THE MANSION.

THE MANSION.

Title: Under the Holly: Christmas-Tide in Song and Story

Compiler: Henry F. Randolph

Release date: April 10, 2016 [eBook #51719]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Judith Wirawan and The Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

UNDER THE HOLLY.

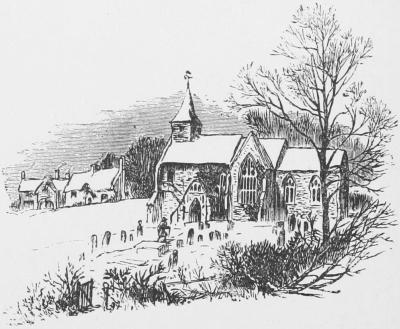

The few Illustrations in this volume are copied from the elegant edition of Irving's "Sketch Book," published by Macmillan & Co., with more than one hundred engravings after designs by Randolph Caldecott.

THE MANSION.

THE MANSION.

Christmas-Tide

IN

SONG AND STORY.

* *

NEW YORK:

ANSON D. F. RANDOLPH AND COMPANY,

38 West Twenty-Third Street.

Copyright, 1887,

By Anson D. F. Randolph and Company.

University Press:

John Wilson and Son, Cambridge.

| Page | |

| Christmas | 9 |

| Christmas Minstrelsy | 17 |

| A Christmas Lullaby | 21 |

| The Old Oak-tree's Last Dream | 23 |

| Little Gottlieb | 31 |

| Tiny Tim's Christmas Dinner | 36 |

| Christmas Carol | 46 |

| Last Night, as I lay Sleeping | 47 |

| Christmas Day in London | 49 |

| Under the Holly-bough | 53 |

| The Little Match-girl | 55 |

| A Rocking Hymn | 60 |

| In Memoriam | 66 |

It was always said of him, that he knew how to keep Christmas well, if any man alive possessed the knowledge. May that be truly said of us, and all of us! And so, as Tiny Tim observed, God bless Us, Every One!

Extract from "The Sketch Book"

of Washington Irving.

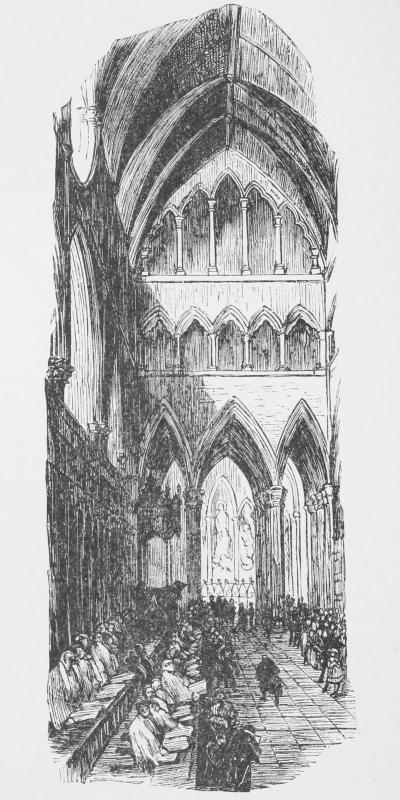

Of all the old festivals, that of Christmas awakens the strongest and most heartfelt associations. There is a tone of solemn and sacred feeling that blends with our conviviality, and lifts the spirit to a state of hallowed and elevated enjoyment. The services of the church about this season are extremely tender and inspiring. They dwell on the beautiful story of the origin of our faith, and the pastoral scenes that accompanied its announcement. They gradually increase in fervor and pathos during the season of Advent, until they break forth in full jubilee on the morning that brought peace and good-will to men. I do not know a grander effect of music on the moral feelings than to hear the full choir and the pealing organ performing a Christmas anthem in a cathedral, and filling every part of the vast pile with triumphant harmony.

It is a beautiful arrangement, also, derived from days of yore, that this festival, which commemorates the announcement of the religion of peace and love, has been made the season for gathering together of family connections, and drawing closer again those bands of kindred hearts which the cares and pleasures and sorrows of the world are continually operating to cast loose; of calling back the children of a family who have launched forth in life, and wandered widely asunder, once more to assemble about the paternal hearth, that rallying-place of the affections, there to grow young and loving again among the endearing mementos of childhood.

There is something in the very season of the year that gives a charm to the festivity of Christmas. At other times we derive a great portion of our pleasures from the mere beauties of Nature. Our feelings sally forth and dissipate themselves over the sunny landscape, and we "live abroad and everywhere." The song of the bird, the murmur of the stream, the breathing fragrance of spring, the soft voluptuousness of summer, the golden pomp of autumn; earth with its mantle of refreshing green, and heaven with its deep delicious blue and its cloudy magnificence,—all fill us with mute but exquisite delight, and we[Pg 11] revel in the luxury of mere sensation. But in the depth of winter, when Nature lies despoiled of every charm, and wrapped in her shroud of sheeted snow, we turn for our gratifications to moral sources. The dreariness and desolation of the landscape, the short gloomy days and darksome nights, while they circumscribe our wanderings, shut in our feelings also from rambling abroad, and make us more keenly disposed for the pleasures of the social circle. Our thoughts are more concentrated; our friendly sympathies more aroused. We feel more sensibly the charm of each other's society, and are brought more closely together by dependence on each other for enjoyment. Heart calleth unto heart; and we draw our pleasures from the deep wells of living kindness, which lie in the quiet recesses of our bosoms, and which, when resorted to, furnish forth the pure element of domestic felicity.

The pitchy gloom without makes the heart dilate on entering the room filled with the glow and warmth of the evening fire. The ruddy blaze diffuses an artificial summer and sunshine through the room, and lights up each countenance into a kindlier welcome. Where does the honest face of hospitality expand into a broader[Pg 12] and more cordial smile, where is the shy glance of love more sweetly eloquent, than by the winter fireside? and as the hollow blast of wintry wind rushes through the hall, claps the distant door, whistles about the casement, and rumbles down the chimney, what can be more grateful than that feeling of sober and sheltered security with which we look round upon the comfortable chamber and the scene of domestic hilarity?

The English, from the great prevalence of rural habits throughout every class of society, have always been fond of those festivals and holidays which agreeably interrupt the stillness of country life; and they were, in former days, particularly observant of the religious and social rites of Christmas. It is inspiring to read even the dry details which some antiquarians have given of the quaint humors, the burlesque pageants, the complete abandonment to mirth and good-fellowship, with which this festival was celebrated. It seemed to throw open every door, and unlock every heart. It brought the peasant and the peer together, and blended all ranks in one warm, generous flow of joy and kindness. The old halls of castles and manor-houses resounded with the harp and the Christmas carol, and their ample boards groaned under the weight[Pg 13] of hospitality. Even the poorest cottage welcomed the festive season with green decorations of bay and holly; the cheerful fire glanced its rays through the lattice, inviting the passenger to raise the latch, and join the gossip knot huddled round the hearth, beguiling the long evening with legendary jokes and oft-told Christmas tales.

One of the least pleasing effects of modern refinement is the havoc it has made among the hearty old holiday customs. It has completely taken off the sharp touchings and spirited reliefs of these embellishments of life, and has worn down society into a more smooth and polished, but certainly a less characteristic surface. Many of the games and ceremonials of Christmas have entirely disappeared, and like the sherris-sack of old Falstaff, are become matters of speculation and dispute among commentators. They flourished in times full of spirit and lustihood, when men enjoyed life roughly, but heartily and vigorously,—times wild and picturesque, which have furnished poetry with its richest materials, and the drama with its most attractive variety of characters and manners. The world has become more worldly. There is more of dissipation and less of enjoyment. Pleasure has expanded into a broader but a shallower stream, and has[Pg 14] forsaken many of those deep and quiet channels where it flowed sweetly through the calm bosom of domestic life. Society has acquired a more enlightened and elegant tone; but it has lost many of its strong local peculiarities, its home-bred feelings, its honest fireside delights. The traditionary customs of golden-hearted antiquity, its feudal hospitalities and lordly wassailings, have passed away with the baronial castles and stately manor-houses in which they were celebrated. They comported with the shadowy hall, the great oaken gallery, and the tapestried parlor, but are unfitted to the light showy saloons and gay drawing-rooms of the modern villa.

Shorn, however, as it is, of its ancient and festive honors, Christmas is still a period of delightful excitement in England. It is gratifying to see that home feeling completely aroused which seems to hold so powerful a place in every English bosom. The preparations making on every side for the social board that is again to unite friends and kindred; the presents of good cheer passing and repassing, those tokens of regard and quickeners of kind feelings; the evergreens distributed about houses and churches, emblems of peace and gladness,—all these have the most pleasing effect in producing fond[Pg 15] associations, and kindling benevolent sympathies. Even the sound of the waits, rude as may be their minstrelsy, breaks upon the mid-watches of a winter night with the effect of perfect harmony. As I have been awakened by them in that still and solemn hour, "when deep sleep falleth upon man," I have listened with a hushed delight, and, connecting them with the sacred and joyous occasion, have almost fancied them into another celestial choir, announcing peace and good-will to mankind.

Amidst the general call to happiness, the bustle of the spirits, and stir of the affections, which prevail at this period, what bosom can remain insensible? It is, indeed, the season of regenerated feeling,—the season for kindling, not merely the fire of hospitality in the hall, but the genial flame of charity in the heart.

The scene of early love again rises green to memory beyond the sterile waste of years; and the idea of home, fraught with the fragrance of home-dwelling joys, re-animates the drooping spirit,—as the Arabian breeze will sometimes waft the freshness of the distant fields to the weary pilgrim of the desert.

He who can turn churlishly away from contemplating the felicity of his fellow-beings, and sit down darkling and repining in his loneliness when all around is joyful, may have his moments of strong excitement and selfish gratification, but he wants the genial and social sympathies which constitute the charm of a merry Christmas.

Dedication of Wordsworth's River Duddon Sonnets,

to his brother Dr. Wordsworth.

By John Addington Symonds.

By Hans Christian Andersen.

The Oak-tree stood stripped of all his foliage, ready to go to rest for the whole winter, and in it to dream many dreams,—to dream of the past, just as men dream.

The tree had once been a little one, and had had a field for its cradle. Now, according to human reckoning, he was in his fourth century. He was the tallest and mightiest tree in the woods; his crown towered high above all the other trees, and was seen far out on the sea, serving as a beacon to ships; but the old Oak-tree had never thought how many eyes sought him out from afar.

High up in his green crown wood-doves had built their nests, and the cuckoo perched to announce spring; and in the autumn, when his leaves looked like copper-plates hammered out thin, birds of passage came and rested awhile[Pg 24] among the boughs, before they flew across the seas. But now it was winter; the tree stood leafless, and the bowed and crooked branches displayed their dark outlines; crows and jackdaws came alternately, gossiping together about the hard times that were beginning, and the difficulty of getting food during the winter.

It was just at the holy Christmas-tide that the Oak-tree dreamt his most beautiful dream: this dream we will hear.

The tree had a foreboding that a festive season was nigh; he seemed to hear the church-bells ringing all round, and to feel as though it were a mild, warm summer day. Fresh and green, he reared his mighty crown on high; the sunbeams played among his leaves and boughs; the air was filled with fragrance; bright-colored butterflies gambolled, and gnats danced,—which was all they could do to show their joy. And all that the tree had beheld during his life passed by as in a festive procession. Knights and ladies, with feathers in their caps, and hawks perching on their wrists, rode gayly through the wood; dogs barked, and the huntsman sounded his bugle. Then came foreign soldiers in bright armor and gay vestments, bearing spears and halberds, setting up their tents, and presently taking them[Pg 25] down again; then watch-fires blazed up, and bands of wild outlaws sang, revelled, and slept under the tree's outstretched boughs, or happy lovers met in the quiet moonlight, and carved their initials on the grayish bark. At one time a guitar, at another an Æolian harp, had been hung up amid the old oak's boughs, by merry travelling apprentices; now they hung there again, and the wind played so sweetly with the strings. The wood-doves cooed, as though they would do their best to express the tree's happy feelings, and the cuckoo talked about himself as usual, proclaiming how many summer days he had to live.

And now it seemed a new and stronger current of life flowed through him, down to his lowest roots, up to his highest twigs, even to the very leaves! The tree felt in his roots that a warm life stirred in the earth,—felt his strength increase, and that he was growing taller and taller. His trunk shot up more and more; his crown grew fuller; he spread, he towered; and still, as the tree grew, he felt that his power grew with it, and that his ardent longing to advance higher and higher up to the bright warm sun increased also.

Already had he towered above the clouds, which drifted below him, now like a troop of[Pg 26] dark-plumaged birds of passage, now like flocks of large white swans.

And every leaf could see, as though it had eyes; the stars became visible by daylight, so large and bright, each one sparkling like a mild, clear eye: they reminded him of dear kind eyes that had sought each other under his shade,—lovers' eyes, children's eyes.

It was a blessed moment; and yet, in the height of his joy, the Oak-tree felt a desire and longing that all the other trees, bushes, herbs, and flowers of the wood might be lifted up with him, might share in this glory and gladness. The mighty Oak-tree, amid his dream of splendor, could not be fully blessed unless he might have all, little and great, to share it with him; and this feeling thrilled through boughs and leaves as strongly, as fervently as though his were the heart of a man.

The tree's crown bowed itself, as though it missed and sought something, looked backward. Then he felt the fragrance of honeysuckles and violets, and fancied he could hear the cuckoo answering himself.

Yes, so it was! for now peeped forth, through the clouds, the green summits of the wood; the other trees below had grown and lifted themselves[Pg 27] up likewise; bushes and herbs shot high into the air, some tearing themselves loose from their roots, and mounting all the faster. The birch had grown most rapidly; like a flash of white lightning, its slender stem shot upward, its boughs waving like pale-green banners. Even the feathery brown reed had pierced its way through the clouds; and the birds followed, and sang and sang; and on the grass that fluttered to and fro like a long streaming green ribbon perched the grasshopper, and drummed with his wings on his lean body; the cockchafers hummed, and the bees buzzed; every bird sang with all his might, and all was music and gladness.

"But the little blue flower near the water,—I want that too," said the Oak-tree; "and the bell-flower, and the dear little daisy!" The tree wanted all these.

"We are here! we are here!" chanted sweet low voices on all sides.

"But the pretty anemones of last spring, and the bed of lilies-of-the-valley that blossomed the year before that! and the wild crab-apple tree! and all the beautiful trees and flowers that have adorned the wood through so many seasons—oh, would that they had lived till now!"

"We are here! we are here!" was the answer; and this time it seemed to come from the air above, as though they had fled upward first.

"Oh, this is too great happiness,—it is almost incredible!" exclaimed the Oak-tree. "I have them all, small and great; not one of them is forgotten! How can such blessedness be possible?"

"In the kingdom of God all things are possible," was the answer.

And the tree now felt that his roots were loosening themselves from the earth. "This is best of all," he said; "now no bonds shall detain me, I can soar up to the height of light and glory; and my dear ones are with me, small and great,—I have them all!"

Such was the old Oak-tree's dream; and all the while, on that holy Christmas Eve, a mighty storm swept over sea and land: the ocean rolled its heavy billows on the shore; the tree cracked, was rent and torn up by the roots, at the very moment when he dreamt that his roots were disengaging themselves from the earth. He fell. His three hundred and sixty-five years were now as a day is to the May-fly.

On Christmas morning, when the sun burst[Pg 29] forth, the storm was laid. All the church-bells were ringing joyously; and from every chimney, even the poorest, the blue smoke curled upward, as from the Druids' altar of old uprose the sacrificial steam. The sea was calm again; and a large vessel that had weathered the storm the night before, now hoisted all its flags, in token of Yule festivity. "The tree is gone,—the old Oak-tree, our beacon," said the crew; "it has fallen during last night's storm. How can its place ever be supplied?"

This was the tree's funeral eulogium, brief but well-meant. There he lay, outstretched upon the snowy carpet near the shore; whilst over it re-echoed the hymn sung on shipboard,—the hymn sung in thanksgiving for the joy of Christmas, for the bliss of the human soul's salvation, through Christ, and the gift of eternal life:—

Thus resounded the old hymn; and every soul lifted up heart and desire heavenward, even as the old tree had lifted himself on his last, best dream,—his Christmas Eve dream.

By Phœbe Cary.

By Charles Dickens.

Then up rose Mrs. Cratchit, Cratchit's wife, dressed out but poorly in a twice turned gown, but brave in ribbons, which are cheap and make a goodly show for sixpence; and she laid the cloth, assisted by Belinda Cratchit, second of her daughters, also brave in ribbons; while Master Peter Cratchit plunged a fork into the saucepan of potatoes, and getting the corners of his monstrous shirt-collar (Bob's private property, conferred upon his son and heir in honor of the day) into his mouth, rejoiced to find himself so gallantly attired, and yearned to show his linen in the fashionable Parks. And now two smaller Cratchits, boy and girl, came tearing in, screaming that outside the baker's they had smelt the goose, and known it for their own; and basking in luxurious thoughts of sage and onion, these young Cratchits danced about the table, and exalted Master Peter Cratchit to the skies,[Pg 37] while he (not proud, although his collars nearly choked him) blew the fire, until the slow potatoes, bubbling up, knocked loudly at the saucepan lid to be let out and peeled.

"What has ever got your precious father then?" said Mrs. Cratchit. "And your brother Tiny Tim! And Martha warn't as late last Christmas Day by half an hour!"

"Here's Martha, mother!" said a girl, appearing as she spoke.

"Here's Martha, mother!" cried the two young Cratchits. "Hurrah! There's such a goose, Martha!"

"Why, bless your heart alive, my dear, how late you are!" said Mrs. Cratchit, kissing her a dozen times, and taking off her shawl and bonnet for her with officious zeal.

"We'd a deal of work to finish up last night," replied the girl, "and had to clear away this morning, mother!"

"Well! never mind so long as you are come," said Mrs. Cratchit. "Sit ye down before the fire, my dear, and have a warm, Lord bless ye!"

"No, no! there's father coming," cried the two young Cratchits, who were everywhere at once. "Hide, Martha, hide!"

So Martha hid herself; and in came little Bob,[Pg 38] the father, with at least three feet of comforter exclusive of the fringe hanging down before him, and his threadbare clothes darned up and brushed to look seasonable, and Tiny Tim upon his shoulder. Alas for Tiny Tim, he bore a little crutch, and had his limbs supported by an iron frame!

"Why, where's our Martha?" cried Bob Cratchit, looking round.

"Not coming," said Mrs. Cratchit.

"Not coming!" said Bob, with a sudden declension in his high spirits; for he had been Tim's blood horse all the way from church, and had come home rampant. "Not coming upon Christmas Day!"

Martha didn't like to see him disappointed, if it were only a joke; so she came out prematurely from behind the closet door, and ran into his arms, while the two young Cratchits hustled Tiny Tim, and bore him off into the wash-house, that he might hear the pudding singing in the copper.

"And how did little Tim behave?" asked Mrs. Cratchit, when she had rallied Bob on his credulity, and Bob had hugged his daughter to his heart's content.

"As good as gold," said Bob, "and better.[Pg 39] Somehow he gets thoughtful, sitting by himself so much, and thinks the strangest things you ever heard. He told me, coming home, that he hoped the people saw him in the church, because he was a cripple, and it might be pleasant to them to remember upon Christmas Day who made lame beggars walk and blind men see."

Bob's voice was tremulous when he told them this, and trembled more when he said that Tiny Tim was growing strong and hearty.

His active little crutch was heard upon the floor, and back came Tiny Tim before another word was spoken, escorted by his brother and sister to his stool beside the fire; and while Bob, turning up his cuffs,—as if, poor fellow, they were capable of being made more shabby,—compounded some hot mixture in a jug with gin and lemons, and stirred it round and round and put it on the hob to simmer, Master Peter and the two ubiquitous young Cratchits went to fetch the goose, with which they soon returned in high procession.

Such a bustle ensued that you might have thought a goose the rarest of all birds,—a feathered phenomenon, to which a black swan was a matter of course; and in truth it was something very like it in that house. Mrs. Cratchit made[Pg 40] the gravy (ready beforehand in a little saucepan) hissing hot; Master Peter mashed the potatoes with incredible vigor; Miss Belinda sweetened up the apple-sauce; Martha dusted the hot plates; Bob took Tiny Tim beside him in a tiny corner at the table; the two young Cratchits set chairs for everybody, not forgetting themselves, and mounting guard upon their posts, crammed spoons into their mouths, lest they should shriek for goose before their turn came to be helped. At last the dishes were set on, and grace was said. It was succeeded by a breathless pause, as Mrs. Cratchit, looking slowly all along the carving-knife, prepared to plunge it in the breast; but when she did, and when the long-expected gush of stuffing issued forth, one murmur of delight arose all round the board, and even Tiny Tim, excited by the two young Cratchits, beat on the table with the handle of his knife, and feebly cried Hurrah!

There never was such a goose. Bob said he didn't believe there ever was such a goose cooked. Its tenderness and flavor, size and cheapness, were the themes of universal admiration. Eked out by apple-sauce and mashed potatoes, it was a sufficient dinner for the whole family; indeed, as Mrs. Cratchit said with great[Pg 41] delight (surveying one small atom of a bone upon the dish), they hadn't ate it all at last! Yet every one had had enough, and the youngest Cratchits in particular were steeped in sage and onion to the eyebrows! But now the plates being changed by Miss Belinda, Mrs. Cratchit left the room alone—too nervous to bear witnesses—to take the pudding up, and bring it in.

Suppose it should not be done enough! Suppose it should break in turning out! Suppose somebody should have got over the wall of the back yard, and stolen it, while they were merry with the goose,—a supposition at which the two young Cratchits became livid! All sorts of horrors were supposed.

Hallo! A great deal of steam! The pudding was out of the copper. A smell like a washing-day! That was the cloth. A smell like an eating-house and a pastry-cook's next door to each other, with a laundress's next door to that! That was the pudding! In half a minute Mrs. Cratchit entered—flushed, but smiling proudly—with the pudding, like a speckled cannon-ball, so hard and firm, blazing in half of half-a-quartern of ignited brandy, and bedight with Christmas holly stuck into the top.

Oh, a wonderful pudding! Bob Cratchit said,[Pg 42] and calmly too, that he regarded it as the greatest success achieved by Mrs. Cratchit since their marriage. Mrs. Cratchit said that now the weight was off her mind, she would confess she had her doubts about the quantity of flour. Everybody had something to say about it, but nobody said or thought it was at all a small pudding for a large family. It would have been flat heresy to do so. Any Cratchit would have blushed to hint at such a thing.

At last the dinner was all done, the cloth was cleared, the hearth swept, and the fire made up. The compound in the jug being tasted, and considered perfect, apples and oranges were put upon the table, and a shovelful of chestnuts on the fire. Then all the Cratchit family drew round the hearth, in what Bob Cratchit called a circle, meaning half a one; and at Bob Cratchit's elbow stood the family display of glass,—two tumblers and a custard-cup without a handle.

These held the hot stuff from the jug, however, as well as golden goblets would have done; and Bob served it out with beaming looks, while the chestnuts on the fire sputtered and cracked noisily. Then Bob proposed:—

"A merry Christmas to us all, my dears. God bless us."

Which all the family re-echoed.

"God bless us every one!" said Tiny Tim, the last of all.

He sat very close to his father's side, upon his little stool. Bob held his withered little hand in his, as if he loved the child, and wished to keep him by his side, and dreaded that he might be taken from him.

"Mr. Scrooge!" said Bob; "I'll give you, Mr. Scrooge, the Founder of the Feast!"

"The Founder of the Feast indeed!" cried Mrs. Cratchit, reddening. "I wished I had him here. I'd give him a piece of my mind to feast upon, and I hope he'd have a good appetite for it."

"My dear," said Bob, "the children! Christmas Day!"

"It should be Christmas Day, I am sure," said she, "on which one drinks the health of such an odious, stingy, hard, unfeeling man as Mr. Scrooge. You know he is, Robert! Nobody knows it better than you do, poor fellow!"

"My dear," was Bob's mild answer, "Christmas Day!"

"I'll drink his health for your sake and the Day's," said Mrs. Cratchit, "not for his. Long life to him! A merry Christmas and a happy[Pg 44] new year! He'll be very merry and very happy, I have no doubt!"

The children drank the toast after her. It was the first of their proceedings which had no heartiness in it! Tiny Tim drank it last of all, but he didn't care twopence for it. Scrooge was the Ogre of the family. The mention of his name cast a dark shadow on the party, which was not dispelled for full five minutes.

After it had passed away, they were ten times merrier than before, from the mere relief of Scrooge the Baleful being done with. Bob Cratchit told them how he had a situation in his eye for Master Peter, which would bring in, if obtained, full five-and-sixpence weekly. The two young Cratchits laughed tremendously at the idea of Peter's being a man of business; and Peter himself looked thoughtfully at the fire from between his collars, as if he were deliberating what particular investments he should favor when he came into the receipt of that bewildering income. Martha, who was a poor apprentice at a milliner's, then told them what kind of work she had to do, and how many hours she worked at a stretch, and how she meant to lie abed to-morrow morning for a good long rest; to-morrow being a holiday she passed at home. Also how[Pg 45] she had seen a countess and a lord some days before, and how the lord "was much about as tall as Peter," at which Peter pulled up his collars so high that you couldn't have seen his head if you had been there. All this time the chestnuts and the jug went round and round; and by and by they had a song, about a lost child travelling in the snow, from Tiny Tim, who had a plaintive little voice, and sang it very well indeed.

By Hans Christian Andersen.

Anonymous.

By Charles Dickens.

The poulterers' shops were still half open, and the fruiterers' shops were radiant in their glory. There were great round, pot-bellied baskets of chestnuts, shaped like the waistcoats of jolly old gentlemen, lolling at the doors, and tumbling out into the street in their apoplectic opulence. There were ruddy, brown-faced, broad-girthed Spanish onions, shining in the fatness of their growth like Spanish Friars, and winking from their shelves in wanton slyness at the girls as they went by and glanced demurely at the hung up mistletoe. There were pears and apples, clustered high in blooming pyramids; there were bunches of grapes, made, in the shop-keepers' benevolence, to dangle from conspicuous hooks that people's mouths might water gratis as they passed; there were piles of filberts, mossy and brown, recalling, in their fragrance, ancient walks among the woods, and pleasant[Pg 50] shufflings ankle-deep through withered leaves; there were Norfolk Biffins, squab and swarthy, setting off the yellow of the oranges and lemons, and, in the great compactness of their juicy persons, urgently entreating and beseeching to be carried home in paper bags and eaten after dinner. The very gold and silver fish, set forth among these choice fruits in a bowl, though members of a dull and stagnant-blooded race, appeared to know that there was something going on; and, to a fish, went gasping round and round their little world in slow and passionless excitement.

The Grocers'! oh, the Grocers'! nearly closed, with perhaps two shutters down, or one; but through those gaps such glimpses! It was not alone that the scales descending on the counter made a merry sound, or that the twine and roller parted company so briskly, or that the canisters were rattled up and down like juggling tricks, or even that the blended scents of tea and coffee were so grateful to the nose, or even that the raisins were so plentiful and rare, the almonds so extremely white, the sticks of cinnamon so long and straight, the other spices so delicious, the candied fruits so caked and spotted with molten sugar as to make the coldest lookers-on feel faint[Pg 51] and subsequently bilious. Nor was it that the figs were moist and pulpy, or that the French plums blushed in modest tartness from their highly decorated boxes, or that everything was good to eat and in its Christmas dress; but the customers were all so hurried and so eager in the hopeful promise of the day, that they tumbled up against each other at the door, crashing their wicker baskets wildly, and left their purchases upon the counter, and came running back to fetch them, and committed hundreds of the like mistakes, in the best humor possible; while the Grocer and his people were so frank and fresh that the polished hearts with which they fastened their aprons behind might have been their own, worn outside for general inspection, and for Christmas daws to peck at if they chose.

IN THE CHURCH.

IN THE CHURCH.

But soon the steeples called good people all to church and chapel; and away they came, flocking through the streets in their best clothes and with their gayest faces. And at the same time there emerged from scores of by-streets, lanes, and nameless turnings, innumerable people, carrying their dinners to the bakers' shops. The sight of these poor revellers appeared to interest the Spirit very much; for he stood with Scrooge beside him in a baker's doorway, and[Pg 52] taking off the covers as their bearers passed, sprinkled incense on their dinners from his torch. And it was a very uncommon kind of torch; for once or twice when there were angry words between some dinner-carriers who had jostled each other, he shed a few drops of water on them from it, and their good humor was restored directly. For they said, it was a shame to quarrel upon Christmas Day. And so it was! God love it, so it was!

By Charles Mackay.

By Hans Christian Andersen.

It was terribly cold; it snowed and was already almost dark, and evening came on,—the last evening of the year. In the cold and gloom a poor little girl, bareheaded and barefoot, was walking through the streets. When she left her own house she certainly had had slippers on; but of what use were they? They were very big slippers, and her mother had used them till then, so big were they. The little maid lost them as she slipped across the road, where two carriages were rattling by terribly fast. One slipper was not to be found again; and a boy had seized the other, and run away with it. He thought he could use it very well as a cradle, some day when he had children of his own. So now the little girl went with her little naked feet, which were quite red and blue with the cold. In an old apron she carried a number of matches and a bundle of them in her hand. No one had[Pg 56] bought anything of her all day, and no one had given her a farthing.

Shivering with cold and hunger, she crept along, a picture of misery, poor little girl! The snowflakes covered her long fair hair, which fell in pretty curls over her neck; but she did not think of that now. In all the windows lights were shining, and there was a glorious smell of roast goose, for it was New Year's Eve. Yes, she thought of that!

In a corner formed by two houses, one of which projected beyond the other, she sat down, cowering. She had drawn up her little feet, but she was still colder, and she did not dare to go home, for she had sold no matches, and did not bring a farthing of money. From her father she would certainly receive a beating; and, besides, it was cold at home, for they had nothing over them but a roof through which the wind whistled, though the largest rents had been stopped with straw and rags.

Her little hands were almost benumbed with the cold. Ah! a match might do her good, if she could only draw one from the bundle, and rub it against the wall, and warm her hands at it. She drew one out. R-r-atch! how it sputtered and burned! It was a warm bright flame, like a[Pg 57] little candle, when she held her hands over it; it was a wonderful little light! It really seemed to the little girl as if she sat before a great polished stove, with bright brass feet and a brass cover. How the fire burned! how comfortable it was! but the little flame went out, the stove vanished, and she had only the remains of the burned match in her hand.

A second was rubbed against the wall. It burned up; and when the light fell upon the wall it became transparent like a thin veil, and she could see through it into the room. On the table a snow-white cloth was spread; upon it stood a shining dinner service; the roast goose smoked gloriously, stuffed with apples and dried plums. And what was still more splendid to behold, the goose hopped down from the dish, and waddled along the floor, with a knife and fork in its breast, to the little girl. Then the match went out, and only the thick, damp, cold wall was before her. She lighted another match. Then she was sitting under a beautiful Christmas tree; it was greater and more ornamented than the one she had seen through the glass door at the rich merchant's. Thousands of candles burned upon the green branches, and colored pictures like those in the print shops looked[Pg 58] down upon them. The little girl stretched forth her hand toward them; then the match went out. The Christmas lights mounted higher. She saw them now as stars in the sky: one of them fell down, forming a long line of fire.

"Now some one is dying," thought the little girl; for her old grandmother, the only person who had loved her, and who was now dead, had told her that when a star fell down a soul mounted up to God.

She rubbed another match against the wall; it became bright again, and in the brightness the old grandmother stood clear and shining, mild and lovely.

"Grandmother!" cried the child, "oh, take me with you! I know you will go when the match is burned out. You will vanish like the warm fire, the warm food, and the great, glorious Christmas tree!"

And she hastily rubbed the whole bundle of matches, for she wished to hold her grandmother fast. And the matches burned with such a glow that it became brighter than in the middle of the day; grandmother had never been so large or so beautiful. She took the little girl in her arms, and both flew in brightness and joy above the earth, very, very high; and up there was neither[Pg 59] cold nor hunger nor care,—they were with God.

But in the corner, leaning against the wall, sat the poor girl with red cheeks and smiling mouth, frozen to death on the last evening of the Old Year. The New Year's sun rose upon a little corpse! The child sat there, stiff and cold, with the matches, of which one bundle was burned. "She wanted to warm herself," the people said. No one imagined what a beautiful thing she had seen, and in what glory she had gone in with her grandmother to the New Year's Day.

From George Wither's "Hallelujah."

By Alfred, Lord Tennyson.

(Cantos XXVIII., XXIX., XXX.)

Obvious printer's errors have been repaired, other inconsistent spellings have been kept, including inconsistent use of hyphen (e.g. "good will" and "good-will").