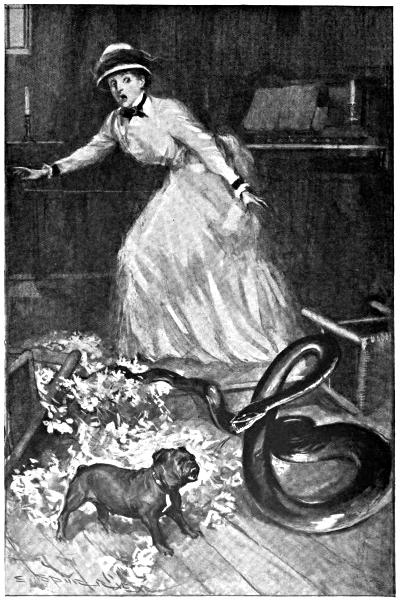

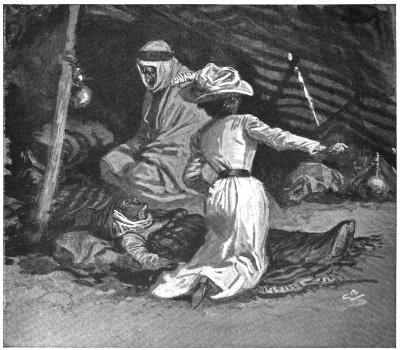

“THE PYTHON LITERALLY LEAPT AT HER, STRIKING AGAIN AND AGAIN.”

Title: The Wide World Magazine, Vol. 22, No. 129, December, 1908

Author: Various

Release date: January 9, 2017 [eBook #53928]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Victorian/Edwardian Pictorial Magazines,

Jonathan Ingram and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Vol. XXII. DECEMBER, 1908. No. 129

By Mrs. K. Compton.

A lady’s account of the fearful ordeal she underwent as a young girl on an estate in Natal—locked up in a tiny church, whither she had gone to practise a Christmas voluntary, with a huge python!

It was Christmas Eve, and one of the hottest days I remember during my sojourn in Natal. The recollection of that day, spite of the many years that have since passed, is so vividly imprinted on my mind that I can still see the heated atmosphere as it danced and shimmered over the cotton bushes and the rows of beans down the hillside.

The last stroke of the twelve o’clock gong summoning the gangs of Kaffirs to their midday repast and siesta had died away, and never a sound broke the stifling noontide stillness save the booming of the surf on the lonely sea-shore, three miles distant from my father’s plantation—the Beaumont Estate, as it is now called. The eye ached as it travelled over the glaring, sun-dried landscape that lay stretched before me, and sought grateful relief in the shady depth of the dark orange grove and spreading loquat trees that sheltered the veranda on which I lounged on my luxurious cane couch.

My father was a retired Anglo-Indian officer, who, having won distinction during the Indian Mutiny, had taken up a “military grant” of about two thousand acres of land in the Colony of Natal. He judged this to be an excellent opening for my brother Malcolm, who, although showing a strong desire to follow in his father’s military footsteps, lacked the capability and application requisite to pass the competitive examinations for the Army.

We had been, by this time, about three years in the Colony, and had half the estate under cultivation. Whether father was satisfied with the results I do not know. But, drowsily reviewing the situation on this particular afternoon, I came to the conclusion that a man who has spent the best years of his life in the Army cannot metamorphose himself immediately into an agricultural success.

I was aroused from my cogitations by Malcolm’s voice exclaiming: “Why, Jessie, I do believe you were asleep!”

“I was, very nearly,” I confessed. “This heat makes the physical exertion of unclosing my eyelids a task to which I do not feel equal.”

“When are you going down to the church?” he asked, as he tapped his cane against the leg of his long riding-boot.

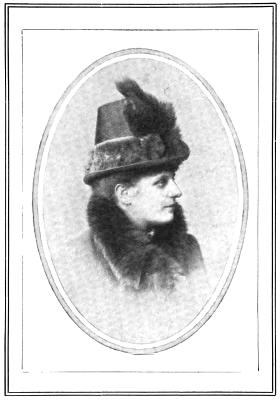

“Now,” I declared, sleepily, “if you will come with me. Sam says he has got enough flowers and greenstuff to fill two churches.” Sam, I should explain, was the Kaffir boy whose duty it was to ring the bell for service, hand the collection-bag round, and gather the flowers for the church decorations. St. John-in-the-Wilderness, as it was called, stood on my father’s land, a shining beacon of corrugated iron and wood.

Struggling to my feet, I reached for my hat and green-lined umbrella, and stood ready, waiting to accompany my brother.

“Don’t take Nellie,” I protested, as the fat old bulldog gambolled about, panting and snorting in spite of the heat, in anticipation of a walk. But Nellie proved obdurate alike to threats and entreaties, and presently scampered off down the hill, leaving us to follow.

Half-way across the Flat we came to one of those exquisite little streams that are so frequently met with on the coast of Natal. Crossing this on stepping-stones, we reached the opposite bank, whence it was but a few paces through the narrow bush path to the clearing in the jungle where stood St. John-in-the-Wilderness.

“Look, Jessie, the door is open!” exclaimed Malcolm. “I suppose that duffer Sam didn’t lock it properly this morning when he put the flowers in.”

“Probably,” I returned, gaining his side on the vestry steps. “The lock has got so stiff that I cannot turn the key myself, so I am not surprised.”

The dim, subdued light inside the church caused us to pause a moment or so before observing the extravagant profusion of flowers, palms, and ferns that Sam had gathered—truly more than enough for the decoration of two churches the size of ours.

“How glorious!” I cried, kneeling by the side of this floral wealth and picking up a bloom of the delicately-tinted waxen ginger. “What would they say to Christmas decorations like this in England?”

“I think,” announced my brother, ignoring my ecstasies, “that I will just run over and inspect a gang at work at the other end of the Flat, and then I’ll join you and we can work undisturbed.”

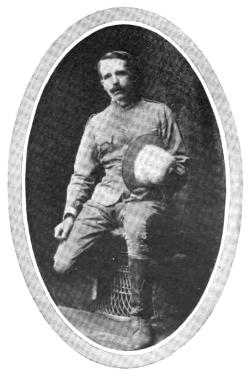

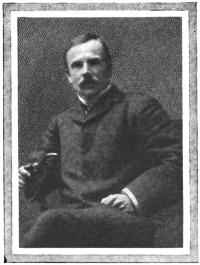

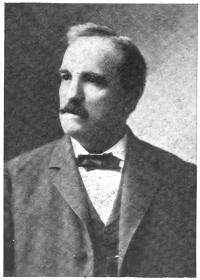

THE AUTHORESS, MRS. K. COMPTON, WHO HERE RELATES HER TERRIFYING ADVENTURE WITH A HUGE PYTHON.

From a Photo. by W. J. Hawker.

I willingly agreed to this arrangement, as I wanted to practise some hymns for the morrow. To astonish our scanty congregation I thought I would put my musical genius to the test and attempt a voluntary.

Picking up his sun helmet and cane, Malcolm prepared to go.

“Don’t be long, there’s a dear,” I said. “And I think you had better lock the door and take the key, because the door won’t keep shut unless it is locked, and I do not care to have it open.”

“What are you afraid of?” laughed Malcolm, as he went out once more into the sunshine.

“Oh, I don’t know, I’m sure, but when I am alone I prefer to have the door shut.” Still laughing, he turned the key in the lock and went off.

Left by myself in the silent little church, I drew off my gloves and prepared to open the harmonium.

It occupied a position under a window in the chancel, on the first of the three wide steps leading to the sanctuary, on the right-hand side of the church. Immediately opposite was the vestry door by which we had entered, and between the harmonium and the vestry lay the pile of flowers and greenstuff for the decorations, so that I, seated at the organ, had my back towards the flowers. Two rush-bottomed chairs stood near, one bearing a basket of extra choice white flowers I intended for the altar vases; the other was on the right side by the harmonium, supporting the small repertoire of music that I needed for the service.

I took my seat leisurely, thinking over my voluntary for the morrow.

I turned over first one piece of music, then another, finally opening a tattered sheet of an old copy of “The Blacksmith of Cologne.” I settled on that; it looked so nice and easy.[213] Played slowly, with a proper amount of expression and a plentiful addition of the tremolo stop, I thought it would make a very telling and appropriate beginning to the Christmas service.

I had barely played a dozen bars of the music when I thought I heard a rustle of leaves behind me, but attributed the sound to some slight current of air from an open window. I was too much engrossed to pay the occurrence much attention, and continued my performance right through to the end, repeating a passage here and there which I thought required a different rendering. Then once again I seemed to hear stirring leaves, and, glancing over my shoulder at the lovely pile of flowers, I noticed the sound could only have been caused by the spray of wild ginger that I had carelessly tossed on the top of the other blooms, and which had apparently rolled down and now lay a few inches apart from the rest.

Rather amused that such a trifle should cause me to interrupt my practising, I again turned to the instrument, intent upon perfecting my piece.

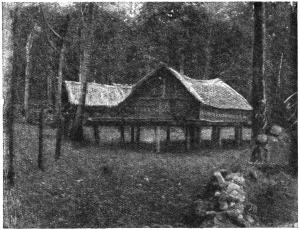

THE CHURCH WHERE THE ADVENTURE HAPPENED AS IT APPEARED IN 1890.

Suddenly I was overtaken by a feeling of unaccountable apprehension, and, at the same time, became aware of a slow, continuous, rustling sound. Turning my head sharply over my shoulder, to my horror and intense surprise I saw the whole mass of leaves and flowers undulating!

Scarcely daring to breathe or move my fingers from the notes, I mechanically continued my playing. The fact that I was a prisoner behind a locked door forced itself on my mind and held me in my place, helpless. For a moment now and then as I watched the mass of verdure was quiet, only to begin upheaving again. What could it be? The suspense was becoming more than I could bear, and I was on the point of shrieking hysterically when my tongue refused utterance, and I felt as if life and strength were oozing out of my fingers.

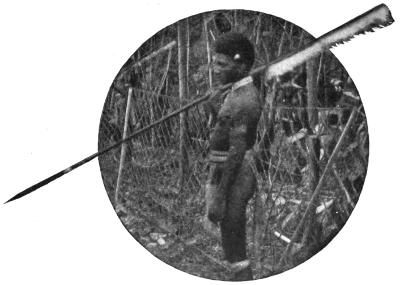

On the farther side of the beautiful, fragrant pile of ferns and flowers appeared the head of an enormous snake. Slowly, quietly, with a gentle dipping movement up and down, it raised itself, and I saw that it was a python.

Then the Kaffirs’ legend was indeed true! They had told us a story which we had regarded in the light of a fable. In spite of our ridicule, they had maintained that a serpent of gigantic dimensions had its haunt in the neighbourhood of our little church. They said that it would suddenly appear from out the bush when the organ was played and lie in the sun as if listening to the music. We had naturally received the story as a Kaffir superstition, and gave it no credence.

But—Heaven help me!—it was no idle tale, but a horrible fact, for there was the immense snake before me.

A tempest of fear seized me. My heart seemed to beat all over me at once, and a singing noise in my head drove me nearly distraught. After a while, however, it appeared to turn into a voice calling upon me to continue playing. “It is your only chance, your only hope,” it seemed to say.

With a supreme effort of will I controlled myself sufficiently to continue my performance.[214] I compelled my hands and feet to move and perform their duty. Never once, however, did I move my eyes from the python, which was gradually drawing the vast length of its body into view.

A faint hope sprang within me that I might lull its savage proclivities with the music, and I forced myself to continue a monotonous droning on the little instrument. Calling to mind the snake-charmers of India, and imitating to my uttermost the mournful wail they produce on their reed whistles, I kept this going until the incessant thud, thud of the bellows seemed to pound on the nerves of my brain and be the only sound I extracted from the little organ.

Presently, with a fresh horror, I observed that the creature was rearing itself up, as if endeavouring to locate the direction whence the music came. Having done so, it gradually made its way round the heap of flowers and palms towards me.

Once the python reared itself to the level of the back rail of the chair where lay my choice white flowers, and for a space of time remained poised in that position, surveying its environment from that improved elevation. During this time its sinuous form quivered in perpetual vibration, and its changeful, scintillating eye gave indication of its exceedingly sensitive nature. It was evidently a creature so susceptible to sound that a human voice, far away across the Flat, borne on the scented, heat-laden air through the open window, smote its delicate organization and sent a tremor through its body, making the exquisite, shaded skin shiver, and bringing into prominence a wonderful iridescent bloom that glistened along the smooth surface of its coils.

Once, in its passage towards me, the snake pushed the chair that impeded its progress an inch or two from its former position, scraping it along the varnished boards, causing a sharp discordant sound.

Instantly the python drew back its awful head, assuming a swan-like attitude. The quivering tongue, as sensitive as a butterfly’s feelers, played and trembled, and its jewelled eyes narrowed and flashed. The creature’s whole position was one of threatening defence. How deadly it looked, how awful in its cruel beauty!

“Heaven send me help!” I inwardly prayed. “Oh, for some means of escape!”

Closer and closer the awful creature undulated directly towards me, pausing now and again as if to prolong my agony of suspense. In reality I believe it was listening, its sensitive ear—or if, as some scientists hold, snakes are deaf, then some subtle sixth sense unknown to us—detecting sounds my dull brain could not catch.

At length it was so close to me I could have stretched out my hand, had I wished, and touched it, and a coil of its body actually lay on my skirt as the creature rested at my side, evidently enjoying the mournful music, which I verily believed to be my funeral dirge. For the end, I thought, must come soon. With this deadly creature so close to me, and in such a position that I could not but disturb it if I moved, I was getting cold and numb with fear. I felt myself getting faint, and realized that I was going to fall. Desperately I fought against the feeling, struggling against my growing weakness.

How long the serpent lay, like a watch-dog, at my feet, how long I played I do not know. I could not measure time; I was in a trance, asphyxiated with fear.

Suddenly a noise seemed to snap something in my brain, and the spell was broken. It was a sharp bark from Nellie, just outside the window.

And, coming nearer through the bush, I heard the echo of my music whistled back to me, as Malcolm, all unconscious of my peril, took up the refrain with which I was endeavouring to soothe my dread visitant to rest and peace.

And now that help was at hand, a new danger and difficulty confronted me. How was I to warn Malcolm? How was I to drag my skirt away from under this monster quickly enough to escape through the open doorway before it struck me?

Long ere I was aware of the approach of help the serpent had shown signs of irritation, its intuitive sensibility detecting the advent of danger, and at the noise of the key grinding in the rusty lock the python gathered its sinuous body under it, as if to obtain greater support for a forward stroke. Then, with its head and a portion of its body reared high above the floor and darting angrily hither and thither, it waited expectantly.

Dazzled with the glaring sunlight outside, Malcolm hesitated on the threshold for a moment, and in that moment Nellie passed him and ran into the church. Even then I could not move my gaze from the snake, or speak or move, or give a symptom of warning But I was aware of poor old Nellie coming towards me, panting and puffing with the heat and fatigue of her walk, and with greeting and gladness in her soft brown eyes.

She was scarcely a yard from me, and I heard my brother call to her: “Go out, Nellie; go out!”

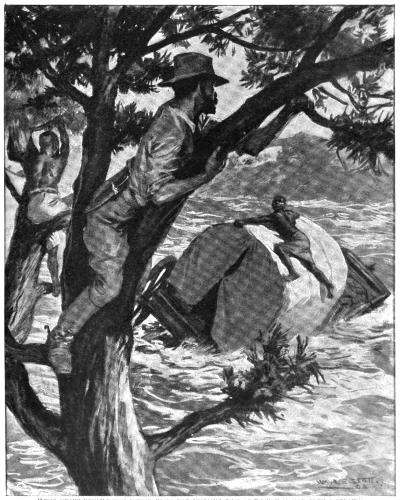

Then there was a sound as if a whip were cutting through the air, and something passed before my vision like a flash of forked lightning[215] in the sky, and I knew that the death-blow had fallen—not on me, but on dear, devoted old Nellie, the bulldog. The python literally leapt at her, striking again and again, as it endeavoured to seize her in its awful coils.

I waited no longer, but sprang from the chair, upsetting it and the books in my flight, and fairly flew to the door. I reached Malcolm in safety, and he dragged me outside, shutting the door behind us, and leaving Nellie and the python in the church. The dog’s piteous cries of agony and fear sickened us, and made Malcolm attempt a rescue. He rushed in once again, calling to the dog, in the vain hope that she might at least die with us at her side. But she could not see; blinded with fright she ran wildly about. Her end was horrible to contemplate, and I pressed my hands to my ears to shut out the sounds, running from the church and close proximity of the fearful creature under whose spell I had been for so long. I sank down under the shade of some trees and thanked God I was safe!

But the cries of poor Nellie, the thud, thud of the bellows, and the mournful dirge I had repeated over and over again banged and clanged unceasingly in my head, remaining with me through many days of utter prostration and exhaustion.

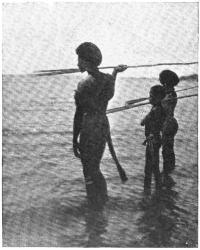

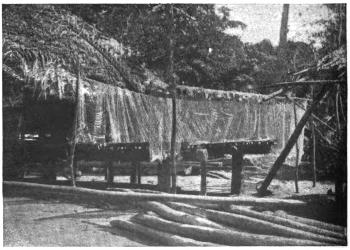

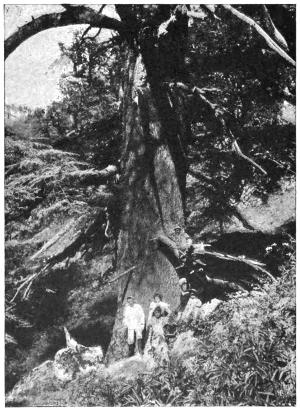

“THE KAFFIRS, SEEING ITS SKIN STRETCHED IN THE SUN TO DRY, LOST THEIR SUPERSTITIOUS BELIEF IN THE MAGIC POWERS OF THE CREATURE.”

The last music that python heard was the crack of Malcolm’s rifle as he shot it in the church. That same afternoon the Kaffirs, seeing its skin stretched in the sun to dry, lost their superstitious belief in the magic powers of the creature, and marvelled at its huge size. The mottled, shaded skin now hangs, faded, dull, and dusty, after many years, on the walls of a college museum, amidst other South African trophies. We buried what remained of poor Nellie in the shadow of St. John-in-the-Wilderness.

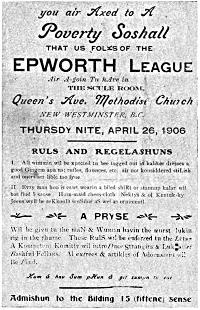

By Arthur Inkersley, of San Francisco.

Now that airships are so much to the fore, this account of the meteoric career of the largest “dirigible balloon” ever constructed—larger even than Count Zeppelin’s unfortunate monster—will be read with interest. The inventor had an ambitious scheme for running luxuriously-fitted aerial liners between New York and San Francisco, but his first ship got no farther than the ascension ground. The photographs accompanying the article are particularly striking.

Some time last year there came from the windy city of Chicago to the hardly less breezy San Francisco a man named John A. Morrell, who built a small airship with a balloon of insufficient size to lift the engines and netting. The craft got loose before the crew of twelve had taken their places and rose from a hundred to two hundred feet in the air, floating away in a southerly direction down the San Francisco peninsula and coming to rest at Burlingame, in San Mateo County, twenty miles from its starting-point.

Nothing daunted by this mishap, Morrell organized the “National Airship Company,” incorporated under the laws of South Dakota, established offices in a leading street of San Francisco, and put forth a glowing prospectus, in which people were invited to invest their money in a sure thing—to wit, an airship a quarter of a mile long, already under construction, and intended to make regular trips between San Francisco and New York City, carrying passengers as comfortably as a Pullman car. The chairs in this remarkable craft were to be made of hollow aluminium tubes and to weigh only seventeen ounces; the bedsteads, of the same material, weighing twenty-seven ounces. The mattresses were to be inflated with a very light gas of a secret nature. Extravagant and fantastic though all this sounds, Morrell possessed the enthusiasm and glibness of the genuine promoter, contriving to obtain many thousands of dollars from credulous people in support of his wild project.

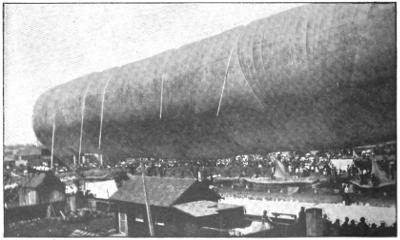

MORRELL’S MONSTER AIRSHIP BEING INFLATED, READY FOR ITS FIRST ASCENT, IN THE PRESENCE OF A VAST CROWD.

From a Photograph.

The National Airship Company established shops in San Francisco, and went to work upon the airship, which was named “Ariel.” The construction was under the direction of George H. Loose, who has had considerable experience in building aeroplanes and airships. It was intended that Loose should be first officer of the aerial liner, but, when the time for making the first ascent came, Loose wisely threw up his job, because Morrell had disregarded his advice in the construction.

A NEAR VIEW OF PART OF THE AIRSHIP, SHOWING ONE OF THE ENGINES AND PROPELLERS—NOTICE THE FLIMSY NETTINGS AND THE MATTRESSES INTENDED TO SUPPORT THE CREW.

From a Photograph.

Nearly every well-known principle of airship construction was violated. The proportions were impracticable, the craft being four hundred and eighty-five feet long and having a diameter of only thirty-four feet. The gas-bag was like a huge snake, having no rigidity, either horizontally or vertically, and not being stiffened by trussing of any adequate sort. A gas-bag of such length and proportionately small diameter should have been strengthened by a vertical framework, or by trusswork of rope or wire, so as to impart rigidity; but nothing of this sort was done. The motive-power was supplied by six separate four-cylinder forty-horse-power automobile engines, hung below the balloon at intervals.

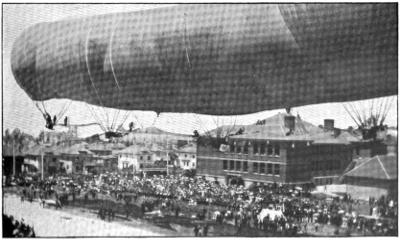

THE AIRSHIP LEAVING THE GROUND AMID THE CHEERS OF THE EXCITED ONLOOKERS.

From a Photograph.

These concentrated weights were carried on a platform, not of planks, but of mattresses, laid down on mere canvas, supported by the netting which covered the gas-bag. Ropes placed round the gas-bag at the points where the engines were situated cut deeply into it, and no arrangements whatever were made to meet the special stresses caused by the steering of so long-drawn-out an affair. Loose’s chief reasons for refusing to make the ascent were that if the envelope were filled with enough gas to render it rigid the emergency valves would open, and if these were tightened the envelope was liable to burst.

Serious as the various defects mentioned were, the most fatal one was the fact that nothing had been done to prevent collapse or deformation caused by sudden expansion or contraction of the gas from changes of temperature. The balloon was one great, undivided bag, containing from four hundred thousand to five hundred thousand cubic feet of gas, but having no compartments or internal air-bags. Its lifting capacity was from eight to ten tons, so that it was much the largest airship ever built in America, even exceeding in dimensions the great “dirigible” of Count von Zeppelin.

It might be supposed that it would be pretty hard to get together a score of persons who would be willing to risk their lives in such an unpractical affair as the Morrell airship; but, strangely enough, the greatest difficulty was experienced in keeping people off the craft. One man, a well-known aeronaut named Captain Penfold, repeatedly begged Morrell to let him make the ascent, but his request was flatly refused. Yet so eager was Penfold that at the last minute he smuggled himself on to the craft and went up with it and—a few moments later—came down with it.

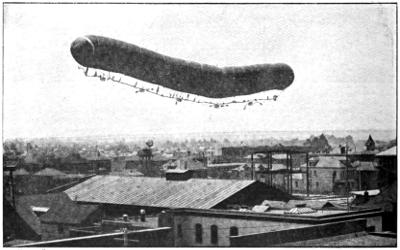

THE “ARIEL” IN MID-AIR. ITS NOSE HAD A DECIDED TILT DOWNWARDS, AND THIS INCREASED UNTIL ALL EQUILIBRIUM WAS LOST.

From a Photograph.

Some time before the attempted ascent was made the airship was conveyed from San Francisco across the Bay to Berkeley, in Alameda County, Cal. The trial trip was fixed for Saturday, May 23rd, and on that morning thousands of excited people were on hand to watch the ascent. The airship was released from its moorings and began to mount into the air, its nose having a decided tilt downwards. The machine had risen scarcely two or three hundred feet when the rear of the balloon had an upward inclination of as much as forty-five degrees.

Morrell shouted to his crew, consisting of engineers and valve-tenders, numbering fourteen or fifteen, to go aft, so as to depress the stern of the machine and cause it to resume its equilibrium. But the shouts and cheers of the people below drowned his voice so that he could not be heard. A moment later the gas rushed into the after-end of the bag with great force, bursting the oiled cloth of which the envelope was constructed, and the cheers had hardly died away before the horror-stricken crowd saw the great balloon collapse and come headlong to the ground, with its nineteen passengers, who included Morrell, eight engineers, five valve-tenders, two photographers with their assistants, and the aeronaut already mentioned.

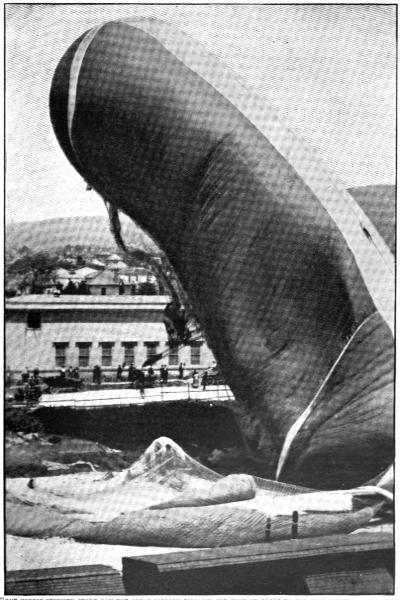

“THE HORROR-STRICKEN CROWD SAW THE GREAT BALLOON COLLAPSE AND COME HEADLONG TO THE GROUND WITH ITS NINETEEN PASSENGERS.” NOTICE THE VALVE-TENDER SCRAMBLING WILDLY ALONG THE NETTING ON TOP OF THE GAS-BAG; HIS AGILITY STOOD HIM IN GOOD STEAD, FOR HE ESCAPED ALMOST UNINJURED.

From a Photograph.

The unfortunate men were entangled in the wreckage of flapping cloth, network, and machinery, running the danger of being struck by the propellers of the engines or of being suffocated by the great volumes of escaping gas. One valve-tender, who was on the top of the great bag, can be seen in one of the photographs climbing along the netting. His agility stood him in good stead, for he escaped from the wreck almost uninjured.

GATHERING UP THE WRECKAGE AFTER THE COLLAPSE OF THE AIRSHIP.

From a Photograph.

It might be supposed that nearly all the men on the ill-fated craft were killed; but, remarkable to relate, not one lost his life. Morrell himself sustained severe lacerations, and had both his legs broken by one of the propellers; Penfold, the persistent, had his right ankle and left instep broken; Rogers, an assistant engineer, suffered a broken right ankle; and another engineer met with broken ribs and ankles. Others were bruised or rendered unconscious by the gas.

Morrell ascribed the disaster to the fact that he was forced by impatient stockholders in the National Airship Company to make the attempted flight before he had worked out certain details of the vessel’s construction thoroughly. It is believed by those who saw the luckless craft that it was constructed flimsily of poor materials and not inflated sufficiently. The ill-starred aeronautic adventure not only cost many broken bones, but some forty thousand dollars (more than eight thousand pounds) in money.

It would naturally be supposed that so complete and disastrous a failure, after the expenditure of so large a sum of money, would have destroyed all confidence in Morrell as a designer of airships, and would have put him out of the business of aerial navigation for all time. But it was not so; the enthusiast still asserts that he has discovered the true principle of the navigation of the air, and that the National Airship Company is ready to proceed with the construction of another craft, much larger and costlier than the first one.

The new airship is to be seven hundred and fifty feet long and forty feet in diameter, equipped with eight gasolene engines, developing nearly three hundred and fifty horse-power and operating sixteen propellers. The inside bag will be of light silk and the outside bag of heavy silk interwoven with a material known as “flexible aluminium,” of which Morrell possesses the secret. The new balloon is to have more than a hundred compartments, many of which might be broken without disturbing the buoyancy or equilibrium of the vessel.

A rigid platform is to be substituted for the canvas and netting cage in which the unfortunate participants in the attempted ascent of the “Ariel” rode. The new vessel is to cost one hundred thousand dollars (more than twenty thousand pounds), and to be capable, if the inventor is to be believed, of a speed of a hundred miles an hour. The really marvellous things about the whole business are the unquenchable enthusiasm of the inventor and the unfailing credulity of those who believe in him.

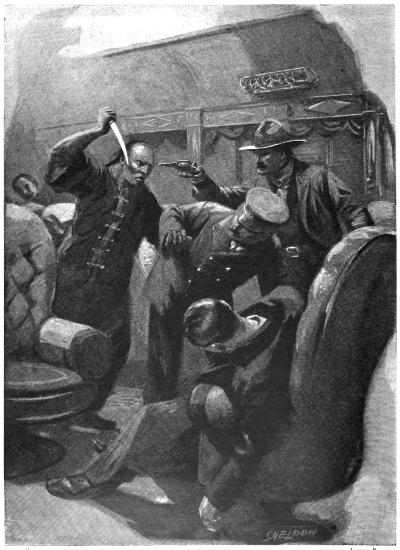

By A. P. Taylor, Chief of Detectives, Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands.

The story of the most disastrous voyage in the annals of the United States transport service. The steamship “Siam” left San Francisco with a cargo of three hundred and seventy three picked army horses and mules, destined for “the front” in the Philippines. She landed two mules alive at Manila. In this narrative Mr. Taylor, who was a passenger on the ill-fated vessel, tells what became of the remainder.

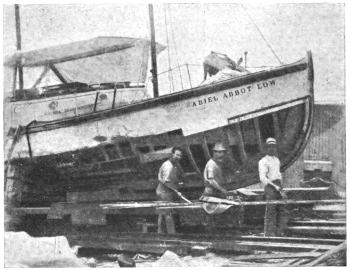

When the Japanese Government recently offered for sale the former Austrian steamship Siam, a prize of the late war, there was concluded one of the most remarkable romances of the United States army transport service. Four flags have so far flown over this steamer, but her career is not likely to conclude under the ensign of the Land of the Chrysanthemum.

Christened on the banks of the Clyde in the early ’nineties as the British tramp steamer Resolve, the vessel later passed into the hands of an Austrian corporation at Fiume, and was renamed the Siam. Fate and charterers sent her to the Pacific Ocean in the second year of the Filipino insurrection, and she was chartered by an American firm of San Francisco, and entered the coal trade between Nanaimo and the Bay City.

In the summer of 1899 the United States War Department assembled at Jefferson City, Missouri, one of the finest trains of experienced army mules and horses ever organised for foreign service. From Cuba, from the northern borders of the United States, from frontier army posts, and, in fact, from every part of the United States where the quartermaster’s insignia were in evidence, these animals were brought to the common rendezvous in Missouri. They were the pick of the army—staid old mules and horses that had been in the service for years, and knew almost as much of military discipline as the men in blue. Their transhipment to the Presidio at San Francisco followed in July, and then the War Department cast about for a vessel in which to ship them to Manila, where General Otis was even then delaying important army movements in order that these animals might accompany the troops to “the front.”

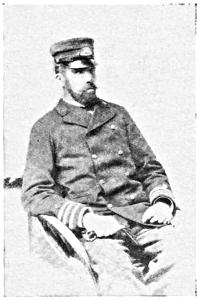

THE AUTHOR, MR. A. P. TAYLOR, CHIEF OF DETECTIVES, HONOLULU, HAWAIIAN ISLANDS.

From a Photograph.

The Siam had just returned from Nanaimo with a cargo of coal. She was a fine, big, ten-knot boat, with Austrian officers and sailors. The War Department decided, although she flew the flag of the Emperor Joseph, that she was just the vessel needed. Early in August, after several weeks of hammering, sawing, and building of superstructures, three hundred and seventy-three horses and mules were sent aboard and placed in separate stalls for the long voyage to Manila. The loading of the animal cargo was a matter of much concern to the War Department, with the result that almost the pick of the packers and teamsters of the army—fifty-six in all—were chosen for the voyage.

In command of these rough-and-ready plainsmen was Captain J. P. O’Neil, 25th Infantry, United States Army. Captain O’Neil was just the sort of man to deal with the cowboys—no army dandy, but a true-blue soldier, and the men admired and loved him.

Among the horses was the thoroughbred presented to General “Joe” Wheeler, United States Army, by the citizens of Alabama after his return from the Cuban campaign. “Beauty” he was called by the men, and he was given a place of honour near the officers’ cabin. Yet another splendid animal was the horse belonging to Miss Wheeler, daughter of the General, who was then an army nurse in the Philippines.

The officers and crew were all Austrians, with the exception of two engineers. The commander was Captain Sennen Raicich, sailor, gentleman, and postage-stamp connoisseur. His hobby was rare stamps, and his cabin was filled with cases containing valuable specimens. Every day he went over his collection, labelling, classifying, and docketing the new ones which he had purchased at the last port. The[222] collection was valued at about twelve thousand dollars, and was insured. Messrs. Xigga and Stepanovich were his two officers. Captain, mates, and crew all hailed from the section of Austria nearest Fiume.

Ten days after leaving San Francisco the Siam reached Honolulu, and the horses and mules were taken ashore and sent to the Government corrals, where they recuperated for two days. During this time Captain O’Neil spent much time considering the arrangement of the stalls. These were arranged along the main deck and in the first hold below. Over the exposed portions of the main deck superstructures had been raised to protect the animals from the elements. The forward deck was loaded with hay and grain for use during the voyage, while between decks was a stock of forage. Over the officers’ section a deck-house was built, and used as a sleeping-place for the cowboys.

The Honolulans took great interest in the horses, and hundreds examined the stalls, which were arranged along the sides of the steamer, the animals facing inward. Small chains hasped to the supports on either side led to the rings of the halters. Cleats were nailed to the flooring to give the animals a footing during storms. The leisure time of the cowboys was spent in making canvas “slings,” intended to be placed beneath the bellies of the animals during bad weather, the ends fastened to rings in the deck above, to assist the animals in keeping on their feet should the vessel roll awkwardly. The transport service had much to learn, and the use of slings was a costly lesson.

For several days the voyage toward the Philippines was delightful. Half-cloudy days and trade winds maintained an even temperature throughout the ship. Officers, crew, cowboys, the few passengers, and the animals were on the best of terms. Captain O’Neil cheerfully looked forward to the day when the Siam should steam into Manila Bay and he could report the voyage successfully ended and without the loss of an animal. Captain O’Neil’s enthusiasm was communicated to the cowboys, and they resolved to make a reputation for the voyage and land their animals safe and sound. Alas for human hopes! That voyage was to prove the most disastrous in the annals of the American transport service.

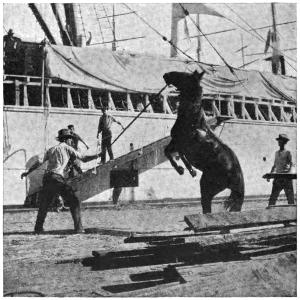

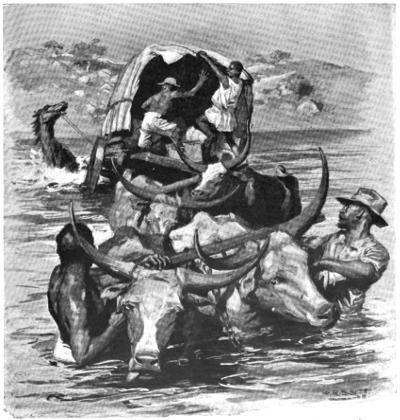

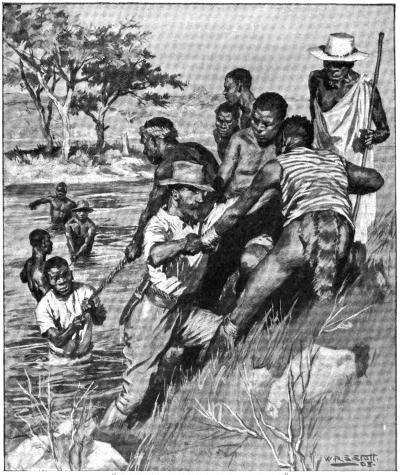

GENERAL WHEELER’S HORSE “BEAUTY” BEING TAKEN ON BOARD THE “SIAM.”

From a Photograph.

On the morning of September 17th came a change in the direction of the wind. The officers consulted the barometer, and the land-lubbers, taking amateurist observations of their own, saw that it was falling. Then came a few gusts, the sky changed, and in a little while a terrific storm burst over the steamer. The vessel rolled, and the horses, unused to such a motion, had difficulty in retaining their feet. Clouds of spray dashed over the bridge and tons of water broke upon the decks. The stalls were flooded and became slippery, and the animals frequently fell. Sometimes a lurch threw at least fifty from their feet. Instantly there was a struggling, kicking mass of horse and mule flesh on the decks. The cowboys, although experiencing the first real nausea during the voyage, bravely went among the helpless brutes and assisted them to their feet. For two days and nights this went on, and few men were able to sleep. Finally things got so bad that Captain O’Neil sent a written request to Captain Raicich to change the course of the vessel to any direction that would give the least motion to the ship.

Those who have never been to sea may not[223] know the danger of putting a vessel about in a sea which is piling up angrily from every direction. The order was sent through the ship that she was to go about, and everyone clung to a support during the manœuvre. Gradually the vessel answered her helm; the roaring wind beat against her hull, heeling her far over, until the landsmen clung desperately to anything handy to prevent them sliding into the boiling sea. At length the manœuvre was safely executed, and all hands breathed a sigh of relief. The vessel scudded before the wind, riding more easily, though she was going far out of her course.

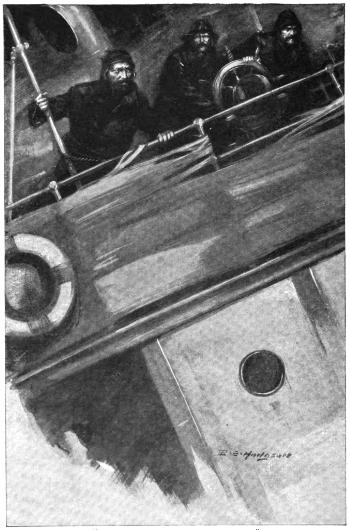

“A TERRIFIC STORM BURST OVER THE STEAMER.”

When the sun broke through the clouds a tropical-looking island loomed up on the horizon, which proved to be the island of Saipan, of the Ladrones group, just to the north of Guam. Whether it was inhabited those aboard did not know, for there was not on the ship a chart or book bearing upon the island. A mysterious column of smoke shot up from a grove of trees as the vessel passed by, followed by a second and a third. A “council of war” was held. Were the mysterious smoke signals sent up by shipwrecked sailors or by natives with questionable intentions? Captain Raicich cut the Gordian knot with the statement that the Siam was under contract to the United States Government at six hundred dollars a day, and as considerable time had already been lost he could not for a moment think of detaining the vessel while an investigating committee went ashore.

After that storm the ship was a hospital, for two hundred and thirty-three horses and mules were more or less injured, and every man devoted his whole time to caring for them. Strange to say, many of the cowboys and mules had been associated for years in Government work, and they were therefore old friends, and the men were sympathetic veterinarian nurses. Six animals died of their injuries.

That storm was a heartrending set-back to the ambitions of Captain O’Neil. However, he made the best of the experience by preparing for similar episodes. One day the engines gave out, and the vessel lay to for several hours while the engineers and firemen worked like Trojans to repair the damage. At first it was decided that the vessel, being then near the Philippines, could make port with the one uninjured engine, but it was finally decided that it would be best[224] to repair the damage at sea. It was well that this decision was arrived at, otherwise the Siam would never have reached port.

On September 29th the steamer was close to Cape Engano, on the northern coast of the island of Luzon. On the morning of September 30th the sky became overcast, the wind freshened, and the barometer fell. In the afternoon there was a peculiar glow in the clouds, which behaved most curiously; they seemed caught in currents of wind and were stretched out across the heavens in orderly lines, parallel with the horizon. To the landsmen none of the signs were ominous, but the ship’s officers sent orders quietly among the crew.

CAPTAIN SENNEN RAICICH, OF THE “SIAM.”

From a Photo. by Antonio Funk.

A passenger, going into the chart-room, from which an officer had made a hurried exit, saw a book on navigation lying there. It was open at a chapter on typhoons, and there were under-scorings where “China Sea,” “The Philippines,” “Yellow Sea,” etc., occurred in the text. The passenger looked at the barometer again, saw that it had fallen, and began to understand. There was an ominous silence throughout the vessel, and a peculiar stagnant feeling impregnated the air. The growing sense of menace affected every living thing aboard; the plainsmen had long since stopped chaffing and the animals stamped uneasily.

Meanwhile the crew were very busy. Canvas shields were taken in, rigging was examined, and the captain went below to the engine-room and consulted with the engineers.

Evening came on, the sea began to stir, and the crests of little waves broke sharply. The Siam was now in sight of the northernmost portion of Luzon, and as Cape Engano was approached she was slowed down, but the captain and officers looked in vain for the lighthouse on the cape. At ten o’clock the commander changed the course of the vessel from west to north, thereby keeping out of the channel above the cape, for he would not risk entering the waterway without first picking up the light.

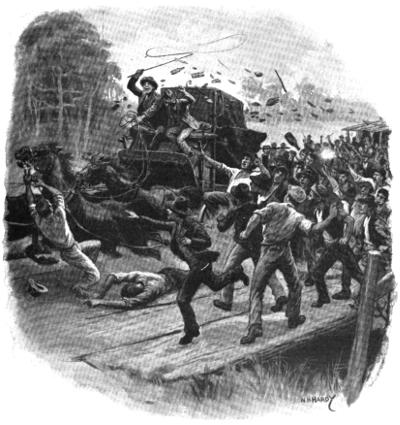

It was well that he formed this decision, for at eleven o’clock the heavens and the sea seemed to meet in a mighty clash. There was one mighty reverberating roar, the steamer heeled over, the wind howled through the rigging, and the stern, lifting high out of the water, permitted the propeller to race, shaking the vessel from stem to stern. The gong and bells rang sharply in the engine-room, the propeller stopped racing, stopped altogether, spun again. The tramping of feet sounded along the decks; orders were shouted from the bridge in Austrian. The cowboys gathered on the main deck and waited anxiously—for what, they did not know. Then the passenger transmitted the knowledge of the open book in the chart-room to the landsmen. A typhoon was on, perhaps, he suggested. “Typhoon” in the China Sea, “hurricane” in the Atlantic, “pampero” off the South American coast, “cyclone” on land—all mean much the same thing. The most terrifying storm a vessel could encounter held the Siam in its mighty grip.

Then, almost without warning, a demoniacal sea and a fearful wind, with legions of horrible, never-to-be-forgotten night terrors, appeared to leap upon the ship from the darkness.

A sickening dread crept into my heart. In fifteen minutes the whole fury of the typhoon was upon us. It was almost midnight of September 30th when we realized, by a glance at the captain’s face as he rushed into the chart-room, that a battle for our lives was upon us. It was human science matched against the ungovernable fury of the elements. Which would win?

I made my way to the bridge, clinging now to a rope, and now down upon my knees with my arms around a stanchion. By main force I held on to the wheel-house, where the captain and his two mates directed the course of the stricken ship. Their faces were set with grim determination, their eyes staring fiercely now at the compass and then at the boiling seas, which pitched and rolled us about like a paper box. The wheel flew round from side to side. One end of the bridge rose and towered above me until I leaned over almost upright against the ascending deck, and as suddenly it fell until it seemed to plough the water. The wind, blowing at eighty miles an hour, tore canvas and rigging to shreds.

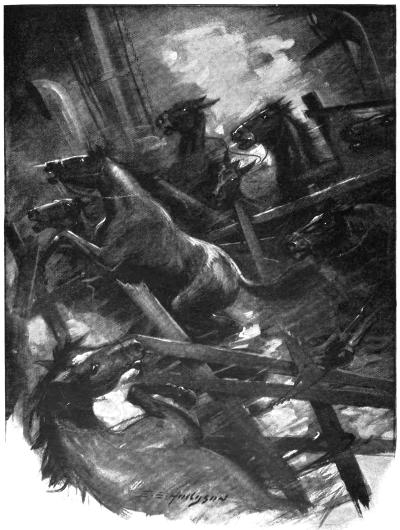

Suddenly the bow lifted high upon a monster wave. Higher, higher, higher it rose, while the stern sank down into a yawning chasm. Simultaneously a huge wave struck us abeam. Down came the bow, and over heeled the steamer upon her side. From below came the nerve-racking bellowing and screaming of the terrified animals as they strove madly to keep their feet. Hoarse shouts came up from the lower decks, where the cowboys were endeavouring to help their charges. Now and then there was a crash as an animal was flung bodily out of its stall across the deck, where it smashed stalls and set other animals loose. Each time the ship rolled I set my teeth, for each swing seemed about to plunge us into the boiling black abyss below. Often my heart seemed to stand still, and I waited for the moment when our devoted band would be hurled into eternity.

Presently half-a-dozen of us descended to the stokehold in order to send ashes up to the deck to be spread under the hoofs of the struggling animals. Out of that stifling hole bucketful after bucketful was hoisted until the deck was strewn with débris. But the heat of the stokehold and the unusual labour caused the amateur stokers to sicken, and, exhausted and nauseated, we climbed to the deck again and lay there gasping.

With morning the storm grew worse. At nine o’clock Captain Raicich determined to heave the ship to, but the plan had to be abandoned, owing to stress of weather. The steamer was compelled to head directly into the wind, which eddied in dizzy concentric circles around a larger circumference. My diary contains the following notes jotted down on the afternoon of October 1st, written mainly in shorthand while I lay ill in my bunk:—

“Good heavens! Another such day and night as we have been having and I believe I shall become insane. Buffeted and tossed about like a feather, careening, rolling, and pitching, the Siam seems ready to take her final plunge. Just now a great wave lifted the bow until it seemed the vessel would stand straight upon her stern; the stern went down and threw us up again with a terrific lift. A wave strikes the bow and races the full length of the vessel, tearing everything loose it can rip from its fastenings. It is sickening. I am writing this in the very midst, the centre, of the worst kind of storm one can encounter at sea. The men are shouting and cursing, the animals pawing and uttering plaintive sounds.

“We don’t know where we are. We know we are heading north-east to get away from ragged reefs which lie to the north of Luzon. We are steaming directly in the face of the typhoon and make no progress. The barometer has fallen twelve points since noon. May Heaven have mercy on us!

“7 a.m., October 2nd.—What terrible sights I have witnessed during this awful time! The storm increased every hour of the night, the barometer going down from 82 to 30, disclosing the fact that we were heading directly toward the centre of the typhoon. We have rolled so heavily that the rail goes under at each dip. The men remained at their posts in the stable division, striving to keep the animals from plunging out of their stalls from sheer terror. Suddenly a mule falls. Men hurry to raise it. A return lurch, and down go a score—a mass of maddened, screaming brutes. From every part of the ship whistle-signals are heard calling for help. None can be offered, and there the poor beasts lie piled up on each other, sliding upon their sides and backs from one side of the ship to the other, tearing strips of flesh from their bodies, causing them to groan piteously in their helplessness. The ship is tossed every way, up and down, side to side. Heavy seas break across the decks.

“Crash! There goes the cowboys’ bunk-house on the poop deck. It is flooded, and the men’s belongings are sweeping into the sea. The water is pouring down into our cabins. Destruction everywhere. Another crash—the rending of timbers in the stable sections. I hear the men shouting warnings and hear their feet tramping across the decks. The stalls have given way entirely. Horses are plunging through the hatchways into the lower stable divisions. A thud, a groan, and they are dead. The rest are piled up in sickening, agonizing masses, rolling, snorting, kicking, and endeavouring to get upon their feet. No man dare move from his holding-place. One has to stand almost upon the cabin wall to keep erect.

“There they lie, all our pets, the captain’s thoroughbred, General Wheeler’s own charger. There are twenty horses dead in one heap. A mule has plunged right down into the engine-room, breaking its legs. It lay there for two hours before Captain O’Neil could shoot the suffering beast. The engineers crawled over the carcass as they stood at the throttles to ease the engines down as the propeller races.

“The terrific battle of the elements outside beggars any description from me. Intensify any storm you have experienced on land a couple of thousand times, add all the terrors that darkness can furnish, add the thoughts of terrible death staring you in the face every minute, with the sights and sounds of Dante’s Inferno, and then perhaps you can gain some idea of our misery.

“A MASS OF MADDENED, SCREAMING BRUTES.”

“At daylight the seas swept across and filled up our decks. Then it was that Spartan measures had to be taken. The hatches were ordered to be battened down, thus confining in a death-trap nearly two hundred mules. We knew it meant death by suffocation to those that were still living, but our own lives were at stake, and to save our own the animals must be sacrificed.

“I am now writing in the chart-room. If we[227] sink, I don’t want to be caught like a rat down in my cabin, although there will be no chance for life in any case if we go down.

“To make our terror worse the Austrian firemen have mutinied. They heard that the captain had given up the ship. They were right, for he told us to prepare for the worst. Think of knowing that we have got to drown! Our boats are all smashed and hanging in bits at the davits. The firemen tumbled up on the deck looking like demons from the underworld. Then Captain O’Neil showed his true nature. He became the hard, steel-like soldier. He sternly ordered them below, but the men did not move. The cowboys knew instinctively that without steam to turn the engines we must surely founder. Two of the cowboys seized the ringleader, and, placing the ends of a lasso about his wrists and thumbs, started to draw the rope over a guy wire, threatening to string him up by the thumbs. Captain O’Neil had turned away when these men took the prisoner in charge. Immediately the frightened crew turned and fled down to the stokehold.

“Who can blame the poor beggars? Life is as sweet to them as to us. Two hours later they came up again, but the display of an army revolver in Captain O’Neil’s hand caused them to retreat.

“The chief engineer, an Englishman, has gone insane. Thirty-three years at sea, and now he has gone to pieces! The terror of the long vigils at the throttle unnerved him. I passed him a little while ago; he was sitting in his cabin wailing piteously, his face blanched with terror. The little Scotch second engineer has been on duty almost every hour since the night of the 30th. His whole back was scalded by steam. Dr. Calkins bound it up in cotton and oil, and he is working as if nothing had happened, brave little fellow.

“6 a.m., Tuesday morning, October 3rd.—Another chapter in my experience of Hades. No one is on duty except the ship’s officers. It is a ship of the dead. I have just taken a look down the upper stable division, and the sight sickened me. The poor brutes of horses and mules, mangled and torn, lay in heaps, the live ones trying to extricate themselves from the dead.

“At last the typhoon has spent itself, and by to-morrow morning we shall probably be able to get back on our course and make a fresh start for Manila. Nearly all the horses and about two hundred mules are wounded as far as we can ascertain. Soon the hatches will be taken off, and we can learn the horrible truth.

“October 4th.—All morning long the dead animals have been hoisted out and thrown overboard. How horrible it all is! The men working in the lower holds are overpowered and compelled to come up on deck every few minutes. We have three steam-winches going. We found only one live mule in the lower hold. Captain O’Neil has been shooting most of the live animals, for they are beyond hope in their terrible condition.

“Captain Raicich told me to-day that for four hours yesterday he did not know whether the ship would pull through. The Siam got into the trough and could not be steered. He said he was prepared then for death. He said he has never before experienced such a terrible storm. We don’t know just where we are yet, as we can take no observations.

“What a terrible change in Captain Raicich’s appearance! He never left the bridge for three days and nights. He, as well as the two men at the wheel, were lashed to stanchions. He wore two oil ‘slickors,’ but they are in ribbons, and the tar from them has sunk into his hair and beard and deep into his skin. He is dirty and wretched-looking. His cheeks are sunken and there is an almost insane glare in his eyes. He looks like a wreck, but in spite of his terrible ordeal he is as decisive in manner as before. Poor fellow, he hardly ate anything during the whole of the typhoon. He saved our lives.

“We have just located our position. We are a hundred miles north of Luzon, and close by are the dreaded coral-teeth we tried to avoid.

“October 5th.—We are now nearing Manila Bay and have cleared up the vessel fairly well and thrown most of the carcasses overboard. The ship is a wreck; everything seems to have been twisted, broken, torn, or damaged in some way. Up to last night we got overboard three hundred and fifty-five carcasses. This morning four more were found dead and two others had to be shot. We now have only twelve animals left, some of which we may land at Manila alive. This is all we have left out of three hundred and seventy-three. Dozens of sharks follow in the wake of the vessel. The Siam’s expedition has been the most disastrous in the transport service.”

As a matter of fact, the Siam actually landed only two animals at Manila. They were little Spanish mules which had been thrown into the coal-hold and, strange to say, had not a scratch upon them. They were and are still known in and about Manila as the “Million-Dollar Beauties” of the quartermaster’s department.

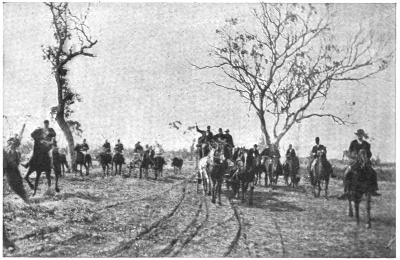

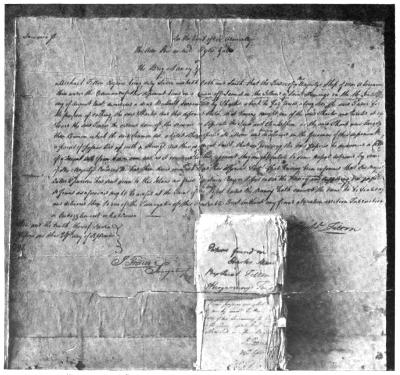

“HE NEVER LEFT THE BRIDGE FOR THREE DAYS.”

I accompanied Captain O’Neil to General Otis’s head-quarters in the ancient Spanish palace in old Manila. When informed of the disaster the General was greatly grieved, and remarked that it would have a serious effect on the plans he had made. Captain O’Neil[228] then presented him with the following report of the voyage, which, although an official document, contains much of the romance connected with the disastrous expedition:—

United States Transport “Siam.”

Adjutant-General Eighth Army Corps, Manila, P.I.

Sir,—I have the honour to report my arrival with the steamship Siam, chartered as a United States animal transport. I left San Francisco, California, on the night of the 19th of August with three hundred and seventy-three animals aboard. We experienced ordinary weather, and arrived in Honolulu, H.I., August 29th, leaving there September 6th.

After leaving Honolulu, and until the 17th of September, we had fairly good weather, and up to this date (a month away from San Francisco) all the animals were in perfect condition. The duties of horse veterinary and nurses were then sinecures. On the morning of the 17th a heavy swell from E.N.E. and N.N.E. struck the ship and made her roll considerably. This swell continued. The next day, Monday, the 18th, the wind rose from[229] S.S.E., and continued to increase in force until it became a gale, blowing from S. and S.S.E., with a big swell from S.S.W. and S.E. This rough sea was extremely trying on the animals; as many as fifty would be thrown from their feet at the same time, and for forty-eight hours I was not able to spare a moment for sleep, and the greatest rest that any man of my detachment had was six hours. I, at this time, sent a written order to the captain of the ship to change the course of the vessel to any direction that would give her the least roll. According to this order, he changed the course to S.E. We were driven several hundred miles out of our course. Wednesday morning the wind abated; we were able to resume our course, and passed the Ladrones, north of Saipan. Wednesday morning the storm began to abate; Wednesday evening and night we were busy caring for the injured and taking stock of our animals. I found two hundred and thirty-three animals injured more or less severely; of these, six (6) died. The greatest care was given to the injured, and they all pulled through remarkably well.

Everything ran smoothly, fair winds and fair seas, until Saturday night, September 30th. We arrived at the head of the island of Luzon (Cape Engano). It was after dark—there was no light—the weather looked threatening. The captain and I discussed the matter and finally decided that it was not safe to try and go through this passage on a stormy night without being able to locate any landmarks. The captain was directed to cruise outside until daylight. About twelve o’clock that night the wind started blowing from N.N.W., gradually increasing into a gale; the vessel was headed into the wind and sea and rode very smoothly until Sunday morning, October 1st, when the wind began to shift, increasing in force, and for the next two days continued changing direction. Until the storm abated Tuesday morning, the wind was blowing from the S.E. The sea raised by this circular wind was tremendous. From Saturday night at twelve o’clock, for fifty-six hours, every man on board the vessel worked like a Trojan. Animals were continually being thrown from their feet, and the men worked getting them to their proper places. As the storm increased, so increased the labour—the men, almost exhausted, continuing their task. I cannot give them too much praise for their utter disregard of danger, and the heroism they displayed in trying to save their charges.

Monday morning, October 2nd, at five o’clock, the captain of the ship gave orders to close the hatches to save the ship, and just then a tremendous sea swept over the vessel, throwing from their feet every animal on the port side of the ship and most of the animals on the starboard side; the vessel continued to do sharp rolling, so that these animals would shoot from one side of the deck to the other. It was absolutely impossible to do anything for them; some men had been injured, and I gave up the fight. I ordered every man to a place of safety in the forecastle, cabins, and chart-room, and we were forced to let the animals stay where they were.

Three hundred and sixty odd animals shifted from side to side of the vessel, and it became too great a risk to make men face it when nothing could be accomplished. When I knew the captain had ordered the hatches closed (which I felt meant suffocation for those animals still alive in the holds), I knew he would not take this step if ingenuity or human skill could possibly avoid the danger. For a few hours I had no confidence in or hope of saving even the vessel. The wind was so strong that she was perfectly helpless; she would not mind her helm though going at forced speed, but had to drift helplessly in the direction the wind drove her.

As soon as it was possible to go upon deck, every effort was made to rescue those animals still living. A few that were fortunately thrown on top of the heap of mangled horses and mules were brought out. Many died from their injuries. Six were saved, but I doubt if they will be of any service for a long time to come.

It is my opinion, and also the opinion of everyone on board this vessel, that had the weather continued as fair as it was up to September 17th, the ship would have arrived in the port of Manila without the loss of a single animal. As it was, every animal that died on this trip did so from the effect of the storms encountered.

A detailed report and copy of the orders on which this vessel was run, and such suggestions as I have been able to make from the experience I had in these two storms, accompany this report.

I have the honour to remain,

Yours respectfully,

(Signed) J. P. O’Neil.

Capt. 25th Infty., A.Q.M., U.S.A.

(Dated) Manila Bay, P.I., October 6th, 1899.

By Mrs. Herbert Vivian.

The recent State trial for high treason at Cetinje was a most sensational affair, the prisoners—many of them ex-Ministers and politicians of high rank being accused of a conspiracy to destroy the Montenegrin Royal Family root and branch. Mrs. Vivian was the only woman present, and her photographs were the only ones taken. Her description of the trial, with its picturesque environment and mediæval atmosphere, will be found extremely interesting.

I feel quite spoilt for home-made pageants or foreign processions after assisting at the sensational State trial for high treason in Montenegro—a sight which transports one at once into mediæval times again. The ordinary person may imagine that it is quite an everyday affair, and that conspirators grow like blackberries on the hedges of Montenegro, but then the ordinary person knows little about foreign lands apart from Norway, Switzerland, or Italy, and less than nothing about the Near East. When I was in Montenegro my family was besieged with inquiries after my safety and hopes that I might escape unhurt from the brigands and bandits who must infest the Black Mountains; whereas in Montenegro the remark that greeted me was that it was very brave of me to pass through so many lands on the way to the principality, but that now I was there all was well.

I think it is time, therefore, to explain that the trial, far from being an everyday affair, was something unheard-of in a land where everyone, though, of course, warring against the fiery Albanian and enjoying a certain amount of friendly sparring with neighbours, adores his beloved Prince and looks on him as chieftain, father, and general Providence all rolled into one.

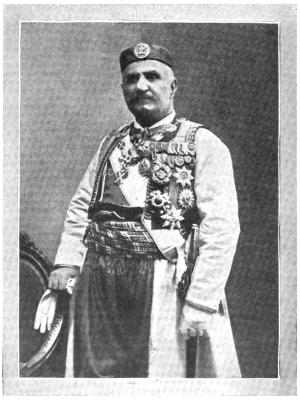

PRINCE NICHOLAS OF MONTENEGRO—THE CONSPIRATORS PLOTTED TO DESTROY NOT ONLY THE PRINCE, BUT THE ENTIRE ROYAL FAMILY.

From a Photograph.

Indeed, Prince Nicholas must be counted among the lucky ones of this earth. He has not only been blessed with talents and tact above those bestowed on the ordinary man, but he has also been watched over by the gods and allotted more luck than falls to the lot of most mortals. Like King Edward, he is popular wherever he goes, and he has a genius for statecraft. When he came to the throne forty years ago Montenegro was absolutely unknown; probably barely one in a hundred of educated people knew that such a place was to be found in the atlas. During those forty years the Prince has fought successful wars against the Turk, more than doubled his territory, married[231] his daughters to some of the greatest partis in Europe, and made the name Montenegro a household word for valiant men and deeds of daring.

But Prince Nicholas, unluckily for himself, married his eldest daughter to a certain Prince Peter Karageorgevitch. This lady died many years ago, and in the course of time Prince Peter was called from his haunts in Switzerland to take the Crown of Servia from the hands of the regicides. Whether he knew anything of their evil plans beforehand need not be discussed here; but, at any rate, ever since the day he entered Belgrade he has been their tool, and as wax in the hands of the ringleaders. Nevertheless, people were astonished when it was discovered last October that bombs were being smuggled over the Turkish frontier, coming from Servia. A plot was discovered to blow up the whole of the Montenegrin Royal House—not only the Prince and his two sons, but the Princess and her two daughters, her daughters-in-law, and even the poor little grandchildren, so that the entire family might be exterminated root and branch!

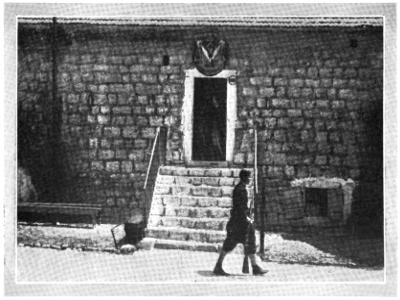

THE EXTERIOR OF THE COURT-HOUSE, SHOWING SENTINEL ON GUARD.

From a Photograph.

The affair was engineered in Belgrade, and the bombs were manufactured by a Servian officer at the State Arsenal of Kragujevats. It was also rumoured by those who might be expected to know that the dreams of the blood-stained authorities in Belgrade are to unite Montenegro, a Slav nation speaking the Servian language, with Servia, and the idea was that if there were no member of the House of Petrovitch left alive the throne might possibly fall to the share of a Prince Karageorgevitch, one of the sons of Prince Nicholas’s eldest daughter.

The Crown Prince George of Servia is not exactly one’s ideal of a model ruler. This young gentleman, whose hobby is said to be to bury cats in the ground up to their necks and then stamp them to death, is more one’s idea of a youthful Nero or Caligula, and Heaven help the nation delivered over to his tender mercies. Before the trial, however, rumours were all that one heard; so everyone was on tiptoe with expectation, wondering what sensational revelations would come to light.

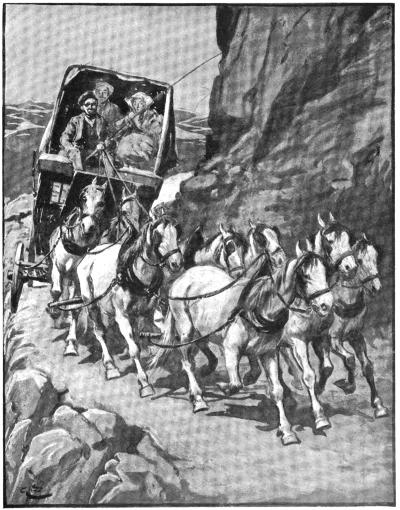

By great good luck we happened to arrive in Montenegro just a week before the trial began.[232] We steamed in one of the excellent boats of the Austrian Lloyd past the grey mountains of Istria and through the wonderful fjords of the Bocche di Cattaro till we cast anchor under the peak of Lovcen. In a victoria drawn by two tough little Dalmatian horses we climbed the mountain side in zigzags, persevering up the vast rocky wall till we found ourselves some four thousand feet above the sea below. I have neither time nor words to describe the view, a task which needs the pen of a poet like Prince Nicholas himself, but must dash on, like our game little horses, to Cetinje, down the steep sides of silver mountains, which gleam in the tropical sun without a vestige of green to relieve their Quaker-like hues.

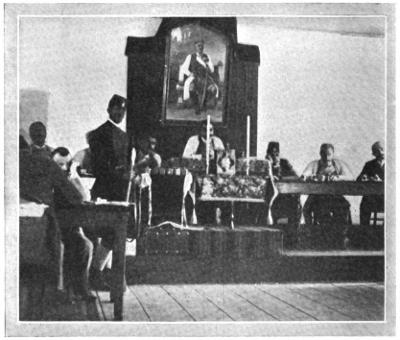

THE JUDGES IN THEIR GORGEOUS NATIONAL COSTUMES—TO THE RIGHT OF THE SOLDIER WILL BE SEEN THE BOMBS WHICH WERE AN IMPORTANT “EXHIBIT” IN THE TRIAL.

From a Photograph.

As a town Cetinje is not thrilling, but it lies in a lovely neighbourhood and is peopled with perhaps the most picturesque race in the world. For the Montenegrins are not only the most magnificent specimens of humanity in point of size, clad in gorgeous raiment which, I feel sure, Solomon in all his glory could not have beaten, but they have behind them a past which can scarcely be beaten by any fighting race on earth.

Some five hundred years ago the Turks defeated all South-Eastern Europe in the Battle of Kossovo, and Servia and Bulgaria entirely, and Roumania to a certain extent, fell under the sway of the Ottomans. Then, the story goes, the bravest and the noblest of those lands, disdaining to live beneath the banner of the Crescent, withdrew to the eyries of the Black Mountains, where, thanks partly to their valour and partly to the favourable position of the land (which is a natural fortress), they defied the Turks. They never intermarried with the inferior races, and so have preserved the magnificent physique and extraordinary distinction of bearing which strikes every stranger who visits Tsernagora. Indeed, if it comes to a question as to who should be the dominant race in Servia and Montenegro, it seems more fit[233] that Servia should be taken under the wing of a race which has done deeds all these centuries instead of merely talking.

We found at the hotel that half the newspapers of the Near East and Vienna were sending correspondents, and we therefore felt ourselves lucky in getting a room in the front looking down the main street, where everything in Cetinje happens, and where, towards sundown, when the siesta is over and the air becomes cool and pleasant, you may find anyone you want to see. Half-way down we saw a crowd of people in national costume (for in Cetinje, thanks to the Prince’s influence, it is universally worn) standing outside a house. “They are waiting to try and get a seat in court to-morrow,” I was told, “but only a score or so will succeed, for there are thirty-two prisoners, each one guarded by a soldier, besides all these journalists to be made room for.”

Through the good offices of the Prince’s secretary, to whom His Highness had confided us, we were provided with tickets, which was lucky for us, for when we arrived within sight of the court-house we found a cordon of soldiers guarding it. We were stopped and our passes examined before we were allowed to proceed. When we reached our destination, a long, low, grey stone building with the Montenegrin two-headed eagle over the door, an officer took us in hand and led us with ceremony to our places. I looked round me with great satisfaction from my red velvet arm-chair in the ranks of the Diplomatic Corps. Not only was I the only English person there save one, but I was the only woman in the whole place.

It was the most thrilling trial I have ever witnessed. At the top of the room, behind a long table beneath the picture of Prince Nicholas, sat the nine judges, all save one in the most gorgeous national costume: long coats of pale green cloth, heavily braided, with waistcoats of vivid carnation red, crossing over to one side and covered with beautiful gold embroidery. Baggy breeches of ultramarine blue and smart top-boots continued the gay effect, which was completed by a bulky sash of striped and gold silk wound round the waist, and containing an assortment of daggers and revolvers; for a good Montenegrin would as soon think of coming out without them as an Englishman without his collar.

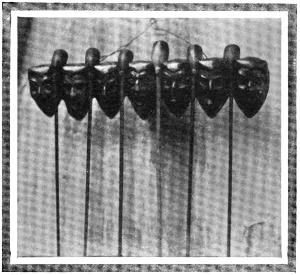

In the middle sat the President, a person of extreme distinction and great dignity, who conducted the proceedings in an irreproachable manner. A small table stood before him, on which a pair of high tapers were placed, and between them was a copy of the Gospels, bound in red velvet and gold metal-work, and a crucifix. On his left hand sat a Mohammedan judge, with red Turkish fez and simpler costume than that of the Montenegrins; and on his right the bombs were all set out on a little table as evidence, guarded by an immense soldier about six-foot-six in height and of a forbidding aspect. It gave one a certain creepy sensation to see, only a few feet away, enough of these infernal machines to send the whole of the court-house into the clouds, and to know that close by were thirty-two desperate men who would stick at no kind of devilry. The bombs were little square flasks of grey metal with screw tops, almost like the fittings of a common dressing-bag or luncheon hamper, and certainly did not betray by their appearance what terrible things they really were. For these particular bombs were manufactured in a very ingenious fashion, and were enough to make an Anarchist tear his hair with envy. At the foot of the table was the black bag in which the infernal machines had been smuggled over the frontier.

A story is told of the conspirator’s journey which brings a touch of comedy into the affair. When he passed through Austria he had the bag registered as luggage, for it was so heavy that he feared it might attract attention if placed in the rack. A mistake was made by the clerk and he was overcharged. The honest official discovered his mistake directly the train started, and telegraphed off to the junction to describe the man, giving orders that the money should be refunded. At the junction the conspirator was found, and the station-master came up to him to inquire if he had not registered a black bag. Overcome with terror and dismay, and thinking he was discovered, the man seized the bag and bolted, leaving the official greatly perturbed and convinced that he had to do with a madman.

The court-house itself was long, low, and white, with a blue ceiling and a boarded floor. A long table ran half-way down either side of the hall to accommodate the journalists, and half-a-dozen arm-chairs were arranged in a good position for the diplomatists. These were almost empty on the first day, and my next-door neighbour, a polite young Turkish attaché, considerately moved out of the way whenever he saw that I was trying to take a photograph. And, indeed, it was not the easiest task in the world to get pictures of the proceedings. The prisoners were a restless set of people, who fidgeted, sprang constantly to their feet, and interrupted the speakers in a very tantalizing way. As there was not very much light a fairly long exposure had to be given, and there were difficulties in propping the camera up satisfactorily and also in disguising my intentions as[234] much as possible. However, I had the satisfaction of knowing that mine were the only photographs taken, for the local photographer who had been commissioned by the authorities to take some pictures declined to try, owing to the obstacles.

The thirty-two prisoners, guarded by soldiers on either side, occupied benches all down the centre of the hall. Some of them were in European dress, thus differing from the majority of Montenegrins. Amongst them were all sorts and conditions of men, from peasants to ex-Ministers of the Crown. It is not often one finds a former Prime Minister, four ex-Ministers, three high State officials, and several Deputies all in one trial for high treason. As a rule, the accused were puny, furtive-looking striplings, a contrast to their stalwart compatriots; but their imprisonment of several months may have had something to do with this. Many were students who had gone to Belgrade to complete their studies and had there imbibed Anarchistic and revolutionary principles. The judge showed great tact and firmness in dealing with them.

THE CONSPIRATORS LISTENING TO THE READING OF THE INDICTMENT.

From a Photograph.

As the long indictment which contained all the particulars of the plot was being read out by the counsel for the Crown—a handsome man in full Montenegrin costume—first one prisoner and then another started from his seat, rudely interrupting and violently contradicting. A clamour then arose from the whole thirty-two. The judge expostulated, begged them to be reasonable, and finally touched a silver hand-bell. The soldiers pulled them down to their seats again, but seemed as gentle in their methods as policemen with Suffragettes. As names were mentioned now and again in the indictment, exclamations of derision and protest were heard from the prisoners. They next complained bitterly that they had no note-books or pencils with which to take down the points and prepare their defence, whereupon the President ordered that paper and pencils should be brought to them at once. The indictment was long, and it finally asked for the death penalty as punishment. At this loud clamours arose, and the excitement grew so intense that a nervous feeling communicated itself to the public. The President by this time despaired of keeping order, and directed that the prisoners should be taken back to their prisons. One alone remained, Raikovitch, the man who brought the bombs into Montenegro, and the principal prisoner.

Raikovitch was a rather good-looking young man, dark and sallow. He had a large, round nose, a round chin, and even his forehead seemed to bulge. But his black, beady eyes struck me as shifty, and he appeared somewhat ill at ease. In spite of his confident manner he would glance round at the pressmen’s table every few seconds to note what effect his defence was having on them. But he had an amazing fluency, and his story flowed on like a river. There was no bullying by Public Prosecutor or judges.

Every now and then the President, tapping his fingers with a pencil, would interrupt the prisoner with a short, sharp question, evidently very much to the point, and he pulled up the prisoner’s counsel very sharply on one occasion for attempting to prompt his client. Presently there was a small stir, for Raikovitch was heard to denounce Vukotic, the nephew of Princess Milena, Prince Nicholas’s wife, as having been in communication with and paid by the conspirators. No one seemed to know who would be accused next, and the Servian Minister, who was present, must have experienced feelings of uneasiness. Raikovitch was next led to the table to examine the black bag, to identify it as his[235] luggage, and acknowledged that those were the bombs he had brought into the country. His defence lasted for the rest of the day.

SOME OF THE AUDIENCE.

From a Photograph.

Next morning, when the prisoners were brought back, the sitting was even more agitated. The ex-Deputy Chulavitch was accused. He leapt to his feet, and in a voice of thunder shouted that he had been betrayed—he had been sold! Later on, however, he acknowledged that he had received thirteen napoleons for his help in the plot. Various other prisoners were accused, but all had answers and excuses at first. Some said they acted on behalf of others. Others said they had taken no active part, but had only known of the conspiracy. They would confess one day, and the next flatly deny everything they had said before. Later on in the trial, however, they found means of communicating with each other, and arranged on a line of common action.

INSIDE THE PRISON AT CETINJE—THE CELL DOORS ARE GENERALLY OPEN AND THE PRISONERS ARE ALLOWED TO TAKE EXERCISE IN THE YARD.

From a Photograph.

Few documents could be produced in evidence against the accused, but a great sensation was caused by the reading of a letter from a Montenegrin, now an officer in the Servian army, to his brother. In it he promised both moral and material support for the plot and enclosed a thousand francs from King Peter. At this there was profound silence in the court, and a deep impression was left on the minds of the public.

A student named Voivoditch then gave the details of the plot. He had brought bombs from Belgrade with the express intention of killing Prince Nicholas and Prince Mirko. It was arranged that various Government offices were to be set on fire and in the confusion bombs were to be thrown against the palace, a small building which would be easily destroyed. Then, acting on the lines of the Servian regicides, the Ministers and principal people in Cetinje were to be assassinated and their houses wrecked.

The trial lasted several weeks, for with fifty persons accused and thirty-two prisoners to examine and hear, things cannot be done in a moment. But the principal witness against the prisoners was a certain Nastitch, a Servian journalist from Serajevo. He brought the gravest charges against the Servian Government. As he had been present at the manufacture of the bombs he said that he was entitled to speak with some authority. Last year he was sent to Kragujevats State Arsenal by a Captain Nenadovitch, cousin of King Peter, who gave him a letter to the Commander from the Servian Crown Prince. In this letter the Prince begged the Commander to allow Nastitch to stay ten days in the arsenal whilst the bombs were being made. They[236] were then given to him to be consigned to Captain Nenadovitch in Belgrade, who told him that they were to be employed in a patriotic enterprise. A little later he was informed that the police had sequestrated the bombs, as Pasitch, the Prime Minister, had been informed of his stay in Kragujevats.

Nastitch then began to perceive that some mischief was being hatched, and that Nenadovitch was trying to throw dust into his eyes. He put two and two together and got a shrewd suspicion of what was really up. So he crossed over to Semlin, in Hungary, from Belgrade, as no letters are safe from being opened by the Servian secret police, and communicated with Tomanovitch, Prime Minister of Montenegro. He asserted that he did not fear denials, since he had documents to prove the truth of what he said. He next produced specifications of the bombs, and then asked the judges to have those in their possession examined to see whether they were not identical. At the conclusion of his evidence Nastitch was applauded loudly by the public, and was cheered as he left the court.

There were several rather interesting little touches in the evidence of other prisoners. One was found to be sending secret messages to a friend written in microscopic handwriting under the postage-stamps of the letter. Under one was written: “Is it true that Stevo has confessed everything?” Stevo being Raikovitch.

Raikovitch was brought up a second time and confronted with various prisoners, who accused him of inventing the whole plot. He met every accusation with complete calm and cynicism. Indeed, it seemed impossible to disturb his sang-froid. He proclaimed aloud that he would laugh even when climbing the steps of the gallows. He was the type of the complete poseur, considering himself the centre of attraction, choosing his language with the utmost care, and throwing himself into appropriate attitudes. When asked if he was not a Socialist, he replied, “Of course I am a Socialist. I must confess, however, that I am not absolutely sure what Socialism is!”

THE GOVERNOR OF THE PRISON (ON RIGHT) AND A MONTENEGRIN.

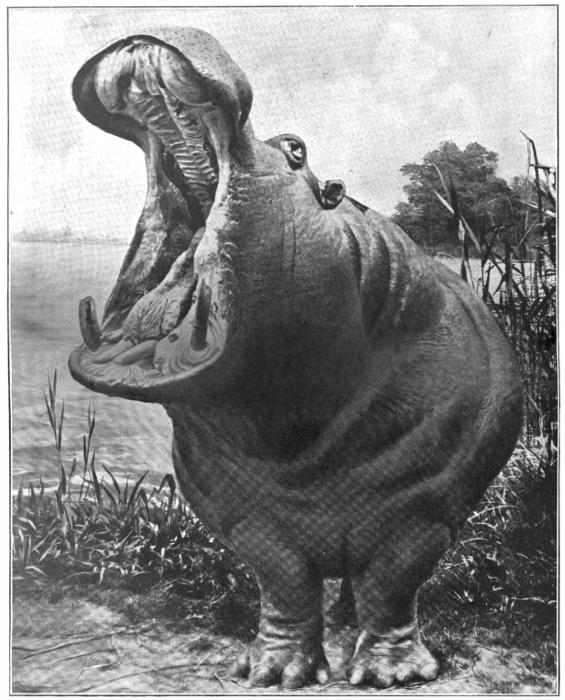

From a Photograph.