From Angeloni. J. Tinney Sculp.

Title: The Antiquities of Constantinople

Author: Pierre Gilles

Release date: September 18, 2016 [eBook #53083]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Turgut Dincer, Brian Wilcox, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org); frontispiece generously made available by the Google Books Library Project (http://books.google.com)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Antiquities of Constantinople, by Pierre Gilles, Translated by John Ball

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/antiquitiesofcon00gill |

From Angeloni. J. Tinney Sculp.

Now Translated into English, and Enlarged with an Ancient Description of the Wards of that CITY, as they stood in the Reigns of Arcadius and Honorius.

With Pancirolus’s Notes thereupon.

To which is added

A large Explanatory Index.

By John Ball, formerly of C. C. C. Oxon.

LONDON.

Printed for the Benefit of the Translator, 1729.

J. Tinney Sculp.

Sir,

No sooner had my Inclinations prevail’d upon me to publish this Author, but my Gratitude directed me where I should make the Dedication. These Labours are yours by many Obligations. Your Services to me demand them, you have express’d a particular Esteem for Pieces of this Kind, you have assisted me with a valuable Collection of Books in the Translation of them, and you have encourag’d the Performance by the Interest of your Friends; so that if there be any Merit in the Publication of it, ’tis you who are entitled to it.

The Knowledge of Antiquity was always look’d upon as a Study worthy the Entertainment of a Gentleman, and was never in higher Estimation among the Nobility and Gentry of Great Britain than it is now. And this Regard which the present Age pays to it, proceeds from a wise Discernment, and a proportionable Value of Things. For we never entertain our Curiosity with more Pleasure, and to better Purposes, than by looking into the Art, and Improvement, and Industry of antient Times, and by observing how they excited their Heroes and great Men to virtuous and honourable Actions by the Memorials of Statuary and Sculpture; the silent Records of their Greatness, and the lasting History of their Glory.

The great Discoveries made of late, and publish’d by a ASociety of Gentlemen, united in the Search of Antiquity, will be lasting Monuments of their Fame in future Times, and will be look’d upon as Arguments of an ingenious Curiosity, in looking into the delectable Situations of Places, in preserving the beautiful Ruines of Antient Buildings, and in setting Chronology in a truer Light, by the Knowledge of Coins and Medals.

But, Sir, what I principally intend in this Dedication, is to do Justice to Merit, and to acquaint the World, That you never look’d upon Licentiousness, and Infidelity, to be any Part of the Character of a fine Gentleman, That Virtue does not sit odly upon Men of a superior Station, and That in you we have an Example of one, who has Prudence enough to temper the innocent Freedoms of Life with the Strictnesses of Duty, and Conduct enough to be Merry, and not Licentious, to be Sociable, and not Austere; a Deportment this, which sets off your Character beyond the most elaborate Expressions of Art, and is not to be describ’d by the most curious Statue, or the most durable Marble. I am, Sir, with very great Regard,

Your most Oblig’d,

And most Obedient Servant,

John Ball.

A The Society of Antiquaries in London.

IT is customary upon a Translation to give some Account both of the Author, and his Writings. The Author Petrus Gyllius, as he stands enroll’d among the Men of Eminency, and Figure in polite Learning, I find to be a Native of Albi, in France. He was in great Reputation in the sixteenth Century, and was look’d upon as a Writer of so good a Taste, and so comprehensive a Genius, that there was scarce any thing in the polite Languages, which had escap’d him. As he had a particular Regard for Men of distinguished Learning, so was he equally honour’d, and esteem’d by them. Francis the First, King of France, the great Patron of Literature, and who was also a good Judge of his Abilities, sent him into Italy, and Greece, to make a Collection of all the choice Manuscripts which had never been printed, but in his Passage it was his Misfortune to be taken by the Corsairs. Some Time after, by the Application and Generosity of Cardinal d’Armanac, he was redeem’d from Slavery. The just Sense this munificent Patron had of his Merit, incited him, when my Author had finish’d more than fourty Years Travels over all Greece, Asia, and the greatest Part of Africa, in the Search of Antiquity, to receive him into his Friendship, and Family; where, while he was digesting, and methodizing his Labours for the Service of the Publick, he dy’d in the Year 1555, and in the 65ᵗʰ Year of his Age.

Although it was his Intention to have published all the Learned Observations he had made in his Travels, yet he liv’d to give us only a Description of the Bosporus, Thrace, and Constantinople, with an Account of the Antiquities of each of those Places. In his Search of what was curious he was indefatigable, and had a perfect Knowledge of it in all its Parts. He had also translated into Latin Theodore’s Commentaries on the Minor Prophets, and sixteen Books of Ælian’s History of Animals. Petrus Belonius is highly reflected upon, in that being his Domestick, and a Companion with him in his Travels, he took the Freedom to publish several of his Works under his own Name: And indeed such a flagrant Dishonesty in acting the Plagiary in so gross a manner, was justly punish’d with the most severe Censures; since it had been Merit enough to have deserv’d the Praises of the Learned World for Publishing such valuable Pieces, with an honourable Acknowledgment of the Author of them.

I have no Occasion to vindicate the Worth and Credit of my Author, whose Fame will live, and flourish, while the Characters given him by Gronovius, Thuanus, Morreri, Tournefort, and Montfaucon are of any Weight. These Great Men have recorded him to future Times, for his deep Insight into Natural Knowledge, his unweary’d Application to the Study of Antiquity, and his great Accuracy and Exactness in Writing.

In the following Treatise, the Reader has before him a full and lively View of one of the most magnificent Cities in the Universe; stately, and beautiful in its Natural Situation, improv’d with all the Art and Advantages of fine Architecture, and furnished with the most costly Remains of Antiquity; so that New Rome, in many Instances of that Kind, may seem to excell the Old.

I hope my Author will not be thought too particular and exact in describing the several Hills and Vales, upon which Constantinople stands, when it is consider’d, that he is delineating the Finest Situation in the World.

The Manner in which he treats on this Subject is very entertaining; and his Descriptions, though with the greatest Regard to Truth, are embellish’d with a Grace and Beauty, almost Poetical. This, I look upon it, was occasion’d by the agreeable Variety of delightful Prospects and Situations, which the Subject naturally led him to describe.

The present State of Constantinople, I mean as to the Meanness and Poverty of its Buildings, is attested by all those, who have either seen, or wrote concerning it; so that ’tis not Now to be compar’d with it self, as it stood in its Antient Glory. The Turks have such an Aversion to all that is curious in Learning, or magnificent in Architecture, or valuable in Antiquity, that they have made it a Piece of Merit, for above 200 Years, to demolish, and efface every thing of that Kind; so that this Account of the Antiquities of that City given us by Gyllius, is not only the Best, but indeed the Only collective History of them.

In tracing out the Buildings of Old Byzantium, the antient Greek Historians, which he perfectly understood, were of great Service to him; this, with his own personal Observations, as residing for some Years at Constantinople, furnish’d him with Materials sufficient for the present History.

The Curious, who have always admir’d the Accuracy of this Work of Gyllius, have yet been highly concern’d, that it wanted the Advantage of Cuts, by which the Reader might have the agreeable Pleasure of surveying with the Eye, what my Author has so exactly describ’d with the Pen.

I have therefore endeavour’d to supply this Defect, by presenting to the View of the Reader a Collection of Figures, which do not only refer to such Curiosities as be will find mention’d in the several Parts of my Author, but such as have been describ’d by other later Travellers; and by this Means I hope I have given a compleat View of whatsoever is most remarkable in the Antiquities of Constantinople. The Catalogue and Order of the Cuts is as follows;

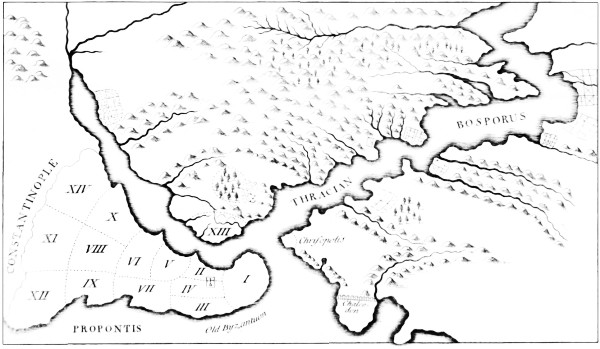

I. The Thracian Bosporus, with the Situation of Constantinople, as antiently divided into Wards; from Du Fresne.

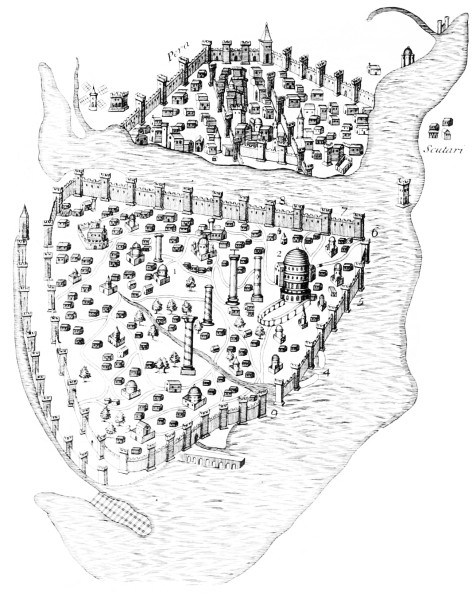

II. A Delineation of that City, as it stood in the Year 1422, before it was taken by the Turks; from the same.

III. The Ichnography, or Plan of the Church of Sancta Sophia; from the same.

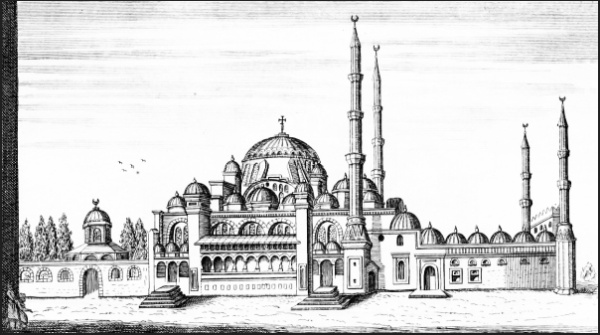

IV. The whole View of the Church of Sancta Sophia; from the same.

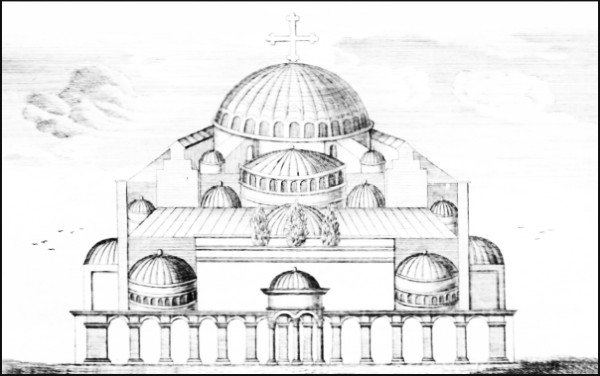

V. The outside Prospect of that Church; from the same.

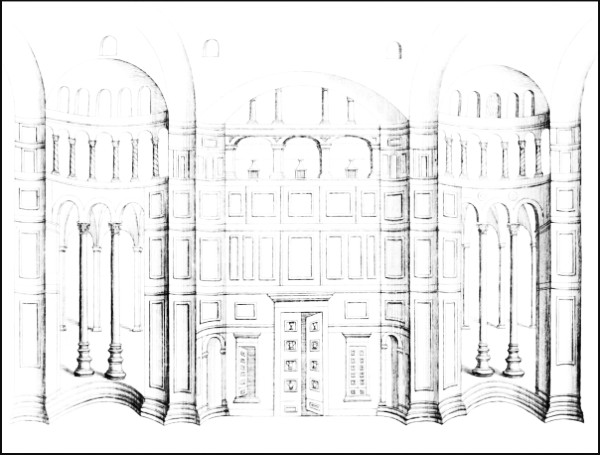

VI. The inside View of it; from the same.

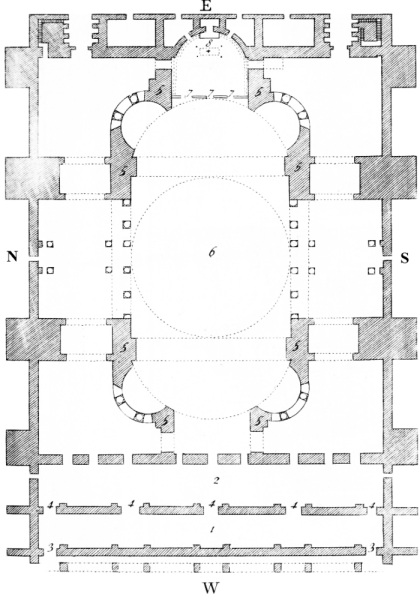

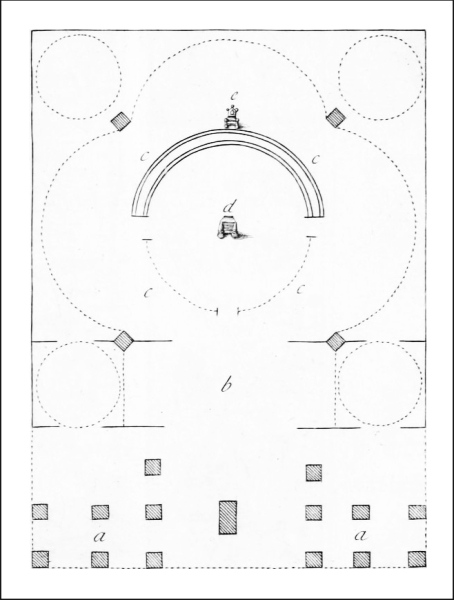

VII. The Plan of the Church of the Apostles; from Sir George Wheler.

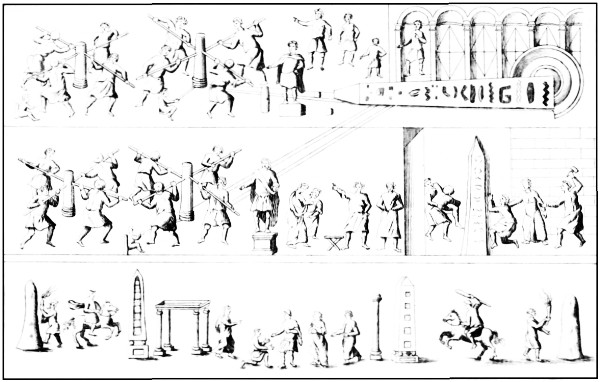

VIII. The antient Hippodrom, with the Thebæan Obelisk, and the Engines by which it was erected; from Spon and Wheler.

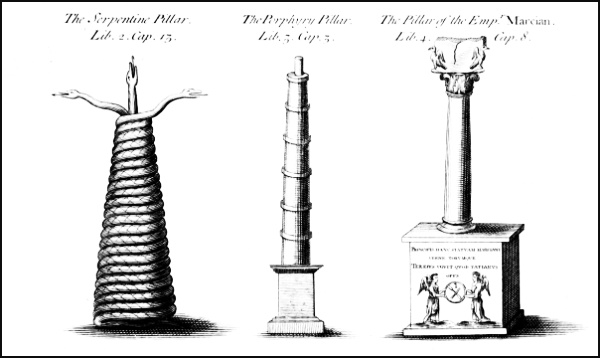

IX. The Three Pillars, viz. the Serpentine and Porphyry Pillars, standing in the Hippodrom, as described by Gyllius, with the Pillar of the Emperor Marcian, since discover’d by Spon and Wheler in a private Garden; from B. Randolph.

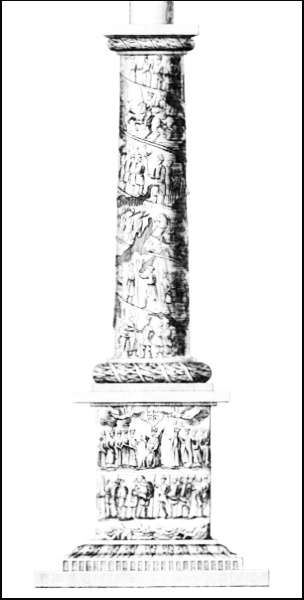

X. The Historical Pillar, described by Gyllius, and since by Tournefort; from Du Fresne.

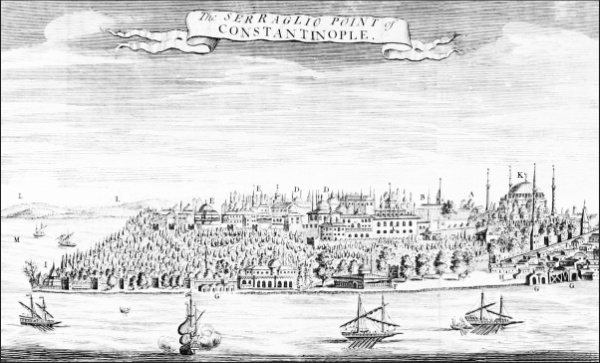

XI. A View of the Seraglio Point, with a Representation of the present Imperial Palace, and the Church of Sancta Sophia; from B. Randolph.

When this Impression was almost finished, a learned Gentleman of the University of Oxon, to whom my best Acknowledgments are due, communicated to me a valuable Passage, relating to the Statues of Constantinople, demolished by the Romans, which he transcribed from the Second Book of Nicetas Choniat, a MS. in the Bodl. Lib. I have added a Translation of it by way of Appendix; and I presume that the Reader will look upon it as a curious and an agreeable Entertainment.

THE Preface of the Author, describing the Situation of Constantinople, the Conveniencies of its Port, and the Commodities in which it abounds,

Page 1

| Book I. | |

|---|---|

Chap. I. Of the Founders of Byzantium, and the different Successes and Revolutions of that City, |

Page 13 |

II. Of the Extent of Old Byzantium, |

p. 20 |

III. Of the Rebuilding it by Constantine the Great, and the Largeness of it in his Time, |

p. 21 |

IV. Of the present Figure, Compass, Length, and Breadth of Constantinople, |

p. 29 |

V. A General Description of Constantinople, |

p. 32 |

VI. The Situation of all the Parts of the City describ’d, |

p. 35 |

VII. Of the First Hill, the Palace of the Grand Seignor, the Church of St. Sophia, and the Hippodrom, |

p. 36 |

VIII. Of the First Valley, |

p. 43 |

IX. Of the Second Hill, |

p. 44 |

X. Of the Second Valley, which divides the Second from the Third Hill, |

p. 48 |

XI. Of the Third Hill, |

p. 50 |

XII. Of the Third Valley, |

p. 54 |

XIII. Of the Fourth Hill, |

p. 55 |

XIV. Of the Fifth Hill, |

p. 59 |

XV. Of the Fifth Valley, |

p. 61 |

XVI. Of the Sixth Hill, |

p. 62 |

XVII. Of the Valley which divides the Promontory of the Sixth Hill from the Seventh Hill, |

p. 64 |

XVIII. Of the Seventh Hill, |

p. 65 |

XIX. Of the Walls of the City, |

p. 67 |

XX. Of the Gates of Constantinople, and the Seven Towers of Old Byzantium, |

p. 70 |

XXI. Of the long Walls, |

p. 72 |

| Book II. | |

|---|---|

Chap. I. Of the Buildings and Monuments of Old Byzantium and Constantinople, |

p. 73 |

II. Of the Antient Monuments of the First Hill, and of the First Ward of the City, |

p. 75 |

III. Of the Church of St. Sophia, |

p. 82 |

IV. A Description of the Church of St. Sophia, as it now appears, |

p. 87 |

V. Of the Statues found on one Side of that Church, |

p. 95 |

VI. Of the Pharo on the Promontory of Ceras, and the Mangana, |

p. 96 |

VII. Of the Bagnio’s of Zeuxippus, and its Statues, |

p. 97 |

VIII. Of the Hospitals of Sampson, and Eubulus, |

p. 100 |

IX. Of the Statue of Eudocia Augusta, for which St. Chrysostom was sent into Banishment, |

p. 101 |

X. Of those Parts of the City which are contain’d in the Third Ward, |

p. 102 |

XI. Of the Hippodrom, its Obelisk, its Statues, and Columns, |

p. 103 |

XII. Of the Colossus, |

p. 108 |

XIII. Of some other Columns in the Hippodrom, |

p. 110 |

XIV. Of the Church of Bacchus, of the Court of Hormisda, and the House of Justinian, |

p. 117 |

XV. Of the Port of Julian and Sophia; of the Portico nam’d Sigma, and the Palace of St. Sophia, |

p. 120 |

XVI. Of the Fourth Ward, |

p. 126 |

XVII. Of the Forum called Augusteum, the Pillar of Theodosius, and Justinian, also of the Senate-house, |

p. 127 |

XVIII. Of the Imperial Palace, and the Basilica, as also of the Palace of Constantine, and of the House of Entrance nam’d Chalca, |

p. 133 |

XIX. Of the Basilica, and the Imperial Walks, |

p. 140 |

XX. Of the Imperial Library and Portico, and also of the Imperial Cistern, |

p. 143 |

XXI. Of the Chalcopratia, |

p. 148 |

XXII. Of the Portico’s situate between the Palace, and the Forum of Constantine, |

p. 150 |

XXIII. Of the Miliarium Aureum, and its Statues; of Fortune, the Goddess of the City, and her Statue, |

p. 152 |

XXIV. Of the Temple of Neptune, and the Church of St. Mina or Menna, of the Stadia, and Stairs of Timasius, |

p. 157 |

XXV. Of the Lausus, and its Statues; viz. a Venus of Cnidos, a Juno of Samos, a Minerva of Lindia, a winged Cupid, a Jupiter Olympius, a Saturn, Unicorns, Tygers, Vultures, Beasts that are half Camels and half Panthers; of the Cistern, in an Hospital, which was call’d Philoxenos, and a Chrysotriclinium, |

p. 159 |

| Book III. | |

|---|---|

Chap. I. Of several Places in the Fifth Ward, and the Second Hill; of the Neorium, of the Port nam’d the Bosporium, of the Strategium, and the Forum of Theodosius, |

p. 164 |

II. Of the Sixth Ward, and the remaining antient Buildings of the Second Hill, |

p. 171 |

III. Of the Porphyry Pillar, the Forum of Constantine, and the Palladium, |

p. 172 |

IV. Of the Senate House, the Nympheum, and the Statues in the Forum of Constantine, of the Labarum and Supparum, of the Philadelphium, of the Death of Arius, and of the Temples of Tellus, Ceres, Persephone, Juno, and Pluto, |

p. 181 |

V. Of the Seventh Ward, |

p. 190 |

VI. Of the Street call’d Taurus, of the Forum, and Pillar of Theodosius, which had winding Stairs within it; of the Tetrapylum, the Pyramidical Engine of the Winds, of the Statues of Arcadius, and Honorius, the Churches of Hirena, and Anastasia, and the Rocks called Scyronides, |

p. 193 |

VII. Of the Eighth Ward, and the Back-part of the Third Hill, |

p. 202 |

VIII. Of the Ninth Ward, of the Temple of Concord, of the Granaries of Alexandria and Theodosius, of the Baths of Anastasia, of the House of Craterus, of the Modius, and the Temple of the Sun and Moon, |

p. 205 |

IX. Of the Third Valley and the Tenth Ward, of the House, and Palace of Placidia, of the Aqueducts of Valentinian, the Baths of Constantius, and the Nympheum, |

p. 209 |

| Book IV. | |

|---|---|

Chap. I. Of the Eleventh Ward, and of the Fourth and Fifth Hill, |

p. 217 |

II. Of the Church of the Apostles, of the Sepulchre of Constantine the Great, of the Cisterns of Arcadius, and Modestus, of the Palace of Placilla, and the Brazen Bull, |

p. 221 |

III. Of the Sixth Hill, and the Fourteenth Ward, |

p. 236 |

IV. Of the Hepdomum, a Part of the Suburbs, of the Triclinium of Magnaura, of the Palace called Cyclobion, of the Statue of Mauritius, and his Arsenal, and also of the Place called the Cynegium, |

p. 238 |

V. Of the Blachernæ, the Triclinium of the Blachernæ, of the Palace, the Aqueduct, and many other Places of Antiquity, |

p. 244 |

VI. Of the Bridge near the Church of St. Mamas, of the Hippodrom, of the Brazen Lyon, and the Tomb of the Emperor Mauritius, |

p. 248 |

VII. Of the Seventh Hill, the Twelfth Ward, and of the Pillar of Arcadius, |

p. 250 |

VIII. Of the Statues, and the ancient Tripos of Apollo plac’d in the Xerolophon, |

p. 255 |

IX. Of the Columns now remaining on the Seventh Hill, |

p. 261 |

X. Of the Thirteenth Ward of the City, called the Sycene Ward, of the Town of Galata, sometimes called Pera, |

p. 264 |

XI. A Description of Galata, of the Temples of Amphiaraus, of Diana, and Venus, of its Theatre and the Forum of Honorius, |

p. 270 |

An Appendix, taken out of a MS. in the Bodleian Library of the University of Oxon, relating to the antient Statues of Constantinople, demolish’d by the Latins, when they took the City, |

p. 285 |

|

A DESCRIPTION Of the CITY of CONSTANTINOPLE, As it stood in the Reigns of Arcadius and Honorius. |

|

|---|---|

A DESCRIPTION Of the WARDS of CONSTANTINOPLE. |

|

The first Region, or Ward. |

p. 3 |

The Second Ward. |

p. 14 |

The Third Ward. |

p. 18 |

The Fourth Ward. |

p. 19 |

The Fifth Ward. |

p. 27 |

The Sixth Ward. |

p. 31 |

The Seventh Ward. |

p. 35 |

The Eighth Ward. |

p. 38 |

The Ninth Ward. |

p. 39 |

The Tenth Ward. |

p. 42 |

The Eleventh Ward. |

p. 44 |

The Twelfth Ward. |

p. 46 |

The Thirteenth Ward. |

p. 48 |

The Fourteenth Ward. |

p. 51 |

A Summary View of the whole City. |

p. 53 |

Some Account of the Suburbs as they are mention’d in the Codes and Law-Books. |

p. 59 |

Of the present Buildings of Constantinople. |

p. 62 |

Constantinople is situated after such a Manner in a Peninsula, that ’tis scarce bounded by the Continent; for on three Sides ’tis inclosed by the Sea. Nor is it only well fortified by its natural Situation, but ’tis also well guarded by Forts, erected in2 large Fields, extending from the City at least a two Day’s Journey, and more than twenty Miles in Length. The Seas that bound the Peninsula are Pontus, or the Black Sea, the Bosporus, and the Propontis. The City is inclosed by a Wall formerly built by Anastasius. ’Tis upon this Account that being secured as it were by a double Peninsula, she entitles her self the Fortress of all Europe, and claims the Preheminence over all the Cities of the World, as hanging over the Straits both of Europe and Asia. For besides other immense Advantages peculiar to it, this is look’d upon as a principal Convenience of its Situation, that ’tis encompassed by a Sea abounding with the finest Harbours for Ships; on the South by the Propontis, on the East by the Bosporus, and on the North by a Bay full of Ports, which can not only be secured by a Boom, but even without such a Security, can greatly annoy the Enemy. For the Walls of Constantinople and Galata straitning its Latitude into less than half a Mile over, it has often destroy’d the Enemies Ships by liquid Fire, and other Instruments of War. I would remark farther, that were it secured according to the Improvements of modern Fortification, it would be the strongest Fortress in the World; viz. if the four ancient Ports, formerly inclosed within its Walls by Booms, were rebuilt; two of which (being not only the Ornament, but the Defence of old Byzantium) held out a Siege against Severus for the Space of three Years; nor could it ever be obliged to a Surrender, but by Famine only. For besides the Profits 3and Advantages it receives from the Propontis and Ægean Sea, it holds an absolute Dominion over the Black Sea; and by one Door only, namely by the Bosporus, shuts up its Communication with any other part of the World; for no Ship can pass this Sea, if the Port thinks fit to dispute their Passage. By which means it falls out, that all the Riches of the Black Sea, whether exported or imported, are at her Command. And indeed such considerable Exportations are made from hence of Hydes of all Kinds, of Honey, of Wax, of Slaves, and other Commodities, as supply a great Part of Europe, Asia and Africa; and on the other hand, there are imported from those Places such extraordinary Quantities of Wine, Oil, Corn, and other Goods without Number, that Mysia, Dacia, Pannonia, Sarmatia, Mæotis, Colchis, Spain, Albania, Cappadocia, Armenia, Media, Parthia, and both Parts of Scythia, share in the great Abundance. ’Tis for this Reason, that not only all foreign Nations, if they would entitle themselves to any Property in the immense Wealth of the Black Sea, but also all Sea Port and Island Towns are obliged to court the Friendship of this City. Besides, ’tis impossible for any Ships to pass or repass, either from Asia or Europe, but at her Pleasure, she being as it were the Bridge and Port of both those Worlds; nay, I might call her the Continent that joins them, did not the Hellespont divide them. But this Sea is thought, in many Respects, to be inferior to that of Constantinople; first, as it is much larger, and then, as not having a Bay as that has, by which its City might be made a Peninsula, and a commodious Port for Ships: 4And indeed if it had such a Bay, yet could it reap no Advantage of Commerce from the Black Sea, but by the Permission of the People of Constantinople. Constantine at first began to build a City upon Sigeum, a Promontory hanging over the Straits of the Hellespont; but quitting that Situation, he afterwards pitch’d upon a Promontory of Byzantium. Troy, I acknowledge, is a magnificent City, but they were blind, who could not discover the Situation of Byzantium; all stark blind, who founded Cities within View of it, either on the Coast of the Hellespont, or the Propontis; which though they maintain’d their Grandeur for some Time, yet at present are quite in Ruins, or have only a few Streets remaining, and which, if they were all rebuilt, must be in Subjection to Constantinople, as being superior in Power to all of them. Wherefore we may justly entitle her the Key, not only of the Black Sea, but also of the Propontis and the Mediterranean Sea. Cyzicus (now called Chazico) is highly in Esteem, for that it joins by two Bridges the Island to the Continent, and unites two opposite Bays, and is, as Aristides informs us, the Bond of the Black, and the Mediterranean Sea; but any Man, who has his Eyes in his Head, may see, that ’tis but a very weak one. The Propontis flows in a broad Sea, between Cyzicus and Europe; by which Means as a Passage is open into both Seas, though the People of Cyzicus should pretend to dispute it; so they on the other hand, should the People of Hellespont or Constantinople contest it with them, could have no Advantage of the Commerce of either of those Seas. I shall say nothing at present of Heraclea, Selymbria, and Chalcedon, seated 5on the Coast of the Propontis, anciently Cities of Renown, both for the Industry of their Inhabitants, and the Agreeableness of their Situation; but they could never share in the principal Commodities of other Towns of Traffick, in the Neighbourhood of the Port of Constantinople, which was always look’d upon as impregnable. The Harbours of those Cities have lain for a considerable time all under Water, so that they were not of sufficient Force to sail the Bosporus and the Hellespont, without the Permission of the Inhabitants of those Places: But the Byzantians rode Masters of the Black Sea, in Defiance of them all. Byzantium therefore seems alone exempted from those Inconveniencies and Incapacities which have happen’d to her Neighbours, and to many other potent and flourishing Cities, which for several Years having lain in their own Ruins, are either not rebuilt with their ancient Grandeur, or have changed their former Situation. All its neighbouring Towns are yet lost: There is only the Name of Memphis remaining. Whereas Babylon, seated in its Neighbourhood, from a small Fort, is become a large and populous City; and yet neither of them is so commodious as Constantinople. I shall take no Notice of Babylon in Assyria, who, when she was in her most flourishing State, had the Mortification to see a City built near her, equal in Largeness to her self: Why is not Alexandria rebuilt, but because she must support her self more by the Industry of her People, than the Agreeableness of her Situation? ’Twas the Sanctity of St. Peter, and the Grandeur of the Roman Name, that contributed more to the 6rebuilding old Rome, than the natural Situation of the Place itself, as having no Convenience for Ships and Harbours. I pass by in Silence Athens and Lacedæmon, which were more remarkable for the Learning and resolute Bravery of their People, than the Situation of their City. I omit the two Eyes of the Sea Coast, Corinth and Carthage, both which falling into Ruins at the same Time, were first repaired by Julius Cæsar; afterwards, when they fell entirely to decay, nobody rebuilt them: And though Carthage is seated in a Peninsula with several Havens about it, yet in no part of it are there two Seas which fall into each other: For though Corinth may be said to lie between two Seas, and is call’d the Fort of Peloponnesus, the Key and Door of Greece; yet is it so far from uniting in one Chanel two Seas, or two Bays adjoining to the Peninsula, that she was never able to make Head against the Macedonians or Romans, as Cyzico and Negropont did; the one by its well built Forts and other War-like Means, and the other by the Strength of its natural Situation. But Constantinople is the Key both of the Mediterranean and Black Sea, which alone, by the best Skill in Navigation, nay though you were to make a Voyage round the World, you will find to meet only in one Point, and that is, the Mouth of the Port. I shall say nothing of Venice, which does not so much enclose the Sea for proper Harbours, as ’tis enclosed by it, and labours under greater Difficulties to keep off the Swellings and Inundations of the Seas, than unite them together. I pass by the Situations of the whole Universe, wherever there are, have, or shall 7be Cities; in none of them shall you find a Port abounding with so many and so great Conveniencies, both for the Maintenance of its Dominion over the Seas, and the Support of Life, as in this City. It is furnish’d with Plenty of all manner of Provisions, being supply’d with Corn by a very large Field of Thrace, extending itself, in some Parts of it, a Length of seven Days, and in others, of a more than twenty Days Journey. I shall say nothing of Asia adjoining to it, abounding with the greatest Fruitfulness both of Corn and Pasture, and the best Conveniencies for their Importation from both Seas. And as to the immense Quantity of its Wines, besides what is the Product of its own Soil, it is furnish’d with that Commodity from all the Coasts of the Bosporus, the Propontis, and the Hellespont, which are all well stock’d with Vineyards; and without the Danger of a long Voyage, Constantinople can, at her Pleasure, import the choicest Wines of all Kinds, and whatever else may contribute to her own Gratification and Delight. ’Tis for this Reason that Theopompus gives her this Character, That ever since she became a Mart-Town, her People were wholly taken up, either in the Market, in the Port, or at Taverns, giving themselves up entirely to Wine. Menander, in his Comedy Auletris, tells us, that Constantinople makes all her Merchants Sots. I bouze it, says one of his Actors, all Night; and upon my waking after the Dose, I fancy I have no less than four Heads upon my Shoulders. The Comedians play handsomely upon them, in giving us an Account, that when their City was besieged, their General had 8no other Way to keep his Soldiers from deferring, but by building Taverns within the Walls; which, tho’ a Fault proceeding from their popular Form of Government, yet at the same time denotes to us the great Fruitfulness of their Soil, and the great Plenty they have of Wine. They who have been Eye-witnesses can best attest, how well they are provided with Flesh, with Venison and Fowls, which they might share more abundantly, but that they are but indifferent Sportsmen. Their Markets are always stored with the richest Fruits of all Kinds. If any Objection be made to this, I would have it consider’d, what Quantities the Turks use, after hard Drinking, to allay their Thirst. And as to Timber, Constantinople is so plentifully supply’d with that, both from Europe and Asia, and will in all probability continue to be so, that she can be under no Apprehensions of a Scarcity that way, as long as she continues a City. Woods of an unmeasurable Length, extending themselves from the Propontis beyond Colchis, a more than forty Days Journey, contribute to her Stores so that she does not only supply the neighbouring Parts with Timber for building Ships and Houses, but even Ægypt, Arabia and Africa, partake in the inexhaustible Abundance; while she, of all the Cities in the World, cannot lie under the want of Wood of any Kind, under which, even in our Time, we have observed the most flourishing Cities, both of Europe and Asia, sometimes to have fallen. Marseilles, Venice, Taranto, are all famous for Fish; yet Constantinople exceeds them all in its Abundance of this Kind. The Port is supply’d 9with vast Quantities from both Seas; nor do they swim only in thick Shoals through the Bosporus, but also from Chalcedon to this Port. Insomuch that twenty Fish-Boats have been laden with one Net; and indeed they are so numberless, that oftentimes from the Continent you may take them out of the Sea with your Hands. Nay, when in the Spring, they swim up into the Black Sea, you may kill them with Stones. The Women, with Osier Baskets ty’d to a Rope, angle for them out of the Windows, and the Fishermen with bare Hooks take a sort of Fish of the Tunny Kind, in such Quantities, as are a competent Supply to all Greece, and a great part of Asia and Europe. But not to recount the different Kinds of Fish they are stock’d with, they catch such Multitudes of Oysters, and other Shell Fish, that you may see in the Fish Market every Day, so many Boats full of them, as are a Sufficiency to the Grecians, all their Fast-Days, when they abstain from all sorts of Fish which have Blood in them. If there was not so considerable a Plenty of Flesh at Constantinople, if the People took any Pleasure in eating Fish, and their Fishermen were as industrious as those of Venice and Marseilles, and were also allow’d a Freedom in their Fishery, they would have it in their Power, not only to pay as a Tribute a third part of their Fish at least to the Grand Seignor, but also to supply all the lesser Towns in her Neighbourhood. If we consider the Temperature of the Climate of New Rome, it must be allow’d by proper Judges, that it far excels that of Pontus. For my own part, I have often experienced it to be a more healthy Air than 10that of Old Rome; and for many Years past, I have scarce observed above a Winter or two to have been very cold, and that the Summer Heats have been allay’d by the northern Breezes, which generally clear the Air for the whole Season. In the Winter, ’tis a little warm’d by the southern Winds, which have the same Effect. When the Wind is at North, they have generally Rain, though ’tis quite otherwise in Italy and France. As to the Plague, ’tis less raging, less mortal, and no more rife among them, than it is, commonly speaking, in great Cities; and which indeed would be less rife, were it not for the Multitudes of the common People, and the foul Way of Feeding among their Slaves. But that I may not seem to flourish too largely in the Praise of this City, never to be defamed by the most sour Cynick, I must confess that there is one great Inconvenience it labours under, which is, that ’tis more frequently inhabited by a savage, than a genteel and civiliz’d People; not but that she is capable of refining the Manners of the most rude and unpolish’d; but because her Inhabitants, by their luxurious way of living, emasculate themselves, and for that Reason are wholly incapable of making any Resistance against those barbarous People, by whom, to a vast Distance, they are encompass’d on all Sides. From hence it is, that although Constantinople seems as it were by Nature form’d for Government, yet her People are neither under the Decencies of Education, nor any Strictness of Discipline. Their Affluence makes them slothful, and their Pride renders them averse to an open Familiarity, and a generous Conversation; so that they avoid [11]all Opportunities of being thrust out of Company for their Insolence, or falling into Dissensions amongst themselves, by which means the Christian Inhabitants of the Place, formerly lost both their City and Government. But let their Quarrels and Divisions run never so high, and throw the whole City into a Flame, as they have many times done, nay tho’ they should rase her even with the Ground, yet she would soon rise again out of her own Ruins, by reason of the Pleasantness of her Situation, without which the Black Sea could not so properly be called the Euxine, as the Axine Sea, (the Inhabitants of whose Coast used to kill all Strangers that fell into their Hands) by reason of the great Numbers of barbarous People who dwell round the Black Sea. It would be dangerous venturing on the Coasts of the Black Sea, either by Land or Water, which are full of Pyrates and Robbers, unless they were kept in a tolerable Order by the Government of the Port. There would be no passing the Straits of the Bosporus which is inhabited on both Shores by a barbarous People, but for the same Reason. And though a Man was never so secure of a safe Passage, yet he might mistake his Road at the Mouth of the Bosporus, being misguided by the false Lights, which the Thracians, who inhabit the Coasts of the Black Sea, formerly used to hang out, instead of a Pharos. ’Tis therefore not only in the Power of Constantinople, to prevent any Foreigners sailing the Black Sea; but in reality no Powers can sail it, without some Assistance from her. Since therefore Constantinople is the Fortress of all Europe, both against the Pyrates of Pontus, 12and the Savages of Asia, was the never so effectually demolish’d, as to all Appearance, yet would she rise again out of her Ruins to her former Grandeur and Magnificence. With what Fury did Severus pursue this City, even to an entire Subversion? And yet when he cool’d in his Resentments against these People, he recollected with himself, that he had destroy’d a City which had been the common Benefactress of the Universe, and the grand Bulwark of the Eastern Empire. In a little time after he began to rebuild her, and order’d her, in Honour of his Son, to be call’d Antonina. I shall end with this Reflection; That though all other Cities have their Periods of Government, and are subject to the Decays of Time, Constantinople alone seems to claim to herself a kind of Immortality, and will continue a City, as long as the Race of Mankind shall live either to inhabit or rebuild her.

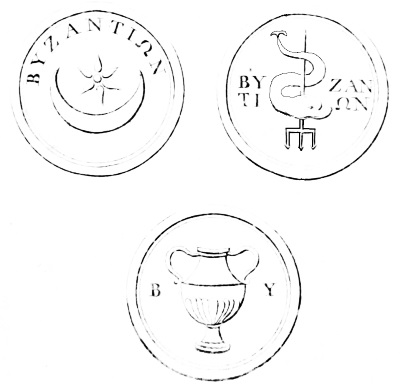

It is recorded by Stephanus and Pausanias, that Byzantium, now call’d Constantinople, was first founded by Byzas the Son of Neptune and Ceroessa, or by a Person named Byzes, Admiral of the 14Fleet of the Megarians, who transplanted a Colony thither. I am of Opinion, that this was the same Person with Byzas. For had it taken its Name from Byzes, this City had more properly been call’d Byzeum than Byzantium. Philostratus, in the Life of Marcus a Sophist of Byzantium, calls the Admiral of that Fleet by the Name of Byzas, when he informs us, that Marcus (whom he would have descended from the ancient Family of Byzas) made a Voyage to Megara, and was exceedingly in Favour with the People there, who had formerly sent over a Colony to Byzantium. This People, when they had consulted Apollo where they should found a City, received in Answer from the Oracle, That they should seek out a Situation opposite to the Land of the Blind. The People of Chalcedon were given to understand by this mystical Answer, that tho’ they had made a Landing there before, and had an Opportunity of viewing the commodious Situation of that and other Places adjacent, yet at last had pitch’d upon the most improper Place of all. As to what is mention’d by Justin, that Byzantium was first founded by Pausanias a Spartan, I take it to import no more than this; that they who affirm that Syca, at present call’d Galata, was first founded by the Genoese, as was Constantinople by Constantine, their Meaning was, that they either rebuilt or enlarged those Places, and not that they were the first Founders of them. For when I find it in Herodotus, that upon the Invasion of Thrace by Darius, the People of Byzantium and Chalcedon were not in the least Expectation of the Arrival of the Phœnician 15Fleet, that having quitted their Cities, they retired into the Inland Shores of the Black Sea, and there founded Mesembria, and that the Phœnicians burnt Byzantium, and Chalcedon; I am of Opinion, that the Lacedæmonians, under the Command of Pausanias, sent a Colony thither, and rebuilt Byzantium, which was before either a Colony of the Megarians, or the Seat of the Subjects of Byzas the Son of Neptune, its first Founder. Eustathius assures us, that it was anciently called Antonina from Antoninus Bassianus, the Son of Severus Cæsar, but that it passed under that Name no longer than his Father liv’d, and that many Years after it was call’d New Rome, and Constantinople, and Anthusa, or Florentia, by Constantine the Great; upon which Account it is call’d by Priscian New Constantinopolitan Rome. It was foretold by the Oracle, that its Inhabitants should be a successful and flourishing People, but a constant Course of Prosperity did not always attend them. ’Twas with great Difficulty that this City first began to make a Figure in the World, in the Struggles it underwent with the Thracians, Bithynians, and Gallogrecians, and in paying a yearly Tribute of eighty Talents to the Gauls who govern’d Asia. ’Twas with greater Contests that it rose to higher Degrees of Eminency, being frequently harass’d, not only with foreign, but domestick Enemies. Mighty Changes it underwent, being sometimes under the popular, sometimes under the aristocratical Form of Government, widely extending its Conquests in Europe and Asia, but especially in Bithynia. For Philarcus observes in the sixth Book of his History, that the Byzantians had 16the same Power over the Bithynians, as the Lacedæmonians had over their Helotæ. This Commonwealth had so great a Veneration for the Ptolemæi Kings of Ægypt, that to one of them nam’d Philadelphus, they pay’d divine Honours, and erected a Temple to him, in the Sight of their City; and so great a Regard had they for the Roman Name, that they assisted them against the King of Macedon, to whom, as degenerating from his Predecessors, they gave the nickname of Pseudo-Philippus. I need not mention the powerful Succours they sent against Antiochus, Perseus, Aristonicus, and the Assistance they gave Antonius, when engaged in a War against the Pyrates. This City alone stood the Brunt of Mithridates’s whole Army landed in their Territories, and at last, though with great Difficulty, bravely repell’d the Invader. It assisted at once Sylla, Lucullus and Pompey, when they lay’d Siege to any Town or Fortification, which might be a Security to their auxiliary Forces in their Passage, either by Sea or Land, or might prove a convenient Port, either for Exportation or Importation of Provision. Joining its Forces at last with Niger against Severus, it became subject to the Perinthians, and was despoil’d of all the Honours of its Government. All its stately Bagnio’s and Theatres, its strong and lofty Walls, (built of square Stone, much of the same Hardness with that of a Grindstone, not brought from Miletus, as Politianus fancies) with which it was fortify’d, were entirely ruin’d. I say, that this Stone was cut out of no Quarry, either of ancient Miletus, or Miletopolis; because Miletus lies 17at too great a Distance from it, and Miletopolis, which is seated near the River Rhyndacus, is no ways famous for Quarries. I saw, by the By, this last City, adjoining to the Lake of Apolloniatus, entirely demolish’d, retaining at present its Name only. The Walls of Byzantium, as Herodian relates, were cemented with so thin a Mortar, that you would by no means think them a conjointed Building, but one entire Stone. They who saw them in Ruins in Herodian’s Time, were equally surpriz’d at those who built, and those who defaced them. Dion, whom Zonaras quotes, reports, that the Walls of Byzantium were exceeding strong, the Copings of which were built with Stones three Foot thick, cramp’d together with Links of Brass; and that it was so firmly compacted inwardly, that the whole Building seem’d to be one solid Wall. It is adorn’d with numerous and large Towers, having Gates in them placed one above another. The Walls on the side of the Continent are very lofty; towards the Sea, not quite so high. It had two Ports within the Walls, secured with Booms, as was their Entrance by two high Forts. I had then no Opportunity of consulting Xenophon in the Original; however I was of Opinion from the Latin Translation, that a Passage in that Author, which is as follows, has a Relation to one of those Ports: When the Soldiers, says he, had passed over from Chrysopolis to Byzantium, and were deny’d Entrance into the City, they threaten’d to force the Gates, unless the Inhabitants open’d them of their own Accord; and immediately hastening to the Sea, they scaled the Walls, and leap’d into the Town, hard by the Sides of the Port, which the Greeks call χηλαὶ, that 18is by the Piles; because they jet out into the Sea, winding into the Figure of a Crab’s Claw. But afterwards meeting with that Author in Greek, I found no Mention there of the Port, but only τὴν χηλὴν τοῦ τείχους, that is, near the Copings of the Wall, or rather the Buttresses that support it. Had it been in the Original χηλὴ τοῦ λιμένος, it ought rather to have been translated the Leg, or the Arm. Dionysius a Byzantian mentions, that the first Winding of the Bosporus contains three Ports. The Byzantians in their time had five hundred Ships, some of which were two-oar’d Galleys; some had Rudders both at Stem and Stern, and had also their Pilates at each, and two Sets of Hands aboard, so that either in an Engagement, or upon a Retreat, there was no Necessity for them to tack about. The Byzantians, both in the Life-time and after the Death of Niger, when besieged for the Space of three Years, acted Wonders; for they not only took the Enemies Ships as they sail’d by them, but dragg’d their three-oar’d Galleys from their Moorings; for diving under Water they cut their Anchors, and by fastening small Ropes from the Stern round their Ancles, they hall’d off their Ships, which seem’d to swim merely by the natural Tyde of the Sea. Nor were the Byzantians the first who practis’d this Stratagem, but the Tyrians frequently, under a Pretence of gathering Shell-Fish, would play the same Trick; which Alexander had no sooner discover’d, than he gave Orders that the Anchors of his whole Fleet, instead of Cables, should be fasten’d to Iron Chains. In this Siege the Byzantians being reduced to great 19Straits, still refused to surrender, making the best Defence they could with Timber taken from their Houses. They also breeded Cables for their Ships out of their Womens Hair; nay sometimes they threw down Statues and Horses upon the Heads of their Enemies. At last their Provision being entirely spent, they took up with Hydes soften’d in Water; and these being gone, they were brought to the extreme Necessity of eating one another: At last, being wholly reduced by Famine, they were forced to a Surrender. The Romans gave no Quarter to the Soldiers, nor the principal Men of the City. The whole Town, with all its stately Walls in which it glory’d, was levelled with the Ground; and all its Theatres and Bagnio’s were demolish’d even to the small Compass of a single Street. Severus was highly pleased with so noble a Conquest. He took away the Freedom of the City, and having deprived it of the Dignity of a Commonwealth, he confiscated the Goods of the Inhabitants; and afterwards making it tributary, he gave it, with all the neighbouring Countrey, into the Hands of the Perinthians. Entering the City afterwards, and seeing the Inhabitants coming to meet him, with Olive-branches in their Hands begging Quarter, and excusing themselves for making so long a Defence, he forbore the Slaughter; yet left the Perinthians in the Possession of the Town, allowing them nevertheless a Theatre, gave Orders for building them a Portico for Hunting, and a Hippodrom, to which he adjoin’d some Bagnio’s, which he built near the Temple of Jupiter, who was called Zeuxippus. He 20also rebuilt the Strategium; and all the Works that were begun by Severus in his Life-time, were finish’d by his Son Antoninus.

THE present Inhabitants of Constantinople tell you, that Old Byzantium stood within the Compass of the first Hill in the Imperial Precinct, where the Grand Seignor’s Seraglio now stands: but I am of Opinion, from what follows it will appear, that it was of a larger Extent. Our modern Writers describe its Situation thus; that it began at the Wall of the Citadel, stretched itself to the Tower of Eugenius, and that it rose gradually up to the Strategium, the Bagnio of Achilles, and the Urbicion. From thence it pass’d on to the Chalcopratia, and the Miliarium Aureum, where there was another Urbicion of the Byzantians: Thence it lengthen’d to the Pillars of Zonarius, from whence, after a gentle Descent, it winded round by the Manganæ and the Bagnio’s of Arcadius, up to the Acropolis. I am inclinable to credit all these Writers, excepting only Eustathius, who tells us, that the Athenians made use of Byzantium, a small City, to keep their Treasure in. But Zosimus, a more ancient Historian, describes Byzantium after this Manner: It was seated, says he, on a Hill, which took up part of the Isthmus, and was bounded by a Bay called Cheras, and the Propontis. At 21the End of the Portico’s built by Severus the Emperor, it had a Gate set up, upon his Reconciliation with the Inhabitants, for giving Protection to Niger his Enemy. The Wall of Byzantium extended itself from the Eastern Part of the City to the Temple of Venus, and the Sea over-against Chrysopolis: from the North it descended to the Dock, and so onward to the Sea, which faces the Black Sea, and through which you sail into it. This, says he, was the ancient Extent of the City; but Dionysius, a more ancient Writer than Zosimus, as appears by his Account, which was written before its Destruction by Severus, tells us, that Byzantium contain’d in Compass at least forty Furlongs, which is a much greater Extent than the preceding Writers reported it. Herodian informs us, that Byzantium, in the Time of Severus, was the greatest City in all Thrace.

IT is recorded by Zonaras, that Constantine being inclinable to build a City, and to give it his own Name, at first pitch’d upon Sardicus a Field of Asia; afterwards, upon the Promontory Sigeum, and last of all upon Chalcedon and Byzantium, for that 22Purpose. Georgius Cedrinus is of Opinion, that he first pitch’d upon Thessalonica, and after he had lived there two Years, being wonderfully taken with the Delightfulness of the Place, he built the most magnificent Temples, Bagnio’s and Aqueducts; but being interrupted in his great Designs by the Plague which raged there, he was obliged to leave it, and passing away for Chalcedon, (formerly overthrown by the Persians, but then upon rebuilding) he was directed by the Eagles frequently carrying the small Stones of the Workmen from thence to Byzantium, where Constantinople ought to be built. Zonaras is of the same Opinion; and only differs as to the Story of the Stones, and says, that they were small Ropes which they used in Building. But this seems to be a Fable taken out of Dionysius a Byzantian Writer, who tells us, that Byzas had been the Founder of Byzantium, in a Place call’d Semystra, seated at the Mouth of the Rivers Cydarus and Barbysa, had not a Crow, by snatching a Piece of the Sacrifice out of the Flames, and carrying it to a Promontory of the Bosporus, directed Byzas to found Byzantium in that Place. But Constantine does not seem to me to have been so oversighted as were the ancient Chalcedonians, for which they stand recorded in the Histories of all Ages. Nay, ’tis distinguishable by any Man of a tolerable Judgment, that Byzantium was a much more commodious Situation for the Roman Empire than that of Chalcedon. The far more ancient Historians, among whom are Sozomen of Salamis and Zosimus, who wrote in the Reign of Theodosius the Less, judged 23more rationally on this Occasion. They tell us, without taking any Notice of Sardica, Thessalonica or Chalcedon, that Constantine debating with himself, where he might build a City, and call it by his own Name, equal in Glory and Magnificence to that of Rome, had found out a convenient Situation for that Purpose, between old Troy and the Hellespont; that he had lay’d the Foundations, and raised part of the Wall to a considerable Height, which is to be seen at this Day on the Promontory Sigeum, which Pliny calls Ajantium; because the Sepulchre of Ajax, which was in that Place, hung over the Chops of the Hellespont: They tell you farther, that anciently some Ships were station’d there, and that the Grecians, when at War with the Trojans, pitch’d their Tents in that Place: That Constantine afterwards came into an Opinion, that Byzantium was a properer Situation; that three hundred and sixty two Years after the Reign of Augustus, he rebuilt, enlarged and fortified it with great and strong Walls, and by an Edict engraven on a Stone Pillar, and publickly fix’d up in the Strategium, near his own Equestrian Statue, order’d it to be called Nova Roma Constantinopolitana. Upon a Computation made, that the Natives were not a sufficient Number to people the City, he built several fine Houses in and about the Forums, of which he made a Present to the Senators and other Men of Quality, which he brought with him from Rome and other Nations. He built also several Forums, some as an Ornament, others for the Service of the City. The Hippodrom he beautify’d with Temples, Fountains, Portico’s, and a Senate-House, 24and allow’d its Members equal Honours and Privileges with those of Rome. He also built himself a Palace, little inferior to the Royal one at Rome. In short, he was so ambitious to make it rival Rome itself in all its Grandeur and Magnificence, that at length, as Sozomen assures us, it far surpassed it, both in the Number of its Inhabitants, and its Affluence of all Kinds. Eunapius a Sardian, no mean Writer, nay though an Enemy to Constantine, describes the vast Extent of Constantinople, in these Words: Constantinople, says he, formerly called Byzantium, allow’d the ancient Athenians a Liberty of importing Corn in great Quantities; but at present not all the Ships of Burthen from Ægypt, Asia, Syria, Phœnicia, and many other Nations, can import a Quantity sufficient for the Support of those People, whom Constantine, by unpeopling other Cities, has transported thither. Zosimus also, though otherwise no very good Friend to Constantine on the score of his Religion, yet frankly owns, that he wonderfully enlarged it; and that the Isthmus was enclosed by a Wall from Sea to Sea, to the Distance of fifteen Furlongs beyond the Walls of old Byzantium. But to what Extent soever Constantine might enlarge its Bounds, yet the Emperors who succeeded him have extended them farther, and have enclosed the City with much wider Walls than those built by Constantine, and permitted them to build so closely one House to another, and that even in their Market Places, that they could not walk the Streets without Danger, they were so crowded with Men and Cattle. Upon this Account it was, that a great part of the Sea which runs round the City was in some Places dry’d up, where by fixing Posts 25in a circular Manner, and building Houses upon them, they made their City large enough for the Reception of an infinite Multitude of People. Thus does Zosimus express himself as to the vast Extent of this City, as it stood in the Time either of Arcadius or Theodosius. Agathius says, that in the Time of Justinian the Buildings were so close and crowded together, that it was very difficult to see the Sky by looking through the Tops of them. The large Compass of this City before Justinian’s Time, we may in some measure collect from an ancient Description of the City, by an unknown but seemingly a very faithful Writer. He assures us, that the Length of the City from the Porta Aurea to the Sea Shore in a direct Line, was fourteen thousand and seventy five Feet, and that it was six thousand one hundred and fifty Feet in Breadth. And yet we cannot collect plainly from Procopius, that in the Reign of Justinian the Blachernæ were enclosed within the Walls, although before his Time the City was enlarged by Theodosius the Less, who as Zonaras and others write, gave Orders to Cyrus the Governour of the City for that Purpose. This Man, with great Diligence and wonderful Dispatch, built a Wall over the Continent from Sea to Sea, in sixty Days. The Inhabitants astonish’d that so immense a Work should be finish’d in so small a Time, cry’d out in a publick manner in the Theatre, in the Presence of Theodosius the Emperor, Constantine built this City, but Cyrus rebuilt it. This drew on him the Envy of his Prince, and render’d him suspected; so that being shaved by the Command of Theodosius, against his Inclinations, 26he was constituted Bishop of Smyrna. The following Inscriptions made to Constantinus, and carv’d over the Gate of Xylocerum and Rhegium, take Notice of him in these Verses.

Over the Gate of Xylocerum (Xylocercum or Xylocricum) in Byzantium, thus:

Over the Gate of Rhegium is this Inscription:

The Reason why Constantine order’d Byzantium to be call’d New Rome, or Queen of the Roman Empire, is mention’d by Sozomen and others; namely, that God appear’d by Night to Constantine, and advised him to build a City at Byzantium worthy his own Name. Some say, that as Julius Cæsar, upon a Plot form’d against him, judg’d it necessary to remove to Alexandria or Troy, stripping Italy at the same time of every thing that was valuable, and carrying off all the Riches of the Roman Empire, leaving the Administration in the Hands of his Friends; so it is said of Constantine, that perceiving himself to be obnoxious to the People of Rome, having drain’d the City of all its Wealth, went over at first to Troy, and afterwards to Byzantium. Zosimus, an implacable Enemy to the Christian Name, alledges an execrable Piece of Villany, as the Cause of his Removal. Constantine, says he, when he had murder’d Crispus, and had been guilty of other27 flagrant Crimes, desiring of the Priests an Expiation for them, their Answer was, That his Offences were so many and enormous, that they knew not which way to atone for them; telling him at the same time, that there was a certain Ægyptian who came from Spain to Rome; who, if he had an Opportunity of speaking to him, could procure him an Expiation, if he would establish in his Dominions this Belief of the Christians, namely, That Men of the most profligate Lives, immediately upon their Repentance, obtain’d Remission of Sins. Constantine readily closed with this Offer, and his Sins were pardon’d. At the Approach of the Festival, on which it was usual with him and his Army to go up to the Capitol, to perform the customary Rites of their Religion; Constantine fearful to be present at that Solemnity, as being warn’d to the contrary by a Dream, which was sent him from the Ægyptian, and not attending the holy Sacrifice, highly disgusted the Senate, and the whole Body of the People of Rome. But unable to bear the Curses and Scandal they threw upon him on that Account, he went in Search of some Place or other equally famous with Rome, where he might build him a Palace, and which he might make the Seat of the Roman Empire, and that at last he had discovered a Place between Troas and Old Ilium, fit for that Purpose; and that there he built him a Palace, laid the Foundations of a City, and raised part of a Wall for its Defence: But that afterwards disapproving the Situation, he left his Works unfinish’d, and settled at Byzantium; and being wonderfully taken with the Agreeableness of the Place, he judged it in all respects to be very commodious28 for an Imperial Seat. Thus far Zosimus, a great Favourite of Julian the Apostate, and an inveterate Enemy to Constantine on the account of his Religion; to whose Sentiments I have so perfect an Aversion, that I cannot give the least Credit to those Enormities he charges him with, and of which he had the greatest Abhorrence, as being a Prince of remarkable Clemency and Goodness, which I am capable of proving abundantly, but that it would prove too great a Digression in the present History. The Truth of it is, that Sozomen and Evagrius both have sufficiently refuted these malicious Reflections. In these Calumnies, I say, I entirely differ from Zosimus, yet in his Description of the Extent, and Compass of the City, I am wholly in his Opinion; who, though an Enemy to Constantine, yet is forced to acknowledge him to have built so large, so noble, so magnificent a City. I am the more induced to give Credit to his History in this Respect, because he lived many Ages nearer to the Time of Constantine than our modern Monks, who, in the Books they have written of Constantinople, give the following Account of it; namely, that Constantine built a Wall from the Tower of Eugenius (which was the Boundary of old Byzantium) to St. Anthony’s Church, and the Church of the Blessed Virgin, call’d Rabdon, quite up to the Exacionion; and that at a Mile’s Distance, it passed on to the old Gates of the Church of St. John the Baptist, stretching itself farther to the Cistern of Bonus, from whence it extended itself to the Armation, and so winded round to St. Anthony’s Church again. I should give my self the Trouble to examine this29 Account, but that I know the Authors are so fabulous, that they are no ways to be depended upon. But this I look upon to be an intolerable Blunder, that they place the Church of St. John Baptist within the Walls built by Constantine, whereas for many Years after his Death it continued without the City: Of which, and many other Errors, I shall take Notice in the following History.

THE Figure of Constantinople is triangular, the Base of which is that Part of it which lies Westward: The top Angle points to the East, where the Peninsula begins. But both the Sides of this Triangle are not equal; for that Side which lies westward winds round the Angle of the Bay in the Figure of a Half-Moon. At a great Distance from thence, it winds about again from North to South. But the South Side of this Triangle veers about to such a Breadth, that if you should draw a strait Line from one Angle of it to the other, it would cut off a Creek, which, in the Middle of it, is at least a quarter of a Mile over. But that Side which faces the North, and is call’d Ceras, the Bay or Horn, should you draw a strait Line over it from one Angle to another, it would cut off not only the whole Bay, but also30 a part of Galata. For this Side inflects inwards in such a manner, that from each Point it circulates in the Form of a Bow, having two smaller Windings of the same Figure in the Middle of it, but lies inwardly into the Continent so far, that the two Horns or Ends of the Bow, which includes them, no ways intercept the Prospect of the Angles of the larger Arch. ’Tis upon this Account that Constantinople may rather seem to be of a triarcular, than a triangular Figure. For right Angles never project beyond their Sides, nor do they inflect inwards. But all semicircular Figures are in a manner both convex and concave also. So that if these three Angles, so far as they project beyond the main Body of the City, were divided from it, Constantinople would form a square oblong Figure, little more than a Mile broad, and almost three times as long. But be that as it will, all are of Opinion, that this City ought to be look’d upon to be of a triangular Figure, because it has three Sides; one of which that faces the Propontis, and the other on the side of the Thracian Continent, are of an equal Length; the third, adjoining to the Bay, is about a Mile shorter than the other two. This City is computed to be near thirteen Miles in Compass, although Laonicus Chalcondylus, in his History of the Ottomans, assures us, that Constantinople contain’d in Compass an hundred and eleven Furlongs; the Length of it, extending itself over the Promontory with six Hills, is no more than thirty Furlongs; but if the Figure of it was an equilateral Triangle, it would not be much above nine Miles in Circumference; and could we suppose its hilly Situation to be widen’d31 into one large Plain, yet then it would not be so large in Compass as the Inhabitants generally reckon it, viz. eighteen Miles. It is observable, that Constantinople does not contain more Bays of Building, as it is situate upon Hills, than it would if it were built upon a Plain; because you cannot so conveniently build upon a Declivity, as you can upon a Level. Nor does the Reason equally hold good, as to the Number of its Houses, and the Number of its Inhabitants. For Constantinople can contain more Men as it is seated upon Hills, than it could if it were seated on a Plain. The Breadth of this City varies in several Places. From the East to the Middle of it, ’tis at least a Mile in Breadth, but in no Place broader than a Mile and a half. It divides itself afterwards into two Branches, where ’tis almost as broad as ’tis long. I can compare it, as to its Figure, to nothing more properly than to an Eagle stretching out his Wings, and looking obliquely to the left, upon whose Beak stands the first Hill, where is the Grand Seignor’s Palace. In his Eye stands the Church of St. Sophia; on the lower part of the Head is the Hippodrom; upon his Neck are the second and third Hills, and the remaining part of the City fill up his Wings, and his whole Body.

Constantinople takes up in Compass the whole Peninsula, which contains seven Hills, of which the eastern Angle of the City includes one, having its Rise at the Promontory, which Pliny calls Chrysoceras, and Dionysius a Byzantian, Bosporium. The first Hill is divided from the second by a broad Valley; the Promontory of Bosporium contains the other six, extending itself from the Entrance of the Peninsula on the East, full West with a continued Ridge, but somewhat convex’d, and hangs over the Bay. Six Hills and five Valleys shoot from the right Side of it, and ’tis divided only by the third and fifth Valleys on the left Side of it, which is all upon the Descent, and has only some small Hills and Vales, which are more steep than the Hills themselves. It has also two Windings which take their Rise from the Top of the first Hill, from whence it ascends by Degrees almost to another Winding, which begins from the Top of the third Hill, where sinking into a gentle Descent, it admits the Valley, which lies between the third and the fourth Hill. From thence it rises again with a moderate Ascent, and continues upon a Level westward almost to the Urbicion, where it rises again. The Plains adjoining to the Promontory differ as to their Level. Those that divide the Promontory33 at the Top, and those at the Foot of it, are very uneven in many Places. The Plain at the Top of the first Hill is seven hundred Paces in Length, and two hundred in Breadth. Shooting hence, it rises almost insensibly to the Top of the second Hill, where ’tis five hundred Paces in Breadth, and is all upon the Descent to the Top of that Hill, where the second Valley, which is also shelving and very narrow, takes its Rise. On the third Hill the Plain is above six hundred Paces in Breadth, but somewhat more upon the Level at the Entrance of the third Valley, which is six hundred Paces broad. From hence you rise by a gentle Ascent to the Plain on the Top of the fourth Hill, which is not above two hundred Paces wide. On the fifth Hill it dilates itself to the Breadth of seven hundred Paces. On the Hill, from whence the fifth Valley takes its Rise, ’tis more narrow; and on the sixth Hill ’tis a little upon the Ascent again. As to the Plain, which extends itself between the Sea and the Bottom of the Promontory, that also is not so even in some Places as it is in others; for it is narrower under the Hills, in the Vales ’tis half as wide again. For winding itself from the Promontory, where it begins, over three Valleys, it is widen’d at that Distance into the Breadth of a thousand Paces, though at the Foot of the Hills it is not above an Acre, or a hundred and twenty Foot in Breadth, except at the Bottom of the third and fifth Hills, where ’tis very narrow, but extends itself over the fourth Valley both in Length and Breadth to a great Degree. At the Foot of the sixth Hill it contracts itself again, except at the Foot of two lesser Hills,34 situated behind the first and second Hills; one of which projects almost to the Sea, the other is at no great Distance from it. But to describe Constantinople in a more easy and comprehensive Manner, I will give the Reader a particular Account of all its Hills and Vales, which indeed make a very lovely and agreeable Prospect. For the six Hills which shoot from the Promontory, (and which for their Likeness you might call Brothers) stand in so regular an Order, that neither of them intercepts the Prospect of the other; so that as you sail up the Bay, you see them all hanging over it in such a manner, that quite round the City you see before you both Sides of every one of them. The first of these Hills jets out to the East, and bounds the Bay; the second and third lie more inward to the South; the others lie more open to the North, so that at one View you have a full Prospect of them. The first lies lower than the second; the second than the third; the fourth, fifth and sixth are in some Places higher, in others somewhat lower than the third, which you may discover by the Level of the Aqueduct. That the first Hill is lower than the third and fourth, may be discover’d by the Tower which supports the Aqueduct, by which the Water is raised into the Air above fifty Foot high. To make this more intelligible, I will divide the City, as to the Length of it, from the Land’s Point on the Shore of the Bosporus, to the Walls on the Neck of the Isthmus, and consider the Breadth of it, as it widens from the Propontis to the Bay called Ceras. The Reason why I divide the City, as to its Breadth, into six Parts, is the natural Situation of35 the Promontory, which itself is divided into six Hills, with Valleys running between them. It was no great Difficulty to distinguish the Roman Hills, because they were entirely disjoin’d by Valleys; but ’tis not so easy to distinguish those of Constantinople, because they are conjoin’d at Top; and besides, the Backs of them do not project in so mountainous a manner as they do in the Front; so that I cannot better describe them, than by calling them a continued Ridge of Hills, divided each of them with Valleys. And therefore to proceed regularly, I shall first give the Reader a Description of the right Side of the Promontory, with its Hills and Vales, and then take Notice of the left Side of it, which stands behind them.

THE first Part of the Breadth of the Promontory is the Front of it, which opening to the Distance of a thousand Paces Eastwards adjoins to the Chaps of the Bosporus. For this Sea winds round the Back of the Promontory in such a Manner, that from the Point where the Bosporus is divided, to the Bay called Ceras, and the Land’s Point of that Sea, it extends itself from North to South to the Distance of fourteen Furlongs; and from thence to a farther Distance of four Furlongs, it winds round from the South-east36 to the South-South-west, even to the Mouth of the Propontis, which joining with the Bosporus, winds round the City to South-west, to the Distance of two Miles more. This Side of the Hill is bounded at the Bottom of it with a Plain of the same Breadth with itself, which is two hundred Paces. There rise upon the Plain some lesser Hills, which are not above four hundred Paces in Height. On the Top of the left Side of these Hills stands the Hippodrom; on the right Side, which faces the South-west, is the Palace of the Grand Seignor. I might not improperly call it the Front of the Promontory, as being almost of an equal Ascent in all its Parts, having a Plain running along it, of an equal Length with itself; besides, it adjoins to the first Hill: I say, for these Reasons I might call it a part of the first Hill; but to understand it more distinctly, I shall treat of it by itself.