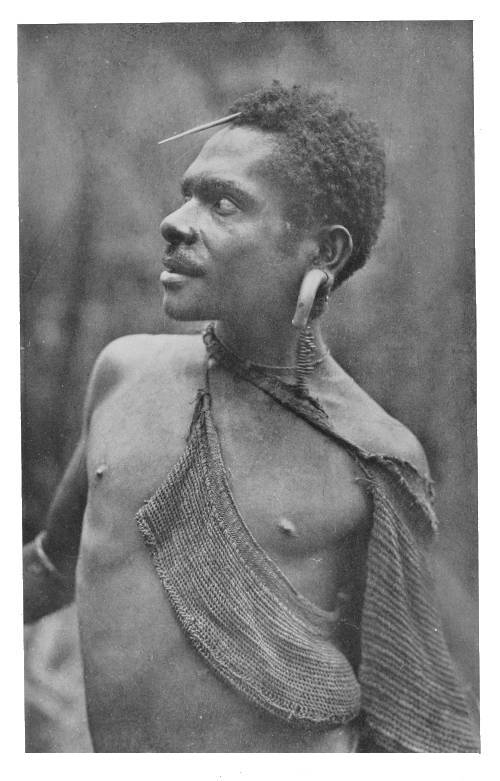

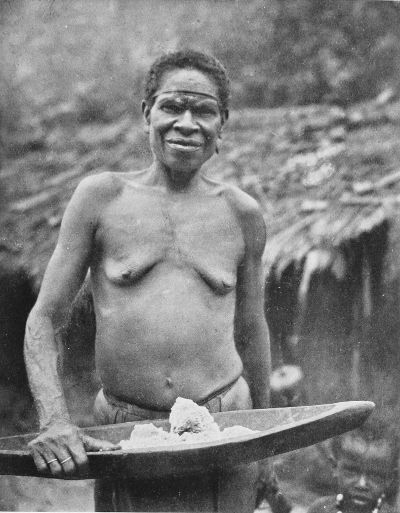

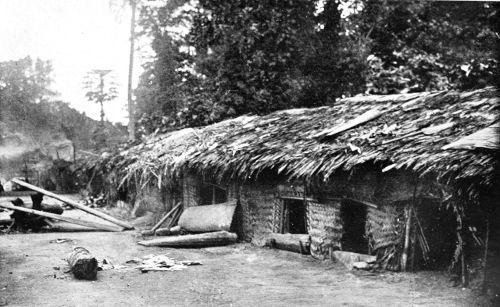

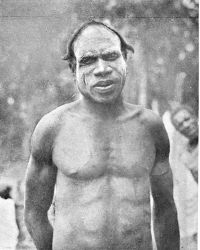

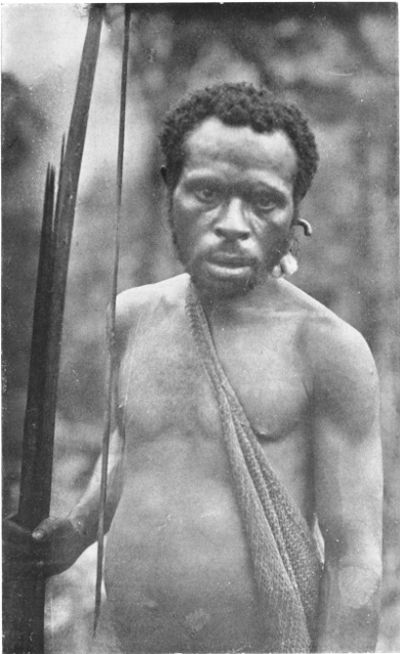

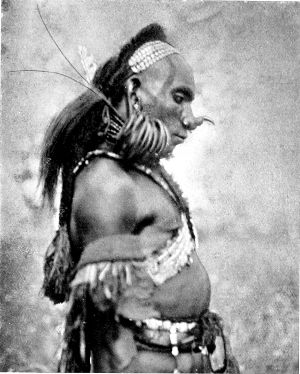

A TAPIRO PYGMY.

[Frontispiece.

Title: Pygmies & Papuans: The Stone Age To-day in Dutch New Guinea

Author: A. F. R. Wollaston

Contributor: Alfred C. Haddon

W. R. Ogilvie-Grant

Sidney Herbert Ray

Release date: October 27, 2016 [eBook #53384]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by deaurider, Turgut Dincer and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

BY

A. F. R. WOLLASTON

AUTHOR OF “FROM RUWENZORI TO THE CONGO”

WITH APPENDICES BY

W. R. OGILVIE-GRANT, A. C. HADDON, F.R.S.

AND SIDNEY H. RAY

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS

NEW YORK

STURGIS & WALTON

COMPANY

1912

PRINTED BY

WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED

LONDON AND BECCLES

TO

ALFRED RUSSEL WALLACE, O.M.

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED

The Committee who organised the late expedition to Dutch New Guinea, paid me the high compliment of inviting me to write an account of our doings in that country. The fact that it is, in a sense, the official account of the expedition has precluded me—greatly to the advantage of the reader—from offering my own views on the things that we saw and on things in general. The country that we visited was quite unknown to Europeans, and the native races with whom we came in contact were living in so primitive a state that the second title of this book is literally true. The pygmies are indeed one of the most primitive peoples now in existence.

Should any find this account lacking in thrilling adventure, I will quote the words of a famous navigator, who visited the coasts of New Guinea more than two hundred years ago:—“It has been Objected against me by some, that my Accounts and Descriptions of Things are dry and jejune, not filled with variety of pleasant Matter, to divert and gratify the Curious Reader. How far this is true, I must leave to the World to judge. But if I have been exactly and strictly careful to give only True Relations and Descriptions of Things (as Iviii am sure I have;) and if my Descriptions be such as may be of use not only to myself, but also to others in future Voyages; and likewise to such readers at home as are desirous of a Plain and Just Account of the true Nature and State of the Things described, than of a Polite and Rhetorical Narrative: I hope all the Defects in my Stile will meet with an easy and ready Pardon.”

To Dr. Alfred Russel Wallace, who has allowed me to inscribe this volume to him as a small token of admiration for the first and greatest of the Naturalists who visited New Guinea, my most sincere thanks are due.

To Mr. W. R. Ogilvie-Grant, Dr. A. C. Haddon, and Mr. Sidney Ray, who have not only assisted me with advice but have contributed the three most valuable articles at the end of this volume, I can only repeat my thanks, which have been expressed elsewhere.

To my fellow-members of the expedition I would like to wish further voyages in more propitious climates.

A.F.R.W.

London,

May, 1912.

| PAGE | |

| Preface | vii |

| Introduction | xix |

| CHAPTER I | |

The British Ornithologists’ Union—Members of the Expedition—Voyage to Java—Choice of Rivers—Prosperity of Java—Half-castes—Obsequious Javanese—The Rijst-tafel—Customs of the Dutch—Buitenzorg Garden—Garoet | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

Expedition leaves Java—The “Nias”—Escort—Macassar—Raja of Goa—Amboina—Corals and Fishes—Ambonese Christians—Dutch Clubs—Dobo | 13 |

| CHAPTER III | |

New Guinea—Its Position and Extent—Territorial Divisions—Mountain Ranges—Numerous Rivers—The Papuans—The Discovery of New Guinea—Early Voyagers—Spanish and Dutch—Jan Carstensz—First Discovery of the Snow Mountains—William Dampier in the “Roebuck”—Captain Cook in the “Endeavour”—Naturalists and later Explorers | 21 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

Sail from the Aru Islands—Sight New Guinea—Distant Mountains—Signal Fires—Natives in Canoes—A British Flag—Natives on Board—Their Behaviour—Arrival at Mimika River—Reception at Wakatimi—Dancing and Weeping—Landing Stores—View of the Country—Snow Mountains—Shark-fishing—Making the Camp—Death of W. Stalker | 35 |

| xCHAPTER V | |

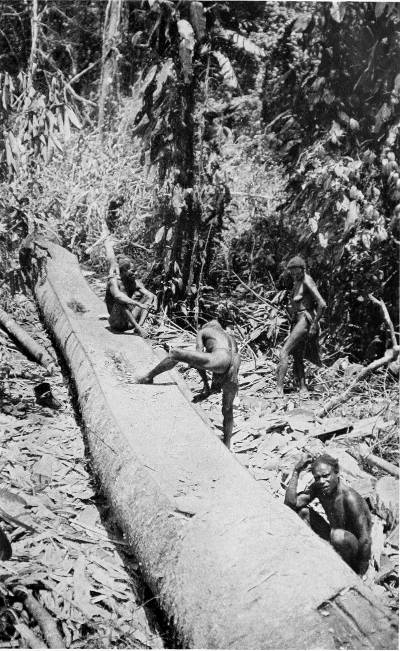

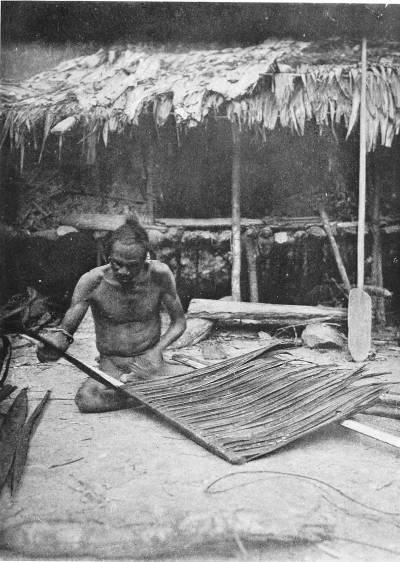

Arrival of our Ambonese—Coolie Considerations—Canoes of the Natives—Making Canoes—Preliminary Exploration of the Mimika—Variable Tides—Completing the Camp—A Plague of Flies—Also of Crickets—Making “Atap”—Trading with the Natives—Trade Goods | 50 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

Difficulties of Food—Coolies’ Rations—Choice of Provisions—Transporting Supplies up the Mimika—Description of the River—A Day’s Work—Monotonous Scenery—Crowned Pigeons—Birds of Paradise and Others—Snakes, Bees, and other Creatures—Rapids and Clear Water—The Seasons—Wind—Rain—Thunderstorms—Halley’s Comet | 65 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

Exploration of the Kapare River—Obota—Native Geography—River Obstructions—Hornbills and Tree Ducks—Gifts of Stones—Importance of Steam Launch—Cultivation of Tobacco—Sago Swamps—Manufacture of Sago—Cooking of Sago—The Dutch Use of Convict Labour | 82 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

Description of Wakatimi—The Papuan House—Coconut Palms—The Sugar Palm—Drunkenness of the Natives—Drunken Vagaries—Other Cultivation—The Native Language—No Interpreters—The Numerals—Difficulties of Understanding—Names of Places—Local Differences of Pronunciation | 95 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

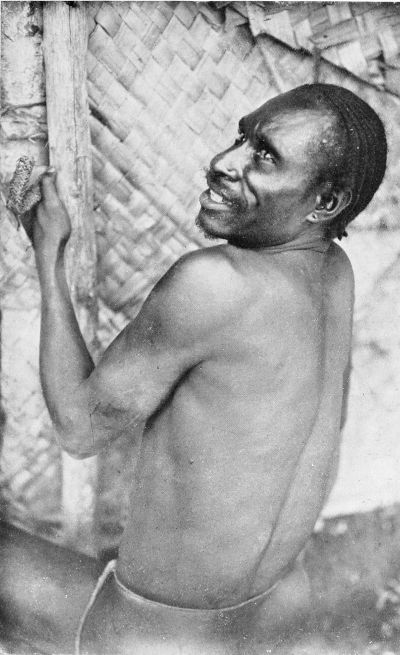

The Papuans of Wakatimi—Colour—Hair—Eyes—Nose—Tattooing—Height—Dress—Widows’ Bonnets—Growth of Children—Preponderancexi of Men—Number of Wives—Childhood—Swimming and other Games—Imitativeness of Children—The Search for Food—Women as Workers—Fishing Nets—Other Methods of Fishing—An Extract from Dampier | 109 |

| CHAPTER X | |

Food of the Papuans—Cassowaries—The Native Dog—Question of Cannibalism—Village Headman—The Social System of the Papuans—The Family—Treatment of Women—Religion—Weather Superstitions—Ceremony to avert a Flood—The Pig—A Village Festival—Wailing at Deaths—Methods of Disposal of the Dead—No Reverence for the Remains—Purchasing Skulls | 124 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

Papuans’ Love of Music—Their Concerts—A Dancing House—Carving—Papuans as Artists—Cat’s Cradle—Village Squabbles—The Part of the Women—Wooden and Stone Clubs—Shell Knives and Stone Axes—Bows and Arrows—Papuan Marksmen—Spears—A most Primitive People—Disease—Prospects of their Civilisation | 141 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

The Camp at Parimau—A Plague of Beetles—First Discovery of the Tapiro Pygmies—Papuans as Carriers—We visit the Clearing of the Tapiro—Remarkable Clothing of Tapiro—Our Relations with the Natives—System of Payment—Their Confidence in Us—Occasional Thefts—A Customary Peace-offering—Papuans as Naturalists | 155 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

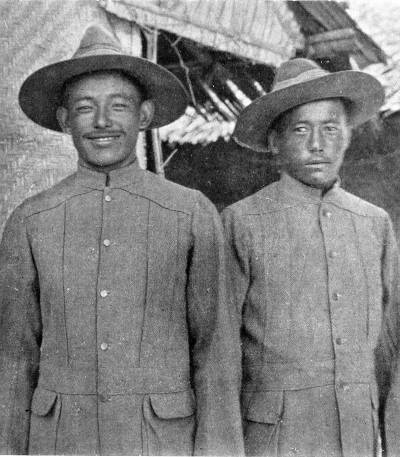

Visit of Mr. Lorentz—Arrival of Steam Launch—A Sailor Drowned—Our Second Batch of Coolies—Health of the Gurkhas—Dayaks the Best Coolies—Sickness—Arrival of Motor Boat—Camp under Water—Expedition moves to Parimau—Explorations beyond the Mimika—Leeches—Floods on the Tuaba River—Overflowing Rivers—The Wataikwa—Cutting a Track | 169 |

| xiiCHAPTER XIV | |

The Camp at the Wataikwa River—Malay Coolies—“Amok”—A Double Murder—A View of the Snow Mountains—Felling Trees—Floods—Village washed Away—The Wettest Season—The Effects of Floods—Beri-beri—Arrival of C. Grant—Departure of W. Goodfellow | 184 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

Pygmies visit Parimau—Description of Tapiro Pygmies—Colour—Hair—Clothing—Ornaments—Netted Bags—Flint Knives—Bone Daggers—Sleeping Mats—Fire Stick—Method of making Fire—Cultivation of Tobacco—Manner of Smoking—Bows and Arrows—Village of the Pygmies—Terraced Ground—Houses on Piles—Village Headman—Our Efforts to see the Women—Language and Voices—Their Intelligence—Counting—Their Geographical Distribution | 196 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

Communication with Amboina and Merauke—Sail in the “Valk” to the Utakwa River—Removal of the Dutch Expedition—View of Mount Carstensz—Dugongs—Crowded Ship—Dayaks and Live Stock—Sea-Snakes—Excitable Convicts—The Island River—Its Great Size—Another Dutch Expedition—Their Achievements—Houses in the Trees—Large Village—Barn-like Houses—Naked People—Shooting Lime—Their Skill in Paddling—Through the Marianne Straits—An Extract from Carstensz—Merauke—Trade in Copra—Botanic Station—The Mission—The Ké Island Boat-builders—The Natives of Merauke described—Arrival of our Third Batch of Coolies—The Feast of St. Nicholas—Return to Mimika | 209 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

Difficulty of Cross-country Travel—Expedition moves towards the Mountains—Arrival at the Iwaka River—Changing Scenery—The Impassable Iwaka—A Plucky Gurkha—Building a xiii Bridge—We start into the Mountains—Fording Rivers—Flowers—Lack of Water on Hillside—Curious Vegetation—Our highest Point—A wide View—Rare Birds—Coal—Uninhabitable Country—Dreary Jungle—Rarely any Beauty—Remarkable Trees—Occasional Compensations | 229 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

Departure from Parimau—Parting Gifts—Mock Lamentation—Rawling explores Kamura River—Start for the Wania—Lose the Propeller—A Perilous Anchorage—Unpleasant Night—Leave the Motor Boat—Village of Nimé—Arrival of “Zwaan” with Dayaks—Their Departure—Waiting for the Ship—Taking Leave of the People of Wakatimi—Sail from New Guinea—Ké Islands—Banda—Hospitality of the Netherlands Government—Lieutenant Cramer—Sumbawa—Bali—Return to Singapore and England—One or two Reflexions | 246 |

| APPENDIX A | |

Notes on the Birds collected by the B.O.U Expedition to Dutch New Guinea. By W. R. Ogilvie-Grant | 263 |

| APPENDIX B | |

The Pygmy Question. By Dr. A. C. Haddon, F.R.S. | 303 |

| APPENDIX C | |

Notes on Languages in the East of Netherlands New Guinea. By Sidney H. Ray, M.A. | 322 |

Index | 347 |

(Except where it is otherwise stated, the illustrations are from photographs by the Author.)

A Tapiro Pygmy | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

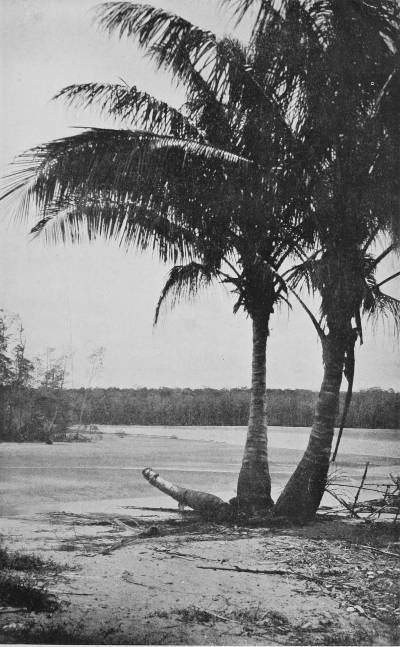

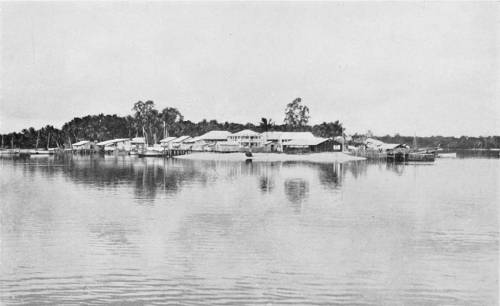

Near the Mouth of the Mimika River | 4 |

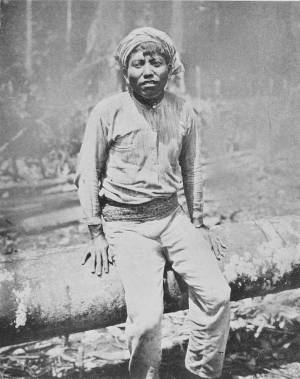

A Convict Cooly of the Dutch Escort | 12 |

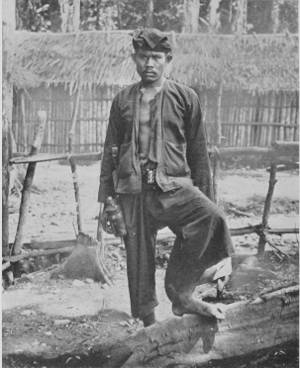

A Malay Cooly from Buton | 12 |

Dobo, Aru Islands | 20 |

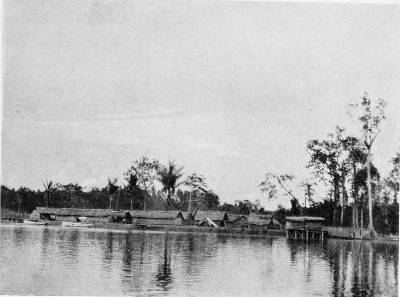

Camp of the Expedition at Wakatimi (Photo by C. G. Rawling and E. S. Marshall) | 48 |

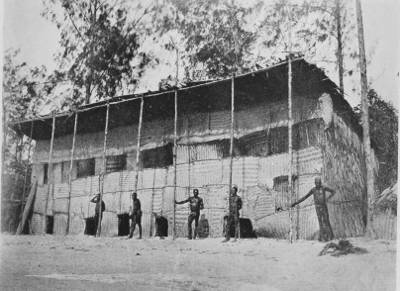

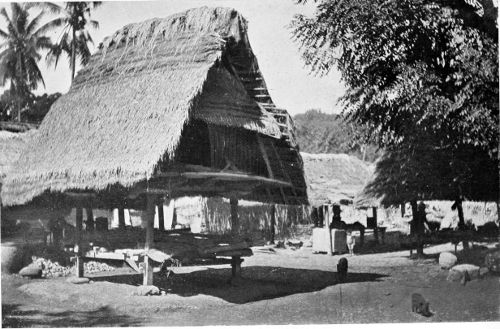

A House for Ceremonies, Mimika (Photo by C. G. Rawling and E. S. Marshall) | 48 |

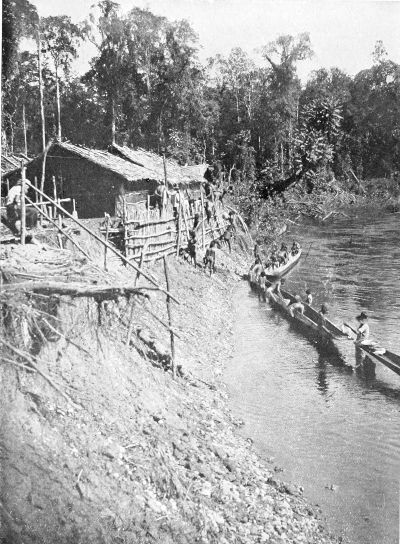

Making Canoes | 50 |

Canoes, Finished and Unfinished | 54 |

Making “Atap” for Roofing | 60 |

Papuan Woman Canoeing up the Mimika | 64 |

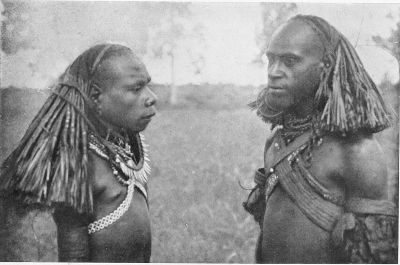

Jangbir and Herkajit, (Photo by C. G. Rawling and E. S. Marshall) | 68 |

Hauling Canoes up the Mimika | 70 |

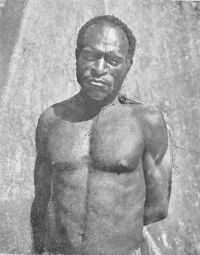

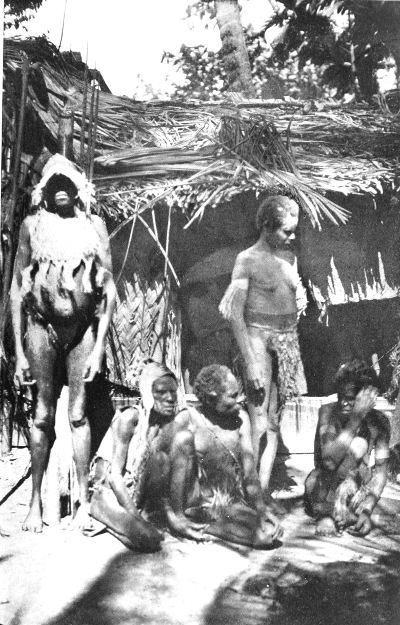

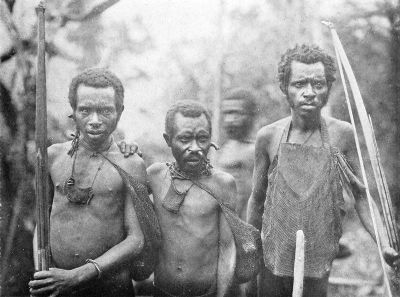

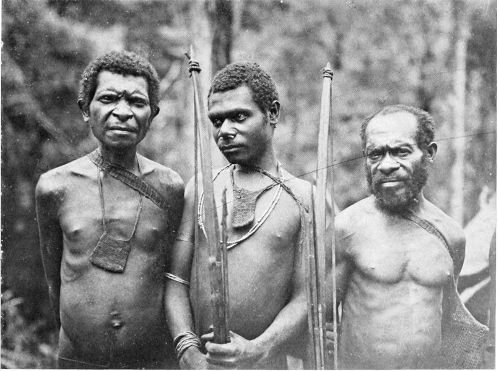

Typical Papuans of Mimika | 74 |

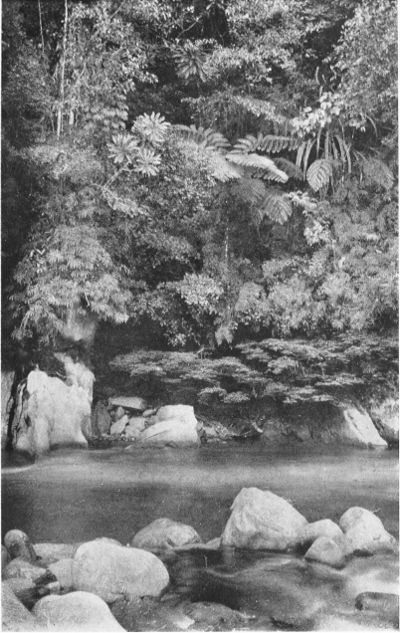

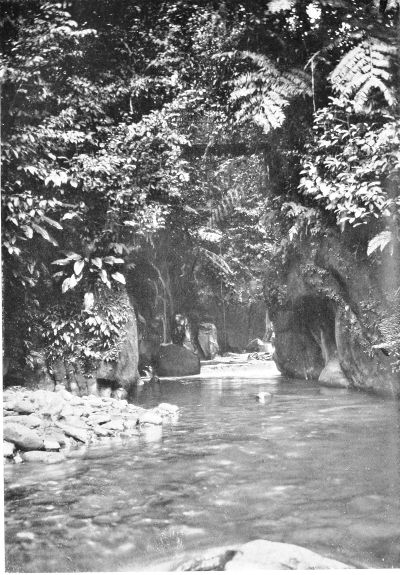

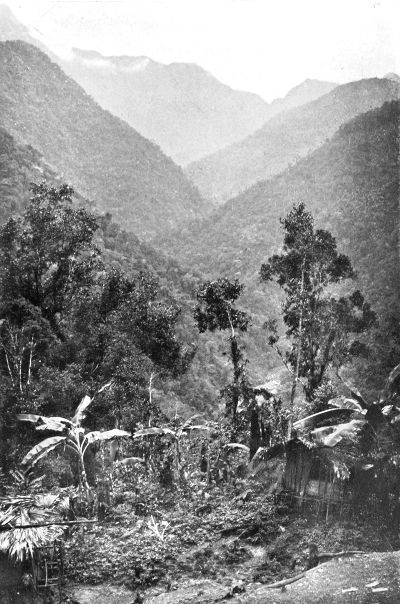

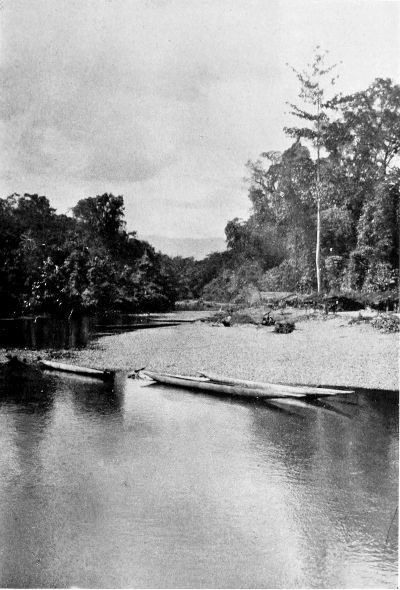

Upper Waters of the Kapare River | 82 |

Vegetation on the Banks of the Kapare River | 86 |

Papuan Woman carrying Wooden Bowl of Sago | 90 |

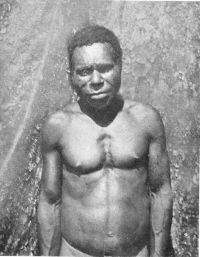

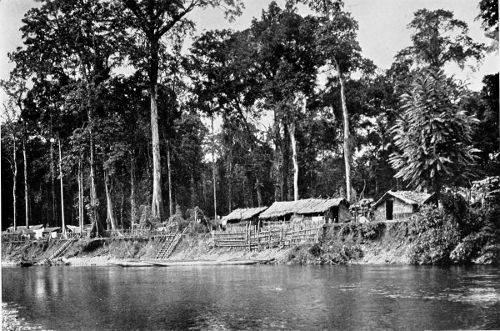

Papuan Houses on the Mimika | 96 |

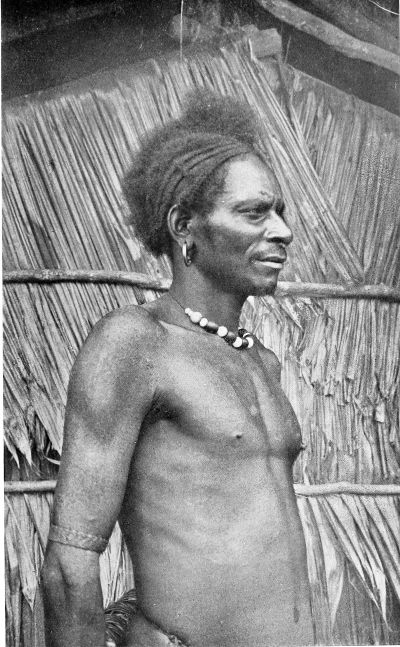

Papuan of the Mimika | 100 |

Papuan of the Mimika | 100 |

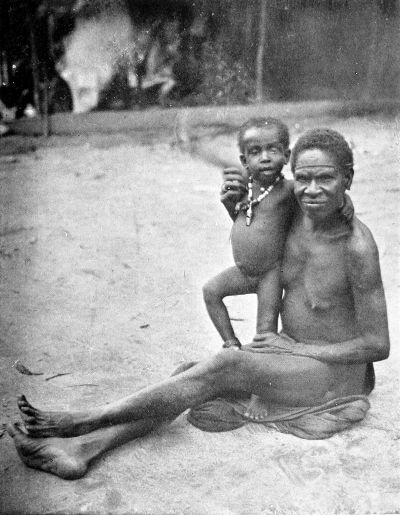

xviA Papuan Mother and Child | 106 |

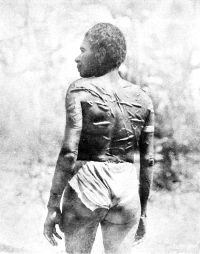

Cicatrization (Photo by C. G. Rawling and E. S. Marshall) | 112 |

Papuan with Face Whitened with Sago Powder | 112 |

Women of Wakatimi | 114 |

Papuan Woman and Child | 120 |

A Papuan of Mimika | 128 |

A Papuan of Mimika | 134 |

Disposal of the Dead: A Coffin on Trestles | 139 |

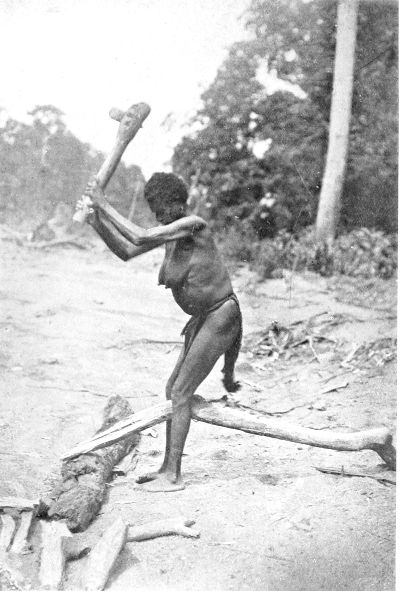

Splitting Wood with Stone Axe, (Photo by C. G. Rawling and | 148 |

A Tributary Stream of the Kapare River | 159 |

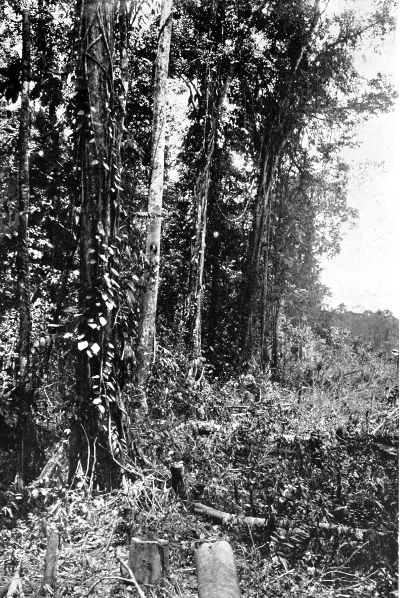

Typical Jungle, Mimika River | 178 |

At the Edge of the Jungle | 182 |

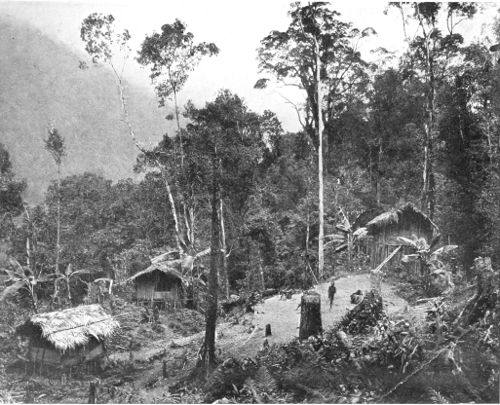

Camp of the Expedition at Parimau | 184 |

The Camp at Parimau: A Precaution against Floods | 188 |

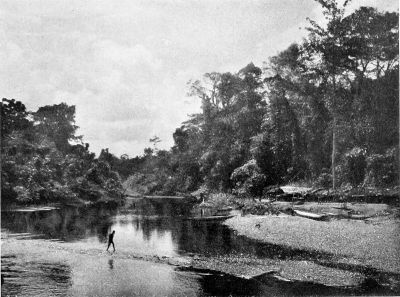

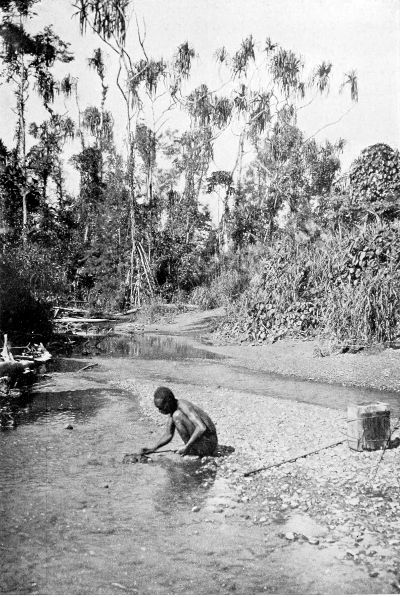

The Mimika at Parimau: Low Water | 190 |

The same in Flood | 190 |

A Tapiro Pygmy | 196 |

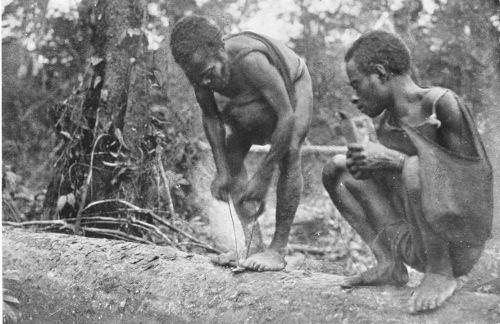

Making Fire (1) | 200 |

Making Fire (2) | 202 |

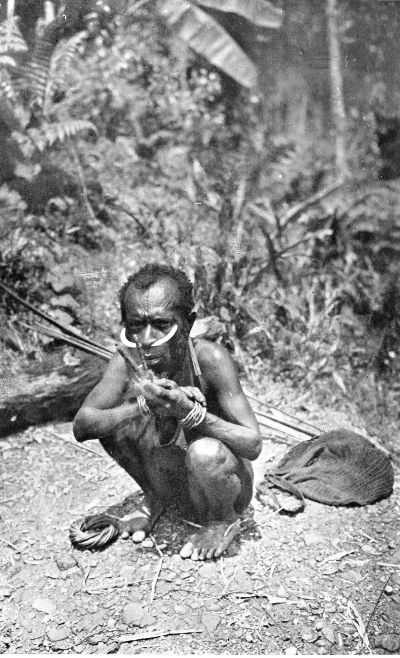

Wamberi Merbiri | 204 |

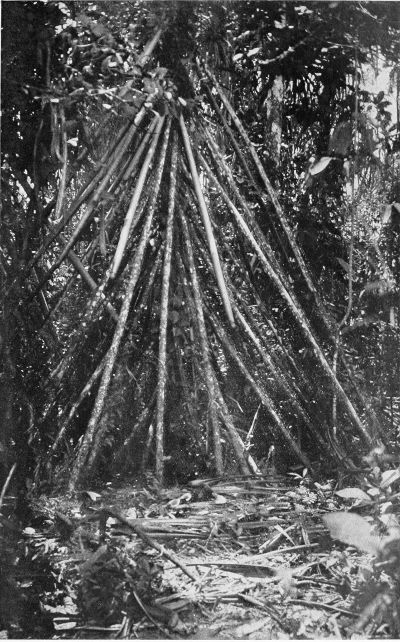

A House of the Tapiro | 206 |

Mount Tapiro from the Village of the Pygmies | 208 |

Types of Tapiro Pygmies | 212 |

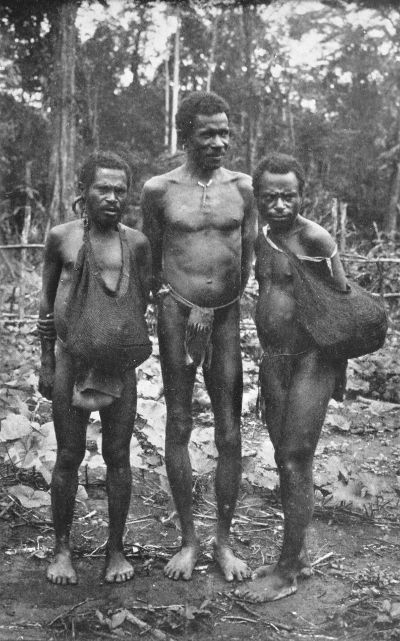

A Papuan with Two Tapiro | 216 |

Natives of Merauke | 226 |

Looking up the Mimika from Parimau | 232 |

Bridge made by the Expedition across the Iwaka River | 234 |

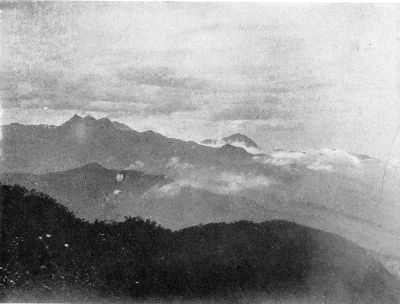

Looking West from above the Iwaka (Photo by C. H. B. Grant) | 238 |

Cockscomb Mountain seen from Mt. Godman (Photo by C. G. | 238 |

Supports of a Pandanus | 242 |

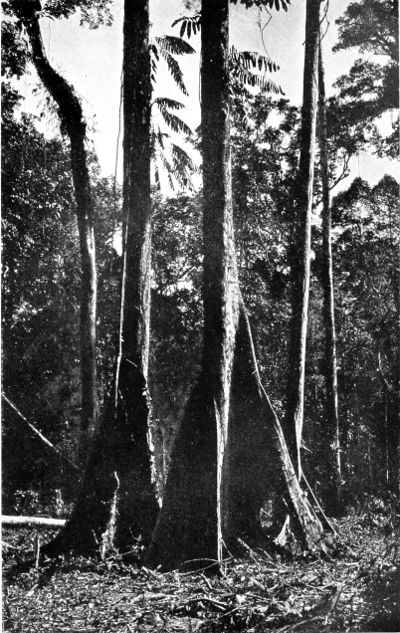

Buttressed Trees | 246 |

Screw Pines (Pandanus) | 250 |

xvii At Sumbawa Pesar | 252 |

Near Buleling | 256 |

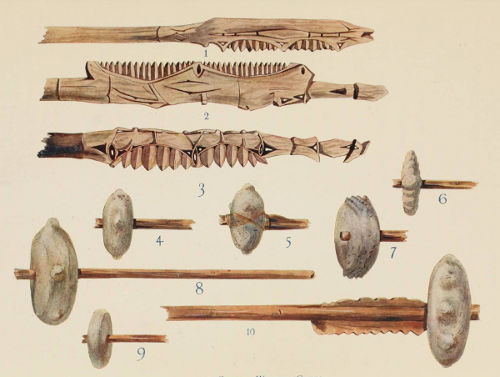

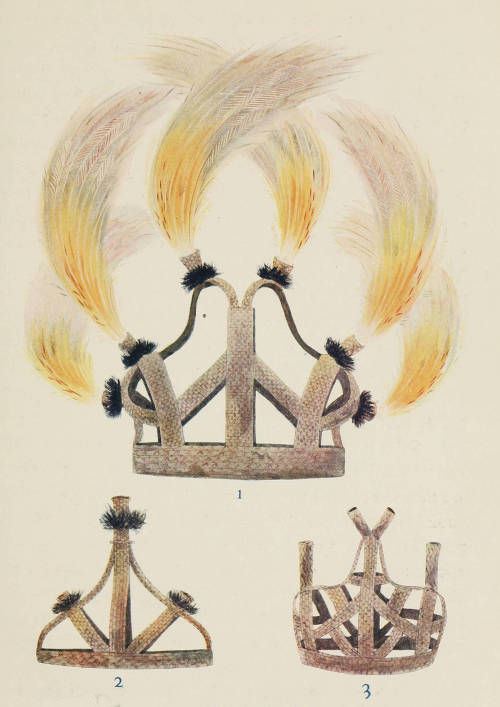

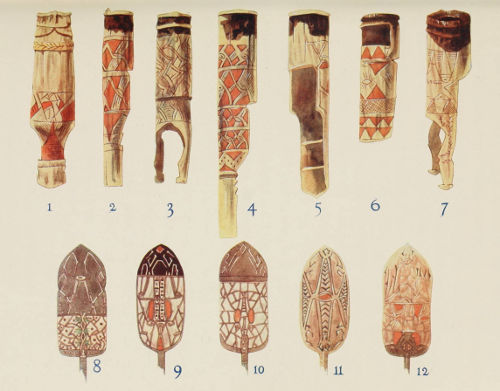

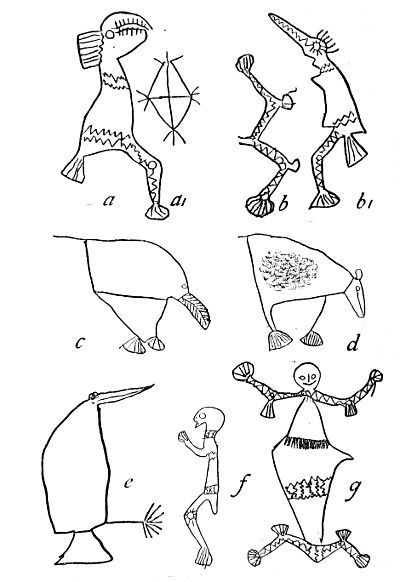

(from Drawings by G. C. Shortridge)

Carved Wooden Clubs and Stone Clubs | 36 |

Head-Dresses, Worn at Ceremonies | 78 |

Stone Axe, Head-Rests and Drums | 142 |

Blades of Paddles, and Bamboo Penis-Cases | 144 |

Bow, Arrows and Spears | 150 |

Ornaments of Papuans | 222 |

A Language Map of Netherlands New Guinea | 342 |

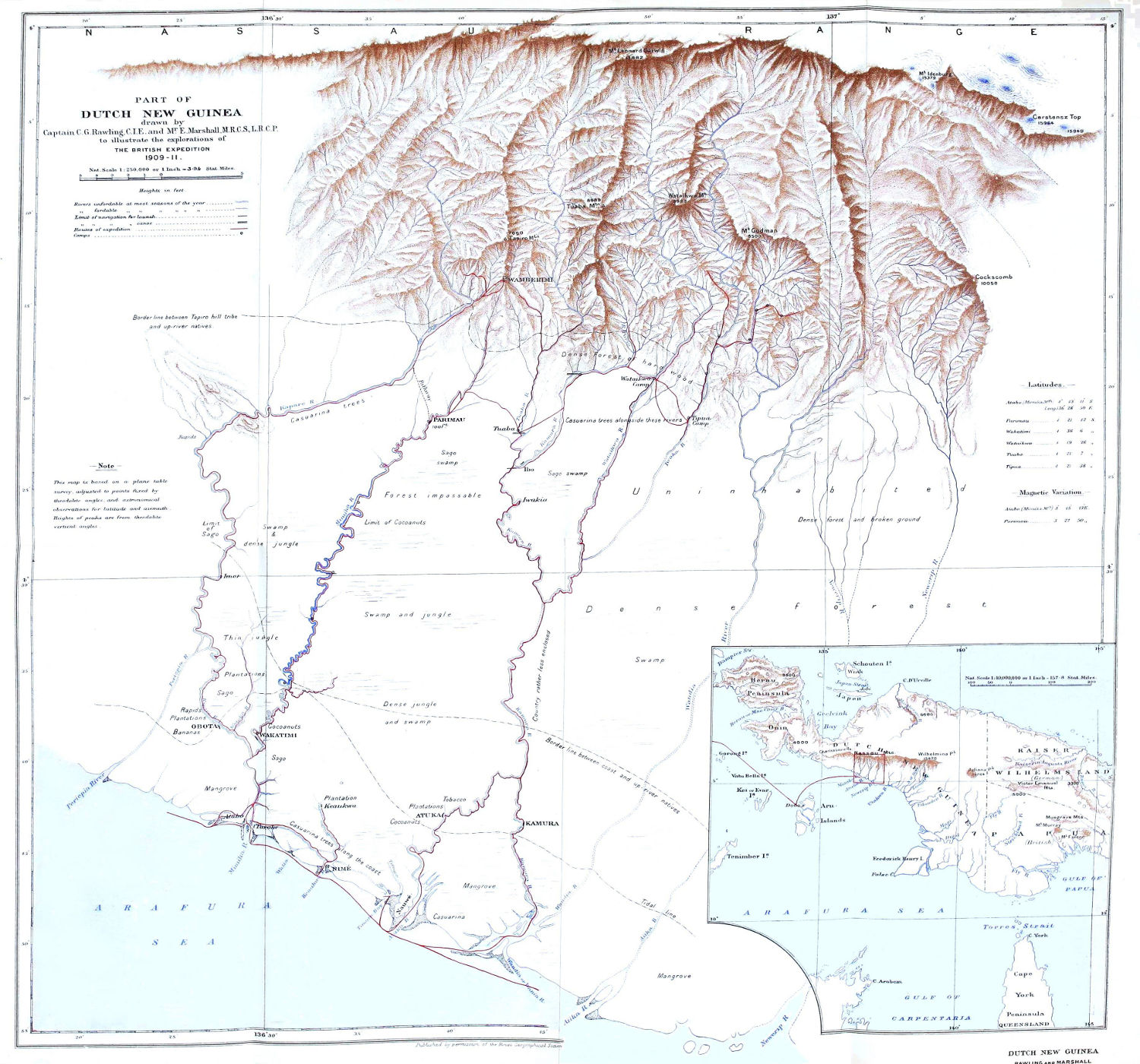

Map of the District Visited by the Expedition | at End |

The wonderful fauna of New Guinea, especially the marvellous forms of Bird- and Insect-life to be found there, have long attracted the attention of naturalists in all parts of the world. The exploration of this vast island during recent years has brought to light many extraordinary and hitherto unknown forms, more particularly new Birds of Paradise and Gardener Bower-Birds; but until recently the central portion was still entirely unexplored, though no part of the globe promised to yield such an abundance of zoological treasures to those prepared to face the difficulties of penetrating to the great ranges of the interior.

The B.O.U. Expedition, of which the present work is the official record, originated in the following manner. For many years past I had been trying to organise an exploration of the Snow Mountains, but the reported hostility of the natives in the southern part of Dutch New Guinea and the risks attending such an undertaking, rendered the chances of success too small to justify the attempt.

It was in 1907 that Mr. Walter Goodfellow, well-known as an experienced traveller and an accomplished naturalist, informed me that he believed a properlyxx equipped expedition might meet with success, and I entered into an arrangement with him to lead a small zoological expedition to explore the Snow Mountains. It so happened, however, that by the time our arrangements had been completed in December, 1908, the members of the British Ornithologists’ Union, founded in 1858, were celebrating their Jubilee, and it seemed fitting that they should mark so memorable an occasion by undertaking some great zoological exploration. I therefore laid my scheme for exploring the Snow Mountains before the meeting, and suggested that it should be known as the Jubilee Expedition of the B.O.U., a proposal which was received with enthusiasm. A Committee was formed, consisting of Mr. F. du Cane Godman, F.R.S. (President of the B.O.U.), Dr. P. L. Sclater, F.R.S. (Editor of the Ibis), Mr. E. G. B. Meade-Waldo, Mr. W. R. Ogilvie-Grant (Secretary), and Mr. C. E. Fagan (Treasurer). At the request of the Royal Geographical Society it was decided that their interests should also be represented, and that a surveyor and an assistant-surveyor, to be selected by the Committee, should be added, the Society undertaking to contribute funds for that purpose. The expedition thus became a much larger one than had been originally contemplated and included:—

Mr. Walter Goodfellow (Leader),

Mr. Wilfred Stalker and Mr. Guy C. Shortridge (Collectors of Mammals, Birds, Reptiles, etc.),

Mr. A. F. R. Wollaston (Medical Officer to the Expedition, Entomologist, and Botanist),

Capt. C. G. Rawling, C.I.E. (Surveyor),

Dr. Eric Marshall (Assistant-Surveyor and Surgeon).

To meet the cost of keeping such an expedition in the field for at least a year it was necessary to raise a large sum of money, and this I was eventually able to do, thanks chiefly to a liberal grant from His Majesty’s Government, and to the generosity of a number of private subscribers, many of whom were members of the B.O.U. The total sum raised amounted to over £9000, and though it is impossible to give here the names of all those who contributed, I would especially mention the following:—

| S. G. Asher, | Mrs. H. A. Powell, |

| E. J. Brook, | H. C. Robinson, |

| J. Stewart Clark, | Lord Rothschild, |

| Col. Stephenson Clarke, | Hon. L. Walter Rothschild, |

| Sir Jeremiah Colman, | Hon. N. Charles Rothschild, |

| H. J. Elwes, | Baron and Baroness James A. de Rothschild, |

| F. du Cane Godman, | P. L. Sclater, |

| Sir Edward Grey, | P. K. Stothert, |

| J. H. Gurney, | Oldfield Thomas, |

| Sir William Ingram, | E. G. B. Meade-Waldo, |

| Lord Iveagh, | Rowland Ward, |

| Mrs. Charles Jenkinson, | The Proprietors of Country Life, |

| E. J. Johnstone, | The Royal Society, |

| Campbell D. Mackellar, | The Royal Geographical Society, |

| G. A. Macmillan, | The Zoological Society of London. |

The organization and equipment of this large expedition caused considerable delay and it was not until September, 1909, that the members sailed from England for the East. Meanwhile the necessary steps were taken toxxii obtain the consent of the Netherlands Government to allow the proposed expedition to travel in Dutch New Guinea and to carry out the scheme of exploration. Not only was this permission granted, thanks to the kindly help of Sir Edward Grey and the British Minister at the Hague, but the Government of Holland showed itself animated with such readiness to assist the expedition that it supplied not only an armed guard at its own expense, but placed a gunboat at the disposal of the Committee to convey the party from Batavia to New Guinea.

On behalf of the Committee I would again take this opportunity of publicly expressing their most grateful thanks to the Netherlands Government for these and many other substantial acts of kindness, which were shown to the members of the expedition. The Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company did all in their power to further the interests of the expedition, and to them the Committee is very specially indebted. To the proprietors of Country Life the thanks of the Committee are also due for the interest and sympathy they have displayed towards the expedition and for the assistance they have given in helping to raise funds to carry on the work in the field.

In various numbers of Country Life, issued between the 16th of April, 1910, and the 20th of May, 1911, a series of ten articles will be found in which I contributed a general account of New Guinea, and mentioned some of the more important discoveries made by the members of the expedition during their attempts to penetrate to the Snow Mountains.

In Appendix A to the present volume will be found a general account of the ornithological results. A detailed report will appear elsewhere, as also, it is hoped, a complete account of the zoological work done by the expedition.

As the reader will learn from Mr. Wollaston’s book, the great physical difficulties of this unexplored part of New Guinea and other unforeseen circumstances rendered the work of the B.O.U. Expedition quite exceptionally arduous; and if the results of their exploration are not all that had been hoped, it must be remembered that they did all that was humanly possible to carry out the dangerous task with which they had been entrusted. Their work has added vastly to our knowledge of this part of New Guinea, and though little collecting was done above 4000 feet, quite a number of new, and, in many cases, remarkably interesting forms were obtained.

There can be no doubt that when the higher ranges between 5000 and 10,000 feet are explored, many other novelties will be discovered and for this reason it has been thought advisable to postpone the publication of the scientific results of the B.O.U. Expedition until such time as the second expedition under Mr. Wollaston has returned in 1913.

The death of Mr. Wilfred Stalker at a very early period of the expedition was a sad misfortune and his services could ill be spared; his place was, however, very ably filled by Mr. Claude H. B. Grant, who arrived in New Guinea some six months later.

As all those who have served on committees mustxxiv know, most of the work falls on one or two individuals, and I should like here to express the thanks which we owe to our Treasurer, Mr. C. E. Fagan, for the admirable way in which he has carried out his very difficult task.

W. R. OGILVIE-GRANT.

PYGMIES AND PAPUANS

PYGMIES AND PAPUANS

The British Ornithologists’ Union—Members of the Expedition—Voyage to Java—Choice of Rivers—Prosperity of Java—Half-castes—Obsequious Javanese—The Rijst-tafel—Customs of the Dutch—Buitenzorg Garden—Garoet.

In the autumn of 1858 a small party of naturalists, most of them members of the University of Cambridge and their friends and all of them interested in the study of ornithology, met in the rooms of the late Professor Alfred Newton at Magdalene College, Cambridge, and agreed to found a society with the principal object of producing a quarterly Journal of general ornithology. The Journal was called “The Ibis,” and the Society adopted the name of British Ornithologists’ Union, the number of members being originally limited to twenty.

In the autumn of 1908 the Society, which by that time counted four hundred and seventy members, adopted the suggestion, made by Mr. W. R. Ogilvie-Grant, of celebrating its jubilee by sending an expedition to explore, chiefly from an ornithological point of view, the unknown range of Snow Mountains in Dutch New Guinea. A Committee, whose Chairman was Mr. F. D. Godman, F.R.S., President and one of the surviving original members of the Society, was appointed to organise the expedition, and subscriptions were obtained from2 members and their friends. The remote destination of the expedition aroused a good deal of public interest. The Royal Geographical Society expressed a desire to share in the enterprise, and it soon became evident that it would be a mistake to limit the object of the expedition to the pursuit of birds only. Mr. Walter Goodfellow, a naturalist who had several times travelled in New Guinea as well as in other parts of the world, was appointed leader of the expedition. Mr. W. Stalker and Mr. G. C. Shortridge, both of whom had had wide experience of collecting in the East, were appointed naturalists. Capt. C. G. Rawling, C.I.E., 13th Somersetshire Light Infantry, who had travelled widely in Tibet and mapped a large area of unknown territory in that region, was appointed surveyor, with Mr. E. S. Marshall, M.R.C.S., L.R.C.P., who had just returned from the “Furthest South” with Sir E. H. Shackleton, as assistant surveyor and surgeon; and the present writer, who had been medical officer, botanist, and entomologist on the Ruwenzori Expedition of 1906-7, undertook the same duties as before.

Prolonged correspondence between the Foreign Office and the Dutch Government resulted, thanks largely to the personal interest of Sir Edward Grey and Lord Acton, British Chargé d’Affaires at the Hague, in permission being granted to the expedition to land in Dutch New Guinea on or after January 1, 1910. The date of landing was postponed by the Government until January in order that there might be no interference with the expedition of Mr. H. A. Lorentz, who it was hoped would be the first to reach the snow in New Guinea by way of the Noord River, a project which he3 successfully accomplished in the month of November, 1909.

On October 29th four of us sailed from Marseilles in the P. & O. S.S. Marmora. Mr. Stalker and Mr. Shortridge, who had already proceeded to the East, joined us later at Batavia and Amboina respectively. At Singapore we found the ten Gurkhas, ex-military police, who had been engaged for the expedition by the recruiting officer at Darjiling; though some of these men were useless for the work they had to do, the others did invaluable service as will be seen later. We left Singapore on November 26th, and as we passed through the narrow Riou Straits we saw the remains of the French mail steamer La Seyne, which had been wrecked there with appalling loss of life a few days earlier. It was believed that scores of persons were devoured by sharks within a few minutes of the accident happening. Two days’ steaming in the Dutch packet brought us to Batavia in Java, the city of the Government of the Netherlands East Indies.

We had hoped that our ten Gurkhas would be sufficient escort for the expedition and that we could do without the escort of native soldiers offered to us by the Dutch Government, but the local authorities decided that the escort was necessary and they appointed to command it Lieutenant H. A. Cramer of the Infantry, a probationer on the Staff of the Dutch East Indian Army. The Government also undertook to transport the whole expedition, men, stores, and equipment, from Java to New Guinea. The undertaking was a most generous one as the voyage from Batavia by mail steamer4 to Dobo in the Aru Islands would have been most costly, and from there we should have been obliged to charter a special steamer to convey the expedition to the shores of New Guinea.

When we left England we had the intention of approaching the Snow Mountains by way of the Utakwa River, which was the only river shown by the maps obtainable at that time approaching the mountains. After a consultation with the Military and Geographical Departments at Batavia it was decided that, owing to the bad accounts which had been received of the Utakwa River and the comparatively favourable reports of the Mimika River, the latter should be chosen as the point of our entry into the country. This decision, though we little suspected it at the time, effectually put an end to our chance of reaching the Snow Mountains.

During the month of December, while stores were being accumulated, and the steamer was being prepared for our use, we had leisure to visit, and in the case of some of us to revisit, some of the most interesting places in Java. A large German ship filled with fourteen hundred American tourists arrived at Batavia whilst we were there, and the passengers “did” Java, apparently to their satisfaction, in forty-eight hours. But a tourist with more time could find occupation for as many days and still leave much to be seen. Germans and Americans outnumber English visitors by nearly fifty to one, and it is to be deplored that Englishmen do not go there in larger numbers, for they would see in Java, not to mention the beauty of its scenery, perhaps the most successful tropical dependency in the world, a vast monument to the genius of Sir Stamford Raffles, who laid the foundation of its prosperity less than one hundred years ago.

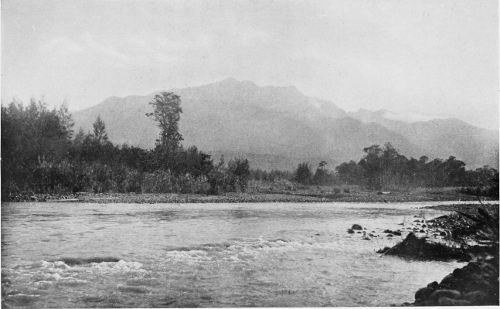

NEAR THE MOUTH OF THE MIMIKA RIVER.

Some idea of the progress which has been made may be learnt from the fact that, whereas at the beginning of the last century the population numbered about four millions, there are to-day nearly ten times that number. Wherever you go you see excellent roads, clean, and well-ordered villages and a swarming peasant population, quiet and industrious and apparently contented with their lot.

There are between thirty and forty volcanoes in the island, many of them active, and the soil is extraordinarily rich and productive, three crops in the rice districts being harvested in rather less than two years. So fertile is the land that in many places the steepest slopes of the hills have been brought under cultivation by an ingenious system of terracing and irrigation in such a way that the higher valleys present the appearance of great amphitheatres rising tier above tier of brilliantly green young rice plants or of drooping yellow heads of ripening grain. The tea plantations and the fields of sugar-cane in Central Java not less than the rice-growing districts impress one with the unceasing industry of the people and the inexhaustible wealth of the island.

One of the features of life in the Dutch East Indies, which first strikes the attention of an English visitor, is the difference in the relation between Europeans and natives from those which usually obtain in British possessions as shown by the enormous number of half-castes. Whilst we were still at Batavia the feast of the6 Eve of St. Nicholas, which takes the place of our Christmas, occurred. In the evening the entire “white” population indulged in a sort of carnival; the main streets and restaurants were crowded, bands played and carriages laden with parents and their children drove slowly through the throng. The spectacle, a sort of “trooping of the colours,” was a most interesting one to the onlooker, for one saw often in the same family children showing every degree of colour from the fairest Dutch hair and complexion to the darkest Javanese. It is easy to understand how this strong mixture of races has come about, when one learns that Dutchmen who come out to the East Indies, whether as civilian or military officials or as business men, almost invariably stay for ten years without returning to Europe. They become in that time more firmly attached to the country than is the case in colonies where people go home at shorter intervals, and it is not uncommon to meet Dutchmen who have not returned to Holland for thirty or forty years. It is not the custom to send children back to Europe when they reach the school age; there are excellent government schools in all the larger towns, and it often happens that men and women grow up and marry who have never been to Europe in their lives. Thus it can be seen how a large half-caste population is likely to be formed. The half-castes do not, as in British India, form a separate caste, but are regarded as Europeans, and there are many instances of men having more or less of native blood in their veins reaching the highest civilian and military rank.

One or two curious relics of former times, which the visitor to Java notices, are worth recording because they show the survival of a spirit that has almost completely disappeared from our own dominions. When a European walks, or as is more usual, drives along the country roads, the natives whom he meets remove their hats from their heads and their loads from their shoulders and crouch humbly by the roadside. Again, on the railways the ticket examiner approaches with a suppliant air and begs to see your ticket, while he holds out his right hand for it grasping his right wrist with his left hand. In former times when a man held out his right hand to give or take something from you his left hand was free to stab you with his kris. Nowadays only a very few privileged natives in Java are allowed to carry the kris.

Another very noticeable feature of life in the Dutch East Indies, which immediately attracts the attention of a stranger, is the astonishing number of excessively corpulent Europeans. If you travel in the morning in the steam tramcar which runs from the residential part of Batavia to the business quarter of the town, you will see as many noticeably stout men as you will see in the City of London in a year, or, as I was credibly informed, as you will see in the city of Amsterdam in a month. It is fairly certain that this unhealthy state of body of a large number of Europeans may be attributed to the institution of the Rijst-tafel, the midday meal of a large majority of the Dutchmen in the East.

This custom is so remarkable that it is worth while to give a description of it. The foundation of the meal, as its name implies, is rice. You sit at table with a8 soup plate in front of you, a smaller flat plate beside it and a spoon, a knife and a fork. The first servant brings a large bowl of rice from which you help yourself liberally. The second brings a kind of vegetable stew which you pour over the heap of rice. Then follows a remarkable procession; I have myself seen at an hotel in Batavia fourteen different boys bringing as many different dishes, and I have seen stalwart Teutons taking samples from every dish. These boys bring fish of various sorts and of various cookeries, bones of chickens cooked in different ways and eggs of various ages, and last of all comes a boy bearing a large tray covered with many different kinds of chutneys and sauces from which the connoisseur chooses three or four. The more solid and bony portions find a space on the small flat plate, the others are piled in the soup plate upon the rice. As an experience once or twice the Rijst-tafel is interesting; but as a daily custom it is an abomination. Even when, as in private houses, the number of dishes is perhaps not more than three or four, the main foundation of the meal is a solid pile of rice, which is not at all a satisfactory diet for Europeans. The Rijst-tafel is not a traditional native custom but a modern innovation, and there is a tendency among the more active members of the community to replace it by a more rational meal.

The houses of the Europeans are of the bungalow type with high-pitched roofs of red tiles and surrounded by wide verandahs, which are actually the living rooms of the house. The Dutch are good gardeners and are particularly fond of trees, which they plant close about their houses and so ensure a pleasant shade, though9 they harbour rather more mosquitoes and other insects than is pleasant. In strange contrast with the scrupulous cleanliness of the houses and the tidiness of the streets, you will see in Batavia a state of things which it is hard to reconcile with the usual commonsense of the Dutch. Through the middle of the town runs a canalised river of red muddy water, partly sewer and partly bathing place and so on of the natives, and in it are washed all the clothes of the population, both native and European. Your clothes return to you white enough, but you put them on with certain qualms when you remember whence they came. The town has an excellent supply of pure water, and it is astonishing that the authorities do not put an end to this most insanitary practice.

Dutch people in the East Indies have modified their habits, especially in the matter of clothing, to suit the requirements of the climate, and while they have to some extent sacrificed elegance to comfort, their costume is at all events more rational than that of many Englishmen in the East, who cling too affectionately to the fashions of Europe and often wear too much clothing. The men, who do the greater part of the day’s work between seven in the morning and one o’clock, wear a plain white suit of cotton or linen. The afternoon is spent in taking a siesta and at about five o’clock they go to their clubs or other amusements in the same sort of attire as in the morning. The ladies, except in the larger towns where European dress is the custom, appear in public during the greater part of the day in a curiously simple costume. The upper part of the body is clothed in a short white cotton jacket, below which the coloured10 native sarong extends midway down the leg. Low slippers are worn on bare feet, the hair hangs undressed down the back and the costume is usually completed by an umbrella. It must be admitted that the effect is not ornamental, but the costume is doubtless cool and comfortable, and it prevents any risk there might be of injury to the health from wearing an excessive amount of clothing. They appear more conventionally dressed about five o’clock, when the social business of the day begins. The ladies pay calls while the men meet at the club and play cards until an uncomfortably late dinner at about nine o’clock.

About an hour’s journey by railway from Batavia is the hill station of Buitenzorg. Although it is hardly more than eight hundred feet above the sea the climate is noticeably cooler (the mean annual temperature is 75°), and one feels immediately more vigorous than down in the low country. The palace of the Governor General, formerly the house of Sir Stamford Raffles, stands at the edge of the Botanic Garden, which alone, even if you saw nothing else, would justify a visit to Java. Plants from all the Tropics grow there in the best possible conditions, and you see them to advantage as you never can in their natural forest surroundings, where the trunks of the trees are obscured by a tangle of undergrowth. Every part of the garden is worth exploring, but one of the most curious and interesting sections is the collection of Screw-pines (Pandanus) and Cycads, which have a weirdly antediluvian appearance. Another very beautiful sight is the ponds of Water-lilies from different parts of the world. The11 native gardener in charge of them informed me that the different species have different and definite hours for the opening and closing of their flowers. I tested his statement in two instances and found the flowers almost exactly punctual. There was no cloud in the sky nor appearance of any change in the weather, and the reason for this behaviour is not easy to explain. At Sindanglaya in the mountains a few miles distant is an offshoot from the Buitenzorg garden, where plants of a more temperate climate flourish, and experiments are made on plants of economic value to the country.

A few hours’ journey east from Buitenzorg is Garoet (2,300 feet above the sea), which lies in a beautiful fertile valley surrounded by forest-covered mountains. The climate is an almost ideal one, the nights are cool and the days are not too hot. A very remarkable feature of the country about Garoet is the great flocks, or rather droves, of ducks which you meet being driven along the roads from the villages to their pastures in the rice fields. These ducks differ from the ordinary domestic duck in their extraordinary erect attitude, from which they have been well called Penguin ducks. Whether their upright posture is due to their walking or not I do not know, but they are excellent walkers and are sometimes driven long distances to their feeding grounds. When a duck is tired and lags behind, the boy who herds them picks it up by the neck, and you may sometimes see him walking along with a bunch of two or three ducks in either hand.

Others of our party visited Djokjakarta and the Buddhist Temples of Boro-Boder in Central Java and the12 mountain resort of Tosari in the volcanic region of Eastern Java. Tosari is more than five thousand feet above the sea, and is of great value to the Dutch as a sanatorium for soldiers and civilians from all parts of the Archipelago. The rainfall is comparatively scanty and the climate is like that of Southern Europe at its best.

A CONVICT COOLY OF THE DUTCH ESCORT.

A MALAY COOLY FROM BUTON.

Expedition leaves Java—The “Nias”—Escort—Macassar—Raja of Goa—Amboina—Corals and Fishes—Ambonese Christians—Dutch Clubs—Dobo.

On December 21st we left Batavia, and on Christmas Day, 1909, we sailed from Soerabaja in the Government steamer Nias, Capt. Hondius van Herwerden. The Nias, a ship of about six hundred tons, formerly a gun-boat in the Netherlands Indies Marine, is now stripped of her two small guns and is used by the Government as a special service vessel. Her last commission before embarking us has been to transport Mr. Lorentz on his expedition to the Noord River in New Guinea three months earlier. Now she was full to the brim of stores and gear of all sorts and her decks were crowded with men. There were five of us and ten Gurkhas. The Dutch escort consisted of Lieutenant H. A. Cramer in command, two Dutch sergeants and one Dutch medical orderly, forty native Javanese soldiers and sixty convicts, most of them Javanese. The convicts were nearly all of them men with more or less long sentences of imprisonment and some of them were murderers in chains, which were knocked off them to their great relief the day after we left Soerabaja. One of the best of the convicts, a native of Bali, was a murderer (see illustration, page 12), who did14 admirable service to the expedition, and was subsequently promoted to be mandoer.1

At Macassar we stopped a few hours only to add to our already excessive deck cargo, and to hear a little of the gossip of Celebes. I was interested to learn that the power of the Raja of Goa, whom I had visited a few years before, had come to an end. That monarch was an interesting survivor of the old native princes of the island. His kingdom extended to within three miles of Macassar, and he was apparently not answerable to any law or authority but his own. The place became a refuge for criminals fleeing from justice, and it was a disagreeable thorn in the side of the Dutch authorities, who were at last compelled to send a small expedition to annex the country. The Raja himself, it was said, came to a very unpleasant end in a ditch.

There had also been a small war on the east side of the island, which resulted in the pacification of the large and prosperous district of Boni. Now the Island of Celebes, which only a few years ago was dominated by savage tribes and where it was unsafe for an European to travel, has been almost completely brought within the Dutch administration, and it seems likely that its enormous mineral and agricultural wealth will soon make it one of the most prosperous islands of the Archipelago.

On December 30th we anchored in the harbour of Amboina, where we were joined by the last member of the expedition, Mr. W. Stalker, who had been for some months collecting birds in Ceram, and recently 15had been engaged in Amboina in recruiting coolies for the expedition. It had been expected that he would go to engage coolies in the Ké Islands, a group of islands about three hundred miles to the south-east of Amboina, where the natives are more sturdy and less sophisticated than the people of Amboina; but circumstances had prevented him from going there, and we had to put up with the very inferior Ambonese, a fact which at the outset seriously handicapped the expedition. We stayed for two days at Amboina, or, as the Dutch always call it, Ambon, buying necessary stores and making arrangements with the Dutch authorities, who agreed to send a steamer every two months, if the weather were favourable, to bring men and further supplies to us in New Guinea.

Amboina is an exceedingly pretty place, and a very favourite station of the Dutch on account of its climate, which is remarkably equable, and its freedom from strong winds or excessive rain. There is a volcano at the north end of the island which has slumbered since 1824, and the place is very subject to earthquakes. A very serious one occurred as recently as 1902, which destroyed hundreds of lives and houses, whose walls may still be seen lying flat in the gardens, but as in other volcanic places the inhabitants have conveniently short memories, and the place has been re-built ready for another visitation.

Like most of the other Dutch settlements in the East, Amboina has been laid out on a rectangular plan, but the uniformity of the arrangement is saved from being monotonous by the tree-planting habits of the16 Dutch. The roads and open spaces are shaded by Kanari trees, which also produce a most delicious nut, and the gardens are hedged with flowering Hibiscus and Oleander and gaudy-leafed Crotons. Roses, as well as many other temperate plants, in addition to “hothouse” plants, flourish in the gardens, and the verandahs of the houses themselves are often decorated with orchids from Ceram and the Tenimber Islands. Birds are not common in the town itself except in captivity, and you see, especially in the gardens of the natives’ houses, parrots and lories, and pigeons from the Moluccas and New Guinea, and you may even hear the call of the Greater bird of paradise. Attracted by the many flowering plants are swarms of butterflies, some of them of great beauty. One of the most gorgeous of these is the large blue Papilio ulysses, which floats from flower to flower like a piece of living blue sky.

The harbour of Amboina is a wide deep channel, which nearly divides the island into two, and in it are the wonderful sea-gardens, which aroused the enthusiasm of Mr. Wallace.2 They are not perhaps so wonderful as the sea-gardens at Banda and elsewhere, but to those who have never seen such things before the many coloured sea-weeds and corals and shells and shoals of fantastic fishes seen through crystal water are a source of unfailing interest. The sea is crowded with fish of every size and form and colour. Nearly eight hundred species have been described from Ambonese waters, and it is worth while to visit the market in the early morning, when the night’s haul is brought in, and before 17the very evanescent colours of the fish have faded. Nearly every man in the place is a fisherman during some part of the day or night, and nobody need starve who has the energy to throw a baited hook into the sea. Most of the fish are caught either in nets very similar to our seine-net or in more elaborate traps which are mostly constructed by Chinamen.

The market is also worth visiting to see the variety of fruit and spices that grow in the island. Amboina has a peculiar form of banana, the Pisang Ambon, with white flesh, dark green skin, and a very peculiar flavour. Besides this there are many other kinds of bananas, mangoes, mangostines, guavas, sour-manilla, soursop, pineapples, kanari nut, nutmeg, cloves, and a small but very delicious fruit, the garnderia.

The native inhabitants of Amboina are a curious mixture of the aboriginal native with Portuguese, Dutch, and Malay blood. There is a strong predominance of the Portuguese type, which shows itself in the faces of many of the people, who still use words of Portuguese origin, and preserve many Portuguese names. A large number of them are Christians, and they rejoice in such names as Josef, Esau, Jacob, Petrus and Domingos.

New Year’s Eve was celebrated by a confusion of fireworks and gun-firing, which lasted from sunset until the small hours of 1910, and by an afternoon service in the Church attended by many hundreds of people. The women, who are usually in Amboina dressed entirely in black, wore for the occasion long white coats, black sarongs and white stockings. The men went more variously clad in straw hats, dinner18 jackets, low waistcoats, white or coloured starched shirts, coloured ties, black trousers, and brown boots. We were interested to find that the great bulk of the stuff from which clothes are made in Amboina is imported from England, and we were assured by a merchant who was interested in the trade that a man can dress himself in so-called European fashion as cheaply in Amboina as he can in this country.

An agreeable feature of life at Amboina, as at other places in the Netherlands Indies, is the hospitality of the Dutch people. A stranger of at all respectable social position is expected to introduce himself to the club, and the residents in the place feel genuinely hurt if he fails to do so. The Societat, or “Soce,” as it is everywhere called, is more of a café than a club according to English ideas, and it exists for conviviality and gossiping rather than for newspaper reading and card playing. It is not even a restaurant in the sense that many English clubs are; the members meet there in the evening but they invariably dine, as they lunch, at home. On the verandah in front of the club is a round table, at which sit after dark large men in white clothes smoking cigars and drinking various drinks. The foreigner approaches with what courage he may and introduces himself by name to the party severally. They make a place for him in the circle and thereafter, with a courtesy which a group of Englishmen would find difficulty in imitating, they continue the conversation in the language of the foreigner. An Englishman is at first a little staggered by the number of pait (i.e. bitter, the name for gin and bitters) and19 other drinks that his hosts consume, and which he is expected to consume also, but, as I remember noticing in the case of their neighbours the Belgians in the Congo, it appears to do them little if any harm.

In the larger places there is a concert at the club once or twice a week—at Bandoeng in Java I heard a remarkably good string quartette—and in almost every place there is a ladies’ night at the club once a week, when the children come to dance to the music of a piano or gramophone, as the case may be. It is a pretty sight and one to make one ponder on the possible harmony of nations—“Harmonie” is commonly a name for the clubs in the Netherlands Indies—to see small Dutch children dancing with little half-castes and, as I have more than once seen, with little Celestials and Japanese.

We left Amboina on New Year’s Day in a deluge of rain, and all that day we were in sight of the forest-covered heights of Ceram to the North. On January 2nd we passed Banda at dawn, and at sunset we got a view of the most South-west point of New Guinea, Cape Van de Bosch. On the morning of January 3rd we dropped anchor in the harbour of Dobo in the Aru Islands. For several miles before we arrived there we had noticed a marked difference in the appearance of the sea. Since we left Batavia we had been sailing over a deep sea of great oceanic depths, sometimes of two or three thousand fathoms, which was always clear and blue or black as deep seas are. Approaching the Aru Islands we came into the shoal waters of the Arafura Sea, which is yellowish and opaque and never exceeds one hundred fathoms in depth. We were, in fact, sailing20 over that scarcely submerged land, which joins the Aru Islands and New Guinea with the Continent of Australia.

Dobo has doubtless changed a good deal in appearance since Mr. Wallace visited it in 1857, the majority of the houses are now built of corrugated iron in place of the palm leaves of fifty years ago; but it cannot have increased greatly in size, for it is built on a small spit of coral sand beyond which are mangrove swamps where building is impossible. The reason of its existence has also changed since the time when it was the great market of all the neighbouring islands, for now it exists solely as the centre of a pearl-fishing industry controlled by an Australian Company, the Celebes Trading Company. Messrs. Clarke & Ross Smith, the heads of this business, rendered us assistance in very many ways, and the sincerest thanks of the expedition are due to them. The primary object of pearl-fishing is of course the collection of pearl-shell which is used for knife handles, buttons, and a hundred other things. Shell of a good quality is worth more than £200 a ton. The pearls, which are occasionally found, are merely accidentals and profitable extras of the trade. Some idea of the extent of this business may be learnt from the fact that more than one hundred boats employing about five thousand men are occupied in the various fleets.

We left Dobo, the last place of civilisation that many of us were to see for a year and more, on January 3rd; and here, as we are almost within sight as it were of our destination, it may be opportune to state briefly the geographical position of New Guinea, and to give a short account of its exploration.

DOBO. ARU ISLANDS.

New Guinea—Its Position and Extent—Territorial Divisions—Mountain Ranges—Numerous Rivers—The Papuans—The Discovery of New Guinea—Early Voyagers—Spanish and Dutch—Jan Carstensz—First Discovery of the Snow Mountains—William Dampier in the “Roebuck”—Captain Cook in the “Endeavour”—Naturalists and later Explorers.

The island of New Guinea or Papua lies to the East of all the great islands of the Malay Archipelago and forms a barrier between them and the Pacific Ocean. To the South of it lies the Continent of Australia separated from it by the Arafura Sea and Torres Strait, which at its narrowest point is less than a hundred miles wide. To the East is the great group of the Solomon Islands, while on the North there are no important masses of land between New Guinea and Japan. The island lies wholly to the South of the Equator, its most Northern point, the Cape of Good Hope in the Arfak Peninsula, being 19´ S. latitude.

The extreme length of the island from E. to W. is 1490 miles, and its greatest breadth from N. to S. is rather more than 400 miles. New Guinea is the largest of the islands of the globe, having an area of 308,000 square miles (Borneo has about 290,000 square miles), and it is divided amongst three countries roughly as follows: Holland 150,000, Great Britain 90,000, and Germany 70,000 square miles. The large territory of22 the Dutch was acquired by them with the kingdom of the Sultan of Ternate, who was accustomed to claim Western New Guinea as a part of his dominions: it is bounded on the East by the 141st parallel of East longitude and partly by the Fly River and thus it comprises nearly a half of the island.

The Eastern half of the island is divided into a Northern, German, and a Southern, British, part. The German territory is called Kaiser Wilhelm Land, and the islands adjacent to it, which have received German substitutes for their old names of New Britain, New Ireland, etc., are known as the Bismarck Archipelago. British New Guinea, which is now administered by the Federal Government of Australia, has been officially renamed the Territory of Papua, and with it are included the numerous islands at its Eastern extremity, the D’Entrecasteaux and Louisiade Archipelagoes.

Only in the British territory has a serious attempt been made at settling and administering the country; the headquarters of the Government are at Port Moresby, and the country is divided into six magisterial districts.

The German possessions are governed from Herbertshöhe in Neu Pommern (New Britain), which is the centre of a small amount of island trade, but the settlements on the New Guinea mainland are few and far between, and it cannot be pretended that the country is German except in name.

The Dutch territory has been even less brought under control than the German. For more than half a century there has been a mission station at Dorei in the N.W. but until 1899 when the Dutch assumed the direct23 control of the country, which was till that time nominally governed by the Sultan of Tidor (Ternate), there was no sign of Dutch rule in New Guinea. Now there are Government stations with small bodies of native soldiers at Manokware, an island in Dorei Bay, and at Fak-fak on the shore of MacCluer Gulf; more recently a third post has been established at Merauke on the South coast near the boundary of British New Guinea, with the object of subjugating the fierce Tugere tribe of that region.

The most important physical feature of New Guinea is the great system of mountain ranges, which run from West to East and form the back-bone of the island. The Arfak Peninsula in the N.W. is made entirely by mountains which reach an altitude of more than 9000 feet. In the great central mass of the island the mountains begin near the S.W. coast with the Charles Louis Mountains, which vary in height from 4000 to 9000 feet. Following these to the East they are found to be continuous with the Snowy Mountains (now called the Nassau Range, the objective of this expedition) which culminate in the glacier-covered tops of Mount Idenberg (15,379 feet), and Mount Carstensz (15,964 feet), and to the East of these is the snow-capped Mount Wilhelmina (15,420 feet), and Mount Juliana (about 14,764 feet).

Leaving Dutch New Guinea and proceeding further to the East we come to the Victor Emmanuel and the Sir Arthur Gordon Ranges, which lie near the boundary of German and British New Guinea. Still further East is the Bismarck Range, often snow covered, and extending24 through the long Eastern prolongation of the island are the great range of the Owen Stanley Mountains, which reach their highest point in Mount Victoria (13,150 feet), and the Stirling Range.

As might be expected in so mountainous a country there is a large number of rivers and some of them are of great size. On the North coast the Kaiserin Augusta River rises in Dutch territory and takes an almost Easterly course through German New Guinea to the sea, while the Amberno (or Mamberamo) rises probably from the slopes of the Snowy Mountains and flows Northwards to Point d’Urville. On the South coast, in British New Guinea besides the Purari, Kikor and Turama Rivers, the most important is the Fly River, which has been explored by boat for a distance of more than five hundred miles. In Southern Dutch New Guinea there are almost countless rivers: chief among them are the Digoel, which has been explored for more than four hundred miles; the Island River, by which a Dutch expedition has recently reached the central watershed of New Guinea; the Noord River by which Mr. H. Lorentz approached Mount Wilhelmina; the Utakwa and the Utanata.

The natives of New Guinea are Papuans and the island is indeed the centre of that race, which is found more or less mixed with other races from the island of Flores as far as Fiji. Though the Papuans in New Guinea itself have been in many places altered by immigrant races, for instance by Malays in the extreme West, and by Polynesian and Melanesian influences in the South and East, there yet remain large regions,25 particularly in the Western half of the country, including the district visited by this expedition, where the true Papuan stock holds its own.

The name Papua, it should be said, comes from the Malay wood papuwah, meaning “woolly” or “fuzzy,” and was first applied to the natives on account of their mops of hair; later the name was applied to the island itself.

Even among those Papuans who are pure-blooded—in so far as one may use that expression in describing any human race—there are very considerable varieties of appearance, but it is still possible to describe a type to which all of them conform in the more important particulars. The typical Papuan is rather tall and is usually well-built. The legs of the low country people are somewhat meagre, as is usually the case among people who spend much of their time in canoes, whilst those of the hill tribes are well developed. The hands and feet are large. The colour of the skin varies from a dark chocolate colour to a rusty black, but it seems to be never of the shining ebony blackness of the African negro. The lips are thick but not full, the teeth are strong but not noticeably good, and the jaws are strong but they can hardly be called prognathous. The forehead is receding, the brows are strong and prominent, and the shape of the face is somewhat oval. The hair is black and “frizzly” rather than “woolly,” it is crisp and hard to the touch, and in some tribes it is grown to a considerable length and dressed in a variety of ornamental fashions. Short hard hair is also found frequently on the chest and on the limbs,26 but on the face it is scanty and frequently altogether absent.

The most characteristic feature is the nose, which is long and fleshy and somewhat “Semitic” in outline, but flattened and depressed at the tip. But these characteristics of the nose would not alone suffice to distinguish the Papuans from others were it not for the fact that the alae nasi are attached at a remarkably high level on the face, and so an unusually large extent of the septum of the nose is exposed. It is owing to this curious formation of the nose that the Papuan is enabled to perform his almost universal practice of piercing the septum nasi and wearing there some ornament of bone or shell.

Apart from physical characteristics many observers have found mental qualities in which the Papuans differ from, and are superior to, neighbouring races; but these things are so difficult to define, and they vary so much according to local circumstances, that it is not wise to use them as conclusive evidence. It may, however, be said without fear of contradiction that no person, who has had experience of Malays and of Papuans, could believe for a moment that they are anything but two very distinct races of men. The origin of the Papuans is not definitely known, and the existence in different parts of the island of small people, who are possibly of Negrito stock, suggests that the Papuans were not the original inhabitants of New Guinea.

The history of the earliest discovery of New Guinea27 is not precisely known, but it is safe to disregard the legends of navigators having found the island before the Portuguese reached the Moluccas and founded a trading centre at Ternate in 1512. The earliest authentic record is of the Portuguese Don Jorge de Meneses, who was driven out of his way on a voyage from Goa to Ternate in 1526, and took refuge in the island of Waigiu. Two years later a Spaniard Alvaro de Saavedra taking spices from the Moluccas to Mexico appears to have reached the Schouten Islands in Geelvink Bay. From there he sailed North and discovered the Carolines and the Mariana Islands, but unfavourable winds drove him back to the Moluccas. In 1529 he set out again, and sailed along a long expanse of coast, which was doubtless the North coast of New Guinea.

In 1546 Ynigo Ortiz de Retes sailed from Ternate to Mexico in his ship San Juan. He touched at several places on the North coast where he hoisted the Spanish flag, and called the island Nueva Guinea, because the natives appeared to him to resemble the negroes of the Guinea coast of Africa. The name, spelt Nova Guinea, appears printed for the first time on Mercator’s map of 1569.

The last important Spanish Expedition was that of Luis Vaz de Torres, who sailed with two ships from Peru, and in 1606 reached the south-east corner of New Guinea. He sailed along the South coast from one to the other end of the island, of which he took possession in the name of the King of Spain. Torres’ voyage through the strait which now bears his name was the first to show that New Guinea was an island,28 but the account of the voyage was not published and the fact of his discovery remained unknown until after 1800.

The seventeenth century was chiefly notable for the explorations of the Dutch, whose East India Company proclaimed a monopoly of trade in the Spice Islands to the exclusion of people of other nationalities. In 1605, Willem Jansz sailed from Banda to New Guinea in the Duyfken. The Ké and Aru Islands were visited and the Cape York Peninsula of Australia was reached, but the importance of that discovery was not realised. On the mainland of New Guinea nine men of the ship’s company were killed and eaten, and the expedition returned to Banda.

Jacques Le Maire and Willem Schouten made an important voyage in 1616 in the Eendracht. Sailing from Europe by way of Cape Horn they crossed the Pacific and discovered New Ireland, where they had trouble with the natives, who (it is interesting to note) gave them pigs in exchange for glass beads. The Admiralty and Vulcan Islands were seen and then, after reaching the coast of New Guinea, they discovered the mouth of the Kaiserin Augusta River and the Schouten Islands.

The next important voyage, and in this chronicle the most important of all, was that of Jan Carstensz (or Carstenszoon) who sailed from Amboina in 1623 with the ships Pera and Arnhem. After visiting Ké and Aru they reached the S.W. coast of New Guinea, where they met with trouble. “This same day (February 11) the skipper of the yacht Arnhem, Dirck29 Meliszoon, without knowledge of myself or the sub-cargo or steersman of the said yacht, unadvisedly went ashore to the open beach in the pinnace, taking with him fifteen persons, both officers and common sailors, and no more than four muskets, for the purpose of fishing with a seine-net. There was great disorder in landing, the men running off in different directions, until at last a number of black savages came running forth from the wood, who first seized and tore to pieces an assistant named Jan Willemsz Van den Briel who happened to be unarmed, after which they slew with arrows, callaways, and with the oars which they had snatched from the pinnace, no less than nine of our men, who were unable to defend themselves, at the same time wounding the remaining seven (among them the skipper, who was the first to take to his heels); these last seven men at last returned on board in very sorry plight with the pinnace and one oar, the skipper loudly lamenting his great want of prudence, and entreating pardon for the fault he had committed.”

The incautious skipper died of his wounds on the following day and so he did not take a part in the most momentous discovery of the voyage. “In the morning of the 16th (February) we took the sun’s altitude at sunrise, which we found to be 5° 6´; the preceding evening ditto 20° 30´; the difference being divided by two comes to 7° 42´; increasing North-easterly variation; the wind N. by E.; we were at about one and a half mile’s distance from the low-lying land in 5 or 6 fathom, clayey bottom; at a distance30 of about 10 miles by estimation into the interior we saw a very high mountain range in many places white with snow, which we thought a very singular sight, being so near the line equinoctial. Towards the evening we held our course E. by S., along half-submerged land in 5, 4, 3, and 2 fathom, at which last point we dropped anchor; we lay there for about five hours, during which time we found the water to have risen 4 or 5 feet; in the first watch, the wind being N.E., we ran into deeper water and came to anchor in 10 fathom, where we remained for the night.”

That is the brief account of the first discovery of the Snow Mountains of New Guinea by Jan Carstensz, whose name is now perpetuated in the highest summit of the range. Very few ships have sailed along that coast in three hundred years, and there are very many days in the year when not a sign of the mountains can be seen from the shore, so it is not very astonishing to find ships’ captains sailing on those seas who still disbelieve the story of the snow. On the same voyage Carstensz crossed the straits and sailed a considerable way down the Cape York Peninsula believing that the land was still New Guinea.

In 1636 Thomas Pool explored a large tract of the S.W. coast; Pool himself was killed by natives, but the expedition discovered three large rivers, the Kupera Pukwa, Inabuka (? Neweripa), and the Utakwa. Tasman sailed along the North coast of New Guinea in 1642 after his discovery of Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania); and in 1644 he was sent to find out whether there was31 a passage between New Guinea and the large “South Land” (Australia). Apparently he cruised along the coast about as far as Merauke, and also touched Australia, but the strait was not discovered.

Throughout the seventeenth century the Dutch East India Company maintained their monopoly of the cloves and nutmegs of the Moluccas, and great consternation was caused when the English tried to obtain these spices direct by sending ships to the Papuan islands. The Moluccas were protected by forts and their harbours safe, therefore in order to prevent the English from obtaining the spices outside the sphere of direct Dutch influence, all trees producing spices were destroyed.

The most important of the English voyages was that of Capt. William Dampier in the Roebuck. He sailed by Brazil and the Cape of Good Hope to Western Australia and thence to Timor. On January 1, 1700, he sighted the mountains of New Guinea; he landed on several islands near the coast, captured Crowned pigeons and many kinds of fishes, which he described in his book. Rounding the N.W. corner of the island he sailed along the North coast and discovered that New Britain was separated from New Guinea by a strait to which he gave his own name.

After the voyages of Philip Carteret, who proved that New Ireland is an island, and of de Bougainville in 1766 the most important is that of Captain James Cook in the Endeavour. He sailed from Plymouth in August 1768, rounded Cape Horn, reached and charted New Zealand, reached the East coast of New Holland (Australia) in April 1770, and sailed along the coast to32 Cape York, which he named. Looking Westward he decided that there was a channel leading from the Pacific to the Indian Ocean, and after sailing through it he came to the coast of New Guinea to the N.W. of Prince Frederick Henry Island, where he was attacked by natives and thence he sailed to Batavia. Thus Captain Cook by sailing through his Endeavour Strait, now called Torres Strait after the original navigator, repeated the discovery of Torres after an interval of more than a century and a half, and the general position and outline of New Guinea became known to the world.

After the voyage of Cook many important additions were made to the charts of New Guinea and its neighbouring islands, notably by the voyages of La Perouse (1788), John MacCluer (1790-1793), D’Entrecasteaux (1792-1793), Duperrey (1823-1824), D. H. Kolff (1826), and Dumont d’Urville (1827-1828).

But during all this time New Guinea was practically no man’s land, and except at Dorei and about the MacCluer Gulf explorations were limited to views from the deck of a ship. Flags were hoisted now and then and the land taken possession of in the name of various sovereigns and companies, amongst others by the East India Company in 1793, but no effective occupation was ever made. The Dutch regained their title to the Western half of the island, but it was not until 1884 that a British Protectorate was proclaimed over the S.E. portion of the island, and over the remainder by Germany in the same year.

Although numerous naturalists, notably Dr. A. R.33 Wallace, Von Rosenberg, and Bernstein, and missionaries had spent considerable periods of time in the country, no very serious attempt was made to penetrate into the interior until 1876, when the Italian naturalist, d’Albertis, explored the Fly River for more than five hundred miles. Since that time a very large number of expeditions have been undertaken to various parts of the island, and it will only be possible to mention a few of them here. In 1885 Captain Everill ascended the Strickland tributary of the Fly River. In the same year Dr. H. O. Forbes explored the Owen Stanley range, and in 1889 Sir William Macgregor reached the highest point of that range.

In Dutch New Guinea very little exploration was done until the beginning of the present century. Professor Wichmann made scientific investigations in the neighbourhood of Humboldt Bay in 1903. Captains Posthumus Meyes and De Rochemont in 1904 discovered East Bay and the Noord River, which was explored by Mr. H. A. Lorentz in 1907.

During the period from 1909 to 1911, whilst our party was in New Guinea, there were six other expeditions in different parts of the Dutch territory. On the N. coast a Dutch-German boundary commission was penetrating inland from Humboldt Bay, and a large party under Capt. Fransse Herderschee was exploring the Amberno River. On the West and South coasts an expedition was exploring inland from Fak-fak, another was surveying the Digoel and Island rivers, and a third made an attempt to reach the Snow Mountains by way of the Utakwa River. But the most successful of34 all the expeditions was that of Mr. Lorentz, who sailed up the Noord River and in November 1909 reached the snow on Mount Wilhelmina, two hundred and eighty-six years after the mountains were first seen by Jan Carstensz.

Sail from the Aru Islands—Sight New Guinea—Distant Mountains—Signal Fires—Natives in Canoes—A British Flag—Natives on Board—Their Behaviour—Arrival at Mimika River—Reception at Wakatimi—Dancing and Weeping—Landing Stores—View of the Country—Snow Mountains—Shark-Fishing—Making the Camp—Death of W. Stalker.

When we left the northernmost end of the Aru Islands behind us the wind rose and torrents of rain descended, and the Arafura Sea, which is almost everywhere more or less shoal water, treated us to the first foul weather we had experienced since leaving England. At dawn on the 4th January we found ourselves in sight of land, and about five miles south of the New Guinea coast. A big bluff mountain (Mount Lakahia) a southern spur of the Charles Louis range determined our position, and the head of the Nias was immediately turned to the East. As we steamed along the coast the light grew stronger, and we saw in the far North-east pale clouds, which presently resolved themselves into ghostly-looking mountains one hundred miles away. Soon the rising sunlight touched them and we could clearly see white patches above the darker masses of rock and then we knew that these were the Snow Mountains of New Guinea, which we had come so far to see. Beyond an impression of their remoteness and their extraordinary steepness we did not learn much of the formation of the mountains from that great distance and they were36 quickly hidden from our view, as we afterwards found happened daily, by the dense white mists that rose from the intervening land.

Following the coast rather more closely we soon found that our approach was causing some excitement on shore. White columns of the smoke of signal fires curled up from the low points of the land and canoes manned by black figures paddled furiously in our wake, while others, warned doubtless by the signals, put off from the land ahead of us and endeavoured to intercept us in our course.

In some of the larger canoes there were as many as twenty men, and very fine indeed they looked standing up in the long narrow craft which they urged swiftly forward with powerful rhythmic strokes of their long-shafted paddles. At the beginning of each stroke the blade of the paddle is at right angles to the boat. As it is pulled backward the propelling surface of the paddle is a little rotated outward, a useful precaution, for the stroke ends with a sudden jerk as the paddle is lifted from the water and the consequent shower of spray is directed away from the canoe.

1. 2. 3. Carved Wooden Clubs. 4-10. Stone Clubs.

The shore was low and featureless, and it was impossible to identify the mouths of the rivers from the very inaccurate chart. It was not safe for the Nias to approach the land closely on account of the shoal water, so Capt. Van Herwerden dropped anchor when he had been steaming Eastwards for about eight hours, and sent the steam launch towards an inlet, where we could see huts, to gather information. A bar of sand prevented the launch from entering the 37 inlet, so they hailed a canoe which ventured within speaking distance, and by repeating several times “Mimika,” the only word of their language that we knew at that time, learnt that we had overshot our destination by a few miles. That canoe, it should be noted, was remarkable on account of two of its crew. One of them held aloft an ancient Union Jack; the other was conspicuously different from the scores of men in the canoes about us, who were all frankly in a bare undress, by wearing an old white cotton jacket fastened by a brass button which was ornamented with the head of Queen Victoria. How the flag and the coat and the button came to that outlandish place will never be known, but it is certain that they must have passed through very many hands before they came there, for certainly no Englishman had ever been there before.

When the launch returned to the ship a crowd of natives, fifty or sixty at the least, came clambering on board leaving only one or two men in each canoe to paddle after the steamer as we slowly returned towards the Mimika. Two men were recognised by Capt. Van Herwerden as having belonged to a party of natives from this coast, who had been taken some years earlier to Merauke, the Dutch settlement near the southernmost point of New Guinea. At Merauke they had got into mischief and had been put in prison from which nine of them escaped, and these two men, probably the only survivors of the party, had contrived to find their way along four hundred miles of coast, peopled by hostile tribes, back to their own country.

The behaviour of our new fellow passengers was very38 remarkable and different from what one expected, though it was obvious enough at the first glance that these were people totally different from the Malayan races both in appearance and demeanour; yet there was none of that exuberance of spirits, child-like curiosity and exhibition of merriment and delight in their novel surroundings described by Wallace3 and Guillemard4 and which I had myself seen on the coast of German New Guinea. A few of them shook hands, or rather held hands, with us and talked loudly and volubly, while the rest stared dumbly at us and then wandered aimlessly about the ship seeking a chance to steal any loose piece of metal. They showed no fear nor did they betray any excitement nor any very keen curiosity about the marvellous things that they were seeing for the first time. They were quite unmoved by the spectacle of the windlass lifting up the anchor, and a casual glance down the skylight of the engine room was enough for most of them. They appeared to take everything for granted without question, and a stolid stare was their only recognition of the wonderful works of the white man’s civilisation. In one respect it is true they were not quite so apathetic and that was in their appetite for tobacco, which they begged from everyone on board, brown and white alike. When they had obtained a supply, they sat in groups about the deck and smoked as unconcernedly as though a passage in a steamship were an affair of every-day occurrence in their lives.

By the time that we eventually anchored off the mouth of the Mimika River it was beginning to grow dark, and Capt. Van Herwerden ordered the natives on board to leave the ship, not having noticed that the canoes had already departed towards the shore. No doubt this was a preconcerted scheme of the natives who wanted to stay on board, but by dint of much shouting two canoes were persuaded to return and take away some of our passengers. It was then quite dark and there was a white mist over the sea, and the spectacle of the procession of black figures passing down the gangway into an apparent abyss, for the canoes were invisible in the gloom, was singularly weird. There was not room for all in the canoes, so about a score of fortunate ones had to stop on board, where they slept in picturesque attitudes about the deck. Five young men chose a place where the iron cover of the steering chain made a pillow a few inches high; they lay on their sides all facing the same way, their arms folded across their chests and their bent knees fitting into the bend of the knees of the man in front, and so close together that the five of them occupied a space hardly more than five feet square.