Title: Historical Characters in the Reign of Queen Anne

Author: Mrs. Oliphant

Release date: December 1, 2016 [eBook #53644]

Most recently updated: January 24, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

|

Index of Illustrations (etext transcriber's note) |

PRINCESS ANNE OF DENMARK.

ENGRAVED BY H. DAVIDSON, FROM MEZZOTINT BY JOHN SMITH, AFTER THE

PAINTING BY W. WISSING AND I. VANDERVAART.

BY

Mrs. M. O. W. OLIPHANT

NEW YORK

THE CENTURY CO.

1894

Copyright, 1893, 1894,

By The Century Co.

The De Vinne Press.

| CHAPTER I | |

|---|---|

| PAGE | |

| The Princess Anne | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| The Queen and the Duchess | 43 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The Author of “Gulliver” | 83 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| The Author of “Robinson Crusoe” | 129 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Addison, the Humorist | 167 |

| Princess Anne of Denmark | FRONTISPIECE |

| Engraved by H. Davidson, from mezzotint by John Smith, after the painting by W. Wissing and I. Vandervaart. | |

| Anne Hyde, Duchess of York | 4 |

| Engraved by T. Johnson, after the painting by Sir Peter Lely, in possession of Earl Spencer. | |

| John Evelyn | 8 |

| Engraved by E. Heinemann, after copperplate by F. Bartolozzi in the British Museum. | |

| Prince George of Denmark | 12 |

| Engraved by R. A. Muller, from mezzotint in the British Museum by John Smith, after the painting by Sir Godfrey Kneller. | |

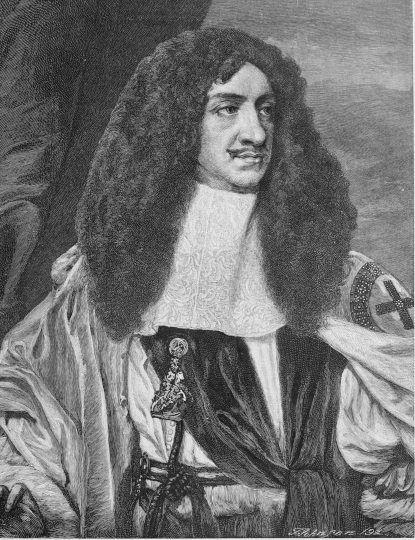

| Charles II. | 16 |

| Engraved by T. Johnson, after original painting by Samuel Cooper, in the gallery of the Duke of Richmond and Gordon. | |

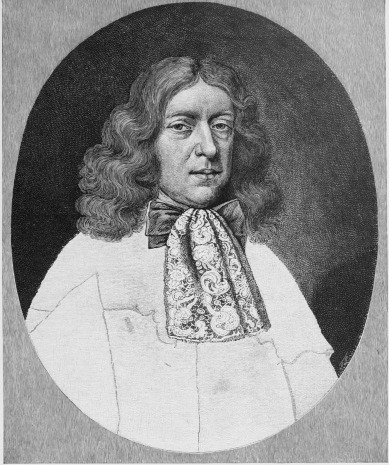

| Henry Compton, Bishop of London | 20 |

| Engraved from life by David Loggan, from print in the British Museum. Engraved by E. Heinemann. | |

| James II. in his Coronation Robes | 24 |

| Engraved by T. Johnson, after the painting by Sir Peter Lely, in possession of the Duke of Northumberland. | |

| Mary, Princess of Orange | 28 |

| Engraved by C. A. Powell, after the painting by Sir Peter Lely, in possession of the Earl of Crawford. | |

| Queen Mary of Modena | 32 |

| Engraved by Charles State, after the painting by Sir Peter Lely, in possession of Earl Spencer. | |

| William III. | 40 |

| From copperplate engraving by Cornelis Vermeulen, after the Painting by Adriaan Vander Werff. | |

| The Duke of Gloucester | 44 |

| Engraved by R. G. Tietze, From mezzotint by John Smith, after the painting by Sir Godfrey Kneller. | |

| Garden Front, Hampton Court | 48 |

| Drawn by Joseph Pennell. Engraved by J. F. Jungling. | |

| The Duke of Gloucester | 52 |

| Engraved by R. A. Muller, from miniature by Lewis Crosse, in the collection at Windsor Castle; by special permission of Queen Victoria. | |

| Queen Anne | 56 |

| From copperplate engraving by Pieter Van Gunst, after the painting by Sir Godfrey Kneller. | |

| Windsor Terrace, Looking Westward | 60 |

| Engraved by J. W. Evans, after aquatint by P. Sandby. | |

| The Duke of Marlborough | 64 |

| Engraved by J. H. E. Whitney, from an engraving by Pieter Van Gunst, after painting by Adriaan Vander Werff. | |

| The Duchess of Marlborough | 72 |

| Engraved by R. G. Tietze, from mezzotint after painting by Sir Godfrey Kneller. | |

| Bishop Gilbert Burnet | 80 |

| Engraved by R. A. Muller, from mezzotint in the British Museum by John Smith, after the painting by John Riley. | |

| Jonathan Swift | 84 |

| From photograph of original Marble Bust of Swift by Roubilliac (1695-1762), now in the Library of Trinity College, Dublin. | |

| Moor Park, Residence of Sir William Temple and of Swift | 88 |

| Drawn by Charles Herbert Woodbury. Engraved by R. Varley. | |

| Dean Swift | 92 |

| From copperplate engraving by Pierre Fourdrinier, after a painting by Charles Jervas. | |

| Stella’s Cottage, on the Boundary of the Moor Park Estate | 96 |

| Drawn by Charles Herbert Woodbury. Engraved by S. Davis. | |

| Hester Johnson, Swift’s “Stella,” painted from Life by Mrs. Delany, on the Wall of the Temple at Delville, and accidentally destroyed | 100 |

| Engraved by M. Haider, from copy of the original by Henry MacManus, R. H. A., now in possession of Professor Dowden. | |

| Sir William Temple | 104 |

| Engraved by R. A. Muller, from an engraving in the British Museum, after a painting by Sir Peter Lely. | |

| Delany’s House at Delville, where Swift stayed | 108 |

| Drawn by Harry Fenn. Engraved by C. A. Powell. | |

| Marley Abbey, the Residence of Vanessa, now called Selbridge Abbey | 112 |

| Drawn by Harry Fenn. Engraved by R. C. Collins. | |

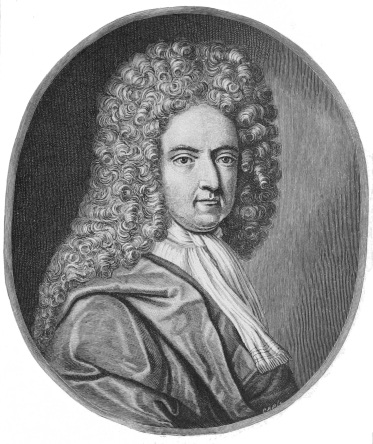

| George, Earl of Berkeley | 120 |

| From an unfinished engraving, in the British Museum, attributed to David Loggan. | |

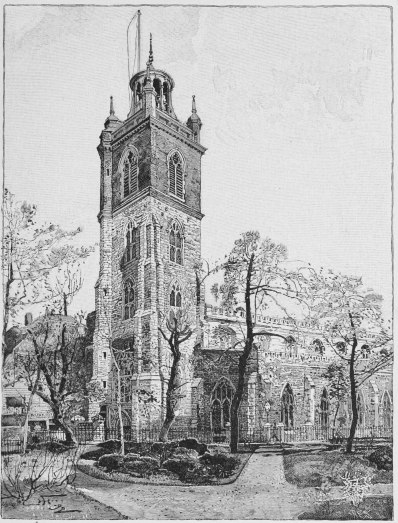

| St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin | 124 |

| Drawn by Harry Fenn. Engraved by C. A. Powell. | |

| Daniel Defoe | 136 |

| Engraved by C. A. Powell, after copperplate by M. Van der Gucht, in the British Museum. | |

| Church of St. Giles, Cripplegate, where Defoe is supposed to have been Baptized | 144 |

| Drawn by Harry Fenn. Engraved by H. E. Sylvester. | |

| Robert Harley, Earl of Oxford | 152 |

| Engraved by John P. Davis, after the original painting by Sir Godfrey Kneller, in the British Museum. | |

| Joseph Addison | 176 |

| Engraved by T. Johnson, from mezzotint by Jean Simon, after painting by Sir Godfrey Kneller. | |

| Sidney, Earl of Godolphin | 192 |

| Engraved by Peter Aitken, from mezzotint by John Smith, in British Museum. Painted by Sir Godfrey Kneller. |

THE reign of Queen Anne is one of the most illustrious in English history. In literature it has been common to call it the Augustan age. In politics it has all the interest of a transition period, less agitating, but not less important, than the actual era of revolution. In war, it is, with the exception of the great European wars of the beginning of this century, the most glorious for the English arms of any that have elapsed since Henry V. set up his rights of conquest over France. Opinions change as to the advantage of such superiorities; and, still more, as to the glory which is purchased by bloodshed; yet, according to the received nomenclature, and in the language of all the ages, the time of Marlborough cannot be characterized as anything but glorious. A great general, statesmen of eminence, great poets, men of letters of the first distinction—these are points in which this period cannot easily be excelled. It pleases the fancy to step historically from queen to queen, and to find in each a center of national greatness knitting together the loose threads of the great web. “The spacious times of great Elizabeth” bulk larger and more magnificently in history than those of Anne, but the two eras bear a certain balance which is agreeable to the imagination.{1} And we can scarcely help regretting that the great age of Wordsworth and Scott, Byron and Wellington, should not have been deferred long enough to make the reign of Victoria the third noblest period of modern English history. But time has here balked us. This age is not without its own greatness, but it is not the next in national sequence to that of Anne, as Anne’s was to that of Elizabeth.

In the reigns of both these queens this country was trembling between two dynasties, scarcely yet removed from the convulsion of great political changes, and feeling that nothing but the life of the sovereign on the throne stood between it and unknown rulers and dangers to come. The deluge, in both cases, was ready to be let loose after the termination of the life of the central personage in the state. And thus the reign of Anne, like that of Elizabeth, was to her contemporaries the only piece of solid ground amid a sea of evil chances. What was to come after was clear to none.

But in the midst of its agitations and all its exuberant life—the wars abroad, the intrigues at home, the secret correspondences, the plots, the breathless hopes and fears—it is half ludicrous, half pathetic, to turn to the harmless figure of Queen Anne in the center of the scene—a fat, placid, middle-aged woman full of infirmities, with little about her of the picturesque yet artificial brightness of her time, and no gleam of reflection to answer to the wit and genius which have made her age illustrious. A monarch has the strangest fate in this respect: as long as she or he lives, the conscious center of everything whose notice elates and elevates the greatest; but as soon as his day is over, a mere image of state visible among his courtiers only as some unthought-of lackey or faded gentleman usher throws from his little literary lantern a ray of passing illumination upon him. The good things of their lives are thus almost counterbalanced by the insignificance of their historical{2} position. Anne was one of the sovereigns who may, without too great a strain of hyperbole, be allowed to have been beloved in her day. She did nothing to repel the popular devotion. She was the best of wives, the most sadly disappointed of childless mothers. She made pecuniary sacrifices to the weal of her kingdom such as few kings or queens have thought of making. And she was a Stuart, Protestant, and safe, combining all the rights of the family with those of orthodoxy and constitutionalism, without even so much offense as lay in a foreign accent. There was indeed nothing foreign about her, a circumstance in her favor which she shared with the other great English queen regnant, who, like her, was English on both sides of the lineage.

All these points made her popular and, it might be permissible to say, beloved. If she had been indifferent to her father’s deprivation, she had not at least shocked popular feeling by any immediate triumph in succeeding him, as Mary had done; and her mild Englishism was delightful to the people after grim William with his Dutch accent and likings. But the historians have not been kind to Anne. They have lavished ill names upon her: a stupid woman,—“a very weak woman, always governed blindly by some female favorite,”—nobody has a civil word to say for her. Yet there is a mixture of the amusing and the tragic in the appearance of this passive figure seated on high, presiding over all the great events of the epoch, with her humble feminine history, her long anguish of motherhood, her hopes so often raised and so often shattered, her stifled family feeling, her profound and helpless sense of misfortune.

There is one high light in the picture, however, though but one, and it comes from one of the rarest and highest sentiments of humanity: the passion of friendship, of which women are popularly supposed to be incapable, but which never existed in more{3} complete and disinterested exhibition than in the bosom of this poor queen. It is sad that it should have ended in disloyalty and estrangement; but, curiously enough, it is not the breach of this close union, but the union itself, which has exposed Anne to the censure and contempt of all her biographers and historians. To an impartial mind we think few things can be more interesting than the position of these two female figures in the foreground of English life. Their friendship brought with it no harm to England; no scandal, such as lurks about the antechamber of kings, and which has made the name of a favorite one of the most odious titles of reproach, could attach in any way to such a relationship. And nothing could be better adapted to enhance the dramatic features of the scene than the contrast between the two friends whose union for many years was so intimate and so complete.

Yet her friend was as like to call forth such devotion as ever woman was. Seldom has there been a more brilliant figure in history than that of the great duchess, a woman beloved and hated as few have ever been; holding on one side in absolute devotion to her the greatest hero of the time, and on the other rousing to the height of adoration the mild and obtuse nature of her mistress; keeping her place on no ground but that of her own sense and spirit, amid all intrigues and opposition, for many of the most remarkable years of English history, and defending herself with such fire and eloquence when attacked, that her plea is as interesting and vivid as any controversy of to-day, and it is impossible to read it without taking a side, with more or less vehemence, in the exciting quarrel. Such a woman, standing like a beautiful Ishmael with every man’s hand against her, yet fearing no man, and ready to meet every assailant, makes a welcome variety amid the historical scenes which so seldom exhibit anything so living, so imperious, so bold and free. That she has got little mercy and no{4}

indulgence, that all chivalrous sentiment has been mute in respect to her, and an angry ill-temper takes possession of every historian who names her name, rather adds to the interest than takes from it. Women in history, strangely enough, seem always to import into the chronicle a certain heat of personal feeling unusual and undesirable in that region of calm. Whether it is that the historian is impatient at finding himself arrested by the troublesome personalities of a woman, and that a certain resentment of her intrusion colors his appreciation of her, or that her appearance naturally possesses an individuality which breaks the line, it is difficult to tell; but the calmest chronicler becomes a partizan when he treats of Mary and Elizabeth, and no man can name Sarah of Marlborough without a heat of indignation or scorn, almost ridiculous, as being so long after date.

To us the unfailing vivacity and spirit of the woman, the dauntless stand she makes, her determination not to be overcome, make her appearance always enlivening; and art could not have designed a more complete contrast than that of the homely figure by her side, with appealing eyes fixed upon her, a little bewildered, not always quick to understand—a woman born for other uses, but exposed all her harmless life to the fierce light that beats upon a throne. For her part, she has no defense to make, no word to say; let them spend all their jibes upon her, Anne knows no reply. Her slow understanding and want of perception give her a certain composure which in a queen answers very well for dignity; yet there is something whimsically pathetic, pitiful, incongruous in the fate which has placed her there, which can scarcely fail to soften the heart of the spectators.

The tragedy of Anne’s life, unlike that of her friend, had no utterance, and there was nothing romantic in her appearance or surroundings to attract the lovers of the picturesque. Yet in the blank of her humble intellect she discharged not amiss{6} the duties that were so much too great for her; and if she was disloyal to her friend in the end, that betrayal only adds another touch of pathos to the spectacle of helplessness and human weakness. It is only the favored few of mankind who are wiser and better, not feebler and less noble, as life draws toward its end.

Anne was, like Elizabeth, the daughter of a subject. Her mother, Anne Hyde, the daughter of the great Clarendon, though naturally subjected to the hot criticism of the moment on account of that virtue which refused anything less from her prince than the position of wife, was not a woman of much individual character, nor did she live long enough to influence much the training of her daughters. Historians have not hesitated to sneer at the prudence with which this young lady secured herself by marriage, when so many fairer than she were less scrupulous—a reproach which is somewhat unfair, considering what would certainly have been said of her had she not done so. Curiously enough, her own father, whether in sincerity or pretense, seems at the moment to have been her most severe critic, exculpating himself with unnecessary energy from all participation in the matter, and declaring that if it were true “the king should immediately cause the woman to be sent to the Tower” till Parliament should have time to pass an act cutting off her head. It would appear, however, from the contemporary narratives of Pepys and Evelyn that he was not so bad as his words, for he seems to have supported and shielded his daughter during the period of uncertainty which preceded the acknowledgment of her marriage, and to have shared in the general satisfaction afterward. But this great marriage was not of much advantage to her family. It did not hinder Clarendon’s disgrace and banishment, nor were his sons after him anything advantaged by their close relationship to two queens.{7}

The Duchess of York does not seem to have been remarkable in any way. She is said to have governed her husband; and she died a Roman Catholic,—the first of the royal family to lead the way in that fatal particular: but did not live long enough to affect the belief or training of her children.

There was an interval of three years in age between Mary and Anne. The eldest, Mary, was like the Stuarts, with something of their natural grace of manner; the younger was a fair English child, rosy and plump and blooming; in later life they became more like each other. But the chief thing they inherited from their mother was what is called in fine language, “a tendency to embonpoint,” with, it is said, a love of good eating, which helped to produce the other peculiarity.

The religious training of the princesses is the first thing we hear of them. They were put under the charge of a most orthodox tutor, Compton, Bishop of London, with much haste and ostentation—their uncle, Charles II., probably feeling with his usual cynicism that the sop of two extra-Protestant princesses would please the people, and that the souls of a couple of girls could not be of much importance one way or another. How they fared in respect to the other features of education is not recorded. Lord Dartmouth, in his notes on Bishop Burnet’s history, informs us that King Charles II., struck by the melodious voice of the little Lady Anne, had her trained in elocution by Mrs. Barry, an actress; while Colley Cibber adds that she and her sister were instructed by the well-known Mrs. Betterton to take their parts in a little court performance when Anne was but ten and Mary thirteen; but whether these are two accounts of the same incident, or refer to distinct events, seems doubtful.

The residence of the girls was chiefly at Richmond, where they were under the charge of Lady Frances Villiers, who had a number of daughters of her own, one of whom, Elizabeth, went with Mary to Holland, and was, in some respects, her{8} evil genius. We have, unfortunately, no court chronicle to throw any light upon the lively scene at Richmond, where this little bevy of girls grew up together, conning their divinity, whatever other lessons might be neglected; taking the air upon the river in their barges; following the hounds in the colder season, for this robust exercise seems to have been part of their training. When their youthful seclusion was broken by such a great event as the court mask, in which they played their little parts,—Mrs. Blogge, the saintly beauty, John Evelyn’s friend, Godolphin’s wife, acting the chief character, in a blaze of diamonds,—or that state visit to the city when King Charles in all his glory took the girls, his heirs, with him, no doubt the old withdrawing-rooms and galleries of Richmond rang with the story for weeks after. Princess Mary, her mind perhaps beginning to own a little agitation as to royal suitors, would have other distractions; but as to the Lady Anne, it soon came to be her chief holiday when the young Duchess of York, her stepmother, came from town in her chariot, or by water, in a great gilded barge breasting up the stream, to pay the young ladies a visit. For in the train of that princess was the young maid of honor, a delightful, brilliant espiègle, full of spirit and wilfulness, who bore the undistinguished name of Sarah Jennings, and brought with her such life and stir and movement as dispersed the dullness wherever she went.

There is no such love as a young girl’s adoration for a beautiful young woman, a little older than herself, whom she can admire and imitate and cling to, and dream of with visionary passion. This was the kind of sentiment with which the little princess regarded the bright and animated creature in her young stepmother’s train. Mary of Modena was herself only a few years older than her stepchildren. They were all young together, accustomed to the perpetual gaiety of the court of Charles II., though, let us hope, kept apart from its license, and{9}

no shadow of fate seems to have fallen upon the group of girls in their early peaceful days. Anne in particular would seem to have been left to hang upon the arm and bask in the smiles of her stepmother’s young lady in waiting at her pleasure—with many a laugh at premature favoritism. “We had used to play together when she was a child,” said the great duchess long after. “She even then expressed a particular fondness for me; this inclination increased with our years. I was often at court, and the princess always distinguished me by the pleasure she took to honor me preferably to others with her conversation and confidence. In all her parties for amusement, I was sure by her choice to be one.”

Mistress Sarah was one of the actors in the mask above referred to; she was in the most intimate circle of the Duke of York’s household, closely linked to all its members, in that relationship, almost as close as kindred, which binds a court together.

And no doubt it added greatly to the attractions which the bright and animated girl exercised over her playmates and companions, that she had already a romantic love-story, and, at a period when matches were everywhere arranged, as at present in continental countries, by the parents, made a secret marriage, under the most romantic circumstances, with a young hero already a soldier of distinction. He was not an irreproachable hero. Court scandal had not spared him. He was said to have founded his fortune upon the bounty of one of the shameless women of Charles’s court. But the imagination of the period was not over-delicate, and probably had he not become so great a man, and acquired so many enemies, we should have heard little of John Churchill’s early vices. About his sister, Arabella Churchill, unfortunately there could not be any doubt; and it is a curious instance of the sudden efflorescence now and then of a race which neither before nor after is of particular{10} note, that Marlborough’s sister should have been the mother of that one illustrious Stuart who might, had he been legitimate, have changed the fortunes of the house—the Duke of Berwick. Had she, instead of Anne Hyde, been James’s duchess, what a difference might have been made in history! Nobody had heard of the Churchills before—they have not been a distinguished race since. It is curious that they should have produced, all unawares, without preparation or warning, the two greatest soldiers of the age.

Young Churchill was attached to the Duke of York’s service, as Sarah Jennings was to that of the duchess. He had served abroad with distinction. In 1672, when France and England for once, in a way, were allies against Holland, he had served under the great Turenne, who called him “my handsome Englishman,” and vaunted his gallantry. He was but twenty-two when he thus gave proofs of his future greatness. When he returned, after various other exploits, and resumed his court service, the brilliant maid of honor, whom the little princess adored, attained a complete dominion over the spirit of the young soldier. There were difficulties about the marriage, for he had no fortune, and his provident parents had secured an heiress for him. But it was at length accomplished so secretly that even the bride was never quite certain of the date, in the presence and with the favor of Mary of Modena herself. Sarah, if the dates are correct, must have been eighteen at this period, and her little princess fourteen. What a delightful interruption to the dullness of Richmond to hear all about it when the Duchess of York came with her train and the two girls could wander away together in some green avenue till Lady Frances sent a page or an usher after them!

Mary of Modena must have been a lover of romances, and true love also, though her youth had fallen to such a gruesome bridegroom as James Stuart; for not only Sarah Jennings{11} and her great general, who were to have so great a hand in keeping that poor lady’s son from his kingdom, but Mary Blogge and her statesman, who was to rule England so wisely in the interest of the opposing side, were both secretly married under the young duchess’s wing, she helping, planning, and sanctioning the secret. How many additional bitternesses must this have put into her cup when she was sitting, a shadow queen, at St.-Germain, and all those people whom she had loved and caressed were swaying the fortunes of England! And who can tell what tender recollections of his secret wedding and the sweet and saintly prude whom King James’s young wife gave him, may have touched the soul of Godolphin in those hankerings after his old master—if it were not, as scandal said, to his old mistress—which moved him from time to time, great minister as he was, almost to the verge of treachery! The Churchills, it must be owned, showed little gratitude to their royal patrons.

When the Princess Mary married and went to Holland with her husband, the position of her sister at home became a more important one. Anne was not without some experience of travel and those educational advantages which the sight of foreign countries are said to bring. She went to The Hague to visit her sister. She accompanied her father, sturdy little Protestant as she was, when he was in disgrace for his religious views, and spent some time in Brussels, from which place she wrote to one of the ladies about the court a letter which has been preserved,—with just as much and as little reason as any other letter of a fifteen-year-old girl with her eyes about her, at a distance of two hundred years,—in which the young lady describes a ball she had seen, herself incognita, at which some gentlemen “danced extremely well—as well if not better than the Duke of Monmouth or Sir E. Villiers, which I think is very extraordinary,” says the girl, no doubt sincerely believing{12} that the best of all things was to be found at home. She had little difficulties about her spelling, but that was common enough. “As for the town,” says the Princess Anne, “methinks tho’ the streets are not so clean as in Holland, yet they are not so dirty as ours; they are very well paved and very easy—they only have od smells.” This is a peculiarity which has outlived her day, and it would seem to imply that England, even before the invention of sanitary science, was superior in this respect at least to the towns of the Continent.

After these unusual dissipations Anne remained in the shade until she married, in 1683, George, Prince of Denmark, a perfectly inoffensive and insignificant person, to whom she gave, during the rest of her life, a faithful, humdrum, but unbroken attachment, such as shows to little advantage in print, but makes the happiness of many a home. This marriage was another sacrifice to the Protestantism of England, and in that point of view pleased the people much. King Charles, glad to satisfy the country by any act which cost him nothing, thought it “very convenient and suitable.” James, unwilling, but powerless, grumbled to himself that “he had little encouragement in the conduct of the Prince of Orange to marry another daughter in the same interest,” but made no effort against it. The prince himself produced no very great impression, one way or another, as indeed he was little fitted to do. “He has the Danish countenance, blonde,” says Evelyn, in his diary; “of few words; spoke French but ill; seemed somewhat heavy, but is reported to be valiant.” He had never any occasion to show his valor during his long residence in England, but many to prove the former quality,—the heaviness,—which was only too evident; but Anne herself was not brilliant, and she was made for friendship, not for passion in the ordinary sense of the word. She never seems to have been in the smallest way dissatisfied with her heavy, honest goodman. He was fond of eating and{13}

drinking, but of no more dangerous pleasures. Her peace of mind was fluttered by no rival, nor her feminine pride touched. Her attendants might be as seductive as they pleased, this steady, stolid husband was immovable, and there is no doubt that the princess appreciated the advantages of this immunity from one of the thorns which were planted in every other royal pillow.

Her marriage had another advantage of giving her a household and court of her own, and enabled her at once to secure for herself the companionship of her always beloved friend. “So desirous was she,” says Duchess Sarah, “of having me always near her, that upon her marriage with the Prince of Denmark, in 1683, it was at her own earnest request to her father I was made one of the ladies of her bedchamber. What conduced to make me the more agreeable to her in this station was, doubtless,” she adds with candor, “the dislike she conceived to most of the other persons about her, and particularly for her first lady of the bedchamber—the Countess of Clarendon, a lady whose discourse and manner could not possibly recommend her to so young a mistress; for she looked like a mad-woman and talked like a scholar. Indeed, her highness’s court was so oddly composed that I think it would be making myself no great compliment if I should say her choosing to spend more of her time with me than with any of her other servants did no discredit to her taste.”

Lady Clarendon was the wife of the great chancellor’s son, and was thus the aunt, by marriage, of the princess—not always a very endearing relationship. She was not a great lady by birth, and though a friend of Evelyn’s and a highly educated woman, might easily be supposed to be a little oppressive in a young household where her relationship gave her a certain authority.

The prince was dull, the princess had not many resources.{14} They settled down in homely virtue, close to the court with all its scandals and gaieties, but not quite of it; and nothing could be more natural than that Anne should eagerly avail herself of the always amusing, always lively companion who had been the friend of her youth. The Cockpit, which was Anne’s residence, had been built as a royal playhouse, first for the sport indicated by its name, then for the more refined amusements of the theater, but had been afterward turned into a private residence, and bought by Charles II. for his niece on her marriage. It formed part of the old palace of Whitehall, and must have been within sight and sound of the constant gaieties going on in that lawless household, in the best of which the princess and her attendant would have their natural share. No doubt to hear Lady Churchill’s lively satirical remarks upon all this, and the flow of her brilliant malice, must have kept the household lively, and brightened the dull days and tedious waitings of maternity, into which Anne was immediately plunged, drawing a laugh even from stupid George in the chimney-corner. And there was this peculiarity to make the whole more piquant; that it was virtue, irreproachable, and no doubt pleasantly self-conscious of its superiority, which thus got its fun out of vice. The two young couples on the other side of the way were immaculate, devoted exclusively to each other, thinking of neither man nor woman save their lawful mates. Probably neither the princess nor her lady in waiting were disgusted by gossip about the Portsmouths and Castlemaines, but took these ladies to pieces with indignant zest and spared no jibe. And though the remarks might be too broad for modern liking, and the fun somewhat unsavory, we cannot but think that amidst the noisy and picturesque life of that wild Restoration era, full of corruption, yet so gay and sparkling to the spectator, this little household of the Cockpit is not without its claims upon our attention. There was not in all Charles’s court so splendid a{15} couple as the young Churchills: he already one of the most distinguished soldiers of the age, she a beautiful young woman overflowing with wit and energy. And Princess Anne was very young; in full possession of that beauté de diable which, so long as it lasts, has its own charm, the beauty of color and freshness and youthful contour. She had a beautiful voice, the prettiest hands, and the most affectionate heart. If she were not clever, that matters but little to a girl of twenty, taught by love to be receptive, and called upon for no effort of genius. Honest George behind backs was not much more than a piece of still life, but an inoffensive and amiable one, taking nothing upon him. If there was calculation in the steadfastness with which the abler pair possessed themselves of the confidence, and held fast to the service of their royal friends, it would be hard to assert that there was not some affection too, at least on the part of Sarah, who had known every thought of her little princess’s heart since she was a child, and could not but be flattered and pleased by the love showered upon her. At all events, in Anne there was no unworthy sentiment; everything about her appeals to our tenderness. When she attained what seems to have been the summit of her desires and secured her type of excellence, the admired and adored paragon of her childhood, for her daily companion, the formal titles and addresses which her rank made necessary became irksome beyond measure to the simple-hearted young woman whose hard fate it was to have been born a princess. The impetuosity of her affection, her rush, so to speak, into the arms of her friend, her pretty youthful sentiment, so fresh and natural, her humility and simplicity, are all pleasant to contemplate. Little more than a year after her marriage, after the closer union had begun, she writes thus:

If you will let me have the satisfaction of hearing from you again before I see you, let me beg of you not to call me “your highness” at{16} every word, but to be as free with me as one friend ought to be with another. And you can never give me any greater proof of your friendship than in telling me your mind freely in all things, which I do beg of you to do: and if it ever were in my power to serve you, nobody would be more ready than myself. I am all impatience for Wednesday. Till then farewell.

Upon this there ensued a little sentimental bargain between the two young women. It was not according to the manners of the time that they should call each other Anne and Sarah, and the fashion of the Aramintas and Dorindas had not yet arrived from Paris. They managed the transformation necessary in a curiously matter-of-fact and English way:

She grew uneasy to be treated by me with the form and ceremony due to her rank; nor could she bear from me the sound of words which implied in them distance and superiority. It was this turn of mind which made her one day propose to me that whenever I should happen to be absent from her we might in all our letters write ourselves by feigned names, such as would import nothing of distinction of rank between us. Morley and Freeman were the names her fancy hit upon, and she left me to choose by which of them I should be called. My frank open temper led me naturally to pitch upon Freeman, and so the princess took the other; and from this time Mrs. Morley and Mrs. Freeman began to converse as equals, made so by affection and friendship.

Very likely these were the names in some young lady’s book which had been in the princess’s childish library,—something a generation before the “Spectator,”—in which rural virtues and the claims of friendship were the chief subjects. Morley is one of the typical names of sentimental literature in the eighteenth century, and might be originally introduced by some precursor of those proper little romances which have in all ages been considered the proper reading for “the fair.”

Mrs. Morley could be no other than the gentle ingénue, the type of modest virtue, and Freeman was of all others the title most suitable for Sarah, the bright and brave. Historians have not been able to contain themselves for angry ridicule of this{17}

little friendly treaty. To us it seems a pretty incident. The princess was twenty, the bedchamber woman twenty-four. Their friendly traffic had not to their own consciousness attained the importance of a historical fact.

The locality in which the royal houses in London stood was very different then from its appearance now. Whitehall at present is a great thoroughfare, full of life and movement, with but one remnant of the old palace,—once the banqueting-hall, now the chapel royal, where the window out of which Charles I. is supposed to have passed to the scaffold is pointed out to strangers,—and still presenting a bit of gloomy, stately front to the street.

St. James’s Park opposite is screened off and separated now by the Horse Guards and other public buildings, a long and heavy line which forms one side of the way. But in those days there were neither public buildings nor busy street. The palace, straggling and irregular, with walls and roofs on many different levels, stood like a sort of royal village between the river and the park, with the turrets of St. James twinkling in the distance, in the sunshine, over the trees of the Mall, where King Charles with all his dogs and gentlemen would stream forth daily for his saunter or his game. The Cockpit was one of the outlying portions of Whitehall upon the edge of the park.

Anne had been but two years married when King Charles died. And then the aspect of affairs changed. The mass in the private chapel, and the presence here and there of somebody who looked like a priest, at once started into prominence and began to alarm the gazers more than the dissolute amusements of the court had ever done. James was not virtuous any more than his brother. One of the first acts which the excellent Evelyn, one of the best of men, had to do as commissioner of the privy seal, was to affix that imperial stamp to a patent by{18} which one of the new king’s favorites was made Countess of Dorchester; but James’s immoralities were not his chief characteristics. He was a more dangerous king than Charles, who was merely selfish, dissolute, and pleasure-loving. James was more; he was a bigoted Roman Catholic, eager to raise his faith to its old supremacy, and the mere thought that the door which had been so bolted and barred against popery was now set open filled all England with the wildest panic. The nation felt itself caught by the torrent which must carry it to destruction. Men saw the dungeons of the Inquisition, the fires of Smithfield, before them as soon as the proscribed priest was readmitted and mass once more openly said at an unconcealed altar. Never was there a more universal or all-influential sentiment. The terror, the unanimity, are things to wonder at. Sancroft and his bishops were not constitutionalists. The personal rule of the king had nothing in it that alarmed them; but the idea of the reintroduction of popery awoke such a panic in their bosoms as drove them, in spite of their own tenets, into resistance; and, for the first time absolutely unanimous, England was at their back. When we take history piecemeal, and read it through the individual lives of the chief actors, we perceive with the strangest sensations of surprise that at these great crises not one of the leaders of the nation was sure what he wanted or what he feared, or was even entirely sincere in his adherence to one party against another. They were the courtiers of James, and invited William; they were William’s ministers, and kept up a correspondence with James. The best of them was not without a treacherous side. They were never certain which was safest, which would last; always liable to lend an ear to temptations from the other party, never sure that they might not to-morrow morning find themselves in open rebellion against the master of to-day. Yet, while almost every individual of note was subject to this strange uncertainty, this confused{19} and troubled vacillation, there was such a sweep of national conviction, so strong a current of the general will, that the supposed leaders of opinion were carried away by it, and compelled to assume and act upon a conviction which was England’s, but which individually they did not possess. Nothing can be made more remarkable, more unexplainable under any other interpretations, than the way in which his entire court, statesmen, soldiers, all who were worth counting, and so many who were not, abandoned King James—some with a sort of consternation, not knowing why they did it, driven by a force they could not resist. No example of this can be more remarkable than that of Clarendon, who received the news of his son’s defection to the Prince of Orange with what seems to be a heartbroken cry: “O God! that my son should be a rebel!” yet, presently, ten days afterward, is drawn away himself in a kind of extraordinary confusion, like a man in a dream, like a subject of mesmeric influence, although in all the following negotiations he maintained James’s cause as far as a man could who did not accept ruin as a consequence. Scarcely one of these men was whole-hearted or had any determined principle in the matter. But in the mass of the nation behind them was a force of conviction, of panic, of determination, that carried them off their feet. The chief names of England appear little more than straws upon the current, indicating its course, but forced along by its fierce sweep and impetus, and not by any impulse of their own.

The Princess Anne occupied a very different position from that of these bewildered statesmen. She had been brought up in the strictest sect of her religion, Protestant almost more than Christian, a churchwoman above all. To those who are capable of thinking about their faith it is always possible to believe in the thoughts of other people, and conceive the likelihood, at least, that they, in their own esteem, if not in any one else’s,{20} may be right—which is the only true foundation of toleration. But it is the people who believe without thinking, who receive what they are taught without exercising any judgment of their own upon the subject, and cling to it in exactly the same form in which they received it, with a conviction that its least important detail is as necessary as its first principle, who furnish that sancta simplicitas which makes the cruelest persecution possible without turning the persecutors into fiends and barbarians. Though her mother had been a Roman Catholic, and her father was one, and though many of her relations belonged to the old church, Anne was a Protestant of the most unyielding kind. She was in herself as good a type of the England of her time as could have been found, far better than her abler and larger-minded advisers. The narrowness of her mind and the rigidity of her faith were above all reassurances of reason, all guarantees of possibility. She was as much dismayed by her father’s determination to liberate and tolerate popery as the least enlightened of his subjects. “Methinks it has a very dismal prospect,” she wrote as early as 1686, only the year after James’s accession. “Attempts,” Lady Marlborough tells us, “were made to draw his daughter into his designs. The king, indeed, used no harshness with her; he only discovered his wishes by putting into her hands some books and papers which he hoped might induce her to a change of religion, and had she had any inclination that way the chaplains about were such divines as could have said but little in defense of their own religion or to secure her against the pretenses of Popery recommended to her by a father and a king.” This low estimate of the princess’s spiritual advisers is whimsically supported by Evelyn’s opinion of Anne’s first religious preceptor,—Bishop Compton,—of whom the courtly philosopher declared after hearing a sermon from him that “this worthy person’s talent is not preaching.”{21}

But Anne required no persuading to stimulate her in the fear of popery and narrow devotion to the church, outside of which she knew of no salvation. No doubt her father’s popish tracts, things which in that age were held to possess many of the properties of the dynamite of to-day, scared the inflexible and unimaginative churchwoman as much as if they had been capable of exploding and doing her actual damage. Her training, so wisely adapted to please the Protestant party, had probably been thought by her father and uncle to be a matter of complete indifference on any other ground; but in this way they reckoned altogether without their princess. With both James’s daughters the process was too successful. They feared popery more than they loved their father. There seems not the slightest reason to suppose that Anne was insincere in her anxiety for the church, or that the panic which she shared with the whole country was affected or unreal. It is impossible that she could expect her own position to be improved by the substitution of her sister and her sister’s husband for the father who had always been kind to her. The Churchills, whose church principles were not perhaps so undeniable, and whose regard for their own interest was great, are more difficult to divine; and yet it appears an unnecessary thing to refer their action to unworthy motives. It is asserted by some that they had some visionary plan after they had overturned the existing economy by the help of William, of bringing in their princess by a side wind and reigning through her over the startled and subjugated nation. But granting that such an imagination might have been conceived in the fertile and restless brain of a young and sanguine woman, it seems impossible to imagine that Churchill—a man of some experience in the world, and some knowledge of William—could even for a moment have believed that the grave and ambitious prince, who was so near the throne, could have been persuaded or forced to waive his wife’s claims, and those still more imperative ones{22} which his position of Deliverer gave him, in order to advance the fortunes of any one else, least of all of the sister-in-law whom he despised.

It is half ludicrous, half pathetic, in the midst of all the tumult and confusion of the time, to note the constant allusions to the princess’s condition, which recurs whenever she is mentioned. There were always reasons why it should be especially cruel to disturb her, and her state had constantly to be taken into account. It was very natural in such circumstances that she should more and more cling to her stronger friend, and find no comfort out of her presence. “Whatever changes there are in the world, I hope you will never forsake me, and I shall be happy,” she writes during this period of excitement and distress. She herself was weak and not very wise. In a sudden emergency neither she nor her husband were good for much. They could carry on the routine of life well enough, but when unforeseen necessities came they stood helpless and bewildered; but Lady Churchill was quick of wit and full of inexhaustible resource. To her it was always given to know what to do.

It is unnecessary here to enter into the history of what is called the Great Revolution. It is the great modern turning-point of English history, and no doubt it is one of the reasons why we have been exempted in later days from the agitations of desperate and bloody revolutions which have shaken all neighboring nations. Glorious and happy, however, scarcely seem to be fit words to describe this extraordinary event. A more painful era does not exist in history. There is scarcely an individual in the front of affairs who was not guilty of treachery at one time or another. They betrayed one another on every hand; they were perplexed, uncertain, full of continual alarms. The king who went away was a gloomy bigot; the king who came was a cold and melancholy alien. Enthusiasm there was none, nor even conviction, except of the necessity of doing something{23} of a wide-reaching and undeniable change. The part which the ladies at the Cockpit played brings the hurry and excitement of the movement to its crisis. Both in their way were anxious for their respective husbands, absent in the suite of James, and still in his power. When the report came that Lord Feversham had begged of James “on his knees two hours” to order the arrest of Churchill, Mrs. Freeman must have needed all her courage; while the faithful Morley wept, yet tried to emulate the braver woman, wondering in her excitement what her own heavy prince was doing, and eager for William’s advance, which, somehow or other, was to bring peace and quiet. That heavy prince meanwhile was mooning about with the perplexed and unhappy king, uttering out of his blond mustache with an atrocious accent his dull wonder, “Est il possible?” as every new desertion was announced, till mounting heavily one evening after dinner, warmed and encouraged by a good deal of King James’s wine, and riding through the cold and dark, in his turn he deserted too. When this event happened, the excitement at the Cockpit was overwhelming. The princess was “in a great fright.” “She sent for me,” says Lady Churchill, “told me her distress, and declared that rather than see her father, she would jump out of window.” King James was coming back to London, sad and wroth, and perhaps the rumor that he would have her arrested lent additional terrors to the idea of encountering his angry countenance. Lady Churchill went immediately to Bishop Compton, the princess’s early tutor and confidential adviser, and instant means were taken to secure her flight. That very night, after her attendants were in bed, Anne rose in the dark, and with her beloved Sarah’s arm and support stole down the back stairs to where the bishop, in a hackney coach, was waiting for her. Other princesses in similar situations have owned to a thrill of pleasure in such an adventure. No doubt at least she breathed the freer when she was out of{24} the palace where King James with his dark countenance might have come any day to demand from her an account of her husband’s behavior, or to upbraid her with her own want of affection. Anyhow, the sweep of the current had now reached her tremulous feet, and she had no power any more than stronger persons of resisting it.

Anne’s position was very much changed by the Revolution. If any ambitious hopes had been entertained or plans formed by her household, they were speedily and very completely brought to an end. The dull royal pair with their two brilliant guides and counselors now found themselves confronted by another couple of very different mark: the serious, somewhat gloomy, determined, and self-concentrated Dutchman, and the new queen, Mary, a person far more attractive and imposing than Anne; two people full of character and power. We have no space here, however, to appropriate to these remarkable persons. William, in particular, belongs to larger annals and a history more important than these sketches. Mary has left an epitome of herself in her letters which is among the most wonderful of individual revelations; but this cannot now be our theme, though the subject is a most attractive one.

Two persons so remarkable threw into the shade even Churchill and Sarah, much more good Anne and George. We have no reason to suppose that Mary entertained any particular sentiment whatever toward her sister, from whom she had been entirely separated for the greater part of her life, and the history of their relations is a painful one from beginning to end. No doubt the queen regarded the household of the princess with the contempt which a woman with so entirely different a code would naturally entertain for a family in which the heads were so lax and secondary, the counselors so prominent. There was nothing in Mary which would help her to understand the feeling with which Anne regarded her friend{25}

Mary. She had herself made use of their influence in the time when it was all important to secure every power in England for William’s service, but a proud distaste for the woman whom the princess trusted as her equal soon awoke in the bosom of the queen. The Churchills, however, served the new sovereigns signally by persuading the princess to yield her own rights, and consent to the conjoint reign, and to William’s life sovereignty—no small concession on the part of the next heir, and one which only the passive character of Anne could have made to appear insignificant.

Had she been a stronger and more intellectual woman, this act would have borne the aspect of a magnanimous and noble sacrifice to the good of the country, of her own interests, and that of her children. As it was, her self-renunciation has got her very little credit, either then or now, and it has been considered rather an evidence of the discretion of the Churchills than of the generosity and patriotism of the princess. These, perhaps, are rather large words to use in speaking of Anne, but it must be remembered that a narrow mind is usually not less, but more, tenacious of personal honor and advantage than a great one, and that the dimmer an understanding may be, the less it is accessible to high reason and noble motive. This sacrifice accomplished, however, there commenced a petty war between Whitehall and the Cockpit, in which perhaps Mary and Lady Churchill (now Marlborough) were the chief combatants, but which from henceforward until her sister’s death became the principal feature in Anne’s life. Continued squabbling is never lovely even when it is between queens and princesses, but in this case the injured person has had no little injustice, and the offender so many partizans that it may not be amiss to make Anne’s side of the question a little more apparent.

If her friend was to blame for embroiling Anne with the queen, it can scarcely be believed that the princess’s case would{26} have been more satisfactory had she been left in her helplessness to the tender mercies of William, and entirely dependent upon his kindness, which must have happened had there been no bold and strong adviser in the matter. There was no generosity in the treatment which Anne received from the royal pair. She had made a sacrifice to the security of their throne which deserved some grace in return. But her innocent fancy for the palace at Richmond, where the sisters had been brought up together, was not indulged, nor would there be much excuse even if she were in the wrong for the squabblings about her lodging at Whitehall. But she cannot be said to have been in the wrong in the next question which occurred, which was the settlement of her own income. This she had previously drawn from her father, according to the existing custom in the royal family, and James had been always liberal and kind to her. But it was a different thing to depend upon the somewhat grudging hand of an economical brother-in-law, who had a number of foreign dependents to provide for, and a great deal to do with the money granted to him. He alarmed her friends on this point at once by a remark made to Clarendon as to what the princess could want with so large an income as thirty thousand a year; and he does not seem at any time or in any particular to have shown consideration for her. Perhaps the Churchills were afraid that their mistress would be less able than usual to help and further their own fortunes, as is universally alleged against them; but, had they been the most disinterested couple in the world, it would still have been their duty to do what they could to secure her against any caprice of the new king, who had no right to be the arbiter of her fate. Lady Marlborough’s strenuous action to bring the question to the decision of Parliament was nothing less than her mistress’s interests demanded. And the sense of the country was so far with them that the princess’s income was settled with very little{27} difficulty upon a more liberal basis than her father’s allowance; which, considering that she, and the children of whom she was every year becoming the mother, were the only acknowledged heirs of the throne, was a perfectly natural and just arrangement.

But the king and queen did not see it in this light. “Friends! what friends have you but the king and me?” Queen Mary asked with indignation. It is not to be supposed that she meant any harm to her sister, but with also a sufficiently natural sentiment could not see what Anne’s objection was to dependence upon herself.

The position on both sides is so clearly comprehensible that the strength of party feeling which makes Lord Macaulay defend the somewhat petty attitude of his favorite monarch on the occasion is very extraordinary. It requires no very subtle penetration to see the difference between an allowance that comes from a father and that which depends upon the doubtful friendship of a brother-in-law. Anne had fully proved her capacity to consider the public weal above her own, and it was unworthy of William even to wish to keep in the position of a hanger-on a woman who had so greatly promoted the harmony of his own settlement.

Parliament finally voted her a revenue of fifty thousand pounds a year, as a sort of compromise between the thirty thousand pounds which King William grudged her and the unreasonably large sum which some of her supporters hoped to obtain; but the king and queen never forgave her, and still less her advisers, for what they chose to consider a want of confidence in themselves.

But William was always impatient of the incapable, and the permission was absolutely denied to him. In all these claims and refusals the position of Lady Marlborough as the princess’s right hand had been completely acknowledged by Queen Mary{28} and her husband, who indeed attempted secret negotiations with her on more than one occasion to induce her to moderate Anne’s claims and to persuade her into compliance with their wishes. “She [the queen] sent a great lord to me to desire I would persuade the Princess to keep the Prince from going to sea; and this I was to compass without letting the Princess know it was the Queen’s desire ... after this the Queen sent Lord Rochester to me to desire much the same thing. The Prince was not to go to sea, and this not going was to appear his own choice.”

Similar attempts were made in the matter of the allowance. And it is scarcely possible to believe that Mary, a queen who was not without some of the absolutism of the Stuart mind, should have failed to feel a certain exasperation with the bold woman who thus upheld her sister’s little separate court and interest, and was neither to be flattered nor frightened into subservience. And very likely this little separate court was a thorn in the side of the royal pair, keeping constant watch upon all their actions, maintaining a perpetual criticism, no doubt leveling many a jibe at the Dutch retainers, and still more at the Dutch master. Good-natured friends, even in the capacity of courtiers, were no doubt found to whisper in the presence-chamber the witticisms with which Sarah of Marlborough would entertain her mistress—utterances not very brilliant, perhaps, but sharp enough. It would not sweeten the temper of the queen if she found out, for instance, that her great William was known as Caliban in the correspondence of Mrs. Morley and Mrs. Freeman. A hundred petty irritations always come in in such circumstances to increase a breach. What the precise occurrence was which brought about the final explosion is not known, but one day after a stormy scene, in which the queen had in vain demanded from her sister the dismissal of Lady Marlborough, an event occurred which took away everybody’s breath.{29}

This was the sudden dismissal, without reason assigned, at least so far as the public knew, of Lord Marlborough from all his offices. He was lieutenant-general of the army, and he was a gentleman of the king’s bedchamber. Up to this time there had been nothing to find fault with in his conduct. William was too good a soldier himself not to appreciate Marlborough’s military talents, and he had behaved, if not with any enthusiasm for the new order of affairs, with good taste at least in very difficult circumstances. His desertion of James and his powerful presence and influence on the opposite side had contributed much to the bloodless victory of the Prince of Orange; but except so far as this went, Marlborough had shown no hostility to his old master. In the convention he had voted for a regency, and when it became evident that William’s terms must be accepted unconditionally or not at all, he had refrained from voting altogether; so that his support might be considered lukewarm. But, on the other hand, he had served with great distinction abroad, acting with perfect loyalty to his new chief while in command of the English forces. In short, his public aspect up to this time would seem on the face of it to have been irreproachable.

This being the case, his sudden dismissal from court filled his friends with astonishment and dismay. Nobody understood its why or wherefore. “An incident happened which I unwillingly mention,” says Bishop Burnet, “because it cannot be told without some reflection on the memory of the queen, whom I always honored beyond all the persons whom I have ever known.” This regretful preface affords an excellent guarantee of the bishop’s sincerity; but Lord Macaulay omits his statement of the case altogether while quoting passages from the then unpublished manuscript which seemed to support his own views. “The Earl of Nottingham,” Burnet continues, “came to the Earl of Marlborough with a message from the King telling him{30} that he had no more use for his services, and therefore he demanded all his commissions. What drew so sudden and hard a message was not known, for he had been with the King that morning and had parted with him in the ordinary manner. It seemed some letter was intercepted that gave suspicions: it is certain that he thought he was too little considered, and that he had upon many occasions censured the King’s conduct and reflected on the Dutch.” Lord Macaulay, on the other hand, ignoring this statement, assures his readers that the real ground of the dismissal had been communicated to Anne on the previous night (notwithstanding that the great general had been privileged to put on the king’s shirt next morning as if nothing had happened), and that it was in reality the discovery of a plot for James’s restoration, conceived by Marlborough, and in which the princess herself was implicated. It was reported to be Marlborough’s intention to move in the House of Lords an address to William, requesting him to dismiss the foreign servants who surrounded him, and of whom the English were bitterly jealous. Such a scheme of reprisals would have had a certain humor in its summary reversal of the position, and no doubt must Sarah herself have had some hand in its construction, if it ever existed. William was as little likely to give up Bentinck and Keppel as Anne was to sacrifice the friends whom she loved, and a breach between the Parliament and the king would have been, it was hoped, the natural result—to be followed by a coup d’état, in which James might be replaced under stringent conditions upon the throne. The sole evidence for this plot is King James himself, who describes it in his diary. Lord Macaulay adds that it is strongly confirmed by Burnet, but this, we take leave to think, is not the case. At the same time there seems no reason to doubt King James, who adds that the plan was defeated by the indiscreet zeal of some of his own fidèles, who feared that Marlborough, were he{31} once master of the situation, would put Anne on the throne instead of her father.

Whether, however, this supposed proposal was, or was not, the reason of Marlborough’s dismissal, it is clear enough that he had resumed a secret correspondence with the banished king at St.-Germain, whom, not very long before, he had deserted. But so had most of the statesmen who surrounded William, even the admiral in whose hands the English reputation at sea was soon to be placed. The sins of the others were winked at while Maryborough was thus made an example of: perhaps because he was the most dangerous; perhaps because he had involved the princess in his treachery, persuading her to send a letter and make affectionate overtures to her father. Is it possible that it was this very letter which Burnet says was intercepted, inclosed most likely in one from Marlborough more distinct in its offers? Here is Anne’s simple performance, a thing not calculated to do either harm or good:

I have been very desirous of some safe opportunity to make you a sincere and humble offer of my duty and submission, and to beg you will be assured that I am both truly concerned for the misfortunes of your condition, and sensible as I ought to be of my own unhappiness: as to what you may think I have contributed to it, if wishes could recall what is past, I had long since redeemed my fault. I am sensible that it would have been a great relief to me if I could have found means to have acquainted you earlier with my repentant thoughts, but I hope they may find the advantage of coming late—of being less suspected of insincerity than perhaps they would have been at any time before. It will be a great addition to the ease I propose to my own mind by this plain confession, if I am so happy as to find that it brings any real satisfaction to yours, and that you are as indulgent and easy to receive my humble submissions as I am to make them in a free disinterested acknowledgment of my fault, for no other end but to deserve and receive your pardon.

These involved and halting sentences by themselves could afford but little satisfaction to the anxious banished court at{32} St.-Germain. To say so much, yet to say so little, though easy to a confused intelligence, not knowing very well what it meant, is a thing which would have taxed the powers of the most astute conspirators. But there could be little doubt that a penitent princess thus ready to implore her father’s pardon, would be a powerful auxiliary, with the country just then in the stage of natural disappointment which is prone to follow a great crisis, and that Marlborough was doubly dangerous with such a card in his hands to play.

A little pause occurred after his dismissal. The court by this time had gone to Kensington, out of sight and hearing of the Cockpit, Whitehall having been burned in the previous year. The princess continued, no doubt in no very friendly mood, to take her way to the suburban palace in the evenings and make one at her sister’s game of basset, showing by her abstraction, and the traces of tears about her eyes, her state of depression yet revolt. But about three weeks after that great event, something suggested to Lady Marlborough the idea of accompanying her princess to the royal presence. It was strictly within her right to do so, in attendance on her mistress, and perhaps it was considered in the family council at the Cockpit that the existing state of affairs could not go on, and that it was best to end it one way or another. One can imagine the stir in the ante-chambers, the suppressed excitement in the drawing-room, when the princess, less subdued than for some weeks past, her eyes no longer red, nor the corners of her mouth drooping, came suddenly in out of the night, with the well-known buoyant figure after her, proud head erect and eyes aflame, her mistress’s train upon her arm, but the air of a triumphant queen on her countenance. There would be a pause of consternation—and for a moment it would seem as if Mary, thus defied, must burst forth in wrath upon the culprit. What glances must have passed between the court ladies behind their fans! What whispers in the{33}

corners! The queen, in the midst, pale with anger, restraining herself with difficulty; the princess, perhaps beginning to quake; but Sarah, undaunted, knowing no reason why she should not be there—“since to attend the princess was only paying her duty where it was owing.”

But next morning brought, as they must have foreseen it would bring, a royal missive, meant to carry dismay and terror, in which Mary commanded her sister to dismiss her friend and make instant submission. “I tell you plainly Lady Marlborough must not continue with you in the circumstances in which her lord is,” the queen wrote; “never anybody was suffered to live at court in my Lord Marlborough’s circumstances.” There is nothing undignified in Mary’s letter. She was in all respects more capable of expressing herself than her sister, and she had so far right on her side that Lady Marlborough’s appearance at court was little less than a deliberate insult to her. “I have all the reason imaginable to look upon you bringing her here as the strangest thing that ever was done, nor could all my kindness for you have hindered me showing you that moment, but I considered your condition, and that made me master of myself so far as not to take notice of it there,” the queen said. The princess’s condition had often to be taken into consideration, and perhaps she was not unwilling that her superiority in this respect to her childless sister should be fully evident. She was then within a few weeks of her confinement—not a moment when an affectionate and very dependent woman could lightly be parted from her bosom friend.

Thus the situation was brought to a climax. It was not to be expected, however, that Anne could have submitted to a mandate which in reality would have taken from her all power to choose her own friends; and her affections were so firmly fixed upon her beloved companion that it is evident life without Sarah would have been a blank to her. She answered in a letter studiously{34} compiled in defense both of herself and her retainer. “I am satisfied she cannot have been guilty of any fault to you, and it would be extremely to her advantage if I could here repeat every word that ever she had said to me of you in her whole life,” says the princess; and she ends entreating her sister to “recall your severe command,” and declaring that there is no misery “that I cannot readily resolve to suffer rather than the thought of parting with her.” But things had gone too far to be stopped by any such appeal. The letter was answered by the lord chamberlain in person with a message forbidding Lady Marlborough to continue at the Cockpit. This was arbitrary in the highest degree, for the house was Anne’s private property, bought for and settled upon her by Charles III.; and it was unreasonable, for Whitehall was lying in ruins, and Queen Mary’s sight at Kensington could not be offended by the spectacle of the couple who had so annoyed her. The princess’s spirit was roused. She wrote to her sister that she herself would be “obliged to retire,” since such were the terms of her continuance, and sent immediately to the Duke of Somerset to ask for a lease of Sion House. It is said that William so far interfered in the squabble—in which indeed he had been influential all along—as to ask the duke to refuse this trifling favor. But of all English noble houses the proud Somersets were the last to be dictated to; and Anne established herself triumphantly in her banishment on the banks of the Thames with her favorite at her side.

A child was born a little later, and the queen paid Anne an angry visit of ceremony a day or two after the event, saying nothing to her but on the vexed subject. “I have made the first step by coming to you,” Mary said, approaching the bed where the poor princess lay, sad and suffering, for her baby had died soon after its birth, “and I now expect you should make the next by removing Lady Marlborough.” The princess, “trembling,{35} and as white as her sheet,” stammered forth her plaintive protest that this was the only thing in which she had disobliged her sister, and that “it was unreasonable to ask it of her,” whereupon Mary, without another word, left the room and the house. It was the last time they ever met, unlikely as such a thing seemed. Anne made various overtures of reconciliation, but as unconditional obedience was promised in none, Mary’s heart was not softened.

The only justification that can be offered for the queen’s behavior was that they had been long separated and had little but the formal tie of relationship to bind them to each other. Anne had been but a child when Mary left England. They were both married and surrounded by other affections when they met again. They had so much resemblance of nature that each seems to have been capable of but one passion. It was Mary’s good fortune to love her husband with all her heart—but to all appearance no one else. She had not a friend among all the ladies who had shared her life for years—no intimate or companion who could give her any solace when he was absent. Natural affection was not strong in their family. They had no mother, nor bond of common relationship except the father whom they both superseded. All this explains to a certain extent her coldness to Anne, and it is very likely she thought she was doing the best thing possible for her sister in endeavoring to separate her from an evil influence, an inferior who was her mistress. But this does not excuse the paltry and cruel persecution to which the younger sister was henceforward exposed. Every honor that belonged to her rank was taken from her, from the sentry at her door to the text upon her cushion at church. She was allowed no guard; when she went into the country the rural mayors were forbidden to present addresses to her and pay the usual honors which mayors delight to pay. The great court ladies were given to understand that whoever visited her would{36} not be received by the queen. A more irritating and miserable persecution could not be, nor one more lowering to the character of the chief performer in it.

Anne was but recovering from the illness that followed her confinement, and with which her sister’s angry visit was supposed to have something to do, when another blow fell upon the band of friends. Marlborough was suddenly arrested and sent to the Tower. There was reason enough perhaps for his previous disgrace in the secret relations with St.-Germain which he was known to have resumed; but the charge afterward made was a purely fictitious one, and he and the other great personages involved had little difficulty in proving this innocence. The correspondence which took place while Lady Marlborough was in town with her husband on this occasion reveals Anne very clearly in her affectionate simplicity.

I hear Lord Marlborough is sent to the Tower; and though I am certain they have nothing against him, and expected by your letter it would be so, yet I was struck when I was told it; for methinks it is a dismal thing to have one’s friends sent to that place. I have a thousand melancholy thoughts, and cannot help fearing they hinder you from coming to me; though how they can do that without making you a prisoner, I cannot imagine. I am just told by pretty good hands that as soon as the wind turns westerly there will be a guard set upon the prince and me. If you hear there is any such thing designed and that ’tis easy to you, pray let me see you before the wind changes: for afterward one does not know whether they will let one have opportunities of speaking to one another. But let them do what they please, nothing shall ever vex me, so I can have the satisfaction of seeing dear Mrs. Freeman; and I swear I would live on bread and water between four walls with her without repining; for so long as you continue kind, nothing can ever be a real mortification to your faithful Mrs. Morley, who wishes she may never enjoy a moment’s happiness in this world or the next if ever she proves false to you.

Whether the wind proving “westerly” was a phrase understood between the correspondents, or if it had anything to do{37} with the event of the impending battle on which the fate of England was hanging, it is difficult to tell. If it was used in the latter sense, the victorious battle of La Hogue, by which all recent discomfitures were redeemed, soon restored the government to calm and the consciousness of triumph, and made conspiracy comparatively insignificant. Before this great deliverance was known, Anne had written a submissive letter to her sister, informing her that she had now recovered her strength “well enough to go abroad,” and asking leave to pay her respects to the queen. To which Mary returned a stern answer declaring that such civilities were unnecessary as long as her sister declined to do the thing required of her. Anne sent a copy of this letter to Lady Marlborough, announcing, as she was now “at liberty to go where I please by the queen refusing to see me,” her intention of coming to London to see her friend, but this intention does not seem to have been carried out. “I am very sensibly touched with the misfortune that my dear Mrs. Freeman has had in losing her son, knowing very well what it is to lose a child,” the princess writes, “but she, knowing my heart so well and how great a share I have in all her concerns, I will not say any more on this subject for fear of renewing her passion too much.” Throughout this separation these little billets were continually coming and going, and we cannot do better than transcribe for the reader some of those innocent letters, so natural and full of the writer’s heart.

Though I have nothing to say to my dear Mrs. Freeman I cannot help inquiring how she and her Lord does. If it be not convenient for you to write when you receive this, either keep the bearer till it is, or let me have a word from you by the next opportunity when it is easy to you, for I would not be a constraint to you at any time, much less now when you have so many things to do and think of. All I desire to hear from you at such a time is that you and yours are well, which next to having my Lord Marlborough out of his enemies’ power, is the{38} best news that can come to her, who to the last moment of her life will be dear to Mrs. Freeman’s....