Duke of York, though absent in his government of Ireland, was at the bottom of it. It was more than conjectured that he entertained serious designs of profiting by the unpopularity of the Government to assert his claims to the crown. This ought to have made the king and queen especially circumspect, but, so far from this being the case, Henry announced his resolve to punish the people of Kent for the murder of Suffolk, which had[2] been perpetrated on their coast. The queen was furious in her vows of vengeance. These unwise demonstrations incurred the anger of the people, and especially irritated the inhabitants of Kent. To add to the popular discontent, Somerset, who had lost by his imbecility the French territories, was made minister in the place of Suffolk, and invested with all the favour of the court. The people in several counties threatened to rise and reform the Government; and the opportunity was seized by a bold adventurer of the name of John Cade, an Irishman, to attempt a revolution. He selected Kent as the quarter more pre-eminently in a state of excitement against the prevailing misrule, and declaring that he belonged to the royal line of Mortimer, and was cousin to the Duke of York, he gave himself out to be the son of Sir John Mortimer, who, on a charge of high treason, had been executed in the beginning of this reign, without trial or evidence. The lenity which Henry V. had always shown to the Mortimers—their title being superior to his own, their position near the throne was of course an element of danger—had not been imitated by Bedford and Gloucester, the infant king's uncles, and their neglect of the forms of a regular trial had only strengthened the opinions of the people as to the Mortimer rights. No sooner, therefore, did Jack Cade assume this popular name, than the people, burning with the anger of the hour against the unlucky dynasty, flocked, to the number of 20,000, to his standard, and advanced to Blackheath. Emissaries were sent into London to stir up the people there, and induce them to open their gates and join the movement. As the Government, taken by surprise, was destitute of the necessary troops on the spot to repel so formidable a body of insurgents, it put on the same air of moderation which Richard II. had done in Tyler's rebellion, and many messages passed between the king and the pretended Mortimer, or, as he also called himself, John Amend-all.

In reply to the king's inquiry as to the cause of this assembly, Cade sent in "The Complaints of the Commons of Kent, and the Causes of the Assembly on Blackheath." These documents were ably and artfully drawn. They professed the most affectionate attachment to the king, and demanded the redress of what were universally known to be real and enormous grievances. The wrongs were those under which the kingdom had long been smarting—the loss of the territories in France, and the loss of the national honour with them, through the treason and mal-administration of the ministers; the usurpation of the Crown lands by the greedy courtiers, and the consequent shifting of the royal expenditure to the shoulders of the people, with the scandals, offences, and robberies of purveyance. The "Complaints" asserted that the people of Kent had been especially victimised and ill-used by the sheriffs and tax-gatherers, and that the free elections of their knights of the shire had been prevented. They declared, moreover, that corrupt men were employed at court, and the princes of the blood and honest men kept out of power.

Government undertook to examine into these causes of complaint, and promised an answer; but the people soon were aware that this was only a pretence to gain time, and that the answer would be presented at the point of the sword. Jack Cade, therefore, sent out what he called "The Requests of the Captain of the Great Assembly in Kent." These "Requests" were based directly on the previous complaints, and were that the king should renew the grants of the Crown, and so enable himself to live on his own income, without fleecing the people; that he should dismiss all corrupt councillors, and all the progeny of the Duke of Suffolk, and take into his service his right trusty cousins and noble peers, the Duke of York, now banished to Ireland, the Dukes of Exeter, Buckingham, and Norfolk. This looked assuredly as if those who drew up those papers for Cade were in the interest of the York party, and the more so as the document went on to denounce the traitors who had compassed the death of that excellent prince the Duke of Gloucester, and of their holy father the cardinal, and who had so shamefully caused the loss of Maine, Anjou, Normandy, and our other lands in France. The assumed murder of the cardinal, who had died almost in public, and surrounded by the ceremonies of the Church, was too ridiculous, and was probably thrown in to hide the actual party at work. The "Requests" then demanded summary execution on the detested collectors and extortioners, Crowmer, Lisle, Este, and Sleg.

The court had now a force ready equal to that of the insurgents, and sent it under Sir Humphrey Stafford to answer the "Requests" by cannon and matchlock. Cade retreated to Sevenoaks, where, taking advantage of Stafford's too hasty pursuit, with only part of his forces, he fell upon his troops, put them to flight, killed Stafford, and, arraying himself in the slain man's armour, advanced again to his former position on Blackheath.

This unexpected success threw the court into[3] a panic. The soldiers who had gone to Sevenoaks had gone unwillingly; and those left on Blackheath now declared that they knew not why they should fight their fellow-countrymen for only asking redress of undoubted grievances. The nobles, who were at heart adverse to the present ministers, found this quite reasonable, and the court was obliged to assume an air of concession. The Lord Say, who had been one of Suffolk's most obsequious instruments, and was regarded by the people as a prime agent in the making over of Maine and Anjou, was sent to the Tower with some inferior officers. The king was advised to disband his army, and retire to Kenilworth; and Lord Scales, with a thousand men, undertook to defend the Tower. Cade advanced from Blackheath, took possession of Southwark, and demanded entrance into the city of London.

The lord mayor summoned a council, in which the proposal was debated; and it was concluded to offer no resistance. On the 3rd of July Cade marched over the bridge, and took up his quarters in the heart of the capital. He took the precaution to cut the ropes of the drawbridge with his sword as he passed, to prevent his being caught, as in a trap; and, maintaining strict discipline amongst his followers, he led them back into the Borough in the evening. The next day he reappeared in the same circumspect and orderly manner; and, compelling the lord mayor and the judges to sit in Guildhall, he brought Lord Say before them, and arraigned him on a charge of high treason. Say demanded to be tried by his peers; but he was hurried away to the standard in Cheapside, and beheaded. His son-in-law, Crowmer, sheriff of Kent, was served in the same manner. The Duchess of Suffolk, the Bishop of Salisbury, Thomas Daniel, and others, were accused of the like high crimes, but, luckily, were not to be found. The bishop had already fallen at the hands of his own tenants at Edington, in Wiltshire.

On the third day Cade's followers plundered some of the houses of the citizens; and the Londoners, calling in Lord Scales with his 1,000 men to aid them, resolved that Cade should be prevented from again entering the city. Cade received notice of this from some of his partisans, and rushed to the bridge in the night to secure it. He found it already in the possession of the citizens. There was a bloody battle, which lasted for six hours, when the insurgents drew off, and left the Londoners masters of the bridge.

On receiving this news, the Archbishops of Canterbury and York, who were in the Tower, determined to try the ruse which had succeeded with the followers of Wat Tyler. They therefore sent the Bishop of Winchester to promise redress of grievances, and a full pardon under the great seal, for every one who should at once return to their homes. After some demur, the terms were gratefully accepted; Cade himself embraced the offered grace, according to the subsequent proclamation against him, dated the 10th of July; but quickly repenting of his credulity, he once more unfurled his banner, and found a number of men ready to rejoin it. This mere remnant of the insurgent host, however, was utterly incapable of effecting anything against the city; they retired to Deptford, and thence to Rochester, hoping to gather a fresh army. But the people had now cooled; the rioters began to divide their plunder and to quarrel over it; and Cade, seeing all was lost, and fearing that he should be seized for the reward of 1,000 marks offered for his head, fled on horseback towards Lewes. Disguising himself, he lurked about in secret places, till, being discovered in a garden at Heathfield, in Kent, by Alexander Iden, the new sheriff; he was, after a short battle, killed by Iden, and his body carried to London.

That the party of the Duke of York had some concern in Cade's rebellion, the Government not only suspected, but several of Cade's followers when brought to execution, are said to have confessed as much. But stronger evidence of the fact is, that there was an immediate rumour that the duke himself was preparing to cross over to England. The court at once issued orders in the king's name, to forbid his coming, and to oppose any armed attempt on his part. The duke defeated this scheme by appearing without any retinue whatever, trusting to the good-will of the people. His confidence in thus coming at once to the very court put the Government, which had shown such suspicion of him, completely in the wrong in the eye of the public.

We are now on the eve of that contest for the possession of the crown, which figures so eminently in history as the Wars of the Roses. The accession of Henry IV., productive of very bloody consequences at the time, had nearly been forgotten through the brilliant successes of his son, Henry V.; but still the heirs of the true line, according to the doctrine of lineal descent, were in existence. The Mortimers, Earls of March, had been spared by the usurping family; and Richard, Duke of York, was now the representative[4] of that line. To understand clearly how the Mortimers, and from them Richard, Duke of York, took precedence of Henry VI., according to lineal descent, we must recollect that Henry IV. was the son of John of Gaunt, who was the fourth son of Edward III. On the deposition of Richard II., who was the son of the Black Prince, the eldest son of Edward III., there was living the Earl of March, the grandson of Lionel, the third son of Edward III., who had clearly the right to precede Henry. This right had been, moreover, recognised by Parliament. But Henry of Lancaster, disregarding this claim, seized on the crown by force, yet took no care to destroy the true claimant. Now, the Duke of York, who was paternally descended from Edmund of Langley, the fifth son of Edward III., was also maternally the lineal descendant of Lionel, the third son through the daughter and heiress of Mortimer, the Earl of March. By this descent he preceded the descendants of Henry IV., and was by right of heirship the undoubted claimant of the English crown.

The Marches had shown no disposition whatever to assert that right, and this had proved their safety. They had been for several generations a particularly modest and unambitious race; and so long as the descendants of Henry IV. had proved able or popular monarchs, their claim would have lain in abeyance. But they were never forgotten; and now that the imbecility and long minority of Henry VI. had created strong factions, and disgusted the people, this claim was zealously revived. Henry IV. had but one real and indefeasible claim to the throne—namely, that of the election of the people, had he chosen to accept it; but this he proudly rejected, and took his stand on his lineal descent from Edward III., where the heirs of his uncle Lionel had entirely the advantage of him.

The people who had favoured, and would have adopted Henry IV., had now become alienated from the house of Lancaster, through the incapacity of the present king, by which they had lost the whole of their ancient possessions, as well as their conquests in France. Nothing remained but heavy taxation and national exhaustion, as the net result of all the wars in that kingdom. In this respect the very glory of Henry V. became the ruin of his son. While the people complained of their poverty and oppression in consequence of those wars, they were doubly harassed by the factious quarrels of the king's relatives. They had attached themselves to the Duke of Gloucester, and he had been murdered by these cliques, and, as was generally believed, at the instigation of the queen. Queen Margaret, indeed, completed the alienation of the people from the house of Lancaster. She was not only French—a nation now in the worst odour with the people of England—but through her they had lost Maine and Anjou.

These circumstances now drew the hearts of the people as strongly towards the Duke of York, as they had formerly been attracted to the house of Lancaster. They began to regard him with interest, as a person whose rights to the throne had been unjustly overlooked. He was a man who seemed to possess much of the modest and amiable character of the Marches. He had been recalled from France, where he was ably conducting himself, by the influence of the queen, as was believed, and sent as governor into Ireland, as a sort of honourable banishment. But though treated in a manner calculated to provoke him, he had retained the unassuming moderation of his demeanour. He had yet made no public pretensions to the crown, and though circumstances seemed to invite him, showed no haste to seize it. There were many circumstances, indeed, which tended to make all parties hesitate to proceed to extremities. True, the queen was highly unpopular, but Henry, though weak, was so amiable, pious, and just, that the people, although groaning under the consequences of his weakness, yet retained much affection for him. There were also numbers of nobles of great influence who had benefited by the long minority of the king, and who, much as they disliked the queen's party, were afraid of being called on, in case another dynasty was established, to yield up the valuable grants which they had obtained.

Thus the kingdom was divided into three parties: those who took part with Somerset and the queen, those who inclined to the Duke of York, and those who, having benefited by the long reign of corruption, were afraid of any change, and endeavoured to hold the balance betwixt the extreme parties. Almost all the nobles of the North of England were zealous supporters of the house of Lancaster, and with them went the Earl of Westmoreland, the head of the house of Neville, though the Earls of Salisbury and Warwick, the most influential members of the family, were the chief champions of the cause of York. With the Duke of Somerset also followed, in support of the crown, Henry Holland, Duke of Exeter, Stafford, Duke of Buckingham, the Earl of Shrewsbury, and the[5] Lords Clifford, Dudley, Scales, Audley, and other noblemen. With the Duke of York, besides the Earls of Salisbury and Warwick, went many of the southern houses.

Such was the state of public feeling and the position of parties when the insurrection of Cade occurred. The Duke of York had made himself additionally popular by his conduct in Ireland. He had shown great prudence and ability in suppressing the insurrections of the natives; and thus made fast friends of all the English who had connections in that island. No doubt the members of his own party used every argument to incite the duke to assert his right to the throne, and so to free the country from the dominance of the queen and her favourites. That it was the general opinion that the Cade conspiracy was a direct feeler on the part of the Yorkists, is clear from Shakespeare, who wrote so much nearer to that day. But when York appeared upon the scene, Cade had already paid the penalty of his outbreak. On his way to town, York, passing through Northamptonshire, sent for William Tresham, the late Speaker of the House of Commons, who had taken an active part in the prosecution of Suffolk. But, on his way to the duke, Tresham was fallen upon by the men of Lord Grey de Ruthin, and murdered. York proceeded to London, as related, and appeared before the king, where he demanded of him to summon a Parliament for the settlement of the disturbed affairs of the realm. Henry promised, and York meanwhile retired to his castle at Fotheringay.

Scarcely had York retired when Somerset arrived from France, and the queen and Henry hailed him as a champion sent in the moment of need to sustain the court party against the power and designs of York. But Somerset came from the loss of France, and, therefore, loaded with an awful weight of public odium; and with her vindictive disregard of appearances, Queen Margaret immediately transferred to him all her old predilection for Suffolk. When the Parliament met, the temper of the public mind was very soon apparent. Out of doors the life of Somerset was threatened by the mob, and his house was pillaged. In the Commons, Young, one of the representatives of Bristol, moved that, as Henry had no[6] children, York should be declared his successor. This proposal seemed to take the house by surprise, and Young was committed to the Tower. But a bill was carried to attaint the memory of the Duke of Suffolk, and another to remove from about the king the Duchess of Suffolk, the Duke of Somerset, and almost all the party in power. Henry refused to accede to these measures, any further than promising to withdraw a number of inferior persons from the court for twelve months, during which time their conduct might be inquired into. On this the Duchess of Suffolk and the other persons indicted of high treason during the insurrection, demanded to be heard in their defence, and were acquitted.

The spirit of the opposite factions ran very high; the party of Somerset accusing that of York of treasonable designs, and that of York declaring that the court was plotting to destroy the duke as they had destroyed Gloucester. York retired to his castle of Ludlow, in Shropshire, where he was in the very centre of the Mortimer interest, and under plea of securing himself against Somerset, he actively employed himself in raising forces, at the same time issuing a proclamation of the most devoted loyalty, and offering to swear fealty to the king on the sacrament before the Bishop of Hereford and the Earl of Shrewsbury. The court paid no attention to his professions, but an army was led by the king against him. York, instead of awaiting the blow, took another road, and endeavoured to reach and obtain possession of London in the king's absence. On approaching the capital, he received a message that its gates would be shut against him, and he then turned aside to Dartford, probably hoping for support from the same population which had followed Cade. The king pursued him, and encamping on Blackheath, sent the Bishops of Ely and Winchester to demand why he was in arms. York replied that he was in arms from no disloyal design, but merely to protect himself from his enemies. The king told him his movements had been watched since the murder of the Bishop of Chichester by men supposed to be in his interest, and still more since his partisans had openly boasted of his right to the crown; but for his own part, he himself believed him to be a loyal subject, and his own well-beloved cousin.

York demanded that all persons "noised or indicted of treason" should be apprehended, committed to the Tower, and brought to trial. All this the king, or his advisers, promised, and as Somerset was one of the persons chiefly aimed at by York, the king gave an instant order for the arrest and committal of Somerset, and assured York that a new council should be summoned, in which he himself should be included, and all matters decided by a majority. At these frank promises York expressed himself entirely satisfied, disbanded his army, and came bareheaded to the king's tent. What occurred, however, was by no means in accordance with the honourable character of the king, and savoured more of the councils of the queen. No sooner did York present himself before Henry, and begin to enter upon the causes of complaint, than Somerset stepped from behind a curtain, denied the assertions of York, and defied him to mortal combat. So flagrant a breach of faith showed York that he had been betrayed. He turned to depart in indignant resentment, but he was informed that he was a prisoner. Somerset was urgent for his trial and execution, as the only means of securing the permanent peace of the realm. Henry had a horror of spilling blood; but in this instance York is said to have owed his safety rather to the fears of the ministers than any act of grace of the king, who was probably in no condition of mind to be capable of thinking upon the subject. There was already a report that York's son, the Earl of March, was on the way towards London with a strong army of Welshmen, to liberate his father. This so alarmed the queen and council that they agreed to set free the duke, on condition that he swore to be faithful to the king, which he did at St. Paul's, Henry and his chief nobility being present. York then retired to his castle of Wigmore.

In the autumn of 1453 the queen was delivered of a son, who was called Edward. There was a cry in the country that this was no son of the king—a cry zealously promoted by the partisans of York—but it did not prevent the young prince from being recognised as the heir-apparent, and created Prince of Wales, Earl of Cornwall and Chester. But the king had now fallen into such a state of imbecility, with periods of absolute insanity, that those who had denied the legitimacy of his mother, Queen Catherine, might well change their opinion; for Henry's malady seemed to be precisely that of his reputed grandfather, Charles VI. of France. Such was his condition, that Parliament would no longer consent to leave him in the hands of the queen and Somerset. In the autumn the influence of Parliament compelled the recall of York to the council; and this, as might have been expected, was immediately[7] followed by the committal of Somerset to the Tower. In February Parliament recommenced its sittings, and York appeared as lieutenant or commissioner for the king, who was incapable of opening it in person. It had been the policy of the queen to keep concealed the real condition of the king, but with York at the head of affairs, this was no longer possible. The House of Lords appointed a deputation to wait on Henry at Windsor. The Archbishop of Canterbury, who was also Lord Chancellor, was dead; and the Lords seized upon the occasion as the plea for a personal interview, according to ancient custom, with the king. Twelve peers accordingly proceeded to Windsor, and would not return without seeing the monarch. They found him in such a state of mental alienation that, though they saw him three times, they could perceive no mark of attention from him. They reported him utterly incapable of transacting any business; and the Duke of York was thereupon appointed protector, with a yearly salary of 2,000 marks. The Lancastrian party, however, took care to define the duties and the powers of this office, so as to maintain the rights of the king. The title of protector was to give no authority, but merely precedence in the council, and the command of the army in time of rebellion or invasion. It was to be revocable at the will of the king, should he at any time recover soundness of mind; and, in case that he remained so long incapacitated for Government, the protectorate was to pass to the prince Edward on his coming of age. The command at sea was entrusted to five noblemen, chosen from the two parties; and the Government of Calais, a most important post, was taken from Somerset, and given to York.

With all this change, the session of Parliament appears to have been stormy. The Duke of York had instituted an action for trespass against Thorpe, the Speaker of the Commons, and one of the Barons of the Exchequer, and obtained a verdict with damages to the amount of £1,000, and Thorpe was committed to prison till he gave security for that sum, and an equal fine to the Crown. In vain did the Commons petition for the release of the Speaker. The Lords refused; and they were compelled to elect a new one. Many of the Lords, not feeling themselves safe, absented themselves from the House, and were compelled to attend only by heavy fines. The Duke of Exeter was taken into custody, and bound to keep the peace; and the Earl of Devonshire, a Yorkist, was accused of high treason and tried, but acquitted. So strong was the opposition of the court party, that even York himself was compelled to stand up and defend himself.

These angry commotions were but the prelude to a more decisive act. The king was found something better, and the fact was instantly seized on by the queen and her party to hurl York from power, and reinstate Somerset. About Christmas the king demanded from York the resignation of the protectorate, and immediately liberated Somerset. This was not done without Somerset being at first held to bail for his appearance at Westminster to answer the charges against him. But he appealed to the council, on the ground that he had been committed without any lawful cause; and the court party being now in the ascendant, he was at once freed from his recognisances. The king himself seemed anxious to reconcile the two dukes, a circumstance more convincing of his good nature than of his sound sense—for it was an impossibility. He would not restore the government of Calais to the Duke of Somerset, but he took it from York and retained it in his own hands. York perceived that he had been regularly defeated by the queen, and he retired again to his castle of Ludlow to plan more serious measures.

The Duke of Norfolk, the Earl of Salisbury and his son, the celebrated Earl of Warwick, destined to acquire the name of the "King-maker," hastened there at his summons, and it was resolved to attempt the suppression of the court party by force of arms. They were quickly at the head of a large force, with which they hoped to surprise the royalists. But no sooner did the news of this approaching force reach the court, than the king was carried forth at the head of a body of troops equal to those of York, and a march was commenced against him. The royal army had reached St. Albans, and on the morning of the 22nd of May, 1455, as it was about to resume its progress, the hills bordering on the high road were covered with the troops of York. This army marching under the banners of the house of York, now for the first time displayed in resistance to the sovereign, halted in a field near the town, and sent forward a herald announcing that the three noblemen were come in all loyalty and attachment to the king; but with a determination to remove the Duke of Somerset from his councils, and demanding that he and his pernicious associates should be at once delivered up to them. The Yorkists declared that they felt this to be so absolutely necessary, that they were resolved to destroy those enemies to[8] the peace of the country, or to perish themselves. An answer was returned by or for the king, "that he would not abandon any of the lords who were faithful to him, but rather would do battle upon it, at the peril of life and crown."

It would have appeared that the royal army had a most decided advantage by being in possession of the town, which was well fortified, and where a stout resistance might have been made in the narrow streets; but, spite of this, the superior spirit of the commanders on the side of York triumphed over the royalists. York himself made a desperate attack on the barriers at the entrance of the town, while Warwick, searching the outskirts of the place, found, or was directed by some favouring persons to a weak spot. He made his way across some gardens, burst into the city, and came upon the royal forces where he was little expected. Aided by this diversion, York redoubled his attack on the barriers, and, notwithstanding their resolute defence by Lord Clifford forced an entrance. Between the cries of "A York! a York!" "A Warwick! a Warwick!" confusion spread amongst the king's forces, they gave way, and fled out of the town in utter rout. The slaughter among the leaders of the royal army was terrible. The Duke of Somerset, the Earl of Northumberland, and Lord Clifford were slain; the king himself was wounded in the neck, the Duke of Buckingham and Lord Dudley in the face, and the Earl of Stafford in the arm. All these were arrow wounds, and it was plain that here again the archers had won the day. The fall or wounds of the leaders, indeed, settled the business, and saved the common soldiers; for though Hall reports that 8,000, Stowe that 5,000 men fell, yet Crane, in a letter to his cousin, John Paston, written at the time, declares that there were only six-score, and Sir William Stonor states that only forty-eight were buried in St. Albans.

The king was found concealed in the house of a tanner; and there York visited him, on his knees renewed his vows of loyal affection, and congratulated Henry on the fall of the traitor Somerset. He then led the king to the shrine of St. Albans, and afterwards to his apartment in the abbey. It might have been supposed that the fallen king, being now in the hands of York and his party, the claims of York to the crown would have been asserted. But at this time York either had not really determined on seizing the throne, or did not deem the public fully prepared for so great a change. On the meeting of Parliament it was reported that York and his friends sought only to free the king from the unpopular ministers who surrounded him, and to redress the grievances of the nation. That party complained—with what truth does not appear—that, on the very morning of the battle, they had sought to explain these views and intentions in letters, which the Duke of Somerset and Thorpe, the late Speaker of the Commons, had withheld from his grace. The king acquitted York, Salisbury, and Warwick of all evil intention, pronounced them good and loyal subjects, granting them a full pardon. The peers renewed their fealty, and Parliament was prorogued till the 12th of November. Thus the first blood in these civil wars had been drawn at the battle of St. Albans and all appeared restored to peace. But it was a deceitful calm; rivers of blood were yet to flow.

Scarcely had Parliament reassembled when it was announced that the king had relapsed into his former condition. Both Lords and Commons refused to proceed with business till this matter was ascertained and settled. The Lords then requested York once more to resume the protectorate for the good of the nation; but this time he was not to be caught in his former snare. He professed his insufficiency for the onerous office, and begged of them to lay its responsibilities on some more able person. He was quite safe in this course, for he had now acquired a majority in the council, and the office of chancellor and the Governorship of Calais were in the hands of his two stout friends, Salisbury and Warwick. Of course, the reply was that no one was so capable or suitable as he; and then he expressed his willingness to accept the protectorate, but only on condition that its revocation should not lie in the mere will of the king, but in the king with the consent of the Lords spiritual and temporal in Parliament assembled. The protectorate was to devolve, as before, on the Prince of Wales, in case the malady of the king continued so long.

York might think that he was now secure from the machinations of the queen, but he was deceived. This never-resting lady was at that very moment actively preparing for his defeat; and no sooner did Parliament meet after the Christmas recess than Henry again presented himself in person, announcing his restoration to health, and dissolved the protectorate. The Duke of York resigned his authority with apparent good-will. Calais and the chancellorship passed from Salisbury and Warwick to the friends of[9] the queen; the whole Government was again on its old footing. Two years passed on in apparent peace to the nation, but in the most bitter party warfare at court. The queen and her associates could never rest while the Duke of York and his friends were permitted to escape punishment for the late outbreak. The relatives of Somerset and the Earl of Northumberland, and of the other nobles slain at St. Albans, were encouraged to demand with eagerness vengeance on the Yorkists. Both parties surrounded themselves more and more with armed retainers, and everything portended fresh acts of bloodshed and discord. The king endeavoured to avert this by summoning a great council at Coventry in 1457. There the Duke of Buckingham made a formal rehearsal of all the offences committed by York and his party; at the conclusion of which the peers fell on their knees and entreated the king to make a declaration that he would never more show grace to the Duke of York, or any other person who should oppose the power of the crown or endanger the peace of the kingdom. To this the king consented; and then the Duke of York, Salisbury, and Warwick renewed their oaths of fealty, and all the lords bound themselves never for the future to seek redress by arms, but only from the justice of the sovereign.

At the close of this council, the Duke of York retired to Wigmore, Salisbury to Middleham, and Warwick to Calais. It was soon found that, notwithstanding all these oaths and these royal endeavours, the same animosity was alive in the two hostile parties, and the king tried still further the hopeless experiment of reconciliation. He prevailed on the leaders to meet him in London. On the[10] 26th of January, 1458, the leaders of the York and Lancaster factions appeared in the metropolis, but they came attended by armed retainers—the Duke of York with 140 horse, the now Duke of Somerset with 200, and Salisbury with 400, besides fourscore knights and esquires. York and his friends were admitted into the city, probably as being more under the control of the authorities; for the lord mayor, at the head of 5,000 armed citizens, undertook to maintain the peace. The Lancastrian lords were lodged in the suburbs. Every day the Yorkists met at the Blackfriars and the Lancastrians at the Whitefriars, and after communicating with each other, the result was sent to the king, who lay at Berkhampstead with several of the judges. The result of their deliberations was this:—The king, as umpire, awarded that the Duke of York, and the Earls of Salisbury and Warwick, should, within two years, found a chantry for the good of the souls of the three lords slain in battle at St. Albans, that both those who slew, and those who were slain at that battle should be reputed faithful subjects; that the Duke of York should pay to the dowager Duchess of Somerset and her children the sum of 5,000, and the Earl of Warwick to the Lord Clifford 1,000 marks; and that the Earl of Salisbury should release to Percy Lord Egremont all the damages he had obtained against him for an assault, on condition that the said Lord Egremont should bind himself to keep the peace for ten years.

The next day, March 25th, the king came to town, and went to St. Paul's in procession, followed by the whole court, the queen conducted by the Duke of York, and the lords of each party walking arm-in-arm before them, in token of perfect reconciliation. But real reconciliation was as distant as ever. The causes of contention lay too deep for the efforts of the simple and well-intentioned king, or even for the subtlest acts of diplomacy. It was the settled strife for a crown; and swords, not oaths, could alone decide it. The whole show was a mocking pageant. The slightest spark might any day light up a flame which would rage through the whole kingdom; and in a little more than a month such a spark fell into the combustible mass. News arrived that a large fleet of merchantmen from Lübeck had been attacked by Warwick as it passed down the Channel, and five sail of them captured after a severe contest, and carried into Calais. As Lübeck was a town of the Hanseatic League, that powerful association—which was in amity with England—speedily sent commissioners to London demanding redress. Warwick was summoned to appear before the council; and, whilst in attendance, a quarrel arose betwixt his followers and those of the court. Warwick believed, or feigned—to escape out of the scrape into which he had fallen—that there was a design upon his life. He fled to his father, Salisbury, and York, and they resolved that their only safety lay in arms. There was a story circulated, and thoroughly believed in by the Yorkist party, that the queen, who never forgot or forgave an enemy, kept a register, written in blood, of all the Yorkist chiefs, and had vowed never to rest till they were exterminated. In fact, both parties were arrived at that pitch of rancour which nothing could appease but the blood of their opponents. The feud was no longer confined to the nobles and their immediate retainers; the leaven of discord had pervaded the whole mass of the nation. The conflicting claims had been discussed till they had penetrated into every village, every family, into the convents of the monks, and the cottages of the poor. One party asserted that the Duke of York was an injured prince, driven from his hereditary right by a usurping family, and now marked to be destroyed by them. The other contended that, though Henry IV. had deposed Richard II., he had been the choice of the nation; that his son had made the name of England glorious; that more than sixty years' possession of the crown was itself sufficient warrant for its retention; that the Duke of York had, over and over again, sworn eternal fealty to Henry VI., which was in itself a renunciation of any claim he might previously possess; and that, in seeking now to deprive the king of his throne, he was a perjured and worthless man. One party argued that York owed his life to the clemency of the king; and the other replied that the king equally owed his to that of York, who had him in his power at St. Albans.

While the nation was thus heating its blood in these disputes, the heads of the different factions were busy preparing to meet each other in the field. The three lords spent the winter in arousing their partisans. Warwick called around him at Calais the veterans who had fought in Normandy and Guienne. On the other hand, the court distributed in profusion collars of white swans, the badge of the young prince; and the friends of the king were invited by letters, under the privy seal, to meet him in arms at Leicester. The spring and summer had come and gone, however, before the rival parties proceeded to actual extremities. The[11] finances of the court impeded its proceedings; and the Yorkist party still averred that it had no object but its own defence and the rescue of the Government from traitors.

At length, on the 23rd of September, 1459, the Earl of Salisbury marched forth from his castle of Middleham, in Yorkshire, to form a junction with York on the borders of Wales. Lord Audley, with a force of 10,000 men, far exceeding that of Salisbury, sought to intercept his progress at Blore Heath in Staffordshire; but the veteran Salisbury was too subtle for his antagonist. He pretended to fly at the sight of such unequal numbers; and having thus seduced Audley to pass a deep glen and torrent, he fell upon his troops when part only were over, and, throwing them into confusion, made a dreadful slaughter of them. Some writers contend that Salisbury had only 500 men with him; but this appears incredible, for they left Lord Audley with 2,000 of his men dead on the field, and took prisoner Lord Dudley, with many knights and esquires. The earl pursued his way unmolested to Ludlow, where York lay, and where they were joined in a few days by Warwick with his large reinforcement of veterans under Sir John Blount and Sir Andrew Trollop.

The king, queen, and lords of their party had assembled an army of 60,000 men. With these they advanced to within half a mile of Ludiford, the camp of York, near Ludlow, on the 10th of October; and Henry, after all his experience, had the goodness, or the weakness, once more to renew his offers of pardon and reconciliation on condition that his opponents should submit within six days. York and his colleagues replied that they had no reliance on his promises because those about him did not observe them, and that the Earl of Warwick, trusting to them last year, nearly lost his life. Yet they still protested that nothing but their own security caused them to arm, and that they had determined not to draw the sword against their sovereign unless they were compelled. It was concluded by the royal party to give battle on the 13th, but they found York posted with consummate military skill. His camp was defended by several batteries of cannon, which played effectively on the royal ranks as they attempted to advance. The royalists, therefore, deferred the engagement till the next morning, and were relieved from that necessity by Sir Andrew Trollop, who was marshal of the Yorkist army, going over in the night with all his Calais auxiliaries to the king. Trollop had hitherto believed the assurances of the Yorkist leaders that they sought only Government redress, and not subversion of the throne; but something had now opened his eyes, and, as he was a staunch royalist, he acted accordingly. This event struck terror and confusion through the Yorkist army. Every man was doubtful of his fellow; the confederate lords made a hasty retreat into Wales, whence York and one of his sons passed over to Ireland, and the rest followed Warwick, who hastened to Devonshire, and thence escaped again to Calais.

Nothing shows so strikingly the feeble councils of the royal camp as that these formidable foes should have been permitted to decamp without any pursuit. A vigorous blow at the now panic-struck enemy might for ever have rid the king of his mortal antagonists. But Henry, always averse from shedding blood, was, no doubt, glad of this unexpected escape from it, and his generals were weak enough to acquiesce. The court returned to London, and satisfied themselves with passing an act of attainder against the Duke and Duchess of York, and their sons, the Earls of March and Rutland, against the Earl and Countess of Salisbury, and their son the Earl of Warwick, the Lord Clinton, and various knights and esquires. Even this was painful to the morbidly tender mind of Henry. He reserved to himself the right to reverse the attainder, if he thought proper, and refused to permit the confiscation of the property of Lord Powis, and two others who had thrown themselves on his clemency.

Meanwhile the insurgent chiefs, though dispersed, were not crushed. York had great popularity in Ireland; Warwick had a strong retreat in Calais. To deprive him of this, the Duke of Somerset was appointed governor, and, encouraged by the conduct of the Calais veterans at Ludiford, set out to drive Warwick from that city. But he met with a very different reception to that which he had calculated upon. He was assailed by a severe fire from the batteries, and compelled to stand out. On making an attempt to reach Calais from Guisnes, he found himself deserted by his sailors, who carried his fleet into Calais, and surrendered it to their favourite commander. Warwick stationed a sufficient force to watch Somerset in Guisnes, and, so little did he care for him, set out with his fleet, and dispersed two successive armaments sent to the relief of Somerset from the ports of Kent. When this had been done, he sailed to Dublin, to concert measures with York, and returned in safety to Calais, having met the high-admiral, the Duke of Exeter, who at sight of him escaped into Dartmouth.

In the spring of 1460 the Yorkists, who had fled so rapidly from the royal army at Ludiford, and had seemed to vanish as a mist, were again on foot, and in a threatening attitude. They had sedulously scattered proclamations throughout the country, still protesting that they had no designs on the crown; that the king was so well assured of it that he refused to ratify the act of attainder, but that he was in the hands of the enemies of the nation. These documents concluded by saying that the maligned lords were resolved now to prove their loyalty in the presence of the sovereign. Following up this, Warwick landed in June, in Kent—next to the marches of Wales the great stronghold of the house of York. He had brought only 1,500 men with him, but he was accompanied by Coppini, the Pope's legate, who had been sent indeed to Henry, but was gained over by Warwick. In Kent they were joined by the Lord Cobham with 400 men; by the Archbishop of Canterbury, who had received his preferment from York during his protectorate; and by a large number of knights and gentlemen of the county. As he advanced towards the capital, people flocked to him from all sides till his army amounted to 30,000, some say 40,000, men. He entered London on the 2nd of July, and, proceeding to the convocation, prevailed on no less than five bishops to accompany him to an interview with the king, who was lying at Coventry. The legate issued a letter to the clergy, informing them that he had laid it before the king; that the Yorkists demanded nothing but personal security, peaceable enjoyment of their property, and the removal of evil counsellors. All this was calculated to turn the credulous, or to prevent them from swelling the forces of the court.

Henry advanced to Northampton, where he entrenched himself in a strong camp. On arriving before it, Warwick made three successive attempts to obtain an interview with the king, but finding it unavailing, the legate excommunicated the royal party, and set up the papal banner in the Yorkist camp. For this he was afterwards recalled by the Pope, imprisoned, and degraded; but for the time it had its effect. Warwick gave the king notice that, as he would not listen to any overtures, he must prepare for battle at two in the afternoon on[13] the 10th of July, 1460. The royal party made themselves certain of victory, but were this time confounded by Lord Grey of Ruthin going over to the enemy, as Sir Andrew Trollop had deserted the other party at Ludlow. Grey introduced the Yorkists into the very heart of Henry's camp, and the contest was speedily decided. Warwick ordered his followers to spare the common soldiers, and direct their attacks against the leaders; and accordingly of these there were slain 300 knights and gentlemen, including the Duke of Buckingham, the Earl of Shrewsbury, and the Lords Beaumont and Egremont. A second time Henry fell into the hands of his rebellious subjects, but they treated him with all respect. The queen and her son escaped into Wales, and thence into Scotland, after having been plundered on the way by their own servants.

RUTLAND BESEECHING CLIFFORD TO SPARE HIS LIFE. (See p. 15.)