Title: The Great Lakes

Author: James Oliver Curwood

Release date: September 4, 2016 [eBook #52976]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank, Charlie Howard, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

book was produced from images made available by the

HathiTrust Digital Library.)

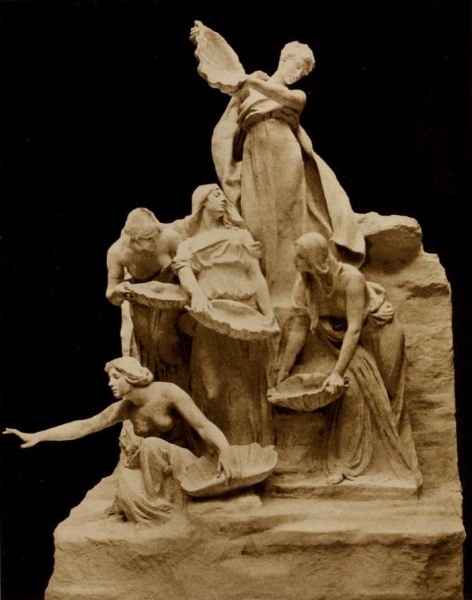

The Fountain of the Great Lakes

Lorado Taft, Sculptor

The Vessels That Plough Them: Their Owners,

Their Sailors, and Their Cargoes

Together with

A Brief History of Our Inland Seas

By

James Oliver Curwood

With 72 Illustrations and a Map

G. P. Putnam’s Sons

New York and London

The Knickerbocker Press

1909

Copyright, 1909

BY

JAMES OLIVER CURWOOD

The Knickerbocker Press, New York

TO HIS

FATHER AND MOTHER

WHOSE ENCOURAGEMENT AND FAITH IN HIM HAVE BEEN UNFAILING,

THE AUTHOR

AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATES THIS BOOK

In this volume, it has been my object to tell of the people and of the picturesque life of the Great Lakes, and to set before my readers actual facts about the cities, the commerce, and the future of the greatest fresh-water seas in the world. For some unaccountable reason, the Great Lakes, notwithstanding the fact that more than thirty million people live in the States bordering their shores, and in spite of the still more remarkable fact that they are doing more than anything else on the American continent for the commercial progress of the nation, have been almost entirely neglected by writers. To-day there are but few people who know that one of the three greatest ports and the largest fleet of freighters in the world are on these unsalted waters; and I mention the fact in this particular place simply to bring home to the casual reader how little is known by the public at large about our Inland Seas. For this reason, I have not dealt with any single side of Lake life, but have attempted to present as many phases of it as I could; and, for the same reason, I have added a brief historical account of the Lakes atvi the end of the book. It has been my desire, too, that these pages, from the beginning, should prove of especial value to those many thousands all over the world who are, or may in the future be, directly interested in the Lakes in a business way; and a great deal of attention has, therefore, been given to the commercial side of my subject—statistics and facts regarding Lake commerce, the opportunities of the present day, and a forecast of what the coming years hold in store for the men who have investments, or who plan to invest in business enterprises, on or about the Great Lakes.

While dwelling upon the importance of the commercial life of the Inland Seas, I wish also to emphasise the fact that I have kept always in mind another large class of people who are keenly interested in my subject, though not from a commercial standpoint. The present volume is designed to interest this latter class by portraying another side of Lake life—the human side, the romance and the tragedy that have played their thrilling parts upon these waters; the wonders of their progress; the story of their ships, their men, their wars, for of all the pages in the history of the North American continent none are more thrilling, or more filled with the romantic and the picturesque, than those which tell the story of our fresh-water seas.

In conclusion, I wish to say that I owe a great debt of gratitude to the scores of Lake “owners,” ship-builders,vii and captains who have aided me, in every way possible, in the preparation of this volume, and without whose personal co-operation the writing of it would have been impossible.

J. O. C.

Detroit, Michigan, 1909.

| PAGE | ||

| PART I | ||

| THE SHIPS, THEIR OWNERS, THEIR SAILORS, AND THEIR CARGOES | ||

| I— | The Building of the Ships | 3 |

| II— | What the Ships Carry—Ore | 25 |

| III— | What the Ships Carry—Other Cargoes | 46 |

| IV— | Passenger Traffic and Summer Life | 68 |

| V— | The Romance and Tragedy of the Inland Seas | 89 |

| VI— | Buffalo and Duluth: the Alpha and Omega of the Lakes | 113 |

| VII— | A Trip on a Great Lakes Freighter | 137 |

| PART II | ||

| ORIGIN AND HISTORY OF THE LAKES | ||

| I— | Origin and Early History | 159 |

| II— | The Lakes Change Masters | 175 |

| III— | The War of 1812 and After | 194 |

| Index | 223 | |

| Page | |

| The Fountain of the Great Lakes | Frontispiece |

| Lorado Taft, Sculptor. | |

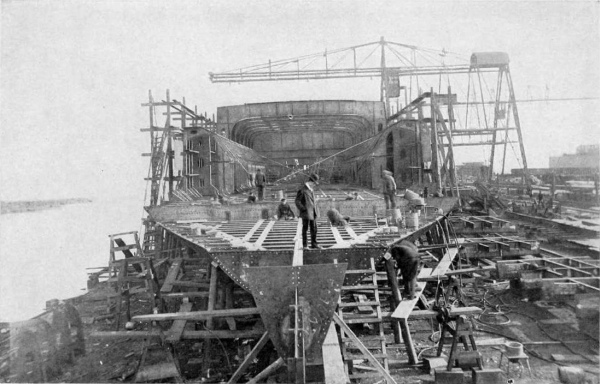

| The First Step in the Making of a Ship—Laying the “Keel Blocks” | 4 |

| Second Step—Laying the Keel, or Bottom of the Ship, on the “Keel Blocks” | 6 |

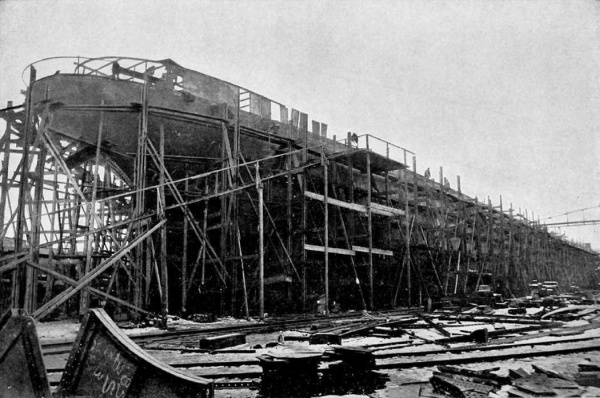

| The Growing Ship | 8 |

| Vessel Almost Ready for Launching | 10 |

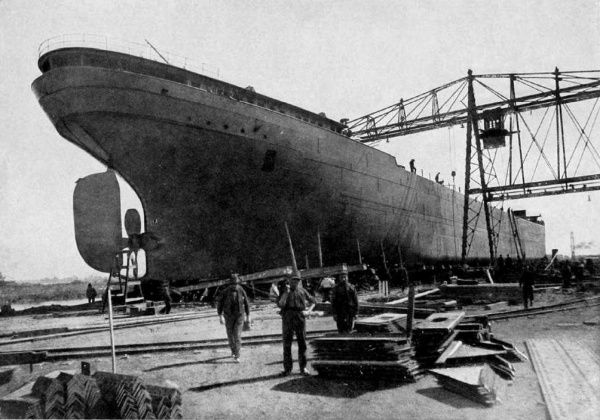

| A Monster of Steel and Iron Ready to be Launched | 12 |

| Weight 9,500,000 lbs. | |

| The Launching | 14 |

| The “Thomas F. Cole,” 11,200 Tons, Being Fitted with Engines and Boilers after her Launching | 16 |

| The “Cole” is the largest ship on the Lakes. Length, 605 feet 5 inches. | |

| Her First Trip—Off for the Ore Regions of the North | 18 |

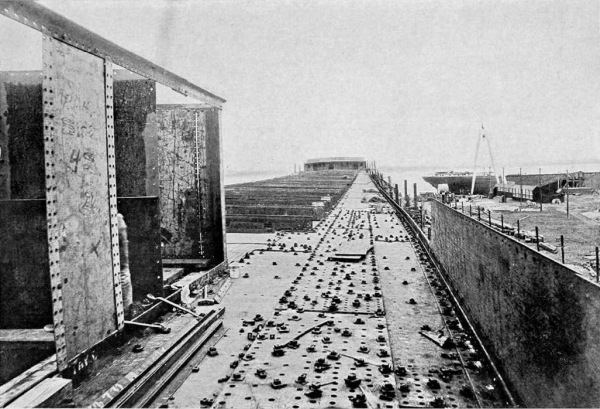

| This Shows Some of the 800,000 Rivets that Go to the Making of a 10,000-Ton Leviathan of the Inland Seas | 22 |

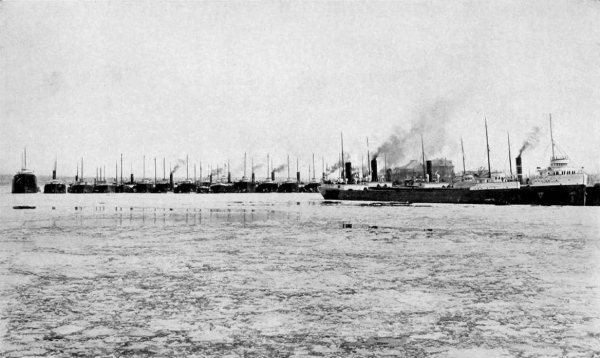

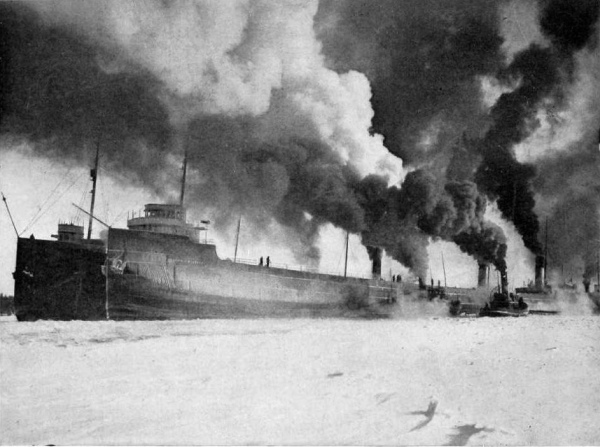

| Ice-Bound. Thirty-two Boats Tied up in the Ice at the Soo | 26 |

| From a Photograph by Lord & Thomas, Sault Ste. Marie, Mich. | |

| A Network of Tracks Running through the Ore Lands | 28xii |

| Captains of the Vessels of the American Steamship Company | 30 |

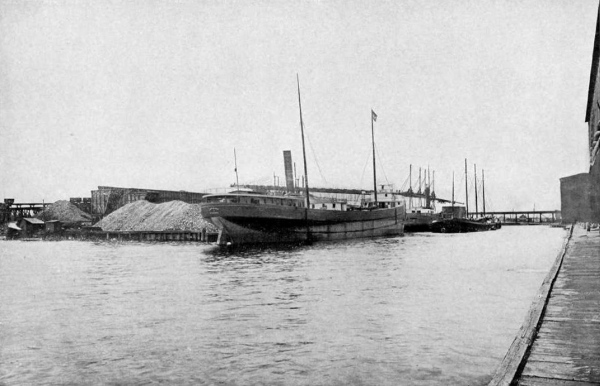

| The “Montezuma” | 32 |

| The largest wooden ship on fresh water being towed out of the Maumee River, Toledo. | |

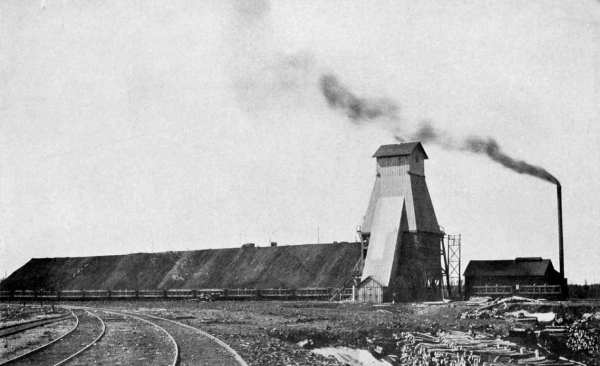

| A Coal Dock at Superior, Wisconsin | 34 |

| The pile of coal is 1400 feet long and 30 feet high. | |

| The Record Load Hauled by One Team out of the Michigan Woods, 20,000 Feet | 36 |

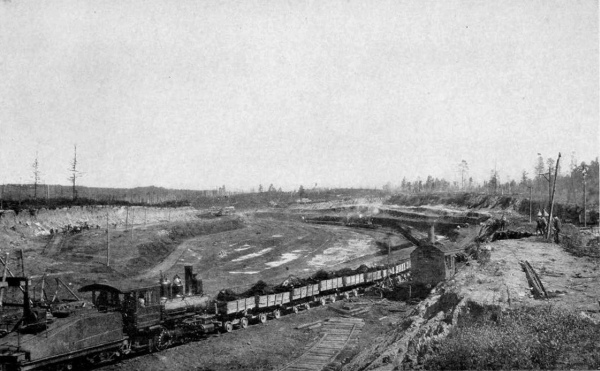

| One Steam Shovel Keeps Three Locomotives and Trains Busy | 38 |

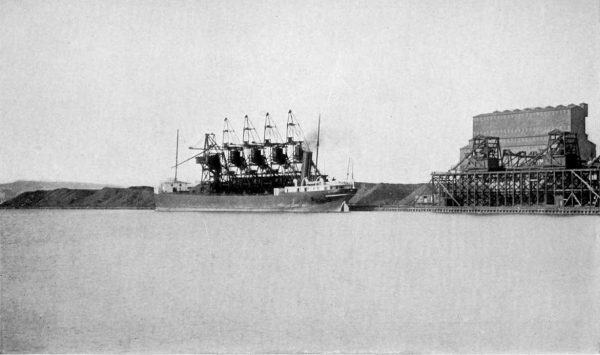

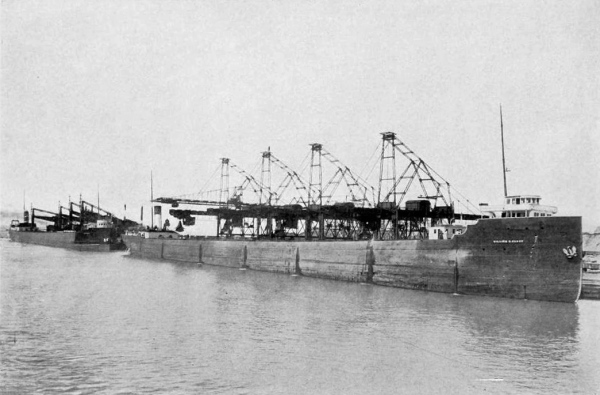

| Steamers at a Modern Ore Unloading Plant at Conneaut | 40 |

| The Main Slip in the Harbour of Conneaut | 42 |

| Conneaut is the second largest ore-receiving port on the Lakes. | |

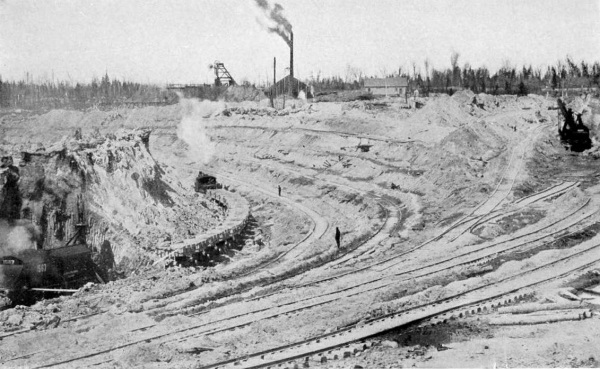

| One of the Huge Open Pits of the Mesaba Range | 44 |

| A Raft of Five Million Pulp Logs on the North Shore of Lake Michigan | 48 |

| Scooping up Ore from the Mahoning Mine at Hibbing | 52 |

| The largest open pit mine in the world. | |

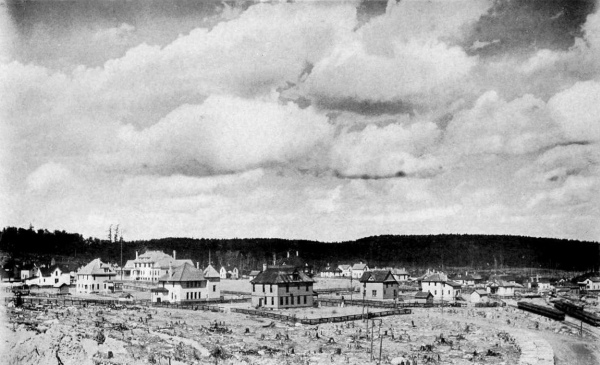

| A Mining Town on the Mesaba Range, where a Few Years ago the Deer and Bear Roamed Undisturbed | 54 |

| Harbour View at Conneaut, Ohio, Showing Docks and Machinery | 56 |

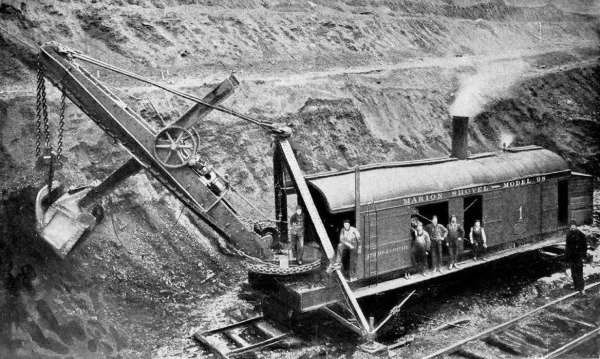

| A Steam Shovel at Work | 58 |

| This removes from 4000 to 8000 tons of ore a day. | |

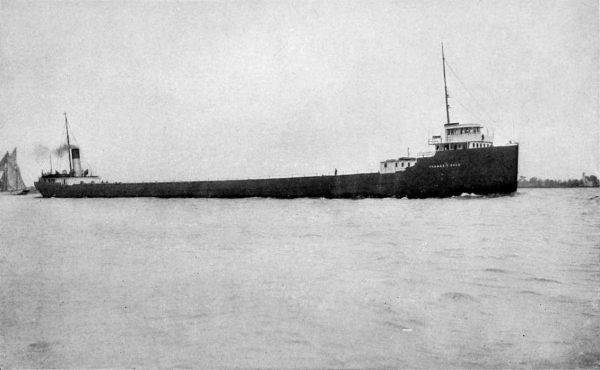

| The Old and the New | 62xiii |

| A modern freight carrier passing one of the old schooners. | |

| A Shaft on One of the Ranges | 66 |

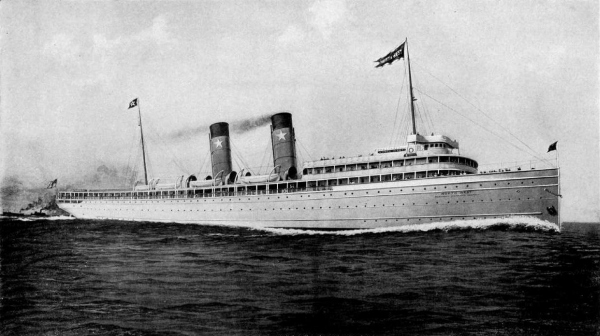

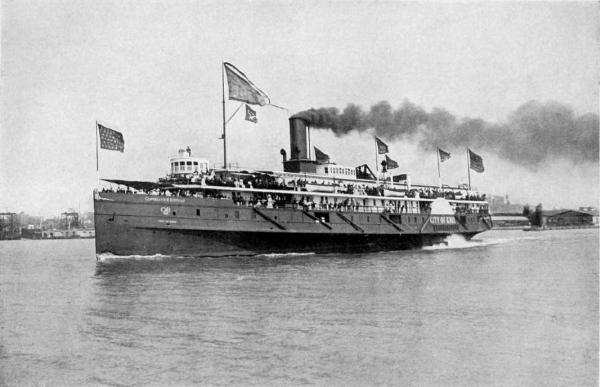

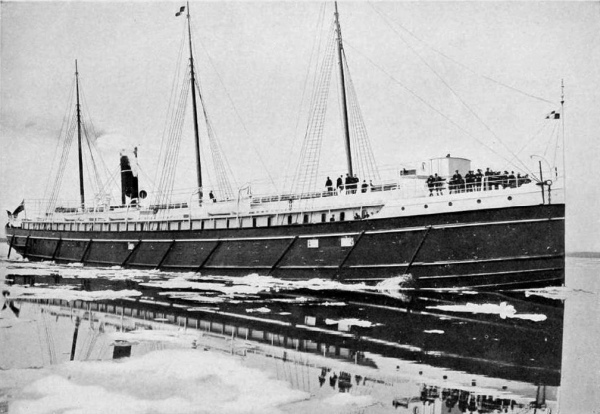

| The “North West” | 68 |

| One of the finest passenger steamers on the Great Lakes. | |

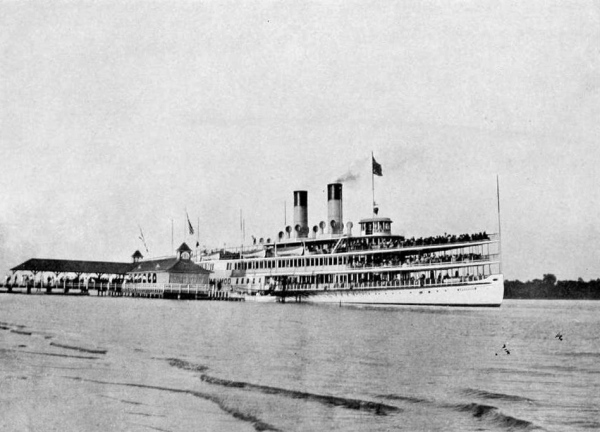

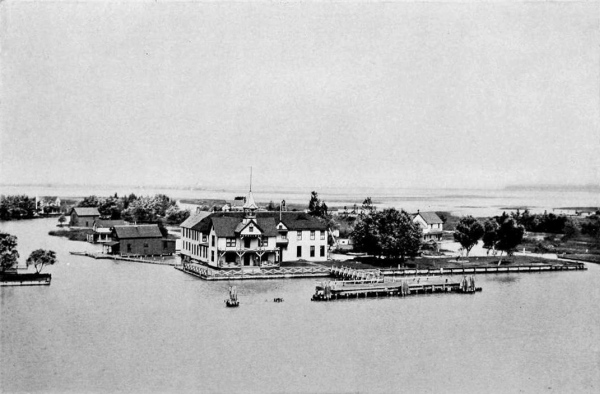

| The Stop at Tashinoo Park, St. Clair Flats | 70 |

| The Landing at Mackinac Dock, Michigan | 72 |

| Hickory Island at the Mouth of Detroit River | 74 |

| From a Photograph by Manning Studio, Detroit. | |

| The “City of Erie” | 76 |

| The fastest steamer on the Lakes, holding a record of 22.93 miles per hour. | |

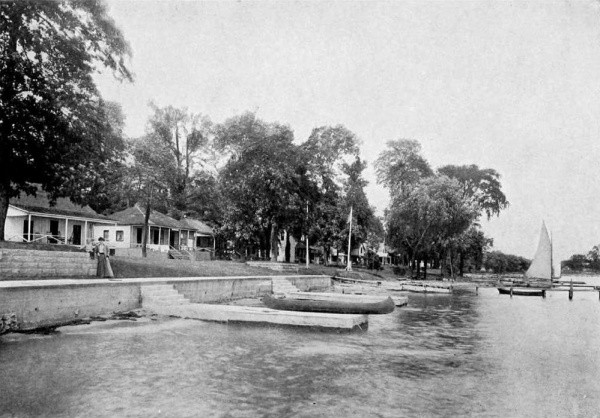

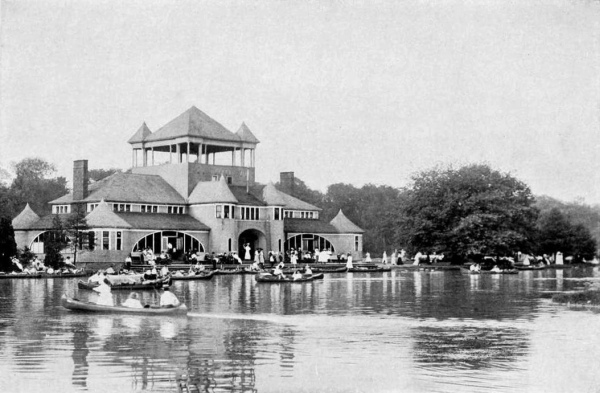

| Little Venice, St. Clair River | 80 |

| Showing the type of “Inns,” where people may pass their holidays at small expense. Courtesy of Northern Steamship Co. | |

| A Scene on Belle Isle, Detroit River | 82 |

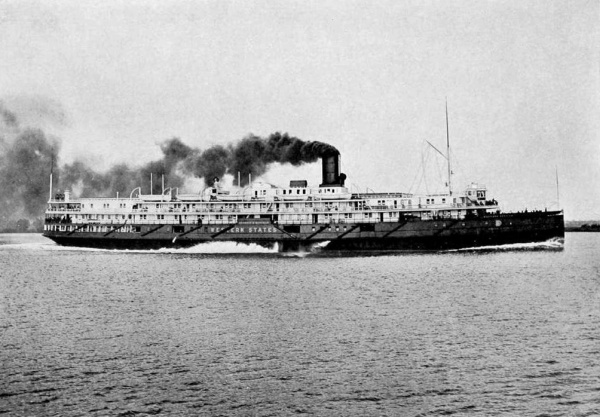

| Steamer “Western States” | 84 |

| One of the largest and fastest boats on the Lakes. Carries 2500 people and her fastest speed is 20 miles an hour. From a Photograph by Detroit Photographic Co. | |

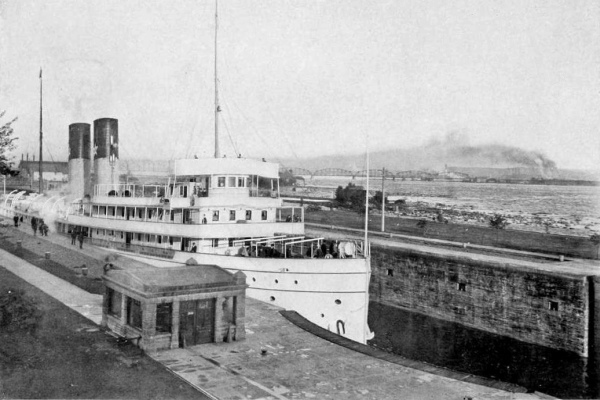

| Steamship “North West” in American Lock | 86 |

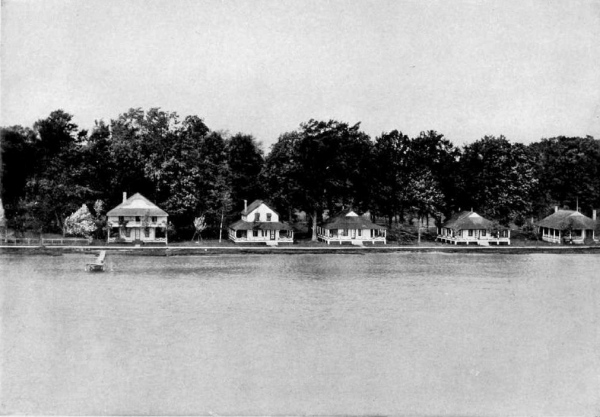

| Cottages Built at Small Expense along the St. Mary’s River | 88 |

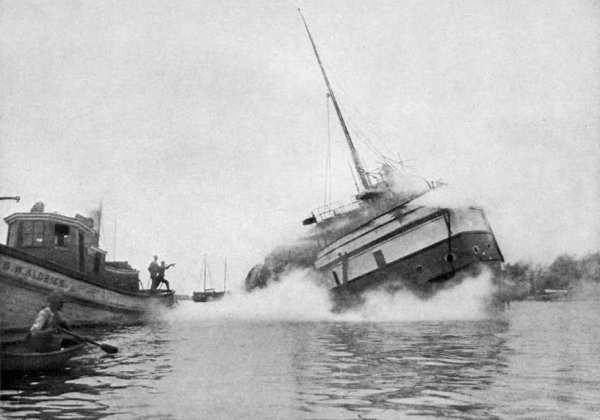

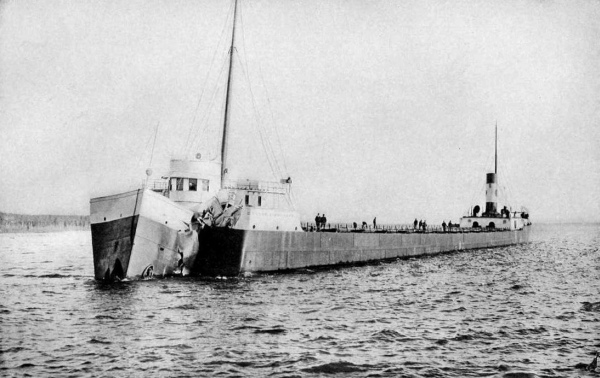

| A Steamer Stripped by a Tow-line by Running between a Steamer and her Consort | 90 |

| From a Photograph by Lord & Rhoades, Sault Ste. Marie, Mich. | |

| A Remarkable Photograph Showing the Big Freighter “Stimson” in a Holocaust of Smoke and Flame | 94 |

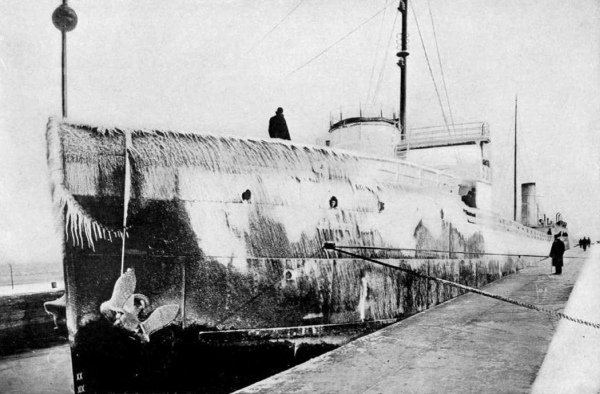

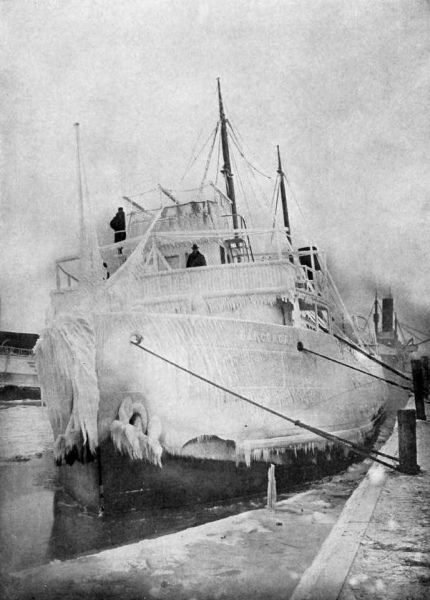

| After a Fierce Night’s “Late Navigation” Run across Lake Superior | 96xiv |

| A Ship that Made the Shore before she Sank. The Work of Raising her in Progress | 100 |

| A Treacherous Sea in its Garb of Greatest Beauty | 102 |

| One phase of Lake navigation. | |

| A View of the “Zimmerman” | 104 |

| After a collision with another freighter. | |

| The Steamer “Wahcondah” | 108 |

| One of the Lake grain carriers which was caught in a storm late in the season after being buffeted by the waves of Lake Superior for about fourteen hours. | |

| This is One of the Most Remarkable Photographs Ever Taken on the Lakes. It Shows a Sinking Lumber Barge just as She Was Breaking in Two | 110 |

| The photograph was taken from a small boat. | |

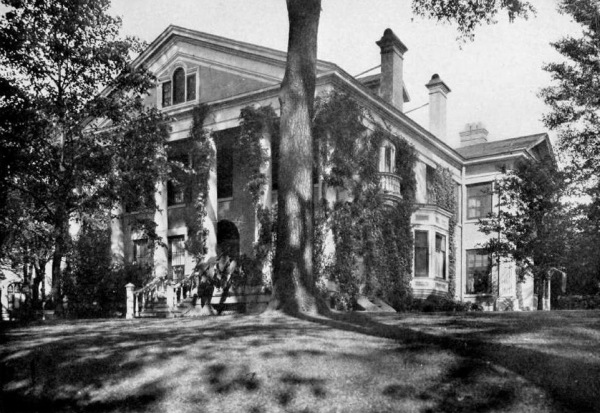

| The Residence of Ansley Wilcox at Buffalo | 114 |

| Where President Roosevelt took the oath of office. Copyright 1908 by Detroit Photographic Co. | |

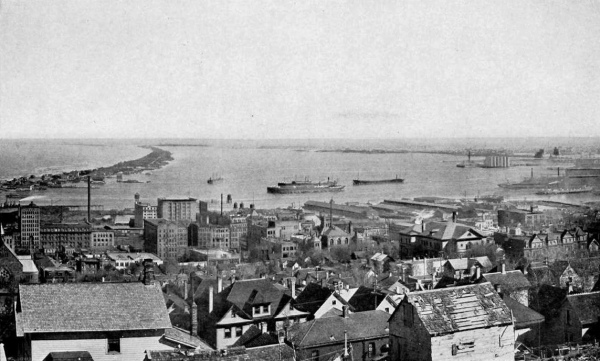

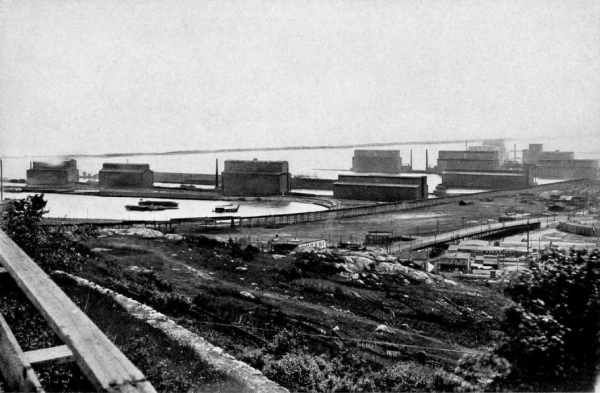

| A Bird’s-eye View of the Harbour of Duluth, Taken from the Hill | 116 |

| From a Photograph by Maher, Duluth. | |

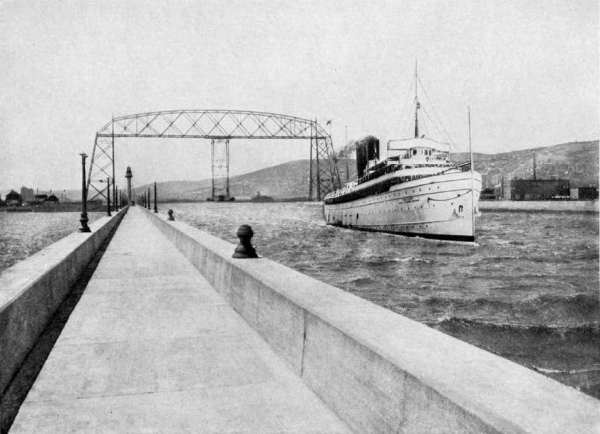

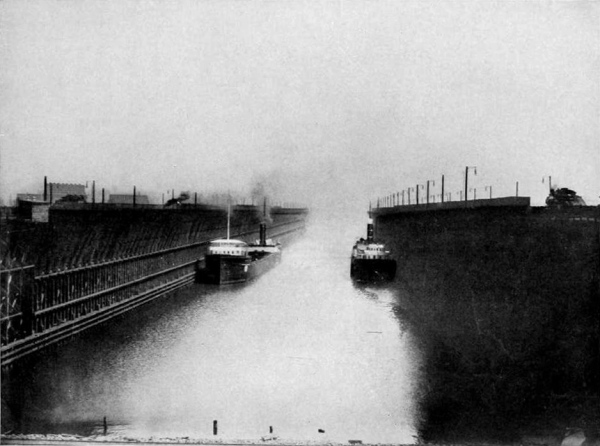

| The Ship Canal and Aërial Bridge, Duluth, Minn. | 118 |

| Copyright 1908 by Detroit Photographic Co. | |

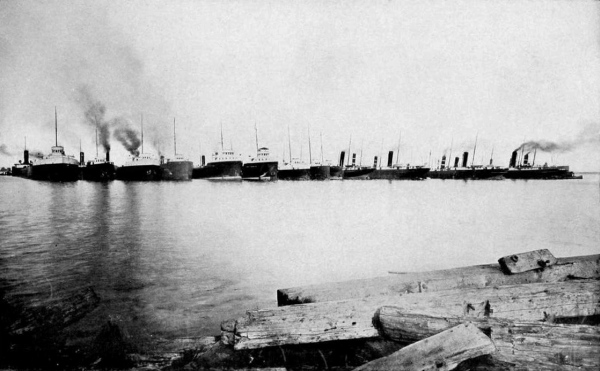

| Fleet of Boats in Duluth Harbour Waiting to Unload | 122 |

| View Looking South-west from the New Chamber of Commerce Building, Buffalo | 124 |

| Unloading at One of the Coal Docks at Duluth | 126 |

| A Fleet of Erie Canal Boats—Capacity of Each 150 Tons | 128xv |

| The boats on the new canal will be 1000 tons each. | |

| The Jack-Knife Bridge at Buffalo | 132 |

| A Scene on Blackwell Canal | 134 |

| The winter home of big boats in Buffalo. | |

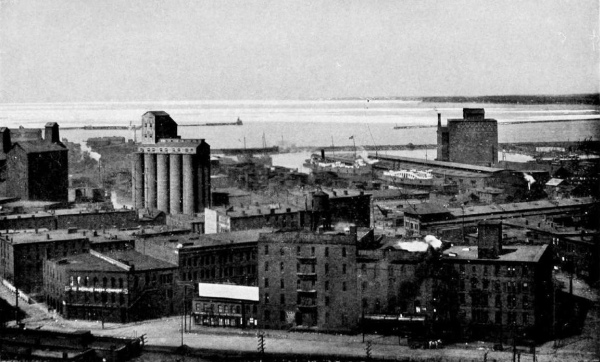

| Some of the Grain Elevators at Duluth, which Have a Combined Storage Capacity of 35,550,000 Bushels | 136 |

| The Mesaba Ore Docks | 138 |

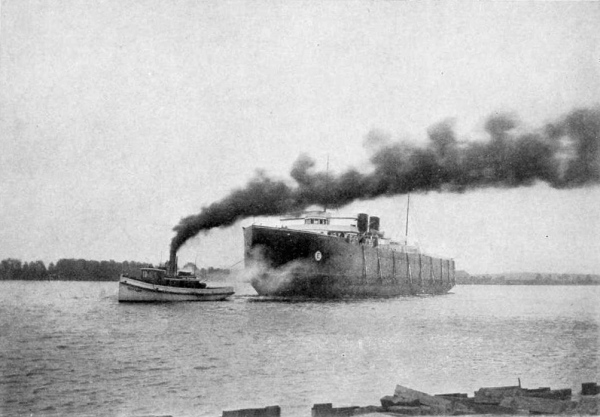

| From the Deck of the Ship the Tug Looks Like an Ant Dragging at a Huge Prey | 142 |

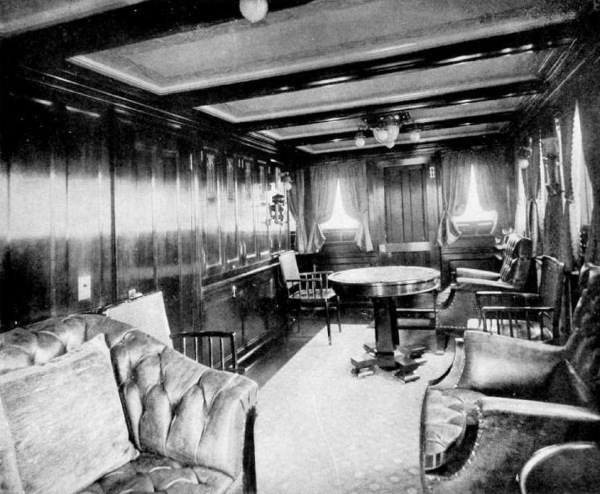

| Observation Room on the “Wm. G. Mather” | 144 |

| Which gives an idea of the luxuriousness of the guests’ quarters on a Great Lakes freighter. | |

| The Luxurious Dining-room on the 10,000-Ton Steamer “J. H. Sheadle” | 146 |

| Tugs Trying to Release Boats Held in the Ice at the Soo | 150 |

| Copyright 1906 by Young, Lord & Rhoades, Ltd. | |

| Whaleback Barges Preparing for Winter Quarters at Conneaut, Ohio | 152 |

| (The Whaleback is a type of vessel that has been tried and found wanting. They are going out of use.) | |

| Ashore | 154 |

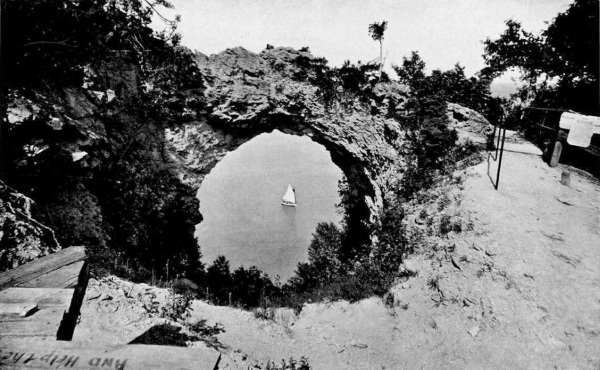

| Arch Rock, Mackinac Island | 160 |

| One of the natural wonders of the world. | |

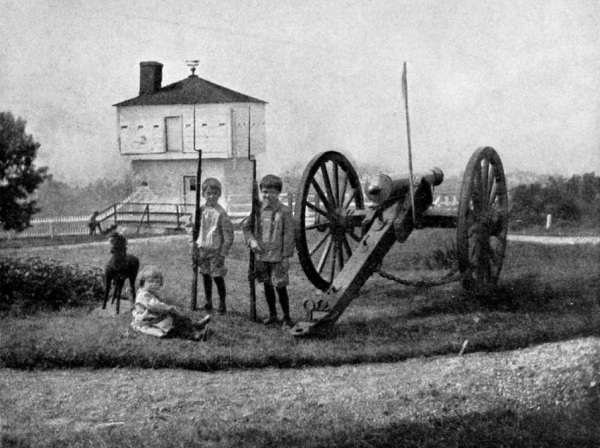

| Fort Mackinac | 168 |

| Marquette’s Grave, St. Ignace, Michigan | 174xvi |

| Monument at Put-in-Bay in Memory of the British and Americans who Died in the Battle of Lake Erie | 182 |

| Old West Blockhouse, Fort Mackinac | 186 |

| Built by the British, about 1780. | |

| The Monument Erected to those who Fought and Died on Mackinac Island | 190 |

| Mackinac Island, Showing Old Fort Mackinac | 194 |

| Once the Scene of Bloodshed and Strife, these Old Trees Stand where French, Indian, and British Fought Years ago | 200 |

| A View of the Historic Battle-ground on Mackinac Island | 206 |

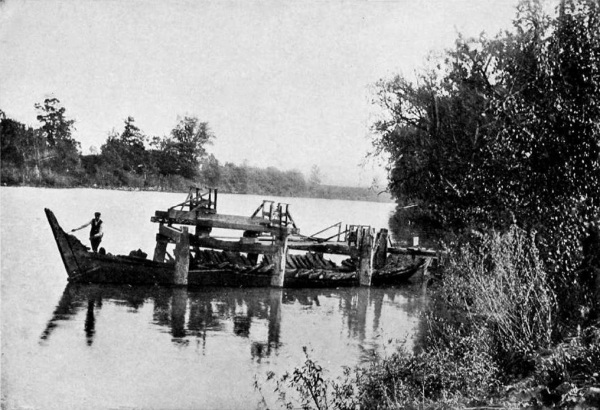

| An Old British Gunboat Discovered in the River Thames | 212 |

| Scene when Admiral Dewey Passed through the Soo Locks | 216 |

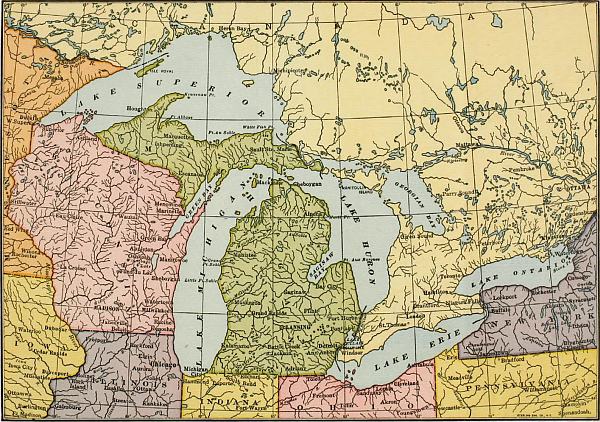

| Map | At End |

Not long ago, I was on a Lake freighter pounding her way up Huron on the “thousand-mile highway” that leads to Duluth. Beside me was a man who had climbed from poverty to millions. He was riding in his own ship. His interests burned ten thousand tons of coal a year. He was one of the ore kings of the North—as rough as the iron he dug, filled to the brim with enthusiasm and animal energy of the Lake breed; a man who had helped to make the Lakes what they are, as scores of others like him have done. Before and behind us there trailed the smoke of a dozen of the steel leviathans of the Inland Seas. I had asked him a question, and there was the fire of a great pride in his eyes when he answered.

“It would make a nation by itself—this Lake country!” he said. “And it would be America. It’s America from Buffalo to Duluth, every inch of it, and the people who are in it are Americans. That’s American smoke you see off there, and American ships are making it; they’re run by a thousand or4 more American captains, and they’re Americans fore ’n’ aft, too. We’ve got only eight States along the Lakes, but if we should secede to-morrow the world would find us the heart and power of the nation. That’s how American we are!”

This is the patriotism one finds in the Lake country, from the roaring furnaces of the East to the vast ore beds of Minnesota. It is representative of the spirit that rules the Inland Seas; it is this spirit that has built an empire, and is building a vaster empire to-day, along the edges of the world’s greatest fresh-water highways.

With more than thirty-four millions of people living in the States bordering on them, possessing one third of the total tonnage of North America, and saving to the people of the United States five hundred million dollars each year, or six dollars for every man, woman, and child in the country, one of the most inexplainable mysteries of the century exists in the fact that the Great Lakes of to-day are as little known to the vast majority of Americans as they were a quarter of a century ago. While revolutions have been working in almost all lines of industry, while States have been made and cities born, America’s great Inland Seas have remained unwatched and unknown except by a comparative few. Upon them have grown the greatest industries of the nation, yet the national ignorance concerning them can hardly find a parallel in history. Were they to5 disappear to-morrow the industrial supremacy of the republic would receive a blow from which it could never recover. The steel industry, as a dominant commercial factor, would almost cease to exist. One half of the total population of the country would be seriously affected, and America would fall far behind in the commercial race of the nations.

Notwithstanding these things, not one person in ten knows what the Great Lakes stand for to-day. While a thousand writers have sung of the greatness and romance of the watery wastes that encircle continents, none has told of those “vast unsalted seas” which mean more to eighty-five millions of Americans than any one of the five oceans. What has been written has been for those who find their commerce upon them; for the owners of ships and the masters of men; for the kings of ore and grain—a little statistical matter here and a little there, but nothing for the millions who are not at hand to feel the pulse of traffic or to see the great commercial pageant as it passes before their eyes. Even of those who live in the States bordering the Great Lakes but few know that these fresh-water highways of traffic possess the greatest shipping port in the world, that upon them floats the largest single fleet of freighters in existence, that in their great construction yards shipbuilding has been reduced to a science as nowhere else on earth, and that in their life the elements of romance and tragedy6 play their parts even as on the big oceans that divide hemispheres.

In a small way the general lack of knowledge of the Great Lakes is excusable, for their development has been so rapid and so stupendous that people have not yet grasped its significance. Within the last quarter of a century or less they have become the industrial magnets of the nation. Along their shores have sprung up our greatest cities, with populations increasing more rapidly than those of New York, Boston, Philadelphia, or San Francisco. In the eight States which have ports on them is more than one third of the total population of the North American continent. Along their three thousand three hundred and eighty-five miles of United States shore line will be built this year more than one half of the tonnage constructed in America, and over their highways will travel at least six times as much freight as all the nations of the world carried through the Suez Canal in 1908.

Just what this means it is hard for one to conceive when told only in figures. Perhaps in no better way can the immensity and importance of their traffic be described than by showing briefly one of the ways in which they earned a “dividend” of six dollars for every person living in the United States in 1907. This immense “dividend” did not go into the coffers of corporations, but actually, though indirectly, into the pockets of the people.

7 It is only fair to the Lakes and the vast interests upon them to use the figures of 1907 instead of those of 1908. In the following pages it is the author’s intention to paint conditions as they actually exist upon our Inland Seas under normal conditions. During 1908, the financial depression that swept over the entire country produced conditions upon the Lakes which, in the author’s opinion, will not be seen again for a great many years to come. “Panic figures” give a wrong impression. Those of 1908 would show a falling off of business in various branches of Lake traffic of from twenty to sixty per cent. As one of the best known vessel-men in Duluth said to me recently, “We can count that the Lakes have lost just one year of progress because of the panic.” In other words, it is highly probable that the business of the Lakes will in this year of 1909 be just about what it should have been under normal conditions in 1908, and there are many who believe that within the next two years the loss of the “panic year” will be more than discounted.

For this reason, in order to show how the Lakes earn their tremendous dividend for the people of the United States, we use the figures of 1907, when traffic was normal. In that year, for instance, it cost a little over ten cents to ship a bushel of grain from Chicago to New York by rail, and only five and one half cents by way of the Lakes and the Erie Canal. This saving on transportation of five cents a bushel8 is divided between the producing farmer and the consuming public. It is a “nickel on which no trust can place its hands”—and this nickel, when multiplied by the number of bushels of grain produced in Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Wisconsin, Iowa, and Michigan, reaches the stupendous figure of ninety-eight million dollars! In the matter of iron ore the saving is still greater. Were it not for this saving all steel necessities, from rails to common kitchen forks, would advance tremendously in price, and the United States would not be able to control the steel markets of the world. To-day you can ship a ton of ore from Duluth to Ashtabula, Conneaut, or Cleveland, a distance of nearly one thousand miles, for less than you can send by rail that same ton from one of these ports to Pittsburg, a distance of only one hundred and thirty miles. In other words, while it costs about eighty cents to send a ton of ore from the vast ranges of the North to an Erie port by ship, the rail rate is seven times greater, which means that the vessels of the Great Lakes saved in 1907 on ore alone no less than one hundred and seventy-three million dollars!

In another way than in this annual saving in cost of transportation are the Lakes fighting a great and almost unappreciated battle for the people. They are to-day the country’s greatest safeguard against excessive railroad charges. They are the governors of the nation’s internal commerce, and will be for all time to come. There is not a State north of the Ohio9 River and east of the Rocky Mountains which is not affected by their cheap transportation, and the day is not distant when hundreds of millions of bushels of grain raised in the Canadian west will go to the seaboard by way of the lake and canal route. At the present time there are about two hundred and forty thousand miles of railroad in the United States, constructed and equipped at a cost of more than thirteen billion dollars; yet, on the basis of ton miles, the traffic on the Lakes will in 1909 be one sixth as great as on all the roads in the country.

These facts are given here to show in a small way the gigantic part the Great Lakes are playing to-day in the industrial progress of the nation. Yet, as paradoxical as it may seem, the nation itself has hardly recognised the truth. The “helping” hand that the Government has reached out has been pathetically weak. In history to come it must be recorded that great men—men of brain and brawn and courage—have “built up” the Lakes, and not the Government. And these men, scores and hundreds of them, are continuing the work to-day. Since the dawn of independence to the present time, the United States has expended for all harbours and waterways on the Great Lakes above the Niagara Falls less than ninety million dollars, yet each year this same Government hands out one hundred and forty million dollars to the army and navy and one hundred and twenty-seven million dollars to the postal service! In the face of this is the astonishing10 fact that, in 1907, the saving in freight rates on Lake Superior commerce alone exceeded by a million dollars the total sum expended by the Government on the Inland Seas since the day the first ship was launched upon them!

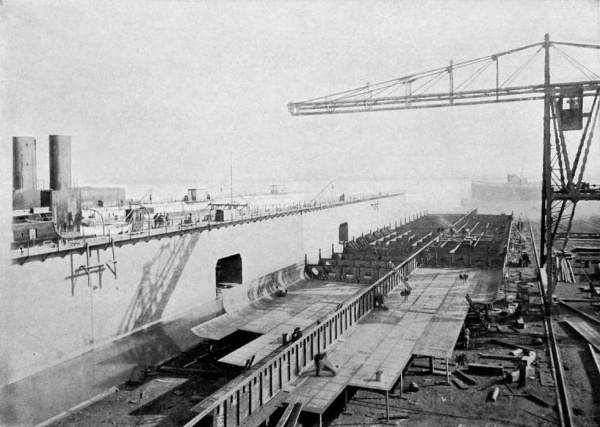

In this building of the “greater empire” of the Lake country there is now no rest. Wherever ships are built the stocks are filled. From the uttermost end of Erie to the shipyards of the north—in Buffalo, Lorain, Cleveland, Toledo, Detroit, West Superior, Chicago, and Manitowoc—the making of American ships is being rushed as never before. In the larger yards powerful arc-light systems allow of work by night as well as by day. The roaring of forges, the hammering of steel, the tumult of labouring men, and the rumbling of giant cranes are seldom stilled. With almost magical quickness a ten-thousand-ton monster of steel rises on the stocks—and is gone. Another takes its place, and even as they follow one another into the sea, racing to fill demands, there still comes the cry: “Ships—ships—we want more ships!”

In the year 1908, it is estimated that very nearly three fifths of the total ship tonnage built in the United States was constructed in these busy yards of the Great Lakes. As early as January they were choked with orders for 1908 delivery, and even that early a number of them had orders running well into 1909. A brief glance at the vessel construction of the Lakes during the six years up to and including11 1907 will give a good idea of the rapid growth of this industry along the Inland Seas. In 1902, the product was forty-two vessels, thirty-two of them being bulk freighters. In 1903, forty-two of the fifty vessels built were bulk freight steamers, with a carrying capacity of 213,250 tons. In 1904, the output was only thirteen vessels, but in 1905 twenty-nine bulk freighters with a carrying capacity of 260,000 tons were built. In 1906, there were turned out from the Great Lakes yards forty-seven vessels, of which forty were bulk freighters, and in 1907, the total was fifty-six vessels, including forty bulk freighters, three package freighters, and one passenger steamer. The early months of 1908 saw contracts in force for the construction of twenty-five bulk freighters for delivery before 1909.

Taking the forty bulk freighters built in 1907, one gets a fair idea of the immensity of Lake traffic. They are but a drop in the bucket—a single year’s contribution to the great argosies of the Inland Seas; yet these forty ships have a carrying capacity of three hundred and sixty thousand tons. In other words, within four days after loading at Duluth they could be discharging this mountain of ore at Erie ports. To carry this same “cargo” by rail would require over three hundred trains of thirty cars each, or a single train seventy miles in length!

But this is not particularly astonishing when one is studying the commerce of the Great Lakes. True,12 it represents considerably over a half of the tonnage built in the United States during 1907, but even at that it “isn’t much to shout about,” as one builder of ships said to me. These men of the Lakes never express surprise at the wonders of the Inland Seas. They are used to them. They meet with them every day of their lives. On either coast these same “wonders” would be made much of. But the Lake breed is not the breed that boasts—unless you drag opinions from them. Why, over in Cleveland there is one man who directs the destinies of twice as many ships as the forty-eight mentioned above—a single commercial navy that can move six hundred and forty-eight thousand tons of ore in one trip, or enough to “make up” a train of sixteen thousand two hundred cars, which train would be one hundred and twenty miles in length! This man’s name is Coulby—Harry Coulby, President and General Manager of the Pittsburg Steamship Company, Lake arm of the United States Steel Corporation. There was a time when Coulby was a poor mechanic, working his ten hours a day. Then he developed “talent” and went into a shipyard draughting-room. Now he is undeniably the king of Lake shipping. His word is law in the directing of more than a hundred vessels, the greatest fleet in the world; and it is law in other ways, for it is common talk in marine circles that he (with the trust behind him) is responsible for nearly every important move on the Great Lakes. He is the eye and the13 ear and the mouth of the trust, and it is the trust that practically fixes the ore rates for each season, and does other things of interest. If these ships of Coulby’s were placed end to end they would reach a distance of eight miles! During the eight months of Lake navigation they can transport as much freight over the “thousand-mile highway” as the combined fleets of all nations take through the Suez Canal in twelve! Yet who has heard of Coulby? How many know of the gigantic fleet he controls? A few thousand Lake people, and that is all. A magnificent illustration is this of the national ignorance concerning the Great Lakes.

A Monster of Steel and Iron Ready to be Launched.

Weight 9,500,000 lbs.

And Coulby is only one of many. The fleet he controls is only one of many. The Lakes breed great men—and they breed great fleets. How many of our millions have heard of J. C. Gilchrist and the Gilchrist fleet?—a man in one way unique in the marine history of the world, and a fleet which, if plying between New York and Liverpool, would be one of the present-day sensations. Gilchrist, like Coulby, “worked up from the depths,” and to-day, as the head of the Gilchrist Transportation Company, he holds down seventy-five distinct jobs! Seventy-five owners have placed seventy-five ships under his generalship, and from each he receives a salary of one thousand dollars a season, or a total of seventy-five thousand dollars. He is one of the Napoleons of the Lakes. He handles ships and men like a magician; his holds are never14 empty; his dividends are always large. There was a day when one thousand dollars looked like a fortune to Gilchrist, and when eight dollars a week was an income of which he was mightily proud. That was when, from away down in Michigan, he turned his face northward toward the Lakes, filled with big ambition and a desire for adventure, but with little more than what he carried on his back. He got work as a sailor before the mast at forty dollars a month and board. From there he graduated to “bell hop” on a passenger steamer, and continued to graduate until the owners of great ships began to see in him those things which they themselves did not possess, and so handed over to him the destiny of the second greatest fleet of freight carriers in the world.

Such men as Coulby and Gilchrist and the ships they have would make the fame of any nation on the high seas. They and men like Captain John Mitchell, who is the head of a fleet of twenty ships, J. H. Sheadle, G. Ashley Tomlinson, and G. L. Douglas, are of the kind that are choking the Great Lakes shipyards with orders, while along the ocean seaboards stocks are rotting and builders of ocean marine are starving. Cleveland claims the headquarters of both of these immense fleets—and Cleveland is fortunate in many other things. She counts her strong men of the Lakes by the score. She is a great owner of ships, a great buyer of ships, and a great builder.

But when it comes to the production of “bottoms,”15 Cleveland and all other Lake cities must give way to Detroit. There was a day when Detroit was one of the important ports of the Lakes, but that day is long past. Now she is the centre of shipbuilding. In 1907, there was built at Detroit more tonnage than in any other city in the United States. Of the vessels launched, twenty-one of the largest took their first dip in or very near Detroit. The tonnage of these vessels aggregated over one half of the total tonnage of the forty freighters constructed for the season’s delivery.

It has been said that Detroit is a great shipbuilding city by accident, and there is a good deal of truth in the assertion. Six years ago the American Shipbuilding Company, the greatest trust of its kind in the world, held undisputed sway over the Lakes. It knew no competition. No combination of capital had dared to grapple with it. With eleven huge construction yards strung along the Lakes between Buffalo, Duluth, and Chicago, it held a monopoly of the shipbuilding industry. It was at this time that one of the country’s great industrial generals sprang up in Detroit. Then he was practically unknown; now as a leader and master of men, he is known in every city of this country where iron and steel are used. His name is Antonio C. Pessano. Detroit must always be proud of this man. He must count in the history of her future greatness, and always her citizens should be thankful that he and his indomitable courage did16 not first appear in Buffalo, Cleveland, or some other Lake city. Mr. Pessano’s ambition was to build at Detroit the most modern shipbuilding plant in the world. Some people laughed at him. Others pitied him. The trust twiddled its fingers, so to speak, and smiled. In the face of it all Mr. Pessano won the confidence of such Gibraltars of industrial finance as George H. Russel, Colonel Frank J. Hecker, Joseph Boyer, William G. Mather, Henry B. Ledyard, and others—won it to the extent of raising one million five hundred thousand dollars, with which he built the greatest shipbuilding yards on the Lakes and which have developed since then into the greatest in America, employing more than three thousand men.

Mr. Pessano’s shipbuilding rival is the president of the trust. His name is Wallace, “son of Bob Wallace, the elder,” Lake men will tell you, for Robert Wallace, the father, was a shipbuilder himself for a great many years. He is very proud of his boy.

“I had three boys,” said he. “Two of ’em went to college, but Jim he wanted an education, so he didn’t take much stock in books, but got out among men. That was what made Jim!”

The “Thomas F. Cole,” 11,200 Tons, Being Fitted with Engines and Boilers after her Launching.

The “Cole” is the largest ship on the Lakes. Length, 605 feet 5 inches.

To-day it is “Jim,” or James C. Wallace, of Cleveland, as he is better known, who is the champion shipbuilder of the world. He is President of the American Shipbuilding Company. Probably in no other part of the world is the romantic more largely associated with modern progress than on the Great Lakes, and in17 these two men—Wallace and Pessano—it is revealed in a singular way. Together they govern shipbuilding on the Inland Seas. Both of these great men began in the dinner-pail brigade. They worked in overalls and grease, not for “experience,” but because they had to; they pulled and heaved with common labourers; they rose, step by step, from the lowest ranks—and to-day, monuments to courage and ambition, they are the earth’s two greatest builders of ships. In a novel such characters would be declared almost impossible. But the Lakes breed such as these. There are others whose careers have been even more remarkable, and I will tell of these later—men whose rise from poverty to wealth and power rivals in romance and adventure the most glowing stories of the Goulds and Astors.

Mr. Pessano, “the independent,” does not entirely monopolise Detroit shipbuilding, for Wallace was there ahead of him with one of the trust’s big yards, which is known under the name of the Detroit Shipbuilding Company. It materially assists in the city’s greatness, and will continue to do so more and more each year. During 1907, it launched six big freighters in Detroit, and that city, together with eight other Lake cities, heaps blessings on the trust. For the trust is most generous and unprejudiced in its distribution of yards. It builds ships in one huge yard at Superior, in two at Chicago, two at Cleveland, and in one at Lorain, Buffalo, Wyandotte, Detroit, and Milwaukee. Among these cities it has distributed over fifteen18 million dollars in capital, and it is estimated that it affords a livelihood for between fifty and sixty thousand people. In 1907, the different yards built twice the tonnage of the next two largest shipbuilding concerns in the world combined—those of Doxford and Sons, of Sunderland, and Harland and Wolff, of Belfast, whose aggregate tonnage was not over one hundred and fifty thousand. The astonishing rate at which Lake shipbuilding is increasing is shown in the fact that the trust’s production for 1907 was twice that of 1905, which was 117,482 tons, divided among twenty vessels. A new factor has come into Lake shipbuilding which will count considerably in the future. This is the Toledo Shipbuilding Company, which purchased the Craig yards in 1906, and which has expended a great deal of money since that time in perfecting its plant, until now it has one of the most modern construction yards on the Lakes.

It would seem that this activity in Lake shipyards must soon supply demands, but such will not be the case for many years to come. While the depression of 1908 has cast its gloom, Lake men cannot see the end of their prosperity. They are in the midst of fortune-making days on the Inland Seas. To-day one of the steel ships of the Lakes is as good as a gold mine, and will continue to be so for a quarter of a century to come. The shipyards are growing each year, but the increase of tonnage is outstripping them, and until cargo and ships are more evenly balanced the owners19 of vessels on the Great Lakes must be counted among the most fortunate men in the world.

It is only natural that these conditions should have developed shipbuilding on the Lakes to a science unparalleled in any other part of the earth. I once had the good fortune to talk with a shipbuilder from the Clyde. He had heard much of the Lakes. He had built ships for them. He had heard of the wonders of shipbuilding in their cities. So he had come across to see for himself.

“I had thought that your ships would not compare with ours,” he said. “You build them so quickly that I thought they would surely be inferior to those of the Clyde. But they are the best in the world; I will say that—the best in the world, and you build them like magicians! You lay their keels to-day—to-morrow they are gone!”

This is almost true. A ten-thousand-ton leviathan of the Lakes can now be built almost as quickly as carpenters can put up an eight-room house. Any one of several shipyards can get out one of these monsters of marine commerce within ninety days, and the record stands with a ten-thousand-ton vessel that was launched fifty-three days after her keel was laid! One hardly realises what this means until he knows of a few of the things that go into the construction of such a vessel. Take the steamer Thomas F. Cole, for instance, launched early in 1907 by the Great Lakes Engineering Works. This vessel is the giant of the Lakes, and is six hundred20 and five feet and five inches long. She is fifty-eight feet beam and thirty-two feet deep, and in a single trip can carry as great a load as three hundred freight cars, or twelve thousand tons. In her are nine million five hundred thousand pounds of iron and steel! What does this mean? It means that if every man, woman, and child in Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota were to join in carrying this material to a certain place, each person would have to transport one pound. In the mass would be eight hundred thousand rivets, ranging in size from five eighths of an inch to one and one eighth inches in diameter.

One who is investigating Lake shipbuilding for the first time will be astonished to discover that the modern freighter is in many ways a huge private yacht. They are almost without exception owned by men of wealth, and their cabins are fitted out even more luxuriously than those of passenger boats, for while these latter are intended for the use of the public, the passenger accommodations of freighters are planned for the friends and families of the owners. So above the deck which conceals ten thousand tons of ore the vessel may be a floating palace. The keenest rivalry exists between owners as to who shall possess the finest ships, and fortunes are expended in the fittings of cabins alone. Nothing that money can secure is omitted. In the words of a builder: “The modern freighter is like a modern hotel—only much more luxuriously furnished.” There is an electric light system throughout21 the ship; the cabins are equipped with telephones; there is steam heat; there are kitchens with the latest cooking devices, elegantly appointed dining-rooms; there are state-rooms which are like the apartments in a palace, and other things which one would not expect to see beyond the black and forbidding steel walls of these fortune-makers of the Lakes.

With the first peep into modern methods one realises that the romantic shipbuilding days of old are gone. No longer does the shape, beauty, and speed of a vessel depend upon the eyes and hands of the men who are actually putting it together. For the ship of to-day is built in the engineering offices. In the draughting-room skilled men lay out the plans and make the models for a ship just as an architect does for a house, and when these plans are done they go to a great building which reminds one of a vast dance hall, and which is known as the “mould loft.” Seemingly the place is not used. Yet at the very moment you are looking about, wondering what this vacancy has to do with shipbuilding, you are walking on the decks of a ship. All about upon the floor, if you notice carefully, you will see hundreds and thousands of lines, and every one of these lines represents a line of the freighter which within three or four months will be taking her trial trip. Here upon the floor is drawn the “line ship” in exactly the same size as the vessel which is to be built. Over certain sections of this “line ship” men place very thin pieces of basswood, which they22 frame together in the identical size and shape of the ship’s plates. By the use of these moulds, or templates, the workman can see just where the rivet holes should be, and wherever a rivet is to go he puts a little spot of paint. These model plates are then numbered and sent to the “plate department,” where the real sheets of steel are made to conform with them and where the one million five hundred thousand or more rivet holes are punched. With the plates ready, the real ship quickly takes size and form.

Some morning a little army of men begins work where to the ordinary observer there is nothing but piles of steel and big timbers. From a distance the scene reminds one of a partly depleted lumber yard. On one side of this, and within a few yards of the water of a slip, are first set up with mathematical accuracy a number of square timbers called “keel blocks.” Upon these blocks will rest the bottom of the ship, and from them to the water’s edge run long shelving timbers, or “ways,” down which she will slide when ready for launching.

Children frequently play with blocks which, when placed together according to the numbers on them, form a map of the United States. This is modern shipbuilding—in a way. It is on the same idea. There is a proper place for every steel plate in the yards, and the numbers on them are what locate them in the ship. A giant crane runs overhead, reaches down, seizes a certain plate, rumbles back, to hover23 for a moment over the growing “floor,” lowers its burden—and the iron workers do the rest. Within a few days work has reached a point where you begin to wonder, and for the first time, perhaps, you realise what an intricate affair a great ship really is, and what precautions are taken to keep it from sinking in collision or storm. You begin to see that a Lake freighter is what might be described as two ships, one built within the other. As the vessel increases in size, as the sides of it, as well as the bottom, are put together, there are two little armies of men at work—one on the outer ship and one on the inner. From the bottom and sides of the first steel shell of the ship there extend upward and inward heavy steel supports, upon which are laid the plates of the “inner ship.” In the space between these two walls will be carried water ballast. The chambers into which it is divided are the life-preservers of the vessel. A dozen holes may be punched into her, but just as long as only this outer and protecting ship suffers, and the inner ship is not perforated, the carrier and her ten-thousand-ton cargo will keep afloat.

When the construction of the vessel has reached a point where men can work on the inner as well as the outer hull, it is not uncommon for six hundred to eight hundred workmen to be engaged on her at one time. Frequently as high as one hundred gangs of riveters, of four men each, are at work simultaneously, and at such times the pounding of the automatic24 riveting machines sounds at the distance of half a mile like a battery of Gatling guns in action. So the work continues until every plate is in place and the vessel is ready for launching, which is the most exciting moment in the career of the ship—unless at some future day she meets a tragic end at sea. One by one the blocks which have been placed under her bottom are removed, until only two remain, one at each end. Then, at the last moment, these two are pulled away simultaneously, and the steel monster slides sidewise down the greased ways until, with a thunderous crash of water, she plunges into her native element.

Thus ends the building of the ship, with the exception of what is known as her “deck work,” the fitting of her luxurious cabins, the placing of her engines, and a score of other things which are done after she is afloat. She is now a “carrier” of the Lakes. A little longer and captain and crew take possession of her, clouds of bituminous smoke rise from her funnels, and with flying pennants and screaming whistles she turns her nose into the great highway that leads a thousand miles into the North—to the land of the ore kings.

Picture a train of forty-ton freight cars loaded to capacity, the engine and caboose both in New York City, yet extending in an unbroken line entirely around the earth—a train reaching along a parallel from New York to San Francisco, across the Pacific, the Chinese Empire, Turkestan, Persia, the Mediterranean, mid the Atlantic—and you have an idea of what the ships of the Great Lakes carry during a single eight months’ season of navigation. At least you have the part of an idea. For were such a train conceivable, it would not only completely engirdle the earth along the fortieth degree of north latitude, but there would still be something like two thousand miles of it left over. In it would be two million five hundred thousand cars, and it would carry one hundred million tons of freight! Were this train to pass you at a given point at the rate of twenty miles an hour, you would have to stand there forty days and forty nights to see the end of it.

Only by allowing the imagination to paint such a26 picture as this can one conceive to any degree at all the immensity of the freight traffic on our Inland Seas.

“A hundred million tons,” repeated the mayor of one of our Lake ports when I told him about it recently. “A hundred million tons! That’s quite a lot of stuff, isn’t it?”

Quite a lot of stuff! It might have been a hundred million bushels and he would have been equally surprised. His lack of enthusiasm does not discredit him. He does not own ships; neither does he fill them. He is like the vast majority of our millions, who have never given more than a passing thought to that gigantic inland water commerce which has largely been the making of the nation. It did not dawn on him that it meant more than a ton for every man, woman, and child on this North American continent; that in dollars it counted billions; that on it depended the existence of cities; that largely because of it foreign nations acknowledged our commercial prestige.

Ice-Bound. Thirty-two Boats Tied up in the Ice at the Soo.

From a Photograph by Lord & Thomas, Sault Ste. Marie, Mich.

No other hundred million tons of freight in all the world is as important to Americans as this annual traffic of the Great Lakes. To move it requires the services of nearly three thousand vessels of all kinds, employing twenty-five thousand men at an aggregate wage of thirteen million dollars a year. A million working people are fed and clothed and housed because of the cargoes this huge argosy carries from port to port.

27 It is impossible to say with accuracy how this hundred million tons of freight is distributed and of what it consists. Only at the Soo and at Detroit are records kept of passing tonnage, so the figures which are given showing the tremendous commerce that passes these places do not include the enormous tonnage which is loaded and emptied without passing through the Detroit River or the Sault Ste. Marie canals. The Detroit River is the greatest waterway of commerce in the world, and in 1906 there passed through it over sixty million tons, or more than three fifths of the total tonnage of the Lakes. Of this about a quarter moved in a northerly direction and three quarters toward the cities of the East. The principal item of the up-bound traffic was 14,000,000 tons of coal, of the south-bound 37,513,600 tons of iron ore, 110,598,927 bushels of grain, 1,159,757 tons of flour, 14,888,927 bushels of flaxseed, and over 1,000,000,000 feet of lumber. In 1907, there was a big increase, the commerce passing through the Detroit River being over 75,000,000 tons.

“And when you are figuring out what the ships carry, be sure and don’t leave out the smoke!” said the captain of an ore carrier, pointing over our port to a black trail half a mile long. “Never thought of it, did you? Well, last year our Lake ships burned three million tons of coal. Think of it! Three million tons—enough to heat every home in Chicago for two years!”

But in this chapter I am not going to deal with smoke; neither with the grain that feeds nations, nor the lumber that builds their homes. They will be described in their time. The backbone of American manufacturing industry—the mainspring of our commercial prestige abroad—is iron; and it is this iron, gathered in the one-time wildernesses of the Northland and brought down a thousand miles by ship, that stands largely for the greatness of the Lakes to-day. “Gold is precious, but iron is priceless,” said Andrew Carnegie. “The wheels of progress may run without the gleam of yellow metal, but never without our ugly ore.” And the Lake country, or three little patches of it, produce each year nearly a half of the earth’s total supply of iron. Farmers in the wake of their ploughshares, our millions of workers in metal, and our other millions whose fingers daily touch the chill of iron have never dreamed of this. Few of them know that eight hundred great vessels are engaged solely in the iron ore traffic; that in a single trip this immense fleet can transport more than three million tons, and that in 1907, they brought to the foundries of the East and South over forty-one million tons. If every man, woman, and child, savage or civilised, that inhabits this earth of ours were to receive equal portions of this one product carried by Lake vessels in 1907, each person’s share would be forty pounds! And still the world is crying for iron. There is not enough to supply the29 demand, and there never will be. The iron ore traffic of the Lakes has doubled during the last six years; it will double again during the next ten—and iron will still be the most precious thing on earth.

If the iron ore mines of the North were to go out of existence to-morrow nearly half of the commerce of the Inland Seas would cease to be. With it would go the strongest men of the Lakes. For our iron has made iron men. In that Northland, along the Mesaba, Goebic, and Vermilion ranges, from Duluth’s back door to the pine barrens of northern Michigan and Wisconsin, they have practically made themselves rulers of the world’s commerce in steel and iron. To follow the great ships of the Lakes over their northward trail into this country is to enter into realms of past romance and adventure which would furnish material for a hundred novels. But people do not know this. The picturesque days of ’49, the Australian fever, and the Klondike rush are as of yesterday in memory—but what of this Northland, where they load dirty ore into dirty ships and carry it to the dirty foundries of the East? Ask Captain Joseph Sellwood; ask the “three Merritts,” Alfred, Leonidas, and N. B.; or John Uno Sebenius, David T. Adams, and Martin Pattison; ask any one of a score of others who are living, and who will tell you of the days not so very long ago when the iron prospectors went out with packs on their backs30 and guns in their hands to seek the “ugly wealth.” These are of the old generation of “iron men”—the men who suffered in the days of exploration and development in the wilderness, who starved and froze, who survived while companions died, who suffered adventures and hardships in the death-like grip of Northland winters that rival any of those in Klondike history. And the new generation that has followed is like them in “the strength of man” that is in them. They are a powerful breed, these iron kings, down to the newest among them; men like Thomas F. Cole, who rose from nothing to a position of power and wealth, and W. P. Snyder, the poverty-stricken Methodist minister’s son, who has fought the Steel Corporation to a standstill and who is talked of as its president of the future.

It will be a great “coming together” for the iron and steel industry, this winning of William Penn Snyder. To-day he is the king of pig iron. When he refused to deal with those who formed the United States Steel Corporation, his friends said that he was ruined. But he stood on his feet alone—and fought. He got a neck hold on the corporation. He cornered pig iron and because of him at the present time the corporation is paying very heavy prices for its outside product. Snyder is worth fifteen million dollars. In 1906, he cleaned up one million five hundred thousand dollars on pig iron alone, and there is no reason for doubting that his 1907 earnings were greater31 still. He is a powerful enemy to have as a friend—and the corporation wants him, and will probably get him.

If you are going into the North to study the ore traffic at close range, the first man you will probably hear of after leaving your ship is Thomas F. Cole, of Duluth. You must know Cole before you go deeper into the subject of the forty or fifty million tons of ore which the ships will carry during the present year of 1909. The United States Steel Corporation will use about thirty million tons of the total output of the ore regions this year, and Cole is the United States Steel Corporation in this big Northland. He is the head of the finest and most delicate industrial mechanism in the world. This mechanism, in a way, is so fine that it may be said to be almost non-existent. It is simply an “organized and capitalized intelligence.” The Steel Corporation will mine some eighteen or twenty million tons of ore in Minnesota alone this year. Yet it owns not a dollar’s worth of property in the State. As a corporation it does no business in the State. It might be described as a huge octopus, and each arm of this octopus, representing a big mining interest, works independently of all other arms and of the body of the octopus itself. Through these arms the corporation accomplishes its aims. Each huge mine has its own executive organisation, is responsible for its own acts—but it must obtain results. The “central intelligence,” or body of32 the corporation, is there to judge results, and Cole is the power that watches over all. Officially he is known as the president of the Oliver Mining Company, the greatest organisation of its kind in existence, which attends not only to the Steel Corporation’s interests in Minnesota, but in Michigan and Wisconsin as well. As the great eye of the world’s largest trust he guards the interests of thirty-one mines, employs fifteen thousand men, and gives subsistence to sixty thousand people.

The “Montezuma.”

The largest wooden ship on fresh water being towed out of the Maumee River, Toledo.

Because of the transportation of this mighty product Cole is as closely associated with the Lakes and their ships as with the ranges and their mines. It has been said that he was “born between ships and mines,” and he has always remained between them. He is one of the most remarkable characters of the Inland Seas. Cole is only forty-seven years old, and for thirty-nine years he has earned his own livelihood, and more. When six years old, his father was killed in an accident in the Phœnix Mine. Baby Tom was the oldest of the widowed mother’s little brood, and he rose to the occasion. At the age of eight he became a washboy in the Cliff stamp mill. He had hardly mastered his alphabet; he could barely read the simplest lines; never in this civilised world did a youngster begin life’s battle with greater odds against him. But even in these days the great ambition was born in him, as it was born in Abraham Lincoln; and like Lincoln, in his little wilderness home of poverty and33 sorrow, he began educating himself. It took years. But he succeeded.

This is the man whose name you will hear first when you enter the mining country. To chronicle his rise from a dusty Calumet office of long ago to his present kingdom of iron would be to write a book of romance. And there are others of the iron barons of the North whose histories would be almost as interesting, even though fortune may have smiled on them less kindly.

From the immensity of the interests which Cole superintends one might be led to believe that the iron ore industry is almost entirely in the hands of the trust. This, however, is not so. For every ship that goes down into the South for the trust another leaves for an independent. Nearly every maker of steel owns a mine or two in the ranges of Minnesota, Michigan, or Wisconsin. There are five of these ranges. The Mesaba and Vermilion ranges, both in Minnesota, produce about two thirds of the total product carried by the ships of the Lakes; the Goebic, Menominee, and Marquette ranges are in Michigan and Wisconsin.

Somehow it is true that nearly every great thing associated with the Lakes is unusual in some way—unusual to an astonishing degree, and the iron ore industry is not an exception. Probably not one person in ten thousand knows that one lone county in this great continent is the very backbone of the steel industry in the United States. This county is in34 Minnesota. It is the county of St. Louis, and is about as big as the State of Massachusetts. Not much more than twenty years ago it was a howling wilderness. Even a dozen years ago the Mesaba bore but little evidence of the presence of man. Now this country is alive with industry. Buried in the wilderness which still exists are thriving towns; where a short time ago deer and bear wandered unmolested, is now the din of innumerable locomotives, the rumbling of thousands of trains, the screeching of whistles, and the constant groaning of steam shovels. There is not a richer county on the face of the earth. In it are over one hundred mines, from which one hundred and twenty-three million tons of ore have been taken since Charlemagne Tower, now Ambassador to Germany, brought down the first carload to Duluth in 1884. These mines afford livelihood for more than two hundred thousand people, and because of them St. Louis County possesses the greatest freight traffic road in existence—the Duluth, Mesaba, and Northern Railway—which, in 1907, carried about fourteen million tons of ore from the mines to the docks.

A Coal Dock at Superior, Wisconsin.

The pile of coal is 1400 feet long and 30 feet high.

This comparatively little corner of Minnesota practically runs the whole State in so far as expenses are concerned. To administer the affairs of the State, including all of its activities, costs about two million six hundred thousand dollars, and, as inconceivable as it may seem, the three railroads in the ore region pay in taxes one fifth of this sum. They pay one35 third of the total railroad tax of the State, notwithstanding the fact that some of the greatest lines in the country centre at Minneapolis and St. Paul. To this must be added about seven hundred thousand dollars paid in direct taxes by the mines themselves, so that the iron ore which the ships of the Lakes bring down to Eastern ports each season pays almost half of the total expense of running the State of Minnesota!

And these mines will add more and more to the State exchequer each year, as will also the mines of the three ranges in Michigan and Wisconsin. For in no part of the world has mining been undertaken on a scale so gigantic as that of the Superior region, and every contrivance known to mining science is being used to increase month by month the mountains of ore which ever fail to satisfy the hungry furnaces of the East. It is predicted by Captain Joseph Sellwood, of Duluth, one of the oldest and greatest of the iron barons, that the time is not distant when the Mesaba range alone will be producing forty million tons of ore a year—as much as all five ranges are producing now.

“It will cost over a billion dollars to get this ore to the docks,” said he. “And seven hundred and fifty million dollars more to land it in Lake Erie ports.”—Nearly a two-billion-dollar mining and transportation business for the people of the Lakes to look forward to, and this from a single range!

“But will not this tremendous activity exhaust36 your mines?” I asked of several of these iron barons. “The ore doesn’t go down to China, and it doesn’t extend all over the State. What is the future?”

The future! Few have thought of this. There are just at present too many millions of dollars in the making to give one time or inclination to picture the days when only black and silent scars will remain to give evidence of the time when this Northland was one of the treasure houses of the earth. But that time must come. Old mining men say so if you can get them to talk about it, and scientific computations, as far as they go, are proof of it. These computations differ, but they agree pretty generally that there are still between a billion and a half and two billion tons of ore in the Superior district. Within the next five years the ships will be bringing down fifty million tons a year, and there is no reason for believing that this will be the maximum. So it is obvious that the ore of the Lake Superior regions will not last beyond the year 1950 unless new deposits are discovered, or methods are found for the utilisation of immense deposits that cannot now be used.

“Will this event not prove ruinous to a large extent to shipping interests?” I asked G. Ashley Tomlinson, of Duluth, and others closely associated with iron and vessel interests. “To-day nearly half of the total tonnage of the Lakes is from the mines. If this industry becomes practically extinct what will become of the hundreds of ships engaged in the traffic?”

37 Mr. Tomlinson’s answer struck me as extremely logical. “The production of ore will probably reach its maximum within the next ten years,” he said. “It will then begin to decline. But the decrease will be gradual, and meanwhile other freight traffic on the Lakes will be increasing so rapidly that each year ships that were intended originally for the ore trade will carry other business. There will be no loss for the ships. The development of our own and the Canadian West has only begun, and the Lakes are the great links of commerce between their vast enterprises of the future and the East. The grain trade of the Canadian West alone will in the not distant future be something tremendous.”

But whatever the future of the ore regions of the North may be, their present is one of great interest and importance to the world at large. Mining, like shipbuilding, has been reduced to a science on the Lakes. A stranger visiting for the first time any one of the five ranges is filled with astonishment. I will never forget the sensations with which I first saw mining on the Mesaba range. We had come up over a forest-clad hill and stood on the very edge of the mine before I had been made aware of its nearness. Below me there stretched a mile of deep, huge scars in the bottom of what seemed to be a great hole dug into the earth. One of these pits, half a mile in diameter, and, as I afterward discovered, nearly two hundred feet in depth, was almost at my feet.

38 “That’s iron ore,” said my companion. “And right there it goes one hundred feet deeper down.”

This was one of the great “open pits” of the Mesaba range. There are many others like it in the Superior regions. They are the most wonderful mines in the world. Imagine that you take a barrel of salt, dig a hole, pour the salt into this hole, and cover it with a few inches of earth. This gives you an idea of one of these ore mines. After the earth has been “stripped” from the top the ore is reached and it is found in much the same way that the salt would be found. In the words of one superintendent, it is “all together.” It is as if Nature, like a pirate, had dug holes here and there in which she had hidden her treasure, covering it over for concealment with a few feet of earth.

Down into these pits and along their edges run the tracks of the ore cars. There is here but little of the shovelling and “picking” of men. Steam shovels, weighing from sixty to seventy-five tons each, do the work. Like a great hand one of these shovels dips down into the soft mass of ore, buries its great dipper until it holds from four to eight tons, and then, groaning and rumbling, slowly lifts its burden aloft, swings it over a car, and the actual work of mining is done. A thousand times a day it will repeat this operation, lifting from three thousand to eight thousand tons of ore. This one shovel keeps busy three locomotives and as many trains of dump cars. And there are nearly two hundred of these shovels in use on the39 Mesaba range alone. It costs only about six cents a ton to mine in this way, after the “stripping” has been done, or, in other words, after the ore has been laid bare. There are two other processes on the ranges where the ore is not so soft or so closely laid. One of these is the milling process, and the other is the blasting out of hard ore. Milling costs about thirty-five cents per ton, and the blasting process from one dollar to one dollar and twenty-five cents.

Why it has for some time been impossible to build ships too fast for the demand may most graphically be shown, perhaps, by quoting a few figures which demonstrate the tremendous energy now being exerted in the ore regions of the North. Figures as a usual thing are uninteresting, but these enter so vitally into the welfare of every American citizen that they should be regarded with more than ordinary respect. As stated before, we are now making nearly half of all the iron and steel produced on earth. In 1880, we made only 1,240,000 tons of steel; in 1890, this had increased to over 4,000,000; in 1900, to 10,188,000 tons, and in 1905, to 20,023,000 tons. Lake ships and Lake mines had to supply this. And now we come to mine figures which almost stagger belief. In 1904, the Mesaba range, for instance, yielded only a little over 12,000,000 tons. In the following year the production was nearly doubled, the ore carriers bringing down 20,153,699 tons, which in 1906 was increased to almost 24,000,000!

40 This enormous annual tonnage of the Mesaba range, together with that of the other four ranges of the Superior region, is carried by rail directly from the mines to the great ore docks of Lake ports. The product of the Mesaba and Vermilion ranges, in Minnesota, is shipped from Duluth and Two Harbors; the eight million tons of the Goebic and Marquette ranges, in Michigan, from Escanaba and Marquette; and the five million tons of the Menominee range, in Wisconsin, from Ashland and Superior.

To these six ports of the Northland come the vikings of the Lakes and their immense fleets. Four of these ports are within a radius of seventy-five miles, and the two others, in Michigan, are about one hundred and fifty miles farther east and south. No other area of lake or ocean in the world is as much travelled by shipping as that along which these ore harbours are situated. The people of Duluth have witnessed blockades of vessels such as have never been seen in the greatest ocean ports. Over this part of Superior there is a constant trail of smoke from the funnels of ships. During one month there were 1221 arrivals and clearances from Duluth alone, an average of forty a day.

Behind these great ships, which rest never a day nor an hour for eight months of the year, are the kings of Lake commerce—such men as J. C. Gilchrist, James Davidson, Captain Mitchell, William Livingstone, Harry Coulby, W. C. Richardson, A. B. Wolvin, G. Ashley41 Tomlinson, and scores of others. To write of these would be to chronicle a history of men who have fought their way to the top through sheer force of the “breed that is in them.”

Take G. Ashley Tomlinson, of Duluth, for instance, whose ships carry a couple of million tons of ore a year. “Not a great record,” as Mr. Tomlinson modestly says, but still enough to supply every man, woman, and child in the United States with a little matter of fifty pounds each twelvemonth! In a novel Tomlinson would make an ideal soldier of fortune; in plain, matter-of-fact life he represents those elements which make the great men of the Lakes. He is forty years old. He has sixteen ships. His income is over one hundred and fifty thousand dollars a year.

Yet Tomlinson began, as did many other Great Lake men of to-day, with just two assets—the clothes on his back and a huge ambition. He started his career as a messenger boy in the State treasurer’s office at Lansing, Michigan. But there was not enough of the strenuous life in this for him, so he went West to become a cowboy. He succeeded, much to his regret; for soon after he had mastered the broncho and could handle a lasso there came the war between the cowboys and the White River Utes. In one of the fights Tomlinson was wounded and afterward captured by the redskins. During the whole of one night he was subjected to torture, and at dawn of the following day, when almost at the point of death, he was delivered42 by a party of ranchmen. Tomlinson was not one to display the white feather—but he had had enough of Western life, and as soon as possible he worked himself from Rawlins, Wyoming, to Chicago on a cattle train. After a time he came to Michigan, and with his savings attended the University of Michigan for about a year. This was enough of “higher education” for him, so he sold his text-books and went to work on the Detroit Journal at the munificent salary of six dollars a week. Newspaper work was all right until Buffalo Bill came along. Tomlinson joined the show, rode a bucking broncho for a year, then “developed” a voice and cast his fortunes with the Mapleson Opera Company. In 1889, he went to New York as a reporter on the Sun, returned the following year to become night editor of the Detroit Tribune, and in 1893 moved to Duluth.

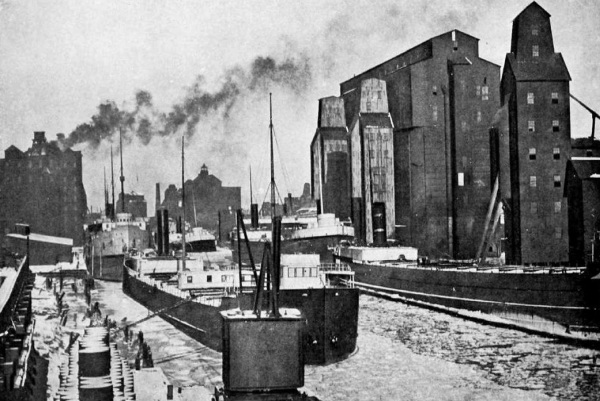

The Main Slip in the Harbour of Conneaut.

Conneaut is the second largest ore-receiving port on the Lakes.

The Lakes began to hold a peculiar fascination for him. He went into the vessel brokerage business mostly on his nerve; but nerve made him money, and his capital began to grow. How fast it has grown during the past dozen years one must judge by his ships and his income. He is president of five steamship companies, vice-president of another, secretary to three more, and a director in the American Exchange Bank, of Duluth, and the Cananea Central Copper Company. He has developed from a typical adventurer of fortune into one of the great men of the Lakes. His romantic career is described here because43 it is illustrative of the fact that brain and brawn, not “pull” and money, have made the vikings and iron barons of the Inland Seas. No millionaires’ sons here, living on their fathers’ prestige—no blue-blooded drones in these regions of the five little seas, where only red blood counts!

When the first ships of the season come up from the South in April or May nearly a million and a half tons of ore are awaiting them in the docks of the ore-shipping ports. There are twenty-six of these ore docks, one of which, at Duluth, has a storage capacity of ninety-six thousand tons. From a distance these docks look like great trestles, from fifty to one hundred feet above the water, some of them running for nearly half a mile out into the lake. Out upon these docks run the cars from the mines. From these cars the ore is dropped into huge pockets, from which run downward long chutes, or spouts. A ten-thousand-ton carrier runs alongside. Her hatches are opened. Into each hatch runs a chute. The chute “doors” are opened, and with a dull, rumbling, rushing sound the ore pours down by force of gravity from the huge pockets above. At dock No. 4, Duluth, 9277 tons were put aboard the steamer E. J. Earling in seventy minutes, being at the rate of 7988 tons an hour. The rapidity with which Lake transportation is carried on is shown in the fact that upon this occasion the Earling was in port only two hours and fifteen minutes before she began her thousand-mile return trip eastward.

44 And now comes the last important phase. One viewing the continuous activity at the mines, the building up of cities on the ranges, and the tremendous interests represented in the great shipping ports may forget that this is but one end of the gigantic industry which makes the United States the steel-maker for the world. At the other end of the fresh-water highways is seen the other half of the picture. Down into Erie come the ships from the North. A few of them go to Chicago, but only a few. Out of a total movement of thirty-seven million tons, in 1906, thirty-two million tons were received at Lake Erie ports. There are eleven of these “receiving ports”—Toledo, Sandusky, Huron, Lorain, Cleveland, Fairport, Ashtabula, Conneaut, Erie, Buffalo, and Tonawanda.

Between these cities there is a constant battle for prestige. Now one leads in tonnage received, now another. At the present time the bitterest rivalry exists between Cleveland, Ashtabula, and Conneaut, the three greatest ore ports in the world. In 1901, Ashtabula led. In 1902, Cleveland bore away the “pennant,” with Ashtabula and Conneaut second and third. Cleveland was still ahead in 1903, but in 1904, Conneaut became the greatest ore-receiving port in the world. In 1905, Ashtabula had again won the ascendency, and in 1906, she maintained her prestige, receiving in that year 6,833,352 tons; Cleveland was second, and Conneaut third. Lorain, Fairport, Ashtabula, Conneaut, and Erie practically exist because45 of the ore which comes down from the northern mines. Seven million dollars are now being expended in the improvement of Ashtabula harbour by the Lake Shore and Pennsylvania railroad companies, and the capacity of the harbour has been doubled since 1905. With the improvement of that harbour Conneaut’s greatest advantage will be gone, for until a comparatively recent date nearly all of the largest vessels went to that port. The tremendous activity in Ashtabula must be seen to be fully appreciated. In one day lately almost four thousand ore and coal cars were moved between that port and Youngstown.

At this end of the great ore industry the wonderful mechanism for the handling of cargoes is even more astonishing than that of the Northland. The ore carrier is run under a huge unloading machine which thrusts steel arms down into the score or more hatches of the vessel, and without the assistance of human hands the cargo is emptied so quickly that the uninitiated observer stands mute with astonishment. How quickly this work is done is shown in the record of the George W. Perkins, which discharged 10,346 tons at Conneaut in four hours and ten minutes.

Once more, after this unloading, the steel monster of the Lakes is all but ready for her long journey into the North. Within a few hours she is reloaded, with a few sonorous blasts of her whistle she bids a last adieu, and again she is off on the long trail that leads to the “ugly wealth” in the ore ranges of Superior.

Not long ago I went to see William Livingstone, President of the Lake Carriers’ Association—Great Admiral, in a way, of the world’s mightiest fleet of steel—an enrolled navy of 593 ships and a tonnage of nearly one million nine hundred thousand. Unconsciously I had come to call this man the Grey Man and the Man who Knows. Both titles fit, as they will tell you from the twin Tonawandas to Duluth. For six consecutive years president of the greatest organisation of its kind on earth, an association of ships made up, if weighed, of half of the iron and steel floating on the Inland Seas, he has become a part of Lake history. I sought him for an idea. I found it.

The Grey Man was at his desk studying over the expenditure of a matter of several millions of dollars for a new canal at the “Soo.” He turned slowly—grey suit, grey tie, grey eyes, grey beard, grey hair—all beautifully blended. He seldom speaks first. He is always fighting to be courteous, yet the days are ten hours too short for him.

47 “I want a new idea,” I opened bluntly. “I want something new in marine—something that will make people sit up and take notice, as it were. Can you help me?”

He swung slowly about in his chair until his eyes rested upon a picture on the wall. It was a picture of the old days on the Lakes. My eyes, too, rested on the old picture. It reminded me of things, and I kept pace with the thoughts that might be his. I saw him, more than half a century before, the stripling son of a ship’s carpenter, swimming in the shadows of the big fore-’n’-afters that were monarchs before steam came—glorious days when ninety-eight per cent. of vessels carried sail, and sailors dispensed law with their fists and bore dirks in their bootlegs. Later I saw the proud moment of his first trip to “sea”—and then, quickly, I noted his rise: his saving dollar by dollar until he bought an interest in a tug, his monopolisation of it later, his climb—up—up—until——

“I’m busy, very busy!” he broke in quietly. “But say, did you ever think of this? Did you ever build a city of the lumber we carry each year, populate that city, feed it with the grain we carry, and warm it with our coal? You can do it on paper and you will be surprised at what you find. It will show you more graphically than anything else just what the ships carry. Try it. You’ll be interested.”

I have kept that idea warm. Now I am going to48 use it. For probably in no better way can the immensity of the lumber, grain, coal, flour, and package freight traffic of the Great Lakes be given. Imagine, then, this “City of the Five Great Lakes.” We will build it, we will people it, feed it, and heat it—and our only material, with the exception of its inhabitants, will be the cargoes of the Lake carriers for a single season. And these carriers? If you should stand at the Lime Kiln Crossing, in the Detroit River, one would pass you on an average every twelve minutes, day and night, during the eight months of navigation; and when you saw their number and size you would wonder where they could possibly get all of their cargoes. The cargoes with which we will deal in this article will be of lumber, grain, flour and coal, for these, with iron ore, constitute over ninety per cent. of the commerce of the Inland Seas.

To build our city we first require lumber. During the 1909 season of navigation about 1,500,000,000 feet of this material will be carried by Lake ships. What this means it is hard to conceive until it is turned into houses. To build a comfortable eight-room dwelling, modern in every respect, requires about 20,000 feet of lumber, and when we divide a billion and a half by this figure we have 75,000 homes, capable of accommodating a population of about 400,000 people. With the thousands of tons of building stone transported by lake each year, the millions of barrels of cement, the cargoes of shingles, sand, and brick, our49 “City of the Lakes” for 1909 would be as large as Buffalo, Cleveland, or Detroit.

But one does not begin fully to comprehend the significance of the enormous commerce of the Great Lakes, and what it means not only to this country but to half of the civilised world, until he begins to figure how long the grain which will be carried by ships during the present year would support this imaginary city of 400,000 adult people. There will pass through the “Soo” canals this year at least 90,000,000 bushels of wheat and 60,000,000 bushels of other grain, besides 7,500,000 barrels of flour, all of which represents the “bread stuff” that is shipped from Lake Superior ports alone. There will, in addition, be shipped by lake at least 50,000,000 bushels from Chicago, Milwaukee, and other ports whose eastbound commerce is not reported at the “Soo.” In short, estimating conservatively from the past four years, it is safe to say that at least 200,000,000 bushels of grain and 11,000,000 barrels of flour will have been transported by the Great Lakes marine by the end of this year’s season of navigation.