Title: The Merry Anne

Author: Samuel Merwin

Illustrator: Thomas Fogarty

Release date: May 1, 2016 [eBook #51916]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger from page images generously

provided by the Internet Archive

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I—DICK AND HIS MERRY ANNE

CHAPTER III—AT THE HOUSE ON STILTS

CHAPTER VIII—THE EVENING OF THE SAME DAY

CHAPTER IX—THE CHASE BEGINS—THURSDAY MORNING

CHAPTER X—THURSDAY NIGHT—THE GINGHAM DRESS

CHAPTER XI—THURSDAY NIGHT—VAN DEELEN'S BRIDGE

CHAPTER XIV—IN WHICH BEVERIDGE SURPRISES HIMSELF

Dear H. K. TV.:

This tale dedicates itself to you as a matter of right. For we grew up together on the bank of Lake Michigan; and you have not forgotten, over there in Paris, the real house on stilts, nor the miles we have tramped along the beach, nor, I am sure, the grim old life-saver on the near Ludington, and his sturdy scorn for our student life-savers at Evanston. And the endless night on Black Lake, with Klondike Andrews at the tiller and never a breath of wind, we shall not forget that. Once we differed: I failed to tempt you into a paddle in the Oki, one fresh spring day three years ago; but then, your instinct of self-preservation always worked better than mine, as the adventure in the Swampscott dory will recall to you.

But, after all, these doings do not make up the reason why the story is partly yours; nor do the changes in the text that sprang from your friendly comment. I will tell you the real reason.

Early, very early, one summer morning, you and I stood on the wheel-house of the P'ere Marquette Steamer No. 4—or was it the No. 3—a few hours from Milwaukee. The Lake was still, the thick mist was faintly illuminated by the hidden sun. Of a sudden, while the steamer was throbbing through the silence, a motionless schooner, painted blue, with a man in a red shirt at the wheel, loomed through the mist, stood out for one vivid moment, then faded away.

That schooner was the Merry Anne; and the man at the wheel was Dick Smiley. What if he should some day chance upon this tale and declare it untrue? know better, for we saw it there.

THE Merry Anne was the one lumber schooner on Lake Michigan that always appeared freshly painted; it was Dick Smiley's wildest extravagance to keep her so. Sky blue she was (Annie's favorite color), with a broad white line below the rail; and to see her running down on the north wind, her sails white in the sun, her bow laying the waves aside in gentle rolls to port and starboard, her captain balancing easily at the wheel, in red shirt, red and blue neckerchief, and slouch hat, was to feel stirring in one the old spirit of the Lakes.

It was a lowering day off Manistee. Out on the horizon, now and then dipping below it, a tug was struggling to hold two barges up into the wind. Within the harbor, at the wharf of the lumber company, lay the Merry Anne. Two of her crew were below, sleeping off an overdose of Manistee whiskey. The third, a boy of seventeen, got up in slavish imitation of his captain,—red shirt, slouch hat, and all,—was at work lashing down the deck load. Roche, the mate, stood on the wharf, the centre of a little group of stevedores and rivermen. “Hi there, Pink,” he shouted at the red shirt, “what you doin' there?”

The boy threw a sweeping glance lake-ward before replying, “Makin' fast.”

“That 'll do for you. There won't be no start this afternoon.”

“But Cap' Smiley said—”

“None o' your lip, or I 'll Cap' Smiley you.

“Pretty ugly, out there, all right enough,” observed a riverman. “Cornin' up worse, too. Give you a stiff time with all that stuff aboard.”

“I ain't so sure about that,” said Roche, with a swagger. “If I was cap'n o' this schooner, she'd start on the minute, but Smiley's one o' your fair-weather sort.”

“Sure he is. He done a heap o' talkin' about that time he brung the William Jones into Black Lake before the wind, the day the John T. Eversley was lost; but Billy Underdown was sailin' with him then, and he told me hisself that he had the wheel all the way—Smiley never done a thing but hang on to the companionway and holler at him to look out for the north set o' the surf outside the piers; and there's my little Andy that ain't nine year old till the sixth o' September, could ha' told him the surf sets south off Black Lake, with a northwest wind. If it hadn't been for Billy, the Lord only knows where Dick Smiley'd be to-day.”

A tug hand had joined the group, and now he addressed himself to Roche.

“Cap'n Peters wants to know if you're a-goin' to try to make it, Mr. Roche.”

“Not by a dam' sight.”

“Well—I guess he won't be sorry to wait till mornin'. What time do you think you 'll want us?”

“Six o'clock sharp.”

“Them's Cap'n Smiley's orders, is they?”

“Them's my orders, and they're good enough for you.”

“Oh, that's all right, of course, only Cap'n Peters, he said if 'twas anybody else, he'd just tie up and wait, but there ain't never any tellin', he says, what Dick Smiley 'll take it into his head to do.”

“You tell your cap'n that Mr. Roche said to come at six in the mornin'.”

“All right. I 'll tell him. Say—Cap'n Smiley ain't anywhere around, is he?”

“No, Cap'n Smiley ain t anywheres around!” mimicked Roche, angrily. “If you want to know whereabouts Cap'n Smiley is, he's uptown skylarkin', that's where he is.”

The river hands laughed at this.

“I reckon he's somethin' of a hand for the ladies, Dick Smiley is, with them blue eyes o' his'n,” said one. “I ain't a-tellin', you understand, but there's boys in town here that could let you know a thing or two if they was minded.”

As a matter of fact, Dick was at that moment in an up-town jewellery shop, fingering a necklace of coral.

“I want a longer one,” he was saying, “with something pretty hanging on the end of it—there, that's the boy—the one with big rough beads and the red rose carved on the end.”

“Must be somebody's birthday, Captain,” observed the jeweller, with a wink.

And Dick, who could never resist a wink, replied: “That's what. Day after to-morrow, too, and I haven't any too much time to make it in.”

“Here's a nice piece—if she likes the real red.”

Dick took it in his hands and nodded over it. “I think that would please her. She likes bright colors.” He drew a wallet from a hip pocket and disclosed a thick bundle of bills.

“I shouldn't think you'd like to carry so much money on you, Captain, in your line of work.”

“It isn't so much. They are most all ones.” But the jeweller, seeing a double X on the top, only smiled and remarked that it was a dark day.

“Yes, too dark. I don't like it. Makes me think of the cyclone three years ago April, when the Kate Howard went down off Lakeville. I spent three hours roosting on the topmast that day. It was black then, like this. If it keeps up, you 'll have to turn on your lights in here.”

“Guess I will. It wouldn't hurt now. Well, good-by, Captain. Drop in again next time you run in here.”

“All right. But there's no telling when that will be. I have to go where Captain Stenzenberger sends me, you know.”

“You don't own your schooner yet, then?”

“No; only a quarter of it. Well, good-by.” And he left the shop with the corals, securely wrapped, stowed in an inside pocket.

The first big drops of rain were falling when he reached the schooner. The deck was deserted, but he found Roche and his wharf acquaintances settled comfortably in the cabin. Their talk stopped abruptly at the sight of his boots coming down the companionway.

“Why isn't the load lashed down, Pete?” he asked, addressing Roche.

“Why—oh, it was lookin' so bad, I thought we'd better wait till you come.”

“Where's the tug? Don't Peters know we want him?”

The loungers were silent. All looked at Roche.

“Why, yes—sure. He ain't showed up yet, though.”

“You ain't goin' to try to make it, are you, Cap'n?” asked a riverman.

“Going to try? We are going to make it, if that's what you mean.”

One of the men rose. “I'm going up the wharf, Cap'n. If you like, I 'll speak to Peters.”

“All right. I wish you would. And say, Pete, you take Pink and see that everything is down solid. I don't care to distribute those two-by-fours all down the east coast.”

Roche went out, and the others got up one by one and took shelter in the lee of a lumber pile on the wharf. A little later, when he saw the tug steaming up the river, Roche shook the rain from his eyes and looked long at the black cloud billows that were rolling up from the northwest, then he slipped below and took a strong pull at his flask. The tug came alongside, and then Roche sought Dick.

“Cap'n, what's the use?” he said in an agitated voice. “Don't you see we're runnin' our nose right into it? Why, if we was a three-hundred-footer, we'd have our hands full out there. I don't like to say nothin', but—”

Smiley, his hat jammed on the back of his head, his shirt, now dripping wet, clinging to his trunk and outlining bunches of muscle on his shoulders and back, his light hair stringing down over his forehead, merely looked at him curiously.

“You see how it is, Cap'n, I—”

“What are you talking about? All right, Pink, make fast there! Who's running this schooner, you or me?”

“Oh, I don't mean nothin', Cap'n; but seein' there ain't no particular hurry—”

“No hurry! Why, man, I've got to lay alongside the Lakeville pier by Wednesday night, or break something. What's the matter with you, anyhow? Lost your nerve?”

“No, I ain't lost my nerve. And you ain't got no call to talk that way to me, Dick Smiley.”

“Here, here, Pete, none of that. We're going to pull out in just about two minutes. If you aren't good for it, I 'll wait long enough to tumble your slops ashore. Put your mind on it now—are you coming or not?”

“Oh, I'm cornin', Cap'n, of course, but—”

“Shut up, then.”

The idlers on the wharf had not heard what was said, but they saw Roche change color and duck below for another pull at his flask.

The tug swung out into the stream; the Merry Anne fell slowly away from the wharf.

“Call up those loafers, Pete,” shouted Smiley, as he rested his hands on the wheel. The two sailors, roused by a shake and an oath, scrambled drowsily upon the deck with red eyes and unsettled nerves, and were set to work raising the jib and double-reefing foresail and mainsail. Captain Peters sounded three blasts for the first bridge, and headed down-stream.

Passing on through the narrow draws of the bridges and between the buildings that lined the river, the Merry Anne drew near to the long piers that formed the entrance to the channel. And Roche, standing with flushed face by the foremast, looked out over the piers at the angry lake, now a lead-gray color, here streaked with foam, there half obscured by the driving squalls. His eyes followed the track of one squall after another as they tore their way at right angles to the surf.

Already the Anne had begun to stagger. At the end of the towing hawser the tug was nosing into the half-spent rollers that got in between the piers, and was tossing the spray up into the wind.

One of the life-saving crew, in shining oilskins, was walking the pier; he paused and looked at them—even called out some words that the wind took from his lips and mockingly swept away. Roche looked at him with dull eyes; saw his lips moving behind his hollowed hands; looked out again at the muddy streaks and the whirling mist, out beyond at the two barges laboring on the horizon, gazed at the white and yellow surf. Then his eye lighted a little, and he made his way back to the wheel.

“Don't be a fool, Dick,” he shouted. “Just look a' that and tell me you can make it. I know better. I'm an old friend, Dick, and I like you better'n anybody, but you mustn't be a dam' fool. Ain't no use bein' a dam' fool.”

“Who are you talking to?”

“Lemme blow the horn, Dick.'Taint too late to stop 'em. We can get back all right—start in the mornin'. Don't you see, Dick—”

Smiley's eyes were fixed keenly on him for a moment; then they swept to the windward pier. He snatched the horn from Roche's hand and blew a blast.

The sailors up forward heard it, and shouted and waved their arms. A tug hand, seeing the commotion, though he heard nothing, finally was made to understand, and Captain Peters slowed his engines. Smiley, meanwhile, was steering up close to the windward pier.

“Tumble off there, Pete,” he ordered. “Quick, now.”

“What you going to do to me? Ain't goin' to put me off there, are you?”

“Get a move on, or I 'll throw you off. There's no room for you here.”

“Hold on there, Dick; I ain't got no clothes or nothin'. And you owe me my pay—”

“You 'll have to go to Cap'n Stenzenberger about that. Here, Pink, heave him off. Quick, now!”

“Don't you lay your hand on me, Pink Harper—”

But the words were lost. The young sailor in the red shirt fairly pitched him over the rail. The life saver, running alongside, gave him a hand. Captain Peters was leaning out impatiently from his wheel-house door, and now at the signal he dove back and hurriedly rang for full steam ahead; it was no place to run chances. And as the schooner passed out into the open lake, leaving the lighthouse behind her, and soon afterward casting off the tug, there was no time to look back at the raging figure on the pier. Though once, to be sure, Dick had turned with a laugh and shouted out a few lines of a wild parody on the song of the day, “Baby Mine.”

The song proved so amusing that, when they were free of the tug and were careening gayly off to the southwest with all fast on board and a boiling sea around them, he took it up again. And braced at a sharp angle with the deck, one eye on the sails, another cast to windward, his brown hands knotted around the spokes of the wheel, he sang away at the top of his lungs:—=

"He is coming down the Rhine.

With a bellyful of wine,"=

Young Harper worked his way aft along the upper rail. His eye fell on the figure of his captain, and he laughed and nodded.

“Lively goin', Cap'n.”

Lively it certainly was.

“Guess there ain't no doubt about our makin' it!”

“Doubt your uncle!” roared the Captain. And he winked at his young admirer.

“Guess Mr. Roche didn't like the looks of it.”

“Guess not.”

Harper crept forward again. And Smiley, with a laugh in his eye, squared his chest to the storm, and thought of the necklace stowed away in the cabin; and then he thought of her who was to be its owner day after to-morrow, and “I wonder if we will make it,” thought he; “I wonder!”

And make it they did. Sliding gayly up into a humming southwest wind, with every rag up and the sheets hauled home, with the bluest of skies above them and the bluest of water beneath (for the Lakes play at April weather all around the calendar), Wednesday afternoon found them turning Grosse Pointe.

The bright new paint was prematurely old now, the small boat was missing from the stern davits, the cabin windows had been crushed in, and one sailor carried his arm in a sling, but they had made it. Harper, hollow-eyed, but merry, had the wheel; Smiley was below, snatching his first nap in forty-eight hours, with the red corals under his head.

“Ole,” called Harper, “wake up the Cap'n, will you? I can't leave the wheel. He said we was to call him off Grosse Pointe.”

So Ole called him, and was soon followed back on deck by another hollow-eyed figure.

“Guess it's just as well Mr. Roche didn't come along,” observed the boy, as he relinquished the wheel. “He'd'a' had all he wanted, and no mistake.”

“He had enough to start with. There wasn't any room for drunks this trip.”

As he spoke, Smiley was running his eye over the familiar yellow bluffs, glancing at the lighthouse tower, at the stack of the water works farther down the coast, at the green billows of foliage with here and there a spire rising above them, and, last and longest, at the two piers that reached far out into the Lake,—one black with coal sheds, the other and nearer, yellow with new lumber.

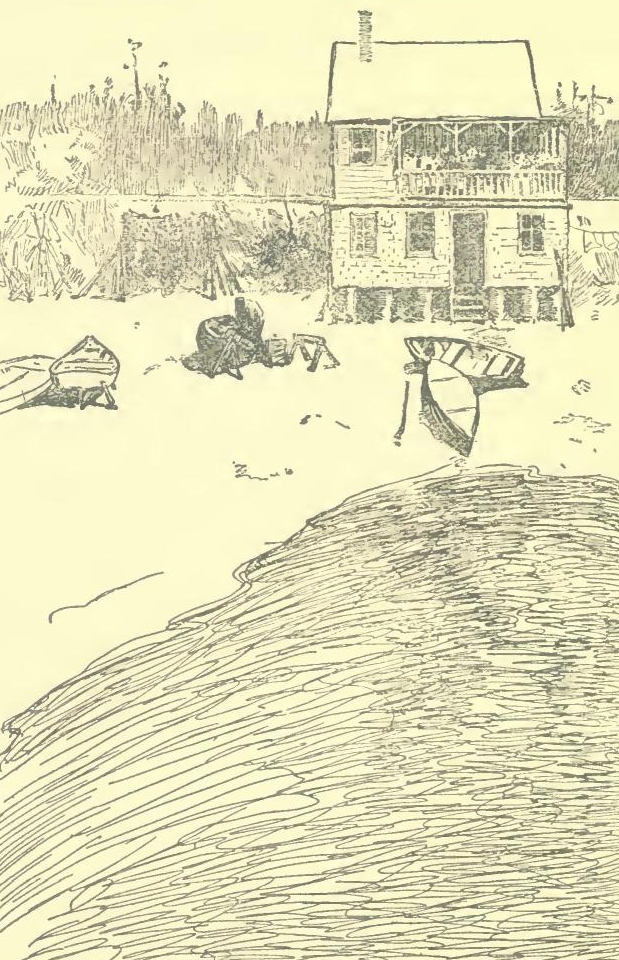

Between these piers, built in the curve of the beach and nestling under the bluff, was a curious patchwork of a house. Built of odds and ends of lumber, even, in the rear, of driftwood, perched up on piles so that the higher waves might run up under the kitchen floor, small wonder that the youngsters of the shore had dubbed it “the house on stilts.”

Old Captain Fargo (and who was not a “Captain” in those days!) had built it with his own hands, just as he had built every one of the sailboats and rowboats that strewed the beach, and had woven every one of the nets that were wound on reels up there under the bluff.

A surprisingly spacious old house it was, too, with a room for Annie upstairs on the Lake side, looking out on a porch that was just large enough to hold her pots and boxes of geraniums and nasturtiums and forget-me-nots.

Smiley could not see the house yet; it was hidden by the lumber piles on the pier. But his eyes knew where to look, and they lingered there, all the while that his sailor's sixth sense was watching the set of the sails and the scudding ripples that marked the wind puffs. He wore a clean red shirt to-day and a neckerchief that lay in even folds around his neck. Redolent of soap he was, his face and hands scrubbed until they shone. And still his eyes tried to look through fifty feet of lumber to the little flowering porch, until a sail came in sight around the end of the pier. Then he straightened up, and shifted his grip on the spokes.

The small boat was also blue with a white stripe. At the stern sat a single figure. But though they were still too far apart to distinguish features, Dick knew that the figure was that of a girl—a girl of a fine, healthy carriage, her face tanned an even brown, and a laugh in her black eyes. He knew, even before he brought his glass to bear on her, that she was dressed in a blue sailor suit, with a rolling blue-and-white collar cut V-shape and giving a glimpse of her round brown neck. He knew that her black hair was gathered simply with a ribbon and left to hang about her shoulders, that her arms were bared to the elbow. He could see that she was carrying a few yards more sail than was safe for a catboat in that breeze, and there was a laugh in his own eyes as he shook his head over her recklessness. He knew that it would do no good to speak to her about it; and her father and mother had never been able to look upon her with any but fond, foolish eyes.

Steadily the Merry Anne drew in toward the pier; rapidly the Captain—so Annie called her boat—came bobbing and skimming out to meet her. A few moments more and Dick could wave his hat and shout, “Ahoy, there!” And he heard in reply, as he had known that he should, a merry “Ahoy, there! I 'll beat you in!” And then they raced for it, Annie gaining, as she generally could, while the schooner was laboriously coming about, and working in slowly under reduced sail. She ran in close to the pier, came up into the wind, and waited there while the crew were making the schooner fast.

At length the stevedores started unloading the lumber and Dick was free. He leaned on the rail and looked down at Annie who had by this time come alongside; and he saw that she had a bunch of blue-and-white forget-me-nots in her hair.

“Well,” she said, looking up, and driving all power of consecutive thought out of Dick's head, as she always did when she rested her black eyes full on his, “well, I beat you.”

“Take me aboard, Annie. I've got something for you.”

“All right, come down. You can take the sheet.”

Dick pushed off from the schooner's side and the Captain filled away toward the shore.

“Hold on, Annie, come about. I don't have to go in yet.”

“Where do you want to go?”

“I don't care—run out a little way.”

Annie brought her about and Dick watched her with admiring eyes. “Well, now,” he began, as they settled down for a run off the wind, “I didn't know whether I was going to get here to-day or not.”

“It was pretty bad.”

“You were thinking of me, weren't you, Annie?”

She smiled and gave her attention to the boat.

“Roche was drunk, and I had to leave him at Manistee.”

“You didn't come down shorthanded, did you, Dick,—in that storm?”

He nodded.

“But how? You couldn't have got much sleep.”

“I didn't get any till this noon.”

“Now, that's just like you, Dick, always running risks when you don't have to.”

“But I did have to.”

“I don't see why.”

“What day's to-day?”

A mischievous light came into her eyes, but her face was demure. “Wednesday,” she replied.

“Yes, I knew that.”

“Why did you ask me, then?”

“Oh, Annie, Annie! When are you going to stop talking that way?”

Again the boat claimed all her attention. He leaned forward and dropped his voice.

“Don't you think I've waited most long enough, Annie?”

“Now, Dick, be sensible.”

“But haven't I been sensible? Not a word have I said for two months. And I told you then I would speak on your birthday.”

“So you really remembered my birthday?”

“Remembered it, Annie! What a girl you are! Do you know how long I've been waiting? And all the boys laughing? It's two years this month. It was on your birthday that I saw you first, you know. And it wasn't a month after that that I spoke to you. How could I help it? Who could have waited longer? And you, with your way of making me think you were really going to say yes, and then just laughing at me.”

“Now, Dick—if you don't stop and be sensible, I 'll take you straight inshore.”

“Oh, you wouldn't do that, Annie?”

“Yes, I would. I will now. Ready about!” The Captain came rapidly up into the wind, but stopped there with sail flapping; for Dick held the sheet, and his hand had imprisoned hers on the tiller.

“Now, Dick—Dick—”

“Wait a minute. Don't be angry with me when I've risked the schooner and everybody aboard her just so's to get down here on your birthday. Promise me you 'll hold her in the wind while I get you your present.”

She hesitated, and looked out toward the horizon.

“Promise me that, Annie, and I 'll let go your hand.”

“You—you've forgotten—what you promised—”

“I know, I said I'd never take hold of your hand again until you put it in mine—didn't I?”

She nodded, still looking away.

“And I've broken the promise. Do you know why, Annie? It's because when you look at me the way you do sometimes, I could break every promise I've ever made—and every law of Congress if I thought it would just keep you looking at me.”

Not a word from Annie.

“Promise me, Annie, that you 'll hold her here?”

Still no word.

“Won't you just nod, then?”

She hesitated a moment longer, then gave one uncertain little nod. He released her hand, held the sheet between his knees, drew the package from his pocket, and displayed the corals. She was trying bravely not to look around, but her glance wavered, and finally she turned and looked at it with eager eyes. “Oh, Dick, did you bring that for me?”

“I surely did.” He held it up, and when she bent her head forward, he slipped it over and around her neck. Her eyes shone as she ran the red beads through her fingers and looked at the carved pendant. Dick leaned back and watched her contentedly. Finally she let her eyes steal upward and meet his, with a smile that was half roguish. “I never really laughed at you, did I, Dick?”

He moved forward with sudden eagerness. “Don't you think now is a good time to say yes, Annie,—now, on your birthday? I own a quarter of the schooner now, you know; and I'm ready to make another payment to-morrow. And don't you see, when we're married you can help me to save, and before we know it we can have a home and a business of our own.” She was bending over the corals. “You didn't really think you could save more with—with me, than you could alone, did you, Dick?”

“Yes, I'm sure of it. It will give me something to work for, don't you see?”

“But—but—” very shyly, this—“Haven't you anything to work for now?”

“Oh, Annie, do you mean that—are you telling me you 'll give me the right to work for you? That's all I want to know.”

“Now, Dick—please let go my hand—you promised, you know—”

“What is a promise now! If you knew how you torture me when you lead me on till I'm half wild and then change around till I don't know what I've said or what you've said or hardly who I am—”

“No, Dick, you mustn't—I mean it. We must go in. See, there's father on the beach. It must be supper-time.”

“Wait a minute—I haven't half told you—”

But she was merciless. The Captain came about and headed shoreward.

“Did you meet the revenue cutter anywhere up the Lake—the Foote? She was here yesterday.”

“There you are again, all changed around! What do I care about the Foote—when I'm just waiting to hear you say the only word that can make my life worth living. Now, Annie—”

“You mustn't, Dick. I've let you say too much now. If you go on, you 'll make me feel that I can't even thank you for your present.”

“Was that all? Were you only thanking me?”

She nodded, and Dick's face fell into gloom. But when the Captain was beached, and Annie had leaped lightly over the rail, she turned and gave him one merry blushing look that completely reversed the effect of her reproof. And as she hurried up to the house, he could only gaze after her helplessly.

IN the morning the William Schmidt, Henry Smiley, Master, came in from Chicago and tied up across the pier from the Merry Anne.

Henry, Dick's cousin, was a short, stocky, man, said to be somewhat of a driver with his sailors. He seldom had much to say, never drank, was shrewd at a bargain, and was supposed to have a considerable sum stowed away in the local savings bank. Though he was wanting in the qualities that made his younger cousin popular, he was daring enough in his quiet way, and he had been known, when he thought the occasion justified it, to run long chances with his snub-nosed schooner.

After breakfast Dick walked across the broad pier between the piles of lumber, and found Henry in his cabin. They greeted each other cordially.

“Sit down,” said Henry. “Did you come down through that nor'wester?”

Dick nodded.

“Have any trouble?”

“Oh, no. Lost some sleep—that's all. You aren't going down to the yards to-day, are you?”

“Yes—I think likely. Why?”

“I 'll go along with you. I'm ready to make another payment on the schooner. I've been thinking it over, and it strikes me I'm paying about three times what she's worth. What do you think? Would it do any harm to have a little talk about it with the Cap'n? You know him better than I do.”

Henry shook his head. “I wouldn't. He is too smart for you. He will beat you any way you try it, and have you thanking him before he is through with you. I have gone all over this ground before, you know. Of course he is an old rascal—but I don't know of any other way you could even get an interest in a schooner. You see, you haven't any capital. He will give you all the time you want, and I don't know but what he's entitled to a little extra, everything considered. But don't say anything, whatever you do. You've got too good a thing here.”

“You think I ought to just shut up and let him bleed me?”

“He isn't bleeding you. Just think it over, Dick. You are making a living, and you already have a quarter interest in your schooner. You couldn't ask much more at your age. Have you heard from him yet, by the way?”

“No.”

“He spoke to me the other day about wanting to see you when you came in. There's another order to come down from Spencer.”

“Where's that?”

“Up in the Alpena country.”

“Lake Huron, eh? Oh—isn't that where you went in the spring?”

“Yes, I've been there. An old fellow named Spencer runs a little one-horse mill, and he's selling timber and shingles. And from what the Cap'n said, I don't think he'd care if you brought along a little venture of your own. That's the way I used to do, when I was paying for the Schmidt.”

“How could I do that?”

“Spencer will give you a little credit. You can stow away a few thousand feet, and clear twenty or thirty dollars. It helps along.”

“All right, I 'll try it. Are you sure the old man won't care?”

“Oh, yes. He's willing enough to do the square thing, so long as it keeps us feeling good and doesn't lose him anything.”

“Say—there's another thing, Henry. I fired Roche, up at Manistee.”

“Fired him?” Henry's brows came together.

“Yes, I had to. I had stood him as long as I could.”

“I don't know what the Cap'n will say about that.”

“I'd like to know what he can say. I was in command.”

“Yes, I know—of course you had a right to; but the thing is to keep on his good side. Suppose we go right down to the yards, and see if you can get your story in before Roche's.”

“What does the Cap'n care about my men, I'd like to know!”

“Now, keep cool, Dick. Roche, you see, used to work for him,—I don't know but what they're related,—and it was because the Cap'n spoke to me about him that I recommended him to you when I did. And look here, Dick,”—Henry smiled as he laid a hand on his cousin's shoulder,—“I'm a good deal older than you are, and you can take my word for it. Don't get sour on things. Of course people will do you if they can; but it's human nature, and you can't change it by growling about it. You are doing well, and what you need now is to keep your eyes open and your mouth shut. Why should you want to hurry things along?”

A flush came over Dick's face. “There's a reason all right enough. You see, Henry, there's a little girl not so very many miles from here—”

“Oho!” thought Henry, “a little girl!” But his face was immobile, excepting a momentary curious expression that passed over it.

“Now don't get to thinking it's all fixed up, because it isn't—not yet. But you see, I've been thinking that when I've got a little something to offer—”

“There's another thing you can take my word for, my boy,” said Henry, with a dry smile; “don't get impetuous. Marrying may be all right, but it wants to be done careful.”

Captain Stenzenberger's lumber yard was a few miles away, at the Chicago city limits. As the two sailors left the pier to walk up to the railway station, Dick was glad to change the subject for the first one that came into his head. “What do you suppose the Foote has been doing here this week, Dick? I heard she put in Tuesday or Wednesday.”

“Looking for Whiskey Jim, I suppose.”

“Oh, are they on that track again?”

“Haven't you seen the papers?”

“No—not for more than a week.”

“Well, it's quite a yarn. From what has been said, I rather guess it's the liquor dealers that are stirring it up this time. There is a story around that he has been counterfeiting the red-seal label on their bottles. I think they're all off the track, though. Anybody could tell 'em that there's no such man. Every time a case of smuggling comes up, the papers talk about 'Whiskey Jim,' no matter if it's up at the straits or down on the St. Lawrence.”

“But what's the trouble now?”

“Oh, they're saying that this fellow is a rich man that has a big smuggling system with agents all around the Lakes and dealers in the cities that are in his pay,—sort of a smuggling trust.”

“Sounds like a fairy story.”

“That's about what it is. The regular dealers have taken up the fight to protect their trade, and one or two of the papers in particular have put reporters on the case, and all that sort of thing. And as usual they're announcing just what they've done and what they're going to do. The old Foote is to make a tour of the Lakes, and look into every port. And if there is any Whiskey Jim, I 'll bet he's somewhere over in Canada by this time, reading the papers and laughing at 'em.” Captain Stenzenberger was seated in his swivel chair in his dingy little one-story office at the corner of the lumber yard. His broad frame was overloaded with flesh. His paunch seemed almost to rest on his thighs as he sat there, chewing an unlighted cigar in the corner of his mouth,—a corner that had been moulded around the cigar by long habit and that looked incomplete when the cigar was not there. His fat neck—the fatter for a large goitre—was wider than his cheeks, and these again were wider than his forehead, so that his head seemed to taper off from his shoulders. A cropped mustache, a tanned, wrinkled face and forehead, and bright brown eyes completed the picture. When his two captains came in, he rested his pudgy hands on the arms of his chair, readjusted his lips around the cigar, and nodded. “How are you, boys?” said he, in a husky voice. “Have a good trip?” This last remark was addressed to Dick.

“First part was bad, but it cleared up later.”

“Did you put right out into that storm from Manistee?”

“Yes—you see I had the wind behind me all the way down. Got to get a new small boat, though.”

The “Captain” did not press the subject. In return for the privilege of buying the schooner by instalments he permitted Dick to pay for the insurance, so the young man could be as reckless as he liked.

Dick now explained that he had come to make a payment, and the transaction was accomplished.

“Step over and have a drink, boys,” was the next formality; and the two stood aside while Stenzenberger got his unwieldy body out of the chair, put on his hat, and led the way out.

Adjoining the lumber yard on the west was a small frame building, bearing the sign, “The Teamster's Friend.” It had been set down here presumably to catch the trade of the market gardeners who rumbled through in the small hours of every morning. In the rear, backed up against a lumber pile, was a long shed where the teams could wait under cover while their drivers were carousing within. A second sign, painted on the end of this shed, announced that Murphy and McGlory were the proprietors of the “sample room and summer garden.” The three men entered, and seated themselves at a table. There was no one behind the bar at the moment, but soon a woman glanced in through the rear doorway.

Stenzenberger smiled broadly on her, and winked. “How d' do, Madge,” he said. “Can't you give us a little something with a smile in it,—one o' your smiles maybe now?”

She was a tall woman, with a full figure and snapping eyes,—attractive, in spite of a crow's-foot wrinkle or so. She returned the smile, wearily, and said, “I 'll call Joe, Mr. Stenzenberger.”

“You needn't do that now, Madge. Draw it with those pretty hands of yours, there's a dear.”

So she came in behind the bar, wiping her hands on her apron, and quietly awaited their orders.

“What 'll it be, boys?”

Dick suggested a glass of beer, but Henry smiled and shook his head. “You might make it ginger ale for me.”

“I don't know what to do with that cousin of yours,” said Stenzenberger to Dick. “He's a queer one. I don't like to trust a man that's got no vices. What are your vices, anyhow, Smiley?”

Henry smiled again. “Ask Dick, there. He ought to know all about me.”

Stenzenberger looked from one to the other; then he raised his foaming glass, and with a “Prosit” and a stiff German nod, he put it down at a gulp.

“Been reading about the revenue case?” Henry asked of his superior.

“I saw something this morning.”

“I've been quite interested in it. Billy Boynton told me yesterday that they had searched his schooner. It's a wonder they haven't got after us if they're holding up fellows like him. Do you think they 'll ever get this Whiskey Jim, Cap'n?”

“No, they talk too much. And they couldn't catch a mud-scow with that old side-wheeler of theirs.”

“Guess that's right. The Foote must have started in here before the Michigan, and she's thirty years old if she's a day. The boys are all talking about it down at the city. I dropped around at the Hydrographic Office after I saw Billy, and found two or three others that had been hauled over. It seems they've stumbled on a pipe-line half built under the Detroit River near Wyandotte, and there's been a good deal of excitement. There's capital behind it, you see; and a little capital does wonders with those revenue men.”

Stenzenberger was showing symptoms of readiness to return to his desk, but Henry, who rarely grew reminiscent, was now fairly launched.

“They can't get an effective revenue system, because they make it too easy for a man to get rich. It's like the tax commissioners and the aldermen and the legislators,—when you put a man where he can rake off his pile, month after month, without there being any way of checking him up, look out for his morals. And where they're all in it together, no one dares squeal. It's a good deal like the railway conductors.

“You remember last year when the Northeastern Road laid off all but two or three of its old conductors for stealing fares? Well, it wasn't a month afterward that one of the 'honest' ones came to me and hired the Schmidt to carry a twelve-hundred-dollar grand piano up to Milwaukee, where he lives. He had reasons of his own for not wanting to ship by rail. No, sir, it wouldn't be hard for me to have sympathy with an honest thief that goes in and runs his chances of getting shot or knocked on the head,—that calls for some nerve,—but these fellows that put up a bluff as lawmakers and policemen and revenue officers and then steal right and left—deliver me!”

“Well, boys, I guess I 'll have to step back. I'm a busy man, you know. Have another before we go?”

“One minute, Cap'n,” said Dick. “There's something I want to talk over with you, if you can spare the time.”

Stenzenberger sat down again. Henry, whose outbreak against the evils of society had stirred up, apparently, some pet feeling of bitterness, now sat moodily looking at the table.

“It's about Roche, Cap'n,” Dick went on. “I had to leave him at Manistee.”

“Why?”

“He drinks too much for me—I couldn't depend on him a minute. He bummed around up there, and got himself too shaky to be any use to me.”

Stenzenberger, with expressionless face, chewed his cigar. “What did you do for a mate?”

“Came down without one.”

“Have you found a man yet?”

“No—haven't tried. I thought you might have some one you could suggest.”

“I don't know. You 'll want to be starting up to Spencer's place in a day or so.” He chewed his cigar thoughtfully for a moment, then dropped his voice. “There's a man right here you might be able to use. Do you know McGlory?”

“No.”

“You do, Henry?”

“Yes, he was my mate for a year.”

“Well,” said Dick, “any man that suited Henry for a year ought to suit me.”

“You 'll find him a good, reliable man,” responded Henry, in an undertone. “He has a surly temper, but he knows all about a schooner.”

“Well,—if he's anywhere around here now, we could fix it right up.”

Stenzenberger looked around. The woman had slipped out. “Madge,” he called; “Madge, my dear.”

She entered as quietly as before.

“Come in, my dear. You know Cap'n Smiley, don't you?”

No, she didn't.

“That's a fact. He's never seen in sample rooms. He sets up to be better than the rest of us; but I say, look out for him. And here's his cousin, another Cap'n Smiley, the handsomest man on the Lakes.” Dick blushed at this. “Sit down a minute with us.”

She shook her head, and waited for him to come to the point.

“Where's that man of yours, my dear? Is he anywhere around?”

“What is it you want of him?”

“I want him to know our young man here. I think they're going to like each other. You tell him we want to see him.”

She hesitated; then with a suspicious glance around the group left the room.

In a moment McGlory appeared, a short, heavy-set man with high cheek-bones, a low, sloping forehead, and a curling black mustache. He nodded to Stenzenberger and Henry, and glanced at Dick.

“Joe,” said the lumber merchant, “shake hands with Cap'n Dick Smiley. He's the best sailor between here and Buffalo, and the only trouble with him is we can't get a mate good enough for him. A man's got to know his business to sail with Dick Smiley. Ain't that so, Henry?”

“I guess that's right.”

“And Henry tells me you're the man that can do it.”

This pleasantry had no visible effect on McGlory. He was looking Dick over.

“I don't know about that, Cap'n. I promised Madge I'd give up the Lake for good.”

“The Cap'n here,” pursued Stenzenberger, “is going to start to-morrow or next day for Spencer, to take on a load of timber and shingles.” His small brown eyes were fixed intently on the saloon keeper as he talked. “And I think we 'll have to keep him running up there for a good part of the summer. Queer character, that Spencer,” he added, addressing Dick. “He has lived all his life up there in the pines. They say he was a squatter—never paid a cent for his land. But he has been there so many years now, I guess any one would have trouble getting him out. He has got an idea that his timber's better than anybody else's. He cuts it all with an old-fashioned vertical saw, and stamps his mark on every piece.”

“Why should it be any better?”

“I don't know that it is, though he selects it carefully. The main thing is, he sells it dirt cheap,—has to, you know, to stand any show against the big companies. He's so far out of the way, no boats would take the trouble to run around there if he didn't. Well, McGlory, we've got a good thing to offer you. You can drop in here once a week or so, you know, to see how things are running. Come over to the office with us and we 'll settle the terms.” Stenzen-berger was rising as he spoke.

“Well, I don't know. I couldn't come over for a few minutes, Cap'n.”

“How soon could you?”

“About a quarter of an hour.”

“All right, we 'll be looking for you. Here, give me half a dozen ten cent straights while I'm here.”

McGlory walked to the door with them, and stood for a moment looking after them.

When he turned and pushed back through the swinging inner doors, he found Madge standing by the bar awaiting him, one hand held behind her, the other clenched at her side, her eyes shooting fire.

He paused, and looked at her without speaking.

“So you are going back to the Lake?” she said, everything about her blazing with anger except her voice—that was still quiet.

He was silent.

“Well, why don't you answer me?”

“What's all this fuss about, Madge? I haven't gone yet.”

“Don't try to put me off. Have you told them you would go back?”

“I haven't told 'em a thing. I'm going around in a minute to see the Cap'n, and we 'll talk it over then.”

“And you have forgotten what you promised me?”

“No, I ain't forgot nothing. Look here, there ain't no use o' getting stagy about this. I ain't told him I 'll do it. I don't believe I will do it.”

“Why should you want to, Joe? Aren't you happy here? Aren't you making more money than you ever did on the Lake?”

“Why, of course.”

“Then why not stay here?”

“There's only this about it,” he replied, leaning against the bar, and speaking in an off-hand manner; “Stenzenberger offers me the chance to do both. I could be in here every few days—see you most as much as I do now in a busy season—and make the extra pay clear.”

“Oh, that's why you have been thinking you might do it?”

“Well, that's the only thing about it that—” He was wondering what was in her other hand. “You see, I can't afford to get the Cap'n down on me.”

“You can't? I should think he would be the one that couldn't afford—”

“Now see here, Madge.” He stepped up to her, and would have slipped his arm around her waist, but she eluded him. “I guess I 'll go over and see what he has to offer, and then I 'll come back, and you and me can talk it all over and see if we think—”

“If we think!” she burst out. “Do you take me for a fool, Joe McGlory? Do you think for a minute I don't know why you want to go—and why you mean to go? Look at that!” She produced a photograph of a pretty, foolish young woman, and read aloud the inscription on the back, “To Joe, from Estelle.”

An ugly look came into his eye. “I wouldn't get excited about that kiddishness if I was you.”

“So you call it kiddishness, do you, and at your age?”

“Well, so long now, Madge. I 'll be back in a few minutes.”

“Joe—wait—don't go off like that. Tell me that don't mean anything! Tell me you aren't ever going to see her again!”

“Sure, there's nothing in it.”

“And you won't see her?”

“Why, of course I won't see her. She ain't within five hundred miles of here. I don't know where she is.”

“You 'll promise me that?”

“You don't need to holler, Madge. I can hear you. Somebody's likely to be coming in any minute, and what are they going to think?” He passed out into the back room, and she followed him.

“How soon will you be back, Joe?” She saw that he was putting on his heavy jacket—heavier than was needed to step over to the lumber office.

“Just a minute—that's all.”

“And you won't promise them anything?”

“Why, sure I won't. I wouldn't agree to anything before you'd had a look at it.”

He watched her furtively; and she stood motionless, trembling a little, ready at the slightest signal to spring into his arms. But he reached for his hat and went out.

She stood there, still motionless, until his step sounded on the front walk; then she ran upstairs and knelt by the window that overlooked the yards. She saw him enter the office. A few moments, and the two men who had been with Stenzenberger came out and walked away. A half-hour, and still Joe was in there with the lumber merchant. An hour—and then finally he appeared, glanced back at the saloon, and walked hurriedly around the corner out of sight. And she knew that he had slipped away from her. The photograph was still in her hand, and now she looked at it again, scornfully, bitterly.

A man entered the saloon below, and she did not hear him until he fell to whistling a music-hall tune. At something familiar in the sound a peculiar expression came over her face, and she threw the picture on the floor and hurried down. When she entered the sample room, her eyes were reckless.

The man was young, with the air of the commercial traveller of the better sort. He was seated at one of the tables, smoking a cigarette. His name was William Beveridge, but he passed here by the name of Bedloe.

“Hello, Madge,” he said; “what's the matter—all alone here?”

“Yes; Mr. Murphy's down town.”

“And McGlory—where's he?”

“He's out too.”

He looked at her admiringly. Indeed, she was younger and prettier, for the odd expression of her eyes.

“Well, I'm in luck.”

“Why?” she asked, coming slowly to the opposite side of the table and leaning on the back of a chair.

But in gazing at her he neglected to reply. “By Jove, Madge,” he broke out, “do you know you're a beauty?”

She flushed and shook her head. Then she slipped down into the chair, and rested her elbows on the table.

“You're the hardest person to forget I ever knew.”

“I guess you have tried hard enough.”

“No—I couldn't get round lately—I've been too busy. Anyhow, what was the use? If I had thought I stood any show of seeing you, I would have come or broken something. But there was always Murphy or McGlory around.” He could not tell her his real object in coming, nor in avoiding the two proprietors, who had watched him with suspicion from the first. “Do you know, this is the first real chance you've ever given me to talk to you?”

“How did I know you wanted to?”

“Oh, come, Madge, you know better than that. How could anybody help wanting to? But”—he looked around—“are we all right here? Are we likely to be disturbed?”

“Why, no, not unless a customer comes in.”

“Isn't there another room out back there where we can have a good talk?”

She shook her head slowly, with her eyes fixed on his face. And he, of course, misread the flush on her cheek, the dash of excitement in her eyes. And her low reply, too, “We'd better stay here,” was almost a caress. He leaned eagerly over the table, and said in a voice as low as hers: “When are you going to let me see you? There's no use in my trying to stay away—I couldn't ever do it. I'm sure to keep on coming until you treat me right—or send me away. And I don't believe that would stop me.”

“Aren't you a little of an Irishman, Mr. Bedloe?”

“Why?”

She smiled, with all a woman's pleasure in conquest. “Why haven't you told me any of these things before?”

“How could I? Now, Madge, any minute somebody's likely to come in. I want you to tell me—can you ever get away evenings?”

“Of course I can, if I want to.”

“To-morrow?”

“Why?”

“There's going to be a dance in the pavilion at St. Paul's Park. Do you ride a wheel?” She nodded.

“It's a first-rate ride over there. There's a moon now, and the roads are fine. Have you ever been there?”

“No.”

“It's out on the north branch—only about a four-mile run from here. We can start out, say, at five o'clock, and take along something to eat. Then, if we don't feel like dancing, we can take a boat and row up the river.”

She rested her chin on her hands, and looked at him with a half smile. “Do you really mean all this, Mr. Bedloe?”

For reply, he reached over and took both her hands. “Will you go?”

“Don't do that, please. Do you know how old I am?”

“I don't care. What do you say?”

“Please don't. I hear some one.”

“No, it's a wagon. I want you to say yes.”

“You—you know what it would mean if—if—”

“If McGlory—Yes, I know. You're not afraid?”

Her face hardened for an instant at this, and then, as suddenly, softened. “No,” she said; “I'm not afraid of anything.”

“And you 'll go?”

She nodded.

“Shall I come here?”

“No, you'd better not.”

“Where shall we meet?”

“Oh—let me see—over just beyond the station. It's quiet there.”

“All right. And I 'll get a lunch put up.”

“No—it's easier for me to do that. I 'll bring something. And now go—please.”

He rose, and slipped around the table toward her. .

“Don't—you must go.”

And so he went, leaving her to gaze after him with a high color.

DICK and Henry did not go directly back, and it was mid-afternoon when they reached the pier. As they walked down the incline from the road, Dick's eyes strayed toward the house on stilts. The Captain lay with nose in the sand, and beside her, evidently just back from a sail, stood Annie with two of the students who came on bright days to rent Captain Fargo's boats. They were having a jolly time,—he could hear Annie laughing at some sally from the taller student,—and they had no eye for the two sailors on the pier. Once, as they walked out, Dick's hand went up to his hat; but he was mistaken, she had not seen him. And so he watched her until the lumber piles, on the broad outer end of the pier, shut off the view; and Henry watched him.

Dick hardly heard what his cousin said when they parted. He leaped down to the deck of the Merry Anne, and plunged moodily into the box of an after cabin. His men, excepting Pink Harper, who was somewhere up forward devouring a novel, were on shore; so that there was no one to observe him standing there by the little window gazing shoreward. Finally, after much chatting and lingering, the two students sauntered away. Annie turned back to make her boat fast; and Dick, in no cheerful frame of mind, came hurrying shoreward.

She saw him leap down from pier to sand, and gave him a wave of the hand; then, seeing that he was heading toward her, she turned and awaited him.

“Come, Dick, I want you to pull the Captain higher up.”

Dick did as he was bid, without a word. And then, with a look and tone that told her plainly what was to come next, he asked, “What are you going to do now?”

“I guess I 'll have to see if mother wants me. I've been sailing ever since dinner.”

“You haven't any time for me, then?”

“Why, of course I have,—lots of it. But I can't see you all the while.”

“No, I suppose you can't—not if you go sailing with those boys.”

Annie's mischievous nature leaped at the chance this speech gave her. “They aren't boys, Dick; Mr. Beveridge is older than most of the students. He told me all about himself the other day.”

“Oh, he did.”

“Yes. He was brought up on a farm, and he has had to work his way through school. When he first came here, he got off the train with only just three dollars and a half in his pocket, and he didn't have any idea where he was going to get his next dollar. I think it's pretty brave of a man to work as hard as that for an education.”

Dick could say nothing. Most of his education had come in through his pores.

“I like Mr. Wilson, too.”

“He is the other one, I suppose?”

Dick, his eyes fixed on the sand, did not catch the mirthful glance that was shot at him after these words. And her voice, friendly and unconscious, told him nothing.

“Yes, he is Mr. Beveridge's friend. They room together.”

“Well, I hope they enjoy it.”

“Now, Dick, what makes you so cross? When you are such a bear, it wouldn't be any wonder if I didn't want to see you.”

He gazed for a minute at the rippling blue lake, then broke out: “Can you blame me for being cross? Is it my fault?”

She looked at him with wondering eyes.

“Why—you don't mean it is my fault, Dick?”

“Do you think it is just right to treat me this way, Annie?”

“What way do you mean, Dick?”

He bit his lip, then looked straight into her eyes and came out with characteristic directness:—

“I don't like to think I've been making a mistake all this while, Annie. Maybe I have never asked you right out if you would marry me. I'm not a college fellow, and it isn't always easy for me to say things, but I thought you knew what I meant. And I thought that you didn't mind my meaning it.”

She was beginning to look serious and troubled.

“But if there is any doubt about it, I say it right now. Will you marry me? It is what I have been working for—what I have been buying the schooner for—and if I had thought for a minute that you weren't going to say yes sooner or later, I should have gone plumb to the devil before this. It isn't a laughing matter. It has been the thought of you that has kept me straight, and—and—can't you see how it is, Annie? Haven't you anything to say to me?”

She looked at him. He was so big and brown; his eyes were so clear and blue.

“Don't let's talk about it now. You're so—impatient.”

“Do you really think I've been impatient?”

She could not answer this.

“Now listen, Annie: I'm going to sail in the morning, away around to a place called Spencer, on Lake Huron; and I could hardly get back inside of ten or twelve days. And if I should go away without a word from you—well, I couldn't, that's all.”

“You don't mean—you don't want me to say before to-morrow?”

“Yes, that's just what I mean. You haven't anything to do to-night, have you?”

She shook, her head without looking at him. “Well, I 'll be around after supper, and we 'll take a walk, and you can tell me.”

But her courage was coming back. “No, Dick, I can't.”

“But, Annie, you don't mean—”

“Yes, I do. Why can't you stop bothering me, and just wait. Maybe then—some day—”

“It's no use—I can't. If you won't tell me to-night, surely ten—or, say, eleven—days ought to be enough. If I went off tomorrow without even being able to look forward to it—Oh, Annie, you've got to tell me, that's all. Let me see you to-night, and I 'll try not to bother you. I 'll get back in eleven days, if I have to put the schooner on my back and carry her clean across the Southern Peninsula,”—she was smiling now; she liked his extravagant moods,—“and then you 'll tell me.” He had her hand; he was gazing so eagerly, so breathlessly, that she could hardly resist. “You 'll tell me then, Annie, and you 'll make me the luckiest fellow that ever sailed out of this town. Eleven days from to-night—and I 'll come—and I 'll ask you if it is to be yes or no—and you 'll tell me for keeps. You can promise me that much, can't you?”

And Annie, holding out as long as she could, finally, with the slightest possible inclination of her head, promised.

“Where will you be this evening?” he asked, as they parted.

“I 'll wait on the porch—about eight.”

For the rest of the afternoon Dick sat brooding in his cabin. When, a little after six, he saw Henry coming down the companionway, his heart warmed.

“Thought I'd come over and eat with you,” said his cousin. “What's the matter here—why don't you light up?”

Dick, by way of reply, mumbled a few words and struck a light. Henry looked at him curiously.

“What is it, Dick?” he asked again.

There had been few secrets between them. So far as either knew, they were the last two members of their family, and their intimacy, though never expressed in words, had a deep foundation. Before the present arrangement of Dick's work, which made it possible for them to meet at least once in the month, they had seen little of each other; but at every small crisis in the course of his struggle upward to the command of a schooner, Dick had been guided by the counsel and example of the older man. Now he spoke out his mind without hesitation.

“Sit down, Henry. When—when I told you about what I have been thinking—about Annie—why did you look at me as you did?”

“How did I look?”

“Don't dodge, Henry. The idea struck you wrong. I could see that, and I want to know why.”

“Well,” Henry hesitated, “I don't know that I should put it just that way. I confess I was surprised.”

“Haven't you seen it coming?”

“I rather guess the trouble with me was that I have been planning out your future without taking your feelings into account.”

“How do you mean,—planning my future?”

“Oh, it isn't so definite that I could answer that question offhand. I thought I saw a future for myself, and I thought we might go it together. But I was counting on just you and me, without any other interests or impediments.”

“But if I should marry—”

“If you marry, your work will have to take a new direction. Your interests will change completely. And before many years, you will begin to think of quitting the Lake. It isn't the life for a family man. But then—that's the way things go. I have no right to advise against it.” Henry smiled, with an odd, half bitter expression. “And from what I have seen since my eyes were opened, I don't believe it would do any good for me to object.”

“You are mistaken there, Henry,” the younger man replied quietly; “it isn't going well at all. I've been pretty blue to-day.”

“Well,” said Henry, with the same odd expression, “I don't know but what I'm sorry for that. That future I was speaking of seems to have faded out lately,—in fact, my plans are not going well, either. And so you probably couldn't count on me very much anyway.”

He paused. Pink Harper, who acted as cook occasionally when the Anne was tied up and the rest of the crew were ashore, could be heard bustling about on deck. After a moment Henry rose, and, with an impulsive gesture, laid his hand on Dick's shoulder. “Cheer up, Dick,” he said. “Don't take it too hard. Try to keep hold of yourself. And look here, my boy, we've always stepped pretty well together, and we mustn't let any new thing come in between us—”

“Supper's ready!” Pink called down the companionway.

Dick was both puzzled and touched; touched by Henry's moment of frankness, puzzled by the reasons given for his opposition to the suggested marriage. It was not like his cousin to express positive opinions, least of all with inadequate reasons. Dick had no notion of leaving the Lake; he could never do so without leaving most of himself behind. Plainly Henry did not want him married, and Dick wondered why.

It was half-past seven, and night was settling over the Lake. Already the pier end was fading, the masts of the two schooners were losing their distinctness against the sky; the ripples had quieted with the dying day-breeze, and now murmured on the sand. The early evening stars were peeping out, looking for their mates in the water below.

On the steps, sober now, and inclined to dreaming as she looked out into the mystery of things, sat Annie. A shadow fell across the beach,—the outline of a broad pair of shoulders,—and she held her breath. The shadow lengthened; the man appeared around the corner of the house. Then, as he came rapidly nearer, she was relieved to see that it was Beveridge.

He was in a cheerful frame of mind as he stepped up and sat beside her. It was pleasant that the peculiar nature of his work should make it advisable to cultivate the acquaintance of an attractive young woman—such a very attractive young woman that he was beginning to think, now and then, of taking her away with him when his work here should be done.

“What do you say to a row on the Lake?” he suggested, after a little.

“I mustn't go away,” said Annie. “I promised I would be here at eight.”

“But it's not eight yet,” Beveridge replied. “Let's walk a little way—you can keep the house in sight, and see when he comes.”

“Well,” doubtfully, “not far.”

They strolled along the beach until Annie turned. “This is far enough.”

“I don't know whether I can let your Captain come around quite so often,” said he, as they sat down on the dry sand, in the shelter of a clump of willows. “It won't do—he is too good looking. I should like to know what is to become of the rest of us.”

This amused Annie. They had both been gazing out towards the schooners, and he had read her thoughts. He went on: “You know it's not really fair. These sailor fellows always get the best of us. He named his schooner after you, didn't he?”

“Oh, no, I don't believe so.”

“Sailors and soldiers—it's the same the world over! There's no chance for us common fellows when they are about. Tell you what I shall have to do—join the militia and come around in full uniform. Then maybe you would be looking at me, too. I don't know but what I could even make you forget him.”

She had to laugh at this. “Maybe you could.”

“I suppose it wouldn't do me any good to try without the uniform, would it?”

She tossed her head now. “So that's what you think of me—that I care for nothing but clothes?”

“Oh, no, it's not the clothes. His red shirt would never do it. But it's the idea of a sailor's life—there is a sort of glitter about it—he seems pluckier, somehow, than other men. It's the dash and the grand-stand play that fetches it. I suppose it wouldn't be a bit of use to tell you that you are too good for him.”

She made no reply, and the conversation halted. Annie gazed pensively out across the water. He watched her, and as the moments slipped away his expression began to change; for he was still a young man, and the witchery of the night was working within him.

“Do you know, I'm pretty nearly mean enough to tell you some things about Dick Smiley. I don't know but what I'm a little jealous of him.”

She did not turn, or speak.

“I'm afraid it is so. I would hardly talk like this if I were not. I thought I was about girl-proof,—up to now, no one has been able to keep my mind off my work very long at a time,—but you have been playing the mischief with me, this last week or so. It's no use, Annie. I wouldn't give three cents for the man that could look at you and keep his head. And when I think of you throwing yourself away on Smiley, just because he's good-looking and a sailor—you mustn't do it, that's all. I have been watching you—”

“Oh,—you have?”

“Yes, and I think maybe I see some things about you that you don't see yourself. I wonder if you have thought where a man like Smiley would lead you?” She would have protested at this, but he swept on. “He can never be anything more than he is. He has no head for business, and even if he works hard, he can't hope to do more than own his schooner. You see, he's not prepared for anything better; he's side-tracked. And if you were just a pretty girl and nothing more,—just about the size of these people around you,—I don't suppose I should say a word; I should know you would never be happy anywhere else. Why, Annie, do you suppose there's a girl anywhere else on the shore of Lake Michigan—on the whole five Lakes—living among fishermen and sailors, as you do, that could put on a dress the way you have put that one on, that could wear it the way you're wearing it now?

“Oh, I know the difference, and I don't like to stand by and let you throw yourself away. You see, Annie, I haven't known you very long, but it has been long enough to make it impossible to forget you. I haven't any more than made my start, but I'm sure I am headed right, and if I could tell you the chance there is ahead of me to do something big, maybe you would understand why I believe I'm going to be able to offer you the kind of life you ought to have—the kind you were made for. I don't want to climb up alone. I want some one with me—some one to help me make it. You may think this is sudden—and you would be right. It is sudden. I have felt a little important about my work, I'm afraid, for I really have been doing well. But ever since you just looked at me with those eyes of yours, the whole business has gone upside down. Don't blame me for talking out this way. It's your fault for being what you are. I expect to finish up my work here pretty soon now, and then I 'll have to go away, and there's no telling where I 'll be.”

Annie was puzzled.

“Oh, you finish so soon? It is only September now.”

“I have to move on when the work is done, you know. I obey orders.”

“But I thought you were a student, Mr. Beveridge?”

He hesitated; he had said too much. Chagrined, he rose, without a word, at her “Come, I must go back now,” and returned with her to the house. And when they were approaching the steps, he was just angry enough with himself to blunder again.

“Wait, Annie. I see you don't understand me. But there is one thing you can understand. I want to go away knowing that you aren't going to encourage Smiley any longer. You can promise me that much. I don't want to talk against him; but I can tell you he's not the man for you; he's not even the man you think he is. Some day I will explain it all. Promise me that you won't.”

But she hurried on resolutely toward the house, and there was nothing to do but follow. “Will you take my word for it, Annie,—that you 'll do best to let him alone?”

She shook her head and hurried along.

On the steps sat a gloomy figure—Dick, in his Sunday clothes, white shirt and collar, red necktie, and all. His elbows rested on his knees, his chin rested on his hands, and the darkness of the great black Lake was in his soul. He watched the approaching figures without raising his head; he saw Beveridge lift his hat and turn away toward the bank; he let Annie come forward alone without speaking to her.

She put one foot on the bottom step, and nodded up at him. “Here I am, Dick. Do you want to sit here or—or walk?”

He got up, and came slowly down to the sand.

“So this is the way you treat me, Annie?”

“I'm not late, am I, Dick? It can't be much after eight.”

“So you go walking with him, when—when—”

“Now, Dick, don't be foolish. Mr. Beveridge came around early, and wanted me to walk, and—and I told him I couldn't stay away—”

She was not quite her usual sprightly self; and the manner of this speech was not convincing. Dick's reply was a subdued sound that indicated anything but satisfaction.

“I'm mad, Annie,—I know I'm mad—and I don't think you can blame me.”

“I—I didn't ask you to come before eight, Dick.”

“Oh, that was it, was it? I suppose you told him to come at seven.”

“Now, Dick,—please—”

But he, not daring to trust his tongue, was angry and helpless before her. After a moment he turned away and stood looking out toward the lights of the schooner. Finally he said, in a strange voice, “I see I've been a fool—I thought you meant some of the things you've said—I ought to have known better; I ought to have known you were just fooling with me—you were just a flirt.”

He did not look around. Even if he had, the night would have concealed the color in her cheeks. But he heard her say, “I think perhaps—you had better go, Dick.”

He hesitated, then turned.

“Good night,” she said, and ran up the steps.

“Say—wait, Annie—”

The door closed behind her, and Dick stood alone. He waited, thinking she might come back, but the house was silent. He stepped back and looked up at her little balcony with its fringe of flowers, but it was deserted; no light appeared in the window. At last he turned away, and tramped out to the Merry Anne. The men were aboard, ready for an early start in the morning; the new mate was settling himself in the cabin. To Dick, as he stood on the pier and looked down on the trim little schooner, nothing appeared worth while. He leaped down to the deck, and thought savagely that he would have made the the same leap if the deck had not been there, if there had been fourteen feet of green water and a berth on the scalloped sand below. But there was one good thing—nothing could rob Dick of his sleep. And in his dreams Annie was always kind.

EARLY in the morning they were off. Dick, glum and reckless, took the wheel; McGlory went up forward and looked after hoisting the jibs and foresail. The new mate had already succeeded, by an ugly way he had, in antagonizing most of the men; but their spirits ran high, in spite of him, as the Merry Anne slipped away from the pier and headed out into the glory of the sunrise.

“Hey, Peenk,” called Larsen, “geeve us 'Beelly Brown.'” And Pink, who needed no urging, roared out promptly the following ballad, with the whole crew shouting the spoken words:—=

Oh, Billy Brown he loved a girl,

And her name was Mary Rowe, O-ho!

She lived way down

In that wick-ed town,

The town called She-caw-go.

(Spoken) WHERE'S THAT?

The place where the Clark streets grow.=

"Oh, Mary, will you bunk with me?”

"Say, ain't you a little slow, O-ho!

'Bout sailin' down

To this wicked town

To tell me you love me so?”

(Spoken) GO 'LONG!

She's givin' 'im the wink, I know.=

Oh, the wind blowed high, an' the wind blowed strong,

An' the Gross' Point' reef laid low, O-ho!

An' Billy Brown

Went down, down, down,

To the bottom of the place below.

(Spoken) WHERE'S MARY?

She's married to a man named Joe.=

“You're makin' noise enough up there,” growled McGlory. Pink, with a rebellious glance, bent over the rope he was coiling and held his peace.

As they started, so they sailed during four days—the Captain reckless, the mate hard and uncommunicative, the men cowed. And at mid-morning on the fourth day they arrived at Spencer.

The Hydrographic Office had at that time worked wonders in charting these Great Lakes of ours, but it had given no notice to the little harbor that was tucked snugly away behind False Middle Island, not a hundred miles from Mackinaw City on the Lake Huron side; merely a speck of an island with a nameless dent behind it. But old Spencer, a lank, hatchet-faced Yankee, had found that a small schooner could be worked in if she headed due west, “with the double sand dune against the three pines till you get the forked stump ranged with the ruined shanty; meet this range and hold it till clear of the bar at the north end of the island; circle around to port; when clear of the bar, hug the inner shore of the island until the mill can be seen behind the trees; then run up into the harbor. Plenty of water here.”

This discovery had resulted in such a curious little mill as can be found only in the back corners of the country,—a low shed with a flat roof; one side open to the day; within, an old-fashioned vertical saw; the whole supplied with power by a rotting, dripping, moss-covered sluiceway.

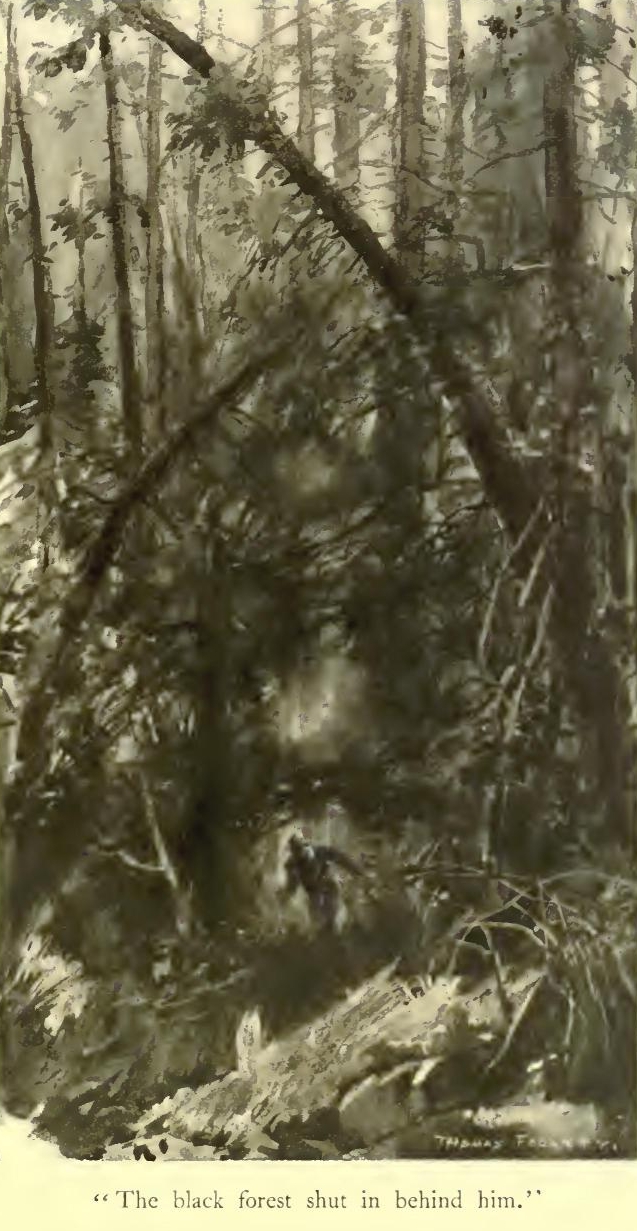

All about were blackened pine stumps—nothing else for a hundred miles. And all through the forest was the sand, drifting like snow over roads and fences, changing the shape of the land in every high wind, blowing into hair and clothes, and adding, with the tall, endless, gray-green mullein stalks, the final touch of desolation to a hopeless land. Here and there, in the clearings, sand-colored farmers and their sand-colored wives struggled to wring a livelihood from the thankless earth. Other farmers had drifted helplessly away, leaving houses and barns to blacken and rot and sink beneath the sand drifts, and leaving, too, rows of graves under the stumps.

Twenty miles down the coast, where a railroad touched, was a feeble little settlement that was known, on the maps, as Ramsey City.

This region had been “cut over” once; it had been burned over more than once; and yet old Spencer, with his handful of employees and his deliberate little mill, wore a prosperous look on his inscrutable Yankee face. There was no inhabited house within ten miles, but he was apparently contented.

McGlory, it seemed, knew the channel; so Dick surrendered the wheel when they were nearing the island, and stood at his elbow, watching the landmarks. The mate volunteered no information, but Dick needed none; he made out the ranges with the eye of a born sailor. But even he was surprised when the Merry Anne swung around into the landlocked harbor and glided up to a rude wharf that was piled with lumber. Behind it was the mill; behind that, at some distance, a comfortable house, nearly surrounded by other smaller dwellings.

“So this is Spencer, eh?” observed Dick.

“This is Spencer,” McGlory replied.

The owner himself was coming down to meet them, reading over a letter from his friend, Stenzenberger, as he walked. His wife came out of her kitchen and stood on her steps to see the schooner. Two or three men in woodman's flannels were lounging about the mill, and these sat up, renewed their quids from a common plug, and stared.

“How are you?” nodded Spencer, pocketing the letter. He caught the line and threw it over a snubbing post. “This Mr.

“Smiley?”

“That's who,” said Dick.

“How are you, Joe?” to McGlory.

“How are you, Mr. Spencer?”

In a moment they were fast, and Dick had leaped ashore. He caught Spencer's shrewd eyes taking him in, and laughed, “Well, I guess you 'll know me next time.”

“Guess I will.” There was a puzzled, even disturbed expression on the lumberman's face. “I was thinking you didn't look much like your cousin. The stuffs all ready for you there. You'd better put one of your men on to check it up. Will you walk up and take a look around the place?”

“Thanks—guess I 'll stay right here and hustle this stuff aboard. I'd like to put out again after dinner.”

Spencer drew a plug from a trousers pocket, offered it to Dick, who at the sight of it shook his head, and helped himself to a mouthful. Then his eyes took in the schooner, her crew, and the sky above them. “Wind's getting easterly,” he observed. “Looks like freshening up. Mean business getting out of here against the wind—no room for beating. You'd better leave your mate to load and have a look at the place.”

“Well, all right; McGlory, see to getting that stuff aboard right off, will you? We 'll try to get out after dinner sometime.”

When Spencer had shown his guest the mill and the houses of his men, he led the way to his own home and seated his guest in the living room. Here from a corner cupboard he produced a bottle and two glasses.

“I've got a little something to offer you here, Mr. Smiley,” said he, “that I think you 'll find drinkable. I usually keep some on hand in case anybody comes along. I don't take much myself, but it's sociable to have around.” Dick tossed off a glass and smacked his lips. “Well, say, that's the real stuff.”

“Guess there ain't no doubt about that.”

“Where do you get it from?”

“I bought that in Detroit last time I was down. Couldn't say what house it's from.”

“Oh, you get out of here now and then, do you r

“Not often—have another?”

“Thanks, don't care if I do.”

“You see I've got a little schooner of my own, the Estelle,—named her after my wife's sister,—and now and then I take a run down the shore to Saginaw or Port Huron, or somewhere.”

“Do you get much lumber out?”

“Enough for a living.”

“I noticed you had a mark on the end of every big stick—looked like a groove cut in a circle—most a foot across.”

“Yes, that's my mark.”

“The idea being that people will know your stuff, I suppose.”

Spencer nodded shortly. “I'm getting out the best lumber on the Great Lakes—that's why I mark it—help yourself to that bottle—there, I 'll just set it where you can reach it.” Dick would have stopped ordinarily at two glasses. To-day he stopped at nothing. “Much obliged. I haven't touched anything as strong as this for two years.”

“Swore off?”

“Sort of, but I don't know that I've been any better off for it. There's nothing so good after sailing the best part of a week.”

“You're right, there ain't. And that's the pure article there—wouldn't hurt a babe in arms. Take another. You haven't been working for Cap'n Stenzenberger many years, have you?”

Throughout this conversation Spencer was studying Smiley's face.

“No, nothing like so long as Henry.”

“How do you get along with him?”

“The Cap'n? Oh, all right. He's a little too smart for me, but I guess he's square enough.”

“Doing a good business, is he?”

“Couldn't say. I don't know much about his business.”

“Oh, you don't?” There was a shade of disappointment in the lumberman's voice as he said this, but Dick, who was reaching for the bottle, failed to observe it.

“McGlory been with you long?”

“No, this is his first trip.”

“You don't say so! Wasn't he with your cousin a while back?”

“Yes, for a year.”

“Thought I'd seen him on the Schmidt. Is he a good man?”

“Good enough.”

“Let's see, wasn't he in with Stenzenberger once?”

“Couldn't say.”