Title: Confederate Military History - Volume 5 (of 12)

Author: Ellison Capers

Editor: Clement A. Evans

Release date: December 21, 2015 [eBook #50737]

Most recently updated: October 22, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Alan and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

| PAGE | |

CHAPTER I. Spirit of Secession—The State Militia—Charleston and the Forts—The Violated Agreement—Major Anderson Occupies Fort Sumter—South Carolina Occupies Pinckney and Moultrie—The Star of the West—Fort Sumter Surrendered—Carolinians in Virginia—Battle of Manassas | 4 |

CHAPTER II. Affairs on the Coast—Loss of Port Royal Harbor—Gen. R. E. Lee in Command of the Department—Landing of Federals at Port Royal Ferry—Gallant Fight on Edisto Island—General Pemberton Succeeds Lee in Command—Defensive Line, April, 1862 | 29 |

CHAPTER III. South Carolinians in Virginia—Battle of Williamsburg—Eltham's Landing—Seven Pines and Fair Oaks—Nine-Mile Road—Gaines' Mill—Savage Station—Frayser's Farm—Malvern Hill | 43 |

CHAPTER IV. The Coast of South Carolina, Summer of 1862—Operations under General Pemberton—Engagement at Old Pocotaligo—Campaign on James Island—Battle of Secessionville | 76 |

CHAPTER V. General Beauregard in Command—The Defenses of Charleston—Disposition of Troops—Battle of Pocotaligo—Repulse of Enemy at Coosawhatchie Bridge—Operations in North Carolina—Battle of Kinston—Defense of Goldsboro | 94 |

CHAPTER VI. South Carolinians in the West—Manigault's and Lythgoe's Regiments at Corinth—The Kentucky Campaign—Battle of Murfreesboro | 111 |

CHAPTER VII. With Lee in Northern Virginia, 1862—The Maneuvers on the Rappahannock—Second Manassas Campaign—Battle of Ox Hill | 120 |

CHAPTER VIII. The Maryland Campaign—The South Mountain Battles—Capture of Harper's Ferry—Battles of Sharpsburg and Shepherdstown | 140 |

CHAPTER IX. Hampton's Cavalry in the Maryland Raid—The Battle of Fredericksburg—Death of Gregg—South Carolinians at Marye's Hill—Cavalry Operations | 165 |

CHAPTER X. Operations in South Carolina, Spring of 1863—Capture of the Isaac Smith—Ingraham's Defeat of the Blockading Squadron—Naval Attack on Fort Sumter—Hunter's Raids | 188 |

CHAPTER XI. South Carolina Troops in Mississippi—Engagement near Jackson—The Vicksburg Campaign—Siege of Jackson | 203 |

CHAPTER XII. South Carolinians in the Chancellorsville Campaign—Service of Kershaw's and McGowan's Brigades—A Great Confederate Victory | 213 |

CHAPTER XIII. Operations in South Carolina—Opening of Gillmore's Campaign against Fort Sumter—The Surprise of Morris Island—First Assault on Battery Wagner—Demonstrations on James Island and Against the Railroad—Action near Grimball's Landing | 223 |

CHAPTER XIV. Second Assault on Battery Wagner—Siege of Wagner and Bombardment of Fort Sumter—Evacuation of Morris Island | 235 |

CHAPTER XV. The Gettysburg Campaign—Gallant Service of Perrin's and Kershaw's Brigades—Hampton's Cavalry at Brandy Station | 257 |

CHAPTER XVI. South Carolinians at Chickamauga—Organization of the Armies—South Carolinians Engaged—Their Heroic Service and Sacrifices | 277 |

CHAPTER XVII. The Siege of Charleston—Continued Bombardment of Fort Sumter—Defense Maintained by the Other Works—The Torpedo Boats—Bombardment of the City—Transfer of Troops to Virginia—Prisoners under Fire—Campaign on the Stono | 291 |

CHAPTER XVIII. South Carolinians with Longstreet and Lee—Wauhatchie—Missionary Ridge—Knoxville—The Virginia Campaign of 1864—From the Wilderness to the Battle of the Crater | 310 |

CHAPTER XIX. The Atlanta Campaign—Battles around Atlanta—Jonesboro—Hood's Campaign in North Georgia—The Defense of Ship's Gap—Last Campaign in Tennessee—Battle of Franklin | 328 |

CHAPTER XX. The Closing Scenes in Virginia—Siege of Richmond and Petersburg—Fall of Fort Fisher—South Carolina Commands at Appomattox | 346 |

CHAPTER XXI. Battle of Honey Hill—Sherman's Advance into South Carolina—Organization of the Confederate Forces—Burning of Columbia—Battles of Averasboro and Bentonville—Conclusion | 354 |

| BIOGRAPHICAL | 373 |

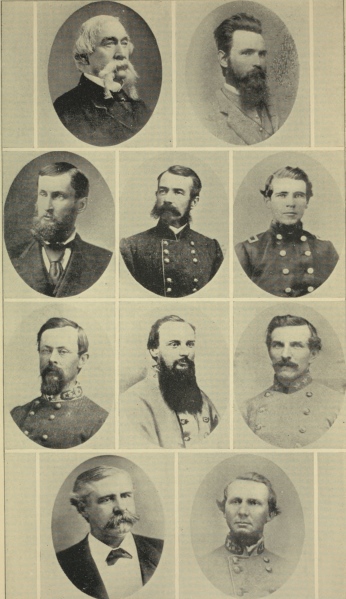

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

| FACING PAGE. | |

| Bee, Barnard E. | 394 |

| Bonham, M. L. | 394 |

| Bratton, John | 394 |

| Butler, M. C. | 383, 394 |

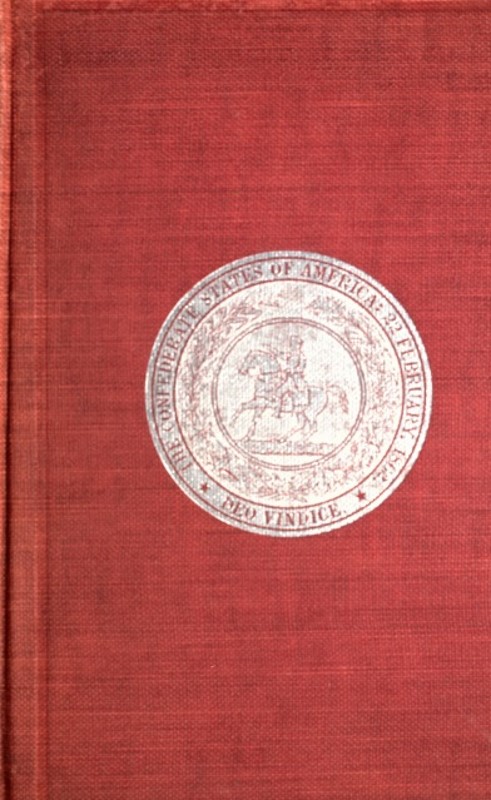

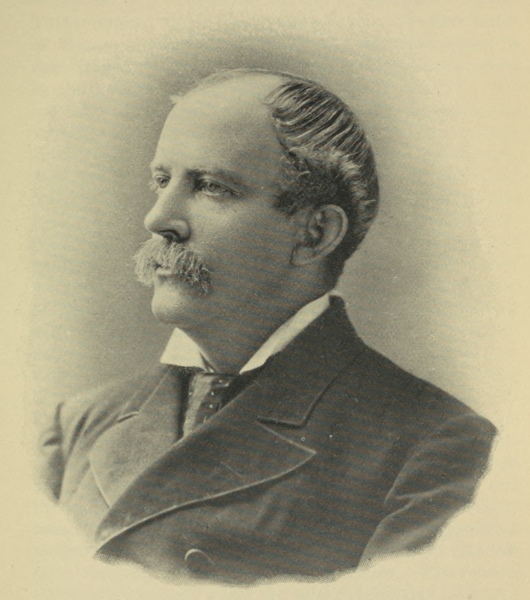

| Capers, Ellison | 1, 409 |

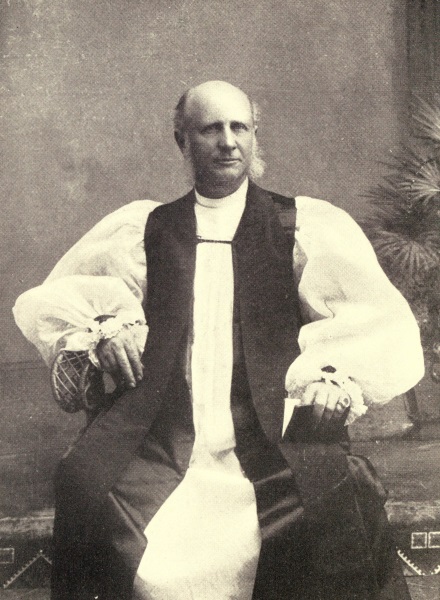

| Charleston, Defenses (Map) | Between pages 296 and 297 |

| Chestnut, James | 394 |

| Connor, James | 417 |

| Drayton, Thos. F. | 394 |

| Dunovant, John | 394 |

| Elliott, Stephen, Jr. | 394 |

| Evans, N. G. | 394 |

| Ferguson, S. W. | 417 |

| Gary, M. W. | 394 |

| Gist, S. R. | 417 |

| Gregg, Maxcy | 417 |

| Hagood, Johnson | 417 |

| Honey Hill, Battle (Map) | 357 |

| Huger, Benjamin | 409 |

| Jenkins, Micah | 417 |

| Jones, David R. | 417 |

| Kennedy, John D. | 417 |

| Kershaw, J. B. | 409 |

| Logan, J. M. | 417 |

| McGowan, Samuel | 409 |

| Manigault, A. M. | 409 |

| Perrin, Abner | 409 |

| Preston, John S. | 417 |

| Ripley, Roswell S. | 409 |

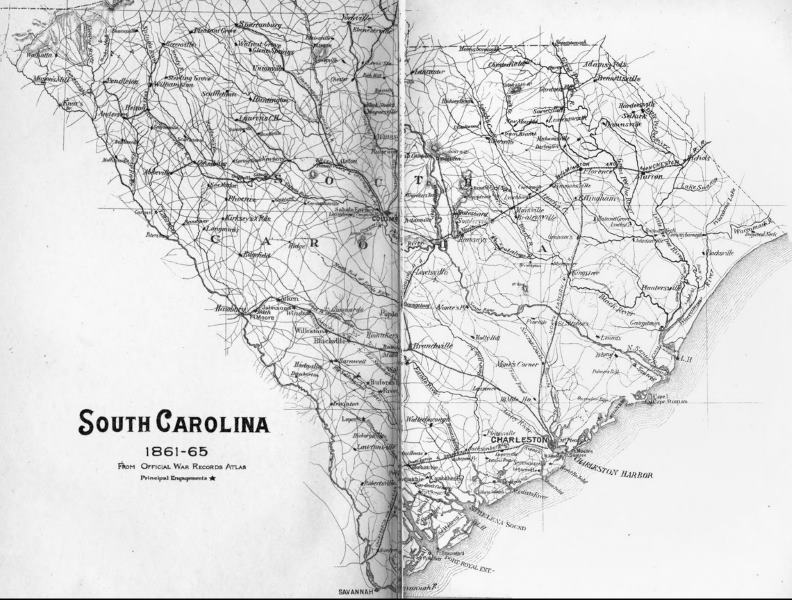

| South Carolina (Map) | Between pages 371 and 372 |

| Stevens, C. H. | 409 |

| Villepigue, J. B. | 409 |

| Wallace, W. H. | 409 |

ELLISON CAPERS

SOUTH CAROLINA

BY

Brig.-Gen. Ellison Capers.

The writer of the following sketch does not attempt, in the space assigned him, to give a complete history of the various commands of Carolinians, who for four years did gallant and noble service in the armies of the Confederacy.

A faithful record of their names alone would fill the pages of a volume, and to write a history of their marches and battles, their wounds and suffering, their willing sacrifices, and their patient endurance, would demand more accurate knowledge, more time and more ability than the author of this sketch can command.

He trusts that in the brief history which follows he has been able to show that South Carolina did her duty to herself and to the Southern Confederacy, and did it nobly.

SPIRIT OF SECESSION—THE STATE MILITIA—CHARLESTON AND THE FORTS—THE VIOLATED AGREEMENT—MAJOR ANDERSON OCCUPIES FORT SUMTER—SOUTH CAROLINA OCCUPIES PINCKNEY AND MOULTRIE—THE STAR OF THE WEST—FORT SUMTER SURRENDERED—CAROLINIANS IN VIRGINIA—BATTLE OF MANASSAS.

From the time that the election of the President was declared, early in November, 1860, the military spirit of the people of South Carolina was thoroughly awake. Secession from the Union was in the air, and when it came, on the 20th of December following, it was received as the ultimate decision of duty and the call of the State to arms. The one sentiment, everywhere expressed by the vast majority of the people, was the sentiment of independence; and the universal resolve was the determination to maintain the secession of the State at any and every cost.

The militia of the State was, at the time, her only arm of defense, and every part of it was put under orders.

Of the State militia, the largest organized body was the Fourth brigade of Charleston, commanded by Brig.-Gen. James Simons. This body of troops was well organized, well drilled and armed, and was constantly under the orders of the governor and in active service from the 27th of December, 1860, to the last of April, 1861. Some of the commands continued in service until the Confederate regiments, battalions and batteries were organized and finally absorbed all the effective material of the brigade.

This efficient brigade was composed of the following commands:

First regiment of rifles: Col. J. J. Pettigrew, Lieut.-Col. John L. Branch, Maj. Ellison Capers, Adjt. Theodore G. Barker, Quartermaster Allen Hanckel, Commissary L. G. Young, Surg. George Trescot, Asst. Surg. Thomas L. Ozier, Jr. Companies: Washington Light Infantry, Capt. C. H. Simonton; Moultrie Guards, Capt. Barnwell W. Palmer; German Riflemen, Capt. Jacob Small; Palmetto Riflemen, Capt. Alex. Melchers; Meagher Guards, Capt. Edward McCrady, Jr.; Carolina Light Infantry, Capt. Gillard Pinckney; Zouave Cadets, Capt. C. E. Chichester.

Seventeenth regiment: Col. John Cunningham, Lieut.-Col. William P. Shingler, Maj. J. J. Lucas, Adjt. F. A. Mitchel. Companies: Charleston Riflemen, Capt. Joseph Johnson, Jr.; Irish Volunteers, Capt. Edward McGrath; Cadet Riflemen, Capt. W. S. Elliott; Montgomery Guards, Capt. James Conner; Union Light Infantry, Capt. David Ramsay; German Fusiliers, Capt. Samuel Lord, Jr.; Palmetto Guards, Capt. Thomas W. Middleton; Sumter Guards, Capt. Henry C. King; Emmet Volunteers, Capt. P. Grace; Calhoun Guards, Capt. John Fraser.

First regiment of artillery: Col. E. H. Locke, Lieut.-Col. W. G. De Saussure, Maj. John A. Wagener, Adjt. James Simmons, Jr.

Light batteries: Marion Artillery, Capt. J. G. King; Washington Artillery, Capt. George H. Walter; Lafayette Artillery, Capt. J. J. Pope; German Artillery (A), Capt. C. Nohrden; German Artillery (B), Capt. H. Harms.

Cavalry: Charleston Light Dragoons, Capt. B. H. Rutledge; German Hussars, Capt. Theodore Cordes; Rutledge Mounted Riflemen, Capt. C. K. Huger.

Volunteer corps in the fire department: Vigilant Rifles, Capt. S. V. Tupper; Phœnix Rifles, Capt. Peter C. Gaillard; Ætna Rifles, Capt. E. F. Sweegan; Marion Rifles, Capt. C. B. Sigwald.

Charleston, the metropolis and seaport, for a time absorbed the interest of the whole State, for it was everywhere felt that the issue of secession, so far as war with the government of the United States was concerned, must be determined in her harbor. The three forts which had been erected by the government for the defense of the harbor, Moultrie, Castle Pinckney and Sumter, were built upon land ceded by the State for that purpose, and with the arsenal and grounds in Charleston, constituted the property of the United States.

The secession of South Carolina having dissolved her connection with the government of the United States, the question of the possession of the forts in the harbor and of the military post at the arsenal became at once a question of vital interest to the State. Able commissioners, Robert W. Barnwell, James H. Adams and James L. Orr, were elected and sent by the convention of the State to treat with the government at Washington for an amicable settlement of this important question, and other questions growing out of the new relation which South Carolina bore to the Union. Pending the action of the commissioners in Washington, an unfortunate move was made by Maj. Robert Anderson, of the United States army, who commanded the only body of troops stationed in the harbor, which ultimately compelled the return of the commissioners and led to the most serious complications. An understanding had been established between the authorities in Washington and the members of Congress from South Carolina, that the forts would not be attacked, or seized as an act of war, until proper negotiations for their cession to the State had been made and had failed; provided that they were not reinforced, and their military status should remain as it was at the time of this understanding, viz., on December 9, 1860.

Fort Sumter, in the very mouth of the harbor, was in an unfinished state and without a garrison. On the night of the 26th of December, 1860, Maj. Robert Ander[Pg 7]son dismantled Fort Moultrie and removed his command by boats over to Fort Sumter. The following account of the effect of this removal of Major Anderson upon the people, and the action of the government, is taken from Brevet Major-General Crawford's "Genesis of the Civil War." General Crawford was at the time on the medical staff and one of Anderson's officers. His book is a clear and admirable narrative of the events of those most eventful days, and is written in the spirit of the utmost candor and fairness. In the conclusion of the chapter describing the removal, he says:

The fact of the evacuation of Fort Moultrie by Major Anderson was soon communicated to the authorities and people of Charleston, creating intense excitement. Crowds collected in streets and open places of the city, and loud and violent were the expressions of feeling against Major Anderson and his action.... [The governor of the State was ready to act in accordance with the feeling displayed.] On the morning of the 27th, he dispatched his aide-de-camp, Col. Johnston Pettigrew, of the First South Carolina Rifles, to Major Anderson. He was accompanied by Maj. Ellison Capers, of his regiment. Arriving at Fort Sumter, Colonel Pettigrew sent a card inscribed, "Colonel Pettigrew, First Regiment Rifles, S.C.M., Aide-de-Camp to the Governor, Commissioner to Major Anderson. Ellison Capers, Major First Regiment Rifles, S.C.M." ... Colonel Pettigrew and his companion were ushered into the room. The feeling was reserved and formal, when, after declining seats, Colonel Pettigrew immediately opened his mission: "Major Anderson," said he, "can I communicate with you now, sir, before these officers, on the subject for which I am here?" "Certainly, sir," replied Major Anderson, "these are all my officers; I have no secrets from them, sir."

The commissioner then informed Major Anderson that he was directed to say to him that the governor was much surprised that he had reinforced "this work." Major Anderson promptly responded that there had been no reinforcement of the work; that he had removed his command from Fort Moultrie to Fort Sumter, as he had a right to do, being in command of all the forts in the harbor. To this Colonel Pettigrew replied that when[Pg 8] the present governor (Pickens) came into office, he found an understanding existing between the previous governor (Gist) and the President of the United States, by which all property within the limits of the State was to remain as it was; that no reinforcements were to be sent here, particularly to this post; that there was to be no attempt made against the public property by the State, and that the status in the harbor should remain unchanged. He was directed also to say to Major Anderson that it had been hoped by the governor that a peaceful solution of the difficulties could have been reached, and a resort to arms and bloodshed might have been avoided; but that the governor thought the action of Major Anderson had greatly complicated matters, and that he did not now see how bloodshed could be avoided; that he had desired and intended that the whole matter might be fought out politically and without the arbitration of the sword, but that now it was uncertain, if not impossible.

To this Major Anderson replied, that as far as any understanding between the President and the governor was concerned, he had not been informed; that he knew nothing of it; that he could get no information or positive orders from Washington, and that his position was threatened every night by the troops of the State. He was then asked by Major Capers, who accompanied Colonel Pettigrew, "How?" when he replied, "By sending out steamers armed and conveying troops on board;" that these steamers passed the fort going north, and that he feared a landing on the island and the occupation of the sand-hills just north of the fort; that 100 riflemen on these hills, which commanded his fort, would make it impossible for his men to serve their guns; and that any man with a military head must see this. "To prevent this," said he earnestly, "I removed on my own responsibility, my sole object being to prevent bloodshed." Major Capers replied that the steamer was sent out for patrol purposes, and as much to prevent disorder among his own people as to ascertain whether any irregular attempt was being made to reinforce the fort, and that the idea of attacking him was never entertained by the little squad who patrolled the harbor.

Major Anderson replied to this that he was wholly in the dark as to the intentions of the State troops, but that he[Pg 9] had reason to believe that they meant to land and attack him from the north; that the desire of the governor to have the matter settled peacefully and without bloodshed was precisely his object in removing his command from Moultrie to Sumter; that he did it upon his own responsibility alone, because he considered that the safety of his command required it, as he had a right to do. "In this controversy," said he, "between the North and the South, my sympathies are entirely with the South. These gentlemen," said he (turning to the officers of the post who stood about him), "know it perfectly well." Colonel Pettigrew replied, "Well, sir, however that may be, the governor of the State directs me to say to you courteously but peremptorily, to return to Fort Moultrie." "Make my compliments to the governor (said Anderson) and say to him that I decline to accede to his request; I cannot and will not go back." "Then, sir," said Pettigrew, "my business is done," when both officers, without further ceremony or leavetaking, left the fort.

Colonel Pettigrew and Major Capers returned to the city and made their report to the governor and council who were in session in the council chamber of the city hall. That afternoon Major Anderson raised the flag of his country over Sumter, and went vigorously to work mounting his guns and putting the fort in military order. The same afternoon the governor issued orders to Colonel Pettigrew, First regiment of rifles, and to Col. W. G. De Saussure, First regiment artillery, commanding them to take immediate possession of Castle Pinckney and Fort Moultrie. Neither fort was garrisoned, and the officers in charge, after making a verbal protest, left and went to Fort Sumter, and the Palmetto flag was raised over Moultrie and Pinckney. In the same manner the arsenal in Charleston was taken possession of by a detachment of the Seventeenth regiment, South Carolina militia, Col. John Cunningham, and Fort Johnson on James island, by Capt. Joseph Johnson, commanding the Charleston Riflemen. The governor also ordered a battery to be built for two 24-pounders on Morris island, bearing on Ship channel, and his order was speedily put into execu[Pg 10]tion by Maj. P. F. Stevens, superintendent of the South Carolina military academy, with a detachment of the cadets, supported by the Vigilant Rifles, Captain Tupper. This battery was destined soon to fire the first gun of the war. In taking possession of the forts and the arsenal, every courtesy was shown the officers in charge, Captain Humphreys, commanding the arsenal, saluting his flag before surrendering the property.

By the possession of Forts Moultrie and Pinckney and the arsenal in Charleston, their military stores fell into the hands of the State of South Carolina, and by the governor's orders a careful inventory was made at once of all the property and duly reported to him. At Moultrie there were sixteen 24-pounders, nineteen 32-pounders, ten 8-inch columbiads, one 10-inch seacoast mortar, four 6-pounders, two 12-pounders and four 24-pounder howitzers and a large supply of ammunition. At Castle Pinckney the armament was nearly complete and the magazine well filled with powder. At the arsenal there was a large supply of military stores, heavy ordnance and small-arms. These exciting events were followed by the attempt of the government to succor Major Anderson with supplies and reinforce his garrison.

The supplies and troops were sent in a large merchant steamer, the Star of the West. She crossed the bar early on the morning of January 9, 1861, and steamed up Ship channel, which runs for miles parallel with Morris island, and within range of guns of large caliber. Her course lay right under the 24-pounder battery commanded by Major Stevens and manned by the cadets. This battery was supported by the Zouave Cadets, Captain Chichester; the German Riflemen, Captain Small, and the Vigilant Rifles, Captain Tupper. When within range a shot was fired across her bow, and not heeding it, the battery fired directly upon her. Fort Moultrie also fired a few shots,[Pg 11] and the Star of the West rapidly changed her course and, turning round, steamed out of the range of the guns, having received but little material damage by the fire.

Major Anderson acted with great forbearance and judgment, and did not open his batteries. He declared his purpose to be patriotic, and so it undoubtedly was. He wrote to the governor that, influenced by the hope that the firing on the Star of the West was not supported by the authority of the State, he had refrained from opening fire upon the batteries, and declared that unless it was promptly disclaimed he would regard it as an act of war, and after waiting a reasonable time he would fire upon all vessels coming within range of his guns.

The governor promptly replied, justifying the action of the batteries in firing upon the vessel, and giving his reasons in full. He pointed out to Major Anderson that his removal to Fort Sumter and the circumstances attending it, and his attitude since were a menace to the State of a purpose of coercion; that the bringing into the harbor of more troops and supplies of war was in open defiance of the State, and an assertion of a purpose to reduce her to abject submission to the government she had discarded; that the vessel had been fairly warned not to continue her course, and that his threat to fire upon the vessels in the harbor was in keeping with the evident purpose of the government of the United States to dispute the right of South Carolina to dissolve connection with the Union. This right was not to be debated or questioned, urged the governor, and the coming of the Star of the West, sent by the order of the President, after being duly informed by commissioners sent to him by the convention of the people of the State to fully inform him of the act of the State in seceding from the Union, and of her claim of rights and privileges in the premises, could have no other meaning than that of open and hostile disregard for the asserted independence of South Carolina. To defend that independence and to resent and resist any and every[Pg 12] act of coercion are "too plainly a duty," said Governor Pickens, "to allow it to be discussed."

To the governor's letter Major Anderson replied, that he would refer the whole matter to the government at Washington, and defer his purpose to fire upon vessels in the harbor until he could receive his instructions in reply. Thus a truce was secured, and meanwhile active preparations for war were made daily by Major Anderson in Fort Sumter and by Governor Pickens on the islands surrounding it. War seemed inevitable, and the whole State, as one man, was firmly resolved to meet it.

The legislature had passed a bill on December 17th providing for the organization of ten regiments for the defense of the State, and the convention had ordered the formation of a regiment for six months' service, to be embodied at once, the governor to appoint the field officers. This last was "Gregg's First regiment," which was organized in January, 1861, and on duty on Sullivan's and Morris islands by the 1st of February following. The governor appointed Maxcy Gregg, of Columbia, colonel; Col. A. H. Gladden, who had been an officer of the Palmetto regiment in the Mexican war, lieutenant-colonel; and D. H. Hamilton, the late marshal of the United States court in South Carolina, major. On March 6, 1861, the adjutant-general of the State reported to Gen. M. L. Bonham, whom the governor had commissioned major-general, to command the division formed under the act of December 17, 1860, that he had received into the service of the State 104 companies, under the said act of the legislature, aggregating an effective force of 8,836 men and officers; that these companies had been formed into ten regiments and the regiments into four brigades.

These regiments were mustered for twelve months' service, were numbered respectively from 1 to 10, inclusive, and commanded by Cols. Johnson Hagood, J. B. Kershaw, J. H. Williams, J. B. E. Sloan, M. Jenkins,[Pg 13] J. H. Rion, T. G. Bacon, E. B. Cash, J. D. Blanding, and A. M. Manigault.

The brigadier-generals appointed by the governor under the act above referred to, were R. G. M. Dunovant and P. H. Nelson. By an act of the legislature, January 28, 1861, the governor was authorized to raise a battalion of artillery and a regiment of infantry, both to be formed and enlisted in the service of the State as regulars, and to form the basis of the regular army of South Carolina. The governor appointed, under the act, R. S. Ripley, lieutenant-colonel in command of the artillery battalion, and Richard Anderson, colonel of the infantry regiment. The artillery battalion was afterward increased to a regiment, and the regiment of infantry converted, practically, into a regiment of artillery. Both regiments served in the forts and batteries of the harbor throughout the war, with the greatest distinction, as will afterward appear. These troops, with the Fourth brigade, South Carolina militia, were under the orders of the government and were practically investing Fort Sumter.

The States of Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas, having left the Union during the month of January, and the Confederate government having been organized early in February, at Montgomery, President Davis, on the 1st of March, ordered Brigadier-General Beauregard to Charleston to report for duty to Governor Pickens. Thenceforward this distinguished soldier became the presiding genius of military operations in and around Charleston.

Repeated demands having been made upon Major Anderson, and upon the President, for the relinquishment of Fort Sumter, and these demands having been refused and the government at Washington having concluded to supply and reinforce the fort by force of arms, it was determined to summon Major Anderson to evacuate the fort, for the last time. Accordingly, on April 11th, General Beauregard sent him the following communication:

Headquarters Provisional Army, C. S. A.

Charleston, April 11, 1861.

Sir: The government of the Confederate States has hitherto foreborne from any hostile demonstrations against Fort Sumter, in hope that the government of the United States, with a view to the amicable adjustment of all questions between the two governments, and to avert the calamities of war, would voluntarily evacuate it.

There was reason at one time to believe that such would be the course pursued by the government of the United States, and under that impression my government has refrained from making any demand for the surrender of the fort. But the Confederate States can no longer delay assuming actual possession of a fortification commanding the entrance of one of their harbors and necessary to its defense and security.

I am ordered by the government of the Confederate States to demand the evacuation of Fort Sumter. My aides, Colonel Chestnut and Captain Lee, are authorized to make such demand of you. All proper facilities will be afforded for the removal of yourself and command, together with company arms and property, and all private property, to any post in the United States which you may select. The flag which you have upheld so long and with so much fortitude, under the most trying circumstances, may be saluted by you on taking it down. Colonel Chestnut and Captain Lee will, for a reasonable time, await your answer.

I am, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

G. T.Beauregard, Brigadier-General Commanding.

Major Anderson replied as follows:

Fort Sumter, S. C., April 11, 1861.

General: I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your communication demanding the evacuation of this fort, and to say, in reply thereto, that it is a demand with which I regret that my sense of honor, and of my obligations to my government, prevent my compliance. Thanking you for the fair, manly and courteous terms proposed, and for the high compliment paid me,

I am, General, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

Robert Anderson,

Major, First Artillery, Commanding.

Major Anderson, while conversing with the messengers of General Beauregard, having remarked that he would soon be starved into a surrender of the fort, or words to that effect, General Beauregard was induced to address him a second letter, in which he proposed that the major should fix a time at which he would agree to evacuate, and agree also not to use his guns against the Confederate forces unless they fired upon him, and so doing, he, General Beauregard, would abstain from hostilities. To this second letter Major Anderson replied, naming noon on the 15th, provided that no hostile act was committed by the Confederate forces, or any part of them, and provided, further, that he should not, meanwhile, receive from the government at Washington controlling instructions or additional supplies.

The fleet which was to reinforce and supply him was then collecting outside the bar, and General Beauregard at once notified him, at 3:20 a. m. on the morning of the 12th of April, that he would open fire on the fort in one hour from that time.

The shell which opened the momentous bombardment of Fort Sumter was fired from a mortar, located at Fort Johnson on James island, at 4:30 on the morning of the 12th.

For over three months the troops stationed on the islands surrounding Fort Sumter had been constantly employed building batteries, mounting guns, and making every preparation for the defense of the harbor, and, if necessary, for an attack on the fort if the government at Washington persisted in its refusal to order its evacuation. Lieut.-Col. R. S. Ripley, an able and energetic soldier, commanded the artillery on Sullivan's island, with his headquarters at Fort Moultrie, Brigadier-General Dunovant commanding the island. Under Ripley's direction, six 10-inch mortars and twenty guns bore on Sumter. The guns were 24, 32 and 42 pounders, 8-inch columbiads and one 9-inch Dahlgren.[Pg 16] The supports to the batteries were the First regiment of rifles, Colonel Pettigrew; the regiment of infantry, South Carolina regulars, Col. Richard Anderson; the Charleston Light Dragoons, Capt. B. H. Rutledge, and the German Flying Artillery, the latter attached to Col. Pettigrew's command, stationed at the east end of the island. These commands, with Ripley's battalion of South Carolina regular artillery and Capt. Robert Martin's mortar battery on Mount Pleasant, made up the force under General Dunovant.

On Morris island, Gen. James Simons was commanding, with Lieut.-Col. W. G. De Saussure for his artillery chief, and Maj. W. H. C. Whiting for chief of staff. The infantry supports on the island were the regiments of Cols. John Cunningham, Seventeenth South Carolina militia, and Maxcy Gregg, Johnson Hagood and J. B. Kershaw, of the South Carolina volunteers. The artillery was in position bearing on Ship channel, and at Cummings point, bearing on Sumter. The fleet making no attempt to come in, the channel batteries took no part in the bombardment of Sumter.

On Cummings point, six 10-inch mortars and six guns were placed. To the command and direction of these guns, Maj. P. F. Stevens was specially assigned. One of the batteries on the point was of unique structure, hitherto unknown in war. Three 8-inch columbiads were put in battery under a roofing of heavy timbers, laid at an angle of forty degrees, and covered with railroad T iron. Portholes were cut and these protected by heavy iron shutters, raised and lowered from the inside of the battery. This battery was devised and built by Col. Clement H. Stevens, of Charleston, afterward a brigadier-general and mortally wounded in front of Atlanta, July 20, 1864, leading his brigade. "Stevens' iron battery," as it was called, was "the first ironclad fortification ever erected," and initiated the present system of armor-plated vessels. The three mortars in battery at[Pg 17] Fort Johnson were commanded by Capt. G. S. James. The batteries above referred to, including Fort Moultrie, contained fifteen 10-inch mortars and twenty-six guns of heavy caliber.

For thirty-four hours they assaulted Sumter with an unceasing bombardment, before its gallant defenders consented to give it up, and not then until the condition of the fort made it impossible to continue the defense. Fort Moultrie alone fired 2,490 shot and shell. Gen. S. W. Crawford, in his accurate and admirable book, previously quoted, thus describes the condition of Sumter when Anderson agreed to its surrender:

It was a scene of ruin and destruction. The quarters and barracks were in ruins. The main gates and the planking of the windows on the gorge were gone; the magazines closed and surrounded by smouldering flames and burning ashes; the provisions exhausted; much of the engineering work destroyed; and with only four barrels of powder available. The command had yielded to the inevitable. The effect of the direct shot had been to indent the walls, where the marks could be counted by hundreds, while the shells, well directed, had crushed the quarters, and, in connection with hot shot, setting them on fire, had destroyed the barracks and quarters down to the gun casemates, while the enfilading fire had prevented the service of the barbette guns, some of them comprising the most important battery in the work. The breaching fire from the columbiads and the rifle gun at Cummings point upon the right gorge angle, had progressed sensibly and must have eventually succeeded if continued, but as yet no guns had been disabled or injured at that point. The effect of the fire upon the parapet was pronounced. The gorge, the right face and flank as well as the left face, were all taken in reverse, and a destructive fire maintained until the end, while the gun carriages on the barbette of the gorge were destroyed in the fire of the blazing quarters.

The spirit and language of General Beauregard in communicating with Major Anderson, and the replies of the latter, were alike honorable to those distinguished soldiers. The writer, who was on duty on Sullivan's island,[Pg 18] as major of Pettigrew's regiment of rifles, recalls vividly the sense of admiration felt for Major Anderson and his faithful little command throughout the attack, and at the surrender of the fort. "While the barracks in Fort Sumter were in a blaze," wrote General Beauregard to the secretary of war at Montgomery, "and the interior of the work appeared untenable from the heat and from the fire of our batteries (at about which period I sent three of my aides to offer assistance), whenever the guns of Fort Sumter would fire upon Moultrie, the men occupying the Cummings point batteries (Palmetto Guard, Captain Cuthbert) at each shot would cheer Anderson for his gallantry, although themselves still firing upon him; and when on the 15th instant he left the harbor on the steamer Isabel, the soldiers of the batteries lined the beach, silent and uncovered, while Anderson and his command passed before them."

Thus closed the memorable and momentous attack upon Fort Sumter by the forces of South Carolina, and thus began the war which lasted until April, 1865, when the Southern Confederacy, as completely ruined and exhausted by fire and sword as Fort Sumter in April, 1861, gave up the hopeless contest and reluctantly accepted the inevitable.

The following is believed to be a correct list of the officers who commanded batteries, or directed, particularly, the firing of the guns, with the commands serving the same:

On Cummings point: (1) Iron battery—three 8-inch columbiads, manned by detachments of Palmetto Guard, Capt. George B. Cuthbert directing, assisted by Lieut. G. L. Buist. (2) Point battery—mortars, by Lieut. N. Armstrong, assisted by Lieut. R. Holmes; 42-pounders, Lieut. T. S. Brownfield; rifle gun, directed by Capt. J. P. Thomas, who, with Lieutenant Armstrong, was an officer of the South Carolina military academy. Iron battery and Point battery both manned by Palmetto Guard. (3)[Pg 19] Trapier battery—three 10-inch mortars, by Capt. J. Gadsden King and Lieuts. W. D. H. Kirkwood and Edward L. Parker; Corp. McMillan King, Jr., and Privates J. S. and Robert Murdock, pointing the mortars; a detachment of Marion artillery manning the battery, assisted by a detachment of the Sumter Guards, Capt. John Russell.

On Sullivan's island: (1) Fort Moultrie—Capt. W. R. Calhoun, Lieutenants Wagner, Rhett, Preston, Sitgreaves, Mitchell, Parker, Blake (acting engineer). (2) mortars—Capt. William Butler and Lieutenants Huguenin, Mowry, Blocker, Billings and Rice. (3) Mortars—Lieutenants Flemming and Blanding. (4) Enfilade—Captain Hallonquist and Lieutenants Valentine and Burnet. (5) Floating battery—Lieutenants Yates and Frank Harleston. (6) Dahlgren battery—Captain Hamilton.

On Mount Pleasant: (1) Mortars—Captain Martin and Lieuts. F. H. Robertson and G. W. Reynolds.

On Fort Johnson: (1) Mortars—Capt. G. S. James and Lieut. W. H. Gibbes.

Immediately upon the fall of Sumter the most active and constant efforts were made by Governor Pickens and General Beauregard to repair and arm the fort, to strengthen the batteries defending the harbor, and to defend the city from an attack by the Stono river and James island. General Beauregard inspected the coast, and works of defense were begun on James island and at Port Royal harbor.

But South Carolina was now to enjoy freedom from attack, by land or sea, until early in November, and while her soldiers and her people were making ready her defense, and her sons were flocking to her standard in larger numbers than she could organize and arm, she was called upon to go to the help of Virginia. William H. Trescot, of South Carolina, in his beautiful memorial of Brig.-Gen. Johnston Pettigrew, has described the spirit with which "the youth and manhood of the South" responded to[Pg 20] the call to arms, in language so true, so just and so eloquent, that the author of this sketch inserts it here. Writing more than five years after the close of the great struggle, Mr. Trescot said:

We who are the vanquished in this battle must of necessity leave to a calmer and wiser posterity to judge of the intrinsic worth of that struggle, as it bears upon the principles of constitutional liberty, and as it must affect the future history of the American people; but there is one duty not only possible but imperative, a duty which we owe alike to the living and the dead, and that is the preservation in perpetual and tender remembrance of the lives of those who, to use a phrase scarcely too sacred for so unselfish a sacrifice, died in the hope that we might live. Especially is this our duty, because in the South a choice between the parties and principles at issue was scarcely possible. From causes which it is exceedingly interesting to trace, but which I cannot now develop the feeling of State loyalty had acquired throughout the South an almost fanatic intensity; particularly in the old colonial States did this devotion to the State assume that blended character of affection and duty which gives in the old world such a chivalrous coloring to loyalty to the crown.... When, therefore, by the formal and constitutional act of the States, secession from the Federal government was declared in 1860 and 1861, it is almost impossible for any one not familiar with the habits and thoughts of the South, to understand how completely the question of duty was settled for Southern men. Shrewd, practical men who had no faith in the result, old and eminent men who had grown gray in service under the national flag, had their doubts and their misgivings; but there was no hesitation as to what they were to do. Especially to that great body of men, just coming into manhood, who were preparing to take their places as the thinkers and actors of the next generation, was this call of the State an imperative summons.

The fathers and mothers who had reared them; the society whose traditions gave both refinement and assurance to their young ambition; the colleges in which the creed of Mr. Calhoun was the text-book of their studies; the friends with whom they planned their future; the very land they loved, dear to them as thoughtless boys,[Pg 21] dearer to them as thoughtful men, were all impersonate, living, speaking, commanding in the State of which they were children. Never in the history of the world has there been a nobler response to a more thoroughly recognized duty; nowhere anything more truly glorious than this outburst of the youth and manhood of the South.

And now that the end has come and we have seen it, it seems to me that to a man of humanity, I care not in what section his sympathies may have been matured, there never has been a sadder or sublimer spectacle than these earnest and devoted men, their young and vigorous columns marching through Richmond to the Potomac, like the combatants of ancient Rome, beneath the imperial throne in the amphitheater, and exclaiming with uplifted arms, "morituri te salutant."

President Lincoln had issued his proclamation calling for 75,000 volunteers to coerce the South; Virginia had withdrawn from the Union, and before the end of April had called Lee, J. E. Johnston and Jackson into her service; the seat of the Confederate government had been transferred from Montgomery, Ala., to Richmond; and early in May, General Beauregard was relieved from duty in South Carolina and ordered to the command of the Alexandria line, with headquarters at Manassas Junction. He had been preceded by General Bonham, then a Confederate brigadier, with the regiments of Colonels Gregg, Kershaw, Bacon, Cash, Jenkins and Sloan—First, Second, Seventh, Eighth, Fifth and Fourth South Carolina volunteers.

Before General Beauregard's arrival in Virginia, General Bonham with his Carolina troops had been placed in command of the Alexandria line, the regiments being at Fairfax Court House, and other points of this line, fronting Washington and Alexandria.

These South Carolina regiments were reinforced during the month of July by the Third, Colonel Williams; the Sixth, Colonel Rion, and the Ninth, Colonel Blanding. The infantry of the Hampton legion, under Col. Wade[Pg 22] Hampton, reached the battlefield of Manassas on the morning of July 21st, but in time to take a full share in that decisive contest.

On the 20th of June, General Beauregard, commanding the "army of the Potomac," headquarters at Manassas Junction, organized his army into six brigades, the First commanded by Bonham, composed of the regiments of Gregg, Kershaw, Bacon and Cash. Sloan's regiment was assigned to the Sixth brigade, Early's; and Jenkins' regiment to the Third, Gen. D. R. Jones. Col. N. G. Evans, an officer of the old United States army, having arrived at Manassas, was assigned to command of a temporary brigade—Sloan's Fourth South Carolina, Wheat's Louisiana battalion, two companies Virginia cavalry, and four 6-pounder guns.

On the 11th of July, General Beauregard wrote to the President that the enemy was concentrating in his front at Falls church, with a force of not less than 35,000 men, and that to oppose him he had only about half that number. On the 17th, Bonham's brigade, stationed at Fairfax, met the first aggressive movement of General McDowell's army, and was attacked early in the morning. By General Beauregard's orders Bonham retired through Centreville, and took the position assigned him behind Mitchell's ford, on Bull run. The Confederate army was in position behind Bull run, extending from Union Mills ford on the right to the stone bridge on the left, a distance of 5 miles.

The brigades were stationed, from right to left, as follows: Ewell, D. R. Jones, Longstreet, Bonham, Cocke, and Evans on the extreme left. Early was in reserve, in rear of the right. To each brigade a section or a battery of artillery was attached, except in the case of Bonham who had two batteries and six companies of cavalry attached to his command. Seven other cavalry companies were distributed among the other brigades. Bonham's position was behind Mitchell's ford, with his[Pg 23] four regiments of Carolinians; Jenkins' Fifth regiment was with General Jones' brigade, behind McLean's ford, and Sloan's Fourth regiment was with Evans' brigade on the left, at the stone bridge. With this disposition of his little army, General Beauregard awaited the development of the enemy's movement against him.

At noon on the 18th, Bonham at Mitchell's ford and Longstreet at Blackburn's ford, were attacked with infantry and artillery, and both attacks were repulsed. General McDowell was engaged on the 19th and 20th in reconnoitering the Confederate position, and made no decided indication of his ultimate purpose. The delay was golden for the Confederates. Important reinforcements arrived on the 20th and on the morning of the 21st, which were chiefly to fight and win the battle, while the main body of Beauregard's army held the line of Bull run. General Holmes, from the lower Potomac, came with over 1,200 infantry, six guns and a fine company of cavalry; Colonel Hampton, with the infantry of his legion, 600 strong, and the Thirteenth Mississippi; Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, from the Shenandoah, with Jackson's, Bee's and Bartow's brigades, 300 of Stuart's cavalry and two batteries, Imboden's and Pendleton's.

The reinforcements were put in line in rear of the troops already in position, Bee and Bartow behind Longstreet, covering McLean's and Blackburn's fords, with Barksdale's Thirteenth Mississippi; Jackson in rear of Bonham, covering Mitchell's ford; and Cocke's brigade, covering the fords further to the left, was strengthened and supported by a regiment of infantry and six guns, and Hampton was stationed at the Lewis house. Walton's and Pendleton's batteries were placed in reserve in rear of Bonham and Bee. Thus strengthened, the army of General Beauregard numbered about 30,000 effectives, with fifty-five guns.

General Beauregard had planned an attack on McDowell's left, which was to be executed on the 21st; but[Pg 24] before he put his right brigades in motion, McDowell had crossed two of his divisions at Sudley's ford, two miles to the left of Evans, who was posted at the stone bridge, and while threatening Evans and Cocke in front, was marching rapidly down the rear of Beauregard's left. Satisfied of this movement, Evans left four companies of the Fourth South Carolina to defend the bridge, and taking the six remaining companies of the Fourth, with Wheat's Louisiana battalion and two guns of Latham's battery, moved rapidly to his rear and left and formed his little brigade at right angles to the line on Bull run and just north of the turnpike road. In this position he was at once assailed by the advance of the enemy, but held his ground for an hour, when Bee, who had been moved up to stone bridge, came to his assistance. Evans, with his Carolinians and Louisianians; Bee, with his Alabama, Mississippi and Tennessee regiments, and Bartow with his Georgia and Kentucky battalions, and the batteries of Latham and Imboden, with heroic fortitude sustained the assault for another hour, before falling back south of the turnpike. It was then evident that the battle was not to be fought in front of Bull run, but behind it, and in rear of General Beauregard's extreme left. Both generals, whose headquarters had been at the Lewis house, three miles away, hurried to the point of attack and arrived, as General Johnston reported, "not a moment too soon." Fifteen thousand splendidly equipped troops of McDowell's army, with numerous batteries, many of the guns rifled, were driving back the little brigade of Evans and the regiments of the gallant Bee and Bartow, and the moment was critical. The presence and example of the commanding generals, the firm conduct of the officers, and the hurrying forward of Hampton with his legion, and Jackson with his brigade, re-established the battle on the line of the Henry house, a half mile south of the turnpike and two miles in the rear of the stone bridge. Beauregard took immediate command on the[Pg 25] field of battle, and Johnston assumed the general direction from the Lewis house, whose commanding elevation gave him a view of the whole field of operations. "The aspect of affairs (he says in his report) was critical, but I had full confidence in the skill and indomitable courage of General Beauregard, the high soldierly qualities of Generals Bee and Jackson and Colonel Evans, and the devoted patriotism of the troops."

At this first stage of the battle, from 8:30 to 11 a. m., the troops from South Carolina actively engaged were the Fourth regiment, Colonel Sloan, and the legion of Hampton. Two companies of the Fourth, thrown out as skirmishers in front of the stone bridge, fired the first gun of the battle early in the morning, and the regiment bore a glorious part in the battle which Evans fought for the first hour, and in the contest of the second hour maintained by Bee, Bartow and Evans. The Fourth lost 11 killed and 79 wounded.

Hampton arrived at the Lewis house in the morning, and being connected with no particular brigade, was ordered to march to the stone bridge. On his march, hearing of the attack on the rear, and the roar of the battle being distinctly heard, he changed the direction of his march toward the firing. Arriving at the Robinson house, he took position in defense of a battery and attacked the enemy in his front. Advancing to the turnpike under fire, Lieut.-Col. B. J. Johnson, of the legion, fell, "as, with the utmost coolness and gallantry, he was placing our men in position," says his commander. Soon enveloped by the enemy in this direction, the legion fell back with the commands of Bee and Evans to the first position it occupied, and, as before reported, formed an important element in re-establishing the battle under the immediate direction of Generals Beauregard and Johnston.

The troops ordered by the commanding generals to prolong the line of battle, formed at 11 o'clock, took position on the right and left as they successively arrived,[Pg 26] those on the left assaulting at once, and vigorously, the exposed right flank of the enemy, and at each assault checking, or repulsing, his advance. No attempt will be made by the author to follow the movements of all of these gallant troops who thus stemmed the sweeping advance of strong Federal brigades, and the fire of McDowell's numerous batteries. He is confined, particularly, to the South Carolina commands.

The line of battle as now re-established, south of the Warrenton turnpike, ran at a right angle with the Bull run line, and was composed of the shattered commands of Bee, Bartow and Evans on the right, with Hampton's legion infantry; Jackson in the center, and Gartrell's, Smith's, Faulkner's and Fisher's regiments, with two companies of Stuart's cavalry, on the left. The artillery was massed near the Henry house. With this line the assaults of Heintzelman's division and the brigades of Sherman and Keyes, with their batteries, numbering some 18,000 strong, were resisted with heroic firmness.

By 2 o'clock, Kershaw's Second and Cash's Eighth South Carolina, General Holmes' brigade of two regiments, Early's brigade, and Walker's and Latham's batteries, arrived from the Bull run line and reinforced the left. The enemy now held the great plateau from which he had driven our forces, and was being vigorously assailed on his left by Kershaw and Cash, with Kemper's battery, and by Early and Stuart. General Beauregard ordered the advance of his center and right, the latter further strengthened by Cocke's brigade, taken by General Johnston's order from its position at the stone bridge.

This charge swept the great plateau, which was then again in possession of the Confederates. Hampton fell, wounded in this charge, and Capt. James Conner took command of the legion. Bee, the heroic and accomplished soldier, fell at the head of the troops, and Gen. S. R. Gist, adjutant-general of South Carolina, was wounded leading the Fourth Alabama. Reinforced, the Federal[Pg 27] troops again advanced to possess the plateau, but Kirby Smith's arrival on the extreme left, and his prompt attack, with Kershaw's command and Stuart's cavalry, defeated the right of McDowell's advance and threw it into confusion, and the charge of Beauregard's center and right completed the victory of Manassas.

In the operations of this memorable day, no troops displayed more heroic courage and fortitude than the troops from South Carolina, who had the fortune to bear a part in this the first great shock of arms between the contending sections. These troops were the Second regiment, Col. J. B. Kershaw; the Fourth, Col. J. B. E. Sloan; the Eighth, Col. E. B. Cash; the Legion infantry, Col. Wade Hampton, and the Fifth, Col. Micah Jenkins. The latter regiment was not engaged in the great battle, but, under orders, crossed Bull run and attacked the strong force in front of McLean's ford. The regiment was wholly unsupported and was forced to withdraw, Colonel Jenkins rightly deeming an assault, under the circumstances, needless.

The following enumeration of losses is taken from the several reports of commanders as published in the War Records, Vol. II, p. 570: Kershaw's regiment, 5 killed, 43 wounded; Sloan's regiment, 11 killed, 79 wounded; Jenkins' regiment, 3 killed, 23 wounded; Cash's regiment, 5 killed, 23 wounded; Hampton's legion, 19 killed, 102 wounded; total, 43 killed, 270 wounded.

Gen. Barnard Elliott Bee, who fell, leading in the final and triumphant charge of the Confederates, was a South Carolinian. Col. C. H. Stevens, a volunteer on his staff, his near kinsman, and the distinguished author of the iron battery at Sumter, was severely wounded. Lieut.-Col. B. J. Johnson, who fell in the first position taken by the Hampton legion, was a distinguished and patriotic son of the State, and Lieut. O. R. Horton, of the Fourth, who was killed in front of his company, had been prominent in the battle of the early morning. At Manassas,[Pg 28] South Carolina was well represented by her faithful sons, who willingly offered their lives in defense of her principles and her honor. The blood she shed on that ever-memorable field was but the token of the great offering with which it was yet to be stained by the sacrifices of more than a thousand of her noblest sons.

The battle of Manassas fought and won, and trophies of the Confederate victory gathered from the plateau of the great strife, and from the line of the Union army's retreat, the South Carolina troops with General Beauregard's command were put into two brigades, Bonham's, the First, and D. R. Jones', the Third. The Second, Third, Seventh and Eighth regiments made up General Bonham's brigade; the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth and Ninth, General Jones' brigade. Gregg's First regiment was at Norfolk, and Hampton's legion was not brigaded. Headquarters were established at Fairfax Court House, and the Confederate line ran from Springfield on the Orange & Alexandria railroad to Little Falls above Georgetown. No event of great importance occurred in which the troops of South Carolina took part, in Virginia, during the remainder of the summer.

AFFAIRS ON THE COAST—LOSS OF PORT ROYAL HARBOR—GEN. R. E. LEE IN COMMAND OF THE DEPARTMENT—LANDING OF FEDERALS AT PORT ROYAL FERRY—GALLANT FIGHT ON EDISTO ISLAND—GENERAL PEMBERTON SUCCEEDS LEE IN COMMAND—DEFENSIVE LINE, APRIL, 1862.

Throughout the summer of 1861, in Charleston and along the coast of South Carolina, all was activity in the work of preparation and defense. On August 21st, Brig.-Gen. R. S. Ripley, whose promotion to that rank had been applauded by the soldiers and citizens of the State, was assigned to the "department of South Carolina and the coast defenses of that State." On assuming command, General Ripley found the governor and people fully alive to the seriousness of the situation, and everything being done which the limited resources of the State permitted, to erect fortifications and batteries on the coast, and to arm and equip troops for State and Confederate service.

Governor Pickens wrote to the secretary of war at Richmond about the time of the Federal expedition to North Carolina, and the capture of the batteries at Hatteras inlet, urgently requesting that Gregg's First regiment might be sent him from Virginia, as he expected an attack to be made at some point on the coast. In this letter he begged that 40,000 pounds of cannon powder be forwarded from Norfolk at once. The governor had bought in December, 1860, and January, 1861, 300,000 pounds from Hazard's mills in Connecticut, for the use of the State, but he had loaned 25,000 pounds to the governor of North Carolina, 5,000 pounds to the governor of[Pg 30] Florida, and a large amount to the governor of Tennessee. Of what remained he needed 40,000 pounds to supply "about 100 guns on the coast below Charleston." The governor estimated the troops in the forts and on the islands around Charleston at 1,800 men, all well drilled, and a reserve force in the city of 3,000. These forces, with Manigault's, Heyward's, Dunovant's and Orr's regiments, he estimated at about 9,500 effective.

On October 1st, General Ripley reported his Confederate force, not including the battalion of regular artillery and the regiment of regular infantry, at 7,713 effectives, stationed as follows: Orr's First rifles, on Sullivan's island, 1,521; Hagood's First, Cole's island and stone forts, 1,115; Dunovant's Twelfth, north and south Edisto, 367; Manigault's Tenth, Georgetown and defenses, 538; Jones' Fourteenth, camp near Aiken, 739; Heyward's Eleventh, Beaufort and defenses, 758; cavalry, camp near Columbia, 173; cavalry, camp near Aiken, 62; arsenal, Charleston (artillery), 68; Edwards' Thirteenth, De Saussure's Fifteenth, and remainder of Dunovant's Twelfth, 2,372.

On the first day of November, the governor received the following dispatch from the acting secretary of war: "I have just received information which I consider entirely reliable, that the enemy's expedition is intended for Port Royal." Governor Pickens answered: "Please telegraph General Anderson at Wilmington, and General Lawton at Savannah, to send what forces they can spare, as the difficulty with us is as to arms." Ripley replied, "Will act at once. A fine, strong, southeast gale blowing, which will keep him off for a day or so." The fleet sailed from Hampton Roads on the 29th of October, and on the 4th of November the leading vessels that had withstood the gale appeared off Port Royal harbor. The storm had wrecked several of the transports, and the[Pg 31] whole fleet suffered and was delayed until the 7th, before Admiral DuPont was ready to move in to the attack of the forts defending this great harbor.

Port Royal harbor was defended by two forts, Walker and Beauregard, the former on Hilton Head island, and the latter on Bay point opposite. The distance across the harbor, from fort to fort, is nearly 3 miles, the harbor ample and deep, and the water on the bar allowing the largest vessels to enter without risk. A fleet of 100 sail could maneuver between Forts Walker and Beauregard and keep out of range of all but their heaviest guns. To defend such a point required guns of the longest range and the heaviest weight of metal.

In planning the defense of Port Royal, General Beauregard designed that batteries of 10-inch columbiads and rifled guns should be placed on the water fronts of both forts, and so directed; but the guns were not to be had, and the engineers, Maj. Francis D. Lee and Capt. J. W. Gregory, were obliged to mount the batteries of the forts with such guns as the Confederate government and the governor of South Carolina could command. The forts were admirably planned and built, the planters in the vicinity of the forts supplying all the labor necessary, so that by September 1, 1861, they were ready for the guns.

Fort Walker mounted twenty guns and Fort Beauregard nineteen, but of this armament Walker could use but thirteen, and Beauregard but seven against a fleet attacking from the front. The rest of the guns were placed for defense against attack by land, or were too light to be of any use. The twenty guns of Walker and Beauregard that were used in the battle with the fleet, were wholly insufficient, both in weight of metal and number. The heaviest of the guns in Walker were two columbiads, 10-inch and 8-inch, and a 9-inch rifled Dahlgren. The rest of the thirteen were 42, 32 and 24 pounders. Of the seven guns in Beauregard, one was a 10-inch colum[Pg 32]biad, and one a 24-pounder, rifled. The rest were 42 and 32 pounders; one of the latter fired hot shot.

Col. William C. Heyward, Eleventh South Carolina volunteers, commanded at Fort Walker, and Col. R. G. M. Dunovant, of the Twelfth, commanded at Fort Beauregard. The guns at Walker were manned by Companies A and B, of the German Flying Artillery, Capts. D. Werner and H. Harms; Company C, Eleventh volunteers, Capt. Josiah Bedon, and detachments from the Eleventh under Capt. D. S. Canaday. Maj. Arthur M. Huger, of the Charleston artillery battalion, was in command of the front batteries, and of the whole fort after Col. John A. Wagener was disabled. The guns in Fort Beauregard were manned by the Beaufort artillery; Company A, Eleventh volunteers, Capt. Stephen Elliott, and Company D, Eleventh volunteers, Capt. J. J. Harrison; Captain Elliott directing the firing. The infantry support at Walker was composed of three companies of the Eleventh and four companies of the Twelfth, and a company of mounted men under Capt. I. H. Screven. The fighting force of Fort Walker then, on the morning of the 7th of November, preparing to cope with the great fleet about to attack, was represented by thirteen guns, manned and supported by 622 men. The infantry support at Fort Beauregard was composed of six companies of the Twelfth, the whole force at Beauregard, under Colonel Dunovant, amounting to 640 men and seven guns.

Brig.-Gen. Thomas F. Drayton, with headquarters at Beaufort, commanded the defenses at Port Royal harbor and vicinity. He removed his headquarters to Hilton Head on the 5th, and pushed forward every preparation in his power for the impending battle. The remote position of Fort Beauregard and the interposition of the fleet, lying just out of range, made it impossible to reinforce that point. An attempt made early on the morning of the 7th, supported by the gallant Commodore Tattnall,[Pg 33] was prevented by the actual intervention of the leading battleships of the enemy. Fort Walker, however, received just before the engagement, a reinforcement of the Fifteenth volunteers, Colonel DeSaussure, 650 strong; Captain Read's battery of two 12-pounder howitzers, 50 men and 450 Georgia infantry, under Capt. T. J. Berry.

The morning of the 7th of November was a still, clear, beautiful morning, "not a ripple," wrote General Drayton, "upon the broad expanse of water to disturb the accuracy of fire from the broad decks of that magnificent armada, about advancing in battle array." The attack came about 9 o'clock, nineteen of the battleships moving up and following each other in close order, firing upon Fort Beauregard as they passed, then turning to the left and south, passing in range of Walker, and pouring broadside after broadside into that fort. Captain Elliott reports: "This circuit was performed three times, after which they remained out of reach of any except our heaviest guns." From this position the heavy metal and long range guns of nineteen batteries poured forth a ceaseless bombardment of both Beauregard and Walker, but paying most attention to the latter.

Both forts replied with determination, the gunners standing faithfully to their guns, but the vastly superior weight of metal and the number of the Federal batteries, and the distance of their positions from the forts (never less than 2,500 yards from Beauregard and 2,000 from Walker), made the contest hopeless for the Confederates almost from the first shot. Shortly after the engagement began, several of the largest vessels took flanking positions out of reach of the 32-pounder guns in Walker, and raked the parapet of that fort. "So soon as these positions had been established," reported Major Huger, "the fort was fought simply as a point of honor, for from that moment we were defeated." This flank fire, with the incessant direct discharge of the fleet's heavy batteries,[Pg 34] dismounted or disabled most of Fort Walker's guns. The 10-inch columbiad was disabled early in the action; the shells for the rifled guns were too large to be used, and the ammunition for all but the 32-pounders exhausted, when, after four hours of hard fighting, Colonel Heyward ordered that two guns should be served slowly, while the sick and wounded were removed from the fort; that accomplished, the fort to be abandoned. Thus terminated the fight at Fort Walker.

At Fort Beauregard, the battle went more fortunately for the Confederates. A caisson was exploded by the fire of the fleet, and the rifled 24-pounder burst, and several men and officers were wounded by these events, but none of the guns were dismounted, and Captain Elliott only ceased firing when Walker was abandoned. In his report, he says: "Our fire was directed almost exclusively at the larger vessels. They were seen to be struck repeatedly, but the distance, never less than 2,500 yards, prevented our ascertaining the extent of injury." General Drayton successfully conducted his retreat from Hilton Head, and Colonel Dunovant from Bay point, all the troops being safely concentrated on the main behind Beaufort.

The taking of Port Royal harbor on the 7th of November, 1861, gave the navy of the United States a safe and ample anchorage, while the numerous and rich islands surrounding it afforded absolutely safe and comfortable camping grounds for the army of Gen. T. W. Sherman, who was specially in charge of this expedition. The effect of this Union victory was to give the fleet and army of the United States a permanent and abundant base of operations against the whole coast of South Carolina, and against either Charleston or Savannah, as the Federal authorities might elect; but its worst result was the immediate abandonment of the whole sea-island country around Beaufort, the houses and estates of the planters being left to pillage and ruin, and thousands of[Pg 35] negro slaves falling into the hands of the enemy. General Sherman wrote to his government, from Hilton Head, that the effect of his victory was startling. Every white inhabitant had left the islands of Hilton Head, St. Helena, Ladies, and Port Royal, and the beautiful estates of the planters were at the mercy of hordes of negroes.

The loss of the forts had demonstrated the power of the Federal fleet, and the impossibility of defending the island coast with the guns which the State and the Confederacy could furnish. The 32 and 42 pounders were no match for the 11-inch batteries of the fleet, and gunboats of light draught, carrying such heavy guns, could enter the numerous rivers and creeks and cut off forts or batteries at exposed points, while larger vessels attacked them, as at Port Royal, in front. It was evident that the rich islands of the coast were at the mercy of the Federal fleet, whose numerous gunboats and armed steamers, unopposed by forts or batteries, could cover the landing of troops at any point or on any island selected.

On the capture of Port Royal, it was uncertain, of course, what General Sherman's plans would be, or what force he had with which to move on the railroad between Charleston and Savannah. The fleet was ample for all aggressive purposes along the coast, but it was not known at the time that the army numbered less than 15,000 men, all told. But it was well known how easily a landing could be effected within a few miles of the railroad bridges crossing the three upper branches of the Broad river, the Coosawhatchie, Tulifinny and Pocotaligo, and the rivers nearer to Charleston, the Combahee, Ashepoo and Edisto. Bluffton, easily reached by gunboats, afforded a good landing and base for operations against the railroad at Hardeeville, only 4 miles from the Savannah river, and 15 from the city of Savannah. On this account, General Ripley, assisted by the planters,[Pg 36] caused the upper branches of the Broad, and the other rivers toward Charleston to be obstructed, and meanwhile stationed the troops at his command at points covering the landings.

General Drayton, with a part of Martin's regiment of cavalry, under Lieutenant-Colonel Colcock, and Heyward's and De Saussure's regiments, was watching Bluffton and the roads to Hendersonville. Clingman's and Radcliffe's North Carolina regiments, with artillery under Col. A. J. Gonzales, Captain Trezevant's company of cavalry, and the Charleston Light Dragoons and the Rutledge Riflemen, were stationed in front of Grahamville, to watch the landings from the Broad. Colonel Edwards' regiment and Moore's light battery were at Coosawhatchie, Colonel Dunovant's at Pocotaligo, and Colonel Jones', with Tripp's company of cavalry, in front of the important landing at Port Royal ferry. Colonel Martin, with part of his regiment of cavalry, was in observation at the landings on Combahee, Ashepoo and Edisto rivers. The idea of this disposition, made by Ripley immediately upon the fall of Forts Walker and Beauregard, was to guard the railroad bridges, and keep the troops in hand to be moved for concentration in case any definite point was attacked.

On the 8th of November, the day after Port Royal was taken, Gen. Robert E. Lee took command of the department of South Carolina and Georgia, by order of the President of the Confederacy. It was evident to him that the mouths of the rivers and the sea islands, except those immediately surrounding the harbor of Charleston, could not be defended with the guns and troops at his command, and, disappointing and distressing as such a view was to the governor and especially to the island planters, whose homes and estates must be abandoned and ruined, General Lee prepared for the inevitable. He wrote to General Ripley, in Charleston, to review the whole subject and suggest what changes should be made.[Pg 37] "I am in favor," he wrote, "of abandoning all exposed points as far as possible within reach of the enemy's fleet of gunboats, and of taking interior positions, where all can meet on more equal terms. All our resources should be applied to those positions." Subsequently the government at Richmond ordered General Lee, by telegraph, to withdraw all his forces from the islands to the mainland. When the order was carried out, it was done at a terrible sacrifice, to which the planters and citizens yielded in patient and noble submission, turning their backs upon their homes and their property with self-sacrificing devotion to the cause of Southern independence. Never were men and women subjected to a greater test of the depth and strength of their sentiments, or put to a severer trial of their patriotism, than were the planters and their families, who abandoned their houses and estates along the coast of South Carolina, and retired as refugees into the interior, all the men who were able entering the army.

At the time of the fall of Forts Walker and Beauregard, Charleston harbor was defended by Forts Moultrie and Sumter, Castle Pinckney and Fort Johnson, and by batteries on Sullivan's and Morris islands. All these were to be strengthened, and the harbor made secure against any attack in front. To prevent the occupation of James island, the mouth of Stono river was defended by forts built on Cole's and Battery islands, and a line of defensive works built across the island. No attempt had been made to erect forts or batteries in defense of the inlets of Worth or South Edisto, but the harbor of Georgetown was protected by works unfinished on Cat and South islands, for twenty guns, the heaviest of which were 32-pounders.

When General Lee took command, November 8th, he established his headquarters at Coosawhatchie, and divided the line of defense into five military districts, from east to west, as follows: The First, from the North[Pg 38] Carolina line to the South Santee, under Col. A. M. Manigault, Tenth volunteers, with headquarters at Georgetown; the Second, from the South Santee to the Stono, under Gen. R. S. Ripley, with headquarters at Charleston; the Third, from the Stono to the Ashepoo, under Gen. N. G. Evans, with headquarters at Adams' run; the Fourth, from Ashepoo to Port Royal entrance, under Gen. J. C. Pemberton, with headquarters at Coosawhatchie; the Fifth, the remainder of the line to the Savannah river, under Gen. T. F. Drayton, with headquarters at Hardeeville.

On the 27th of December, General Lee wrote to Governor Pickens that his movable force for the defense of the State, not including the garrisons of the forts at Georgetown and those of Moultrie, Sumter, Johnson, Castle Pinckney and the works for the defense of the approaches through Stono, Wappoo, etc., which could not be removed from their posts, amounted to 10,036 Confederate troops—the Fourth brigade, South Carolina militia, 1,531 strong; Colonel Martin's mounted regiment, 567 strong; two regiments from North Carolina, Clingman's and Radcliffe's; two regiments from Tennessee, the Eighth and Sixteenth, and Colonel Starke's Virginia regiment; the Tennesseeans and Virginians making a brigade under Brigadier-General Donelson. The above, with four field batteries, made up the force scattered from Charleston to the Savannah river, and stationed along the line, on the mainland, in front of the headquarters above named.

Nothing of great importance occurred for the remainder of the year 1861 along the coast of South Carolina, except the sinking of a "stone fleet" of some twenty vessels across the main ship channel on December 20th, in Charleston harbor. This was done by the order of the United States government to assist the blockade of the port, and was pronounced by General Lee as an "achievement unworthy of any nation."

On January 1, 1862, at Port Royal ferry, was demonstrated the ease with which a large force could be placed on the mainland under the protection of the fleet batteries. Brig.-Gen. Isaac Stevens landed a brigade of 3,000 men for the purpose of capturing a supposed battery of heavy guns, which, it was believed, the Confederates had built at the head of the causeway leading to Port Royal ferry. Landing from Chisolm's island, some distance east of the small earthwork, Col. James Jones, Fourteenth volunteers, had promptly withdrawn the guns in the earthwork, except a 12-pounder, which was overturned in a ditch. Believing the movement to be an attack in force upon the railroad, Colonel Jones disposed his regiment and a part of the Twelfth, under Lieut.-Col. Dixon Barnes, with a section of Leake's battery, and 42 mounted men, under Major Oswald, for resisting the attack, forming his line about a mile from the ferry. But there was no engagement. The deserted earthwork was easily captured, and the 12-pounder gun righted on its carriage and hauled off, under the constant bombardment of the vessels in the Coosaw river. The opposing troops caught glimpses of each other, and fired accordingly, but not much harm was done on either side. Colonel Jones lost Lieut. J. A. Powers and 6 men killed and 20 wounded by the fire of the gunboats, and Colonel Barnes, 1 man killed and 4 wounded; 32 casualties. The Federal general reported 2 men killed, 12 wounded and 1 captured. During the winter and early spring the fleet was busy exploring the rivers, sounding the channels, and landing reconnoitering parties on the various islands.

Edisto island was garrisoned early in February, and the commander, Col. Henry Moore, Forty-seventh New York, wrote to the adjutant-general in Washington, on the 15th, that he was within 25 miles of Charleston; considered Edisto island "the great key" to that city, and with a reinforcement of 10,000 men could "in less than three days be in Charleston."

It will be noted in this connection that early in March, General Lee was called to Richmond and placed in command of the armies of the Confederacy, and General Pemberton, promoted to major-general, was assigned to the department of South Carolina and Georgia. Major-General Hunter, of the Federal army, had assumed command instead of General Sherman, the last of March, and reported to his government, "about 17,000 troops scattered along the coast from St. Augustine, Fla., to North Edisto inlet." Of these troops, 12,230 were on the South Carolina coast—4,500 on Hilton Head island; 3,600 at Beaufort; 1,400 on Edisto, and the rest at other points. The force on Edisto was advanced to the northern part of the island, with a strong guard on Little Edisto, which touches the mainland and is cut off from the large island by Watts' cut and a creek running across its northern neck. Communication with the large island from Little Edisto is by a bridge and causeway, about the middle of the creek's course.

This being the situation, General Evans, commanding the Third district, with headquarters at Adams' run, determined to capture the guard on Little Edisto and make an armed reconnoissance on the main island. The project was intrusted to Col. P. F. Stevens, commanding the Holcombe legion, and was quite successfully executed. On the morning of March 29th, before day, Colonel Stevens, with his legion, Nelson's battalion, and a company of cavalry, attacked and dispersed the picket at Watts cut, crossed and landed on the main island west of the bridge, which communicated with Little Edisto. Moving south into the island, he detached Maj. F. G. Palmer, with seven companies, 260 men, to attack the picket at the bridge, cross over to Little Edisto, burn the bridge behind him, and capture the force thus cut off on Little Edisto, which was believed to be at least two companies. Palmer carried the bridge by a charge, and crossing over, left two of his staff, Rev. John D. McCul[Pg 41]lough, chaplain of the legion, and Mr. Irwin, with Lieutenant Bishop's company of the legion, to burn the bridge, and pushed on after the retreating force. Day had broken, but a heavy fog obscured every object, and the attack on the Federals was made at great disadvantage. Palmer captured a lieutenant and 20 men and non-commissioned officers, the remainder of the force escaping in the fog. Colonel Stevens marched within sound of the long roll beating in the camps in the interior, and taking a few prisoners, returned to the mainland by Watts' cut, and Palmer crossed his command and prisoners over at the north end of Little Edisto in a small boat, which could only carry five men at a time, flats which were on the way to him having failed to arrive. Several of the Federal soldiers were killed and wounded in this affair, the Confederates having two slightly wounded. But for the dense fog the entire force on Little Edisto would have been captured.