Title: My Winter on the Nile

Author: Charles Dudley Warner

Release date: June 1, 2016 [eBook #52212]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger from page images generously

provided by the Internet Archive

O Commander of the Faithful. Egypt is a compound of black earth and green plants, between a pulverized mountain and a red sand. Along the valley descends a river, on which the blessing of the Most High reposes both in the evening and the morning, and which rises and falls with the revolutions of the sun and moon. According to the vicissitudes of the seasons, the face of the country is adorned with a silver wave, a verdant emerald, and the deep yellow of a golden harvest.

From Amrou, Conqueror of Egypt, to the Khalif Omar.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I.—AT THE GATES OF THE EAST.

CHAPTER II.—WITHIN THE PORTALS.

CHAPTER VI.—MOSQUES AND TOMBS.

CHAPTER VII.—MOSLEM WORSHIP.—THE CALL TO PRAYER.

CHAPTER IX.—PREPARATIONS FOR A VOYAGE.

CHAPTER XI.—PEOPLE ON THE RIVER BANKS.

CHAPTER XII.—SPENDING CHRISTMAS ON THE NILE.

CHAPTER XIII.—SIGHTS AND SCENES ON THE RIVER.

CHAPTER XIV.—MIDWINTER IN EGYPT.

CHAPTER XV.—AMONG THE RUINS OF THEBES.

CHAPTER XVI.—HISTORY IN STONE.

CHAPTER XVIII.—ASCENDING THE RIVER.

CHAPTER XIX.—PASSING THE CATARACT OF THE NILE.

CHAPTER XX.—ON THE BORDERS OF THE DESERT.

CHAPTER XXII.—LIFE IN THE TROPICS. WADY HALFA.

CHAPTER XXIII.—APPROACHING THE SECOND CATARACT.

CHAPTER XXIV.—GIANTS IN STONE.

CHAPTER XXV.—FLITTING THROUGH NUBIA.

CHAPTER XXVI.—MYSTERIOUS PHILÆ.

CHAPTER XXVIII.—MODERN FACTS AND ANCIENT MEMORIES.

CHAPTER XXIX.—THE FUTURE OF THE MUMMY'S SOUL.

CHAPTER XXX.—FAREWELL TO THEBES.

CHAPTER XXXI.—LOITERING BY THE WAY.

CHAPTER XXXIV.—THE WOODEN MAN.

CHAPTER XXXV.—ON THE WAY HOME.

CHAPTER XXXVI.—BY THE RED SEA.

CHAPTER XXXVII.—“EASTWARD HO!”

“My Winter on the Nile,” and its sequel, “In the Levant,” which record the experiences and observations of an Oriental journey, were both published in 1876; but as this volume was issued only by subscription, it has never reached the large public which is served by the general book trade.

It is now republished and placed within the reach of those who have read “In the Levant.” Advantage has been taken of its reissue to give it a careful revision, which, however, has not essentially changed it. Since it was written the Khedive of so many ambitious projects has given way to his son, Tufik Pasha; but I have let stand what was written of Ismail Pasha for whatever historical value it may possess. In other respects, what was written of the country and the mass of the people in 1876 is true now. The interest of Americans in the land of the oldest civilization has greatly increased within the past few years, and literature relating to the Orient is in more demand than at any previous time.

The brief and incidental allusion in the first chapter to the peculiarity in the construction of the oldest temple at Pæstum—a peculiarity here for the first time, so far as I can find, described in print—is worthy the attention of archaeologists. The use of curved lines in this so-called Temple of Neptune is more marked than in the Parthenon, and is the secret of its fascination. The relation of this secret to the irregularities of such mediaeval buildings as the Duomo at Pisa is obvious.

Hartford, October, 1880.

The Mediterranean—The East unlike the West—A World risked for a Woman—An Unchanging World and a Pickle Sea—Still an Orient—Old Fashions—A Journey without Reasons—Off for the Orient—Leaving Naples—A Shaky Court—A Deserted District—Ruins of Pæstum—Temple of Neptune—Entrance to Purgatory—Safety Valves of the World—Enterprising Natives—Sunset on the Sea—Sicily—Crete—Our Passengers—The Hottest place on Record—An American Tourist—An Evangelical Dentist—On a Secret Mission—The Vanquished Dignitary

Africa—Alexandria—Strange Contrasts—A New World—Nature—First View of the Orient—Hotel Europe—Mixed Nationalities—The First Backsheesh—Street Scenes in Alexandria—Familiar Pictures Idealized—Cemetery Day—A Novel Turn Out—A Moslem Cemetery—New Terrors for Death—Pompey's Pillar—Our First Camel—Along the Canal—Departed Glory—A set of Fine Fellows—Our Handsome Dragomen—Bazaars—Universal Good Humor—A Continuous Holiday—Private life in Egypt—Invisible Blackness—The Land of Color and the Sun—A Casino

Railways—Our Valiant Dragomen—A Hand-to-Hand Struggle—Alexandria to Cairo—Artificial Irrigation—An Arab Village—The Nile—Egyptian Festivals—Pyramids of Geezeh—Cairo—Natural Queries.

A Rhapsody—At Shepherd's—Hotel life, Egyptian plan—English Noblemen—Life in the Streets—The Valuable Donkey and his Driver—The “swell tiling” in Cairo—A hint for Central Park—Eunuchs—“Yankee Doodles” of Cairo—A Representative Arab—Selecting Dragomen—The Great Business of Egypt—An Egyptian Market-Place—A Substitute for Clothes—Dahabeëhs of the Nile—A Protracted Negotiation—Egyptian wiles

Sight Seeing in Cairo—An Eastern Bazaar—Courteous Merchants—The Honored Beggar—Charity to be Rewarded—A Moslem Funeral—The Gold Bazaar—Shopping for a Necklace—Conducting a Bride Home—A Partnership matter—Early Marriages and Decay—Longings for Youth

The Sirocco—The Desert—The Citadel of Cairo—Scene of the Massacre of the Memlooks—The World's Verdict—The Mosque of Mohammed Ali—Tomb of the Memlook Sultans—Life out of Death

An Enjoyable City—Definition of Conscience—“Prayer is better than Sleep”—Call of the Muezzin—Moslems at Prayer—Interior of a Mosque—Oriental Architecture—The Slipper Fitters—Devotional Washing—An Inman's Supplications

Ancient Sepulchres—Grave Robbers—The Poor Old Mummy—The Oldest Monument in the World—First View of the Pyramids—The resident Bedaween—Ascending the Steps—Patent Elevators—A View from the Top—The Guide's Opinions—Origin of “Murray's Guide Book”—Speculations on the Pyramids—The Interior—Absolute Night—A Taste of Death—The Sphinx—Domestic Life in a Tomb—Souvenirs of Ancient Egypt—Backsheesh!

A Weighty Question—The Seasons Bewitched—Poetic Dreams Realized—Egyptian Music—Public Garden—A Wonderful Rock—Its Patrons—The Playing Band—Native Love Songs—The Howling Derweeshes—An Exciting Performance—The Shakers put to Shame—Descendants of the Prophet—An Ancient Saracenic Home—The Land of the Elea and the Copt—Historical Curiosities—Preparing for our Journey—Laying in of Medicines and Rockets—A Determination to be Liberal—Official life in Egypt—An Interview with the Bey—Paying for our Rockets—A Walking Treasury—Waiting for Wind

On Board the “Rip Van Winkle”—A Farewell Dinner—The Three Months Voyage Commenced—On the Nile—Our Pennant's Device—Our Dahabeëh—Its Officers and Crew—Types of Egyptian Races—The Kingdom of the “Stick”—The false Pyramid of Maydoon—A Night on the River—Curious Crafts—Boat Races on the Nile—Native Villages—Songs of the Sailors—Incidents of the Day—The Copts—The Patriarch—The Monks of Gebel é Tayr—Disappointment all Round—A Royal Luxury—The Banks of the Nile—Gum Arabic—Unfair Reports of us—Speed of our Dahabeëh—Egyptian Bread—Hasheesh-Smoking—Egyptian Robbers—Sitting in Darkness—Agriculture—Gathering of Taxes—Successful Voyaging

Sunday on the Nile—A Calm—A Land of Tombs—A New Divinity—Burial of a Child—A Sunday Companion on Shore—A Philosophical People—No Sunday Clothes—The Aristocratic Bedaween—The Sheykh—Rare Specimens for the Centennial—Tracts Needed—Woman's Rights—Pigeons and Cranes—Balmy Winter Nights—Tracking—Copying Nature in Dress—Resort of Crocodiles—A Hermit's Cave—Waiting for Nothing—Crocodile Mummies—The Boatmen's Song—Furling Sails—Life Again—Pictures on the Nile.

Independence in Spelling—Asioot—Christmas Day—The American Consul—A Visit to the Pasha—Conversing by an Interpreter—The Ghawazees at Home—Ancient Sculpture—Bird's Eye View of the Nile—Our Christmas Dinner—Our Visitor—Grand Reception—The Fire Works—Christmas Eve on the Nile

Ancient and Modern Ruins—“We Pay Toll—Cold Weather—Night Sailing—Farshoot—A Visit from the Bey—The Market-Place—The Sakiyas or Water Wheels—The Nile is Egypt

Midwinter in Egypt—Slaves of Time—Where the Water Jars are Made—Coming to Anchor and how it was Done—New Years—” Smits” Copper Popularity—Great Strength of the Women—Conscripts for the Army—Conscription a Good Thing—On the Threshold of Thebes

Situation of the City—Ruins—Questions—Luxor—Ivarnak—Glorification of the Pharaohs—Sculptures in Stone—The Twin Colossi—Four Hundred Miles in Sixteen Days

A Dry City—A Strange Circumstance—A Pleasant Residence—Life on the Dahabeëh—Illustrious Visitors—Nose-Rings and Beauty—Little Fatimeh—A Mummy Hand and Thoughts upon it—Plunder of the Tombs—Exploits of the Great Sesostris—Gigantic Statues and their Object—Skill of Ancient Artists—Criticisms—Christian Churches and Pagan Temples—Society—A Peep into an Ancient Harem—Statue of Meiùnon—Mysteries—Pictures of Heroic Girls—Women in History

An Egyptian Carriage—Wonderful Ruins—The Great Hall of Sethi—The Largest Obelisk in The World—A City of Temples and Palaces

Ascending the River—An Exciting Boat Race—Inside a Sugar Factory—Setting Fire to a Town—Who Stole the Rockets?—Striking Contrasts—A Jail—The Kodi or Judge—What we saw at Assouan—A Gale—Ruins of Kom Ombos—Mysterious Movement—Land of Eternal Leisure

Passing the Cataract of the Nile—Nubian Hills in Sight—Island of Elephantine—Ownership of the Cataract—Difficulties of the Ascent—Negotiations for a Passage—Items about Assouan—Off for the Cataracts—Our Cataract Crew—First Impressions of the Cataract—In the Stream—Excitement—Audacious Swimmers—Close Steering—A Comical Orchestra—The Final Struggle—Victory—Above the Rapids—The Temple of Isis—Ancient Kings and Modern Conquerors

Ethiopia—Relatives of the Ethiopians—Negro Land—Ancestry of the Negro—Conversion Made Easy—A Land of Negative Blessings—Cool air from the Desert—Abd-el-Atti's Opinions—A Land of Comfort—Nubian Costumes—Turning the Tables—The Great Desert—Sin, Grease and Taxes

Primitive Attire—The Snake Charmer—A House full of Snakes—A Writ of Ejectments—Natives—The Tomb of Mohammed—Disasters—A Dandy Pilate—Nubian Beauty—Opening a Baby's Eyes—A Nubian Pigville

Life in the Tropics—Wady Haifa—Capital of Nubia—The Centre of Fashion—The Southern Cross—Castor Oil Plantations—Justice to a Thief—Abd-el-Atti's Court—Mourning for the Dead—Extreme of our Journey—A Comical Celebration—The March of Civilization.

Two Ways to See It—Pleasures of Canal Riding—Bird's Eye View of the Cataracts—Signs of Wealth—Wady Haifa—A Nubian Belle—Classic Beauty—A Greek Bride—Interviewing a Crocodile—Joking with a Widow—A Model Village

The Colossi of Aboo Simbel, the largest in the World—Bombast—Exploits of Remeses II.—A Mysterious Temple—Feting Ancient Deities—Guardians of the Nile—The Excavated Rock—The Temple—A Row of Sacred Monkeys—Our Last View of The Giants

Learning the Language—Models of Beauty—Cutting up a Crocodile—Egyptian Loafers—A Modern David—A Present—Our Menagerie—The Chameleon—Woman's Rights—False Prophets—Incidents—The School Master at Home—Confusion—Too Much Conversion—Charity—Wonderful Birds at Mecca

Leave “well enough” Alone—The Myth of Osiris—The Heights of Biggeh—Cleopatra's Favorite Spot—A Legend—Mr. Fiddle—Dreamland—Waiting for a Prince—An Inland Excursion—Quarries—Adieu

Downward Run—Kidnapping a Sheykh—Blessed with Relatives—Making the Chute—Artless Children—A Model of Integrity—Justice—An Accident—Leaving Nubia—A Perfect Shame

The Mysterious Pebble—Ancient Quarries—Prodigies of Labor—Humor in Stone—A Simoon—Famous Grottoes—Naughty Attractions—Bogus Relics—Antiquity Smith

Ancient Egyptian Literature—Mummies—A Visit to the Tombs—Disturbing the Dead—The Funeral Ritual—Unpleasant Explorations A Mummy in Pledge—A Desolate Way—Buried Secrets—Building for Eternity—Before the Judgment Seat—Weighed in the Balance The Habitation of the Dead—Illuminated—Accommodations for the Mummy—The Pharaoh of the Exodus—A Baby Charon—Bats

Social Festivities—An Oriental Dinner—Dancing Girls—Honored by the Sultan—The Native Consul—Finger Feeding—A Dance—Ancient Style of Dancing—The Poetry of Night—Karnak by Moonlight—Amusements at Luxor—Farewell to Thebes

“Very Grammatick”—The Lying in Temple—A Holy Man—Scarecrows—Asinine Performers—Antiquity—Old Masters—Profit and Loss—Hopeless “Fellahs”—Lion's Oil—A Bad Reputation—An Egyptian Mozart

Mission School—Education of Women—Contrasts—A Mirage—Tracks of Successive Ages—Bathers—Tombs of the Sacred Bulls—Religion and Grammar—Route to Darfoor—Winter Residence of the Holy Family—Grottoes—Mistaken Views—Dust and Ashes—Osman Bey—A Midsummer's Night Dream—Ruins of Memphis—Departed Glory—A Second Visit to the Pyramids of Geezeh—An Artificial Mother

Al Gezereh—Aboo Yusef the Owner—Cairo Again—A Question—The Khedive—Solomon and the Viceroy—The Khedive's Family Expenses—Another Joseph—Personal Government—Docks of Cairo—Raising Mud—Popular Superstitions—Leave Taking

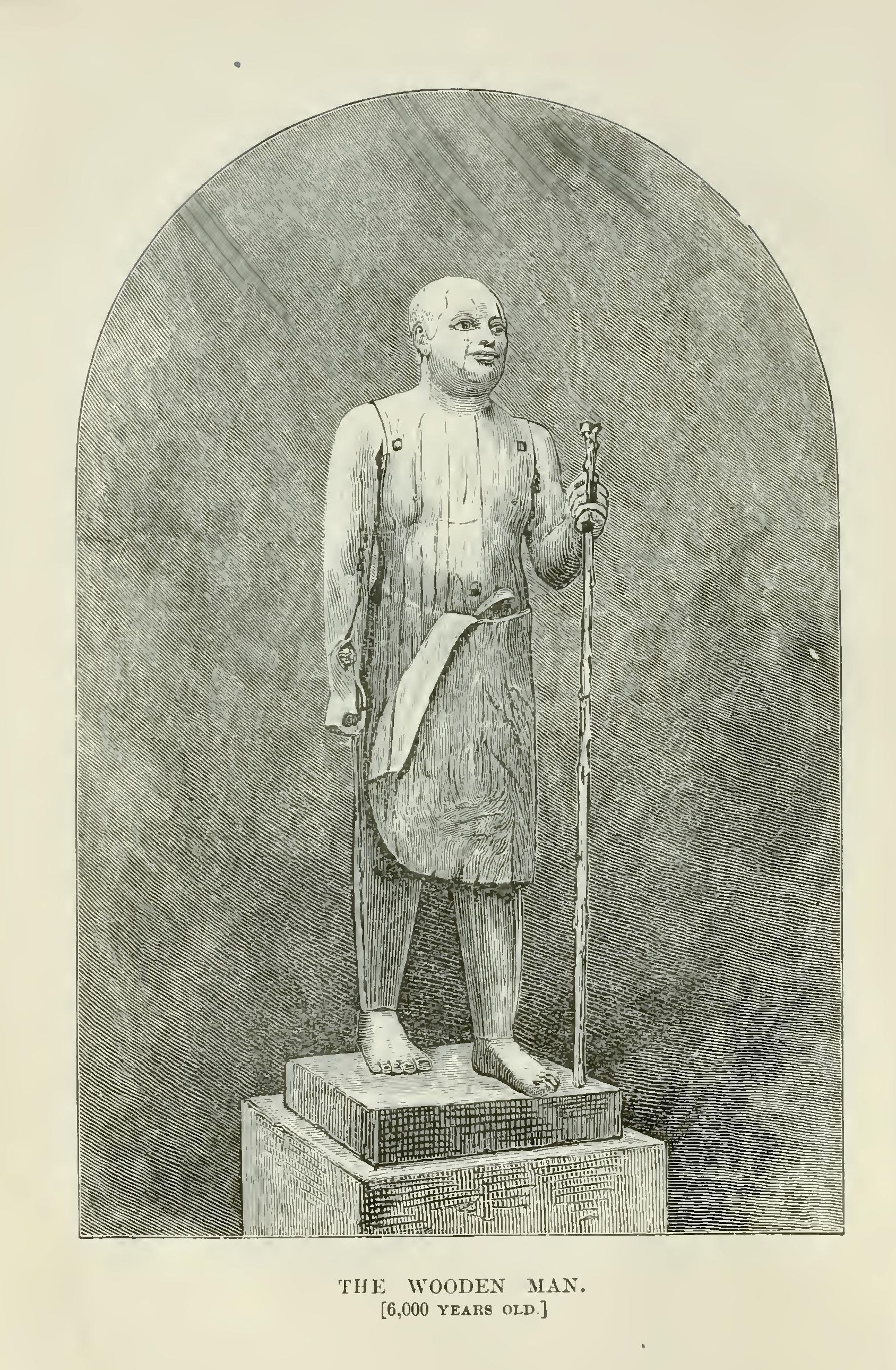

Visiting a Harem—A Reception—The Khedive at Home—Ladies of the Harem—Wife of Tufik Pasha—The Mummy—The Wooden Man Discoveries of Mariette Bey—Egypt and Greece Compared—Learned Opinions

Leaving our Dahabeeh—The Baths in Cairo—Curious Mode of Execution—The Guzeereh Palace—Empress Eugenia's Sleeping Room—Medallion of Benjamin Franklin in Egypt—Heliopolis—The Bedaween Bride—Holy Places—The Resting Place of the Virgin Mary—Fashionable Drives—The Shoobra Palace—Forbidden Books—A Glimpse of a Bevy of Ladies—Uncomfortable Guardians.

Following the Track of the Children of Israel—Routes to Suez—Temples—Where was the Red Sea Crossed?—In sight of the Bitter Lakes—Approaching the Red Sea—Faith—The Suez Canal—The Wells of Moses—A Sentimental Pilgrimage—Price of one of the Wells—Miriam of Marah—Water of the Wells—Returning to Suez—A Caravan of Bedaweens—Lunch Baskets searched by Custom Officers—The Commerce of the East

Leaving Suez—Ismailia—The Lotus—A Miracle—Egyptian Steamer—Information Sought—The Great Highway—Port Said—Abd-el-Atti again—Great Honors Lost—Farewell to Egypt

THE Mediterranean still divides the East from the West. Ages of traffic and intercourse across its waters have not changed this fact; neither the going of armies nor of embassies, Northmen forays nor Saracenic maraudings, Christian crusades nor Turkish invasions, neither the borrowing from Egypt of its philosophy and science, nor the stealing of its precious monuments of antiquity, down to its bones, not all the love-making, slave-trading, war-waging, not all the commerce of four thousand years, by oar and sail and steam, have sufficed to make the East like the West.

Half the world was lost at Actium, they like to say, for the sake of a woman; but it was the half that I am convinced we never shall gain—for though the Romans did win it they did not keep it long, and they made no impression on it that is not, compared with its own individuality, as stucco to granite. And I suppose there is not now and never will be another woman in the East handsome enough to risk a world for.

There, across the most fascinating and fickle sea in the world—a feminine sea, inconstant as lovely, all sunshine and tears in a moment, reflecting in its quick mirror in rapid succession the skies of grey and of blue, the weather of Europe and of Africa, a sea of romance and nausea—lies a world in Everything unlike our own, a world perfectly known yet never familiar and never otherwise than strange to the European and American. I had supposed it otherwise; I had been led to think that modern civilization had more or less transformed the East to its own likeness; that, for instance the railway up the Nile had practically “done for” that historic stream. They say that if you run a red-hot nail through an orange, the fruit will keep its freshness and remain unchanged a long time. The thrusting of the iron into Egypt may arrest decay, but it does not appear to change the country.

There is still an Orient, and I believe there would be if it were all canaled, and railwayed, and converted; for I have great faith in habits that have withstood the influence of six or seven thousand years of changing dynasties and religions. Would you like to go a little way with me into this Orient?

The old-fashioned travelers had a formal fashion of setting before the reader the reasons that induced them to take the journey they described; and they not unfrequently made poor health an apology for their wanderings, judging that that excuse would be most readily accepted for their eccentric conduct. “Worn out in body and mind we set sail,” etc.; and the reader was invited to launch in a sort of funereal bark upon the Mediterranean and accompany an invalid in search of his last resting-place.

There was in fact no reason why we should go to Egypt—a remark that the reader will notice is made before he has a chance to make it—and there is no reason why any one indisposed to do so should accompany us. If information is desired, there are whole libraries of excellent books about the land of the Pharaohs, ancient and modern, historical, archaeological, statistical, theoretical, geographical; if amusement is wanted, there are also excellent books, facetious and sentimental. I suppose that volumes enough have been written about Egypt to cover every foot of its arable soil if they were spread out, or to dam the Nile if they were dumped into it, and to cause a drought in either case if they were not all interesting and the reverse of dry. There is therefore no onus upon the traveler in the East to-day to write otherwise than suits his humor; he may describe only what he chooses. With this distinct understanding I should like the reader to go with me through a winter in the Orient. Let us say that we go to escape winter.

It is the last of November, 1874—the beginning of what proved to be the bitterest winter ever known in America and Europe, and I doubt not it was the first nip of the return of the rotary glacial period—that we go on board a little Italian steamer in the harbor of Naples, reaching it in a row-boat and in a cold rain. The deck is wet and dismal; Vesuvius is invisible, and the whole sweep of the bay is hid by a slanting mist. Italy has been in a shiver for a month; snow on the Alban hills and in the Tusculan theatre; Rome was as chilly as a stone tomb with the door left open. Naples is little better; Boston, at any season, is better than Naples—now.

We steam slowly down the harbor amid dripping ships, losing all sight of villages and the lovely coast; only Capri comes out comely in the haze, an island cut like an antique cameo. Long after dark we see the light on it and also that of the Punta della Campanella opposite, friendly beams following us down the coast. We are off Pæstum,' and I can feel that its noble temple is looming there in the darkness. This ruin is in some sort a door into, an introduction to, the East.

Pæstum has been a deadly marsh for eighteen hundred years, and deserted for almost a thousand. Nettles and unsightly brambles have taken the place of the “roses of Pæstum” of which the Roman poets sang; but still as a poetic memory, the cyclamen trails among the debris of the old city; and the other day I found violets waiting for a propitious season to bloom. The sea has retired away from the site of the town and broadened the marsh in front of it. There are at Pæstum three Greek temples, called, no one can tell why, the Temple of Neptune, the Basilica, and the Temple of Ceres; remains of the old town wall and some towers; a tumbledown house or two, and a wretched tavern. The whole coast is subject to tremors of the earth, and the few inhabitants hanging about there appear to have had all their bones shaken out of them by the fever and ague.

We went down one raw November morning from Naples, driving from a station on the Calabrian railway, called Battipaglia, about twelve miles over a black marshy plain, relieved only by the bold mountains, on the right and left. This plain is gradually getting reclaimed and cultivated; there is raised on it inferior cotton and some of the vile tobacco which the government monopoly compels the free Italians to smoke, and large olive-orchards have been recently set out. The soil is rich and the country can probably be made habitable again. Now, the few houses are wretched and the few people squalid. Women were pounding stone on the road we traveled, even young girls among them wielding the heavy hammers, and all of them very thinly clad, their one sleazy skirt giving little protection against the keen air. Of course the women were hard-featured and coarse-handed; and both they and the men have the swarthy complexion that may betoken a more Eastern origin. We fancied that they had a brigandish look. Until recently this plain has been a favorite field for brigands, who spied the rich traveler from the height of St. Angelo and pounced upon him if he was unguarded. Now, soldiers are quartered along the road, patrol the country on horseback, and lounge about the ruins at Pæstum. Perhaps they retire to some height for the night, for the district is too unhealthy for an Italian even, whose health may be of no consequence. They say that if even an Englishman, who goes merely to shoot woodcock, sleeps there one night, in the right season, that night will be his last.

We saw the ruins of Pæstum under a cold grey sky, which harmonized with their isolation. We saw them best from the side of the sea, with the snow-sprinkled mountains rising behind for a background. Then they stood out, impressive, majestic, time-defying. In all Europe there are no ruins better worthy the study of the admirer of noble architecture than these.

The Temple of Neptune is older than the Parthenon, its Doric sister, at Athens. It was probably built before the Persians of Xerxes occupied the Acropolis and saw from there the flight of their ruined fleet out of the Strait of Salamis. It was built when the Doric had attained the acme of its severe majesty, and it is to-day almost perfect on the exterior. Its material is a coarse travertine which time and the weather have honeycombed, showing the petrifications of plants and shells; but of its thirty-six massive exterior columns not one has fallen, though those on the north side are so worn by age that the once deep fluting is nearly obliterated. You may care to know that these columns which are thirty feet high and seven and a half feet in diameter at the base, taper symmetrically to the capitals, which are the severest Doric.

At first we thought the temple small, and did not even realize its two hundred feet of length, but the longer we looked at it the larger it grew to the eye, until it seemed to expand into gigantic size; and from whatever point it was viewed its harmonious proportions were an increasing delight. The beauty is not in any ornament, for even the pediment is and always was vacant, but in its admirable lines.

The two other temples are fine specimens of Greek architecture, also Doric, pure and without fault, with only a little tendency to depart from severe simplicity in the curve of the capitals, and yet they did not interest us. They are of a period only a little later than the Temple of Neptune, and that model was before their builders, yet they missed the extraordinary, many say almost spiritual beauty of that edifice. We sought the reason, and found it in the fact that there are absolutely no straight lines in the Temple of Neptune. The side rows of columns curve a little out; the end rows curve a little in; at the ends the base line of the columns curves a trifle from the sides to the center, and the line of the architrave does the same. This may bewilder the eye and mislead the judgment as to size and distance, but the effect is more agreeable than almost any other I know in architecture. It is not repeated in the other temples, the builders of which do not seem to have known its secret. Had the Greek colony lost the art of this perfect harmony, in the little time that probably intervened between the erection of these edifices? It was still kept at Athens, as the Temple of Theseus and the Parthenon testify.

Looking from the interior of the temple out at either end, the entrance seems to be wider at the top than at the bottom, an Egyptian effect produced by the setting of the inward and outer columns. This appeared to us like a door through which we looked into Egypt, that mother of all arts and of most of the devices of this now confused world. We were on our way to see the first columns, prototypes of the Doric order, chiselled by man.

The custodian—there is one, now that twenty centuries of war and rapine and storms have wreaked themselves upon this temple—would not permit us to take our luncheon into its guarded precincts; on a fragment of the old steps, amid the weeds we drank our red Capri wine; not the usual compound manufactured at Naples, but the last bottle of pure Capri to be found on the island, so help the soul of the landlady at the hotel there; ate one of those imperfectly nourished Italian chicken's orphan birds, owning the pitiful legs with which the table d'hote frequenters in Italy are so familiar, and blessed the government for the care, tardy as it is, of its grandest monument of antiquity.

When I looked out of the port-hole of the steamer early in the morning, we were near the volcanic Lipari islands and islets, a group of seventeen altogether; which serve as chimneys and safety-valves to this part of the world. One of the small ones is of recent creation, at least it was heaved up about two thousand years ago, and I fancy that a new one may pop up here any time. From the time of the Trojan war all sorts of races and adventurers have fought for the possession of these coveted islands, and the impartial earthquake has shaken them all off in turn. But for the mist, we should have clearly seen Stromboli, the ever-active volcano, but now we can only say we saw it. We are near it, however, and catch its outline, and listen for the groans of lost souls which the credulous crusaders used to hear issuing from its depths. It was at that time the entrance of purgatory; we read in the guide-book that the crusaders implored the monks of Cluny to intercede for the deliverance of those confined there, and that therefore Odilo of Cluny instituted the observance of All Souls' Day.

The climate of Europe still attends us, and our first view of Sicily is through the rain. Clouds hide the coast and obscure the base of Ætna (which is oddly celebrated in America as an assurance against loss by fire); but its wide fields of snow, banked up high above the clouds, gleam as molten silver—treasure laid up in heaven—and give us the light of the rosy morning.

Rounding the point of Faro, the locale of Charybdis and Scylla, we come into the harbor of Messina and take shelter behind the long, curved horn of its mole. Whoever shunned the beautiful Scylla was liable to be sucked into the strong tide Charybdis; but the rock has lost its terror for moderns, and the current is no longer dangerous. We get our last dash of rain in this strait, and there is sunny weather and blue sky at the south. The situation of Messina is picturesque; the shores both of Calabria and Sicily are mountainous, precipitous and very rocky; there seems to be no place for vegetation except by terracing. The town is backed by lofty circling mountains, which form a dark setting for its white houses and the string of outlying villages. Mediaeval forts cling to the slopes above it.

No sooner is the anchor down than a fleet of boats surrounds the steamer, and a crowd of noisy men and boys swarms on board, to sell us muscles, oranges, and all sorts of merchandise, from a hair-brush to an under-wrapper. The Sunday is hopelessly broken into fragments in a minute. These lively traders use the English language and its pronouns with great freedom. The boot-black smilingly asks: “You black my boot?”

The vender of under-garments says: “I gif you four franc for dis one. I gif you for dese two a seven franc. No? What you gif?”

A bright orange-boy, we ask, “How much a dozen?”

“Half franc.”

“Too much.”

“How much you give? Tast him; he ver good; a sweet orange; you no like, you no buy. Yes, sir. Tak one. This a one, he sweet no more.”

And they were sweet no more. They must have been lemons in oranges' clothing. The flattering tongue of that boy and our greed of tropical color made us owners of a lot of them, most of which went overboard before we reached Alexandria, and would make fair lemonade of the streak of water we passed through.

At noon we sail away into the warm south. We have before us the beautiful range of Aspromonte, and the village of Reggio bear which in 1862 Garibaldi received one of his wounds, a sort of inconvenient love-pat of fame. The coast is rugged and steep. High up is an isolated Gothic rock, pinnacled and jagged. Close by the shore we can trace the railway track which winds round the point of Italy, and some of the passengers look at it longingly; for though there is clear sky overhead, the sea has on an ungenerous swell; and what is blue sky to a stomach that knows its own bitterness and feels the world sinking away from under it?

We are long in sight of Italy, but Sicily still sulks in the clouds and Mount Ætna will not show itself. The night is bright and the weather has become milder; it is the prelude to a day calm and uninteresting. Nature rallies at night, however, and gives us a sunset in a pale gold sky with cloud-islands on the horizon and palm-groves on them. The stars come out in extraordinary profusion and a soft brilliancy unknown in New England, and the sky is of a tender blue—something delicate and not to be enlarged upon. A sunset is something that no one will accept second-hand.

On the morning of December 1st., we are off Crete; Greece we have left to the north, and are going at ten knots an hour towards great hulking Africa. We sail close to the island and see its long, high barren coast till late in the afternoon. There is no road visible on this side, nor any sign of human habitation, except a couple of shanties perched high up among the rocks. From this point of view, Crete is a mass of naked rock lifted out of the waves. Mount Ida crowns it, snow-capped and gigantic. Just below Crete spring up in our geography the little islands of Gozo and Antigozo, merely vast rocks, with scant patches of low vegetation on the cliffs, a sort of vegetable blush, a few stunted trees on the top of the first, and an appearance of grass which has a reddish color.

The weather is more and more delightful, a balmy atmosphere brooding on a smooth sea. The chill which we carried in our bones from New York to Naples finally melts away. Life ceases to be a mere struggle, and becomes a mild enjoyment. The blue tint of the sky is beyond all previous comparison delicate, like the shade of a silk, fading at the horizon into an exquisite grey or nearly white. We are on deck all day and till late at night, for once enjoying, by the help of an awning, real winter weather with the thermometer at seventy-two degrees.

Our passengers are not many, but selected. There are a German baron and his sparkling wife, delightful people, who handle the English language as delicately as if it were glass, and make of it the most naïve and interesting form of speech. They are going to Cairo for the winter, and the young baroness has the longing and curiosity regarding the land of the sun, which is peculiar to the poetical Germans; she has never seen a black man nor a palm-tree. In charge of the captain, there is an Italian woman, whose husband lives in Alexandria, who monopolizes the whole of the ladies' cabin, by a league with the slatternly stewardess, and behaves in a manner to make a state of war and wrath between her and the rest of the passengers. There is nothing bitterer than the hatred of people for each other on shipboard. When I afterwards saw this woman in the streets of Alexandria I had scarcely any wish to shorten her stay upon this earth. There are also two tough-fibered and strong-brained dissenting ministers from Australia, who have come round by the Sandwich Islands and the United States, and are booked for Palestine, the Suez Canal and the Red Sea. Speaking of Aden, which has the reputation of being as hot as Constantinople is wicked, one of them tells the story of an American (the English have a habit of fastening all their dubious anecdotes upon “an American”) who said that if he owned two places, one in Aden and the other in H——, he would sell the one in Aden. These ministers are distinguished lecturers at home—a solemn thought, that even the most distant land is subjected to the blessing of the popular lecture.

Our own country is well represented, as it usually is abroad, whether by appointment or self-selection. It is said that the oddest people in the world go up the Nile and make the pilgrimage of Palestine. I have even heard that one must be a little cracked who will give a whole winter to high Egypt; but this is doubtless said by those who cannot afford to go. Notwithstanding the peculiarities of so many of those one meets drifting around the East (as eccentric as the English who frequent Italian pensions) it must be admitted that a great many estimable and apparently sane people go up the Nile—and that such are even found among Cook's “personally conducted.”

There is on board an American, or a sort of Irish-American more or less naturalized, from Nebraska, a raw-boned, hard-featured farmer, abroad for a two-years' tour; a man who has no guide-book or literature, except the Bible which he diligently reads. He has spent twenty or thirty years in acquiring and subduing land in the new country, and without any time or taste for reading, there has come with his possessions a desire to see that old world about which he cared nothing before he breathed the vitalizing air of the West. That he knew absolutely nothing of Europe, Asia, or Africa, except the little patch called Palestine, and found a day in Rome too much for a place so run down, was actually none of our business. He was a good patriotic American, and the only wonder was that with his qualification he had not been made consul somewhere.

But a more interesting person, in his way, was a slender, no-blooded, youngish, married man, of the vegetarian and vegetable school, also alone, and bound for the Holy Land, who was sick of the sea and otherwise. He also was without books of travel, and knew nothing of what he was going to see or how to see it. Of what Egypt was he had the dimmest notion, and why we or he or anyone else should go there. What do you go up the Nile for? we asked. The reply was that the Spirit had called him to go through Egypt to Palestine. He had been a dentist, but now he called himself an evangelist. I made the mistake of supposing that he was one of those persons who have a call to go about and convince people that religion is one part milk (skimmed) and three parts water—harmless, however, unless you see too much of them. Twice is too much. But I gauged him inadequately. He is one of those few who comprehend the future, and, guided wholly by the Spirit and not by any scripture or tradition, his mission is to prepare the world for its impending change. He is en rapport with the vast uneasiness, which I do not know how to name, that pervades all lands. He had felt our war in advance. He now feels a great change in the air; he is illuminated by an inner light that makes him clairvoyant. America is riper than it knows for this change. I tried to have him definitely define it, so that I could write home to my friends and the newspapers and the insurance companies; but I could only get a vague notion that there was about to be an end of armies and navies and police, of all forms of religion, of government, of property, and that universal brotherhood is to set in.

The evangelist had come aboard on an important and rather secret mission; to observe the progress of things in Europe; and to publish his observations in a book. Spiritualized as he was, he had no need of any language except the American; he felt the political and religious atmosphere of all the cities he visited without speaking to any one. When he entered a picture gallery, although he knew nothing of pictures, he saw more than any one else. I suppose he saw more than Mr. Ruskin sees. He told me, among other valuable information, that he found Europe not so well prepared for the great movement as America, but that I would be surprised at the number who were in sympathy with it, especially those in high places in society and in government. The Roman Catholic Church was going to pieces; not that he cared any more for this than for the Presbyterian—he, personally, took what was good in any church, but he had got beyond them all; he was now only working for the establishment of the truth, and it was because he had more of the truth than others that he could see further.

He expected that America would be surprised when he published his observations. “I can give you a little idea,” he said, “of how things are working.” This talk was late at night, and by the dim cabin lamp. “When I was in Rome, I went to see the head-man of the Pope. I talked with him over an hour, and I found that he knew all about it!”

“Good gracious! You don't say so!”

“Yes, sir. And he is in full sympathy. But he dare not say anything. He knows that his church is on its last legs. I told him that I did not care to see the Pope, but if he wanted to meet me, and discuss the infallibility question, I was ready for him.”

“What did the Pope's head-man say to that?”

“He said that he would see the Pope, and see if he could arrange an interview; and would let me know. I waited a week in Rome, but no notice came. I tell you the Pope don't dare discuss it.”

“Then he didn't see you?”

“No, sir. But I wrote him a letter from Naples.”

“Perhaps he won't answer it.”

“Well, if he doesn't, that is a confession that he can't. He leaves the field. That will satisfy me.”

I said I thought he would be satisfied.

The Mediterranean enlarges on acquaintance. On the fourth day we are still without sight of Africa, though the industrious screw brings us nearer every moment. We talk of Carthage, and think we can see the color of the Libyan sand in the yellow clouds at night. It is two o'clock on the morning of December the third, when we make the Pharos of Alexandria, and wait for a pilot.

EAGERNESS to see Africa brings us on deck at dawn. The low coast is not yet visible. Africa, as we had been taught, lies in heathen darkness. It is the policy of the Egyptian government to make the harbor difficult of access to hostile men-of-war, and we, who are peacefully inclined, cannot come in till daylight, nor then without a pilot.

The day breaks beautifully, and the Pharos is set like a star in the bright streak of the East. Before we can distinguish land, we see the so-called Pompey's Pillar and the light-house, the palms, the minarets, and the outline of the domes painted on the straw-color of the sky—a dream-like picture. The curtain draws up with Eastern leisure—the sun appears to rise more deliberately in the Orient than elsewhere; the sky grows more brilliant, there are long lines of clouds, golden and crimson, and we seem to be looking miles and miles into an enchanted country. Then ships and boats, a vast number of them, become visible in the harbor, and as the light grows stronger, the city and land lose something of their beauty, but the sky grows more softly fiery till the sun breaks through. The city lies low along the flat coast, and seems at first like a brownish white streak, with fine lines of masts, palm-trees, and minarets above it.

The excitement of the arrival in Alexandria and the novelty of everything connected with the landing can never be repeated. In one moment the Orient flashes upon the bewildered traveler; and though he may travel far and see stranger sights, and penetrate the hollow shell of Eastern mystery, he never will see again at once such a complete contrast to all his previous experience. One strange, unfamiliar form takes the place of another so rapidly that there is no time to fix an impression, and everything is so bizarre that the new-comer has no points of comparison. He is launched into a new world, and has no time to adjust the focus of his observation. For myself, I wished the Orient would stand off a little and stand still so that I could try to comprehend it. But it would not; a revolving kaleidoscope never presented more bewildering figures and colors to a child, than the port of Alexandria to us.

Our first sight of strange dress is that of the pilot and the crew who bring him off—they are Nubians, he is a swarthy Egyptian. “How black they are,” says the Baroness; “I don't like it.” As the pilot steps on deck, in his white turban, loose robe of cotton, and red slippers, he brings the East with him; we pass into the influence of the Moslem spirit. Coming into the harbor we have pointed out to us the batteries, the palace and harem of the Pasha (more curiosity is felt about a harem than about any other building, except perhaps a lunatic asylum), and the new villas along the curve of the shore. It is difficult to see any ingress, on account of the crowd of shipping.

The anchor is not down before we are surrounded by rowboats, six or eight deep on both sides, with a mob of boatmen and guides, all standing up and shouting at us in all the broken languages of three continents. They are soon up the sides and on deck, black, brown, yellow, in turbans, in tarbooshes, in robes of white, blue, brown, in brilliant waist-shawls, slippered, and bare-legged, bare-footed, half-naked, with little on except a pair of cotton drawers and a red fez, eager, big-eyed, pushing, yelping, gesticulating, seizing hold of passengers and baggage, and fighting for the possession of the traveler's goods which seem to him about to be shared among a lot of pirates. I saw a dazed traveler start to land, with some of his traveling-bags in one boat, his trunk in a second, and himself in yet a third, and a commissionaire at each arm attempting to drag him into two others. He evidently couldn't make up his mind, which to take.

We have decided upon our hotel, and ask for the commissionaire of it. He appears. In fact there are twenty or thirty of him. The first one is a tall, persuasive, nearly naked Ethiop, who declares that he is the only Simon Pure, and grasps our handbags. Instantly, a fluent, business-like Alexandrian pushes him aside—“I am the commissionaire”—and is about to take possession of us. But a dozen others are of like mind, and Babel begins. We rescue our property, and for ten minutes a lively and most amusing altercation goes on as to who is the representative of the hotel. They all look like pirates from the Barbary coast, instead of guardians of peaceful travelers. Quartering an orange, I stand in the center of an interesting group, engaged in the most lively discussion, pushing, howling and fiery gesticulation. The dispute is finally between two:

“I Hotel Europe!”

“I Hotel Europe; he no hotel.”

“He my brother, all same me.”

“He! I never see he before,” with a shrug of the utmost contempt.

As soon as we select one of them, the tumult subsides, the enemies become friends and cordially join in loading our luggage. In the first five minutes of his stay in Egypt the traveler learns that he is to trust and be served by people who haven't the least idea that lying is not a perfectly legitimate means of attaining any desirable end. And he begins to lose any prejudice he may have in favor of a white complexion and of clothes. In a decent climate he sees how little clothing is needed for comfort, and how much artificial nations are accustomed to put on from false modesty.

We begin to thread our way through a maze of shipping, and hundreds of small boats and barges; the scene is gay and exciting beyond expression. The first sight of the colored, pictured, lounging, waiting Orient is enough to drive an impressionable person wild; so much that is novel and picturesque is crowded into a few minutes; so many colors and flying robes, such a display of bare legs and swarthy figures. We meet flat boats coming down the harbor loaded with laborers, dark, immobile groups in turbans and gowns, squatting on deck in the attitude which is the most characteristic of the East; no one stands or sits—everybody squats or reposes cross-legged. Soldiers are on the move; smart Turkish officers dart by in light boats with half a dozen rowers; the crew of an English man-of-war pull past; in all directions the swift boats fly, and with their freight of color, it is like the thrusting of quick shuttles, in the weaving of a brilliant carpet, before our eyes.

We step on shore at the Custom-House. I have heard travelers complain of the delay in getting through it. I feel that I want to go slowly, that I would like to be all day in getting through—that I am hurried along like a person who is dragged hastily through a gallery, past striking pictures of which he gets only glimpses. What a group this is on shore; importunate guides, porters, coolies. They seize hold of us, We want to stay and look at them. Did ever any civilized men dress so gaily, so little, or so much in the wrong place? If that fellow would untwist the folds of his gigantic turban he would have cloth enough to clothe himself perfectly. Look! that's an East Indian, that's a Greek, that's a Turk that's a Syrian-Jew? No, he's Egyptian, the crook-nose is not uncommon to Egyptians, that tall round hat is Persian, that one is from Abys—there they go, we haven't half seen them! We leave our passports at the entrance, and are whisked through into the baggage-room, where our guide pays a noble official three francs for the pleasure of his chance acquaintance; some nearly naked coolie-porters, who bear long cords, carry off our luggage, and before we know it we are in a carriage, and a rascally guide and interpreter—Heaven knows how he fastened himself upon us in the last five minutes—is on the box and apparently owns us? (It took us half a day and liberal backsheesh to get rid of the evil-eyed fellow) We have gone only a little distance when half a dozen of the naked coolies rush after us, running by the carriage and laying hold of it, demanding backsheesh. It appears that either the boatman has cheated them, or they think he will, or they havn't had enough. Nobody trusts anybody else, and nobody is ever satisfied with what he gets, in Egypt. These blacks, in their dirty white gowns, swinging their porter's ropes and howling like madmen, pursue us a long way and look as if they would tear us in pieces. But nothing comes of it. We drive to the Place Mehemet Ali, the European square,—having nothing Oriental about it, a square with an equestrian statue of Mehemet Ali, some trees and a fountain—surrounded by hotels, bankers' offices and Frank shops.

There is not much in Alexandria to look at except the people, and the dirty bazaars. We never before had seen so much nakedness, filth and dirt, so much poverty, and such enjoyment of it, or at least indifference to it. We were forced to strike a new scale of estimating poverty and wretchedness. People are poor in proportion as their wants are not gratified. And here are thousands who have few of the wants that we have, and perhaps less poverty. It is difficult to estimate the poverty of those fortunate children to whom the generous sun gives a warm color for clothing, who have no occupation but to sit in the same, all day, in some noisy and picturesque thoroughfare, and stretch out the hand for the few paras sufficient to buy their food, who drink at the public fountain, wash in the tank of the mosque, sleep in street-corners, and feel sure of their salvation if they know the direction of Mecca. And the Mohammedan religion seems to be a sort of soul-compass, by which the most ignorant believer can always orient himself. The best-dressed Christian may feel certain of one thing, that he is the object of the cool contempt of the most naked, opthalmic, flea-attended, wretched Moslem he meets. The Oriental conceit is a peg above ours—it is not self-conscious.

In a fifteen minutes walk in the streets the stranger finds all the pictures that he remembers in his illustrated books of Eastern life. There is turbaned Ali Baba, seated on the hindquarters of his sorry donkey, swinging his big feet in a constant effort to urge the beast forward; there is the one-eyed calender who may have arrived last night from Bagdad; there is the water-carrier, with a cloth about his loins, staggering under a full goat-skin—the skin, legs, head, and all the members of the brute distended, so that the man seems to be carrying a drowned and water-soaked animal: there is the veiled sister of Zobeide riding a grey donkey astride, with her knees drawn up, (as all women ride in the East), entirely enveloped in a white garment which covers her head and puffs out about her like a balloon—all that can be seen of the woman are the toes of her pointed yellow slippers and two black eyes; there is the seller of sherbet, a waterish, feeble, insipid drink, clinking his glasses; and the veiled woman in black, with hungry eyes, is gliding about everywhere. The veil is in two parts, a band about the forehead, and a strip of black which hangs underneath the eyes and terminates in a point at the waist; the two parts are connected by an ornamented cylinder of brass, or silver if the wearer can afford it, two and a half inches long and an inch in diameter. This ugly cylinder between the restless eyes, gives the woman an imprisoned, frightened look. Across the street from the hotel, upon the stone coping of the public square, is squatting hour after hour in the sun, a row of these forlorn creatures in black, impassive and waiting. We are told that they are washerwomen waiting for a job. I never can remove the impression that these women are half stifled behind their veils and the shawls which they draw over the head; when they move their heads, it is like the piteous dumb movement of an uncomplaining animal.

But the impatient reader is waiting for Pompey's Pillar. We drive outside the walls, though a thronged gateway, through streets and among people wretched and picturesque to the last degree. This is the road to the large Moslem cemetery, and to-day is Thursday, the day for visiting the graves. The way is lined with coffee-shops, where men are smoking and playing at draughts; with stands and booths for the sale of fried cakes and confections; and all along, under foot, so that it is difficult not to tread on them, are private markets for the sale of dates, nuts, raisins, wheat, and doora; the bare-legged owner sits on the ground and spreads his dust-covered untempting fare on a straw mat before him. It is more wretched and forlorn outside the gate than within. We are amid heaps of rubbish, small mountains of it, perhaps the ruins of old Alexandria, perhaps only the accumulated sweepings of the city for ages, piles of dust, and broken pottery. Every Egyptian town of any size is surrounded by these—the refuse of ages of weary civilization.

What a number of old men, of blind men, ragged men—though rags are no disgrace! What a lot of scrawny old women, lean old hags, some of them without their faces covered—even the veiled ones you can see are only bags of bones. There is a derweesh, a naked holy man, seated in the dirt by the wall, reading the Koran. He has no book, but he recites the sacred text in a loud voice, swaying his body backwards and forwards. Now and then we see a shrill-voiced, handsome boy also reading the Koran with all his might, and keeping a laughing eye upon the passing world. Here comes a novel turn-out. It is a long truck-wagon drawn by one bony-horse. Upon it are a dozen women, squatting about the edges, facing each other, veiled, in black, silent, jolting along like so many bags of meal. A black imp stands in front, driving. They carry baskets of food and flowers, and are going to the cemetery to spend the day.

We pass the cemetery, for the Pillar is on a little hillock overlooking it. Nothing can be drearier than this burying-ground—unless it may be some other Moslem cemetery. It is an uneven plain of sand, without a spear of grass or a green thing. It is covered thickly with ugly stucco, oven-like tombs, the whole inconceivably shabby and dust covered; the tombs of the men have head-stones to distinguish them from the women. Yet, shabby as all the details of this crumbling cheap place of sepulture are, nothing could be gayer or more festive than the scene before us. Although the women are in the majority, there are enough men and children present, in colored turbans, fezes, and gowns, and shawls of Persian dye, to transform the graveyard into the semblance of a parterre of flowers. About hundreds of the tombs are seated in a circle groups of women, with their food before them, and the flowers laid upon the tomb, wailing and howling in the very excess of dry-eyed grief. Here and there a group has employed a “welee” or holy man, or a boy, to read the Koran for it—and these Koran-readers turn an honest para by their vocation. The women spend nearly the entire day in this sympathetic visit to their departed friends—it is a custom as old as history, and the Egyptians used to build their tombs with a visiting ante-chamber for the accommodation of the living. I should think that the knowledge that such a group of women were to eat their luncheon, wailing and roosting about one's tomb every week, would add a new terror to death.

The Pillar, which was no doubt erected by Diocletian to his own honor, after the modest fashion of Romans as well as Egyptians, is in its present surroundings not an object of enthusiasm, though it is almost a hundred feet high, and the monolith shaft was, before age affected it, a fine piece of polished Syenite. It was no doubt a few thousand years older than Diocletian, and a remnant of that oldest civilization; the base and capital he gave it are not worthy of it. Its principal use now is as a surface for the paint-brushes and chisels of distinguished travelers, who have covered it with their precious names. I cannot sufficiently admire the naïveté and self-depreciation of those travelers who paint and cut their names on such monuments, knowing as they must that the first sensible person who reads the same will say, “This is an ass.”

We drive, still outside the walls, towards the Mahmoodéeh canal, passing amid mounds of rubbish, and getting a view of the desert-like country beyond. And now heaves in sight the unchanged quintessence of Orientalism—there is our first camel, a camel in use, in his native setting and not in a menagerie. There is a line of them, loaded with building-stones, wearily shambling along. The long bended neck apes humility, but the supercilious nose in the air expresses perfect contempt for all modern life. The contrast of this haughty “stuck-up-ativeness” (it is necessary to coin this word to express the camel's ancient conceit) with the royal ugliness of the brute, is both awe-inspiring and amusing. No human royal family dare be uglier than the camel. He is a mass of bones, faded tufts, humps, lumps, splay-joints and callosities. His tail is a ridiculous wisp, and a failure as an ornament or a fly-brush. His feet are simply big sponges. For skin covering he has patches of old buffalo robes, faded and with the hair worn off. His voice is more disagreeable than his appearance. With a reputation for patience, he is snappish and vindictive. His endurance is over-rated—that is to say he dies like a sheep on an expedition of any length, if he is not well fed. His gait moves every muscle like an ague. And yet this ungainly creature carries his head in the air, and regards the world out of his great brown eyes with disdain. The Sphinx is not more placid. He reminds me, I don't know why, of a pyramid. He has a resemblance to a palm-tree. It is impossible to make an Egyptian picture without him. What a Hapsburg lip he has! Ancient, royal? The very poise of his head says plainly, “I have come out of the dim past, before history was; the deluge did not touch me; I saw Menes come and go; I helped Shoofoo build the great pyramid; I knew Egypt when it hadn't an obelisk nor a temple; I watched the slow building of the pyramid at Sakkara. Did I not transport the fathers of your race across the desert? There are three of us; the date-palm, the pyramid, and myself. Everything else is modern. Go to!”

Along the canal, where lie dahabeëhs that will by and by make their way up the Nile, are some handsome villas, palaces and gardens. This is the favorite drive and promenade. In the gardens, that are open to the public, we find a profusion of tropical trees and flowering shrubs; roses are decaying, but the blossoms of the yellow acacia scent the air; there are Egyptian lilies; the plant with crimson leaves, not native here, grows as high as the arbutilon tree; the red passion-flower is in bloom, and morning-glories cover with their running vine the tall and slender cypresses. The finest tree is the sycamore, with great gnarled trunk, and down-dropping branches. Its fruit, the sycamore fig, grows directly on the branch, without stem. It is an insipid fruit, sawdust-y, but the Arabs like it, and have a saying that he who eats one is sure to return to Egypt. After we had tried to eat one, we thought we should not care to return. The interior was filled with lively little flies; and a priest who was attending a school of boys taking a holiday in the grove, assured us that each fig had to be pierced when it was green, to let the flies out, in order to make it eatable. But the Egyptians eat them, flies and all.

The splendors of Alexandria must be sought in books. The traveler will see scarcely any remains of a magnificence which dazzled the world in the beginning of our era. He may like to see the mosque that marks the site of the church of St. Mark, and he may care to look into the Coptic convent whence the Venetians stole the body of the saint, about a thousand years ago. Of course we go to see that wonder of our childhood, Cleopatra's Needles, as the granite obelisks are called that were brought from Alexandria and set up before a temple of Caesar in the time of Tiberius. Only one is standing, the other, mutilated, lies prone beneath the soil. The erect one stands near the shore and in the midst of hovels and incredible filth. The name of the earliest king it bears is that of Thothmes III., the great man of Egypt, whose era of conquest was about 1500 years before St. Mark came on his mission to Alexandria.

The city which has had as many vicissitudes as most cities, boasting under the Cæsars a population of half a million, that had decreased to 6,000 in 1800, and has now again grown to over two hundred thousand, seems to be at a waiting point; the merchants complain that the Suez Canal has killed its trade. Yet its preeminence for noise, dirt and shabbiness will hardly be disputed; and its bazaars and streets are much more interesting, perhaps because it is the meeting-place of all races, than travelers usually admit.

We had scarcely set foot in our hotel when we were saluted and waited for by dragomans of all sorts. They knocked at our doors, they waylaid us in the passages; whenever we emerged from our rooms half a dozen rose up, bowing low; it was like being a small king, with obsequious attendants waiting every motion. They presented their cards, they begged we would step aside privately for a moment and look at the bundle of recommendations they produced; they would not press themselves, but if we desired a dragoman for the Nile they were at our service. They were of all shades of color, except white, and of all degrees of oriental splendor in their costume. There were Egyptians, Nubians, Maltese, Greeks, Syrians. They speak well all the languages of the Levant and of Europe, except the one in which you attempt to converse with them. I never made the acquaintance of so many fine fellows in the same space of time. All of them had the strongest letters of commendation from travelers whom they had served, well-known men of letters and of affairs. Travelers give these endorsements as freely as they sign applications for government appointments at home.

The name of the handsome dragoman who walked with us through the bazaars was, naturally enough, Ahmed Abdallah. He wore the red fez (tarboosh) with a gay kuffia bound about it; an embroidered shirt without collar or cravat; a long shawl of checked and bright-colored Beyrout silk girding the loins, in which was carried his watch and heavy chain; a cloth coat; and baggy silk trousers that would be a gown if they were not split enough to gather about each ankle. The costume is rather Syrian than Egyptian, and very elegant when the materials are fine; but with a suggestion of effeminacy, to Western eyes.

The native bazaars, which are better at Cairo, reveal to the traveler, at a glance, the character of the Orient; its cheap tinsel, its squalor, and its occasional richness and gorgeousness. The shops on each side of the narrow street are little more than good-sized wardrobes, with room for shelves of goods in the rear and for the merchant to sit cross-legged in front. There is usually space for a customer to sit with him, and indeed two or three can rest on the edge of the platform. Upon cords stretched across the front hang specimens of the wares for sale. Wooden shutters close the front at night. These little cubbies are not only the places of sale but of manufacture of goods. Everything goes on in the view of all the world. The tailor is stitching, the goldsmith is blowing the bellows of his tiny forge, the saddler is repairing the old donkey-saddles, the shoemaker is cutting red leather, the brazier is hammering, the weaver sits at his little loom with the treadle in the ground—every trade goes on, adding its own clatter to the uproar.

What impresses us most is the good nature of the throng, under trying circumstances. The street is so narrow that three or four people abreast make a jam, and it is packed with those moving in two opposing currents. Through this mass comes a donkey with a couple of panniers of soil or of bricks, or bundles of scraggly sticks; or a camel surges in, loaded with building-joists or with lime; or a Turkish officer, with a gaily caparisoned horse impatiently stamping; a porter slams along with a heavy box on his back; the water-carrier with his nasty skin rubs through; the vender of sweetmeats finds room for his broad tray; the orange-man pushes his cart into the throng; the Jew auctioneer cries his antique brasses and more antique raiment. Everybody is jostled and pushed and jammed; but everybody is in an imperturbable good humor, for no one is really in a hurry, and whatever is, is as it always has been and will be. And what a cosmopolitan place it is. We meet Turks, Greeks, Copts, Egyptians, Nubians, Syrians, Armenians, Italians; tattered derweeshes, “welees” or holy Moslems, nearly naked, presenting the appearance of men who have been buried a long time and recently dug up; Greek priests, Jews, Persian Parsees, Algerines, Hindoos, negroes from Darfoor, and flat-nosed blacks from beyond Khartoom.

The traveler has come into a country of holiday which is perpetual. Under this sun and in this air there is nothing to do but to enjoy life and attend to religion five times a day. We look into a mosque; In the cool court is a fountain for washing; the mosque is sweet and quiet, and upon its clean matting a row of Arabs are prostrating themselves in prayer towards the niche that indicates the direction of Mecca. We stroll along the open streets encountering a novelty at every step. Here is a musician a Nubian playing upon a sort of tambour on a frame; a picking, feeble noise he produces, but he is accompanied by the oddest character we have seen yet. This is a stalwart, wild-eyed son of the sand, coal-black, with a great mass of uncombed, disordered hair hanging about his shoulders. His only clothing is a breech-cloth and a round shaving-glass bound upon his forehead; but he has hung about his waist heavy strings of goats' hoofs, and those he shakes, in time to the tambour, by a tremulous motion of his big hips as he minces about. He seems so vastly pleased with himself that I covet knowledge of his language, in order to tell him that he looks like an idiot.

Near the Fort Napoleon, a hill by the harbor, we encounter another scene peculiar to the East. A yellow-skinned, cunning-eyed conjurer has attracted a ring of idlers about him, who squat in the blowing dust, under the blazing sun, and patiently watch his antics. The conjurer himself performs no wonders, but the spectators are a study of color and feature. The costumes are brilliant red, yellow, and white. The complexions exhaust the possibilities of human color. I thought I had seen black people in South Carolina; but I saw a boy just now standing in a doorway who would have been invisible but for his white shirt; and here is a fat negress in a bright yellow gown and kerchief, whose jet face has taken an incredible polish; only the most accomplished boot-black could raise such a shine on a shoe; tranquil enjoyment oozes out of her. The conjurer is assisted by two mites of children, a girl and a boy (no clothing wasted on them), and between the three a great deal of jabber and whacking with cane sticks is going on, but nothing is performed except the taking of a long snake from a bag and tying it round the little girl's neck. Paras are collected, however, and that is the main object of all performances.

A little further on, another group is gathered around a storyteller, who is reeling off one of the endless tales in which the Arab delights; love-adventures, not always the most delicate but none the less enjoyed for that, or the story of some poor lad who has had a wonderful career and finally married the Sultan's daughter. He is accompanied in his narrative by two men thumping upon darabooka drums, in a monotonous, sleepy fashion, quite in accordance however with the everlasting leisure that pervades the air. Walking about are the venders of sweets, and of greasy cakes, who carry tripods on which to rest their brass trays, and who split the air with their cries.

It is color, color, that makes all this shifting panorama so fascinating, and hides the nakedness, the squalor, the wretchedness of all this unconcealed poverty; color in flowing garments, color in the shops, color in the sky. We have come to the land of the sun.

At night when we walk around the square we stumble over bundles of rags containing men who are asleep, in all the corners, stretched on doorsteps, laid away on the edge of the sidewalk. Opposite the hotel is a casino, which is more Frank than Egyptian. The musicians are all women and Germans or Bohemians; the waiter-girls are mostly Italian; one of them says she comes from Bohemia, and has been in India, to which she proposes to return. The habitués are mostly young Egyptians in Frank dress except the tarboosh, and Italians, all effeminate fellows. All the world of loose living and wandering meets here. Italian is much spoken. There is little that is Oriental here, except it may be a complaisance toward anything enervating and languidly wicked that Europe has to offer. This cheap concert is, we are told, all the amusement at night that can be offered the traveler, by the once pleasure-loving city of Cleopatra, in the once brilliant Greek capital in which Hypatia was a star.

EGYPT has excellent railways. There is no reason why it should not have. They are made without difficulty and easily maintained in a land of no frosts; only where they touch the desert an occasional fence is necessary against the drifting sand. The rails are laid, without wooden sleepers, on iron saucers, with connecting bands, and the track is firm and sufficiently elastic. The express train travels the 131 miles to Cairo in about four and a half hours, running with a punctuality, and with Egyptian drivers and conductors too, that is unique in Egypt. The opening scene at the station did not promise expedition or system.

We reach the station three quarters of an hour before the departure of the train, for it requires a longtime—in Egypt, as everywhere in Europe—to buy tickets and get baggage weighed. The officials are slower workers than our treasury-clerks. There is a great crowd of foreigners, and the baggage-room is piled with trunks of Americans, 'boxes' of Englishmen, and chests and bundles of all sorts. Behind a high counter in a smaller room stand the scales, the weigher, and the clerks. Piles of trunks are brought in and dumped by the porters, and thrust forward by the servants and dragomans upon the counter, to gain them preference at the scales. No sooner does a dragoman get in his trunk than another is thrust ahead of it, and others are hurled on top, till the whole pile comes down with a crash. There is no system, there are neither officials nor police, and the excited travelers are free to fight it out among themselves. To venture into the mêlée is to risk broken bones, and it is wiser to leave the battle to luck and the dragomans. The noise is something astonishing. A score or two of men are yelling at the top of their voices, screaming, scolding, damning each other in polyglot, gesticulating, jumping up and down, quivering with excitement. This is your Oriental repose! If there were any rule by which passengers could take their turns, all the trunks could be quickly weighed and passed on; but now in the scrimmage not a trunk gets to the scales, and a half hour goes by in which no progress is made and the uproar mounts higher.

Finally, Ahmed, slight and agile, handing me his cane, kuffia and watch, leaps over the heap of trunks on the counter and comes to close quarters with the difficulty. He succeeds in getting two trunks upon the platform of the scales, but a traveler, whose clothes were made in London, tips them off and substitutes his own. The weighers stand patiently waiting the result of the struggle. Ahmed hurls off the stranger's trunk, gives its owner a turn that sends him spinning over the baggage, and at last succeeds in getting our luggage weighed. He emerges from the scrimmage an exhausted man, and we get our seats in the carriage just in time. However, it does not start for half an hour.

The reader would like to ride from Alexandria to Cairo, but he won't care to read much about the route. It is our first experience of a country living solely by irrigation—the occasional winter showers being practically of no importance. We pass along and over the vast shallows of Lake Mareotis, a lake in winter and a marsh in summer, ride between marshes and cotton-fields, and soon strike firmer ground. We are traveling, in short, through a Jersey flat, a land black, fat, and rich, without an elevation, broken only by canals and divided into fields by ditches. Every rod is cultivated, and there are no detached habitations. The prospect cannot be called lively, but it is not without interest; there are ugly buffaloes in the coarse grass, there is the elegant white heron, which travelers insist is the sacred ibis, there are some doleful-looking fellaheen, with donkeys, on the bank of the canal, there is a file of camels, and there are shadoofs. The shadoof is the primitive method of irrigation, and thousands of years have not changed it. Two posts are driven into the bank of the canal, with a cross-piece on top. On this swings a pole with a bucket of leather suspended at one end, which is outweighed by a ball of clay at the other. The fellah stands on the slope of the bank and, dipping the bucket into the water, raises it and pours the fluid into a sluice-way above. If the bank is high, two and sometimes three shadoofs are needed to raise the water to the required level. The labor is prodigiously hard and back-straining, continued as it must be constantly. All the fellaheen we saw were clad in black, though some had a cloth about their loins. The workman usually stands in a sort of a recess in the bank, and his color harmonizes with the dark soil. Any occupation more wearisome and less beneficial to the mind I cannot conceive. To the credit of the Egyptians, the men alone work the shadoof. Women here tug water, grind the corn, and carry about babies, always; but I never saw one pulling at a shadoof pole.

There is an Arab village! We need to be twice assured that it is a village. Raised on a slight elevation, so as to escape high water, it is still hardly distinguishable from the land, certainly not in color. All Arab villages look like ruins; this is a compacted collection of shapeless mud-huts, flat-topped and irregularly thrown together. It is an aggregation of dog-kennels, baked in the sun and cracked. However, a clump of palm-trees near it gives it an air of repose, and if it possesses a mosque and a minaret it has a picturesque appearance, if the observer does not go too near. And such are the habitations of nearly all the Egyptians.

Sixty-five miles from Alexandria, we cross the Rosetta branch of the Nile, on a fine iron bridge—even this portion of the Nile is a broad, sprawling river; and we pass through several respectable towns which have an appearance of thrift—Tanta especially, with its handsome station and a palace of the Khedive. At Tanta is held three times a year a great religious festival and fair, not unlike the old fair of the ancient Egyptians at Bubastis in honor of Diana, with quite as many excesses, and like that, with a gramme of religion to a pound of pleasure. “Now,” says Herodotus, “when they are being conveyed to the city Bubastis, they act as follows:—for men and women embark together, and great numbers of both sexes in every barge: some of the women have castanets on which they play, and the men play on the flute during the whole voyage; and the rest of the women and men sing and clap their hands together at the same time.” And he goes on to say that when they came to any town they moored the barge, and the women chaffed those on shore, and danced with indecent gestures; and that at the festival more wine was consumed than all the rest of the year. The festival at Tanta is in honor of a famous Moslem saint whose tomb is there; but the tomb is scarcely so attractive as the field of the fête, with the story-tellers and the jugglers and booths of dancing girls.

We pass decayed Benha with its groves of Yoosef-Effendi oranges—the small fruit called Mandarin by foreigners, and preferred by those who like a slight medicinal smell and taste in the orange; and when we are yet twenty miles from Cairo, there in the south-west, visible for a moment and then hidden by the trees, and again in sight, faintly and yet clearly outlined against the blue sky, are two forms, the sight of which gives us a thrill. They stand still in that purple distance in which we have seen them all our lives. Beyond these level fields and these trees of sycamore and date-palm, beyond the Nile, on the desert's edge, with the low Libyan hills falling off behind them, as delicate in form and color as clouds, as enduring as the sky they pierce, the Pyramids of Geezeh! I try to shake off the impression of their solemn antiquity, and imagine how they would strike one if all their mystery were removed. But that is impossible. The imagination always prompts the eye. And yet I believe that standing where they do stand, and in this atmosphere, they are the most impressive of human structures. But the pyramids would be effective, as the obelisk is not, out of Egypt.

Trees increase in number; we have villas and gardens; the grey ledges of the Mokattam hills come into view, then the twin slender spires of the Mosque of Mohammed Ali on the citadel promontory, and we are in the modern station of Cairo; and before we take in the situation are ignominiously driven away in a hotel-omnibus. This might happen in Europe. Yes; but then, who are these in white and blue and red, these squatters by the wayside, these smokers in the sun, these turbaned riders on braying donkeys and grumbling dromedaries; what is all this fantastic masquerade in open day? Do people live in these houses? Do women peep from these lattices? Isn't that gowned Arab conscious that he is kneeling and praying out doors? Have we come to a land where all our standards fail and people are not ashamed of their religion?

O CAIRO! Cairo! Masr-el-Kaherah, The Victorious! City of the Caliphs, of Salah-e'-deen, of the Memlooks! Town of mediaeval romance projected into a prosaic age! More Oriental than Damascus, or Samarcand. Vast, sprawling city, with dilapidated Saracenic architecture, pretentious modern barrack-palaces, new villas and gardens, acres of compacted, squalid, unsunned dwellings. Always picturesque, lamentably dirty, and thoroughly captivating.

Shall we rhapsodize over it, or attempt to describe it? Fortunately, writers have sufficiently done both. Let us enjoy it. We are at Shepherd's. It is a caravansary through which the world flows. At its table d'hote are all nations; German princes, English dukes and shopkeepers, Indian officers, American sovereigns; explorers, savants, travelers; they have come for the climate of Cairo, they are going up the Nile, they are going to hunt in Abyssinia, to join an advance military party on the White Nile; they have come from India, from Japan, from Australia, from Europe, from America.

We are in the Frank quarter called the Ezbekeëh, which was many years ago a pond during high water, then a garden with a canal round it, and is now built over with European houses and shops, except the square reserved for the public garden. From the old terrace in front of the hotel, where the traveler used to look on trees, he will see now only raw new houses and a street usually crowded with passers and rows of sleepy donkeys and their voluble drivers. The hotel is two stories only, built round a court, damp in rainy or cloudy weather (and it is learning how to rain as high up the Nile as Cairo), and lacking the comforts which invalids require in the winter. It is kept on an ingenious combination of the American and European plans; that is, the traveler pays a fixed sum per day and then gets a bill of particulars, besides, which gives him all the pleasures of the European system. We heard that one would be more Orientally surrounded and better cared for at the Hotel du Nil; and the Khedive, who tries his hand at everything, has set up a New Hotel on the public square; but, somehow, one enters Shepherd's as easy as he goes into a city gate.