Title: How? or, Spare Hours Made Profitable for Boys and Girls

Author: Kennedy Holbrook

Release date: February 27, 2016 [eBook #51315]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Although this book is ostensibly a “boy’s book,” many things which it contains are equally useful to girls; and have been tried by the latter with entirely satisfactory results. In fact, it was to afford amusement and occupation, on rainy Saturdays and during the long vacation, to the children of both sexes in my own family, that the book was first written; and it was only an afterthought which led me to give it to the public.

Everything it contains has been deduced from my own experience or that of some trustworthy friend. While it has been my aim to meet the wants of children of all ages and in every condition of life, I have studiously avoided every subject which might be a source of anxiety to the most careful parent.

It is with the hope that this little work may fulfill its mission in other families where it may be received, as happily as it has done in mine, that I send it on its way.

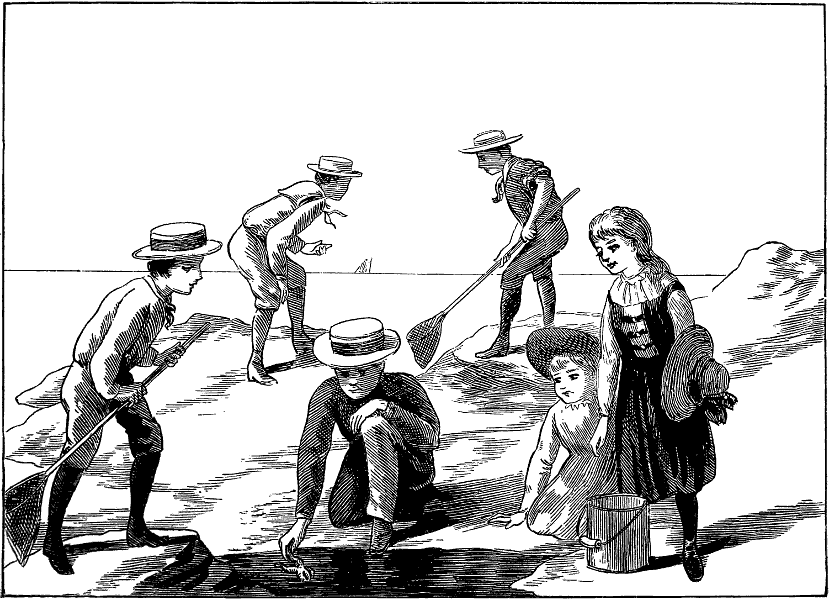

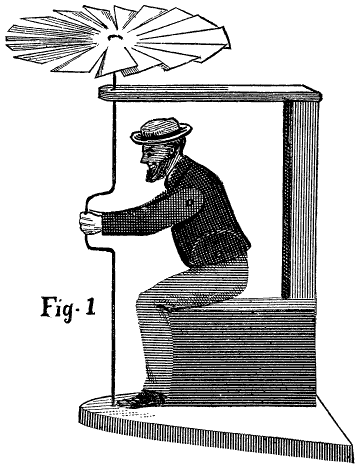

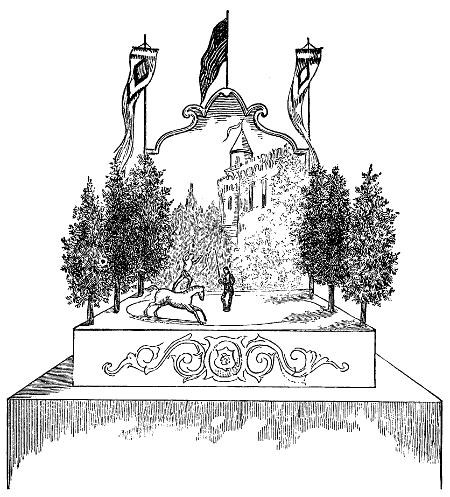

This amusing little puppet is very easily constructed, and, like several other mechanical toys in this book, furnishes much entertainment for the little folks. Even the baby will sit in her high chair, half-hours together, watching the little man turning his crank, while she claps her tiny hands and crows at so delightful an exhibition of untiring energy.

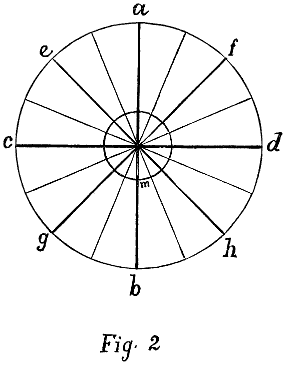

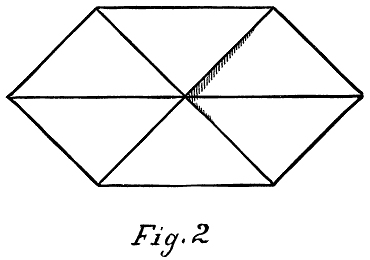

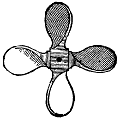

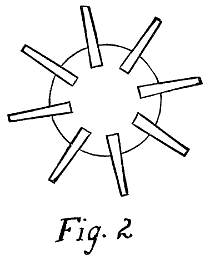

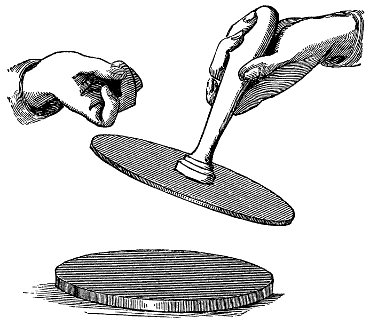

Cut from cardboard a disc like Fig. 2, which shall measure about six inches across; then by means of a ruler draw the lines a b c d; half-way between these points make four others, corresponding to e f g h; and lastly, between all these, still another set of lines. Make the circle, m, one-and-a-half inches in diameter, and with a pair of sharp scissors cut through all these lines, to the edge of the smaller ring. Bend one edge of each of these triangular pieces slightly upward, as indicated by the shading, and the opposite edge downward; also bend a piece of wire a foot long, so as to form the crank indicated in the illustration.

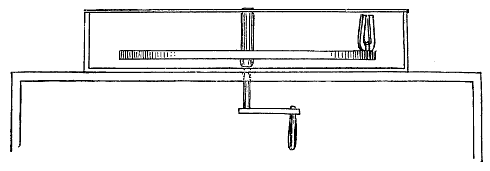

8Next make a frame-work for the figure to rest upon: this should consist of a three-cornered piece of wood, six inches long for the bottom, a stick six or seven inches long for the upright, and lastly, the support for the upper part of the wire, with a small hole in one end for the latter to pass through. Fasten these pieces together with small brad-nails, and secure the upright to the bottom piece by a screw or nail passing up from below. The wire, having the crank already bent in the proper place, may now be passed up through the hole, and the other end sunk down into another, bored a short distance into the bottom 9board, directly below the upper one. Then the wire may be fastened to the windmill, by passing it through a little one side, then back again through on the other side of the center; twisting the end once or twice about the main stem beneath the windmill; it now turns with the windmill, and it is needless to say that the friction in the holes should be as slight as possible.

The figure is to be cut from a piece of cardboard and is made in five pieces. The lower half, which comprises the box, legs, and body up to the dotted line, is in one piece; the head and body to the lower edge of the belt, consists of two pieces, cut precisely alike, and lapping on either side of the lower part of the body over the dotted line, to give strength to the image. A pin passed through the belt, and bent down on the other side, will hold it in place, and allow sufficient play to the figure. There are two arms, cut from the same pattern, and pivoted at the shoulders with another pin. The hands are finally brought together, with the crank between them, and lightly secured on either side with two or three stitches.

10To impart life to this creation, it is placed over a furnace register through which the hot air is briskly rising. If the machine works easily, the current of air above a stove may suffice.

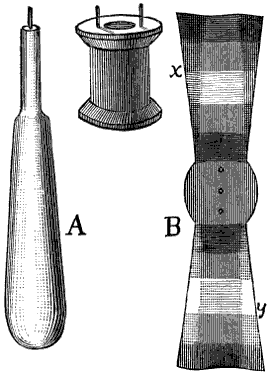

This amusing toy consists of an empty spool with two pins driven into its head, as seen in the figure. With a pair of pliers break off the heads of the pins before driving them in position, then take a piece of soft wood and make a spindle, like that represented in the figure at A, and drive another headless pin into the small end. Lastly, cut from a piece of cardboard a figure like the one marked B, making three holes, a a a, with the point of a darning-needle, corresponding to the two pins in the spool and the one in the spindle.

Bend the edges marked x and y in opposite directions.

Now place the spool on the spindle and wind a piece of twine around the spool; then place the piece of pasteboard upon the top, letting the pins pass up through the row of holes in its center.

11Holding the machine upright in the left hand, with a quick movement of the right, jerk the string from the spool, and the cardboard will fly through the air with a very graceful motion.

If stripes of color are added to the ends, as seen in the cut, a much prettier effect is produced while the whirligig is in operation. These stripes can be painted in red, white, and blue water colors, or may be formed by pasting on narrow strips of bright-colored paper.

If the first trial does not succeed, wind the string in the other direction, or put on the “card flyer,” with the other side next the spool. The same causes which make it soar away in the one case will hold it yet more firmly to the spool in the other.

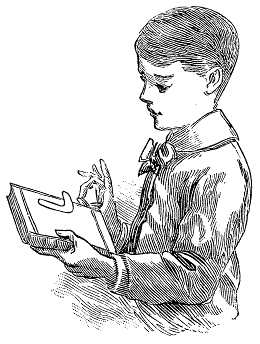

Do any of my boy readers know how to make a book? Not the fine volumes turned out by the thousand in our great publishing houses, but the little individual books made by boys and girls, and needing for their construction only an old used-up ledger, a small tin pan of paste, and scraps cut from newspapers or books. These bits may consist simply of poems, or they may be “a little of all sorts.”

I recently saw a very nice book of this kind made by a boy of twelve, which was composed entirely of humorous pictures and jokes, culled from several illustrated and daily papers, one or two almanacs, and various other chance publications, which he had collected during the 12year. Whenever he found any bright or witty thing, he would carefully preserve the clipping by putting it in a large paper box he kept in a convenient place for that purpose.

He reserved the pasting for rainy days and winter evenings, and as he took much pains with the arrangement and neat appearance of his book, this operation was necessarily slow, and formed a pleasant occupation for many hours which would otherwise have been wasted.

In making such a book, do not try to complete it in a week or even a month, but let it, like my boy friend’s, furnish amusement for a year.

Get your father and mother interested, and ask them to save any scraps they may see, and think appropriate for the purpose.

A handsomely bound scrap-book, specially designed for this use, would certainly be the most desirable thing to have; but if such a book cannot be obtained, an old ledger does very nicely in its place, and if, after it is completed, you cover it carefully with a piece of smooth brown paper and print its title neatly on the back, it will look very well on any table where you may wish to keep it.

If the latter is used, cut from it every other two leaves, reserving the third, through the book. Next be careful to trim all your clippings neatly, leaving no extra paper beyond the edges. Fit the different slips nicely on the pages, filling the little spaces left from the longer articles with any little jokes or bits of poetry you may have. Frequently a whole piece of newspaper poetry is hardly worth preserving, but some one of its stanzas may be very 13pretty and just the thing to fill up a place you may have left.

It is well to collect all these little things you can find, for they always come in nicely when pasting, and your book looks much better when finished if the original surface is entirely covered.

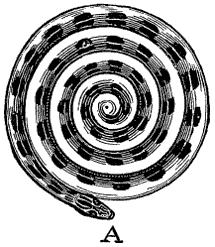

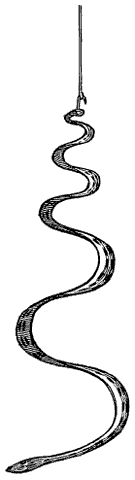

Cut from a piece of Bristol board, or stiff paper, a circle measuring four inches in diameter; then with a pencil mark it like Fig. A. With your paints and pencil make its head as nearly like a snake’s as possible; and mark the body with stripes or checks, as your fancy may dictate. Cut through the deep black line, put a pin through the dot on the tail, and drive it into a slender stick of wood, which must be held or caught over the stove or register. The rising current of heated air causes the snake to revolve and apparently writhe, in a very natural manner. This little toy, so simple in its construction, 14affords an endless amount of entertainment to the little folks of the family, and is well worth the trouble and time you may spend in making it.

The hot air from a lamp or gas jet will also impart activity to this mimic reptile.

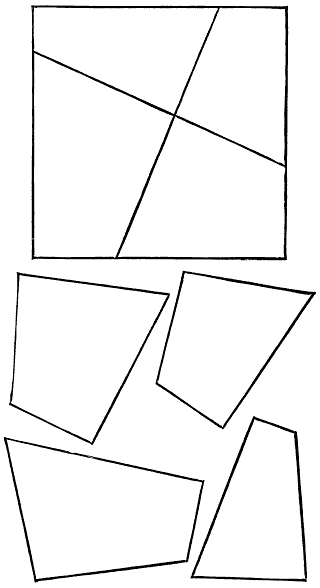

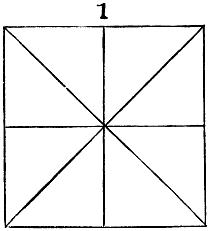

Take a square of paper or cardboard, and cut it into four pieces, as shown in the engraving. Now try to put them back in the form of a square. This seemingly simple puzzle, has kept our young people busy a whole evening, and was only accomplished at last by marking each piece before it was cut apart.

Procure two pieces of glass about six inches square, join any two of their sides, and separate the opposite sides with a piece of wax, so that their surfaces may be at a slight angle; immerse this apparatus about an inch in a basin of water, and the water will rise between the plates and form a beautiful geometrical figure called a hyperbola.

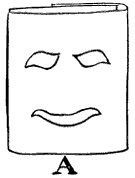

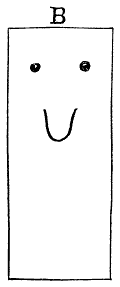

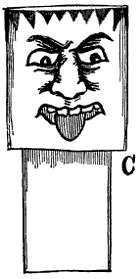

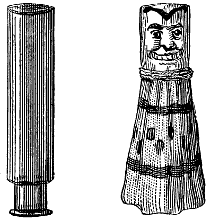

Take a card one-and-one-half inches wide, and fold around it a piece of unruled note paper, so that the card can easily slide up and down; then paste this case on the under side. Now cut three holes in the paper for the eyes and mouth, as seen in A; place the strip of card within this and mark the points for the eyes and root of tongue; then slipping it out once more, the eyes can be carefully finished, and the tongue cut to fit in the mouth, and to extend some distance down on the chin, see Fig. B. Then by putting the two pieces together, pulling the tongue in its place through the opening, very amusing expressions 16can be produced, by simply moving the pasteboard up and down in the paper. Fig. C represents the two parts put together.

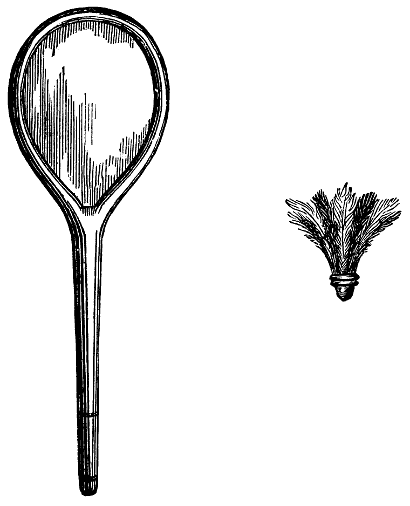

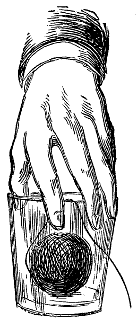

Take a round, well shaped orange; cut it evenly into quarters, numbering them at one end to aid in putting the parts together again. Next cut out of kid four pieces exactly like the four pieces of orange peel; then, with strong linen thread, sew over and over three seams, thus joining the four pieces, but leaving one seam open. In putting together be careful to place 1 next to 2, and so on, just as they were in the orange. Ravel out an old yarn stocking, or cut into narrow strips an old cashmere one, and after making a little round ball of any soft woolen material, commence winding it evenly with the raveled yarn, trying occasionally if it is near the size of the kid covering. When nearly large enough wind it in such a way that it shall just fit the cavity, and then carefully sew up the remaining side.

Great care should be exercised in forming the inner ball, and in cutting the kid. The wrists of old kid gloves make capital coverings. An old rubber overshoe cut in very fine strips and wound carefully, forms a nice center, but it is better to use the soft wool yarn next the cover, as it is more pliable and makes a better shaped ball.

Prepare this ball during your leisure moments in the long winter evenings; and it will then be ready for the first game, when the bright spring sunshine reminds you of summer sports once more.

Take five tooth-picks, weave them together, as seen in the illustration, which perhaps is easiest done by holding the three diverging ones between the thumb and forefinger of the left hand at the point a, and insert the other two successively, first b, then c. Now lay the figure upon any flat surface, letting the end c extend a short distance beyond the edge. If you touch a lighted match to c, in a moment each stick will leap into the air as if suddenly endowed with life and animation, quite unusual in such inert objects.

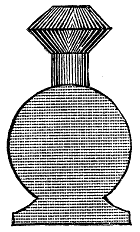

A glass bottle when freed from its top can be utilized in many ways, and most boys will be glad to know how to get rid of this troublesome portion without smashing the whole thing into fragments.

A red-hot poker with a pointed end is the instrument used. First make a mark with a file to begin the cut; then apply the hot iron, and a crack will start, which will follow the iron wherever it is carried. This is, on the whole, simple, and better than the use of strings wet with turpentine, etc.

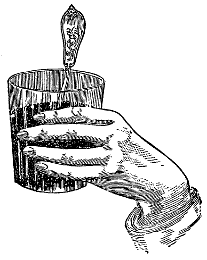

Take a common vial, or small bottle, cut off the rim by using the hot poker as directed above. Let the vial now be nearly filled with common rain water, and applying the finger to its mouth, turn it quickly upside down: on removing the finger it will be found that only a few drops will escape. Without a cork or stopper of any kind, the water will be retained within the bottle by the pressure of the external air, the weight of the air without the vial being so much greater than the small quantity within it. Now let a bit of tape be tied round the middle of the bottle, to which the two ends of a string may be attached, so as to form a loop to hang on a nail; let it be thus suspended in a perpendicular manner, with the mouth downward: and this is the barometer.

When the weather is fair, or inclined to be so, the 19water will be level at its lower surface, or perhaps concave, like an individual butter plate turned upside down; but when disposed to be stormy, a drop will appear at the mouth, which will enlarge till it falls, and then another drop, so long as the humidity of the atmosphere continues.

With a few cents any boy can buy the chemicals required for this barometer, and obtain an instrument much more reliable than many of the cheaper grades for sale in the stores. Put two drams of pure nitrate of potash, and half a dram of chloride of ammonium reduced to a powder, into two ounces of pure alcohol, and place this mixture in a clear glass bottle, covering the top with a piece of rubber or thin kid pierced with small holes.

If the weather is to be fine, the solid matters remain at the bottom of the bottle, and the alcohol is as transparent as usual. If rain is to fall in a short time, some of the solid particles rise and fall in the alcohol, which becomes somewhat thick and troubled. When a storm, tempest, or even a squall is about to come on, all the solid matter rises from the bottom of the bottle and forms a crust on the surface of the alcohol which appears to be in a state of fermentation. These appearances take place twenty-four hours before the tempest ensues, and the point of the horizon from which it is to blow is indicated by the particles gathering most on the side of the tube opposite to that part whence the wind is to come. The longer the diameter of the bottle the better for this kind of barometer.

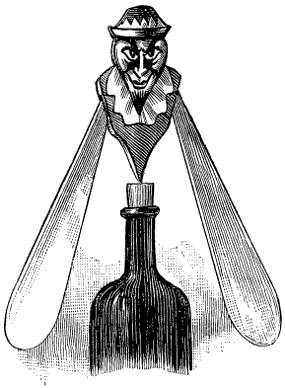

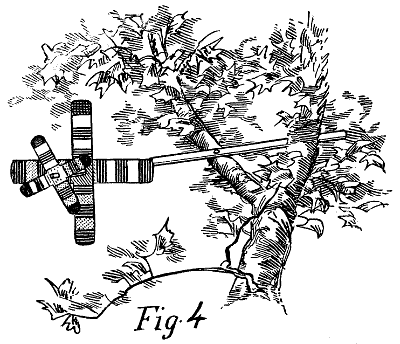

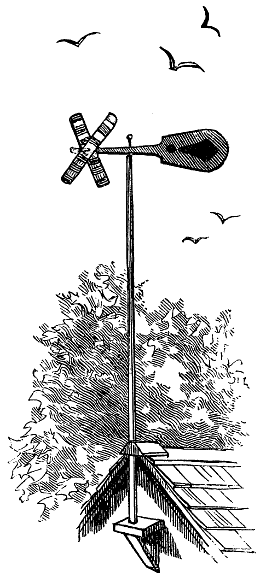

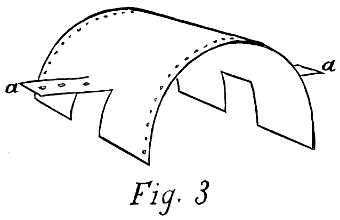

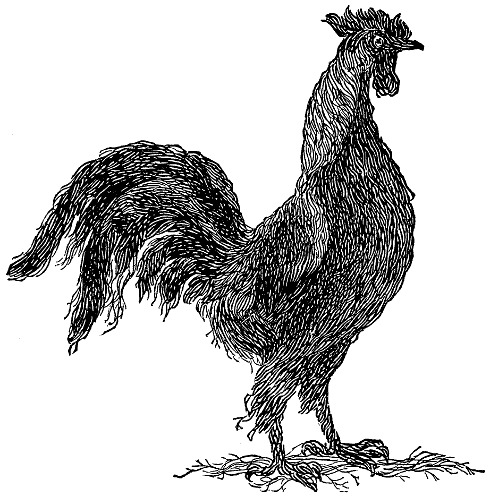

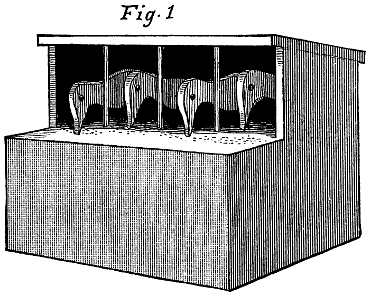

From a piece of soft wood whittle out a head and body like that in the illustration, making slits on either side for the insertion of the wings. These oar-shaped appendages are generally made from a shingle, and are affixed to the body by pressing them firmly into the slits. The whole thing can be painted to suit the fancy; water colors spread on rather thickly answer quite as well for small objects of this class, if protected by a good coating of varnish, made by dissolving a few cents’ worth of white shellac in a small quantity of alcohol. It is important that the oars are of the same weight and placed at equal angles with the body for this plaything to be successful.

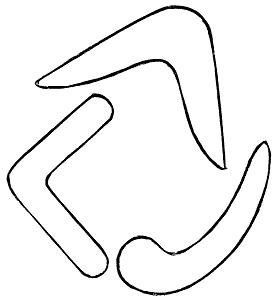

The boomerang is a weapon which has long been known as peculiar to the Australian savages, who are wonderfully skilled in its use.

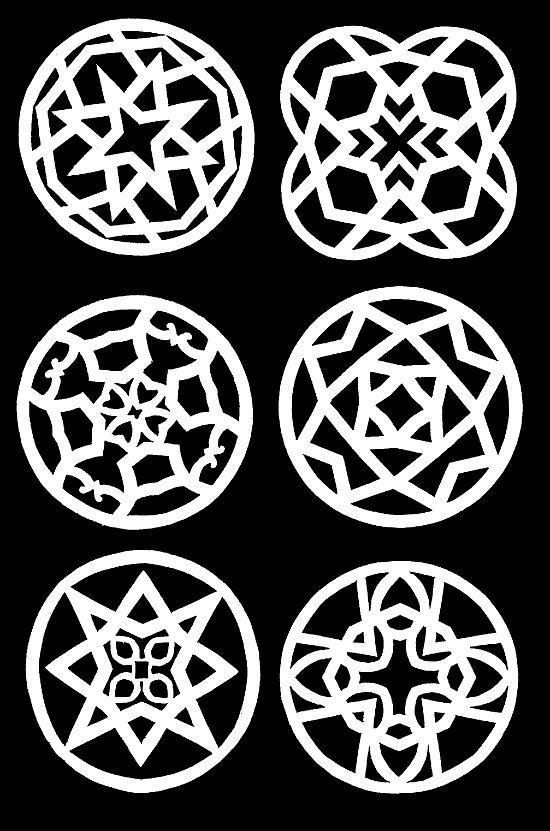

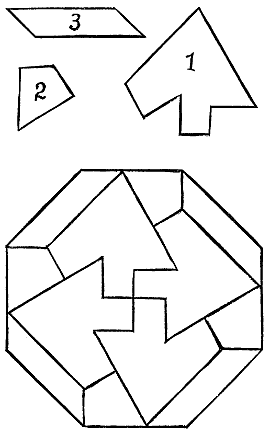

It consists of an irregular shaped piece of hard wood, so constructed that by its aid, the unsuspecting game can be killed at an angle widely diverging from the line of direction in which it was thrown. Instances have been cited in which the boomerang, in the hands of these untutored savages, has accomplished wonderful feats. One of the favorite ways of throwing consists in sending the weapon in such a manner that it shall skim along just above the ground for about a hundred feet, then, rising in the air, double back upon its course, and hit a mark only a few feet in front of the thrower. Of course we do not expect to equal the savages in its use, when recent investigations show that it has taken the experience of generations upon generations of men and hundreds of years, to bring it to its present degree of excellence; but every boy may derive much fun from practicing with the little cardboard boomerang 22cut of stiff pasteboard in either of the forms given in the preceding page. To throw this, place it upon a book, one end extending beyond the edge; then, with a ruler or small stick, strike it forcibly upon the edge, and it will fly through the air and back again, in an amusing, lively manner, quite unlike any other missile in a boy’s collection. It may be sent on its way by simply snapping it with the forefinger of the right hand while it is held on the book in your left. If you should try making one of wood to use out-of-doors, try it in the middle of a large open lot, for there is no telling what mischief it might do if it only had the chance.

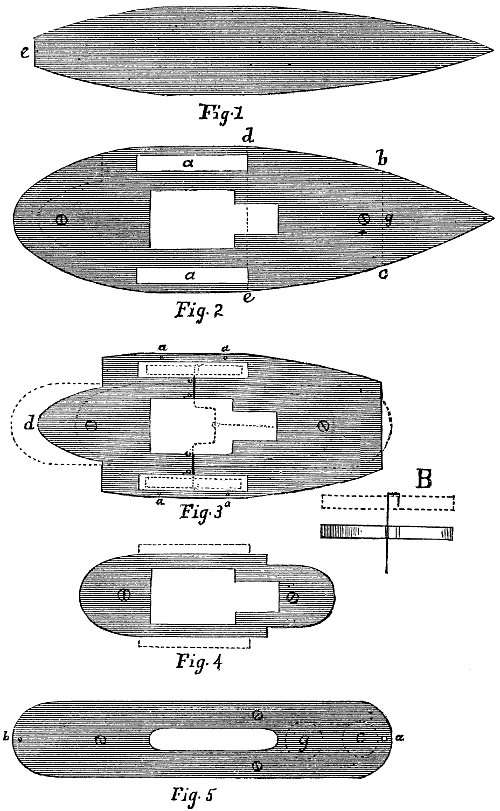

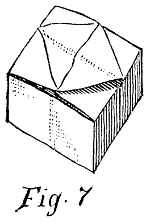

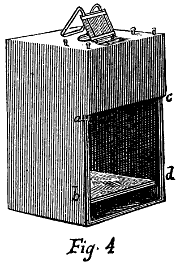

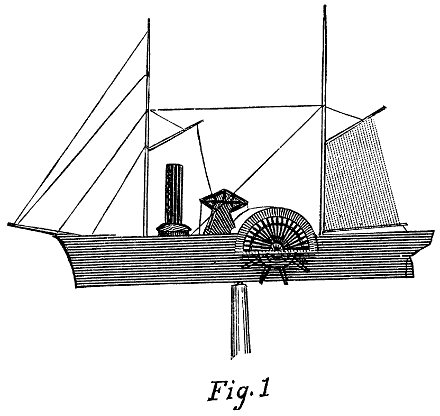

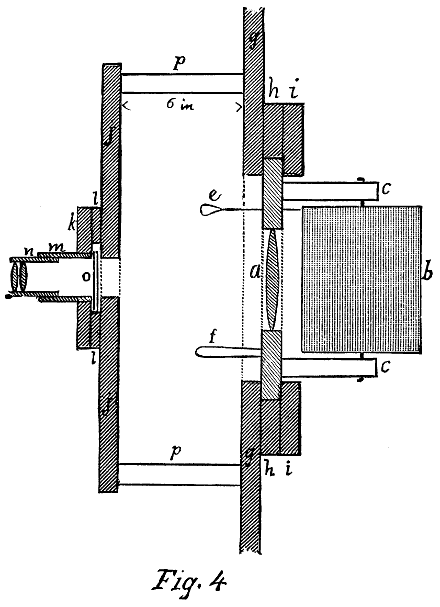

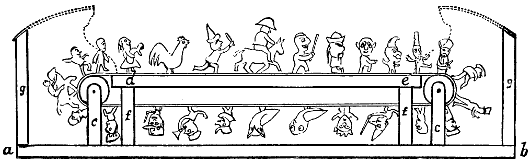

The following, although requiring considerable skill in joining, can readily be made by any boy of fifteen, if he is at all skillful in the use of carpenter’s tools, and has a fair endowment of those two excellent qualities, patience 23and perseverance, so absolutely indispensable to success in almost any undertaking.

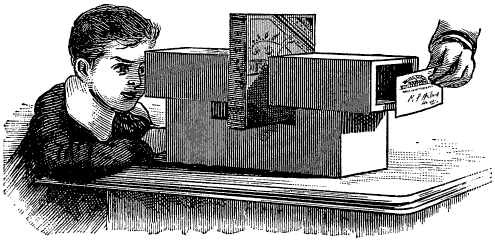

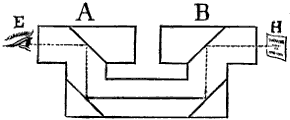

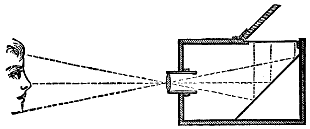

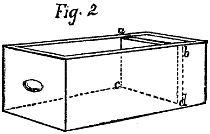

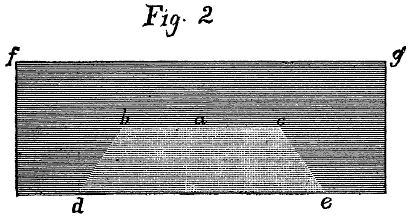

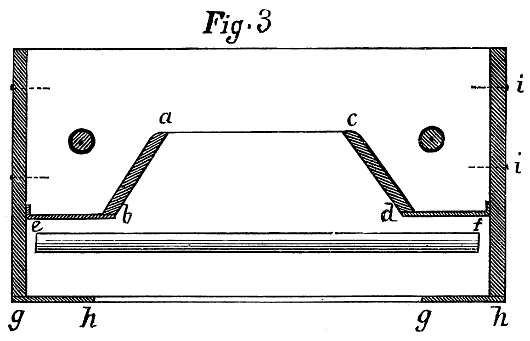

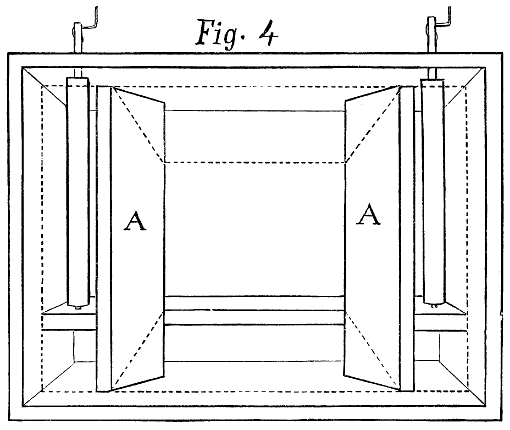

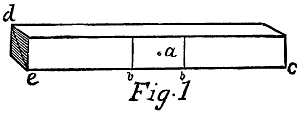

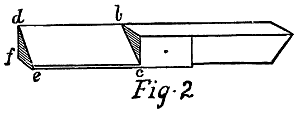

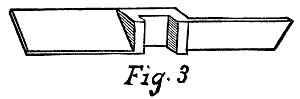

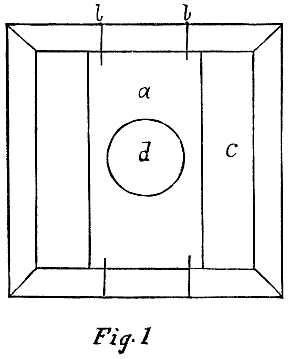

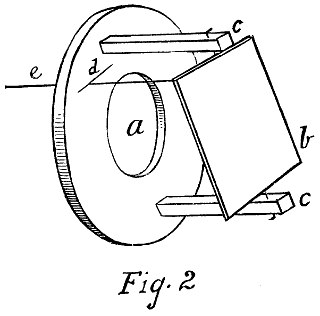

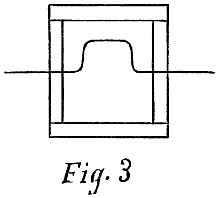

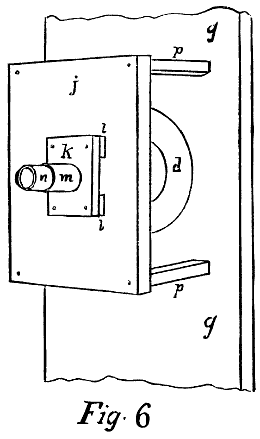

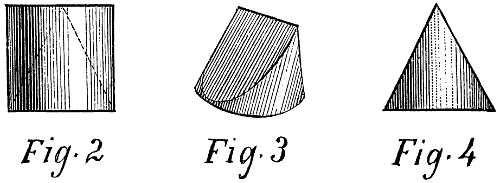

This telescope consists of a series of square wooden tubes, with an inside diameter of about five inches, so carefully joined together that no ray of light can find its way in through the crevices. The oblique lines are pieces of looking-glass, with their faces turned toward each other. Now, by placing the eye at E, of course it would seem that anything at H could be seen directly through the tubes A B, while if a book or other opaque object be interposed, as shown in Fig. 2, it would seem equally a matter of course that the view would be obstructed; this, however, is not the case, as the mirrors reflect the object through the tube and it appears as plainly as when the book is removed.

To those unfamiliar with its construction this magic telescope, by which you apparently see through a solid substance, is an unfailing source of wonder.

The object at H should be quite brilliantly lighted, as some of the rays are absorbed in the passage of the reflection through the tube; especial care should also be taken to place the mirrors at a slant, exactly midway between the horizontal and the upright, or, to speak more scientifically, at an angle of 45 degrees to the line of the tubes.

The tubes A and B should not be so far apart at the place where the book is inserted as to permit the backs of the mirrors to be easily seen.

Take a large-sized piece of alum, and pour over it a pint of boiling water, letting it stand until the water has taken up or dissolved all the alum it will. If at the end of a few hours any alum remains undissolved, you may be sure the water contains all the alum it can hold in a liquid state, and the solution is called a “saturated solution of alum.”

During the summer, while the grasses are in their most perfect state, select such as you think will look well crystallized, and put them into a vase or wide-mouthed bottle to dry, being careful to spread them well apart, so that they may retain their perfect shape in drying. If the season of grasses should pass before you have a chance to collect them, the season of weeds is always at hand. Any boy, in his wanderings over marsh or mountain, through woods or our quiet village street, during even the coldest winter months, could not fail to see some beautiful sprays of seed-pods crowning many of our most common weeds, which if crystallized, would make a very pretty and acceptable present to mother for the corner bracket, or the shelf which seemed just a little bare before. Having secured your grasses or weeds, both together if you like, and having your saturated solution of alum at hand, lay as many tops of the grasses in a flat dish as will fill it without crowding, then pour the liquid over them, being careful that the parts you wish crystallized are under the surface. Let them lie in this position until well coated with the alum. When finished remove them and put in 25others. Continue in this manner until all are treated. If only a few crystals are desired they may be obtained by dipping the heads one at a time in the solution and slightly shaking them after each immersion. When all have been dipped, commence with the first and repeat the process. Do this until the crystals formed are as large as you wish them to be.

In making these crystals the coloring should be added to the solution of alum in proportion to the shade which it is desired to produce. Coke, with a piece of lead attached to it in order to make it sink in the solution, is a good substance for a nucleus, if a cluster of crystals are to be formed. Any form, if wound around with knitting cotton, can be used, or the grasses above described can be dipped in these colored solutions, and very pretty results obtained.

Yellow: muriate of iron. Blue: solution of indigo in sulphuric acid. Pale blue: equal parts of alum and blue vitriol. Crimson: infusion of madder and cochineal. Black: Japan ink thickened with gum. Green: equal parts of alum and blue vitriol, with a few drops of sulphate of iron. Milk white: a crystal of alum held over a glass containing ammonia will become a milky white color upon its surface.

[Note.—To make an infusion of a substance you simply pour boiling water over it. The madder and cochineal are in the dry form, and only a little water should be used, as too much will make the color less brilliant.]

When small pieces of camphor are placed in a basin of pure water, a very peculiar motion commences; some of the pieces turn as if on an axis, others go steadily round the vessel, some seem to be pursuing others, and thus they continue forming a very curious and pleasing appearance; but if a single drop of sulphuric acid be put into the water, the motion of the camphor instantly stops. If a piece of camphor be lighted, and then carefully placed on the water, it burns with a bright flame, moving about with great rapidity, as if in search of something, but is instantly stopped by a drop of sulphuric acid.

Dissolve in seven different tumblers containing warm water, half ounces of sulphates of iron, copper, zinc, soda, alumina, magnesia, and potash. Pour them all, when completely dissolved, into a large flat dish, and stir the whole with a glass rod or bit of broken glass for a while. Place the dish in a warm place where it will be free from dust and will not be shaken. After due evaporation has taken place, the whole will begin to shoot out into crystals. These will be of various colors and forms, some little ones being gathered together in small groups, and other larger ones scattered throughout the whole fluid. By a little careful study you will soon be able to distinguish each crystal separately, from its peculiar form and color, 27thus learning an interesting lesson in chemistry, while making a beautiful ornament for your room. Be sure and preserve it carefully from the dust.

Procure two common clay pipes; break off the stem of one about three inches from the little end. Take a cork that exactly fits into the bowl of the other pipe, cut a hole through it large enough to insert the mouth-piece already broken off, and draw this through the opening till its larger end is even with the surface of the cork. Insert the cork in the bowl, and fill the end of the stem which touches the flame with a tiny ball of clay or chalk. Through this clay make a hole with a needle, and a blowpipe is the result, which answers very well for any experiment a boy may be likely to try.

Although it is impossible to give any detailed account of glass blowing which would be practicable for small boys, yet a child can amuse himself for hours, by simply melting bits of glass and joining them together; or by melting small glass tubes and drawing them out to mere threads; or again, blowing them up into tiny balloons until their surface is as thin as a soap bubble and almost as fragile. These little tubes are smaller than the end of 28a pipe-stem, about four inches long, and made of very thin glass. A dozen can be procured for ten or twelve cents at any place where chemical supplies are to be found. A short tallow candle, held in a cheap tin candlestick, answers for the flame; and the tobacco-pipe, converted into the blowpipe just described, can be used in any of the experiments here given. Take a piece of a broken window pane, hold it in the left hand very near the candle flame, then holding the blowpipe so that the shorter end nearly touches the flame, blow steadily through the pipe-stem a current of air into the flame, which sends it upon the glass and soon reduces the part in contact with it to a red-hot melting mass; this can be worked into various shapes by forming it with the aid of pincers; or it can easily be joined to pieces of different colors, by holding the two together and turning the full force of the blaze upon them.

The little tubes may be heated in the same manner, and one end be closed air tight, by pinching it tightly while still hot; then, after heating the portion near the end to a red heat, lay the blowpipe aside, and, taking the tube away from the flame, blow into the open end with the mouth. If this is done quickly, before the glass has had time to cool, a pretty bubble or balloon is the result.

A simple glass siphon can be made by taking one of the above tubes and heating it at a point about one-third of its length from the end, till the surface appears a rosy 31red; then carefully bending it over the round part of a clothes-pin, till the two ends form parallel lines.

A simple experiment with the siphon affords considerable amusement to the little folks, and is well worth trying. Take two tumblers, place them side by side, and fill one with water. Now fill the siphon with water and place the longer end in the empty tumbler, and the shorter one well down in the water of the other. Immediately the laborer will begin to work, pumping water into the empty vessel, and will not stop until he has reduced the water in the full tumbler to a level with the end of the tube.

Many kinds of stones containing more or less metallic ores, can be readily melted by means of the blowpipe. When the specimens are small they can be placed upon a piece of mica, and then presented to the flame; or a clay receptacle can be made for the purpose, by simply hollowing out a small cavity in one side of a lump of clay. Large ones can be held in the hand or with the pincers as in the case of the glass melting.

Within the past few years soap-bubble parties have been quite the style among our young people, and not a few of the older members of society have joined in the frolic with as much zest as their younger competitors. 32Usually at such gatherings, after the guests have all arrived, the hostess, having previously secured two or three boxes of bonbons, or other equally inexpensive trifles for prizes, presents each of her guests with an ordinary clay pipe, and leading the way to the room in which the bowls of soap-suds are already prepared, shows her prizes, and challenges all to the contest. If fine, large iridescent bubbles are desired, it is well to add a small quantity of glycerine to the water used. It is said that if the mixture of glycerine and water is allowed to stand some hours before it is used the effect is much better. Hot water and soap can be added just before the party enter, and only two bowls of the soap mixture are necessary for quite a large party. These should be placed upon small side tables or stands at opposite ends of the room. Two or three reliable persons should be chosen for judges to decide the contest. The parents or some older members of the family, at whose house the party is held, usually perform this duty. I should have added, when speaking of the soap mixture, that the common yellow soap intended for laundry use, is much better for this purpose than the finer toilet varieties most commonly used by amateur soap-bubble blowers.

If the end of a tobacco-pipe be dipped in melted resin, at a temperature a little above that of boiling water, taken out, and held nearly in a vertical position and blown through, bubbles will be formed of all possible sizes, from that of a hen’s egg, down to sizes which can hardly be 33discerned by the naked eye, and from their silvery luster, and reflection of the different rays of light, they have a pleasing appearance. Some that have been formed these eight months, are as perfect as when first made. They generally assume the form of a string of beads, many of them perfectly regular, and connected by a very fine fiber, but the production is never twice alike. If expanded over a gas jet by means of a small rubber tube, they would probably float around the upper part of the room.

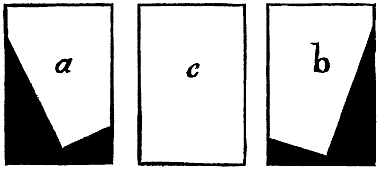

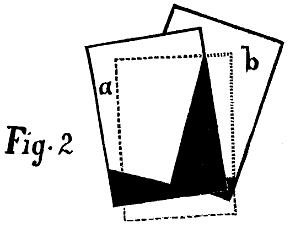

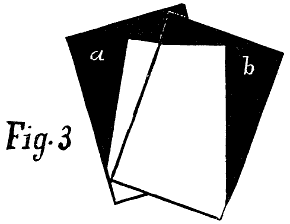

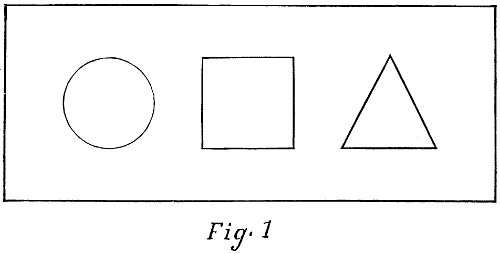

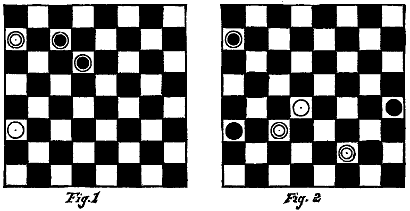

Take three cards of the same size, and thick enough to prevent the black surface from showing through; ink or paint over the whole of one side of c, having the other side perfectly white, and the others, a and b, in the parts shown in Fig. 1; they are now ready for use.

Fig. 2 shows the first arrangement of them, a and b lapping over each other so that when c is placed in the 34position shown by dotted lines the whole face presents a perfectly white surface. Show this to your audience; then, still holding them in sight, inform them in a neat little speech, that by aid of some magic power you possess, you can readily change these same cards to black, or back again, at will. Now holding them with their backs away from you, in such a manner that the card c cannot be seen by the other boys, turn them upside down and spread out what were the lower parts of a and b. You have them now in the position indicated by Fig. 3, and after carefully turning c you will find them presenting a uniformly black surface. Should any bit of white show at the lower corner, cover it with your thumb. When they are arranged to your satisfaction, hold them up in front of you, and while saying over some cabalistic words, such as, for instance, “Presto, agramento, calafesto—change!” blow upon their faces and turn them around to your audience, which will probably be greatly surprised at this undeniable evidence of your magic skill.

Instead of white, the ordinary playing cards may be used, blacking the back of one to represent c. These are much more showy than the plain white ones, and the trick is not so easily discovered if slight bits of black are seen, as those having black spots are generally taken for the purpose.

One day a little fellow who had been repeatedly mystified 37by this trick, saw the cards which his brother had prepared lying on the table. He took them up, examined them carefully for a moment, then, with his little face all aglow at the revelation, he exclaimed, “Ha! I’ve found out how you do it now, you just blow charcoal on the other part.” How he got rid of the part already black, he did not explain, nor did we think to ask him, but he had at last solved the puzzle of their turning black, and that was all he cared to do at the time.

Hold a ring between thumb and forefinger at some distance from the boy addressed, and giving him a crooked stick, ask him to close one eye and try to catch the ring on the stick. This game looks so very simple, that any boy is certain he can do it at one thrust, and is only made aware of its difficulties after several unsuccessful attempts.

Desire the person who has thought of a number to triple it, and to take the exact half of that; triple that half if the number was even, or if odd multiply the larger half by 3; and ask him how many times that answer contains nine: for the answer will contain the double of that number of nines, and one more if it be odd. Thus if the number thought of is 5, its triple will be 15, which cannot be 38divided by 2 without a remainder. The greater half of 15 is 8. If we multiply this by 3 we have 24, which contains 9 twice. So we shall have 2 + 2 + 1 = 5, the number first thought of.

In an old book published over half a century ago, I came across this puzzle; and finding it gave an evening’s entertainment to our young folks, I introduce it here for the benefit of those boys who take especial delight in games of an arithmetical nature.

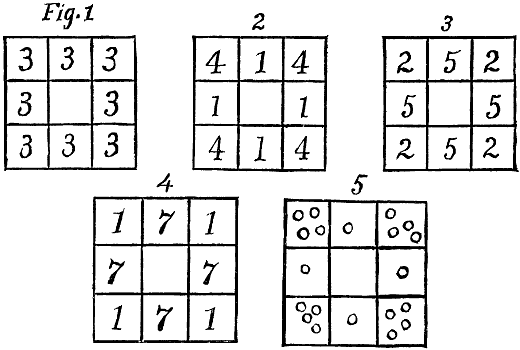

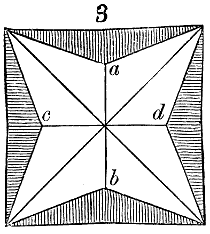

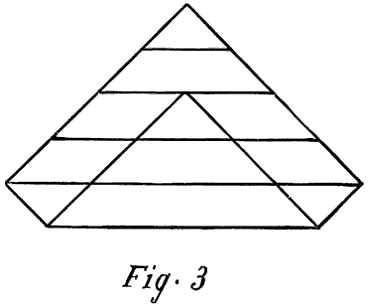

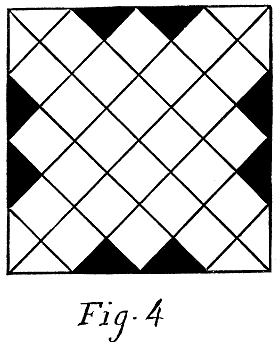

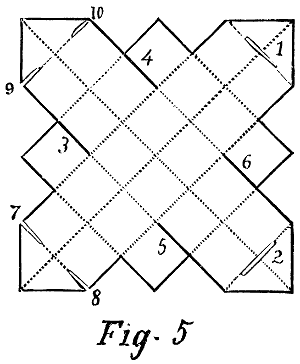

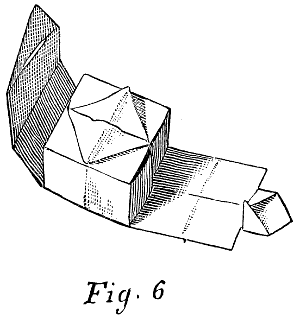

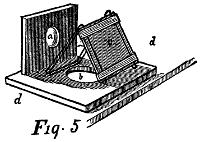

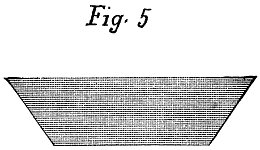

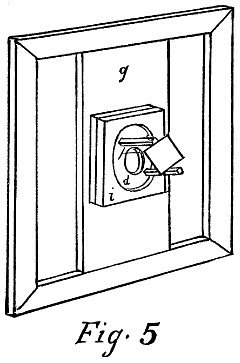

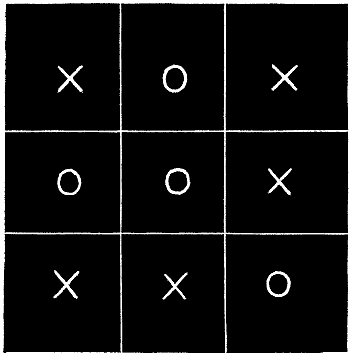

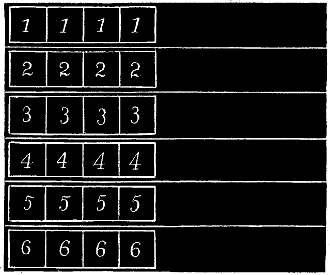

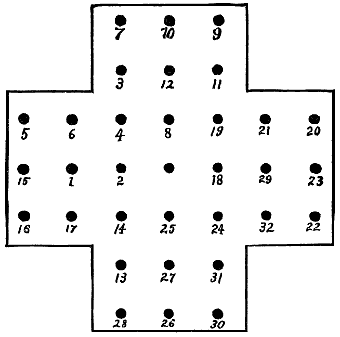

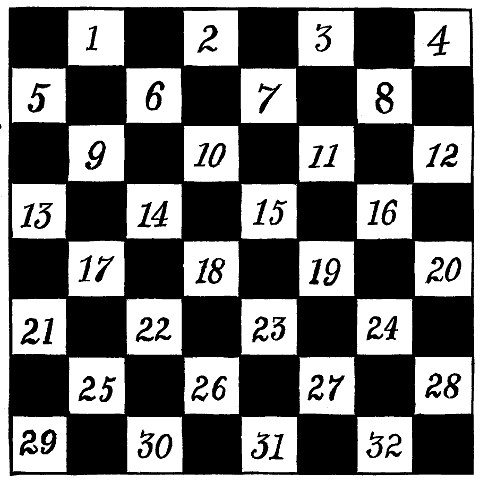

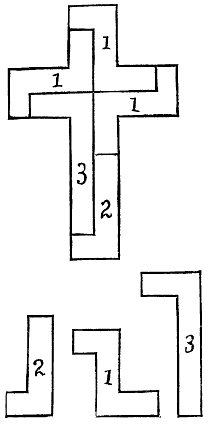

Out of thin cardboard—old business cards answer this purpose nicely—make thirty-two blank counters, the size of a dime. Then upon a piece of note-paper mark off a figure just three inches square, and divide it by lines into nine compartments, each containing one square inch. The puzzle is, to arrange the counters in the external cells of the square four different times, and each time to have nine in a row, yet to have the sum of the counters different, and varying from twenty to thirty-two. If you will inspect the following figures you will see how this is possible: the first represents the original disposition of the 39counters in the cells of the square; the second, that of the same counters when four are taken away; the third, the manner in which they must be disposed when these four are brought back with four others; and the fourth with the addition of four more. There are always nine in each external row, and yet in the first case the whole number is twenty-four, in the second it is twenty, in the third twenty-eight, and in the fourth thirty-two. The numbers are substituted in the place of the counters in the above figures for convenience, but Fig. 5 represents the disposition of the counters, as indicated in Fig. 2.

By knowing the last figure of the product of any two numbers, to tell the other figures. If the number seventy-three be multiplied by each of the numbers in the following arithmetical progression, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 24, 27, the products will terminate with the nine digits, in this order, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1; the numbers themselves being as follows: 219, 438, 657, 876, 1095, 1314, 1533, 1752, and 1971. Let, therefore, a little bag be provided, consisting of two partitions, into one of which put several tickets, marked with the number 73, and into the other put as many tickets, 3, 6, 9, etc., up to 27. Then open that part 40of the bag containing the number 73, and ask a person to take out one ticket only; after which, dexterously change the opening, and desire another person to take a ticket from the other part. Let them now multiply their two numbers together, and tell you the last figure of the product, by which you will readily determine from the foregoing series what the remaining figures must be. Suppose, for example, the numbers taken out of the bag were 73 and 12, then as the product of these two numbers, which is 876, has 6 for its last figure, you will readily know it is the fourth of the series and the other two figures must be 8 and 7.

These numbers must not exceed 9. Let him think of two or three numbers, double the first and add 1 to the product, multiply the whole by 5, and add to that product the second number. If there be a third, make him double the first sum and add 1 to it; then desire him to multiple the new sum by 5, and to add to it the third number. If there should be a fourth number, you must proceed in the same manner, desiring him to double the preceding sum, to add 1 to it, to multiply by 5, and then to add the fourth number, and so on. Then ask the number arising from the addition of the last number thought of, and if there were two numbers subtract 5 from it: if three, 55; if four, 555, and so on, for the remainder 41will be composed of figures, of which the first on the left will be the first number thought of, the next the second, and so of the rest.

Suppose the numbers thought of to be 3, 4, 6; by adding 1 to 6, the double of the first, we have 7, which being multiplied by 5 gives 35; if 4, the second number thought of, be then added, we shall have 39, which doubled gives 78, and if we add 1, and multiply 79 by 5, the result will be 395. Lastly, if we add 6, the third number thought of, the sum will be 401, and if 55 be deducted from it we shall have for the remainder 346, the figures of which 3, 4, and 6, indicate in order the three numbers thought of.

As boys are always interested in short cuts in arithmetical processes, it may be well to insert for the benefit of those who are studying multiplication, a method of proving their examples which I learned a short time ago from an old banker of New York. This rule is simply to add the digits of both multiplicand and multiplier, divide both answers by 9, and multiply the remainders; divide this product by 9 and the remainder will be, if the example is correct, the same as that obtained by adding the digits of the product and dividing that answer by 9. For instance, suppose after multiplying 4359 by 2786 we have 12144174 for the answer; now instead of performing this operation over a second time to make sure our answer is correct, we simply add the digits in 4359 and divide the 42sum 21 by 9, we find we have 3 left. As it is the only remainder we have to deal with, we need not keep the other figures. By adding the digits in the multiplier we obtain 23, which divided by 9 gives 2 and 5 remainder. Now, multiplying the first remainder by the second we have 15: this product divided by 9 gives 1 and 6 remainder. If the product 12144174 is correct, the sum of its digits divided by 9 will leave 6 for a remainder. Performing the operation, we find the sum of its digits is 24, divided by 9 equals 2 and 6 remainder. As both the remainders correspond, the answer was correct. After a little practice you will find you can prove your examples very quickly by this method, and where a number of sums are given without the answers it will be of invaluable assistance, besides saving you a great amount of labor.

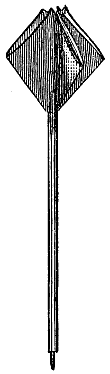

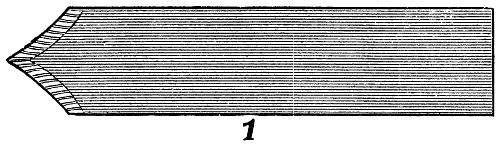

The dart, and its larger brother the javelin, were among the earliest weapons used in warfare, and were very skilfully thrown, not only by the Roman soldiers, but by the Goths and other savage tribes who lived in the regions north of them.

These javelins were large affairs, measuring some six or seven feet in length; the handle, a tough piece of wood, was generally four and one-half feet in length, and an inch in diameter, while the rest of the length was taken up by the barbed triangular-shaped head.

Ever since those days children of all nations and climes 43have made toy implements, resembling those in general appearance, but varying much in size and materials used.

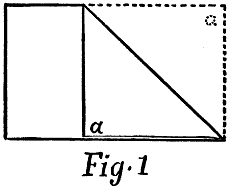

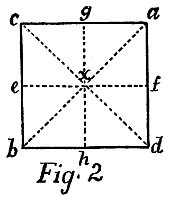

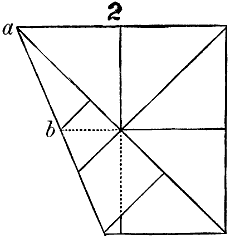

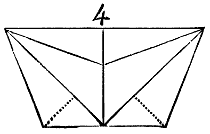

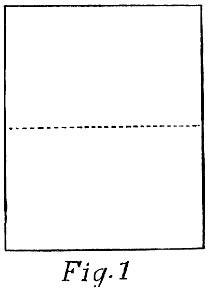

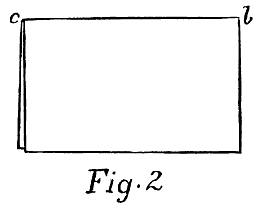

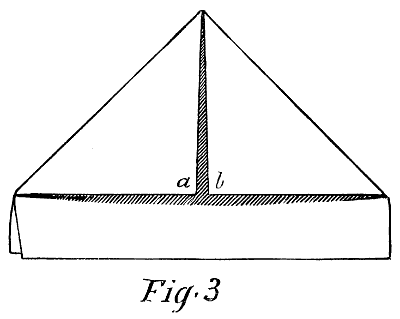

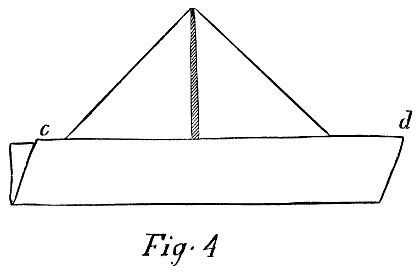

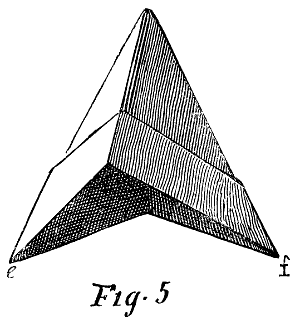

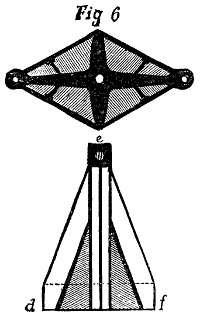

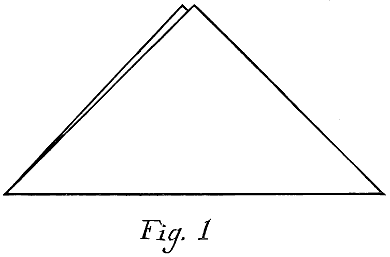

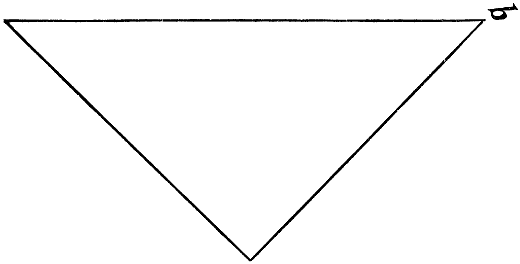

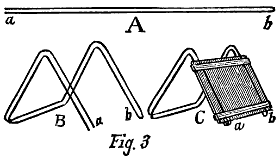

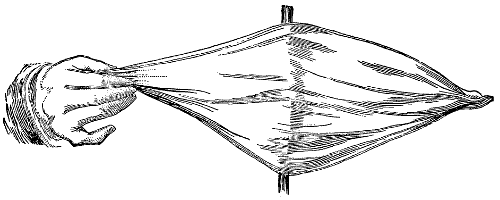

The little dart described below is perhaps the tiniest and least formidable of them all; but even this should not be carelessly tossed about the room in which others are playing; when, however, thrown in the open air, and away from others who might be hurt, there is considerable amusement derived from the airy bit of flying wood, which always comes down with such unerring certainty upon its spear-like head. To make this dart, take half a sheet of note-paper, double it diagonally across, so that its top edge may fall evenly upon that of one side (see Fig. 1), and cut off the surplus piece of paper which remains uncovered at the bottom of the page. Open your square, and fold it again in the other diagonal line c, d (the first is represented on Fig. 2, as a, b). Now, opening again, fold upon the line e, f, then, after opening, upon g, h. Crease all the folds as you make them. Now, having prepared your handle, which consists of a piece of wood about 8 inches long and the size of a lead pencil, cut across one end at right angles, with slits nearly or quite an inch in depth; take your paper and open it flat once more. Fold the diagonals so that the four points, a, b, c, d, shall all meet together above x, and the 44lines ax, bx, cx, and dx shall meet at the central line of the figure, and the four shorter lines, ex, fx, etc., form the outside edges of the figure. Insert a tiny wedge or knife-blade at the bottom of the slits, and press the paper down in the opening, bringing the folded edges through each of the four slits; remove the wedge, and the paper will be firmly held in its place. Insert a needle or headless pin in the other end of the wood, and the dart is ready for use.

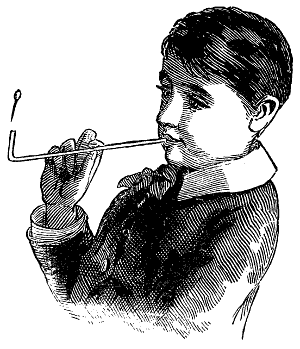

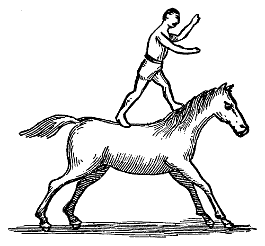

This amusing feat I first saw performed in our little district school-house, many years ago.

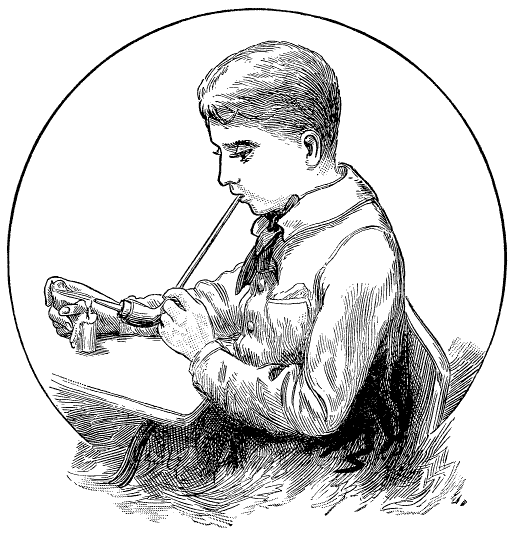

One morning, while the teacher was busy with his class at the blackboard, one of the boys drew an old clay pipe-stem from his pocket, and producing a small green gooseberry and a pin from some other part of his clothing, gave us boys to understand that he was about to perform some wonderful trick with them. We were of course all attention, and as the teacher’s back remained 45turned toward us, he proceeded to astonish us with his remarkable feat. He first stuck the pin through the gooseberry, and then let it fall, point downward, into one end of the pipe-stem; then, placing the other end to his mouth, and holding his head thrown well over backward, he blew into the opening, and the gooseberry and pin arose quite clear of the tube, and began dancing and balancing above it in a very funny way. How long it would have continued its gyrations I cannot tell, probably until his breath gave out, but just then a little boy in the front row made some exclamation, and straightway the teacher’s head came around, the pipe-stem, pin, and gooseberry went on a voyage of discovery out of the school-house window, and the boy got a thrashing for his pains. But the feat was often performed by us all after that, and some years later, when a second generation of boys were having over again the tricks and sports their older brothers had outgrown, I saw the same principle applied under more favorable conditions. Instead of the straight pipe-stem, which necessitated throwing the head over backward, to insure its perpendicular position, a tube bent at a right angle near one end was used, and the balancing of the pin could be much more easily watched by the performer. Instead of the gooseberry, a currant, pea, or any light, round fruit can be substituted, and a small glass tube may take the place of the pipe-stem.

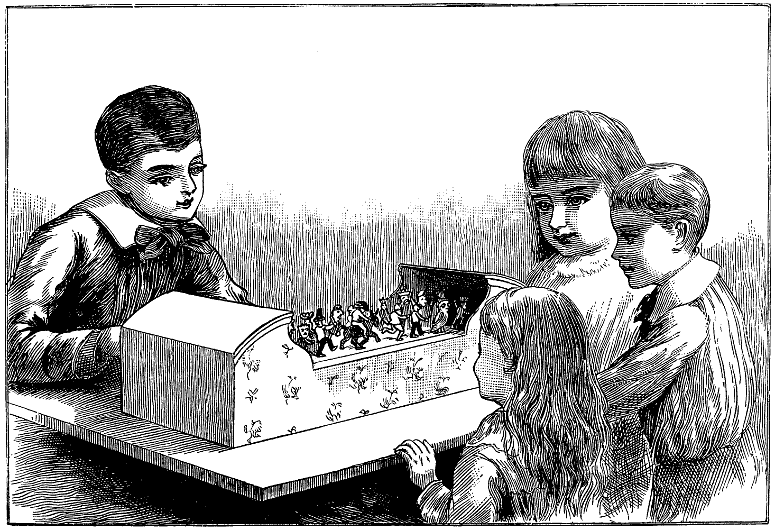

Procure a deep, smooth soap-box, and decide how high you wish the back and front to be; then take a piece of brown paper, the exact size of the sides of the box, and mark on it a curve, which shall unite the high back with the low front. After this has assumed a perfectly satisfactory form, cut it out and tack it on one side of the box. Mark the outline carefully on both side-pieces, and saw the boards as indicated by the line; cut the front straight across, and rasp and sand-paper the edges till they are very smooth and well rounded. Next paint the box inside and out, excepting the bottom, which is to be fastened to the sled, with a thick coat of burnt umber, and give it a good drying. Then with light-blue paint, make a narrow band, one-fourth of an inch wide, entirely around each side, the back, and the front, about half an inch from the edge. Stencil a pretty design on the back, and the name of the little owner on each side; let this thoroughly dry, and finish with two coats of varnish. A little seat can be fitted in the back part if desired, but a pillow answers the purpose much better.

Procure a stick of wood of any length, and an inch and a half square at the ends. Saw it into pieces six inches 47in length, being careful to cut it evenly, that the blocks may be rectangular in form. Round off the tops slightly at the edges and paint them brown, then give the sides and ends a good coating of yellow.

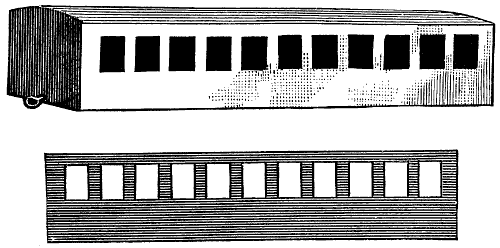

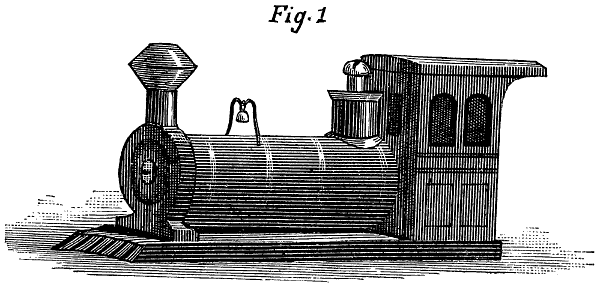

If you have no oil paints, it would be a good investment to get a few tubes, as they are not expensive, and are of invaluable assistance in adding beauty and naturalness to many things a boy can make. For the cars, a tube of chrome yellow, one of Indian-red, and one of black would be needed, but as those are not over seven or eight cents apiece the whole cost would be small. The windows can perhaps be most conveniently put on by “stencilling.” To do this, cut a piece of stout paper or thin cardboard the exact size of the side of the car, and mark the windows on it in their proper places (see Fig. 2). Then cut out the windows thus drawn with the point of a sharp penknife. Catch the card firmly upon the surface by 48driving two or three fine pins through it into the wood. Finally, with your brush moderately filled with the black paint, cover all the yellow surface exposed through the openings; then remove the card very carefully and one side of your car will be complete. After painting the whole set, another long time will be needed for drying. During the meantime obtain a few screw-eyes and hooks, and, when perfectly dry, screw a hook into the left and an eye into the right end of each car, join them into a train, and you will find you have a strong set of cars with which your little brother can play to his satisfaction, without a fear of breaking. The locomotive is more difficult to make, but with a little care any boy of ten can be quite certain of success.

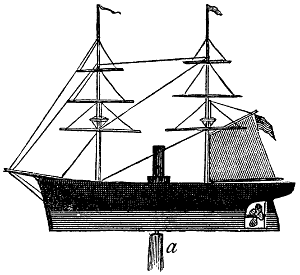

The thin ends of a common soap-box afford very good material for the base of this locomotive, while the end of 49a curtain-roller makes a capital boiler. The cab can be cut from a cigar-box, and a button-mold will do for the boiler-head. First cut from the thicker wood a base in shape like Fig. 1, and seven inches long by one and a half wide; with a jackknife bevel it on either side of the pointed end to correspond to the shape of the pilot, as shown in the cut. Saw the roller even at either end just four inches in length. Next cut from a solid block of wood a smoke-stack three inches high and an inch in diameter across the top. The cab is cut from the cigar-box wood, and consists of a front like a, two side-pieces like b, and a top like that seen in Fig. 1; round off the edges of the top to give it a slightly convex surface like the tops of the cars. Now, with brads, fasten these three parts together. Then with a long, slender brass screw fasten the button-mold and smoke-stack on front of the boiler. The screw should have as large a head as it is possible to find, and should be long enough to extend half an inch or more into the round section of wood or boiler. Cover 50the whole, excepting the cab, with two thick coats of black paint, being careful that the first is perfectly dry before the second is put on. After the blackened surface is thoroughly dry and hard, put the red stripes on the pilot, as seen in the cut: and for the brass bands around the boiler use chrome yellow. The cab is painted Indian-red, and after this is perfectly dry, the windows are painted on with black, as in the cars.

The little ornamental lines on the cab are made with the yellow paint. A large round-headed brass screw driven through a low flat spool (such as is used for button-hole twist), into the top of the boiler in front of the cab, makes a good steam-chest and whistle, and adds the finishing touch to this indestructible little toy. If you anticipate making this train of cars for a Christmas present, begin it in time, as paint dries much more slowly in winter than in summer, and it is absolutely necessary that each coat be perfectly dry before the next is applied. Varnishing 51greatly improves the durability and appearance of the painted surface. Shellac dissolved in alcohol makes the best varnish for this kind of work. It should be made moderately thick, and if intended for light-colored work, white shellac should be used, as the dark leaves a slight stain upon the surface. I forgot to add in its proper place that a brass button, caught in on top by a stiff wire, is made to represent a bell. The wire should be first bent into the shape seen in the illustration; the button then hung in position, and the wire finally driven into the holes made to receive it.

The tender consists of a piece of wood the same width but only half the length of one of the cars, and one inch high. This is painted black with a narrow band of yellow running around the sides near the top, and is fastened to the locomotive and car by means of the screw-eye and hook.

The locomotive for this train can be made like the one already described, and the cars are cut from a rectangular stick, in the same manner as the passenger cars. These should receive a thick coat of Indian-red paint, and if this does not cover well, that is, if any of the wood shows through, another coat should be given. After the paint 52is perfectly dry, put on one edge of the side, near the top, a number in white, and two or three letters in the same color, to represent the sides of the freight cars on different lines. If desired, the cars can be painted different colors, and the side decorations copied from the car you mean to represent. Give the whole a good varnishing with the shellac dissolved in alcohol, and allow plenty of time to elapse before the toy is used, for it to become perfectly dry and hard.

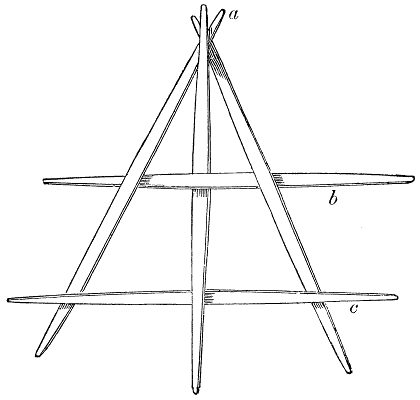

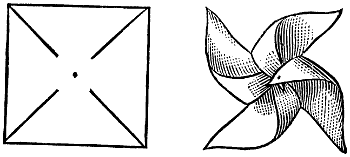

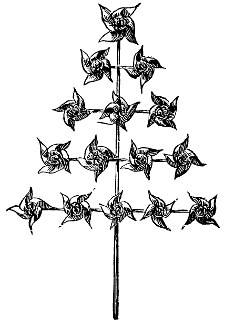

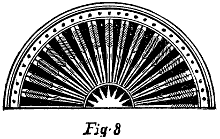

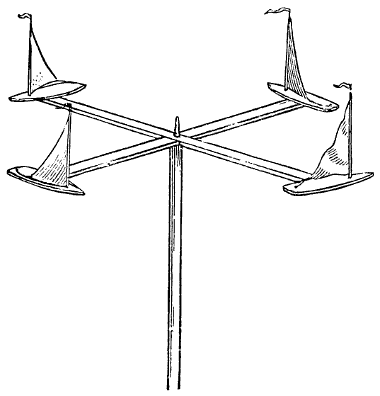

Take a thin stick of wood a foot and a half or two feet long, and nail to it four cross-pieces, graduated in length and six or seven inches apart. The shorter, at the top, should measure about six inches. Cut out of stiff, colored paper (the greater the variety the prettier the effect) fifteen pieces, each three inches square, and slit each piece as indicated by the diagonal lines in the figure. Out of pretty tissue-paper cut three round pieces for each mill, 53about the size of a silver dollar, and with a dull knife scrape their edges, that they may slightly curl like the petals of a rose; crinkle them at the center if intended for a rose, or from the edge toward the center if for asters or marigolds, and thrust a large, strong pin through the middle of each disk, drawing the flower well down over the head; then, bending the opposite corners of each square of paper so that they shall all rest over the central dot marked on each (Fig. 1), force the pin with the flower on its head, down through the five thicknesses of paper, driving it well into the wood of the frame. In doing this care should be taken to avoid creasing the curved edges of the windmills. They are placed upon the frame-work as indicated in the cut.

54Very pretty windmills are often made of only two shades, common note-paper being used for the wheels, and a bright, rosy pink tissue-paper for the flowers. Indeed, those made of common brown wrapping-paper without any flowers at all give more satisfaction in a light wind than the more elaborate ones described above.

Most boys love flowers; and many families, especially in the country, would keep more through the winter than they do, if they had the space and time to devote to them, necessary for their preservation. A number of pots, sufficiently large to hold good-sized plants, take up considerable room; and no little time is required each day, to keep the pots clean and the plants well watered. Now, boys, I have a suggestion to make, which I intend for your ears alone. Why can’t you make a winter garden, and, if necessary, take care of it through the season? It will amply repay you for your labor, and do much toward brightening the home life through the long dreary months, when everything without is covered with ice and snow.

First procure a soap-box, the best and tightest you can find: if any cracks are too wide to be easily closed with putty, nail laths over them on the inside, line their edges, and, in fact, stop every seam and crevice with good thick 55layers of putty. Next paint over the entire inside with any colored pigment you may have, as it does not show when the box is filled with earth, but simply aids in making it water-tight.

Now take four strong pieces of wood, about two and a half feet long; smooth them well and sand-paper; be sure both ends are cut off evenly, and that each leg is the same length as the other three, and, finally, nail them firmly to the four corners of the box, letting the tops come in line with its upper edge, and give the whole thing two good coats of Indian-red. A very pretty stand is made by substituting the straight trunks of young forest trees with their bark left on in place of the smooth, painted legs; bore holes in the bottom of the legs and insert casters, and finish by giving the entire outer surface a thick coating of varnish. Then get a good wheelbarrow-load of fine leaf-mold, about half that quantity of sand, and some common garden soil. Stir these well together, and fill the box half full with the mixture, first covering the bottom with pebbles, to secure drainage. Before this, however, bore a hole with a good-sized gimlet in the bottom of the box, and fit a soft pine peg to close it from the under side. When the plants are watered this peg can be removed, and a dish placed beneath the opening to catch the surplus water.

You are now ready for the plants. I find almost any garden plants thrive well in this box, so any favorites you 56may have will soon make themselves at home in these new quarters. It is well to put vines around the edge, as they fall over, and their glossy green leaves and stems form an agreeable contrast to the dark-red background of the box itself. In my present winter garden I have German and Cenilworth ivy, partridge-berry, and the common inch-plant for vines. In the center is a large salvia, taken up so carefully that the great ball of dirt was not shaken from its roots. On one side is a calla lily, and on the other a feverfew of the large double variety. At the ends are fuchsias and heliotrope, and scattered over the other available spots are verbenas and petunias, sweet peas and lobelia; one or two fish-geraniums of bright colors also found a place, and a little wood-violet nestled in one corner has bloomed since early spring. A beautiful large purple pansy, too, has been blooming all winter in another corner of the box.

Over this garden are two hanging-pots, one filled with pink oxalis, and the other with a Chinese pink; both have contributed their full share of blossoms during the entire season, and neither seems to tire of well-doing. I must now tell you how to care for these beautiful pets, for they must receive some attention, which, however, is very small when compared with that required by their sisters in pots. First, always water them with warm water (almost as hot as you can bear your hand in), pour this around the roots in sufficient quantities to thoroughly 57moisten the soil. A good rule to be observed in watering your plants is to pour on the water until it begins to run out of the hole in the bottom of the box. With such thorough wetting down they will not need water oftener than twice a week, except when the sun is very hot, and the moisture evaporates quickly. A little carbonate of ammonia added to the water greatly improves their growth, and half-a-dozen grains of permanganate of potash added once a fortnight to the warm bath turns their foliage a rich dark green. With a whisk broom, sprinkle them once or twice a week with water which is also warm, but not as hot as that used on their roots; this operation takes but little time, scarcely five minutes, and as the stand is on casters it can be easily moved to the middle of the room, and each side can then receive its full share of the washing. It is safe to predict that if any boy would make the stand, and supply it with rich soil, his mother or some one of his sisters would only be too happy to plant and care for the flowers it might hold.

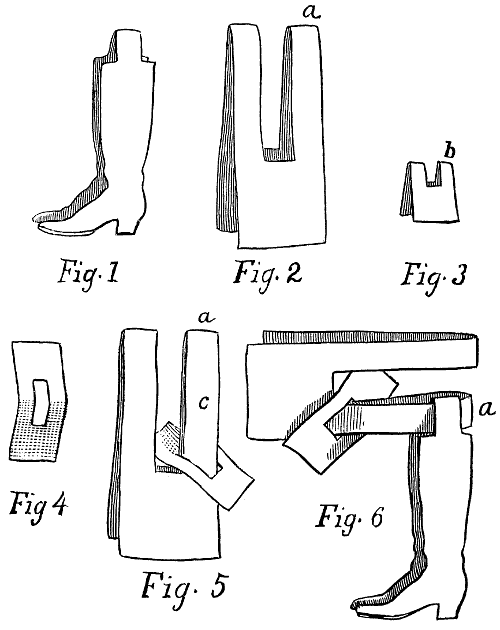

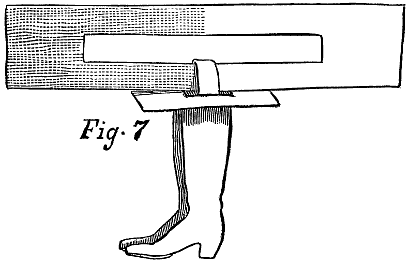

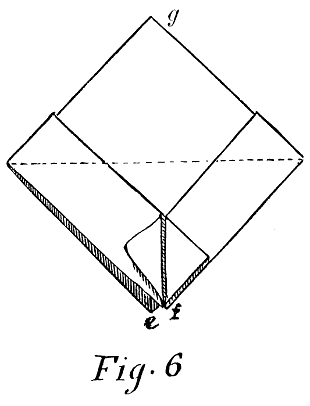

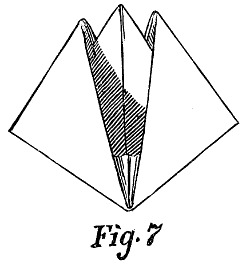

First take a piece of paper, double it, and cut from it a pair of boots, the fold in the paper coming at the top of the boots, and consequently joining them together. Then 58take another piece, fold it and cut it in the form of Fig. 2, a being the folded end. Fold still another piece and cut it like Fig. 3, b representing the folding side. Now open the smaller piece, as in Fig. 4, and push the point a through the opening in its center (Fig. 5). Then put one boot through the loop of the long arm, c, between a and 59the smaller piece, which has been pushed forward as far as it will go (Fig. 6). Now pull the smaller piece down over a, and open the largest piece, and the boots are fastened on to the larger paper in such a way that it is rather hard for the uninitiated to extricate them.

After they are fastened in place, with your finger-nail smooth out the creases made at a, Fig. 5, as their appearance might furnish a clue toward solving the mystery. It is best when cutting Fig. 2 to avoid the creasing if possible.

When you pass them to your friends to take off, explain that they are not to bend the boots. It is an excellent plan to make the last-named articles of cardboard, while the other parts are simply of note-paper.

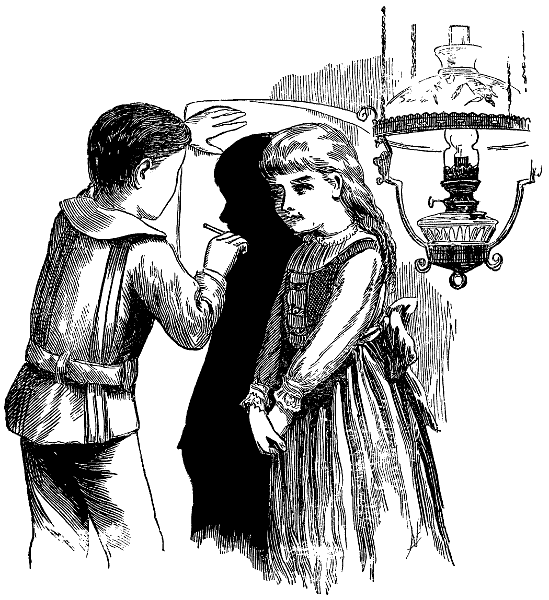

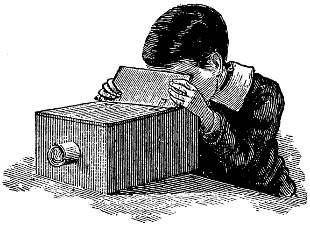

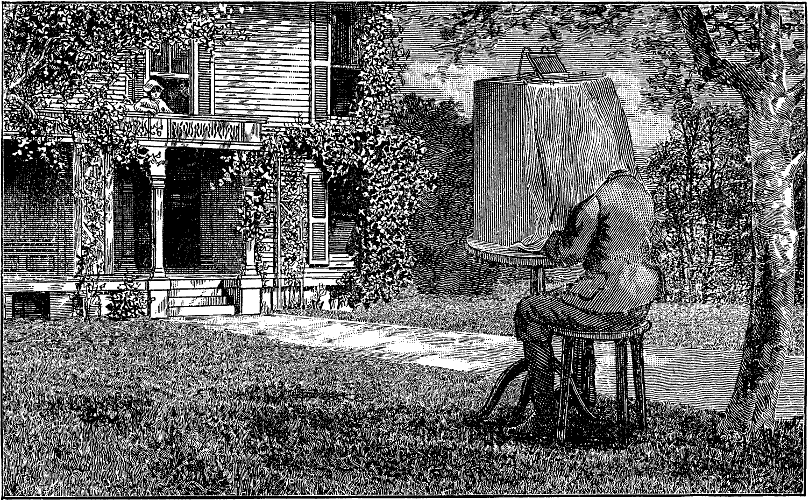

The person whose portrait is to be taken must sit so that his shadow is thrown upon a sheet of cardboard or thick white paper placed against the wall. To obtain a sharp outline there should be a fixed distance between the lamp, wall, and sitter, which can easily be found by experiment. The sitter must keep perfectly still while the outline of the shadow is quickly traced upon the paper. A tumbler or roll of paper may be placed between the head of the sitter and the wall, to aid in holding the head quiet. The tracing is then cut out with a pair of scissors or a sharp penknife, and placed upon a dark cloth or paper. This is a very pleasing amusement for a cold winter’s evening, and the results are often profile likenesses not only very striking but often wonderfully accurate.

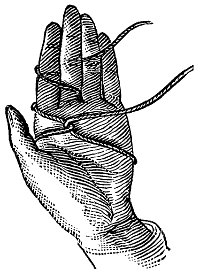

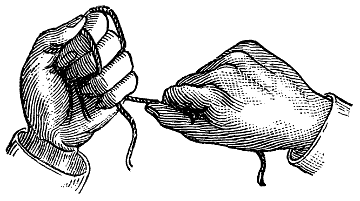

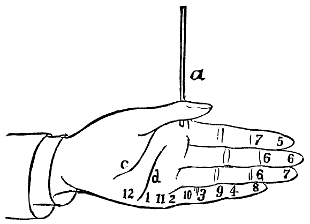

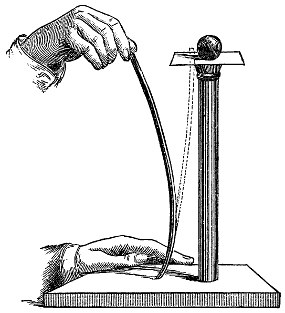

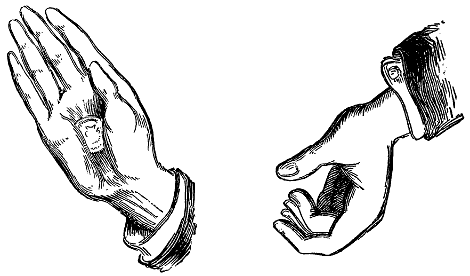

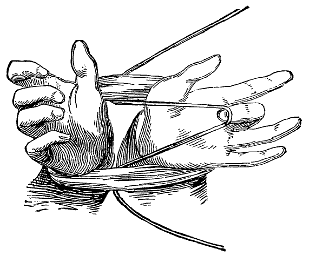

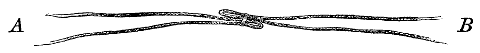

No boy feels himself perfectly at home if he has not one pocket at least full of strings, and a good sharp jackknife at his command. Although the jackknife often gets lost, the string is usually at hand, and most boys will probably be glad to learn how a good strong cord can be broken without injury to the hands. Take the cord and 63pass it around the left hand, as shown in Fig. A, so as to form a cross or double loop over the palm. One end is then wound round the fingers, and the other seized in the right hand. Then, by closing both hands, and giving a very sharp, quick pull, the string will be broken at the cross in the left hand.

64For those boys living in the country who have a musical turn, but have never seen this little instrument, I write the following description of

Find a good straight corn-stalk, and with your jackknife cut four slits from joint to joint, as seen in the upper figure. Then from a bit of wood cut a bridge, as shown just below. With the point of the knife lift the three strings and insert the bridge. Then carefully raise the bridge to its upright position, spread the strings until they rest in the grooves cut in the bridge for that purpose, and put a similar bridge at the other end. Make the bow in the same manner, of a smaller section of a stalk, and the instrument is complete. I have never heard a very decided tune played on this fiddle, but perhaps some of my readers may be able to get music from this simple little instrument.

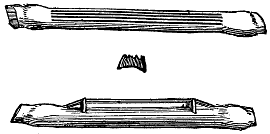

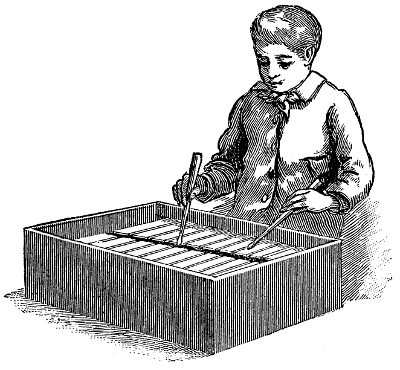

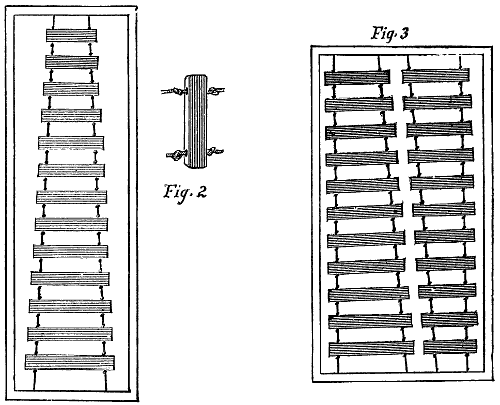

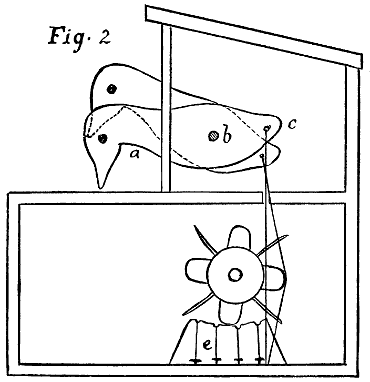

The xylophone is an instrument of great antiquity, having been used in a slightly different form by both Greeks and Hebrews. It is now sometimes used in connection with other instruments in our larger orchestras, in which case, however, the bars are usually made of metal. Its construction is very simple, and any boy having a good ear for music can readily make one.

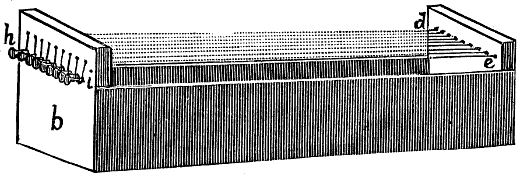

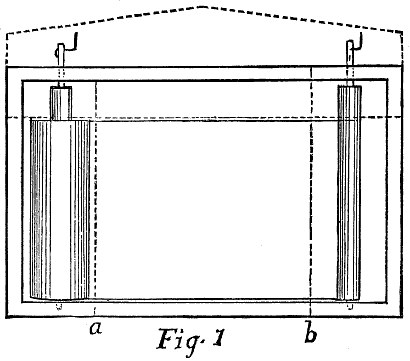

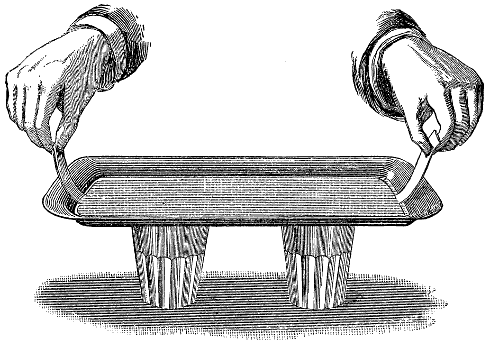

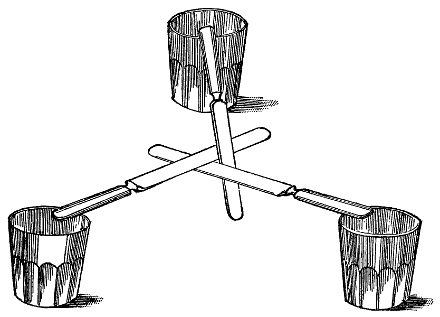

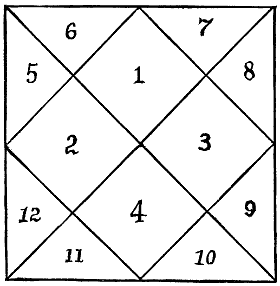

The instrument is composed of strips of wood of various sizes, and thick enough to allow the passage of a stout piece of twine or fish-line, as seen in the illustration. The largest strips give the lowest notes. The first note of the scale may be a strip of any convenient size, and the succeeding strips are tuned by carefully cutting away from 66the under side until the desired tone is produced. They are strung upon cords, in the manner shown in Fig. 2, a knot being made on each side to keep the strip in place; and finally, across the upper part of a box, in order to give sufficient resonance of sound. In putting these strips together, it is necessary to have the holes through which they are strung at a slight angle, or in the direction of the slant which the strings take when fastened to the frame.

The arrangement seen in Fig. 3 is perhaps best adapted to the usual form of a box, and affords a greater range of 67notes. It would be well to letter the upper part of the bars with the name of the note they are intended to produce, and the wood should be thoroughly seasoned from which these bars are made.

It is well to have the lowest note not the first of the scale but a fifth below, and the highest three or four notes above the octave. This will give sufficient compass for any air you may care to play.

A good ear for music is of the greatest importance to insure success in constructing an instrument of this description, and it would simply be a waste of time and patience for any boy not so blessed, to venture upon the undertaking.

Little wooden mallets are sometimes used to play upon this xylophone, but the little drumsticks belonging to the common toy drum are better for the purpose.

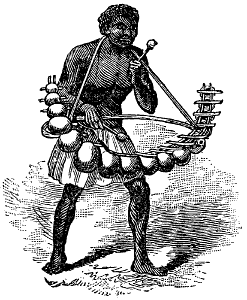

Among the tribes of southern Africa an instrument of this class holds the chief place in their festivals, and is played upon with considerable skill by many of their native musicians. This piano, called by them “marimba,” consists of two bars of wood placed side by side; in the most southern portions quite straight, but farther north, bent round so as to resemble half the tire of a carriage-wheel; across these are placed about fifteen wooden keys, each of which is two or three inches broad, and fifteen or eighteen inches long, and their thickness, as in the case of the xylophone, is regulated according to the deepness of the note required. Each of the keys has a calabash beneath it; from the upper part of each a portion is cut off to enable them to embrace the bars, and form hollow sounding-boards to the keys, which also are of different sizes, according to the note required; and little drumsticks, like those spoken of above, elicit the music. Rapidity of execution seems much admired among them, and the music is pleasant to the ear.

In Angola, the Portuguese use the marimba in their dances.

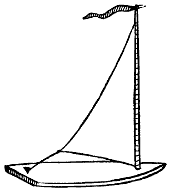

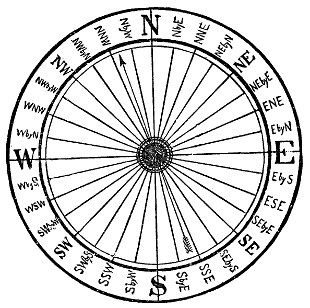

This simple little musical instrument derives its name from Æolus, god of the winds, who is said to have lived 69at Stromboli, then called Strongyle, while he reigned over the Æolian islands, just north of Sicily. His island was entirely surrounded by a wall of brass, and by perfectly smooth precipitous rocks. Here he dwelt in continual joy and festivity with his wife and children; the latter, six sons and as many daughters, are said to be a poetic type of the twelve months of the year. And here he kept the winds, tied up in bags, in perfect subjection, only letting them out when called upon to do so by Neptune, god of the sea. As the winds served Æolus on his little isle, so we force them to serve us in our far-away western homes, by operating upon our instrument and making music to soothe and calm us when we are too tired or indolent to make it for ourselves. The simplest form this instrument can have is a single string of strong waxed silk, stretched between two bits of wood, inserted under the lower window-sash, sufficient space being allowed between the window-sill and the sash for the vibration of the string.

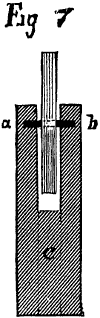

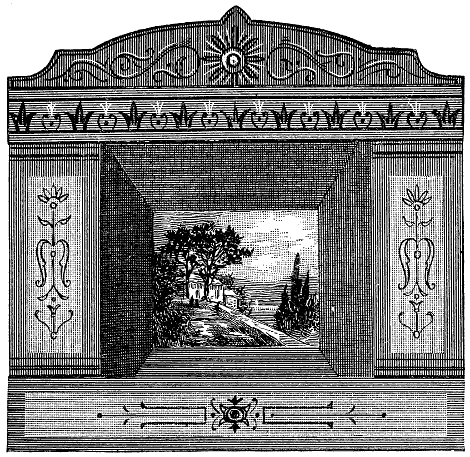

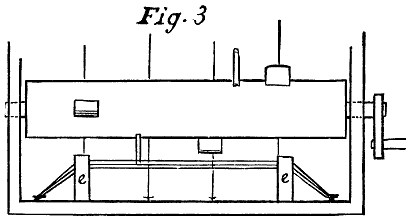

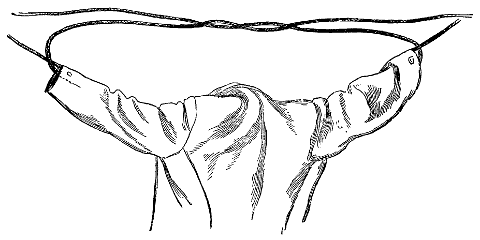

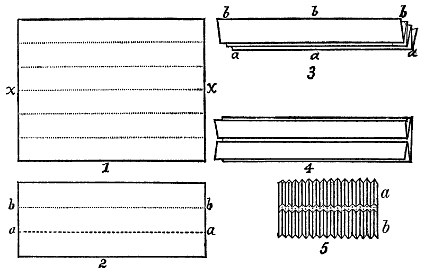

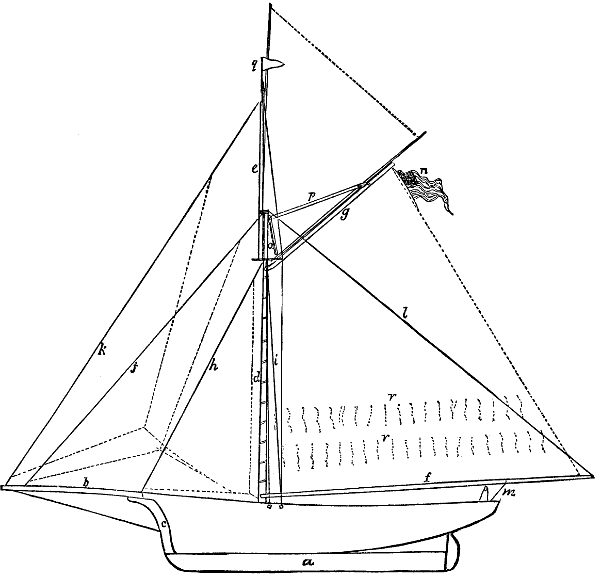

The other and more satisfactory harp is made like that 70in the engraving, and is not so difficult an undertaking, that any boy who can handle carpenter’s tools need fear to try it. Take two long strips of thin, soft pine wood, four and five inches wide respectively, and a little shorter than the sash is wide, to allow for the length of the pegs at one end; then from common seven-eighths of an inch board make two other pieces in shape like b, six inches wide, six high, on the narrower, and seven on the back or longer side. With a small gimlet make in both ends a row of eight or nine holes, at equal distances from each other, and half an inch from the edge of the slanting top, for the strings to pass through; then with a larger gimlet bore in one end only, the second row of holes, h i, to hold the pegs upon which the ends of the strings are to be wound. Nail the parts together as in the cut, making the lower edges of the pieces meet at the bottom; then from the outside of d e draw through as many pieces of violin string (the smallest or E string) as you have holes in your wood. Hold these by knots on the outside, and having brought them across the box pass them through the corresponding holes in the other end, and twist them around the pegs below, in the same manner that the strings are fastened in the violin itself. Unlike the violin, however, these should not be drawn too tight, simply stretched evenly across, and must all be tuned in unison. That is, having drawn one as tight as 71you think best, draw the others, one at a time, till they give forth the same musical note when snapped with the finger. Now put another thin piece of board across the top which shall just cover it like the lid of a desk. This was purposely left out in the illustration, that the arrangement of the strings might be more fully seen, but is necessary in the complete instrument. If catgut cannot be readily obtained, strong pieces of sadlers’ silk, well waxed, may be used in its place, although the tones resulting are not as musical, or the strains as soft and lulling in character, as those produced by the former.

After the instrument is properly tuned, place it upon the ledge of an open window, and let the sash down upon it, when, if there is any breeze stirring, it will pour forth strains of sweet, drowsy music, beautifully described by the poet Thomson, as supplying the most suitable harmonies for the Castle of Indolence.

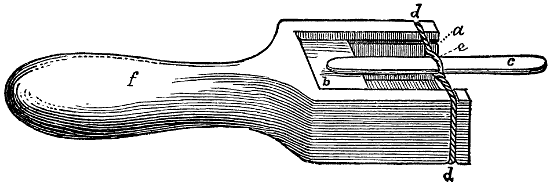

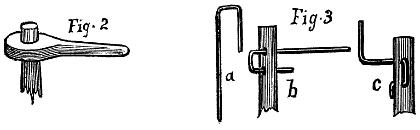

Take a piece of soft wood, five or six inches long, and whittle out of one end a hollow box, open at the top and outer end, like that represented in the illustration. Cut a groove around the inside, near the top, for the cover to slide in. Make this cover of a very thin piece of tough 72wood, and one-third as long as the opening, pushing it, when completed, well up against the inner end of the box; see b, in the figure, for size and position of cover.

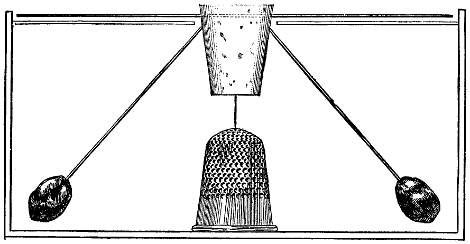

The handle, f, is simply for convenience in holding the instrument. Pass a piece of strong string or fish-line twice around the box at the point d, and after drawing it as tightly as possible, tie it firmly on the under side.

Out of hard, tough wood make a thin, slender tongue, c, and place this between the two strings at e. Now twist this tongue over and over, each time drawing out the longer end, to allow of the other sliding by the edge of the cover. At each revolution of c the string is twisted tighter around the box, and if the end of c is touched, the other end strikes with more force upon the cover b.

When sufficiently tight, grasp the handle with your left hand, and having the point well over the cover, commence with the third finger of your right hand and 73strike down on the end c with the fingers in their order, giving quick and repeated blows, like the successive taps of a drum. The music produced, if not strictly melodious, is quite enchanting to the average American school-boy.

I have now come to one of the most fascinating and at the same time useful employments a boy can have; one which not only affords amusement for the time being, but, if properly executed, furnishes home with much which is useful or ornamental, at scarcely any expense beyond the mere time and labor consumed in the work.

How many of my readers know how to make things of papier-maché? None who are old enough to read these directions are too young to make really useful objects or pretty playthings of this inexpensive medium; indeed, many of the children of India, Persia, and many other Asiatic countries support themselves, and in some instances whole families, by making ornaments of papier-maché.

In Germany this art is carried to a great extent, and a large proportion of the German toys so common in our stores, as well as the jointed bodies of the expensive French and German dolls, are made of this material.

Papier-maché means “softened paper,” and is simply 74any old soft paper converted into pulp by water; the poorer the paper the better. Cheap newspapers, such as tear with a mere touch, thin handbills and posters, are all particularly suited for this purpose.

For a first trial it would be well to take some simple object, and a cup would perhaps make as good a beginning as any. First have some good flour-paste made, by pouring into boiling water enough flour, which has previously been moistened with cold water, to make a substance rather thicker than boiled starch; this should be stirred only enough to unite the flour with the water, and to prevent burning. Add to this one or two old newspapers and a dish of water, a broad brush for the paste, and any prettily shaped tea-cup conveniently at hand, and you have all the materials required. A bag filled with sand or stuffed hard with cotton is a great help in molding, although not indispensable to the operation. Take the cup, which should be well smeared over with sweet-oil or lard, and cutting out a piece of paper sufficiently large, wet it, and press it down on the cup, using the fingers, or the sand bag, if you have it, for the purpose; then with the brush spread the paste over the paper, and lay on this another piece; press this down as before and continue the process until twenty or thirty paper coverings have been used. After the first two or three layers, it is not necessary to use pieces which entirely cover the surface; 75any sized scraps will do if they are so placed that the same thickness is preserved throughout. The outer surface should be as smooth and even as possible. When this is completed, let it dry for a day or two in any moderately warm place, as it is not well to dry it too quickly. When it seems sufficiently hard, remove the mold, and you will have a pasteboard cup with an uneven edge which must be trimmed with a sharp knife and smoothed with sand-paper.

It might be well to trim off the top before removing the mold, as you would be more certain of getting it even by so doing. After this the cup can be painted in any manner desired.

A plaque can readily be molded upon the inside of a plate or saucer, and a pretty work-basket can be made upon a shallow bowl. Toy boats are made in the same manner as the cup, upon wooden molds cut out for the purpose.

Card Receivers.—These are generally flat dishes or shallow cups, made to hold visiting-cards, or the varied collections from Christmas, Easter, and New-year’s. They may be molded on plates, saucers, or small bowls, or receiving their concave shape from a plaque or saucer, they can be cut into any fantastic form your fancy may dictate. A large, well-shaped grape-leaf, or the catalpa, would furnish pretty designs to those who have no confidence in their own skill in that direction.

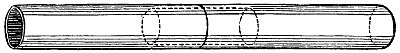

76Umbrella Holders.—Take any cylinder with a smooth surface, about two feet in length, and six to ten inches in diameter, for the mold; make upon it a coating of papier-maché about half an inch in thickness. It is made much stronger by rolling it during the pasting. The bottom may be of the same material, or a wooden disk made to perfectly fit into the cylinder. The whole surface should be thoroughly sand-papered and given two or three good coats of paint. A simple band of gold paint around top and bottom forms a pretty finish, but a large bunch of peonies or poppies, freely painted upon one side, greatly improves its appearance.

By reducing a quantity of paper and paste into a pulp, and allowing that to become a little dried—still moist, but not liquid—a number of objects can be molded, such as animals, boats, marbles, etc., by simply forming them with the hands and allowing them to dry.

Paper pulp is sometimes mixed with common blue clay and glue, instead of flour-paste, used as a binding material.

A beautiful vase can easily be made of papier-maché by forming a frame-work of pasteboard, and joining it together with a few stitches or with narrow strips of strong paper pasted across the edges. Make this frame-work as near the form and size of your vase as it is possible for you to get; then with your thin paper line it inside and 77out, until it seems as thick as you desire. Trim and sand-paper off the upper edge, and cover with one or two extra layers to insure a rounded edge common in earthenware vases. Stand it on a smooth, even table or board to make it flat on the bottom, and let it have plenty of time to dry. Next make from the paper pulp and fine clay preparation spoken of above a rose, poppy, or other flower, with its leaves and buds, resembling as nearly as possible those on the bisque vases so fashionable just now. This may seem at first a very difficult undertaking, but by molding one petal at a time, and placing each in position with glue as it is finished, the work is comparatively simple. Do not undertake a difficult flower at first. If in summer, you may take any from the garden, and after enlarging every part in the same proportions, make it your model. When the flowers, stems, and leaves are all in place, let them become thoroughly dry, then after painting the body of your vase with shades of blue, red, or olive, so applied that they give a clouded effect to the whole, color your flowers as nearly as you can like the natural ones of the same species, and the stems and leaves the proper shades of brown or green. Let this paint thoroughly dry, and then varnish with the white shellac dissolved in alcohol spoken of elsewhere in this book, if a very light surface is to be covered, or with the dark shellac or common varnish if the surface is intended to be dark. The floral 78decorations are not absolutely necessary, and a very pretty vase is made by simply painting the smooth surface with any graceful or pretty design, and varnishing it subsequently to give it the desired polish.

In the skillful management of paper, the Japanese are acknowledged to take the lead, as their balloons and kites, lanterns and fire-screens, now so commonly seen in this country, will testify.

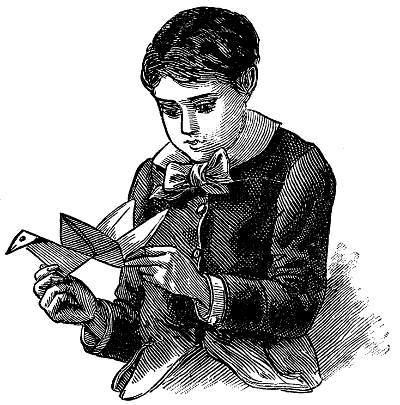

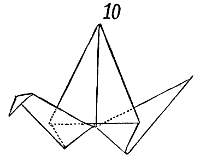

Many of the grotesque and hideous monsters, which 79nevertheless are artistic in form and decorative in effect, are made of paper pulp, with the necessary materials added to give it the proper degree of hardness; and in articles made of folded or crinkled paper they have no equals, while in some instances they apparently infuse life itself into their airy creations. By simply folding a square piece of paper in the manner here described, they produce a bird-like figure, which will move its wings in quite a natural and amusing manner.

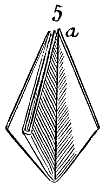

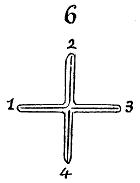

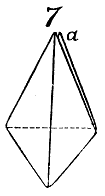

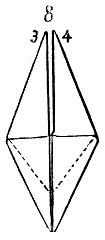

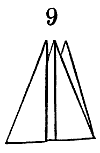

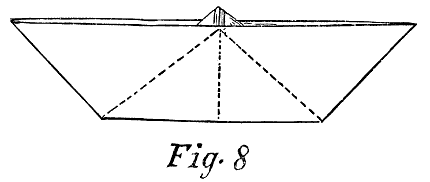

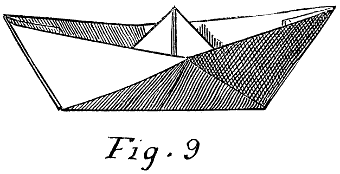

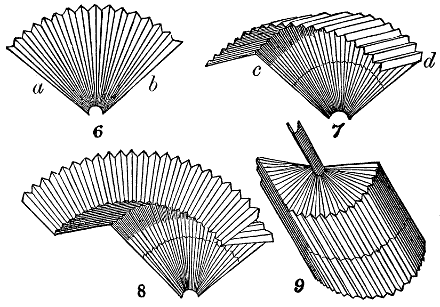

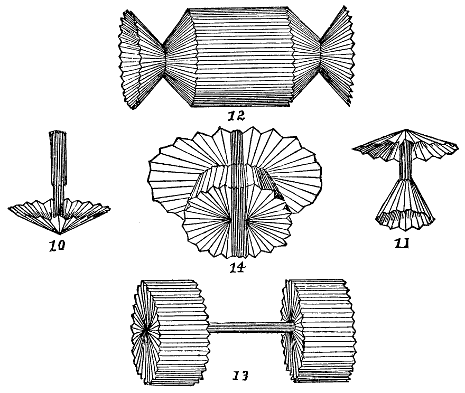

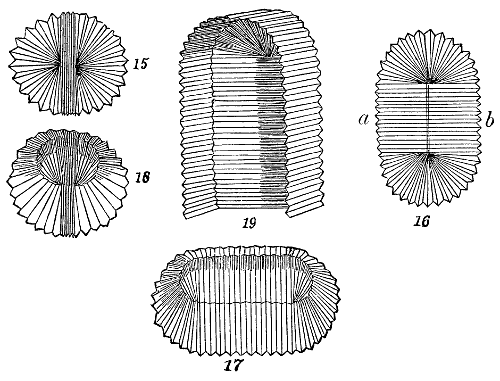

A leaf of paper—letter-paper is good for the purpose—is cut into an exact square; fold this cornerwise, and then through the middle each way, as indicated in Fig. 1. This done, turn over each corner in succession, so that the edge of the square will be along one of the cornerwise folds, as in Fig. 2, and fold sharply the portion from a to b. Do this eight times, twice with each corner, first turning it one way and then the other, till it has the folds shown in 80Fig. 3. Turn inward two of these portions, indicated by the shading, as in Fig. 4; this will draw together the other two sides; fold it closely across the middle, a b, as in Fig. 5; then repeat the same in the other direction, folding on the line c d. This is done to mark the folds, which may be made more completely by pressing them with the finger-nail. Now it will be easy to bring the corners of the square up together, making a figure like No. 5 or like No. 6, when looking down on the meeting of the points at a. Then bring the points 1 and 2 together, also 3 and 4, 81and your figure will be like No. 7. Take the two outside points at a and turn them down, folding at the dotted line, and you have Fig. 8. Now turn down the other two points, 3 and 4, one forward, the other backward, making Fig. 9, with two broad points inside and two narrow ones outside. Turn and fold these narrow points to the right and left, and turn down the end of one point to form the head, and you have the bird, Fig. 10. Take it by the head and tail, as shown in the final view, and move them to and from each other. After a little careful working, when the folds become flexible in the proper places, you will make the bird flap its wings. It can be done after a few trials, if not on the first, and is sure to afford amusement to all.

Fill a quill with quicksilver, seal it at both ends with good hard wax; then have an egg boiled, take a tiny piece of shell off the small end, and thrust in the quill with the quicksilver; lay it on the floor, and it will not cease tumbling so long as any heat remains in it; or if you put quicksilver into a small bladder, and then blow it up, upon warming the bladder it will skip about as long as heat remains in it.

Take a saturated solution of alum, and, having spread a few drops of it over a plate of glass, it will rapidly crystallize. When this plate is held between the observer and the sun or a lamp-flame, with the eye very close to the smooth side of the glass plate, there will be seen three beautiful halos of light at different distances from the luminous body. The smallest, which is the innermost circle, is the whitest, the second is larger and more colored, with its blue rays extending outward, and the third is very large and highly colored.