Title: The Pansy Magazine, November 1887

Author: Various

Editor: Pansy

Release date: August 28, 2016 [eBook #52909]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Emmy, Juliet Sutherland and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

|

GOLD MEDAL, PARIS, 1878.

BAKER'S Breakfast Cocoa. Warranted absolutely pure Cocoa, from which the excess of Oil has been removed. It has three times the strength of Cocoa mixed with Starch, Arrowroot or Sugar, and is therefore far more economical, costing less than one cent a cup. It is delicious, nourishing, strengthening, easily digested, and admirably adapted for invalids as well as for persons in health.

——————

Sold by Grocers everywhere. ——————

W. BAKER & CO., Dorchester, Mass.

|

Greatest inducements ever offered. Now's your time to get up orders for our celebrated Teas and Coffees and secure a beautiful Gold Band or Moss Rose China Tea Set, or Handsome Decorated Gold Band Moss Rose Dinner Set, or Gold Band Moss Decorated Toilet Set. For full particulars address

FACE, HANDS, FEET,

and all their imperfections, including Facial

Development, Hair and Scalp, Superfluous

Hair, Birth Marks, Moles, Warts, Moth,

Freckles, Red Nose, Acne, B’lk Heads, Scars,

Pitting and their treatment. Send 10c. for

book of 50 pages, 4th edition. Dr. John H. Woodbury,

37 North Pearl St., Albany, N. Y. Established 1870.

In every household old-fashioned and worn jewelry and plate accumulate, becoming “food” for burglars or petty thieves.

If the readers of Babyland will get out their old gold, old silver, old jewelry, and send it by mail or express to me, I will send them by return mail a certified check for full value thereof.

We warrant these Dyes to color more goods, package for package, than any other Dyes ever made, and to give more brilliant and durable colors.

| THE DIAMOND GOLD, SILVER, BRONZE and COPPER | PAINTS |

For gilding Fancy Baskets, Frames, Lamps, Chandeliers, and for all kinds of ornamental work. Equal to any of the high priced kinds and only 10 cts. a package. Also Artists’ Black for Ebonizing.

Sold by Druggists everywhere. Send postal for Sample Card and directions for coloring Photographs and doing fancy work.

|

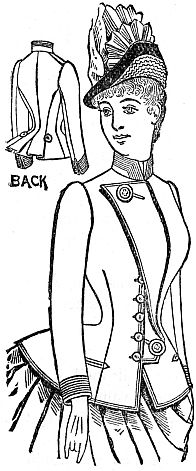

DRESS STAY. |

Soft, Pliable and Absolutely unbreakable. Standard Quality, 15 cents per yard. Cloth covered, 20 cents. Satin covered, 25 cents. For sale everywhere. Try it.

| LADIES’ FANCY WORK |

Ingalls’ Illustrated Catalogue of Stamping Outfits, Felt, Linen and Silk Stamped Goods, Fancy Work Materials, Books, Briggs Transfer Patterns, etc., sent free for one 2-c. stamp.

J. F. Ingalls, Lynn, Mass. |

CANDY! | Send one, two, three or five dollars for a retail box, by express, of the best Candies in the World, put up in handsome boxes. All strictly pure. Suitable for presents. Try it once. Address

C. F. GUNTHER, Confectioner, 78 Madison Street, Chicago. |

Farm-Life for Young People, by Ik Marvel (Donald G. Mitchell), Out-of-Door Papers by John Burroughs, together with Walking, Rowing, and The Training of Dogs, three papers by Louise Imogen Guiney, will form a delightful phase of the coming volume.

A Painter of Child-Life. (First Art Paper.) A beautiful art-paper for children, by the English art-writer, T. Letherbrow, about the English painter, Warwick Brookes, who was once a little “tear-boy” in the Manchester cotton-mills, and afterwards rose to great eminence in art. This remarkable article is to have twenty exquisite illustrations of child-life from photographs of the artist’s paintings and drawings.

Daniel Webster in New Hampshire. (First Historical Article.) Reminiscences, anecdotes, and gossip about the great statesman, given to the author, Miss Amanda B. Harris, by Webster’s early friends and neighbors in New Hampshire, or gathered from unpublished letters. With portraits from life-photographs, and many sketches.

About Rosa Bonheur. (Second Art Paper.) This charming account of the wonderful French woman who has painted the finest animal pictures since Landseer has been written for Wide Awake by Rosa Bonheur’s friend of many years, the American artist, Henry Bacon. The picture of her in studio dress painting the famous “Head of a Lion” was drawn by Mr. Bacon; the portrait of her at eighteen is from a painting by her brother, Auguste Bonheur. Full of anecdote and with many pictures.

The Story of Boston Common, by Edward Everett Hale, is now complete in MS., and the long-expected series, touching much of early American history, will be given, in three or more chapters, with historic and modern pictures, during the coming summer.[3a]

The Medal Children of the Renaissance. (Third Art Paper.) An art article for young readers by Frances H. Throop about some high-born children of the fifteenth century, whose portraits were sculptured or cast in medallions; these lovely medals are preserved in European museums and collections, being regarded as precious art-treasures; and Miss Throop has made casts and drawings from the originals to illustrate her paper.

An Old House on Royal Street. (Second Historical Article.) This delightful paper about old New Orleans and early Louisiana by Mrs. M. E. M. Davis (author of In War-Times at La Rose Blanche), written in the old house that was General Jackson’s headquarters, abounds in reminiscences of Indian, French, Spanish and Creole days, of Jackson, Galvez, the pirate Lafitte, Bienville, Pere Antoine, Don Almonaster, and other famous men of the Southwest. Full of portraits.

Elbridge S. Brooks will contribute a series of practical papers for young people embodying suggestions helpful to them in their desire to get on in the world. The papers will be a departure from the customary “Letters to Young Men.” They will be, rather, in the spirit of appreciation and comradeship, and will endeavor to indicate and open toward the possibilities that exist for the boys and girls of America in these busy days that are merging into the twentieth century.

For Business Boys will be pithy, unforgettable, lifting words, straight from man to boy, as felt and said by a man whose business writing is even better known than his name—a companion paper to Mr. Brooks’ series.[4a]

Among Sir Walter Ralegh’s Homes. (Third Historical Article.) Sir Walter is everybody’s hero, and Mrs. Raymond Blathwayt has written a charming paper about his birthplace and his young days, and she has sent over many beautiful photographs of his old haunts made expressly for Wide Awake; the manuscript itself has been prepared under the friendly supervision of Dr. Brushfield the English antiquarian and great Ralegh authority.

Typical Children of England, by Julia Cartwright, will be a notable article, illustrated with most charming pictures of English children of the present day, all from life studies—the aristocratic type, the peasant type, the athletic, the spiritual, etc.

Brilliant additions to the preceding serials and specialties will include ballads, poems, and the following

Further papers about Famous Pets are in preparation; Tangles will have new novelties; The Contributors and the Children, and other departments, will grow in interest; the artistic features will continue to delight young and old alike.

| BABYLAND | What Babies and Mammas may look for during 1888. |

The twelve numbers of Babyland for 1888 will be like twelve Christmas stockings stuffed full of delights—the choicest nuts, candies and raisins of jingledom and storyland; and there will be three special big delicious bon-bons besides.

Me and Toddlekins is a story told by “Me,” whose other name is Mew-mew, and written down by Margaret Johnson, with cunning pictures of “Me” and Toddlekins, and their doings, drawn by the same Margaret Johnson.

Six New Finger Plays will be contributed by Emilie Poulsson. The instant popularity of the first series of Finger Plays, among little children, mothers, and kindergarten teachers, has tempted Miss Poulsson to prepare six more; the verses are delightfully amusing and graceful, and the pictorial instructions showing how to play the Plays, and the pictures themselves, will be by the same artist, Mr. L. J. Bridgman.

Allie and the Crickets will be the subject of six dear little stories that the crickets told to Baby Allie—some on the hearth as she sat in her mother’s lap at twilight, some when she was at play out in the sunny fields—very cunning little stories all of them (which Clara Doty Bates overheard and has related for other babies). Many pictures.

Babyland will be full of pictures, too, big and beautiful, little and funny; and it will be printed in large clear black letters, as usual, on strong fine paper, and have pretty pink covers. All sent by mail for 50 cents a year.

| OUR LITTLE MEN AND WOMEN | A glimpse into 1888. |

This magazine for youngest readers will be even more entertaining in text and pictures than in the past, and in the stories will be hidden bits of wisdom as well. There will be seventy-five full-page pictures.

Stories of Captain John Smith and Princess Pocahontas, twelve of them, will be related by Frances A. Humphrey; they will be accompanied with many historical pictures.

Laura’s Holidays, a serial story in twelve chapters, by Henrietta K. Eliot, will relate what one little girl did in a year of holidays. Full-page pictures by Elizabeth S. Tucker.

Tiny Folks in Armor is the title of twelve talks about beetles, by Fannie A. Deane. There will be pictures of the beetles.

There will be a set of Twelve Flower Poems by Clara Doty Bates, whose bird poems have been so popular the past year.

Buffy’s Letters to his Mistress, six in all, will be published by the kind permission of Elizabeth F. Parker. Buffy is a coon-cat, and his doings will be pictured by L. J. Bridgman.

Little People of the Plaza will be told about in six Mexican stories by Jennie Stealey. Some Mexican animals also.

Adapted from the French there will be Susanna’s Auction, in six funny chapters, each chapter with funny pictures.

Besides these serials and series, there will be a treasury of short stories and verses, bright and interesting, and full of pictures as a Christmas pudding with plums. The best magazine for home and school reading. $1.00 a year by mail.

| THE PANSY | Pansy’s Own Magazine. Something about 1888. |

Up Garret is the title of Pansy’s new serial, and readers of “A Sevenfold Trouble” will be glad to know it is a sequel to that story, and to continue their acquaintance with its people.

The Golden Text Stories for 1888 will be given under the title of We Twelve Girls, and they will be the actual accounts of how twelve girls tried to live by certain golden texts.

The “Little Red Shop” has roused such interest that Margaret Sidney will relate more about Jack, Cornelius, Rosalie, and the baby, in a sequel to be called The Old Brimmer Place.

Treasures: Their Hiding and Finding is the title of a new serial by Rev. C. M. Livingston, full of wise entertainment.

By Charles R. Talbot. 12mo, cloth, $1.50.

An escapade of a bright young fellow who “shipped” for a yachting cruise in vacation.

The story has nothing to do with the question whether it pays to know one’s work and do it and “be,” as the phrase goes, “a gentleman”; but, if the reader chooses to think of them, he will find plenty of stimulant.

By Elbridge S. Brooks, author of The American Indian, In Leisler’s Times, In No-Man’s Land, and others. 12mo, cloth, $1.50.

An historic tale connected with a holiday in every month of the year.

There is the snapdragon Christmas quarrel of James I. of England with his sons about the release of Sir Walter Raleigh; a New Year’s meeting of Margery More with Henry VIII; how William Penn got his motto “Be true, be leal, be constant,” on St. Valentine’s Day; how the Earl of Kildare kept St. Patrick’s; the wise men of Gotham fool King John on the first of April; and so on through the months.

These stories out of history practise one in the times they take him back to.

By Mrs. G. R. Alden (Pansy, author of the hundred Pansy books and editor of The Pansy magazine). 12mo, cloth, 1.50.

What is very widely known, but to many obscurely known as the Chautauqua movement is told with a fulness that people would lack the patience to read, if the tale began there and stopped there.

Begins with a little civilized girl and a runaway—actually a tramp. But trust Pansy for making good company.

A novel with the distinctly double purpose of showing how the Reading Circles gather together for self-improvement the most impossible people young and old, and of recommending religious life.

12 mo, cloth, illustrated, each, 1.25.

Four Boy Stories. By Charles R. Talbot. Brisk and unconventional, bright as boy stories can be. Girl stories, too.

Story of Honor Bright.

Royal Lowrie: A General Misunderstanding.

Royal Lowrie’s Last Year at St. Olaves.

A Double Masquerade: A Romance of the Revolution.

12mo, cloth, illustrated, each, 1.25. Four books of disconnected short stories.

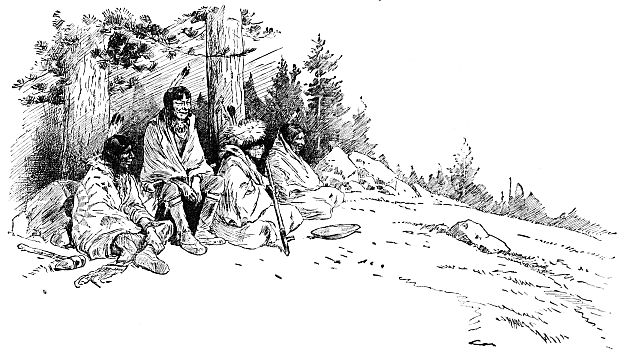

Thirteen boys’ stories. By James Otis, Kate Foote, Mary Hartwell Catherwood, J. E. Cottin, Ernest Ingersoll, Flora Haines Apponzi, C. E. S. Wood, F. L. Stealey, Ellen Olney Kirk, Helen E. Swett, Alice Wellington Rollins and Anna Leach.

By Joaquin Miller, Marion Harland, Mary Catherine Lee, H. F. Marsh, Kate Ganett Wells, George F. Hebard, A. M. Griffin, James Otis, John Preston True, George Varney and Mary B. Claflin.

Stories of Travel. By Annie Sawyer Downs, Charlotte S. Fursdon, Mary Gay Humphreys, Culling Cliver Eardley, Rose G. Kingsley, S. W. Duffield, Arthur Gilman, Julian B. Arnold, David Ker, Lucy C. Lillie, Mrs. Raymond Blathwayte, Arthur F. J. Crandall and C. E. Andrews.

Twenty-five. By Emma W. Demeritt, Caroline Atwater Mason, Frederick Schwatka, Rose G. Kingsley, F. L. Stealey, Lizzie W. Champney, Hamilton W. Mabie, Nora Perry, Granmere Julie, Jane Howard, D. C. McDonald, Mrs. Mary A. Parsons, Margaret LeBoutillin, Belle Stewart, Lucy Lincoln Montgomery, Erskine M. Hamilton, Garry Gains, Theodora R. Jenness, Louise Stockton, H. M. S., Mrs. Annie A. Preston, B. P. Shillaber and Charles E. Bolton.

3 vols., 12mo, each 1.25.

By Frank H. Converse. A Philadelphia street-boy’s race with fortune takes him to Boston and farther. Somehow he gets into the way of picking out the proper thing to do and doing it.

By Minna Caroline Smith. A Western story of city and country boys together who have a good time and get experience.

By Philip D. Haywood. A boy sea-story. It begins well: “I go to sea.”

18 volumes, 12mo, cloth, 1.50.

Take these four:

To review their lives and work and catch the spirit of both in 300 or 400 pages of easy type is to give the bones of biography; which is all nine tenths of us have the time to read; and the other tenth are glad of the bones before they come to the more elaborate whole.

The other fourteen:

Edited by Pansy. First and second series, 4to, boards, each .75.

Sketches, tales and pictures on Old-World subjects.

First and second series. Edited by Pansy. 4to, boards, each .75.

Sketches, tales and pictures on New-World subjects.

By Anna F. Burnham. 4to, boards, .75.

Big letters, big pictures, and easy stories of elephants, lions, tigers, lynxes, jaguars, bears, and many others.

By Anna F. Burnham. 4to, boards .75.

Big letters, big pictures, and easy stories of farm and house animals.

By Margaret Sidney. Illustrated, 12mo, cloth, 1.50.

Story of five little children of a fond and faithful and capable “mamsie.” Full of young life and family talk. How they lived in the little brown house and how they came to go out of it. One of the most successful books of a bright and always cheery writer.

By Margaret Sidney. Illustrated, 16mo, cloth, 1.00.

Eight rollicking stories of children. And some of the children are those same Peppers.

By Margaret Sidney. 12mo, cloth, 1.25.

For older readers. Eleven stories in which New England dialect, customs, ways, and people appear with many in-door and out-door notions.

Square 8vo, boards, tinted edges, 1.50; cloth, gilt edges, 2.25.

Two boys go to the Water Color Exhibition and make numerous sketches of what they see there. Between the pictures is picture-talk.

Then the professor discourses on tools and colors and books and schools and models—in general, means of art.

Then an account of the Children’s Hour: a novel art school. And portraits, examples and sketches of twenty-four American Artists. With a few useful words on architecture.

4to, boards, 1.50; cloth, 2.25.

Poems of all the year round, done up with pictures for children at Christmas.

4to, boards, 1.50; cloth, 2.25.

A picture-and-story-book by New England authors.

4to, boards, gilt edges, 1.50; cloth, 2.25. By John G. Whittier.

And nearly two hundred other poems for children with as many pictures for children.

4 vols, 12mo, cloth, each, 1.00.

By Abel B. Berry. A New Hampshire historical story of Indian times.

By Belle C. Greene. A story of family life in one of the shut-in nooks of New Hampshire, Sherburne “Holler,” where souls are sometimes out of all proportion to their surroundings.

For children, and for those who love children. From the German of Madame Spyri by Lucy Wheelock. Five delightful tales of present life in Switzerland.

A story for children and those who love children. From the German of Madame Spyri by Lucy Wheelock. The pleasant and unpleasant people and circumstances somehow fall together naturally to work up a little earthly paradise, the delights of which in no way depend on accidental surroundings but on generosity of soul.

Three instructive and interesting books by Mrs. A. E. Anderson-Maskell. 12mo, cloth, each 1.00.

4 volumes, 16mo, 3.00.

Four books of nearly a dozen each short stories and sketches by many authors.

What a wise physician said to a frail young girl and her mother together, and what the gymnasium is good for.

Three baccalaureate sermons.

A competent man’s series of talks on emergencies. Much in a little book.

Eighty-three successful men say what they think of the means of success and avoidance of failure. With these opinions the author makes this book—a little book with a great deal in it.

Two delightful Swiss stories. Madame Spyri.

A short treatise on the hygiene of alcohol.

Alaska. Its Southern coast and the Sitkan Archipelago. By Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore. Illustrated from photographs. 12mo, cloth, 1.50.

History of the American People. By Arthur Gilman, M. A. 12mo, cloth, 668 pages, fully illustrated, 1.50. A scholarly history short and fairly full and, what is of great account for popular use, sympathetic. A patriotic work well done.

China. By Robert K. Douglas. 12mo, cloth, 566 pages, fully illustrated, 1.50. Very brief as to history. Chiefly an account of present customs.

Egypt (The History of). By Clara Erskine Clement. 12mo, cloth, 100 full page illustrations, 476 pages, 1.50. A sketch from the earliest date to the British occupation.

India (The History of). By Fannie Roper Feudge. 12mo, cloth, 100 full-page illustrations, 640 pages, 1.50. An account of the country and people as they are by a resident; with a brief survey of history.

Japan and its Leading Men. By Charles Lanman. 12mo, cloth, illustrated, 1.50. Sketches of eminent Japanese men with a glance at the national history.

Spain (The History of). By Prof. James Albert Harrison. 12mo, cloth, 100 full-page illustrations, 717 pages, 1.50. A brief but careful history.

Switzerland (The History of). By Harriet D. Slidell Mackenzie. 12mo, cloth, 100 full-page illustrations, 385 pages, 1.50. The story of a most interesting people in simple language.

Donal Grant. 12mo, cloth, 1.50. “It was granted, however, that if a boy stayed with him long enough he was sure to turn out a gentleman.”—Let that sentence out of it stand for the book.

Imagination (The) and other Essays. 12mo, cloth, 1.50. A volume of essays mostly on literary subjects.

Warlock o’ Glenwarlock. 12mo, cloth, illustrated, 1.50. A lad without fortune works his way in Scotland.

What’s Mine’s Mine. 12mo, cloth, 1.50. A novel which shows in action the beauty of love and faithfulness.

Weighed and Wanting. 12mo, cloth, 1.50. A noble woman escapes a sordid husband.

Dorothy Thorn of Thornton. By Julian Warth. A vigorous, even, well-sustained, intensely interesting, wholesome story.

The Full Stature of a Man. By Julian Warth. The author’s first novel; a very promising one.

Gladys: A Romance. By Mary G. Darling. This skein is untangled in a perfectly natural fashion—when you look back from the finis, which means a great deal more than it says.

Grafenburg People. By Reuen Thomas. A novel out of a row in the church—a good one; that is, novel, not row.

Romance of a Letter. By Lowell Choate. A life with an inflexible purpose turns out happy or not, according to—what? The old question: When do we arrive at “years of discretion?”

Rusty Linchpin and Luboff Archipovna. By Madame Kokhanovsky. Two stories of Russian life, of characteristic simplicity and interest.

Whosoever, therefore, shall confess me before men, him will I confess also, before my Father which is in heaven.

He was a burning and a shining light.

Come unto me, all ye that labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.

It is lawful to do well on the Sabbath days.

I SHALL have to begin the story for you, or you would never understand. It happened that the twelve girls in Mr. Shepard’s Bible class were very nearly of an age; were class-mates in day school, as well as on Sundays, and were very fond of one another.

They lived in different parts of the country, but were gathered in Clayville at boarding-school.

It came to pass that on this year of which I write, they were to be widely scattered; only one was to return to the school in the fall. It was because of this fact that the thought grew up, out of which grows my story. On the last Sabbath before they separated, Mr. Shepard gave to each a tiny book of texts; one for each week, with the hint that he would like them to live by those words in the coming year.

This set them to thinking and to talking. After many plans, it was finally agreed that they should each select a month in which to write a letter that should give some account of an experience connected with one of the verses for that month. These letters were to be passed by mail from one member of the class to another until each had read them; and I, being a particular friend of several of the girls, have the privilege of reading them, and of making a copy for you, my Blossoms.

Cora Stevens had the month of November, and, without more introduction, I give you her letter:

I hope you every one miss me as much as I do you! Really and truly, I am dreadfully homesick for school! But this is my special letter, so I must not take time for anything else. I’m sorry I promised to write the first one, because I don’t know just how to write it, and I have such a mean, silly little story to tell, that I’m ashamed of it, anyhow.

I chose that verse about “confessing before men,” for the one to write my letter on. And I meant to go to the young people’s meeting, and to the Band, and confess Him in some way that would be nice to tell; and I didn’t do anything of the kind.

Don’t you think my story is about a cat! Who would have supposed that a cat would get mixed up with a verse like that?

We went to grandma’s, as usual, for the month of November, but things there were very unusual, for aunt Kate was married, and the house was full of company and confusion.

It is about the wedding day that I’m to tell you. I wish you could have seen the tables after they were ready. They did look too lovely for anything! The central table was magnificent. All the old silver and queer, quaint china which have been in grandma’s family for ages, had been brought out for decoration, and people say that the tablecloth was the finest piece of old damask that has ever been used in this part of the world. If I had Nettie’s descriptive powers, I could give you a picture of the whole; but as it is, I want you to confine your attention to one dish—the loveliest cut-glass beauty that was ever seen. It was amber-colored sometimes, with little threads of crimson running through it, which reminded one of a sunset. Besides, it was a very peculiarly-shaped dish, and as frail as a cobweb. Uncle Fred found it in Paris, and brought it to the bride. Uncle Fred, you understand, is the bridegroom.

Well, it was on the special wedding table, just before the bride’s seat, and was filled with the most exquisite flowers.

Grandma did not want the dish used, because it was so frail and so rare, but aunt Kate insisted that it should be placed just there, and be filled with orange-buds.

Grandma had just seen that the very last touches had been put to the table, and had taken the children in for a look, and then had said, as she shut the dining-room door: “Now, don’t one of you children open that door again. I wouldn’t have anything go wrong in there for a great deal.”

Then she went up to take a last look at aunt Kate, before she became Mrs. Fred Somerville.

Just at that moment little Sallie Evans came[3] running down the hall, her eyes full of tears. Her mamma had called her just as grandma took the children in to see the tables, and she had missed the sight.

“And now I sha’n’t see them at all, till everything is spoiled,” she said, “for they aren’t going to let the little bits of cousins come to the first table.” And she sobbed outright.

Now it never entered my mind that grandma meant me, when she said, “You children,” because—well, because, you know, I am thirteen, and there are three at home, younger than I, and I’m used to being trusted. So I said, “Never mind, Sallie, I’ll let you look at them; but you must look fast, for it is almost time for the wedding.”

So, in we went. And Sallie, who is the most beauty-loving little creature of eight, whom I ever saw, seemed to have eyes only for that lovely glass dish, which she had never seen before. She clasped her hands together with an eager little “Oh!” and ran towards it. I don’t suppose she would have touched it, but I was excited, and so afraid she would, that I ran after her, calling out, “Don’t touch anything!” and put out my hand to prevent it. And then, I don’t know how it happened—does anybody know how such accidents happen? The lace from my sleeve caught in one of the points of the glass, or in one of the stems of flowers, or somehow,—I don’t suppose I could do it again if I tried,—but over that glass went, the water pouring itself out in the most disgusting way, on the damask cloth, and a long crooked piece snapped from the upper edge of the dish!

O, dear! Don’t ask me how I felt. I couldn’t describe it, even though I were sitting on the dear old bed at No. 7, with half a dozen of you beside me, and the rest cuddled around close at hand.

There wasn’t any time to do anything. I heard them calling, at that moment, for I was one of the bridesmaids. I just had to force back my tears and my fright, and run and take my place in the procession. We all got through it somehow. I hope aunt Kate heard what the minister said; I didn’t; but it is safe to say that she was not thinking of what I was.

Immediately after the ceremony, we went to the dining-room, and then the awful accident was discovered. I don’t know which I was the most sorry for, grandma or myself. I didn’t mean to tell about it then, because I thought it wouldn’t be the proper time; and then, of course, it would be dreadful to have to speak before them at all.

But what should grandma do, after we were all seated, and the eating had begun, but lean over to aunt Kate and say in a low tone: “That is some of Jill’s work; if I don’t get rid of a cat who can open doors, before I am a day older, it will be because I am not smart enough.”

Now, Jill is the cutest cat that was ever born, I do believe; there isn’t a door in grandma’s house that she cannot manage to open almost as well as though she had hands.

I never thought of her blaming the cat; and now the story came out, just as they guessed it had happened, and all the people at our end of the table talked it over.

Even then, I don’t know whether I would have spoken, because Jill is only a cat, you know, and her feelings couldn’t be hurt by bearing blame that didn’t belong to her for a few hours, until I could see grandma alone. But, just as I was thinking that, I heard grandma say: “The fault rests with little John. I charged him a dozen times to keep watch of that cat, and not on any account let her out of the barn to-day; and that is all the good it did! I think I have given John a lesson on obedience that he will remember.”

Now John is the little errand boy; a real nice chubby little fellow, who was very fond of aunt Kate, and who had never tasted wedding cake, and he was to drive one of the carriages to the depot that very day, to see the bridal party off.

It all came over me like a flash—how grandma would forbid his coming in to the wedding supper, and how she would not let him drive to the depot, but would send him to bed; and I felt just as though I should choke!

Even then, it didn’t seem to me that I could speak out then and there; and I don’t believe I could have done it, but for the verse.

Girls, I know you don’t see how the verse is coming in, and I can’t explain myself how it seemed to fit; there was certainly nothing about “confessing” Jesus in my telling of what I had done. And yet, you see, I knew I ought to tell,[4] and I know it is what Jesus would do in my place, and it would be showing that I wanted to copy him, and—well, anyhow, it seemed to fit exactly, though I can’t explain it. And I spoke right out, loud and fast: “Grandmother, it wasn’t the cat; John didn’t let the cat out; it was I did it.”

My voice sounded so loud that it almost seemed as though they could hear me down at the church; the people at our table all stopped talking, and I just knew they could hear my heart beat.

“You!” said grandma. “You let the cat out?”

“No, ma’am,” I said, “I broke the dish.”

Then she questioned, and I answered, until somehow, she had the whole story.

I don’t think any tears dropped, but my eyes and my throat felt full of them. It didn’t seem to me that I could say another word, and then grandma said: “Well, well, child, there are worse things in the world than broken dishes. Eat your wedding cake, and think no more about it.” And I heard her call one of the waiters, and say to him: “Tell little John that he may dress himself again in his best suit, and come to the dining-room as soon as he is ready.” Then I knew that I had been none too soon with my confession.

And the bride, my dear, sweet aunt Kate, leaned over toward me and spoke low, “There are better things than glass dishes,” she said; “there are little nieces who are true.”

And papa looked across the table at me, and nodded, and smiled.

And in spite of the lovely broken dish, and the tablecloth, and my being ashamed, and all, I never felt happier in my life.

And as for the verse, if you girls can’t fit it to the cat story, I shall not be surprised; for I can’t explain it myself, but I know they fitted when the time came. Good-by!

Water that flows from a spring, does not freeze in the coldest winter. And those sentiments of true friendship which flow from the heart cannot be frozen by adversity.

THERE are four of us young people at home: first I, who am sixteen, then there is a long gap, and next comes Katie, who is eight, and Bessie, who is six, and last of all baby Harry, who is not yet two. But we were all a year younger when what I mean to tell you of happened, for that was a year ago.

I spoke of Katie and Bessie and Harry and myself as the young people, because I think I am rather too old to be called a child, and I didn’t know how else to put it, but I don’t at all mean to call father and mother old. It is true father has a great many gray streaks in his hair, but I think that is more from care than from age.

It makes me sad, however, very sad, to see father’s hair changing color; but when I speak of it, he only laughs and says: “The whites are gaining the ascendency, and the aborigines becoming extinct.”

Father and mother have not looked like themselves since the summer mother was so ill. That was the most dreadful period of my life, I am sure. For a long time we thought she couldn’t recover. She was ill, of course, to begin with, and then the expense of having a doctor and nurse preyed on her mind and made against her. I really believe mother minded that more than the pain she suffered! At one time she got so nervous with thinking of it, that she said Dr. May’s visits did her more harm than good, and declared she wouldn’t see him again; but Dr. Armstrong, our minister, happened to come in just then, and he soon reasoned her out of all that and made her see things differently.

There couldn’t possibly be a nicer minister than Dr. Armstrong,—I can’t begin to say how much I love him; better, indeed, than anybody in the world, outside of home, except a dear friend, Miss Judith Hepburn. Miss Judith lives next door to us; she is old and very poor; she has, in fact, nothing in the world but the house she lives in, and so she occupies only one of the rooms on the first floor, and lives on the rent from the others. But Miss Judith is as happy as if she possessed all this world has to offer, and happier, too, for that matter, and this[5] is because she is such a true Christian. “Whatever befalls us is good,” she says, “whether it comes in the shape of prosperity or of adversity, because everything is bestowed by a loving Hand.”

I forgot to say, all this while, that my name is Annie—Annie Gray—but Miss Judith never calls me anything but “Martha.” She commenced this when mother was ill, because I kept so busy, and perhaps, too, because I was “troubled about many things,” for indeed I was all during her illness, and for a long time after, too, for the debt we owed to the doctor and nurse hung like a black cloud over the household. It is different with some people, but debt has always seemed a very serious evil to us. I believe father has dreaded it almost more than anything else, and up to mother’s illness, he had always avoided it; but the demands which sickness makes are very great, and can’t be easily disregarded.

Ah! how often I have heard father say: “Owe no man anything,” after which he would always add, “whether this is a Divine command,[6] or only loving counsel I cannot say, but, in either case, I shall not willingly disregard it.”

Well, it was right funny, but soon after mother’s illness, Dr. Armstrong commenced his Friday evening lectures to the congregation “On Secular Matters,” as he said in his notice. Father took me to the first one, and I couldn’t help giving his hand a squeeze when he gave out the subject, “Debts: How They are Made, and How They May be Paid.” I can’t remember the words he used, which is a pity, but Dr. Armstrong’s words, as well as his thoughts, are forcible, but I know the sense of it all was that debts are generally commenced in a small way, little by little, little by little, they are added one to the other, till presently an account is presented to us of such overwhelming proportions that we despair of ever wiping it out. “But I trust,” he added, “that none of my friends who find themselves in this unhappy situation will give way for a moment to a feeling of discouragement. Step by step have we been led into trouble; let us retrace our way in like manner, step by step. Begin from this moment a system of judicious retrenchment; lay aside sums, never mind how trifling, toward the liquidation of your debt, and little by little it will melt away, till, almost unconsciously to yourself, it has disappeared, and you, again a free man, ‘can look the whole world in the face.’”

“Ah, that was practical! That was what I needed!” said father, as we came out after the lecture was over, “and I, for one, shall not ‘approve the doctrine and immediately practice the contrary.’ No; from this very moment I shall begin to retrench and put by. Ah, Annie, ‘a word in season,’ how good it is! I was almost ready to despair till now.”

And that was the beginning of our saving. First, coffee was given up; mother always drank tea, and so no one was inconvenienced by that but father; then butter was dispensed with, and the cheapest meat and vegetables in the market were selected, and mother decided that so many things were unnecessary about our clothes, that Katie declared after a while mother would think we could do without buttons on our dresses. But my happy part of the day, during all this anxious time, was the twilight when there was no work for me to do and I could run in and sit by Miss Judith’s bright little fire and talk over things with her. It was on one of these evenings, after Miss Judith’s usual greeting of, “Well, Martha, how has the work come on to-day?” that I said, “Indeed, Miss Judith, I wish I were not such a ‘Martha,’ and that I might ‘choose the better part,’ like Mary. But then, what can I do? Wouldn’t it be wrong for me to throw things on mother when she isn’t strong, and don’t you think our Saviour would think so, too? Then, besides, mother would have to be a ‘Martha,’ for the work must be done. I am sure it is all very puzzling to me, anyway.”

“I do not wonder that you say so, dear,” said Miss Judith, “for older heads than yours have puzzled over the same question, and certain it is that were it not for the ‘Marthas’ in the world the whole system of society would come to a stand-still. But, then, Annie, we are told that Martha was ‘cumbered with serving’; she allowed her work, it would seem, to absorb her faculties to the exclusion of other and more important things; we need not do that, need we? Has not each one of us, even the busiest among us, leisure sufficient to consecrate his work to God in prayer, and ask His blessing upon it, and His help in it? Then, my child,” she continued, “observe the words of our Saviour, ‘Mary has chosen the better part’; that is better than Martha, but perhaps there is a ‘better part,’ still, or the best part, in which labor and worship are united, in which, while ‘not slothful in business,’ we are still ‘fervent in spirit serving the Lord.’ This would seem to me the best part, and surely the best example is that of the blessed Saviour Himself, who ‘came not to be ministered to, but to minister,’ who ‘went about doing good,’ and ‘followed up days of toil with nights of prayer.’ Yes, my dear, the necessity of serving is evidently laid upon you, and you have not the choice of your part in life, but the manner in which you act your part is within your power. Don’t forget, dear child, that you ‘serve the Lord Christ,’ and ‘whatsoever you do, do it heartily as unto Him.’ He has taken a journey into a far country now, but he will come again to inspect your work; be faithful, dear Annie, and watch and pray.”

That little talk with Miss Judith did me real[7] good. My little talks with her always do, and mother says that she is the greatest possible comfort to her, for she shows her how useful one may be, even where one has only sympathy and counsel to bestow; and father says that there is a healing and strengthening power in her words, which is far better than a gift of silver and gold, for it enables you to “rise up and walk” under the burden of life.

The children certainly did bear the privations we underwent well, but Katie said to me privately one night, “I never did want something good to eat as badly in my life. I am real glad Thanksgiving Day is so near.” But when the day before Thanksgiving came, and mother asked if I should get anything different for dinner next day, father shook his head with such a decided “no” that there was nothing more to be said, but it was undoubtedly a change; we had never known what it was not to have turkey and pudding then. I was most grieved, however, at the thought of not having my usual present for Miss Judith. I had always, on that day, carried her in her dinner, and on the waiter a five dollar bill; but as I went up stairs at night, father slipped five dollars into my hand, saying, “This is for Miss Judith, Annie. We must not forget, in our efforts to retrench, the debt we owe our Heavenly Father.”

That was enough to put me in a proper frame for the next day, even if I had not already had sufficient to be thankful for. I had quite made up my mind that mother was to go to church, and let me mind Harry, but there was a great deal of persuading necessary to get her up to the point. However, I succeeded at last, and after they were all gone and I had washed up the breakfast things, Master Harry began to show symptoms of sleepiness, so I tucked him in his little cradle, and began rocking him to and fro, singing all the while one of Miss Judith’s favorite hymns:—

Over and over I sang it, till at last the white lids closed, and I was getting up softly to slip away, when ting-a-ling! went the door-bell, with such a sound through the house that Harry stirred, then opened his blue eyes to their fullest extent, and I was obliged to get him quiet again before answering the bell. When at last I did go down, lo! not a creature was to be seen: only a hamper-basket covered with a white cloth with a paper pinned on top, on which was written: “For Mr. Gray; from a friend.”

It was just as much as I could do to get the basket into the kitchen, and then, oh! the good things that met my eyes. First of all, a turkey ready dressed, then a roll of golden butter, then several jars of sausage-meat and jelly, then a bunch of celery, and last a great iced cake. This completed the contents, but no; as I lifted out the lower cloth there lay a sealed envelope directed, as the basket had been, to father. This I laid aside till his return, but what to do about the other things was puzzling. They are clearly intended for father’s Thanksgiving dinner, I thought, but unless the turkey is put to roast right away it won’t be done in time. Shall I, or shall I not? I said to myself. Then I remembered how feeble dear mother looked when she set out; how she feared the services would be too much for her strength. Yes, I said decidedly, by way of answering my doubts, a warm nourishing dinner will be just what she needs, and so, without more ado, I set to work. The baby (bless his little heart!) was real good, and let me, get well “under way” before he waked up. There was no keeping the secret of the dinner, however, when the front door was once entered, for the savory odor of the roasting turkey told the tale at once, and the whole party hurried into the kitchen to find out what it meant.

“O, father!” I said, when the exclamations over the first part of my recital had sufficiently subsided to admit of my getting in a word, “there was a letter for you in the basket, too.”

“This will give us the name of the donor,” said he, as he opened it. But, no indeed, there was no name inside, only some notes neatly folded. “Five, ten, fifteen, twenty, twenty-five dollars,” said father, counting them out on the table. “God be praised for all His mercies,[8] and God bless the giver!” said he, fervently, while mother turned away to get Miss Judith’s dinner ready, and hide her tears, for poor mother was actually crying.

“Take this, too, Annie,” said father, putting another five on the one already lying on the waiter, when at last it was ready for me to take in. Of course I had to stop and tell Miss Judith the wonderful news about the basket, and when I got back again mother was putting the last dish on the table; then, going to our places, we stood with bowed heads while father said the grace I had always been accustomed to hear, but which seemed to have gained new meaning and beauty,—

“Supply the wants of others, O Lord, and give us grateful hearts, for Christ’s sake.”

We never knew the secret of that Thanksgiving basket, nor did we ever inquire into it, but we all had a notion that Dr. Armstrong could have thrown light upon the subject if he had chosen to.

MARGARET threw an old shawl over her head and went out the side door. This had been a hard day. Weston had been very cross, and insisted upon having her run a great many errands for him, some of them unnecessary.

This, too, was the first day of the fall term of school, and Margaret had so wanted to be early at school to secure her old seat; for she had heard that Helen Marcy was going to try to get it first. She had almost forgotten her new resolves in the morning when her step-mother had told her she would have to stay home to-day and help her.

As the tears came into Margaret’s eyes, Mrs. Moore had remarked: “Now’s a good time to show your religion. A girl that’s joined the church shouldn’t go around pouting all day because she’s asked to do a little work; especially when she’s been off doing nothing at the seashore.”

It was all true, Margaret knew it, but it seemed so hateful of her to say it. It had been so hard to bear.

After tea she walked down to the gate and stood staring out into the darkness.

It was a very hard life, all just as black and unlovely as that dark autumn evening.

She glanced back at the house. There was Johnnie bending over his books, the gaslight above him brought him out in clear relief against the dark room. Naughty Johnnie! How he had teased her every time he came near her that day! Nobody cared for her much. She gazed down the street. Here and there a light gleamed out. Across the way there was a bright fire in the fireplace, and the family seemed to be having a happy time, sitting around the table, sewing, reading, laughing and talking. The little girl was sitting in her father’s lap. How Margaret longed for such a pleasant evening in their home. She turned involuntarily back to the house. Her father and Mr. Wakefield, the minister, had gone out just after tea, and Mrs. Moore had gone to her own room directly after the dishes were washed. The house was all dark, save Johnnie’s one gas jet. It was just unbearable. No other girl in the world had such a hard lot. It couldn’t possibly be any worse.

Yes, she really thought so, this poor silly little girl.

But she did not altogether forget her Heavenly Father. She remembered presently, with a glad thrill of joy, that she belonged to the rich King of all the earth. He could help her. She would ask Him.

Down went her head on the gate-post, and she told her Father in Heaven all about it, and how she could not possibly stand it.

Then she raised her head with a confident feeling that now all would be well, and fell to planning different ways in which her prayer might be answered.

She didn’t exactly want her step-mother to die! She was rather shocked at the thought. That was a very wrong thought for a Christian girl to have.

Poor little Margaret! She thought she loved Jesus, and was trying with all her might to serve him, but she still had to learn the command: “Honor thy father and thy mother.”

Throwing that disagreeable thought aside, she went on. How could it all be changed? Perhaps some rich, unheard-of relative of her mother’s would die and leave a vast fortune to her as her mother’s only daughter. Then what would she do? She would give her father enough so that he wouldn’t have to work anymore. She would—yes, she would show a very Christian spirit toward Mrs. Moore. She would re-furnish the house, and hire several servants for her, and give her enough to buy beautiful dresses. The boys should be sent to college, and she,—she would go off to boarding-school and study as much as she liked, and never have to stay home and wash dishes. She would have plenty of money to give away. She would buy a great many flowers to give to poor sick people. Her room should be beautifully furnished, and she would invite all the poor girls in school there and give them nice times.

She was just treating those imaginary girls to chocolate creams and marshmallow drops, when she heard her father’s step coming swiftly down the street, and his voice say: “Margaret, you should not be out in this chilly night air.” Then she turned and followed him into the house. She had to give up her musings for a while and help Johnnie with his arithmetic lesson, but she promised herself more castle-building when she went to her own room, before she slept.

But presently her father called her. “Margaret,” he said, “I have a letter here from your Aunt Cornelia. She wishes you to come and spend the winter with her and attend school. Would you like to go?”

Margaret’s heart bounded with joy. Not alone with the pleasure of going to Aunt Cornelia, but with a sort of triumphant feeling that her prayer was answered, and that so soon. She resolved complacently that she should always pray for everything. Poor child! She thought her faith was very great.

It was quite dark in the room and Margaret could not see her father’s face as he said this, but his voice was very kind. The door into the hall was partly open, and the streak of light which came from it fell upon the sofa, and showed the dim outlines of Mrs. Moore lying there with her head bound up in a handkerchief. There was a faint odor of camphor and vinegar pervading the room and Margaret’s conscience smote her as she remembered her hard thoughts out by the gate. Perhaps Mrs. Moore had been suffering all day from a sick headache, and that was why she was so severe. The little girl’s heart softened and she resolved to pray that the headache be cured, which, however, she forgot to do. You must remember how full her heart was of excitement, and pity this poor young Christian.

It was all settled that evening that she should go in a week, and she went up to her room to write a letter overflowing with thanks to dear Aunt Cornelia, and then went to bed to dream of the new life.

How easy it would be to be a Christian, living with Aunt Cornelia, she thought, while she was dressing the next morning. God must have seen how utterly impossible it was for her to serve him truly here in her home, and so planned this for her. But her thoughts were interrupted by a knock at her door, and Johnnie called out:

“Say, Mag, she’s sick, an’ father’s gone for the doctor, an’ he said you must come an’ get some breakfast, an’ West’s cross, an’ it rains like sixty, an’ the wood’s all wet, an’ I can’t make the fire burn. Can’t you come quick?”

Had Margaret known all the trials that were to come to her that day, she would have stopped, in that little minute that stood between her bright hopes of the night before, and the unknown future, to ask her Heavenly Father for strength for what was to come. But she did not. Perhaps it was some shadow of coming trouble that made her reach out her hand and push the letter she had written into her upper bureau drawer. Then she hastened down-stairs. Desolation reigned there. Johnnie’s books and slate were scattered over the dining-room table, just as he had left them the night before. Weston had added to the confusion by spending his evening in cutting bits out of several newspapers for his scrap-book, and little white snips were scattered thick over the floor. Margaret remembered that the dining-room always before looked nice when she came down in the morning. It did make a difference to have a mother around, even if she was only a step-mother.

Out in the kitchen Johnnie was rattling the stove and the smoke was pouring out of every crevice.

It was late that morning before the new minister got his breakfast, and the steak was smoky and the coffee muddy-looking, but he smiled pleasantly at Margaret’s red face and told her that she had done well for the first time.

While they were at breakfast, Mr. Moore came in with the doctor.

They went directly up-stairs, but soon came down again, the doctor taking out his medicine-case and calling for glasses and water. Mr. Moore looked anxious and worried. Margaret tried to hear the doctor’s replies to her father’s troubled questions, but she only caught words now and then:

“Inflammatory rheumatism.” “System completely run down.” “Rest for several months.”

These were the bits of phrases that came to Margaret through the open kitchen door, as she[12] stood by the faucet drawing water for the doctor. The rest of the sentences were drowned by the rush of the water, but Margaret could easily imagine it, and her heart stood still.

She knew that this meant many things that the doctor did not say.

It meant that she could not go to Aunt Cornelia’s; that she must spend the winter at home; that she must be the one who must constantly wait on the sick woman. She could even now hear the irritable words which she imagined her step-mother would use to her when she didn’t do everything just right.

Then a great rebellion arose in her heart.

“God hasn’t answered my prayer at all,” she said to herself, and the great disappointment made her hand shake as she set the water-pitcher down before the doctor.

Mr. Moore didn’t think his little girl had heard the doctor’s words, and he looked after her with a troubled sigh as she went back to the kitchen. How should he tell her? Would she storm and cry as she had been wont to do when her will was crossed? He decided that he would not tell her that day.

The breakfast dishes washed, Johnnie at school, and her father up-stairs, Margaret betook herself to the kitchen to wail out her sorrow and pity herself. She dared not go to her own room, lest she should be heard. Rebellion was in her soul, and the more she cried the more she pitied herself and cried again. Mr. Wakefield, coming to the kitchen to ask for some warm water, found Margaret with her arms on the table, and her head on her arms, sobbing great angry, disappointed sobs. He stopped in dismay.

“Why, Margaret, what is the matter? Is there anything I can do for you?”

“No, there isn’t! God hasn’t answered my prayer! You said he would! Now I’ve got to stay at home and wait on her! I don’t believe he heard me at all!”

Margaret fairly screamed this out. She had worked herself into such a state that she scarcely knew what she was saying. Was this the gentle, humble Christian he had received into the church but two days before? This thought passed through the minister’s mind, but he was too wise to express it to the excited little girl. He only asked quietly:

“Margaret, does your father always say ‘yes’ to you when you ask for something?”

“Why, no; of course not!” she said, in surprise.

“And suppose you should ask for something, and he should say No, would you come and tell me that your father would not answer you?”

She did not answer this time, and Mr. Wakefield went on:

“Suppose your father knows that what you ask would be very hurtful to you, would you think him cruel to refuse you?”

“But this isn’t hurtful! It’s best for me! God wants me to be a Christian, and I never can be one in this house!” she burst out.

“Margaret, which do you think knows best, you who know so little, or God who made you, and who sees all things that ever have happened or ever will happen in your life? My little friend, I am afraid you didn’t pray in the right spirit,”—

“O, yes, I did!” she interrupted eagerly.[13] “I believed. I thought of course He would give it to me.”

“But believing is not the only thing. You forgot to put one little sentence in, ‘Thy will be done.’ If you had put it in words your prayer would sound something like this: ‘Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be Thy name, Thy kingdom come, Margaret Moore’s will be done,’”—

At this Margaret couldn’t help smiling through her tears.

“Your kind Heavenly Father didn’t give you just what you asked for, because he saw that it would not be best for you. Perhaps he saw that his servant must learn patiently to serve him at home, among trials, before she would ever make the right kind of servant out in the world. He will answer your prayer in some other way than the one you had planned, Margaret. He loves you a great deal better than you love yourself. Can’t you trust him?”

And then the minister went away without his hot water. Went back to his room to pray for the poor little troubled disciple down-stairs. And Margaret sat and thought. She saw now just how foolish and wicked she had been. She had a long struggle with her rebellious heart, kneeling on the bare floor with her head on the kitchen table, but she conquered at last, and the peace of God filled her heart. She was resolved now to give up her own way and try to do God’s way. “But, dear Jesus,” she prayed, “I’ll have to be helped a great deal, for I can’t do it alone, and I know I shall cry if they say much about Aunt Cornelia.”

Margaret had found the right way to do all she could herself and trust in Jesus for the rest, and to give up her life, her will, her whole self into his keeping.

But she remembered that she had other duties and that her father might be down-stairs at any moment, so she hastened to her room to wash away the traces of tears.

Half-way down the stairs she paused. “Would not it please Jesus if she were to knock at mother’s door and ask if there was anything she could do?”

She retraced her steps softly and gave a very gentle knock. Her father came from the darkened room, his face so careworn that it almost startled her. “Father, please don’t look so worried. Everything will be all right. I can keep house,” she said.

Her father regarded her with a tender, sorrowful look.

“Does my little girl know that she cannot go away this winter?”

“Yes, sir; I know it. Never mind that. It’s all right, father.”

Mr. Moore was so amazed and pleased at this new character exhibited by his daughter that he scarcely knew what to say.

“I am very sorry it is so, Margaret, but your mother is very sick. She has been under a great strain this summer. You will have to wait on her and be a general help. I would hire some one else to do it if I could afford it, but I cannot. Your mother’s sister, Amelia, who has been living in Brierly with her brother, will come, I think, and keep house, and then the minister need not go away, for we need all the money we can get now to pay the doctor’s bills.”

Margaret’s face fell.

“Must we have her? Isn’t there some one else we can have?” she said, lowering her voice.

“Not without paying for it,” said her father, sadly.

“Couldn’t I do the work?” she asked.

“No, Margaret; you will have all you can do to wait on your mother, and,” he added, “I am afraid you cannot even go to school here at home,—for a time, at least. I am sorry, but I don’t see any other way out just now.”

Margaret felt very much like bursting into tears again, but a glance at her father’s worn face changed her feelings.

“Never mind, father, I’ll do all I can, and be as good as I can.” And she wound her arms around her father’s neck and kissed him.

If she only could have known how much that kiss comforted her father. He went back into[14] the darkened room with a lightened heart and a feeling that there must be something in religion, for it had changed Margaret wonderfully.

Margaret snatched the first hour that came to her to write a letter to Aunt Cornelia, telling her how impossible it was for her to come to her, and how very sorry she was, and soon there came a long, sympathetic, helpful answer, and with it a little book bound in green and silver. “To help you when you feel discouraged,” the good auntie wrote.

On the first page Margaret opened, her eyes met these words:

And they sang a little tune in her heart as she thought of all she must bear that long winter.

IT was a warm, sunny Sunday morning, and consequently Robbie Ellsworth was allowed to go to church. This was quite a luxury to him, because he had but recently recovered from the measles, and his mother was rather afraid to have him go.

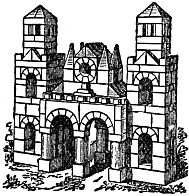

The notices were all given out, at least so the people thought, when the minister announced that there would be a meeting of the congregation the next day, to raise money for a new church. That building, they saw, was altogether too small, and he did hope they would get a new one started very soon, as a lot was donated in a fine location.

Then came the sermon. It was about little things. Robbie listened attentively, as the minister told how many great things had been started and helped by little boys and girls, and by people with little money or talent.

At the dinner table Robbie’s father remarked, “How anxious Dr. Sullivan is for a new church! But he won’t get it—not very soon, anyway. The people don’t care enough about it, though I’m sure they need one badly.”

“Dear me!” thought Robbie to himself, “I do wish Dr. Sullivan could get the new church. I’m sure he ought to have it if he wants it.”

“He wants a brick one,” Mr. Ellsworth continued, “but in my opinion a frame building would do this time. Brick costs too much.”

“I wish he could have a brick church,” thought Robbie. “It would be so much nicer.”

Then he went to thinking about what Dr. Sullivan said in his sermon, and pretty soon he began to wonder if he couldn’t help with the new church. All the afternoon he thought about it, and finally a plan came into his little mind, which he thought of so much that he could hardly sleep that night. But he didn’t want anybody to know anything about it, so he went to sleep as fast as he could.

Fortunately for his plans, Monday was as pleasant as Sunday, and about ten o’clock Robbie went to Mrs. Ellsworth.

“Mamma, I want to go take a walk,” he said.

“Why, Robbie dear, you would get lost.”

“But I only want to go around to Uncle Will’s,” pleaded the little fellow.

Now Uncle Will was a doctor, a great favorite with his little nephew, and he lived only around the corner, in the new house which he had just built.

“I think you may go, then,” said Mrs. Ellsworth, “as you don’t have to cross the street to get there. I am going down to papa’s office, and will tell him to stop for you when he comes home.”

“No, mamma,” said Robbie, “I’d rather not. I have a very much reason for wanting to come home alone.”

That was his way of saying he had a very good, and, in his eyes, important reason, which he didn’t want to give. So his mother agreed, kissed him good-by, and he started out, first getting his little green wheelbarrow from the hall closet.

He trudged along down one street, up another, till he stopped on the stone steps of “Uncle Will’s house,” and gave the bell such a pull as only a boy of about Robbie’s size knows how.

Aunt Flora greeted her small visitor very[15] warmly, laughing at his wheelbarrow, but he pushed right by her, and trudged into Uncle Will’s office, pushing his wheelbarrow before him. Uncle Will was engaged in discussing the cholera germ with a brother physician, but he turned and welcomed his nephew cheerily:

“Well, my man! What can I do for you to-day? Will you cart a wheelbarrow of books around to the library for me?”

“Mamma wouldn’t let me,” said Robbie. “I came to see if you would let me have one wheelbarrowful of the bricks that were left over—out in the back yard.”

“Certainly,” said Uncle Will. “You can go right out and get them.”

So Robbie turned again, too eager to even thank his uncle, pushed his wheelbarrow through the dining-room, and was soon taking down bricks from the pile by the back stoop.

His barrow didn’t hold but about a half-dozen, and soon Irish Mary was lifting it up the steps, and he arrived again before his uncle’s door.

“Are they my very own, Uncle Will,” he asked, as that gentleman turned to look at his load, “to use just as I want to?”

“Your very own,” said the doctor, “to do what you please with. If you wish, you may throw them in the cistern. But what are they for?”

“I would rather not tell, Uncle Will.”

“Very well, sir. Success to your project, whatever it is.”

Down the steps bumped the wheelbarrow, with its owner behind, and down the street they went again, though this time on the other side of the block. There were not many pedestrians on the street, but the few Robbie met smiled at him and his load of bricks. He looked at all the houses attentively, and finally mounted the steps of one with difficulty, all the time afraid his bricks would fall out, and rang the bell a little more gently than he had at his uncle’s.

The Rev. Dr. Sullivan came to the door. He knew Robbie. “Good-morning, young man!” he said. “What can I do for you?”

“Nothing,” said Robbie. “I’ve brought you the first load of bricks for the new church.”

“The new church!” said the doctor.

“Yes, sir. You said yesterday you wanted one, and papa said you wanted a brick one. So I’ve brought the first load. They’re my very own, sir, to use just as I want to.”

“Well, well!” said Dr. Sullivan, “I am very much obliged to you,” and Robbie thought his voice sounded almost as his did when he had the croup. Moreover, he took out his handkerchief and rubbed his eyes. Then he took the wheelbarrow in his arms, and having deposited the contents in his backyard, returned it to the owner. “The bricks shall be used, young man,” he said, “every one of them, for the new church. Thank you very much for your help.”

Then Robbie returned home, jubilant at having been able to help his minister.

As for the minister, he took a paper, and went out. The first man he met was Mr. Lawrence, the wealthiest person in his church.

“Mr. Lawrence,” he said, “we have started, and the first load of bricks for the new church has arrived.”

“Indeed!” said Mr. Lawrence, and after a little more talk he put down his name for quite a sum of money. Dr. Sullivan went on telling every one that the first load of bricks had arrived, and it was astonishing how encouraging those bricks were! When the congregation met that afternoon, their pastor announced that some hundred dollars had been raised for the church, and that the first load of bricks had come.

Of course it was a good while before the church was really built, for there were architects and masons and carpenters to be consulted; but it was really built, and it was not till then that the minister told who had furnished “the first load of bricks,” and how he really started the whole thing.

And the six bricks that Robbie had brought in his little wheelbarrow were built into the wall of the church, and everybody thanked him for his part of the work.

Now the best thing about this story is that it is all true. The minister’s name may not have been Dr. Sullivan, and the boy’s name may not have been Robbie Ellsworth, and his wheelbarrow may not have been green, but it brought the bricks that are in the “Brick Church,” as it is called, of one of the largest cities in the Eastern States.

FROM the further corner of the fence, one end fastened to a bush near by, hung a spider’s silken web, regular as if made on geometrical principles. In the centre of this sat a good-sized spider, the proprietress, who had just finished devouring the most of an unwary fly, whose bloodless remains lay at her side. Up to the spider came two ants—Zed and Zoo.

“Excuse me,” said the spider, looking at them suspiciously, “for having any doubts as to the safety of making your acquaintance. But you have just been communicating with my greatest enemy, the wasp, and have been watching with heartless interest the destruction of one of my family. I am sure I hope you have no personal designs upon my life. The wasp is such a very daring foe, that I fear you, even though you are so small.”

“I assure you,” replied Zed, “that our interest in the wasp’s doings was wholly due to ignorance, and we are no friends of hers, nor have we any design against you.”

“Very well,” replied the spider, whose name[18] was Luxz, “I am very glad. I feel in a pretty good humor this morning, having just finished a most delicious fly. I say finished, or I would offer you some. All spiders like flies. I had a most unpleasant disappointment yesterday. I was over on the window-sill of the house yonder, and saw a large fly resting on a piece of paper. Of course I sprang after him, but there was no fly there! I walked over and over him, too! One of my neighbors suggests that it was a picture; as if an intelligent spider couldn’t tell the difference between a picture and a fly!”

The two ants nodded their assent to this highly probable statement.

“You spin a great deal, I suppose?” asked Zoo.

“O, yes!” said Luxz; “I am as busy as can be. I can spin little fine threads, and coarser ones, and dance and swing all around on them. But of course the most of my time is occupied with work. It is a good deal of work to make a web, although you might not think so. There were some boys coming past here to school as I had just finished a nice web, quite a while ago, and they knocked it all down. I built another, then another, but every time those wicked creatures would destroy it, and then laugh at my dismay. Finally my pockets were as empty as could be, and I was all out of silk, so I had to go and kill another spider, and occupy her web for a time. But this I built myself.”

“You catch a good many flies?”

“Yes, indeed. They are not very sagacious animals, though sometimes I will find one that I can’t entice into my web after the greatest endeavors. We are all very cunning, but we have to look out for some of the birds. A neighbor of mine was swinging one morning, as fine as could be, and a swallow came along, that had his nest up under the eaves, and—well, that was the last of her. The wasps, as I have already mentioned, are very bad. If one of them gets caught in our webs, we unfasten the threads as quickly as we can, and let her go, fearing that if we don’t, we shall get the worst of it.

“Our threads are very convenient,” Luxz continued, after a moment’s pause, “for we can let one end of them float out, and they stick to anything they touch, making a thoroughfare for us. I remember once those same boys put me on a chip in a large tub of water, and again laughed at my discomfiture. But I was equal to the emergency, and had soon spun out a thread the outer end of which a draught of air floated to the side of the tub, and when my tormentors were not looking, I escaped along it. We can fasten the end of our thread to the top of anything, and let ourselves down by spinning out more, or rise by pulling it in.”

“Have you any children?” asked Zed.

“O, yes!” replied Luxz, “I have some just hatching. As you go around the corner of that board you can see the nest—all fuzzy, like cotton. A few are just crawling out. They are very small as yet.”

Then the ants bade the spider good-day, and went down the fence, stopping as they passed it to see the nest, where the little wee spiders were just taking their first few steps among the delicate filmy threads surrounding their eggs. How many there were!

A fly was the next insect which absorbed the attention of our travellers, as he was poised on a grease-spot at the edge of a board along which they were walking. It was just a common house-fly, but as they were not very familiar to Zed and Zoo, he was an object of as great interest to them as any which they had met in their peregrinations.

“Good-morning,” he buzzed, “I am searching for something to eat. I have just been driven out of the house yonder, by some immense people with great cloths in their hands. They have put up frames in the windows with wire ropes in them, and I can’t get into that well-filled table. There is a man there with a bald head, too,—just the place for an enterprising fly. But these people do hate us!”

“Too bad,” said Zed sympathetically; “but if you lazy flies would make homes of your own, as ants do, and not go about where you’re not wanted, you and others would be far more contented.”

“Well,” said the fly thoughtfully, “I’m sure I don’t see why we don’t. Possibly no fly ever thought of it. It doesn’t seem to be intended that we should. I never could work out in the hot sun the way you do. The people don’t molest very often,—not as much as they’d like[19] to; we have too sharp eyes, and too many of them. We each have hundreds and hundreds of little eyes, and every one moves and looks in a different way. It’s rather difficult to come up behind us, as the elephant did.”

“How was that?” asked Zoo.

“Don’t you know?

“I’m not sure about the story; it’s just possible that it may be taken from the New York paper, but, anyway, we believe it, and often laugh at the grasshopper.”

“What do you eat?” asked Zed.

“Anything I find, almost. Flies are not at all particular. We can enjoy anything that any one does. Our mouths are hollow tubes, through which we suck whatever we wish to eat. This is a very convenient way.”

“You have enemies,” remarked Zoo. “We have just been calling on a spider who is longing for a taste of some of you.”

“You don’t say so!” cried the fly. “She is not very near here, is she? Those spider-webs are the great torment of our lives. I have had several friends caught and eaten by the spiders. The way they wind their fine, yet strong threads about one, is something remarkable. I know a pretty good verse about them, too:

That’s real pathetic, isn’t it, now?”

“Very,” answered Zed and Zoo, together.

“I met a Southern fly once,” continued the talkative fly, “and they have more enemies down there than we do in the North. Take the lizards and chameleons, for instance—”

“Oh! we know about them,” cried the little ants.

“And then the walking-sticks,” continued the fly, not pausing at the interruption, but rather looking severely at his visitors; “now, a man up here couldn’t hit on one of us with a walking-stick if he tried all day. But it’s quite different down there! A walking-stick is not a stick by the aid of which people walk, but a walking-stick, that is, a stick that walks. It is a very strange insect, and is so exactly like the broken twig of a tree, with the little branches and all, that the most sagacious person can’t tell them apart, without seeing them walk. They are called ‘devil’s walking-sticks’ by some, and we flies think it very appropriate, for they are dreadful for us—that is, for Southern flies. The people will put a walking-stick in a room full of flies, and in a short time he will have killed them all! Think how dreadful!”

“Do you know any more poetry?” asked Zed, who was rather of a literary disposition.

“Well, now, I do know a real cute little song about a fly, written by some man or other, who evidently had a baby. I will sing it for you.”

And the fly buzzed:

THE Poplar Street Pansy Society began with a large membership and every other flattering prospect. The leaders were wide awake, bright boys and girls who meant success, come what might. Everything went on finely for the first year. Meetings were held regularly; the attendance included nearly all the members every time, in bad weather as well as good, and no matter what invitations were given elsewhere to parties or rides. The members, with rare exceptions, were thoroughly loyal to their society.

This became so well known that, at length, when entertainments were about to be given at the same time of the society meetings its members were passed by when the lists of invitations were being made out, for it was commonly said you might as well invite the man in the moon as one of the Poplar Street Society; that they would not leave that dear society to see the Emperor of China pass through the city. Some were cruel enough to say that these Pansies just worshiped their society.

In spite of all the outside parties and sneers the society kept right on its way. At last it grew to be such a power, so many of the young folks had joined it, that ladies, wishing a company of the youth at their homes, were compelled to consult the convenience of the Poplar Street Pansy Society.

If there was to be a meeting of the society at a certain time, particularly if it was to be a public one, everything must needs yield to it. Thither the fathers and mothers would go, no matter what other attractions offered.

Thus this Poplar Street Society came to be known as the popular society.

But the Roman Empire had its decline and fall. Why should not this society? Certain boys and girls had come in who cared more for place than for progress. They wanted to be highly thought of and to receive the offices. On one occasion four of them insisted upon being chosen president. Of course three of the four were offended and declared they would withdraw.

Some others said they must be appointed on the programme committee and be allowed to manage things generally or they would establish a rival society. A few insisted that the time had now come for a change; that the old programme of singing, recitations, games, etc., was poky; that a little dancing and card-playing ought to be allowed a part of the time.

To this it was answered that the Poplar Street Pansy Society was established for mental and moral growth and not for a dancing-school or card-party; that those who must have such things could find them elsewhere.

Thus a division came. Two parties arose. The matter was discussed in the schoolroom and three times daily in forty or more different dining-rooms. Many bitter things were said. The meetings would sometimes break up in confusion. Then some parents interfered by refusing to allow their children to attend. The dance and card portion withdrew. Several who wanted the offices or wished to have the most to say, came no more. Some had moved out of the city.

So there came a time when a very few attended the meeting. The many empty seats filled the few present with sadness. Then came a motion to dissolve the society; it was seconded, put and lost by one vote only. Then it was resolved to appoint a committee who should confer with some wise ones and see what could be done and report at the next meeting, or, if they thought best, adjourn the society till better times.

The committee consisted of two boys and one girl, this girl being the very one whose perseverance had brought the society into being and held it together at times when it seemed ready to go to pieces.