Title: The Downfall of the Dervishes; or, The Avenging of Gordon

Author: Ernest Nathaniel Bennett

Release date: March 21, 2016 [eBook #51520]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brian Coe, John Campbell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

Obvious typographical errors and punctuation errors have been corrected after careful comparison with other occurrences within the text and consultation of external sources.

More detail can be found at the end of the book.

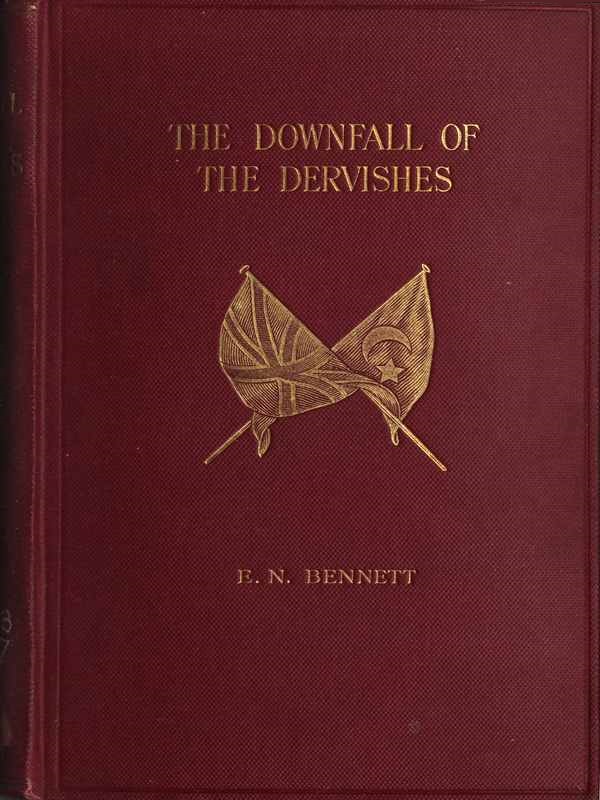

Art Photogravure Co. Ltd.

Lord Kitchener of Khartoum.THE DOWNFALL OF THE DERVISHES

OR

THE AVENGING OF GORDON

BEING A PERSONAL NARRATIVE OF THE

FINAL SOUDAN CAMPAIGN OF 1898

BY

ERNEST N. BENNETT, M. A.

FELLOW AND LECTURER OF HERTFORD COLLEGE, OXFORD

SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT FOR "THE WESTMINSTER GAZETTE"

WITH A PORTRAIT, MAP AND PLANS

LONDON

METHUEN & CO.

NEW YORK

NEW AMSTERDAM BOOK COMPANY

1899

TO

MY FRIEND

H. R. H.

I DEDICATE THIS LITTLE BOOK

In the following pages I have aimed at furnishing some account of the interesting experiences which fell to our lot during the recent campaign in the Sudan.

My best thanks are due to several friends for the assistance they have rendered me, and I feel especially grateful to H.H. Prince Christian Victor of Schleswig-Holstein and Major Stuart-Wortley, C.M.G., for their very kind help in supplying me with much additional and interesting information about the work of the Gunboats and the Friendly Tribes.

I must also acknowledge the courteous permission accorded me by the Editor of[viii] the Westminster Gazette to use in the compilation of this book some of the letters which I had previously contributed to the columns of his newspaper.

ERNEST N. BENNETT.

Hertford College, Oxford,

1st November 1898.

CHAPTER I

From Cairo to the Atbara

PAGE

Correspondents' Permits—Academic Obstacles—Fellow-Passengers to Alexandria—French Animosity in Egypt—Indifferentism of Egyptian Natives—An Interesting Dinner—Preparations for the Campaign—Egyptian Magic—A Native "Medium"—Ali buys a Sword—Departure from Cairo—A Matrimonial Quarrel—Rumours about the Khalifa—Discomforts of the Night Journey—The Luxor Hotel—Malevolent Spiders—Karnak—By Rail to Shellal—Imbecility of Ali's Brother—Hospital Arrangements—Dreariness of a Nile Voyage—Cheerfulness of Tommy Atkins—A Classic Tale of Horror—Death of a Soldier—From Wady Halfa in a Cattle Truck—Abu Ahmed—First Night at the Atbara—Chequered Career of the El Tahra—Life at Atbara Camp—The Plagues of Egypt up to Date—Perverse Camels—Failure of our Attempts to overtake Lancers

CHAPTER II

From the Atbara to Wad Hamed

A Crowded Ghyassa—A Talking Mummy—Slatin Pasha—Animal Life on the Banks—The Pyramids of Meroe—Work for Archæologists—A Gaalin Sheikh—A Dervish Deserter—Abu Klea—A Sandstorm—Arrival [x] at Wad Hamed—We meet the Sirdar—Types of the War Correspondent—Entomology—Insect Life in the Sudan—Desert Circulating Library—Fly-fishing in the Nile—Military "Fatigues"—Fugitives from Omdurman—Our Camp Life at Wad Hamed—Thirst in the Tropics—How we Dined—Good-bye to Wad Hamed

CHAPTER III

The Week before the Battle

Embarkation of Friendlies—The Shabluka Cataract—Our Delay at Rojan Island—First Glimpse of Omdurman—The Evening Ride from Hagir—The Joys of Good Health—Sudanese Wives—Importance of the "Drink Camel"—An Adventurous Greekling—Mr. Villiers' Bicycle—Um Teref Camp—Sudanese Music—The First Dervish—Scorpion v. the "Father of Spiders"—A Cavalry Reconnaissance—A Rainy Night—Within Twenty-five Miles of Omdurman—Deserted Villages—A Disappointing Capture—Seg-et-Taib—The Water Question—Corpses in the River—The Khalifa's Army in Sight—The Ridge of Kerreri—Sururab—Gunboats at Work—Troublesome Donkeys—Sniping—A Tropical Downpour spoils our Rest—Mr. Villiers and Myself stung by Scorpions—Chasing Hares on the March—Cavalry Scouts on Kerreri—Howitzers in Action—Skirmishing with the Khalifa's Cavalry—Waiting for the Dervish Advance—The Khalifa halts—The Evening before the Battle—The Perils of a Night Attack—False Alarms

CHAPTER IV

The Battle of Omdurman

A Comfortable Breakfast—All ready for the Dervishes—Egyptian Cavalry engage the Enemy—Gunboats to the Rescue—The Joy of Battle—Here they come!—A [xi] Splendid Spectacle—The Dervishes open Fire—The First Shell—A Dervish Battery—Effect of our Shell Fire—Wounded Men—Curious Tricks played by Bullets—Maxims at Work—A Dervish Cavalry Charge—Persistent Sharpshooters—The Army leaves the Zeriba—The Lancers' Charge—Mutilation of the Dead—Wounded Horses—Killing the Wounded Dervishes—Renewal of the Fight—Steadiness of the Sudanese and Egyptians—Final Repulse of the Enemy—Dreadful Effects of our Fire—Men falling out—We halt beside a Khor—Regimental Music—Escape of the Khalifa—Death of Hon. Hubert Howard—A Champagne Dinner in the Street—The End of Mahdism

CHAPTER V

Gunboats and Gaalin

The Sirdar's Fleet—Difficulties of Navigation—The Loss of the Zaphir—Concentration of Friendlies at Wad Hamed—Their Love for Firearms—Rout of a Dervish Detachment—Gunboats shell the Kerreri Ridge and Riverside Villages—Some Faint-hearted Friendlies—Gallantry of the Gaalin—Tuti Island—The Shelling of the Mahdi's Tomb—Gunboats silence the Forts—Lyddite Shells—Maxim Fire upon the Fugitives—Gunboats proceed up the River—The Fate of Gordon's old Flotilla

CHAPTER VI

After the Battle

The Mahdi's Tomb—A Wounded Man lands under False Pretences—Villiers' Bicycle in Omdurman—Loathsome Streets—The Arsenal—Dervish Ammunition—The "Man-stopping" Bullet—Awful Effects of Modern Rifle Fire—The Gordon Memorial Service—Varieties of Loot—A Tommy's Quaint Mistake—Enrolment [xii] of Dervishes under the Khedive's Flag—Charles Neufeld—The Austrian Sisters—Slatin Pasha in Camp—Good-bye to Omdurman—We strike on a Sandbank—Our Sleeping Arrangements—Failure of Attempts to move Gunboat—A Soldier Drowned—A Dead Egyptian—We get off the Bank—Loss of my Luggage—Cross goes to Hospital—Delays on Homeward Journey—Mohammedan Divorce Laws—A Camel dies from the Bite of an Asp—A Good Dinner—From Alexandria to Marseilles—Announcement of Cross's Death—The Future of the Sudan

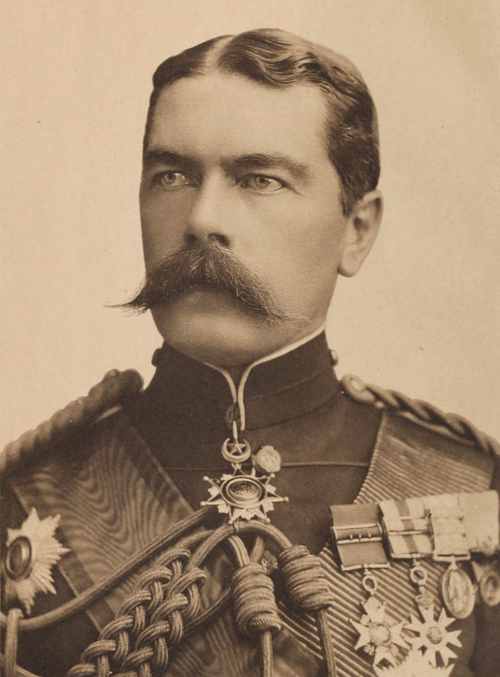

MAP AND PLANS

| The Nile from the Atbara to Khartum | Facing page 104 |

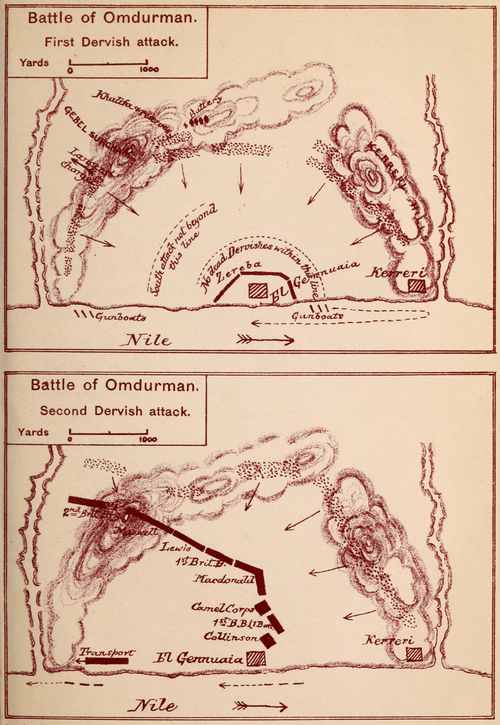

| The Battle of Omdurman (two plans) | Facing page 202 |

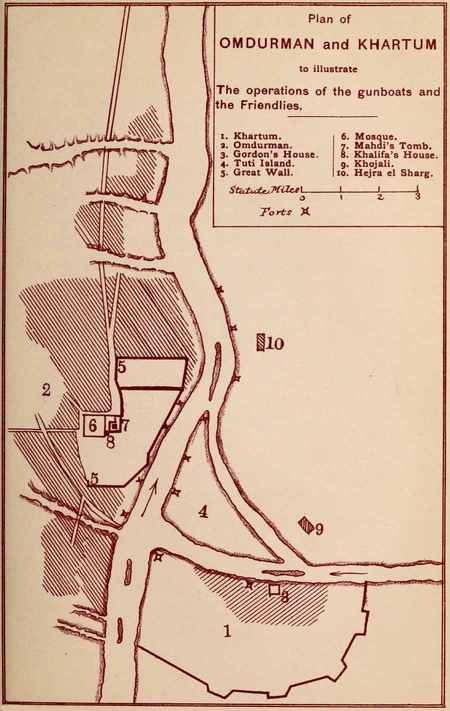

| Plan of Omdurman and Khartum to illustrate the Operations of the Gunboats and the Friendlies | Facing page 214 |

THE DOWNFALL OF THE DERVISHES

Towards the end of last July I heard to my great joy, from the editor of the Westminster Gazette, that a permit had been granted me to act as his special correspondent during the forthcoming campaign in the Sudan. Sinister rumours had been afloat for a long time to the effect that the utmost difficulty would be experienced in securing such permission, and several officials at the Foreign Office had warned applicants that even in the event of a formal pass beyond Wady Halfa being accorded, there would be no certainty that correspondents would be allowed to proceed actually to the front. The baselessness of these apprehensions was amply[2] shown by subsequent events. War correspondents in the recent campaign had little to complain of on the score of any curtailment of their liberty of movement, though the Sirdar's subsequent refusal to take any pressmen to Fashoda may have provoked some unreasonable criticism.

A day or two after the receipt of the Sirdar's permit I happened to meet at dinner an old college acquaintance, Mr. Henry Cross, who had rowed five in the 'Varsity boat of 1888. When I told him of my intended visit to the Sudan, he was all eagerness to join me; but as he was utterly inexperienced in the sort of travel that would fall to our lot before Khartum was reached, I did my best to dissuade him from making any rash resolves of the sort on the spur of the moment. The daily round of a war correspondent's life amid a charming environment of scenery and climate is simply delightful, when to the joys of an open-air existence and abundant exercise there is added the pleasant excitement which springs from a risk of danger. Such delights as these I had experienced during the Cretan troubles in the spring of 1897, but from what[3] one knew personally of tropical travel, and what one gathered from various accounts of the Sudan, one realised that the forthcoming campaign would be in the Lancer's words, already become historical, "no bloomin' picnic." Accordingly I laid before Cross graphic and horrible pictures of sandstorms and sunstroke and the other unpleasantnesses which one might expect to meet amid the torrid plains of the Sudan. Would that my advice had been acted upon and his bright young life preserved! As it was, my friend secured a permit through the editor of the Manchester Guardian, and rapidly made his preparations for departure. Our last meeting before we left Charing Cross was at Bletchley Junction, and over some railway tea and a couple of buns we made our final arrangements.

The great difficulty which I had to surmount before leaving England arose from a gigantic heap of examination papers which went far towards filling up my college rooms. The limits of time imposed by the authorities who preside over the destinies of University and other examinations appear sometimes to the fevered imagination of the anxious employé[4] to be strongly flavoured with the ancient Egyptian spirit of "bricks without straw." Under time pressure of this kind one's ethical system becomes quite distorted. How heartily one gets to hate the good little boys and girls who write four or five pages of cram! With what satisfaction one surveys the work of the stripling whose indifference or ignorance has curtailed the product of his mental training within the more reasonable limits of a few lines, to be marked after a single synoptic glance! However, with the aid of several hirelings, whose unskilled labour sufficed to execute the merely clerical portion of my task, I contrived to break the back of this obstacle to my happiness. The penultimate batch was finished at the Charing Cross Hotel, the final lot completed just before our train steamed into Folkestone.

I shook off the dust of these papers from my garments, and stepped upon the steamer's deck a free agent. Away with lectures and pupils and essays, the solemnity of the Senior Common Room, and the good-humoured toleration of the smart undergraduate! Farewell for many a week to dear Oxford—with[5] its scouts and "bedders"—porters and proctors—bursars and battels! Just as I was leaving the walls of the college a copy reached me from a continental professor of his Acta Apostolorum Apocrypha, to which I had furnished a slight contribution some months ago. "Pray accept this trifle," I said to a sorrowful friend, "for your own edification during the 'Long'; I am now going to another region rich in apocryphal acts, to wit, those of the war correspondent."

There is no need to dwell upon the trite journey to Alexandria. Such a subject may well be left to the pen of the tourist, who, under the capable management of Dr. Lunn, enjoys at the same time economic and religious satisfaction, and travels at reduced fares to further the reunion of Christendom. The Messageries steamer which conveyed us from Marseilles carried, as is generally the case, scarcely any passengers, except a conglomerate mass of human beings at the foc'sle, and very little freight. Nevertheless, thanks to the enormous subsidy furnished by the French Government, these half-empty steamers invariably afford good accommoda[6]tion and excellent food. On board our boat were Major Mitford and Lieutenant Winston Churchill. The latter gentleman was going out to be attached to the 21st Lancers, and in the intervals of campaigning conversation and graphic accounts of his recent experiences on the Indian frontier, he supplied us with luminous information as to the principles and practice of Tory Democracy. Another fellow-passenger with whom I was privileged to enjoy a good deal of pleasant conversation was an Egyptian Bey of high official rank. As we neared Alexandria, he told me a great many interesting facts about the bombardment of 1882. He was present during the engagement, and ridiculed the ground which was alleged at the time for the action of our ironclads. Sir Beauchamp Seymour had been ordered from home to "prevent the construction of fresh fortifications at all costs," and when a number of Arabi's levies were seen to be shovelling some spadefuls of sand upon the wretched mounds which stretched towards Ras-el-tin, the concentrated fire of our warships opened upon the whole line of so-called "fortifications." The Egyptian artillerymen[7] did their best, although some of their heaviest guns were not fired from ignorance of their mechanism; nor was the assistance rendered them by a host of men, women, and even children, of much practical utility. My friend told me he saw one of these amateur gunners endeavouring to load a breech-loading Krupp by shoving a shell wrong way about down the mouth of the gun! The shell, of course, stuck fast, and its base projected from the muzzle.

We reached Alexandria by August 2nd, on which day was fought, exactly one hundred years before, the Battle of the Nile. The words which were used to describe this achievement, "It was not a victory, it was a conquest," might, exactly one month afterwards, have been well used of another British triumph before the walls of Omdurman! But whereas the Mahdist enemy has vanished never to reappear, our ancient adversaries, the French, are still in Egypt with all their traditional eagerness to thwart and injure us—an eagerness which seems to be increased, if possible, by their realisation of the fact that their power in Egypt is gradually waning. I[8] learnt from an authority of the highest standing that in a list of official appointments made from day to day there is a marked decrease in the number of French names, and of course a corresponding increase in English ones. It is certain, too, that the vast majority of educated Egyptians are coming to realise clearly the injury which is inflicted on their country by the obstinacy and perversity of the French, whose policy is one of sheer obstruction to any measure of progress suggested by the British advisers of the Khedive, however reasonable its conditions and beneficial its results. The present scheme of new irrigation works at Philae, which will bring thousands of fresh acres under cultivation and increase the revenue enormously, has, needless to say, received the most violent opposition from the French. How long are we going to tolerate this absurd political farce? When will a British Government have the courage to inform the world that we officially recognise what is already a fait accompli, and intend to remain in sole and permanent possession of a country for which we have done so much?

Several amusing stories are told in Cairo of[9] the animosities which often exist between Englishmen and Frenchmen as individuals. Some time ago, a naval lieutenant in uniform entered the Bar Splendid, near the Esbekiyeh Gardens, and called for some refreshment. Three Frenchmen entered simultaneously, and as the lieutenant raised the glass to his lips his arm was jogged so roughly that half the liquor was spilt. He turned to the three Frenchmen, but as they did not look at him he concluded that the occurrence was a mere accident due to his neighbours' clumsiness, but unnoticed by them. He therefore raised his half-filled glass once more, and this time actually saw one of the Frenchmen deliberately jog his arm. Justly furious at this uncalled for insult, the Englishman, who was an excellent "bruiser," laid about him with such vigour and dexterity that in a twinkling two of his assailants were sprawling on the sanded floor of the restaurant. He turned to the third. "No, you're too small," said he, and forthwith seizing the diminutive Gaul by the back of his collar, he slid him under one of the tables, and, leaving the trio in their undignified positions, he walked quietly out of the café[10] and reported the occurrence to his superior officer. Next day, three Frenchmen, whose features were somewhat discoloured and bedraggled, rang the bell at the lieutenant's quarters with a view to "demand satisfaction." But on the doorstep stood the lieutenant's servant, a huge bluejacket, who informed the visitors that a British officer could not cross swords with persons of their inferior social standing. As the Frenchmen were persistent and noisy, the sailor exclaimed, "Well, it was my master's day yesterday, but, strike me blue, it's mine to-day!" and with that he cleared for action by rolling up his sleeves. The sight, however, of his brawny arms, coupled with a vivid recollection of le box as practised by the British, appeared to impress the three would-be duellists, and they speedily withdrew.

We stayed for several days at Shepheard's, where the semi-comatose servants gradually awoke from the lethargy which overtakes them out of the season, and did their best to make us comfortable. The general torpor which seizes upon Cairo during the hot summer months was broken during our stay by the[11] incessant despatch of troops to the front. Every afternoon detachments of infantry and cavalry marched briskly through the streets towards the station with drums and fifes, and "Auld Lang Syne" was played as the train steamed away. It was curious to notice how infinitesimal was the interest which seemed to be aroused in the passers-by. The Egyptian natives scarcely took the trouble to glance at the columns as they marched past in full war kit and brown kharki uniforms. A little knot of Europeans, whose smallness served to emphasise the emptiness of the hotel, would step out upon the verandah—where, by the way, the temperature was nearly 100° in the shade—and follow with their eyes the passing battalions; but otherwise no interest whatever seemed to be aroused by their departure. The fact is, that it never occurs to Egyptians of the lower classes that they have any share or lot in what is perpetrated by the powers that be. They are, as Aristotle expressed it, "slaves by nature," and centuries may roll by before any other political sentiment is instilled into this most conservative of nations than that of fear and acquiescence. At the same[12] time, this lack of interest is certainly not prevalent to the same extent amongst the educated and enlightened sections of Egyptian society. Whatever may be the divergency of opinion à propos of various questions of internal reform, or larger problems as to the ultimate government of the country—whatever be the diverse opinions on topics such as these amongst the educated natives—there is a practically unanimous approval of two enterprises now in hand—the new Barrage of the Nile, and the recovery of the Sudan.

The social life of the upper classes in Egypt is gradually yielding to European influences. Much has been accomplished in this direction during the space of a single generation. Egyptian gentlemen, whose fathers wore the turban and loose native dress, now get their tweed suits and patent leather boots from English firms. The position of women too is steadily improving as education advances, and home life, to the dismay of the "Old Egyptian" party, is being slowly but steadily revolutionised in the direction of greater freedom and independence for the ladies. Some time ago I received a most kind invitation from an[13] Egyptian Pasha to dine with him. I dressed and drove off to his house, thinking, of course, that I should merely share a tête-à-tête meal with His Excellency. What was my surprise to meet in a kind of drawing-room the Pasha's wife and three charming daughters, who all spoke English, French, German, and Arabic with fluency! An excellent dinner was served, towards the end of which a strange compound made its appearance in a large tureen. I was on the point of declining this delicacy, when it flashed upon me that the mess of pottage must be meant for plum-pudding, and had been prepared expressly in my honour. It was even so. As I ladled some of the pudding into a soup plate I expressed my keen satisfaction at the appearance of this British dish; and I think that my enthusiastic remarks led the family to believe that the staple article of diet in English households was plum-pudding, served at all meals all the year round. After dinner we returned to the drawing-room, where the Misses Pasha played admirably a variety of selections from Grieg and Brahms, and finally, "God Save the Queen," at the close of a very pleasant evening, which gave me a[14] vivid impression of the advancement which is being gradually effected in the home life of the more enlightened Egyptians, though, of course, the liberty enjoyed by my kind hostess and her accomplished daughters is as yet the exception rather than the rule.

Our few days in Cairo were fully taken up with preparations for the campaign. One consequence of the inrush of officers and correspondents was a dearth of horses. The neighbourhood had been ransacked for animals, and if the demand continued it seemed as though Ammianus' prediction, slightly altered, would become true of Cairo, "Creditur jam equos defuturos esse." The price of riding horses advanced by leaps and bounds, and as the Government had been offering from £20 to £25 for them, I thought myself lucky when I learnt from my friend, Mr. A. V. Houghton, that he had kindly secured me a passable steed for £17, 10s. Beasts outworn, with irregular gait and hair in scanty tufts, were being purchased by despairing voyagers in default of better horseflesh.

Then came the choice of servants, and many of the individuals who offered themselves were[15] quaint enough. Before the final selection, batches were paraded before me from time to time, some of whom were alleged to be bilingual, nay, even trilingual; but in most cases a little viva voce examination revealed the fact that their English consisted of little else than half a dozen "swear words"; others again were persons with a "past," and so unsuitable for the future. In Egypt one can rarely put any trust in written "characters," for such documents, either forged or secured from former servants, can be purchased in the bazaars at so much a dozen, the price, of course, varying according to the social status of the master whose signature they are alleged to bear. All that a disreputable Arab in search of employment has to do is to ask the shopman for a testimonial to the zeal and honesty of "Ali" or "Mahmoud," according as his name is one or the other. After one's choice had fallen upon a comparatively blameless Ethiopian from Dongola as cook, and a Cairene Egyptian as säis, the rejected candidates were dispersed by the jubilant pair amid a babel of imprecations heaped upon each others' relatives dead and alive. Finally, the grateful[16] cook came to me in the evening, and amid the laughter of my friends, solemnly presented me with a worked cholera belt, which, he declared, his swarthy daughter had expressly knitted for my comfort in the Sudan. With many blushes I accepted this useful present.

Our stores were purchased from Messrs. Walker of Cairo, a veritable firm of Egyptian Whiteleys, from whom one can buy anything, from condensed milk to a trotting camel. It is on occasions like this that a bachelor, unaccustomed to anything like a quantitative analysis of the food he consumes from day to day, deplores the absence of feminine assistance. He knows what he wants but not how much of it. Acting under the prejudiced advice of a chocolate-coloured shopman, we laid in large quantities of things comparatively useless, and neglected the weightier matters. For example, our rice gave out after three weeks, while we had enough pepper to last us a lifetime.

We were altogether very busy in Cairo, and had little time for any side issues. This was a pity, as my companion wished to visit the pyramids, the mosques, and so[17] on, while I personally wanted to see something of the magical practices which still prevail to a considerable extent in Cairo.

Egyptian magic was, of course, famous in antiquity. The author of Exodus speaks of it, and, at a later date, Celsus, the able opponent of Christianity, declared, strangely enough, that Christ worked all His miracles by means of magic which He had learnt in Egypt! I have heard on excellent authority that necromancy is still practised in Cairo, and if our departure could have been delayed I should have done my best, with the aid of some Egyptian friends, to be present at one of these séances for the evocation of the dead. Another species of magic consists of gazing into ink in order to see pictures prophetic of the future. This practice is, after all, simply a form of the katoptromancy or crystal-gazing which was used for divination in the remotest antiquity, and still yields results full of psychological, if no longer of supernatural, interest. Scripture appears to contain several references to the curious phenomena which frequently exist in connection with crystal-gazing. The Hebrew[18] divination by Urim and Thummim, and by cups, of which we read, was almost certainly based on this ancient practice; and at a still later period St. Paul compares our imperfect conceptions of what lies beyond things temporal to the perplexing images which can be "seen through a mirror in a riddle" (δι' ἐσόπτρου ἐν αἰνίγματι). Mr. Lane's delightful book, The Modern Egyptians, contains an account of the ink-gazing which is still carried on by young boys.

I should like to add to these remarks on Egyptian magic a most curious account which I had first-hand from an official who was high in the favour of the late Khedive, Tewfik Pacha. During the critical weeks which immediately preceded the bombardment of Alexandria, my informant was suddenly summoned to an immediate audience with His Highness. Several matters of vital importance were discussed between the Khedive and his Minister, and the latter went home pledged to the utmost secrecy with respect to what he had learnt. Soon after entering his house, his wife mentioned to him that during the course of the afternoon she had[19] heard from another lady of a wonderful medium, whom she had asked to call that evening. After a short time the medium in question, an extremely old woman of the very poorest class, arrived, and the Minister laughingly promised his wife to test the genuineness of the visitor's gifts. When admitted to his presence the old creature almost immediately fell down in a kind of fit, and to his amazement he heard proceeding from her lips in strange tones, quite unlike her normal voice, the very words spoken to himself two hours before by the Khedive under pledge of the most stringent secrecy!

Shortly before leaving Cairo my cook Ali appeared before me with a huge two-handed Dervish sword, which he had purchased out of his own money for twenty piastres. The creature had already the day before begged me to buy him a rifle for defensive purposes, as I was quite unable to eradicate from his mind the belief that his kitchen utensils and himself might at any moment during the next six weeks be exposed to an attack from a frenzied rush of Dervishes. I could not see my way to[20] gratify his wishes in this respect. To have a cook bending over the fire with a belt full of cartridges, or walking round one's tent with a loaded rifle—these were indeed added terrors to the perils of a Sudan campaign. He was, however, permitted to wear the gigantic sword, as I thought it might come in handy for cutting wood or opening tins of meat.

We were not sorry to get out of Cairo. The moist heat which prevailed in the town clogged all the pores of the skin and was extremely trying. Just before we left, a detachment of the Grenadier Guards entrained for the front. These fine fellows were marched from Abbasseeyeh to the station—no great distance—in the hottest part of the day, between twelve o'clock and two. When they reached the station the perspiration was streaming from their faces, and they were kept at "attention" to prevent them from drinking water in this condition. But the heat had already begun to tell in several cases; three men fell prostrate, and quite a number were attacked by violent sickness. The drainage, too, of the city was in a deplorable condition. The old native system had been recently abolished, and during the[21] period of transition sanitation was in a state of chaos. Which things are an allegory! In consequence probably of the escape of sewage into water-pipes, enteric fever and diphtheria were far from infrequent, and quite recently two young officers of the 21st Lancers had succumbed to these fatal diseases.

When we arrived at the railway station in the evening en route for the South, we found our servants already there. But how transformed! Ali and the säis had exchanged their native cotton garments for brand new suits of yellow kharki, purchased at my expense. From some association of ideas in connection with the forthcoming campaign, they were "got up" in a pseudo-military fashion, with brass buttons and shoulder straps. As Ali the cook stood before us in his ill-fitting garments, with an enormous crusading sword in one hand and a kitchen colander and soup ladle in the other,—a kind of walking allegory of Peace and War,—we laughed so much that we could scarcely ask for our tickets. At the last moment a native rushed into the station closely pursued by his wife. The man was evidently bent on securing a seat in the train, but his better half[22] disapproved of this, and as he was getting into the carriage she suddenly struck a violent blow at his hand luggage. It was a most effective stroke. The bundle he carried exploded like a shell, and its contents lay scattered in hopeless confusion over the platform. Long before the baffled husband could collect the disjecta membra of his travelling kit, the train steamed off into the darkness, and he was left to settle matters with his triumphant wife.

We rapidly left Cairo behind us, and with it the joys and comforts of civilisation. It was a positive relief to feel that we had now commenced in real earnest to travel the twelve hundred miles which separated us from our final goal far away in the Sudan. Still, at the time of our departure from Cairo, no certainty was felt that there would be any fighting at all. Rumours were persistently current that the Khalifa and his forces had retreated from Omdurman. It would, as somebody said, be simply a case of cherchez la femme. If the women and children became panic-stricken and retired, it was certain that the Dervishes would lose heart and make a poor show of resistance. Take, for instance, the case of Berber. Here a[23] vigorous defence might reasonably have been expected, but it was afterwards found that an exodus of the women brought about the total evacuation of the town, which our advancing forces thus occupied without any fighting whatever. Still it was too early to speculate on the amount of opposition our troops were likely to encounter. Whether there would be one or more sharp struggles before we found ourselves face to face with the ramparts of Omdurman; whether even then those ramparts would be held by Dervishes driven to bay and fighting with their old desperate courage, or we should bivouac in a deserted city—all these things, we felt, lay verily on the knees of the gods!

Our first taste of discomfort was provided by the night journey to Luxor. Soon after leaving Cairo the motion of the train raises an almost continuous cloud of dust, which penetrates into the carriages, scheme one never so wisely. One may put the glass windows up or merely raise the wooden venetians according as one prefers the alternative of being almost asphyxiated by too little air or stifled by too much dust. Even with the windows up the[24] dust insinuates itself into the compartment somehow; and if one can sleep through the night one finds next morning a thick layer of dust over everything, and reflects with astonishment and dismay on the condition of one's lungs and internal economy in general. The train was not a "troop train" in the special sense, but it contained a good many officers. It is worth noticing, by the way, that Egyptian officers, even of high military rank, travel second class with British sergeant-majors and warrant officers. As no horse boxes would be available for the conveyance of our animals for two days, we were compelled to stay a couple of nights at the Luxor Hotel. The dreariness of this hotel out of the season was still more marked than at Shepheard's. Outside, all blistered by the heat, hung the quaint notice, as a warning to that species of knicker-bockered tourist who shoots gulls from the Clacton cliffs, "Il est défendu de chasser dans le jardin." The servants shuffled listlessly about, the long corridors were covered with dust, and forlorn notices about church services which were no longer served, and trained nurses who had vanished, were[25] almost the only outward and visible signs of the past season, with its crowded table d'hôte, the vulgar chatter of American globe-trotters, and the irritating atmosphere of valetudinarianism.

At the hotel we met two hard-worked transport officers, Captain Hall and Lieutenant Delavoy, busied night and day with the incessant despatch of stores and ammunition to the front. People are often apt to forget to what an extent the success of a campaign is due to the honest work of the Army Service Corps and transport officials. Upon these departmental troops fell the onerous labour of forwarding for many weeks all the stores required for the feeding of some twenty-three thousand men and several thousand animals.

Our recent campaigns in the Sudan have been unique in military history from the fact that the army's line of communication with its base was ultimately over twelve hundred miles in length. Every ounce of food, with the exception of a little fresh meat occasionally obtained along the line of march, had to be conveyed from Cairo by river, rail, or camel. The best thanks of the public are due to the[26] indefatigable labours of the transport officers and men, many of whom were not brought by their work within the area which will be covered by the forthcoming medal.

As we sat at dinner in the cool of the evening under the palms and tamarisks, somebody chanced to look under the table and saw a number of large yellowish tarantulas waltzing about our feet. A panic ensued, and the meeting rose as one man and got upon chairs, until these repulsive insects were driven away by the waiters. The incident forcibly recalled the famous congress of ladies which was convened to demonstrate the Superiority of Woman over Man, and was broken up by a small box of mice opened by a son of Belial in the audience. These horrid spiders, whose bite is very painful, and, in the case of young children, occasionally fatal, seemed to be ubiquitous at Luxor; nor did they even respect the sanctity of our bedrooms. Medical psychologists tell of a case in which a gentleman suffering from hallucinations declared that he saw "pink pachyderms" in his bath, but was unable to secure a specimen owing to the rapidity of the creature's movements. But I[27] had much rather see a pink pachyderm—which may after all be merely subjective—inside my tub than a brace of tortoiseshell tarantulas, whose objectivity is undoubted, racing round and round the bath and cutting off one's retreat.

We took the opportunity afforded us by our enforced wait at Luxor to visit the temples. No tickets were demanded, no touts clamoured at one's heels and interfered with one's reflections. We rode to Karnak in the moonlight, and after dismounting we were suddenly mobbed by scores of dogs, who came rushing upon us from the Bedawin houses near the ruins. The animals became so menacing and approached so close that I was compelled to use my revolver. The pariah doggie in Egypt does not seem to be quite like his Constantinople cousin, who is probably descended partly from the jackals who accompanied the Turkish armies from their Asiatic settlements. The puppies of these pariah dogs are, by the way, the dearest little creatures in the world, with rough woolly coats like tiny bears.

There is absolutely nothing in the world to compare with the temple of Karnak in point of magnificence and grandeur. When one[28] gazes on the colossal pillars, the huge pylons, and the rows and rows of sculptured sphinxes, it would be alike difficult and painful to believe that all this mighty effort, this outcome of the blood and sweat of thousands, could after all be based on a mere delusion and groundless enthusiasm. On the contrary, one may wonder whether the full force of the religious motive which raised these giant structures has not been to some extent lost in later ages. At anyrate, it seems certain that in the West our religious consciousness has never been marked by that intense appreciation of God's omnipotence which underlay the creation of such stupendous monuments. On the contrary, there seems to be a tendency in modern Christianity to anthropomorphise the Deity into the official Head of a scheme of charity organisation, to which the belief in a future life, so powerful a factor in the ancient religion of Egypt, is attached as a subsequent phase of subsidiary importance. As the race grows less and less disposed to endure physical pain and discomfort, we clamour more and more for tangible and material blessings, and refuse to be comforted by any contemplation of[29] the problematic joys of another world. There is something to be said for this point of view, and much evil has undoubtedly been done by the reckless bestowal on suffering humanity of "cheques to be cashed on the other side of Jordan." Still, if this process continues, it is difficult to realise how, in the conduct of future generations, any place can be found for a religious and supernatural, as distinct from a merely ethical, obligation.

The railway journey from Luxor to Shellal, a village on the river bank just above the first cataract, where the railway terminates, ought to have taken about eight hours, but it took over sixteen. All the trains have third-class carriages or rather trucks, and an excellent object lesson in Oriental procrastination was afforded at the moment when the train started. All night long crowds of natives had been sleeping on the ground just outside the station with all their curious goods and chattels—beds and bundles and babies—around them. Scarcely one of them made the slightest effort to get on board the train until the whistle went, and then a terrific scramble took place. "Gyppies" of all sizes, sexes, and ages rushed[30] wildly down the line, trying to hurl their baggage into the carriages and then climb up after it. This went on for some three hundred yards, and despite the increasing speed of the train most of these procrastinating creatures contrived to find some sort of place on it. If they failed, they simply went to sleep again till the day following, when they tried again.

The traffic on this line was enormous, and the rolling stock available could scarcely bear the unusual strain put upon it. We were repeatedly stopped on the way by a variety of accidents. First of all a carriage got off the rails; then an axle became red hot from lack of grease, and set fire to the woodwork; and finally a train in front of us left the metals, and a long interval elapsed while two lengths of rail were taken up and straightened. The line has, from motives of false economy, been laid in a miserably inefficient manner, and an official casually informed me that trains ran off the rails about three times a week. One of the most difficult things to deal with was the transport of horses and mules. Sometimes one saw a loose box filled with sixteen mules all kicking together, and on the steamers[31] accidents continually happened amongst the crowded horses.

As we ran past Assouan down to the water's edge at Shellal, the graceful temple of Philae in midstream was flooded with an orange glow from the setting sun. Along the bank a forest of slender masts and lateen sails stood out against the sky. Across the river the strange rocks, bared of all earth and vegetation and polished smooth by the flying sand, have assumed the oddest shapes, and look for all the world like the primeval work of some Titanic infant at play.

The sight of a luggage van at a terminus was enough to drive any inexperienced voyager to utter despair. When we arrived at Shellal the moon had not yet risen, and the feeble light of a few lanterns was all we had wherewith to disentangle our separate lots of luggage and stores from the general mélange. The chaos of luggage was fearful. Under the weight of two of our store cases an officer's sword had been bent almost into the prophetic pruning hook, and a band-box belonging to our one lady passenger had, with all that it contained, been squashed absolutely flat. Everybody[32] had to see after his own possessions or he was lost. Later on, as the boat steamed off from Shellal, an officer who had entrusted the embarkation of his horse to his säis was horrified to see the man calmly sitting on the bank smoking a cigarette with the horse beside him.

During our stay at Shellal we slept in the garden of a shabby one-storeyed house, dignified with the title of the "Spiro Hotel." This was run by one of those ubiquitous Greeks who invariably turn up in the East where there is any chance of making money. All along the line of advance to Omdurman we were accompanied by Greeks, who trafficked in bread, fresh meat, and the like. Like the Irishman and the Jew, the Greek seems to flourish the more the further he is removed from his native country.

By this time our horses had caused us such signal inconvenience, and it was becoming so difficult amid the congested traffic to find room for them, that Cross and I determined to do without our mounts. Accordingly, we sold one to an officer at a slight profit, and sent the other back to Cairo. If British officers could march on foot to Khartum from the point[33] where rail and river failed us, why shouldn't we? If one is taking part in a campaign where there is a probability of a reverse, a sound horse may be useful; but one felt on the present occasion that, if any running away was to be done, it would not fall to our lot.

At Shellal a brother of Ali's, called Mahmoud, suddenly turned up from some quarter or other, and we annexed him at a moderate rate of pay. His was the most unskilled labour I have ever witnessed. He generally drove the tent pegs into the ground sloping inwards, and with the notches inside instead of out! When he loaded a camel, he would place a Gladstone bag on one side and a heavy box of stores on the other, and then looked quite surprised when the camel rose and the whole structure fell with a crash to the ground. At times like these his imbecile features would be illumined with a fearful smile, and if we rebuked his folly and menaced him with punishment, his grin became broader and broader. When on one occasion I smote him with a thorn stick, his mirth became so uproarious that we abandoned all hope of his reformation, and merely gave Ali orders that in future his brother's activities were to be strictly[34] confined to the hewing of wood and drawing of water.

A large base hospital, with two hundred beds, had been established at Assouan, and throughout the line of advance strenuous efforts were being made to cope with any demands upon the medical service. It is generally admitted that at the Atbara fight the medical arrangements were not as complete as they might have been, and considerable confusion is said to have been produced by the inadequacy of the accommodation for the wounded. This time, however, Surgeon-General Taylor had arrived on the scene, and throughout the campaign there was no cause for complaint. In addition to base hospitals at Assouan, Atbara, Rojan Island, and elsewhere, each brigade had no less than five field hospitals attached to it. The National Aid Society proffered its assistance, undertaking to send its own transport; but the Sirdar refused the offer, with the idea probably that an army in the field ought to supply its own medical requirements. Some of the officials of the Society were, I heard, incensed at this refusal; for they alleged, with some reason, that during a campaign nobody "goes sick"[35] unless he is practically too ill to move about, and that the voluntary assistance rendered by the Society may be of the greatest service to a large number of devoted men who, despite their sufferings, are too keen and patriotic to enrol themselves on the sick-list—the only means of securing treatment from the Army Medical Corps. Just before we embarked, a batch of invalided men passed northwards on their way to Cyprus, where the climate is comparatively cool in August. Sunstroke was beginning to claim its victims; a sergeant and a private of the Northumberland Fusiliers had already succumbed to the heat, which, amid the rocks of Philæ, was driving the quicksilver up to 110° in the shade. The Nile was still rising perceptibly day by day, and in one spot I saw hundreds of tons of Government stores—reserve supplies for ten thousand men—which would have to be moved, as the waters gave promise of reaching an abnormal height this year. Scores of natives found employment about the landing-stage as porters, and were perpetually fighting over the division of the luggage and the bakshish. I noticed four of these men, during a frantic struggle on the river bank,[36] collapse into the water, where they still continued their combat of words and blows, even when occasionally submerged—

Quamquam sunt sub aqua sub aqua maledicere tentant.

We journeyed towards Wady Halfa in the old stern-wheeler Ibis, which was crowded with officers of the Lancashire Fusiliers, and as it towed a large barge on either side full of the rank and file of the 2nd Battalion, we made slow progress. There is but little incident to chronicle on a Nile voyage, and it is difficult to understand why, even in winter, people select the Nile as the river par excellence for steamboat tours. The eye falls continually upon bleak hills and dreary sand plains on either bank, relieved only by occasional patches of dhurra and date palms, while the monotony which hangs like a pall over everything Egyptian—landscape, architecture, sculpture—becomes in time most oppressive and wearisome. The fact is, that were it not for the social pleasures one may, or may not, derive from several weeks' sojourn on one of Cook's steamers, nobody except a few souls really interested in the antiquities of Upper Egypt would undertake this voyage.

The Tommy Atkinses were packed like sardines on the barges, but seemed to be in excellent spirits throughout the voyage. They continually talked about the coming battle, and were as keen as possible to get a sight of the Dervishes. All this arose, of course, from sheer love of adventure and fighting, for the campaign could scarcely be regarded as undertaken in defence of "our hearth and home," and was only indirectly waged for the sake of our country. As we advanced up the river the soldiers grew more musical day by day. Local lyrics from the North alternated with Moody and Sankey hymns, and occasionally some very fair attempts at harmony helped to beguile the tedium and discomfort of the voyage. In one respect the result of the "territorial system" in our British regiments is not altogether good. Numerous little coteries exist amongst the men enlisted from the same families and districts, and the result is that the bonds of discipline between non-commissioned officers and privates tend to become relaxed. I noticed, for instance, to my surprise, that some of the sergeants were sitting down on the[38] deck playing cards with the men—a species of camaraderie which is certainly not desirable.

A few hours before we reached Assouan the ruins of Kumombo had come in sight. This town, the ancient Ombi, was once, if we may trust an unknown imitator of Juvenal, the scene of a strange and horrible fight between the residents and some malevolent visitors from Denderah, a hundred miles farther down the river. The cause of the encounter has quite a modern flavour about it—each town imagined it had secured the sole and exclusive means of Salvation—

Inde furor vulgo quod numina vicinorum

Odit uterque locus, cum solos credat habendos

Esse deos quos ipse colit.

The pious citizens of Ombi worshipped the crocodile. At Tentyra this ugly beast appeared on the dinner-table, and was devoured with all the added relish which would arise from cooking and eating the deity of a hostile sect. The Tentyrites, in fact, specialised in crocodiles. Plunging into the river they climbed upon the saurians' backs—so Pliny tells us,—and when the crocodile opened his jaws they neatly placed[39] a cudgel across his back teeth, and so steered their captive to the shore. After landing they stood round in a circle and swore roundly at the crocodile, and this scolding so alarmed the timid monster that it "threw up" all the bodies it had eaten, which thus secured a respectable funeral.

Our four days' journey by river from Wady Halfa was only twice broken, once by an hour's halt at Korosko to send off telegrams and take on board some chickens and fresh limes. The other halt was a sad one. A young private of the Fusiliers, after a brief illness, died of internal hæmorrhage, caused, possibly, by lifting heavy luggage. There were, of course, no hospital arrangements on board the crowded barges, but his comrades placed the sick man in as cool a spot as could be found, and tended him as well as they could. But the case was hopeless, and on 11th August the poor fellow died. The steamer drew up beside the bank, and a section of the dead man's company speedily dug a grave in the dry sand. The colonel read the burial service, and after a little heap of stones had been piled above the grave, soon to be obliterated by the drifting sand of[40] the desert, we steamed on our way southwards. Amid the excitement of battle and sudden death, one looks with something akin to indifference as men are struck down by shell-splinter and bullet—it is all part of the day's work, and all must take their chance. But amid quieter surroundings the feelings have freer play, and we all felt, I think, that there was a peculiar element of sadness about this young soldier's death. As the end approached he lay half conscious in a corner of the deck, unmindful of all that passed around him—the swirl and rush of the torrent, and the ceaseless chatter of his comrades.

His eyes

Were with his heart, and that was far away—

away, perhaps, in the far-off Lancashire village where his boyhood was spent and his friends awaited his return.

On 12th August universal dismay was caused on board by the news that our supply of ice had given out. The Arab restaurateur was promptly kicked for his gross negligence, but this did little good. The weather was stifling hot, and unless we wished to drink lukewarm soda water some means had to be devised.[41] The best thing to do if one cannot secure ice in the Sudan is to put one's bottles into a canvas bucket, full of water. The sides are slightly porous and the consequent evaporation brings down the temperature of the contents. Otherwise, merely placing the bottles in straw cases, and then immersing them up to the neck in water, serves to keep the drink fairly cool. The restaurateur, who charged us no less than eight shillings a day for food, really deserved the kicking which he received, for ever since the commencement of the voyage he had consistently dropped one course a day from the dinner, so that if the journey had been prolonged much further, our dinner promised to become a negative quantity.

We were not sorry to leave the Ibis at Wady Halfa, and the Tommies must have been delighted to get, even for an hour or so, an opportunity of stretching their limbs. The train, consisting of a number of horse boxes and open trucks, stood waiting for us, and after a brief delay we steamed off for our thirty-six hours' run across the open desert to the Atbara. Cross, Major Stuart-Wortley, and I found ourselves ensconced in a covered[42] cattle-truck, half full of baggage; but we got our beds out, and speedily made ourselves as comfortable as possible under the circumstances. In the middle of the truck stood a big "zia," and we managed to have this filled with decent water before we left—a sensible precaution, as only two wells exist along these three hundred and fifty miles of desert railway; and when three men have to cook and "wash up" and cool their drinks, not to mention a succession of personal ablutions, the possession of a big "zia" full of good water is a great alleviation of the cattle-truck's discomforts.

In the old days of vacillation and weakness, which ended in the surrender of the Sudan, and thus spread untold miseries over thousands and thousands of square miles, the selection of Wady Halfa as the frontier of Egypt was made in defiance of the best expert opinion on the subject. But if the advice of, at anyrate, one of the experts consulted by the Conservative Government of the day had reached England a little earlier, it seems very probable that El Debbeh, the obvious and natural frontier post under the circumstances of the time, would have been chosen instead of a spot[43] two hundred and fifty miles farther north. The advice in question was, I believe, given to Lord Salisbury on a Monday; but as the fate of the Government was already sealed, and it was known that the Thursday following would see the Ministry out of office, there was no time to effect the proposed change, and Wady Halfa was thus left as the temporary frontier town of the Khedive's loyal provinces, and an enormous tract of country, which would have been protected by a garrison at El Debbeh, was left to Dervish control and devastation.

As we neared the end of our journey the train again skirted the Nile, and whenever we halted crowds of natives grouped themselves along the line, either to sell eggs and dates or simply to stare. The railway is still a source of never-ending wonderment. The simple unmechanical minds of these Arabs seem to regard an engine as a being endowed with life and will-power; and quite recently a village sheikh near Berber protested to a railway official against the cruelty of forcing a small engine to draw a long line of heavily laden trucks. All these people are really ex-Dervishes, and I noticed a fair number of the genuine[44] "fuzzy-wuzzies" amongst them. One of their sheikhs came up and informed us that when we got to Omdurman the Khalifa would fight like Sheitan (the devil). These natives appeared to vastly enjoy the blessings of peace. How vividly impressed they must have been by the constant succession of trains passing across the desert, laden with fighting men and countless tons of stores, visible evidences of the power and wealth of the conquering Inglizi!

As we approached Abu Hamed, the scene of the sharp, brief fight last year, we noticed some object roll along the side of the line; and when the train pulled up we learnt that a non-commissioned officer had fallen off one of the carriages. In a few minutes the missing Fusilier picked us up, walking along quite coolly without having sustained a scratch. On a subsequent journey another poor fellow was not so lucky, for he fell off in the same way, and was instantly cut to pieces by the wheels.

The sun was setting as we neared Berber, and in the distance across the river the outlines of "Slatin's Hill" stood sharply out against the sky. This was the spot where the fugitive took shelter at a critical moment when pursuit[45] seemed close upon his heels and capture imminent. On our own side of the stream the train ran slowly through the scattered suburbs of Berber, and one realised how, as on every occasion during the Khalifa's attempts to oppose our advance, the Dervishes had blundered, by selecting Abu Hamed for the fight instead of Berber. At the latter place there were fully five miles of detached mud-huts extending inland from the river. Not a particle of cover would have been available for an attacking force, and the expulsion of a resolute body of Dervishes from the shelter of these mud walls would have cost us dear.

When the train finally crawled into the vast area covered by the Atbara camp, it was quite dark, and, amid the confusion, Cross and I, with two officers, thought it best to sleep as we were on the ground beside the railway. However, as bad luck would have it, a heavy shower of rain descended upon our devoted selves just as we had fallen off to sleep, and the downpour was followed by a strong wind from the river, which covered our quaternion with a thick layer of sand and dust. A more unpleasant night it would be difficult to[46] imagine, as, beside the dust and wet, it was extremely difficult to breathe amid the clouds of sand. At last I could stand the discomfort no longer, and, jumping up, I seized my bed and bolted for an enclosure hard by. Here my onset was suddenly barred by the bayonet of a sentry, who brought his rifle down to the "charge"; but a little explanation secured a passage for myself and my half-soaked bed, and I found an empty tent, to which my three companions came running like rabbits.

We enjoyed a few hours' sleep before dawn, and then reported ourselves to Colonel Wingate and General Rundle, the commandant. We learnt from the former that the 21st Lancers and some gunners had crossed the river that day with the intention of making their way by land to the proposed camp just north of Shabluka. As these were the last troops who would ascend the left bank of the river, it was imperative that the two camels which we had purchased for our stores should proceed at once by the same route; and as this route promised to be an interesting one, Cross and I determined to accompany our beasts of burden on foot in the absence of our[47] horses. Accordingly we secured an order for the transport across the river of ourselves, our servants, camels, and stores in the old paddle-boat El Tahra. This ancient tub had a rather peculiar history. She had fifteen years ago formed one of the Government flotilla on the upper Nile. When the evacuation of the Sudan took place an Egyptian battery fired half a dozen shells into her and sank her at Rafia to prevent the Dervishes from making use of her. The El Tahra, however, was destined for something better than this inglorious fate, and she was raised, patched up, and throughout the recent campaign performed much useful service. Amongst her more notable achievements was the embarkation of the officers and crew of the ill-fated Zaphir after they were left stranded on the bank without an ounce of baggage. The scars inflicted by her former masters were quite visible, as the big holes torn by the shells had been neatly covered with iron plating.

Orientals are wonderfully good at renovating old vessels. A few years ago I crossed from Galata to Scutari in a vessel which twenty years ago had been condemned as unseaworthy by our[48] Board of Trade. She was then bought for a mere song by a Turkish company, which began to patch her up. In the middle of this process the venerable craft broke her back and fell in two; but the Orientals were not discouraged. They set to work again and put the fragments together, and the result of their zeal and patience has now been steaming to and fro between Europe and Asia amongst the choppy waters of the Sea of Marmora for several years.

The prospect of speedily leaving the Atbara camp behind us was a pleasant one. The place was absolutely detestable; no one had a good word for it. The air was full of flying clouds of dust raised by an interminable succession of blasts from the river. Often before one could get a cup of coffee to one's lips it was coated with a layer of dust. In order to keep the eyes from being inflamed one was driven to wear huge goggles or a gossamer veil over the face.

In addition to the moral training which is alleged to result from all forms of worry and vexation, our discomforts during the campaign frequently possessed an exegetical value. One[49] realised more forcibly than hitherto the meaning of some of the "Plagues of Egypt." Nile boils are only too well known amongst the hapless officials who dwell along the banks of the river. Again, as the ancient narrative speaks of the dust as the vehicle of malignant forms of insect life, so now bacilli are spread broadcast by this means. When we woke up in the morning and shook an inch of dust from our blankets, we were lucky not to find in addition that our mouths and throats were ulcerated; and men suffering from enteric fever and other internal inflammations found their recovery retarded, and often, I am afraid, prevented, by the penetrating dust which they were compelled to swallow and breathe, however fast tents were tied up or windows fastened.

Another abomination was the plague of flies. At meals one made a sweep to get rid of these beasties and then a rush to convey the food to one's lips; but even in this brief space a couple of flies often found time to get their beaks into the morsel and so perished miserably. Tobacco was useless against these Sudanese flies; they seemed to enjoy the fumes. The[50] only way to circumvent them was to sacrifice a little jam on a bit of bread and put it aside to attract the vermin. In a twinkling bread and jam had become invisible. Nothing was to be seen but a thick bunch of greedy flies jostling each other like people at an "early door."

On 16th August, owing to a series of those vexatious delays which are inseparable from Eastern travel, we did not get our two camels to the water's edge until nearly six o'clock, and even then the perverse beasts absolutely refused to get into the barge which was to convey them to the other side. At length we tied their legs together, and then dragged and shoved them over the plank by main force. How utterly one loathes a camel sometimes! Its disposition is morose and malignant even from its birth; it is full of original sin, and any affection lavished upon it is quite wasted. In a word, the camel is a hopelessly depraved beast—

Monstrum nulla virtute redemptum.

The other day I came across a magazine article by a writer who claimed to know all about camels, and he spoke sympathetically[51] of the "soft, purring sound" which issued from the animal's lips. What an amazing euphemism for the horrid guttural snorts with which the peevish brute protests against any attempt to control its movements or put a load upon its back. There is no chivalry in the camel's breast. It will bite a pound of flesh out of you as you lie asleep, or if you are riding will suddenly turn round as you are admiring the scenery and nibble your legs.

At length the obstinate creatures were ferried over the river, but before they were loaded and ready to start it was already dark. On the bank I met Howard for the first time since his Balliol days, and he most kindly offered to lend me his second horse if I cared to ride after the Lancers; but as Cross had no horse I decided to stay with him.

As Cross, Howard, and myself stood there in the brief twilight, how little we dreamt that I alone of the trio should live to return from the campaign! No thought of coming disaster overshadowed us as we laughed and chatted together. It is not always so. I have personally known three cases in which brave[52] men, accustomed to the perils of battle, suddenly experienced a vivid presentiment that they would be struck down in the approaching fight, and in each case a bullet found its mark in their bodies.

Howard rode off, and then Cross and I set out to overtake the column already encamped thirteen miles away. The general lie of the ground I knew. If we followed the telegraph lines we should reach the village of Abu Selim, and thence a sharp turn to the left would bring us to the Lancers' camp beside the Nile. Starting as we did at seven, we hoped to reach our goal by midnight, and then a few hours' sleep would have intervened before a fresh move forward at four next morning. But the scheme fell through. None of the servants knew the way in the dark; there was no moon, and the starlight was not strong enough to show the telegraph posts. We struggled on in the uneven scrub, pushing through mimosa thorns and falling over logs of palm wood, while our servants struck matches to look for the hoof-marks of the cavalry. After two hours of this wearisome work we had advanced less than three miles,[53] and we saw that the enterprise was hopeless. We sat down on a stump and reviewed the situation. Neither of us had been overfed that day. Cross had had some cocoa at dawn, a cup of bovril at midday, and tea and bread at four o'clock. My own diet had been the same as his, minus the afternoon meal. I have a great belief, personally, in the hygienic value of temporary starvation, but as we sat there in the dark, Cross paid scant attention to my eulogies upon the utility of emptiness, and very wisely voted for our immediate return to the starting-place. I did not like to give up our scheme, but there was not much in the way of alternative, so after a noisy palaver with our servants, reinforced by three suspicious-looking Arabs, who emerged from the bush, we finally sent one camel and two servants along the bank, and after another two hours' floundering through the scrub, found ourselves again opposite the junction of the Atbara and Nile. We felt that the stores would probably pick up the column sooner or later, but as for ourselves, it would be foolish to be wandering about the west bank, nearer the Dervish country, without military escort.[54] Woe betide any stragglers who chanced to fall into the hands of the Dervishes at present! The best thing to do would be to empty five chambers of one's revolver and keep the sixth for one's self!

One of the suspicious-looking Arabs walked back with us and showed us a dear little hut made of wattled branches, which would shelter us for the night. Our guide turned out to be a native who had suffered at the hands of the cruel Mahmoud just before that scoundrel was defeated and captured at the battle of the Atbara in the spring. He bared his arm and showed us a hideous wound, now healed over, where a Dervish spear had cut through his flesh from shoulder to elbow. The poor man had lost his wife and child—slain, both of them, by the savage Baggaras. This incident, one among thousands of the same kind, may give one some idea of the cruel sufferings to which whole tribes were abandoned by our cowardly evacuation of the Sudan. We had put our hand to the plough, and then drew back.

We had a good square meal, washed down by a bottle of claret, the solitary survivor of[55] four. Its three companions had fallen from the camel's back, and lay shattered on the ground, with their life-juice ebbing fast. That night I dreamt that I was shooting rabbits amongst bracken in Essex, and suddenly awoke, to find myself covered with a quantity of vegetable matter. Everyone has experienced the curious feeling of hopeless bewilderment which occasionally comes over a man when he wakes in the dark amid fresh surroundings, and wonders where on earth and what on earth he is; whether he is in this world or the next. I found ultimately that the camel had literally eaten us out of house and home, for it had ambled up in the night and devoured the wattled branches of our hut to such an extent that the sides and roof suddenly collapsed upon our sleeping forms.

Early on the morning of the 17th our old friend the El Tahra came in sight, and we hailed her and crossed again to the Atbara. Next day, with the rest of the correspondents still remaining in the camp, we embarked on board a native ghyassa which was towed up the river by the gunboat Tamai. We were thoroughly crowded and uncomfortable on this miserable barge, and even when we stepped on to the lower deck of the gunboat the dirt and confusion was indescribable. The first night I attempted in the dark to get a little exercise in this way, but I fell over a live goat into the middle of a dead sheep newly slaughtered, and resolved to do without any further exercise until I landed.

The Arab servants were quite happy amid these horrid surroundings, and according to[57] their wont would sit about in groups telling stories till the small hours of the morning. One of their tales, I learnt, concerned a mummy which arose and talked to the Bedawin who unearthed it. In view of certain evidence which has lately been forthcoming, it is just possible that some substratum of truth may have underlaid this weird story. The evidence to which I allude is contained in the following account, which is alleged to be authentic.

A short time ago an Englishman who was travelling in Mexico happened to discover a mummied body of which the extremities were missing. He carried off his find to the home of a Mexican friend whose guest he was, and after dinner showed the mummy to the master and mistress of the house. The case with its contents was placed on the billiard table, and the trio sat on a couch some distance off, when suddenly a voice seemed to issue from the box. The Englishman turned to his host to compliment him on his supposed ventriloquism, when he saw that both the Mexican and his wife were deadly pale, and the lady in a fainting condition. He rushed to the case on the table and declares that as he[58] stooped over it he heard articulate speech issue from the mummied form inside! The voice, however, was only momentary, and after a time his host informed him that already before he entered the room the sound had been heard by his wife and himself proceeding from the box.

This mummy is now, I hear, in England, and one authority who has been consulted suggests that the employment of the Röntgen rays might perhaps reveal in the mummy's interior some mechanical device employed by the ancients to produce the semblance of the human voice. That some contrivance of this kind was known in antiquity seems almost certain. Priestcraft sometimes caused the statues of gods to talk, as, for example, the famous statue of Memnon amongst the ruins of Thebes. In the case before us some vibration may have started this venerable clockwork into renewed activity, just as nowadays the pressure of infantile fingers causes the mechanical doll to squeak and gibber, or cry "Papa," "Mamma."

At length Colonel Wingate took pity on our abject position in the ghyassa, and we were[59] permitted to leave the society of "Gyppy" officers and native servants, and have our meals on the upper deck.

The gunboat conveyed the Staff of the Intelligence Department, including Slatin Pasha. The long years of hardship endured at Omdurman have left few traces on Slatin; he is always in excellent spirits, and a most kind and unselfish travelling companion. He told me that he was utterly weary of the Sudan, and would, like many others, be heartily glad to see the last of campaigning in these torrid regions. He told me, too, many interesting things about Omdurman and the prisoners still in the Dervishes' power; and how the Austrian mission-sister had been compelled to marry a Greek by the Khalifa on the quaint ground that it was indecorous for an unmarried lady to reside at Omdurman without adequate protection.

The Nile becomes much more interesting above the Atbara, and the banks in places are clothed with dense vegetation. We stopped several times to take in wood for the engine, and at one of our halting-places, Zeibad, during a ramble on shore, I found the bushes[60] full of little doves (turtur Senegalensis), and a flock of wild geese got up, offering a fine shot had one carried a gun. A few hundred yards away I noticed a line of huge Marabout storks. The plumage of these birds is very striking, and I have heard it suggested that when on one occasion during the Atbara campaign a correspondent rode back to camp in hot haste with the report that he had been chased by Dervishes, he had really fallen in with a line of Marabout storks, and mistaken their mottled plumage for Arab "gibbehs." Farther along the bank we skirted a huge marsh—a perfect paradise for a sportsman: teal, duck, and snipe rose in vast coveys; on a tall bush a large fishing eagle was perched, which paid scant attention to the steamer; while at the foot two small crocodiles or very large water-lizards lay basking in the sunshine. On every side a multitude of cranes, secretary birds, and the sacred ibis stalked solemnly about in dignified silence. The whole formed a charming picture of animal life undisturbed by the presence of man—every creature working out its own perfection in "delight and liberty."

The voyage was full of interest. By day we wrote up our diaries, took photographs of interesting bits of river scenery, or occasionally got a shot at a wild duck or goose, which formed a welcome addition to our larder. About half-way to Shabluka we sighted the curious pyramids of Meroe, thirteen or fourteen in number. These seem to be often irregular in shape, and are not nearly so large as the pyramids of Ghizeh or Sakhara. They stand all solitary in a waste of sand and rock, strange enigmatic relics of a vanished race. The region of Meroe once formed a kingdom in itself, which succeeded the Ethiopian kingdom of Napata, lower down the river. The dynasties of the Meroitic kings attained considerable power, and were able to retain their independence when the rest of Egypt became subject to foreign control. Meroe was formerly a flourishing centre for caravan and river-borne trade, but this seems to have disappeared by the Christian era, for in Nero's time it is described as a desolate wilderness, and this fact seems to render untenable the belief that the Queen Candace mentioned in the Acts was the sovereign of Meroe. From the[62] time of Justinian to the 14th century Meroe was absorbed in the kingdom of Dongola, whose inhabitants professed the Jacobite form of Christianity. Quite recently I heard that an altar had been found somewhere in the Meroe region with an inscription to Isa (Jesus), who still lives in the tradition of the country as a great Sheikh. Now that the Sudan has been opened up, and travellers need not fear a compulsory experience of the Khalifa's hospitality at Omdurman, one of the first steps which English archæologists ought to undertake is the investigation of the countless ruins, tombs, inscriptions, and so forth, which exist south of Wady Halfa. No one, for instance, has yet deciphered the script which is met with amongst the ruins in the Wady Ben Naga. Lepsius explored these ruins in 1844, and published some of the curious inscriptions in his Denkmäler; but until a bilingual inscription is discovered which will, like the Rosetta Stone, furnish a clue to this mysterious writing, Egyptologists will continue to sigh over its inscrutable characters. Professor Sayce had asked me to bring back some "squeezes" and photographs from the[63] Meroitic inscriptions; but, alas, on the return journey the squeeze paper and photographic apparatus were lost by the capsizing of some ghyassas, and so I could do nothing in the cause of palæography.

A short distance past the pyramids we caught up a curious procession wending its way along the bank. A famous Gaalin sheikh, Hamara Wad Abu Sin, was journeying southwards to join the Anglo-Egyptian forces. This important ally led the way on foot, followed by a retainer armed with a Remington. Then came a baggage camel carrying the personal luggage of the chieftain, and the rear was brought up by two men and two boys. When the gunboat got opposite the old sheikh, he at once jumped into the river and swam to us, followed by one of the small boys, who kept his master's bundle of clothes out of the water. Wad Abu Sin is head of the Shukryeh tribe, and is noted throughout the Sudan for his personal bravery. His father was mudir of Khartum under Gordon, and he himself was a prisoner in that town until he managed to escape through Abyssinia. It was touching to see the old man's joy at meeting Slatin, his[64] fellow-sufferer under the cruel tyranny of the Khalifa.

At Magyrich, on the western bank, we found the Lancers encamped in a beautiful palm grove, and Cross and I were especially glad to see our camel with the two servants, who had evidently managed to pick up the column. Some distance lower down than Magyrich we had already passed two little groups of Lancers. One batch of twelve stood on the bank, and asked us to take them on board, as their horses had broken down; the other party consisted of only two men, whose comrade had just died of sunstroke, and been buried by the survivors under a mimosa bush.

At 5 a.m. a man swam to the boat from the shore, who turned out to be a deserter from Omdurman. He stated that when he left two of the Dervish boats were on the point of starting to the South, in order, perhaps, to fetch grain, and that the Khalifa was at present with his army, at the outermost of the Omdurman lines of defence, about three miles to the north of the town. This seemed to confirm the general belief, which was afterwards verified, that the decisive battle would not be fought in[65] front of the Kerreri ridge, some ten miles north of the capital, but in front of Omdurman itself.

The sight of Metemmeh was full of interest. On the opposite bank lay the ingeniously constructed forts of Shendy, with solid mud walls, thirty-five feet thick. Miles back beyond Metemmeh, in the desert, lay Abu Klea, and between the two the hamlets of Abu Kru and Gubat. The fighting which we were destined to experience before Omdurman was as nothing compared with the desperate struggles in 1885, when the gallant column of British troops fought its way through overwhelming numbers from Abu Klea to the Nile. Englishmen may well be proud of this splendid feat of arms, unexampled as it is in the history of the Sudan campaigns. Major Stuart-Wortley, who was present at the series of fights from Abu Klea to the Nile, pointed out to me the mud-hut to which Sir Herbert Stewart had been carried. How pitiful to think that the lives of this gallant leader and many another brave man were sacrificed in vain! Instead of helping to save the beleaguered city and rescue Gordon, the dearly-won victory of Abu Klea only[66] seemed to hasten the destruction of Khartum. The Mahdist forces were so incensed by the sight of their wounded comrades brought back after the battle, that they demanded to be led at once to the assault, and captured the town almost without resistance.