Title: The Overland Route to the Road of a Thousand Wonders

Creator: Union Pacific Railroad Company. Passenger Department

Southern Pacific Company. Passenger Department

Release date: April 24, 2016 [eBook #51849]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Rick Morris and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

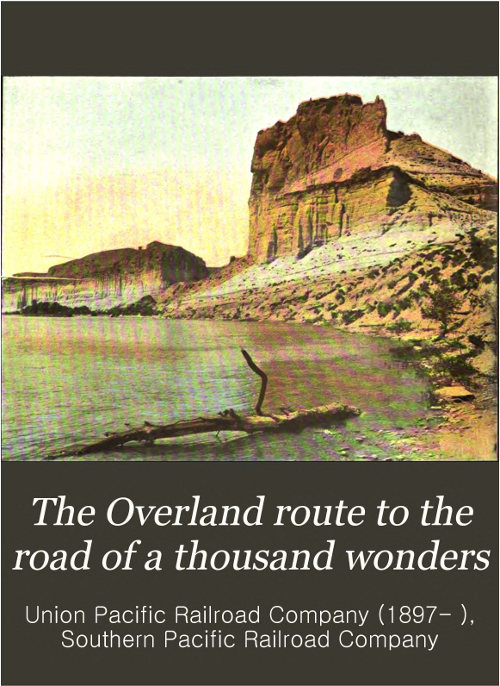

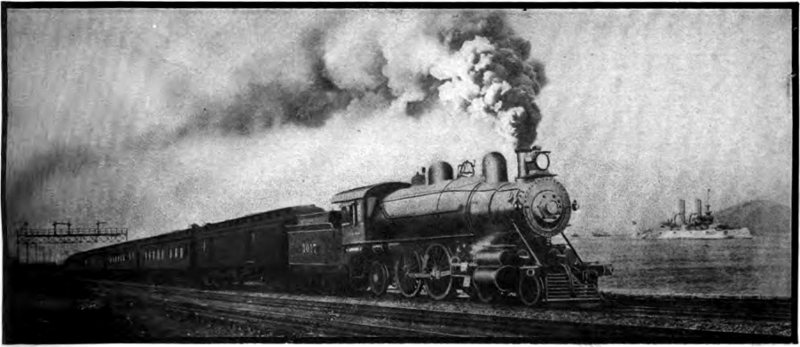

The ROUTE OF The UNION PACIFIC & The SOUTHERN PACIFIC FROM OMAHA TO SAN FRANCISCO

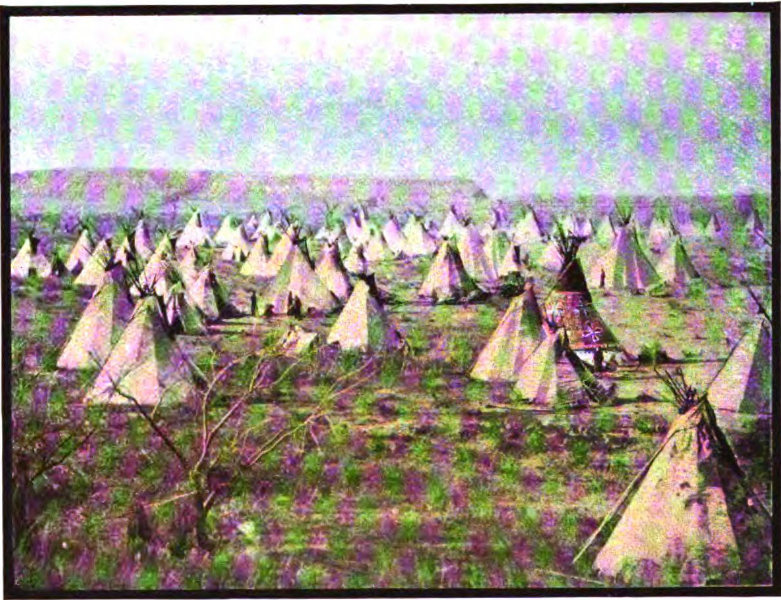

A JOURNEY OF EIGHTEEN HUNDRED MILES WHERE ONCE The BISON & The INDIAN REIGNED

Over the wagon trail of the hardy Pioneers runs the Overland Route as pictured in these pages; over vast plains, once prairie, now farmland; past the high outpost of the Rockies; across the surface of that strange inland sea, Great Salt Lake; over the crest of the high Sierra; through picturesque canyon and valley to the Golden Gate

ISSUED BY THE

UNION PACIFIC AND SOUTHERN PACIFIC

PASSENGER DEPARTMENTS

1908

The OVERLAND ROUTE

Union Pacific & Southern Pacific between Omaha & San Francisco

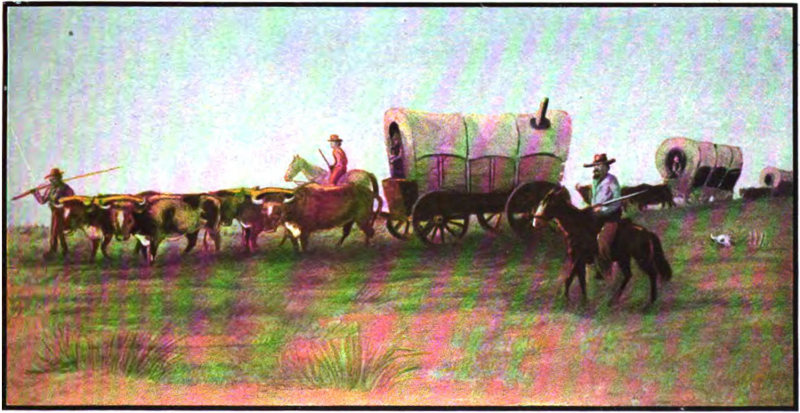

DEFENDING THE WORK TRAIN. THERE WAS AN INDIAN ARROW SHOT FOR EVERY SPIKE DRIVEN IN THE IRON TRAIL OF THE OVERLAND ROUTE. ENCOUNTERS WERE NUMEROUS AND OFTEN FATAL.

THE BUFFALO—CORONADO’S HUMP BACKED OXEN—PASSED WHEN THE WAGON TRAIL GAVE WAY TO THE RAILROAD

The memory of the Overland Trail will not soon pass away. Traces of it are left here and there in the West, but the winds and rain and the erosion of civilization have nearly rubbed it out. Yet in its time it was the greatest wagon way. All in all, from the Council Bluffs crossing of the Missouri to the Golden Gate of the Pacific, it was two thousand miles long.

Vague are legend and story, prior to the nineteenth century, of the country it was to traverse. One legend indicates that Coronado visited the land of the “humpbacked oxen” in the sixteenth century; a tale of like uncertainty credits Baron La Honton with a visit to Great Salt Lake in the century following. The Franciscan friars, Escalante and Dominguez, saw Utah Lake in 1776, and carried home strange stories of a sea of salt farther north.

The Lewis and Clark expedition to the mouth of the Columbia, starting from St. Louis in 1804, is the beginning of the history of the Overland Trail. Soon after came the Astor party, which in 1811 founded Astoria. Thirteen years later, a most adventurous spirit, a daring hunter and pioneer, Jim Bridger, began his picturesque career in the West. Caring for no neighbors in the wilderness, at home in the high mountains, on the treeless plains or in the desert, this fearless and intelligent man sent out much accurate information and guided the Mormon “First Company” to its future home.

In 1843 the Pathfinder, General John C. Fremont, began to spy out the military ways across the West, and the same year the Oregon pioneers took the first wagons westward to the Pacific.

The trail that began with the journey of these Oregon pioneers was widened and deepened by the wheels of the Mormons in 1847; and when the herald of the first California Golden Age sent forth a trumpet call in ’Forty-nine, heard around the world, the trail was finished from Great Salt Lake across the mountains to the sea.

That era had its great men, for great men make eras. Ben Holladay, William N. Russell, and Edward Creighton gave to the trail the Overland Stage Line and the Pony Express and the telegraph.

Dating the beginning of transcontinental wagon travel from the days of ’Forty-nine, it was twenty years before the railway reached California. The period was one of great out-of-doors men and women—the last of American pioneers. When the old trail was in full tide of life, it was filled with gold-seekers from the Missouri to the Pacific. A hundred thousand souls passed over it yearly. Towns, stirring and turbulent, some now gone from the map and some grown to be cities, flourished as the green bay tree. Omaha, Salt Lake, and San Francisco, and such lesser places as Julesburg, Cheyenne, Laramie, Carson, Elko, and Virginia City were picturesquely lively. Hardly was there a stage station without its stirring story of swift life and sudden death, and long and short haired characters with fighting reputations were to be found anywhere from St. Joseph to San Francisco.

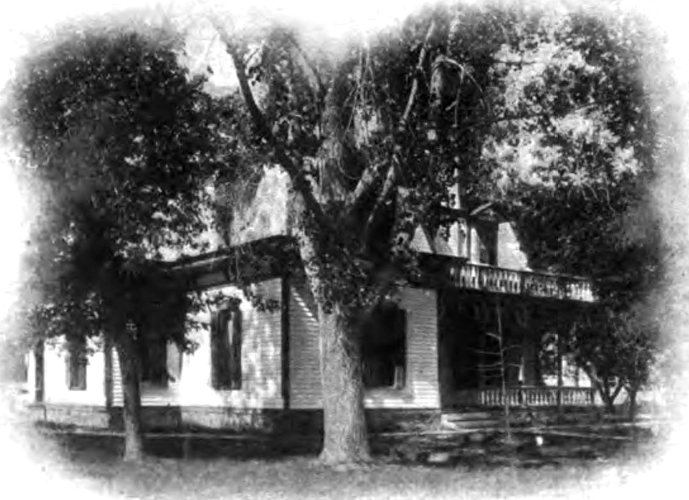

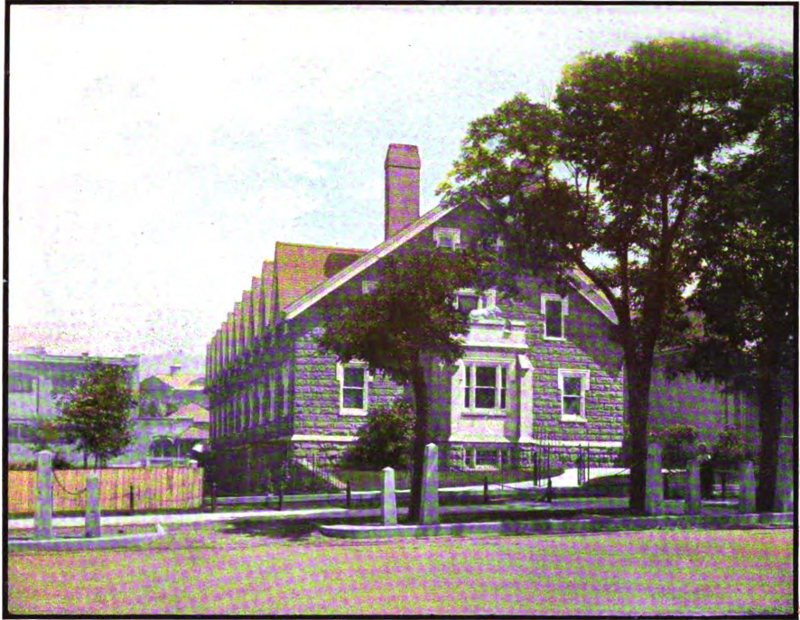

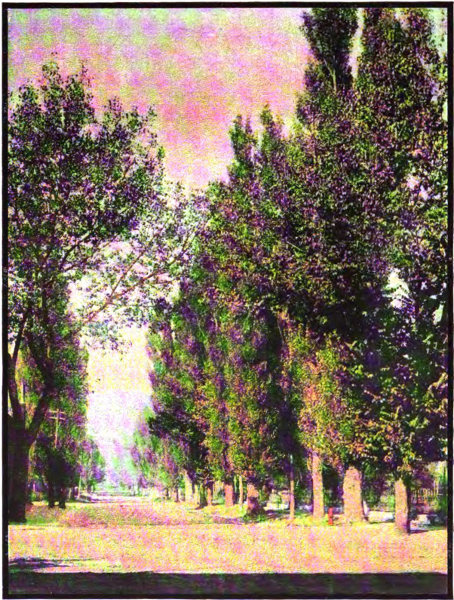

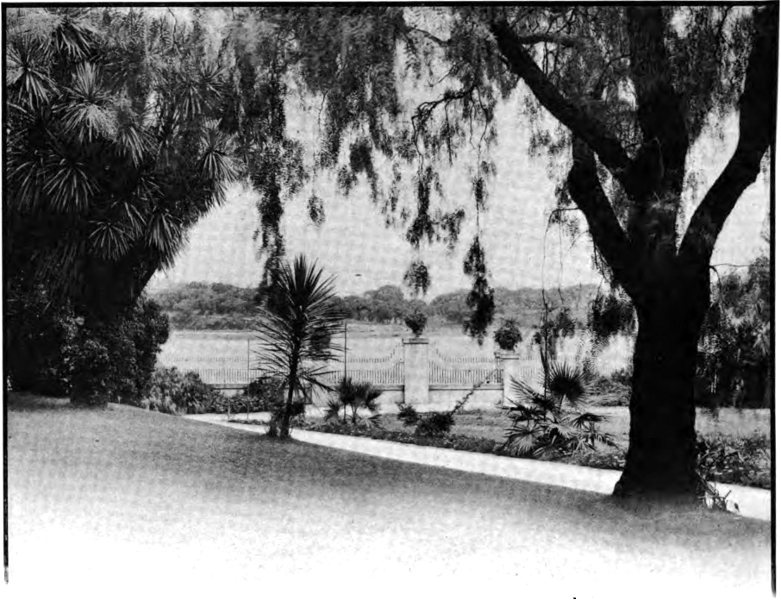

HANSCOMB PARK, OMAHA, IS PLEASANT WITH SHADY TREES AND SPARKLING WATERS

The traffic of the old trail was of long wagon trains of emigrants; of great ox outfits laden with freight for the mines; of Holladay’s coaches, six teams in full gallop, station to station; of the fast riders of the Pony Express, and of all other manner of moving men and beasts that might join the line of the westward march. Outlaws lived along the trail and as opportunity offered, plundered its followers; the protesting savages having no place upon it, but perceiving in it an instrument to alienate their dominion, burned its wagon trains and destroyed its stages as opportunity offered. At times great herds of buffalo obliterated sections of the trail. Yet it held its own until the golden spike was driven, and passed away as a wagon road only when the need for it passed. But the railway lines that took up the burden of stage coach and Pony Express and ox team, have marked the way of the trail upon the map of the West so that it shall endure as long as the West endures.

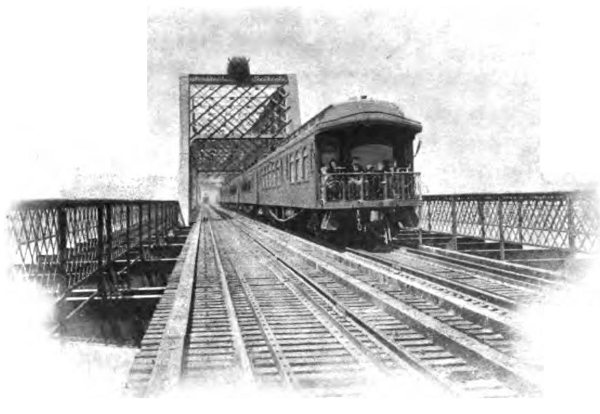

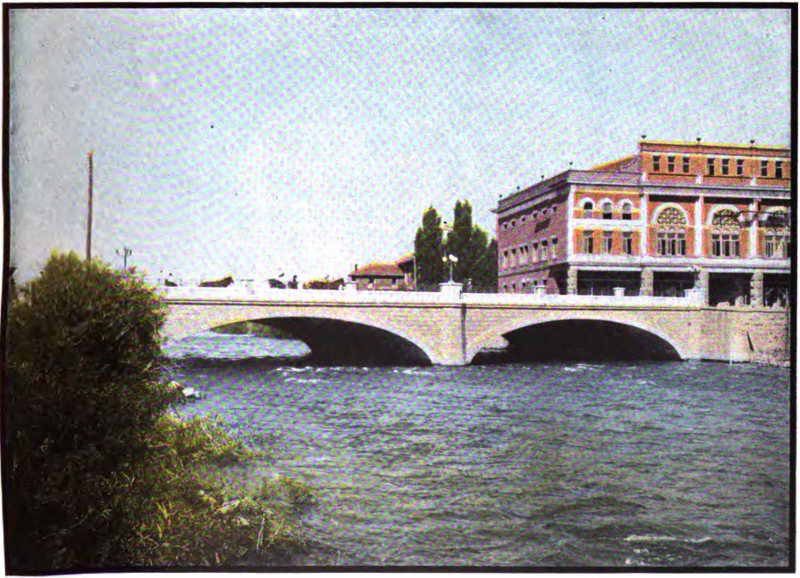

THE OVERLAND ROUTE BEGINS AT THE MISSOURI, CROSSING FROM COUNCIL BLUFFS TO OMAHA ON A DOUBLE TRACK BRIDGE OF STEEL

In the early days when the gold seekers sought San Francisco across the Isthmus, around the Horn, or by way of the trail, it is said that a Dutch landlord in San Francisco greeted his guests with the query: “Did you come the Horn around, the Isthmus across, or the land over?” Through some such distinction from the waterways, the wagon road from the Missouri came by its name, and to-day the railroad that succeeded it is known everywhere as the Overland Route. The railway came in the face of opposition and predictions of disaster. The builders were men to whom difficulty merely meant more effort, men who were not to be denied. The Pacific Railroads, as they were styled, were two; the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific. Starting, one from the center, the other from the extreme westward verge of the United States, they rapidly moved towards a junction; the Union Pacific being built westward 8 from Council Bluffs; the Southern Pacific eastward from Sacramento. On May 10, 1869, they met at Promontory, Utah, and then and there was signalized the spanning of the continent by the driving of the golden spike. In the presence of eleven hundred people, this last spike was driven into a tie of polished California laurel by Leland Stanford, president of the Central Pacific, and Thomas C. Durant, president of the Union Pacific. A prayer was said, the pilots of the engines touched, and a libation of wine was poured between, and the message, “The last rail is laid, the last spike driven, and the Pacific Railroad is completed,” was flashed to the President of the United States.

By a decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, the beginning of the Overland Route is at Council Bluffs, in Iowa.

The “Bluffs,” according to tradition, were for centuries the meeting place of Indians to settle tribal disputes—a supreme court place of the aborigines. The city antedates Omaha many years, and has buildings that were old when Omaha was born. As a place of beauty and much activity Council Bluffs is well worth a pause in a journey to visit.

The first rails of the Overland Route were laid westward from Omaha in July, 1865. There was no rail line between Omaha and Des Moines, and the first seventy-horse power engine was brought by wagons from Des Moines to begin the work of construction. Ties came from Michigan and Pennsylvania at a cost sometimes of $2.50 each. All supplies had to be brought from the East.

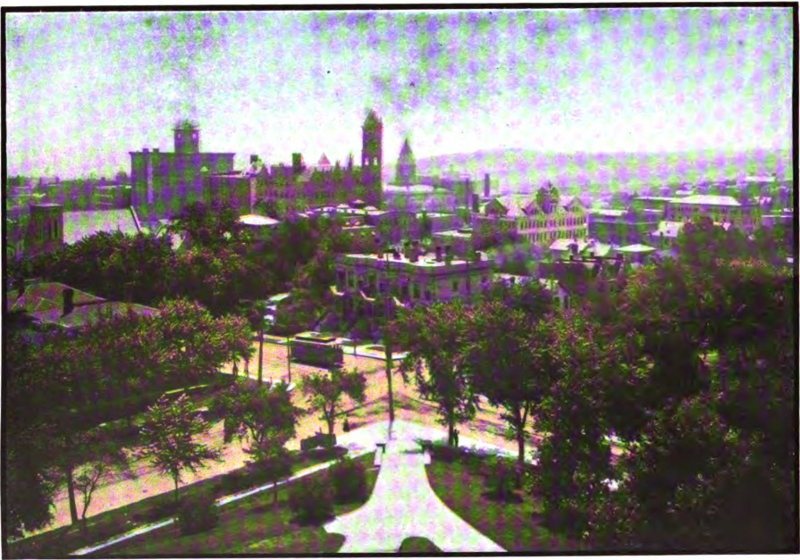

OMAHA, METROPOLIS OF NEBRASKA, IN FIFTY YEARS HAS GROWN FROM A VILLAGE TO ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT CITIES OF THE WEST

The Council Bluffs and Nebraska Ferry Company was organized July 23, 1853. The promoters and the Indian Chiefs met in dignified conclave and with pow-wow and peace-pipe a treaty was concluded and, title acquired to 9 the townsite and ratified by the Government, Omaha was founded in the following year. The town that was once a fringe along the waterfront has spread back over the uplands, and with great business blocks and beautiful homes has become a city of a hundred and fifty thousand people, a fitting gateway to the great West.

THE EASTERN ENTRANCE TO THE UNION-PACIFIC BRIDGE ACROSS THE MISSOURI IS FITTINGLY CROWNED WITH A BUFFALO’S HEAD

Near by is the site of historic Florence, gathering place of the Mormons after their enforced and hasty exodus from their persecutors at Nauvoo, Illinois. This was in the winter of 1846, and, after a brief rest, from here on April 6, 1847, began the march of the first company of one hundred and forty-three men, three women and two children to Salt Lake over an unbroken trail, accomplished without the loss of one soul. The journey occupied one hundred and nine days, in striking contrast with the present fifty-six hour trip of the Overland Limited from Omaha to San Francisco. The first company toiled through sand in canvas covered wagons; the Overland Limited traveler has at his disposal modern drawing rooms, state rooms, and sleeping car sections, a club cafe, with writing desk, tables, and easy chairs, an observation parlor with easy seats and library and a recessed rotunda, giving an open air view of the scenery. Instead of circling a smoky camp fire with frying pan and toasting fork, he dines at ease in a tastefully appointed car, supplied with the best the markets of two sides of the continent afford, while at night he can, at will, read in his electric lighted berth, the trials of earlier wanderers.

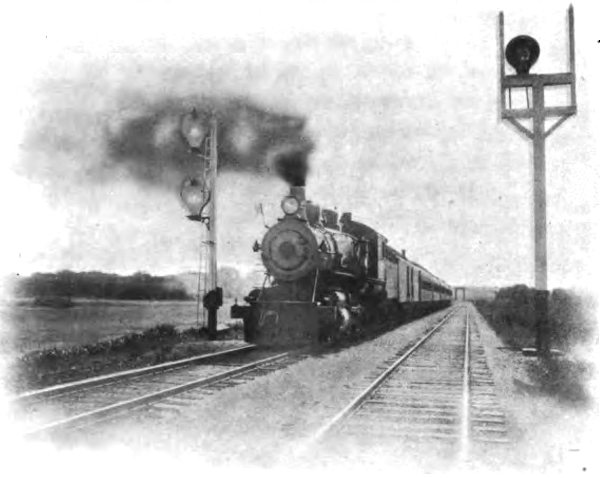

THE BLOCK SYSTEM EFFECTUALLY SAFEGUARDS THE TRAINS OF THE OVERLAND ROUTE

Leaving Omaha, the Overland Limited passes through South Omaha, third place in the United States in the packing of meat products. Just beyond may be noted to advantage the block safety system, in operation on the Overland Route all the way to San Francisco.

Fremont, well situated at the junction of the Platte and Elkhorn 10 valleys, is a prosperous and beautiful city of ten thousand people. The next stop is Columbus, a place of four thousand people, junction point of the Norfolk branch. Citizen George Francis Train, the irrepressible, decided that Columbus was the geographical center of the United States, and announced that the capital should be removed there at once; but so busy was the country with the Civil War at the time, that the idea was seemingly overlooked and has remained unadopted.

From Columbus the passenger is carried over a way that does not waver from a straight line for forty-one miles. On every side is unrolled a pastoral panorama as splendid as any in the world. To view it, when the headers and binders are at work in the golden fields interspersed with stretches of green growing corn, is to grasp the greatness of agricultural Nebraska.

From Omaha westward to the first glimpse of the white summits of the Rockies, the way is through visions of country loveliness. As the Limited ascends on its journey westward and rises above the corn levels nearer the Missouri, meadows join the grain fields. Stacks of hay are deployed over the plains as are soldiers on a battlefield. The homes of farmers are impressive with evidence of a prosperous and proper pride. The fences are straight and symmetrical, the houses all well painted; there are great red barns to remind you of Pennsylvania, and active windmills tower over all as landmarks. The scene is given life by high grade cattle, sleek horses, and flocks of well kept sheep. Above is bent over the landscape a sky of clear blue, where troop the vagrant clouds amid its arches, and all is permeated with air pure and sweet beyond description. Such is Nebraska.

HERDS OF HIGH GRADE CATTLE HAVE USURPED THE PASTURES OF THE BUFFALO

The agricultural area along the line of the Overland Route, east of the Rockies, from producing nothing fifty years ago, now yields annually 11 a half billion dollars, and this apart from and in addition to the immense livestock and mineral output. Nebraska alone has a property value exceeding two billion dollars.

CATTLE NOONING AT NORTH BEND, NEBRASKA, NEAR THE PLATTE RIVER

Grand Island is a thousand feet higher than Omaha. Here Robert Stuart of the Astor party camped in 1812 and called the island in the river Le Grande Isle. On Independence Day, 1857, a little company of Germans from Davenport, Iowa, named their newly started town after the island, now grown to a prosperous city of ten thousand people. Among other things they do here is to make a thousand pounds of beet sugar annually for each inhabitant. Grand Island and the section immediately to the west to old Fort Kearney and beyond were the scene of many Indian fights when the Overland Route was being built.

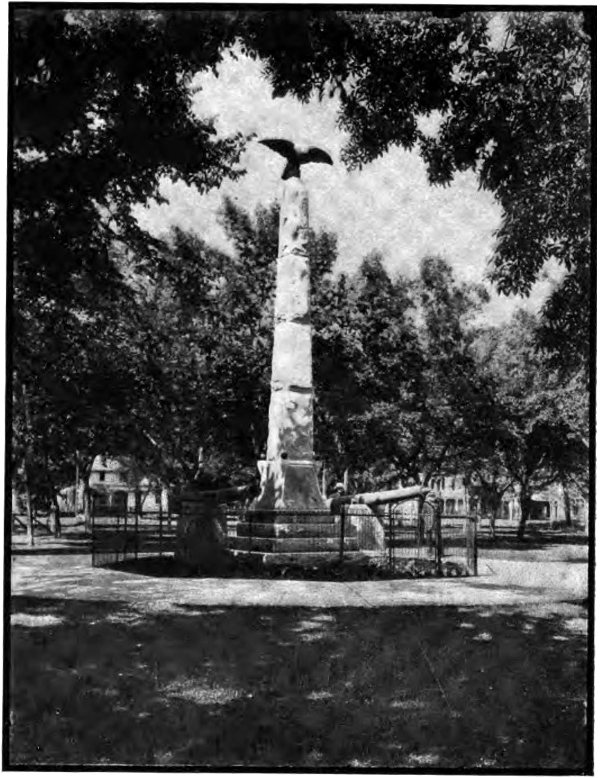

IN THE CITY PARK OF COLUMBUS, THE SEAT OF PLATTE COUNTY, IS A MEMORIAL TO THE CIVIL WAR HEROES

Kearney is the next town of importance westward. Not far from here is the site of old Fort Kearney, where in these early days of progress were acted more stories of desperate fights and literally hair-raising adventures than Fenimore Cooper ever dreamed of, and where Major Frank J. North, with his four companies of Pawnee Indians made history defending the Overland Route against hostile Indians during the construction period. As an Indian fighter he had no superior. It was fun alive for him to take a band of scouts and clean out a whole tribe of hostiles, and he did it so frequently that his name became a terror to the Indians. The Plum Creek, Ogalalla, and Summit Springs campaigns under Major North’s direction did much to prove conclusively to the Sioux and Cheyennes that he was their absolute master. Kearney is now a city of eight thousand people, and is the site of the 12 State Normal School. To the northwest from Kearney runs a branch line through the beautiful Wood River Valley, opening to the city a great tributary territory.

Lexington, now a prosperous town of twenty-five hundred people, was once called Plum Creek. Here in 1867 the Southern Cheyennes, under Chief Turkey Leg, captured and burned a freight train. In the subsequent campaign already alluded to, they were thoroughly subdued and many of them made good Indians. Lexington is now more famous for its great irrigation system than for Indians. Great grain and vegetable crops are raised.

West of Lexington sixty-six miles is North Platte, a place of four thousand people, and much more lively than the North Platte River. Here we have a good view of the river, which in summer time is the laziest thing that moves in all Nebraska. Like Hammerton’s summer air, it “has times of noble energy and times of perfect peace.” North Platte has great agricultural and stock interests; hence have been shipped a million tons of hay per annum. Here is the home of Buffalo Bill, most famous perhaps of all the plains’ scouts. Near by is his famous Scouts’ Rest ranch.

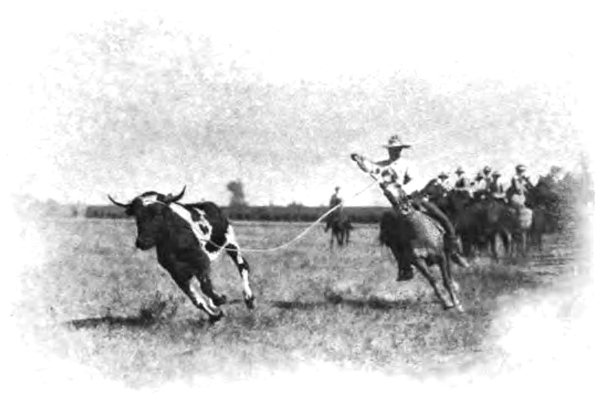

From Kearney westward to Julesburg are little towns, around some of which cluster memories of earlier days. To Ogalalla, for instance, in Texas cattle-driving time were driven thousands of long-horns from the Lone Star State to start by rail for the eastern markets.

THE ROUTE RUNS BY A SEA OF WIND-WAVED GRAIN NEAR SHELTON AND GIBBON, NEBRASKA

The West had many styles of wildness, and the cowboy style was one. It was different from all others. The writer was familiar with them and can discriminate. There was system usually in the frontier wildness; men killed each other, but for some cause great or small. But cowboy wildness was not to be measured by rule or reason. The cowboy was picturesque. He wore a roll around his broad brimmed hat, a red 13 sash around his waist, big spurs, high heeled boots with the Lone Star of Texas embroidered on the top, an open shirt and two six-shooters. In appearance he was one-half Mexican and the other half savage. Opportunity to shoot down a man or “up a town” meant the more fame was his when he should return to the Brazos. His touch upon the trigger was as “light and free” as the touch of Bret Harte’s Thompson and there was no limit, while ammunition and targets lasted, to the “mortality incident upon that lightness and freedom.”

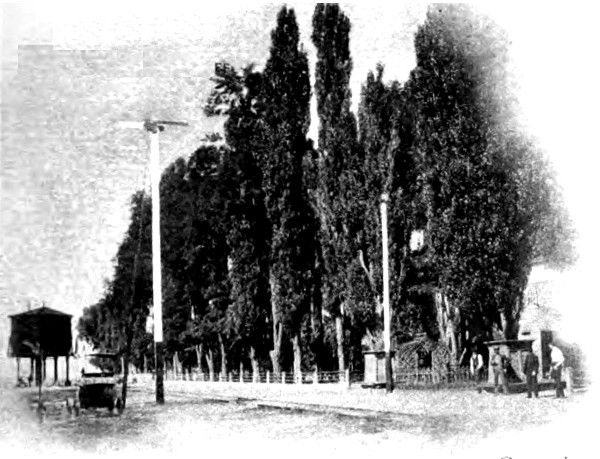

THE “OVERLAND ROUTE” STATION AT COLUMBUS

Julesburg, 372 miles west of Omaha, was in 1865 an important stage station on the Overland Route, and as a supply point was the subject of much attention from the Indians. On one occasion a thousand Sioux and Cheyennes attacked it, but were finally driven off. The station was named after one Jules, agent for Ben Holladay’s stage line. He was killed by J. A. Slade, a noted desperado, who fought both for and against law and order. His career and that of his faithful wife are set forth in Mark Twain’s “Roughing It.”

AT NORTH PLATTE, NEBRASKA, COLONEL CODY (BUFFALO BILL) HAS A RANCH WHICH HE NAMED “SCOUT’S REST” IN MEMORY OF FRONTIER DAYS

Long after Julesburg was an Overland Route railway station, the buffalo fed on the plains around it. These animals should have some share in the credit for the construction of the Overland Railways. Their destruction, if deplorable, was a factor in the success of the builders. They provided sustenance for the brawn of the workman almost all the way across the plains from Omaha to the Rockies, and while rib steaks and succulent humps comforted the inner man their robes kept warm the outer one. The camp hunter did not have to travel far for meat those days. Time was, and not so many years ago, when an Indian would trade a buffalo robe for a cup of sugar or a yard of red flannel, but now save in a few parks and exhibition places 14 the buffalo has passed away. The plains were at one time strewn with their white bones. It was the custom of the Mormons to use the frontal bones of their skulls as tablets whereon to write brief messages to the wagon trains following. One may be seen in the Commercial Club museum, Salt Lake City, bearing in Brigham Young’s writing the inscription:

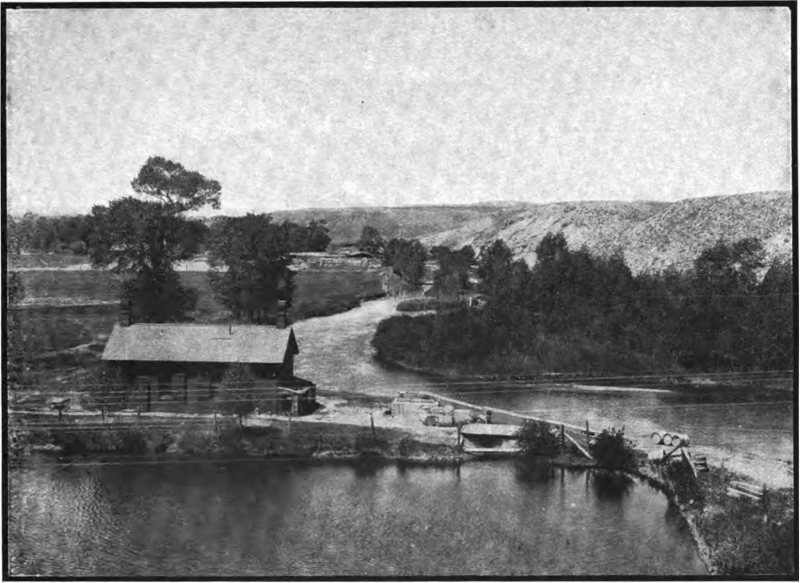

THE NORTH PLATTE, KNOWN TO CIVILIZATION SINCE THE EXPEDITION OF JOHN JACOB ASTOR IN 1812

“Pioneers camped here June 3, ’47, making fifteen miles a day. All well.

Brigham Young.”

After Sidney, a rich farming town of two thousand people, and in 1868 a military post of importance, the Overland Limited stops at Cheyenne. Shortly before reaching Cheyenne, Long’s Peak, with snow-clad summit appears above the horizon.

WYOMING COWBOYS DELIGHT TO MATCH THEIR SKILL

Five hundred and sixteen miles west and a mile higher than Omaha on the last and highest of the tablelands that fringe the plains is Cheyenne, capital of Wyoming and a growing, lively city of fifteen thousand people. Above it loom the massive Rockies; around it are great plains, partly irrigated from the great five hundred million-gallon reservoir. Here each summer is held one of the most picturesque and representative gatherings in the country—the Frontier Day celebration, when the mountains and the most distant plains yield up their cattlemen and cowboys, their hunters, trappers, Indians, and outpost men generally to contest for honors in riding, tieing 15 steers, horse breaking, shooting and other frontier sports. No gayer or more picturesque crowd ever assembled than this.

THE WYOMING COWPUNCHER IS STILL IN EVIDENCE AS A PICTURESQUE AND USEFUL FACTOR OF THE PLAINS LIFE

Cheyenne is a great livestock center, has railway shops, is the junction for the Denver and Kansas City branch of the Union Pacific, and is making progress as a mercantile and manufacturing place. With its beautiful Carnegie library and half million dollar Federal building and other excellent buildings, there is little to recall the town of the early sixties, when its reputation was extended as a shipping center for the long trails of cattle, and noted as a famous place for carved saddles. Among its first pioneers was James B. Hickok (Wild Bill), a brave gentleman, a great scout and guide, and noted throughout the West as a superb horseman, and one of the most wonderful marksmen with a six-shooter that ever lived. He was chief of scouts under Custer in the Indian campaigns of 1868-69 and the latter paid him high tribute in his book, “My Life on the Plains.”

Westward from Cheyenne the Overland Route rises steadily to the summit of the Rockies, the crest of which it passes through by a long tunnel to the slope whence waters flow to the Pacific. Near this tunnel is the Ames monument.

AN INDIAN ENCAMPMENT AT CHEYENNE, WYOMING

Here on the summit at Sherman, eight thousand feet above sea level, one may pause for a sweeping glance that can take in the watersheds of two oceans. The atmosphere is so clear that the eye can view the country for hundreds of miles, though to the untrained sight, distances are deceiving. Silhouetted against the northern sky is Long’s Peak; northward the range breaks down on to 16 the Black Hills with their Twin Mountains; eastward the country slopes symmetrically to the plains, treeless, level to where their horizon meets the curve of the sky. Westward are tumbled a confusion of mountains immeasurable, and far off to the southwestward if the weather be clear, may be seen the sparkling ridge of the Snowy Range, refreshing with its suggestion of coolness.

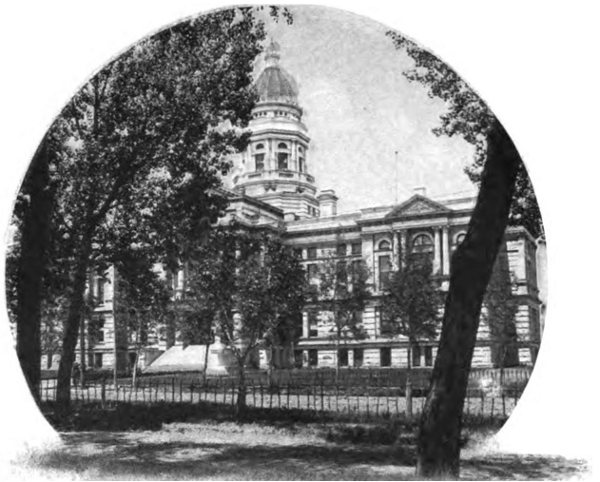

THE STATE CAPITOL. CHEYENNE, WYOMING

The roadbed of the Union Pacific is the best in the world. It is absolutely dustless, and the stability of steel and ties insures the smoothest possible riding. No other roadbed may equal this, for none other has access to the famous Sherman granite, the best and cleanest ballasting material known, which has created this unrivaled pink trail across plains and mountains.

EXPERIMENTS ON THE GOVERNMENT FARM AT CHEYENNE HAVE PRODUCED WONDERFUL RESULTS ON UNIRRIGATED LAND RECLAIMED FROM THE SAGE-BRUSH PLAINS.

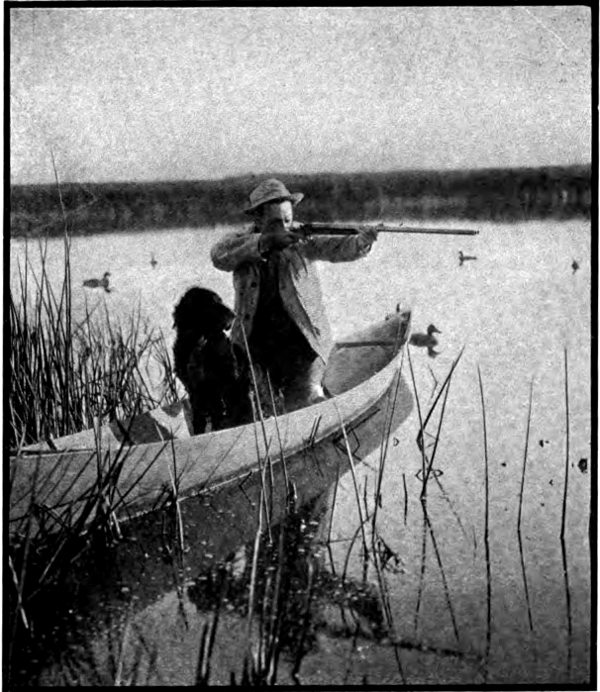

Laramie has railroad shops and other industries. A clean and prosperous city, the far reaching Laramie plains, once the bed of an ancient sea, make of it a great livestock center. The State University, the United States Experiment Station, the State Normal School, and the State School of Music are here. The fishing and hunting in the streams and mountains 17 that can be readily reached from Laramie, constitute one of the few really first-class hunting grounds left in the United States. More of wilderness is accessible from Laramie and neighboring stations than perhaps from any other railway station in our country.

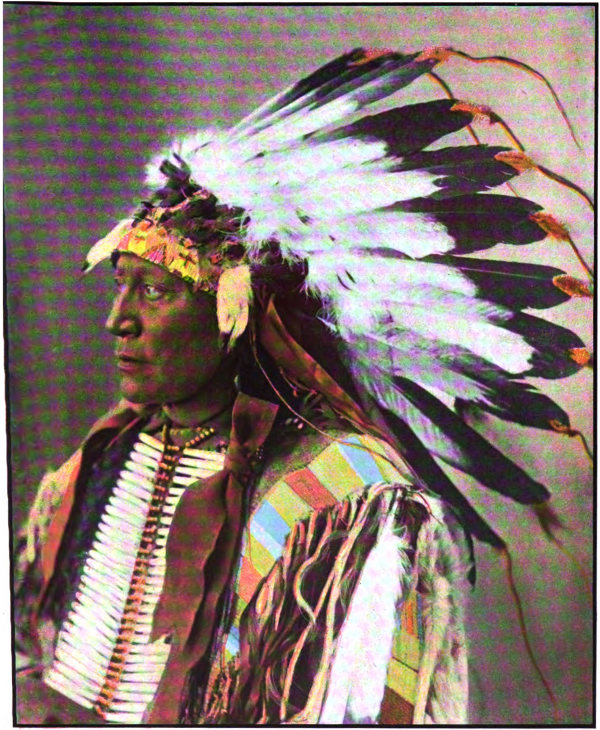

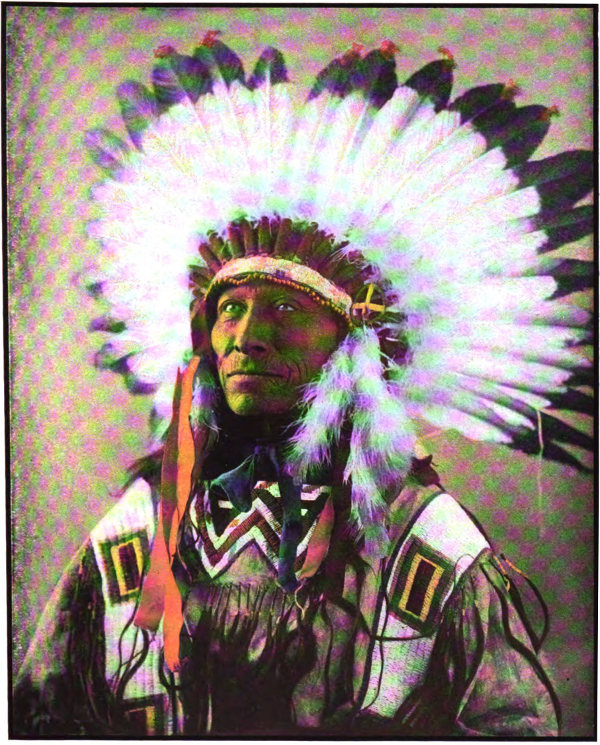

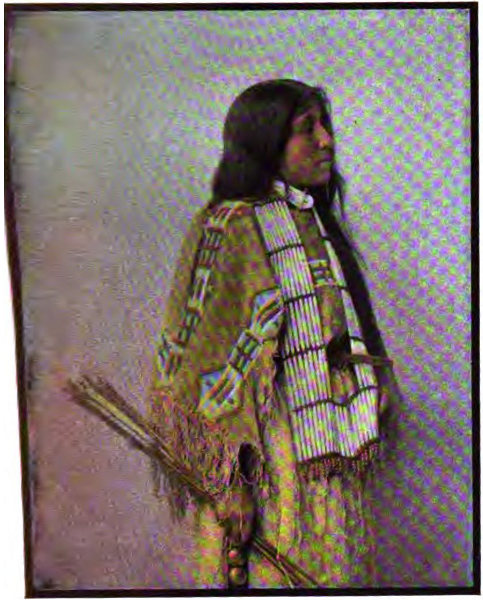

AN ORIGINAL AMERICAN. CHIEF OF A DISAPPEARING RACE

Copyright by F A Rinehart, Omaha.

Laramie is the center of a wonderful mineral section; near by are soda lakes large enough to raise all the world’s biscuits for centuries to come.

West of Laramie and fifteen miles away rises Elk Mountain, 11,511 18 feet high, which by its isolation was a noted landmark in the days of the trail. Northward twenty miles, dark and rugged, is Laramie Peak, another landmark of the Rockies, rising blue and solitary from the plain. Both peaks are visible from the car windows.

Passing beautiful Rock River, we reach Hanna, on the eastern border of the great coal measure of Wyoming. Six thousand people live here, but only half are on the surface at any one time. Between Medicine Bow and Fort Steele, now abandoned but once a celebrated fort, the best views of the Medicine Bow range are to be had. At Fort Steele are hot springs, and we cross again the North Platte River, but at an altitude some four thousand feet higher than the Nebraska crossing.

Rawlins, named after Grant’s Secretary of War, is an important distributing point of three thousand people, whence hunters, miners, and stockmen outfit for the Wind River Valley and other sections north and south. From Rawlins the ascent is made to the Divide, seven thousand one hundred and four feet above sea level, the highest point between Sherman and Ogden. The grades are gentle now, for along here some of the heaviest and most skillful work in the reconstruction of the Overland Route was done.

PASSENGER STATION AND GROUNDS AT CHEYENNE

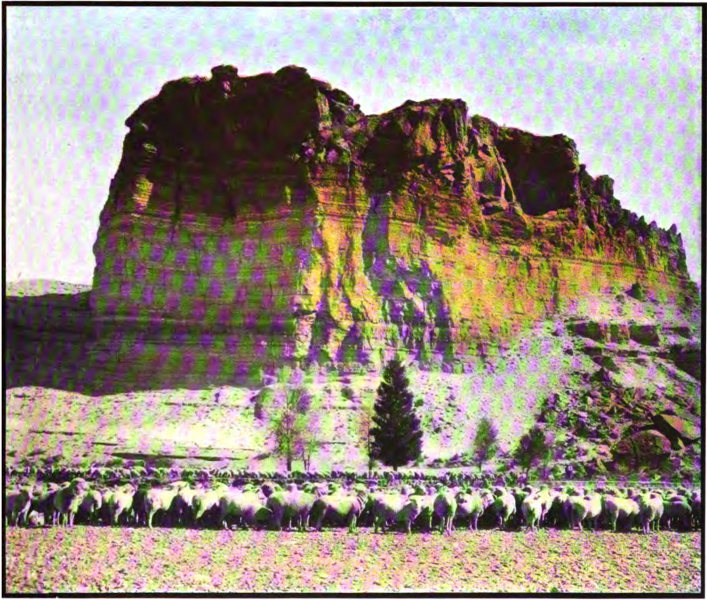

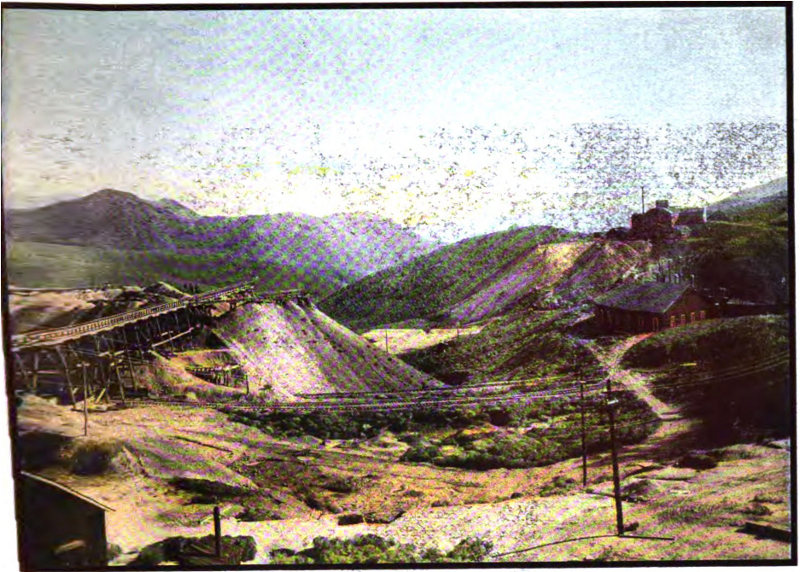

The next stop is at Rock Springs, the greatest coal mining town in the West. The town itself has the typical appearance of an active country town, and there is little on the surface to indicate the labyrinthine workings of the great underground measures, part of the vast mineral 19 treasure house of the state. Wyoming is a state of both underground and over-ground industries, with its coal mines, gold mines, copper mines, its great flocks of sheep and herds of cattle, and lastly a newly developed agricultural field of great possibilities.

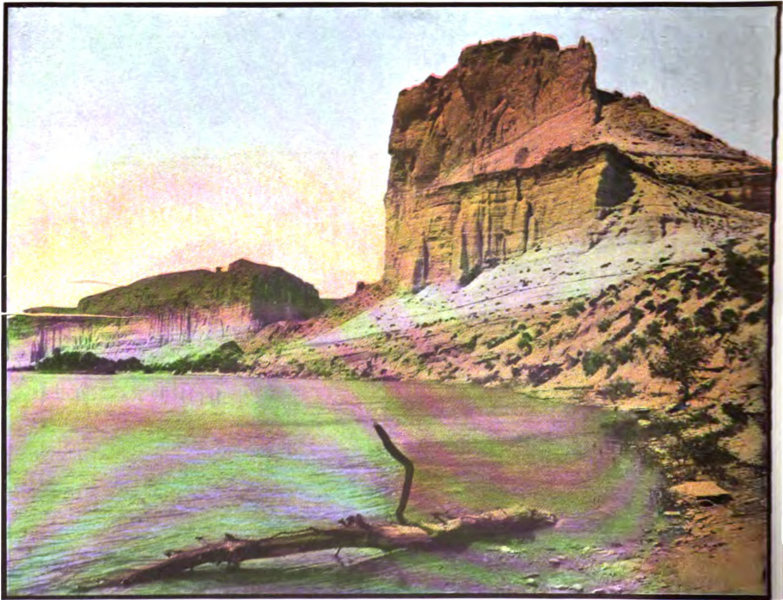

Green River is a lively railway center with division headquarters. The beautiful river of that name is of clear water, but gains its color from the copper-green shale over which it runs. The wonderfully colored shales give to the rocks that rise above it an added interest to their striking forms. This is the paradise of the geologist. The Green River Shales varying in thickness from a knife’s blade to several feet, are full of fossils, fish, insects, and whatnot of ancient life. In them have been uncovered the skeletons of huge ancient monsters. Agates and other gems are found hereabouts in great variety and quantity.

At the next stop, Granger, the line of the Overland Route to Portland, Seattle, Tacoma and Spokane branches off to the northwest.

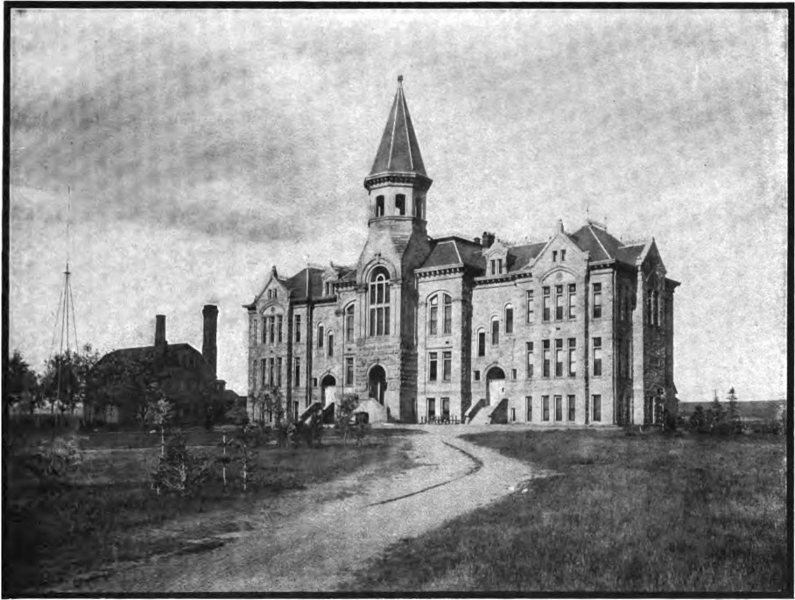

AT LARAMIE IS LOCATED THE UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING

From Leroy, seventy-four miles west of Green River, the new line to Bear River is taken, avoiding the old time Tapioca hill. This new stretch of road is most picturesque; the approach to the famous Aspen tunnel is through the historic Pioneer Valley, about which the train climbs with graceful sweeps. Next to the cut-off over Great Salt Lake the Aspen tunnel affords the best illustration of what genius and money may do to accomplish wonders in railway construction. The tunnel, a mile and a tenth long, passes through Aspen ridge, four hundred and fifty-six 20 feet below the mountain top and at an altitude of seven thousand two hundred and ninety-six feet. The distance saved is ten miles, the greatest grade is forty-three feet to the mile, and the sharpest curve three degrees, thirty-six inches.

Evanston, nine hundred and twenty-seven miles from Omaha, is the end of a division, a prettily placed city with a Federal building, a Carnegie library and many natural attractions. The streams provide great trout fishing, and many hunting parties start on mountain expeditions from Evanston. Just beyond we pass Castle Rock, a symmetrical stone sentinel posted in the desert and which in the day of wagon migration was a welcome sign that not far beyond the “Promised Land” would be found. To the south lie the Uintah Mountains.

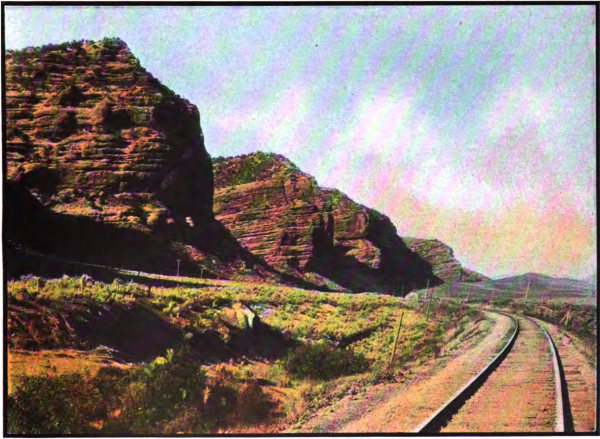

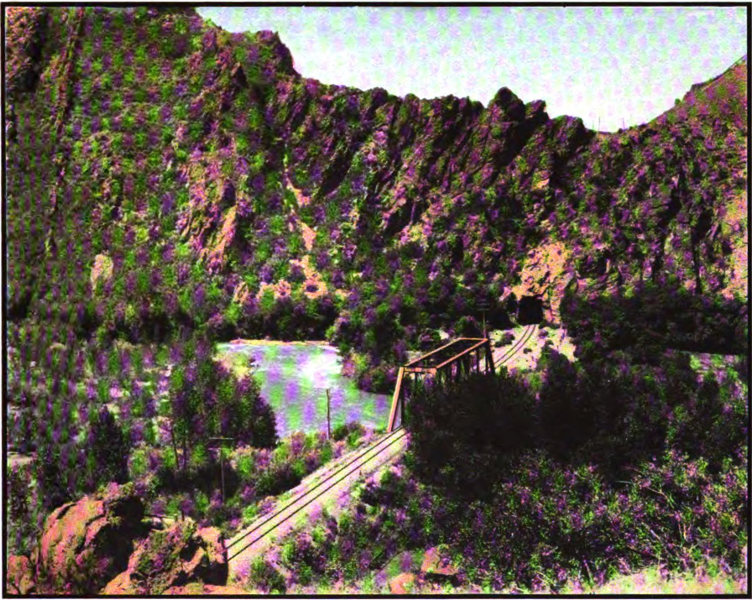

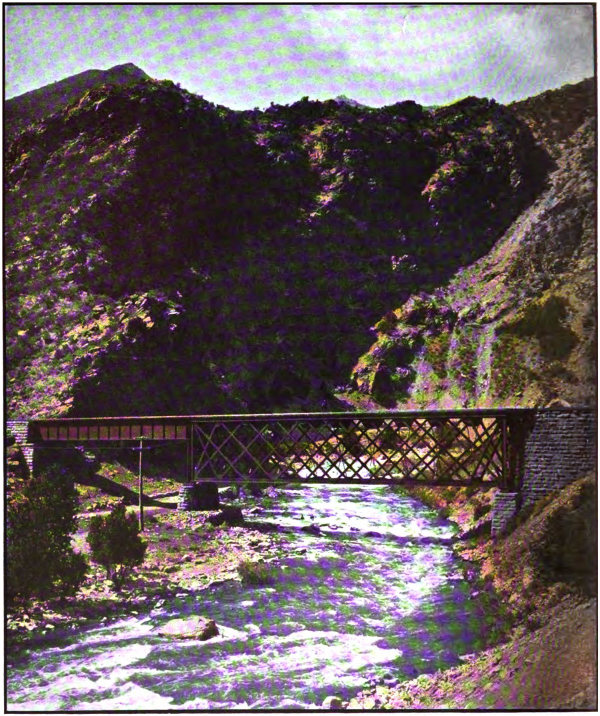

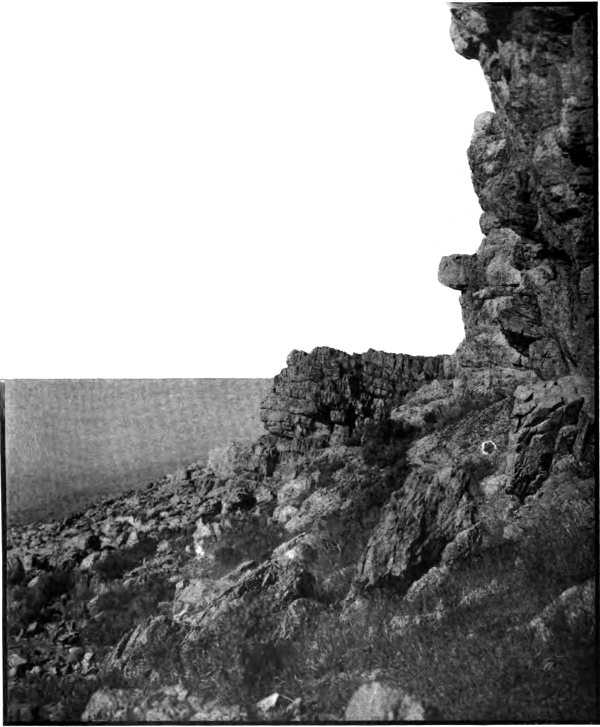

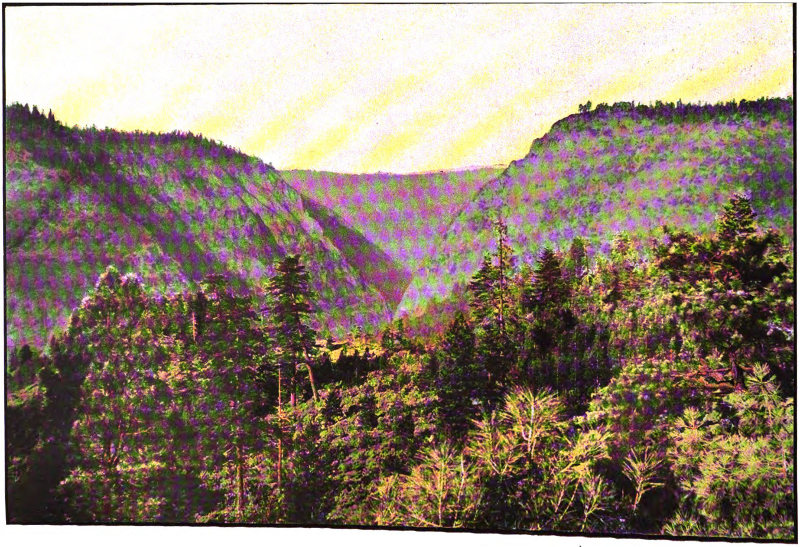

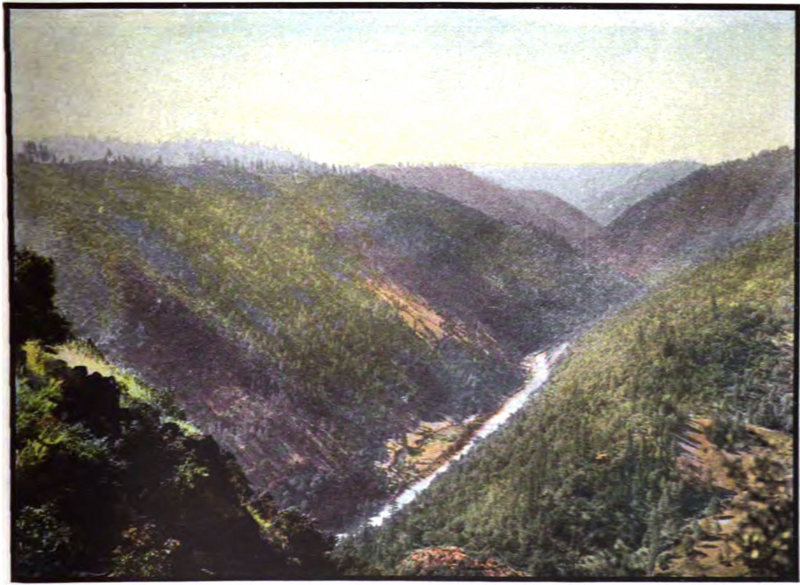

Yet a little way beyond the graving tools of nature have wrought out two canyons, indescribable in their beauty, infinite in their variety.

AT FORT SANDERS, A FEW MILES SOUTH OF LARAMIE, IN 1867, GENERAL GRANT AND HIS SUITE WERE PHOTOGRAPHED EN ROUTE OVER THE UNION PACIFIC TO ARRANGE TREATIES WITH THE INDIAN TRIBES WHICH OPPOSED THE RAILROAD CONSTRUCTION

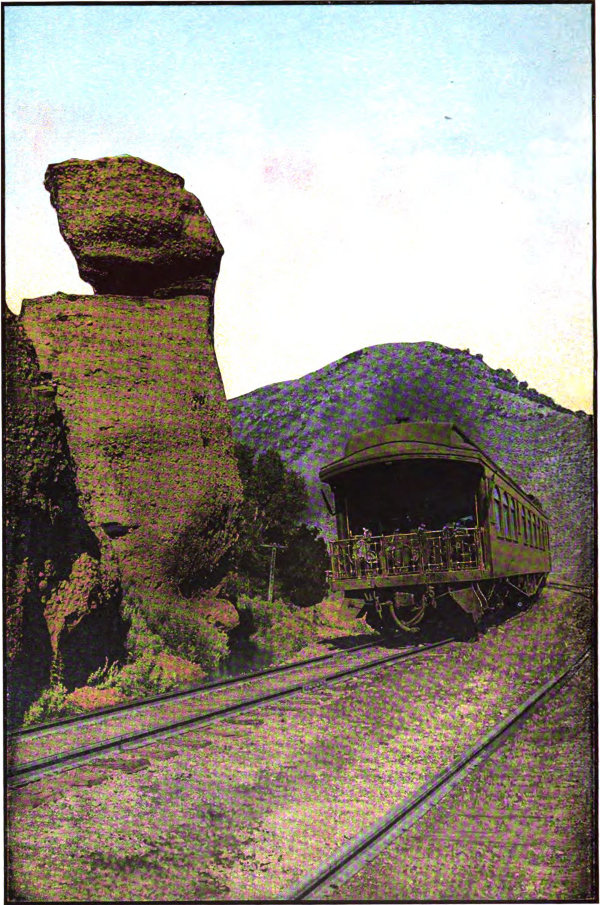

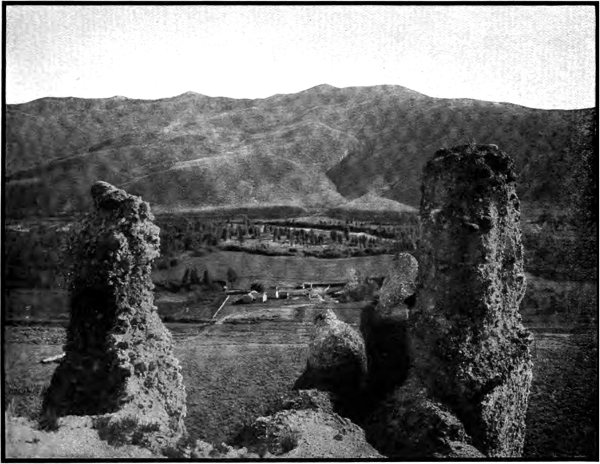

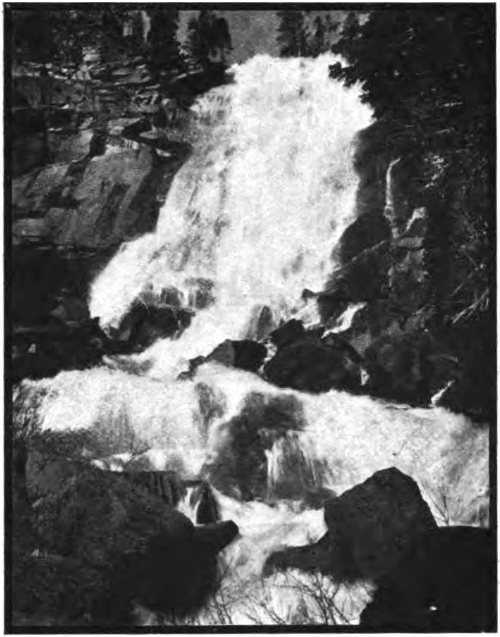

The train drops gently into Echo Canyon, running over rails alongside a mountain torrent. All along the way are Nature’s cathedrals. There are turrets and domes of gray stone, matching the architecture of an oriental city. At almost every step of the journey through the canyons are new and exquisite pictures, rock-framed, or strange monuments of stone. Immense rocks, perched on the verges of precipices, seem to threaten a fall into the abyss. The train passes under frowning cliffs, crossing and recrossing the rushing river; now by waterfalls and cascades; now bursting into a zone of sunshine, then into the twilight between 21 higher walls. The colors are the gray of rock and green of pine, with here and there a splash of iron red.

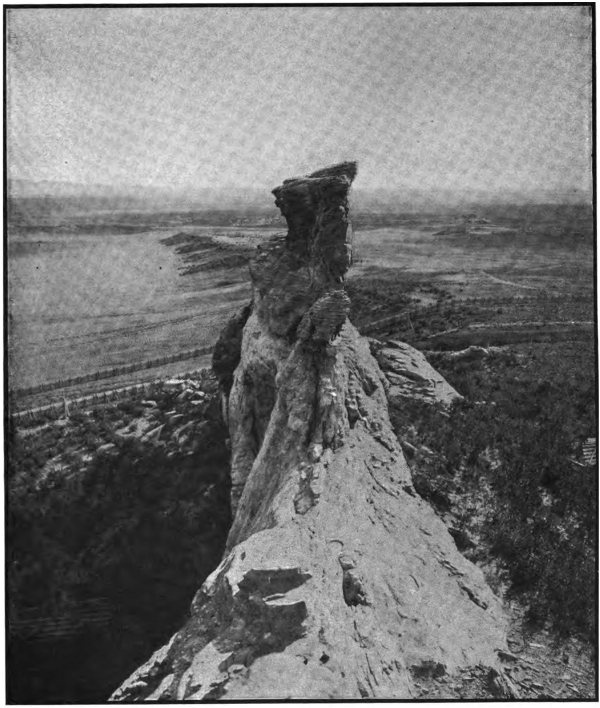

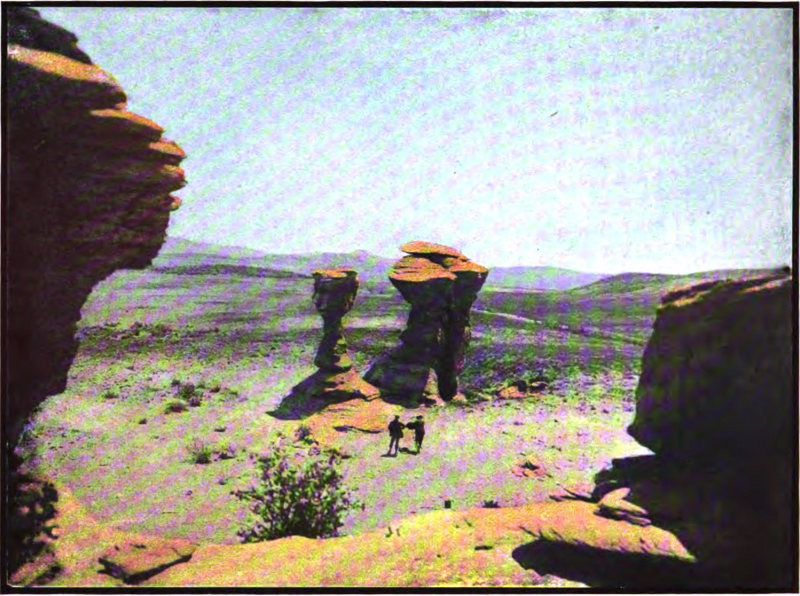

EROSION HAS SCULPTURED MANY MONUMENTS OF WEIRD SHAPES AND BRIGHT COLORS FROM THE RED SANDSTONE OF THE LARAMIE PLAINS

Winged Rock, Kettle Rocks, Hood Rock, Hanging Rock, Pulpit Rock, The Narrows, Steamboat Rock, Monument Rock, The Cathedral, Battlement Rock, The Witches, Eagle’s Nest, The Devil’s Slide, The Devil’s Gap, and The Devil’s Gate are names given to wonderful rock formations which can be comprehended only by the eye, words being 22 valueless. The canyon walls are from five hundred to eight hundred feet high, and possess more weird and striking rock formations than any other known canyons of equal length.

AT COLORES, ROCKS TURNED BY THE LATHE OF THE WINDS INTO UNUSUAL SHAPES, ARE IN SIGHT FROM THE CAR WINDOW

Out of the Canyon the train breaks into one of Utah’s wonderful valleys, and in a little while reaches the Union Station at Ogden.

Here the passenger who wishes to visit Salt Lake makes an hour’s side trip through a garden section to the capital of Zion. There is no extra expense—all Overland Route tickets are good via Salt Lake or will be made good upon presentation to the Ogden Union Depot Ticket Agent.

Salt Lake has been famous more than half a century. In the lifetime of the great Overland Trail it was the great oasis in the two thousand mile journey between the “States” and the Pacific; and westward or eastward bound, the travelers looked forward to it with fond anticipation. To the Mormons it was Zion—home of their faith and haven from persecution, where they might build a kingdom.

Salt Lake came into life on July 24, 1847, when there was not an American settlement west of the Missouri and California was under Mexican dominion. With the arrival of the first train of one hundred and twenty-one wagons began far western agriculture. The new comers put their hands to the plow the clay of their coming and began the first irrigation canal built by the white race in America. And while redeeming the 23 wilderness and making the deserts blossom, they built a city with such careful planning of streets and open places, of statues and public buildings, such attractions of tree and vine, of home and temple, of park and boulevard, that it has become a place of great interest to all travelers, even though world-wide weary.

Salt Lake has that historic interest due such an oasis of the old Overland Trail, where, before the days of that Trail, came a little band of people so strong in their faith that unfaltering they left trodden ways a thousand miles to build their temple in the desert. With background of mountains (the Wasatch Range) and face set toward a marvelous, silent sea, Salt Lake’s estate is one of natural charm.

Metropolis of the great intermountain country, with fertile, irrigated valleys, the city’s destiny is perhaps chiefly to be forecasted in manufactures. To-day, with its mountains of minerals, cheap coal, great smelters (placed a proper distance from the city’s homes), it has first rank among the ore reducing centers of the country.

The great turtle-shaped Tabernacle houses the sweetest organ in the world—one that sings and almost speaks. Its acoustic properties are such that a whisper lives from one end to the other. Seven thousand people may at one time hear a spoken word. Near by is the Temple, a building of remarkable architectural interest, home of the Mormon church and sanctuary of its secrets. The museum adjoins the Tabernacle. The Lion House, the Bee Hive and Amelia’s Palace have part in history.

The new Union Depot of the Overland Route in Salt Lake City will be in architecture and appointments equal to any in the country.

ROCK RIVER, FULL OF LUSTY TROUT, COMES SPARKLING FROM DISTANT SNOW PEAKS AND PASSES UNDER A MODERN BRIDGE

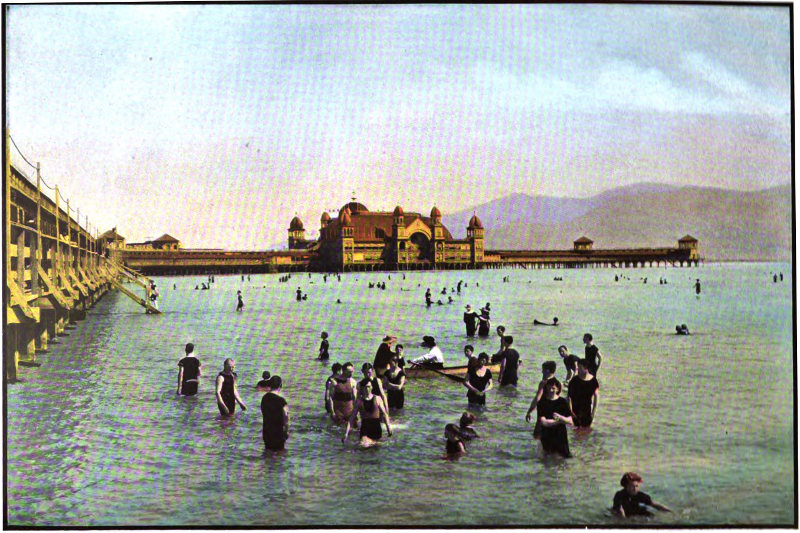

The greatest charm of Salt Lake City is in the many broad, tree-lined avenues, with streams of water flowing along the curbs. On either side in the principal residence districts, are beautiful homes, largely built from the proceeds of Utah mines. The public buildings are attractive, and the city park a resting place with lovely lawns and flowers and groves. The hot springs (within the city) and Fort Douglas should be visited, nor should any stranger depart without passing an afternoon at Saltair, the principal bathing resort on Salt Lake, with its immense pavilion, promenade walks, and wharves extending far out into the salt water. Here one may float for hours in warm, buoyant salt water—buoyant and salty indeed beyond any other water on earth save the Dead Sea.

No people are more kindly and hospitable than those of Salt Lake. They differ among themselves as to the plan of salvation, but are united in the belief that if there be a heaven on earth, Salt Lake is that heaven, and its portals are open to all who may choose to add themselves to the eighty thousand there now.

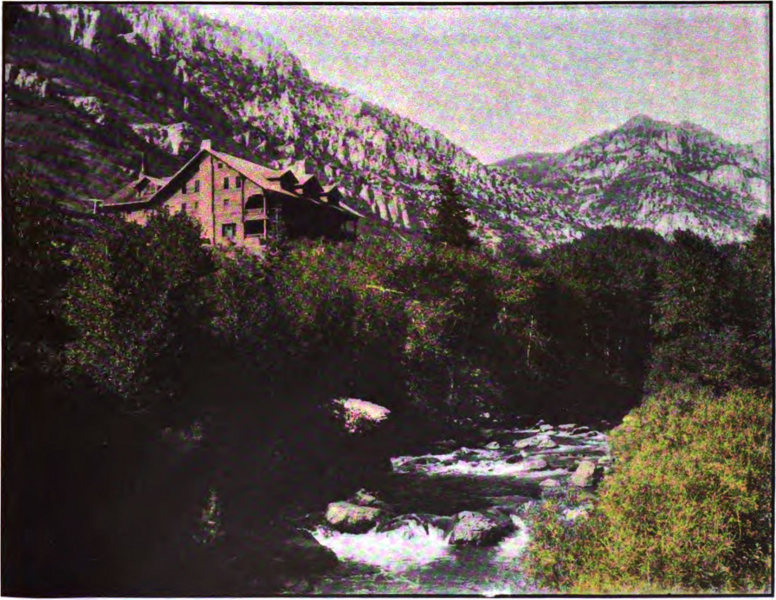

Ogden has some twenty thousand people. Its present considered commercial and manufacturing importance is but a suggestion of the greatness to be. Ogden Canyon, easy of access, is a mountain rift with beauty of stream and wall. The sugar mills and electric power plants are interesting.

GREEN RIVER RUNS OVER COPPER-STAINED ROCKS AND PEBBLES THROUGH A COUNTRY OF ROMANTIC SCENERY AND ABUNDANCE OF WILD GAME.

Utah is great in agriculture, fruit growing, stock raising and mining. The mines have yielded four hundred million dollars—gold, silver, copper, 25 lead, and coal. The fruits are of fine flavor and exceptional keeping quality. Of its agricultural area, a large proportion is as gardenlike, perhaps, in its intensive cultivation, as any part of the West, with proportionately rich yields. The livestock and sheep industries, have made many wealthy or well-to-do.

Before journeying farther west it may be well to consider the two eras in the history of the Pacific Railroads.

The total first cost of the Pacific Railroads—Union and Central Pacific—was $115,214,587.79. Such was the report of the Secretary of Interior to the committee of inspection. The work was undertaken westward from Omaha (1865) and eastward from Sacramento (1863). The intense rivalry generated by the desire of each company to build as far as possible before the junction should be effected resulted in marvelous celerity in construction, if the conditions be taken into consideration. Collis P. Huntington said before the Senate Committee of Congress:

“There were difficulties from end to end; from high and steep mountains; from snows; from deserts where there was scarcity of water, and from gorges and flats where there was an excess; difficulties from cold and from heat; from a scarcity of timber, and from obstructions of rock; difficulties in keeping supplied a large force on a long line; from Indians, and from want of labor.”

NEAR THE TOWN OF GREEN RIVER, RISE NUMBERS OF SANDSTONE BUTTES IN INFINITE VARIETY OF SHAPE AND COLOR. THE ENTRANCE TO THE INFERNO MIGHT WELL BE IMAGINED HERE

WYOMING IS FAMOUS FOR ALWAYS KEEPING ITS LAVISH PROMISES TO SPORTSMEN.

For six hundred miles there was not one white inhabitant; for stretches of one hundred miles not a drink of water.

Yet ten miles of track were laid in one day, and for several days faster than ox teams could follow with loads. Twenty-five thousand workmen were employed, and more than five thousand teams. At one time thirty ships were en route from the Atlantic coast to San Francisco with supplies. Between January, 1866, and May 10, 1869, over two thousand miles of railroad were constructed through the wilderness.

Less dramatic has been the reconstruction of the Pacific railroads, and yet not less in interest. By the year 1900, the transcontinental traffic of the country and its promise for the future had outgrown its first main highway. To the present owners and management, under the direction of the president, E. H. Harriman, fell the task of reconstruction; the task of tearing up the old track and replacing it with new; of abandoning a large part of the route and choosing new grades; of cutting through mountains by tunnels where formerly the track was laid around or over them; of replacing wooden bridges with steel; and short sidetracks with long ones. The expense of the work of reconstruction to date probably nearly equals the first cost.

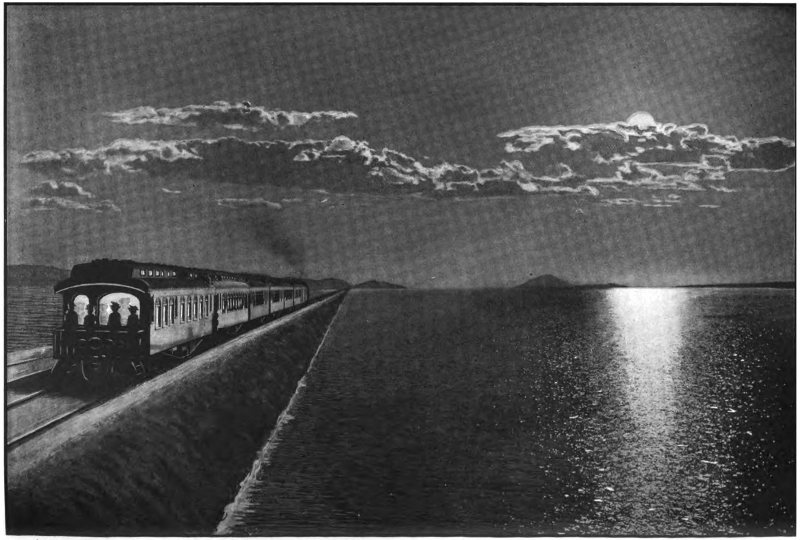

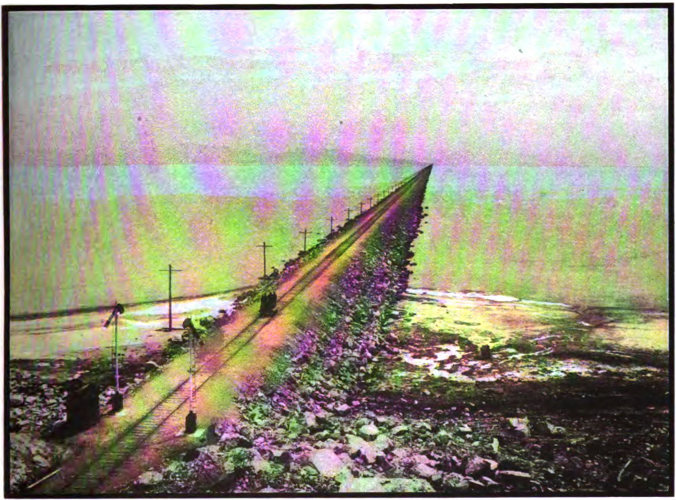

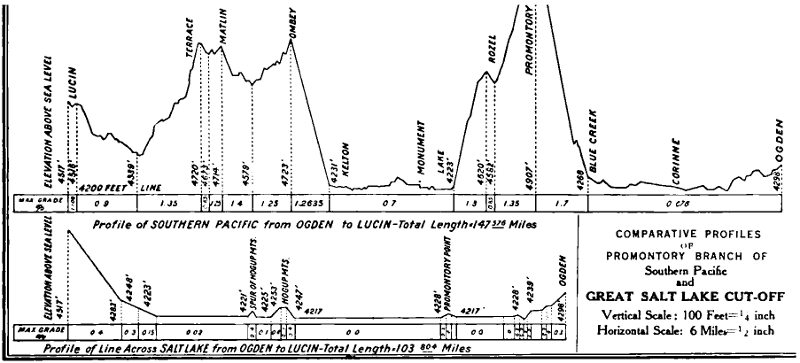

In this work of rebuilding, the eight-million dollar Great Salt Lake cut-off stands prominently as the most startling of achievements in railway work. The old road through the country where the golden spike was driven was abandoned as a part of the main highway for a distance of 146.68 miles. To save grades and distance, the cut-off was built across the heart of the lake from Ogden to Lucin, 102.91 miles and so nearly straight that it is only one-third of a mile longer than an air line.

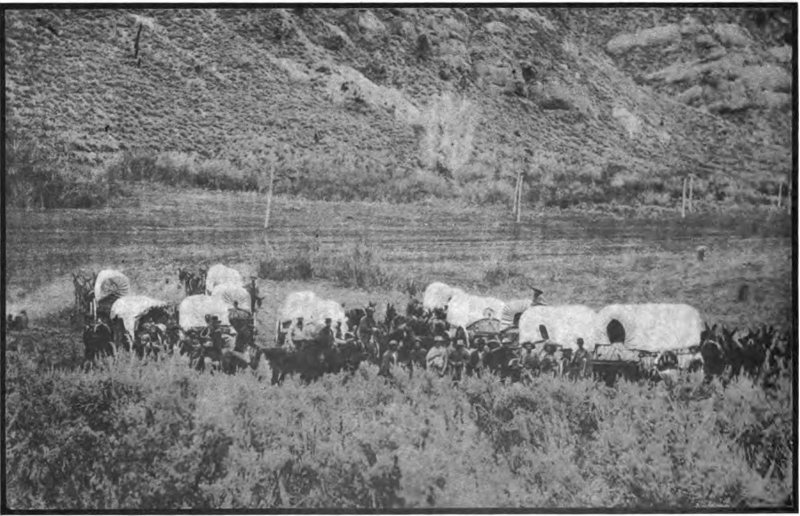

AN OVERLAND COACH, PHOTOGRAPHED IN THE DAYS OF THE MORMON EXODUS FROM ILLINOIS TO UTAH

CHIEF WHITE WHIRLWIND IN HIS WAR ARRAY. A GRIM AND FORMIDABLE WARRIOR IN BYGONE DAYS OF THE OVERLAND ROUTE

Copyright by F. A. Rinehart, Omaha.

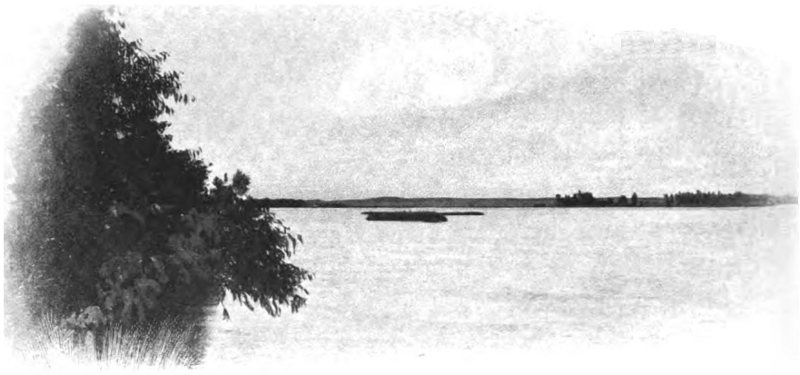

The curves which have been thus saved by the new line would be sufficient to turn a train around eleven times. The power saved in moving an average freight train because of less grades would lift an average man eight thousand five hundred miles. The power saved in moving such a train because of the shorter distance would be sufficient to carry a man two hundred round trips between New York and San Francisco. The heart of Great Salt Lake is crossed by the Overland Limited by daylight. The lake covers two thousand square miles, is eighty-three miles long and 28 fifty-one miles wide; its greatest depth is thirty feet. In every five pounds of water there is one of salt of which thirteen ounces is common salt, a density exceeded only by the Dead Sea.

Twenty-seven and a half miles of the cut-off are over the water, with roadway sixteen feet wide at the bottom and seventeen feet above the lake’s surface. The work began in June, 1902, and on November 13, 1903, the track was completed across the lake. During that time in supplying piles for trestles and subsequent fills a forest of two square miles—thirty-eight thousand two hundred and fifty-six trees—was transplanted into the waters of Great Salt Lake. Each day hundreds of carloads of gravel were poured in between the piles to make a solid pathway—sometimes more than four hundred cars in one day. The roadway is on the surface of a foot of rock ballast and beneath that a coat of asphalt upon a plank floor three inches thick, resting upon a practically indestructible substructure. For thirty-six miles there is no grade at all. The steepest grade in the one hundred and three miles is five inches to the hundred feet. The saving in the vertical feet in grades compared with the old route is fifteen hundred and fifteen feet; in degrees of curvature 3.919.

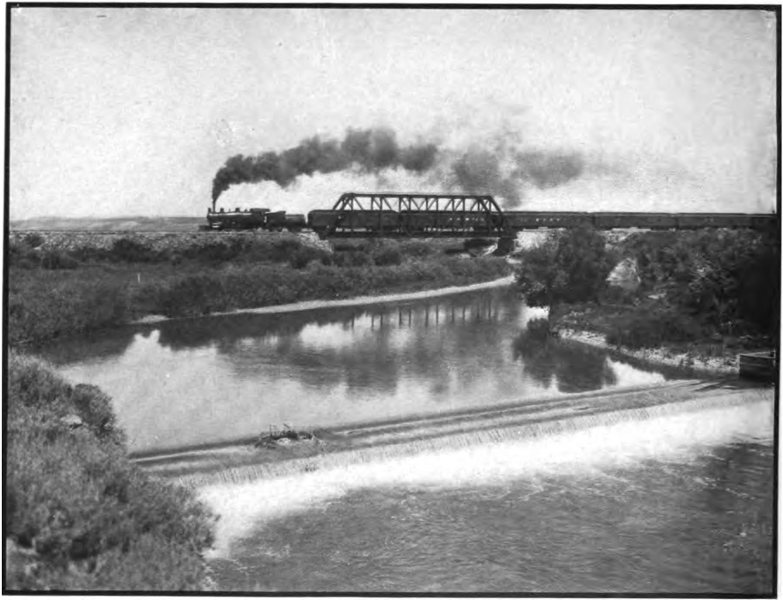

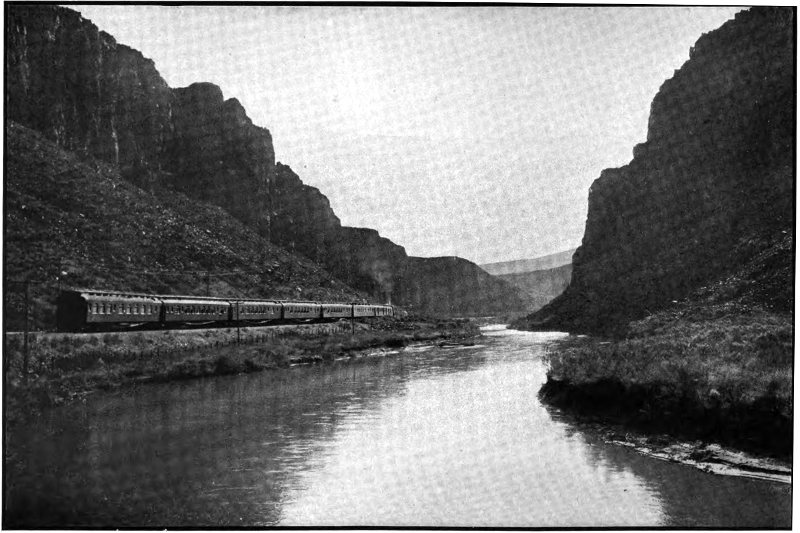

THE “OVERLAND LIMITED” CROSSING HAM’S FORK, NEAR GRANGER, WYOMING

There is something fascinating about Great Salt Lake—something in its weird, silent waters that draws you to it irresistibly. There are no words to describe the impression made when first you see it lying out there in the desert, its dense green waters reaching away to the dusky mountains that mark its farther shore. Other waters, alive, break with 29 white crested riffles at the touch of the breeze; but these waters seem dead, and naught but the fury of a storm can break their placidity. No craft ply upon their surface, and nothing lives within them save a queer shrimp, a third of an inch long, and small flies before their wing stage; and but for the gulls, herons, and pelicans that came to the lake some time in the misty past, there would be no show of life upon its broad expanse. These same birds fly twenty miles for fresh water and food.

Over this strange sea, with no counterpart on the continent, the travelers of the world now pass. East and west the scenes of the two most majestic ranges of America spread before their eyes; but the enchantment of this ride across the lake of mystery will linger in the memory long after the beauty of mountain peak and grandeur of mountain wall shall have passed to the realm of things forgotten.

Westward from Lucin the route follows the old overland trail to the eastern base of the Sierra, across a region for half a century described in geographies as the Great American Desert.

This one-time desert is now proved to be possessed of mineral riches beyond dreams—gold, silver, copper, iron, soda, borax, sulphur, and other minerals in abundance. Agriculturally, too, the Carson Valley within the “Desert,” under Uncle Sam’s nine million dollar irrigation enterprise, is proving the worth of Nevada soil and water properly associated.

In 1833 Kit Carson and Jim Beckwith, with a few Crow Indians, crossed Nevada, and in 1846 Carson guided Fremont across it, but the Mormons were the first settlers.

ECHO CANYON, UTAH, WHERE THE SHRIEK OF THE LOCOMOTIVE REVERBERATES AMID A THOUSAND CLIFFS AND PEAKS

PULPIT ROCK IN ECHO CANYON. FROM THIS NATURAL ROSTRUM BRIGHAM YOUNG IS SAID TO HAVE PREACHED HIS FIRST SERMON IN THE “PROMISED LAND” TO HIS FOLLOWERS, IN 1847

In 1860 the famous pony express service of Jones, Russell & Company was begun between Sacramento and Salt Lake City, with schedule of three and one-half days. The first express left Sacramento, April 4, 1860, and the first arrived from Salt Lake City April 13, 1860. The record for time was held by the relay of pony express riders that carried President Lincoln’s message from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Sacramento, seventeen hundred and eighty miles, in five days and eighteen hours. The through stage line across Nevada was established in 1865, when the Overland stage Company extended the line between Virginia City and Sacramento (in operation since 1860) to Salt Lake City and connected with Ben Holladay’s line thence to the Missouri River. The through telegraph line was completed across Nevada in 1865.

IMAGINATION RUNS RIOT AMID THE BRILLIANT COLORING, THE CURIOUS CARVINGS OF THE CLIFFS OF THE ECHO AND WEBER CANYONS. A FERTILE FANCY HAS STYLED THESE “THE WITCHES’ ROCKS”

Nevada is in great part the bed of an ancient ocean ribbed with lean mountains. Multitudes of travelers have noted that the rain, driven in from the Pacific, falls heavily in the valleys of California and up the western slopes of the Sierra, and on the summit of the mountains creates a deep blanket of snow, but to thirsty Nevada gives little save the snow fed rivers that flow down the mountain sides. So while they see skies marvelously clear and crests of brown far-off hills snow-crowned (under the sunlight seemingly tipped with flame), and drink the rare air, to the fevered face a balm and to the lungs as rare old wine to the palate, yet they pass it by and see nothing in the waste out of which to create a home. The Sierra watershed and government money are to change all that. Changed, also, is its mining life to-day. Capital, with new railroads—yes, and Capital, new railroads,—yes, and automobiles,—have torn the mask from the face of this treasure land. The dawn of the day of this land of mystery between the Rockies and the Sierra is here. Salt Lake City is now probably the greatest smelting center of the world and the once named ‘Great American Desert’ is helping give as neighbors to the green fields, running streams and fruitful orchards of the Mormon haven, the tall chimneys and mighty fires of many furnaces. Discoveries of new mining districts follow hard one upon the heels of another.

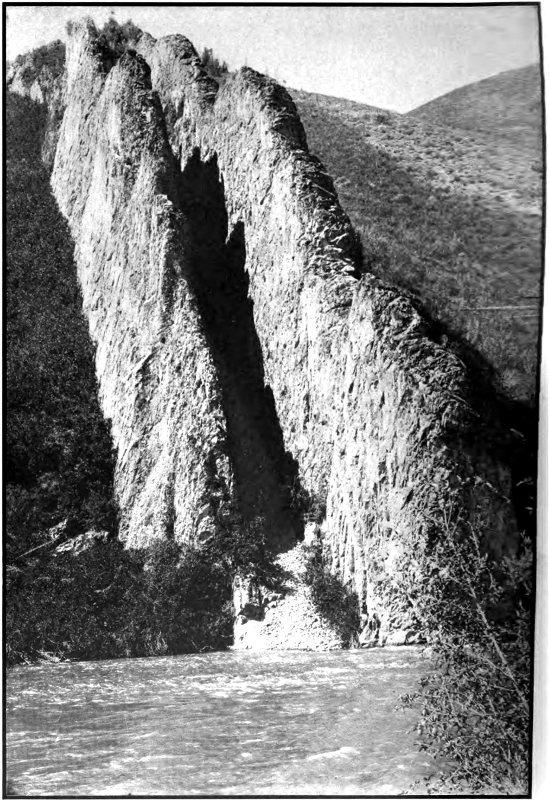

THRUST FROM THE RED SOIL RISE TWO DAZZLING WALLS OF WHITE—FORTY FEET HIGH, TWENTY FEET APART; SHEER FROM THE BRINK OF THE CLIFF TO THE WATERS OF WEBER RIVER—THE DEVIL’S SLIDE

When the glaciers in the infinite past were set in flow, grinding rocks to make soil from which food could be raised for races of men not then in existence save in the mind of God, Nevada and Utah were not left valueless. Rather, when the world was freighted for its long voyage, some of the richest stores were given this intermountain land to keep, and jealously has she guarded them with barren mountains for sentinels and lusterless sage for a cloak.

“A wide domain of mysteries

And signs that men misunderstood

A land of space and dreams; a land

Of seas, salt lakes and dried up seas.

A land of caves and caravans,

And lonely walls and pools;

A land that has its purposes and plans.”

CROSSING WEBER BRIDGE THE TRAIN PLUNGES INTO A TUNNEL HEWN THROUGH THE ROCK, LEAVING THE SERPENTINE RIVER FOR AWHILE

ALL DAY LONG HEAVY SHADOWS HANG OVER DEVIL’S GATE AND THE FOAMING WATERS CHAFE AGAINST ITS ROCKY PORTALS

So wrote Joaquin Miller thirty years ago; more and more the “purposes and plans” of the great basin become apparent. In forty-seven years Nevada alone has yielded in treasure $1,700,000,000.

But the store of riches is not alone in mines. Silt-laden rivers born in snow-clad mountain heights for untold centuries have carried their riches into the great basin. The principal streams of Nevada have no outlet 35 but disappear in sinks. The Truckee, rising at Lake Tahoe almost at the summit of the Sierra, tumbles down the mountain side to a last resting place in Pyramid and Mud Lakes. The Carson River, rising in equally lofty heights, sinks in a lake of the same name, and the Humboldt, companion to the railway through central Nevada, flows from the Great Wells at the base of the Ruby Range and westerly finds its way 120 miles to a vanishing point in Humboldt Lake.

To give life to the desert by joining again these streams with the silt-surface earth of the Nevada valleys through irrigation, is the task now in hand. Ere finished, the commonwealth should be as great in agriculture and horticulture as in mining.

In Nevada’s 110,000 square miles are many thousands of fertile acres requiring but the touch of water to make them productive. Here are some of the great grazing lands of America. A total of not far from 10,000 carloads of cattle, horses and sheep is exported from Nevada every year.

IN OGDEN CANYON IS THE HERMITAGE, BUILT AMID ROMANTIC SURROUNDINGS AND ATTRACTING MANY LOVERS OF TROUT AND SCENERY

The Great Salt Lake Cut-off of the Overland Route westward from Ogden is now of course the main line; the old line runs to the north of Great Salt Lake, crossing the mountains at Promontory at an elevation of 4907 feet and rejoining the Great Salt Lake Cut-off at Umbria Junction. Through trains no longer are operated via Promontory and in the march of progress that station which one day held the attention of the entire country as the junction point of two great railways binding together the East and the West is now only a name on a side line. Yet the day of its birth was one 36 of glory. New York City celebrated it with the chimes ringing out Old Hundred and a salute of one hundred guns; Philadelphia rang all its bells in celebration and Chicago rejoiced with a mass meeting where Vice President Colfax spoke, and sent through the decorated streets a parade four miles in length. Omaha turned loose with all of its firearms and paraded with every able-bodied man in town in line, and closed the day with fireworks and illuminations. As usual, San Francisco was fore-handed with its rejoicing, starting its celebration two days in advance of the driving of the golden spike, and continuing it two days thereafter to preserve a proper equilibrium. Bret Harte wrote a poem for the event.

The reasons for abandoning the old historic route in favor of the new mid-sea pathway across Great Salt Lake are more eloquently expressed in the diagram on page 47 than can be done by words.

Westward from Ogden, on the new route passing the Lake stations and then Lucin and Montello, the first place of importance is Cobre, junction point with the new Nevada Northern Railway with its line southward through Cherry to Ely, a distance of 153 miles. At Ely is a mountain of copper, one of the great mines of the world. Vast development work is under way here. The Cherry Creek section has gold and silver; as far back as 1876 twenty carloads of ore were teamed 150 miles to the railway and shipped to a smelter, returning an average of $800 to the ton. Absence of transportation has prevented development until now.

THE ENTRANCE TO THE BEAUTIFUL OGDEN CANYON IS BUT A SHORT CAR RIDE FROM THE CITY. ITS SPARKLING WATERS FORM THE BASE OF THE CIVIC SUPPLY

THE OLD MORMON TRAIL, PATHWAY OF THE PIONEERS, CAN STILL BE TRACED NEAR SALT LAKE CITY

Wells, end of the first section going west, is the source of the Humboldt River. There are some thirty springs, very deep,—some perhaps a thousand feet—and never failing. They made of Humboldt Wells a great camping and watering place in the days of the old Overland Trail, three roads, the Grass Creek, the Thousand Springs Valley and the Cedar Pass, converging here. Wells is headquarters for a great cattle country, with ranges extending into Idaho on the North and Utah on the east, and is the supply town for many rich mining districts.

The little town of Deeth is a trading center with all the promise of several hundred square miles of tributary territory very little developed and very rich in mineral resources.

IT IS A FAR CRY FROM THESE DAYS OF THE OVERLAND LIMITED TO THE PRAIRIE SCHOONER OF PIONEER DAYS WHEN TIME AND DISTANCE SEEMED ALMOST UNLIMITED

Elko is picturesquely lively and on the verge of a business renaissance. It has had many ups and downs in a varied life. A million dollars in freight charges were paid here the first year after the railroad was finished, and thirty years ago it had waterworks, a bank, hotels, courthouse, churches, etc., when Nevada was almost terra incognita. Today it has more people (probably 2500 all told) than ever before. The shales near by possess gases rich beyond measure, which may be developed to furnish light, heat and power for the rich two hundred mile section of which Elko is the commercial center. It is a town of attractive homes, good 38 schools and churches. The Tuscarora, Columbia and Mountain City mining districts use Elko as a gateway to the world. There are good mineral springs here, including a “chicken soup” spring, alleged to supply food and medicine to any traveling Ponce de Leons.

THE STATUE OF BRIGHAM YOUNG, THE SUCCESSFUL LEADER TO THE PROMISED LAND

At Carlin are railroad shops, and the employees with the assistance of the Company maintain a handsome library. The old emigrant road divided just before reaching Carlin and reunited at Gravelly Ford. Once upon a time Shoshone Indians were plentiful hereabouts.

At Palisade, the Eureka and Palisade Railroad, eighty miles long, delivers its train loads of ore from the iron, silver and lead mines to the south for shipment to the smelters along the Overland Route. Rich oases, such as Pine Valley and Diamond Valley, are along the branch.

AN EARLY PHOTOGRAPH OF AN OVERLAND CARAVAN CLOSE TO SALT LAKE CITY

Battle Mountain is the junction of the Overland Route and Nevada Central Railway, a line ninety-three miles long, extending southward to Austin, once a famous mining camp and yet the center of a mining district 39 of much prominence. Battle Mountain lies three miles to the south. In the early sixties it was the scene of a fierce fight between immigrants and Indians. The Indians, while admitting they were worsted, claim to this day “heap white men killed.” The town is in the center of a productive agricultural section, and the Galena, Pittsburg, Copper Canyon and other productive mining districts, such as are springing up all over Nevada, help make it prosperous.

At the right of the station in Golconda are several mineral springs of much value, ranging in temperature from cold to hot enough to boil an egg in a minute. A good hotel is connected with the springs, which in any populous country would be visited by thousands of ill people. The great gold and copper deposits of Golconda are now being developed and extensive furnaces built.

THE MORMON TEMPLE AT SALT LAKE CITY, BUILT OF STONE FROM THE NEIGHBORING MOUNTAINS, STANDS BY THE SPACIOUS TABERNACLE, FAMOUS FOR ITS ACOUSTICS AND THE MUSIC OF ITS CHOIR

Winnemucca, “Napoleon of the Piutes,” was the best known chief of that tribe of Indians, and Winnemucca town was named in his honor. It is a lively place and has perhaps as large a trading area as any city in the West. For thirty years a stage ran between here and Boise City, Idaho, two hundred and fifty miles. Until the building of the Oregon Short Line Winnemucca was gateway to all of Southern Idaho. Today its trade area covers Northern Nevada and Eastern Oregon. The Paradise mines, 25 miles northeast; the Kennedy mines, 50 miles south; and the great sulphur mines, 30 miles northwest, use it as a trading depot. The business 40 done in the enterprising town of 2,000 people is not to be measured by its population.

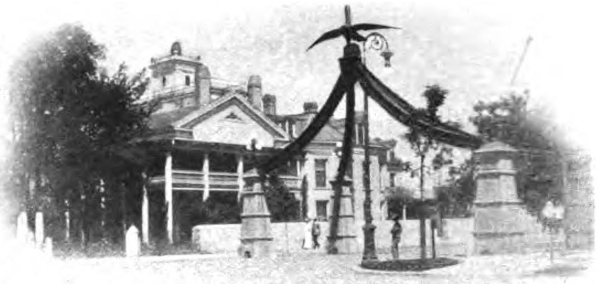

EAGLE GATE IS ONE OF THE INTERESTING MONUMENTS OF EARLIER ZION

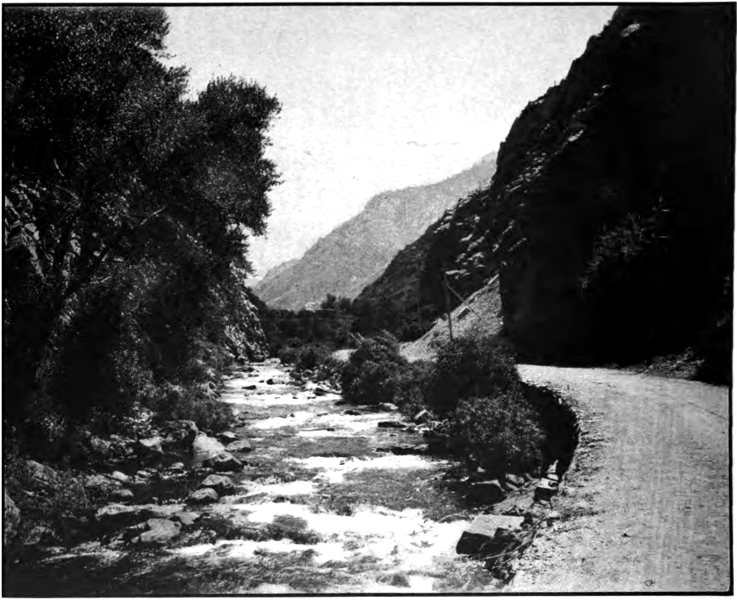

Humboldt and Humboldt House for thirty-five years have been famous among Overland travelers as a place of delight with shady groves, green lawns and flowing fountains. Apples, peaches, plums, and cherries grow in the oasis. At a point near Humboldt the old Oregon trail diverged from the Overland Route toward Northern California and Southern Oregon. All along through this section of Nevada, the Overland Route takes the way prepared by the Humboldt River.

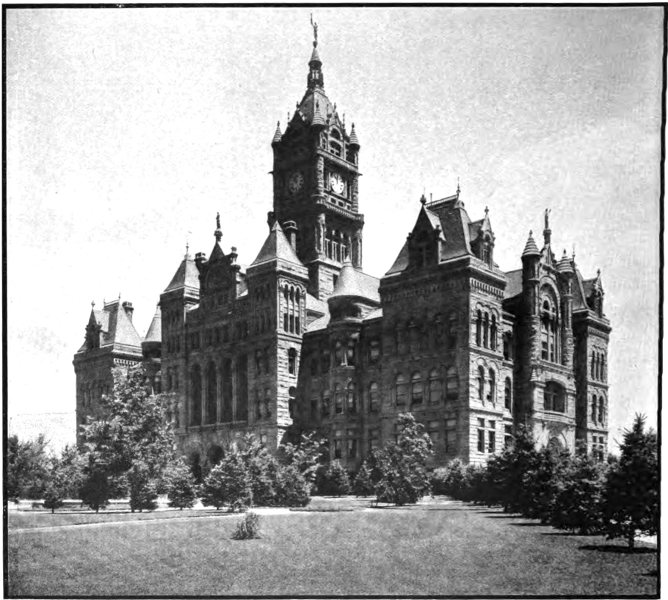

SALT LAKE CITY AND COUNTY BUILDING, SHOWS WELL THE MODERN PROGRESS OF THE CITY

No longer, however, does it wind with the stream, but burrows through mountains and spans the river as often as need be to save curves, distance and grades. In the last few years $10,531,425 have been spent in recreating this section of the main trans-continental highway.

THE LION HOUSE, BUILT BY BRIGHAM YOUNG TO SHELTER HIS FAMILY

Lovelock, with its irrigation canals, great alfalfa fields and herds of cattle, is made by the union of the waters of the Humboldt and the fertile soil of its meadows. In a few years Lovelock will be multiplied a hundred fold in Nevada. An hour’s ride beyond is a favored section for the mirage, a summer-time illusion. It is said in the days of the trail many an emigrant thought he saw in the distance a second Lovelock, more lovely, only to be undeceived at even.

THE TITHING HOUSE IS ONE OF THE EARLIEST STRUCTURES

At Hazen, the overland trains leave the passengers who are to go fortune hunting in Southern Nevada among the mines. Rawhide, Fairview, Wonder, Tonopah, Goldfield, Bullfrog, Manhattan, Rhyolite, Beatty and a score more of millionaire making camps already well known to prospectors, capitalists, and stock brokers throughout the country, are reached by the Nevada-California branch railway from Hazen, which connects at Mina with the Tonopah and Goldfield Railroad. In these regions the scenes of the Comstock Lode days of half a century ago are being repeated. Towns are created overnight—millionaires are made between meals. Stock exchanges ride high upon the enormous output of the mining certificates. Goldfield, but recently a desert, is a city of ten thousand people with good hotels, banks, daily papers, water, electric and gas plants, railroad, telegraph and telephone service, and indeed all the utilities of a modern city. Tonopah is of like history with somewhat smaller population. Here are all the cosmopolitan and adventurous spirits that are lured by gold, making these camps on the human side picturesque beyond measure. Marvelous are the stories, the true ones perhaps most so of all. One man went to Tonopah on $150 he had borrowed; in three years he was worth $2,000,000. Another owned a bed, a tent, and a ten days’ food supply; Goldfield—and today he owns a million dollars. A few men leased a mine; in five months they added to their property two million dollars. Little wonder it is a land of optimism; each treasure seeker has such examples before him to inspire him with hope; and the Nevada camps are the most hopeful and probably the most wonderful mining camps in the world.

TO SALTAIR, ON THE BORDERS OF GREAT SALT LAKE, CLOSE TO THE CITY, GO THOUSANDS DAILY TO BATHE IN ITS STRANGE WATERS, TOO SALT FOR LIFE, TOO HEAVY FOR THE LIGHTER WINDS TO CURL, TOO BUOYANT TO SWIM IN SWIFTLY

Hazen is also the junction point for another railroad, a fourteen-mile branch line to Fallon, the commercial center of the Truckee-Carson reclamation project.

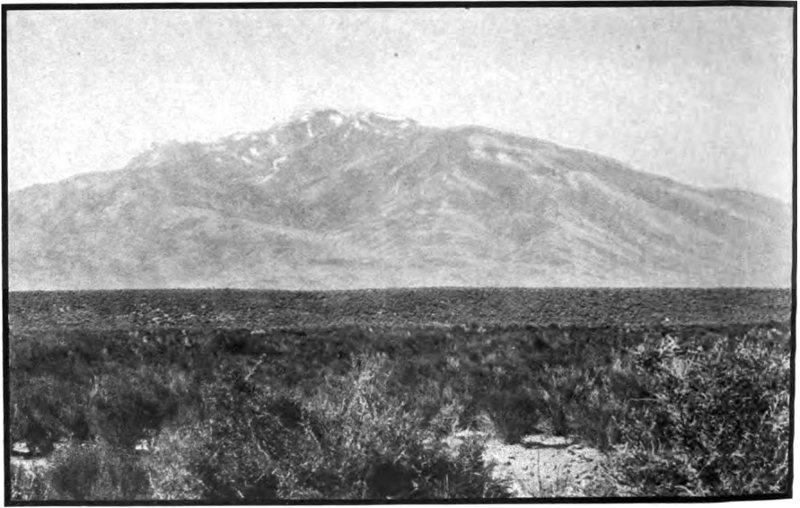

PROMONTORY POINT AT THE EASTERN END OF GREAT SALT LAKE. HERE WAS THE JUNCTION OF THE TWO LINES WHERE THE LAST SPIKE WAS DRIVEN, BINDING THE NORTH AMERICAN CONTINENT WITH A TRAIL OF STEEL

ACROSS THE SILENT DESOLATE SEA, THE TRAIN RUNS ON THE GREAT SALT LAKE CUT-OFF, THE BUILDING OF WHICH IS ONE OF THE TRIUMPHS OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

THE PELICAN REARS ITS YOUNG ON THE LONELY ISLANDS OF THE INLAND SEA

The United States Government has diverted the waters of the Truckee and Carson Rivers by a series of canals, reservoirs and laterals upon 250,000 acres of the bed of an ancient lake with deep rich soil composed of materials washed down from the surrounding mountains. Already water is ready to irrigate about 100,000 acres, of which a large part is Government land and the remainder either railroad or privately owned land which can be purchased at reasonable figures. About 50,000 acres have been settled upon and nearly one thousand farms more are ready for settlement.

LOOKING WESTWARD ALONG THE PATHWAY MADE FROM SHORE TO SHORE WHERE TIME AND NATURE WERE DEFEATED

The Government has invested several million dollars in the project and guarantees the water supply. The public land may be taken up under the Homestead Act and it is the purpose of the Reclamation Service that settlers shall have farm units varying in size from forty to one hundred and sixty acres, according to the location, smoothness of the surface and quality of land. The average size of the farms is 80 acres. The intensive cultivation possible under an irrigation system makes it most profitable to till a farm of moderate size. The railroad lands are now on sale at an average price of about $5 per acre and other privately owned lands may be secured at from $5 to $20 per acre. The cost of the water system is assessed against the land on the basis of ten equal annual payments and 46 is now determined to be $30 per acre or $3 per year without interest. There is additional charge for maintenance of the canal system, which in 1908 amounted to 40c per acre. The only other charges to settlers are $6.50 for a forty-acre farm and $8 for an eighty-acre farm, the Government fees for filing; save that if the farm is within the railroad grant limit the fee becomes $8 for a forty-acre farm and $11 for an eighty-acre farm. The filing charge before United States Commissioner at Fallon is $1.

SEAGULLS IN COUNTLESS NUMBERS GIVE LIFE TO THIS AMERICAN DEAD SEA

THE PLAINS AND MOUNTAINS OF NEVADA HAVE A CHARM ABOVE THE RICHES THEY YIELD TO THE INSISTENT SEEKER

With water absolutely assured by the Government and the fertility of the land unquestioned, no one possessed of energy and good health with sufficient money to purchase the actual needs of a residence and farm cultivation, say from $1000 to $2000, need fear failure. The Carson Valley is to be a great garden spot, rich in small fruits such as apples, pears, peaches; rich in surface crops such as potatoes, onions, sugar beets; rich in dairy products, in great fields of alfalfa and herds of live stock. An experimental farm is maintained by the Government and already it has been proved that almost any temperate zone crop can be grown successfully. Probably the highest cash markets in America, the great mines of Nevada, Utah and California, are near at hand and the surplus can be exported 47 to the eastern and western borders of the continent and perhaps yet farther.

A STORY NOT NEEDING WORDS—WHY THE OLD ROUTE WAS ABANDONED

The Nevada & California Railway extends southward into the Owens River Valley from Mina, well known for its agricultural oases along the river, for its mines and for its superb scenery, its western wall of mountains being the highest and most impressive in the United States proper.

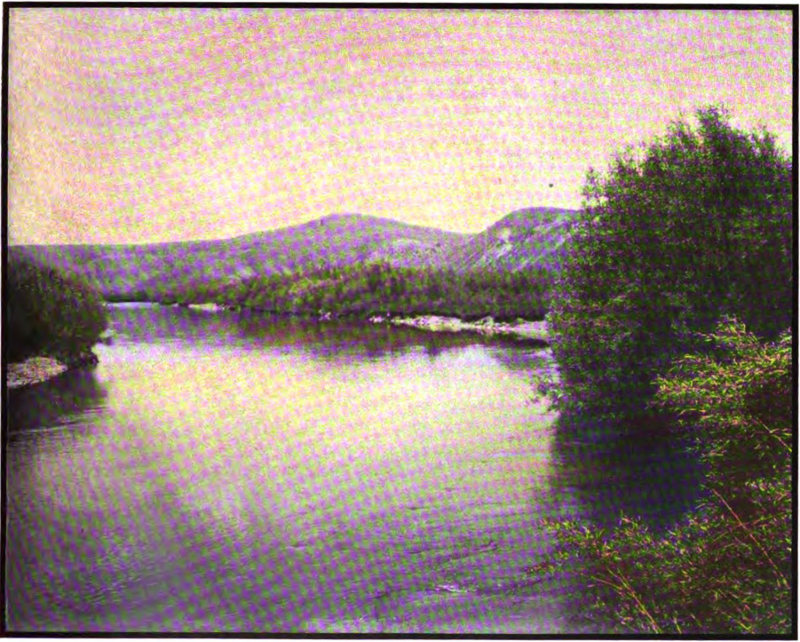

THE HUMBOLDT RIVER, CROSSED AT RYNDON, PROVES NEVADA NOT EVERYWHERE THE DESERT IT IS TOO OFTEN ASSUMED TO BE

IN PALISADE CANYON, NEVADA, THE OVERLAND LIMITED FOLLOWS THE COURSE OF THE RIVER, WHICH REFLECTS EVER CHANGING PICTURES OF CASTELLATED CLIFFS AND VERDANT BANKS

AT HUMBOLDT STATION, ONE OF NEVADA’S RAPIDLY SPREADING OASES

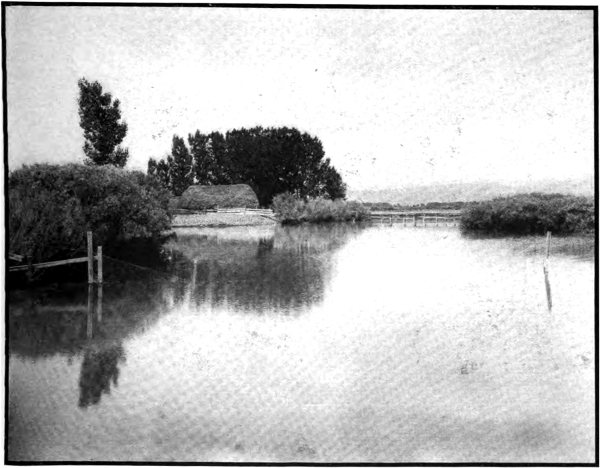

IRRIGATION AT LOVELOCK AND MANY OTHER PLACES IN NEVADA IS RAPIDLY SHOWING THAT NOT ALL ITS WEALTH LIES IN MINES

Reno, the most important and substantial Nevada cities, is 18,000 people and growing rapidly. To it the Virginia and Truckee Railroad brings business from the south, while the Nevada-California-Oregon Railway connects it with Northern California, Plumas and Modoc Counties (now being further developed by new lines under construction) and Southern Oregon. There is much good farming territory tributary; the Truckee meadows and Carson Valley are close by. The Truckee-Carson project will add to its trade greatly. The two factors giving greatest force to Reno’s forward movement are, however, the establishment of great railway terminals and shops by the Overland Route at Sparks, adjoining Reno, and the position 50 of the city as the chief commercial center of the richest, and now the most actively exploited mining area in America. It has all the utilities of a city even to suburban electric railway service, is kept informed by four newspapers and carries $6,000,000 in deposit in six banks. The Nevada State University is one of the foremost schools of the West, and in its mining and agricultural department work ranks especially high. The Mackay Mining Building, dedicated June 6, 1908, is the pride of the university.

Carson City, Nevada’s capital, is a beautiful place of 5,000 people on the Virginia & Truckee Railway, thirty-one miles from Reno. It is the oldest town in the State, has an abundance of good water and good shade, creditable State buildings, and a United States branch mint. It trades freely with Southwestern Nevada and the Inyo Valley of California.

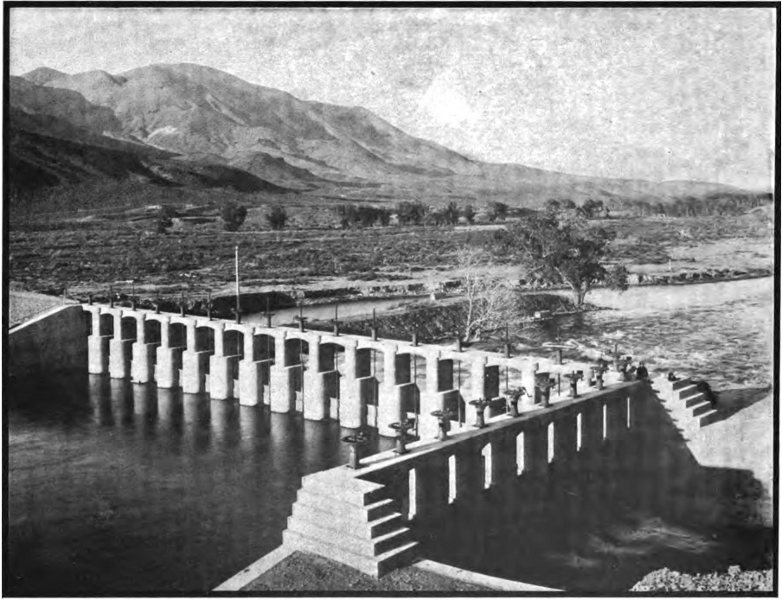

THE HEAD GATES NEAR HAZEN, NEVADA, OF THE CARSON-TRUCKEE IRRIGATION PROJECT WHEREBY THE GOVERNMENT PLANS TO GIVE IRRIGATED LANDS TO SETTLERS AT THE COST OF THE WATER

Virginia City, fifty-two miles from Reno on the Virginia & Truckee Ry., and the adjoining town of Gold Hill, are famous places, once the center of tremendous mining activity. The treasure houses underneath held wonderful stores of wealth. Virginia City at one time had 30,000 people, one-third of the population being always underground. The place was built on the steep slope of Mount Davidson, 6200 feet above sea-level. Until the discovery of the Comstock Lode (an ore-channel four miles long and three-quarters of a mile wide, along the eastern base of Mount Davidson, eighteen miles southeast of Reno), men worth $200,000 were called rich, and the world’s millionaires could be counted on one’s fingers. In June, 1859, miners (among whom were Peter O’Riley, Patrick McLaughlin, 51 James Finney, John Bishop, W. P. T. Comstock, and a man named Penrod) working in the ravine along the base of Mount Davidson, were much annoyed by a strange blue-black substance that clogged their rockers. Finally a sample was taken to Nevada City, Cal., for assay. It yielded over $6,000 per ton in gold and silver. Since the day of the rush that followed that discovery, work on the Comstock Lode has never ceased. From that ore-channel have been taken more than $700,000,000; the Consolidated California Virginia took out in six years $119,000,000 and paid $67,000,000 in dividends. Of the history of that wonderful time, little can be said here, and such men as William Sharon, John P. Jones, John W. Mackay, James G. Fair, I. W. Requa, Marcus Daly, Adolph Sutro, made famous by their connections with the Comstock Lode, must be passed by with merely mention of names. Mark Twain’s “Roughing It” and contemporary works, provide “mighty interesting” reading about that treasure era.

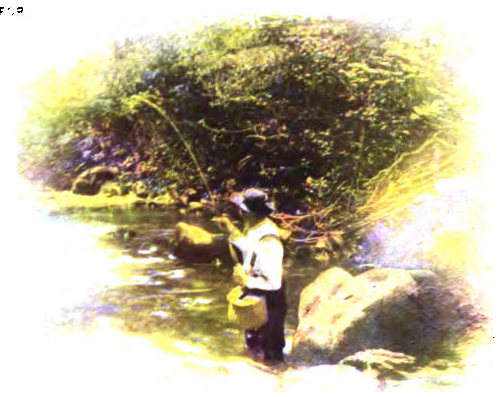

A WESTERN MINNEHAHA

Copyright by F. A. Rinehart, Omaha.

AT RENO MODERN BUILDINGS AND THE FINE BRIDGE THAT SPANS THE TRUCKEE MARK THE UPBUILDING OF NEVADA’S PRINCIPAL CITY

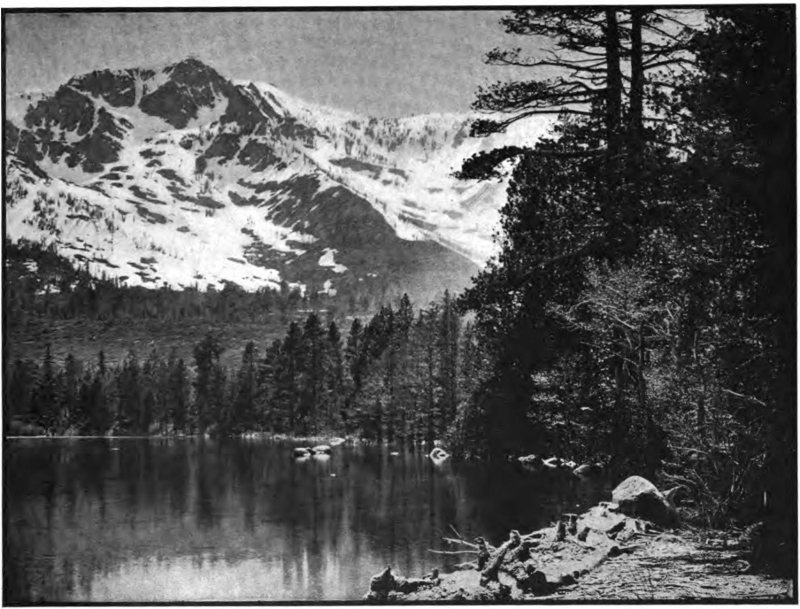

Reno is at the foot of the Sierra Nevada, the great wall rising to the 52 westward and separating California from the rest of the country. This highest of mountain chains in our country extends several hundred miles north and south. Perhaps no other range of mountains in the world has attractions so great or of such variety. The Sierra Nevada, the Snowy Range, or, as John Muir has more aptly termed it, the Range of Light, has many main ridges extending from 6,000 to 12,000 feet above sea level, with guardian peaks over 14,000 feet high. Highest of all and greatest mountain peak in the United States outside of Alaska is Mt. Whitney, 14,529 feet high. These mountains which the Overland Route crosses on its way to the Pacific have the greatest coniferous forests on earth. Among its peaks nestle the largest and most numerous of mountain lakes. Between its walls are unsurpassed mountain chasms. Its streams, unexcelled in beauty, possess the greatest potential power of all the waters of American mountains.

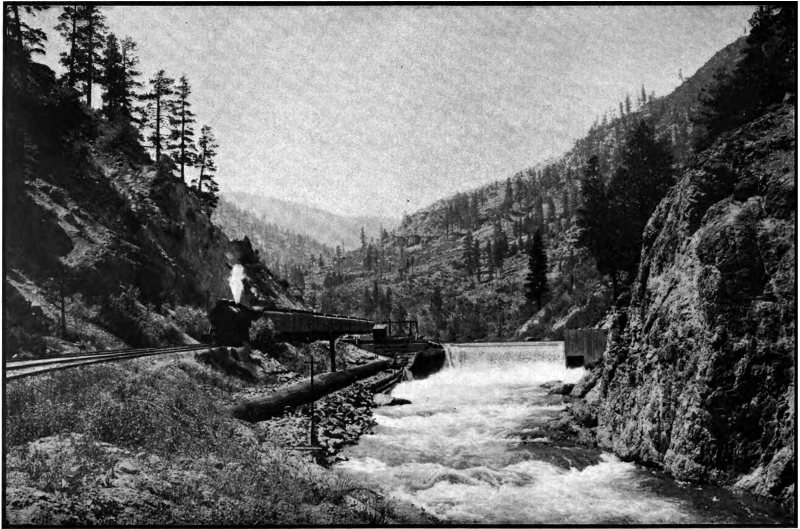

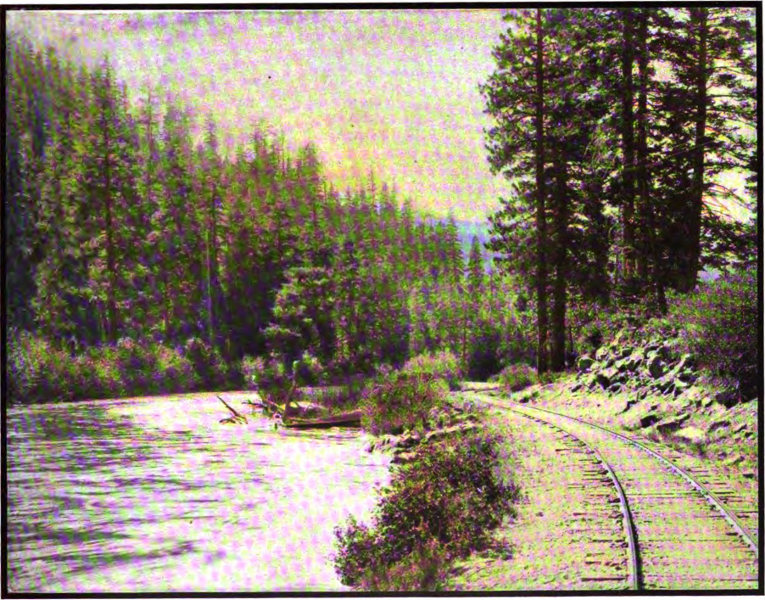

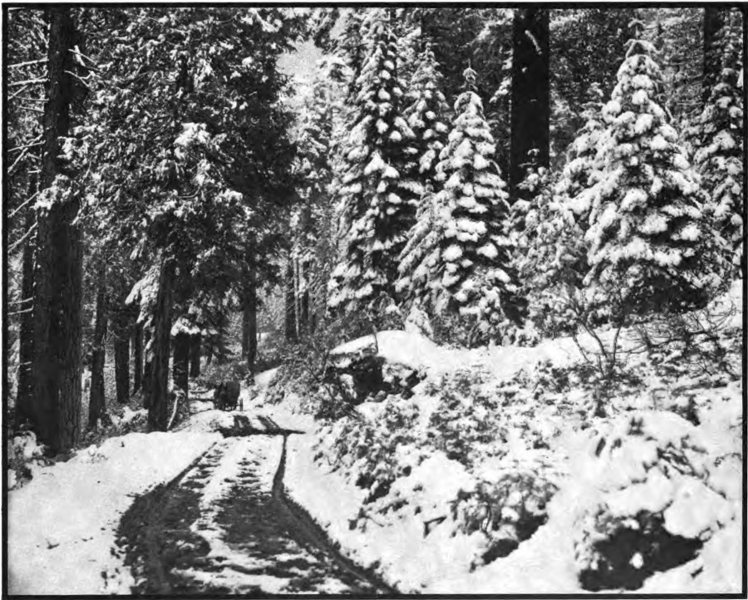

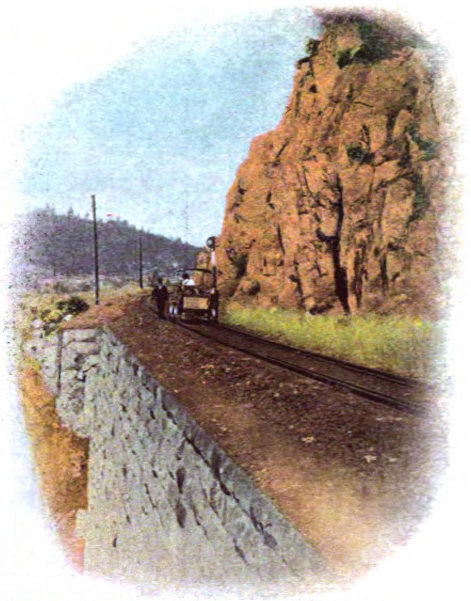

The Sierra Nevada is crossed by the Overland Route along a scenic pathway associated with much of interest in history and tradition. Here were the greatest obstacles in the way of the pioneer railroad builders. Nature seemed here to have rallied her forces for a final stand. Here Theodore Judah, the pioneer pathfinder of the railway, found his most difficult work. The climb up the mountain side is up the canyon of the beautiful Truckee River, a famous trout stream, a journey lined with beautiful forests of pine and mountain walls.

A STREET IN CARSON CITY, NEVADA, WHERE FAMOUS FOOTPRINTS AND FOSSIL REMAINS OF PREHISTORIC MONSTERS HAVE BEEN FOUND

At Boca, Prosser Creek and Iceland, the “chief crop” is ice; at Floriston, paper; at Truckee, lumber and box stock; and at Lake Tahoe, a very good time. Boca is junction with the Boca & Loyalton road, a forty mile line northward through Sierra and Plumas Valleys—noted for its forests, beautiful little valleys, and lakes. Truckee is a lumbering and railroad town of two 53 thousand people, Thence, a distance of 14 miles farther up the river, runs the Lake Tahoe Railway to the shore of Lake Tahoe.

VIRGINIA CITY, NEVADA, AS IN THE DAYS OF THE COMSTOCK LODE. STILL FURNISHES RICH YIELDS OF PRECIOUS MINERALS

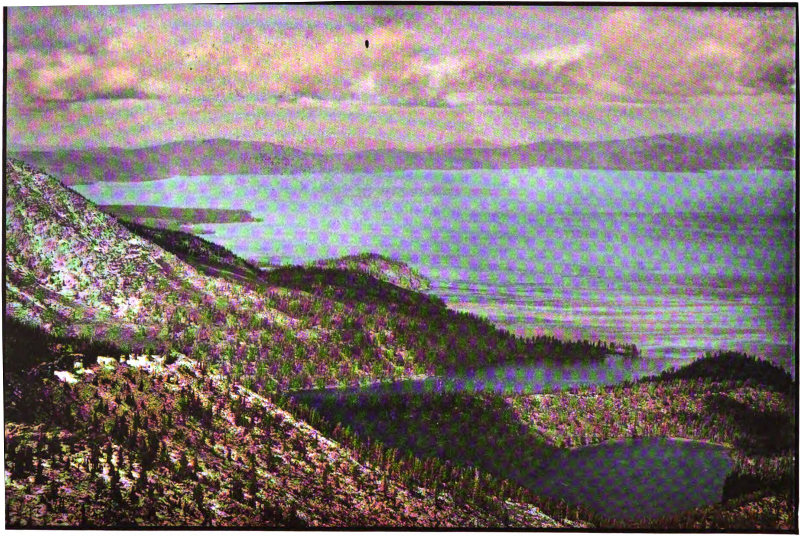

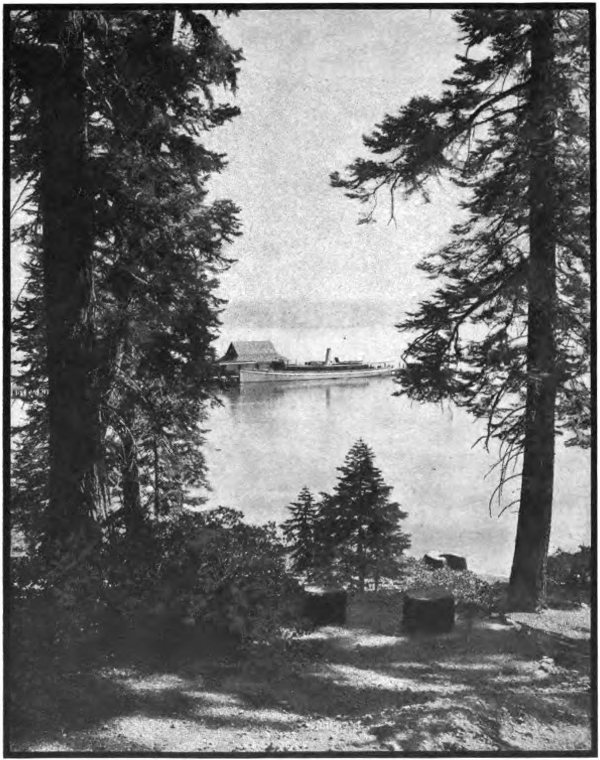

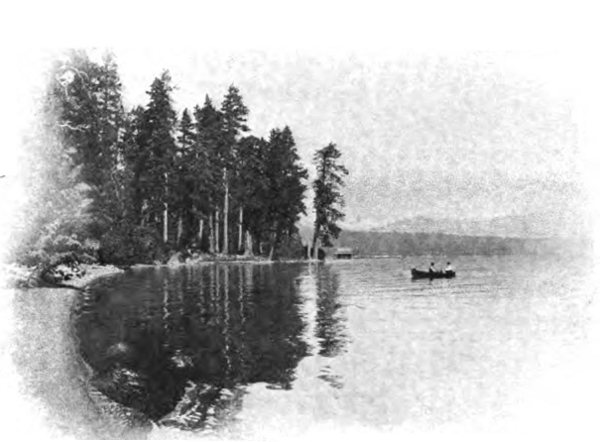

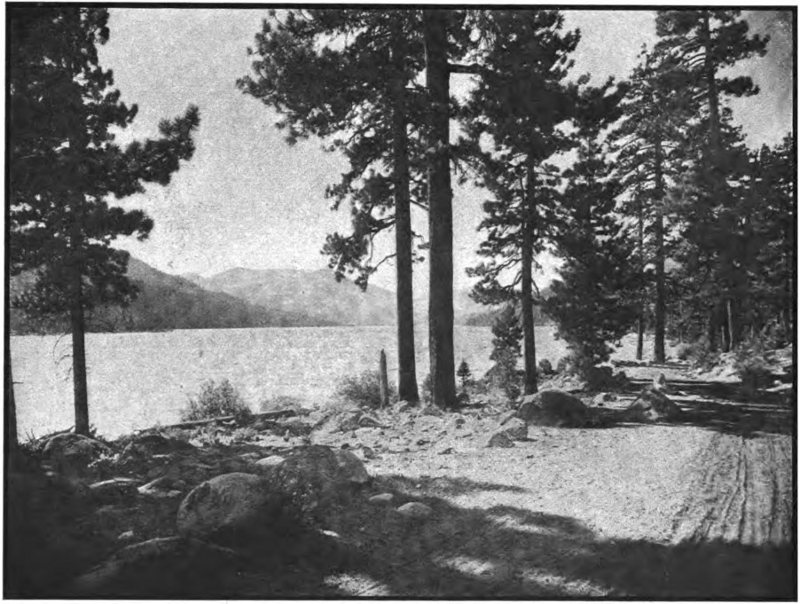

Lake Tahoe, largest of the world’s mountain lakes, is 23 miles long by 13 miles broad, 6,220 feet above sea-level, and over 2,000 feet deep. It is a body of the purest, clearest, and most wonderfully tinted water imaginable, held in a mountain rimmed cup with its edge crested with ever present snow, sparkling as a jewel. Between snow line and the lake are beautiful pine forests, in which, half hidden, are such famous resorts as Tahoe Tavern, McKinney’s, Tallac, Glenbrook, Brockway, and Tahoe City. The summer climate with great abundance of sunshiny days, the invigorating pine-scented atmosphere, and the cool nights and delightful days, alone make of Tahoe and its neighboring Sierra lakes—Fallen Leaf, Cascade, and others—an unsurpassed summer place. But when are added the forests, the scenery of the Snowy Range, the fishing and hunting, and the out of door sports, the first place among mountain lake resorts must be given to this region. A swift and well fitted steamer circles the lake every summer day from Tahoe Tavern.

The trout of Tahoe, the Truckee river, and neighboring lakes and streams, make good the claim that no place excels this region for the fisherman. Usually they run from three to six pounds in weight, but specimens weighing over thirty pounds have been taken.

Such out of door joys as boating, horseback riding, mountain climbing, and hunting, can be enjoyed under the most favorable conditions. Excursions up Freel’s Peak, and Mt. Tallac, and to Glen Alpine, are very much worth while. Of the hotel accommodations, it is, perhaps, enough to say, that one may be comfortable in a tent or a cabin, or enjoy hotel service unexcelled at any summer resort in America.

THE OVERLAND LIMITED AT FLORISTON CLOSE TO THE CALIFORNIA LINE, THE PORTAL TO A RIDE THROUGH SCENES OF GREAT BEAUTY

West of Truckee on the Overland Route, we pass Webber, Donner, and Independence Lakes. The unfortunate Donner party camped by the lake of that name, snowed in, in the winter of 1846-47, losing 43 of its 83 members before relief came in February. Of these mountain glacial lakes, cups of clear water, there are some six thousand in the region between Truckee and the Tule river to the south.

The summit of the Sierra is reached twelve miles west of Truckee, 7018 feet above the sea-level. Along this part of the journey the track is protected by snow-sheds, but the sides of the sheds are latticed and there are many intervening stretches of clear track, so the scenery is not lost.

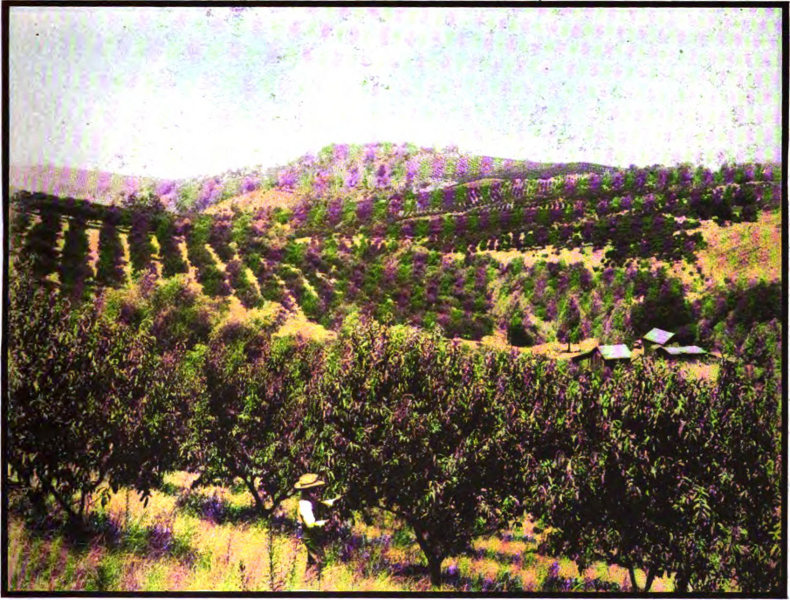

The ride down the western wall of the Sierras is one of entrancing interest. At the summit during the winter of 1907 were many feet of snow. Ravines were filled with it, snow-sheds covered with it, and trees made snow mounds by it; and yet scarce three hours’ ride away, roses brightened porches and roofs, the scent of orange blossoms filled the air, early peaches and almonds bloomed in the orchards, the fields were vividly green with foot high grain, and the hills aflame with wild poppies. It is this transition from snowy winter to blooming spring that is perhaps the most delightful experience of the westbound traveler during the colder months over the Overland Route as the train glides swiftly from the summit to the sea.

THE TRUCKEE RIVER IS ONE OF THE MOST GENEROUS AND MOST EASILY FISHED OF TROUT STREAMS

LAKE TAHOE, TWENTY-THREE MILES LONG, THIRTEEN WIDE, SURROUNDED BY SNOW CLAD MOUNTAINS, SET AS THE MAIN JEWEL OF A PENDANT OF GLEAMING LAKES, HAS NO PEER IN ALL AMERICA

CAVE ROCK, LAKE TAHOE, WHERE THE BIG TROUT LOVE TO LIE IN THE SHADY DEPTHS

At Cape Horn the road follows a shelf hewn around the face of the mountain; sheerly below, 1200 feet, is the American river in its winding canyon, while above the mountain wall rises to the clouds.

From Cape Horn the Sacramento Valley, fair and fruitful, is spread below as a great relief map of orchards, villages and cities, and winding rivers and green slopes. Past Emigrant Gap, Cowles, Dutch Flat and Gold Run—historic names—these mark the center of the greatest excitement America ever knew over placer mines. Colfax has interest partly in golden fruit and partly in gold. Twenty miles away, and reached by the Nevada county Narrow Gauge, are the thriving cities of Grass Valley and Nevada City, once great mining camps, and yet owning much mineral importance. They are now among California’s most important cities with prospects of advancement still bright before them.

TAHOE TAVERN—MOST MODERN OF HOSTELRIES IN EQUIPMENT, IS DESIGNED IN HARMONY WITH ITS SURROUNDINGS OF PINEY WOODS AND WILD FLOWER GARDENS

All down this slope of the Sierra, past beautiful Auburn, a modern town, and yet with a touch of ancient days, half hidden in foliage and flowers, with orange and peach blossoms, are natural sanitariums where people suffering from asthma and other throat and lung troubles are surprising their home doctors continually by getting well. From Auburn, Newcastle (center of the great Placer County fruit belt) Penryn and neighboring 58 stations, are shipped each year thousands of cars of green fruit, principally peaches, to the Eastern markets. No other section of the west ships so many cars of fresh peaches to market and its fame as an orange growing section is growing rapidly.

THE PAVILION AT TALLAC, ANOTHER POPULAR LAKE RESORT

The Overland Route joins the Road of a Thousand Wonders (between Portland, Oregon, and Los Angeles) at Roseville, a great railway center to be, with fifty-seven miles of yards, round-houses of sixty-four stalls, machine and car shops, club house, icing plant and hospital. From Roseville to Sacramento the nineteen mile journey is made past horse ranches (a notable one at Ben Ali), and great dairy farms.

Sacramento, the capital city of California, is a manufacturing and wholesale center, with an ever increasing and diversified trade extending up to central Oregon on the North, and to central Nevada on the East. Its post office receipts, school attendance, and directory returns, indicate the city has a population of practically 50,000. The railway shops of the Southern Pacific cover twenty acres, and employ 3,000 people. The rich tributary country about Sacramento amounts to 600,000 acres in area. Its bank capital and resources are greater than in many cities of over a hundred thousand people.

THE STEAMER “TAHOE” DAILY CIRCLES THE SAPPHIRE WATERS OF THE LAKE

Here was born the Central Pacific Railroad. Theodore D. Judah had been employed by a California company to build a road from Sacramento to Folsom 59 (forty miles), but his eyes were ever turning Sierraward. At last he gained the attention of Stanford, Huntington, Hopkins, and the Crockers, and succeeded in interesting them in the stupendous project of building a railroad, which, in a hundred miles was to rise from about sea-level to almost half a mile; then to drop 3300 feet and then crossing ten ranges of mountains, was to find a way to meet the western end of a road from the Missouri, by the waters of Great Salt Lake.

LAKE TAHOE’S SHORES ARE RICH IN SHELTERED COVES WHERE THE TRANSPARENT WATERS REFLECT THE PINES

MOUNT TALLAC, ONE OF THE SNOW CLAD PEAKS THAT GUARD LAKE TAHOE: 9,785 FEET HIGH, IT IS EASILY ACCESSIBLE AND THE SCENES FROM ITS SUMMIT ARE OF GREAT BEAUTY

FROM THE SMALLER ATTENDANT LAKES DROP MANY BEAUTIFUL FALLS, WELL WORTH VISITING

DONNER LAKE. SCENE OF A WINTER TRAGEDY IN EARLY CALIFORNIA DAYS

It was done. The story of the doing cannot be told here. It is one of volumes, and simply the names of the men whose daring and genius solved its problems may be mentioned. It was a combination predestined, irresistible, a union of men for whom opportunity needed to knock but lightly, who saw the grandeur of the task before them and rose to its inspiration. Each had his allotted place to which he seemed peculiarly fitted and each, through the sheer love of the work and indomitable purpose made perfect his part in this modern conquest of America. Judah, the great engineer, saw the work through, and then, in a few months, died—but fame is his. Senator A. A. Sargent framed the laws that made the work possible. Senator Leland Stanford was the great political executive who handled the road’s relations with the Government—a many sided, brilliant man, and a mighty pioneer, in farming, fruit growing, and stock raising, as well as railroad building. Charles Crocker was the master mind in the field, and organizer of men and affairs, and withal, much beloved by all who knew him. Judge Crocker, the road’s first attorney, was of inestimable value to it, but so noiseless, modest and retiring, that his relations with the line are almost forgotten. Mark Hopkins was the trained man of business, who directed the office affairs, carrying in his brain every detail of the enterprise, and working upon it night and 61 day. Collis P. Huntington, famous in every line of work he undertook, outlived his associates, and became one of the world’s greatest builders and financiers. To Mr. Huntington and to Edward H. Harriman (whose financial genius and constructive ability have contributed more in high class, modern railways to the advancement of the West than any other man), the empire beyond the Missouri and the Mississippi owes more than to any other two.

SHY DEER WATCH THE PASSING TRAINS FROM THE LEAFY COVERTS OF THE CANYONS

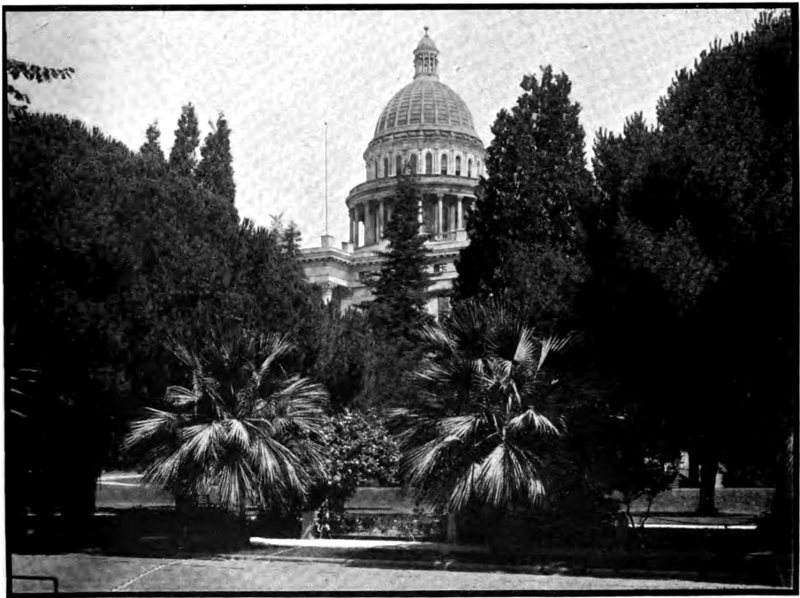

Sacramento has many places of interest; the capitol building and its fine grounds, Sutter’s Fort, and the Crocker Art Gallery being among them. The city has beautiful tree lined avenues, fine houses with flower gardens, lawns, and citrus and deciduous fruit, good urban and suburban electric line service, railways radiating in four directions, and three more—two steam and one electric—under construction; altogether a modern, charming city with such unusual out of doors attractions as only California can give.

NEAR NEWCASTLE THE WILDER SCENERY GIVES PLACE TO PEACEFUL ORCHARDS

Among public works is the handsome Government building, in which are the post office, land office, weather bureau, and other Government 62 offices. In yards the magnolia blooms and the broad leaves of the plantain and banana arrest the eye. Palms are plentiful and with variety; orange and lemon trees are numerous. Camellias bloom in profusion.

The journey from Sacramento to San Francisco may be made over the ninety mile direct route via Benicia or the longer way through Stockton. The Benicia Route is through deciduous fruit sections, of which Davis and Elmira are business centers and junctions respectively for lines through the west side of the Sacramento Valley and up the beautiful Capay Valley. The Overland Route from Elmira follows along the marshes of upper Suisun Bay, where tens of thousands of wild ducks and wild geese find a home.

At Suisun, a branch line leads to the Napa and Sonoma Valleys, famous these forty years past for fruits and wine and rural loveliness. Suisun has many fruit establishments. Beyond, fifteen miles, is Benicia, with its Government post and arsenal.

UP AT SUMMIT THE DOMAIN OF KING SNOW, BEAUTIFUL TO LOOK AT THOUGH FRIGID IN WELCOME, IS SWIFTLY LEFT BEHIND

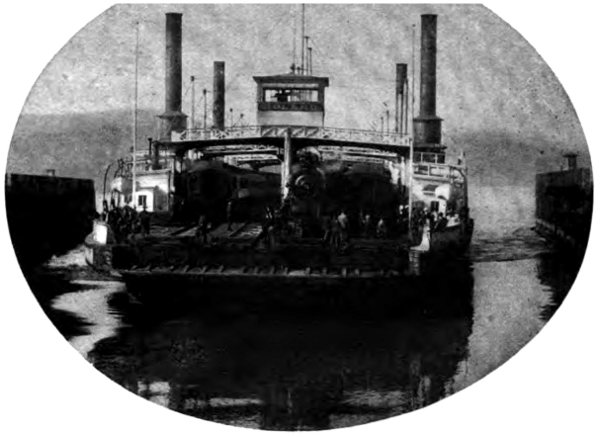

Thence the great double ferryboat, the Solano, swallows the train, and moves across the picturesque Carquinez straits, a mile wide, to Port Costa. This is the largest ferryboat in the world, and perhaps the only double one. Its two paddle wheels may be made to revolve in opposite directions, turning the boat around almost in its own length. As one crosses, to the left lies Suisun Bay, to the right, San Pablo Bay. The ferry unloads its trains at Port Costa, place of mammoth grain warehouses 63 with capacity for more than 350,000 tons. Thirty deep-sea ships may unload here at one time.

THE TRAIN DROPS QUICKLY FROM THE REGION OF PINES AND FROST INTO A FAIRYLAND OF PALMS AND FLOWERS

A few miles beyond Port Costa is Vallejo Junction; thence the ferry boat El Capitan carries passengers the intervening four miles to Vallejo, and to Mare Island Navy Yard. From the train you may catch a glimpse of the warships at anchor, of the wooded island where Uncle Sam has three thousand employees, and of Vallejo, upon its hills facing it, a lively city of 12,000 people.