THE ART OF BOOKBINDING. A PRACTICAL TREATISE.

BY JOSEPH W. ZAEHNSDORF.

TECHNOLOGICAL HANDBOOKS.

ART OF BOOKBINDING.

TECHNOLOGICAL HANDBOOKS.

1. DYEING AND TISSUE-PRINTING. By William Crookes,

F.R.S., V.P.C.S. 5s.

2. GLASS MANUFACTURE.

INTRODUCTORY

ESSAY,

by H. J. Powell, B.A. (Whitefriars Glass Works);

CROWN

AND

SHEET

GLASS,

by Henry Chance, M.A. (Chance Bros., Birmingham);

PLATE

GLASS, by H. G.

Harris, Assoc. Memb. Inst. C.E. 3s. 6d.

3. COTTON SPINNING; Its Development, Principles, and

Practice. By R. Marsden, Editor of the “Textile Mercury.” With an

Appendix on Steam Engines and Boilers. 3rd edition, revised, 6s.

6d.

4. COAL-TAR COLOURS, The Chemistry of. With special

reference to their application to Dyeing, &c. By Dr. R. Benedikt.

Translated from the German by E. Knecht, Ph.D. 2nd edition, enlarged,

6s. 6d.

5. WOOLLEN AND WORSTED CLOTH MANUFACTURE. By Professor

Roberts Beaumont. 2nd edition, revised. 7s. 6d.

6. PRINTING. By C. T. Jacobi, Manager of the Chiswick

Press. 5s.

7. BOOKBINDING. By J. W. Zaehnsdorf.

9. COTTON WEAVING. By R. Marsden. In preparation.

TECHNOLOGICAL HANDBOOKS.

THE ART

OF

BOOKBINDING.

A PRACTICAL TREATISE.

BY

JOSEPH W. ZAEHNSDORF.

WITH

PLATES

AND

DIAGRAMS.

SECOND EDITION, REVISED AND ENLARGED.

LONDON: GEORGE BELL AND SONS,

YORK STREET, COVENT GARDEN.

1890.

CHISWICK PRESS:—C.

WHITTINGHAM AND CO.,

TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE.

DEDICATED TO

HUGH OWEN, ESQ., F.S.A.,

AS A SLIGHT

ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF HIS COUNSEL AND

FRIENDSHIP, AND IN ADMIRATION OF HIS

KNOWLEDGE OF

BOOKBINDING.

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION.

The

first edition of this book was written for the use of

amateurs, but I found that amongst the members of

the trade my little volume had a large sale, and in a short

time the edition became exhausted. Repeated applications

for the book have induced me to issue this second edition.

I have adhered to the arrangement of the first, but a great

deal of fresh matter has been added, which I trust will be

found useful. Should any of my fellow-workmen find

anything new to them I shall be satisfied, knowing that I

have done my duty in spreading such knowledge as may

contribute towards the advancement of the beautiful art of

bookbinding.

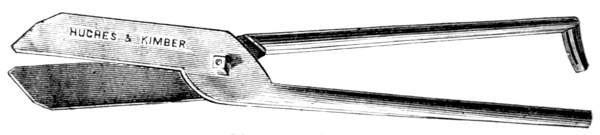

I have to record my obligations to those gentlemen who

have assisted me by courteously describing the various

machines of their invention with which the book is illustrated.

The object, however, of illustrating this work with

engravings of machines is simply to recognize the fact that

books are bound by machinery. To a mechanical worker

must be left the task of describing the processes used in

this method.

-

LIST OF PLATES.

- FLORENTINE …

Frontispiece

-

◊

GROLIER …

-

◊

GASCON …

-

◊

RENAISSANCE …

-

◊

ANTIQUE

WITH

GOLD

LINE …

-

◊

DEROME …

-

◊

GROLIER …

-

◊

MAIOLI …

CONTENTS. |

|---|

PART I.—FORWARDING. |

PAGE |

| CHAPTER

I. Folding: Refolding — Machines — Gathering |

3–8 |

| CHAPTER

II. Beating and Rolling: Machines |

9–12 |

| CHAPTER

III. Collating: Interleaving |

13–19 |

| CHAPTER

IV. Marking up and Sawing in |

20–23 |

| CHAPTER

V. Sewing: Flexible — Ordinary |

23–32 |

| CHAPTER

VI. Forwarding: End Papers — Cobb Paper — Surface

Paper — Marbled Paper — Printed and other Fancy

Paper — Coloured Paste Paper |

33–36 |

| CHAPTER

VII. Pasting up |

36–37 |

| CHAPTER

VIII. Putting on the End Papers |

38–41 |

| CHAPTER

IX. Trimming |

41–44 |

| CHAPTER

X. Gluing up |

45–46 |

| CHAPTER

XI. Rounding |

46–48 |

| CHAPTER

XII. Backing |

48–51 |

| CHAPTER

XIII. Mill-boards |

51–57 |

| CHAPTER

XIV. Drawing-in and Pressing |

57–59 |

| CHAPTER

XV. Cutting |

59–66 |

| CHAPTER

XVI. Colouring the Edges: Sprinkled Edges — Colours

for Sprinkling — Plain Colouring — Marbled Edges — Spot

Marble — Comb or Nonpareil Marble — Spanish

Marble — Edges — Sizing |

67–77 |

| CHAPTER

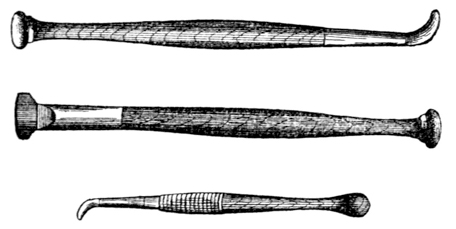

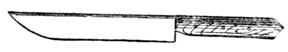

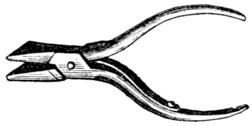

XVII. Gilt Edges: The Gold Cushion — Gold

Knife — Burnishers — Glaire Water or Size — Scrapers — The

Gold Leaf — Gilt on Red — Tooled Edges — Painted

Edges |

78–83 |

| CHAPTER

XVIII. Head-Banding |

83–86 |

| CHAPTER

XIX. Preparing for Covering: lining up |

87–90 |

| CHAPTER

XX. Covering: Russia — Calf — Vellum or

Parchment — Roan — Cloth — Velvet — Silk

and Satin — Half-bound Work |

90–97 |

| CHAPTER

XXI. Pasting Down: Joints — Calf, Russia, etc. |

97–100 |

| CHAPTER

XXII. Calf Colouring:

Black — Brown — Yellow — Sprinkles — Marbles — Tree-marbles — Dabs |

100–108 |

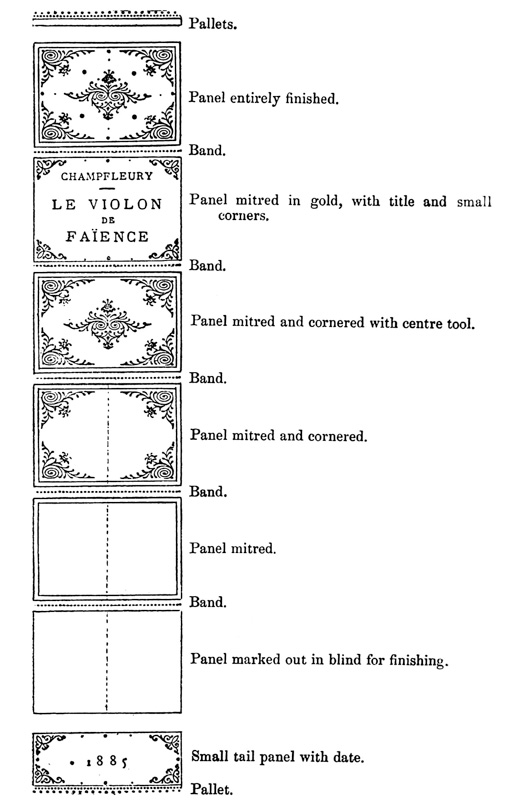

PART II. — FINISHING.

CHAPTER

XXIII. Finishing:

Tools and Materials required for Finishing — Polishing

Irons — Gold-rag — India-rubber — Gold-cushion — Gold

Leaf — Sponges — Glaire — Cotton

Wool — Varnish — Finishing — Morocco — Gold Work — Inlaid

Work — Porous — Full Gilt Back — Run-up — Mitred

Back — Pressing — Graining — Finishing with Dry

Preparation — Velvet — Silk — Vellum — Blocking |

111–153 |

GENERAL INFORMATION.

CHAPTER

XXIV. Washing and Cleaning:

Requisites — Manipulation — Dust — Water

Stains — Damp Stains — Mud — Fox-marks — Finger-marks, commonly called

“Thumb-marks” — Blood Stains — Ink Stains (writing) — Ink

Stains (Marking Ink, Silver) — Fat Stains — Ink — Reviving

Old Writings — To Restore Writing effaced by

Chlorine — To Restore MSS. faded by time — To Preserve

Drawings or Manuscripts — To fix Drawings or Pencil

Marks — To render Paper Waterproof — To render Paper

Incombustible — Deciphering Burnt Documents — Insects — Glue — Rice

Glue or Paste — Paste — Photographs — Albumen — To

Prevent Tools, Machines, etc., from Rusting — To

Clean Silver Mountings — To Clean Sponges |

157–172 |

| GLOSSARY |

173 |

| INDEX |

181 |

INTRODUCTION.

Bookbinding carries us back to the time when

leaden tablets with inscribed hieroglyphics were

fastened together with rings, which formed what to us

would be the binding of the volumes. We might go even

still further back, when tiles of baked clay with cuneiform

characters were incased one within the other, so that if the

cover of one were broken or otherwise damaged there still

remained another, and yet another covering; by which care

history has been handed down from generation to generation.

The binding in the former would consist of the

rings which bound the leaden tablets together, and in the

latter, the simple covering formed the binding which

preserved the contents.

We must pass on from these, and make another pause,

when vellum strips were attached together in one continuous

length with a roller at each end. The reader

unrolled the one, and rolled the other as he perused the

work. Books, prized either for their rarity, sacred

character, or costliness, would be kept in a round box or

case, so that the appearance of a library in Ancient Jerusalem

would seem to us as if it were a collection of

canisters. The next step was the fastening of separate

leaves together, thus making a back, and covering the

whole as a protection in a most simple form; the only

object being to keep the several leaves in connected

sequence. I believe the most ancient form of books

formed of separate leaves, will be found in the sacred

books of Ceylon which were formed of palm leaves, written

on with a metal style, and the binding was merely a silken

string tied through one end so loosely as to admit of each

leaf being laid down flat when turned over. When the

mode of preserving MS. on animal membrane or vellum in

separate leaves came into use, the binding was at first only

a simple piece of leather wrapped round the book and tied

with a thong. These books were not kept on their edges,

but were laid down flat on the shelves, and had small cedar

tablets hanging from them upon which their titles were

inscribed.

The ordinary books for general use were only fastened

strongly at the back, with wooden boards for the sides, and

simply a piece of leather up the back.

In the sixth century, bookbinding had already taken its

place as an “Art,” for we have the “Byzantine coatings,”

as they are called. They are of metal, gold, silver or

copper gilt, and sometimes they are enriched with precious

stones. The monks, during this century, took advantage

of the immense thickness of the wooden boards and frequently

hollowed them out to secrete their relics in the

cavities. Bookbinding was then confined entirely to the

monks who were the literati of the period. Then the art

was neglected for some centuries, owing to the plunder and

pillage that overran Europe, and books were destroyed to

get at the jewels that were supposed to be hidden in the

different parts of the covering, so that few now remain to

show how bookbinding was then accomplished and to what

extent.

We must now pass on to the middle ages, when samples

of binding were brought from the East by the crusaders,

and these may well be prized by their owners for their

delicacy of finish. The monks, who still held the Art of

Bookbinding in their hands, improved upon these Eastern

specimens. Each one devoted himself to a different branch:

one planed the oaken boards to a proper size, another

stretched and coloured the leather; and the work was thus

divided into branches, as it is now. The task was one of

great difficulty, seeing how rude were the implements then

in use.

The art of printing gave new life to our trade, and,

during the fifteenth century bookbinding made great

progress on account of the greater facility and cheapness

with which books were produced. The printer was then

his own binder; but as books increased in number, bookbinding

became a separate art-trade of itself. This was a

step decidedly in the right direction. The art improved so

much, that in the sixteenth century some of the finest

samples of bookbinding were executed. Morocco having

been introduced, and fine delicate tools cut, the art was

encouraged by great families, who, liking the Venetian

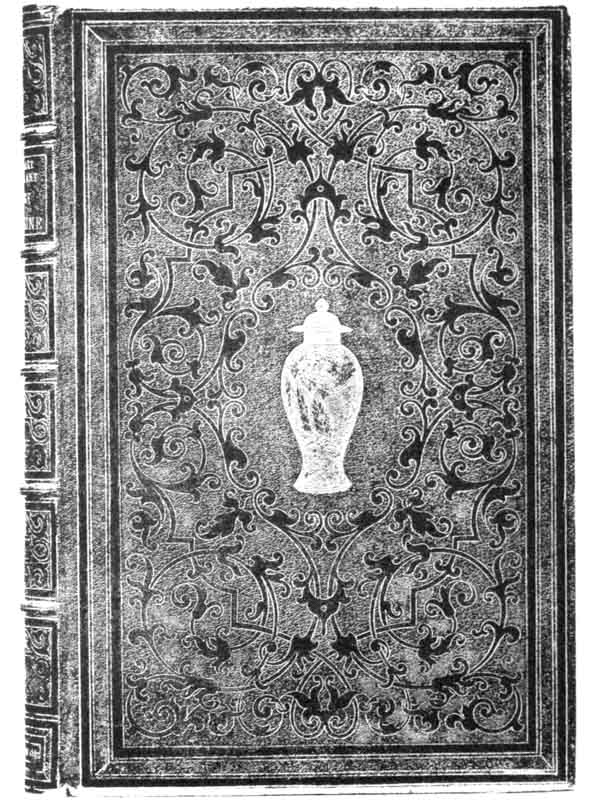

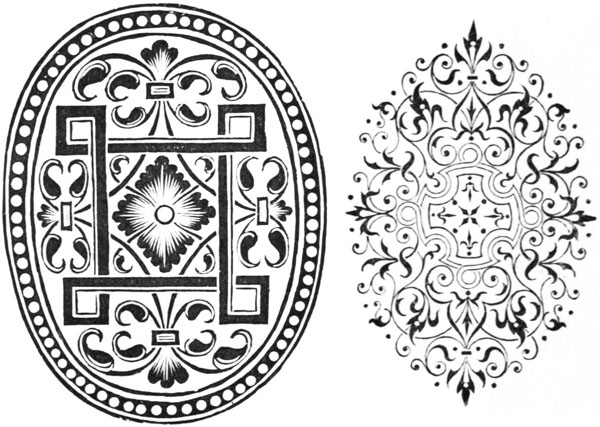

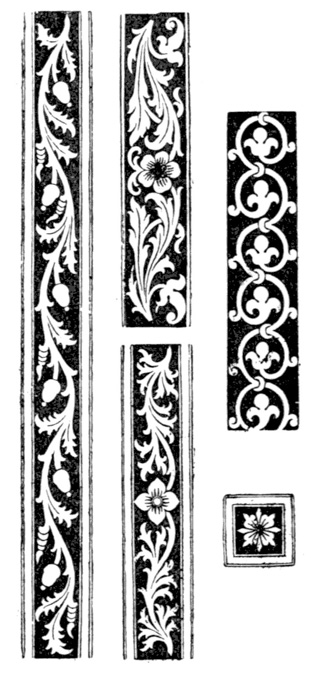

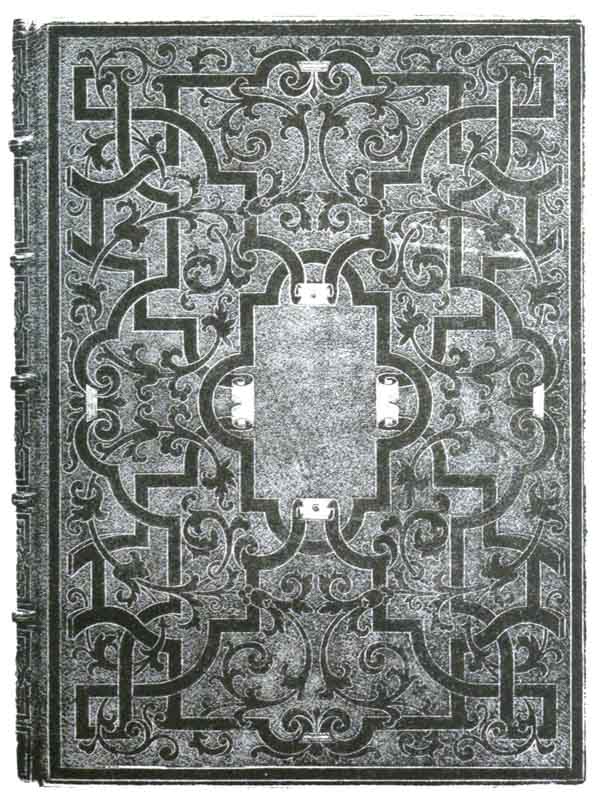

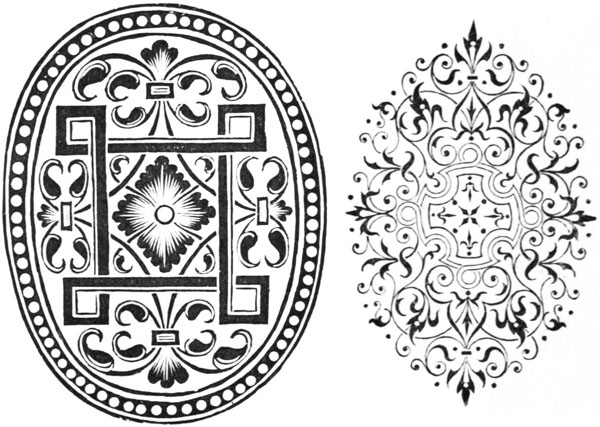

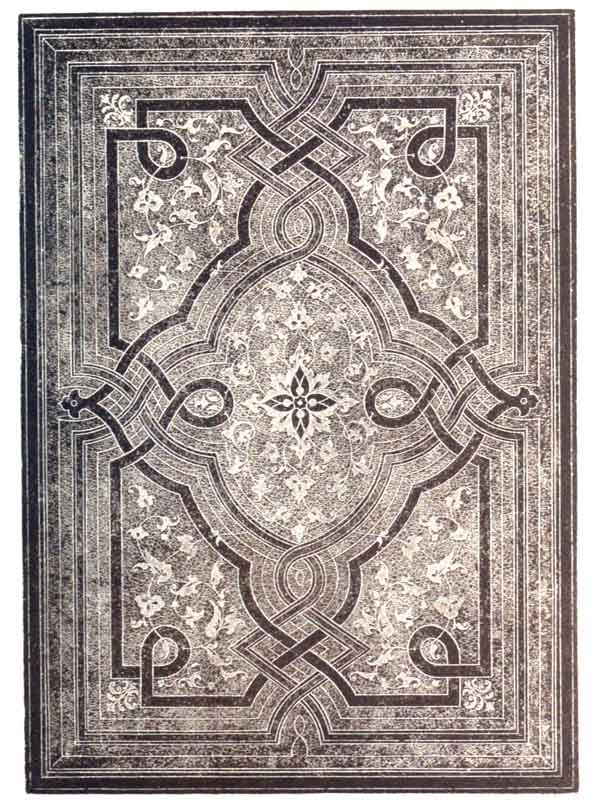

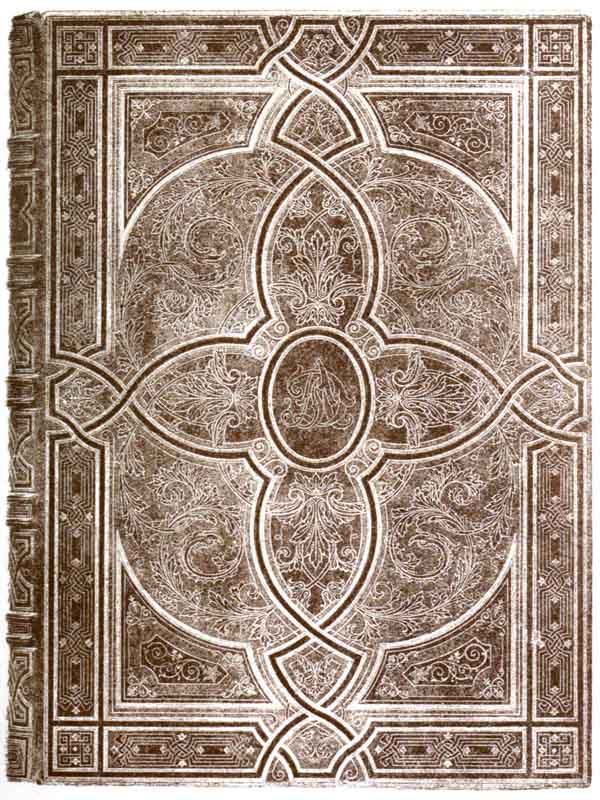

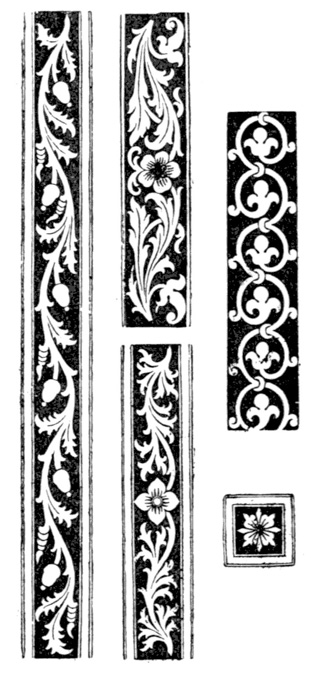

patterns, had their books bound in that style. The annexed

woodcut will give a fair idea of a Venetian tool. During

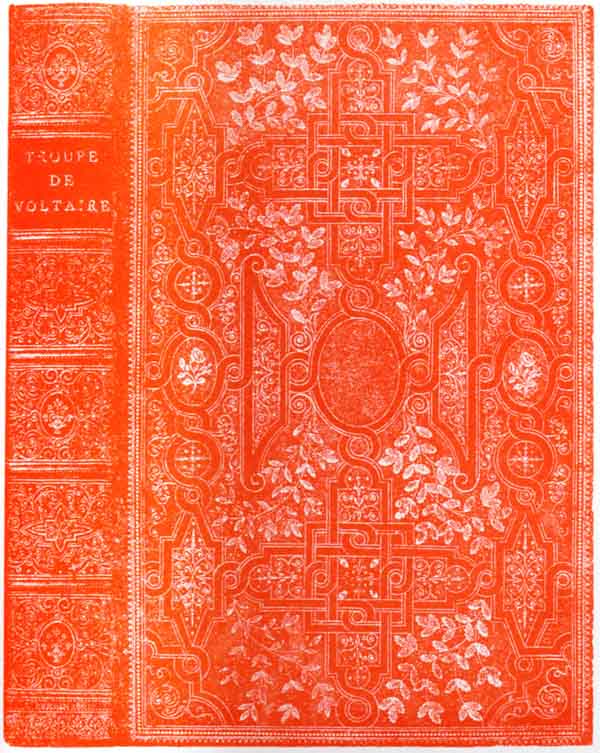

this period the French had bookbinding almost entirely in

their hands, and Mons. Grolier, who loved the art, had his

books bound under his own supervision in the most costly

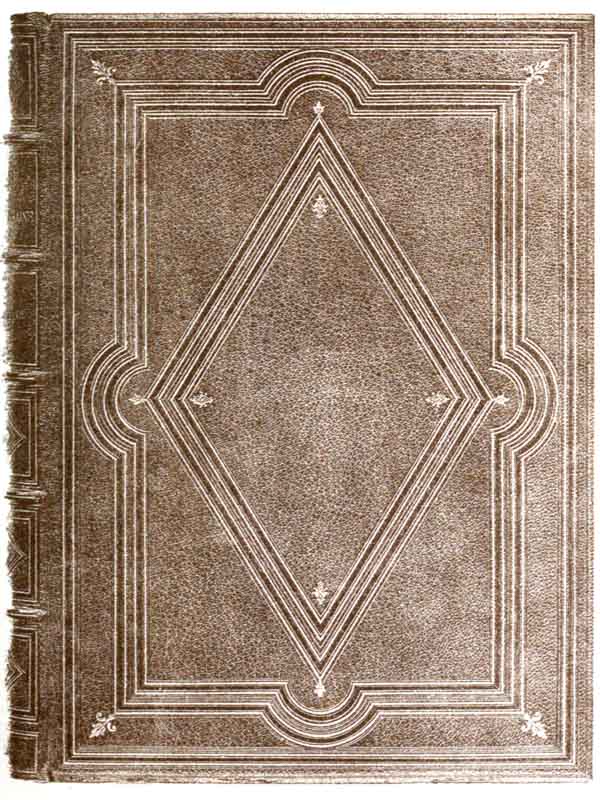

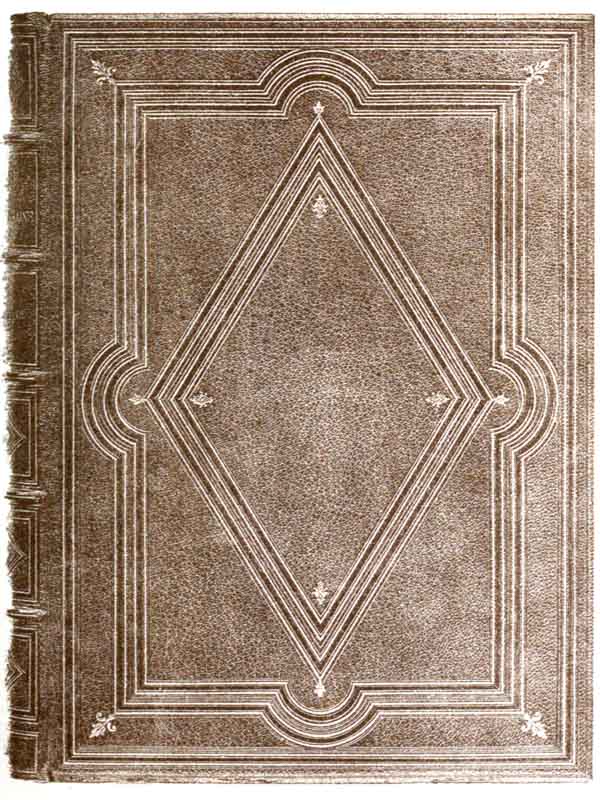

manner. His designs consisted of bold gold lines arranged

geometrically with great accuracy, crossing one another and

intermixed with small leaves or sprays. These were in

outlines shaded or filled up with closely worked cross lines.

Not, however, satisfied with these simple traceries, he embellished

them still more by staining or painting them

black, green, red, and even with silver, so that they formed

bands interlacing each other in a most graceful manner.

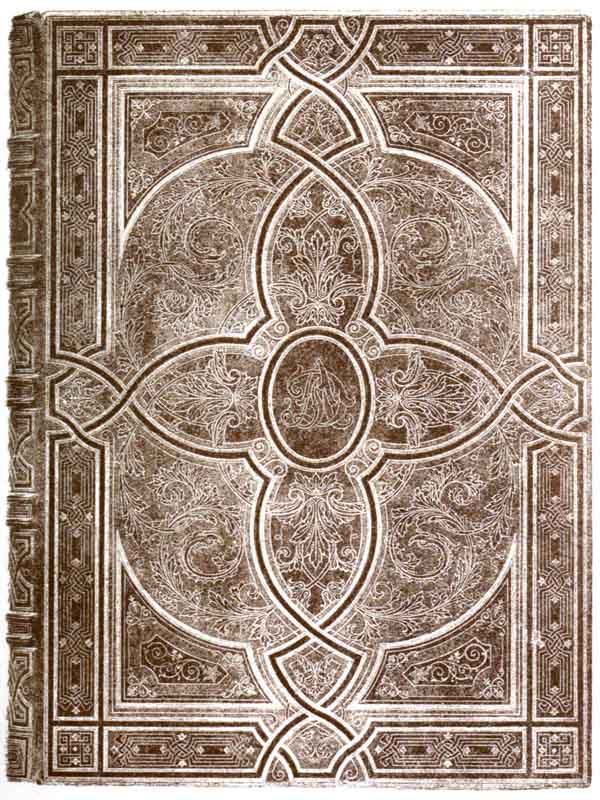

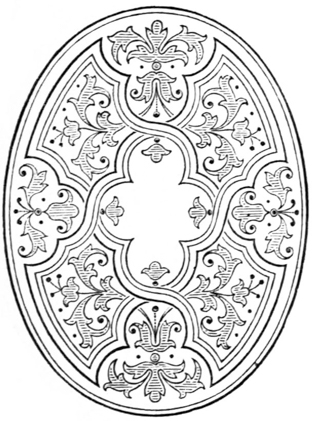

Opposite is a centre block of Grolier. It will be seen how

these lines entwine, and how the small tools are shaded

with lines. If the reader has had the good fortune to see

one of these specimens, has he not wondered at the taste

displayed? To the French must certainly be given the

honour of bringing the art to such a perfection. Francis I.

and the succeeding monarchs, with the French nobility,

placed the art on such a high eminence, that even now we

are compelled to look to these great masterpieces as models

of style. Not only was the exterior elaborate in ornament,

but the edges were gilded and tooled; and even painted.

We must wonder at the excellence of the materials and the

careful workmanship which has preserved the bindings,

even to the colour of the leather, in perfect condition to

the present day.

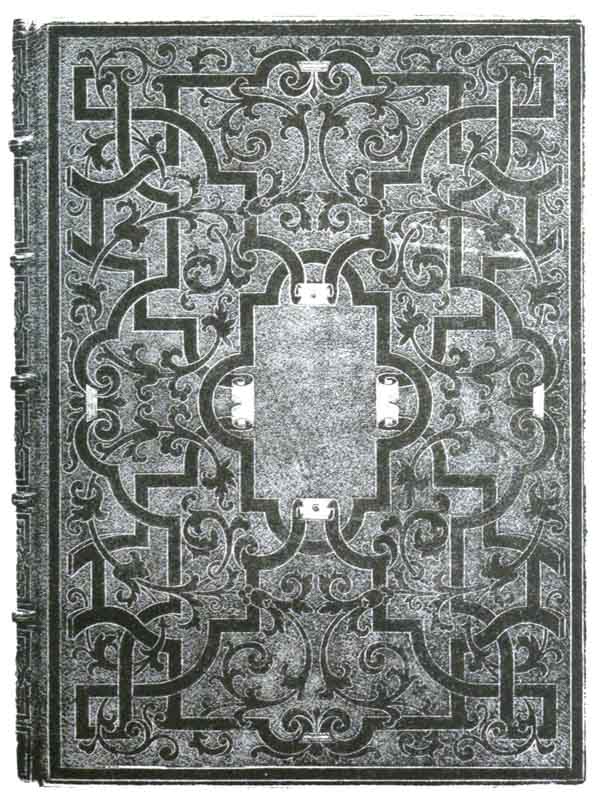

Grolier.

There is little doubt that the first examples of the style

now known as “Grolier” were produced in Venice, under

the eye of Grolier himself, and according to his own

designs; and that workmen in France, soon rivalled and

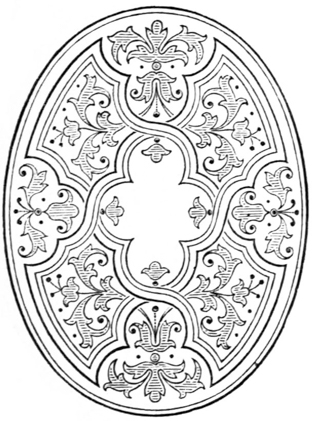

excelled the early attempts. The work of Maioli may be

distinctly traced by the bold simplicity and purity of his

designs; and more especially by the broader gold lines

which margin the coloured bands of geometric and

arabesque ornamentation.

All books, it must be understood, were not bound in so

costly a manner, for we find pigskin, vellum and calf in

use. The latter was especially preferred on account of its

peculiar softness, smooth surface, and great aptitude for

receiving impressions of dumb or blind tooling. It was

only towards the latter part of the sixteenth century that

the English binders began to employ delicate or fine

tooling.

During the seventeenth century the names of Du Sueil

and Le Gascon were known for the delicacy and extreme

minuteness of their finishing. Not disdaining the bindings

of the Italian school, they took from them new ideas; for

whilst the Grolier bindings were bold, the Du Sueil and

Le Gascon more resembled fine lace work of intricate

design, with harmonizing flowers and other objects, from

which we may obtain a great variety of artistic character.

During this period embroidered velvet was much in use.

Then a change took place and a style was adopted which

by some people would be preferred to the gorgeous bindings

of the sixteenth century. The sides were finished

quite plainly with only a line round the edge of the boards

(and in some instances not even that) with a coat of arms

or some badge in the centre.

Towards the end of the seventeenth century bookbinding

began to improve, particularly with regard to forwarding.

The joints were true and square, and the back was made to

open more freely. In the eighteenth century the names of

Derome, Roger Payne, and others are prominent as masters

of the craft, and the Harleian style was introduced.

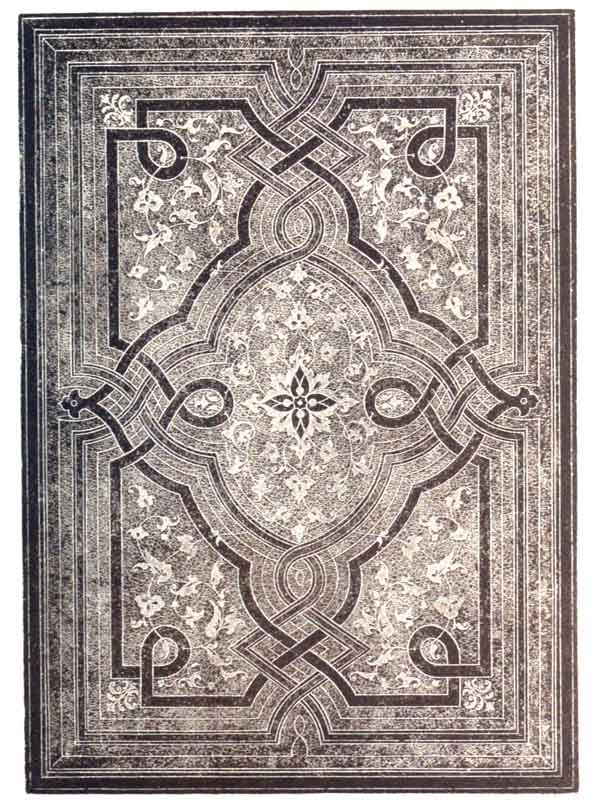

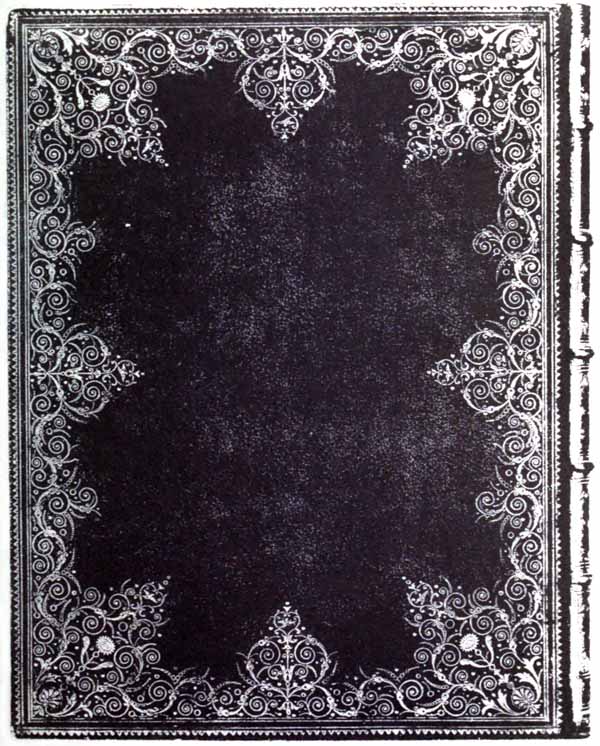

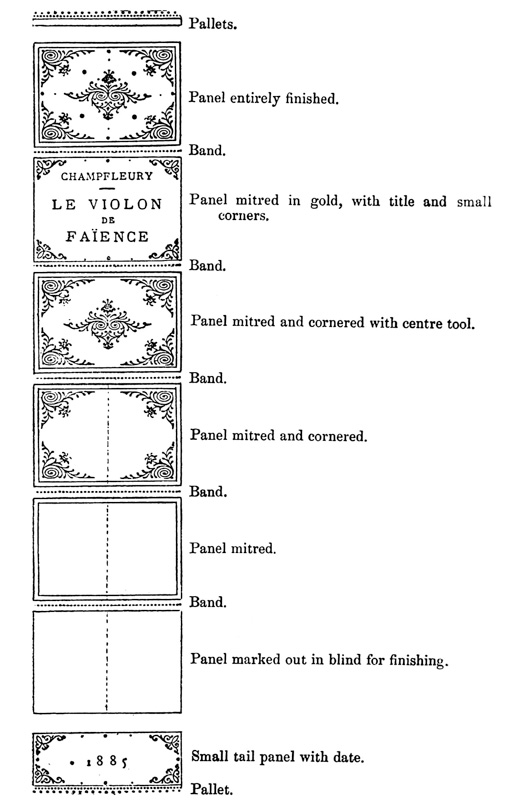

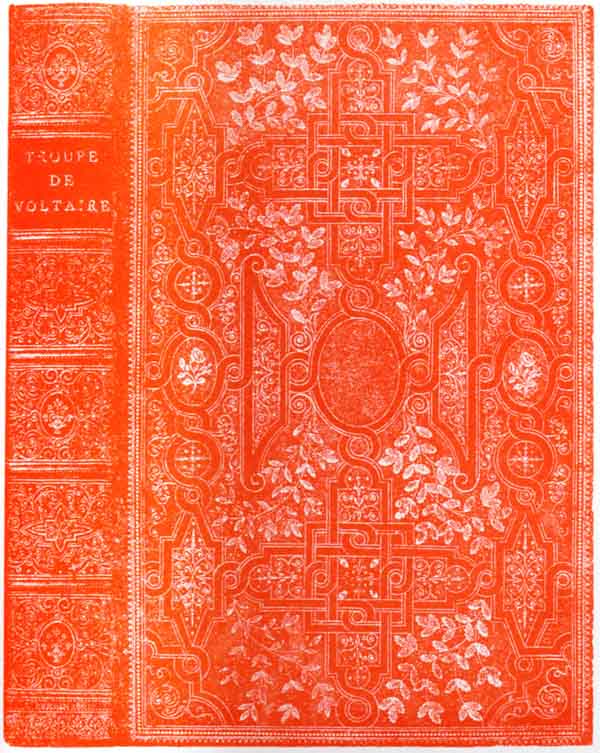

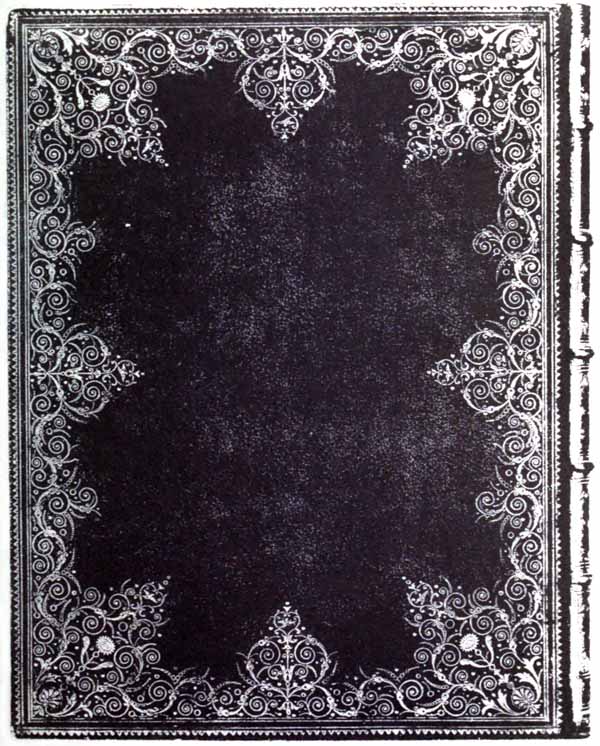

The plate facing may be fairly estimated as a good

specimen of Derome. Notice the extreme simplicity and

yet the symmetry of the design; its characteristic feature

being the boldness of the corners and the gradual diminishing

of the scroll work as it nears the centre of the

panel. Morocco and calf were the leathers used for this

binding.

GASCON.

8vo

T. Way, Photo-lith.

Hand coloured calf was at this period at its height, and

the Cambridge calf may be named as a pattern of one of

the various styles, and one that is approved of by many at

the present day—the calf was sprinkled all over, save a

square panel left uncoloured in the centre of the boards.

Harleian.

The Harleian style took its name from Harley, Earl of

Oxford. It was red morocco with a broad tooled border

and centre panels. We have the names of various masters

who pushed the art forward to very great excellence during

this century. Baumgarten and Benedict, two Germans of

considerable note in London; Mackinly, from whose house

also fine work was sent out, and by whom good workmen

were educated whose specimens almost equal the work of

their master. There were two other Germans, Kalthoeber

and Staggemeier, each having his own peculiar style.

Kalthoeber is credited with having first introduced painting

on the edges. This I must dispute, as it was done in the

sixteenth century. To him, however, must certainly be

given the credit of having discovered the secret, if ever

lost, and renewing it on his best work. We must now

pass on to Roger Payne, that unfortunate and erring man

but clever workman, who lived during the latter part of

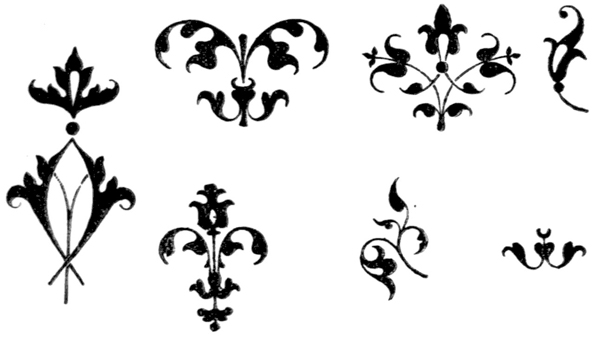

the eighteenth century. His taste may be seen from the

woodcut. He generally used small tools, and by combining

them formed a variety of beautiful designs. He cut most

of these tools himself, either because he could not find a

tool cutter of sufficient skill, or that he found it difficult to

pay the cost. We are told by anecdote, that he drank

much and lived recklessly; but notwithstanding all his

irregular habits, his name ought to be respected for the

work he executed. His backs were firm, and his forwarding

excellent; and he introduced a class of finishing that was

always in accordance with the character or subject of the

book. His only fault was the peculiar coloured paper with

which he made his end papers.

Roger Payne.

Coloured or fancy calf has now taken the place of the

hand-coloured. Coloured cloth has come so much into use,

that this branch of the trade alone monopolizes nearly

three-fourths of the workmen and females employed in

bookbinding. Many other substitutes for leather have

been introduced, and a number of imitations of morocco

and calf are in the market; this, with the use of machinery,

has made so great a revolution in the trade, that it is now

divided into two distinct branches—cloth work and extra

work.

I have endeavoured in the foregoing remarks to raise

the emulation of my fellow craftsmen by naming the most

famous artists of past days; men whose works are most

worthy of study and imitation. I have refrained from

any notice or criticism of the work of my contemporaries;

but I may venture to assure the lover of good bookbinding

that as good and sound work, and as careful finish, may be

obtained in a first-rate house in London as in any city in

the world.

In the succeeding chapters, I will endeavour in as plain

and simple a way as I can to give instructions to the

unskilled workman how to bind a book.

PART I.

FORWARDING.

|3|

THE ART OF BOOKBINDING.

CHAPTER I.

FOLDING.

We commence

with folding. It is generally the first thing

the binder has to do with a book. The sheets are either

supplied by the publisher or printer (mostly the printer);

should the amateur wish to have his books in sheets,

he may generally get them by asking his bookseller for

them. It is necessary that they be carefully folded, for

unless they are perfectly even, it is impossible that the

margins (the blank space round the print) can be uniform

when the book is cut. Where the margin is small, as in

very small prayer books, a very great risk of cutting into

the print is incurred; besides, it is rather annoying to see

a book which has the folio or paging on one leaf nearly at

the top, and on the next, the print touching the bottom;

to remedy such an evil, the printer having done his

duty by placing his margins quite true, it remains with the

binder to perfect and bring the sheet into proper form by

folding. The best bound book may be spoilt by having

the sheets badly folded, and the binder is perfectly justified

in rejecting any sheets that may be badly printed, that is,

not in register. |4|

The sheets are laid upon a table with the signatures

(the letters or numbers that are at the foot of the first

page of each sheet when folded) facing downwards on the

left hand side. A folding-stick is held in the right hand, and

the sheet is brought over from right to left, the folios being

carefully placed together; if the paper is held up to the

light, and is not too thick, it can be easily seen through.

Holding the two together and laying them on the table the

folder is drawn across the sheet, creasing the centre; then,

holding the sheet down with the folder on the line to be

creased, the top part is brought over and downwards till

the folios or the bottom of the letterpress or print is again

even. The folder is then drawn across, and so by bringing

each folio together the sheet is completed. The process is

extremely simple. The octavo sheet is generally folded

into 4 folds, thus giving 8 leaves or 16 pages; a quarto,

into 2, giving 4 leaves or 8 pages, and the sheets properly

folded, will have their signatures outside at the foot of the

first page. If the signature is not on the outside, one

may be certain that the sheet has been wrongly folded.

I say generally; at one time the water or wire mark on

the paper and the number of folds gave the size of the

book.

There are numerous other sizes, but it is not necessary

to give them all; the process of folding is in nearly all

cases the same; here are however, a few of the sizes given

in inches.

| Foolscap 8vo. |

6 5 ⁄ 8 |

× |

4 1 ⁄ 8 |

| Demy 12mo. |

7 3 ⁄ 8 |

× |

4 3 ⁄ 8 |

| Crown 8vo. |

7 1 ⁄ 2 |

× |

5 |

| Post 8vo. |

8 |

× |

5 |

| Demy 8vo. |

9 |

× |

5 1 ⁄ 2 |

| Medium 8vo. |

9 5 ⁄ 8 |

× |

5 3 ⁄ 4 |

| Small Royal 8vo. |

10 |

× |

6 1 ⁄ 4 |

| Large Royal 8vo. |

10 1 ⁄ 2 |

× |

6 3 ⁄ 4 |

| Imperial 8vo. |

11 |

× |

7 1 ⁄ 2 |

| Demy 4to. |

11 |

× |

9 |

| Medium 4to. |

11 3 ⁄ 4 |

× |

9 5 ⁄ 8 |

| Royal 4to. |

12 1 ⁄ 2 |

× |

10 |

| Imperial 4to. |

15 |

× |

11 |

| Crown Folio. |

15 |

× |

10 |

| Demy Folio |

18 |

× |

11 |

As a final caution, the first and last sheets must be carefully

examined; very often the sheet has to be cut up or

divided, and the leaf or leaves placed in various positions

in the book.

It is also advisable to cut the head of the sheets, using

the folding-stick, cutting just beyond the back or middle

fold; this prevents the sheet running into a side crease

when pressing or rolling. Should such a crease occur the

leaf or sheet must be damped by placing it between wet

paper and subjecting it to pressure; no other method is

likely to erase the break.

Refolding.—With regard to books that have been issued

in numbers, they must be pulled to pieces or divided. The

parts being arranged in consecutive order, so that not so

much difficulty will be felt in collating the sheets, the

outside wrapper is torn away, and each sheet pulled singly

from its neighbour, care being taken to see if any thread

used in sewing is in the centre of the sheet at the back;

if so, it must be cut with a knife or it will tear the paper.

As the sheets are pulled they must be laid on the left hand

side, each sheet being placed face downwards; should they

be placed face upwards the first sheet will be the last and the

whole will require rearranging. All advertisements may be

placed away from the sheets into a pile; these will be found

very handy for lining boards, pasting on, or as waste.

The title and contents will generally be found in the last

part; place them in their proper places. The sheets must

now be refolded, if improperly folded in the first instance. |6|

Turn the whole pile (or book now) over, and again go

through each sheet; alter by refolding any sheet that may

require it. Very often the sheets are already cut, and in this

case the section must be dissected and each leaf refolded

and reinserted in proper sequence, and placed carefully

head-line to head-line. Great care must be exercised, as

the previous creasings render the paper liable to be torn

in the process.

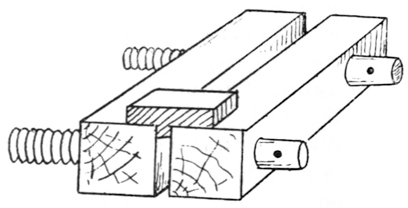

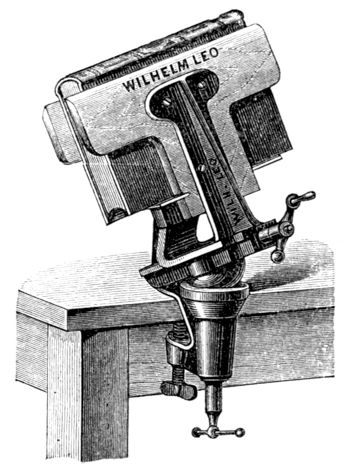

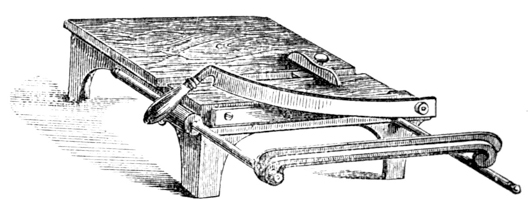

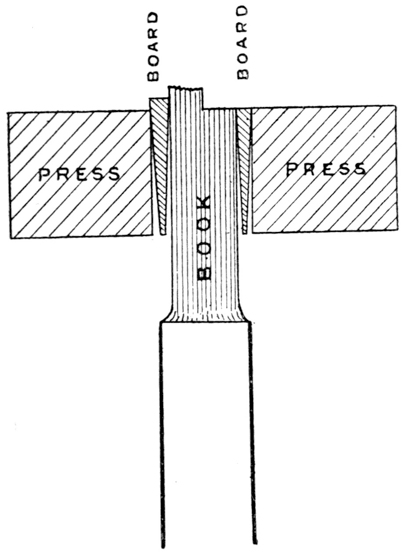

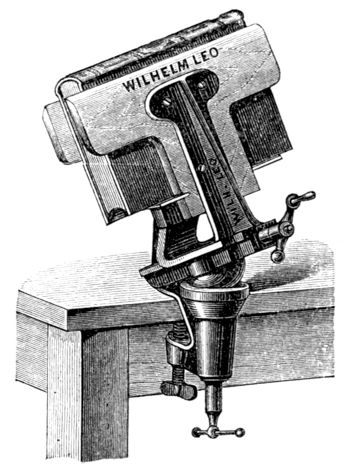

Knocking-down Iron screwed into Press.

Books that have been bound and cut would be rendered

often worse by refolding, and as a general rule they are left

alone. Bound books are pulled to pieces in the same

manner, always taking care that the thread is cut or

loose before tearing the sheet away; should trouble arise

through the glue, etc., not coming away easily, the back

may be damped with a sponge lightly charged with water,

or perhaps a better method is to place the book or books

in a press, screw up tightly, and soak the backs with thin

paste, leaving them soaking for an hour or two; they will

want repasting two or three times during the period; the

whole of the paper, glue, and leather can then be easily

scraped away with a blunt knife; a handful of shavings

rubbed over the back will make it quite clean, and no difficulty

will be met with if the sections are taken apart while

damp. The sections must, as pulled, be placed evenly one on |7|

the other, as the paper at back retains sufficient glue to cause

them to stick together if laid across one another; the whole

must then be left to dry. When dry the groove should be

knocked down on a flat surface, and for this the knocking-down

iron screwed up in the lying press is perhaps the

best thing to use. The groove is the projecting part of the

book close to the back, caused by the backing, and is the

groove for the back edge of the mill-board to work in by

a hinge; this hinge is technically called the “joint.”

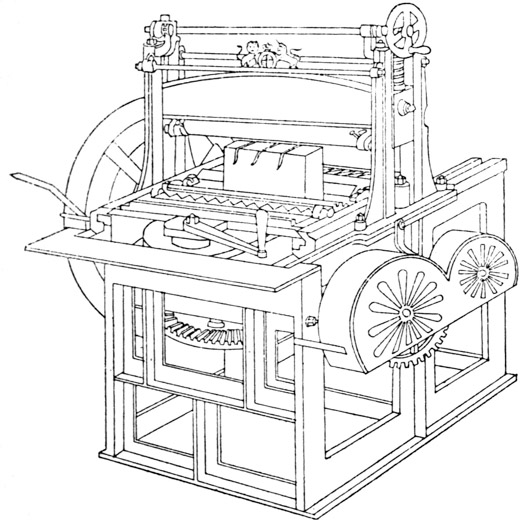

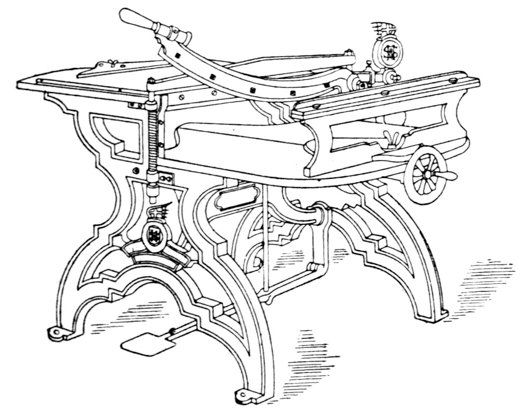

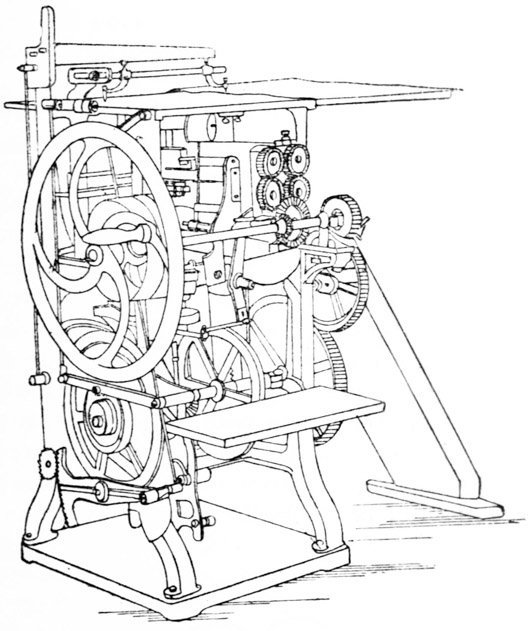

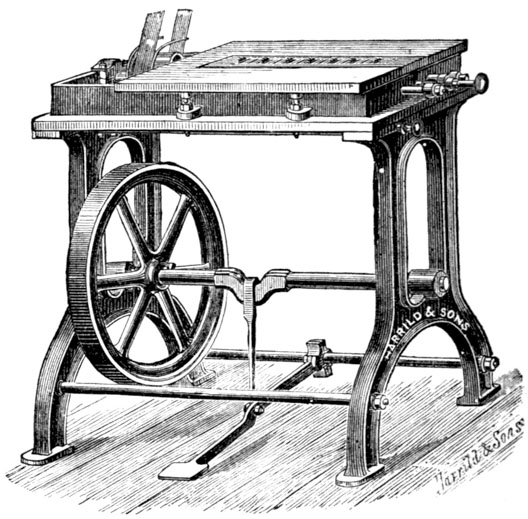

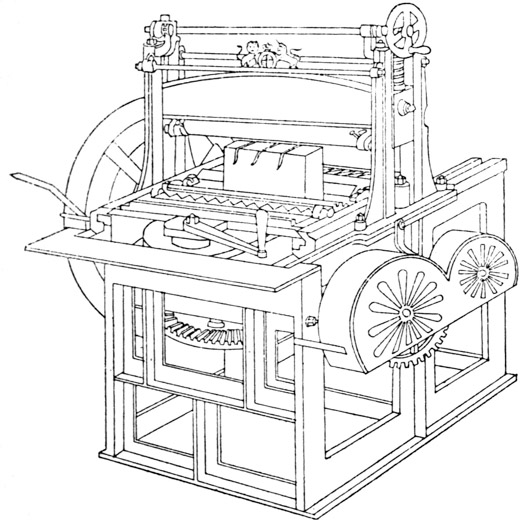

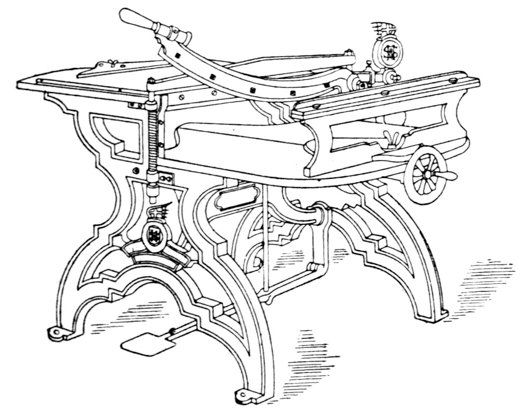

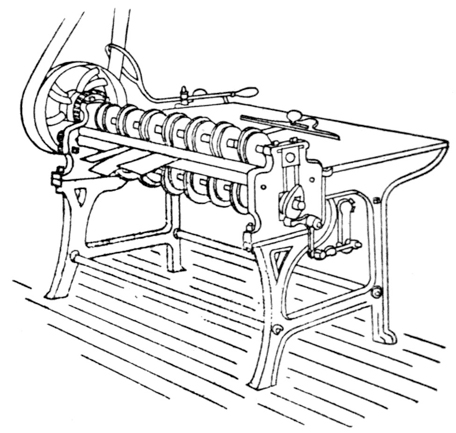

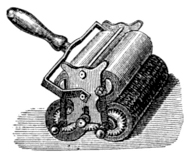

Martini’s Folding Machine.

Machines.—There are many folding machines made by

the various machinists; the working of them, however, is

in nearly all cases identical. The machine is generally |8|

fed by a girl, who places the sheet to points, the arm

lifting up at given periods to allow placing the sheet.

Another arm carrying a long thin blade descends, taking

the sheet through a slot in the table, where it is passed

between rollers; another set of rollers at right angles

creases it again. The rollers are arranged for two, three, or

more creasings or folds. The sheets are delivered at the

side into a box, from which they are taken from time to

time. The cut is one of Martini’s, and is probably the

most advanced.

Gathering.—A gathering machine has been patented which

is of a simple but ingenious contrivance for the quick

gathering of sheets. The usual way to gather, is by laying

piles of sheets upon a long table, and for the gatherer to

take from each pile a sheet in succession. By the new

method a round table is made to revolve by machinery,

and upon it are placed the piles of sheets. As the table

revolves the gatherer takes a sheet from each pile as it

passes him. It will at once be seen that not only is space

saved, but that a number of gatherers may be placed at the

table; and that there is no possibility of the gatherers

shirking their work, as the machine is made to register

the revolutions. By comparing the number of sheets with

the revolutions of the table, the amount of work done can

be checked.

CHAPTER II.

BEATING

AND

ROLLING.

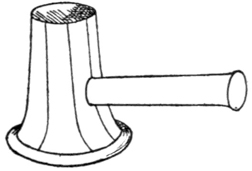

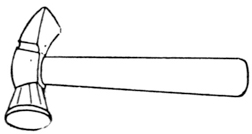

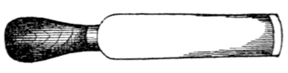

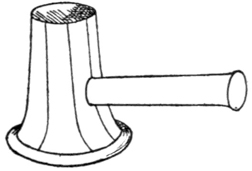

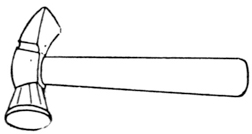

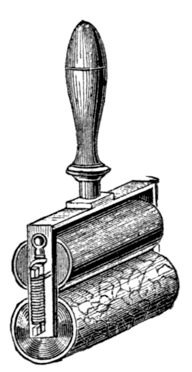

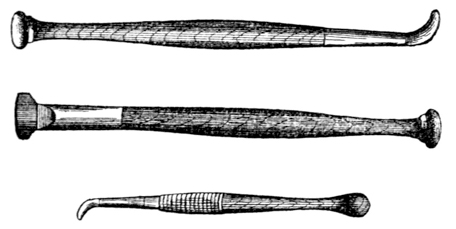

Beating Hammer.

The object of beating or rolling is to make the book as

solid as possible. For beating, a stone or iron slab, used

as a bed, and a heavy hammer, are necessary. The stone

or iron must be perfectly smooth, and should be bedded

with great solidity. I have in use an iron bed about two feet

square, fitted into a strongly-made box, filled with sand,

with a wooden cover to the iron when not in use. The

hammer should be somewhat bell-shaped,

and weigh about ten

pounds, with a short handle, made

to fit the hand. The face of the

hammer and stone (it is called a

beating-stone whether it be stone

or iron), must be kept perfectly

clean, and it is advisable always to have a piece of paper at

the top and bottom of the sections when beating, or the

repeated concussion will glaze them.

The book should be divided into lots or sections of about

half an inch thick, that will be about fifteen to twenty sheets,

according to the thickness of paper. A section is now to

be held on the stone between the fingers and thumb

of the left hand; then the hammer, grasped firmly in

the right hand, is raised, and brought down with rather

more than its own weight on the sheets, which must

be continually moved round, turned over and changed

about, in order that they may be equally beaten all over. |10|

By passing the section between the finger and thumb, it

can be felt at once, if it has been beaten properly and

evenly. Great care must be taken that in each blow of

the hammer it shall have the face fairly on the body of

the section, for if the hammer is so used that the greatest

portion of the weight should fall outside the edge of the

sheets the concussion will break away the paper as if cut

with a knife. It is perhaps better for a beginner to practise

on some waste paper before attempting to beat a book; and

he should always rest when the wrist becomes tired. When

each section has been beaten, supposing a book has been

divided into four sections, the whole four should be beaten

again, but together.

I do not profess a preference to beating over rolling because

I have placed it first. The rolling machine is one of

the greatest improvements in the trade, but all books should

not be rolled, and a bookbinder, I mean a practical bookbinder,

not one who has been nearly the whole of his lifetime

upon a cutting machine, or at a blocking press, and

who calls himself one, but a competent bookbinder, should

know how and when to use the beating hammer and when

the rolling machine.

There are some books, old ones for instance, that should

on no account be rolled. The clumsy presses used in

printing at an early date gave such an amount of pressure

on the type that the paper round their margins has sometimes

two or three times the thickness of the printed

portion. At the present time each sheet after having been

printed is pressed, and thus the leaf is made flat or nearly

so, and for such work the rolling machine is certainly better

than the hammer.

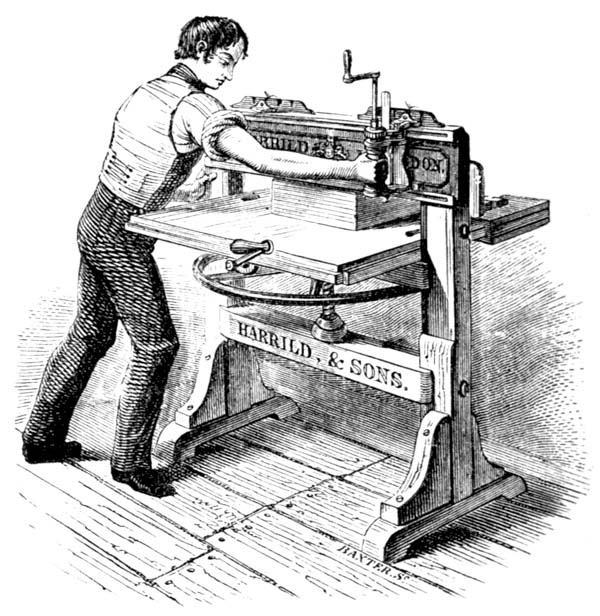

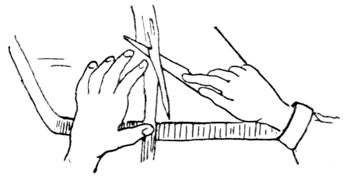

To roll a book, it is divided into sections as in beating,

only not so many sheets are taken—from six upwards,

according to the quality of the work to be executed. The

sheets are then placed between tins, and the whole passed |11|

between the rollers, which are regulated by a screw, according

to the thickness of sections and power required.

The workman, technically called “Roller,” has to be very

careful in passing his books through, that his hand be

not drawn in as well, for accidents have from time to

time occurred through the inattention of the Roller

himself, or of the individual who has the pleasure of

applying his strength to turning the handle.

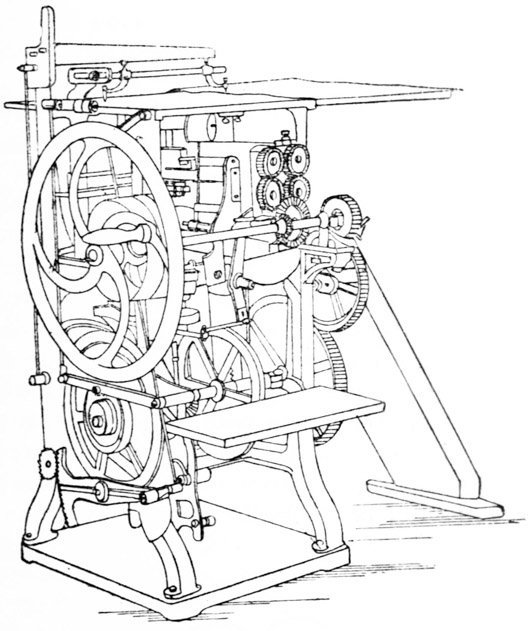

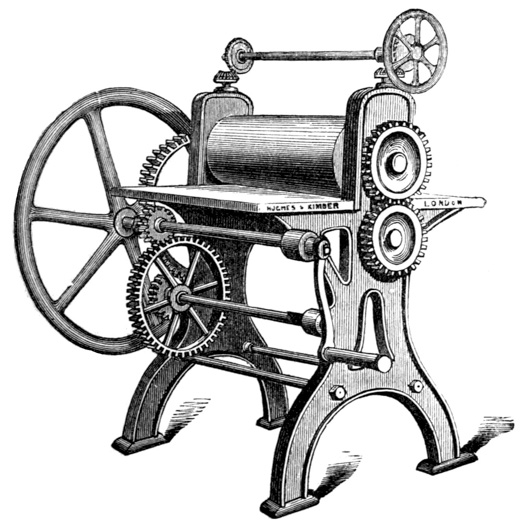

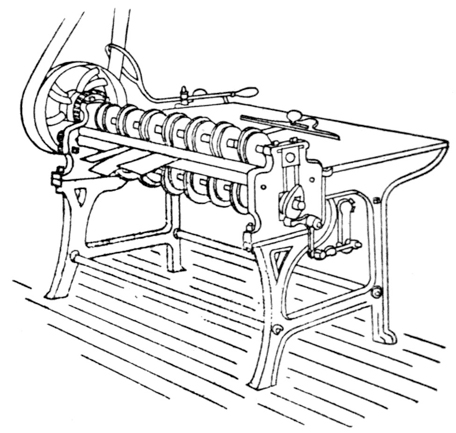

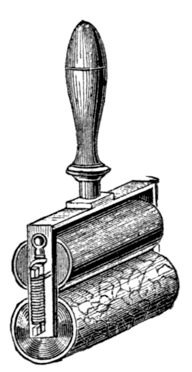

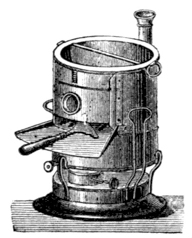

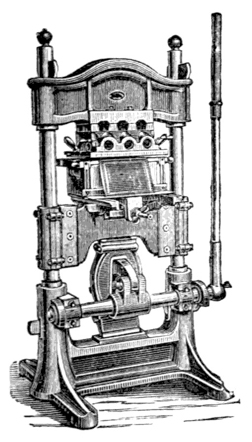

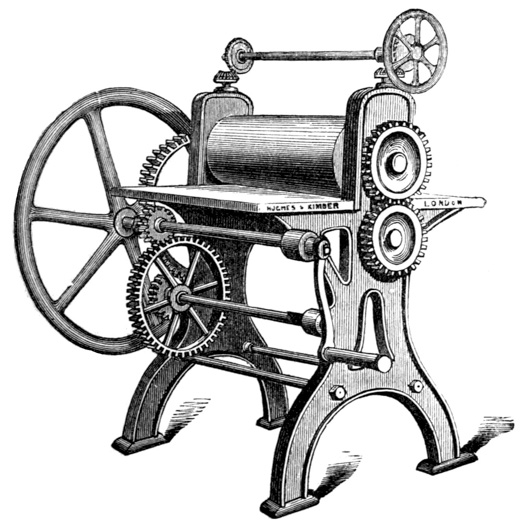

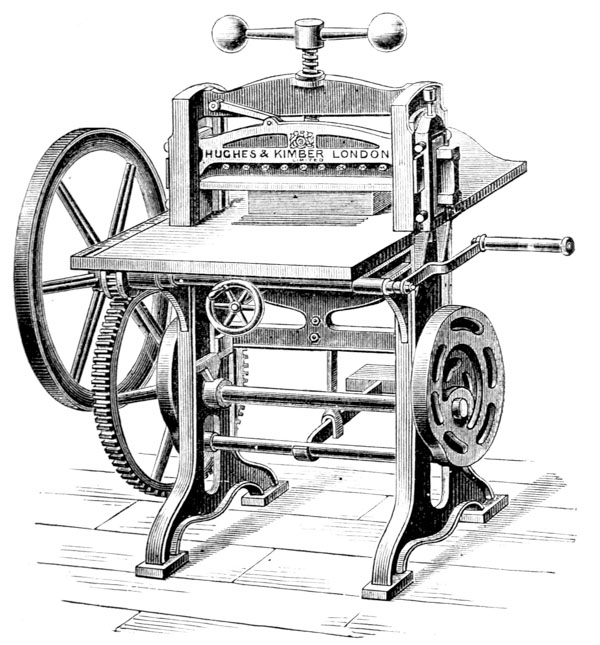

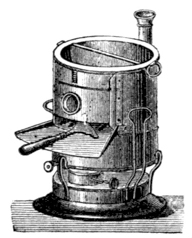

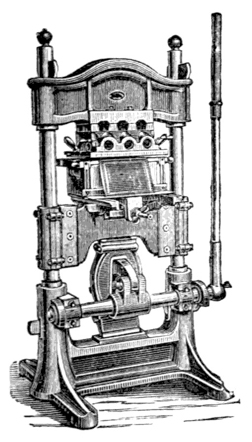

Rolling Machine.

I never pass or hear a rolling machine revolving very

rapidly without having vividly brought to my mind a very

serious accident that happened to my father. He was

feeling for a flaw on one of the rollers, and whilst his hands

|12|

were at the edge of the rollers the man turned the handle,

drawing the whole hand between the heavy cylinders. The

accident cost him many months in the hospital, and he

never regained complete use of his right hand.

Great care must be used not to pass too many sheets

through the machine at one time; the same applies to the

regulating screw. The amount of damage that can be done

to the paper by too heavy a pressure is astonishing, as

the paper becomes quite brittle, and may perhaps even be

cut as with a knife.

Another caution respecting new work. Recently printed

books, if submitted to heavy pressure, either by the beating

hammer or machine, are very likely to “set off,” that is,

the ink from one side of the page will be imprinted to its

opposite neighbour; indeed, under very heavy pressure,

some ink, perhaps many years old, will “set off;” this is

due in a great measure to the ink not being properly

prepared.

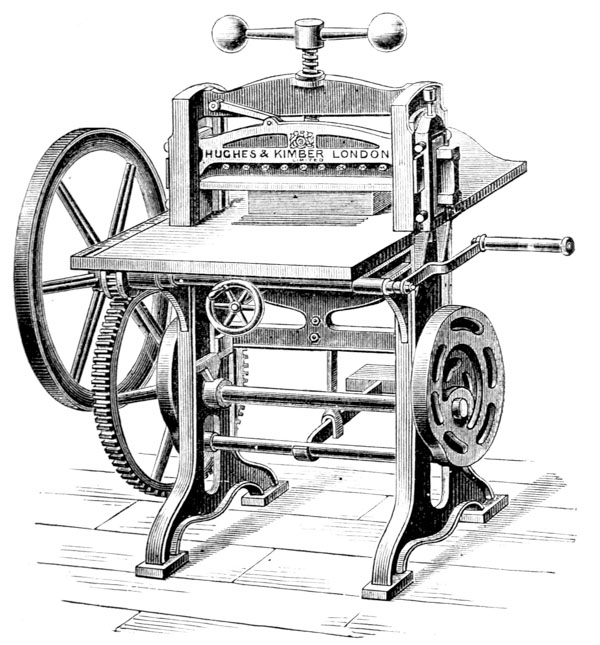

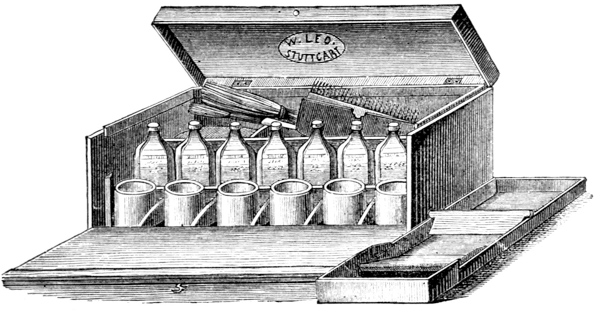

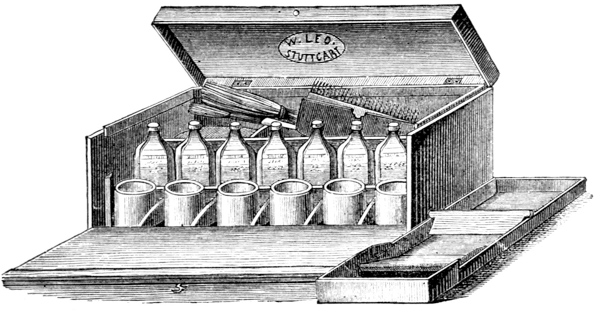

Machines.—Of the many rolling machines in the market

the principle is in all the same. A powerful frame, carrying

two heavy rollers or cylinders, which are set in motion,

revolving in the same direction, by means of steam or by

hand. In many, extra power is supplied by the use of extra

cog-wheels; the power is, however, gained at an expense

of speed. The pressure is regulated by screws at the top.

CHAPTER III.

COLLATING.

To collate, is to ensure that each sheet or leaf is in its

proper sequence. Putting the sheets together and placing

plates or maps requires great attention. The sheets must

run in proper order by the signatures: letters are mostly

used, but numbers are sometimes substituted. When letters

are used, the alphabet is repeated as often as necessary,

doubling the letter as often as a new alphabet is used, as

B, C, with the first

alphabet,1

and AA, BB, CC or Aa, Bb,

Cc, with the second repetition, and three letters with the

third, generally leaving out J, V, W. Plates must be

trimmed or cut to the proper size before being placed in

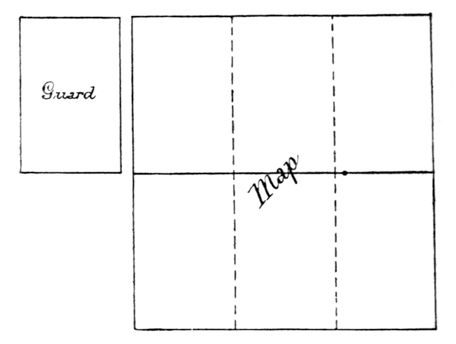

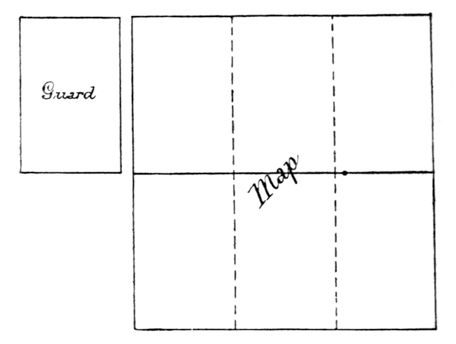

the book, and maps that are to be folded must be put on

guards. By mounting a map on a guard the size of the

page, it may be kept open on the table beside the book,

which may be opened at any part without concealing the

map: by this method the map will remain convenient for

constant reference. This is technically called “throwing

out” a map.

To collate a book, it is to be held in the right hand, at

the right top corner, then, with a turn of the wrist, the

back must be brought to the front. Fan the sections out,

then with the left hand the sheets must be brought back

to an angle, which will cause them when released to

spring forward, so that the letter on the right bottom |14|

corner of each sheet is seen, and then released, and the

next brought into view. When a work is completed in

more than one volume, the number of the volume is indicated

at the left hand bottom corner of each sheet. I

need hardly mention that the title should come first, then

the dedication (if one), preface, contents, then the text,

and finally the index. The number on the pages will,

however, always direct the binder as to the placing of the

sheets. The book should always be beaten or rolled before

placing plates or maps, especially coloured ones.

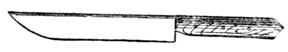

Presuming that we have a book with half a dozen plates,

the first thing after ascertaining that the letter-press is

perfect, is to see that all the plates are there, by looking

to the “List of Plates,” printed generally after the contents.

The plates should then be squared or cut truly,

using a sharp knife and straight edge. When the plates

are printed on paper larger than the book, they must be

cut down to the proper size, leaving a somewhat less

margin at the back than there will be at the foredge when

the book is cut. Some plates have to face to the left,

|15|

some to the right, the frontispiece for instance; but as a

general rule, plates should be placed on the right hand, so

that on opening the book they all face upwards. When

plates consist of subjects that are at a right angle with

the text, such as views and landscapes, the inscription

should always be placed to the right hand, whether the

plate face to the right or to the left page. If the plates

are on thick paper they should be guarded, either by

adding a piece of paper of the same thickness or by cutting

a piece from the plate and then joining the two again

together with a piece of linen, so that the plate moves on

the linen hinge: the space between the guard and plate

should be more than equal to the thickness of the paper.

If the plate is almost a cardboard, it is better and stronger

if linen be placed both back and front. Should the book

consist of plates only, sections may be made by placing two

plates and two guards together, and sewing through the

centre between the guards, leaving of course a space between

the two guards, which will form the back.

With regard to maps that have to be mounted, it is

better to mount them on the finest linen, as it takes up

the least room in the thickness of the book. The linen

should be cut a little larger than the map itself, with a

further piece left, on which to mount the extra piece of

paper, so that the map may be thrown out as before

described. The map should first be trimmed at its back,

then pasted with rather thin paste; the linen should then be

laid carefully on, and gently rubbed down and turned over,

so that the map comes uppermost; the pasted guard should

then be placed a little away from the map, and the whole

well rubbed down, and finally laid out flat to dry. To do this

work, the paste must be clean, free from all lumps, and

used very evenly and not too thickly, or when dry every

mark of the brush will be visible. When the map is dry

it should be trimmed all round and folded to its proper |16|

size, viz.—a trifle smaller than the book will be when cut.

If it is left larger the folds will naturally be cut away, and

the only remedy will be a new map, which means a new

copy of the work. For all folded maps or plates a corresponding

thickness must be placed in the backs where

the maps go, or the foredge will be thicker than the back.

Pieces of paper called guards, are folded from

1 ⁄ 4

inch to 1 inch in width, according to the size of the book, and

placed in the back, and sewn through as a section. Great

care must be taken that these guards are not folded too

large, so as to overlap the folds of the map, if they do so,

the object of their being placed there to make the thickness

of the back and foredge equal will be defeated.

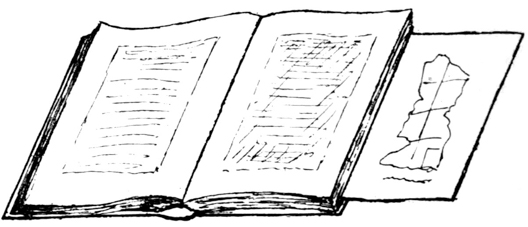

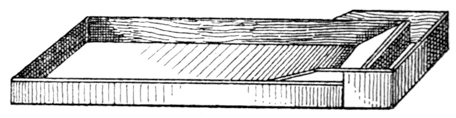

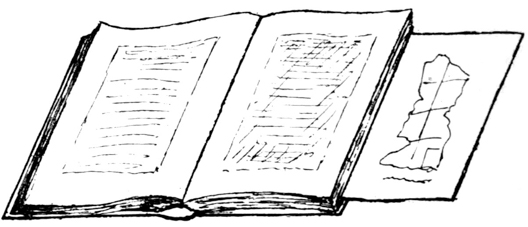

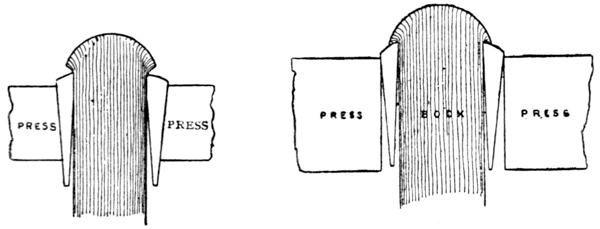

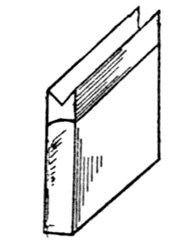

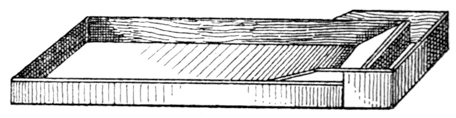

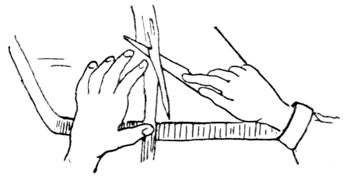

Shewing Book with Map thrown out.

In a great measure, the whole beauty of the inside work

rests in properly collating the book, in guarding maps,

and in placing the plates. When pasting in any single

leaves or plates, a piece of waste paper should always be

placed on the leaf or plate the required distance from the

edge to be pasted, so that the leaf is pasted straight. It

takes no longer to lay the plate down upon the edge of a

board with a paper on the plate, than it does to hold the

plate in the left hand, and apply the paste with the right

hand middle finger; by the former method a proper amount

of paste is deposited evenly on the plate and it is pasted

in a straight line; by the latter method, it is pasted in some |17|

places thickly, and in some places none at all. I have

often seen books with the plates fastened to the book

nearly half way up to its foredge, and thus spoilt, only

through the slovenly way of pasting. After having placed

the plates, the collater should go through them again when

dry, to see if they adhere properly, and break or fold them

over up to the pasting, with a folding stick, so that they

will lie flat when the book is open. I must again call

attention to coloured plates. They should be looked to

during the whole of binding, especially after pressing.

The amount of gum that is put on the surface, which is

very easily seen by the gloss, causes them to stick to the

letter-press: should they so stick, do not try to tear them

apart, but warm a polishing iron and pass it over the plate

and letter-press, placing a piece of paper between the iron

and the book to avoid dirt. The heat and moisture will

soften the gum, and the surfaces can then be very easily

separated. By rubbing a little powdered French chalk over

the coloured plates before sticking them in, these ill effects

will be avoided.

It sometimes happens that the whole of a book is composed

of single leaves, as the “Art Journal.” Such a book

should be collated properly, and the plates placed to their

respective places, squared and broken over, by placing a

straight edge or runner about half an inch from its back

edge, and running a folder under the plate, thus lifting it to

the edge of the runner. The whole book should then be

pressed for a few hours, taken out, and the back glued up;

the back having been previously roughed with the side

edge of the saw. To glue such a back, the book is placed

in the lying press between boards, with the back projecting

about an eighth of an inch, the saw is then drawn over

it, with its side edge, so that the paper is as it were rasped.

The back is then sawn in properly, as explained in the

next chapter, and the whole back is glued. When dry, the |18|

book is separated into divisions or sections of four, six, or

eight leaves, according to the thickness of the paper, and

each section is then overcast or over sewn along its whole

length, the thread being fastened at the head and tail (or

top and bottom); thus each section is made independent of

its neighbour. The sections should then be gently struck

along the back edge with a hammer against a knocking-down

iron, so as to imbed the thread into the paper, or the

back will be too thick. The thread should not be struck so

hard as to cut the paper, or break the thread, but very

gently. Two or three sections may be taken at a time.

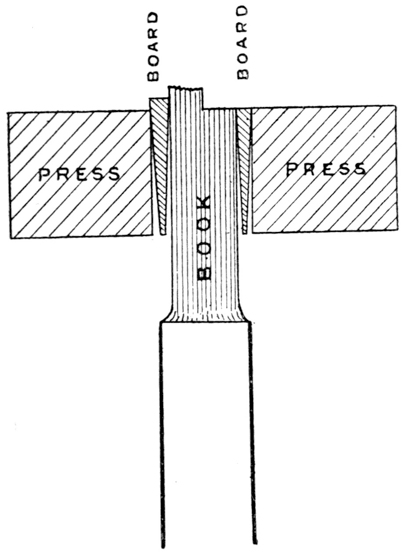

After having placed the plates, the book should be put

into the press (standing or otherwise) for a few hours. A

standing press is used in all good bookbinding shops.

The Paris houses have a curious way of pressing their

books. The books are placed in the standing press; the

top and bottom boards are very thick, having a groove cut

in them in which a strong thin rope is placed. The press

is screwed down tightly, when, after some few minutes has

elapsed, the cord or rope is drawn together and fastened.

The pressure of the screw is released, the whole taken out

en bloc, and allowed to remain for some hours, during which

time a number of other batches are passed through the

same press.

When taken out of the press the book is ready for

“marking up” if for flexible sewing, or for being sawn in

if for ordinary work.

Interleaving.—It is sometimes required to place a piece

of writing paper between each leaf of letter-press, either for

notes or for a translation: in such a case, the book must be

properly beaten or rolled, and each leaf cut up with a hand-knife,

both head and foredge; the writing paper having

been chosen, must be folded to the size of the book and

pressed. A single leaf of writing paper is now to be

fastened in the centre of each section, and a folded leaf |19|

placed to every folded letter-press leaf, by inserting the one

within the other, a folded writing paper being left outside

every other section, and all being put level with the head;

the whole book should then be well pressed.

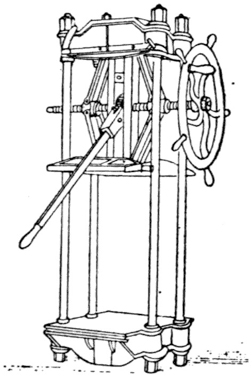

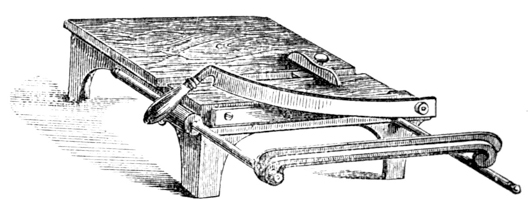

Boomer Press.

If by any chance there should be one sheet in duplicate

and another missing, by returning the one to the publisher

of the book the missing sheet is generally replaced; this,

of course, has reference only to books of a recent date.

There is a new press of American

invention that has come under my

notice. It will be seen that it acts

on an entirely new principle, having

two horizontal screws instead of one

perpendicular. The power is first

applied by hand and finally by a

lever and ratchet-wheel in the centre.

A pressure guage is affixed to

each press, so that the actual power

exerted may be ascertained as the

operation proceeds. The press can

be had from Messrs. Ladd and Co.,

116, Queen Victoria Street, E.C.;

and they claim that it gives a pressure equal to the hydraulic

press, without any of the hydraulic complications.

CHAPTER IV.

MARKING

UP

AND

SAWING

IN.

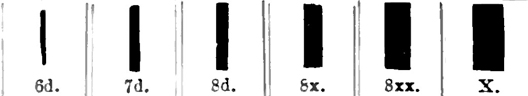

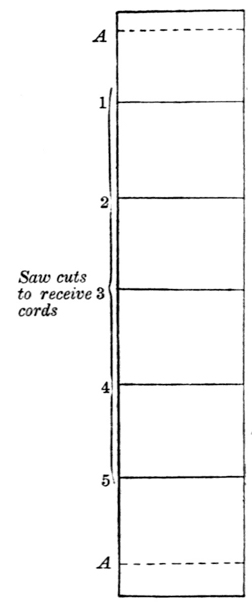

A.

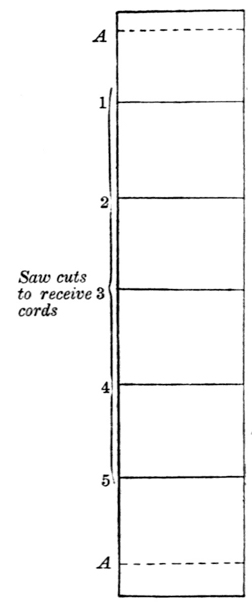

Saw marks for catch-up stitch.

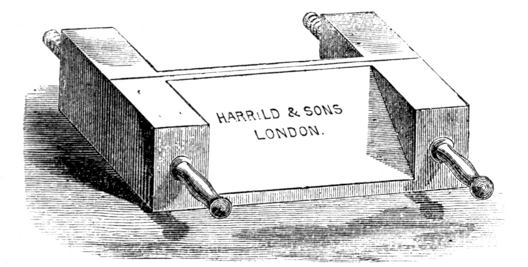

The books having been in the press a sufficient time, say

for a night, they are taken out, and run through again

(collated) to make sure that they are all correct. A book

is then taken and knocked straight both head and back

and put in the lying press between boards, projecting from

them about

1 ⁄ 8

inch; some binders prefer cutting boards, I

prefer pressing boards, and I should advise the use of

them, as the whole can be knocked up together. They

should be held between the fingers of each hand, and the

back and head knocked alternately on the cheek of the

press. The boards are then drawn back the required

distance from the back of the book: the book and boards

must now be held tightly with the left hand, and the

whole carefully lowered into the press; the right hand

regulating the screws, which should then be screwed up

tightly. The book is now quite straight, and firmly fixed

in the press, and we have to decide if it is to be sewn

flexibly or not. If for flexible binding the book is not to

be sawn in, but marked; the difference being, that with

the latter the cord is outside the sheets; with the former

the cord is imbedded in the back, in the cut or groove made

by the saw. We will take the flexible first, and suppose

that the book before us is an ordinary 8vo. volume, and

that it is to be cut all round.

The back should be divided into six equal portions,

leaving the bottom, or tail, half an inch longer than the

rest, simply because of a curious optical illusion, by which,

|21|

if the spaces were all equal in width, the bottom one would

appear to be the smallest, although accurately of the same

width as the rest. This curious

effect may be tested on any framed

or mounted print. A square is now

to be laid upon the back exactly to

the marks, and marked pretty black

with a lead pencil; the head and

tail must now be sawn in to imbed

the chain of the kettle stitch, at a

distance sufficient to prevent the

thread being divided by accident in

cutting. In flexible work great

accuracy is absolutely necessary

throughout the whole of the work,

especially in the marking up, as the

form of the bands will be visible

when covered. It will be easily

seen if the book has been knocked

up straight by laying the square at

the head when the book is in the

press, and if it is not straight, it

must be taken out and corrected.

If the book is very small, as for

instance a small prayer book, it is

usually marked up for five bands, but only sewed on three;

the other two being fastened on as false bands when the

book is ready for covering. There would be no gain in

strength by sewing a small book on five bands.

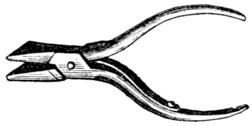

When the book is to be “sawn in,” it is marked up as

for flexible work, but the back is sawn, both for the bands and

kettle stitch, with a tennon saw. In choosing the saw, it

should be one with the teeth not spread out too much; and

it is advisable to have two of different widths. Care must

be taken that the saw does not enter too deeply, and one |22|

must, in all cases, be guided in the depth by the thickness of

the cord to be used. The size of the book should determine

the thickness of the cord, as the larger the book, the

stronger and thicker must be the cord. Suitable cord is

to be purchased at all the bookbinder’s material shops,

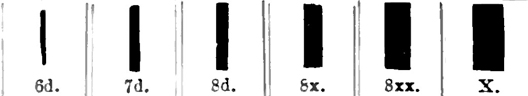

and it is known by the size of the book, such as 12mo.,

8vo., 4to. cord.

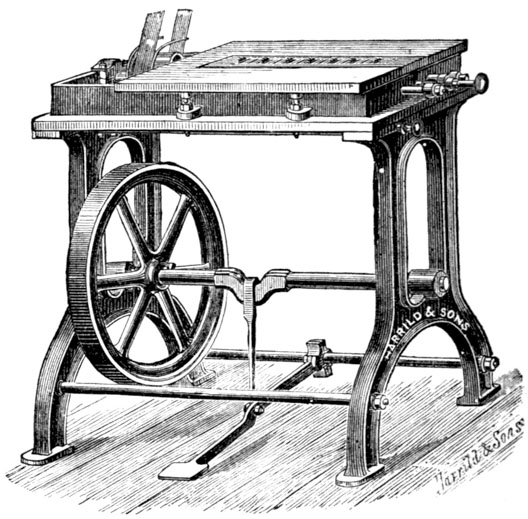

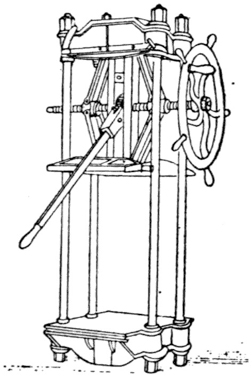

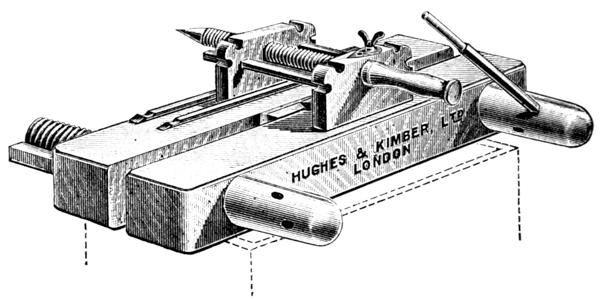

Sawing-in Machine.

I think nothing looks worse than a book with great

holes in the back, sometimes to be seen when the book is

opened, which are due to the inattention of the workmen.

Besides, it causes great inconvenience to the forwarder if

the cords are loose, and the only thing he can do in such a

case is to cram a lot of glue into the grooves to keep the

cord in its place. If, on the other hand, the saw cuts are |23|

not deep enough, the cord will stand out from the back,

and be distinctly seen when the book is finished, if not

remedied by extra strips of leather or paper between the

bands when lining up. It is better to use double thin

cord instead of one thick one for large books, because the

two cords will lie and imbed themselves in the back,

whereas one large one will not, unless very deep and wide

saw cuts be made. Large folios should be sawn on six or

seven bands, but five for an 8vo. is the right number, from

which all other sizes can be regulated.

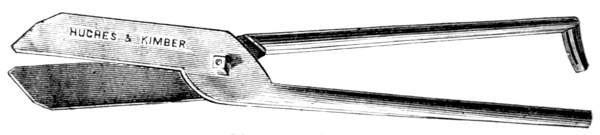

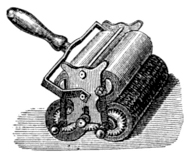

Saw benches have been introduced by various firms.

They can be driven either by steam or foot. It will be

seen that the saws are circular, and can be shifted on the

spindle to suit the various sized books. As the books

themselves are slid along the table on the saws, the advantage

is very great in a large shop where much work

of one size is done at a time.

CHAPTER V.

SEWING.

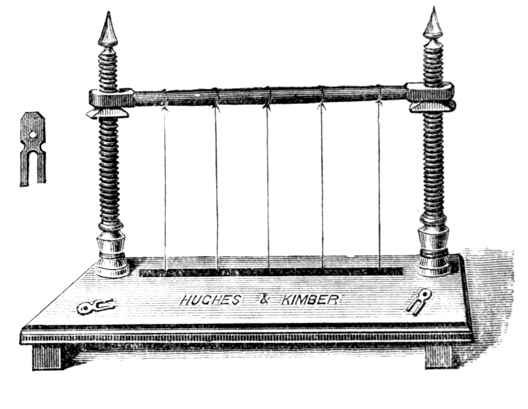

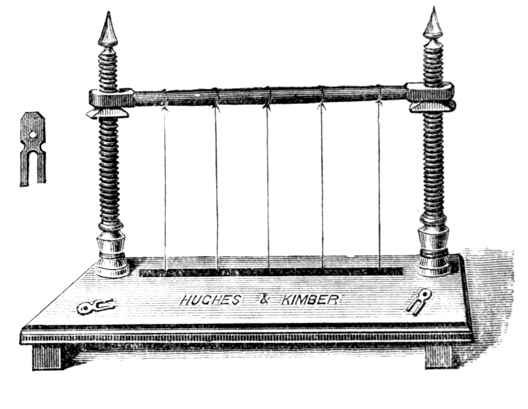

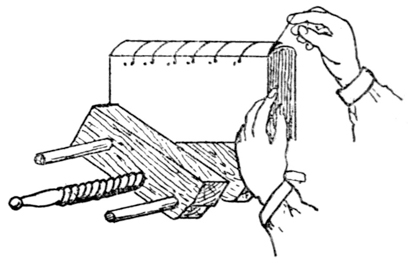

Flexible Work.—The

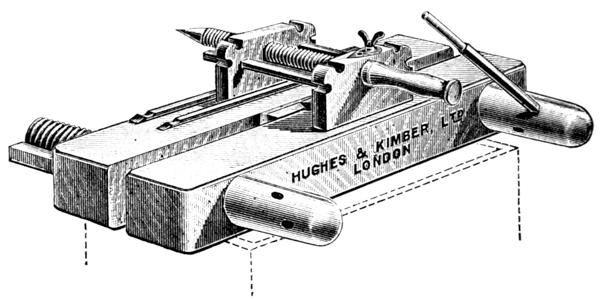

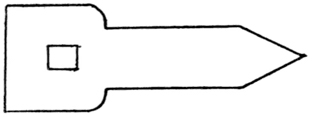

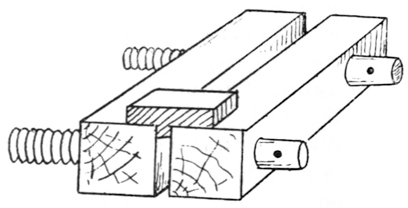

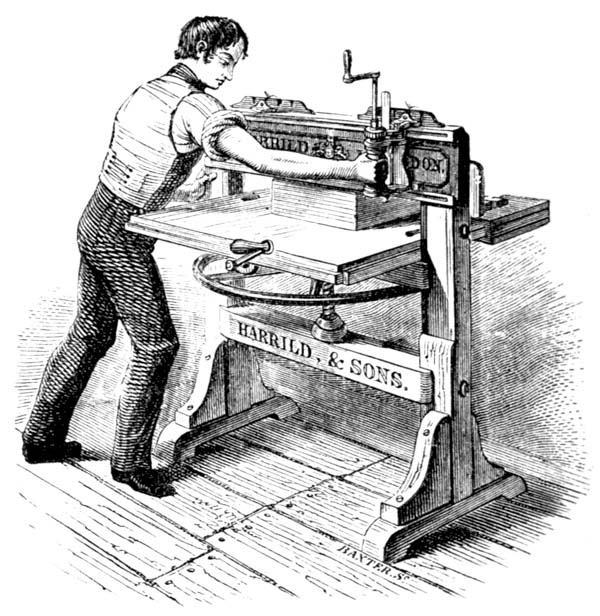

“sewing press” consists of a bed,

two screws, and a beam or cross bar, round which are fastened

five or more cords, called lay cords. Five pieces of cord

cut from the ball, in length, about four times the thickness

of the book, are fastened to the lay cords by slip knots;

the other ends being fastened to small pieces of metal called

keys, by twisting the ends round twice and then a half

hitch. The keys are then passed through the slot in the

bed of the “press,” and the beam screwed up rather tightly;

but loose enough to allow the lay cords to move freely |24|

backwards or forwards. Having the book on the bed of

the press with the back towards the sewer, a few sheets

(better than only one) are laid against the cords, and they

are arranged exactly to the marks made on the back of the

sections. When quite true and perpendicular, they should

be made tight by screwing the beam up. It will be better

if the cords are a little to the right of the press, so that

the sewer may get her or his left arm to rest better on the

press.

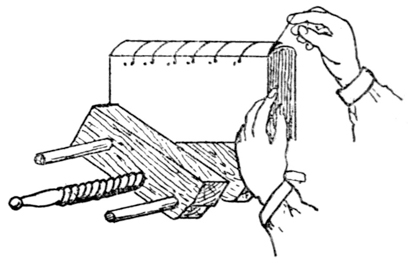

Sewing Press.

If when the press is tightened one of the cords is loose,

as will sometimes happen, a pencil, folding-stick or other

object slipped under the lay cord on the top of the beam

will tighten the band sufficiently. The foreign sewing

presses have screws with a hook at the end to hold the

bands, the screws running in a slot in the beam: in practice

they are very convenient.

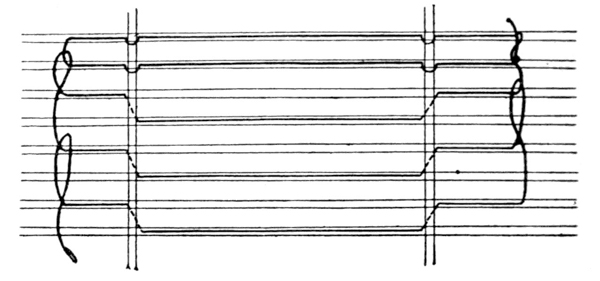

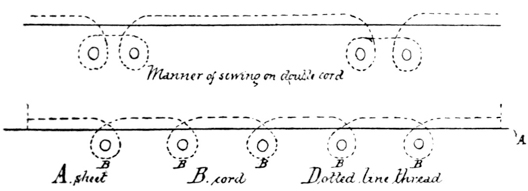

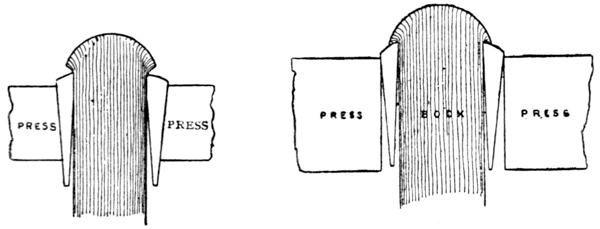

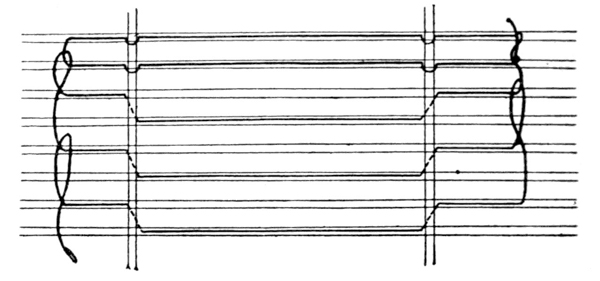

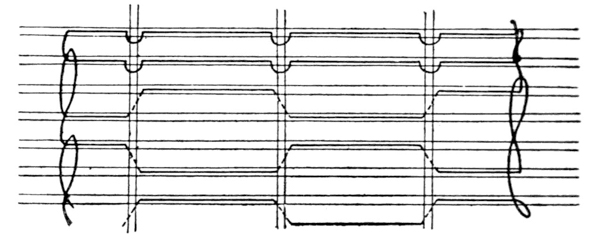

Ordinary sewing. 2 sheets on 2 bands.

Ordinary sewing. 2 sheets on 3 bands.

Ordinary sewing. 2 sheets on 5 bands.

The thick lines shewing the direction

of the thread.

The first and last sections are overcast usually with

cotton or very fine thread. The first sheet is now to be

laid against the bands, and the needle introduced through

the kettle stitch hole on the right of the book, which is the

|25|

head. The left hand being within the centre of the sheet,

the needle is taken with it, and thrust out on the left of the

mark made for the first band; the needle being taken with

the right hand, is again introduced on the right of the

same band, thus making a complete circle round it. This

is repeated with each band in succession, and the needle

brought out of the kettle stitch hole on the left or tail

of the sheet. A new sheet is now placed on the top, and

treated in a similar way, by introducing the needle at the

left end or tail; and when taken out at the right end or top,

the thread must be fastened by a knot to the end, hanging

from the first sheet, which is left long enough for the purpose.

A third sheet having been sewn in like

manner,2

the needle must be brought out at the kettle stitch, thrust

between the two sheets first sewn, and drawn round the

thread, thus fastening each sheet to its neighbour by a kind

of chain stitch. I believe the term “kettle stitch” is

only a corruption of “catch-up stitch,” as it catches each

section as sewn in succession. This class of work must be

done very neatly and evenly, but it is easily done with a

little practice and patience. This is the strongest sewing

executed at the present day, but it is very seldom done, as

it takes three or four times as long as the ordinary sewing.

The thread must be drawn tightly each time it is passed

round the band, and at the end properly fastened off at the

kettle stitch, or the sections will work loose in course of

time. Old books were always sewn in this manner, and

when two or double bands were used, the thread was

twisted twice round one on sewing one section, and twice

round the other on sewing the next, or once round each

cord. In some cases even the “head-band” was worked at

|27|

the same time, by fastening other pieces of leather for the

head and tail, and making it the catch-up stitch as well.

When the head-band was worked in sewing, the book was,

of course, not afterwards cut at the edges. When this was

done, wooden boards were used instead of mill boards, and

twisted leather instead of cord, and when the book was

covered, a groove was made between each double band.

This way is still imitated by sticking a second band or

cord alongside the one made in sewing, before the book is

covered. The cord for flexible work is called a “flexible

cord,” and is twisted tighter and is stronger than any

other. In all kinds of sewing I advise the use of Hayes’

Royal Irish thread, not because there is no other of good

manufacture, but because I have tried several kinds, and

Hayes’ has proved to be the best. The thickness of the cord

must always be in proportion to the size and thickness of

the book, and the thickness of the thread must depend on

the sheets, whether they be half sheets or whole sheets. If

too thick a thread is used, the swelling (the rising caused in

the back by the thread) will be too much, and it will be impossible

to make a proper rounding or get a right size

“groove” in backing. If the sections are thick or few, a

thick thread must be used to give the thickness necessary

to produce a good groove.

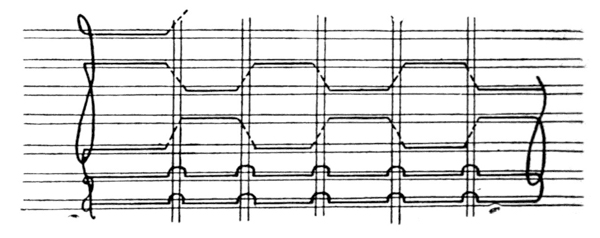

Flexible sewing.

If the book is of moderate thickness, the sections may be

knocked down by occasionally tapping them with a piece |28|

of wood loaded at one end with lead, or a thick folding-stick

may be used as a substitute. I must again call particular

attention to the kettle stitch. The thread must not

be drawn too tight in making the chain, or the thread will

break in backing; but still a proper tension must be kept or

the sheets will wear loose. The last sheet should be fastened

with a double knot round the kettle stitch two or

three sections down, and that section must be sewn all

along. The next style of sewing, and most generally used

throughout the trade, is the ordinary method.

Ordinary Sewing is somewhat different, inasmuch as

the thread is not twisted round the cord, as in flexible work,

when the cord is outside the section. In this method the

cord fits into the saw cuts. The thread is simply passed

over the cord, not round it, otherwise the principle of sewing

is the same, that is, the thread is passed right along the

section, out of the holes made, and into them again; the

kettle stitch being made in the same way. This style of

work has one advantage over flexible work, because the

back of the book can be better gilt. In flexible work, the

leather is attached with paste to the back, and is flexed, and

bent, each time the book is opened, and there is great risk

of the gold splitting away or being detached from the

leather in wear. Books sewn in the ordinary method

are made with a hollow or loose back, and when the

book is opened, the crease in the back is independent of

the leather covering; the lining of the back only is creased,

and the leather keeps its perfect form, by reason of the lining

giving it a spring outwards. Morocco is generally used

for flexible work; calf, being without a grain, is not suitable,

as it would show all the creases in the back made by

the opening. This class of sewing is excellent for books

that do not require so much strength, such as library bindings,3

but for a dictionary or the like, where constant |29|

reference or daily use is required, I should sew a book flexibly.

Some binders sew their books in the ordinary way, and

paste the leather directly to the back, and thus pass it for

flexible work; but I do not think any respectable house

would do so. A book that has been sewed flexibly will not

have any saw cut in the back, so that on examination, by

opening it wide, it will at once be seen if it is a real flexible

binding or not.

Intelligence must, however, be used; a book that has

already been cased (or bound and sewn on cords) must of

necessity have the saw cuts or holes, and such a book

would show the cuts.

There is another mode called “flexible not to show.”

The book is marked up in the usual way as for flexible,

and is also slightly scratched on the band marks with the

saw; but not deep enough to go through the sections. A

thin cord is then taken doubled for each band, and the

book is sewn the ordinary flexible way; the cord is knocked

into the back in forwarding, and the leather may be stuck

on a hollow back with bands, or it may be fastened to the

back itself without bands.4

However simple it may appear in description to sew a

book, it requires great judgment to keep down the swelling

of the book to the proper amount necessary to form a good

backing groove and no more. In order to do this, the

sheets must from time to time be gently tapped down with

a piece of wood or a heavy folding-stick, and great care

must be observed to avoid drawing the fastening of the

kettle stitch too tight, or the head and tail of the book will

be thinner than the middle; this fault once committed has

no remedy.

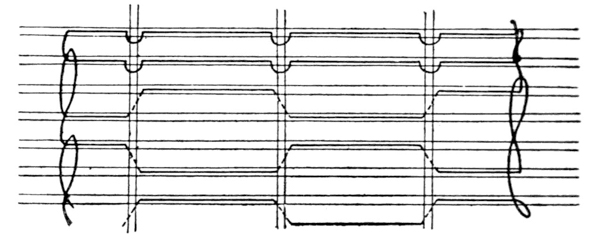

If the sections are very thin, or in half sheets, they may,

if the book is very thick, be sewn “two sheets on.” The

needle is passed from the kettle stitch to the first band of |30|

the first sheet and out, then another sheet is placed on the

top, and the needle inserted at the first band and brought

out at band No. 2, the needle is again inserted in the first

sheet and in at the second band and out at No. 3, thus

treating the two sections as one; in this way it is obvious

that only half as much thread will be in the back. With

regard to books that have had the heads cut, it will be necessary

to open each sheet carefully up to the back before it is

placed on the press, otherwise the centre may not be

caught, and two or more leaves will be detached after the

book is bound.

The first and last sections of every book should be overcast

for strength. With regard to books that are composed

of single leaves, they are treated of in Chapter III. They

are to be overcast, and each section treated as a section of

an ordinary book, the only difference being, that a strong

lining of paper should be given to the back before covering,

so that it cannot “throw up.”

When a book is sewn, it is taken from the sewing press

by slackening the screws which tighten the beam, so that

the cord may be easily detached from the keys and lay

cords. The cord may be left at its full length until the

end papers are about to be put on, when it must be reduced

to about three inches.

Brehmer’s patent wire book and pamphlet sewing

machine is an introduction well adapted to the use of the

stationer, where thick and hand-made paper will bear such

a method. It will not, in my opinion, ever be found

eligible for library or standard books. Its high price will

debar it from the trade generally; but it is to be feared

that a sufficient number of really good books may be sewn

with it to cause embarrassment to the first-rate binder,

who will be baffled in making good work of books which

may have been damaged by the invention of sewing books

with wire. |31|

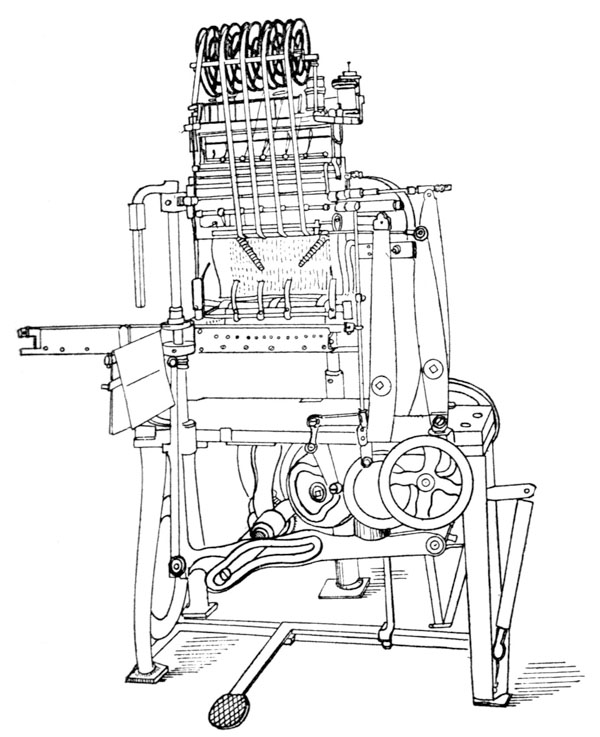

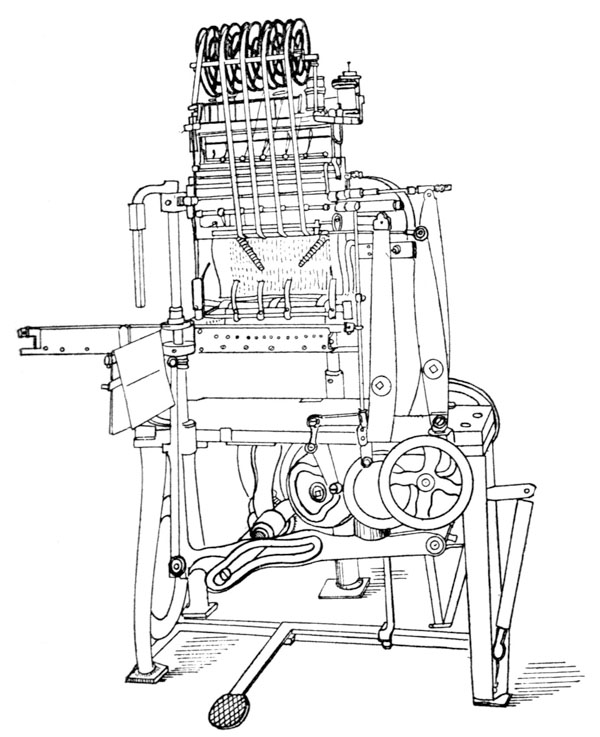

Smythe’s Sewing Machine.

The novelty of this machine is, that the book is sewn

with wire instead of thread. The machine is fed with

wire from spools by small steel rollers, which at each

revolution supply exactly the length of wire required to

form little staples with two legs. Of these staples, the

machine makes at every revolution as many as are required |32|

for each sheet of the book that is being sewn—generally

two or three, or more, as necessary. These wires or staples

are forced through the sections from the inside of the

folds; and as the tapes are stretched, and held by clasps

exactly opposite to each staple-forming and inserting apparatus,

the legs of each staple penetrate the tapes, and

project through them to a sufficient distance to allow of

their being bent inwards towards each other, and pressed

firmly against the tapes. With pamphlets, copy-books,

catalogues, &c., no tape is used, the staples themselves

being sufficient. About two thousand pamphlets or sheets

can be sewn in one hour.

Another machine, and I believe the latest, is the “Smythe.”

The sewer sits in front of the machine and places the

sheets, one at a time, on radial arms which project from a

vertical rod. These arms rotate, rise, and adjust the

sheets, so as to bring them in their proper position under

the curved needles. As each arm rises, small holes are

pierced, by means of punches in the sheets, from the

inside, to facilitate the entrance and egress of the needles.

The loopers then receive a lateral movement to tighten

the stitch, and this movement is made adjustable, in order

that books may be sewn tight or loose, as required. About

20,000 sheets can be sewn in a day, and no previous sawing

is required. Thread is used with this machine.

CHAPTER VI.

FORWARDING.

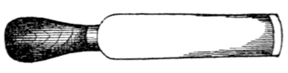

End Papers.—The end papers should always be made,

that is, the coloured paper pasted to a white one; the

style of binding must decide what kind of ends are to be

used. I give a slight idea of the kinds of papers used and

the method of making them.

Cobb Paper is a paper used generally for half-calf bindings,

with a sprinkled edge, or as a change, half-calf, gilt

top. The paper is stained various shades and colours in

the making, and I think derives its name from a binder

who first used it. Being liked by the trade, they have

distinguished the paper by calling it “Cobb paper,” which

name it has kept.

Surface Paper.—This is a paper, one side of which is

prepared with a layer of colour, laid on with a brush very

evenly. Some kinds are left dull and others are glazed.

The darker colours of this paper are generally chosen for

Bibles or books of a religious character, and the lighter

colours for the cloth or case work. There are many other

shades which may be put into extra bindings with very good

effect, and will exercise the taste of the workman. For

example, a good cream, when of fine colour and good

quality, will look very well in a morocco book with either

cloth or morocco joints.

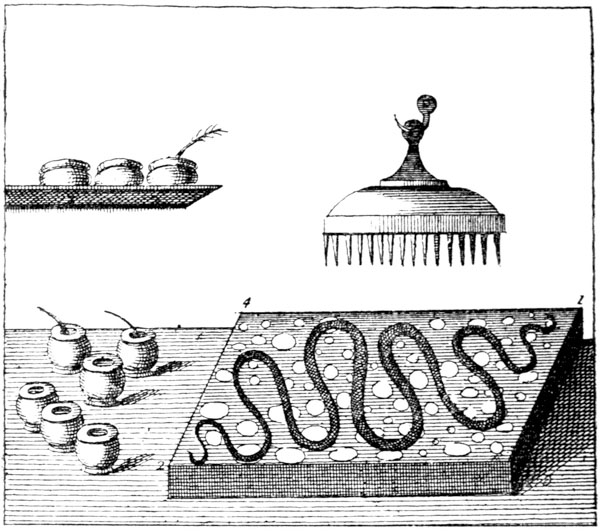

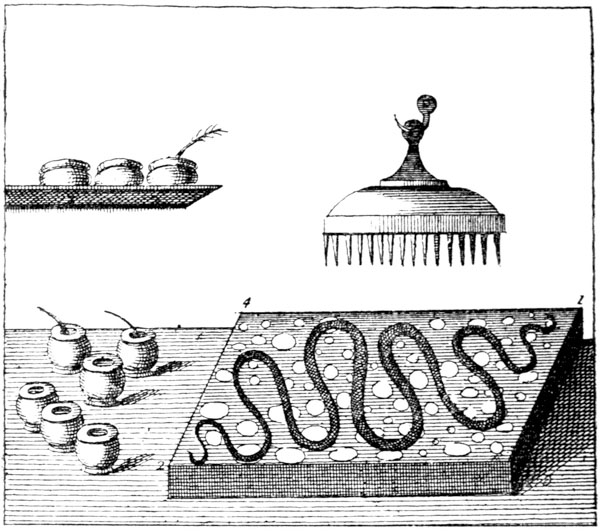

Marbled Paper.—This paper has the colour disposed

upon it in imitation of marble; hence its name. It is

produced by sprinkling properly prepared colours upon

the surface of a size, made either of a vegetable emulsion, |34|

or of a solution of resinous gum. It is necessary, in

either preparing an original design or in matching an

example, to remember that the veins are the first splashes

of colour thrown on the size, and assume that form in

consequence of being driven back by the successive colours

employed.

We have it on the authority of Mr. Woolnough,5

that the

old Dutch paper was wrapped round toys in order to evade

the duty imposed upon it. After being carefully smoothed

out, it was sold to bookbinders at a very high price, who

used it upon their extra bindings, and if the paper was not

large enough they were compelled to join it. After a time

the manufacture was introduced into England, but either

the colours are not prepared the same way, or the paper

itself may not be so suitable, the colours are not brought

out with such vigour and beauty, nor do they stand so well,

as on the old Dutch paper. Some secret of the art has

been lost, and it baffles our ablest marblers of the present

day to reproduce many of the beautiful examples that may

be seen in some of the old books.

For further remarks on marbled paper and marbling see

chapter on colouring edges.

Printed and other Fancy Paper may be bought at fancy

stationers; the variety is so great that description is impossible,

but good taste and judgment should always be

used by studying the style and colour of binding. Of late

years a few firms have paid some attention to this branch,

and have placed in the market some very pretty patterns

in various tints.

The foreign binders are very fond of papers printed in

bronze, and some are certainly of a most elaborate and

gorgeous description. Many houses have their own

favourite pattern and style. All papers having bronze on |35|

them should be carefully selected and the cheaper kinds

eschewed, the bronze in a short time going black.

Coloured Paste Paper.—This kind the binder can easily

make for himself. Some colour should be mixed with paste

and a little soap, until it is a little thicker than cream. It

should then be spread upon two sheets of paper with a paste

brush. The sheets must then be laid together with their

coloured surfaces facing each other, and when separated they

will have a curious wavy pattern on them. The paper should

then be hung up to dry on a string stretched across the room,

and when dry glazed with a hot iron. A great deal of it

is used in Germany for covering books. Green, reds, and

blues have a very good effect.

There are many other kinds of paper that may be used,

but the above five different varieties will give a very good

idea and serve as points to work from. The many bookbinders’

material dealers send out pattern books, and in

them some hundreds of patterns are to be found.

Before leaving the subject of ends, it may be as well to

mention that morocco, calf, russia, silk, etc., are often used

on whole bound work; these must, however, be placed in

the book when has been covered.

After having decided upon what kind of paper is to be

used, two pieces are cut and folded to the size of the book,

leaving them a trifle larger, especially if the book has been

already cut. Two pieces of white paper must be prepared

in the same way. Having them ready, a white paper is

laid down, folded, on a pasting board (any old mill-board

kept for this purpose), and pasted with moderately thin

paste very evenly; the two fancy papers are laid on the

top quite even with the back or folded edge; the top fancy

paper is now to be pasted, and the other white laid on that:

they must now be taken from the board, and after a squeeze

in the press between pressing boards, taken out, and hung

up separately to dry. This will cause one half of the white |36|

to adhere to one half of the marble or fancy paper. When

they are dry, they should be refolded in the old folds and

pressed for about a quarter of an hour. When there are

more than one pair of ends to make, they need not be

made one pair at a time, but ten or fifteen pairs may be

done at once, by commencing with the one white, then two

fancy, two white, and so on, until a sufficient number have

been made, always pressing them to ensure the surfaces

adhering properly; then hang them up to dry. When dry

press again, to make them quite flat. As this is the first

time I speak about pasting, a few hints or remarks on the

proper way will not be out of place here. Always draw

the brush well over the paper and away from the centre,

towards the edges of the paper. Do not have too much

paste in the brush, but just enough to make it slide well.

Be careful that the whole surface is pasted; remove all

hairs or lumps from the paper, or they will mark the book.

Finally, never attempt to take up the brush from the paper

before it is well drawn over the edge of the paper, or the

paper will stick to the brush and turn over, with the risk

of the under side being pasted. While the ends are pressing

we will proceed with further forwarding our book.

CHAPTER VII.

PASTING

UP.

The

first and last sheet of every book must be pasted up or

down,—it is called by both terms; and if the book has too

much swelling, it must be tapped down gently with a

hammer. Hold the book tightly at the foredge with the

left hand, knuckles down; rest the back on the press, and hit |37|

the back with the hammer to the required thickness. If

the book is not held tightly, a portion of the back will slip

in and the hollow will always be visible; so I advise that

the back be knocked flat on the “lying press” and placed

in it without boards, so that the back projects. Screw the

press up tightly, so that the sheets cannot slip. A knocking-down

iron should then be placed against the book on its left

side, and the back hammered against it; the “slips” or cords

must be pulled tight, each one being pulled with the right

hand, the left holding the slips tightly against the book so

that they cannot be pulled through. Should it happen that

a slip is pulled out, nothing remains but to re-sew the book,

unless it is a thin one, when it may possibly be re-inserted

with a large needle. But this will not do the book any good.

The slips being pulled tight, the first and last section

should be pasted to those next them. To do this, lay the

book on the edge of the press and throw the top section

back; lay a piece of waste paper upon the next section

about

1 ⁄ 8

or

1 ⁄ 4

inch from the back, according to the size of

the book, and paste the space between the back and the

waste paper, using generally the second finger of the right

hand, holding the paper down with the left. When pasted,

the waste paper is removed, and the back of the section put

evenly with the back of the book, which is now turned over

carefully that it may not shift; the other end is treated in

the same manner. A weight should then be put on the top,

or if more than a single book, one should lie on the top of

the other, back and foredge alternately, each book to be half

an inch within the foredge of the book next to it, with a few

pressing boards on the top one. When dry the end papers

are to be pasted on.

CHAPTER VIII.

PUTTING

ON

THE

END

PAPERS.

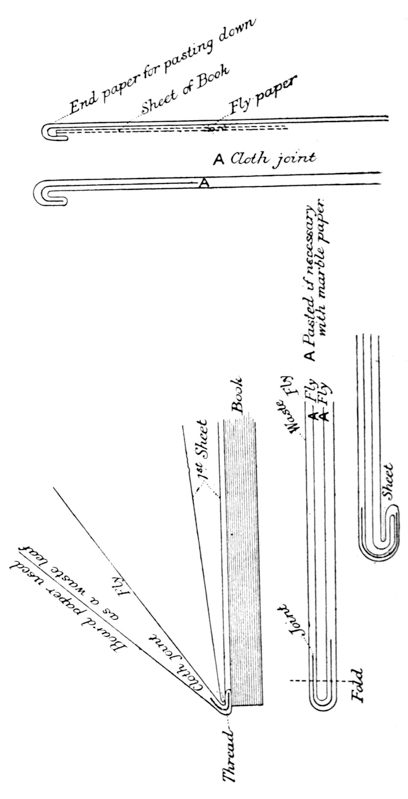

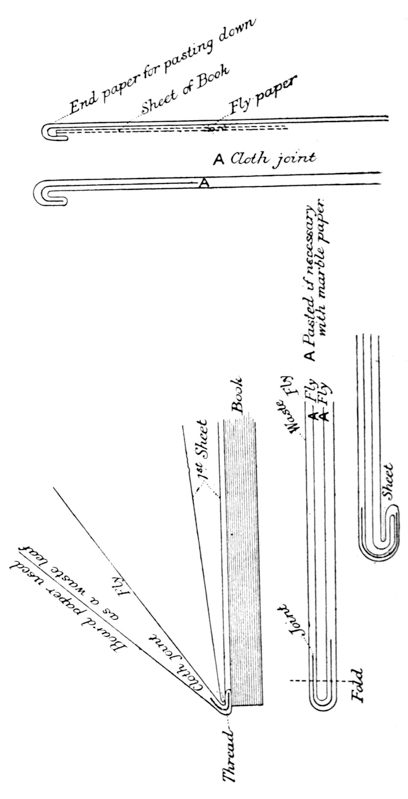

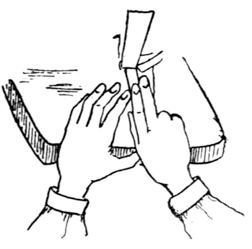

Two single leaves of white paper, somewhat thicker than the

paper used for making the ends, are to be cut, one for each

side of the book. The end papers are to be laid down

on a board, or on a piece of paper on the press to keep them

clean, with the pasted or made side uppermost, the single

leaves on the top. They should then be fanned out evenly

to a proper width, about a quarter of an inch for an 8vo., a

piece of waste paper put on the top, and their edges pasted.

The slips or cords thrown back, the white fly is put on the

book, a little away from the back, and the made ends on

the top even with the back, and again left to dry with the

weight of a few boards on the top.

If, however, the book or books are very heavy or large,

they should have “joints” of either bookbinders’ cloth or

of leather of the same colour as the leather with which the

book is to be covered. Morocco is mostly used for the

leather joints. If the joints are to be of cloth, it may be

added either when the ends are being put on, or when the

book is ready for pasting down. If the cloth joint is to be

put on now, the cloth is cut from 1 to 3 inches, according

to the size of book, and folded quite evenly, the side of the

cloth which has to go on the book being left the width intended

to be glued; that is, a width of 1 inch should be

folded

3 ⁄ 4

one side, leaving

1 ⁄ 4

the other, the latter to be put

on the book. The smallest fold is now glued, the white fly

put on, and the fancy paper on the top; the difference

being, that the paper instead of being made double or

folded is single, or instead of taking a paper double the |39|

size of the book and folding it, it is cut to the size of the

book and pasted all over. It will be better if the marble

paper be pasted and the white put on and well rubbed

down, and then the whole laid between mill-boards to dry.

A piece of waste or brown paper should be slightly fastened

at the back over the whole, (turning the cloth down on

the book) to keep it clean and prevent it from getting

damaged.

The strongest manner is to overcast the ends and cloth

joint to the first and last section of the book, as it is then

almost impossible either for the cloth or ends to pull away

from the book.

If, however, the cloth joint is to be put on after the book

is covered, the flys and ends are only edged on with paste

to the book just sufficient to hold them while it is being

bound; and when the book is to be pasted down, the ends

are lifted from the book by placing a thin folding-stick

between the ends and book and running it along, when

they will come away quite easily. The cloth is then cut

and folded as before and fastened on, and the ends and flys

properly pasted in the back.

Morocco joints are usually put in after the book is

covered, but I prefer that if joints of any kind are to go in

the book they should be put in at the same time as the

ends. Take great care that the ends are quite dry after

being made before attaching them, or the dampness will

affect the beginning and end of the book and cause the

first few leaves to wrinkle.

When the ends are quite dry the slips should be unravelled

and scraped, a bodkin being used for the unravelling,

and the back of a knife for the scraping. The object of

this is, that they may with greater ease be passed through

the holes in the mill-board, and the bulk of the cord be more

evenly distributed and beaten down, so as not to be seen

after the book has been covered. |41|

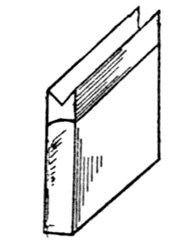

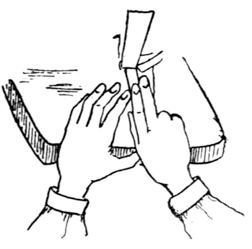

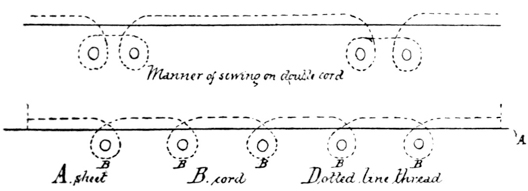

Method of sewing Ends on to Book that cannot

tear away.

First and last sheet are not overcasted