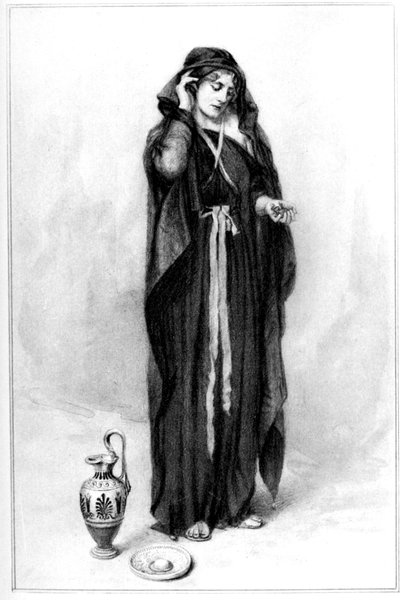

PHÆDRA

Gertrude Demain Hammond, R.I.

Title: Women of the Classics

Author: Mary Sturgeon

Release date: November 9, 2016 [eBook #53487]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Tonsing and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

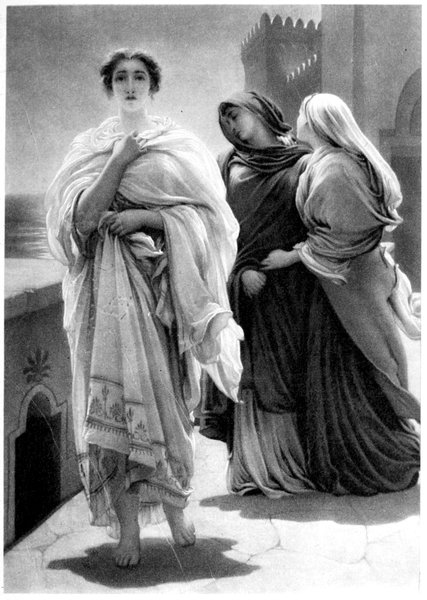

PHÆDRA

Gertrude Demain Hammond, R.I.

| PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

| INTRODUCTION | 9 | |

| WOMEN OF HOMER | ||

| HELEN | 15 | |

| ANDROMACHE | 29 | |

| PENELOPE | 39 | |

| CIRCE | 60 | |

| CALYPSO | 73 | |

| NAUSICAA | 85 | |

| WOMEN OF ATTIC TRAGEDY | ||

| I. | ÆSCHYLUS | |

| CLYTEMNESTRA | 99 | |

| ELECTRA | 117 | |

| CASSANDRA | 135 | |

| IO | 148 | |

| II. | SOPHOCLES | |

| JOCASTA | 163 | |

| ANTIGONE | 185 | |

| III. | EURIPIDES | |

| ALCESTIS | 209 | |

| MEDEA | 227 | |

| PHÆDRA | 243 | |

| IPHIGENIA | 256 | |

| A WOMAN OF VIRGIL | ||

| DIDO | 273 | |

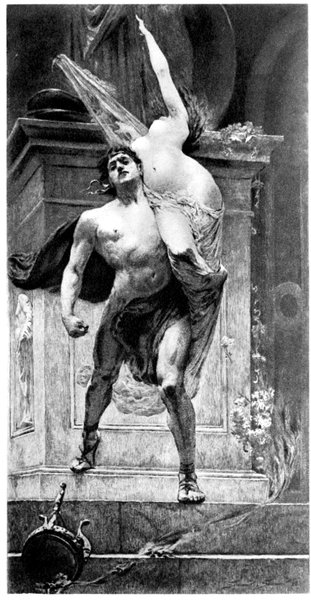

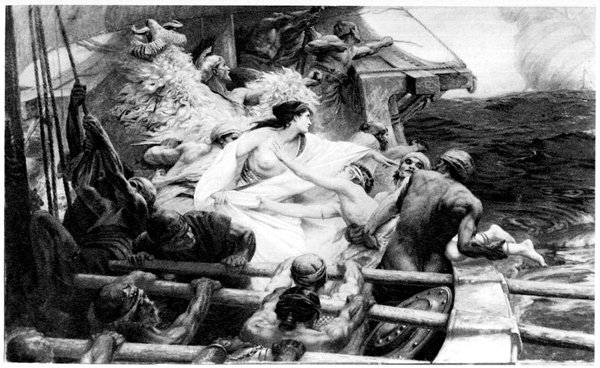

| PHÆDRA | Gertrude Demain Hammond, R.I. | Frontispiece |

| Facing page | ||

|---|---|---|

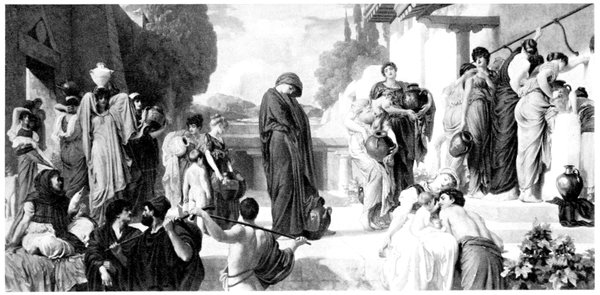

| HELEN | Lord Leighton | 20 |

| ANDROMACHE | Lord Leighton | 34 |

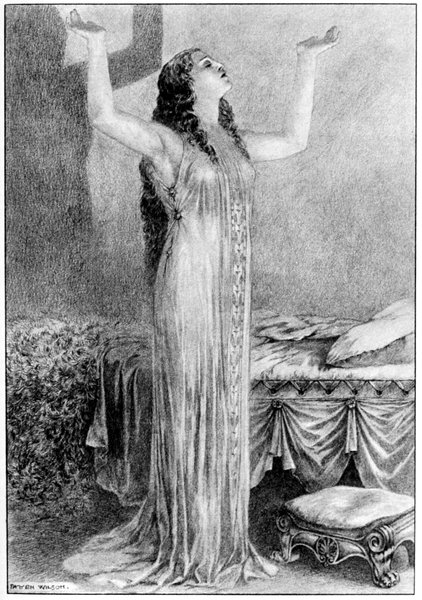

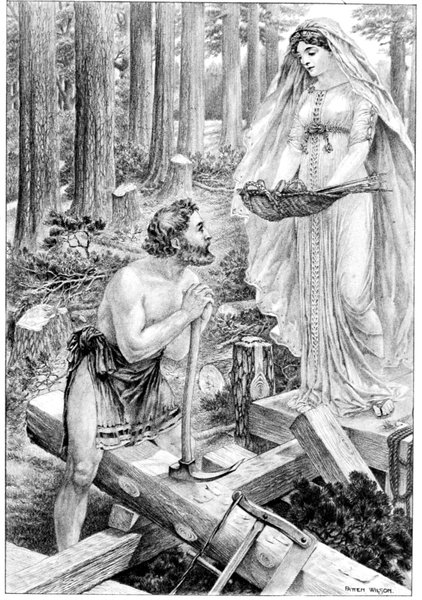

| PENELOPE | Patten Wilson | 50 |

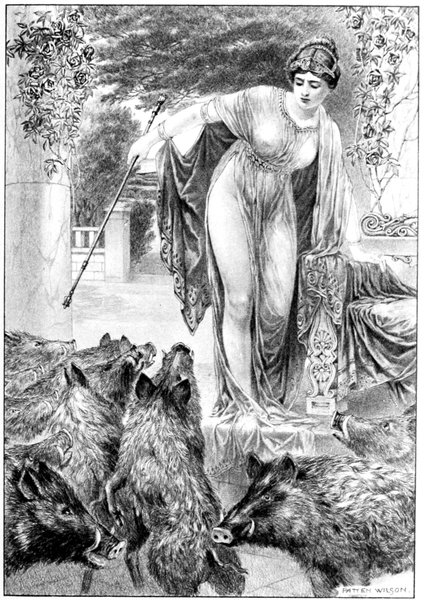

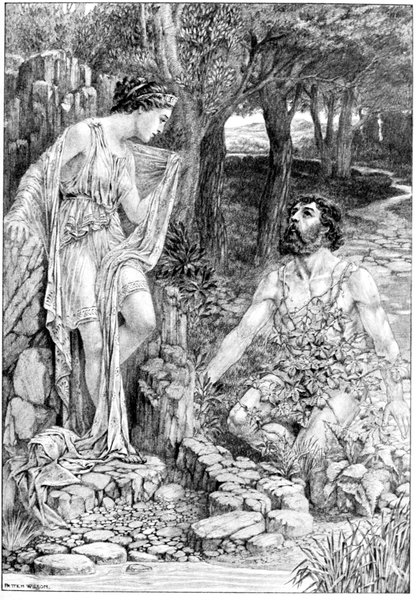

| CIRCE | Patten Wilson | 66 |

| CALYPSO | Patten Wilson | 82 |

| NAUSICAA | Patten Wilson | 94 |

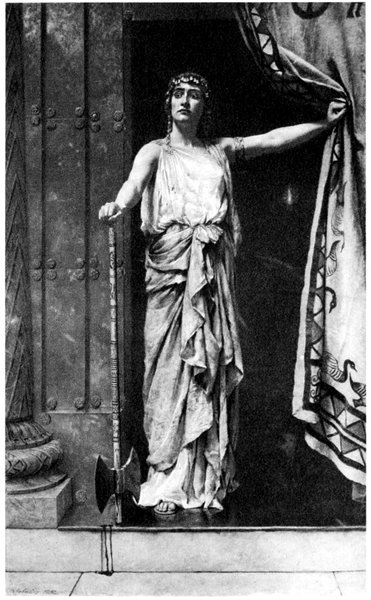

| CLYTÆMNESTRA | Hon. John Collier | 114 |

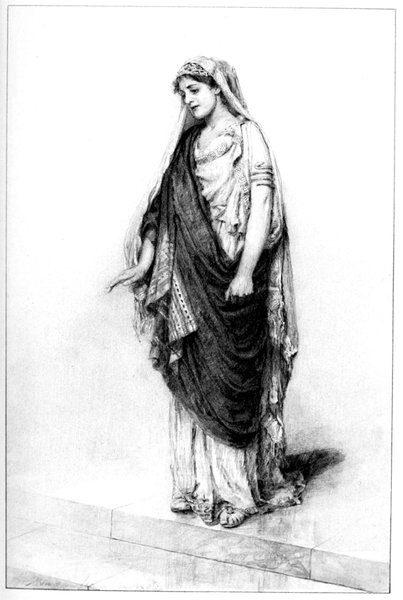

| ELECTRA | Gertrude Demain Hammond, R.I. | 128 |

| CASSANDRA | Solomon J. Solomon, R.A. | 140 |

| JOCASTA | Gertrude Demain Hammond, R.I. | 172 |

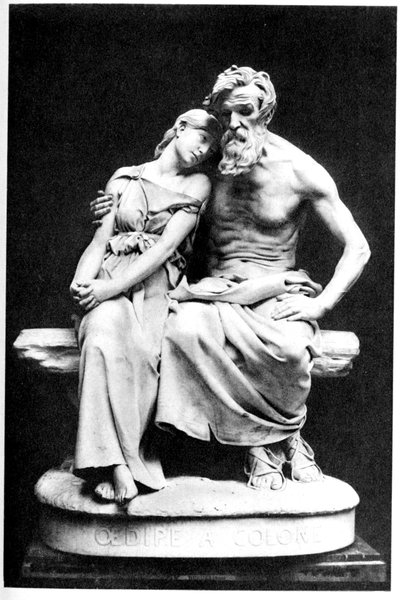

| ANTIGONE | From the Statue by Hugues | 192 |

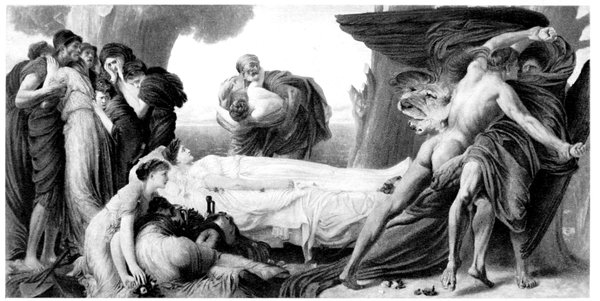

| ALCESTIS | Lord Leighton | 224 |

| MEDEA | Herbert Draper | 238 |

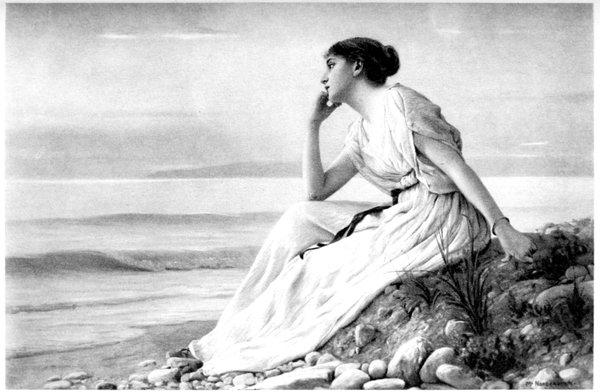

| IPHIGENIA | M. Nonnenbruch | 260 |

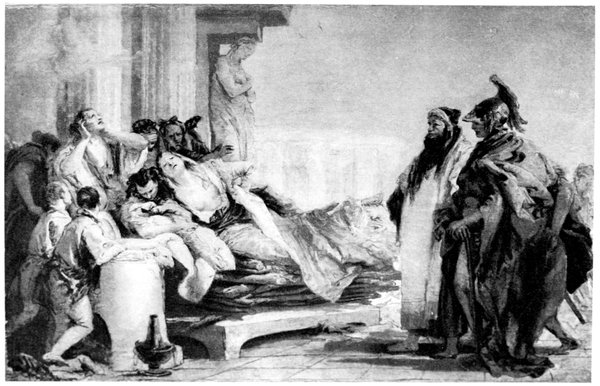

| DIDO | Gianbattista Tiepolo | 284 |

The women in this book are the heroines of Homer, of Attic Tragedy, and of the Æneid of Virgil. Their stories are taken out of the best modern translations of the old poems; and they are retold from the human standpoint, with the minimum of critical comment.

It is curious, when we reflect a moment, how little we really know about the women of the classics. Their names have been familiar to us as long as we can remember. We have always been vaguely conscious of a glory clothing them—sometimes sombre and troubled, often gracious and serene, occasionally enchanting. About the greatest of them some floating hints of identity ripple on the surface of the mind. But we can by no means fit these little fragments into any clear outline of the sublime beauty of their originals. And when we light upon a reference to them in our reading, or stand before one of the innumerable works of art which they have inspired, memory is baffled. We have no clue to the spell that they have cast upon the centuries: the spell itself has no power over us; and we grope in vain for the key which would admit us to a world of delight.

There were reasons for this state of affairs when translations were few and costly: when scholars were merely pedants and when the classics were sealed to women. But nous avons changé tout cela. Fine translations can be bought for a few shillings. Women are themselves engaging in the study of the old languages and of the sciences which are 10akin to them. Scholarship is growing more human; and the awakened spirit of womanhood, having become conscious of itself, cannot fail to be profoundly interested in that earlier awakening which, twenty-five centuries ago, evoked creatures so splendid. Of the women of Attic Tragedy Professor Gilbert Murray has said, in his Rise of the Greek Epic: “Consider for a moment the whole magnificent file of heroines in Greek Tragedy, both for good and evil.... I doubt if there has ever in the history of the world been a period, not even excepting the Elizabethan Age and the Nineteenth Century, when such a gallery of heroic women has been represented in Drama.”

By bringing these women together into a single volume, it is hoped to make their stories easily accessible; and by quoting some of the most beautiful passages from the poems in which they live, it is hoped to send the reader back to the poets themselves. It has not been possible to include all the heroines in the available space; and several of those who are missing have only been omitted under the direst necessity. But all the greatest are here; and an effort has been made to choose each group so that it shall represent as far as may be the characteristics of its own poet. The source of the story is indicated in each case, and has been closely followed.

A word may be necessary on one or two points, to those who are coming to these stories from the classics with an unfamiliar eye. It will be found that there is a singular reticence here on that aspect of love which engrosses modern literature. It is occasionally treated by Euripides; but even he handles the theme delicately and with reserve. Nowhere in these stories—with the exception of Dido, 11who of course belongs to a later civilization than the Greek women—is the love which leads to marriage dealt with explicitly. It is implicit sometimes, and we who have been born into a heritage of romanticism, may delightedly trace it out and make the most of it. But the old poet never does: indeed, he hardly seems to realize that he has put it there. He belongs to a time when women were not wooed and won, but literally bought ‘with great store of presents,’ or acquired in other prosaic ways, which vary according to the several epochs and their customs. The love of men and women is treated from the point of view of husband and wife, of sister and brother, of daughter and father, rather than from the standpoint of the feverish hopes and fears of romantic passion. Marriage is not so much the culmination as the starting-point of an eventful story; and the heroic devotion of sister and daughter is crowned, no less than wifely fidelity, with everlasting honour. We must therefore be prepared for a change from the warmth and glow of romance to the tonic air of a more austere idealism.

Again, these women are not the complex creatures of modern civilization. The earliest of them, Homer’s women, are drawn in outline only. They are great and splendid; and because they were created for an aristocratic audience, they are noble, dignified, and placed high above the small things of common life. There is hardly any comedy in Homer, and reality is far away. When we come to the dramatists we find, as we should expect, a great advance in characterization. The women are stronger, more real, more complete. But they are still very far from the psychological subtlety of modern drama.

There is, too, a singular reticence about the personal 12appearance of the heroines. We are rarely told what manner of women they were to look at. Virgil comes one step nearer to our modern love of description when he portrays Dido as she rides out on the fatal morning of the hunt; and when he paints the glowing figure of Camilla as she rushes into battle. But it would be very hard to discover what was the colour of Helen’s eyes, although the old German Faustbuch of the Middle Age has dared to assert that they were ‘black as coals.’ Homer has a more excellent way. Instead of enumerating the charms of his heroine, as it were in a catalogue of perfections, he brings her into the presence of hostile folk, who on all counts have reason to hate her, and in a few vivid phrases shows the potent effect of her beauty upon them.

We shall find that the heroines have a system of ethics which is different from that of our own day; and strange moral contradictions may present themselves to our astonished eyes. Electra, with the tenderest love for her dead father, will not rest until the death of her guilty mother has been compassed. Antigone, infinitely gentle to the blind Œdipus, is capable of resolute opposition to the law as it is embodied in Creon. But though the lines of moral demarcation are differently placed, they are not blurred. Revenge is a duty in this primitive saga upon which the poets drew for their material; and in which there is much that is savage and terrible.

Greek drama was a religious ritual closely bound to ancient myth and heroic legend, from which the poets could not escape. Hence, if these stories are approached in an analytical mood, they will be found barbarous and wildly improbable. If we give the rein to humour, we shall be overcome by frequent absurdities. The best way is to 13come to them quite simply, leaving the comic and the critical spirits a little way behind.

Grateful thanks are due to the translators and publishers who have kindly given permission to quote the passages used herein; and the author wishes humbly to acknowledge the debt she owes to critical work in this field. She is especially conscious of help from Professor Gilbert Murray in interpreting some of the Women of Tragedy. A note of the sources of the quotations will be found at the end of each chapter.

In the twilight of early Greek history, one event and one name blaze like beacons. They are the siege of Troy and the name of Helen. They have not come down to us as cold fact, but burning through a mist of legend and poetry. The historian cannot name the date of the Trojan war; and the archæologist, whose labours have been so fruitful at Mycenæ and in Crete, can only point doubtfully to the ancient site of Troy.

Yet that event, and its cause, fair Helen of Sparta, may be said to mark the beginning of national life for the Greeks. Perhaps it was more than two thousand years before Christ when all the little peoples of Greece first joined themselves against barbarian Asia. Troy fell; and although the victory brought little material reward to the Greeks; though they sailed back to their island homes poorer and sadder than when they left, they had in fact achieved momentous gains. For the struggle had first taught them the strength of unity: it had launched them on their long and triumphant feud against barbarism; and it had laid the base from which they might go on to build, through the long, slow centuries, the civilization that we inherit.

There was no historian to record the event. But it lived on, in memory and in legend; and as the people became more settled, wandering bards made songs about it. The rich Mycenæn Age flourished and died; and the Homeric civilization took its place. Probably it was then that the floating fragments of the Tale of Troy first were woven together, providing material for the Homeric epics that we know 16as the Iliad and the Odyssey. Probably they were not written down at first. They were composed, and recited, in separate parts, in the halls of the great lords, who loved to look back on this glorious event of their national life, and to hear the names of their remote and half-mythical ancestors brought into the story. Thus Homer, no matter who he or his school may have been, comes to represent a high stage of civilization. His poems have a lofty tone, a chivalrous spirit, a sweet cleanliness of thought and of word, which do not belong to a primitive, uncivilized people. They do not, as a fact, belong naturally to the early period of which he sings. In the time of that grim struggle before the dawn of history, there must have been much that was ugly, dark and barbarous. This is proved to us by the survival of some of the older legends upon which Homer worked. They tell of unnatural crime and of deeds of horror such as he never mentions; and they give us, too, a very different interpretation of the story of Helen. Homer puts aside all these vestiges of a primitive past. He is composing lays for a people who have a keen sense of honour, a supreme ideal of beauty and a love of home; who have a religious feeling strong enough to reverence the gods, despite their many hieratic quarrels, and who hold womanhood in high esteem. So when we come to him to hear about Helen, we find a very sweet and gracious figure, quite unlike the Helen of the later poets. With them she was degraded from her rank of demi-god. She was regarded as a real figure, brought down to the level of ordinary existence, and judged by the common standard. The romantic charm of the Homeric conception faded; and her name had for centuries an evil sound. It has passed through many vicissitudes since. In late Greek literature, 17one or two poets tried to return to the reverent attitude of Homer: but in the Middle Ages she became again a byword and a reproach. At the Renaissance, something of her early worship as an ideal of beauty was revived, and our own Marlowe has passionately expressed the thought of that age about her:

It is this vision of Helen, as the supreme ideal of beauty, that modern poets and scholars have tried to recapture. They have put aside the varied allegorical and ethical and realistic conceptions of her, as the efforts of a more sophisticated age; and they have tried to return directly to the fine simplicity of Homer himself. Only thus, they believe, can we stand at the right point of view with regard to Helen; and only thus can we see her as she was to the Greeks, a symbol of beauty incorruptible. We, who have to make our own choice in the matter, cannot do better than try to stand at the point where the moderns have placed us.

We come then at once to the Iliad, where, in the Third Book, Helen makes her first appearance in the world’s literature. War has been raging round the walls of Troy for nearly ten years. Now a truce is called; and in the palace of the old king Priam, word goes round that Paris, the author of the long feud, is to fight in single combat with Menelaus, whom he has wronged. For Paris had brought the bane of war upon Ilios. At his birth, the oracles of the gods had demanded that he should die; and 18Priam, his father, sorrowfully handed over the wailing baby to the priest, to be exposed upon Mount Ida. But first he tied an old ring about his neck; and when Paris was strangely saved from death, and grew up to be the fairest and strongest of all the shepherd youths on Ida, he came one day by accident to Ilios. There, by means of the jewel hanging from his neck, he was made known as the son of the king. Thenceforward the poor shepherd was the best beloved of all the princes. Life went gaily; and for a while he was utterly content. But he had left behind, amidst the groves of Mount Ida, a sweet wood-nymph who loved him well, Enone. And when after a time he began to tire of life in the palace, he remembered her and thought longingly of the freshness and beauty of the mountain. So one day in summer he went to seek Enone. All day long he searched the forest, but could not find her; and coming tired at evening to a fragrant glade, he fell asleep. When he awoke, night was hushed all around, and stars peeped through the slender branches overhead. It was midnight and there was no moon; but it was not dark. The glade was filled with a soft radiance such as he had never seen before, and when he raised his wondering eyes, he saw the majestical figures of goddesses shining upon him: Hera, queen of Olympus, Athena, the wise maid of Zeus, and Aphrodite, the laughing goddess of love. Sweetly they smiled on him; and as he stood in wondering awe, the deep, rich tones of Hera sank upon his spirit, promising him greatness and power, and the lordship over many lands. Then Athena, resting her starlike gaze upon him, promised him wisdom and courage; and Aphrodite, with a little mocking laugh at power and at wisdom, promised him the fairest woman in the world. Only, and this was to be the 19price of the gift, he was to be the arbiter between them: he was to declare which was most beautiful.

There was only one answer possible to Paris. Ambition had no lure for him. Why fight and strive and spend the happy days in effort merely to be called great? And wisdom had no appeal for him either; she seemed austere and cold. What had she to do with the joy and grace and sweetness that his soul loved? To the sublimity of Hera he bent in awe. The shining purity of Athena smote his glance to the earth. But the voice of Aphrodite wooed him, and her winsome smile set him trembling with delight. He reached out to her the golden prize of beauty.

So Paris was to gain the fairest woman in the world. It seemed an honest promise, full of the happiest portent; and the young prince soon set out upon his search for a bride over the western seas. But Aphrodite was no better than a cheat, and had invoked on Paris, though he did not know it then, the curse of guilty love. For the exquisite child who was to be the world’s queen of beauty had grown up in the home of Tyndareus, king of Sparta; and even while the goddess gave her word to Paris, was happily married to Menelaus there. To her and to her husband Paris came in his wanderings, led unwittingly by the laughter-loving goddess, and clothed by her in beauty like a god. They feasted him and did him honour; and sitting at the banquet which they made to him, he told the strange tale of his life and his quest.

Helen listened to his story with a sudden prescience of what was to come; and rising softly, left the banqueting hall and went away to implore the goddess to avert the doom. But she was no match for Aphrodite. Anger and 20entreaty could not move the wanton Olympian, but she would grant one boon—Helen should be oblivious of all her past. Under the spell, the love of husband and child faded out; and even the memory of them vanished when on that spring morning in the garden of the palace, Paris met her beside the stream, ‘’twixt the lily and the rose.’

Together they fled in the dewy morning, Paris urging his horses with guilty haste to the ships. And there, with Menelaus thundering along the road after them, they set sail for Troy, fulfilling the old prophecy, and lighting a brand by their deed which should burn the sacred city to the ground. For Tyndareus, when he chose a husband for Helen amongst her many suitors, had won a promise that they would all defend the one who gained her. Agamemnon, brother to Menelaus, and the great overlord of the Hellenic princes, now summoned the allies to avenge his brother, and for ten years they toiled at fitting out a fleet. Then they ‘launched a thousand ships,’ and sailed to punish Ilios for the sin of Paris.

HELEN OF TROY

Lord Leighton

By permission of Henry Graves & Co Ltd

21Meantime, Helen had wakened sadly from the spell of Aphrodite. Little by little memory of her home came back, and with it came remorse. She was lonely too, and disillusion crept upon her. The Trojans, who at first had welcomed her as a goddess, soon began to look askance at her when rumours came of the great siege that was preparing. Mothers and wives of the Trojan princes held aloof; and soon the only friends left to her were the kind old king and Hector, the noble defender of the city. But there was worse behind. Little by little the truth dawned that Paris, for whom she had lost so much, and who had seemed so godlike in his strength and beauty, was very poor humanity indeed. The story of Enone was told to her; and that showed him unfaithful. And when the Leaguer actually lay beneath the walls, she soon found that Paris was a coward too.

Now, in this Third Iliad, we find that the cruel siege had wasted Troy for nearly ten years. The armies, reduced by death and pestilence and famine, were beginning to murmur against the worthless cause of all their misery; and Paris, for very shame, could no longer shelter himself within the city. At this eleventh hour he issued out to meet Menelaus in single combat. Helen was sitting in her inner hall, weaving a purple web and embroidering upon it the battle scenes which ebbed and flowed around the walls. Time and sorrow had only given her beauty an added charm. She was still young, fresh, and exquisitely fair, as on that spring morning in Lacedaemon when Aphrodite graced her for the meeting with Paris. To her, as her sweet face bent over the web, the goddess Iris brought the news of the impending combat: “They that erst waged tearful war upon each other in the plain, eager for deadly battle, even they sit now in silence, and the battle is stayed, and they lean upon their shields, and the tall spears are planted by their sides. But Paris and Menelaus dear to Ares will fight with their tall spears for thee; and 22thou wilt be declared the dear wife of him that conquereth.”

At the name of Menelaus a wave of homesickness filled Helen’s heart. Great tears flooded her eyes, and drawing on a shining veil, she left her embroideries and hastened out to the Skaian gates to watch the duel. But there, sitting upon the tower, were Priam and his counsellors; and Helen and her maids hesitated at sight of them. They were feeble old men. The fire and strength of youth had gone, leaving in their place the cold wisdom of age. They and their people had suffered deeply because of Helen; and they had every cause to hate her. Yet as she approached, veiled and slackening her pace from fear when she saw them, all their wrongs were forgotten in wonderment at her beauty. They who had potent reasons to revile her were saying softly among themselves, almost in awe, as those who had seen a vision: “’Small blame is it that Trojans and well-greaved Achaians should for such a woman long time suffer hardships; marvellously like is she to the immortal goddesses to look upon.’ ... So said they; and Priam lifted up his voice and called to Helen: ‘Come hither, dear child, and sit before me, that thou mayst see thy former husband and thy kinsfolk and thy friends. I hold thee not to blame; nay, I hold the gods to blame who brought on me the dolorous war of the Achaians’.” “And Helen, fair among women, spake, and answered him: ‘Reverend art thou to me and dread, dear father of my lord. Would that sore death had been my pleasure when I followed thy son hither, and left my home and my kinsfolk and my daughter in her girlhood and the lovely company of mine age-fellows. But that was not so, wherefore I pine with weeping’.”[2]

23Then Helen pointed out to the king and the elders the great heroes of the Greek line: “This is wide-ruling Agamemnon, one that is both a goodly king and mighty spearman. And he was husband’s brother to me, ah shameless me; if ever such an one there was.” Odysseus, too, and Ajax and Idomeneus, she can see; but two whom her eyes seek longingly are not there, her twin brothers, Castor and Pollux. “Either they came not in the company from lovely Lacedaemon; or they came hither indeed in their seafaring ships, but now will not enter into the battle of the warriors, for fear of the many scornings and revilings that are mine.”[2]

Presently, Paris and Menelaus are engaged in fight below the walls, with Helen looking on from above in fearful expectancy. It was an unequal fight. Aphrodite had joined the side of Paris; and when, despite her tricks, Menelaus was gaining on his opponent, the goddess enveloped Paris in a cloud and carried him off. In plain words, he ran away; and Helen, shamed and indignant, received a summons from Aphrodite to go to her cowardly lover. She turned in wrath upon the goddess: “Strange queen, why art thou desirous now to beguile me? Go and sit thou by his side, and depart from the way of the gods; neither let thy feet ever bear thee back to Olympus, but still be vexed for his sake and guard him till he make thee his wife or perchance his slave. But thither will I not go—that were a sinful thing—to array the bed of him; all the women of Troy will blame me hereafter; and I have griefs untold within my soul.”[2]

Aphrodite triumphs, however, menacing Helen with terrible threats; and leads her back to the house of Paris. Meanwhile, the gods ‘on golden pavement round the board of 24Zeus’ had decreed that Troy should fall: Hera and Athena were to wreak their vengeance upon it, for the insult of Paris. The truce broken, the armies rushed into conflict again, and two of the gods who were warring for Troy, were driven back to Olympus. Then Hector came into the palace to rouse his brother, and found him sitting in Helen’s room, polishing his armour. To the scornful reproaches of Hector, Paris gave only puerile answers, and Helen turned from him to Hector in passionate scorn. “Dear brother mine, would that on the day that my mother bare me, a billow of the loud-sounding sea might have swept me away before all these things came to pass. Howbeit, seeing that the gods devised all these ills in this wise, would that then I had been mated with a better man, that felt dishonour and the multitude of men’s reproachings. But as for him, neither has he now sound heart, nor ever will have; therefore deem I moreover that he will reap the fruit.”[2]

Hector answered her with a gentle word, and went out, bearing on his shoulders the doom of Troy. In his chivalrous kindness to Helen, he is a worthy son of Priam; and when he was slain at last, fighting for his beloved city alone with the terrible Achilles, Helen joined her lament to those of his mother and his wife, in perhaps the most noble tribute to his memory: “Hector, of all my brethren of Troy, far dearest to my heart. Truly my lord is godlike Paris who brought me to Troy-land; would that I had died ere then. For this is now the twentieth year since I went thence and am gone from my own native land, but never yet heard I evil or despiteful word from thee; nay, if any other haply upbraided me in the palace halls, whether brother or sister of thine or brother’s fair-robed wife, or 25thy mother, then wouldst thou soothe such with words and refrain them, by the gentleness of thy spirit and by thy gentle words. Therefore bewail I thee with pain at heart, and my hapless self with thee, for no more is any left in wide Troy-land to be my friend and kind to me, but all men shudder at me.”[2]

Almost with these words the poem closes, telling us nothing of the dreadful sack of Troy by the Achaians, after they had entered the city through the device of the wooden horse. Our last glimpse of Helen in the Iliad is as she wails her mournful threnos over the body of Hector.

We hear no word of the Greek calamity in the fall of Achilles, or how Paris was slain by the arrow of the outcast Philoctetes, with perfect poetical justice. Nothing is told of the massacre of Priam and his sons; of the burning of the city; of the carrying off of its wealth and of its fair women when the Greeks, sated with revenge at last, set sail for Argos. And we hear no word of the most amazing fact of all—the reconciliation of Helen and Menelaus. We know from the Odyssey that they were reconciled, but how, Homer does not say. Legend and song have been busy with the theme, however, and the most beautiful story has been woven by Andrew Lang into his Helen of Troy. There we see how Aphrodite in the midst of the slaughter and outrage, led Helen in safety to the ships, while Menelaus raged through the city seeking her, grimly determined to give her over to the vengeance of the army.

Lulled again by the arts of Aphrodite, Helen has completely forgotten all that has happened in the dreadful interval of the years since she last fell asleep at Lacedaemon. But Menelaus feels the fierce anger rise in his heart against her. He seizes and binds her, and carries her off to deliver her to the vengeance of the people. He reminds them of all they have endured and suffered, and calls upon them to mete to her the just death for such an one as she. But when the soldiers in their rage would have stoned her; when Menelaus rushed upon her with uplifted spear, Aphrodite drew the veil from before her matchless face.

So Helen went home to Lacedaemon again, the dear wife of Menelaus. And when we take up the second great 27Homeric epic, the Odyssey, we find her the serene and gracious hostess of young Telemachus. All the hateful past is purged away, and chaste as the moon-goddess,

She still remembers the horror of those days; and when Menelaus is wondering who the stranger prince is who has sought their hospitality, Helen’s quick wit perceives how like he is to Odysseus. Is not this, she asks, the son whom Odysseus left in his house as a new-born child when the war began?

It is indeed the son of Odysseus; and by the irony of fate he has come to inquire from the very author of his sorrows, news of the father who, for aught Helen knows, has long ago been driven by Poseidon to the House of Hades.

But the ready tears of heroes are soon dried. They cheer Telemachus so far as they may by tales of his father’s craft and courage before Troy; and Helen mixes for him the cup of Nepenthe, which steeps memory in a mist and banishes care and calls a smile to the lips. She does not herself taste of the magic drink, however; she has no wish to forget. Secure now in the peace of home and enfolded by generous forgiveness, she will always remember, until she comes to pass through Lethe on her way to the Elysian fields. And there, when the time came, she was translated 28‘where falls not rain, or hail, or any snow.’ A shrine was built to her, and Greek men and maidens worshipped her as one of the immortal gods themselves.

1. From Mr Andrew Lang’s Helen of Troy (G. Bell and Sons Ltd.).

2. From Messrs Lang, Leaf, and Myers’s translation of the Iliad (Macmillan and Co. Ltd.).

3. From Professor J. W. Mackail’s translation of the Odyssey (John Murray).

Andromache was the young wife of Hector, Priam’s warrior son and defender of Troy. Over against the figure of Helen in the Iliad her gentle integrity stands in mute reproach. It is as though Homer, whose chivalry to Helen will not permit him to censure her, yet feels the claim of a larger chivalry—to womanhood itself. So he seems impelled to create this type of gracious purity, vindicating wifely honour and motherly tenderness; and proving at the same time that if his race had a high ideal of beauty, it had also a profound regard for domestic ties.

Helen and Andromache, therefore, stand side by side in the action of the poem. Their destinies are linked: their lives are passed within the same walls: they own the same relationship to king Priam and to Hecuba the queen; and they are united in suffering. But always they are as far apart in spirit as conscious guilt on the one hand and indignant rectitude on the other ever held two daughters of Eve. Andromache, like all the men and women of heroic poetry, was very human. And we have the feeling that she could not rise to Hector’s generosity toward the Spartan woman for whose sake Paris had brought the war on Ilios. Perhaps the reason was that she had suffered more deeply on Helen’s account. And if she had joined in those reproaches which Helen wailed about in her threnos over Hector’s body, it was from bitter cause.

Andromache had been happy, and a princess, in her girlhood days, before Paris brought a Greek bride from Sparta. 30Her father was Eëtion, king of Thebes, in ‘wooded Plakos’; and in those times she had a gentle mother and seven strong brothers. But the Greeks came, and in the long years when the Leaguer lay beneath Troy, their terrible hero Achilles had ravaged the countries around, and had taken the city of Thebes. He had slain Eëtion her father and the seven fine youths who were her brothers. Her mother, too, though ransomed from the Greeks for a great price, had died of grief; and Andromache, utterly forlorn, had found refuge in the halls of Priam. She found a mate there too; and in the love of Hector, her father and mother and brothers were all given back to her.

Homer makes the tender devotion of this noble pair stand out in gracious contrast to the stormy passion of Paris and Helen. Yet he does not tell us much about Andromache. He does not describe her—indeed, he very rarely draws a picture of his women—but we know that she is beautiful. In some subtle way there is left on our mind an impression of blended grace and dignity, of sweetness and tenderness and fidelity; but we are not directly told that she possesses these qualities. We do not even see her till, in the Sixth Book of the Iliad, the time has come for her to part from her husband.

The Greeks were at the very gates of Troy, and the last phase had come for the sacred city. Diomedes had driven their god Ares from the field, bellowing with the pain of a wound; and Hector, who saw the end was coming, hurried into the palace to rouse his followers and beg the queen to pray for the cause of Troy in the Temple of Athena. Then, before returning to the fight, he snatched the opportunity to see his wife and child once more. At first he could not find them. Andromache was not in the palace, nor in 31the Temple of Athena where the matrons of the city were propitiating the goddess. She had heard that the Trojans were hard pressed, and in fear for her husband she had gone down to the tower to watch the battle from the walls.

“Hector hastened from his house back by the same way down the well-builded streets. When he had passed through the great city and was come to the Skaian gates, whereby he was minded to issue upon the plain, there came his dear-won wife running to meet him.... So she met him now, and with her went the handmaid bearing in her bosom the tender boy, the little child, Hector’s loved son, like unto a beautiful star.... So now he smiled and gazed at his boy silently, and Andromache stood by his side weeping, and clasped her hand in his, and spake and called upon his name. ‘Dear my lord, this thy hardihood will undo thee, neither hast thou any pity for thine infant boy, nor for me forlorn that soon shall be thy widow; for soon will the Achaeans all set upon thee and slay thee. But it were better for me to go down to the grave if I lose thee; for never more will any comfort be mine, when once thou, even thou, hast met thy fate, but only sorrow’.”[4]

So she weeps to him, forgetting the heroic, as heroes often do in overwhelming human sorrow. Hector is human too; and as she pours out all the pleas that touch him most nearly—her love for him, his love for her, and their mutual love for their child—he cannot utter the reply of the soldier and defender of his people. Andromache thinks she sees an instant of wavering in his eyes; she catches at it wildly, and rushes on to tell of a place where he and his men may screen themselves from the enemy. But that word has lost her cause. Hector’s great refusal is brave and gentle: “Surely ... I have very sore shame ... if like a coward I 32shrink away from battle. Moreover mine own soul forbiddeth me.... Yea of a surety I know ... the day shall come for holy Ilios to be laid low.... Yet doth the anguish of the Trojans hereafter not so much trouble me, neither Hekabe’s own, neither king Priam’s, neither my brethren’s ... as doth thine anguish in the day when some mail-clad Achaian shall ... rob thee of the light of freedom.... But me in death may the heaped-up earth be covering, ere I hear thy crying and thy carrying into captivity.”[4]

Andromache can find no answer, and there is silence between them as Hector turns to caress his boy. But the child shrinks to his nurse in fear of the shining helmet and nodding crest; and the parents laugh through their tears.

“Then his dear father laughed aloud, and his lady mother; forthwith glorious Hector took the helmet from his head, and laid it, all gleaming, upon the earth; then kissed he his dear son and dandled him in his arms, and spake in prayer to Zeus and all the gods, ... ‘Vouchsafe ye that this my son may likewise prove even as I, pre-eminent amid the Trojans, and as valiant in might, and be a great king of Ilios. May men say of him, “Far greater is he than his father,” as he returneth from battle; ... and may his mother’s heart be glad’.”[4]

In his warrior-prayer Andromache cannot join; and to us who know the fate of Hector’s son, there is appalling irony in this appeal to the gods. She takes her boy into her arms, smiling tearfully.

“And her husband had pity to see her, and caressed her with his hand and spake and called upon her name: ‘Dear one, I pray thee be not of over-sorrowful heart; no man against my fate shall hurl me to Hades.... But 33go thou to thine house and see to thine own tasks ... but for war shall men provide, and I in chief of all men that dwell in Ilios.’

“So spake glorious Hector, and took up his horsehair-crested helmet; and his dear wife departed to her home, oft looking back, and letting fall big tears.”[4]

But the end had not quite come for Hector and his beloved Troy. For a time the tide of battle rolled back against the Greeks, and while Achilles fumed idly in his tent, Hector pressed upon them until he had forced them back to their ships. The immortals came into the field again; and success swayed to one or the other side, as Zeus to the Trojans or Hera to the Greeks lent aid. Then Hector slew Patroclus, the dear friend of Achilles; and that event drew the Greek hero forth at last, raging in grief and anger. Furnished with new armour by his goddess-mother Thetis, Achilles went out against the Trojans like a destroying flame. He drove them into the city with terrible slaughter; and then faced Hector alone outside the Skaian gates, and slew him there.

Meanwhile Andromache had won a little hope again, from the past few days of success to the Trojan arms. She knew nothing of the duel, and her husband’s fate at the hands of Achilles; but was sitting quietly within her hall, while the maids prepared warm baths for his return.

“Then she called to her goodly-haired maids through the house to set a great tripod on the fire, that Hector might have warm washing when he came home out of the battle—fond heart, and was unaware how, far from all washings, bright-eyed Athene had slain him by the hand of Achilles. But she heard shrieks and groans from the battlements, and her limbs reeled, and the shuttle fell from her hands 34to the earth. Then again among her goodly haired maids she spake: ‘Come two of ye this way with me that I may see what deeds are done ... terribly I dread lest noble Achilles have cut off bold Hector from the city by himself and chased him to the plain and ere this ended his perilous pride that possessed him, for never would he tarry among the throng of men but ran out before them far, yielding place to no man in his hardihood.’

“Thus saying she sped through the chamber like one mad, with beating heart, and with her went her handmaidens. But when she came to the battlements and the throng of men, she stood still upon the wall and gazed, and beheld him dragged before the city:—swift horses dragged him recklessly toward the hollow ships of the Achaians. Then dark night came on her eyes and shrouded her, and she fell backward and gasped forth her spirit.”[4]

We must not dwell upon the grim vengeance which Achilles took upon the dead body of Hector, for the life of his friend; nor the wonderful funeral rites for Patroclus; nor the pitiful story of old Priam’s visit to Achilles at dead of night, to beg for the body of his great son:

CAPTIVE ANDROMACHE

Lord Leighton

By permission of the Berlin Photographic Co. 133 New Bond St. W.

35But when the poor insulted body was at last recovered, all the city went out to meet it and bring it in with lamentation. Andromache led the women, wailing in her grief: “Husband, thou art gone young from life, and leavest me a widow in thy halls. And the child is yet but a little one, child of ill-fated parents, thee and me; nor methinks shall he grow up to manhood, for ere then shall this city be utterly destroyed. For thou art verily perished who didst watch over it, who guardest it and keptest safe its noble wives and infant little ones. These soon shall be voyaging in the hollow ships, yea and I too with them, and thou, my child, shalt either go with me unto a place where thou shalt toil at unseemly tasks, labouring before the face of some harsh lord, or else some Achaian will take thee by the arm and hurl thee from the battlement, a grievous death.... And woe unspeakable and mourning hast thou left to thy parents, Hector, but with me chiefliest shall grievous pain abide. For neither didst thou stretch thy hands to me from a bed in thy death, neither didst speak to me some memorable word that I might have thought on evermore as my tears fall night and day.”[4]

Andromache’s foreboding was only too completely fulfilled, for although Homer does not tell us of it, we know that when the truce for Hector’s funeral was over, Troy fell into the hands of the Greeks. The horrors of that day are related over and over again by the poets—the ruthless massacre of Priam and his sons, the capture of the women and children and the burning of the city. Euripides tells us in his Troades what befell Andromache. This drama, written centuries after the Iliad, has been called by Professor Gilbert Murray, “the first great expression of pity for mankind in European literature.” The subject was, indeed, one to evoke profoundest pity, and the poet, reflective and humane, seems to select it purposely to reveal the dreadful underside of war. He brings the figure of Hecuba upon the stage, weighed down under innumerable woes: Cassandra, too, in a dark prophetic frenzy, foretelling her own doom and that of Agamemnon: Helen, confronted 36at last by Menelaus; and Andromache, borne in the chariot of her captor, with the baby Astyanax in her arms.

Leader of Chorus.

O most forlorn

Of women, whither go’st thou, borne

Mid Hector’s

bronzen arms, and piled

Spoils of the dead, and pageantry

Of them that hunted

Ilion down?

Andromache.

Forth to the Greek I go,

Driven as a beast is driven.

Hecuba. Woe! Woe!...

Andromache.

Mother of him of old, whose mighty spear

Smote Greeks like chaff, see’st thou

what things are here?

Hecuba.

I see God’s hand, that buildeth a great crown

For littleness, and hath cast the

mighty down....

Andromache.

O my Hector! best beloved,

That, being mine, wast all in all to me,

My

prince, my wise one, O my majesty

Of valiance!...

Thou art dead,

And I war-flung to slavery and the

bread

Of shame in Hellas, over bitter seas.[5]

But the crowning horror remains. As Andromache and the queen are taking mournful leave of each other, a hurried messenger arrives from the Greek leaders. His message is almost too dreadful to utter; but he stammers it at last—the victors have resolved that Andromache’s son must die. They will spare no slip of Priam’s stock to be a future menace; and Astyanax is to be cast down therefore from the city towers.

To Andromache it is an appalling blow, worse than all 37that she has yet suffered. She cannot realize it at first, and answers the herald in broken, incredulous phrases. But when the man, ruefully trying to soothe her meanwhile, at last makes it clear to her that her child must die, all her gentleness is suddenly swept away in fierce wrath against her enemies.

Her own wrongs, though deep and shameful, she could bear; but the cruelty to her child is insupportable. All the graciousness and dignity of her nature break down under it; and carried beyond herself, she calls down wild curses upon her conquerors, and upon Helen, the origin of all her woes. Then, suddenly realizing the futility of her rage and her powerlessness to save Astyanax, she yields him to the Herald in a poignant outburst of grief:

So Andromache was taken alone into captivity. Of all that befell her there we do not know; but there are hints and fragments which suggest that the gods must have relented a little, at sight of her misery. For long afterward, when the Trojan prince Æneas set out to found another Troy in Latium, he anchored his fleet one day in the bay of Chaonia. And there, as he wandered upon the shore, he found Andromache. Her cruel captor was dead; and she was married to Helenus, the brother of Hector. But 38she had not forgotten her hero-husband, and when Æneas and his companions came upon her first, she was paying devotions at his tomb:

4. From Messrs Lang, Leaf, and Myers’s translation of the Iliad (Macmillan and Co. Ltd.). 1909 Edition.

5. From Professor Gilbert Murray’s translation of the Troades (George Allen and Co. Ltd.).

6. From E. Fairfax Taylor’s translation of the Æneid (Everyman’s Library).

We come now to the Odyssey, the second Homeric epic; and to its heroine, wise Penelope.

Nominally, we have left the Iliad behind by a space of several years. Troy had fallen, and the Greeks were homeward bound, fewer in number and sadder at heart than when the fleet had sailed ten years before. Some few of them reached home in safety. But for the most part, the return voyages were only accomplished with tremendous hardship and peril; and many who had escaped death at Troy found it at the hands of Poseidon, earth-shaking sea-god. Of proud Agamemnon, and the fate that awaited him in his palace at Mycenæ, we shall hear presently. We are concerned now with the wanderings of Odysseus, and how he won home at last to the faithful love of Penelope.

But after all, the connexion between the Iliad and the Odyssey is only nominal. The links between them, although they seem strong and real at first, do not in any sense unite the two poems. It is true that there is the imaginary relation of time; that the Odyssey relates the subsequent adventures of one of the heroes who actually fought at the siege of Troy; and, more important still, that it shows him to possess upon the whole the same qualities which he possessed in the Iliad. But when that is said, there remains the fact of a contrast between the poems which almost persuades us that in the Odyssey we are in a different world. This contrast is best seen in the antithesis between the two heroes of the poems; and indeed between the two 40great heroines too. In the Iliad, Achilles stands for physical beauty and strength, young enthusiasm and ardent courage. When Odysseus appears there, as he sometimes does, he is overshone by the splendour of Achilles. Although he is the brain of the enterprise, he is in quite a secondary place to the physical magnificence of the younger hero. When we come to the later poem, however, we find that intelligence has risen to the higher plane. Odysseus is now the hero—not, like Achilles, an ideal of bodily strength and beauty: not a man of wrath, flaming over the battlefield in vengeance for his friend: not merely a warrior, product of a warlike age. Odysseus is by no means lacking in courage; and he has not outgrown the need for war. But he has many other qualities besides, and his fighting is usually prompted by necessity.

It is significant that the character of Achilles is developed in conflict with the war-god, Ares; while Odysseus is whelmed in a ‘sea of troubles,’ literally heaped upon him by Poseidon. Struggling constantly against the rage of the elements, Odysseus becomes alert and cautious, patient and painstaking and resourceful: a great constructive energy, as contrasted with the destroying fury of Achilles. The poet’s epithet for Odysseus is ‘subtle’ as that for Achilles had been ‘swift’; and the emphasis is always laid upon his qualities of brain and nerve. He is not a very imposing figure, and has little physical beauty. When his friends would praise him, it is gifts of mind rather than of body to which they refer. He is ‘the just one’ who does no injury ‘as is the way of princes’; the kindly ruler, who is ‘like a father’ to help his people; the faithful husband who can flatter and cajole his goddess-gaoler, in desperate anxiety to be home with his dear wife; the loyal 41comrade who will risk the enchantments of Circe rather than forsake his men without an effort; the gracious master whose servants ‘mourn and pine’ because of his long absence. And all the way through the poem, in passages which are too numerous to quote, there is a running tribute to his wisdom. Zeus himself, with other gods and goddesses; kings and queens; nymphs, naiads and enchantresses; swineherds and domestic servants; soldiers and sailors; strangers and homefolk; friends and enemies, all add their word to the eulogium of his wit.

Now Penelope, who is the perfect mate for such a man as this, is for that very reason contrasted with Helen as strongly as her husband is contrasted with the hero of the Iliad. It is not merely that her personality is totally unlike Helen’s, although that is true. The contrast is rooted in something deeper—in the whole conception of the poet, the manner of life out of which the poem came, the theme of which it treats. In the Iliad we are quite literally moving amongst demi-gods. Helen, reputed daughter of Tyndareus, is really the child of Zeus; and Achilles has the nereid Thetis for his mother. Something of their divine origin clings to them, making them awful and magnificent. In all that they do and are they are greater than mere human folk. They move majestically, and they are not to be approached too nearly, or judged by the common standard, or compared with the ordinary race of men. Troy itself, to which their names cling, was a city built by gods.

But Odysseus and Penelope are frankly mortal; and in that one fact they approach nearer to us by many degrees. They are no longer colossal figures hovering, as it were, about the base of Mt. Olympus, and driven this way and that in the surge of Olympian quarrels. They are a man 42and woman, with their feet firmly planted upon the earth, and their affections rooted there too. They claim no kinship with the gods: they take no part in Olympian warfare: they have no care for the issues which are called great. Their story, reduced to its elements, is of the simplest kind: the call of dear home ties upon the man, the fidelity and prudence of the woman. And in this ‘touch of common things,’ Penelope becomes a much more real figure than Helen.

Of course that is not to say that Penelope is ‘real’ in the technical sense of the word. She is in fact almost as much a creature of romance as Helen is. But she appears before us as a living woman with human hopes and joys and sorrows; with human virtues too, and certain very human weaknesses. We can never regard the heroine of the Iliad just in this way. If we could, and if we dared to lift the veil which the poet always interposes between us and the character of Helen, it would stand revealed slight and trembling in its amiability: fatally soft, with no vein of essential strength. Now it is that essential strength which characterizes Penelope. The wooers realized it; and Antinous made it the chief point of his defence:

43There is a significant silence about Penelope’s beauty; and she has not eternal youth as Helen has. But when we have seen her eyes light upon her boy Telemachus, and the radiance of her face as the strange old beggarman told her about her husband, we shall waive the question of æsthetics. We shall be prepared to maintain Penelope’s beauty against all-comers; and we shall not be much concerned that the poet rather avoids the subject. For he would not dream of a soul which did not know that sweetness and dignity and a gentle heart, grief endured patiently and love unswerving, would make for themselves a worthy habitation. Beside Helen’s exquisite fairness, Penelope would seem a little faded; and her sweet gravity would be almost a reproach. She cannot compare for one moment with Calypso, as Odysseus had to confess when the goddess blamed him for his homesickness:

The keynote of the Odyssey is struck here; and here too we may find a hint of all that Penelope means. The thought of home is to dominate the poem, as something so dear and sacred that innumerable toils are suffered and infinite perils undergone to win back to it. And this shining ideal of home is to be incarnate in Penelope. She is to represent in her own person all that sweetens and comforts life: all the domestic virtues which establish and perpetuate it. Thus, beside Helen as the ideal of beauty—of 44physical perfection—Penelope stands as the ideal of mental and moral worth.

Telemachus, whom Odysseus had left at home as a baby twenty years before, had been sent by Athena to seek his father. The goddess had appeared to him as he sat in his father’s hall in Ithaca, lowering upon those unbidden guests who were his mother’s suitors. She had asked what the unseemly revel might mean; and he had told of the long absence of his father.

The goddess counselled immediate action—to go and seek Odysseus; and while the minstrel sang to the carousing suitors, Telemachus inwardly resolved that he would set sail as soon as might be for Pylos and Sparta, whither Athena directed him for tidings of his father. But he knew that he must act quietly; and above all, that his purpose must be 45kept a secret from his mother. She would certainly prevent his going, did she know, fearing to lose son as well as husband.

Meantime, as he pondered the matter, Penelope was listening from her lofty bower to the minstrel’s song in the hall below. He sang of the return of the heroes from Troy; and the words reawakened in her the old pain of longing for her husband. At last she could not bear to hear it any longer:

She is a touching figure, as she ventures out among the revellers and begs the old man to change the theme of his lay. But Telemachus was not in the mood to see the pathos of the scene. The charge that Athena had laid on him had suddenly given him his manhood; and in 46the new sense of responsibility, he spoke a little harshly to his mother, bidding her go back to her loom and housewifery.

While his mother slept, Telemachus lay awake in his own inner room revolving plans whereby to carry out the command of Athena. He determined first to confront the suitors publicly, before a formal assembly of the Ithacans, and charge them with their insolence and riotous greed. So, with the first light of morning, he summoned the people to a meeting in the market-place, and called upon the wooers to cease their persecution of his mother and quit his house. Antinous, answering haughtily for them all, invented a coward’s excuses for their conduct. Penelope was to blame, he said, for she would not decide between them; but constantly put them off with various cunning devices. With one pretext alone—that of weaving a shroud for Icarius—she had kept them in suspense for many months.

Therefore, declared Antinous, because Penelope had deceived them in this manner, they would not depart until she had chosen a husband from among them. Telemachus might spare his protests; indeed, he would be better advised to coerce his mother, since they were determined to remain in his house and devour his substance, until Penelope should yield. But Telemachus was a child no longer, and could not be threatened with impunity. And to their base suggestion that he should favour them against his mother, he gave a spirited reply. Nothing should induce him to give Penelope in marriage against her will:

48The assembly broke up; and Telemachus hastily fitted out a ship and sailed to seek Odysseus, all unknown to Penelope. The suitors continued their carousals day after day, rioting and making merry, in feigned contempt of Telemachus and his quest. But when after a time he did not return, they grew uneasy. They had jeered at his threats of vengeance, deeming him an untried boy; but who knew what might happen now, since he had sailed with a crew of the stoutest fellows in the island? Might he not return with help and drive them out? Antinous took counsel with his friends, and determined on a murderous plan. They would man a ship, sail after Telemachus, and lie in wait for his return, between the islands of Ithaca and Samé; and that should be the last cruise that Telemachus should make.

Meanwhile Penelope, busy with her household duties, believed her son to be away with the flocks. She stayed within the women’s rooms; and except for the clamour of the wooers, or the occasional song of the minstrel, nothing came to her ears. But now Medon the herald heard of the plot which was afoot against his young master, and came to warn her of it. She greeted him with a bitter question. Had he come to order her maids to spread the banquet for the suitors? Would that they might never feast again! Had they not shame to deal so unjustly with her absent husband—he who had always dealt justly with them, who had never in word or deed done injury to any? But Medon had a harder thing yet to say; and as gently as might be, he told her of the going of Telemachus and of the suitors’ plot to slay him.

Penelope is overwhelmed with grief, and Medon’s explanation of her son’s errand does not soothe her. She believes that he is lost to her for ever, like his father; and when the herald has left her, she throws herself down upon the floor of her room, wailing:

She casts about in her mind as to how she may save her son; and it seems to her best to send a trusty messenger 50to the father of Odysseus, for help and counsel. But the old nurse Euryclea gives good advice. She confesses that she had known of the departure of Telemachus; but he had sworn her with a great oath not to reveal it. It is of no use to mourn about it; and since they can do nothing to bring him back, the better way is to go and supplicate their guardian goddess, Athena, the Maid of Zeus, for his safety. For her part, she believes that Telemachus will not be forsaken in his need. Penelope wisely takes the advice of the old nurse. She bathes, puts on clean raiment, and taking in her hand an offering of barley-flour, she ascends to her own chamber and makes supplication to Athena:

PENELOPE

Patten Wilson

51Even while Penelope prayed, Athena was busy on her behalf; and was bringing home to her both husband and son. Odysseus she had convoyed safely to Ithaca, and was now leading him in disguise to the swineherd’s cottage. And to Telemachus she had shown a way to escape the murderous suitors, and was bringing him swiftly to the father whom he had never seen. Of their meeting, and of their cunning plan for vengeance on the suitors, it would take too long to tell. But in the morning, Penelope was gladdened by the return of her son; and a little later, a poor old beggar (no other than Odysseus himself) came among the suitors as they sat in the hall. They glowered upon him angrily, and proud Antinous set the vagabond Irus to fight him, for their sport. But the old beggar had unexpected strength, and Irus was defeated. Whereon the suitors began to bait Odysseus with jeers and taunts; and one hurled a stool at him. At this impious deed, the guests were horrified; and Penelope, hearing of it where she sat among her women, longed to make amends to the old man for the cruel act. She descended into the great hall, and spoke reprovingly to Telemachus for allowing one who had sought the shelter of their home to be treated so basely.

But Telemachus hugged his secret knowledge of the beggar’s identity, and kept silence, while Penelope returned to her bower. The hall was cleared at last, and then he and his father laid their plans for the slaying of the suitors on the following day. The noisy crew had all gone to rest; and when Odysseus and his son had agreed upon a plan of action, Telemachus followed them, leaving his father alone in the great hall. It was a moment for which Penelope had been waiting; and she came down from her room again, to question the beggar of his wanderings. There was no light in the hall but that of the fire; and she ordered a 52cushioned chair to be brought near, so that the old man might sit while she talked with him.

Cunning Odysseus evaded her question. She might ask him anything but that, he said; for it gave him too much sorrow to think of his country and his race. Penelope was only too willing to be turned aside, burning as she was to ask for news of Odysseus. So she told the old man of her husband, and of his sailing for Troy, and of how she was pining for his return.

She told him about the wooers, and the device of the shroud, which gained her three years’ respite. But a treacherous servant had betrayed her, and she had been compelled to finish her task.

53But having related so much of her own story, she asked again for the old man’s name and race; and above all, would not he say whether he had seen or heard aught of her husband? Odysseus needed all his subtlety now, as he invented a tale of Crete and the great city of Cnossos, and Minos the king who was his ancestor; and how on one occasion her husband had indeed taken shelter with him there.

There was one thing more which Odysseus must do before he could reveal himself; and meantime he could only comfort Penelope by assuring her that her husband still lived and was even now on his way home to her. She shook her head sadly: that was too good to believe: the kind old man was only trying to comfort her. But it was time for him to go to bed; and because he disliked the giddy young serving-maids, Penelope called up the old nurse Euryclea, and bade her wash the beggar’s feet with as much 54care as if he were her master returned at last. That he was indeed her master the nurse divined the instant that her fingers touched an old scar upon his foot. But Odysseus hastily whispered her to say nothing of what she had discovered; and soon the palace was asleep, with the old beggar stretched upon sheepskins in the forecourt.

At dawn next morning Odysseus awoke, and prayed to Zeus to help him in the great deed that he was to do that day. Soon the suitors were astir, and the usual preparations were begun for the banquet. Penelope herself came down from her room, to watch what would happen. For, as she had told the beggar the night before, she could not withhold her decision any longer. This day she must choose between the suitors. And because they were all alike hateful to her she would decide the question by a test: she would consent to take for her husband that man who could shoot with Odysseus’ bow.

She went up into the high Treasure-chamber, and sorrowfully took down the great bow that a friend in Sparta had 55given to Odysseus long ago. She carried it forth among the suitors; and Telemachus, who was eager for the contest which he knew would end for them in a shameful death, swiftly set up the twelve axes in a row, through which they were to shoot. Odysseus leaned silently against the door-post, still in his beggar’s disguise; whilst one after another of the suitors tried to bend the bow. But one after another miserably failed to bend it, although a great fire was lit and a cake of lard was brought to make the bow supple. At last, in rage and despair, they had to abandon the attempt; and then Odysseus humbly asked if he might be allowed to try. This was a pre-arranged signal between father and son; and in the instant outcry that arose at the old man’s presumption, Penelope and her maids were led away. Then Odysseus, with his son and two faithful serving-men who were in the secret, made a bold attack upon the suitors. They were greatly outnumbered, but their plans had been laid warily, and Athena was on their side. Through a grim struggle they prevailed at last, and did not cease until vengeance was complete and every evil suitor had been slain. But Penelope, although she heard the horrible din in the hall below, had no idea of its cause. It was probably, she thought, another of the frequent brawls between these tumultuous wooers. She was still completely ignorant of Odysseus’s return; and when the old nurse came running to her with the joyful news, she believed her to be mad. She had looked so long and so despairingly for this event that now it had come she was utterly incredulous. Even when she heard all the ghastly story of the slaying of the suitors, and came into the hall where her husband stood awaiting her, she could not realize that it was he.

Telemachus could not comprehend the reason for his mother’s silence, and broke into impulsive chiding. He could not see that the very steadfastness of her nature would not allow her to be lightly convinced.

Truly, it is Greek meeting Greek, in this encounter between the wit of Penelope and that of the man she dare not hope is really her husband. Odysseus grows 57angry at last, and that gives the victory to his wife. For when he orders that a bed shall be made for him apart, she says cunningly to the maid:

Now Odysseus had built the bed himself, literally round the trunk of a standing tree; and by this token she is trying him. In his answer she perceives that he truly is her husband, for none but he could know how wonderfully their bed was built.

Odysseus is indignant at the suggestion that his wonderful handiwork has been destroyed; but Penelope does not mind about his anger, for she is convinced at last that he is indeed her husband.

Odysseus’s anger quickly melts as he clasps his sweet wife in his arms; and so we may leave Penelope in her happiness. Homer has one word more to say about her, however. It occurs, with apparent naïveté, almost like a curious little afterthought, in the last book of the poem. But there is really exquisite art in it. The souls of the suitors have gone wailing on their way to the World of the Dead; and there they meet the great Greek heroes who died at Troy. There too, they meet the haughty spirit of King Agamemnon, murdered by his wife on his return to Mycenæ. To him the suitors tell their tale of 59the faithful wife of Odysseus, and their ignominious end. And then from Agamemnon’s lips, bitterly contrasting his wife with Penelope, falls what is perhaps the noblest and most impressive tribute to her:

7. From Professor J. W. Mackail’s translation of the Odyssey (John Murray).

8. From Mr H. B. Cotterill’s translation of the Odyssey (Harrap & Co.).

Penelope is not the only woman in the Odyssey, although she is far the most prominent. Round her are grouped three other woman-figures—Calypso, Circe, and Nausicaa; and although two of them are goddesses rather than women, they seem none the less deliberately chosen, with the sweet youthfulness of Nausicaa, to enhance the dignity of Penelope.

They come into the story as incidents in the adventures of Odysseus, as he is driven from point to point on his weary voyage homeward. Calypso and Circe, dwelling each in a lonely island of the sea, lure him and hold him from Penelope against his will. But it is of no avail to change his purpose. They have many charms, and they can sing sweetly to ease the heart from pain. They live a dainty and a joyous life, which he may share if he will; and which he does share for a time. They are more beautiful than Penelope; they have strange lore, and a knowledge of enchantments; they have, too, eternal youth and kinship with the immortals. But when all is said, they cannot compare with the dear human soul who is waiting for Odysseus in Ithaca; and this contrast the poet makes us clearly see, in the way in which Odysseus always turns with longing to the thought of Penelope.

So it is, too, with Nausicaa. This fresh young daughter of King Alcinous, just a fair mortal girl, might be Penelope’s very self, when twenty years before Odysseus had taken away Icarius’s child to be his wife. One would think that there must be something quite irresistible about her to 61the toil worn man just escaped from death. She is so brave and helpful; and so prudent too, as she tells him a little wistfully that he must not enter the city in her company. Yet, though we feel that Odysseus cannot but admire this spirited young creature, she does but serve to remind him of one in whom similar beauty and wisdom have grown to maturity.

Thus we have another comparison from which Penelope gains; and thus all three of these other women of the Odyssey serve to throw the heroine into stronger relief. The poet accomplishes this very cunningly. He does not bring them into direct contact with Penelope: they are never, so to speak, on the stage together. That would be too severe a contrast—one from which Penelope would suffer, as well as they. But at distant times and places, each is brought separately into the circle of Penelope’s life, by rivalry for the love of her husband. So they stand in the poem, not only as a graceful setting to the figure of the heroine; but they occupy in relation to Odysseus the same position which the suitors occupy in relation to Penelope. There is a perfect balance of the poem here, and one can only marvel at the art which built it so. For the suitors serve on the one hand to show Penelope’s fidelity; and on the other hand, by their arrogance and brutality, they make a complete foil to the just and subtle Odysseus. Penelope cannot cope with them; she knows them too well to dare the effect of a downright refusal; and she sets her wits to work to keep them at bay, while she longs and prays for her husband’s return. In conflict with them, her loyalty shines; and there are developed all her many merits as queen and housewife and mother. But in the conflict we get at the same time, through their 62sensuality and impiousness, a sense of the absolute contrast with Odysseus.

The three minor women of the Odyssey serve a similar double purpose. They stand to the hero as the suitors stand to Penelope. If Odysseus’s loyalty to his wife does not come perfectly scathless through the ordeal—if we cannot hold him entirely blameless for the year spent with Circe—the test does nevertheless reveal his essential constancy. That is indeed the poet’s purpose; as well as to give a bright and graceful touch to an exciting story of adventure. But he had also another purpose, which we have already seen—to make of these rivals of Penelope a charming setting, in which she should shine with added lustre.

We hear all about Circe when Odysseus is telling the story of his adventures to King Alcinous. He relates how he had sailed a second time from Aeolia, sadly and wearily, because of the folly of his men. For they had been well within sight of their beloved Ithaca, and Odysseus, worn out with his long vigil at the main-sheet, had dropped asleep. It was an evil opportunity for the curious crew, who were burning to know what was contained in the great skin sack that their commander had stored below so carefully. Within a trice the Bag of the Winds was cut, letting loose on them havoc and destruction.

They fared back to King Aeolus, and humbly begged his help once more. But he would not a second time labour to imprison the winds for men on whom the gods had obviously laid a curse of foolishness; and they had to sail away unfriended. For six days they rowed hard against adverse weather; and on the seventh their evil fortune lured them to the land of the Laestrygonians. Not one of the ships that 63entered the harbour ever came out again. Only Odysseus and his own men, who lay outside awaiting them, were saved from the hands of that cruel race.

Such was the coming of Odysseus to the land of Circe; and of all the strange and terrible things that had yet befallen him, the strangest and most terrible he was to receive at her hands. At first all went well. The ship ran smoothly into a fair haven: they landed in safety, and for two days and nights they rested on the shore, Odysseus himself shooting them venison for their food. In all this time no human creature had been seen; but Odysseus in his explorations had seen one sign of habitation—a curl of smoke rising from an oaken coppice. That gave at least some hope of succour; but when he called his men to search the wood with him, he found that their courage had been completely broken. Their sufferings from the savage Cyclops and the Laestrygonians had taught them to fear the unknown rather than to hope from it; and none would volunteer for the expedition. So a council was called, lots were cast, and those on whom the lots fell went off most unwillingly, led by Eurylochus.

The island lay low upon the sea, with only one hill-peak; and when they climbed the hill the circling waters could be seen stretching away to the horizon’s edge, without another glimpse of land. It would seem that they were utterly cut off: that there was no possible succour anywhere but in the mysterious valley below them; and the knowledge 64spurred them to seek out the dweller in the wood, and so perhaps find help and counsel.

In a wide and shallow valley, where the oaks had been cleared away and the sun streamed hotly upon a southern slope, they came upon the house of Circe, daughter of the sun. No human figure could be seen:

Even these creatures made no sound to break the silence that was like a menace, while the sailors stopped awe-struck at the sight. The great house, with its many halls and shining marble pillars, fascinated their sight; and the strange beasts which leapt and fawned around them seemed to invite them to enter. But while they stood in doubt, dreading to advance and yet withheld from flight by some impalpable, resistless power, the sound of a sweet voice rose upon the air. Softly at first it floated out to them, in trembling notes; and they stole forward, drawn by the exquisite melody, until they stood upon the very threshold of Circe’s house.

Circe, with a lurking smile of malice on her lips, came forward to welcome them. She was very lovely, with the 65youthful, changeless beauty of the immortals; but though Homer does not tell us so, we know that there was sensuality in the curving fullness of her mouth and a cruel gleam in the eyes over which the white lids drooped. With sweet words and fluttering movements of her soft hands, she brought them in and bade them sit; and busied herself, with swift and stealthy eagerness, to mix and pour a luscious drink of Pramnian wine and honey. But before she gave the cup into their hands, she furtively dropped into it one of her secret baneful drugs; and as they greedily drank, their human shape was instantly transformed to that of swine.

One of the crew, however, had not entered; and when his comrades did not return, he ran back to the ship to tell of what had happened. Odysseus, suspecting some evil, slung on his sword, seized his bow, and sped away to Circe’s house. But suddenly in his path stood the god Hermes, Messenger of Zeus, in the likeness of a handsome youth. The god held up an arresting hand.

Then Hermes foretold all that should befall Odysseus in Circe’s house, thinking to deter him. But when he would persist in the attempt to save his men, the god gave Odysseus a plant that should be an antidote to Circe’s poison.

Below her courtesy an evil intent was lurking, as Odysseus knew too well; and presently she served to him the same poisoned drink with which she had bewitched his men. But the plant of moly that Hermes had given him made him proof against her drugs. The wine failed of its effect, and Circe, angrily taking her wand, smote Odysseus with it, crying: “Begone now to the sty and couch among your band.”

CIRCE

Patten Wilson

67Her mischievous purpose faded on the instant, and she became full of fawning admiration and wonder. Her malice was changed; but something even more dangerous took its place. She began with sweet words to smooth away Odysseus’s anger, fondling him and begging him to remain with her and be her husband. But Odysseus remembered the warning of the god, and at first he would not yield. He was sullen and suspicious, and would not answer her gently until she had sworn to release his men.

Then the ship was hauled into a cave, and their companions were induced to come up to Circe’s house, where they all joined in feasting and merriment. Cautious Eurylochus tried to dissuade them; but Odysseus would give no heed to his warning; and there followed a long interval of riotous pleasure over which Circe and the river-nymphs 68who were her handmaidens presided as queens. The days went by uncounted in luxurious ease; and if, in rare moments, Odysseus had an uneasy flash of memory, Circe’s caressing voice would flatter and soothe him into complacence again, persuading him to stay yet a little longer.

So she would cajole them, and so the blandishments of Circe proved far more effectual than her drugs. For a whole year the thought of home and friends was driven away, while jollity filled out the indolent hours. But satiety came at last, and memory began to reawaken. With rough home-truths, the sailors broke the spell that Circe had cast upon their commander. They called him out from her odorous, shadowy halls; and under the clear sunlight that suddenly made Circe hateful, they reproached him with his dalliance, and bade him flee at once if he would save his soul alive. There was no withstanding them; and indeed Odysseus had no wish to do so.

When evening came, he claimed from Circe the fulfilment of her promise to send them safely back.... He would be sad at leaving her, he said, since the time had passed 69so pleasantly in her sunny island; but now his men are beginning to complain and he himself (though that he did not tell her) had suddenly grown weary and remorseful. It all seemed very simple: and he had not much misgiving. Circe had only to speak the word, that they might have safe convoy, and return to Ithaca. Surely the gods must have laughed in irony at the man who thought to part from Circe so lightly, knowing as they did the whole cost of that parting for him. Circe was not to be cast off and forgotten, as a mere incident of Odysseus’s adventures. Her reply was proud, and of ominous import. Since they wished to go, she would not detain them; but let Odysseus summon all his courage:

The awful words fell horribly on Odysseus’s ear. So they might not then simply hoist sail and away, gaily bound for Ithaca? Instead, there was yet to make the bitterest voyage that even Odysseus had made—a dark and awesome journey to the nether world, there to see and hold converse with the dead prophet, Tiresias.

But so it was decreed, and since all his grief and horror could not alter it, he begged of Circe at least to tell him how 70he might find his way to the dread World of the Dead, and how he might return in safety from it. Circe smiled inscrutably. She knew that the passage there is all too easily won.

She told him all that he must do there; how he must pass right through the crowding shadowy forms, and where two loud-thundering rivers meet he must dig a trench and pour out a drink-offering before the dead. But he must not let them partake of it, and must keep them at bay with drawn sword till the prophet Tiresias should appear and prophesy to him of his return.